Exhibition dates: 6th February – 9th April 2012

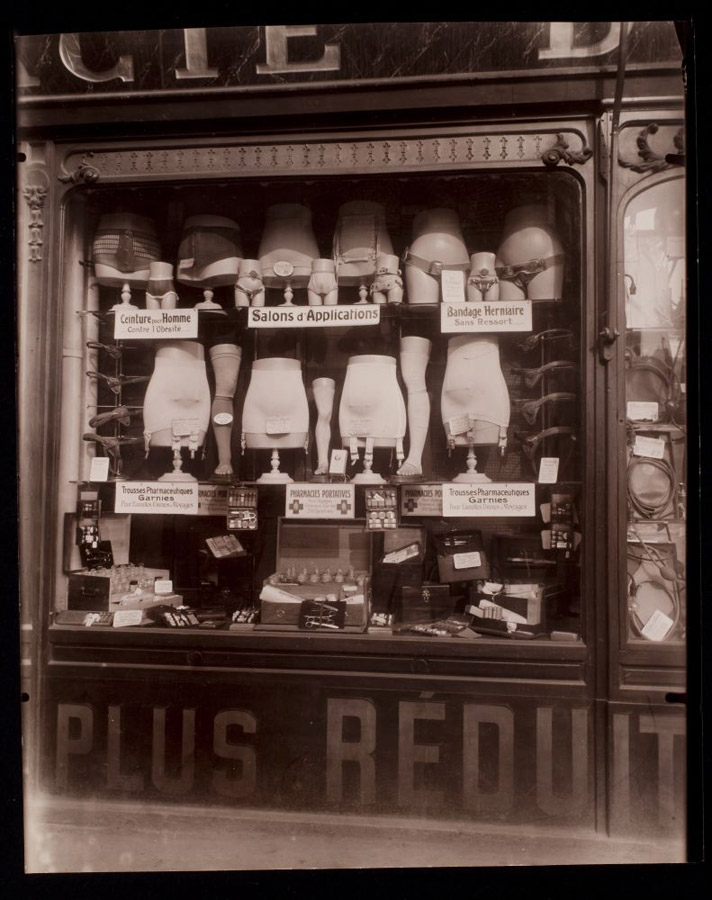

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Coin, Boulevard de la Chapelle et rue Fleury 76,18e

June 1921

Matte albumen silver print

6 13/16 x 9 inches (17.3 x 22.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

“These are simply documents I make.”

Eugène Atget

“One might think of Atget’s work at Sceaux as… a summation and as the consummate achievement of his work as a photographer – a coherent, uncompromising statement of what he had learned of his craft, and of how he had amplified and elaborated the sensibility with which he had begun. Or perhaps one might see the work at Sceaux as a portrait of Atget himself, not excluding petty flaws, but showing most clearly the boldness and certainty – what his old friend Calmettes called the intransigence – of his taste, his method, his vision.

John Szarkowski

The first of two postings about the work of Eugène Atget, this exhibition at MoMA the first in twenty-five years to focus on his “Documents for artists.” Atget was my first hero in photography and the greatest influence on my early black and white photography before I departed and found my own voice as an artist. Through his photographs, his vision he remains a life-long friend. He taught me so much about where to place the camera and how to see the world. He made me aware. For that I am eternally grateful.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to MOMA for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Cour, 7 rue de Valence

June 1922

Matte albumen silver print

7 x 8 15/16 inches (17.8 x 22.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Cour, 41 rue Broca

1912

Albumen silver print

6 5/8 x 8 1/4 inches (16.9 x 21cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

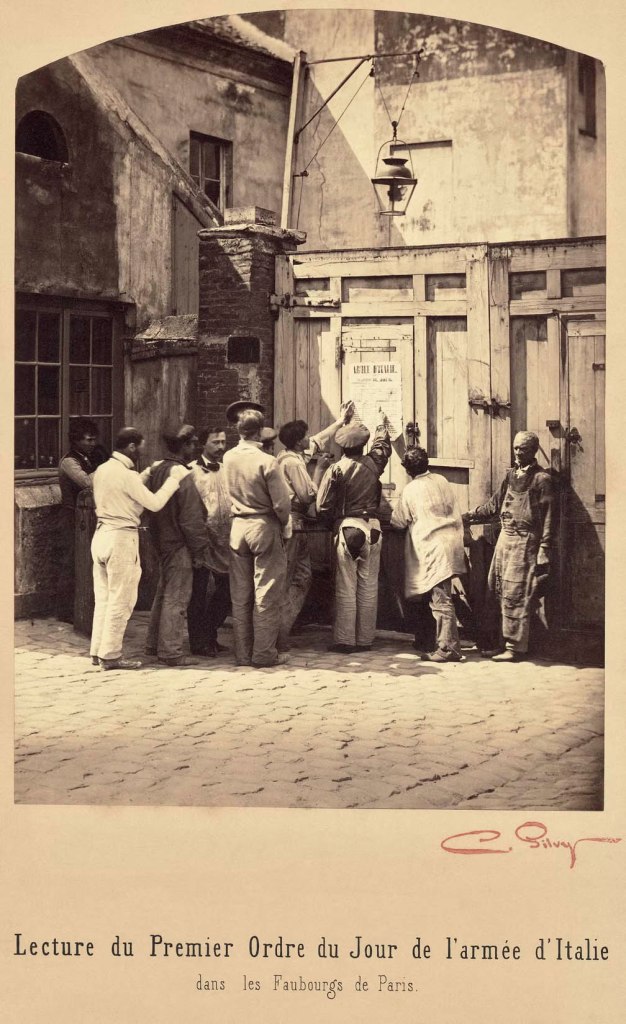

The sign above the entrance to Eugène Atget’s studio in Paris read Documents pour artistes (Documents for artists), declaring his modest ambition to create photographs for others to use as source material in their work. Atget (French, 1857-1927) made more than 8,500 pictures of Paris and its environs in a career that spanned over thirty years, from the late nineteenth century until his death. To facilitate access to this vast body of work for himself and his clients, he organised his photographs into discrete series, a model that guides the organisation of this exhibition. The works are presented here in six groups, demonstrating Atget’s sustained attention to certain motifs or locations and his consistently inventive and elegant methods of rendering the complexity of the three-dimensional world on a flat, rectangular plate.

