Exhibition dates: 23rd April 2023 – 4th February 2024

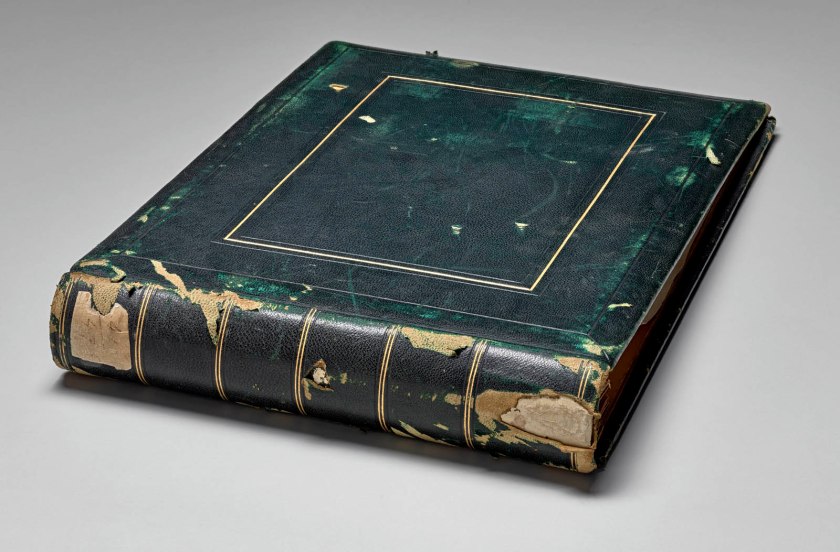

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Album of 37 photographs

c. 1887-1888

37 albumen prints

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

There are some beautiful photographs in this mid-week posting by the most eminent Indian photographer of the 19th century, Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905).

Dayal had access to the upper echelons of British and Indian society where he photographed in the Western tradition of formal portraiture and more personal views of the British occupiers and Indian nobility, namely the Maharaja of the semi-independent “princely states” of central India.

“Dayal posed and composed Indian royalty exactly as he did his photographs of British leadership, with the most important person in the center, often surrounded by advisers and subordinates. Head-on to the camera, stately but not overly formal, viceroys and rajahs alike became accessibly human but at imposing removes.”1

Will Heinrich in an article for the New York Times observes that what really stands out, what is really shocking are “the rows of Indian servants lined up like stiff accessories behind rickshaws, buggies and English garden parties” and the fact that “they were photographed that way by an Indian photographer complicates any easy read of what they mean.” And that none of the Indian servants is identified.

This should not be shocking at all… for the Indian world, as the British world, was all about status and power. You can see British servants lined up outside and behind the owners of stately homes in the United Kingdom. And they won’t be named. That’s because their social status made them invisible in name if not in physical appearance. They were servants.

And it should come as no surprise that Dayal photographs Indians in the way that he does because he aspired to enter the highest levels of British and Indian society – through his talent yes but also using that talent to advance his social climbing and social standing. By imitating Westernised portraiture of the ruling class both British and Indian, he sought to cement his stature as one of the country’s top photographers, picturing both the country and people through “an archive of depictions of meaningful sites, important occasions, and significant people that was essential to running a profitable studio.”

He took photographs of superb pictorial refinement and luxurious tonality. Through his talent and business acumen he became a man of importance, he had access to the upper echelons of society and his name is still known today … unlike all the anonymous men (and one woman) who are lost to the mists of time.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Will Heinrich. “The Photographer Who Immortalized British Viceroys and Maharajahs,” on The New York Times website August 31st, 2023 [Online] Cited 04/09/2023

Many thankx to the Cleveland Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

A map of central and northern India showing some of the cities where Dayal took photographs in this posting.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Detachment of Bhopal Battalion at Indore

1886

Albumen print

Image: 19.1 x 26.5cm (7 1/2 x 10 7/16 in.)

Paper: 19.1 x 26.5cm (7 1/2 x 10 7/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

In state and military portraits, people seated in chairs and in the middle are generally of the highest rank. Amid these Indian soldiers sits a lone British officer. The Bhopal Battalion had seen combat just six years earlier during the Second Anglo-Afghan War, helping to keep Afghanistan a British-friendly buffer against Russia’s desire to expand into India. This detachment includes a number of Sikhs, identifiable by their neatly trimmed beards and turbans that cover their ears. Members of that religious group were avidly recruited by the British Indian Army due to their reputed ferocity and courage in battle.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Detachment of Bhopal Battalion at Indore (detail)

1886

Albumen print

Image: 19.1 x 26.5cm (7 1/2 x 10 7/16 in.)

Paper: 19.1 x 26.5cm (7 1/2 x 10 7/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

The Duke and Duchess of Connaught, with Col. Adam, Captain H.V. Benett, Col. Becher, Gen. Knowles, Captain Herbert, Col. Cavaye, Mrs. Cavaye, and Gen. R. Gellispie, Mhow

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.1 x 26.6cm (7 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.)

Paper: 19.1 x 26.6cm (7 1/2 x 10 1/2 in.)

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

This gathering of British military officers was occasioned by the visit of Queen Victoria’s seventh child, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (1850-1942) (seated, second from left). His wife, Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia, is the woman on the right. As commander in chief of the Bombay Presidency from 1886 to 1890, the prince performed military inspections and embarked on diplomatic missions throughout India. Dignitaries’ visits were routinely commemorated with a professional photograph. The photographer often took the image for free, counting on the purchase of prints by those wanting to feature the dignitary in their parlours on walls and tables or in albums.

In 2016, the museum acquired 37 photographs made by Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905), hailed as the first great Indian photographer. This exhibition marks the Cleveland debut of these rare images, all of which come from a single album and were shot in 1886 and 1887, an important juncture in the artist’s life. On display alongside Dayal’s photographs are historical Indian paintings, textiles, clothing, and jewellery from the museum’s collection. These objects provide viewers with insight into the cultural context and help translate the objects in the photographs from monochrome into colour.

Dayal was a surveyor working for the British government when he took up photography as a hobby in 1874. In 1885, he attempted to make it his career and by 1887 had cemented his stature as one of the country’s top photographers, British or Indian. This rare early album pictures both the maharajas of princely India and the British colonial elite.

Dayal produced formal portraits but also more personal views of the Indian nobility. In a moving portrait of a 10-year-old maharaja, Dayal reveals the boy beneath the crown. Weighed down by necklaces and jewels, he occupies a chair that is too tall for him; his stockinged feet curl under so they touch the ground.

Dayal’s talent also won him access to the highest levels of British society. He photographed government meetings and leisurely afternoons of badminton and picnics, costume parties, and even a private moment of communion between an Englishman and his bulldog. Dayal portrayed how the British brought England with them to India and in some images, the Indian servants who supported that lifestyle. The photographer cultivated his relationship with the military by documenting troop manoeuvres, several views of which are included.

