Exhibition dates: 8th June – 3rd September 2023

Curator: Isabel Tejeda

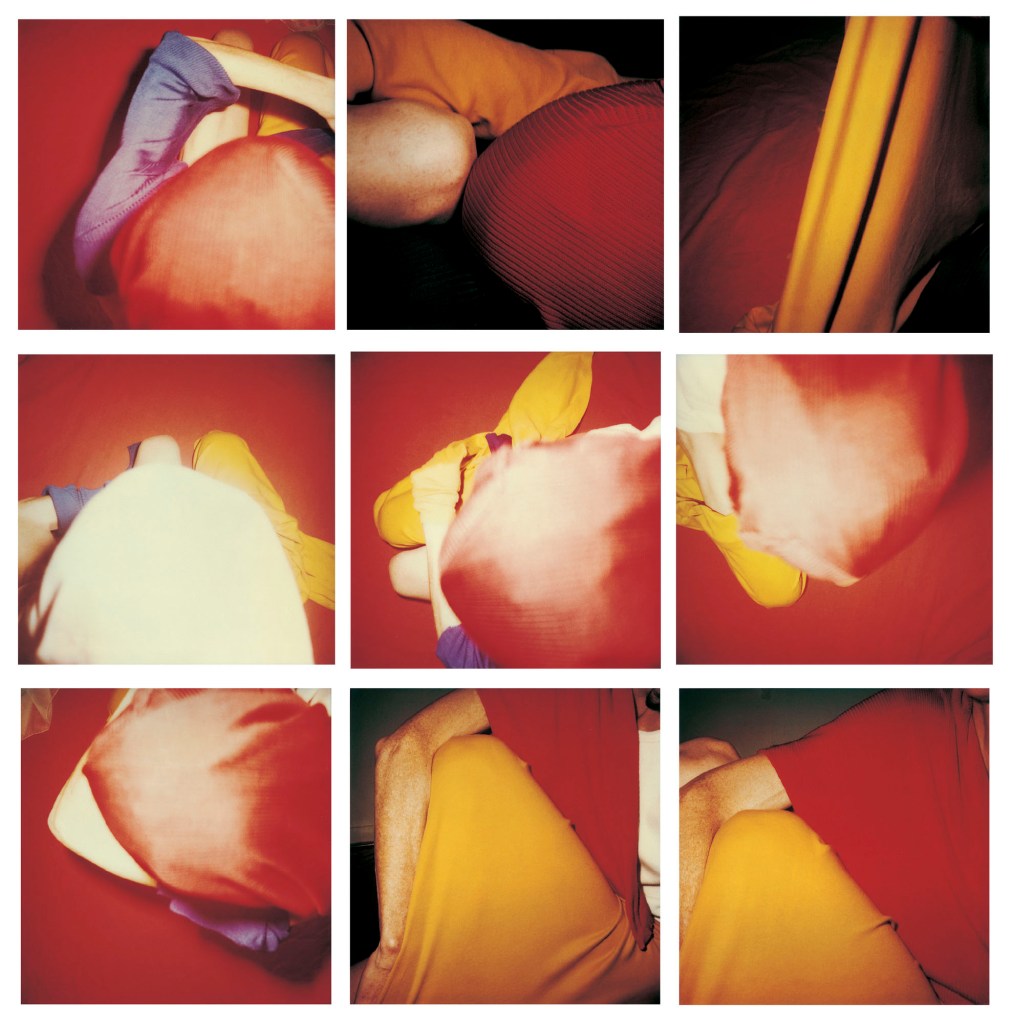

Johan Hagemeyer (Dutch, 1884-1962)

Tina Modotti in the role of María de la Guarda in the film The Tiger’s Coat, Hollywood

1920

Gelatin silver print

© Johan Hagemeyer

Courtesy: Galerie Bilderwelt, Reinhard Schultz

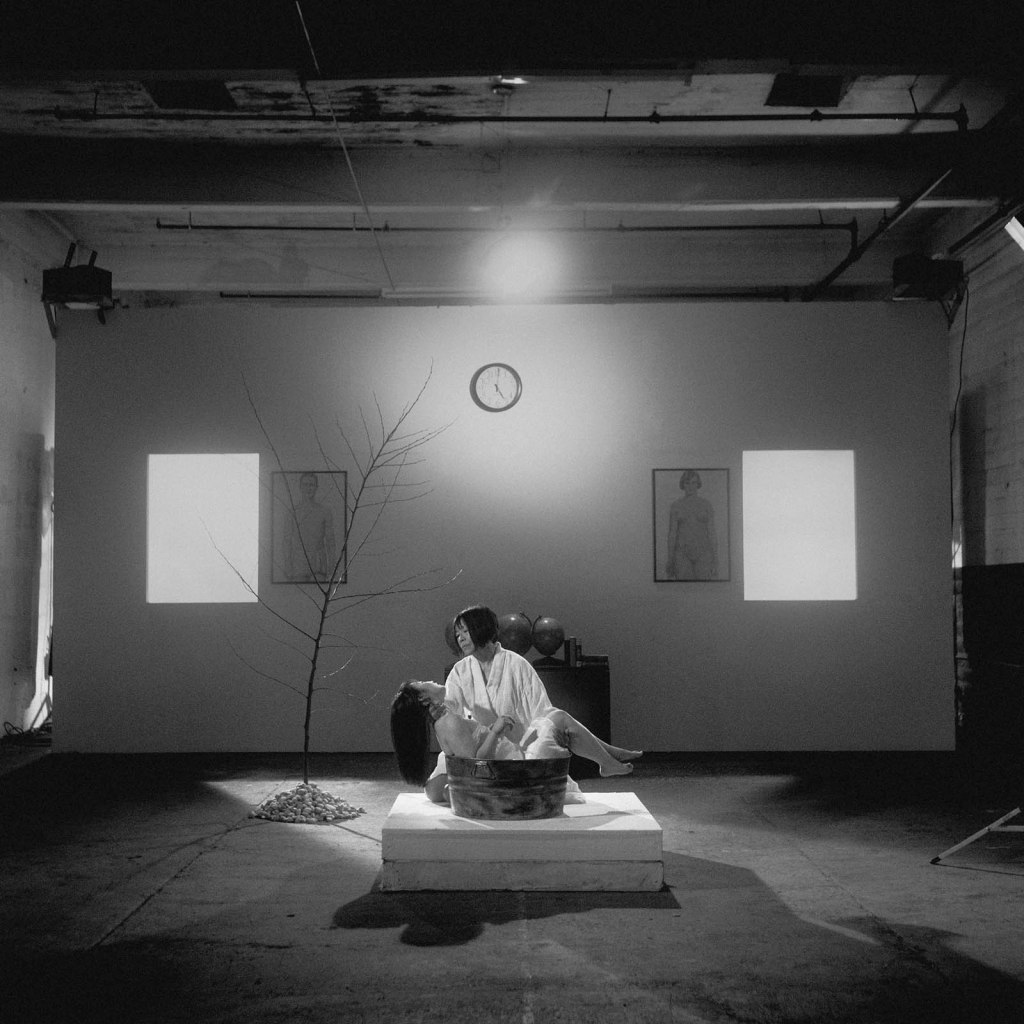

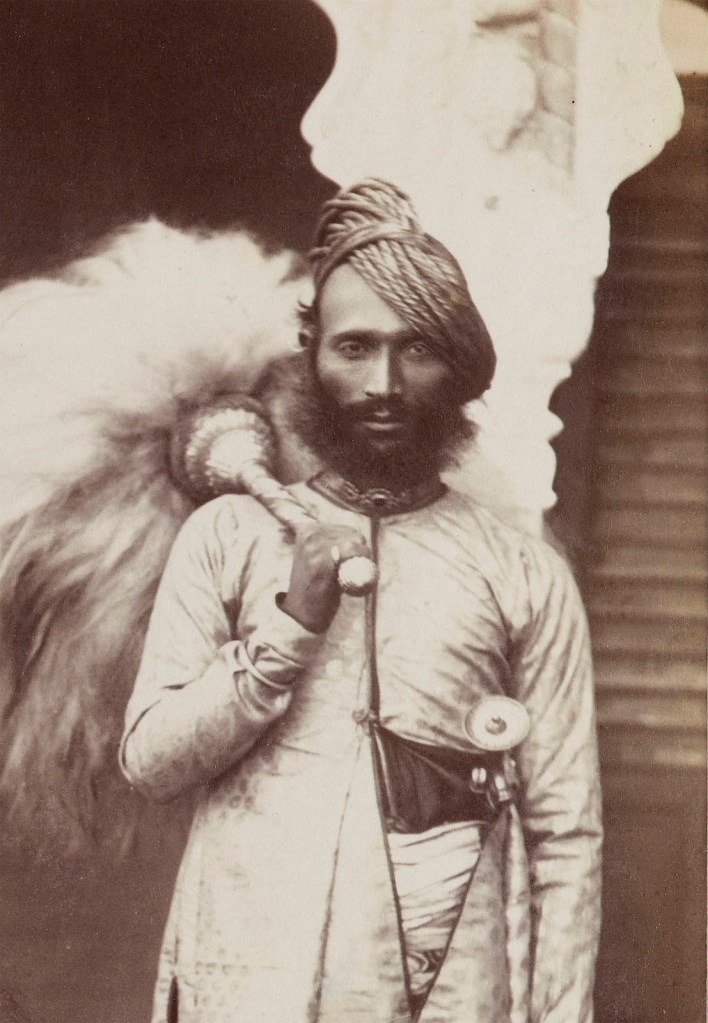

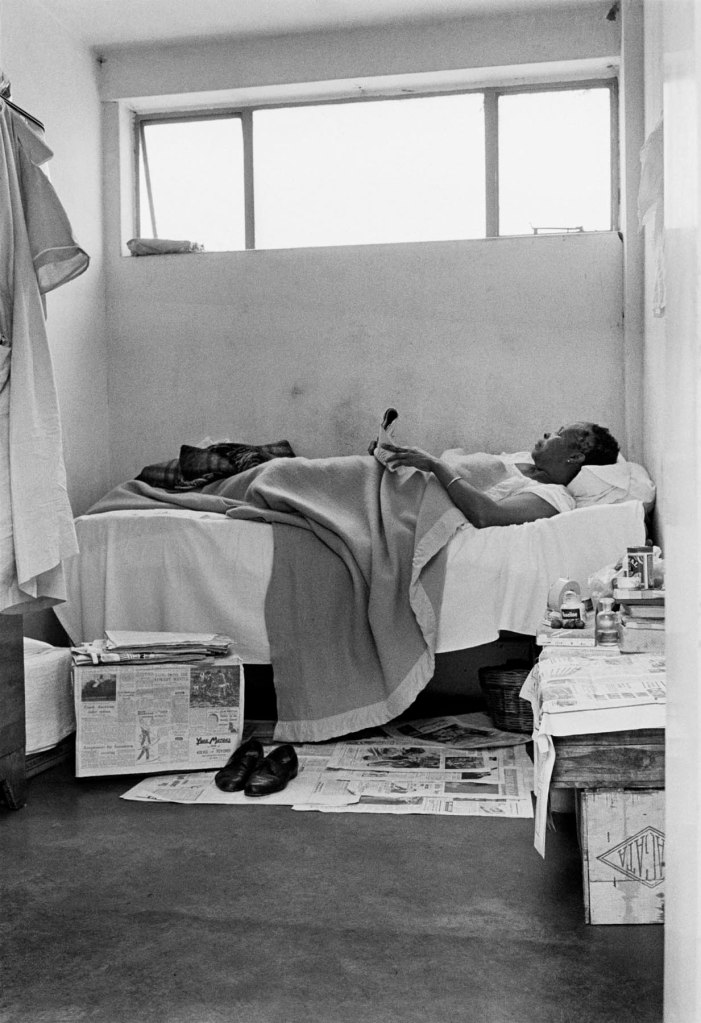

Tina Modotti’s first contact with the performing arts came upon her arrival in San Francisco in 1913, at just 16 years old.

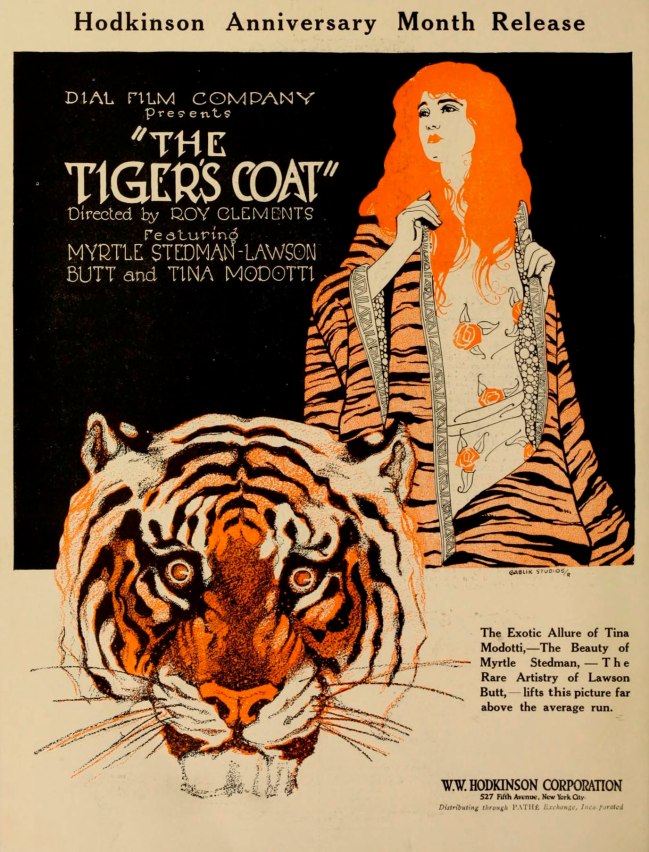

After performing theatre works, in 1920 she will participate in three films: The Tiger’s Coat (1920) by Roy Clements, in which she interpreted the role of the Mexican Jean Ogilvie; Riding with Death (1921) by Jacques Jaccard, in the personage of Rosa Carilla; and I Can Explain (1922) by George D. Baker, with Carmencita Gárdez.

The I of the world

Strong fierce compassionate women! Intelligent, class-conscious human beings who embrace social and political change, with photography being the agent for that change. I would embrace Tina Modotti as this type of artist – her photography a “reflection of her way of seeing life, social sensitivity and revolutionary fervour.”

She was a surrealist/feminist artist who represented the lives and “conditions of workers, women and their role within the community” through both the forms and symbols of working class emancipation and through “honest photography” – eloquent photographs of everyday Mexican life that have a biting directness linked to a surreal reality. Surrealism does not always involve the strange and absurd.

Much as Eugène Atget’s photography “which focussed on seemingly ordinary sights on the streets of Paris – a door knocker, a mannequin, a window rail – is seen as a forerunner of Surrealist and modern approaches to photography…”1 so both Atget and Modotti’s rejection of artistic self-consciousness and “artistic effects” in favour of in Atget’s case, “simple documents”, and in Modotti’s case, “honest photography”, lead to photographs that examine the fleeting nature of material objects and reality itself.

Modotti inserts her/self into these honest photographs through an embodiment of spirit. She brings to her photography how she feels about the world, what she feels passionately about in that world, what she cares deeply about… and in the process of “capturing time, light and memory shapes new states of beings and opens possibilities where by the improbable and the impossible are envisioned as an embodiment of the photographers past, present and future imaginings.”

Through a melding of the artist’s political, social, and aesthetic ideals and through her sur/reality, she becomes the I of the world.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ “Surrealism did not always involve the strange and absurd. For example, the photography of Eugène Atget (1857-1927), which focussed on seemingly ordinary sights on the streets of Paris – a door knocker, a mannequin, a window rail – is seen as a forerunner of Surrealist and modern approaches to photography… Only a year before his death, in 1926, Atget was approached by Man Ray for approval to use his photograph, L’Eclipse – Avril 1912 for the front cover of the publication La Révolution Surréaliste. Despite protestations that, “these are simply documents I make,” Atget’s rejection of artistic self-consciousness combined with his pictures of an old, often hauntingly deserted Paris, appealed to Surrealists.”

Anonymous. “Surrealist photography,” on the V&A website [Online] Cited 07/08/2020

Many thankx to Fundación MAPFRE for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“In reality, what I try to produce is not art, but honest photography, without tricks or manipulations, while most photographers still look for “artistic effects” or the imitation of other means of graphic expression, which results a hybrid product and one that fails to impart to the work that they produce the most valuable trait that it should have: PHOTOGRAPHIC QUALITY.”

Tina Modotti quoted in “On Photography,” Mexican Folkways, Vol. 5, No. 4, 1929, reprinted in Robert Miller, Tina Modotti, and Spencer Throckmorton, Tina Modotti : Photographs (New York: Robert Miller Gallery, 1997)

Pure your gentle name, pure your fragile life,

bees, shadows, fire, snow, silence and foam,

combined with steel and wire and

pollen to make up your firm

and delicate being.

Part of the epitaph for Tina Modotti on her tomb by Chilean poet Pablo Neruda

The life of Tina Modotti (Udine, Italy, 1896 – Mexico City, 1942) was marked by some of the most important historical events of the 1920s and 1930s. Born in northern Italy, she soon emigrated to the United States, where she met Edward Weston in 1923, who will significantly influence her career. In that same year they moved together to Mexico where she developed photographic work for almost a decade that started from modernist aesthetics to immediately give way to a very personal look, a reflection of her way of seeing life. Her social sensitivity developed in parallel to her political militancy and her activism within the Communist Party, within which she will treat David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera or Frida Kahlo. With her desire to awaken consciences, Modotti made images that denounce injustices and honour the dispossessed. Some of them, with a strong propaganda sense, were made for periodicals and magazines.

