Exhibition dates: 24th May – 13th October, 2019

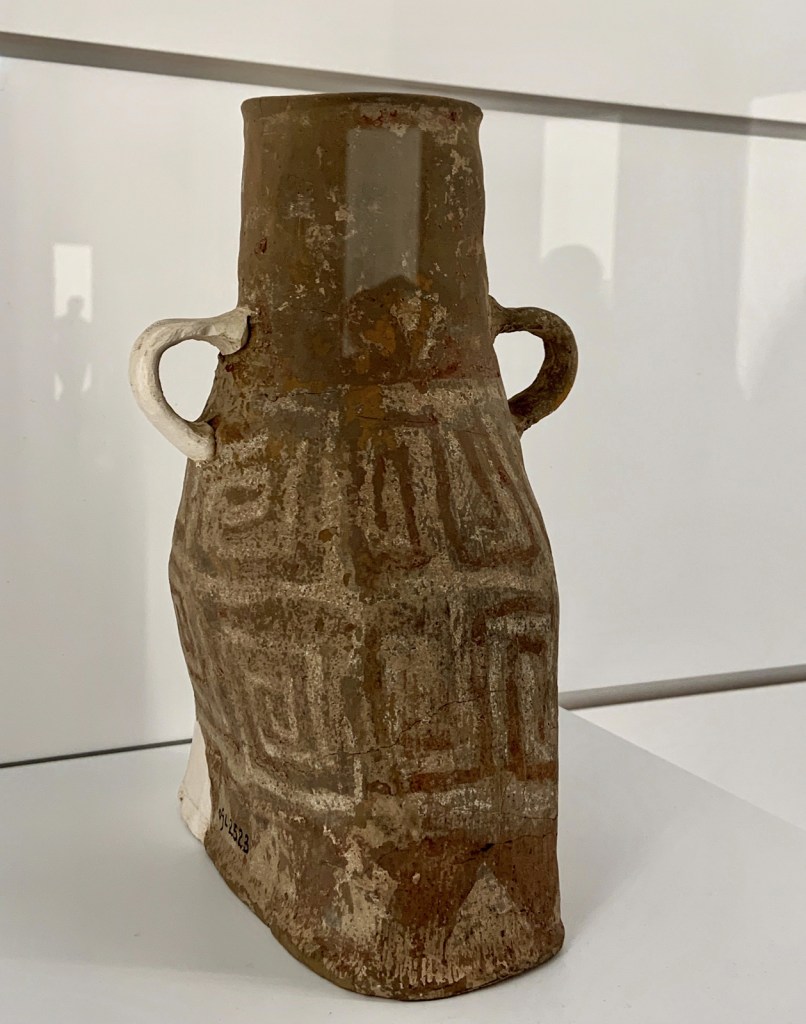

Censer

灰陶熏炉

Qin dynasty, 221 – 207 BCE

Earthenware

Xi’an Museum, Xi’an

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

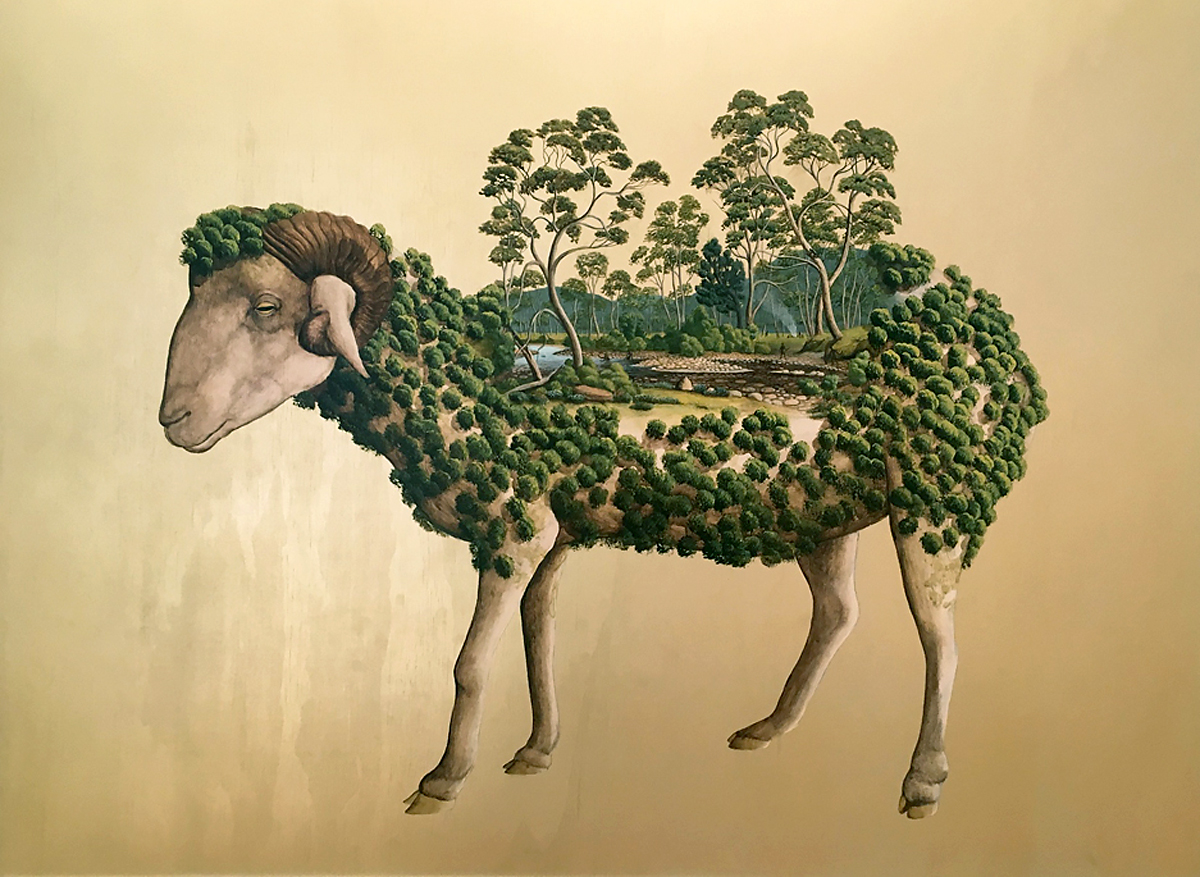

The best thing about this exhibition were the beautiful lidded containers, flasks, everyday vessels and censers; cows, sows, goats, mythical creatures and smaller soldiers. The female attendant was divine.

Other than that I refrain from comment for fear of incriminating myself!

