Exhibition dates: 18th June – 30th July 2011

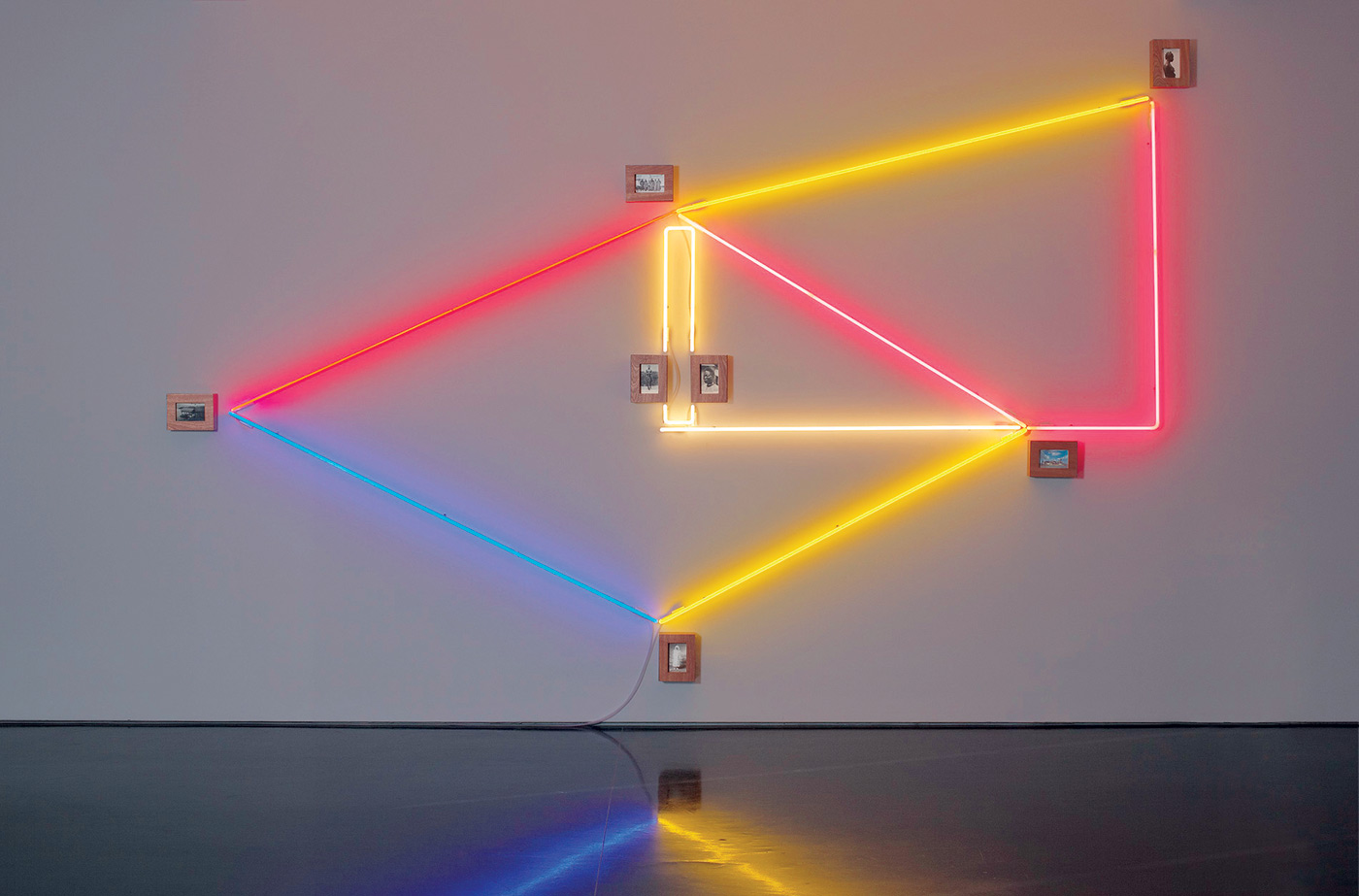

Brook Andrew Paradise installation at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

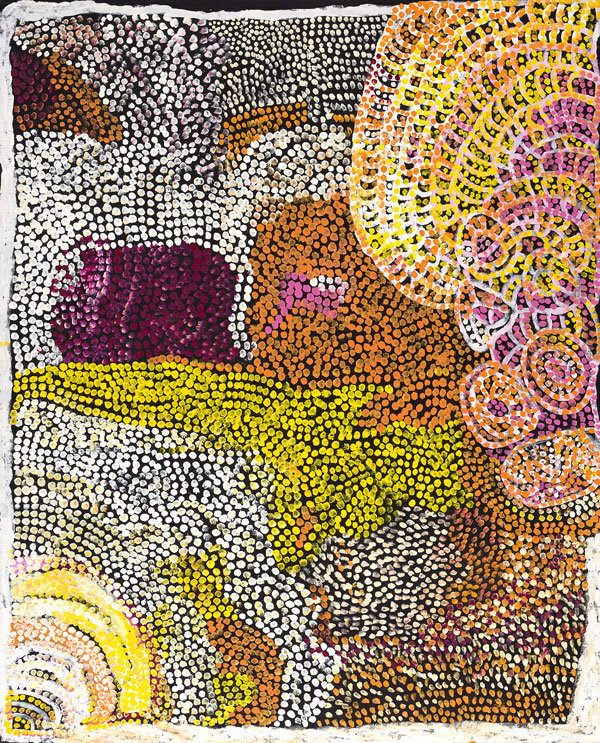

This is a strong, refined photo-ethnographic exhibition by Brook Andrew at Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne, one that holds the viewers attention, an exhibition that is witty and inventive if sometimes veering too closely to the simplistic and didactic in some works.

