Exhibition dates: Tuesday 22nd July – Saturday 26th July, 2014

Artists represented: Philip Potter, John Storey, John Englart, Barbara Creed, Ponch Hawkes, Rennie Ellis

Curators: Dr Marcus Bunyan and Nicholas Henderson

Figure 1

Photographer unknown

The original eight hour day banner

1856

This is my catalogue essay that accompanies the exhibition Out of the closets, into the streets: gay liberation photography 1971-73 at Edmund Pearce Gallery, Melbourne. It’s a bit of a read (3,000 words) but stick with it. I hope you like the insights into the background of the images and the people in the exhibition.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to all the artists for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. Download the Being (t)here catalogue essay (2.2Mb pdf)

Being (t)here: Gay liberation photography in Australia 1971-73

“For the colour and the soundtrack to be part of the politics, even a central part of the politics… meant something new by way of embodiment. Much of the political action was about being there, about putting one’s body on the line. A demonstration, sit-in or blockade is centrally about occupying space. A nonviolent movement tried to occupy space with bodies, not bullets.

It was a key feature of the new left that this embodied politics couldn’t stop in the streets: that is, the public arena as conventionally understood. ‘Being there’ politically also applied to households, classrooms, sexual relations, workplaces and the natural environment.”1

I came out as a gay man in 1975, six years after Stonewall and only a few short years after the photographs in this exhibition were taken. The first open acknowledgement of my nascent sexuality was to walk into a newsagent in Notting Hill Gate, London, head down, red as a beetroot and pick up a copy of Gay Times. I literally flung the money at the person behind the counter and ran out. I was so embarrassed. I was seventeen.

From the gay rag I found the name of the local convenor of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) and went to meet him at his home. John was the very first openly gay man that I had ever met. We became lifelong friends. He used to hold coffee evenings a couple of times a week in his flat so that the local gay men had somewhere safe and secure to meet – to chat and laugh, to talk about love and life. Once a month there was a pub that we all went to in the country for a bit of a dance night, but that was it unless you went up to London to a nightclub.

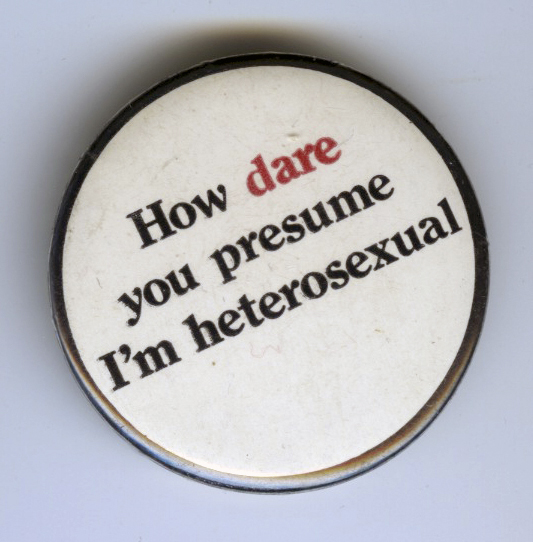

None of us were very active politically, although we kept an eye on the papers and we all understood the discrimination and persecution we faced. But by the very act of being openly gay, as most of us were, we were making a political statement. I was openly gay at college in London and stopped “passing” as something I was not (a straight man) by coming out to my family and friends. I placed my being – there, there and there, in different contexts, so that my family, friends and the community could not ignore my sexuality. I never lived in fear but there was a great deal of self-loathing going on behind the scenes. In those days you were always thought of as “abnormal” and defective if you were a poofter. And there was the guilt of that association. As James Nichols observes, “To be gay or lesbian meant belonging to a genealogy of suffering, to have a dramatic, if not a tragic, destiny. Despite the many battles and certain victories that ensued, the homosexual remained a victim in the collective consciousness; a hidden man.”2 William Leonard continues the theme: “If concealment is a psychic wounding that divides each gay man against himself, it is also a collective division that precludes the forms of public association and political affiliation on which gay liberation depends. As gay men confront their own internalised feelings of self-recrimination, if not disgust, they begin to rattle the closet door and seek out, in public, others of their own kind.”3 And rattle the closet door I did. I flaunted my hi-vis identity for all to see. If the liberation movement meant putting your body on the line – not so much by consciously protesting on the streets but by being visible in whatever setting as a gay man – then I certainly did that.

