Exhibition dates: 27th August 2013 – 12th January 2014

Gohar Dashti (Iranian, b. 1980)

Untitled #5

2008

I love that this archive gives a presence to disparate voices.

This is an important exhibition, one that challenges “Western notions about the ‘Orient,’ examines the complexities of identity, and redefines documentary as a genre.” The work of 12 women artists from Iran and the Arab World challenge stereotypes and provides insight into political and social issues. “The images – ranging from fine art to photojournalism – refute the conception that Arab and Iranian women are “oppressed and powerless,” instead reinforcing that some of the most significant photographic work in the region today is being done by women.”

Marcus

Many thankx to The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Gohar Dashti (Iranian, b. 1980)

Untitled #2

2008

Tanya Habjouqa (Jordanian, b. 1975)

Untitled

2009

From the Women of Gaza series

Tanya Habjouqa (Jordanian, b. 1975)

Untitled

2009

From the Women of Gaza series

Rania Matar (Lebanese/Palestinian/American, b. 1964)

Stephanie, Beirut, Lebanon

2010

Rania Matar (Lebanese/Palestinian/American, b. 1964)

Alia, Beirut, Lebanon

2010

Rula Halawani (Palestinian, b. 1964)

Untitled XIII

2002

Lalla Essaydi (Moroccan, b. 1956)

