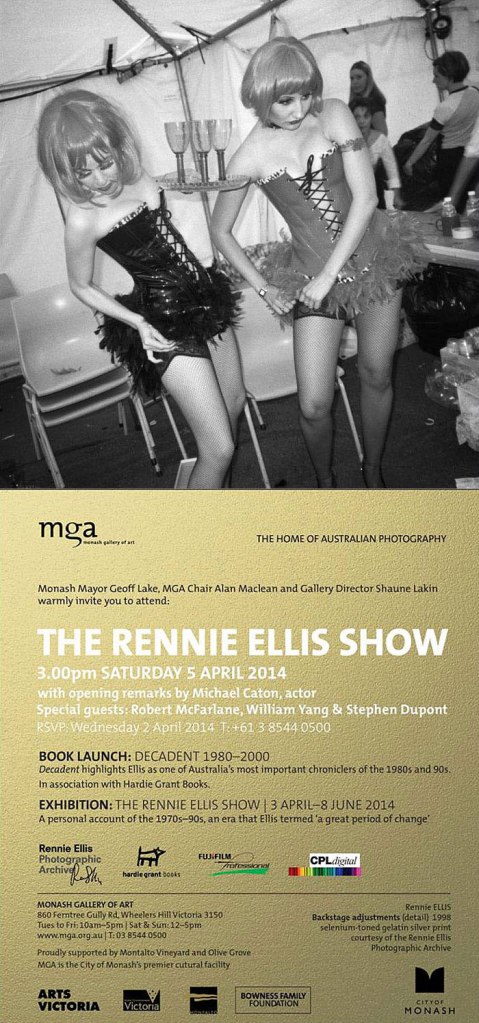

December 2018

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this posting contains images and names of people who may have since passed away.

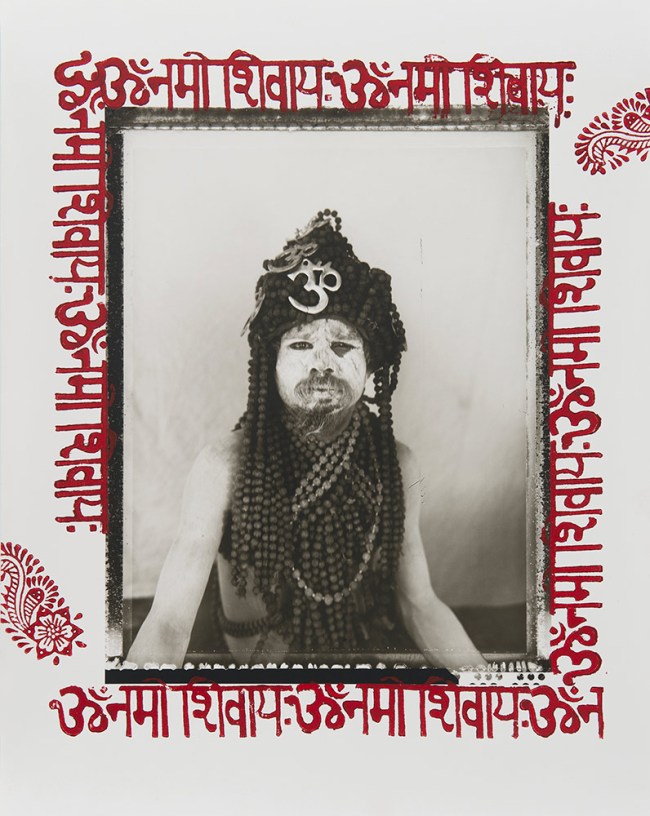

Anonymous photographer

Parlour, Broken Hill, New South Wales

1895

Gelatin silver print

A German Rönisch piano with a copy of “A Country Girl” above the keyboard (I can’t find any reference online to this song?). To the right, a two-panel screen with Christmas cards, one with the words “Hearty Greetings” and another with the date “1895”.

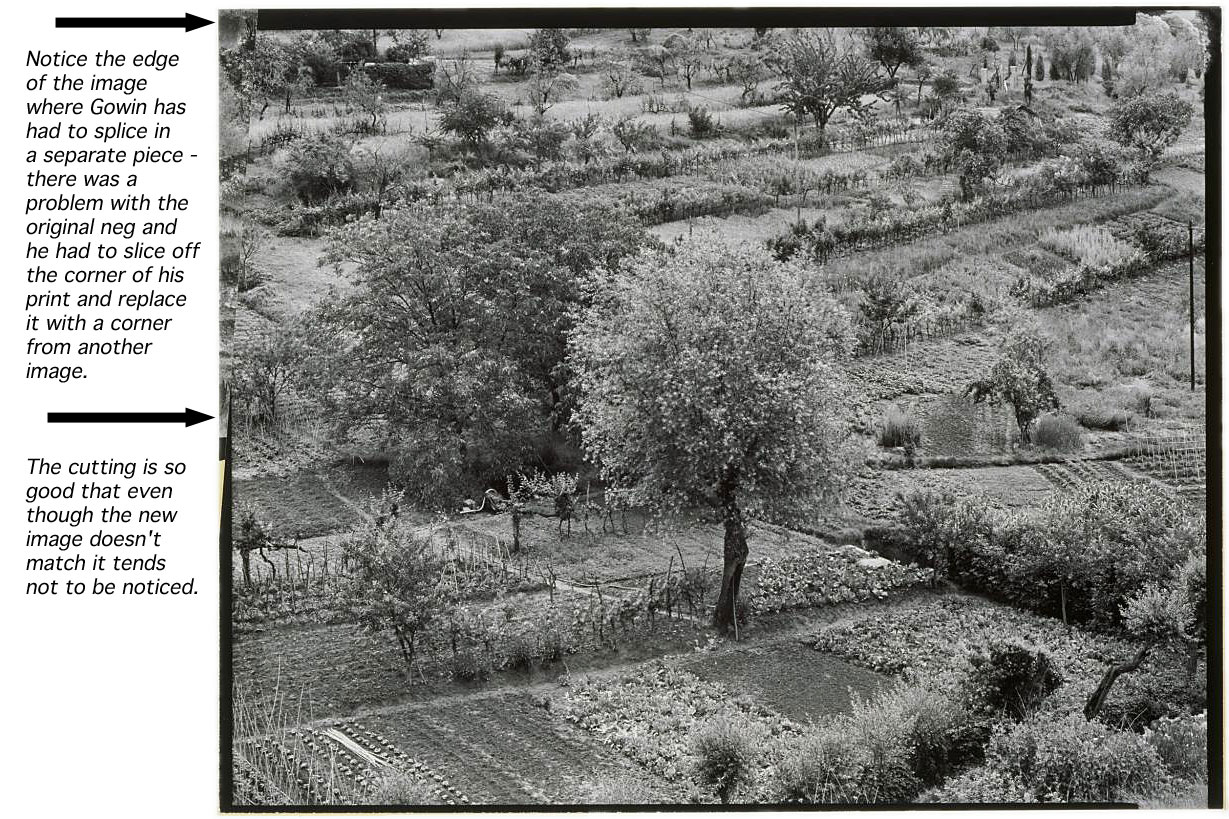

The last posting for 2018 features a selection of Australian black and white photographs that belong to a friend of mine, who has kindly allowed me to scan and publish them. The images have been digitally cleaned after scanning. The titles of the photographs are annotated on the back of the images.

The photographs are mainly of pastoral, colonial, outback, station, homestead and mining life, and picture the remoteness of these properties and towns c. 1910s-1950s. They also evidence the nature of white, colonial, patriarchal society much in evidence on pastoral stations during this time period. Hardly a women appears in these photographs, and Indigenous Australians usually only appear as stockmen or trackers.

Of most interest to me are the photographs of Poolamacca Station, c. 1910.

