Exhibition dates: 13th November 2013 – 16th March 2014

Featured artists include Margaret Bourke-White, Constantin Brancusi, Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp, Germaine Krull, Fernand Léger, Wyndham Lewis, László Moholy-Nagy, Piet Mondrian, Man Ray, Alexander Rodchenko, and Charles Sheeler, among others.

Many thankx to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the art work for a larger version of the image.

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Untitled (Rayograph)

1922

Gelatin silver print

11 15/16 x 9 3/8 in. (30.32 x 23.81cm)

Collection SFMOMA, purchase

© Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

“I am young, I am twenty years old; yet I know nothing of life but despair, death, fear, and fatuous superficiality cast over an abyss of sorrow. I see how peoples are set against one another, and in silence, unknowingly, foolishly, obediently, innocently slay one another. I see that the keenest brains of the world invent weapons and words to make it yet more refined and enduring. And all men of my age, here and over there, throughout the whole world see these things; all my generation is experiencing these things with me. What would our fathers do if we suddenly stood up and came before them and proffered our account? What do they expect of us if a time ever comes when the war is over? Through the years our business has been killing; – it was our first calling in life. Our knowledge of life is limited to death. What will happen afterwards? And what shall come out of us?”

Erich Maria Remarque. All Quiet on the Western Front, 1929

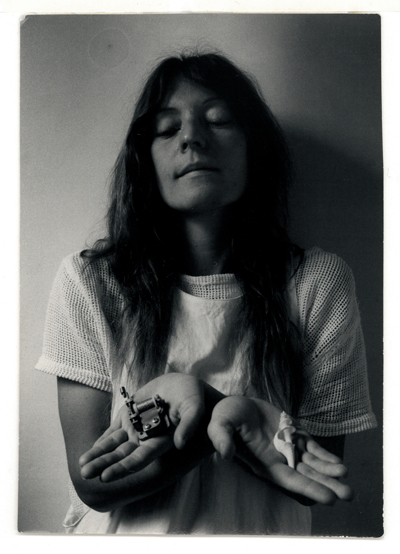

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Portrait of Joris Ivens, Amsterdam

c. 1928

Gelatin silver print

7 3/8 x 6 1/4 in. (18.77 x 15.88cm)

Collection SFMOMA, gift of Simon Lowinsky

© Germaine Krull Estate

Germaine Krull (29 November 1897 – 31 July 1985), was a photographer, political activist, and hotel owner. Her nationality has been categorised as German, Polish, French, and Dutch, but she spent years in Brazil, Republic of the Congo, Thailand, and India. Described as “an especially outspoken example” of a group of early 20th-century female photographers who “could lead lives free from convention”, she is best known for photographically-illustrated books such as her 1928 portfolio Métal...

Having met Dutch filmmaker and communist Joris Ivens in 1923, she moved to Amsterdam in 1925. After Krull returned to Paris in 1926, Ivens and Krull entered into a marriage of convenience between 1927 and 1943 so that Krull could hold a Dutch passport and could have a “veneer of married respectability without sacrificing her autonomy.”

