Exhibition dates: 11th April – 20th July, 2025

Curators: Jeff L. Rosenheim, Joyce Frank Menschel Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs. Virginia McBride, Research Associate in the Department of Photographs, provided assistance.

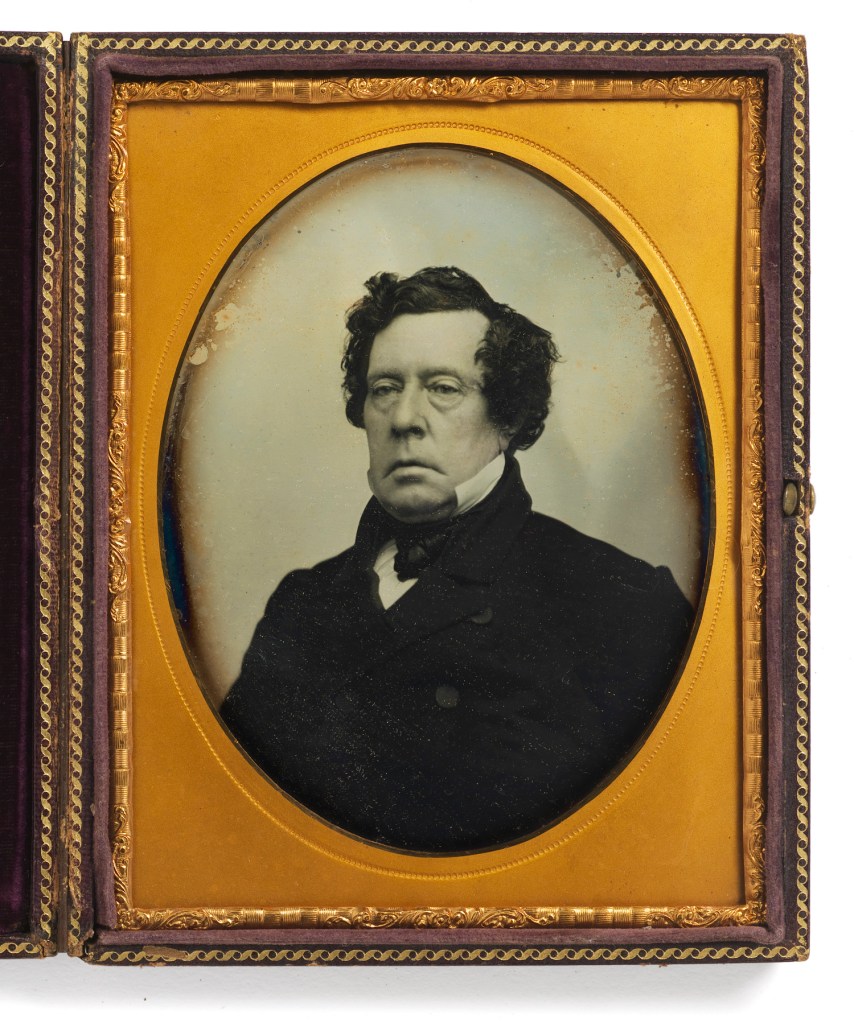

Unknown Maker

Woman Wearing a Tignon

c. 1850

Daguerreotype with applied colour

Case (open): 3 1/8 × 7 1/4 in. (8 × 18.4cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

It’s just nice to be able to post on this eclectic exhibition – to see the installation photographs with vitrines full of the wonders of the age, outdoors, indoors, objects, people, landscapes, daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes, salted paper prints, albumen silver prints, cyanotypes, platinum prints, and gelatin silver prints, cartes de visite, stereographs, and cabinet cards.

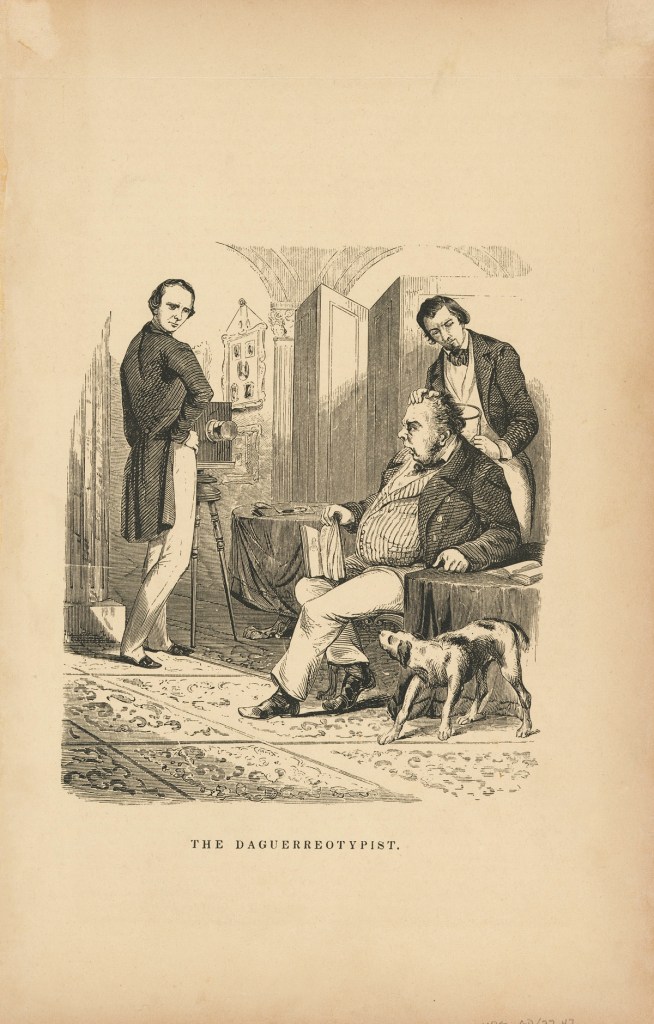

Can you imagine having your photograph taken for the first time?

Entering the photographers studio, com(posing) yourself in front of the camera and the process and performance of doing that, even as the photographer composed you on the glass plate in the camera. A double composition, the constituent parts making the whole, a dance between the sitter, the camera and the photographer.

And there you are, exposed in camera, the latent image revealed by vapour, a talismanic object radiating your spirit.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to The Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation views of the exhibition The New Art: American Photography, 1839-1910 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, April – July, 2025

This exhibition presents a bold new history of American photography from the medium’s birth in 1839 to the first decade of the 20th century. Drawn from The Met’s William L. Schaeffer Collection, major works by lauded artists such as Josiah Johnson Hawes, John Moran, Carleton Watkins, and Alice Austen are shown in dialogue with extraordinary photographs by obscure or unknown practitioners made in small towns and cities from coast to coast. Featuring a range of formats, from daguerreotypes and cartes de visite to stereographs and cyanotypes, the show explores the dramatic change in the nation’s sense of itself that was driven by the immediate success of photography as a cultural, commercial, artistic, and psychological preoccupation. In 1835, even before the nearly simultaneous announcement of the invention of the new art in Paris and London, the American philosopher essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson noted with remarkable vision: “Our Age is Ocular.”

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Installation views of the exhibition The New Art: American Photography, 1839-1910 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, April – July, 2025

The New Art: American Photography, 1839-1910 will feature more than 250 photographs drawn from the Museum’s William L. Schaeffer Collection

This spring, The Metropolitan Museum of Art will present an adventurous new history of American photography from the medium’s birth in 1839 to the first decade of the 20th century. Drawn from the Museum’s William L. Schaeffer Collection – a magnificent recent promised gift to The Met by trustee Philip Maritz and his wife Jennifer – major works by lauded artists such as Josiah Johnson Hawes, John Moran, Carleton E. Watkins, and Alice Austen, will be presented in dialogue with extraordinary photographs by obscure or unknown practitioners made in small towns and cities from coast to coast. The exhibition’s many photographs by little-studied makers, early practitioners, and intrepid amateurs have been selected to reveal the artists’ ingenuity, aesthetic ambition, and lasting achievement. In some 275 photographs – most never before seen – The New Art: American Photography, 1839-1910 explores the nation’s shifting sense of self, driven by the immediate success of photography as a cultural, commercial, artistic, and psychological preoccupation. The presentation will be on view from April 11 through July 20, 2025.

“Through an impressive array of 19th- and early 20th-century images that capture the complexities of a nation in the midst of profound transformation, this exhibition offers something new even for those well-versed in the history of photography,” said Max Hollein, The Met’s Marina Kellen French Director and Chief Executive Officer. “Thanks to the generosity of Jenny and Flip Maritz, we can study and celebrate these formerly hidden treasures by hundreds of both known and unknown makers finally ready for their close-ups. Our hope is to give these works their rightful place in the ever-expanding history of the medium.”

Jeff L. Rosenheim, Joyce Frank Menschel Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs, added, “The camera and its myriad democratic products – rivals to the greatest literature of the era – are clearly the origin of modern communication and global image-sharing today. If we want to forge a deeper appreciation of contemporary art and the role of the camera in the lives of today’s picture makers, we must recognise and respect the stunning visual power and authenticity of early American photography.”

Carefully assembled over the last 50 years by the Connecticut collector and private dealer William L. Schaeffer, the collection includes splendid photographs in superb condition from every stage of the medium’s early technical development: daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes, salted paper prints, albumen silver prints, cyanotypes, platinum prints, and gelatin silver prints. The exhibition also features an extensive display of three types of card-mounted photographs – cartes de visite, stereographs, and cabinet cards – each wildly popular in the mid- to late 19th century. When seen through binocular viewers, all the stereographs in the show will be visible in three dimensions.

This is not the first exhibition at The Met to feature photographs drawn from the famous collection of 19th-century photographs amassed by Schaeffer. In 2013, the Museum included more than a dozen Civil War views in Photography and the American Civil War. These are now part of the Museum’s collection through the direct support of another Museum trustee, Joyce Frank Menschel. The gifts by the Maritzes to The Met, as well as those by Joyce Menschel, mark a pinnacle in the institution’s ongoing effort to build the finest holdings of 19th-century American photography in the nation.

