Exhibition dates: 11th September, 2019 – 2nd February, 2020

Visited October 2019 posted January 2020

Curators: Martin Myrone, Senior Curator, pre-1800 British Art, and Amy Concannon, Curator, British Art 1790-1850

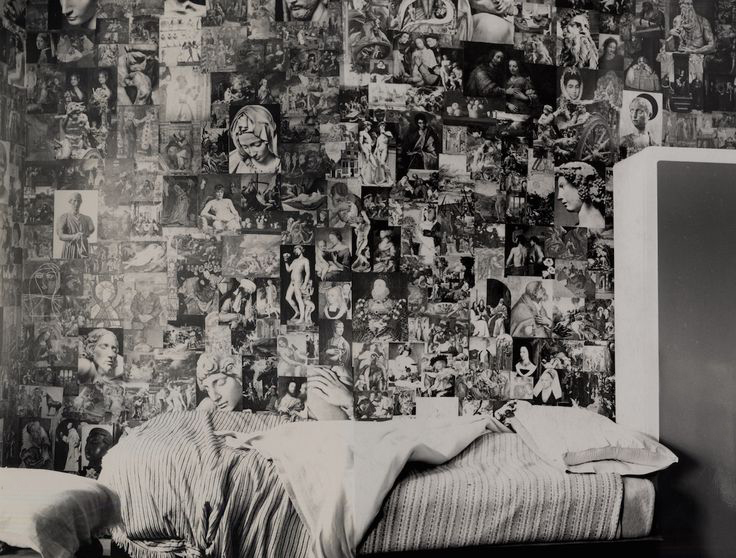

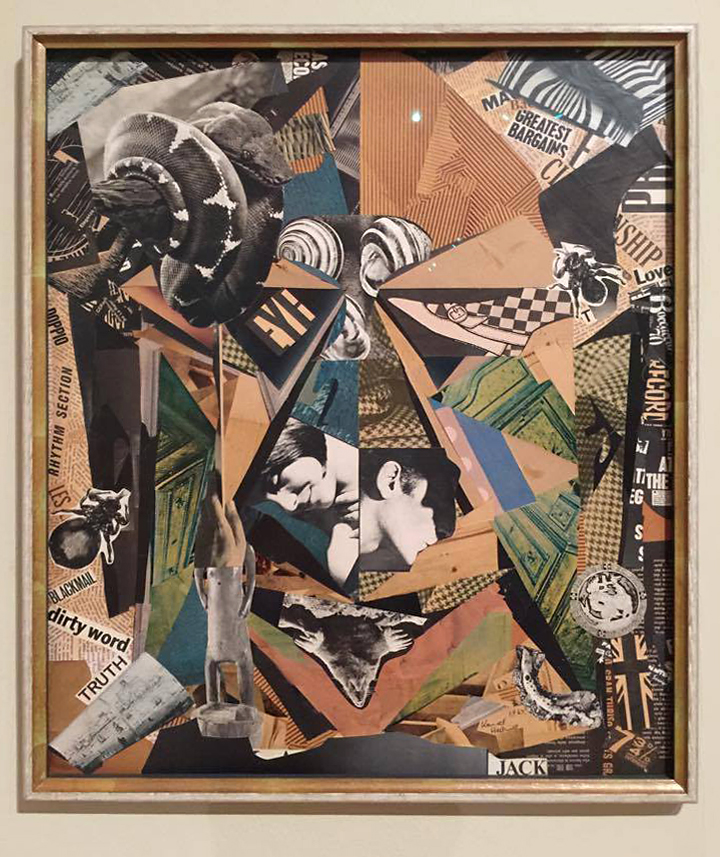

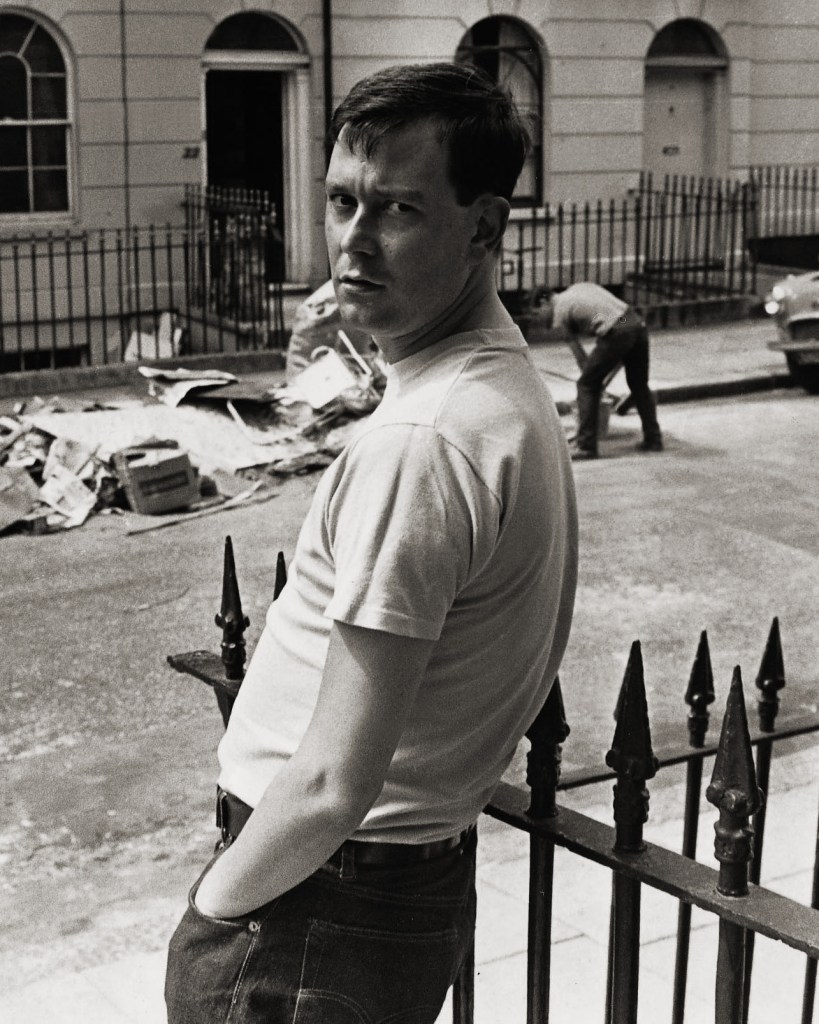

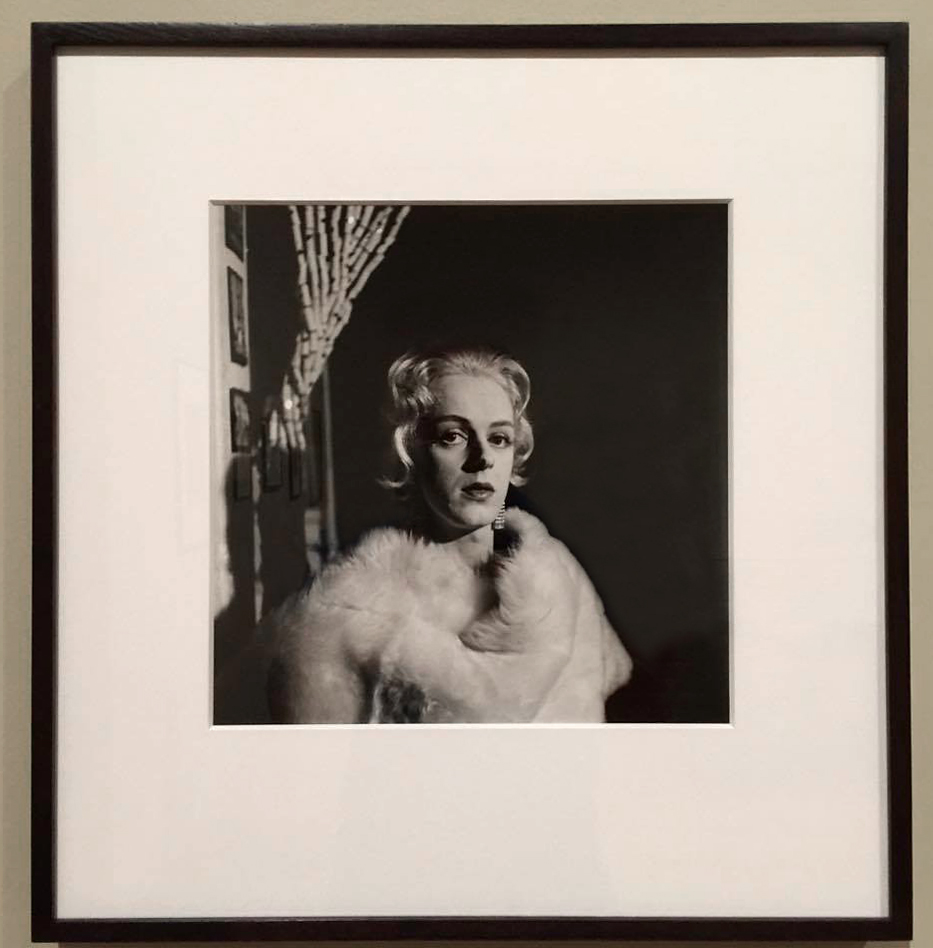

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

This first of two parts of this humongous posting. This exhibition has to be one of the highlights of my (art) life. The techniques, the colours, the forms and the MAGIC of Blake’s compositions brought me to tears.

I will write more on the work in the second part of the posting.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Tate Britain for allowing me to publish the media images in the posting. All other installation photographs as noted © Dr Marcus Bunyan. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Every page is a window open in Heaven … interwoven designs companion the poems, and gold and yellow tints diffuse themselves over the page like summer clouds. The poems [of Songs of Innocence] are the morning song of Blake’s genius.”

W.B. Yeats

“Blake sang of the ideal world, of the truth of the intellect, and of the divinity of the imagination. … The only writer to have written songs for children with the soul of a child … he holds, in my view, a unique position because he unites intellectual sharpness with mystic sentiment.”

James Joyce

Installation views of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain

© Tate

Photos: Seraphina Neville

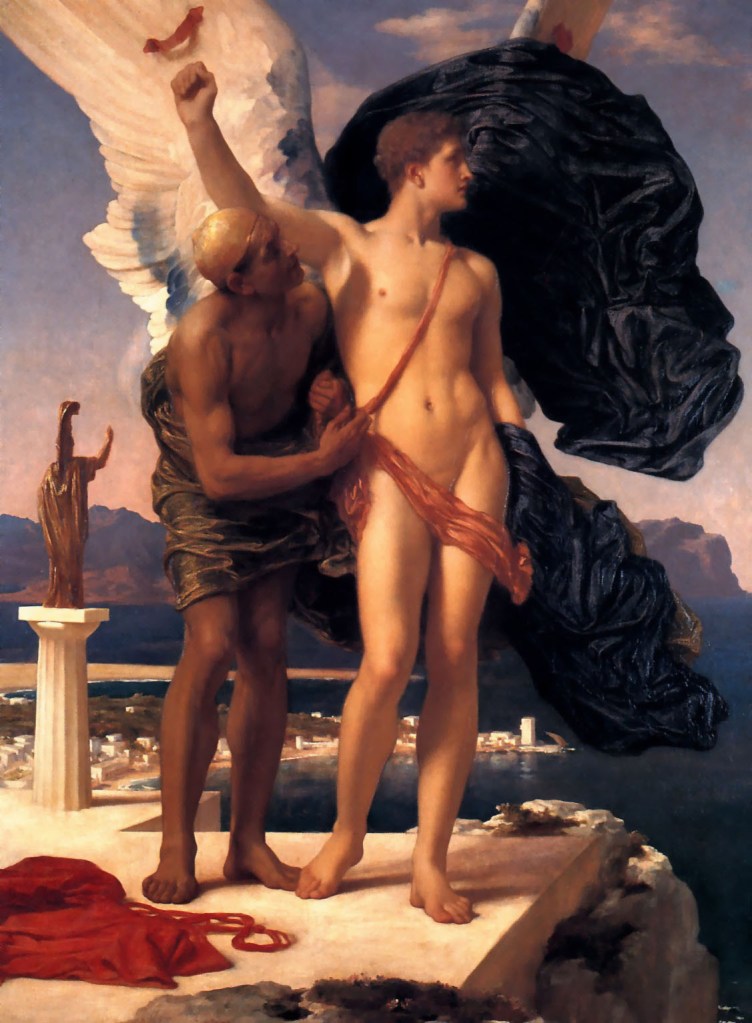

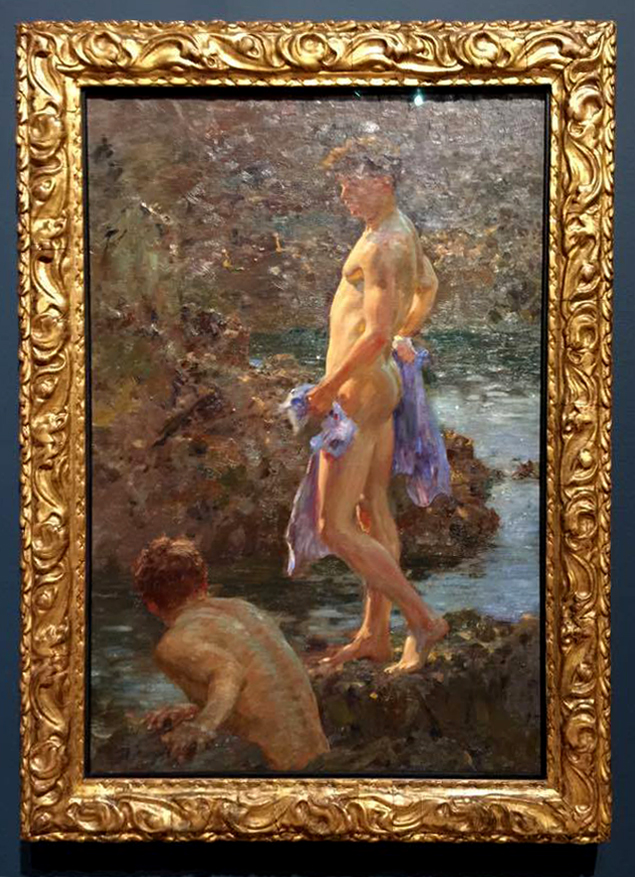

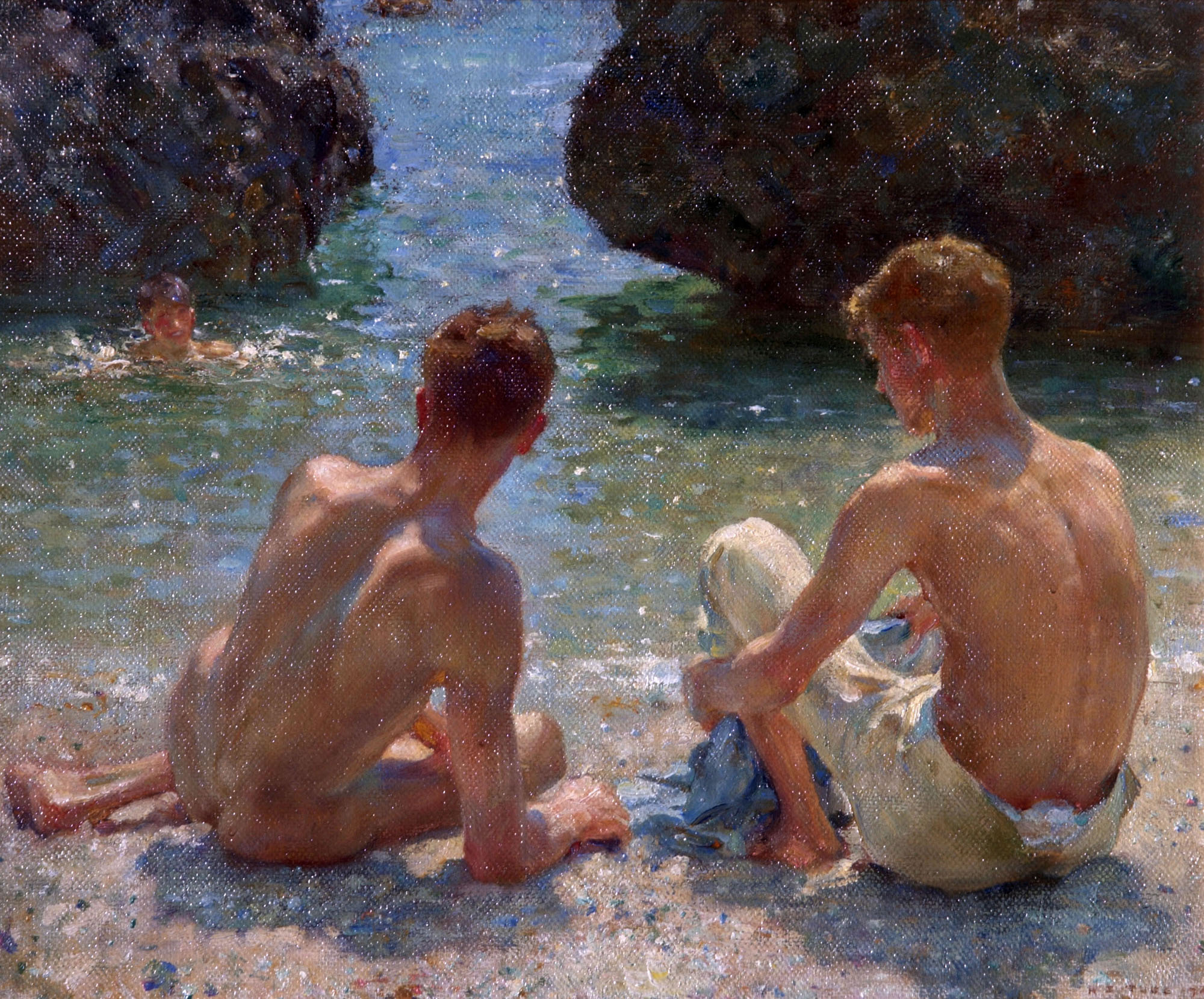

Tate Britain presents the largest survey of work by William Blake (1757-1827) in the UK for a generation. A visionary painter, printmaker and poet, Blake created some of the most iconic images in the history of British art and has remained an inspiration to artists, musicians, writers and performers worldwide for over two centuries. This ambitious exhibition brings together over 300 remarkable and rarely seen works and rediscovers Blake as a visual artist for the 21st century.

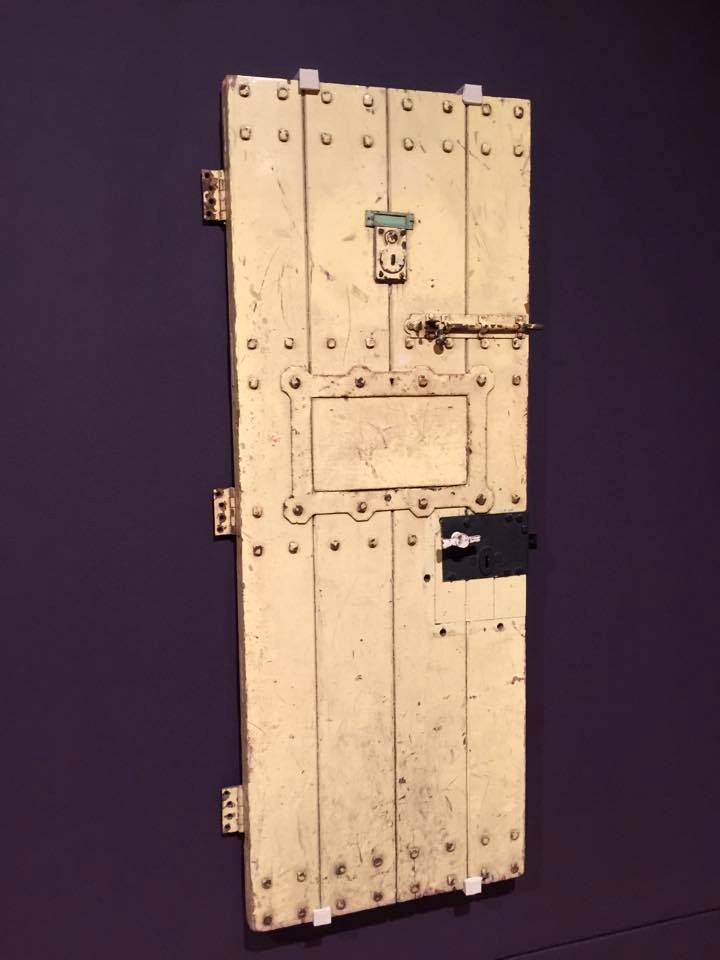

Tate Britain reimagines the artist’s work as he intended it to be experienced. Blake’s art was a product of his tumultuous times, with revolution, war and progressive politics acting as the crucible of his unique imagination, yet he struggled to be understood and appreciated during his life. Now renowned as a poet, Blake also had grand ambitions as a visual artist and envisioned vast frescos that were never realised. For the first time, The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan c. 1805-1809 and The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth c. 1805 have been enlarged and projected onto the gallery wall on the huge scale that Blake imagined. The original artworks are displayed nearby in a re-staging of Blake’s ill-fated exhibition of 1809, the artist’s only significant attempt to create a public reputation for himself as a painter. Tate has recreated the domestic room above his family hosiery shop in which the show was held, allowing visitors to encounter the paintings exactly as people did over 200 years ago.

The exhibition also provides a vivid biographical framework in which to consider Blake’s life and work. There is a focus on London, the city in which he was born and lived for most of his life. The burgeoning metropolis was a constant source of inspiration for the artist, offering an environment in which harsh realities and pure imagination were woven together. Blake’s creative freedom was also dependent on the unwavering support of those closest to him: his friends, family and patrons. Tate Britain highlights the vital presence of his wife Catherine Blake who offered both practical assistance and became an unacknowledged hand in the production of the artist’s engravings and illuminated books. The exhibition showcases a series of illustrations to Pilgrim’s Progress 1824-1827 and a copy of the book The Complaint, and the Consolation, or, Night Thoughts 1797, now thought to be coloured by Catherine.

