Exhibition dates: 31st July – 31st October 2010

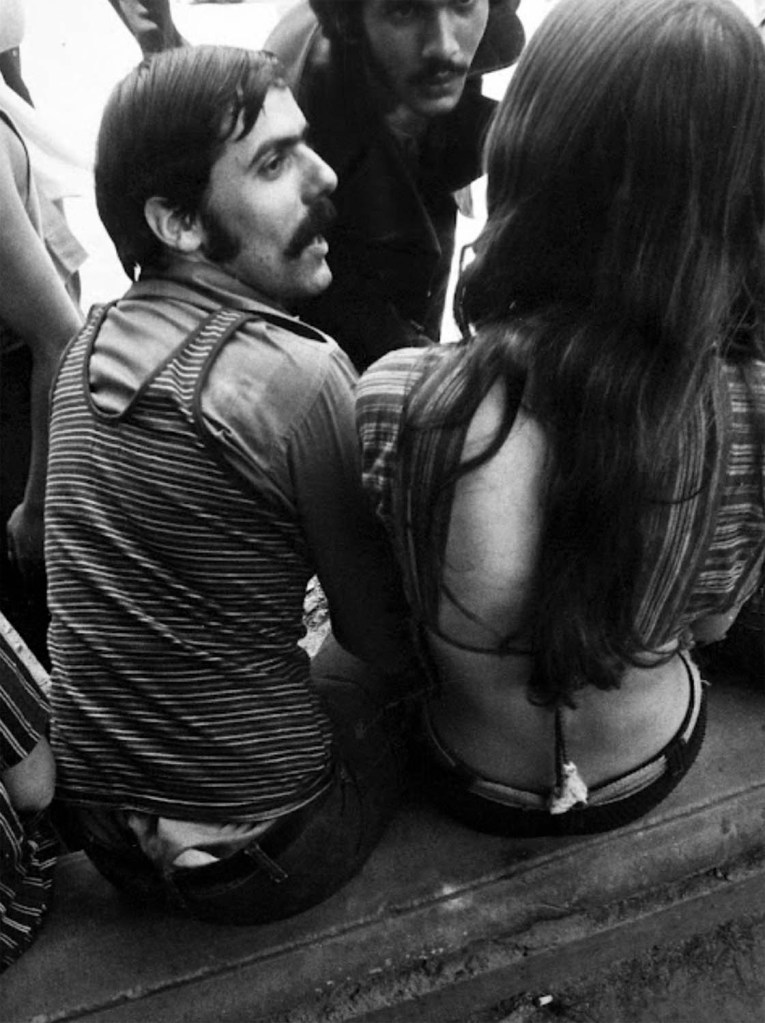

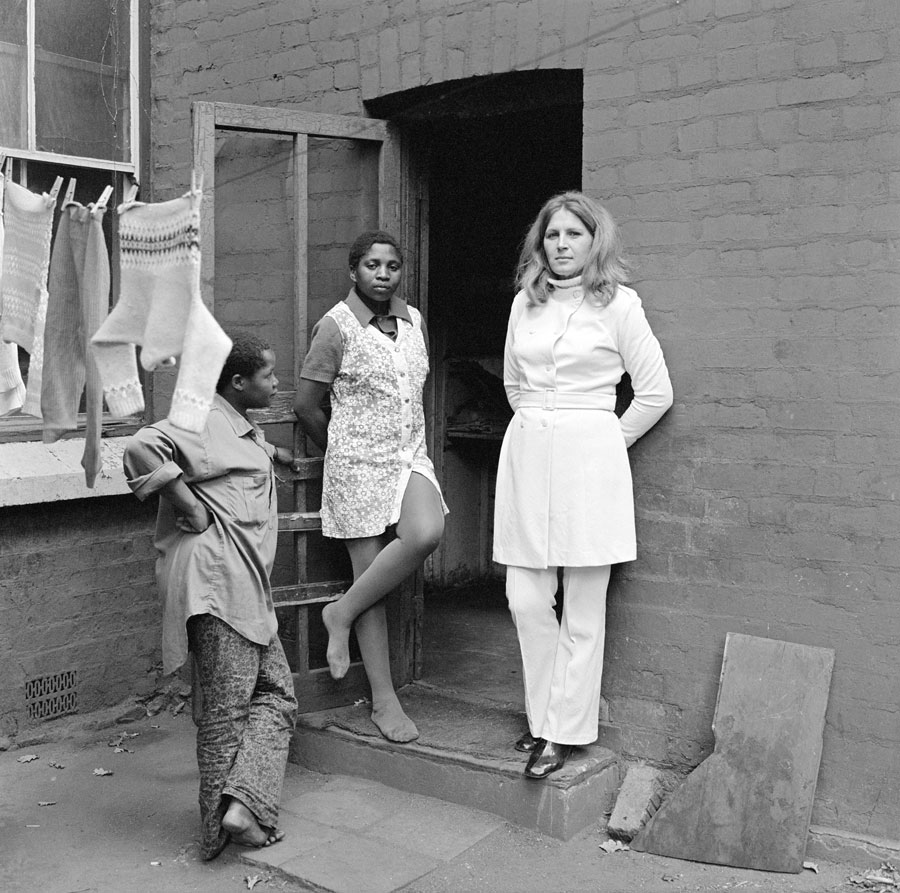

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Vale Street

1975

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant, 1982

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

“A face tells the story of what a person is thinking. The eyes reveal the suffering.”

Carol Jerems

Time and Truth: Looking again at the work of Carol Jerrems

This is a solid exhibition of the photographs of Carol Jerrems at Heide Museum of Modern Art, accompanied by small selections of the work of Larry Clark and William Yang and the sequence The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1979) by Nan Goldin.

I like Jerrems work: it is strong, frontal, direct and truthful. What I dislike is the hagiography that has grown up around this artist, the mythologizing of Saint Jerrems. We don’t need a saint of Australian photography; what we need is an appreciation of the artist, the person and her legacy. While the personal history of this artist is well known – facing depression, putting herself in danger, sexually active, documenting the counter-culture sharps and skinheads and urban indigenous people, the photographing of women and her death at far too young an age – few people actually look at the photographs clearly.

