Exhibition dates: 12th May – 7th August 2011

Many thankx to Susanne Briggs for her help and for AGNSW for allowing me to publish the text and photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

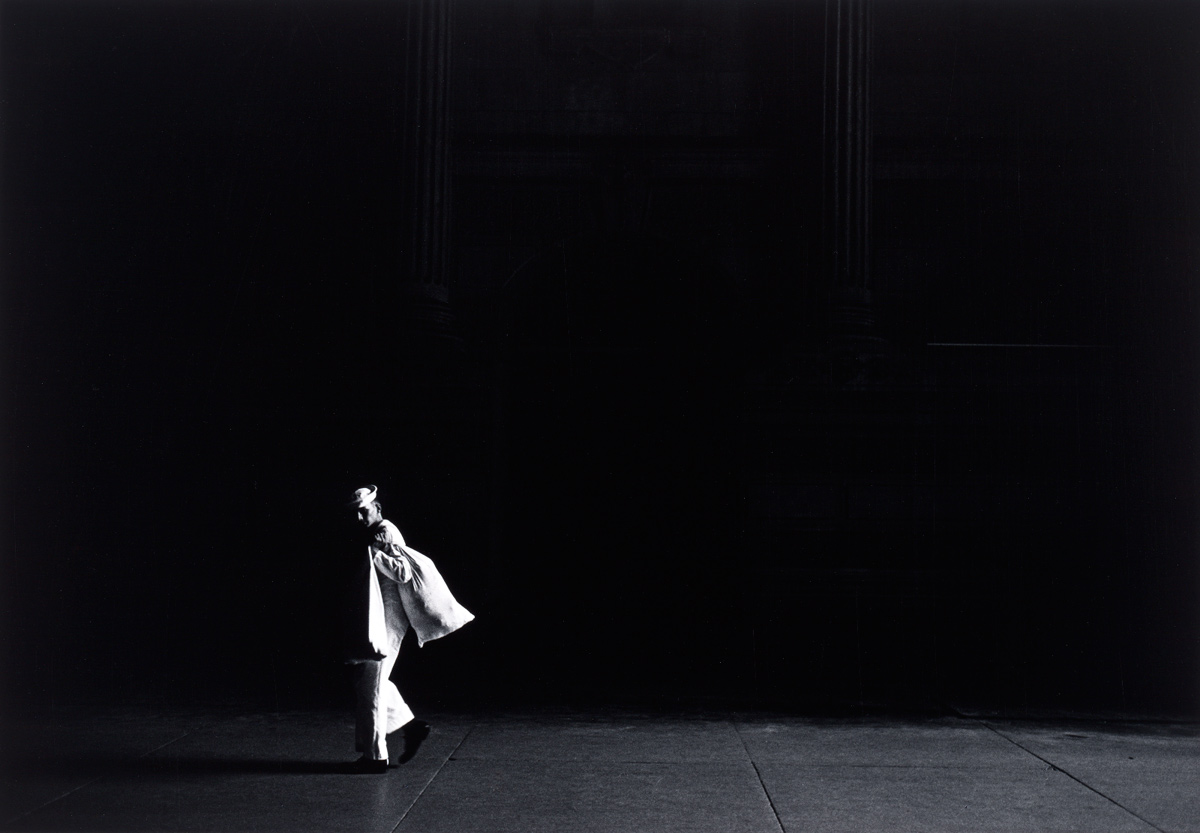

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kazuo Ohno

1980

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

“The camera is generally assumed to be unable to depict that which is not visible to the eye. And yet the photographer who wields it well can depict what lies unseen in his memory.”

Eikoh Hosoe

This exhibition brings together four seminal series by Eikoh Hosoe, a leading figure in modern Japanese photography. Taken over five decades, The butterfly dream 1960-2005, Kamaitachi 1965-1968 and Ukiyo-e projections 2002-2003 are driven by Hosoe’s longstanding fascination for the revolutionary dance movement butoh and for its charismatic founders, Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno. Together these series epitomise his unique style, which combines photography with elements of theatre, dance, film and traditional Japanese art, and uses mythology, metaphor and symbolism. Using the latest digital technology, Hosoe prints his photographs on washi paper, mounting them in the traditional Japanese manner as scrolls and folding screens, thereby suggesting a new way of ‘reading’ his series as a continuous narrative. Hosoe’s interest in examining the beauty and strength of the human body is best seen in his acclaimed series of extremely abstract nudes, Embrace 1969-1970. The models are butoh dancers associated with Hijikata.

For over fifty years, internationally acclaimed Japanese photographer Eikoh Hosoe has been producing cutting edge works demonstrating a unique mastery of the photographic medium. Early on in his career he abandoned the documentary style prevalent in the post-war years and produced photographs that breathed a sense of experimentation and freedom into photography. By calling on mythology, metaphor and symbolism he created images that broke the bounds of traditional photography. Hosoe developed a unique style situated at the crossroads of several different art forms, combining photography with elements of theatre, dance, film and traditional Japanese art.

From the early days of his career Hosoe’s destiny became linked to butoh, the revolutionary performance movement formed in post-war Japan. His close relationship to Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno, the two pivotal figures of butoh dance, forms the basis for his seminal series such as Kamaitachi, Embrace, The butterfly dream and Ukiyo-e projections, included in this exhibition.

This exhibition also highlights Hosoe’s extraordinary creativity and mastery of photographic printing techniques. Having experimented with both film-based and digital techniques to develop new methods of photographic expression, in recent years, he has started to use digital printing technologies on Japanese handmade paper (washi) and mounts his works in the form of traditional Japanese scrolls and screens. These ‘photo-scrolls’ provide a fascinating new reading of Hosoe’s work and underline his commitment to push the boundaries of photographic expression.

Hosoe gained recognition in the late 1950s when he began to develop his close-ups of the human body. Embrace, a series of black-and-white, abstract nude photographs, encapsulates Hosoe’s strive for originality in this photographic genre.

Through the novelist, Yukio Mishima, Hosoe was to meet Tatsumi Hijikata, one of the founders of Butoh dance. After seeing Hijikata’s performance, adapted from the novel Kinjiki (Forbidden Colours) by Mishima in a small Tokyo theatre, Hosoe was inspired and began photographing the Butoh dancer, a collaboration which continued for many years and culminated in the series Kamaitachi (1965-1968). This series, shot on various locations in the rural Tohoku region, integrated elements of dance, theatre and documentary into a cinematic work that aimed to recreate and dramatise Hosoe’s childhood memories.

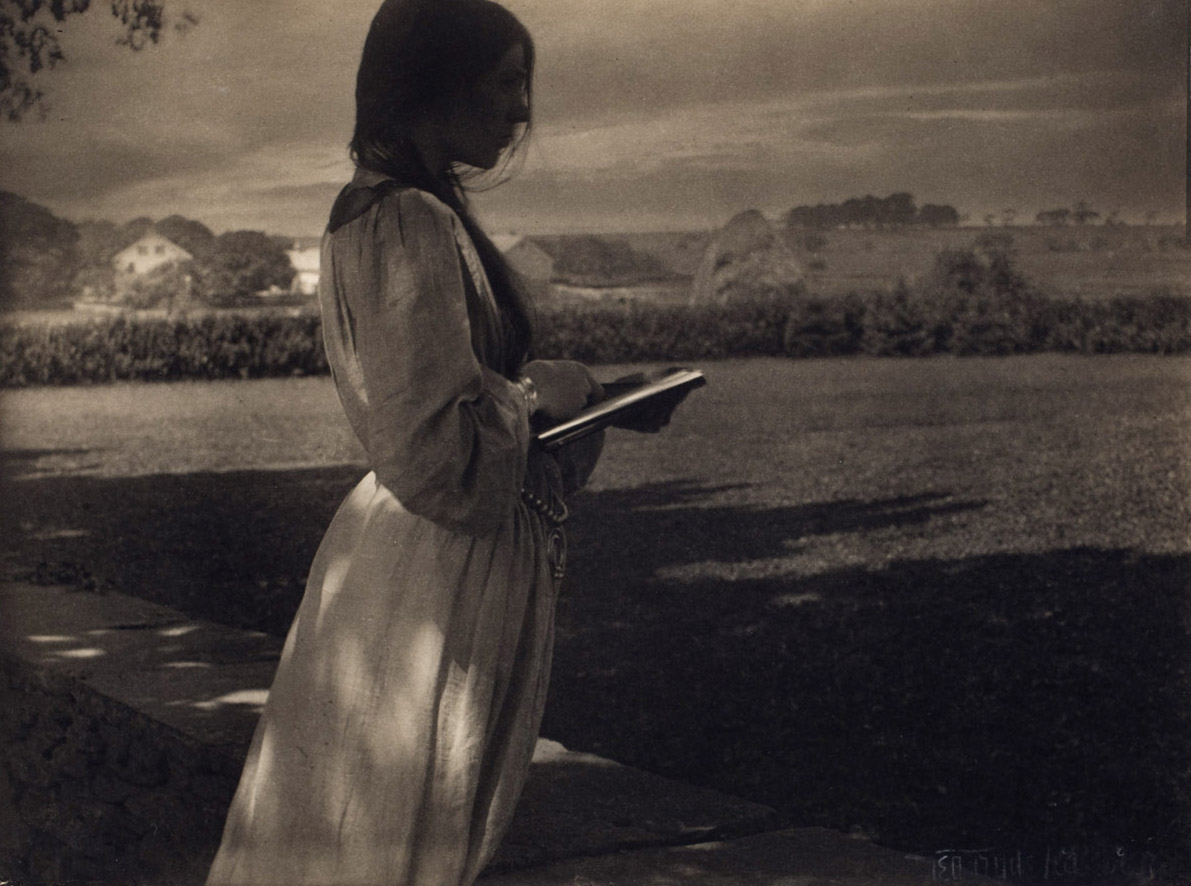

Hosoe’s association with Butoh also led him to photograph the renowned Butoh performer, Kazuo Ohno. Released in 2006 in celebration of Ohno’s 100th birthday, the series The butterfly dream is a poignant visual documentary of Ohno’s artistic development over 46 years. While they retain the drama intrinsic to Butoh, Hosoe’s photographs of Ohno focus in on details of Ohno’s body, the curve of a wrist or a facial expression caught between agony and ecstasy.

