Exhibition dates: 28th January – 4th May 2014

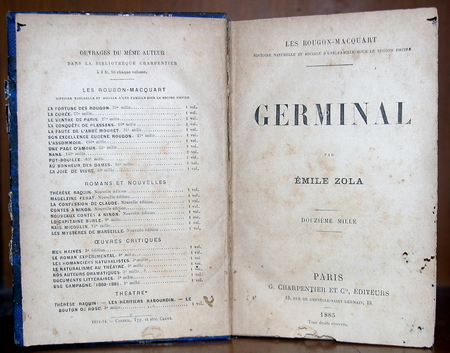

Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris)

Quai d’Anjou, 6h du matin

1924

Albumen silver print from glass negative

17.7 x 22.8cm (6 15/16 x 8 15/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, William Talbott Hillman Foundation Gift, 2005

If there is one city in the world in which I would really like to live, it would be Paris. I have loved her since first going there as a teenager and she has never foresaken that love: always romantic, beautiful, intriguing, Paris is my kind of city. As a flâneur there is much to observe, much to digest and assimilate through periods of reflection.

Where do you start? Steichen, Stieglitz, Fox Talbot, Marville, Brassaï, Jeanloup Sieff, Cartier-Bresson, Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, Nadar, any photographer of note but above all Atget – all acquiescent to her charms. Strange as it may seem, it is not that the photographer takes photos of Paris (as though possessing an object of desire), but that the city allows these revelations to occur as a kind of benediction, a kind of divine blessing. Am I making any sense here? Perhaps I am just too much in love, but having photographed in Pere-Lachaise Cemetery for example, there is nothing quite like the feeling I get when in the City of Light.

The photographs in this posting are magnificent. The intimacy of the Brassaï, the tonality of the Steichen; the dankness of the Marville and the informality of the Stieglitz. The first two Atget are cracking images. Note how the auteur éditeur uses the darkness of the tree trunks to divide the picture plane, better than anyone has done before or since. It is a pleasure to be able to show you Atget’s Work Room with Contact Printing Frames (c. 1910, below), an image I have never seen before in all the years I have been looking at his work. Make sure you enlarge the image to see all the details including the simplicity of the trestle table: “On the table are the wooden frames the photographer used to contact print his glass negatives; at right are several bins of negatives stacked vertically; below the table are his chemical trays; on the shelves above are stacks of paper albums – a shelf label reads escaliers et grilles (staircases and grills).”

I am particularly taken by the feather duster, the parcels wrapped in newspapers and tied with string, and intrigued by the print of a moonrise(?) over a bridge high up, tacked to the wall (see detail image below). Obviously this image meant a lot to him because it is the only one in the room and it would have taken a bit of an effort to put it up there. I wonder whose image it is, and what bridge it is of…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to The Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Oysters and a glass of wine, a corner café, the Sunday bird market on the Île de la Cité, a lover’s stolen kiss: Paris has loomed large in the imagination of artists, writers, and architects for centuries. For 175 years, it has attracted photographers from around the world who have succumbed to its spell and made it their home for part, if not all, of their lives.

Paris as Muse: Photography, 1840s-1930s (January 27 – May 4, 2014) celebrates the first 100 years of photography in Paris and features some 40 photographs, all drawn from the Museum’s collection. Known as the “City of Light” even before the birth of the medium in 1839, Paris has been muse to many of the most celebrated photographers, from Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (one of the field’s inventors) and Nadar to Charles Marville, Eugène Atget, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. The show focuses primarily on architectural views, street scenes, and interiors. It explores the physical shape and texture of Paris and how artists have found poetic ways to record its essential qualities using the camera.”

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris)

Nôtre Dame

1922

Albumen silver print from glass negative

18.2 x 22.1cm (7 1/8 x 8 11/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Joseph M. Cohen Gift, 2005

Atget likely avoided Nôtre Dame during his early career as it was already well documented by other photographers. In his old age, however, he worked more for his own pleasure and during the last five years of his life photographed the cathedral regularly. He always viewed it in an eccentric way – either in the distance, as here, or in detail.

Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris)

Untitled [Atget’s Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]

c. 1910

Albumen silver print from glass negative

20.9 x 17.3cm (8 1/4 x 6 13/16 in.)

