Exhibition dates: 21st February – 22nd June 2014

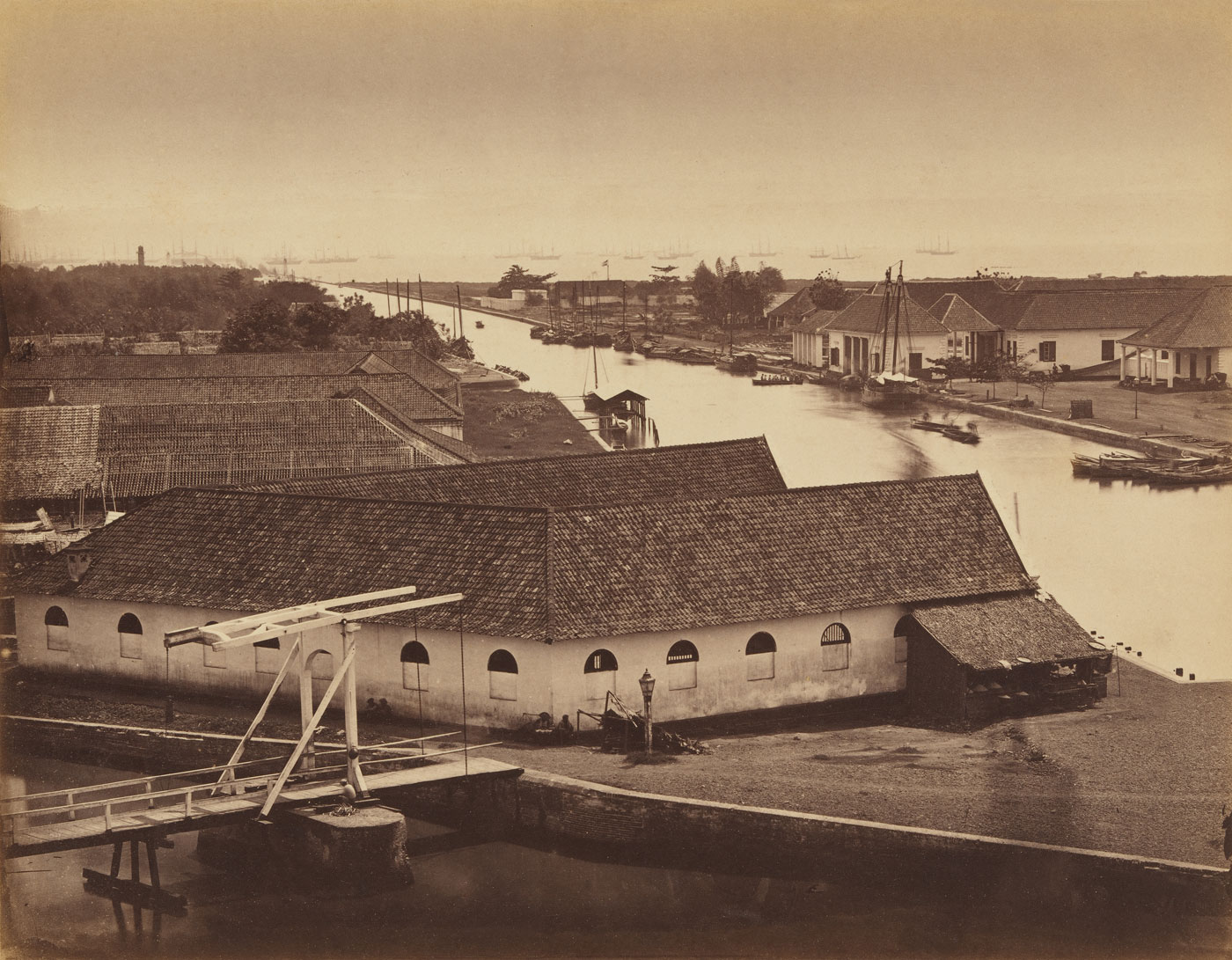

Woodbury & Page (established Jakarta 1857-1900)

Batavia roadstead

c. 1865

Albumen silver photograph

19.4 x 24.5cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Dutch East Indies and Indonesian photography, and more broadly Asia-Pacific photography, has been a burgeoning area of interest, research and collecting for some time now. Although this is far from my area of expertise, with the quality of the work shown in this posting, you can understand why. Since 2005, “the National Gallery of Australia’s Asian photographs collection has grown to nearly 8000 and in excess of 6500 prints are from Indonesia.”

