Exhibition dates: 27th March – 9th September 2012

WARNING: this posting contains photographs of nudity. If you do not like please do not look.

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

![Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-1859 Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-1859](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/chauvassaignes_seated-nude-web.jpg?w=650)

Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 – after 1900)

Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]

1856-1859

Salted paper print from glass negative

19.1 x 15.2cm (7.5 x 6 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1998

Public domain

This corner of a painter’s atelier somewhere in France in the middle of the nineteenth century is scarcely tethered to time or place; it could as easily be a loft in New York today or, had photography existed four centuries earlier, a studio in the Italian Renaissance. What is surprising here is the absence of even the thinnest disguise – no swags of drapery, elaborate coiffure, or skeins of beads as are commonly found in the work of other purveyors of “studies for artists.” Here, the model is utterly naked. With her intelligent head and dirty feet, this young woman helped found the matter-of-fact modelling sorority joined a decade later by Édouard Manet’s Olympia.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850 Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/moulin_two-nudes-standing-web.jpg?w=650)

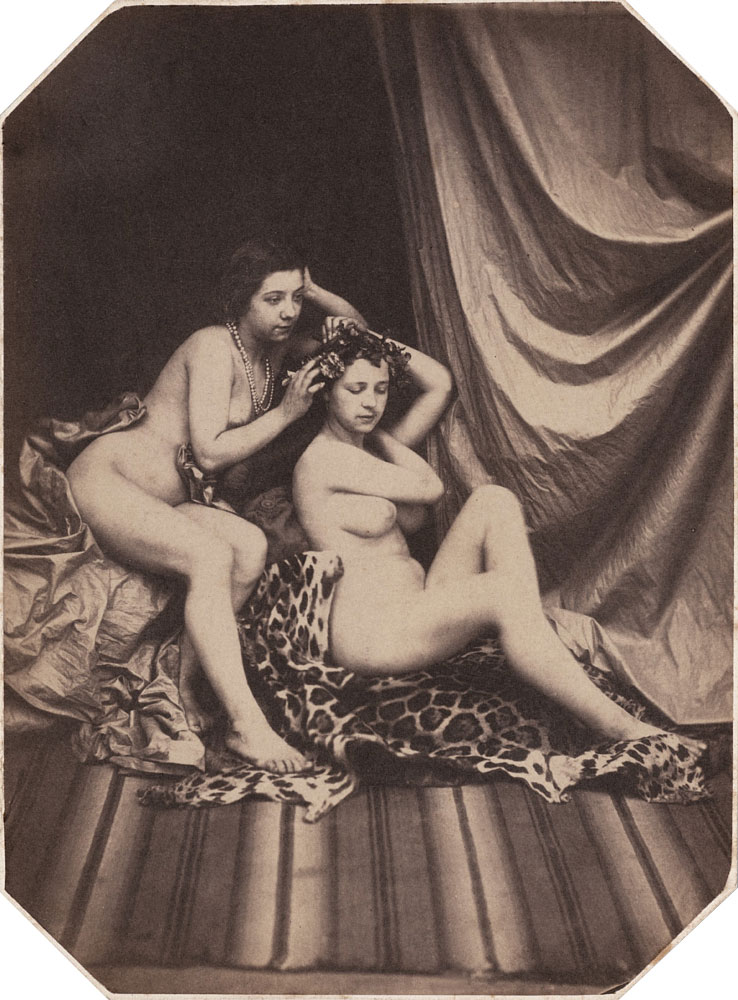

Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 – after 1875)

Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

Visible: 14.5 x 11.1cm (5 11/16 x 4 3/8 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Rubel Collection, Purchase, Anonymous Gift and Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997

Public domain

Although Moulin was sentenced in 1851 to a month in jail for producing images that, according to court papers, were “so obscene that even to pronounce the titles… would be to commit an indecency,” this daguerreotype seems more allied to art than to erotica. Instead of the boudoir props and provocative poses typical of hand-coloured pornographic daguerreotypes, Moulin depicted these two young women utterly at ease, as unselfconscious in their nudity as Botticelli’s Venus.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Seated Female Nude]' c. 1850 Unknown photographer (French) '[Seated Female Nude]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/seated-female-nude.jpg)

Unknown photographer (French)

[Seated Female Nude]

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

9.1 x 6.9cm (3 9/16 x 2 11/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credit Line: Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

Public domain

This daguerreotype was surely intended to serve artistic purposes, but the odd twist of the body and the strange relationship of the three visible limbs seem to render it inappropriate for artistic emulation. Such tension between an artistic ideal and realistic means – between the classicism of an academic pose and the awkwardness of the camera’s rendering of human movement – seems emblematic of the dilemma faced by the nascent medium striving to be an art.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1853 Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1853](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/julien-vallou-de-villeneuve-standing-female-nude.jpg)

Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866)

[Standing Female Nude]

c. 1853

Salted paper print from paper negative

12 x 16cm (4 3/4 x 6 5/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1993

Public domain

A student of the painter Jean François Millet (1814-1875) and a lithographer of scenes of daily life, costume, and erotica in the 1820s and 1830s, Vallou reportedly took up photography in the early 1840s. Because his early photographs have not been identified, it has been assumed that they depicted naked women, a subject for which it was to improper to acknowledge authorship.

Between 1851 and 1855, Vallou made a series of small-scale paper photographs of female nudes that he marketed (and legally registered) as models for artists. Vallou’s nudes have long been associated with those of Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), who is known to have used photographs in his painting process. Though no absolute one-to-one correspondence can be pointed to, there are some striking similarities in pose, and the heavy, soporific quality of Vallou’s models is very close to Courbet’s concept of the nude.

Text from the Metropolitan Muesum of Art website

![Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-1854 Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-1854](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/durieu_nude_ph8976-web.jpg?w=650)

Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874)

Untitled [Seated Female Nude]

1853-1854

Albumen silver print from glass negative

6 13/16 × 4 11/16 in. (17.3 × 11.9cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Henry R. Kravis Gift, 2005

Public domain

Durieu was a lawyer and early advocate and practitioner of photography in France who, in 1853-1854, made a series of photographic studies of nude and costumed figures as models for artists. The French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix helped him pose the figures and later praised the prints, from which he sketched, as “palpable demonstrations of the free design of nature.” While the painter saw the accurate transcription of reality as a virtue of photography, Durieu knew that a good photograph was not simply the result of the correct use of the medium but, more significantly, an expression of the photographer’s temperament and vision. In an important article he emphasised the interpretative nature of the complex manipulations in photography and explained that the photographer must previsualise his results so as to make a “picture,” not just a “copy.”

This photograph proves Durieu’s point: through the elegant contours of the drapery, the smooth modelling of the flesh, and the grace and restraint of the pose, the picture attains an artistic poise that combines Delacroix’s sensuality with Ingres’s classicism, and rivals both.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855 Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/marle_standing-male-nude-web.jpg?w=650)

Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 – after 1867)

Untitled [Standing Male Nude]

c. 1855

Salted paper print from paper negative

25.7 x 17.6cm (10 1/8 x 6 15/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Ezra Mack Gift and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1991

Marlé’s photograph was probably intended as an aid for painters and sculptors. The jury-rigged arrangement of podium, books, and potted tree, as well as the painting held in the background by a studio assistant, may strike the modern viewer as an incongruous contrast to the heroic gesture of the model. Marlé and those who bought his photograph, however, would have been absorbed by the grand academic pose and likely would have thought the awkward accoutrements of little consequence.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Nadar (French, Paris 1820 - 1910 Paris) '[Standing Female Nude]' 1860-1861 Nadar (French, Paris 1820 - 1910 Paris) '[Standing Female Nude]' 1860-1861](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/nadar-standing-female-nude.jpg)

Nadar (French, Paris 1820 – 1910 Paris)

[Standing Female Nude]

1860-1861

20.2 x 13.3cm (7 15/16 x 5 1/4 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1991

Public Domain

Famed for his portraits of writers, artists, and left-wing politicians, Nadar is known to have photographed only three female nudes. This one was made at the behest of the painter Jean-Léon Gérôme to assist in the process of painting Phryné before the Areopagus, displayed at the Salon of 1861. Gérôme’s painting depicts the moment when the famous courtesan Phryné, on trial for impiety, is suddenly unveiled by her lawyer; persuaded by Phryné’s divine beauty, the jurors acquit her.

Like Phryné, who is said to have modelled for the ancient Greek painter Apelles and other artists of antiquity, Nadar’s model, Marie-Christine Leroux (1820-1863), was widely sought by artists of her time and was the basis for the character Musette in Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de bohème.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Depicting the human body has been among the greatest challenges, preoccupations, and supreme achievements of artists for centuries. The nude – even in generalised or idealised renderings – has triggered impassioned discussions about sin, sexuality, cultural identity, and canons of beauty, especially when the chosen medium is photography, with its inherent accuracy and specificity. Through September 9, 2012, Naked before the Camera, an exhibition of more than 60 photographs selected from the renowned holdings of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, surveys the history of this subject and explores some of the motivations and meanings that underlie photographers’ fascination with the nude.

“In every culture and across time, artists have been captivated by the human figure,” commented Thomas P. Campbell, Director of the Metropolitan. “In Naked before the Camera, we see how photographers have used their medium to explore this age-old subject and create compelling new images.”

The exhibition begins in the 19th century, when photographs often served artists as substitutes for live models. Such “studies for artists” were known to have been used by the French painter Gustave Courbet, whose Woman with a Parrot (1866), for instance, is strikingly similar to photographer Julien Vallou de Villeneuve’s Female Nude of 1853. Even when their stated purpose was to aid artists, however, the best of these 19th-century photographs of the nude were also intended as works of art in their own right. Two recently acquired photographs, made in the mid-1850s by an unknown French artist, are striking examples. Not only are they larger than all other photographic nudes from the time, they stand out due to an extraordinary surface pattern that interrupts the images and suggests a view through gossamer or a photograph printed on finely pleated silk rather than paper. The elegant Female Nude harkens back to an Eve or Venus and is vignetted by the camera lens as if seen through a peephole, while her male counterpart is shown in strict profile in a pose that recalls precedents from antiquity. Each figure draws from the past while being presented in a strikingly modern way, without any equivalent among other 19th-century studies for artists.

Not all photographers of the nude were motivated by artistic desire. The second section of Naked before the Camera includes photographs made for medical and forensic purposes, as ethnographic studies, as tools to analyse anatomy and movement, and – not surprisingly – as erotica. The lines between such categories were not always clearly drawn; some photographers called their images “studies for artists” merely to evade the censors, while viewers of the G. W. Wilson Studio’s Zulu Girls (1892-93) or Paul Wirz’s ethnographic photographs of scantily clad Indonesians from the 1910s and 1920s were undoubtedly titillated by the blending of exoticism and eroticism.

Beginning in the fertile period of modernist experimentation that followed on the heels of World War I, photographers such as Brassaï, Man Ray, Hans Bellmer, André Kertész, and Bill Brandt found in the human body a perfect vehicle for both visual play and psycho-sexual exploration. In Distortion #6 (1932) by André Kertész, a woman’s body is stretched and pulled in the reflections of a fun-house mirror – a figure from a Surrealist dream that stands in stark contrast to the images of perfect feminine beauty by earlier photographers.

In mid-20th-century America, photographers more often communicated an intimate connection with their subjects. Following the example of Alfred Stieglitz’s famed portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe, photographers such as Edward Weston, Harry Callahan, and Emmet Gowin made many nude studies of their wives. Callahan’s photograph of his wife and daughter, Eleanor and Barbara, Chicago (1954), for instance, gives the viewer access to a private, tender moment of intimacy.

In the wake of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and the AIDS crisis that began in the 1980s, artists began to think of the body as a politicised terrain and explored issues of identity, sexuality, and gender. Diane Arbus’s Retired man and his wife at home in a nudist camp one morning, N.J. (1963) and A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C. (1968), Larry Clark’s untitled image (1972-1973) from the series Teenage Lust, and Hannah Wilke’s Snatch Shot with Ray Gun (1978) are among the works featured in the concluding section of the exhibition.

Press release from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Nude with Mirror]' c. 1850 Unknown photographer (French) '[Nude with Mirror]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/nude-with-mirror.jpg)

Unknown photographer (French)

[Nude with Mirror]

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

Dimensions: visible: 7 x 5.7cm (2 3/4 x 2 1/4 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Rubel Collection, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997

Public domain

![Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Reclining Female Nude]' c. 1853 Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Reclining Female Nude]' c. 1853](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/julien-vallou-de-villeneuve-reclining-female-nude.jpg)

Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866)

[Reclining Female Nude]

c. 1853

Salted paper print from paper negative

11.8 x 16.0cm (4 5/8 x 6 5/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1993

Public domain

A student of the painter Jean François Millet and a lithographer of scenes of daily life, costume, and erotica in the 1820s and 1830s, Vallou reportedly took up photography in the early 1840s, but his early photographs have not been identified. Perhaps they depicted naked women, a subject for which it was improper to acknowledge authorship.

