Exhibition dates: 13th October 2023 – 4th February 2024

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this posting contains images and names of people who may have since passed away.

O. G. Rejlander (British born Sweden, 1813-1875)

No title (The Virgin in prayer)

c. 1858-1860

Albumen silver photograph

20.2 × 15.4cm irreg. (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 2002

Public domain

This is an ambitious, complex but flawed exhibition of photographic works from the NGV Collection. Further comment in Part 2 of the posting…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the NGV for allowing me to publish the media images in the posting. Other photographs in the posting are public domain. All installation images are by Marcus Bunyan.

Photography: Real and Imagined examines two perspectives on photography; photography grounded in the real world, as a record, a document, a reflection of the world around us; and photography as the product of imagination, storytelling and illusion. On occasion, photography operates in both realms of the real and the imagined.

Highlighting major photographic works from the NGV Collection, including recent acquisitions on display for the very first time, Photography: Real and Imagined examines the complex, engaging and sometimes contradictory nature, of all things photographic. The NGV’s largest survey of the photography collection, the exhibition includes more than 300 works by Australian and international photographers and artists working with photo-media from the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Text from the NGV website

Installation view of the entrance to the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne with introduction wall text to the right

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Introduction

Photography was once described by writer and critic Lucy Lippard as having ‘a toe in the chilly waters of verisimilitude’. Photographs, Lippard posits, may be a close – rather than exact – reflection of truth. This proposition raises a raft of questions. Is reality so uncomfortable that we only engage with it partially, or out of necessity? Can a photograph show the truth, and if it does, whose truth is it showing – the photographer’s, the subject’s or the viewer’s? If truth is the end game, what does this mean for creative practice and other types of photography? The suggestion that photography is only partially, and somewhat uncomfortably, engaged with the notion of truth highlights the complexity encountered when trying to nearly encapsulate any selection of photographs.

Through works from the NGV Collection, Photography: Real and Imagined teases out connections between iconic and lesser known photographs, putting them in a dialogue with one another that both explores and transcends the time in which they were made. It dos not set out to be a history of photography, but historical context does inform the content, leading to nuanced discussions of past and present, real and imagined.

Introductory wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at right, Mike and Doug Starn’s Invictus (1992); and at left works by John Kauffmann, Norman Deck and Edward Steichen (see below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

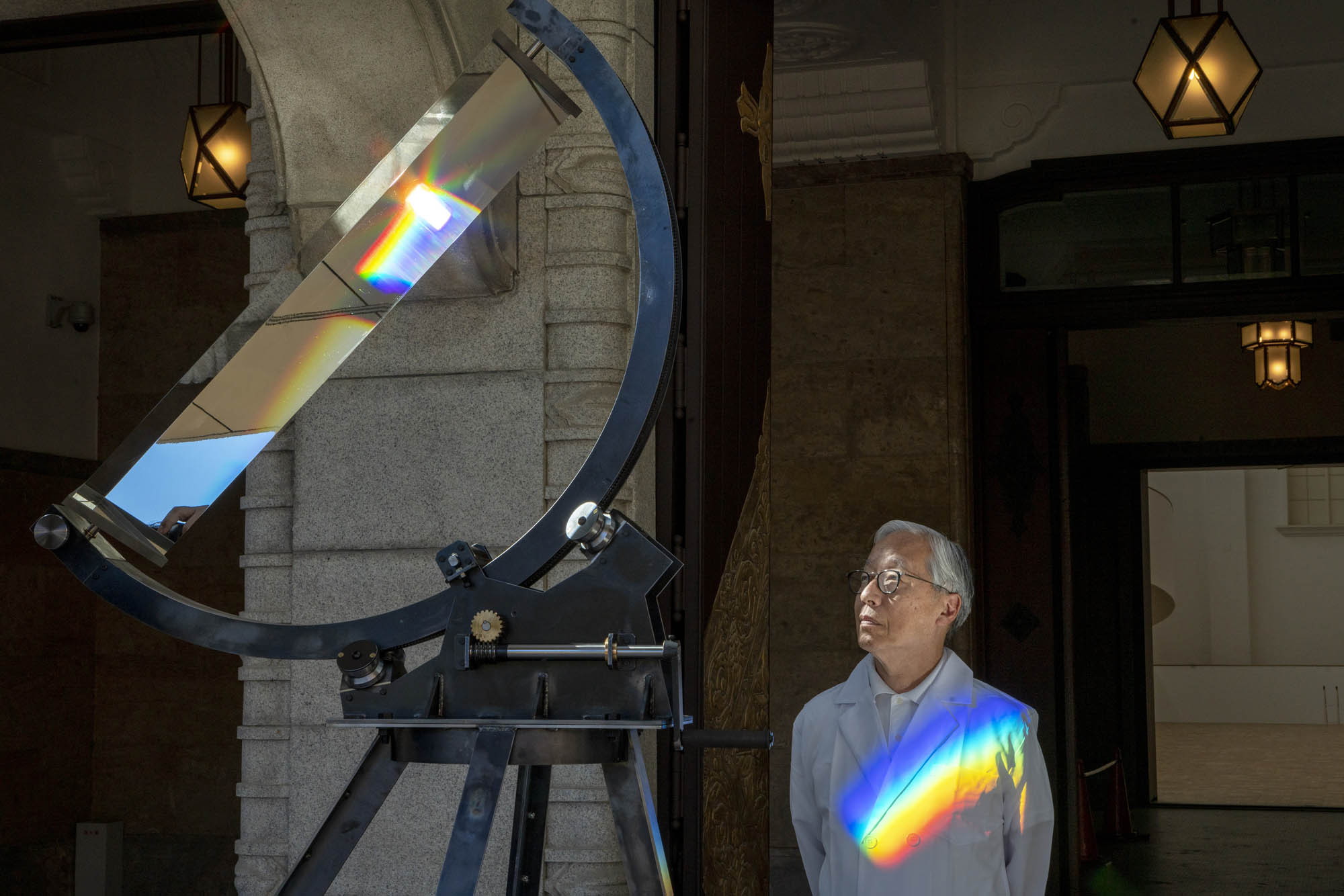

The sun was the light source that enabled the earliest photographs to be made in the 1830s. More than 150 years later the sun is the subject of this photographic sculpture by Mike and Doug Starn that embraces the possibilities of light and its potential effects on photography, in terms of both producing an image and as a force contributing to its irreparable damage. In the centre of their installation, the circular form of a sun seems to pulse and leach out of the layers of exposed orthographic film, which is stretched and layered across steel beams and held with pipe clamps and tape.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at top left, John Kauffmann’s The Cloud (c. 1905, below); at bottom left, Kauffmann’s The grey veil c. 1919; at top right, Norman Deck’s Sunset, Parramatta River (1909); and a bottom right, Edward Steichen’s Moonrise (1904)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

John Kauffmann (Australian, 1864-1942)

The cloud

c. 1905

Gelatin silver photograph

28.2 × 37.2cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Mr John Bilney, 1976

Public domain

John Kauffmann (Australian, 1864-1942)

The grey veil

c. 1919

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of the Herald & Weekly Times Limited, Fellow, 1990

Public domain

The Yarra River, the Princes Bridge and the Melbourne city skyline beyond shimmer in this photograph by John Kauffmann. And yet, they are not the image’s subject. Using a highly refined Pictorialist treatment, a reduced tonal range and luminous mid tones, the artist has manipulated light to the extent that the feeling and atmospheric qualities become the focus of the image – it is the impression that is paramount. With the choice of title, too, the photograph moves away from a specific documentation of place or time.

Wall text from the exhibition

Norman Deck (Australian 1882-1980)

Sunset, Parramatta River

1909

Gelatin silver photograph

30.5 × 24.9cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Joyce Evans, 1993

Public domain

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at centre, David Thomas’ The Movement of Colour (White), Taking a Monochrome for a Walk (London) (2010-2011), with at right works by David Noonan, Hiroshi Sugimoto, László Moholy-Nagy and Susan Fereday (see below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

David Thomas (British, b. 1951, Australia 1958- )

The Movement of Colour (White), Taking a Monochrome for a Walk (London) (installation view)

2010-2011

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of an anonymous donor through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2015

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“It was made during a residency at the Centre for Drawing Research at Wimbledon School of Art University of the Arts London… and plays on Paul Klee’s definition of drawing as taking a line for a walk on a page… this is taking a monochrome for a walk in the world where the monochrome becomes a key for seeing other colours… an interval in the world. It also suggests the ideas of movement in time and feelings of impermanence.”

