Exhibition dates: 22nd November 2013 – 23rd March 2014

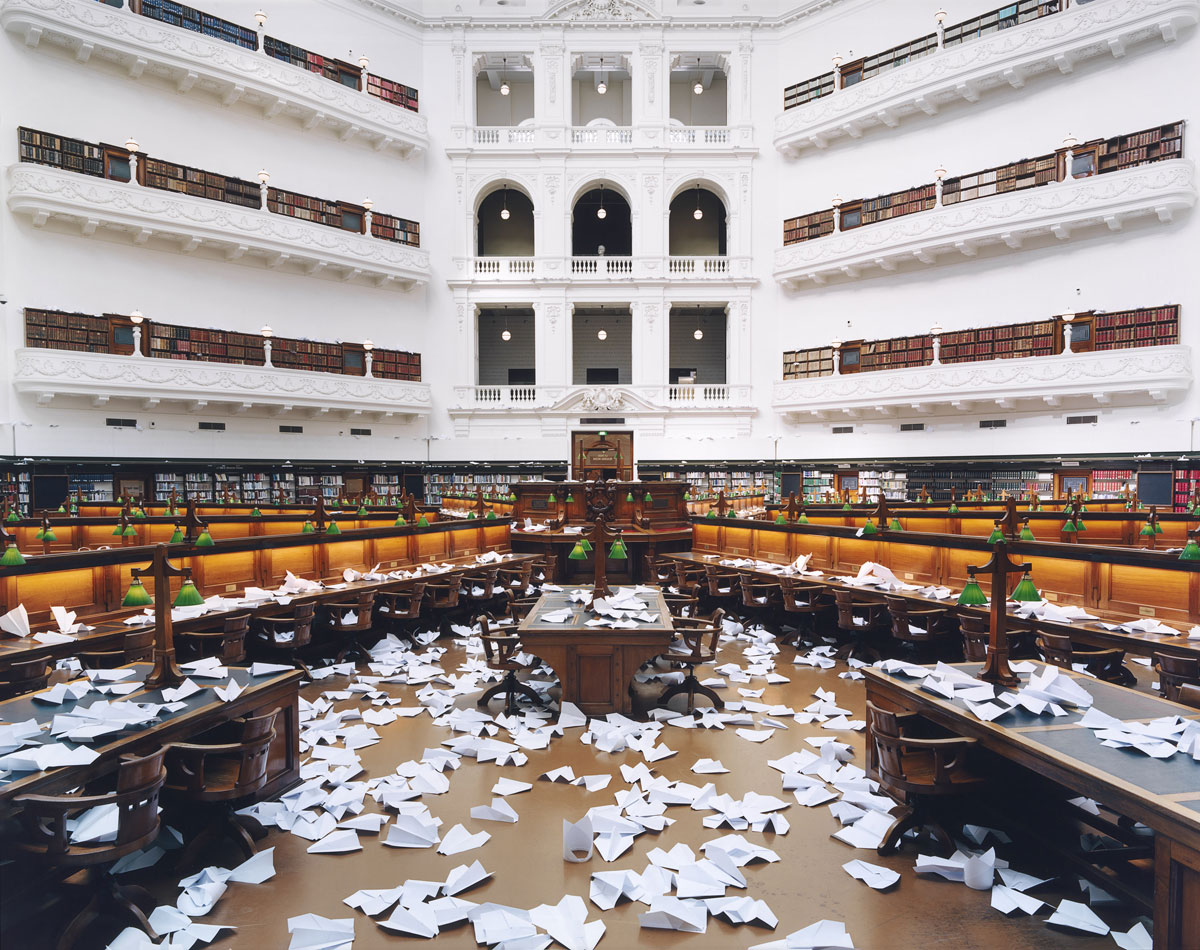