In the first photograph, Christmas Day, Poolamacca Station, north of Broken Hill, New South Wales (below) what is going on in the photograph remains a bit of a mystery. A man lies, apparently comatose, on a mattress outside, on the ground, in the strong midday sun (note the short length of the shadows). The man to the right reaches forward to clasp his hand, while other men around clasp each other’s hands to form a circle around the body. Some men look down at the body on the mattress, others stare straight at the camera, smoking cigars. A handsome man with a moustache, on bended knee and wearing a waistcoat, third from left, smiles broadly at the camera. A man at the back of the group rests his head against the stone of the building, eyes closed, as though he is drunk. The length of the exposure can be judged by the several blurred figures, particularly of the man standing and the head of the man at right rear.

Several scenarios are possible: is the man lying on the mattress really ill? Is it some kind of religious play being performed on Christmas Day? Are they all drunk and mucking about? And/or is it some kind of game, a charade? The circle of hands suggests to me it is a type of friendship game for the person lying on the mattress, a bond between them all, a supposition reinforced by the handsome man smiling at the camera. If the situation were serious, he would not be smiling. The second photograph, taken at the same time (before or afterwards?), features the men now accompanied by women, piled high on a cart pulled by four horses. At left behind the front horses can be seen what I believe is the same corrugated iron and building that appears at left in the first image. We can only guess the narrative in the first photograph because we do not have enough clues. Nevertheless, the photograph and its story remain a fascinating mystery.

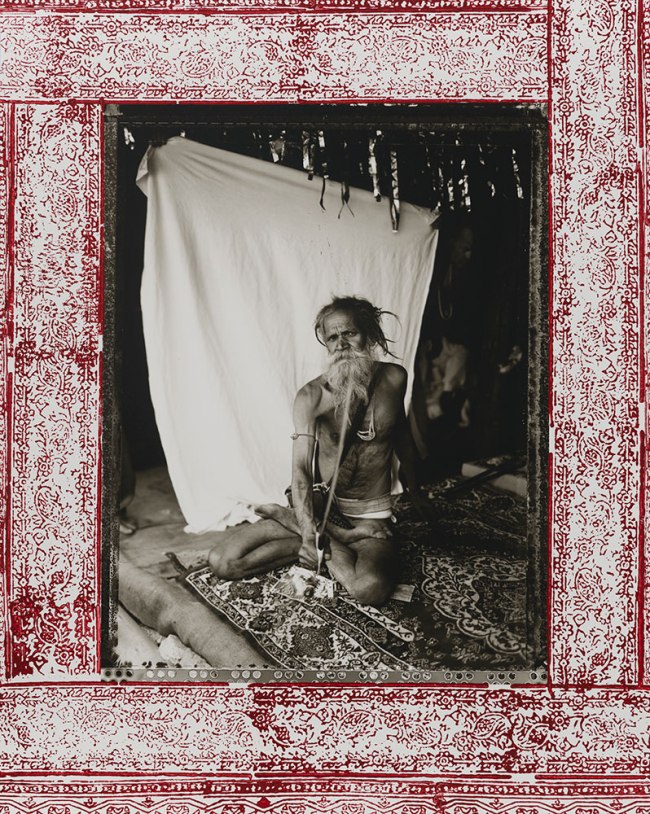

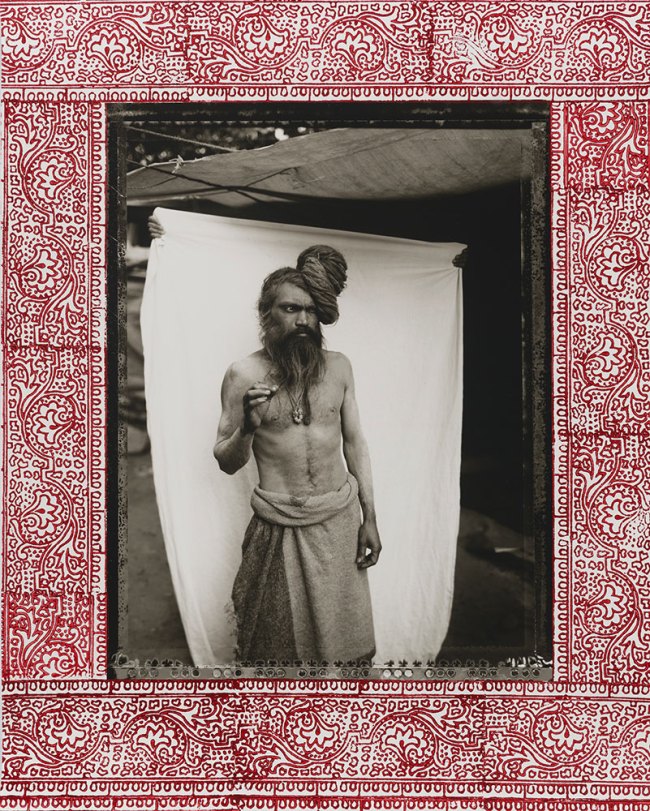

The third and fourth photographs also tell an enigmatic story. Again, they have both been taken at the same time, as can be seen by the same riveted water tank behind each group in the photographs. The same fair-haired child also appears at right in the first photograph and sitting in his mother’s lap in the second photograph. From the length of his white apron, the white man in the photograph is possibly a cook or butcher at Poolamacca Station. The photographs also put lie to George Dutton’s claim that “in 1910 there was only two boys left” at Poolamacca Station (see extract from The Mutawintji research project report below).

What we have here is, possibly, an interracial marriage or partnership, a frontier marriage? whose Australian

“… boundary-crossing lovers are still omitted from the historical memory of the nation. Despite their long-term, cross-generational legacies, these unions virtually became a secret of state. …

These lovers generated families at the core of the cultural and historical interface that became the Australian nation. However, the young coloniser state did not like it.

From the coming of Federation until the 1960s, love affairs between Aboriginal people and others were severely restricted across all of northern Australia. Queensland moved rapidly to curb courtship and marriage between white Australian men and Aboriginal women. Western Australia and the Northern Territory followed. That didn’t mean that relationships stopped. Love often prevailed. …

Police and missionary enforcers placed white working class men living with Aboriginal women under sexual surveillance, forcing them to either apply for permits or be arrested. Many were fined or jailed. The Chief Protectors, who had the power to decide who could marry whom, regularly refused their written requests to marry.

Although largely untouched by the new laws, magistrates, pastoralists, police and missionaries also fell in love with Aboriginal women. It was not uncommon for cattle station owners and managers to practice a form of cross-frontier polygamy, sustaining relationships with both a white wife and an Aboriginal woman. …

Australian lovers who were willing to cross these punitive marriage bars showed an uncommon courage. Out of this “illicit love” came new generations who carry on the battles for their ancestors and their communities. Some are the very same people who are required today to justify their Aboriginality because of mixed descent. They have to keep explaining who they are and why they are speaking out.”1

What these rare photographs speak of is a love, an intimacy, and affection within a family unit. Just look at the gentleness as the man holds the child’s hands and the smile on the mother’s face. It is just a gorgeous photograph of love and happiness between white and black, of a smiling women with her children. Passed down through time, it is a privilege to be able to look, to understand, to feel the power of this relationship all of these years later.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

All of these photographs have been digitally cleaned. Many thankx to my friend Daniel for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

1/ Professor Ann McGrath. “Celebrating white men and their black lovers,” on The Sydney Morning Herald website [Online] Cited 30/12/2018

1910s Australia

Anonymous photographer

Christmas Day, Poolamacca Station, north of Broken Hill, New South Wales

c. 1910

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Christmas Day, Poolamacca Station, north of Broken Hill, New South Wales (detail)

c. 1910

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Christmas guests, Poolamacca Station, north of Broken Hill, New South Wales

c. 1910

Gelatin silver print

Poolamacca Station

It is situated about 50 kilometres (31 mi) north of Broken Hill and 174 kilometres (108 mi) north east of Mannahill at the eastern end of the Barrier Range adjoining Sturts Meadows. The station currently occupies an area of 40,000 acres (16,187 ha). The abandoned township of Tarrawingee is situated within the boundaries of the station.

The property was established in the 1860s with the first owners of the run being Messrs Jones and Goode. In 1867 a shepherd staged a hoax with a white quartz gold find that lead to an aborted gold rush to the area. The first property in the area was Mount Gipps Station In 1865 with Corona, Mundi Mundi and Poolamacca being established shortly afterward. Sidney Kidman worked at Poolamacca during the 1870s as a boundary rider and stockman.

