Exhibition dates: 13th February – 6th June, 2010

Curators: Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., Director of the Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation, and Robin Garr, Director of Education, Bruce Museum

Many thankx to Mike Horyczun, Director of Public Relations and the Bruce Museum for allowing me to publish the images in the posting. Please click on the photographs for even larger version of the image.

Marcus

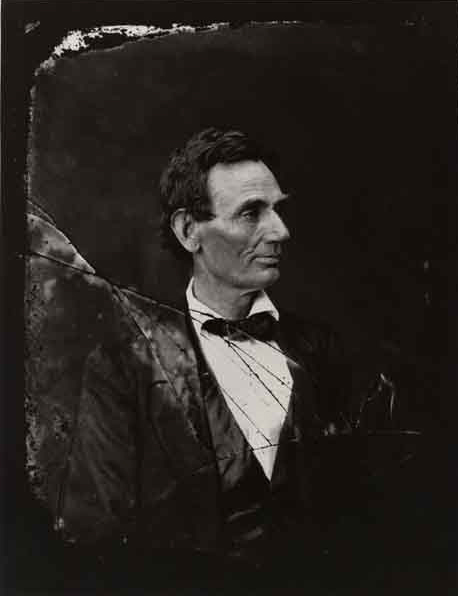

Alexander Hesler (American, 1823-1895)

Abraham Lincoln

June 3, 1860 Springfield, Illinois

Alexander Hesler or Hessler (1823-1895) was an American photographer active in the U.S. state of Illinois. He is best known for photographing, in 1858 and 1860, definitive iconic images of the beardless Abraham Lincoln. …

Hesler’s known portraits include photographs of the two chief Illinois political figures of his day, Lincoln and federal senator Stephen A. Douglas. In the 1860 presidential election, Lincoln’s friends took steps to have Hesler’s images copied and recirculated, cementing their stature as works of Lincoln image-making.

Hesler was an award-winning photographer whose goal was to create photographs of lasting artistic value. He was recognised for the quality of both his portrait work and his outdoor photography. Upon Hesler’s retirement in 1865, he transferred his Chicago studio and negatives to a fellow photographer, George Bucher Ayres. Several of Hesler’s best-known images of Lincoln are platinum prints produced by Ayres from Hesler negatives.