~ David Thomas

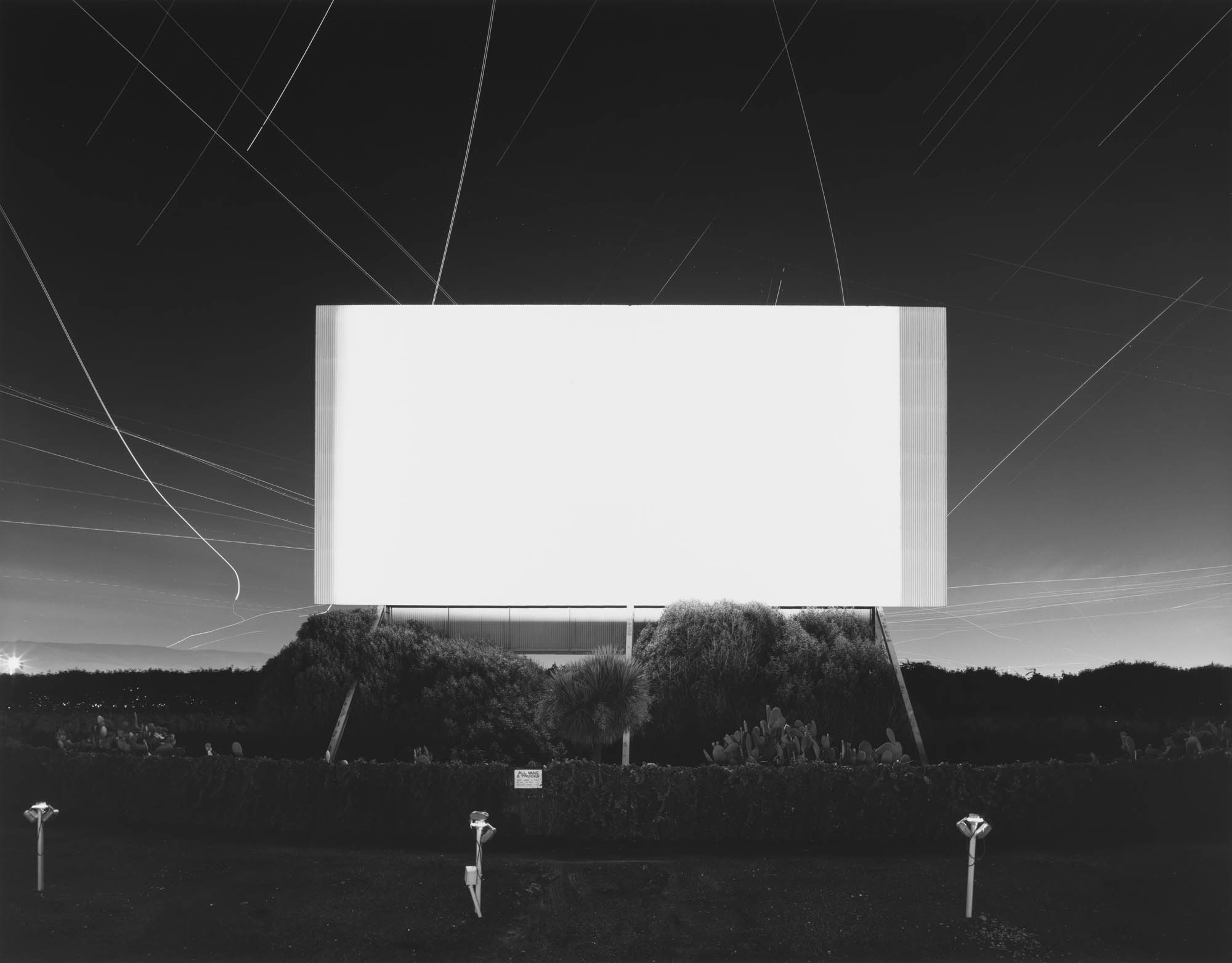

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at top right, David Noonan’s Untitled (1992); at bottom left, Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Winnetka Drive-In, Paramount (1993); at top right, László Moholy-Nagy’s Fotogram, 1925 (1925); and at bottom right, Susan Fereday’s Untitled (2001)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Light and time are both the means and subject of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Drive-In Theaters series. To produce the images, the artist directs his camera at the movie screen. Once the film starts, Sugimoto opens the lens shutter of his large-format camera and shuts it the moment the movie ends. The result is a visual condensation of the moving images and projected light of the film for its duration into a vivid, hovering rectangle of virtually pulsating light and, in the case of this drive-in cinema, the surrounding human-made and astronomical light, too.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing David Noonan’s Untitled (1992)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian 1895-1946, Germany 1920-1934, England 1935-1937, United States 1937-1946)

Fotogram, 1925

1925

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented by the National Gallery Society of Victoria, 1985

Public domain

From 1922 to 1943 László Moholy-Nagy experimented extensively with the photogram process – he was passionate about the optical effects and inherent properties of these camera-less images freed from a purely representational mode. In this work a pale shape, an organic swathe, streams across a page while curved shapes dance at the base. A halo above emits small geometric patterns. The work is a celebration of abstraction of the image – of the effects of playing with light, objects and photographic paper in a darkroom.

Wall text from the exhibition

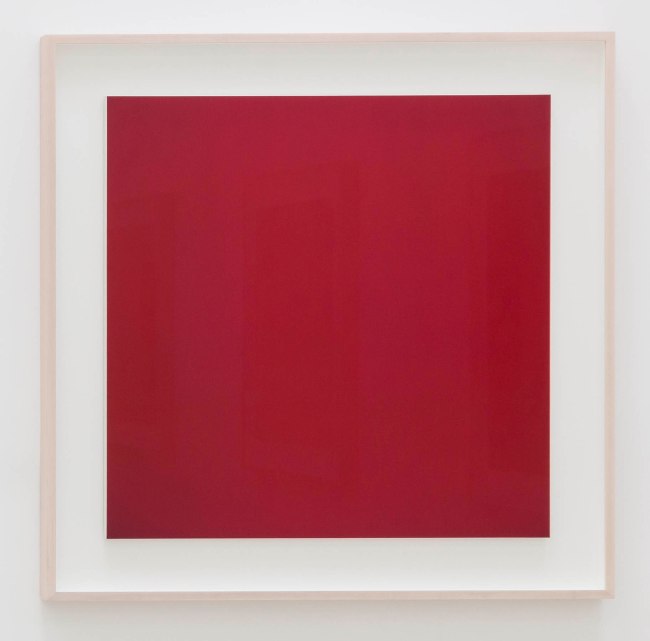

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at left, Barbara Kasten’s Composition 8T (2018, below); and at right, Lydia Wegner’s Purple square (2017, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Barbara Kasten (American, b. 1936)

Composition 8T

2018

Digital type C print

160.0 x 121.9cm (image and sheet)

ed. 1/1

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased NGV Foundation, 2018

© Barbara Kasten, courtesy Kadel Willborn, Düsseldorf

This photograph from Barbara Kasten’s Collisions/Compositions series continues her practice of creating architectural spaces in the studio using a range of materials, such as plexiglas and mirrors, which she lights and photographs at close range. Influenced by Constructivism and the teachings of the Bauhaus, specifically the work of László Moholy-Nagy, Kasten has experimented with the parameters of abstract photography for around five decades. She has written of her ongoing fascination with light in the creation and conceptual development of her photographs, saying, ‘The interdependency of shadow and light is the essence of photographic exploration and an inescapable part of the photographic process’.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Lydia Wegner’s Purple square (2017)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at left, Todd McMillan’s Equivalent VIII (2014); and at right, Sue Pedley’s Sound of lotus 1 (2000)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at back left, Thomas Ruff’s Portrait (V. Liebermann D) (1999); and at back second left, Ruff’s Portrait (A. Koschkarow) (2000)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at left, Thomas Ruff’s Portrait (V. Liebermann D) (1999); and at right, Ruff’s Portrait (A. Koschkarow) (2000)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

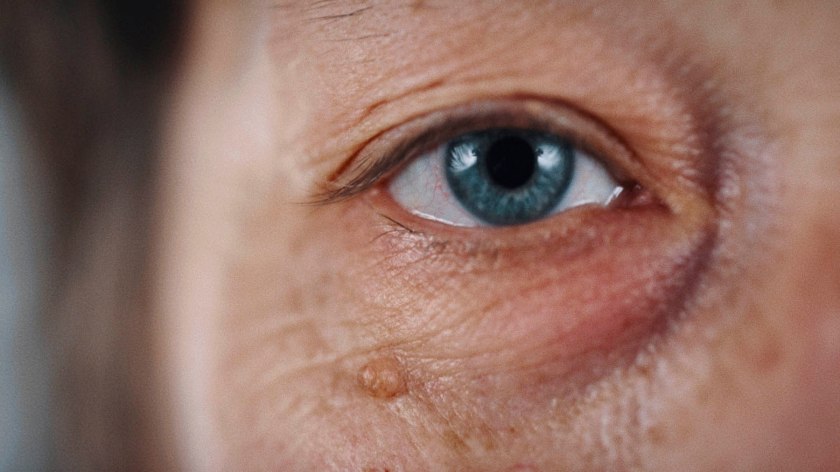

The earnest gazes of the man and woman in these two monumental photographs by Thomas Ruff are so calm and serene that they bely the intense experience of viewing their enlarged faces. Applying a standardised approach – similar to a generic passport photograph – these portraits have a timeless quality that invites you to attempt to ‘read’ their faces and to search for clues as to the inner state of the person. Ruff, however, lets nothing slip. The faces are known to the artist but remain anonymous to the viewer.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Robert Rooney’s AM-PM: 2 Dec 1973-28 Feb 1974 (1973-1974) (detail)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Featuring some of the most iconic photographs ever created alongside contemporary approaches to the photographic medium, Photography: Real & Imagined is the largest survey of the NGV’s Photography collection in the institution’s history and features more than 270 photographs by Australian and international practitioners.

Four years in the making, this landmark exhibition features photographs from across the 200-year period since the invention of photography in the 19th century, including work by leading international photographers including Man Ray, Cindy Sherman, Wolfgang Tillmans, Gilbert & George and Nan Goldin, alongside Australian photographers Max Dupain, Olive Cotton, Mervyn Bishop, Polly Borland, Destiny Deacon and Darren Sylvester.

Through twenty-one thematic sections, this large-scale exhibition explores the proposition that a photograph can be grounded in the real world, recording, documenting and reflecting the world around us; or be the product of imagination, storytelling and illusion; and on occasion operate in both realms. The thematic sections explore subject matter such as light, place and environment, consumption, conflict, community, and death.

Exhibition highlights include Mervyn Bishop’s important photograph of former Prime Minister of Australia, Gough Whitlam, pouring sand into the open palm of Gurindji Elder Vincent Lingiari. The 1975 image captures the historic meeting between these two figures where Lingiari received the crown lease of his ancestral lands. Also on display is Joe Rosenthal’s World War II photograph Raising the flag on Iwo Jima, 1945, in which American marines raise their country’s flag over the Japanese Island. Both Bishop and Rosenthal’s photographs were staged, or re-constructed for better pictorial effect, illustrating the fluid space between the real and imagined.

The exhibition also presents fashion and advertising photography, including key examples by Lilian Bassman, Athol Smith, Horst P. Horst and Dora Maar. These images showcase a world of designer fashion and high-end products, which set a standard in advertising that continues today. Ilse Bing’s Surrealist inspired photograph commissioned by Elsa Schiaparelli to launch her new perfume Salut in 1934 is a highlight of the exhibition.

Highlighting an area of focused collecting for the NGV, the exhibition recognises the work of women practicing in the early 20th century, including Barbara Morgan whose acclaimed photo montage City shell, 1938, shows an unexpected view of the then recently completed Empire State Building.

Through to the current day, Photography: Real & Imagined presents contemporary photographers of the 21st century including Zanele Muholi, Richard Mosse and Alex Prager. Highlights include Cindy Sherman’s celebrated self-portrait in the guise of Renaissance aristocrat. Also on display will be the oldest photographic work in the NGV Collection, an early 19th century portrait by Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot, one of the inventors of the medium, as well as examples of daguerreotypes, unique images on silver plated copper sheets that are amongst the earliest forms of photography.

The exhibition is accompanied by a major publication – the most ambitious book published on the NGV Photography Collection, generously supported by the Bowness Family Foundation. The publication comprises essays from NGV Senior Curator of Photography, Susan van Wyk, Susan Bright and David Campany; alongside texts by Curator of Photography, Maggie Finch and external authors from Australia, Europe, North America and Southeast Asia.