After intense research work due to the limited production of the photographer, this exhibition will bring together around 200 photographs, mostly vintage copies, and relevant documentary material. The show will also include works by photographers around her, such as Edward Weston, and one of the films that Modotti starred in in Hollywood.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE website

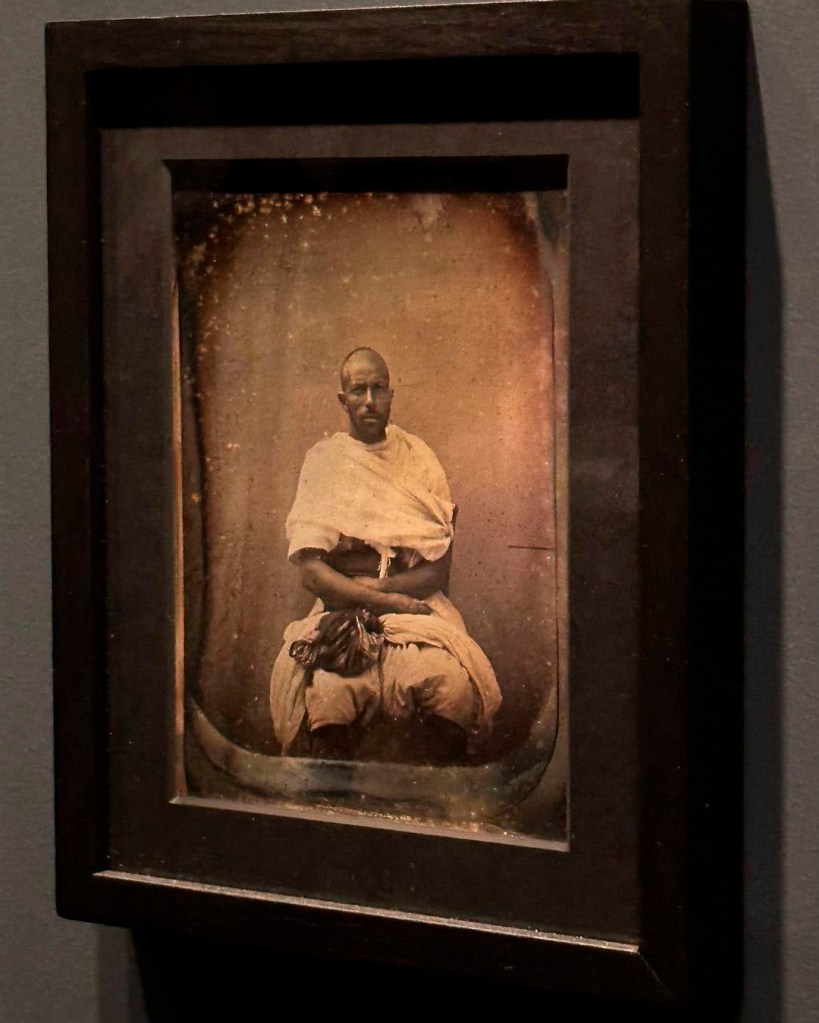

The Tiger’s Coat movie poster

1920

From The Moving Picture World 1920

The Tiger’s Coat is a 1920 American silent drama film directed by Roy Clements and starring Lawson Butt, Tina Modotti and Myrtle Stedman.

Tina Modotti (Udine, 1896 – Mexico City, 1942) lived in the eye of the storm throughout her life. Her interesting life and artistic career were framed by some of the most important historical events of the 1920s and 1930s and by her constant double commitment: artist-photographer and revolutionary-anti-fascist militant.

Born into a working-class family in Udine, in northern Italy, she emigrated and grew up in the United States, where she became a film actress in Hollywood in the 1920s and met Edward Weston, who introduced her to photography and with whom she moved to Mexico in 1923.

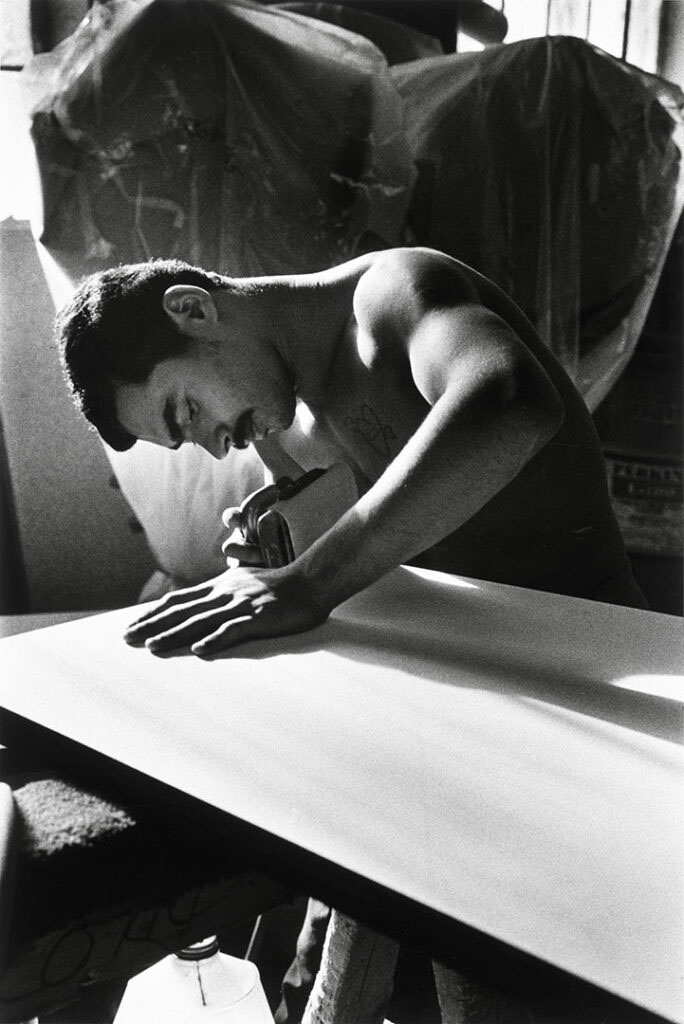

Almost all his photographic work was produced between that date and 1930. During these Mexican years, and following her apprenticeship with Weston, Modotti evolved from an interest in abstract forms to a gaze centred on the human being and on denouncing inequality and injustice. The precarious conditions of workers, urban poverty, and the role of women in the community became, among other similar issues, the main themes of a photography conceived as political propaganda.

This exhibition, Tina Modotti’s most extensive to date, is the result of extensive research, which has made it possible to bring together many vintage prints by Modotti. In addition to the nearly 250 photographs on display, grouped chronologically into four sections, the exhibition includes documentary material, one of the films that Modotti starred in in Hollywood and some works by Edward Weston.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE website

Tina Modotti

Tina Modotti’s life was marked by some of the most important historical events of the 1920s and 1930s. The nomadic life she led and the turbulent political militancy caused Modotti to suddenly leave many of the countries where she lived, which, as the curator of the exhibition, Isabel Tejeda points out, “decontextualizes and disarranges her production from the start, so that it is impossible to accurately date many of her images”, although it can be stated that almost all of his photographic work was produced between 1923 and 1930.

During these Mexican years, and after his apprenticeship with Weston, the artist evolved from the perfection of formalism to a different and personal perspective conditioned by his way of seeing life, as an emigrant, woman and political activist in which his attraction to the human being and social injustices stands out.

He then portrayed the precarious conditions of workers, inequalities and misery in urban areas. It also focused on women and their role within the community, and on the forms and symbols of the emancipation of the working class. In his desire to raise awareness, Modotti made images that denounce injustices and honour the dispossessed, some of which were for propaganda purposes and intended to be printed in magazines and other publications.

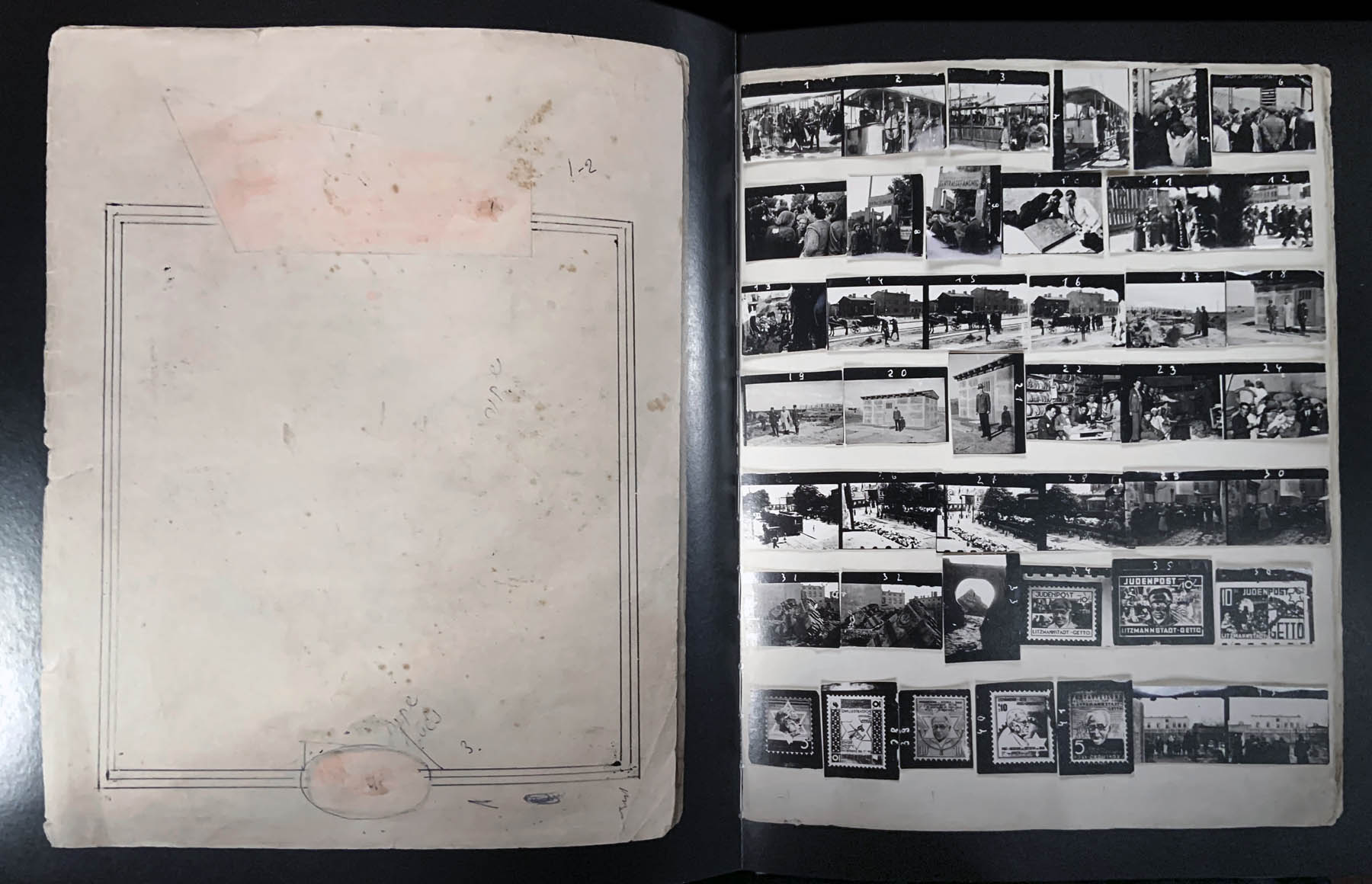

The exhibition presented by Fundación MAPFRE is made up of approximately 240 photographs, mostly period copies, which are grouped into four sections: Early years: from Udine to Los Angeles, Mexico on the other side of the camera, Photography and political commitment and The move to political action: Spain at war.

In addition to emphasising her relationship with Spain, the exhibition reconstructs the figure of Modotti, both as an artist / photographer and as a revolutionary / anti-fascist militant. In addition, there is an extensive amount of documentary material and one of the films that Modotti starred in in Hollywood. The tour is completed with works by photographers from his immediate surroundings, such as Edward Weston.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE website

