Exhibition dates: 21st September 2013 – 16th March 2014

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Beachy Head Tripper Boat, 1967

1967

© National Media Museum

“Be more aware of composition

Don’t take boring pictures

Get in closer

Watch camera shake

Don’t shoot too much”

Tony Ray-Jones from his diaries

Growing up in the 1960s we used to get taken to Butlins holiday camps (Billy Butlin founded the company, a chain of large holiday camps in the United Kingdom, to provide affordable holidays for ordinary British families). It was a great treat to be away from the farm, to be by the sea, even if the beach was made of stones. Looking back on it now you realise how seedy it was, how working class… but as a kid it was oh, so much fun!

Tony Ray-Jones photographed these environments (mainly the British at play by the sea) and their opposites – afternoon tea taken at Glyndebourne opera festival for example (Glyndebourne, 1967, below) – drawing on the tradition of great British social documentary photography by artists such as Bill Brandt. TRJ even pays homage to Brandt in one of his photographs, Dickens Festival, Broadstairs, c. 1967 (below) which echoes Brandt’s famous photograph Parlourmaid and Under-parlourmaid Ready to Serve Dinner, 1933 by changing “point of view” from up close, personal, oppressive and interior to distance, isolation, leisure/work and exterior.

Through his photographs Ray-Jones adds his own style and humour, using “a new conception of photography as a means of expression, over and above its accepted role as a recorder.” He does it all as an intimate expression of his own personality, his maverick, outsider, non-conformist self. I feel – and that is the key word with his art – that he had a real empathy with his subject matter. There is a twinkle in his eye that becomes embedded in his photographs. There is an honesty, integrity and respect for the people he is photographing, coupled with a wicked sense of humour and the most amazing photographic eye. What an eye he had!

To be able to sum up a scene in a split second, to previsualise (think), intuitively compose, frame and shoot in that twinkle of an eye, and to balance the images as he does is truly the most incredible gift, the quintessential British “decisive moment”. Look at the structural analysis of Location unknown, possibly Worthing (1967-1968, below) that I have presented in a slide show. This will give you a good idea of the visual complexity of Ray-Jones’ images… and yet he makes the sum of all components seem grounded (in this case by the man’s feet) and effortless. Devon Caranicas has observed that TRJ possessed a quick wit and adeptness for reducing a complex narrative into a single frame, the photographed subjects transformed into social actors of supreme stereotypes. The first part is insightful, but social actors of supreme stereotypes? I think not, because these people are not acting, this is their life, their humanity, their time out from the hum-drum of everyday working class life. They do not pose for TRJ, it’s just how they are. Look at the musicality of the first five images in the posting – how the line rises and falls, moves towards you and away from you. Only a great artist can do that, instinctively.

I cannot express to you enough the utmost admiration I have for this man’s art. In my opinion he is one of greatest British photographers that has ever lived (Julia Margaret Cameron, William Henry Fox Talbot, Roger Fenton, Francis Bedford, Frederick H. Evans, Cecil Beaton, Peter Henry Emerson and Herbert Ponting would be but a few others that spring to mind). He photographed British customs and values at a time of change and pictured a real affection for the lives of ordinary working class people. Being one of the them, he will always hold a special place in my heart.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Media Space at Science Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Although the entirety of the images from Only in England were shot throughout the politically and socially turbulent late 60’s and early 70’s both artists shy away from depicting the culture clashes that so often visually defined this period. Instead, they each opted to turn their lens onto the quintessential country side, and in doing so, pay homage to a traditional type of English life that was becoming a sort of sub-culture in itself – a way of living that was not yet touched by the encroaching globalisation, or “americanisation,” of the UK.”

