August 2011

MONA exterior, Hobart

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

“Lyotard writes,”We must not begin with transgression, we must immediately go to the very end of cruelty, construct the anatomy of polymorphous perversion, unfold the immense membrane of the libidinal ‘body,’ which is quite the inverse of a system of parts.” Lyotard sees this “membrane” as composed of the most heterogeneous items: human bone and writing paper, steel and glass, syntax and the skin on the inside of the thigh. In the libidinal economy, writes Lyotard: “All of these zones are butted end to end … on a Moebius strip … a moebian skin [an] interminable band of variable geometry (a concavity is necessarily a convexity at the next turn) [with but] a single face, and therefore neither exterior nor interior.”

Jean-François Lyotard quoted in Victor Burgin. In/Different Spaces 1

“Taking a walk is also an extremely immediate form of experience. Serge Daney describes the act of perception while taking a walk: ‘Because I am not particularly fond of bravura pieces, I always need a transition from one thing to the next. And I am glad that I can find it through by body and experience of walking…’

The visual memory of the walker / viewer determines the sequence of the pictures. Since the 1960s Marcel Broodthaers has defined the exhibition as a cinematic sequence of pictures and objects, thereby subverting the fixity of the single object through recontextualisation.”

Serge Daney quoted in Hans Obrist. “In the Midst of Things, At the Centre of Nothing.”2

Libidinal, Moebic MONA

My analogy: you are standing in the half-dark, your chest open, squeezing the beating heart with blood coursing between your fingers while the other hand is up your backside playing with your prostrate gland. I think ringmeister David Walsh would approve.

My best friends analogy: a cross between a car park, night club, sex sauna and art gallery.

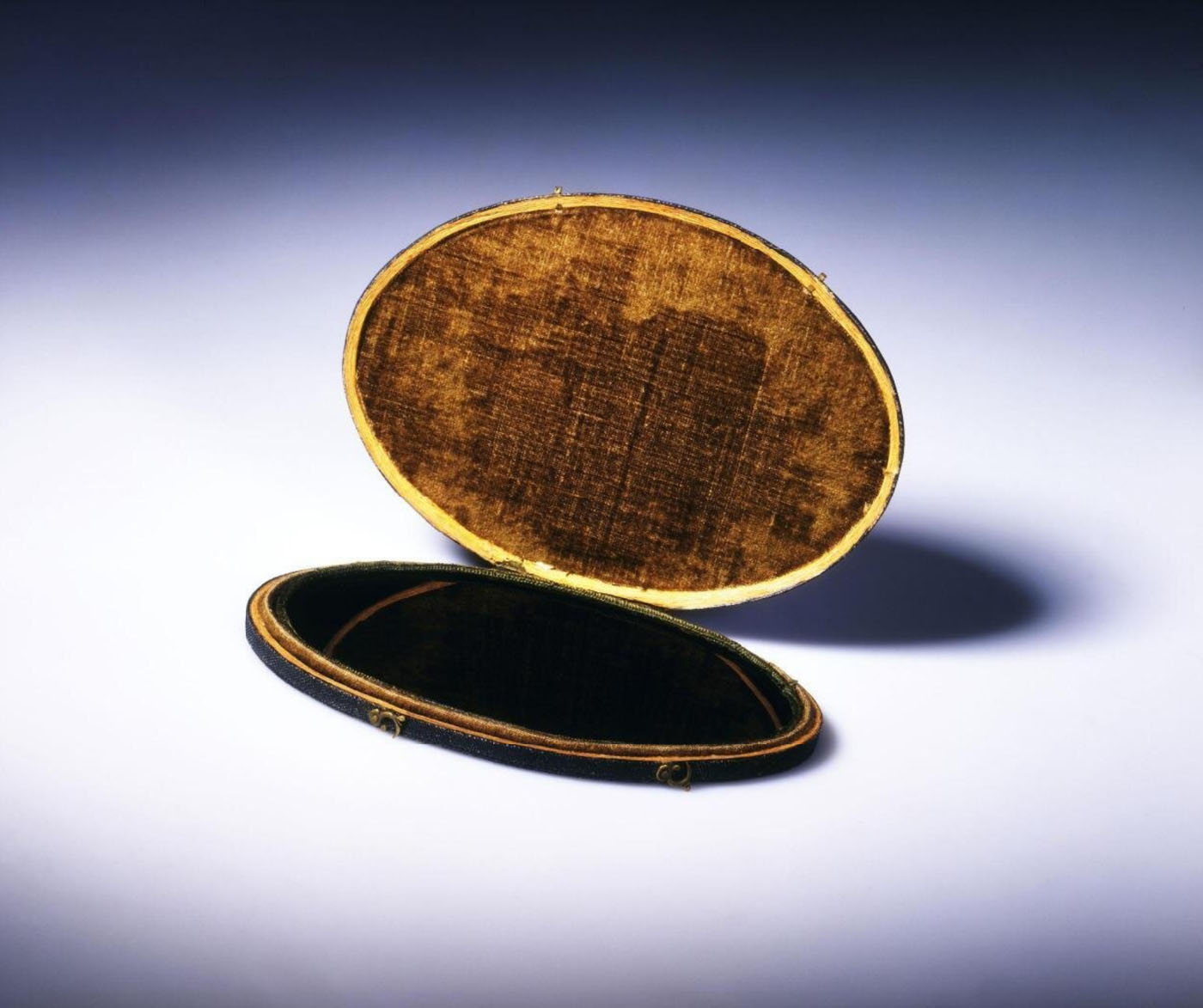

Weeks later I am still thinking about the wonderful immersive, sensory experience that is MONA. Peter Timms in an insightful article in Meanjin calls it a post-Google Wunderkammer, or wonder chest.3 It can be seen as a mirabilia – a non-historic installation designed primarily to delight, surprise and in this case shock. The body, sex, death and mortality are hot topics in the cultural arena4 and Walsh’s collection covers all bases. The collection and its display are variously hedonistic, voyeuristic, narcissistic, fetishistic pieces of theatre subsumed within the body of the spectacular museum architecture.