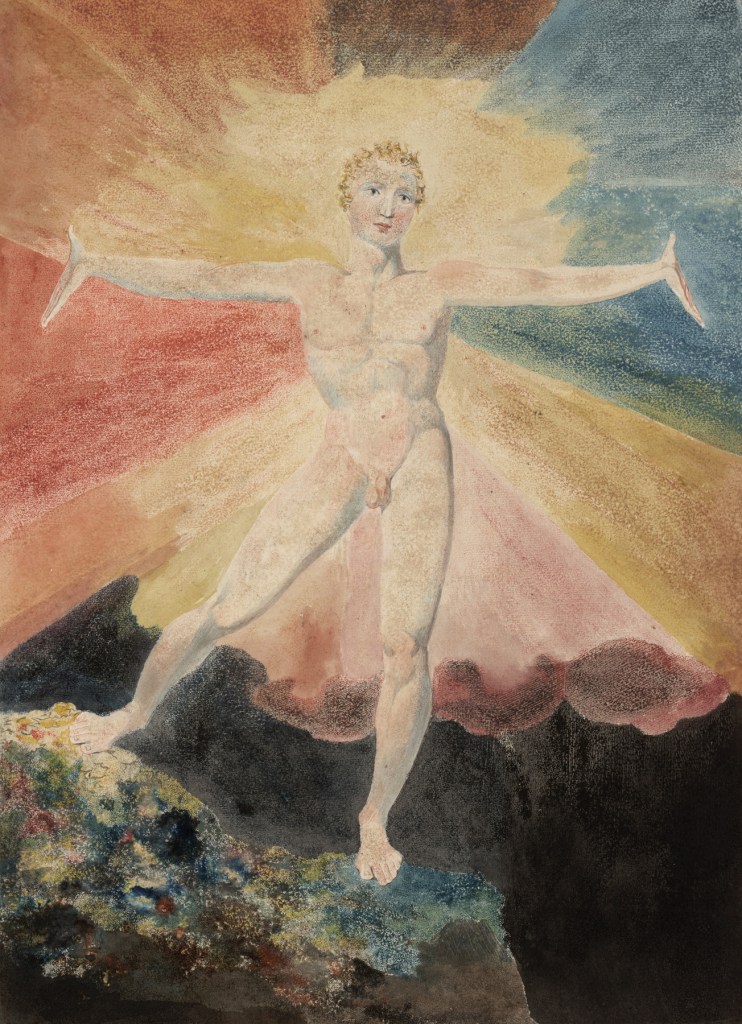

William Blake was a staunch defender of the fundamental role of art in society and the importance of artistic freedom. Shaped by his personal struggles in a period of political terror and oppression, his technical innovation, and his political commitment, these beliefs have inspired the generations that followed and remain pertinent today. Tate Britain’s exhibition opens with Albion Rose c. 1793, an exuberant visualisation of the mythical founding of Britain, created in contrast to the commercialisation, austerity and crass populism of the times. A section of the exhibition is also dedicated to his illuminated books such as Songs of Innocence and of Experience 1794, his central achievement as a radical poet.

Additional highlights include some of Blake’s best-known works including Newton 1795 – c. 1805 and Ghost of a Flea c. 1819-1820. This intricate painting was inspired by a séance-induced vision and is shown alongside a rarely seen preliminary sketch. The exhibition closes with The Ancient of Days 1827, an illustration for an edition of Europe: A Prophecy, completed only days before the artist’s death.

William Blake at Tate Britain is curated by Martin Myrone, Senior Curator, pre-1800 British Art, and Amy Concannon, Curator, British Art 1790-1850. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue from Tate Publishing and a programme of talks and events in the gallery.

Text from Tate Britain

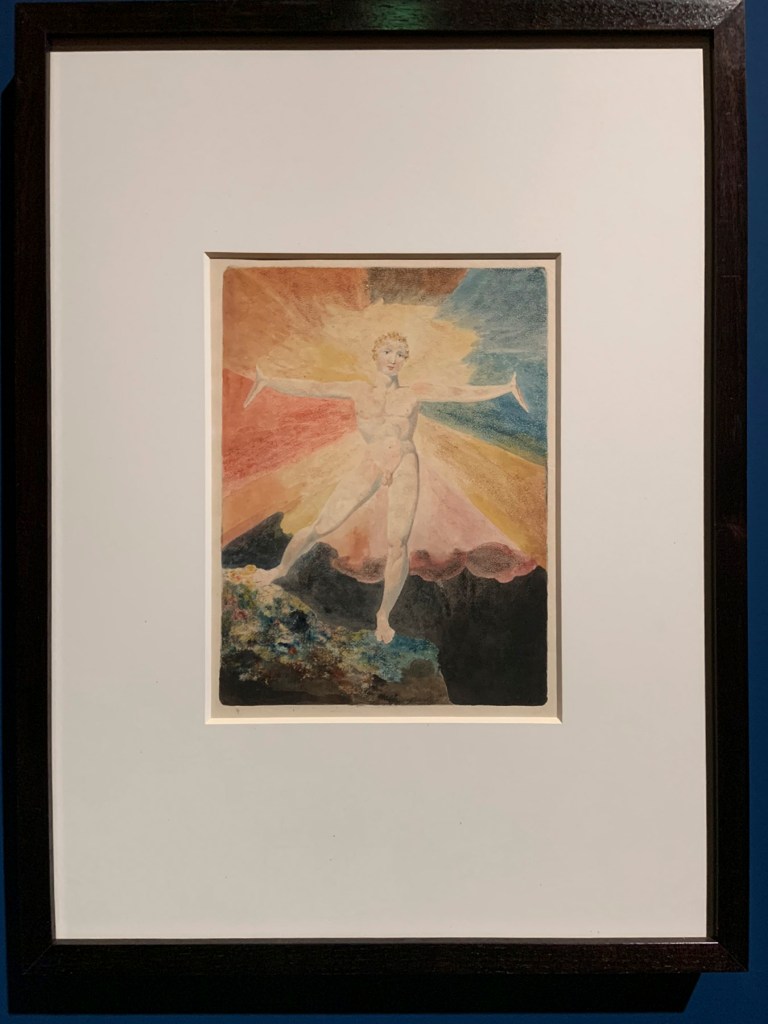

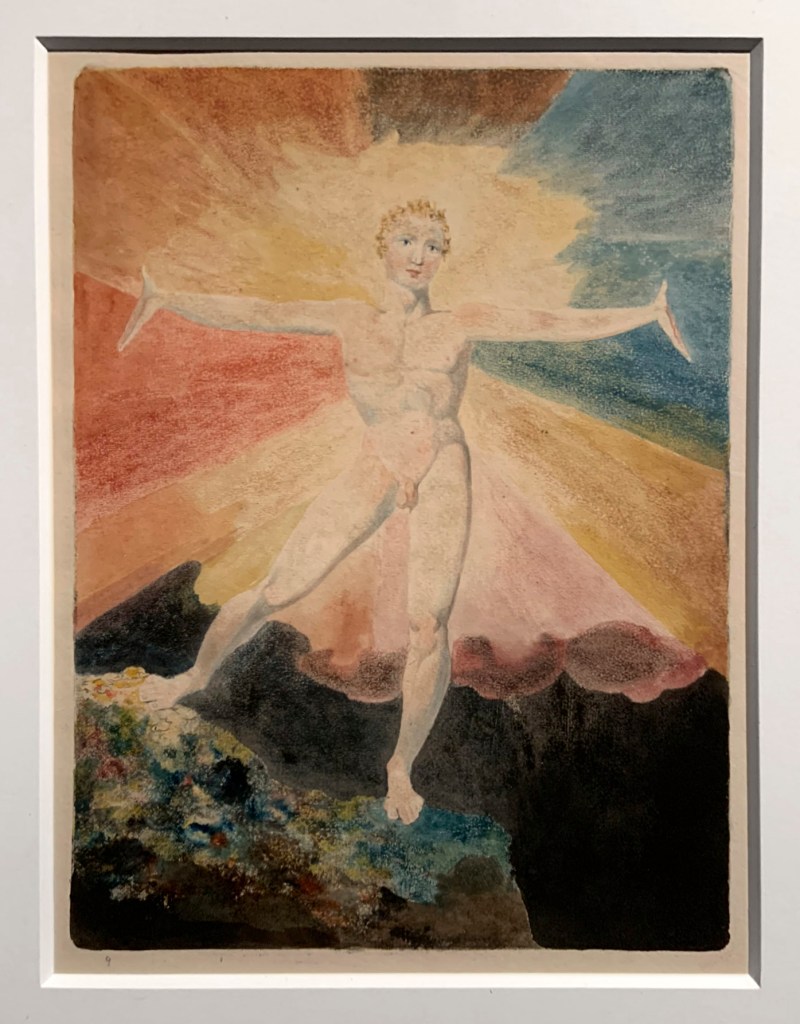

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Albion Rose (installation views)

c. 1793

Colour engraving

250 x 211 mm

Courtesy of the Huntington Art Collections

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

This image exemplifies how any single work by Blake might have multiple meanings. It can be related to several different strands within Blake’s poetry and thought. The figure has been reinterpreted many times, as a symbol of youthful rebellion, spiritual freedom and of creativity.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Albion Rose

c. 1793

Colour engraving

250 x 211 mm

Courtesy of the Huntington Art Collections

William Blake

The art and poetry of William Blake have influenced generations. He has inspired many creative people, political radicals and independent minds. His images and words are admired around the world for their originality and spirituality.

Blake lived at a time of radical thought, war and global unrest. The British Empire was expanding. New ideas about social justice developed alongside rapid industrialisation. Blake created imaginative images and texts that resonated with this changing world. They drew on his deeply felt religious beliefs and personal struggles.

The exhibition is organised chronologically. It takes us through the ups and downs of Blake’s creative and professional life. The full range of Blake’s work is on display here. His commercial engravings, original prints, his unique ‘illuminated books’ and paintings are all included. These have been drawn from public and private collections from around the world. To preserve these rarely seen objects, the light levels across the exhibition are deliberately low.

Blake’s art and poetry have appealed to many kinds of people, for different reasons. His work has provoked diverse interpretations. This exhibition does not try to explain Blake’s imagery and symbolism in a definitive way.

Instead it considers the reception of his art and how it was experienced by his contemporaries. It sets out the personal and social conditions in which it was made. In doing so we hope to reveal the circumstances that gave Blake the freedom to create such innovative works.

Wall text

Room 1

The art and poetry of William Blake have influenced generations. He has inspired many creative people, political radicals and independent minds. His images and words are admired around the world for their originality and spirituality.

Blake lived at a time of radical thought, war and global unrest. The British Empire was expanding. New ideas about social justice developed alongside rapid industrialisation. Blake created imaginative images and texts that resonated with this changing world. They drew on his deeply felt religious beliefs and personal struggles.

The exhibition is organised chronologically. It takes us through the ups and downs of Blake’s creative and professional life. The full range of Blake’s work is on display here. His commercial engravings, original prints, his unique ‘illuminated books’ and paintings are all included. These have been drawn from public and private collections from around the world. To preserve these rarely seen objects, the light levels across the exhibition are deliberately low.

Blake’s art and poetry have appealed to many kinds of people, for different reasons. His work has provoked diverse interpretations. This exhibition does not try to explain Blake’s imagery and symbolism in a definitive way. Instead it considers the reception of his art and how it was experienced by his contemporaries. It sets out the personal and social conditions in which it was made. In doing so we hope to reveal the circumstances that gave Blake the freedom to create such innovative works.

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Joseph Making himself Known to his Brethren (installation views)

1784-1785

India ink and watercolour over graphite on paper

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing at left, Blake’s Joseph’s Brethren Bowing down before him (1784-1785) and at right, Joseph Ordering Simeon to be Bound (1784-1785)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

The story of Joseph

Blake’s bitter view of the contemporary art world has its origins in the disappointments and frustrations he experienced early in his career.

In 1785 Blake exhibited these three watercolour designs showing the biblical story of Joseph. Blake showed them at the annual exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, the main showcase for contemporary art.

Students at the Academy were encouraged to depict serious, dramatic subject matter in a classical style. But these exhibitions were filled with more commercial artworks. The exhibition catalogue, also on display here, shows the dominance of portraits, landscapes and light-hearted ‘fancy’ subjects. Being watercolours, Blake’s designs were shown in a separate space where they got less public attention than the oil paintings in the main gallery.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Joseph’s Brethren Bowing down before him (installation views)

1784-1785

India ink and watercolour over graphite on paper

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London with at bottom middle, Drawing of the legs of Cincinnatus (c. 1779-1780)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake wall text

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Drawing of the legs of Cincinnatus (installation view)

c. 1779-1780

Ink and wash over graphite on paper

Bolton Museum and Archive

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

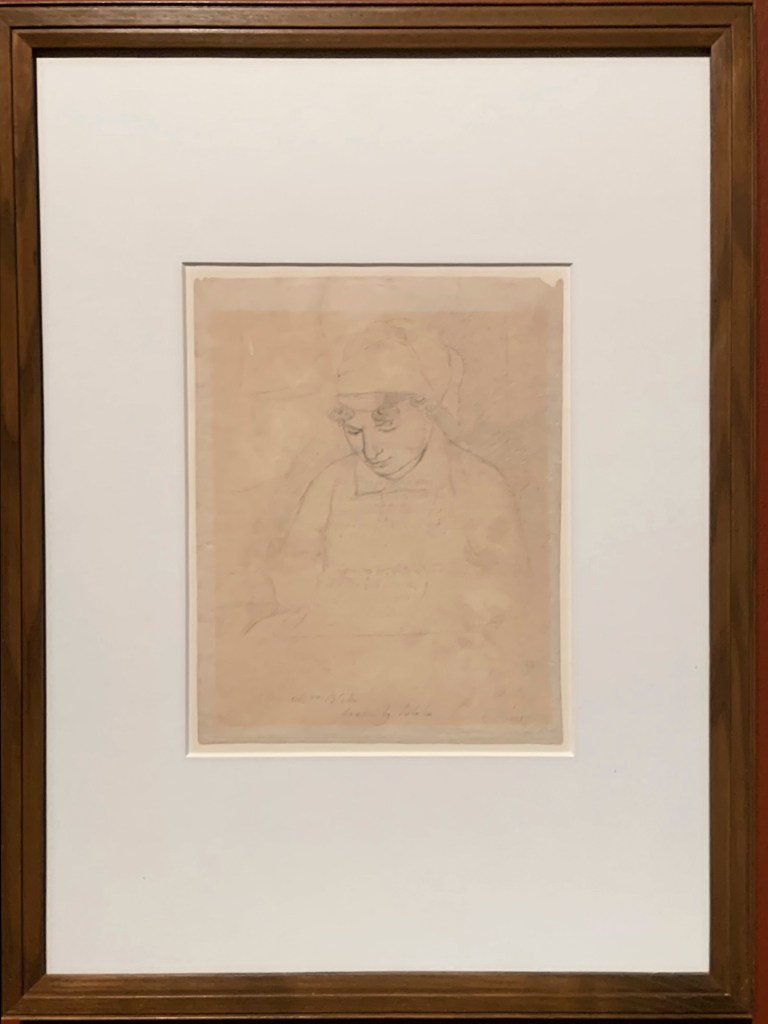

This intimate and apparently casually-drawn portrait shows Catherine Blake (née Boucher, 1762-1831). William and Catherine were married from 1782 until Blake’s death in 1827. Catherine played a huge part in Blake’s creative and commercial work. She helped him with printing and colouring his works, even finishing some of his drawings. Blake’s extraordinary vision depended on his partnership with Catherine.

Wall text

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Catherine Blake (installation view)

1805

Graphite on paper

286 x 221 mm

Tate. Bequeathed by Miss Alice G.E. Carthew 1940

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Catherine Blake

1805

Graphite on paper

286 x 221 mm

Tate. Bequeathed by Miss Alice G.E. Carthew 1940

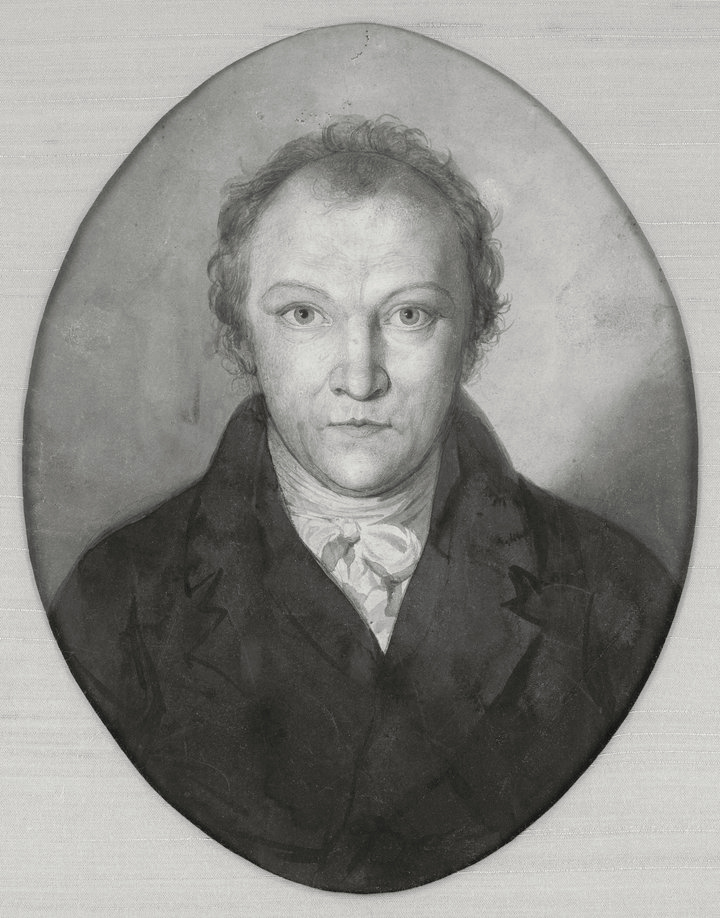

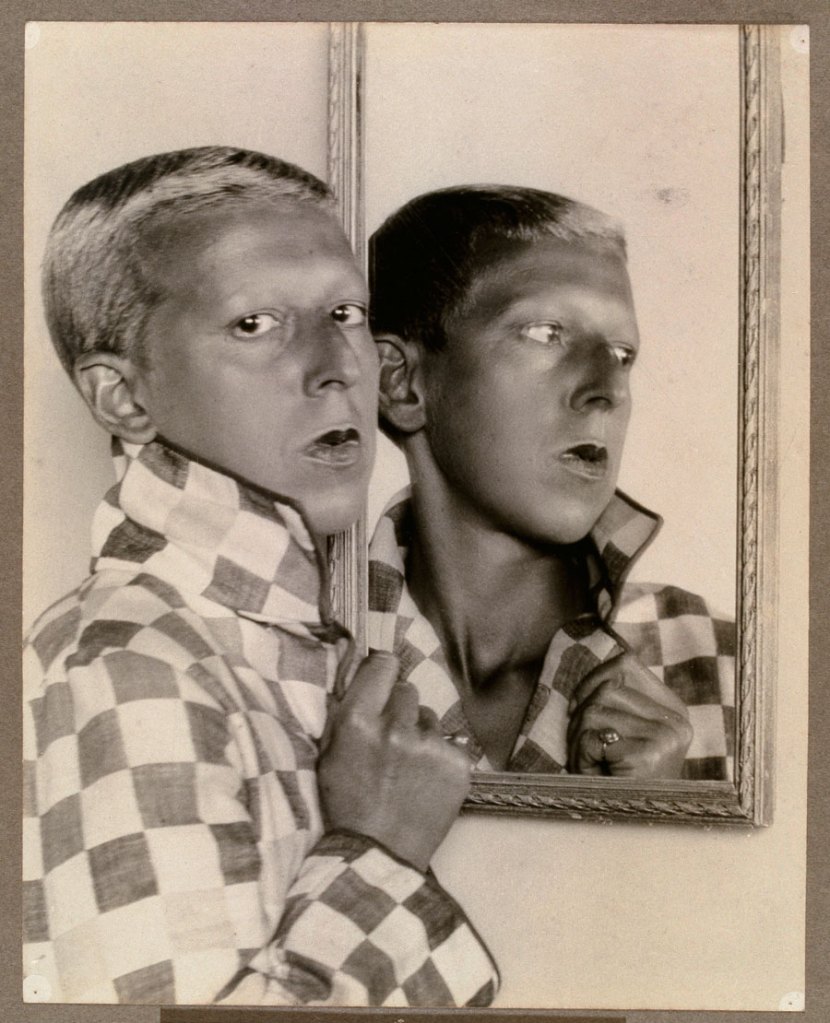

A portrait of William Blake, thought to be his only self-portrait, will be exhibited in the UK for the first time in a major survey of his work at Tate Britain. In the 200 years since its creation, the detailed pencil drawing only been shown once before and never in the artist’s own country. It offers a unique insight into the visionary painter, printmaker and poet responsible for some of Britain’s best loved artwork and will be displayed alongside a sketch of Blake’s wife Catherine from the same period, highlighting her vital contribution to his life and work.

Created when Blake was around 45 years old, the work is thought to present an idealised likeness. Rather than showing Blake as a painter or engraver, signs of his creative intensity are conveyed in his direct hypnotic gaze. This compelling image was produced after 1802, at a turning-point in Blake’s life. Having lived in Sussex for three years and been falsely accused of treason, Blake returned to his native city of London and was re-establishing himself as an artist. The portrait shows Blake as an isolated and misunderstood figure.

A crucial presence in Blake’s life, Catherine offered both practical assistance and became an unacknowledged hand in the production of his engravings and illuminated books. His visual art and poetry began to develop in original ways only after their marriage in 1782. At the time she was illiterate but learnt to read and write with her husband and became an accomplished printmaker in her own right. Together, these rare examples of Blake’s portraiture highlight the ways in which his extraordinary vision was dependent on the domestic stability of his life with Catherine.

Text from the Tate Britain website

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Portrait of William Blake (installation view)

c. 1802

Graphite with black, white and grey washes on paper

Collection of Robert N. Essick

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

This is probably a self-portrait drawn by Blake when he was in his 40s. It does not present him in the act of writing or drawing. Instead, the image invites us to see his intense gaze as a sign of his creative force. This perhaps reflects his claim that he saw visions. Blake’s art and personal behaviour divided contemporary opinion. A few friends and supporters accepted him as a genius. Many others considered him eccentric or questioned his mental health.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Portrait of William Blake (installation view)

c. 1802

Graphite with black, white and grey washes on paper

Collection of Robert N. Essick

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

‘Blake be an artist!’

Blake was born in London in 1757, the son of a fairly successful shopkeeper in Broad Street, Soho. Blake wanted to be an artist from an early age. His family indulged his passion. They bought prints and plaster casts for him to copy, paid for drawing lessons and funded his training as an apprentice engraver. In 1779 he enrolled as a student at the Royal Academy of Arts. This gallery explores the art he created in the years that followed. It was during this time that he developed his ambitions as an original artist and poet.

The Royal Academy encouraged its students to imitate the great art of the past. They were expected to copy antique sculptures and look to Renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Raphael for inspiration.

Blake later rejected the more rigid ideas associated with Academic teaching. He sought to create a more personal vision and began to identify with the ‘Gothic’ artists of the medieval past. He felt the Academy was being taken over by portrait painters motivated by self-interest. But he did admire some ambitious and individualistic figures there. These included James Barry and Henry Fuseli. Blake took seriously their ideas about painting great public works full of moral purpose and drama. The conflict between such aims and the realities of a cynical and market-driven art world would be a shaping force in Blake’s creative life.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Academy Study (installation view)

1779-1780

Graphite on paper

Lent by the British Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Early drawings and watercolours

Blake’s earliest drawings typically used sweeping lines and areas of grey washed ink or watercolour. His figures make grand gestures in bare, even abstract, settings.

