Exhibition dates: 25th August – 20th November 2011

Filippo Lippi (Italian, 1406-1469)

Portrait of a Man and a Woman at a Casement

c. 1440

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

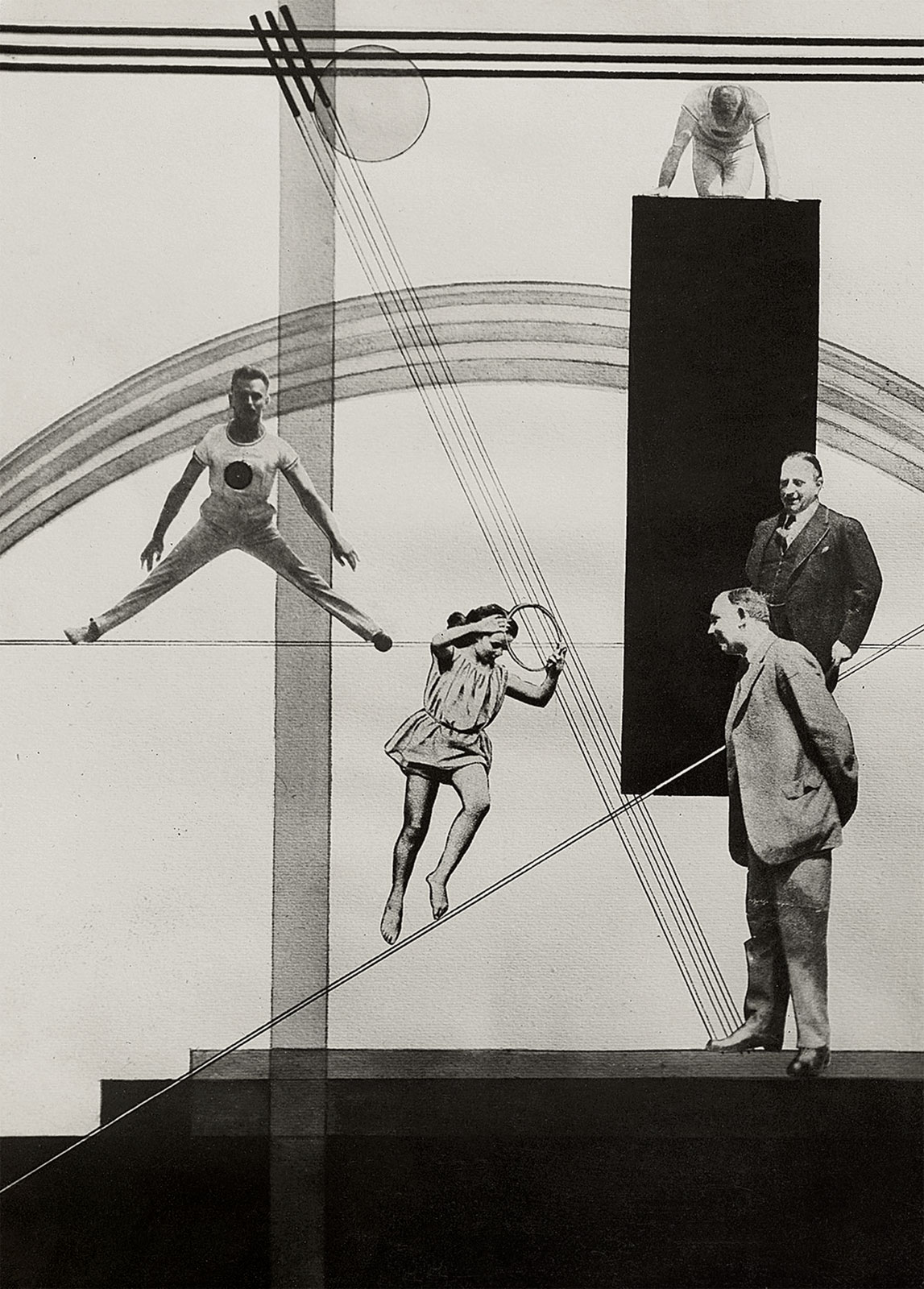

The Legend of the Surface, the Facies

“Facies simultaneously signifies the singular air of a face, the particularity of its aspect, as well as the genre or species under which this aspect should be subsumed. The facies would thus be a face fixed to a synthetic combination of the universal and the singular: the visage fixed to the regime of representation, in a Helgian sense.