In 1877 the property was put up for auction by the trustees of the estate of Messrs E. M. Bagot and G. Bennett. At this stage the property was approximately 900 square miles (2,331 km2) in size along with a flock of 34,906 sheep. The property comprised ten separate runs including the 64,000 acre Bijerkerno run to the 25,000 acre Torrowangee run.

John Brougham acquired a half share in Poolamacca in 1889 and later secured the lease outright. Brougham remained at Poolamacca until 1915 when he moved to Adelaide. In 1892 approximately 50 Aboriginal people, were moved to Poolamacca station which under the regime of the late owner, Mr J. Brougham, constituted a sanctuary for the last remaining Aboriginal inhabitants of the Barrier Ranges and adjacent areas.

The lease was later split into two properties: Poolamacca and Wilangee in the 1920s. Moss Smith sold the property in 1927 to the Pastoral company of Adelaide following the death of his daughter whose body was found buried in a warren in Poolamacca late the year before after she had gone missing for four months.

In 2002 the property was acquired by the Indigenous Land Corporation with the title holders being the Wilyakali Aboriginal Corporation when the property occupied an area of 507 square kilometres (196 sq mi).

Text from the Wikipedia website

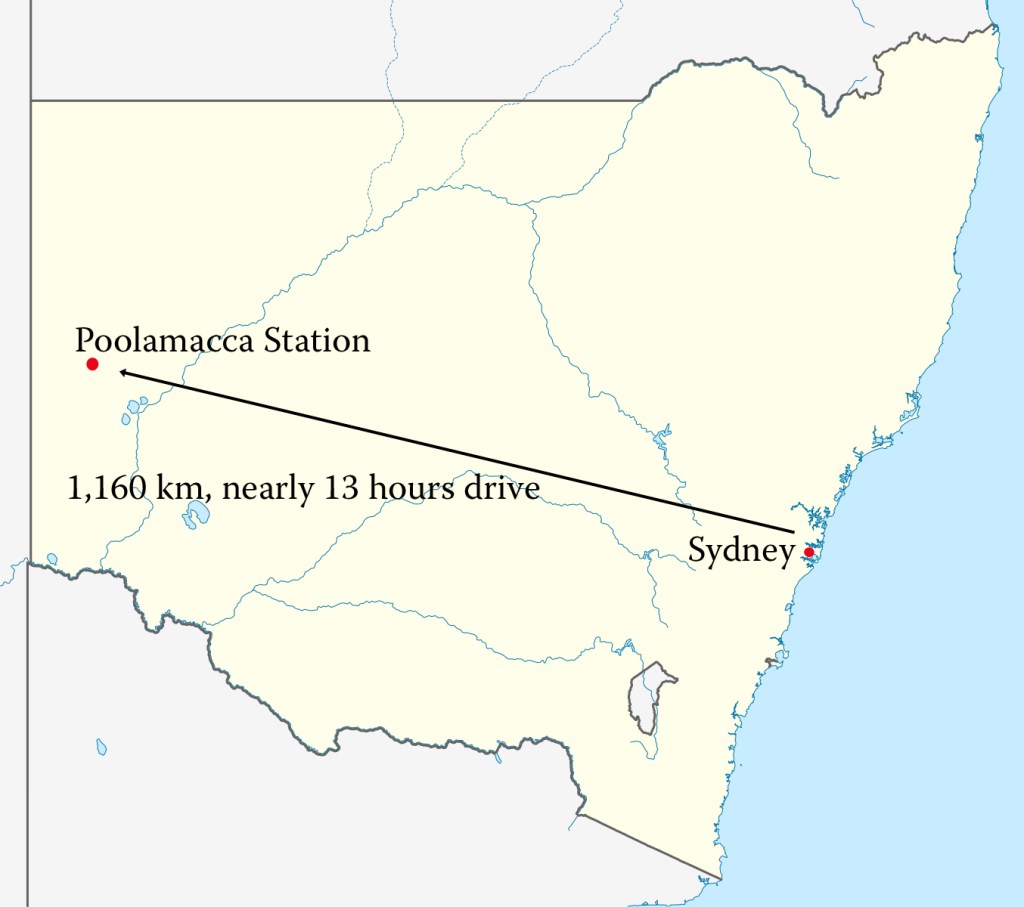

Sydney to Poolamacca map, New South Wales, Australia

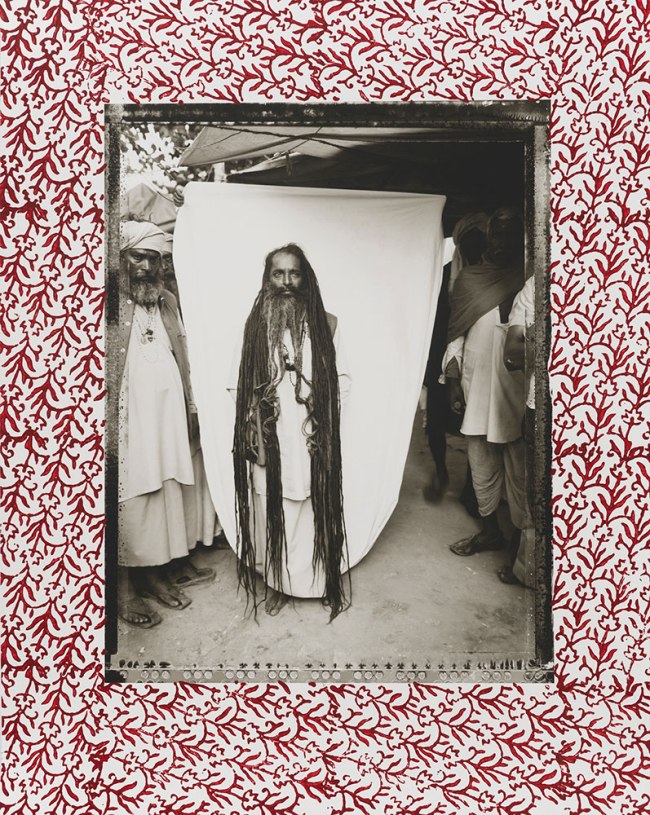

Anonymous photographer

Poolamacca Station, north of Broken Hill, New South Wales

c. 1910

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Poolamacca Station, north of Broken Hill, New South Wales (detail)

c. 1910

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Poolamacca Station, north of Broken Hill, New South Wales

c. 1910

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Poolamacca Station, north of Broken Hill, New South Wales (detail)

c. 1910

Gelatin silver print

Extracts from The Mutawintji research project

Keith Brougham, the son of John Brougham, the owner of Poolamacca (and brother of John Brougham Jnr of Gnalta station, now part of Mutawintji National Park), describes how the first pastoralists mapped out their original station boundaries by including the best waterholes:

“The wild aborigines were a help by following their tracks, as they knew of any existing water away from the river… One old aborigine who claims to be from one of the wild tribes told me the walkabout was a good sign to watch for – at that time a mob were having a hunt for a new hunting ground and had camped about midday. While they were stopped a pregnant woman had a baby there. Next day they were off again, mother and child and went straight to a waterhole, which the white people found by following their tracks” (Brougham, K.W.C. 1920, West of the Darling, MS, State Library of South Australia, p. 14)

… In 1862, the area north-west of Mt Murchison on the Darling River near present day Wilcannia was still frontier country. Mt Gipps station7, set up in 1865 (Kearns 1982), was the first station in the Broken Hill area. It included the country to the north of Broken Hill and the hill that was to become the Broken Hill mine and city. Mt Gipps was followed soon after by Poolamacca, Corona and Mundi Mundi.

No actual descriptions of the annexation of Mutawintji by pastoralists have been found so far, but as permanent waterholes are few to the north-west of the Darling River, descriptions of the annexure of other important water sources such as Yancannia in the mid 1860s suggest that there was likely to have been conflict. Yancannia station, to the north of Mutawintji, had been established by 1865 and contemporary accounts describe conflict with the local Aboriginal people. By 1872 the Aboriginal people of Yancannia gave the owners “very little trouble” and “a few of them [were] very useful” (Reid in Shaw, M.T. 1987, Yancannia Creek, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, p. 104).