Exhibition Overview

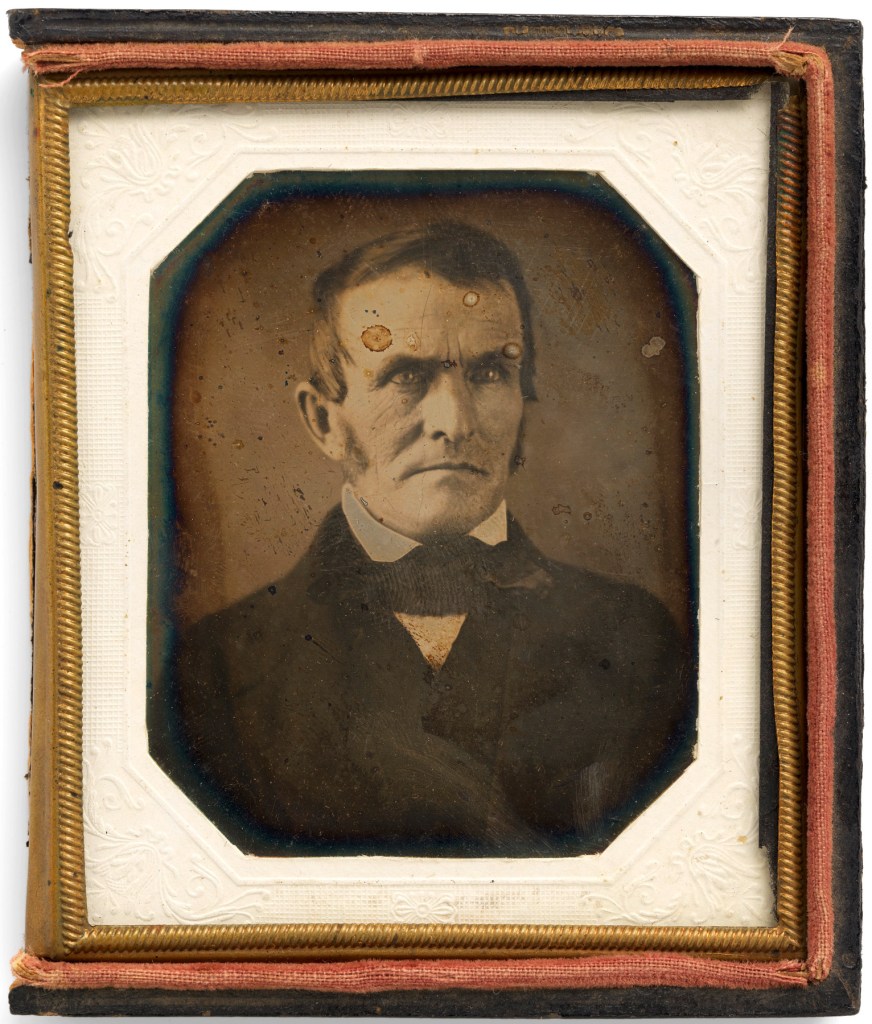

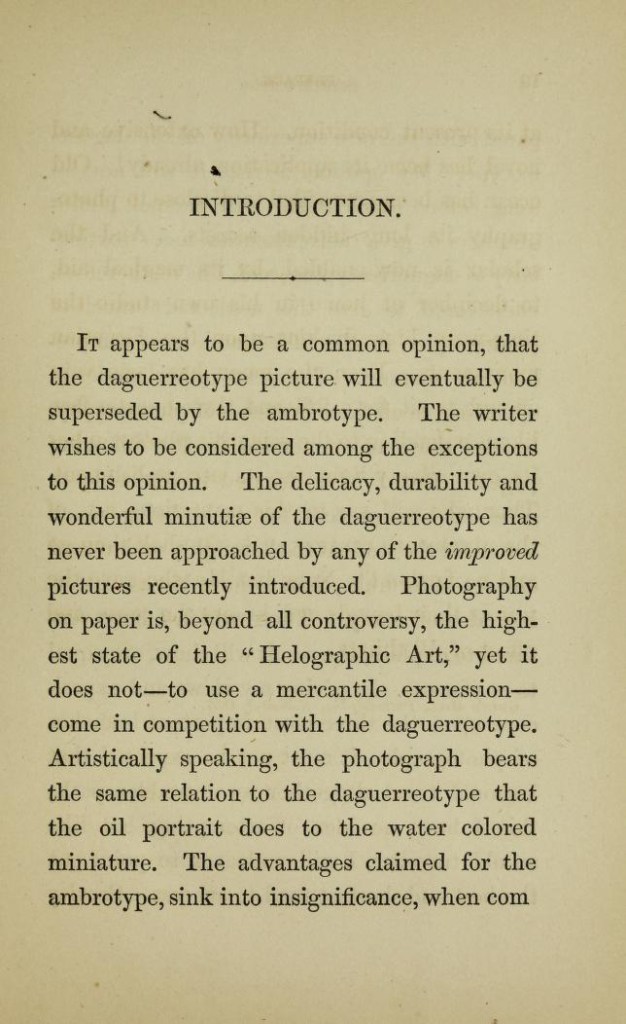

In 1839, the invention of photography transformed the world. In December of that year, when the first daguerreotypes were exhibited in New York, former mayor Philip Hone marvelled in his diary at what he described as “one of the wonders of modern times,” adding that “like other miracles, one may almost be excused for disbelieving it without seeing the very process by which it is created.”

The daguerreotype’s remarkable ability to hold permanently an unimaginably detailed likeness on its surface – an image heretofore only seen fleetingly in a mirror – seemed in equal measure unbelievable and perfectly real, darkly mysterious yet scientifically verifiable, a shadowy fiction and yet a beautiful truth. The supernatural quality of the new art was noted by many around the world. As one reviewer, writing for a Baltimore weekly in January 1840, admitted, “We can find no language to express the charm of these pictures painted by no mortal hand.”

Photography arrived almost simultaneously with the steam locomotive, the steam ship, and the electric telegraph – all inventions that dramatically shortened the distances between people and places and forever changed the way civilisations communicate. The medium developed during the age of the type-crazy broadside, the morning and the evening newspaper, and the illustrated weekly. It was also the time of the birth of mercantile libraries (previously only the wealthy had access to books and libraries), and, not surprisingly, of eye strain. The era saw the medical specialisation in the study of eye maladies and the development of optometry and ophthalmology. In 1835, just before the concurrent announcement of the invention of the new art in Paris and London, the American philosopher and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson noted in his private journal: “Our age is ocular.”

Organised primarily by picture format across three galleries, The New Art illustrates what photography looked like for the average working citizen as well as those at the top of the economic scale. Exhibition visitors can see the clothes individuals wore at work and home, their attitudes to the camera singly and in groups, their ways of sitting or standing or touching, and how they honoured their children and respected their ailing and recently deceased family members. They can look at newly constructed storefronts, see how farmers worked their fields, and measure where new towns met the wilderness. They can observe the near total devastation of Native American communities, especially those living in the Plains, and confront the vicious cruelty of slavery and the influential role of the camera in the Civil War, still the crucible of American history.

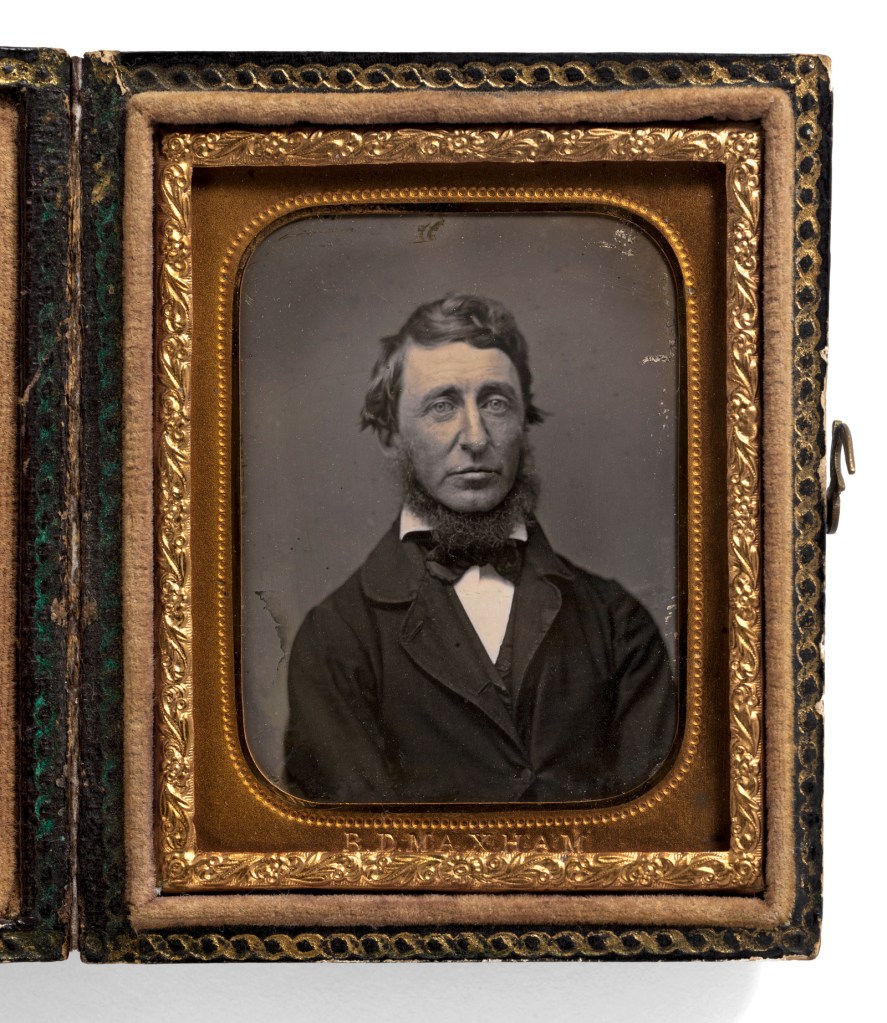

In daguerreotypes, tintypes, and paper prints, viewers can also begin to see and comprehend how African Americans during the Civil War, throughout the Reconstruction era, and leading into the 20th century slowly began to replace negative stereotypes with positive self-images. This effort was explicitly nurtured by Frederick Douglass, who had long advocated visits to photography studios. In his nearly constant lecturing circuit across the country, he argued persuasively that no one could be truly free until each individual could sit for and possess their own photographic likeness. In The New Art, men and women of color definitively hold the camera’s attention and the viewer’s as well.

Seen together in The New Art, the subjects in these photographs are not just sitters molded by a camera operator, but the cocreators of their own portraits. One can see this clearly in their eyes and in their many small, seductive gestures. Confronting a photograph that left an artist’s studio more than 150 years ago can be a humbling experience. The magic of photography brings one face to face with the past, and the present is never more vital than it is in these early pictures. That is the medium’s essence, its beauty, and its pathos.

Cameras

The exhibition will also showcase a small selection of 19th-century American cameras to further immerse visitors in the photography process. These have been kindly lent to The Met by Eric Taubman and the Penumbra Foundation.

Press release from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Unknown Maker (American)

Young Man with Rooster

1850s

Daguerreotype with applied color

Case (open): 3 5/8 × 6 1/4 in. (9.2 × 15.9cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

Josiah Johnson Hawes (American, 1808-1901)

Winter on the Common, Boston

early 1850s

Salted paper print from glass negative

7 5/16 × 9 5/16 in. (18.5 × 23.7cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

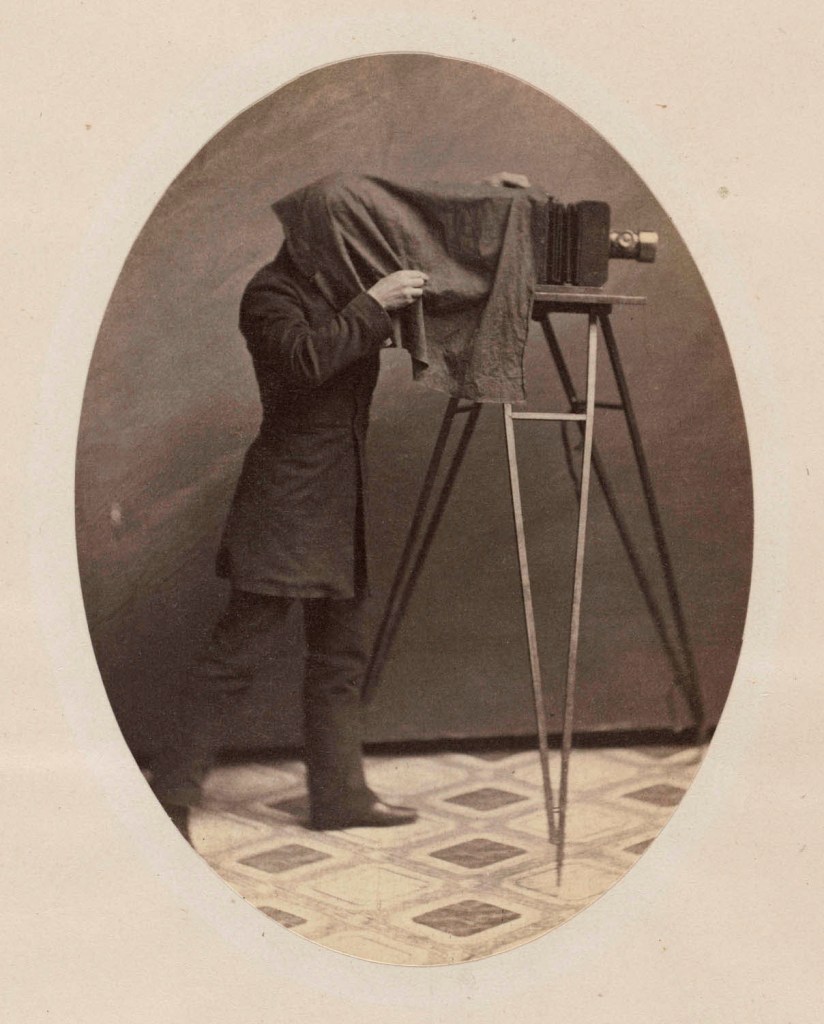

Unknown Maker

Studio Photographer at Work

c. 1855

Salted paper print from glass negative

5 1/8 × 3 13/16 in. (13 × 9.7cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