Hosoe’s latest colour work, Ukiyo-e Projections, revisits his early work by linking it into ukiyo-e and Butoh dance. This series was born when he found out that the experimental Asbestos Dance Studio, founded by Hijikata and his wife, was to close in 2003 after forty years of activity. Upon hearing about the closure, Hosoe felt the need to pay a photographic tribute “to express gratitude for all that it had produced.” Ukiyo-e Projections was completed on stage at the Studio during a series of sessions in 2002 and 2003. For this series Hosoe created what he calls a “photographic theatre,” projecting a mixture of his own photographs with ukiyo-e prints on to the white-painted bodies of young Butoh dancers. The series explores many of the themes that recur in his work: sexuality, the human form and movement.

Eikoh Hosoe: Theatre of Memory highlights Hosoe’s mastery of photography through his four seminal series, Embrace, Kamaitachi, The Butterfly Dream and Ukiyo-e Projections, showing Hosoe’s sensibility for theatre, performance and the human body. It further demonstrates his creativity and mastery of photographic printing techniques. Throughout his career Hosoe, a master printer, has experimented with both film-based and digital techniques to develop new methods of photographic expression. In recent years, he has combined new printing technologies with Japanese washi paper to present his work on traditionally made silk screens and scrolls.

This is the first solo exhibition of Hosoe’s works in Australia. Hosoe, 77, is currently completing a new series of works on the sculpture of Auguste Rodin. The exhibition Eikoh Hosoe – Theatre of memory is realised in collaboration with Studio Equis, France.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website

Photographer Eikoh Hosoe on his work and inspirations

Eikoh Hosoe – a leading figure in modern Japanese photography – came to the Art Gallery of New South Wales to launch the exhibition ‘Eikoh Hosoe: theatre of memory’. In this video he discusses his work and inspirations.

