Exhibition dates: 5th November 2023 – 31st March 2024

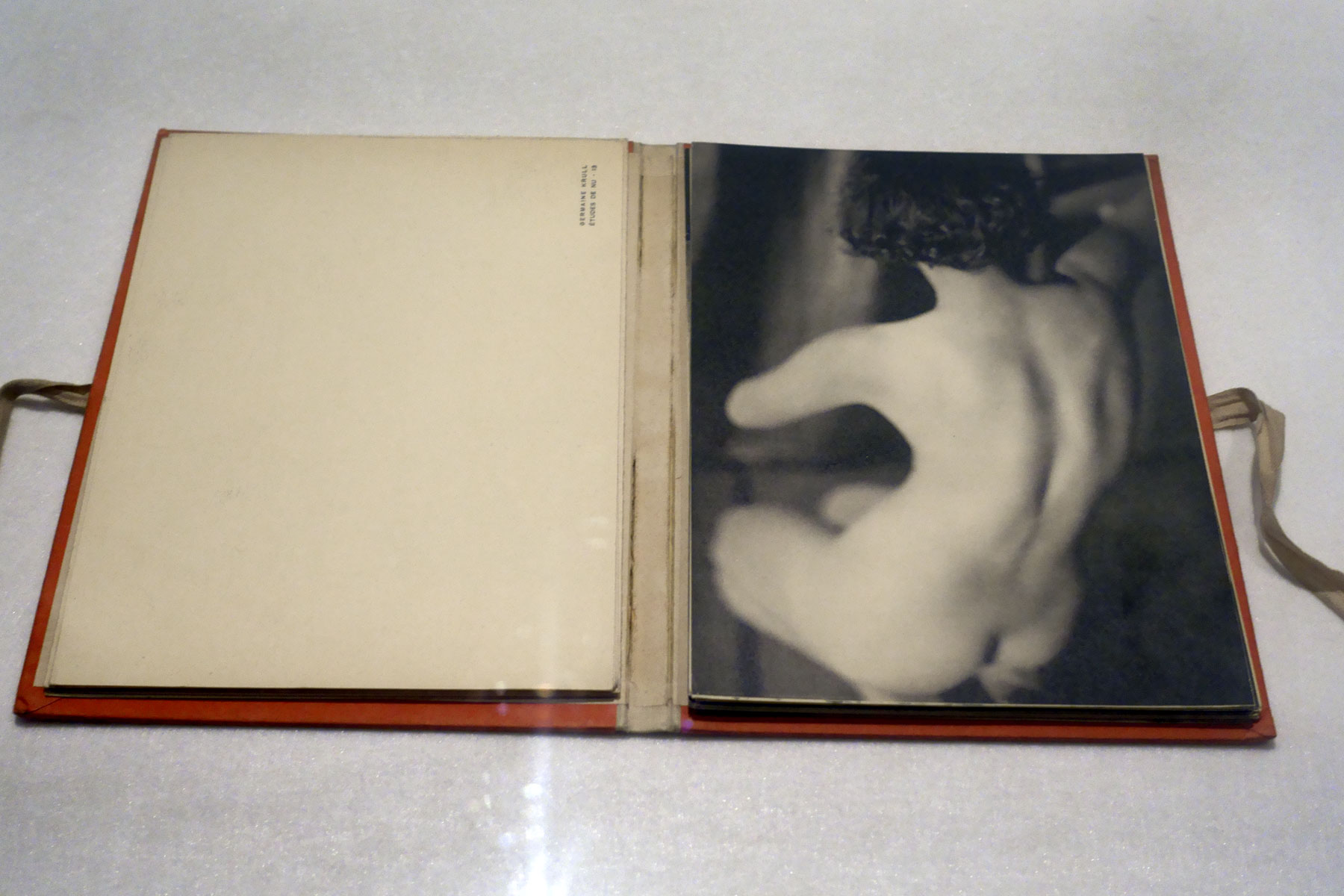

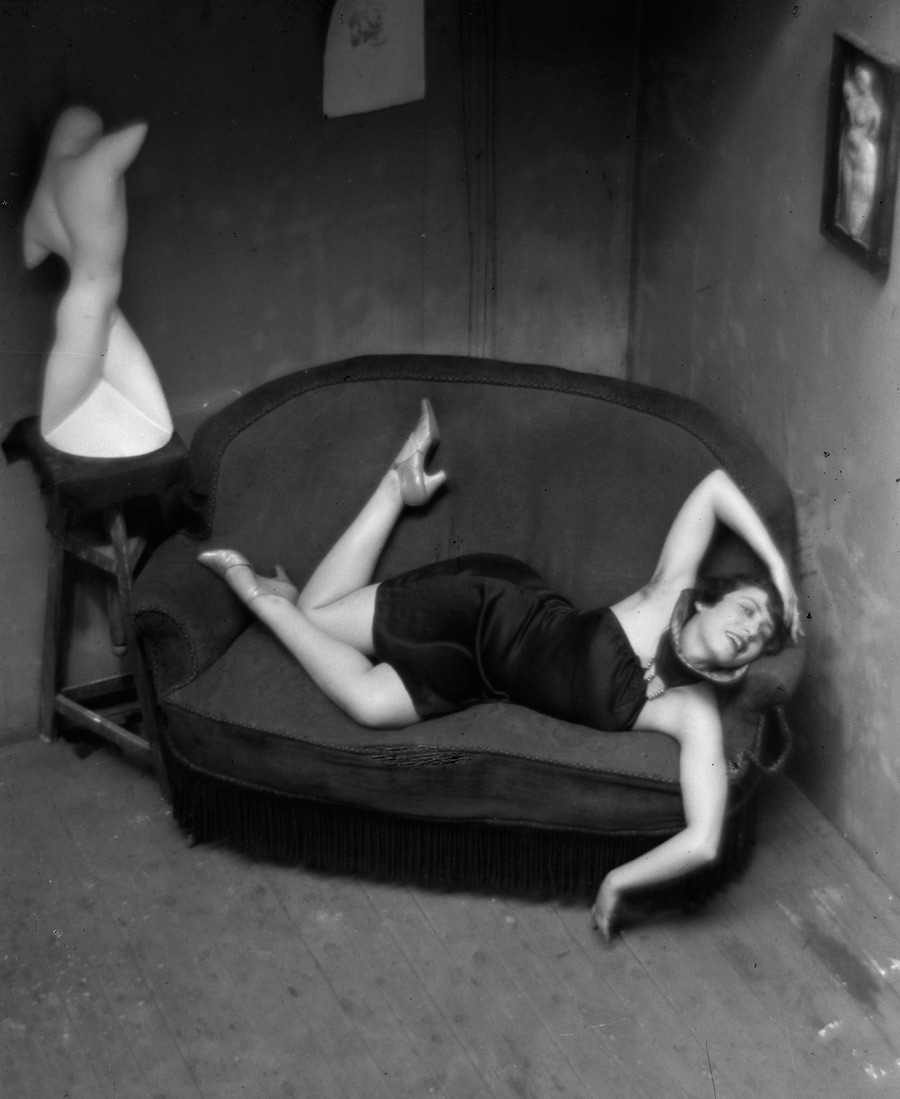

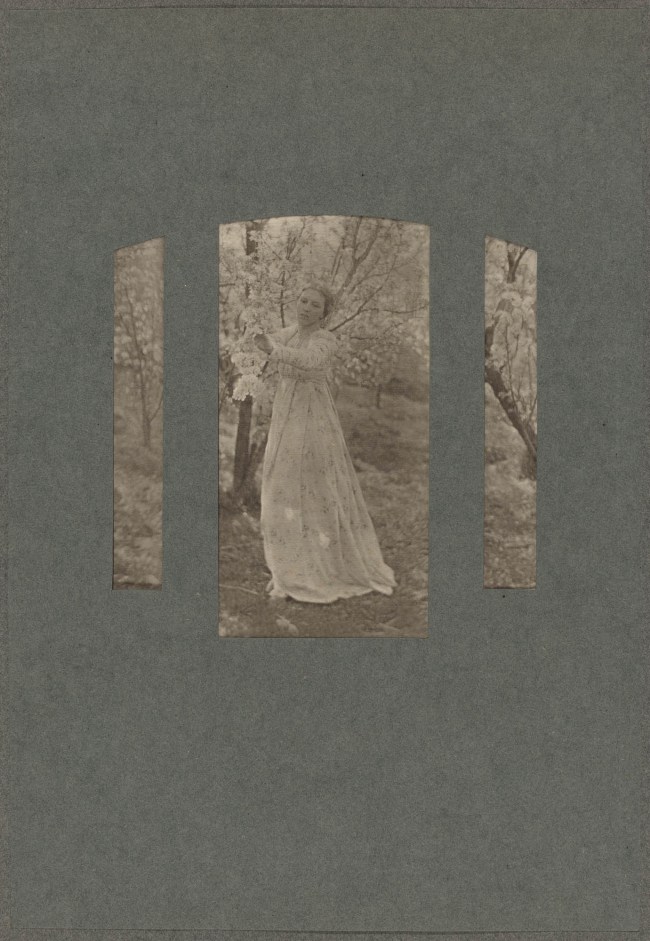

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Untitled (La Estrellita, “Spanish” Dancer), San Francisco, California

1919

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19.7 x 14.6cm (7 3/4 x 5 3/4 in.)

Mat: 16 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 17 1/4 x 15 1/4 in.

Collection of the Oakland Museum of California, Gift of Estrellita Jones

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

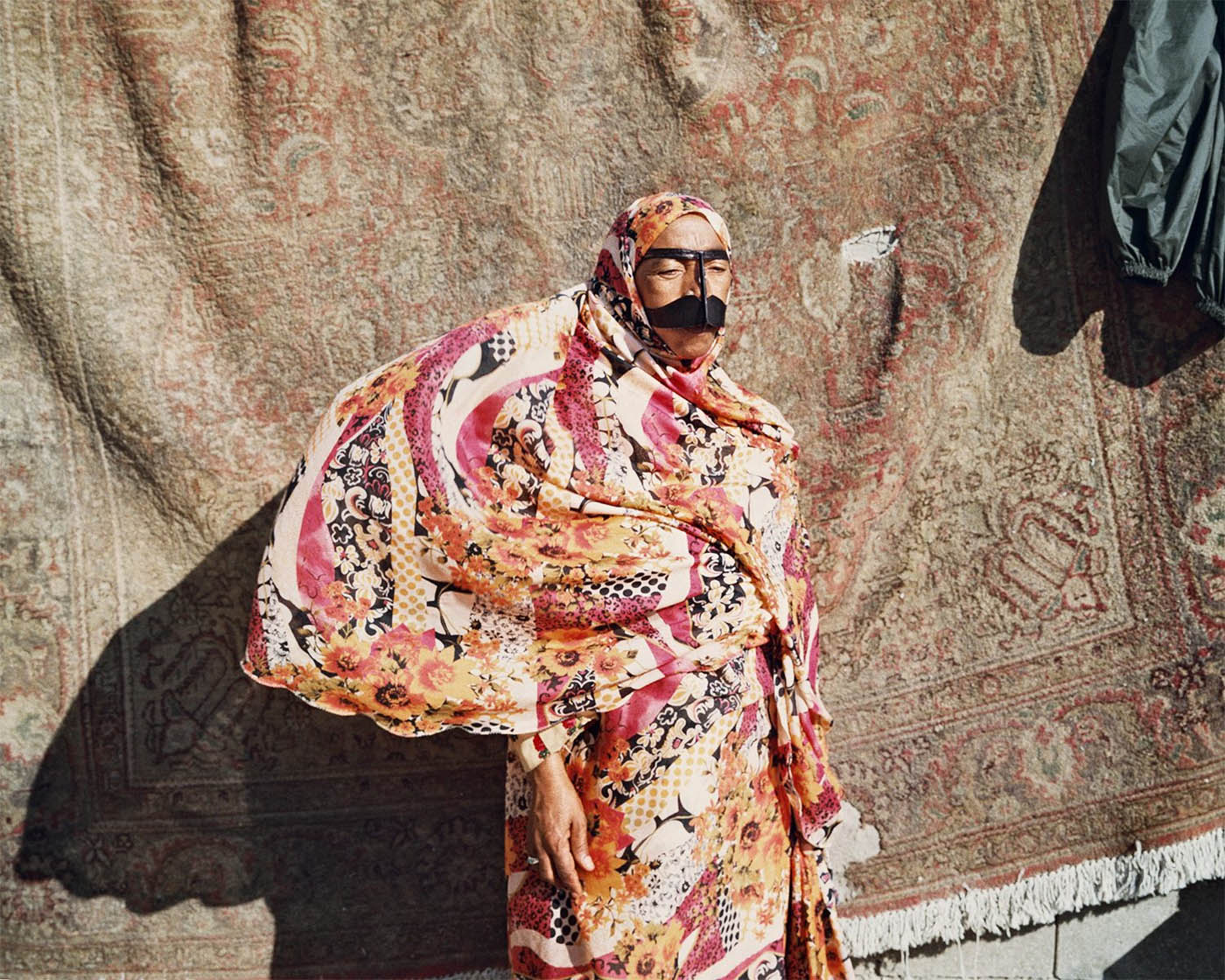

Stella Hurtig Jones was a famous American vaudeville performer who traveled the world as a flamenco and tango dancer during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One of Lange’s earliest professional portraits, the composition uses the soft focus and diffused light that characterises pictorial photography, popular among celebrities. Lange photographed Hurtig Jones as herself, rather than as her stage persona La Estrellita (The Little Star), perhaps in recognition of her recent retirement. As European travel waned during World War I and movies replaced vaudeville as mass entertainment, the allure of traditional Spanish dance diminished. La Estrellita married, started a perfume business, and moved from Hollywood to the Bay Area.

Label text from the exhibition

Full of the world

Just when you think that you know the work of an artist photographs emerge that you have never seen before, photographs that challenge the canon of famous images on which the reputation of the artist rests. Such is the case in this two part posting on the work of social documentary photographer Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965). See Part 1 of the posting.

In this posting it is not the famous photographs such as White Angel Breadline, San Francisco, California (1933); Nettie Featherston, Wife of a Migratory Laborer with Three Children, near Childress, Texas, from The American Country Woman (June 1938); Near Coolidge, Arizona. Migratory cotton picker with his cotton sack slung over his shoulder rests at the scales before returning to work in the field (November 1940, printed c. 1965); and Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother) (March 1936) which impress the senses, for their affect is known well enough.