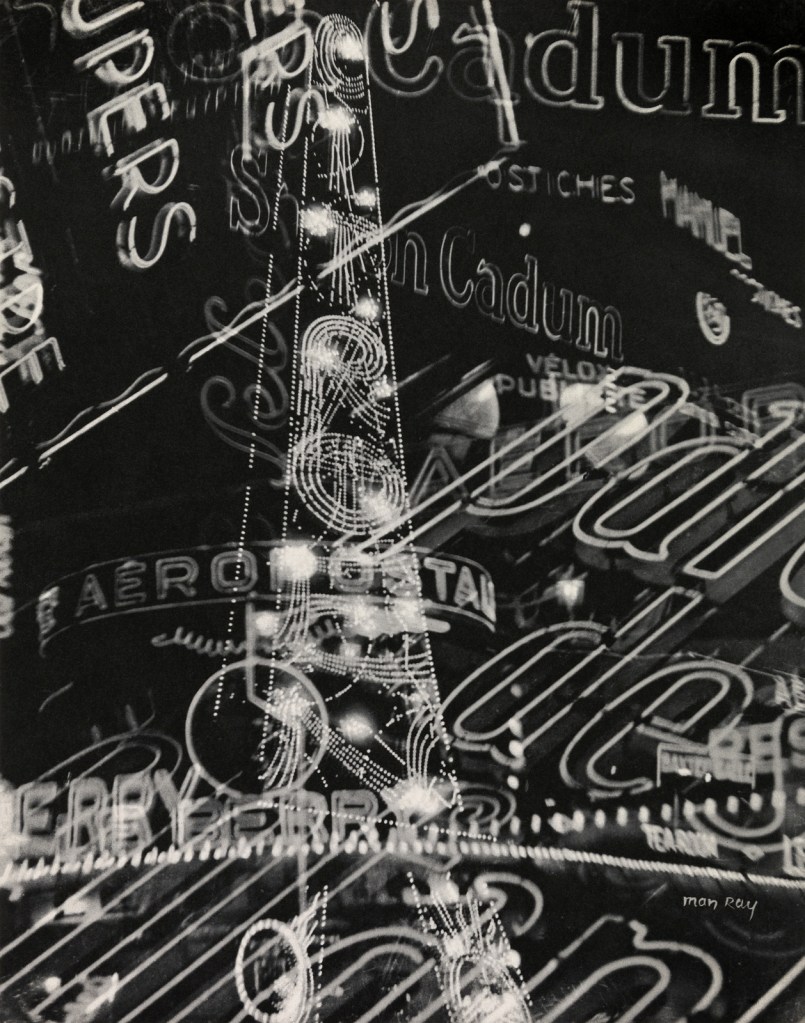

In 1925 the American artist Man Ray purchased forty-two photographs from Atget, who lived down the street from him in Montparnasse. Man Ray believed he detected a kindred Surrealist sensibility in the work, to which suggestion Atget replied, “These are simply documents I make.” This humility belies the extraordinary pictorial sophistication and beauty that is characteristic of much of Atget’s oeuvre and his role as touchstone and inspiration for subsequent generations of photographers, from Walker Evans to Lee Friedlander. This exhibition bears witness to his success, no matter the unassuming description he gave of his life’s work.