Why the face? – Because in the face the corporeal surface makes visible something of the movements of the soul, ideally.”

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpetriere (trans. Alisa Hartz). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2003, p. 49

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Bode Museum for allowing me to publish the artwork in the posting. Please click on the images for a larger version.

Jacopo Bellini (Italian, 1400-1470)

Saint Bernardino of Siena

Between c. 1450 and c. 1455

Tempera and gold leaf on panel

Weber Collection, New York

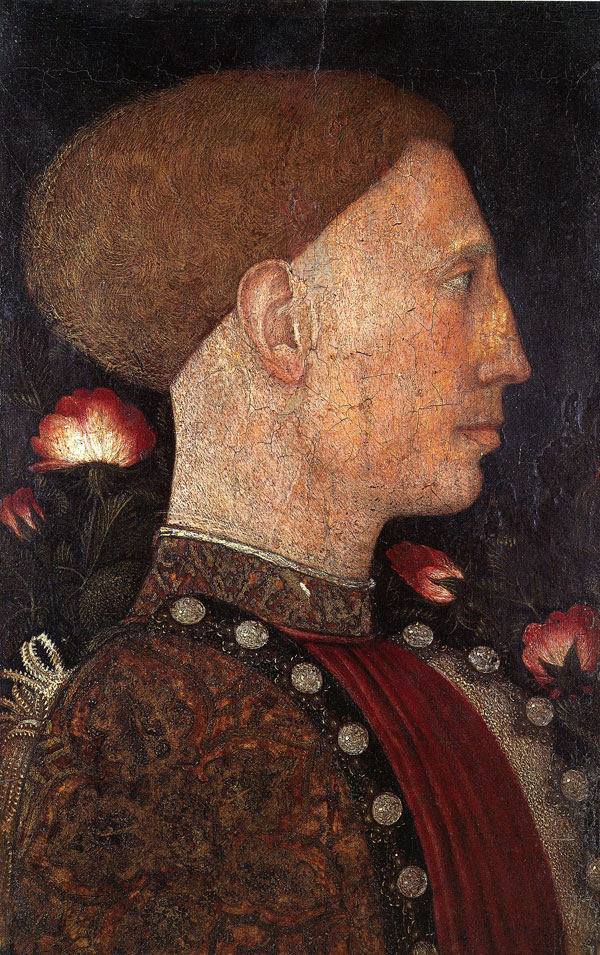

Pisanello (Antonio Pisano) (Italian, 1395-1455)

Portrait of Leonello d’Este

c. 1444

Bergamo, Accademia Carrara

© Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

Pisanello (c. 1395 – c. 1455), known professionally as Antonio di Puccio Pisano or Antonio di Puccio da Cereto, also erroneously called Vittore Pisano by Giorgio Vasari, was one of the most distinguished painters of the early Italian Renaissance and Quattrocento. He was acclaimed by poets such as Guarino da Verona and praised by humanists of his time, who compared him to such illustrious names as Cimabue, Phidias and Praxiteles.

Filippo Lippi (Italian, 1406-1469)

Portrait of a Lady

c. 1445

Paint on poplar panel

Height: 49.5 cm (19.4 in)

Width: 32.9 cm (12.9 in)

Gemäldegalerie

Andrea del Castagno (Italian, 1420-1457)

Portrait of a Man

c. 1450

Tempera on panel

Height: 54cm (21.2 in)

Width: 40.5cm (15.9 in)

Andrew W. Mellon collection

National Gallery of Art

Andrea Mantegna (Italian, 1431-1506)

Portrait of Cardinal Ludovico Trevisano

c. 1459

Berlin, National Museums in Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

© National Museums in Berlin, Jörg P. Anders

Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431 – September 13, 1506) was an Italian painter, a student of Roman archeology, and son-in-law of Jacopo Bellini. Like other artists of the time, Mantegna experimented with perspective, e.g. by lowering the horizon in order to create a sense of greater monumentality. His flinty, metallic landscapes and somewhat stony figures give evidence of a fundamentally sculptural approach to painting. He also led a workshop that was the leading producer of prints in Venice before 1500.