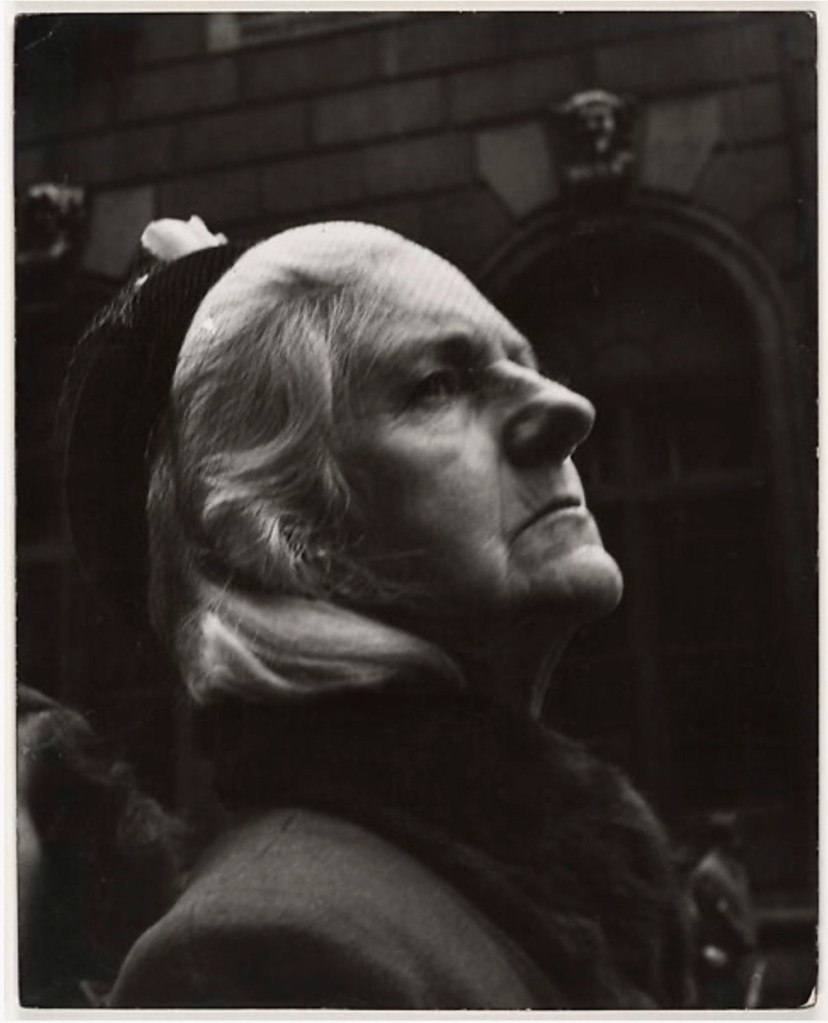

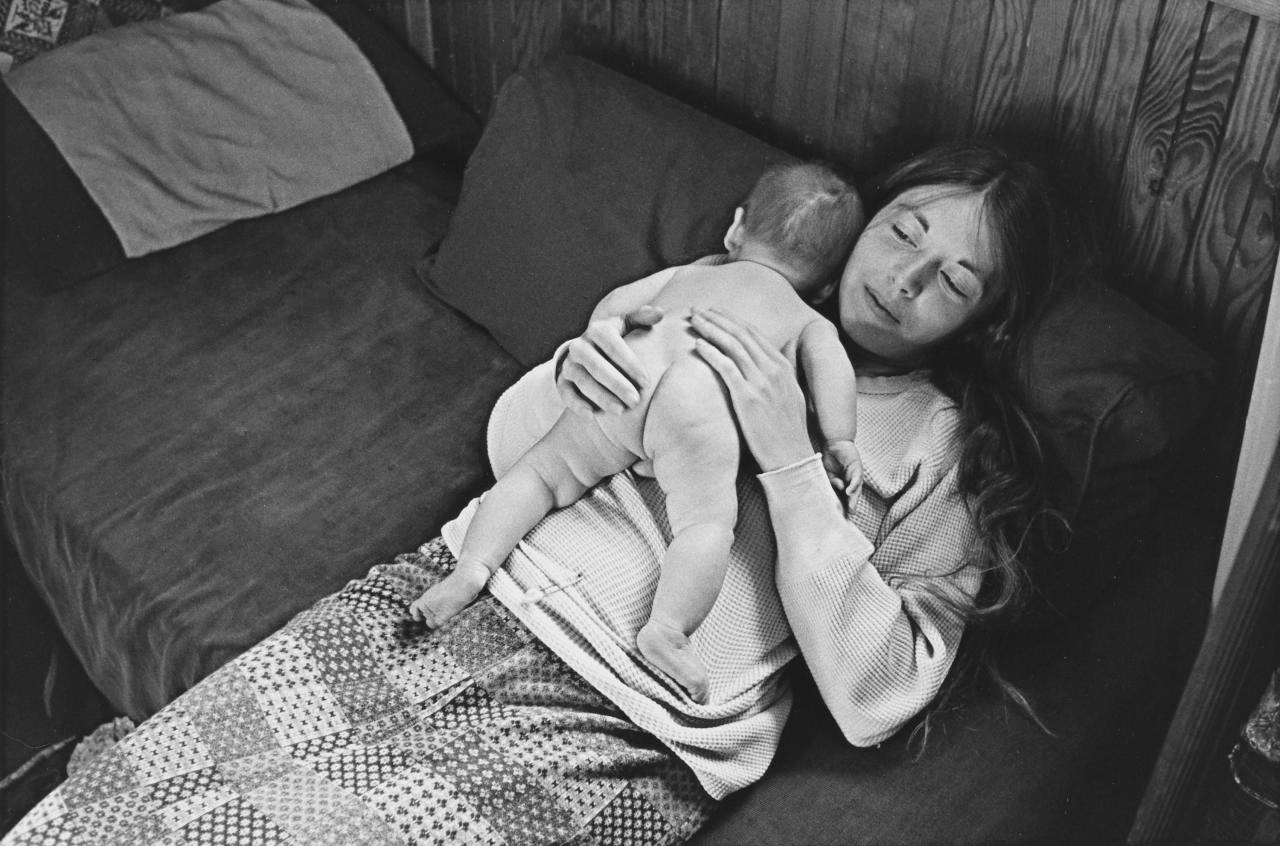

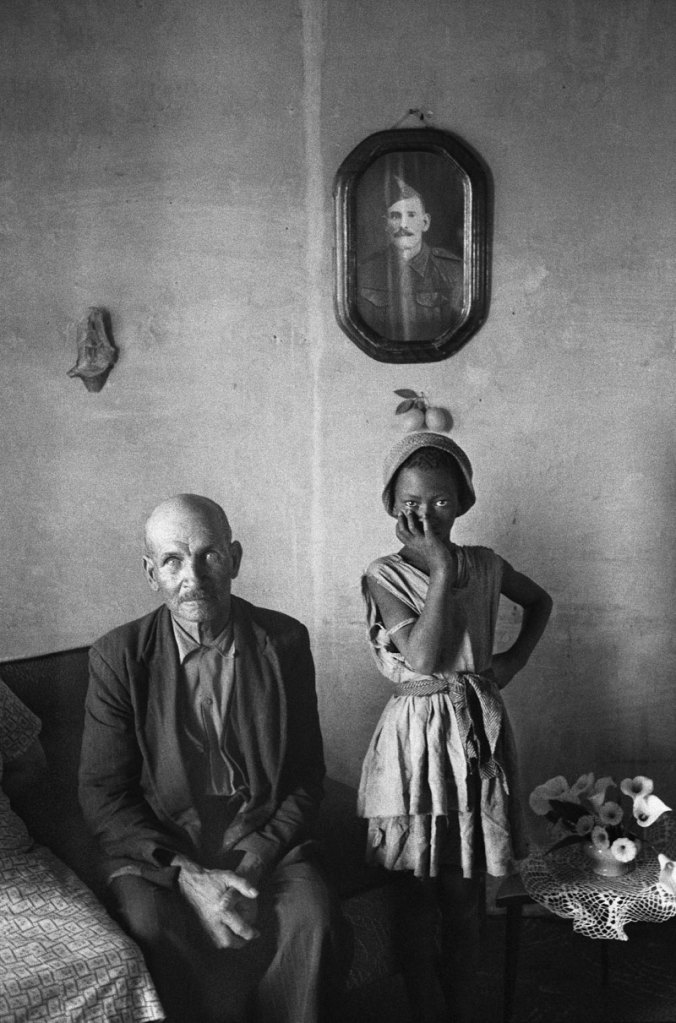

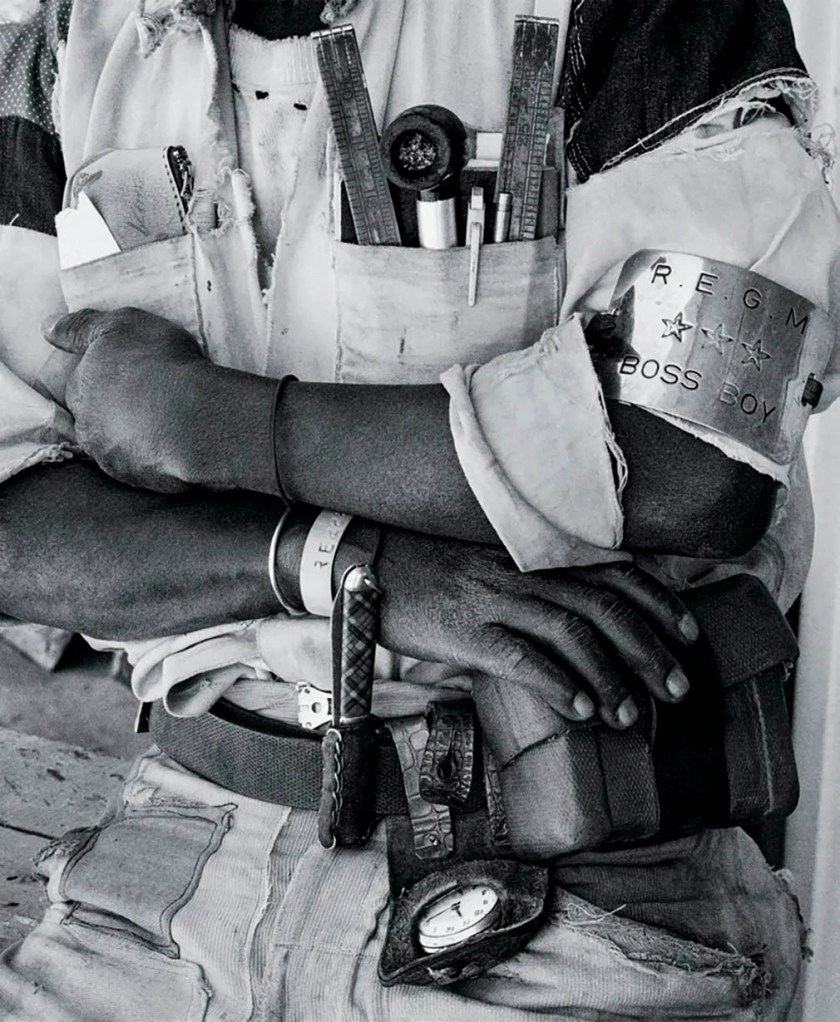

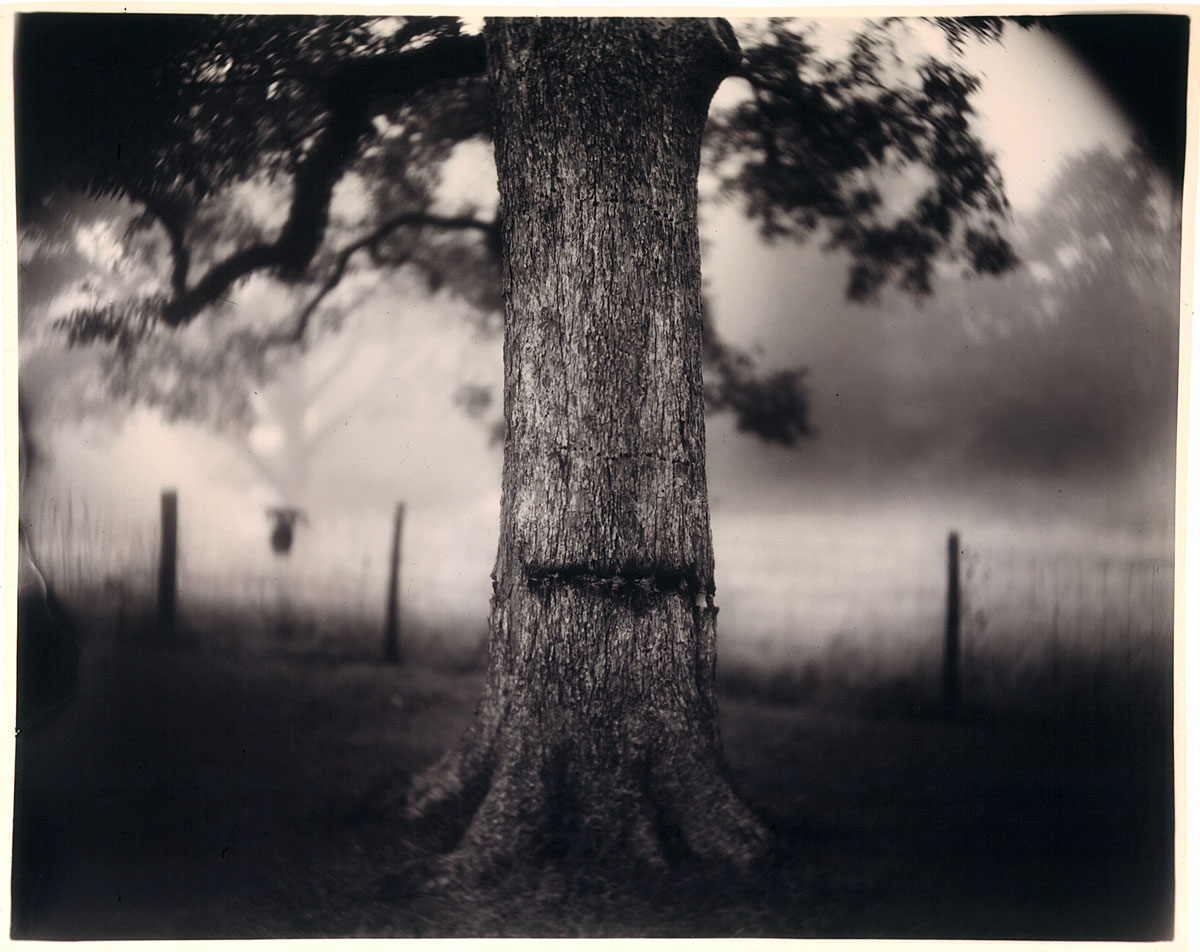

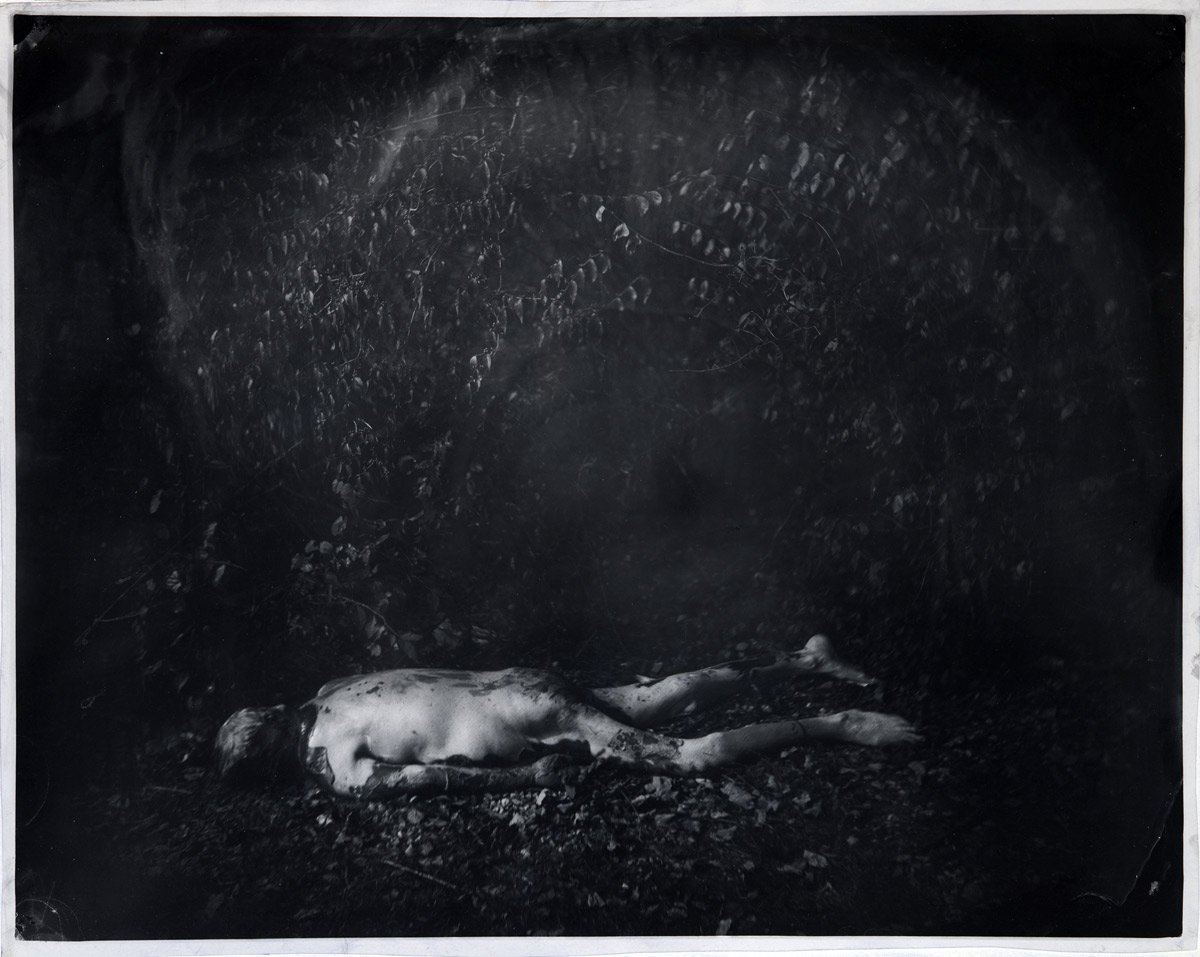

Most of the photographs are 8″ x 10″ prints, mainly portraits, that are usually dark and contrasty, small and emotionally intense. Jerrems images are made full frame (the modernist conceit of filing out a negative carrier, so that if the negative was printed full frame there would be a black border around the picture) to avoid cropping in the darkroom. This shows good previsualisation by the artist, the composition of the image made at the time of the exposure. There is a closeness to the framing of the portraits and a conversant ambiguity about all of her backgrounds – mainly low depth of field, anonymous places (perhaps a brick wall or a close up of a street corner). In fact it is difficult to pin down any actual place in her photographs unless you are told in the title of the work. The contextlessness of her backgrounds