Unknown Maker (American)

Laundress with Washtub

1860s

Ambrotype with applied colour

Case: 4 1/8 x 3 1/4 in. (4.2 x 3.2cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

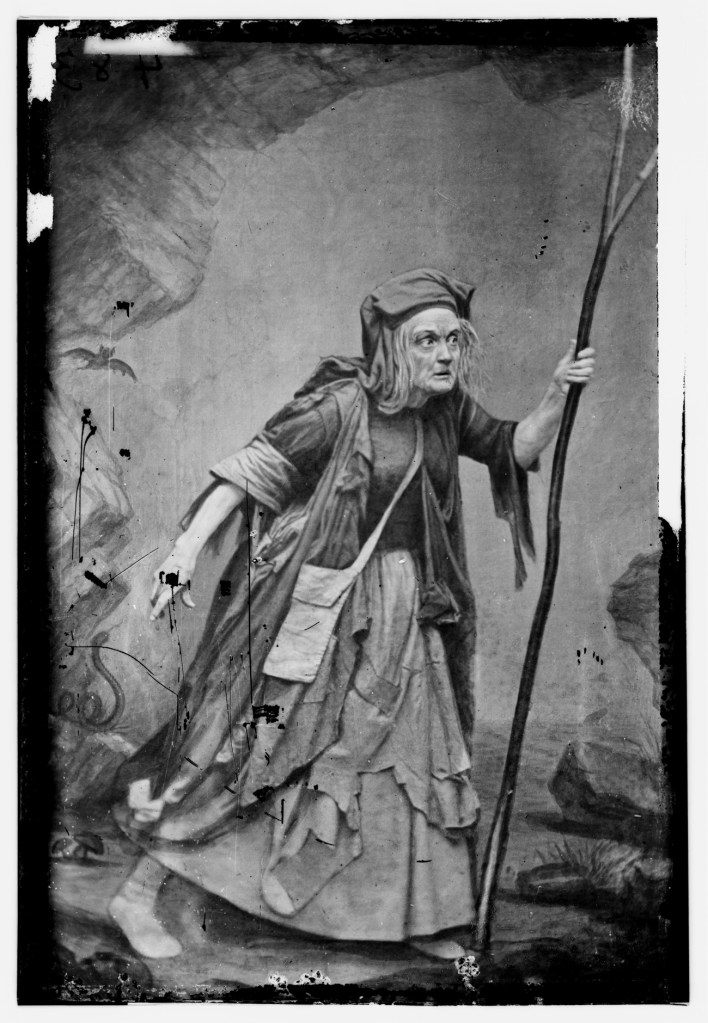

Unknown Maker (American)

Actor Playing Hamlet, Holding a Skull

1860s

Tintype with applied colour

Case: 6 1/4 × 4 15/16 in. (15.8 × 12.6cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

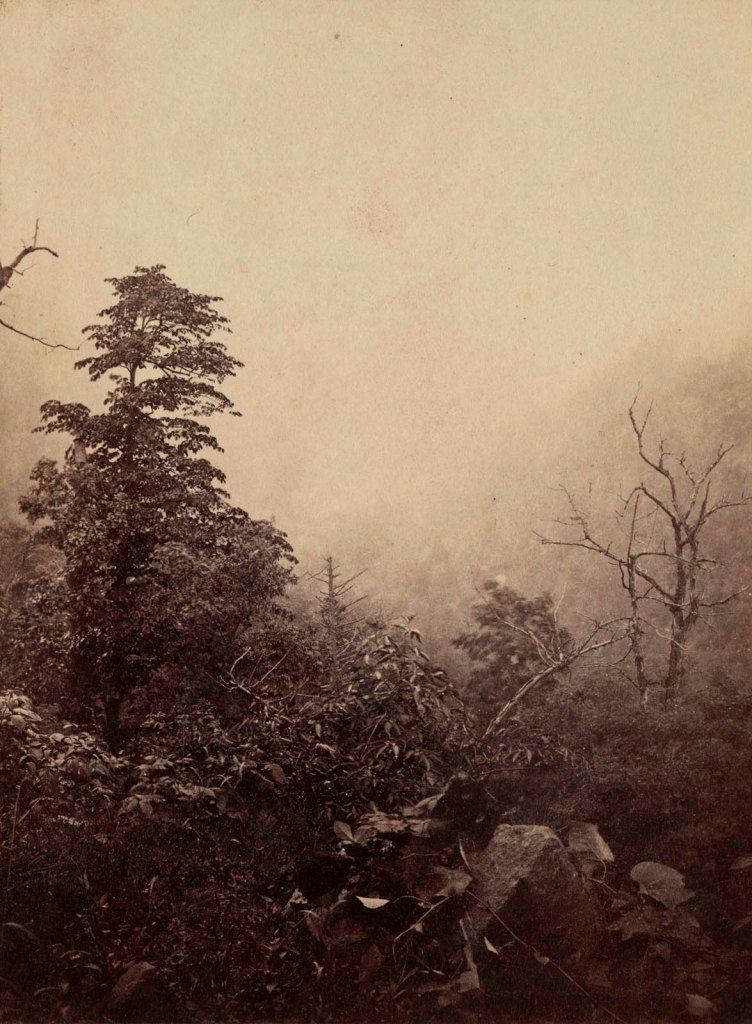

John Moran (American born England, 1821-1903)

Showing Weather Among the Alleghenies

1861-1862

Albumen silver print from glass negative

4 3/4 × 3 5/8 in. (12.1 × 9.2cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

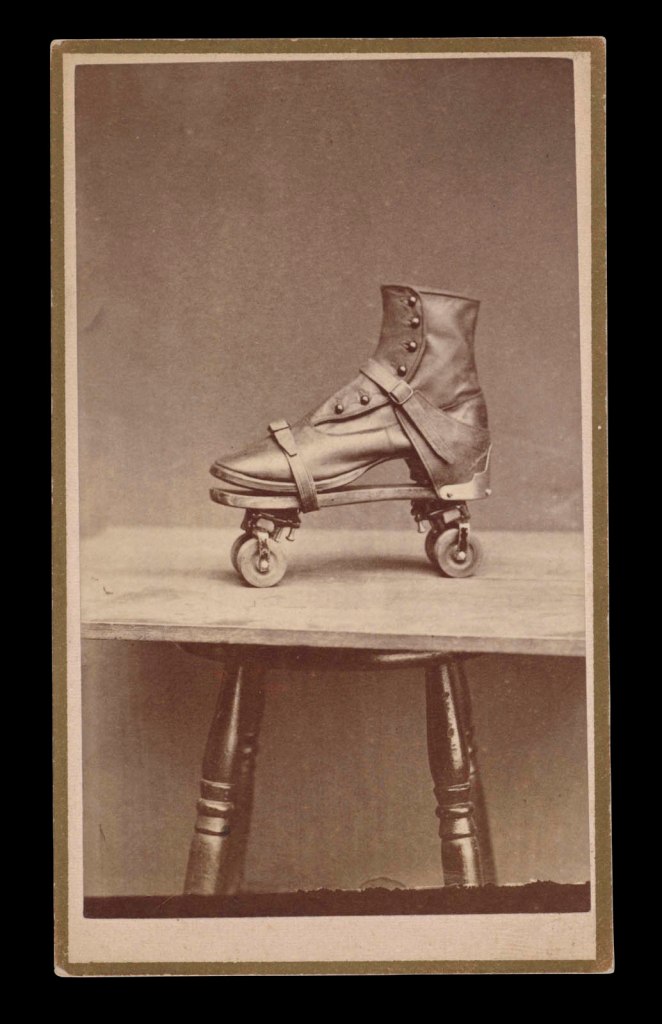

Unknown Maker

Roller Skate and Boot

1860s

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Mount: 4 1/8 × 2 7/16 in. (10.5 × 6.2cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