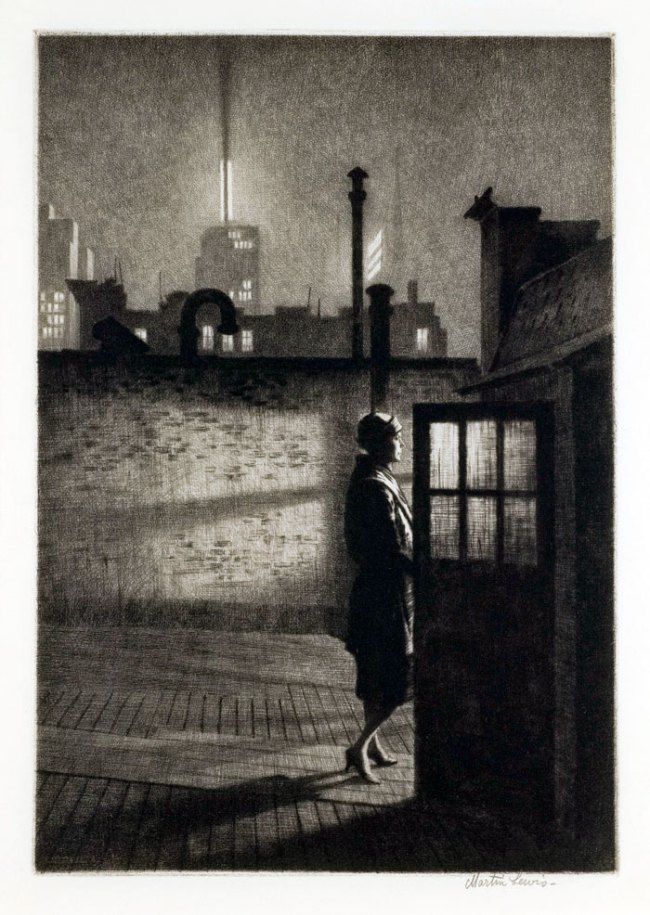

The experience starts with the ferry ride from the wharf in Hobart to the museum – the only way to arrive. During the 20 minutes of the journey mental baggage seems to drop away as you look over the water to the industrial zinc works, pass under bridges and then the museum comes into view. Perched on a promontory of land the museum rises like a rusted ancient temple. After disembarking you climb a colossal staircase to the entrance of the museum, all angles and mirrored surfaces. You enter one of two Roy Grounds listed modernist buildings built in the 1950s – beautiful, crisp white spaces that house the shop and a cafe, cloakroom and inquiry desk where you collect your ‘O’, an iPhone-like device that tracks all the artworks that you look at. The are no didactic text panels in the museum freeing the viewer to just experience, all data such as artists names and educational information and the tit-bit Gonzo text being accessed through the ‘O’. Into the large enclosed forecourt space a spiral staircase with a circular lift in the centre descends into the abyss (an inspired piece of design) and your journey proper has begun. Three levels deep into the ground you travel, the space carved out of solid rock. Impressive.

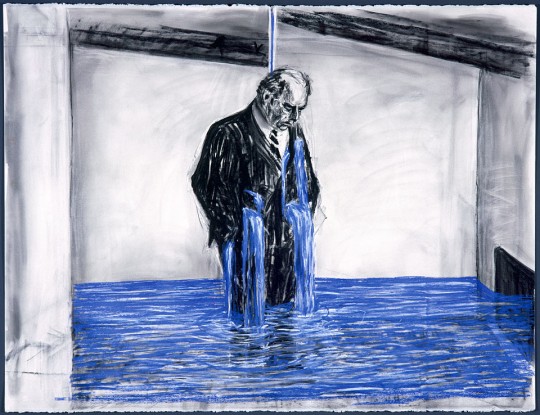

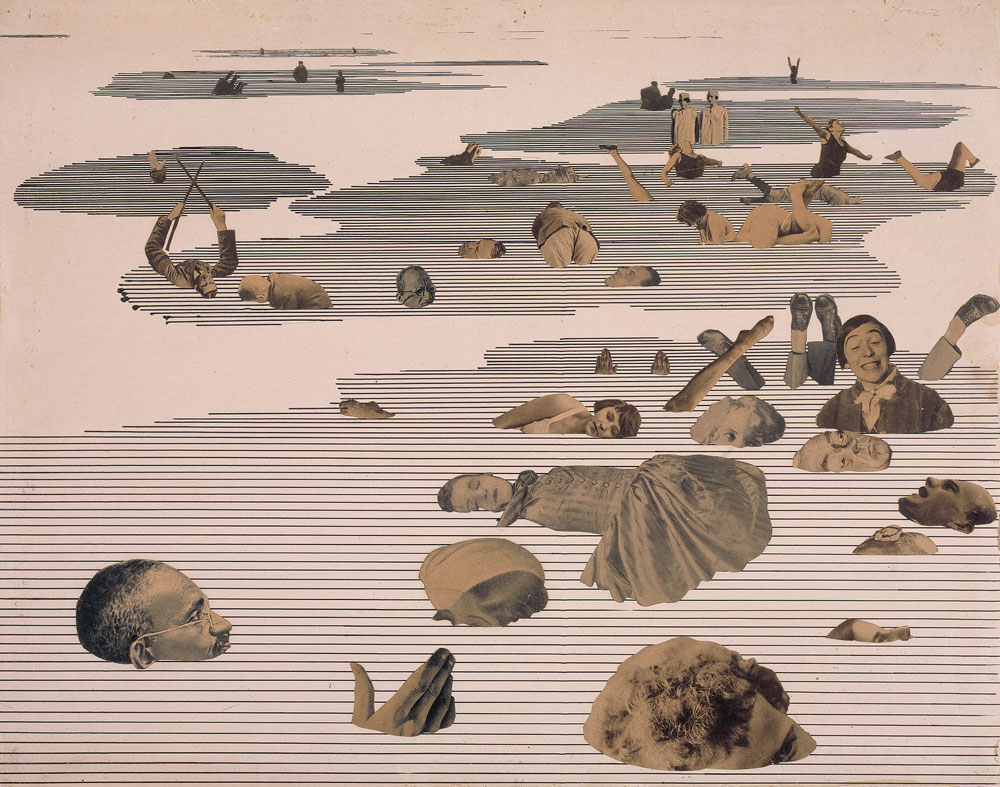

The museum is the body and the artworks are the organs, fragments of the whole exhibition (that of the actual museum). The experience is very kinaesthetic as the body gets lost within the space of the gallery. We wandered like flâneur among the darkened, cinema-like spaces, almost floating from one area to the next, discovering, feeling disorientated, following underground passages, tunnels and stairs, emerging into light and then descending into the abyss again. Hours passed. Like a Moebius strip there seemed to be no interior/exterior to the body. As Lyotard notes the membrane of the libidinal ‘body’ is composed of the most heterogeneous items: here was rock, steel, shit, bestiality, intestines, brain, touch, burial etc… the curating of the collection within the space “creating a safe space for the appreciation and consideration of seemingly extreme and subversive practices.”5

Into this space of controlled transgression, the carnivalesque mise-en-scène allow the artists to delve into the deeper and darker areas of the human condition: “as Anthony Everitt once said of Damien Hirst [to] ‘open up paths for the viewer into areas of experience which are not anti-moral or amoral but extra-moral… a world where bad taste is driven to the point of elegance and disgust is filtered into delight’.”6