Between 1851 and 1855, however, Vallou made a series of photographs of female nudes that he marketed (and legally registered) as models for artists. Vallou’s nudes have long been associated with those of Gustave Courbet, who is known to have used photographs in his painting process. Although no absolute one-to-one correspondence can be pointed to, the heavy soporific quality of Vallou’s models is very close to Courbet’s concept of the nude, and the reclining figure displayed here is strikingly similar in pose to the painter’s Woman with a Parrot (1866), on view in the galleries for nineteenth-century painting.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

Nu féminin allongé sur un canapé Récamier (Female nude lying on a Recamier sofa)

c. 1856

Albumen silver print from glass negative

21.7 x 32.9cm (8 9/16 x 12 15/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Public domain

The central figure in French photography of the 1850s, Le Gray was a master of many genres including landscape and seascape, architectural photography, and portraiture. Only four nude studies by Le Gray are known, however, each in a single example. In this striking image, the photographer departed from the usual academic treatment of the nude, such as he might have learned from his years in the painting studio of Paul Delaroche, in favor of a more psychologically charged spirit. The daybed’s velvet upholstery, the tassels on the pillow, and the heavy curtain fabric have a reassuring and familiar presence, but the serpentine locks of hair evoke Medusa and hint at strangulation, while the legs and feet cross and tense in the manner of a crucifixion. Withdrawn in sleep – or is it death? – the beautiful young woman reminds one of a drowning victim, an Ophelia freshly recovered from the Seine, a theme favoured by the painters and poets of Paris.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1856 Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1856](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/standing-female-nude.jpg)

Unknown photographer (French)

[Standing Female Nude]

c. 1856

Salted paper print from collodion glass negative

43.4 x 28.3cm (17 1/16 x 11 1/8 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest; Edwynn Houk and Hans P. Kraus Jr., Alfred Stieglitz Society, Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Anonymous, Adam R. Rose and Peter R. McQuillan, Joseph M. Cohen, Susan and Thomas Dunn, Kurtz Family Foundation, W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg, Christian Keesee Charitable Trust, and Robert A. Taub Gifts; and Funds from various donors, 2012

Public domain

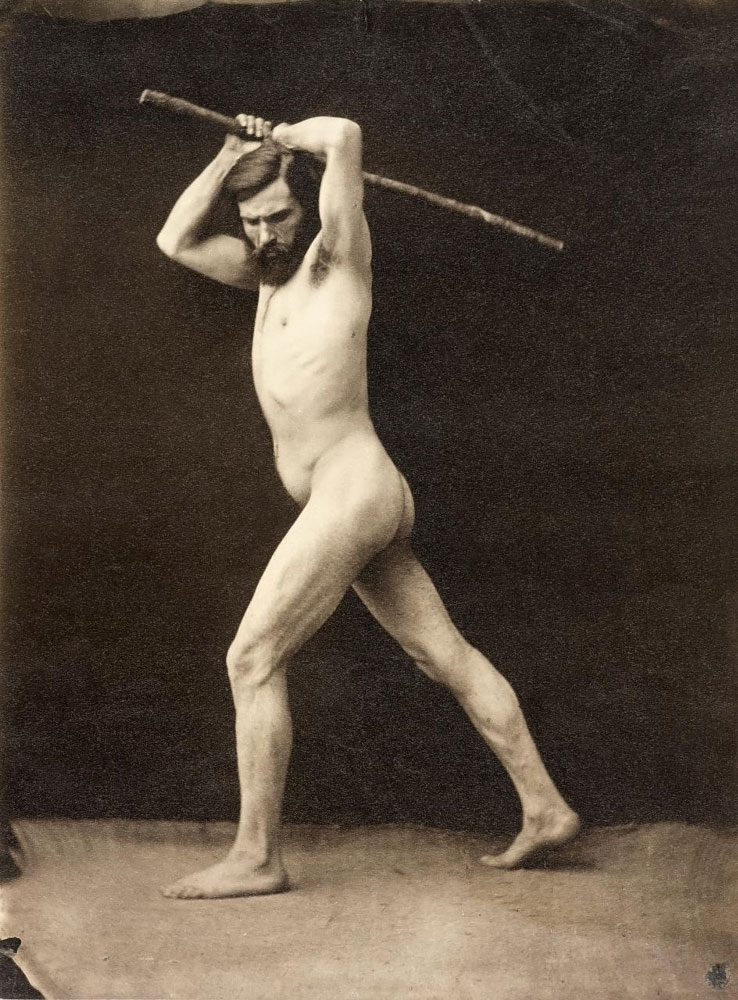

The original impulse behind these boldly ambitious figure studies may have been to aid a painter or sculptor, but they are nonetheless without parallel in the early history of photography. Enlarged to the size of drawn académies – drawings of the live model that were a standard part of art instruction in France – their scale alone sets them apart from the more modest productions of Vallou de Villeneuve, Durieu, and other artists of the 1850s. More unusually, the images are interrupted by a surface pattern that gives the impression that the photographs are printed on finely pleated silk rather than paper – likely the result of a technical error. Instead of wiping clean his glass-plate negatives and starting over as virtually all other photographers would have done, this artist recognised that the pattern created a veil that, like time or memory, removed the images from their merely utilitarian purpose and elevated them from the mundane to the realm of art.

Just as the eye and mind may be pleasantly torn between bravura brushwork and the ostensible subject of a painting, there is a tension here between the beauty of the subject – the elegant female draped in gossamer; the strict profile and geometric setting of the male – and the visible traces of their creation, such as the flowing surface pattern and the strong vignetting of the female, which suggests a view spied through a peephole.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Male Nude]' c. 1856 Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Male Nude]' c. 1856](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/standing-male-nude.jpg)

Unknown photographer (French)

[Standing Male Nude]

c. 1856

Salted paper print from collodion glass negative

43.4 x 28.4cm (17 1/16 x 11 3/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest; Edwynn Houk and Hans P. Kraus Jr., Alfred Stieglitz Society, Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Anonymous, Adam R. Rose and Peter R. McQuillan, Joseph M. Cohen, Susan and Thomas Dunn, Kurtz Family Foundation, W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg, Christian Keesee Charitable Trust, and Robert A. Taub Gifts; and funds from various donors, 2012

Public domain

Oscar Gustav Rejlander (British born Sweden, 1813-1875)

Ariadne

1857

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Mount: 16 1/16 in. × 13 1/16 in. (40.8 × 33.2cm)

Image: 8 1/4 × 6 1/2 in. (21 × 16.5cm); oval

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Public domain

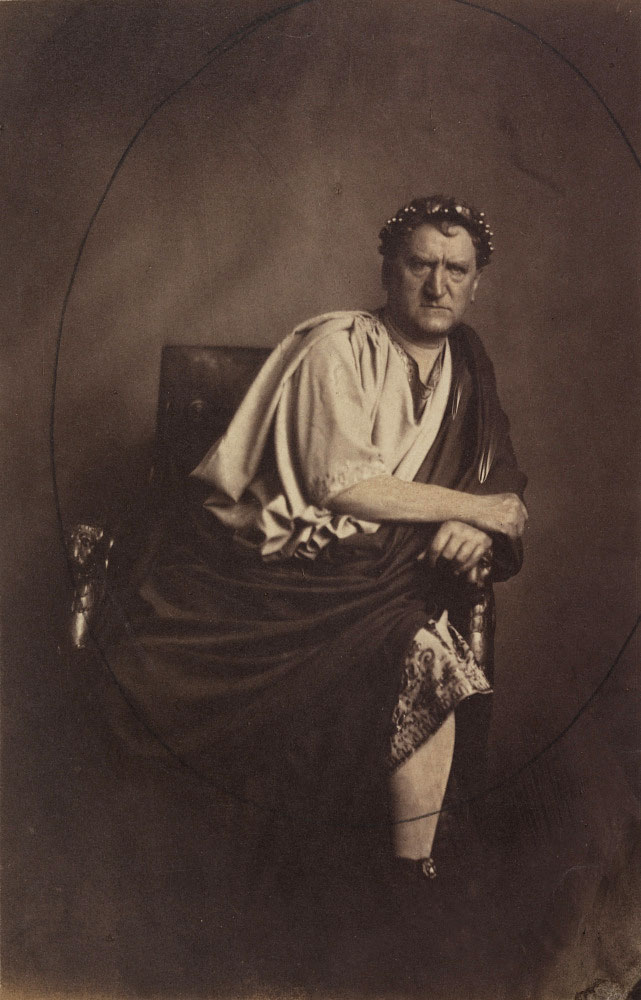

Working in a place – Victorian England – where any photographic nude was considered offensive because the process implied not only the “nastiness” of the artist and vendor, but also “the degradation of the person who serves as model on the occasion,” Rejlander sought to ally his work with that of noted painters. This nude study is one of a series based on figures in the work of Raphael, Titian, Correggio, Rubens, Murillo, and Gainsborough; the precedent here is Titian’s Venus and Adonis, and Rejlander’s intention was to show how the painter adhered to or strayed from the ways a real body can twist and turn. Critic A. H. Wall defended the propriety of Rejlander’s Studies from the Nude, saying, “Refined and ennobled by art, real beauty, palpable flesh and blood, speaks of nothing but its own inherent loveliness.”

Such references to painting did not always afford adequate protection, however. Writing of Rejlander’s famous Two Ways of Life, photographer and critic Thomas Sutton wrote, “There is no impropriety in exhibiting such works of art as Etty’s Bathers Surprised by a Swan or the Judgment of Paris but there is impropriety in allowing the public to see photographs of nude prostitutes, in flesh-and-blood truthfulness and minuteness of detail.”

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Female Nude with Mask]' c. 1870 Unknown photographer (French) '[Female Nude with Mask]' c. 1870](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/female-nude-with-mask.jpg)

Unknown photographer (French)

[Female Nude with Mask]

c. 1870

Albumen silver print from glass negative

26 x 19.1cm (10 1/4 x 7 1/2 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

Public domain

Even as she seems to part her tresses to expose her naked body, the model here masks her face in an effort to conceal her identity. While drawing, painting, and sculpture of the human figure commonly involve elements of transformation, idealisation, or the combination of features from various models, photography usually presents a recognisable image of its subject. It was not uncommon, therefore, for models who routinely posed nude for artists in other media to hide their faces when standing naked before the camera. For the viewer – not always an artist looking for help in figure drawing – the mask added an element of erotic frisson.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