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1990

This straightforward study by Atget of his own work room offers a rare glimpse of the inner sanctum of an auteur éditeur, as he described his profession. On the table are the wooden frames the photographer used to contact print his glass negatives; at right are several bins of negatives stacked vertically; below the table are his chemical trays; on the shelves above are stacks of paper albums – a shelf label reads escaliers et grilles (staircases and grills). Atget used these homemade albums to organise his vast picture collection from which he sold views of old Paris to clients.

Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris)

Untitled [Atget’s Work Room with Contact Printing Frames] (detail)

c. 1910

Albumen silver print from glass negative

20.9 x 17.3cm (8 1/4 x 6 13/16 in.)

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1990

Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris)

Marchand de Vin, Rue Boyer, Paris

1910-1911

Albumen silver print from glass negative

21.5 x 17.6cm (8 7/16 x 6 15/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Joseph M. Cohen Gift, 2005

Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris)

Boulevard de Strasbourg, Corsets, Paris

1912

Gelatin silver print from glass negative

22.4 x 17.5cm (8 13/16 x 6 7/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection

Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005

Atget found his vocation in photography in 1897, at the age of forty, after having been a merchant seaman, a minor actor, and a painter. He became obsessed with making what he termed “documents for artists” of Paris and its environs and compiling a visual compendium of the architecture, landscape, and artefacts that distinguish French culture and history. By the end of his life, Atget had amassed an archive of more than eight thousand negatives, which he organised into such categories as Parisian Interiors, Vehicles in Paris, and Petits Métiers (trades and professions).

In Atget’s inventory of Paris, shop windows figure prominently and the most arresting feature mannequin displays. In the 1920s the Surrealists recognised in Atget a kindred spirit and reproduced a number of his photographs in their journals and reviews. Antiquated mannequins such as the ones depicted here struck them as haunting, dreamlike analogues to the human form.