Bullets Revisited #3

2012

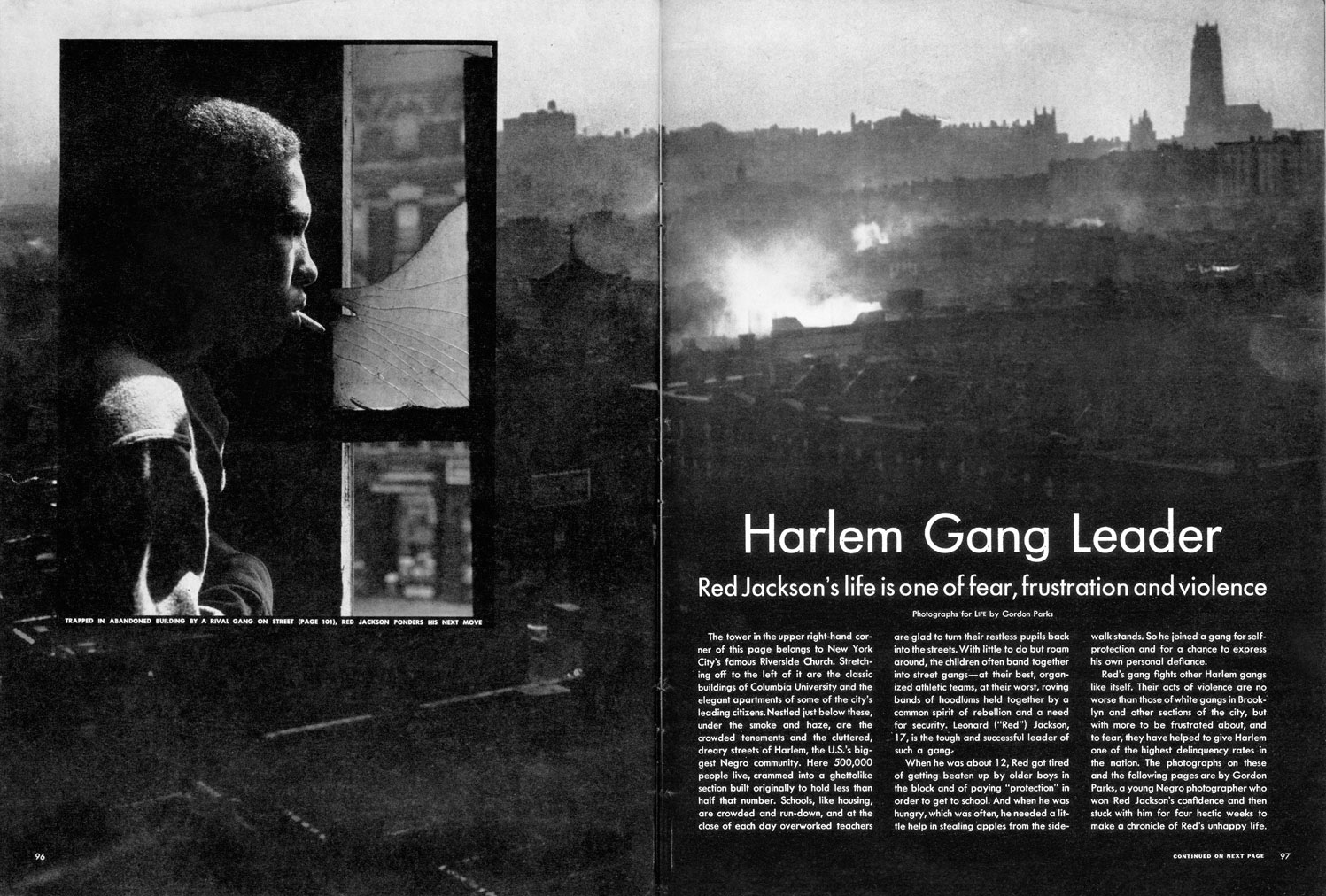

Power and passion will be on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) in an exhibition of works by 12 women photographers from Iran and the Arab World. The first of its kind in North America, the exhibition features approximately 100 photographs and two videos, created almost entirely within the last decade, that challenge stereotypes and provide insight into political and social issues. The images – ranging from fine art to photojournalism – refute the conception that Arab and Iranian women are “oppressed and powerless,” instead reinforcing that some of the most significant photographic work in the region today is being done by women. On view from August 27, 2013 – January 12, 2014, She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World highlights the rich artistic expression of pioneering photographers Jananne Al-Ani, Boushra Almutawakel, Gohar Dashti, Rana El Nemr, Lalla Essaydi, Shadi Ghadirian, Tanya Habjouqa, Rula Halawani, Nermine Hammam, Rania Matar, Shirin Neshat, and Newsha Tavakolian. Accompanying the exhibition is a new publication, She Who Tells a Story (MFA Publications, September 2013), authored by exhibition curator Kristen Gresh, the MFA’s Estrellita and Yousuf Karsh Assistant Curator of Photographs. This exhibition is generously supported by the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Additional support from the Barbara Jane Anderson Fund.

“She Who Tells a Story brings together recent photographs from 12 groundbreaking artists,” said Malcolm Rogers, Ann and Graham Gund Director of the MFA. “Their works tell stories that evoke a range of emotion, challenge our perception, and present the Middle East with a fresh perspective.”

In Arabic, the word rawiya means “she who tells a story.” These photographs are a collection of stories about contemporary life in Iran and the Arab World. The exhibition will explore themes of “Deconstructing Orientalism,” “Constructing Identities,” and “New Documentary,” revealing the individuality of each artist’s work, while allowing glimpses into the region’s social and political landscapes. The MFA has acquired 18 of the works on view in the Henry and Lois Foster Gallery in the Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art. Acquisitions made in 2013 include Roja (Patriots) from the series Book of Kings (2012) by Shirin Neshat; the complete series of nine photographs in Mother, Daughter, Doll (2010) by Boushra Almutawakel; three prints from the series Women of Gaza (2009) by Tanya Habjouqa; two photos from the series The Metro (2003) by Rana El Nemr; two prints from the series Qajar (1998) by Shadi Ghadirian; and Untitled #2 from Today’s Life and War (2008) by Gohar Dashti.

“Reflecting on the power of politics and the legacy of war, the photographs in this exhibition challenge Western notions about the ‘Orient,’ examine the complexities of identity, and redefine documentary as a genre,” said curator Kristen Gresh, who was first exposed to this work while living abroad for 15 years, teaching history of photography in Paris and Cairo.

Historically, Orientalism refers to depictions by European or American artists of the East, including Middle Eastern, North African, and Eastern cultures – often presenting the “Orient” as culturally inferior. The history of photography in the area has largely consisted of images created by outsiders, ranging from pyramids and sacred biblical sites to staged harem scenes and belly dancers. Coupled with myths and traditional tales like the “Persian” Queen Sheherazade and the “Arabian” Thousand and One Nights, misconceptions continue to persist to this day. These stereotypes are shattered with Shirin Neshat’s groundbreaking series Women of Allah (1993-97). The series grew out of a visit she made to her native Iran 15 years after the Iranian Revolution (1979). On view are four portraits from the series – Untitled (1996), Speechless (1996), I Am Its Secret (1993) and Identified (1995) – each of which incorporate elements of the veil (or hijab), gun, text and gaze and break down Orientalist myths, showing women empowered in the face of opposition. Among the earliest photographs in the exhibition, they are overlaid with Persian script from contemporary Iranian women writers and evoke the role that women played in the Iranian Revolution. The series marked a turning point in the recent history of representation and debates about the veil, inspiring exploration by other photographers.

