Exhibition dates: 28th May – 1st September 2013

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Five Day Forecast [Prévisions à cinq jours]' 1988 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Five Day Forecast (Prévisions à cinq jours)' 1988](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_02-web.jpg)

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Five Day Forecast (Prévisions à cinq jours)

1988

5 gelatin silver prints in a frame, 15 plates engraved plastic

24 1/2 x 97 in (62.2 x 246.4cm) overall

Lillian and Billy Mauer Collection

© Lorna Simpson

A fascinating practice!

Identity, memory, gender, representation, the body, the subject, felt, text, images, video, gesture, reenactment, concept and performance, all woven together seamlessly like a good wig made of human hair…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Jeu de Paume for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Stereo Styles [Styles stéréo]' 1988 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Stereo Styles (Styles stéréo)' 1988](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_15-web.jpg)

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Stereo Styles (Styles stéréo)

1988

10 dye-diffusion black-and-white Polaroid prints, 10 engraved plastic plaques

57 3/4 x 125 1/4 x 1 3/8 in (146.7 x 318.1 x 3.5cm) overall

Collection of Melva Bucksbaum and Raymond Learsy

© Lorna Simpson

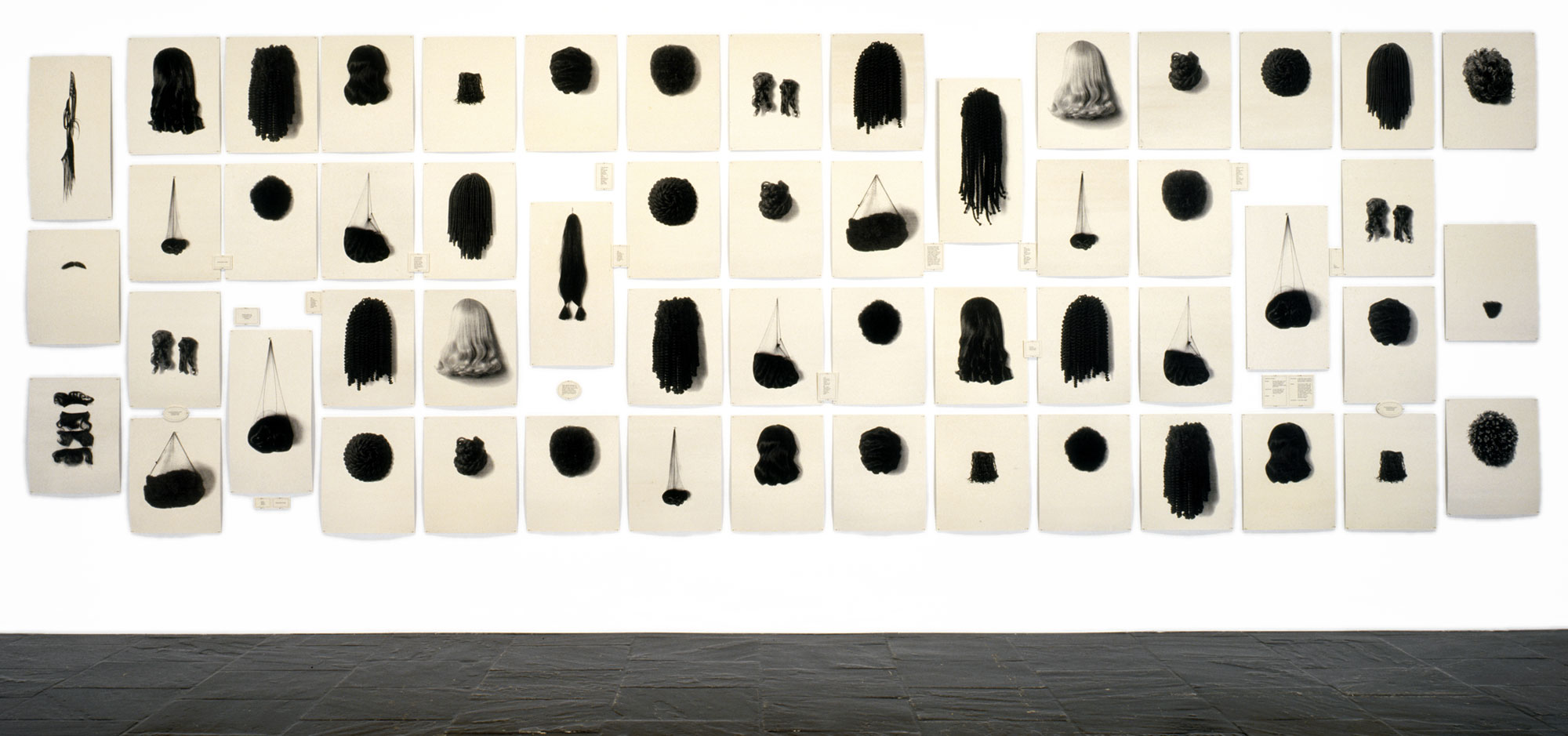

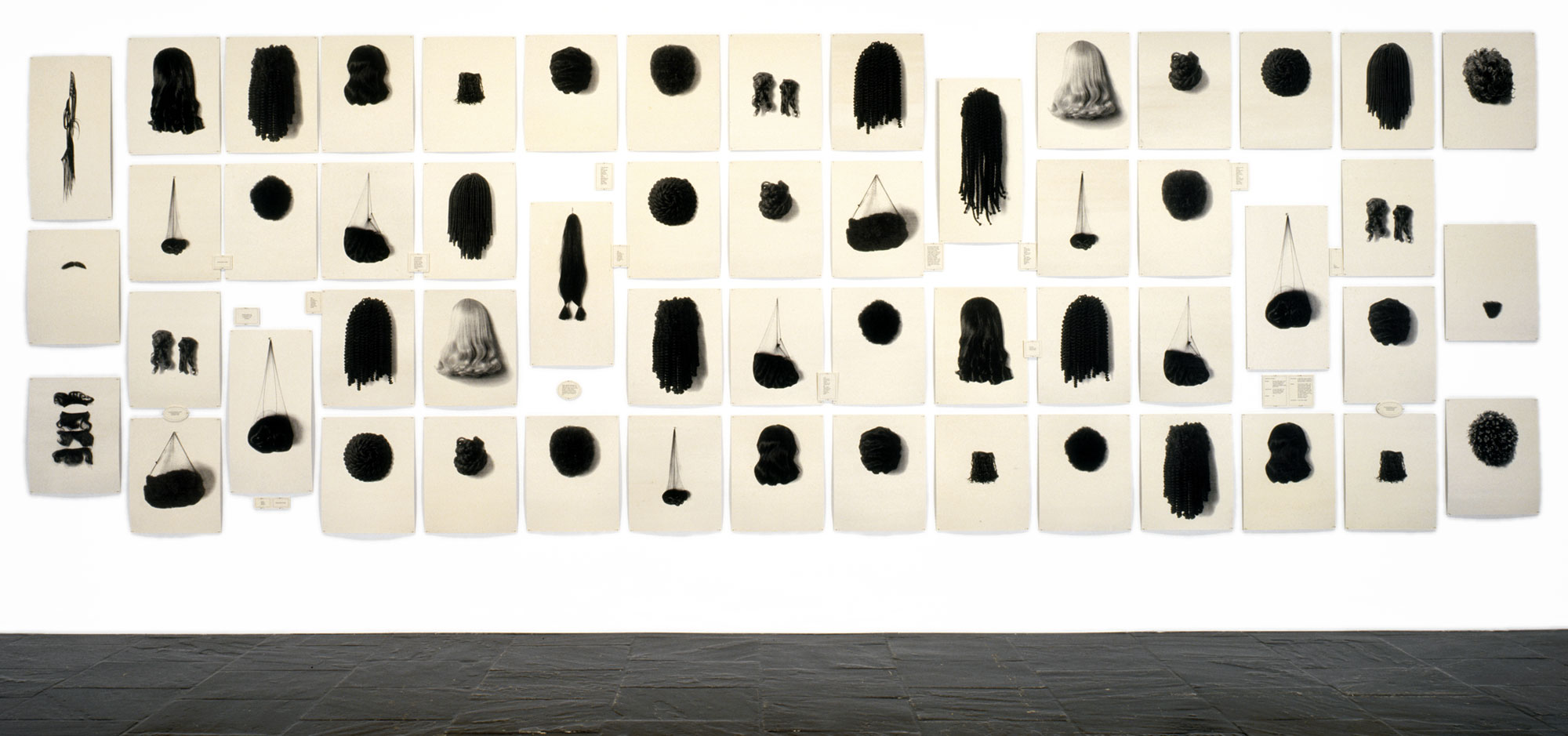

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Wigs II

1994-2006

Serigraph on 71 felt panels (images and text)

98 x 265 in (248.9 x 673.1cm) overall

Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels

© Lorna Simpson

Lorna Simpson surprised her audiences in 1994 when she began to print her photographs on felt, inspired by its materiality after seeing an exhibition of the sculpture of Joseph Beuys in Paris “where the piano and walls were covered for a beautiful installation.” Simpson questioned whether the medium might be appropriate in a far different way for her work given the perspective afforded her by the passage of time. With the felt pieces, Simpson turned away from photography’s traditional paper support, magnified the already larger-than-life-size of the images within her large photo-text pieces to extremely large-scale multi-part works, and, most critically, absented the figure, in particular, the black woman in a white shift facing away from the camera for which she had received critical acclaim.