Text from the Wikipedia website

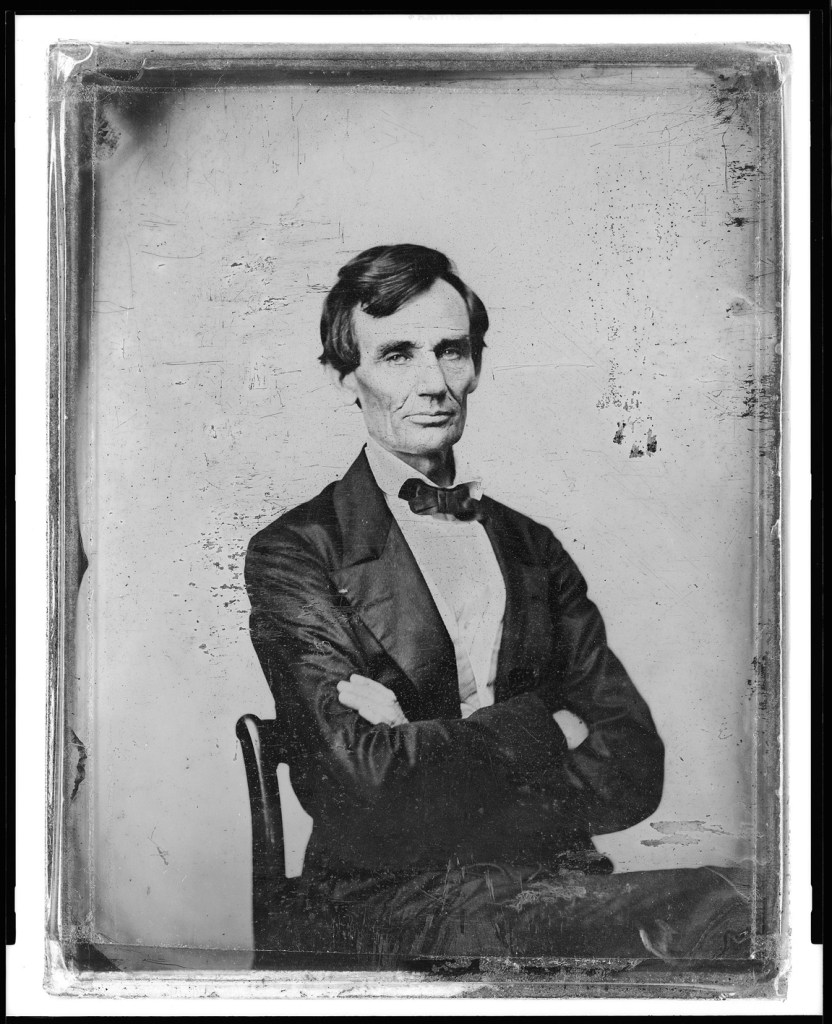

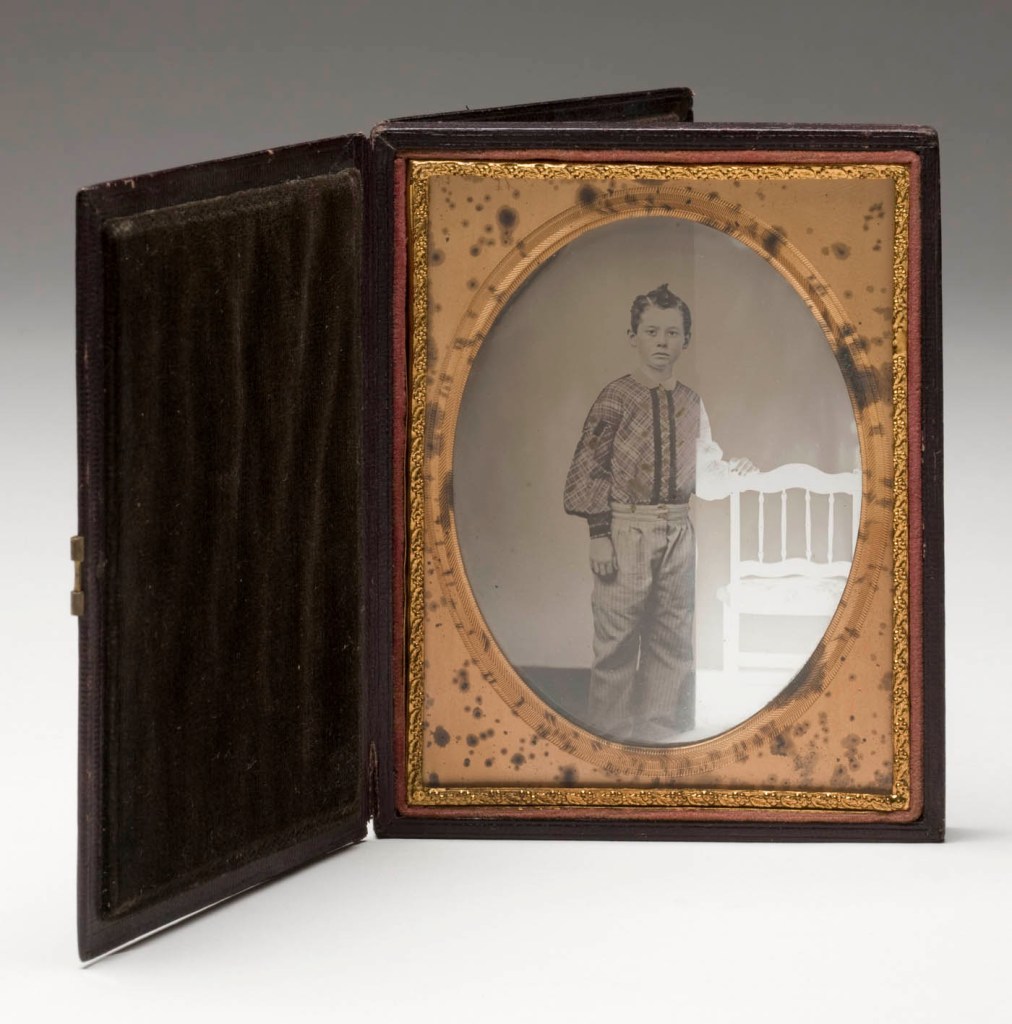

Preston Butler

Abraham Lincoln

August 13, 1860 Springfield, Illinois

Ambrotype

Plate 5 3/4 x 4 1/2 in

Library of Congress

Abraham Lincoln as candidate for United States president. Half-length portrait, seated, facing front.

Thought to be the last beardless portrait of Lincoln, this photo was “made for the portrait painter, John Henry Brown, noted for his miniatures in ivory. … ‘There are so many hard lines in his face,’ wrote Brown in his diary, ‘that it becomes a mask to the inner man. His true character only shines out when in an animated conversation, or when telling an amusing tale. … He is said to be a homely man; I do not think so.'” (Source: Ostendorf, p. 62)

Published in: Lincoln’s photographs: a complete album / by Lloyd Ostendorf. Dayton, OH: Rockywood Press, 1998, pp. 62-63.

Between 1856, the year of Preston Butler’s arrival in Springfield, and Feb. 11, 1861, when President-elect Abraham Lincoln departed from Springfield, Butler took at least 8 photographs of Lincoln and at least 1 photograph of Mary, Willie and Tad Lincoln. Also, in 1857 or 1858, Butler photographed each of the 4 sides of Springfield’s public square. These photographs are the primary source of information about the appearance of the public square in Lincoln’s Springfield.

Abraham B. Byers (American, 1836-1920)

Abraham Lincoln

May 7, 1858 Beardstown, Illinois

Ambrotype

The Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut, presents its newest exhibition Lincoln, Life-Size, from February 13, 2010, through June 6, 2010. The exhibition features photographs of Abraham Lincoln reproduced full size, hanging alongside original 19th-century images and artefacts that tell the story of Lincoln’s tumultuous presidency. The exhibition is drawn from the Meserve-Kunhardt Collection which it has on loan from the Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation. Lincoln, Life-Size is supported by Fieldpoint Private Bank & Trust, New England Land Company, Ltd., a Committee of Honor co-chaired by Tom Clephane and Nat Day, and the Charles M. and Deborah G. Royce Exhibition Fund.