In addition to Neshat, others have had an impact on the history of visual representation and the perception of Orientalist stereotypes. In the diptych Untitled I & II (1996) Iraqi-born Jananne Al-Ani uses the women in her family (and herself) to show a progression in veiling, from unveiled to fully veiled, and back again. The installation of the large-format prints have the effect of trapping the viewer between the women’s unblinking stares, using the power of the lens to address myths about the oppression of Muslim women. Moroccan-born Lalla Essaydi, a former painter and alumnus of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (SMFA), uses iconography from 19th-century Orientalist paintings as inspiration to explore and question her own cultural identity. In the triptych Bullets Revisited #3 (2012), the most expansive work in the exhibition at 5 1/2 x 12 1/2 feet, and Converging Territories #29 (2004), she uses calligraphy (a typically male art form) to suggest the complexity of gender roles within Islamic culture. In Bullets Revisited #3, silver and golden bullet casings evoke symbolic violence, referencing her fear about growing restrictions on women in a new, post-revolutionary era that followed demonstrations and protests in the Arab world that began in 2010.

Like Neshat’s and Al-Ani’s work from the 1990s, the iconic series Qajar (1998) by Iranian artist Shadi Ghadirian was a point of departure for many photographers of the time. Ghadirian, who currently lives in Tehran, took pictures that illustrated issues of identity and being female in Iran. The nine prints on view from the Qajar series juxtapose young women in traditional dress with then-forbidden objects, such as boom boxes, musical instruments, and makeup, suggesting tension between tradition and modernity, restriction and freedom, public and private. Also included in the exhibition is another, later Ghadirian series that presents juxtapositions – Nil, Nil (2008), which brings to the forefront the experience of women at home during war, invoking untold tales of loss and waiting. The series includes images of bullets protruding from a handbag; a grenade in a bowl of fruit; and a military helmet hanging on the wall next to a headscarf, bringing to mind the complexities of male and female public personas and private desires.

Ghadirian’s early staged portraits laid the foundation for later photographers to address the subject of identity, including Boushra Almutawakel, a native of Yemen. Her series Mother, Daughter, Doll (2010) uses the veil to challenge social trends and the rise of religious extremism, which calls for women – and even young girls – to cover their bodies in public. The staged portraits do not denounce the hijab, but protest the extremist notions of covering bodies and the trend toward black. The nine prints on display show smiles from mother and daughter fade as their colorful clothing disappears from one picture to the next. The series ends with an image of an empty pedestal draped in black fabric as mother, daughter and doll are completely eliminated – a statement about erasing the individual through dress. Almutawakel offers a sensitive perspective on the public and private lives of young women, as does Lebanese-born Rania Matar in her series A Girl and Her Room (2009, 2010). These six portraits of young women from the Middle East capture girls in their bedrooms, surrounded by their belongings. Despite a diversity of settings and sitters, the series reflects the universally-shared experiences of coming of age and the complexities of being a young woman.