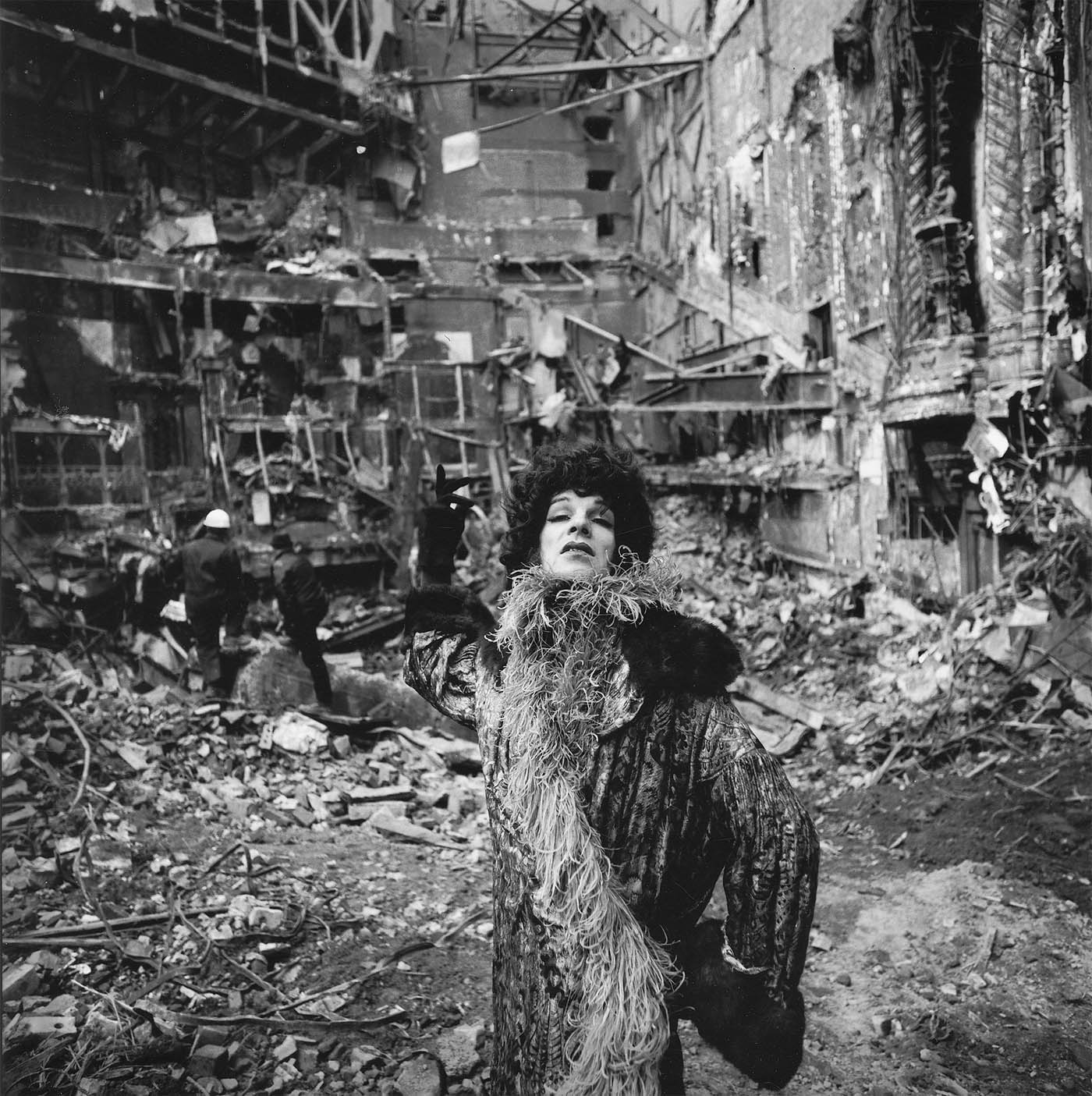

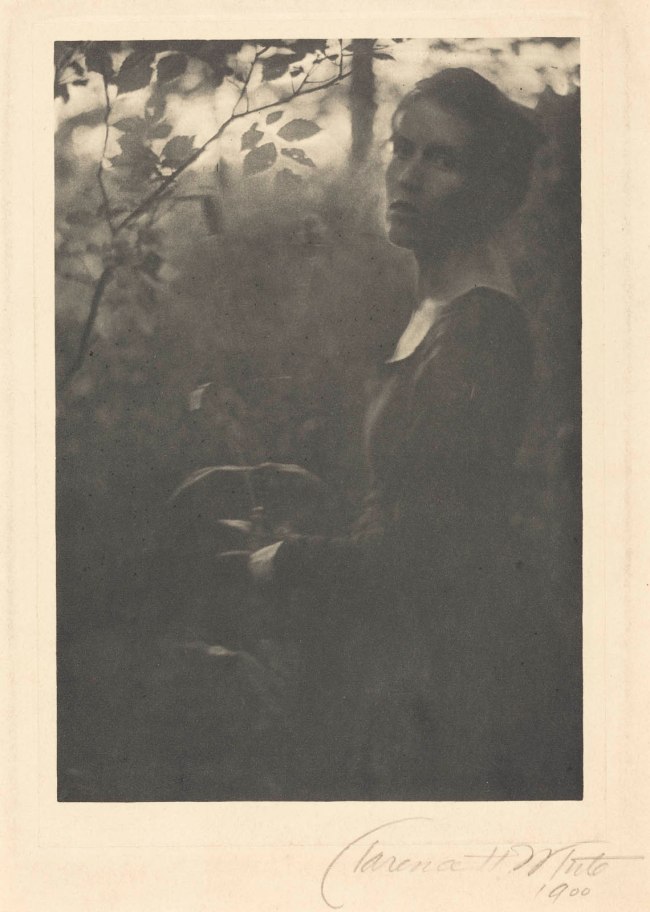

Rather, it is the relatively unknown early Pictorialist photographs, the earthy photographs of Irish people, and photographs that challenge the formalist construction of images of the disintegration of families and communities during the Great Depression – images that are far more avant-garde and experimental than I would have expected from Lange – which shine in the mind’s eye (in one’s imagination or memory).

The ethereal Pictorialist portraits (this posting) with their asymmetrical construction, trembling? vibrational? negative space, luminous light and low depth of field are a delightful surprise… as are the 1950’s Irish portrait photographs (Part 1 of the posting) full of earthy, brooding darkness – with faces that are “pure Ireland.” What intensity in these images, clearly and empathetically seen.

