Exhibition dates: 11th December, 2010 – 25th April, 2011

Many thankx to the Museum of Sydney for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All images © Arthur Wigram Allan, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW.

More photographs can be found on the An Edwardian Summer website.

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

We left Medlow at 10.15 am & drove through Blackheath & Mt Victoria to Bathurst

Nd

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

AWA & Boyce at lunch

Nd

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Kitty and Katha working at the drawn work

Nd

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Family and friends

Arthur Allen spent many hours recording his home life and outings with family and friends. The Allens’ circle comprised a large extended family and a close-knit group of friends, who came and went as they liked and were always welcome at the various Allen households. They often stayed at the Allens’ properties on the coast and in country New South Wales, as did visiting celebrities, particularly those from the theatre.

While the social and legal status of Australian women improved toward the end of the 19th century, the Allen girls, their cousins and a small group of friends were still taught by governesses. This in turn helped to foster close ties between the members of their social class.

Sydney society among the wealthy classes was like a big, familiar club of relatives and friends, with a continual round of visiting, parties and picnics that also included, for example, visiting naval officers. There were also lively, large-scale social events organised to coincide with special occasions, such as the visit of the Duke of York in 1901, and charity fundraisers for causes in Australia and abroad, including annual Red Cross charity balls and local functions to support soldiers serving in the war.

Arthur Allen owned many cars but drove only one type – Detroit Electric broughams, one of which is now in the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Its batteries needed charging every 60 kilometres, but the recharging device was formidable.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website [Online] Cited 11/01/2020

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Wedding Group at ‘Merioola’, Saturday 23rd December 1911. Wedding Group consisting of Lieutenant Knowles (best man), Joyce Pat and Kitty, Alex Leeper’s two daughters Valentine and Molly [Kitty’s half-sisters]

December 1911

PX*D596 Negative 240

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

11 November 1917 Mrs Frank Osborne and Miss Catterall wait in the back of one of Arthur Allens Detroit Electric broughams

1917

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

An Edwardian Summer, a new book and an exhibition opening 11th December 2010 at the Museum of Sydney showcases for the first time an extraordinary collection of photographs that capture Sydney at the turn of the century at one of the most rapidly changing times in Australia’s history.

A talented amateur photographer, lawyer and Sydney identity Arthur Wigram Allen was fascinated by the social and technological changes that occurred during his lifetime, 1862-1941. Allen created 51 albums now held by the State Library of NSW.

In 1885 after the sudden death of his father and uncle and at the age of just 23, Allen was thrust into the role of heading up the family law firm founded by his grandfather George Allen, known internationally today as Allens Arthur Robinson. While Allen’s photographs span 1890-1934, the book and exhibition concentrate on the Edwardian years, 1890s-1915, a brief often overlooked but important period in Australia’s history that heralded a new century of significant inventions and social changes, including powered flight, the rise of the motorcar and a new federated Australia.

Through Allen’s lens, we see the first mixed bathing on Sydney beaches, sporting events, pageants and processions, dramatic shipwrecks, the latest fashions as well as intimate family events such as motoring and harbour excursions and bush picnics. Meticulously captioned by Allen, his exquisitely personal and beautiful photographs capture a time of optimism and new ideas as Sydney emerged from the strict moral codes of the Victorian era.

Both the book and exhibition feature art works from the era by Australian artists including Arthur Streeton, Rupert Bunny, Grace Cossington Smith and Theodore Penleigh Boyd. The exhibition will also showcase items from the Historic Houses Trust collection and from the Powerhouse Museum, including examples of Edwardian fashion, children’s dress up costumes, jewellery and accessories and furniture.

Text from the Sydney Museum website [Online] Cited 08/04/2011 no longer available online

Sydney lawyer and identity Arthur Wigram Allen, a tirelessly enthusiastic photographer, was fascinated by the social and technological changes occurring during his lifetime. His talent for amateur photography produced extraordinary pictures that offer a fresh insight into the Edwardian years in Sydney.

The Edwardian era was sandwiched between the great achievements of the Victorian age and the global catastrophe of World War I. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 heralded a new century of significant inventions and social changes, including powered flight, the rise of the motorcar and a new federated Australia.

An Edwardian Summer will present a selection of Arthur Allen’s beautiful images, depicting intimate moments with family and friends, motoring and harbour excursions, theatrical celebrities, bush picnics, the introduction of surf bathing on Sydney beaches, processions, pageants and mass celebrations, and new freedoms in fashion. Most have never before been published, and they form an unrivalled personal pictorial record of these rapidly changing times.

