Exhibition dates: 19th September, 2024 – 5th January, 2025

Curator: Exhibition curated by Clément Chéroux, director of the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson.

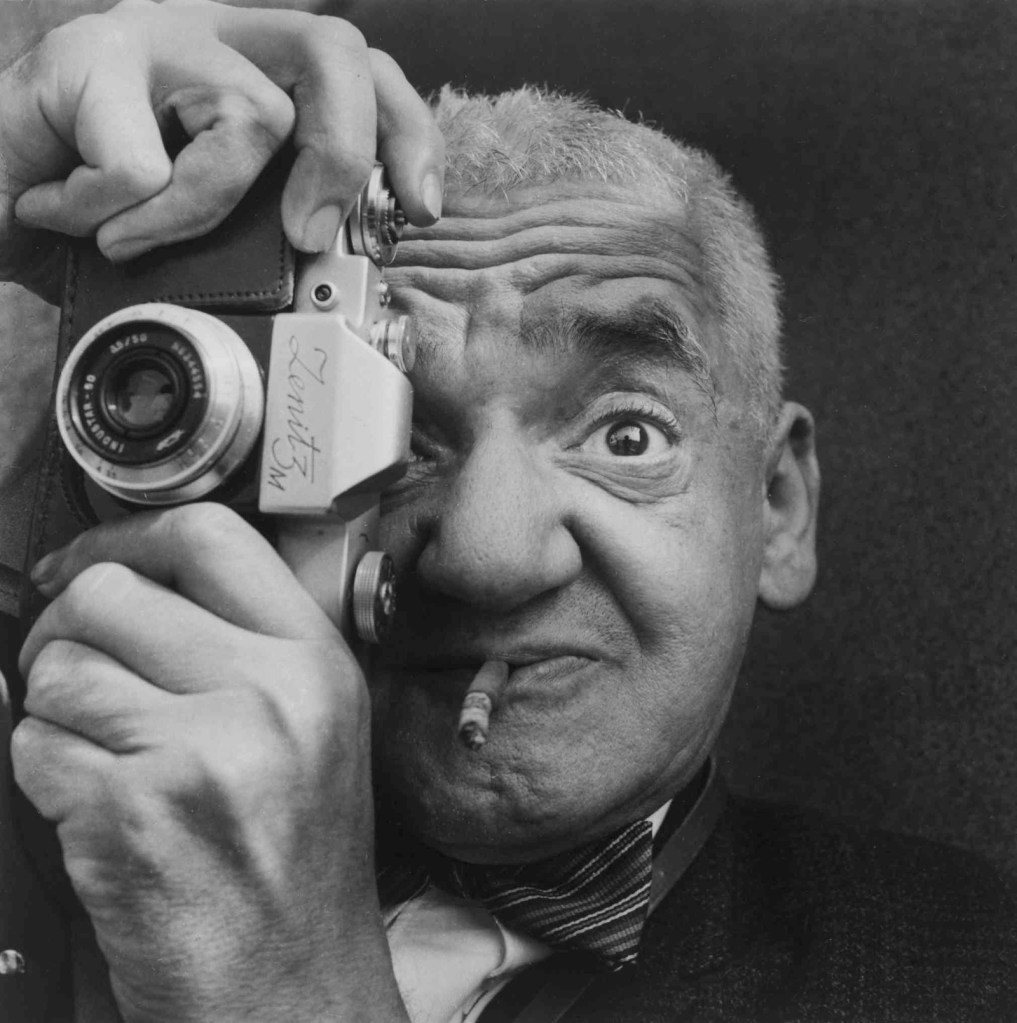

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968)

Self-Portrait with Speed Graphic Camera

October 13th 1950

Gelatin-silver print

© International Center of Photography. Collection Friedsam

Self Seen

I’ve posted on this exhibition once before when it was shown at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris. While there some photographs that are the same in both postings there are new photographs to admire here. So, let’s have some fun with the text!

I started playing around with ideas in my head… and instead of the “autopsy of the spectacle” – an examination to discover the cause of the spectacle – I inverted that statement to make it the “spectacle of the autopsy”.

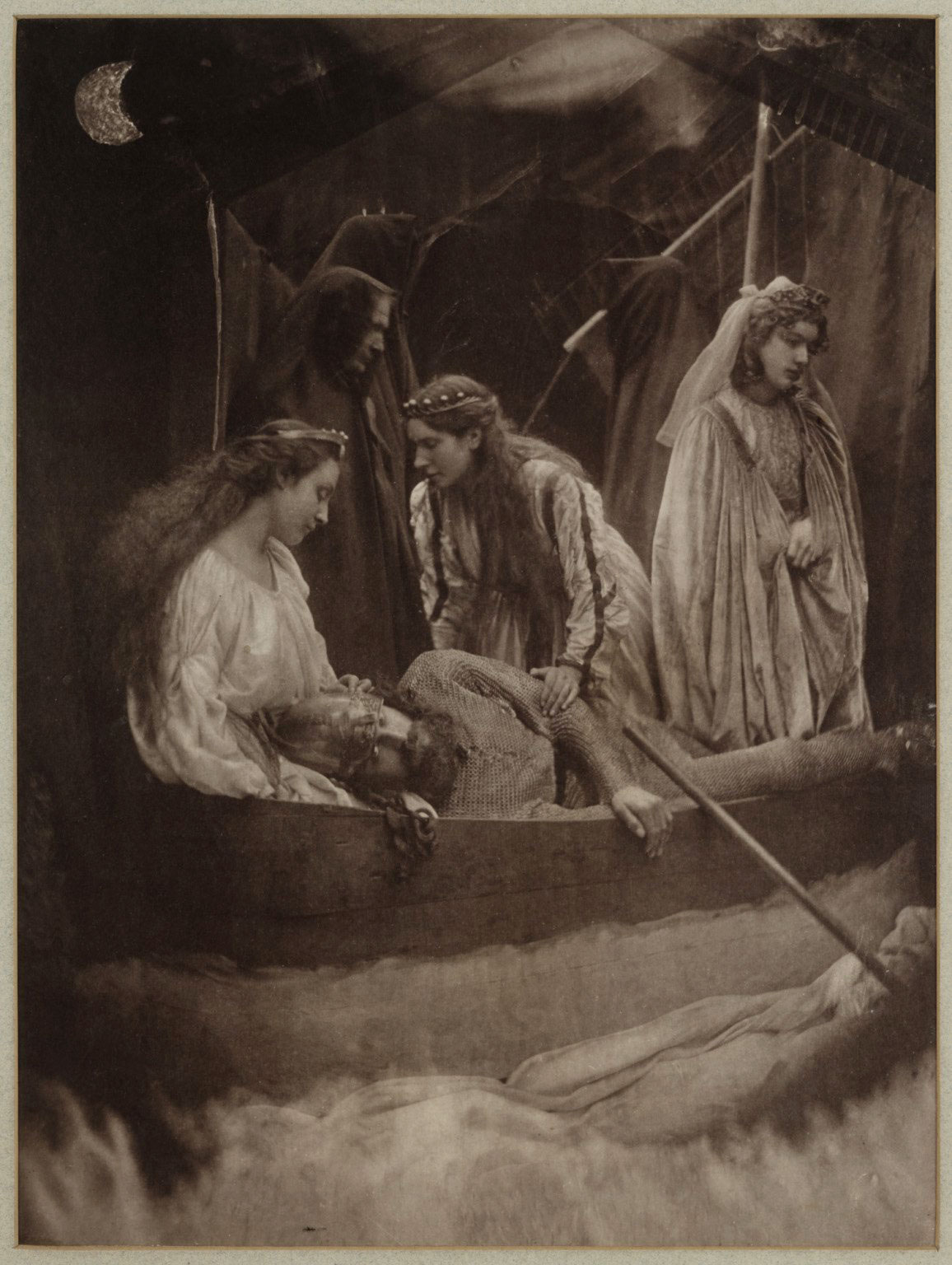

What immediately came to mind when I did this was the spectacle, the spectacular, painting that is Rembrandt’s early masterpiece The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632, below), that tableau – French, late 17th century (in the sense ‘picture’, figuratively ‘picturesque description’) – of figures, spectators, gathered around the corpse of the “criminal Aris Kindt (alias of Adriaan Adriaanszoon), who was convicted for armed robbery and sentenced to death by hanging.”1