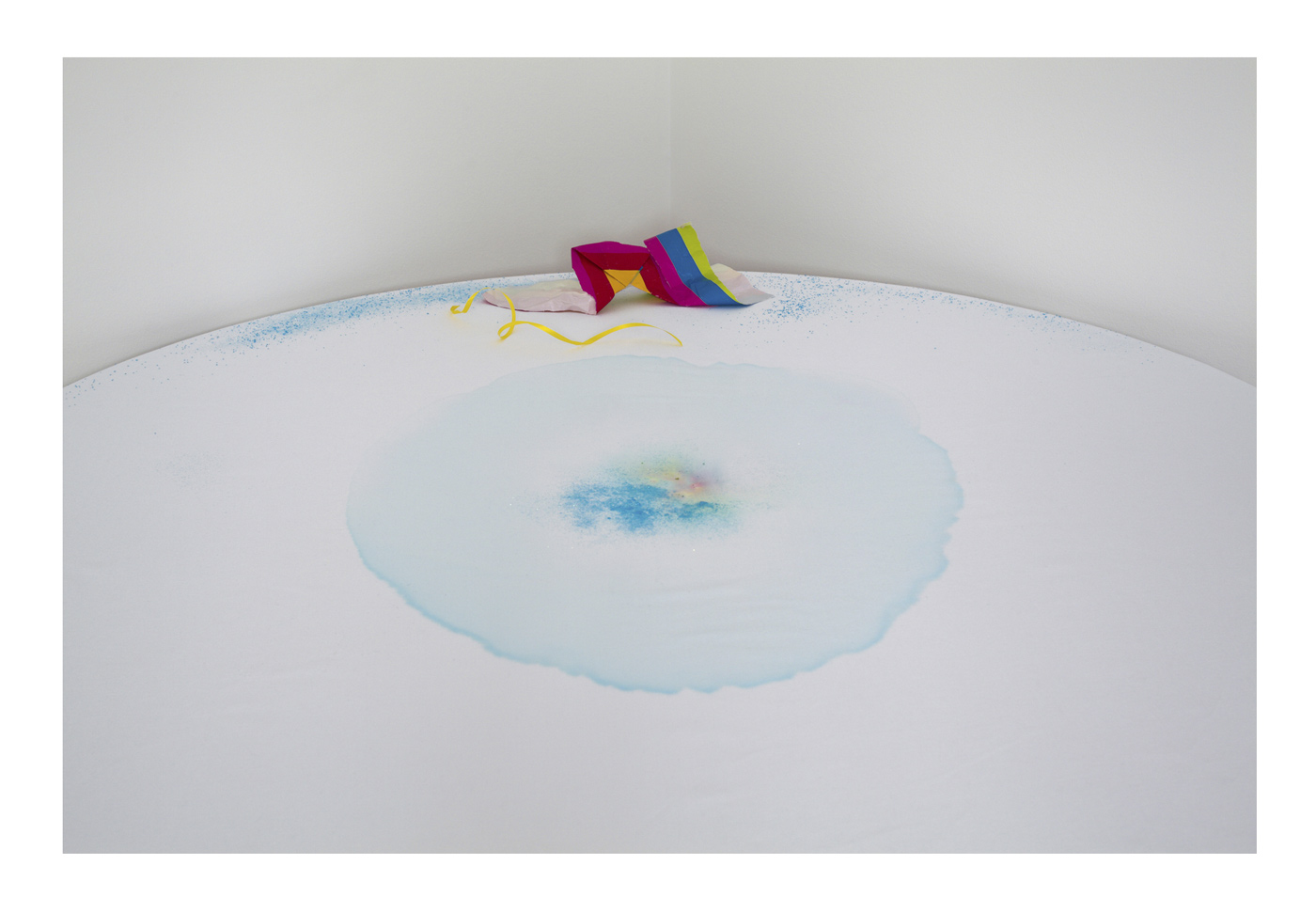

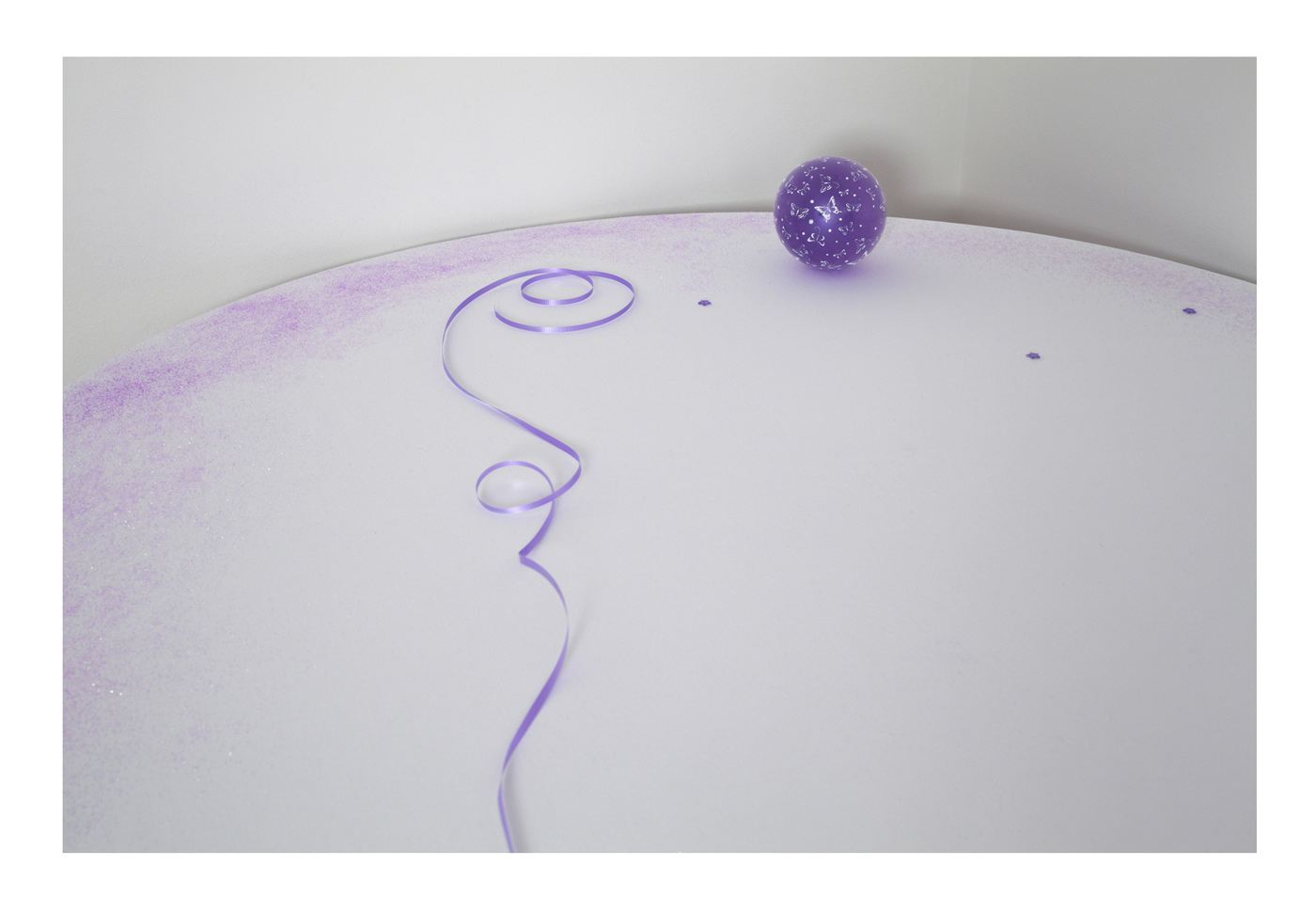

Ross Coulter (Australian, b. 1972)

