Exhibition dates: 31st January – 4th May 2014

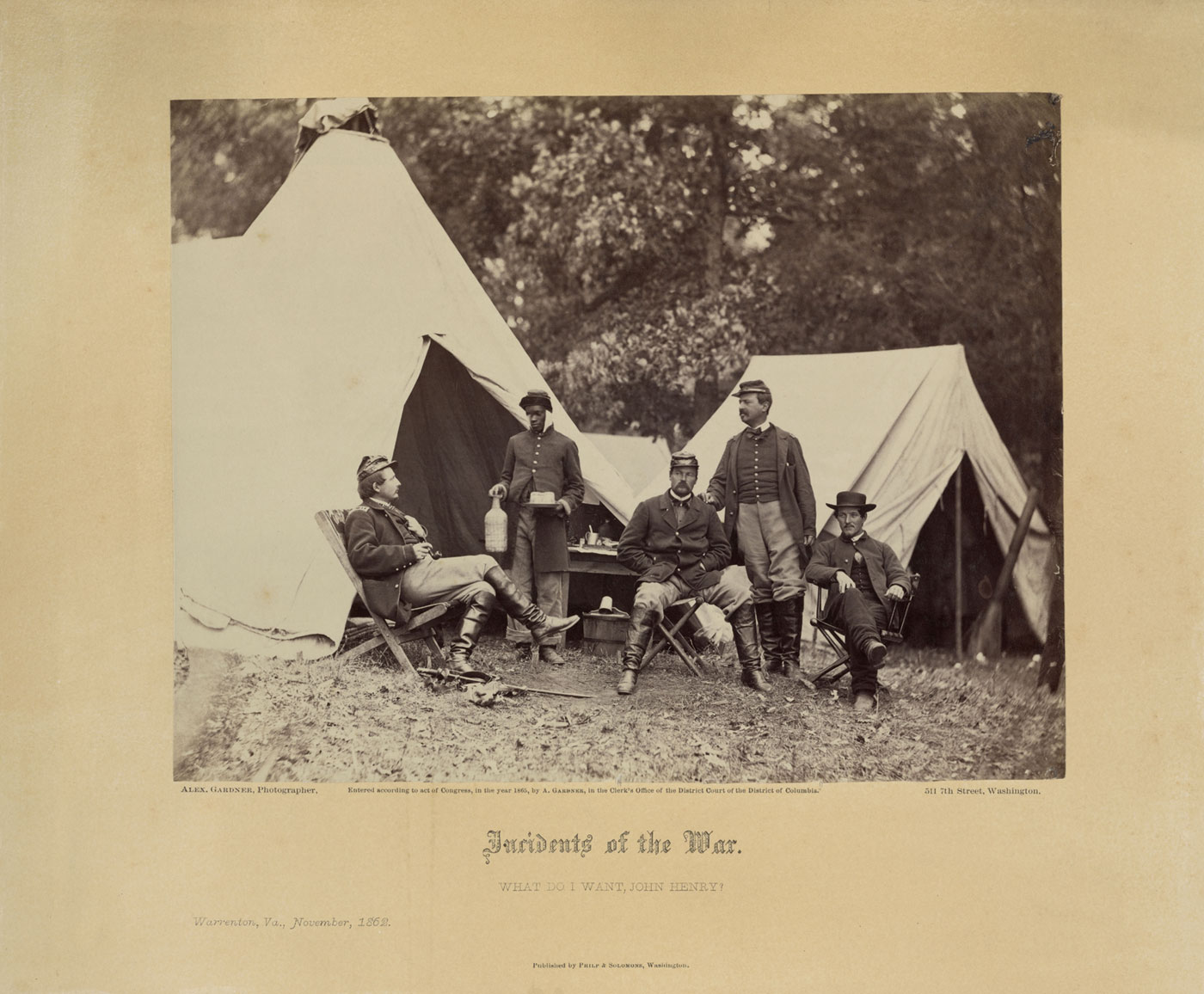

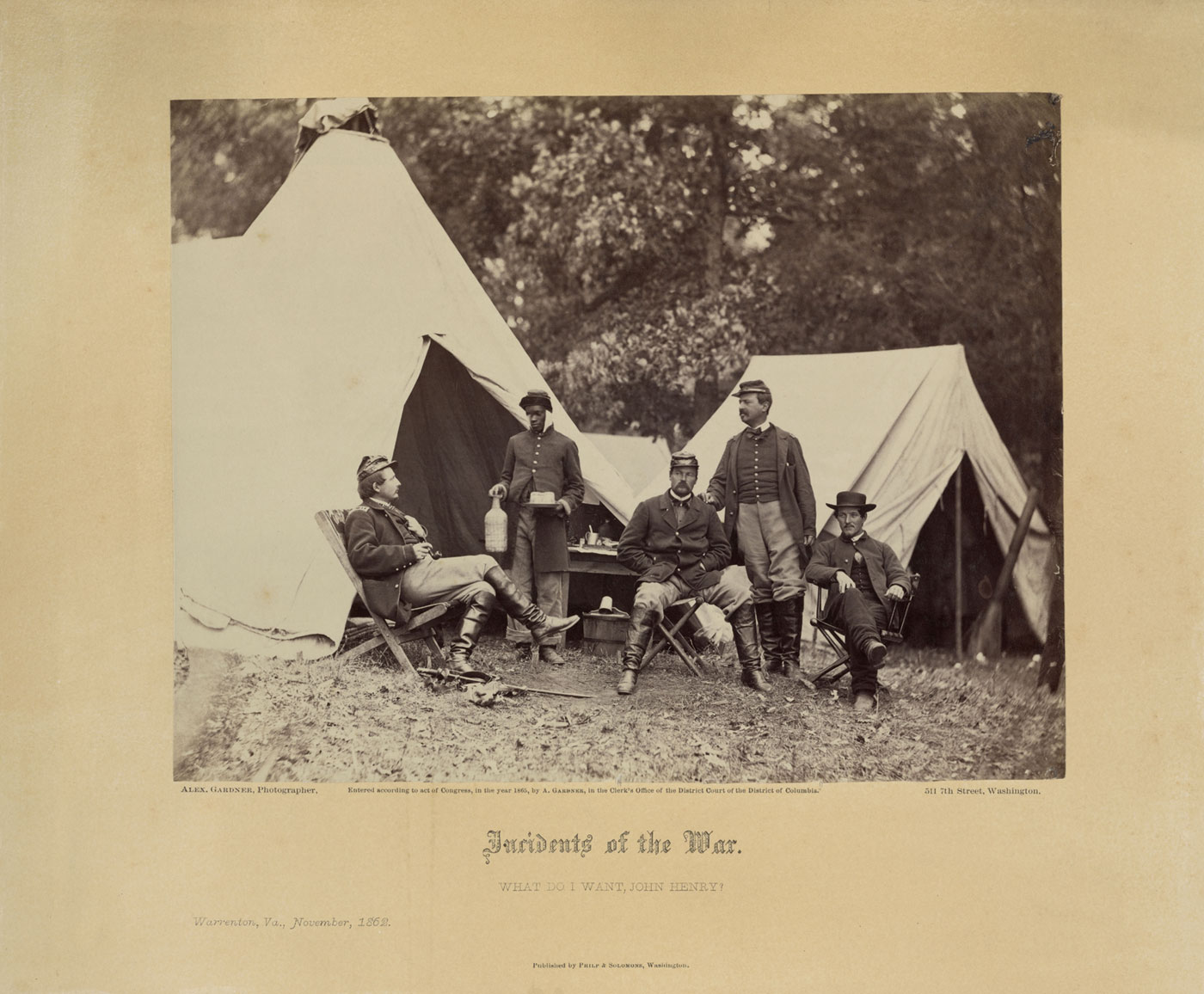