Absolutely beautiful tonality to the prints. They seem to have a wonderful stillness to them as well.

On a personal note, Gael Newton, Senior Curator, Photography at the National Gallery of Australia is retiring. I would like to thank her for promoting, researching and writing about all forms of photography over the years and to congratulate her on significantly extending the NGA’s photography collection. A job well done.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Gael Newton and the National Gallery of Australia for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Dirk Huppe (Indonesia, 1867-1931)

O Kurkdjian & Co (Established Surabaya, Java 1903-1935)

Mature canes, fertilized with artificial guano, Java Fertilizer Co.,

Semarang 1914

Carbon print photograph

74.6 x 99.6cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Atelier O Kurkdjian & Co (Established Surabaya, Java 1903-1935)

Bromo eruption of December

1915

Gelatin silver photograph

17.7 x 24cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Purchased 2007

S. Satake (Japanese, working Indonesia 1902 – c. 1937)

Eruption

Java c. 1930

Gelatin silver photograph

16.2 x 21.8cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

While Indonesia might be the second most popular destination for outbound Aussies, the history of the Indonesian archipelago’s diverse peoples and the colonial era Dutch East Indies, remains unfamiliar. In particular the rich heritage of photographic images made by the nearly 500 listed photographers at work across the archipelago in the mid 19th – mid 20th century, is poorly known, both in the region and internationally.

The Gallery began building its Indonesian photographic collection in 2006. It is unique in the region: the largest and most comprehensive collection excluding the archives of the Dutch East Indies in the Netherlands. It was not until the late 1850s with the arrival of photographs printed on paper from a master glass negative, that images of Indonesia – the origin of nutmeg, pepper and cloves, much desired in the West – began circulating worldwide.