Lincoln, Life-Size is organised by guest curator Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., Director of the Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation, and Robin Garr, Director of Education, Bruce Museum. Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., is the great-great-grandson of Frederick Hill Meserve one of this country’s premiere Lincoln collectors. Frederick Hill Meserve’s passion for Lincoln was ignited in the 1880s when his father, William Neal Meserve, who had served in the Civil War, asked him to hunt for photographs to illustrate his handwritten war diary. Five generations of the family have preserved this massive historical record over the past century.

The exhibition chronicles the toll of war etched into the face of our 16th president. Life-size enlargements of Lincoln’s portraits circle the entire central gallery. Visitors will experience what it was like to stand before him and look into his eyes. Beneath this facial timeline of his presidency is a selection of photographs of people who touched his life and events that nearly wore him out.

The show explores the time from Abraham Lincoln’s arrival in Washington in 1857 through his assassination in 1865. Photographs chronicle events as the war unfolds, his son dies, and he struggles with generals and mounting death tolls. In the photographs, Lincoln is revealed in a variety of poses, each bearing a significance that attests to the historic nature of his life, be it as he is grappling with emancipation or drafting words that would become sacred; serving as husband and father or being pulled in all directions by his constituents; and ultimately as he holds the country together throughout the turbulent times of the Civil War.