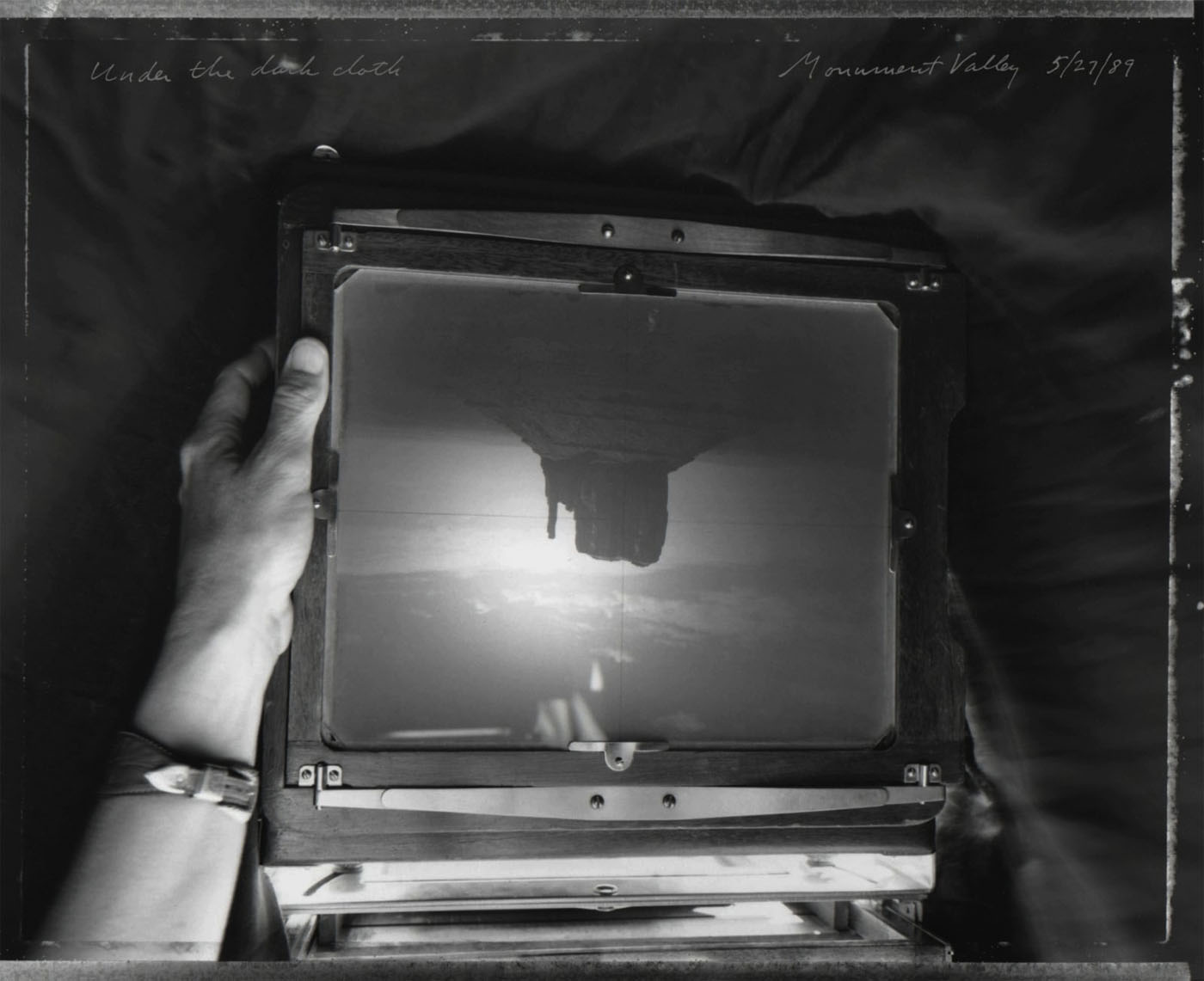

A Note on the Prints

Atget made photographs with a view camera resting on a tripod. An example of his 24-by-18-centimeter glass plate negatives is on display here. Each print was made by exposing light-sensitive paper to the sun in direct contact with one of these negatives, which Atget numbered sequentially within each series. He frequently scratched the number into the emulsion on the negative, and thus it appears in reverse at the bottom of most prints. He also inscribed the number, along with the work’s title, in pencil on the verso of each print. These titles appear (with English translations where necessary) on the individual wall labels, preserving Atget’s occasionally idiosyncratic titling practices. The Abbott-Levy Collection at The Museum of Modern Art, to which the prints in this exhibition belong (except where noted), is composed of close to 5,000 distinct photographs and 1,200 glass plate negatives that were in Atget’s studio at the time of his death. The Museum purchased this collection in 1968 from photographer Berenice Abbott and art dealer Julien Levy, thanks to the unflagging efforts of John Szarkowski, then director of the Department of Photography, and in part to the generosity of Shirley C. Burden.

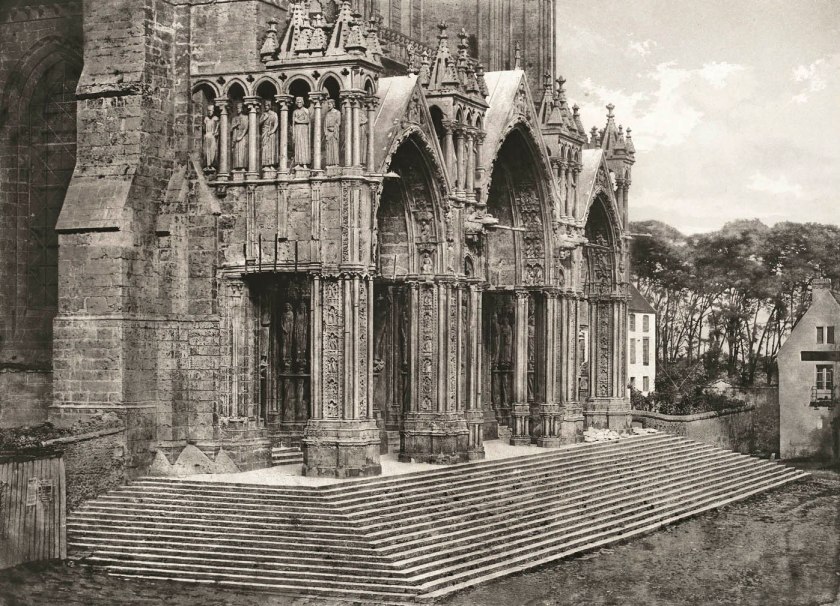

Fifth arrondissement

For more than thirty years, Atget photographed in and around Paris. Curiously, given the depth of this investigation, he never photographed the Eiffel Tower, generally avoided the grand boulevards, and eschewed picture postcard views. Instead Atget focused on the fabric of the city: facades of individual buildings (both notable and anonymous), meandering streetscapes, details of stonework and ironwork, churches, shops, and the occasional monument. Even a selective cross section of the photographs he made in the fifth arrondissement over the course of his career suggests that his approach, while far from systematic, might yet be termed comprehensive.

Courtyards

Atget clearly relished the metaphorical and physical aspects of the courtyard – a space that hovers between public and private, interior and exterior – and he photographed scores of them, both rural and urban. The motif was chosen as the backdrop for what was likely Atget’s first photograph of an automobile (Cour, 7 rue de Valence), and it was versatile enough to transform itself depending on where Atget placed his camera (see the two views of the courtyard at 27 quai d’Anjou). The dark areas that appear in the upper corners of some prints are the result of vignetting: a technique in which the light coming through the camera’s lens does not fully cover the glass plate negative, allowing Atget to create an arched pictorial space that echoed the physical one before his camera.

Wall text from the exhibition

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Rue de la Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève

June 1925

Gelatin silver printing-out-paper print

6 11/16 x 8 3/4 inches (17 x 22.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Maison où Mourut Voltaire en 1778, 1 rue de Beaune

1909

Albumen silver print

8 9/16 x 7 inches (21.8 x 17.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Balcon, 17 rue du Petit-Pont

1913

Albumen silver print

8 5/8 x 6 15/16 inches (21.9 x 17.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