10,000 paper planes – aftermath (1) (installation view)

2011

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

This is the first of a two-part posting on the huge Melbourne Now exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. The photographs in this posting are from the NGV International venue in St Kilda Road. The second part of the posting features photographs of work at NGV Australia: The Ian Potter Centre at Federation Square. Melbourne Now celebrates the latest art, architecture, design, performance and cultural practice to reflect the complex cultural landscape of creative Melbourne.

Keywords

Place, memory, anxiety, democracy, death, cultural identity, spatial relationships.

The best

Daniel Crooks An embroidery of voids 2013 video.

Highlights

Patricia Piccinini The Carrier 2012 sculpture; Mark Hilton dontworry 2013 sculpture.

Honourable mentions

Stephen Benwell Statues various dates sculpture; Rick Amor mobile call 2012 painting; Destiny Deacon and Virginia Fraser Melbourne Noir 2013 installation.

Disappointing

The weakness of the photography. With a couple of notable exceptions, I can hardly recall a memorable photographic image. Some of it was Year 12 standard.

Low points

~ The lack of visually interesting and beautiful art work – it was mostly all so ho hum in terms of pleasure for the eye

~ The preponderance of installation / design / architectural projects that took up huge areas of space with innumerable objects

~ The balance between craft, form and concept

~ Too much low-fi art

~ Too much collective art

~ Little glass art

~ Weak third floor at NGV International

~ Two terrible installations on the ground floor of NGVA

Verdict

As with any group exhibition there are highs and lows, successes and failures. Totally over this fad for participatory art spread throughout the galleries. Too much deconstructed / performance / collective design art that takes the viewer nowhere. Good effort by the NGV but the curators were, in some cases, far too clever for their own (and the exhibitions), good. 7/10

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the NGV for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. All photographs © Dr Marcus Bunyan unless otherwise stated. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Please note: All text below the images is from the guide book.

“Although the word “new” recurs like an incantation in the catalogue essays many exhibits are variations on well-worn themes. The trump cards of Melbourne Now are bulk and variety… It’s astonishing that curators still seem to assume that art which proclaims its own radicality must be intrinsically superior to more personal expressions. Yet mediocrity recognises no such distinctions. Most of this show’s avant-garde gestures are no better than clichés.”

John Macdonald. “Review of Melbourne Now,” in the Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 11 January, 2014 [Online] Cited 03/10/2022

“A rich, inspiring critical context prevails within Melbourne’s contemporary art community, reflecting the complexity of multiple situations and the engaging reality of a culture that is always in the process of becoming. Local knowledge is of course specific and resists generalisation – communities are protean things, which elide neat definition and representation. Notwithstanding the inevitable sampling and partial account which large-scale survey exhibitions unavoidably present, we hope that Melbourne Now retains a sense of semantic density, sensory intensity and conceptual complexity, harnessing the vision and energy that lie within our midst. Perhaps most importantly, the contributors to Melbourne Now highlight the countless ways in which art is able to change, alter and invigorate the senses, adding new perspectives and modes of perceiving the world in which we live.”