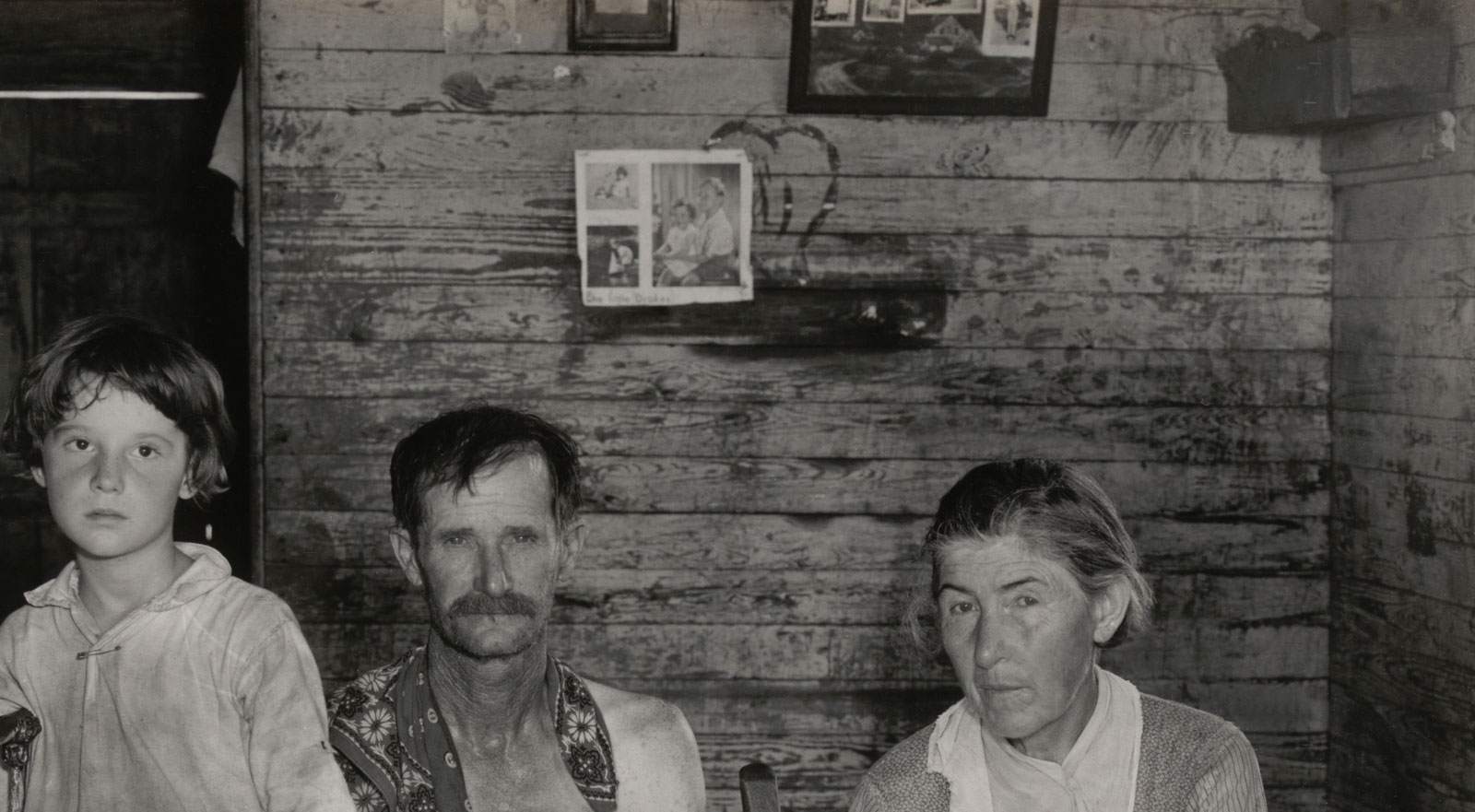

Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 – 1882 Washington, D.C.)

