Exhibition dates: 14th June – 15th September 2013

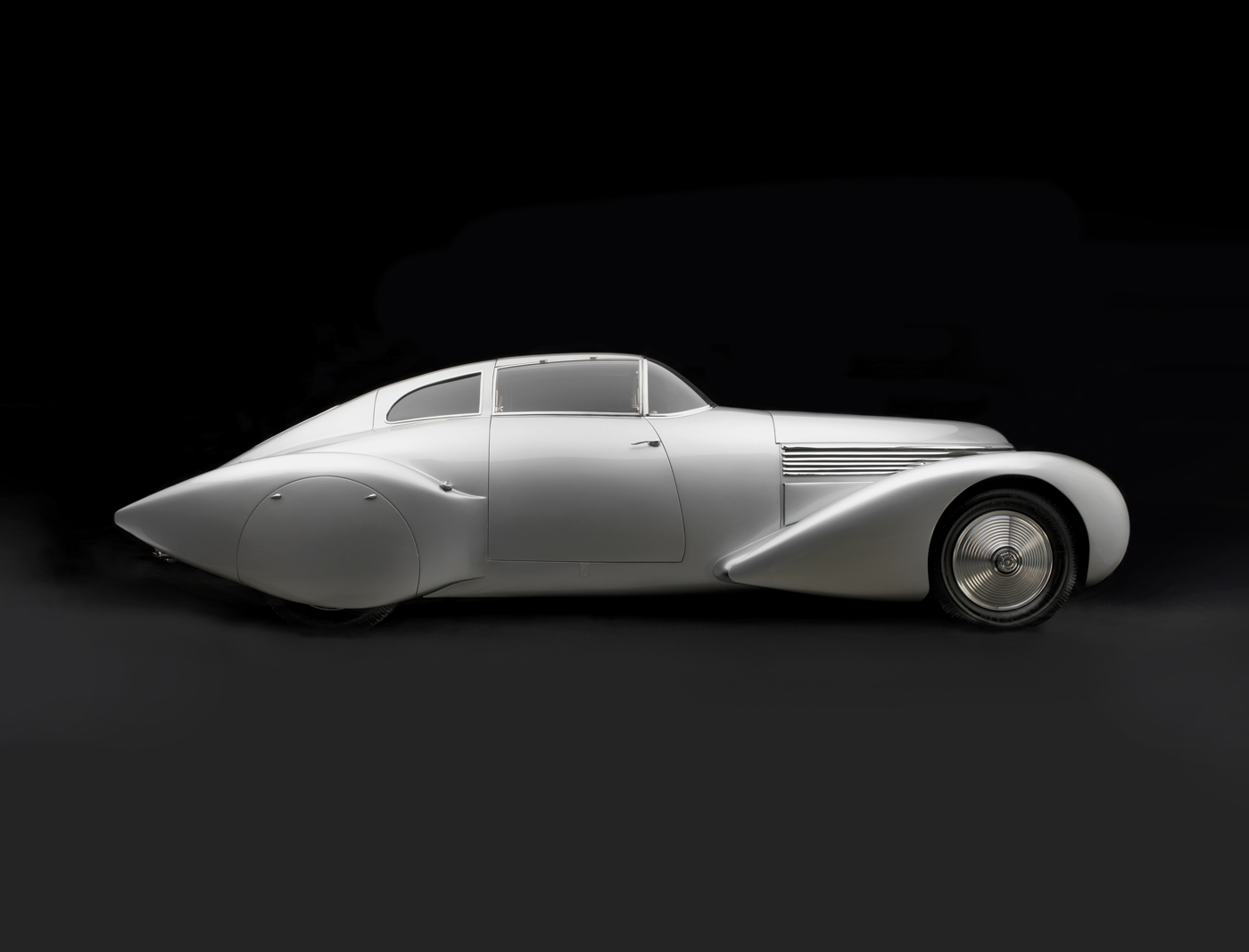

Jordan Model Z Speedway Ace Roadster

1930

Collection of Edmund J. Stecker Family Trust

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

OMG, OMG, OMG a bumper posting of car porn!

Some of these are just ravishing (my favourite is the Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet “Xenia” Coupe, 1938) and the elegant, eloquent photography (including some wonderfully framed detail shots), highlights the sensuousness of these objects of desire. Also, notice the almost negligible rear view windows in most of the cars…

What happened to this kind of style detail in today’s cars?

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to The Frist Center for the Visual Arts for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Bugatti Type 46 Semi-profile Coupe

1930

Collection of Merle and Peter Mullin

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Ettore Bugatti lived on a baronial estate in Alsace-Lorraine in eastern France. His father Carlo created elegant, Art Deco style furniture. His younger brother Rembrandt was an accomplished sculptor of animals. Although he was trained as an apprentice engineer, Ettore possessed the dreamy soul of an artist. From 1911 to 1939, he built hand-crafted automobiles of sporting competence, which, thanks to the styling talents of Ettore’s young son Jean, were also hauntingly beautiful.

Working with factory designer Joseph Walter, Jean Bugatti initially designed an Art Deco Superprofile coupe with rakish, valance-free fenders, a steeply canted windscreen, a roof with a perfect radius, and dramatic sweep panels. This has been called by Paul Kestler, author of Bugatti: Evolution of Style, “one of the landmarks in coach building history, made at the moment when classic lines were yielding to something more aerodynamic.” Only a few Superprofile coupes were built. One original survives in the Louwman Collection, Netherlands.