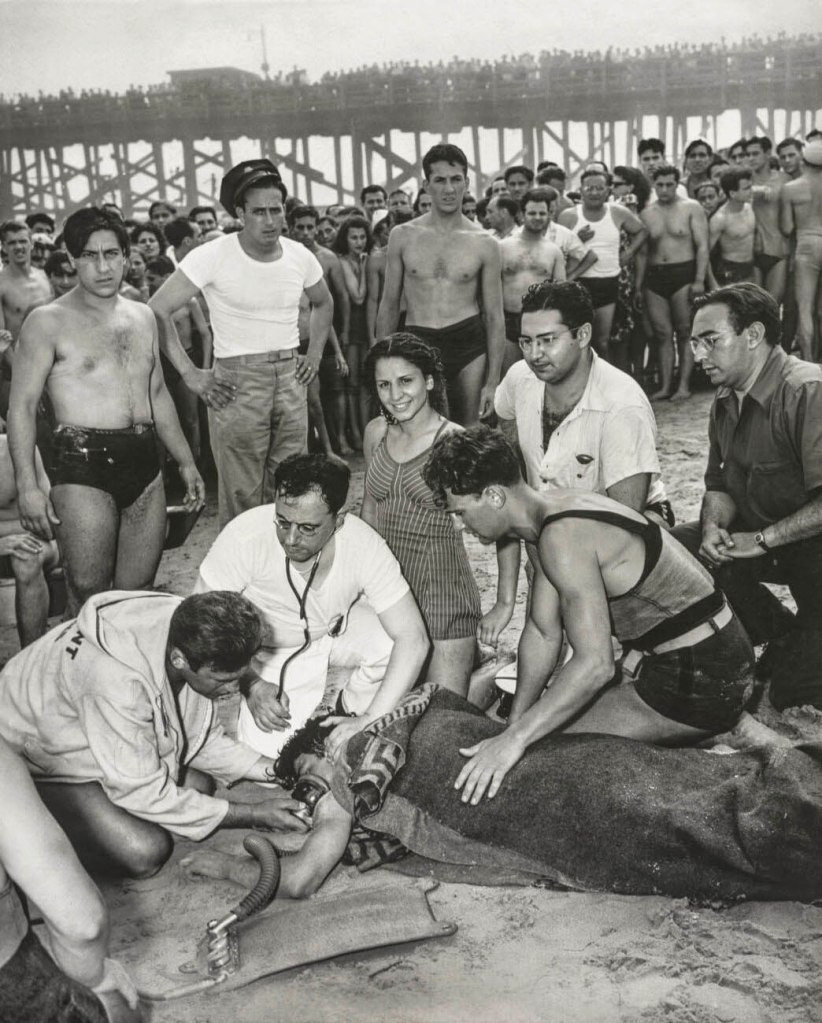

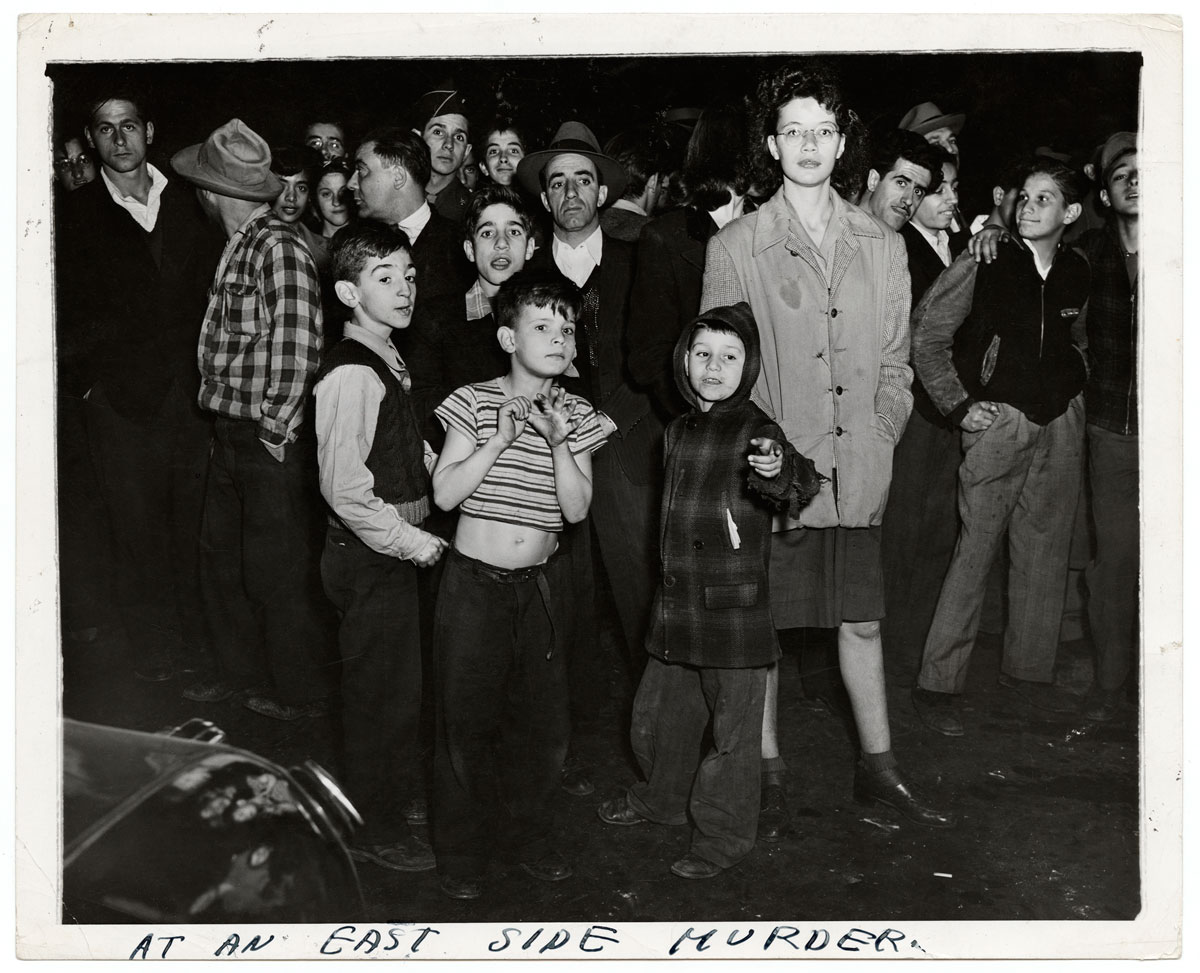

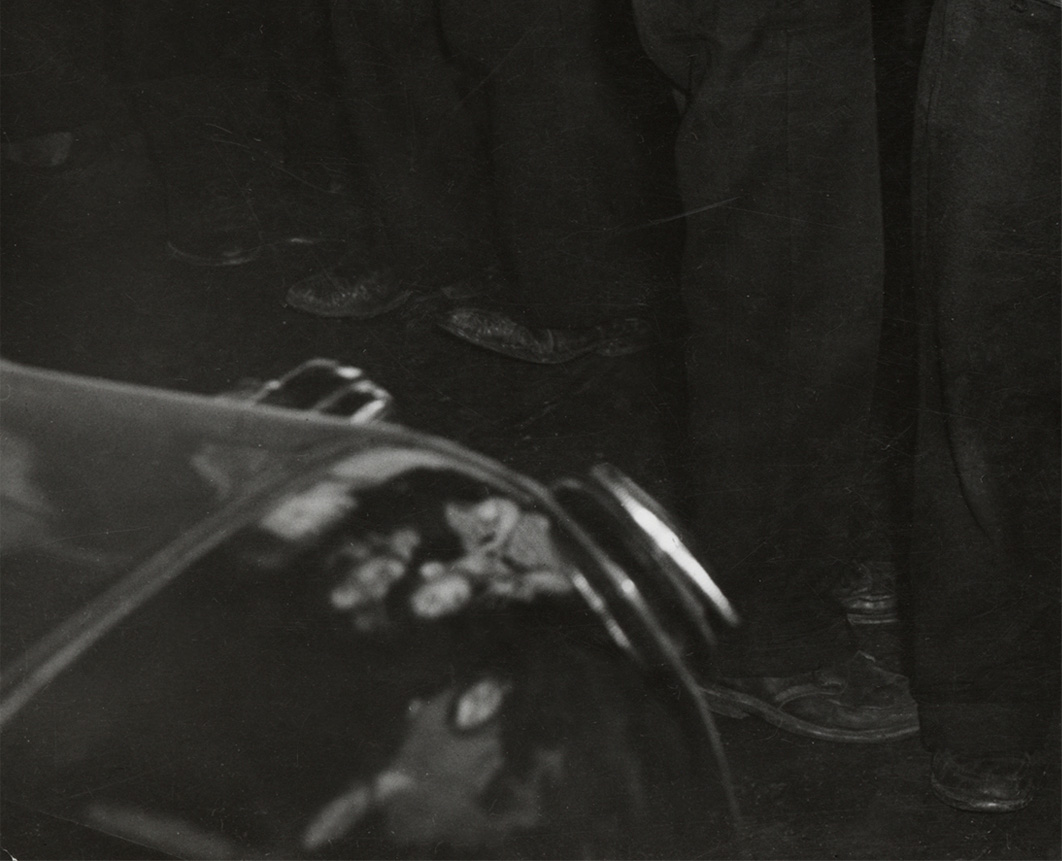

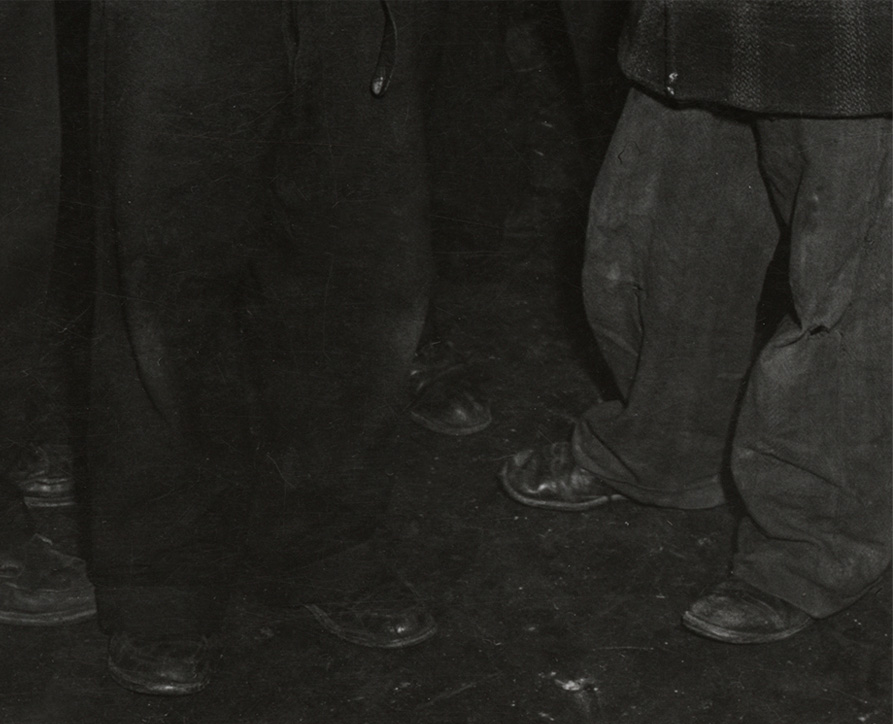

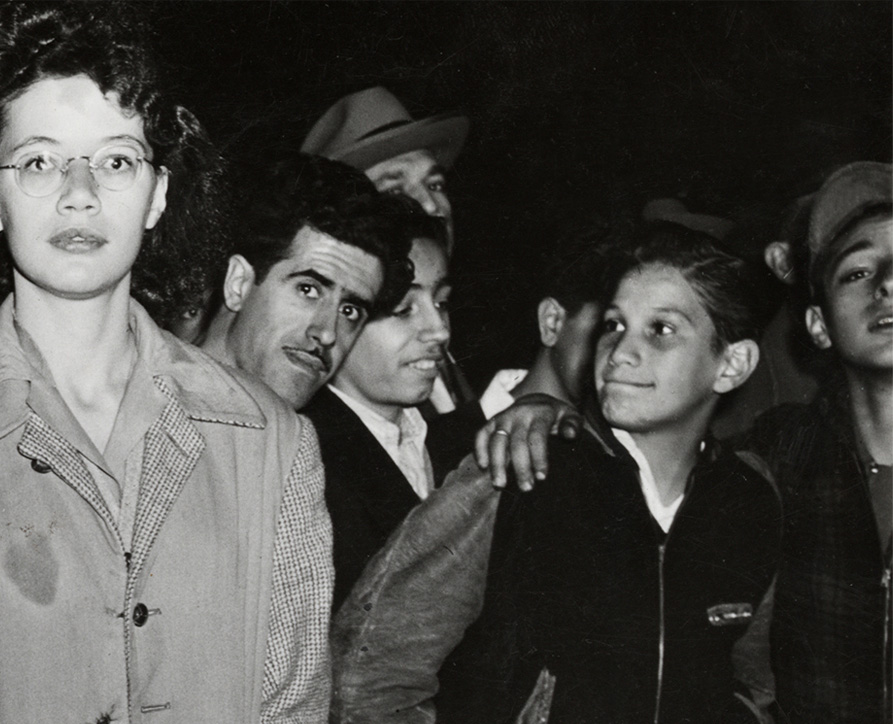

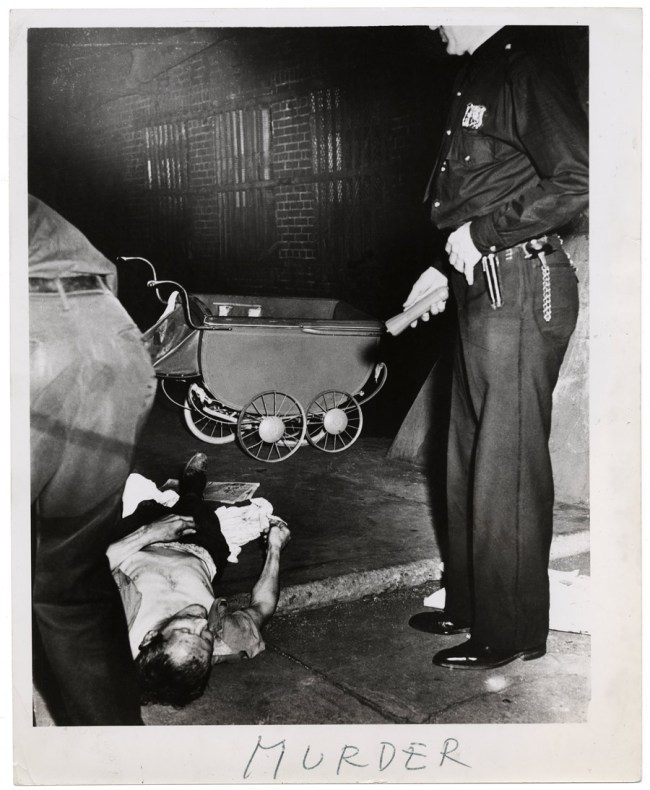

Fast forward a few centuries to the “Murder is my business” photographs of Arthur Fellig (alias Weegee) and I again observe spectators gathered around the body of a corpse, either physically examining it or wilfully ignoring it (Drowning victim, Coney Island c. 1940, below), where the men “examine” the drowning victim surrounded by men that stare and the women who smiles for the camera. With the crowd behind, all are physically and metaphorically drawn in to the spectacle of the autopsy and the presence of the camera. “”Spectacle is Capital to such a degree of accumulation that it becomes an image,” explained Guy Debord in 1967. Weegee understood this well.”