Dr Jeremy Beckett, Dr Luise Hercus, Dr Sarah Martin (edited by Claire Colyer). The Mutawintji research project report. MUTAWINTJI: Aboriginal Cultural Association with Mutawintji National Park. Published in 2008 by the Office of the Registrar, Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), pp. 9-10.

It is clear from the Bonney records that people moved backwards and forwards between Yancannia, Momba, Tarella, Wonnaminta, Poolamacca and Gnalta/Mootwingee stations from the 1860s and through the 1880s. Bonney lists about 44 people as living at Momba and Tarella around 1881; some of the people from Momba have been traced and the descendents of some of the people Bonney described are Aboriginal owners of Mutawintji National Park. …

In 1892 about 50 Aboriginal people, including Outalpa George, were camped near Olary. At about this time they moved to Poolamacca station which “under the regime of the late owner, Mr J. Brougham, constituted a sanctuary for the last remaining Aboriginal inhabitants of the Barrier Ranges and adjacent areas” (Mawson, D. and Hossfeld, P.S. 1926, ‘Relics of Aboriginal Occupation in the Olary District’, Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 50, pp. 17-25).

Keith Brougham, the son of John Brougham, writes about the 1890s:

“[in] 1892 [at] Poolamacca … we were amazed by the number of Aboriginals that were there… I had a boy mate staying with me and about two hundred blacks were camped in a sort of inlet in the hills of Silverton Hill, as it was called west of the homestead … The Aboriginals were practically in their wild state and did not speak our language” (Brougham MS n.d, p.1)

“… cotton dresses, high coloured and a great favourite of the [women] went as soon as they were landed, and olive oil for the [women’s] hair, always in demand” (Brougham MS n.d, p.2).

“[the Aboriginal people] were very handy in the woolshed at shearing time. The [women] did all the piece picking and men on the tables and picking up. The pickers were excellent at their job and all had a good eye, male and female” (Brougham MS n.d, p.3)

“… At Poolamacca my mother … employed a … girl who was neat and tidy, an extra good worker, and in 1896 she was really good” (Brougham MS n.d, p.12)

“… [at] Euriowie we had a lot of aboriginals working in the creeks surrounding this country picking up slugs of pure tin and bagging it” (Brougham MS n.d, p.23).

The APB [Aboriginal Protection Board] minutes recorded between 1890 and 1901 seldom mention the Mutawintji area. The only stations in the far north-west that received help from the APB were Poolamacca, occasionally Sturts Meadows, and the fringe camps at Milparinka, Tibooburra, Wanaaring and Wilcannia. The only station that consistently received rations throughout 1890-1901 was Poolamacca. Sturts Meadows (just to the west of Mutawintji) received rations in 1893, 1897 and 1898. Most stations either managed to fully employ the Aboriginal people living there or provided food and clothing of some sort without asking for compensation. …

During John Brougham’s time at Poolamacca during the 1890s and early 1900s, the station was something of a sanctuary for Aboriginal people but many had moved on by the time the Brougham family left. Some followed the Broughams to Gnalta station (now part of Mutawintji National Park) while others went to stations like Yancannia, where a large number of Aboriginal people lived and worked (Shaw, M.T. 1987, Yancannia Creek, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne). …

According to George Dutton, who was born on Yancannia station, there was a sizeable Aboriginal population at Poolamacca until about 1910, but almost none thereafter. George Dutton told Jeremy Beckett:

“At Poolamacca in 1901 there was a big mob of blackfellas, two hundred men without the women and kids. When I went back in 1910 there was only two boys left and graves all round” (Beckett, J. 1978, ‘George Dutton’s Country: Portrait of an Aboriginal Drover’, Aboriginal History, vol. 2 (1), pp. 19).

Dr Jeremy Beckett, Dr Luise Hercus, Dr Sarah Martin (edited by Claire Colyer). The Mutawintji research project report. MUTAWINTJI: Aboriginal Cultural Association with Mutawintji National Park. Published in 2008 by the Office of the Registrar, Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), pp. 14-16.

Anonymous photographer

Banjo playing in the garden, Broken Hill, far west of outback New South Wales

c. 1910-1920

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Banjo playing in the garden, Broken Hill, far west of outback New South Wales (detail)

c. 1910-1920

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Banjo playing in the garden, Broken Hill, far west of outback New South Wales (detail)

c. 1910-1920

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Dr Tham?, Wagga Wagga, New South Wales

c. 1900-1910

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Dr Tham?, Wagga Wagga, New South Wales (detail)

c. 1900-1910

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Horse and trap, Wagga Wagga, New South Wales

c. 1910

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Largs Pier Hotel, North-western suburb of Adelaide, South Australia

c. 1910

Gelatin silver print

Largs Pier Hotel

Largs Pier Hotel is located on the corner of The Esplanade and Jetty Road in Largs Bay, South Australia.

The Largs Pier Hotel opened in 1882 on the same day as the Largs Bay Railway and Pier. Believed to be 23rd of December according to The Port Adelaide Historical Society. From 1882 till around 1892 the Largs Pier was the primary port of call for New Australians travelling from Europe. Many of these immigrants spent their first nights in Australia at the hotel.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Largs Pier Hotel, South Australia today

1930s Australia

Anonymous photographer

Alice Springs

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Alice Springs (detail)