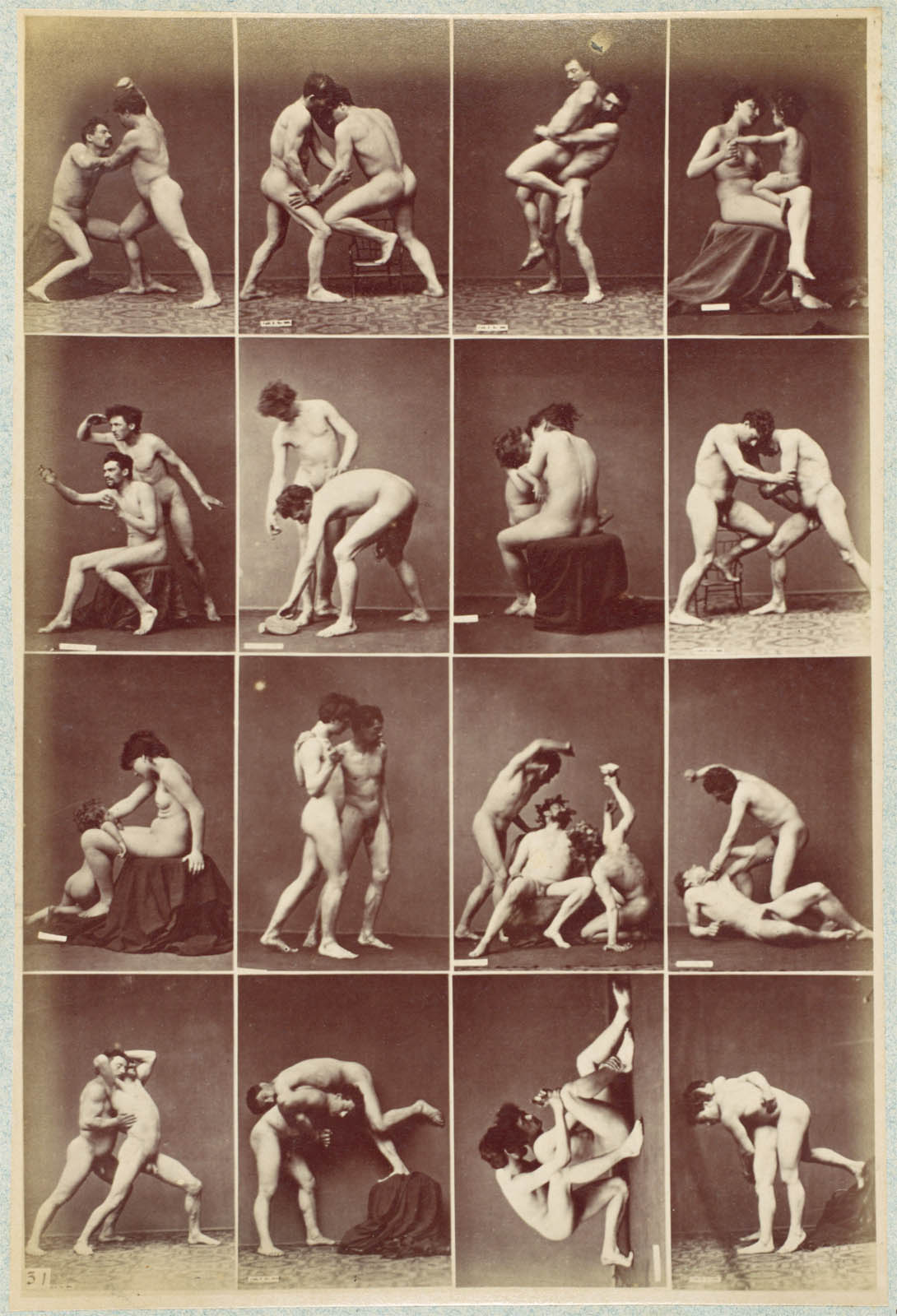

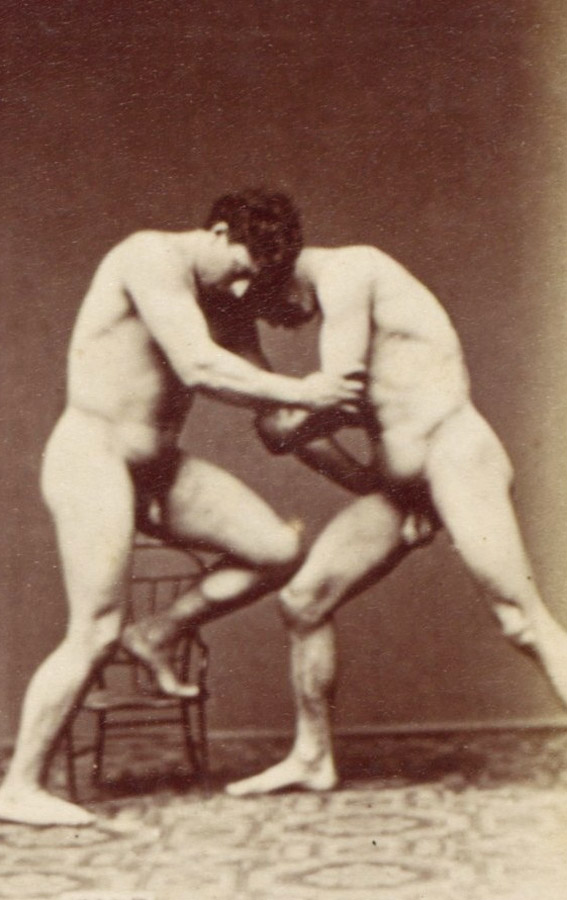

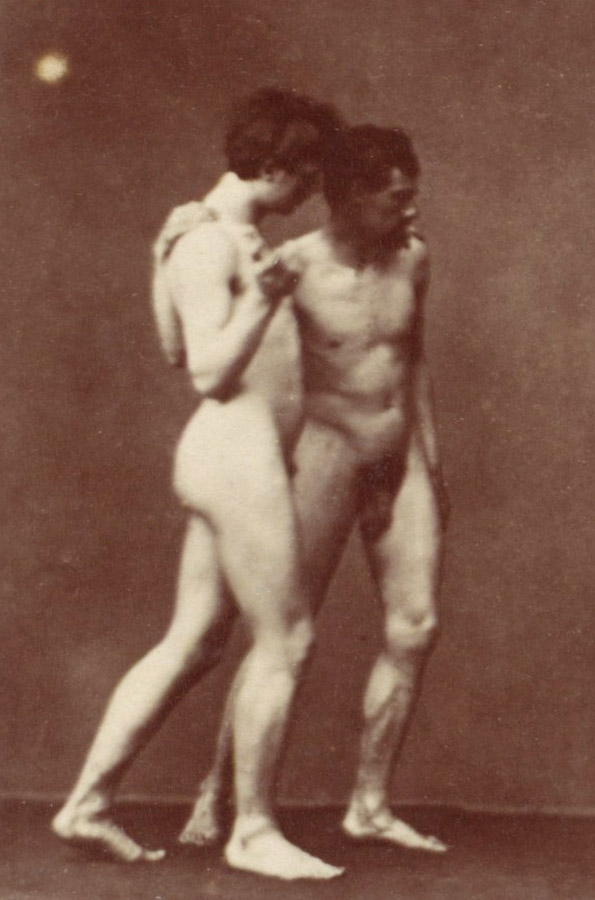

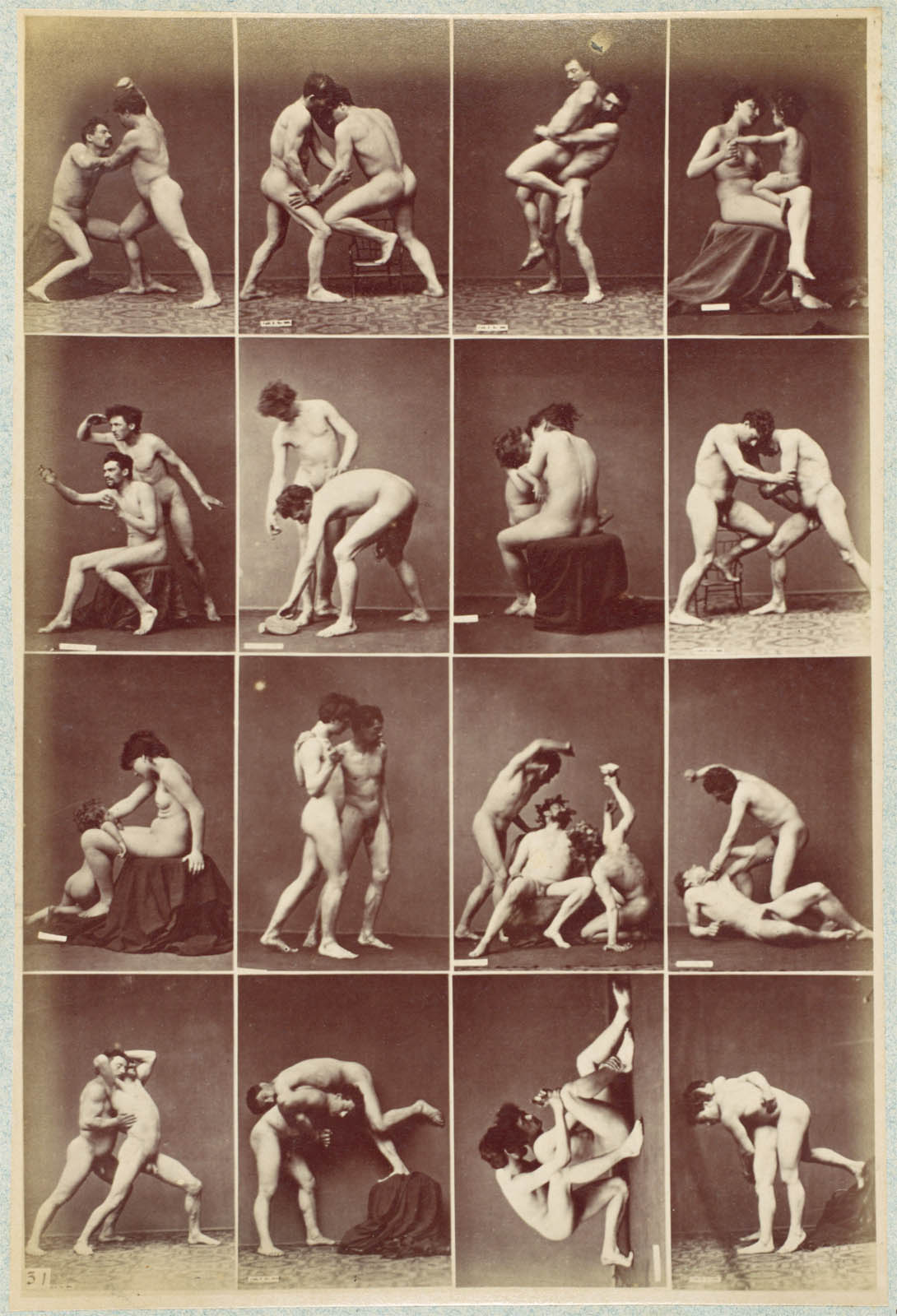

Louis Igout (French, 1837-1881)(Photographer)

A. Calavas (French)(Editor)

Plate from Album d’Études – Poses

c. 1880

Albumen silver prints from glass negatives

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1993

Public domain

This album is an excellent example of the type of photography produced in the nineteenth century as an aid to artists in the study of contour, modelling, and proportion, and as a vocabulary of expression, gesture, and pose sanctioned by the art of antiquity and the Old Masters. Groupings representing Cain and Abel, the Drunken Silenus, Hercules and Antaeus, the Dying Gaul, the Cnidian Aphrodite, and others are recognisable among the photographs. Single prints showing sixteen small images, such as the page shown here, served as a type of stock catalogue, allowing clients to survey a broad range of possible poses and order larger prints of those which best served their needs.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

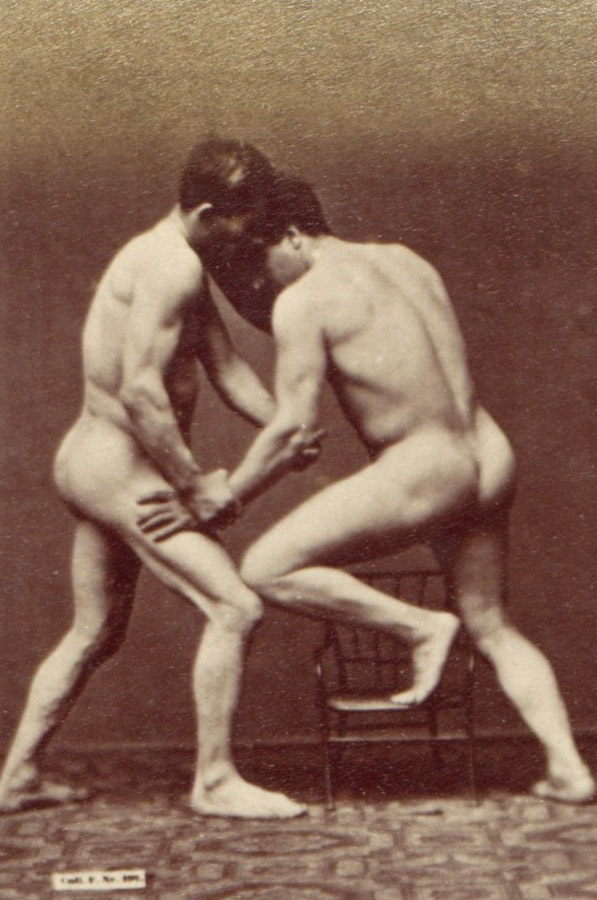

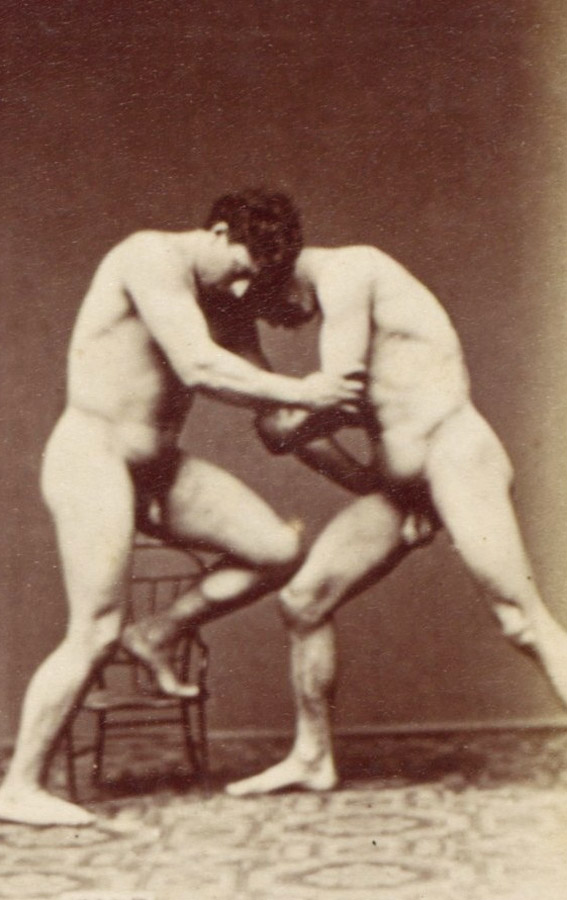

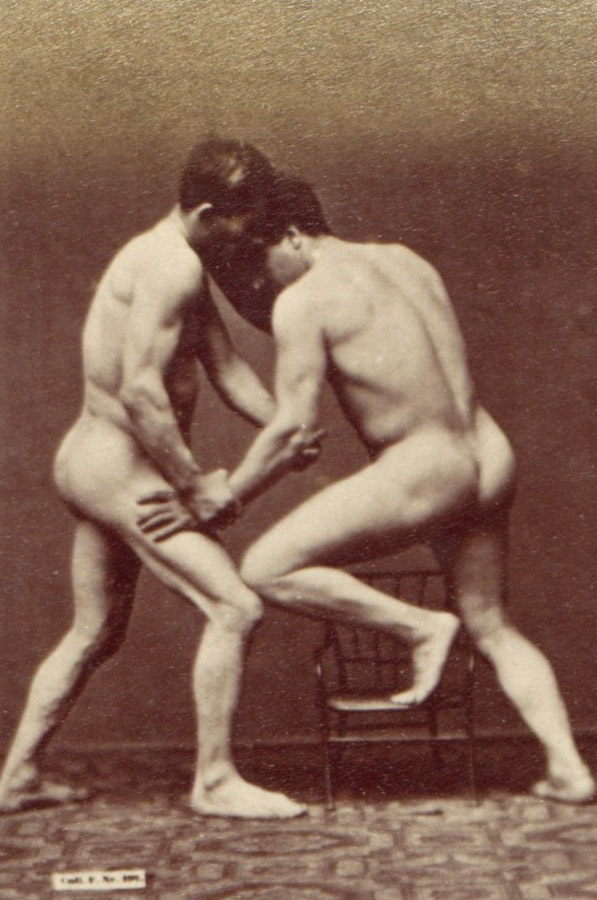

Louis Igout (French, 1837-1881)(Photographer)

A. Calavas (French)(Editor)

Plate from Album d’Études – Poses (details)

