Exhibition dates: 29th June – 10th October, 2021

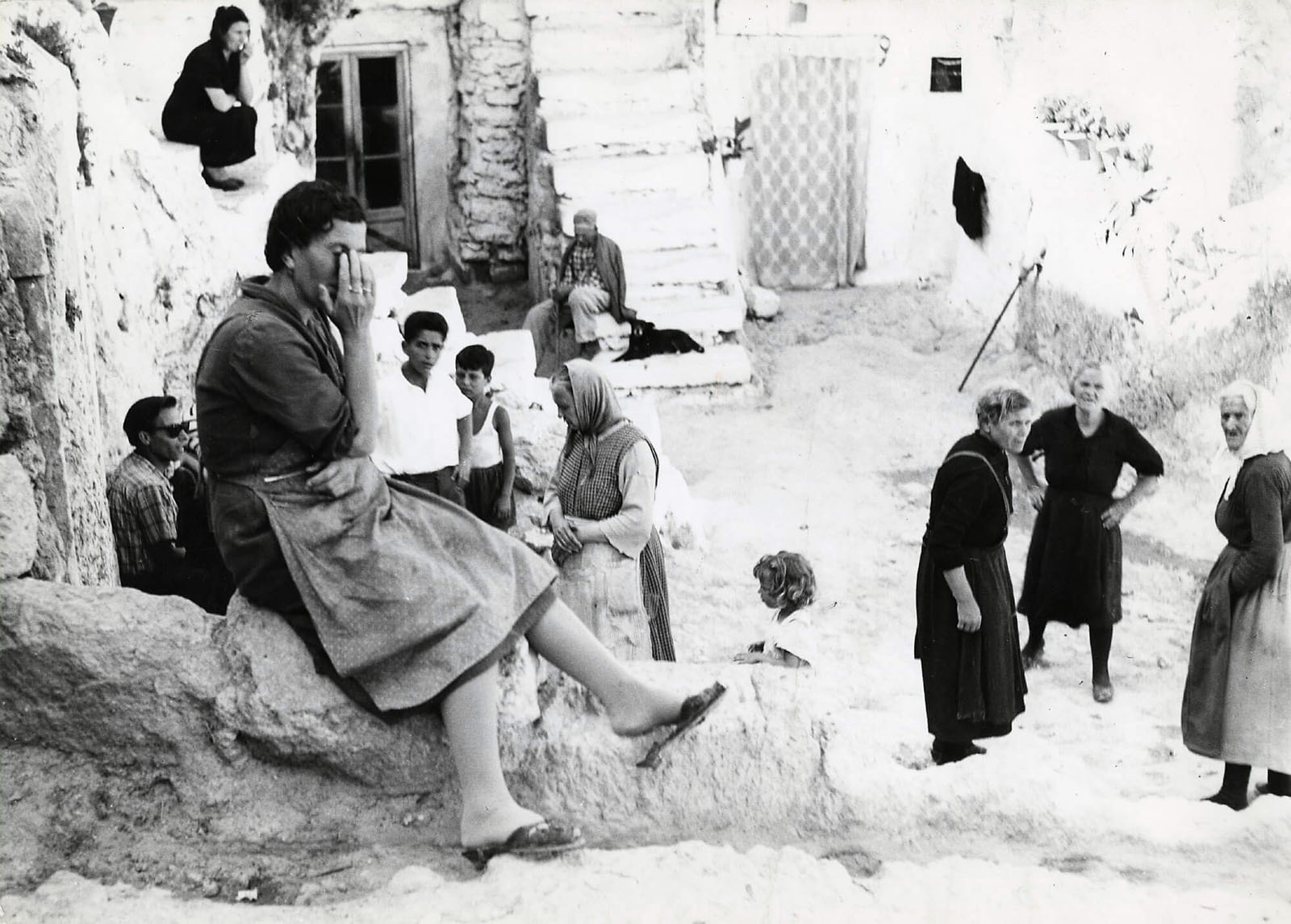

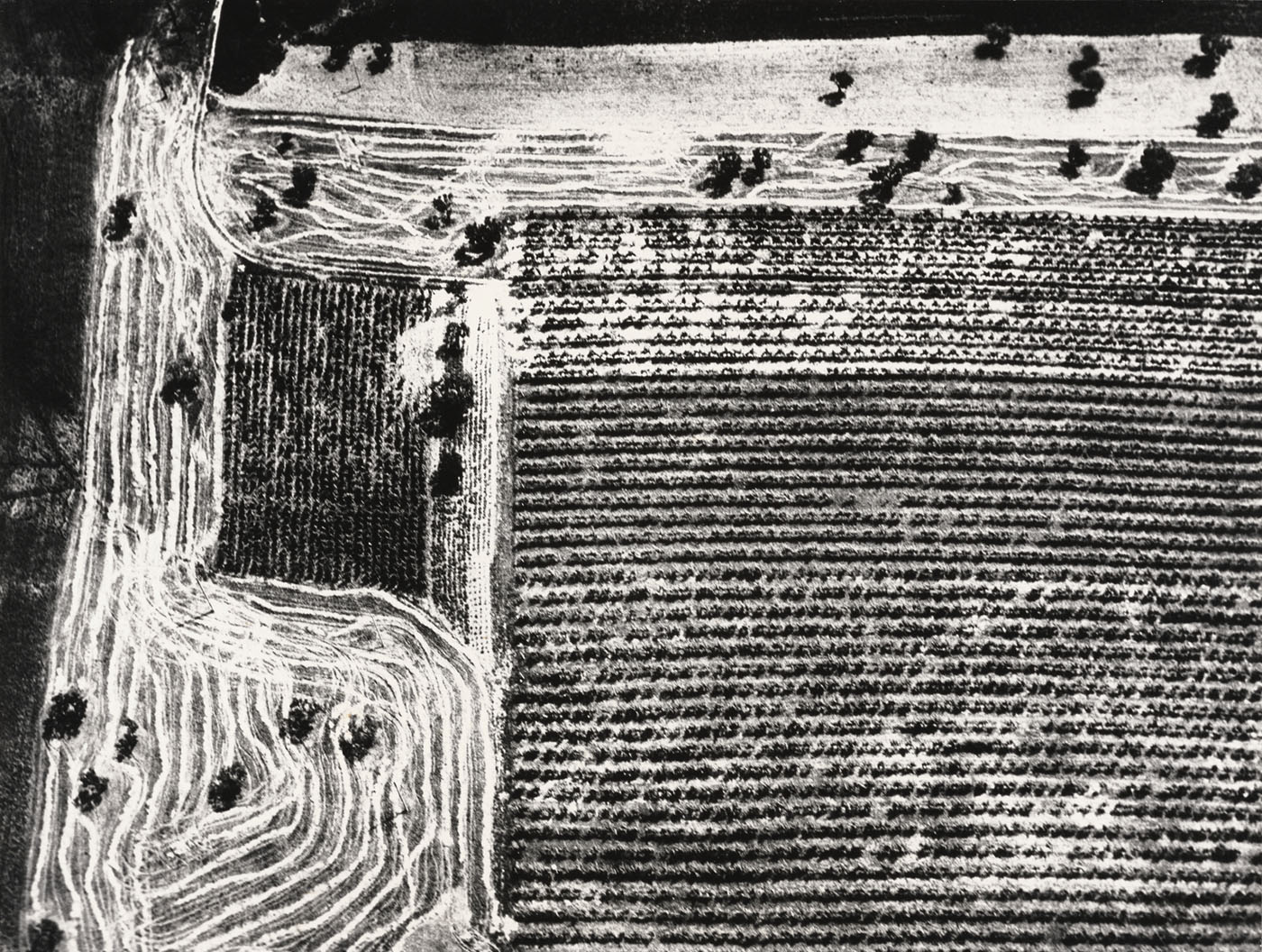

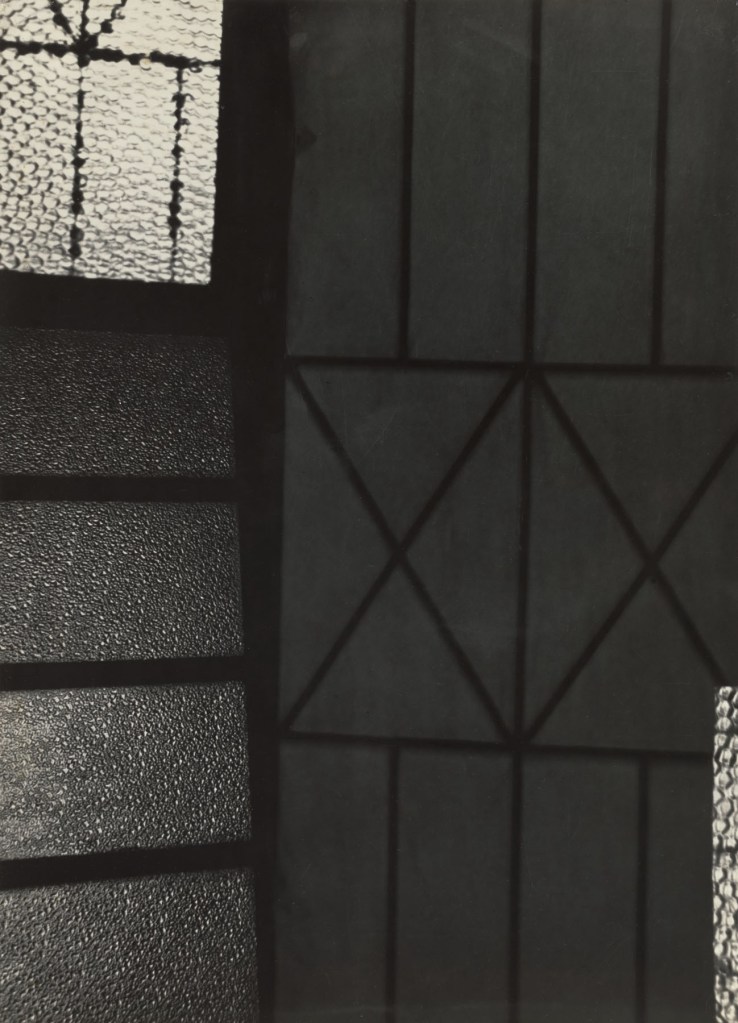

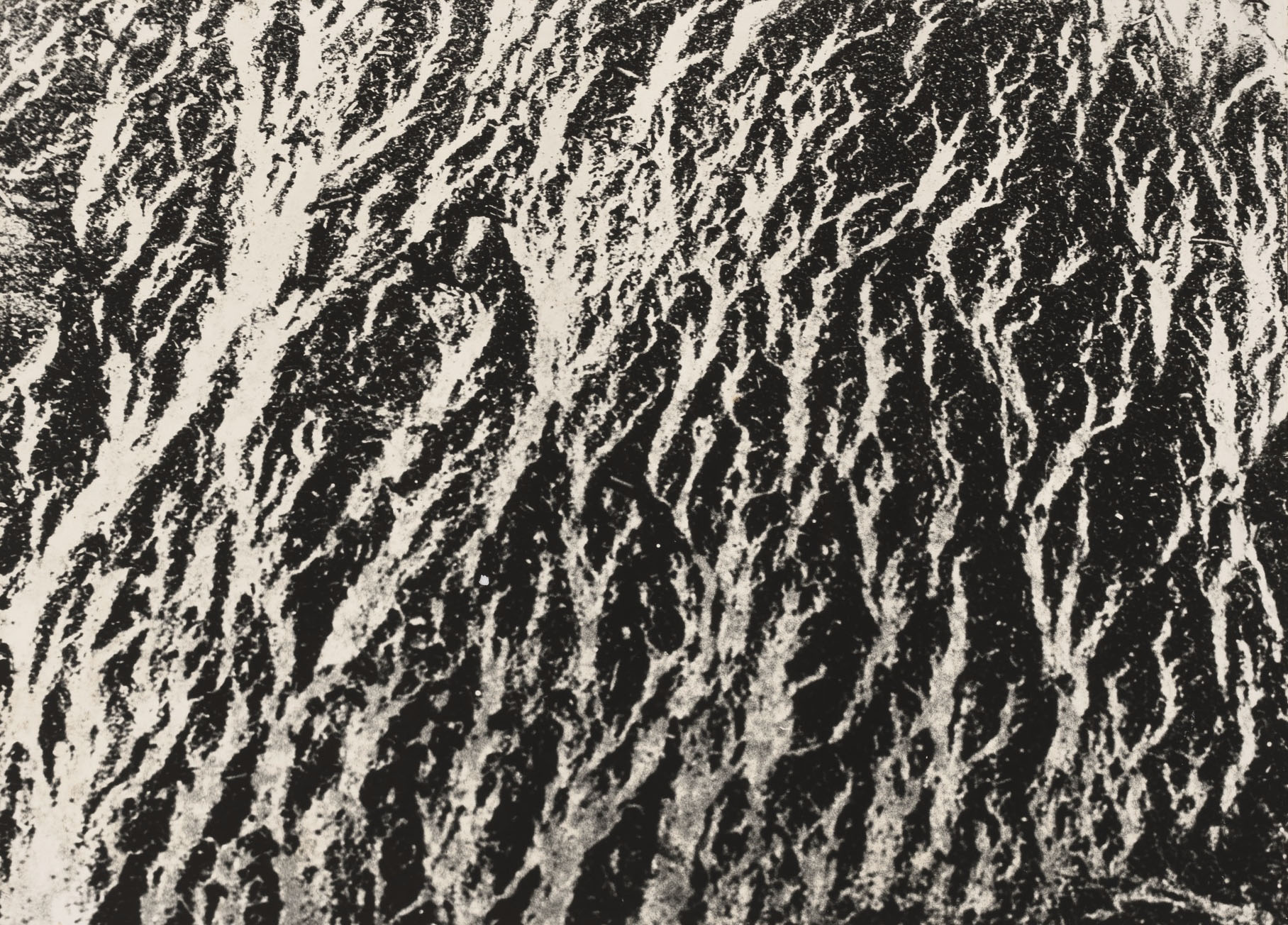

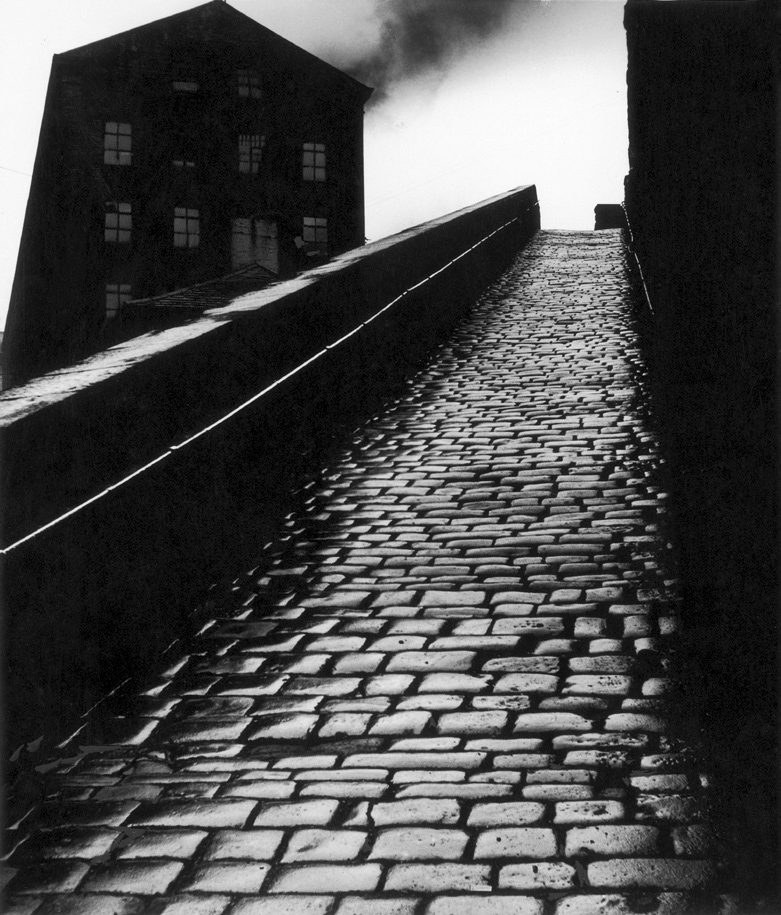

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Apulia (Puglia)

1958

Gelatin silver print

28.2 × 39.2cm (11 1/8 × 15 7/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

The realist illusionist

When I look at the work of Mario Giacomelli, his photographs remind me why I love the practice of photography.

They discombobulate and disorientate me; they challenge me to see the world in a different way; they reveal new things over time the more one looks at them… and they act as momento mori for both human and land. His conceptual photographs, for that is what they are, are refreshed time and time again – through their impressions, through their graphic nature, and their lack of grounding in a fixed reality.

Whether it be the abstract photographs from the series Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes, the shimmering figures from the series Scanno (are they really one negative!), the groundlessness of the figures in Young Priests, the abstract figuration of The Good Earth, or the spatial levitation of Metamorphosis of the Land / Awareness of Nature, the viewer is forced to reassess their relationship with the physical object (the photograph) and its representation and interpretation of our passage on this earth. As has been said of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, “The ways that stories are linked by geography, themes, or contrasts creates interesting effects and constantly forces the reader to evaluate the connections.”

Giacomelli’s photographs are active in this way: they act on the perceptions of the viewer in order to challenge what we understand of the interaction between human beings (he continued to photograph in his hometown of Senigallia for almost 50 years), and the interaction between human beings and the land (where his photographs “function as commentary on the capacity of both natural occurrences and human interventions to change the character of the land.”) As with many artists, the concerns that were present when he started photography – his subject matter informed by the people and places closest to him – remained with him for the rest of his life. Except he turned personal stories into universal narratives.

All of Giacomelli’s sequences (he conceived many of his series as sequences) required periods of sustained observation, where the artist embedded himself with and in his subject matter. Only in this way could the artist understand the spirit of the land and its people, his people. He had an innate ability to describe people and the land in a specific time and place… which, on reflection, seem to be timeless, like a fairy-tale or a lament. Places and people steeped in the past but in the photographs hovering on the edge of his nowhere.

The text for the series Metamorphosis of the Land in this posting perfectly sums up how much time Giacomelli took over a series, how conceptual his series were, and the artistic techniques he used to manipulate reality:

The photographs gathered under the title Metamorphosis of the Land were created over roughly two decades in the countryside surrounding Senigallia. Without a horizon line to anchor them, they are disorienting, requiring the viewer to rely on a lone house or tree as a focal point. Perspectival ambiguity abounds: Did Giacomelli take the photographs from an elevated or lowered vantage point? Did he hold the camera parallel or perpendicular to the land? Is this confusion a result of the inherent “verticality” of the hilly Marche region, or did Giacomelli rely on darkroom manipulation (such as printing on diagonally tilted sheets of photo paper) to create right-angled configurations of shapes that should otherwise recede in the distance, following the tenets of one-point perspective?

These ambiguities are further intensified by Giacomelli’s intention for this body of work to address issues of ecological neglect and loss. Deeply attuned to the rural geography and agricultural practices of the Marche, he was wary of the consequences that accompanied the shift from centuries-old systems of subdivided fields and crop rotation to modern methods of mechanisation and fertilisation that overtax the land by keeping it in constant use. The series is one of lament.

In his later series of transformation tales Giacomelli once again disrupts the flow of temporal reality. As he reflects on the death of his mother, his own mortality and the changing nature of the landscape, his photographs “mark a noticeable shift from Giacomelli’s earlier position of critiquing the slow degradation of the land to one that sets the stage for a more metaphysical contemplation of the interconnectivity of space, time, and being.” Of course, this contemplation had always been there since the beginnings of his photography where, “metaphysically speaking, understanding time means understanding the shared world that man encounters and with which man interacts.”

Through art techniques (double exposures, variable perspectives, slow shutter speeds, moving his camera during exposure, abrupt cropping, slight overexposure to reverse tonal values, the development of the negative, painting or scratching of areas on the negative to introduce elements of the absurd or surreal, use of high-contrast paper and darkroom manipulations) and conceptual structures (inspired by poems to create parallel narratives, repurposing “an image made for one series in another series, reinforcing the sense of fluidity that connects all of his work”), Giacomelli seeks to confront the inevitability of his own mortality and thus his return to earth. As he observes, “Of course [photography] cannot create, nor express all we want to express. But it can be a witness of our passage on earth…”

In Giacomelli’s unique interpretation of figure | ground lies his elevation into the “pantheon” of photographic stars. A self-taught artist, he was not encumbered or impeded by traditional photographic practice but described his own visual photographic language, instantly recognisable as his (once seen, never forgotten) signature. A stamp on the verso of each print in the series Awareness of Nature describes the series as “the work of man and my intervention (the signs, the material, the randomness, etc.) recorded as a document before being lost in the relative folds of time.”

In my humble opinion there is no fear, only elation, that Giacomelli’s essential work will ever be lost to the folds of time.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thanks to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas / corpora;

(I intend to speak of forms changed into new entities;)

Ovid. Metamorphoses, Book I, lines 1–2

Be ahead of all parting, as if it had already happened,

like winter, which even now is passing.

For beneath the winter is a winter so endless

that to survive it at all is a triumph of the heart.Be forever dead in Eurydice, and climb back singing.

Climb praising as you return to connection.

Here among the disappearing, in the realm of the transient,

be a ringing glass that shatters as it rings.Be. And know as well the need to not be:

let that ground of all that changes

bring you to completion now.To all that has run its course, and to the vast unsayable

numbers of beings abounding in Nature,

add yourself gladly, and cancel the cost.

Rainer Maria Rilke. Sonnets to Orpheus II, 13

“Of course [photography] cannot create, nor express all we want to express. But it can be a witness of our passage on earth, like a notebook…

… For me each photo represents a moment, like breathing. Who can say the breath before is more important than the one after? They are continuous and follow each other until everything stops. How many times did we breathe tonight? Could you say one breath is more beautiful than the rest? But their sum makes up an existence.”

Mario Giacomelli, 1987

Born into poverty and largely self-taught, Mario Giacomelli became one of Italy’s leading photographers. After purchasing his first camera in 1953, he began creating humanistic portrayals of people in their natural environments and dramatic abstractions of the landscapes. He continued to photograph in his hometown of Senigallia, on the Adriatic coast of Italy, for almost fifty years. Rendered in high-contrast black and white, his photographs are often gritty and raw, but always intensely personal.

This exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Daniel Greenberg (1941-2021) and is made possible through gifts made by him and Susan Steinhauser.

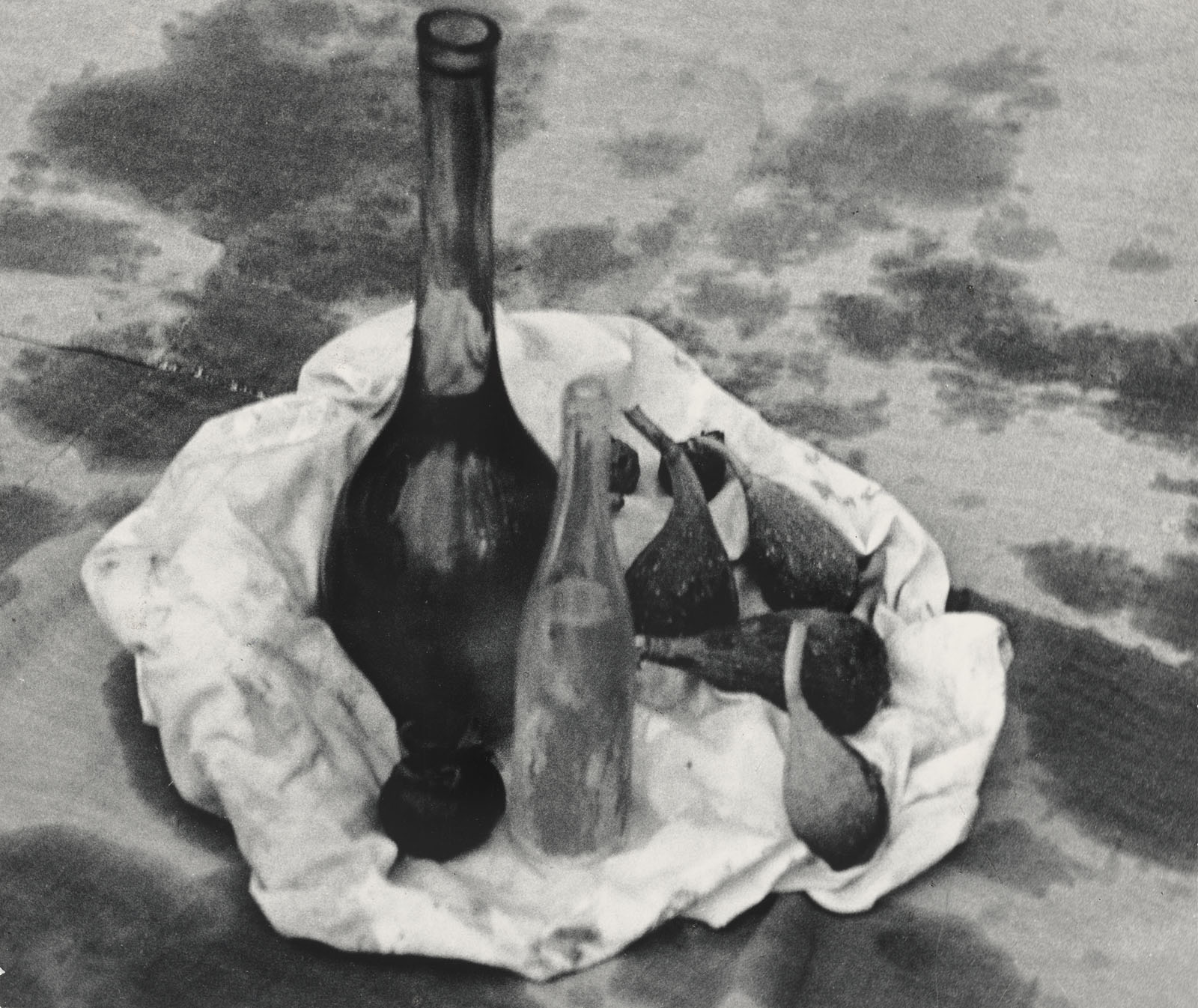

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Still Life with Figs (Natura morta con fichi)

1960

Gelatin silver print

28.2 × 33.7cm (11 1/8 × 13 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Known for his gritty, black-and-white images, Mario Giacomelli is recognised as one of the foremost Italian photographers of the 20th century. Drawn from the Getty Museum’s deep holdings, the exhibition Mario Giacomelli: Figure | Ground features 91 photographs that showcase the raw expressiveness of the artist’s style, which echoed many of the concerns of postwar Neorealist film and Existentialist literature.

The exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Daniel Greenberg (1941-2021) and was made possible through generous gifts from him and his wife, Susan Steinhauser. As photography collectors for more than two decades and founding members of the Getty Museum Photographs Council, Greenberg and Steinhauser have been generous donors to the Getty. All of the photographs in this exhibition were donated by Greenberg and Steinhauser or purchased in part with funds they provided.

“After the Museum’s yearlong closure, we are particularly pleased to be able to reopen the Center for Photographs at the Getty Center with two important exhibitions that highlight the Museum’s extensive collections,” says Timothy Potts, Maria Hummer-Tuttle and Robert Tuttle Director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “We are especially pleased to honour the extraordinary contributions of Dan Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, whose gifts of works by Giacomelli are the basis of the first monographic exhibition of the artist in a U.S. museum in 35 years. The exhibition and its catalogue are testament both to their passion as collectors and their generosity as benefactors to the Getty Museum over many years.”

Mario Giacomelli: Figure | Ground

Born into poverty, Mario Giacomelli (1925-2000) lived his entire life in Senigallia, a town on the Adriatic coast in Italy’s Marche region. He lost his father at an early age and took up poetry and painting before apprenticing as a printmaker, which became his livelihood. After purchasing his first camera in 1953, Giacomelli quickly gained recognition for his unique approach to photographing people, landscapes, and people in the landscape. Although photography was initially relegated to Sundays, when his printshop was closed, and to his immediate surroundings in the Marche, he became one of Italy’s most prominent practitioners.

Giacomelli’s use of flash, grainy film, and high-contrast paper resulted in bold, geometric compositions with deep blacks and glowing whites. He most frequently focused his camera on the people, landscapes, and seascapes of the Marche. He often spent several years exploring a photographic idea, expanding and reinterpreting it, or repurposing an image made for one series for inclusion in another. By applying titles derived from poetry, he transformed familiar subjects into meditations on the themes of time, memory, and existence.

Among Giacomelli’s earliest photographs are portraits of family and friends. His first, sustained body of work was Hospice, which he began in 1954 and later titled Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes, after a poem by the writer Cesare Pavese. Depicting residents of the home for the elderly in Senigallia and made with flash, the images are characterised by their unflinching scrutiny of individuals living out their last days. Additional early series on view include Scanno (1957-59) and Young Priests (1961-1963), both of which further demonstrate Giacomelli’s ability to describe people in a specific time and place. In both series, figures clothed in black are set against stark white backgrounds. While there is an underlying sense of furtiveness or foreboding in the Scanno images, the Young Priests series, which Giacomelli later titled I Have No Hands That Caress My Face, is uncharacteristically light-hearted. Another series, The Good Earth, follows a farming family going about daily life, planting and harvesting crops and tending to livestock in the countryside surrounding Senigallia; the intermingling of generations suggests the cyclical nature of existence.

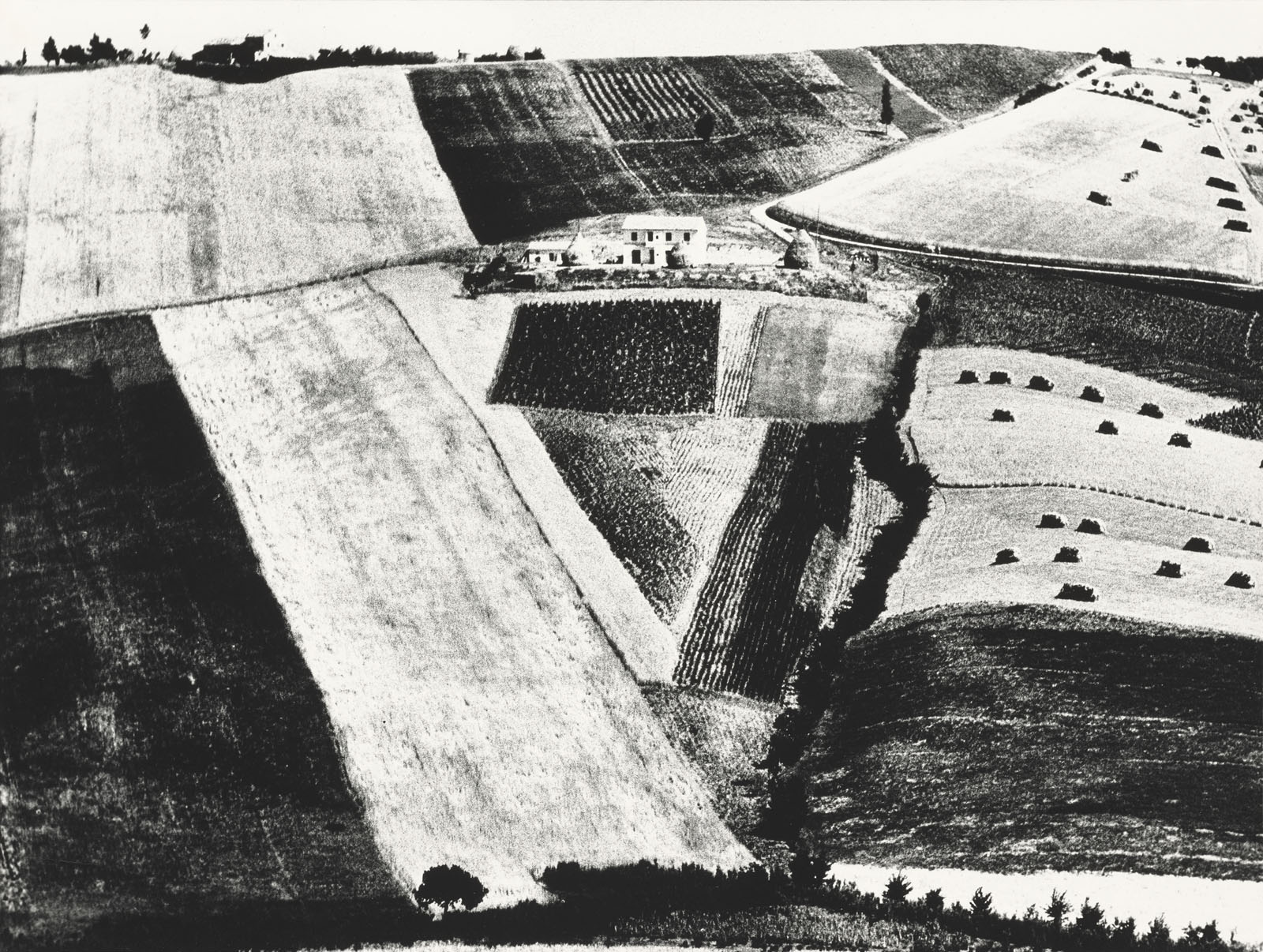

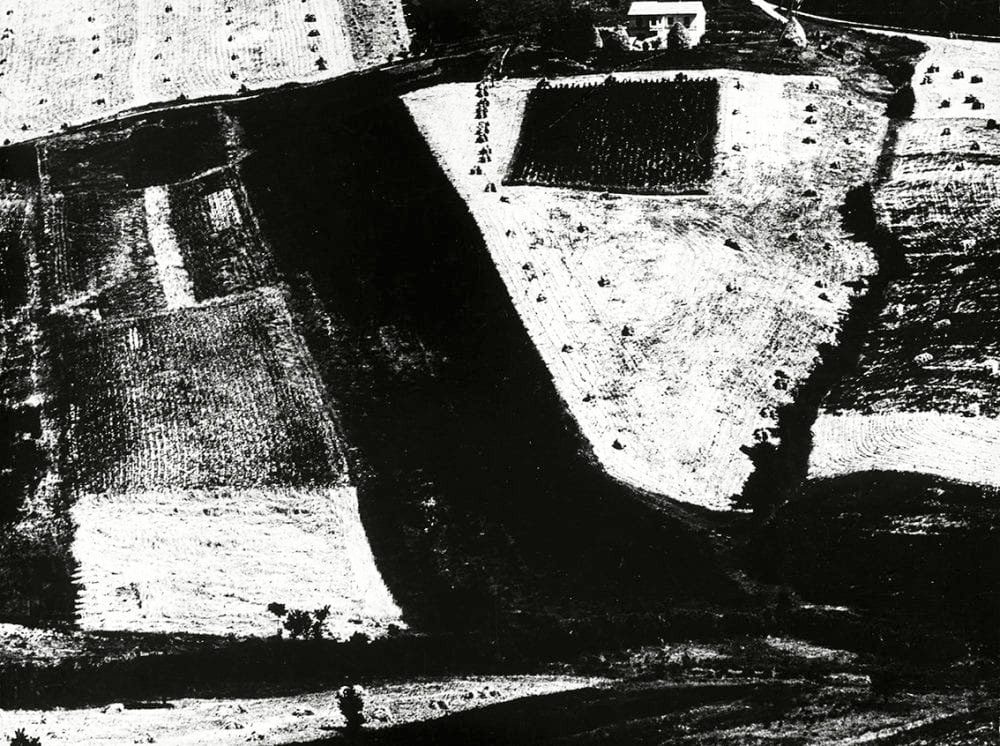

Landscapes feature prominently in Giacomelli’s engagement with photography from the beginning. The exhibition features several early works dating from the 1950s, as well as signature series, such as Metamorphosis of the Land (1958-1980) and Awareness of Nature (1976-1980). Both series portray fields and small farms in the Marche region, many of which he revisited as seasons changed and crops were rotated. Giacomelli wanted to show how modernised cultivation practices were overtaxing the land and changing the landscape. He often photographed from a low or an elevated vantage point – including from a plane – to eliminate the horizon and create disorienting patchworks of geometric shapes or pulsating configurations of plowed furrows.

In his later years, Giacomelli created several series that intersperse landscapes with figure studies. He often merged the two genres in double exposures or by experimenting with slow shutter speeds and moving his camera during exposure to blur the lines between figure and ground. Several of these series were inspired by poems, both as composed by himself or by others. Giacomelli reflects on the interconnectedness of space, time, and being, in these works, which have a metaphysical quality. I Would Like to Tell This Memory is one of his last bodies of work. Incorporating various props, such as a mannequin, a stuffed dog, and stuffed birds, the images in the series suggest that the artist is reflecting on the inevitability of his own mortality.

“It is exciting to present this collection of Mario Giacomelli photographs assembled by Dan Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser over a period of almost twenty years,” says Virginia Heckert, curator of photographs at the Museum and curator of both exhibitions. “Not only does the exhibition introduce a new audience to Giacomelli’s work, but it does so through the eyes of the collectors, who were drawn to his expressive portrayals of people and the land.”

Press release from the J. Paul Getty Museum

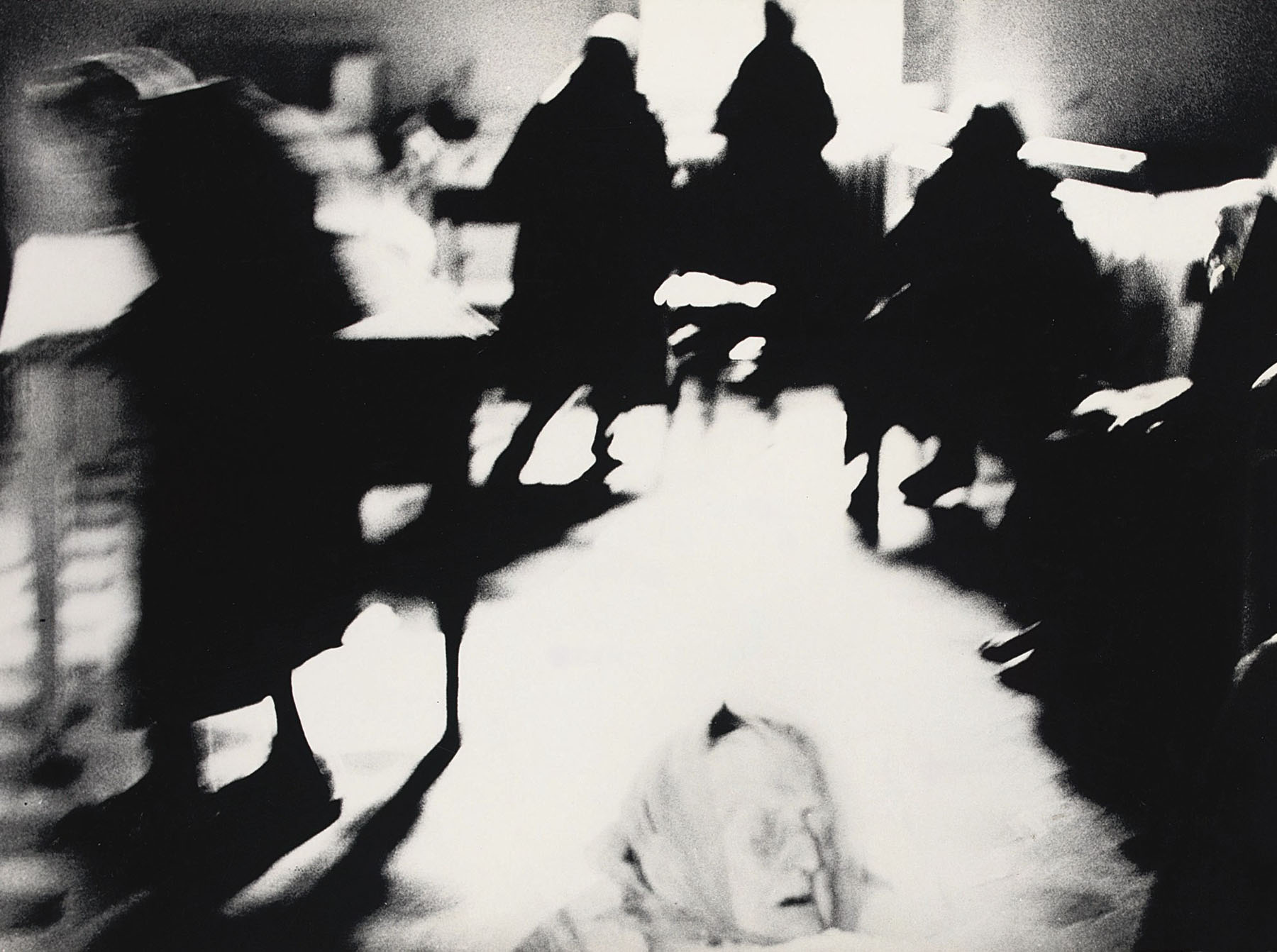

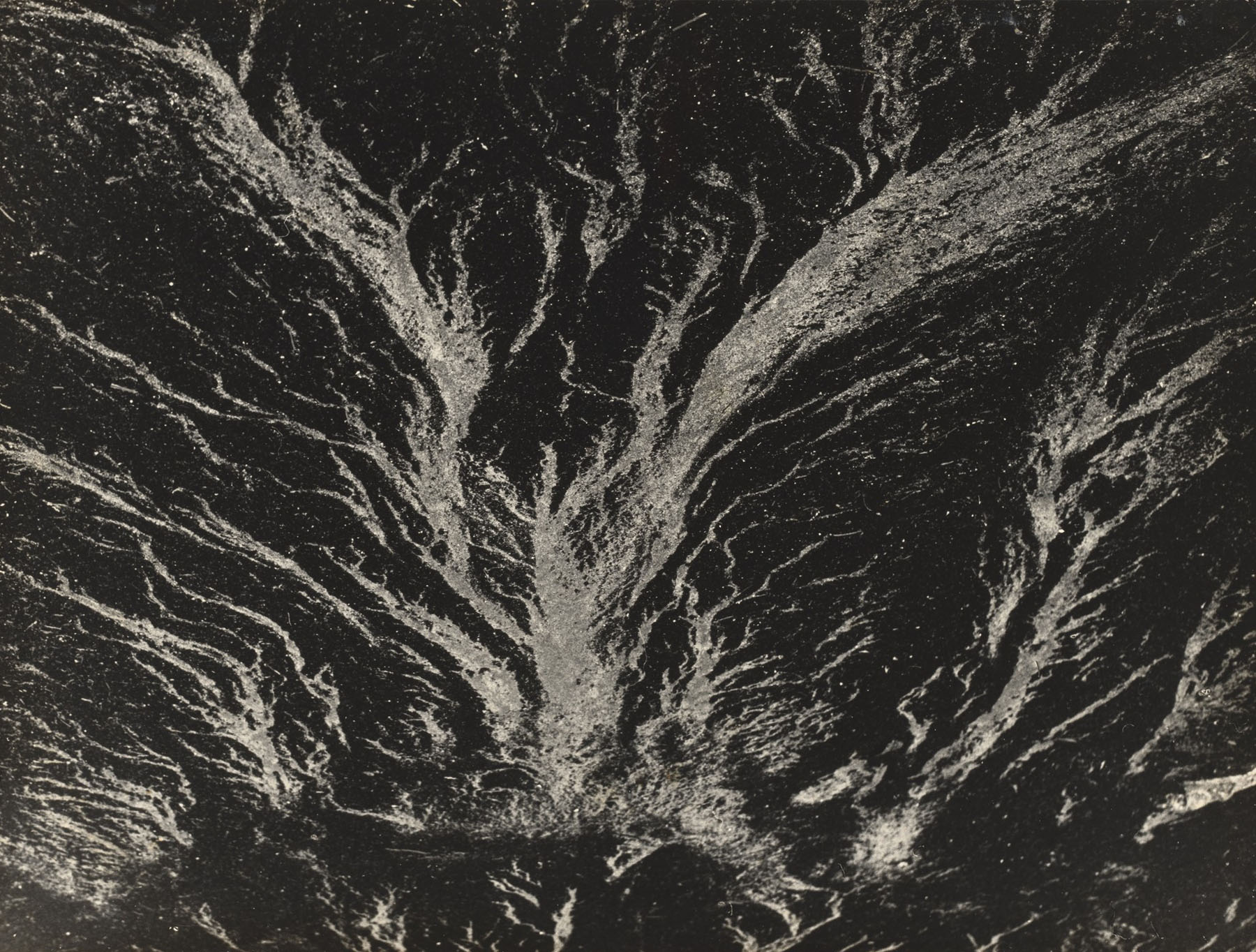

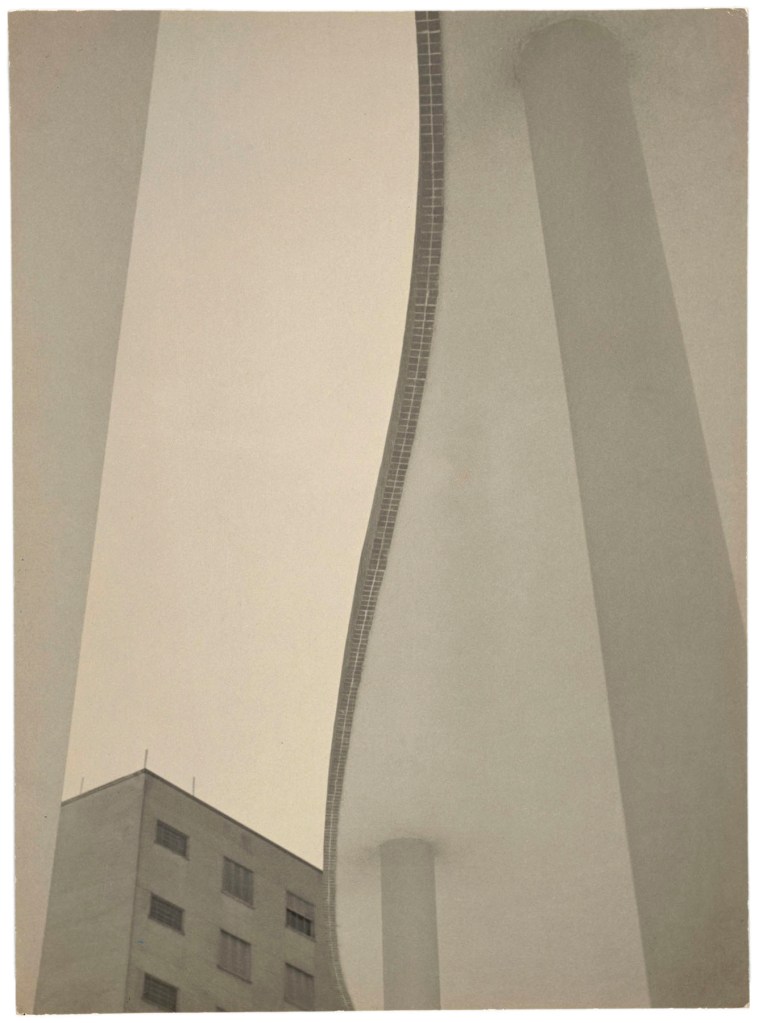

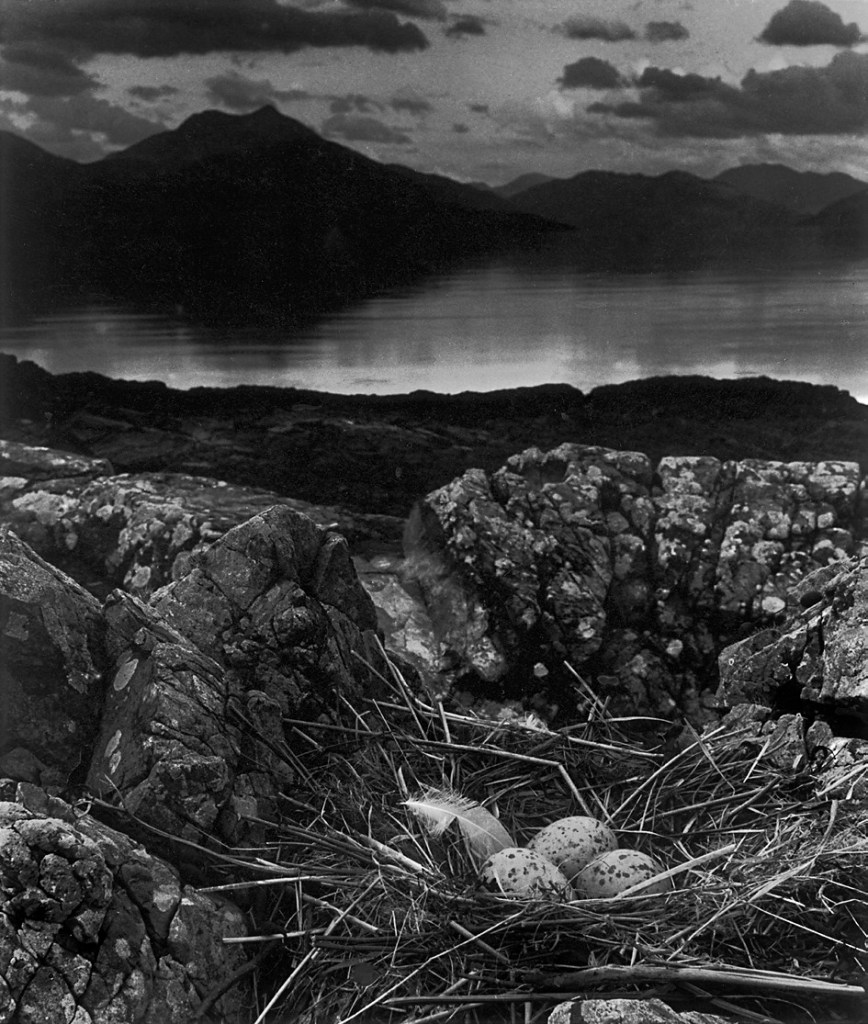

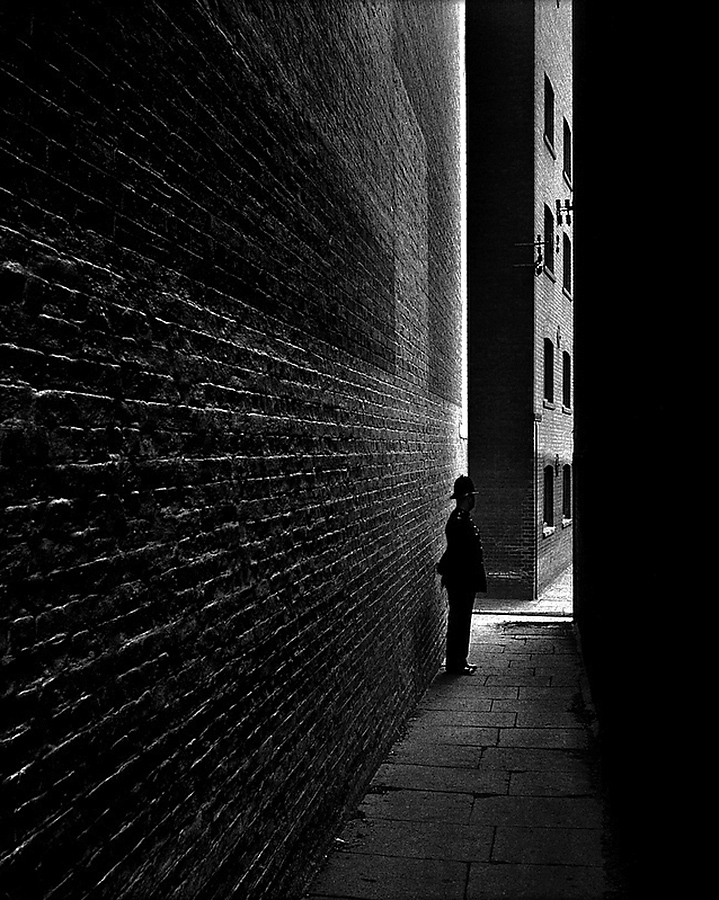

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Infinite

about 1986-1988

Gelatin silver print

29.5 × 38.8cm (11 5/8 × 15 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli: Figure / Ground

Mario Giacomelli (1925-2000) is widely regarded as one of the foremost Italian photographers of the twentieth century. Born into poverty, he lived his entire life in Senigallia, a town on the Adriatic coast in Italy’s Marche region. After losing his father at age nine and completing elementary school at eleven, he apprenticed as a typesetter and printer, while also teaching himself to paint and write poetry. With money given to him by a resident of the ospizio (hospice) where his mother worked, he opened a printshop, a business that ensured lifelong financial stability. His engagement with photography began shortly thereafter, occurring primarily on Sundays, when the shop was closed.