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

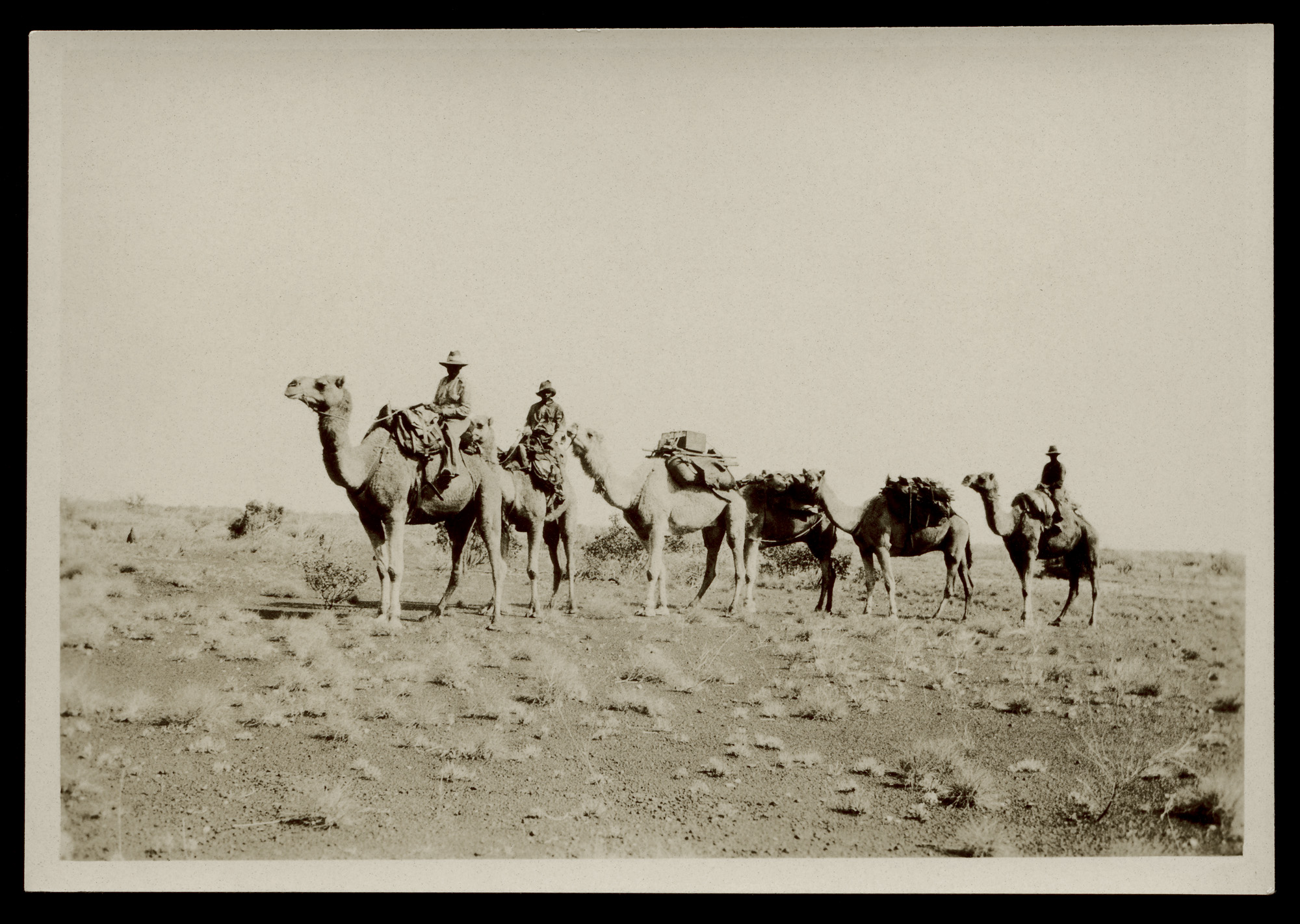

Police camels

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

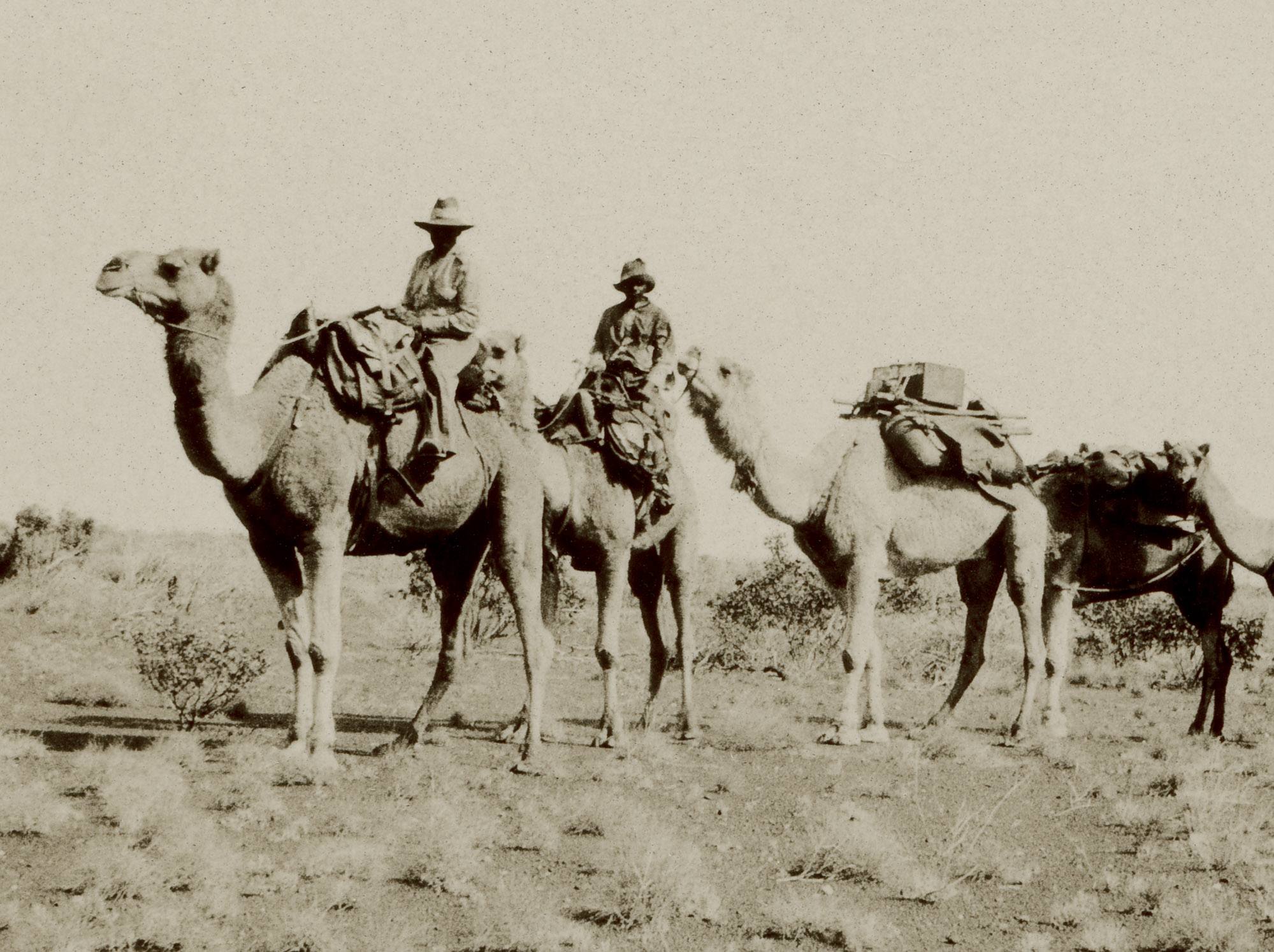

Anonymous photographer

Police camels (detail)

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Note the Aboriginal police tracker second from left. This could be in the Northern Territory.

Anonymous photographer

At the Granites

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

This photograph is possibly from around the Granites gold mine in the Tanami Desert of the Northern Territory of Australia. You can make out the word “gold” on the truck behind the men.

Gold was discovered in the Tanami Desert by Alan Davidson. He arrived in the area in 1898 prospecting until 1901. He took the name Tanami for the region from local Aboriginal people who visited his camp. “On inquiry [he] learned that the native name of the rockholes (from [which the party obtained water] was Tanami, and that they “never died,” he said. Davidson showed the gold specimens to these Aboriginal people, who recognised it and described “mobs of similar stone to the east, together with a large creek containing plenty of water and fish. This they said was “two days’ sleep to the south of east”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Anonymous photographer

At the Granites (detail)

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Note the man crouching at left holding a Kodak box camera, and the folding camera (most probably a Kodak as well) at the feet of the man third from right.

Anonymous photographer

At the Granites (detail)