Anonymous text on the ART WEDNESDAY website September 26th, 2013 [Online] Cited 05/03/2014. No longer available online

“Ray-Jones printed his black and white pictures small, in a dark register of tonally very dense prints. The National Media Museum has lots of these, and perhaps to devote the cavernous new space only to such small pictures would have been a mistake. Even backed up with a mass of supporting material, including the fascinating pages from Ray-Jones’ diaries, the prints would struggle to fill the space. So only the first section is devoted to about 50 beautiful little Ray-Jones vintage prints. Two whole sections have been added to the exhibition to flesh it out…

[Parr] has unfortunately chosen to print them [Ray-Jones prints] in a way quite alien to anything Ray-Jones ever made: they are printed in Parr’s own way, as larger, paler, more diffuse things in mid-tones that Ray-Jones would never have countenanced. They are printed, inevitably, by digital process…

Sadly, these Ray-Jones by Parr prints add up to an appropriation of the former by the latter: they are Martin Parr pictures taken from Tony-Ray Jones negatives, and it would have been better not to have shown them so. They are fine images, but they should have been seen in some other way: on digital screens, perhaps, or as modern post-cards. Anything to make quite explicit the clear break with Ray-Jones’ own prints. That the images they contain are very fine is not in doubt. But I take leave to question whether they “present a new way of thinking through creative use of the collections”. They are well labelled and for specialists there will be no difficulty in knowing that they are not by Ray-Jones. But for the public I am not so sure. Suddenly two-thirds of the show are in this larger, modern, digitally printed form, either by Parr himself or by Ray-Jones-through-Parr. It looks as if that is the dominant group…”

Extract from Francis Hodgson. “Two Exhibitions of Tony Ray-Jones – Two Ways of Giving Context to Photographs,” on the Photomonitor website, September 2013 Cited 05/03/2014 no longer available online