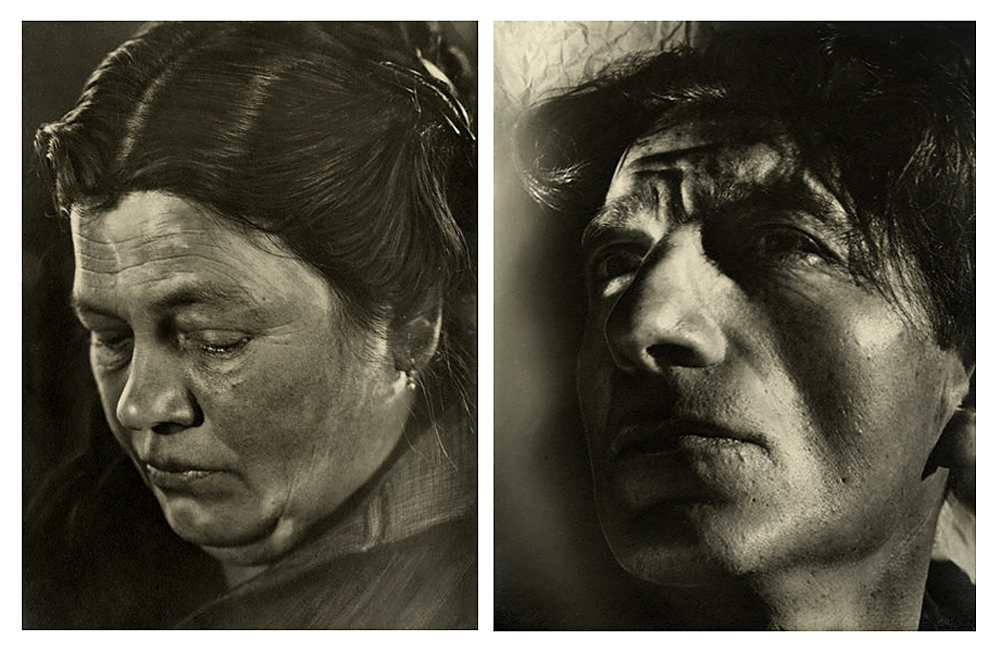

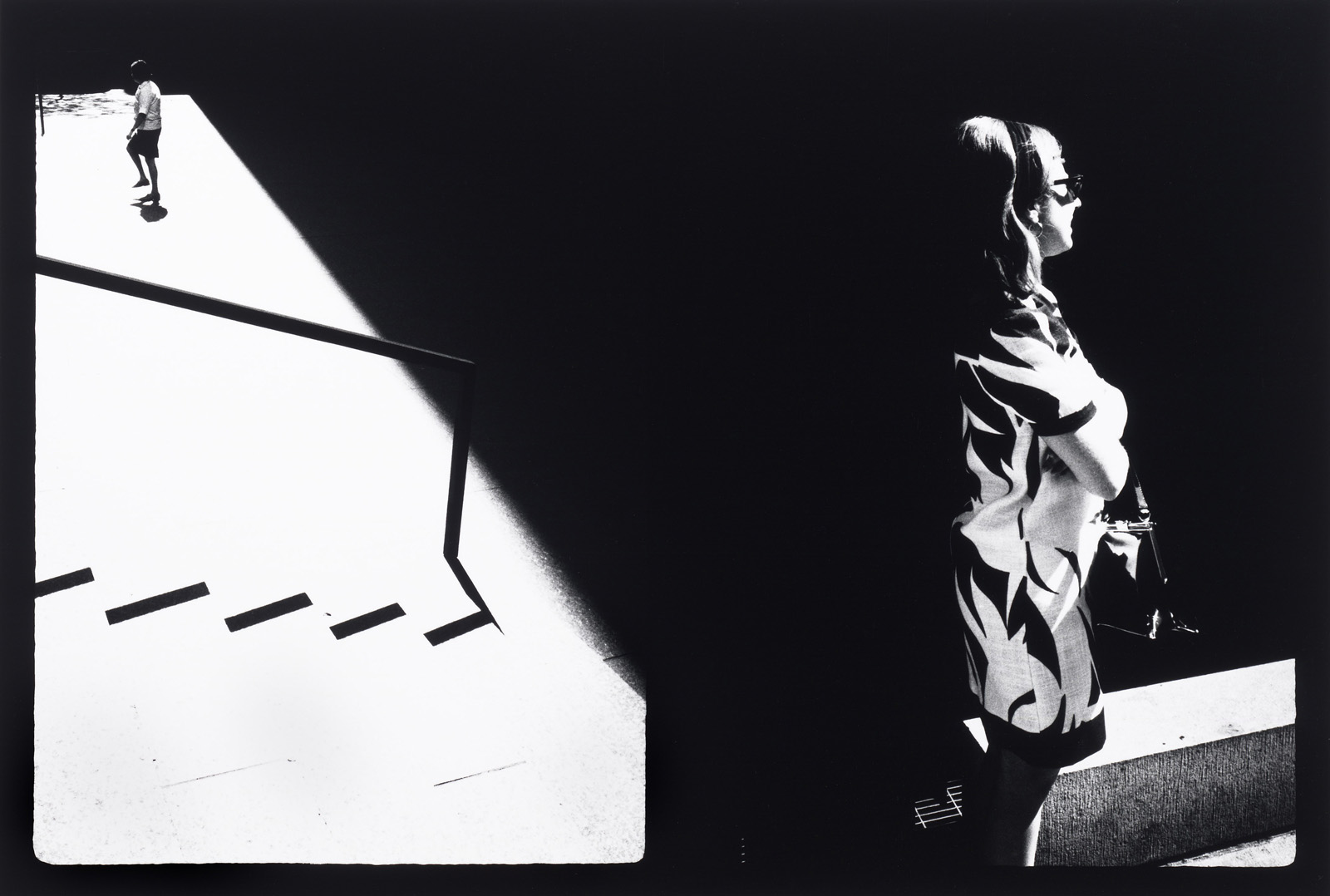

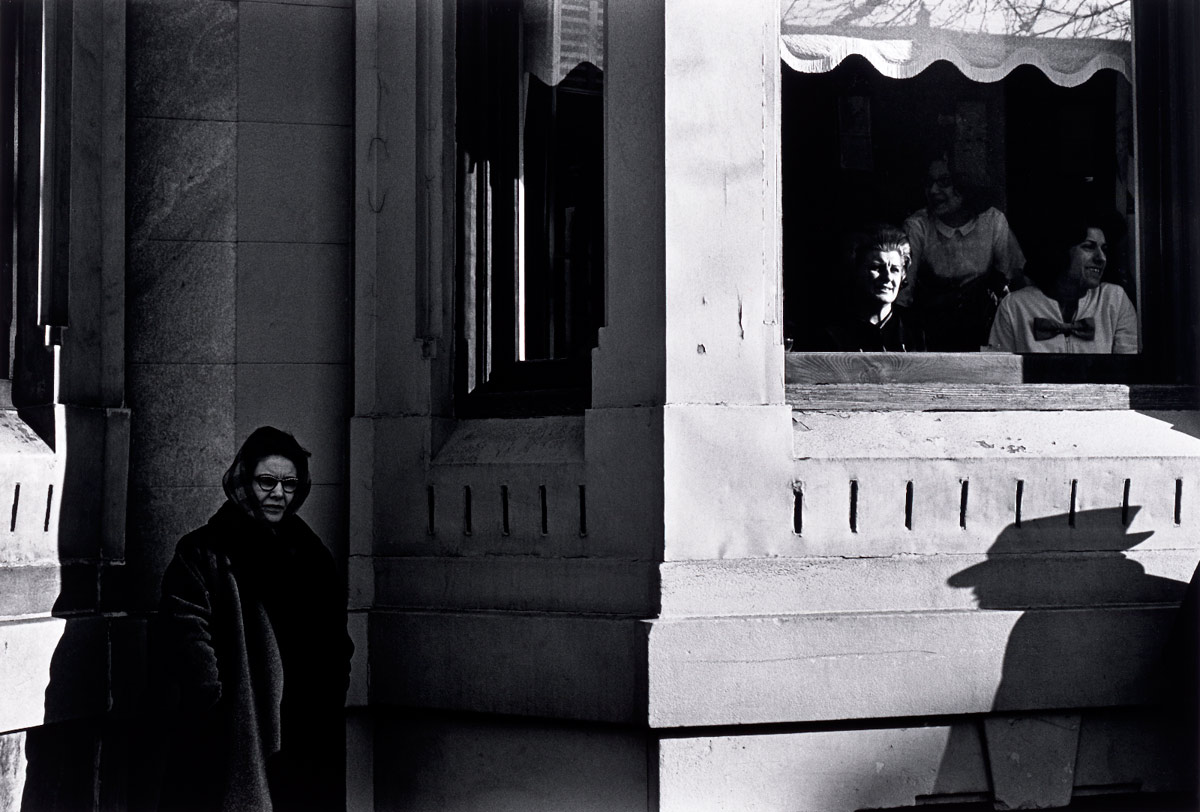

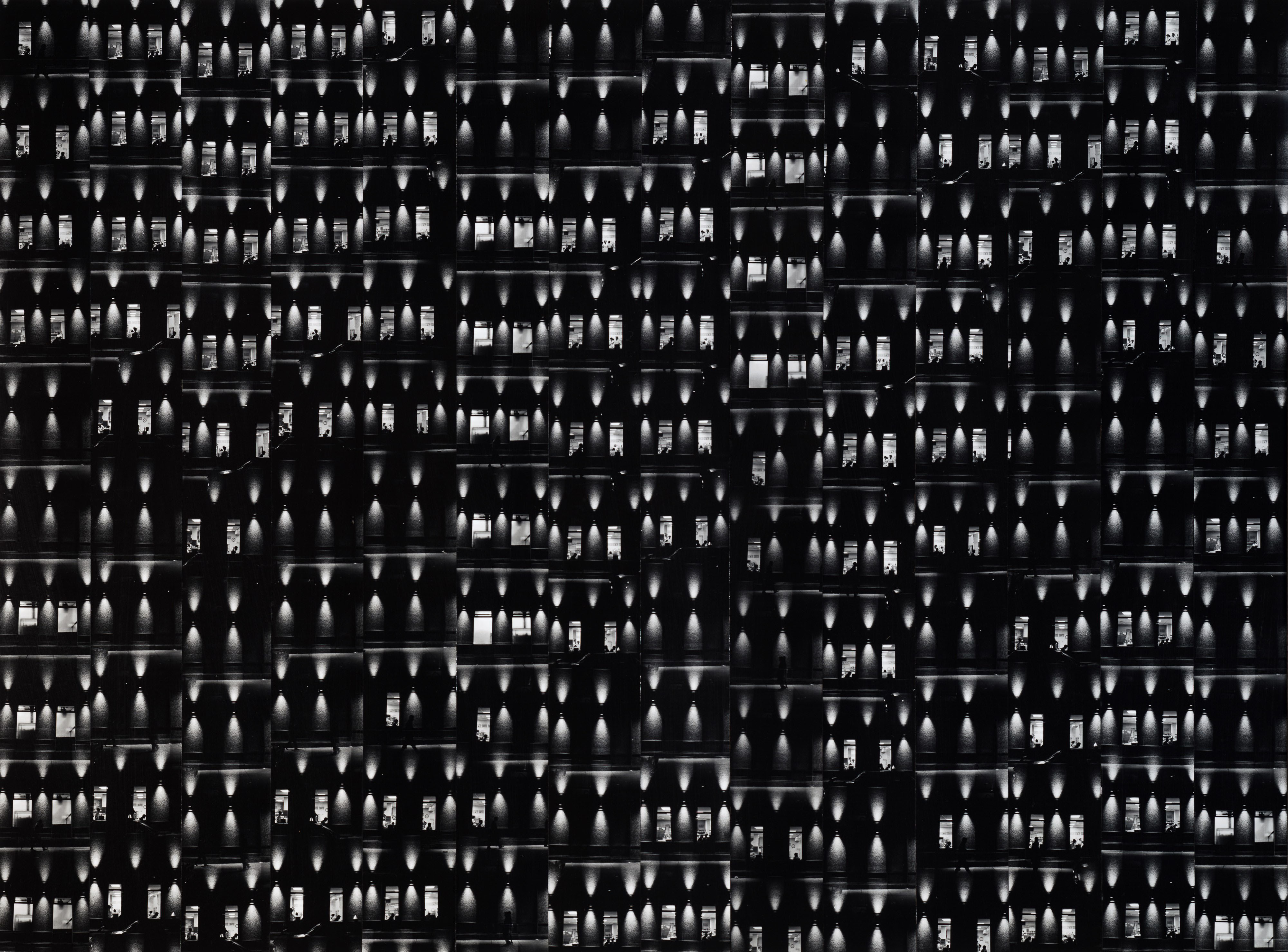

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kazuo Ohno

1994

From the series The butterfly dream 1960-2005

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

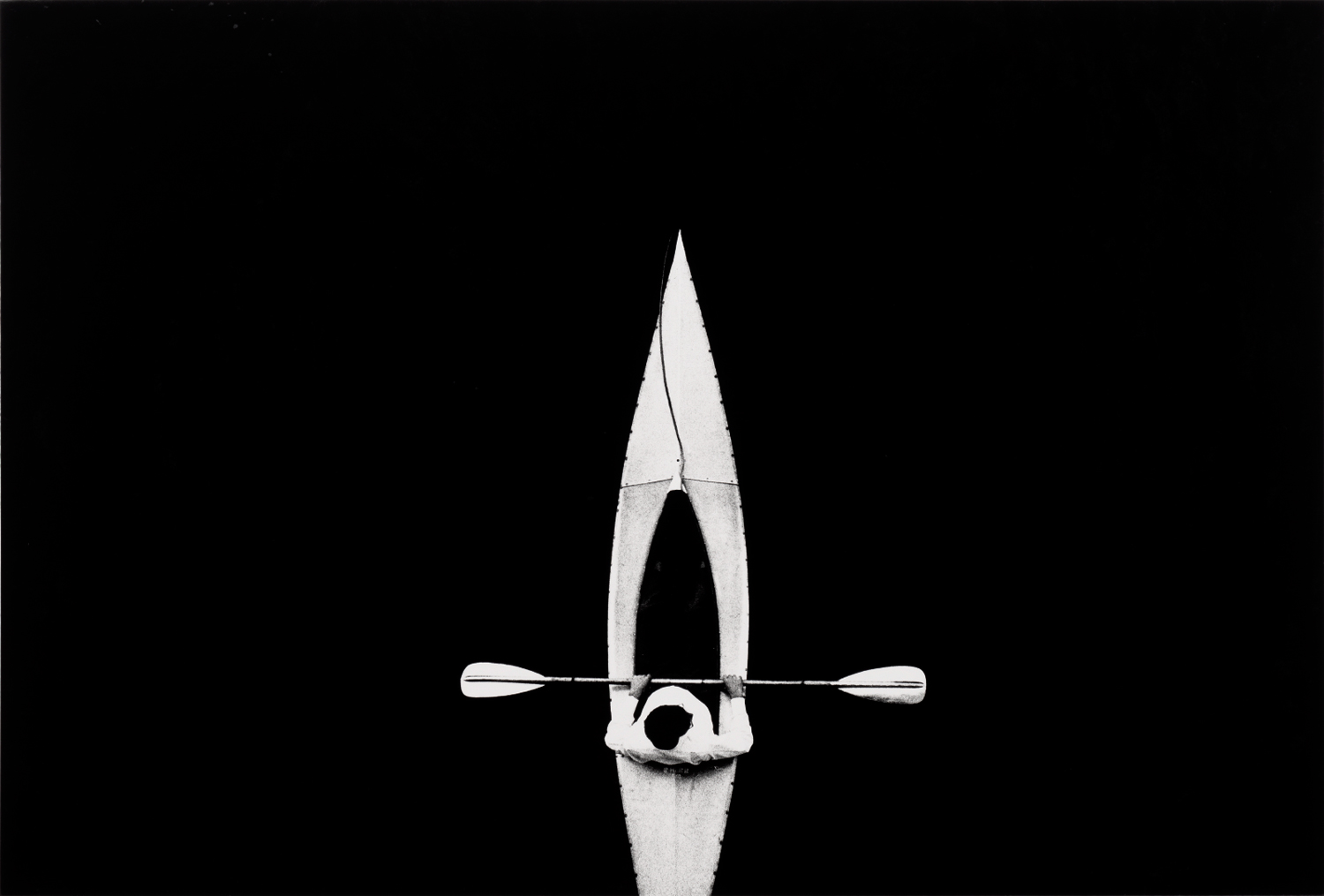

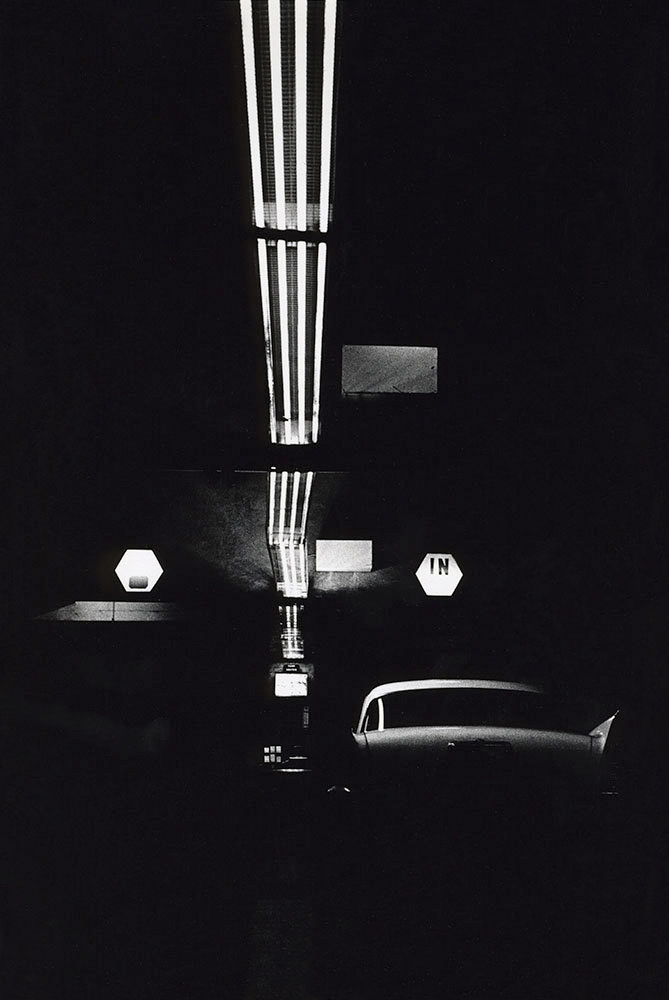

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kazuo Ohno

1996

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

The Butterfly Dream

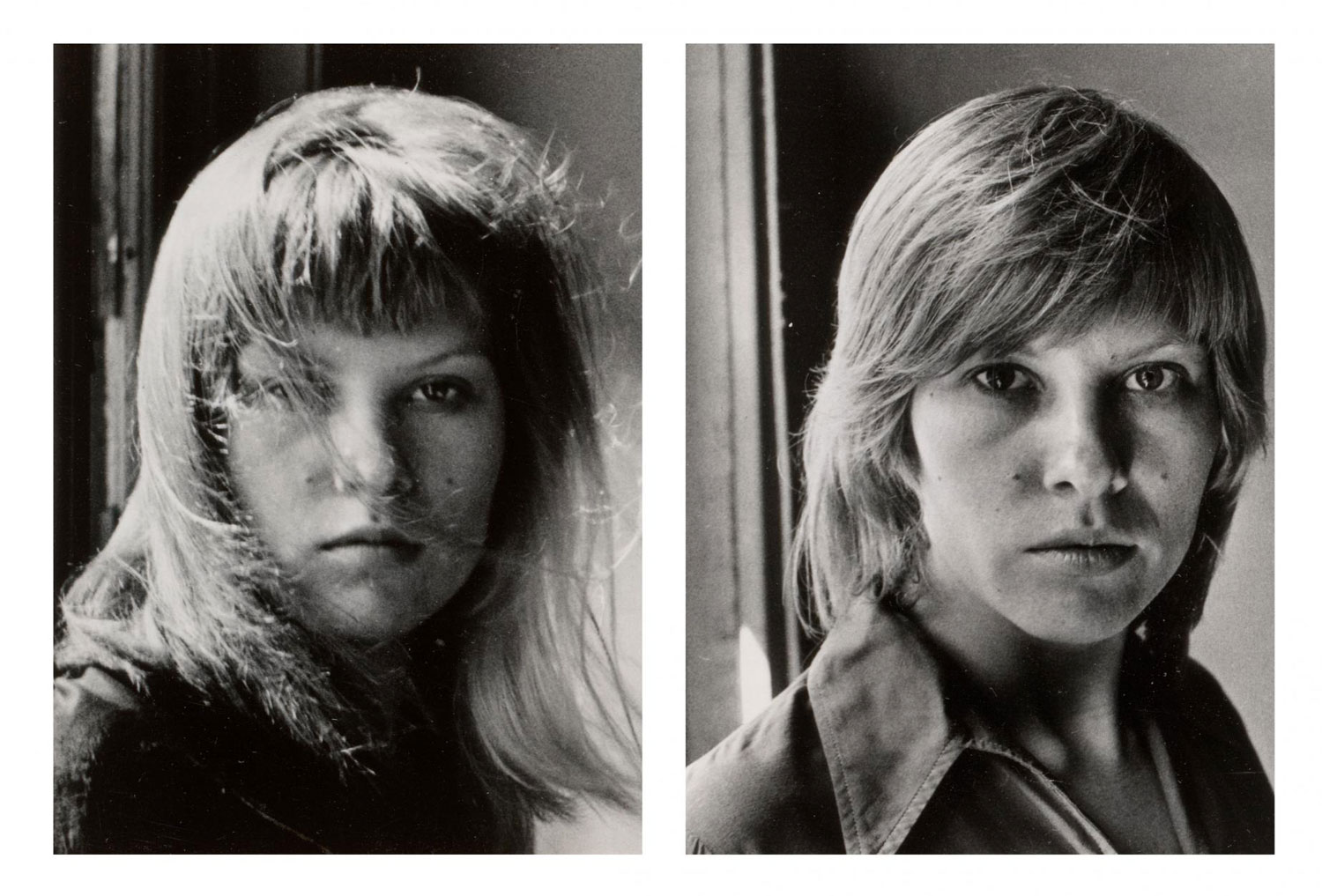

The butterfly dream – a collection of photographs taken over a period of 46 years – represents Hosoe’s homage to the charismatic butoh dancer Kazuo Ohno. It was published as a book, which was released on 27 October 2006 in celebration of Ohno’s 100th birthday.

Originally an instructor in physical education and performer of modern dance, Ohno befriended Tatsumi Hijikata in the 1950s and became a pivotal fi gure in the development of the butoh performance movement. Ohno’s poetic dance style stems from his belief in the transcendental nature of human experience, that the human body has a memory of sensations and knows no limits of self-expression.

Following closely his friend’s extremely long and successful career – Ohno continued to perform late into his 90s – Hosoe has captured some of the most poignant and magical moments in the history of butoh. In honour of Ohno’s long-held conviction in the importance of achieving freedom of body and mind, Hosoe named his photographic exploration of Ohno’s unique art after the famous Daoist allegory in which the philosopher Zhuangzi dreamt he was a butterfly, but once awake, wondered if he was a man dreaming to be a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming to be Zhuangzi.