(perhaps a yawn would suffice)

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Victoria for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. All photographs are iPhone images © Marcus Bunyan and the National Gallery of Victoria. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Epic accounts of China’s ruling dynasties, philosophies, inventions and social customs during ancient times have been passed down through the centuries in the writings of philosophers, imperial scribes and military strategists. However, it was not until archaeologists in the twentieth century unearthed evidence – masterful bronzes, delicately crafted jades and boldly decorated ceramics – that the advanced levels of civilisation, artistry and refined aesthetics that existed in the past were more fully revealed. This provided a greater understanding of the rituals, social customs, preparation for the afterlife and quest for immortality that remained central to Chinese culture.

The greatest discovery of all was in 1974, when local farmers digging an irrigation well in Lintong district, Xi’an, unearthed fragments of the terracotta warriors. With this astounding discovery the legends of ancient China’s first emperor, Qin Shihuang, were confirmed. In their size and number, the terracotta warriors are unique in world history and signify Qin Shihuang’s quest for immortality, his affiliation with China’s mythical rulers, and his supreme imperial mandate as the son of heaven.

Text from the National Gallery of Victoria website

Lacquered vessel, Ding

陶胎漆鼎

Warring States period, 475 – 221 BCE

Lacquer on earthenware

Shangluo City Museum, Shangluo

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lidded container, He (left)

彩绘陶盒

Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 220 CE

Earthenware, pigments

Ganquan County Museum, Yan’an

Lidded container, He (right)

彩绘陶盒

Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 220 CE

Earthenware, pigments

Ganquan County Museum, Yan’an

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Jar for storing grain (left)

彩绘陶仓

Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 220 CE

Earthenware, pigments

Ganquan County Museum, Yan’an

Jar for storing grain (right)

彩绘陶仓

Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 220 CE

Earthenware, pigments

Ganquan County Museum, Yan’an

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ceramic ware with boldly painted decoration became widely used as substitutes for bronze vessels during the Qin (221 – 207 BCE) and Han (207 BCE – 220 CE) dynasties. The spontaneous and energetic decoration indicates they were produced in large numbers and therefore affordable to the general public. Vessels like these were used as utensils in daily life as well as modest tomb ware to contain provisions for the afterlife, like grain, wine and other foods. Ceramic ware like water pourers or incense burners also served as affordable utensils used in ceremonies and rituals.

Wall text from the exhibition

Flask, Hu

彩绘陶壶

Spring and Autumn period, 771 – 475 BCE

Earthenware, pigments

Longxian County Museum, Baoji

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

These Han dynasty ceramic vessels maintain the elegant shapes and decorative features of Zhou dynasty bronze vessels produced 1000 years earlier. Free-flowing painted designs reference nature motifs and auspicious subjects like clouds and dragons. The Four-sided flask displays ringed handles in solid relief on either side in a direct reference to identically shaped bronze vessels from the Zhou dynasty.

Wall text from the exhibition

Hollow brick with snake and tortoise

玄武纹空心砖

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware

Maoling Museum, Xingping

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

The Qin state capital city changed location on numerous occasions before establishing its grandest city and ultimate capital at Xianyang in 350 BCE. Vast palaces were constructed with wooden structures and clay-tiled roofs. Palaces were decorated with magnificent murals that featured geometric and floral designs as well as figures and animals. At the fall of the Qin empire in 207 BCE, the palaces were destroyed, with the grandest of them, Epang Palace, so large it reportedly burned for more than three months. Today, nothing but foundations remain; however, an idea of their grandeur and decoration can be gained from bricks and roof tiles. Four of the bricks display the four protective spirits representing each of the cardinal directions: the turtle (north), dragon (east), vermilion bird (south) and tiger (west).

Wall text from the exhibition

Flask, Hu

彩绘陶壶

Spring and Autumn period, 771 – 475 BCE

Earthenware, pigments

Longxian County Museum, Baoji

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ritual objects and ancestral treasures

Before the establishment of a nationally unified state by Emperor Qin Shihuang in 221 BCE, China had a long history of opposing kingdoms, self-governing territories and dynasties whose customs, beliefs and refined artisanship influenced the Qin dynasty and its creativity. Family prestige, social harmony and a belief in immortality and the afterlife were central to the creation of auspicious and ceremonial objects used for burial rituals, ancestor worship and encouraging good fortune. This gallery displays some of the most exquisitely crafted of these objects, produced from the beginning of the Zhou dynasty to the end of the Han dynasty (1046 BCE – 220 CE).

Jade was believed to possess magical powers that could maintain the human life force of air or breath after death, and beautifully carved jade objects would often accompany bodies in burial to help purify the deceased’s soul for its journey to the afterlife. Bronze objects with decorative motifs and inscriptions were created to represent a symbolic connection to China’s earliest dynasties and a ‘mandate from heaven’ to rule. Gold is thought to have been introduced to China from Central Asia and was mostly used for decoration on clasps, buckles and ceremonial objects.

Wall text from the exhibition

Belt plaque

金牌饰

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Gold, jade, agate, turquoise

Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Xi’an

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

In contrast to jade, which symbolised wealth and spiritual purity, and bronze, used to produce ritual objects, gold was used to a lesser extent and served a primarily decorative purpose. The tradition of using gold for personal adornment is believed to have come to China from Central Asia, and gold became a favoured material from the Spring and Autumn period (771-475 BCE) onwards. Objects that represented personal status, such as belt hooks, belt plaques and personal adornments, were usually cast in solid gold and often featured stylised geometric dragon motifs and inlaid semiprecious stones like turquoise and agate.

Wall text from the exhibition

Door ring holder in the form of a mythological beast, Pushou

四神兽面纹玉铺首

Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 220 CE

Jade

Maoling Museum, Xingping

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

This impressive door ring holder (pushou) in the form of a taotie mythological beast mask would support a large ring from its lower section and be positioned in the centre of doors or gateways. Its size is evidence of the grandeur of the palace or mausoleum building it once adorned. Its fierce appearance, with bulging eyes, was believed to ward off evil spirits, and its curling motifs ingeniously incorporate the four protective spirits in each corner. The four holy creatures are (clockwise from top left) the white tiger, the azure dragon, the vermilion bird and the black tortoise.