c. 1880

Albumen silver prints from glass negatives

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1993

Public domain

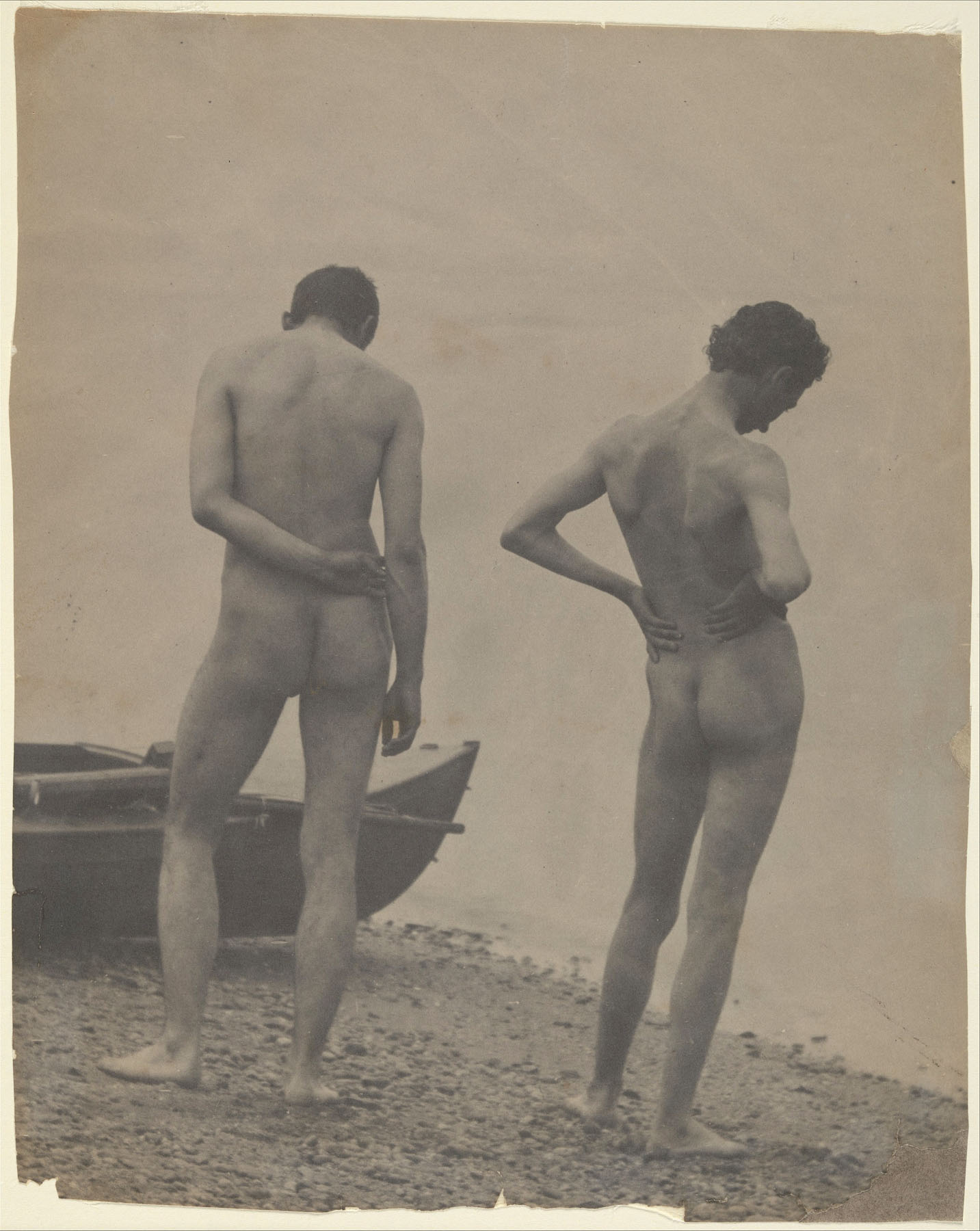

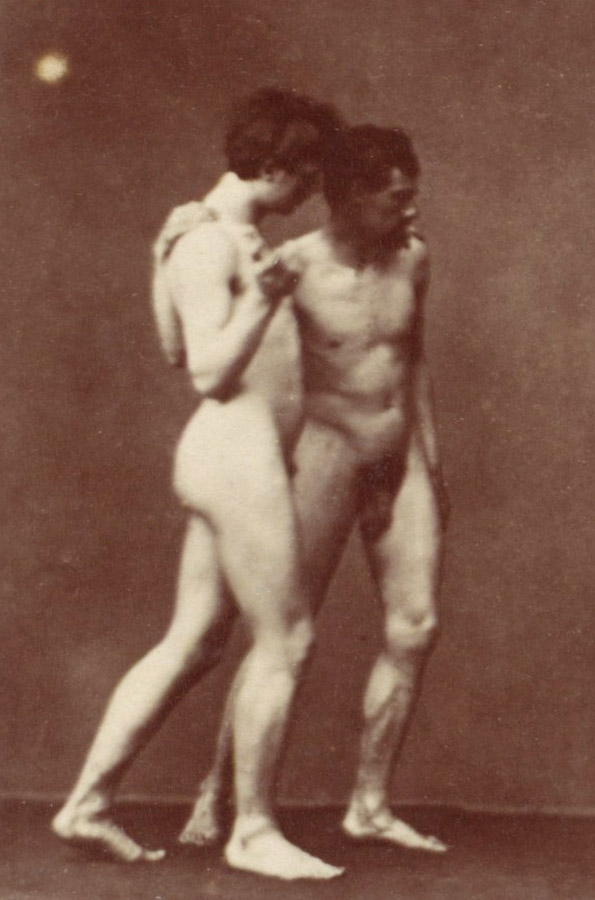

Thomas Eakins (American, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1844–1916 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

[Thomas Eakins and John Laurie Wallace on a Beach]

c. 1883

Platinum print

25.5 x 20.4cm (10 1/16 x 8 1/16 in.), irregular

Metropolitan Museum of Art

David Hunter McAlpin Fund, 1943

Public domain

The great American painter and photographer Thomas Eakins was devoted to the scientific study of the human form and committed to its truthful representation. While he and his students at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts were surrounded by casts of classical sculpture, Eakins declared that he did not like “a long study of casts. … At best they are only imitations, and an imitation of imitations cannot have so much life as an imitation of life itself.” Photography provided an obvious solution.

This photograph, in which Eakins and a student affected the elegant contrapposto stances of classical sculpture, was probably taken during an excursion with students to Manasquan Inlet at Point Pleasant, New Jersey, during the summer of 1883. Valuing his photographs not only as studies for paintings but also for their own sake, Eakins carefully printed the best images on platinum paper. In this case, he went to the additional trouble of enlarging the original, horizontally formatted image and cropping it vertically to better contain the perfectly balanced figures.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Albert Londe (French, 1858-1917) Paul Marie Louis Pierre Richer (French, 1849-1933) '[Male Musculature Study]' c. 1890 Albert Londe (French, 1858-1917) Paul Marie Louis Pierre Richer (French, 1849-1933) '[Male Musculature Study]' c. 1890](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/male-study.jpg)

Albert Londe (French, 1858-1917)

Paul Marie Louis Pierre Richer (French, 1849-1933)

[Male Musculature Study]

c. 1890

Albumen silver print

Image: 14.9 x 9.6 cm (5 7/8 x 3 3/4 in.)

Mount: 14.9 x 9.9 cm (5 7/8 x 3 7/8 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gift of Charles Isaacs and Carol Nigro, 2012

Author of a treatise on the importance of the camera in medical practice, Albert Londe declared, “the photographic plate is the scientist’s true retina.” In collaboration with a laboratory director and professor of anatomy at the École des Beaux-Arts, Londe found that photographs intended for physiological analysis could also serve artistic applications. Their careful portraits of athletes – whether taken with stop-action cameras specially designed by Londe or in static poses such as the example here – were used in scientific texts on musculature and became templates for illustrations to aid artists in rendering ideally proportioned figures.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Guglielmo Plüshow (Italian born Germany, 1852–1930) '[Young Male Nude Seated on Leopard Skin]' 1890s-1900s Guglielmo Plüshow (Italian born Germany, 1852–1930) '[Young Male Nude Seated on Leopard Skin]' 1890s-1900s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/plushow-young-male-nude-seated-on-leopard-skin.jpg)

Guglielmo Plüshow (Italian born Germany, 1852–1930)

[Young Male Nude Seated on Leopard Skin]

1890s-1900s

Albumen silver print from glass negative

22.2 x 16.2cm (8 3/4 x 6 3/8 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Museum Accession

Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Censors have long struggled to keep pace with evolving technology and expanding distribution networks of photographic erotica. In nineteenth-century France, government officials regularly seized thousands of photographs similar to the daguerreotype displayed here, which were deemed lewd.

Male nudity has frequently been subject to stricter control than pornography featuring women. The Arcadian photographs of Plüshow and his cousin and student Wilhelm von Gloeden were avidly collected in the late nineteenth century, but in the 1930s many of their prints and negatives, considered deviant by the Italian Fascist government, were destroyed. For much of the twentieth century, it was illegal in the United States to mail photographs that might be judged prurient, forcing photographers to mask genitalia and pubic hair with strategic props or with overpainting that could be easily removed by purchasers. Sale of erotic male physique magazines and bodybuilder pin-ups, ostensibly circulated to promote fitness, was legalised in a 1962 Supreme Court ruling, which concluded that “portrayals of the male nude cannot fairly be regarded as more objectionable than many portrayals of the female nude that society tolerates.”

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

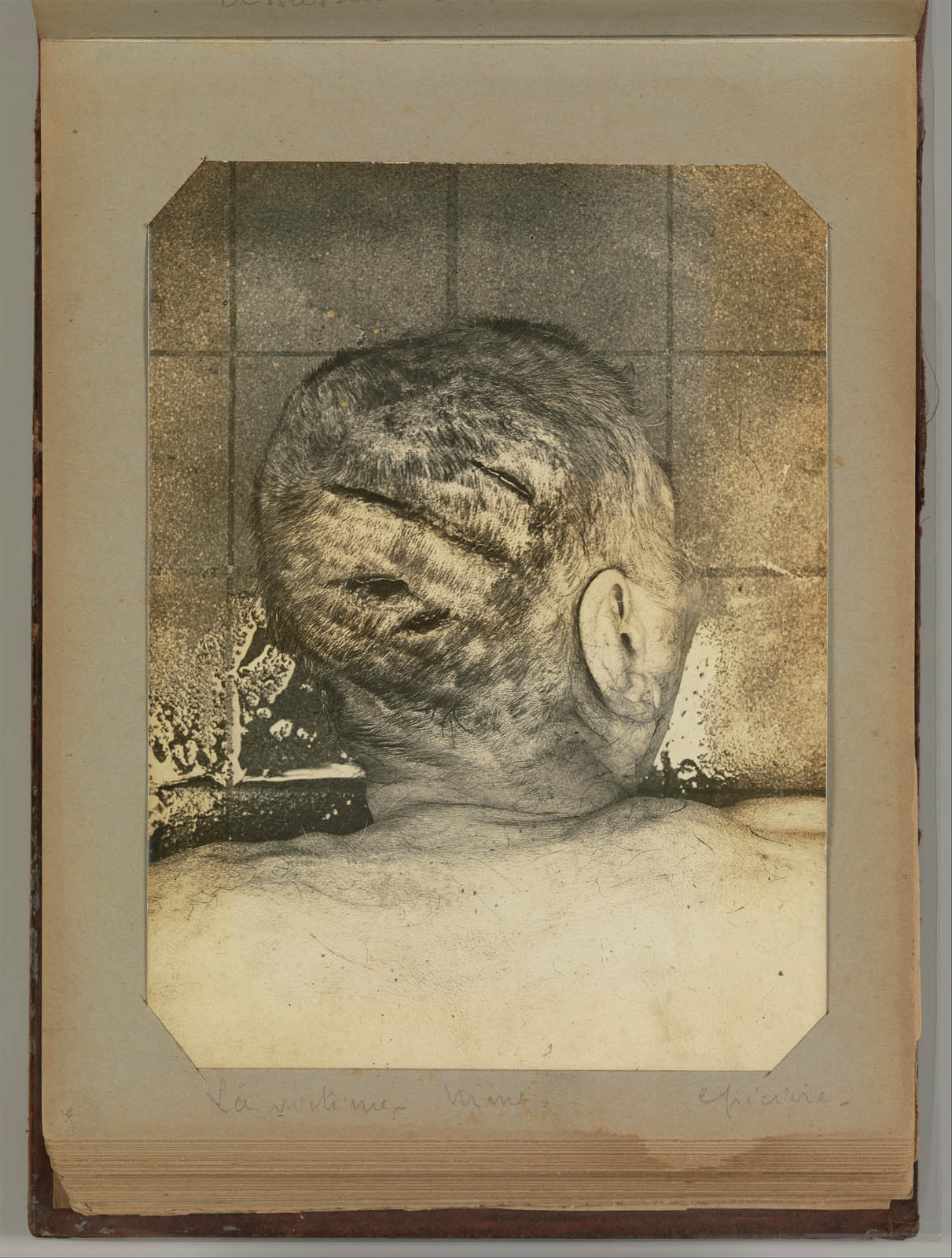

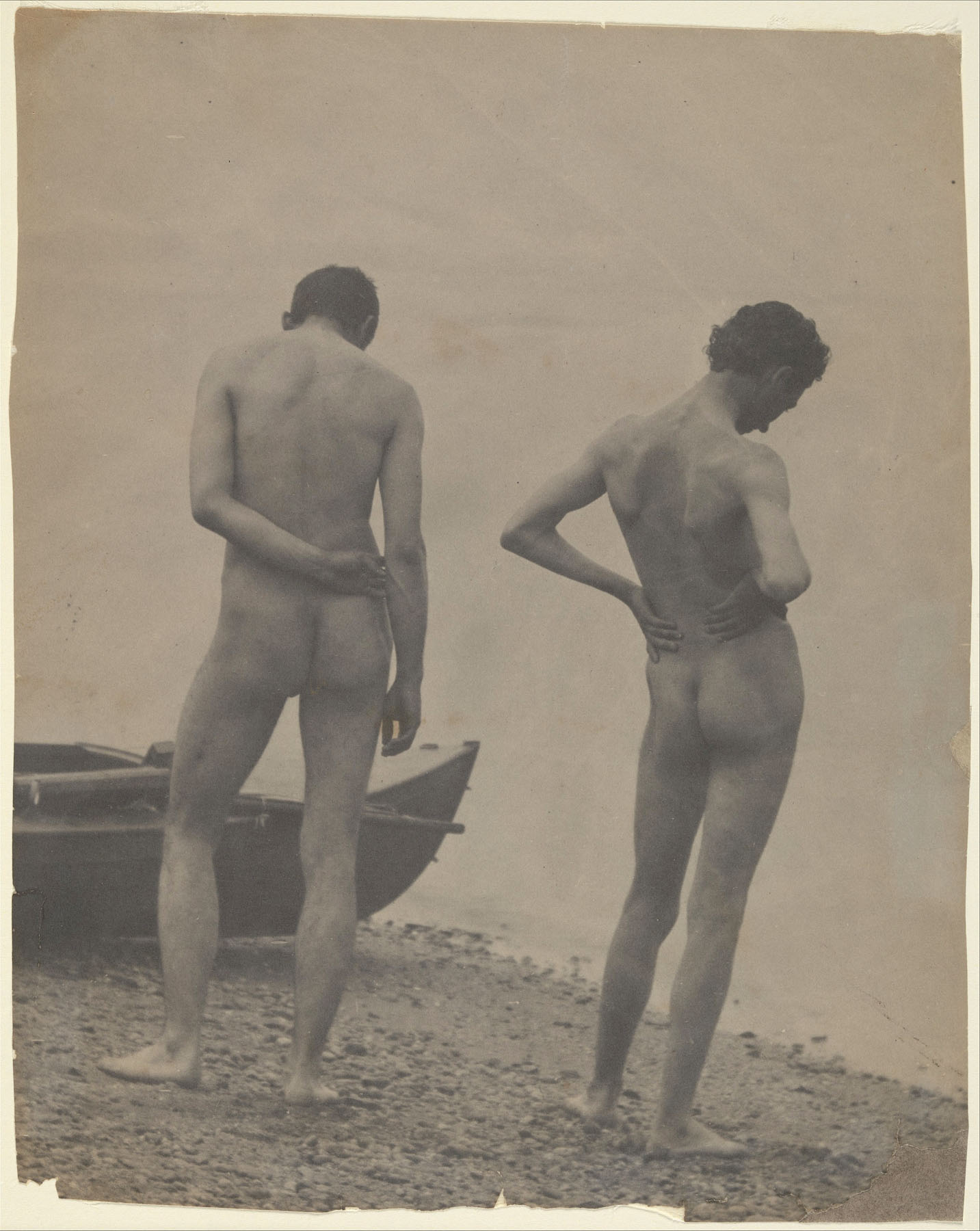

Attributed to Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853–1914)

Assasination of C. Lecomte 711 Rue des Martyrs

1901-1908

From Album of Paris Crime Scenes

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 24.3 x 31cm (9 9/16 x 12 3/16in.)