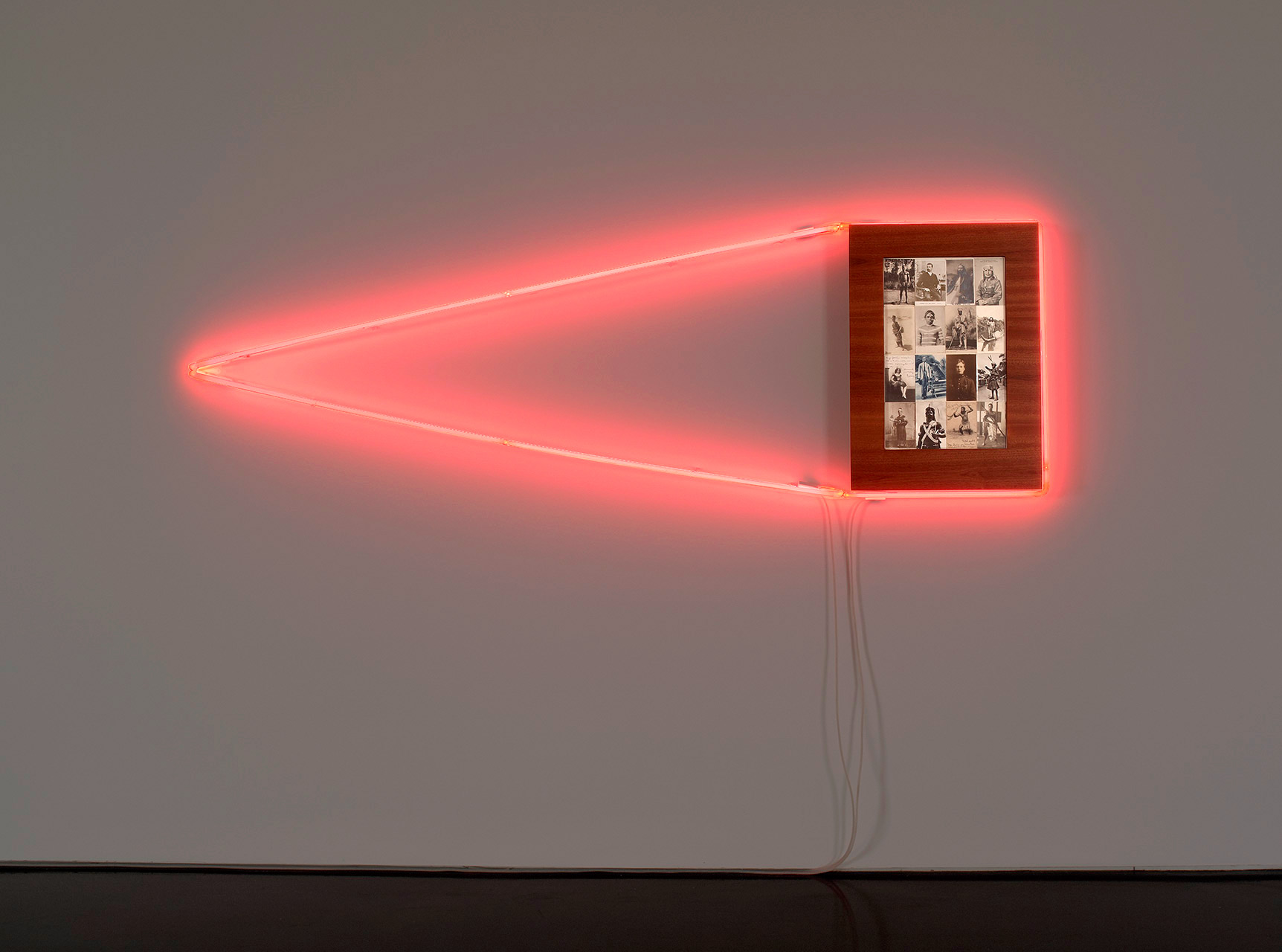

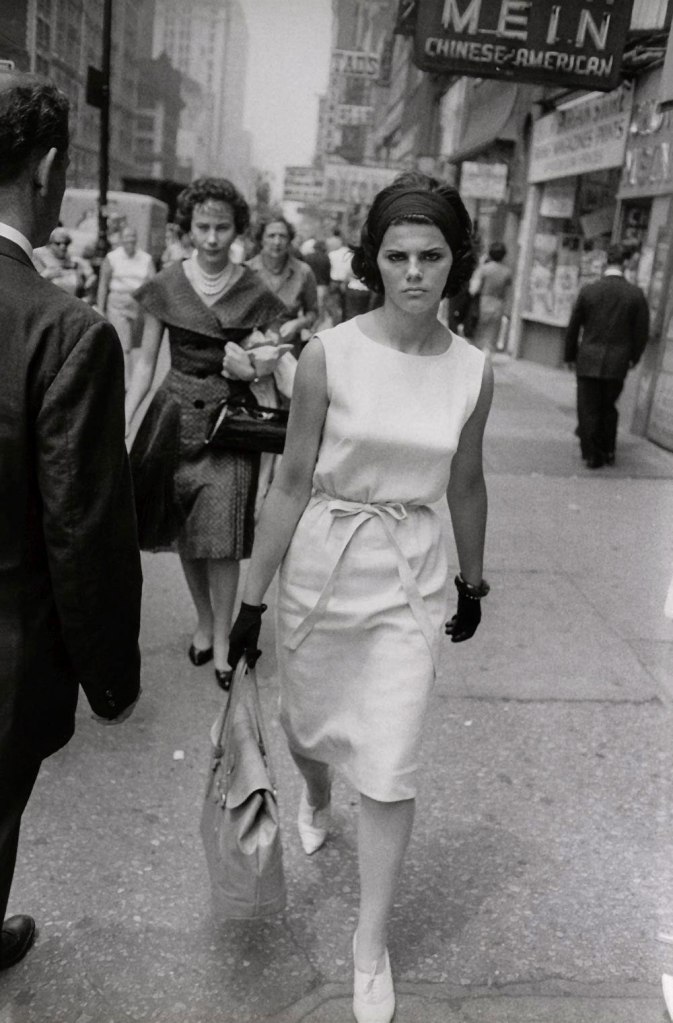

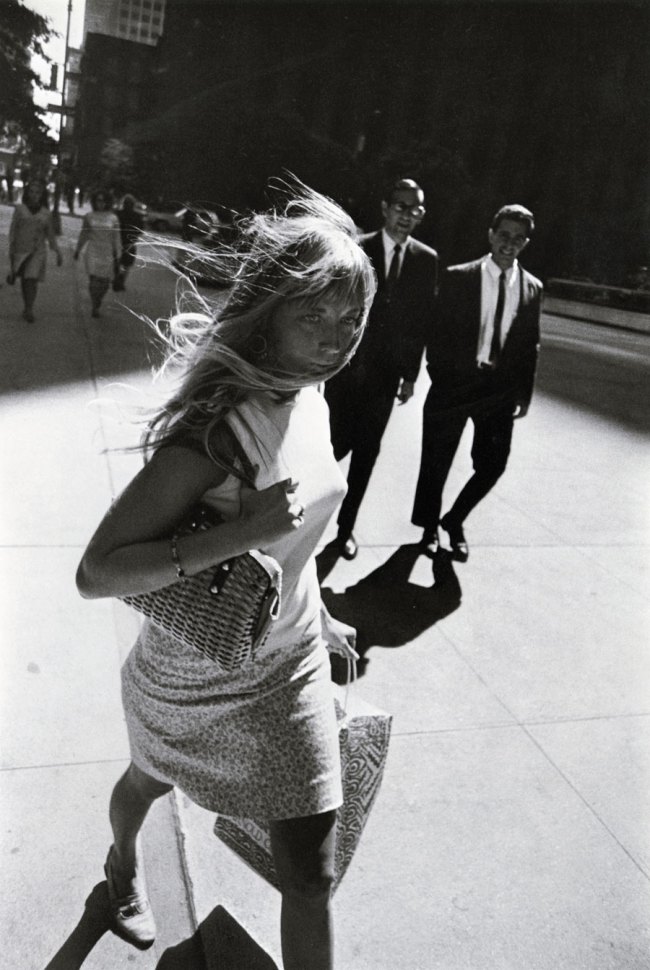

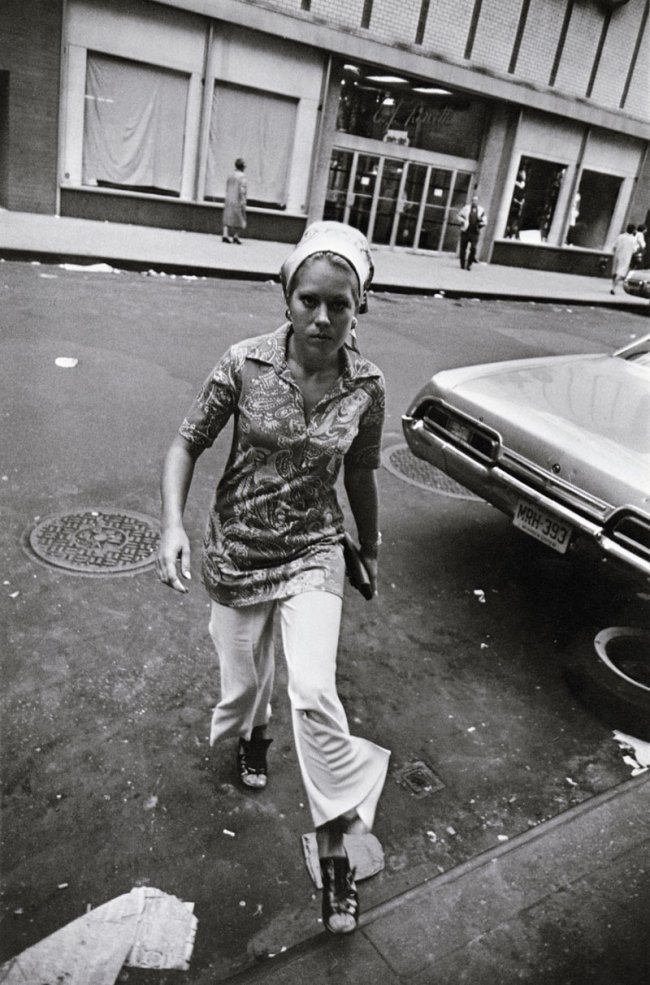

Rare postcards of Indigenous peoples and their colonising masters and surrounded by thick polished wood frames (the naturalness of the wood made smooth and perfect) and coloured neon lights that map out the captured identities, almost like a highlighting texta and forms of urban graffiti. This device is especially effective in works such as Men and Women (both 2011, below) with their male and female neon forms, and Flow Chart (2011, below) that references an anthropological map.