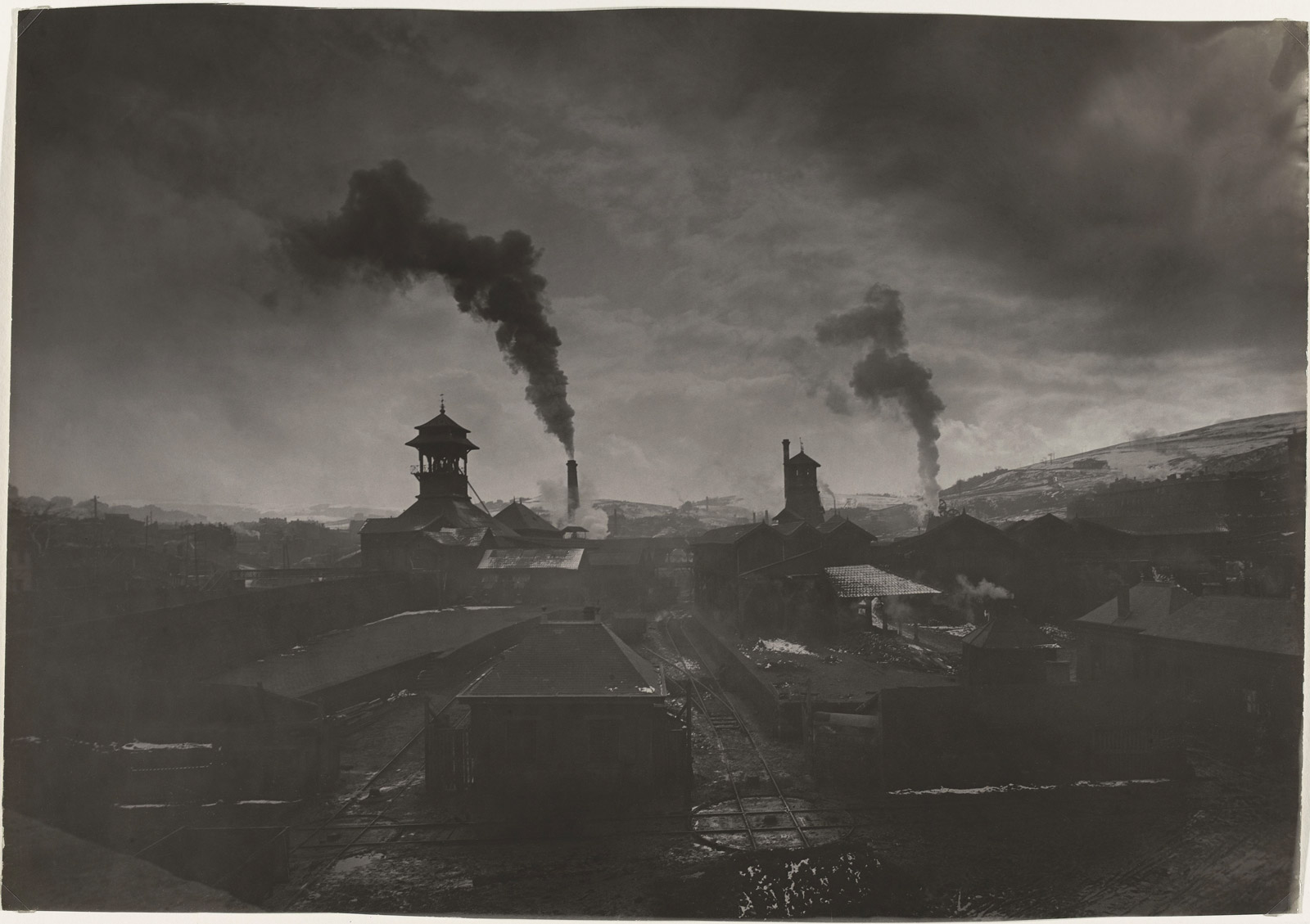

In Paris between 1926 and 1928, Krull became friends with Sonia Delaunay, Robert Delaunay, Eli Lotar, André Malraux, Colette, Jean Cocteau, André Gide and others; her commercial work consisted of fashion photography, nudes, and portraits. During this period she published the portfolio Métal (1928) which concerned “the essentially masculine subject of the industrial landscape.” Krull shot the portfolio’s 64 black-and-white photographs in Paris, Marseille, and Holland during approximately the same period as Ivens was creating his film De Brug (“The Bridge”) in Rotterdam, and the two artists may have influenced each other. The portfolio’s subjects range from bridges, buildings and ships to bicycle wheels; it can be read as either a celebration of machines or a criticism of them. Many of the photographs were taken from dramatic angles, and overall the work has been compared to that of László Moholy-Nagy and Alexander Rodchenko. In 1999-2004 the portfolio was selected as one of the most important photobooks in history.