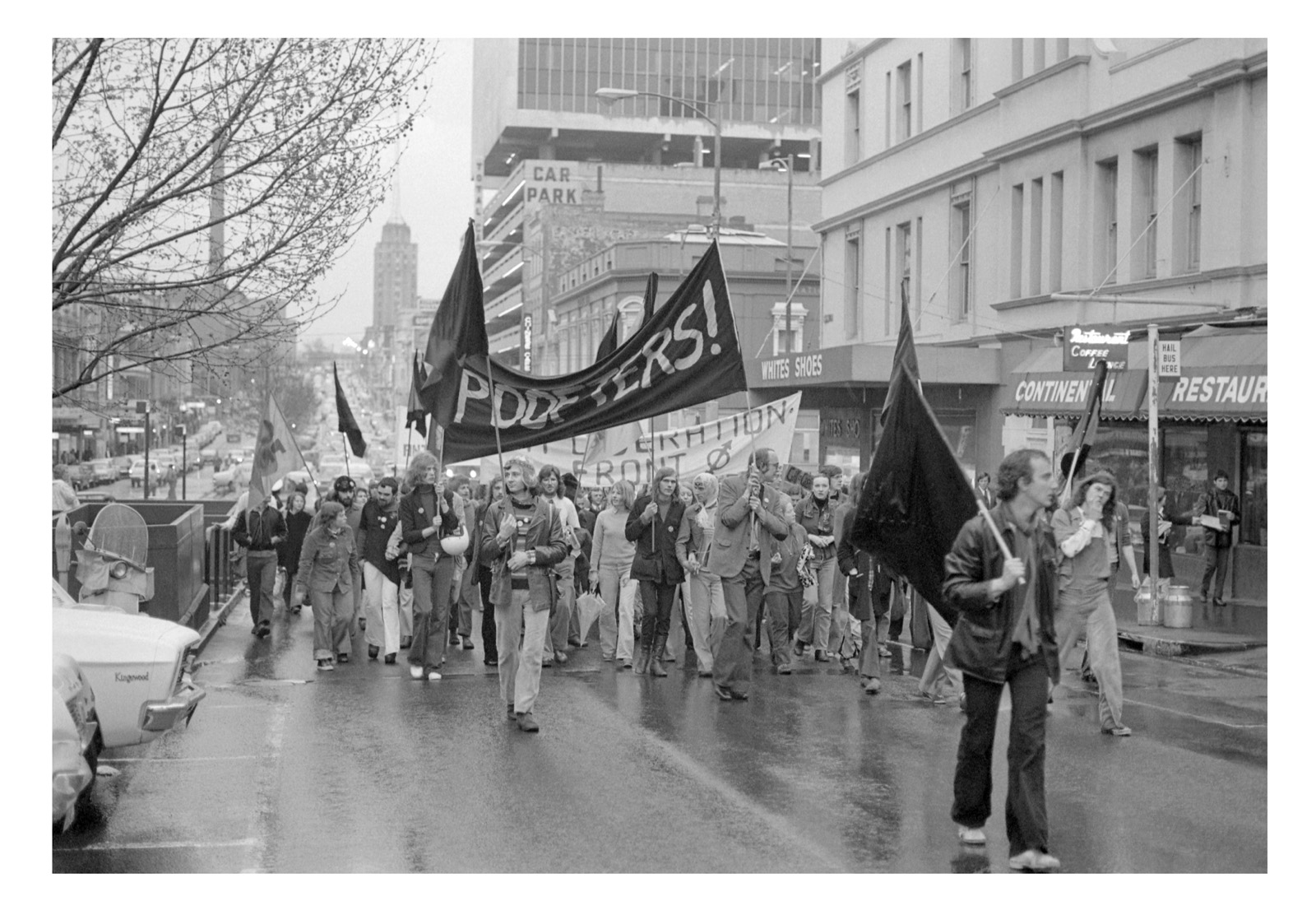

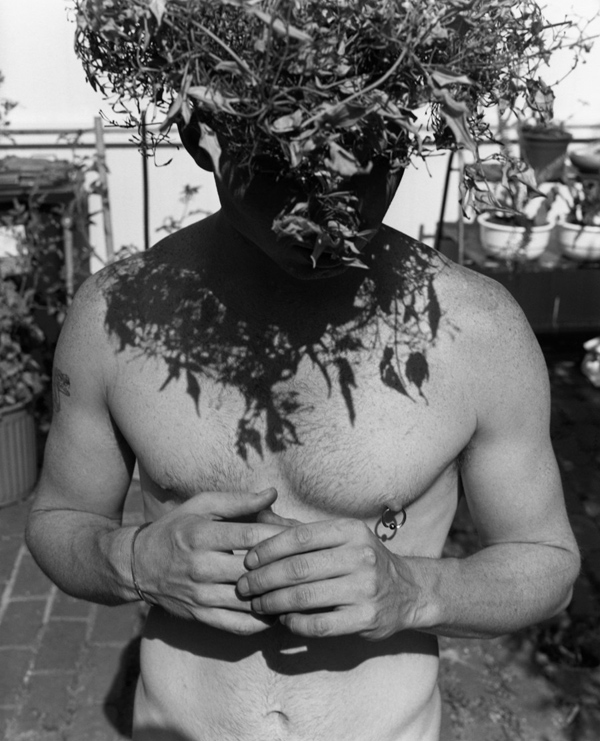

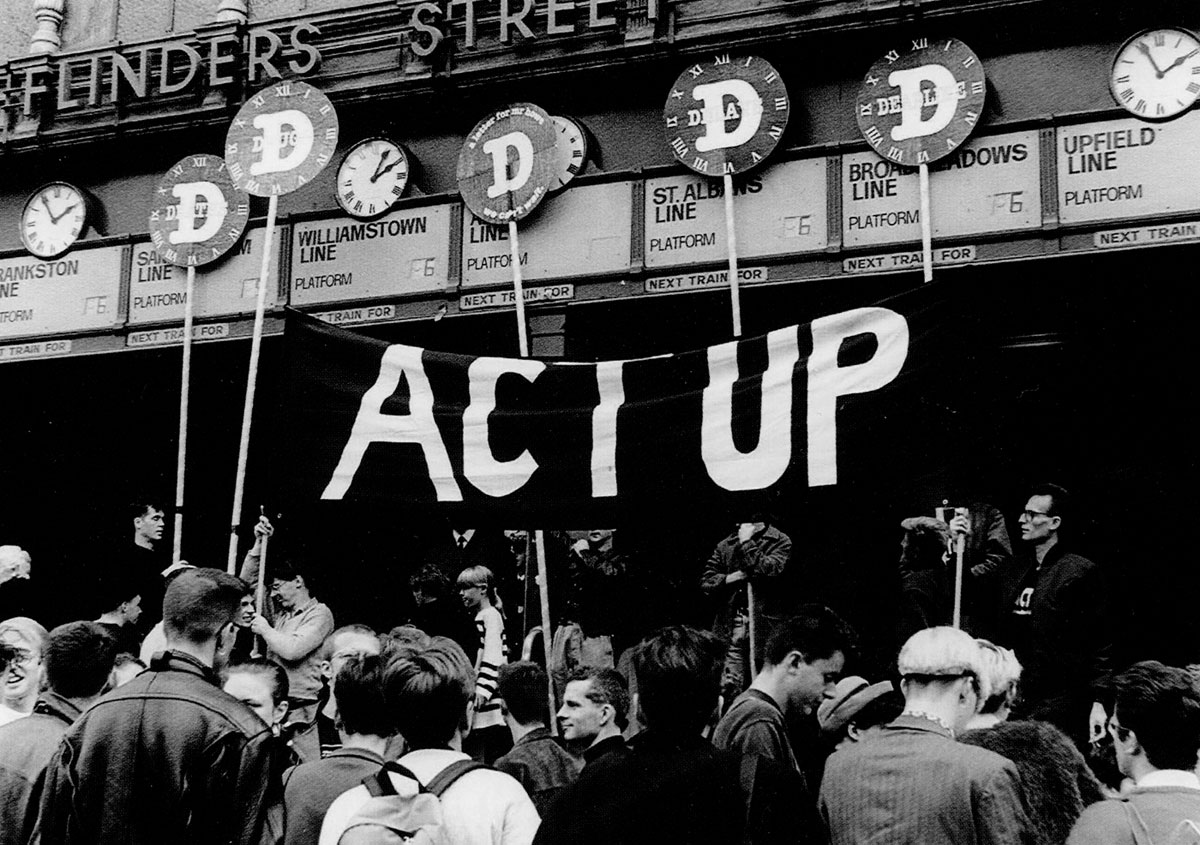

Photography documented this Gay Liberation thing, the emergence in public and private of gay people. It not only documented this visibility but also represented it in very aesthetic and artistic ways that up until now have not really been recognised as such. This is where the photographs in this exhibition make their presence known. As gay people found their voice in the early 1970s artists, often at the very beginning of their careers, were there to capture meetings in lounge rooms, consciousness raising groups and street protests. The photographer as artist was not just a witness to these events but actively participated in these actions, which they envisioned in a subjective way. Unlike earlier images of protest marches where there is an observational distance between the photographer / event which allowed for the depiction of environment and numbers (for example in the 8 hour day marches, see figures 1-4) – from the mid-1960s onwards there is a seismic shift in how photographs represent social change and observed history. Now the photographer marches with the inmates and becomes an intimate participant in the proceedings (see figures 5-6).