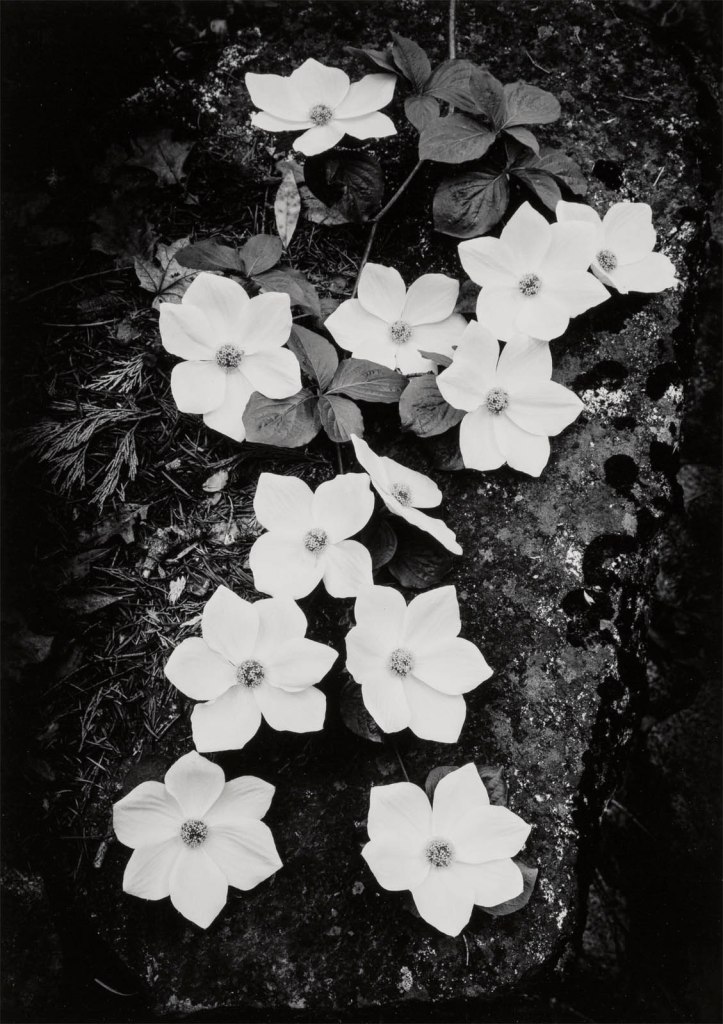

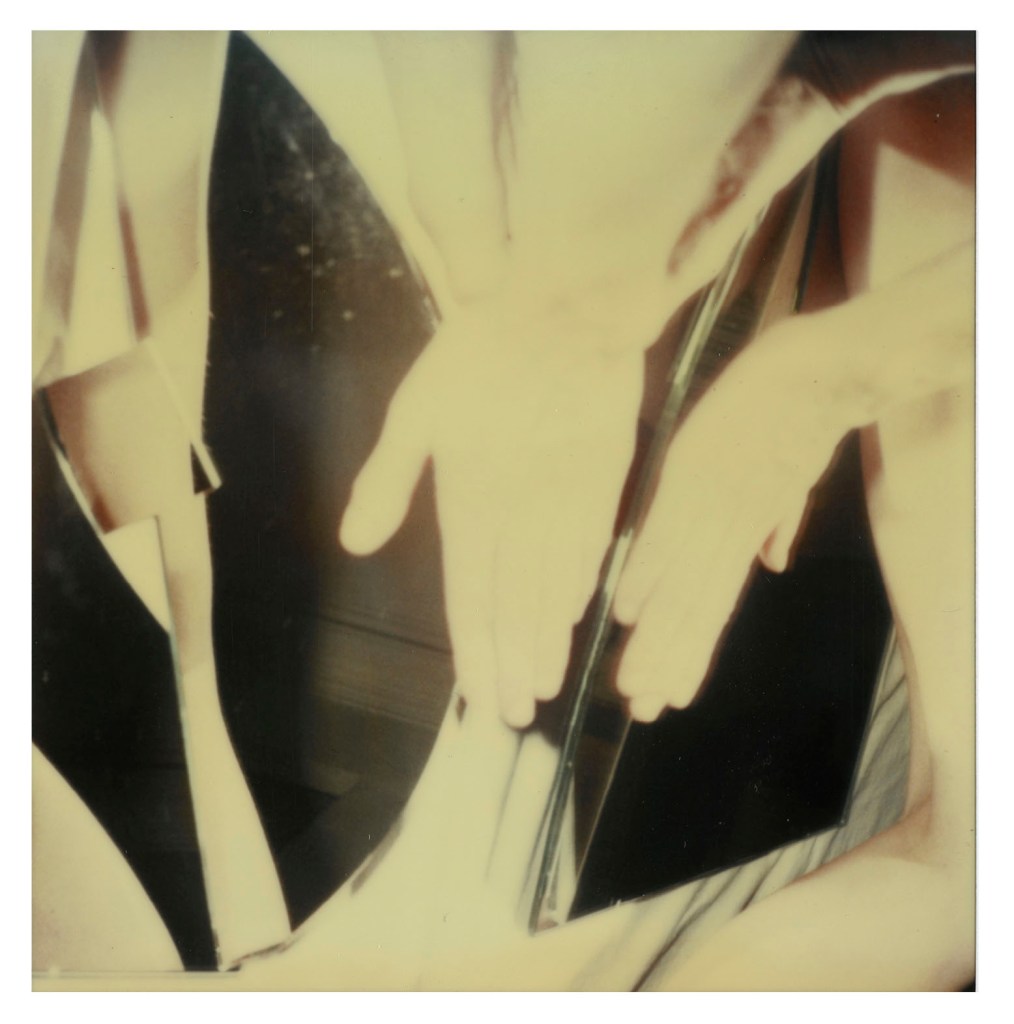

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Circus tent

Mexico, 1924

Platinotype

Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

Acquisition

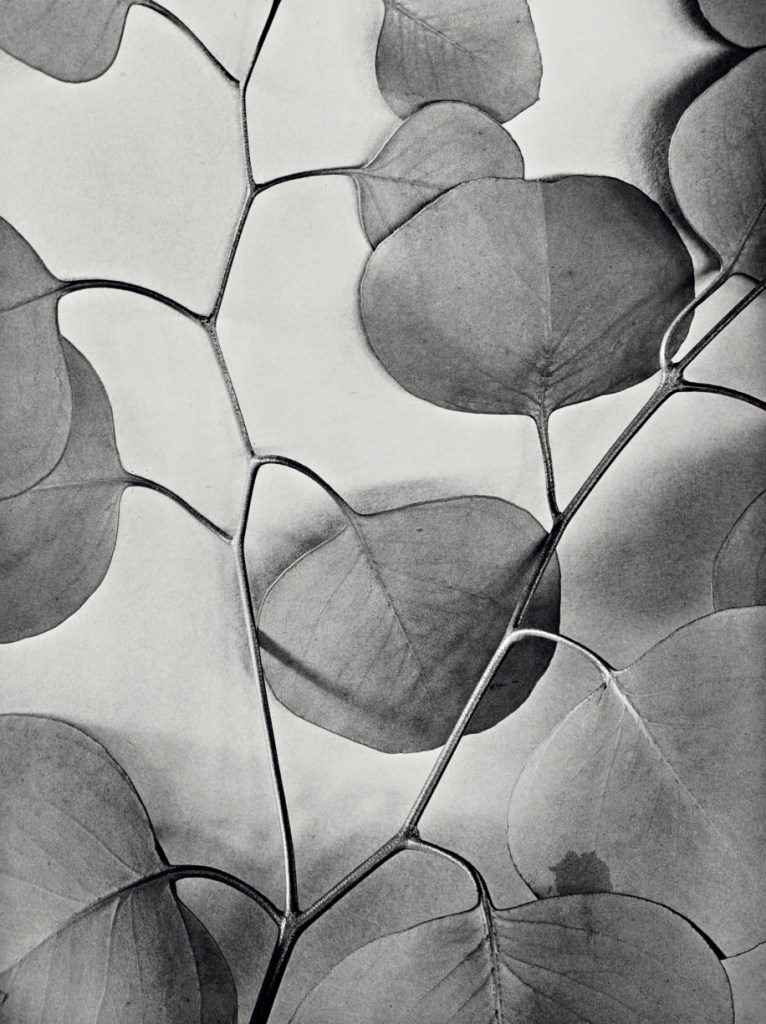

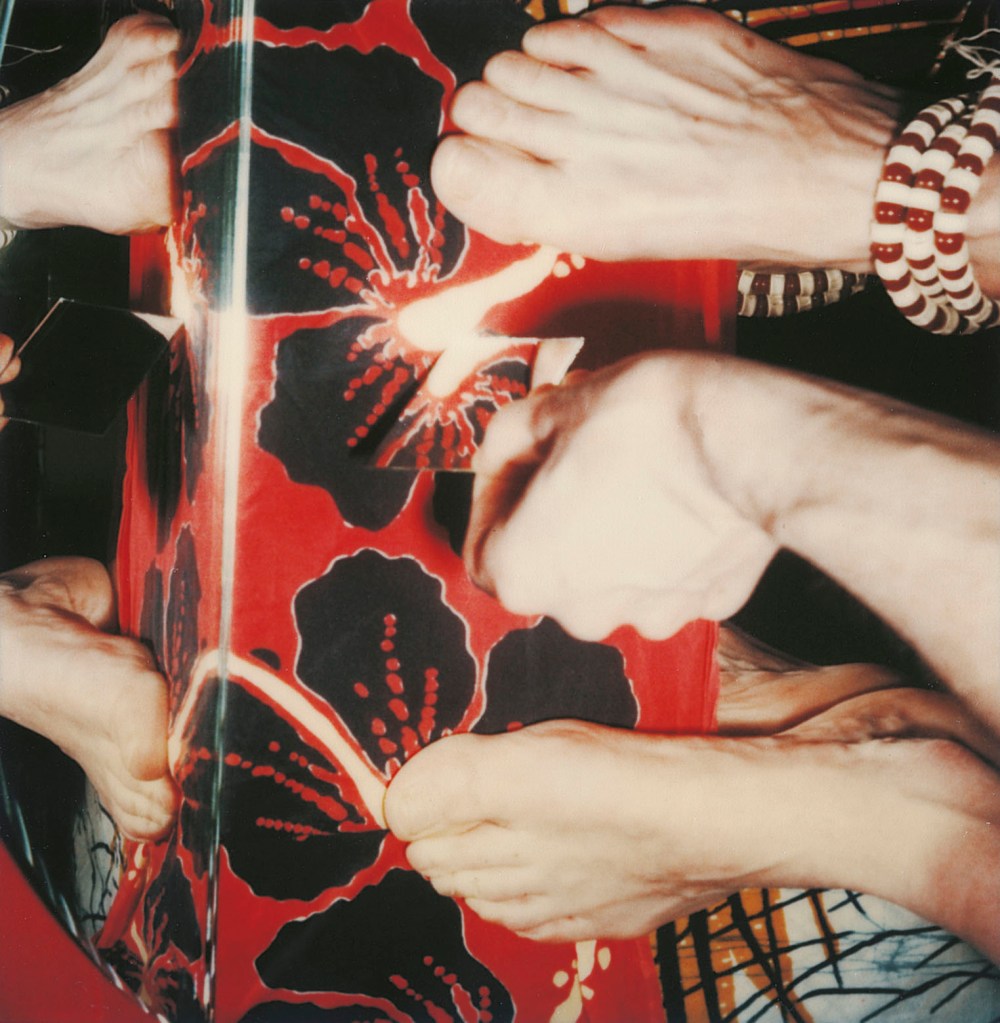

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Roses

Mexico, 1924

Paladiotype, period or vintage impression

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

Roses, Mexico, is an extreme close-up of four roses. Cropped to fill the frame from edge to edge, this is not a traditional still-life photograph of roses arranged in a vase. Here, the roses lay prone and slightly wilted, just beyond their prime, thus reflecting the passage of time and the ephemerality of delicate blooms. Much like a traditional vanitas still life that asked the viewer to contemplate mortality by reflecting on the fleeting nature of material objects, Roses brings this subject to modern photography. As photography historian Carol Armstrong notes, Roses “calls on the line of figural abstraction identified, not with [Alfred] Stieglitz, [Paul] Strand and the ‘straight’ photograph, but with Georgia O’Keeffe and her blown-up genital flowers, which like [Edward] Weston’s single-object photographs reduced the flora still-life that had been the traditional purview of the female painter to one (or two or four) item(s), expanded to fill the entire field of the image.”

The theme of the still-life preoccupied Modotti throughout much of her brief photography career. A relative newcomer to photography, she made use of the still-life photograph as a means to work through various formal issues including composition, framing, light, pattern, and tone. At this time, she was working with a large-format camera, which was unwieldy, not easy to transport, and forced the photographer to carefully compose the image, rather than creating images on the move with a handheld camera. The still-life, which was easy to set up and did not alter, was the perfect vehicle for mastering the myriad technical complexities of a photograph.

Karen Barber. “Tina Modotti Artist Overview and Analysis,” on The Art Story website 12 Nov 2018 updated 2023 [Online] Cited 06/08/2023

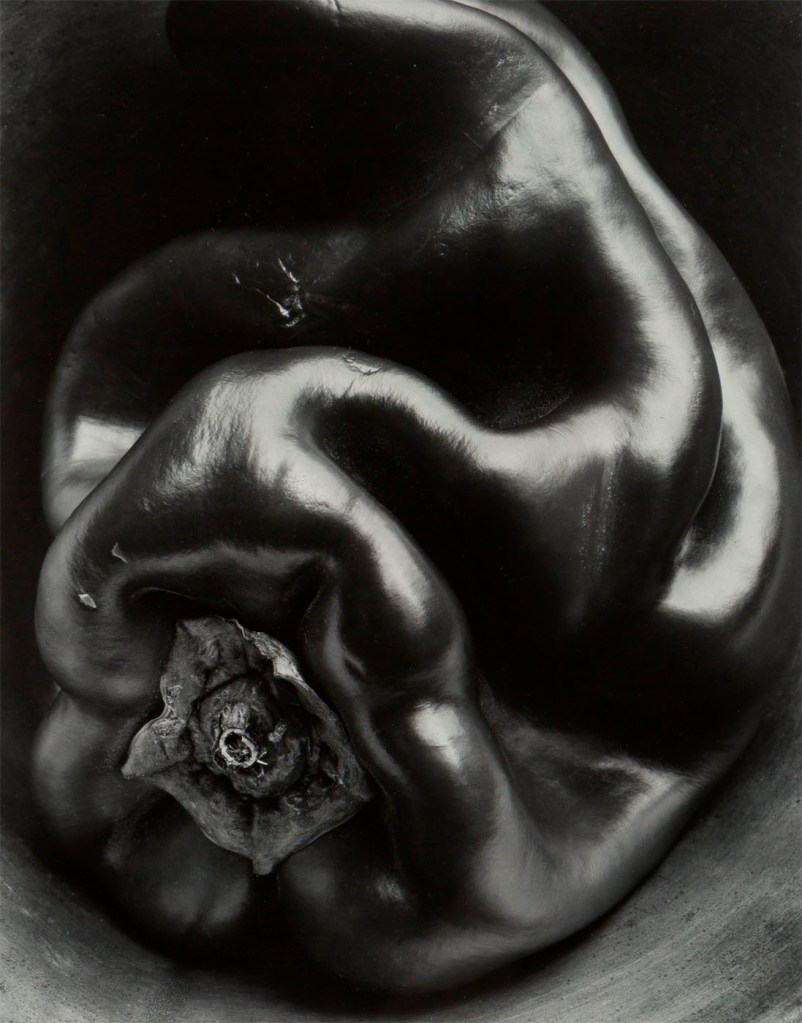

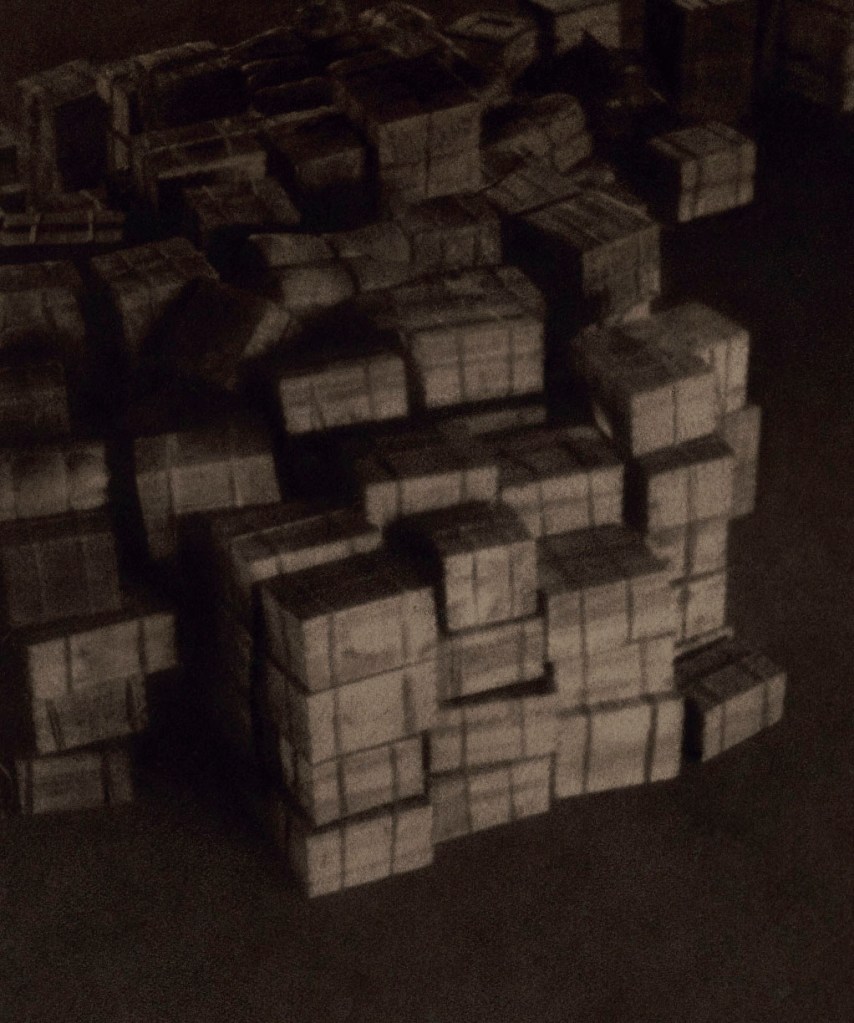

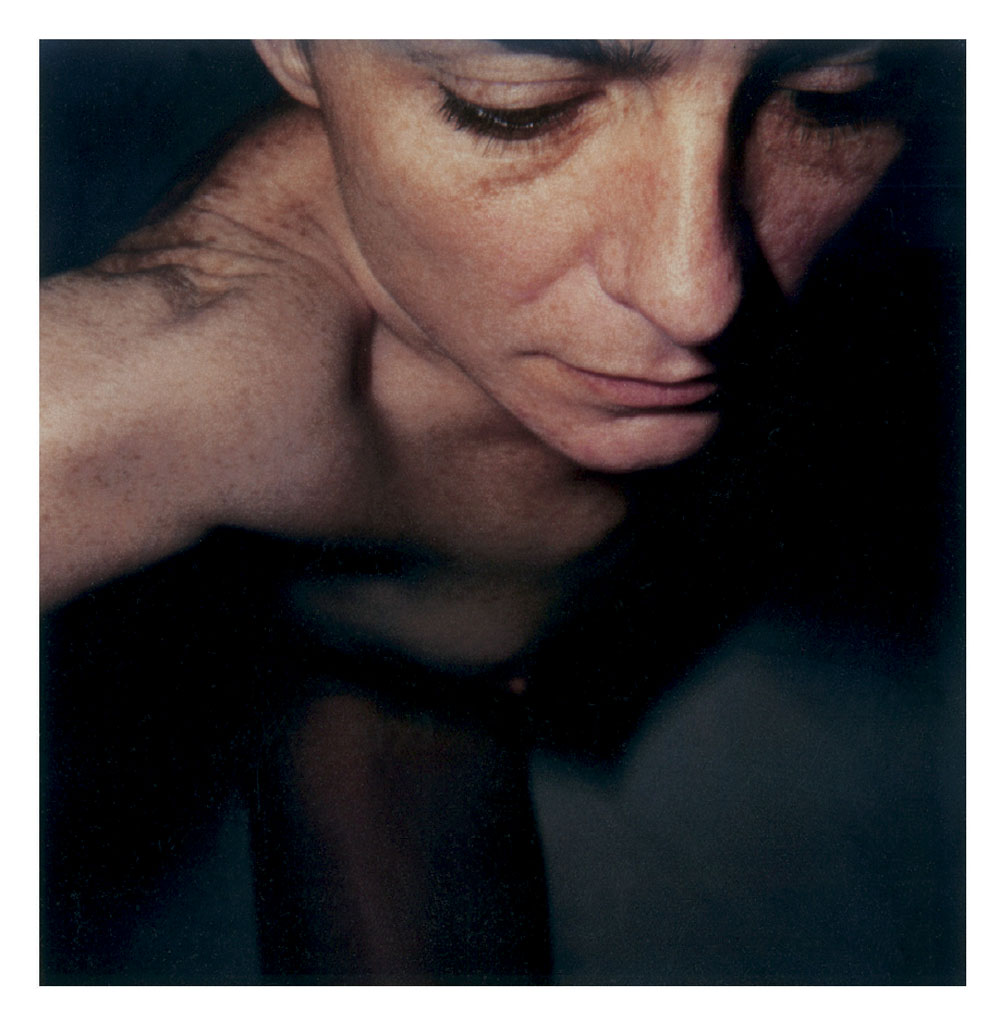

Edward Weston (1886-1958)