By 1928 Krull was considered one of the best photographers in Paris, along with André Kertész and Man Ray. Between 1928 and 1933, her photographic work consisted primarily of photojournalism, such as her photographs for Vu, a French magazine. Also in the early 1930s, she also made a pioneering study of employment black spots in Britain for Weekly Illustrated (most of her ground-breaking reportage work from this period remains immured in press archives and she has never received the credit which is her due for this work). Her book Études de Nu (“Studies of Nudes”) published in 1930 is still well-known today.

Text from the Wikipedia website

El Lissitzky (Russian, 1890-1941)

Untitled

c. 1923

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 x 7 1/4 in. (24.13 x 18.42cm)

Collection SFMOMA, gift of anonymous donors

© Estate of El Lissitzky / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (November 23, 1890 – December 30, 1941), better known as El Lissitzky, was a Russian artist, designer, photographer, typographer, polemicist and architect. He was an important figure of the Russian avant garde, helping develop suprematism with his mentor, Kazimir Malevich, and designing numerous exhibition displays and propaganda works for the Soviet Union. His work greatly influenced the Bauhaus and constructivist movements, and he experimented with production techniques and stylistic devices that would go on to dominate 20th-century graphic design.

Lissitzky’s entire career was laced with the belief that the artist could be an agent for change, later summarised with his edict, “das zielbewußte Schaffen” (goal-oriented creation). Lissitzky, of Jewish origin, began his career illustrating Yiddish children’s books in an effort to promote Jewish culture in Russia, a country that was undergoing massive change at the time and that had just repealed its antisemitic laws. When only 15 he started teaching; a duty he would stay with for most of his life. Over the years, he taught in a variety of positions, schools, and artistic media, spreading and exchanging ideas. He took this ethic with him when he worked with Malevich in heading the suprematist art groupUNOVIS, when he developed a variant suprematist series of his own, Proun, and further still in 1921, when he took up a job as the Russian cultural ambassador to Weimar Germany, working with and influencing important figures of the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements during his stay. In his remaining years he brought significant innovation and change to typography, exhibition design, photomontage, and book design, producing critically respected works and winning international acclaim for his exhibition design. This continued until his deathbed, where in 1941 he produced one of his last works – a Soviet propaganda poster rallying the people to construct more tanks for the fight against Nazi Germany. In 2014, the heirs of the artist, in collaboration with Van abbemuseum and the leading worldwide scholars, the Lissitzky foundation was established, to preserve the artist’s legacy and prepare a catalogue raisonné of the artists oeuvre.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Alexander Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1956)

Pozharnaia lestnitsa from the series Dom na Miasnitskoi (Fire Escape, from the series House Building on Miasnitskaia Street)

1925

Gelatin silver print

9 x 6 in. (22.86 x 15.24cm)

Collection SFMOMA, Accessions Committee Fund: gift of Frances and John Bowes, Evelyn Haas, Mimi and Peter Haas, Pam and Dick Kramlich, and Judy and John Webb

© Estate of Alexander Rodchenko / RAO, Moscow / VAGA, New York

Raoul Ubac (French, 1910-1985)

Penthésilée

1937

Gelatin silver print

15 1/2 x 11 1/4 in. (39.37 x 28.58cm)

Collection SFMOMA, gift of Robert Miller

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Raoul Ubac (31 August 1910, Cologne – 24 March 1985, Dieudonne, Oise) was a French painter, sculptor, photographer and engraver. Ubac’s mother’s family ran a tannery and his father was a magistrate. In his early years he traveled through some parts of Europe on foot. He originally intended to become a waterways and forestry inspector. His interest in art was aroused when he made his first visit to Paris in 1928 and met several artists, including Otto Freundlich.

After returning to Malmédy he read the Manifeste du Surréalisme (1924) by André Breton. He met that document’s author André Breton and other leading Surrealists in 1930, and dedicated himself to capturing the movement’s dream aesthetic in photography after settling in Paris, attending the first showing of Luis Buñuel’s film L’Age d’or (1931). He attended the Faculté des Lettres of the Sorbonne briefly but soon left to frequent the studios of Montparnasse. About 1933-34 he attended the Ecole des Arts Appliqués for more than a year, studying mainly drawing and photography. In the course of a visit to Austria and the Dalmatian coast in 1933, he visited the island of Hvar where he made some assemblages of stones, which he drew and photographed, for example Dalmatian Stone (1933). Disillusioned with Surrealism, Ubac abandoned photography after the Second World War in favour of painting and sculpture, and died in France in 1985.

