Exhibition dates: 8th February – 18th May 2014

John F Williams (Australian, 1933-2016)

The Rocks, Sydney

1973

Gelatin silver photograph

22.6 x 34.1cm

Purchased 1989

© John F Williams

Australian vernacular photography. Such a large subject. Such a small exhibition.

With only 27 photographs from various artists (18 of which are shown in this posting), this exhibition can only ever be seen as the runt of the litter. I would have thought such a large area of photographic investigation needed a more expansive exposition than is offered here. There are no photobook, photo booth, Aboriginal, anonymous, authorless, family, gay or marginalised cultural photographs / snapshots. There are no light leaks, blur, fingers obstructing lenses, double exposures – all examples of serendipity and happenstance which could enter into an aesthetic arena.

Vernacular photography1 can be defined as the “creation of photographs, usually by amateur or unknown photographers both professional and amateur, who take everyday life and common things as subjects… Examples of vernacular photographs include travel and vacation photos, family snapshots, photos of friends, class portraits, identification photographs, and photo-booth images. Vernacular photographs are types of accidental art, in that they often are unintentionally artistic.”2 ‘Found photography’ is the recovery of a lost, unclaimed, or discarded vernacular photograph or snapshot.

While all of the photographs in the exhibition are unique images, some are definitely not vernacular in their construction – they are planned and staged photographs, what I would call planned happenstance (after John Krumboltz’s theory of career development). A perfect example of this are the photographs by Sue Ford (Sue Pike, 1963, printed 1988, below), Anne Zahalka (The girls #2, Cronulla beach, 2007, below) and Fiona Hall (Bondi Beach, Sydney, Australia, October 1975, below) which have an air of ceremonial seriousness that belies their classification as part of this exhibition. My favourites are the fantastic images by Glen Sloggett – witty, colourful, humorous with the photographer “acutely aware of the photographer and photograph’s role in pointedly constructing a narrative around Australian identity and history” – they are nevertheless self-deprecating enough that this does not impact on their innate “found” quality, as though the artist had just wandered along and captured the shot.

The route that the AGNSW has taken is similar to that of MoMA. Residing in the collection and shot by artists, these “vernacular” photographs are placed in a high art context. Their status as amateur or “authorless” photographs is undermined. This exhibit does not present vernacular photographs as just that. As the article on the One Street blog notes, what is being exhibited is as much about what has been collected by the AGNSW, its methodical and historicising classification, as it is about vernacular photographic form: chance, mistake and miscalculation. It is about creating a cliché from which to describe an ideal Australian identity, be it the beach, larrikinism, or the ANZAC / sporting “warrior”, and not about a true emotional resonance in the image that is created by, or come upon by, chance.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Art Gallery of New South Wales for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

1/ “Vernacular photography,” on One Way Street blog 20th October 2007 [Online] Cited 11/05/2014

“What is vernacular photography? Too broad to be understood as a genre per se, it can encompass anonymous snapshots, industrial photography, scientific photography, “authorless” photography, advertising, smut, as well as work that might be perceived as “other” than any of this random list. It could be understood as an oppositional photography – outside technical or artistic histories, yet, especially with the snapshot, it could also be entirely conventionalised, a manifestation of visual banalities, or an image so enigmatic that its meaning or genesis is entirely obscured. It is mistakes & failures as much as it may not be, & how we understand the images may or may not be separate from their initial intents. Is this a category we are making up?

The idea of the vernacular in photography is also an indication of photography as a medium informing the everyday, prevalent, “naturalised.””

2/ Szarkowski, John. “INTERVIEW: “Eyes Wide Open: Interview with John Szarkowski” (2006)” by Mark Durden, Art in America, May, 2006, cited in “Vernacular photography,” on Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 11/05/2014. No longer available online

Ed Douglas (United States of America, Australia, b. 6 May 1943)

City-spaces #28, (John Williams), Sydney

1976 printed 2012

From the series City-spaces 1975-78

Purchased with funds provided by the Photography Collection Benefactors’ Program 2012