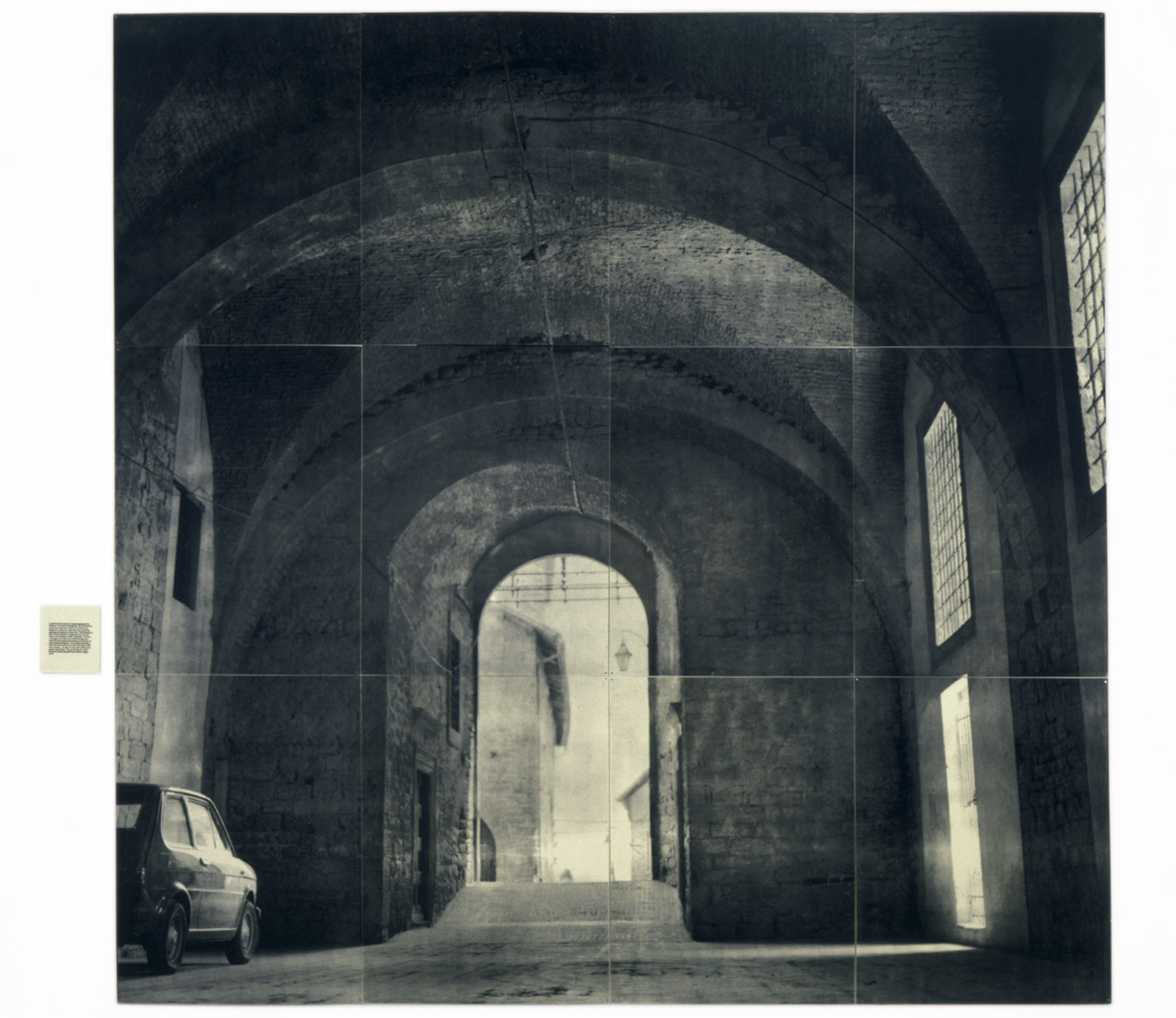

Ever-present, nevertheless, were her thematic concerns. The first felts offered surrogates for the body in a taxonomy of her own photographs of Wigs, with voicings “in and around gender,” and expanded upon the investigation of the role of coiffure in the construction of identity in Simpson’s photo-texts (such as Stereo Styles, Gallery 1). In the mid-1990s, such felts were succeeded by a series of photographs of interior and exterior scenes that were accompanied by long text passages printed on separate small felts. In these works the figure was replaced, as Okwui Enwezor wrote, “by the rumour of the body.”