Antonio del Pollaiuolo (Italian, 1429-1498)

Portrait of a Young Lady

c. 1465

Berlin, National Museums in Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

© National Museums in Berlin, Jörg P. Anders

Antonio del Pollaiuolo (Italian, 1429-1498)

Portrait of a Young Woman

c. 1465-1470

© Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan

Piero del Pollaiuolo (Italian, 1443–1496)

Portrait of Galeazzo Maria Sforza

c. 1471

Tempera on panel

Height: 65cm (25.5 in)

Width: 42cm (16.5 in)

Uffizi Gallery

Piero Pollaiuolo painted this portrait during one of Galeazzo Maria Sforza’s visits to Florence. The work is based on a similar portrait by his brother, Antonio. That the portrait is of Sforza is beyond doubt, as copies exist bearing Sforza’s name. Restored in 1994.

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1445-1520)

Profile Portrait of a Young Lady (Simonetta Vespucci?)

c. 1476

Berlin, National Museums in Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

© National Museums in Berlin, Jörg P. Anders

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi (c. 1445 – May 17, 1510), known as Sandro Botticelli, was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance. He belonged to the Florentine School under the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici, a movement that Giorgio Vasari would characterise less than a hundred years later in his Vita of Botticelli as a “golden age”. Botticelli’s posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century; since then, his work has been seen to represent the linear grace of Early Renaissance painting.