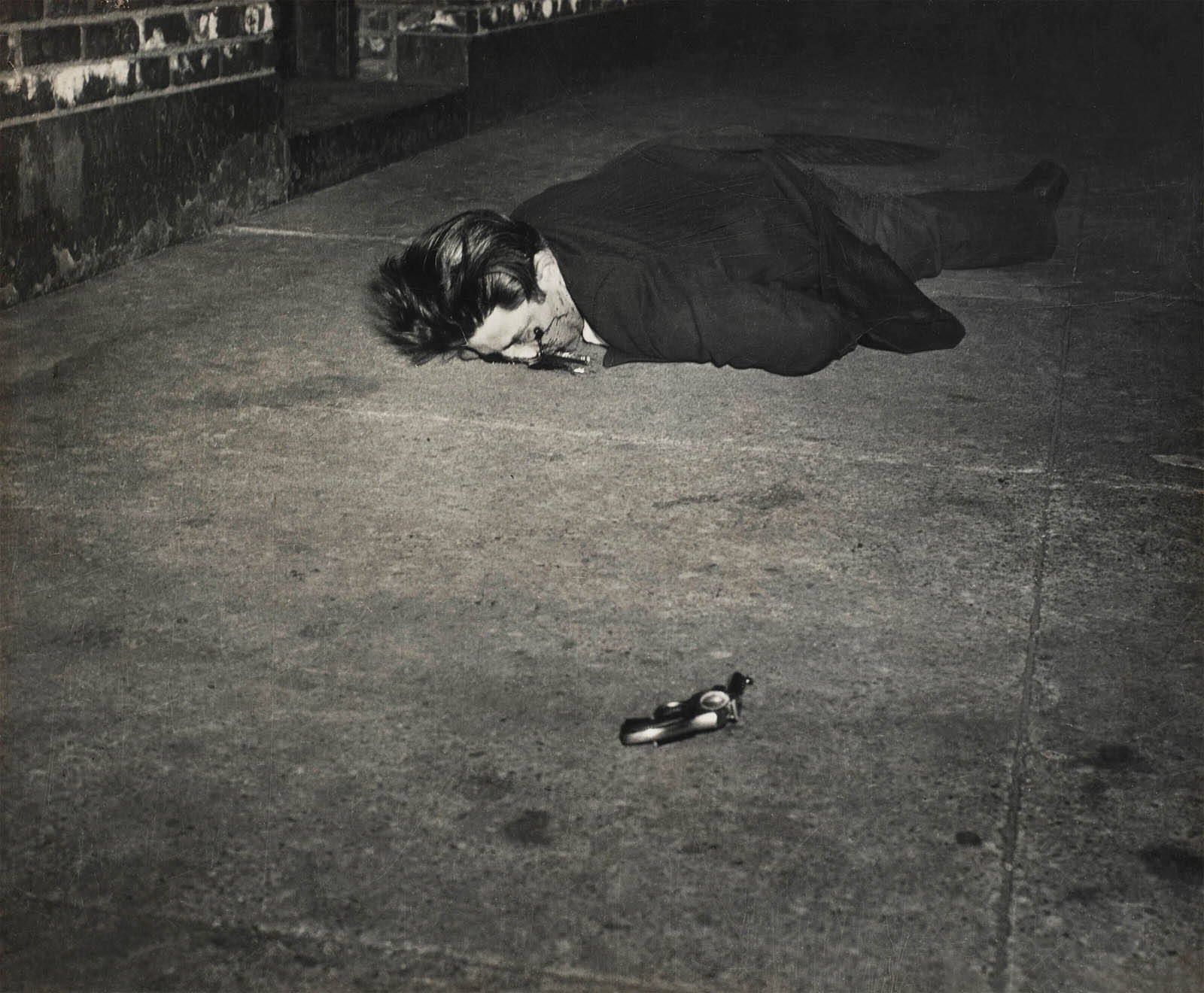

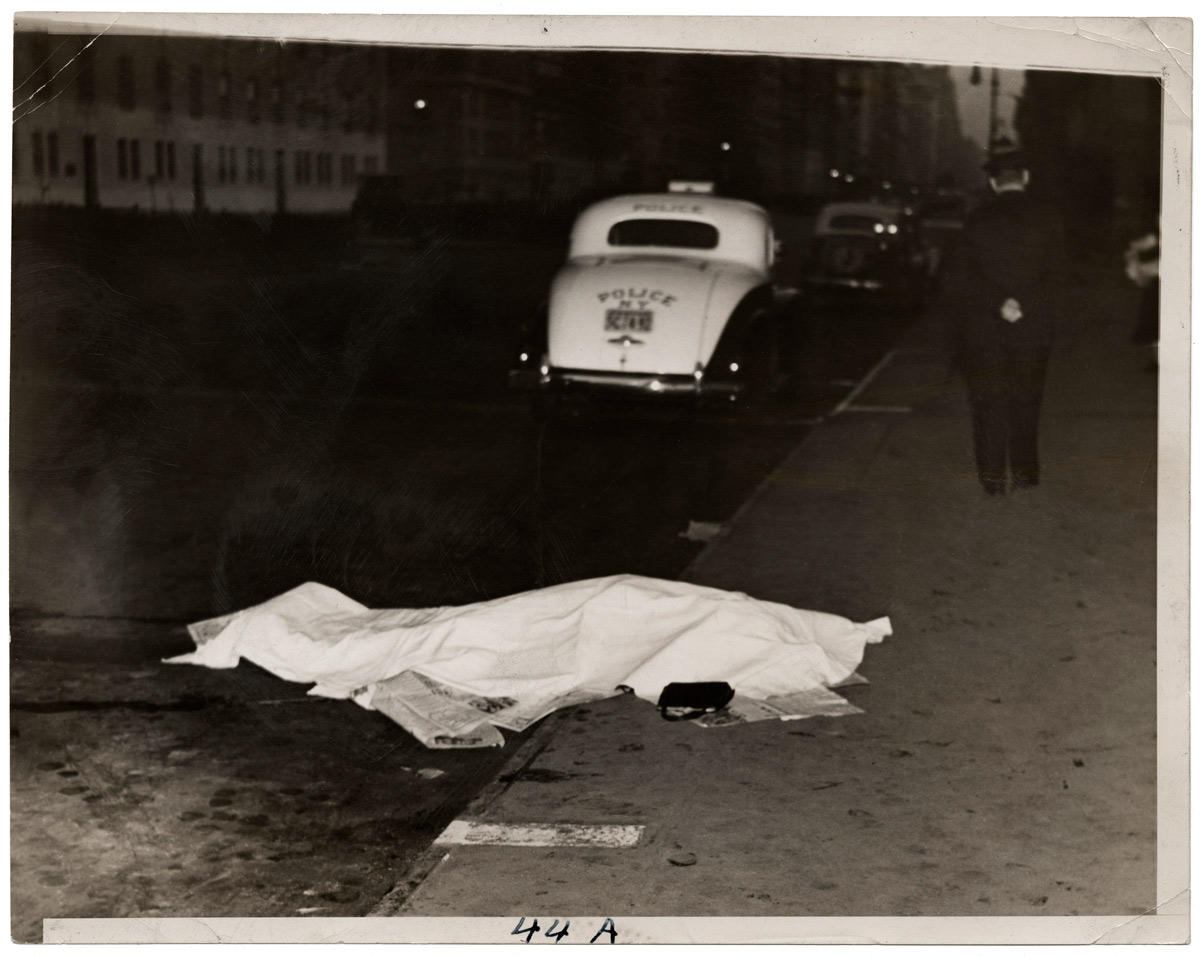

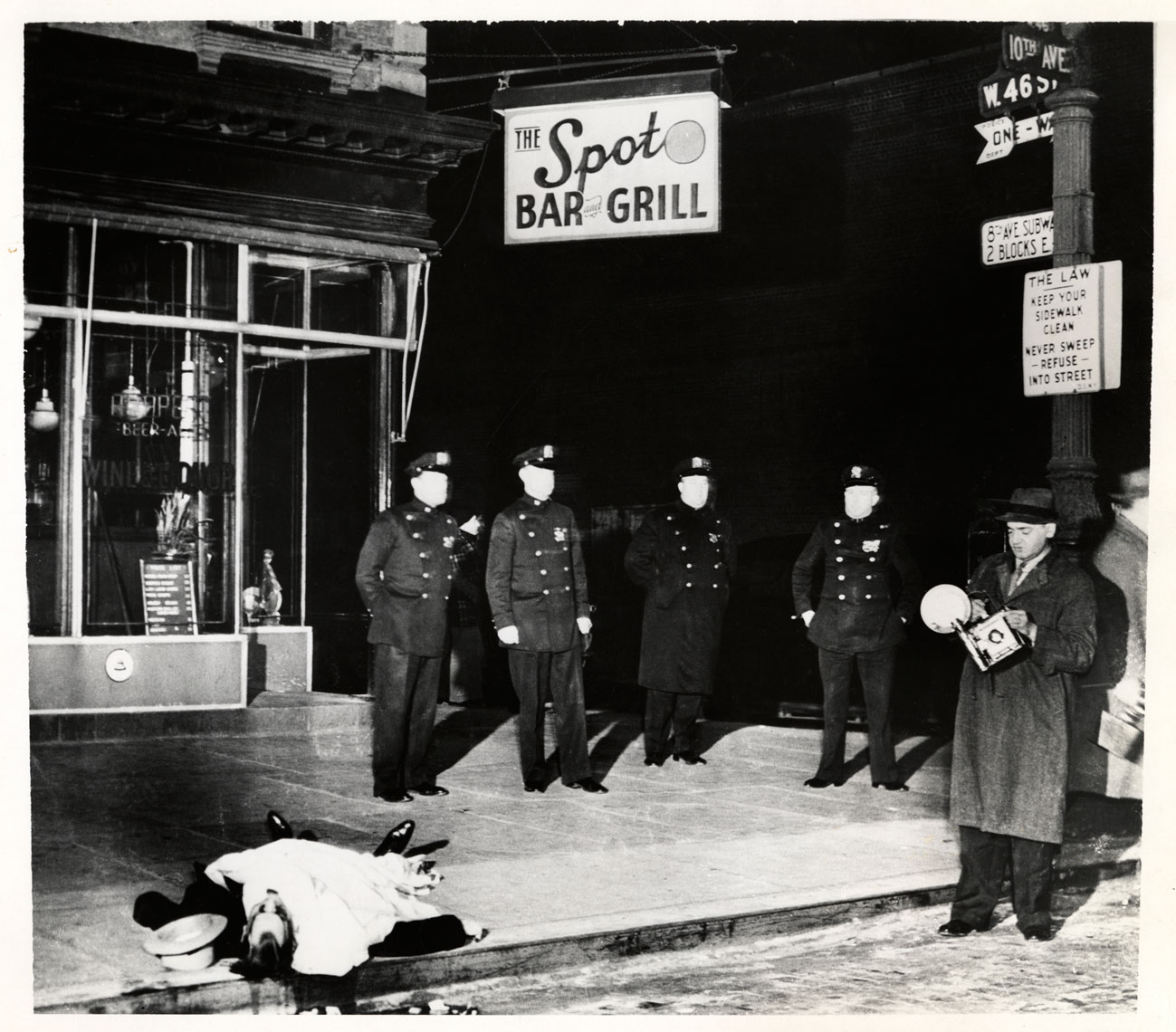

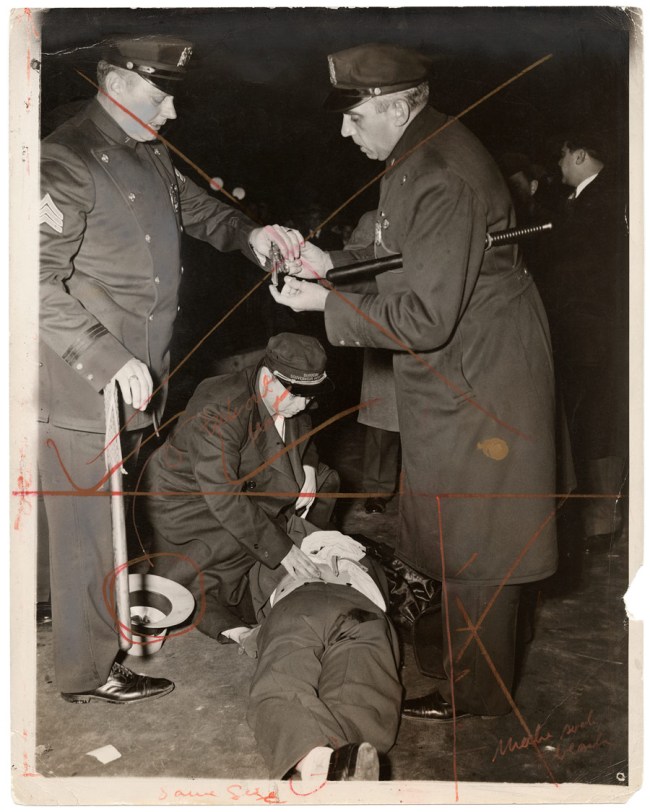

In other photographs such as Body of Andrew Izzo, killed by off-duty policeman Elegio Sarro (1942, below) and Body of Dominic Didato (1936, below) Weegee’s camera becomes the spectator, standing in for us as we crane our necks to get a better view of the action. Together, the camera and the viewer, perform what could be seen as a form of “necropsy” – from the Greek words nekros (meaning “corpse”) and opsis (meaning “to view”), and together they mean “to look at the dead body with naked eyes” – that is, a macroscopic examination of a dead body.

Witness, and we do stand witness in Weegee’s photographs looking at dead bodies with naked eyes, the perspectival viewpoint of the bodies of both Andrew Izzo and Dominic Didato similar to the elongated perspective in the painting by Rembrandt, the shading of the face in that painting – the umbra mortis (shadow of death) – now supplanted by the reversed body, head shaded / covered in blood, surmounted with out flung gun and boater.

While these photographs fail “to give shape to feelings of compassion, grief, horror (as if the pictorial repetition of events were a way of understanding these events, being able to live with them)”2 finally, in the derivation of the word “autopsy” – and in the spectacular images of Weegee – we may begin to understand that these photographs are as much about us, the spectator and viewer, and our discontinuous nature (we die) as they are about the pictured bodies. For the meaning of the word autopsy – early 17th century (in the sense ‘personal observation’): from modern Latin autopsia, from Greek, from autoptos ‘self-revealed’, from autos ‘self’ + optos ‘seen’ – reveals as much about ourselves as it does the object of our attention.

Looking at mortality with naked eyes, our self-revealed, our self seen, reflected back to us in the photographs of Weegee.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Anonymous. “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp,” on the Wikipedia website Nd [Online] Cited 05/12/2024

2/ Leah Dickerman. “Gerhard Richter’s Enigmatic Cycle in The Long Run,” on the MoMA website March 1, 2019 [Online] Cited 05/12/2024

Many thankx to Fundación MAPFRE for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Weegee knew the power of imagery to speak to larger truths about human nature and society. He captured New York as it truly was: gritty, raw, and filled with contrasts. His work turned the everyday violence and chaos of the city into art, making the mundane extraordinary. In Weegee’s own words, “I picked a story that meant something.” He had an instinct for identifying moments that held deeper significance, even if they were just snapshots of daily life in a chaotic metropolis.”

Danny Dutch. “Weegee: The Lens Behind New York’s Darkest Hours,” on the Danny Dutch website Nd [Online] Cited 12/11/2024

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

1632

Oil on canvas

216.5cm × 169.5cm (85.2 in × 66.7 in)

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Drowning victim, Coney Island

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

© Weegee Archive / International Center of Photography, New York / Collection Galerie Berinson, Berlin

Installation view of the exhibition Weegee. Autopsy of the Spectacle at Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid showing at right Weegee’s Self-portrait, Distortion (1955, below)

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Self-portrait, Distortion

1955

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Installation view of the exhibition Weegee. Autopsy of the Spectacle at Fundacion Mapfre, Madrid showing at left Weegee’s Body of Andrew Izzo, killed by off-duty policeman Elegio Sarro (1942, below); at second left, [Outline of a Murder Victim] (1942); and at right, Body of Dominic Didato, (1936, below)

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Body of Andrew Izzo, killed by off-duty policeman Elegio Sarro

1942

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Body of Dominic Didato

1936

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Dominick Didato, aka Terry Burns, who you see above in a photo made by Arthur Fellig, aka Weegee, lies dead on a New York City street where he was gunned down today in 1936. He was killed for interfering with rackets run by Lucky Luciano. It was a low percentage play. Luciano was literally the most powerful mobster in the U.S. at the time, and as the saying goes, you come at the king, you best not miss.

Anonymous. “Urban Decay,” on the Pulp International website August 22, 2024 [Online] Cited 11/11/2024

The work of Arthur H. Fellig, known as Weegee (Zolochiv, Ukraine, 1899 – New York, 1968), is, in a sense, an enigma that this exhibition seeks to unravel. His photographs of the underworld and the fringe circles of New York nightlife in the 1930s and 1940s quickly gained wide international recognition. However, the same cannot be said for the photographs he took after settling in Hollywood in 1948: images of Californian high society and the social life of major film celebrities, whom he often portrayed in a markedly ironic or satirical manner, sometimes (as in the case of the “photocaricatures”) as a result of his later work in the laboratory. At the time, critics emphasised the radical opposition between the two periods, openly praising the former and dismissing the latter. In these photographs of his Californian experience (1948-1951), Weegee expressed his critical vision of society and culture from a perspective that anticipated the well-known cultural and social analyses of ‘the society of the spectacle’ (Guy Debord).

Weegee. Autopsy of the Spectacle aims to show the profound coherence that, beyond their stylistic and thematic differences, links these two stages, as well as to highlight the relevance of the critical perspective from which Weegee’s images expose the features and mechanisms of our time as a ‘society of the spectacle’.

Exhibition organised by the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in collaboration with Fundación MAPFRE.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE website

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Police and onlookers with body of Joseph “Little Joe” La Cava, killed during the feast of San Gennaro

1939

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

The above photo shows the murder scene of a mid-level gangster named Joseph “Little Joe” La Cava, and occurred in New York City on Mulberry Street at the Feast of San Gennaro today in 1939. We’ll go out on a limb and say the festive atmosphere took a fatal hit too. Luckily, the celebration usually went for a week, so we suppose it was salvaged. La Cava was gunned down along with Rocco “Chickee” Fagio… Also interesting, cops being cops, the flatfoot closest to La Cava looks incongruously jocular as he chats with a higher-up. If this wasn’t the most unforgettable Feast of San Gennaro in Little Italy’s history it had to be close.

Anonymous. “Urban Decay,” on the Pulp International website August 22, 2024 [Online] Cited 11/11/2024