Inspired by the earlier Superprofile design, Walter and Bugatti’s Semi-profile coupes like the one in this exhibition had a more practical and equally attractive notchback rear treatment and twin exposed spare wheels. The chassis of this Bugatti Type 46 was made in 1929 and bodied in 1934 in Czechoslovakia by coach builder Oldřich Ulik. Originally a two-door sedan, it was re-bodied by Barry Price, with period-perfect coachwork in the exact style of Jean Bugatti’s Semi-profile coupe. The interior is elephant hide leather. In Bugatti circles, a magnificent re-creation like this one is welcomed, when it is done so beautifully.

valance-free fenders: this type of motor vehicle wheel covering did not make use of the then popular valance, a piece of metal added to the side of the fender that prevented splashing along the body

Cord L-29 Cabriolet

1929

Collection of Auburn Cord Duesenberg Automobile Museum

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Errett Lobban Cord rose to national prominence after rescuing the Auburn Automobile Company of Auburn, Indiana, in 1928. Seeing an opportunity for a uniquely engineered luxury automotive brand, Cord encouraged Fred and August Duesenberg to build what he envisioned as America’s finest motorcar.

Noted race car constructor Harry A. Miller and his associates were retained by Cord to engineer a radical front-drive chassis. The innovative and luxurious L-29 Cord, unfortunately introduced just as the New York Stock Market crashed, combined its engine, transaxle, and clutch into one co-located assembly, eliminating a conventional driveshaft. This permitted a 10-inch lower chassis and necessitated a lengthy hood that appeared even longer because the designer, Al Leamy, surrounded the radiator with an integrated sheet-metal assembly, finished to match the car’s colour.

The lowslung Cord’s bodylines were exquisite. Features include an Art Deco styled transaxle cover, an elegant streamlined grille that evoked the styling of Harry Miller’s racing cars, sweeping clamshell fenders, sleek body side reveals which accentuated the car’s length, and a low roofline. These are embellished by myriad Art Deco styled details ranging from accented fender trim, tapered headlamp shapes, etched door-handle detailing and tiny, but exquisite instrument panel dials.

The L-29 Cord’s art moderne styling and engineering prowess attracted buyers of taste and style who were not afraid to try something different. Owners included the era’s most prominent and controversial architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, who bought a new L-29 Convertible Phaeton in 1929 and drove it for many years. This stunning cabriolet, was purchased in the 1950s by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Wright’s legal caretaker until his death in 1959. Wright had many of his cars painted in a bright hue called Taliesin orange. The finish of this Cord is a close approximation.

Henderson KJ Streamline

1930

Collection of Frank Westfall

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

With its 1,200-cc, 40-brake horsepower, in-line four-cylinder engine, the 1930 Henderson Model KJ Streamline could exceed 100 mph. In an era when streamlining was used sparingly in motorcycle design, American Orley Ray Courtney’s enclosed bodywork was virtually unknown on production two-wheelers (except for a few racing machines), making the KJ an unusual and beautiful example of Art Deco design.

Courtney believed that the motorcycle industry failed to provide weather protection and luxury for its riders. His radically streamlined KJ body shell was unlike anything ever done on two wheels. The sleek vehicle had a curved, vertical-bar grille, reminiscent of the Chrysler Airflow, and the rear resembled an Auburn boat-tail speedster. The panels were hand-formed of steel with a power hammer.

Stunningly beautiful but impractical and hard to ride, the Streamline’s complex curved body was heavy and was difficult to make. In 1941, Courtney filed for a patent for a second motorcycle design with fully enclosed fenders. Perhaps he was influenced by the fact that the Indian Motocycle Company had introduced its partially skirted fenders in 1940, and that motorcyclists were becoming more accepting of this trend.*

* In 1923, Indian Motorcycle Company became Indian Motocycle Company and retained that name until the company closed in 1953.

Model 40 Special Speedster™

1934

Owned and restored by Edsel & Eleanor Ford House, Grosse Pointe Shores, Michigan

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Edsel B. Ford, President of Ford Motor Company of Dearborn, Michigan, asked his styling chief, Eugene T. “Bob” Gregorie, to build a “continental” roadster that could have limited production potential. Gregorie sketched alternatives and then built a 1/25th scale model that he tested in a small wind tunnel. Because of its 1934 Ford (also known as Model 40) origins, the roadster became known as the Model 40 Special Speedster.

Assisted by Ford Aircraft personnel, Gregorie’s team fabricated a taper-tailed aluminium body, mounted over a custom welded tubular structural framework. This car resembles the 1935 Miller-Ford Indianapolis 500 two-man race cars, but it was designed and built prior to their construction. This car’s long, low proportions were unlike anything Ford Motor Company had ever built. The Speedster weighs about 2,100 pounds. Its engine is now a 100-brake horsepower Mercury flathead V-8.

This Model 40 was one of Edsel Ford’s personal vehicles. After his death in 1943, the Speedster passed through several owners. Bill Warner, founder of Florida’s Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, read an article that mentioned that the Model 40 Special Speedster was owned by a fellow Floridian. Warner tracked the Speedster down, bought it, and later sold it to Texas mega-collector John O’Quinn. After O’Quinn died in 2009, Edsel Ford II arranged for the speedster’s purchase. In August 2010, this car was restored by RM Restorations, Blenheim, Ontario, Canada.

