Exhibition dates: 17th June – 16th October 2011

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

The former whaling ship, the ‘Terra Nova’

1911

Gelatin silver print

Canterbury Museum NZ

“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

John 15:13

It is difficult to describe how heroic a figure Robert Scott, ‘Scott of the Antarctic’ was to a child of the Empire growing up in the 1960s. He and his doomed party were, and still are, the quintessential heroes of my youth. Despite what we now know of Scott’s failures in leadership and organisation, he and his comrades remain embedded in English consciousness as all that is noble about the explorers of the time. They may have failed to become the first to reach the South Pole and died on the return journey but what a magnificent effort it was, what camaraderie and fortitude they showed in the face of adversity.

At the centre of the exhibition at the Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney is a representation of Scott’s base camp at Cape Evans. Visitors can walk inside the life-size hut and get a sense of the everyday realities for the 25 expedition members, from the cramped conditions and homeliness of the hut, to the wealth of specimens collected and experiments conducted. The exhibition also reunites the artefacts used by Scott and his team together with scientific specimens collected during the 1910-1913 expedition for the first time since their use in Antarctica. The exhibition uses life-size reproductions of the photographs of Herbert Ponting. At this scale it enables the viewer to inspect in intimate detail the habitus of their lives.

What a master of photography Ponting was. His photographs are classically framed and formally restrained; his use of light is magical. The camera always seems to be in the perfect position to capture the subject, neither too high or low but beautifully balanced so that the eye is led into the photograph, to investigate those wonderful nooks and crannies of the image plane. Because of the excellent quality press images I have been able to close in on details of the photographs (a la Ken Burns). The receding row of male faces to the left of Scott’s birthday dinner, June 1911 (below) that lead to Scott as the focal point at the head of the table, flags of St. George flying above, the two standing men acting as vertical counterpoints to the equipoise of the horizontal perspectival point – and then we glimpse the punctum of the piece of bread held between darkened fingers and thumb of the man caught in mid-conversation with his neighbour. Also note the framed images on the wall behind at top left, bearing witness to the fact that living is more civilised in such a desolate place if you are surrounded by images of culture and home.

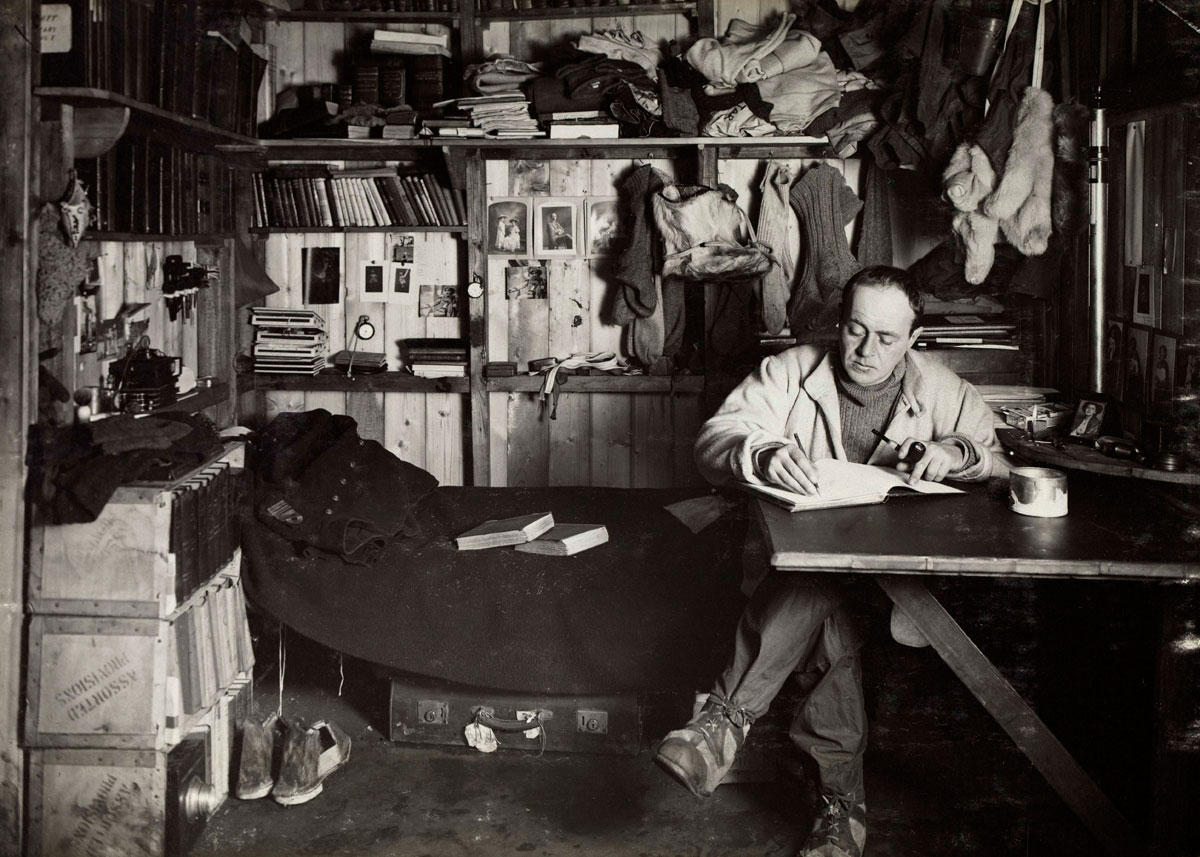

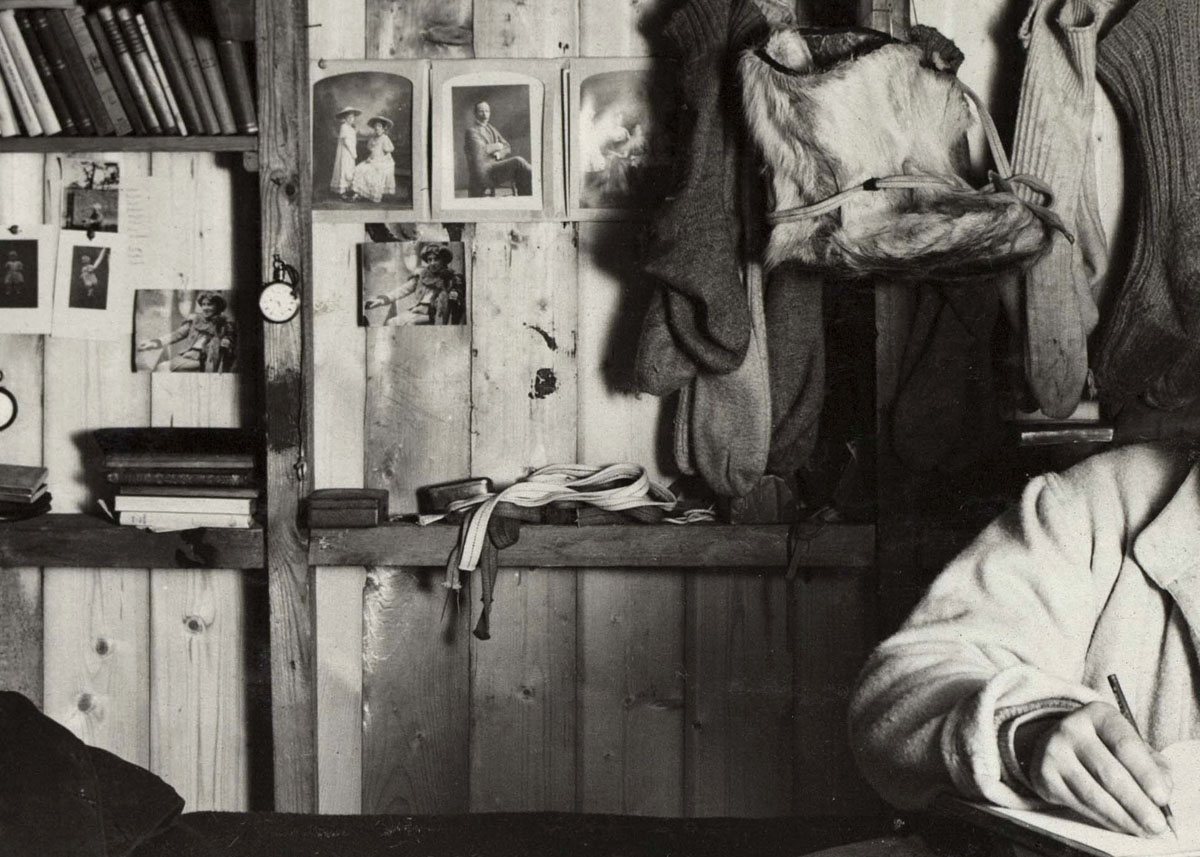

This remembrance becomes poignant in the photograph Scott writing in his area of the expedition hut, Scott’s cubicle (below). In the detail of the image we observe candid photographs of what are presumably Scott’s wife in two photographs that are slightly different from each other, his wife and child, his father and small photographs of his children pinned to the hut’s wall. Memories of home and family that become multiple momenti mori – the death of the people in the images pinned to the wall, the death present in Pontings’ photograph (the little death at the point in time that the photograph was taken) and the death of Scott himself. The pocket watch hung from a wooden post only adds to this sense of refractive timelessness.