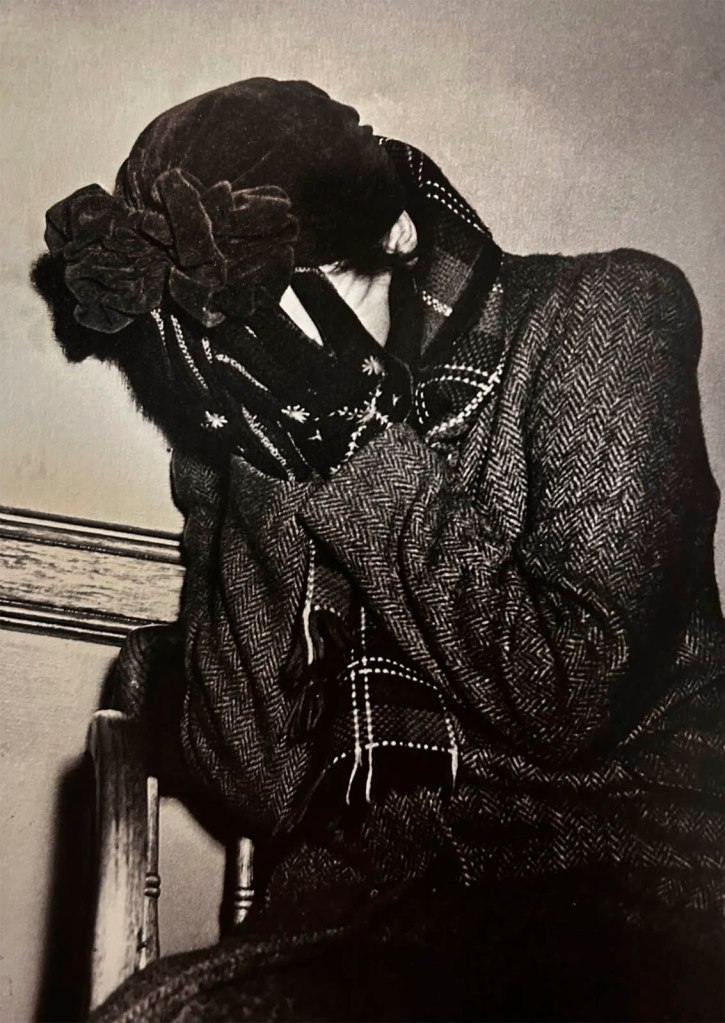

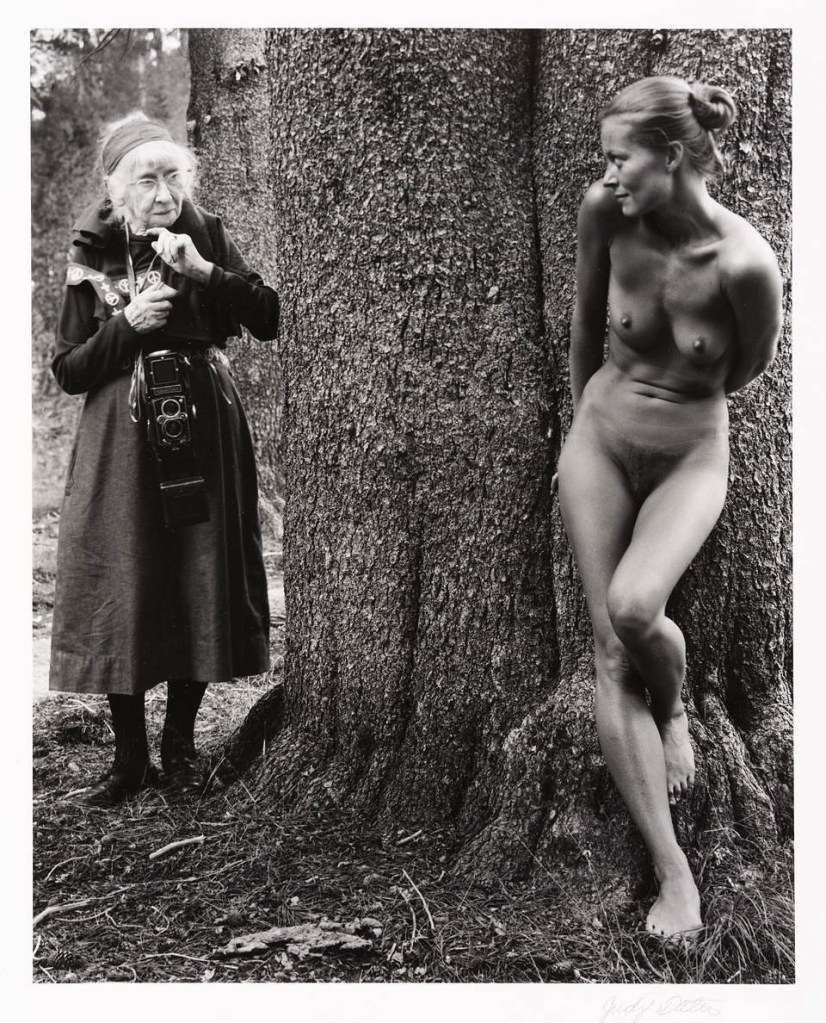

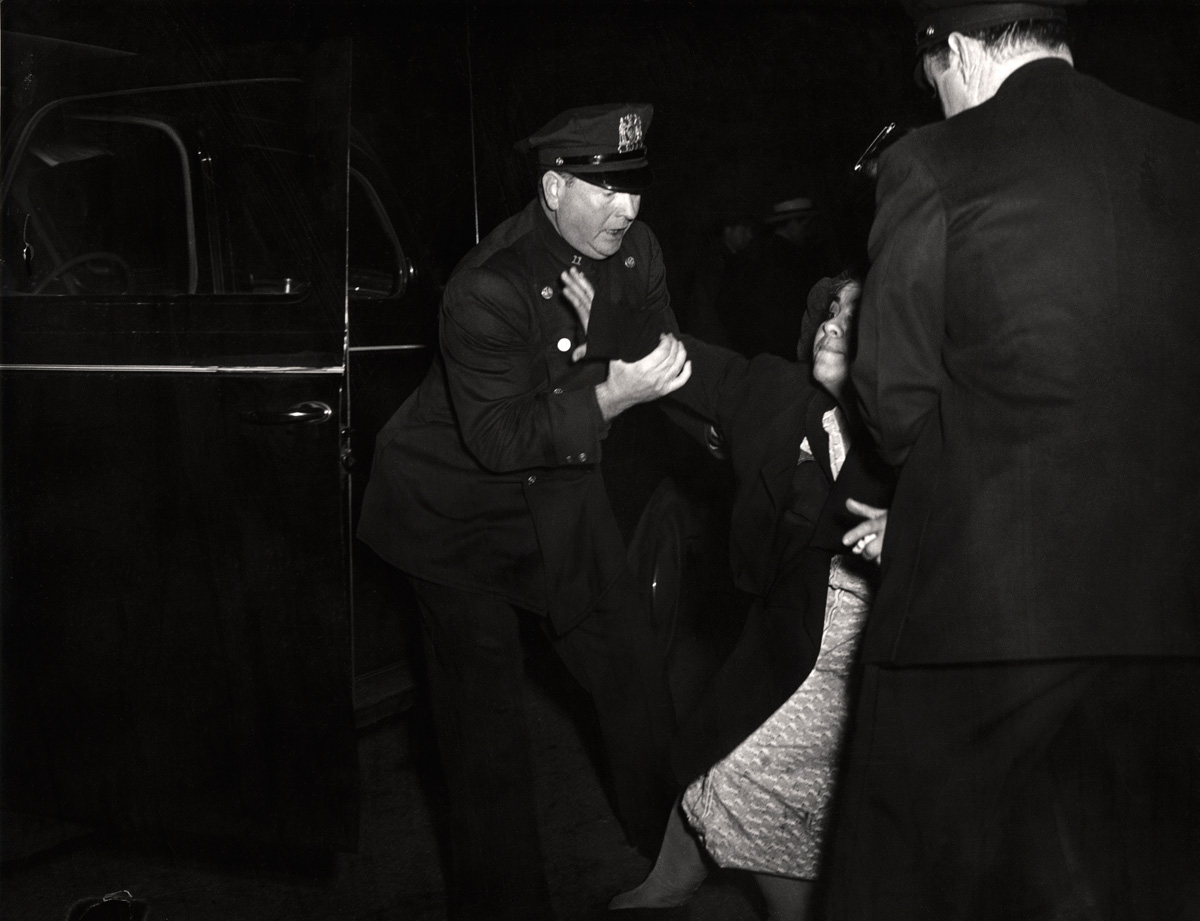

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Nurse Irma Twiss Epstein, accused of killing a baby

1942

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

“Distraught and pale with grief, Irma Twiss Epstein, 32-year-old nurse, whose own baby died 18 months ago, is booked on a homicide charge in the death of a baby whose crying, she said, ‘drove me crazy.’ Miss Epstein, Bronx Maternity Hospital nurse, is accused of giving a powerful drug to the 20 hour-old daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Castro Vallee, whose only other child died after birth 11 years ago. Another infant, 4 days old, was revived by nurses and doctors after Miss Epstein was found in a hallway hysterically sobbing: ‘eyedropper, baby.’ Hospital records showed she entered service there in 1940 and after nine months took a leave of absence to have a baby. Police said she had been in Bellevue’s psychopathic ward two years ago for observation after tasking an overdose of sleeping tablets. She told police at Morrisania Station she expected to be married soon.”

PM Daily, December 23, 1940 quoted on the International Center of Photography website

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Harry Maxwell shot in a car

1941

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

A pivotal figure of American photography in the first half of the twentieth century, Arthur H. Fellig, known by his pseudonym Weegee (Zolochiv, 1899 – New York, 1968) was an immensely popular artist thanks to the news photographs he took in New York in the 1930s and 1940s. This new exhibition aims to reveal a lesser-known facet of his career: the work he did between 1948 and 1951 in Hollywood, where he focused on the “society of the spectacle”.

Key themes

High-impact photographs

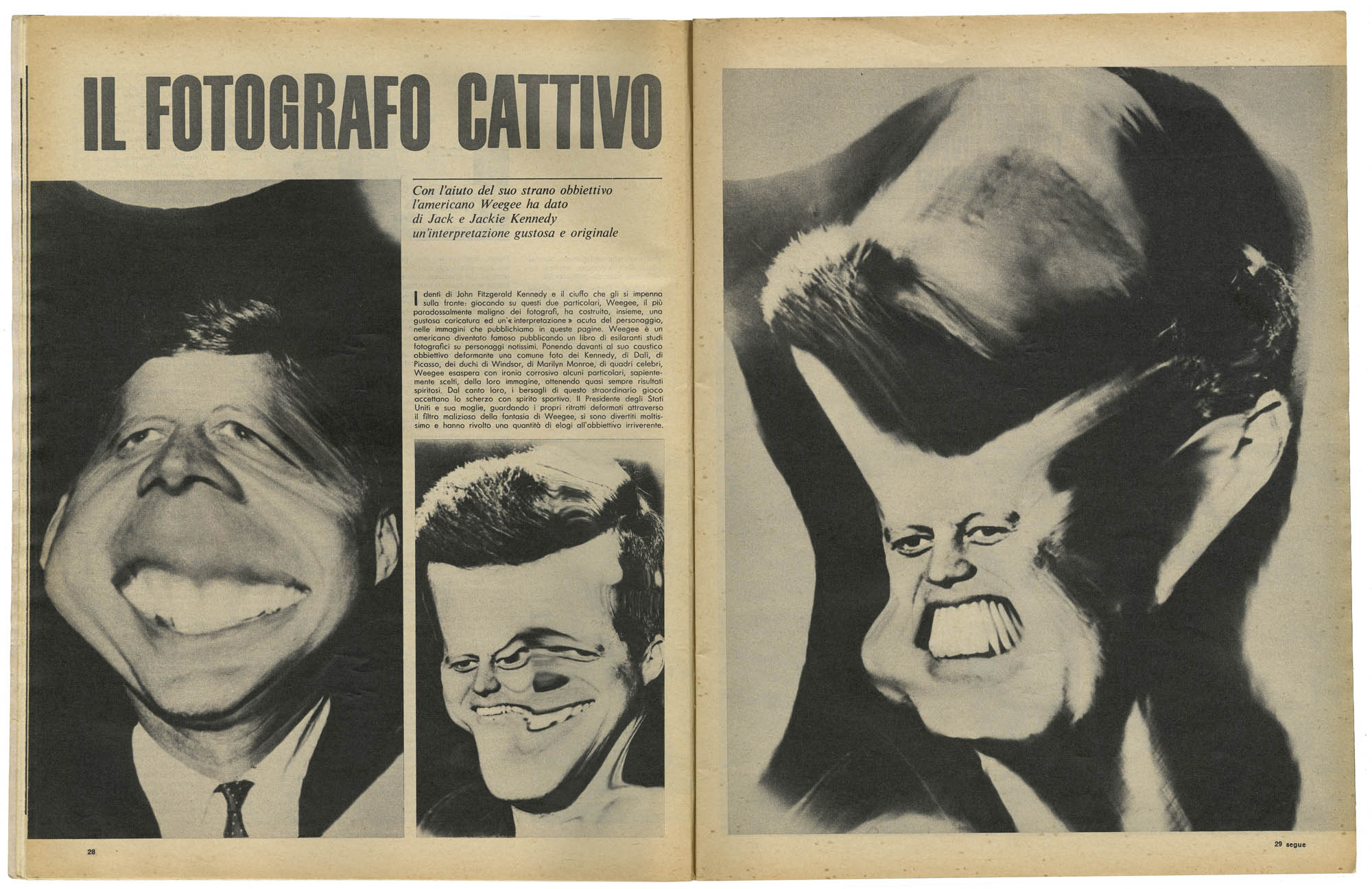

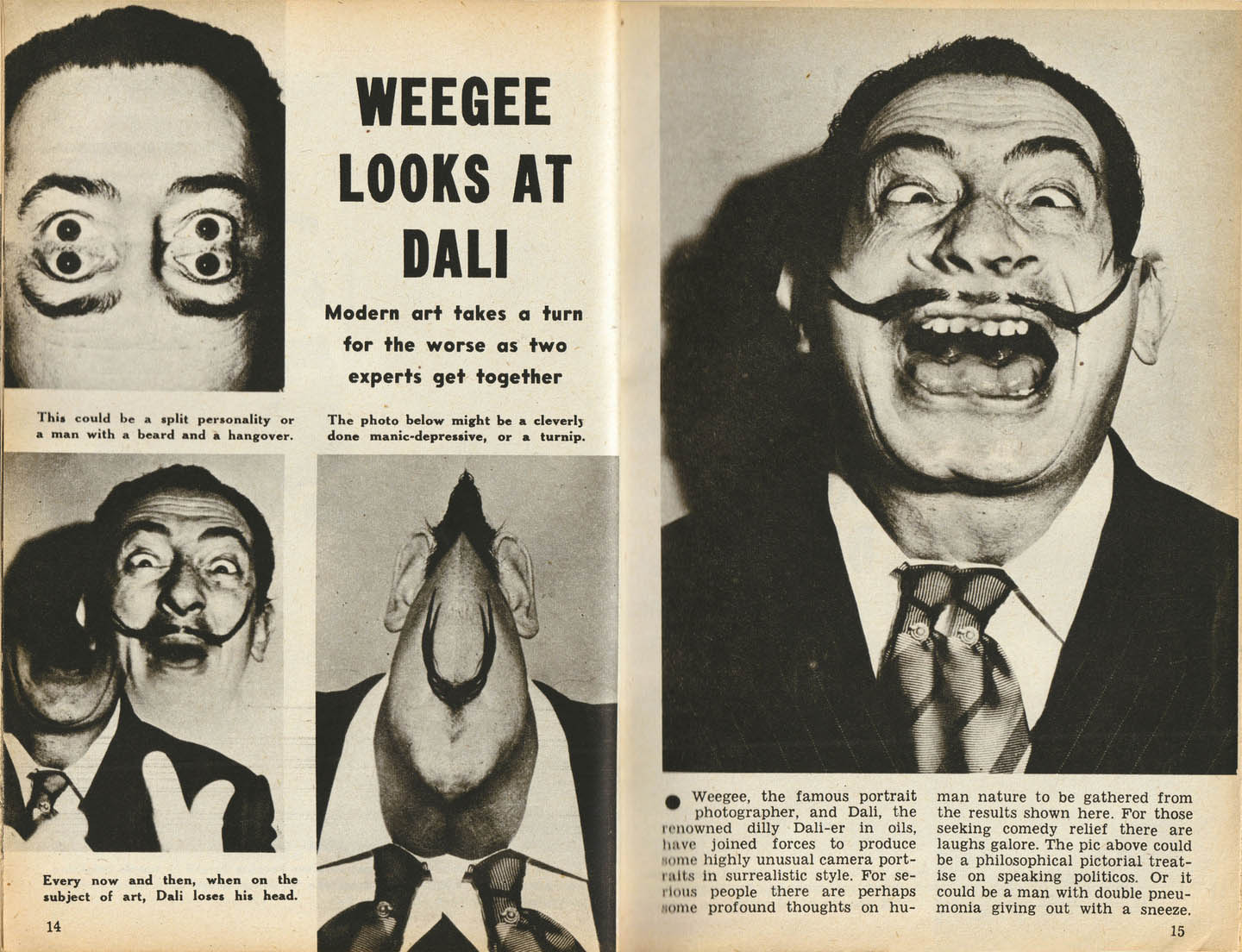

Some of Weegee’s photographs were veritable “visual punches”. This is true of the pictures he took of murders, corpses, fires and prisoners during the years spent covering crimes and accidents in New York, as well as of his later work, like the series showing circus artist Egle Zacchini being fired from a cannon at a speed of 100 metres per second, or his photo-caricatures of Marilyn Monroe, President Kennedy and other prominent personalities. His images almost always had a powerful impact on viewers, making them think not only about the scene they were contemplating but also about how they were looking at it.