Page: 23 x 29cm (9 1/16 x 11 7/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Howard Gilman Foundation Gift, 2001

Public domain

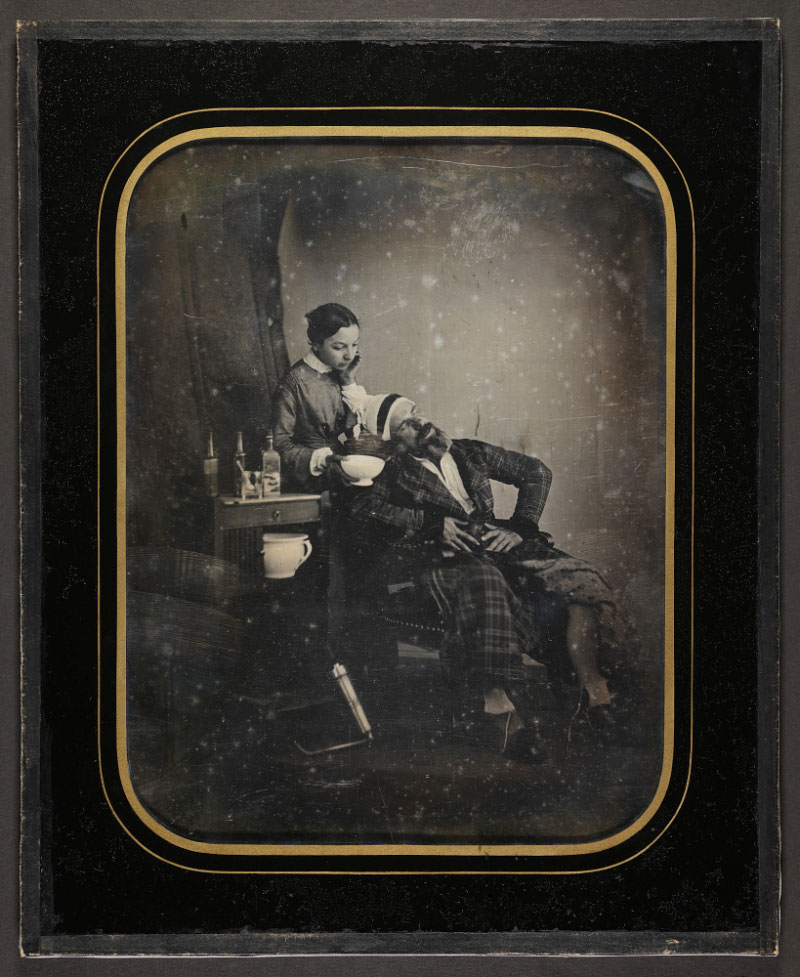

Alphonse Bertillon, the chief of criminal identification for the Paris police department, developed the mug shot format and other photographic procedures used by police to register criminals. Although the images in this extraordinary album of forensic photographs were made by or under the direction of Bertillon, it was probably assembled by a private investigator or secretary who worked at the Paris prefecture. Photographs of the pale bodies of murder victims are assembled with views of the rooms where the murders took place, close-ups of objects that served as clues, and mug shots of criminals and suspects. Made as part of an archive rather than as art, these postmortem portraits, recorded in the deadpan style of a police report, nonetheless retain an unsettling potency.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Attributed to Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853–1914)

Untitled

1901-1908

From Album of Paris Crime Scenes

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 24.3 x 31cm (9 9/16 x 12 3/16in.)

Page: 23 x 29cm (9 1/16 x 11 7/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Howard Gilman Foundation Gift, 2001

Public domain

Attributed to Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853–1914)

Untitled

1901-1908

From Album of Paris Crime Scenes

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 24.3 x 31cm (9 9/16 x 12 3/16in.)

Page: 23 x 29cm (9 1/16 x 11 7/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Howard Gilman Foundation Gift, 2001

Public domain

![Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916 Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/cavendish-bentinck-morrell-cavorting-by-the-pool-at-garsington.jpg)

Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938)

[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]

c. 1916

Gelatin silver print

8.8 x 6.3cm (3 7/16 x 2 7/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Rebelling against the narrow values of upper-class Edwardian society, Lady Ottoline Morrell, an eccentric hostess to Bloomsbury, surrounded herself in London and on her estate at Garsington with a large circle of friends including Bertrand Russell, W. B. Yeats, D. H. Lawrence, T. S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Aldous Huxley, and E. M. Forster. These images of an improvised dance show Lady Ottoline’s ten-year-old daughter, Julian, and her slightly older companions embroiled in a naked whirl, pagan in its exuberance, that reflects the emancipated attitudes of the photographer’s circle.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916 Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/cavendish-bentinck-morrell-cavorting-by-the-pool-at-garsington-a.jpg)

Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938)

[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]

c. 1916

Gelatin silver print

8.8 x 6.2cm (3 7/16 x 2 7/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

![Edward Weston (American, Highland Park, Illinois 1886 - 1958 Carmel, California) '[Nude]' 1925 Edward Weston (American, Highland Park, Illinois 1886 - 1958 Carmel, California) '[Nude]' 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/weston-nude.jpg)

Edward Weston (American, Highland Park, Illinois 1886 – 1958 Carmel, California)

[Nude]

1925

Gelatin silver print

Image: 14.8 x 23.4 cm (5 13/16 x 9 3/16 in.)

Mount: 35.2 x 43.9 cm (13 7/8 x 17 5/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Public domain

In his early attempts to merge the realism of photography with the expressive effect of abstract art, Weston honed in on close-up details of his subjects. That the faces of his models were often cropped or averted served practical as well as aesthetic purposes, enabling the photographs to be read as figure studies rather than as individual portraits while also protecting the privacy of the friends and lovers who served as models.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![George Platt Lynes (American, East Orange, New Jersey 1907–1955 New York) '[Male Nude]' 1930s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/lynes-male-nude-1.jpg)

George Platt Lynes (American, East Orange, New Jersey 1907–1955 New York)

[Male Nude]

1930s

Gelatin silver print

24.5 x 18.9cm (9 5/8 x 7 7/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© Estate of George Platt Lynes

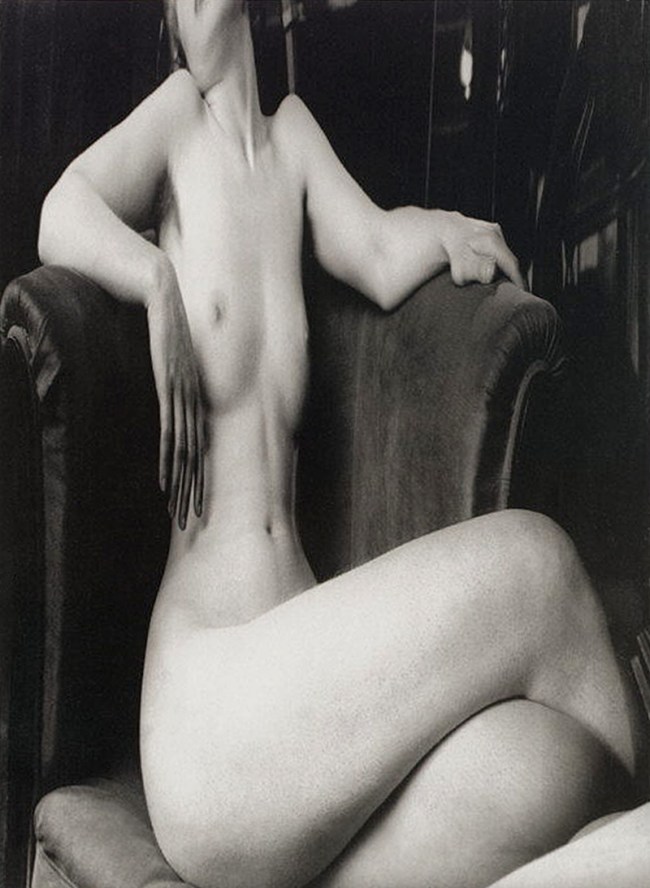

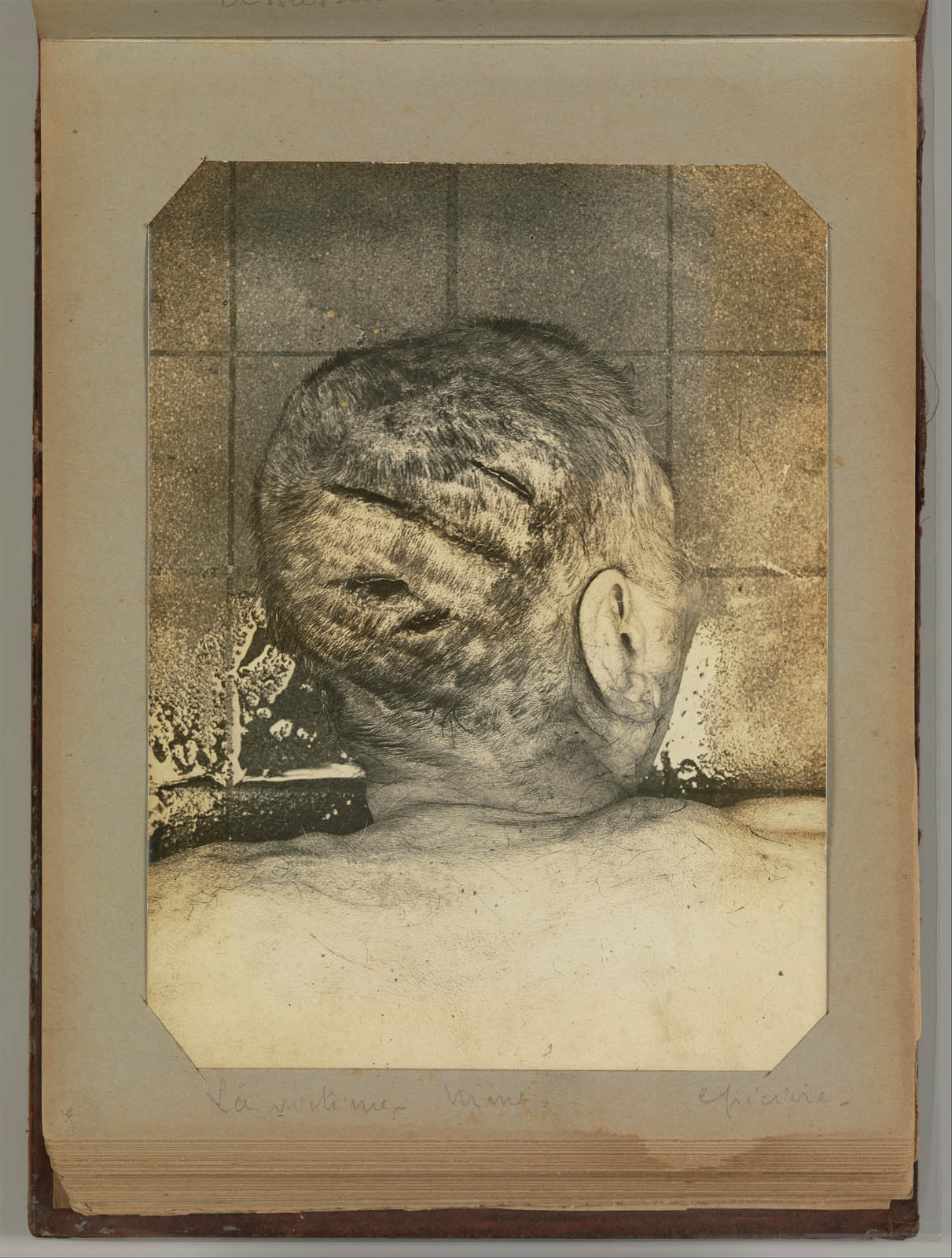

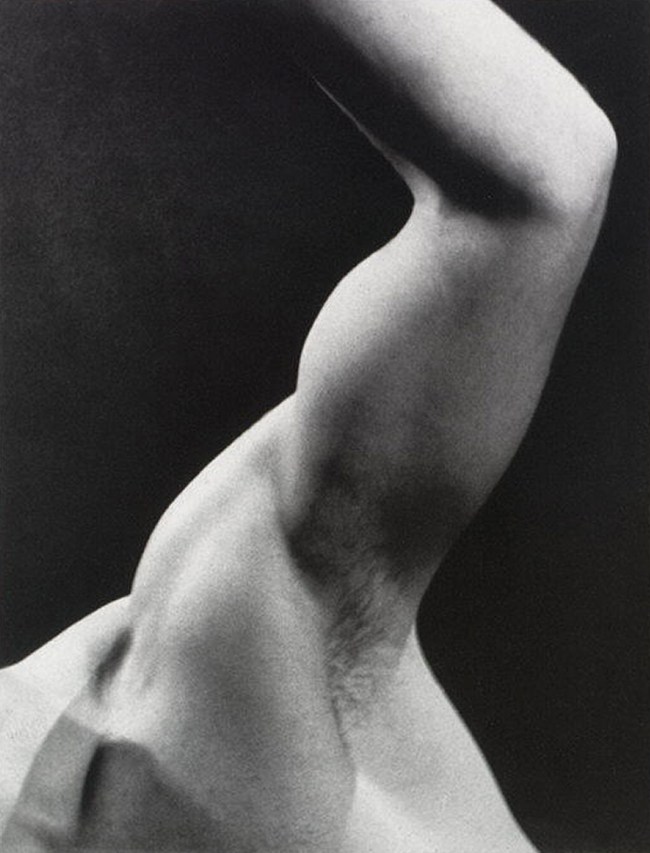

Brassaï (French born Romania, Brasov 1899 – 1984 Côte d’Azur)

Nude

1931-1934

Gelatin silver print

14.1 x 23.5cm (5 9/16 x 9 1/4 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2007