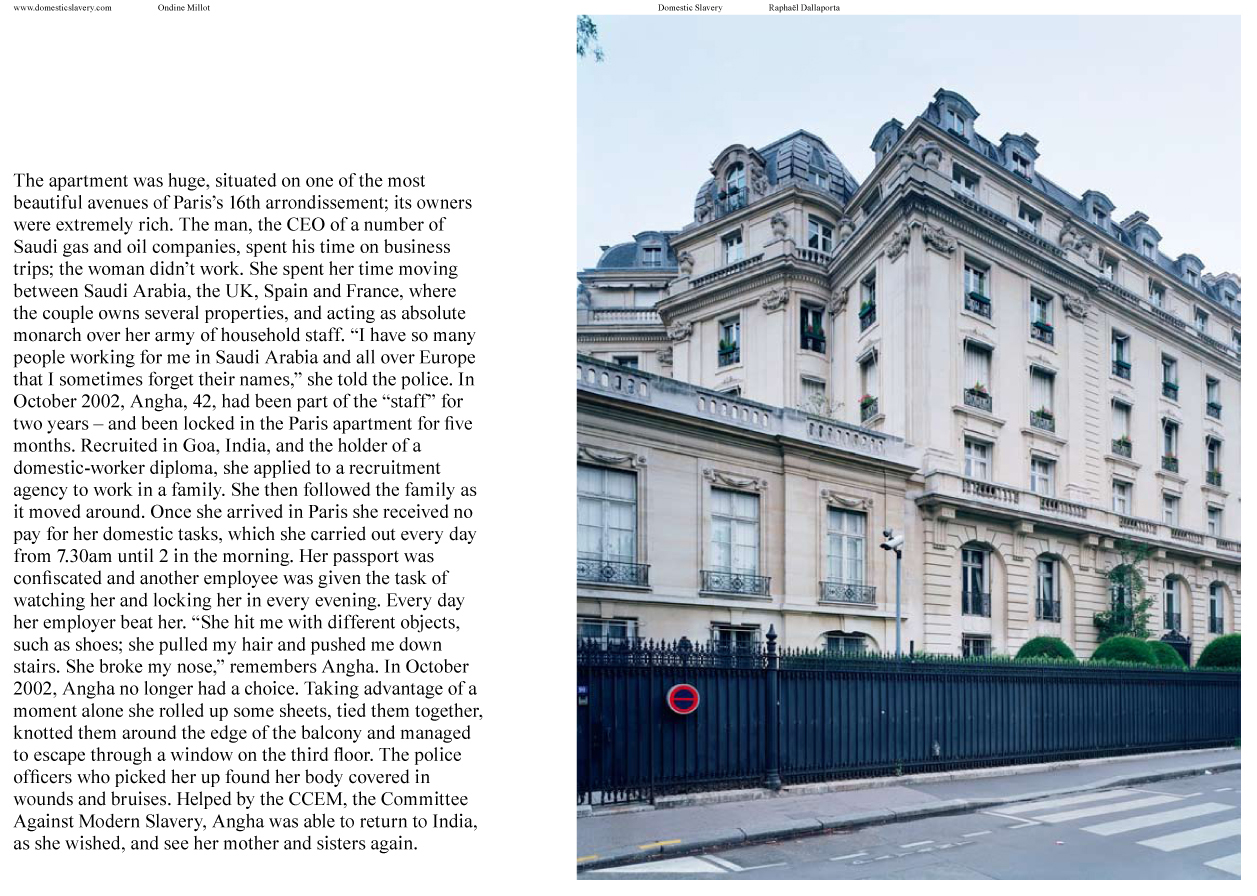

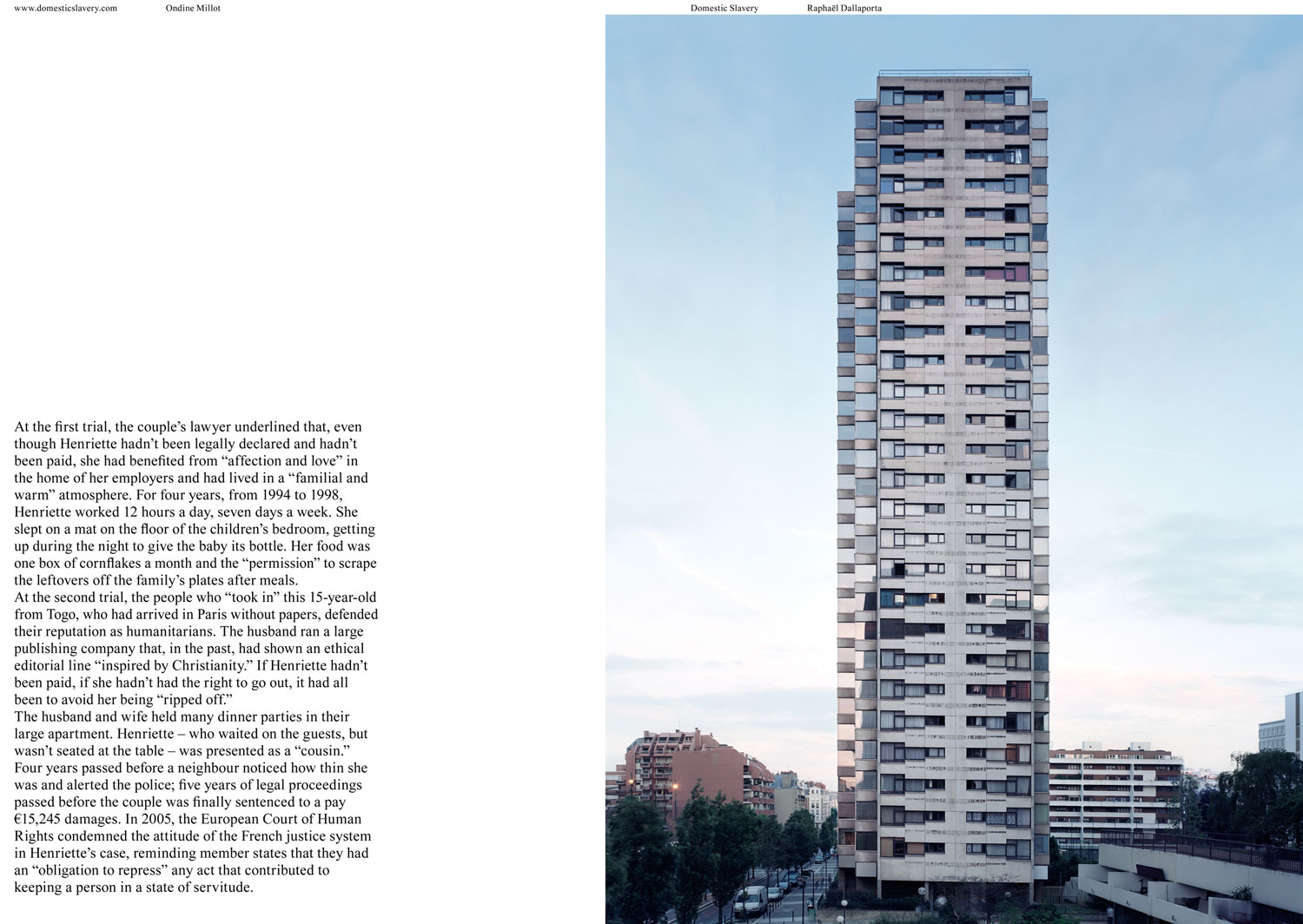

Eugène Atget: “Documents pour artistes“ presents six fresh and highly focused cross sections of the career of master photographer Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927), drawn exclusively from The Museum of Modern Art’s unparalleled holdings of his work. The exhibition, on view at MoMA from February 6 through April 9, 2012, gets its name from the sign outside Atget’s studio door, which declared his modest ambition to create documents for other artists to use as source material in their own work. Whether exploring Paris’s fifth arrondissement across several decades, or the decayed grandeur of parks at Sceaux in a remarkable creative outburst at the twilight of his career, Atget’s lens captured the essence of his chosen subject with increasing complexity and sensitivity. Also featured are Atget’s photographs made in the Luxembourg gardens; his urban and rural courtyards; his pictures of select Parisian types; and his photographs of mannequins, store windows, and street fairs, which deeply appealed to Surrealist artists living in Paris after the First World War. The exhibition is organised by Sarah Hermanson Meister, Curator, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art.