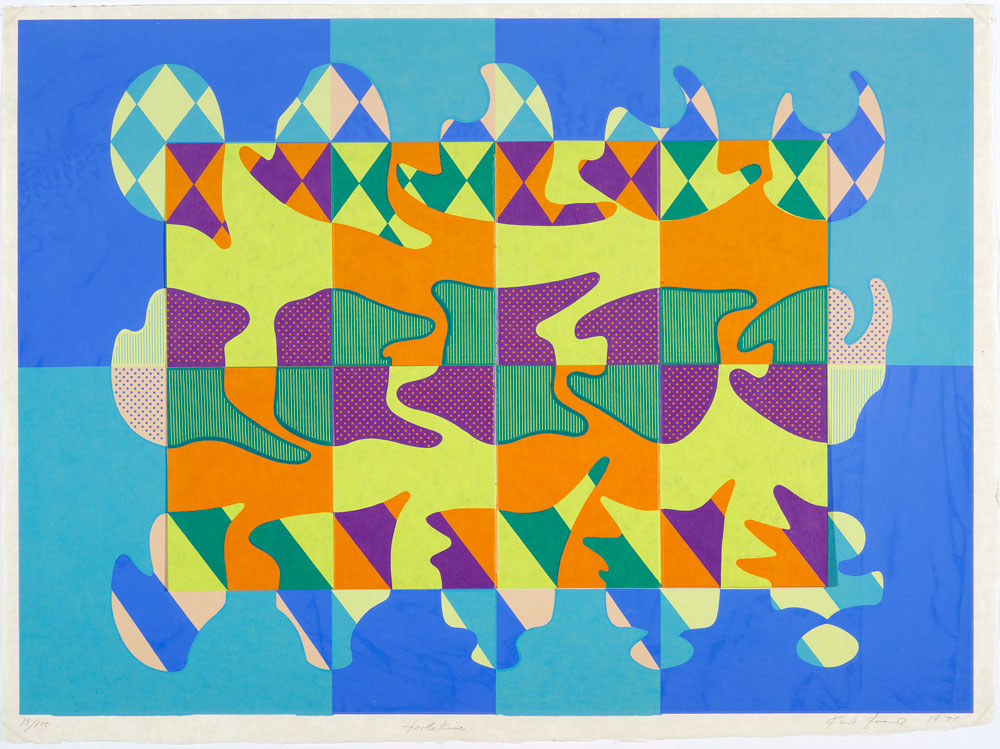

While some of the works were spotlit in the darkened galleries, “this dramatic lighting working to decontextualise the art objects, evoking a crepuscular and “timeless” sense of space, out of which the individual pieces emerged,”7 there also seemed to be an affinity between the building itself and the artworks (relating to the concept of affinity in museum curation). The diversity of installation techniques made an acknowledgement of the institutionalising processes part of the viewer’s experience of the show, disrupting a unified, totalising presentation of these objects and their cultures as “exhibition.”8 The intertextual tableaux mixed a Damien Hirst spin painting with Egyptian sculpture, ancient artefacts with Fat Cars. The context of the objects and their relationship to each other and the architecture is how the works are “framed.” This device emphasises the aesthetic rather than information and encourages the viewer to think about the relationship between the artefacts, objects and contemporary works. These inventive arrangements create a meta-narrative that offers the possibility of multiple interpretations to the viewer, multiple truths. All of this undertaken as the body moves through the spaces of the gallery and gets “lost”. As Norman Bryson has observed, “Architecture is sensed primarily through the eye and through bodily movement, and these sensations also play a key role in the way in which the contents of museums make their impact.”9