© The Estate of Brassai

One of the most radically abstract of Brassaï’s nudes, this image was published in 1933 in the inaugural issue of the avant-garde magazine Minotaure. With the figure’s head and legs cut off by the picture’s edges, the twisting, truncated torso seems to float in space like an apparition – an ambiguous, organic form with an uncanny resemblance to a phallus. This transformation of the female figure into a fetish object is a hallmark of Surrealism that reflects the important influence of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory on European art of the early twentieth century.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

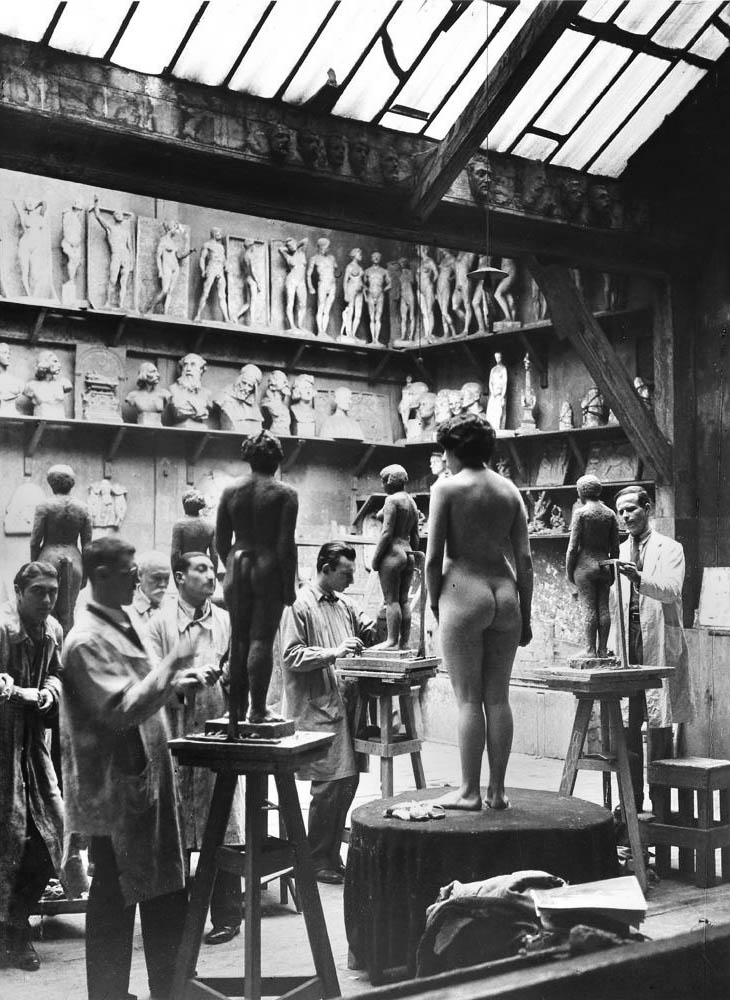

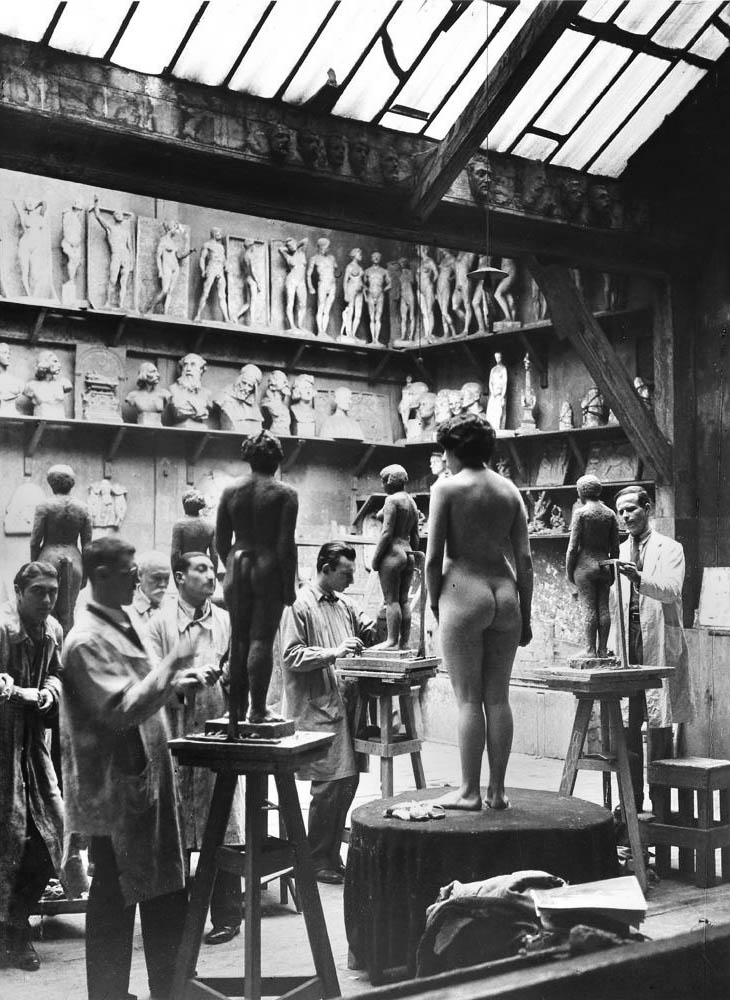

Brassaï (French born Romania, Brasov 1899 – 1984 Côte d’Azur)

L’Académie Julian

1931, printed 1950s

Gelatin silver print

29.7 x 23.7cm (11 11/16 x 9 5/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

© Estate Brassaï Succession – Paris

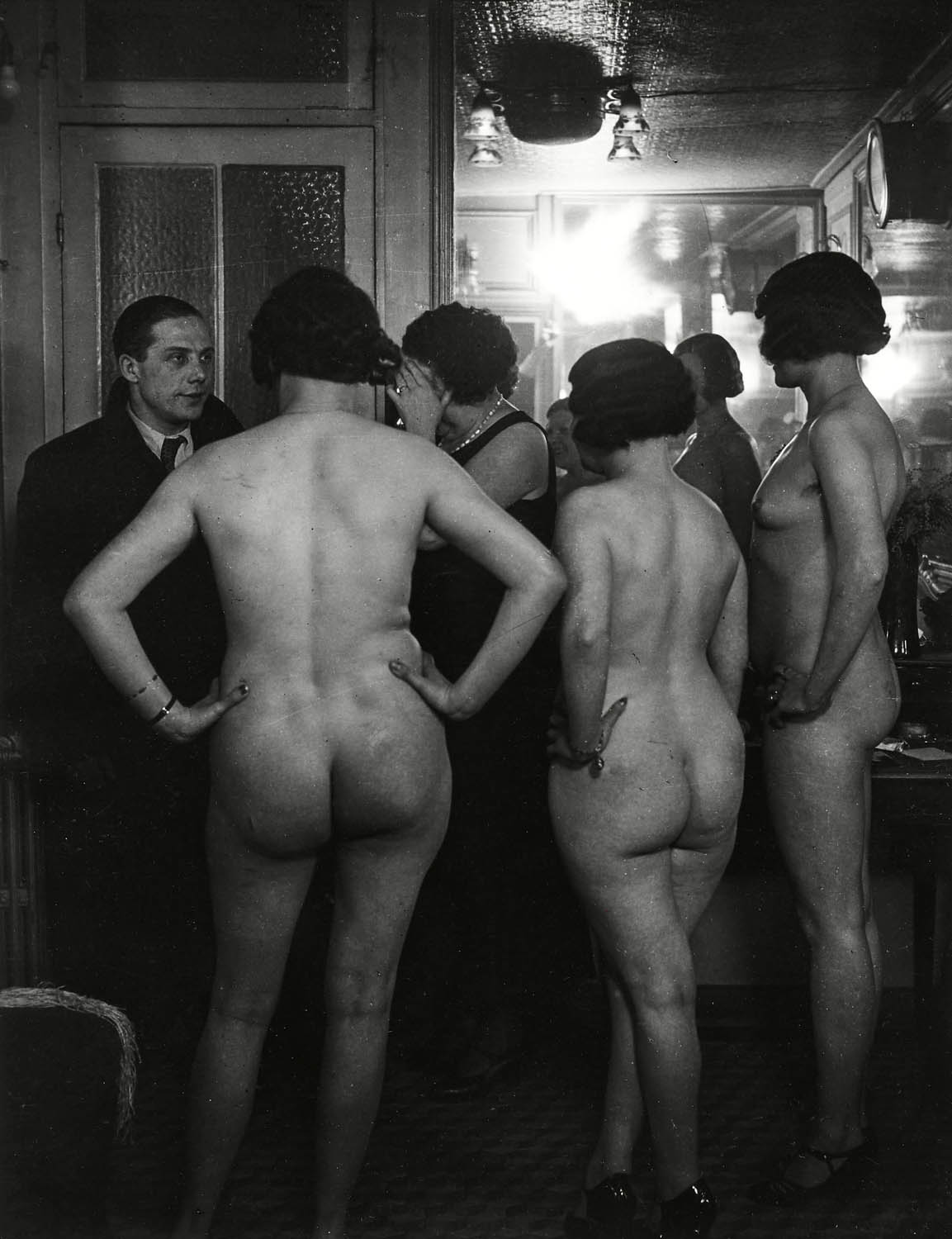

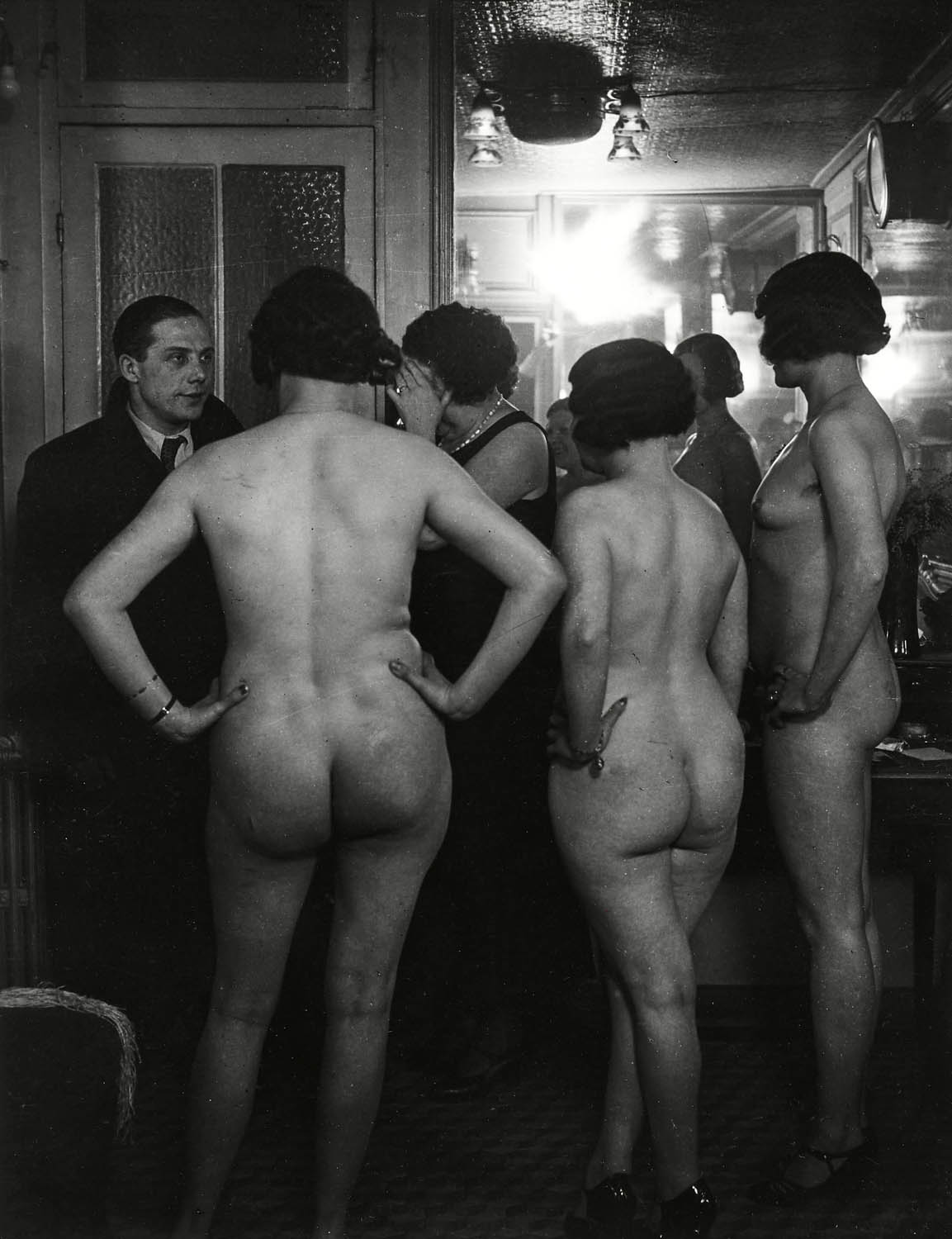

Brassaï (French born Romania, Brasov 1899 – 1984 Côte d’Azur)

Introductions at Suzy’s

1932-1933, printed later

Gelatin silver print

23.1 x 16.8cm (9 1/16 x 6 5/8 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© Estate Brassaï Succession – Paris

Brassaï made his name as a chronicler of the night, with images that ranged from reflections on wet cobblestones to the denizens of bars and brothels. Like so many of his photographs, Introductions at Suzy’s was not an impromptu scene caught by an undetected observer but rather a carefully constructed tableau meant to highlight the dynamic between buttoned-up bourgeois clients and Suzy’s bevy of prostitutes, naked but for their bracelets and high heels. The “client” was actually Brassaï’s friend and bodyguard; the “girls,” however, were not stand-ins.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Brassaï (French, 1899-1984)

Chez Suzy / Armoire à glace dans un hôtel de passe, rue Quincampoix (Mirrored cabinet in a brothel, rue Quincampoix)

1932, printed 1950s

Gelatin silver print

23.3 x 16.8cm (9 3/16 x 6 5/8 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Warner Communications Inc. Purchase Fund, 1980

© Estate Brassaï Succession – Paris

A keen observer of Parisian nightlife in the 1930s, Brassaï was drawn to the visual conundrums and optical innuendos of everyday life. The play of reflections and absences in this image, made in a Paris brothel, suggests the materialization of subconscious impulses. Evoking Freud’s definition of desire as the sensation arising from a perceived absence of remembered pleasure, this blatantly sexual scene suggests but withholds a specific narrative.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

André Kertész (American born Hungary, Budapest 1894 – 1985 New York City)

Distortion #6

1932

Gelatin silver print

23.4 x 17.3cm (9 3/16 x 6 13/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© The Estate of André Kertész / Higher Pictures

Although Kertesz had long been interested in mirrors, reflections, and the idea of distorting the human figure, he did not seriously investigate their photographic possibilities until 1933, when the risqué French magazine Le Sourire commissioned him to make a series of figure studies. Using a funhouse mirror from a Parisian amusement park, Kertesz, who had never photographed nudes before, spent four weeks making about two hundred negatives.