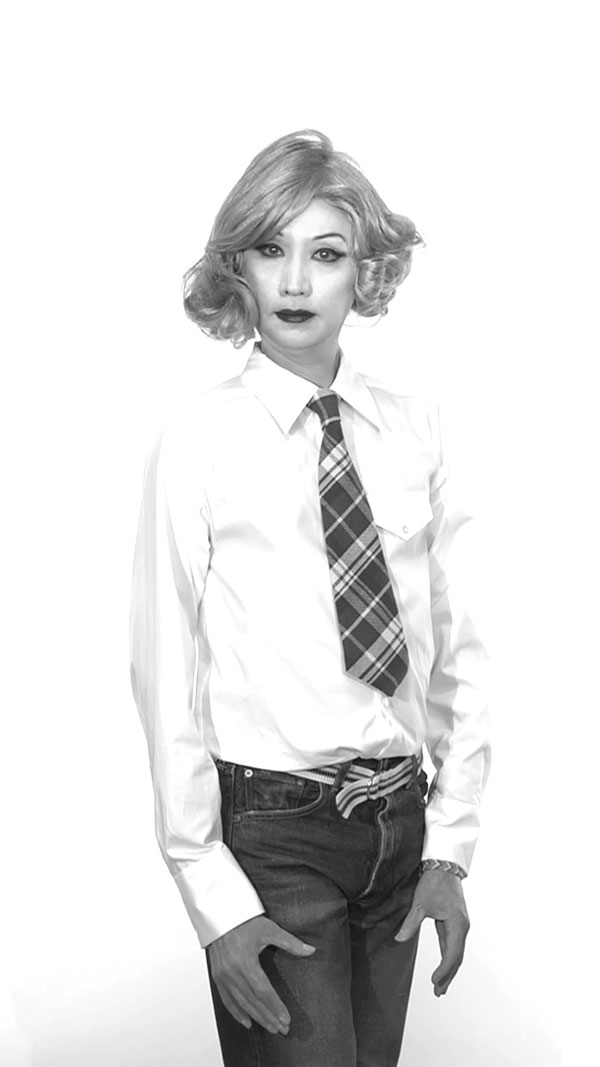

Identity is further investigated in the work of photojournalist Newsha Tavakolian, who currently lives in Tehran and whose recent photos of the Iranian elections appeared in publications from The New York Times to Time magazine. After experiencing difficulty photographing in public in 2009, she turned to fine art photography to address social issues. The exhibition presents six portraits, six imaginary CD covers, and a six-screen video from her series Listen (2010), all portraying professional singers who, as women, are forbidden by Islamic tenets to perform in public or to record CDs in their native country of Iran. Tavakolian’s singers do not appear with microphones, although each is clearly caught mid-song. Her passion for these women’s stories inspired her to create the imaginary CD covers that represent the character of each performer. The accompanying video shows the women emotionally mouthing unheard words, suggesting the idea of imposed silence. Metaphors of music, voice and expression, are also found in other works on display, such as in the Qajar series, and in Mystified (1997) by Neshat.

Tavakolian represents a generation of post-revolutionary Iranian photographers, while Neshat represents a generation of artists born before the revolution but who have left the country. Neshat left her native country in 1974 to study art in the United States before the upheaval in 1979, and she continues to draw on her cultural heritage. Eight images from her series Book of Kings (2012) will be on view in the exhibition. This recent series, translating its title from the 1,000-year-old Persian epic Shahnameh, marked a return to black-and-white photography and is composed of portraits of groups of individuals that Neshat calls the Masses, the Patriots, and the Villains. The figures in this series stand for the thousands that participated in protests, particularly the Iranian Green Movement (2009) and the Arab Spring (2011). The Masses are represented by headshots of Arab and Iranian men and women whose faces are overlaid with calligraphy – except for the eyes and mouth. The pictures are meant to be shown side by side to simulate power of the people. Just as she did in Women of Allah, Neshat pursues paradoxes of past and present and power and submission; Book of Kings also demonstrates her development and evolution as an artist.