Other works such as Monument 1 (2011, below) lay the postcards into the rungs of a small step ladder covered in white paint that has echoes of the colonisers renovation of suburban homes and becomes a metaphor for the Indigenous peoples being stepped on, oppressed and downtrodden. In a particularly effective piece, Monument 2 (2011, below) the viewer stares down into a black box with multiple layers of neon that spell out the words ‘I see you’ in the Wiradjuri language: we can relate this work to Lacan’s story of the sardine can, where the point of view of the text makes us, the viewer, seem rather out of place in the picture, an alien in the landscape. The text has us in its sights making us uncomfortable in our position.

The work Paradise (2011, six parts, above) can certainly be seen as paradise lost but the pairing of black / white / colour postcards is the most reductive of the whole exhibition vis a vis Indigenous peoples and the complex discourse involved in terms of oppression, exploitation, empowerment, identity, mining rights and land ownership. The two quotations below can be seen to be at opposite ends of the same axis in this discourse. My apologies for the long second quotation but it is important to understand the context of what Akiko Ono is talking about with regard to the production of Indigenous postcards.

“White… has the strange property of directing our attention to color while in the very same movement it exnominates itself as a color. For evidence of this we need look no further than to the expression “people of color,” for we know very well that this means “not White.” We know equally well that the color white is the higher power to which all colors of the spectrum are subsumed when equally combined: white is the sum totality of light, while black is the total absence of light. In this way elementary optical physics is recruited to the psychotic metaphysics of racism, in which White is “all” to Black’s “nothing”…”

Victor Burgin 1

“In his study of Aboriginal photography, Peterson also looks at the dynamics of colonial power relations in which both European and Aboriginal subjects are constituted in and by their relations to each other. Peterson in the main writes about two different contexts of the usage of photography of Aboriginal people

1. popular usage of photographs, especially in the form of postcards in the early twentieth century (Peterson 1985, 2005)

2. anthropologists’ ethnographic involvement with photography (Peterson 2003, 2006).

Regarding the first, Peterson depicts how the discourses of atypical (that is, disorganised) family structures and destitution among Aboriginal people were produced and interacted with the prevalent moral discourses of the time. He makes an important remark about the interactive dimensions that existed between the photographer and the Aboriginal subject. Hand-printed postcards in the same period showed much more positive images of Aboriginal people (Peterson 2005: 18-22). These were ‘real’ photographs taken by the photographers who had daily interactions with Aboriginal people…

Peterson gives greater attention to photographs taken by anthropologists for scientific purposes, and in this second context provides a more detailed treatment of his insight regarding the discrepancies between the colonisers’ discourse and the actual visual knowledge that photography offers…

These two contexts are not, of course, mutually exclusive. By dealing with image ethics and the changing photographic contract, Peterson (2003) shows the interlocking formations of popular image, anthropological knowledge and Aboriginal self-representation. In particular, it is important to remember that Aboriginal people have not always rejected collaboration with and appropriation of the idioms of the coloniser. Aboriginal people were not bothered by posing for photographers to produce images such as ‘naked’ Aboriginal men and women in formal pose, accompanied by an ‘unlikely combination’ of weapons (Peterson 2005); and at times complex negotiations occurred between the photographer and the photographed – resulting in both consent and refusal (Peterson 2003: 123-31).

These anecdotes suggest the necessity of unravelling the ‘lived’ dimensions of colonial and / or racial subjugation and resistance to that subjugation from the site of their occurrence …

Rather than scrutinising the authenticity of Aboriginality or taking it for granted that ethnographic photography is doomed to reproduce a colonial or anthropological power structure, it is more important to attend to the ‘instances in which colonized subjects undertake to represent themselves in ways that engage with the colonizer’s own terms’, as Pratt (1992: 7, emphasis in the original) suggests. She proposes the term ‘autoethnography’ to refer to these instances: ‘If ethnographic texts are a means by which Europeans represent to themselves their (usually subjugated) others, autoethnographic texts are those the others construct in response to or in dialogue with those metropolitan representations’ (Pratt 1992).

Akiko Ono 2

The work Paradise buys into the first quotation in a big way, playing as it does with the idioms of black / white / colour. It can also be seen as a form of autoethnographic text that uses rare postcards to critique historical relations between peoples and cultures. What it does not do, I feel, is delve deeper to try to understand the “interlocking formations of popular image, anthropological knowledge and Aboriginal self-representation” and resistance to that subjugation from the site of their occurrence. As the quotation observes “Aboriginal people have not always rejected collaboration with and appropriation of the idioms of the coloniser” and it is important to understand how the disciplinary systems of the coloniser (the ethnographic documenting through photography) were turned on their head to empower Indigenous people who undertake to represent themselves in ways that engage with the coloniser’s own terms. Nothing is ever just black and white. It is the interstitial spaces between that are always the most interesting.