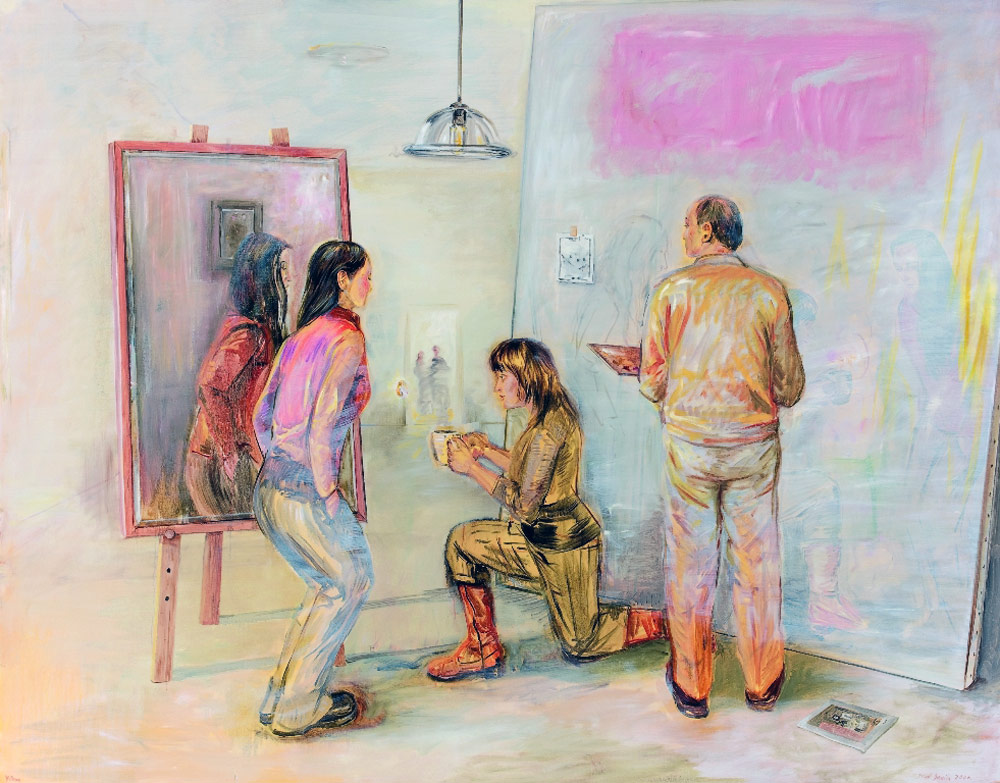

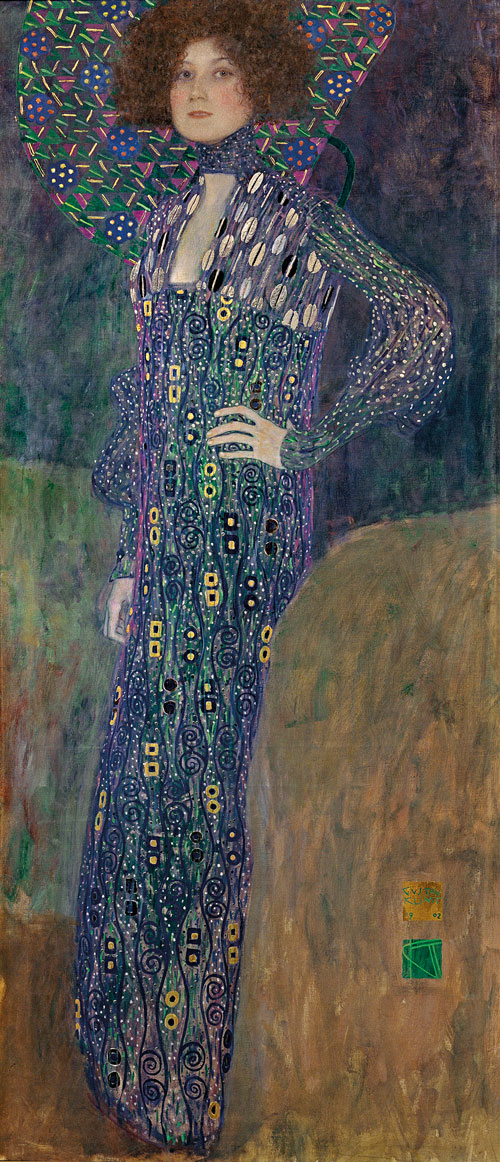

The Gemäldegalerie – National Museums in Berlin and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, have joined forces in organising a major exhibition on the genesis of the Italian portrait. For Berlin, the Bode Museum presents itself as the ideal location to hold such an exhibition: on its opening in 1904, it was conceived by its founder, Wilhelm von Bode, as a ‘Renaissance Museum’ on the Museum Island. The Bode Museum will host the first stage of the exhibition, running from 25 August to 20 November 2011, before it subsequently goes on show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, from 19 December 2011 to 18 March 2012.

More than 150 key works, including paintings, drawings, medals and busts, are about to go on display for the first time together. The more than 50 lenders include the Uffizi in Florence, the Louvre in Paris and the National Gallery in London. Among the exhibition’s many highlights is Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine from the Czartoryski Collection, Cracow.

The exhibition highlights depictions of the appearance and personality of real people. Portraits of feminine beauty vie with portraits of generals, princes and humanists, offering us a fascinating insight into the age of the early Renaissance.