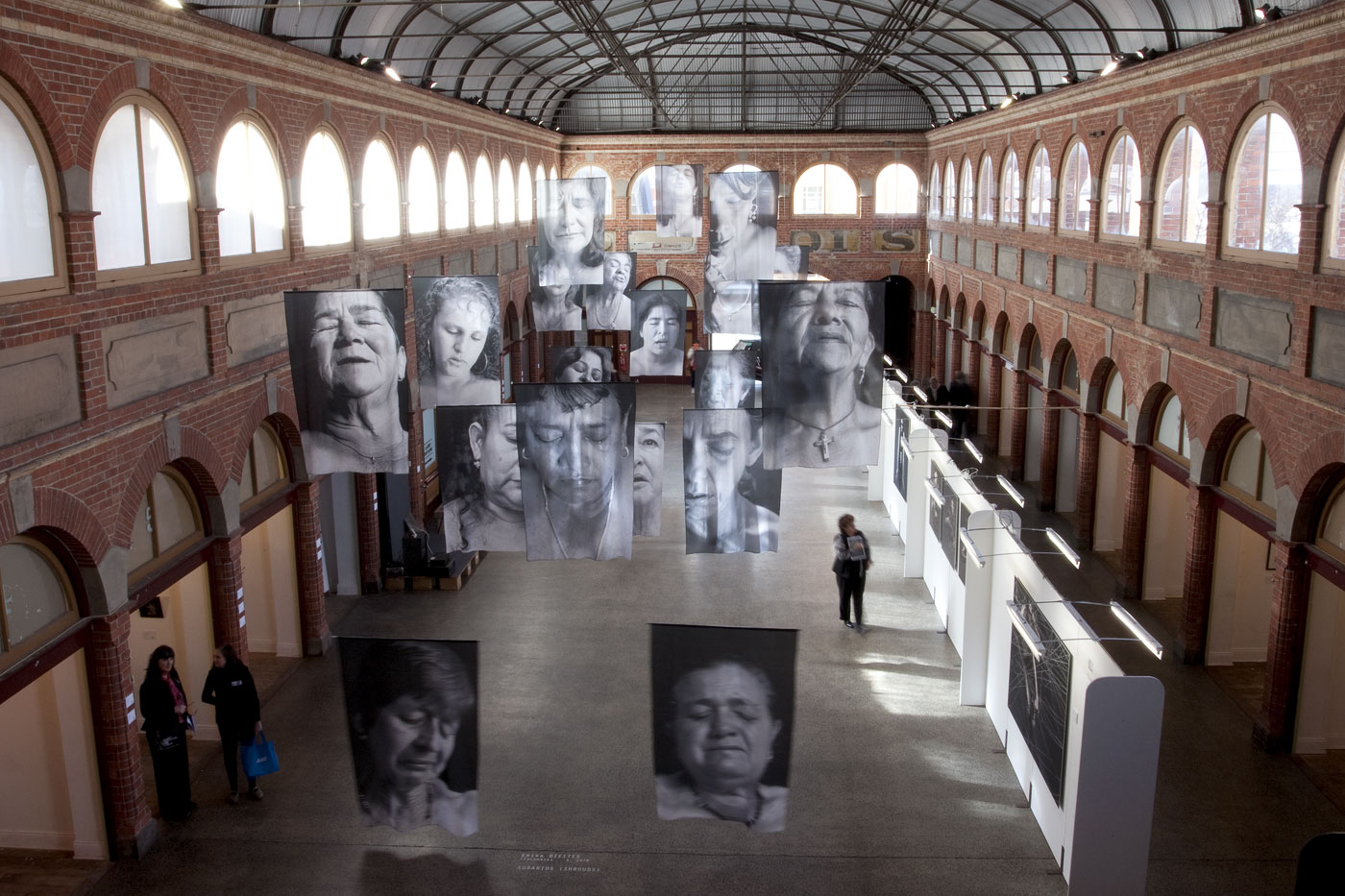

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Please remind me of who I am (detail)

2009

50 found photo booth portraits, 50 ink drawings on paper, 100 bronze elements

Overall installation dimensions variable

Collection of Isabelle and Charles Berkovic

© Lorna Simpson

For each multi-part photo-booth piece, Simpson sets in bronze frames these small inexpensive shots as well as her drawings of selected details of the photographs. Self-styled and performed, these photographs were used for a variety of purposes by their now anonymous sitters, ranging from sober, formal ID photos to glamorous, often theatrically playful mementos. Encompassing photo booth shots of different sizes from the 1920s to the 1970s (a few in colour), Simpson’s constellations of many images for each work offer a collective portrait of self-portraiture (Gather, 2009) and continue her ongoing explorations of identity and memory, explicitly phrased in the title of one of them: Please remind me of who I am (2009).

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Waterbearer [Porteuse d'eau]' 1986 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Waterbearer [Porteuse d'eau]' 1986](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lornasimpson_004-web.jpg)

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Waterbearer (Porteuse d’eau)

1986

Gelatin silver print, vinyl letters

59 x 80 x 2 1/2 in (149.9 x 203.2 x 5.7cm) overall

Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris / Brussels

© Lorna Simpson

Waterbearer shows a woman from the back, pouring water from an elegant silvery metallic pitcher in one hand and from an inexpensive plastic jug in the other, echoing art historical renderings of women at wells or in the domestic settings of Dutch still-life paintings. As if balancing the scales of justice, this figure also symbolically offers disjunctions of means and class. In the accompanying text, Simpson explicitly addresses memory and the agency of speakers: “She saw him disappear by the river, they asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory.”

For her first European retrospective, the Jeu de Paume presents thirty years of Lorna Simpson’s work. For this Afro-American artist, born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1960, the synthesis between image and text is profound and intimate. If one were to consider Lorna Simpson as a writer, the textual element of her works could have an autonomous life as prose poems, very short stories or fragments of scripts. And yet, her texts are inseparable from her images; there is a dynamic between the two that is both fragile and energising, which links them unfailingly. Lorna Simpson became known in the 1980s and 90s for her photographs and films that shook up the conventions of gender, identity, culture and memory.

Throughout her work, the artist tackles the complicated representation of the black body, using different media, while her texts add a significance that always remains open to the spectator’s imagination. In her recent work, Lorna Simpson has integrated archive images, which she reinvents by positioning herself in them as subject. As the artist underlines: “The theme I turn to most often is memory. But beyond this subject, the underlying thread is my relationship to text and ideas about representation.” (Lorna Simpson)

This retrospective reveals the continuity in her conceptual and performative research. In her works linking photography and text, as well as in her video installations, she integrates – while continually shaking them up – the genres of fixed and moving images, using them to ask questions about identity, history, reality and fiction. She introduces complexity through her use of photography and film, in her exploitation of found objects, in the processes she develops to take on the challenges she sets herself and to spectators.