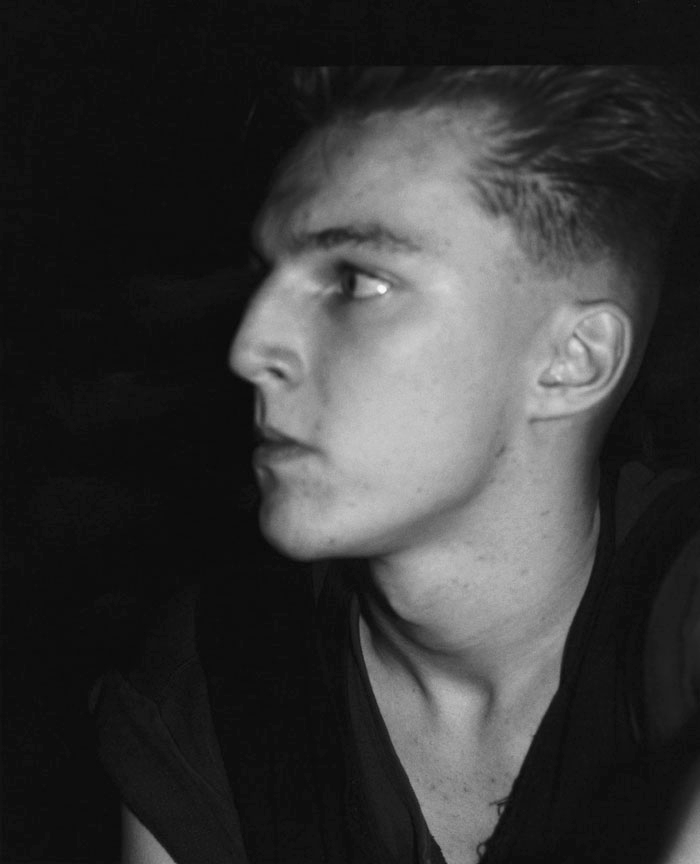

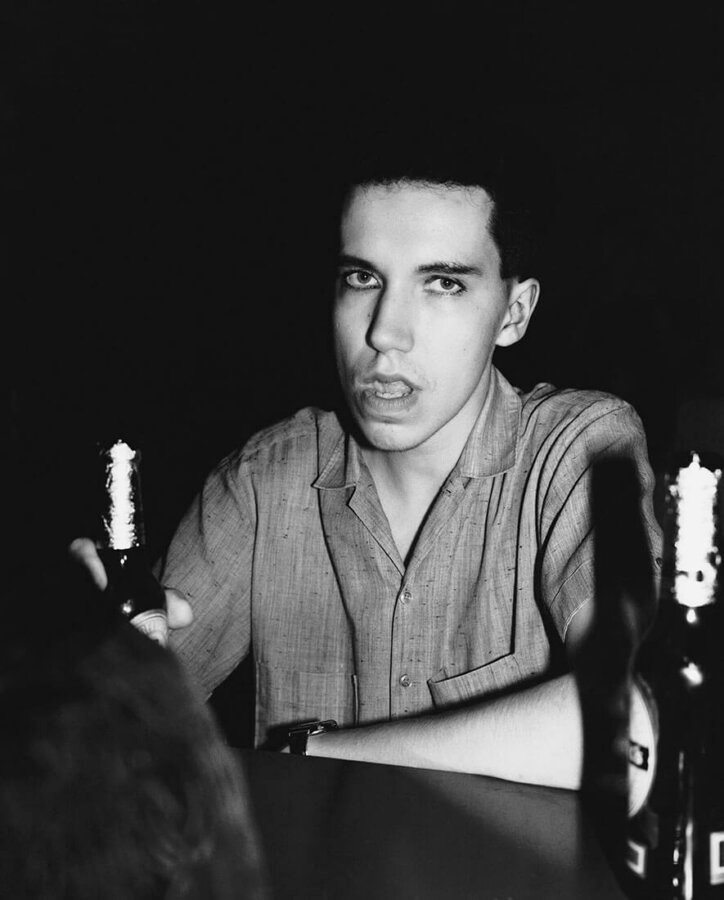

After purchasing his first camera in 1953, Giacomelli quickly gained recognition for the raw expressiveness of his images, which echoed many of the concerns of postwar Neorealist film and Existentialist literature, with their interests in the conditions of everyday life and in ordinary people as thinking, feeling individuals. His preference for grainy film and high-contrast paper resulted in bold, geometric compositions with deep blacks and glowing whites. Most frequently focusing his camera on the people, landscapes, and seascapes of the Marche, Giacomelli often spent several years exploring a photographic idea, expanding and reinterpreting it, or repurposing an image made for one series for inclusion in another. By applying titles derived from poetry, he transformed familiar subjects into meditations on the themes of time, memory, and existence.

Forming Giacomelli

As a young man, Giacomelli served briefly in the Italian army during World War II. His photographic practice shows the influence of two approaches prevalent in postwar European photography: humanism, which is often associated with photojournalism; and artistic expression as a means of exploring the inner psyche, which derived from the theory of Subjective photography advanced by Otto Steinert (German, 1915-1978). In Italy, these approaches found their respective counterparts in the camera clubs La Gondola (The Gondola), established in Venice in 1948, and La Bussola (The Compass), begun in Milan in 1947. Giacomelli, who was self-taught as a photographer, exchanged ideas with and learned from members of both clubs. He was also a cofounder of Misa, a local chapter of La Bussola named after Senigallia’s principal river.

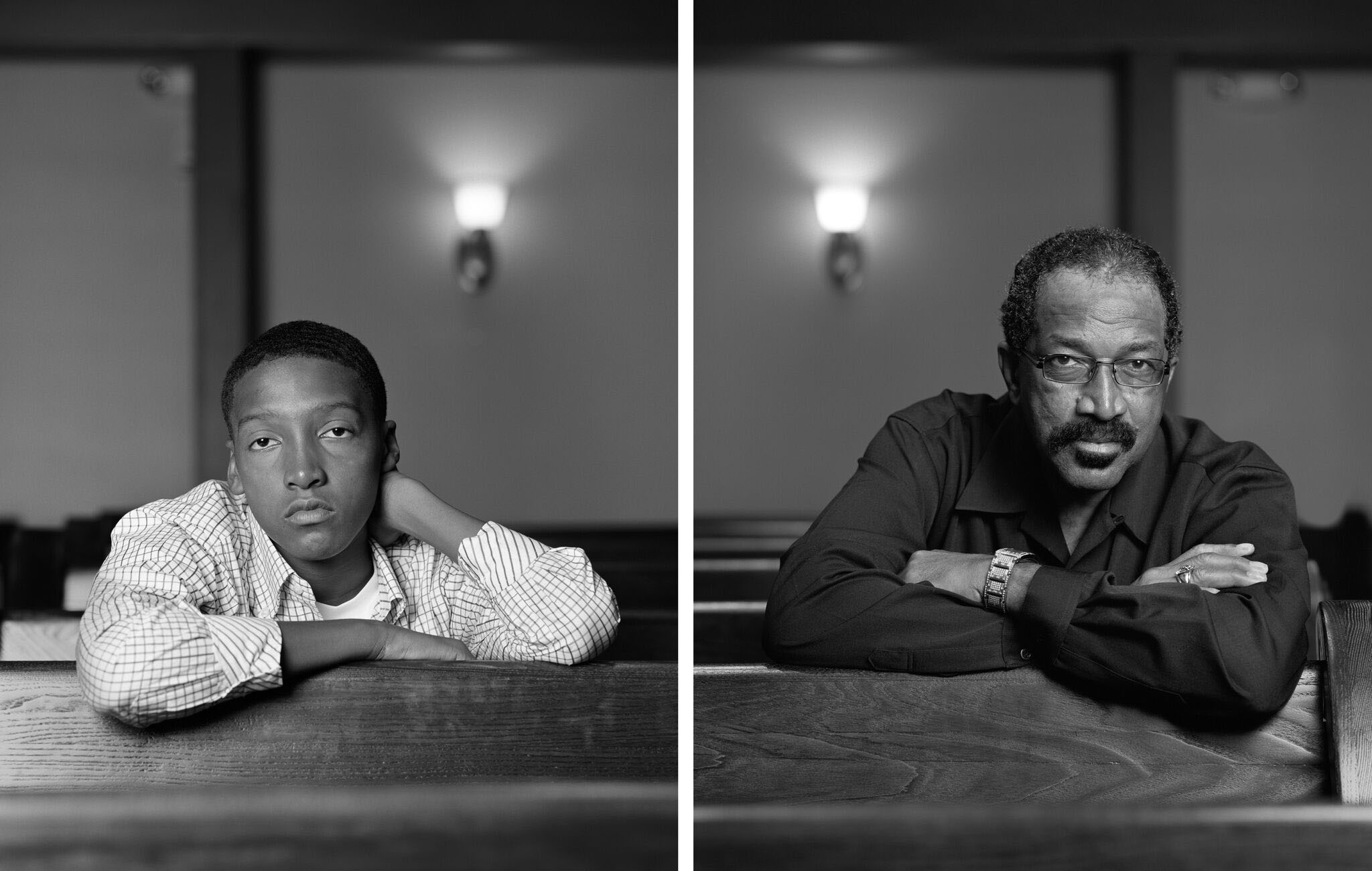

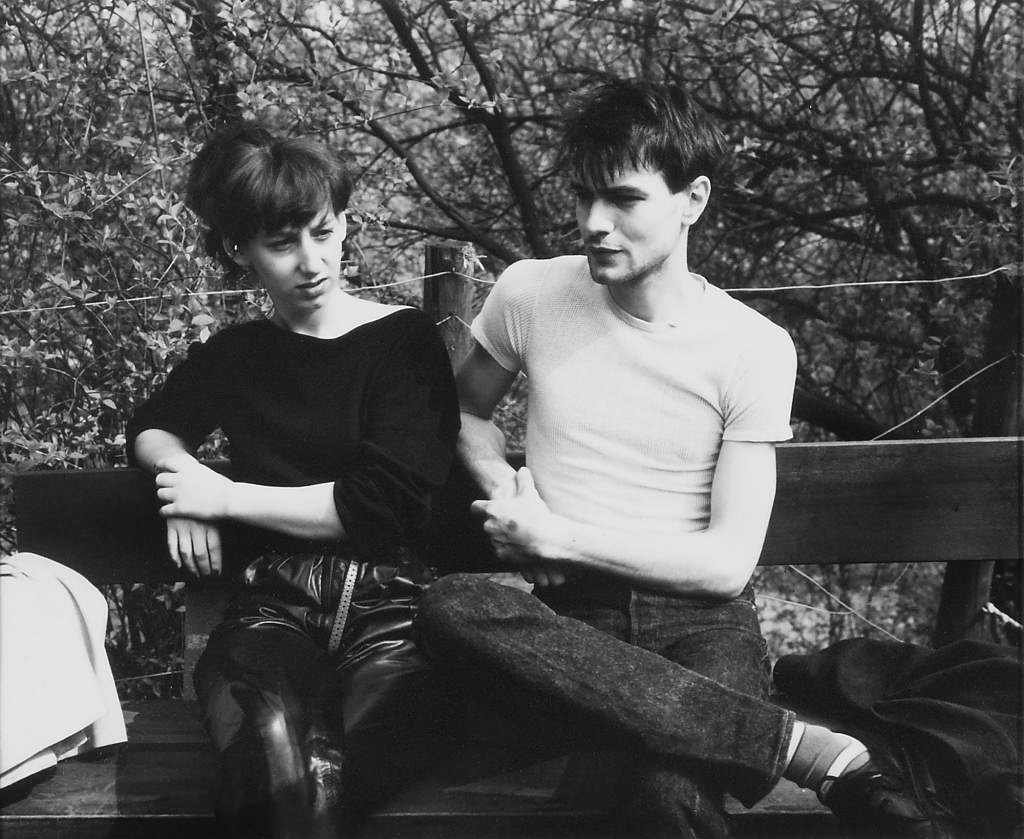

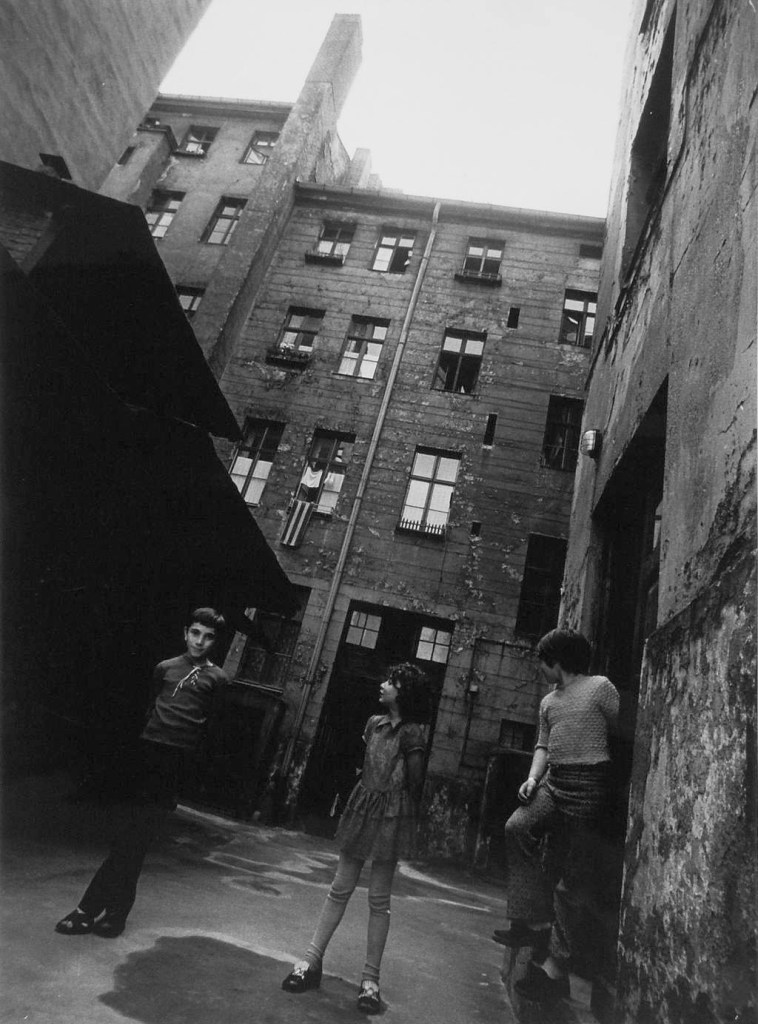

Senigallia’s people and places were recurring motifs in Giacomelli’s work. In addition to revealing his interest in the different communities of his hometown, these photographs of a Romani family and of children frolicking on the beach demonstrate his ability to combine humanist and expressive impulses. Giacomelli understood that graininess, movement, and high contrast could do more than simply provide a veneer of abstraction; they also heighten the emotive power of images.