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

1950s Australia

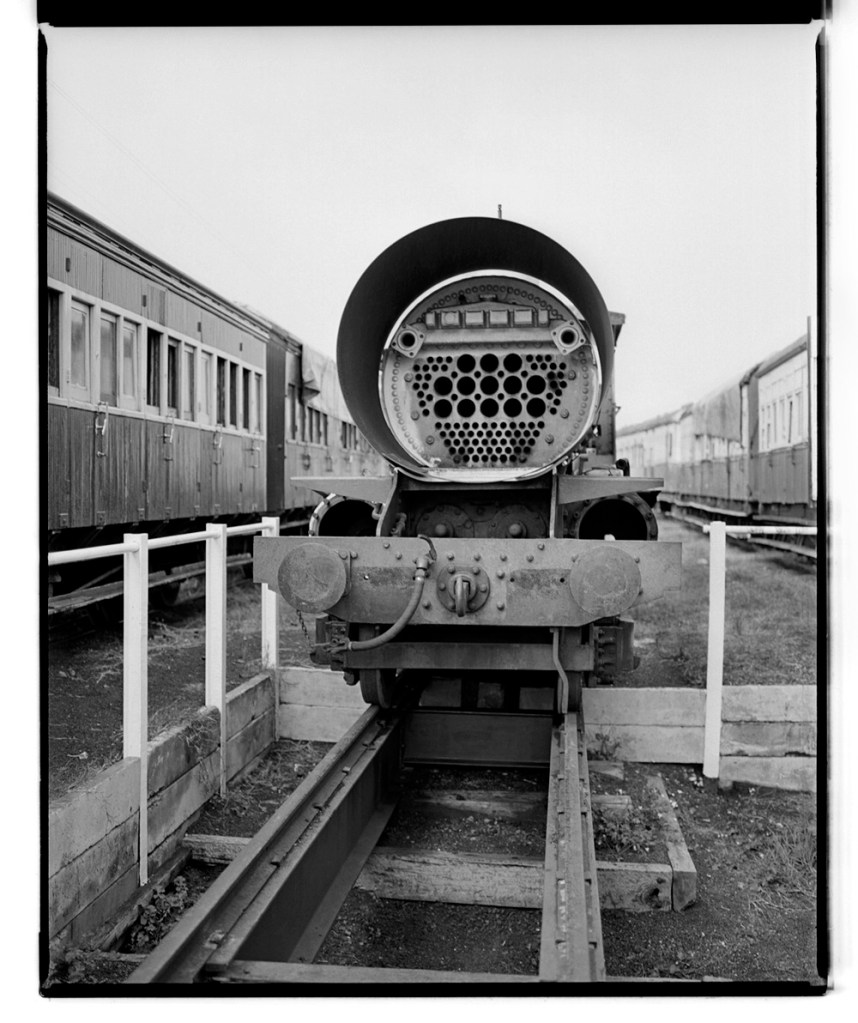

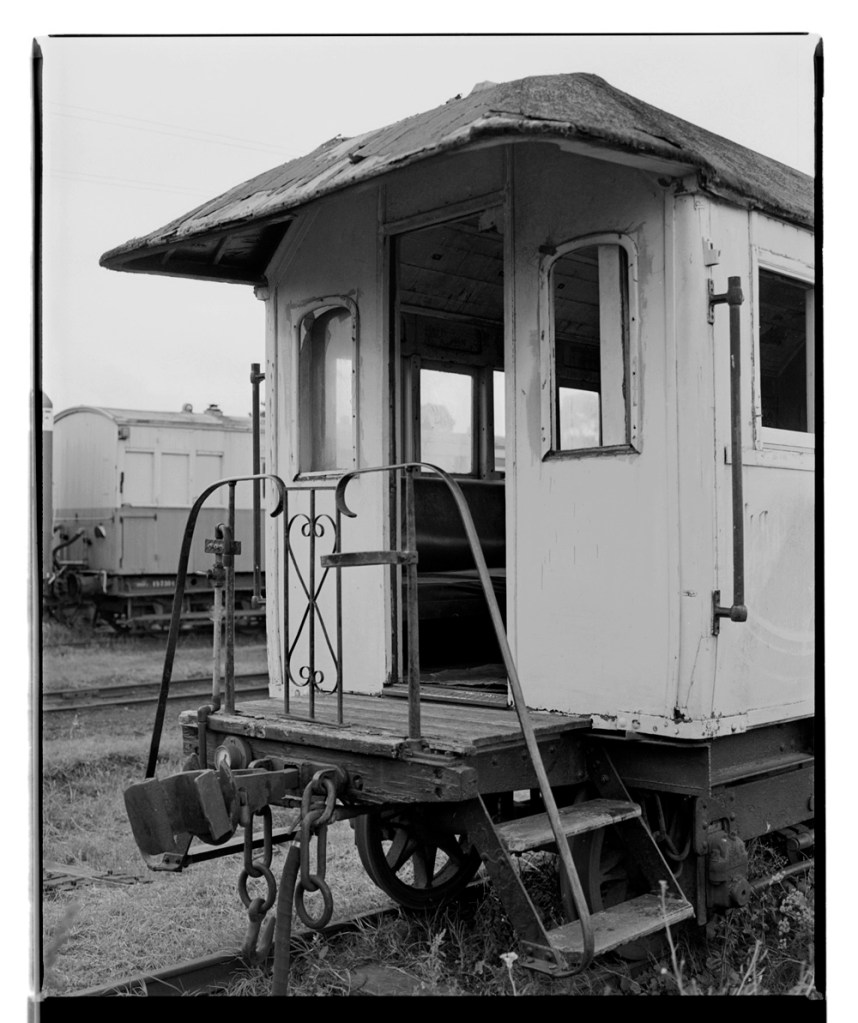

Anonymous photographer

Roy Hill Homestead, Pilbara region of Western Australia

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Roy Hill Homestead, Pilbara region of Western Australia (detail)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Roy Hill Homestead

Statement of significance

Roy Hill Station has strong heritage significance as it has aesthetic, historical, scientific, and social values. It represents more than a hundred years of life on a Pilbara station, and its buildings and structures, reflect an evolutionary pattern of development. Roy Hill Station was the home of Alexander Langdon (Alex) Spring who made an enormous contribution to local government in the region between 1940-1970. He was a Councillor for 31 years, and was the first President of the East Pilbara Shire in 1972. He was made a Freeman of the Shire of East Pilbara in 1973. becoming the 13th Freeman in Western Australia.

Roy Hill continues to have significance as a large pastoral station, representing some of the other stations which owners did not want included in the Shire of East Pilbara Heritage Inventory.

History

Nat Cooke, the owner of Mallina Station near Port Hedland, founded Roy Hill Station in 1886 after searching for new pastures when Mallina had suffered a number of years of drought. With gold on his mind Cooke was always looking for gold bearing ore in his search for new grazing land. He was successful in bringing gold rock specimens to the authorities in 1886 though he had to accept a share with two other prospectors in the reward for the first gold found in the district. Despite his gold mining efforts around Nullagine, Nat Cooke started a going concern on Roy Hill Station which is situated on the headwaters of the Fortescue River. The first official lease of 20.000 acres was granted to D McKay in January 1890.

H L Spring was one of a consortium who established Roy Hill Pastoral Company in 1919 with Jim Smith as Manager. Mount Fraser. an adjoining station, was incorporated in 1919. bringing the lease up to approx. one million acres. Initially the property was set up as a cattle station. By 1925 there were 11,500 head of cattle. In 1928 sheep were introduced and the sheep numbers built up to 46.000 by the mid 1960s. At the same time 5,000-7,000 cattle were maintained. Roy Hill Station was one of the first in Australia to transport large numbers of cattle by truck from about 1925.

As Roy Hill was centrally located in relation to the other stations, it became a natural meeting point for a range of activities, particularly the meetings of the Nullagine Road Board. Roy Hill still remained an isolated station which greatly benefited from the introduction of the Flying Doctor Service and the School of the Air. Oral history collected from past employees of Roy Hill Station highlights the contribution made by the Aboriginal stockman to the running of the station. About 20 Aboriginal stockmen were employed during the 1930s.

The Spring family was associated with Roy Hill Station for many decades. It was managed after 1938 by Alex Spring who later became the first Shire President of the East Pilbara Shire, formed in 1972. The large, once gracious homestead had wide verandahs shading the windows. Surrounding the homestead were vegetable gardens and large flower beds, along with alfalfa for the milking cows and working horses, irrigated by water pumped from the river.

Evidence of the importance of Roy Hill’s central position in the district is found in the old Post Office and General Store situated next to the homestead. The old iron building still shows signs of its years of service as some furniture and shelving remain in the Post Office and Store. The main road used to lead people right past the Roy Hill Store and Post Office, but has since been realigned. The Post Office played a vital role for the people of the isolated Nullagine district, maintaining its own postcode for a number of years. The Post Office and Store closed in 1971.