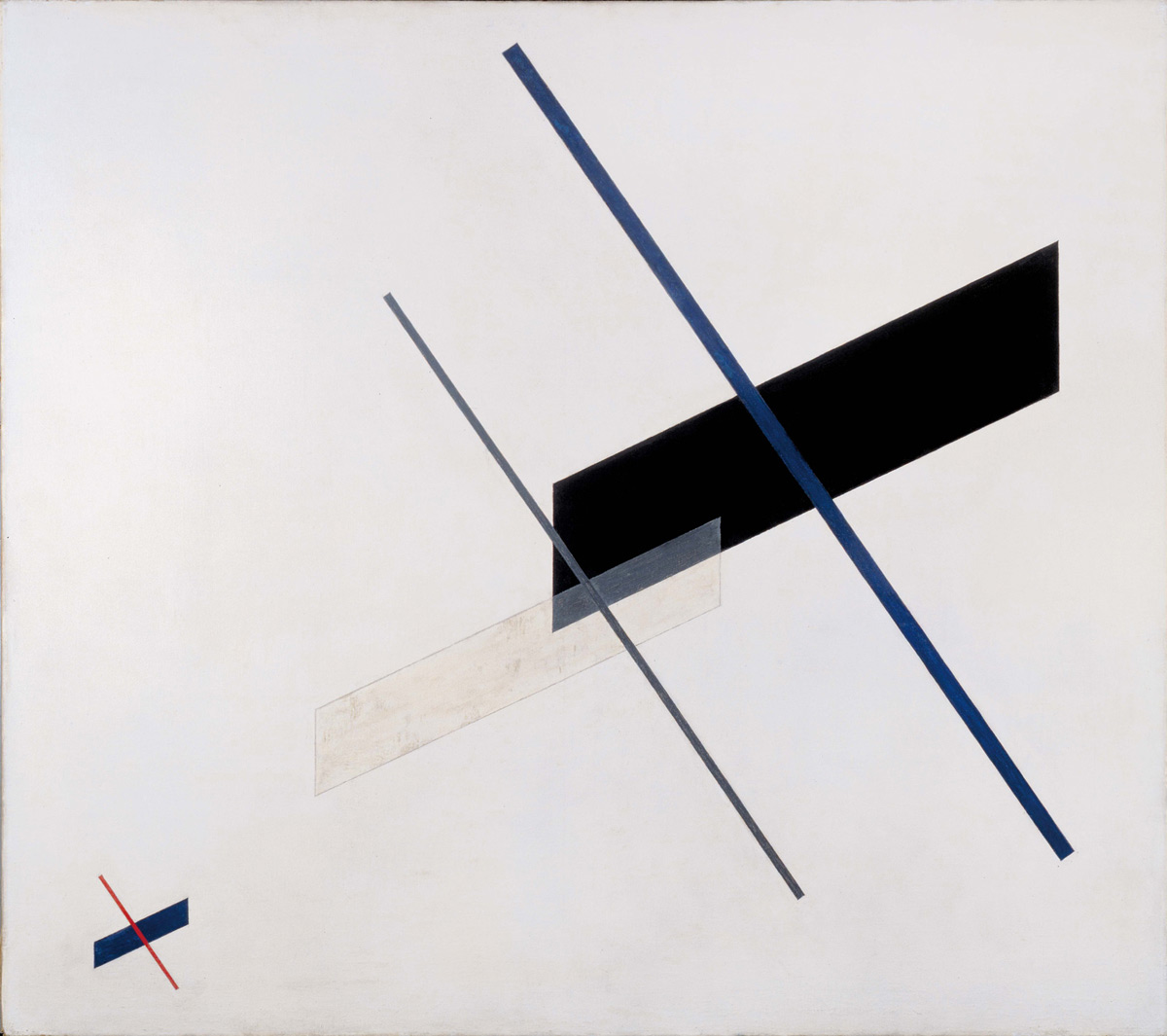

At the heart of the exhibition stands the Italian Renaissance portrait. The Italian art of portraiture evolved under the influence of antique models. However, it was equally shaped by the innovations of the great Netherlandish painters. The history of the art of portraiture, from Pisanello up to Verrocchio, Botticelli, Bellini and Leonardo, is retold in a selection of magnificent and sensational key works, including paintings, sculptures, medals and drawings. The exhibition focuses both on the art produced at the Italian courts, as well as the development of the portrait in Florence and Venice.

A unique architectural and lighting concept, especially designed for the exhibition, takes into account the individual qualities of each exhibit in its presentation. Of crucial importance here is the aesthetic experience, both of the quality of the artworks and of the materials used in creating them.