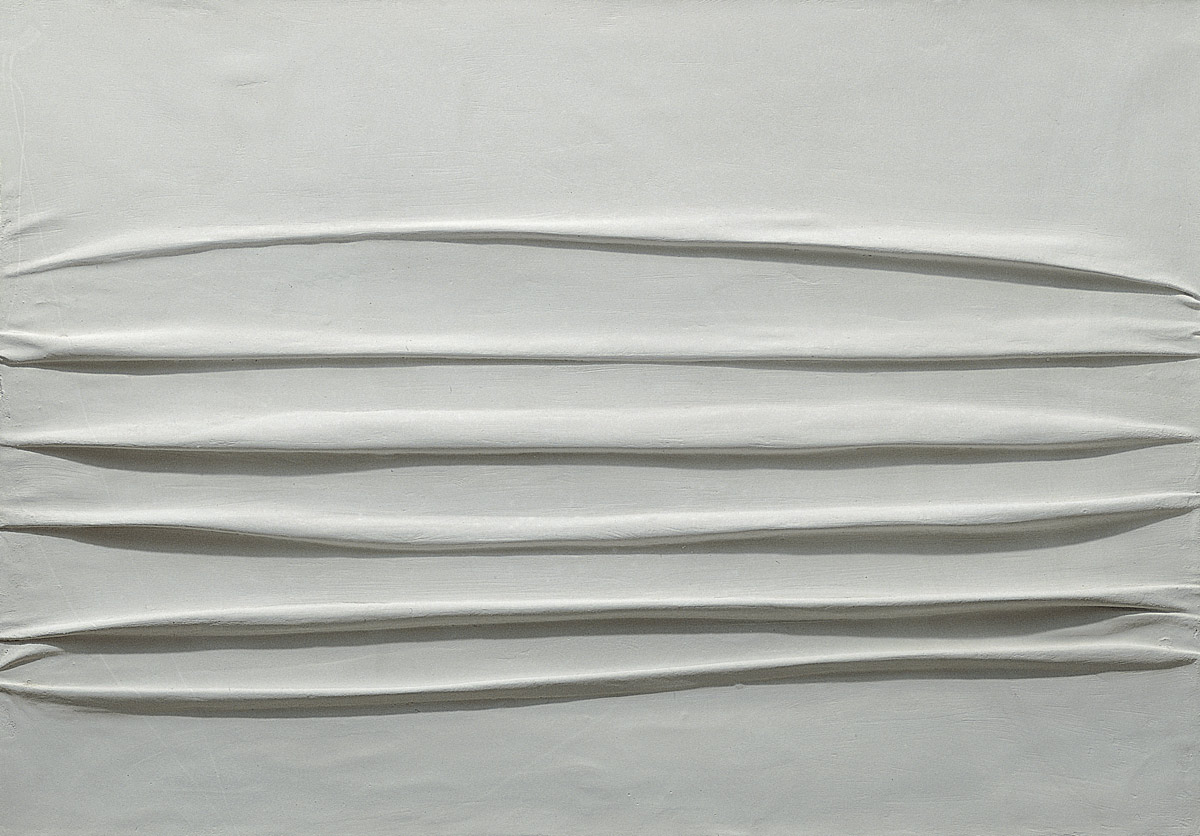

Sensuous Steel: Art Deco Automobiles is an exhibition of Art Deco automobiles from some of the most renowned car collections in the United States. Inspired by the Frist Center’s historic Art Deco building, this exhibition features spectacular automobiles and motorcycles from the 1930s and ’40s that exemplify the classic elegance, luxurious materials, and iconography of motion that characterises vehicles influenced by the Art Deco style.

Fascination with automobiles transcends age, gender, and environment. While today automotive manufacturers often strive for economy and efficiency, there was a time when elegance reigned. Influenced by the Art Deco movement that began in Paris in the early 1920s and propelled to prominence with the success of the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925, automakers embraced the sleek new streamlined forms and aircraft-inspired materials, creating memorable automobiles that still thrill all who see them. The exhibition features 18 automobiles and two motorcycles from some of the most important collectors and collections in the United States.

While today automotive manufacturers often strive for economy and efficiency, there was a time when elegance reigned. Like the Frist Center’s historic building, the automobiles included in Sensuous Steel display the classic grace and modern luxury of Art Deco design. An eclectic, machine-inspired decorative style that thrived between the two World Wars, Art Deco combined craft motifs with industrial materials and lavish embellishments. The movement began in Paris in the early 1920s and was propelled to prominence in with the success of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925. Automakers embraced the sleek iconography of motion and aircraft-inspired materials connotative of Art Deco, creating memorable automobiles that still thrill all who see them.

“Sensuous Steel is the first major museum auto exhibition devoted entirely to Art Deco automobiles, and there could be no more fitting a venue than the Frist Center’s landmark historic Art Deco building, which was completed in 1934,” notes Frist Center Executive Director Dr. Susan H. Edwards. “Art Deco styling influenced everything from architecture to sleek passenger trains and luxury liners, furniture, appliances, jewellery, objets d’art, signage, fashionable clothing and, of course, automobiles. The works in this exhibition convey the breadth, diversity, and stunning artistry of cars designed in the Art Deco style.”

“Rapidly changing and ever-evolving, the automobile became the perfect metal canvas upon which industrial designers expressed the vital spirit of the interwar period,” explains Guest Curator Ken Gross. “To give the illusion of dramatic movement and forward thrust, cars of the 1930s and ’40s merged gentle curves with angular edges. These automobiles were made from the finest materials and sported beautifully crafted ornamentation, geometric grillwork, and the elegant miniature statuary of hood ornaments. The classic cars of the Art Deco age remain today as among the most visually exciting, iconic and refined designs of the twentieth century.”

Press release from The Frist Center for the Visual Arts website

Voisin Type C27 Aérosport Coupe

1934

Collection of Merle and Peter Mullin

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Pioneer French aeronautical expert Gabriel Voisin was an eccentric visionary whose aircraft greatly benefited his country during World War I. He later became an automobile manufacturer, achieving, in the words of designer Robert Cumberford, “sometimes… amazing results.”

Voisin’s chief designer, André “Noël-Noël” Telmont, who was trained as an architect, based the style of this Type C27 Aérosport after the earlier Voisin Aérodyne’s radical new look. Telmont was inspired by aviation and architecture, whereas other French coach builders such as Joseph Figoni turned to the female form and imitated its soft curves. Gabriel Voisin unveiled the Aérosport at the 1935 Madrid Auto Salon. With the Aérosport, Telmont presented wonderfully balanced Art Deco coachwork that featured new, modern, and aerodynamic themes. The Aérosport’s profile outlined the cross-section of an imaginary wing. The semi-circular roof line traced the contours of a cockpit, and the larger surfaces simulated a fuselage.