© Ed Douglas

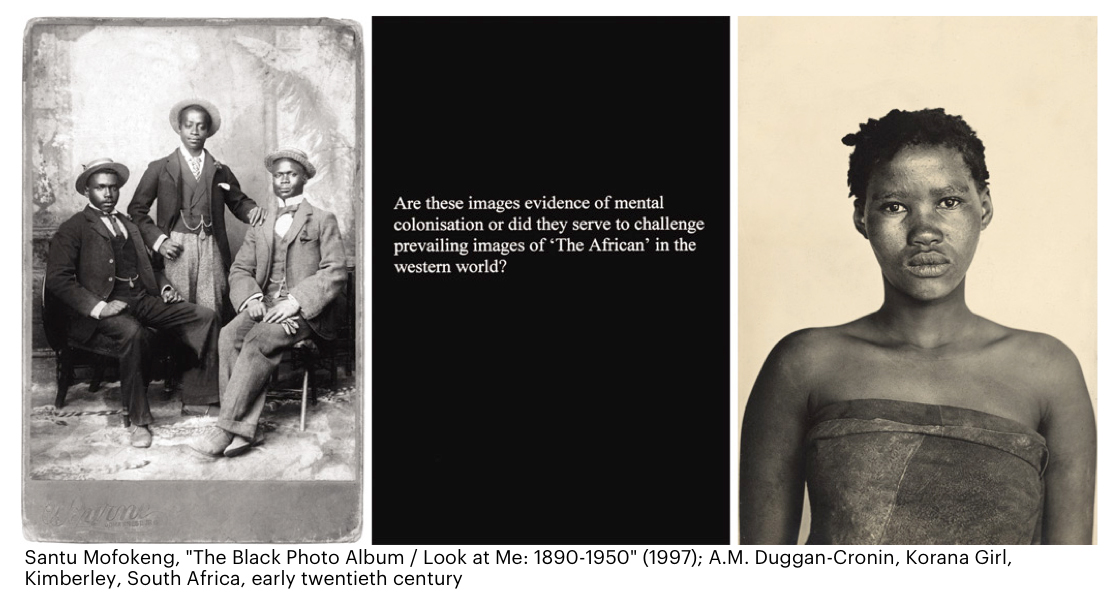

Words and Photos: Geoffrey Batchen’s Writing About Vernacular Photography

“At first, I was simply interested in bringing attention to a diverse range of photographic objects and practices that had not been much written about. But I soon recognised that these objects represented a significant challenge to the predominant history of photography. This history, dominated by the values and tropes of art history, was not well-equipped to talk about photographs that were openly commercial, hybrid and mundane. Ie: the history of photography ignores most types of photography. My interest, therefore, has become more methodological and theoretical, in an effort to establish new ways to think of photography that could address the medium as a whole. I suggest that any substantial inclusion of vernacular photographs into a general history of photography will require a total transformation of the character of that history…

I suggest that any inclusion of vernacular photography in the larger story, will require a complete transformation of the character of that story; it will require a new kind of history altogether. My writings may have encouraged this idea, but I am just one of many scholars who have been pursuing this goal. Indeed, I would say that this idea is now the norm. The next step is to look beyond this and engage other parts of the history of photography that have been similarly neglected. For example, there are many researchers at the moment that are examining the photographs produced outside Europe and the United States, such as China, Indonesia, and Africa…

Snapshots are complicated objects. They are unique to each maker and almost always completely generic. They happily adopt the visual economy that mediates most photographic practices: same but different. You might say that every snapshot is an authentic copy of a prescribed set of middle-class values and familiar pictorial clichés. That does not make them any less fascinating, especially for people who treasure them. But it does make them difficult to write about…

It is certainly possible to recognise the existence of regional practices of photography. I wrote, for example, about the making of fotoescultura in Mexico, and about a specific form of ambrotype in Japan. No doubt one could claim to see some regional aspects of snapshots made in the United States that distinguish them from ones made in Australia or, say, Indonesia. But the more challenging task is to talk about those things that can’t be seen. For example, snapshots made in Australia and China may look exactly the same to my eye, but it stands to reason that they don’t mean the same thing (after all, access to the camera for personal photos is a fairly recent phenomenon in China). We must learn how to write these kind of differences.”

Interview by LG. “Words and Photos: Geoffrey Batchen’s Writing About Vernacular Photography,” on the LesPHOTOGRAPHES.com website Nd (translated from the French) [Online] Cited 04/05/2014. No longer available online

Ed Douglas (United States of America, Australia, b. 6 May 1943)

City-spaces #40, Sydney

1976 printed 2012

From the series City-spaces 1975-78

Gelatin silver photograph

23.6 x 30.7cm image

Purchased with funds provided by the Photography Collection Benefactors’ Program 2012