The artistic diversity evident in these early portraits, the various roles the images served and their historical contexts all resonate with suspense. The Gemäldegalerie – National Museums in Berlin and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York embarked on an intense collaboration to present this to the general public. Masterpieces from New York and the rich collections of the National Museums in Berlin, not just from the Gemäldegalerie itself but also from the Sculpture Collection, Kupferstichkabinett and Numismatic Collection, offer visitors an unprecedented insight into this epoch. Furthermore, for the first time the show in the Bode Museum also encompasses all media of Italian Renaissance portraiture – medals, drawings, sculptures and panel paintings.

Portraits – either in the form of a painting, photograph and less often a medal – have become commonplace today, but between the 5th and 15th century independent portraits of individual people were rare and the exclusive reserve of rulers and historic figures. Only in the 15th century did it again become customary for artists on both sides of the Alps to produce independent portraits of men and women. Today’s exhibition Renaissance Faces pays homage to Italy’s contribution to this first great age of European portraiture and conveys a sense of the innovative ways in which artists responded to the challenge of creating individual portraits and how they explored questions of identity that arose as a result.

When selecting the exhibits, the organisers’ chief aim was to highlight the prevailing conventions and decisive innovations in a period spanning more than eight decades. Set against the backdrop of Italy’s geographical, political and cultural complexities in the 15th century, the exhibition is divided into three clearly outlined thematic sections. The first of these is Florence, as it was here that the independent portrait first appeared on a significant scale. The visitor’s gaze is then directed to the courts of Ferrara, Mantua, Bologna, Milan, Urbino, Naples and finally papal Rome. The circle is then completed in Venice, where a portrait tradition only established itself remarkably late in the century. In each section, works in all media are juxtaposed with each other to give visitors the chance to see for themselves how the various art forms mutually influenced each other with their own unique qualities.