The exhibition will also include artworks by Rupert Bunny, Ethel Carrick Fox, Arthur Streeton and Grace Cossington Smith, examples of male and female fashion including evening and day wear, motoring ensembles and children’s dress-up costumes, jewellery and accessories, furniture and decorative embellishments characteristic of the Edwardian era.

Text from the Sydney Museum website [Online] Cited 11/01/2020

Installation views of the exhibition An Edwardian Summer: Sydney & beyond through the lens of Arthur Wigram Allen at the Museum of Sydney, December 2010 – April 2011

Arthur Wigram Allen

Sydney lawyer and identity Arthur Wigram Allen, a tirelessly enthusiastic photographer, was fascinated by the social and technological changes occurring during his lifetime. His talent for amateur photography produced extraordinary pictures that offer a fresh insight into the Edwardian years in Sydney.

Arthur Wigram Allen was born in 1862 into a large family of wealthy Sydney solicitors. One of 11 children and third in a line of six boys he attended Sydney Grammar School before moving to Melbourne in 1880 to study law at Trinity College at the University of Melbourne. In 1885 after the sudden death of his two elder brothers Arthur assumed control of the familíes Sydney firm and many business interests.

Allen married Ethel Lamb in 1891 and they went on to have four children: Ethel Joyce, born in 1893, Arthur Denis Wigram in 1894, Ellice Margaret in 1896 and Marcia Maria in 1905.

Fascinated by the new inventions of the era, he became interested in photography, purchasing the latest cameras. He soon proved to be a talented amateur photographer, capturing images of his family and friends, the city and its surrounds.

Arthur died in 1941, aged 79; his photographs, taken from the 1890s through to 1934, provide a detailed photographic record of a changing society and the emergence of the great city of Sydney.

A man of extraordinary vitality, Allen was fascinated by the times in which he lived, and tried to photograph everything he saw: family and friends; visiting ships and theatrical celebrities; bush picnics; the first mixed bathing on Sydney beaches; dramatic shipwrecks; processions, pageants and mass celebrations; coal miners; domestic life and fashion; house interiors; and sporting events. These photographs, contained in 51 albums, are now held by the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, and provide a view of the dramatic changes that took place in Edwardian Sydney.

Arthur Allen’s photographs span 1890 to 1934, but the Edwardian Summer exhibition and book concentrate on those depicting the Edwardian years, a brief, often-overlooked but important period in Australia’s history. The photographs, most of them never published before, form an unrivalled personal pictorial record of these rapidly changing times.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website [Online] Cited 11/01/2020