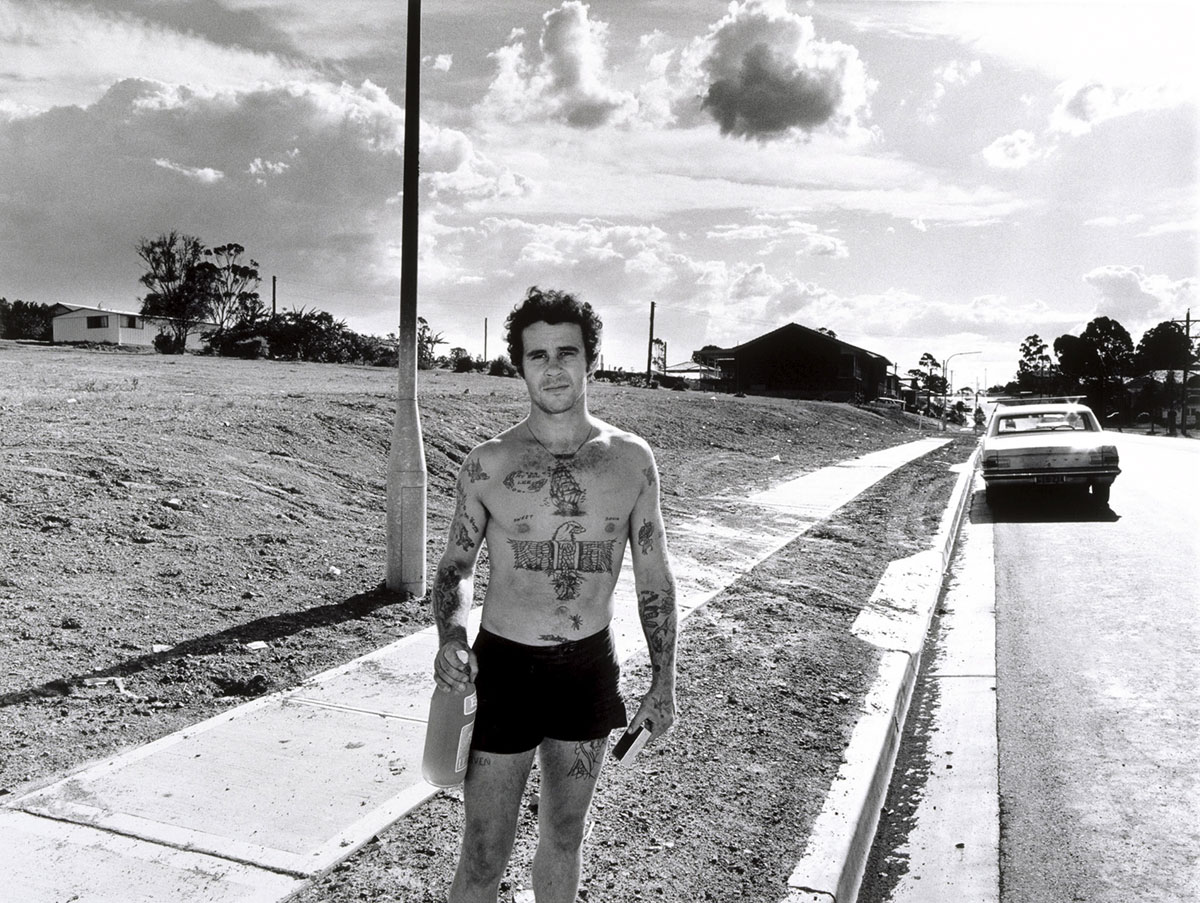

Australia had a minor role in the history of photography in Indonesia. A pair of young British photographers, Walter Woodbury and James Page (operators of the Woodbury & Page studios located in the Victorian goldfields and Melbourne) arrived in Jakarta in 1857. From around 1900 a trend toward more picturesque views and sympathetic portrayals of indigenous people appeared. Old images were given new life as souvenir prints and sold through hotels and resorts or used for cruise ship brochures.

A particular feature of Garden of the East is the display of family albums. Both amateur and professional images in the Indies were bound in distinctive Japanese or Batik-patterned cloth boards as records of a colonial lifestyle. Hundreds of these once-treasured narratives of now lost people ended up in the Netherlands in the 1970s and 80s in estate sales of former Dutch colonial and Indo (mixed race) family members who had returned or immigrated after the establishment of the Republic of Indonesia in 1945.

Text from the National Gallery of Australia website

S. Satake (Japanese, working Indonesia 1902 – c. 1937)

Women on road to Buleleng

Bali c. 1928

Gelatin silver photograph

16.2 x 22.0cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Woodbury & Page (established Jakarta 1857-1900)

Gusti Ngurah Ketut Jelantik, Prince of Buleleng with his entourage in Jakarta in 1864 on the visit of Governor-General LAJW Sloet van de Beele

1864

Albumen silver photograph

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Garden of the East: Photography in Indonesia 1850s-1940s is the first major survey in the southern hemisphere of the photographic art from the period spanning the last century of colonial rule until just prior to the establishment of the Republic of Indonesia in 1945. The exhibition provides the opportunity to view over two hundred and fifty photographs, albums and illustrated books of the photography of this era and provides a unique insight into the people, life and culture of Indonesia. The exhibition and accompanying catalogue reveals much new research and information regarding the rich photographic history of Indonesia. Garden of the East is on display in Canberra only.

The exhibition is comprised of images created by more than one hundred photographers and the majority have never been exhibited publicly before. The works were captured by photographers of all races, making images of the beauty, bounty, antiquities and elaborate cultures of the diverse lands and peoples of the former Dutch East Indies. Among these photographers is the Javanese artist Kassian Céphas, whose genius as a photographer is not widely known at this time, a situation which the National Gallery of Australia hopes to address by growing the collection of holdings from this period and by continuing to stage focused exhibitions such as Garden of the East.

As was the case in other Southeast Asian ports, the most prominent professional photographers at work in colonial Indonesia came from a wide range of European backgrounds until the 1890s, when Chinese photography studios began to dominate. The exhibition focuses on the leading foreign studios of the time, in particular Walter B Woodbury, one of the earliest photographers at work in Australia in the 1850s as well as the Dutch East Indies. However Garden of the East also includes images created by lesser known figures whose work embraced the new art photography styles of the early twentieth century including: George Lewis, the British chief photographer at the Surabaya studio founded by Armenian Ohannes Kurkdjian, the remarkable German amateur photographer Dr Gregor Krause; American adventurer and filmmaker André Roosevelt; and the only woman professional known to have worked in the period, Thilly Weissenborn, whose works were intertwined with the tourist promotion of Java and Bali in the 1930s. Chinese studios are well-represented, although little is known of their founders and many employed foreign photographers.