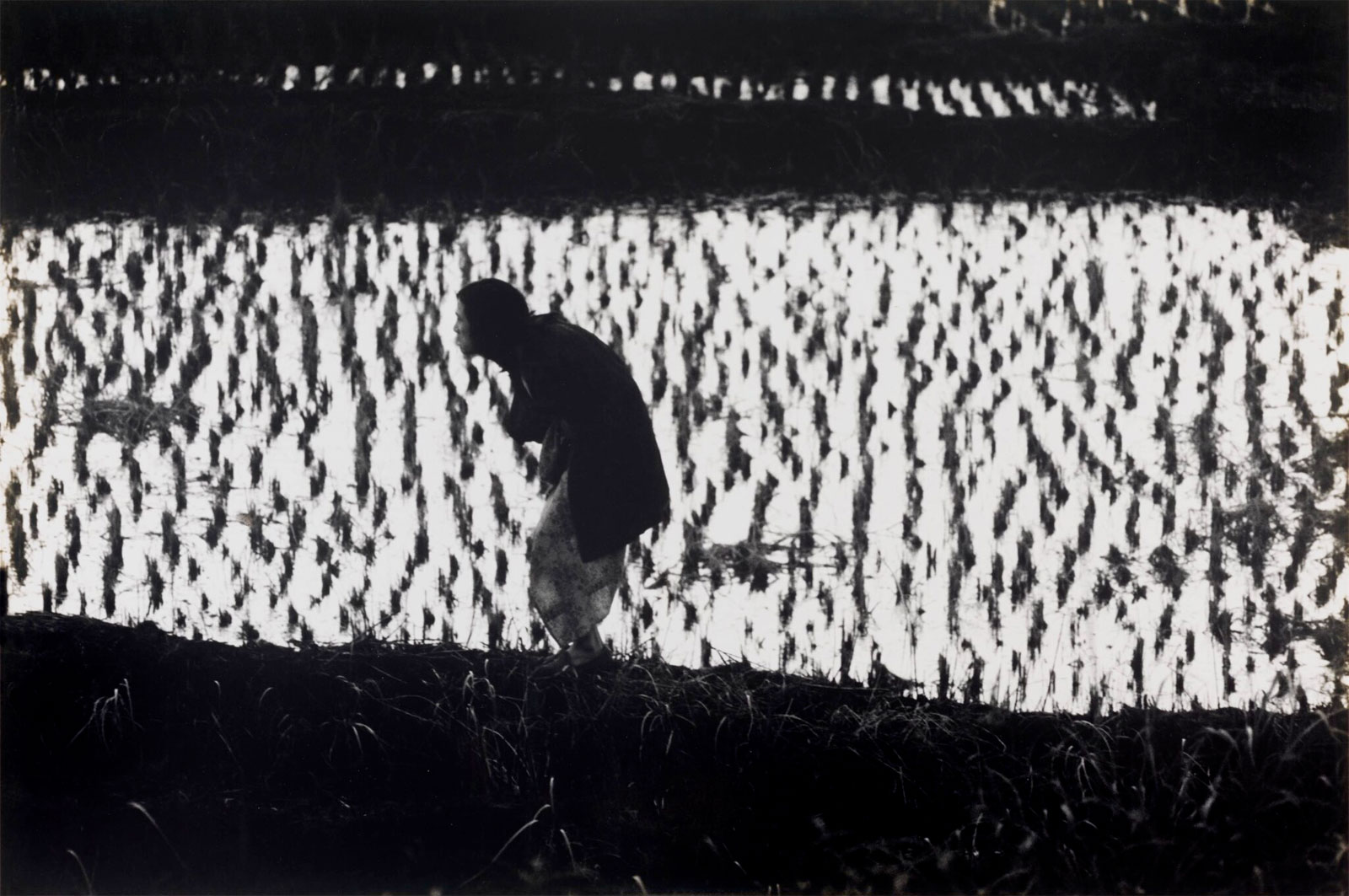

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kamaitachi #12

1968

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

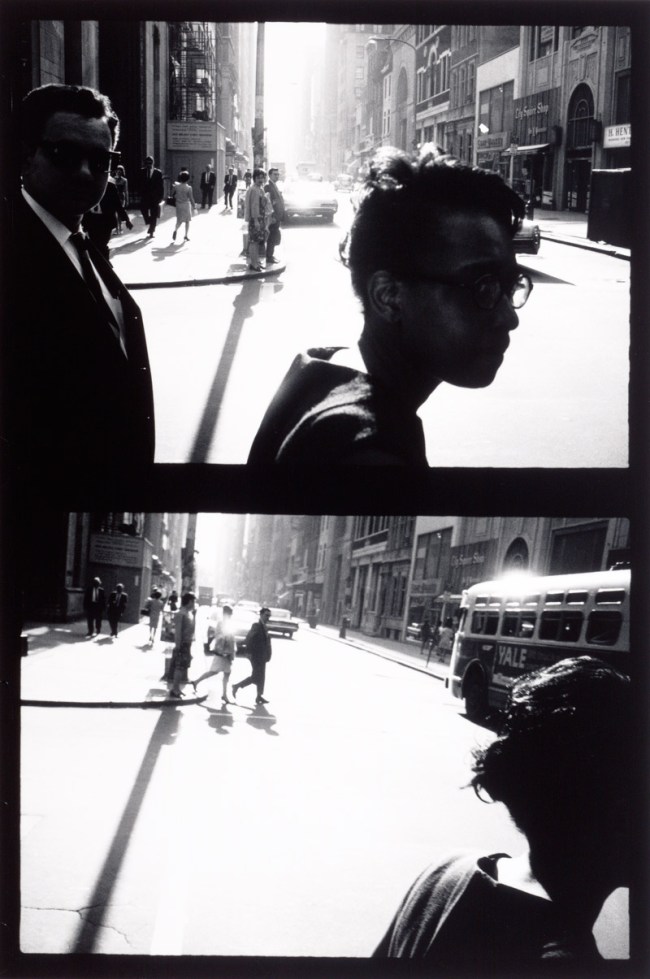

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kamaitachi #14

1965

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kamaitachi #17

1965

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

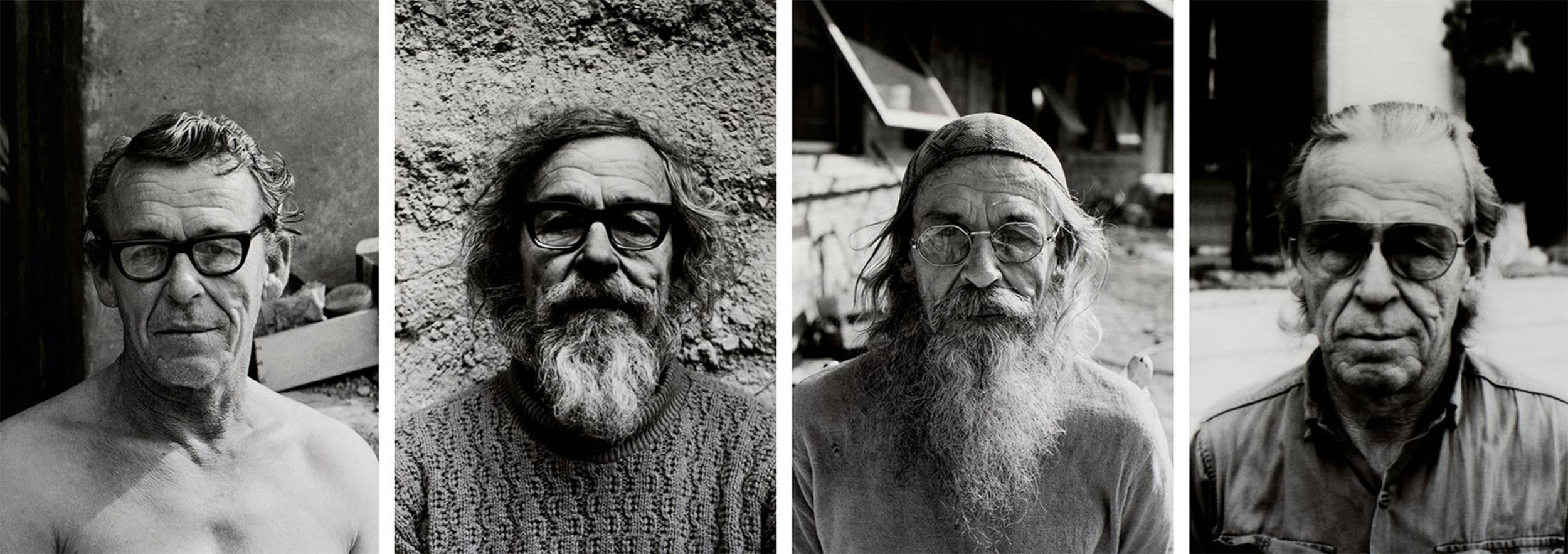

Centered on the Japanese myth of Kamaitatchi, a mythical folkloric monster believed to have existed in rural Japan, these photographs were created collaboratively by the photographer Eikoh Hosoe and the choreographer and dancer Tatsumi Hijikata (1928-86) over several years in the late 1960s. The famed choreographer, who established the abstract dance style of Butoh, performed in front of Hosoe’s camera, enacting the movement of the monster Kamaitachi.