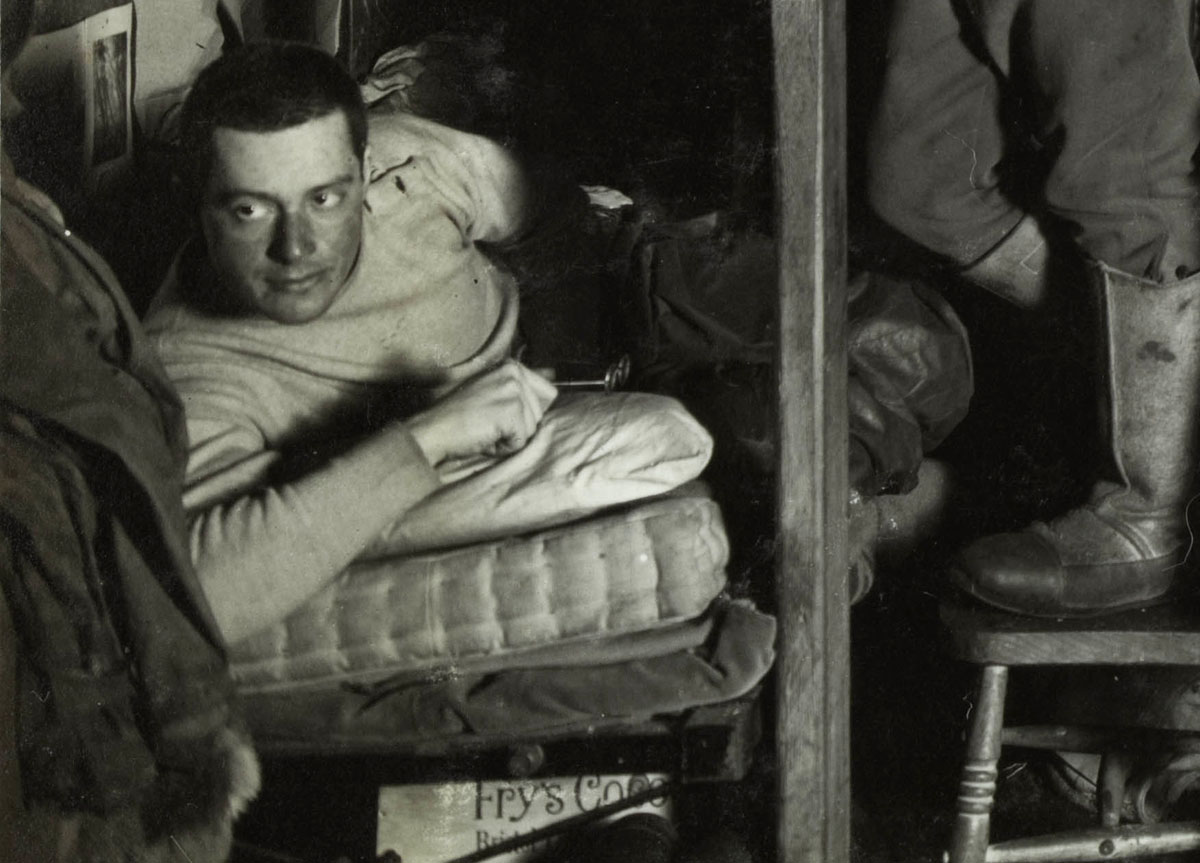

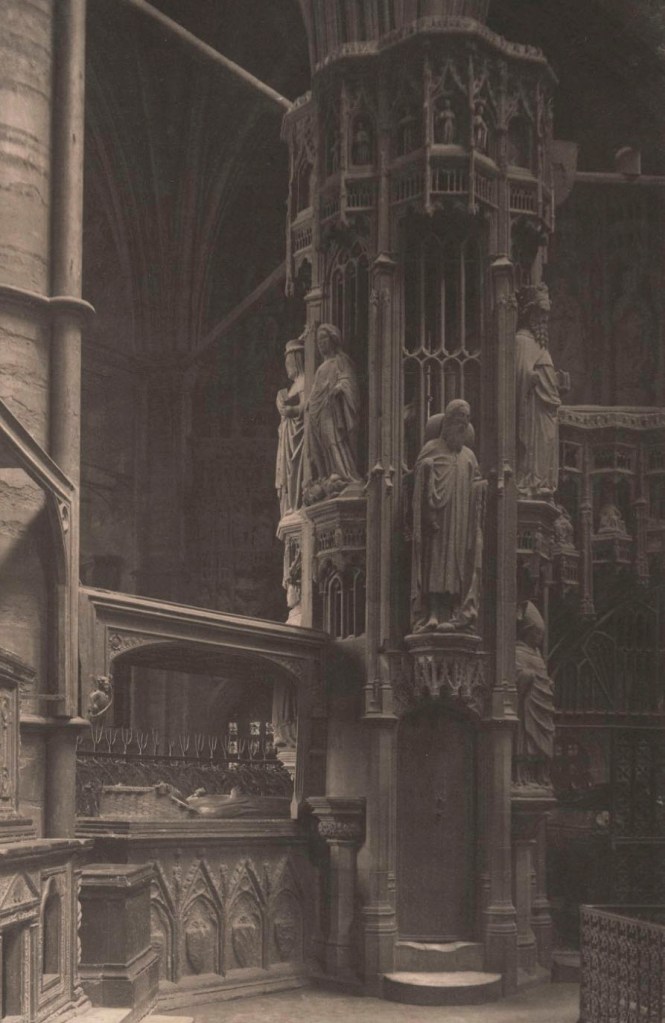

The sense of these men living in close quarters in this community is beautifully captured in Ponting’s photograph The Tenements, 9 October 1911 (below). Three vertical lozenges project into the space from the bottom of the image, each containing its own theatrical diorama. The balance and space between the men looking across, down, up and out of the image is outstanding. The distance between Oates in the top centre and the man on the right seems somehow infinite in the photograph, like the distance in Alfred Hitchcock’s film North by Northwest where Cary Grant is waiting for the bus in the middle of nowhere and on the other side of the road is another man, also waiting. The spatial tension between the two men in the photograph is palpable, emphasised by the stacked horizontal shelf behind them. The gaze of the man at bottom left allows the viewer some room for escape from the confines of the tenements and the confines of the image plane, for without that gaze the viewer would be caught with no way out. In the detail of this man we can, as before, note the importance of personal remembrances of home with a picture pinned on the wall behind his bunk and a Fry’s Cocoa box stored underneath.

And so to the final few photographs in the posting: the famous photograph of Scott and the Polar Party at the South Pole (below) taken by Henry Bowers. Taken the day after the party had arrived at the South Pole, only to discover that Roald Amundsen had beaten them to their goal by five weeks, Bowers (seated at bottom left) used a string to release the shutter of the camera that can just be seen in his right hand in the photograph – a photograph that was then printed by Herbert Ponting from the recovered glass plate negative. In the detail of Scott and Oates in this photograph you can see the weariness, anguish and defeat in faces that are sun and wind damaged, knowing that they had to trek all the way back from this awful place (as Scott himself said, “Great God! This is an awful place”).