Regular introductory talks for students are held on weekdays during term times, and free drop-by guided tours each Thursday and Sunday at 10.30am during the exhibition period.

Tony Ellwood AM, Director, NGV, said: ‘This exhibition celebrates the collections and achievements of the NGV’s photography department, which has presented more than 180 exhibitions in its 55-year history. The exhibition is a testament to the strength of the NGV Collection, with so many key examples of the history of photography represented, from the earliest examples from the 19th century, through to contemporary images being produced right now in the twenty-first century. We are grateful for the support of the many donors and philanthropists, such as the Bowness Family Foundation, who have helped to grow and strengthen the NGV’s photography collection.’

Press release from the NGV

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne at top left, O. G. Rejlander’s The Virgin in prayer (c. 1858-1860, below); at bottom left, Henry Peach Robinson’s Elaine watching the shield of Lancelot (1859); at centre, Ruth Hollick’s Thought (1921); and at right Cindy Sherman’s Untitled (1988) from the History Portraits series 1988-1990

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

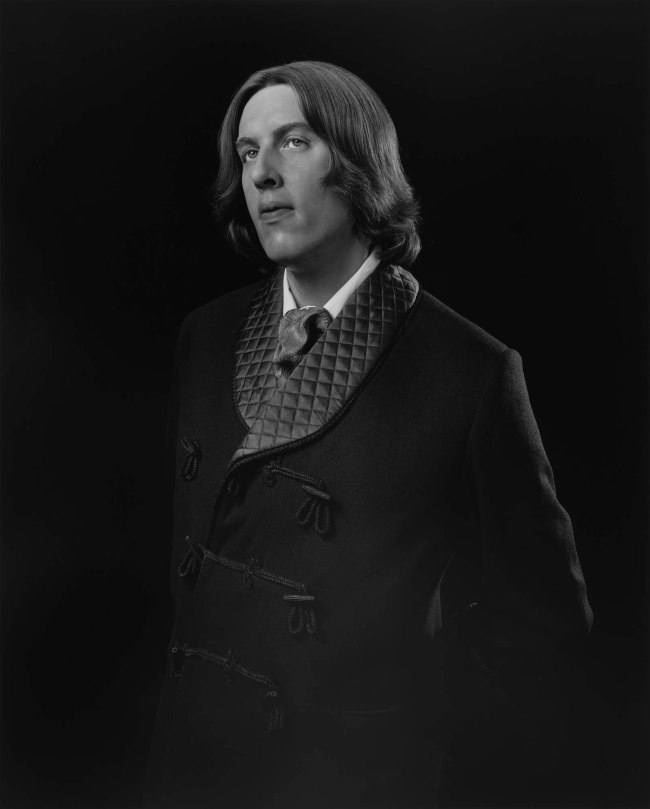

Describing the complex conundrum presented by Cindy Sherman in this photograph, photographer and curator Patrick Pound once wrote: ‘Fake chested and with a face like a mask, here Cindy Sherman is costumed to the max. She stares out like a disapproving Renaissance figure who has just walked off set from a Peter Greenaway extravaganza. Here we have a photographer looking like a painting that walked out of a film. Sherman’s photographs speak of the fragilities of the visage in an image-saturated world where information and construction slip into foreplay. In Sherman’s photographic world gender and identity is a compilation album. There is a toughness to the excess that is all her own’.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing O. G. Rejlander’s The Virgin in prayer (c. 1858-1860, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Henry Peach Robinson (English, 1830-1901)

Elaine watching the shield of Lancelot

1859

Albumen silver photograph

24.3 × 19.3cm (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased from Admission Funds, 1988

Public domain

In the 1850s Henry Peach Robinson was renowned for producing elaborately staged narrative images based on scenes from popular literary sources. He was particularly interested in Arthurian legends and drew upon these stories as inspiration for some of his most admired photographs. Elaine watching the shield of Lancelot is based on Alfred Tennyson’s version of the story of Lancelot and Elaine. Peach Robinson has recreated the scene in which the lovelorn Elaine gazes dreamily at the shield of Lancelot. She is shown as a woman who has shunned reason and propriety and abandoned herself to the intensity of her emotions, making this photograph both a tragic love story and a cautionary narrative.

Wall text from the exhibition

Ruth Hollick (Australian, 1883-1977)

Thought

1921

Gelatin silver photograph

37.4 × 25.3cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented through The Art Foundation of Victoria by Mrs Lucy Crosbie Morrison, Member, 1993

Public domain

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Bernd and Hilla Becher’s Coal tipple, Goodspring, Pennsylvania 1975 from the Artists and Photographs folio 1975

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

In 1959, German-born artists Bernd and Hilla Becher began travelling throughout Europe to create photographic typologies of vanishing industrial architecture (a practice they continued for more than four decades). While predominantly documenting German structures and landscapes, they occasionally worked overseas. This image, four views of a coal tipple, was taken on their first trip to North America in the mid 1970s. The Bechers constructed a system for comparing structures: photographed from a consistent angle, with virtually identical lighting conditions, printed at the same size and often displayed in grids.

Wall text from the exhibition

Edward Ruscha (American, b. 1937)

Twentysix Gasoline Stations (installation view)

1963, published 1967

Artist’s book: photo-offset lithograph and printed text, 48 pages, printed cover, glued binding

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Robert Rooney through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, 2009

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

With the first publication of Twentysix Gasoline Stations, and his subsequent artist books, Edward Ruscha’s work was influential in initiating the widespread interest in photographic book publishing that continues today. Ruscha’s use of photographs as a means of recording – a seemingly unemotional, detached cataloguing of the world – and simply as a ‘device to complete the idea’ influenced the interest in serial imaging adopted by many conceptual artists. Ruscha’s use of the book format was also crucial, providing a transportable way of presenting art in varied contexts that existed as a type of ‘map’ to be read and interpreted, with the subject matter becoming less important than the documentation as a whole.

Wall text from the exhibition

John Baldessari (American 1931-2020)

Fable: A Sentence of Thirteen Parts (with Twelve Alternate Verbs) Ending in a Fable (installation views)

1977

Artist’s book: photo-offset lithography on concertina fold-out in cross formation, folded paper cover

9.8 × 14.0 × 1.8cm (closed) 70.0 × 126.5cm approx. (overall, opened)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, Friends of the Gallery Library, 2017

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Conceptual artist John Baldessari, is renowned for his often-playful investigations into ideas of language, image and authenticity, once said: ‘I was always interested in language. I thought, why not? … And then I also had a parallel interest in photography … I could never figure out why photography and art had separate histories. So I decided to explore both’. Taking art off the walls and requiring someone to unfold and activate it is a central idea of this artist’s book. A visual puzzle, it invites an interaction between looking and reading, creating your own fables as you jump from image to word to image again.

Wall text from the exhibition

Eve Sonneman (American, b. 1946)

Real time (installation view)

1968-1974, published 1976

Artist’s book: photo-offset lithograph and printed text, 46 folios, printed paper cover, glued binding

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased NGV Supporters of Photography, 2021

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Eve Sonneman’s photobook Real time includes paired photographs, each separated by a black line border. The diptychs allow for the occurrence of movement and gestures and changes between the artist’s camera clicks. The ordered presentation, however, takes the images away from a straight documentary reading and to a consideration of their ‘objectness’. After first showing the photographs at MoMA, New York, then photography curator, John Szarkowski, set up a mentorship for Sonneman with the photographer Diane Arbus. As Sonneman recalled: ‘[Arbus] loved my pictures and we got along great. For two years she helped me edit’. Sonneman then published the images through the newly established Printed Matter in New York in 1976.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at top left, Carol Jerrems and Virginia Fraser’s book A Book About Australian Women (published 1974); at top centre, Nan Goldin’s book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (published 1986); and at bottom left, Tracey Emin’s Exploration of the Soul (published 1994)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at bottom left, Harold Cazneaux’s book The Bridge Book (published 1930); and at top right, Lee Friedlander’s book The American Monument (published 1976)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

The American Monument (installation view)

Published by The Eakins Press Foundation, New York, 1976

Half-tone plate

Shaw Research Library, National Gallery of Victoria

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Berenice Abbott (American 1898-1991, worked in France 1921-1929)

Changing New York (installation view)

Published by E. P. Dutton & Co, New York, 1939

Half-tone plate and letterpress text

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased NGV Foundation, 2022

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at top left, Man Ray’s book Photographs by Man Ray Paris 1920-1934 (published 1934); at bottom left, Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore’s book Aveux non Avenus (Disavowals or Cancelled Confessions) (published 1930); at top right, Bill Brandt’s book Perspective of Nudes (published 1961); and at bottom right, Germaine Krull’s book Nude studies (Études de nu) (published 1930)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Photographs today are often viewed in galleries in frames, hung on walls. Many photographs, however, were originally created for display in combination with text and graphic design; to be laid out on a page and reproduced in different formats; to be held, worn on the body, published, and shared.

With recognition of these expanded histories of photography, and the contemporary resurgence in publishing, this exhibition includes artist books, magazines and photobooks that use the photographic image in print, publishing and design. These two cases include examples that show the influence of Surrealism, the New Objectivity and Constructivist graphic design in dynamic modern publications.

Artist and author Martin Parr has described the photobook as the ‘supreme platform’ for photographers to share the work with a broad audience. The 1920s to the 1970s were arguably the most important period for the publication of photobooks. These two cases include examples that show the influence of modernist, humanist and documentary photography traditions in innovative publications from this time. These include exhibition catalogues, examples of first edition books, publications published in larger un-editioned print runs and coveted collectable limited-edition books and portfolios.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Man Ray’s book Photographs by Man Ray Paris 1920-1934 (published 1934) with at right, Man Ray’s Anatomies (1930, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky) (American, 1890-1976)

Anatomies

1930

Gelatin silver photograph

Please note: this photograph is not in the exhibition

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) Marcel Moore (French, 1892-1972)

Aveux non Avenus (Disavowals or Cancelled Confessions) (installation view)

Published by Éditions du Carrefour, Paris, 1930

Illustrated book: photogravure, letterpress text, 237 pages, 10 leaves of plates, paper cover, stitched binding

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Shaw Research Library, acquired through the Friends of the Gallery Library endowment, 2017

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Aveux non Avenus, by the celebrated poet, writer, sculptor and photographer Claude Cahun, was published in 1930 by Éditions du Carrefour, Paris, in an edition of five hundred. The book comprises a series of texts in French: poems, literary aphorisms, recollections of dream sequences and philosophical thoughts, ideas and meanderings. Pierre Mac Orlan, a French novelist who wrote the preface to the book, described Mademoiselle Claude Cahun’s text as ‘de poèmes-essais et d’essais-poèmes’, or ‘poem-essays and essay-poems’, and said that overall ‘the book is virtually entirely dedicated to the word adventure’

The alliterative title presents a conundrum for English translation – ‘aveux’ meaning ‘avowals’ or ‘confessions’, and ‘non avenus’ meaning ‘voided’ – and is variously translated as Disavowals, Denials, and Unavowed confessions, among other things. Curator Jennifer Mundy has written that the title suggests ‘an affirmative expression immediately followed by some form of negation or retraction’.