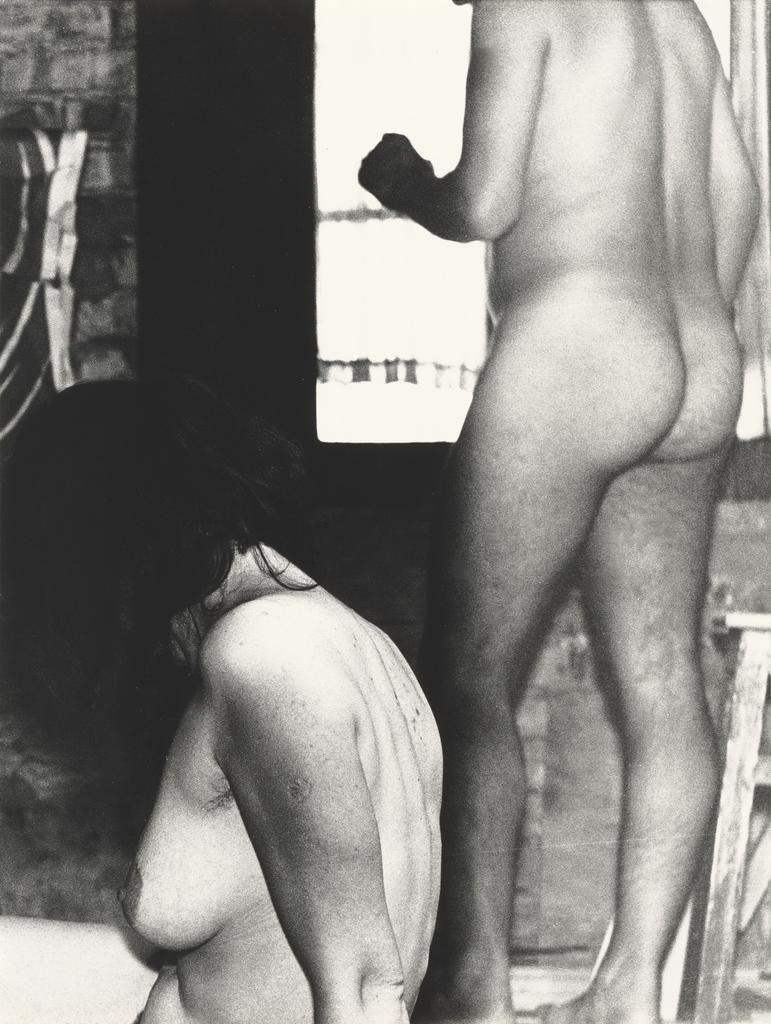

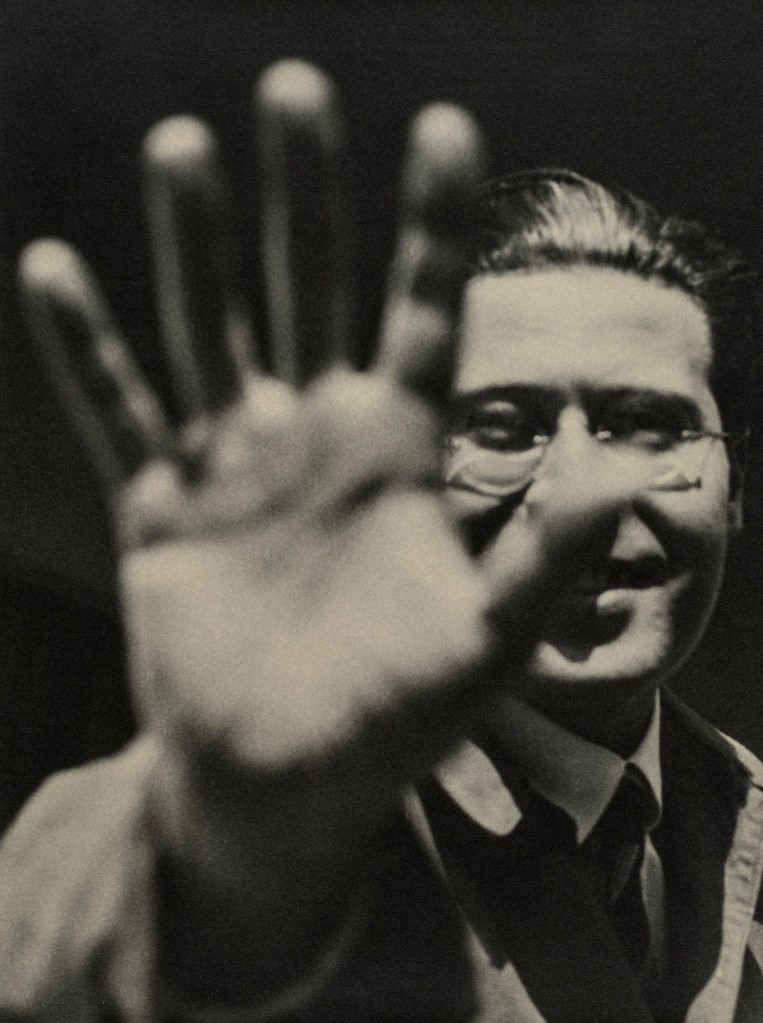

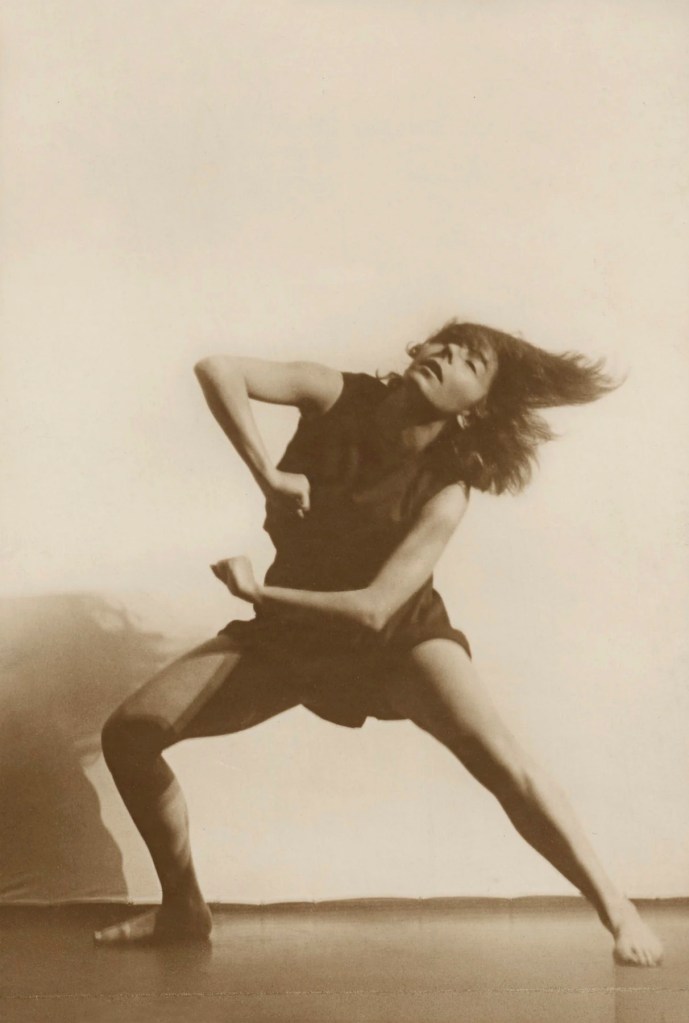

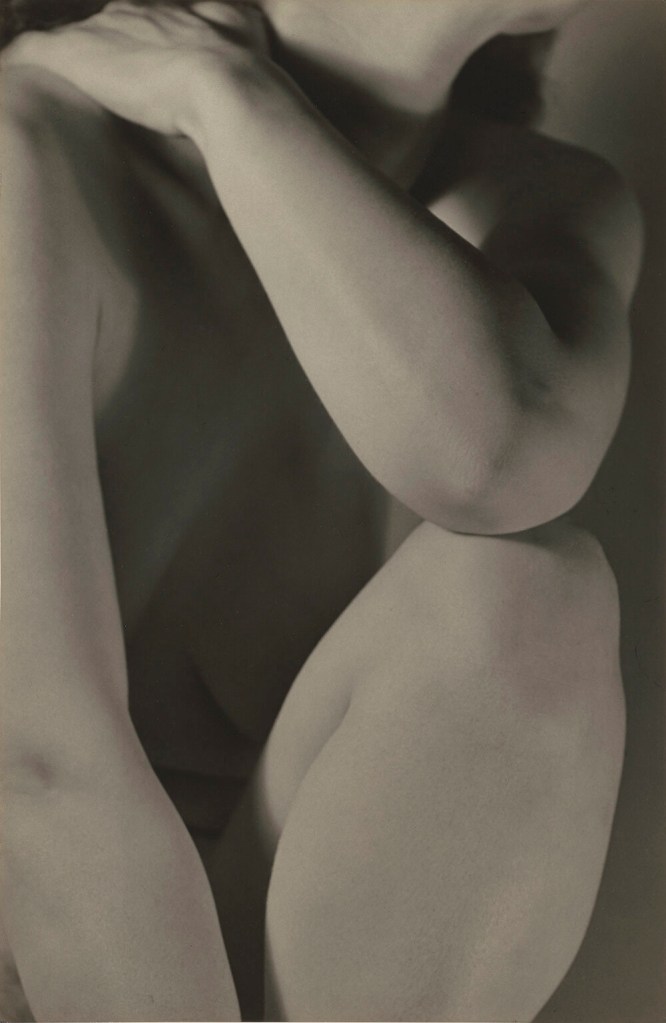

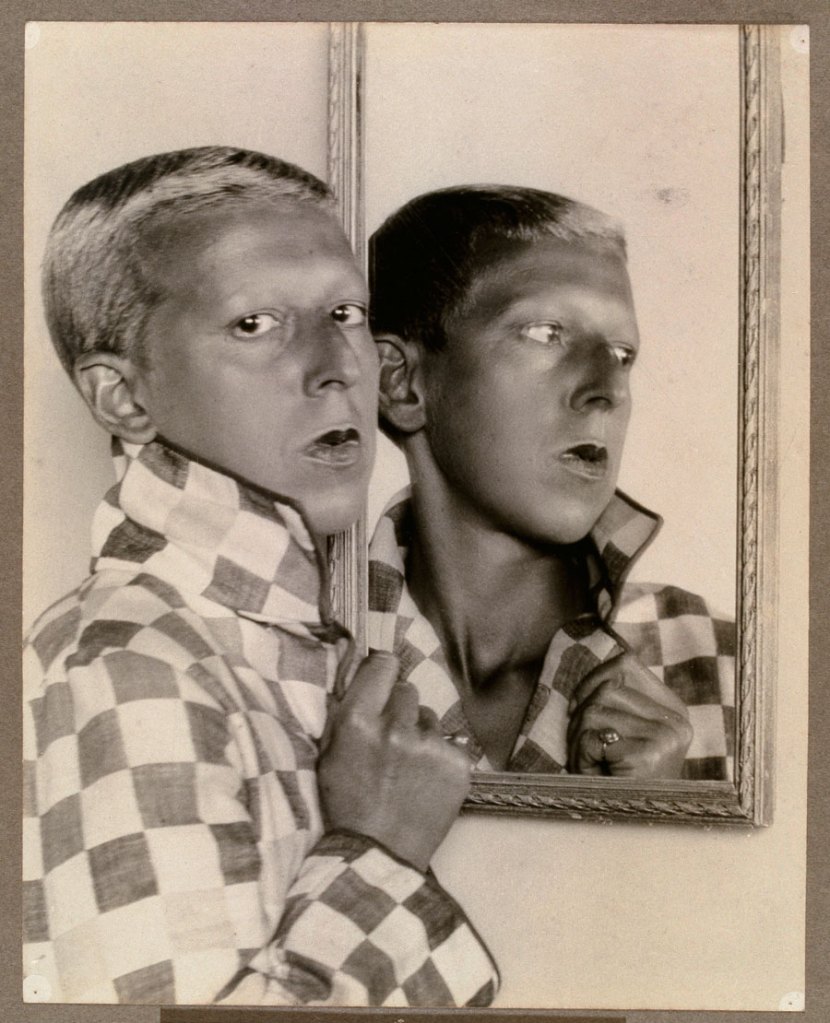

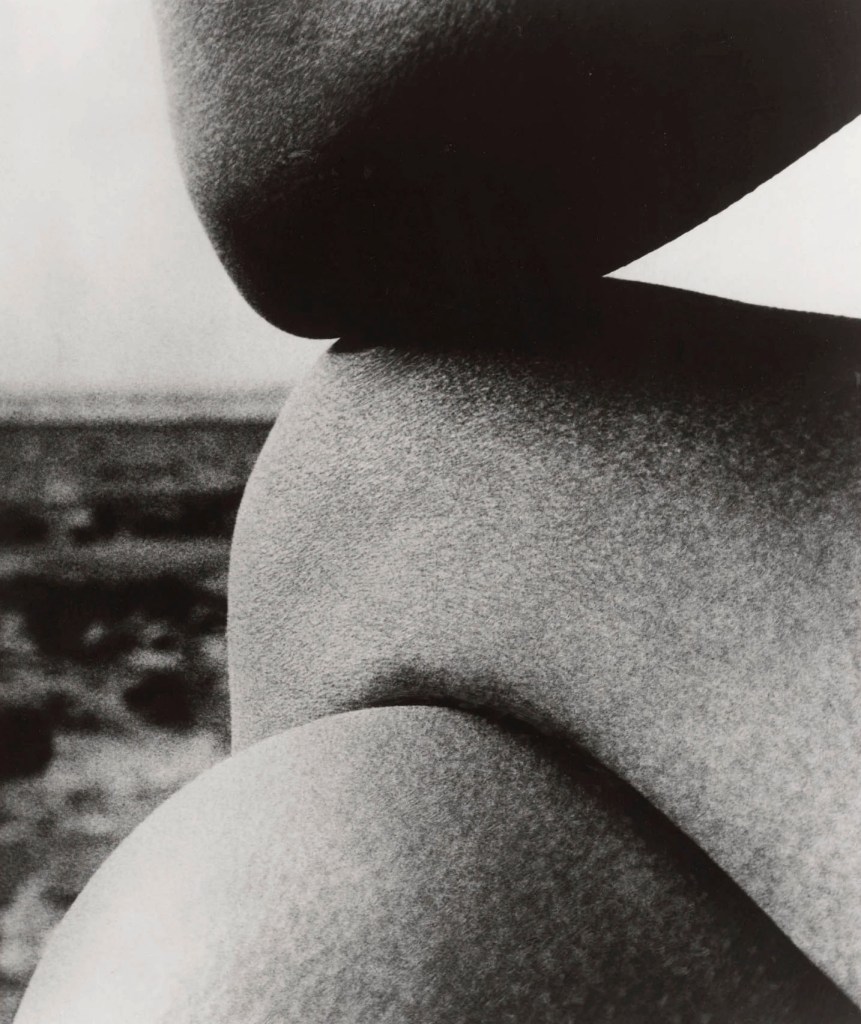

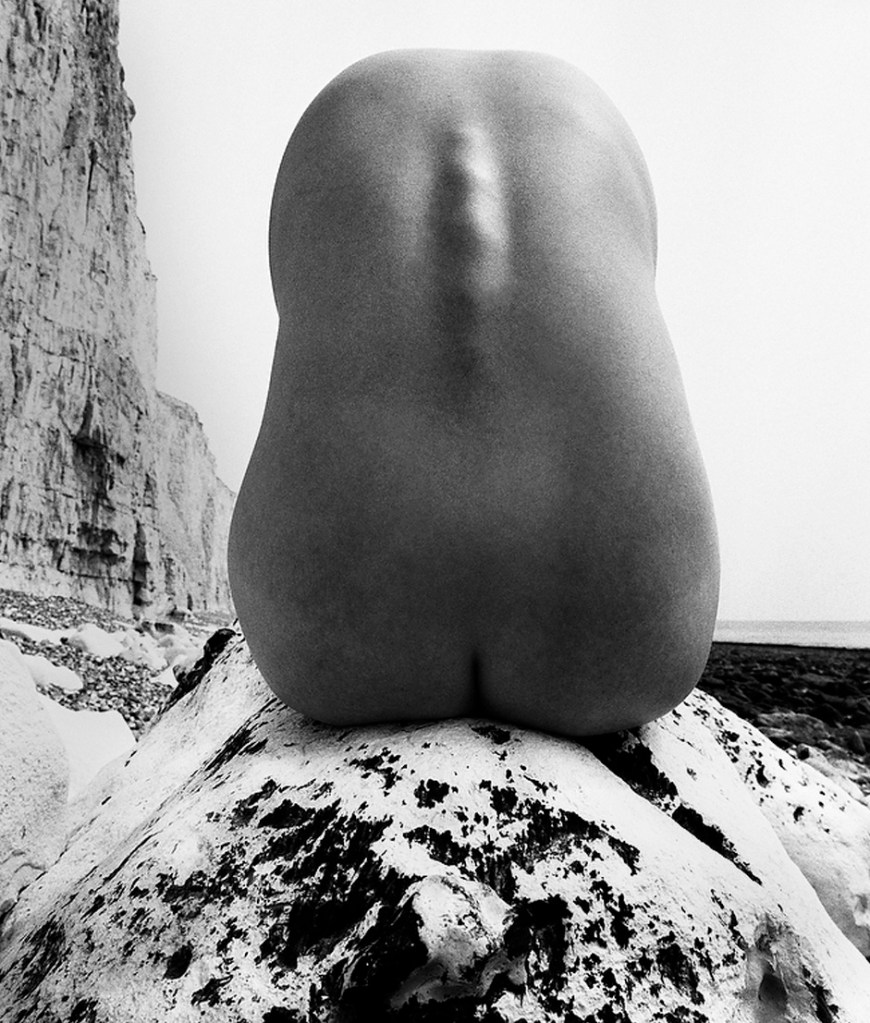

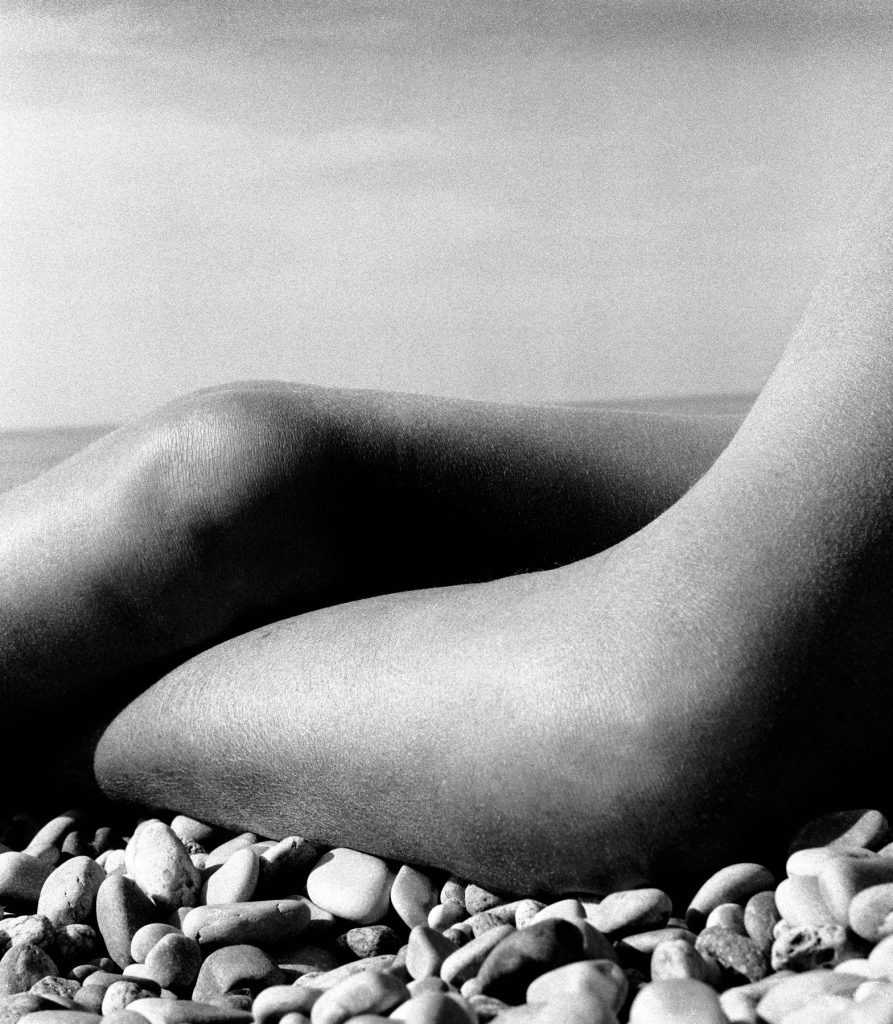

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Figure (The Nude), No. 271

1958; printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

40.2 × 30.1cm (15 13/16 × 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

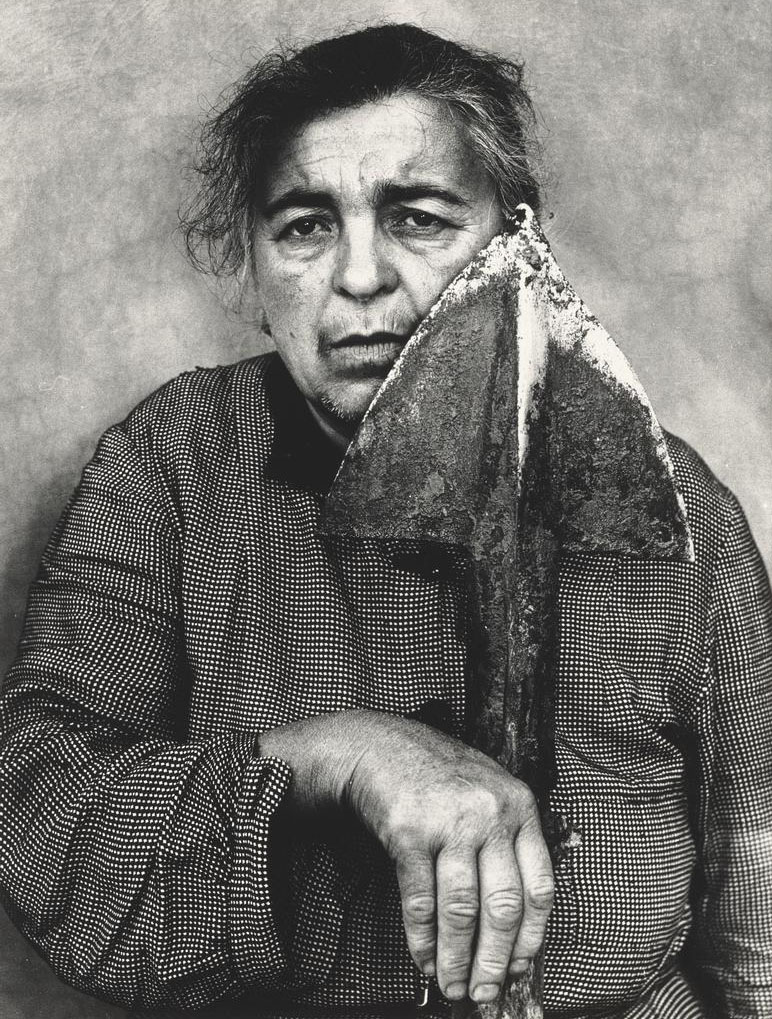

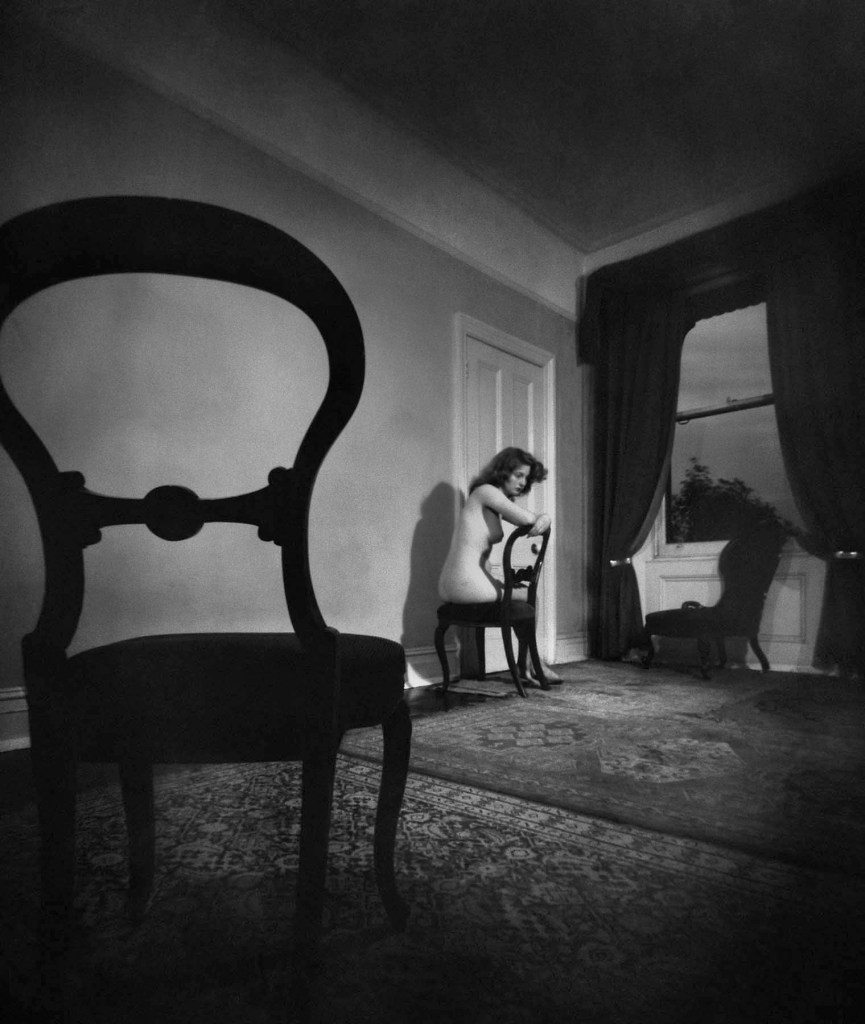

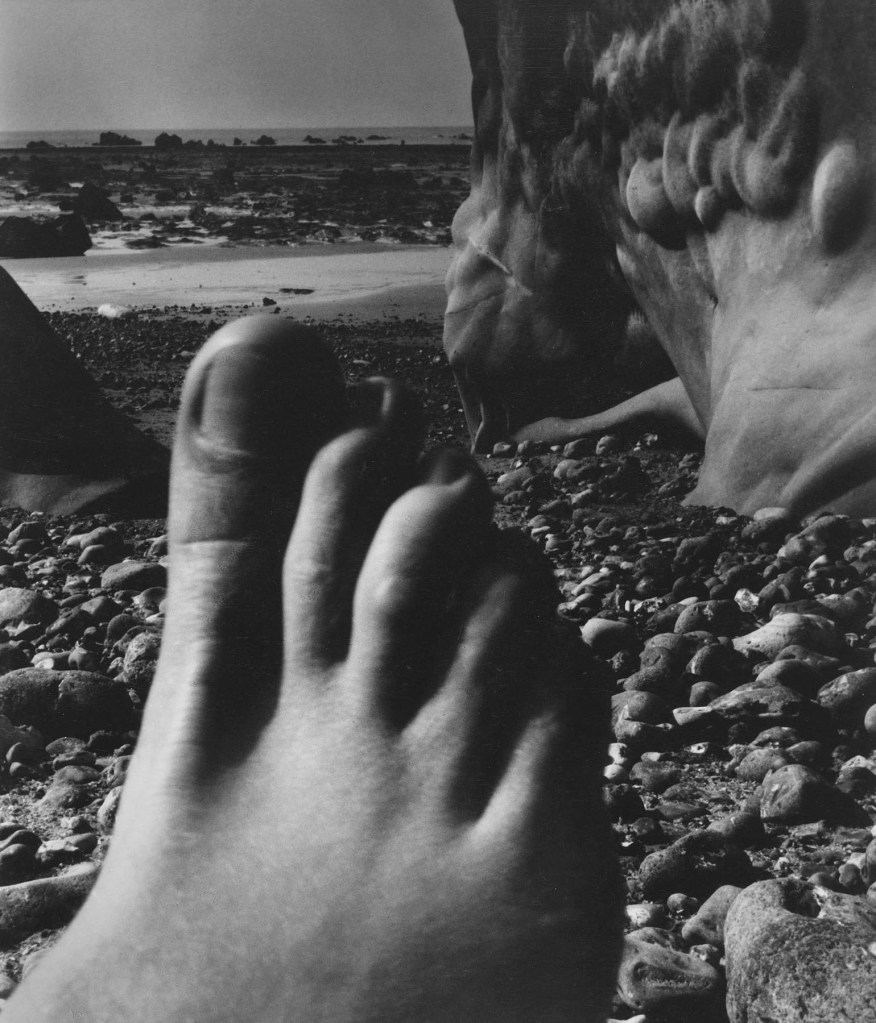

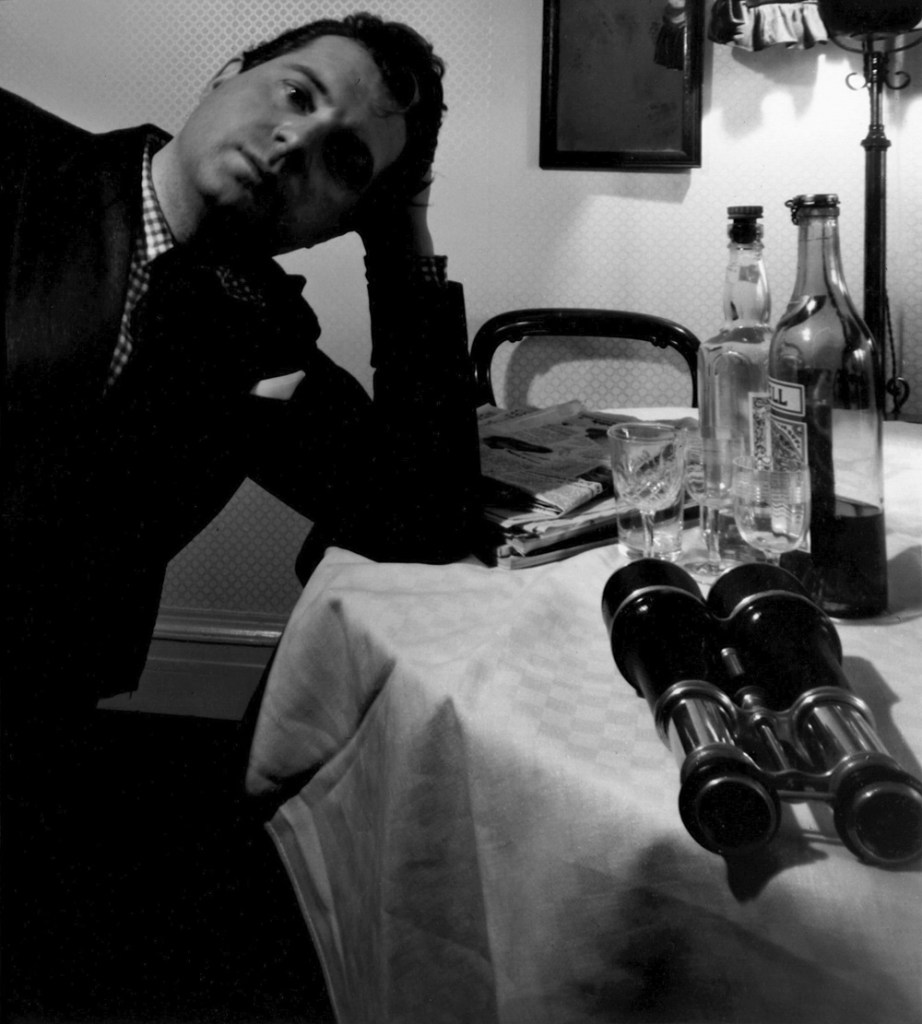

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Figure (My Mother), No. 130

1956; printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

40.1 × 30.1cm (15 13/16 × 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Early work (1956-1960)

In 1955 Giacomelli acquired the secondhand Kobell camera with a Voigtländer lens that he would employ for the rest of his career. He later described it as something that had been “cobbled up,” held together with tape and always losing parts. Made by the Milanese manufacturers Boniforti & Ballerio, the camera used 120 roll film to produce 6 x 9 cm negatives and accommodated interchangeable lenses and a synchronised flash. For Giacomelli, it was not a device to record reality but a means of personal expression. His early association with members of local and national camera clubs and his experimentation with natural and artificial lighting, multiple exposures, and other in-camera and darkroom techniques soon led to the refinement of a unique visual language.

Among Giacomelli’s earliest photographs are portraits of family and friends; the image of his mother holding a spade is one of his most notable. He also staged still lifes and figure studies in his home and garden; the nudes shown here depict the photographer and his wife, Anna. Relatively conventional in composition, these works give a sense of Giacomelli learning his craft, while also indicating the extent to which his subject matter was informed by the people and places closest to him.