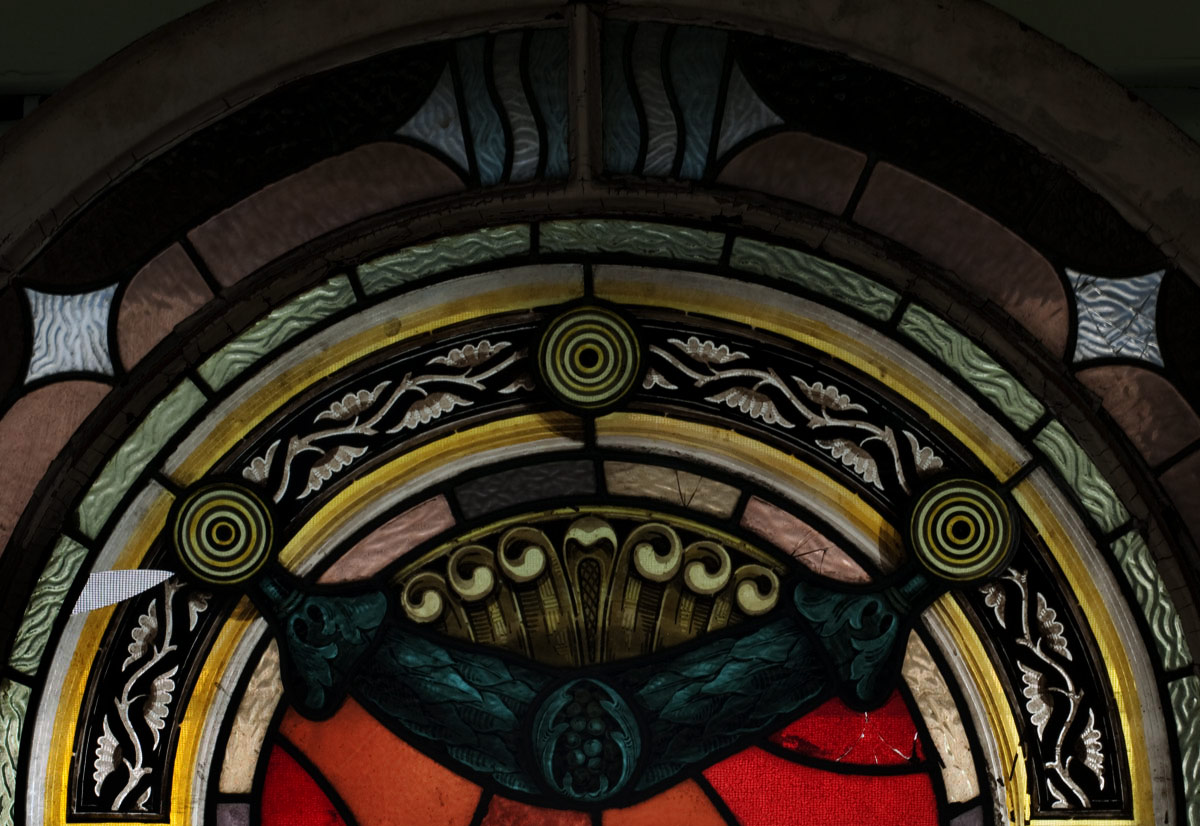

The exhibition gathers her large format photo-texts of the mid 1980s, which brought her to the attention of the critics (Gestures / Reenactments, Waterbearer, Stereo Styles), her work in screenprints on felt panels since the 1990s (Wigs, The Car, The Staircase, Day Time, Day Time (gold), Chandelier), a group of drawings (Gold Headed, 2013), and also her “Photo Booths,” ensembles of found photos and drawings (Gather, Please remind me of who I am…). The exhibition is also an opportunity to discover her video installations: multivalent narratives that question the way in which experience is created and perceived more or less falsely (Cloudscape, 2004, Momentum, 2010), among them, Playing Chess, a new video installation made especially for the occasion.

About the exhibition

Joan Simon

In her critically acclaimed body of work spanning more than thirty years, Lorna Simpson questions identity and memory, gender and history, fact and fiction, playing eye and ear in tandem if not in synchrony to prompt consideration of how meaning is constructed. That she has often described herself as an observer and a listener informs an understanding of both her approach and her subjects. In her earliest black-and-white documentary street photographs (1978-1980), Simpson isolated gestures that bespoke an intimacy between those framed in her viewfinder, recording what was less a decisive moment than one of coming into relation. Some of these photographs seem to capture crossed glances, pauses in an ongoing conversation. Others are glimpses of occasions, transitional events identifiable by a white confirmation or wedding dress, which convey a sense of palpable silence in exchanges between people just out of earshot.

When Simpson began to stage her own photographs in 1985 and to write accompanying texts, she came in closer. She allowed us to see a carefully framed black body, abstracted in gesture and in white clothing, yet also permitted us to read seemingly overheard comments that redirected and recomplicated the view. While her images captured gestures, her narratives imbued these images frozen in a never-changing present with memory, a past. The title of her first photo-text work, made in 1985, and of the exhibition of that year in which it was first exhibited was Gestures / Reenactments, and one can argue that all Simpson’s work is built on the juxtaposition of gestures and reenactments, creating meaning in the resonant gap between the two. It is a gap that invites the viewer / reader to enter, all the while requiring an active reckoning with some inalienable truths: seeing is not necessarily believing, and what we might see is altered not only by our individual experiences and assumptions but also, critically, by what we might hear.

The exhibition

Whether for still or moving picture productions, Lorna Simpson (b. 1960) uses her camera as catalyst to question identity and gender, genres and history, race and class, fact and fiction, memory and meanings. Assumptions of photographic “truth” are challenged and qualified – indeed redirected – by the images she creates that are inseparable from the texts she writes to accompany them, by the soundings she chooses for videos, or by her pairings of vintage photographs with newly made renderings. The Jeu de Paume presents lorna Simpson’s first large-scale exhibition in Europe beginning with her earliest photo-text pieces of the 1980s through her newest video installation, Chess, 2013, which makes its debut in Paris.

Works in the exhibition show the artist drawing on traditional photo techniques such as gelatin silver prints in an intimate synthesis with speakerly texts (Gallery 1). They also show Simpson’s creation of new combines, among them serigraphs on felt with writings and images invoking film noir (Gallery 2), a video installation of three projections based on historic photographs and her own prior still photos (Gallery 3), constellations of recuperated photo-booth photos with her drawings isolating details from them as well as vintage photographs together with those re-staged by the artist (Gallery 4), and a video focusing on performance as well as time itself and its reversal (Gallery 5).

The exhibition’s parcours [route] reveals turning points in Simpson’s oeuvre as well as thematic continuities. The earliest pieces in the show are Simpson’s performative proto-cinematic photo-texts, beginning with the 1985 Gestures/ Reeactments, a title literally evocative of the work’s visual / verbal aspect while also paradigmatically descriptive of what would be her conceptual practice for the next three decades. Simpson herself makes a rare appearance in her work in two related pieces in the show: the 2009 epic still photo work 1957-2009 (Gallery 4), for which the artist re-enacted scenes from vintage photos, and Chess, 2013, (Gallery 3), which features re-enactments of some of the same photos.