In conclusion this an elegant exhibition of old and new, an autoethnographic text that seeks to address critical issues that look back at us and say – ‘I see you’.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Burgin, Victor. In/Different Spaces: Place and Memory in Visual Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995, p. 131

2/ Ono, Akiko. “Who Owns the ‘De-Aboriginalised’ Past? Ethnography meets photography: a case study of Bundjalung Pentecostalism,” in Musharbash, Yasmine and Barber, Marcus (eds.,). Ethnography & the Production of Anthropological Knowledge: Essays in honour of Nicolas Peterson. The Australian National University E Press [Online] Cited 16/07/2011 (no longer available online)

~ Peterson, N. 1998. “Welfare colonialism and citizenship: politics, economics and agency,” in N. Peterson and W. Sanders (eds.,). Citizenship and Indigenous Australians: Changing Conceptions and Possibilities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 101-17.

~ Peterson, N. 1999. “Hunter-gatherers in first world nation states: bringing anthropology home,” in Bulletin of the National Museum of Ethnology 23 (4), pp. 847-61.

~ Peterson, N. 2003. “The changing photographic contract: Aborigines and image ethics,” in C. Pinney and N. Peterson (eds.,). Photography’s Other Histories. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 119-45.

~ Peterson, N. 2005. “Early 20th century photography of Australian Aboriginal families: illustration or evidence?” in Visual Anthropology Review 21 (1-2), pp. 11-26.

~ Peterson, N. 2006. “Visual knowledge: Spencer and Gillen’s use of photography in The Native Tribes of Central Australia,” in Australian Aboriginal Studies (1), pp. 12-22

~ Pratt, M. L. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writings and Transculturation. London: Routledge

Footnote 1. Peterson has built up a collection of process-printed (that is, mass-produced) postcard images and hand-printed images dating from 1900 to 1920 (that is, real photographic postcards), over 20 years, during which time he obtained a copy every time he saw a new image. He feels confident that he has seen two-thirds of the process-printed picture postcards from the period although it is harder to estimate how many hand-printed images were circulating (Peterson 2005: 25n.3). He had a collection of 528 process-printed postcards (Peterson 2005: 25) and 272 hand-printed photographs (p. 18) by 2005.

Many thankx to Olivia Radonich for her help and to Tolarno Galleries for allowing me to publish the text and photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. Images courtesy the artist and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne. Photos by Christian Capurro.

Brook Andrew Paradise installation at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Paradise 1 (red)

2011

Rare postcards, sapele, and neon

24.5 x 28.5 x 8cm

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Paradise 2 (orange)

2011

Rare postcards, sapele, and neon

24.5 x 34 x 8cm

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Paradise 3 (yellow)

2011

Rare postcards, sapele, and neon

24.5 x 28.5 x 8cm

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Paradise 4 (green)

2011

Rare postcards, sapele, and neon

25 x 33.5 x 8cm

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Paradise 5 (magenta)

2011

Rare postcards, sapele, and neon

24.5 x 28 x 8cm

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Flow Chart

2011

Rare postcards, sapele and neon

283 x 449.5 x 8.5cm

Brook Andrew Paradise installation at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