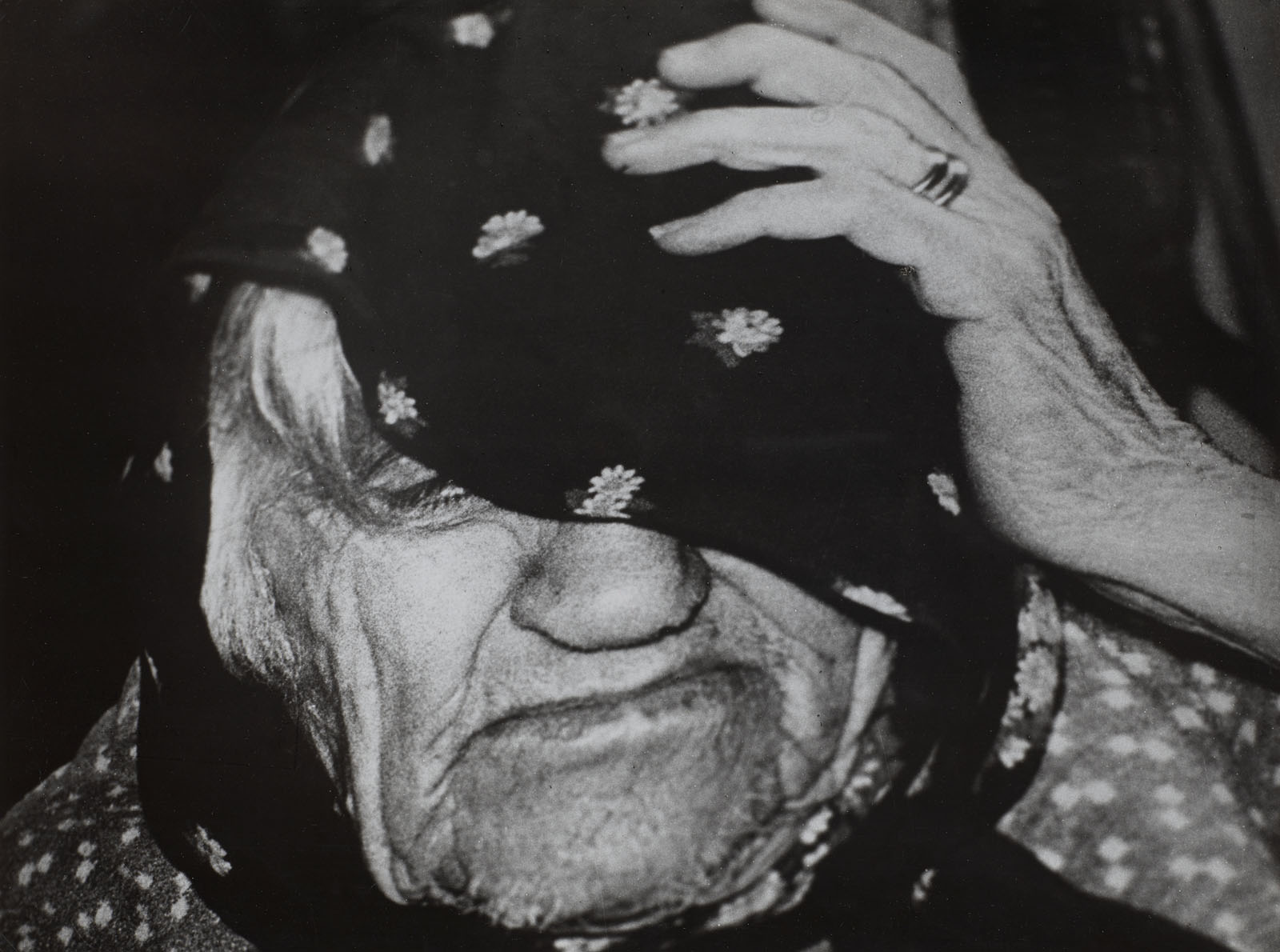

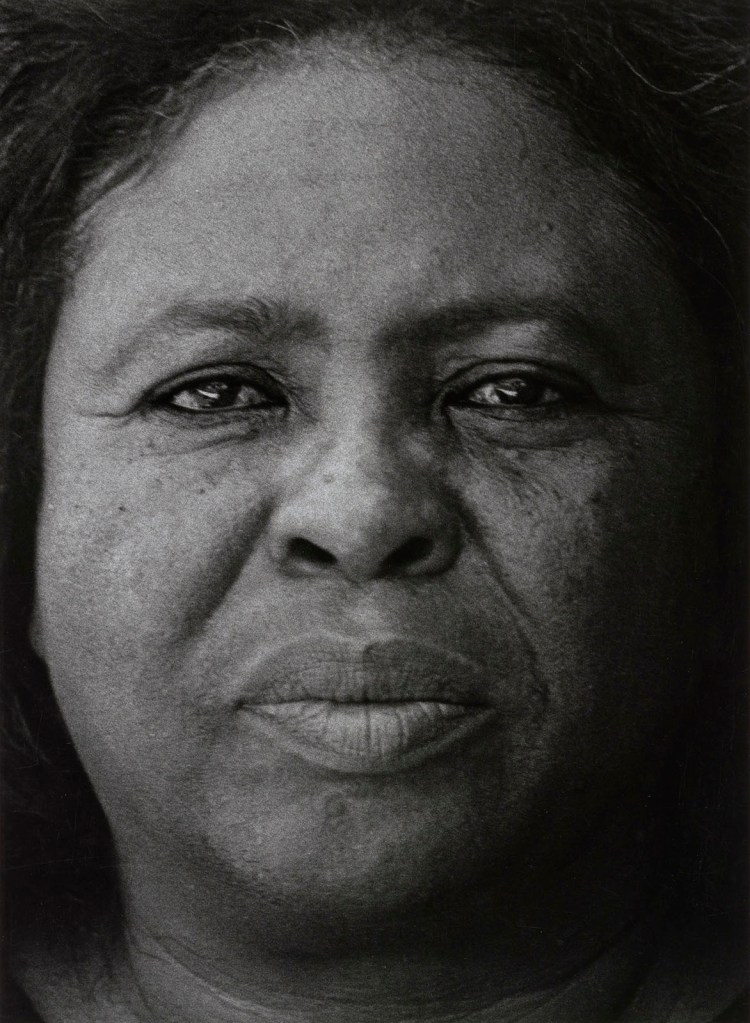

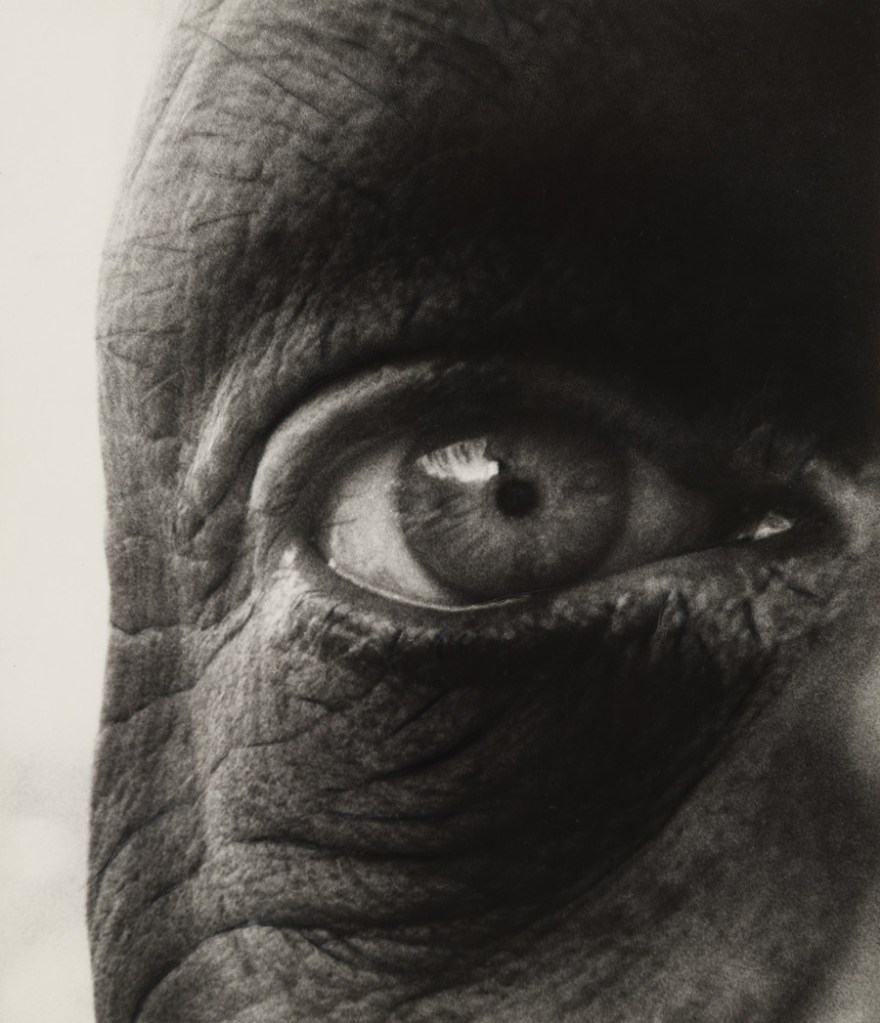

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Hospice / Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes (Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi)

c. 1954-1957

Gelatin silver print

29.2 × 38.9cm (11 1/2 × 15 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes, No. 97 (Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi, No. 97)

Negative 1966; print 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.3cm (11 7/8 × 15 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes, No. 95 (Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi, No. 95)

Negative 1966; print 1981

Gelatin silver print

40.2 × 30.1cm (15 13/16 × 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

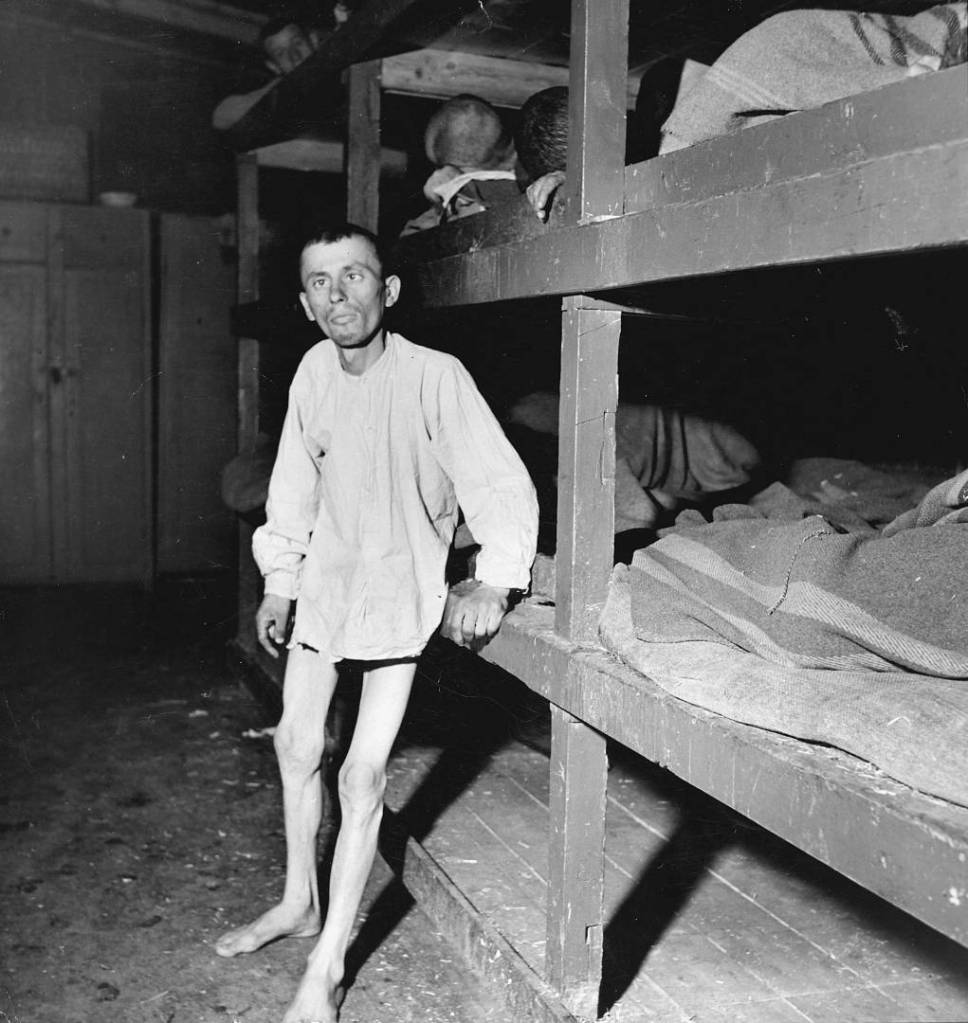

Hospice | Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes (1954-1983)

The first body of work that Giacomelli exhibited as a series was Hospice. It depicts residents of the home for the elderly in Senigallia where his mother was a laundress and which he visited for several years before he began photographing there. Made with flash, the resulting images are characterised by their unflinching scrutiny of individuals living out their last days. He later referred to these as his truest and most direct photographs because they reflected his own fear of growing old.

Giacomelli continued this series for almost three decades, renaming it Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes in 1966 after the first few lines of a poem by the writer Cesare Pavese (Italian, 1908-1950). For a portfolio published in 1981 he heightened the unsettling qualities of mental and physical decline and isolation by tightly cropping his negatives and printing on paper that was curled rather than flat.

“Death will come and will have your eyes – this death that accompanies us from morning till evening, unsleeping.”

~ Translated by Geoffrey Brock, 2002

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Lourdes

1957

Gelatin silver print

23.3 × 37.6cm (8 3/4 × 14 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Lourdes

1957

Gelatin silver print

26.7 × 38.1cm (10 1/2 × 15 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Lourdes (1957 and 1966)

In contrast to Hospice / Death Will Come and It Will Have Your Eyes, the series Lourdes depicts people living with illness, injury, or disability who are in search of miraculous healing. Giacomelli received a commission to photograph at this Catholic pilgrimage site in southern France in 1957.

Tremendously pained by what he saw, he shot just a few rolls of film, returned the fee that had been advanced, and did not show anyone the images for some time. He travelled to Lourdes again in 1966, with his wife and second child. This time he, too, was in search of a cure, for their son, who had lost the ability to speak following an accident.

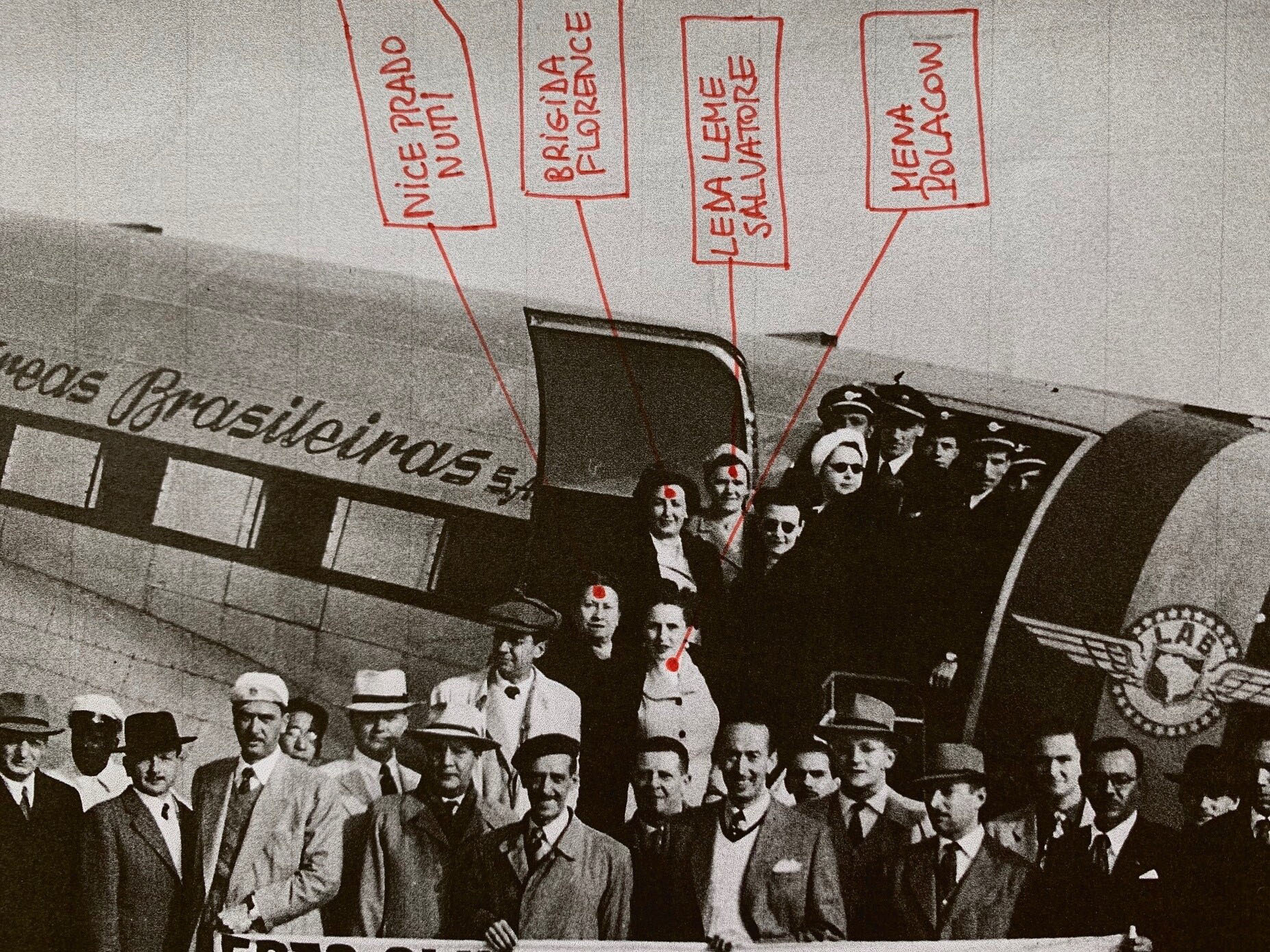

Lourdes is the only series that Giacomelli created outside Italy, although a group of photographs made in Ethiopia (1974) and another in India (1976) have been attributed to him. Giacomelli purchased cameras and film for two individuals who were planning travel to these countries, and both of them drew on previous discussions with him when they photographed at their respective locations. Giacomelli later made prints from the negatives and signed his name to several of them, acknowledging the collaboration.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Apulia (Puglia)

Negative 1958, printed 1970

Gelatin silver print

28.6 × 40cm (11 1/4 × 15 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Apulia (Puglia)

Negative 1958, printed 1960

Gelatin silver print

28.7 × 23.5cm (11 5/16 × 9 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

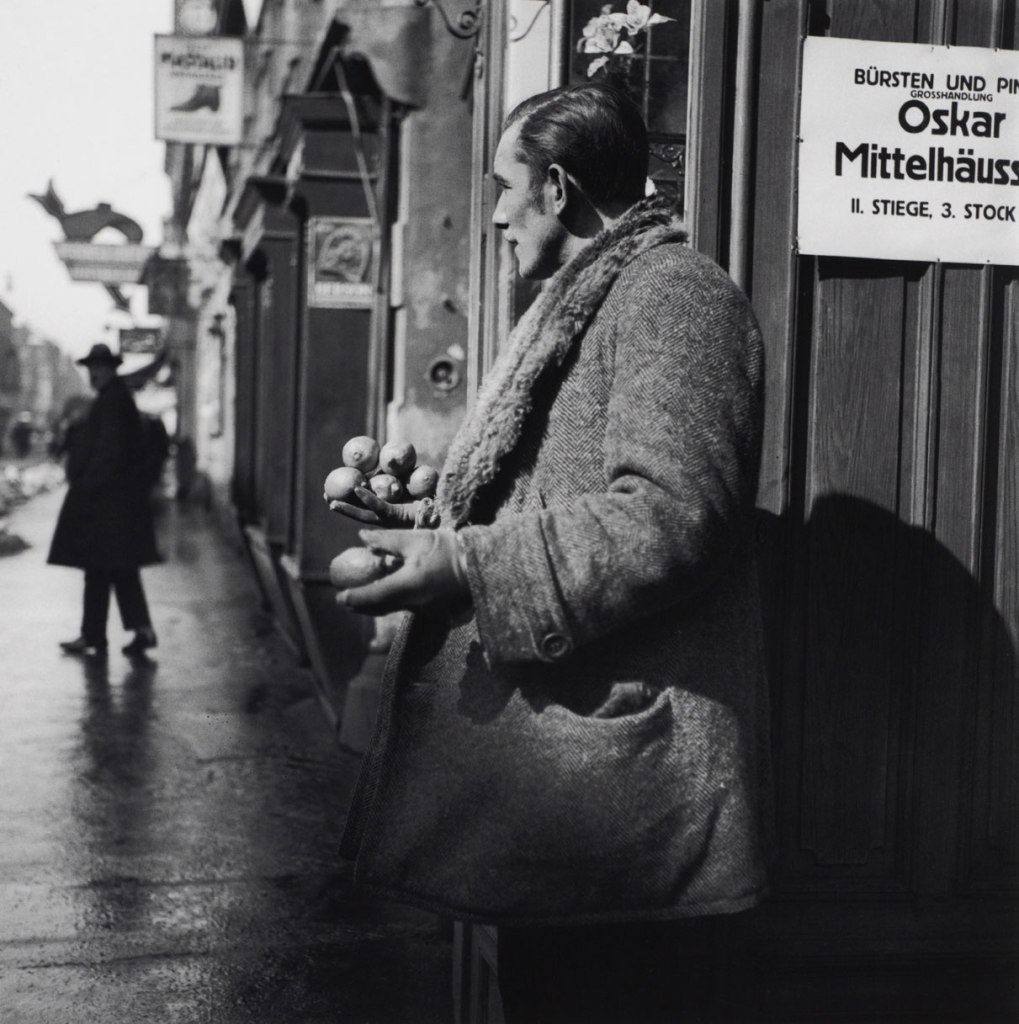

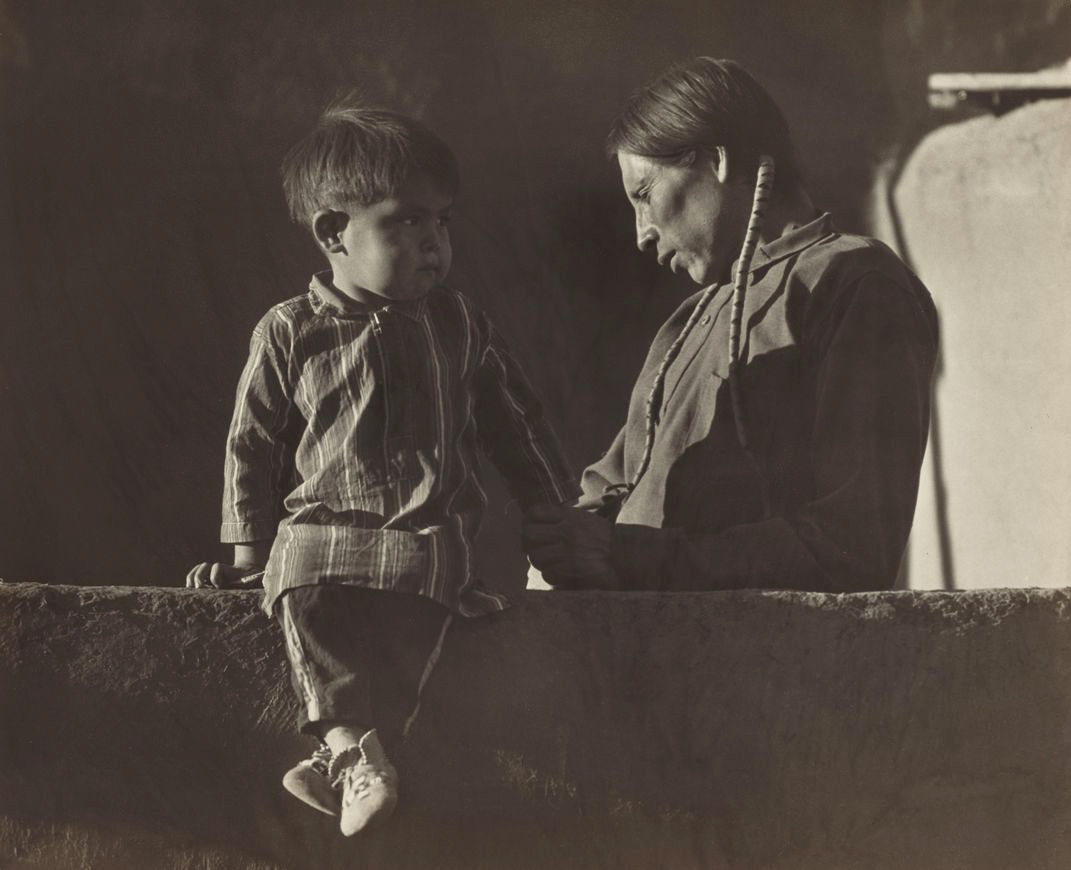

Apulia (Puglia) (1958)

Giacomelli operated his printshop, Tipografia Marchigiana, in the centre of Senigallia. The successful establishment became a gathering place for photographers, artists, and critics, and provided the address stamped on the verso of all his photographs. In its early years, the business occupied the majority of Giacomelli’s time, leaving only Sundays for photography excursions. While he most often explored his hometown, its beaches, and the surrounding countryside in the Marche region, he occasionally traveled farther afield.

For this series, made in Apulia, Italy’s most southeastern province (the “heel of the boot”), a journey of about 330 miles was required. There he focused his attention on the interaction of multiple generations of townspeople gathering leisurely against the simple, whitewashed architecture typical of hillside towns such as Rodi Garganico, Peschici, Vico del Gargano, and Monte Sant’Angelo. These images provide insight into Giacomelli’s ability to engage his subjects, while also underscoring a fundamental humanistic impulse in his work.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Scanno

negative 1957-1959, printed later

Gelatin silver print

29.8 × 39.6cm (11 3/4 × 15 9/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Scanno

negative 1957-1959, printed 1980s

Gelatin silver print

26.8 × 34cm (10 9/16 × 13 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Scanno, No. 52

1957-1959; printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.2cm (11 7/8 × 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Scanno, No. 57

1957-1959; printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.2cm (11 7/8 × 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Scanno

1957-1959

Gelatin silver print

37.9 × 28.4cm (14 15/16 × 11 3/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

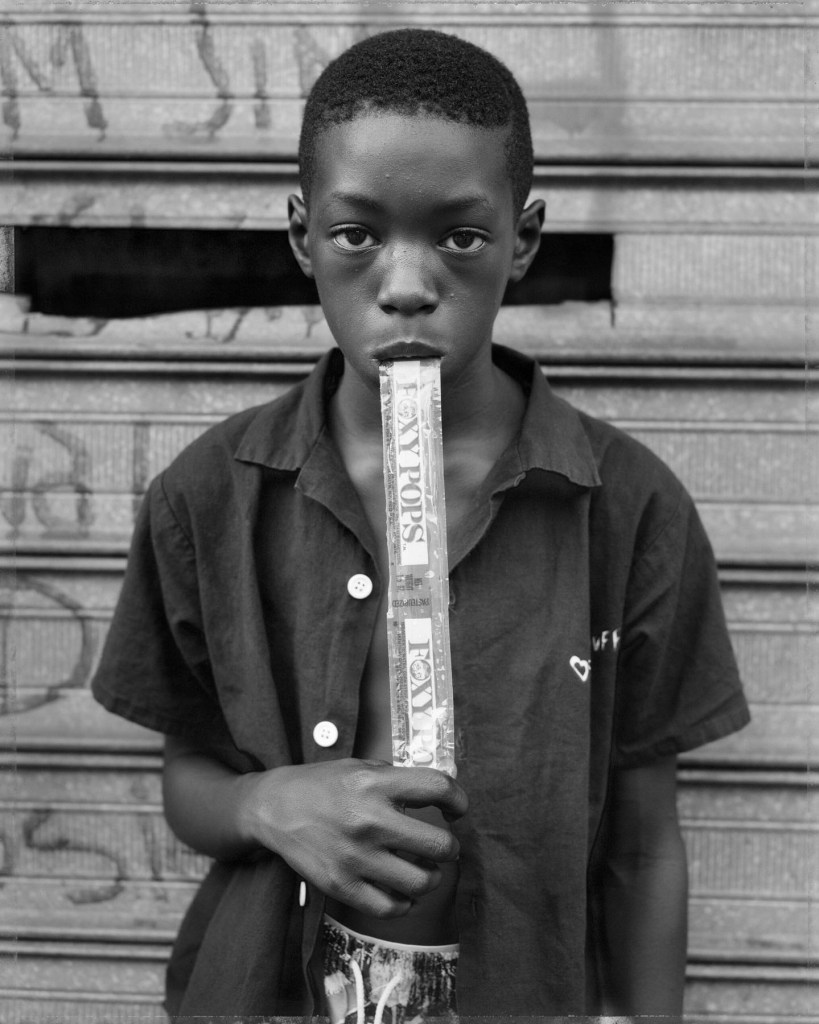

Scanno (1957-1959)

Following his sustained observation of hospice residents in Senigallia, the photographs that Giacomelli made during trips to Scanno in 1957 and 1959 further demonstrate his ability to describe people in a specific time and place. In this town located in the Apennine Mountains of central Italy, about 270 miles south of Senigallia, Giacomelli encountered men and women going about their daily chores or gathering in the square, draped in dark garments or cloaks, their heads covered with hats or scarves. Even when congregating, subjects seem to be isolated or lost in thought. Whether in sharp focus or blurred by movement, the occasional individual who looks directly into his camera suggests a sense of mystery or furtiveness. Giacomelli used a slow shutter speed and shallow depth of field to photograph these stark, black-clad figures against whitewashed architectural settings, introducing indistinct passages that amplify the fairy-tale mood of a town that appears to be irretrievably steeped in the past.