© Ed Douglas

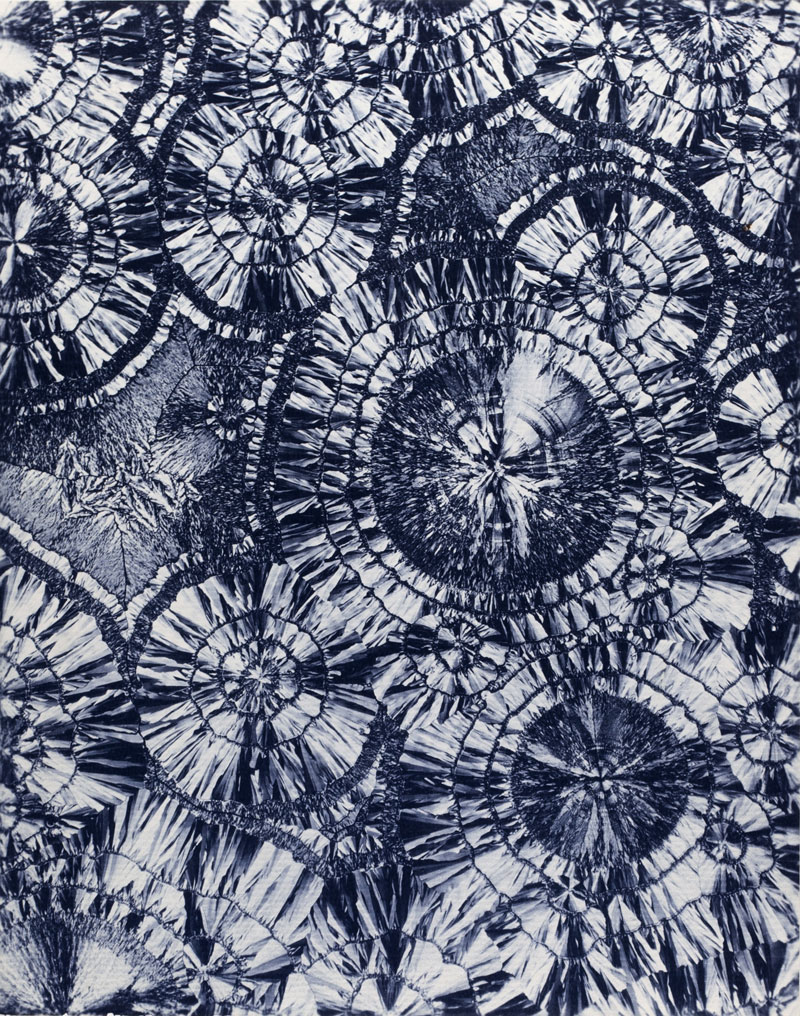

After relocating from USA to Australia in 1973, Ed Douglas spent a few years living in the country prior to taking on a teaching position at Sydney College for the Arts in 1976. The series City-spaces was commenced in Sydney and then developed further when Douglas moved to Adelaide in 1977. Having been schooled in the formal traditions of American documentary photography, Douglas’s images appear like notations of an urban explorer attempting to locate himself in a new country. Seemingly fragmentary, they look at the specificities of the mundane and the ordinary. Close acquaintances such as photographers Ingeborg Tyssen and John F. Williams appear in City spaces #29 and City spaces #28, indicating the personal nature of the series.

Intimately scaled and tonally rich, the black and white images exalt the formal beauty which can be found in the random textures of daily existence. They are also permeated with gentle humour and a sense of quiet drama that unfolds in the strangely misplaced confluences of objects, figures and spaces. Douglas’s interest in the formal and emotional qualities of topography was emblematic of new approaches in documentary photography of the time. His 1983 series of colour photographs depicting the gypsum mine on Kangaroo Island (collection of AGNSW) developed this trajectory further by fusing the aesthetics of abstraction and objective documentation.

Gerrit Fokkema (Papua New Guinea, Australia, b. 1954)