I have put a photograph by Herbert Ponting, Captain Lawrence Edward Grace Oates during the British Antarctic Expedition of 1911-1913, below the detail of him at the South Pole. The face is almost unrecognisable from the strong, handsome face in Ponting’s picture, the prominent nose now blackened and dark being the only thing that make it recognisably the same person. In the detail of Ponting’s photograph, if you enlarge it, you can see two small points of light in his eyes, probably the light of the polar sun when Ponting took the photograph. For me these two spots of light become portents of what was to come as Oates walked out into a blizzard saying those immortal words, “I am just going outside and may be some time”. To me these points of light seared into his retina are like the driving snow that he walked out into in such a selfless act. It is very emotional for me as an Englishman and as a human being to look into the face of this man knowing what he was eventually to go through.

Though they failed in their quest to become the first to the South Pole, for this child, for this man they will forever remain my heroes.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Australian National Maritime Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

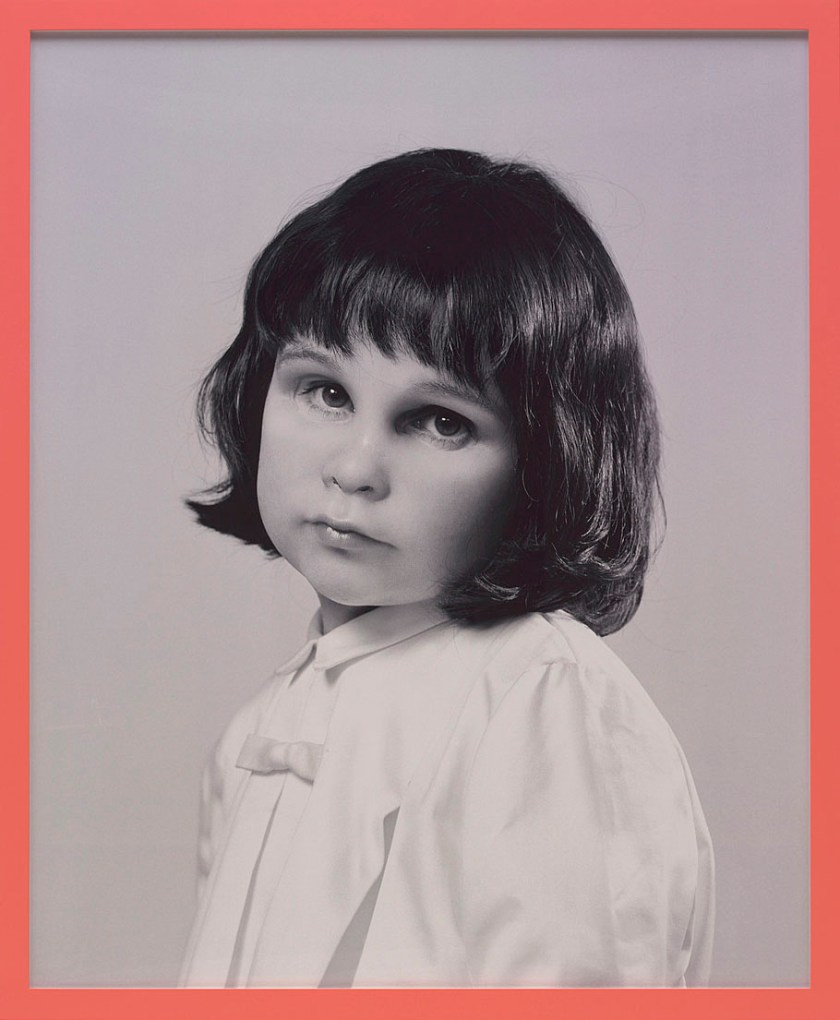

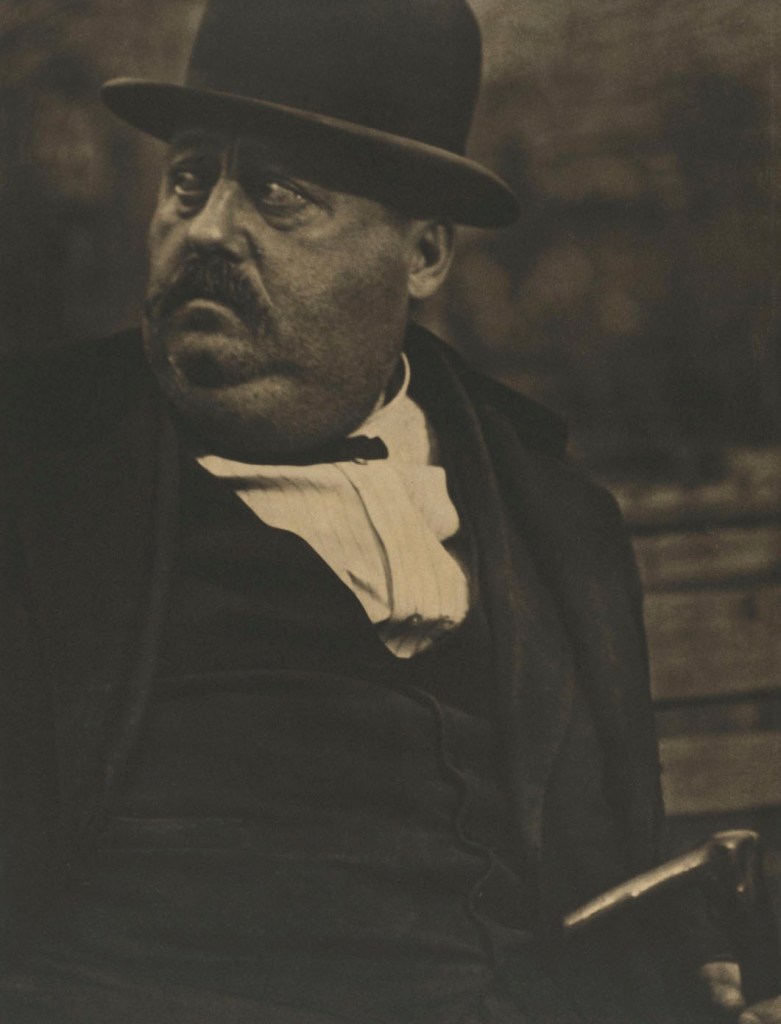