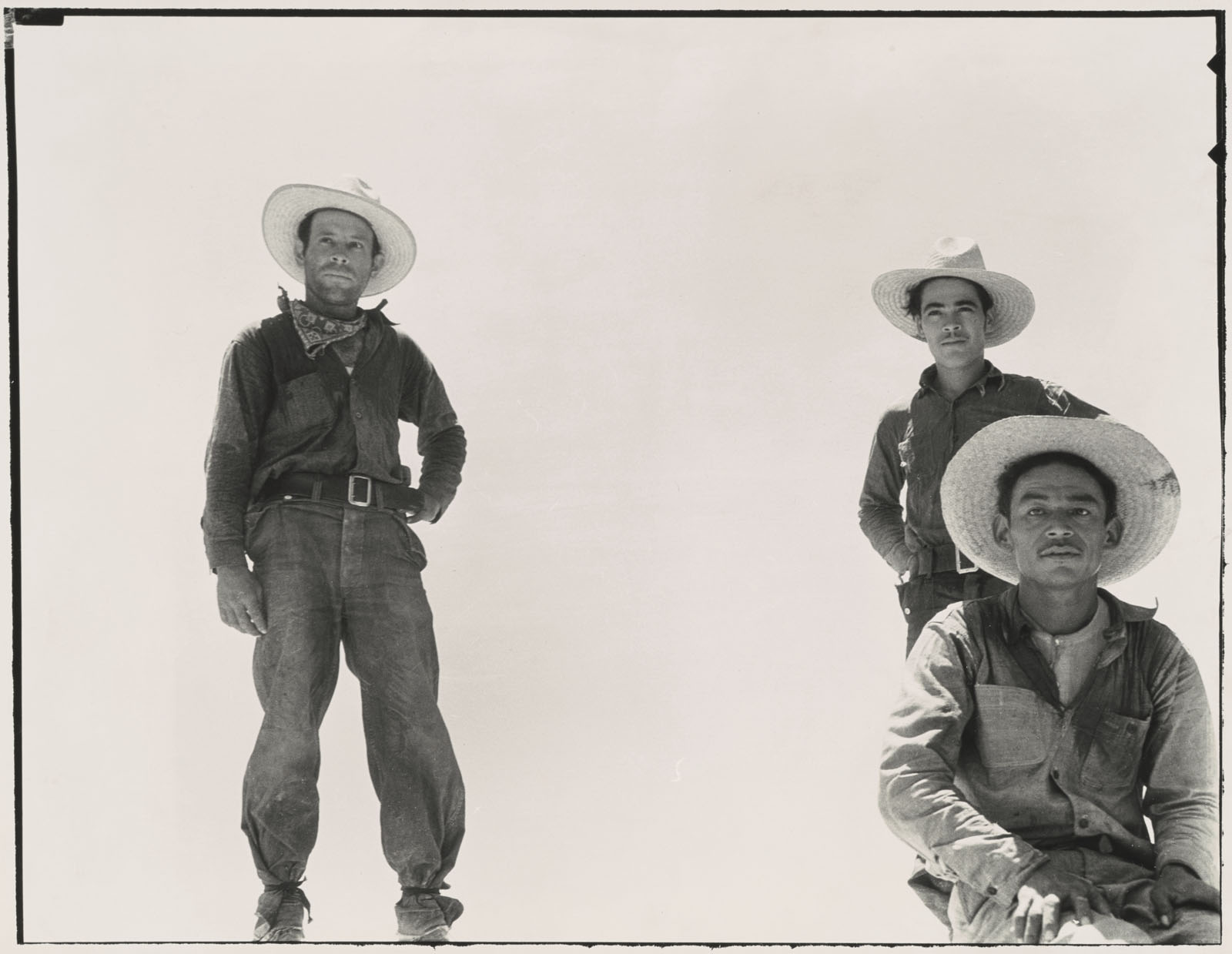

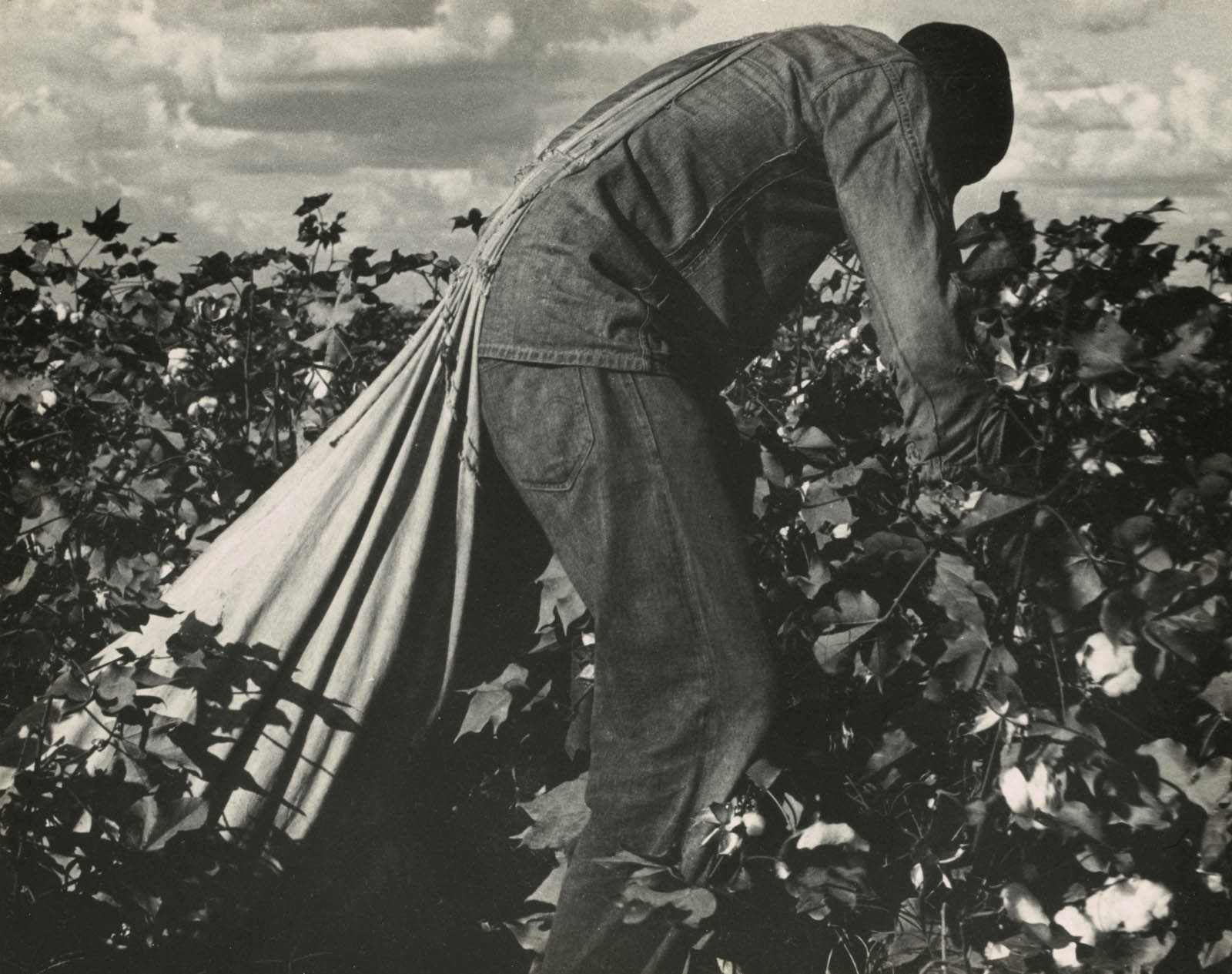

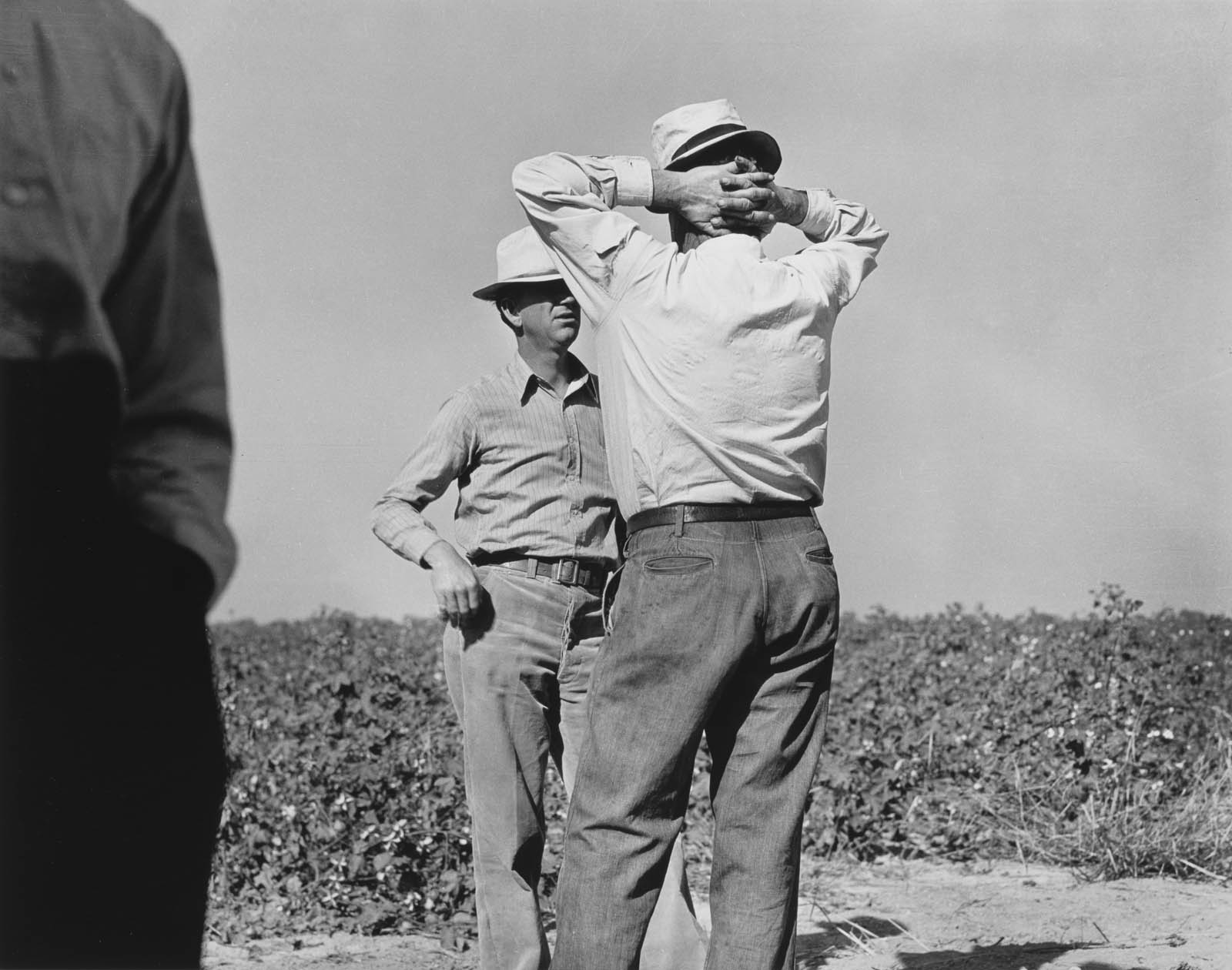

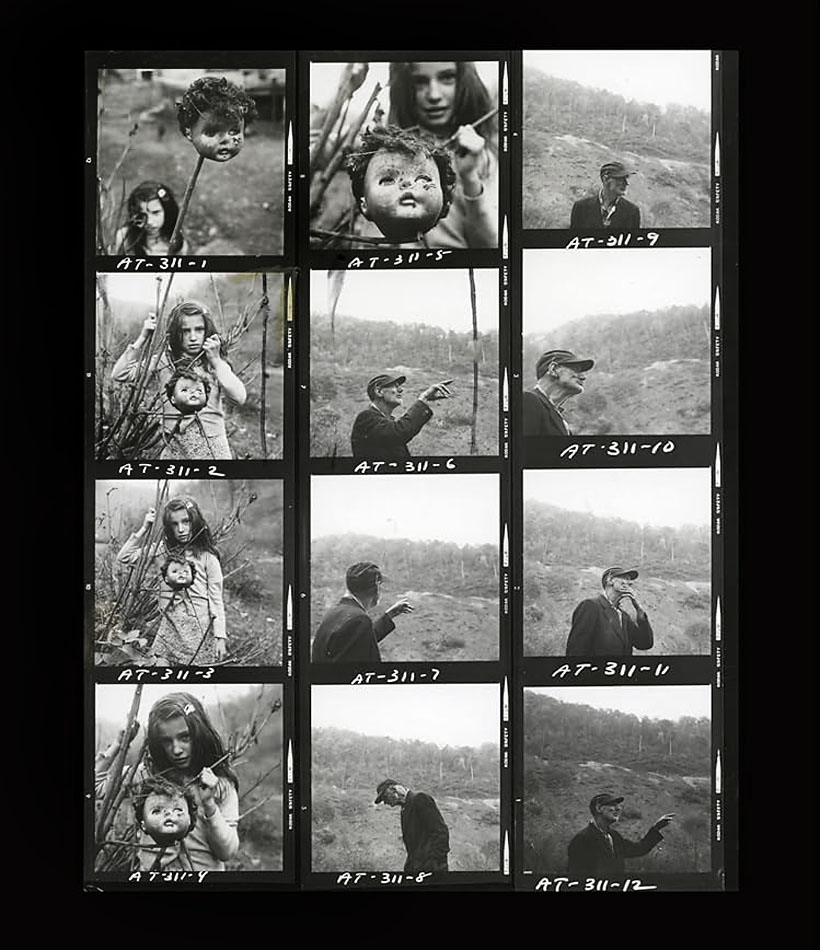

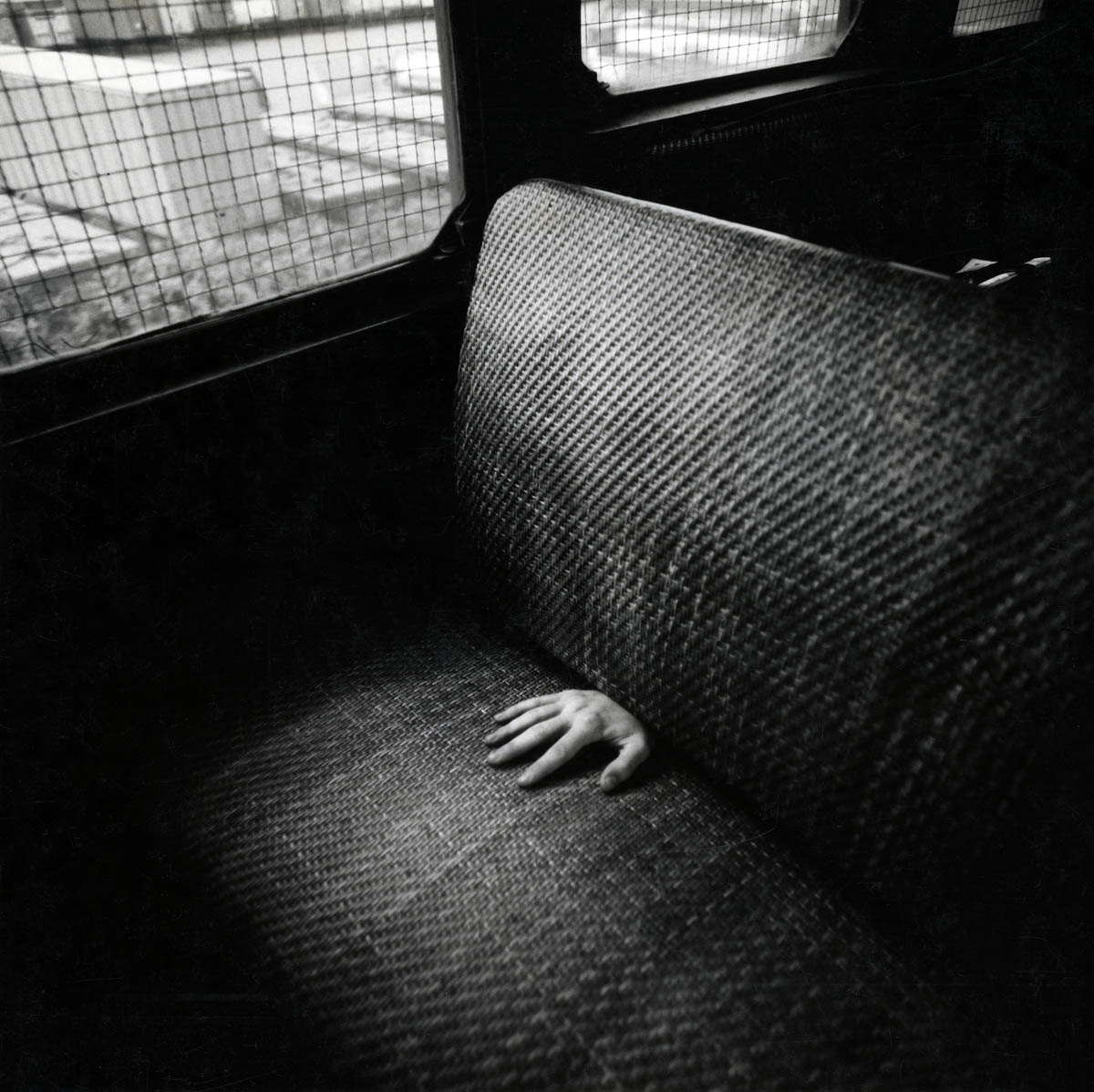

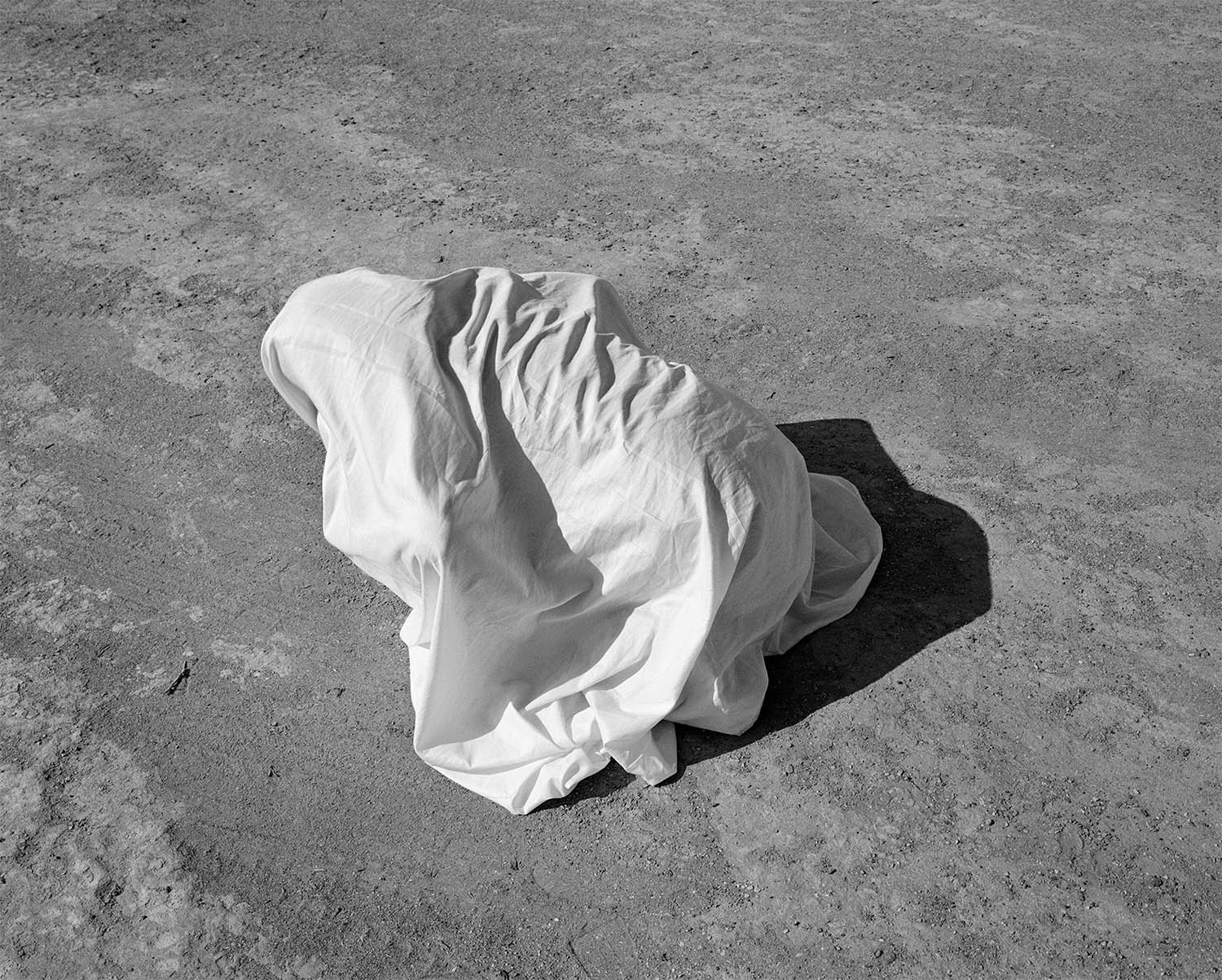

But it is the abstract figurative studies in which I am most interested… images that disrupt Lange’s normative representation in her social documentary photographs of humanity and their resilience. In photographs such as On the Plains a Hat Is More Than a Covering (1938, below) and Jake Jones’s Hands, Gunlock County, Utah (1953) – taken fifteen years apart but which could have been taken the same day, on a theme the artist was obviously interested in – Lange dissects the body, closing in on gnarled hands, weatherbeaten hats as metaphor for a tough life, well lived. These are images in which we see very little (as opposed to Barthes assertion that in photography’s realism a photo is an image in which we see everything) … but implicitly understand the sublime blur of legend of these workers and their hats.

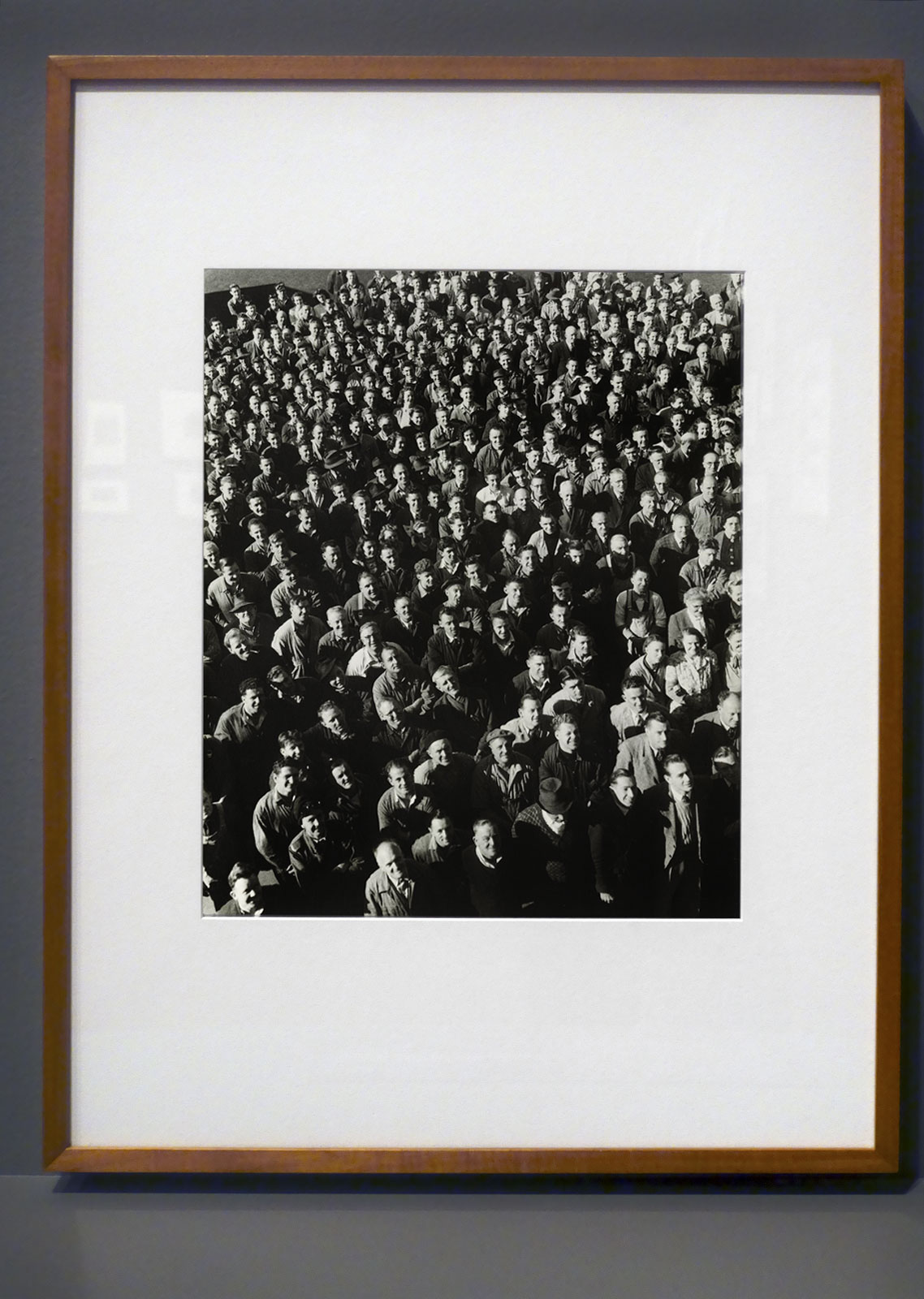

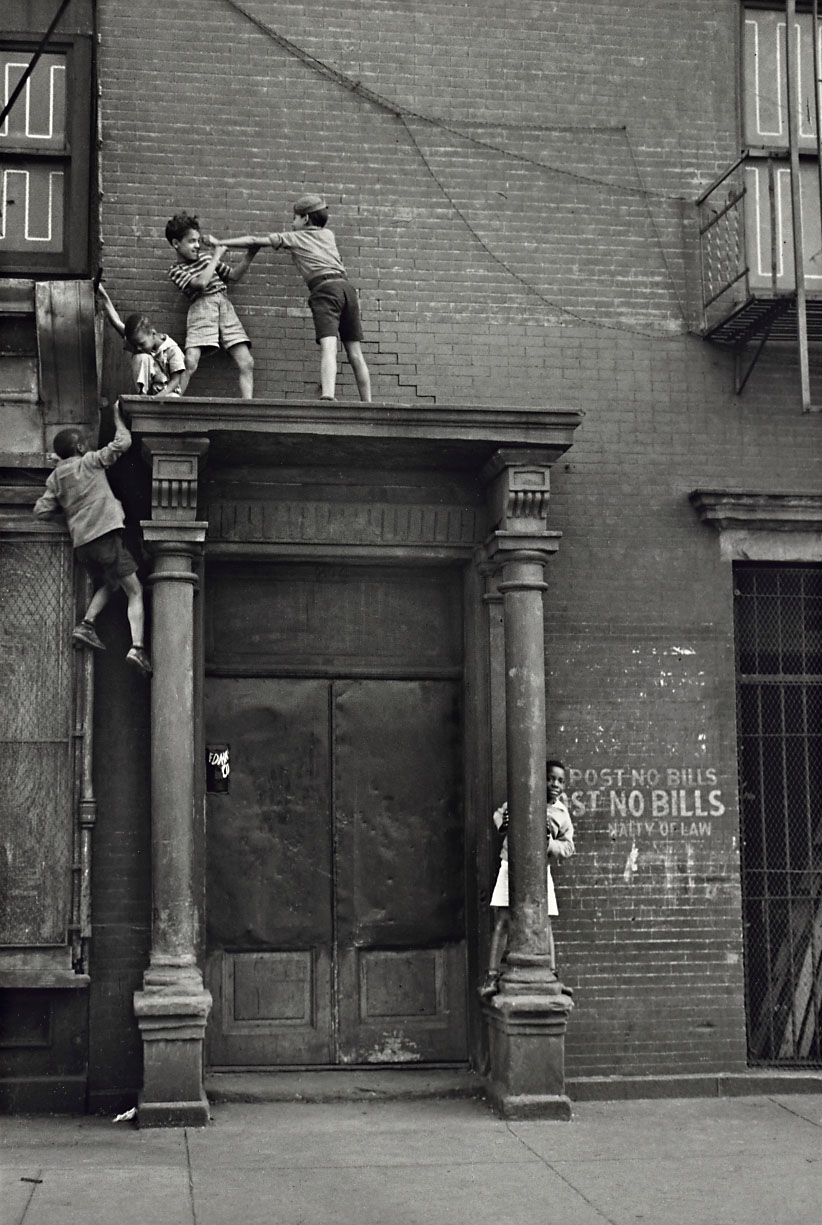

Other photographs dial up the figurative abstraction. Demonstration, San Francisco (1934, below) is a study of light, shape and form, an almost Constructivist image of fragments and negative space: hand, pole, amorphous mass of shoulder, face turned away, hat and declarative “FEED US!” banner; San Francisco Waterfront (1934) is a beautifully rendered abstract pictorial space evidencing the despair of humanity through light and form: witness, the clasped hands at rear like sentinels, the thumb pointing left… while below, covered head in hand, the thumb points vertically to the surmounted ear, which echoes the cropped ear and hair at the bottom of the photo, while to the right the two buttons of the jacket lead us to the ascending column of four buttons back to the portentous, clasping, guarding hands above. A masterpiece of photographic pictorial construction. Further, with their radical pictorial construction and cropping of the picture frame, masterpieces such as Dispossessed Arkansas farmers (1935) are truly avant-garde and experimental photographs for their time, something I don’t normally associate with the work of Dorothea Lange. As my friend Jonathan Kamholtz observes of the photographs I have been discussing, Lange “tended to lose interest in the backgrounds. The pictorial space is really very shallow. This contributes to their theatricality – not in the sense that they are false or artificial, but that each one displays character, costume, fate.”