Woman hosing, Canberra

1979

Gelatin silver photograph

34.9 x 46.5 cm image

© Gerrit Fokkema

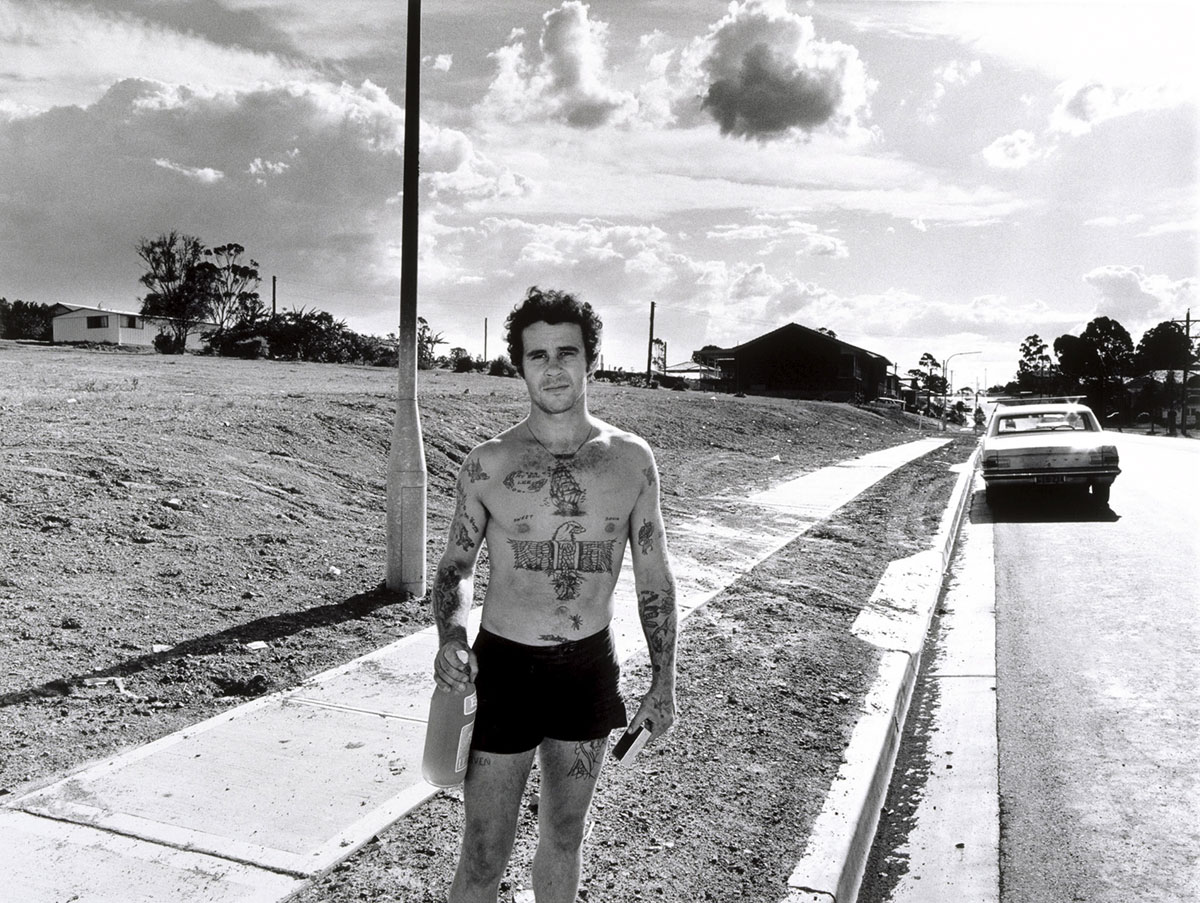

Gerrit Fokkema’s photographs of everyday Sydney and Canberra in the early 1980s are examples of Australian photography becoming more self-aware. These decisive snapshots of suburban life reveal an irony and conjure Fokkema’s own history growing up in Queanbeyan. Though captured in seemingly banal settings, the images intrigue, pointing to issues beyond what is represented in the frame. The housewife watering the road and a young tattooed man in front of a car are both depicted alone within a sprawling suburban landscape, suggesting the isolation and boredom in the Australian dream of home ownership. The sense of strangeness in these images is consciously sought by Fokkema, aided by his embrace of the glaring and unforgiving ‘natural’ Australian light.

Gerrit Fokkema’s Woman hosing, Canberra is an affectionate and gently ironic portrait of suburban life in Canberra. Fokkema was familiar with his subject matter, raised as he was in the nearby township of Queanbeyan. After studying photography at Canberra Technical College 1974-77 he became the staff photographer for the Canberra Times in 1975. He held his first exhibition in the same year at the Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney. His career as a photo-journalist lead him to work with the Sydney Morning Herald in 1980 and participation with several international Day in the life of…. projects between 1986 and 1989.