His style was based on the innovative art of the 1760s and 1770s, especially the drawings of James Barry, Henry Fuseli, and John Flaxman. They became well known for creating works with strong visual and emotional impact and communicating ideas in a bold way.

Blake’s subjects were often drawn from history, literature and the Bible. This was in keeping with the teaching of the Royal Academy and traditional ideas about ‘high art’. However, Blake’s subject matter from these early years is sometimes unclear. Spiritual forms, ghosts and visions start to appear. This means that the story and meaning of his individual works can be difficult to decipher.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing Blake’s Age Teaching Youth (c. 1785-1790)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

An Allegory of the Bible (installation view)

c. 1780-1785

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate, Bequeathed by Miss Rachel M. Dyer 1969

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Blake started using more colours in the mid-1780s. The mysterious subject matter of this design is new as well. The title is not the artist’s own. It was added by later commentators, as is often the case with Blake’s symbolic designs.

Wall text from the exhibition

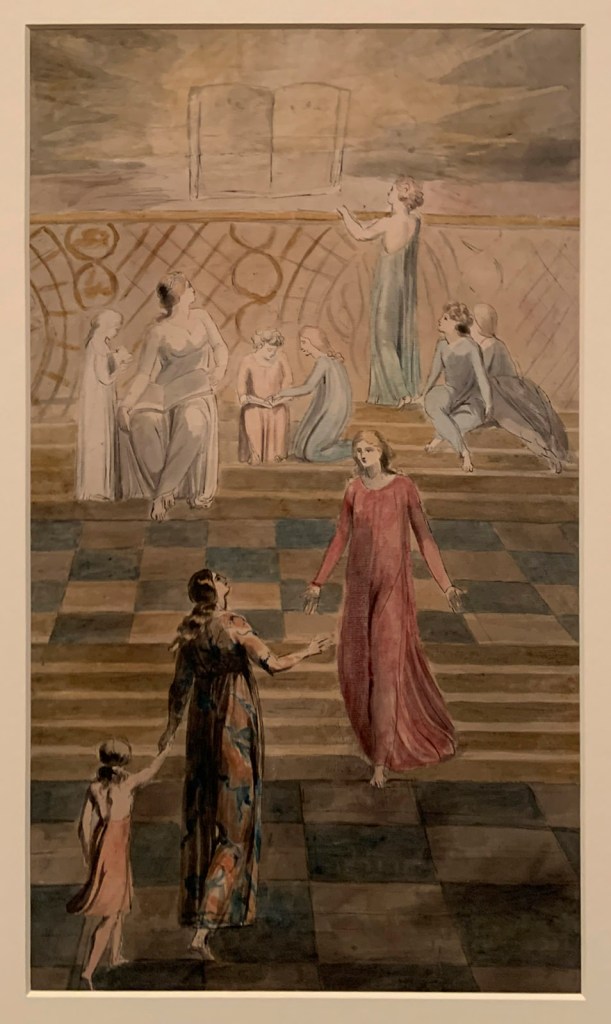

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

An Allegory of the Bible

c. 1780-1785

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate, Bequeathed by Miss Rachel M. Dyer 1969

The title of this work is not Blake’s, but its theme seems to be the revelation of knowledge.

Unusually, the foreground and background were both painted initially with a single base colour. The figures and the screen behind those in the background were applied straight onto the white paper. The screen and the lower half of the sky behind it were originally painted a deep rose, with a red lake pigment that is probably brazilwood. This has lost so much colour, except at the edges, that it gives the unintended effect of a flat brown base tone to the whole screen.

Gallery label, September 2004

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing Blake’s The Good Farmer, Probably the Parable of the Wheat and the Tares (c. 1780-1785)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

This is an illustration of one of Christ’s parables, which appears in several biblical sources.

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Good Farmer, Probably the Parable of the Wheat and the Tares (installation view)

c. 1780-1785

Ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Bequeathed by Miss Alice G.E. Carthew 1940

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Tiriel

In the late 1780s Blake had established a reputation as a designer and poet among a small circle of friends. He began writing an epic poem, which he also intended to illustrate. It is not clear how Blake would have funded the production of an illustrated edition and it was not published.

Blake’s manuscript and many of the surviving drawings are displayed here. The story combined elements of Greek tragedy and Shakespeare. It also drew on supposedly ancient Gaelic stories (actually composed by the Scottish writer James Macpherson in the 1760s). The narrative concerns a king, now blind, his arguments with his sons and daughters, and his encounter with his elderly parents, Har and Heva. The language is dramatic, with exaggerated imagery suggesting surging emotions, ‘Thunder & fire & pestilence’.

The project represents the culmination of Blake’s early efforts as a painter and poet. It also exposes how his ambitions to combine epic images and texts were frustrated by conventional publishing techniques.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing

c. 1786

Watercolour and graphite on paper

Support: 475 × 675 mm

Tate. Presented by Alfred A. de Pass in memory of his wife Ethel 1910

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

The subject is from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream illustrating Titania’s instruction to her fairy train in the last scene:

Hand in hand, with fairy grace,

Will we sing, and bless this place.

Oberon and Titania, King and Queen of the fairies, are on the left. Puck, the perplexer of mortals, faces us. The fairies Moth and Peaseblossom are easily identifiable.

During the 1780s there was a growing taste for Shakespeare illustrations. Blake had formed a print-publishing partnership in 1784. If the approximate dating of this work is correct, it may represent an attempt by Blake to break into this market.

Supernatural and fantastical subject matter like this enjoyed great popularity in Blake’s time.

Wall text from the exhibition and gallery label, August 2004

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing (installation view details)

c. 1786

Watercolour and graphite on paper

Support: 475 × 675 mm

Tate. Presented by Alfred A. de Pass in memory of his wife Ethel 1910

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

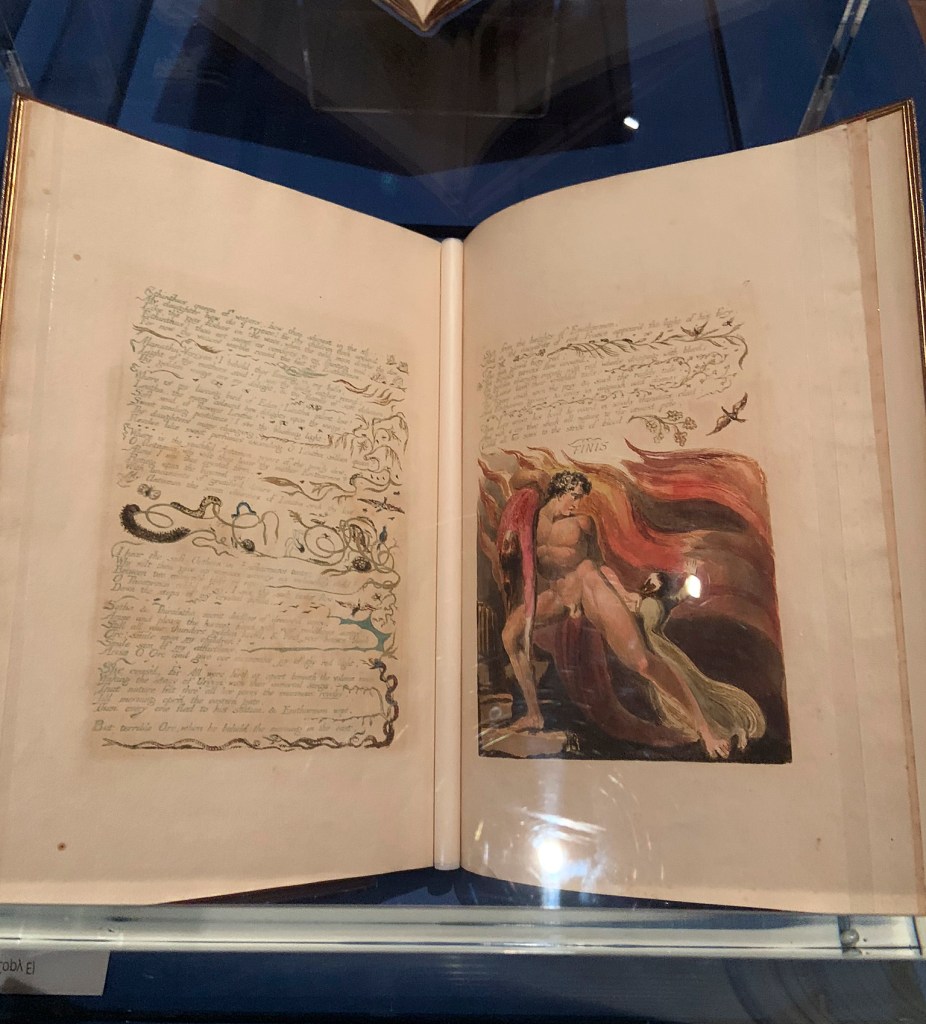

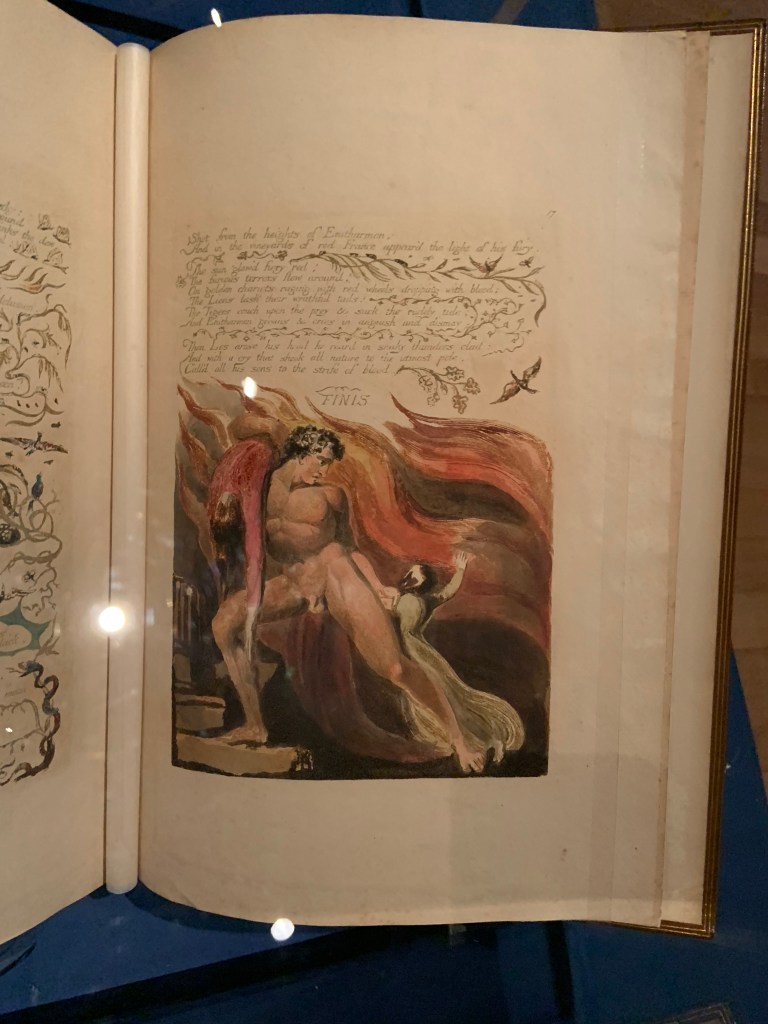

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Europe, A Prophecy (Copy E) (installation views)

1794

Book, 17 plates on 10 leaves

Open to plates 17: Ethinius queen of waters... and 18 Shot from the heights of Enitharrnon

Relief and white-line etching with colour printing and hand colouring

Library of Congress. Lessing J. Rosenwald collection, 1806

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

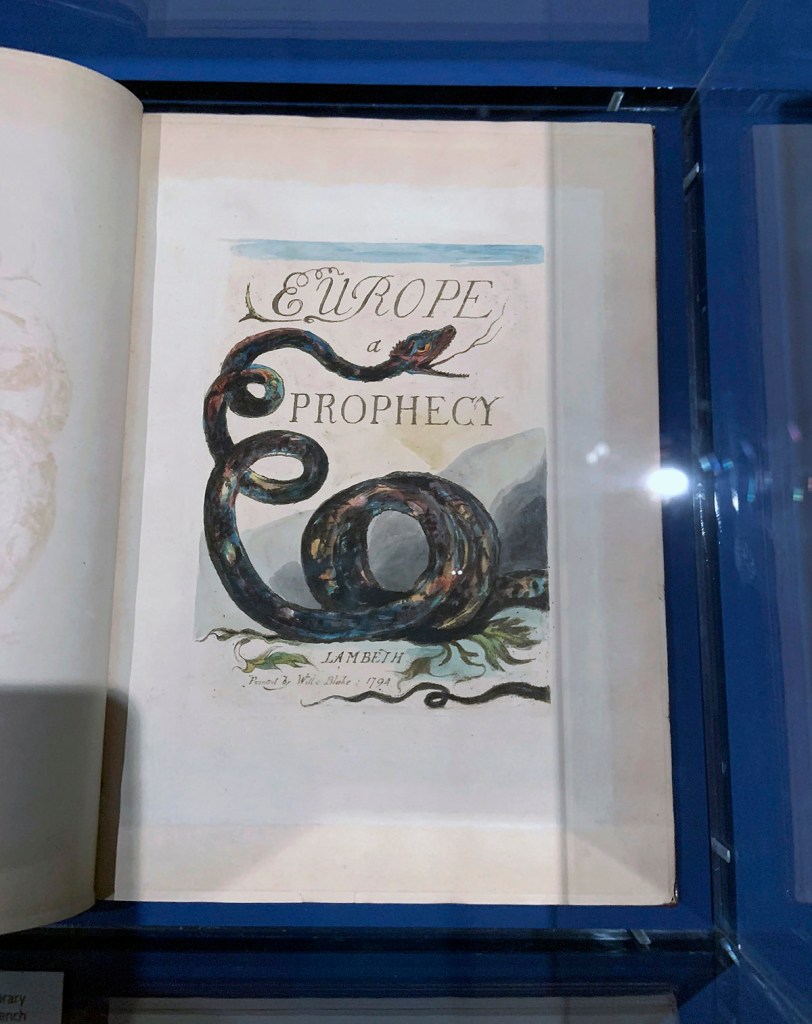

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Europe, A Prophecy (Copy A) (installation views)

1794

Book, 17 plates on 17 leaves

Open to Plate 2, title page

Colour-printed relief etching in dark brown with pen and black ink, oil and watercolour on paper

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Europe, A Prophecy relates contemporary historical events – specifically the French Revolution – in an epic, symbolic form. As Blake’s biographer Alexander Gilchrist (1828-1861) observed of the book: ‘It is hard to describe poems wherein the dramatis personae are giant shadows, gloomy phantoms; the scene, the realms of space; the time, of such corresponding vastness, that eighteen hundred years pass as a dream’. Catherine Blake is likely to have coloured many of the plates in this copy, including the title page. This copy, may be that bought from Blake by the painter George Romney (1734-1802).

Label text

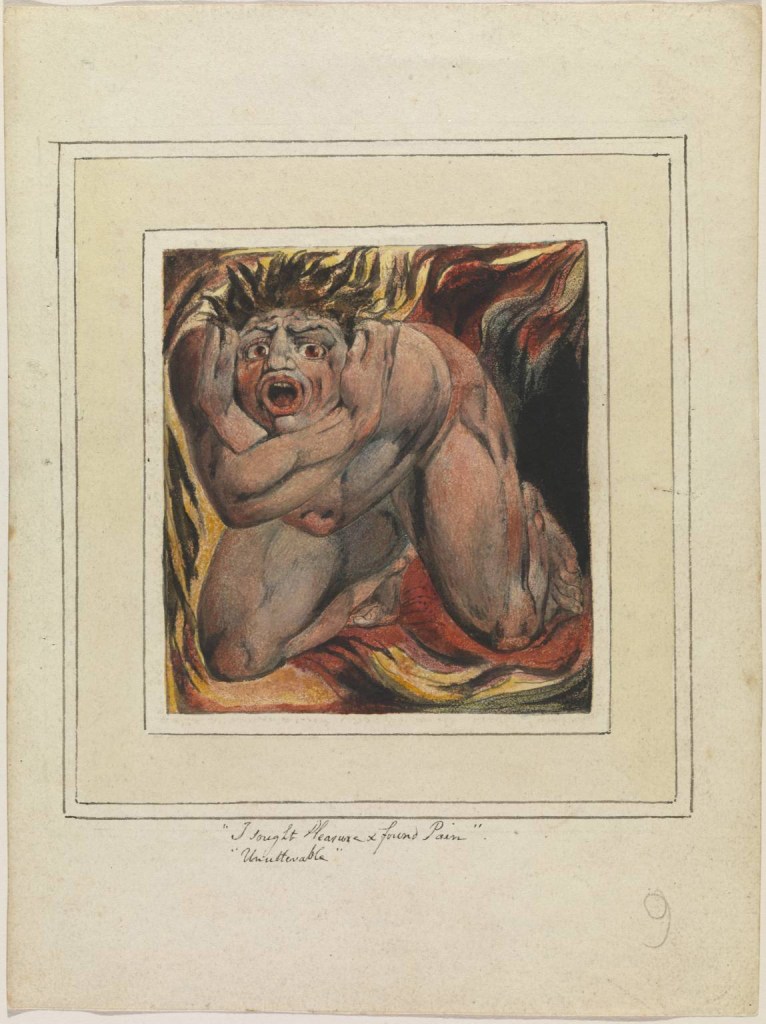

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

First Book of Urizen pl. 6 ‘I sought Pleasure & found Pain, Unntennable’

1796, printed c. 1818

Etching with paint, watercolour and ink on paper

Tate. Purchased with funds provided by the Art Fund, Tate Members, Tate Patrons, Tate Fund and individual donors 2009

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

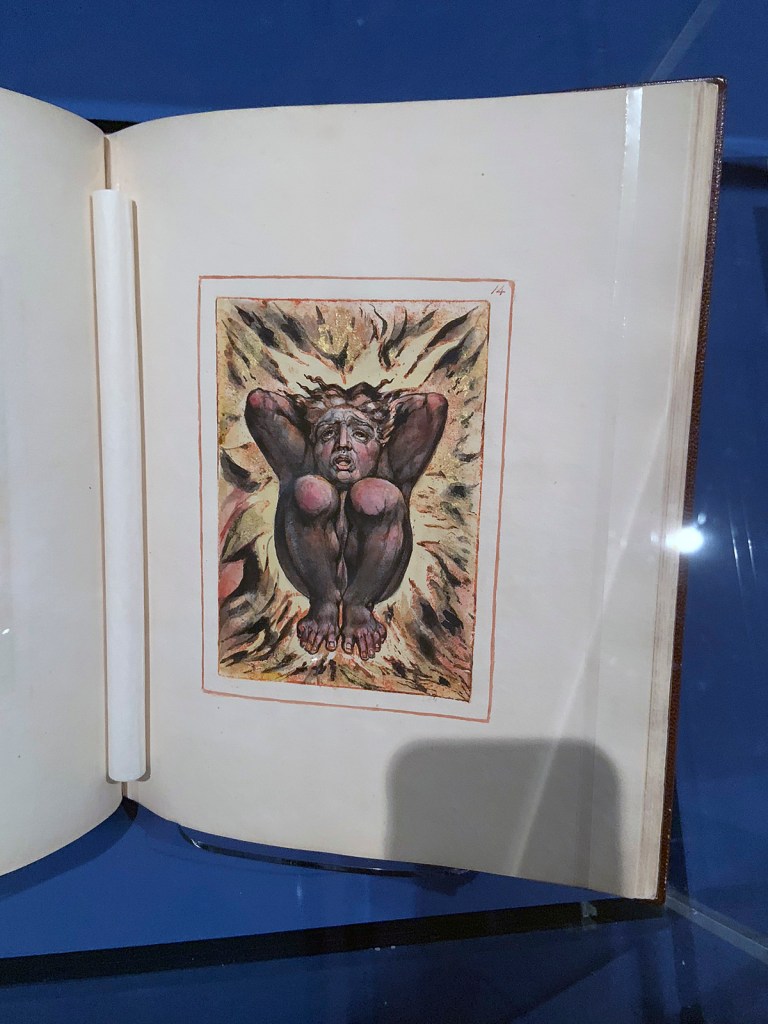

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The First Book of Urizen (Copy G) (installation views)

1794, printed c. 1818

27 leaves, open to plate number 14

Relief etching printed in yellow brown with watercolour and gold

Library of Congress. Lessing J. Rosenwald collection, 1807

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

During his lifetime, Blake’s books were appreciated by collectors for their visual qualities far more than for their political and literary content. The First Book of Urizen was first printed in 1794. It was already strongly visual. In this new copy, printed in around 1818, Blake has enhanced this full-page image with intense colouring and gold.

Label text

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (Copy H) (installation view)

c. 1790

Book, 27 plates on 15 leaves

Open to title page

Relief etching with hand-colouring

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

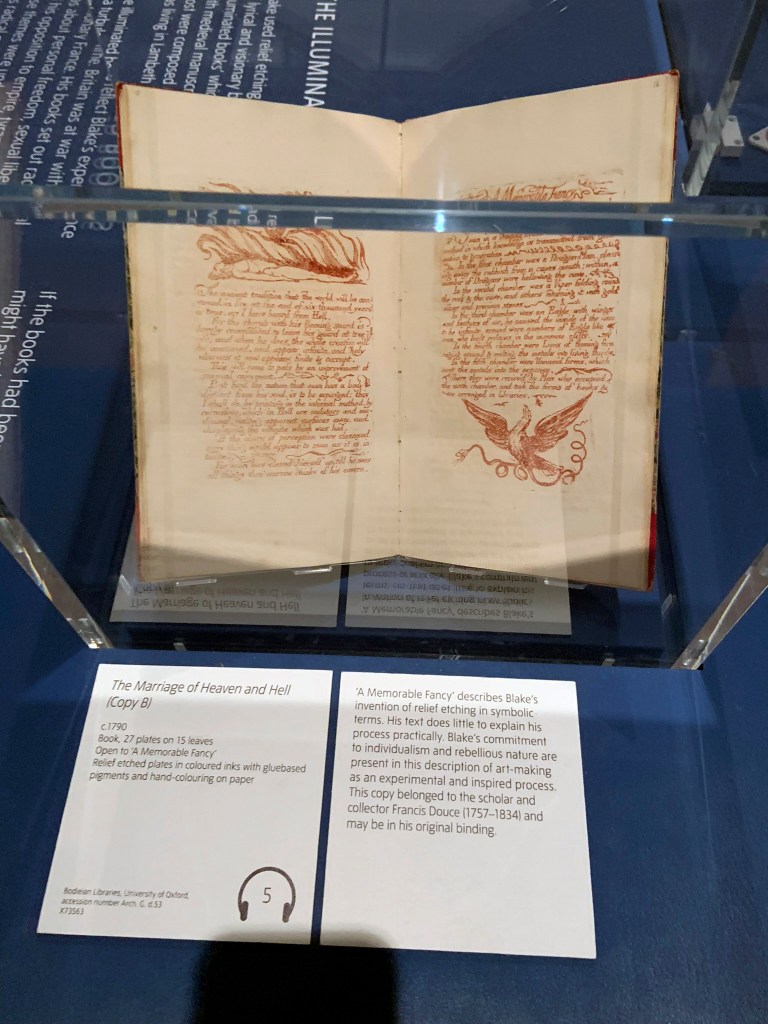

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (Copy B) (installation views)

c. 1790

Book, 27 plates on 15 leaves

Open to A Memorable Fancy

Relief etched plates in coloured inks with glue-based pigments and hand-colouring paper

Bodlieian Libraries, University of Oxford

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

A Memorable Fancy describes Blake’s invention of relief etching in symbolic terms. His text does little to explain his process practically. Blake’s commitment to individualism and rebellious nature are present in this description of art-making as an experimental and inspired process. This copy belonged to the scholar and collector Francis Douce (1757-1834) and may be in his original binding.