Portrait of Tina Modotti

1924

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

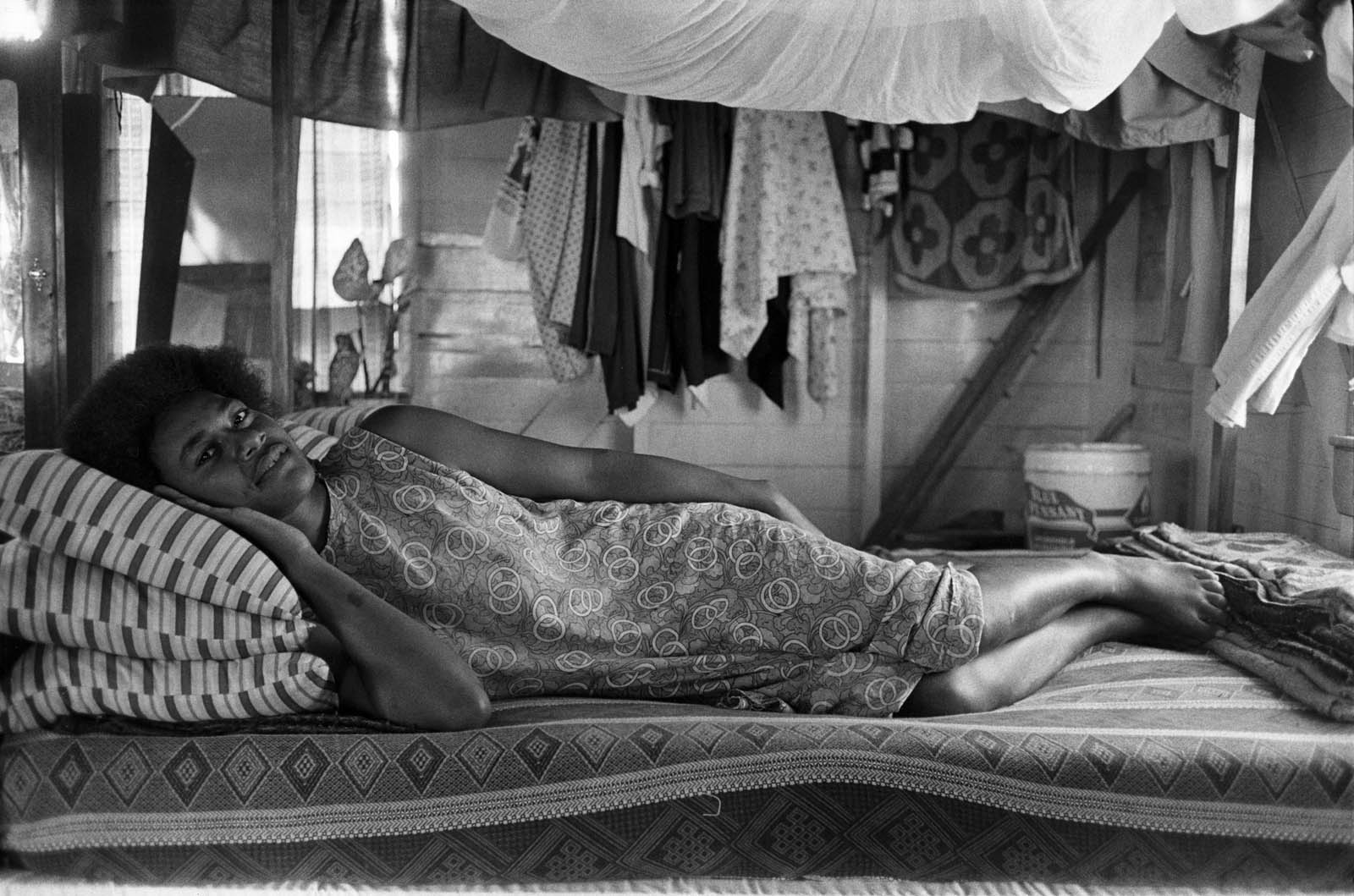

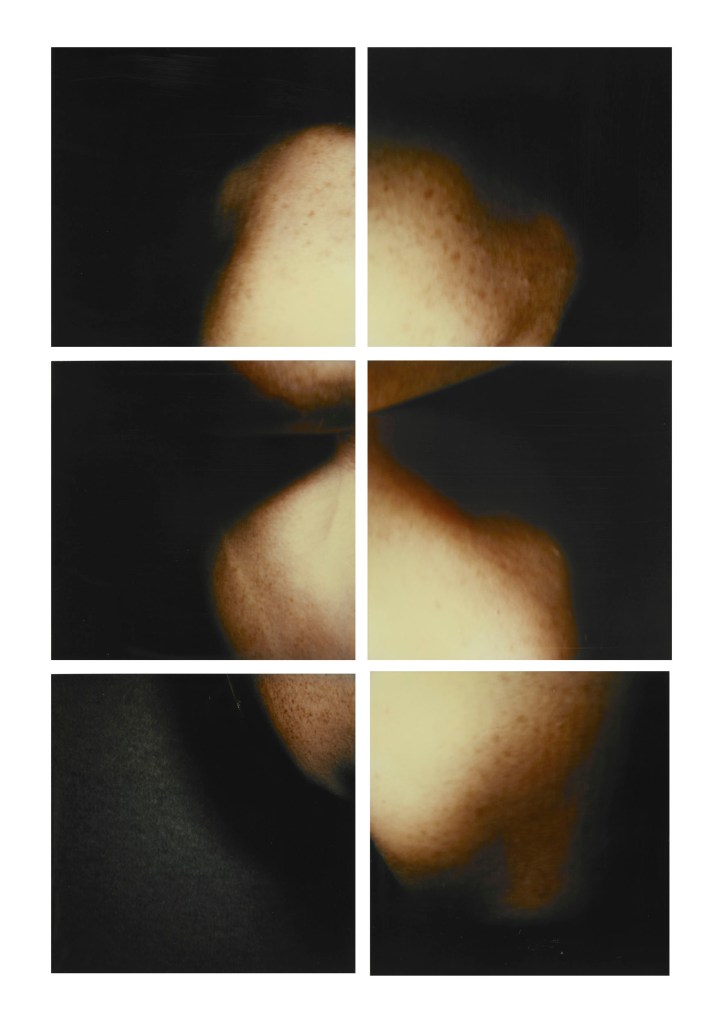

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Elisa

1924

Palladium print

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Donation of Edward Weston

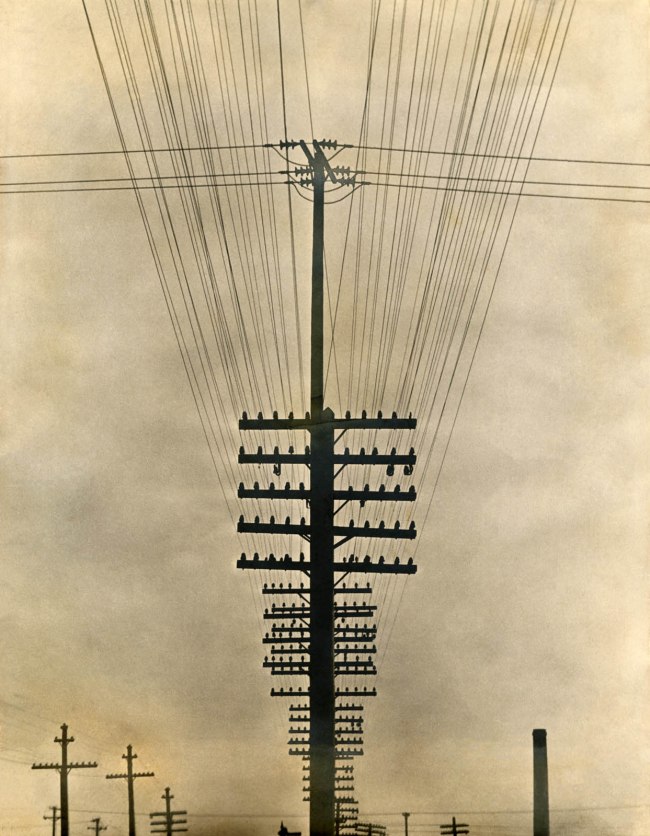

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Telegraph cables

c. 1924-1925

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Post with Cables

Mexico City, c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

In this 1925 photograph of isolated telephone wires, Modotti shifts the perspective, removing any reference to the ground that holds the telephone poles in place. Instead, the carefully composed image focuses on the angles and patterns produced by the wires and clouds, to create a work that mingles modernism and social concerns. During this period Mexico was undergoing increased modernization and industrialization, which Modotti symbolizes in her photograph of telephone wires. Modotti thus presents an optimistic view of Mexico’s modernization and the promise of instant communication brought about by the installation of telephone systems that seemed to open up Mexico to the rest of the world.

Lauded by the Mexican avant-garde group, Estridentistas, who aligned their work with the Mexican Revolution and sought to modernize Mexico, Modotti’s photograph was included in their journal Horizonte because it represented dynamism, technology, and progress. The photograph’s framing and its use of oblique angles and unusual perspective, brought it into alignment with other modernist painters and photographers, including Paul Strand, Charles Sheeler, and Charles Demuth, but also with European avant-garde photographers like László Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, and Albert Renger-Patzsch. Although the tendency to focus on the subject / object was characteristic of her former mentor Edward Weston’s work, Diego Rivera praised Modotti’s work as “more abstract, more ethereal, and even more intellectual” than Weston’s.

Karen Barber. “Tina Modotti Artist Overview and Analysis,” on The Art Story website 12 Nov 2018 updated 2023 [Online] Cited 06/08/2023

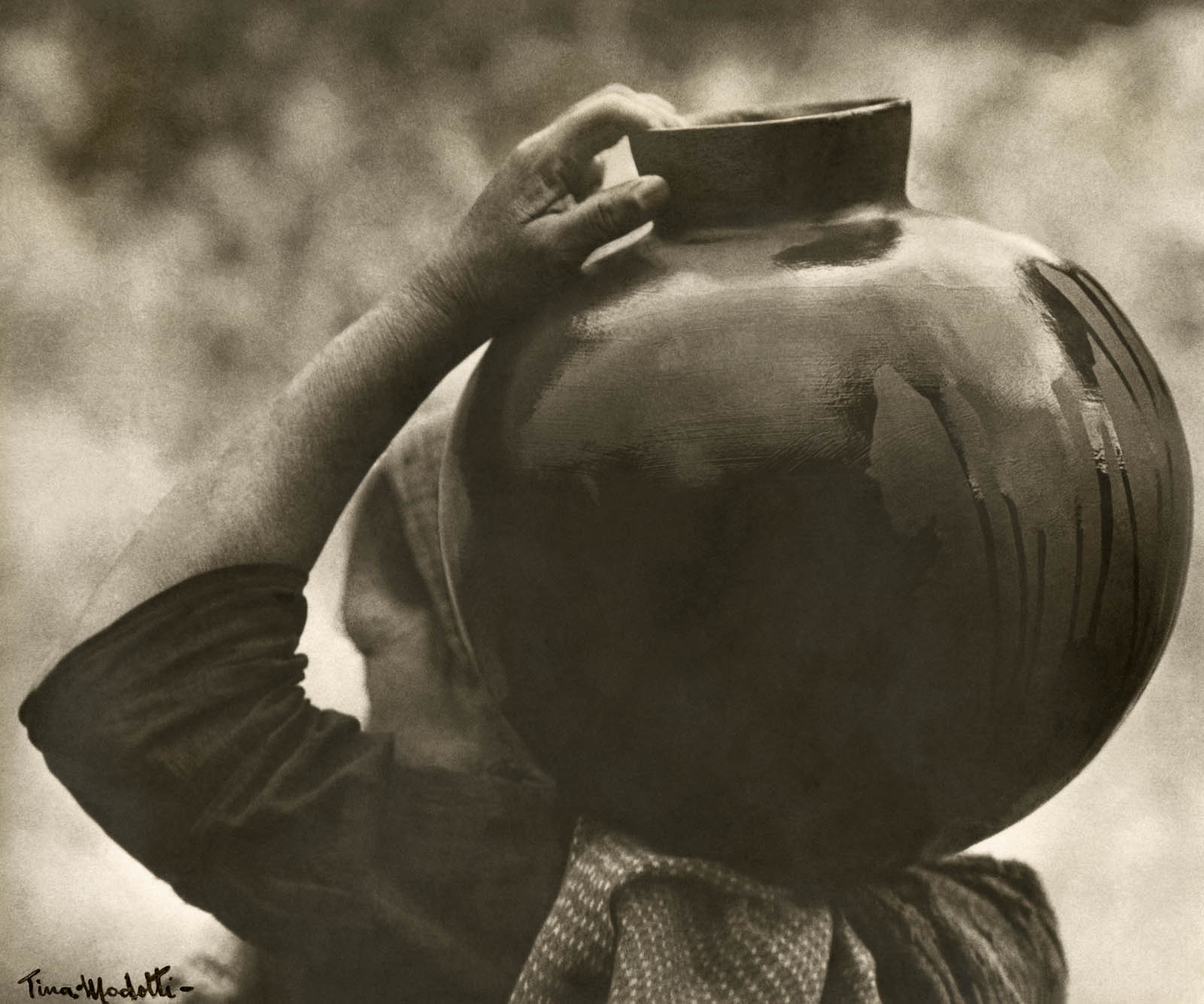

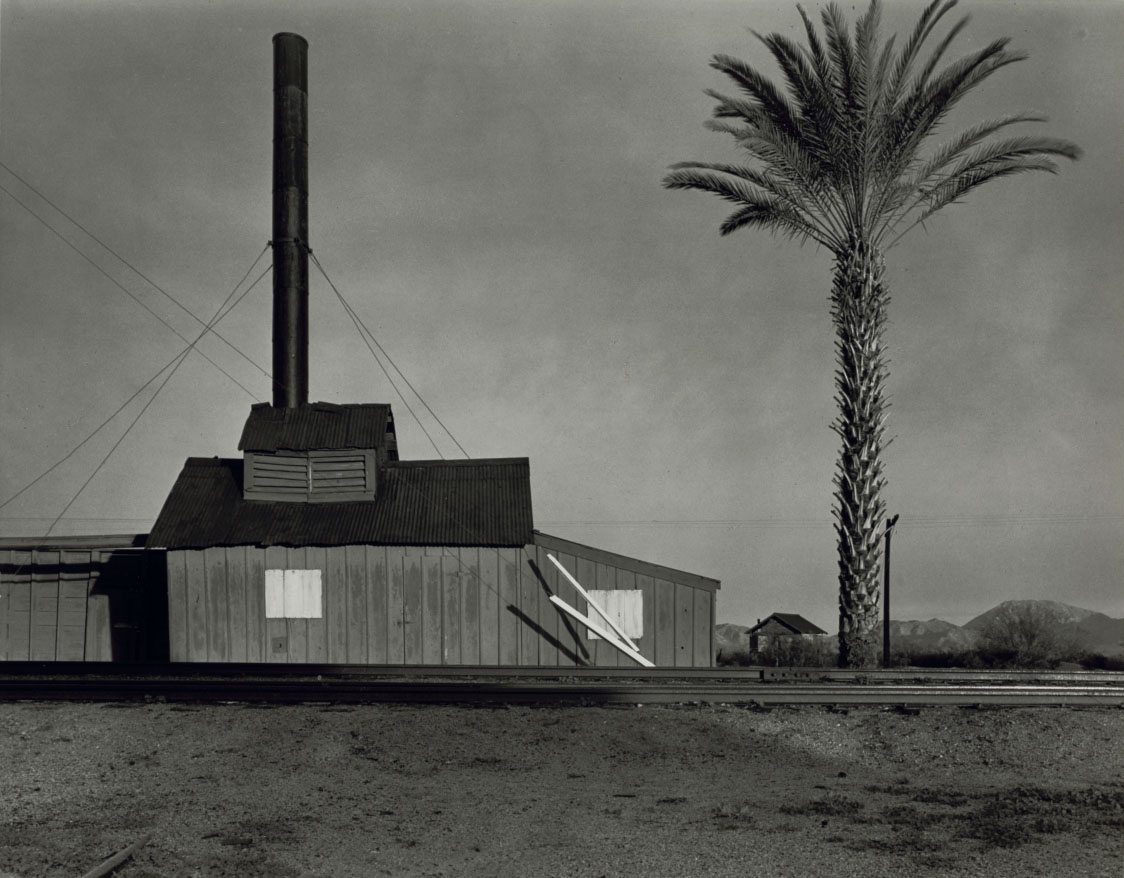

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Zapotec peasant woman with a jug on her shoulder

1926

Platinotype

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Untitled (Indians carrying loads of corn husks for the making of “tamales”)

1926-1929

Gelatin silver print

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

Art Supporting Foundation donation, John “Launny” Steffens, Sandra Lloyd, Shawn and Brook Byers, Mr. and Mrs. George F. Jewett, Jr., and anonymous donors

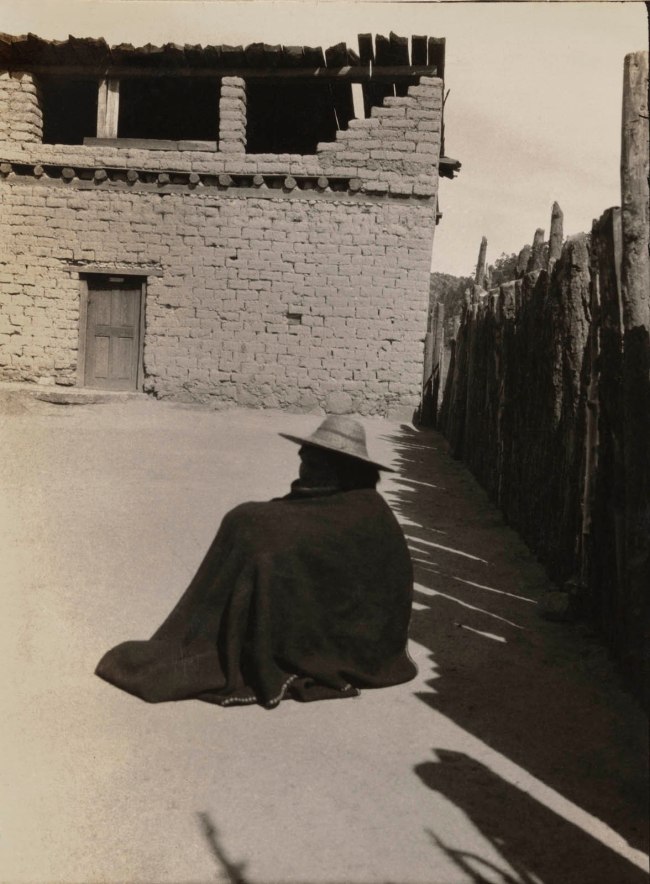

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Untitled

c. 1926-1929

Gelatin silver print

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

Art Supporting Foundation donation, John “Launny” Steffens, Sandra Lloyd, Shawn and Brook Byers, Mr. and Mrs. George F. Jewett, Jr., and anonymous donors

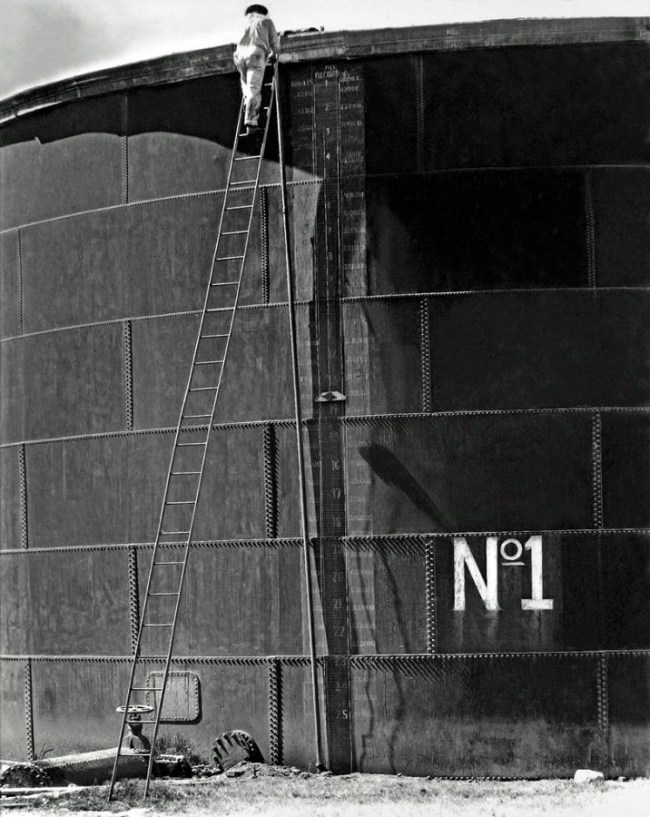

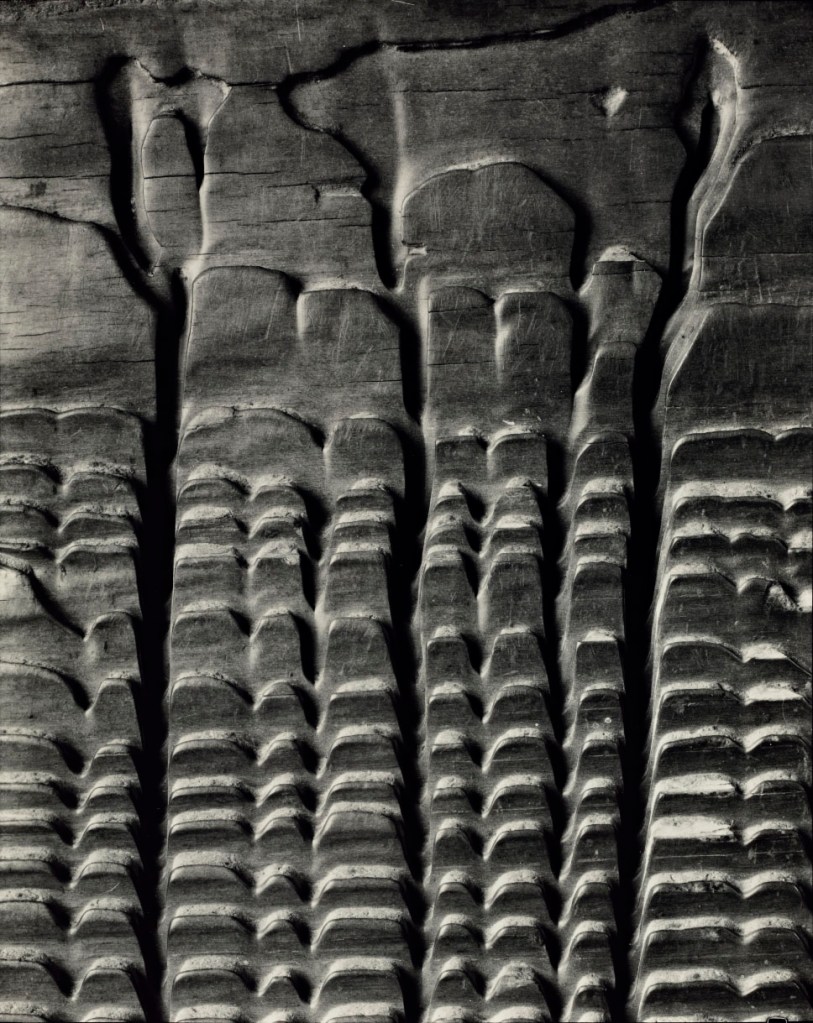

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Tank Nr. 1

1927

Gelatin silver print

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Workers’ Parade

1926

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

Workers Parade

A closely cropped image of a sea of sombreros, Workers Parade, much like her earlier photograph Roses, focuses in on the subject by eliminating all extraneous information. The politically charged subject matter, along with the unusual camera angle, attention to light and dark, and the texture and pattern produced by photographing the scene from above recalls the slightly later work of Alexander Rodchenko, and in particular, his Gathering for a Demonstration (1928). The ubiquitous sombrero would have been immediately recognizable to the Mexican viewer for its connection to the campesinos and trabajadores, the Mexican workers, who were gathered for the annual May Day parade in Mexico City. May Day, traditionally celebrated on the first of May, commemorates International Workers’ Day, often with large parades and gatherings as a demonstration of solidarity among workers. This was a calendar event that Modotti had been familiar with since childhood due to her father’s involvement in these very same parades.