The society of the spectacle

First published in 1967, Society of the Spectacle is one of the most important books by the philosopher Guy Debord, founding member of the Situationist International. It paints an incisive portrait of contemporary society, presumably replaced by its represented image. Throughout the work, Debord critically exposes the theory and practice of the spectacle, explaining how it governs our experience of time, history, goods, territory and happiness. In the twenty-first century, when immediacy reigns supreme, Debord’s ideas resound as the severest, most lucid assessment of the meanness and bondage of a society – the society of the spectacle – in which we all live.

Critique of the society of the spectacle

Class consciousness and empathy for the disadvantaged permeate Weegee’s work, as he never forgot his humble beginnings. Yet his most famous images are snapshots of accidents, fires and murders, in which he underscores the idea that bystanders are also spectators of the tragedies they contemplate, watching a scene in much the same way as cinema-goers watch Hollywood films (which are not all that different to the events captured by Weegee’s camera). He also used trick photography to critique the image of actors, singers, broadcasters, politicians and other public figures.

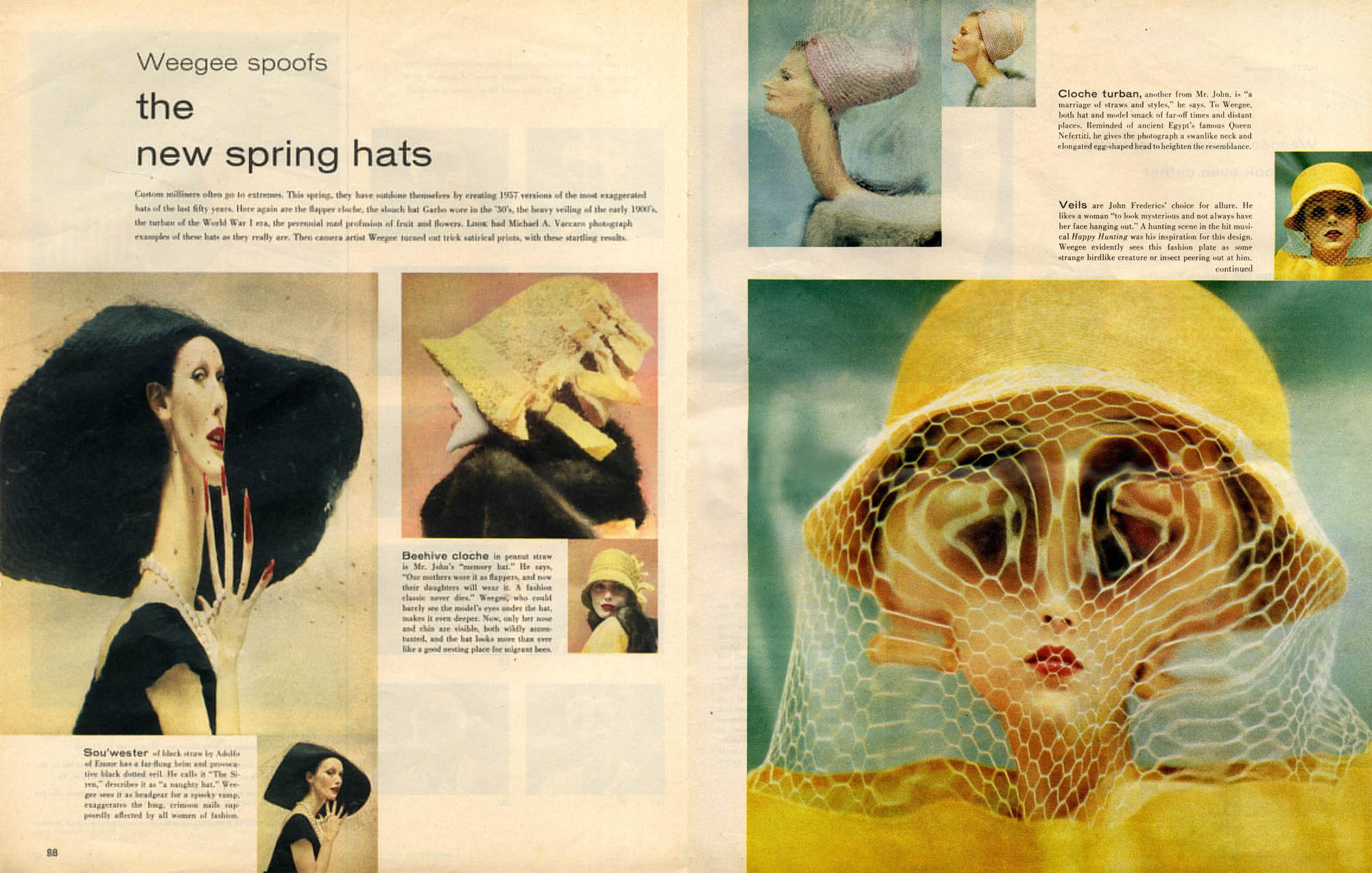

Weegee’s “satires”, as he called them, were visionary, appearing several years before the Situationist International first posited its theories. As Clement Che roux, curator of the exhibition, has pointed out, during his first period in New York, Weegee proved that the tabloids were selling news as a spectacle, and after 1945 he exposed how the media system radically spectacularised celebrities.

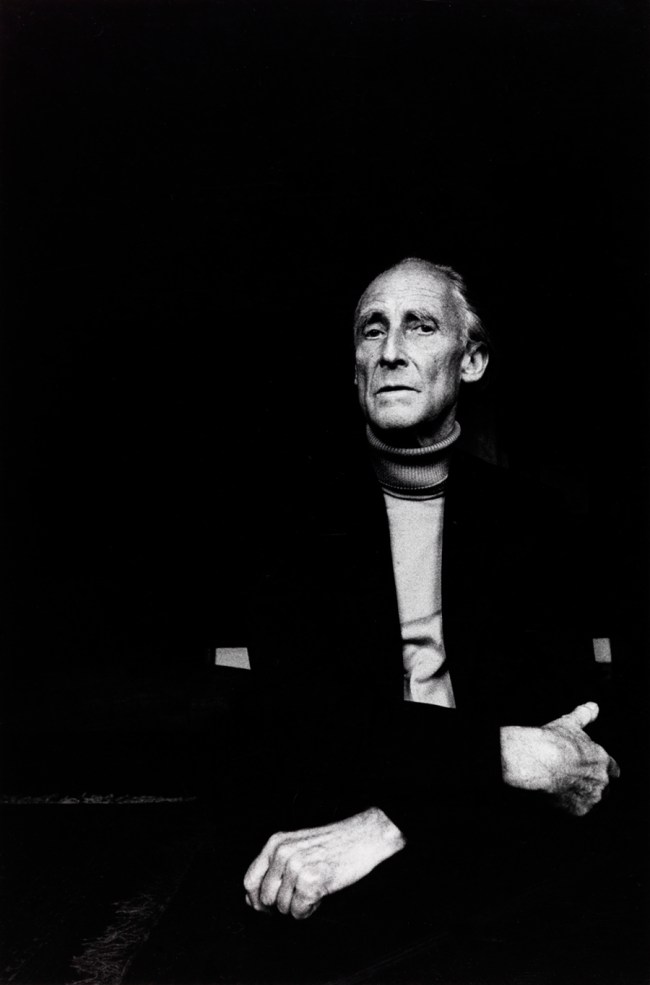

Biography

Weegee was born Usher Felig on 12 June 1899 to a Jewish family in Zolochiv, now in western Ukraine. At the age of ten he travelled to the United States to be reunited with his father, and immigration officers on Ellis Island registered him as Arthur Fellig. At 14, having settled into New York’s Lower East Side, a poor neighbourhood at the time, he left school and started working to help support his family. After trying several jobs, he became an itinerant photographer. He subsequently worked for the photographers Duckett & Adler and later in the ACME Newspictures agency laboratories. In 1935, he went into business for himself as a freelance photojournalist. He began using the pseudonym Weegee around 1937, and in 1941, the year he joined the Photo League (a group of freelance photographers who firmly believed in the emancipating power of images and fought for social justice), he started signing his prints as “Weegee the Famous”. In 1943, his work was included in a group exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

In 1945 he compiled his best photos in a book titled Naked City, which was a huge critical and commercial success. In the spring of 1948 Weegee moved to Hollywood, where he worked in cinema as a technical consultant and occasionally as an actor. In addition to photographing parties, he devised several trick photography techniques and used them to caricature celebrities. After four years on the West Coast, in December 1951 he returned to New York, although he did not resume his former practice. From that moment until his death on 26 December 1968, Weegee mainly capitalised on his fame to publish more books, do lecture tours, and widely circulate his photo-caricatures in the press.

The exhibition

There is a mystery in Weegee’s work which the exhibition now on view at Fundacio n MAPFRE aims to unravel. From very early on, the artist was internationally renowned for his photographs taken in the 1930s and 1940s and printed in the New York tabloids: corpses, fires, detainees in police wagons, etc. But Weegee had another group of works which, at first glance, might seem diametrically opposed to his reportage: the photo-caricatures of public figures created in Hollywood between 1948 and 1951. Critics highlighted the opposition between these two periods, praising the former and rejecting the latter. Weegee: Autopsy of the Spectacle attempts to reconcile both bodies of work by showing that, stylistic differences aside, they are fundamentally consistent in their portrayal of the “society of the spectacle” which was taking shape in the United States at that time.

In his early years, the artist photographed lurid, violent subjects, but those shots were often deeply ironic and exposed the “spectacular” nature of the depicted events. His images were printed in newspapers, and Weegee often included spectators or fellow photographers – individuals gawking at a traffic accident or murder scene – in the fore or background of his compositions. In a consistent manner, during the second part of his career the artist mocked the Hollywood spectacle: the short-lived fame, the adoring crowds who flocked to see “celebrities”, and the banal society scene. Weegee personally edited and altered these ironic, satirical images in the lab, anticipating the theories of the Situationist International and the critique of the society of the spectacle and its commodification, and always acted in consonance with his own political convictions.

The exhibition curated by Clement Che roux, director of Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, features over one hundred photographs and a variety of documentary material. With a new perspective on Weegee’s oeuvre, the itinerary is divided into three sections and offers a sweeping overview of his work.

The spectacle of news reportage

In 1935, Weegee went into business for himself as a freelance photojournalist. Thanks to a radio tuned to the police frequency which he installed in his car – basically a mobile office where he kept everything he needed to take photos – Weegee was always one of the first to arrive at the scene of a crime, fire or traffic accident. It was the Prohibition era, and gang violence was rampant in New York. Every night for ten years, Weegee covered the city’s accidents and crimes with flash photographs and, starting in 1940, did the same for the NP Daily, a newspaper with Marxist leanings. As the artist himself confessed, “Murder is my business.”

In addition to fires and crimes, during this period Weegee also took highly expressive portraits of the individuals who emerged from police wagons after a raid. At a time when it was considered criminal for a man to wear women’s clothes, some of those detainees tried to hide their faces while others basked in the attention, exiting the vehicle as if making a stage entrance. With these images, the artist emphasised the idea that social relations and the world in general were becoming pure spectacle.

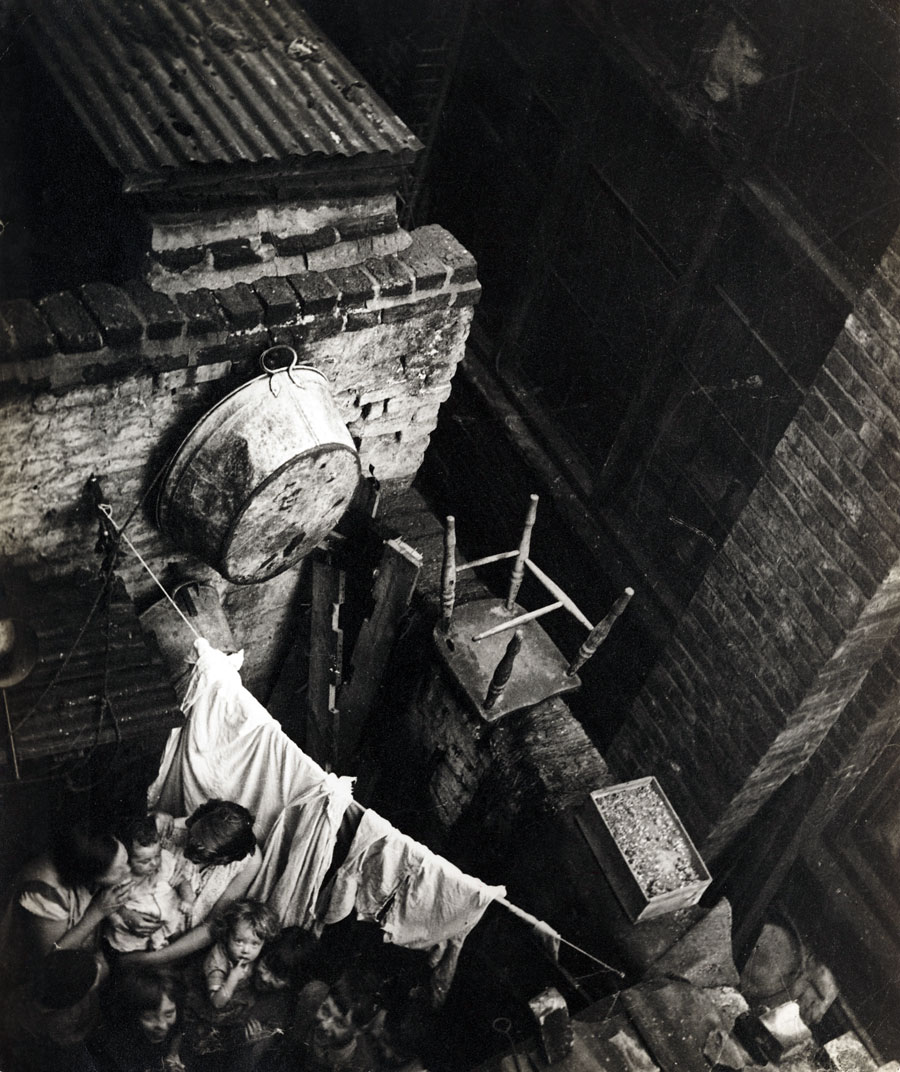

At the same time, Weegee never forgot his roots as the son of poor Jewish immigrants and was keenly aware of the living conditions of the most destitute. For this reason, he also captured homeless people and acts of racial and everyday discrimination against the underprivileged, making his photographs “genuine social documents”.