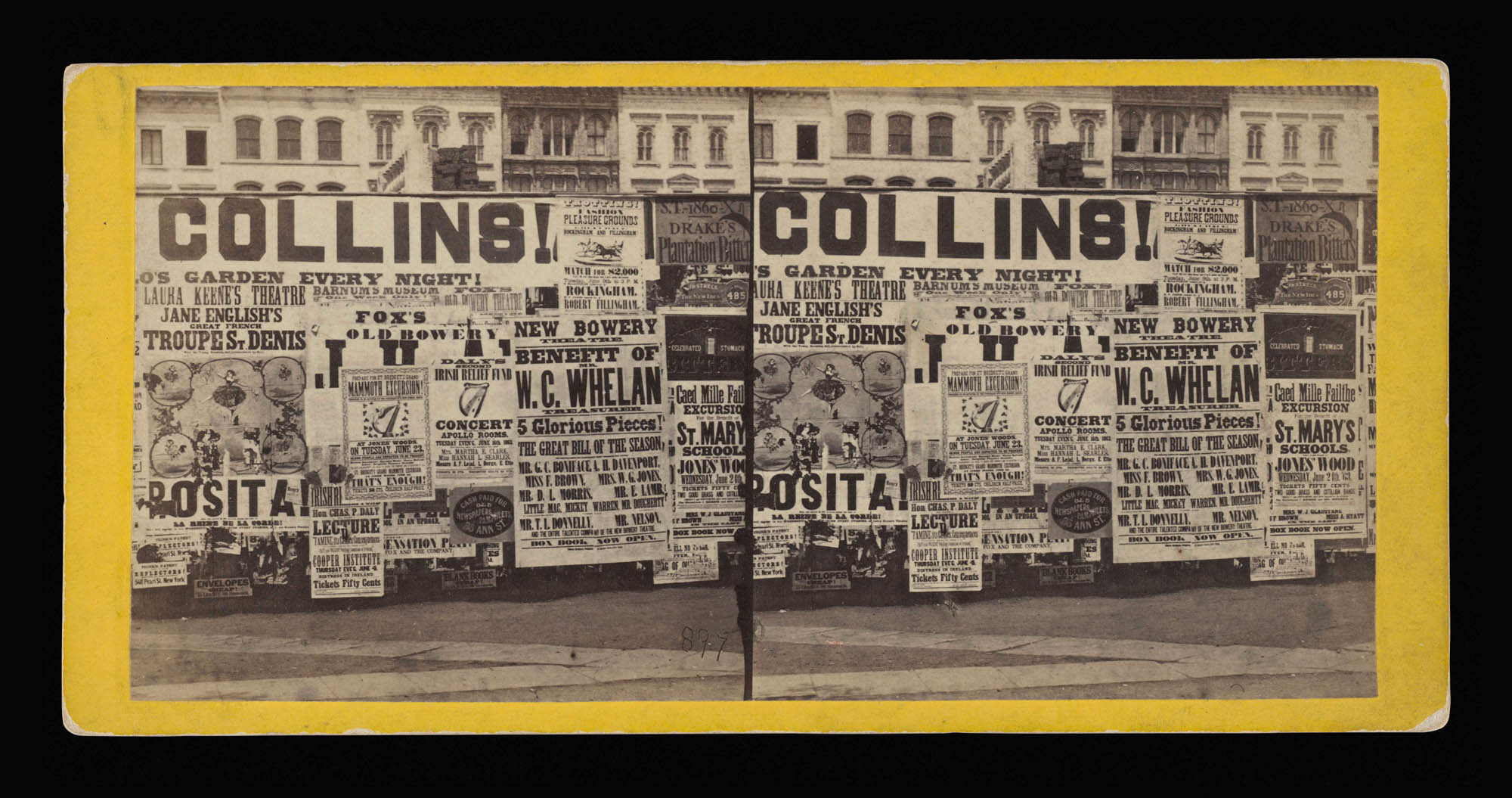

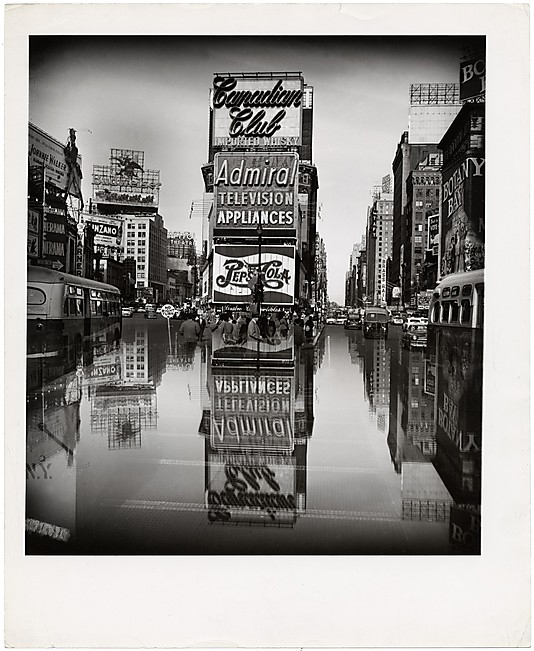

Unknown Maker (American)

Published by E. & H. T. Anthony (American, 1862-1880s)

Specimens of New York Bill Posting, No. 897 from the series

“Anthony’s Stereoscopic Views”

1863

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Mount: 3 1/4 × 6 3/4 in. (8.3 × 17.1 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

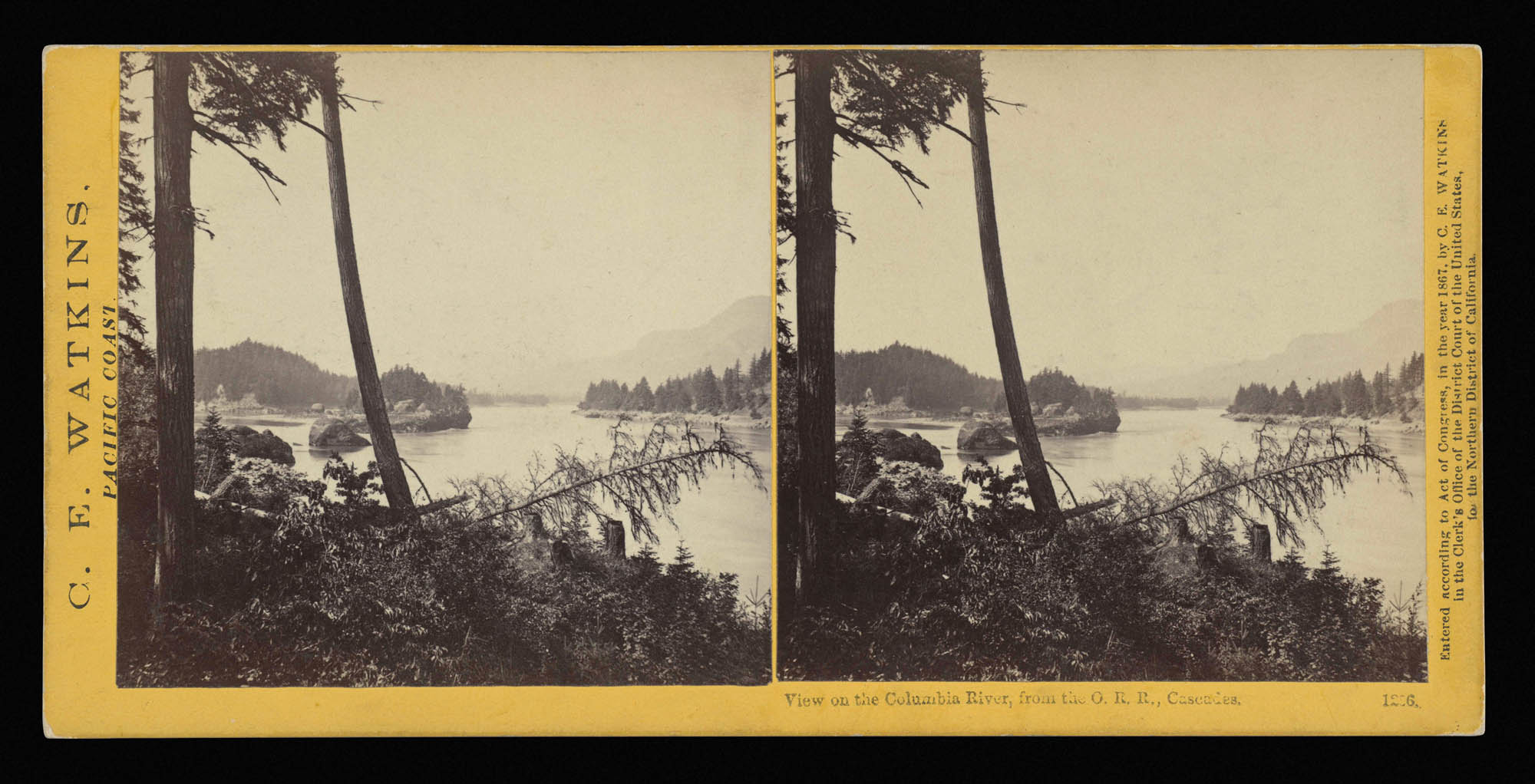

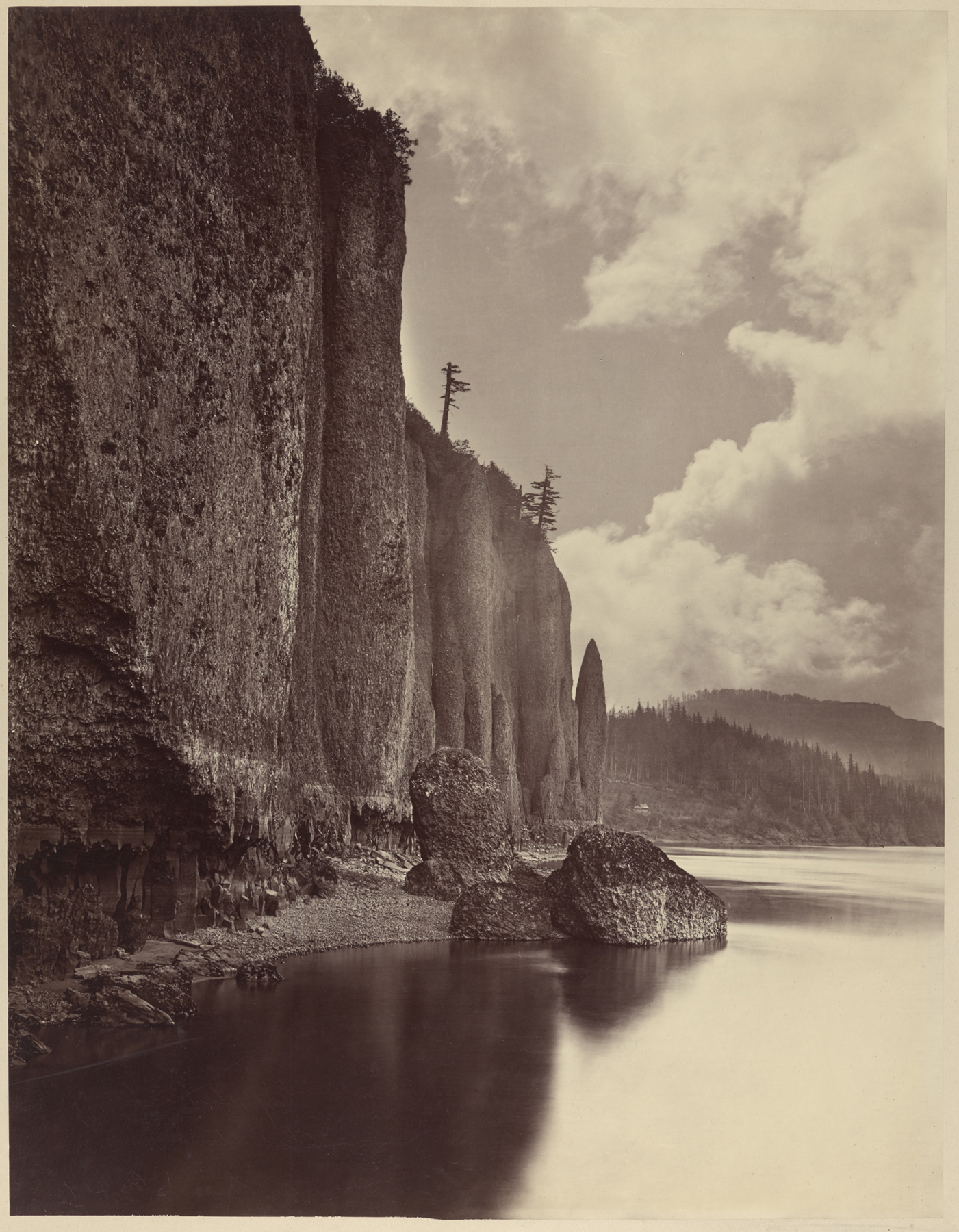

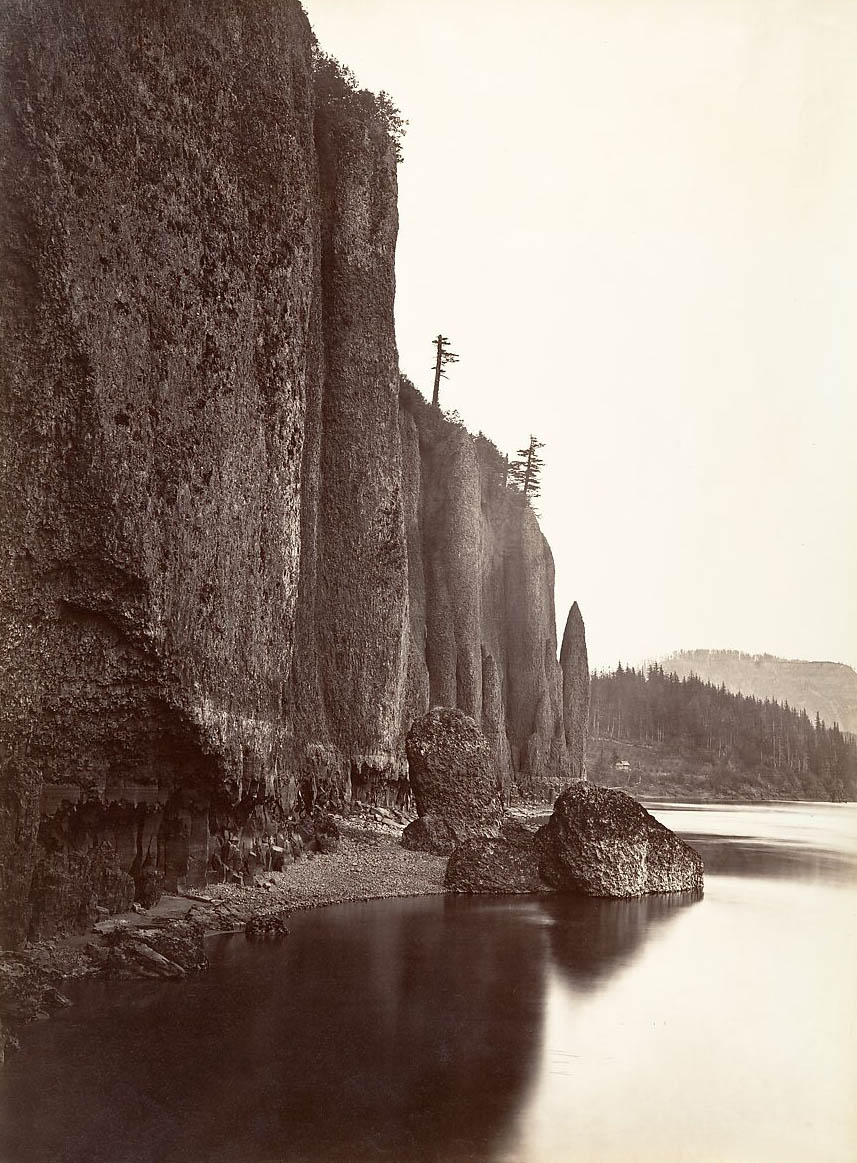

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

View on the Columbia River, from the O.R.R., Cascades, No. 1286 from the series “Pacific Coast”