Hosoe captured Hijikata’s transformation into Kamaitachi as they traveled from Tokyo to a small farming village in Yamagata in the Tohoku region of Japan. Often thought to be a weasel, Kamaitachi appears in a whirlwind to cut its victims with a sickle, but his cuts neither draw blood nor cause pain. In the village, Hijikata ran around in a rice field, interacted with villagers and farmers, and played with children. The artists stated that their collaboration in the rural Tohoku region (where the both artists were born) was their symbolic departure from the increasingly modernised capital city Tokyo while they had worked professionally.

Text from the Minneapolis Institute of Art website

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kamaitachi #23

1965

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kamaitachi #35

1968

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kamaitachi #37

1965

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kamaitachi #38

1968

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

Kamaitachi

Eikoh Hosoe’s long association with the revolutionary performance movement butoh came about through his encounter in 1959 with one of its founders, Tatsumi Hijikata. Hosoe collaborated with Hijikata on several series including Kamaitachi, which is acknowledged as the finest illustration of Hosoe’s hybrid photographic style, combining performance and documentary with a dramatic, virile aesthetic that embodies the founding principles of Hijikata’s ankoku butoh or ‘dance of darkness’.

The dramatic and intense energy that Hijikata generated with his dance not only captured Hosoe’s imagination but also opened up new ways for the young photographer to approach themes such as sexuality, gender and the human body.

Driven by the desire to re-enact his childhood memories when he was evacuated from Tokyo during World War Two, Hosoe had Hijikata perform kamaitachi, the legendary weasel-like demon that haunted the rice paddies in the extremely sparse, rural landscape of the Tohoku region from where they both came. Fusing reality (Hijikata interacting with the landscape and village people) and performance, Hosoe’s ‘subjective documentary’ series opened new ground in Japanese post-war photography.

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Kamaitachi #8

1965

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

Kamaitachi: Toward a Vacuum’s Nest

Shuzo Takiguchi

“When we are photographed, our bodies and souls become the victims of sacrifice in a ritual that strips our shadows away. The Eskimo, believed that their spirits resided in their shadows and that shamans had the power to steal them. Sir James George Frazer’s Golden Bough is not the only work to recount the dazzling drama of fate, or of life and death, that unfolds between man and his shadow.

Like life, death comes and goes – perhaps for a short time, perhaps longer. Narcissus’s story will continue to dominate our lives in ways that will become increasingly complicated over time; however, the camera (or, according to villagers in Sikkim, “the evil eye in a box”) seems to have reduced us, in one fell swoop, to the physics of light and shade. The objective lens seems opened to all of Nature, where all roads lead. The fact is, however, that it turns upside down once in the darkness and then is transformed into Nature.

To what extent were Katsu Kaishu,1 Baudelaire, and other luminaries of the early modern era who posed before the camera – tenuously sustained by their recognition of Nature amid a strange confusion of affectation and narcissism – aware of the evil lurking in the lens? Whatever the case, we will eventually see that, like the naked eye, the lens exists always “in its savage state.”2 We are seldom aware of the bizarre fact (or perhaps we just accept it as a self-evident truth) that both the thieves of shadows (photographers) and the thieves’ victims (subjects) are human beings.

I find it almost impossible to believe that the camera could truly capture, for example, the desire of a bird in flight at a certain moment or at any moment. All too often, the photographer unknowingly loses sight of reality, and the reality runs or rolls away, just outside the frame. Or, surprisingly, reality may be there in a corner of the image, invisible and therefore completely unnoticed. And so here I am reminded of Man Ray’s trenchant modern maxim: “Photography is not art.”

Before we even look at the Kamaitachi images, I want to stress the importance of distinguishing them from the generic concept referred to as staged photography. They are strictly, categorically, different from posed photographs of modern narcissists. If Hosoe had not met Tatsumi Hijikata, the phenomenal butoh master, he could not have created this extraordinary series. Hijikata is a man who – metaphorically speaking – can transmogrify in an instant into a phantasmagorical bird. This is not even theatrical photography, but rather a rare instance in which the camera obscura becomes a theater. And it is the paradoxical existence of the camera – which can photograph a vast void when we mean to capture a concrete object – that proves to be a stroke of luck for Hijikata, the master of movement.

Like the lens, Hijikata is a unique dancer, always aware that the “eye exists in its savage state.”3 His “dance experience” is never a matter of leaping across a stage, pretending to be a swan: if a bird is what he has in mind, Hijikata becomes a raven. The raven plunges to the ground far below the stage. Then it runs, if it wants to run, or flies, if it wants to fly. For Hijikata, hasn’t the paradoxical vacuum dwelling in the camera become a divine machine at a certain moment? Then, voluntarily or involuntarily, we may reach the lights of purgatory, for which we have yearned, beyond the millennia of human history.

At the very least, I see here an inevitable force striving to preserve the relationship between photographer and subject. In all likelihood, no other work approaches the original meaning of the term “happening” (however simplified it may be in this case) as closely as this one. Tatsumi Hijikata uses his dance artistry to abruptly penetrate the center of the vacuum between time and space, and he descends to the ground closest to the place where we were born.

He has arrived at the vacuum’s nest, the home of kamaitachi, the “sickle-weasel.”

Today it would seem that the kamaitachi belong to legend and mythology. What are kamaitachi? Memories from my childhood flood back to me: my father was a country doctor, and several times I saw farmers, claiming to have been bitten by a kamaitachi, carried to the threshold of our house. Those were frightening moments, smelling of blood, like the first bolt of lightning streaking across a dark sky. I heard the farmers say they were attacked out of the blue, under a rice-drying rack or an ancient persimmon tree. But no one bore a grudge against that invisible weasel. In fact, a family of actual weasels made their home in the loft of the thatched shed behind our house. Every once in a while, I would see them dart across a field, always taking the shortest path and then disappearing. They lived among people but avoided them. The rumour was that the disreputable little creatures were so wary and agile that they never took the same path twice. I wonder whatever happened to them. One book defines kamaitachi as a laceration from the localised vacuum created by a dust devil. No one really knows the truth. The days of kamaitachi are long gone.

Was kamaitachi a spirit of the soil, a phantom that appeared only to farmers? If so, that invisible flying blade must have been incredibly sharp to leap through the sky and pierce flesh.

It is hard to say whether Tatsumi Hijikata is a spirit of the soil or the air; however, even before we can contemplate the question, he approaches the ground almost vertically and rushes like a gale into a farming village. This village is in a rice-growing district, where Japan’s most inconsistent and absurd social reality anomalously persists. Hijikata appears suddenly, like a hawk diving to the ground – or a kidnapper from heaven.

The god of the rice fields smiles on this scene. A faint trace of that smile is on the kagura theatrical dance mask, but it isn’t the embarrassed smile replayed endlessly on television. It is a smile that could exist among demons, a smile that was present even on a footpath between barren rice fields during a terrible famine, a startling but comical smile from the realm of the unconscious.

At a precise moment, our dancer and photographer approach a timeworn village – their footsteps only faintly audible – and they capture a brief moment in the empty village, where zinnias and other flowers bloom, coated with white soil dust. The entire village, mesmerised like a haunted house, enthrals them.

Is he a hawk that has just landed – or a leaping weasel? It is foolish to ask. It is our dancer who would be wounded. The villagers gaze at him innocently, as though he reminds them of a long-forgotten priest. They smile, without knowing why, at the arrival of the oblivious fool. Their smiles become the same smile of the footpath between rice fields. It is a smile that borders on terror.

A girl smiles like a shrine maiden whom the gods have endowed with evil and innocence in perfect balance. Were the girls born fairies? Sooner or later they will experience the orgasm of life and death. Then they will depart. Will they return to the earth or to the sky? No one knows which path they will take.

In any case, two contradictory, endless journeys await them.

Hairy vacuum! Bloody vacuum! Biting vacuum! You must continue to exist on this earth!

The desire for the heavens will inexorably lead to a desire for the bowels of the earth. Then the excrescence will head for the huge void, and vice versa. The cosmic metamorphosis that this phenomenon seeks will occur, extremely and tangibly. The vacuum theater, too, is part of the evolution.

To arrive at the source of the phantom of ecstasy, we must dig deeper and deeper, day by day.