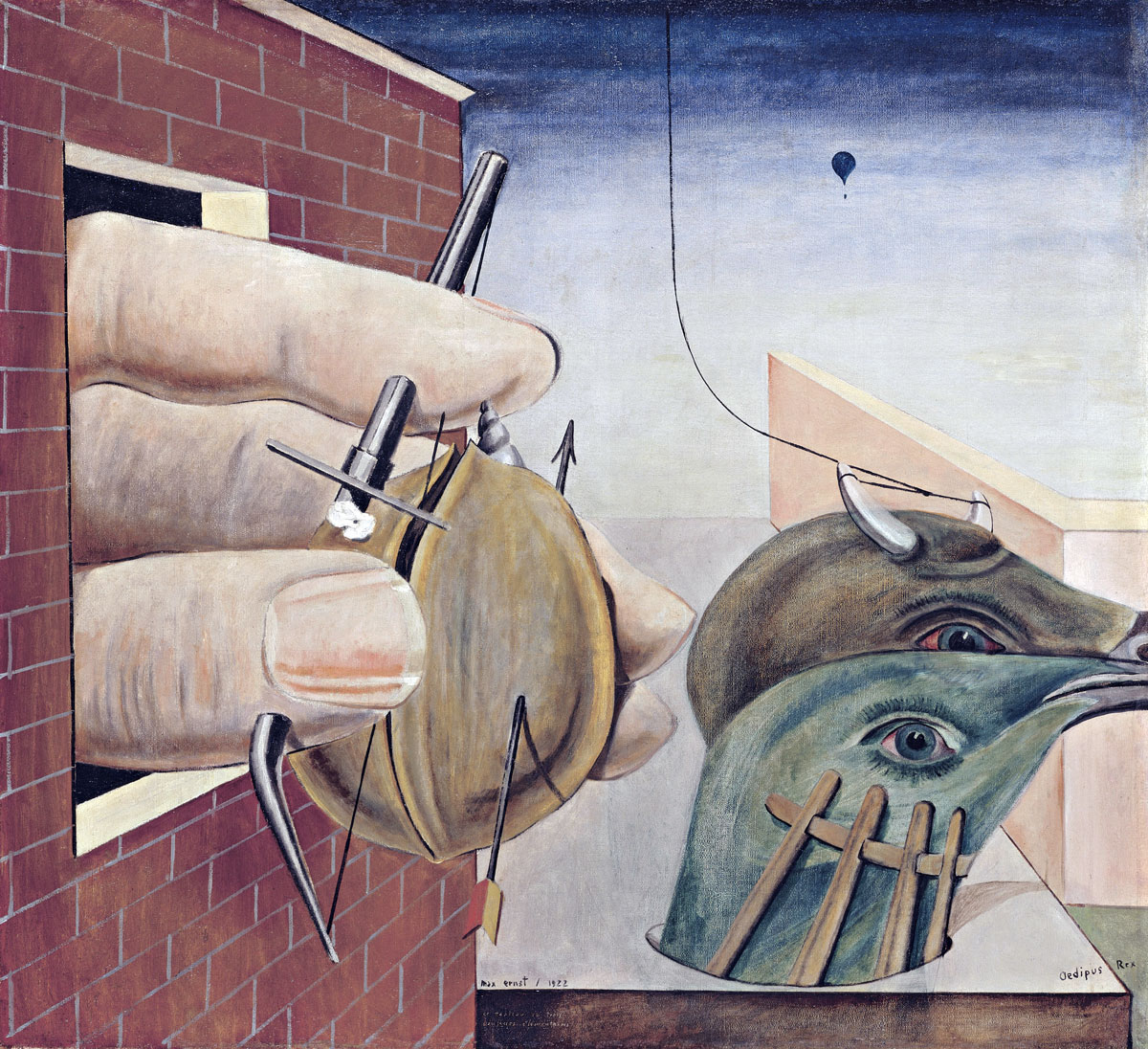

Fokkema uses the ‘decisive moment’ of photo-journalism to reveal the incidental quirks of ordinary life in this image. The bland uniformity of the streetscape, with its identical archways and mundanely shuttered doors, is punctuated by the absurd proposition of a woman watering the street rather than the adjacent grass. Her presence is the only sign of life in an otherwise inanimate scene, and her actions suggest a kind of strangeness that lies within the normality of suburbia. Many of Fokkema’s images play with such chance incidences and odd juxtapositions, revealing his interest in surrealism and the notion of automatism. Indeed, the repeated archways and the lone figure inhabiting otherwise empty urban space of Woman hosing, Canberra recall the proto-typical surrealist painting, Mystery and melancholy of a street 1914, by Giorgio de Chirico. Fokkema’s image is, however, very much a product of Australia – of its bright ‘available’ light and of the dream of home-ownership. Fokkema has continued to document the Australian way of life. In 1986 he left newspapers to freelance as a commercial photographer and published Wilcannia, portrait of an Australian town. He has since exhibited works based on tender observations of his family members and of family life.

© Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Gerrit Fokkema (Papua New Guinea, Australia, b. 1954)

Blacktown man

1983

Gelatin silver photograph

30.6 x 40.6cm image

© Gerrit Fokkema

The work of Gerrit Fokkema exhibits a particular sensitivity to the uneasiness of people in Australian landscapes, both urban and rural. Fokkema was born in New Guinea in 1954, but raised in Canberra and worked as a press photographer before freelancing from 1986. Although his photographs demonstrate an interest in the formal qualities of landscape, the sense of rhythm his compositions generate also evoke the monotony of Australian space – sweeping terracotta roofs and long straight paths. This monotony is only interrupted by the presence of the human figure, usually isolated, alone and awkwardly out of place. In Blacktown Man 1983, the flat image of the man appears dramatically superimposed on the land and sky of the suburban street. By reminding us of our sometimes uncomfortable relationship with the spaces we inhabit, Fokkema’s work rejects any attempt to romanticise Australian life.

Trent Parke (Australian, b. 1971)

Backyard swing set, QLD

2003

From the series Minutes to midnight

Type C photograph

109.9 x 164cm

Gift of Albie Thoms in memory of Linda Slutzkin, former Head of Public Programmes, Art Gallery of New South Wales 2006

© Trent Parke

Australian vernacular photography traces developments in photographic practice from the postwar period through to the present day, with images ranging from documentary or ‘straight’ photography (where the subjects are usually unaware of the camera), through to those that look self-reflexively at the constructed nature of the medium.

The increasing role of photography in the latter part of the 20th century attests to the rising need Australians felt to apprehend the nation, personal identity and society through images. Many of these photographs offer frank perspectives on Australian culture without the romanticising tendencies of earlier photographers. Photographing the everyday became a way of understanding how Australia saw (and sees) itself, with recurrent themes such as beach culture, suburbia, race relations, protest and the role of women among the central concerns of image-makers then and now.

By the 1960s Australian photographers were comparing their work with international peers, thanks to photographic publications and the watershed 1959 tour of The family of man exhibition organised by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Institutional support for photography didn’t come until the 1970s; however those committed to the medium forged on, intent on capturing their visions of Australia photographically. The family of man exhibition toured Australia in 1959 and was enormously influential, with its themes of birth, love and death common to all humanity. However, possibilities for Australian photographers to be noticed were rare until the 1970s due to the lack of institutional support. Nonetheless, photographers from David Moore and Robert McFarlane to the young Sue Ford forged on, trying to find their own vision of Australian life and how it could be represented photographically. This exhibition looks at some of the photographers from then as well as those working more recently – such as Anne Zahalka, Trent Parke and Glenn Sloggett – to consider their various approaches to the depiction of modern Australian life.

In the Australian Photography Annual of 1947, photographer and director of the Art Gallery of NSW Hal Missingham wrote: “In a country supposedly occupied by people indulging in a vigorous outdoor life, where are the [photographic] records of beach and sport… where are the photographs of the four millions of people who live and work in our cities? What are they like – what do they do – what do they wear, and think?”

Text from the AGNSW website

Jeff Carter (Australia, 05 Aug 1928 – Oct 2010)

The Sunbather

1966

Gelatin silver photograph

39.1 x 27.6cm image

© Jeff Carter

“I don’t regard photography as an art form, although I know it can be for others… To me the camera is simply an unrivalled reporter’s tool. It is an aid to getting the story “properly true,”” Jeff Carter said in 2006. Working mainly as a photojournalist, Carter wanted to make images that depicted social reality. He aimed to show the ‘unknown’, those people who are rarely seen. His approach resulted in frank, arguably even unflattering, images of Australian life, such as this of a beach-goer in the 1960s, heralding the changing social mores of the time.