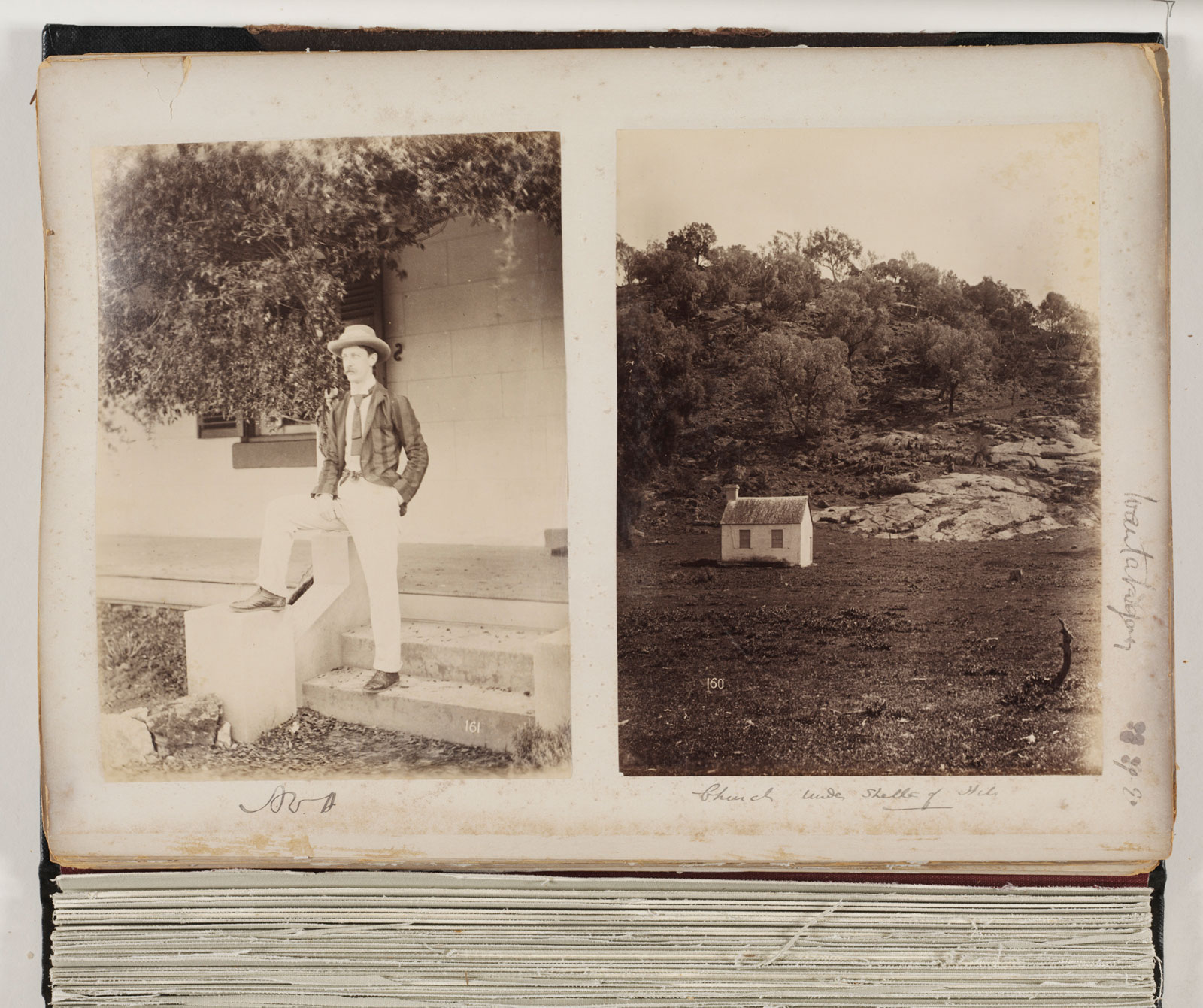

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Self-portrait

August – October 1890

PX*D 562 negative 162

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Arthur Wigram Allen (or AWA as he often referred to himself) was a man of many interests and a talented amateur photographer, capturing images of family and friends, city and surrounds. He is seen here on the steps of Wantabadgery homestead, site of a famous siege in 1879 between police and the gang of bushranger Captain Moonlight.

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Album 05: Photographs of the Allen family

August 1890 – October 1890

PX*D 562 FL576221 / FL576430

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Cecil Healy in the dinghy, ‘Port Hacking’, October 16 1904

1904

PX*D 575 negative 858

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Cecil Healy (1881-1918) found fame as the captain of Manly Surf Club and a champion swimmer; he won gold and silver medals in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics.

Cecil Patrick Healy (28 November 1881 – 29 August 1918) was an Australian freestyle swimmer of the 1900s and 1910s, who won silver in the 100 m freestyle at the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm. He also won gold in the 4 × 200 m freestyle relay. He was killed in the First World War at the Somme during an attack on a German trench. Healy was the second swimmer behind Frederick Lane to represent Australia in Swimming and has been allocated the number “2” by Swimming Australia on a list of all Australians who have represented Australia at an Open International Level.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

[Roller skating on the verandah at Moombara]

Nd

PX*D575 negative 836

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Roller skating on the verandah at Moombara, September 24, 1904. “Ethel and I and the children came down this afternoon for the Michaelmas holidays bringing Janet & Bob Rabete also. Immediately on arrival Joyce, Denis & Bob began to skate on the verandah and they used Janet & Margaret as horses to pull them along. Margaret also had some splendid rides on her tricycle”

Perhaps the greatest joy for the Allen children was the family’s waterfront holiday house, Moombara, where they played, swam, rode horses and roller skated around the verandah. Roller skating was a popular pastime of the era, with numerous rinks being built from the inner city to the beaches in the late 1880s. The Sydney Skating Club was formed in 1906 and skating displays were a common form of entertainment.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Childhood

The four Allen children had a happy home life. Their somewhat reserved Victorian mother was balanced by their gregarious father, and as in many affluent families of the era they had numerous domestic helpers, including a nurse, Florence, who remained with the family until the children were almost grown.