Among Modotti’s earliest politically motivated photographs, Workers Parade brings together her formal concerns with her interest in using art to express her political beliefs and her desire to make her photography socially relevant. On a symbolic level, as noted by Sarah Lowe, Workers Parade conveys the power of unity by “suggesting that the source of power to make political changes lies with the peasants.” This photograph signaled a turning point in Modotti’s work toward a new modern form of photography that addressed contemporary issues and events in order to instigate and effect change.

Karen Barber. “Tina Modotti Artist Overview and Analysis,” on The Art Story website 12 Nov 2018 updated 2023 [Online] Cited 06/08/2023

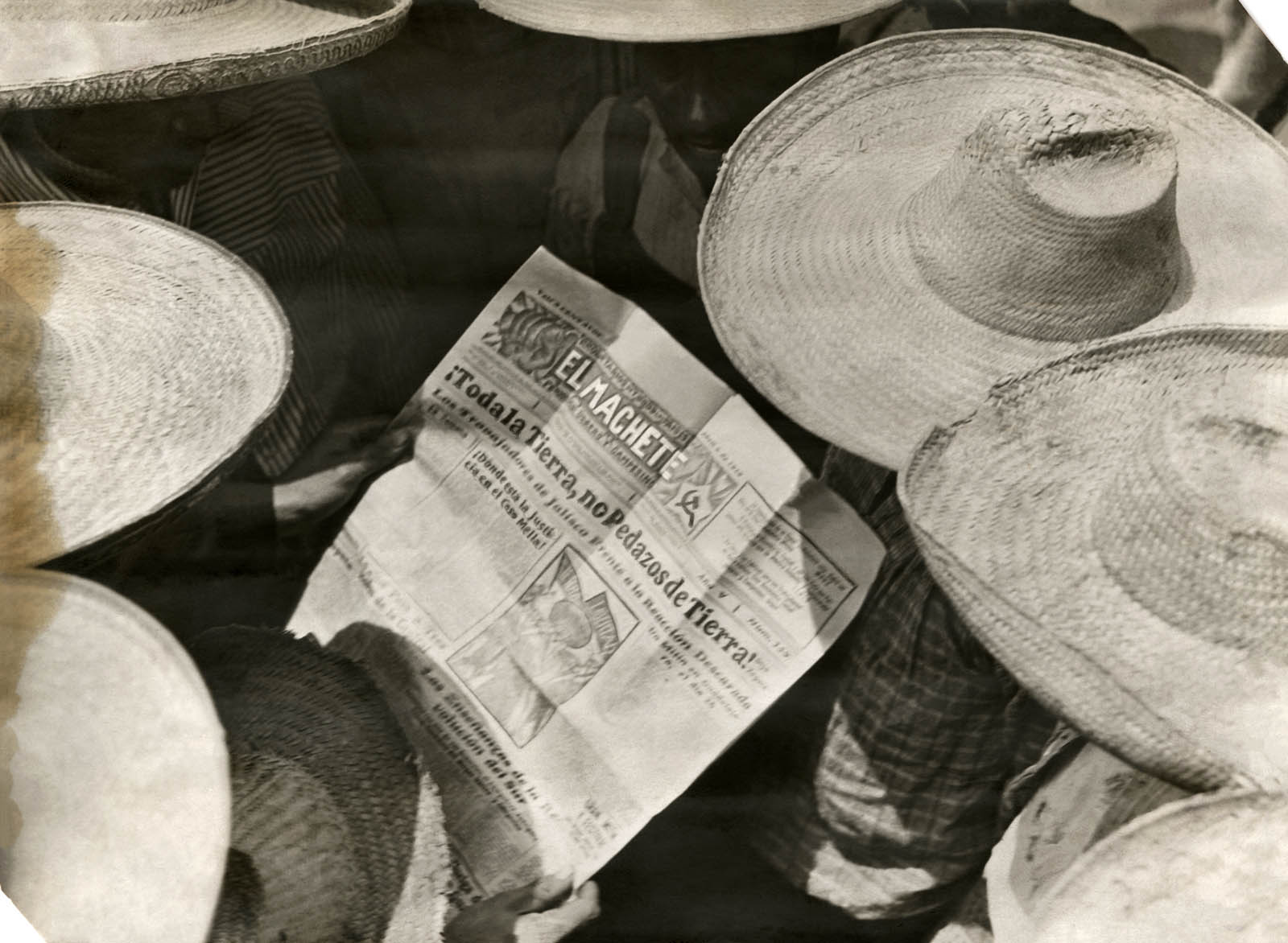

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Men reading “El Machete”

c. 1927

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

In this photograph of a peasant reading El Machete, the newspaper of the Mexican Communist Party, Modotti brings her careful attention surrounding composition, cropping, light and dark, and texture, to a subject with great social and political significance. Modotti had joined the Communist Party of Mexico this same year after learning that Italy had fallen to fascism. She brought her revolutionary zeal to her photographs of the late 1920s, many of which she published in Communist newspaper El Machete, a newspaper for workers and peasants. Whilst many photographers of this period, including Edward Weston and Paul Strand, were focused on a romanticized view of a timeless Mexico, Modotti turned to her camera to its people and to the real effects of its ongoing changes. She often collaborated with workers to produce photographs that were intended to raise class-consciousness and depict their daily lives.

At a moment when new governmental education reforms sought to educate the lower and working classes in Mexico, a seemingly straightforward image of a man reading a newspaper also had subversive undertones, particularly to the middle class. As Sarah Lowe notes: “The young obrero reading El Machete is a reminder that the Revolution’s promise of universal literacy would only be fulfilled by the activism of the people.” Although she viewed photography through the lens of modernism, she also believed that photography was a form of mass communication and an important means of enhancing visual literacy.

Karen Barber. “Tina Modotti Artist Overview and Analysis,” on The Art Story website 12 Nov 2018 updated 2023 [Online] Cited 06/08/2023

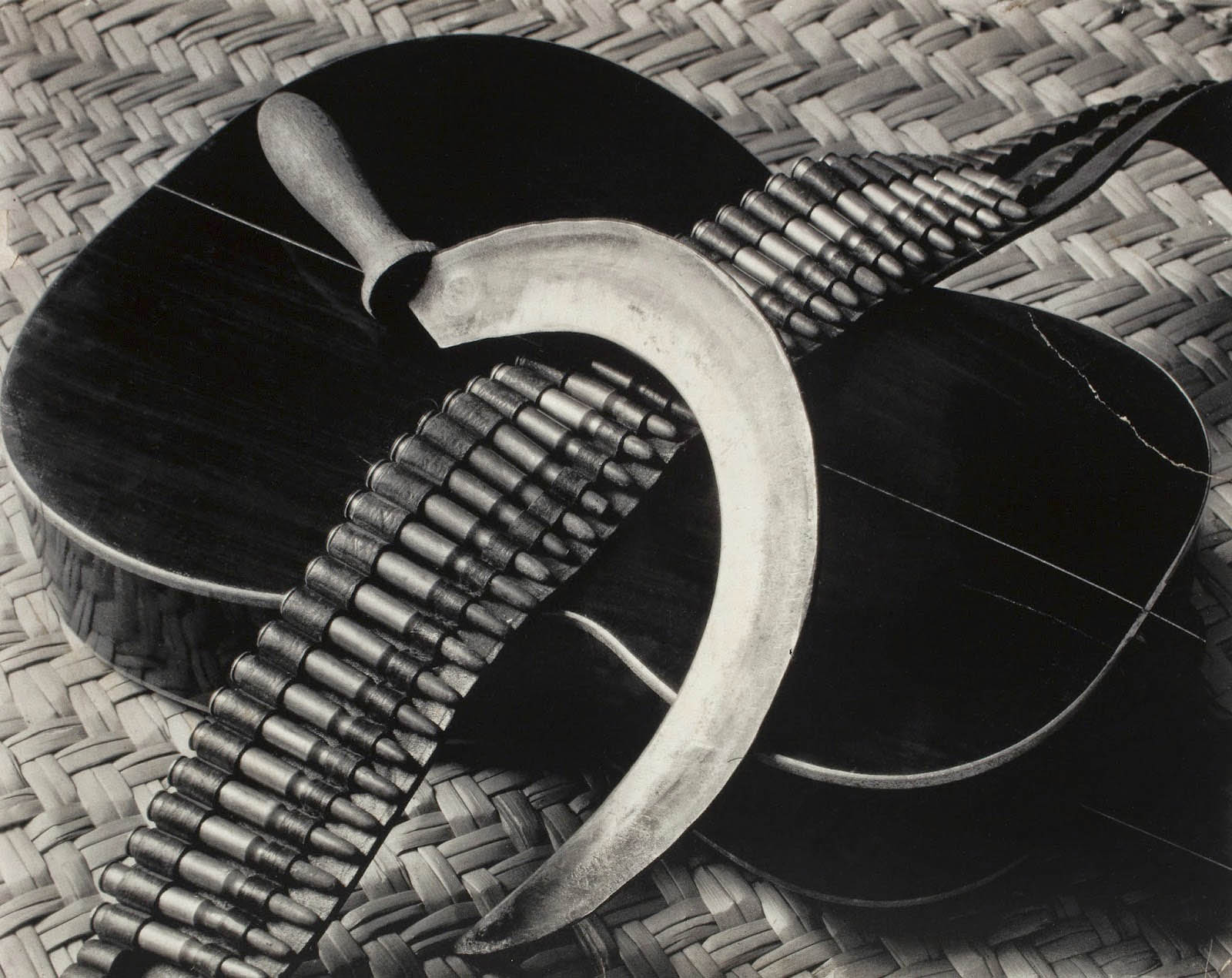

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Bandolier, Corn, Sickle

1927

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

A carefully composed photograph of a bandolier, an ear of corn, and a sickle, married Modotti’s interest in the photographic still life with objects symbolic of Mexico and the revolution – the sickle, a popular Communist symbol, corn, a symbol of Mexico and its rural farmers, and the bandolier (a pocketed belt for holding ammunition), the symbol of the Mexican Revolution. Politically active after 1925, Modotti joined the Communist Party of Mexico (CPM) in 1927. Due to her Communist-inflected worldview, her photographs from the late 1920s took a decided turn toward Communist symbolism, in lieu of overt propaganda.

As Sarah Lowe has stated, “her eloquent arrangements – founded on a stringent formal control – relocates the commonplace into the realm of the symbolic. They become potent revolutionary icons, offering a metaphorical union of artista [artist], campesino [farm laborer], and soldado [soldier], thus functioning as both formal still life and propaganda.” Lowe further suggests that in so doing, Modotti created a new kind of political picture. In this respect, Modotti’s relationship with Frida Kahlo becomes more than a shared friendship, and also incorporates shared artistic practice. Kahlo also infused still-lives with political objects and slogans, and as such transforms a seemingly domestic process of making art into a highly charged political statement.

Karen Barber. “Tina Modotti Artist Overview and Analysis,” on The Art Story website 12 Nov 2018 updated 2023 [Online] Cited 06/08/2023

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Canana, sickle and guitar

1927

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Hat, hammer and sickle

México 1927

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Committee of the Organisation of the Pioneers of the Communist Party of Mexico

Mexico City, 1928

Gelatin silver print

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Woman with flag

México City, c. 1928

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

The life of Tina Modotti (Udine, August 16th 1896 – Mexico City, January 5th 1942) was influenced by some of the most important historical events of the 1920s and 30s. A citizen of the world – as many have considered her – Modotti’s work and her life have been surrounded by uncertainties that have only been resolved after in depth study, although some gaps still remain.

Modotti lived in several countries, among them Spain, which coupled with her agitated political militancy led to the dispersion of her work. Consequently, as pointed out by the show’s curator Isabel Tejeda, this “decontextualizes and disorients her production, making it impossible to date many of her images with precision.” Nevertheless, one could argue that most of her photographic work was produced between 1923 and 1930 while she was in Mexico. During those years, after her apprenticeship with Edward Weston, Modotti evolved from the perfection of abstract forms to a different and more personal gaze that was conditioned by her outlook on life and her notable attraction to human beings and social injustice. She went on to portray the precarious conditions of workers, inequalities, and misery in urban areas. Likewise, she focused on women and their role within the community as well as the forms and symbols of working class emancipation. In her eagerness to promote awareness, Modotti produced images denouncing injustice, while honouring the dispossessed; some had propagandistic purposes and were intended for publications and magazines.

The exhibition being presented at Fundación MAPFRE is the most comprehensive show dedicated to Tina Modotti to date. Thanks to the work of Isabel Tejeda, we are able to contemplate a large number of the artist’s originals that have been assembled through the curator’s research. Nearly 200 photographs (predominantly vintage prints) have been grouped chronologically into four sections. Furthermore, a wide range of documentary materials will be on display along with the projection of one of the Hollywood films Modotti featured in. The exhibition is completed with works by photographers that were closely related to her, such as Edward Weston. This exhibition reconstructs Modotti’s figure without fissures for the first time, both in terms of her facets as an artist / photographer and as a revolutionary / antifascist militant.

KEYS

Tina Modotti and film

Tina Modotti’s first contact with the performing arts took place in San Francisco, in 1913, when she was only 16 years old. In 1920, after participating in a few plays, she made her way into the world of film. At the time, actresses were sought out to embody heroines, adventurers, or femme fatales. With her dark hair and complexion, Tina seemed to fit the prototype of an exotic woman; a cliché that she would try to distance herself from shortly after. Modotti was cast in three films: Tiger’s Coat (1920) by Roy Clemens, in the role of Jean Ogilvie; Riding with Death (1921) by Jacques Jaccard, as Rosa Carilla; and I Can Explain (1922) by George D. Baker, as Carmencita Gárdez.

Ideal of beauty, social ideal, political ideal

After her instruction with Edward Weston (it should be noted that she did not receive a formal education in photography) Tina Modotti’s work developed within the group that dominated artistic life in Mexico in the 1920s. Between 1926 and 1929 Modotti dissected popular Mexican life; not only were individuals worthy of her attention, but also water tanks, houses, the corn peasants ate and the hats they wore, sickles symbolising communism, machetes, or the woman (appearing like a sculpture) who carried a flag and personified the commitment to the revolutionary struggle. All of her images possess great clarity and substance. They leave no room for rhetoric, while allowing for the artist’s political, social, and aesthetic ideals to fuse into one.