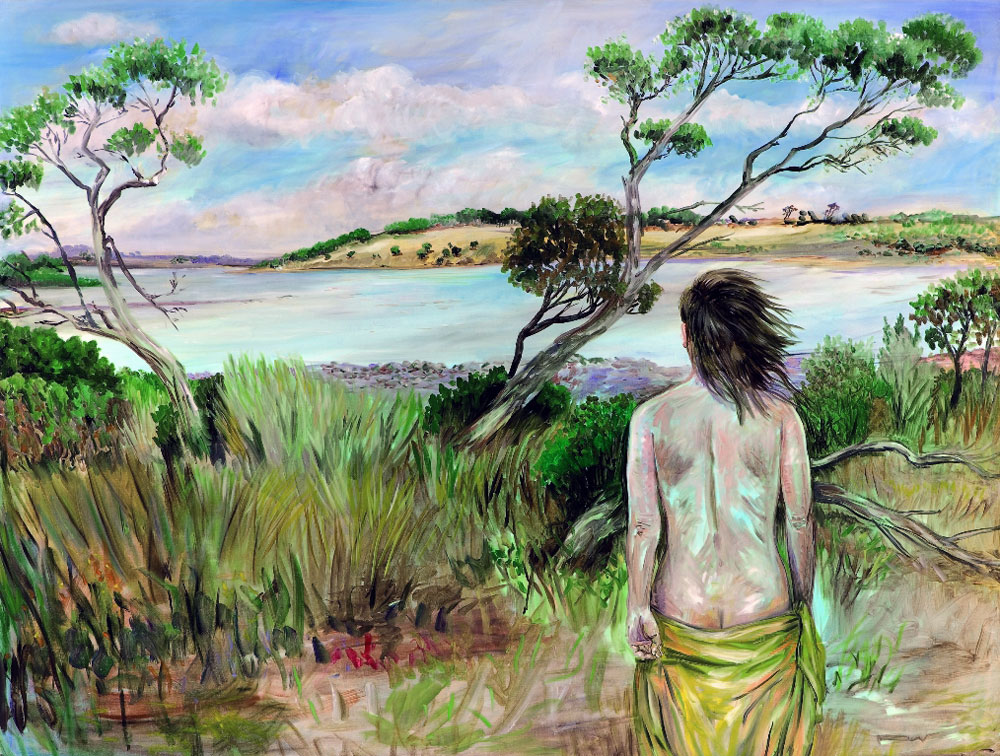

In a society dominated by family descent and social hierarchies, conventions were binding. And it is precisely these conventions that are depicted in profile portraits from 15th-century Italy. Profile portraits were equally popular as reliefs or paintings. Compared with the far more naturalistic art produced north of the Alps, which people in 15th-century Italy were definitely familiar with, this form of portrait seems at first a little surprising, as the Italian artists present the sitters in a soft light and at a slight angle to the picture plane. The sitters are seen standing either at a window or behind a parapet and gaze at the viewer. Sometimes a hand is seen resting on the edge of the painted frame. When looking at these images, it is clear that Italian portraits are not primarily concerned with achieving an accurate likeness, at least not in the conventional sense. Italian portraits do not so much reveal personality, rather convey social conventions and cultural identity.

The profile portrait was frequently given such exceptional importance in Italy, because it largely drew from Roman coins and reliefs for inspiration. But the profile portrait has always been the most elementary form of capturing someone’s likeness. Informal, direct and frontal views have become so familiar to us in portraits today thanks to photography that we first have to be resensitised to the unique possibilities inherent in the profile portrait. For one, it makes it possible to objectify a person’s outer appearance and allows physiognomies to convey cultural meaning. The pleasing aspect of a high forehead, the refinement or contemptuousness expressed in a raised brow, the aristocratic curve of a nose and the severity or gentleness of a chin and jawline – all these are physiognomical characteristics that come to stand as emblems for beauty, rank and power.

Press release from the Bode Museum website quoting the exhibition catalogue

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1445-1520)

Portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici

c. 1478

Washington, National Gallery of Art

© Art Resource, New York

Antonello da Messina (Italian, 1430-1479)

Portrait of a Young Man

1478

Berlin, National Museums in Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

© National Museums in Berlin, Jörg P. Anders

Antonello da Messina, properly Antonello di Giovanni di Antonio, but also called Antonello degli Antoni and Anglicised as Anthony of Messina (c. 1430 – February 1479), was an Italian painter from Messina, Sicily, active during the Early Italian Renaissance. His work shows strong influences from Early Netherlandish painting although there is no documentary evidence that he ever travelled beyond Italy. Giorgio Vasari credited him with the introduction of oil painting into Italy. Unusually for a south Italian artist of the Renaissance, his work proved influential on painters in northern Italy, especially in Venice.

Hans Memling (Italian, c. 1433-1494)

Portrait of a Man at a Loggia

c. 1480

Oil on panel

Height: 40cm (15.7 in)

Width: 28cm (11 in)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Davide Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1452-1525)

Selvaggia Sassetti (born 1470)

Between 1487 and 1488

Tempera on panel

Height: 57.2cm (22.5 in)

Width: 44.1cm (17.3 in)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Leonardo da Vinci (Italian, 1452-1519)

Lady with an Ermine (portrait of Cecilia Gallerani)

1489-1490

Kraków, owned by Princes Czartoryski Foundation, at the National Museum

© bpk / Scala

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci,known as Leonardo da Vinci , was an Italian polymath of the Renaissance whose areas of interest included invention, drawing, painting, sculpture, architecture, science, music, mathematics, engineering, literature, anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, paleontology, and cartography. He has been variously called the father of palaeontology, ichnology, and architecture, and is widely considered one of the greatest painters of all time (despite perhaps only 15 of his paintings having survived).

Lorenzo di Credi (Italian, 1459-1537)

Portrait of a Young Woman

c. 1490s

Oil on panel

Height: 58.7cm (23.1 in)

Width: 40cm (15.7 in)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Gentile Bellini (Italian, 1429-1507)

Self-portrait

c. 1496

Black chalk and charcoal on paper

Height: 23 cm (9 in)

Width: 19.4 cm (7.6 in)