.

Gallery 1 introduces the artist’s signature, indeed iconic early images of the 1980s – a black figure in white clothing, face turned away from the camera or cropped out of the frame – accompanied by precisely crafted, allusive texts that recomplicate what is seen by what is heard in these voicings. The intention to deny a view of a face, as Simpson says, “was related to the idea that the one thing that people gravitate to in photography is the face and reading the expression and what that says about the person pictured, an emotional state, who they are, what they look like, deciphering and measuring. Who is being pictured, what is actually the subject? Photographing from the back was a way to get viewers’ attention as well as to consciously withdraw what they might expect to see.”

The performative photo-text works in Gallery 1 are Gestures / Reenactments, 1985 (created as part of her thesis project for her MFA at the University of California, San Diego), Waterbearer and Twenty Questions (A Sampler) (the first works that Simpson made when she moved to New York in 1986), as well as Five Day Forecast, 1988, and Stereo Styles, 1988. Beginning with Waterbearer, all of these except Gestures / Reenactments (which features a black male) show a black female in a white shift played by artist Alva Rogers, who was often mistaken for Simpson herself.

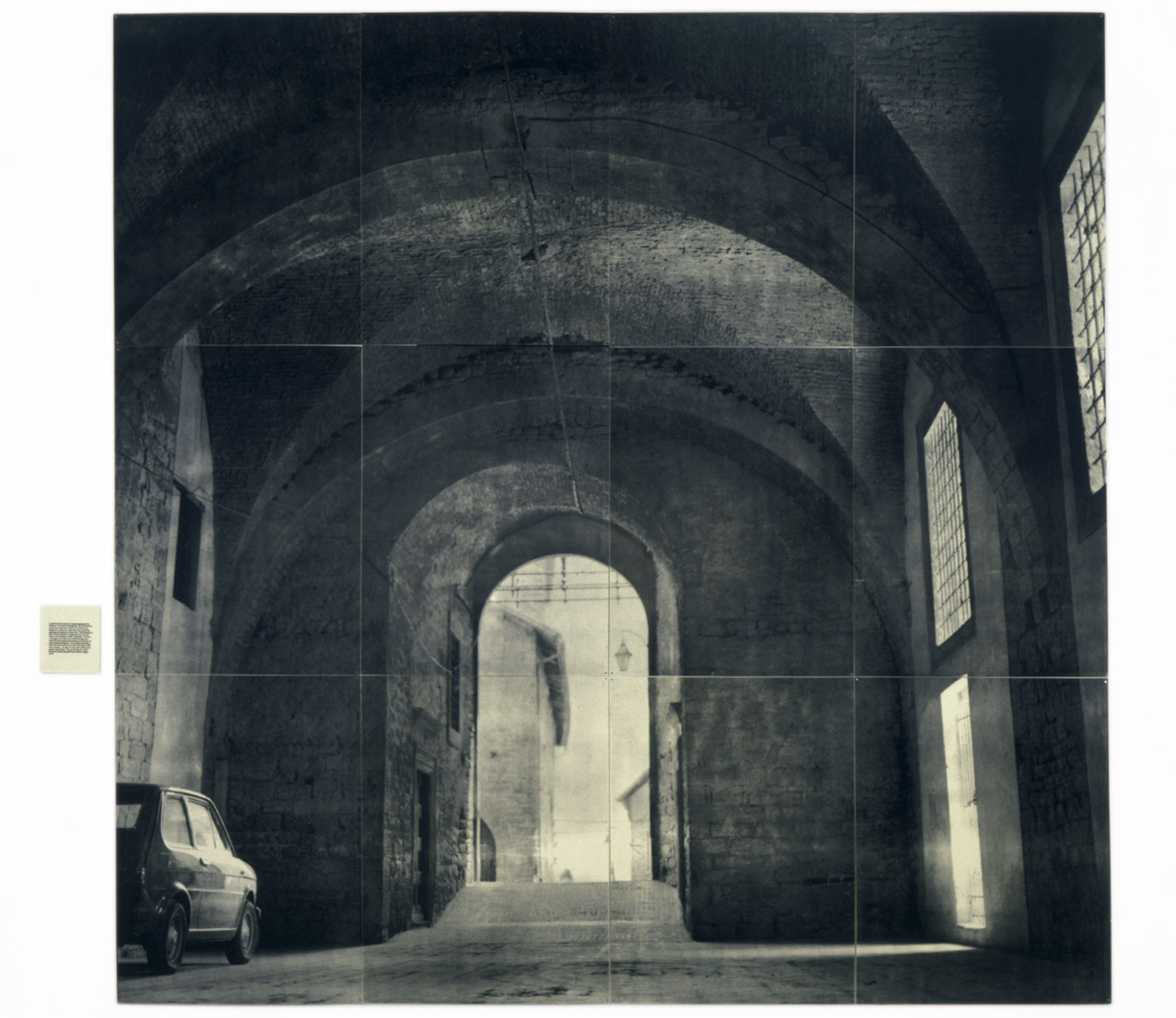

Gallery 2 marks important changes the artist made during the ’90s, most notably Simpson’s surprising shift to printing her photographs on felt and absenting the human figure. At first she used surrogates for the body, seen in the many and various wigs she photographed and which she accompanied with texts that continued to address ideas of identity and gender (Wigs, 1994-2006). She used photographs taken during her travels for the next series of felt works, which were interior and exterior scenes (The Car, 1995, The Rock, 1995, The Staircase, 1998) that in both imagery and texts invoked film noir. These works led almost inevitably to the start of Simpson’s film and video work in 1997. (Her earliest photo-texts will be recognised by the viewer as proto-cinematic with their multiple frames and conversational voices.)