Label text

Relief etching

Blake conceived his technique of relief etching in around 1788. He claimed this was under the inspiration of his brother Robert, who had died in 1787. The technical details of his method have long fascinated and frustrated scholars and collectors and remain debated.

Engraving and etching involve making lines in a copper plate which are filled with ink to create the printed image. Relief etching, on the other hand, involves using acid to eat away areas of the plate that you want to leave unprinted. The remaining surfaces are inked and printed. Relief etching allowed Blake to combine hand-written texts and images on a single plate. These were normally entirely separate processes. Blake also experimented in printing with colours, and added pen and ink, watercolour and later on gold to create more dense, painterly images.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

There is no Natural Religion (Copy B) (installation view)

c. 1788 (composition date)

c. 1794 (print date)

Book, 11 plates on 11 leaves

Open to Plate 10. I Mans Perceptions are not Bounded…

Colour-printed relief etching on paper

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

This collection of short philosophical statements was one of Blake’s first experiments in relief etching. This copy, printed in coloured inks, was produced in 1794.

Label text

Room 2

Making prints, making a living

“I curse & bless Engraving alternately because it takes so much time & is so untractable.

tho capable of such beauty & perfection”

~ William Blake

Blake was trained as a reproductive engraver. This exacting craft involved copying an image by cutting fine lines onto a metal plate so that it could be printed and reproduced many times. Blake enjoyed the precision of this work. He gained a good reputation and engraving provided him with an income throughout his life. He was sometimes employed to design as well as engrave illustrations, and for a short period from 1784 ran his own print publishing business with his friend and fellow engraver James Parker.

While Blake admired the uncompromising qualities of older prints, the market favoured more obviously decorative techniques. Blake could adapt his style, but he found the limitations of commercial work frustrating.

Around 1788 Blake invented a new form of printmaking, ‘relief etching’. He described the technique in poetic rather than practical terms so his exact methods remain mysterious. The process allowed Blake to print in colour and combine texts and images. Blake used the technique to create a succession of visionary books. These engaged with the most pressing moral and political questions of the day, including revolution, sexual freedom and the slave trade. Blake’s illuminated books combined poetry and images in experimental ways. His images rarely illustrate the text directly. He also printed some of the images separately without words. Later in life Blake continued to print copies for fellow artists and rare book collectors, adding richer colours and gold to make them more visually enticing.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Joseph of Arimathea among the Rocks of Albion (installation view)

c. 1810

Engraving using carbon ink on paper

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Joseph of Arimathea among the Rocks of Albion (installation view)

c. 1810

Engraving using carbon ink on paper

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

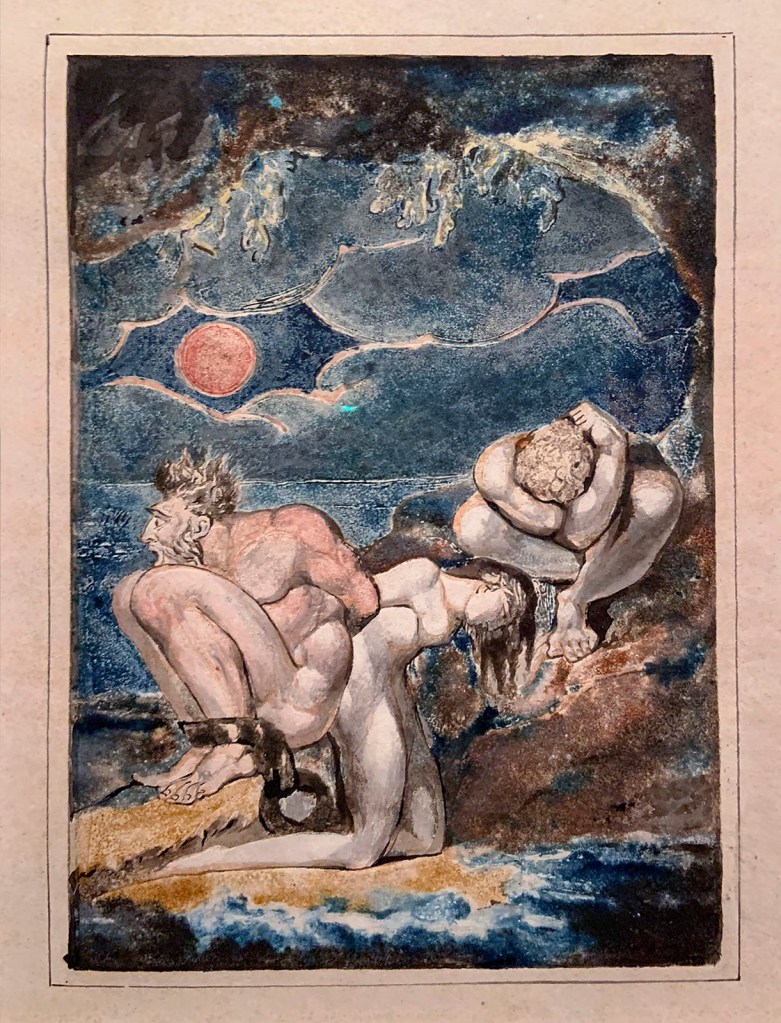

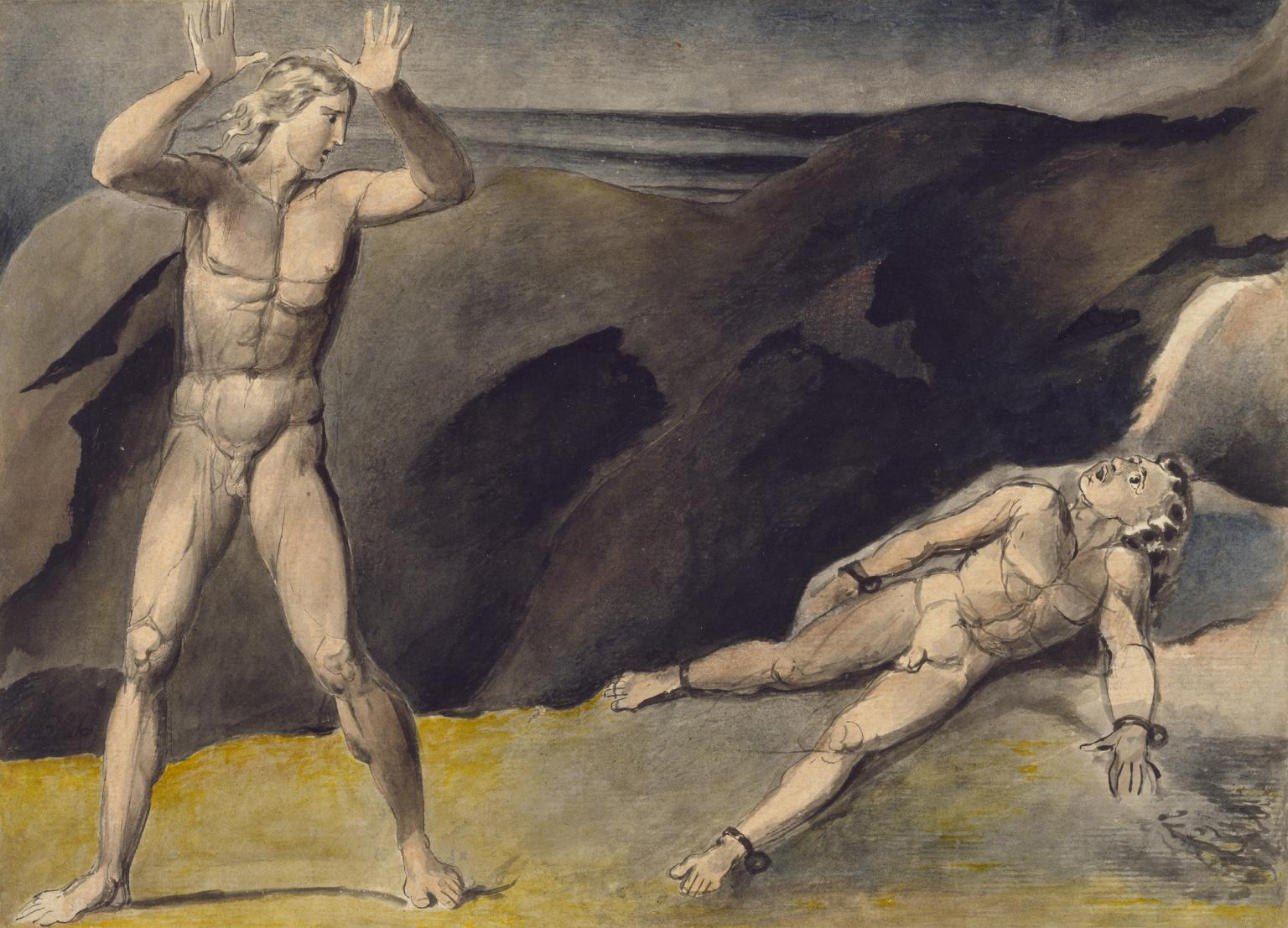

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Los and Orc

c. 1792-1793

Ink and watercolour on paper

217 × 295 mm

Tate. Presented by Mrs Jane Samuel in memory of her husband 1962

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

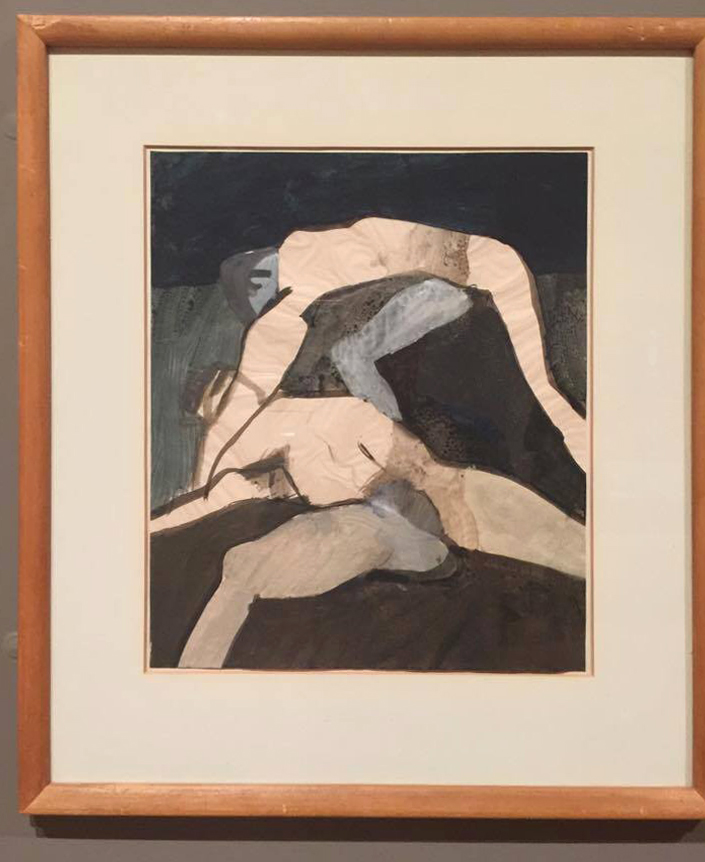

This watercolour represents a turning-point in Blake’s art because it depicts a subject taken from his invented mythology which he used across the illuminated books. The figures appear to be the characters Los, representing imagination, and the chained Orc, the spirit of rebellion.

Wall text from the exhibition

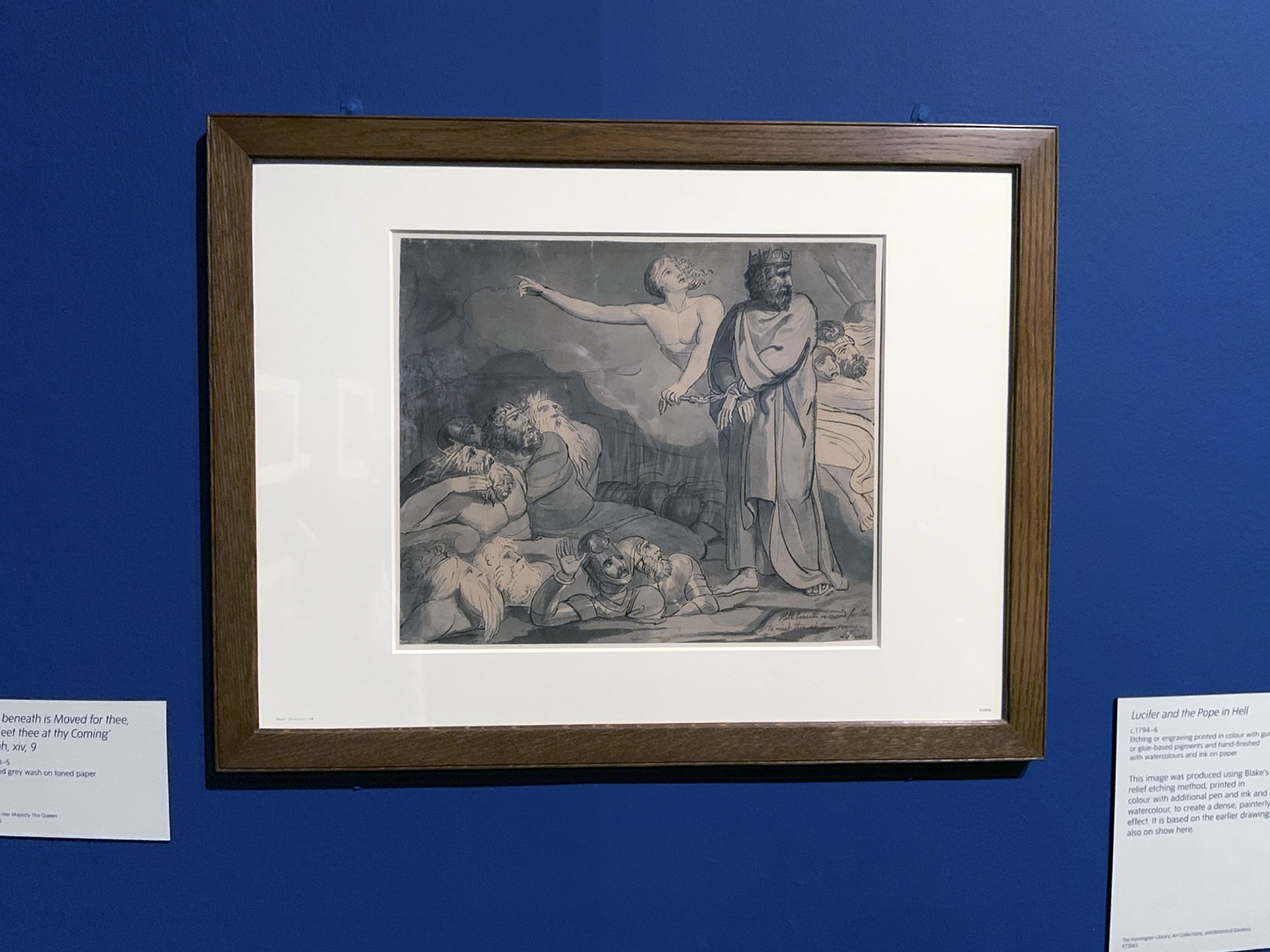

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Hell beneath is Moved for thee, to Meet thee at thy Coming (installation view)

Isaiah, xiv, 9

c. 1780-1785

Ink and grey wash on toned paper

Lent by her Majesty The Queen

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Lucifer and the Pope in Hell (installation view)

c. 1794-1796

Etching or engraving printed in colour with gum or glue-based pigments and hand-finished with watercolours and ink on paper

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

This image was produced using Blake’s relief etching method, printed in colour with additional pen and ink and watercolour, to create a dense, painterly effect. It is based on an earlier drawing.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Frontispiece to ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’ (installation view)

c. 1795

Relief etching, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Plate 4 of ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’ (installation view)

c. 1795

Relief etching, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Frontispiece to ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’ (installation view)

c. 1795

Relief etching, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Small Book of Designs: Plate 7, ‘Of life on his forsaken mountains’ (installation view)

1794

Colour-printed relief etching with hand-colouring, on paper

Lent by the British Museum, London

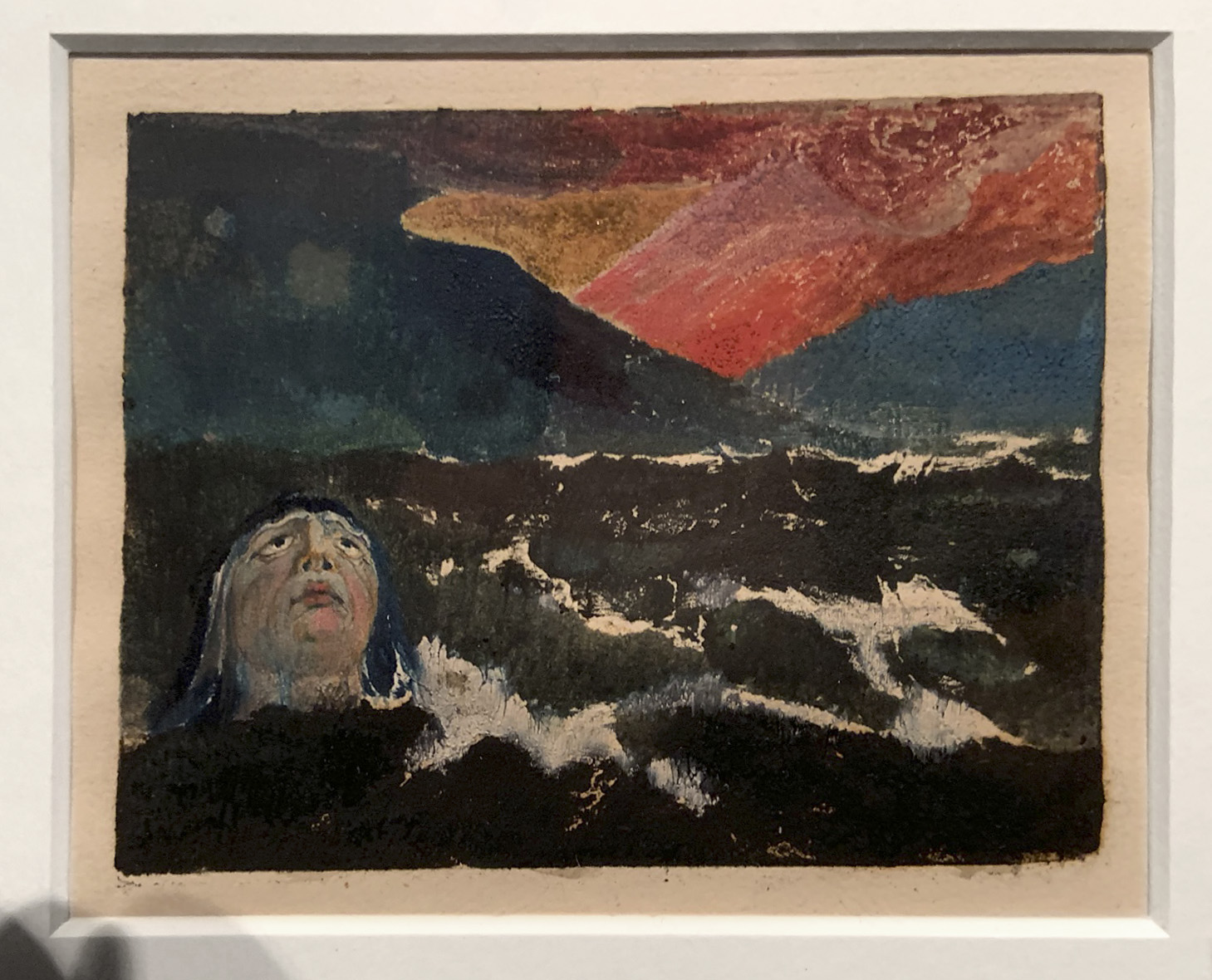

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Small Book of Designs: Plate 8, ‘dark seascape with figure in water’ (installation view)

1794

Colour-printed relief etching with hand-colouring, on paper

Lent by the British Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Small Book of Designs: Plate 7, ‘Of life on his forsaken mountains’ (installation view)

1794

Colour-printed relief etching with hand-colouring, on paper

Lent by the British Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

A Small Book of Designs copy A object 7 The First Book of Urizen plate 23

1796

Colour-printed relief etching with hand-colouring, on paper

The William Blake Archive, The British Museum

Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Small Book of Designs: Plate 8, ‘dark seascape with figure in water’ (installation view)