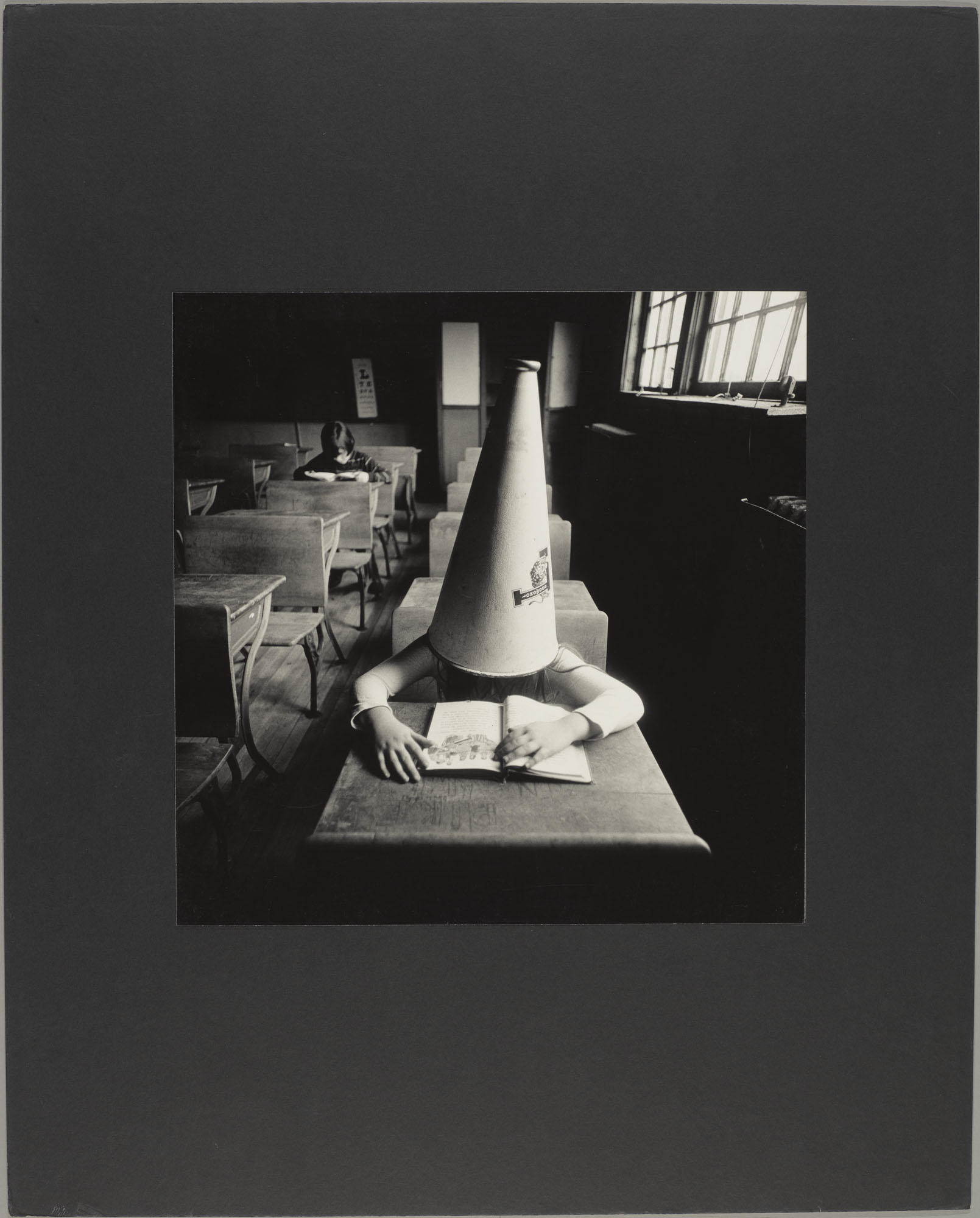

Forearmed with this knowledge, I start looking at her well known images with fresh eyes… and its all there in more subtle form: the low angle of the camera looking up at the subject, the geometric shape of hands and arms, the solid blocks of bodies filling the picture frame, the sculptural, abstract shape of bodies in fields (Migratory Field Worker Picking Cotton in San Joaquin Valley, 1938), the flattening of bodies one against another (May Day, San Francisco, California, 1934) and the disassociation of human identity through the occlusion of faces (This man is a labor contractor in the pea fields of California 1936, below; Damaged Child, Shacktown 1936, below; Washington, Yakima Valley, near Wapato 1939, below).

Dorothea Lange was an incredibly intelligent and passionate artist who removed her ego from the act of taking photographs, who lost herself in the visual experience in order to take photographs to effect social change, who connected with the world in order “to experience love, hate, and passion in every form in one’s body.”1

“That the familiar world is often unsatisfactory cannot be denied, but it is not, for all that, one that we need abandon,” she argued. “We need not be seduced into evasion of it any more than we need be appalled by it into silence… Bad as it is, the world is potentially full of good photographs. But to be good, photographs have to be full of the world.”2

And full of the spirit of the artist.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Carl Jung quoted in Nicos Hadjicostis. Destination Earth: A New Philosophy of Travel by a World-Traveler. Bamboo Leaf Press, 2016, p. 42.

2/ Dorothea Lange and Daniel Dixon, “Photographing the Familiar,” Aperture 1, no. 2 (1952), 15.

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“When you enter into the visual world, detaching yourself from all the holds on you… it is a mental disengagement so that you live, for maybe two or three hours, as completely as possible a visual experience, where you feel that you have lost yourself, your identity.”

Dorothea Lange quoted in Dyanna Taylor and Public Broadcasting Service (U.S.), directors. American Masters – Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning. Kanopy Streaming, 2014.

“The researcher ought to hang up exact science and put away the scholar’s gown, to say farewell to his study, and wander with human heart through the world, through the horror of prisons, madhouses, and hospitals, through drab suburban pubs, in brothels, and gambling dens, through the salons of elegant society, the stock exchanges, the socialist meetings, the churches, the revivals and ecstasies of the sects, to experience love, hate, and passion in every form in one’s body.”

Carl Jung quoted in Nicos Hadjicostis. Destination Earth: A New Philosophy of Travel by a World-Traveler. Bamboo Leaf Press, 2016, p. 42.

During her long, prolific, and groundbreaking career, the American photographer Dorothea Lange made some of the most iconic portraits of the 20th century. Dorothea Lange: Seeing People reframes Lange’s work through the lens of portraiture, highlighting her unique ability to discover and reveal the character and resilience of those she photographed.

Featuring some 100 photographs, the exhibition addresses her innovative approaches to picturing people, emphasising her work on social issues including economic disparity, migration, poverty, and racism.

“Five years earlier I would have thought it enough to take a picture of a man, no more. But now, I wanted to take a picture of a man as he stood in his world.”

“A single photographic print may be “news,” a “portrait,” “art,” or “documentary” – any of these, all of them, or none.”

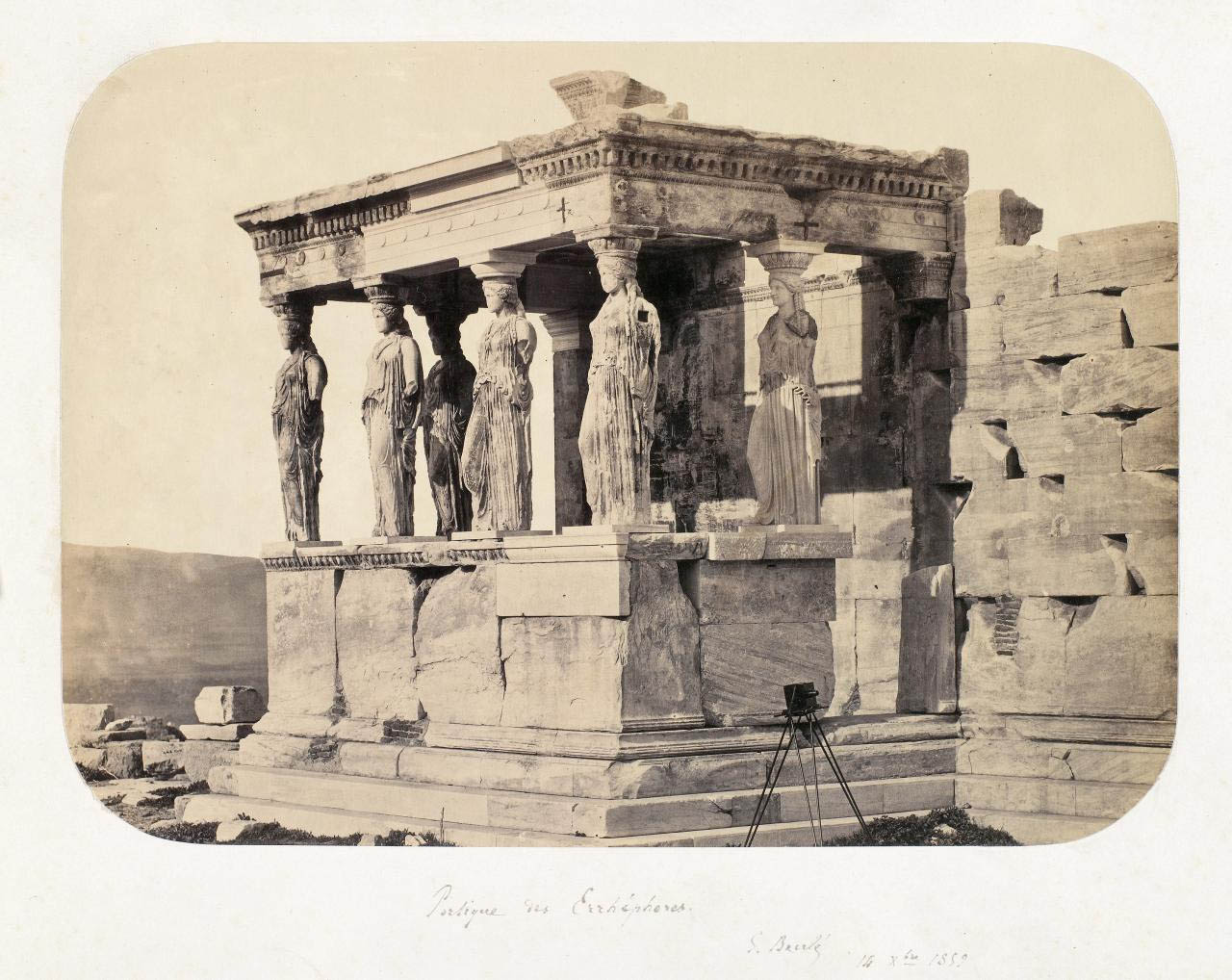

“The whole world is a museum. To walk through the streets, as though down a museum corridor. … To step into a supermarket as though setting forth in the National Gallery – is an experience and an exercise in vision.”

Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Untitled (Fleishhacker Portrait)

1920

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15.4 x 15.1cm (6 1/16 x 5 15/16 in.)

Mat: 16 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 17 1/4 x 15 1/4 in.

Collection of the Oakland Museum of California, Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Maynard Dixon and Son Daniel

1925

Gelatin silver print

Image: 13.8 x 10.8cm (5 7/16 x 4 1/4 in.)

Sheet: 15.1 x 11cm (5 15/16 x 4 5/16 in.)

Mat: 14 x 12 in.

Frame (outside): 15 1/4 x 13 1/4 in.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2000.50.1 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Portrait of Adele Raas, San Francisco

1927

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15.5 x 12.7cm (6 1/8 x 5 in.)

Mat: 14 x 12 in.

Frame (outside): 15 1/4 x 13 1/4 in.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of the Raas Family

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Untitled (Portrait of William)

1929

elatin silver print

Image/sheet: 25 x 20cm (9 13/16 x 7 7/8 in.)

Mat: 18 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 18 1/4 x 15 1/4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

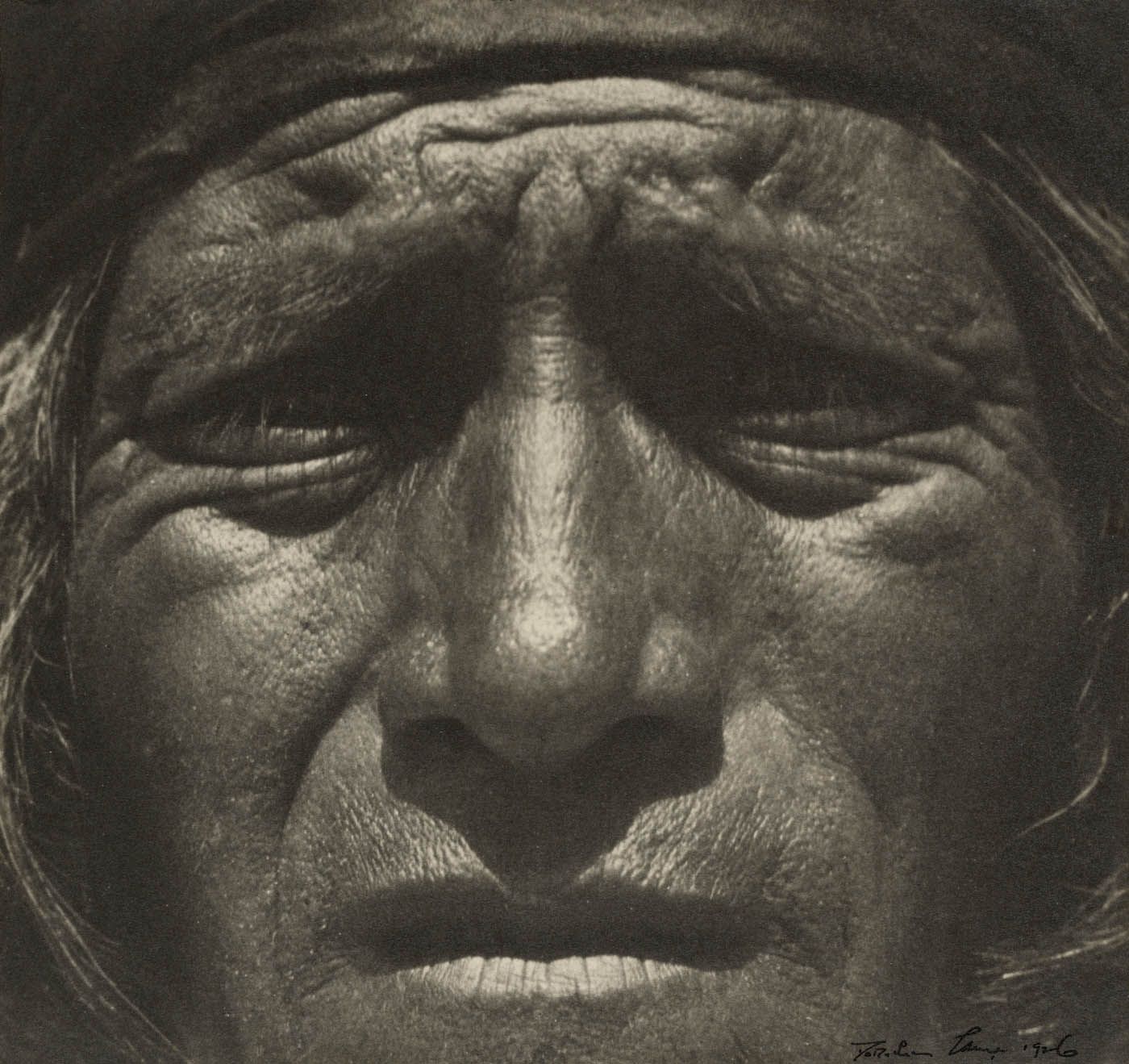

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Hopi Man, Arizona

1923, printed 1926

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18.4 x 19.7cm (7 1/4 x 7 3/4 in.)

Mount: 19.3 x 20.4cm (7 5/8 x 8 1/16 in.)

Mat: 15 1/4 x 15 in.

Frame (outside): 16 1/2 x 16 1/4 in.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XP.912.4

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

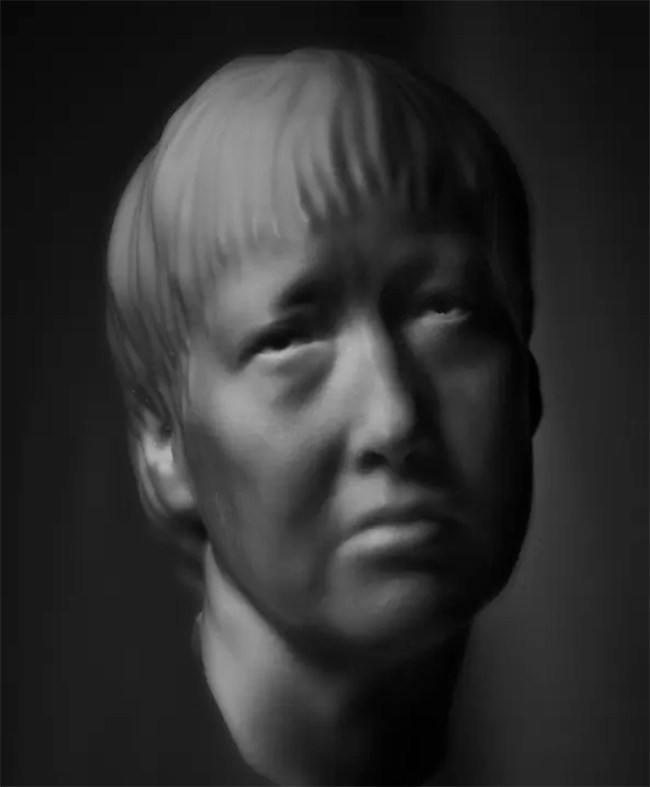

Lange embraced the chance to experiment outside her studio. In August 1923, she visited Walpi Village of the Hopi Nation with her then-husband Maynard Dixon, an avid outdoor painter. She had begun to crop some of her portraits to accentuate a gaze, hand, touch, or torso – a way of capturing the essence of a person, paradoxically showing less to reveal more.

When printing Hopi Man, Lange focused so closely on the subject’s face that his features resemble a map of his experience. She undercut her own effort to reach meaningfully across the cultural divide, however, because she did not record the man’s name or any other information about him. As a portrait, Hopi Man risks picturing a type or class of person rather than this individual’s character.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Clausen Child and Mother

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15.6 x 21cm (6 1/8 x 8 1/4 in.)

Mat: 14 x 17 in.

Frame (outside): 15 1/4 x 18 1/4 in.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Henri Cartier-Bresson, by exchange

Lange frequently photographed the subject of mother and child, a long-standing Western art historical tradition rooted in depictions of the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus and modernised and secularised in high-end portrait studios. Here Frances Clausen stares directly at the camera while her mother, Gertrude, sits in shadow, looking away. Lange focuses on the child’s inquisitive gaze, as well as her affectionate bond to and emerging independence from her mother. Lange’s expertise photographing children – acquired from her early studio work – led to some of her most important photographs made during the Great Depression, displayed in the next galleries.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Maynard Dixon

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 14.1 x 13.4cm (5 9/16 x 5 1/4 in.)