Kertész accentuated the narrow ribcage and long waist of the ideal contemporary woman by photographing his model in a carnival mirror. If the top half of this beautiful nude resembles those Modigliani painted, the swell of the haunch recalls Mannerist nudes and their nineteenth-century revivals, especially Ingres’ grande odalisque.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

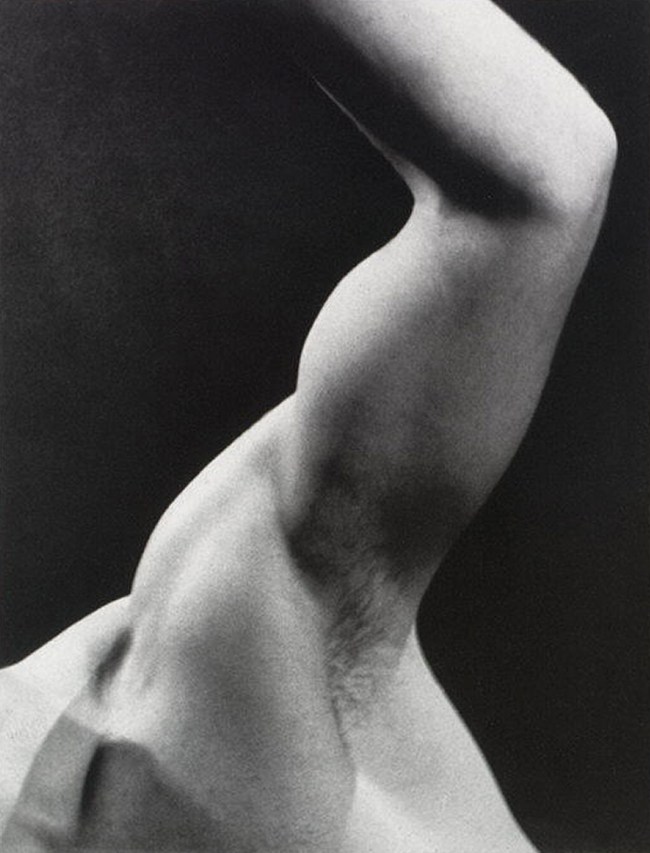

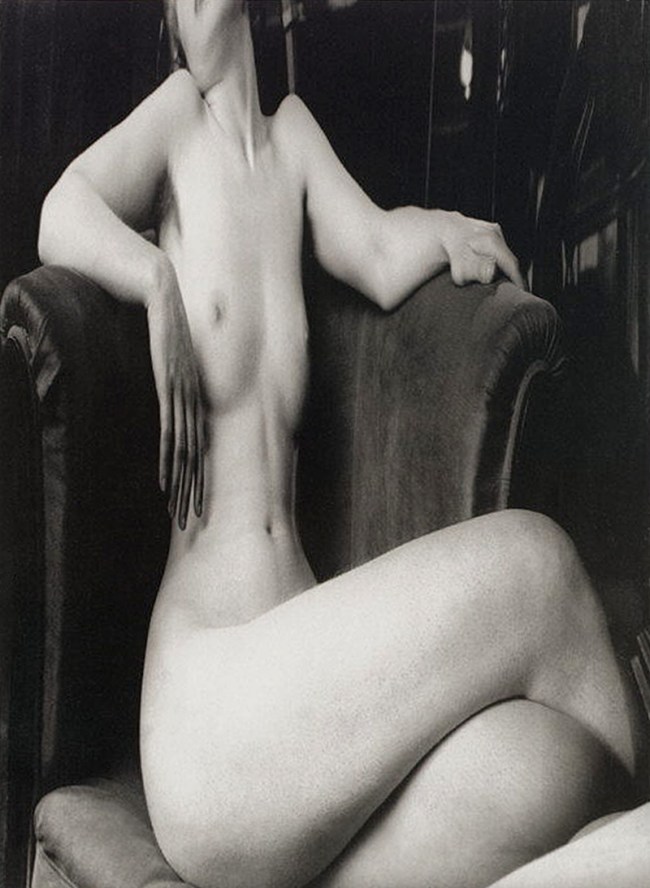

Man Ray (American, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1890 – 1976 Paris)

Arm

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

29.7 x 23.0cm (11 11/16 x 9 1/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© 2012 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris

Man Ray’s photograph of an arm is cropped so abstractly that it seems to metamorphose into other body parts – a knee, a calf, a thigh – or into some utterly unidentifiable yet heroic form. This image appeared on the cover of Formes Nues (1935), which also included the work of Brassaï, László Moholy-Nagy, Franz Roh, and George Platt Lynes, among others.

In the magazine’s introduction, Man Ray wrote, “were it not for the fact that photography permits me to seize and to possess the human body and face in more than a temporary manner, I should quickly have tired of this medium.”

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Paul Outerbridge Jr. (American, New York 1896 – 1959 Laguna Beach, California)

Nude with Mask and Hat

c. 1936

Carbro print

43.3 x 30.0cm (17 1/16 x 11 13/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Warner Communications Inc. Purchase Fund, 1977

Outerbridge was a successful commercial photographer, but although he found such work stimulating, he also made photographs as a means of personal expression throughout his career. Photographing nude models in colour in the 1930s was challenging – not only in the difficulty of correctly capturing skin tones using complicated new processes, but also because finding a venue to publish or exhibit the work was unlikely. Although he began by posing his models in the manner of painted masterpieces, Outerbridge’s compositions became increasingly provocative in the late 1930s. The sexualised charge and commercial palette of works such as this were not in keeping with attitudes of the period and were not shown during the artist’s lifetime.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Hans Bellmer (German born Poland, Katowice 1902–1975 Paris)

La Poupée

1936

Gelatin silver print with applied colour

Mount: 9 5/8 in. × 7 1/2 in. (24.5 × 19cm)

Image: 5 5/16 × 5 9/16 in. (13.5 × 14.1cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In his nightmarish tableaux of mutilated and reassembled dolls posed in domestic interiors, Bellmer grappled with the base condition of the human body and with the bodily fragment as fetish object. Mannequins and dolls – simultaneously familiar and strange – supplied the material for his primal expressions of terror and awe, which often evoked the innocent violence and latent sexuality of childhood games. Whether they are read as Freudian emblems of the uncanny or as ominous harbingers of Nazi atrocities, Bellmer’s images exemplify the Surrealist view of the female body as the source of simultaneous fascination and revulsion.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

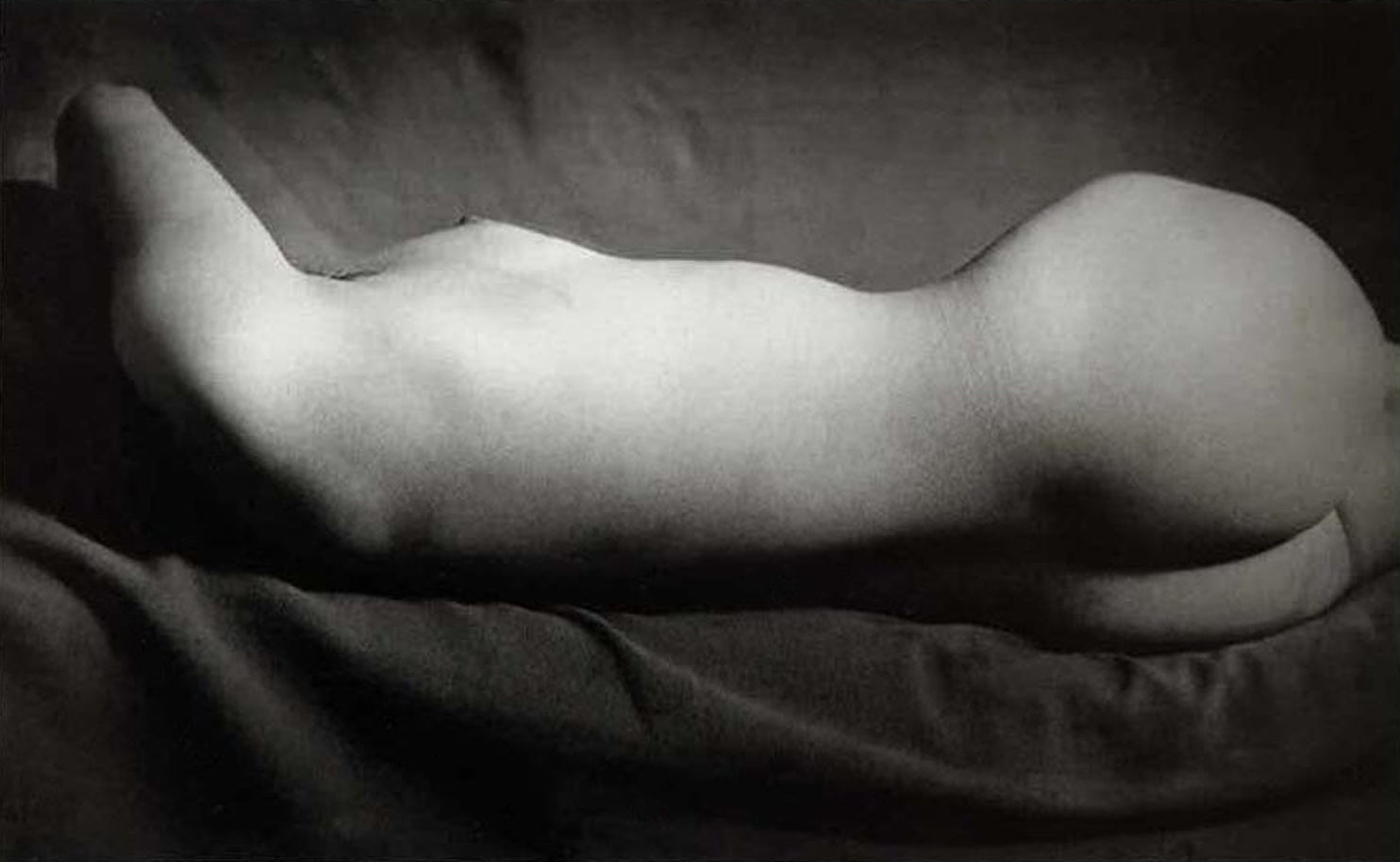

Edward Weston (American, Highland Park, Illinois 1886 – 1958 Carmel, California)

Printer: Brett Weston (American, Los Angeles, California 1911-1993 Kona, Hawaii) or Cole Weston (American, 1919-2003)

Nude on Sand, Oceano

1936, printed c. 1954

Gelatin silver print

19.1 x 24.2cm (7 1/2 x 9 1/2 in.)

David Hunter McAlpin Fund, 1957

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Charis Wilson, the model for this series, admitted to being shocked upon seeing Weston’s nudes for the first time, as she had previously known only the romantically retouched photographs of depilated bodies then popular. In studying Weston’s work she found, “I couldn’t get past the simple amazement at how real they were. Then I began to see the rhythmic patterns, the intensely perceived sculptural forms, the subtle modulations of tone, of which these small, perfect images were composed. And I began to appreciate the originality of the viewpoint that had selected just these transitory moments and made them fast against the current of time.”