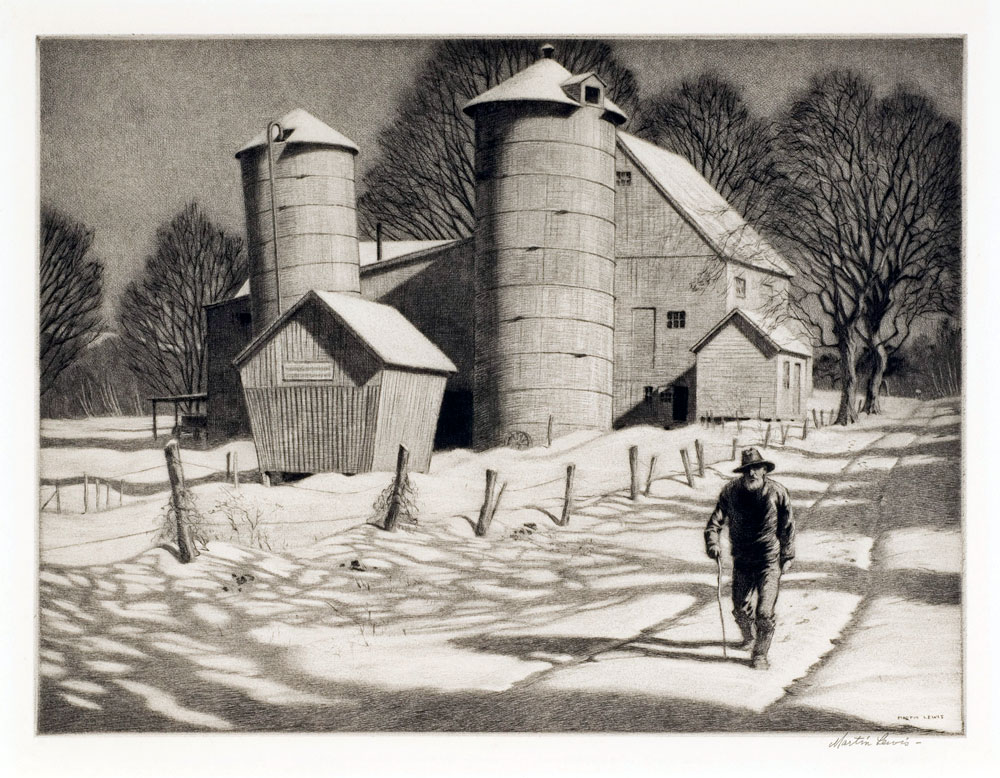

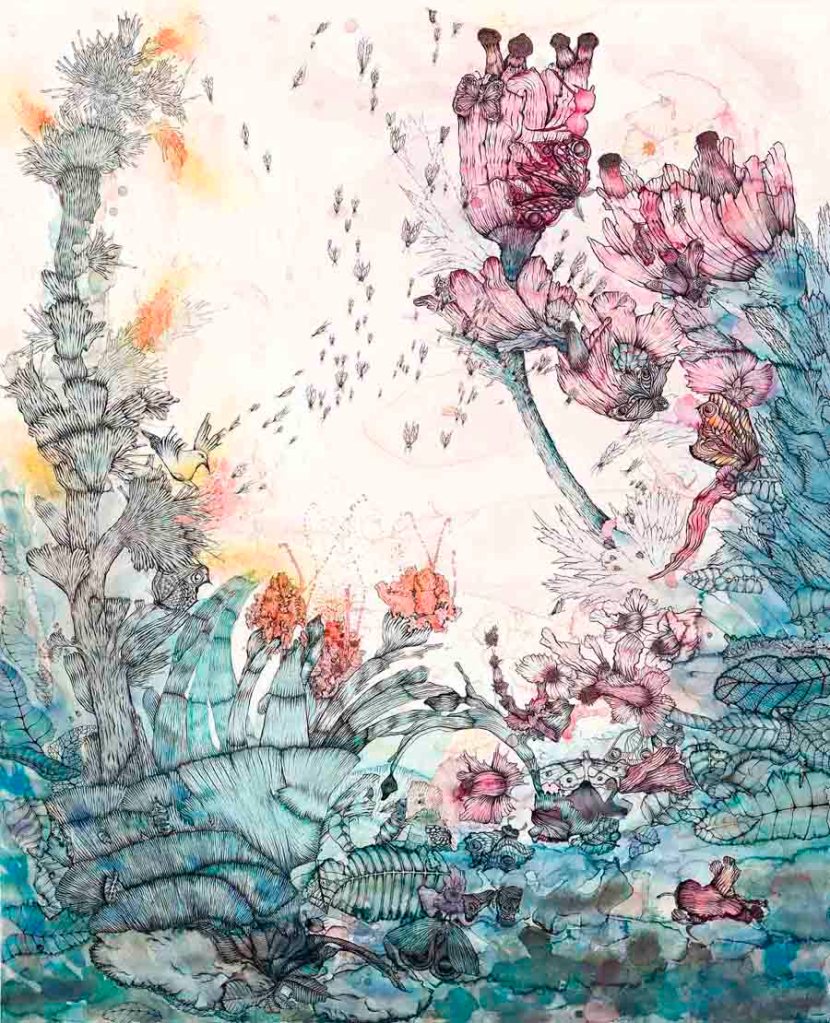

While the items are not explicitly related in terms of subject, medium or style through unexpected confrontation the works spring to dissonant life. Most of the time. When this process doesn’t work the viewer is left a little flat feeling, and…. so? wandering from piece to piece becoming slightly disenchanted. Little of the work at MONA took me to new spaces; in fact some of it was pretty mediocre, including the very dated Sir Sidney Nolan Snake (1970 to 1972, see below) that is permanent ‘wallpaper’ and takes up a whole, beautiful gallery wall. The tri-screen video by Russian collective AES+F, the works by Anselm Kiefer and the ancient artefacts (most of all) were notable exceptions. The museum is not a place for prolonged concentration and contemplation. This is not really the point of the place. The whole museum is a sensory, immersive surprising experience that cannot be broken down to its parts. David Walsh’s collection does tick all the fashionable boxes: here a Juan Davila, there a Del Kathyrn Barton, now a Howard Arkeley as though his buyers have advised him on just what to buy, but it is his personal vision, his collection. You can’t argue with that.

On of the problems of lumping all of these works together is obvious: “Ancient objects whose meaning is lost to us, medieval utensils, Christian religious images, and art objects made by modern masters were reduced to one meaning – stylistic resemblances providing evidence of the essential nature of humanity.”10 In other words a return to the globalising view of humanity evidenced by Edward Steichen’s MoMA world touring photographic exhibition of the 1950s The Family of Man. Conversely, when this strategy works well it promotes for the viewer different modes and levels of ‘interpretation’ through subtle juxtaposition of ‘experience’. As Emma Barker has observed, “we still need a curator to stimulate readings of the collection and to establish those ‘climatic zones’ which can enrich our appreciation and understanding of art… Our aim must be to generate a condition in which visitors can experience a sense of discovery in looking at particular paintings, sculptures or installations in a particular room at a particular moment, rather than find themselves standing on the conveyer belt of history.”11 Within this plastic space experience is paramount, allowing the viewer to develop their own reading without relying on the curatorial interpretation of history, setting new parameters for the relationship between viewer and object. As Barker notes such juxtapositions are a more natural strategy for a private collector than for a museum curator, with exhibitions and displays according to this dialectical principle happening with more frequency.12 The museum looses its fundamental didactic, educational purpose.

Other problems may also become evident. In a museum whose spectacular architecture was specifically designed for David Walsh’s collection it will be interesting to see how outside, touring exhibitions (such as the recently installed Experimenta Utopia Now exhibition) display in the space, especially given the psychosexual nature of his collection and its relationship to the building. If the quality of the temporary exhibitions is overwhelmed by the architecture, if the labyrinthine, enigmatic and layered nature of the space (all those floating bridges and the huge Void that can be seen in the photographs below) engulfs lesser works then it may well fall very flat.

At the end of the day we emerged into the afternoon light, expelled from the museum in a tidal wave of humanity, exhausted, satiated. Where else in Australia could you spend all day at a museum and not have seen enough? On flying home you can log into the MONA website to retrieve your ‘O’ tour, to see what art you liked and what you didn’t; what pieces you saw and all those that somehow you missed! The physical and its remembrance transported into the virtual.

Since Laura Mulvey’s essay of 1974 “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” we have been aware of the voyeuristic and fetishistic character of our psychosexual relation to cinema. Engulfed in the dark cube, that psychosexual panorama, the cinematic labyrinth that is MONA has the viewer absenting themselves in front of the art in favour of the Eye and the Spectator.13 Spectatorship and their attendant erotics has MONA as a form of fetishistic cinema. It is as if what Barthes calls “the eroticism of place” were a modern equivalent of the eighteenth century genius loci, the “genius of the place.”

The place is spectacular, the private collection writ large as public institution, the symbolic power of the institution masked through its edifice. The art become autonomous, cut free from its cultural associations, transnational, globalised, experienced through kinaesthetic means; the viewer meandering through the galleries, the anti-museum, as an international flaneur. Go. Experience!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Lyotard, Jean-François. Économie Libidinale. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1974, pp. 10-11 quoted in Burgin, Victor. In/Different Spaces: Place and Memory in Visual Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995, p. 150

2/ Obrist, Hans Ulrich. “In the Midst of Things at the Center of Nothing,” in Harding, Anna (ed.,). Curating: The Contemporary Museum and Beyond, (Art & Design Magazine Profile No. 52), London: A.D., 1997, p. 88

3/ Timms, Peter. “A Post-google Wunderkammer: Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art Redefines the Genre,” in Meanjin, Vol. 70, No. 2, Winter 2011. pp. 31-39

4/ Keidan, Lois. “Showtime: Curating Live Art in the 90s,” in Harding, Anna (ed.,). Curating: The Contemporary Museum and Beyond, (Art & Design Magazine Profile No. 52), London: A.D., 1997, p. 41

5/ Ibid., p. 41

6/ Ibid., p. 41

7/ Staniszewski, Mary Anne. The power of display: a history of exhibition installations at the Museum of Modern Art. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1998, p. 84

8/ Ibid., p. 97

9/ Bryson, Norman. “A Walk for a Walk’s Sake,” in De Zegher, Catherine (ed.,). The Stage of Drawing: Gesture and Act. London: Tate, 2003, pp. 149-58.