allows the viewer to focus on the people placed before her lens and here Jerrems gets up close and personal, trying to capture the truth of her subjects, their soul (in this sense she is like Diane Arbus, thrusting her camera into places it was not supposed to go until something gives – the subject gives up, drops the mask, even if just for a split second, and click, the artist has their image). The mainly head and shoulders photographs of women are most impressive in this regard as Jerrems portrays the women’s strength and vulnerability as are the photographs of the artist herself in hospital fighting her debilitating illness, the most moving, emotional photographs in the exhibition.

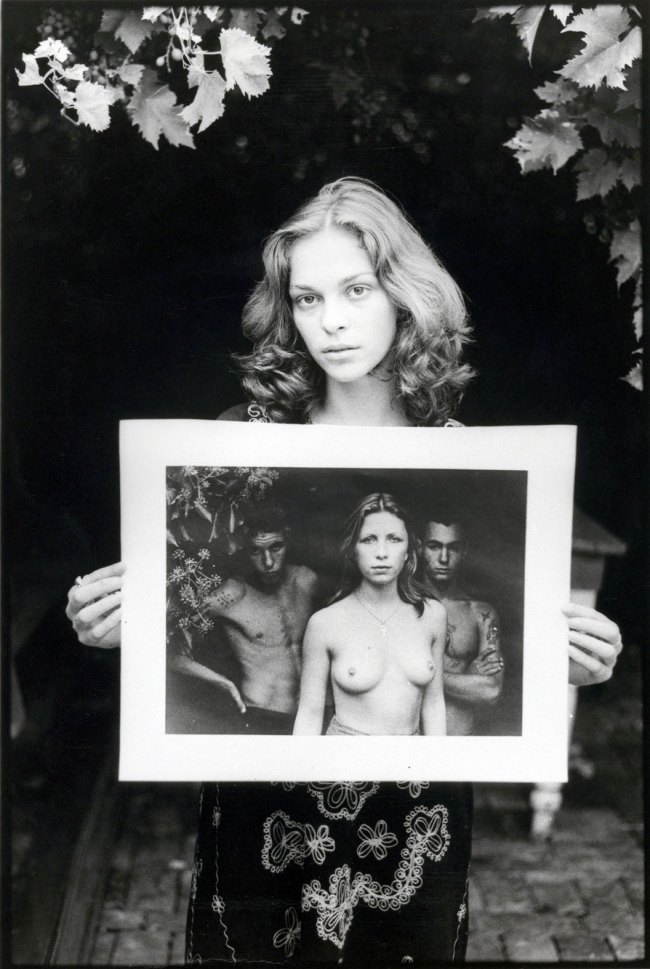

Other photographs show constructed intimacies between people, the camera and the artist. In Esben and Dusan, Cronulla (1977, above), Jerrems uses the yin yang black, white background to frame the two protagonists, bringing forward the body of Esben in the right portion of the frame and letting Dusan recede into the darkness. In Boys (1973) two bodies are photographed in a bed, legs and arms entwined but the print is so dark that you would never know they were two boys unless you were told – and this adds to a sense of mystery, the imaging of the most beautiful, sensitive, abstract embrace. Mark Lean with Arms Crossed (1975) shows a cocky, self-assured Lean staring directly at the camera as though it were not there, as though he were conversing directly with Jerrems, the camera an extension of the artist capturing his brave-aura: one camera, one lens, one vision. If you study the contact sheet for the photograph Vale Street (1975, above), Jerrems eventually draws the central luminous figure forward in the frame to create the now iconic image while the two acolytes hover, brooding and menacing in the darkened background.

As Kathy Drayton has observed, “Her photographs engage the viewer in an intimate relationship with her subjects. It’s not always a friendly intimacy – sometimes her subjects look defensive, irritated or even menacing, but you always sense that you’re seeing beyond the mask into the soul.”1