Max Delany. “Metro-cosmo-polis: Melbourne now” 2013

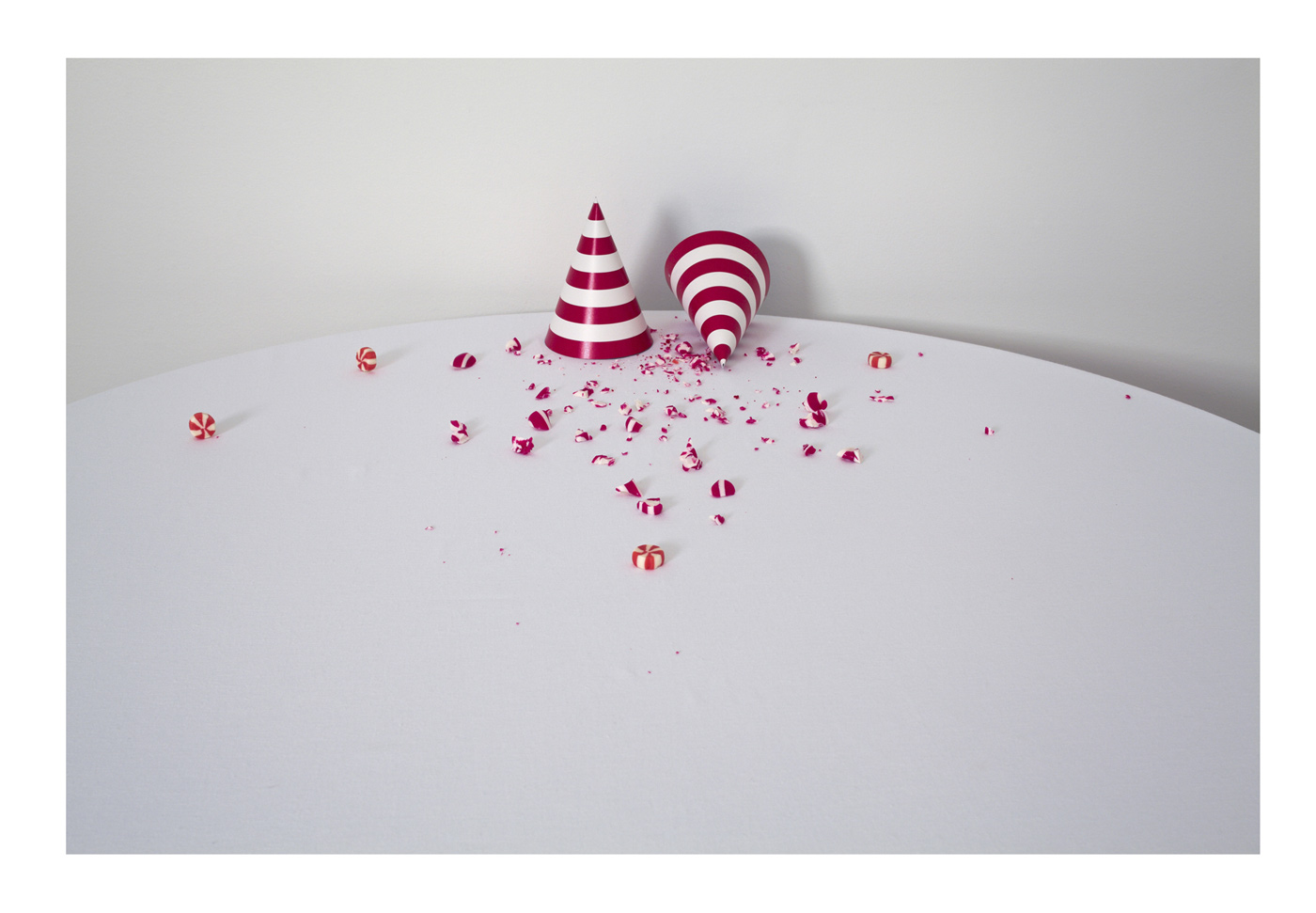

Ross Coulter (Australian, b. 1972)

10,000 paper planes – aftermath (1)

2011

Type C photograph

156 x 200cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased NGV Foundation, 2012

© Ross Coulter

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

Last photo: © National Gallery of Victoria

With 10,000 paper planes – aftermath (1), 2011, Coulter encountered Melbourne’s intellectual heart, the State Library of Victoria (SLV). Being awarded the Georges Mora Foundation Fellowship in 2010 allowed Coulter to realise a concept he had been developing since he worked at the SLV in the late 1990s. The result is a playful intervention into what is usually a serious place of contemplation. Coulter’s paper planes, launched by 165 volunteers into the volume of the Latrobe Reading Room, give physical form to the notion of ideas flying through the building and the mind. This astute work investigates the striking contrast between the strict discipline of the library space and its categorisation system and the free flow of creativity that its holdings inspire in the visitor.

Laith McGregor (Australian, b. 1977)

Pong ping paradise (installation view)

2011

Private collection, United States of America

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

The drawings OK and KO, both 2013, which decorate the horizontal surfaces of two table-tennis tables and contain four large self-portraits portraying unease and concern, are more restrained. The hirsute beards of McGregor’s earlier works have evolved into all enveloping geometric grids, their hand-drawn asymmetry creating a subtle sense of distortion that contradicts the inherently flat surface of the tables.

Rick Amor (Australian, b. 1948)

Mobile call (installation view)

2012

Private collection, Melbourne

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

Best known for his brooding urban landscapes, Amor’s work in Melbourne Now, Mobile call, 2012, stays true to this theme. The painting speaks to the heart of urban living in its depiction of a darkened city alleyway, with dim, foreboding lighting. A security camera on the wall surveys the scene, a lone, austere figure just within its watch. The camera represents the omnipresent surveillance of our modern lives, and an uneasy air of suspicion permeates the painting’s subdued, grey landscape. Amor’s reflections on the urban landscape are solemn, restrained and often melancholic. Quietly powerful, his work alludes to a mystery in the banality of daily existence. Mobile call is a realistic portrayal of a metropolitan landscape that opens our eyes to a strange and complex world.

Steaphan Paton (Australian, Gunai and Monero Nations, b. 1985)

Cloaked combat (installation view detail)

2013

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

Cloaked combat, 2013, is a visual exploration of the material and technological conflicts between cultures, and how these differences enable one culture to assert dominance over another. Five Aboriginal bark shields, customarily used in combat to deflect spears, repel psychedelic arrows shot from a foreign weapon. Fired by an unseen intruder cloaked in contemporary European camouflage, the psychedelic arrows rupture the bark shields and their diamond designs of identity and place, violating Aboriginal nationhood and traditional culture. The jarring clash of weapons not only illustrates a material conflict between these two cultures, but also suggests a deeper struggle between old and new. In its juxtaposition of prehistoric and modern technologies, Cloaked combat highlights an uneven match between Indigenous and European cultures and discloses the brutality of Australia’s colonisation.

Zoom project team

Curator: Ewan McEoin / Studio Propeller; Data visualisation: Greg More / OOM Creative; Graphic design: Matthew Angel; Exhibition design: Design Office; Sound installation: Marco Cher-Gibard; Data research: Serryn Eagleson / EDG Research; Digital survey design: Policy Booth

Zoom (installation view details)

2013

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan

Anchored around a dynamic tapestry of data by Melbourne data artist Greg More, this exhibit offers a window into the ‘system of systems’ that makes up the modern city, peeling back the layers to reveal a sea of information beneath us. Data ebbs and flows, creating patterns normally inaccessible to the naked eye. Set against this morphing data field, an analogue human survey asks the audience to guide the future design of Melbourne through choice and opinion. ZOOM proposes that every citizen influences the future of the city, and that the city in turn influences everyone within it. Accepting this co-dependent relationship empowers us all to imagine the city we want to create together.