The society of spectators

“The Curious Ones” is the title of a chapter in Naked City, the compilation of Weegee’s best photographs that he published in 1945. Thanks to that book, which was a huge critical and commercial success, he began to attend New York’s important society events much more frequently, photographing them exactly as he would a crime or accident scene. This is illustrated by two images taken in New York on 22 November 1943, The Critic and In the Lobby at the Metropolitan Opera, Opening Night. The artist was particularly interested in representing human emotions and tried to prevent his subjects from altering their expressions to pose for the camera. Little by little, he began to portray the witnesses to events that happened after dark in New York City, attempting to reflect the entire range of possible human reactions to a tragedy, from astonishment to nervous laughter or tears. Other photographers who came to the same scenes also caught his interest, prompting him to reflect on the very act of taking photos.

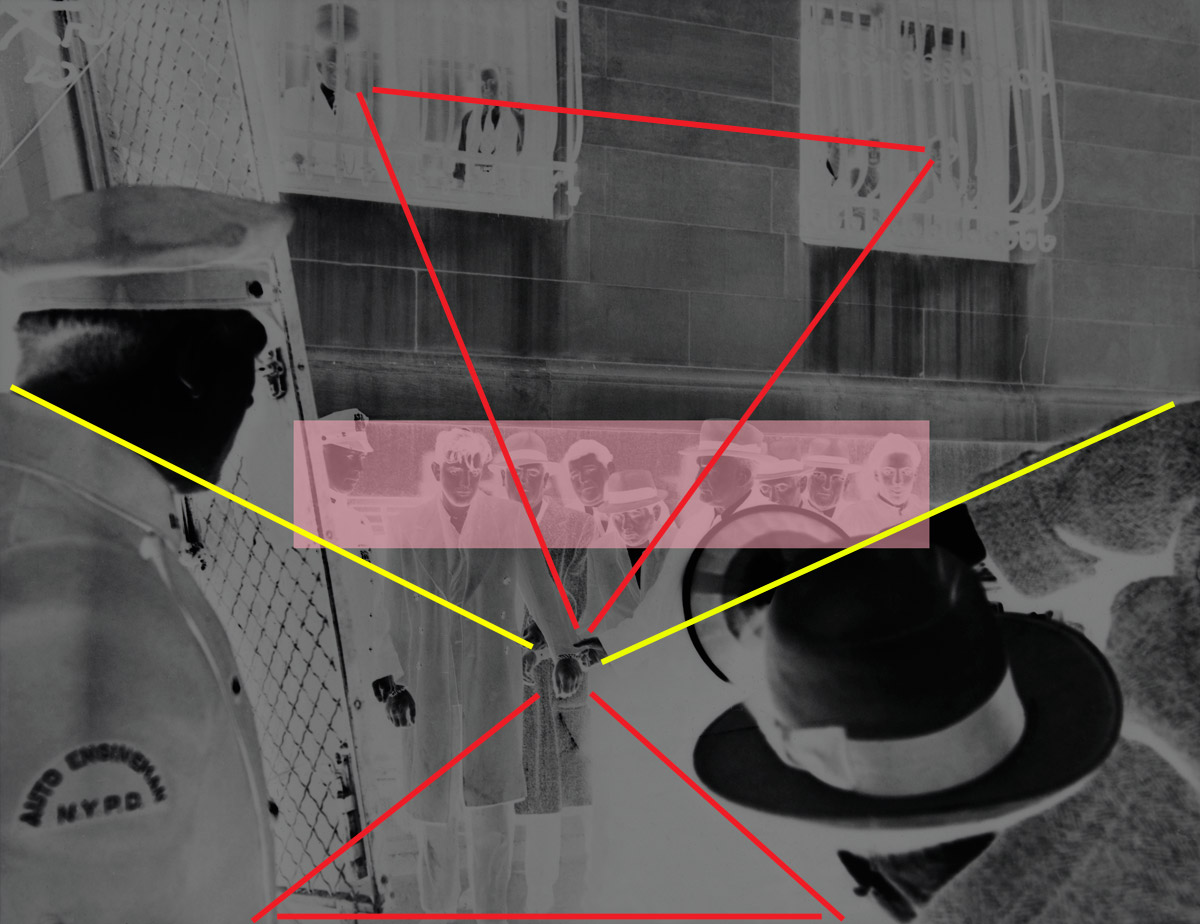

With all this repertoire, Weegee showed how ordinary individuals became voyeurs by treating the scene of the crime as a theatrical stage. Recalling the moment in 1939 when he took the photograph Balcony Seats at a Murder, he explained, “The detectives are all over […]. To me this was drama. This was like a backdrop. I stepped back about a hundred feet. I used flash powder and I got this whole scene. The people on the fire escapes, the body, everything!”

The comedy of the spectacular

In 1967, Guy Debord wrote that “the spectacle is capital to such a degree of accumulation that it becomes an image” in his book Society of the Spectacle. Weegee, who understood this very well, photographed every sight that struck him as out of the ordinary. Fascinated by the makeup of crowds, he portrayed them enjoying a peaceable Sunday afternoon at the beach on Coney Island or celebrating the end of World War II in Chinatown; but he was also drawn to carnival and circus attractions and to cinemas, where he photographed movie-goers in the dark, engrossed in the film on screen.

Tired of murders and crime scenes, in 1948 Weegee moved to Hollywood and traded the direct, documentary-style photography he had practised in New York for manipulated images that required hours in the lab. During his stint in California, he turned his lens upon actors, singers, broadcasters and society figures. His vision of these individuals was not usually very flattering, photographing them from behind or in awkward situations. In some cases he would later distort the images using a kaleidoscope, photomontage or multiple exposure. Weegee created what he called “photo-caricatures”, a tradition that started among amateur photographers in the late nineteenth century and was originally known as “photographic amusements”, although he stated in his autobiography that his photo-caricatures had never been done before. Though a celebrity himself, the artist used photography to criticise the star system.

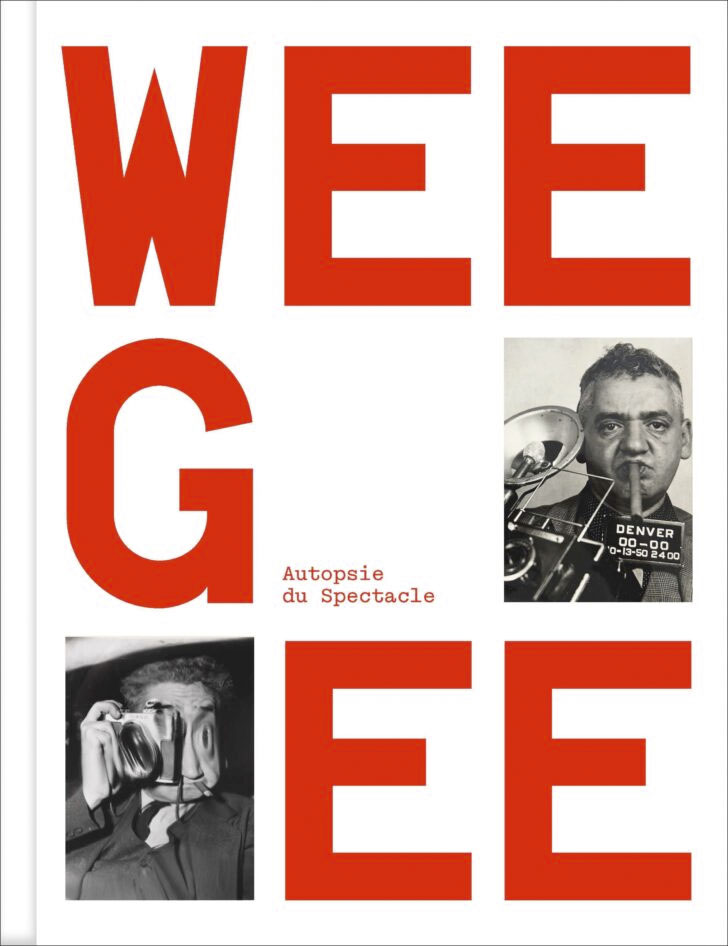

Catalogue

The exhibition, organised by Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in partnership with Fundacion MAPFRE, is accompanied by a publication titled Weegee. Autopsia del espectáculo, in which the majority of the images on display are reproduced. The catalogue contains a text by Clement Che roux, the show’s curator and director of Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, and two more essays by Cynthia Young, a curator specialised in photojournalism, and Isabelle Bonnet, a lecturer at the Sorbonne and photography expert. The writer, curator and photography lecturer David Campany has also made an important contribution to the volume, in which he compares Weegee and Stanley Kubrick based on their collaboration on Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

The original edition in French was published by Éditions Textuel with Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, and the Spanish-language edition has been co-published with Fundación MAPFRE.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York

c. 1939

Gelatin-silver print

© International Center of Photography. Louis Stettner Archives, Paris

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Holiday Accident in the Bronx

July 30th 1941

Gelatin-silver print

© International Center of Photography

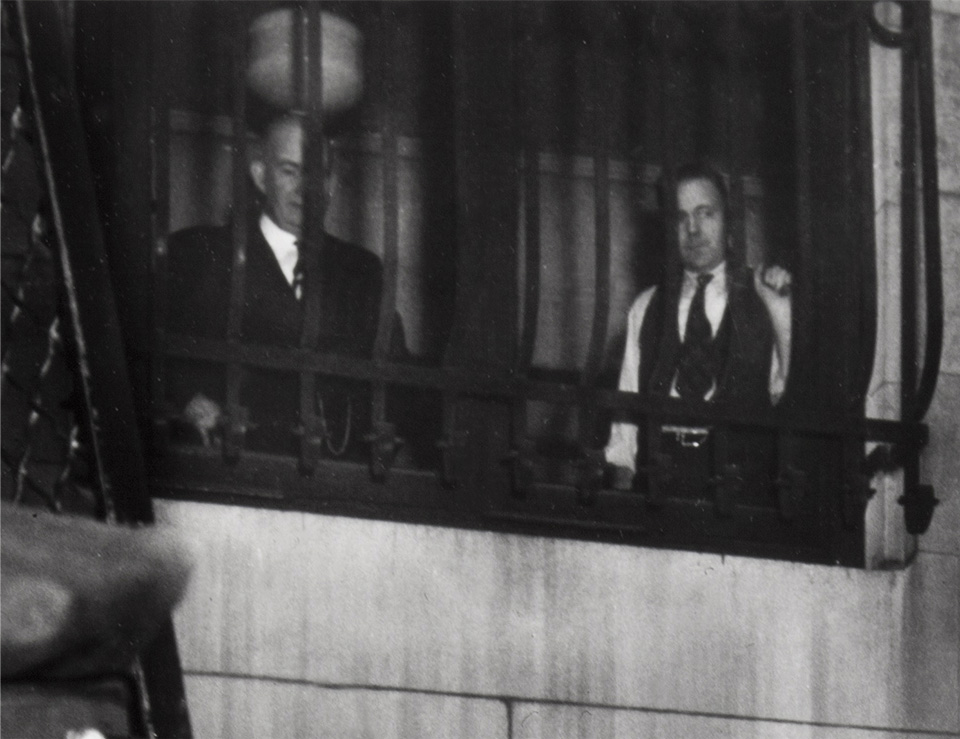

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Charles Sodokoff and Arthur Webber Use Their Top Hats to Hide Their Faces, New York

January 26th 1942

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography. Louis Stettner Archives, Paris

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Balcony Seats at a Murder

1939

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Arrests made during a gambling raid in lower Manhattan’s Liberty Street

October 1942

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

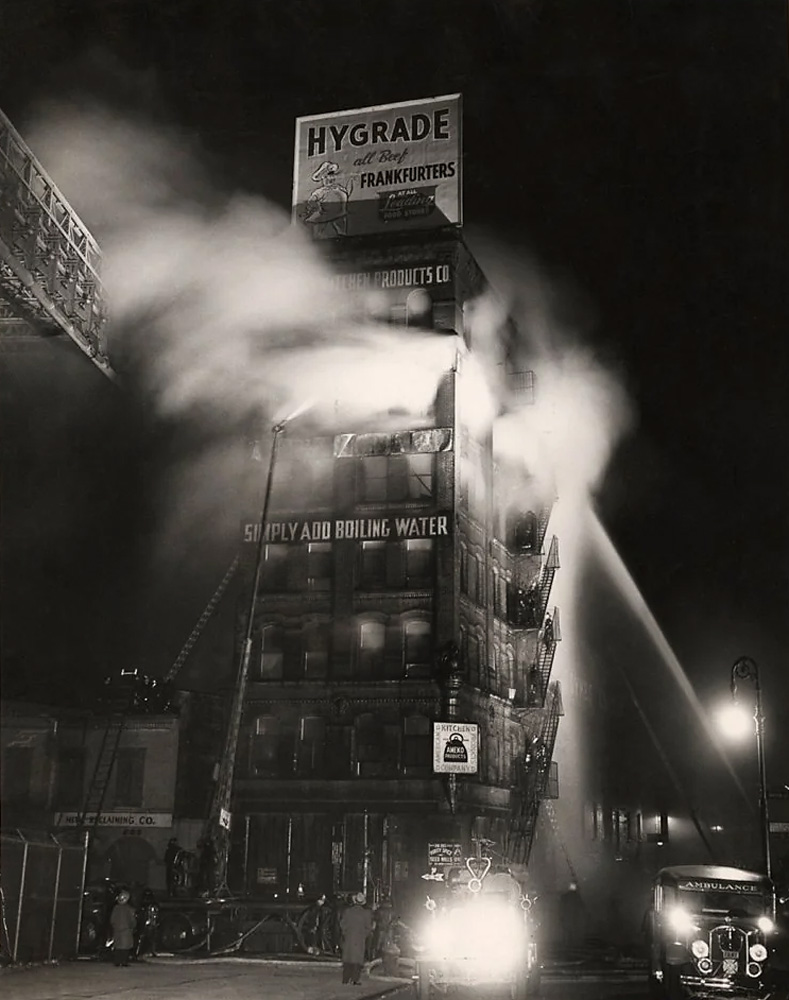

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Simply adding boiling water

1943

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]' 1947 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]' 1947](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-fire-in-loft-building.jpg?w=800)

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]

1947

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

There’s still a mystery to Weegee. The American photographer’s career seems to be split in two. First are his stories for the New York press from 1935-1945. Then, photo-caricatures of public personalities developed during his Hollywood period, between 1948 and 1951, which he continued to produce for the rest of his career. How can these diametrically opposed bodies of work coexist? Critics have enjoyed highlighting the opposition between the two periods, praising the former and disparaging the latter. This project seeks to reconcile the two parts of Weegee by showing that, beyond formal differences, the photographer’s approach is critically coherent.

The spectacle is omnipresent in Weegee’s work. In the first part of his career, coinciding with the rise of the tabloid press, he was an active participant in transforming news into spectacle. To show this, he often included spectators or other photographers in the foreground of his images. In the second half of his career, Weegee mocked the Hollywood spectacular: its ephemeral glory, adoring crowds, and social scenes. Some years before the Situationist International, his photography presented an incisive critique of the Society of the Spectacle.