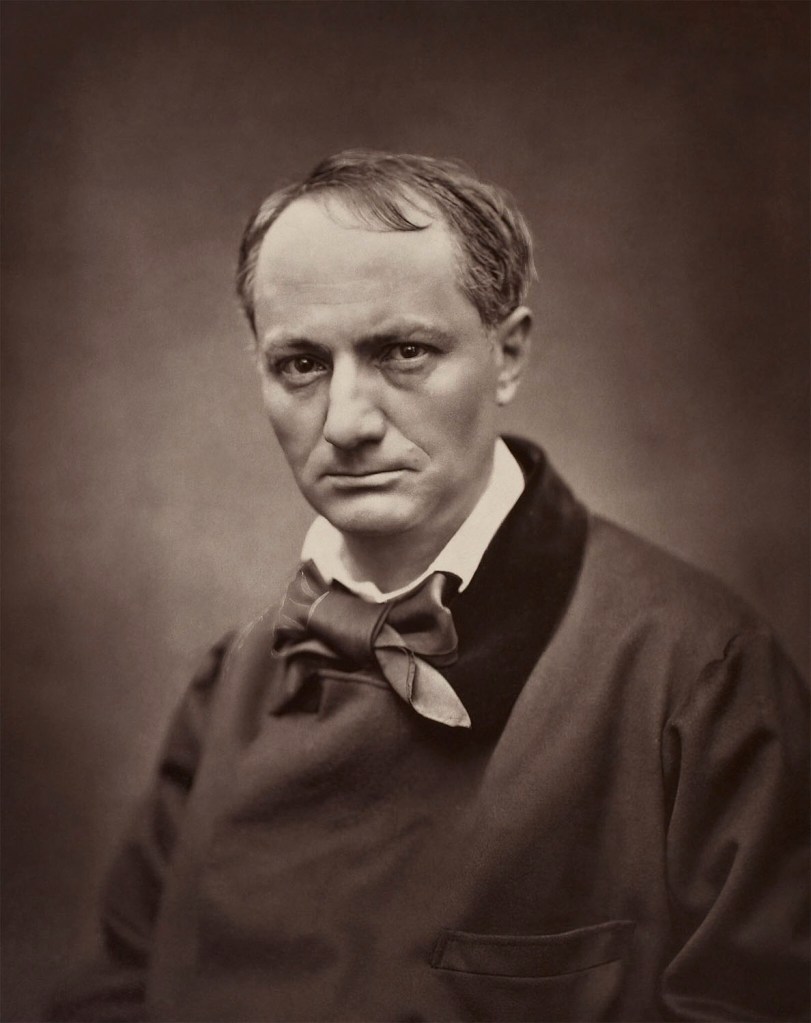

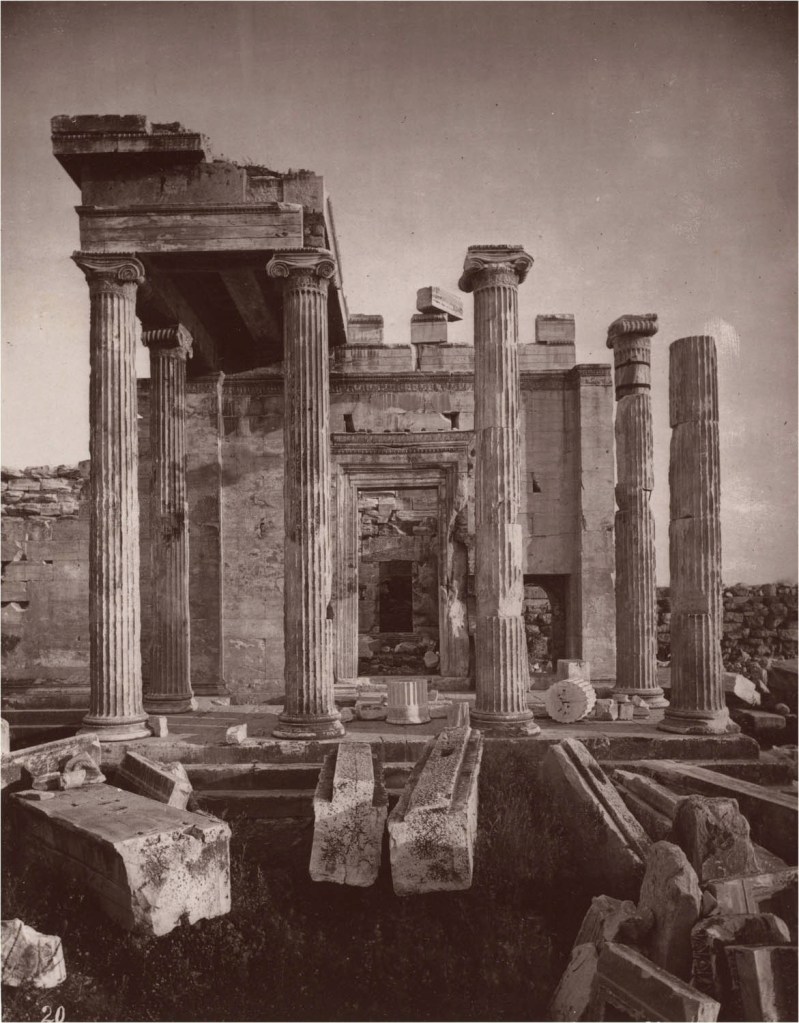

Anonymous photographer

Captain Robert Falcon Scott

Nd

Gelatin silver print

Licensed with permission of the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge

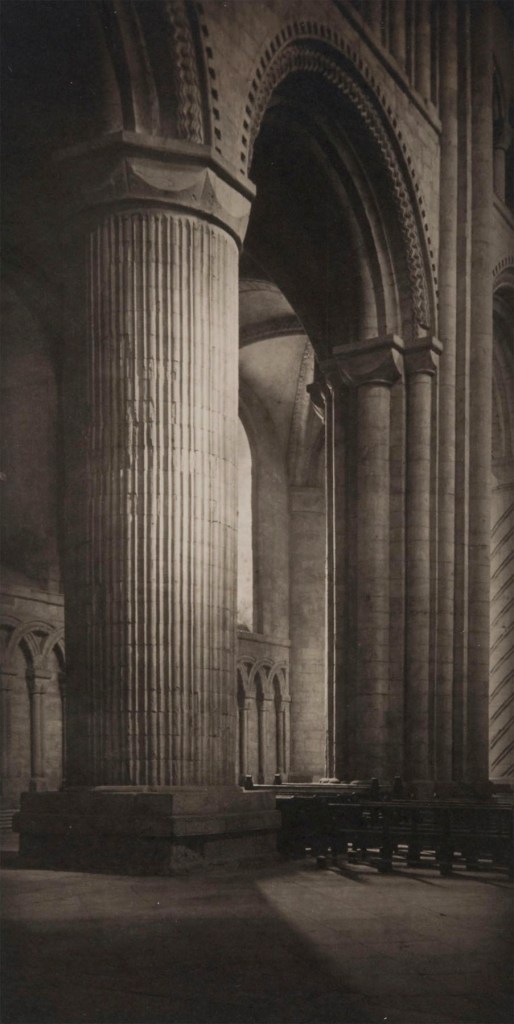

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Members of the ‘Terra Nova’ expedition with Scott in the centre

1911

Gelatin silver print

Canterbury Museum NZ

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Scott’s birthday dinner, June 1911

1911

Gelatin silver print

Canterbury Museum NZ

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Scott’s birthday dinner, June 1911 (detail)

1911

Gelatin silver print

Canterbury Museum NZ

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Scott writing in his area of the expedition hut, Scott’s cubicle

1911

Gelatin silver print

Pennell Collection, Canterbury Museum NZ

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Scott writing in his area of the expedition hut, Scott’s cubicle (detail)

1911

Gelatin silver print

Pennell Collection, Canterbury Museum NZ

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

The Tenements, 9 October 1911

1911

Gelatin silver print

Pennell Collection, Canterbury Museum NZ

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

The Tenements, 9 October 1911 (detail)