What Do I Want, John Henry? Warrenton, Virginia

November 1862

Albumen photograph from the album Incidents of the War

Photography collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs

The New York Public Library Astor, Lennox and Tilden Foundations

This posting continues my fascination with the American Civil War, with new photographs from the exhibition to compliment the posting I did when it was staged at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, April – September 2013.

I have included fascinating close-up details: the collar of African-American Union soldier John Henry flapping in the breeze during the long time exposure (What Do I Want, John Henry? Warrenton, Virginia November 1862, below); the pale grey/blue eyes of George Patillo which have been added to the plate afterwards1 (The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John) etc… 1861-1863, below); the horrific branding of the slave Wilson Chinn who had the initials of his owner burned into his head (Emancipated Slaves Brought from Louisiana by Colonel George H. Banks, December 1863, below); and the crumpled coat of Allan Pinkerton, Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, as he poses with his president (President Abraham Lincoln et al, October 4, 1862, below).

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ “The daguerreotype, like all photographic processes before 1873 [including Ambrotypes], was sensitive to blue light only, so that red dresses registered black and people with blue eyes appeared to have no irises and looked quite strange.”

Davies, Alan. An Eye for Photography: The camera in Australia. Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press / State Library of New South Wales, 2002, p. 8.

Many thankx to the New Orleans Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 – 1882 Washington, D.C.)

What Do I Want, John Henry? Warrenton, Virginia (detail)

November 1862

Albumen photograph from the album Incidents of the War

Photography collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs

The New York Public Library Astor, Lennox and Tilden Foundations

Andrew Joseph Russell (American, 1830-1902)

Confederate Method of Destroying Rail Roads at McCloud Mill, Virginia

1863

Albumen silver print from glass negative

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Russell made several photographs of the discovery by the Union army of the simple but effective method developed by the Confederates to destroy Union railroad track. Using the ties as fuel, the soldiers stacked the iron rails in X formations and burned them until they could be twisted and made unusable. Federal engineers employed similar tactics to destroy Southern railroads, and this photograph has been published, inaccurately, as “Sherman’s Neckties.” The title refers to Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, who during the Atlanta Campaign on July 18, 1864, gave the following explicit order to his corps: “Officers should be instructed that bars simply bent may be used again, but if when red hot they are twisted out of line they cannot be used again. Pile the ties into shape for a bonfire, put the rails across and when red hot in the middle, let a man at each end twist the bar so that its surface becomes spiral.”

Anonymous. “Confederate Method of Destroying Rail Roads at McCloud Mill, Virginia 1863,” on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 05/03/2021

Unknown photographer

Captain Charles A. and Sergeant John M. Hawkins, Company E, “Tom Cobb Infantry,” Thirty-eighth Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry

1861-1862

Quarter-plate ambrotype with applied colour

David Wynn Vaughan Collection

Photo: Jack Melton

The vast majority of war portraits, either cased images or cartes de visite, are of individual soldiers. Group portraits in smaller formats are more rare and challenged the field photographer (as well as the studio gallerist) to conceive and execute an image that would honour the occasion and be desirable – saleable – to multiple sitters. For the patient photographer, this created interesting compositional problems and an excellent opportunity to make memorable group portraits of brothers, friends, and even members of different regiments.

In this quarter-plate ambrotype, Confederate Captain Charles Hawkins of the Thirty-eighth Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry, on the left, sits for his portrait with his brother John, a sergeant in the same regiment. They address the camera and draw their fighting knives from scabbards. Charles would die on June 13, 1863, in the Shenandoah Valley during General Robert E. Lee’s second invasion of the North. John, wounded at the Battle of Gaines’s Mill in June 1862, would survive the war, fighting with his company until its surrender at Appomattox.

![Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861-1863 Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861-1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-web.jpg)

Unknown photographer

[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, “Henry Volunteers,” Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]

1861-1863

Ambrotype

Plate: 8.3 x 10.8cm (3 1/4 x 4 1/4 in.)

David Wynn Vaughan Collection

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The four Pattillo boys of Henry County were brothers who all enlisted together in Company K of the 22nd Regiment of the GA Volunteer Infantry on August 31, 1861.

Benjamin, seated on the left holding a Confederate hand-grenade, made a 50-dollar bounty during his tenure from April 5 to June 20, 1862. He was shot in the stomach at 2nd Manassas on August 30, 1862, and died in the General Hospital in Warrenton, VA, the next day.

George, second from the left, was detailed for shoemaking at Augusta, GA in November of 1862 until the close of the war. He was the only Pattillo to make it out of the Civil War without an injury. He made 35 cents per shoe and made 106 shoes in February 29, for $37.10. The pay for a soldier was 3 dollars per day.

James, second from the right, was discharged in March of 1862 but reenlisted afterwards. He was shot in the foot in the Battle of Second Deep Bottom on August 16, 1864. The injury resulted in the amputation of his third toe. Pension records show he was at home on wounded furlough to close of the war.