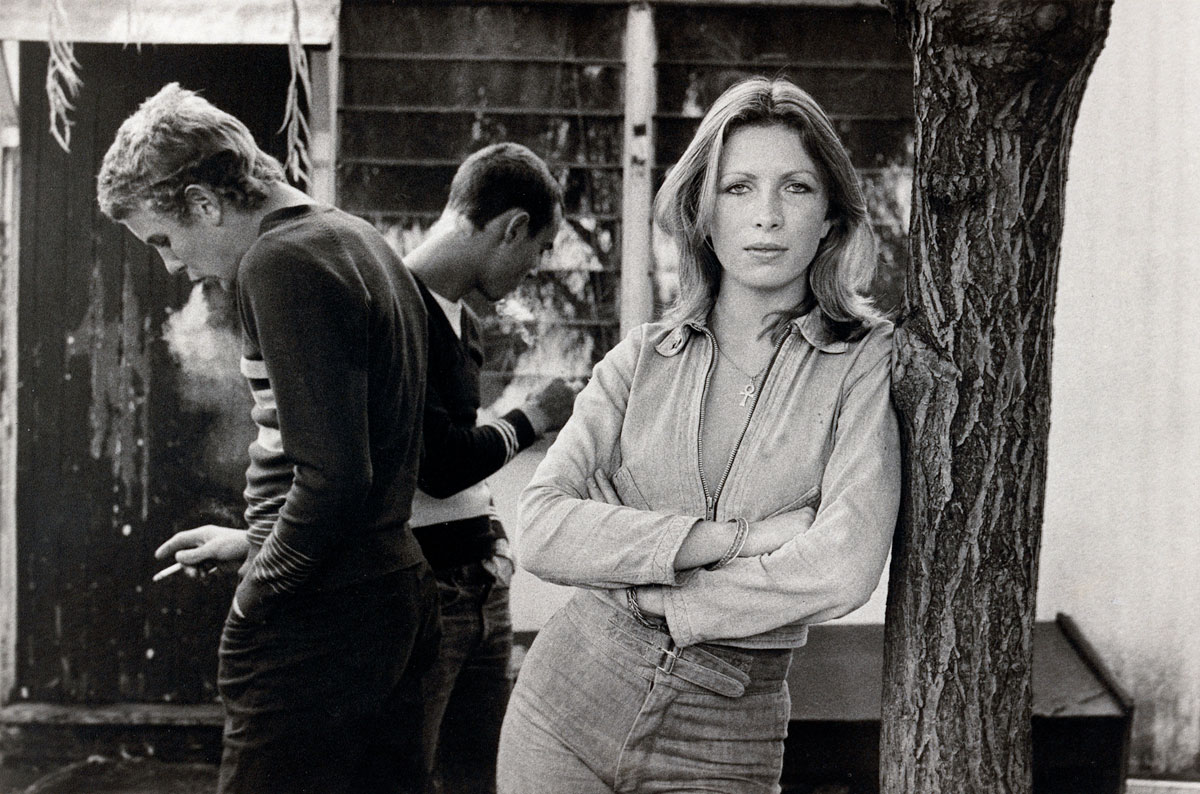

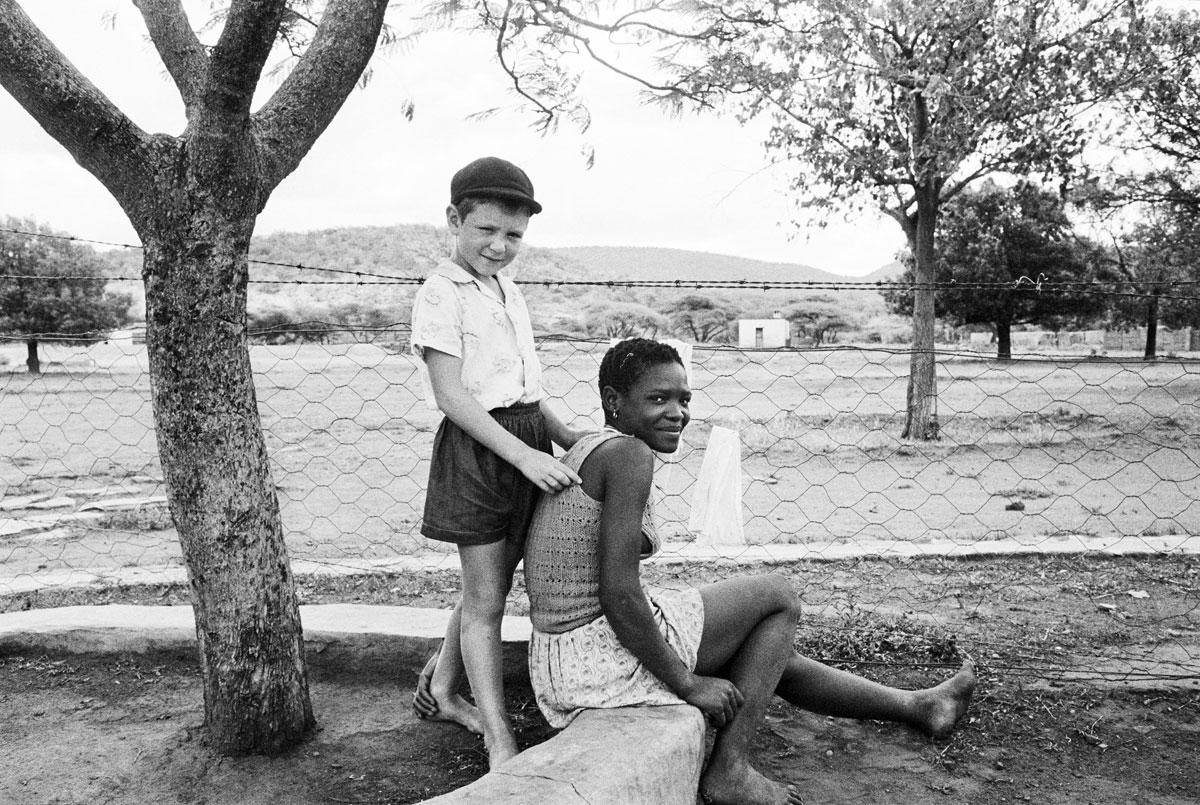

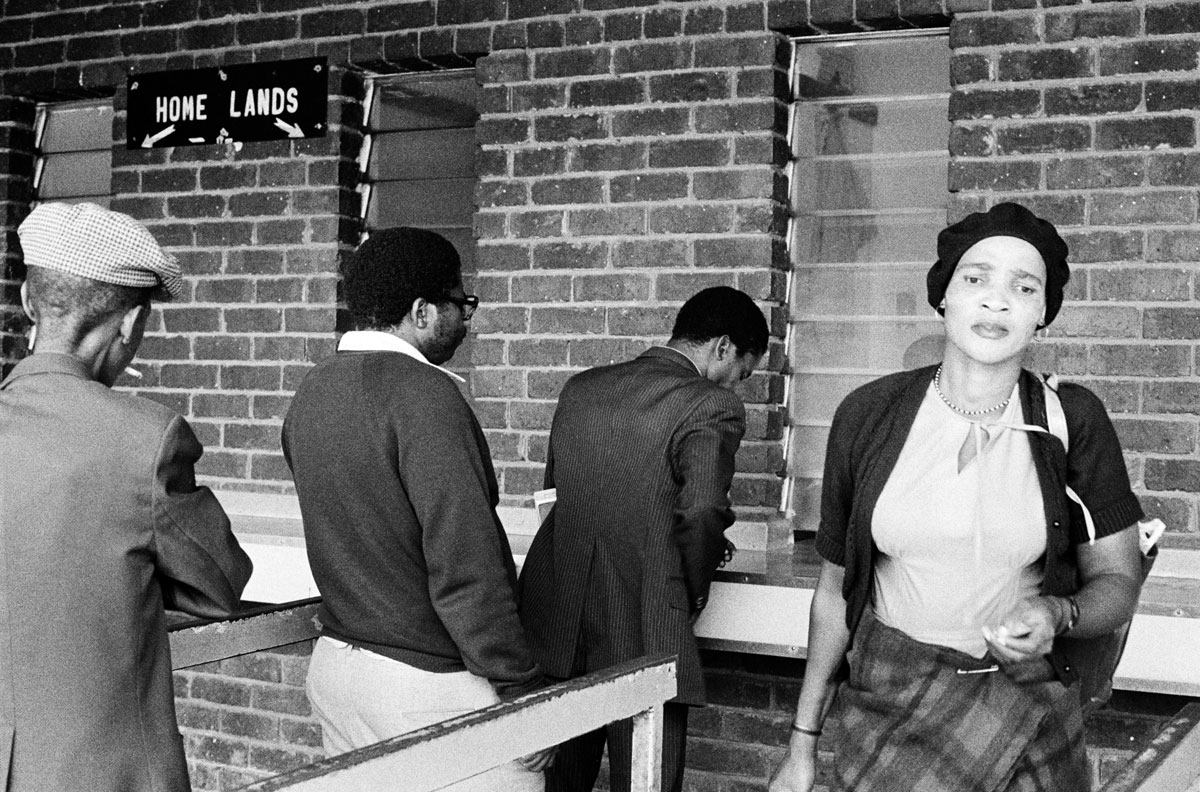

Jerrems saw herself as a serious photographer; if something happened she felt she should be commenting on it. She was also quite naive but always pushed herself and her art into sometimes dangerous places. She would have thought ‘how do I say something that is true’ and her endeavour, which is also constructed, was seeing things in terms of opportunities for a good photograph. Jerrems removed the safeguards; she got right in there among her volatile characters, her potential sexual predators: let’s just see what happens when the safety fence goes down. Although I believe there is a lack of really good photographs that Jerrems made (what I call highlight pieces, namely the iconic Vale Street, Mozart Street, and Mark and Flappers all 1975, see photographs below) there is a consistency to her work and how it exemplifies an exchange that takes place between the artist and the world. What I would call “a good deal.”

When looking at art, one of the best experiences for me is gaining the sense that something is open before you, that wasn’t open before. I don’t mean accessible, I mean open like making a clearing in the jungle, or being able to see further up a road, or just further on. And also like an open marketplace – where there were always good trades. There is the feeling that if you put in a certain amount of honesty, then you would get something back that made some room for you in front – some room that would allow you to look forward, and maybe even walk into that space. Seeing Jerrems work gives you that feeling.

Jerrems had the power to draw themes together, to ramp up the intensity, to empower her photographs and she was possibly on the way to becoming the things that people now say she was, but her early death curtailed this journey. Her photographs have social significance and photographic integrity and evidence time in the visible – the time in which Jerrems took them, the 1970s, and the truthfulness of her self and her style. I would have loved to have seen Jerrem’s response to the film still work of Cindy Sherman, the layering of the Sherman personas and the challenge to the feminist critique. As it is Jerrems photographs are very frontal in today’s terms and, because of her early death, she lacked the opportunity to interact with the development of more complex theories. The layers present at the time are now conflated into seemingly one layer, supported by back stories and obfuscation that clouds the work – it’s naked frontality and boldness. This obfuscation formalises her legacy into mythology.