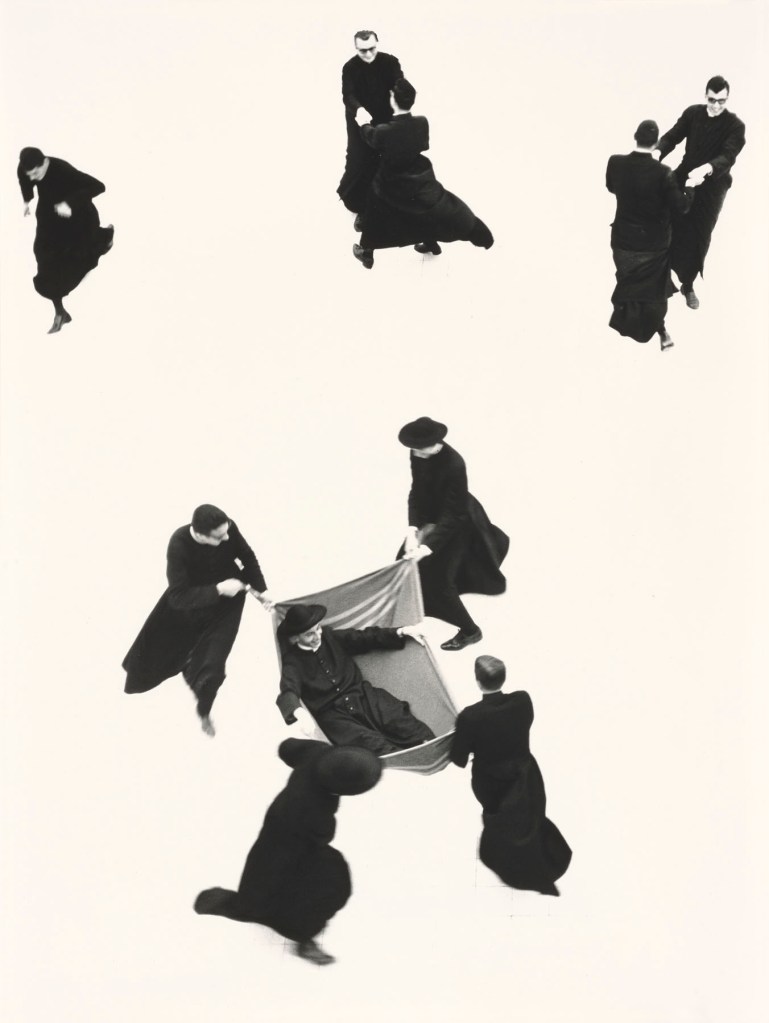

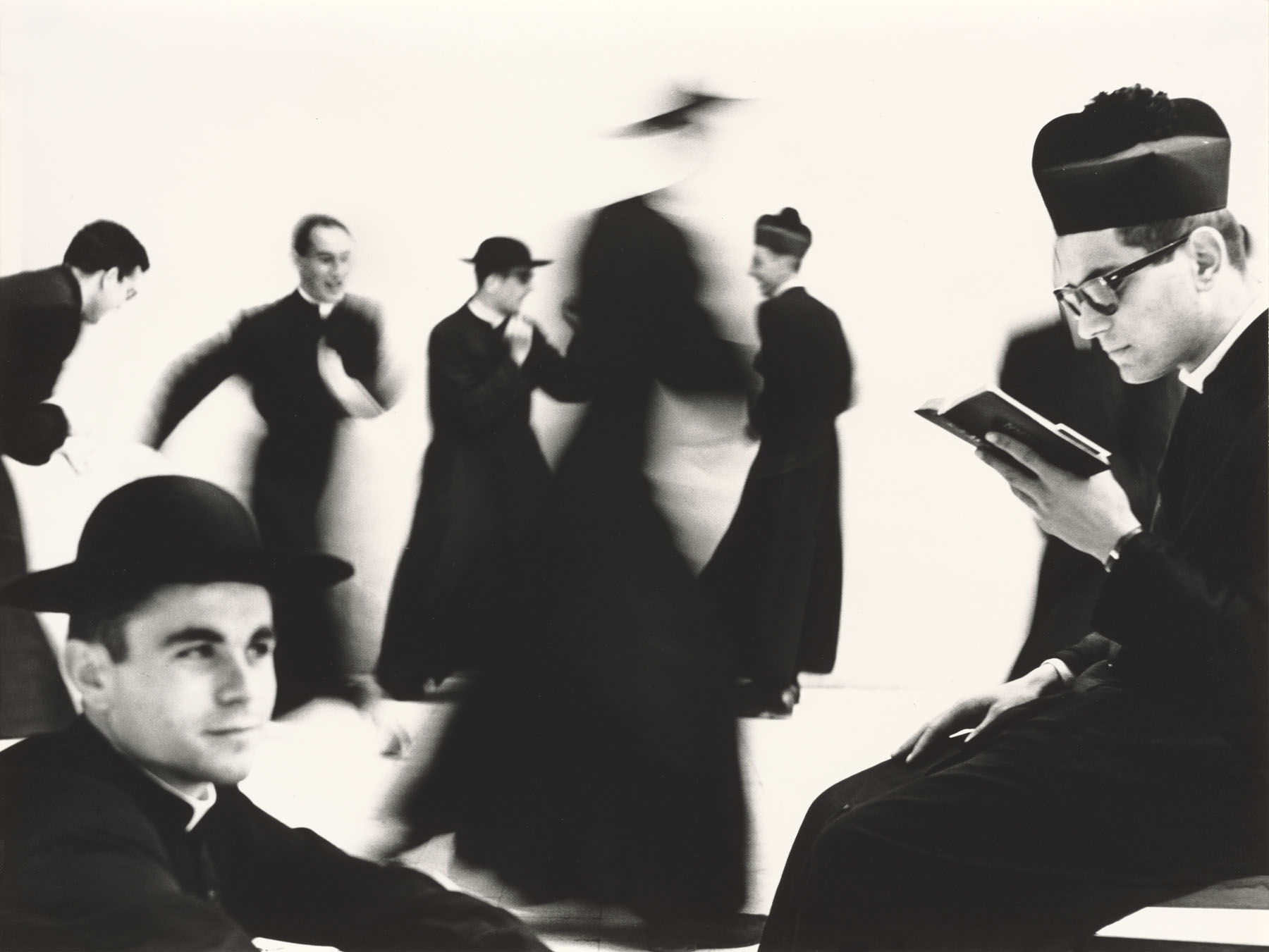

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Young Priests (Pretini)

Negative 1961-1963

Gelatin silver print

29 × 38.6cm (11 7/16 × 15 3/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Young Priests, No. 70 (Pretini, No. 70)

Negative 1961-1963; print 1981

Gelatin silver print

40.3 × 30.1cm (15 7/8 × 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

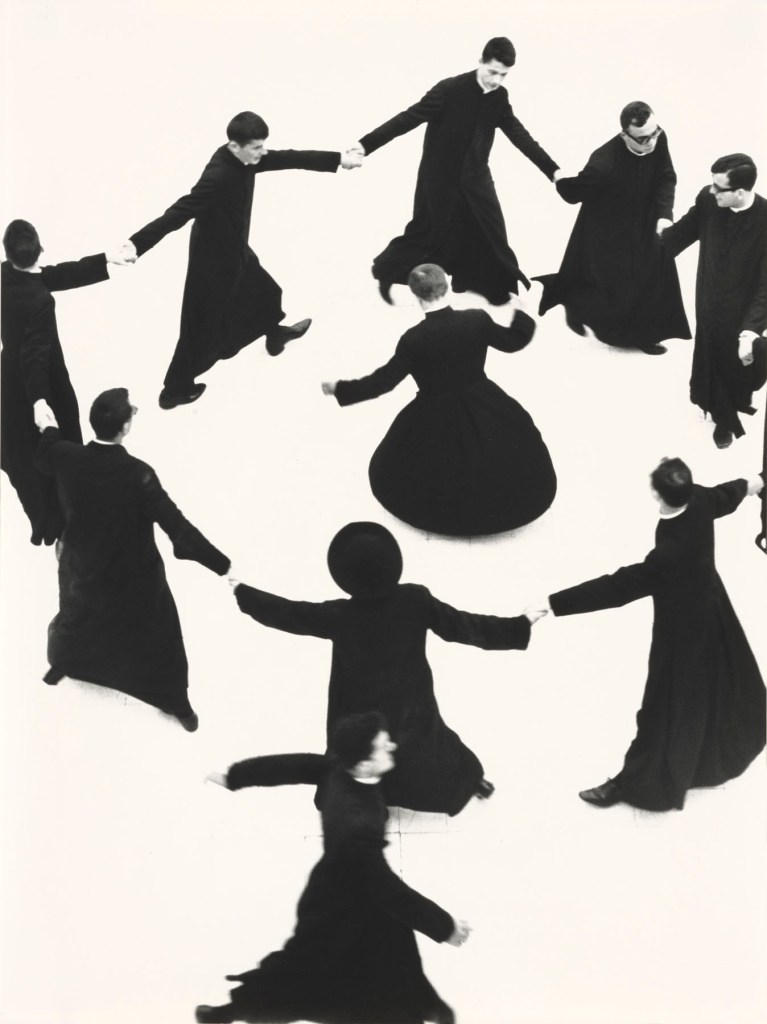

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Young Priests, No. 72 (Pretini, No. 72)

Negative 1961-1963; print 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.2cm (11 7/8 × 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Young Priests, No. 71 (Pretini, No. 71)

Negative 1961-1963; print 1981

Gelatin silver print

40.3 × 30.1cm (15 7/8 × 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Young Priests, No. 74 (Pretini, No. 74)

Negative 1961-1963; print 1981

Gelatin silver print

40.3 × 30.1cm (15 7/8 × 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

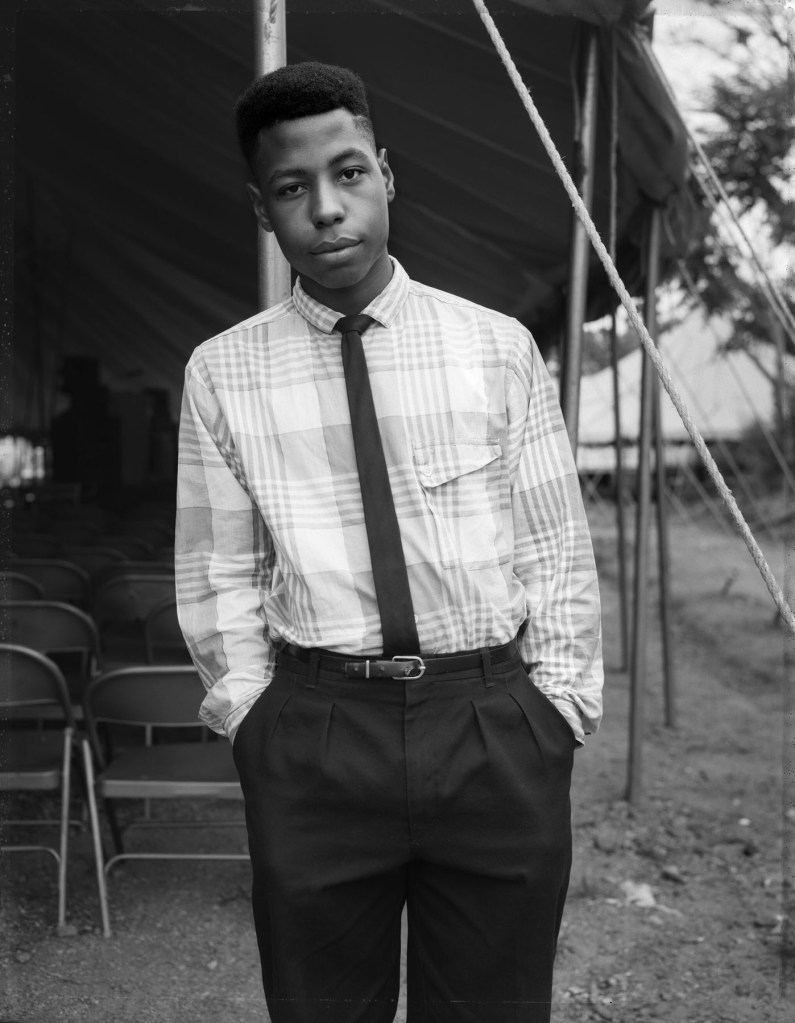

Young Priests | I Have No Hands That Caress My Face (1961-1963)

Among Giacomelli’s most memorable images are those of pretini (young priests) in the seminary of Senigallia, whom he captured playing in the snow or relaxing in the courtyard. Once again juxtaposing the distinctive shapes of black-clad figures (this time, seminarians in cassocks) against a white ground (snow-covered or sun-drenched settings), these photographs suggest a more lighthearted mood than is evident in other series. Although appearing to have been choreographed, they are the result of the priests’ unbridled joviality as they run, throw snowballs, or play ring-around-the-rosy, and of Giacomelli’s foresight to let the scenes unfold as he recorded them from the building’s rooftop.

After Giacomelli had won the trust of the seminarians, his interaction with them was brought to an abrupt end when he provided the young men with cigars for photographs he intended to submit to a competition on the theme of smoking. The rector denied him further access. Giacomelli later applied the title I Have No Hands That Caress My Face to this series, from the first two lines of a poem by Father David Maria Turoldo (Italian, 1916-1992) about young men who seek solitary religious life. This title lends poignancy to the moments of exuberance and camaraderie that accompanied study for such a calling.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Landscape: Flames on the Field (Paesaggio, fiamme sul campo)

1954; printed 1980

Gelatin silver print

28.6 × 39cm (11 1/4 × 15 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

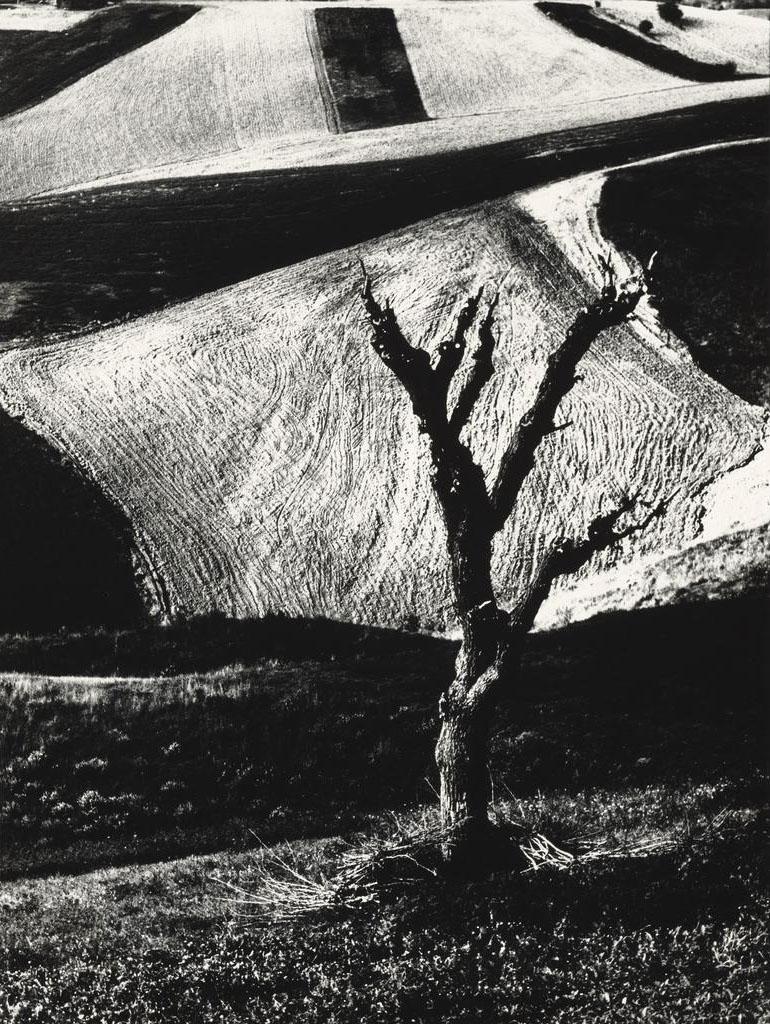

Early landscapes (1954-1960)

Italy’s Marche region is characterised by rolling hills, small farms, and frazioni (hamlets), all of which were among the first motifs that Giacomelli photographed. As with his portraits and figure studies from this period, the compositions of his early landscapes were fairly conventional, with foreground, middle-ground, and background elements organised around a clearly discernible horizon line. As he refined his technique, however, Giacomelli often positioned himself at the top of a hill pointing his camera downward or at the base aiming it upward, thereby eliminating the horizon and creating a disorienting patchwork of geometric shapes. His development of the negative, use of high-contrast paper, and manipulations in the darkroom further enhanced the distinctively graphic qualities of his images. It was not uncommon for him to scratch forms into his negatives to add dramatic counterpoints.

Over the years, Giacomelli returned to certain sites multiple times, documenting them during different seasons and crop rotations. He would later incorporate photographs made for one purpose into a series that had other ambitions, most notably to function as commentary on the capacity of both natural occurrences and human interventions to change the character of the land.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Good Earth (La Buona Terra)

1964-1966

Gelatin silver print

14.3 × 38.9cm (5 5/8 × 15 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Good Earth (La Buona Terra)

1964-1966; printed before 1980

Gelatin silver print

30.3 × 40.3cm (11 15/16 × 15 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Good Earth (La Buona Terra)

1964-1966; printed early 1970s

Gelatin silver print

28.9 × 38.9cm (11 3/8 × 15 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Good Earth (La Buona Terra)

1964-1966; printed 1970s

Gelatin silver print

28.6 × 39.4cm (11 1/4 × 15 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Good Earth, No. 146 (La Buona Terra, No. 146)

1964-1965; printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30 × 40.2cm (11 13/16 × 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Good Earth, No. 208 (La Buona Terra, No. 208)

1964-1965; printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30 × 40.2cm (11 13/16 × 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Good Earth, No. 219 (La Buona Terra, No. 219)

1964-1965; printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30 × 40.2cm (11 13/16 × 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

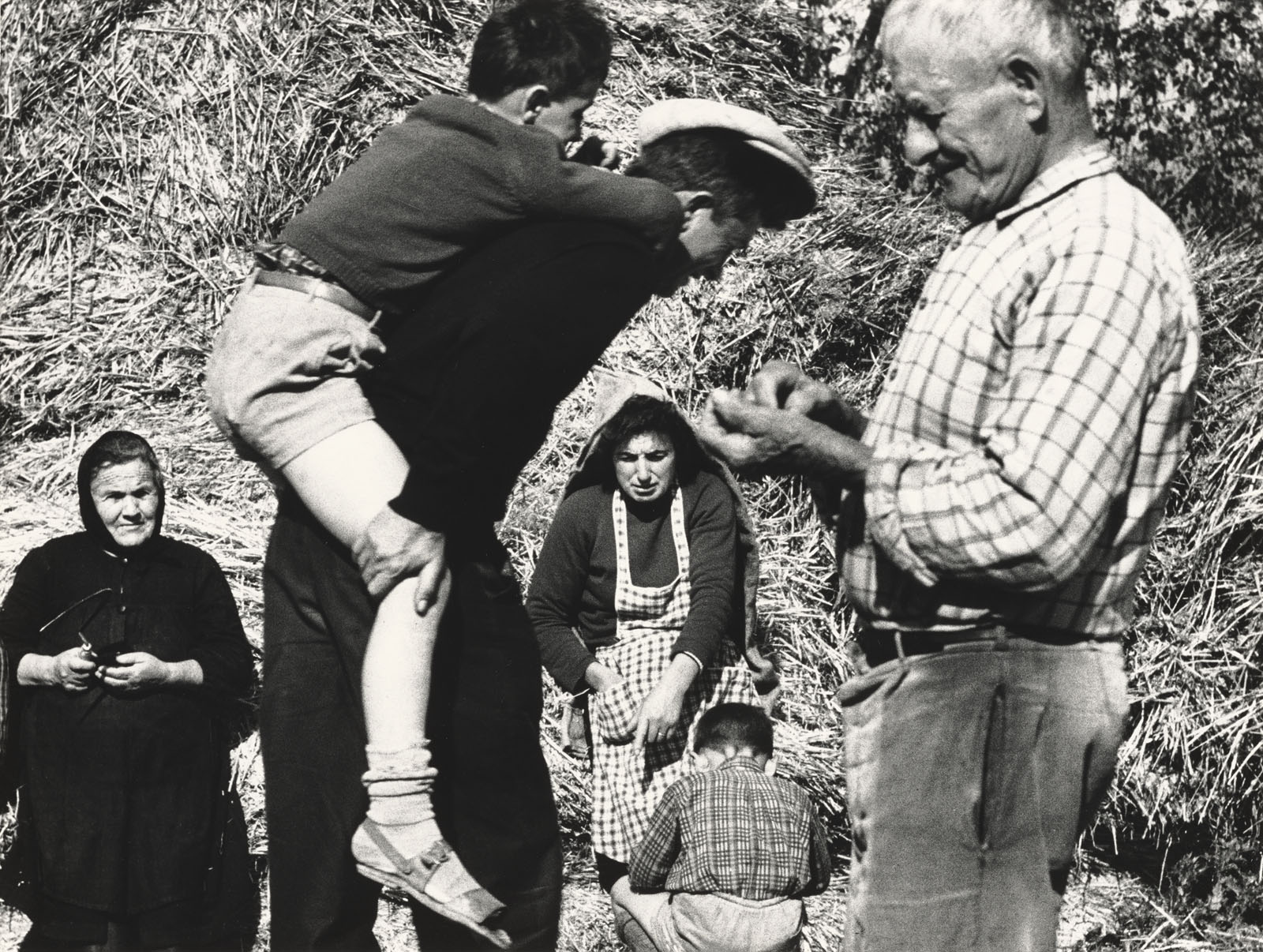

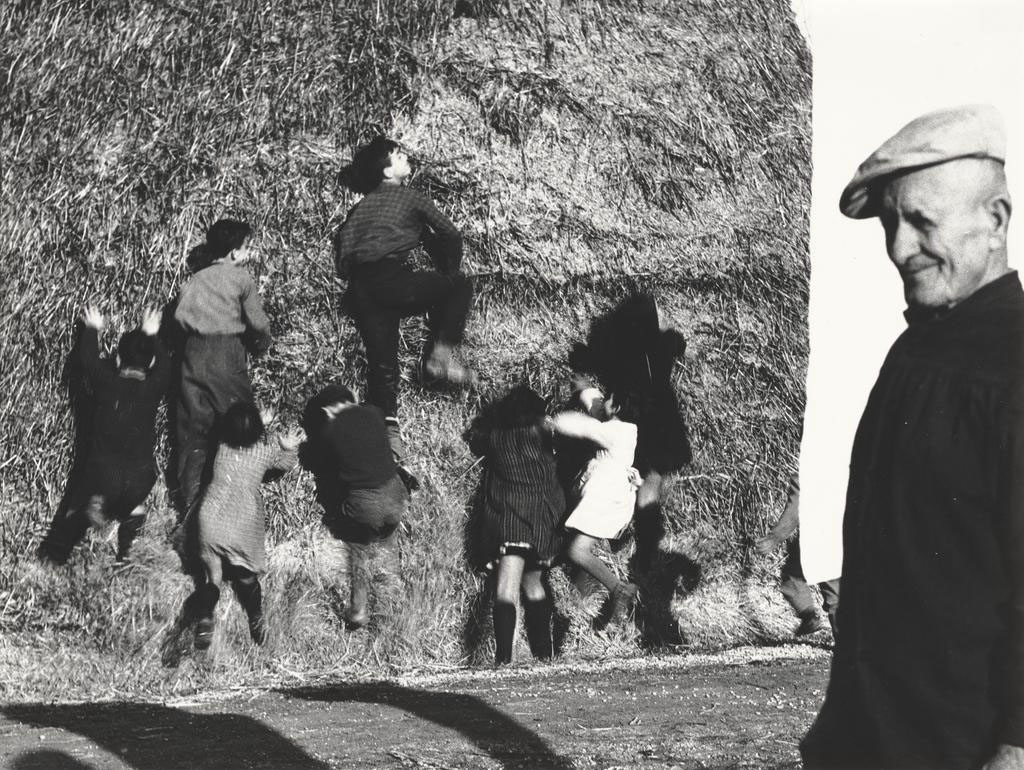

The Good Earth (1964-1966)

For this series, Giacomelli followed a farming family off and on over several years as they went about their daily lives in the countryside surrounding Senigallia, planting and harvesting crops and tending livestock. Once he had gained their trust, he began to make photographs that underscored the cyclical nature of their existence, including both the intermingling of multiple generations and the interweaving of daily chores and responsibilities with moments of leisure and renewal. The Good Earth tells a story of resilience, self-sufficiency, and continuity. The last of these is symbolised by the recurring motif of towering haystacks that serve as the backdrop for work, play, and the celebration of a young couple’s wedding.