Ambiguities around the title aside, there is a strong visual aspect to the book too. The texts are each demarcated with a complex and fantastical photogravure created by Cahun’s partner, Marcel Moore. These photogravure (where an image from the negative of a photograph is etched into a metal plate, similar to printmaking) are collages made up of photographic images of, and by, Cahun. Throughout the book, graphic devices of stars, eyes and lips are also used to separate sections of text. Aveux non Avenus, which has been described as an anti-realist or surrealist-autobiography of the multi-disciplinary Cahun, exists as a potential critique of the autobiography format altogether, is wonderfully irreducible.

Maggie Finch and Isobel Crombie. “Claude Cahun,” in the 2019 July/August edition of NGV Magazine on the NGV website 9th April 2020 [Online] Cited 28/01/2024

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) and Marcel Moore (French, 1892-1972)

Untitled

1930

In Aveux non avenus 1930

published by Éditions du Carrefour, Paris

illustrated book: heliographs

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Shaw Research Library, acquired through the Friends of the Gallery Library endowment, 2017

Germaine Krull (German, 1897-1985)

Nude Studies (Études de Nu) (installation view)

Published by Librarie des arts décoratifs, Paris, 1930

24 photogravures, letterpress on paper, white cloth-backed orange paper-covered board portfolio with ribbons

National Gallery of Victoria

Purchased, NGV Foundation, 2022

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Bill Brandt (English born Germany, 1904-1983)

Perspective of Nudes (installation view)

Published Bodley Head, London, 1961

Half-tone plate

Shaw Research Library, National Gallery of Victoria

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932)

Art Forms in Nature: Examples from the Plant World Photographed Direct from Nature (installation view)

Published by A. Zwemmer, London, 1929

Half-tone plate

Shaw Research Library, National Gallery of Victoria

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Karel Teige typographer (Czechoslovakia 1900-1951)

Karel Paspa photographer (Czechoslovakia 1862-1936)

ABECEDA (Alphabet) (installation view)

Published by J. Otto, Prague, 1926

Photomontage

National Gallery of Victoria

Shaw Research Library, acquired through the Friends of the Gallery Library endowment, 2017

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Aleksandr Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1958) and Varvara Stepanova (Russian, 1894-1958)

USSR in Construction, no. 12 (Parachute issue) (URSS en Construction) (installation view)

1935

Illustrated journal: colour rotogravure, 22 pages with fold-out inserts, lithographic cover

National Gallery of Victoria

Purchased, NGV Supporters of Prints and Drawings, 2019

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at top left, Eliza Hutchinson’s No. 9 (2010); at bottom left, Ewa Narkiewicz’s Copper flax #4 (1999); at centre top, Harry Nankin’s The first wave: fragment 2 (1996); at centre bottom, Peter Peryer’s Seeing (1989); and at right, Aaron Siskind’s New York (1950)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

In much the same way that tactile writing systems such as braille are impenetrable to those with vision, a photograph printed in two dimensions can be incomprehensible for people with vision impairment. Each system presents a conversion – of letters, texts and illustration – into raised dots on a page; of visible wavelengths of light into an image on a light-sensitive surface. Each relies on an irreversible alteration of the surface. Seeing, the title of this Peter Peryer photograph, infers an action – seeing something. Yet the conversion into a photographic image draws attention to the impenetrability of both acts.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at left, Gregory Crewdson’s Untitled (1999) from the Twilight series (1998-2002); at centre, Malerie Marder’s Untitled (2001); and at right, Anne Zahalka’s Sunday, 2:09pm (1995)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Gregory Crewdson (American, b. 1962)

Untitled (installation view)

1999

From the Twilight series 1998-2002

Type C photograph

121.9 × 152.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Kaiser Bequest, 2000

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Anne Zahalka (Australian, b. 1957)

Sunday, 2:09pm

1995, printed 2019

From the Open House series 1995

Colour cibachrome transparency, light box

121.7 × 161.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2019

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at left, Polly Borland’s Untitled (2018); and at right, Anne Zahalka’s Sunday, 2:09pm (1995)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at rear from left to right, Gregory Crewdson’s Untitled (1999) from the Twilight series (1998-2002); at second left, Malerie Marder’s Untitled (2001); and centre, Anne Zahalka’s Sunday, 2:09pm (1995); and at right, Alex Prager’s Crowd #11 (Cedar and Broad Street) (2013, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Alex Prager’s Crowd #11 (Cedar and Broad Street) (2013, below)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Alex Prager (American, b. 1979)

Crowd #11 (Cedar and Broad Street)

2013

Inkjet print

149.7 × 142.0cm (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Bowness Family Fund for Contemporary Photography, 2014

Alex Prager’s staged photographs openly reference the aesthetics of mid-twentieth century American cinema, fashion photography and the photographs of Cindy Sherman. Her images resemble film stills and are packed with emotion and human melodrama. Working with actors, directing their placement and interaction to create a hyperreal dramatisation of crowd behaviour, Prager’s narrative tableaux pair the banal and fantastic, the everyday and the theatrical, real life and cinematic representation. In this image we have a bird’s eye view of a mass of people crossing the road. We can see the patterns of movement, contact and avoidance and a suggestion of the narrative possibilities of the interacting crowd.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at second right, Pat Brassington’s Rosa (2014); and at right, Yvonne Todd’s Werta (2005)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

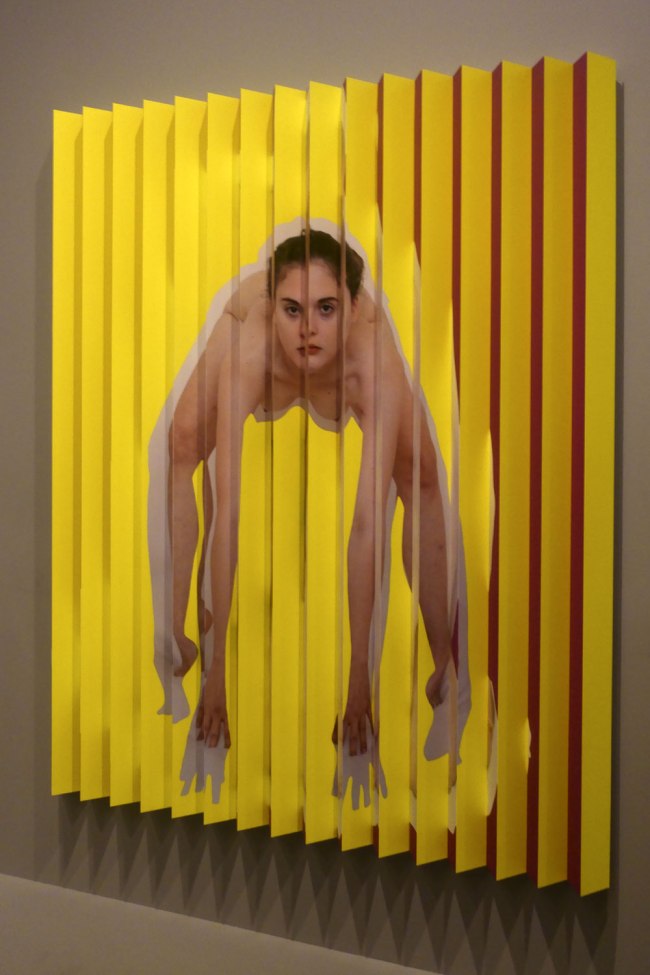

Zoë Croggon (Australian, b. 1989)

Fonteyn (installation view)

2012

Digital type C print

102.8 × 99.9cm

Purchased with funds arranged by Loti Smorgon for Contemporary Australian Photography, 2013

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Loretta Lux’s The Drummer (2004, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Loretta Lux (German, b. 1969)

The drummer

2004

Cibachrome photograph

45.0 x 37.7cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, NGV Foundation, 2006

© Loretta Lux. VG Bild-Kunst/Copyright Agency, 2023

Loretta Lux is known for her eerie, hyperreal photographs of children. The luminous pallor of the boy’s skin and the subtle tonal range throughout the photograph is achieved through Lux’s delicate use of digital manipulation to reduce the palette in her image. Lux’s history as a painter informs photographs such as this, which seem to owe as much of a debt to Old Master paintings as modern technology. Her skilful combination of photographic reality and painterly effect gives the image a profoundly disconcerting quality that is reminiscent of the fantastical (and disturbing) character of Oskar, the little drummer boy, in the Günter Grass novel The Tin Drum (1959).