Visually striking, seductively charming, and highly informative, these photographs and objects offer new insights into the early career of India’s most important 19th-century photographer and into British and Indian life at the height of the colonial “Raj.”

Text from the Cleveland Museum of Art website

Unknown artist (Central India, Madhya Pradesh)

A Ruler Seated on a Terrace Worshipping at a Shrine of Radha and Krishna

c. 1800

Gum tempera and gold on paper

25.1 x 20cm (9 7/8 x 7 7/8 in.)

Purchase and partial gift from the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection; Severance and Greta Millikin Purchase Fund

A noble clad in a black woollen shawl and a red turban, both with delicate floral embroidery, kneels before a small shrine with icons of Krishna fluting alongside his lover Radha. An attendant dressed in white holds a fly whisk that denotes the kneeling figure’s royal status. The black sky with light horizon suggests that the sun has recently set. In spite of the individualised facial features, this noble remains unidentified. Both figures have rosaries of rudraksha beads usually worn by followers of Shiva, instead of Krishna.

Unknown maker (Indian)

Ornament

1800s

Gold with green enamel ground, white sapphires, rubies, and pearls

Diameter: 5.2 cm (2 1/16 in.)

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Wade

Circular ornaments were worn as pendants, sewn onto textiles, or pinned into hair. The decorative motif made of colourful gems depicting flowering plants was introduced during the reign of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (1628-1658) and remained popular through the 1800s.

Unknown maker (Indian)

Medallion

1800s

Silver gilt with rubies and emeralds

Diameter: 5.4 cm (2 1/8 in.)

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Wade

Circular ornaments were worn as pendants, sewn onto textiles, or pinned into hair. The decorative motif made of colorful gems depicting flowering plants was introduced during the reign of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (1628-1658) and remained popular through the 1800s.

Unknown maker (Indian)

Pendant

1700s

Northwestern India, Rajasthan, Rajput Kingdom of Jaipur

Gold, emerald, diamonds, enamel, and pearl

Overall: 7.4 x 4.8 cm (2 15/16 x 1 7/8 in.)

Bequest of Anne Jessop Smith

The large green emerald on one side of this pendant was probably imported to India from Columbia. Delicately incised with a lotus blossom, a symbol of the sun, it is surrounded by inset diamonds in organic, petal-like shapes. Emeralds, especially prized for their green colour, were associated with the planet Mercury in Hindu astrology and with the power to ward off evil in Islam. On the reverse, a peacock and two peahens surrounded by flowers are rendered using blue, green, and red glass.

Attributed to Balchand (Indian, active 1595 – c. 1650)

Portrait of Murad Bakhsh (1624-1661)

c. 1635; borders c. 1700s

Mughal India, court of Shah Jahan (reigned 1628-1658)

Gum tempera and gold on paper

Overall: 28.4 x 25.7cm (11 3/16 x 10 1/8 in.)

Painting: 4.3 x 3.5cm (1 11/16 x 1 3/8 in.)

Gift in honour of Madeline Neves Clapp; Gift of Mrs. Henry White Cannon by exchange; Bequest of Louise T. Cooper; Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund; From the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection

The miniature portrait of a Mughal prince is now mounted on an album page. Originally, it was in a gemstone setting as a “portrait jewel” to be worn by family and supporters at court. India’s ruling elite had been wearing portrait jewels since Sir Thomas Rowe (about 1581-1655) presented British portrait miniatures and cameos to the Mughal emperor as part of a diplomatic gift in 1616, when he successfully negotiated for British access to India’s ports.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

His Highness Maharaja Scindia of Gwalior

1887

Albumen print

Image: 25.5 x 18.4cm (10 1/16 x 7 1/4 in.)

Paper: 25.5 x 18.4cm (10 1/16 x 7 1/4 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Ten-year-old Madho Rao Scindia, the Maharaja of Gwalior (1876-1925; reigned 1886-1925), inherited the throne one year before this photograph was taken. Acceptance of both Indian and British cultural influences can be seen in the contrast of his garb, which is Indian from turban to shoe, with the Western-style furniture, clock, and books. Reflected in the glass balls on the table, which may be an inkwell or perfume jar, are the other people in the room during the shot. The person on the left in the top ball may be the photographer, Lala Deen Dayal.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

His Highness Maharaja Scindia of Gwalior (detail)

1887

Albumen print

Image: 25.5 x 18.4cm (10 1/16 x 7 1/4 in.)

Paper: 25.5 x 18.4cm (10 1/16 x 7 1/4 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

In 1887, a photographer named Lala Deen Dayal took a picture of Frederick Temple-Blackwood, First Marquess of Dufferin and Ava [below]. The men were in Shimla, in the foothills of the Himalayas, because the British colonial government in India moved there every summer to escape the heat of Kolkata. Dufferin was the British viceroy, and Dayal, who had worked as a surveyor for the colonial government before leaving to pursue his passion as a freelancer, was his official photographer.

Dayal posed Dufferin, a short, balding, goateed, intelligent-looking man, at the center of the photo, behind a round table covered in a patterned cloth. To either side of him sit three other men, all seven constituting the Supreme Council of Government of India. Beneath them is an enormous, intricately patterned carpet; behind them, a nondescript curtain and rough wooden walls. They look like what they were: fresh conquerors who hadn’t yet built themselves palaces.

They also look pretty discomfited by the camera in what were still its early days. Two look at the viceroy, who leans aside to deliver some incidental remark; one gazes at the floor; two stare stiffly into nowhere; and only one councillor, like a faint glimmer of self-awareness within the raj, peers suspiciously into the lens.

The photograph became one of a deep file of stock images available in Dayal’s shop. One souvenir album, assembled by an unidentified purchaser and later broken apart, was partially acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2016. In “Raja Deen Dayal: King of Indian Photographers,” the museum combines this cache of 37 photographs with roughly contemporary miniature paintings and objets to create a small but incisive look at cross-cultural projections of power – Dayal was official photographer to the British military commander in chief, too, as well as to the Nizam of Hyderabad, who gave him the title Raja.