In this revolutionary era, the artist evidences an empathy with the events being photographed, an up close and personal point of view. Whatever meeting or protest they were there to record was important to them, be it anti-Vietnam war, anti-Apartheid, pro abortion, nuclear disarmament, Gay Liberation, Women’s Liberation, Aboriginal rights, anti-fascist marches and student protests from around the world. And it didn’t matter whether the photographers were gay, straight or whatever. People appropriated public and private space as a form of collective activism, using social movement cultures to re-make the world. The ways of imagining life and transformation, of imaging life and transformation were enabled by the photographer actively participating in these events. The photographer’s “second sight” did not consist in “seeing” but in being there.

As Professor Barbara Creed states of her interest in artistically documenting these actions, “I was very keen on the slogan – ‘The personal is political’. I was in favour of political action of all kinds – direct action, demonstrations, marches, meetings, consciousness raising groups, media publicity, television appearances, coming out at work, talks to schools etc. I was also very interested in the possibility of using artistic practices (film, photography, poetry, fiction, art) to build solidarity among gay people and to help change public opinion.”4

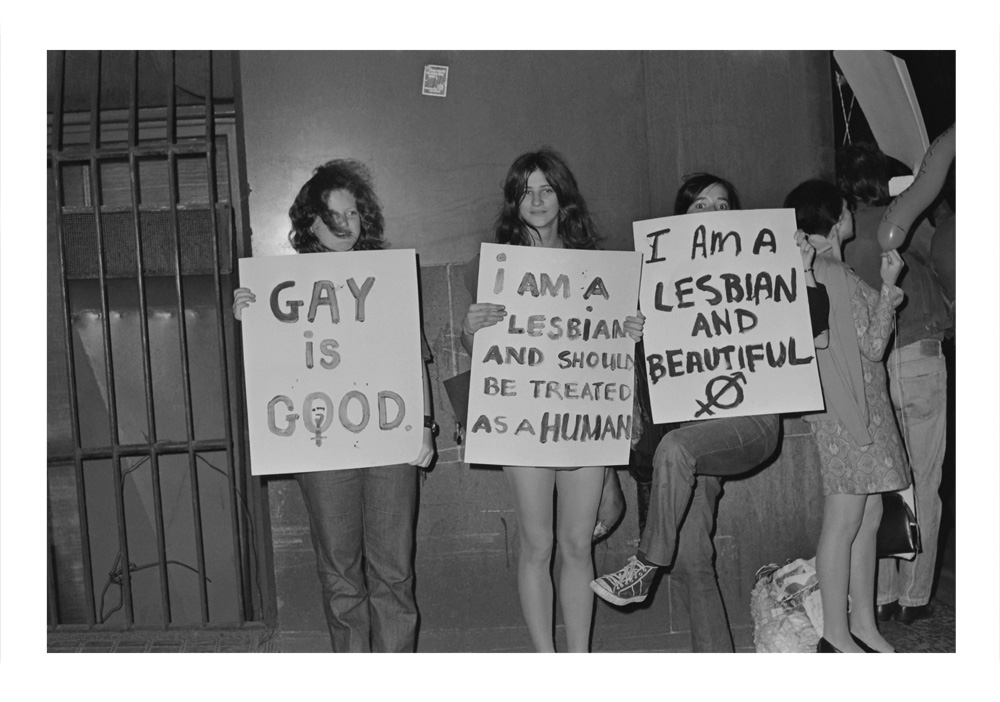

While “the early demonstrations illustrated in this exhibition did often include sympathetic “straights” – a term that seems to have disappeared from the language – for whom gay liberation was part of a wider set of cultural issues,”5 for gay men pictured in the photographs these meetings and marches could be seen as a form of “coming out”, or a place to find solidarity, friendship or sex.6 Gay Pride Week in 1973, for example, was seen as a chance to target, “all the institutions of our oppression: the police courts, job discrimination, the bigoted churchmen and politicians, the media, the psychiatrists, the aversion therapists, the military, the schools, the universities, the work-places … It will also seek to change the mind of the prejudiced, the fearful, the conditioned, the sexually repressed, all those who in oppressing us, oppress themselves.”7 It was also intended to say to gay and straight alike, “gay is good, gay is proud, gay is aggressively fighting for liberation. It will say to gays: come out and stand up. Only you can win your own liberation. Come out of the ghettos, the bars and beats, from your closets in suburbia and in your own minds and join the struggle for your own liberation.”8