1911

Gelatin silver print

Pennell Collection, Canterbury Museum NZ

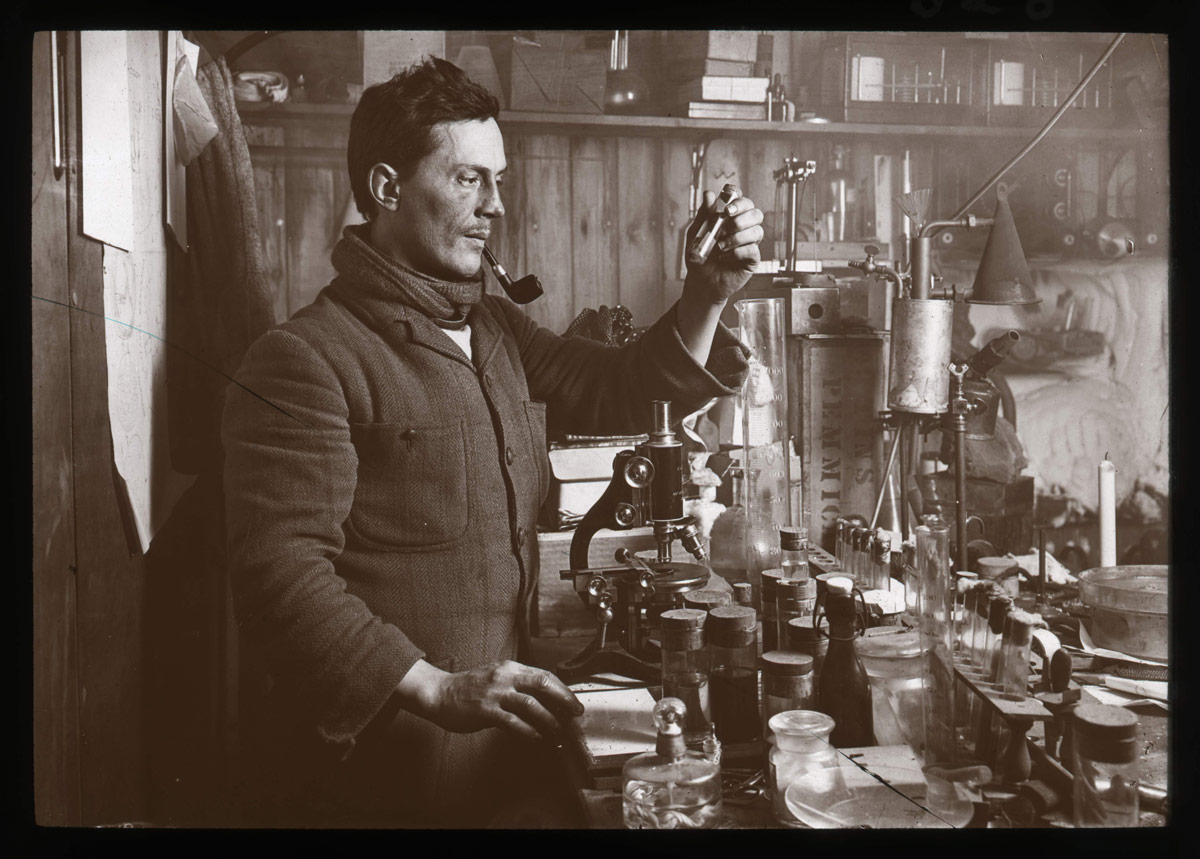

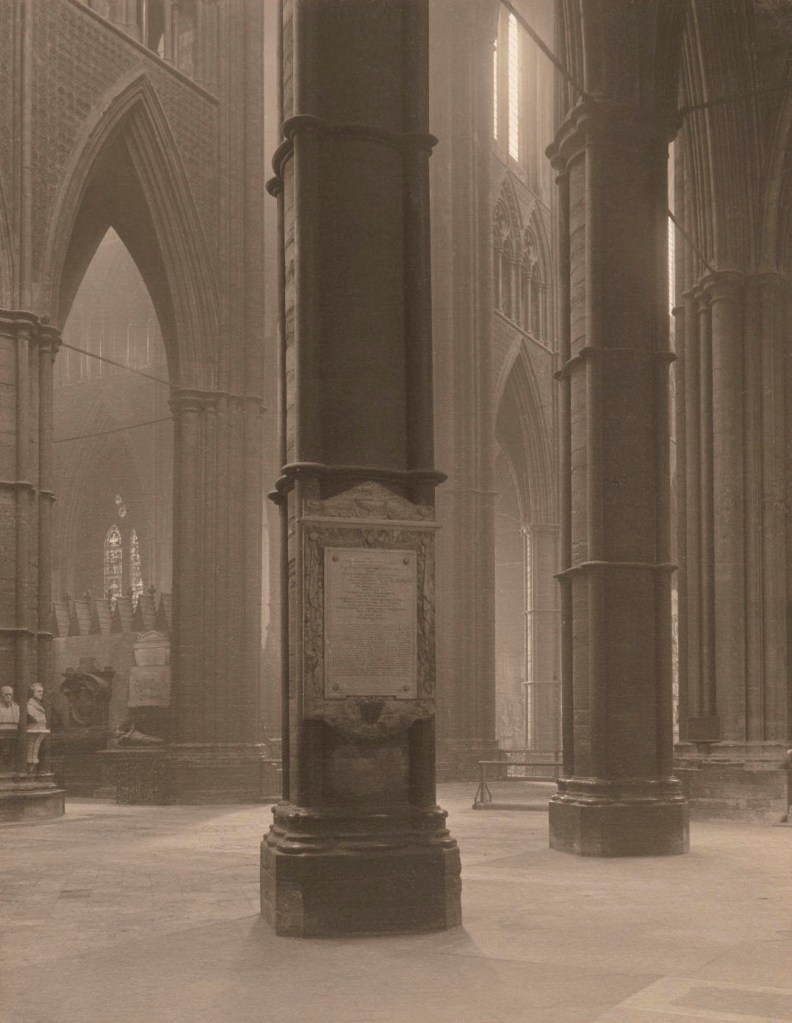

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Edward Atkinson in the laboratory

1911

Silver gelatin print

Canterbury Museum NZ

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Edward Atkinson in the laboratory (detail)

1911

Silver gelatin print

Canterbury Museum NZ

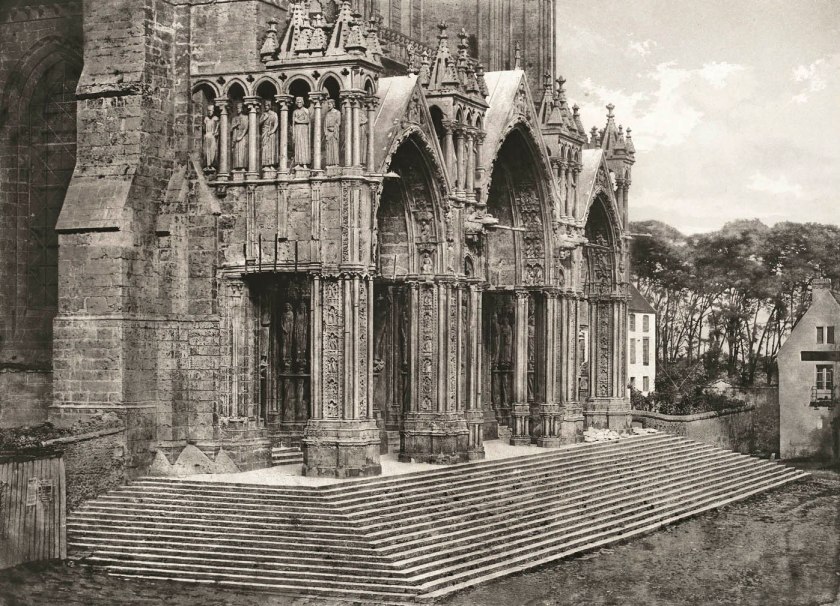

One hundred years after its tragic end, the definitive story of British explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition to Antarctica is being told in a major international exhibition coming to the Australian National Maritime Museum this June.

Scott’s Last Expedition will reunite real artefacts used by Scott and his team together with rare scientific specimens collected during the 1910-1913 expedition for the first time since their use in Antarctica.

When Scott set off on what was his second journey to explore the Antarctic on board the former whaling ship Terra Nova, he could not have predicted it would be his last. Tragically he and four of his colleagues died on the return trek to the South Pole two years later, having lost the race to be first. The exhibition however will go beyond the familiar tales of the journey to the Pole and the death of the Polar party to explore the Terra Nova expedition from every angle.

“Over the years public perceptions of Scott have varied greatly, from hero to flawed leader, and discussions of what really happened still captivate people,” said museum director Mary-Louise Williams today. “This exhibition will give visitors a unique opportunity to immerse themselves in this epic journey and the remarkable landscape of Antarctica,” she said.

Visitors will uncover Scott the man, learn more about the people who made up the expedition and explore every fascinating detail of this historic journey. At the centre of the exhibition will be a life-size representation of Scott’s Cape Evans’ base camp. Visitors can walk inside and get a sense of the everyday realities for the expedition’s members… from the cramped conditions and homeliness of the hut to the wealth of specimens collected and scientific investigations conducted.