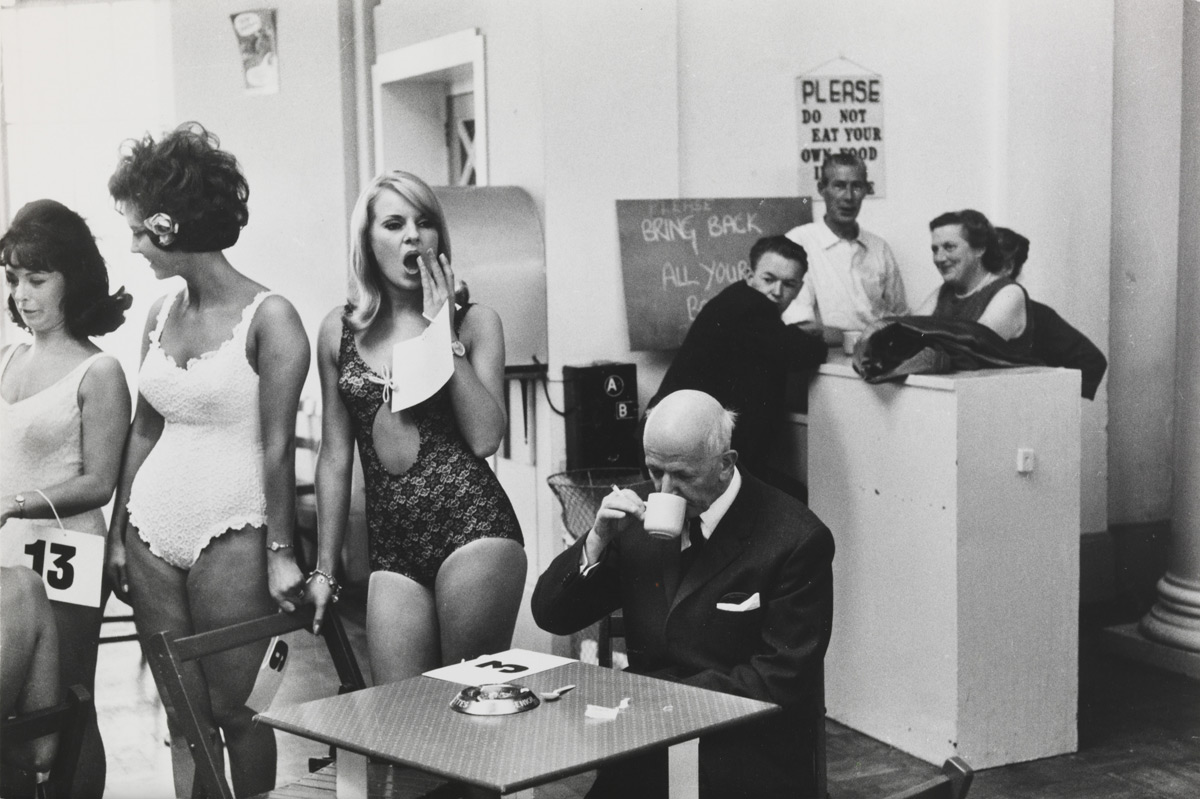

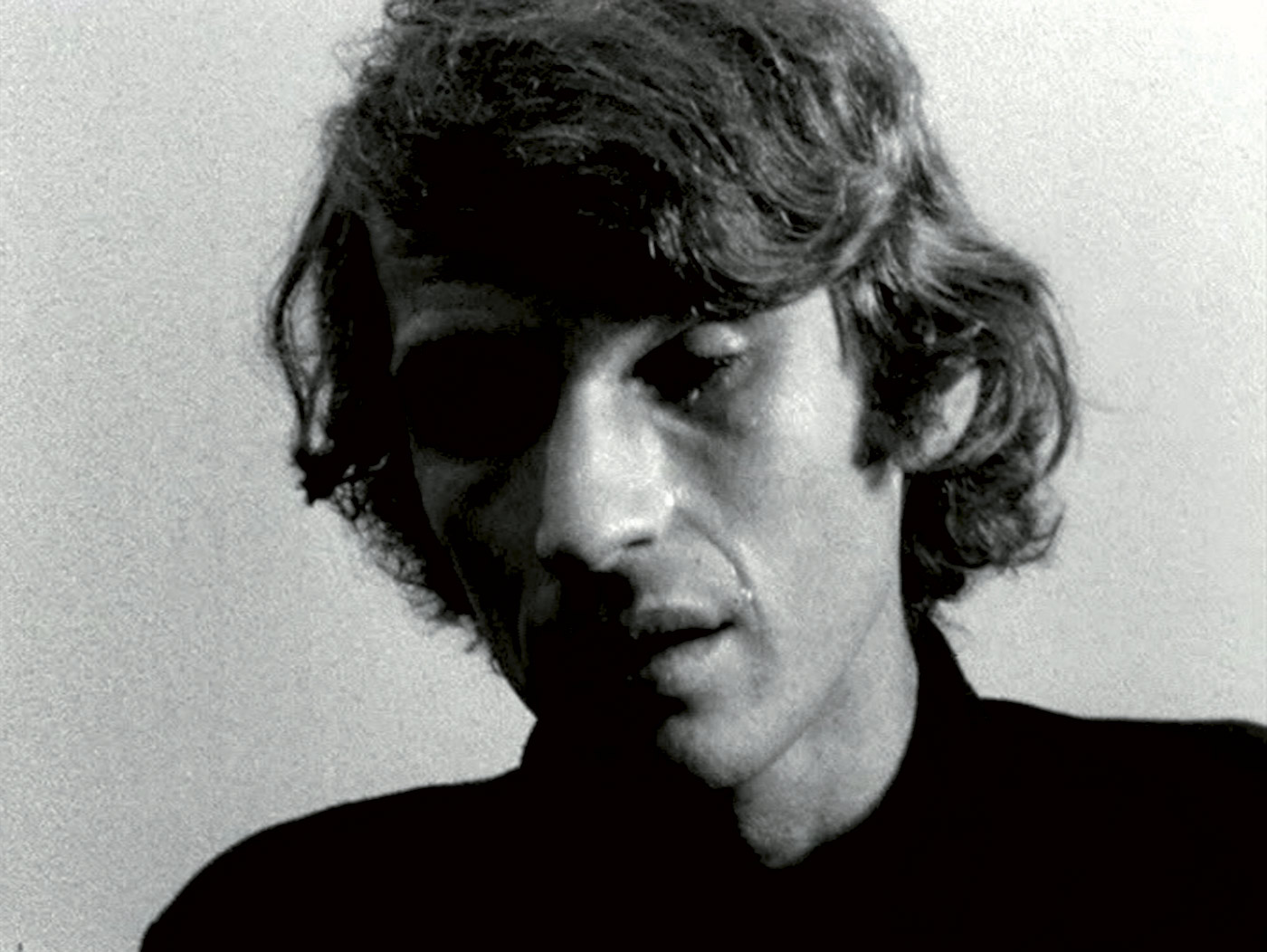

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Beauty contestants, Southport, Merseyside, 1967

1967

© National Media Museum

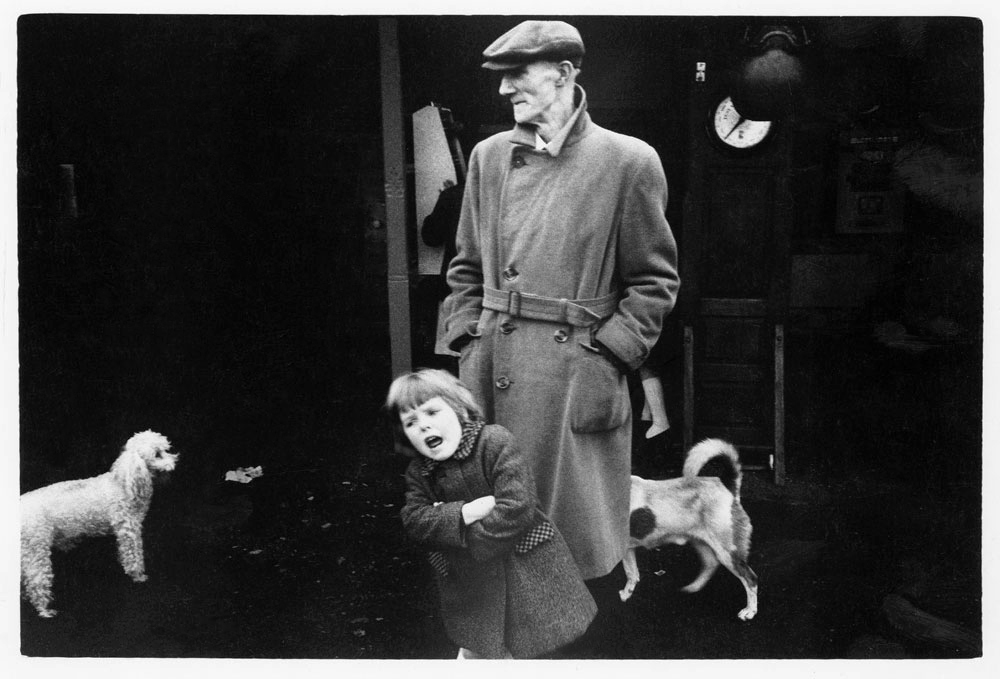

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Brighton Beach, West Sussex, 1966

1966

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Eastbourne Carnival, 1967

1967

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Blackpool, 1968

1968

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Location unknown, possibly Worthing

1967-1968

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones Location unknown, possibly Worthing (1967-68) picture analysis by Dr Marcus Bunyan