10/ Staniszewski, op. cit. p. 129

11/ Barker, Emma. “Exhibiting the Canon: The Blockbuster Show,” in Barker, Emma (ed.,). Contemporary Cultures of Display. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999, p. 55

12/ Ibid., p. 45

13/ O’Neill, Paul. “The Curatorial Turn: From Practice to Discourse,” in Rugg, Judith and Sedgwick, Michèle (eds.,). Issues in Curating Contemporary Art and Performance. Bristol: Intellect, 2007, pp. 13-28

Many thankx to Delia Nicholls for all her help and to MONA for allowing me to publish most of the photographs in the posting (all except the top two and the one of us inside Babylonia that were taken by Fredrick White). Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

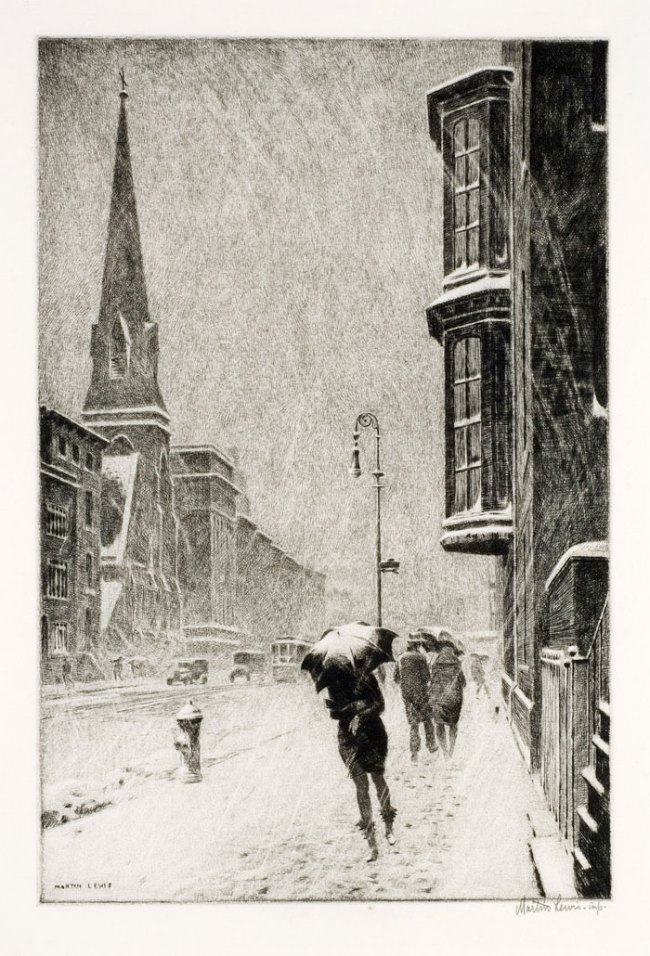

Zinc works from the ferry on the way to MONA

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

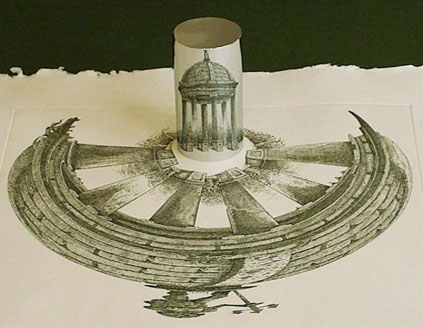

3d schematic from the O, showing the levels and nodes indicating art works visited, MONA

The Void

February 2011

Museum of Old and New Art – interior

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

B1 walkway overlooking The Void

February 2011

Museum of Old and New Art – interior

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

Loop System Quintet/Untitled (stool for guard)

Left:

Taiyo Kimura (Japanese, b. 1970)

Untitled (stool for guard)

2007

Mixed media, clothes, cd player, speaker

Right:

Conrad Shawcross (English, b. 1977)

Loop System Quintet

2005

Waxed machined oak, five light bulbs, electric motor and gearbox, drive shafts, cogs, universal joints, flange units, screws, bolts, nuts, washers

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

Callum Morton (Australian born Canada, b. 1965)

Babylonia

2005

Wood, polystyrene, epoxy resin, acrylic paint, light, carpet, mirror and sound

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

Sculptor Fredrick White and Marcus Bunyan inside Callum Morton’s Babylonia wearing the ‘O’