Frank Hurley is the sole Australian photographer represented in the exhibition. Hurley is noted as the only Australian known to have worked in Indonesia before the Second World War and toured Java in mid-1913, on commission to promote tourist cruises from Australia to the Indies for the Royal Packet Navigation Company.

“We are delighted to host this exhibition and believe that Australia’s geographic, political and cultural position in the Asia-Pacific region makes it very appropriate that the National Gallery of Australia should celebrate the rich and diverse arts of our region,” said Ron Radford AM, Director, National Gallery of Australia. “A dedicated Asia-Pacific focused policy has been long-held by the Gallery, but it was not until 2005 that we focused on early photographic art of the region. Progress, however, has been rapid and all the photographs in Garden of the East have been recently acquired for the National Gallery’s permanent collection,” he said.

“From a small holding in 2005 of less than two hundred photographs from anywhere in Asia, of which only half a dozen were by any Asian-born photographers, the National Gallery of Australia’s Asian photographs collection has grown to nearly 8000 and in excess of 6500 prints are from Indonesia,” Ron Radford said.

“Garden of the East presents images, both historic and homely and is a ‘time travel’ opportunity to visit the Indies through more than two hundred and fifty works on show, made by both professional and amateur family photographers. Images as diverse as the Indonesian archipelago itself, which was once described by nineteenth century travel writers as the Garden of the East,” said Gael Newton, Senior Curator of Photography, National Gallery of Australia and exhibition Curator.

Garden of the East: Photography in Indonesia 1850s-1940s follows the large 2008 survey exhibition Picture Paradise: Asia-Pacific photography 1840s-1940s. This was the first of the new Asia-Pacific collection focus exhibitions. In 2010, the Gallery staged an early photographic portrait exhibition to coincide with a conference hosted in partnership with the Australian National University entitled Facing Asia. A number of other small Asian collection shows have also been held since 2011.

The National Gallery of Australia is delighted to stage this exhibition to coincide with the Focus Country Program, an initiative organised by the Australian Government’s key cultural diplomacy body, the Australia International Cultural Council. The AICC has chosen Indonesia as its Focus Country for 2014 and will organise a series of events across the Indonesian archipelago to promote Australian arts and culture, as well as our credentials in sport, science, education and industry. This exhibition will also mark the 40th anniversary of dialogue relations between Australia and the Association of South East Asian Nations. The National Gallery of Australia is proud to be presenting an exhibition of Indonesian photography in celebration of Australia’s close cultural relations with Indonesia and the Asia-Pacific region.

Press release from the National Gallery of Australia website

Kassian Céphas (Javanese, 1845-1912)

Man climbing the front entrance to Borobudur

Central Java 1872

Albumen silver photograph

22.2 x 16.1cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Kassian Cephas or Kassian Céphas was a Javanese photographer of the court of the Yogyakarta Sultanate. He was the first indigenous person from Indonesia to become a professional photographer and was trained at the request of Sultan Hamengkubuwana VI. After becoming a court photographer in as early 1871, he began working on portrait photography for members of the royal family, as well as documentary work for the Dutch Archaeological Union. Cephas was recognised for his contributions to preserving Java’s cultural heritage through membership in the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies and an honorary gold medal of the Order of Orange-Nassau. Cephas and his wife Dina Rakijah raised four children. Their eldest son Sem Cephas continued the family’s photography business until his own death in 1918.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Kassian Céphas (Javanese, 1845-1912)

Young Javanese woman

c. 1885

Albumen silver photograph

13.7 x 9.8cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Garden of the East: photography in Indonesia 1850s-1940s offers the chance to see images from the last century of colonial rule in the former Dutch East Indies. It includes over two hundred photographs, albums and illustrated books from the Gallery’s extensive collection of photographic art from our nearest Asian neighbour.