Jerrems work does not need this. She struggled with her art, to get the best out of herself and her visualisation, to step into those spaces that I mentioned earlier. What we need is an appreciation of the time of her endeavour and the truthfulness of her art. To say that the work achieved fulfilment is to deny the importance of her death.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Drayton, Kathy quoted in Wilmoth, Peter. “The ’70s stripped bare,” on The Age website. July 17th, 2005. [Online] Cited 05/10/2010

Many thankx to Jade Enge and Heide Museum of Modern Art for allowing me publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on all of the photographs for a larger version of the image.

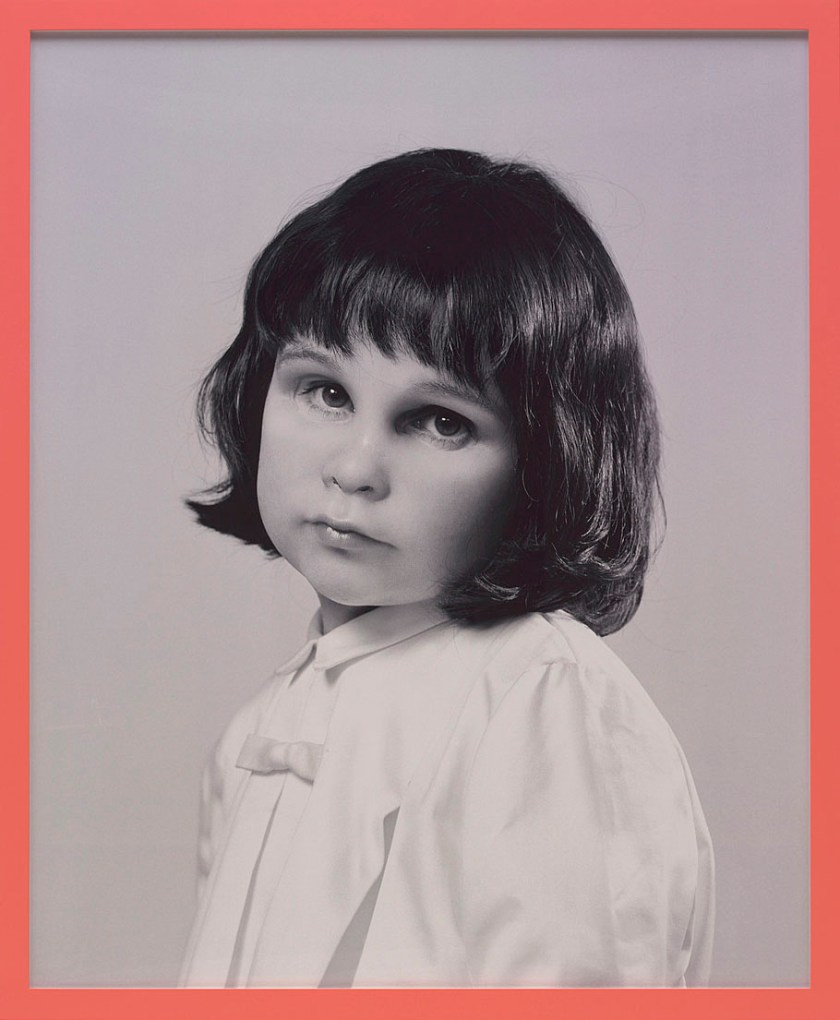

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Mozart Street

1975

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant, 1982

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Mark and Flappers

1975

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of James Mollison, 1994

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

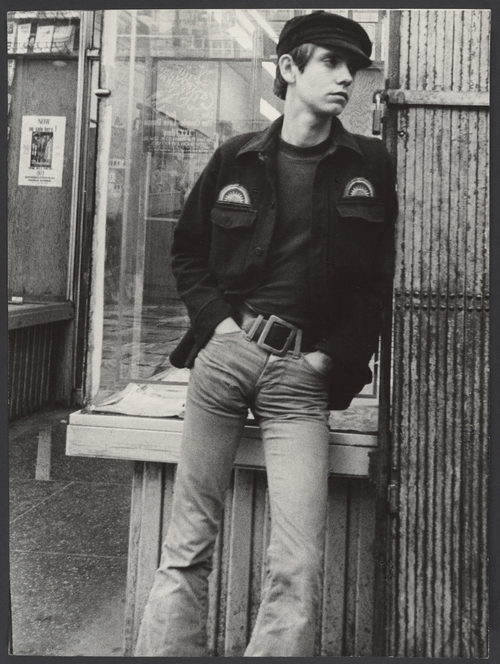

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Sharpies

1976

Gelatin silver print

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Dusan and Esben

1977

Gelatin silver print

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Flying Dog

Nd

Gelatin silver print

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Butterfly Behind Glass

1975

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of Mrs Joy Jerrems, 1981

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Evonne Goolagong, Melbourne

1973

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of Mrs Joy Jerrems, 1981

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

Featuring the exceptional talent of four photographers whose images capture people, places and events with candid intimacy, Up Close traces the significant legacy of Australian photographer Carol Jerrems (1949-1980) alongside that of contemporary artists Larry Clark (USA), Nan Goldin (USA) and William Yang (Sydney). According to Guest Curator Natalie King, ‘Up Close takes its inspiration from the way each artist candidly depicts a social milieu and urban life of the 1970s and early 1980s’. Sharing an interest in sub-cultural groups and individuals on the margins of society, each artist reveals a remarkable capacity to provide an empathetic glimpse into semi-private worlds through intimate depictions of people and their surroundings.

Newly discovered prints by Jerrems are included as well as rare archival material from Jerrems’ family and previously unseen out-takes from Kathy Drayton’s documentary film, ‘Girl in the Mirror.’ It is 30 years since Jerrems’ death and 20 years since the first and only survey of her work was presented. Jerrems’ photographic practice was associated with a feminist and political imperative; as she put it: ‘the society is sick and I must help change it’. This exhibition uncovers Jerrems’ preoccupation with people and their environment, subcultures, forgotten and dispossessed groups, especially Aboriginal communities of the time.