1794

Colour-printed relief etching with hand-colouring, on paper

Lent by the British Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

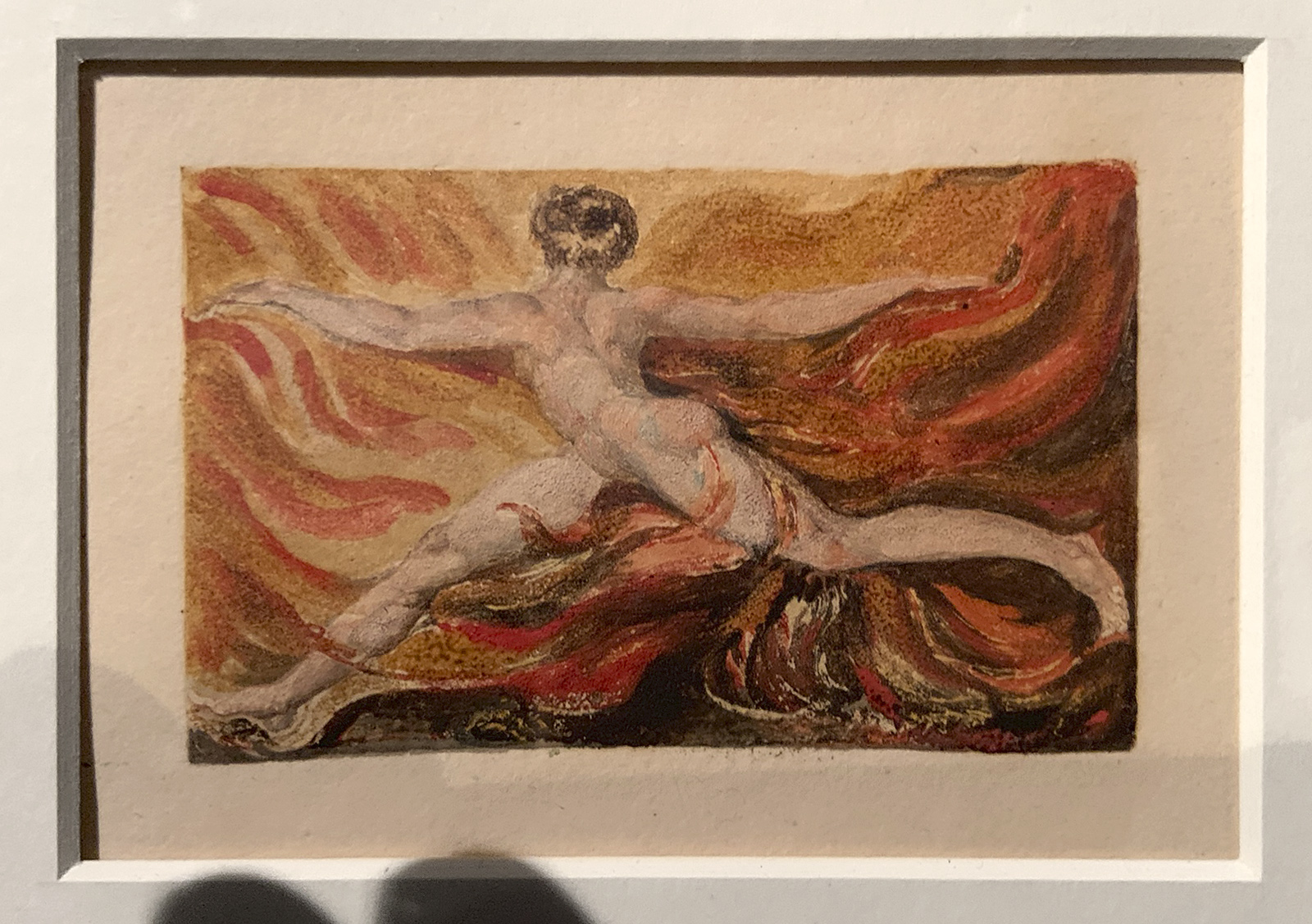

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Small Book of Designs: Plate 9, ‘Lo, a shadow of horror’ (installation view)

1794

Colour-printed relief etching with hand-colouring, on paper

Lent by The British Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

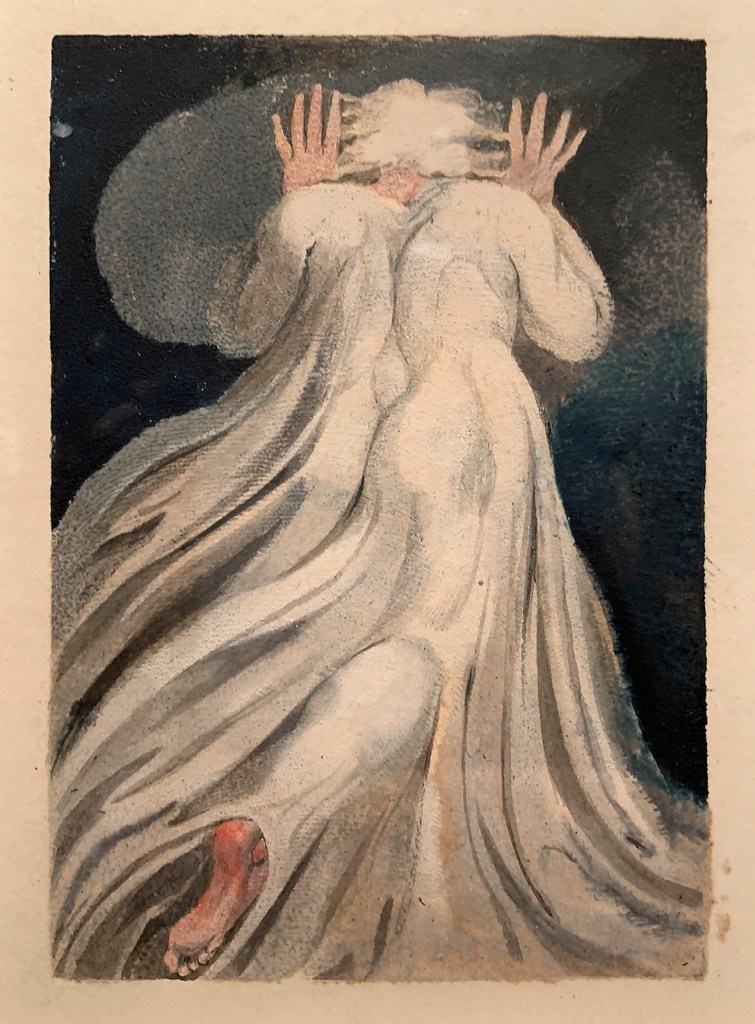

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Small Book of Designs: Plate 11, ‘Gowned Male Seen from behind’ (installation view)

1794

Colour-printed relief etching with hand-colouring, on paper

Lent by The British Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

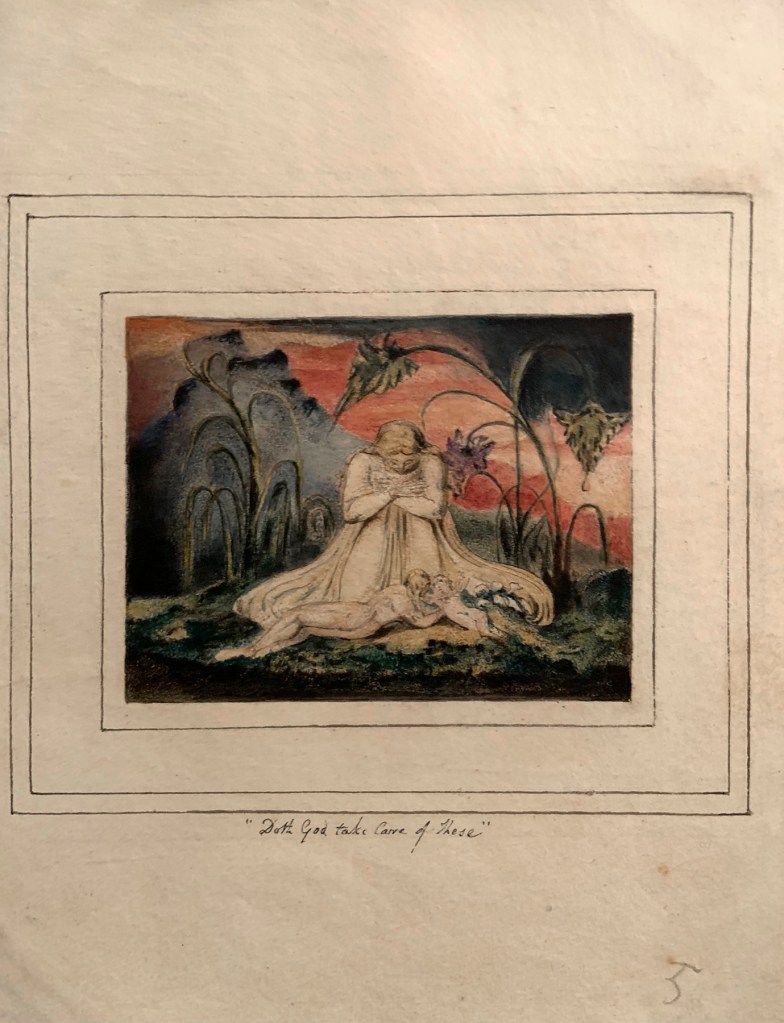

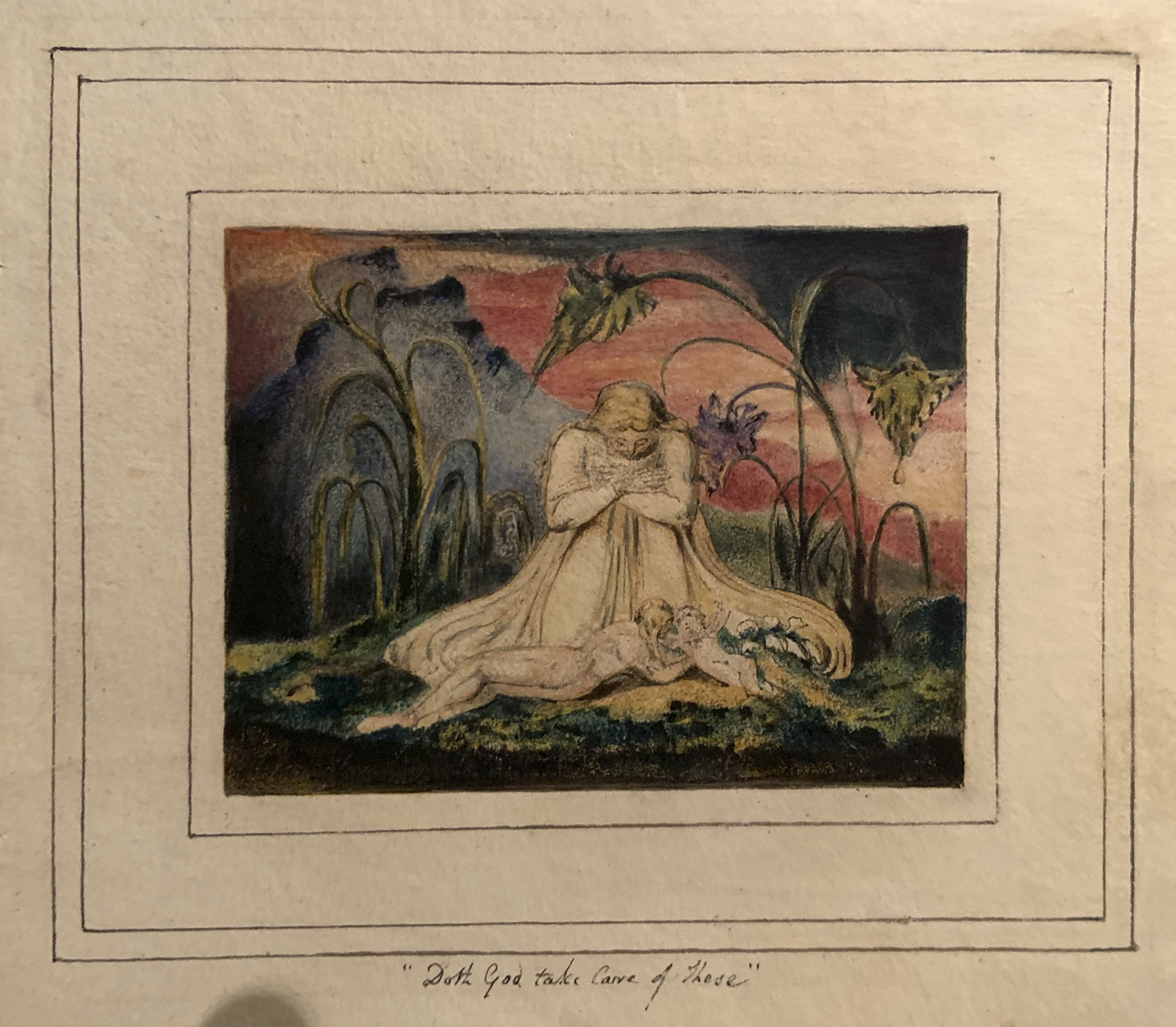

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Book of Thel, Plate 6 ‘Doth God take Care of these’ (installation views)

1796, c. 1818

Etching with paint, watercolour and ink on paper

Tate. Purchased with funds provided by the Art Fund, Tate Members,Tate Patrons, Tate Fund and individual donors 2009

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Copy A, Plate 7 in ‘The First Book of Urizen’ (installation view)

1794

Colour relief etching predominantly in black, grey and pink, with hand-colouring, on paper

Lent by The British Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Copy A, plate 12, Design from ‘Preludium’ in ‘The First Book of Urizen’ (installation view)

1794

Colour-printed relief etchings with hand-colouring, on paper

Lent by The British Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

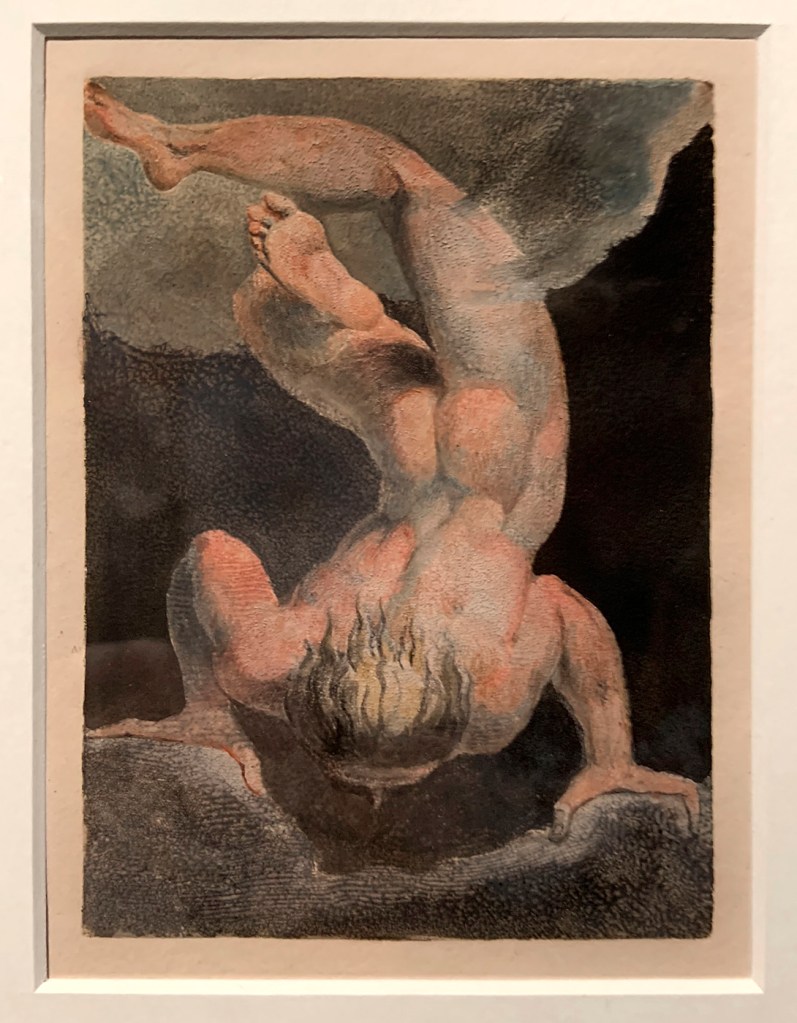

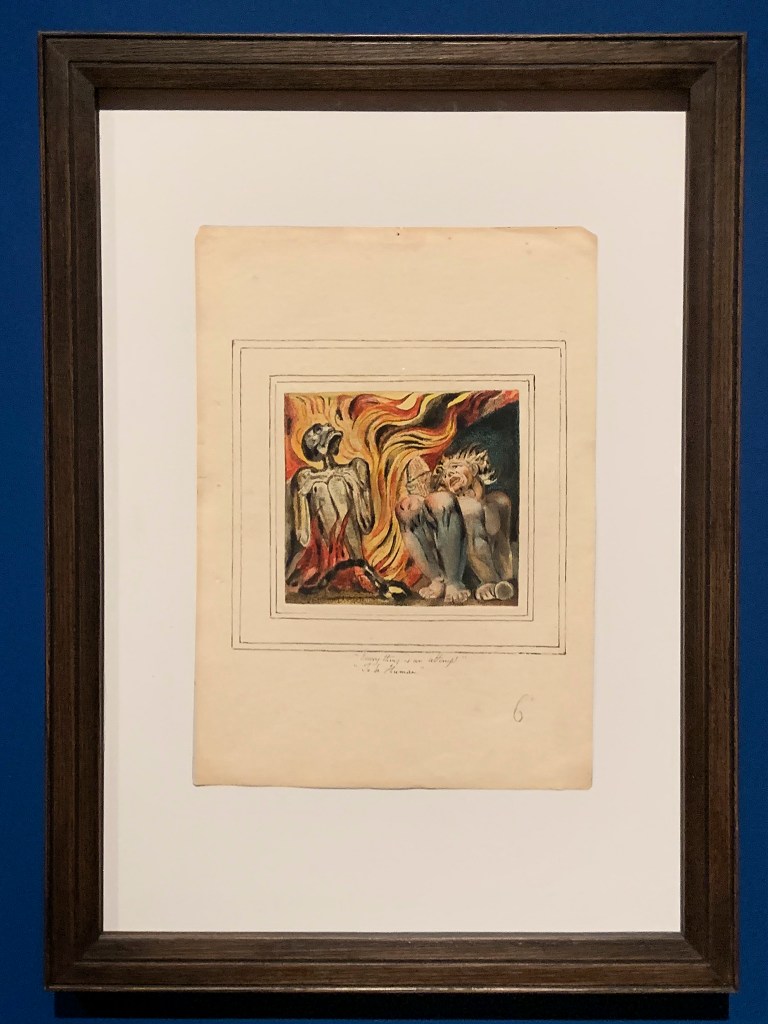

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

First Book of Urizen, Plate 10 ‘Every thing is an attempt, To be Human’ (installation views)

1796, c. 1818

Etching with paint, watercolour and ink on paper

Tate. Purchased with funds provided by the Art Fund, Tate Members, Tate Patrons, Tate Fund and individual donors 2009

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

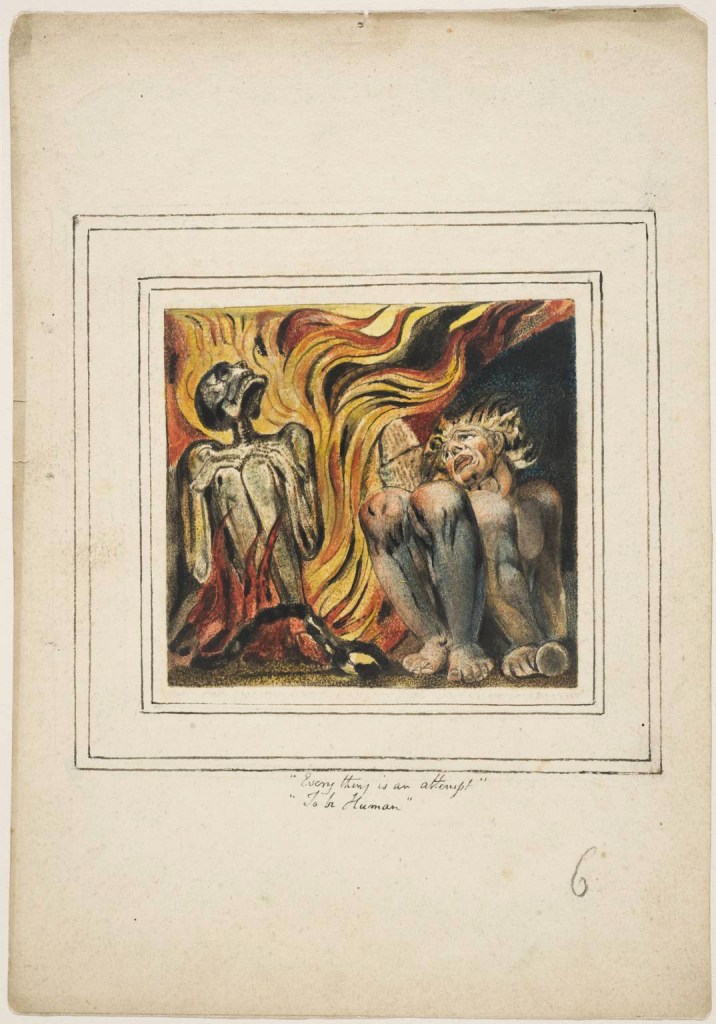

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

First Book of Urizen, Plate 10 ‘Every thing is an attempt, To be Human’

1796, c. 1818

Etching with paint, watercolour and ink on paper

Tate. Purchased with funds provided by the Art Fund, Tate Members, Tate Patrons, Tate Fund and individual donors 2009

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

“I was in a Printing house in Hell, & saw the method in which knowledge is transmitted from generation to generation.”