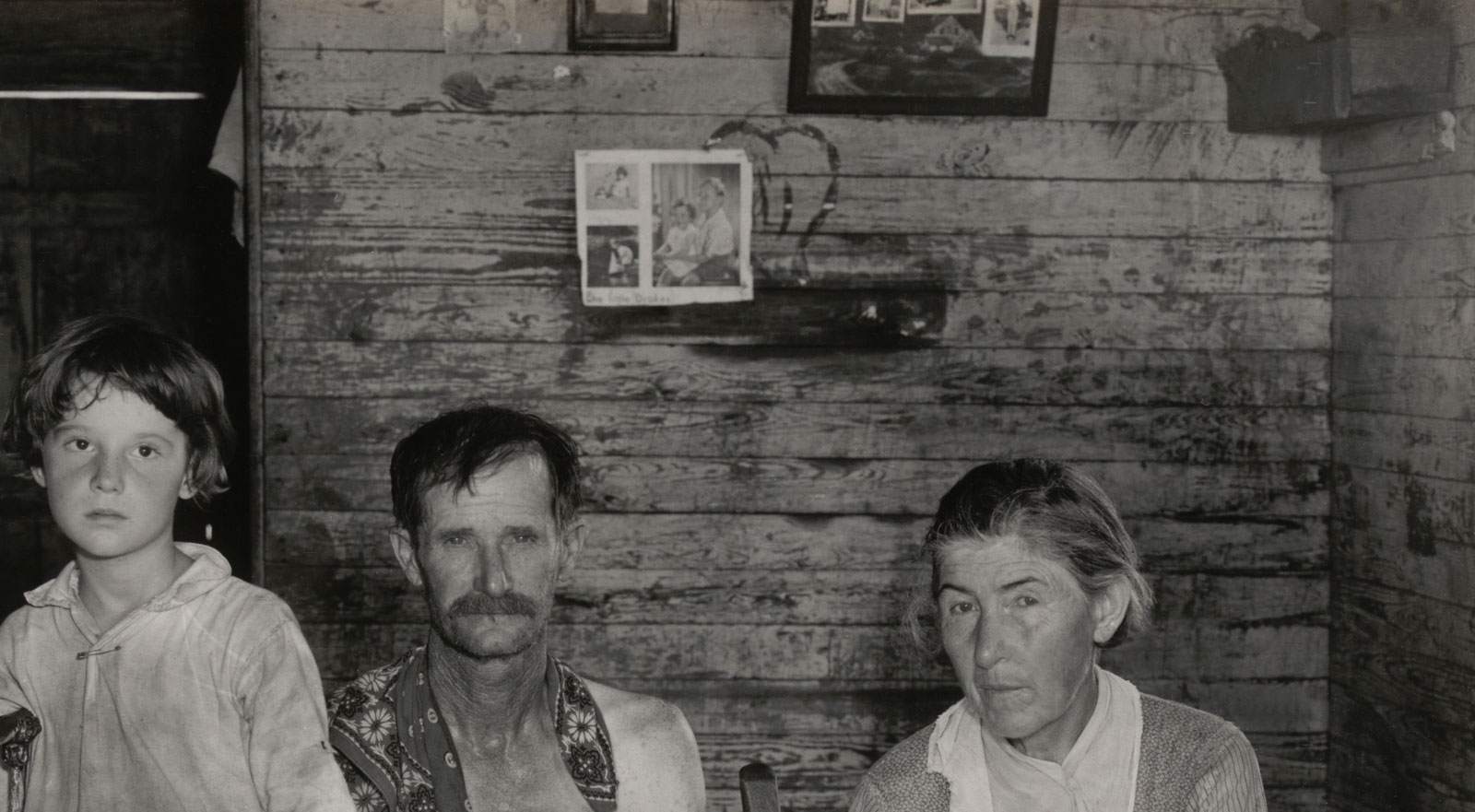

Fascinated by the eccentricities of English social customs, Tony Ray-Jones spent the latter half of the 1960s travelling across England, photographing what he saw as a disappearing way of life. Humorous yet melancholy, these works had a profound influence on photographer Martin Parr, who has now made a new selection including over 50 previously unseen works from the National Media Museum’s Ray-Jones archive. Shown alongside The Non-Conformists, Parr’s rarely seen work from the 1970s, this selection forms a major new exhibition which demonstrates the close relationships between the work of these two important photographers.