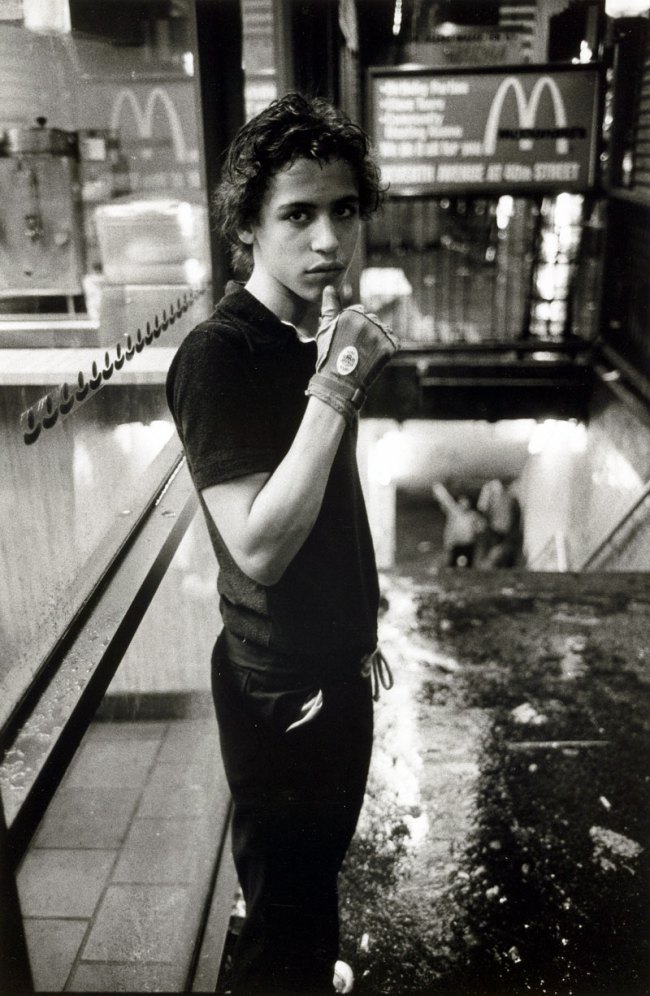

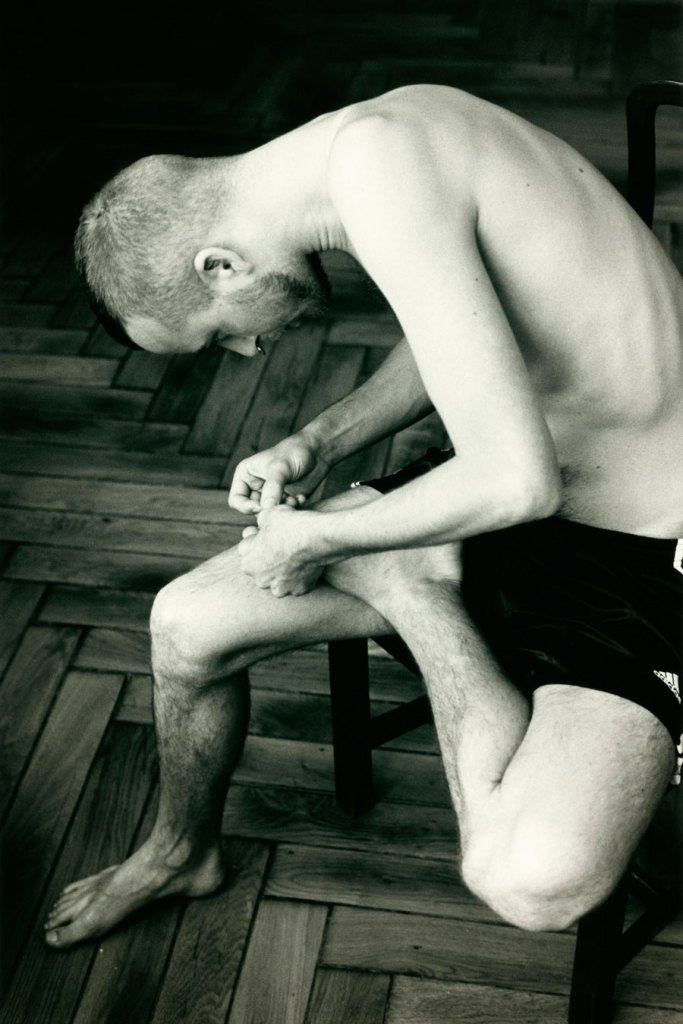

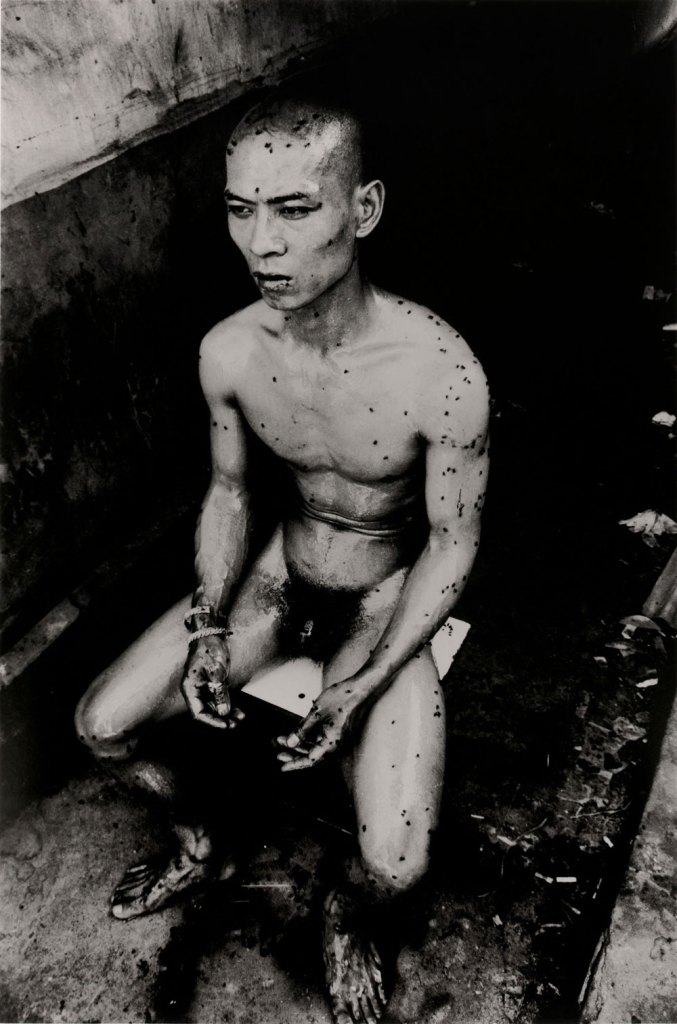

Larry Clark unflinchingly turned the camera onto himself and his amphetamine-shooting coterie to produce Tulsa (1971), a series of photographs repeatedly cited for its raw depiction of marginalized youth. This significant publication and photographic series influenced Goldin and a generation of artists who aspired to break with the more traditional documentary modes. With its grainy shot-from-the-hip style, Tulsa exposes a world of sex, death, violence, anxiety and boredom capturing the aimlessness and ennui of teenagers.

First shown at Frank Zappa’s birthday party in 1979 at the Mudd Club in New York, Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency has evolved to be an iconic work of its time. Goldin’s snapshot aesthetic is evident in this immersive installation of close to 700 slides full of saturated colour and intimate framing accompanied by a soundtrack. Mining the emotional depths of her friends, lovers and family, Ballad signals a riveting intimacy whilst uncovering the bohemian life of New York’s Lower East Side. Goldin says, ‘I was documenting my life. It comes directly from the snapshot, which is always about love…’