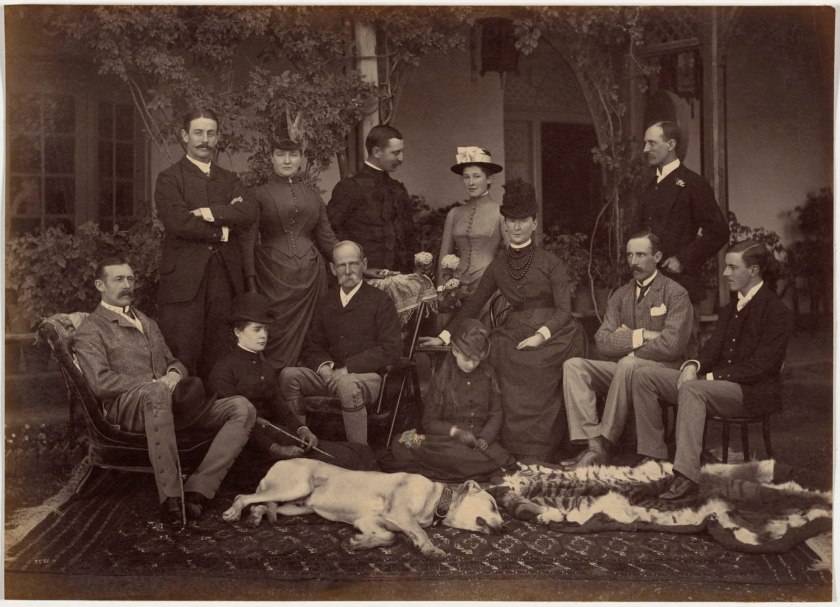

An acute wall label next to “His Eminence Commander in Chief and Party, Simla” [below] draws attention to the tiger skin on the floor, flung carelessly under British feet; beside the photo, on the gallery wall, to illustrate the Indian association of this animal with royalty, hangs a 19th century painting from Rajasthan showing a “Tiger Hunt of Ram Singh II.”

It’s just one of the show’s many examples of the casual degradations of imperial rule, which also include an English-style silver teapot with a goddess for a handle, and a painting of an Indian servant walking British dogs – a mordant wall label notes that Indian art traditionally pictured “dogs and jackals” only in cremation grounds. But it’s the rows of Indian servants lined up like stiff accessories behind rickshaws, buggies and English garden parties that really stand out. They’re shocking, but the fact that they were photographed that way by an Indian photographer complicates any easy read of what they mean.

Also in 1887, give or take a year or two, Dayal made a portrait of “His Highness the Maharaja of Rewa,” one of the semi-independent “princely states” of central India. Draped in gold and jewels, with a stylized footprint of Vishnu painted on his forehead, slumping comfortably sideways in an ornate chair with his stocking feet curled underneath, the boy king is pretty much the opposite of the severely styled Dufferin. But Dayal posed and composed Indian royalty exactly as he did his photographs of British leadership, with the most important person in the center, often surrounded by advisers and subordinates. Head-on to the camera, stately but not overly formal, viceroys and rajahs alike became accessibly human but at imposing removes. In retrospect, Dayal’s pictures aren’t just portraits of royal and imperial power – they’re portraits of the nascent power of photography.

Will Heinrich. “The Photographer Who Immortalized British Viceroys and Maharajahs,” on The New York Times website August 31st, 2023 [Online] Cited 04/09/2023

Unknown maker (Indian)

Cap

1800s

Velvet embroidered with gilt-silver–wrapped silk thread (zari); silk: lining; rubies, pearls, and spinels

Overall: 6.3 x 15.2 x 15.2 cm (2 1/2 x 6 x 6 in.)

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Wade 1916.1477

Historically in India, head coverings were worn in outdoor and formal contexts and can signal age, allegiance, and status among Indian men and boys. A low round cap such as this was worn primarily by the well-educated aristocratic boys in the king’s circle. The painstaking process of creating the ornament involved wrapping gilt-silver wire of various dimensions around a silk thread core to create a textured appearance for the flowers and vines.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Maharaja of Rewa and Classmates

1886

Albumen print

Image: 19.8 x 27.1cm (7 13/16 x 10 11/16 in.)

Paper: 19.8 x 27.1cm (7 13/16 x 10 11/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Deen Dayal uses the arrangement of people and the architecture to point to the most important person in the photograph. Here, the Maharaja of Rewa is placed front and center. In this image, the young maharaja is shown with Indian teachers, but the instructional tools are Western: bound books and a raised relief globe (with Asia visible).

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Maharaja of Rewa and Sardars

1886

Albumen print

Image: 19.7 x 26.9cm (7 3/4 x 10 9/16 in.)

Paper: 19.7 x 26.9cm (7 3/4 x 10 9/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Deen Dayal uses the arrangement of people and the architecture to point to the most important person in the photograph. Here, the Maharaja of Rewa is placed front and centre. “Sardars,” inscribed on the picture’s mount, refers to the military officials surrounding him. After 1858, British influence dictated that Indian rulers be educated in European history and ideas as well as their local culture and history.

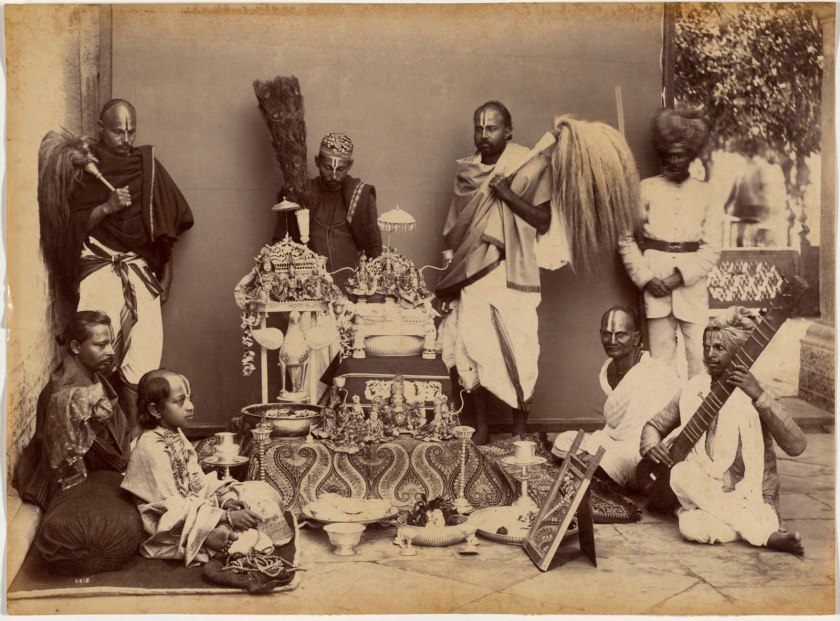

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Maharaja of Rewa in Prayer

1886

Albumen print

Image: 20 x 27.2cm (7 7/8 x 10 11/16 in.)

Paper: 20 x 27.2cm (7 7/8 x 10 11/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Performing religious devotions was part of a maharaja’s duty to protect his kingdom. Praying before an altar, the maharaja fingers prayer beads and sits opposite a mirror, an auspicious object in Hindu worship. The lines painted on the men’s foreheads indicate that they are devotees of the Hindu god Vishnu. This group portrait demonstrates three ways rulers serve the state: by being a military commander, a worldly scholar, and, in this image, an observant Hindu.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

His Highness the Maharaja of Rewa

1886

Albumen print

Image: 20 x 27.2cm (7 7/8 x 10 11/16 in.)