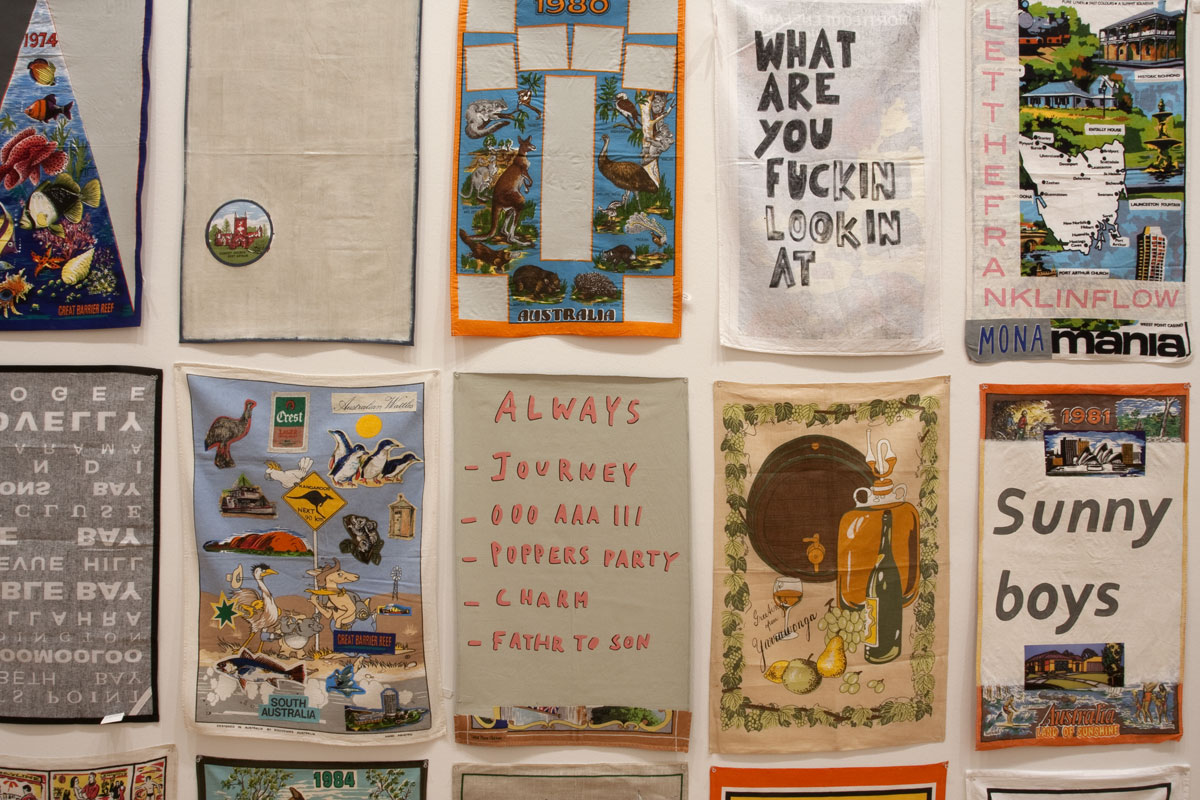

Installation view of Jon Campbell DUNNO (T. Towels) 2012 (left) and Reko Rennie Initiation, 2013 (right)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

Jon Campbell (Australian born Northern Ireland, b. 1961)

DUNNO (T. Towels) (installation view details)

2012

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan

For Melbourne Now Campbell presents DUNNO (T. Towels), 2012, a work that continues his fascination with the vernacular culture of suburban Australia. Comprising eighty-five tea towels, some in their original condition and others that Campbell has modified through the addition of ‘choice’ snippets of Australian slang and cultural signifiers, this seemingly quotidian assortment of kitsch ‘kitchenalia’ is transformed into a mock heroic frieze in which we can discover the values and dramas of our present age.

Reko Rennie (Australian, Gamilaraay (Kamilaroi) b. 1974)

Initiation (installation view)

2013

Synthetic polymer paint on plywood (1-40)

300.0 x 520.0cm (overall)

Collection of the artist

© Reko Rennie, courtesy Karen Woodbury Gallery, Melbourne

Supported by Esther and David Frenkiel

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

Initiation, 2013, a mural-scale, multi-panelled hoarding that subverts the negative stereotyping of Indigenous people living in contemporary Australian cities. This declarative, renegade installation work is a psychedelic farrago of street art, native flora and fauna, Kamilaroi patterns, X-ray images and text that addresses what it means to be an urban Aboriginal person. By yoking together contrary elements of graffiti, advertising, bling, street slogans and Kamilaroi diamond geometry, Rennie creates a monumental spectacle of resistance.