For photographers it was a chance to picture a changing world. As Sydney photographer Roger Scott has observed, “I knew I could make a point with my camera. It was exciting. The old conservative world was ending and a new Australia was beginning.”9 With the birth of a new Australia came the end of the White Australia policy when the Whitlam Government passed laws to ensure that race would be totally disregarded as a component for immigration to Australia in 1973; with it came the presence of gay people on the streets shouting ‘come out, come out, wherever you are’ – but certainly not in the newspapers or on television for there was, essentially, the suppression of any reference to, or reportage of ‘homosexuals’ in the mainstream press in Australia.10 If they were pictured, gay people still usually turned away from the camera or had their faces blacked out for fear of discrimination and abuse. As artist John Storey notes, “Conservatism flooded the media, government and all the rest. Homophobia was everywhere but was not a term used in public.”11

As for what prompted artists to document organisations and events, Professor Creed remarks, “I loved to film life around me. I had access to good equipment. I thought it was important to have a visual record of the emergence of Gay Liberation. I believed that films and photos would help to create a sense of community for everyone involved in Gay Liberation. Many members of Gay Lib had been ‘closeted’ all of their lives and so it was a new experience for them to join what is best described as an alternative family. In those days, the Gay Lib group was relatively small – perhaps 30-40 members, so we all knew each other. We held regular meetings, joined CR groups, took part in demonstrations, went away for weekend group events, held dances etc. I also wanted to capture the way we looked, couples together, friends, what we wore, our fashions and styles. Some of the guys had a fantastic sense of style – much more than many of the women who were in revolt against ‘feminine’ fashion. I hoped my films and photos would give support to the gay community and to our emerging sense of forming a new identity.”12

By their very embodiment, the art and politics of these photographs awakens what Roland Barthes calls the “intractable reality” of the image 13 – that prick of consciousness (the punctum), that madness that documents activism and freedom from persecution as both aesthetic and ethical, performative and political. Here, the idea of “being there” – being fully present, in mind and body; being there at the marches; being in the images; being in front of the image looking at it; coupled with the physical presence of the photograph, manifests itself most strongly. Even today, the photographs shock the viewer with their intractable reality. You can just feel the passion of these people, the police presence, the fear, and the authenticity of the photographers’ voice – raw, in your face, people really standing up to be counted.