William Blake, ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’ c. 1790

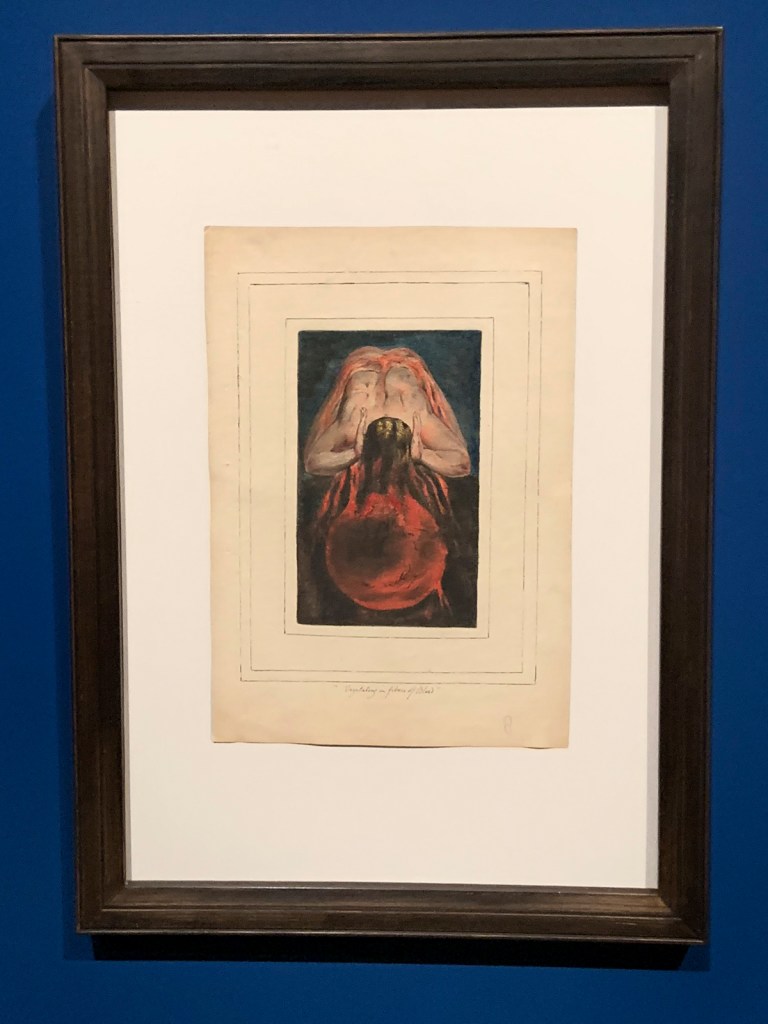

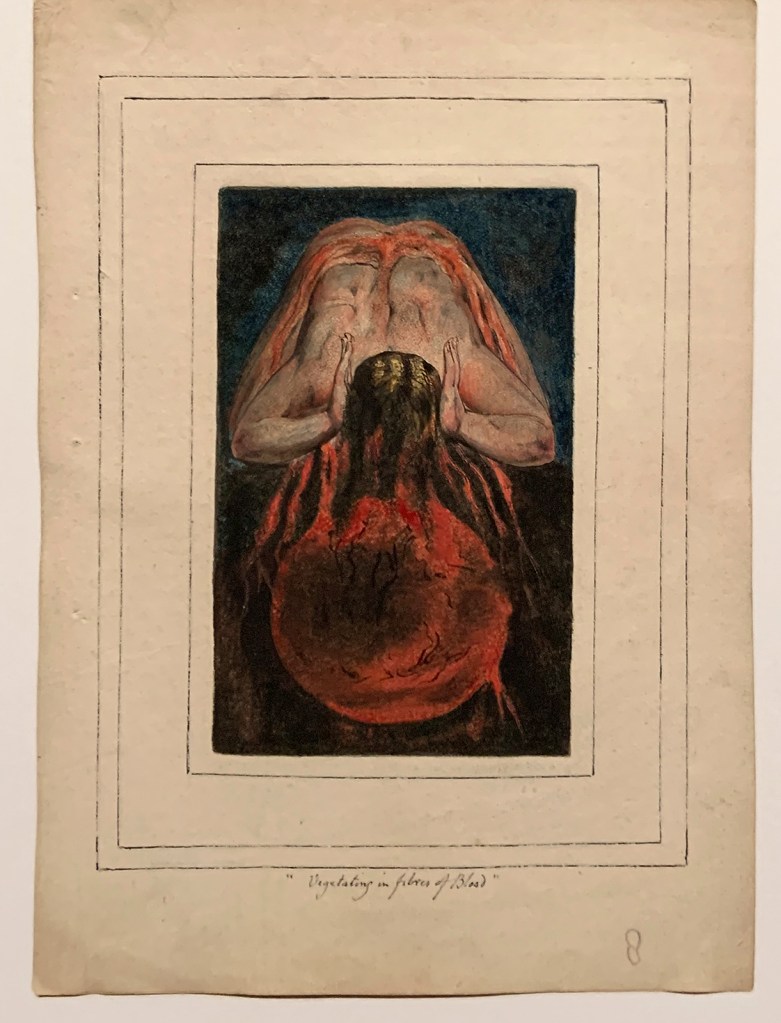

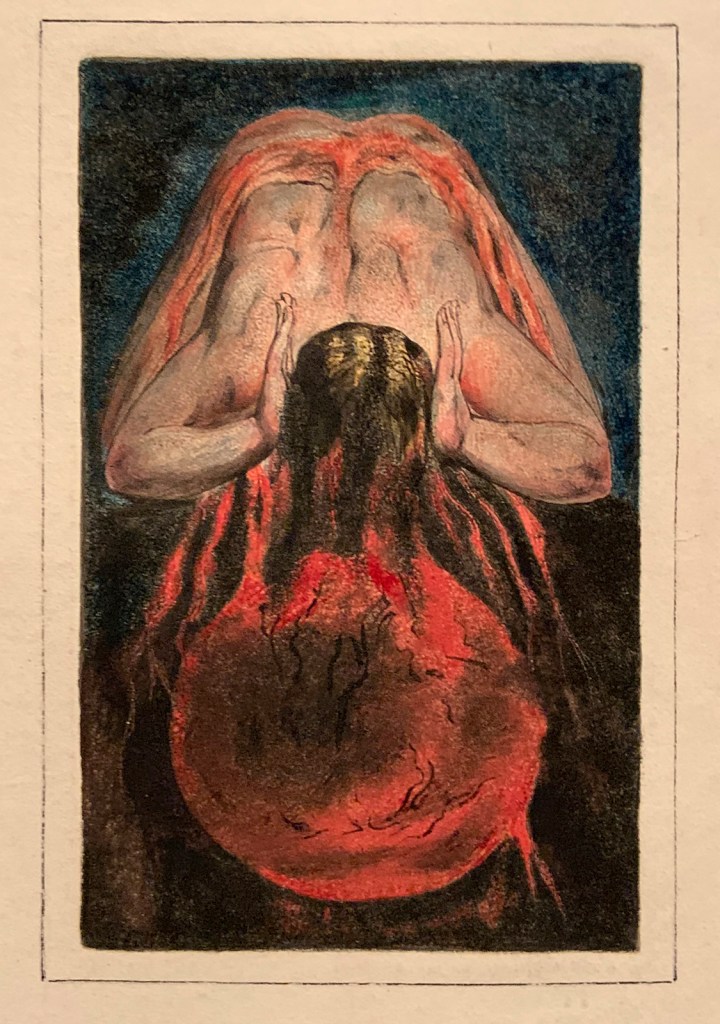

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

First Book of Urizen, Plate 15 (installation views)

1796, c. 1818

Etching with paint, watercolour and ink on paper

Tate. Purchased with funds provided by the Art Fund, Tate Members, Tate Patrons, Tate Fund and individual donors 2009

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

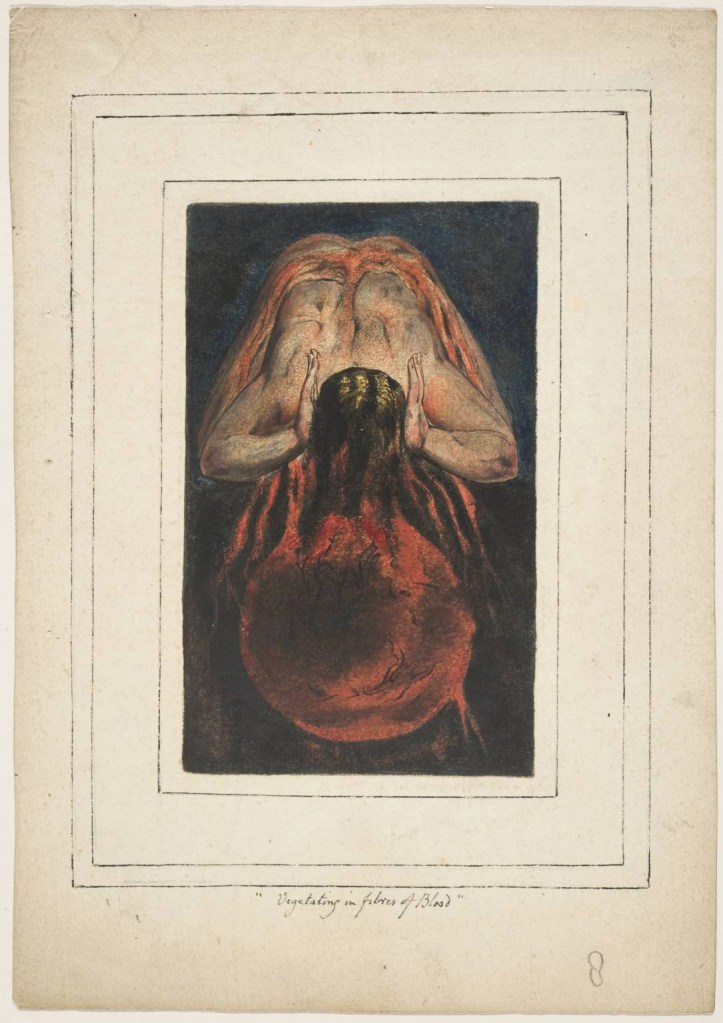

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

First Book of Urizen, Plate 15 ‘Vegetating in fibres of Blood’

1796, c. 1818

Etching with paint, watercolour and ink on paper

Tate. Purchased with funds provided by the Art Fund, Tate Members, Tate Patrons, Tate Fund and individual donors 2009

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

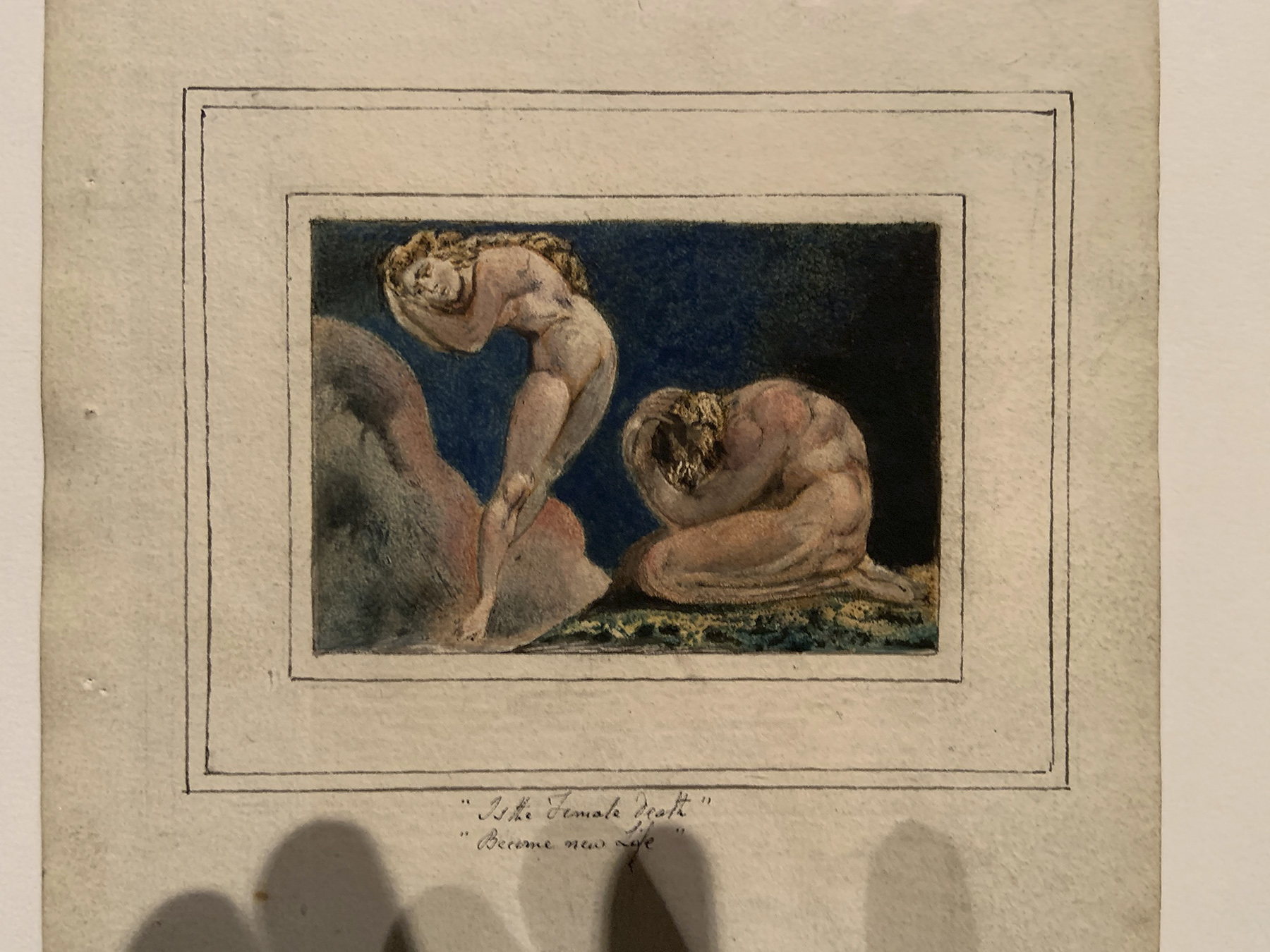

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

First Book of Urizen, Plate 17 ‘Is the Female Death, Become new Life’ (installation views)

1796, c. 1818

Etching with paint, watercolour and ink on paper

Tate. Purchased with funds provided by the Art Fund, Tate Members, Tate Patrons, Tate Fund and individual donors 2009

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

First Book of Urizen, Plate 17 ‘Is the Female Death, Become new Life’

1796, c. 1818

Etching with paint, watercolour and ink on paper

Tate. Purchased with funds provided by the Art Fund, Tate Members, Tate Patrons, Tate Fund and individual donors 2009

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Songs of Innocence and of Experience

Songs of Innocence (1789), Songs of Experience (1793) and the combined Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794) are the best known of Blake’s illuminated books. He sold more copies of these books than any other (although he probably printed no more than 30 in his lifetime).

The poems deal with themes of childhood and morality, and include striking observations about suffering and social injustice. The visual style is highly decorative. The dense crowding of texts and borders is suggestive of illustrations to children’s books or even embroidered samplers.

Wall text

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

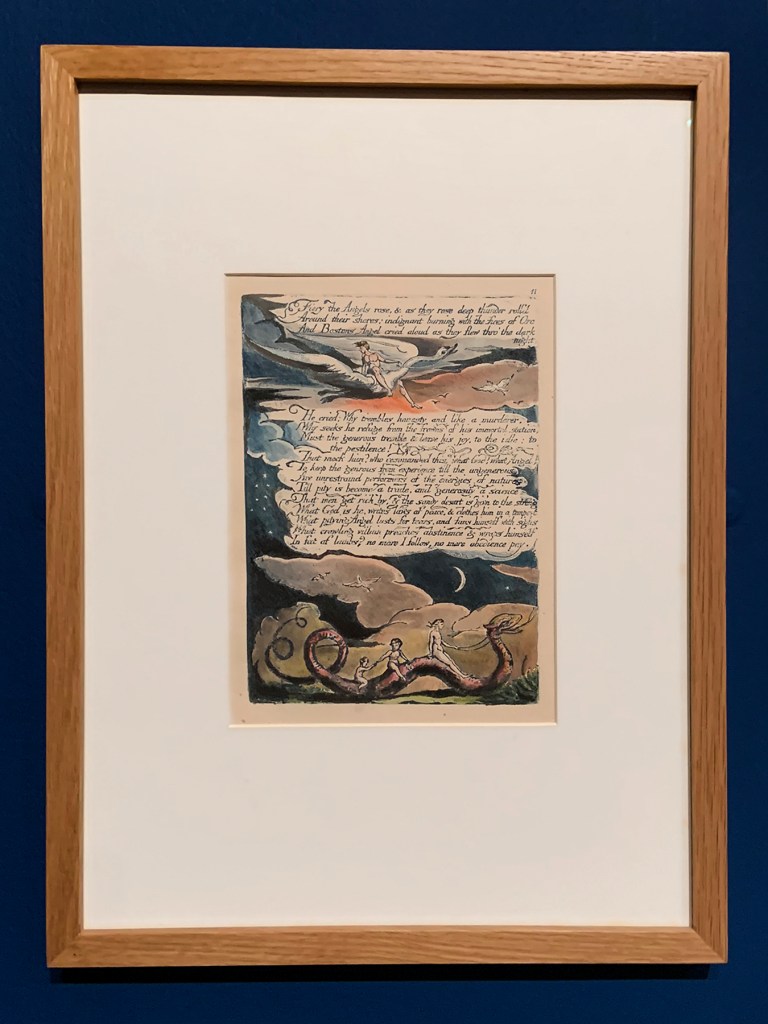

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

America, A Prophecy (Copy M) Plate 13, ‘Fiery the Angels Rose…’ (installation view)

1793

18 plates on 18 leaves, disbound

Colour-printed relief etching in brown with ink and watercolour on paper

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

The American War of Independence (1775-1783) was the key historical event of Blake’s youth. It shattered the British elite’s assumptions that they could rule over a global, English-speaking empire. For many others, including Blake, it was a heroic overturning of the oppressive old order. Blake’s poem deals with historical events in mythical terms. The central character is Orc, the spirit of revolution, who pursues the ‘shadowy daughter of Urthona’. It was produced at a time when the French Revolution inspired both hope and fear that revolution would spread across Europe.

Wall text

Room 3

Patronage and independence

Throughout his life Blake depended upon the support of family and friends. These included several fellow-artists and amateurs, including John and Ann Flaxman, Thomas Stothard and George Cumberland. In the 1790s Blake started selling works to Thomas Butts, a senior civil servant. Butts became his most important patron, eventually owning up to 200 works by the artist. The Rev. Joseph Thomas also commissioned series of watercolours illustrating Milton and Shakespeare. The wealthy poet William Hayley was another important supporter. In 1800-1803 Blake went to work for Hayley, moving with Catherine to Sussex.

The move opened up new connections, with the Rev. John Johnson and Elizabeth Ilive, Countess of Egremont. The support of Flaxman, Butts, Hayley and their friends gave Blake a degree of financial stability. Blake’s patrons were well-off and socially established, much more so than the artist. They admired the artist’s unconventional character and independent spirit. But Blake resented being their employee and the advice they sometimes offered. As a result these relationships often became strained.

Wall text from the exhibition

Edward Young (British, 1683-1765)

Night Thoughts (installation view)

1797

Book, 43 plates on 43 leaves

Engravings with hand-colouring

By courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Blake produced over 530 watercolours for Edward Young’s long poem on ‘life, death and immortality’. He created bold designs in large margins around each sheet of the printed text. These often give literal form to ideas in the text. Publisher Richard Edwards commissioned Blake, but later abandoned the project and closed down his business. Blake had asked for over £100 for the designs but was paid only £21. He despaired, writing in 1799: ‘I am laid by in a corner as if I did not Exist’. This copy was hand-coloured by Blake or by Catherine Blake.

Label text

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Christ Child Asleep on the Cross (installation view)

1799-1800

Tempera on canvas Lent by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Christ Blessing the Little Children (installation views)

1799

Tempera on canvas

Tate. Presented by the executors of W. Graham Robertson through the Art Fund 1949

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Christ Blessing the Little Children

1799

Tempera on canvas

Tate. Presented by the executors of W. Graham Robertson through the Art Fund 1949

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

This painting is from of a group of fifty illustrations to the Bible commissioned by Blake’s patron, Thomas Butts. Its subject is taken from chapter 10 of St Mark’s Gospel. Christ, seated beneath a spreading tree, blesses children brought to him while he was preaching. To the left is one of his disciples, who tries to send the children away. Christ tells the disciples:

Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God… Whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child, he shall not enter therein.

Gallery label, August 2004

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Body of Christ Borne to the Tomb (installation views)

c. 1799-1800

Tempera on canvas mounted onto cardboard

Tate. Presented by Francis T. Palgrave 1884

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

The frame is original and may even have been chosen by Blake.

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Body of Christ Borne to the Tomb

c. 1799-1800

Tempera on canvas mounted onto cardboard

Tate. Presented by Francis T. Palgrave 1884

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

This tempera is very well preserved, mainly because it was painted on thin linen canvas, stuck onto thin cardboard. This is stiff enough to reduce the cracking that develops on flexible canvas. It also made it unnecessary to add the animal glue lining which has spoilt the opaque white effect of Blake’s chalk preparatory layer in many temperas. As a result, Blake’s delicate painted details can still be seen as he intended.

This is the only Blake tempera in this room in a frame dating from the time it was painted. Blake may have chosen the frame design himself.

Gallery label, August 2004

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

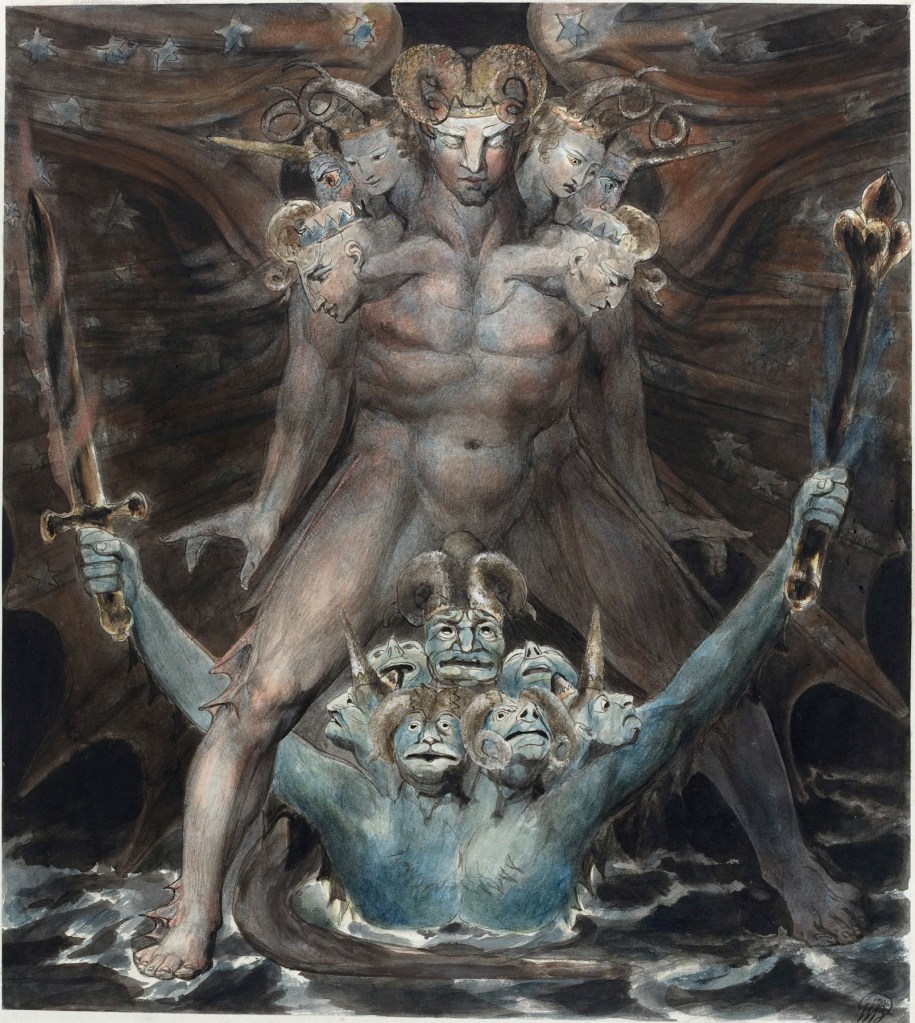

The Great Red Dragon and the Beast from the Sea (installation views)

c. 1805

Ink with watercolour over graphite on paper

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection, 1943

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Great Red Dragon and the Beast from the Sea

c. 1805

Ink with watercolour over graphite on paper

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection, 1943

Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Number of the Beast is 666 (installation views)

c. 1805

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Rosenbach, Philadelphia

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Number of the Beast is 666

c. 1805

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Rosenbach, Philadelphia

Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

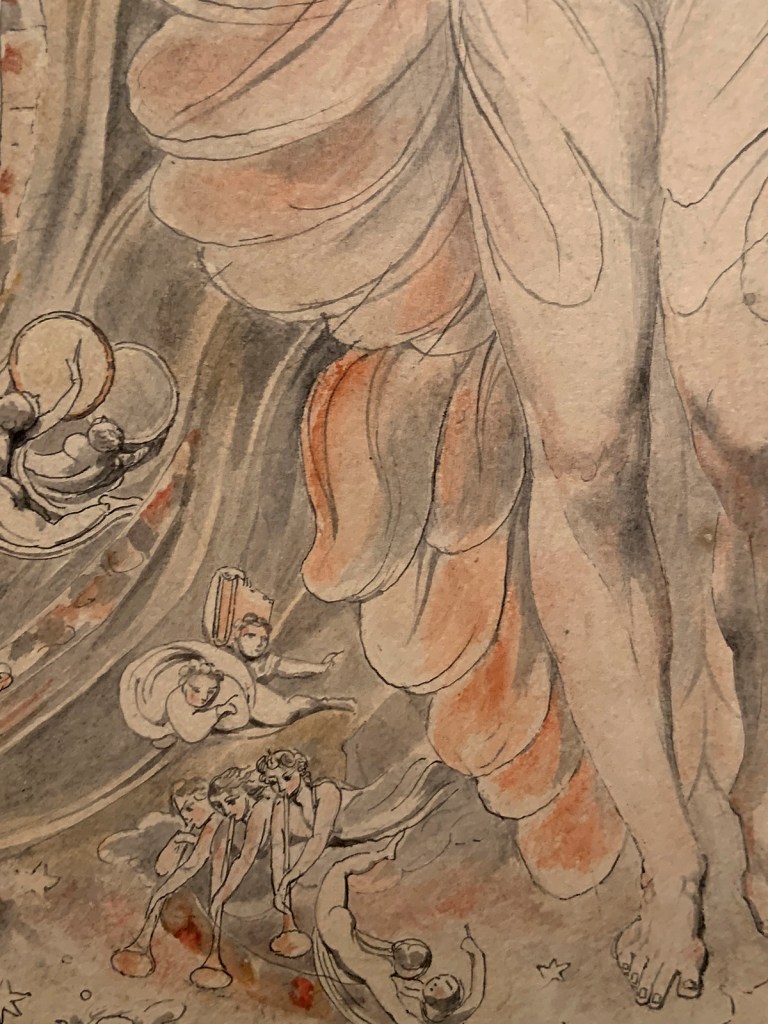

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Satan in his Original Glory: ‘Thou wast Perfect till Iniquity was Found in Thee’ (installation views)

c. 1805

Ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by the executors of W. Graham Robertson through the Art Fund 1949

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

This watercolour shows how such works have changed over time. There is a strip of much stronger blue colour at the bottom right edge, in an area which had been masked from the light in the past.