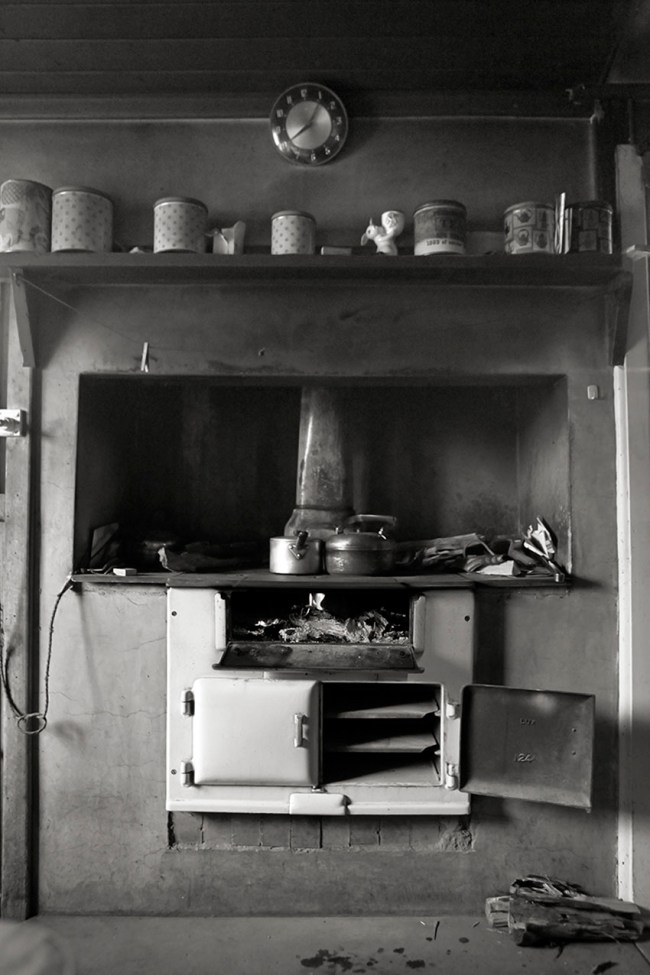

Physical description

Roy Hill Homestead is situated 1km off the main road halfway between Newman and Nullagine. Roy Hill Station consists of a large number of buildings which demonstrate the dynamic process of running a pastoral station over a period of more than a century. There are a number of corrugated iron sheds built at different times for mechanical work and storage of station equipment. Close by is the aircraft directional beacon available for the nearby airstrip if a plane was lost. The original airstrip was approx. 6 miles from the homestead. Part of the very old cattle stockyards still stand next to a disused cattle killing hoist, reflecting a time when pastoralists regularly butchered cattle for their home consumption. The yards were the main trucking yards and general handling yards.

The large main house is one of a number of buildings that have been erected on the station since the turn of the century. It has cement block walls with a corrugated iron roof. Surrounding the large and once gracious home is a wide verandah. The house originally consisted of three bedrooms, a living room, guest room, dining room and school room. Nearby the house is a cluster of older buildings including a ‘Nissan hut’ shaped kitchen and dining room for workers and the old Post Office. Office and General Store.

The Post Office, Office and General Store has corrugated iron walls and a gabled tin roof. Inside the Post Office are the pigeon holes and other associated post office fittings. The service hatch for the Post Office is still visible from the outside. The General Store (to the rear of the Post Office) still has its shelves in place and much of the old equipment that has been collected there over the years gives a feeling of stepping back into another time. In the immediate vicinity of the homestead property are other remnants from the past.

Concrete pads found amongst the grass are the remains of Aboriginal stockmens quarters and the many rainwater tanks are reminders of the need to collect and store all water needed for consumption. A light aircraft parked near the airstrip is an important vehicle for transport and for mustering.

Today the house stands unoccupied and the owner and any employees live in transportable homes near the old house.

Shire of East Pilbara. “Roy Hill Homestead and former Post Office,” on the the State Heritage Office, Government of Western Australia website Nd [Online] Cited 15/03/2022

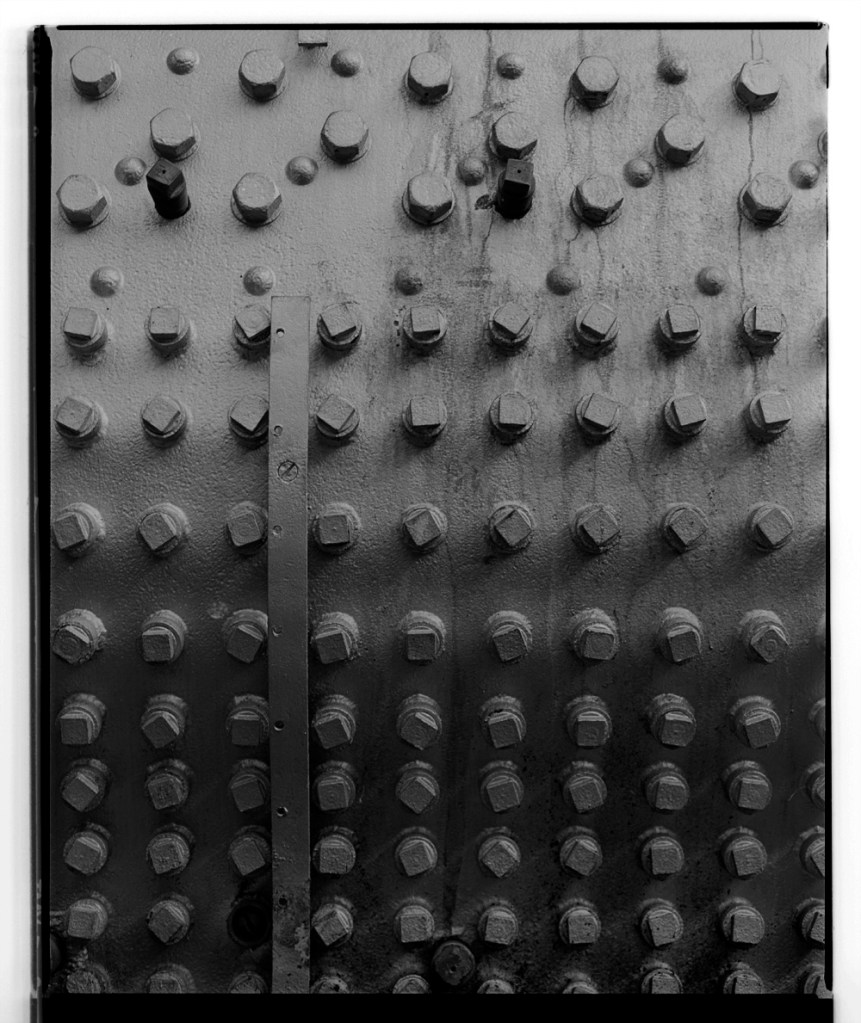

Anonymous photographer

Mundiwindi Station, Pilbara region of Western Australia

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Mundiwindi

Mundiwindi just off the Jigalong Mission Road in Western Australia is a locality about 1000km north-northeast of Perth. Mundiwindi is at an altitude of about 575m above sea level. The nearest ocean is the Indian Ocean about 410km north-northwest of Mundiwindi. The nearest more populous place is the town of Newman which is 71km away with a population of around 3,500.

Mundiwindi is a ghost town in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. The town is around 1,150 kilometres (710 mi) north east of Perth and 124 kilometres (77 mi) south east of Newman, along the Jigalong Mission road. The town was established in 1914 as a telegraph station. The station was closed in 1977. The telegraph station was a link on the Australian Overland Telegraph Line linking the settled regions of Australia to the submarine cable at Broome. A weather station operated at the site between 1915 and 1981.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Anonymous photographer

Mundiwindi Station, Pilbara region of Western Australia (detail)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Anonymous photographer

Cardawan Station, central Western Australia

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Stockman (Australia)

In Australia a stockman (plural stockmen) is a person who looks after the livestock on a large property known as a station, which is owned by a grazier or a grazing company. A stockman may also be employed at an abattoir, feedlot, on a livestock export ship, or with a stock and station agency. …

History

The role of the mounted stockmen came into being early in the 19th century, when in 1813 the Blue Mountains separating the coastal plain of the Sydney region from the interior of the continent was crossed. The town of Bathurst was founded shortly after, and potential farmers moved westward, and settled on the land, many of them as squatters. The rolling country, ideal for sheep and the large, often unfenced, properties necessitated the role of the shepherd to tend the flocks.

Early stockmen were specially selected, highly regarded men owing to the high value and importance of early livestock. All stockmen need to be interested in animals, able to handle them with confidence and patience, able to make accurate observations about them and enjoy working outdoors.

Australian Aborigines were good stockmen who played a large part in the successful running of many stations. With their intimate bonds to their tribal places, and local knowledge they also took considerable pride in their work. After the gold rushes white labour was expensive and difficult to retain. Aboriginal women also worked with cattle on the northern stations after this practice developed in northern Queensland during the 1880s. A Native administration Act later stopped the employment of women in the cattle camps. Aborigines and their families received the regular provision of food and clothing to retain their labour, but were paid only a small wage.