Wall text from the exhibition

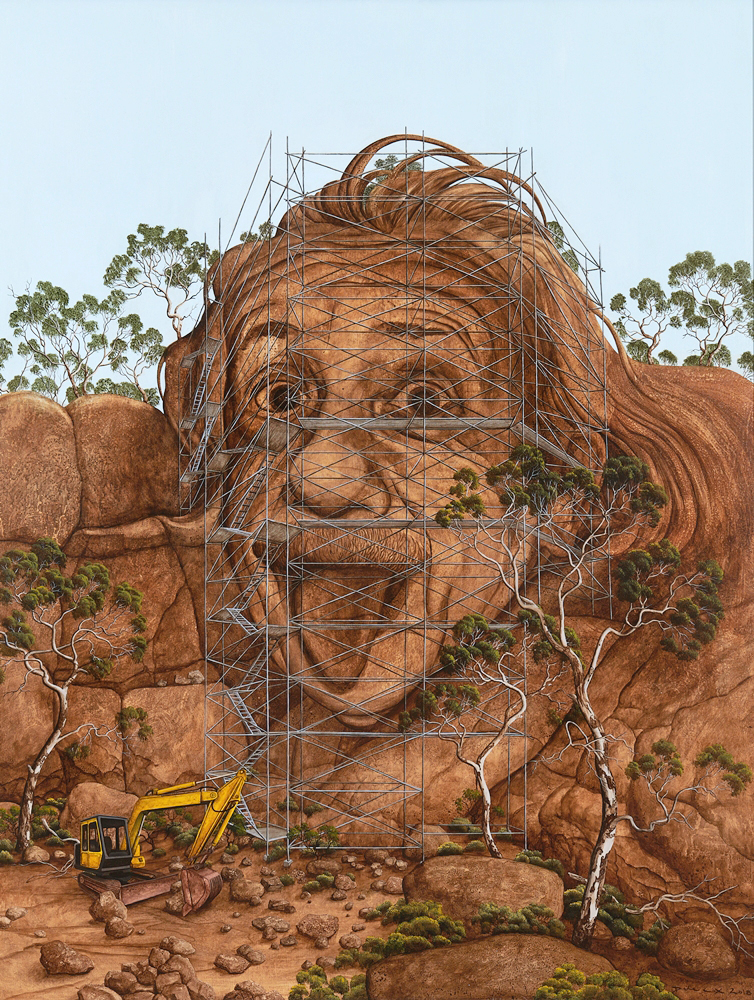

In a dual presentation of Chinese art and culture past and present, the Melbourne Winter Masterpieces series at the National Gallery of Victoria will present China’s ancient Terracotta Warriors alongside a parallel display of new works by one of the world’s most exciting contemporary artists, Cai Guo-Qiang, at NGV International, May 2019.

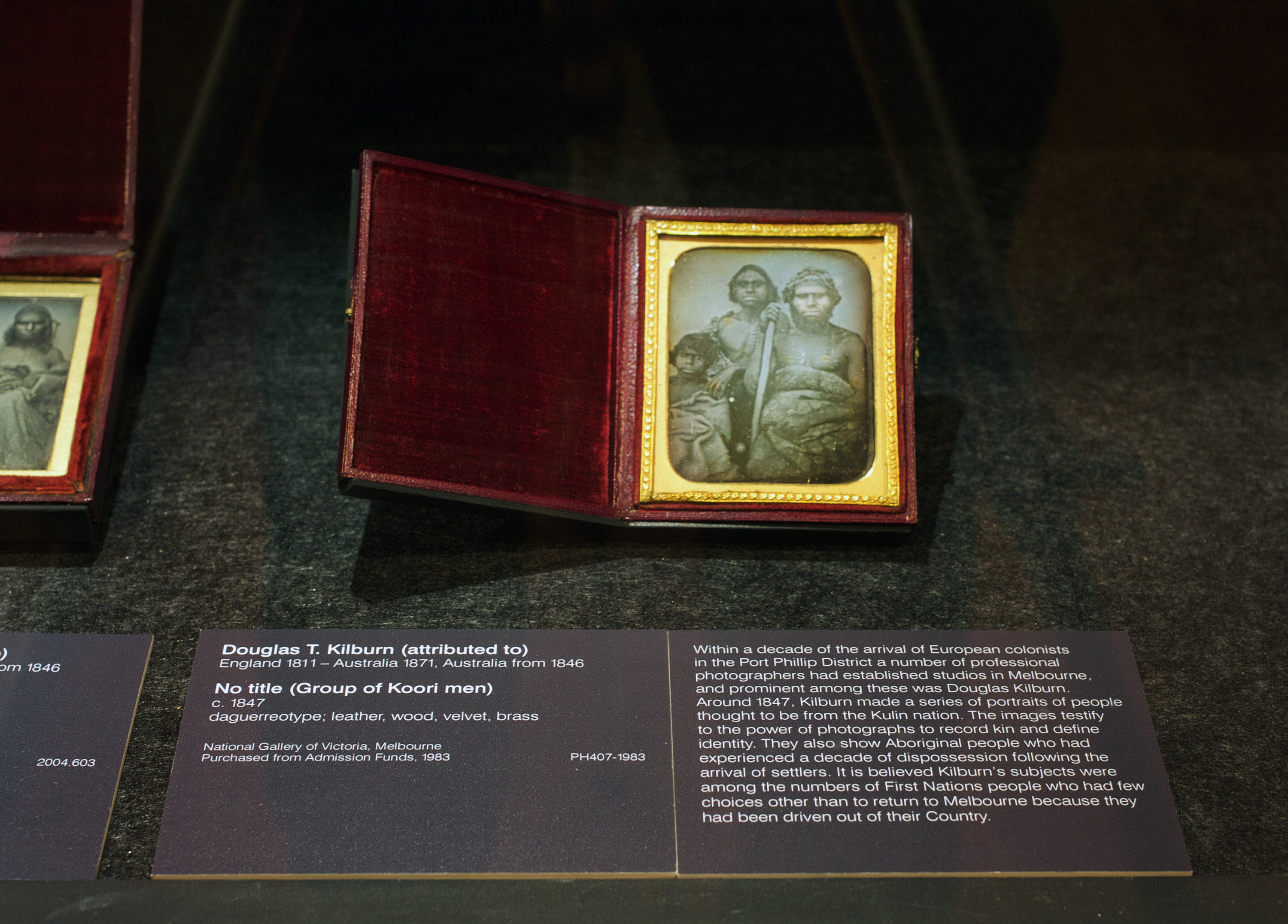

Terracotta Warriors: Guardians of Immortality is a large-scale presentation of the Qin Emperor’s Terracotta Warriors, which, discovered in 1974 in China’s Shaanxi province, are regarded as one of the greatest archaeological finds of the twentieth century and widely described as the eighth wonder of the world. The exhibition will feature eight warrior figures and two life-size horses from the Imperial Army, as well as two half-size replica bronze chariots, each drawn by four horses.

These sculptures will be contextualised by an unprecedented Australian presentation of more than 150 exquisite ancient treasures of Chinese historic art and design lent by leading museums and archaeological sites from across Shaanxi province. These include priceless gold, jade and bronze artefacts that date from the Western Zhou through to the Han dynasties (1046 BC – 220AD). Illuminating more than a millennium of Chinese history, the exhibition will showcase the magnificence and authority of the once-entombed figures and reveal, through the intricate display of accompanying objects and artefacts, the sophistication that characterised the formative years of Chinese civilisation.