The family enjoyed many excursions to local Sydney attractions as well as seaside visits, picnics and journeys further afield, including to their beach property at Port Hacking. The children celebrated birthdays with elaborate parties and were dressed in the latest fashions, which were still very much influenced by Britain. Little girls had to contend with layers of petticoats, profuse frills and, during the 1890s and 1900s, increasingly wide-brimmed hats; and neither boys nor girls could be seen in public without hats, gloves, coats and shoes.

Public education in New South Wales, established in the 1860s, also grew steadily towards the century’s end. The three Allen girls, however, like many children from wealthier families, were tutored at home by a governess. The only boy, Denis, attended a private boarding school and was then sent to England to complete his schooling.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

This afternoon Marcia Lamb [centre] and I took Lord Orford and Lady Dorothy Walpole [right], also Nell Knox [left] for a drive to South Head, Bondi and Coogee

February 22, 1911

PX*D594 negative 4188

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Brief stop on a drive to South Head, Bondi and Coogee, February 22, 1911. As Sydneysiders embraced the outdoors, they began picnicking at every opportunity, flocking to local beauty spots or favourite retreats such as Coogee Beach. Although the beach was thronged with bathers and spectators, Coogee’s headland provided a quieter spot for picnicking and, for Arthur Allen, taking photographs. Seen here is his camera equipment, including the box of his Guardia and Newman camera that took 5 x 4 inch (13 x 10 cm) photographic plates. The women are wearing elaborate motoring hats with scarves, which were also useful for securing their hats on a windy cliff to prevent their hair from blowing out of style.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

The beach

The pleasures of sea-bathing had been discouraged in colonial Sydney on the grounds of both risk and indecency, and early laws prohibited bathing during daylight hours. People gradually defied the daylight bathing laws and by 1900 there were reports in the press of whole families bathing. In 1902, a male swimmer at Manly Beach entered the water at midday. Although arrested, he was not charged, and by 1903 new laws were introduced that permitted surf bathing but required neck-to-knee outfits and prohibited the sexes to mingle. Mixed bathing soon followed, but swimming attire continued to be stringently regulated for some years to come.

Sydneysiders increasingly flocked to the coast to enjoy the cooling summer breezes and the glorious ocean views. The ‘pleasure palaces’ near many beaches provided popular entertainment for all ages. For picnics, families sought out Clark Island, quiet beaches around Middle Harbour or the popular Manly Beach.

Bondi and Coogee beaches in Sydney’s east were connected to the city by public transport and provided the ideal day-trip for large crowds of visitors. With growing numbers of people taking to the surf, the dangers of beach bathing became apparent, and in 1906 the first surf lifesaving club in the world was founded at Bondi Beach.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Sea bathing: Coogee

January 27, 1900

PX*D 582 negative 2563

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

The immense and immediate popularity of sea bathing: Coogee Beach on a summer’s day. The boy in the tie and straw boater contrasts with the enthusiastic swimming groups clad in simple black singlets and shorts or cut-down dresses. In truth, most are just paddling, as few had learnt to swim properly.

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Wonderland city near Bondi

December 26, 1906

PX*D580 negative 2002

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Wonderland city near Bondi (there were 26 000 people there today). Wonderland city, a large amusement park, the Royal Aquarium and Pleasure Grounds at Tamarama near Bondi, December 26, 1906. By 1901, Bondi Beach was already a fashionable tourist destination. A tramline had been built to the beach in 1894, and a large amusement park, the Royal Aquarium and Pleasure Grounds, had opened at nearby Tamarama in 1887. Wonderland City – promoted as ‘Sydney’s Great Playground’ – opened in December 1906, also at Tamarama. Described as the Coney Island of Australia, its 50 major attractions were ‘designed by artists in architecture and landscape gardening’, with ‘no expense spared in achieving the highest standard of excellence’.1 The wooded slopes featured pleasure palaces, brightly coloured sideshows, a switchback (roller-coaster), scenic railway, slippery dips and underground rivers.

1/ Caroline Mackaness (ed.), An Edwardian Summer: Sydney and Beyond through the Lens of Arthur Wigram Allen, Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 2010

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Walter resting after lunch

November 19, 1898

PX*D566 negative 3649

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Rex Walter and I went to day to Bulli mainly to see some land which had been offered to us to purchase but also to show Walter (Who had never been to Illawarra) the scenery. We lunched at the fig tree not far from the Pass Road at the Bulli “B” pit.