Installation view of Reko Rennie Initiation, 2013

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Janet Burchill (Australian, b. 1955)

Jennifer McCamley (Australian, b. 1957)

The Belief (installation view)

2004-2013

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

Shields from Papua New Guinea held in the National Gallery of Victoria’s collection provided an aesthetic catalyst for the artists to develop an open-ended series of their own ‘shields’. The Belief includes shields made by Burchill and McCamley between 2004 and 2013. In part, this installation meditates on the form and function of shields from the perspective of a type of reverse ethnography. As the artists explain:

“The shield is an emblematic form ghosted by the functions of attack and defence and characterised by the aggressive display of insignia … We treat the shield as a perverse type of modular unit. While working with repetition, each shield acts as a carrier or container for different types and registers of content, motifs, emblems and aesthetic strategies. The series as a whole, then, becomes a large sculptural collage which allows us to incorporate a wide range of responses to making art and being alive now.”

Janet Burchill (Australian, b. 1955)

Jennifer McCamley (Australian, b. 1957)

The Belief (detail)

2004-2013

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

Melbourne Now is an exhibition unlike any other we have mounted at the National Gallery of Victoria. It takes as its premise the idea that a city is significantly shaped by the artists, designers, architects, choreographers, intellectuals and community groups that live and work in its midst. With this in mind, we have set out to explore how Melbourne’s visual artists and creative practitioners contribute to the dynamic cultural identity of this city. The result is an exhibition that celebrates what is unique about Melbourne’s art, design and architecture communities.

When we began the process of creating Melbourne Now we envisaged using several gallery spaces within The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia; soon, however, we recognised that the number of outstanding Melbourne practitioners required us to greatly expand our commitment. Now spreading over both The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia and NGV International, Melbourne Now encompasses more than 8000 square metres of exhibition space, making it the largest single show ever presented by the Gallery.

Melbourne Now represents a new way of working for the NGV. We have adopted a collaborative curatorial approach which has seen twenty of our curators work closely with both external design curators and many other members of the NGV team. Committing to this degree of research and development has provided a great opportunity to meet with artists in their studios and to engage with colleagues across the city as a platform not only for this exhibition, but also for long-term engagement.

A primary aim throughout the planning process has been to create an exhibition that offers dynamic engagement with our audiences. From the minute visitors enter NGV International they are invited to participate through the exhibition’s Community Hall project, which offers a diverse program of performances and displays that showcase a broad concept of creativity across all art forms, from egg decorating to choral performances. Entering the galleries, visitors discover that Melbourne Now includes ambitious and exciting contemporary art and design commissions in a wide range of media by emerging and established artists. We are especially proud of the design and architectural components of this exhibition which, for the first time, place these important areas of practice in the context of a wider survey of contemporary art. We have designed the exhibition in terms of a series of curated, interconnected installations and ‘exhibitions within the exhibition’ to offer an immersive, inclusive and sometimes participatory experience.

Viewers will find many new art commissions featured as keynote projects of Melbourne Now. One special element is a series of commissions developed specifically for children and young audiences – these works encourage participatory learning for kids and families. Artistic commissions extend from the visual arts to architecture, dance and choreography to reflect Melbourne’s diverse artistic expression. Many of the new visual arts and design commissions will be acquired for the Gallery’s permanent collections, leaving the people of Victoria a lasting legacy of Melbourne Now.

The intention of this exhibition is to encourage and inspire everyone to discover some of the best of Melbourne’s culture. To help achieve this, family-friendly activities, dance and music performances, inspiring talks from creative practitioners, city walks and ephemeral installations and events make up our public programs. Whatever your creative interests, there will be a lot to learn and enjoy in Melbourne Now. Melbourne Now is a major project for the NGV which we hope will have a profound and lasting impact on our audiences, our engagement with the art communities in our city and on the NGV collection. We invite you to join us in enjoying some of the best of Melbourne’s creative art, design and architecture in this landmark exhibition.

Tony Ellwood

Director, National Gallery of Victoria

Foreword from the Melbourne Now exhibition guide book

Destiny Deacon (Australian, K’ua K’ua and Erub/Mer peoples 1957-2024)

Virginia Fraser (Australian)

Melbourne Noir (installation view details)

2013

Installation comprising photography, video, sculptural diorama dimensions (variable) (installation)

Collection of the artists

© Destiny Deacon and Virginia Fraser, courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan

Adapting the quotidian formats of snapshot photography, home videos, community TV and performance modes drawn from vaudeville and minstrel shows, Deacon’s artistic practice is marked by a wicked yet melancholy comedic and satirical disposition. In decidedly lo-fi vignettes, friends, family and members of Melbourne’s Indigenous community appear in mischievous narratives that amplify and deconstruct stereotypes of Indigenous identity and national history. For Melbourne Now, Deacon and Fraser present a trailer for a film noir that does not exist, a suite of photographs and a carnivalesque diorama. The pair’s playful political critiques underscore a prevailing sense of postcolonial unease, while connecting their work to wider global discourses concerned with racial struggle and cultural identity.

Darren Sylvester (Australian, b. 1974)

For you (installation view details)

2013

Based on Yves Saint Laurent Les Essentials rouge pur couture, La laque couture and Rouge pur couture range revolution lipsticks, Marrakesh sunset palette, Palette city drive, Ombres 5 lumiéres, Pure chromatic eyeshadows and Blush radiance

Illuminated dance floor, sound system

605 x 1500 x 198cm

Supported by VicHealth; assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan

For Melbourne Now Sylvester presents For you, 2013, an illuminated dance floor utilising the current palette of colours of an international make-up brand. By tapping into commonly felt fears of embarrassment and the desire to show off in front of others, For you provides a gentle push onto a dance floor flush in colours already proven by market research to appear flattering on the widest cross-section of people. It is a work that plays on viewers’ vanity while acting as their support. In Sylvester’s own words, this work ‘will make you look good whilst enjoying it. It is for you’.