Presented in parallel, Cai Guo-Qiang: The Transient Landscape, will see contemporary artist, Cai Guo-Qiang, create all new art works inspired by his home country’s culture and its enduring philosophical traditions, including a monumental installation of 10,000 suspended porcelain birds. Spiralling over visitors’ heads, the birds create a three-dimensional impression of a calligraphic drawing of the sacred Mount Li, the site of the ancient tomb of China’s first emperor, Qin Shihuang, and his warriors. Cai will collaborate on the exhibition’s design, creating breathtaking immersive environments for the presentation of both his work and the Terracotta Warriors.

Drawing on Cai’s understanding of ancient Chinese culture and his belief that a dialogue with tradition and history can invigorate contemporary art, he will also create a monumental porcelain sculpture of peonies, placed at the centre of a 360-degree gunpowder drawing.

Tony Ellwood AM, Director, NGV said: ‘Thirty-six years ago, in 1982, the National Gallery of Victoria presented the first international exhibition of China’s ancient Terracotta Warriors only several years after their discovery. History will be made again in 2019, when the Qin Emperor’s Terracotta Army will return to the NGV for the 2019 Melbourne Winter Masterpieces exhibition series – this time in a sophisticated dialogue with the work one of China’s most celebrated contemporary artists, Cai Guo-Qiang.’

Of the parallel presentation, Cai said: ‘They are two rivers of time separated by two millennia, each creating a course at their own individual speed across a series of shared galleries. The ancient and the contemporary – two surges of energy that crisscross, pull, interact and complement each other, generating a powerful tension and contrast, each attracting and resisting the other.’

Jeff Xu, Founder and Managing Director, Golden Age Group said: ‘This exhibition will inspire Australian and international audiences to delve deeper into the many rich and diverse facets of China’s heritage. As Principal Partner, Golden Age is pleased to support such an ambitious world-exclusive showing in Victoria, demonstrating our commitment to Melbourne as the cultural capital. We believe this exhibition will leave a lasting impression on this city for decades to come.’

This exhibition was organised by the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, in partnership with Shaanxi Provincial Cultural Relics Bureau, Shaanxi History Museum, Shaanxi Cultural Heritage Promotion Centre, and Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum of the People’s Republic of China.

Press release from the National Gallery of Victoria [Online] Cited 14/07/2019

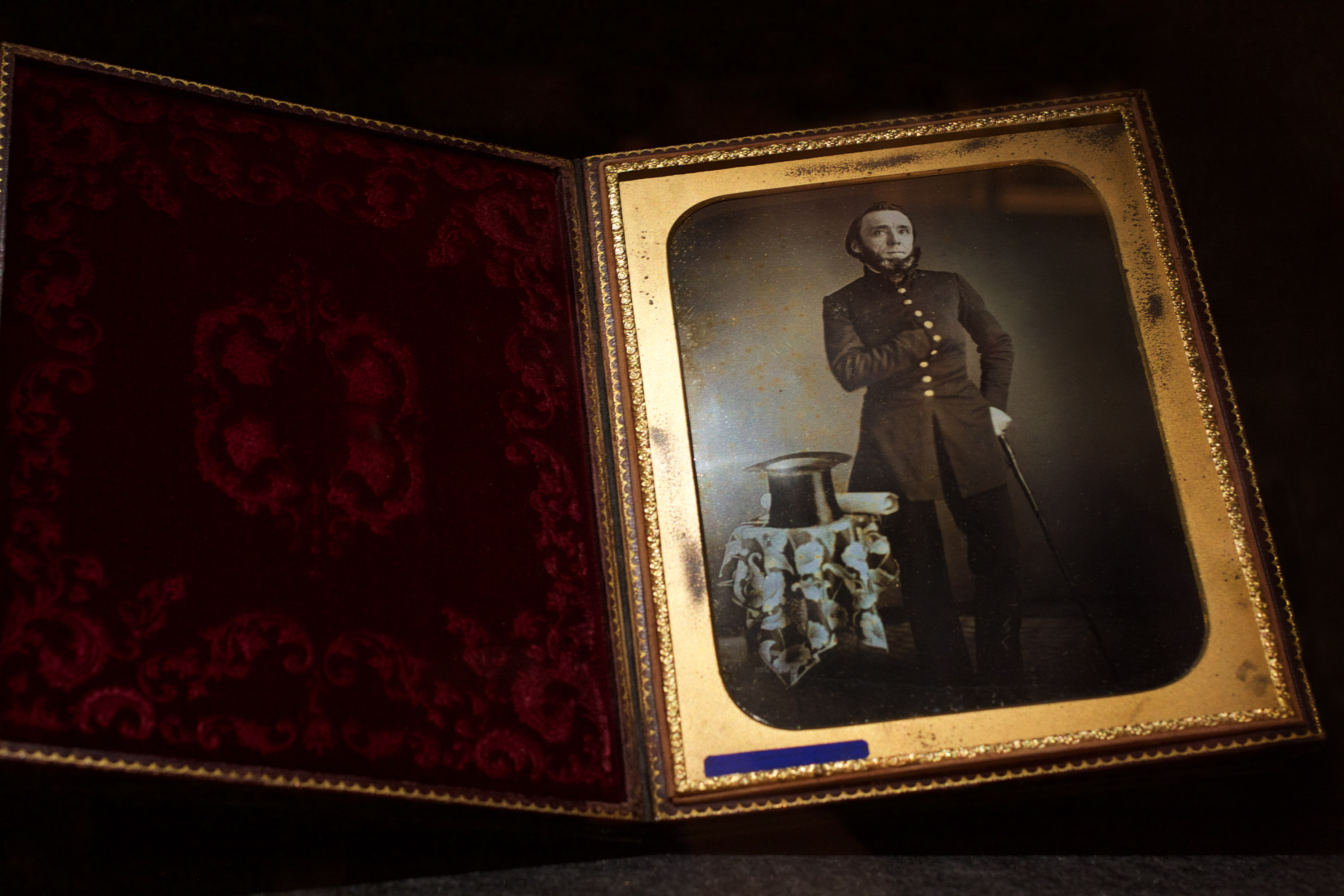

Armoured general

铠甲将军俑

Qin dynasty, 221 – 207 BCE

Earthenware

Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, Xi’an

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

This general, the largest of the terracotta warriors in the exhibition, has a distinguished beard and moustache and displays a stance of importance. His position of authority is indicated by his headdress, which is the same style as that of the adjacent unarmoured general, and is further enforced by decorative tassels on his chest and back that act as insignias of rank. Generals and other high-ranking officers wore long armoured tunics that tapered from the waist to a triangular shape at the front, protecting their vital organs.