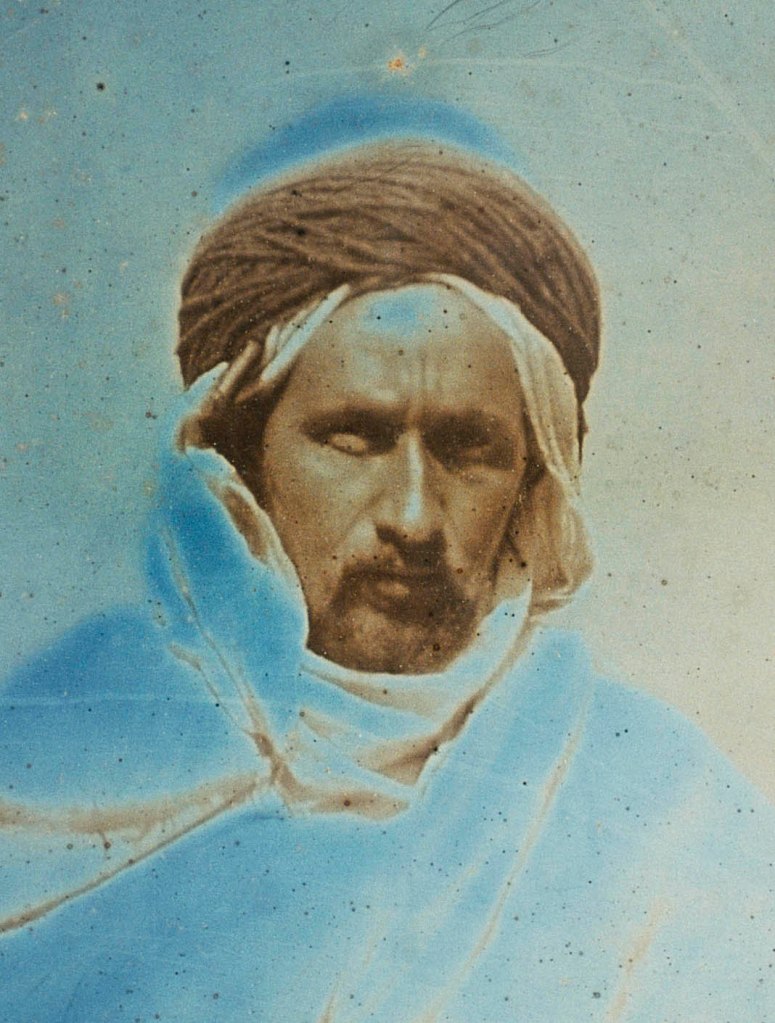

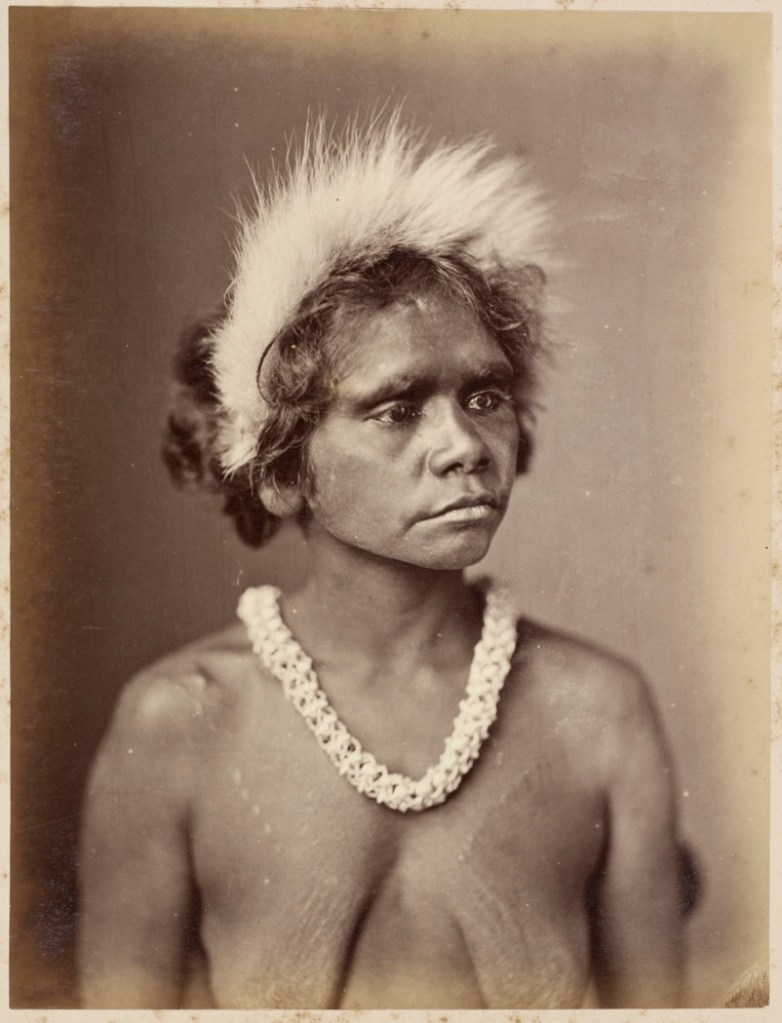

Mexican social landscape

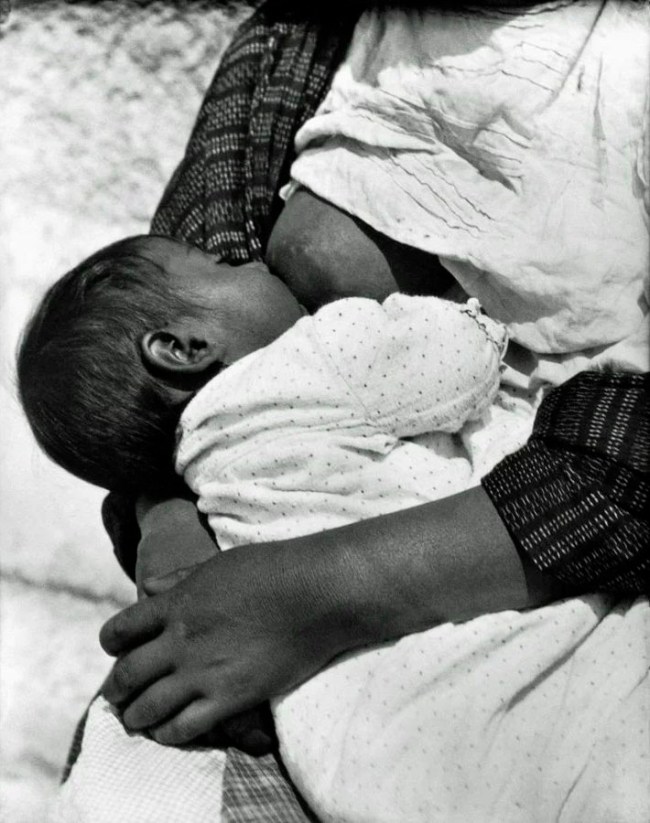

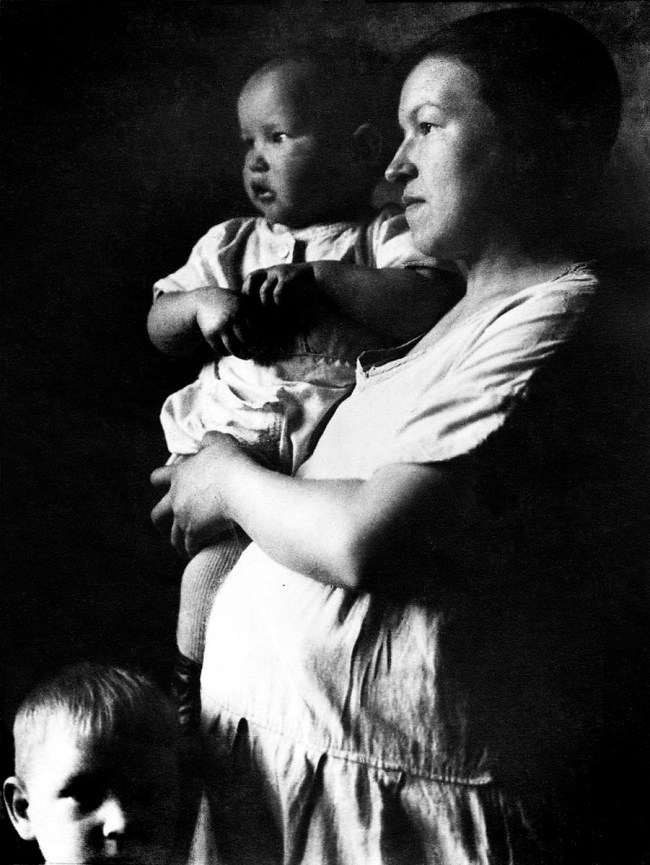

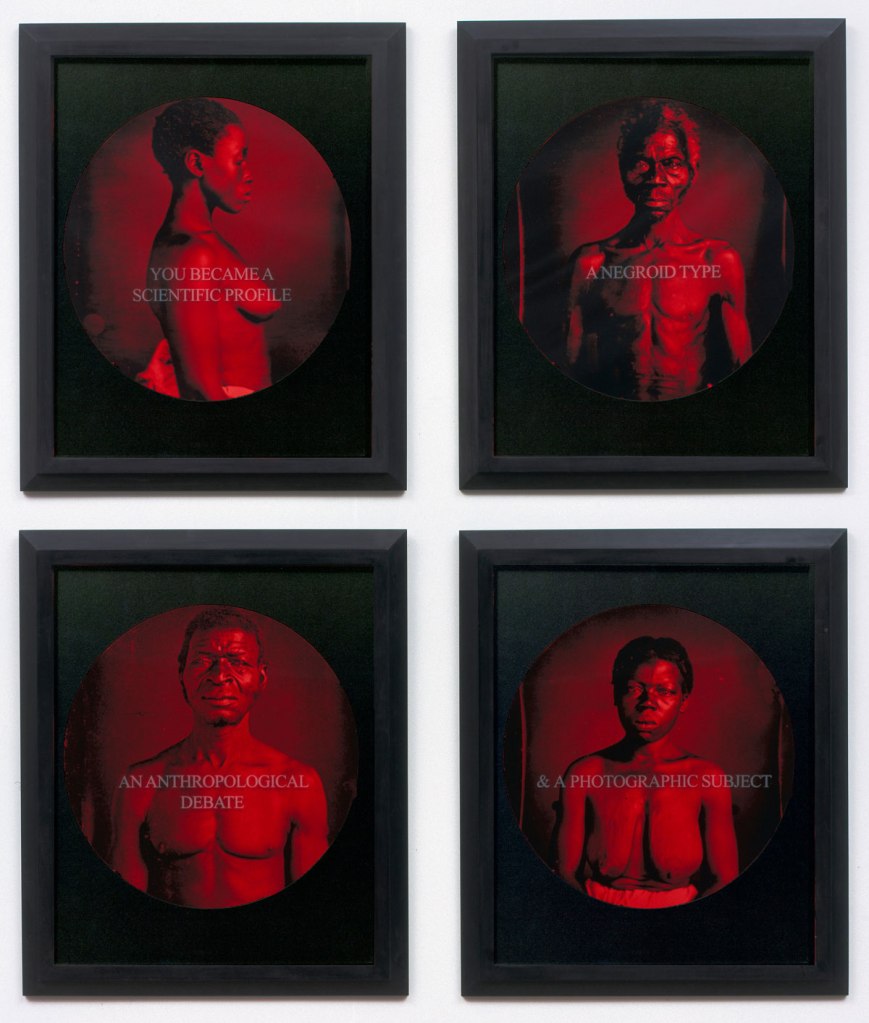

Some authors have pointed to Tina Modotti’s proletariat origins as the basis for her way of confronting social motifs and human figures. If some have defined this part of her work as “reportage photography”, one must point out that the artist’s curiosity and will to capture a person’s life in one image separates her from simple illustrative intent. One could argue that her portrayals of indigenous Mexican people, women, babies, and children are ethnographic photographs, albeit produced in a spontaneous way without an anthropological purpose. Therefore, despite being her point of departure, Modotti distances herself from the travellers who ventured into Mexican lands with a manner of curiosity that lay between science and romanticism.

International Red Aid

The Spanish section of the MOPR (International Red Aid) was established clandestinely in 1923 with the objective of disseminating political propaganda amid the climate of Primo de Rivera’s (1923-1930) dictatorship and had as another of its objectives to defend the Spanish Republic and its anti-fascist ideals. The MOPR spread throughout the entire world after its founding in the Soviet Union in 1922. Politically, the organisation had to follow the directives of the Communist Party, but in its facet dedicated to solidarity it played a key role in humanitarian aid. In Spain, after the October Revolution in Asturias in 1934, it became the main organisation dedicated to helping and aiding political detainees and their families. However, during the Spanish Civil War, the MOPR would constitute the true basis for the medical system of the Republican military.

The exhibition

Tina Modotti’s life was marked by some of the most important historical events decades of the 1920s and 1930s. Citizen of the world, as many have considered her, both her life like her work are surrounded by gaps that only after an in-depth study have could be completed, although not entirely.

The nomadic life that she led and the agitated political militancy caused Modotti to leave with sudden departure from many of the countries where she lived, which, as the curator of the exhibition points out, Isabel Tejeda, “decontextualizes and messes up her production from the start, so it is impossible to accurately date many of her images”, although it can be said that almost all her photographic work was produced between 1923 and 1930. During these Mexican years, and after her apprenticeship with Weston, the artist evolved from the perfection of the abstract forms to a different and personal perspective conditioned by her way of

seeing life, in which her attraction to human beings and social injustices stand out. She then portrayed the precarious conditions of workers, inequalities and misery in urban areas. She also focused on women and their role within the community, and on forms and symbols of the emancipation of the working class. In her eagerness to raise awareness, Modotti goes on to make images that denounce injustices and honour the dispossessed, some of which have a propaganda purpose and are intended to be printed in magazines and other publications.

The exhibition that Fundación MAPFRE is presenting is the most extensive that has been made of Tina Modotti until today. Thanks to the work of Isabel Tejeda, today we can see in our exhibition halls a great number of period prints (vintage copies) by the author, gathered after a deep work of research. There are about two hundred and forty photographs that are grouped together chronologically in four sections. In addition, an extensive amount of documentary material is shown and one of the films Modotti starred in in Hollywood. The selection is completed with works by photographers from her immediate environment, such as Edward Weston.

Text from Fundación MAPFRE

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Man with log

1928

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

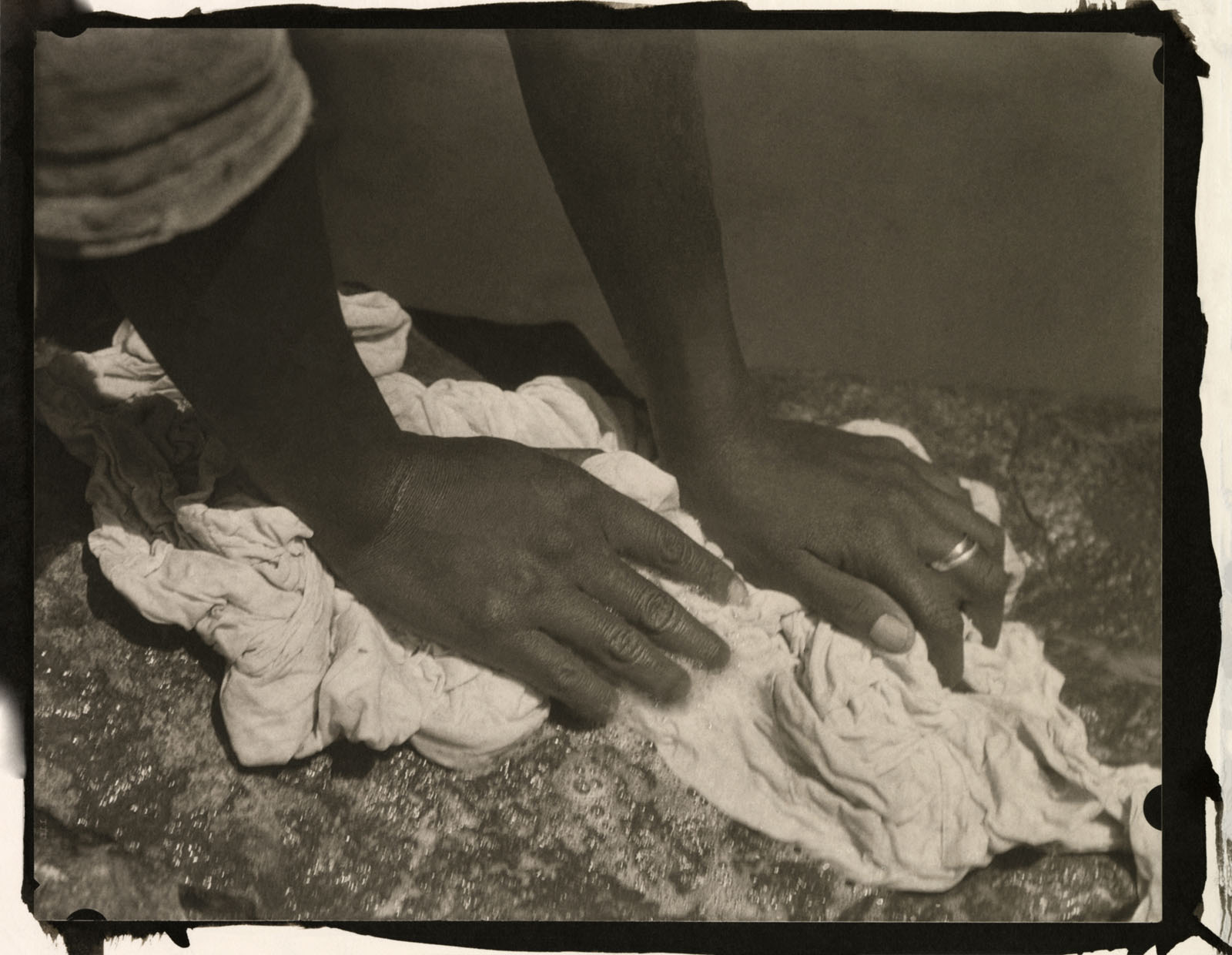

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Woman’s hands washing clothes

1928

Gelatin silver print. Later print, printed by Manuel Álvarez Bravo

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Baby Nursing

1926-1927

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

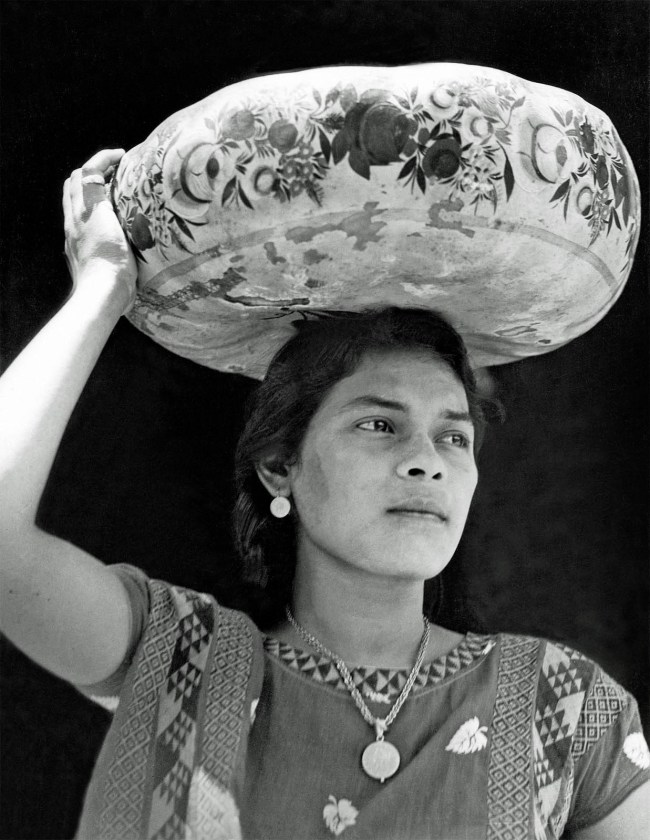

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Mujer con Jicara en la cabeza (Woman with Jicara on her head)

Juchitán, Oaxaca, 1929

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

In this iconic black and white photograph, a woman dominates the picture frame. Standing with arm raised holding a large gourd on her head, she gazes off to the right, somewhere out of the picture frame. She wears a circular pendant and earrings, and a traditional Tehuana dress with geometric patterns, the costume that has been so well made visible by the work of Modotti’s friend, Frida Kahlo. The careful framing, cropping, and pose emphasize the image’s angular forms. Shot from below to emphasize the woman’s noble and heroic stature, the photograph was taken during a trip to Tehuantepec in Southern Mexico. Unlike Modotti’s earlier photographs, the photographs taken in Tehuantepec were largely unposed, typically street photographs that captured the daily lives of the women that lived there.

Like other artists and writers in Mexico, Modotti was influenced by Mexicanidad, which embraced native cultures and indigenous subjects as part of the larger renewal in Mexican art and culture in the 1920s. This interest is evident in Woman from Tehuantepec. One of Modotti’s most iconic images, it became a potent symbol of Mexicanidad and an exercise in photographic modernism. As Sarah Lowe has noted, “the image function[s] like still life, precisely because Modotti chose not just any woman, but a well-known Mexican type – the Tehuana – to photograph. As pictured by Modotti, these women of Tehuantepec were an ideal subject, and provided her with an already-given meaning since Tehuantepec is a matriarchal society, there women have a significant voice in the running of the local economy and politics. Modotti uses the Tehuana to make a powerful political point: that women were capable of independent political action.”

