Exhibition dates: 24th August, 2024 – 12th January, 2025

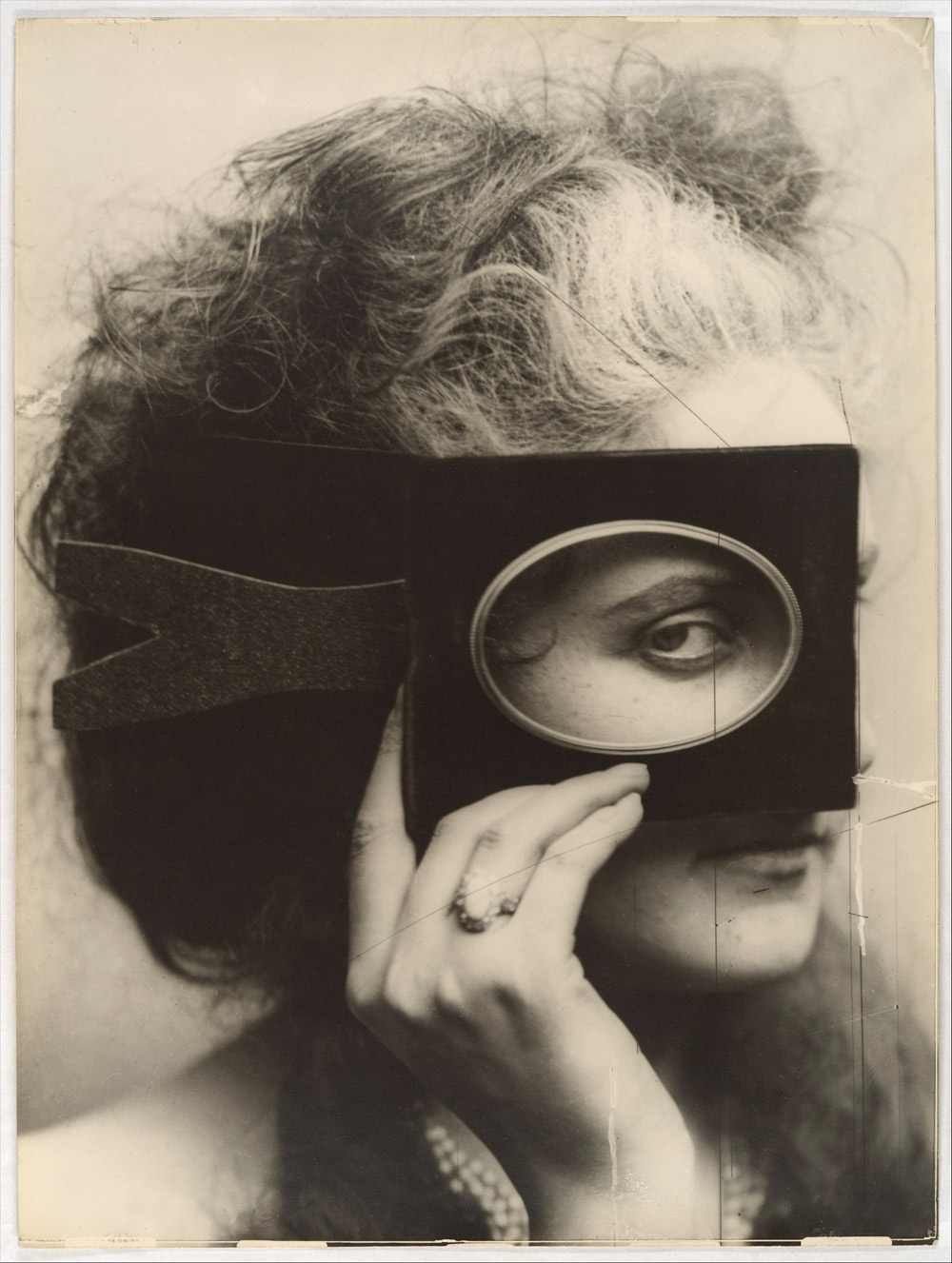

Victor Plumier (Belgian, 1820-1878)

Lady in Costume

About 1850

Daguerreotype, half plate

5 1/2 × 4 1/2 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Past present

Magnificent photographs that bring past presence into present consciousness.

Costume. variedly, the term “costume,” indicating clothing exclusively from the eighteenth century onward, can be traced back to the Latin consuetudo, meaning “custom” or “usage.”