A lack of funds meant the factory was unable to fully develop this model. Telmont sold the car to Moïse Kisling, a leading European artist. After a front-end crash, the coupe was kept in a disassembled state at the Saliot garage near Paris for years. With the information provided by period photos of the Type C27, this renovated body was built in France to match the original in every detail. The car has its original chassis, a correct Voisin engine and transmission parts, and accessories from one of the two original Type C27s.

Packard Twelve Model 1106 Sport Coupe by LeBaron

1934

Collection of Robert and Sandra Bahre

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Pierce-Arrow Silver Arrow Sedan

1933

Collection of Academy of Art University Automobile Museum, San Francisco

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

With its dignified advertising, elegant styling, and respectable dealers, Buffalo, New York-based Pierce-Arrow rivalled Packard for prestige. The staunchly conservative Pierce-Arrow clung to six-cylinders long after Packard and Cadillac introduced V-8s. Facing tough competition, sales slumped and Pierce merged with Studebaker in 1926.

In 1932, Phillip O. Wright designed a streamlined fastback coupe on the Pierce-Arrow V-12 chassis. He moved to Studebaker headquarters in South Bend, Indiana, where his rakish design evolved into a sporty sedan with a low roofline, envelope front and skirted rear fenders, and faired-in headlamp nacelles. With its 175-brake horsepower V-12, a Silver Arrow could top 115 mph. In a sea of boxy sedans, the sleek Pierce-Arrow show car was the height of modernity. Five hand-built Silver Arrows toured 1933 auto shows, where they caused a sensation. At the Chicago Century of Progress, the Silver Arrow upstaged Cadillac’s Aero-Dynamic coupe, Duesenberg’s “Twenty Grand,” and Packard’s “Car of the Dome,” with its audacious, aircraft-like shape.

Priced at a then-expensive $10,000, the Silver Arrow was one of thirty-eight different 1933 Pierce-Arrow models. Sales slipped to just 2,152 units in total. After succumbing in mid-1938, Pierce-Arrow is best remembered for its magnificent Silver Arrow. This is one of three survivors.

faired-in headlamp nacelles: a fairing, primarily found on aircraft, is a streamlined structure used to create a more aerodynamic outline; a nacelle refers to any streamlined housing or enclosure; in this instance, the forward facing headlamps are enclosed within a housing and placed with a fairing that does not extend beyond the curvilinear profile of the overall design

Chrysler Imperial Model C-2 Airflow Coupe

1935

Collection of John and Lynn Heimerl, Suffolk, VA

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Cord 810 “Armchair” Beverly Sedan

1936

Collection of Richard and Debbie Fass

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Delahaye 135M Figoni & Falaschi Competition Coupe

1936

Collection of Jim Patterson/The Patterson Collection

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

This stunning Delahaye was one of French coach builders Joseph Figoni and Ovidio Falaschi’s first aerodynamic coupe designs. With its dramatic enclosed fenders and hand-crafted aluminium body, it was built on one of the fifty short chassis designed by the Delahaye Company for sporty two-seater models. It was equipped with a four-speed competition-style manual transmission, appropriate to a sporty coupe intended for rally competition. The dashboard included a Jaeger rally clock, and the trunk had only enough room to carry a spare tire. The engine was a highly reliable 4-litre Delahaye six with three downdraft Solex carburettors.

The coupe’s striking design emphasised flowing lines with teardrop-shaped chrome accents on the hood and the front and rear fenders. The door handles and headlights were flush with the body. The dashboard was made of rich, golden wood, a Figoni & Falaschi signature. A sliding metal sunroof and a windshield that opened outward at the bottom afforded ventilation.

A French racing driver named Albert Perrot commissioned this coupe. The Comtesse de la Saint Amour de Chanaz displayed it at a concours d’elegance in Cannes. It was successfully hidden from the Germans during World War II. After the war, it reportedly belonged to actress Dolores del Rio, a well-known owner of exotic cars who lived in Mexico City and Los Angeles.

After several more owners, Don Williams, of the Blackhawk Collection, purchased the coupe in the late 1990s. Some time earlier, the Delahaye’s original engine had broken down; it was replaced with a postwar model, and the old engine was retained. In 2004, the Delahaye became the property of Mr. James Patterson, who re-installed the original engine and had the car beautifully restored.