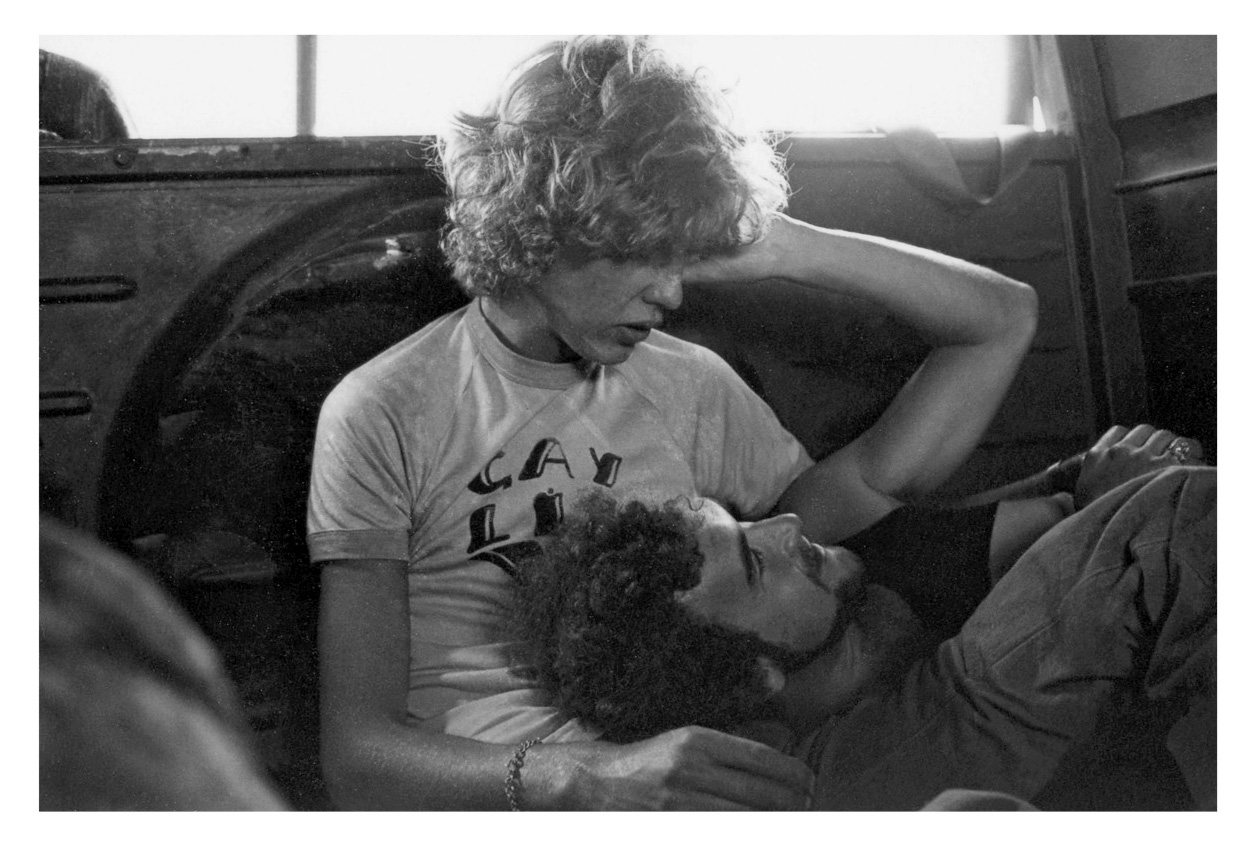

There is also another side to these photographs – the documentation of the more private moments (meetings, consciousness raising groups, friends in the car etc) and the portrayal of gays one on one, close up and personal with the camera in mugshots used in a grid for the cover of CAMP Ink magazine in 1972. Only today can we truly appreciate the intimacy and beauty of these photographs: the photographs of two young gay men in the back of a VW Kombi van that exists only as a 35mm contact print, now scanned and rescued from oblivion; or the presence of gays posing for the camera against a neutral backdrop, every pore of their skin able to be seen (a precursor to the large colour portraits of Thomas Ruff). As Professor Creed states of her desire to capture these intimate moments, “In the 70s film, media and television rarely if ever depicted us at all – let alone our public or private lives. I have always been drawn to the aesthetic power of film and photography to represent the inner world and inner lives of people. The visual image is a great leveller – it reveals the commonality of living things, the need for affection, companionship, community. Contrary to popular myths of the time, gays and lesbians also have a need for intimacy, as does everyone else. When I made my documentary, Homosexuality A Film For Discussion, I included a segment of intimate moments between couples before the commencement of the documentary street interviews, to link the two (private and public together) and to show that many of the negative comments from the general public about loneliness did not match the actual lives of gay people.”14

So where did the photographs that were taken by these artists end up? Often they were collectively passed from hand to hand and used in newsletters, pamphlets and magazines such as CAMP Ink. As Jill Matthews, who compiled the album of Adelaide photographs observes, “The groups and events were very collective enterprises. In those days anyone who had a camera took photos. If people took photos of you, you asked for copies or they gave you prints. There were many prints made and various people had copies. At the time the use of the photos was personal and collective. The newsletters were collective enterprises with everyone chipping in, using whatever was to hand. There was no editor, although some efforts were made to achieve a sense of continuity. Making the newsletters were always fun group events, with a lot of different things you could do, they were basically parties really.”15

Eventually the photographs settled in personal archives and were largely forgotten or were donated to institutions such as the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives (now the Australian Queer Archives). And then they all but disappeared from view.

A second (but different) “coming out”

With this exhibition these eclectic photographs re-emerge in a kind of second “coming out.” Having been put away for so many years they appear in the clear light of day, in the clear light of new thinking about their artistic merit and how they act as memory aids to feelings and relationships, events and politics.