Atget made more than 8,500 pictures of Paris and its environs in a career that spanned over 30 years, from the late-19th century until his death. To facilitate access to this vast body of work for himself and his clients, he organised his photographs into discrete series, a model that guides the organisation of this exhibition. More than 100 photographs are presented in six groups, demonstrating Atget’s sustained attention to certain motifs or locations and his consistently inventive and elegant methods of rendering the complexity of the three-dimensional world on a flat, rectangular plate.

With seemingly inexhaustible curiosity, Atget photographed the streets of Paris. Eschewing picture-postcard views, and, remarkably, never once photographing the Eiffel Tower, he instead focused on the fabric of the city, taking pictures along the Seine, in every arrondissement, and in the “zone” outside the fortified wall that encompassed Paris at the time. His photographs of the fifth arrondissement are typical of this approach, and include facades of individual buildings (both notable and anonymous), meandering streetscapes, details of stonework and ironwork, churches, and the occasional monument.

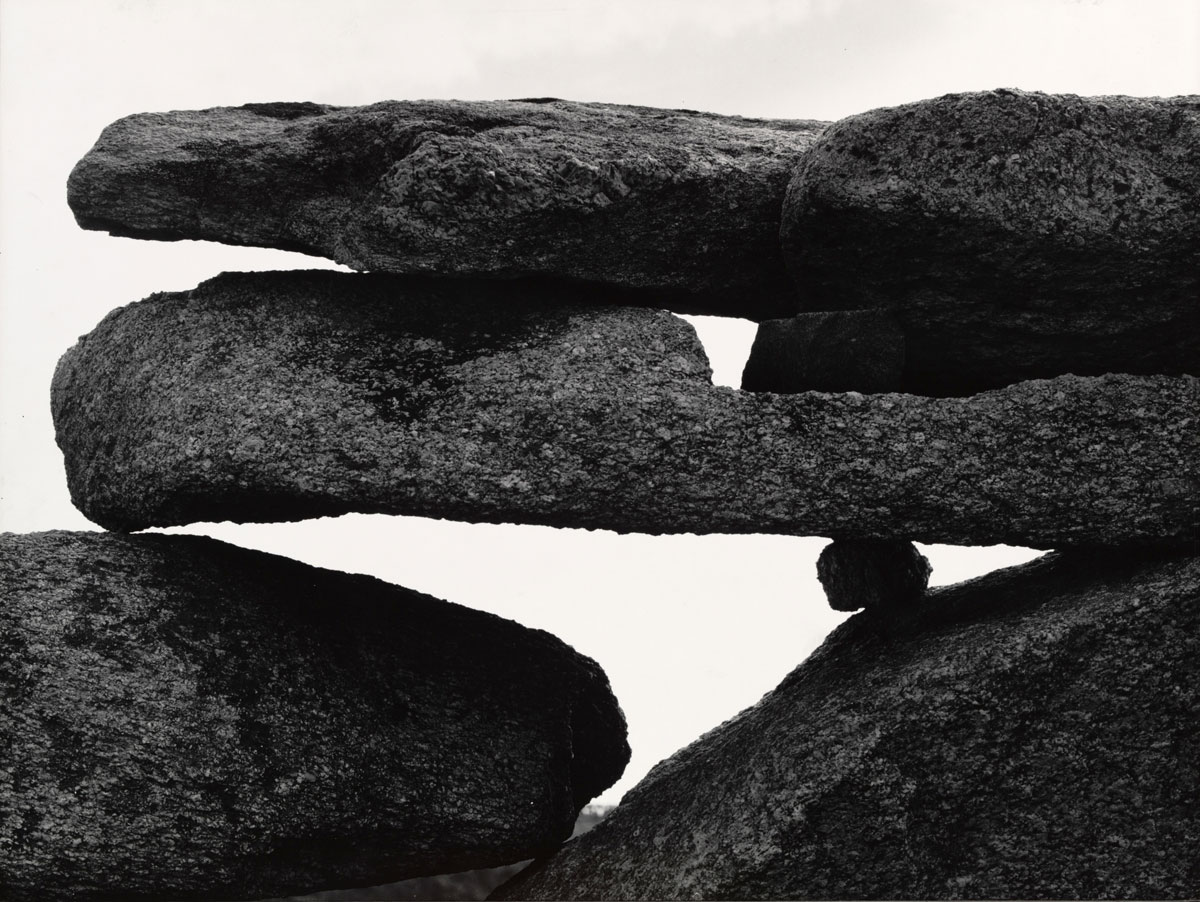

Between March and June 1925, Atget made 66 photographs in the abandoned Parc de Sceaux, on the outskirts of Paris, almost half of which are on view in this exhibition. His approach was confident and personal, even quixotic, and his notations of the time of day for certain exposures read almost like diary entries. These photographs have long been recognised as among Atget’s finest, and this is the first opportunity for audiences outside of France to appreciate the full diversity and richness of this accomplishment.

Atget photographed the Jardin de Luxembourg more than any other Parisian park, likely reflecting his preference for its character and its proximity to his home and studio on rue Campagne-Première in Montparnasse. His early photographs there tend to capture human activity – children with their governesses or men conversing in the shade – but this gave way to a more focused exploration of the garden’s botanical and sculptural components following the First World War, and culminated in studies that delicately balance masses of light and shadow, as is typical of Atget’s late work.

Atget firmly resisted public association with the Surrealists, yet his work – in particular his photographs of shop windows, mannequins, and the street fairs around Paris – captured the eye of artists with decidedly avant-garde inclinations, such as Man Ray and Tristan Tzara. Man Ray lived down the street from Atget, and the young American photographer Berenice Abbott, while working as Man Ray’s studio assistant, made Atget’s acquaintance in the mid-1920s – a relationship that ultimately brought the contents of Atget’s studio at the time of his death to MoMA, almost 40 years later.