Karen Barber. “Tina Modotti Artist Overview and Analysis,” on The Art Story website 12 Nov 2018 updated 2023 [Online] Cited 06/08/2023

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Tehuantepec woman with jicalpextle

1929

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

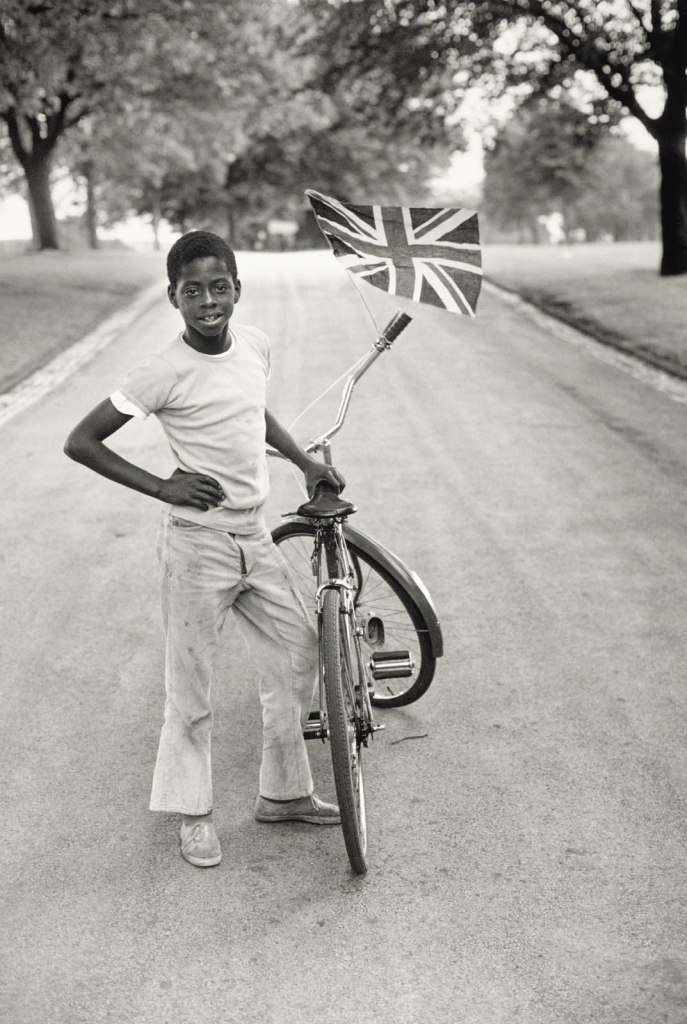

Tina Modotti (Udine, 1896 – Mexico City, 1942) took part in some of the most relevant historical events of the first half of the 20th century, such as the economic migration of Europeans to America at the turn of the century, the birth of silent film in the West Coast of the United States, post-revolutionary agrarianism in Mexico, political muralism, the vindication of indigenous Mexican culture, the incorporation of women into the public sphere, the battle between Stalinists and Trotskyists after the revolution of 1917, International Red Aid, and the Spanish Civil War. To some degree, despite the abundance of biographies written about her, certain biographical gaps still exist that are slowly being filled. She was one of the pioneers of women’s photography during the 1920s and although nearly 400 images can be attributed to Modotti today, the number continues to rise with each new discovery; this exhibition being one example. Likewise, Tina Modotti exerted a great influence on later Mexican photography, from Manuel Álvarez Bravo to Graciela Iturbide.

Modotti took up photography through Edward Weston, although she exceeded the North American artist’s formalist teachings through the immediate construction of her own autonomous compositions that possess a unique and personal vision.

Modotti arrived in Mexico after spending her teenage years in San Francisco and Los Angeles and was part of the “Mexican Renaissance”; a time of post-revolutionary cultural splendour. Integrated within the circle of Mexican artists and muralists, her work incorporated a type of embodied photography into Weston’s formalism. Her gaze was influenced by her modest upbringing, being an economic immigrant and a woman, and by her sensibility toward social injustice. A member of the Mexican Communist Party since 1927, she denounced the situation of dispossessed people with her camera, focusing on the construction of a new imaginary for Mexican women.

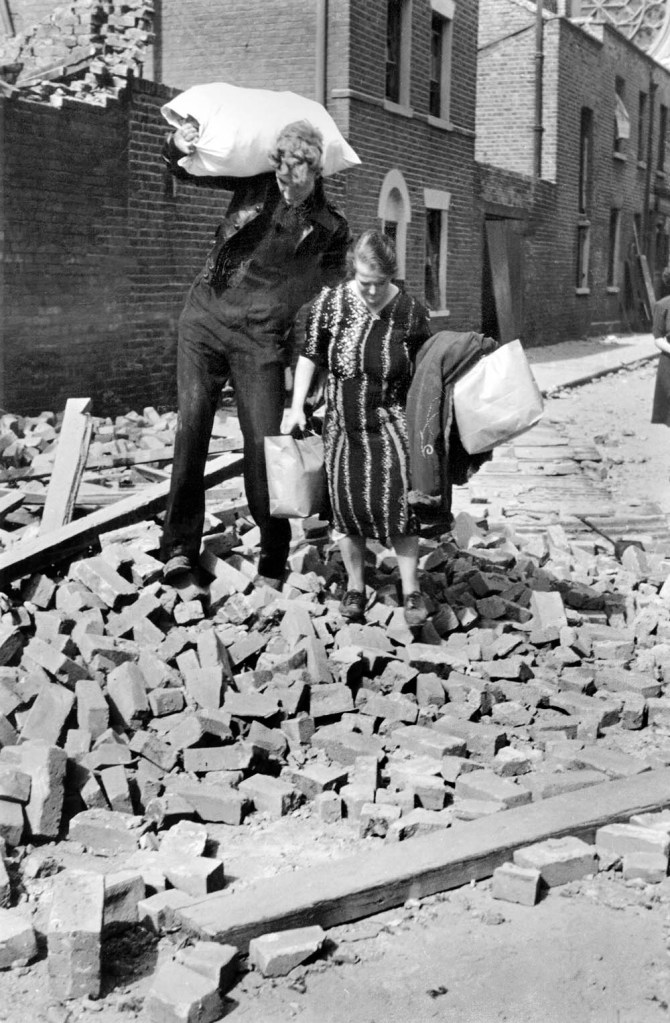

After being expelled from Mexico in 1930 for being a communist, her photographic militancy soon became full-fledged activism. Apparently, Modotti abandoned photography in the 1930s to dedicate herself to political militancy. Mid-way through the decade, she was sent to Spain by the Communist Party where she would have a key role throughout the Civil War. Taking on the coordination of International Red Aid (MOPR), she organised the escape from Spain of the so-called “children of the war”, coordinated the management of military hospitals – where she also worked as a nurse – and carried out propagandistic and political tasks. At the end of the conflict she crossed the Pyrenees along with thousands of political exiles.

She died in Mexico City in 1942.

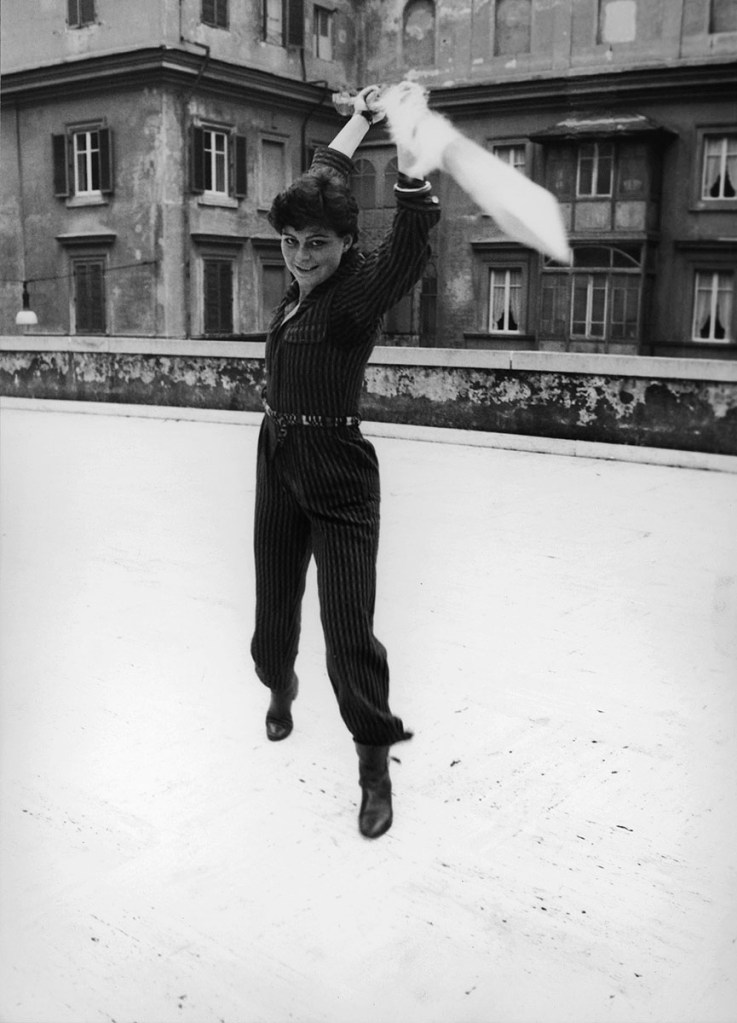

Early Years: From Udine to Los Angeles

Tina Modotti was born in 1896 into a modest family from Udine. In 1906 her father migrated to the United States in hopes of reuniting the family later. She arrived to San Francisco on her own in 1913, a city that was home to nearly twenty thousand Italians at the time. She worked in the textile industry, but also took part in the amateur theatre scene. In 1915 she met Roubaix de l’Abrie Richey (Robo) who she moved to Los Angeles with. There she met Edward Weston, modelling for him from 1920 onward. She also wrote and published her first poems and tried her luck in film, taking part in three movies. In The Tiger’s Coat, Modotti played the role of a Mexican Woman. Her physical appearance, dark hair, and Mediterranean skin typecast her into the stereotypical roles U.S. audiences associated with the exotic, romantic, and wicked myth of Latina women. Likewise, as can be observed in her family albums, she played with her ability to shift identities through clothing and costume (she posed dressed up as a ballerina in a pair of pants symbolising the empowerment of modern women and as a character from the Arabian Nights).

Mexico: On the Other Side of the Camera

In 1923 Tina Modotti moved to Mexico City with Edward Weston where they opened a portrait studio. The pair explored and took photographs of the country; this can be observed in Convent of Tepotzotlán and in Zuno’s house, the courtyard (whose exact authorship is unknown, as is the case with other photographs in this exhibition). At the time, the nation was experiencing what became known as the “Mexican Renaissance”. Modotti allowed herself to be influenced by this cultural splendour, soon becoming one of its prominent figures and transforming Mexican photography.

Her work evolved rapidly in Mexico. Modotti incorporated a personal gaze into the formalist perfection she learned from Weston that was influenced by her outlook on life and her attraction to human beings and the denouncement of social injustice (for example, in this section one can compare the photographers’ different approaches when depicting the circus tent or portraying the anthropologist Anita Brenner and the champion of the Náhuatl language Luz Jiménez).

During these early years Modotti worked on several still lives composed mainly of flowers, such as lilies, geraniums, roses, and cacti. Nevertheless, the artist also produced portraits in which she captured the powerful bond between a mother and her daughter (An aztec baby or Luz and baby) that went beyond the mere commodification of female bodies. Some of these images were later used in illustrated magazines of the time as examples of a Mexican identity whose origin was grounded in indigenous culture.

She also documented the work of Mexican muralists, such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, among others. Modotti’s photographs were featured in some of the most important publications of the time, including Idols Behind Altars by Anita Brenner and the monograph by Ernestine Evans on muralism in Mexican Folkways magazine.

In late 1926 Weston returned to the United States. Earlier that year Modotti had acquired a new Graflex camera in San Francisco that was lighter than the Corona she previously used. With renewed energy, she set off to photograph Mexico, which for her was embodied in its people.

Photography and Political Commitment. Mexico Is Its People

After becoming affiliated to the Communist Party in 1927, Modotti’s political commitment became more accentuated. She was part of International Red Aid and also collaborated as a translator and a photographer with the newspaper El Machete, whose audience was mainly peasants. Similarly, she attended and photographed demonstrations and participated in political associations such as Manos Fuera de Nicaragua (Hands Off Nicaragua).

She avoided poses and portrayed individuals in real situations, both in the city and in countryside villages; a line of citizens at Monte de Piedad Nacional to pawn their belongings, peasants at agrarian schools, tortilla, cabbage, and hat sellers, corn porters, washerwomen, mothers carrying their children, children at Colonia de la Bolsa living in poverty, popular festivities, etc. Some of them were published in newspapers, such as El Machete, and subsequently in foreign magazines, such as AIZ, Der Arbeiter-fotograf, New Masses, and Put’ Mopr.

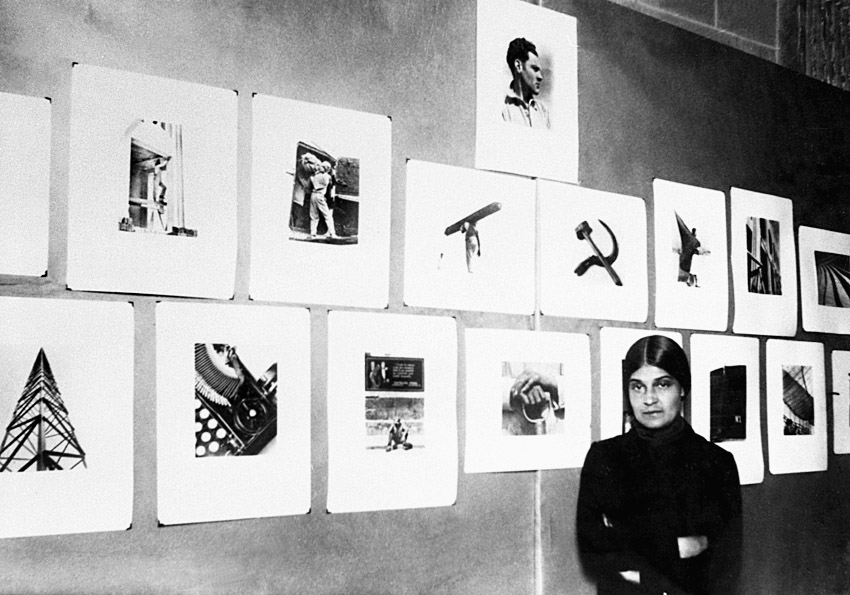

Modotti contemplated the dilemma of representation. How to find a visual language that was accessible to the people without betraying her aesthetic principles? She found a formula in symbolic photography. For example, Woman with flag is not merely an image about communism; instead, it expresses the ability of human beings to become empowered through willpower and political ideals. Modotti also produced still lives whose juxtaposed elements represent basic abstract concepts that speak of the people as an emancipated entity and of a communist vision of the future born from the land itself (Sickle, canana and corn cob and Guitar neck, canana and corn cob). In her photographic manifesto of 1929, coinciding with her solo exhibition at the Biblioteca Nacional, Modotti declared that she did not consider herself an “artist”, but rather a “photographer”; a trade she conceived as any other, in consonance with her proletariat ideas.

Toward Political Action: Spain at War

In 1930 Tina Modotti was expelled from Mexico and returned to Europe after having been falsely accused of taking part in an attack against Mexican president Pascual Ortiz Rubio. She spent a short time in Berlin, trying to continue her photographic pursuit unsuccessfully. However, Modotti would soon move to the Soviet Union where she focused on her activities as a member of International Red Aid (MOPR).

The Communist Party sent Modotti to Spain during the Spanish Republic. When the Civil War broke out, she coordinated MOPR under different aliases, reorganizing the Cuatro Caminos Worker’s Hospital (whose purpose was tending to injured militants), supervising, reporting, and writing articles under the names María, Carmen Ruiz, and Vera Martini for MOPR’s newspaper Ayuda. Semanario de la solidaridad [Help. Weekly of Solidarity], and supervising propaganda (in other words, the dissemination of the organisation’s activities). Politically dependent on the Communist Party, MOPR played a major role in humanitarian aid during the war, becoming the main organisation geared toward helping and aiding political detainees and their families, as well as being an important part of the Republican military health system.

In 1937 Modotti participated in the organisation of the Second International Congress for the Defense of Culture in Madrid, Valencia, and Barcelona. Among the participants were André Malraux, Anna Seghers, Ernest Hemingway, Aleksey Tolstoy, Octavio Paz, Elena Garro, Rafael Alberti, María Teresa León, Robert Capa, and Gerda Taro.

There is no trace of the photographs Modotti produced in Spain, although some authors suspect that three of the 17 images found in Viento del pueblo, poesía en la guerra [Wind of the People, Poetry in War] by Miguel Hernández might be hers. What seems to be clear is that the publication of the book of poems as a photobook was Modotti’s idea.

She returned to Mexico with Vittorio Vidali, her partner at the time, and died prematurely in 1942 due to a heart attack. After Modotti’s passing, her Mexican friends and Spanish republican exiles honoured her in Mexico City. The last photograph she produced, which will be on display for the first time in this exhibition, was of her dog Suzi.

Her work was progressively forgotten until the 1970s when it began to be exhibited and studied.

Text from Fundación MAPFRE

Anonymous photographer

Italian photographer, actress and political activist Tina Modotti (1896-1942) at an exhibition of her work at the National Library in Mexico City in December 1929

1929

Gelatin silver print

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896-1942)

Portrait of a Pregnant Woman

Berlin, Germany, 1930

Gelatin silver print

Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive, Mexico City

Her extensive political activism and bohemian lifestyle earned her enemies. When on January 10, 1929, Julio Antonio Mella was assassinated, and shortly thereafter an assassination attempt was made on Mexican President Pascual Ortiz Rubio, the press suspected Modotti as the perpetrator. Called “the fierce and bloody Tina Modotti,” she was expelled from the country in 1930.

First, she moved to Weimar Berlin, then, after the rise to power of Hitler, she moved to Moscow, Warsaw, Paris, and Madrid, always finding friends in Communist circles. From 1936 she participated in the Spanish Civil War using the pseudonym Maria. She stayed in Spain until the collapse of the Republican government in 1939 when she returned to Mexico. In 1942 she died in a taxi from heart failure which many described as suspicious. Diego Rivera believed that it was her lover Vittorio Vidali who orchestrated her death because Tina Modotti “knew too much.”