Wall text from the exhibition

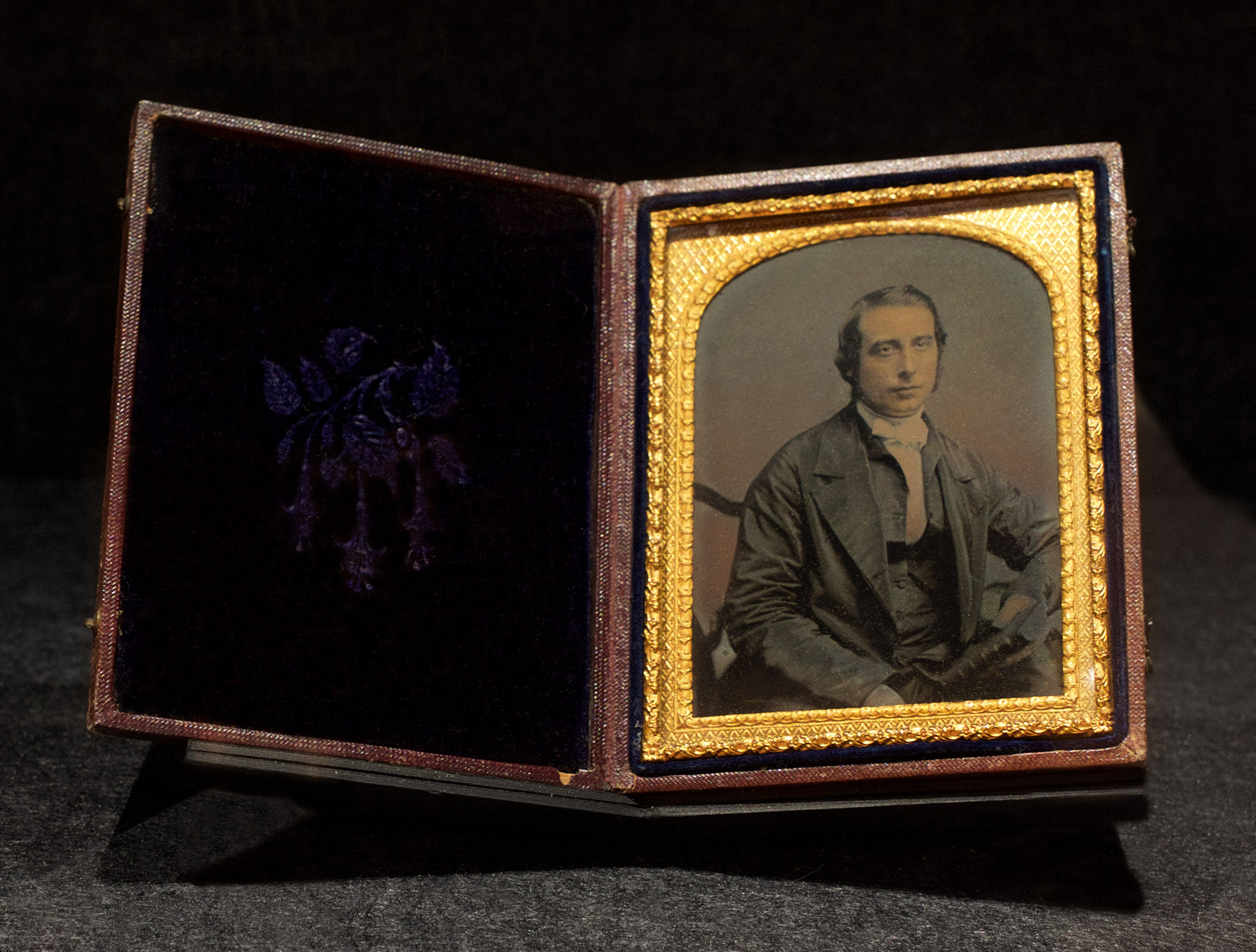

Armoured military officer

中级铠甲军吏俑

Qin dynasty, 221 – 207 BCE

Earthenware

Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, Xi’an

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Standing warriors weigh between 150 and 300 kilograms and usually consist of seven different parts: a plinth, feet, legs, torso, arms, hands and head. Clay was kneaded by foot, and the torso section was built up with a coil layering technique. Other parts were created by pressing soft clay into moulds, in a process similar to making roof tiles or drainage pipes. To give each warrior a unique appearance, different moulds were used and the position of fingers and arms was manipulated while the clay was soft. Folds of clothing or armour plates were added to the torso, and head features were developed with additional small pieces of clay to define the cheekbones, chin, ears, nose and hair.

Wall text from the exhibition

Standing archer

立射俑

Qin dynasty, 221 – 207 BCE

Earthenware

Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, Xi’an

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

The release of energy and sense of movement at the moment of firing an arrow results in archers displaying the most elegant and dramatic stances of all the terracotta warriors. The standing archer’s feet are slightly parted for balance, and he stares intently into the distance as if following the flight of an arrow just released from his bow. Displaying the topknot and braiding of a warrior, he wears a simple gown that allows freedom of movement. When created, the warriors were painted in bright colours and coated with lacquer, but this colouring had mostly been lost by the time of their excavation. New techniques of colour preservation are currently being developed at the terracotta warriors site.

Wall text from the exhibition

Unarmoured infantryman

战袍武士俑

Qin dynasty, 221 – 207 BCE

Earthenware

Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, Xi’an

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Unarmoured or light infantrymen are distinguished by their hair gathered in a top knot and their absence of armour. Their simple robes and low-slung belts give them a less military appearance; however, their half-closed right hand would have originally held a sword. We can clearly see that this figure has been reconstructed from many small broken parts. Of more than 2000 warriors unearthed to date, none have been discovered intact. It is speculated that shortly after their completion at the fall of the Qin dynasty, the victorious Han entered the terracotta warriors’ underground passages, smashed the contents and set the wooden passages on fire.

Wall text from the exhibition

Terracotta warriors

The discovery of the terracotta warriors, one of the most significant archaeological finds of the twentieth century, was made by chance. In March 1974, seeking water during a period of drought, local farmers began digging an irrigation well in Lintong district, Xi’an. Little more than a metre below ground, they unearthed fragments of the terracotta army, including a warrior’s head and a group of bronze arrowheads. Had the farmers commenced their digging a metre to the east, the warriors may have remained undetected.

The enormous tomb mound of China’s first emperor, Qin Shihuang, is located 1.5 kilometres from the terracotta warriors. While this has been the Qin emperor’s recognised tomb site over the centuries, astoundingly the creation of the warriors who guarded it was never recorded and knowledge of their existence was lost over time. It was recorded that the emperor employed and conscripted up to 700,000 workers to construct his mausoleum, the terracotta army and other buried items, making it the largest and most ambitious mausoleum construction in China’s history. To date, approximately 2000 of an estimated 8000 warriors have been excavated, and the pieces on display here represent the variety of individuals created, their positions within the army and their styles of apparel.