Wall text from the exhibition

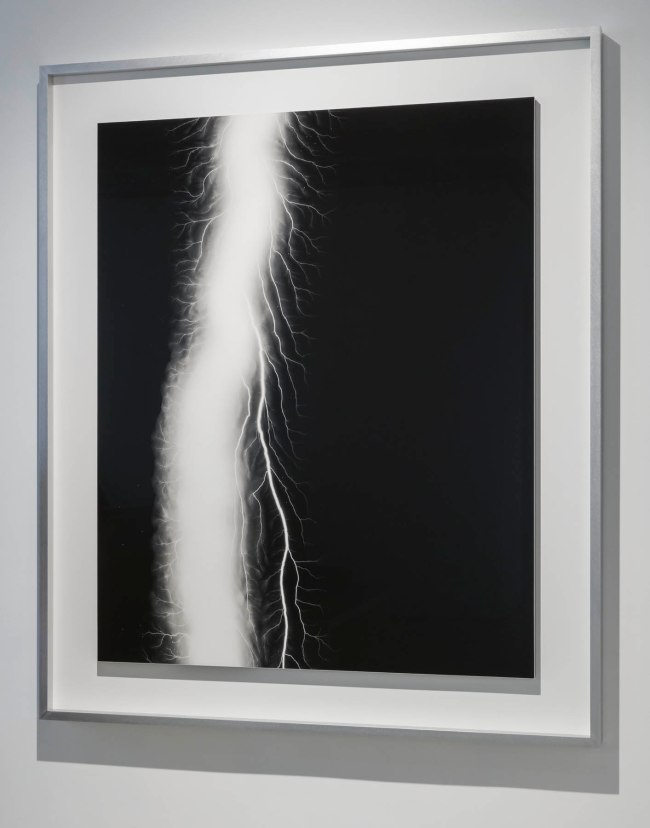

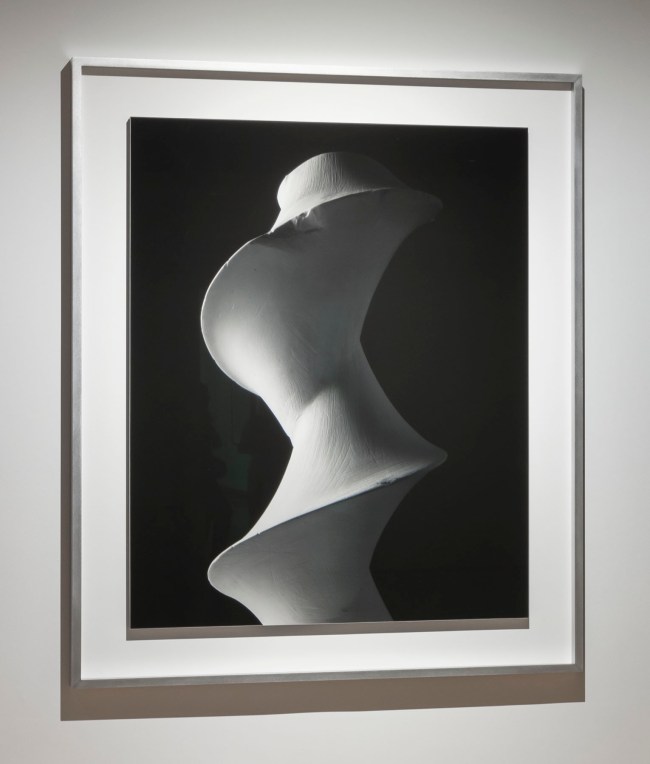

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at bottom left, Raoul Ubac’s Penthésilée (c. 1938, below); at top centre, André Kertész’s Satiric Dancer, Paris (1926, below); and at right, Max Dupain’s Impassioned clay (1936, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

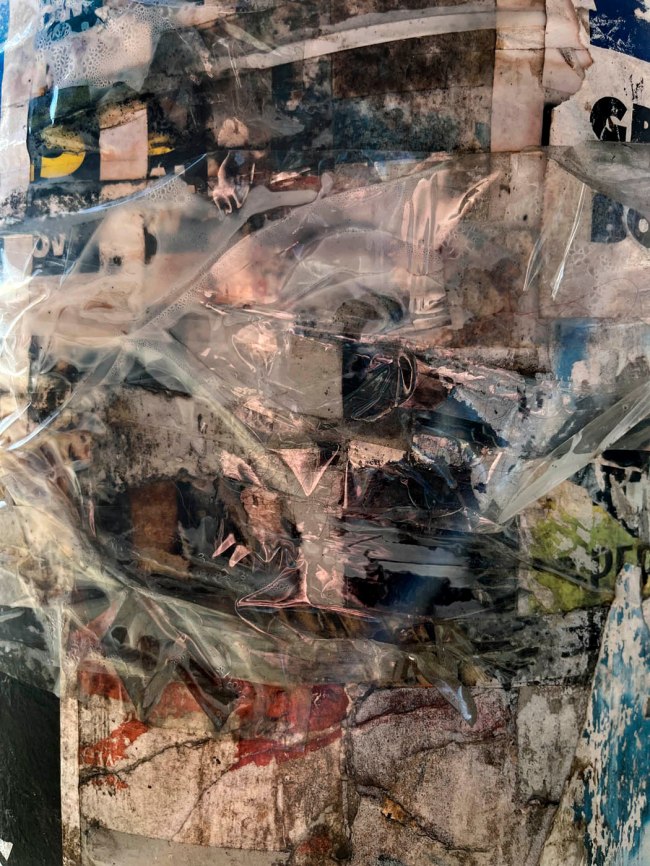

Raoul Ubac (Belgian, 1909-1985)

Penthésilée

c. 1938

Gelatin silver photograph

31.0 × 41.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased NGV Foundation, 2013

From the mid 1930s onwards Surrealist photographer Raoul Ubac experimented with collage, photomontage and solarisation. These processes disrupted the surface of his photographs, enabling him to create new and fantastic realities and introducing an element of chance into his image making. Penthésilée is from his most important series of photographs. The image is based on the story of Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, who was killed by Achilles while fighting alongside the Trojans. To represent this mythic battle Ubac created this complex photomontage by cutting up, collaging, rephotographing and solarising photographs of nude female figures. The resulting image has an uncanny sense of movement suggesting the height of battle.

Wall text from the exhibition

André Kertész (Hungarian 1894-1985, France 1925-1936, United States 1936-1985)

Satiric Dancer, Paris

1926, printed c. 1972

Gelatin silver photograph

Purchased, 1973

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Max Dupain’s Impassioned clay (1936, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

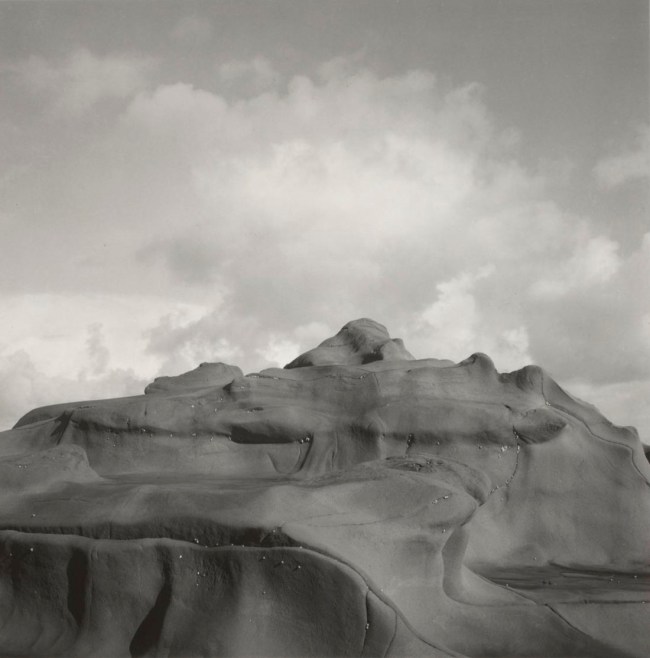

Max Dupain (Australian 1911-1992)

Impassioned clay

1936

Gelatin silver photograph

50.4 × 36.7cm irreg.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

William Kimpton Bequest, 2016

Public domain

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at left, Pat Brassington’s Rosa (2014); and at right, Yvonne Todd’s Werta (2005)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Yvonne Todd selects her subjects, most often young women, from ‘call outs’ seeking certain types, people encountered on the street, or modelling agencies where she invariably chooses those with little or no industry experience. In her studio Todd uses costumes, heavy make-up and wigs to style her models. Costuming is an important aspect of Todd’s practice; her interest lies in in what she describes as, ‘the way they carry character and narrative connotations’. Todd’s finished photographs are heavily reworked using Photoshop so that they appear obviously artificial. This overt use of artifice shifts her images from simply being nostalgic recreations to being strangely familiar and undeniably creepy.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at back left, Robyn Stacey’s Nothing to see here (2019) and at back centre, Polly Borland’s Untitled (2018)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Robyn Stacey (Australian, b. 1952)

Nothing to see here

2019

From the Nothing to See Here series 2019

Lenticular image

155.5 × 119cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2020

This large-scale lenticular photograph shows the face of a woman projected onto a curtain. The curtain suggests a hidden cinema screen; however, Robyn Stacey’s curtains cannot be pulled back. From one viewpoint a beautiful face with eyes softly closed as if in sleep appears, but as you move past the image you can only see the curtain. The curtain becomes what the artist described as ‘a membrane between reality and allegory’ and acts as the screen as the portrait appears and disappears.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation views of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Polly Borland’s lenticular photograph Untitled (2018) from the MORPH series

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Polly Borland (Australia, b. 1959)

Untitled

2018

From MORPH series 2018

Inkjet print on rice paper on lenticular cardboard

216.0 × 172.7 × 13.0cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2019

© Polly Borland

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at left, Narelle Autio’s two photographs Untitled from The Seventh Wave series (1999-2000); and at centre right, Selina Ou’s Convenience (2001)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Narelle Autio’s two photographs Untitled from The Seventh Wave series (1999-2000)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Narelle Autio (Australian, b. 1969)

Untitled (installation view)

2000

From The Seventh Wave series 1999-2000

Gelatin silver photograph

90.0 × 134.1cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds arranged by Loti Smorgon for Contemporary Australian Photography, 2001

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at back centre, Selina Ou’s Convenience (2001); and at right, Rosemary Laing’s welcome to Australia (2004)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at back left, Ben Shahn’s Young cotton picker, Pulaski County, Arkansas. Schools for coloured children do not open until January 1st so as not to interfere with cotton picking 1935; and back right, Lewis Hine’s Finishing garments, 10 Hanover Ave., Boston, Massachusetts 1912; and at right in the cabinet, Kusakabe Kimbei’s album (Landscape and portraits) (1880s-1910s)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Shahn (Lithuanian 1898-1969, United States c. 1925-1969)

Young cotton picker, Pulaski County, Arkansas. Schools for coloured children do not open until January 1st so as not to interfere with cotton picking (installation view)

1935, printed c. 1975

Gelatin silver photograph

21.7 × 32.8cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1975

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940)

Finishing garments, 10 Hanover Ave., Boston, Massachusetts

1912

Gelatin silver photograph

11.4 × 16.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1980

Public domain

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Kusakabe Kimbei’s album (Landscape and portraits) (1880s-1910s)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at left, John Thomson’s The crawlers (1876-1877, below); at top right, Heather George’s Stockyards, stockmen in distance. Wave Hill Station, Northern Territory (1952); and at bottom right, Fred Kruger’s Group of Aborigines in hop gardens, Coranderrk (1876, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing John Thomson’s The crawlers (1876-1877, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

John Thomson (Scottish 1837-1921)

The crawlers

1876-1877

From the Street Life in London series 1877

Woodbury type

11.5 × 8.7cm (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Felton Bequest, 1977

Public Domain

Heather George (Australian 1907-1983)

Stockyards, stockmen in distance. Wave Hill Station, Northern Territory (installation view)

1952, printed 1978

From the Northern Territory series 1952

Gelatin silver photograph

Purchased, 1980

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

In 1952 the Australian magazine Walkabout included a series of images made by photojournalist Heather George at Wave Hill Station in the Northern Territory. The vast pastoral lease on the lands of the dispossessed Gurindji people would later become famous as a turning point in the recognition of land rights for Australia’s First Nations peoples, but when George visited, it was a place of entrenched, officially sanctioned discrimination. In George’s photograph, the Gurindji stockmen appear overshadowed by the stockyards in the foreground, perhaps reflecting the attitude of pastoralists who, having been granted leases, took advantage of people living on Country, exploiting them as an unpaid workforce.