Magda Michalska. “Tina Modotti: Photographer Made Revolutionary,” on the Daily Art website 2 October 2022 [Online] Cited 06/08/2023

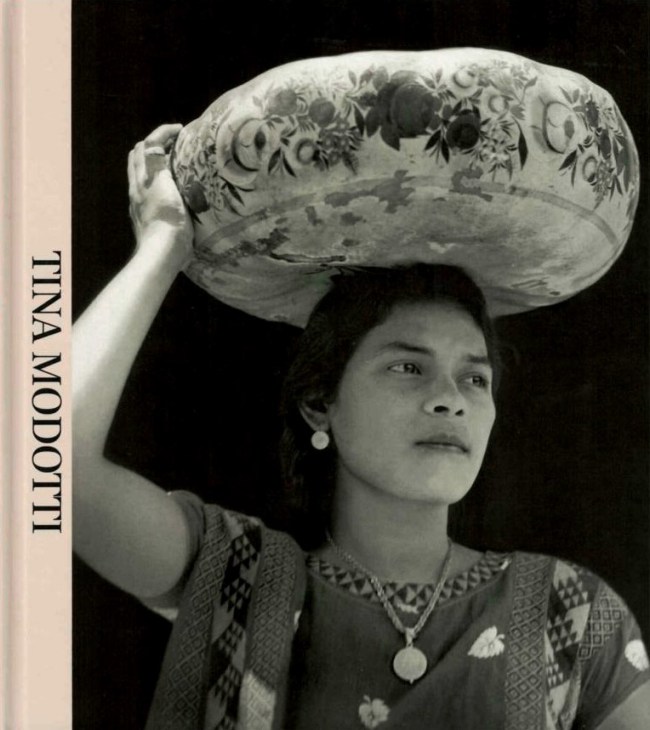

Tina Modotti exhibition at Fundación MAPFRE catalogue cover

The Legacy of Tina Modotti

Her work was largely unknown until the 1990s, when a cache of her remarkable photographs was discovered in an Oregon farmhouse. Long overshadowed by her extraordinary life and her relationship with Edward Weston, she was viewed as his muse, rather than as a gifted photographer in her right. Despite a remarkably short career in photography – just seven years – she created a body of iconic images that confirmed her place in history. By fusing rigorous formalism with a desire to effect social change, she reconceived revolutionary photography through the language of modernism. Her work is now a touchstone in the history of photography, reflecting equally the tenets of modernist photography and the experience of post-revolutionary Mexico. Modotti’s photographs continue to inspire many, including many women and activists interested in making a socially and politically relevant art.

In the realms of Straight Photography, Modotti’s work is interesting to consider in comparison to that of Dorothea Lange and Imogen Cunningham, three women known to have had a dialogue in 1925 when Modotti returned to San Francisco for a short while. Like Cunningham and Lange, Modotti excelled in formal technique and as such influenced the next generation of highly skilled photographers. In subject matter and energy however, there is also a strong Surrealist and feminist edge to the work of Modotti extending her field of influence even wider. She is one of many European artists, including Leonora Carrington and Leonor Fini, who found freedom of expression in Mexico City; in this respect Modotti’s oeuvre adds to the history of a place as cultural and artistic capital for a time.

Karen Barber. “Tina Modotti Artist Overview and Analysis,” on The Art Story website 12 Nov 2018 updated 2023 [Online] Cited 06/08/2023

KBr Fundación MAPFRE

Av. del Litoral, 30 08005 Barcelona

Phone: +34 932 723 180

Opening hours:

Tuesdays – Sundays (and public holidays) 11am – 8pm

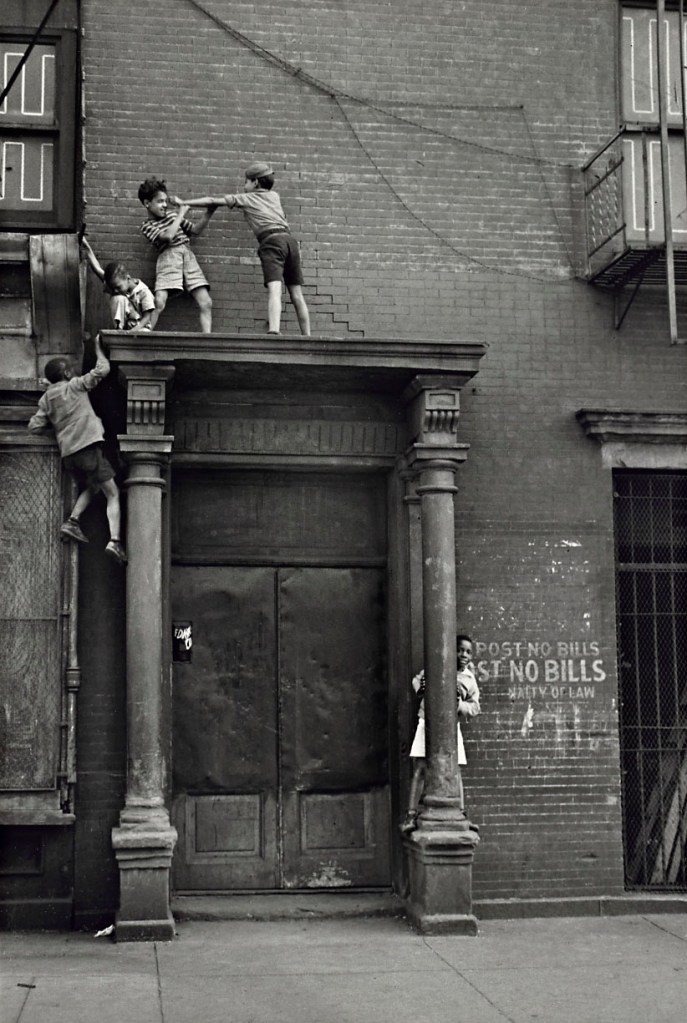

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Boulevard de Clichy, Paris' [Boulevard de Clichy, París] 1951 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Boulevard de Clichy, Paris' [Boulevard de Clichy, París] 1951 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/03.-id40_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aubervilliers, France' [Aubervilliers, Francia] 1947 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aubervilliers, France' [Aubervilliers, Francia] 1947 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/02.-id37_p.jpg?w=801)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Concentric Circles, Construction Site, New York' [Círculos concéntricos, obra, Nueva York] 1952 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Concentric Circles, Construction Site, New York' [Círculos concéntricos, obra, Nueva York] 1952 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/11.-id737_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Manhole, Times Square, New York' [Tapa de alcantarilla, Times Square, Nueva York] 1954 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Manhole, Times Square, New York' [Tapa de alcantarilla, Times Square, Nueva York] 1954 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/08.-id68_p-b.jpg?w=689)

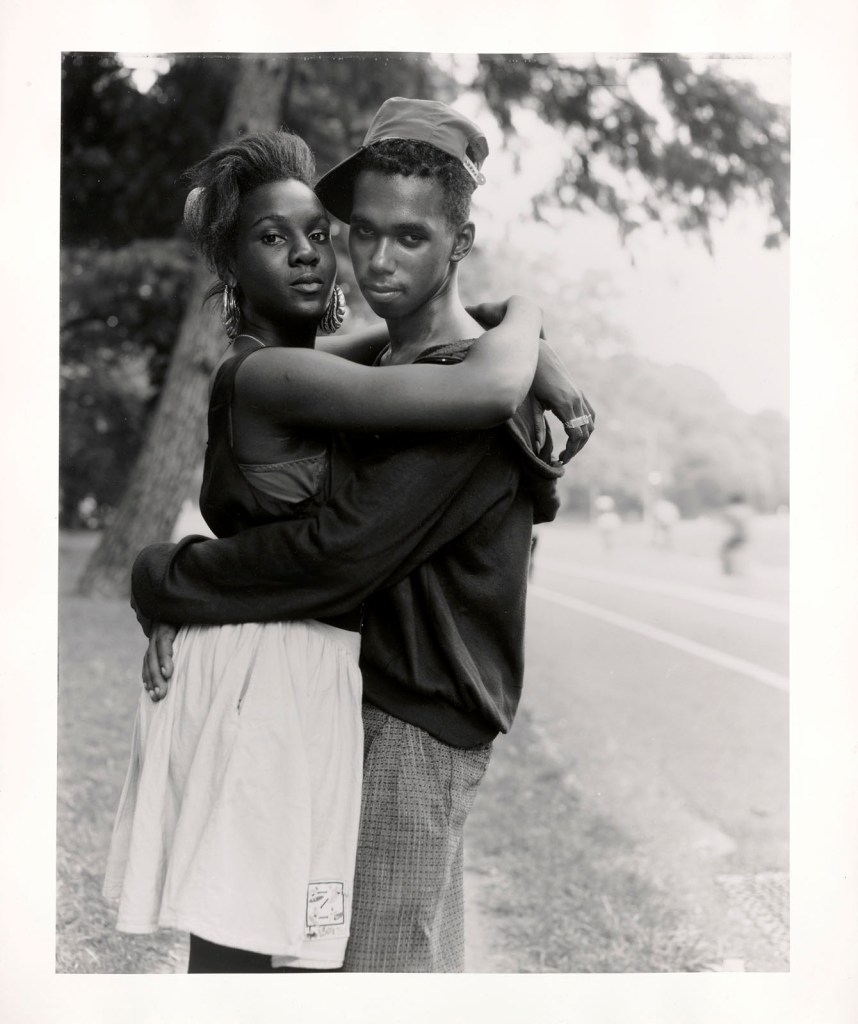

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, New York' [Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, Nueva York] 1954 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, New York' [Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, Nueva York] 1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/09.-id1_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Nancy Listening to Jazz, Greenwich Village, New York' [Nancy escuchando jazz, Greenwich Village, Nueva York] 1958 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Nancy Listening to Jazz, Greenwich Village, New York' [Nancy escuchando jazz, Greenwich Village, Nueva York] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/10.-id4211_p.jpg?w=744)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman Holding Newspaper, New York' [Mujer sujetando un periódico, Nueva York] 1946 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman Holding Newspaper, New York' [Mujer sujetando un periódico, Nueva York] 1946](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/01.-id1732_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Train Station Near Málaga, Spain' [Estación de tren cerca de Málaga, España] 1951 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Train Station Near Málaga, Spain' [Estación de tren cerca de Málaga, España] 1951](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/05.-id74_p.jpg?w=675)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Tony, "Pepe and Tony, Spanish Fishermen", Ibiza, Spain' [Tony, "Pepe y Tony, pescadores españoles", Ibiza, España] 1956 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Tony, "Pepe and Tony, Spanish Fishermen", Ibiza, Spain' [Tony, "Pepe y Tony, pescadores españoles", Ibiza, España] 1956](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/04.-id4569_p.jpg?w=669)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Commuters, Evening Train, Penn Station, New York' [Volviendo del trabajo en el tren de la tarde, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Commuters, Evening Train, Penn Station, New York' [Volviendo del trabajo en el tren de la tarde, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/06.-id179_p.jpg?w=684)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman with White Glove, Penn Station, New York' [Mujer con guante blanco, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman with White Glove, Penn Station, New York' [Mujer con guante blanco, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/07.-id461_p.jpg?w=683)

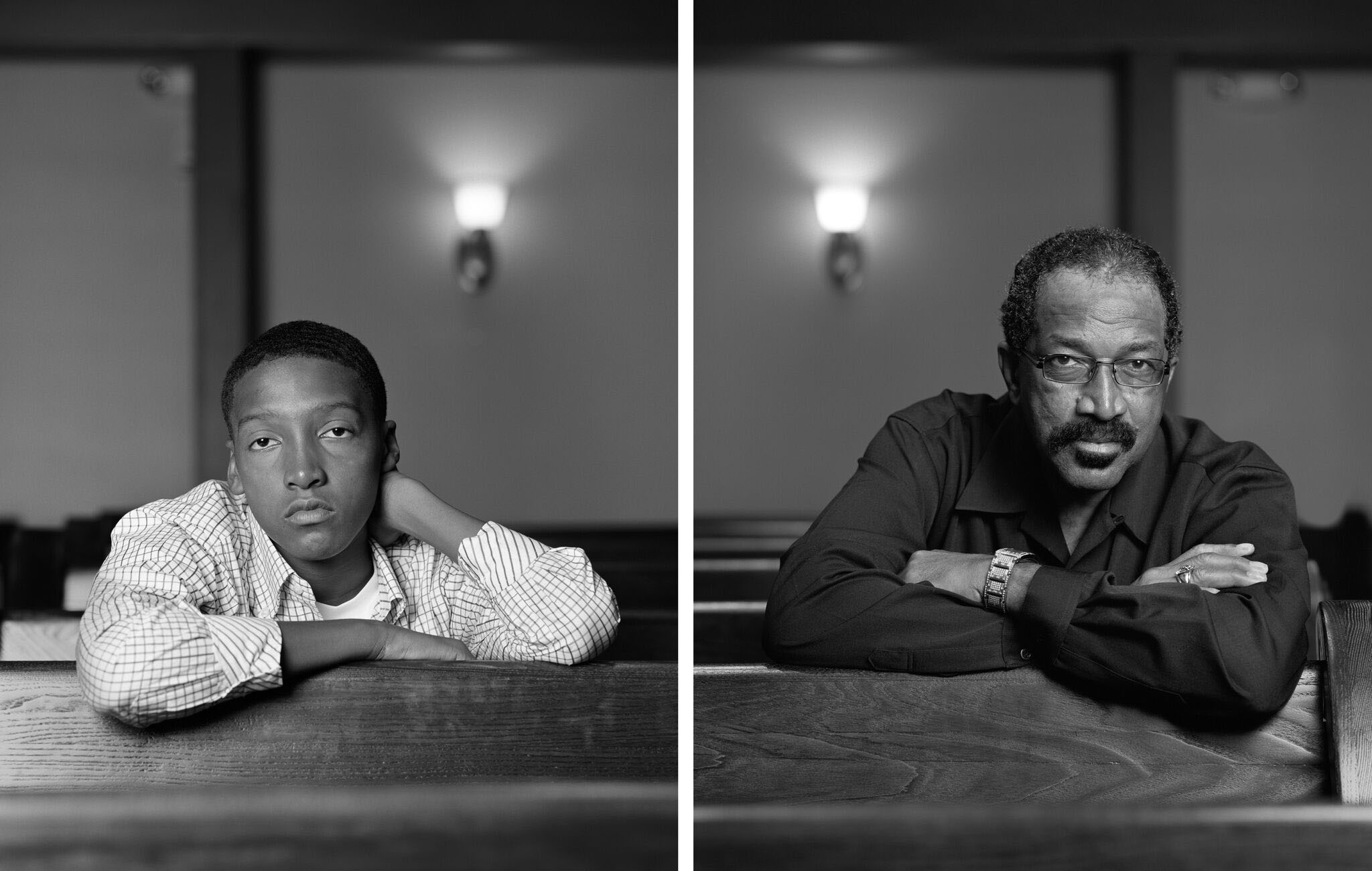

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aluminum Foundry, Soviet Union' [Fundición de aluminio, Unión Soviética] 1975 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aluminum Foundry, Soviet Union' [Fundición de aluminio, Unión Soviética] 1975](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/13.-id648_p.jpg?w=686)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Assembly Line Worker, Long Island City, New York' [Trabajadora en cadena de montaje, Nueva York] 1972-1974 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Assembly Line Worker, Long Island City, New York' [Trabajadora en cadena de montaje, Nueva York] 1972-1974](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/12.-id96_p-1.jpg?w=691)

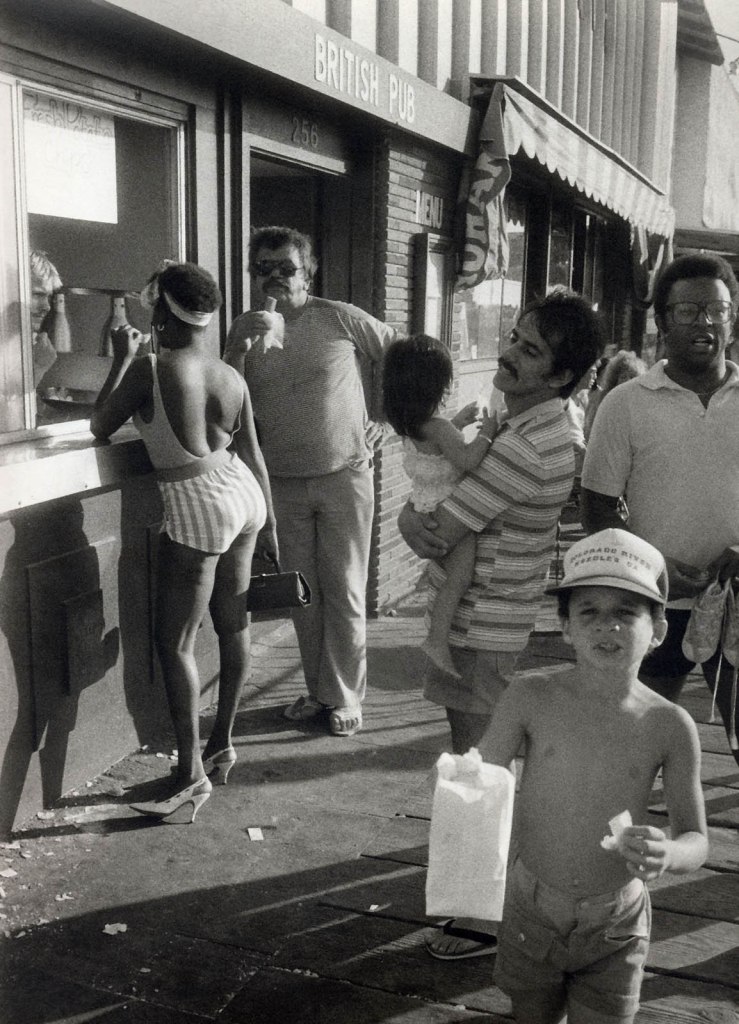

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Demonstrators on March in Support of United Farm Workers, New York' [Manifestantes en una marcha de apoyo a la Unión de Campesinos, Nueva York] 1975-1976 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Demonstrators on March in Support of United Farm Workers, New York' [Manifestantes en una marcha de apoyo a la Unión de Campesinos, Nueva York] 1975-1976](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/14.-id1307_p.jpg?w=685)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Self-Portrait, Santiago, Chile' [Autorretrato, Santiago de Chile] 2000-2001 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Self-Portrait, Santiago, Chile' [Autorretrato, Santiago de Chile] 2000-2001](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/16.-id1627_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Women from Texas, Fifth Avenue, New York' [Mujeres de Texas, Fifth Avenue, Nueva York] 1975 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Women from Texas, Fifth Avenue, New York' [Mujeres de Texas, Fifth Avenue, Nueva York] 1975](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/15.-id145_p.jpg?w=694)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris' [Jardin du Luxembourg, París] 1997 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris' [Jardin du Luxembourg, París] 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/17.-id2978_p.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.