This gallery also reveals how Simpson continues to use her felt medium and returns to her own archive of images as well as found objects. Three related works, though no longer using text, nevertheless “comment” on each other: a video of a performance (Momentum, 2010) inspired by an early 1970s performance at Lincoln Center generated felt works based on vintage photographs of this famous New York theatre – Chandelier, 2011, Daytime, 2011, and Daytime (gold), 2011 – as well as the Gold Headed (2013) drawings, based on the dancers costumed head to foot in gold. Drawings are perhaps the least known medium in Simpson’s practice, and while they reveal the fluid gestures of her hand, visitors will recognise in these gold heads turned from the viewer an echo of the position of the figures in Gallery 1.

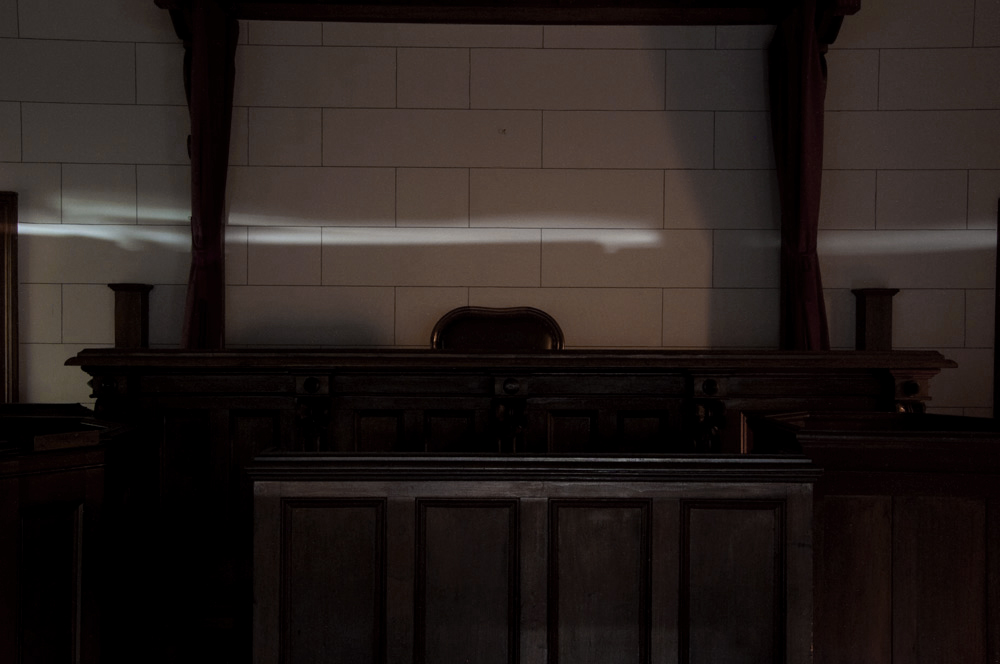

Gallery 3 is devoted to Simpson’s newest video, Chess, 2013, which is based on historic photos as well as her own earlier photographic piece, 1957-2009 (Gallery 4), in which she restaged found vintage photographs. Chess and 1957-2009 mark the rare instances in which Simpson has herself appeared in her work.

Gallery 4 presents reenactments that use quotidian photographic genres to explore constructions of identity and that offer a collective portrait of photographic portraiture over time. All of the works in this gallery are based on found photographs Simpson purchased on eBay and each depicts anonymous subjects performing for the camera. 1957-2009 is based on photographs in a vintage album; Gather and Please remind me of who I am are constellations of bronze-framed found photo-booth images (from the 1920s to the 1970s) accompanied by Simpson’s similarly framed drawings of details from the photographs.

Gallery 5 offers Simpson’s video installation Cloudscape, 2004, which focuses on performance itself and the soundings of a body, that of artist Terry Adkins whistling a hymn. Embodying memory (and the distortions of it) as she did in her earliest photo-works but playing also with the particularities of video, Simpson loops the video to play forward and backward. In this process a new melody is created even as the stationary figure appears same but different.

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess [Échecs]' 2013 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess (Échecs)' 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_08-web.jpg)

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Chess (Échecs)

2013

HD video installation with three projections, black & white, sound

10:25 minutes (loop)

Score and performance by Jason Moran

Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels

© Lorna Simpson

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess [Échecs]' 2013 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess (Échecs)' 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_07-web.jpg)

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Chess (Échecs)

2013

HD video installation with three projections, black & white, sound

10:25 minutes (loop)

Score and performance by Jason Moran

Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels

© Lorna Simpson

“Gestures” and “reenactments” could both be described as the underlying methods of Simpson’s practice for the decades to follow. Whether working with photographs she herself staged, found photographs, or archival film footage, her images captured gestures (as in her earliest documentary photographs of 1978-1980) while her series of multiple images, accompanied by texts, proposed simultaneous (if not synchronous) reenactments. This method also applied to works in which she replicated found images, whether turning images from her films into drawings, or using herself to re-play roles depicted by anonymous figures she had discovered in vintage photographs, either for staged still photographs (as in 1957-2009, 2009), or for moving pictures (as in the video Chess, 2013).