The first emperor’s mausoleum, according to the grand historian

Han dynasty historian and scribe Sima Qian (145 – 86 BCE) wrote a detailed account of the construction and interior of Qin Shihuang’s mausoleum in his text Records of the Grand Historian – Basic Annals of Qin:

‘In the ninth month, the First Emperor was interred at Mount Li. When he first came to the throne, the digging and preparation work began. Later, when he had unified China, 700,000 men were sent there from all over the empire. They dug through three layers of groundwater, and poured in bronze for the outer coffin. Palaces and scenic towers for a hundred officials were constructed, and the tomb was filled with rare artefacts and wonderful treasure. Craftsmen were ordered to make crossbows and arrows primed to shoot at anyone who entered the tomb. Mercury was used to simulate the hundred rivers, the Yangtze and Yellow River, and the great sea, and set to flow mechanically. Above were representations of the heavenly constellations, below were the features of the land. Candles were made from fat of “man-fish”, calculated to burn and not extinguish for a long time. The Second Emperor said: “It would be inappropriate for the concubines of the late emperor who have no sons to be out free”, [and] ordered that they should accompany the dead, and a great many died. After the burial, it was suggested that it would be a serious breach if the craftsmen who constructed the mechanical devices and knew of its treasures were to divulge those secrets.

Therefore after the funeral ceremonies had completed and the treasures [had been] hidden away, the inner passageway was blocked, and the outer gate lowered, immediately trapping all the workers and craftsmen inside. None could escape. Trees and vegetation were then planted on the tomb mound such that it resembles a hill.’

Wall text from the exhibition

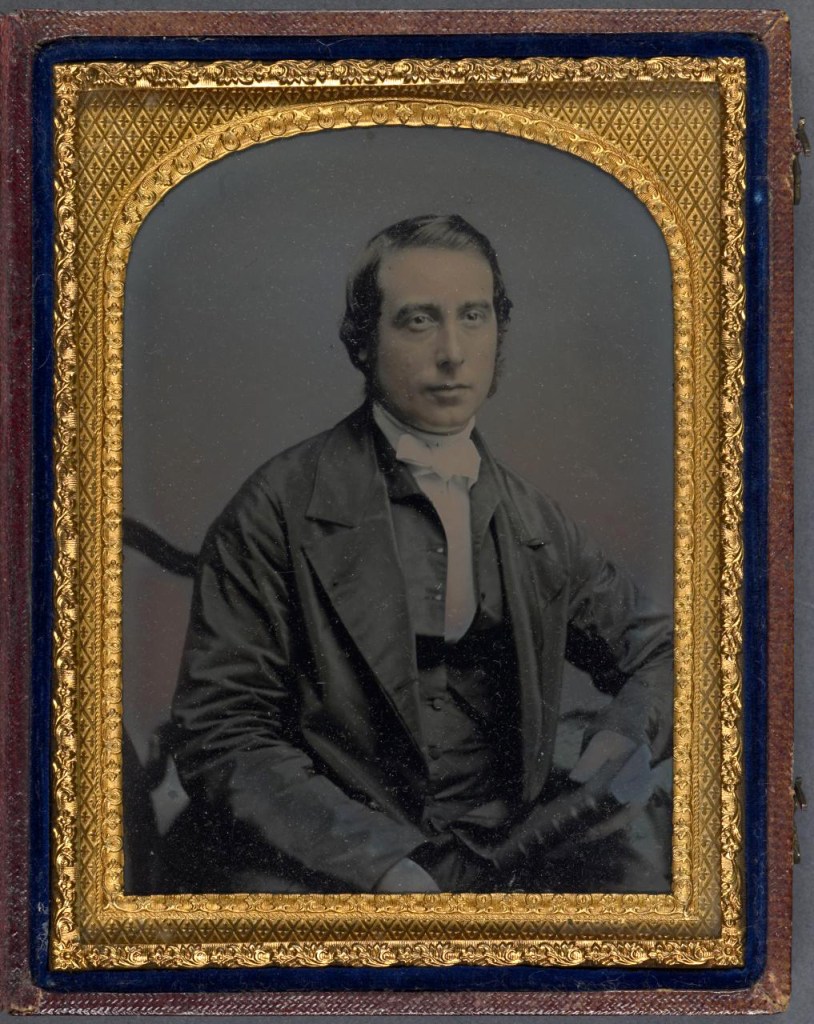

Armoured military officer

中级铠甲军吏俑

Qin dynasty, 221 – 207 BCE

Earthenware

Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, Xi’an

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Civil official

文官俑

Qin dynasty, 221 – 207 BCE

Earthenware

Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, Xi’an

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

In preparation for the afterlife, Emperor Qin Shihuang not only produced a terracotta army for his protection, but also ceramic administrators to look after government and civil affairs. This terracotta figure was discovered at a site adjacent to the emperor’s tomb, more than a kilometre from the terracotta army. Twelve civil officials were discovered, as well as the bones of twenty actual horses, one chariot and one charioteer. The officials all feature moustaches and a small tuft of chin hair and wear small hats believed to symbolise their status as officials or public conveyances. The attire of some civil officials includes baggy robes and a belt from which a pouch (presumably carrying a sharpening stone) and knife (to inscribe bamboo slats used for record keeping) hang.

Wall text from the exhibition

Chariot horse

车马

Qin dynasty, 221 – 207 BCE

Earthenware

Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, Xi’an

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Horses were fundamental to the strength of Chinese rulers and sacrificial horse burials had been practised since the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – 1046 BCE). This is particularly notable at the tomb of Duke Jing of Qi (reigned 547 – 490 BCE), which contained a pit with the remains of over 600 horses. At several separate excavation sites in the vicinity of Emperor Qin Shihuang’s tomb, the remains of real horses and chariots have been discovered. However, the first emperor is significantly noted as the first to create life-sized horse replicas as an integral part of the terracotta army’s military formation. While the adjacent horse features a hole on each side to prevent cracking during firing, this example was ventilated through its detachable tail.