Renowned for its beauty, the Illawarra district was home to towering forests of turpentine and fig trees and tangled, dense stands of ferns and cabbage palms, tinted by the conspicuous red flowers of the Illawarra flame tree. Arthur Allen, his brother Walter and brother-in-law Rex travelled in a horsedrawn wagonette to Bulli, a small coal-mining town in the northern Illawarra, via the steep Bulli Pass road, which was built in 1867. The journey down the Bulli Pass afforded many spectacular views of the south coast.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

The bush

In the later 19th century, city dwellers’ attitudes to the Australian bush changed. Formerly a foreign wilderness, it now became a place of Arcadian bliss, offering something peculiarly Australian and very different from the more familiar urban landscapes.

Nationalism increased in the 1890s, and with it the Australian bush legend was born. Artists such as Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin created nostalgic bush scenes, depicting rural life as a simplistic and uniquely Australian ideal. Writers such as Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson fashioned similar impressions in poetry and prose, strengthening the link between the bush and the Australian national identity.

By the early 1900s, the attributes of bush life were seen as an intrinsic part of the nation’s greatness. Bush characters were imbued with the same pioneering qualities as the diggers on the goldfields. By World War I these characteristics would be identified as uniquely Australian traits in our soldiers.

Expanded road and railway networks in the second half of the 19th century opened the bush to city visitors. Roads were cut to link sights of interest, and clear tracks were carved into the bush to allow access to vantage points. Swathes of descriptive tourist guides promoted the state’s many health, holiday and tourist resorts.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Crossing a creek, Belmore Falls, south of Robertson, on the edge of the Illawarra escarpment

February 13, 1899

PX*D567 negative 3822

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

The Belmore Falls, south of Robertson, are on the edge of the Illawarra escarpment at the headwaters of Barrengarry Creek. They cascade into the Barrengarry Creek Valley, with the main fall dropping a spectacular 78 metres. A road from Robertson was cut through the scrub in 1887, making the falls accessible to tourists, who had been arriving in increasing numbers since the Southern Highlands railway to Mittagong was opened in 1867. The picturesque scenery and cooler climate of the Southern Highlands had made the region a popular summer holiday retreat for well-to-do Sydneysiders. Guesthouses and country homes were built from the 1870s, encouraging the expansion of road networks to connect various sights of interest.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

“Lunch at the head of the river” Royal National Park. Frida, Herbert, Ethel, William Wate, Jack, Hilda

Nd

PX*D566 negative 3656

Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, November 26, 1898

In 1879, an area 32 kilometres south of Sydney was dedicated as Australia’s first national park. It could be reached by road or rail, and swiftly became ‘a national pleasure ground’1 and a popular destination for Sydneysiders on a day-trip. Picnic sites were fashioned throughout the park, rustic bridges and furniture decorated the landscape and imported flora and fauna enhanced the native scenery. By 1886 a boatshed and jetties had been established, enabling visitors to hire boats and explore the park via its waterways. Parties of ladies and gentlemen favoured the freshwater river above the dam, rowing to suitable locations for a relatively informal picnic on the rocky banks by the water.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