Mount: 16.4 x 14.2 cm (6 7/16 x 5 9/16 in.)

Mat: 14 x 11 in.

Frame (outside): 15 1/4 x 12 1/4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Maynard Dixon (January 24, 1875 – November 11, 1946) was an American artist. He was known for his paintings, and his body of work focused on the American West. Dixon is considered one of the finest artists having dedicated most of their art to the U.S. Southwestern cultures and landscapes at the end of the 19th-century and the first half of the 20th-century. He was often called “The Last Cowboy in San Francisco.”

Through his work with the Galerie Beaux Arts, a cooperative gallery in San Francisco, Dixon played a pivotal role ensuring the West Coast supported the work of local, modern artists. He was married for a time to photographer Dorothea Lange, and later to painter Edith Hamlin.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Native American Girl, Taos, New Mexico

1931

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 5.3 x 5.3cm (2 1/16 x 2 1/16 in.)

Mount: 13.2 x 10.5cm (5 3/16 x 4 1/8 in.)

Mat: 10 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 11 1/4 x 15 1/4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

In summer 1931, escaping the Depression-era turmoil of San Francisco, Lange and Dixon bought their first car and drove to New Mexico with their children. Her few surviving photographs from this trip reveal significant steps in her transition away from studio portraiture and toward a more straightforward approach to photographing people. A series of pictures portrays this unidentified Indigenous girl in a direct documentary style. Although her expression reveals few emotions, she looks squarely at the lens in one photograph and seems comfortable in front of the camera.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Native American Girl, Taos, New Mexico

1931

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 5.4 x 5.4cm (2 1/8 x 2 1/8 in.)

Mount: 13.3 x 10.4cm (5 1/4 x 4 1/8 in.)

Mat: 10 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 11 1/4 x 15 1/4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

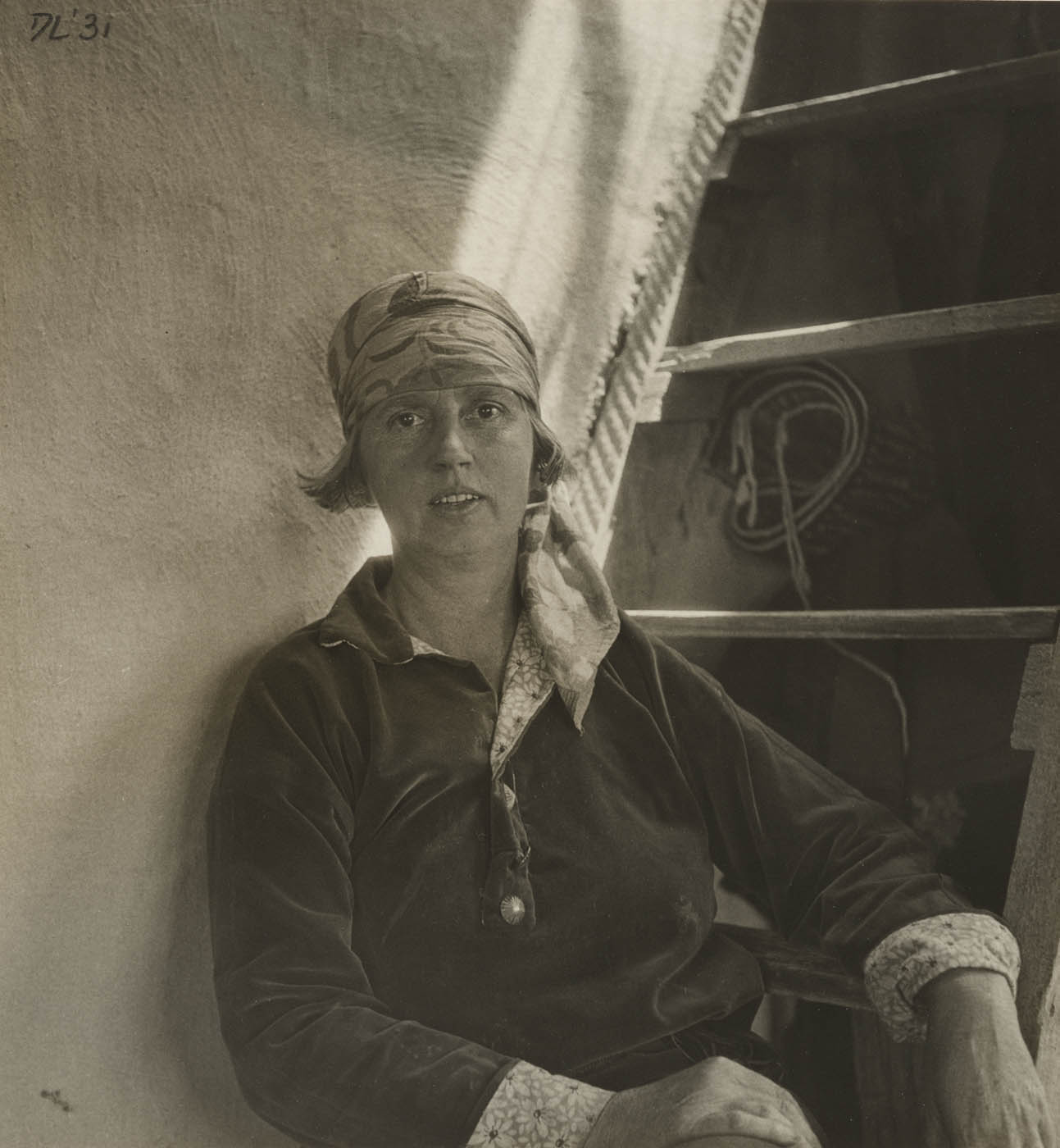

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Dorothy Brett, Painter, Taos, New Mexico

1931

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 8.6 x 8.2cm (3 3/8 x 3 1/4 in.)

Mat: 14 x 11 in.

Frame (outside): 15 1/4 x 12 1/4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Lange met Dorothy Brett in 1931 when the photographer and her family spent several months in Taos. Born into an aristocratic British family, Brett rebelled against their expectations, attending art school and becoming a painter. In London she befriended writers associated with the Bloomsbury group, including D. H. Lawrence, who was recruiting people to go to New Mexico to form a utopian society. Brett was the only person who followed him, but she was so enchanted with the area that she lived there for the rest of her life.

Label text from the exhibition

Hon. Dorothy Eugénie Brett (10 November 1883 – 27 August 1977) was an Anglo-American painter, remembered as much for her social life as for her art. Born into an aristocratic British family, she lived a sheltered early life. During her student years at the Slade School of Art, she associated with Dora Carrington, Barbara Hiles and the Bloomsbury group. Among the people she met was novelist D.H. Lawrence, and it was at his invitation that she moved to Taos, New Mexico in 1924. She remained there for the rest of her life, becoming an American citizen in 1938.

Her work can be found in the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington D.C., in the Millicent Rogers Museum and the Harwood Museum of Art, both in Taos. Also at the New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe, the Roswell Museum and Art Center, Roswell, New Mexico and in many private collections.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Demonstration, San Francisco

1934

Gelatin silver print

Image: 12.1 x 14.3cm (4 3/4 x 5 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 12.1 x 14.3cm (4 3/4 x 5 5/8 in.)

Mount: 14.6 x 23.8cm (5 3/4 x 9 3/8 in.)

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Joseph M. Cohen Gift, 2005

In 1934, as Lange began to forge a new documentary practice, she sought “to take a picture of a man as he stood in his world.” With no clients to please, she drew on insights she had learned from modernism, especially its celebration of close-up studies and dramatic angles. Like other artists, she also found that signs – such as the protest poster declaring “… FEED US!” – could root a photograph in a specific time and place and give agency to those she depicted, allowing them to speak. With carefully composed pictures like this one, Lange was acknowledging the power of modernist photography to tell stories in simple, dynamic ways.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Andrew Furuseth

1934

Gelatin silver print

Image: 20.5 x 19.6cm (8 1/16 x 7 11/16 in.)

Sheet: 21.1 x 20.3cm (8 5/16 x 8 in.)

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Andrew Furuseth was an American labor leader known for organising seamen during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He helped create the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific and the International Seamen’s Union, heading both as their president. Lange met 80-year-old Furuseth around the time of the San Francisco waterfront strikes of 1934. She had been photographing labor organisers and protesters at May Day events around the city while Furuseth was working to help moderate the seamen’s anger to avoid a damaging strike. Her portrayal of Furuseth in profile against a dark background – eyes closed, deep in thought – emphasises his years of experience and a weary strength.

Label text from the exhibition

Andrew Furuseth (March 17, 1854 – January 22, 1938) of Åsbygda, Hedmark, Norway was a merchant seaman and an American labor leader. Furuseth was active in the formation of two influential maritime unions: the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific and the International Seamen’s Union, and served as the executive of both for decades.

Furuseth was largely responsible for the passage of four reforms that changed the lives of American mariners. Two of them, the Maguire Act of 1895 and the White Act of 1898, ended corporal punishment and abolished imprisonment for deserting a vessel.

Furuseth was credited as the key figure behind drafting and enacting the Seamen’s Act of 1915, hailed by many as “The Magna Carta of the Sea” and the Jones Act of 1920 which governs the workers’ compensation rights of sailors and the use of foreign vessels in domestic trade. In his later years, he was known as “the Old Viking”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Street Meeting, San Francisco

1934

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 23.5 x 17.5cm (9 1/4 x 6 7/8 in.)

Mat: 16 x 13 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 14 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Stenographer with Mended Stockings, San Francisco, California

1934, printed 1950s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 34 x 26.6 cm (13 3/8 x 10 1/2 in.)

Sheet: 35.2 x 27.8 cm (13 7/8 x 10 15/16 in.)

Mat: 20 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Lange’s portrait of a Depression-era stenographer omits her face to focus on her dark, creased dress, tattered hosiery, and woven shoes. Her stockings are stitched up the front, mended to keep them – and her – going for another day or two. They reveal the grit and fortitude of San Francisco’s working women during a time when jobs were scarce and people had to conserve all their resources in the face of financial insecurity.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Wandering Boy, Camp Carlton, California

1935

Gelatin silver print

Image: 34 x 25.1cm (13 3/8 x 9 7/8 in.)

Sheet: 35.3 x 28 cm (13 7/8 x 11 in.)

Mount: 38.1 x 28 cm (15 x 11 in.)

Mat: 20 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

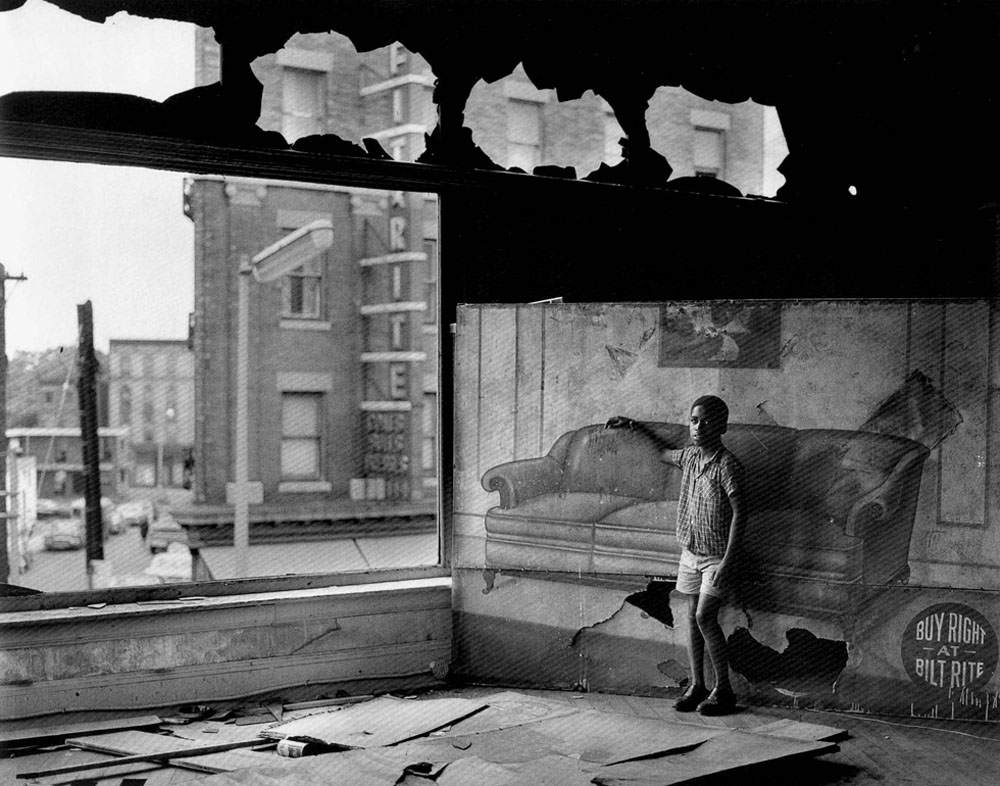

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Black sharecropper with twenty acres. He receives eight cents a day for hoeing cotton. Brazos river bottoms, near Bryan, Texas

June 1938, printed c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.1 x 19.2cm (9 1/2 x 7 9/16 in.)

Sheet: 25.3 x 20.5cm (9 15/16 x 8 1/16 in.)

Mat: 18 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

American photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) created some of the most groundbreaking portraits of the 20th century. Through pictures of labourers, demonstrators, refugees, migrant farmers, the unjustly incarcerated, and others, Lange captured the spirit of human endurance while recording some of the profound social inequities of the period. Her work expanded the boundaries of portraiture and helped spark the development of modern documentary photography.

Dorothea Lange: Seeing People reframes Lange’s art through the lens of portraiture and highlights her capacity to spotlight the humanity and resilience of those she photographed. She began her career as a studio portrait photographer, and even as she ventured far outside her studio people remained key to her mission. Focusing on Lange’s abiding concern for those in need, this exhibition reveals her lifelong investigation into how photography – and portraits in particular – could help bring about collective change.

One of the most important documentary photographers of her time, Lange sought to transform how we see and understand one another. Motivated by an ever-growing interest in social justice, she was also an intrepid reporter who traveled extensively in the United States and around the world to create indelible and influential photographs. This exhibition illuminates the centrality of portraiture in Lange’s career and its role in exposing the impacts of economic disparity, climate change, migration, and war – issues that remain equally urgent today.

Wall text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Unemployed Man, San Francisco, California

1934, printed before 1950

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.8 x 19.1cm (9 3/4 x 7 1/2 in.)

Sheet: 25.2 x 19.6cm (9 15/16 x 7 11/16 in.)

Mat: 16 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

This man is a labor contractor in the pea fields of California. “One-Eye” Charlie gives his views. “I’m making my living off of these people (migrant laborers) so I know the conditions,” San Luis Obispo County, California

February 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.1 x 19.7cm (9 1/2 x 7 3/4 in.)

Sheet: 25.4 x 20.3cm (10 x 8 in.)

Mat: 18 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Migratory Pea Pickers, Nipomo, California

March 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19.4 x 24.5cm (7 5/8 x 9 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 25.7cm (8 x 10 1/8 in.)

Mat: 13 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 14 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Post Office and Postmistress, Widtsoe, Utah

April 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.4 x 19.3cm (9 5/8 x 7 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 25.4 x 20.3cm (10 x 8 in.)

Mat: 16 x 13 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 14 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

When Lange photographed Widtsoe, Utah, for the Resettlement Administration, the town’s population had dwindled to 17 families. Cycles of drought devastated the region’s agricultural economy and the RA stepped in to buy out landowners and relocate them. Signs of desolation are evident in this portrait of the town’s postmistress at the post office. Perched on cinder blocks, surrounded by dusty earth, the building appears to teeter – an effect intensified by Lange’s skewed composition. The stoic presence of the postmistress, who is posed neatly within the doorframe, hints at the stabilising role women often play in Lange’s compositions.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Plantation Owner, Mississippi Delta, near Clarksdale, Mississippi

June 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18.7 x 24.1cm (7 3/8 x 9 1/2 in.)

The Art institute of Chicago, Purchased with funds provided by Vicki and Thomas Horwich

In 1938, a cropped version of this photograph was featured in the publication of Archibald MacLeish’s book-length poem Land of the Free. The cropped photograph focused attention on the “plantation owner” and erased four of the Black men, leaving just one silhouetted in the background. MacLeish’s poem proclaims, “All you needed for freedom was being American” – yet Lange’s original picture, and the subsequent cropped version, reveals the fallacy of this sentiment. Both point to how African Americans were barred from achieving the freedom that MacLeish claims was available to all Americans. Paul Taylor appears at the far left edge interviewing the owner.