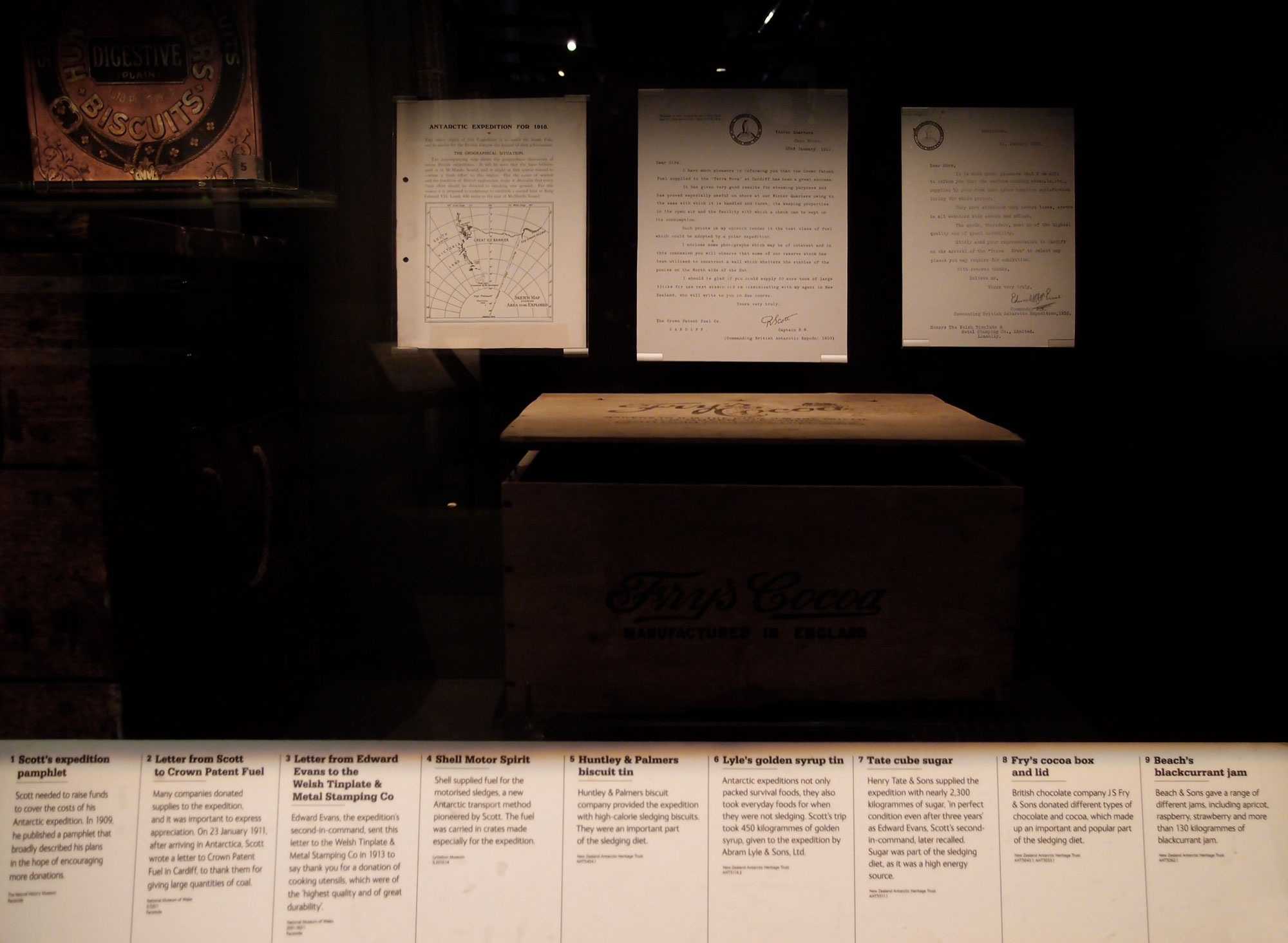

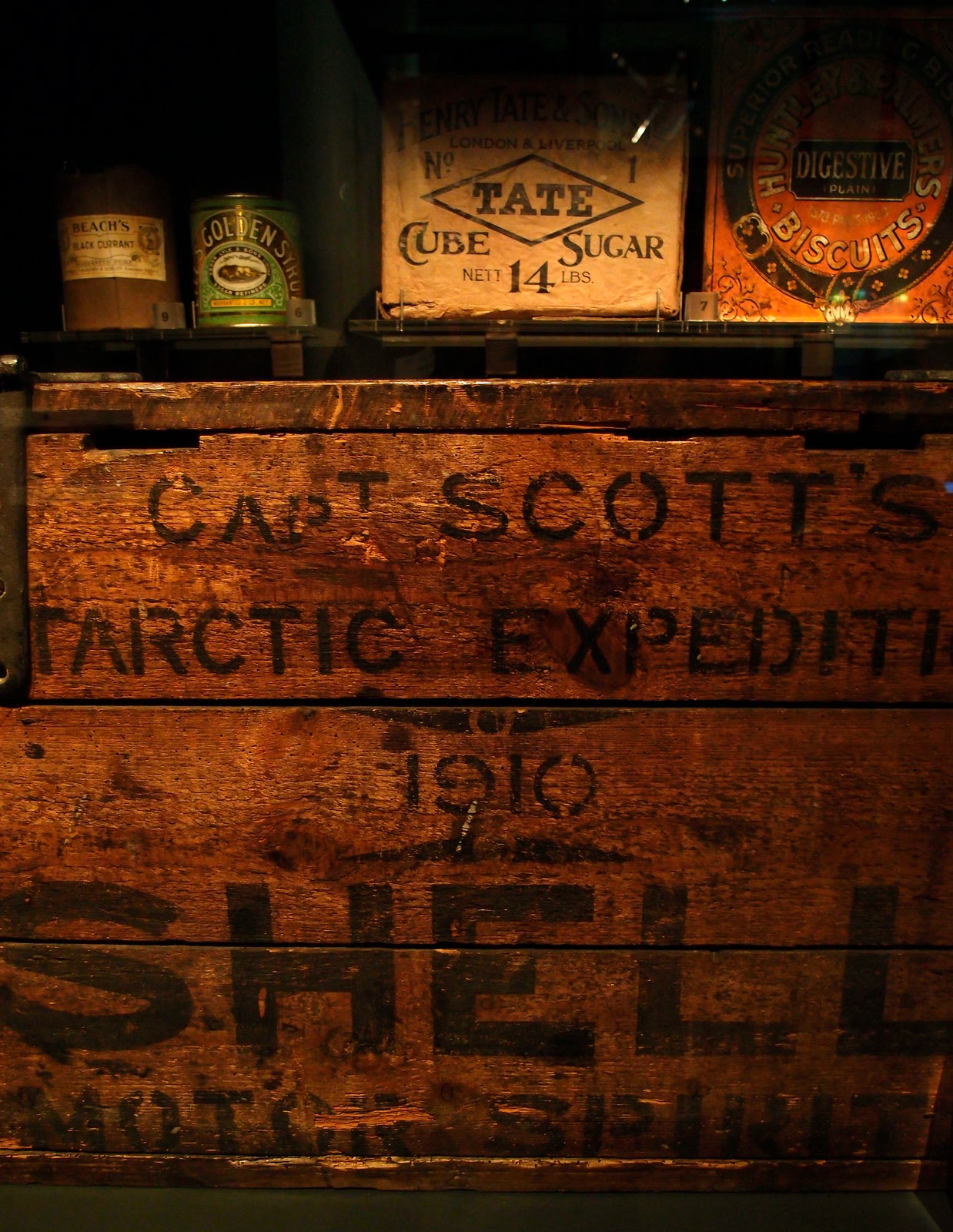

Original artefacts, equipment, clothes, and personal effects will be displayed for the first time in Australia and show the group’s attempts to make life in one of the most hostile environments on Earth as bearable as possible. Food tins including Fry’s Cocoa, Trufood Trumilk, and Symington’s Pea Flour recovered from the hut will be on display together with instruments, a microscope, and even Scott’s gramophone.

Photographs of the environment and life in camp taken by expedition photographer Herbert Ponting and poignant letters and diaries by various expedition members create a vivid picture of what life was like… working in hostile conditions, the struggles for survival and the strength of human endurance and courage.

Scott’s Terra Nova expedition made a significant contribution to Antarctic science. The expedition included a full scientific program with a large team of scientists making new discoveries which directly led to a greater understanding of Antarctica. The scientists had to endure harsh Antarctic conditions to carry out their work. It was cold, windy and completely dark in winter and, if not careful, the scientists could easily get frostbitten. And yet despite the conditions, the expedition left a rich legacy that continues to inspire and inform today.

Natural History Museum, London, the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand and the Antarctic Heritage Trust, New Zealand, have collaborated to create this exhibition to commemorate the centenary of the expedition and celebrate its achievements.