Paper: 20 x 27.2cm (7 7/8 x 10 11/16 in.)

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Deen Dayal’s status as an Indian person may have helped him gain access to Indian rulers at the start of his career. The year before he received the patronage of British officials, Deen Dayal photographed ten-year-old Venkat Raman Singh (1876-1918; reigned 1880-1918), the Maharaja of Rewa. The studio portrait reveals the boy beneath the crown. He straddles a Western-style chair that is too tall for him, curling under his stockinged feet so they touch the floor. One of his many necklaces holds a painted or photographic portrait similar to the portrait jewel pendant in the nearby case.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

His Highness the Maharaja of Rewa

1886

Albumen print

Image: 26.7 x 20.3cm (10 1/2 x 8 in.)

Paper: 26.7 x 20.3cm (10 1/2 x 8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Deen Dayal’s status as an Indian person may have helped him gain access to Indian rulers at the start of his career. The year before he received the patronage of British officials, Deen Dayal photographed ten-year-old Venkat Raman Singh (1876-1918; reigned 1880-1918), the Maharaja of Rewa. The studio portrait reveals the boy beneath the crown. He straddles a Western-style chair that is too tall for him, curling under his stockinged feet so they touch the floor. One of his many necklaces holds a painted or photographic portrait similar to the portrait jewel pendant in the nearby case.

Unknown maker (Indian)

Turban Ornament (Sarpech)

1800s

Gilt silver with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, topaz, blue sapphires, yellow sapphire

Overall: 10.2 x 8.4cm (4 x 3 5/16 in.)

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Wade

This type of ornament would have been affixed to the front of a turban as an emblem of high noble status. The raised central element mimics the shape of an eagle feather or plume.

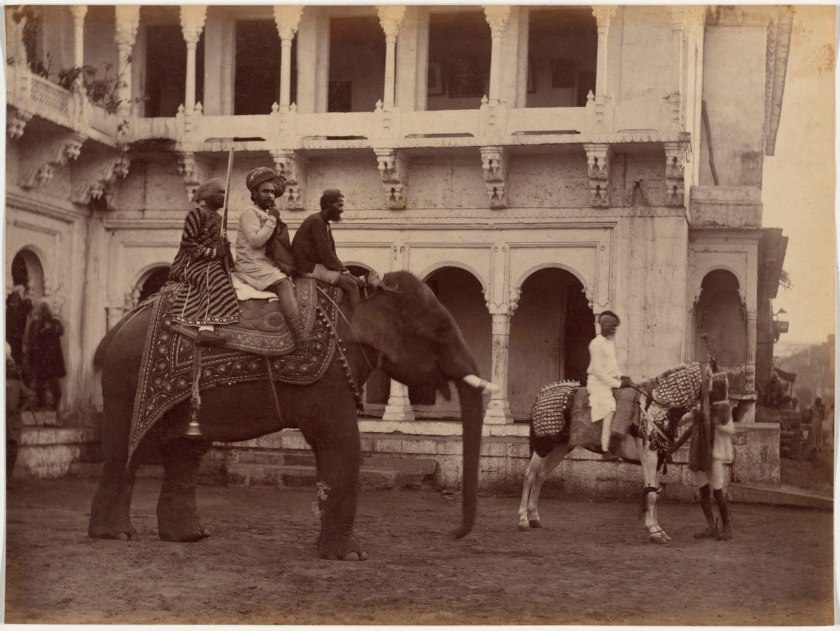

Unknown artist (Indian)

Royal Elephant Ramkali with a Mahout

c. 1761

Northwestern India, Rajasthan, Rajput kingdom of Mewar, Udaipur, Court of Ari Singh (reigned 1761-73)

Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper

Painting: 20.6 x 21.4cm (8 1/8 x 8 7/16 in.)

Overall: 24.1 x 25cm (9 1/2 x 9 13/16 in.)

Gift of Dr. Norman Zaworski

The mahout (elephant driver), directs the confident female elephant at a brisk trot, with bells swinging in response to her movements. This painting belongs to a series depicting the elephants in the royal stables at Udaipur, each one named in the upper margin. Elephants have been a potent emblem for royalty in India for more than three thousand years.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Ramkishore Singh of Rewa

1886

Albumen print

Image: 20.3 x 27.3cm (8 x 10 3/4 in.)

Paper: 20.3 x 27.3cm (8 x 10 3/4 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Ramkishore Singh, likely a high-ranking official or merchant, is depicted twice in the album, each time aboard a luxurious type of transport. In one photograph [above], he rides atop an elephant, a creature associated with India, power, and fortitude, preceded by an attendant on horseback. In the other [below], he rides in a European-style carriage pulled by two horses, flanked by attendants on camels (native to parts of India) and horses. Like the images of Britons in their carriages and rickshaws, these depictions suggest the sitter’s wealth through his possession of servants, animals, and vehicles.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Ramkishore Singh of Rewa

1886

Albumen print

Image: 18.6 x 27cm (7 5/16 x 10 5/8 in.)

Paper: 18.6 x 27cm (7 5/16 x 10 5/8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

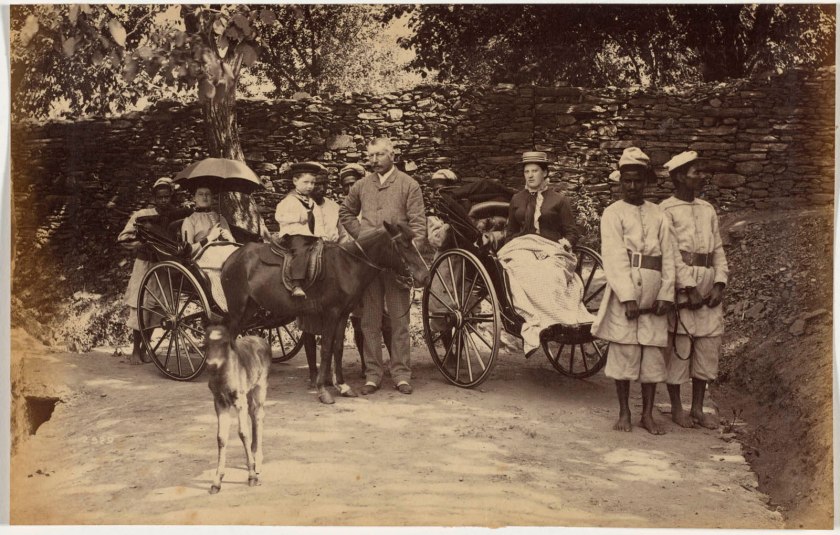

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Colonel F. G. Oldham, Simla

1887

Albumen print

Image: 13 x 20.3cm (5 1/8 x 8 in.)