This watercolour shows Satan as he once was, a perfect part of God’s creation, before his fall from grace. His orb and sceptre symbolise his role as Prince of this World. It is also an extreme example of the damaging effects of over-exposure to light. The sky was originally an intense blue, now only visible at the lower right edge. The only colours which have survived unaltered are the vermilion red Blake used for the flesh, and red ochre in Satan’s wings. The paper has yellowed considerably. There is no evidence left of any yellow gamboge or pinkish red lakes.

Gallery label, September 2004

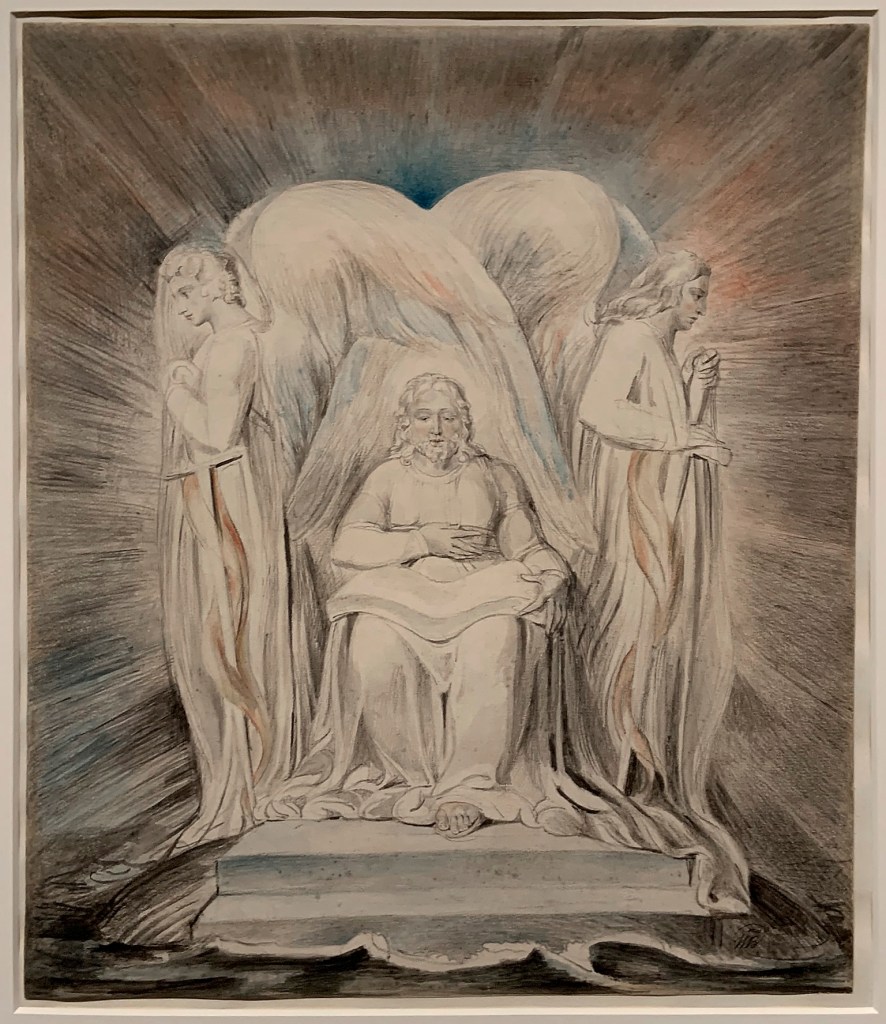

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Christ Girding Himself with Strength (installation view)

c. 1805

Chalk and watercolour over pencil on paper

280 × 325 mm

Bristol Culture: Bristol Museums & Art Gallery

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

David Delivered out of Many Waters

c. 1805

Ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by George Thomas Saul 1878

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

This work shows how Blake responded visually to textual sources. It is an illustration to Psalm 18, in which David (at the bottom of the image with his arms stretched wide) calls out to God for salvation from his enemies. Christ appears above, riding upon seven cherubim (angels), not one as in the text. Blake’s gentle, linear style, formal composition and free interpretation of a written source made him attractive to many modern artists. Paul Nash saw Blake as representing a British imaginative tradition.

Gallery label, August 2004

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Crucifixion: ‘Behold Thy Mother’

c. 1805

Ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by the executors of W. Graham Robertson through the Art Fund 1949

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Blake often treated subjects from Jerusalem’s history. Christian thought is centred on Christ’s crucifixion at Calvary outside the city, when he died to redeem mankind. His cross, his resurrection and return to earth three days after his death are central to Stanley Spencer’s Resurrection of the Soldiers altarpiece at Sandham; sketches for this are shown in the display case to your left.

Spencer believed that the soldiers had a ‘perfect understanding’ of the sacrifice they had to make. This suggests that both Blake’s ‘Mental Fight’ to build the Jerusalem of peace in England, and the soldiers’ physical fight are equally valid.

Gallery label, July 2008

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Magdalene at the Sepulchre (installation views)

c. 1805

Pen, ink and watercolour on paper

427 × 311 mm

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Angel Rolling away the Stone

c. 1805

Watercolour on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the Morse gift

Two angels in white the one at the head, and the other at the feet / Matw. cn. 28th v. 2nd And below there was a great earthquake, for the angel of the Lord descended from heaven, and came and rolled back the stone from the door. /17.

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Angel Rolling away the Stone (detail)

c. 1805

Watercolour on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the Morse gift

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

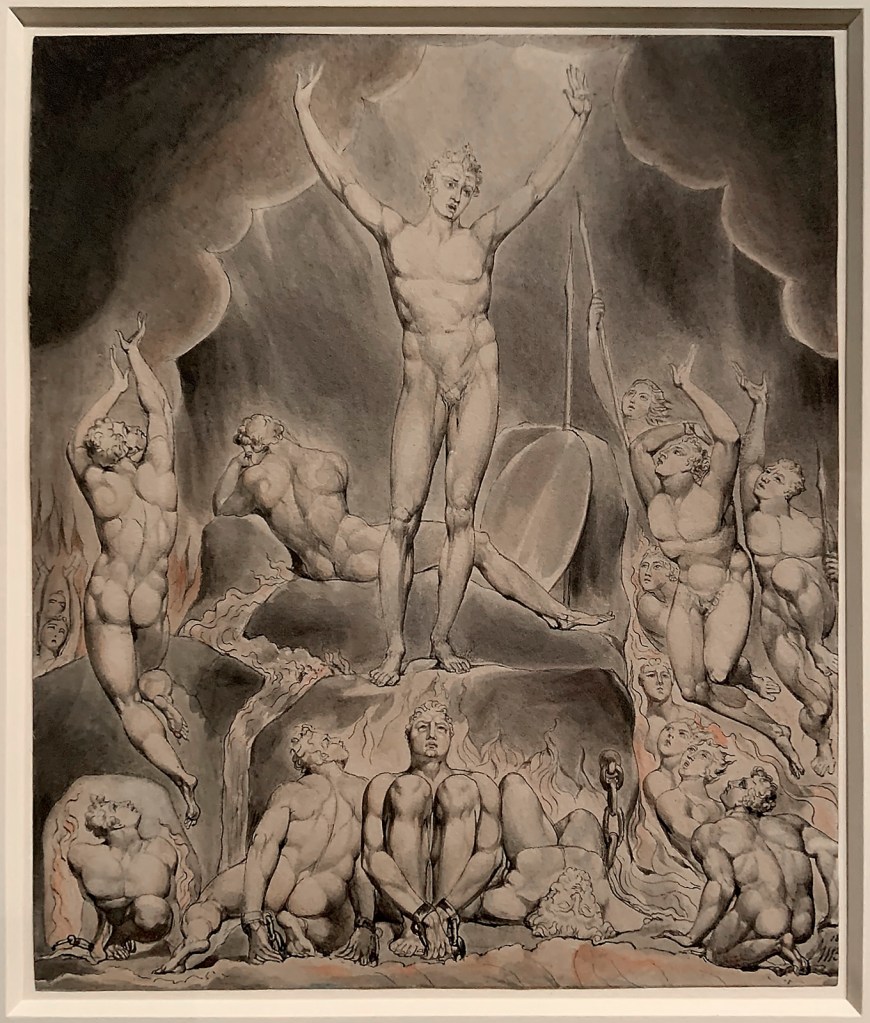

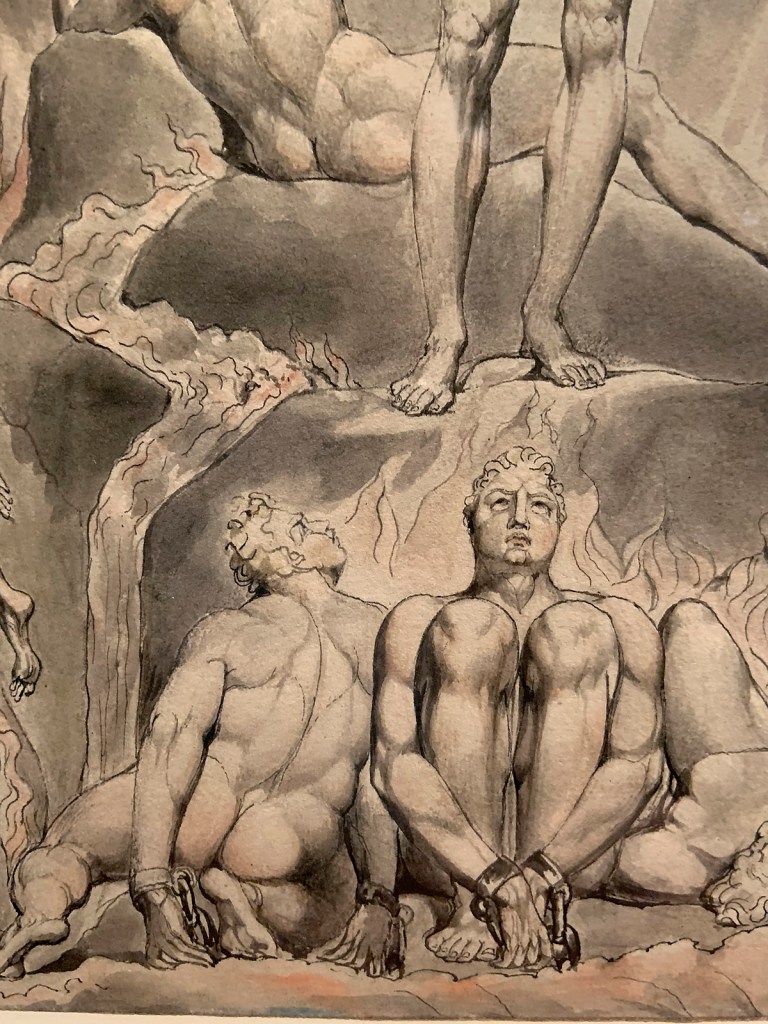

Illustrations to Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ Plate 1: ‘Satan Arousing the Rebel Angels’ (Thomas set) (installation views)

1807

12 designs on 12 sheets

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

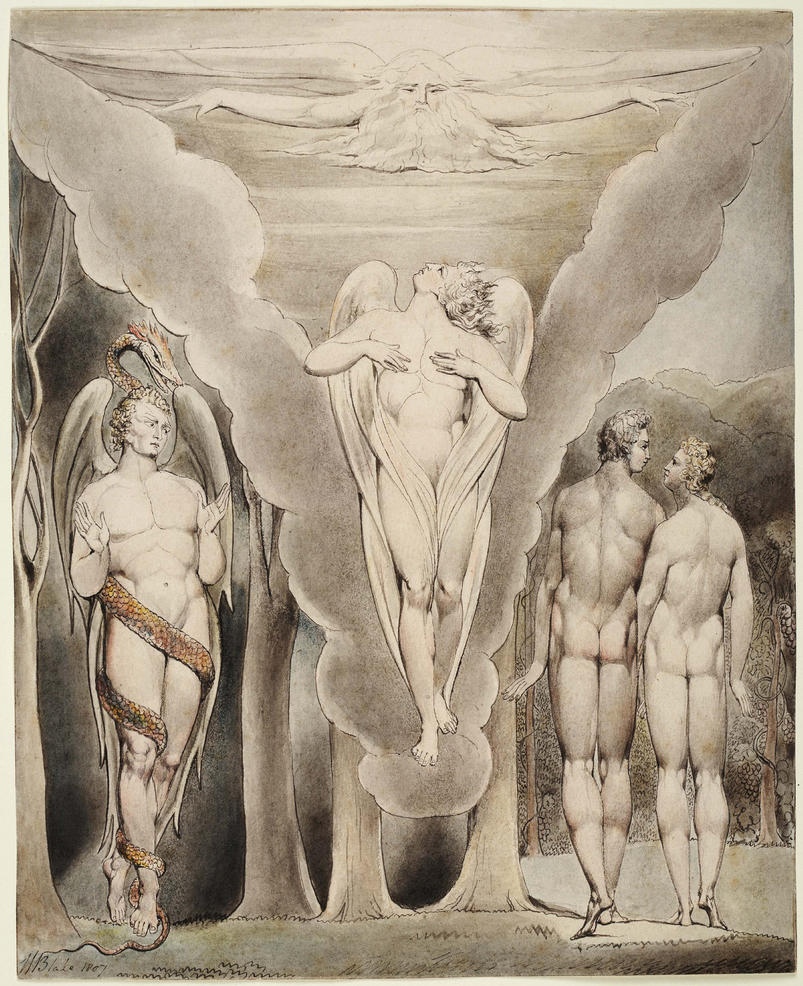

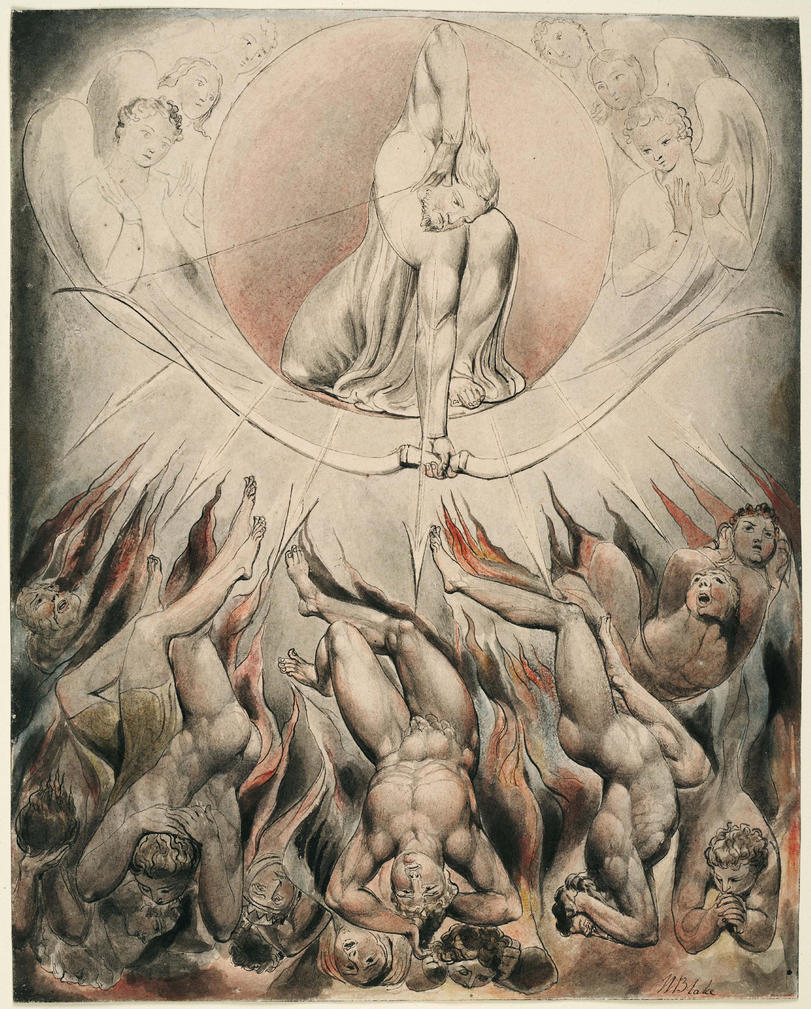

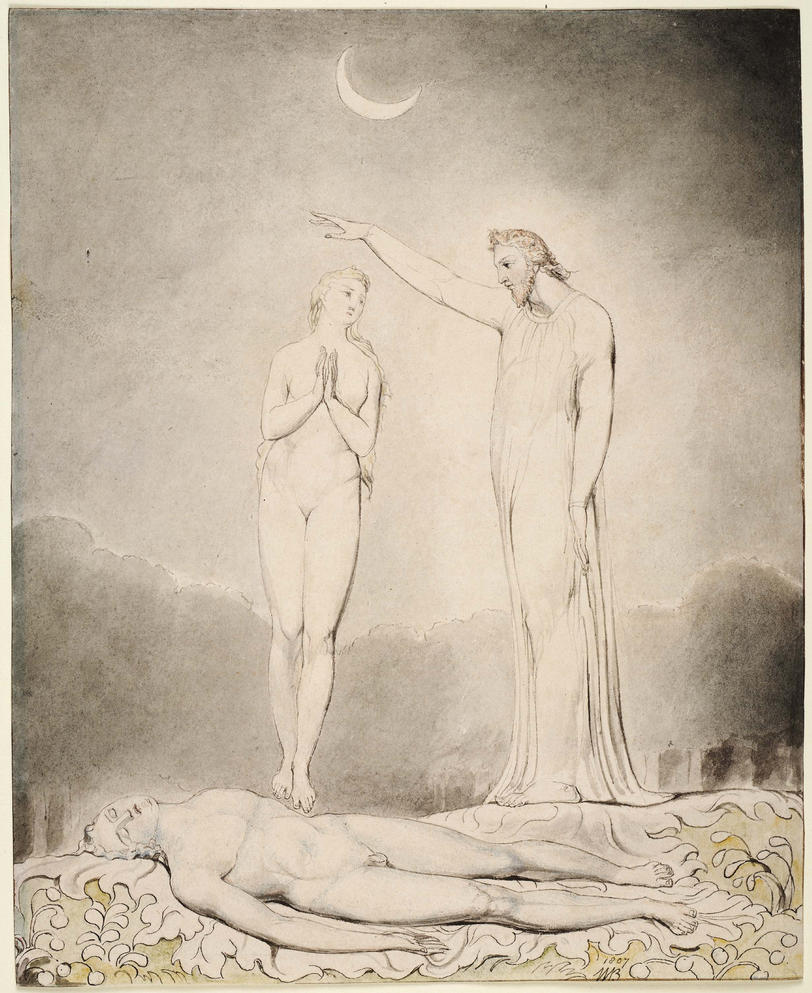

John Milton’s epic poem describes Adam and Eve’s banishment from the Garden of Eden. Satan, the rebellious fallen angel, is a major character. Blake made these illustrations for the Rev. Joseph Thomas, following an introduction from Flaxman.

There are three sets: the Thomas set (1807), the Butts set (1808) and the incomplete Linnell set (1822).

The Thomas set

The paintings of the Thomas set are each approximately 10x 8.25 inches. They were commissioned by the Reverend Joseph Thomas at an unrecorded date, sometime before 1807. Although the sheets were trimmed at some time, obliterating the date from several, some still retain the date of 1807, establishing the year of their completion. Thomas’ grandson inherited them from his father, and sold them at Sotheby’s in 1872. By 1876 they were in the collection of Alfred Aspland, who by 1885 took them to Sotheby’s again, dispersing the set among several buyers. Henry Huntington reunited the works in 1914, and today they are still in the collection of the Huntington Library.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Reverend Joseph Thomas

The Rev. Joseph Thomas of Epsom, Surrey, was a clergyman and friend of Flaxman. Flaxman put him and Blake in touch, leading to a series of commissions. Thomas had married an heiress, Millicent Pankhurst. He held no church appointment and was free to pursue his artistic and scholarly interests.