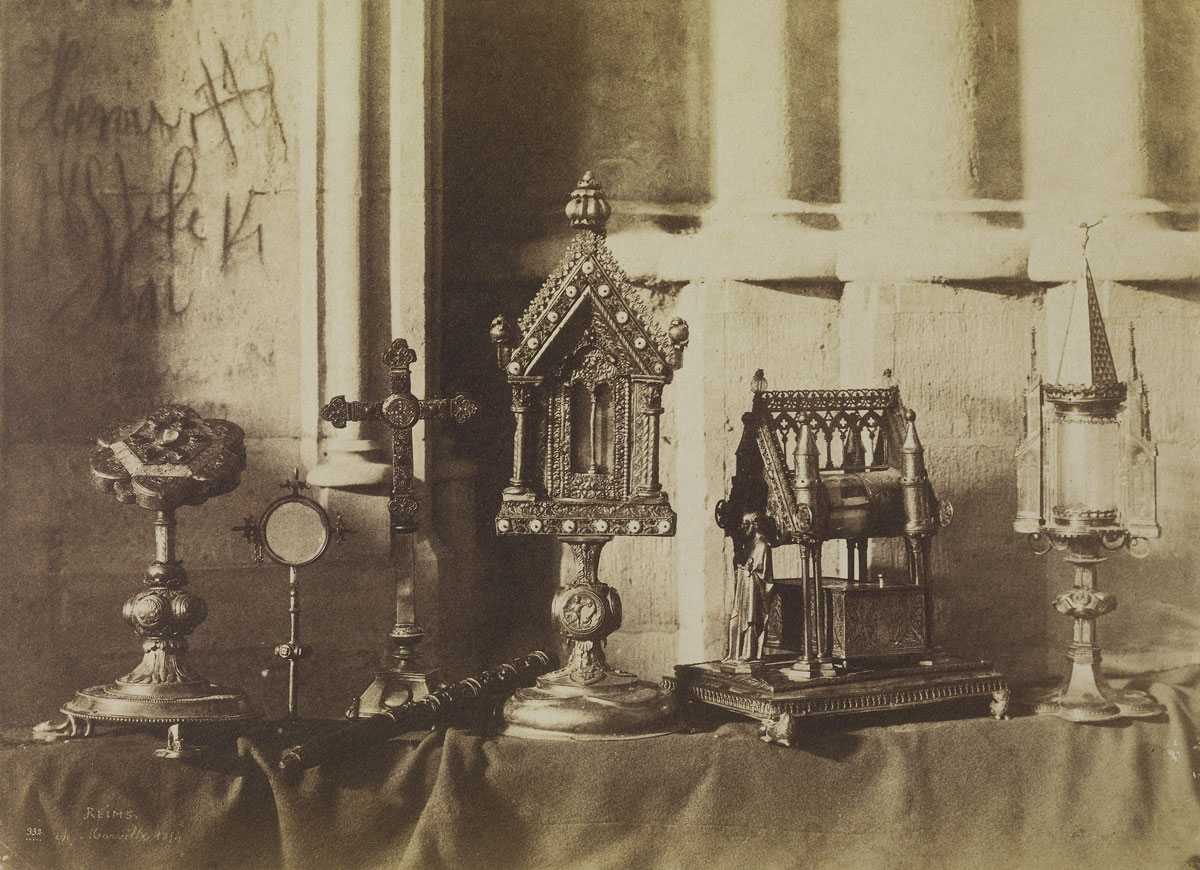

Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858)

Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904)

Untitled [The Pavillon de Flore and the Tuileries Gardens]

1849

Daguerreotype

15.2 x 18.7cm (6 x 7 3/8 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Taken in September 1849 from a window of the École des Beaux-Arts, this daguerreotype exhibits the dazzling exactitude and presence that characterise these mirrors of reality. True to the daguerreotype’s potential, stationary objects are rendered with remarkable precision; under magnification one can clearly discern minute architectural details on the Pavillon de Flore, features of statuary and potted trees in the Tuileries Gardens, even the chimney pots on the buildings in the background along the rue de Rivoli.

Daguerre himself had chosen a nearly identical vantage point in 1839 for one of his earliest demonstration pieces, and it may well have been with that archetypal image in mind that Choiselat and Ratel made this large daguerreotype a decade later. Choiselat and Ratel, among the earliest practitioners to utilise and improve upon Daguerre’s process, first published their methods for enhancing the sensitivity of the daguerreotype plate in 1840 and had achieved exposure times of under two seconds by 1843. Unlike Daguerre’s long exposure, which failed to record the presence of moving figures, this image includes people (albeit slightly blurred) outside the garden gates, on the Pont Royal, and peering over the quai wall above the floating warm-bath establishment moored in the Seine. Still more striking is the dramatic rendering of the cloud-laden sky, achieved by the innovative technique of masking the upper portion of the plate partway through the exposure.

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 1800-1877)

The Boulevards at Paris

May-June 1843

Salted paper print from paper negative

15.1 x 19.9cm (5 15/16 x 7 13/16 in. )

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Talbot traveled to Paris in May 1843 to negotiate a licensing agreement for the French rights to his patented calotype process and, with Henneman, to give first hand instruction in its use to the licensee, the Marquis of Bassano.

No doubt excited to be traveling on the continent with a photographic camera for the first time, Talbot seized upon the chance to fulfil the fantasy he had first imagined on the shores of Lake Como ten years before. Although his business arrangements ultimately yielded no gain, Talbot’s views of the elegant new boulevards of the French capital are highly successful, a lively balance to the studied pictures made at Lacock Abbey. Filled with the incidental details of urban life, architectural ornamentation, and the play of spring light, this photograph, unlike much of the earlier work, is not a demonstration piece but rather a picture of the real world. The animated roofline punctuated with chimney pots, the deep shopfront awning, the line of waiting horse and carriages, the postered kiosks, and the characteristically French shuttered windows all evoke as vivid a notion of mid-nineteenth-century Paris now as they must have when Talbot first showed the photographs to his friends and family in England.

A variant of this scene, taken from a higher floor in Talbot’s Paris hotel, appeared as plate 2 in The Pencil of Nature.