Atget clearly relished the metaphorical and physical aspects of the courtyard – a space that hovers between public and private, interior and exterior – and he photographed scores of them, both rural and urban. This exhibition marks the first time these pictures have been grouped together, allowing the public to appreciate previously unexplored aspects of the Abbott-Levy Collection, which includes prints of nearly 5,000 different images.

Only a tiny fraction of the negatives Atget exposed during his lifetime are photographs of people, yet they have attracted attention disproportionate to their number. With few exceptions, this segment of his creative output can be divided into three types: street merchants (petits métiers); ragpickers (chiffonniers) or Romanies (romanichels, or Gypsies), who lived in impermanent structures just outside the fortified wall surrounding Paris; and prostitutes. As with each section of this exhibition, Atget’s career is represented by the finest prints drawn from critically distinct and essential aspects of his practice, allowing a fresh appreciation of photography’s first modern master.

Press release from the MoMA website

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Luxembourg

1923-1925

Matte albumen silver print

6 7/8 x 9 inches (17.5 x 22.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Luxembourg

1923-1925

Matte albumen silver print

7 x 8 13/16 inches (17.8 x 22.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Luxembourg

1902-1903

Albumen silver print

6 5/8 x 8 3/8 inches (16.8 x 21.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Jardin de Luxembourg

Atget photographed the Jardin de Luxembourg more than any other Parisian park, likely reflecting his preference for its character as well as its proximity to his home and studio on rue Campagne-Première in Montparnasse (about a ten-minute walk away). His photographs of the gardens made around 1900 tend to capture human activity (children with their governesses, men conversing in the shade), but this gave way to a more focused exploration of the garden’s botanical and sculptural components following the First World War and culminated in studies that delicately balance masses of light and shadow, typical of Atget’s late work.

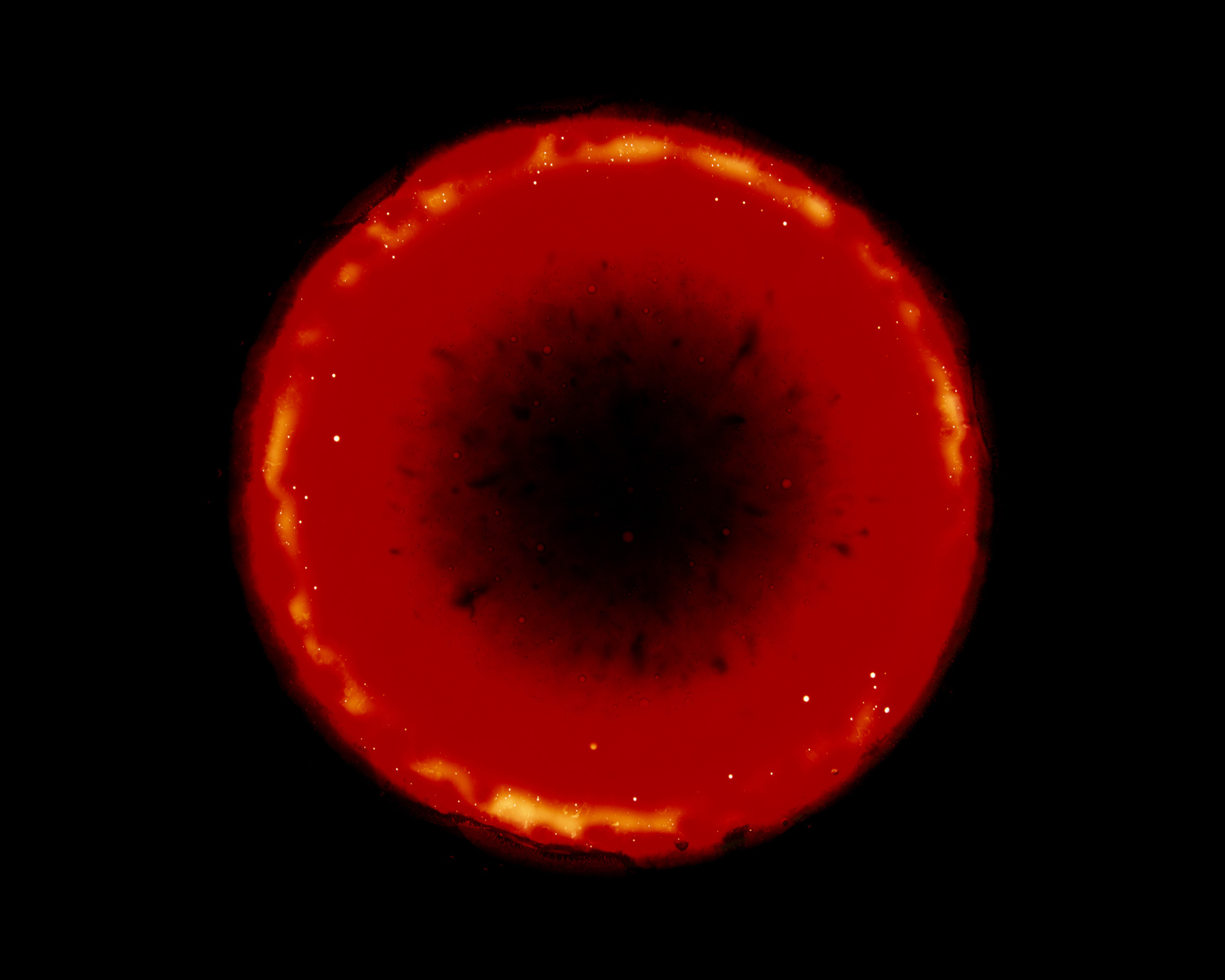

Parc de Sceaux

Between March and June 1925, Atget made sixty-six photographs in the abandoned Parc de Sceaux, on the outskirts of Paris. His approach was confident and personal, even quixotic, and his notations of the time of day for certain exposures read almost like diary entries. John Szarkowski wrote of this body of work: “One might think of Atget’s work at Sceaux as… a summation and as the consummate achievement of his work as a photographer – a coherent, uncompromising statement of what he had learned of his craft, and of how he had amplified and elaborated the sensibility with which he had begun. Or perhaps one might see the work at Sceaux as a portrait of Atget himself, not excluding petty flaws, but showing most clearly the boldness and certainty – what his old friend Calmettes called the intransigence – of his taste, his method, his vision. Atget made his last photograph at Sceaux after its restoration had begun. He perceived that the effort to tidy the grounds in anticipation of their conversion to a public park would fundamentally alter the untended, decayed grandeur that had been his muse.”