John, seated on the right, was admitted to Chimborazo Hospital #2 in Richmond on May 31, 1862, because of a case of Dysentery. He returned to duty on June 14, 1862, but was wounded at the Seven Days’ battles near Richmond on June 28,1862. He was admitted to C. S. A. General Hospital at Charlottesville on November 20, 1862, and again on December 16, 1862. He returned to duty on December 17, 1862, but pension records show he was discharged on account of wounds in March of 1863.

David Wynn Vaughan. “Patillo Brothers,” on the Historynet.com website [Online] Cited 04/03/2021

![Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' (detail) 1861-1863 Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' (detail) 1861-1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-detail.jpg)

Unknown photographer

[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, “Henry Volunteers,” Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry] (detail)

1861-1863

Ambrotype

Plate: 8.3 x 10.8cm (3 1/4 x 4 1/4 in.)

David Wynn Vaughan Collection

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Myron H. Kimball (American, active 1860s)

Emancipated Slaves Brought from Louisiana by Colonel George H. Banks

December 1863

Albumen silver print from glass negative

13.2 x 18.3cm (5 3/16 x 7 3/16in.), oblong oval

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In December 1863, Colonel George Hanks of the 18th Infantry, Corps d’Afrique (a Union corps composed entirely of African-Americans), accompanied eight emancipated slaves from New Orleans to New York and Philadelphia expressly to visit photographic studios. A publicity campaign promoted by Major General Nathaniel Banks of the Department of the Gulf, and by the Freedman’s Relief Association of New York, its sole purpose was to raise money to educate former slaves in Louisiana, a state still partially held by the Confederacy. One group portrait, several cartes de visite of pairs of students, and numerous portraits of each student were made.

When this photograph was published as a woodcut in “Harper’s Weekly” of January 30, 1864, it was accompanied by the biographies of the eight emancipated slaves, which served successfully to fan the abolitionist cause. Two are quoted below.

AUGUSTA BROUJEY is nine years old. Her mother, who is almost white, was owned by her half-brother, named Solamon, who still retains two of her children.

WILSON CHINN is about 60 years old. He was “raised” by Isaac Howard of Woodford County, Kentucky. When 21 years old he was taken down the river and sold to Volsey B. Marmillion, a sugar planter about 45 miles above New Orleans. This man was accustomed to brand his negroes, and Wilson has on his forehead the letters “V. B. M.” Of the 210 slaves on this plantation 105 left at one time and came into the Union camp. Thirty of them had been branded like cattle with a hot iron, four of them on the forehead, and the others on the breast or arm.

In his negative, Kimball retouched the brand on Wilson Chinn’s forehead to make the initials appear more visible on the print.

Anonymous. “Emancipated Slaves Brought from Louisiana by Colonel George H. Banks December 1863,” on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 05/03/2021

Myron H. Kimball (American, active 1860s)

Emancipated Slaves Brought from Louisiana by Colonel George H. Banks (detail)

December 1863

Albumen silver print from glass negative

13.2 x 18.3cm (5 3/16 x 7 3/16in.), oblong oval

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The slave (at back left) with those letters was Wilson Chinn, who was about 60 years old at the time. When he was 21 years old he was sold to Volsey B. Marmillion, a sugar planter about 45 miles above New Orleans. Marmillion branded his slaves, including Wilson. Those are Marmillion’s initials, horrifically burned into Wilson’s forehead in the image.

Russell Lord, photography curator at NOMA

Andrew Joseph Russell (American, 1830-1902)

Slave Pen, Alexandria, Virginia

1863

Albumen silver print from glass negative

25.6 x 36.5cm (10 1/16 x 14 3/8 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Better known for his later views commissioned by the Union Pacific Railroad, A. J. Russell, a captain in the 141st New York Infantry Volunteers, was one of the few Civil War photographers who was also a soldier. As a photographer-engineer for the U.S. Military Railroad Construction Corps, Russell’s duty was to make a historical record of both the technical accomplishments of General Herman Haupt’s engineers and the battlefields and camp sites in Virginia. This view of a slave pen in Alexandria guarded, ironically, by Union officers shows Russell at his most insightful; the pen had been converted by the Union Army into a prison for captured Confederate soldiers.

Between 1830 and 1836, at the height of the American cotton market, the District of Columbia, which at that time included Alexandria, Virginia, was considered the seat of the slave trade. The most infamous and successful firm in the capital was Franklin & Armfield, whose slave pen is shown here under a later owner’s name. Three to four hundred slaves were regularly kept on the premises in large, heavily locked cells for sale to Southern plantation owners. According to a note by Alexander Gardner, who published a similar view, “Before the war, a child three years old, would sell in Alexandria, for about fifty dollars, and an able-bodied man at from one thousand to eighteen hundred dollars. A woman would bring from five hundred to fifteen hundred dollars, according to her age and personal attractions.”

Late in the 1830s Franklin and Armfield, already millionaires from the profits they had made, sold out to George Kephart, one of their former agents. Although slavery was outlawed in the District in 1850, it flourished across the Potomac in Alexandria. In 1859, Kephart joined William Birch, J. C. Cook, and C. M. Price and conducted business under the name of Price, Birch & Co. The partnership was dissolved in 1859, but Kephart continued operating his slave pen until Union troops seized the city in the spring of 1861.

Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 – 1882 Washington, D.C.)

Ruins of Gallego Flour Mills, Richmond

1865

Albumen silver prints from glass negatives

16.3 x 36.9cm (6 7/16 x 14 1/2 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In 1861, at the outset of the Civil War, the Confederate government moved its capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia, to be closer to the front and to protect Richmond’s ironworks and flour mills. On April 2, 1865, as the Union army advanced on Richmond, General Robert E. Lee gave the orders to evacuate the city. A massive fire broke out the following day, the result of a Confederate attempt to destroy anything that could be of use to the invading Union army. In addition to consuming twenty square blocks, including nearly every building in Richmond’s commercial district, it destroyed the massive Gallego Flour Mills, situated on the James River and seen here. Alexander Gardner, Mathew B. Brady’s former gallery manager, then his rival, made numerous photographs of the “Burnt District” as well as this dramatic panorama from two glass negatives. The charred remains have become over time an iconic image of the fall of the Confederacy and the utter devastation of war.