Wall text from the exhibition

Fred Kruger (German 1831-1888, Australia 1860-1888)

Group of Aborigines in hop gardens, Coranderrk

1876

Albumen silver photograph

13.3 × 20.2cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Mrs Beryl M. Curl, 1979

Public domain

In 1876 Fred Kruger was commissioned to produce two series of photographs at Coranderrk, a settlement and working farm established to rehouse dispossessed people of the Kulin Nation. One of the many subjects he photographed was the productive farmland and the activities of the community working the land. Kruger’s photograph shows a multigenerational group of people in the lush Arcadian setting of the hop garden, but what it obscures is the reality of exploitation and poverty that afflicted First Nations people in this place. Kruger’s photographs met a brief to promote the so-called ‘civilising’ work of colonial authorities but in doing so represented a largely imagined reality and created an effective form of propaganda.

Wall text from the exhibition

Selina Ou (Australian, b. 1977)

Convenience (installation view)

2001

From the Serving You Better series 2001

Type C photograph

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds arranged by Loti Smorgon for Contemporary Australian Photography, 2005

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at top left, Kusakabe Kimbei’s Vegetable peddler (1880s, below); at bottom left, David Wadelton’s Richmond hairdresser (1979, below); at top centre, Rennie Ellis’ Between strips, Kings Cross (1970-1971, below); at bottom centre, Brassai’s Washing up in a brothel, Rue Quincampoix (La Toilette, rue Quincampoix (Bidet)) (1932, below); and at right, Wolfgang Sievers’ Shiftchange at Kelly and Lewis engineering works, Springvale, Melbourne (1949, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Kusakabe Kimbei (Japanese, 1841-1934)

Vegetable peddler

1880s

Albumen silver photograph, colour dyes

20.6 × 26.3cm (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gerstl Bequest, 2000

Public domain

Japanese photographer Kusakabe Kimbei established his studio in 1881, making photographs for the domestic and tourist markets. Most of the photographs in this elaborate album are conventional, staged domestic scenes; picturesque views of popular tourist attractions; and street scenes. This image, however, stands alone in the album as an unusual view of contemporary life. Despite the women weavers wearing traditional dress and working hand-operated looms, the factory in which they are working is lit by electric lights and they are supervised by men wearing European-style dress. Unlike its companion works in Kimbei’s album, this photograph speaks to the industrialisation that was part of the Meiji-era modernisation in Japan.

Wall text from the exhibition

Kusakabe Kimbei (Japanese, 1841-1934)

Kusakabe Kimbei (日下部 金兵衛; 1841-1934) was a Japanese photographer. He usually went by his given name, Kimbei, because his clientele, mostly non-Japanese-speaking foreign residents and visitors, found it easier to pronounce than his family name

Kusakabe Kimbei worked with Felice Beato and Baron Raimund von Stillfried as a photographic colourist and assistant. In 1881, Kimbei opened his own workshop in Yokohama, in the Benten-dōri quarter. From 1889, the studio operated in the Honmachi quarter. By 1893, his was one of the leading Japanese studios supplying art to Western customers. Many of the photographs in the studio’s catalogue featured depictions of Japanese women, which were popular with tourists of the time. Kimbei preferred to portray female subjects in a traditional bijinga style, and hired geisha to pose for the photographs. Many of his albums are mounted in accordion fashion.

Around 1885, Kimbei acquired the negatives of Felice Beato and of Stillfried, as well as those of Uchida Kuichi. Kusakabe also acquired some of Ueno Hikoma’s negatives of Nagasaki. Kimbei retired as a photographer in 1914.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing David Wadelton’s Richmond hairdresser (1979, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

David Wadelton (Australian, b. 1955)

Richmond hairdresser

1979

Gelatin silver photograph

13.4 × 20.2cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of David Wadelton through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, 2015

© David Wadelton

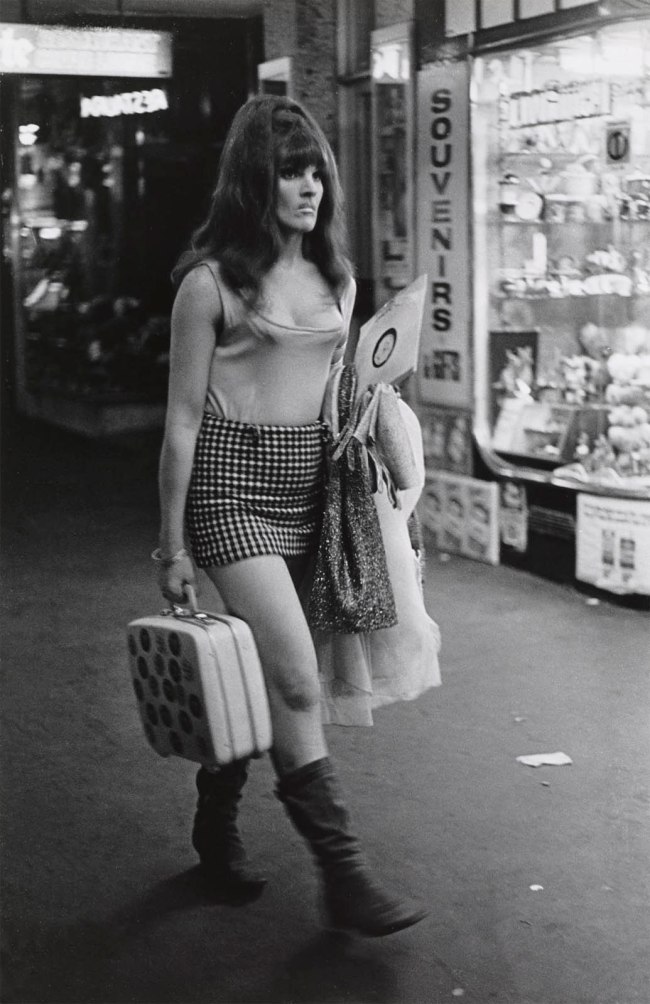

Rennie Ellis (Australian, 1940-2003)

Between strips, Kings Cross

1970-1971; 2000 {printed}

from the Kings Cross series 1971

gelatin silver photograph

37.1 x 24.1 cm (image) 40.3 x 30.4 cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 2005

© Rennie Ellis Photographic Archive

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Brassaï’s Washing up in a brothel, Rue Quincampoix (La Toilette, rue Quincampoix (Bidet)) (1932, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Brassaï (Hungarian-French, 1899-1984)

Washing up in a brothel, Rue Quincampoix

(La Toilette, rue Quincampoix (Bidet))

1932; printed c. 1979

from The secret of Paris in the 30s series 1931–1935

Gelatin silver photograph

20.5 × 29.2cm (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1980

Public Domain

In the 1930s Brassaï became well-known for his photographs of the nightlife of Paris, but it was the sex workers, along with other characters of the city’s underbelly, who excited his imagination. Reflecting on this time, he wrote, ‘Rightly or wrongly, I felt at that time that this underground world represented Paris at its least cosmopolitan, at its most alive, its most authentic, that in these colourful faces of its underworld there had been preserved, from age to age, almost without alteration, the folklore of its remote past’. This photograph presents a matter-of-fact view – there is nothing exotic or erotic about the woman washing herself as her client ties his shoes and prepares to leave.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Wolfgang Sievers’ Shiftchange at Kelly and Lewis engineering works, Springvale, Melbourne (1949, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Wolfgang Sievers (Australian born Germany, 1913-2007)

Shiftchange at Kelly and Lewis engineering works, Springvale, Melbourne

1949; printed 1986

Gelatin silver photograph

49.4 × 40.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1986

© National Library of Australia

Wolfgang Sievers arrived in Australia in 1938, bringing photographic equipment, rigorous training in modernist photography, a firmly held belief in the union of art and industry, left-leaning political views, and the self-declared desire to ‘assist this country through my knowledge as thanks for the freedom I can enjoy here’. The human face of industrial Australia is captured in Sievers’s celebrated photograph of the change of shift at a Melbourne engineering works, showing a sea of men and women surging into work. The upturned, smiling faces of the masses speaking to Sievers’s firmly held belief in the dignity of work.

Wall text from the exhibition

Rosemary Laing (Australian, 1959-2024)

welcome to Australia (installation view)

2004

Type C photograph

110.8 × 224.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds from the Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2005

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

This photograph by Rosemary Laing makes an obviously ironic statement, as curator Kyla MacFarlane notes: ‘The title and compositional beauty of this photograph … purposefully jar against its subject matter – the remote Woomera Immigration Detention and Processing Centre in South Australia. Photographing the site while the sun sits low in the sky, Laing observes the Centre’s mechanisms of containment and surveillance – a violent presence on the red dirt and gravel road, and sun-tinged, cloudless sky of its remote location’. The photograph’s formal emptiness reflects the lack of freedom imposed on those seeking asylum and the loss of their civil liberties once detained.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at left, Rosemary Laing’s welcome to Australia (2004, above); and at right, four photographs from Michael Cook’s Civilised series (2012)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Dorothea Lange’s Towards Los Angeles, California (1936, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Dorothea Lange (United States 1895-1965)

Towards Los Angeles, California

1936; c. 1975 {printed}

Gelatin silver photograph

39.6 x 39.1cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1975

In this photograph Dorothea Lange has ironically juxtaposed the aspiration of clean, comfortable train travel with the exhausting reality of the unemployed traversing America in search of work in the 1930s. Renowned for making photographs that combine empathy and clear-eyed observation, Lange also believed that photographs and text should be presented together to amplify the messages carried in both mediums. She understood that captions ‘fortified’ her photographs and that they should ‘not only (carry) factual information, but also add clues to attitudes, relationships and meanings’. Although it doesn’t have a caption, the opportunistic combination of image and text in this image highlights the gulf between the haves and have nots.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at top left, Alfred Stiegliz’s The steerage (1907, below); at bottom left, David Moore’s Migrants arriving in Sydney (1966, below); at centre, Charles Nettleton’s Hobsons Bay railway pier (1870s, below); at top right, Maggie Diaz’s The Canberra, Port Melbourne (1961-1967); and at bottom right, Paul Haviland’s Passing steamer (1910)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Alfred Stieglitz (American 1864-1946, Germany 1881-1990)

The steerage

1907, printed 1911

Photogravure

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1979

Public domain

Alfred Stieglitz was a pioneering photographer, publisher and gallery director. The steerage, arguably his most important photograph, is regarded as his first great modernist work. The composition, with its compressed space, apparent lack of horizon and striking diagonal lines, is suggestive of avant-garde painting of the time. Showing the densely packed lower decks of the of the transatlantic steamer Kaiser Wilhelm II, Stieglitz’s oblique reference to the return movement of unsuccessful immigrants to America offers an insight into the social outcomes and complexities of mass global migration in the early twentieth century.