Wall text from the exhibition

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Parc de Sceaux

June 1925

Gelatin silver printing-out-paper print

7 x 8 7/8 inches (17.8 x 22.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Parc de Sceaux, mars, 8 h. matin

1925

Gelatin silver printing-out-paper print

7 1/16 x 8 13/16 inches (17.9 x 22.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Parc de Sceaux, 7 h. matin

March 1925

Matte albumen silver print

6 15/16 x 9 1/16 inches (17.6 x 23cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

People of Paris

Only a tiny fraction of the negatives Atget exposed during his lifetime feature the human figure as a central element. With few exceptions, this segment of his creative output can be divided into three types: street merchants (petits métiers); zoniers – ragpickers (chiffonniers) and Romanies (romanichels, or Gypsies) – who lived in impermanent structures in the zone just outside the fortified wall surrounding Paris; and prostitutes. The painter André Dignimont commissioned Atget to pursue this third subject in the spring of 1921, but the decidedly untawdry resulting images of brothels and prostitutes are only obliquely suggestive of the nature of their trade, so it is not difficult to imagine why the commission was concluded after only about a dozen negatives.

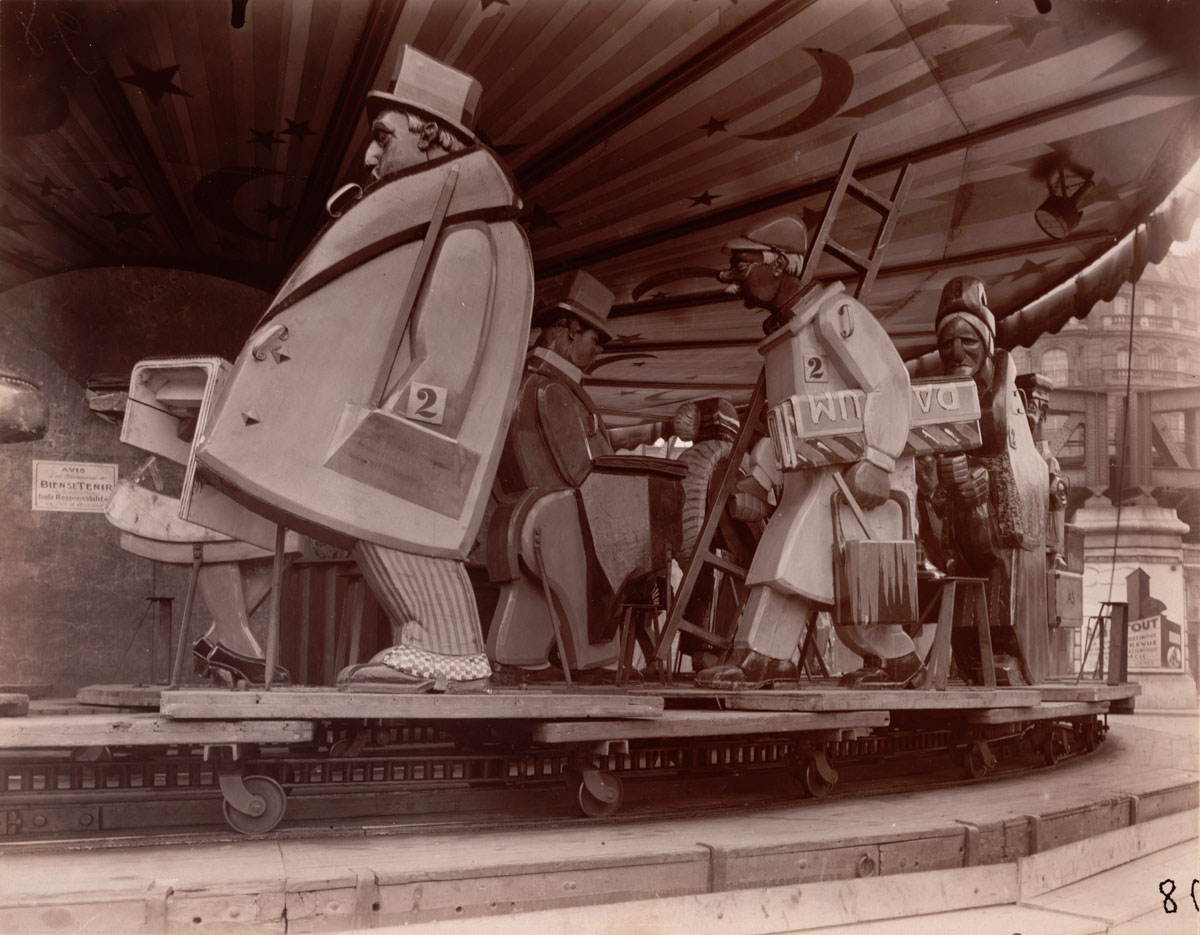

Surrogates and the Surreal

Atget’s photograph Pendant l’éclipse (During the eclipse) was featured on the cover of the seventh issue of the Parisian Surrealists’ publication La Révolution surréaliste, with the caption Les Dernières Conversions (The last converts), in June 1926. The picture was uncredited, as were the two additional photographs reproduced inside. Although Atget firmly resisted the association, his work – in particular his photographs of shop windows, mannequins, and the street fairs around Paris – had captured the attention of artists with decidedly avant-garde inclinations, such as Man Ray and Tristan Tzara. Man Ray lived on the same street as Atget, and the young American photographer Berenice Abbott (working as Man Ray’s studio assistant) learned of the French photographer and made his acquaintance in the mid-1920s – a relationship that ultimately brought the contents of Atget’s studio at the time of his death (in 1927) to The Museum of Modern Art almost forty years later.