Anonymous. “Ruins of Gallego Flour Mills, Richmond December 1865,” on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 05/03/2021

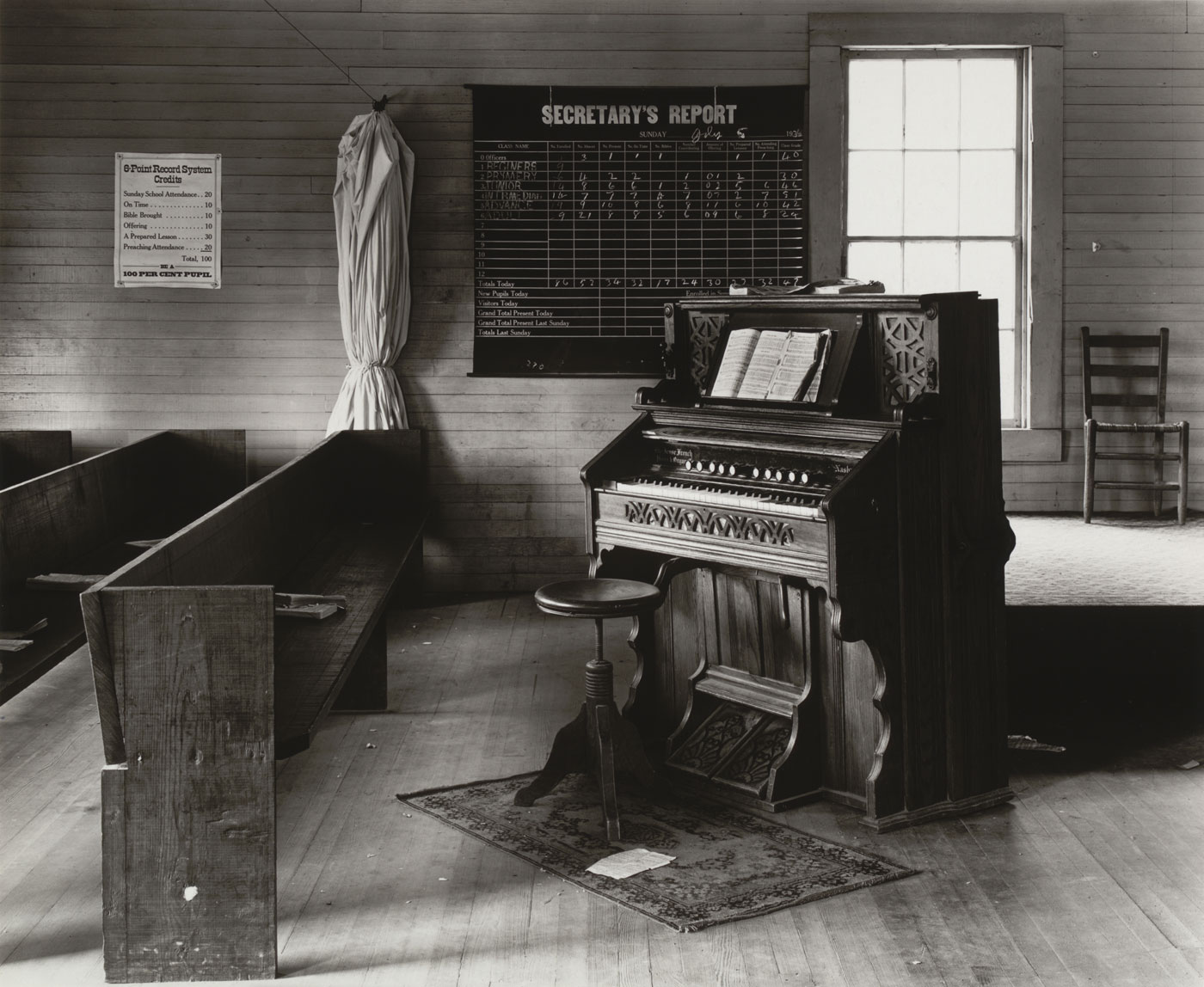

George N. Barnard (American, 1819-1902)

Ruins of Mrs. Henry’s House, Battlefield of Bull Run; Bull Run, Mrs. Henry’s House, 21 July 1861

March 1862

Albumen silver print from glass negative

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Despite their preparations, Mathew B. Brady and his corps of field photographers did not return with a single photograph from the war’s first land battle, at Bull Run, Virginia, in July 1861. And no Southern photographers are known to have attempted to photograph the battle preparations or aftermath. Won by Confederate General Robert E. Lee, the Battle of First Manassas (as it is still known in the South) was fought along a creek near the farmhouse in this photograph. Made eight months after the battle, this landscape by Brady operative George N. Barnard shows the ruins of Judith Henry’s house.

According to contemporary reports, Mrs. Henry was an invalid octogenarian widow who, because of her infirmities, was unable to leave the site of the battle that took place surrounding her home along Bull Run Creek. By removing her to a gully nearby, her children helped her survive the first charge. But when the fighting increased in ferocity, they returned her to her residence, where she was later found dead of bullet wounds.