Chess, 2013, Simpson’s video installation made expressly for this exhibition, draws on images from 1957-2009, her still photograph ensemble of 2009 (on view in Gallery 4). For both, in a departure from her earlier videos and prior staged photographs, Simpson herself performs. In 1957-2009, by reenacting scenes from found vintage prints with which they are shown, Simpson is “mirroring both the male and the female character, in dress, pose, expression, and setting. When I would mention the idea of working with mirrors [for the Chess video] people would often mention the famous portraits of Picasso and Picabia taken at a photo studio in New York by an anonymous photographer who placed the subject at a table in front of two mirrored panels at seventy-degree angles. The result is a five-way portrait that includes views that are not symmetrical and that offer slightly different angles: a surrealist trope of trick photography.”

Though the artist first rejected the idea of working with the mirror device used in these historic portraits, which she had seen many times, she decided to take it on fully and reconstruct it in her studio for this new video project after art historian and sociologist Sarah Thornton sent her “a beautiful image of an unknown man of African descent in a white straw hat, which had been in an exhibition at MoMA [catalogue page 61]. It was a five-way portrait probably taken by the same photographer who had taken the portraits of Picasso and Picabia. I could no longer resist or dismiss this idea. I felt that it was demanding my attention.”

Shot in Simpson’s studio over the weekend of December 8, 2012, Chess is comprised of three video projections. For two of them Simpson again plays both female and male chess-players, and with the help of makeup and hair assistants, she now allows her characters to age. The third projection shows pianist Jason Moran performing his improvised score for this project, which was inspired by discussions between artist and composer about “mirroring in music,” especially “in the work of musician Cecil Taylor, who employs mirroring in his compositions.”

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

The Car

1995

Serigraph on 12 felt panels with felt text panel

102 x 104 in (259.1 x 264.2cm)

Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels

© Lorna Simpson

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

The Car (detail)

1995

Serigraph on 12 felt panels with felt text panel

102 x 104 in (259.1 x 264.2cm)

Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels

© Lorna Simpson

Lorna Simpson

1957-2009 (detail)

2009

299 gelatin silver prints, framed

5 x 5 in. (12.7 x 12.7cm) each (image size)

Rennie Collection, Vancouver

© Lorna Simpson

While collecting photo booth images on eBay, Simpson found the first of the vintage photographs – a woman in a tight sweater-dress leaning on a car – that would generate 1957–2009 (2009). The artist subsequently bought the entire album and in 2009 restaged these photographs of an anonymous black woman and sometimes a man performing for their camera between June and August 1957 in Los Angeles, which they may have done in the hope of gaining movie work in Hollywood or as an independent project of self-invention. For 1957-2009, Simpson reenacted both female and male roles, and the 299 images are comprised of both the 1957 originals and Simpson’s 2009 remakes. Simpson again reenacted a selection of these vignettes for her video installation Chess, 2013.

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Cloudscape [Paysage nuageux]' 2004 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Cloudscape (Paysage nuageux)' 2004](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_10-web.jpg?w=650&h=645)

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Cloudscape (Paysage nuageux)

2004

Video projection, black & white, sound

3:00 minutes (loop)

Centre national des arts plastiques, purchase in 2005

Photo courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels

© Lorna Simpson/Centre national des arts plastiques

Lorna Simpson’s video installation Cloudscape (2004) isolates one man, Simpson’s friend, the artist and musician Terry Adkins, in a dark room, spotlighted as he whistles a hymn and is enveloped in fog. Focusing on the ephemerality of performance, the artist employs a technique afforded by her medium to play with time as well. Simpson runs the video forward and then also backward in a continuous loop, creating new visual and oral / aural permutations of gesture and reenactment. In the reversal of the time sequence, the image remains somewhat familiar while the tune turns into something else, a different melody.

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Momentum

2010

HD video, color, sound

6:56 minutes

Courtesy the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris/Brussels

© Lorna Simpson

As Simpson explored new mediums, such as film and video starting in 1997 or found photographs in the late 1990s, she continued to work in parallel with her felt serigraphs. In this gallery are three related sets of works that, unlike her earlier photo-text pieces, are all based on a personal memory: performing as a youngster, age 12, in gold costume, wig, and body paint in a ballet recital at New York’s Lincoln Center. Simpson re-staged such a performance for her video Momentum (2010).

Jeu de Paume

1, Place de la Concorde

75008 Paris

métro Concorde

Phone: 01 47 03 12 50

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday: 12am – 8pm

Saturday and Sunday: 11am – 7pm

Closed Monday

Jeu de Paume website

Lorna Simpson website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Five Day Forecast [Prévisions à cinq jours]' 1988 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Five Day Forecast (Prévisions à cinq jours)' 1988](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_02-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Stereo Styles [Styles stéréo]' 1988 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Stereo Styles (Styles stéréo)' 1988](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_15-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Waterbearer [Porteuse d'eau]' 1986 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Waterbearer [Porteuse d'eau]' 1986](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lornasimpson_004-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess [Échecs]' 2013 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess (Échecs)' 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_08-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess [Échecs]' 2013 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess (Échecs)' 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_07-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Cloudscape [Paysage nuageux]' 2004 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Cloudscape (Paysage nuageux)' 2004](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_10-web.jpg?w=650&h=645)

![Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Man on girders, Empire State Building]' c. 1931 Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Man on girders, Empire State Building]' c. 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/man-on-girders-web.jpg?w=650&h=838)

![Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Steelworker touching the tip of the Chrysler Building]' c. 1931 Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Steelworker touching the tip of the Chrysler Building]' c. 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/steelworker-touching-the-tip-web.jpg?w=650&h=930)

You must be logged in to post a comment.