Wall text from the exhibition

David Moore (Australia, 1927-2003)

Migrants arriving in Sydney

1966

Gelatin silver photograph

26.7 × 40.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1991

© Estate of David Moore

David Moore was Australia’s pre-eminent photojournalist of the 1960s. His work was regularly seen in leading local and international magazines. Moore’s Migrants arriving in Sydney, was commissioned and published by National Geographic in 1966. This now iconic image shows the climactic moment when a ship carrying migrants to Australia docks at Sydney harbour. The tightly framed photograph reveals a range of emotions on the faces of a group of people about to disembark and begin a new life. “We must do more than record the sensational, the bizarre, and the tragic. The lens of the camera must probe, with absolute sincerity, deep into the lives of ordinary men and women and show how we work and play.” David Moore, 1953

Text from the National Gallery of Victoria website

THIS IS NOT CORRECT NGV!

In 2015, Judy Annear [Head of Photography at the Art Gallery of New South Wales] said of this famous photograph: “It’s great to consider that it’s not actually what it seems.” Years after the photo was published, it emerged that four of the passengers in it were not migrants but Sydneysiders returning home from holiday.

Charles Nettleton (English 1825-1902, Australia 1854-1902)

Hobsons Bay railway pier

1870s

Albumen silver photograph

12.8 × 19.2cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1992

Public domain

Maggie Diaz (American, 1925-2016, Australia 1961-2016)

The Canberra, Port Melbourne

1961-1967, printed 2014

Pigment print

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2015

As a young woman, Maggie Diaz had been fascinated by the work of French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. Her photographs are a ‘slice of life’ offering similar insights into the everyday experiences of people wherever she encountered them. The ship she photographed at Melbourne’s Station Pier in the 1960s was The Canberra, the largest of the passenger ships sailing between Britain and Australia at that time. Often bringing British migrants on assisted passages, the ship also held personal significance for Diaz: as a migrant from the United States, she travelled one-way from the US to Australia on The Canberra’s maiden voyage in 1961.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing four photographs from Michael Cook’s Civilised series (2012)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Michael Cook (Australian / Bidjara, b. 1968)

Civilised #11

2012

From the Civilised series 2012

Inkjet print

100.0 x 87.5cm

ed. 3/8

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased NGV Foundation, 2013

© Michael Cook and Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin

Bidjara artist Michael Cook poses a question in his Civilised series: ‘What makes a person civilised?’ In these photographs he represents the ways Europeans – English, French, Portuguese and Spanish colonists – responded to First Nations people when they arrived on these shores. The artist asserts that his Civilised series ‘suggests how different history might have been if those Europeans had realised that the Aborigines were indeed civilised’.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at right, Narelle Autio’s two photographs Untitled from The Seventh Wave series (1999-2000)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing at third left bottom, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Sunday on the banks of the Marne (1938, below); at fourth left top, Gabriel de Rumine’s Caryatid porch of Erechtheum, Acropolis, Athens (1859, below); at fourth left bottom, Lee Friedlander’s Mount Rushmore (1969, below); at centre top, John Williams’ Clovelly Beach, Sydney (1969, below); at top right, Eugène Atget’s The roller coaster, Invalides funfair (Montagnes russes, fête des Invalides) (1898, below); and at bottom right, Roger Scott’s Ghost train, Sydney Royal Easter Show (1972? 1975? below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing David Goldblatt’s The playing fields of Tladi, Soweto, Johannesburg, August 1972

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Harold Cazneaux (Australian born New Zealand, 1878-1953)

Fairy Lane steps

1910

Bromoil print

24.8 × 18.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1979

© The Cazneaux family

Harold Cazneaux was one of the most important and influential Australian photographers of the early twentieth century. He had a great love of the natural world but early in his career also found a rich subject in the inner-city streets of Sydney. Cazneaux made photographs that appear lively and spontaneous, although given the limitations of the equipment at the time they are almost certain to have been staged to a degree. His charming studies of children at play in city streets transformed the bleak, impoverished urban environments of inner-city Sydney into a wonderful playground.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Helen Levitt’s New York (Boys fighting on a pediment) c. 1940

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009)

New York (Boys fighting on a pediment)

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

31.8 × 21.1cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Bowness Family Fund for Photography, 2022

Public domain

Francis Bedford (attributed to) (English, 1815-1894)

Fairy Glen, Betws-y-Coed

(Ffos Noddyn, Betws-y-Coed)

c. 1860

from the No title (Stephen Thompson album) (1859 – c. 1868)

Albumen silver photograph

13.7 × 17.8cm (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased from Admission Funds, 1988

Public domain

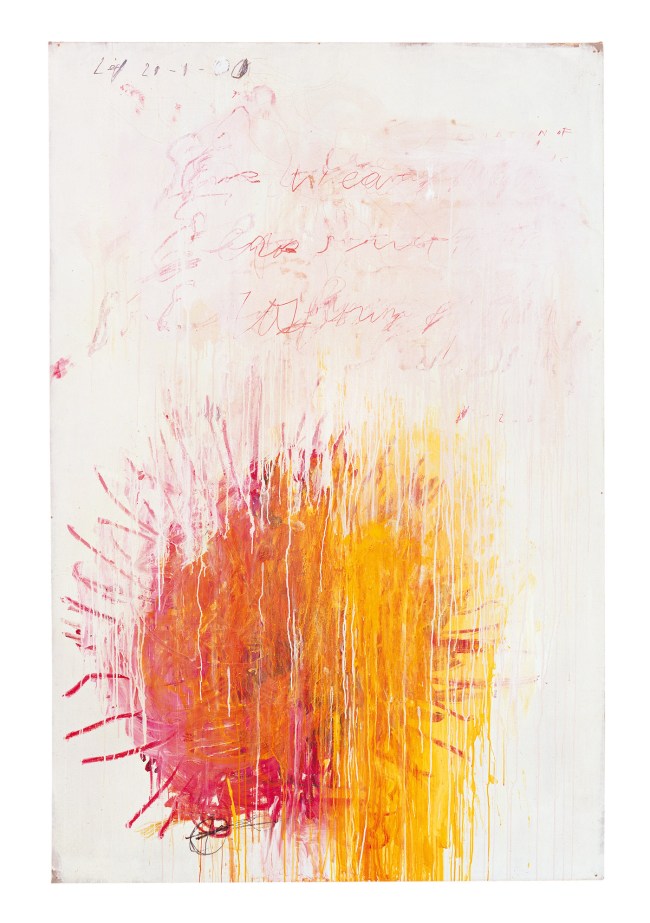

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908-2004)

Sunday on the banks of the Marne, Juvisy, France

1938; (1990s) {printed}

Gelatin silver photograph

29.1 x 43.9 cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased NGV Foundation, 2015

2015.566

© Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

In 1938 Henri Cartier-Bresson photographed a group of people picnicking on the banks of the river Marne. It is a celebratory image showing a quintessential aspect of everyday life in France: long Sunday lunches. But it also reveals something of the revolutionary politics of the period and their profound influence on Cartier-Bresson in the 1930s. In 1938 the left-wing Popular Front swept into power in France and the newly elected government mandated two weeks paid leave for all workers. At the time, Cartier-Bresson worked for the Paris-based communist press and was commissioned by Regards magazine to photograph an extended series that looked at the social impact of this initiative.

Wall text from the exhibition

Gabriel de Rumine (European, 1841-1871)

No title (Caryatid porch of Erechtheum, Acropolis, Athens)

1859

Albumen silver photograph

25.7 × 35.8cm irreg. (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented by the National Gallery Women’s Association, 1995

Public domain

Installation view of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing Lee Friedlander’s Mount Rushmore (1969, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lee Friedlander (United States, b. 1934)

Mount Rushmore

1969; printed c. 1977

Gelatin silver print

18.3 × 27.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1977

© Lee Friedlander, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco and Luhring Augustine, New York

Installation views of the exhibition Photography: Real & Imagined at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne showing John Williams’ Clovelly Beach, Sydney (1969, below)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

John Williams (Australian, 1933-2016)

Clovelly Beach, Sydney

1969; printed 1988

Gelatin silver photograph

25.6 × 25.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1989

© John Williams

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

The roller coaster, Invalides funfair (Montagnes russes, fête des Invalides)

1898

From the Festivals and Fairs series in the Art in Old Paris series 1898-1927

Albumen silver photograph

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Patrick Pound through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, 2020

Public domain

Roger Scott (Australian, b. 1944)

Ghost train, Sydney Royal Easter Show

1972? 1975?