Most of the daguerreotype images from the 1840s, the first decade of photography in Indonesia, are lost and can only be glimpsed in reproductions in books and magazines of the mid nineteenth century. It was not until the late 1850s that photographic images of Indonesia – famed origin of exotic spices much desired in the West – began circulating worldwide. British photographers Walter Woodbury and James Page, who arrived in Batavia (Jakarta) from Australia in 1857, established the first studio to disseminate large numbers of views of the country’s lush tropical landscapes and fruits, bustling port cities, indigenous people, exotic dancers, sultans and the then still poorly known Buddhist and Hindu Javanese antiquities of Central Java.

The studios established in the 1870s tended to offer a similar inventory of products, mostly for the resident Europeans, tourists and international markets. The only Javanese photographer of note was Kassian Céphas who began work for the Sultan in Yogyakarta in the early 1870s. In late life, Céphas was widely honoured for his record of Javanese antiquities and Kraton performances, and his full genius can be seen in Garden of the East.

Most of the best known studios at the turn of the century, including those of Armenian O Kurkdjian and German CJ Kleingrothe, were owned and run by Europeans. Chinese-run studios appeared in the 1890s but concentrated on portraiture. Curiously, relatively few photographers in Indonesia were Dutch. From the 1890s onward, the largest studios increasingly served corporate customers in documenting the massive scale of agribusiness, particularly in the golden economic years of the Indies in the early to mid twentieth century. From around 1900, a trend toward more picturesque views and sympathetic portrayals of indigenous people appeared. This was intimately linked to a government sponsored tourist bureau and to styles of Pictorialist art photography that had just emerged as an international movement in Europe and America. As photographic studios passed from owner to owner, old images were given new life as souvenir prints sold at hotels and resorts and as reproductions in cruise-ship brochures.

Amateur camera clubs and Pictorialist photography salons common in Western countries by the 1920s were slower to develop in Asia and largely date to the postwar era. Locals, however, took up elements of art photography. Professionals George Lewis and Thilly Weissenborn (the only woman known from the period) and amateurs Dr Gregor Krause and Arthur de Carvalho put their names on their prints and employed the moody effects and storytelling scenarios of Pictorialist photography. Krause was one of the most influential photographers. He extensively published his 1912 Bali and Borneo images in magazines and in two books in the 1920s and 1930s, inspiring interest in the indigenous life and landscape as well as the sensuous physical beauty of the Balinese people.

Postwar artists and celebrities – including American André Roosevelt, who used smaller handheld cameras – flocked to the country to capture spontaneity and daily life around them, to affirm their view of Bali as a ‘last paradise’ , where art and life were one. In 1941, Gotthard Schuh published Inseln der Götter (Islands of the gods), the first modern large-format photo-essay on Indonesia. While romantic, the collage of images and text in Schuh’s book presented a vital image of the diverse islands, peoples and cultures that were to be united under the flag of the Republic of Indonesia in 1949.

A particular feature of Garden of the East is a selection of family albums bound in distinctive Japanese or Batik patterned cloth boards as records of a colonial lifestyle (for the affluent) in the Indies. Hundreds of these once treasured narratives of now lost people ended up in the Netherlands in the 1970s and 1980s in estate sales of former Dutch colonial and Indo (mixed race) family members who had returned or immigrated after the establishment of the Republic of Indonesia.

Gael Newton. “Princes, Portraits and Panoramas,” in the National Gallery of Australia Artonview 76 Summer 2013, pp. 20-22 [Online] Cited 12/06/2014

Sem Céphas (Indonesia, 1870-1918)

Portrait of a Javanese woman

c. 1900

Gelatin silver photograph, colour pigment hand painted photograph

image

38.5 x 23.8cm

Purchased 2007

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gotthard Schuh (Swiss, 1897-1969)

Inseln der Götter (Islands of the gods) [book cover]

1941

Hardcover w/dust jacket

154pp, text in German

Plates in photogravure

28.5 x 22.5cm

Gotthard Schuh (December 22, 1897 in Schöneberg near Berlin – December 29, 1969 in Küsnacht, Zurich) was a Swiss photographer, painter and graphic artist.

Photographer

In 1931 his first photos were published in a Zurich magazine and in 1932 he held a photography exhibition in Paris, where he met Picasso, Léger and Braque.