Kupferstichkabinett Berlin

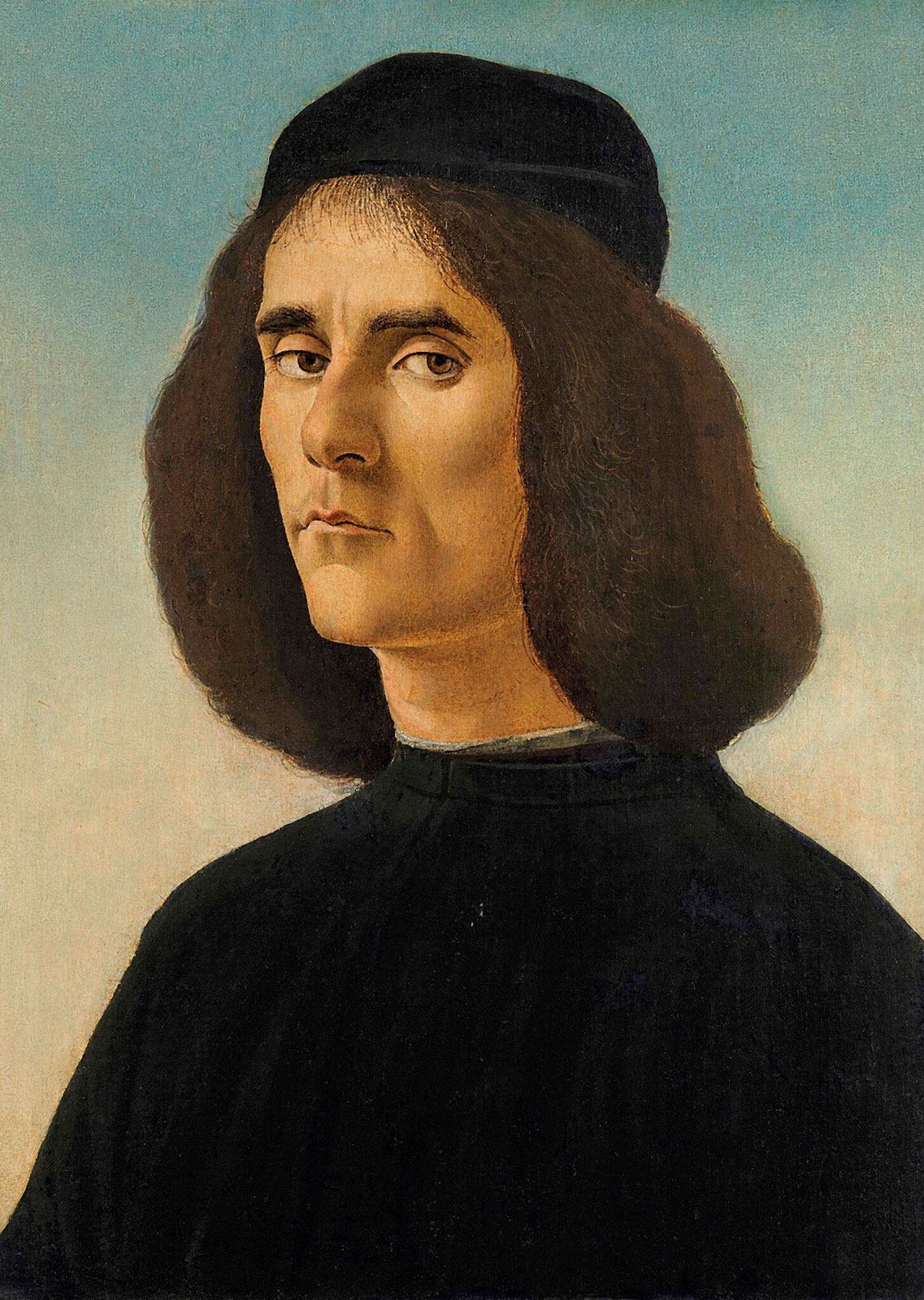

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1445-1510)

Portrait of Michael Tarchaniota Marullus

1497

Tempera from wood transferred to canvas

Height: 49cm (19.2 in)

Width: 35cm (13.7 in)

Institut Cambó

Bode Museum

Museum Island Berlin,

Am Kupfergraben 1, 10117 Berlin

Opening hours:

Monday closed

Tuesday – Sunday 10.00am – 6.00pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.