Wall text from the exhibition

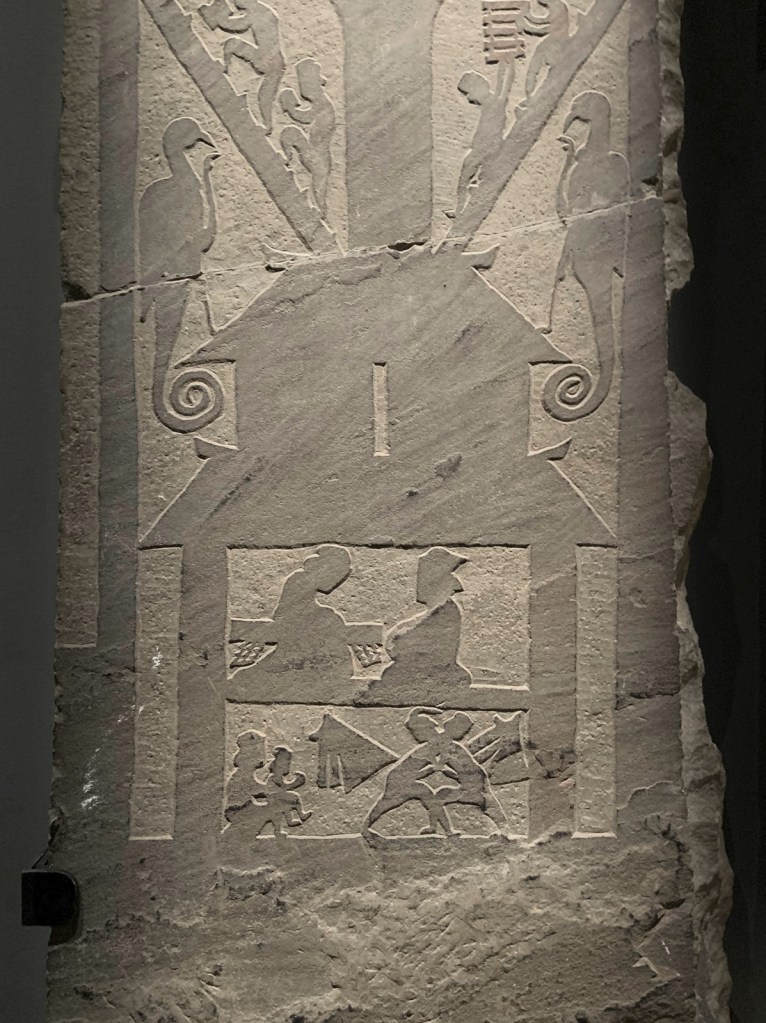

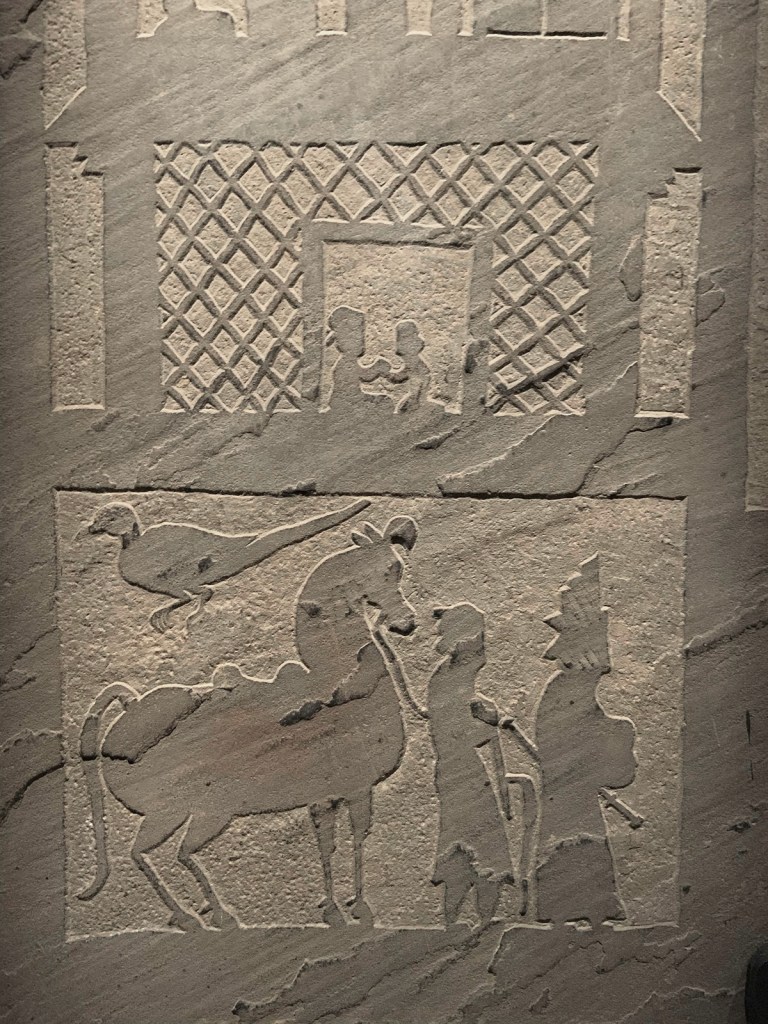

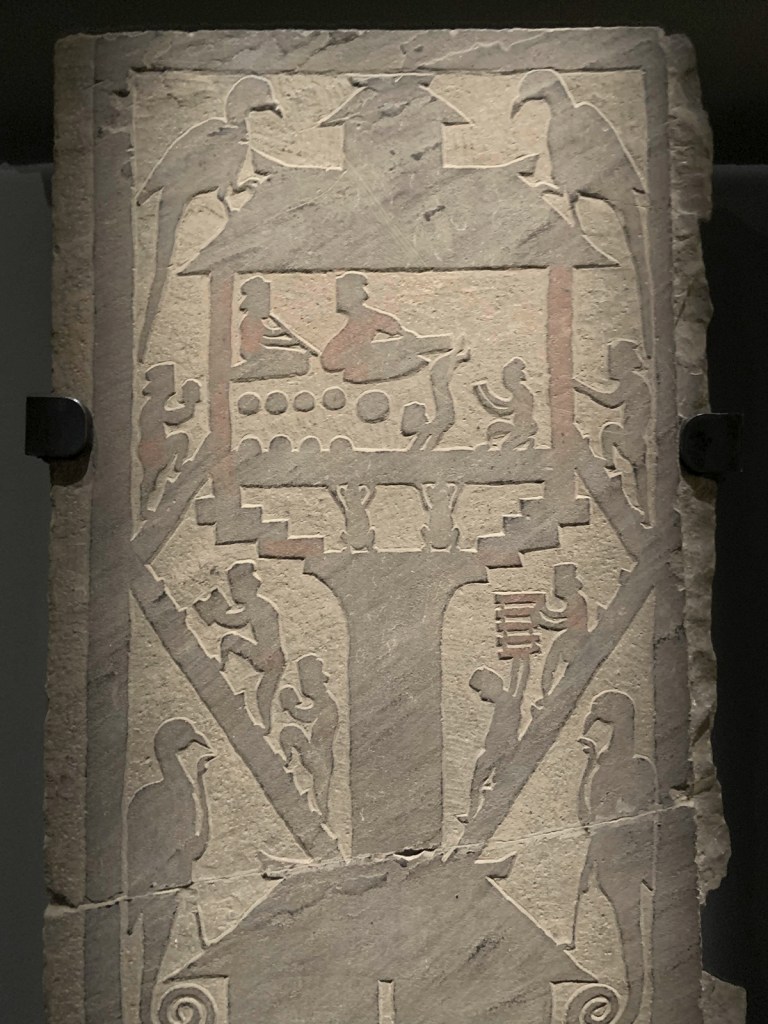

Tomb gate

画像石

Eastern Han dynasty, 25 – 220 CE

Stone, pigments

Suide County Museum

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

This graphically decorated tomb gate depicts animated events and scenes of daily life typical of the Qin (221 – 207 BCE) and Han (207 BCE – 220 CE) dynasties. The lintel displays a hunting scene with men on horseback galloping at full speed – some with lances and others shooting arrows – in pursuit of wild animals. The inner left and right supports feature images of people wrestling, playing instruments, nursing children, performing acrobatics, walking with a horse, carrying goods or climbing stairs. Mythical birds, creatures and people are pictured on the rooftops and on the curling vines of the outer supports.