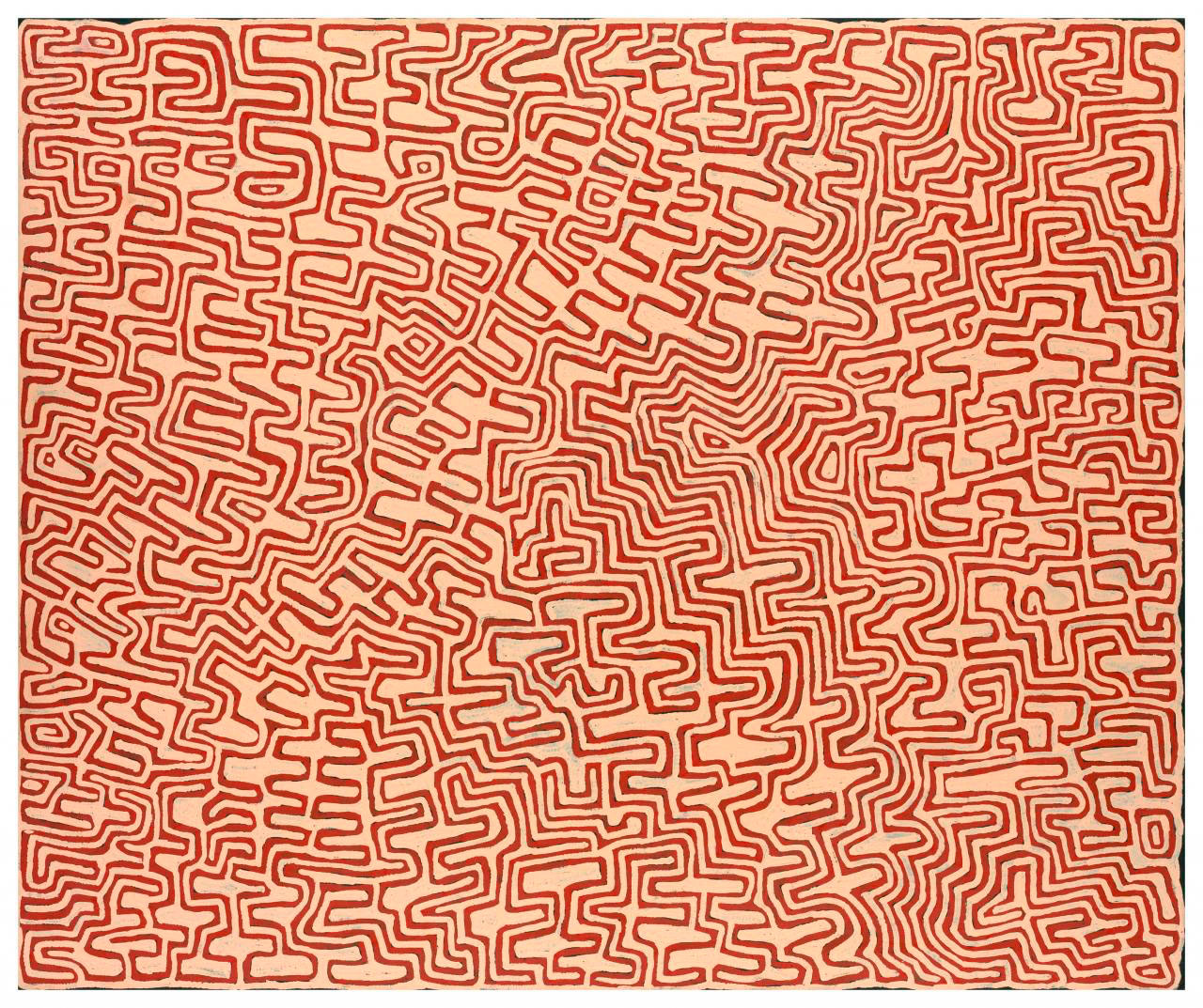

Men

2011

Rare postcards, sapele, and neon

82 x 264 x 12.5cm

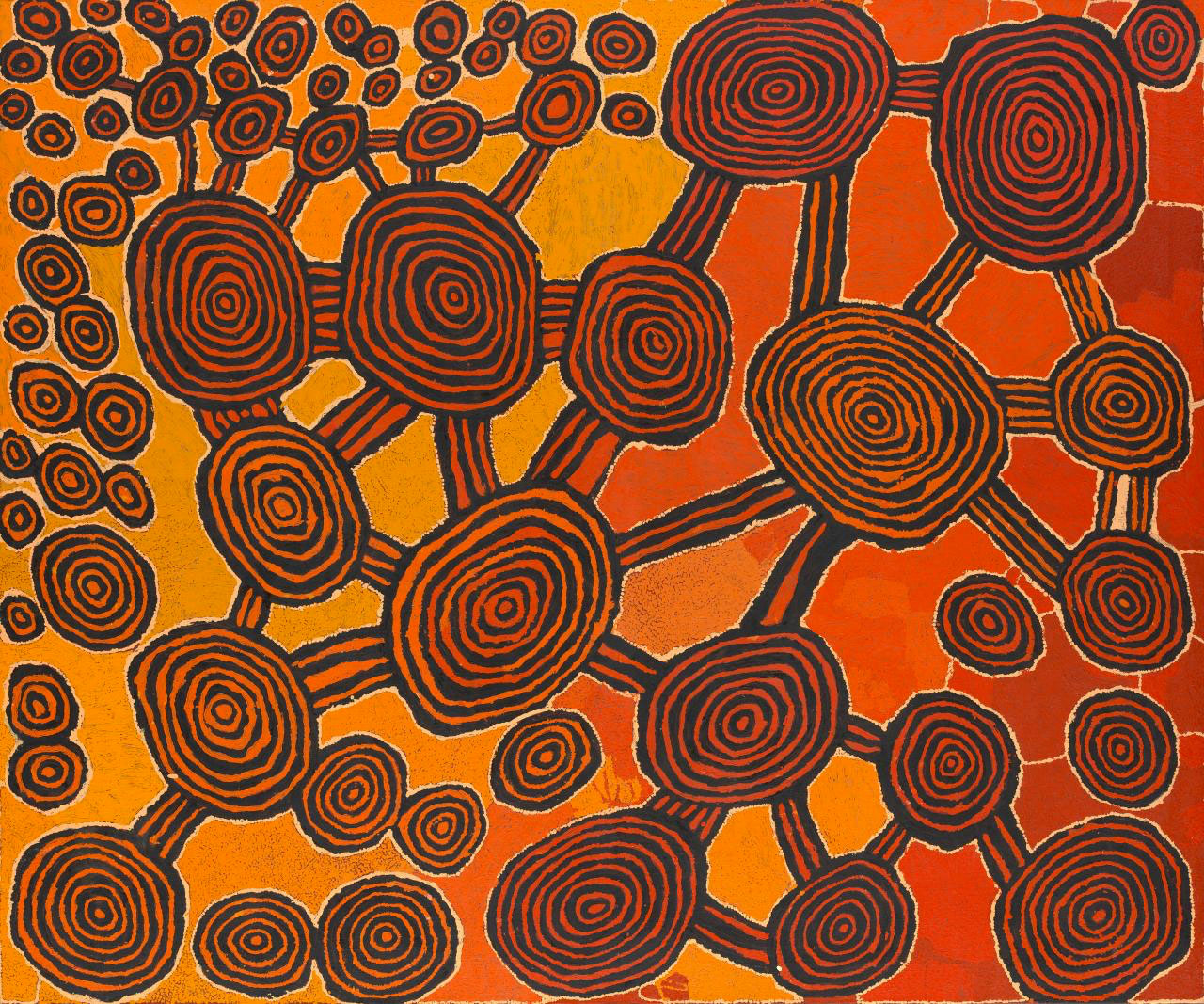

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Women

2011

Rare postcards, sapele, and neon

179 x 179 x 6cm

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Women (detail)