The News Spectacle

“News photography is my meat.” After many years as a printer for press agencies, Weegee started his own business as a photojournalist in 1935. In order to be the first to arrive at the site of a murder, fire, or traffic accident, he set up a radio in his car, tuned to the police frequency. For a decade, using a flash, he took photographs of news in New York every night.

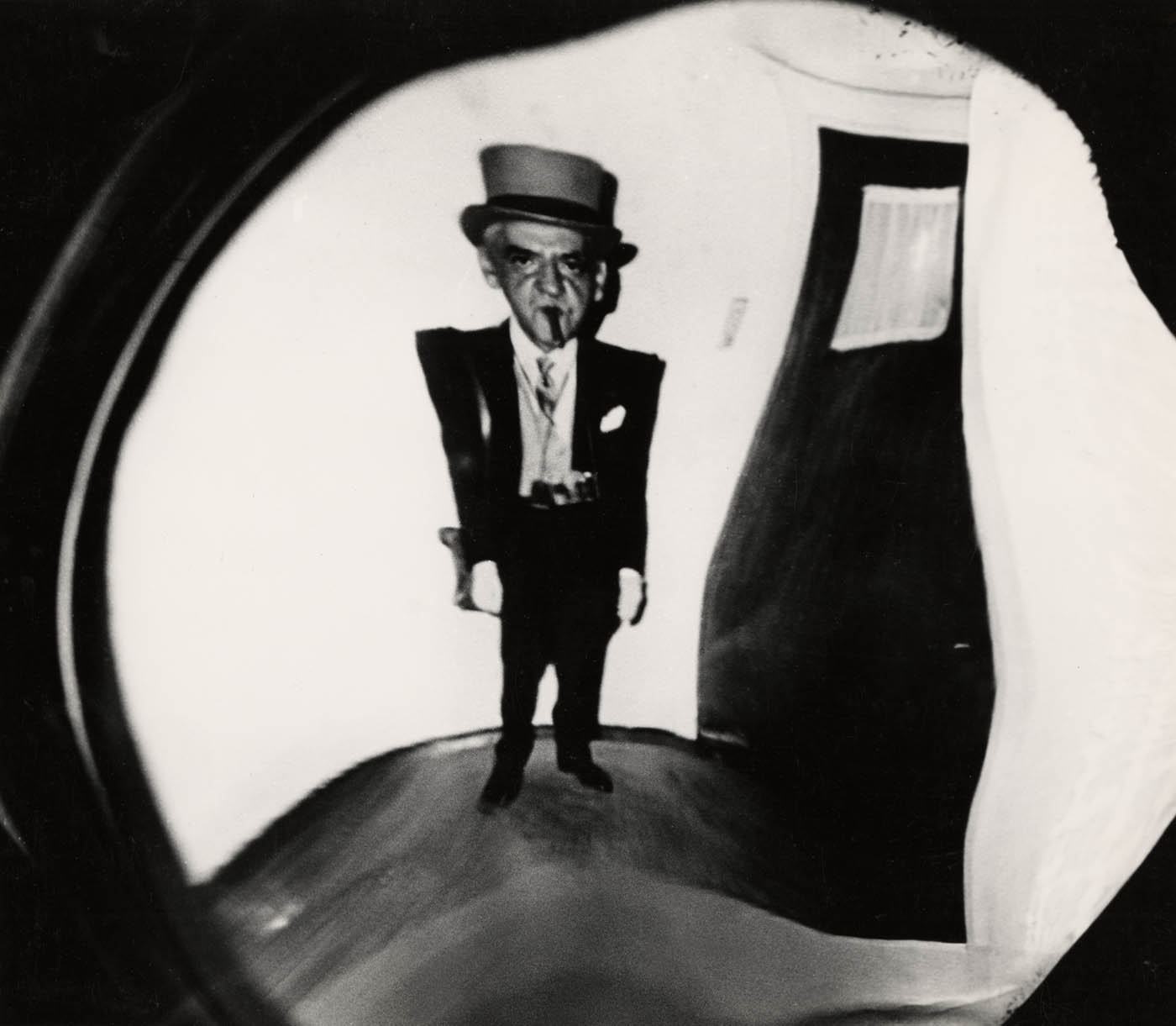

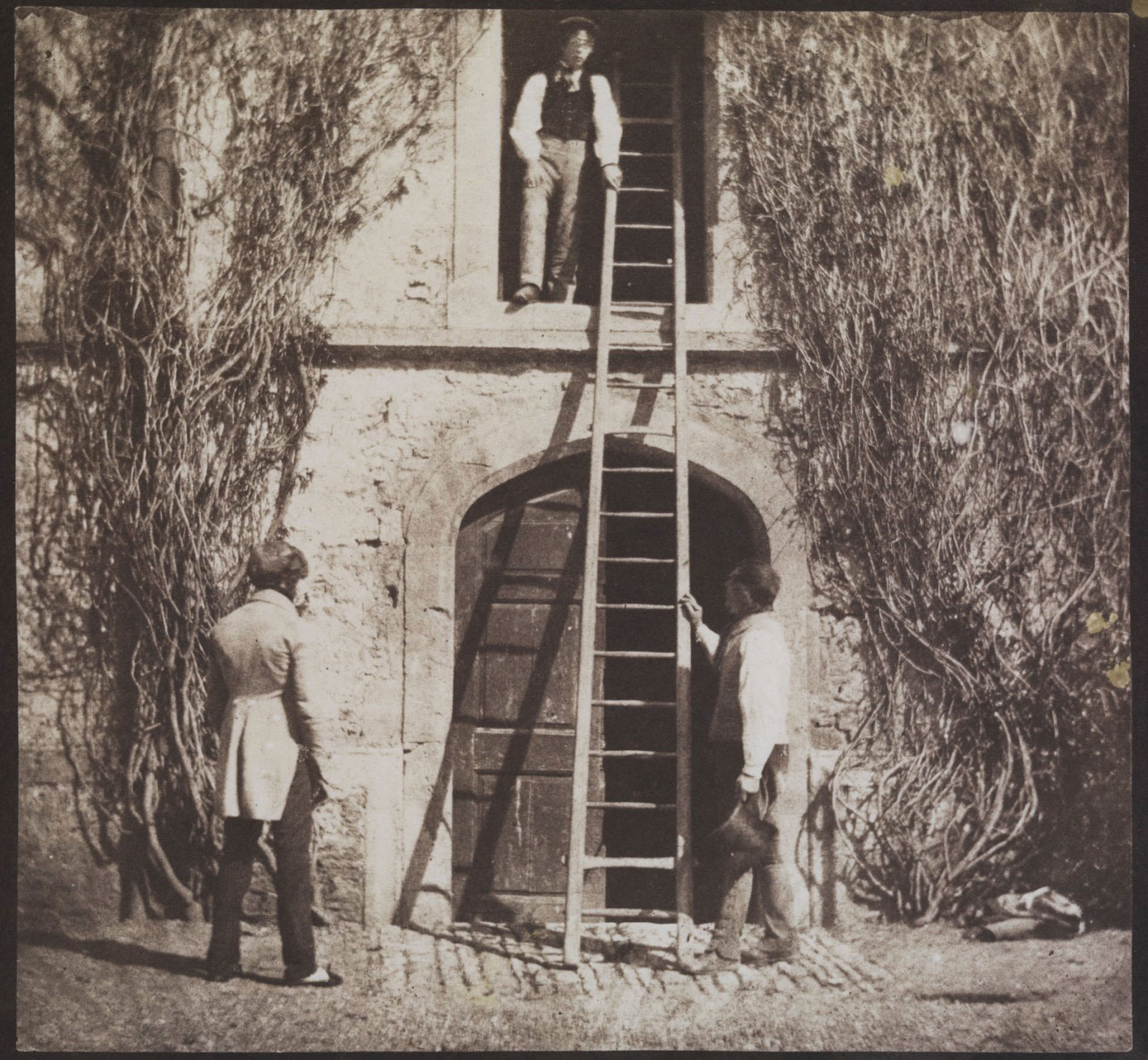

Weegee Himself

“I have always been a doer and not a thinker.” Weegee enjoyed putting himself in front of the camera, re-enacting circumstances he was confronted with in his daily work. In the name of pedagogy, and probably a little out of narcissism and self-advertisement, he took pictures of himself writing captions for his photographs in the back of his car, in police wagons and behind bars, never without his camera.

Murder Is My Business

“I used to be an expert on murder.” From 1935 to 1945, Weegee spent his nights roaming the city looking for shocking images. Even after Prohibition, New Yorkers’ dreams were punctuated by explosion sounds caused by rival gangs settling scores. The photographer learned to create expressive images which the booming tabloids were particularly fond of.

Off Road

“Sudden death for one…, sudden shock for the other.” American culture is fascinated by twisted metal. In the 19th century, a railroad company staged public collisions between locomotives destined for the junkyard. Weegee photographed many traffic accidents, introducing the “car crash” genre, later adopted by other figures, such as Andy Warhol, J. G. Ballard, David Cronenberg, etc.

The Tragedy of Fire

“Murders and fires (my two best sellers, my bread and butter).” In the darkness of the city, like a moth to a flame, Weegee took photographs of fires. The urban landscape of New York, with its many substandard buildings, provided him with many such opportunities. The combination of fire, smoke and gushing water offered a particularly photogenic spectacle that the press adored.

On The Spot

“The Parade never ceases as the ‘pie’ Wagons unload.” When he wasn’t in the field, Weegee waited at the entrance of the police station for the prison wagon to return with its load of offenders arrested in the night. At a time when it was a criminal act for a man to dress as a woman, some tried to hide their faces, while others took the opportunity to step out of the wagon as if onto a stage.

In Flagrante Delicto

“When criminals tried to cover their faces, it was a challenge to me. I literally uncovered not only their faces, but their black souls as well.” Faced with Weegee’s scrutinising lens, defendants often tried to conceal their identities. In his autobiography, the photographer recounts the many stratagems he developed to oblige them to reveal themselves. Clearly, they didn’t always work.

Social Documents

“The people in these photographs are real.” Coming from a Jewish family who emigrated to the United States from Ukraine at the beginning of the 20th century, experiencing extreme poverty upon their arrival, Weegee was quite aware of standards of living among the underprivileged. He took photographs of ordinary forms of discrimination, people with small trades, and the homeless. His photographs can be seen, in his own words, as “veritable social documents.”

Society of the Spectators

“The Curious ones” is a chapter title from Weegee’s best-seller: Naked City. The photographer takes an interest in people who, like himself, indulge unreservedly in the act of looking. He often includes them in the scenes he photographs, framing them in close-up to create veritable portraits of on-lookers. His work is a particularly striking testimony to the society of spectators developing in the United States at the time.

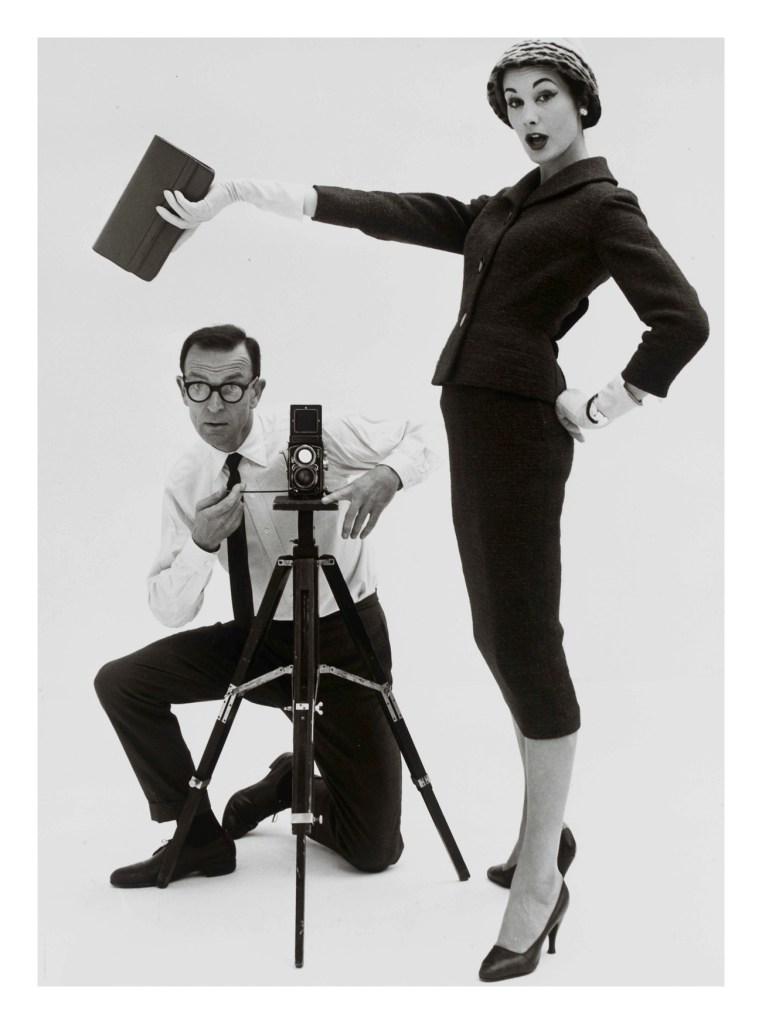

Meta Photo Co.

“I have no time for messages in my pictures.” Yet Weegee often included other photographers in his compositions as if, through this mise en abyme, he was inciting people to reflect on what it meant to take a photograph. An image from 1942, published in PM’s Weekly, is a good example. Three reporters and the words “Meta Photo Co.” on a window in the background of the photograph indicate there is something to be learned here about photography itself.

The Critic

“‘What is the best picture you ever took?’ Without hesitation I answer, ‘A picture I took at the opening of the Metropolitan Opera House. I consider this to be my masterpiece.'” The circumstances were contrived. Weegee went to a working-class neighbourhood to pick the woman up, then brought her to the entrance of this gala. The image illustrates the widening gap between the rich and the poor under American capitalism. It also reflects the critical power of a simple look.

Looking at Death

“I stepped back far enough to take in the whole scene: the puzzled detectives examining the body, the people on the fire escape, watching… it was like a stage setting.” Balcony seat at a murder: by including spectators in many of his images, Weegee imagines crime scenes as theatrical scenes, underscoring how American society transforms news into spectacle.

Spectators

“When I take a picture of a fire, I forget all about the burning building and I go out to the human element.” After years of tirelessly documenting events of the New York night, Weegee began taking photographs of the individuals who witnessed them. He was thus able to take portraits of groups expressing the full range of human reactions to tragedy, from surprise and tears to nervous laughter.

Out of Frame

“The curious […] ones always rushing by […] but always finding time to stop and look at.” On July 28, 1945, at 9:40 a.m., as a thick fog enveloped New York, a small plane crashed into the 79th floor of the Empire State Building. Weegee photographed spectators trying to catch a glimpse of it. People discovering his photographs in newspapers found themselves in the same position as these observers, a voyeuristic one.