Paper: 13 x 20.3cm (5 1/8 x 8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

In Deen Dayal’s shots of large groups, the sitters are artfully arranged in close proximity, some even touching. But in his family portraits, at least in this album, the individuals are separated. Francis Oldham (1839-1923), an engineer at the India Public Works Department, poses with his wife Nora, their son Brian, an unidentified woman, and rickshaw drivers.

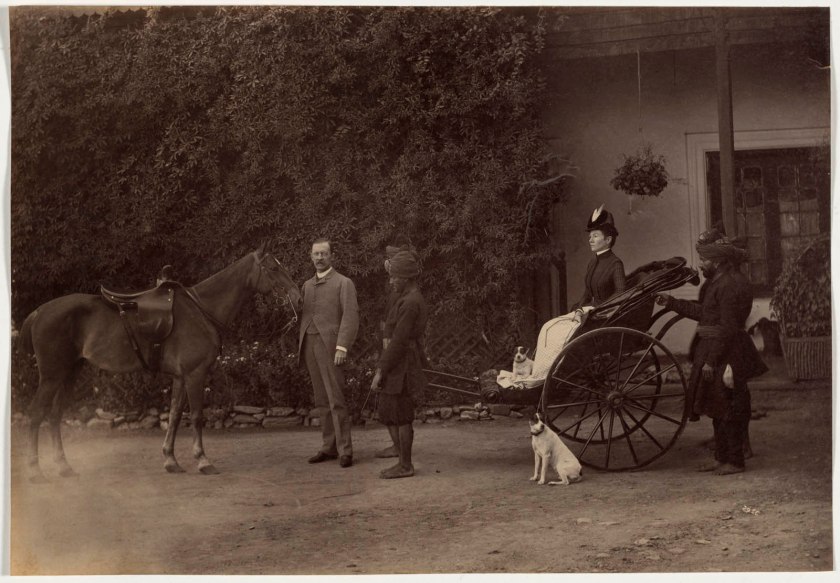

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Colonel H.R. Thuillier and His Wife Emmeline Williams Thuillier, Simla

1887

Albumen print

Image: 18.1 x 26.1cm (7 1/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

Paper: 18.1 x 26.1cm (7 1/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

In Deen Dayal’s shots of large groups, the sitters are artfully arranged in close proximity, some even touching. But in his family portraits, at least in this album, the individuals are separated. The above image features Colonel H. R. Thuillier (1838-1922) holding his horse’s bridal, his wife Emmeline, their two terriers, and rickshaw drivers. Thuillier became the surveyor general of India the year this photograph was taken by Deen Dayal, who had just given up surveying for photography.

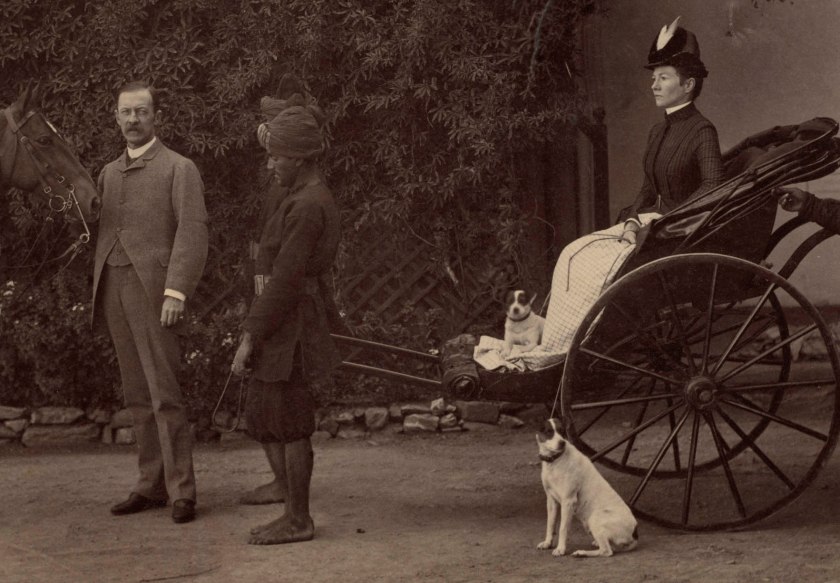

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Colonel H.R. Thuillier and His Wife Emmeline Williams Thuillier, Simla (detail)

1887

Albumen print

Image: 18.1 x 26.1cm (7 1/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

Paper: 18.1 x 26.1cm (7 1/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

His Honor The Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab and Party, Simla

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.5 x 27.4cm (7 11/16 x 10 13/16 in.)

Paper: 19.5 x 27.4cm (7 11/16 x 10 13/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

This photograph may commemorate a family reunion of the Lyalls. In 1887 James Lyall (1838-1916) (possibly on the left) was appointed lieutenant governor of the Punjab region, the same year that his elder brother Alfred Lyall (1835-1911) (second from left) retired as lieutenant governor of North-Western Provinces. After recovering from a serious illness, Alfred visited James in Simla. The women are likely Alfred’s daughter Mary Evelina Lyall (1868-1948) (left) and “Mrs. Lyall,” possibly Mary’s aunt, James Lyall’s wife. A master at staging group portraits, Deen Dayal used symmetry, proximity, height, and other formal devices to indicate the sitters’ interrelationships and relative ranks.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Lord Dufferin and the Supreme Council of Government of India, Simla

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.4 x 27.3cm (7 5/8 x 10 3/4 in.)

Paper: 19.4 x 27.3cm (7 5/8 x 10 3/4 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Each summer, the British government left the heat of Calcutta for Simla in the foothills of the Himalayas, where this photograph was taken. In 1885 Deen Dayal began spending his summers there to be near the officials, who were both subjects and clients. The viceroy, or British ruler, of India, Frederick Temple-Blackwood, 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava (1826-1902), sits at the centre of this staged meeting of the Supreme Council. Deen Dayal made images of Lord Dufferin and his wife, herself an amateur photographer, that led to his appointment as photographer to the viceroy, which resulted in access to other members of the British elite.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

His Eminence Commander in Chief and Party, Simla

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.5 x 27.2cm (7 11/16 x 10 11/16 in.)