Highlights of the exhibition include Leonard Volk’s bronze life mask of Lincoln’s head and hands, glass negatives by Mathew Brady, original albumen war prints by Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan, and carte-de-visites of Lincoln, his family, his cabinet, and his generals. Viewers can study official government war maps, view a Thomas Nast drawing depicting the slavery issue, and walk around an early “triptych” photograph that portrays Lincoln, Grant, or Sherman, depending on where the viewer stands. An oversize “imperial” print shows Lincoln just days before delivering his Gettysburg address. In another imperial print a lab technician’s thumb print obliterates Lincoln at his second inaugural, but what is visible is a spectator in the crowd who appears to be John Wilkes Booth. Another photograph of Booth has these words written on the back side: “Recognize him and kill him.” Lincoln, Life-Size also include artefact related to Lincoln and his era.

“We have presented these works so that viewers can see how the toll the war and personal tragedies aged him during his years in office,” said Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr. “In fact, he was just 56 years old when he was assassinated.” This is the first museum exhibition dedicated to the collection of the Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation, which is now housed on the campus of SUNY Purchase. The recent book, Lincoln, Life-Size, co-authored by Phillip B. Kunhardt III, Peter W. Kunhardt and Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr. is available in the Bruce Museum Store. A full array of exhibition programming related to the exhibition is scheduled.

Text from the Bruce Museum website [Online] Cited 01/06/2010. No longer available online

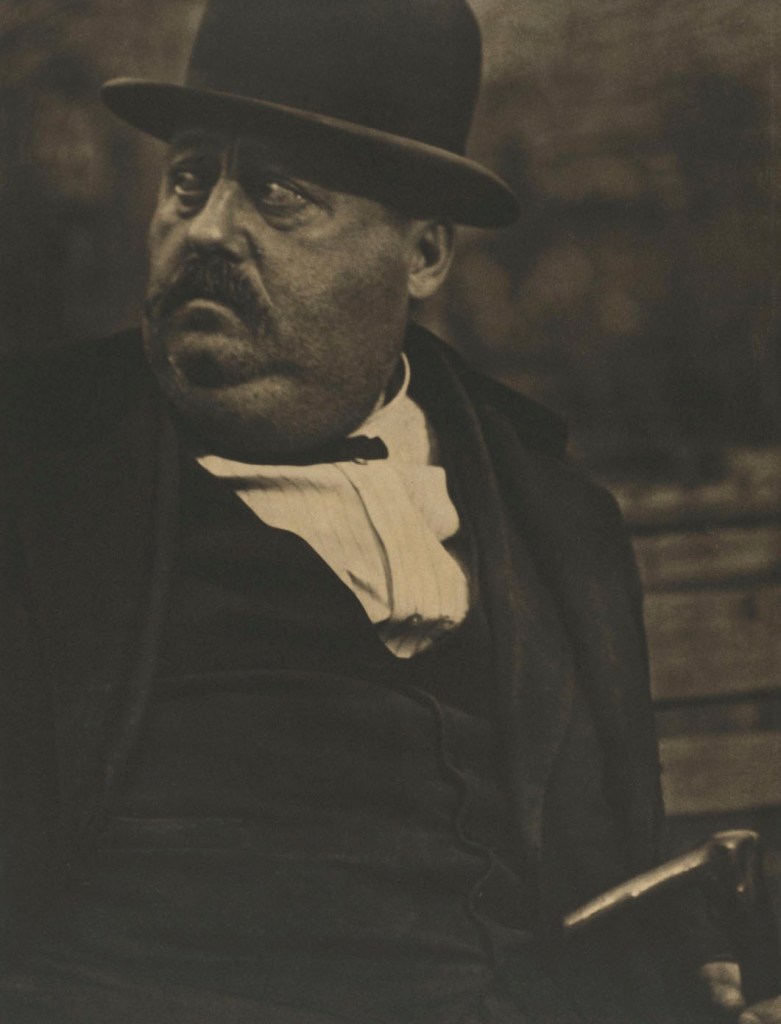

Mathew B. Brady (American, c. 1822-1896)

Abraham Lincoln

January 8, 1864 Washington, DC

National Archives and Records Administration

Anthony Berger (American born Germany, 1832 – after 1897)

Abraham Lincoln

February 9, 1864 Washington, DC

Collodion negative

Quarter-plate glass transparency

10.9 x 8.7cm (case)

Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Galleries

Library of Congress

This is one of a series of photographs that Anthony Berger took of President Abraham Lincoln at the Brady Gallery in Washington in the winter of 1864, as the Civil War dragged on. Modern albumen print from 1864 wet-plated collodion negative. National Portrait Gallery.