While analogue photographic images carry Roland Barthes imprint ‘this has been’ – in other words, a photograph is a depiction of something that has already happened, that is already dead – images do not have fixed or settled meanings. As Scott McQuire insightfully observes, meaning in images “is always transactive: it is the result of complex and dynamic processes of interpretation, contestation and translation. Evidence and testimony is always to be actively produced in the complex present… the photograph’s combination of unprecedented visual detail, which seems to anchor the image in a particular time and place, [is] coupled to the endless capacity for images to travel into new times and places.”16 He goes on to say that photographic history is littered with images that have their meaning altered by entry into a new setting. The images in this exhibition are a case in point for I am examining them as artworks as much as they can be seen as documentary evidence of things that have been.

We should not be afraid of this new interpretation for, as McQuire notes, “Too often when we talk about ‘context’ in relation to a photograph, it is as if there is a finite set of connections that might be fully reproduced, if only we had the time or resources. In other words, the polysemy of the image is given a cursory and limited acknowledgement, in the hope that it can be thereby tamed. Rather than this partial, rather defensive acknowledgement of the fragility of meaning, I am arguing that we need to begin with acceptance of the irreducible openness of technological images. This quality is integrally related to the capacity of any image to circulate and appear in new situations.”17 In other words there is no definitive context for any image and we should not be afraid to approach new interpretations of the work or the coexistence of many possible meanings within that work. This process can be seen as analogous in a contextual sense to the construction of what the French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941) called the ‘composite’ in the physical sense, which he defined as, “construction / model where things different in kind are reconciled through our experience over time. Differences are reconciled not unified. The composite embraces ideas of complexity and multiplicity, allowing different conventions, materials and contents to coexist in an artwork. It therefore permits complexities and relationships of readings to coexist. The viewer becomes aware of new and shifting layers of content revealed over the time of viewing, and of our role in constructing, interpreting and experiencing content(s). This is not just theoretical, it is the way we experience and negotiate the world everyday, as complexity in the continuum of time and space.”18 The viewer thus creates a composite view of these images in the here and now.

The images importance, then, lies in the interplay between the historical and the contemporary, between self-representation and imposed representation, and the relationship between subject and photographer. Their residence in the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives (ALGA) archive (now the Australian Queer Archives (AQuA), which undoubtedly preserves them, marks this institutional passage, this transition of marginalised histories from private to public, “which does not always mean from the secret to the non-secret.” Under the privileged topology of ALGA they are classified and ordered and made available for study and research, but we must also acknowledge that archives give shape to and regulate cultural memory. They influence our perception of the past and present. As Jacques Derrida writes in Archive Fever: “”There is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory.” He indicates that the stakes are high over the memorialisation and excavation of sites and people’s histories.”19 This does not mean that ALGA does not promote an active engagement with the works it holds in safe keeping, far from it. They encourage the use of the archive by artists and the recontextualisation and renarrativisation of the images in this exhibition, from documentary objects to visual art works and back again, could not have occurred without their forthright help. But as Mathias Danbolt notes in his excellent article Not Not Now: Archival Engagements in Queer Feminist Art, archives will always be sites of contestation: “The conversations on archives in queer and feminist contexts tend to center on ways to break with the strictures and structures of archival logics, in order to give room for alternative forms of historical (and herstorical) transmissions. But even though archival logics tend to be a continual object of critique in feminist and queer work, the desire for archives is still present… If the process of archivisation is fundamentally about conferring historical status upon material, how to avoid that the status as archival disconnect the queer feminist “past” from the “present” – the “then” from the “now”?”20 Danbolt goes on to suggest that this process is a balancing act, “between the desire for having a history, and the anxiety for being historicised, in the sense of being cut off – metaphorically, practically, systemically – from the present.”21

For me, then, this exhibition is as much about freeing these images from the guardianship of the archive, if ever so briefly, to let them live again in the real world, to let them speak for themselves, as those first gay protesters did all those years ago. To free them of the shackles of being seen as “historical” documentary photographs, the official history of gay liberation in Australia and for them to be seen works of art in their own right. It is about the representation of queer identity through the evidence of photography – from that place, in that time, now breathing in a different era, these people fighting for their liberty. It is about these images and the people in them being (t)here.

In contemporary society, where we are flooded with a maelstrom of images, I believe it is important to contemplate these images for more than just a few seconds in order to understand their history and importance not just for the past, but also for the present and the future. Today, we compose our stories and our histories out of fragments and alterations of spaces. We gather together our sources (in archives, for example) and try and make sense of the past in the present for the future. This process of understanding is about an acknowledgement of the past in the present for the future. Again I say, it is about being (t)here.