Assembling over 250 outstanding commissions, acquired and loaned works and installations, Melbourne Now explores the idea that a city is significantly shaped by the artists, designers and architects who live and work in its midst. It reflects the complexity of Melbourne and its unique and dynamic cultural identity, considering a diverse range of creative practice as well as the cross-disciplinary work occurring in Melbourne today.

Melbourne Now is an ambitious project that represents a new direction for the National Gallery of Victoria in terms of its scope and its relationship with audiences. Drawing on the talents of more than 400 artists and designers from across a wide variety of art forms, Melbourne Now will offer an experience unprecedented in this city; from video, sound and light installations, to interactive community exhibitions and artworks, to gallery spaces housing working design and architectural practices. The exhibition will be an immersive, inclusive and participatory exhibition experience, providing a rich and compelling insight into Melbourne’s art, design and cultural practice at this moment. Melbourne Now aims to engage and reflect the inspiring range of activities that drive contemporary art and creative practice in Melbourne, and is the first of many steps to activate new models of art and interdisciplinary exhibition practice and participatory modes of audience engagement at the NGV.

The collaborative curatorial structure of Melbourne Now has seen more than twenty NGV curators working across disciplinary and departmental areas in collaboration with exhibition designers, public programs and education departments, among others. The project also involves a number of guest curators contributing to specific contexts, including architecture and design, performance and sound, as well as artist-curators invited to create ‘exhibitions within the exhibition’, develop off-site projects and to work with the NGV’s collection. Examples of these include Sampling the City: Architecture in Melbourne Now, curated by Fleur Watson; Drawing Now, curated by artist John Nixon, bringing together the work of forty-two artists; ZOOM, an immersive data visualisation of cultural demographics related to the future of the city, convened by Ewan McEoin; Melbourne Design Now, which explores creative intelligence in the fields of industrial, product, furniture and object design, curated by Simone LeAmon; and un Retrospective, curated by un Magazine. Other special projects present recent developments in jewellery design, choreography and sound.

Numerous special projects have been developed by NGV curators, including Designer Thinking, focusing on the culture of bespoke fashion design studios in Melbourne, and a suite of new commissions and works by Indigenous artists from across Victoria which reflect upon the history and legacies of colonial and postcolonial Melbourne. The NGV collection is also the subject of artistic reflection, reinterpretation and repositioning, with artists Arlo Mountford, Patrick Pound and The Telepathy Project and design practice MaterialByProduct bringing new insights to it through a suite of exhibitions, videos and performative installations.

In our Community Hall we will be hosting 600 events over the four months of Melbourne Now offering a daily rotating program of free workshops, talks, catwalks and show’n’tells run by leaders in their fields. And over summer, the NGV will present a range of programs and events, including a Children’s Festival, dance program, late-night music events and unique food and beverage offerings.

The exhibition covers 8000 square metres of space, covering much of the two campuses of the National Gallery of Victoria, and moves into the streets of Melbourne with initiatives such as the Flags for Melbourne project, ALLOURWALLS at Hosier Lane, walking and bike tours, open studios and other programs that will help to connect the wider community with the creative riches that Melbourne has to offer.

Melbourne Now Introduction

Alan Constable (Australian, b. 1956)

No title (teal SLR with flash)

2013

Earthenware

15.5 x 24 x 11cm

Collection of the artist

© Alan Constable, courtesy Arts Project Australia, Melbourne

Photo: © National Gallery of Victoria

A camera’s ability to act as an extension of our eyes and to capture and preserve images renders it a potent instrument. In the case of Constable, this power has particular resonance and added poignancy. The artist lives with profound vision impairment and his compelling, hand-modelled ceramic reinterpretations of the camera – itself sometimes referred to as the ‘invented eye’ – possess an altogether more moving presence. For Melbourne Now, Constable has created a special group of his very personal cameras.

Linda Marrinon (Australian, b. 1959)

Installation view of works including Debutante (centre)

2009

Tinted plaster, muslin

Collection of the artist

© Linda Marrinon, courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Supported by Fiona and Sidney Myer AM, Yulgilbar Foundation and the Myer Foundation

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

Marrinon’s art lingers romantically somewhere between the past and present. Her figures engage with notions of formal classical sculpture, with references to Hellenistic and Roman periods, yet remain quietly contemporary in their poise, scale, adornments and subject matter. Each work has a sophisticated and nonchalant air of awareness, as if posing for the audience. Informed by feminism and a keen sense of humour, Marrinon’s work is anti-heroic and anti-monumental. The figures featured in Melbourne Now range from two young siblings, Twins with skipping rope, New York, 1973, 2013, and a young woman, Debutante, 2009, to a soldier, Patriot in uniform, 2013, presented as a pantheon of unlikely types.

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Vox: Beyond Tasmania (installation view)

2013

Wood, cardboard, paper, books, colour slides, glass slides, 8mm film, glass, stone, plastic, bone, gelatin silver photographs, metal, feather

267 x 370 x 271cm

Collection of the artist

© Brook Andrew, courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Photo: © National Gallery of Victoria

Andrew’s Vox: Beyond Tasmania, 2013, renders palpable as contemporary art a central preoccupation of his humanist practice – the legacy of historical trauma on the present. Inspired by a rare volume of drawings of fifty-two Tasmanian Aboriginal crania, Andrew has created a vast wunderkammer containing a severed human skeleton, anthropological literature and artefacts. The focal point of this assemblage of decontextualised exotica is a skull, which lays bare the practice of desecrating sacred burial sites in order to snatch Aboriginal skeletal remains as scientific trophies, amassed as specimens to be studied in support of taxonomic theories of evolution and eugenics. Andrew’s profound and humbling memorial to genocide was supported in its first presentation by fifty-two portraits and a commissioned requiem by composer Stéphanie Kabanyana Kanyandekwe.