Seeing in the Dark

“It’s hard to photograph people and get natural expressions. The minute they see the camera, they ‘freeze’ up on you.” Weegee was especially interested in depicting emotions on the faces of observers. Concerned that his presence would change their reaction, he had the ingenious idea of taking their photographs in the darkness of a theatre using infrared film. The result is a series of stunning portraits of wide-eyed spectators.

She Gestures of Art

“I used the same technique […] whether it was a murder, a pickpocket, or a society ball.” Following the success of his book Naked City, Weegee was routinely invited to high society events in New York, which he took pleasure in photographing as news items. In October 1945, at the opening of an exhibition by painter Stuart Davis at the MoMA, he captured the strange gestures of the art world.

The Theatre of the Spectacular

“Spectacle is Capital to such a degree of accumulation that it becomes an image,” explained Guy Debord in 1967. Weegee understood this well. He took photographs of all that was visually uncommon: crowds at Coney Island, fairground attractions, stars, acrobats, clowns… and finally, himself. A few years before the Situationist International, he pioneered a visual form of critique of the Society of the Spectacle.

In the Company of Crowds

“And this is Coney Island on a quiet Sunday afternoon […]. A crowd of over a MILLION is usual and attracts no attention.” On a Brooklyn beach, in Times Square or in Chinatown celebrating victory over Nazi power, Weegee never missed the opportunity to photograph crowds. Beyond “mass ornament,” theorised a few years earlier by Siegfried Kracauer, he was fascinated by the ways in which the people constitute themselves as images.

The Cannonball Woman

“Punch in Pictures.” That’s how one magazine described an article on Weegee. The scoop-hunter knows better than anyone else how to produce hard-hitting images. In 1943, Weegee photographed circus performer Egle Zacchini, nicknamed Miss Victory, or The Cannonball Woman, shot out of a cannon at 360 feet per second. As war was raging in Europe, it was a strange metaphor for the role of women in the conflict.

A Circus Community

“Someday they, too, will be stars.” Weegee especially enjoyed hanging around behind the scenes of fairgrounds in the suburbs. He photographed the way a performer at Sammy’s Bar placed her money in her stocking. Elsewhere, a dwarf with a forced smile, a melancholy clown slumped in his dressing room, what remains of the parade after the crowd passes by. Many of his photographs display the ambiance of a sad party.

Photo-caricatures

“I was tired of gangsters lying dead with their guts spewed in the gutter, of women crying at tenement-house fires, of automobile accidents […]. I was off to Hollywood.” In the City of Angels, Weegee not only photographs the celebrities he meets, he delights in making caricatures of them with what he calls his “elastic lens,” now mocking the star system.

The Spyglass

“I have used the camera to provoke good old-fashioned belly laughs.” In 1963, Weegee was invited to the set of Stanley Kubrick’s Doctor Strangelove. The director was a great fan of Weegee, and had begun his own career as a press photographer. On set, Weegee applied a new technique for the tubular distortion of faces, as if one were looking through the small end of a spyglass.

Trick Inventory

“Their originality was such that they sold like hot cakes.” This is how Weegee described his photo-caricatures, the first of which appeared in papers in 1947. For 20 years and up until his death in 1968, he would regularly publish these works. Around fifty of the publications are known today. There are most likely many more. In his daily work, the photo-caricature came to definitively replace the news item.

Weegee, Ouija

“I’m called Weegee which comes from Ouija.” The pseudonym Weegee refers to the name of a board used in seances to decipher messages from the beyond. Weegee liked to describe himself as a “psychic photographer”, able to predict in advance where a story will take place. On the scene, he said he photographed using his “third eye.” Whether clairvoyant or voyeur, Weegee was able to see, better than anyone else, transformations in American society.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Afternoon Crowd at Coney Island

July 21st 1940

Gelatin-silver print

© International Center of Photography. Courtesy Galerie Berinson, Berlin

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Anthony Esposito, Booked on Suspicion of Killing a Policeman, New York

January 16th 1941

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography. Louis Stettner Archives, Paris

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

[Black Buick with dead passenger pulled out of the Harlem River, New York]

February 23, 1942

Gelatin silver print

© Weegee Archive/International Center of Photography

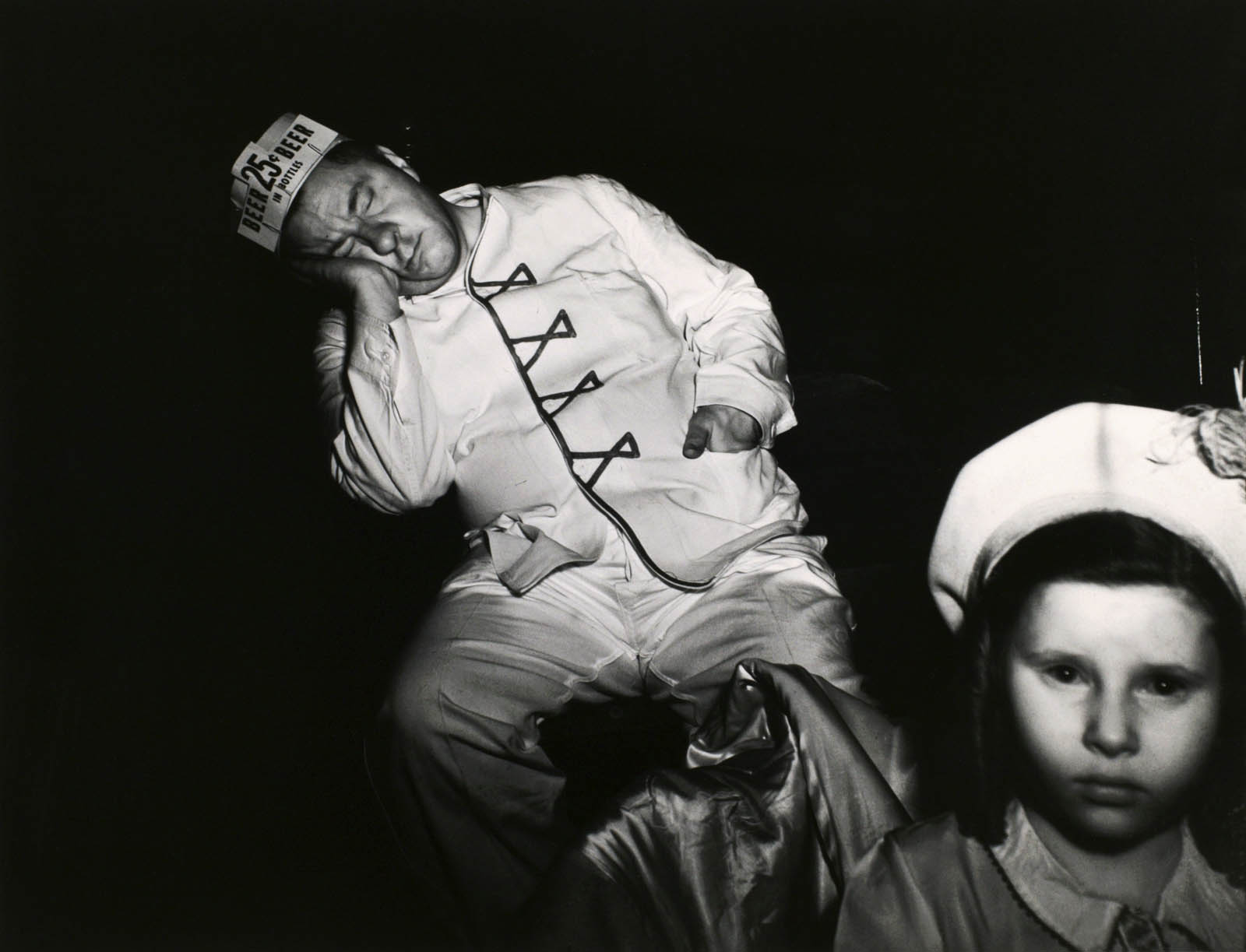

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Sleeping at the Circus, Madison Square Garden, New York

June 28th 1943

Gelatin-silver print

© International Center of Photography

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

The Critic, New York

November 22nd 1943

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography. Collection Friedsam

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

[After the opera, Sammy’s on the Bowery, New York]

1943-1945

© Weegee Archive/International Center of Photography

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Charlie Chaplin, Distortion

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Charles de Gaulle, Distortion

1959

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

“Il Fotografo cattivo”, Epoca, vol. XIII, No. 636, December 1962

© International Center of Photography. Collection privée Paris

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968)

Self-Portrait

c. 1963

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Fundación MAPFRE

Recoletos Exhibition Hall

Paseo Recoletos 23, 28004 Madrid

Opening hours:

Mondays (except holidays): 2pm – 8pm

Tuesday to Saturday: 11am – 8pm

Sunday and holidays: 11am – 7pm

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968) '[Black Buick with dead passenger pulled out of the Harlem River, New York]' February 23, 1942 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968) '[Black Buick with dead passenger pulled out of the Harlem River, New York]' February 23, 1942](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/weegee-black-buick.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968) '[After the opera, Sammy's on the Bowery, New York]' 1943-1945 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine, 1899-1968) '[After the opera, Sammy's on the Bowery, New York]' 1943-1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/weegee-after-the-opera.jpg)

![Unidentified photographer. 'Untitled [Weegee covering the morning line-up at police headquarters, New York]' c. 1939 Unidentified photographer. 'Untitled [Weegee covering the morning line-up at police headquarters, New York]' c. 1939](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-a.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle' at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at second left, Weegee's 'Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York (Gay Deceiver)' (1939); and at top right, a magazine print of his photograph 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' (1941) Installation view of the exhibition 'Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle' at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at second left, Weegee's 'Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York (Gay Deceiver)' (1939); and at top right, a magazine print of his photograph 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' (1941)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/weegee-installation-hcb.jpg)

![Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' 1941 Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-untitled-young-man-smoking-cigarette-in-crashed-car-while-waiting-for-ambulance-new-york-1941.jpg)

![Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Tenement sleeping during heat spell, Lower East Side, New York]' May 23, 1941 Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Tenement sleeping during heat spell, Lower East Side, New York]' May 23, 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-tenement-sleeping-during-heat-spell-lower-east-side-new-york.jpg)

![Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]' 1947 Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]' 1947](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-fire-in-loft-building.jpg)

![Weegee (American, born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 - 1968 New York) '[Outline of a Murder Victim]' 1942](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/weegee-outline-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York]' January 16, 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York]' January 16, 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/3-weegee_anthony-esposito-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/17-weegee_19982_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/6-weegee_19969_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/15-weegee_19961_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/16-weegee_19972_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled ["Ruth Snyder Murder" wax display, Eden Musée, Coney Island, New York]' c. 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled ["Ruth Snyder Murder" wax display, Eden Musée, Coney Island, New York]' c. 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/5-weegee_7221_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Hats in a pool room, Mulberry Street, New York]' c. 1943 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Hats in a pool room, Mulberry Street, New York]' c. 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/14-weegee_15595_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Body of Dominick Didato, Elizabeth Street, New York]' August 7, 1936 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Body of Dominick Didato, Elizabeth Street, New York]' August 7, 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/8-weegee_2070_1993-web.jpg?w=650)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and lodge member looking at blanket-covered body of woman trampled to death in excursion-ship stampede, New York]' August 18, 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and lodge member looking at blanket-covered body of woman trampled to death in excursion-ship stampede, New York]' August 18, 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/11-weegee_1016_1993-web.jpg?w=650)

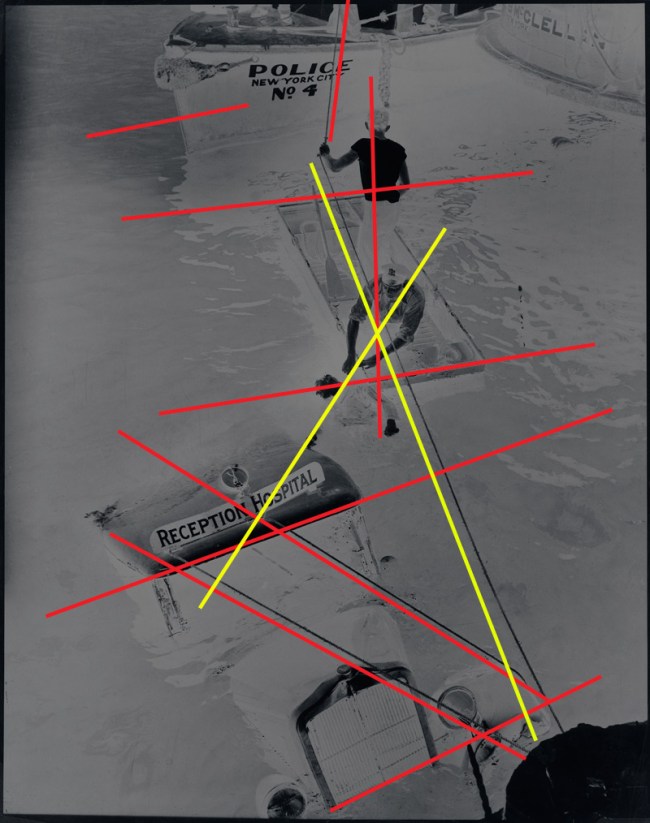

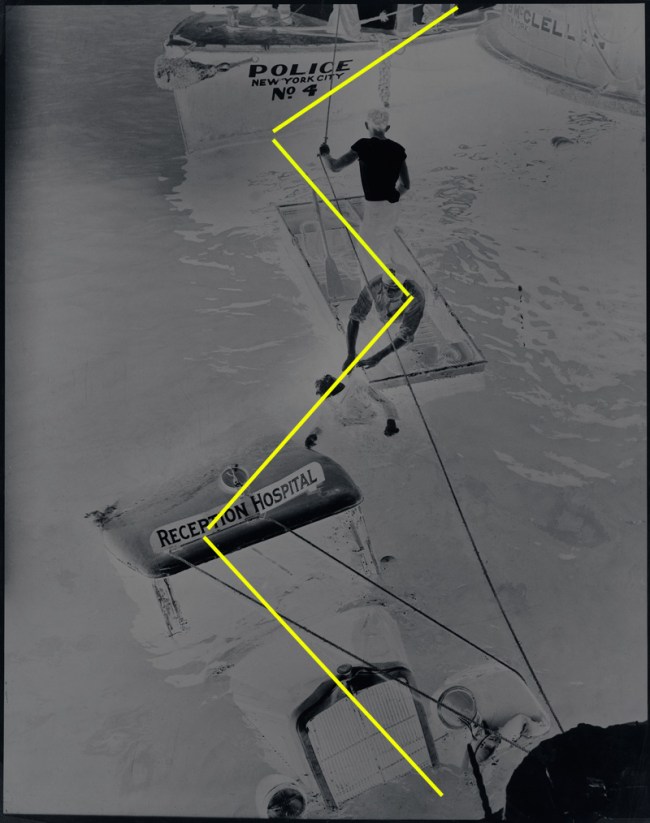

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and assistant removing body of Reception Hospital ambulance driver Morris Linker from East River, New York]' August 24, 1943 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and assistant removing body of Reception Hospital ambulance driver Morris Linker from East River, New York]' August 24, 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/9-weegee_133_1982-web.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.