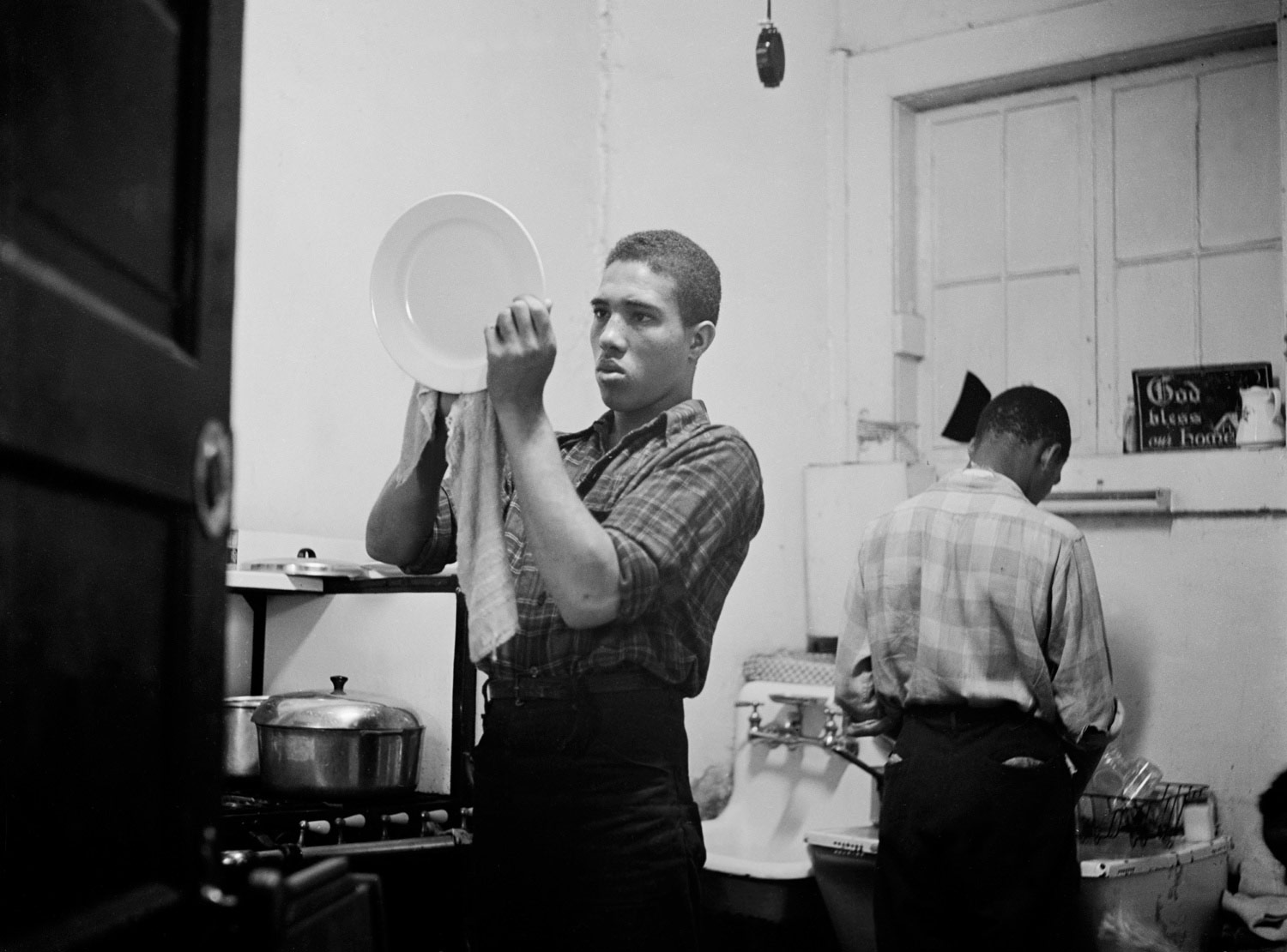

In addition to addressing social and political issues, She Who Tells a Story also presents a new kind of documentary – artistic imagination brought to real-life experiences. Themes of war, occupation, protest, and revolt, as well as concerns about photography as a medium, all find a place in this new genre. Just as Ghadirian’s Nil, Nil recounted stories of war, Iranian Gohar Dashti’s work also tackles the subject. Both photographers grew up during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988). Dashti’s Today’s Life and War (2008) is a series of theatrical, staged photographs in which a couple pursues ordinary activities in a fictionalised battlefield. In Untitled #5, they sit as newlyweds in the shell of an abandoned car and in Untitled #7, on the ground at a makeshift traditional table celebrating the Persian New Year, Nowruz. The remaining four prints show the couple performing daily routines but interrupted by symbols of war – a tank, missile head, wall of sandbags. Dashti’s images are metaphors for the experience of war and recall her own memories of childhood living near the Iran-Iraq border.