Anonymous. “Ruins of Mrs. Henry’s House, Battlefield of Bull Run March 1862,” on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 05/03/2021

![Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-web.jpg)

Unknown maker

[Civil War Portrait Lockets]

1860s

Tintypes and albumen silver prints in brass, glass, and shell enclosures

Brian D. Caplan Collection

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

![Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s (detail) Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-detail.jpg?w=650&h=696)

Unknown maker

[Civil War Portrait Lockets] (detail)

1860s

Tintypes and albumen silver prints in brass, glass, and shell enclosures

Brian D. Caplan Collection

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

More than 200 of the finest and most poignant photographs of the American Civil War have been brought together for the landmark exhibition Photography and the American Civil War, opening January 31 at New Orleans Museum of Art. Organised by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the exhibition will examine the evolving role of the camera during the nation’s bloodiest war. The “War between the States” was the great test of the young Republic’s commitment to its founding precepts; it was also a watershed in photographic history. The camera recorded from beginning to end the heartbreaking narrative of the epic four-year war (1861-1865) in which 750,000 lives were lost. This exhibition will explore, through photography, the full pathos of the brutal conflict that, after 150 years, still looms large in the American public’s imagination.

“This extraordinary exhibition transcends geographic divisions in its intense focus on the participants in the Civil War,” said Susan M. Taylor, Director of New Orleans Museum of Art. “It becomes an exploration of shared human traits: hope, resolution, stoicism, fear, and sadness. We are delighted to share this important statement about American history and identity with the people of New Orleans and the Gulf region.”

Exhibition overview

Photography and the American Civil War will include: intimate studio portraits of armed Union and Confederate soldiers preparing to meet their destiny; battlefield landscapes strewn with human remains; rare multi-panel panoramas of the killing fields of Gettysburg and destruction of Richmond; diagnostic medical studies of wounded soldiers who survived the war’s last bloody battles; and portraits of Abraham Lincoln as well as his assassin John Wilkes Booth. The exhibition features groundbreaking works by Mathew B. Brady, George N. Barnard, Alexander Gardner, and Timothy O’Sullivan, among many others. It also examines in-depth the important, if generally misunderstood, role played by Brady, perhaps the most famous of all wartime photographers, in conceiving the first extended photographic coverage of any war. The exhibition addresses the widely held, but inaccurate, belief that Brady produced most of the surviving Civil War images, although he actually made very few field photographs during the conflict. Instead, he commissioned and published, over his own name and imprint, negatives made by an ever-expanding team of field operators, including Gardner, O’Sullivan, and Barnard.

Approximately 1,000 photographers worked separately and in teams to produce hundreds of thousands of photographs – portraits and views – that were actively collected during the period (and over the past century and a half) by Americans of all ages and social classes. In a direct expression of the nation’s changing vision of itself, the camera documented the war and also mediated it by memorialising the events of the battlefield as well as the consequent toll on the home front.

“The massive scope of this exhibition mirrors the tremendous role that photography played in describing, defining, and documenting the Civil War,” said Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photography. “The technical, cultural and even discursive functions of photography during the Civil War are critically traced in this exhibition, as is the powerful human story, a story of the personal hopes and sacrifices and the deep and tragic losses on both sides of the conflict.

Press release from the New Orleans Museum of Art website

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Unknown maker

[Presidential Campaign Medals with Portraits of John C. Breckinridge, Stephen A. Douglas and Edward Everett]

1860

Tintype

Brian D. Caplan Collection

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-web.jpg?w=650&h=806)

Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 – 1882 Washington, D.C.)

[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]

October 4, 1862

Albumen silver print from glass negative

22.4 x 18cm (8 13/16 x 7 1/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

Copy Photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Two weeks after he recorded the carnage at Antietam, Alexander Gardner returned to the battlefield to photograph the visit of President Abraham Lincoln. The president made the seventy-mile journey to Maryland to pay his respects to the wounded on both sides and to confer with his field generals. Gardner made about twenty-five photographs, mostly portraits of a strained meeting between Lincoln and General George B. McClellan, commander of the Union Army of the Potomac. He also made this formal field portrait of Lincoln posed with Allan Pinkerton, his diminutive Secret Service chief (left), and General John McClernand. Founder in 1850 of the eponymous detective agency, Pinkerton proved to be a particularly poor gatherer of military intelligence in his advisory role as a spy for the army. Many believe he significantly overestimated the strength of Robert E. Lee’s forces – an error that dramatically prolonged the war by contributing to McClellan’s extreme caution at attacking the enemy.

Anonymous. “President Abraham Lincoln October 4, 1862,” on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 05/03/2021

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 (detail) Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-detail.jpg)

Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 – 1882 Washington, D.C.)

[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland] (detail)

October 4, 1862

Albumen silver print from glass negative

22.4 x 18cm (8 13/16 x 7 1/16 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

Copy Photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

![Unknown maker (American); Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s - 1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865 Unknown maker (American); Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s - 1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/lincoln-mourning.jpg?w=650&h=867)

Unknown maker (American)

Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s – 1880s

[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]

Photograph, corsage

April 1865

Black and white silk with tintype set inside brass button

20 x 9cm (7 7/8 x 3 9/16 in.)

Image: 2 x 2cm (13/16 x 13/16 in.)

Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2013

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

![Unknown maker (American); Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' Photograph, corsage April 1865 (detail) Unknown maker (American); Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' Photograph, corsage April 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp265063-lincoln-memorial-button-web.jpg?w=650&h=867)

Unknown maker (American)

Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s – 1880s

[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln] (detail)

Photograph, corsage

April 1865

Black and white silk with tintype set inside brass button

20 x 9cm (7 7/8 x 3 9/16 in.)

Image: 2 x 2cm (13/16 x 13/16 in.)

Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2013

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

About the time of Abraham Lincoln’s long funeral tour, April 21 to May 3, 1865, enterprising vendors produced mourning corsages featuring black silk ribbons adorned with small circular photographs of the president. The likeness is a tintype copy of a portrait from February 9, 1864, that Anthony Berger had made of President Lincoln in Mathew B. Brady’s Washington gallery. The corsage would have been worn on one’s lapel and then carefully preserved as a memento mori of the war’s final casualty.

George N. Barnard (American, 1819-1902)

Bonaventure Cemetery, Four Miles from Savannah

1866

Albumen silver print from glass negative

34 x 26.4cm (13 3/8 x 10 3/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005

Photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

![Unknown maker '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862 Unknown maker '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp269309-chess-board-web.jpg?w=650&h=640)

Unknown maker

[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]

1862

Albumen silver prints from glass negatives

Brian D. Caplan Collection

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

![Unknown maker '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862 (detail) Unknown maker '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp269309-chess-board-detail.jpg)

Unknown maker

[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals] (detail)

1862

Albumen silver prints from glass negatives

Brian D. Caplan Collection

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Confederate Sergeant in Slouch Hat]' 1861-1862 Unknown photographer (American) '[Confederate Sergeant in Slouch Hat]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/confederate-with-clown-like-chevrons-closeup-web.jpg?w=650&h=689)

Unknown photographer (American)

[Confederate Sergeant in Slouch Hat]

1861-1862

Ambrotype

David Wynn Vaughan, Jr. Collection

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Attributed to, Oliver H. Willard (American, active 1850s-70s, died 1875)

Ordnance, Private

1866

Albumen silver print from glass negative

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Fund, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2010

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This hand-coloured portrait provides a good look at the colours of war – at least as worn by the Union army. It comes from a set of photographs commissioned in 1866 by Montgomery Meigs, Quartermaster General of the United States Army during and after the Civil War. Known as “the army behind the army,” the Quartermaster Corps is the army’s oldest logistical branch. Then and now it is charged with clothing, transporting, and sustaining large field armies far away from their base camps. Meigs understood the historical value of permanently recording the clothing (with accurate colours) and personal accoutrements worn by soldiers and officers during the war. The portraits by Oliver H. Willard, still a relatively obscure photographer, all show the same soldier / actor wearing a wide variety of uniforms and posing with the tools and emblems of his service and rank.

Anonymous. “Ordnance, Private 1866,” on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 05/03/2021

![Unknown photographer (American) '[James A. Holeman, Company A, "Roxboro Grays," Twenty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia]' 1861-1862 Unknown photographer (American) '[James A. Holeman, Company A, "Roxboro Grays," Twenty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/james-holeman-closeup-web.jpg?w=650&h=755)

Unknown photographer (American)

[James A. Holeman, Company A, “Roxboro Grays,” Twenty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia]

1861-1862

Ambrotype

David Wynn Vaughan Collection

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Captain James A. Holeman of Person County, Roxboro lost his life during the Civil War.

Unknown photographer (American)

Sojourner Truth, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance”

1864

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Carte-de-visite

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2013

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Born Isabella Baumfree to a family of slaves in Ulster County, New York, Sojourner Truth sits for one of the war’s most iconic portraits in an anonymous photographer’s studio, likely in Detroit. The sixty-seven-year-old abolitionist, who never learned to read or write, pauses from her knitting and looks pensively at the camera. She was not only an antislavery activist and colleague of Frederick Douglass but also a memoirist and committed feminist, who shows herself engaged in the dignity of women’s work. More than most sitters, Sojourner Truth is both the actor in the picture’s drama and its author, and she used the card mount to promote and raise money for her many causes: I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance. SOJOURNER TRUTH.

The imprint on the verso features the sitter’s statement in bright red ink as well as a Michigan 1864 copyright in her name. By owning control of her image, her “shadow,” Sojourner Truth could sell it. In so doing she became one of the era’s most progressive advocates for slaves and freedmen after Emancipation, for women’s suffrage, and for the medium of photography. At a human-rights convention, Sojourner Truth commented that she “used to be sold for other people’s benefit, but now she sold herself for her own.”

Anonymous. “Sojourner Truth, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance” 1864,” on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 05/03/2021

Sojourner Truth (c. 1797 – November 26, 1883) was the self-given name, from 1843 onward, of Isabella Baumfree, an African-American abolitionist and women’s rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, Ulster County, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man. Her best-known extemporaneous speech on gender inequalities, “Ain’t I a Woman?”, was delivered in 1851 at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army; after the war, she tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for former slaves.

Text from the Wikipedia website

![Unknown maker (American; Alexander Gardner, American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.; Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company, American, active Boston) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865 Unknown maker (American; Alexander Gardner, American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.; Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company, American, active Boston) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp274835-murder-web.jpg?w=650&h=1223)

Unknown maker (American; Alexander Gardner, American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.; Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company, American, active Boston)

[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]

April 20, 1865

Ink on paper with three albumen silver prints from glass negatives

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

On the night of April 14, 1865, just five days after Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox, John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln at the Ford Theatre in Washington, D.C. Within twenty-four hours, Secret Service director Colonel Lafayette Baker had already acquired photographs of Booth and two of his accomplices. Booth’s photograph was secured by a standard police search of the actor’s room at the National Hotel; a photograph of John Surratt, a suspect in the plot to kill Secretary of State William Seward, was obtained from his mother, Mary (soon to be indicted as a fellow conspirator), and David Herold’s photograph was found in a search of his mother’s carte-de-visite album. The three photographs were taken to Alexander Gardner’s studio for immediate reproduction. This bill was issued on April 20, the first such broadside in America illustrated with photographs tipped onto the sheet.