The first ever major London exhibition of work by British Photographer, Tony Ray-Jones (1941-1972) will open at Media Space on 21 September 2013. The exhibition will feature over 100 works drawn from the Tony Ray-Jones archive at the National Media Museum alongside 50 rarely seen early black and white photographs, The Non-Conformists, by Martin Parr (1952).

Between 1966 and 1969 Tony Ray-Jones created a body of photographic work documenting English customs and identity. Humorous yet melancholy, these photographs were a departure from anything else being produced at the time. They quickly attracted the attention of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London where they were exhibited in 1969. Tragically, in 1972, Ray-Jones died from Leukaemia aged just 30. However, his short but prolific career had a lasting influence on the development of British photography from the 1970s through to the present.

In 1970, Martin Parr, a photography student at Manchester Polytechnic, had been introduced to Ray-Jones. Inspired by him, Parr produced The Non-Conformists, shot in black and white in Hebden Bridge and the surrounding Calder Valley. This project started within two years of Ray-Jones death and demonstrates his legacy and influence.

The exhibition will draw from the Tony Ray-Jones archive, held by the National Media Museum. Around 50 vintage prints will be on display alongside an equal number of photographs which have never previously been printed. Martin Parr has been invited to select these new works from the 2700 contact sheets and negatives in the archive. Shown alongside these are Parr’s early black and white work, unfamiliar to many, which has only ever previously been exhibited in Hebden Bridge itself and at Camerawork Gallery, London in 1981.

Tony Ray-Jones was born in Somerset in 1941. He studied graphic design at the London School of Printing before leaving the UK in 1961 to study on a scholarship at Yale University in Connecticut, US. He followed this with a year long stay in New York during which he attended classes by the influential art director Alexey Brodovitch, and became friends with photographers Joel Meyerowitz and Garry Winogrand. In 1966 he returned to find a Britain still divided by class and tradition. A Day Off – An English Journal, a collection of photographs he took between 1967-1970 was published posthumously in 1974 and in 2004 the National Media Museum held a major exhibition, A Gentle Madness: The Photographs of Tony Ray-Jones.

Martin Parr was born in Epsom, Surry in 1952. He graduated from Manchester Polytechnic in 1974 and moved to Hebden Bridge in West Yorkshire, where he established the ‘Albert Street Workshop’, a hub for artistic activity in the town. Fascinated by the variety of non-conformist chapels and the communities he encountered in the town he produced The Non-Conformists. In 1984 Parr began to work in colour and his breakthrough publication The Last Resort was published in 1986. A Magnum photographer, Parr is now an internationally renowned photographer, filmmaker, collector and curator, best-known for his highly saturated colour photographs critiquing modern life.

Only in England: Photographs by Tony Ray-Jones and Martin Parr will run at Media Space, Science Museum from 21 September 2013 – 16 March 2014. The exhibition will then be on display at the National Media Museum from 22 March – 29 June 2014. The exhibition is curated by Greg Hobson, curator of Photographs at the National Media Museum, and Martin Parr has been invited to select works from the Tony Ray-Jones archives.

Greg Hobson, curator of Photographs at the National Media Museum says, “The combination of Martin Parr and Tony Ray-Jones’ work will allow the viewer to trace an important trajectory through the history of British photography, and present new ways of thinking about photographic histories through creative use of our collections.” Martin Parr says, “Tony Ray-Jones’ pictures were about England. They had that contrast, that seedy eccentricity, but they showed it in a very subtle way. They have an ambiguity, a visual anarchy. They showed me what was possible.”

The Tony Ray-Jones archive comprises of approximately 700 photographic prints, 1700 negative sheets, 2700 contact sheets, 600 boxes of Ektachrome / Kodachrome transparencies. It also includes ephemera such as notebooks, diary pages, and a maquette of England by the Sea made by Tony Ray-Jones.