Periodically Giacomelli asked the family, with whom he maintained a friendship beyond this project, to use their tractor to plough patterns in fields that lay fallow. The resulting images, which form the basis of his series Awareness of Nature, address the issue of humankind’s interventions in the landscape. Examples are on display in the final gallery of the exhibition.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Metamorphosis of the Land (Metamorfosi della terra)

1976

Gelatin silver print

29.2 × 39.4cm (11 1/2 x 15 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Metamorphosis of the Land, No. 2 (Metamorfosi della terra, No. 2)

1971, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

29.5 × 39.1cm (11 5/8 x 15 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Metamorphosis of the Land, No. 10 (Metamorfosi della terra, No. 10)

1974, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.2cm (11 7/8 x 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Metamorphosis of the Land, No. 19 (Metamorfosi della terra, No. 19)

Before 1966, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.2cm (11 7/8 x 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Metamorphosis of the Land, No. 283 (Metamorfosi della terra, No. 283)

Before 1968, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.2cm (11 7/8 x 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Metamorphosis of the Land (Metamorfosi della terra)

1958; printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

40.2cm × 30.2cm (15 13/16 x 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Metamorphosis of the Land, No. 5 (Metamorfosi della terra, No. 5)

1971, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

40.2cm × 30.1cm (15 13/16 x 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

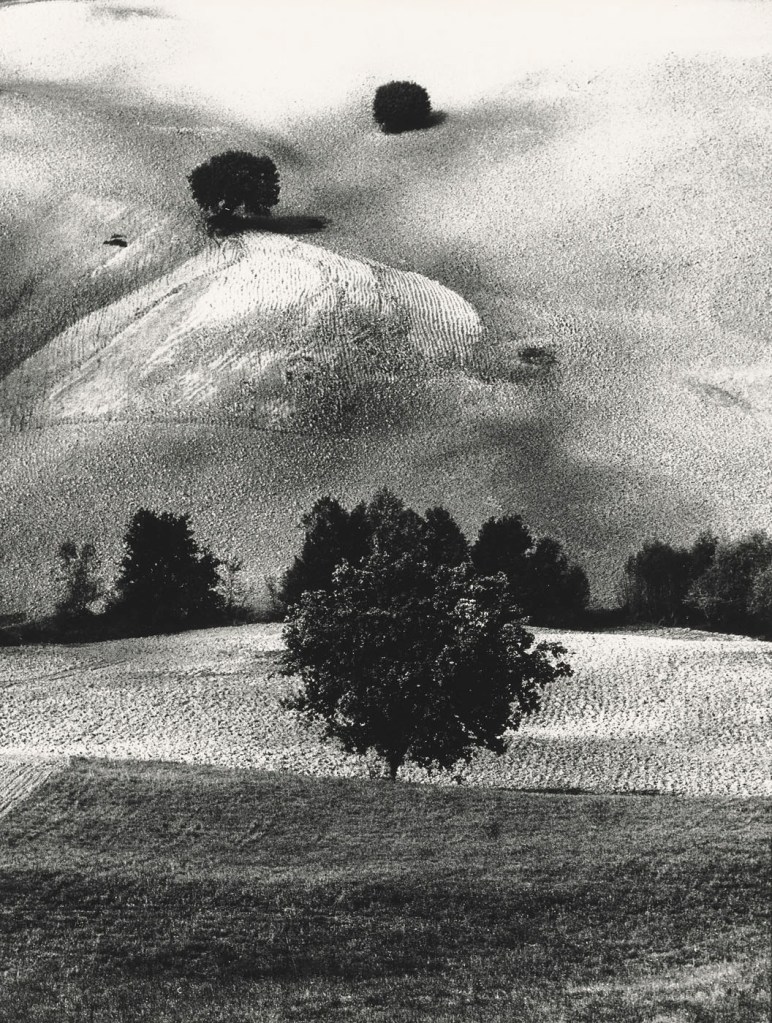

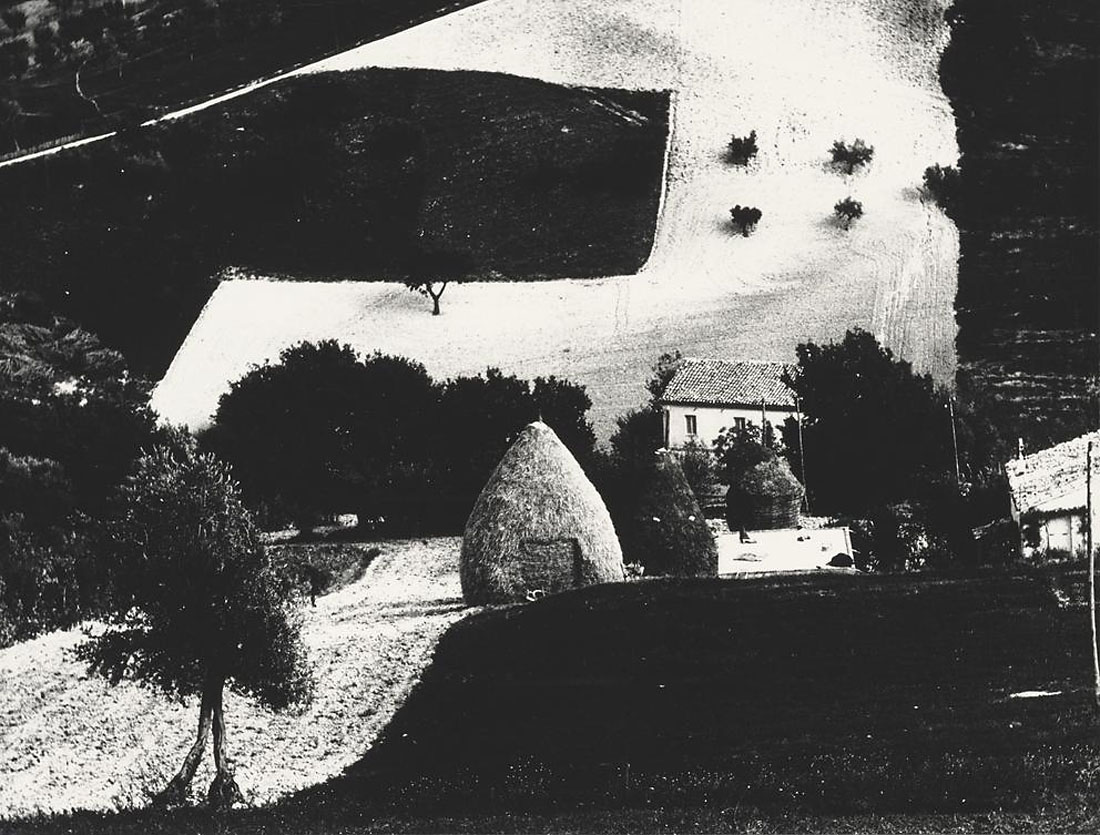

Metamorphosis of the Land (1958-1960)

The photographs gathered under the title Metamorphosis of the Land were created over roughly two decades in the countryside surrounding Senigallia. Without a horizon line to anchor them, they are disorienting, requiring the viewer to rely on a lone house or tree as a focal point. Perspectival ambiguity abounds: Did Giacomelli take the photographs from an elevated or lowered vantage point? Did he hold the camera parallel or perpendicular to the land? Is this confusion a result of the inherent “verticality” of the hilly Marche region, or did Giacomelli rely on darkroom manipulation (such as printing on diagonally tilted sheets of photo paper) to create right-angled configurations of shapes that should otherwise recede in the distance, following the tenets of one-point perspective?

These ambiguities are further intensified by Giacomelli’s intention for this body of work to address issues of ecological neglect and loss. Deeply attuned to the rural geography and agricultural practices of the Marche, he was wary of the consequences that accompanied the shift from centuries-old systems of subdivided fields and crop rotation to modern methods of mechanisation and fertilisation that overtax the land by keeping it in constant use. The series is one of lament.

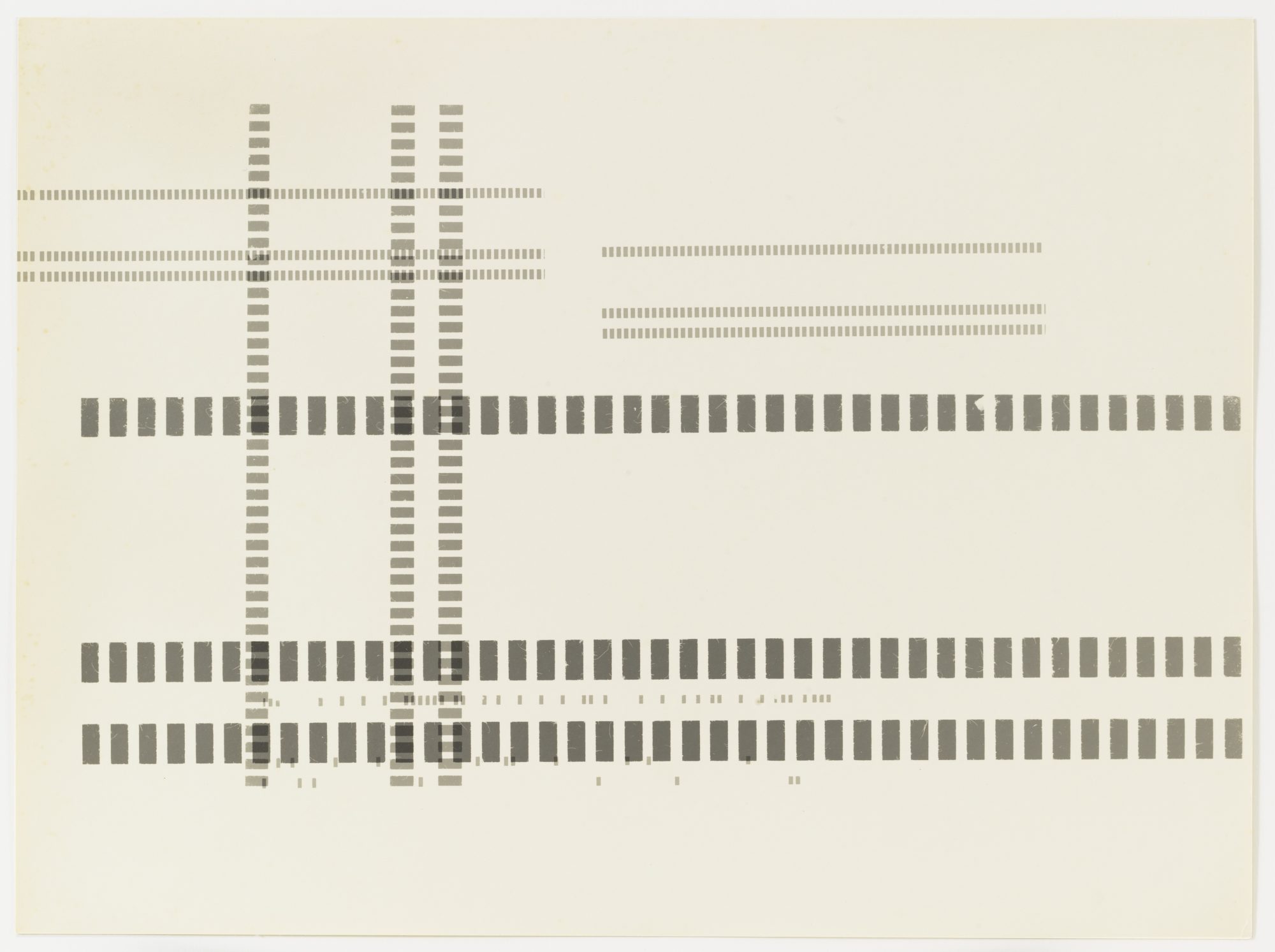

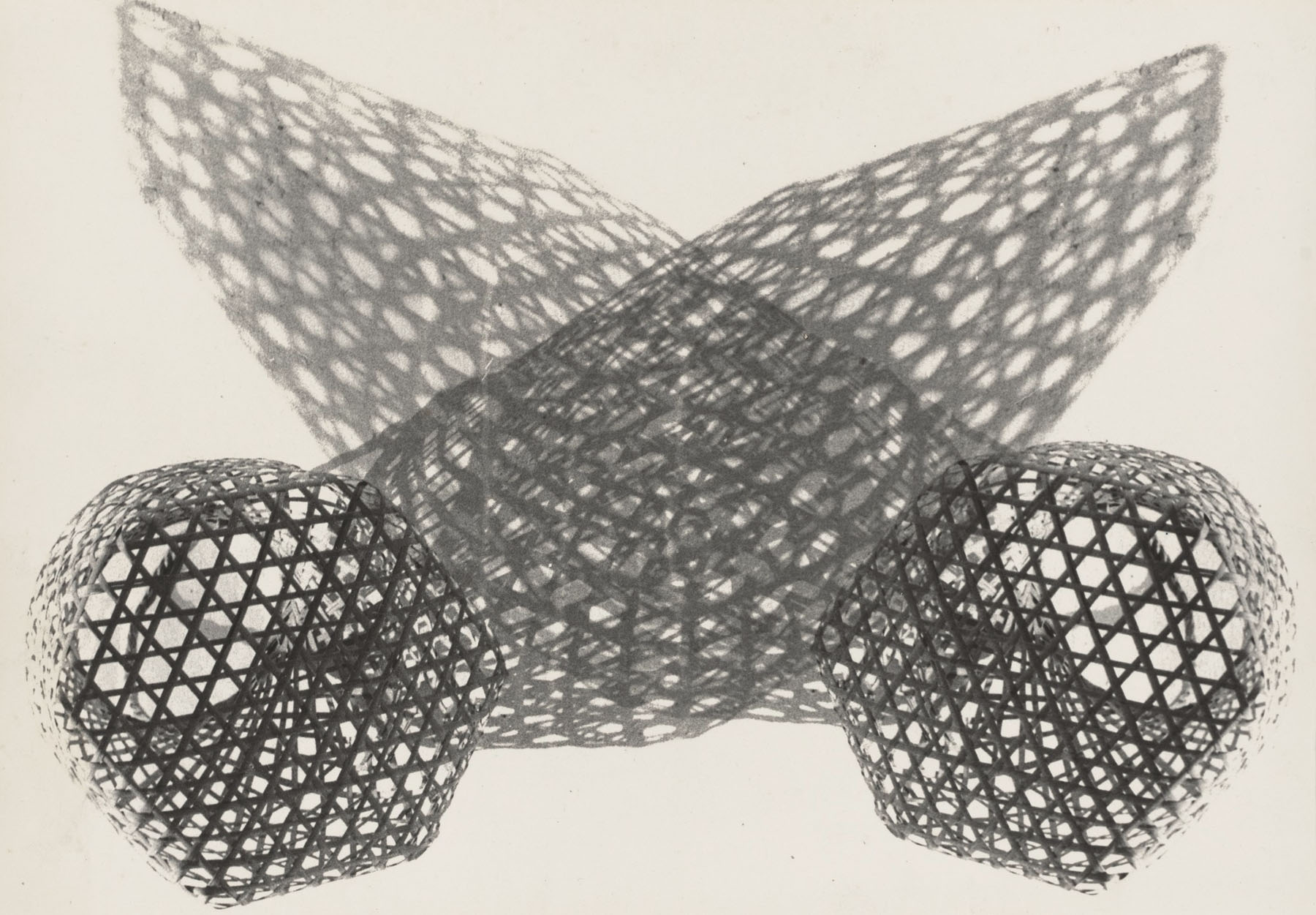

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Awareness of Nature (Presa di coscienza sulla natura)

1976

Gelatin silver print

29.7 × 39.5cm (11 11/16 x 15 9/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Awareness of Nature, No. 3 (Presa di coscienza sulla natura, No. 3)

1970-1974, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.2cm (11 7/8 x 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Awareness of Nature, No. 38 (Presa di coscienza sulla natura, No. 38)

1970, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.3cm (11 7/8 x 15 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Awareness of Nature, No. 171 (Presa di coscienza sulla natura, No. 171)

1980, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.3cm (11 7/8 x 15 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Awareness of Nature, No. 471 (Presa di coscienza sulla natura, No. 471)

1980, printed 1981

Gelatin silver print

40.2 x 30.1cm (15 13/16 x 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Awareness of Nature (1976-1980)

The photographs in this series are among Giacomelli’s most iconic, notable for their gritty, graphic abstraction, which he achieved with an aerial perspective and by using expired film to exaggerate the contrast between black and white. Finding a poetic reciprocity in portraying land that was undergoing “sad devastation” with film that was “dead,” Giacomelli perceived these images as a means of resuscitating his beloved Marche countryside and endowing it with a different kind of beauty. The ploughed fields pulsate with a rhythmic intensity that is absent from previous pictures, in part because he asked that some of these furrows be cut into the land (by the farming family he featured in The Good Earth). A stamp on the verso of each print describes the series further as “the work of man and my intervention (the signs, the material, the randomness, etc.) recorded as a document before being lost in the relative folds of time.” The images resonate conceptually with the Land Art, or Earth Art, movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, in which artists used the landscape to create site-specific sculptures and art forms. As was his custom, Giacomelli incorporated photographs from earlier series, which may have been made from a neighbouring hilltop or did not include his interventions.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

My Marche (Le mie Marche)

1975-1980

Gelatin silver print

25.1 × 37.7cm (9 7/8 x 14 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

My Marche (Le mie Marche)

1970s-1980s

Gelatin silver print

19.7 × 28.1cm (7 3/4 x 11 1/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

My Marche (Le mie Marche)

1970s-1990s

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.3cm (11 7/8 x 15 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

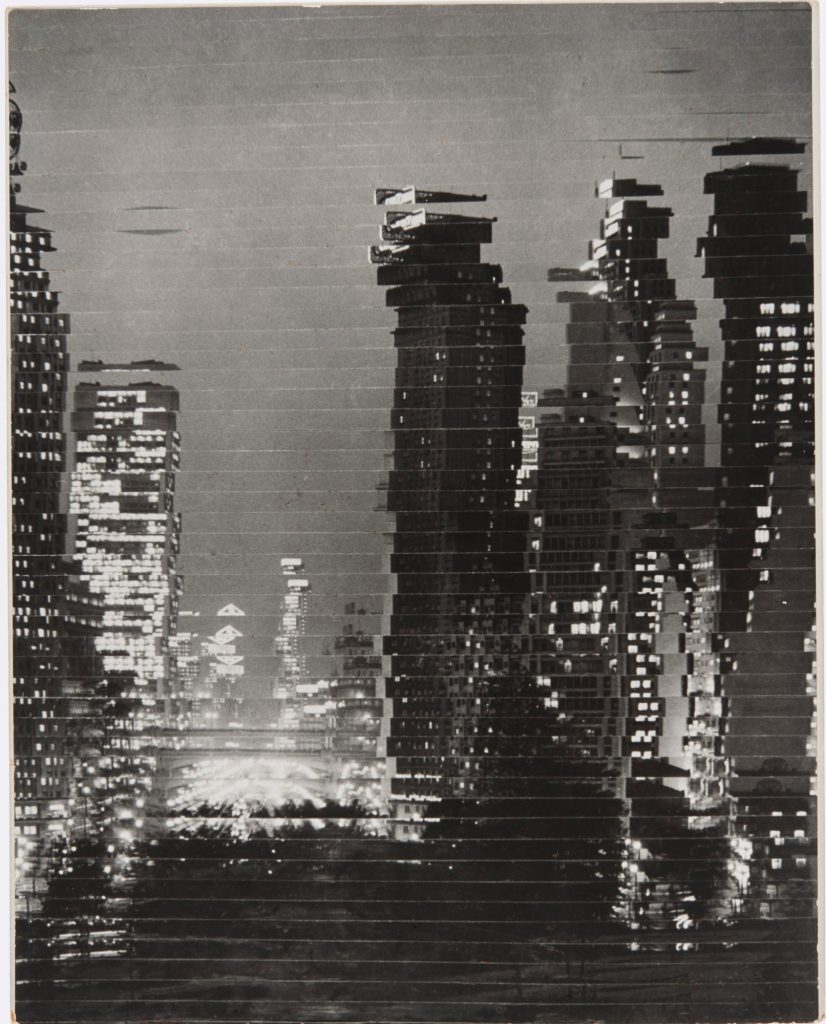

Late work (1980s)

Giacomelli conceived many of his series as sequences that tell the stories of individuals in a particular time and place. He interspersed portraits with landscapes, but he also merged these genres in double exposures or by experimenting with slow shutter speeds and moving his camera during exposure to blur the lines between figure and ground. And once again, he often repurposed an image made for one series in another series, reinforcing the sense of fluidity that connects all of his work. Several of these sequences were inspired by poems, not in an attempt to illustrate them, but to create parallel narratives.

Although the photographs in this section derive from several different series, they share a sense of setting the location or mood. Most easily categorised as landscapes, they mark a noticeable shift from Giacomelli’s earlier position of critiquing the slow degradation of the land to one that sets the stage for a more metaphysical contemplation of the interconnectivity of space, time, and being. The majority were made in the 1980s, when Giacomelli was reflecting on the loss of his mother (who died in 1986), his growing international reputation as a photographer, and his own mortality.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Sea of My Stories (Il mare dei miei racconti)

1984, printed 1990

Gelatin silver print

30.3 × 40.3cm (11 15/16 x 15 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Sea of My Stories (Il mare dei miei racconti)

1983-1987

Gelatin silver print

27.6 × 34.9cm (10 7/8 x 13 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

The Sea of My Stories (1983-1987)

Giacomelli noted that the sea referred to in the title of this series was that of his childhood, the Adriatic, but in fact it was the sea of his entire lifetime. He made his first photographs along Senigallia’s shore after purchasing a camera in 1953. Some thirty years later, curiosity about how an aerial perspective might transform people’s appearance led him to hire a friend who owned an airplane to fly him above the region’s beaches. The resulting compositions create abstract patterns from the shapes and shadows of bathers, deck chairs, umbrellas, and boats against the sand.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

I Would Like to Tell This Memory (Questo ricordo lo vorrei raccontare)

2000

Gelatin silver print

22.1 × 29.5cm (8 11/16 x 11 5/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

I Would Like to Tell This Memory (Questo ricordo lo vorrei raccontare)

2000

Gelatin silver print

22.4 × 30.2cm (8 13/16 x 11 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

I Would Like To Tell This Memory (2000)

The poetic title of this series reflects the increasingly pensive mood of Giacomelli’s late work. We occasionally glimpse the photographer himself as he engages with an odd assortment of props, including stuffed dogs and birds, a mannequin and mask. His abrupt cropping, slight overexposure to reverse tonal values, and painting or scratching of areas on the negative introduce elements of the absurd or surreal as means to confront the inevitability of his own mortality. The series, one of his last, is a meditation on melancholy, loss, and the passage of time.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Theater of Snow (Il teatro della neve)

1981-1984

Gelatin silver print

24.2 × 31.2cm (9 1/2 x 12 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Theater of Snow (Il teatro della neve)

1981-1984

Gelatin silver print

28.9 × 38.4cm (11 3/8 x 15 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Reflecting on Giacomelli

Giacomelli died in November 2000 after a long illness. He had continued working on several photographic series until his final days, with the poignantly titled I Would Like to Tell This Memory attesting to his deeply introspective temperament. From his unpromising beginnings as an impoverished, poorly educated boy, Giacomelli redirected the course of his life, maintaining a successful printing business that provided financial security and dedicating himself to the arts as a means of self-expression. Though he was self-taught in poetry, painting, and photography, it was with this last medium that he created a sense of continuity and fluidity throughout his life. He gained international acclaim as one of Italy’s most prominent photographers despite having made the majority of his photographs in his hometown of Senigallia and the neighbouring Marche region.

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Stories of the Land (Storie di terra)

Negative 1955; print 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.2cm (11 7/8 × 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Stories of the Land (Storie di terra)

Negative 1956; print 1981

Gelatin silver print

30.1 × 40.2cm (11 7/8 × 15 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

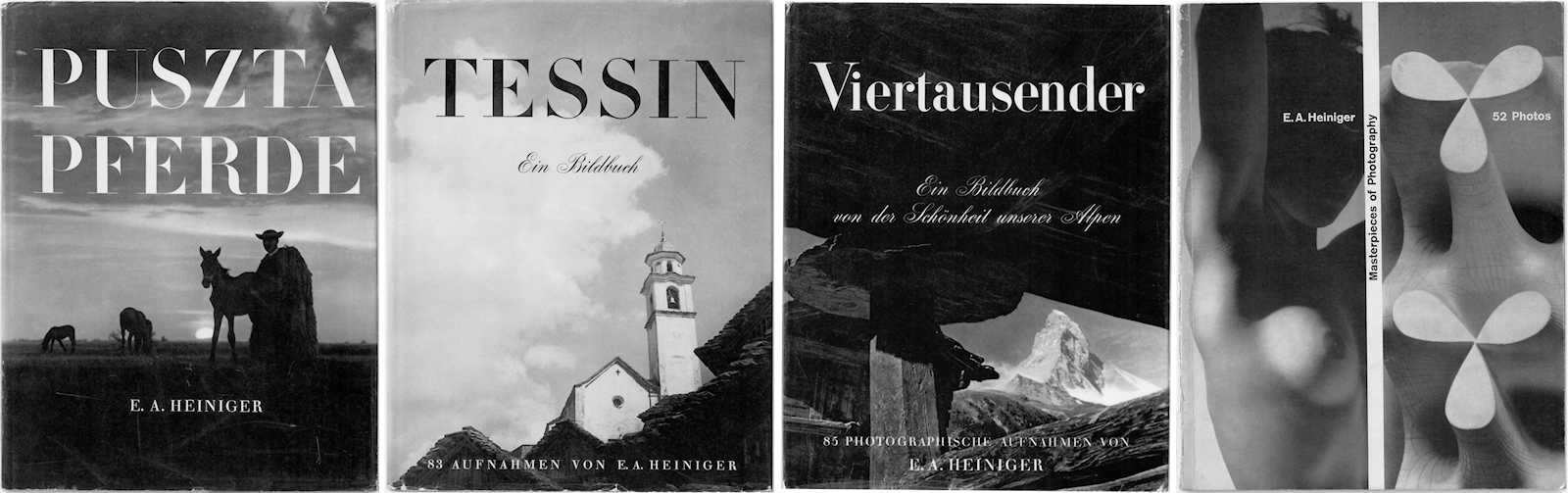

Collecting Giacomelli

Between 2016 and 2020, Los Angeles-based collectors Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser donated 109 photographs by Mario Giacomelli to the J. Paul Getty Museum. Their collection covers broad swaths of Giacomelli’s oeuvre, from some of his earliest images to those made in the final years of his life. Drawn from their donations, this exhibition is conceived not as a comprehensive retrospective but as an opportunity to consider the collectors’ vision in assembling these holdings over a period of twenty years, teasing out what they perceived to be key concerns of Giacomelli’s practice: people (la gente) and the landscape (paesaggio), as well as people in the landscape – the “figure/ground” relationship of the exhibition’s subtitle.