Text from various sources

Co-organised by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, Flesh and Metal: Body and Machine in Early 20th-Century Art presents more than 70 artworks that explore a central dynamic of art making in Europe and the Americas between the 1910s and the early 1950s. On view from November 13, 2013 to March 16, 2014 at the Cantor Arts Center, the exhibition includes a rich group of paintings, sculptures, photographs, drawings, prints, and illustrated books from the collection of SFMOMA. Taken together, the works offer a fresh view of how artists negotiated the terrain between the mechanical and the bodily – two oppositional yet inextricably bound forces – to produce a wide range of imagery responding to the complexity of modern experience.

The exhibition is part of the collaborative museum shows and extensive off-site programming presented by SFMOMA while its building is temporarily closed for expansion construction. From the summer of 2013 to early 2016, SFMOMA is on the go, presenting a dynamic slate of jointly organised and traveling exhibitions, public art displays and site-specific installations, and newly created education programs throughout the Bay Area.

“We are thrilled to pair SFMOMA’s world-class collection with Stanford’s renowned academic resources,” said Connie Wolf, the John and Jill Freidenrich Director of the Cantor Arts Center. “Cantor curators and the distinguished chair of the Department of Art and Art History guided seminars specifically for this exhibition, with students examining art of the period, investigating themes, studying design and display issues, and developing writing skills. The students gained immeasurably by this amazing experience and added new research and fresh perspectives to the artwork and to the exhibition. We are proud of the results and delighted to present a unique and invaluable partnership that will enrich the Stanford community, our museum members, and our visitors.”

SFMOMA’s Curator of Photography Corey Keller concurred: “The opportunity to work with our colleagues at Stanford has been a remarkable experience both in the galleries and in the classroom. We couldn’t be prouder of the exhibition’s unique perspective on a particularly rich area of SFMOMA’s collection that resulted from our collaboration.”