1867

Albumen silver prints from glass negatives

Mount: 3 1/4 × 6 3/4 in. (8.2 × 17.1cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

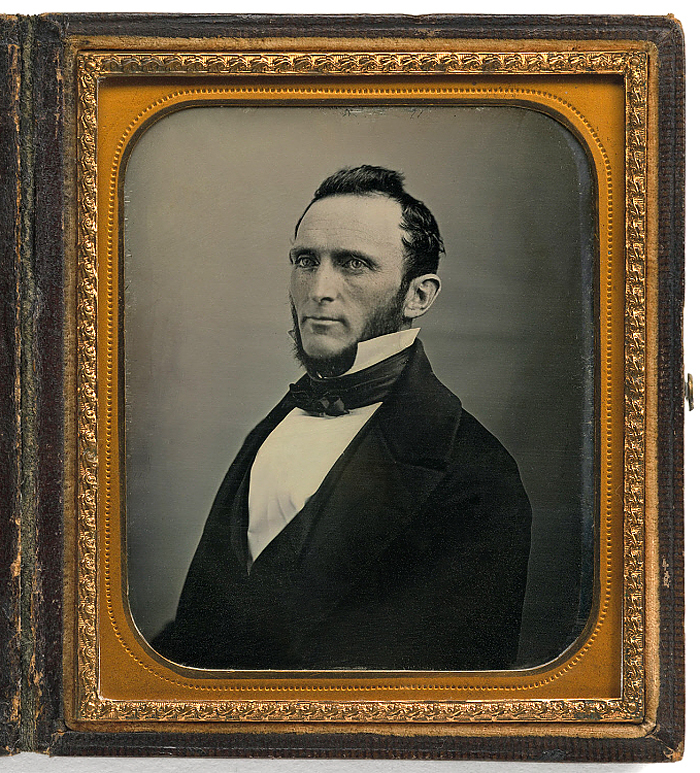

Albert Cone Townsend (American, 1827-1914)

A Politician

1865-1867

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Mount: 4 × 2 7/16 in. (10.1 × 6.2cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The New Art: American Photography, 1839-1910

Introductory panel

The world changed dramatically in September 1839 when photography was introduced to the public and quickly emerged as one of the wonders of modern times. Its invention marks the dawn of our own media-obsessed age in ways that become clear when we explore in depth the special language of daguerreotypes, tintypes, cartes de visite, stereographs, and other early photographic processes and formats.

This exhibition presents an adventurous new history of American photography from the medium’s beginnings to the first decade of the twentieth century. Major works by established artists are shown in dialogue with superb, never-before-seen photographs by obscure or unknown practitioners working in large urban centres and small towns across the expanding country. Tracing technological advancements and the development of picture formats, The New Art charts the remarkable change in the nation’s sense of itself that was driven by the phenomenal success of photography as a cultural, commercial, and artistic preoccupation.

All the works of art on view are drawn from an extraordinary promised gift to The Met of more than seven hundred rare photographs offered by Jennifer and Philip Maritz in celebration of the Museum’s 150th anniversary in 2020. The donors acquired the collection from William L. Schaeffer, a renowned Connecticut private photography dealer who had quietly built it over the last half century.