From 1932 he joined the Zürcher Illustrierte under Arnold Kübler, working with Hans Staub and Paul Senn, and until 1937 Schuh also worked freelance for Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, Paris Match and Life. His assignments during 1938/1939 took him all over Europe and to Indonesia. He and Marga divorced in 1939.

After about ten years as a reporter he became the first picture editor for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. He and Edwin Arnet created the NZZ supplement Das Wochenende, which showcased Swiss and international photography in addition to his own reportage.

From this period a significant part of his own photographic work illustrated books, of which the most successful was Inseln der Götter published in 1941, the result of his almost 11-month journey through Singapore, Java, Sumatra and Bali, undertaken just before the war. It was a mixture of reportage and self-reflection, with a poetic quality that, though individual images may be read either way, Schuh sometimes valued over documentary authenticity:

“Everyone just depicts what he sees, and everyone just sees what corresponds to his being.”

This is evident in the book Begegnungen which Schuh published in 1956, in which he combined older and more recent images in free association, in accord with the objectives of the ‘Kollegium Schweizerischer Photographen’, the Academy of Swiss Photographers which he founded together with Paul Senn, Walter Läubli, Werner Bischof and Jakob Tuggener, a loose group that promoted an ‘auteur’ emphasis. Their first exhibition in 1951 marked a renewal of photography in Switzerland after the conservatism and nationalism of the war years. Critic Edwin Arnet identified the ethos of the group:

“Their photography has abandoned the sphere of technical experimentation … , the abstract and the avant-garde. It has become more wholesome, concentrating again more on the poetry of real things.”

In 1955 Edward Steichen selected two of Schuh’s photographs for the world-touring Museum of Modern Art exhibition The Family of Man seen by an audience of 9 million. One, taken in Italy, is a stolen image of lovers resting beside their discarded bicycles amongst long summer grass in an olive grove, while the other, taken in Java, shows a boy stretching balletically across the pavement as he plays marbles.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Thilly Weissenborn (Javanese / Indonesian, 1883-1964)

Indonesia 1902 – Netherlands 1964

A dancing-girl of Bali, resting

c. 1925

Photogravure

21.1 x 15.9cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Thilly Weissenborn (1883-1964) was the first professional woman photographer of the former Dutch East Indies and one of the few photographers working in the early 20th century in the area who were Indonesian born. Her works were widely used to expand the newly developed tourism industry of the East Indies.

Early life

Margarethe Mathilde Weissenborn was born on 22 March 1883 or 1889, to Cornelia Emma Angely Lina da Paula (née Roessner) and Hermann Theodor Weissenborn in either Surabaya, or Kediri, on East Java of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). Her parents were German-born, naturalized Dutch citizens and operated a coffee plantation in Kediri. In 1892, her mother returned with Thilly and her siblings to the Netherlands and took up residence in The Hague. They were joined by their father the following year. After five years, the oldest son and the father left for Tanganyika in German East Africa to become planters there. Else, one of Thilly’s older sisters, who had studied photography in Paris, opened a photographic studio in The Hague in 1903, where Thilly began working. In 1912, she left the Netherlands and returned to Java, in the company of her brother Theo to join their brother Oscar, who was living in Bandung.

Career

In 1913, Weissenborn found employment in a prestigious photographic studio in Surabaya which was founded by Onnes Kurkdjian, an Armenian, called Atelier Kurkdjian. The studio was the only agent for Kodak in East Java. Kurkdjian had died by the time Weissenborn arrived and the studio, which employed thirty photographers, was managed by an Englishman, GP Lewis. Weissenborn honed her craft under Lewis’ tutelage learning both photographic and retouching techniques. In 1917, she moved to Garut in West Java and managed a photographic studio GAH Lux in the Garoetsche Apotheek en Handelsvereeniging Company, a pharmacy owned by Denis G. Mulder. Mulder moved to Bandung in 1920 and turned over his property to Weissenborn, who changed the firm name to Foto Lux. In 1930, she established Lux Fotograaf Atelier NV, which she operated for a decade in Garut.