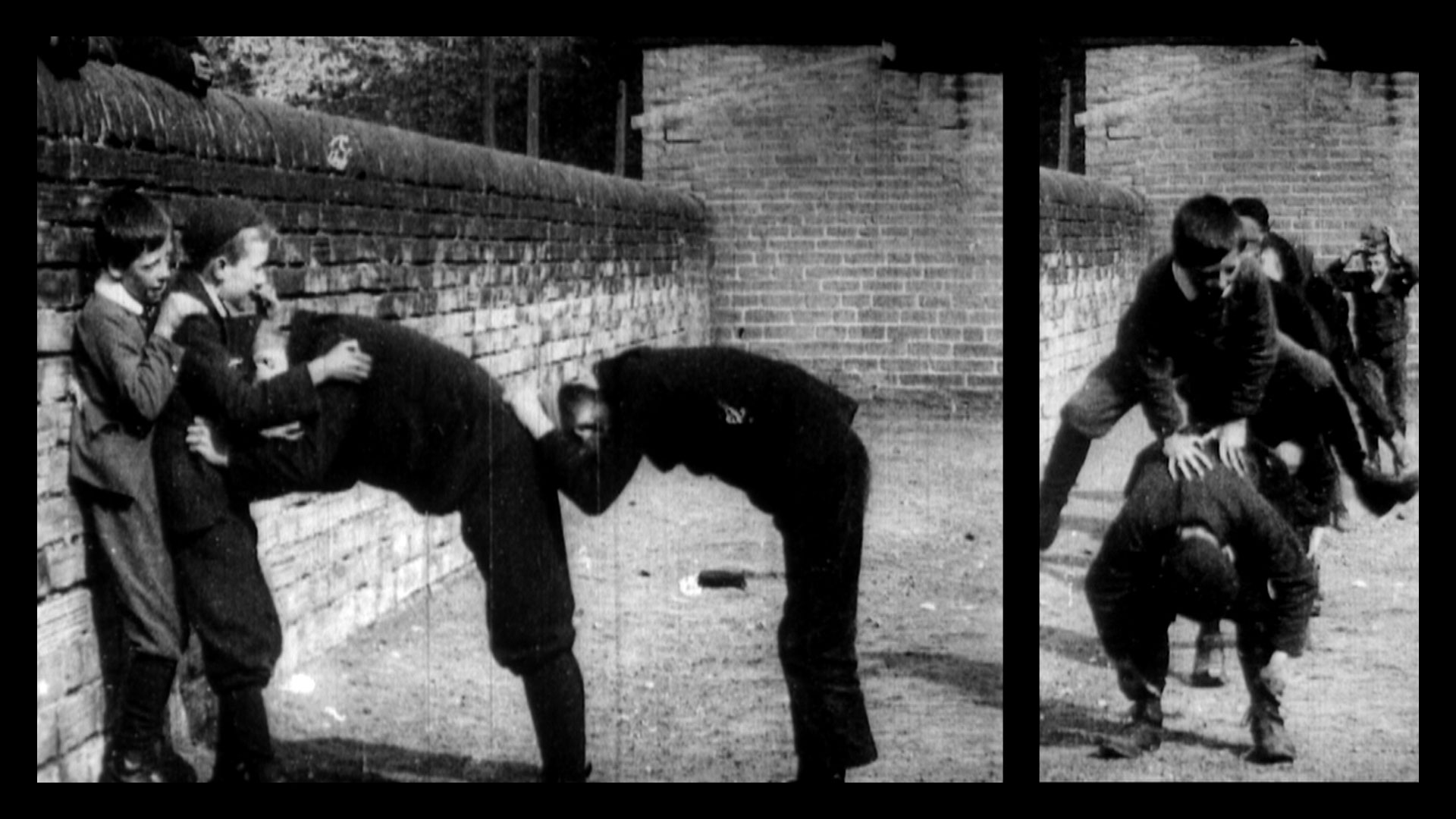

Exhibition overview

The exhibition is organised into four thematic sections dealing with the human figure, the imagination, the urban landscape, and the object, which together reveal a range of artists’ responses to the conditions of modernity. At the beginning of the 20th century, many hailed the machine as a symbol of progress. “Speed” and “efficiency” entered the vocabularies of art movements such as Futurism (in Italy), Purism (in France), Vorticism (in England), and Constructivism (in Russia), all of which adapted the subject matter and formal characteristics of the machine. Factories and labourers were presented positively as emblems of modernity, and mechanisation became synonymous with mobility and the possibility of social improvement. Countering this utopian position were proponents of the Dada and Surrealist movements (based largely in Germany and France), who found mechanical production problematic. For many of these artists who had lived through the chaos and destruction of World War I, the machine was perceived as a threat not only to the body, but to the uniquely human qualities of the mind as well. These artists embraced chance, accident, dream, and desire as new paths to freedom and creativity, in contrast to their counterparts who maintained their faith in an industrially enhanced future.

Though art from the first half of the 20th century is often viewed as representing an opposition between the rational, impersonal world of the machine and the uncontrollable, often troubling realm of the human psyche, the work in this exhibition suggests a more nuanced tension. In fact, artists regularly perceived these polarities in tandem. The codes of the bodily and the industrial coalesce in Fernand Léger’s machine aesthetic, on view in his 1927 painting Two Women on a Blue Backgound and an untitled collage from 1925. For his “rayographs,” Man Ray made use of mass-produced objects, but deployed them in a lyrical and imaginative manner – placing them on photosensitised paper and exposing it to light. Constantin Brancusi’s The Blond Negress (1927) and Jacques Lipchitz’s Draped Woman (1919) update the tradition of the cast bronze figure by introducing impersonal geometries. And even the seemingly formulaic surfaces of Piet Mondrian’s abstract paintings eventually reveal the artist’s sensitive hand.”