Press release from the Australian National Maritime Museum

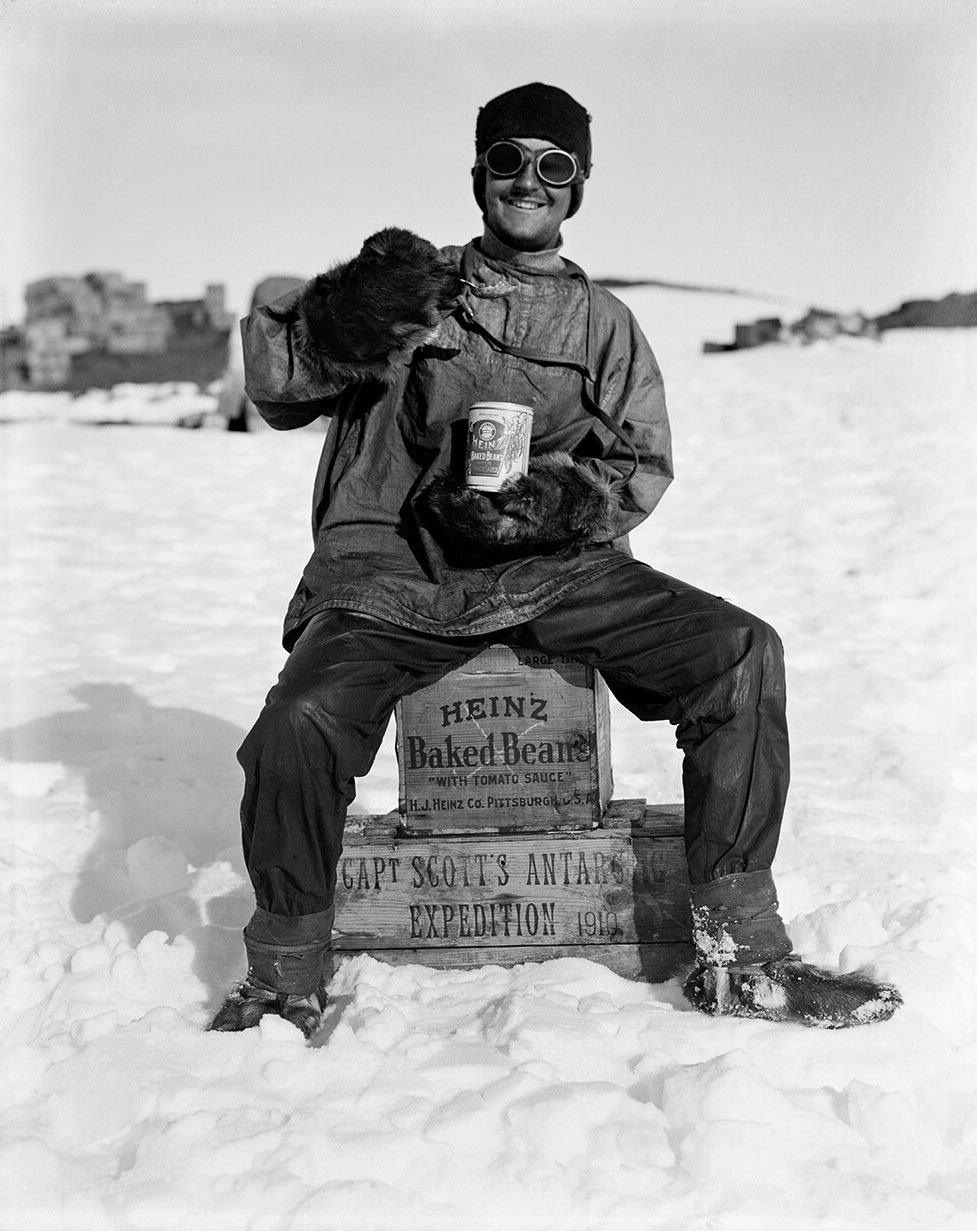

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

A member of the team tucks into a tin of Heinz baked beans in the Ross Dependency, during Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova Expedition to the Antarctic, January 1912

1912

Silver gelatin print

Canterbury Museum NZ

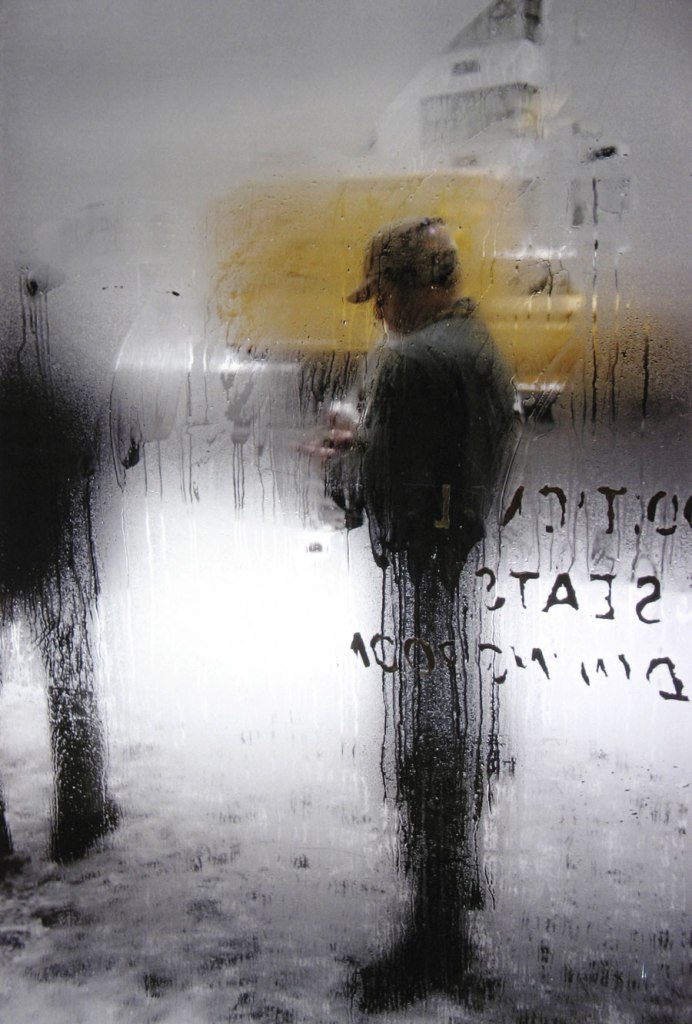

Neerav Bhatt (photographer)

Installation view of the exhibition Scott’s Last Expedition at the Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney, June – October 2011

CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Scott and the Polar Party at the South Pole

Left to right: Captain Lawrence Oates, Lieutenant Henry Bowers (seated), Captain Robert Falcon Scott, Dr Edward Wilson (Seated), Petty Officer Edgar Evans

1912

Licensed with permission of the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge.

Notice the camera release cord in the right hand of Lieutenant Henry Bowers.