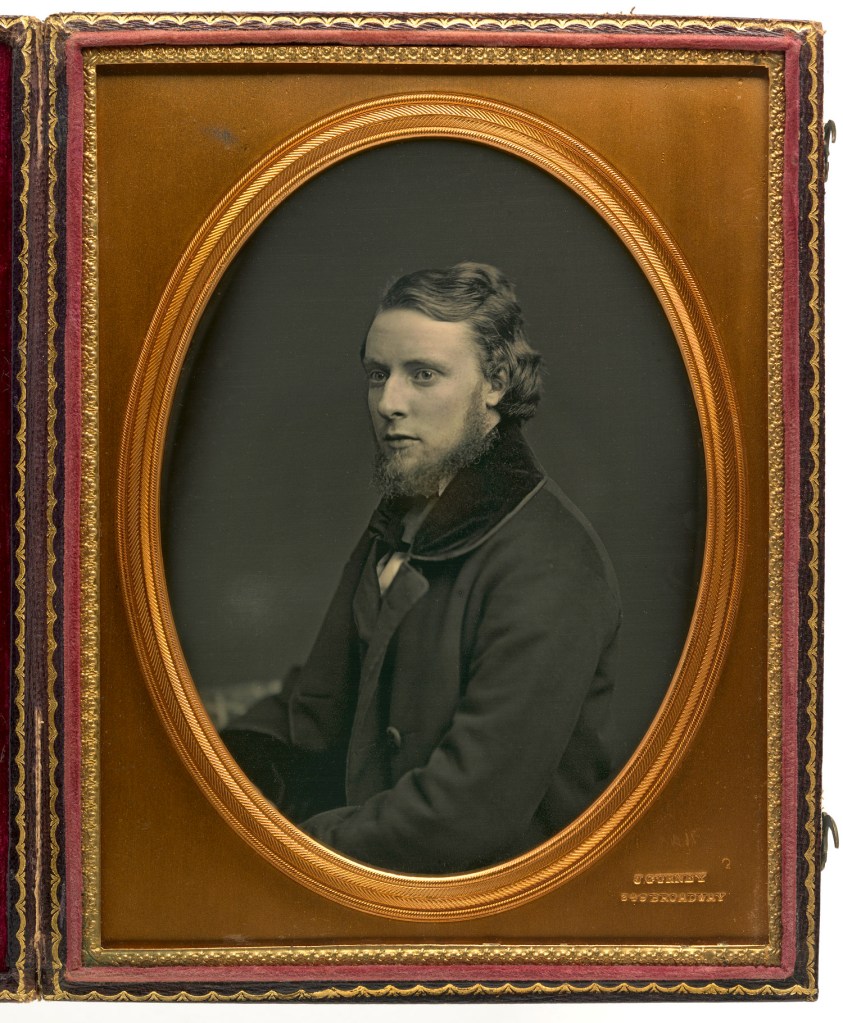

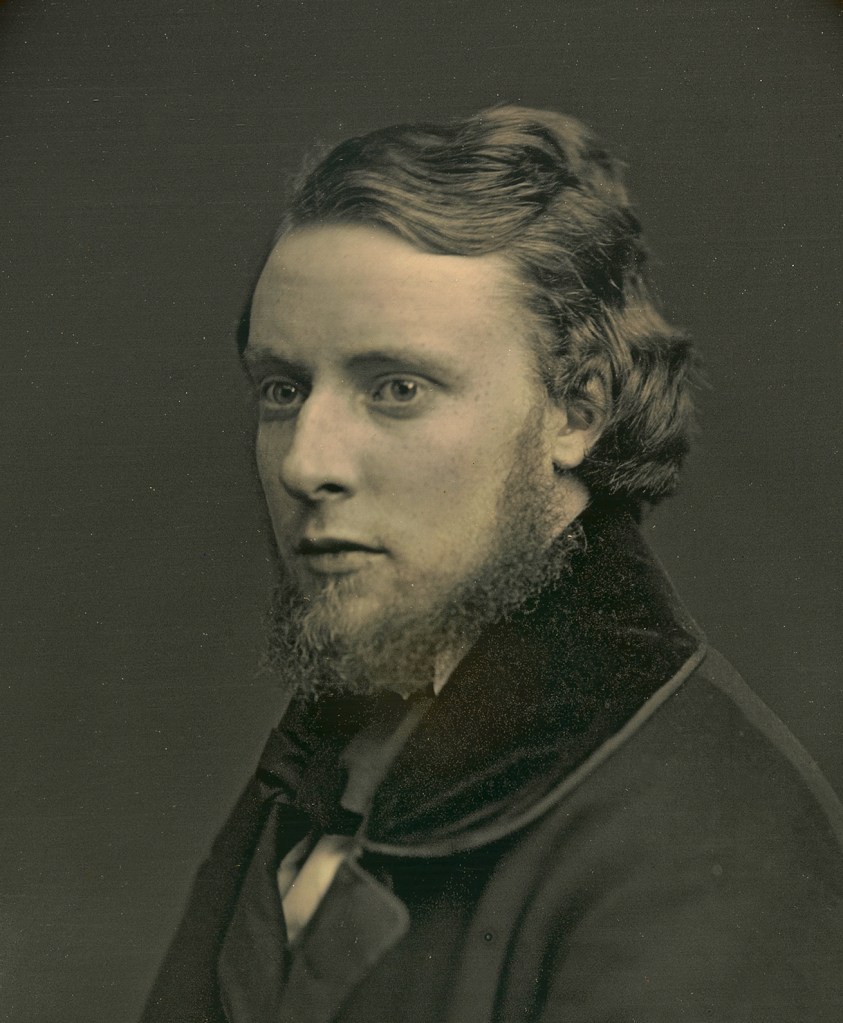

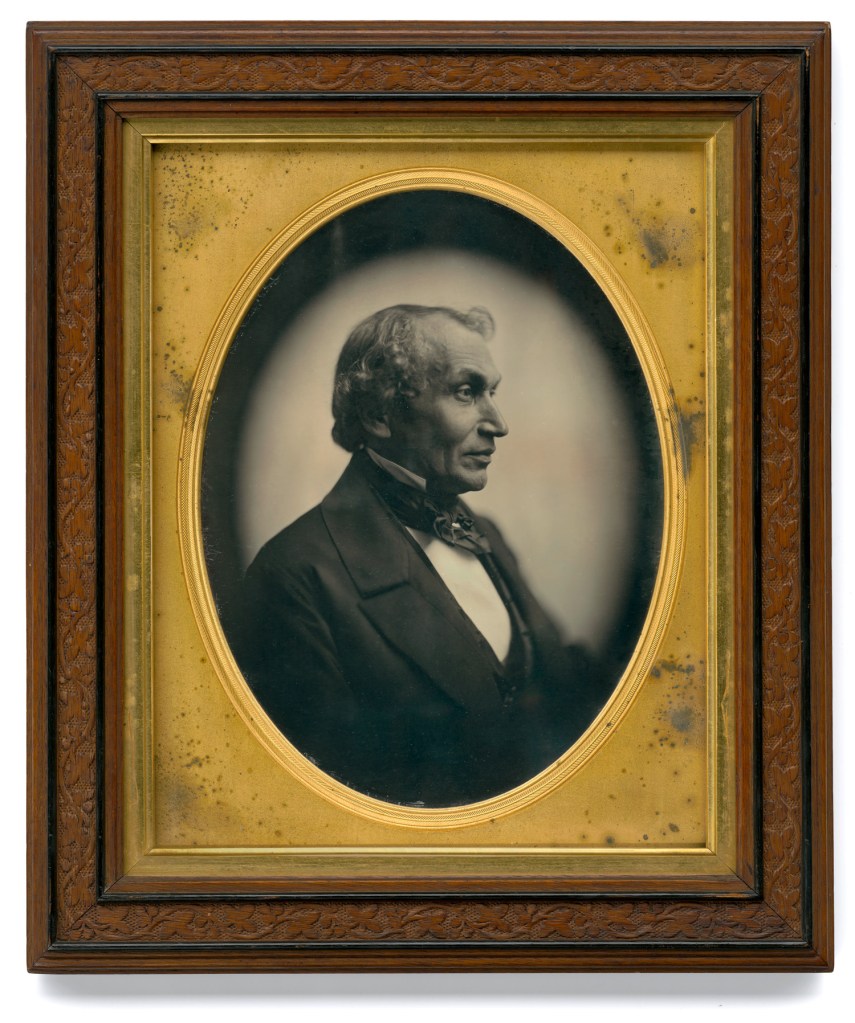

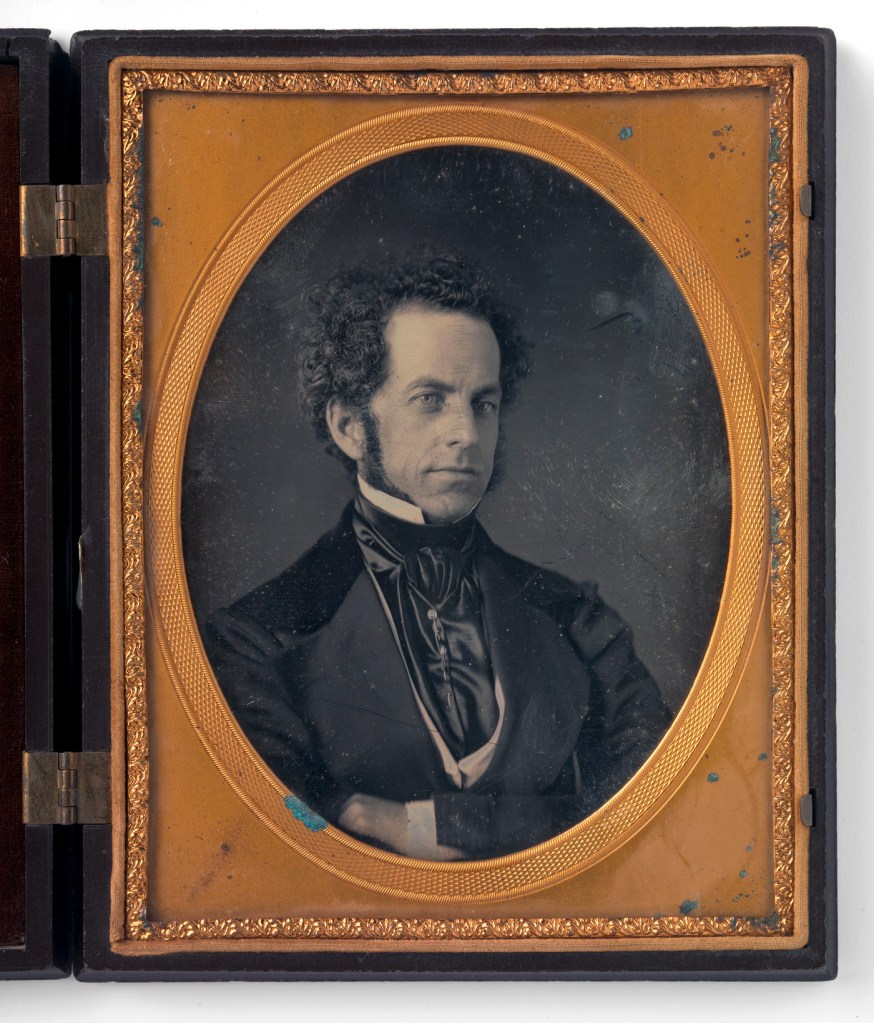

Daguerreotypes

The daguerreotype is a photographic image formed on the surface of a silver-plated sheet of copper fumed with iodine. Exposed in a wood box camera and developed with hot mercury vapours, each daguerreotype is unique. Invented in France by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and announced to the world in August 1839, it was the dominant form of photography in the U.S. for twenty years, until around 1860. The daguerreotype’s ability to permanently hold a detailed image – before then seen only fleetingly in a mirror – was astonishing. The shimmering result seemed in equal measure unbelievable and perfectly real, darkly mysterious yet scientifically verifiable, a shadowy fiction and a beautiful truth. In the U.S. the daguerreotype provided an opportunity for self-representation to many strata of society that were previously excluded from the realm of portraiture.

Ambrotypes

The ambrotype is similar in its process to the daguerreotype, but it uses a sheet of glass rather than copper as the image support. Popular in the U.S. from 1854 to 1870, the technique – invented in England but named by an American – was the predictable next development of photography. Although less visually alluring, it had marked advantages over the daguerreotype: it was cheaper to produce, it was easier to see (without glare) in most lighting conditions, and it eliminated the lateral reversal of the image characteristic of the earlier process. This was especially helpful with certain patrons who were annoyed, for example, by a jacket buttoning backward or a wedding ring appearing on the incorrect hand.

Tintypes

The tintype is a distinctively American style of photograph. Patented in February 1856 by Hamilton Lamphere Smith, the technique was inexpensive and relatively easy to master. It appealed as much to enterprising itinerant picture makers, who traveled to rural communities and made outdoor portraits and views, as it did to artists operating brick-and-mortar galleries. Rather than a coating of silver emulsion on copper (the daguerreotype) or glass (the ambrotype), the tintype’s support is a common sheet of blackened iron. Despite its misleading name, which was not in use until 1863, there is no tin present in a tintype. The process was wildly popular in the U.S. until the end of the nineteenth century.

Paper-print Photographs

From 1839 until the start of the Civil War in 1861, most photographs were made on metal (daguerreotypes and tintypes) or glass (ambrotypes). Beginning in the late 1850s, however, paper was widely adopted as the physical support for photographs. This gallery primarily features paper-print photographs and albums that date from 1850 to 1910. They are known by a variety of names that reflect changes in materiality and date of production: salted paper prints, generally made from paper negatives; albumen silver prints, made from glass negatives; and gelatin silver and platinum prints, made from glass or flexible film negatives. In this era, two formats of card-mounted paper-print photographs enjoyed remarkable success: the small carte-de-visite portrait and the stereographic view.

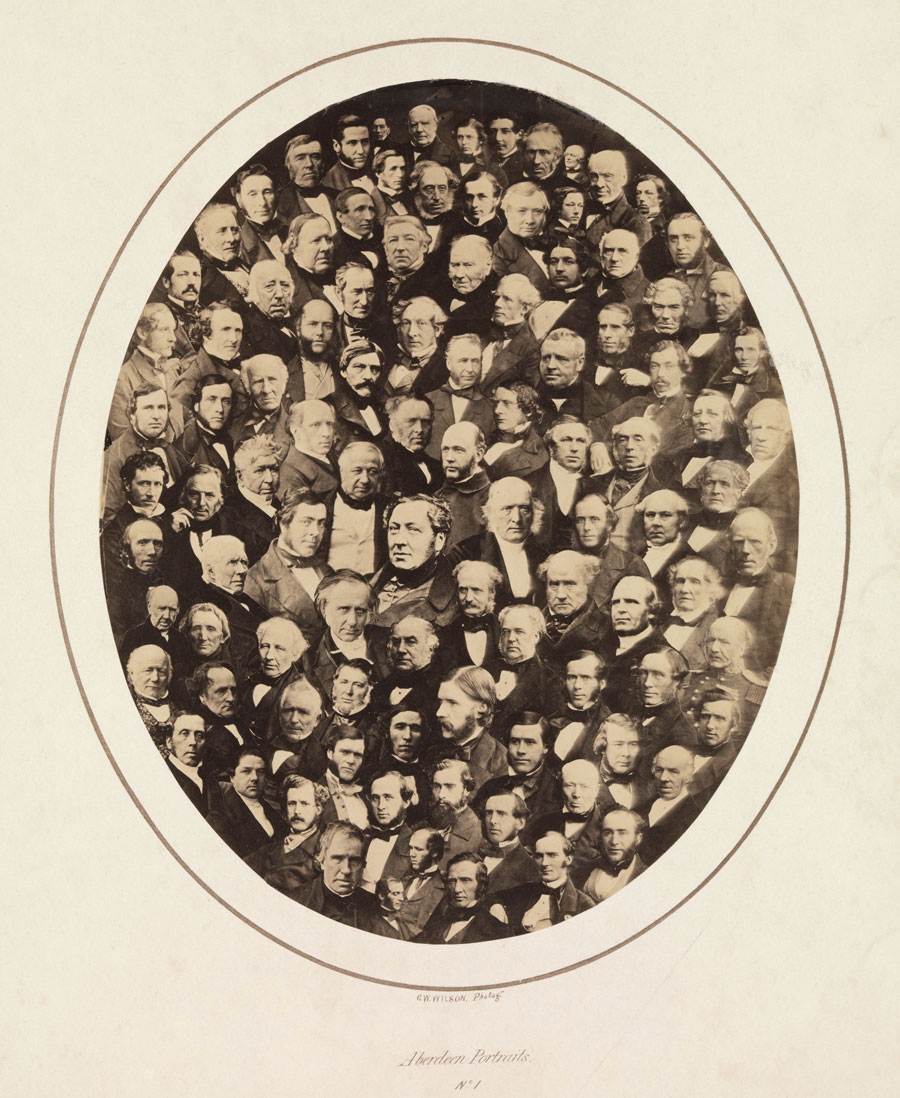

Cartes de Visite

The carte de visite – commonly known as a “cdv” – is a small photograph, usually an albumen silver print made from a glass negative, affixed to a 4-by-2½-inch stiff paper card. Invented in France in the mid-1850s as a portrait medium, it was the world’s first mass-produced and mass-consumed type of photographic collectible. Most photographers marked the mounts with their gallery names as a means of self-promotion and what today we would call brand-building. Ubiquitous in the U.S. from just before 1860 to 1880, the democratic, Victorian-age novelty was wildly popular with the public. “Cartomania,” as the phenomenon was known, is worthy of attention today as a resonant precursor to our own obsession with sharing images of celebrities and ourselves via social media.