“The Famous Profile” by Anthony Berger, manager of Brady’s Gallery, Washington D.C., made direct from an original collodion negative in the Meserve collection (M-82). One of seven poses taken by Berger on Tuesday February 9, 1864, it is perhaps the most familiar of Lincoln profiles, a more handsome pose than its companion view (0-89) because Lincoln’s profile is less severe and his left eyebrow is more visible.

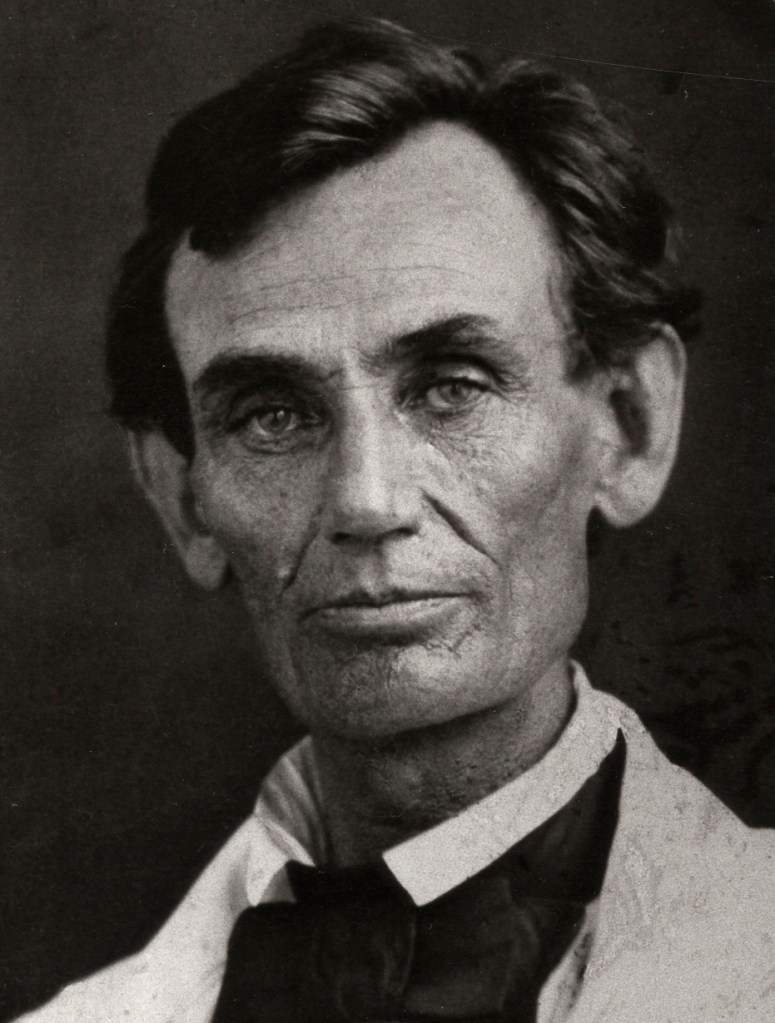

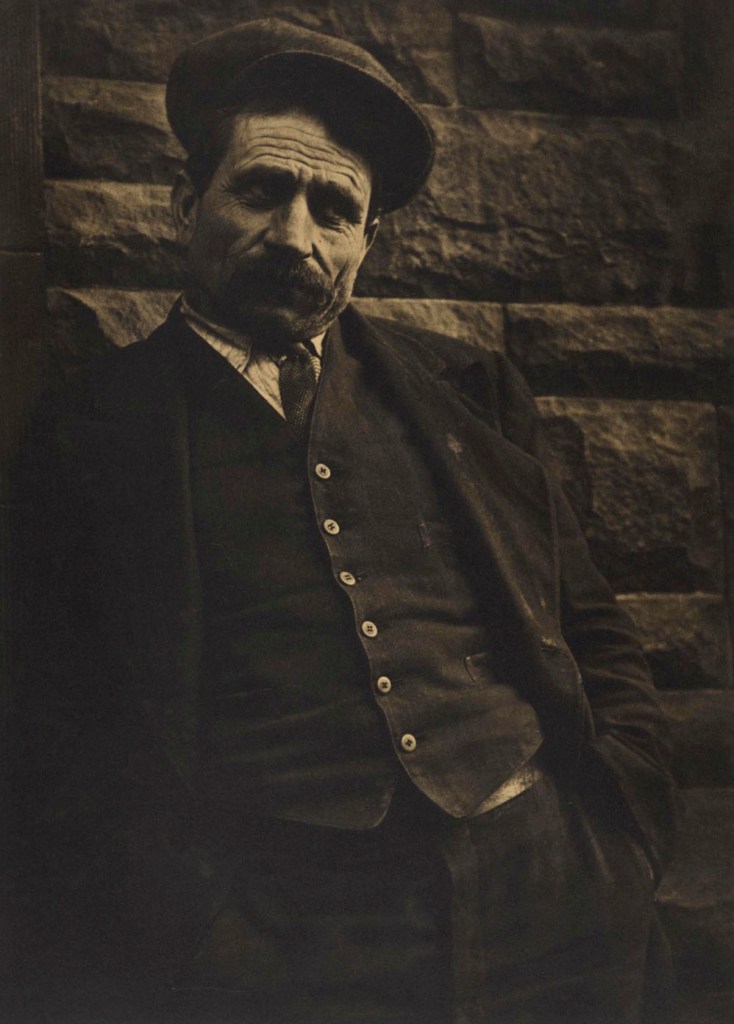

Alexander Gardner (Scottish 1821-1882; emigrated America 1856)

Abraham Lincoln

November 8, 1863 Washington, DC

Library of Congress

Alexander Gardner (Scottish 1821-1882; emigrated America 1856)