And the witness is an instantaneous flash.”

by Shuzo Takiguchi

Translated by Connie Prener

1/ Officer credited with the modernisation of Japan’s navy (1823-1899)

2/ Allusion to Andre Breton’s Le Surréalisme et la peinture

3/ Ibid.,

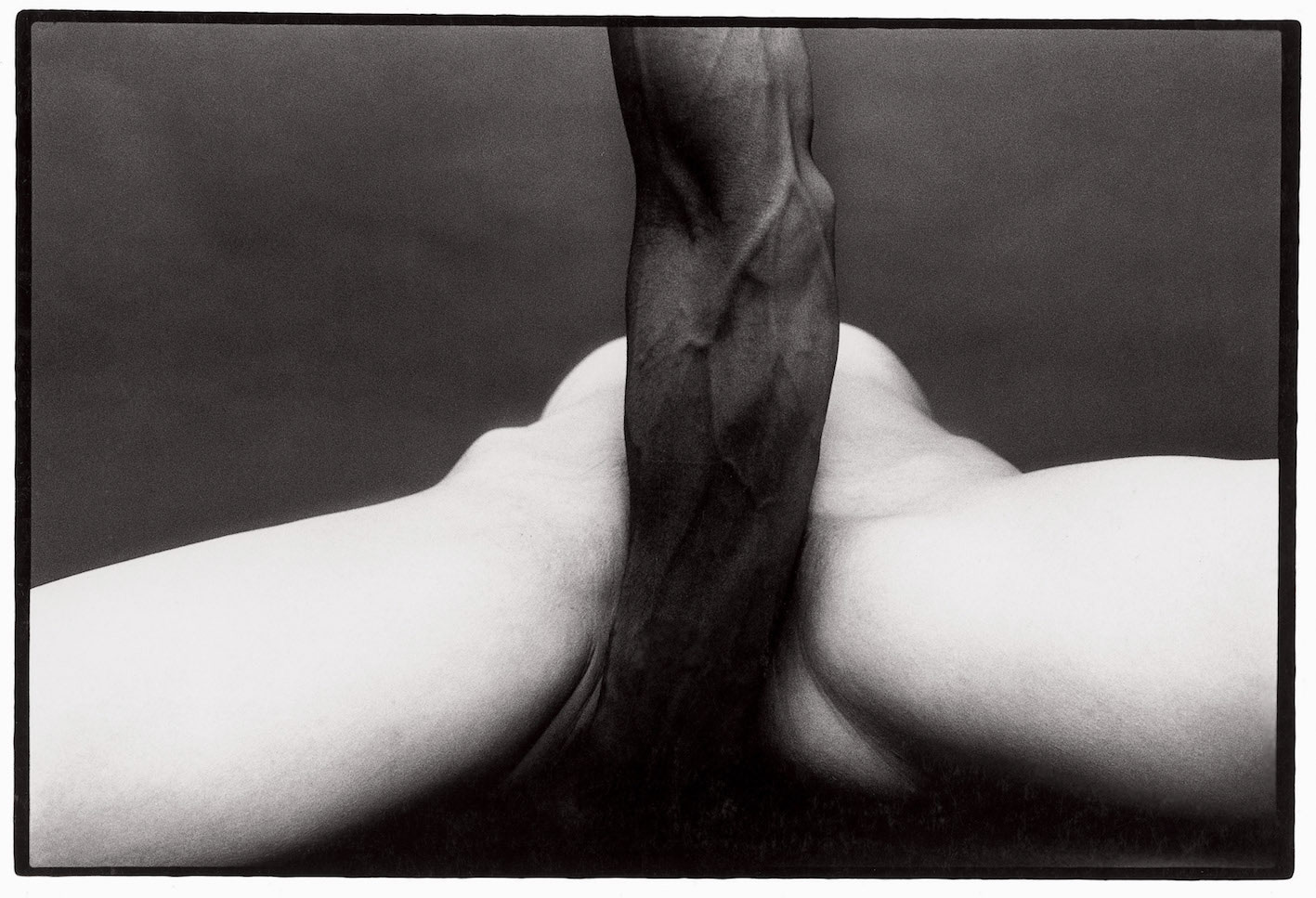

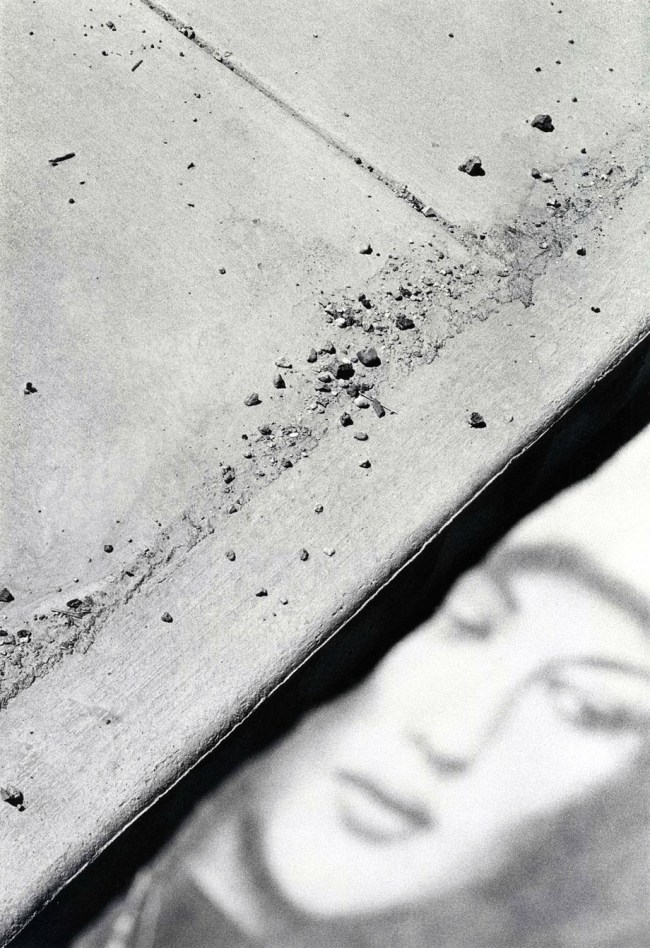

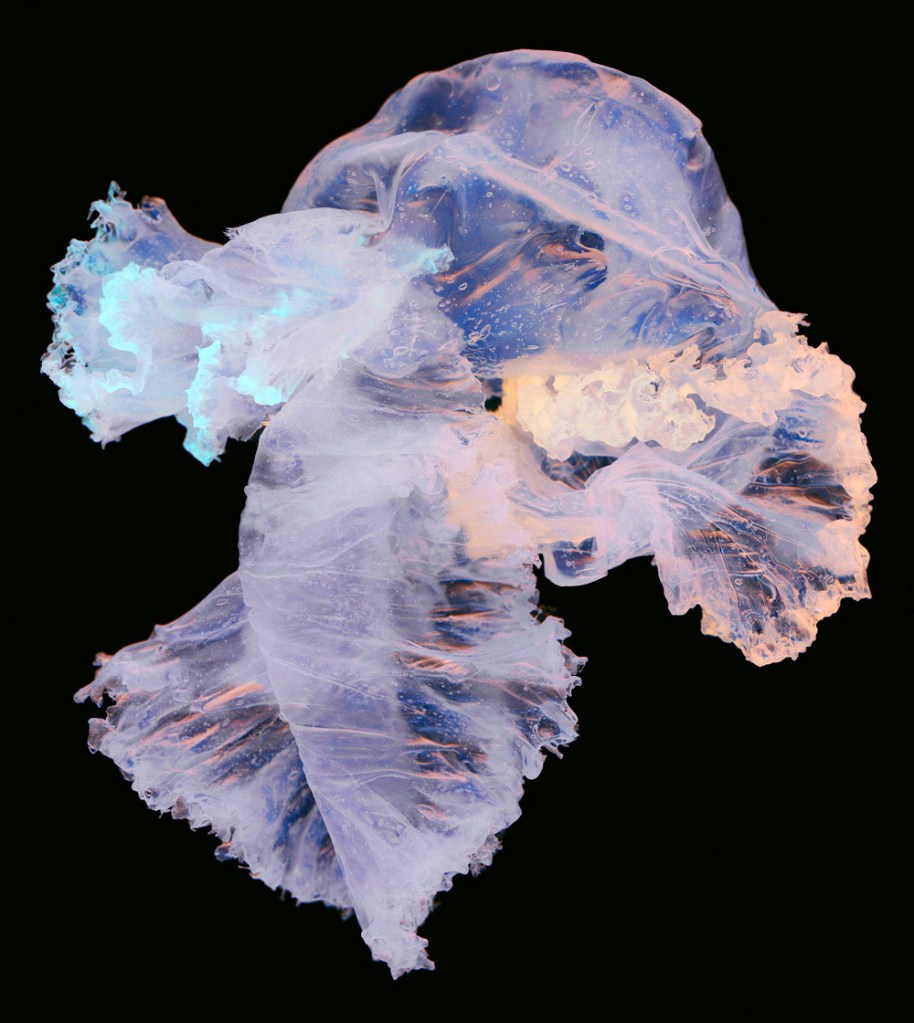

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Embrace #48

1970

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

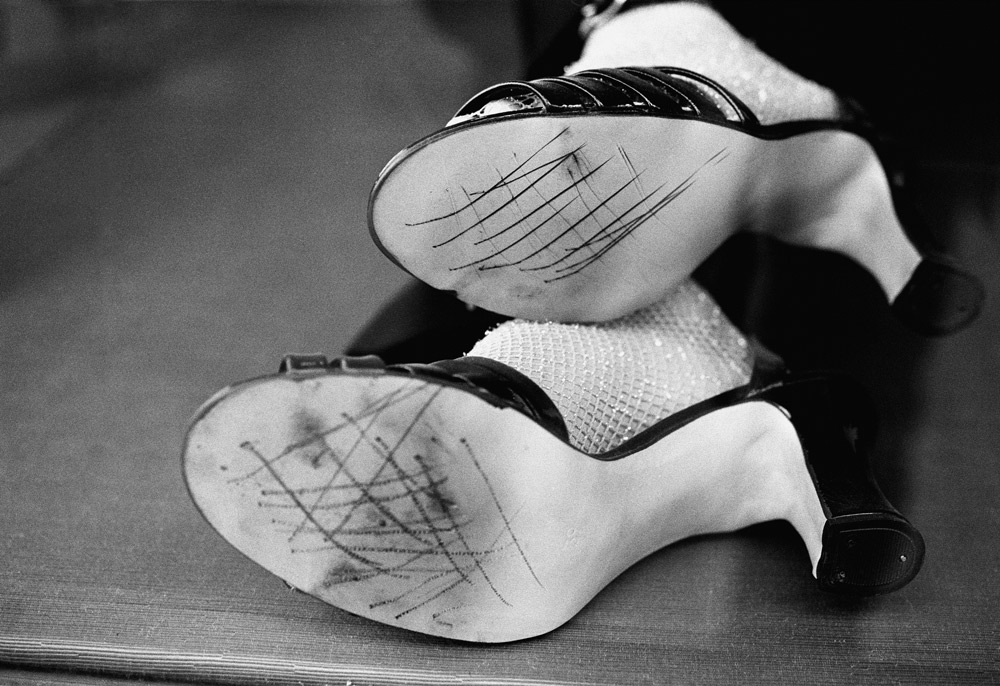

Embrace

First published as a book in 1971, Embrace represents a return to the study of the human body that Hosoe undertook in earlier series such as Man and woman (1959) or Ordeal by roses (1963). In this new body of work, however, he abandoned the strong contrast and dramatic, baroque visual aesthetic in favour of the purity of the human form. Showing abstract fragments of male and female nudes in intimate placement, the series is not merely about eroticism or the dialogue of rivalry between the opposite sexes but is also a celebration of the pure beauty of the human body.

By depersonalising the bodies of his models, Hosoe attempted to reach a universal expression of corporeality. The extreme abstraction of these images focuses the attention on the flesh, which, according to Hosoe’s belief, is the essence of human beings.

The author Yukio Mishima comments on this series: ‘The viscosity which is associated with sex – those earthly odours and temperatures of soft and indeterminately formed internal organs – has been painstakingly removed from these photographs. To me this is a series filled with a hard, athletic beauty. First and foremost, it is about form.’

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Embrace #52

1970

Gelatin silver print

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

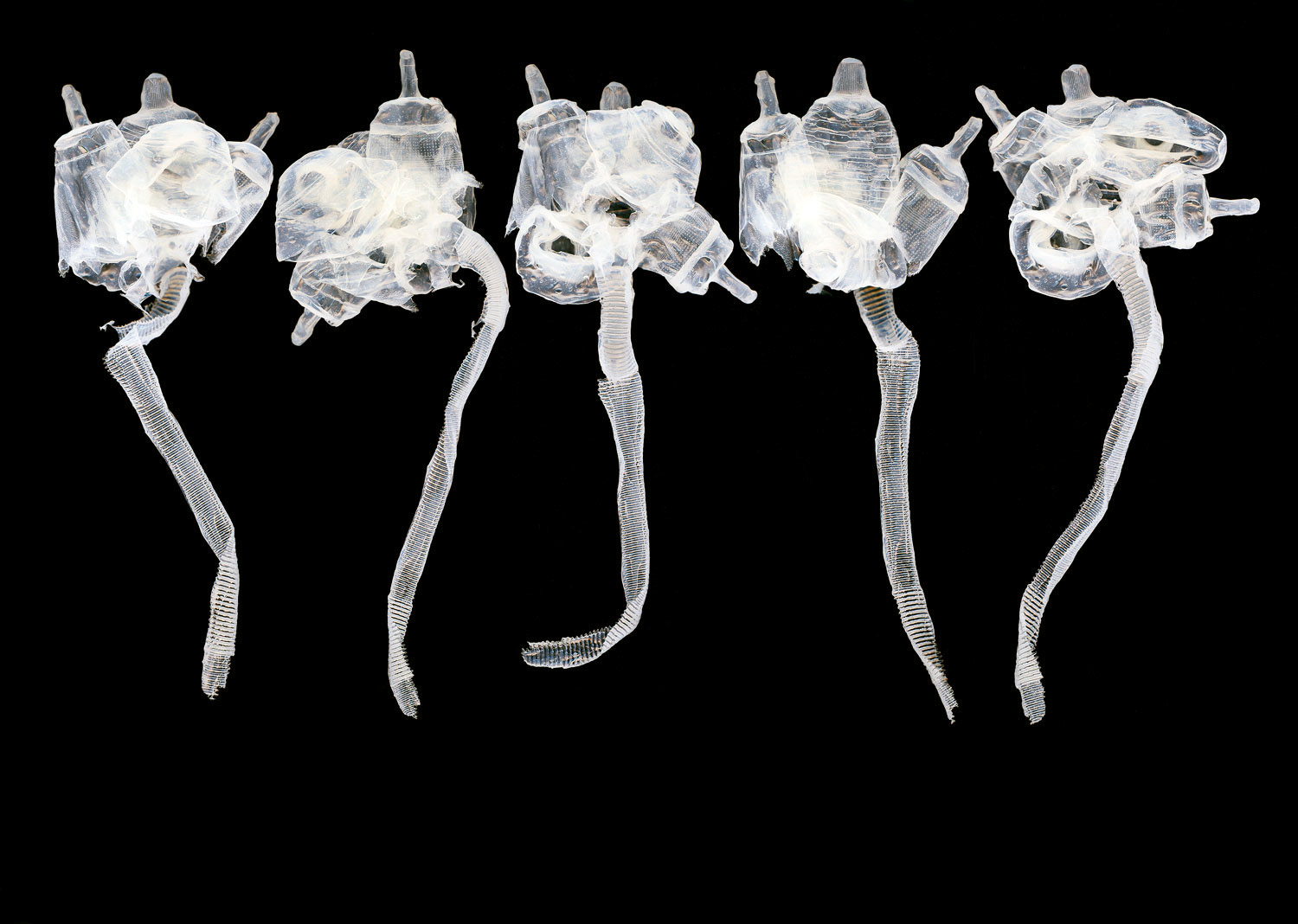

Ukiyo-e Projections

When Hosoe heard the news that the Asbestos Dance Studio, founded by Tatsumi Hijikata and his wife Akiko Motofuji, was to close in April 2003 after 40 years of activity, he felt the need to pay tribute to the achievements of this experimental studio. With the help of Hijikata’s widow, he organised a series of performances in 2002 and 2003, in which the dancers were asked to coordinate their movements in accordance with images from his own work, as well as from 19th-century Japanese paintings and woodblock prints projected on their naked, white-painted bodies.