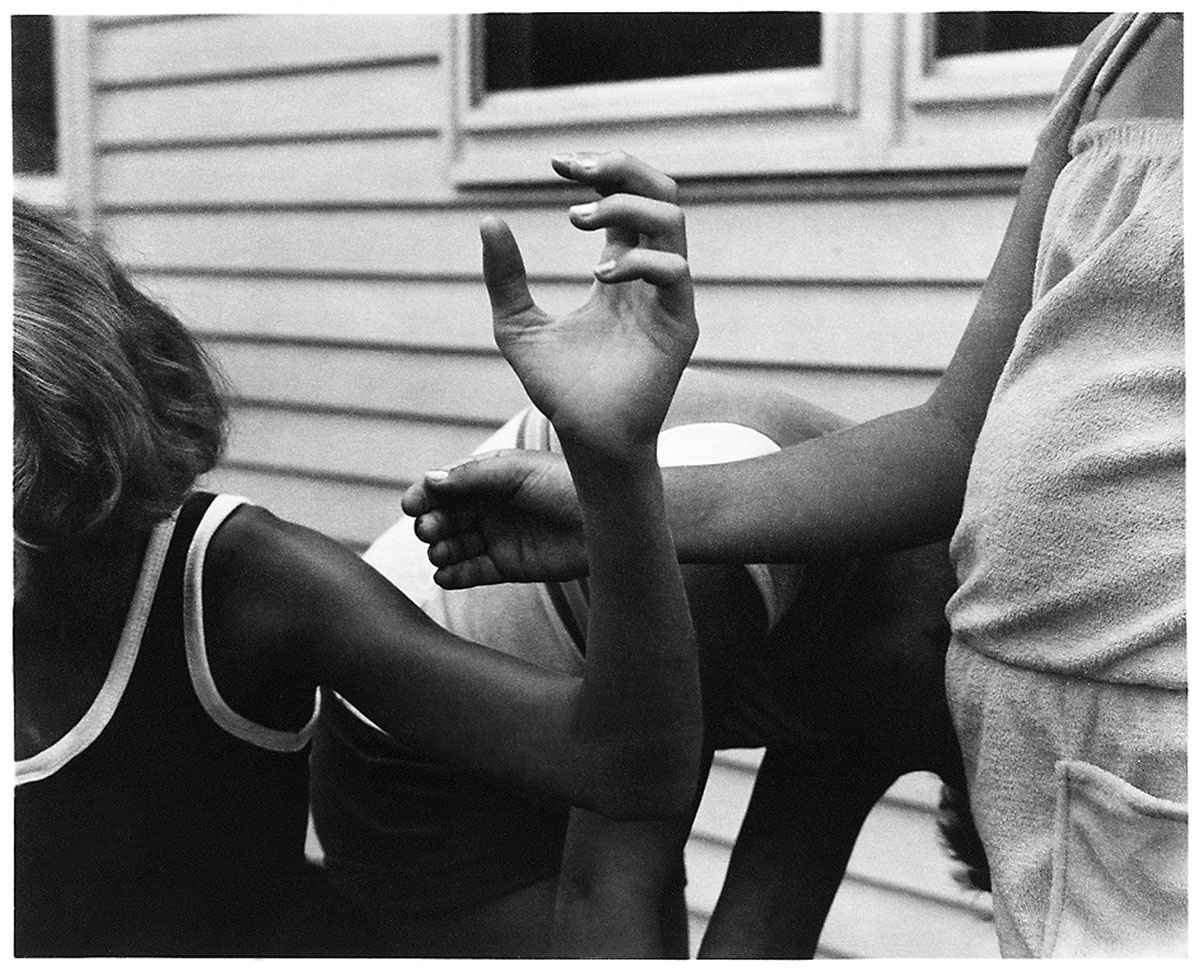

Alfred Stieglitz (American, Hoboken, New Jersey 1864 – 1946 New York)

A Snapshot, Paris

1911, printed 1912

Photogravure

13.8 x 17.4cm (5 7/16 x 6 7/8 in.)

Gift of J. B. Neumann, 1958

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, Stieglitz trained to be an engineer in Germany and moved to New York in 1890. His lifelong ambition as an artist (and advocate for the arts) was to prove that photography was as capable of artistic expression as painting or sculpture. As the editor of Camera Notes, the journal of the Camera Club of New York, and then later Camera Work (1902-1917), Stieglitz espoused his belief in the aesthetic potential of the medium. He published work by photographers who shared his conviction alongside European modernists such as Auguste Rodin, Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brancusi, and Francis Picabia.