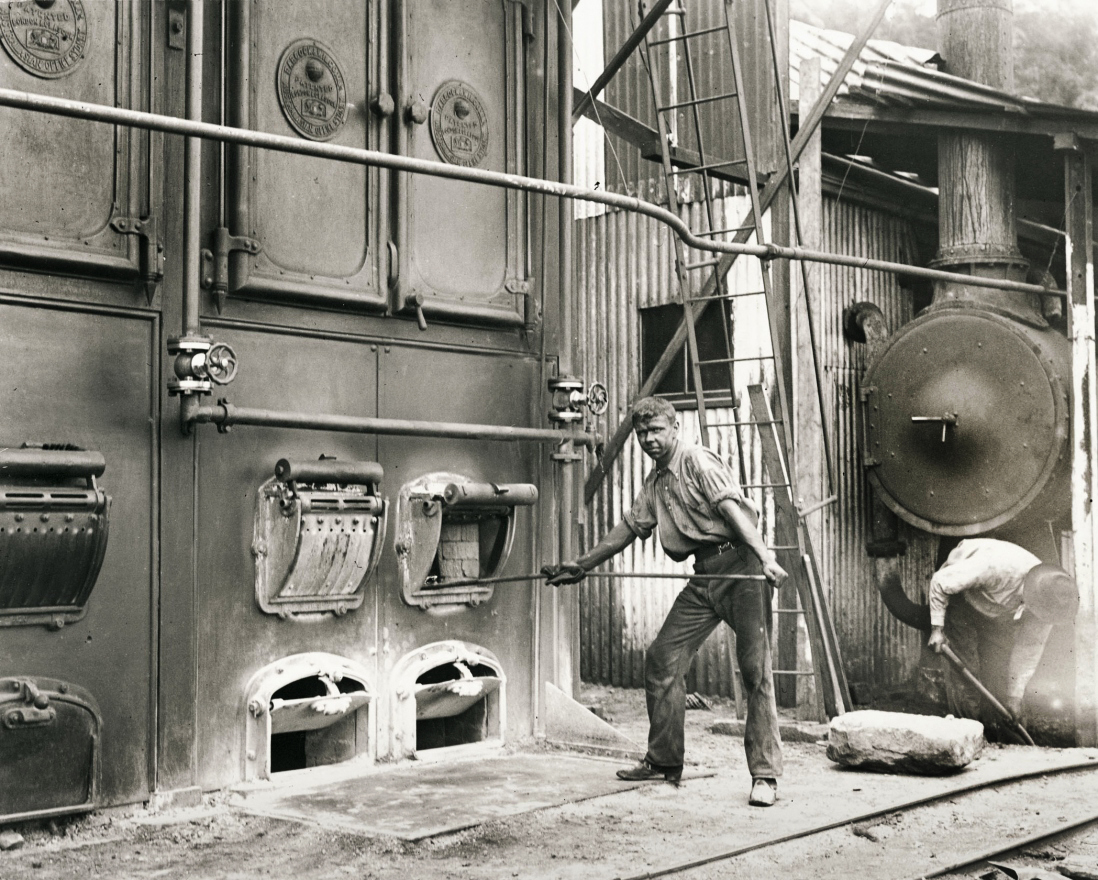

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

One of the new boilers just installed at the mine

November 22, 1907

PX*D581 negative 2403

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

One of the new boilers just installed at the mine. November 22, 1907.

Mt Kembla was one of a series of towns established in the Illawarra region in the mid 19th century after coal mining began at nearby Mt Keira in 1848. The first coal export from the Illawarra left Wollongong harbour in 1849 destined for Sydney. Coal was mined at Mt Kembla from 1865, and in 1880 the Mount Kembla Coal and Oil Company was formed, building a loading wharf at Port Kembla in 1883 and installing a rail link from Mount Kembla to Port Kembla in 1886. By 1900, the Illawarra mines employed 2300 men. In 1902 a disastrous gas explosion, caused by the naked flames of the miners’ torches, killed 94 men.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Further afield

During the Edwardian era, touring became immensely popular. With the introduction of better working conditions and shorter working hours many people had more leisure time, and took every opportunity to enjoy it. Even before the arrival of the motorcar, a growing love of the outdoors led the people of Sydney to flock to beauty spots in the Blue Mountains and Southern Highlands. Rural and waterside retreats around Sydney were as popular then as they are now, and the Allen family and their friends spent many weekends and vacations at their holiday houses at Port Hacking and Burradoo in the Southern Highlands.

To escape the hectic and at times unhealthy city, Sydneysiders sought the more relaxed lifestyle offered in rural locations. People began to enjoy the physical pleasures of life outdoors and the benefits of sun and clean air, and this was reflected in the way they behaved and dressed away from the confines of the city.

People who lacked their own transport could still enjoy tourism via the ever-expanding railway network. For those with private carriages and later motorcars, the ability to travel was only limited by the condition of the roads. The coming of the motorcar changed both the physical development of Sydney and the way people spent their leisure time, as they toured ever further.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Florence and the children on the lawn at Moombara

July 1903

PX*D 572 negative 6

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

One of the most important people in the lives of the Allen children was their nurse, Florence, who remained with the family until the children were almost grown. She is shown here relaxing with her charges on the lawn at Moombara, the family holiday home that Arthur Allen purchased in 1903. Located between the unspoilt landscape of the Royal National Park and the beaches of Cronulla, it was built on a steep slope with a magnificent view over the river and pristine bushland. Soon after Allen bought the property, a second storey was added to accommodate the family and their many visitors. It was a popular place for family and friends to spend their honeymoon, and came to be nicknamed ‘Honeymoombara’.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

‘Moombaha’. 5.45 pm on the wharf, Jacob having just caught a large conger eel, Little Turriell Bay at Port Hacking