In an era of ubiquitous media images, the photographs in this exhibition deserve our attention and contemplation for they are survivors – images that perceptively visualise the initial stages of Gay Liberation in Australia, images that are still alive in the present. Their contemporary re-emergence may lead the community to finally have some iconographic images of the early stages of gay resistance and visibility – intimate representations of protests, meetings and events that ultimately changed the lives of many GLBTI people. They may also have some damn good art upon which to feast their eyes.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

July 2014

Word count: 3,423

Endnotes

1/ Connell, Raewyn. “Ours is in colour: the new left of the 1960s,” in Carolyn D’Cruz and Mark Pendleton (eds.,). After Homosexual: The Legacies of Gay Liberation. Perth: UWA Publishing, 2013, p. 43.

2/ Nichols, James. “Sébastien Lifshitz Releasing ‘The Invisibles: Vintage Portraits of Love and Pride’,” on The Huffington Post website 05/01/2014 [Online] cited 02/05/2014.

3/ Leonard, William. “Altman on Halperin: politics versus aesthetics in the constitution of the male homosexual,” in Carolyn D’Cruz and Mark Pendleton (eds.,). After Homosexual: The Legacies of Gay Liberation. Perth: UWA Publishing, 2013, p. 197.

4/ Email text in response to the question ‘What were your politics during your involvement with Gay Liberation/events (Gay Pride Week etc)’ to co-curator Nicholas Henderson 01/06/2014.

5/ Altman, Dennis. “Out of the closets, into the streets.” Catalogue essay. Melbourne, 2014, p. 2.

6/ Ibid.,

7/ Anon. “Gay Pride Week,” in Melbourne Gay Liberation Newsletter, 1973 quoted in Ritale, Jo and Willett, Graham. “Rennie Ellis at Gay Pride Week, September 1973,” in The La Trobe Journal No. 87, May 2011, pp. 87-88 [Online] Cited 11/07/2014.

8/ Ibid., p. 88.

9/ Scott, Roger quoted in Scott, Roger; McFarlane, Robert and Hock, Peter. Roger Scott: from the street. Neutral Bay, N.S.W.: Chapter & Verse, 2001, p. 13.

10/ Email text from co-curator Nicholas Henderson 12/03/2014.

11/ Email text from John Storey to co-curator Nicholas Henderson 17/05/2014.

12/ Email text in response to the question ‘What prompted you to document the organisations/events?’ to co-curator Nicholas Henderson 01/06/2014.

13/ Barthes, Roland. Camera lucida: Reflections on photography. Hill and Wang, 1st American edition, 1981.

14/ Email text in response to the question ‘One of the aspects of your photographs that I am quite intrigued by is the documentation of the more private moments (meetings, consciousness raising groups, friends in the car etc), what brought you to photograph these subjects?’ to co-curator Nicholas Henderson 01/06/2014.

15/ Jill Matthews notes from telephone conversation to Nicholas Henderson, Tuesday 22 April 2014.

16/ McQuire, Scott. “Photography’s afterlife: Documentary images and the operational archive,” in Journal of Material Culture 18(3) 2013, p. 227.

17/ Ibid.,

18/ Thomas, David. “Composite Realities Amid Time and Space: Recent Art and Photograph,” on the Centre for Contemporary Photography website [Online] Cited 12/07/2014. No longer available online

19/ Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996, 4, note 1 quoted in Eckersall, Peter. “The Site is a Stage/The Stage is a Site,” on the Archaeology and Narration blog, Saturday, April 9, 2011 [Online] Cited 05/07/2014.

20/ Danbolt, Mathias. “Not Not Now: Archival Engagements in Queer Feminist Art,” in Imhoff, Aliocha and Quiros, Kantuta (eds.,). Make an effort to remember. Or, failing that, invent. Bétonsalon No. 14, 2013, p. 4. ISSN: 2114-155X.

21/ Ibid., p. 5.

Figure 2

John F. Shale (Australian, 1855-1924)

Mounted police assembled in the square during the General Strike, Brisbane

1912

Figure 3

Photographer unknown

Eight Hour Day parade in Brisbane

1912

Figure 4

Photographer unknown

Women evening students’ float on Park Street in the 1940s

Photo, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW

Figure 5

Ponch Hawkes (Australian, b. 1946)

Poofters!

1973, printed 2014

Digital C type print on Kodak Endura Matte

© Ponch Hawkes

Figure 6

John Englart (Australian, b. 1955)

Gay Pride Week poster, Gay Pride march outside the Town Hall Hotel, Sydney Town Hall

Sydney, 1973

Digital C type print on Kodak Endura Matte

© John Englart

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.