Press release from SFMOMA and the Cantor Arts Center

![Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975) 'La mitrailleuse en état de grâce' (The Machine Gun[neress] in a State of Grace) 1937 Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975) 'La mitrailleuse en état de grâce' (The Machine Gun[neress] in a State of Grace) 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/fleshandmetal_01_bellmer-web.jpg?w=650&h=651)

Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975)

La mitrailleuse en état de grâce (The Machine Gun[neress] in a State of Grace)

1937

Gelatin silver print with oil and watercolour

26 x 26 in. (66.04 x 66.04cm)

Collection SFMOMA, gift of Foto Forum

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Hans Bellmer (13 March 1902 – 23 February 1975) was a German artist, best known for the life sized pubescent female dolls he produced in the mid-1930s. Historians of art and photography also consider him a Surrealist photographer.

Bellmer was born in the city of Kattowitz, then part of the German Empire (now Katowice, Poland). Up until 1926, he’d been working as a draftsman for his own advertising company. He initiated his doll project to oppose the fascism of the Nazi Party by declaring that he would make no work that would support the new German state. Represented by mutated forms and unconventional poses, his dolls were directed specifically at the cult of the perfect body then prominent in Germany. Bellmer was influenced in his choice of art form by reading the published letters of Oskar Kokoschka (Der Fetisch, 1925).

Bellmer’s doll project is also said to have been catalysed by a series of events in his personal life. Hans Bellmer takes credit for provoking a physical crisis in his father and brings his own artistic creativity into association with childhood insubordination and resentment toward a severe and humourless paternal authority. Perhaps this is one reason for the nearly universal, unquestioning acceptance in the literature of Bellmer’s promotion of his art as a struggle against his father, the police, and ultimately, fascism and the state. Events of his personal life also including meeting a beautiful teenage cousin in 1932 (and perhaps other unattainable beauties), attending a performance of Jacques Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann (in which a man falls tragically in love with an automaton), and receiving a box of his old toys. After these events, he began to actually construct his first dolls. In his works, Bellmer explicitly sexualised the doll as a young girl. The dolls incorporated the principle of “ball joint”, which was inspired by a pair of sixteenth-century articulated wooden dolls in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum.

Bellmer produced the first doll in Berlin in 1933. Long since lost, the assemblage can nevertheless be correctly described thanks to approximately two dozen photographs Bellmer took at the time of its construction. Standing about fifty-six inches tall, the doll consisted of a modelled torso made of flax fibre, glue, and plaster; a mask-like head of the same material with glass eyes and a long, unkempt wig; and a pair of legs made from broomsticks or dowel rods. One of these legs terminated in a wooden, club-like foot; the other was encased in a more naturalistic plaster shell, jointed at the knee and ankle. As the project progressed, Bellmer made a second set of hollow plaster legs, with wooden ball joints for the doll’s hips and knees. There were no arms to the first sculpture, but Bellmer did fashion or find a single wooden hand, which appears among the assortment of doll parts the artist documented in an untitled photograph of 1934, as well as in several photographs of later work.

Bellmer’s 1934 anonymous book, The Doll (Die Puppe), produced and published privately in Germany, contains 10 black-and-white photographs of Bellmer’s first doll arranged in a series of “tableaux vivants” (living pictures). The book was not credited to him, as he worked in isolation, and his photographs remained almost unknown in Germany. Yet Bellmer’s work was eventually declared “degenerate” by the Nazi Party, and he was forced to flee Germany to France in 1938. Bellmer’s work was welcomed in the Parisian art culture of the time, especially the Surrealists around André Breton, because of the references to female beauty and the sexualization of the youthful form. His photographs were published in the Surrealist journal Minotaure, 5 December 1934 under the title “Poupée, variations sur le montage d’une mineure articulée” (The Doll, Variations on the Assemblage of an Articulated Minor).