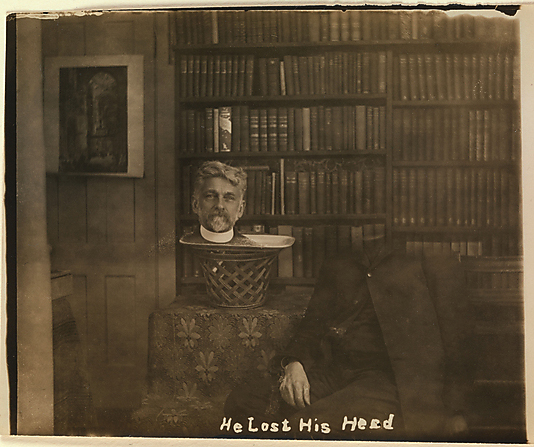

Cabinet Cards

A cabinet card is essentially an oversize carte de visite. In vogue for three decades in the U.S. beginning around 1870, the 6 1/2-by-4 1/2-inch card-mounted photograph offered picture makers significantly more space and freedom to compose their visual narratives. After the deadly seriousness of the Civil War, cabinet cards frequently fulfilled a growing appetite for light-hearted diversion. They often feature elaborate props and accessories, exotic backdrops, and, as the century progressed, increasingly playful indoor and outdoor scenes.

Stereographs

Introduced in the late 1850s and prevalent into the twentieth century, the stereograph was not only a culturally significant invention but also a commercial boon to American photographers. When viewed through a device known as a stereoscope (or stereopticon), a pair of photographs of the same subject – made from two slightly different points of view – are perceived in the brain as a single, seemingly three-dimensional image. The dazzling binocular effect created an immersive experience, offering inexpensive armchair travel and a window on the world to millions of Americans.

Cyanotypes

Invented in 1842 by the British scientist John Herschel, a cyanotype is a naturally blue photograph made with iron salts. Early on, most cyanotypes took the form of nature studies made without a camera by placing botanical specimens (or other objects) directly in contact with sensitised paper and then exposing the composition in the sun. In the 1870s architects and engineers began using the process to duplicate their drawings, resulting in what are generally known as “blueprints.” Both economical and easily developed, the cyanotype reemerged in the late 1880s as a favourite choice of professional photographers and amateurs alike. It was often selected for large municipal documentary projects such as those seen here.

Intro and Section Wall Texts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

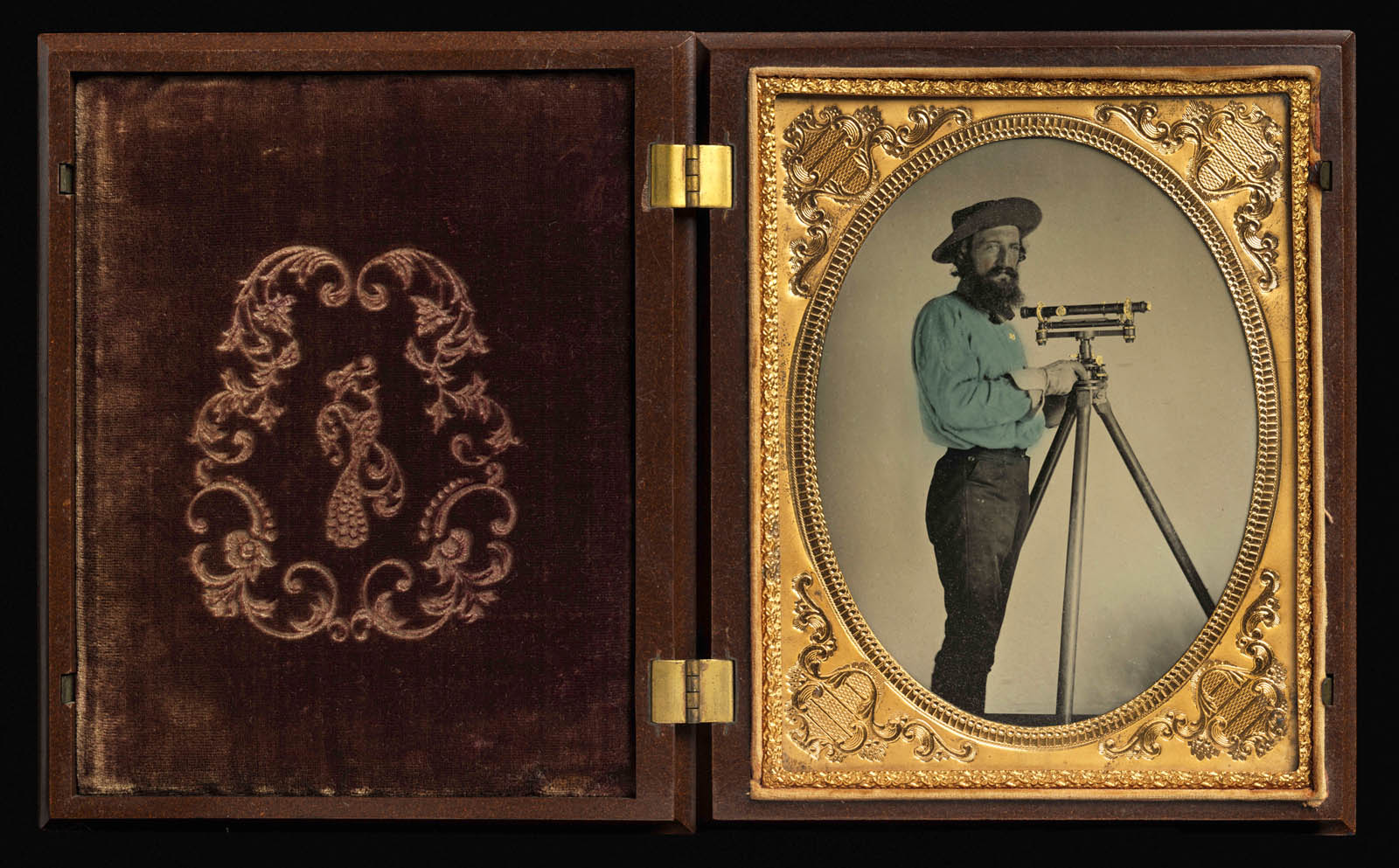

Unknown Maker (American)

Railroad Worker (?) with Wye Level

c. 1870

Tintype with applied color

Case (open): 6 5/16 × 10 3/8 in. (16 × 26.4cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

Unknown Maker (American)

Musician

1870s

Tintype, with lock of hair and cut paper

Case (open): 2 × 3 1/2 in. (5.1 × 8.9cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

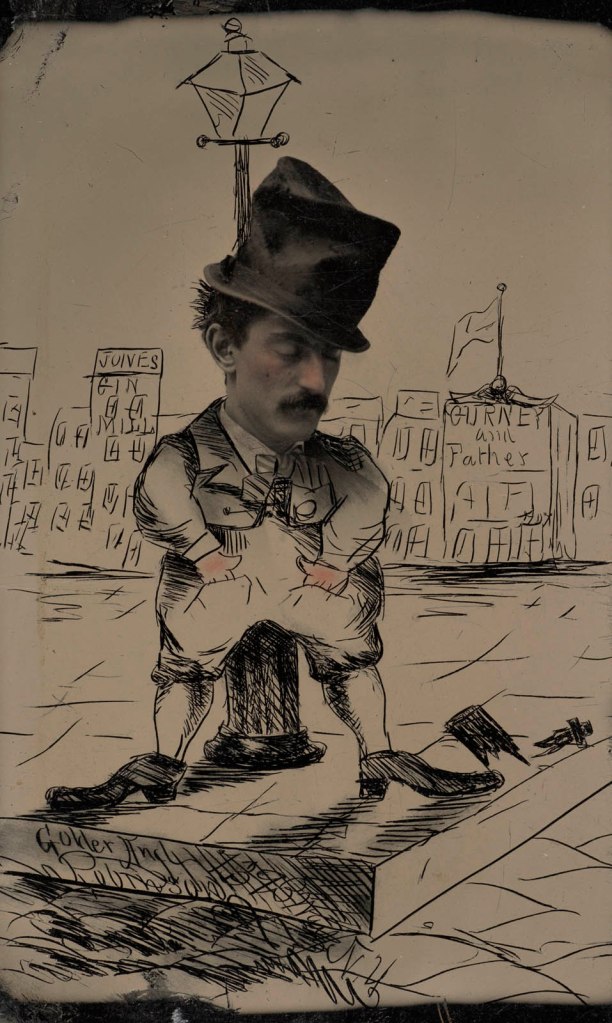

Golder & Robinson (American, active 1870s)

Comic Novelty Portrait

1870s

Tintype with applied colour

4 × 2 7/16 in. (10.1 × 6.2cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

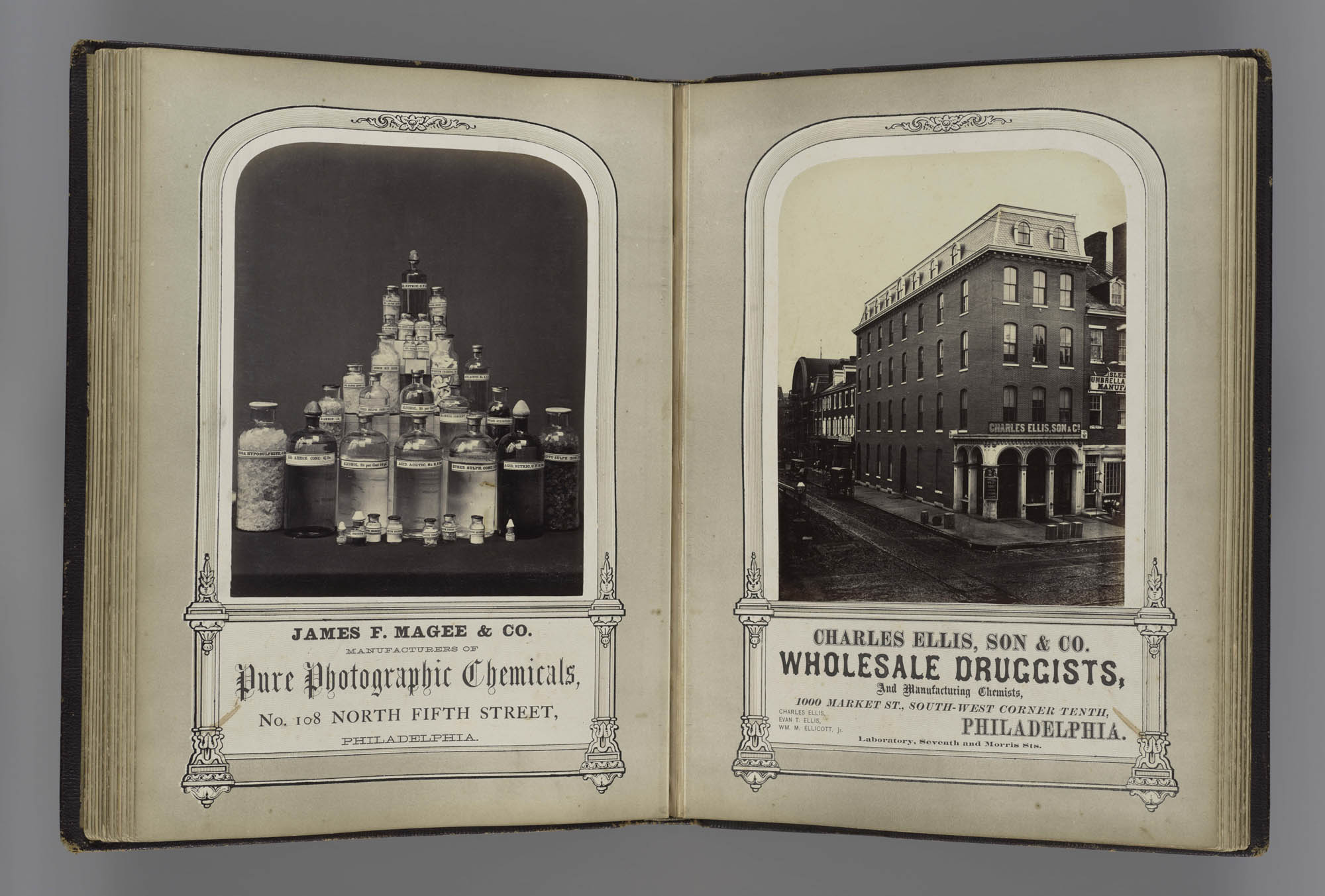

Wenderoth, Taylor & Brown (American, active 1864-1871)