Text from the Wikipedia website

For more information on the role and conditions of Aboriginal stockmen, please see the book Aborigines in the Northern Territory Cattle Industry by Dr Frank Stevens, Australian National University Press, 1974.

“Perhaps nowhere in Australia have working and living conditions for Aborigines been so bad as on Northern Territory cattle stations. Though the Aborigines’ skill in handling cattle is acknowledged by their white employers, rarely have they gained recognition in any material way. None were paid full wages, many were fortunate if they received any cash wages at all, almost all lived in appalling conditions, and many were subjected to physical violence.

These facts emerge clearly from Dr Stevens’s thorough research into the conditions obtaining on Territory pastoral properties in the 1960s. During surveys in 1965 followed up in 1967, Dr Stevens questioned employers and both black and white workers in the industry, eliciting some revealing replies. It was apparent that the Aboriginal workers were fully aware of their degraded position and the way in which they were exploited.

Where possible Dr Stevens visited the Aboriginal station ‘camps’, though he met with opposition from some station owners, reluctant to allow him free access. In almost all of them the living conditions were primitive, the best of accommodation being little more than a corrugated iron hut. Few camps had running water or cooking facilities.

In the growing awareness of the Aborigines’ plight in Australia, this book is an important testimony of the conditions in which many lived and worked, conditions that must no longer be allowed to exist.”

Book jacket

Anonymous photographer

Cardawan Station, central Western Australia (detail)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

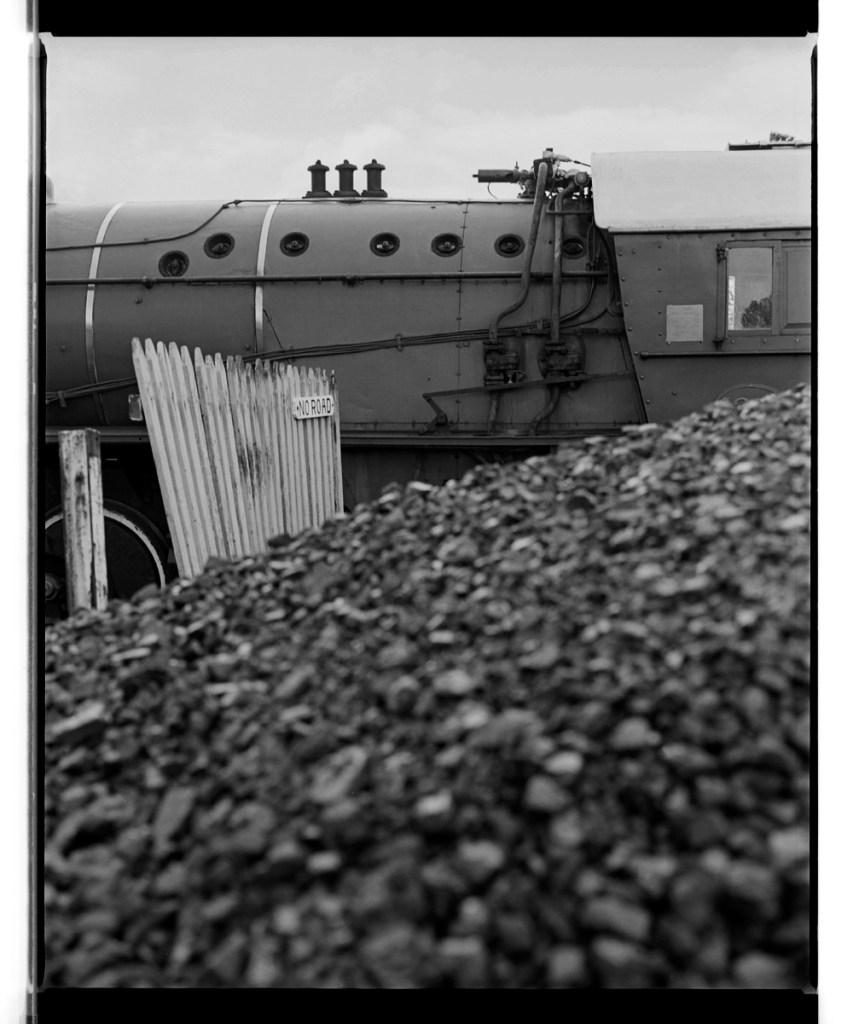

Anonymous photographer

Railway Hotel, Lake Austin township, Murchison region of Western Australia

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Austin, Western Australia

Austin is an abandoned town in the Murchison region of Western Australia. The town is located south of Cue on an island in Lake Austin and for this reason was also known as Lake Austin and The Island Lake Austin.

The lake and the town are both named after surveyor Robert Austin, who was the first European to explore and chart the area. Austin initially named the lake the Great Inland Marsh but the name was later changed to Lake Austin. The townsite was gazetted in 1895. When Austin travelled through the area he described it as very indifferent but also added the geological features indicate rich goldfields.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Anonymous photographer

Railway Hotel, Lake Austin township, Murchison region of Western Australia (detail)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

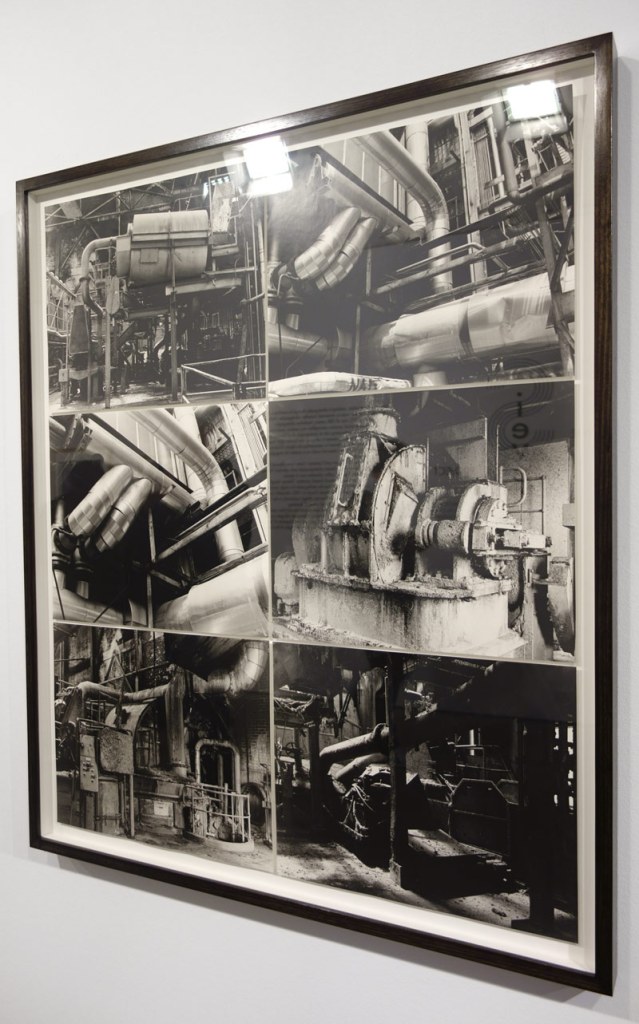

![Zoë Croggon (Australian, b. 1989) 'Comalco Aluminium Used in the Construction of the National Gallery of Victoria [7] (after Wolfgang Sievers)' 2014 Zoë Croggon (Australian, b. 1989) 'Comalco Aluminium Used in the Construction of the National Gallery of Victoria [7] (after Wolfgang Sievers)' 2014](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/installation-h.jpg?w=650)

![Zoë Croggon (Australian, b. 1989) 'Comalco Aluminium Used in the Construction of the National Gallery of Victoria [18] (after Wolfgang Sievers)' 2014 Zoë Croggon (Australian, b. 1989) 'Comalco Aluminium Used in the Construction of the National Gallery of Victoria [18] (after Wolfgang Sievers)' 2014](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/installation-i.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.