Paper: 19.5 x 27.2cm (7 11/16 x 10 11/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

In 1887 Deen Dayal was appointed photographer to the commander in chief of the British Indian Army, Field Marshal Frederick Roberts (1832-1914) (seated, third from left). This casually dressed group of Roberts’s family and friends had just enjoyed a week of formal events, including a “fancy dress” ball celebrating the 50th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne. That party inaugurated a ballroom built onto Roberts’s home. The following day, Roberts was made Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire. The tiger skin attests to British success at big game hunting. Its use as a rug reveals a very different attitude toward this favoured pastime among the British than the Indians, for whom it symbolised royal power.

Unknown artist (Indian)

Tiger Hunt of Ram Singh II

c. 1830-1840

Northwestern India, Rajasthan, Rajput kingdom of Kota, court of Ram Singh II (reigned 1826–66)

Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper

Painting: 25.3 x 49.1cm (9 15/16 x 19 5/16 in.)

Seventy-fifth anniversary gift of Dr. Norman Zaworski

Set against the dramatic backdrop of the cliffs that define the landscape of the small princely kingdom of Kota, a majestic tiger has just been shot by the king. Noisemakers with a firebrand drive the tiger out of the forest, and men at the right keep bears at bay. The women and musicians in two small boats look on in admiration.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

His Eminence Commander in Chief and Party, Simla (detail)

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.5 x 27.2cm (7 11/16 x 10 11/16 in.)

Paper: 19.5 x 27.2cm (7 11/16 x 10 11/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

In 2016, the museum acquired 37 photographs by Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905), hailed as the first great Indian photographer. These images, which show the British ruling elite in India and two boy maharajas and their nobles, had all once been part of a single photo album. Popular from the 1850s until the spread of digital photography in the 1990s, photo albums are precious mementos of a time or place. They served as status symbols and objects that defined one’s identity for future generations.

The album in question had been ordered from the photographer’s studio around 1888, probably by a male British official serving in or visiting India in late 1887 or 1888. This exhibition marks the United States debut of these rare, early photographs by Deen Dayal. On display alongside them are historical Indian paintings and luxurious textiles, clothing, and jewelry from the museum’s collection that help bring the photographs to life.

The client would have chosen which images he wanted in the volume, and he seems to have greatly favored portraits. Captions elegantly handwritten in English on the mounts identify the subjects. Most of the prints came from Deen Dayal’s stock images – an archive of depictions of meaningful sites, important occasions, and significant people that was essential to running a profitable studio. Nonetheless, it is likely that the purchaser of the album met many of the British individuals he selected – perhaps had tea or dinner at their homes – and spent time at a number of the locales depicted. If the visitor was on official business, he may even have been received at the courts of these maharajas. After all, this album was a souvenir of his time in India, something to jog his own memory in the future and to pass down the story of his glorious adventure in India to later generations.

How personal were this man’s connections with the sitters? A young woman identified as Miss Lyall appears in three different photographs and a Mrs. Lyall (most likely a sister-in-law but possibly a mother) in two of them. Was the album commissioned by someone courting Miss Lyall, perhaps even her future husband? We may never know, even though we can track the biographies of many of the British sitters and of the two 10-year-old maharajas, both of whom remained on the throne for almost 40 years.

What do these images, taken 135 years ago by an Indian whose business relied heavily on a British clientele, suggest about the British colonists and the Indian people over whom they ruled? Deen Dayal portrayed how the British brought England with them to India and, in a number of pictures, the Indian servants who supported that colonial lifestyle. These servants are never identified or even referred to in the captions. We see them posing alongside the British horses and dogs they walk, feed, and groom; hovering in the background at a picnic ready to offer more food; and standing at attention behind British carriages.

Visually striking, seductively charming, and providing much food for thought, Deen Dayal’s photographs and the related Indian art objects offer new insights into the early career of India’s most important historic photographer and into British and Indian life in late 19th-century India.

Anonymous. “The Photos of Raja Deen Dayal: The first great Indian photographer,” in Cleveland Art, 2023 issue 2 Nd [Online] Cited 04/09/2023

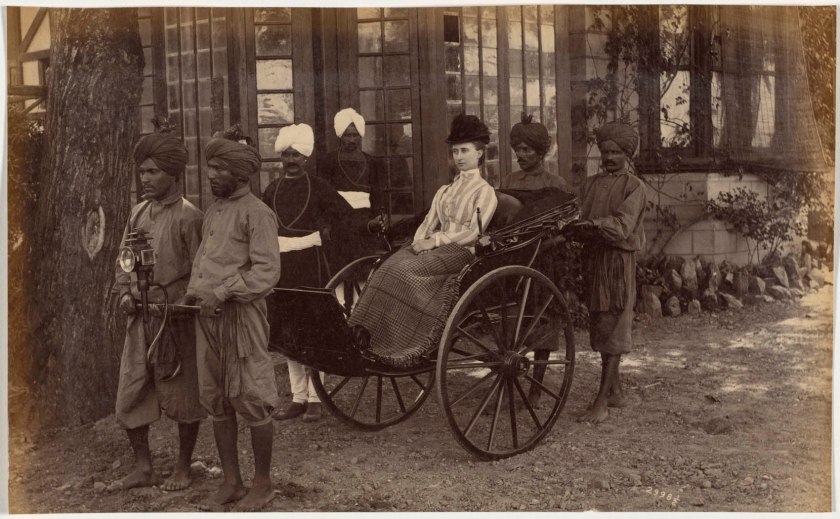

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Miss Lyall, Simla

1887

Albumen print

Image: 12.4 x 20.3cm (4 7/8 x 8 in.)

Paper: 12.4 x 20.3 cm (4 7/8 x 8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Miss Lyall, Simla (detail)

1887

Albumen print

Image: 12.4 x 20.3cm (4 7/8 x 8 in.)

Paper: 12.4 x 20.3 cm (4 7/8 x 8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Mrs. and Miss Lyall, Simla

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.9 x 27cm (7 13/16 x 10 5/8 in.)

Paper: 19.9 x 27cm (7 13/16 x 10 5/8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

A number of Deen Dayal’s Simla portraits include rickshaws, which were items of great novelty, being found in India only in Simla at the time. The two-wheeled, human-powered passenger cart first appeared in Japan around 1870 and was introduced to Simla around 1880 by a Scottish missionary. The town’s steep hills required four drivers, two to pull and two to push. Horse-drawn buggies were another common means of transport. Miss Lyall and Mrs. Lyall also appear in the photograph, suggesting that they had a significant personal relationship with the purchaser of the album.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Mrs. and Miss Lyall, Simla (detail)

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.9 x 27cm (7 13/16 x 10 5/8 in.)

Paper: 19.9 x 27cm (7 13/16 x 10 5/8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Sir Auckland Colvin and Family, Simla

1887

Albumen print

Image: 20 x 26.9cm (7 7/8 x 10 9/16 in.)