John F Williams (Australia, 1933-2016)

Sydney

1964, printed later

Gelatin silver photograph

24.3 x 24.3 cm image

© John F Williams

Sydney photographer, lecturer and historian John F. Williams has a long and personal interest in the ramifications of the Allies’ commitment to and sacrifice in the First World War which he later explored in his 1985 series From the flatlands. Williams became an amateur street photographer, inspired by Henri Cartier-Bresson and the photojournalist W. Eugene Smith. He read The family of man catalogue and saw the exhibition in 1959 but he rejected its “saccharine humanism and deliberate ahistoricism” choosing instead to socially document the raw character of Australia.1

When interviewed in 1994 Williams said: “After the [First World War] you had a range of societies which were pretty much exhausted, and they tended to turn inwards. In a society like Australia which had a poorly formed image of itself, where there was no intellectual underpinning, the image of the soldier replaced everything else as a national identity.”2

Sydney expresses the ‘Anzac spirit’ born in the battlefields of Gallipoli, the Somme and Flanders, a character study of an independent, introspective soldier. With an air of grit, determinedly smoking and wearing his badge, ribbons and rosemary as remembrance, Sydney stands apart from the crowd, not marching with his regiment. Williams embraced the ‘element of chance’ or the ‘decisive moment’ as he documented the soldier in a public place observing the procession. Taken from a low angle and very close up the man is unaware of the photographer at the moment the shot was taken, apparently lost in his own memories. The old soldier represents a generation now lost to history but portraits such as these continue to reinforce the myth of national identity.

1/ Jolly, M. “Faith sustained,” in Art Monthly, September 1989, pp. 18-19

2/ “John Williams – photographer and historian: profile,” in Sirius, winter, Macquarie University, Sydney, 1994, p. 5

© Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Robert McFarlane (Australia, b. 1942)

Happening Centennial Park, Sydney

c. 1968

Gelatin silver photograph

25.9 x 17.6cm image

© Robert McFarlane

Hal Missingham (Australia, 08 Dec 1906 – 07 Apr 1994)

Surf carnival, Cronulla

1968, printed 1978

Media category

Gelatin silver photograph

38.1 x 26.3cm image

© Hal Missingham Estate

Photographer and former Art Gallery of NSW director, Hal Missingham wrote in the 1947 Australian Photography annual: “In a country supposedly occupied by people indulging in a vigorous outdoor life, where are the [photographic] records of beach and sport…? Where are the photographs of the four millions of people who live and work in our cities? What are they like – What do they do – What do they wear, and think?” This image points to Missingham’s own attempts to answer that question. An interesting counterpoint to the images taken at Cronulla around 40 years later, here Missingham shows a group of young women standing behind a fence watching as young men train to be lifesavers.

Hal Missingham often holidayed at his beach house at Garie in the Royal National Park south of Sydney, not far from Cronulla. In 1970 he published Close focus a book of photographic details of rocks, pools, sand and driftwood. As a beachcomber and observer of beach culture Missingham delighted in his immediate environment. Surf carnival, Cronulla is a quintessential Australian scene, one that frames an important aspect of national identity and culture. As passive observers, the 1960s was a time when many girls were still ‘minding the towels’ for the boys who surfed or competed in carnivals. Barricaded from the beach and its male activity the young women in bikinis are oblivious to the photographer who has foregrounded their relaxed tanned bodies behind the wire as they in turn observe and discuss the surf lifesavers in formation at the water’s edge. Although a beach is accessible for the majority of Australians and is now an accepted egalitarian space where women bodysurf, ride surfboards and compete along with beachgoers from diverse ethnic backgrounds, Surf carnival, Cronulla suggests a specific demography.

© Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Fiona Hall (Australia, b. 1953)

Bondi Beach, Sydney, Australia, October 1975

1975

Gelatin silver photograph

28.2 x 27.9cm image

Hallmark Cards Australian Photography Collection Fund 1987

© Fiona Hall

Australian vernacular photography considers how photographers have used their cameras to depict Australian life, and how ideas of the nation have been constructed through photographic images.

Sixteen Australian photographers are represented by some 27 photographs taken from the 1960s to the 2000s. The photographs range from the more conventionally photo-documentary through to later works by photographers positioned more consciously in an art context. A selection of photography books of the period are also on display.

Artists include: Jeff Carter, Ed Douglas, Peter Elliston, Gerrit Fokkema, Sue Ford, Fiona Hall, Robert McFarlane, Hal Missingham, David Moore, Trent Parke, Roger Scott, Glenn Sloggett, Ingeborg Tyssen, John F Williams, William Yang and Anne Zahalka. Each of these artists in their own way interweave personal, documentary and fictional aspects through their images.

The works in Australian vernacular photography expose the sense of humour or larrikinism often seen as typical to Australia through showing aspects of beach and urban culture that hadn’t been imaged so bluntly before the 1960s. The characters that emerge range from leathery sunbathers, beer-drinking blokes and hippies, to beach babes, student protesters and suburban housewives, shedding light on the sense of liberation and self-recognition that arose during this period.

As photography struggled to gain recognition as an art form in the mid 20th century, the influence of exhibitions such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York’s Family of Man, which toured Australia in 1959, was vital in allowing Australian photographers to compare their work to that of their international peers.

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, photographers such as Jeff Carter, Sue Ford, David Moore, Roger Scott and John F Williams worked in a photo-documentary mode that was less about staging a shot or creating formal harmony within the frame than about capturing a moment of lived reality. To this end, such photographs involved minimal intervention from the photographer, both before and after the shutter release. Subjects were often unaware of being photographed and extensive darkroom manipulation was frowned upon, the rawness of prints was supposed to signal authenticity.