The descriptions of the alleged conspirators combined with their photographic portraits proved invaluable to the militia. Six days after the poster was released Booth and Herold were recognised by a division of the 16th New York Cavalry. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Edward Doherty, demanded their unconditional surrender when he cornered the two men in a barn near Port Royal, Virginia. Herold complied; Booth refused. Two Secret Service detectives accompanying the cavalry, then set fire to the barn. Booth was shot as he attempted to escape; he died three hours later. After a military trial Herold was hanged on July 7 at the Old Arsenal Prison in Washington, D.C.

Surratt escaped to England via Canada, eventually settling in Rome. Two years later a former schoolmate from Maryland recognised Surratt, then a member of the Papal Guard, and he was returned to Washington to stand trial. In September 1868 the charges against him were nol-prossed after the trial ended in a hung jury. Surratt retired to Maryland, worked as a clerk, and lived until 1916.

Anonymous. “Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold April 20, 1865,” on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 05/03/2021

The New Orleans Museum of Art

One Collins Diboll Circle, City Park

New Orleans, LA 70124

Phone: (504) 658-4100

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 10am – 5pm

Closed Mondays

The New Orleans Museum of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

0.000000

0.000000

![Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atgets-work-room-web1.jpg?w=650&h=783)

![Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857–1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 (detail) Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857–1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atget-workroom-detail-web.jpg)

![Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858) Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904) 'Untitled [The Pavillon de Flore and the Tuileries Gardens]' 1849 Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858) Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904) 'Untitled [The Pavillon de Flore and the Tuileries Gardens]' 1849](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/the-pavillon-de-flore-web.jpg)

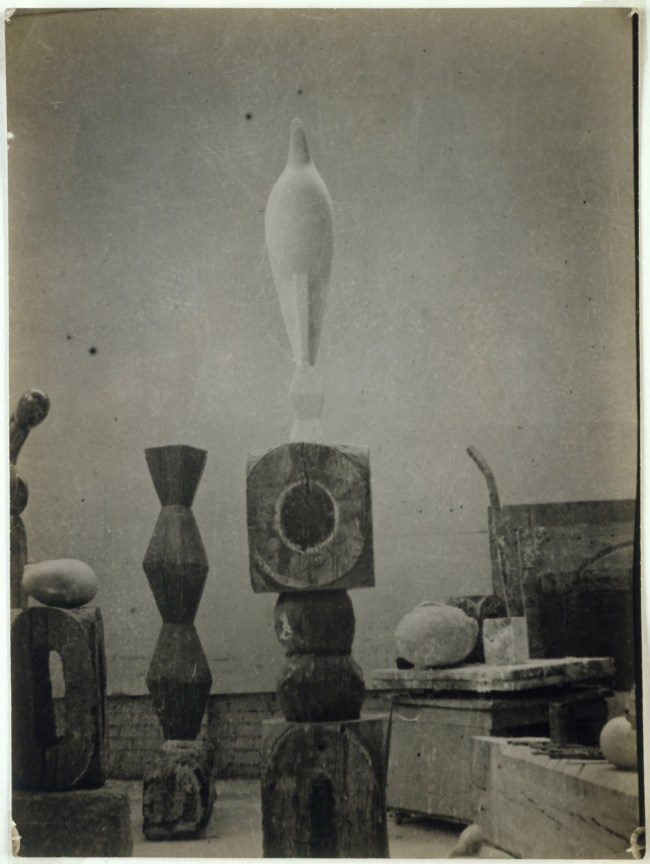

![Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 - 1973 West Redding, Connecticut) 'Untitled [Brancusi's Studio]' c. 1920 Edward J. Steichen (American born Luxembourg, Bivange 1879 - 1973 West Redding, Connecticut) 'Untitled [Brancusi's Studio]' c. 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/edward_steichen_brancusis_studio_1920-web.jpg?w=650&h=816)

![Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861-1863 Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861-1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-web.jpg)

![Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' (detail) 1861-1863 Unknown photographer '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' (detail) 1861-1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-detail.jpg)

![Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-web.jpg)

![Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s (detail) Unknown maker. '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-detail.jpg?w=650&h=696)

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-web.jpg?w=650&h=806)

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 (detail) Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821 - 1882 Washington, D.C.) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-detail.jpg)

![Unknown maker (American); Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s - 1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865 Unknown maker (American); Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s - 1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/lincoln-mourning.jpg?w=650&h=867)

![Unknown maker (American); Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' Photograph, corsage April 1865 (detail) Unknown maker (American); Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' Photograph, corsage April 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp265063-lincoln-memorial-button-web.jpg?w=650&h=867)

![Unknown maker '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862 Unknown maker '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp269309-chess-board-web.jpg?w=650&h=640)

![Unknown maker '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862 (detail) Unknown maker '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp269309-chess-board-detail.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Confederate Sergeant in Slouch Hat]' 1861-1862 Unknown photographer (American) '[Confederate Sergeant in Slouch Hat]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/confederate-with-clown-like-chevrons-closeup-web.jpg?w=650&h=689)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[James A. Holeman, Company A, "Roxboro Grays," Twenty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia]' 1861-1862 Unknown photographer (American) '[James A. Holeman, Company A, "Roxboro Grays," Twenty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/james-holeman-closeup-web.jpg?w=650&h=755)

![Unknown maker (American; Alexander Gardner, American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.; Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company, American, active Boston) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865 Unknown maker (American; Alexander Gardner, American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.; Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company, American, active Boston) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/dp274835-murder-web.jpg?w=650&h=1223)

You must be logged in to post a comment.