December 7, 1904

PX*D 575 negative 921

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Moombara was located on Little Turriell Bay at Port Hacking. In 1901-02 nearly a third of a million tonnes of sand had been removed from the Simpsons Bay area of the estuary to create access to a fish hatchery in Cabbage Tree Basin. This helped to make the area more navigable for boating and better for fishing, both pastimes that the Allens and their friends enjoyed. With increasing numbers of residential subdivisions, the area’s waterways became popular for recreational use.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Joyce preparing to dive 15 January 1905

1905

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Out and about

Edwardian Sydney offered entertainment for every taste. Apart from the large-scale parades, military displays and massed bands that accompanied public celebrations, annual events such as the Royal Easter Show and the Public Schools’ Amateur Athletics Association carnival drew crowds from all walks of life. Expanding tram and rail networks carried passengers to venues such as the Zoo (then at Moore Park), Sydney Stadium at Rushcutters Bay and the Glaciarium Skating Rink, which operated at Ultimo from 1907.

Among the more popular leisure activities was horse racing, with racecourses as far afield as Randwick, Canterbury, Moorefield and Warwick Farm. The annual amateur picnic race held at Bong Bong, near Moss Vale, was as popular with Sydneysiders as with locals.

The growth in international sporting competition also provided spectacles for large crowds. Due to Australia’s success in rowing, the world championship sculling contest was regularly held on the Parramatta River, while in 1909 the Davis Cup tennis tournament came to Rose Bay. Cricket, cycling, athletics and football were also popular, with the Sydney Cricket Ground a versatile venue.

Text from the An Edwardian Summer website

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Ladies double championship rowing race held on the Parramatta River between Abbotsford and Mortlake

Saturday 4 August 1906

PX*D 579 negative 1817

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

On Saturday 4 August 1906, eager onlookers crowded the banks of the Parramatta River and hundreds of launches, boats and steamers plied the water in anticipation of the veteran scullers’ handicap and the ladies’ double sculling championship, contested by a field of ten crews. One week earlier, Stanbury and Towns had competed for stakes of £500 each plus a lucrative share of the steamer takings, but on this day the ladies rowed for a more modest £20. On the 1.5-mile (2.4-km) course between Abbotsford and Mortlake, the Newcastle team of Mrs Hyde and Mrs Woodbridge narrowly beat Misses G and K Lewis of North Sydney for first place.

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Joyce and Denis at the ostrich farm

15 November 1903

PX*D 573 negative 580

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Children hold baby Emus at Ostrich Farm at South Head, 15 November 1903. Joseph Barracluff’s Ostrich Farm at South Head was established in 1889, when ostrich feathers were a popular women’s fashion accessory for boas, hats and fans. Arriving in Australia from Lincolnshire in 1884, Barracluff originally established a small business selling feathers from a shop on Elizabeth Street, before setting up the farm with birds reportedly imported from South Africa and Morocco. A trip to Barracluff’s farm soon became a popular excursion, and patrons could select feathers to be cut directly from a flock of 100 birds. In 1901, as a memento of her visit, the women of Sydney presented the Duchess of Cornwall and York with a gold mirror and fan embellished with tortoiseshell and Barracluff’s feathers, grown and curled on site.

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

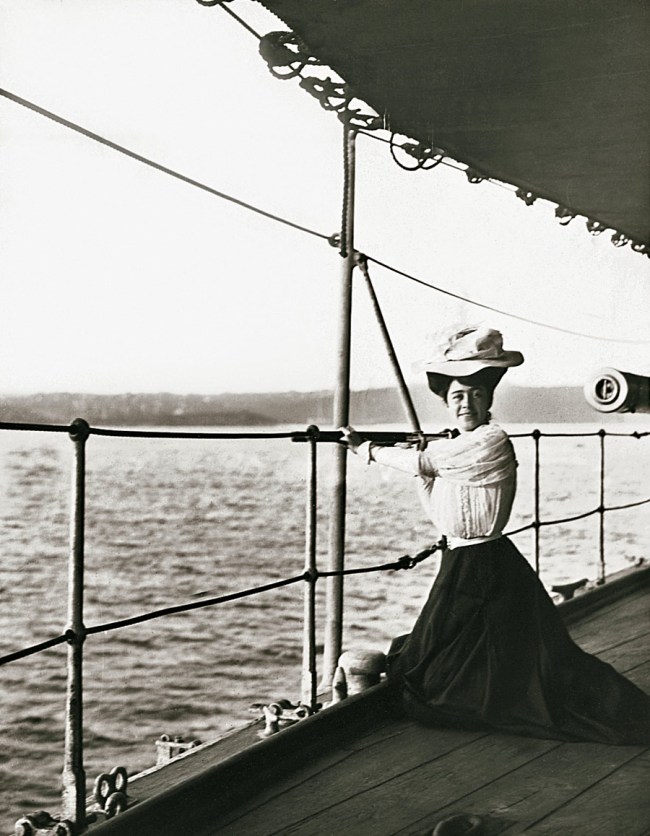

The ‘Electra’ … T. H. Kelly, Denis, Miss Kelly, Joyce, W. Kelly. The children’s first experience of yachting Arthur Allen. The children’s first experience of yachting