Gelatin silver print

30.4 × 45.6cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Mr James Mollison, 1994

© Roger Scott

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

Federation Square

Corner of Russell and

Flinders Streets, Melbourne

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Peter Leiss (Australian, b. 1951) 'Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the rear of the Photographers' Gallery]' c. 1975-1980 Peter Leiss (Australian, b. 1951) 'Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the rear of the Photographers' Gallery]' c. 1975-1980](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/leiss-william-heimerman2-web.jpg)

![Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atgets-work-room-web1.jpg?w=650)

![Carol Jerrems. 'Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the Dog Rocks near Geelong]' c. 1975-1980 Carol Jerrems. 'Untitled [Bill Heimerman and Ian Lobb at the Dog Rocks near Geelong]' c. 1975-1980](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/jerrems-william-heimerman-ian-lobb-web.jpg?w=650)

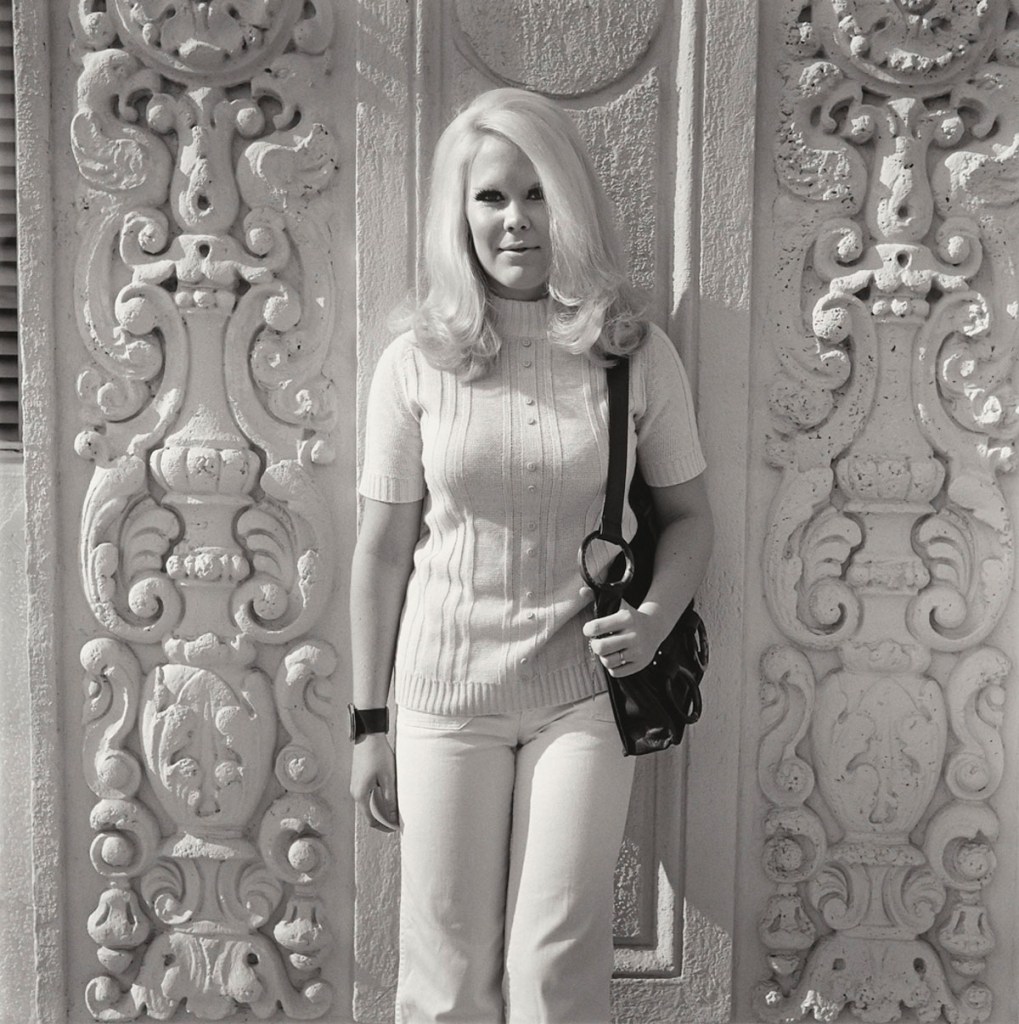

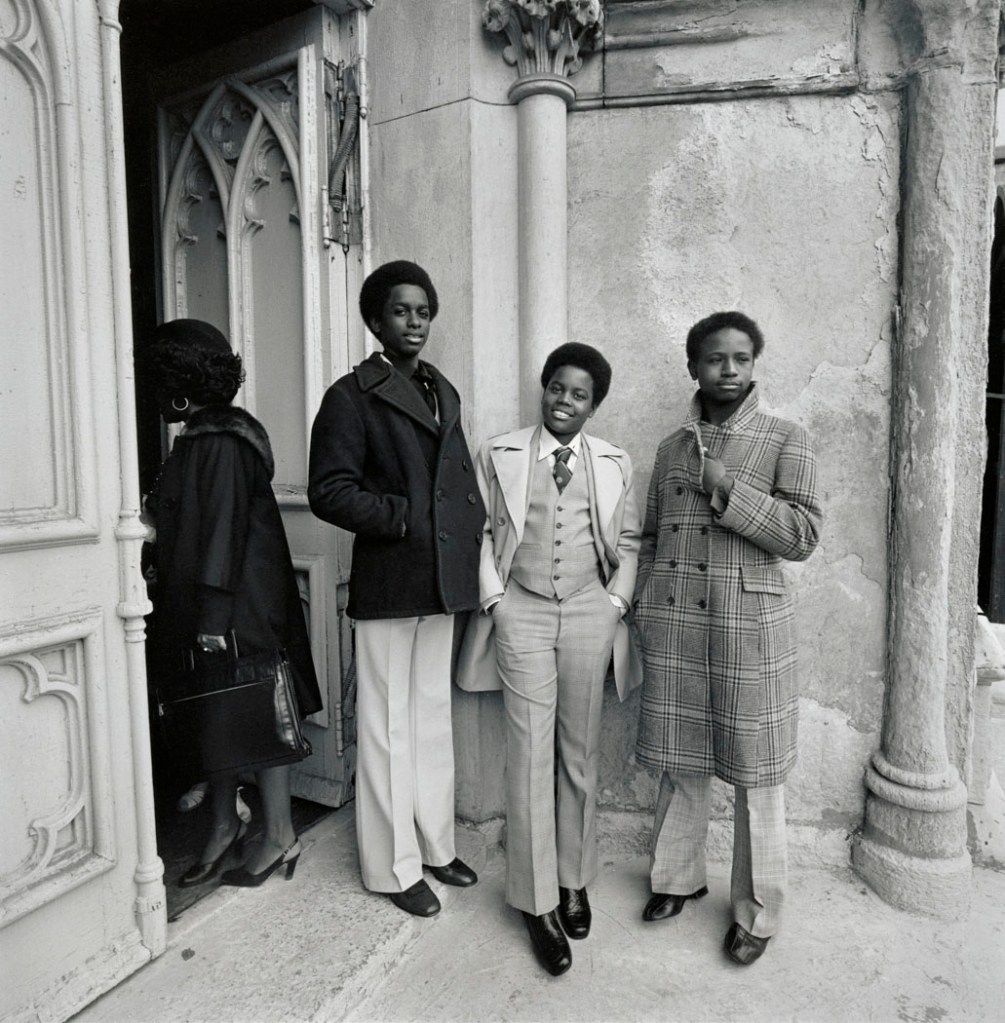

![Garry Winogrand (American, 1928-1984) 'Untitled [Liberace with his mother]' New York, 1954 Garry Winogrand (American, 1928-1984) 'Untitled [Liberace with his mother]' New York, 1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/83204a.jpg)

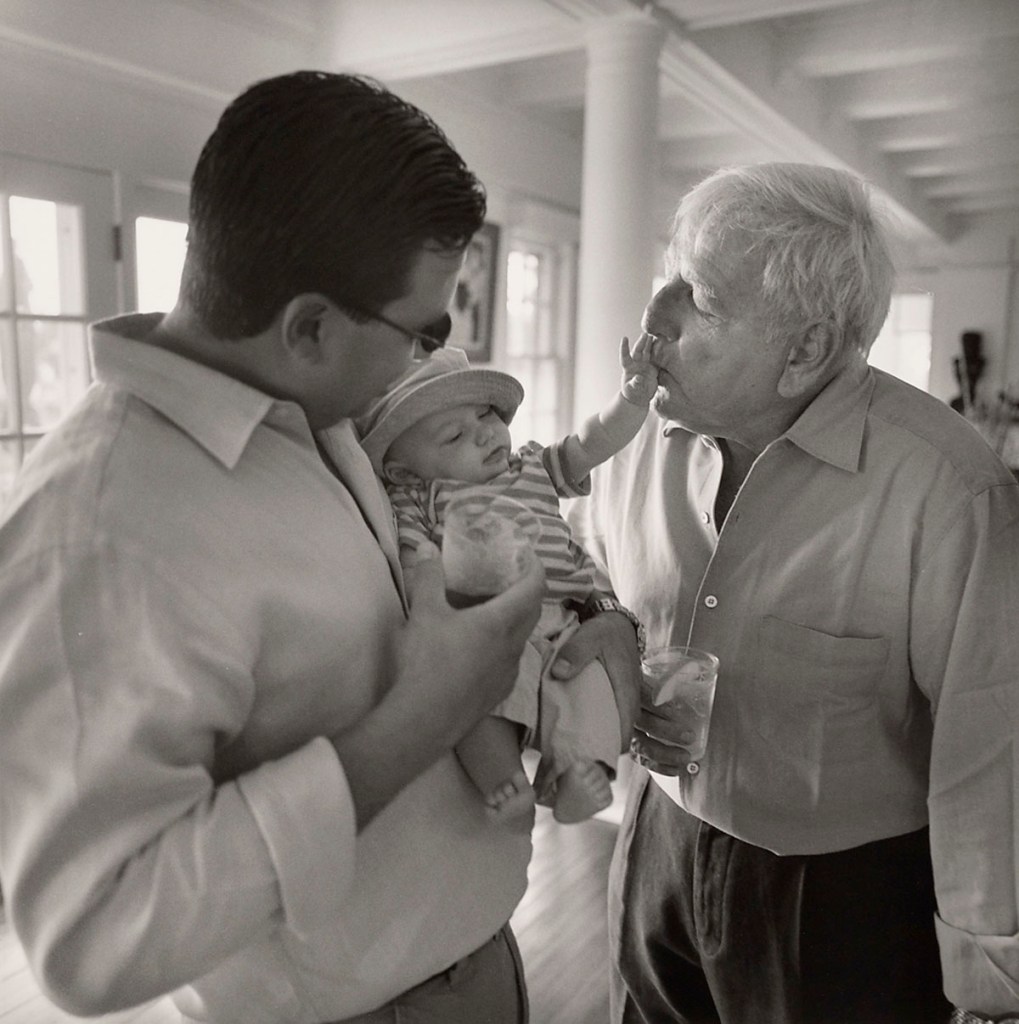

![Max Yavno (American, 1911-1985) 'Untitled [Opening Night at the San Francisco Opera]' 1947 Max Yavno (American, 1911-1985) 'Untitled [Opening Night at the San Francisco Opera]' 1947](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/92143117.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.