The Gallery of Arts & Manufacturers of Philadelphia

1871

Albumen silver prints from glass negative

Open: 13 3/4 x 19 in. (34.9 x 48.3cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

Anna K. Weaver (American, 1847/48-1913)

Welcome

1874

Albumen silver print from glass negative

10 7/8 x 17 1/2 in. (27.8 x 44.5cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

Chauncey L. Moore (American, died 1895)

Young Man Laying on Roof

1880s-1890s

Albumen silver print

Mount: 4 1/4 × 6 1/2 in. (10.8 × 16.5cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

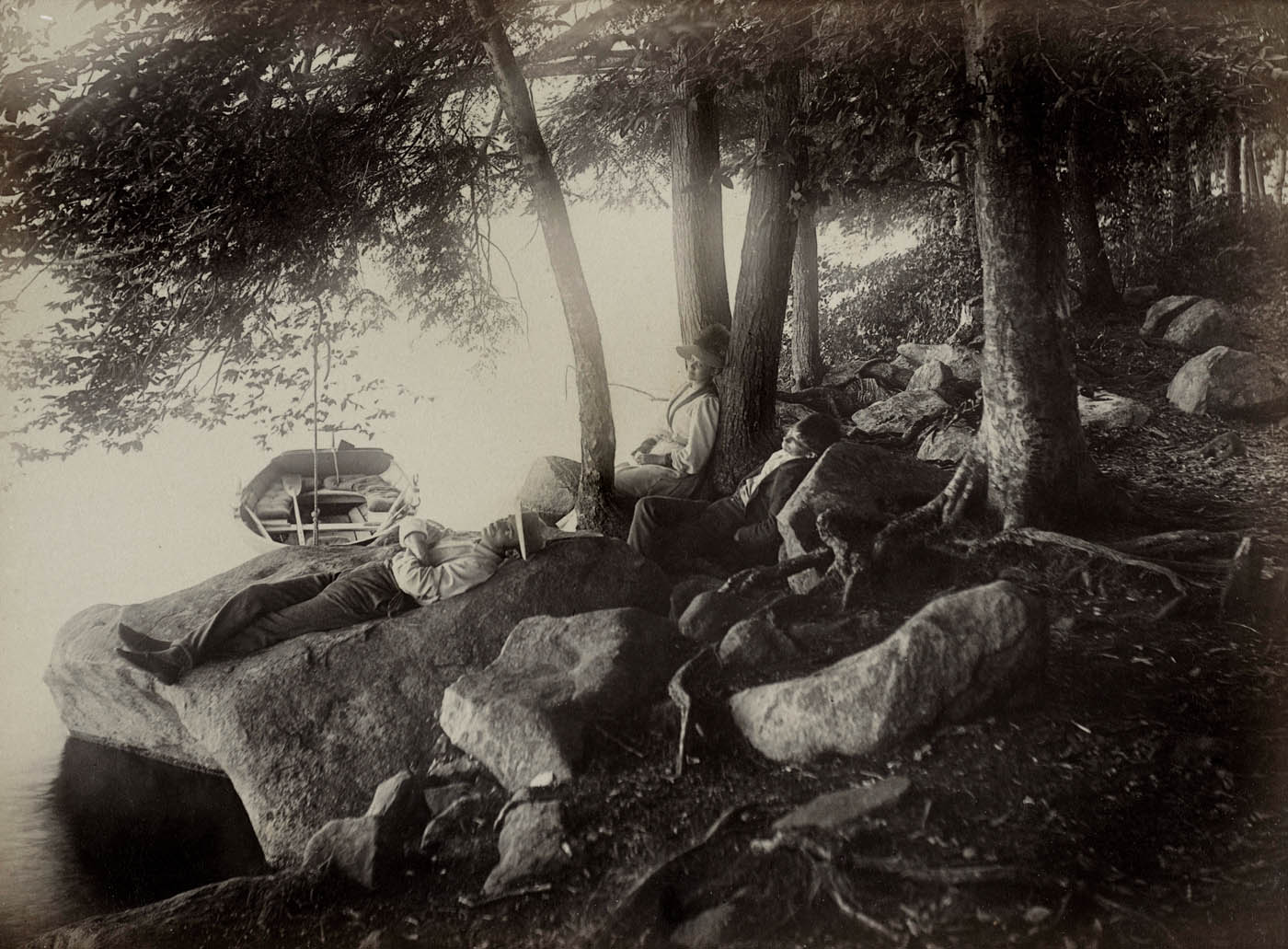

Alice Austen (American, 1866-1952)

Group on Petria, Lake Mahopac

August 9, 1888

Albumen silver print from glass negative

6 × 8 1/8 in. (15.2 × 20.7cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

Unknown Maker (American)

Schoolmaster Hill Tobogganing, Franklin Park, Roxbury, Massachusetts

1905

Cyanotype

7 × 9 1/4 in. (17.8 × 23.5cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection

Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Thursday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Closed Wednesday

![Lewis Carroll (British, Daresbury, Cheshire 1832 - 1898 Guildford) '[Alice Liddell]' June 25, 1870 from the exhibition '2020 Vision: Photographs, 1840s-1860s' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dec 2019 - Dec 2020 Lewis Carroll (British, Daresbury, Cheshire 1832 - 1898 Guildford) '[Alice Liddell]' June 25, 1870 from the exhibition '2020 Vision: Photographs, 1840s-1860s' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dec 2019 - Dec 2020](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/lewis-carroll-alice-liddell.jpg?w=898)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854 Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-surveyor-a.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854 Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-surveyor-b.jpg?w=878)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Classical Head]' probably 1839 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Classical Head]' probably 1839](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/bayard-classical-head.jpg?w=931)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-a.jpg?w=850)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-b.jpg?w=876)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-c.jpg)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-d.jpg)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-e.jpg)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-f.jpg?w=863)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-g.jpg)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-h.jpg?w=875)

![Unknown artist (American) '[Studio Photographer at Work]' c. 1855 Unknown artist (American) '[Studio Photographer at Work]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/unknown-artist-american-studio-photographer-at-work-c-1855.jpg?w=825)

![Unknown artist (American) '[Boy Holding a Daguerreotype]' 1850s Unknown artist (American) '[Boy Holding a Daguerreotype]' 1850s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/unknown-american-active-1850s-boy-holding-a-daguerreotype-1850s.jpg?w=877)

![Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[California Oak, Santa Clara Valley]' c. 1863 Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[California Oak, Santa Clara Valley]' c. 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/watkins-california-oak-santa-clara-valley.jpg?w=827)

![Pietro Dovizielli (Italian, 1804-1885) '[Spanish Steps, Rome]' c. 1855 Pietro Dovizielli (Italian, 1804-1885) '[Spanish Steps, Rome]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/dovizielli-spanish-steps.jpg?w=787)

![Edouard Baldus (French (born Prussia), 1813-1889) '[Amphitheater, Nîmes]' c. 1853 Edouard Baldus (French (born Prussia), 1813-1889) '[Amphitheater, Nîmes]' c. 1853](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/baldus-amphitheater.jpg)

![Lewis Dowe (American, active 1860s-1880s) '[Dowe's Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois]' 1860s Lewis Dowe (American, active 1860s-1880s) '[Dowe's Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois]' 1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/lewis-dowe-dowes-photograph-rooms-sycamore-illinois-1860s.jpg)

![E. & H. T. Anthony (American) '[Specimens of New York Bill Posting]' 1863 E. & H. T. Anthony (American) '[Specimens of New York Bill Posting]' 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/e-h-t-anthony-specimens-of-new-york-bill-posting-1863.jpg)

![Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832-1909 Luxor) and James Robertson (British, 1813-1881) [Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem] 1856-1857 Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832-1909 Luxor) and James Robertson (British, 1813-1881) [Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem] 1856-1857](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/beato-dome.jpg)

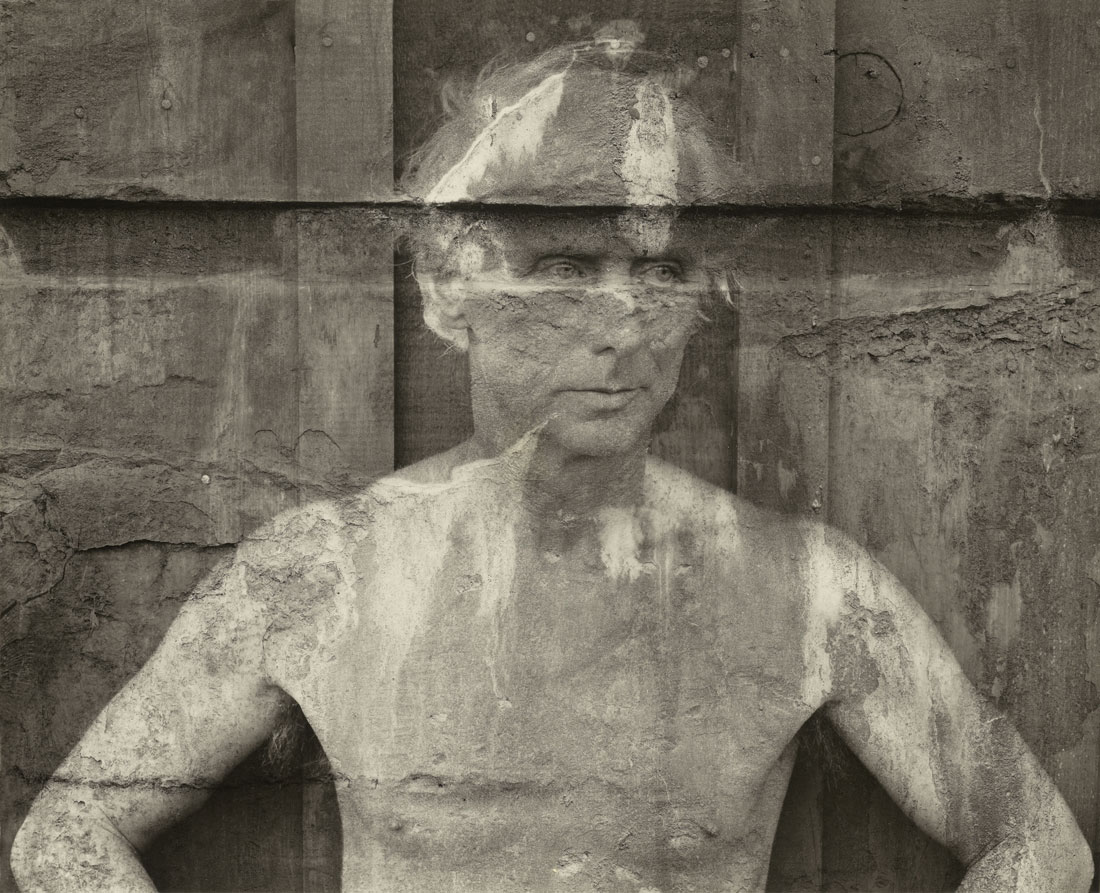

![R.C. Montgomery (American, active 1850s) '[Self-Portrait (?)]' 1850s R.C. Montgomery (American, active 1850s) '[Self-Portrait (?)]' 1850s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/r.c.-montgomery-self-portrait-1850s.jpg?w=623)

![Unknown (American) '[Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter]' c. 1865 Unknown (American) '[Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter]' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/unknown-american-decapitated-man-with-head-on-a-platter-c-1865.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.