Wall text from the exhibition

Mythical creatures

石兽

Eastern Han dynasty, 25 – 220 CE

Stone

Xi’an Beilin Museum, Xi’an

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Large stone beasts lined ‘spirit paths’ leading to the tombs of emperors, royals and aristocrats to protect them in the afterlife. These two magnificent Han dynasty examples stride forward with teeth displayed and powerful tails gracefully balanced behind. The female rests her front paw on a playful infant beast, representing natural harmony, and the male beast places his paw on a ball, representing his supremacy.

Wall text from the exhibition

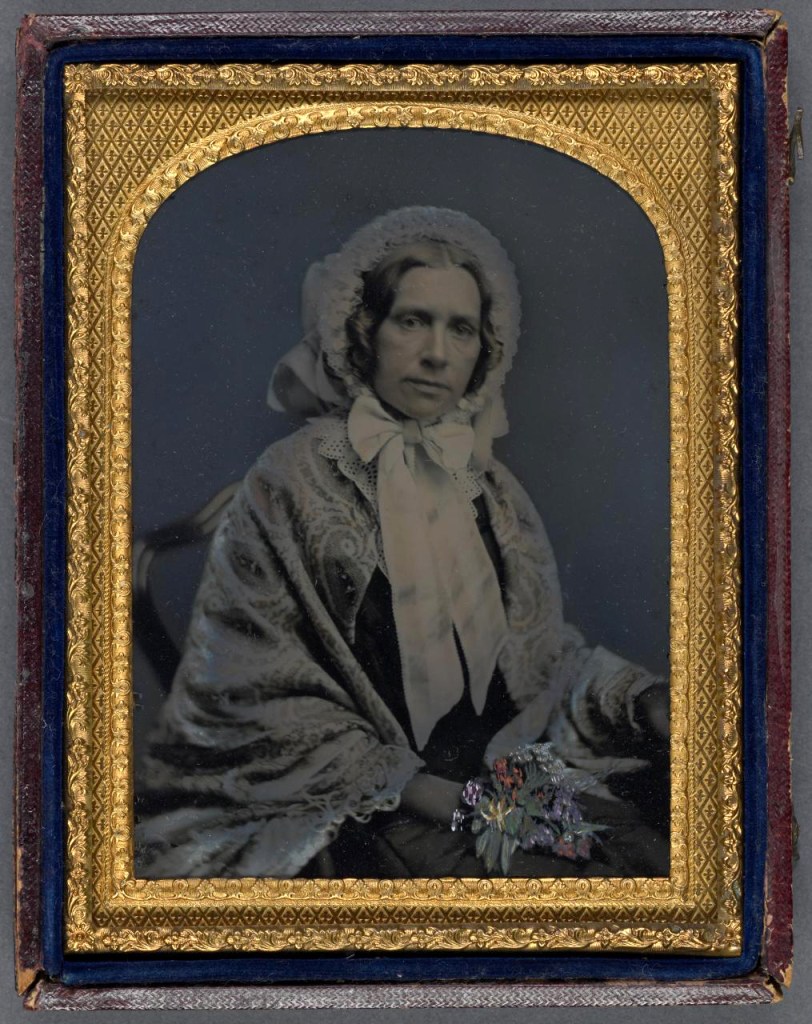

Female attendant

粉彩女俑

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware, pigments

Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Xi’an

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Excavated from the Yangling tomb of the fourth Han emperor, Jing, this female attendant displays the rounded shoulders typical of a Han dynasty beauty. She wears multi-layered robes with wide sleeves and the splayed lower section fashionable among women of the time. The position of her hands, concealed in her sleeves, elegant stance and gentle expression suggest that she is waiting to attend the imperial household members.

Wall text from the exhibition

Standing soldiers

彩绘步兵俑

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware, pigments

Xianyang Museum, Xianyang

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Large cavalrymen

彩绘骑马俑

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware, pigments

Xianyang Museum, Xianyang

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

A terracotta army of more than 2400 horses with riders and standing figures was discovered in 1965 by villagers levelling land at Yangjiawan, approximately twenty-two kilometres north-east of Xi’an. Due to the large number of military objects found, the site is believed to be a satellite tomb in the burial complex of the first Han emperor, Gaozu, associated with the military generals Zhou Bo and his son Zhou Yafu. Each standing warrior carries a shield and wears a loose rove, and one has painted armour. Colour remains visible on these figures and provides a good indication of their original appearance.

Label text from the exhibition

Goat

陶山羊

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware

Han Yangling Museum, Xianyang

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Cow

陶牛

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware

Han Yangling Museum, Xianyang

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Wild male dog

陶狼犬(公)

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware

Han Yangling Museum, Xianyang

Domestic female dog

陶家犬(母)

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware

Han Yangling Museum, Xianyang

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Sow

陶母猪

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware

Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Xi’an

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Group of ten soldiers

男武士俑–十人组

Western Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 9 CE

Earthenware

Han Yangling Museum, Xianyang

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

More than 40,000 small-scale terracotta warriors were discovered and excavated during the 1990s from pits adjacent to the Han Yangling tomb of Emperor Jing. Created seventy years after Qin Shihuang’s life-sized terracotta warriors, they served the same purpose as tomb guardians but were of a scale that could be more practically produced. The torsos, legs and heads were moulded separately then joined with moist clay before firing. Arms, made from wood, clothing, made from cloth, and armour, made from leather, have all perished during their 2000 years underground. The variety of faces produced from different moulds suggest a multicultural nation and the many regions and ethnicities present in the Han dynasty army.

Label text from the exhibition

Wellhead

绿釉陶井

Han dynasty, 207 BCE – 220 CE

Glazed earthenware

Xi’an Museum, Xi’an

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

NGV International

180 St Kilda Rd, Melbourne

Opening hours:

Open daily, 10am – 5pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.