Label text from the exhibition

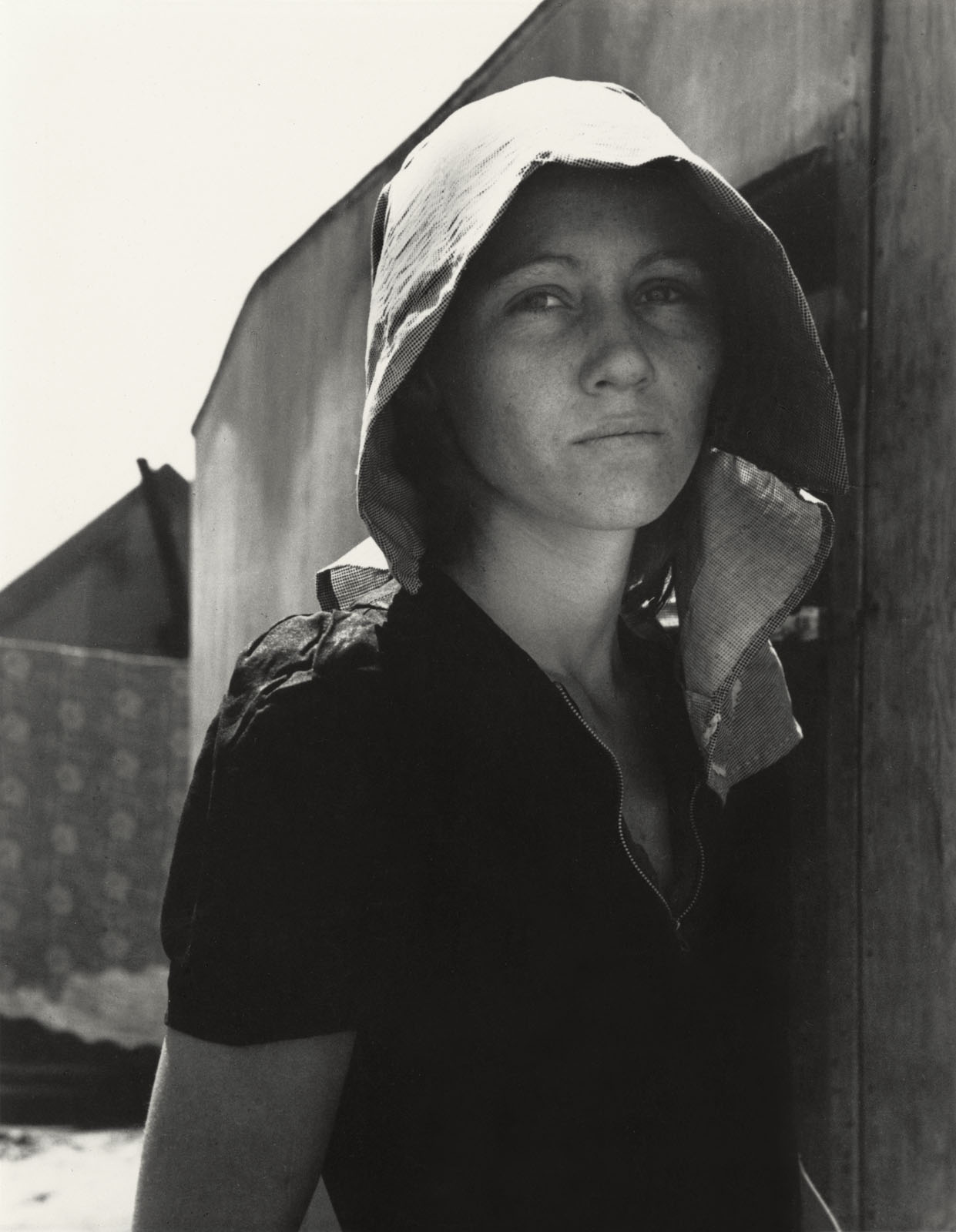

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Drought Refugees from Oklahoma Camping by the Roadside, Blythe, California

August 17, 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24 x 19.1cm (9 7/16 x 7 1/2 in.)

Mount: 33.02 x 28.26 cm (13 x 11 1/8 in.)

Mat: 20 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 21 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

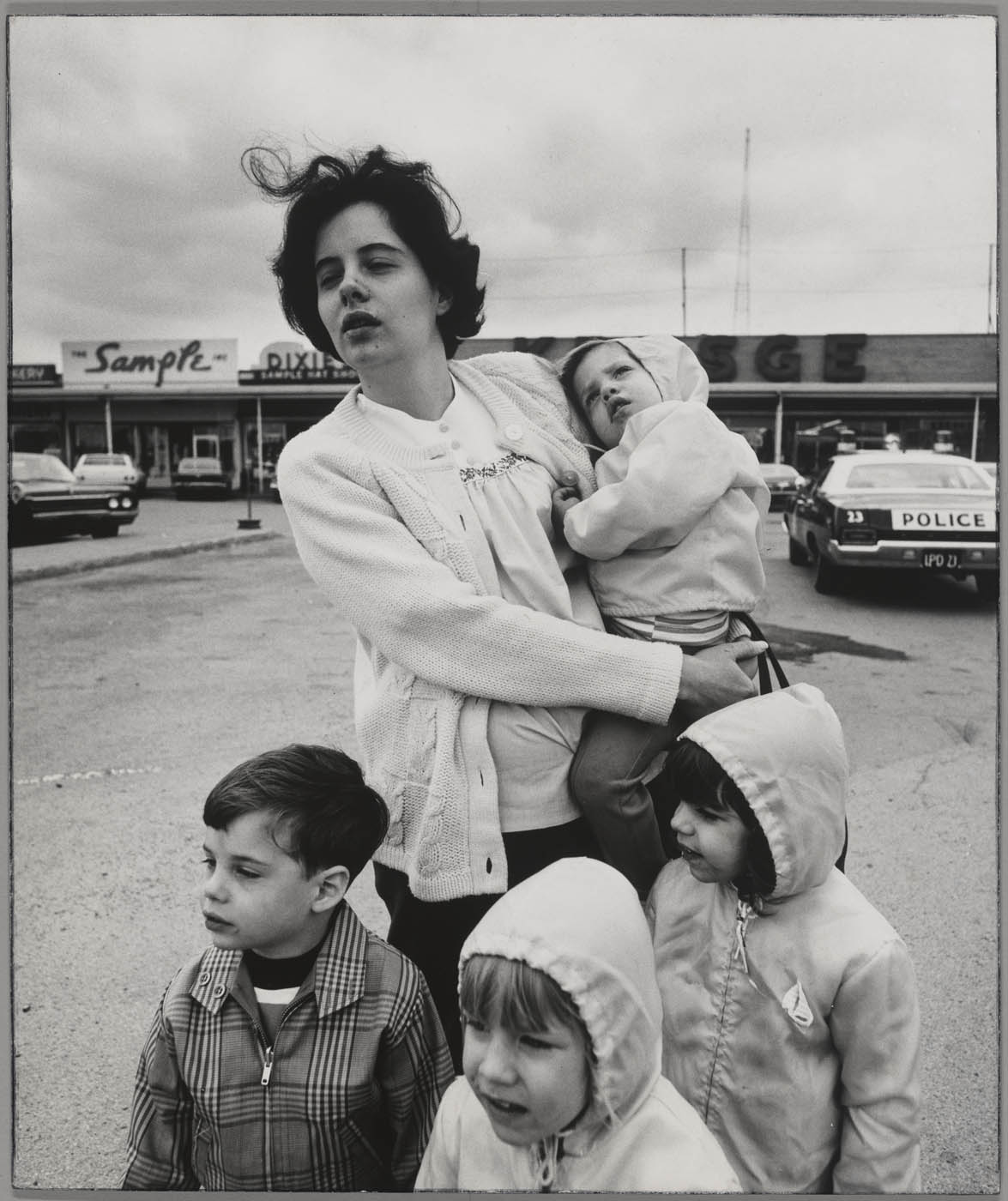

As a result of droughts and erosion that destroyed tillable land and crops in Oklahoma and Arkansas, thousands of farmers moved west with their families to start their lives over in places such as Blythe. Zella, Jess, and Jesse Power were among these families. It is not clear when the Powers began their move to California, but Jesse was born in Blythe, so Zella may have been pregnant during their journey. Lange’s field notes indicate that the Powers were a family of seven; an older sibling’s foot may be glimpsed in the lower right. With her furrowed brow and slumped posture, Zella exemplifies the difficulties faced by migrant mothers seeking better lives for themselves and their families in places that did not promise immediate relief.

Label text from the exhibition

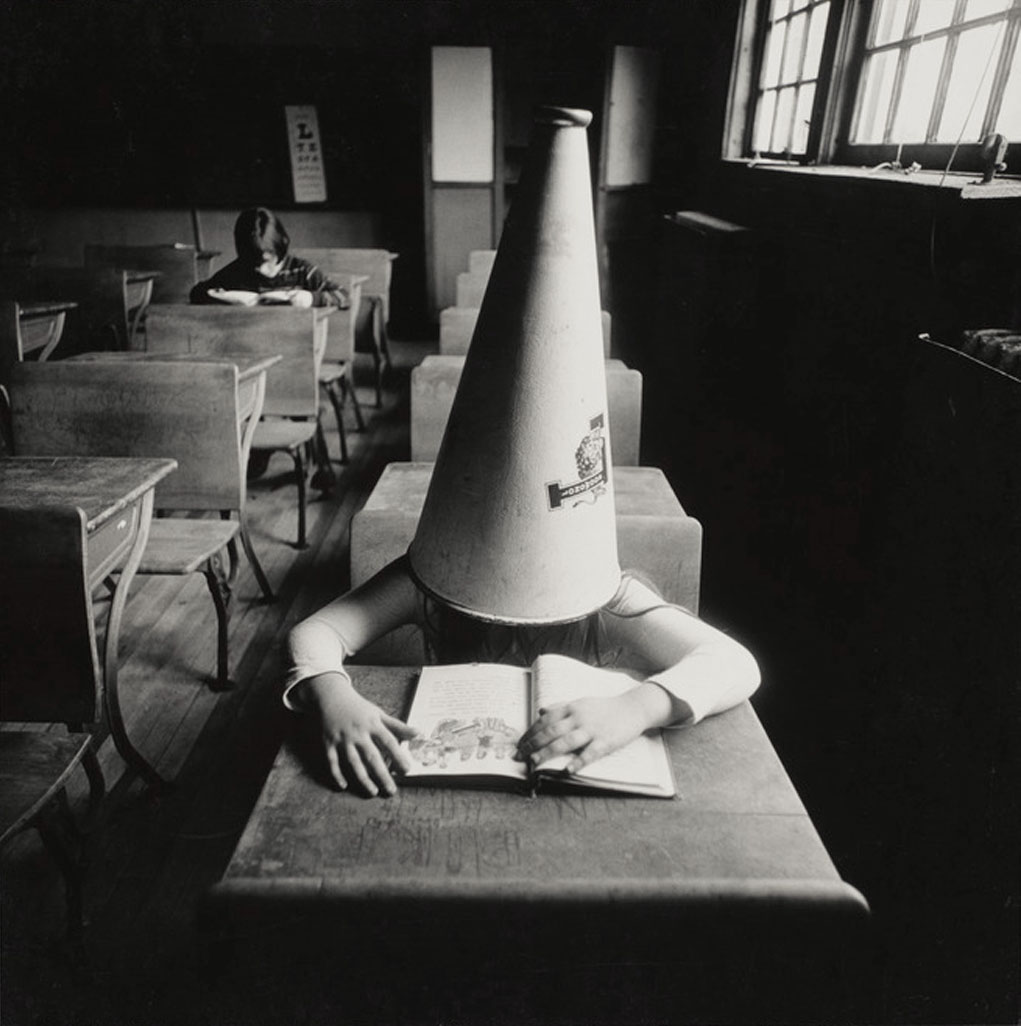

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Child Living in Oklahoma City Shacktown [Damaged Child, Shacktown]

August 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.2 x 19.4cm (9 1/2 x 7 5/8 in.)

Mat: 17 x 14 in.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase

This photograph of a bruised girl with a hollow gaze is one of many Lange made depicting the exploitation of migrant children during the Great Depression. The portrait suggests the range of emotional and physical harm children experienced as they, too, struggled to survive economic hardship.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Eighty-year-old woman living in squatters’ camp on the outskirts of Bakersfield, California. “If you lose your pluck you lose the most there is in you – all you’ve got to live with”

November 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19 x 24.4cm (7 1/2 x 9 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 25.5cm (8 x 10 1/16 in.)

Mat: 13 x 16 in.

Frame (outside): 14 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Young Cotton Picker, San Joaquin Valley, California

November 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.1 x 18.4cm (9 1/2 x 7 1/4 in.)

Collection of the Oakland Museum of California, Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Alabama Plow Girl, near Eutaw, Alabama

1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19.1 x 19.4cm (7 1/2 x 7 5/8 in.)

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2001

Lange travelled to the American South in 1936 while employed by the Resettlement Administration. Near Eutaw, Alabama, she photographed Black tenant farmers like this shoeless girl plowing a field in the punishing summer heat. In the South, Lange witnessed the oppressive working conditions endured by Black tenants, who farmed land predominantly held by white owners and often struggled to access New Deal resources. Southern Black farmers faced undue difficulty during the Depression as economic disaster exacerbated the oppression and poverty produced by the region’s racist agricultural system.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Migratory Workers Harvesting Peas near Nipomo, California

Spring 1937

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19.4 x 24.5cm (7 5/8 x 9 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 20.6 x 25.4cm (8 1/8 x 10 in.)

Mat: 13 x 16 in. frame (outside): 14 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

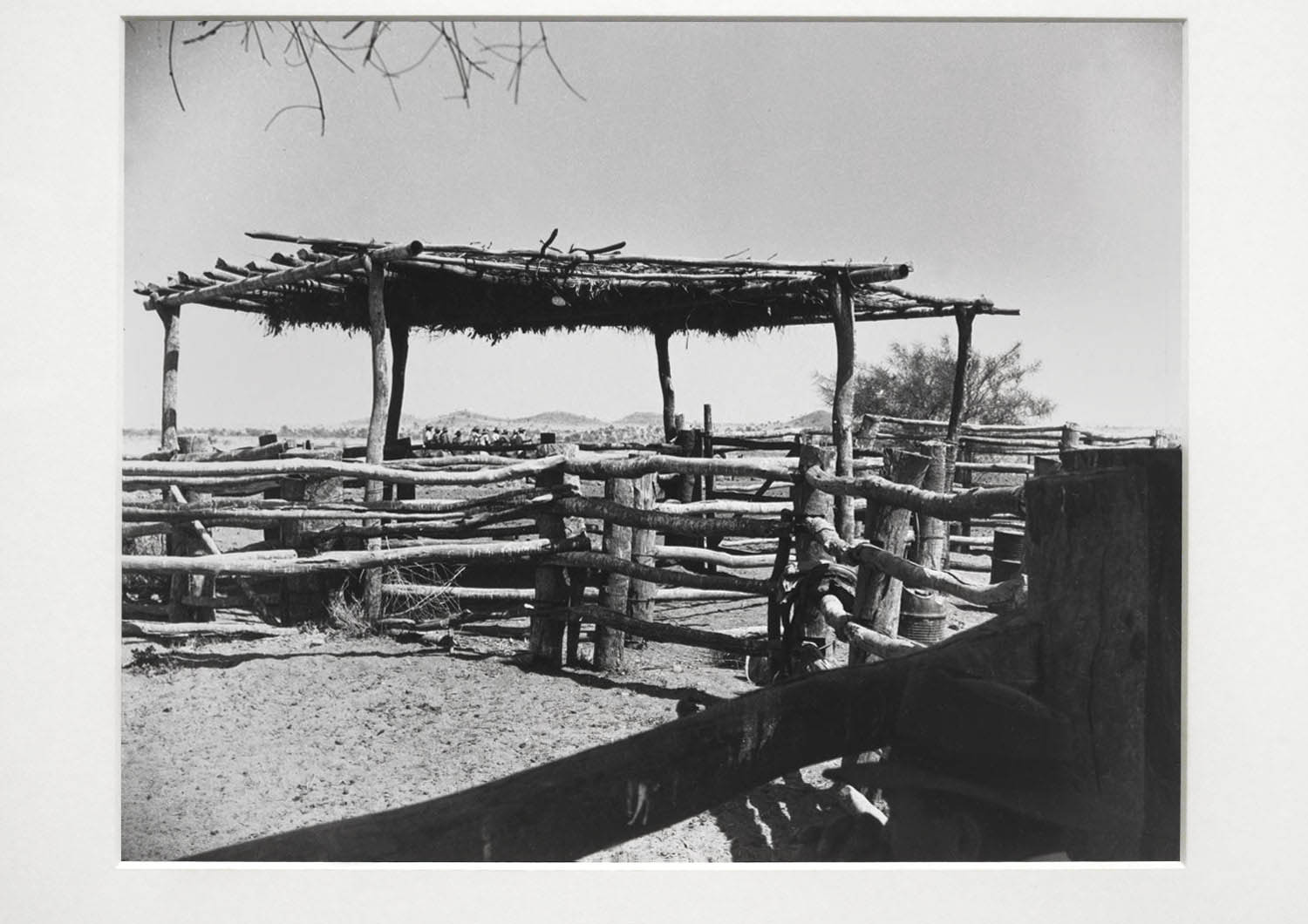

Country store on dirt road. Sunday afternoon. Note the kerosene pump on the right and the gasoline pump on the left. Rough, unfinished timber posts have been used as supports for porch roof. Black men are sitting on the porch. Brother of store owner stands in doorway, Gordonton, North Carolina

July 1939, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.5 x 34.3cm (9 5/8 x 13 1/2 in.)

Sheet: 25.6 x 35.4cm (10 1/16 x 13 15/16 in.)

Mat: 16 x 20 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 21 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Rainey Curry Baynes II, the store owner’s brother, leans in the doorway conversing with five Black men. On the far right is Arthur Thorpe, and the man wearing overalls is Joe Carrington. The men appear relaxed in Baynes’s presence, but it is unclear whether their demeanour is genuine or for the benefit of Lange’s camera. They may have been sharecroppers or tenant farmers indebted to the Baynes brothers, or simply customers of the store.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Washington, Yakima Valley, near Wapato. One of Chris Adolph’s Younger Children. Farm Security Administration Rehabilitation Clients

August 1939

Gelatin silver print

Image: 20.83 x 25.4cm (8 3/16 x 10 in.)