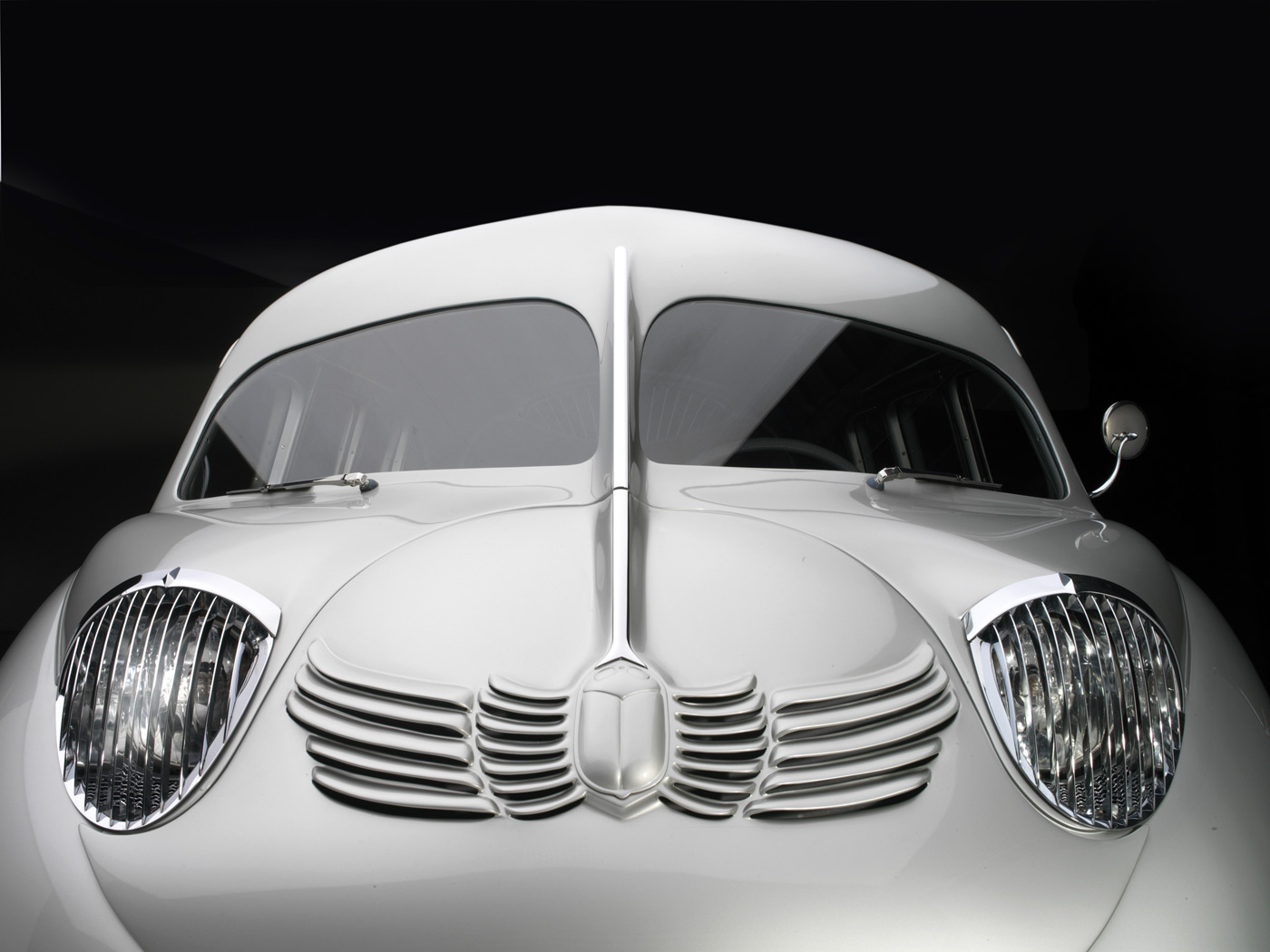

Stout Scarab

1936

Collection of Larry Smith

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

American aeronautical designer William Bushnell Stout modelled this sturdy Ford Tri-Motor after his own 3-AT aircraft. The futuristic Scarab (named for the Egyptian symbol based on a beetle) has a smooth and startling shape, with a tubular frame covered with aluminium panels surrounding a rear-mounted Ford flathead V-8. The Scarab’s passenger compartment is positioned within the car’s wheelbase. Access to the interior is through a central door on the right side, and there is a narrow front door on the left for the driver. This unusual configuration anticipated the first minivan.

The “turtle-shell” styling celebrated the Art Deco influence, beginning with decorative “moustaches” below the split windshield. It continues to be evident in the headlamps covered with thin grilles, and culminates in fan-shaped vertical fluting, framing the elegant cooling grilles. The Scarab’s design was even more radically different than other cars of the era like the ill-fated Chrysler Airflow. At $5,000, it was very expensive, and the Depression-wracked buying public did not recognise its many advantages.

Stout’s investors, like William K. Wrigley, the chewing gum magnate, and Willard Dow of Dow Chemical, purchased Scarabs, as did tire company owner Harvey Firestone and Robert Stranahan of Champion Spark Plug. At least six cars were built; some sources say nine. Scarab number five was shipped to France for the editor of Le Temps, a Paris newspaper. In the early 1950s, this Scarab was offered for sale on a Parisian used car lot and returned to America.

Delahaye 135MS Roadster

1937

Courtesy of The Revs Institute for Automotive Research @ the Collier Collection

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Parisian coach builders Joseph Figoni and Ovidio Falaschi produced this very special Delahaye 135MS Roadster for the 1937 Paris Auto Salon. Instead of conventional pontoon fenders that protruded from the car’s body, Figoni incorporated them into the body, heightening the impression of a singular, flowing form. Using Art Deco ornamentation, he punctuated the car’s hood with scalloped chrome trim that accentuated the curves of the fenders. Its all-aluminium body is built on a short 2.70-meter competition chassis. The dark red leather interior and matching carpets were provided by Hermès, a French company begun in the eighteenth century and known for its fine carriage building.

This low, sleek car appears to be moving when it is standing still. The avant-garde design caused a sensation at the Paris Auto Salon, and its completion provided Figoni & Falaschi with the opportunity to file four new patents: for the aerodynamic design that stabilised the front fenders; for the disappearing front windshield; for the special lightweight competition tubular seats; and for the disappearing convertible top. The original design also featured a central light mounted in the front grille. The door handles were mounted flush to the body surface, augmenting the roadster’s modern, clean look. In early 1938, this roadster returned to the Figoni & Falaschi shop, where the central headlight was removed, and front and rear bumpers were installed to protect the car from daily driving hazards.