Paper: 20 x 26.9cm (7 7/8 x 10 9/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Deen Dayal’s large glass plate negatives and view camera required daylight to capture people without a blur, so his large group portraits are usually set before the sitters’ homes in their gardens. The equipment also dictated that scenes be carefully posed, not candid, shots. Sir Auckland Colvin (1838-1908) and his daughters were photographed in 1887, the year he became lieutenant governor of North-Western Provinces, a position his father had once held. The sitters are arranged so they orbit two framed photographs displayed on a table, presumably depictions of Colvin’s deceased wife and son. Thanks to photography, the entire Colvin family was reunited.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Picnic party, Mashobra

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.3 x 26.1cm (7 5/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

Paper: 19.3 x 26.1cm (7 5/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

This scene is from one of many lavish entertainments hosted by caterer, restaurateur, and hotelier Federico Peliti (Italian, 1844-1914) at his forested country estate outside Simla. In the photograph, Peliti is on horseback and his wife Judith on the swing. Swings have a long history as items of leisurely pleasure in Europe and India. Badminton, which originated in England in 1873, was popular in India. Deen Dayal may have been invited to document this gathering because he and Peliti, an amateur photographer, both belonged to the Photographic Society of Bombay.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Picnic party, Mashobra (detail)

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.3 x 26.1cm (7 5/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

Paper: 19.3 x 26.1cm (7 5/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

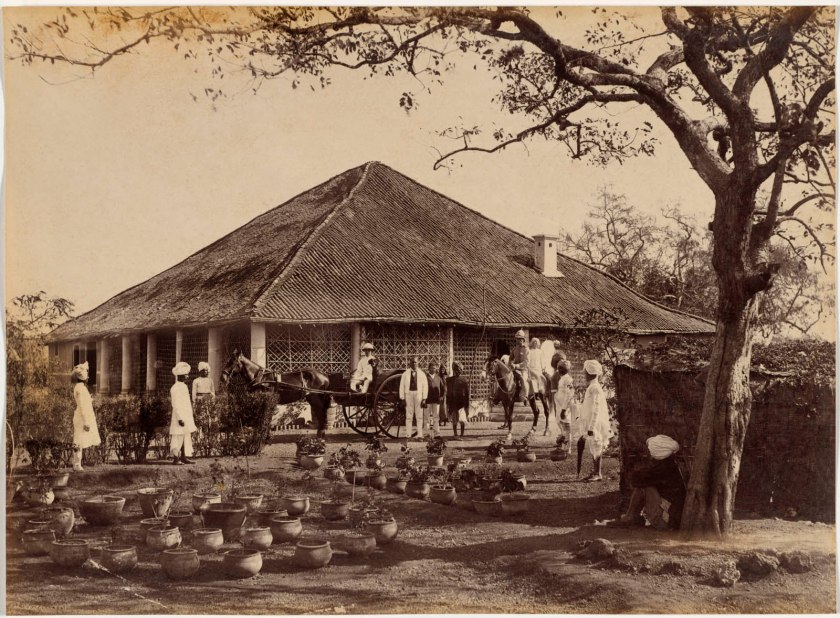

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Reverend Loche at Neemuch

1887

Albumen print

Image: 19.4 x 26.5cm (7 5/8 x 10 7/16 in.)

Paper: 19.4 x 26.5cm (7 5/8 x 10 7/16 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

This building is a “dak bungalow,” one of the British government guesthouses that were central to the lives of British travellers in India. This network of houses offered places to eat, stay, rent fresh horses, and conduct business while traveling between residences. The bungalows’ wide latticed verandahs admitted breezes, kept out pests, and provided some privacy. The average British Indian military household had at least six servants; eleven Indian servants are shown here, including the only Indian woman pictured in this exhibition. Many images in this album show servants, but they are never mentioned in the captions.

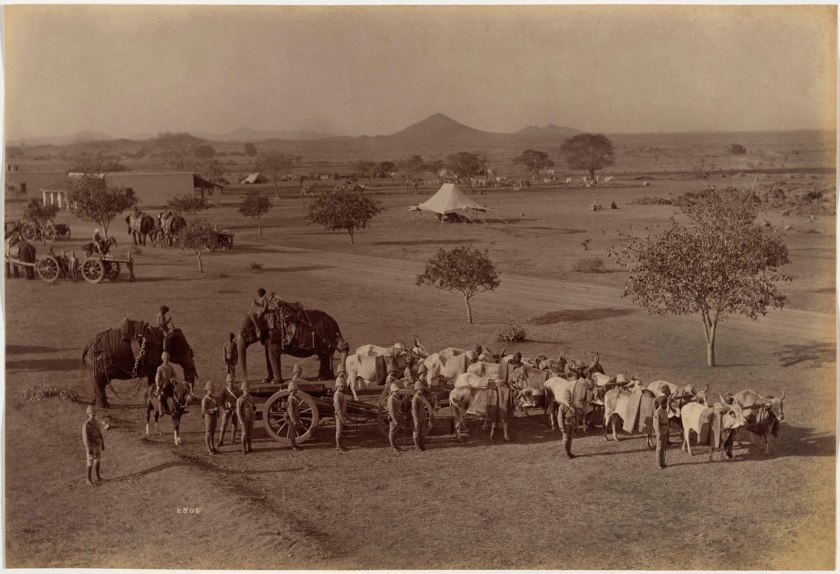

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Heavy Field Battery, Jhansi

1886

Albumen print

Image: 18.3 x 27cm (7 3/16 x 10 5/8 in.)

Paper: 18.3 x 27cm (7 3/16 x 10 5/8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Exercises involving elephant batteries, which were exotic to European eyes, attracted spectators; photographs of them were excellent souvenirs of these military forces employed by the British Indian Army. Elephants had been employed in warfare in India since at least the 500s BC, but with the advent of heavy artillery, their function switched from attack to support. They transported big guns and supplies and worked in logging and construction. It took many cattle to pull a load that could be handled by two elephants.