Collection of the Oakland Museum of California, Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

End of Shift, Richmond, California

1942, printed 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image: 75.7 x 59.5cm (29 13/16 x 23 7/16 in.)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase

Fortune magazine commissioned Lange to document the bustling shipyards in Richmond, north of Oakland, where newly desegregated defence firms were rapidly constructing transport, cargo, and warships for the United States Navy. With its tight cropping and dynamic configuration, End of Shift focuses on the rushing legs and torsos of shipbuilders leaving a wartime facility. Lange expressed the urgency of their work in defence production without showing their individual features. The angled composition and complex interplay of light and shadow demonstrate Lange’s understanding of how modern design techniques could convey the force and energy of a group working together on a project critical to the nation’s defence.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Street Encounter, Richmond, California

c. 1943

Gelatin silver print

Image: 21.7 x 17.9cm (8 9/16 x 7 1/16 in.)

Frame (outside): 18 3/4 x 15 3/4 in.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri (Gift of Hallmark Cards, Inc.)

Dressed for work as a welder, this woman was one of thousands who moved to Richmond, California, during the early 1940s to seek employment in the expanding wartime shipbuilding yards. On assignment for Fortune magazine, Lange documented the upheaval wrought by Richmond’s rapidly growing population and diversifying workforce. Lange’s field notes described this picture as an “Item on race relations. Scene on main street. The girl was a taxi driver in New Orleans. She came to Richmond with her husband two years ago.” Recognising the power of words in her pictures, Lange included a sign that could be read as “Serve You” or “Serve Your Country,” but which actually says “Serve Yourself” – a wry comment on the national unity promoted by the era’s patriotic propaganda.

Label text from the exhibition

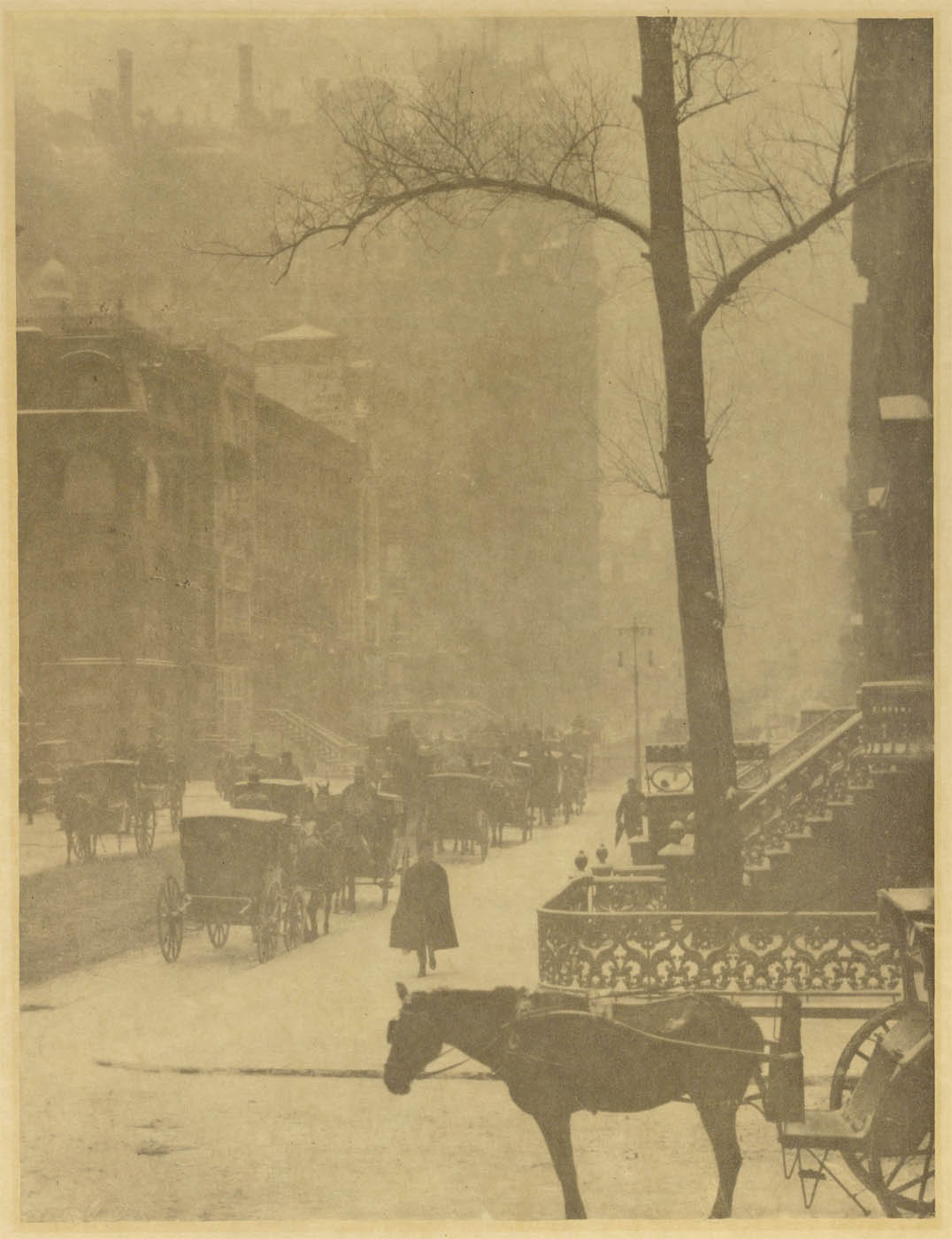

Early Portraits

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1895, Dorothea Lange learned photography in New York City before embarking in 1918 on a round-the-world trip. When forced to cut her journey short and find employment in San Francisco, she secured a position at the photo-finishing counter of a variety store. She soon opened her own portrait studio and worked among a cohort of bohemian artists and intellectuals including Imogen Cunningham, Consuelo Kanaga, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and the painter Maynard Dixon, who would become her first husband.

Bay Area high-society and cultural figures became Lange’s clients and the subjects of her studio portraits. These early pictures combine elements of the pictorial style in which she was trained, such as soft focus and diffused light, with an emerging modernist aesthetic that included dramatic cropping and unusual angles. She used light, shadow, and carefully constructed poses to articulate the character, attitude, and individuality of her models: “I really and seriously tried, with every person I photographed, to reveal them as closely as I could.”

Poverty and Activism

Although she had a highly successful studio practice, Lange in 1933 was compelled by the nation’s worsening economic conditions to rethink her occupation and carry her cameras into the city. “There in my studio I was surrounded by evidence of the Depression,” she said. “I remember well standing at that one window and just watching the flow of life. … I was driven by the fact that I was under personal turmoil to do something.”

Out in the streets during the early years of the Great Depression, Lange saw poverty, breadlines, strikes, and labor demonstrations. Her photographs from this period portray the unemployment and unrest that plagued San Francisco, and also document the activism of workers who organised to change their conditions. In 1934, Lange met the agricultural economist Paul Taylor. The two formed an important professional and personal partnership (they married the following year). Lange soon shifted her attention to the plight of migrant farmers, who were moving to California to seek work.

The Great Depression

As the Great Depression deepened, Dorothea Lange focused her lens on the families who had fled westward in the face of economic hardship caused by depleted land and failed farm tenancy in the South and Midwest. When she was working for government agencies, she documented the success of rural cooperatives and the unsanitary conditions in California migrant camps while striving to humanise the large numbers of people seeking shelter and employment. For Lange, portraiture offered a way to visualise the impacts of migration, racism, and environmental change, as well as the legacy of slavery, to gain public support for government aid programs.

During this period Lange cemented her style of documenting people. Her empathetic, highly detailed, and sharply focused depictions show labourers within their living and working environments. Some subjects are alone, but many are seen with family and other members of their communities. These photographs provided evidence of economic disaster and bore witness to the resulting human tragedy while underscoring her subjects’ strength and resilience. This powerful merging of portraiture and documentary photography expanded the boundaries of both traditions, transforming them in ways that resonate deeply today.

World War II

During World War II, Dorothea Lange focused on the impact of the war on Americans at home as well as the nation’s complicated racial dynamics. Nowhere is this seen more acutely than in her portraits of individuals of Japanese ancestry who were forced to abandon their homes in response to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s executive order (see nearby panel).

Lange also recorded the epochal shifts in California’s social fabric sparked by the growing defence industries, which helped rebuild the economy. Hired by Fortune magazine, she documented the Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, where well-paid jobs attracted African Americans, Native Americans, and women into what had previously been a white male-dominated workforce. Yet as the population of Richmond quickly swelled, and as these newly empowered groups began to assert themselves, the changes also provoked housing shortages and social unrest.

Postwar America

Despite frequent health struggles, in the 1950s Dorothea Lange pursued photographic stories about a variety of American communities in the western United States. These include a project about urban life, for which she roamed the Bay Area; Three Mormon Towns, a collaboration made with Ansel Adams and Paul Taylor in Utah for Life magazine; and an environmental critique produced with photographer Pirkle Jones about the flooding of a Northern California town to create a reservoir. Wide-ranging in subject matter, Lange’s photographs reveal an extraordinary ability to portray the continued transformation of the American West and shine a light on the environmental and human consequences of the postwar economic boom.

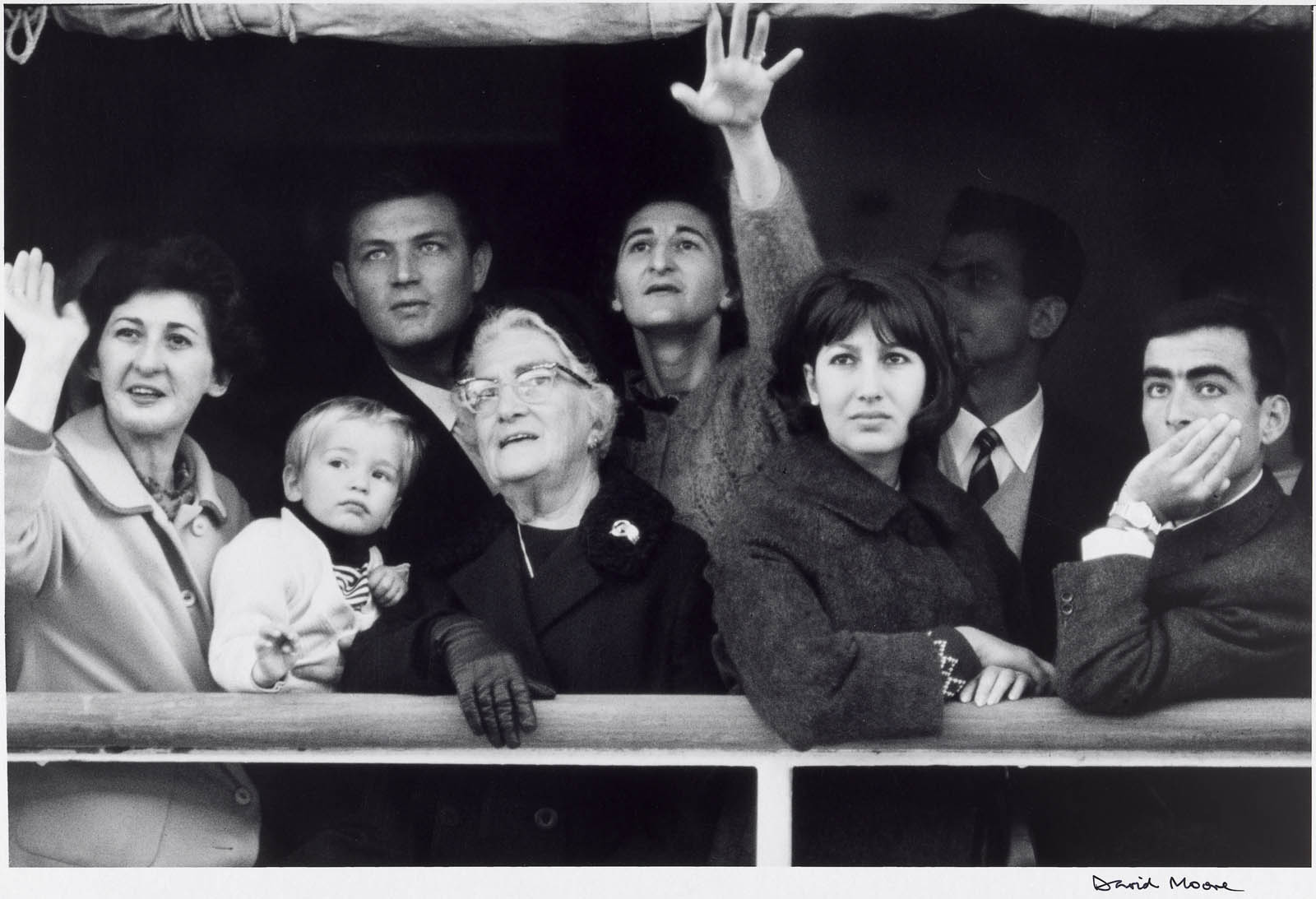

World View

Dorothea Lange began working globally in 1954. Her first trip overseas was to Ireland, where she documented the kinship and community of country villages for Life magazine. Her husband, Paul Taylor, began consulting on international economic development for the US State Department and, in 1958, they traveled abroad for eight months, visiting Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam, and other countries; in the early 1960s, the couple traveled to Venezuela and Egypt. Continuing to concentrate on portraiture, Lange found a new sort of beauty and serenity in these foreign environments as well as ties to the economic and social disparities she had photographed in the United States. While photographs taken during these trips confirm her ongoing creativity in the face of declining health, profound cultural differences made it more difficult for Lange to connect with people.

Lange devoted the last years of her life to her family and to organising a retrospective exhibition of her photographs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She passed away in late 1965, but her legacy continues in the enduring resonance of her photographs and the new generations of photographers who use portraiture and documentary styles to prompt social change.

Travel

Beginning in 1922, Lange traveled with her first husband, artist Maynard Dixon, to Arizona and New Mexico, where she produced portraits of Indigenous Americans. The few photographs that remain from these excursions show Lange testing new strategies. She started to experiment with portraits that featured just a fragment of a person – their hands or face, for example – perhaps inspired by the modernist work of photographer Alfred Stieglitz, whom she had met in 1923. She also shed the soft-focus pictorial style of her earlier studio portraits in favour of a more direct approach. Although Lange interacted only briefly with the Indigenous people she photographed, she witnessed some of the “harsh and unjust treatment” they faced. The sensitivity and experimentation seen in these early photographs helped establish Lange’s expansive concept of portraiture, which impacted her later work.

The Resettlement Administration and the Farm Security Administration

From mid-1935, Dorothea Lange worked for the federal government’s Resettlement Administration (RA), reorganised as the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in 1937. Created to revitalise the country’s faltering agricultural economy, the RA helped farmers acquire land through low interest loans, administered projects on soil conservation and reforestation, and supported resettlement for those who could no longer work their land.

To document and report on its efforts, the RA established a historical division. Led by economist Roy Emerson Stryker, it enlisted some of America’s finest documentary photographers, including Walker Evans, Russell Lee, Marion Post Wolcott, Arthur Rothstein, and Ben Shahn. Stryker hired Lange on the strength of her earlier photographs documenting agricultural conditions for the state of California. In pictures of migrant labourers in California, tenant farmers in Alabama, drought refugees from Oklahoma, and others, Lange recorded the work and aspirations of the agencies. She covered a wide range of socially engaged stories that highlighted themes of human struggle and resilience, but the federal agencies – eager to garner widespread public and congressional support – discouraged depictions of racial oppression.

Migrant Mother March 1936

Human Erosion in California depicts a mother and three children at a migrant labor camp. Lange carefully composed the portrait to capture the woman’s face – prematurely etched by years of labor and worry – and her daughters embracing her. Migrant Mother, as the photograph is commonly known, has been compared to a Renaissance-era Madonna and child and described as an icon of 20th-century art, revered for its empathetic portrayal. Lange did not record the mother’s name. Only in 1978 was she finally identified as Florence Owens Thompson, a woman of Cherokee descent from Oklahoma. At the time of the photograph, Owens Thompson and her family were driving back home from California, where her husband had been working in a sawmill. When their car broke down, they were stranded at a nearby pea pickers’ camp. First published in a newspaper editorial urging government aid for migrant labourers, Migrant Mother prompted support from the state and the picture become an emblem of the power of photography to bring about social change. It also raises questions about the ethics of documentary photography and the dynamics between photographer and subject. Lange recalled that Owens Thompson “seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.” Owens Thompson, however, received little benefit and was never given a copy of the photograph.

Executive Order 9066

In February 1942, months after the Japanese attack on the Pearl Harbor naval base, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The order paved the way for the removal of more than 120,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry – the majority of whom were American citizens – from the West Coast to inland incarceration camps. Denying individuals their civil liberties, the government registered and tagged people before loading them onto buses and transporting them to rudimentary “assembly centers” and, eventually, one of 10 detention camps spread across seven states. The last camp closed four years after Roosevelt issued the order.

Soon after the initial order, the government’s War Relocation Administration (WRA) hired Lange to document this process. Opposed to the government’s actions, Lange believed it was important to record for history “what we did.” Through poignant portraits, she also depicted the resilience of Japanese Americans forced to abandon the lives and businesses they had built and face incarceration. Fearing that Lange’s portraits would elicit too much sympathy, the WRA did not release the photographs during the war.