2011

Rare postcards, sapele, and neon

179 x 179 x 6cm

Tolarno Galleries is pleased to present Paradise, a major solo exhibition by Brook Andrew. Widely regarded as a multi-disciplinary artist, Brook Andrew’s Jumping Castle War Memorial was a highlight of the 17th Biennale of Sydney. Recently his major installation, Ancestral Worship 2010, was included in 21st Century: Art in the First Decade at Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane. His powerful new installation – Marks and Witness: A Lined crossing in Tribute to William Barak 2011 – was commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria and is currently on display at Federation Square, Melbourne.

Paradise expands Brook Andrew’s interest in forgotten histories. His new works ask us to think about what has disappeared from our worlds, literally, and also from our consciousness. The exhibition features a number of assemblages made in neon and wood and incorporating rare postcards and photographs collected over many years. Men 2011 includes the original postcard that became the source for Sexy and Dangerous, Andrew’s iconic work of 1995.

Brook Andrew’s continuing search for curious portrait images from the 19th and early 20th century represents his fascination with the way the camera has documented a particular ‘colonial’ gaze and an interest in the exotic. Outlining or highlighting these images in glorious coloured neon emphasises this point.

However bright the neon, Brook Andrew’s works are characterised by a formal beauty and simplicity that explores conceptually complex ideas and themes. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Monument 4, a ‘boomerang bar’ or Monument 2, a black lacquer box of neon containing the words ‘I see you’ in Wiradjuri. Gazing into this ‘well of words’ is like looking into infinity.

Brook Andrew’s work is held in every major collection in Australia. An important survey of his work: Brook Andrew Eye to Eye was presented by Monash University Museum of Art in 2007. In 2008 his work was showcased in Theme Park at AAMU Museum of Contemporary Aboriginal Art in The Netherlands. Major publications accompanied both of these solo exhibitions.”

Press release from Tolarno Galleries

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Monument 2

2011

Black lacquer, wood, perspex, neon, mirror and wire

38 x 99 x 87cm

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Monument 2 (detail)

2011

Black lacquer, wood, perspex, neon, mirror and wire

38 x 99 x 87cm

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

18 lives in Paradise

Single box detail

2011

The basic unit used in 18 Lives in Paradise is a cardboard printed box 50 x 50 x 50 cm. The boxes are the building blocks for a sculpture, wall or any other structure. The box is also a parody of the courier box – those containers daily transported around the globe in the vast movement of lives and identities today. What was thought of as fixed may not be so.

The images are sourced from postcards. The postcards range from the early to mid-twentieth century and form part of a worldwide curiosity in indigenous people, circus acts and personalities, environment and resources … The images come together as an assemblage of ‘freaks’ and represent the collision paths of indigenous and non-indigenous cultures; those being documented out of curiosity and those belonging to dominant cultures who have used the land and its people for entertainment and wealth.

18 Lives in Paradise can form a column or wall. It can be a barrier, a beacon or epitaph. En masse, the boxes are a symbol of many lives whose identities are sometimes twisted for the gaze of the curious world.

Brook Andrew 2011

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Monument 1

2011

Black lacquer, are postcards, wood, mirror and metal

104.5 x 69.5 x 58cm

Tolarno Galleries

Level 4, 104 Exhibition Street

Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia

Phone: +61 3 9654 6000

Opening hours:

Tues – Fri 10am – 5pm

Sat 1pm – 4pm

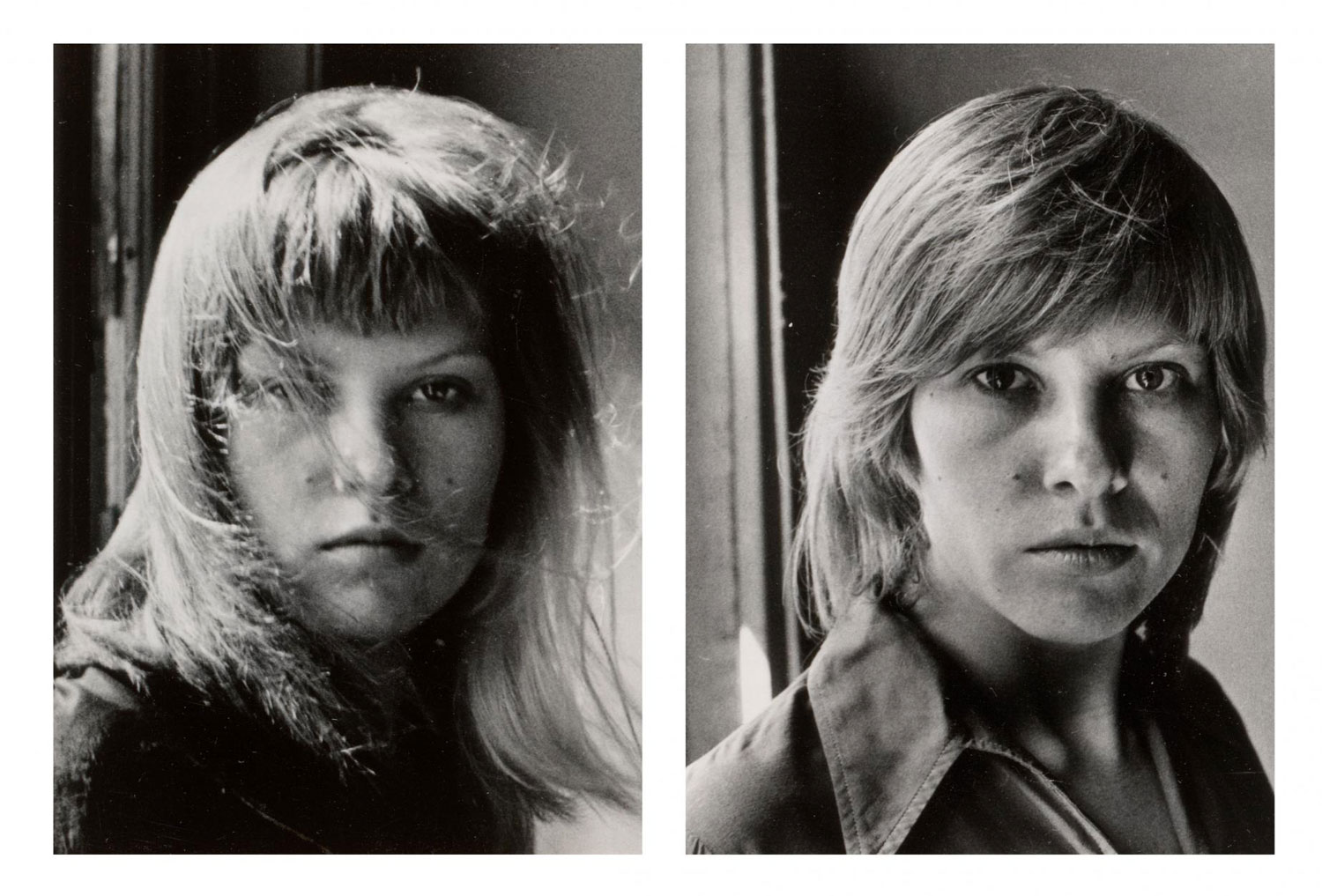

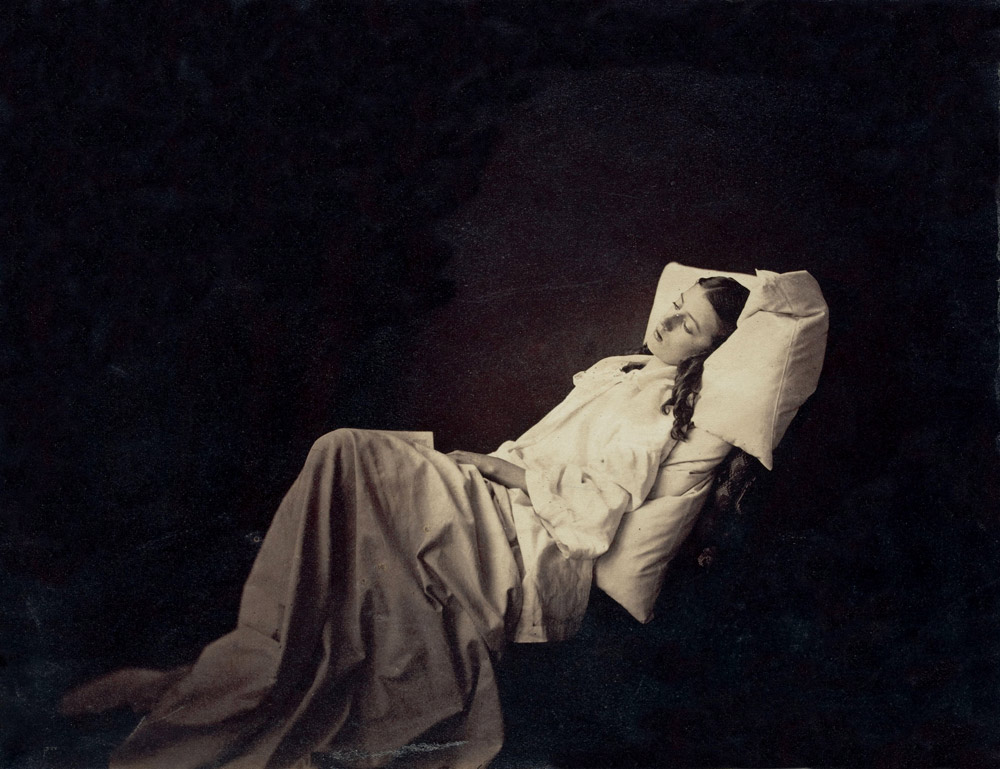

![Sue Ford (1943-2009) 'Untitled [Bliss at Yellow House, King's Cross, Sydney]' c. 1972–1973 Sue Ford (1943-2009) 'Untitled [Bliss at Yellow House, King's Cross, Sydney]' c. 1972–1973](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/008.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.