The fatal journey

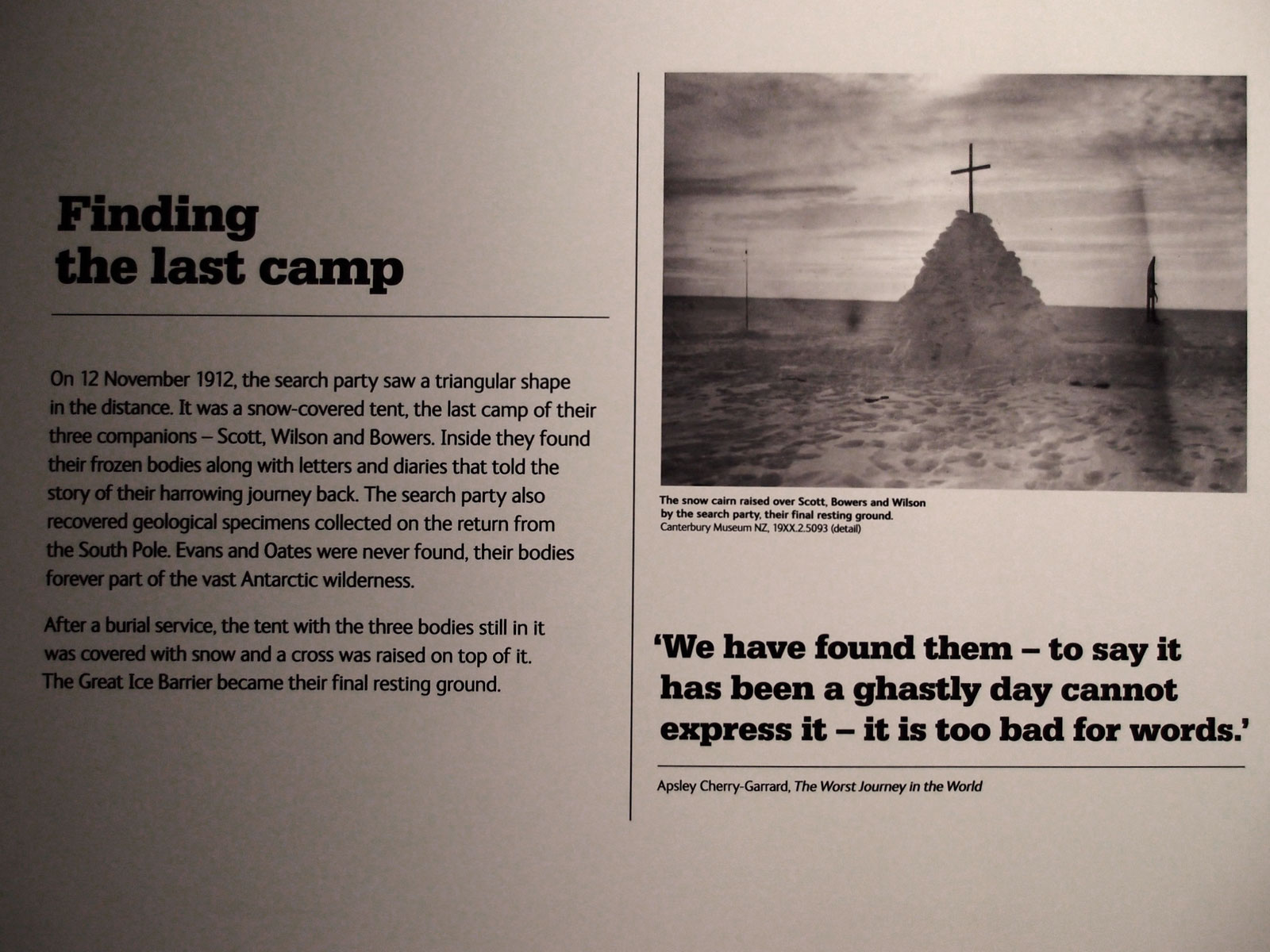

Scott’s 1,450 km journey to the geographic South Pole began on 1 November 1911, two weeks after the Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen left his base camp at the Bay of Whales. Amundsen reached the pole first – on 14 December 1911 – and then raced back to tell the world their news. Scott and his team reached the Pole a month later on 17 January 1912 having been beset by fierce weather conditions. The disappointment was immense. The return journey was undertaken in horrid weather with harsh, intense cold and violent blizzards that, in the end, defeated them. Evans failed first, suffering concussion from a fall; Oates suffered dramatic frostbite to his feet – gangrene had set in – and he crawled out of the tent saying the now famous words, “I am just going outside and may be some time”. The remaining men – Scott, Wilson and Bowers – were weak with malnutrition, starvation and exhaustion and perished on or around 29/30 March 1912 – some three weeks after the world learned that Amundsen had reached the Pole first.

Captain Robert Falcon Scott at the South Pole (detail)

Captain Lawrence Oates at the South Pole (detail)

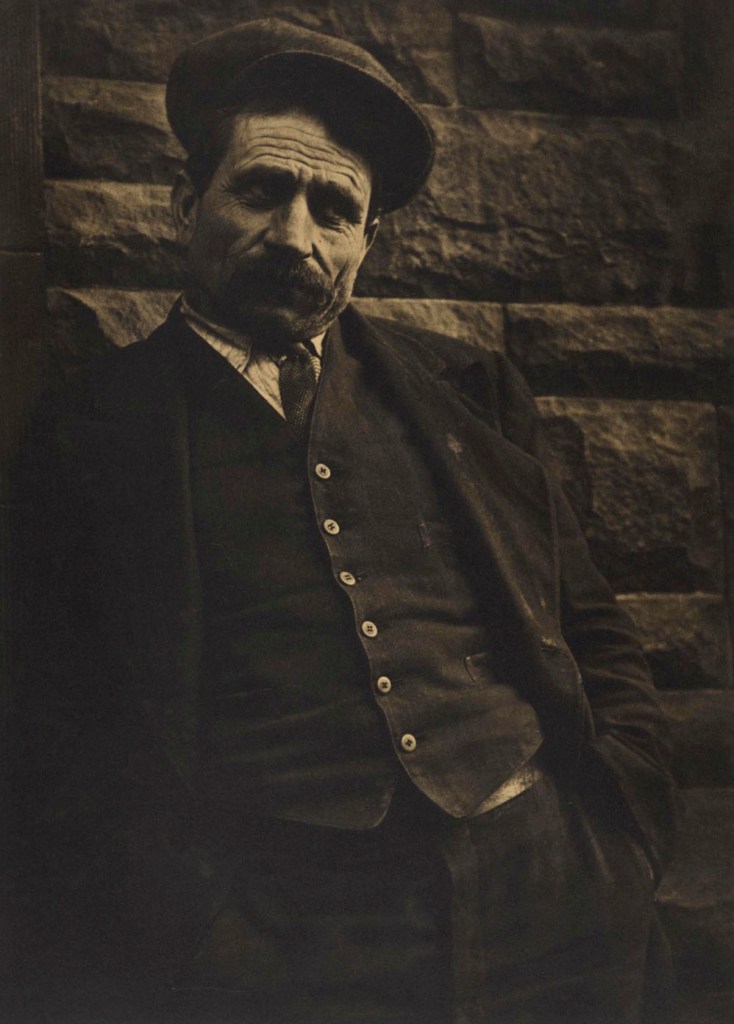

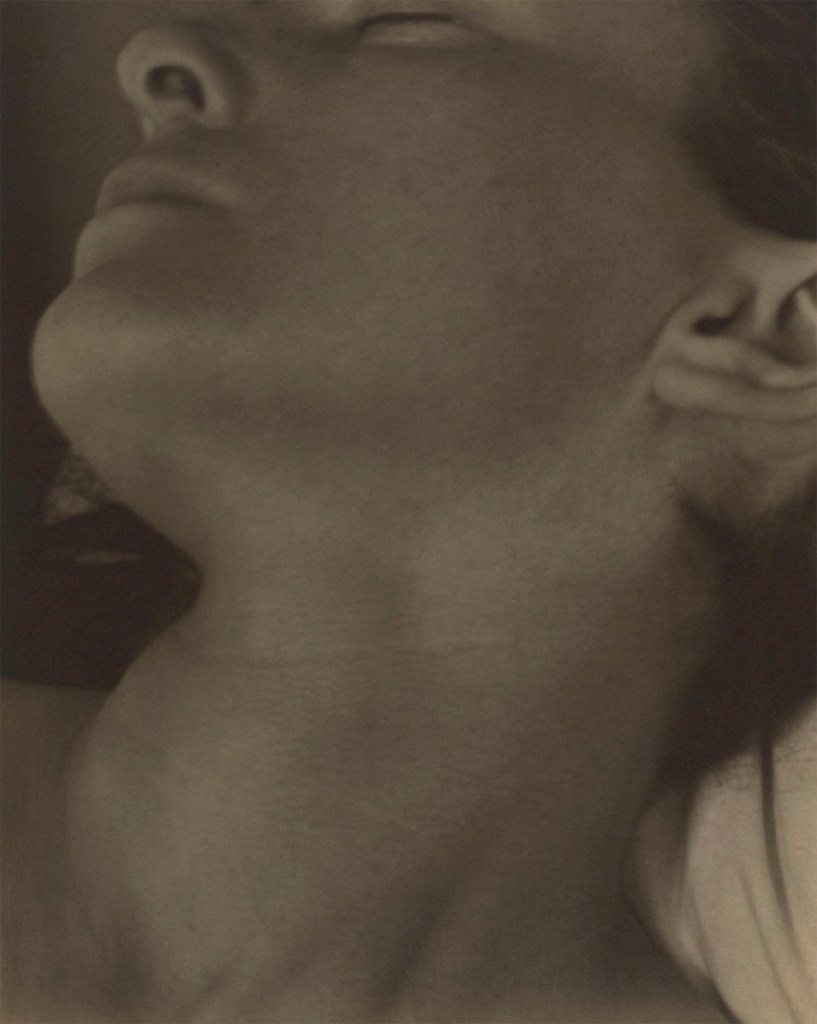

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Captain Lawrence Edward Grace Oates during the British Antarctic Expedition of 1911-1913

c. 1911

Silver gelatin print

Photographic Archive, Alexander Turnbull Library

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Captain Lawrence Edward Grace Oates during the British Antarctic Expedition of 1911-1913 (detail)

c. 1911

Silver gelatin print

Photographic Archive, Alexander Turnbull Library

Anonymous photographer

The snow cairn raised over Scott, Bowers and Wilson by the search party, their final resting ground (detail)

1912

Silver gelatine print

Canterbury Museum NZ

Australian National Maritime Museum

2 Murray Street

Darling Harbour

Sydney NSW 2000

Australia

Opening hours:

Every day 10am – 4.00pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.