Abraham Lincoln

February 5, 1865 Washington, DC

Library of Congress

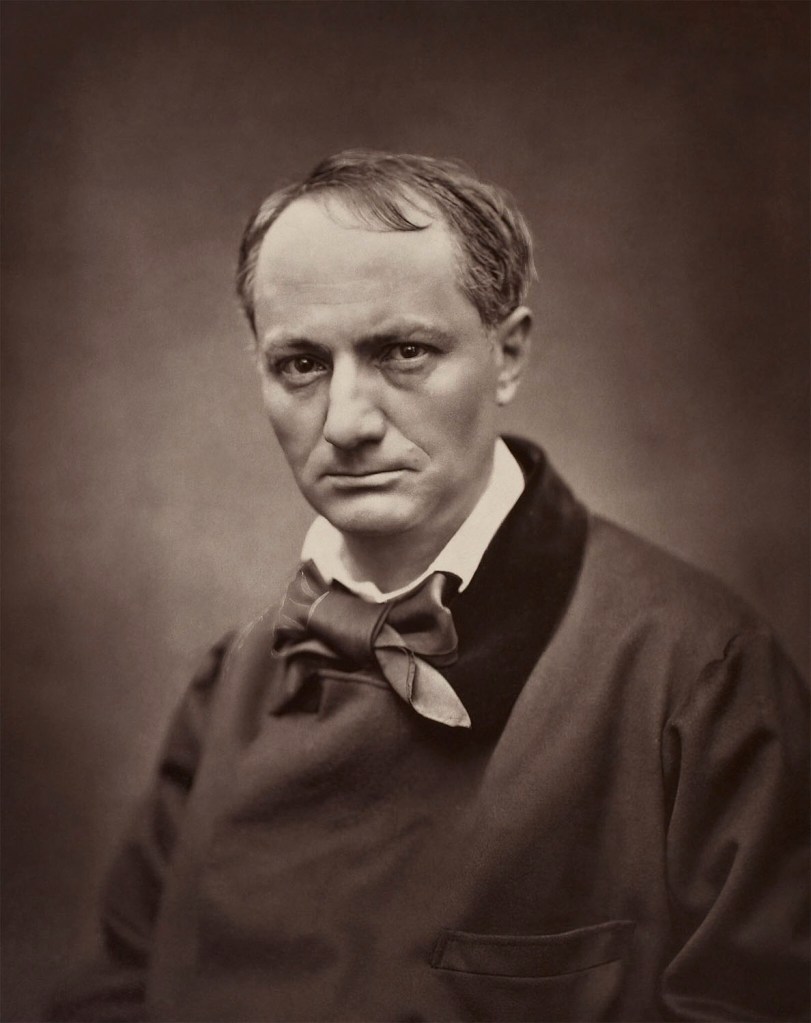

Alexander Gardner was a Scottish photographer who immigrated to the United States in 1856, where he began to work full-time in that profession. He is best known for his photographs of the American Civil War, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, and the execution of the conspirators to Lincoln’s assassination.

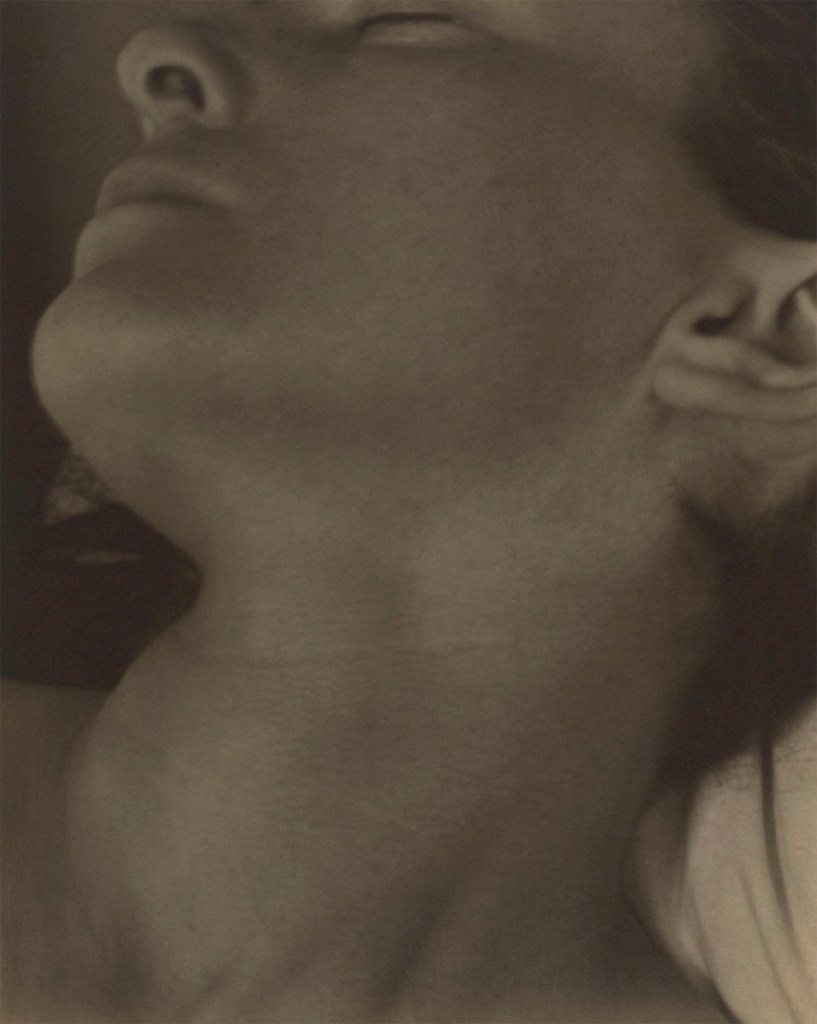

This is one of the last photos taken of Lincoln, who was assassinated ten weeks later, on April 14, 1865.

Alexander Gardner (Scottish 1821-1882; emigrated America 1856)

Abraham Lincoln (detail)

February 5, 1865 Washington, DC

Library of Congress

The Bruce Museum

1 Museum Drive in Greenwich, Connecticut, USA.

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 10am – 5pm

Closed Mondays and major holidays

You must be logged in to post a comment.