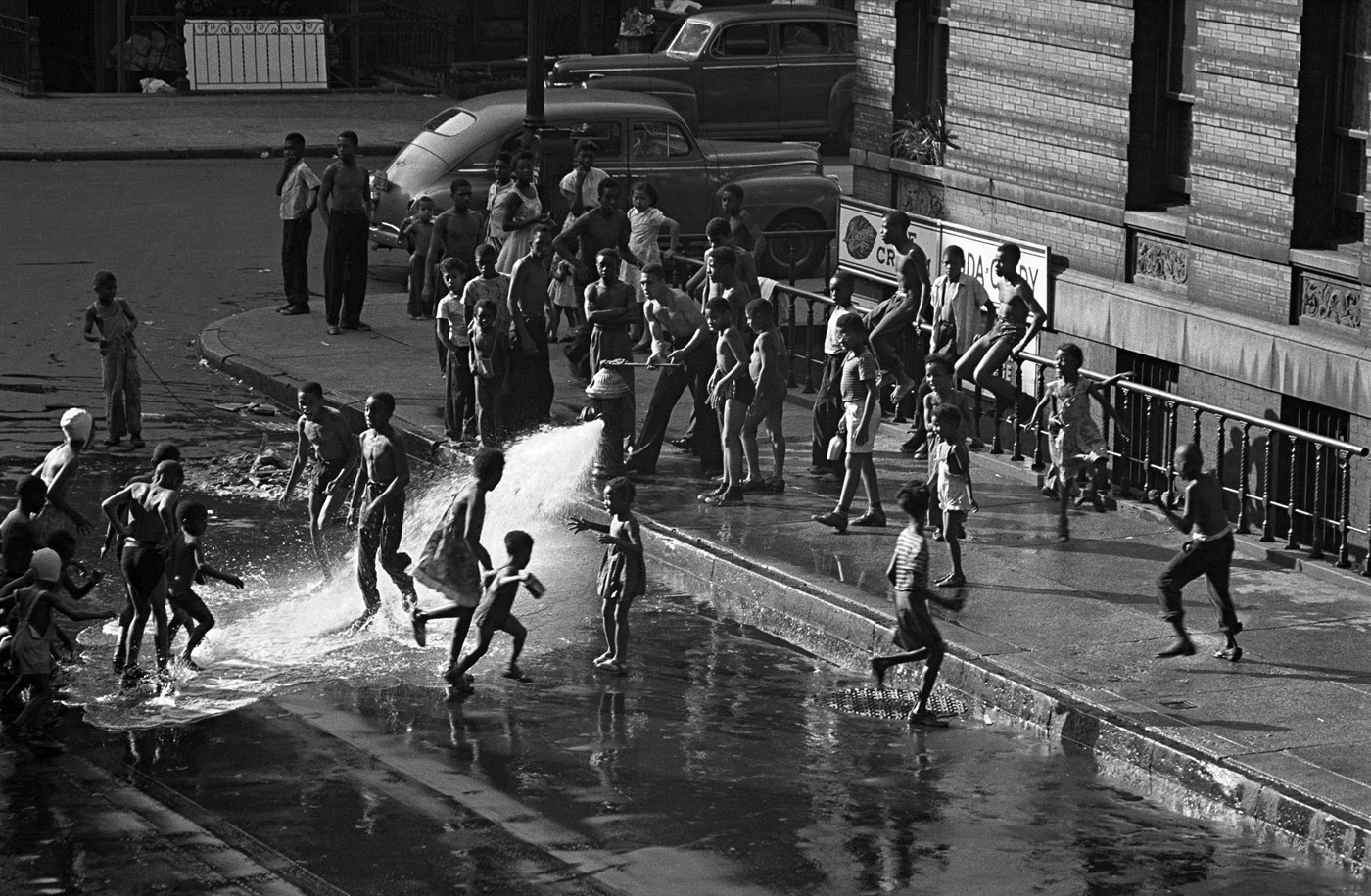

Alternatives to Dashti’s staged documentaries can be found in the works of Egyptian Rana El Nemr and Jordanian Tanya Habjouqa, both of whom directly capture people in urban settings. In The Metro (2003), El Nemr inconspicuously shoots passengers in the car designated for women, seated or standing, deep in thought. The images convey how anonymous daily life can be, and how people interact with one another in public spaces. Habjouqa’s Women of Gaza (2009) records the experience of women in Gaza, who, like all residents of the occupied territory, live with limited freedom. Taken over a span of two months, the images celebrate modest pleasures, including a picnic on the beach, a boat ride, and an aerobics class. Habjouqa gently portrays the bright side of her subjects’ lives. Women of Gaza is one example of photojournalism on display.

Another area of exploration for Middle Eastern photographers is the medium itself. Al-Ani, Rula Halawani, and Nermine Hammam push the boundaries of photography in new ways. Al-Ani’s works Aerial I and Shadow Sites II, a single channel video, depict the Jordanian landscape from an airplane. The nearly nine-minute video, made exclusively from photographs that dissolve one into another, combine nature, flight, and technology. Halawani, a native of Palestine who currently resides in East Jerusalem, addresses the experience of destruction and displacement. In Negative Incursions (2002), a series of pictures of the 2002 Israeli invasion of the West Bank, she photographs scenes of war and then enlarges and prints them in their negative form. This technique obscures the specifics of time and place, increasing the dramatic intensity and resulting in powerful images of tanks in action, grieving mothers and families in the rubble of the aftermath. Streaks of light among the ruins are a metaphor for the plight of the Palestinian people, while thick black borders imitate the shape of a television screen to convey Halawani’s criticism of media coverage.