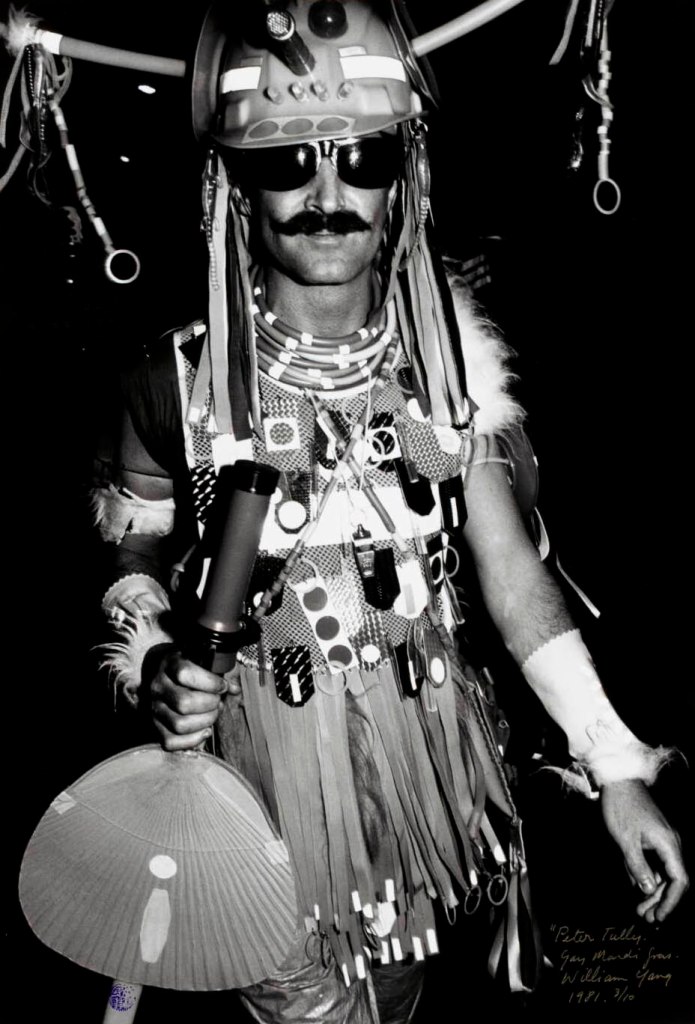

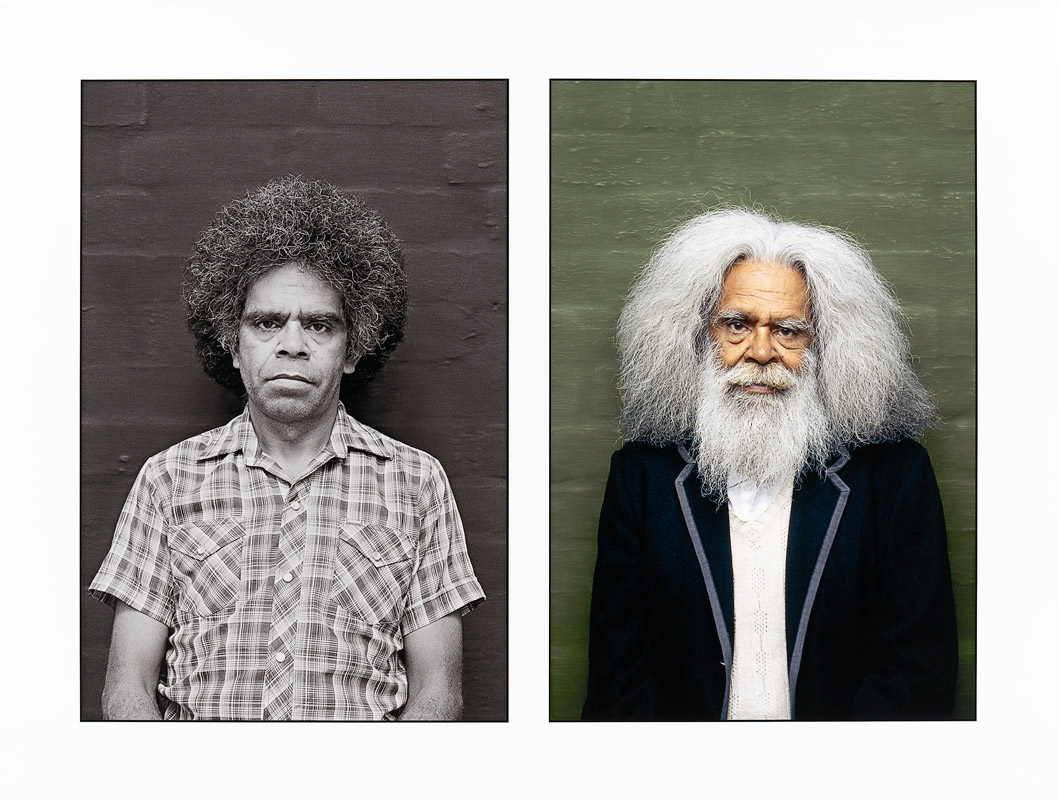

William Yang’s photographs from the 1970s further the snapshot aesthetic through journeying into the intimate world of his particular social milieu: drag queens, Sydney gay and inner-city culture. Yang’s direct, unpretentious photographs provide a unique chronicle of marginalised groups especially as he put it: “… people who are gay, who were invisible, who were too scared to come out. During gay liberation people became visible, people became politicised, and there was a Mardi Gras that was a symbol of the movement.”

Up Close reveals how photographic practices provide an empathetic glimpse into semi-private worlds with close up depictions of people and their surroundings.

The accompanying publication provides for the first time an in-depth account of Carol Jerrems’ work alongside that of her peers and will feature a number of newly commissioned essays. Edited by Natalie King and co-published by Heide and Schwartz City, it will be available at the Heide Store from 31 July.”

Press release from the Heide Museum of Modern Art website

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Juliet Holding Vale Street

1976

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of Mrs Joy Jerrems 1981

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Lynn

1976

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant 1982

© Ken Jerrems & the Estate of Lance Jerrems

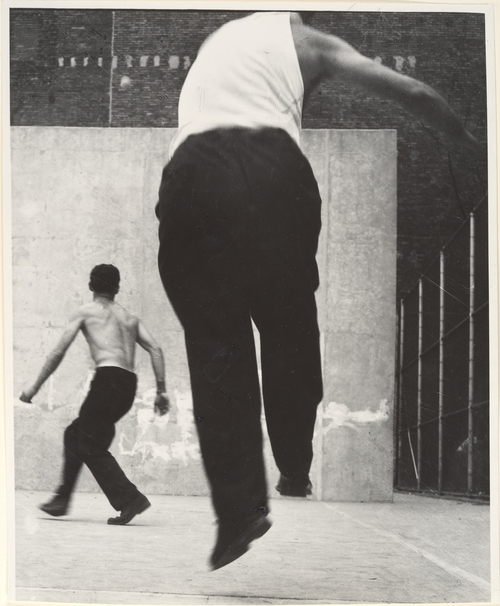

Larry Clark (American, b. 1943)

Untitled

1979

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1980

© Larry Clark

Image courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

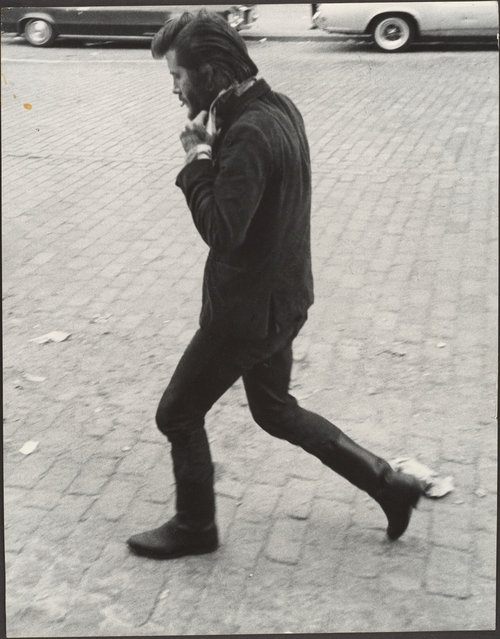

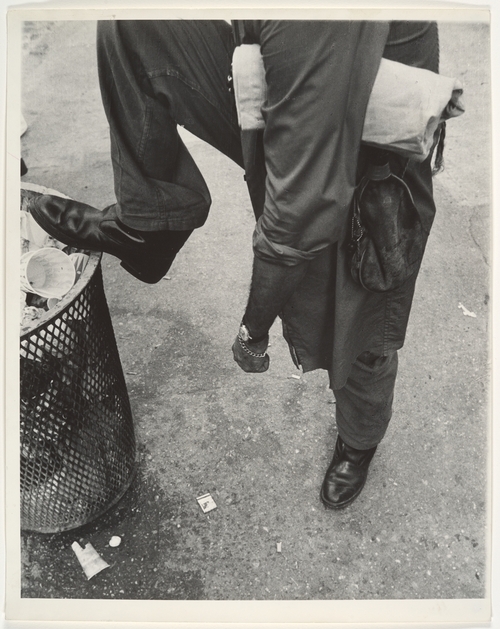

Larry Clark (American, b. 1943)

No Title (Billy Mann)

1963

from the portfolio Tulsa

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1980

Image courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

William Yang (Australian, b. 1943)

Peter Tully, Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras

1981

Gelatin silver print

edition 2/10

40.4 x 27cm

National Library of Australia

Courtesy of the artist

Heide Museum of Modern Art

7 Templestowe Road, Bulleen, Victoria 3105

Opening hours:

(Heide II & Heide III)

Tues – Sun 10.00am – 5.00pm

![Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Head of Man with Hat and Cigar]' c. 1960 from the exhibition 'Hipsters, Hustlers, and Handball Players: Leon Levinstein's New York Photographs, 1950-1980' at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, June - October, 2010 Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Head of Man with Hat and Cigar]' c. 1960 from the exhibition 'Hipsters, Hustlers, and Handball Players: Leon Levinstein's New York Photographs, 1950-1980' at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, June - October, 2010](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/leon-levinstein-head-of-man-with-hat-and-cigar.jpg)

![Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Beach Scene: Woman Wearing Paper Bag Hat, Coney Island, New York]' 1950s Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Beach Scene: Woman Wearing Paper Bag Hat, Coney Island, New York]' 1950s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/leon-levinstein-beach-scene.jpg?w=809)

You must be logged in to post a comment.