He aided the French Resistance during the war by making fake passports. He was imprisoned in the Camp des Milles prison at Aix-en-Provence, a brickworks camp for German nationals, from September 1939 until the end of the Phoney War in May 1940. After the war, Bellmer lived the rest of his life in Paris. Bellmer gave up doll-making and spent the following decades creating erotic drawings, etchings, sexually explicit photographs, paintings, and prints of pubescent girls… Of his own work, Bellmer said, “What is at stake here is a totally new unity of form, meaning and feeling: language-images that cannot simply be thought up or written up … They constitute new, multifaceted objects, resembling polyplanes made of mirrors … As if the illogical was relaxation, as if laughter was permitted while thinking, as if error was a way and chance, a proof of eternity.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Objet Surréaliste à fonctionnement symbolique – le soulier de Gala (Surrealist object that functions symbolically – Gala’s Shoe)

1932/1975

Shoe, marble, photographs, clay, and mixed media

48 x 28 x 14 in. (121.92 x 71.12 x 35.56 cm)

Collection SFMOMA, purchase, by exchange, through a gift of Norah and Norman Stone

© Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Marcel Jean (French, 1900-1993)

Le Spectre du Gardenia (The Specter of the Gardenia)

1936/1972

Wool powder over plaster, zippers, celluloid film, and suede over wood

13 1/2 x 7 x 9 in. (34.29 x 17.78 x 22.86 cm)

Collection SFMOMA

Purchase through a gift of Dr. and Mrs. Allan Roos

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

With zippers for eyes and a filmstrip collar around its neck, this figure composes an anxious portrait, but its tactile surface of black cloth, faded red velvet, and zippers is charged with the eroticism of imagined touch. Jean originally called this work Secret of the Gardenia after an old movie reel he discovered, along with the velvet stand, at a Paris flea market. As the artist later recalled, Surrealism’s leader André Breton “always pressed his friends to center their interest on Surrealist objects,” and “he made a certain number himself.” Chance discoveries like the movie reel and velvet stand that inspired this work provided a trove of uncanny items for Surrealists to include, combine, and transform in their works.

Text from the MoMA website [Online] Cited 01/03/2014

Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976)

La famille nombreuse (The Numerous Family)

1926

Oil on canvas

32 1/8 x 25 5/8 in. (81.61 x 65.1cm)

Collection SFMOMA, gift of Peggy Guggenheim

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Giorgio de Chirico (Italian, 1888-1978)

Les contrariétés du penseur (The Vexations of the Thinker)

1915

Oil on canvas

18 1/4 x 15 in. (46.36 x 38.1cm)

Collection SFMOMA, Templeton Crocker Fund purchase

© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Fernand Léger (French, 1881-1955)

Deux femmes sur fond bleu (Two Women on a Blue Background)

1927

Oil on canvas

36 1/2 x 23 5/8 in. (92.71 x 59.94cm)

Collection SFMOMA, fractional gift of Helen and Charles Schwab

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Constantin Brancusi (Romanian, 1876-1957)

La Négresse blonde (The Blond Negress)

1926

Bronze with marble and limestone base

70 3/4 x 10 3/4 x 10 3/4 in. (179.71 x 27.31 x 27.31 cm)

Collection SFMOMA, gift of Agnes E. Meyer and Elise S. Haas

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University

328 Lomita Drive at Museum Way

Stanford, CA 94305-5060

Phone: 650-723-4177

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Sunday 11am – 5pm

Closed Monday and Tuesday

Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

0.000000

0.000000

![Barbara Creed (Australian, b. 1943) 'Untitled [Gay Liberation Front banner]' Melbourne, 1973 Barbara Creed (Australian, b. 1943) 'Stills from a Super 8mm film of a Women’s Liberation march' Melbourne, 1973](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/barbara-creed-gay-liberation-front-1973.jpg)

![Barbara Creed (Australian, b. 1943) 'Untitled [Gay Lib Woman]' Melbourne, 1973 Barbara Creed (Australian, b. 1943) 'Stills from a Super 8mm film of a Women’s Liberation march' Melbourne, 1973](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/barbara-creed-gay-lib-woman-1973.jpg)

![Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975) 'La mitrailleuse en état de grâce' (The Machine Gun[neress] in a State of Grace) 1937 Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975) 'La mitrailleuse en état de grâce' (The Machine Gun[neress] in a State of Grace) 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/fleshandmetal_01_bellmer-web.jpg?w=650&h=651)

You must be logged in to post a comment.