Wall text from the exhibition

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Fête du Trône

1925

Gelatin silver printing-out-paper print

6 7/16 x 8 7/16 inches (16.4 x 21.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Fête de Vaugirard

1926

Gelatin silver printing-out-paper print

6 13/16 x 8 3/4 inches (17.3 x 22.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Avenue des Gobelins

1925

Gelatin silver printing-out-paper print

8 1/4 x 6 1/2inches (21 x 16.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Romanichels, groupe

1912

Gelatin silver printing-out-paper print

8 3/8 x 6 11/16 inches (21.2 x 17cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

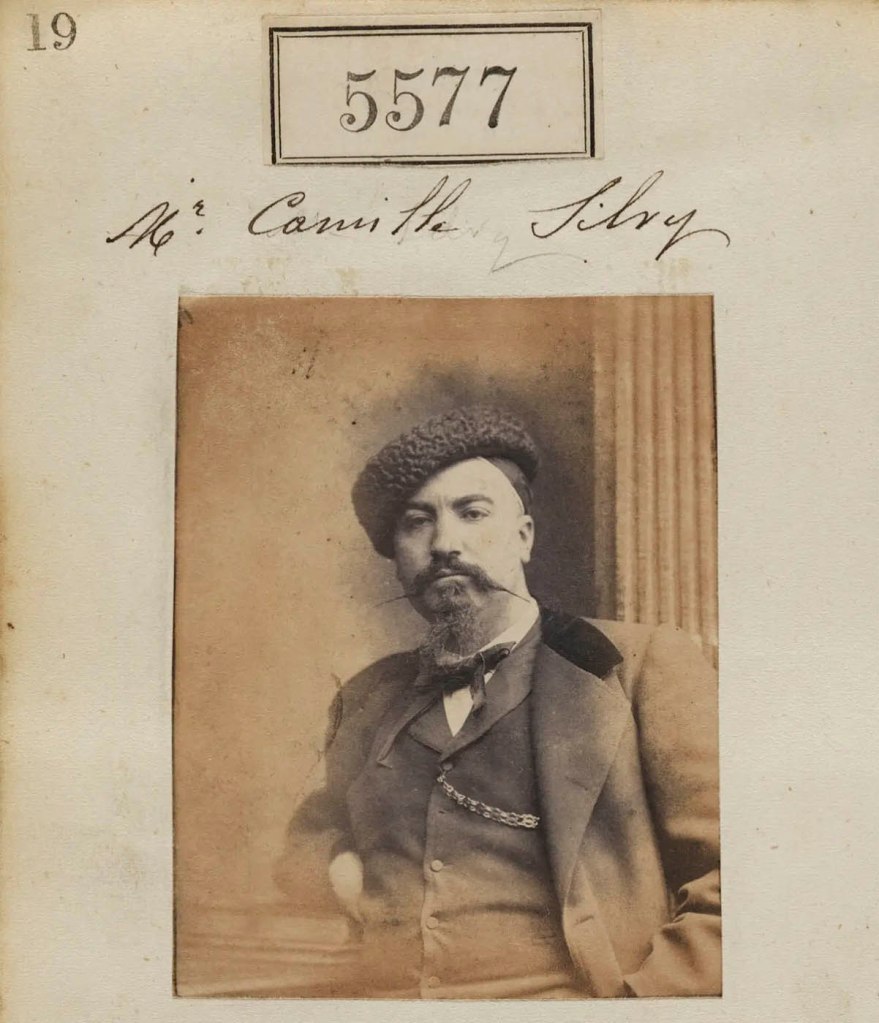

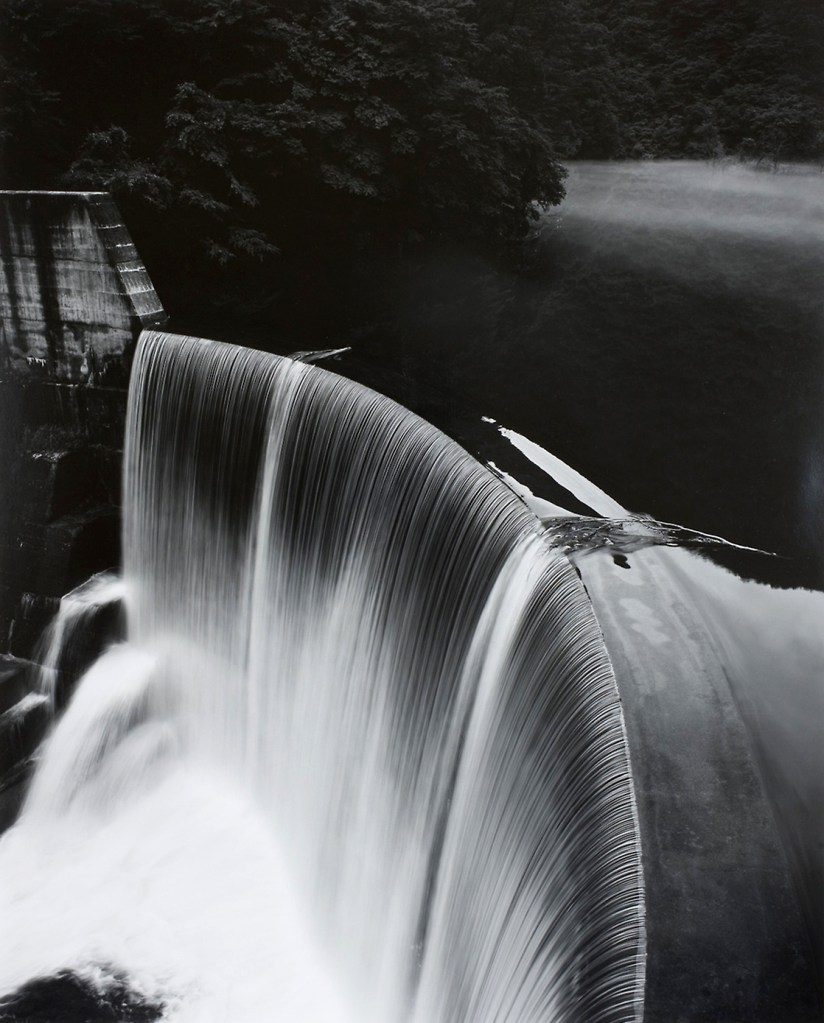

![Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910) '[River Scene, France]' Negative 1858; print 1860s from the exhibition 'Camille Silvy, Photographer of Modern Life, 1834-1910' at the National Portrait Gallery, London, July - Oct 2010 Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910) '[River Scene, France]' Negative 1858; print 1860s from the exhibition 'Camille Silvy, Photographer of Modern Life, 1834-1910' at the National Portrait Gallery, London, July - Oct 2010](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/silvy-river-scene-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.