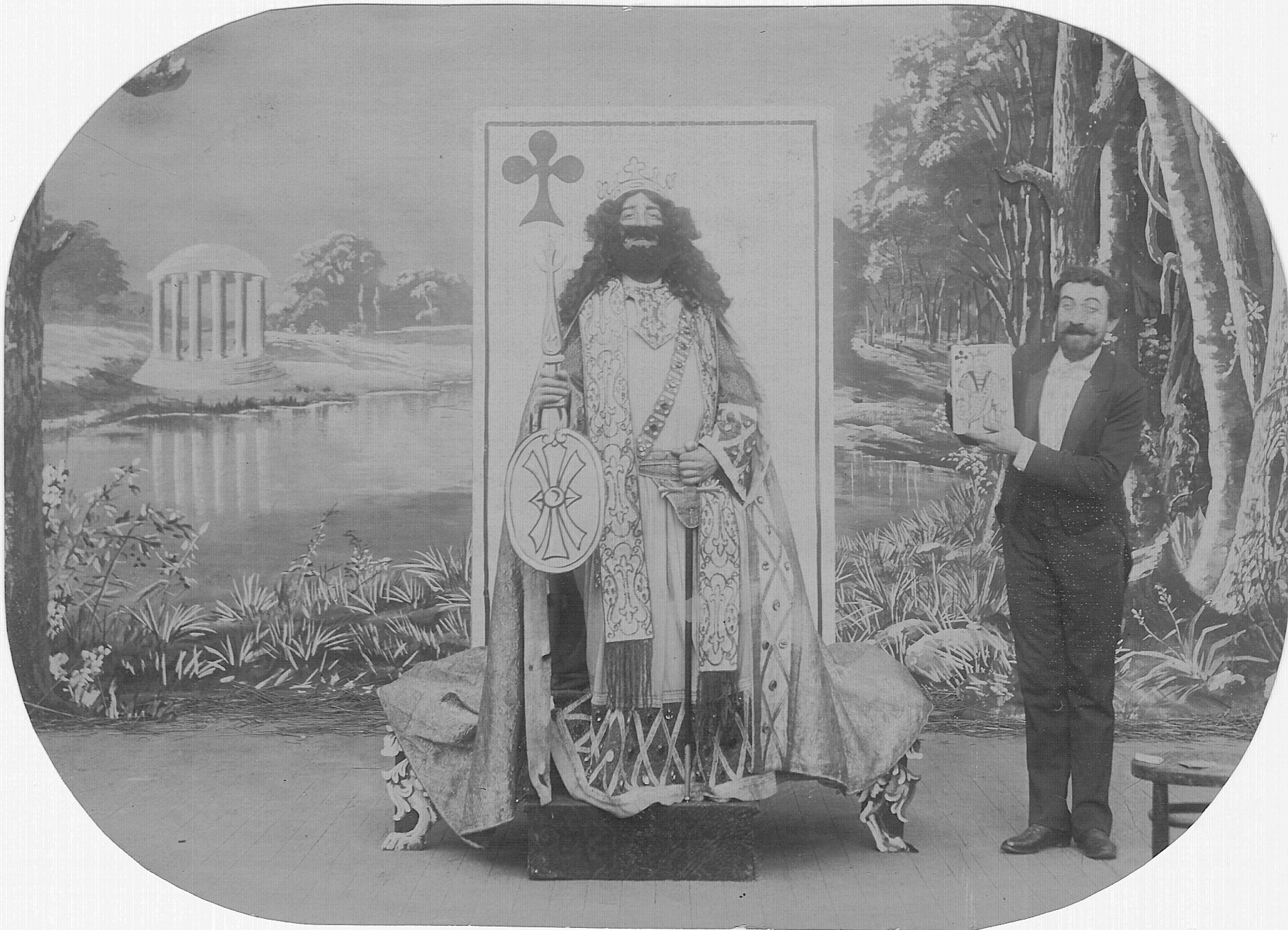

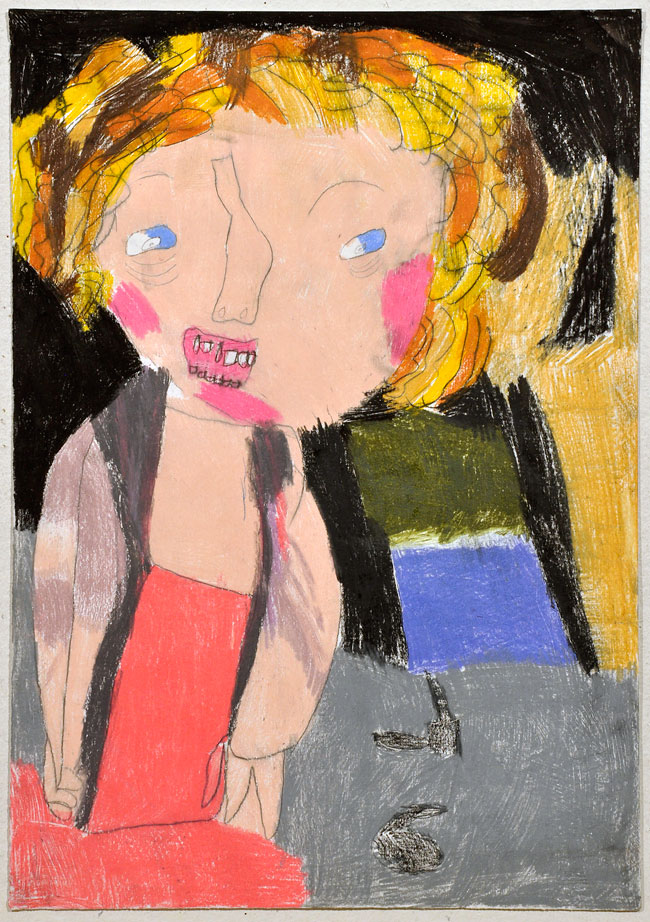

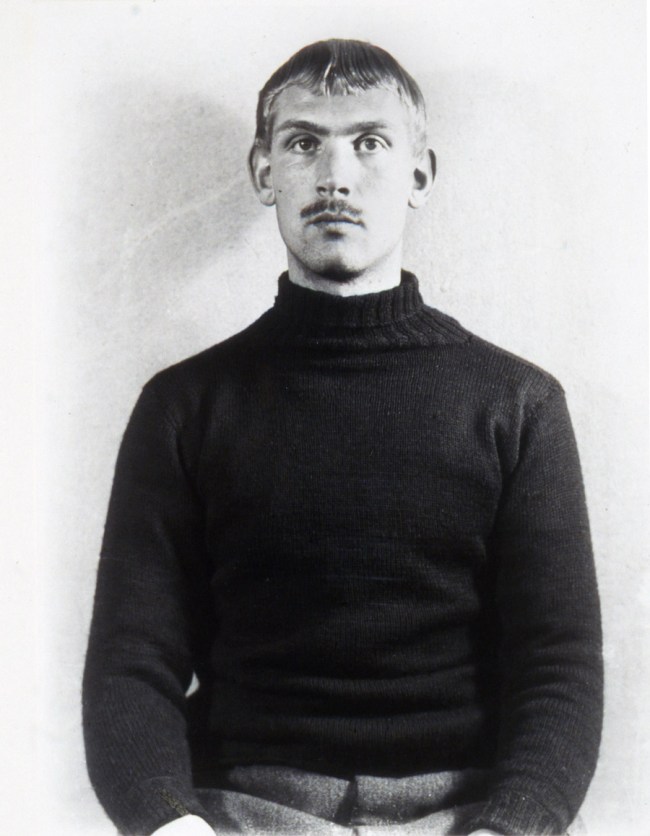

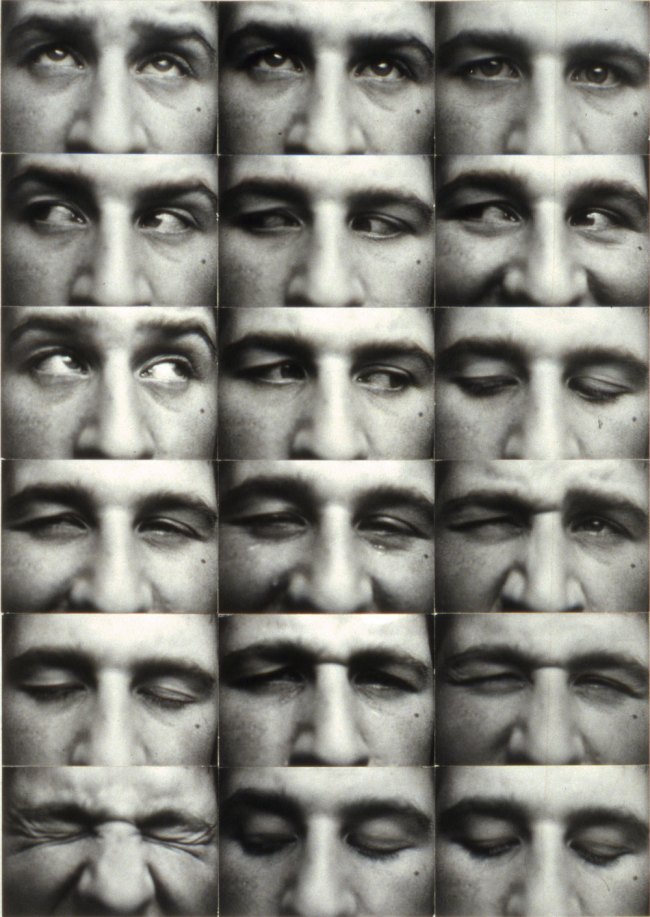

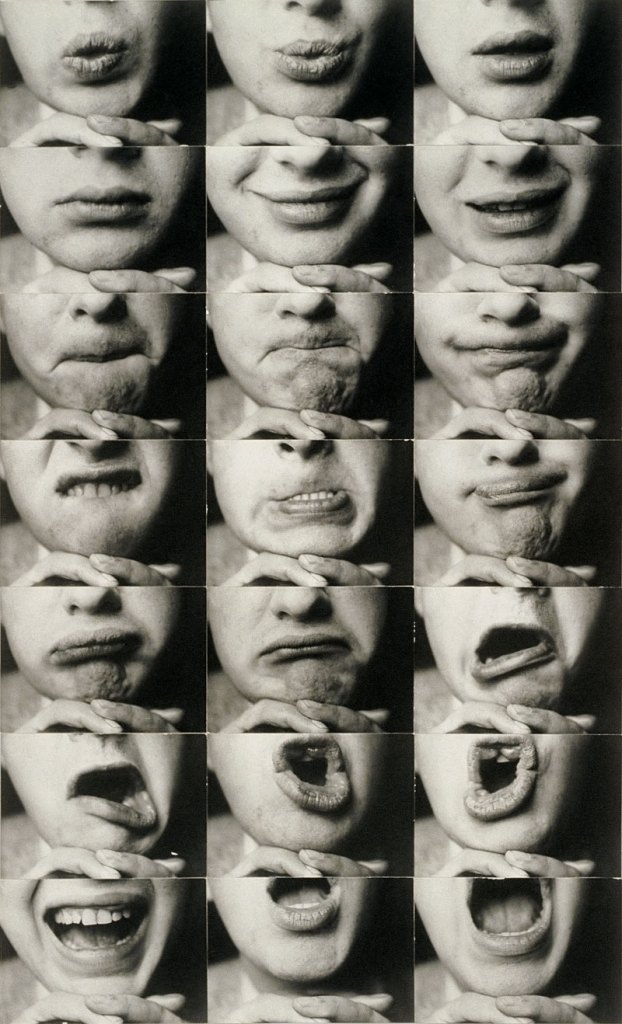

Portrait gallery

Various artworks by various artists

Museum of Old and New Art – interior

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

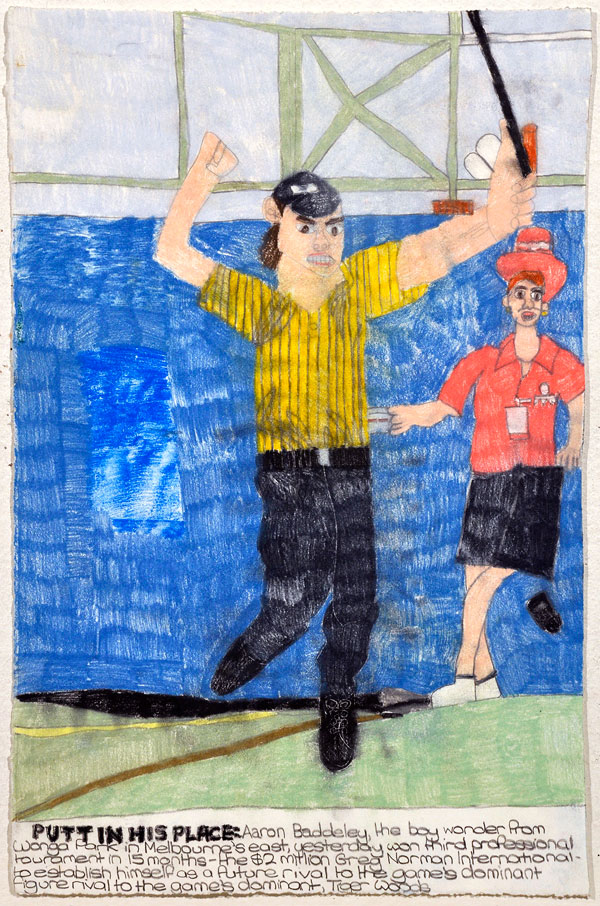

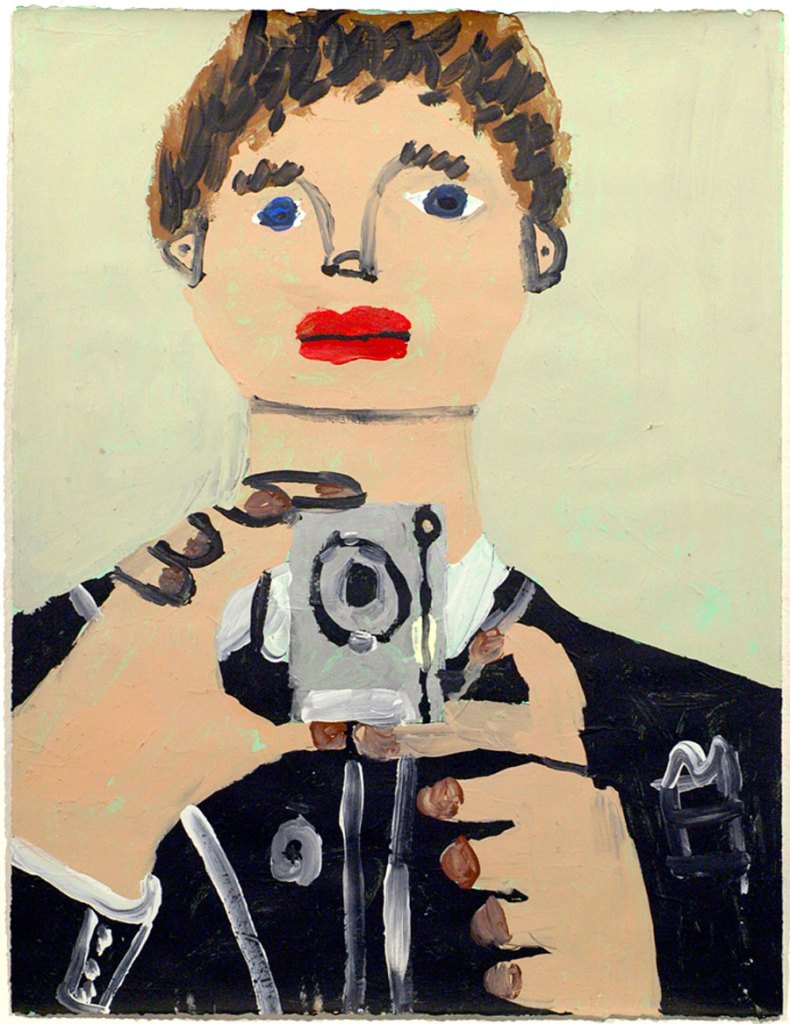

Masturbation. It is a source of endless irony to me that when I was young, and desperately in need of endless fucking, no one was interested in helping me out, whereas now, older and slower, I could fill even my desired adolescent quota. What saved me then was my right hand, even though I call myself left-handed. Surely the hand that you wank with (I guess John Holmes was ambidextrous) defines you just as much as the hand you write with? Anyway, who writes anymore? It’s so much easier to type. Mental masturbation allows me to pretend I’m a mental John Holmes, takes both hands. But no brains.