Media Space is a collaboration between the Science Museum (London) and the National Media Museum (Bradford). Media Space will showcase the National Photography Collection of the National Media Museum through a series of exhibitions. Alongside this, photographers, artists and the creative industries will respond to the wider collections of the Science Museum Group to explore visual media, technology and science.

Press release from the Science Museum website

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Bacup coconut dancers, 1968

1968

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Bournemouth, 1969

1969

Vintage Gelatin Silver Print

16 x 25cm (6 x 10 inches)

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Location unknown, possible Morecambe, 1967-68

1967-1968

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Mablethorpe, 1967

1967

Vintage Gelatin Silver Print

14 x 21cm (6 x 8 inches)

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Ramsgate, 1967

1967

© National Media Museum

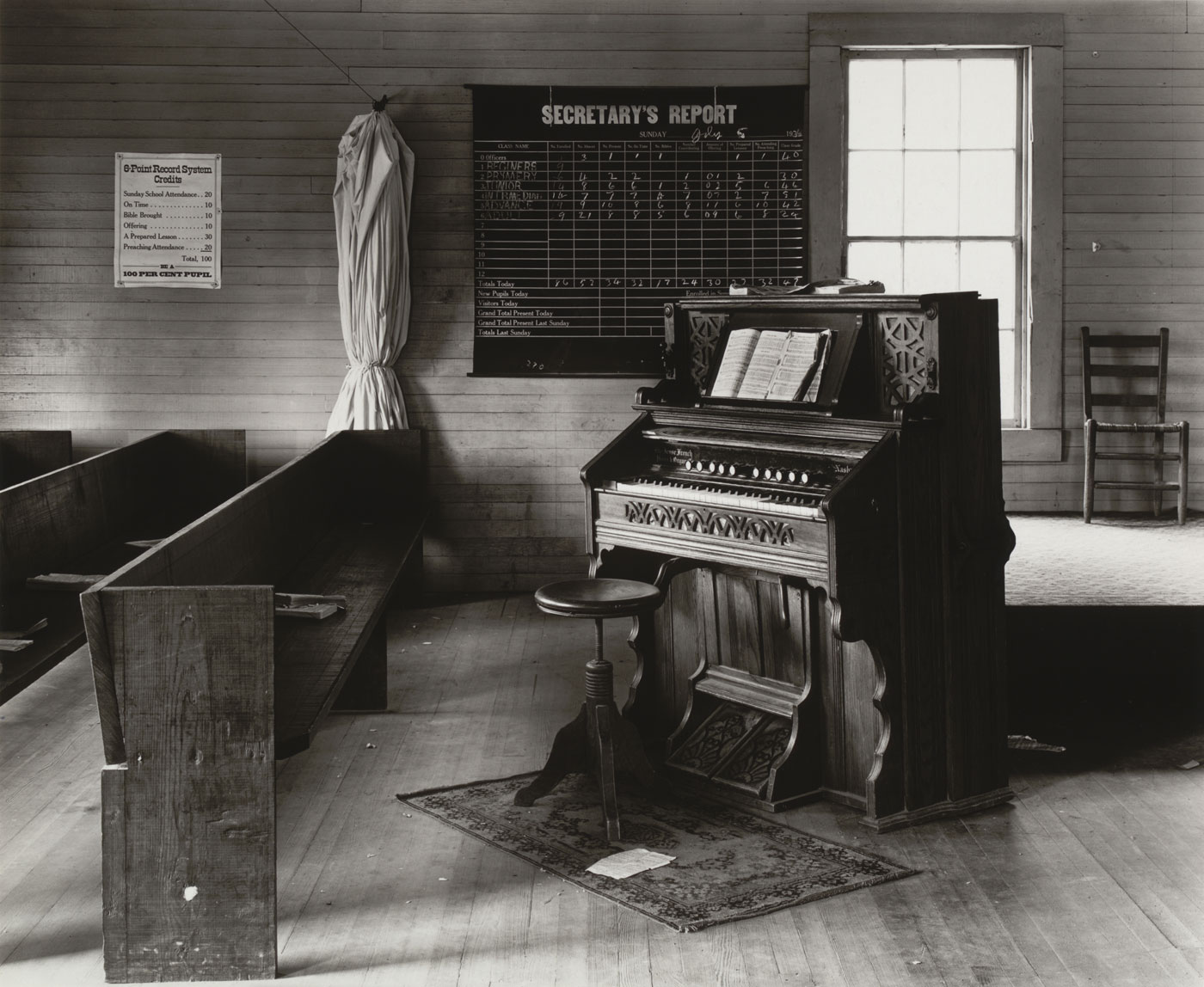

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Mankinholes Methodist Chapel, Todmorden

1975

© Martin Parr/ Magnum

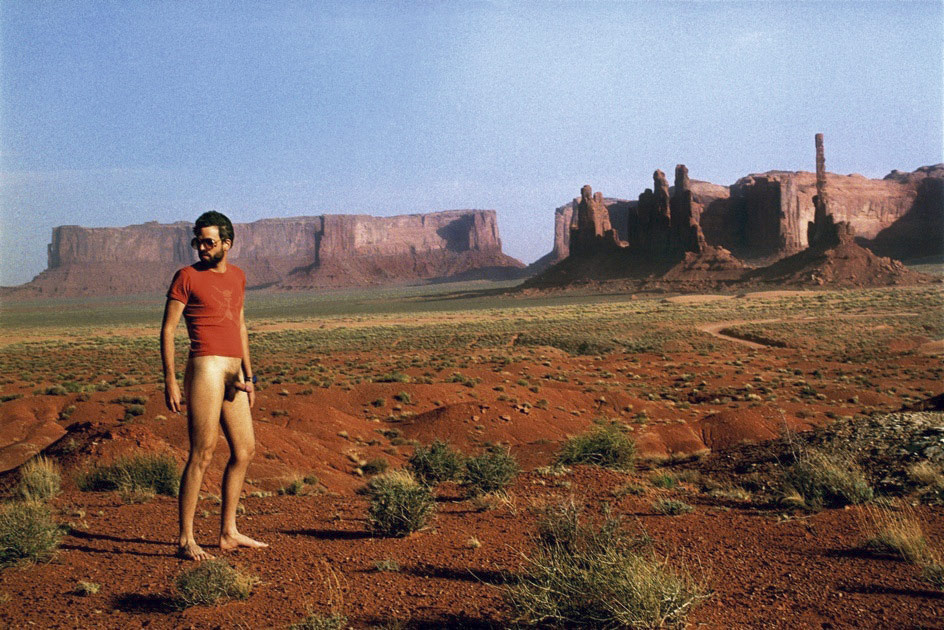

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Cruft’s Dog Show, London, 1966

1966

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Dickens Festival, Broadstairs, c. 1967

c. 1967

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Dickens Festival, Broadstairs, c. 1967

c. 1967

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Wormwood Scrubs Fair, London, 1967

1967

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Untitled

1960s

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Trooping the Colour, London, 1967

1967

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Untitled

1960s

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Glyndebourne, 1967

1967

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Elderly woman eating pie seated in a pier shelter next to a stuffed bear, 1969

1969

© National Media Museum

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Blackpool, 1968

1968

Vintage Gelatin Silver Print

21 x 14.5cm (8.25 x 5.70 ins)

Tony Ray-Jones (English, 1941-1972)

Tom Greenwood cleaning

1976

© Martin Parr/ Magnum

Media Space at Science Museum

Exhibition Road, South Kensington,

London SW7 2DD

Opening hours:

Open seven days a week, 10.00 – 18.00

![Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975) 'La mitrailleuse en état de grâce' (The Machine Gun[neress] in a State of Grace) 1937 Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975) 'La mitrailleuse en état de grâce' (The Machine Gun[neress] in a State of Grace) 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/fleshandmetal_01_bellmer-web.jpg?w=650&h=651)

You must be logged in to post a comment.