This approach resulted in images that seemed to offer a frank perspective on Australian culture, without the romanticising tendencies of earlier photography, which had sought to construct ideals rather than document what was actually there. As artists began to realise what they could do with the camera, so too did the images evolve. By the 1980s and ’90s photographers were making images that showed the subject’s awareness of being photographed, as with Gerrit Fokkema, or presented a harsh, even aggressive perspective on the depicted situations by removing people altogether, as with Peter Elliston. This signalled the increasingly self-conscious role of photographers themselves in the equation, suggesting the influence of post-modern theories of subjectivity and their effect on the images produced.

By the time we reach the 2000s, artists such as William Yang, Anne Zahalka and Trent Parke are acutely aware of the photographer and photograph’s role in pointedly constructing a narrative around Australian identity and history. The exhibition maps out this history and offers unexpected insight into the construction of a particularly Australian vernacular within photographic practice.

Press release from the AGNSW

Sue Ford (Australia, 1943 – 06 Nov 2009)

Sue Pike

1963, printed 1988

Media category

Gelatin silver photograph

34.2 x 34.2cm image

Gift of Tim Storrier 1989

© Estate of Sue Ford

Sue Ford’s photograph of her friend Sue Pike blow-drying her hair in the kitchen captures the young woman preparing for a night out. Ford often photographed those close to her as well as continually making self-portraits throughout her career. The photograph is domestic and intimate, showing a common aspect of life for young women in the 1960s. It suggests the procedure of preening necessary to go out and find ‘marriage and children’, while the alcohol and cigarette indicates the emerging movement for women’s liberation.

“My earliest “studio portraits” … were of my friends from school … These photo sessions were approached with a ceremonial seriousness, My friends usually brought different clothes with them and during the sessions we would change clothes and hairstyles.” Sue Ford 1987 1

Sue Ford took the majority of her photographs at this time with the camera set on a 1/60th of a second at f/11, a ‘recipe’ she wrote which had more chance of success. Poetic, fragmentary text relating to Ford’s 1961 photo-essay in “A sixtieth of a second: portraits of women 1961-1981” identify the young women’s recipe for flirtatious endeavour – ‘gossamer hairspray’, ‘peroxide’, ‘plucked eyebrows’, ‘big hair rollers to achieve “La Bouffant”‘, ‘Saturday nite’ and ‘Jive’. Sue Pike exemplifies the era of girls preparing for a night out with the boys in their ‘FJ Holdens and Hot Rods’. Staged in the kitchen, probably on a Saturday afternoon, Sue Pike, in a padded brunch coat with hair in rollers plugged into a portable hair dryer, will be a part of the action, the gossip and camaraderie. A further portrait taken in the same year shows Sue Pike metamorphosed as a beautiful bride, carefully coifed ash blonde hair under a white net veil, eyes momentarily shut, traditionally decorated with pearls and posy. Ford suggests in her prose and portraits that there are choices to be made – ‘marriage and children’ or mini-skirts and the Pill, as her old school friends go in different directions.

1/ Ford. S. “A sixtieth of a second: portraits of women 1961-1981,” Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide, 1987, p. 4

© Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Anne Zahalka (Australia, b. 1957)

The girls #2, Cronulla beach

2007

Type C photograph

72.5 x 89.5cm image

Gift of the artist 2011. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program

© Anne Zahalka. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

As part of a generation of Australian women artists who came to the fore in the early 1980s, Anne Zahalka’s practice has always been concerned with questioning dominant myths and cultural constructs. The broad sweep of Zahalka’s oeuvre has often been underpinned by a common strategy: the world in her images appears as theatre where place, gender and national identity are questioned.

Many of Zahalka’s more recent works are located outside the studio though the natural environment can be seen to be equally constructed. In The girls #2, Cronulla beach, the photographer has returned to the seaside, which was the setting for one of her most iconic series, Bondi: playground of the Pacific 1989. The girls was made as a response to the Cronulla riots and after an introduction to Aheda Zanetti, the designer of the burqini. Zahalka “also knew of a documentary film being made following the recruiting of Lebanese men and women into the lifesaving club. It seemed like there was change adrift on the beachfront.”1 The permutations and post-modern anxiety about what constitutes Australian identity seen in the Bondi… series, have spilled out into the real world. But the image of these young Muslim women lifeguards seems to celebrate the potential to transgress accepted value systems.

Anne Zahalka said in 1995: “I am primarily concerned with… representations to do with place, identity and culture. Through the appropriation and reworking of familiar icons and styles I seek to question (and understand) their influence, meaning and value.” Twelve years later, Zahalka continues this line of inquiry with the series Scenes from the Shire. In this image, three Muslim girls wearing Burqinis (swimwear made for Muslim women conceived by Lebanese-Australian designer Aheda Zanetti) are standing cross-armed on Cronulla beach, a lifesaving raft is in the background. Zahalka made this work in response to the Cronulla riots of 2005. The image juxtaposes Muslim tradition with the Australian icon of the lifesaver, suggesting cultural overlap and changing national identity.

1. A. Zahalka et al, “Hall of mirrors: Anne Zahalka portraits 1987-2007,” Australian centre of photography, Sydney 2007, p. 43

William Yang (Australia, b. 1943)

Ruby’s kitchen Enngonia

2000, printed 2002

From the series miscellaneous obsessions

Type C photograph

35.5 x 53.5cm image

© William Yang

William Yang was born in North Queensland, a third generation Chinese-Australian. He is known both as a photographer and for his monologues with slides which he has presented around the world to great acclaim. One of these, Sadness 1992, was adapted for the screen by Tony Ayres and won AWGIEs amongst other awards. A major retrospective of Yang’s work, Diaries, was held at the State Library of NSW in 1998. Through April 24 – June 1, 2003 Yang presented all his monologues at Belvoir St Theatre, Sydney.