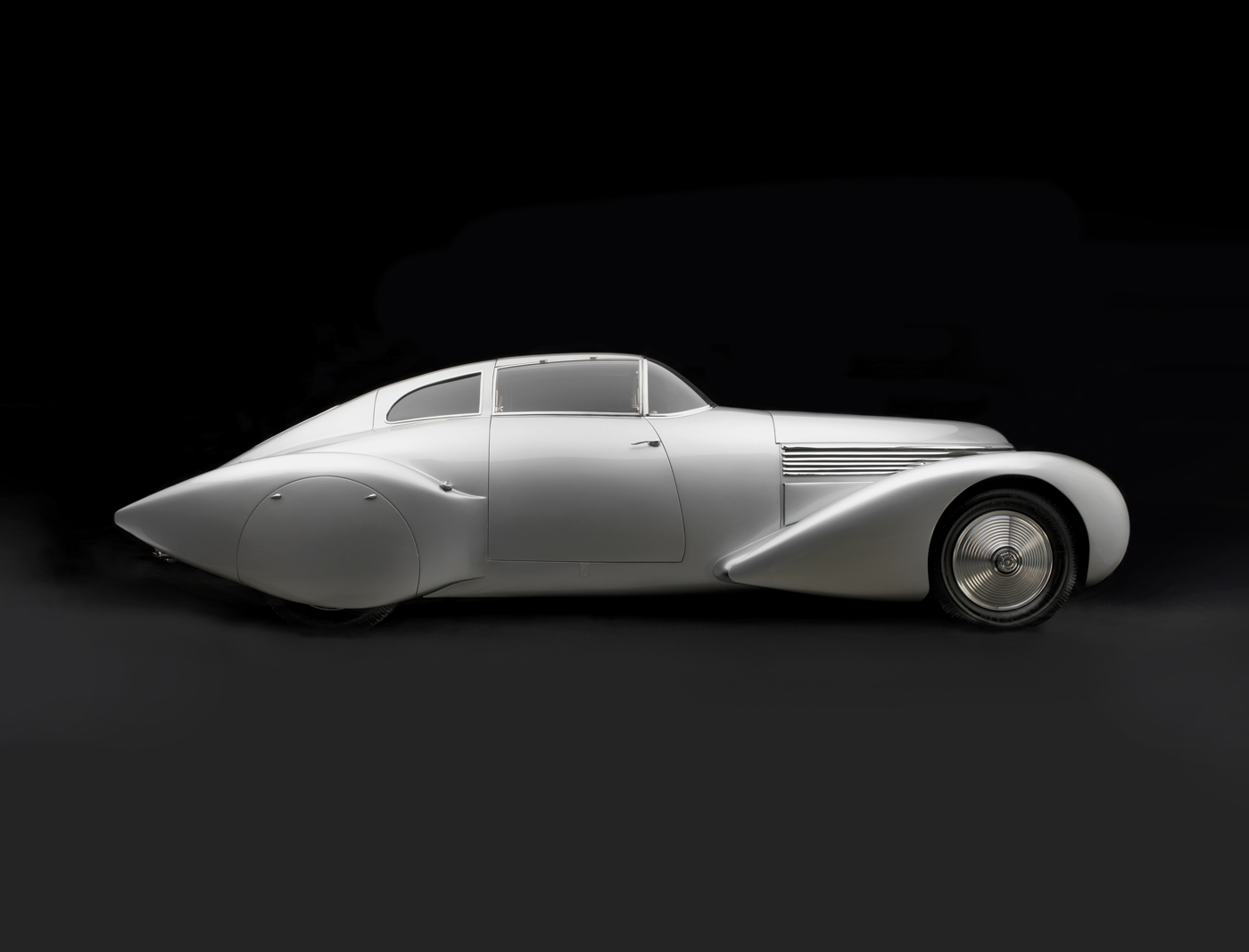

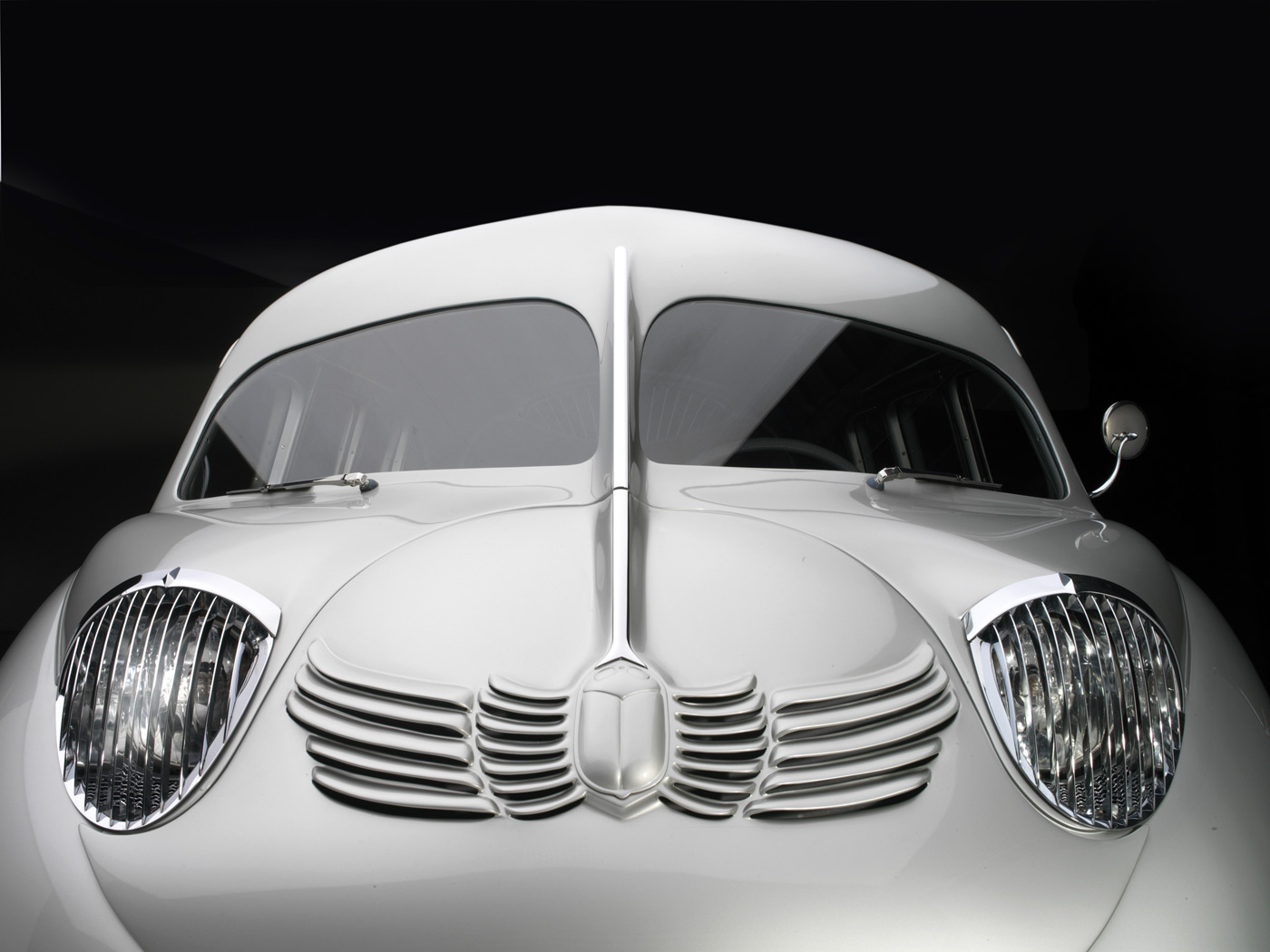

Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet “Xenia” Coupe

1938

Collection of Peter Mullin Automotive Museum Foundation

Top photo: Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Overhead photo: Anonymous from the internet

André Dubonnet was France’s aperitif baron as well as an amateur racing driver and inventor. Dubonnet worked with engineer Antoine-Marie Chedru to develop and patent an independent front-suspension system in 1927 that was used by General Motors and Alfa Romeo. Following the 1932 Paris Auto Salon, Dubonnet acquired a French built Hispano-Suiza chassis, which he used to create a rolling showcase for his ideas. This car was designed by Jean Andreau, known for avant-garde streamlined aircraft and automotive creations, and hand-built in the coach building shop of Jacques Saoutchik.

The body resembled an airplane fuselage. Curved glass was used, including a panoramic windscreen (not seen again until General Motors cars of the 1950s), and Plexiglas side windows that opened upward in gullwing fashion. The side doors, suspended on large hinges, opened rearward in “suicide” fashion. A tapered fastback was crowned with a triangular rear window. The car featured Dubonnet’s hyperflex independent front suspension system.

The original Hispano-Suiza chassis sat high off the ground, and the “Xenia” – named for Dubonnet’s deceased wife, Xenia Johnson – was built atop the frame, so while its overall appearance is sleek and elegant, it is a comparatively tall and heavy car. Dramatically different from its contemporaries, the “Xenia” appears far more modern than almost any other 1930s-era automotive design.

.

Talbot-Lago T-150C-SS Teardrop Coupe

1938

Collection of J. Willard Marriott, Jr.

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

The sporting Talbot-Lago T-150-C chassis inspired the design of many open roadsters and closed cars, most notably a series of curvaceous custom coupes. Sensational in their heyday, the French-produced Talbot-Lagos remain highly valued today. Streamlined, sleek, and light enough to race competitively, they were called Goutte d’Eau (drop of water), and, in English, they quickly became known as the Teardrop Talbots. Famed Parisian coach builders Joseph Figoni and Ovidio Falaschi patented the car’s distinctive aerodynamic shape.