The result of this ‘photographic theatre’ was stunning: a mysterious four-dimensional space transcending ordinary space and time was created as the two-dimensional images were projected on the three-dimensional bodies. The idea to use shunga – the erotic woodblock prints by noted ukiyo-e artists such as Utamaro, Hokusai and others – stemmed from Hosoe’s conviction that Hijikata’s archaic, ecstatic dance style had its roots in this particular art genre of the Edo period (1603-1868).

Exploring many of the themes that recur in Hosoe’s work – sexuality, the human form, movement and the passage of time – this series epitomises his unique approach in synthesising photography with various forms of visual and performance arts.

Eikoh Hosoe (Japanese, 1933-2024)

Ukiyo-e Projections #2-36

2003

© Eikoh Hosoe/Courtesy Studio Equis

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art Gallery Road, The Domain

Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

Opening hours:

Open every day 10am – 5pm

except Christmas Day and Good Friday

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) [Farmer, Westerwald (Bauer, Westerwald)] 1910 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) [Farmer, Westerwald (Bauer, Westerwald)] 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/sander-farmer.jpg?w=794&h=1024)

![Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Powerhouse mechanic]' 1920 catalogue size Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Powerhouse mechanic]' 1920 catalogue size](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/hine_powerhousemechanic-actual.jpg?w=329&h=471)

![Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Powerhouse mechanic]' 1920 catalogue size Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Powerhouse mechanic]' 1920 catalogue size](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/hine_powerhousemechanic-print2.jpg)

![Alfred Steiglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Georgia O'Keefe hand on back tire of Ford V8]' 1933 Alfred Steiglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Georgia O'Keefe hand on back tire of Ford V8]' 1933](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/stieglitz_alfred_portraitgeorgiaokeefe-web3.jpg?w=650&h=811)

![W. Eugene Smith (American, 1918-1978) '[Frontline Soldier with Canteen at Saipan]' June 1944 W. Eugene Smith (American, 1918-1978) '[Frontline Soldier with Canteen at Saipan]' June 1944](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/w.-eugene-smith-soldier.jpg?w=650&h=842)

![Sue Ford (1943-2009) 'Untitled [Bliss at Yellow House, King's Cross, Sydney]' c. 1972–1973 Sue Ford (1943-2009) 'Untitled [Bliss at Yellow House, King's Cross, Sydney]' c. 1972–1973](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/008.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.