Michel Seuphor (Belgian, 1901-1999)

Paris

1929

Gelatin silver print

11.4 x 16.4cm (4 1/2 x 6 7/16 in.)

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1994

© 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Belgian painter, poet, designer, and art critic Seuphor moved to Paris in 1925 and entered the artistic community of such expatriate artists as Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Theo van Doesburg. Little is known about his work with the camera except that this photograph was made the year Seuphor founded Cercle et Carré (Circle and Square), a group dedicated to abstraction that would include Kandinsky, Mondrian, Jean Arp, Kurt Schwitters, and Le Corbusier.

Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858)

Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904)

Défilé sur le Pont-Royal

May 1, 1844

Daguerreotype

Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

In January 1839 the Romantic painter and printmaker Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) showed members of the French Académie des Sciences an invention he believed would forever change visual representation: photography. Each daguerreotype (as Daguerre dubbed his invention) is an image produced on a highly polished, silver-plated sheet of copper.

Using an “accelerating liquid” of their own devising, the daguerreotypists Choiselat and Ratel were able to reduce exposure times from minutes to seconds, which allowed them to capture events as they happened. Here the mounted guards stationed along one of Paris’s most famous bridges registered clearly on the daguerreotype plate, but even with a short exposure time the moving crowds and rolling carriages became a blur of activity.