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

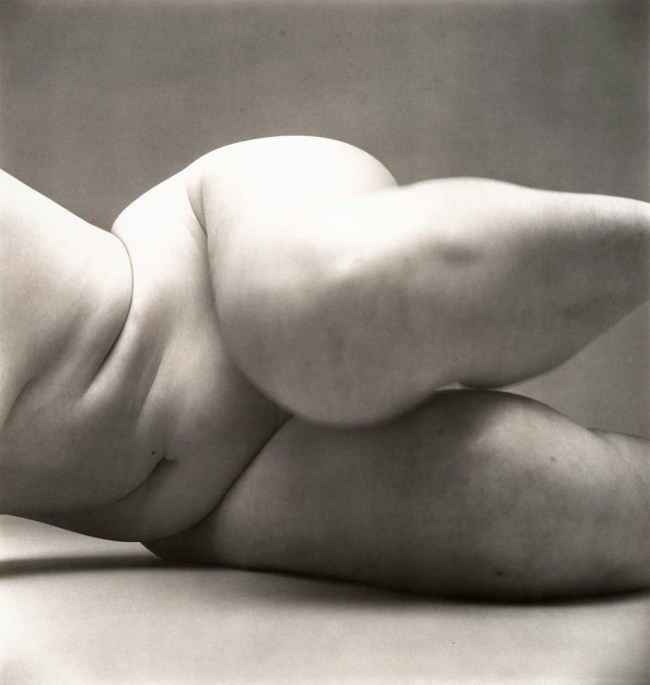

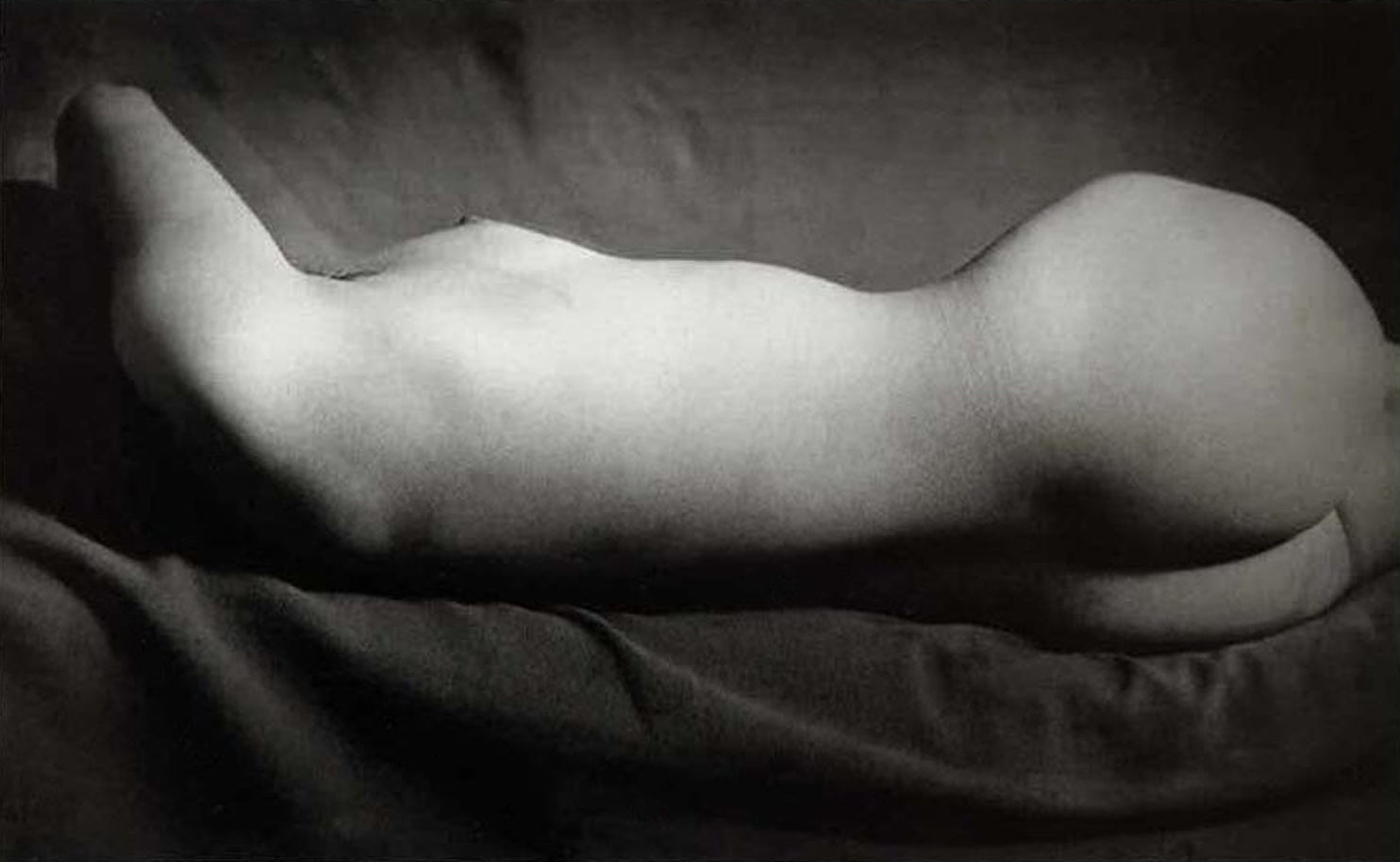

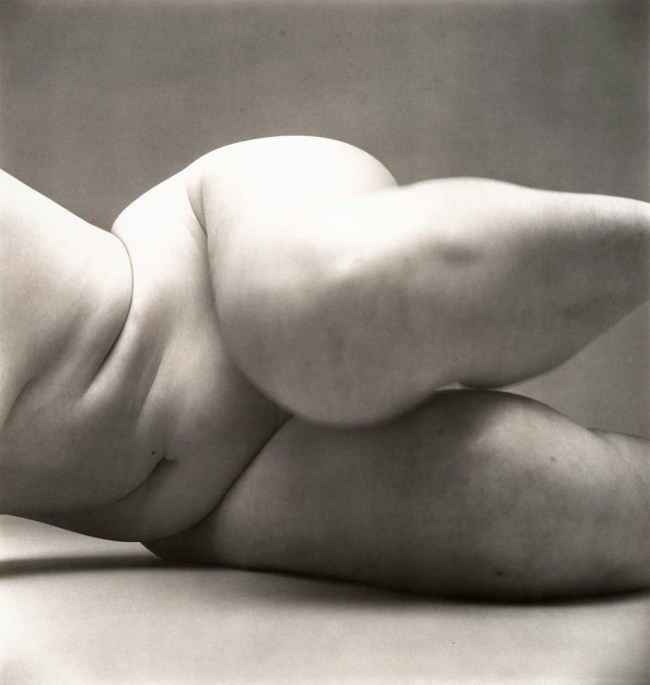

Irving Penn (American, Plainfield, New Jersey 1917 – 2009 New York City)

Nude No. 57

1949-1950

Gelatin silver print

39.4 x 37.5cm (15 1/2 x 14 3/4 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gift of the artist, 2002

© 1950-2002 Irving Penn

By 1950, Penn was a well-known Vogue portrait and fashion photographer but had already made, privately, a major series of nudes – a personal but lesser-known body of work. During the week, he photographed models wearing fashionable clothes for the magazine, but weekends and evenings he made studies of female nudes. The women were full-bodied and the photographs unorthodox, recalling the form and spirit of archaic fertility idols.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Harry Callahan (American, 1912-1999)

Eleanor and Barbara

1954

Gelatin silver print

22.8 x 22.1cm (9 x 8 11/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gift of Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1993

© The Estate of Harry Callahan; Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Muses throughout his career, Callahan’s wife and daughter played, posed, and aged before his lens. With their attention to the physicality of light, however, Callahan’s photographs transcend mere family portraiture by calling attention to the simple beauty of life’s fleeting moments. “He just liked to take the pictures of me,” Eleanor recalled in her nineties. “In every pose. Rain or shine. And whatever I was doing. If I was doing the dishes or if I was half asleep. And he knew that I never, never said no. I was always there for him. Because I knew that Harry would only do the right thing.”

Eleanor Callahan died in February 2012 at the age of ninety-five.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)

Retired man and his wife at home in a nudist camp one morning, N.J.

1963

Gelatin silver print

39.9 × 37.9cm (15 11/16 × 14 15/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Joyce Frank Menschel, and Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gifts; Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest; and Marlene Nathan Meyerson Family Foundation, Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, Diana Barrett and Robert Vila, Elizabeth S. and Robert J. Fisher, Charlotte and Bill Ford, Lita Annenberg Hazen Charitable Trust and Hazen Polsky Foundation Inc., Jennifer and Joseph Duke, Jennifer and Philip Maritz, Saundra B. Lane, The Jerry and Emily Spiegel Family Foundation and Pamela and Arthur Sanders, Anonymous, and The Judith Rothschild Foundation Gifts, 2007

© The Estate of Diane Arbus

Arbus’s interest in the tension between revelation and concealment comes into starkest focus in the portraits she made at Sunshine Park, a family nudist camp in New Jersey. While nudism might be considered the ultimate form of exposure, it often required a different kind of cover-up. As the artist remarked in an unpublished article written for Esquire magazine in 1966: “For many of these people, their presence here is the darkest secret of their lives, unsuspected by relatives, friends, and employers in the outside world, the disclosure of which might bring disgrace.”

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

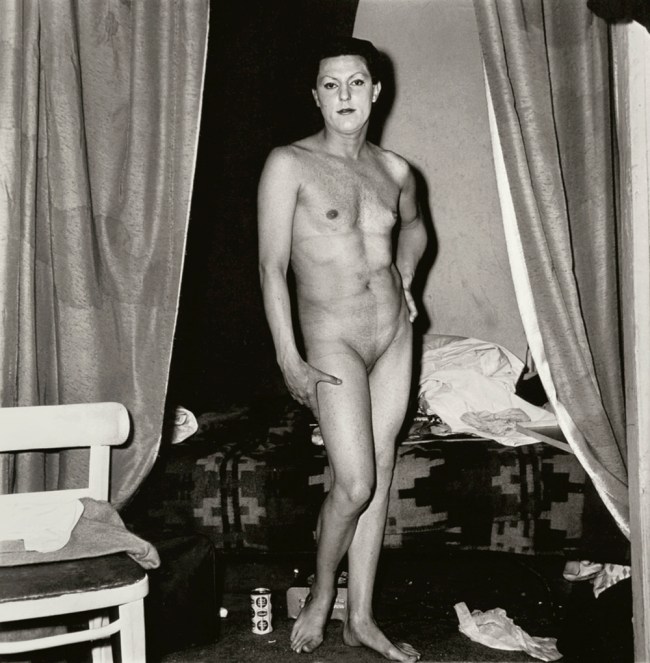

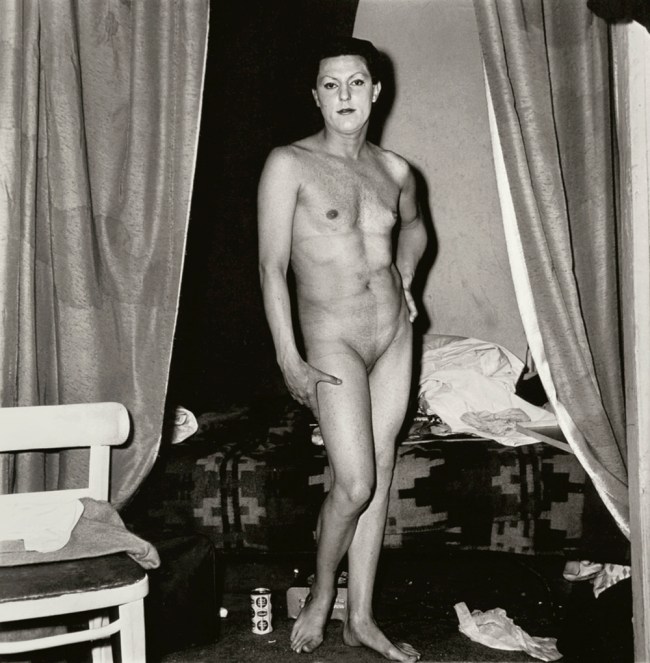

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)

A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C.

1968

Gelatin silver print

38.2 x 36.2cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Joyce Frank Menschel, and Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gifts; Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest; and Marlene Nathan Meyerson Family Foundation, Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, Diana Barrett and Robert Vila, Elizabeth S. and Robert J. Fisher, Charlotte and Bill Ford, Lita Annenberg Hazen Charitable Trust and Hazen Polsky Foundation Inc., Jennifer and Joseph Duke, Jennifer and Philip Maritz, Saundra B. Lane, The Jerry and Emily Spiegel Family Foundation and Pamela and Arthur Sanders, Anonymous, and The Judith Rothschild Foundation Gifts, 2007

© The Estate of Diane Arbus

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987 Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/16_morrisroe_untitled-web.jpg?w=650)

Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989)

Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]

c. 1987

Gelatin silver print

28.4 x 20.8cm (11 3/16 x 8 3/16 in.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2009

© The Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection) at Fotomuseum Winterthur

Sexuality and mortality – which many would say are central preoccupations of humankind – are key to Morrisroe’s biography and art. The son of a drug-addicted mother, a teenage hustler, and a precocious punk queer, Morrisroe carried a bullet (shot by a disgruntled john) in his chest from the age of eighteen and consequently walked with a limp that added one more element to his outsider self-image. Sex and death were persistent themes in his work, with pronounced poignancy after his 1986 AIDS diagnosis. In this work, Morrisroe has taken a page from a gay S&M magazine, cut out the shapes of two naked men, and used the sheet as a negative to print a unique image in which the figures – literally absent – appear as dark silhouettes against a netherworld of sexual activity.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Thursday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Closed Wednesday

The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Alban-Adrien Tournachon (French , 1825-1903) and Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Pierrot Yawning' 1854 from the exhibition 'Still Performing: Costume, Gesture, and Expression in 19th Century European Photography' at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City Alban-Adrien Tournachon (French , 1825-1903) and Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Pierrot Yawning' 1854 from the exhibition 'Still Performing: Costume, Gesture, and Expression in 19th Century European Photography' at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/tournachon-and-nadar-pierrot-yawning.jpg?w=857)

![Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-1859 Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-1859](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/chauvassaignes_seated-nude-web.jpg?w=650)

![Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850 Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/moulin_two-nudes-standing-web.jpg?w=650)

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Seated Female Nude]' c. 1850 Unknown photographer (French) '[Seated Female Nude]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/seated-female-nude.jpg)

![Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1853 Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1853](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/julien-vallou-de-villeneuve-standing-female-nude.jpg)

![Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-1854 Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-1854](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/durieu_nude_ph8976-web.jpg?w=650)

![Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855 Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/marle_standing-male-nude-web.jpg?w=650)

![Nadar (French, Paris 1820 - 1910 Paris) '[Standing Female Nude]' 1860-1861 Nadar (French, Paris 1820 - 1910 Paris) '[Standing Female Nude]' 1860-1861](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/nadar-standing-female-nude.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Nude with Mirror]' c. 1850 Unknown photographer (French) '[Nude with Mirror]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/nude-with-mirror.jpg)

![Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Reclining Female Nude]' c. 1853 Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Reclining Female Nude]' c. 1853](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/julien-vallou-de-villeneuve-reclining-female-nude.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1856 Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1856](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/standing-female-nude.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Male Nude]' c. 1856 Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Male Nude]' c. 1856](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/standing-male-nude.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Female Nude with Mask]' c. 1870 Unknown photographer (French) '[Female Nude with Mask]' c. 1870](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/female-nude-with-mask.jpg)

![Albert Londe (French, 1858-1917) Paul Marie Louis Pierre Richer (French, 1849-1933) '[Male Musculature Study]' c. 1890 Albert Londe (French, 1858-1917) Paul Marie Louis Pierre Richer (French, 1849-1933) '[Male Musculature Study]' c. 1890](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/male-study.jpg)

![Guglielmo Plüshow (Italian born Germany, 1852–1930) '[Young Male Nude Seated on Leopard Skin]' 1890s-1900s Guglielmo Plüshow (Italian born Germany, 1852–1930) '[Young Male Nude Seated on Leopard Skin]' 1890s-1900s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/plushow-young-male-nude-seated-on-leopard-skin.jpg)

![Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916 Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/cavendish-bentinck-morrell-cavorting-by-the-pool-at-garsington.jpg)

![Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916 Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/cavendish-bentinck-morrell-cavorting-by-the-pool-at-garsington-a.jpg)

![Edward Weston (American, Highland Park, Illinois 1886 - 1958 Carmel, California) '[Nude]' 1925 Edward Weston (American, Highland Park, Illinois 1886 - 1958 Carmel, California) '[Nude]' 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/weston-nude.jpg)

![George Platt Lynes (American, East Orange, New Jersey 1907–1955 New York) '[Male Nude]' 1930s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/lynes-male-nude-1.jpg)

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987 Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/16_morrisroe_untitled-web.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.