Documentary Portraiture

Lange’s work during the 1930s synthesised her ideas about portraiture and documentary photography. With new purpose, she used the techniques, compositional strategies, and social skills she had cultivated in her portrait studio to frame the people and events she recorded. By 1940 she had distilled her understanding of documentary photography as an art form that “records the social scene of our time. It mirrors the present and documents for the future.”

Yet these photographs were also documents that followed the government’s New Deal economic doctrine – they emphasised getting the country back on its feet through perseverance, hard work, regulatory reforms, and government relief. This mix of presumed objectivity, propaganda, and documentary storytelling in service of a critical national agenda proved to be particularly powerful. As photography historian Beaumont Newhall later wrote, Lange was “resolved to photograph the now, rather than the timeless; to capture somehow the effects on people of the calamity which overwhelmed America.”

Lange’s Titles

You will notice Lange’s varied approach to titles across her career. Sometimes she simply used someone’s name or the location where a picture was made. Other titles describe or poetically evoke what she saw. Lange also created elaborate captions, often taken from interviews or conversations with those whom she photographed. This was an experimental documentary technique, which relied on Lange’s memory and prolific note taking. These long captions are seen especially in work she made for government agencies during the 1930s and 1940s.

Lange and her editors frequently retitled photographs when exhibiting or publishing them. For this exhibition, we have used Lange’s original titles when known. In a few instances we have updated language in original titles to reflect contemporary usage.

Wall text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Migrant Agricultural Worker’s Family, Nipomo, California

March 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 26.67 x 34cm (10 1/2 x 13 3/8 in.)

Sheet: 27.94 x 35.56 cm (11 x 14 in.)

Mat: 18 x 22 in.

Frame (outside): 19 x 23 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Florence Owens Thompson

Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother) captures the worry, need, and insecurity of everyday Americans during the Great Depression. It is one of the most recognisable American photographs. And it almost wasn’t taken.

In spring 1935, Lange was driving home from a long trip photographing migrant worker camps when she passed a sign pointing toward a pea pickers camp. Lange had already taken many photographs of pea pickers. She tried to convince herself that she didn’t need any more. But about 20 miles later, she turned around.

We don’t know exactly what happened when Lange doubled back – this time, she didn’t take notes. And she didn’t ask many questions. Lange assumed that she had come upon a mother and her three children, there among the waves of workers coming to pick peas, California’s cash crop.

But that wasn’t true. Florence Owen Thompson was traveling with her family from elsewhere in California. The family had set up a camp on the side of the road while her husband and son went into town to resolve some car troubles. When they returned, she mentioned a photographer had taken some photos. Thompson never expected one of those photographs to immortalise her as the “Migrant Mother.” Decades later she wrote a letter to the editor of her local paper expressing irritation with her likeness being misused. In a later interview, Thompson expressed regret at ever allowing Lange to take the photo saying, “I wish she hadn’t taken my picture. I can’t get a penny out of it. [Lange] didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.”

Anonymous. “The Real Lives of People in Dorothea Lange’s Portraits,” on the National Gallery of Art website November 03, 2023 [Online] Cited 25/02/2024

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother)

March 1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 34.1 x 26.8 cm (13 7/16 x 10 9/16 in.)

Mount: 34.8 x 27.1 cm (13 11/16 x 10 11/16 in.)

Frame (outside): 28 5/8 x 22 5/8 x 1 3/8 in.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Grandfather and Grandson of Japanese Ancestry at a War Relocation Authority Center, Manzanar, California

July 1942

Gelatin silver print

Image: 26.4 x 33.7cm (10 3/8 x 13 1/4 in.)

Sheet: 28 x 35.3cm (11 x 13 7/8 in.)

Mat: 16 x 20 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 21 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Grandfather and Grandchildren Awaiting Evacuation Bus, Hayward, California

1942

Gelatin silver print

Image: 26.4 x 22.7cm (10 3/8 x 8 15/16 in.)

Sheet: 35.4 x 27.8cm (13 15/16 x 10 15/16 in.)

Frame (outside): 20 3/4 x 16 7/8 in.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri (Gift of Hallmark Cards, Inc.)

In the spring of 1942, Dorothea Lange requested another leave from her Guggenheim fellowship when she was hired to document the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February1942, which allowed military commanders to set up security zones wherever they thought necessary, with the full authority to remove anyone from these areas regardless of nationality or age. In March, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, announced that all persons of Japanese ancestry would have to leave the Pacific Coast military zone, which included California, western Oregon and Washington, and southern Arizona. Though no specific charges were placed against any individuals, approximately 120,000 men, women, and children – more than two-thirds of them native-born American citizens – were ordered to abandon their homes and businesses and be relocated to internment camps established by the federal government. Two of the ten camps, Manzanar and Tule Lake, were in California as were twelve of the preliminary holding areas called assembly centers. The U.S. Army was responsible for gathering the Japanese Americans and retaining them in the makeshift assembly centers – race tracks, fairground exhibition halls, empty automobile showrooms – until the camps were ready. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was established in March 1942 to oversee management of the camps. In a letter dated 1 April1942 to Moe, Lange requested a postponement of her Guggenheim fellowship explaining: the Japanese (aliens and citizens) are being evacuated from California. The War Relocation Authority has asked me to make photographic documentation of this situation. It’s too worth-while to refuse… It interrupts my fellowship, but is in line with my work.

For the next four months, Lange documented the internees as they were evicted from their homes and businesses, tagged and labeled, and then shuffled by trains and motor convoys to various assembly centers before they were incarcerated. She photographed at only one of the actual internment camps, Manzanar, in the desert of Owns Valley in Southern California. Although Lange was a government employee while recording what is now universally acknowledged as a gross violation of justice, her sympathies were with the Japanese Americans.

Scope and Content

Lange was hired by the San Francisco Regional Office of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) in early April 1942 as a photographer investigator to document the evacuation of Japanese Americans from Northern California. Lange completed her work at the end of July 1942. It has been estimated that of the approximately 13,000 existing photographs taken for the federal government, Lange made over 700. Because of the political nature of her relocation photography, she was required to turn over to the WRA all of her negatives, prints, and undeveloped film; thus, very little of this material is contained within the museum’s archive. Following the end of the war, a complete file of Lange’s WRA negatives and prints was placed in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., with a duplicate set of prints placed at the Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.

Anonymous. “Guide to the Lange (Dorothea) Collection 1919-1965,” on the Online Archive of California website Nd [Online] Cited 25/02/2024

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Japanese American-Owned Grocery Store, Oakland, California

March 1942

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19 x 24.4cm (7 1/2 x 9 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 25.4 cm (8 x 10 in.)

Mat: 14 x 18 in. frame (outside): 15 x 19 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

On December 8, 1941, a day after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, Tatsuro Masuda, the 25-year-old American-born owner of the Wanto Company store in Oakland, posted a sign on his building: “I AM AN AMERICAN.” Masuda’s bold assertion of his national identity did little good. In March 1942, Masuda, a University of California graduate, closed the store that his father had founded 26 years earlier. In August 1942, he and his family were incarcerated at the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona. They were not released until October 1944. They never returned to Oakland.

Label text from the exhibition

Tatsuro Masuda

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in 1942. The order forced the unjust incarceration of more than 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent (the majority of whom were American citizens). The War Relocation Authority hired Lange to document this process. Lange was horrified by what she witnessed. She chronicled her subjects in a sympathetic light, so much so that her photographs were censored during the war.

Lange began by photographing Japanese Americans as they prepared to abandon their homes. She took this picture of a grocery store on a street corner in Oakland, California, in March 1942, a month after the executive order was issued.

Tatsuro Masuda ran the Wanto Company store (look for its name on the windows), opened by his father in 1900. Fearful of growing anti-Japanese sentiments, Masuda paid for the “I AM AN AMERICAN” sign to be installed the day after Pearl Harbor. By the time Lange took the photograph, Masuda decided to close the store. Japanese Americans were forced to sell or relinquish any property they couldn’t carry with them. He moved to Fresno with his new wife, Hatsue Kuge. In August the couple (now expecting their first child) were incarcerated at Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona. Their second child was born at Gila, as well. They weren’t released until October 1944.

Anonymous. “The Real Lives of People in Dorothea Lange’s Portraits,” on the National Gallery of Art website November 03, 2023 [Online] Cited 25/02/2024

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Richmond, California

1944, printed 1950s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17 x 16.8 cm (6 11/16 x 6 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 25.2 x 20.2 cm (9 15/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

Mat: 16 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

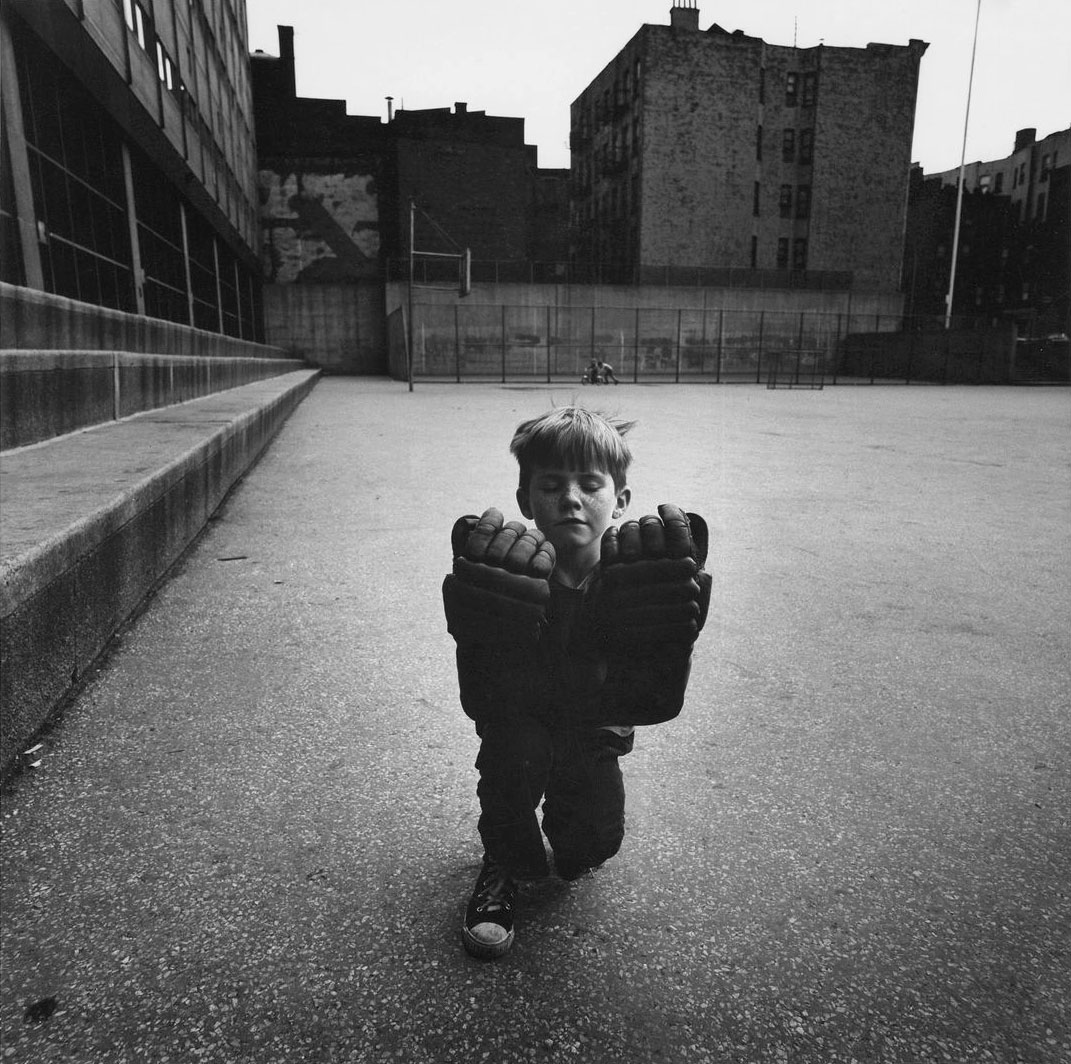

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Richmond, California from City Life

1952

Gelatin silver print

Image: 25 x 21cm (9 13/16 x 8 1/4 in.)

Sheet: 28.1 x 23.4cm (11 1/16 x 9 3/16 in.)

Mat: 17 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 18 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Anne Carter Johnson, Saint George, Utah

1953

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19 x 18.8cm (7 1/2 x 7 3/8 in.)

Sheet: 25.2 x 20.3cm (9 15/16 x 8 in.)

Mat: 14 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Self-Portrait in Window, Saint George, Utah

1953

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 23.8 x 18.6cm (9 3/8 x 7 5/16 in.)

Mount: 24.2 x 19.1cm (9 1/2 x 7 1/2 in.)

Mat: 16 x 13 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 14 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Among the places Lange visited for the Life magazine photo-essay Three Mormon Towns (produced with Ansel Adams and Paul Taylor) was Saint George, Utah. A formerly secluded pastoral community, the area had grown into a town with gas stations and motels to accommodate visitors to nearby Zion National Park. The town’s modernisation infringed upon the community’s prior isolation from mainstream American culture, and Lange feared that some of its early pioneer principles might be lost. Perhaps equating her own fragile health with the town’s vulnerability, Lange photographed her face and camera reflected in the window of a dilapidated building, calling the picture a self-portrait.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Jake Jones’s Hands, Gunlock County, Utah

1953

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 16.6 x 12.8cm (6 9/16 x 5 1/16 in.)

Mount: 17.1 x 13.7cm (6 3/4 x 5 3/8 in.)

Mat: 14 x 11 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 12 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Annie Halloran’s Hands

1954

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19.3 x 19.4cm (7 5/8 x 7 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 20.3cm (8 x 8 in.)

Mat: 15 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 16 x 15 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Family Portrait from Death of a Valley

1956

Gelatin silver print

Image: 27.1 x 25.7cm (10 11/16 x 10 1/8 in.)

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of an anonymous donor in memory of Merrily Page

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

These family portraits were abandoned in a home in Monticello, California, when residents were forced to relocate. The Napa County town was destroyed and flooded in 1957 after the creation of Lake Berryessa, a reservoir formed by the new Monticello Dam. Lange made this photograph for the series Death of a Valley, a collaboration with photographer Pirkle Jones, reproduced in a 1960 edition of Aperture magazine. Lange’s “portrait” of forsaken family photographs communicates a sense of lost memories and the human costs of development. It demonstrates not only Lange’s prescient environmentalism but also her long-standing concern for the disintegration of families and communities.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Korean Child

1958

Gelatin silver print

Image: 14.7 x 11.1cm (5 13/16 x 4 3/8 in.)

Sheet: 16 x 12.4cm (6 5/16 x 4 7/8 in.)

Mount: 19 x 14cm (7 1/2 x 5 1/2 in.)

Mat: 14 x 11 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 12 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Lange and Taylor traveled to South Korea in 1958 and encountered people still reeling from a divisive war. When visiting a classroom, Lange focused on a group of excited students. But when she printed Korean Child for her 1966 retrospective exhibition, she radically cropped her negative to concentrate on one boy’s serene features. Since her early portraits of the 1920s, Lange had used dramatic cropping to shape the meaning of her photographs. Here, by isolating the boy’s calm face from the chaos surrounding him, she created a more universal exploration of the innocence of childhood in a nation then torn by war and poverty.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Indonesian Woman

1958

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 12 x 9.5cm (4 3/4 x 3 3/4 in.)

Mat: 14 x 11 in.

Frame (outside): 15 x 12 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Bad Trouble over the Weekend, Steep Ravine, California

1964, printed later

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.3 x 15.2cm (9 9/16 x 6 in.)

Sheet: 25.1 x 20.4cm (9 7/8 x 8 1/16 in.)

Mat: 16 x 14 in.

Frame (outside): 17 x 15 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

For years, Lange and Taylor spent many weekends with their children and grandchildren at a rented cabin on Steep Ravine above Stinson Beach, just north of San Francisco. Bad Trouble over the Weekend was made during one such stay near the end of Lange’s life – she had already been diagnosed with terminal cancer. She cropped the photograph to focus on her daughter-in-law Mia Dixon’s hands, which cradle her unseen face. The gesture and the caption suggest the emotional weight of Lange’s flagging health, although she provided few narrative details. The photograph communicates both a personal and a universal connotation of “trouble,” telling an ambiguous story for viewers to imagine and, perhaps, identify with.

Label text from the exhibition

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Pledge to the Flag, San Francisco

1942, printed c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 31.7 x 13.9cm (12 1/2 x 5 1/2 in.)

Mat: 22 x 16 in.

Frame: 23 x 17 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

National Gallery of Art

National Mall between 3rd and 7th Streets

Constitution Avenue NW, Washington

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965) 'Child Living in Oklahoma City Shacktown [Damaged Child, Shacktown]' August 1936 Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965) 'Child Living in Oklahoma City Shacktown [Damaged Child, Shacktown]' August 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/5558-093-web.jpg)

![Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976) 'New York [Wall Street]' Negative 1915; print 1916 Photogravure Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976) 'New York [Wall Street]' Negative 1915; print 1916 Photogravure](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/strand-wall-street-a.jpg)

![Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976) 'New York [Wall Street]' Negative 1915; print 1916 Photogravure Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976) 'New York [Wall Street]' Negative 1915; print 1916 Photogravure](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/strand-wall-street-b.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.