14 April 1901

PX*D 571 negative 95

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Yachting built up a strong following among the wealthy during the Edwardian years, with boats from the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron regularly competing in organised races on the harbour. Joining Arthur Allen and his two elder children, Joyce and Denis, in this photo are members of the Kelly family: Thomas, William and their sister. Thomas Kelly was managing director of the family firm, the Sydney Smelting Company, and chairman of the Australian Alum Company; his brother William was a politician. Both brothers were considered dashing young men about town. The Kellys were keen yachtsmen and closely involved with Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron, founded in 1863.

A day on the harbour

Sydney’s waterways were the focus of both industry and pleasure in the Edwardian era. From its colonial foundations Sydney Cove had developed as the hub of a trading port and working harbour with a strong shipbuilding industry and other maritime trades.

During the Edwardian years, full-rigged ships gradually disappeared from Sydney Harbour, and after the bubonic plague arrived in 1900, large areas of residential and commercial buildings around Darling Harbour, Millers Point and The Rocks were resumed by the government and rebuilt.

By the early 1900s Circular Quay was dominated by ferry wharves and served as an interchange for all the traffic – pedestrian and vehicular – between Sydney and the north shore. This was the heyday of the harbour ferry, with commuter craft dominating the waters during peak hour. On weekends, the ‘great picnic trade’ ferried Sydney’s multitudes to the harbour’s pleasure destinations, many of which were owned and operated by the ferry companies.

Other Sydneysiders preferred to spend a day on the water, enjoying a leisurely steamer excursion, messing about in a small boat or sailing a yacht. Sporting events provided a further form of entertainment, with annual yachting and rowing regattas held on the harbour.

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

Another who is not quite so sure

Nd

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967)

The ‘Euryalus’ in dock

17 August 1905

PX*D 577 negatives 1279

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

HMS Euryalus was the flagship of the Australian station of the Royal Navy between 1904 and 1905. The 144-metre armoured cruiser was built in England in 1901, and Arthur Allen photographed it in August 1905, while it was being overhauled in the Sutherland Dock at Cockatoo Island.[1] Soon afterwards the Euryalus was replaced by HMS Powerful, and in 1920 it was broken up in Germany. On its completion in 1890, the Sutherland Dock was the world’s largest dry dock. The island’s smaller Fitzroy Dock had been built by convicts between 1839 and 1847. Cockatoo Island became the Commonwealth Naval Dockyard in 1913 and shipbuilding continued there until the dockyard closed in 1991.

Museum of Sydney

cnr Bridge & Phillip Streets, Sydney

Opening hours:

Open daily 10am – 5pm

![Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967) 'Wedding Group at 'Merioola', Saturday 23rd December 1911. Wedding Group consisting of Lieutenant Knowles (best man), Joyce Pat and Kitty, Alex Leeper's two daughters Valentine and Molly [Kitty's half-sisters]' December 1911 Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967) 'Wedding Group at 'Merioola', Saturday 23rd December 1911. Wedding Group consisting of Lieutenant Knowles (best man), Joyce Pat and Kitty, Alex Leeper's two daughters Valentine and Molly [Kitty's half-sisters]' December 1911](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/arthur-wigram-allen-wedding-group.jpg)

![Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967) '[Roller skating on the verandah at Moombara]' Nd Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967) '[Roller skating on the verandah at Moombara]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/allen-roller-skating.jpg)

![Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967) 'This afternoon Marcia Lamb [centre] and I took Lord Orford and Lady Dorothy Walpole [right], also Nell Knox [left] for a drive to South Head, Bondi and Coogee' February 22, 1911 Arthur Wigram Allen (Australian, 1894-1967) 'This afternoon Marcia Lamb [centre] and I took Lord Orford and Lady Dorothy Walpole [right], also Nell Knox [left] for a drive to South Head, Bondi and Coogee' February 22, 1911](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/allen-afternoon.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.