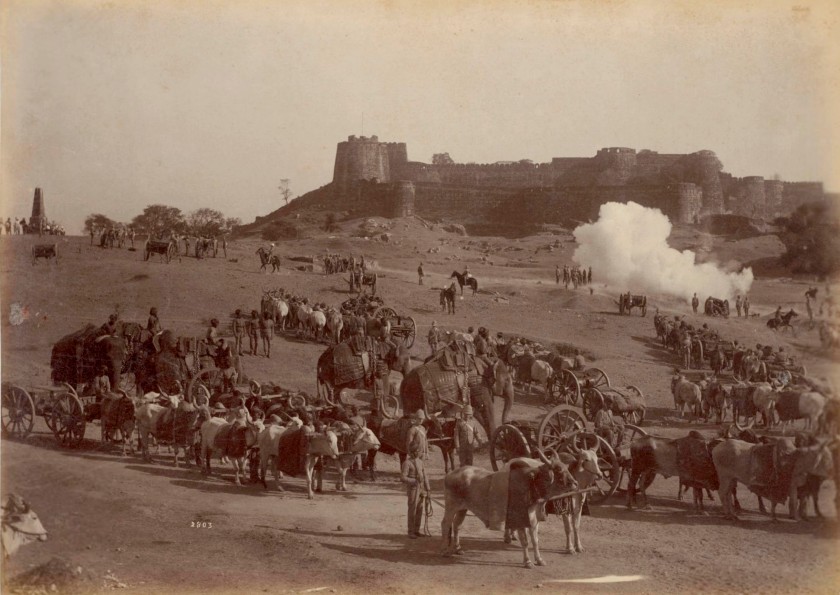

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Jhansi Fort and Elephant Battery

1886

Albumen print

Image: 19.4 x 27.2 cm (7 5/8 x 10 11/16 in.)

Paper: 19.4 x 27.2 cm (7 5/8 x 10 11/16 in.)

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Mr. Brown’s Horses, Jhansi

1887

Albumen print

Image: 18.9 x 27.6cm (7 7/16 x 10 7/8 in.)

Paper: 18.9 x 27.6cm (7 7/16 x 10 7/8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade

Imported into India in great numbers by the British, horses were used for both transportation and sports such as riding, polo, and racing. Caring for the animals fell largely to Indian servants. Captions on the photographs’ mounts specify the owners of these animals (note that Major Sparks also has a monkey and pet deer). However, none of the Indian servants is identified. Nor would they have received a copy of the photograph because of their low social status, which was far below that of Deen Dayal.

Teapot (Indian)

c. 1860-1890

Silver

Overall: 14 x 21 x 13.5 cm (5 1/2 x 8 1/4 x 5 5/16 in.)

Gift of Dr. Ranajit K. Datta

Made either for export or to appeal to the British community living in colonial splendor in India, this pot is a rare testament to the influence of the British Empire on consumer design during the period. Shri Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth, crowns the vessel as an apt divinity to preside over the horse races depicted on the belly of the teapot.

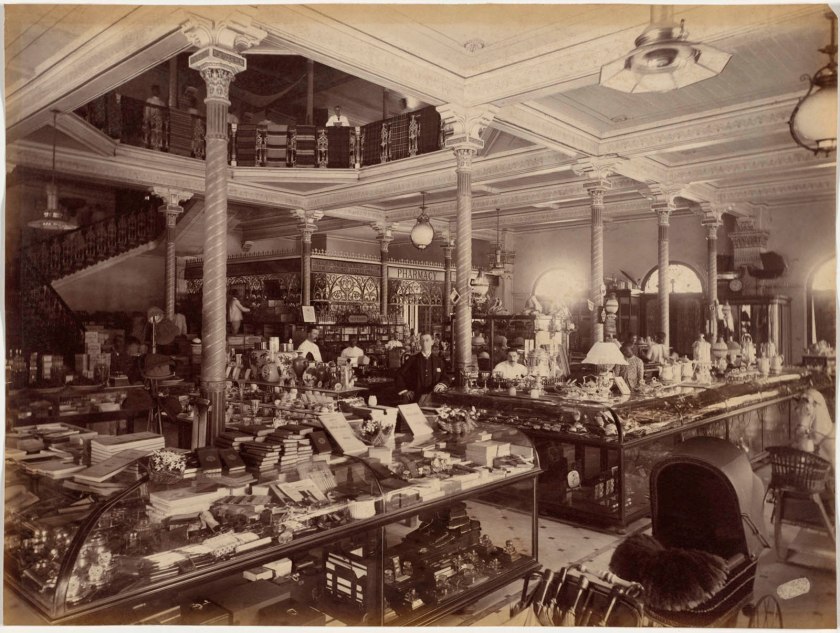

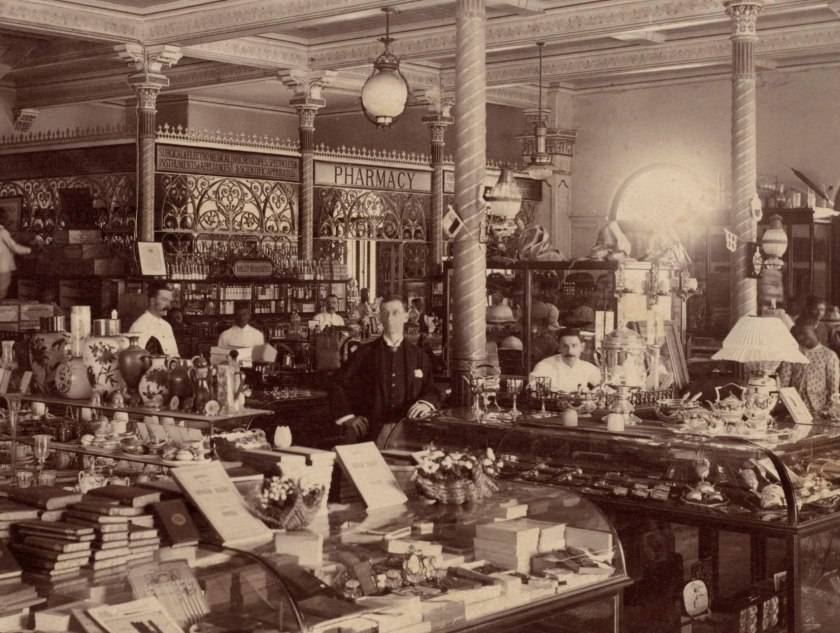

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Treacher and Co.’s Shop in the Fort, Bombay

1886

Albumen print

Image: 19.6 x 26.3cm (7 11/16 x 10 3/8 in.)

Paper: 19.6 x 26.3cm (7 11/16 x 10 3/8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

The English in India approximated life back home instead of adopting local ways. This image, probably one of Deen Dayal’s stock photographs, proved to those back in England that the comforts of home were readily available in India. Treacher’s, a multi-story emporium in Bombay, offered a plethora of products ranging from drugs, wine, and electro-medical instruments to silver tea sets and rocking horses. Many goods were imported, but some local craftsmen had mastered traditional European forms for objects including furniture and silver.

Raja Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Treacher and Co.’s Shop in the Fort, Bombay (detail)

1886

Albumen print

Image: 19.6 x 26.3cm (7 11/16 x 10 3/8 in.)

Paper: 19.6 x 26.3cm (7 11/16 x 10 3/8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund

Cleveland Museum of Art

11150 East Boulevard

Cleveland, Ohio 44106

Opening hours:

Tuesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays, Sundays 10.00am – 5.00pm

Wednesdays, Fridays 10.00am – 9.00pm

Closed Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.