The Getty Museum also acknowledges the Mario Giacomelli Archive, based in Senigallia, Sassoferrato, and Latina, Italy, for assistance in confirming titles and dates. Throughout his career, Giacomelli returned to individual images, rethinking and reworking them for subsequent series, often complicating the task of assigning definitive titles or dates. Thanks as well to Stephan Brigidi of the Bristol Workshops in Photography for providing information about the artist’s 1981 portfolios, La gente and Paesaggio. The portfolio prints are interspersed throughout the four galleries of the exhibition, presented in shallower frames with a slightly wider face.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

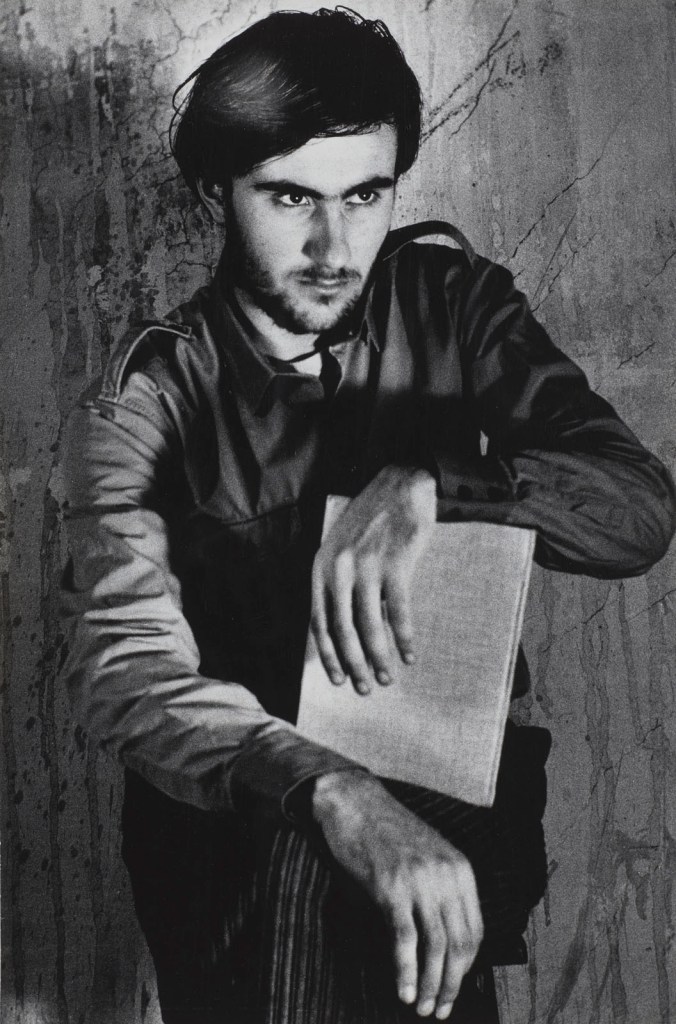

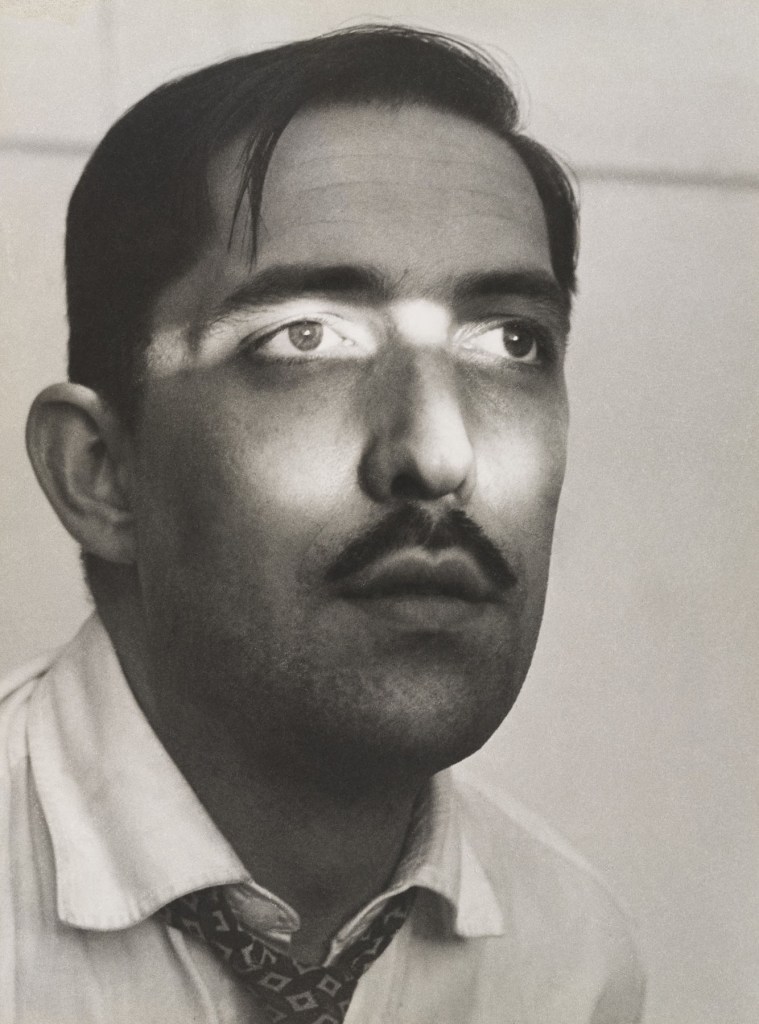

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

The Painter Mauro Marinelli

Negative 1960; print probably 1966

Gelatin silver print

36.2 × 24cm (14 1/4 × 9 7/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (1925-2000) had a poet’s eye for the startlingly abstract order man can impose on nature and a poet’s understanding of the great disorder that is the human condition.

Giacomelli became an apprentice in typography when he was 13. As a young man, he worked as a typographer, painting on weekends and writing poetry. Inspired by the wartime movies of filmmakers like Fellini, Giacomelli taught himself still photography. He found his art in the generally impoverished countryside around Senigallia, a small town on the shores of the Adriatic Sea, where he lived all his life and whose farmlands and people were the subjects of his spare, often darkly expressionist work.

In 1954, Giacomelli began to photograph the home for the elderly where his mother had worked, completing the series in 1983. Empathetic but grittily unsentimental, the pictures show many women seemingly marooned in the sea of old age. In 1985-87, Mr. Giacomelli revisited the subject for his series Ninna Nanna, which means lullaby. This time, the deeply lined, gaunt faces of the aged are a bleak counterpoint to the bold lines and patterns found in the fields and on the sides of houses.

Giacomelli’s overhead views of mystifyingly abstract, horizonless landscapes, which he took from the time he snapped his first pictures, in late 1952, through the 1990’s, place him in the company of photographers like William Garnett and Minor White. Giacomelli’s 1970s images of geometric patterns in the fields of his hometown, Senigallia, bear striking parallels to Aaron Siskind’s contemporaneous photographs of wall abstractions.

Adapted from the artist’s New York Times obituary

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Children at the sea (Bambini al mare)

1959

Ferrotyped gelatin silver print

24.2 x 39.4cm (9 1/2 x 15 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Landscape: Tobacco

1955-1956, printed 1980

35.9 x 26.7cm (14 1/8 x 10 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

Reproduced courtesy Mario Giacomelli Archive

© Rita and Simone Giacomelli

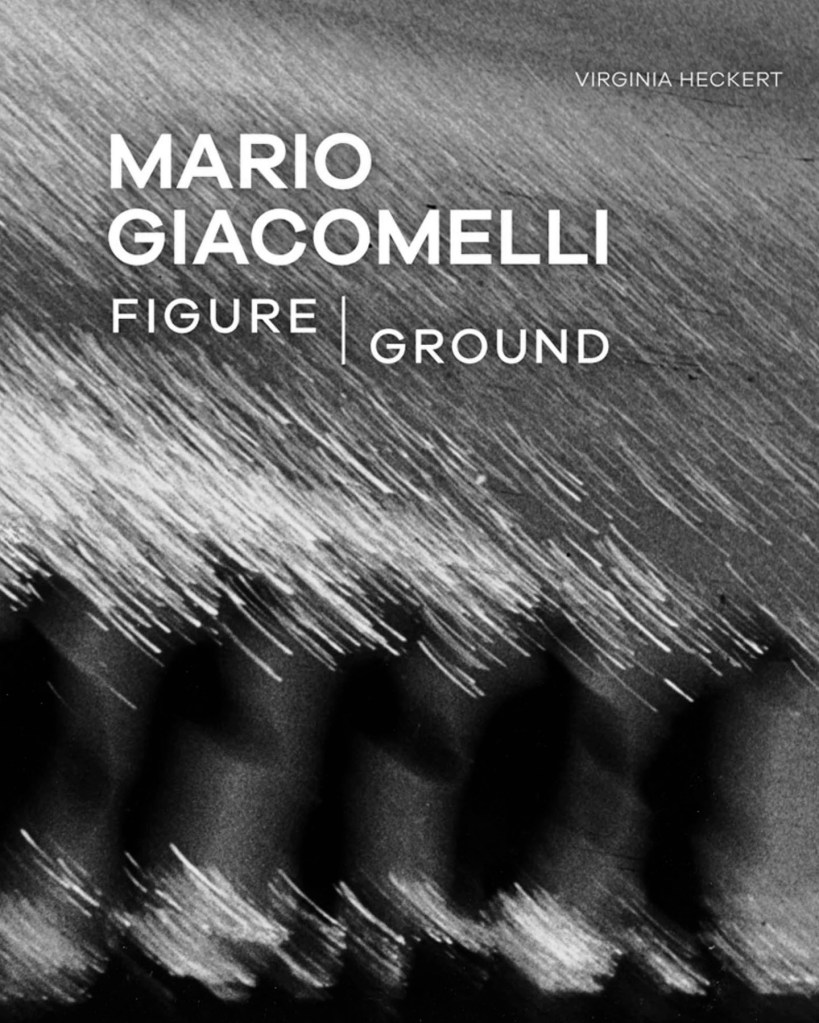

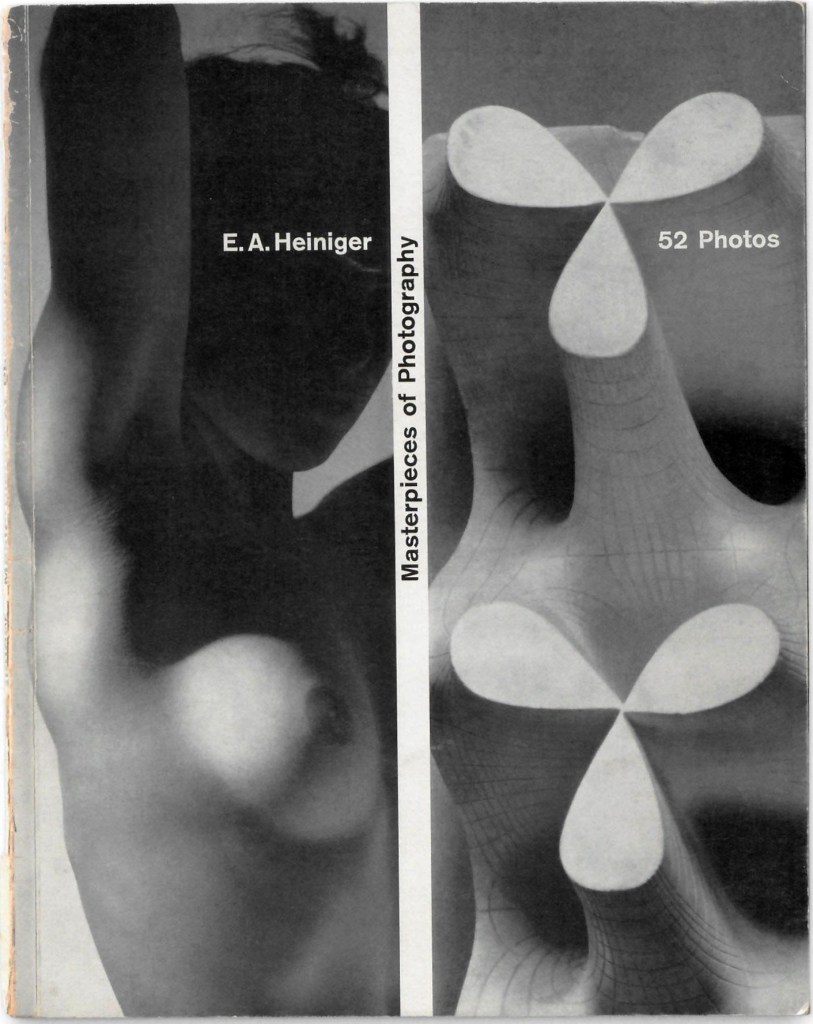

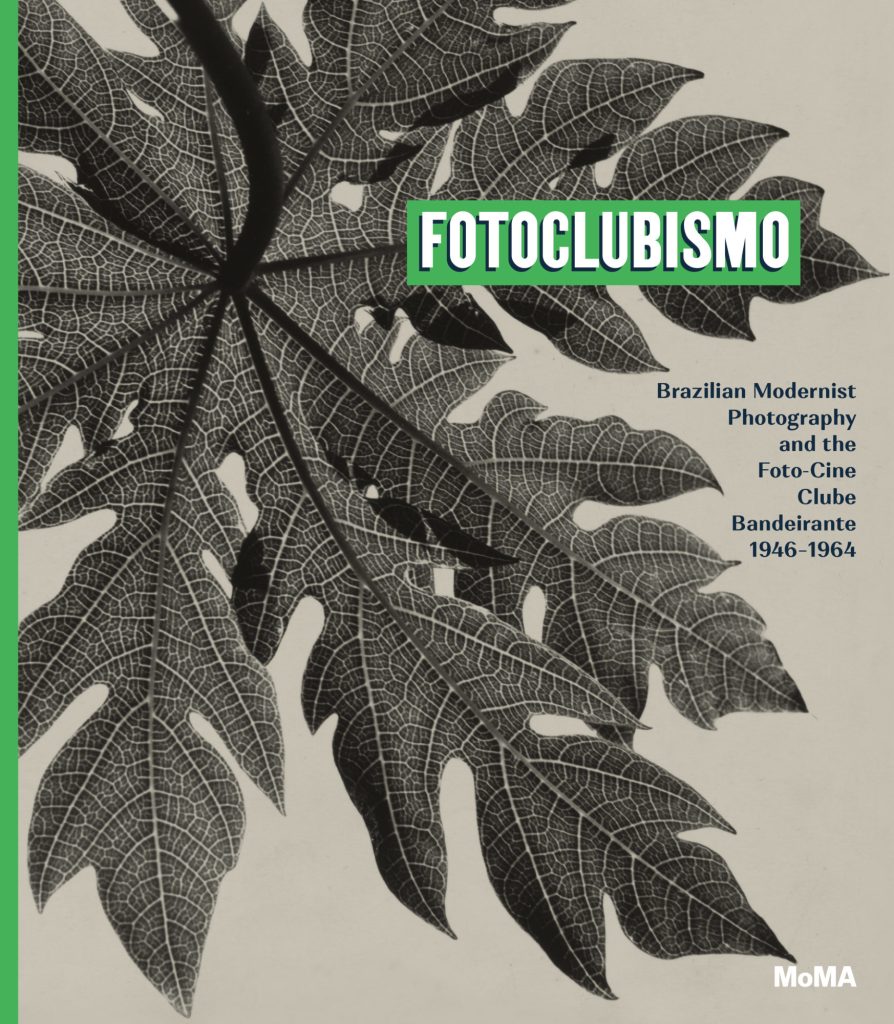

Mario Giacomelli: Figure | Ground book cover

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

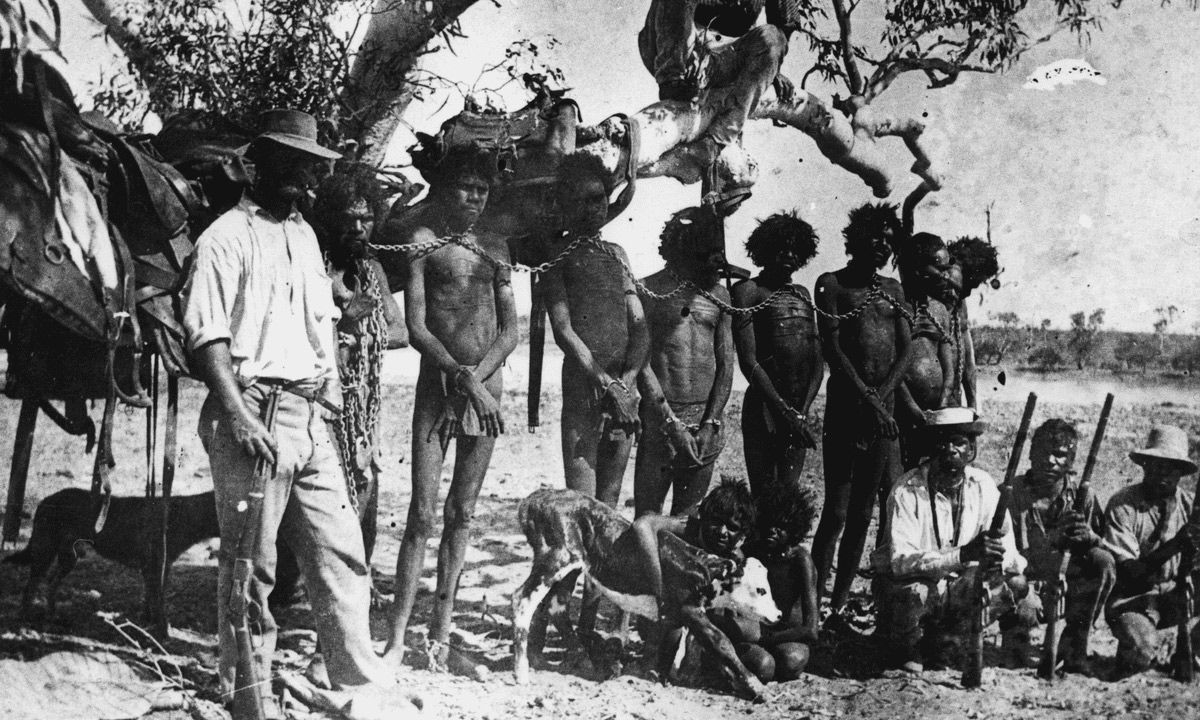

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Australian Aborigines in chains]' Nd Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Australian Aborigines in chains]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/australian-aborigines-c-web.jpg)

![Aboriginal Protection Board (1952-1969) (publisher) Department of Child Welfare and Social Welfare (1970-1975) "Untitled [Deb Ball]" Dawn magazine, October 1965 back cover Aboriginal Protection Board (1952-1969) (publisher) Department of Child Welfare and Social Welfare (1970-1975) "Untitled [Deb Ball]" Dawn magazine, October 1965 back cover](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/dawn-october-1965-back-cover.jpg?w=781)

![Marion Post Wolcott (American, 1910-1990) '[Haircutting in Front of General Store and Post Office on Marcella Plantation, Mileston, Mississippi]' 1939 from the exhibition 'The New Woman Behind the Camera' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, July - Oct, 2021 Marion Post Wolcott (American, 1910-1990) '[Haircutting in Front of General Store and Post Office on Marcella Plantation, Mileston, Mississippi]' 1939 from the exhibition 'The New Woman Behind the Camera' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, July - Oct, 2021](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/wolcott-haircutting.jpg)

![Lucy Ashjian (American, 1907-1993) '[Savoy Dancers]' 1935-1943 Lucy Ashjian (American, 1907-1993) '[Savoy Dancers]' 1935-1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/lucy-ashjian-savoy-dancers.jpg?w=845)

![Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997) '[Boy with a Cat]' 1934 Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997) '[Boy with a Cat]' 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/dora-maar-boy-with-a-cat.jpg?w=770)

![Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942) 'La técnica [or, Mella's Typewriter]' 1928 Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942) 'La técnica [or, Mella's Typewriter]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/tina-modotti-la-technica.jpg?w=821)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Daily Life, German Lorca and Solitude with bottom right, Ademar Manarini's 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' (c. 1951) Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Daily Life, German Lorca and Solitude with bottom right, Ademar Manarini's 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' (c. 1951)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/fotoclubismo-installation-i.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Daily Life, German Lorca and Solitude with bottom right, Ademar Manarini's 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' (c. 1951) Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Daily Life, German Lorca and Solitude with bottom right, Ademar Manarini's 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' (c. 1951)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/fotoclubismo-installation-k.jpg)

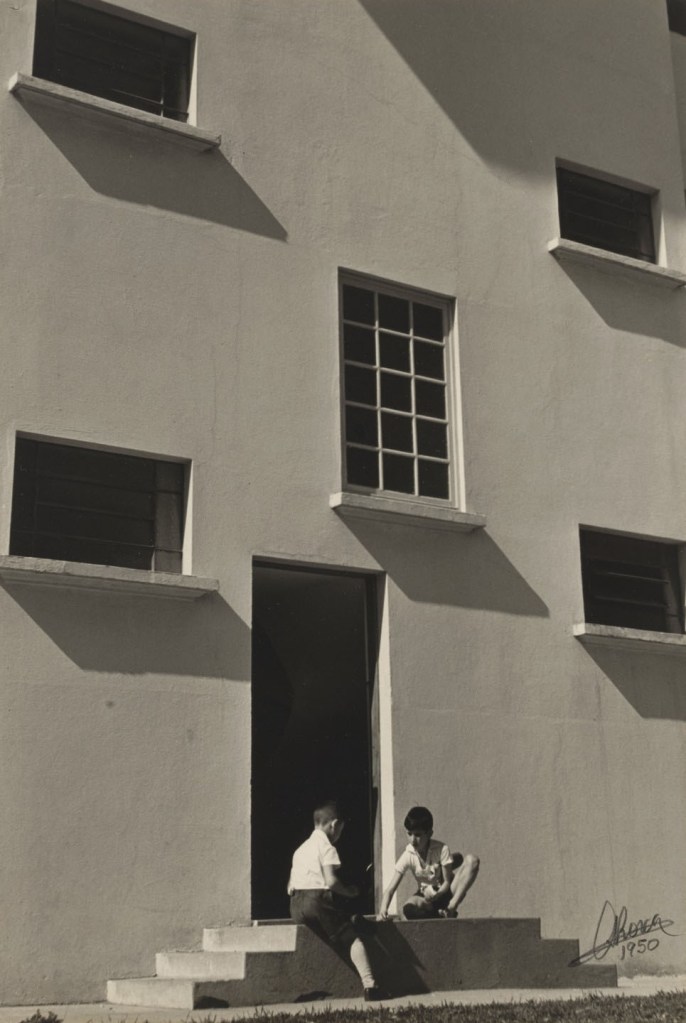

![Ademar Manarini (Brazilian, 1920-1989) 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' c. 1951 Ademar Manarini (Brazilian, 1920-1989) 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' c. 1951](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/manarini-housing-complex.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Simplicity and Gertrude Altschul, with at top left, Thomaz Farkas' 'Ministry of Education' (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro] (c. 1945); and at right, Gertrudes Altschul's 'Lines and Tones' (Linhas e Tons) (c. 1953) Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Simplicity and Gertrude Altschul, with at top left, Thomaz Farkas' 'Ministry of Education' (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro] (c. 1945); and at right, Gertrudes Altschul's 'Lines and Tones' (Linhas e Tons) (c. 1953)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/fotoclubismo-installation-t.jpg)

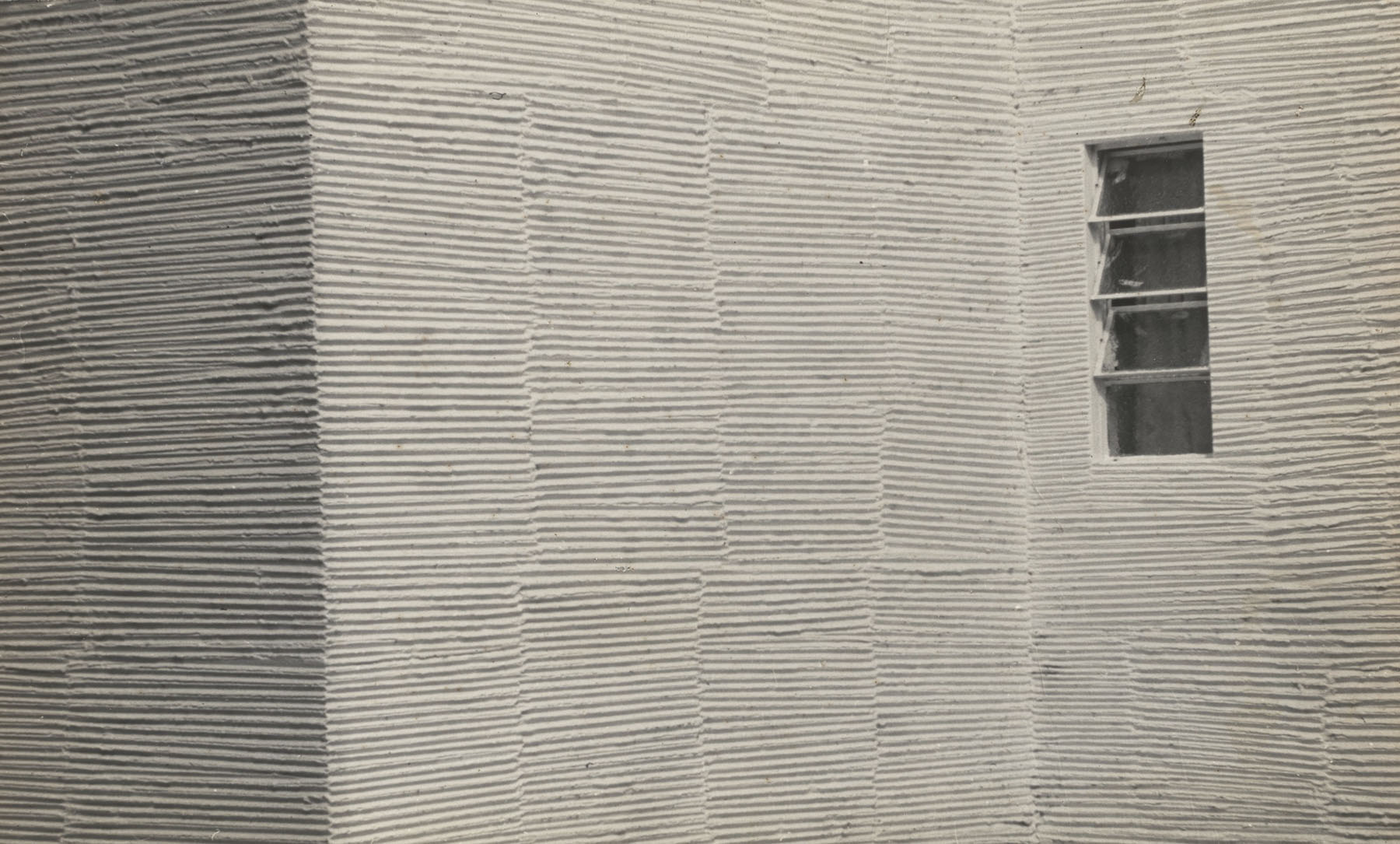

![Thomaz Farkas (Brazilian, born Hungary. 1924-2011) 'Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro]' c. 1945 Thomaz Farkas (Brazilian, born Hungary. 1924-2011) 'Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/farkas.jpg?w=934)

![Underwood & Underwood (American, founded 1881, dissolved 1940s) '[Women's Campaign Train for Hughes]' 1916 from the exhibition 'In Focus: Protest' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, June - Oct, 2021 Underwood & Underwood (American, founded 1881, dissolved 1940s) '[Women's Campaign Train for Hughes]' 1916 from the exhibition 'In Focus: Protest' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, June - Oct, 2021](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/underwood-underwood-womens-campaign-train-for-hughes.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.