Brook Andrew (Australian, b. 1970)

Vox: Beyond Tasmania (details)

2013

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan

Daniel Crooks (New Zealand, b. 1973)

An embroidery of voids (stills)

2013

Colour single-channel digital video, sound, looped

Collection of the artist

© Daniel Crooks, courtesy Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne and Sydney

Supported by Julie, Michael and Silvia Kantor

Photos: © National Gallery of Victoria

Commissioned for Melbourne Now, Crooks’s most recent video work focuses his ‘time-slice’ treatment on the city’s famous laneways. As the camera traces a direct, Hamiltonian pathway through these lanes, familiar surroundings are captured in seamless temporal shifts. Cobblestones, signs, concrete, street art, shadows and people gracefully pan, stretch and distort across our vision, swept up in what the artist describes as a ‘dance of energy’. Exposing the underlying kinetic rhythm of all we see, Crooks’s work highlights each moment once, gloriously, before moving on, always forward, transforming Melbourne’s gritty and often inhospitable laneways into hypnotic and alluring sites.

Jan Senbergs (Australian, 1939-2024)

Extended Melbourne labyrinth

2013

Oil stick, synthetic polymer paint wash (1-4)

158 x 120cm (each)

Collection of the artist

© Jan Senbergs, courtesy Niagara Galleries

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

Senbergs’s significance as a contemporary artist and his understanding of the places he depicts and their meanings make his contribution to Melbourne Now essential. Drawing inspiration from Scottish poet Edwin Muir’s collection The labyrinth (1949), Senbergs’s Extended Melbourne labyrinth, 2013, takes us on a journey through the myriad streets and topography that make up our sprawling city. His characteristic graphic style and closely cropped rendering of the city’s urban thoroughfares is at once enthralling and unsettling. While the artist neither overtly celebrates nor condemns his subject, there is a strong sense of Muir’s ‘roads that run and run and never reach an end’.

Patrick Pound (Australian, b. 1962)

The gallery of air (installation view details)

2013

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan

For Melbourne Now Pound has created The gallery of air, 2013, a contemporary wunderkammer of works of art and objects from across the range of the NGV collection. There are Old Master paintings depicting the effect of the wind, and everything from an exquisite painted fan to an ancient flute and photographs of a woman sighing. When taken as a group these disparate objects hold the idea of air. Added to works from the Gallery’s collection is an intriguing array of objects and pictures from Pound’s personal collection. On entering his installation, visitors will be drawn into a game of thinking and rethinking about the significance of the objects and how they might be activated by air. Some are obvious, some are obscure, but all are interesting.

Marco Fusinato (Australian, b. 1964)

Aetheric plexus (Broken X) (installation view)

2013

Alloy tubing, lights, double couplers, Lanbox LCM DMX controller, dimmer rack, DMX MP3 player, powered speaker, sensor, extension leads, shot bags

880 x 410 x 230cm

Collection of the artist

© Marco Fusinato, courtesy Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne and Sydney

Supported by Joan Clemenger and Peter Clemenger AM

Photo: © National Gallery of Victoria

For Melbourne Now, Fusinato presents Aetheric plexus (Broken X), 2013, a dispersed sculpture comprising deconstructed stage equipment that is activated by the presence of the viewer, triggering a sensory onslaught with a resonating orphic haze. The work responds to the wider context of galleries, in the artist’s words, ‘changing from places of reflection to palaces of entertainment’ by turning the engulfed audience member into a spectacle.

Installation view of Susan Jacobs Wood flour for pig iron (vessel for mixing metaphors) 2013 with Mark Hilton dontworry 2013 in the background

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

In her most recent project, Jacobs fabricates a rudimentary version of the material Hemacite (also known as Bois Durci) – made from the blood of slaughtered animals and wood flour – which originated in the late nineteenth century and was moulded with hydraulic pressure and heat to form everyday objects, such as handles, buttons and small domestic and decorative items. The attempt to re-create this outmoded material highlights philosophical, economic and ethical implications of manufacturing and considers how elemental materials are reconstituted. Wood flour for pig iron (vessel for mixing metaphors), 2013, included in Melbourne Now, explores properties, physical forces and processes disparately linked across various periods of history.

Mark Hilton (Australian, b. 1976)

dontworry (installation view)

2013

Cast resin, powder

The Michael Buxton Collection, Melbourne

© Mark Hilton, courtesy Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © National Gallery of Victoria

dontworry, 2013, included in Melbourne Now, is the most ambitious and personal work Hilton has made to date. A dark representation of events the artist witnessed growing up in suburban Melbourne, this wall-based installation presents an unnerving picture of adolescent mayhem and bad behaviour. Extending across nine intricately detailed panels, each corresponding to a formative event in the artist’s life, dontworry can be understood as a deeply personal memoir that explores the transition from childhood to adulthood, and all the complications of this experience. Detailing moments of violence committed by groups or mobs of people, the installation revolves around Hilton’s continuing fascination with the often indistinguishable divide between truth and myth.

Mark Hilton (Australian, b. 1976)

dontworry (installation view details)

2013

Cast resin, powder

The Michael Buxton Collection, Melbourne

© Mark Hilton, courtesy Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan

NGV International

180 St Kilda Road

Opening hours

Daily 10am – 5pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.