Art. I’m not at all sure that conceptual art and traditional art are the same thing. One can come from muscle memory, from pragma; at its best it’s not at all conscious. The former, though, is so self-aware it’s often targeting its own self-awareness. Check out the Hirst and the Pylypchuk at the other end of the gallery.

David Walsh 2011

Corten Stairwell

February 2011

Museum of Old and New Art – interior

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

Corten Stairwell & Surrounding Artworks

February 2011

Museum of Old and New Art – interior

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

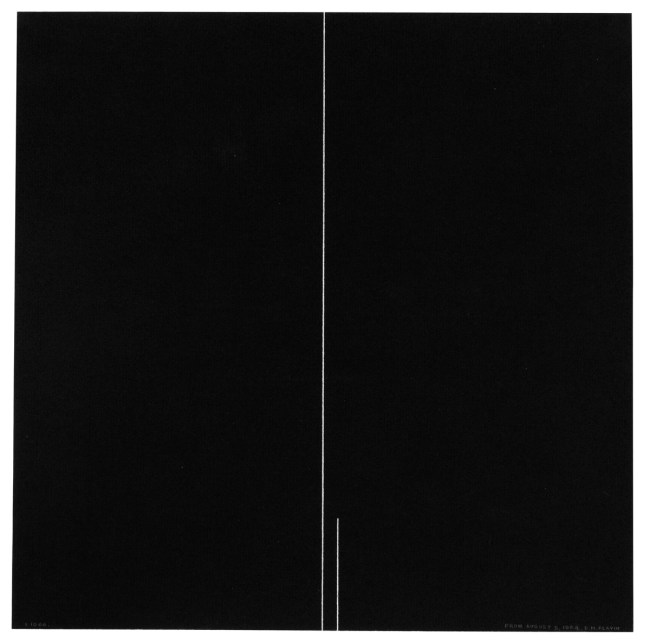

The Nolan Gallery

Sir Sidney Nolan (Australian, 1917-1992)

Snake

1970 to 1972

Mixed media on paper, 1620 sheets

Jannis Kounellis (Greece, 1936-2017)

Untitled

2002

Jute coffee bags, coal; three parts

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

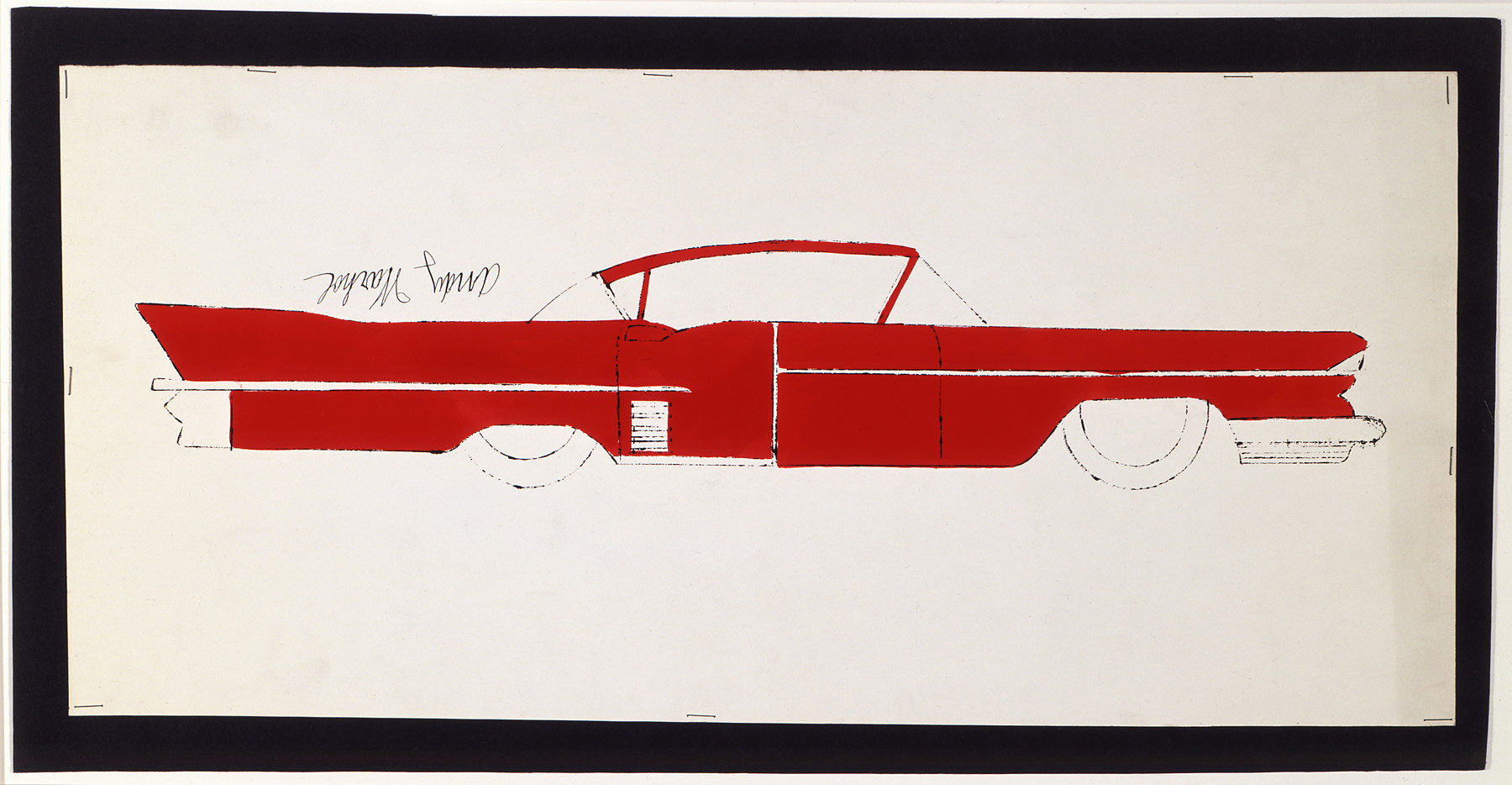

Erwin Wurm (Austrian, b. 1954)

Fat Car

2006

Steel chassis and body; leather interior, with polystyrene and fibreglass

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

Image Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

Museum of Old and New Art

655 Main Road Berriedale

Hobart Tasmania 7011, Australia

Opening hours:

Fridays – Mondays, 10am – 5pm

MONA website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.