Blake produced several series of watercolours for Thomas illustrating the poetry of the 17th-century writer John Milton, and Shakespeare’s plays. Thomas also purchased a few published works by Blake.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Illustrations to Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ Plate 1: ‘Satan Arousing the Rebel Angels’ (Thomas set)

1807

12 designs on 12 sheets

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Google Art Project, Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Illustrations to Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ Plate 2: ‘Satan, Sin, and Death: Satan Comes to the Gates of Hell’ (Thomas set)

1807

12 designs on 12 sheets

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Google Art Project, Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Illustrations to Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ Plate 4: ‘Satan Spying on Adam and Eve’s Descent into Paradise’ (Thomas set)

1807

12 designs on 12 sheets

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Google Art Project, Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

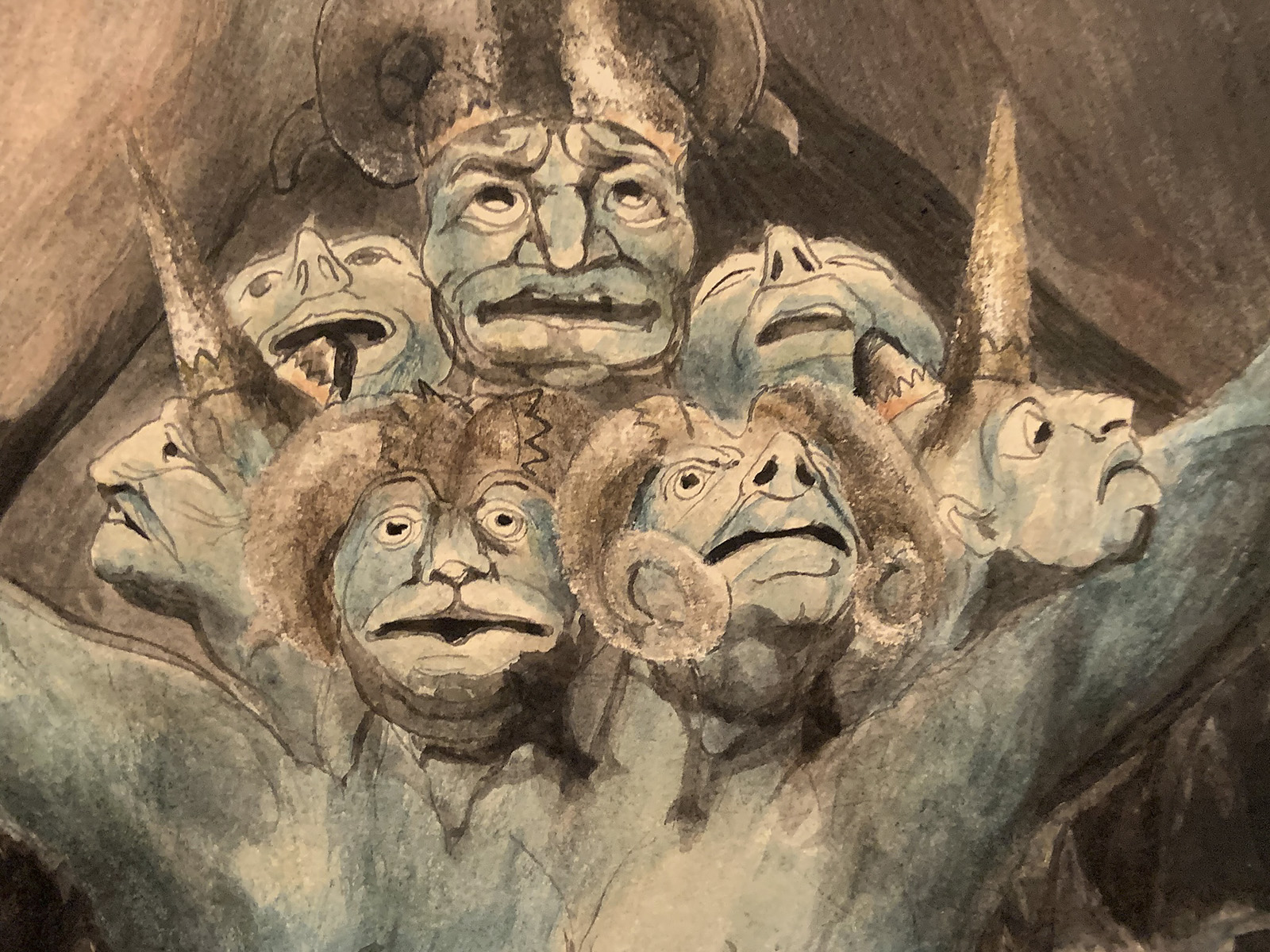

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Illustrations to Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ Plate 7: ‘The Rout of the Rebel Angels’ (Thomas set) (installation view)

1807

12 designs on 12 sheets

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Illustrations to Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ Plate 7: ‘The Rout of the Rebel Angels’ (Thomas set)

1807

12 designs on 12 sheets

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Google Art Project, Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

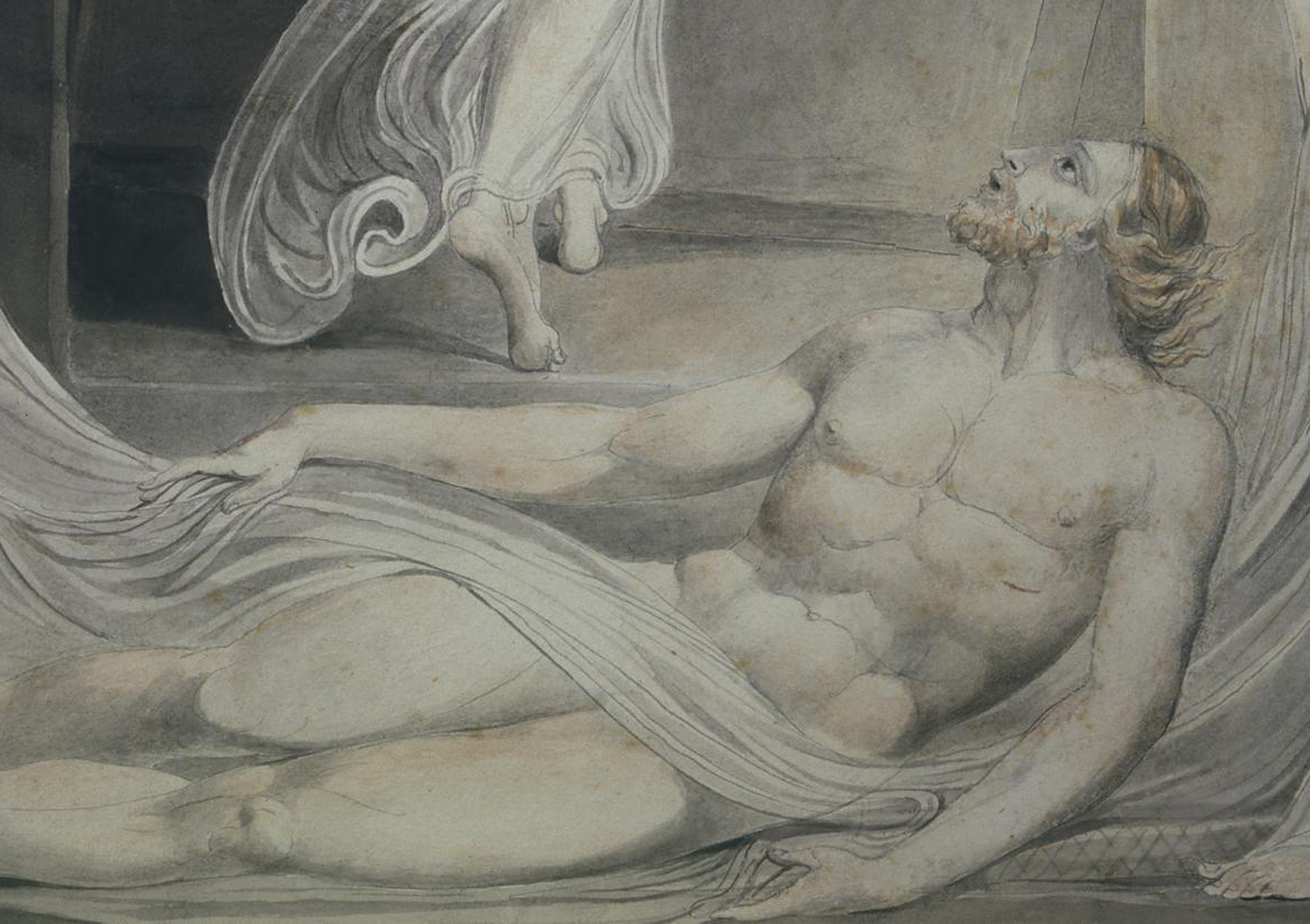

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Illustrations to Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ Plate 8: ‘The Creation of Eve’ (Thomas set) (installation views)

1807

12 designs on 12 sheets

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Illustrations to Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ Plate 8: ‘The Creation of Eve’ (Thomas set)

1807

12 designs on 12 sheets

Ink and watercolour on paper

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Google Art Project, Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

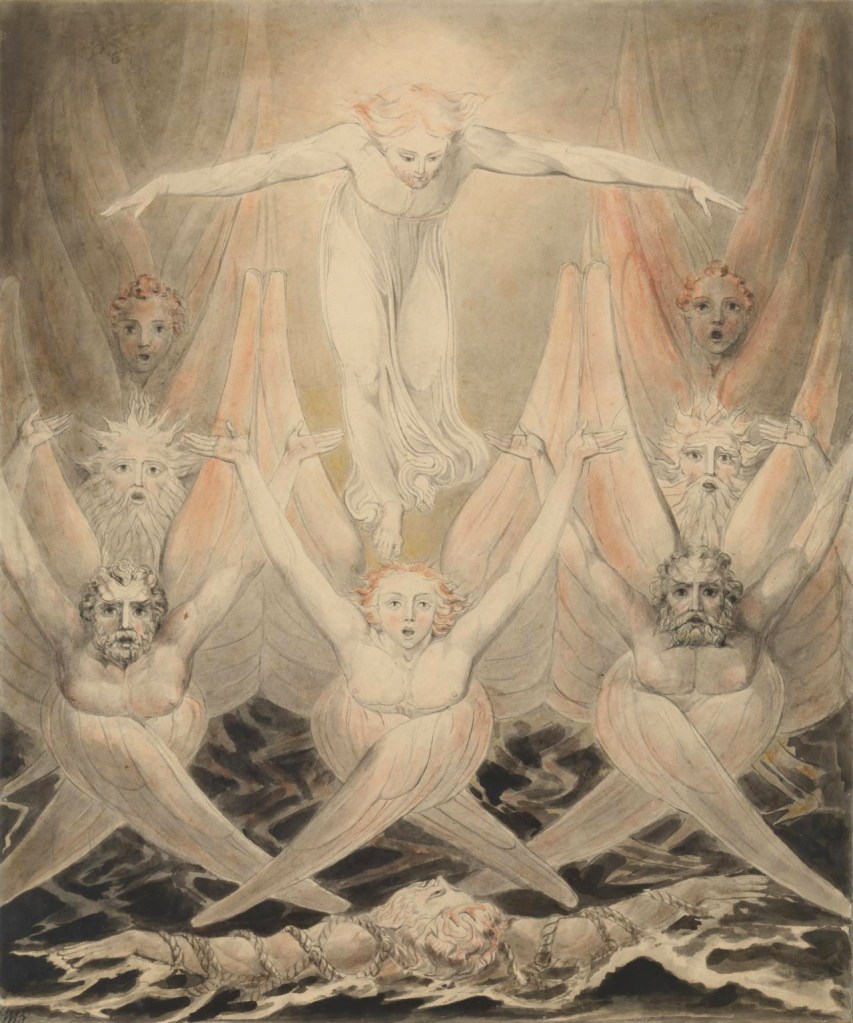

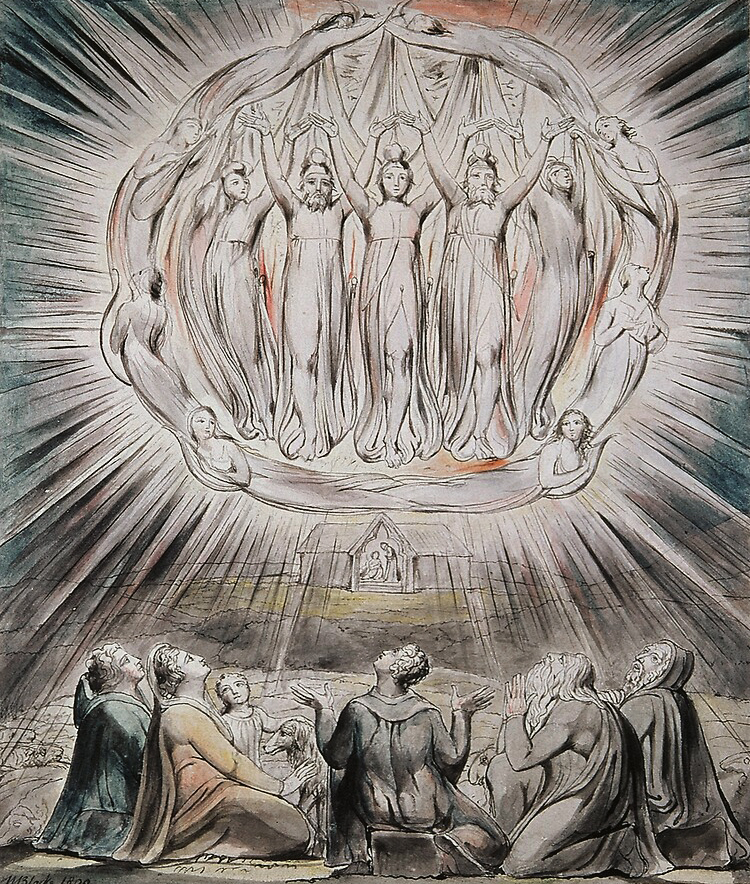

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Illustrations to Milton’s Hymn ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’ Plate 2: ‘The Angels appearing to the Shepherds’ (installation views)

1809

6 designs on 6 sheets

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

The Whitworth, The University of Manchester

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Blake was paid two pounds for each of these six designs by Thomas, twice what he was paid by Butts for the individual Bible watercolours. He made another set of these illustrations for Thomas Butts. Milton’s poem celebrates the birth of Christ, and the retreat of pagan and evil forces.

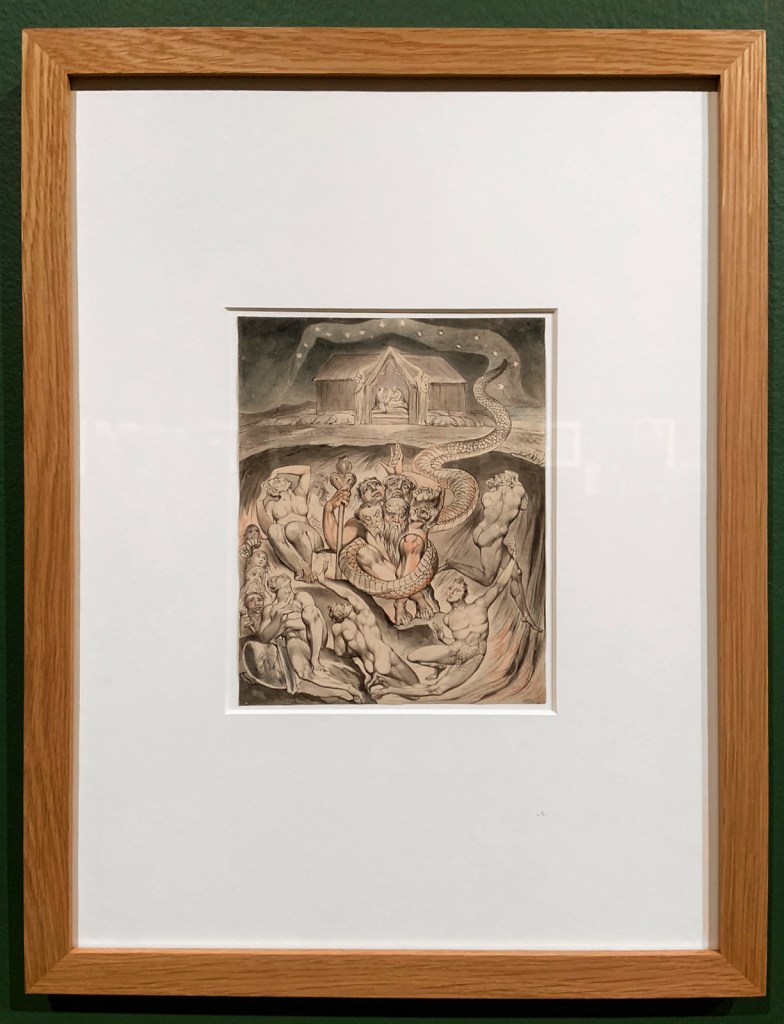

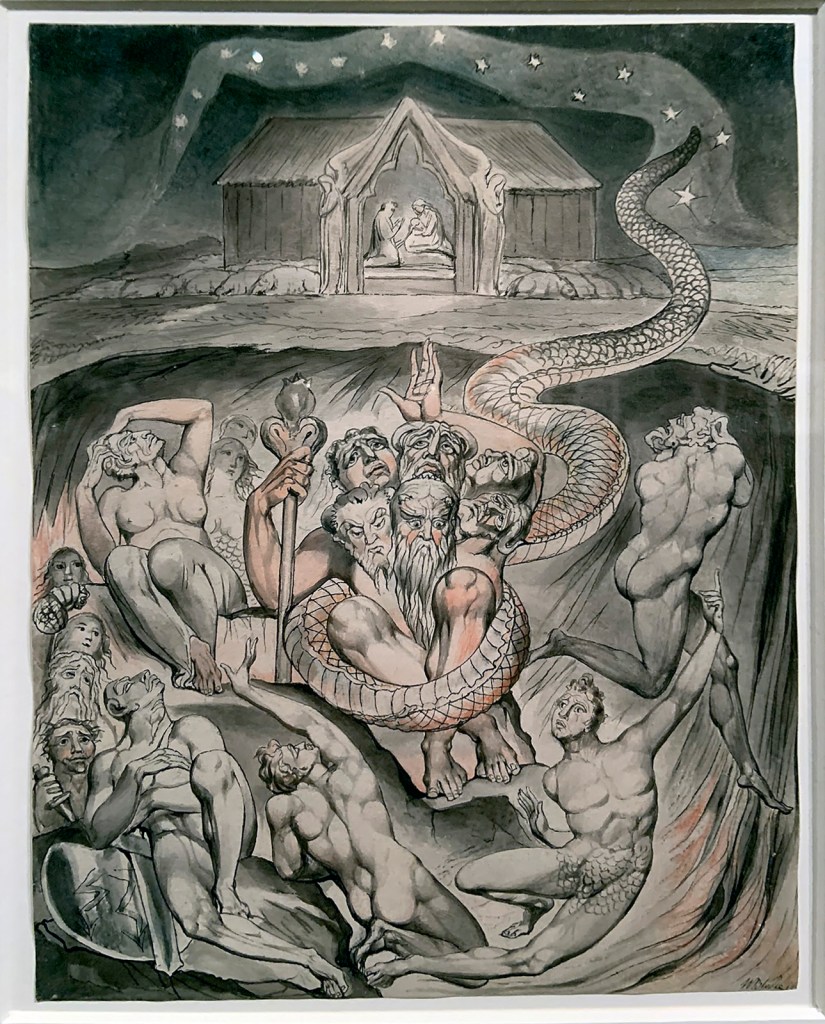

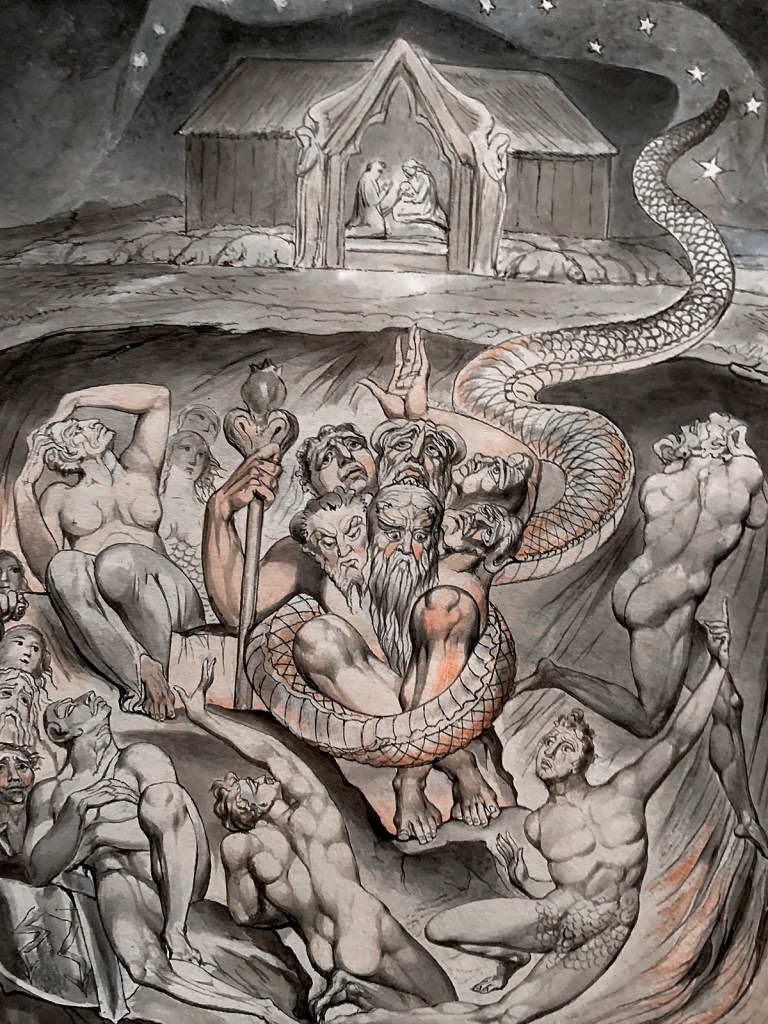

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Illustrations to Milton’s Hymn ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’ Plate 3: ‘The Descent of Typhon and the Gods into Hell’ (installation views)

1809

6 designs on 6 sheets

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

The Whitworth, The University of Manchester

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Tate Britain

Millbank, London SW1P 4RG

United Kingdom

Phone: +44 20 7887 8888

Opening hours:

10.00am – 18.00pm daily

![Attributed to Oscar G. Rejlander (British born Sweden, 1813-1875) '[Landscape]' c. 1855 Attributed to Oscar G. Rejlander (British born Sweden, 1813-1875) '[Landscape]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/rejlander-landscape-c-1855-web.jpg?w=909)

You must be logged in to post a comment.