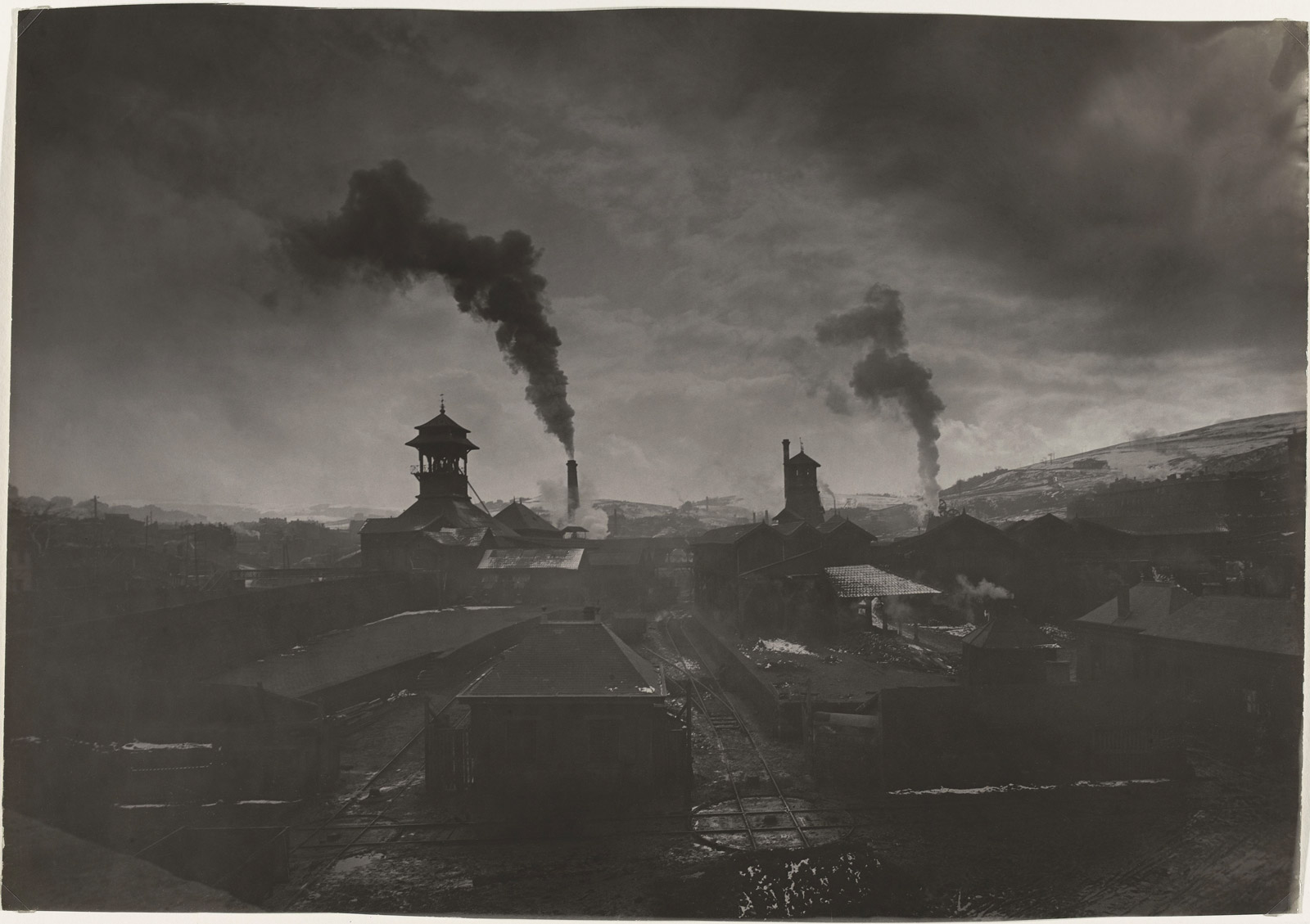

Charles Marville (French, Paris 1813 – 1879 Paris)

Rue Traversine (from the Rue d’Arras)

c. 1868

Albumen silver print from glass negative

34.8 x 27.5cm (13 11/16 x 10 13/16 in. )