Yang has documented various subcultures over the last 30 years and this is reflected in his photographs as well as his monologues. A remarkable storyteller with a unique style, his current work is a synthesis of his ongoing concerns. While these concerns spring very much from his experiences growing up with a Chinese background in far north Queensland, through to his exploration of the gay community in Sydney, the work transcends the personal and becomes a meditation on the subtleties of the ordinary and everyday.

This series of images reflects Yang’s current life of travel and contact with his far flung friends and extended family. Though the subject, at its most superficial, is food, where, when and who is there at the time is of equal importance. Consequently each photograph in the series presents a web of connections and is underpinned with similar intentions to Yang’s other work, regardless of the subject.

“I don’t think I have a great technical attitude but I am interested in people,” William Yang said in 1998. Yang is known for his candid photographs of friends and situations he encounters. The images are usually accompanied by a story about his life, sometimes handwritten on the print itself, sometimes spoken aloud in performative contexts. He uses narrative as a way of locating his images in a particular moment in his personal history as well as social history at large. Yang explores themes around Australian and gay identity in a way that is frank and sometimes confronting. In this work, from a series about food, a chunk of kangaroo meat sits casually atop a laminate bench; other Australian icons such as Wonder White and Weet-Bix are also visible. The work allows for a multiplicity of signs to coexist: the slaughtered Australian mascot, the drab generic kitchen, the processed ‘white’ bread, with the Chinese-Australian photographer observing it all.

Glenn Sloggett (Australia, b. 1964)

Cheaper & deeper

1996

From the series Cheaper & deeper

Type C photograph

80.0 x 79.9cm image

Gift of Amanda Love 2011. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program

© Glenn Sloggett

Based in Melbourne, Glen Sloggett has exhibited extensively across Australia, including a touring exhibition with the Australian Centre for Photography, New Australiana 2001. Internationally, his work was included in the 11th Asian Art Biennale in Bangladesh, 2004 and the 9th Mois de la Photo ‘Image and Imagination’ in Montreal 2005.

Sloggett’s work depicts scenes from Australian suburbia with a startling mix of warmth and melancholy. Devoid of people, his photographs reflect the isolation and abandonment that afflicts the fringes of Australian urban centres. His images don’t flinch from the ugly, kitsch, and bleak. Sloggett says, “No matter where I go, I always find places and environments that are in the process of falling down. These are the images of Australia that resonate most strongly for me as an artist. I want to capture the last signs of optimism before inevitable disrepair.” (Glen Sloggett, quoted in A. Foster. Cheaper and deeper, ex. Bro. ACP 2005) His images of disrepair are infused with black humour and at the same time, affection for Australian suburbia.

From dumpy derelict flats to pavements graffitied with the words ‘mum killers’, Sloggett’s photographs capture an atmosphere of neglect. One classic image depicts a pink hearse, with the slogan Budget burials cheaper & deeper!! stencilled in vinyl on the side window. Another image shows an industrial barrel, on which is scrawled the evocative word ‘Empty’. In a third image, a dog rests on the pavement outside ‘Kong’s 1 hour dry cleaning’ – the bold red and yellow lettering on its window in stark contrast to the cracked paint of the exterior wall, and half-clean sheet that forms a makeshift curtain. These images have a profundity that is at once touching and surprising; as Alasdair Foster has commented, “In a world of rabid materialism and shallow sentiment, Sloggett’s photographs show us that life really is much cheaper and deeper.”

These five works by Glenn Sloggett serve as forms of photographic black humour. Devoid of people and always in colour, his photographs often take mundane elements from the world and make us notice their tragicomedy. This group is rooted in a play with text, where the tension between what is written and what we see is paramount. Sloggett makes comment on Australian life and culture, showing how the fringes of towns and the paraphernalia of the everyday give insight into the Australian psyche.

Glenn Sloggett (Australia, b. 1964)

Hope Street

2000

From the series Cheaper & deeper

Type C photograph

80.4 x 80.6cm image

Gift of Amanda Love 2011. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program

© Glenn Sloggett

Glenn Sloggett (Australia, b. 1964)

Empty

2000

From the series Cheaper & deeper

Type C photograph

80.4 x 80.6cm image

Gift of Amanda Love 2011. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program

© Glenn Sloggett

Glenn Sloggett (Australia, b. 1964)

Kong’s 1 hour dry cleaning

1998

From the series Cheaper & deeper

Type C photograph

80.2 x 80.0cm image

Gift of Amanda Love 2011. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program

© Glenn Sloggett

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art Gallery Road, The Domain

Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

Opening hours:

Open every day 10am – 5pm

except Christmas Day and Good Friday

![Ed Ruscha (American, b. 1937) '708 S. Barrington Ave. [The Dolphin]' 1965 Ed Ruscha (American, b. 1937) '708 S. Barrington Ave. [The Dolphin]' 1965](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/708-s-barrington-ave-the-dolphin-1965-web.jpg?w=650&h=644)

You must be logged in to post a comment.