Hammam’s Cairo Year One (2011-2012), addressing the 18-day uprising in Egypt (January 2011) and its aftermath, also experiments with uses of photography. It consists of 13 prints in two parts: Upekkha (reference to Buddhist concept of equanimity) and Unfolding (reference to folding Japanese screens). In Upekkha, Hammam imbeds photographs of soldiers in Tahrir Square within peaceful landscape scenes from postcards from her personal collection, showing the vulnerability of the young men. In contrast, the second part of the series, Unfolding, was created after the uprising was over, when it was difficult for her to photograph. In the two prints, she combines reproductions of 17th and 18th Japanese screens with photos of police brutality.

Press release from The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston website

Nermine Hammam (Egyptian, b. 1967)

Dreamland I

2011

Nermine Hammam (Egyptian, b. 1967)

The Break

2011

Rana El Nemr (Egyptian, b. 1974)

Metro #7

2003

Newsha Tavakolian (Iranian, b. 1981)

Don’t Forget This Is Not You (for Sahar Lotfi)

2010

Newsha Tavakolian (Iranian, b. 1981)

I Am Eve (for Mahsa Vahdat)

2010

Boushra Almutawakel (Yemeni, b. 1969)

Mother, Daughter, Doll series

2010

Shadi Ghadirian (Iranian, b. 1974)

Nil, Nil #4

2008

Shadi Ghadirian (Iranian, b. 1974)

Untitled

1998

From Qajar series

Shirin Neshat (Iranian, b. 1957)

Roja

2012

Shirin Neshat (Iranian, b. 1957)

Speechless

1996

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Avenue of the Arts

465 Huntington Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts

Opening hours:

Saturday – Monday, Wednesday 10am – 5pm

Thursday – Friday 10am – 10pm

Closed Tuesdays

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Air vents, New York]' 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Air vents, New York]' 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/air-vents-web.jpg?w=650&h=502)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[42nd Street at First Avenue, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[42nd Street at First Avenue, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/42nd-street-at-first-avenue-web.jpg?w=650&h=512)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Oceano Dunes, California]' 1934 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Oceano Dunes, California]' 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/oceano-dunes-california-web.jpg?w=650&h=509)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Stoop with broom, arrow, and pushcart, New York]' 1944 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Stoop with broom, arrow, and pushcart, New York]' 1944](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/stoop-with-broom-web.jpg?w=650&h=495)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Airshafts, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Airshafts, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/airshafts-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Courtyard, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Courtyard, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/courtyard-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[House, Ewing Street, Staten Island, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[House, Ewing Street, Staten Island, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/house-ewing-street-web.jpg?w=547&h=677)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Sutton Place, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Sutton Place, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/sutton-place-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Skylight and fences, Midtown, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Skylight and fences, Midtown, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/skylight-and-fences-web.jpg?w=547&h=677)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Wrought iron fence, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Wrought iron fence, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/wrought-iron-fence-web.jpg?w=563&h=700)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Church door, Bowery, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Church door, Bowery, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/church-door-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Pillars and tree, New York]' 1944 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[Pillars and tree, New York]' 1944](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/pillars-and-tree-web.jpg)

![Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[St. Francis Grocery & Fruit, New York]' c. 1945 Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993) '[St. Francis Grocery & Fruit, New York]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/st-francis-grocery-and-fruit-web.jpg)

![Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, Calcutta 1815 - 1879 Kalutara, Ceylon) '[Kate Keown]' 1866 Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, Calcutta 1815 - 1879 Kalutara, Ceylon) '[Kate Keown]' 1866](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/4-_kate-keown-web.jpg?w=650&h=656)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Namandi spirit [Queensland, Australia]' 2002 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Namandi spirit [Queensland, Australia]' 2002](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/tersappen_namandi_spirit_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Full moon [France]' 1997 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Full moon [France]' 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_fullmoon_france_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Brazil]' 1991 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Brazil]' 1991](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_mountain_brazil_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Las Palmas, Spain]' 1992 Claudia Terstappen (Australian born Germany, b. 1959) 'Mountain [Las Palmas, Spain]' 1992](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/terstappen_portugal_web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.