Gift of Howard Stein, 2010

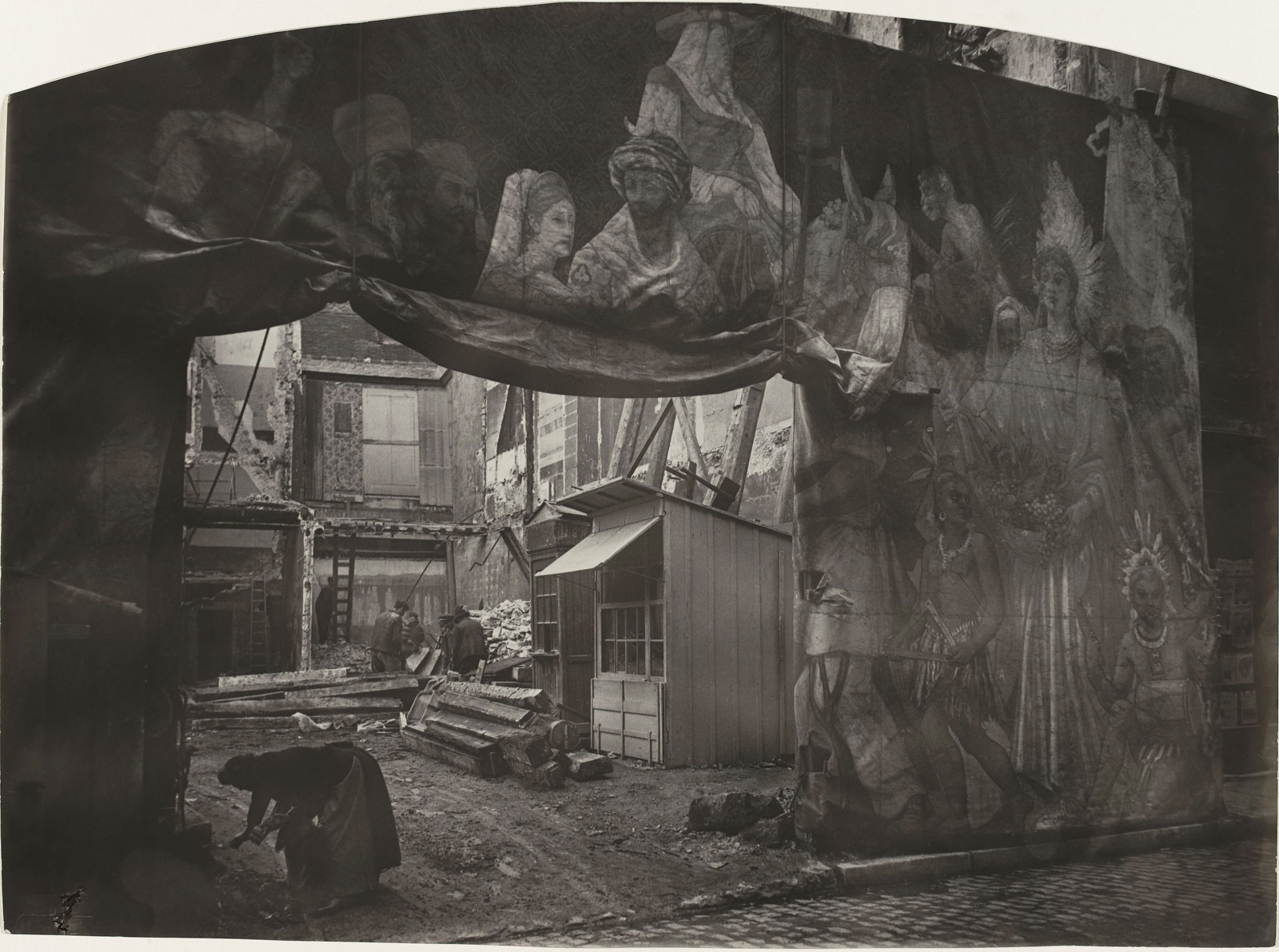

Brassaï (French born Romania, Brașov 1899 – 1984 Côte d’Azur)

Street Fair, Boulevard St. Jacques, Paris

1931

Gelatin silver print

22.9 x 17.1cm (9 x 6 3/4 in.)

Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2007

© The Estate of Brassai

Born in Transylvania, Gyula Halász studied painting and sculpture in Hungary and moved to Paris in 1924 to work as a journalist. About 1930 he changed his name to Brassaï and took up photography. The camera became a constant companion on his nightly walks through the city’s seamier quarters, where he aimed his lens at showgirls, prostitutes, ragpickers, transvestites, and other inhabitants of the demimonde. His first and most famous book of photographs, Paris de nuit (Paris by Night), published in 1933, includes a variation of this scene of three masked women tempting men into a sideshow.

Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 – 1973 West Redding, Connecticut)

Untitled [Brancusi’s Studio]

c. 1920

Gelatin silver print

24.4 x 19.4cm (9 5/8 x 7 5/8 in.)

Gift of Grace M. Mayer, 1992

Reprinted with permission of Joanna T. Steichen.

Steichen lived in Paris on and off from 1900 to 1924, making paintings and photographs. A cofounder with Alfred Stieglitz of the Photo-Secession, Steichen offered his former New York studio to the fledgling organisation as an exhibition space in 1905. Known first as the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession and later simply by its address on Fifth Avenue, 291, the gallery introduced modern French art to America through the works of Rodin, Matisse, Cézanne, and, in 1914, Constantin Brancusi.

Steichen and Brancusi, who met at Rodin’s studio, became lifelong friends. This view of a corner of Brancusi’s studio on the impasse Roncin shows several identifiable works, including Cup (1917) and Endless Column (1918). The photograph’s centrepiece is the elegant polished bronze Golden Bird (1919), which soars above the other forms. Distinct from Brancusi’s studio photographs – subjective meditations on his own creations – Steichen’s view is more orchestrated, geometric, and objective. Golden Bird is centred, the light modulated, and the constellation of masses carefully balanced in the space defined by the camera. A respectful acknowledgment of the essential abstraction of the sculpture, the photograph seems decidedly modern and presages the formal studio photographs Steichen made in the service of Vanity Fair and Vogue beginning in 1923.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Thursday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Closed Wednesday

![Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atgets-work-room-web1.jpg?w=650&h=783)

![Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857–1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 (detail) Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857–1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atget-workroom-detail-web.jpg)

![Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858) Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904) 'Untitled [The Pavillon de Flore and the Tuileries Gardens]' 1849 Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858) Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904) 'Untitled [The Pavillon de Flore and the Tuileries Gardens]' 1849](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/the-pavillon-de-flore-web.jpg)

![Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 - 1973 West Redding, Connecticut) 'Untitled [Brancusi's Studio]' c. 1920 Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 - 1973 West Redding, Connecticut) 'Untitled [Brancusi's Studio]' c. 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/edward_steichen_brancusis_studio_1920-web.jpg?w=650&h=816)

You must be logged in to post a comment.