Figoni & Falaschi built twelve “New York-style” Talbot-Lago coupes between 1937 and 1939, so-called because the first was introduced at the 1937 New York Auto Show at the Grand Central Palace. Five more cars, built in a notchback Teardrop style, were named “Jeancart” after a wealthy French patron. It took Figoni & Falaschi craftsmen 2,100 hours to complete a body. No two Teardrop coupes were exactly alike.

Talbot’s president, Antony Lago, offered a top-of-the-line SS (Super Sport) version with independent front suspension. The competition engine, a 4-litre six cylinder topped with a hemi head, could be fitted with three carburettors for 170-brake horsepower. Some cars were equipped with an innovative Wilson pre-selector gearbox, with a fingertip actuated lever that permitted instant shifts without the driver having to take his hand off the steering wheel. In 1938, a racing model T-150C-SS Coupe finished third at the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

This car was the first “New York-style” Teardrop coupe. Its first owner was Freddie McEvoy, an Australian member of the 1936 British Olympic bobsled team. A prominent player on the Hollywood scene, McEvoy’s ready access to celebrities made him an ideal concessionaire for luxurious automobiles.

hemi head: an internal combustion engine that is designed with hemispherically shaped chambers that optimised combustion and permitted larger valves for more efficiency

pre-selector gearbox: a type of manual gearbox or transmission that allows a driver to use levers to “pre-select” the next gear to be used, and with a separate foot pedal control, engage the gear in one single operation

Tatra T97

1938

Collection of Lane Motor Museum

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

One of the most advanced designs of the pre-World War II era came from Czechoslovakia. Czech-based Koprivnicka vozovka evolved into Nesseldorfer Waggonfabrik and was renamed Tatra in 1927 after the country’s prominent mountain range. Tatra vehicles became known for innovative engineering and high quality. The engineer largely responsible was Hans Ledwinka, who had worked under automotive and aircraft pioneer Edmund Rumpler. Ledwinka was an early proponent of air-cooled engines, a rigid backbone chassis, and independent suspension.