Weissenborn became the first significant woman photographer in Indonesia and was one of the few photographers working in the era who were Indonesian-born. Her works were marked by a lyrical quality and her attempt to capture the idyllic nature of the landscape. She is most known for her photographs of architectural interiors, landscapes, and portraits, which were produced for the burgeoning tourist industry. Some of her works were featured in Dutch tourism guide published in 1922, as Come to Java. Her photographs also made up the majority of the images in Louis Couperus’ work Oostwaarts (Eastward, 1923). Weissenborn travelled throughout the East Indies, and particularly worked in Bali, trying to capture the exotic nature of the islands, while at the same time, retaining the dignity of locals she photographed. Ironically, her images were at times appropriated and used in prurient manners, such as a photograph of two women on a road carrying water, one who has a pot on her head, which was used for a French novel titled L’Île des seins nus (Island of Bare Breasts). In time, her portrait images changed from partially-clad images to the more artistic images of dancing girls. These were featured in such magazines as Inter-Ocean, Sluyter’s Monthly and Tropical Netherlands, which marketed a more civilised Bali to international tourists.

Later life

During World War II, the 16th Army of Japan landed in West Java at the end of February, 1942. After subduing the population, around 30,000 American, Australian, British, Dutch, and Indo-European civilians were transported to civilian internment camps. In 1943, Weissenborn was interned in the Japanese prisoner of war camp Kareës in Bandung. Women and children were kept in the camp until 1945. The town of Garut was destroyed by fire and then in the aftermath of the Indonesian National Revolution, Weissenborn’s studio was completely destroyed and all of her glass negatives were lost in 1947. That same year, she married Nico Wijnmalen and the couple moved to Bandung.

In 1956, the Indonesian government repudiated the remaining terms of the Hague Round Table Conference forcing Weissenborn and Wijnmalen to return to Holland. Weissenborn died 28 October 1964 at Baarn, in Utrecht Province, The Netherlands and is buried in the Baarn New General Cemetery.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Thilly Weissenborn (Javanese / Indonesian, 1883-1964) (attributed to)

I Goesti Agoeng Bagoes Djelantik, Anakagoeng Agoeng Negara, Karang Asem

1931

Gelatin silver photgraph

14 x 9.7cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

Purchased 2006

Unknown photographer

Working Bali 1930s

I Goesti Agoeng Bagoes Djelantik, Anakagoeng Agoeng Negara, Karang Asem

Bali 1931

Gelatin silver photograph

14.0 x 9.7cm

Collection National Gallery of Australia

National Gallery of Australia

Parkes Place, Canberra

Australian Capital Territory 2600

Phone: (02) 6240 6411

Opening hours:

Open daily 10.00 am – 5.00 pm

(closed Christmas day)

![Gotthard Schuh (Swiss, 1897-1969) 'Inseln der Götter' (Islands of the gods) [book cover] 1941 Gotthard Schuh (Swiss, 1897-1969) 'Inseln der Götter' (Islands of the gods) [book cover] 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/insel-de-gotter.jpg)

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Studienkopf zur Stuttgarter Iphigenie [Study of a Head for Stuttgart Iphigenia]' 1870 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Studienkopf zur Stuttgarter Iphigenie [Study of a Head for Stuttgart Iphigenia]' 1870](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_studienkopf-web.jpg?w=650&h=815)

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Poesie, Zweite Fassung [Poetry, Second Version]' 1863 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Poesie, Zweite Fassung [Poetry, Second Version]' 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_poesie-web.jpg?w=650&h=807)

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Lucrezia Borgia, Bildnis einer Römerin in weißer Tunika und rotem Mantel [Lucrezia Borgia, Portrait of a roman in white tunic and red cloak]' 1864/1865 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Lucrezia Borgia, Bildnis einer Römerin in weißer Tunika und rotem Mantel [Lucrezia Borgia, Portrait of a roman in white tunic and red cloak]' 1864/1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_borgia-web.jpg?w=650&h=781)

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Das Urteil des Paris [The Judgement of Paris]' 1870 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Das Urteil des Paris [The Judgement of Paris]' 1870](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_paris-web.jpg)

![Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Ruhende Nymphe [Resting Nymph]' 1870 Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1880) 'Ruhende Nymphe [Resting Nymph]' 1870](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/feuerbach_nymphe-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.