The Tatra was a perfect platform for the new emphasis on streamlining being pioneered by aircraft and Zeppelin designer Paul Jaray. A short front end flowed to a curved roofline that gracefully sloped into a long fastback tail. When integrated fenders and a full undertray were added, wind resistance was dramatically reduced. A prominent rear dorsal fin ensured high-speed stability.

Tatra was arguably the first production car to take advantage of effective streamlining. The T97 used a horizontally opposed, rear-mounted, four cylinder engine with a rigid backbone chassis, four-wheel independent suspension and hydraulic drum brakes. Four were built in 1937, followed by 237 in 1938, and 269 in 1939. Top speed was 80.78 mph, which was truly remarkable for a 40-hp car at the time.

According to automobile designer Raffi Minasian, “The Tatra T97 was one of the most interesting and well-developed engineering and design intersections of the Deco period.” It may have lacked the usual flamboyance of the traditional French coach builders of the period, but it manifested the expression of Art Deco design as a merger of science and industry where form was dictated by function.

Bugatti Type 57C by Vanvooren

1939

Collection of Margie and Robert E. Petersen, Courtesy of the Petersen Automotive Museum, Los Angeles

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

The Great Depression was slow to impact France, due to that country’s high tariffs and restricted trade, but by the early 1930s, sales of luxury automobiles dwindled. Ettore Bugatti and his brilliant son Jean understood that a special model was imperative to help their company survive. The resulting new Type 57’s styling was at once contemporary and affordable, with custom coachwork available for the very wealthy.

For racing, a normally-aspirated, 3.3-litre straight 8-powered Type 57, on an ultra-low “S” chassis, was fitted with streamlined open coachwork. The factory successes included averaging 135.45 mph for one hour, 123.8 mph for 2,000 miles, and 124.6 mph for 4,000 kilometres. An avid horseman, “Le Patron,” as Bugatti was known, was convinced automobile competition improved the breed, as it did with thoroughbred racing.

The greatest coach builders of France: Gangloff, Saoutchik, Letourneur & Marchand, and Vanvooren, as well as Britain’s Corsica, and Graber of Switzerland, all built custom coachwork on the Type 57 chassis. This special Type 57C was the property of Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, Prince of Persia and future Shah of Iran.

When Pahlavi married Egypt’s Princess Fawzia, many nations sent extravagant wedding presents. A gift from France, this cabriolet’s drophead coachwork – a study in sweeping lines and fluid Art Deco ornamentation – was constructed by coach builder Vanvooren of Paris, in the style of Figoni & Falaschi. The windscreen can be lowered into the cowl for an even racier appearance.

Delage D8-120S Saoutchik Cabriolet

1939

Collection of John W. Rich, Jr.

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

La Belle Voiture Francaise: The Beautiful French Car. Coined by the French public to describe the automobiles created by Louis Delage, these words became the slogan for one of France’s oldest and most renowned automobile companies. Coach builders favoured the Delage chassis to showcase their designs, winning numerous concours d’legance.

The Delage D8-120S, a new model for 1938, offered a lowered chassis, (“S” stood for Surbaisse) and the 3.5-litre straight 8’s output was increased. The bare chassis could be purchased for 105,000 French francs. The custom coachwork is estimated to have cost an additional 45,000 French francs, making the D8-120S one of France’s most expensive luxury cars. This car was commissioned for the 1939 Paris Auto Salon by the French government, which was promoting French cars in Europe and the United States. Jacques Saoutchik, one of France’s premier coach builders, created its coachwork, which includes patented sliding parallel doors that opened outward with a pantograph mechanism, then slid rearward, permitting easy access.

The completed cabriolet was hidden away by the workshop prior to the German invasion of France. After World War II, the D8-120S was used by the Provisional Government of the French Republic for official duties. It was sold in 1949 and the buyer installed faired-in headlights and a postwar Delage grille. The D8-120S passed through several more owners before it was restored to its original condition, with the exception of its modern faired-in headlights.

Indian Chief

1940

Collection of Gary Sanford

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Chrysler Thunderbolt

1941

Collection of Chrysler Group, LLC

Photograph © 2013 Peter Harholdt

Detroit-based carmaker Chrysler touted the Thunderbolt and its companion, the Newport Phaeton, as cars of the future. With its aerodynamic body shell, hidden headlights, enclosed wheels, and a retractable one-piece metal hardtop, the sensational Thunderbolt conveyed the message that tomorrow’s Chryslers would leave more prosaic rivals in the dust.

Following the design of Chief Designer Ralph Roberts, both the Thunderbolt and the Phaeton models were built by LeBaron, an American coach building company. Associate designer Alex Tremulis suggested these cars be promoted as “new milestones in Airflow design,” hinting that without the 1934 Airflows, Chrysler styling might not have evolved so far. The Thunderbolt’s full-width hood, which flowed uninterrupted from the base of the windshield to the slender front bumper, and its broad decklid, were made of steel, as was the folding top, a feature designed and patented by Roberts not previously seen on an American car. Fluted, anodised aluminium lower body side trim ran continuously from front to rear. Removable fender skirts covered the wheels, which were inset in front, so they could turn.

Priced at $8,250, eight Thunderbolts were planned, but only five were built, of which four survive. World War II’s interruption meant that while a few features found their way onto production Chryslers, these unique cars were not replicated when hostilities ceased.

Frist Center for the Visual Arts

919 Broadway, Nashville, Tennessee, 37203

Opening hours:

Monday: 10.00am – 5.30pm

Tuesday: Closed

Wednesday: Closed

Thursday: 10.00am – 8.00pm

Friday: 10.00am – 5.30pm

Saturday: 10.00am – 5.30pm

Sunday: 1.00 – 5.30pm

Frist Center for the Visual Arts website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

0.000000

0.000000

You must be logged in to post a comment.