Gesture. late Middle English: from medieval Latin gestura, from Latin gerere ‘bear, wield, perform’. The original sense was ‘bearing, deportment’, hence ‘the use of posture and bodily movements for effect in oratory’.

Expression. the action of making known one’s thoughts or feelings. a look on someone’s face that conveys a particular emotion. late Middle English: from Latin expressio(n- ), from exprimere ‘press out, express’.

The emotions and the sentiments, the gestures and the expressions.

The actor and the stage, the photographer and the sitter.

The staged photograph and the tableaux vivant.

The Self and the Other.

Today, something happens when we look at these photographs. Today, the social spaces, gestures and expressions in these photographs are not fixed, monological re-presentations or presences. Our experience of the photographs enables them to be seen as nodes within a network caught up in a system of social and cultural references, whose unity is variable and relative.1

Thus,

” …in my reading (of the photograph), I relied upon a number of semiological systems, each one being a social / cultural construct: the sign language of clothes, of facial expressions, of bodily gestures, of social manner, etc. Such semiological systems do indeed exist and are continually being used in the making and reading of images. Nevertheless the sum total of these systems cannot exhaust, does not begin to cover, all that can be read in appearances.”2

The intertextuality of images.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Roland Barthes. “From Work to Text” and Michel Foucault. The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences in Kurt Thumlert. Intervisuality, Visual Culture, and Education. [Online] Cited 10/08/2006. No longer available online

2/ John Berger and Jean Mohr. Another Way of Telling. New York: Pantheon Books, 1982, p. 112

Many thankx to the Nelson-Atkins Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“There is no perfection, no infinite completeness. But always, there is a way to move toward being whole. The capital letter, the Self is a wholeness that does not and will never exist. It is a direction that I move toward no matter the meanders of my feet.”

Kendrick VanZant

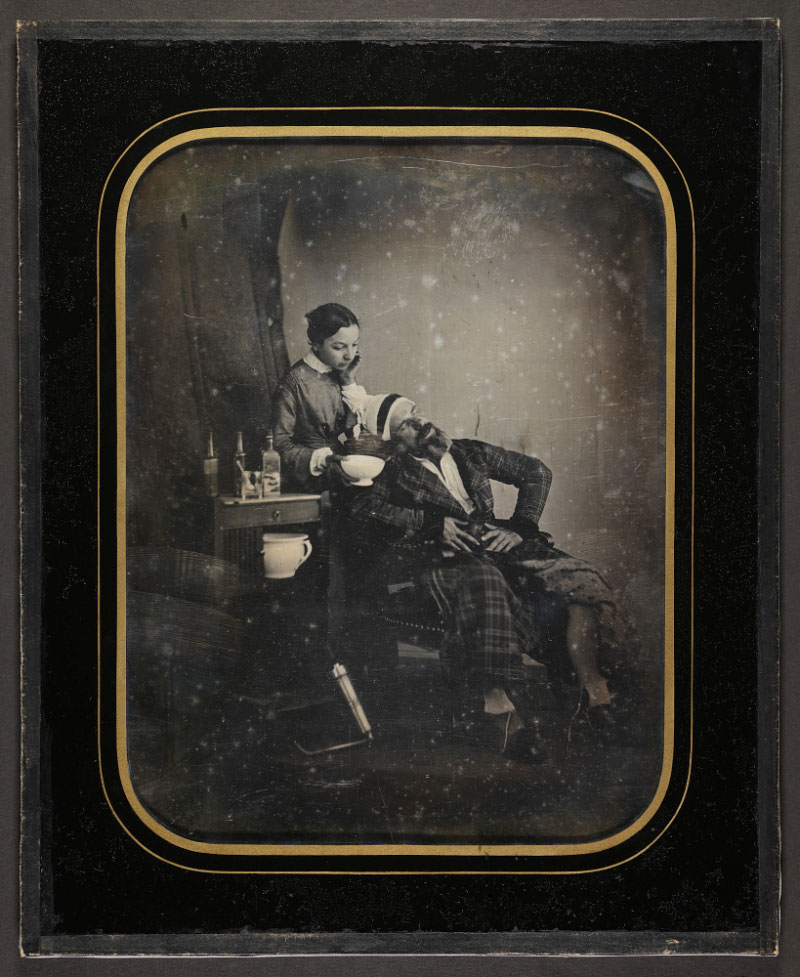

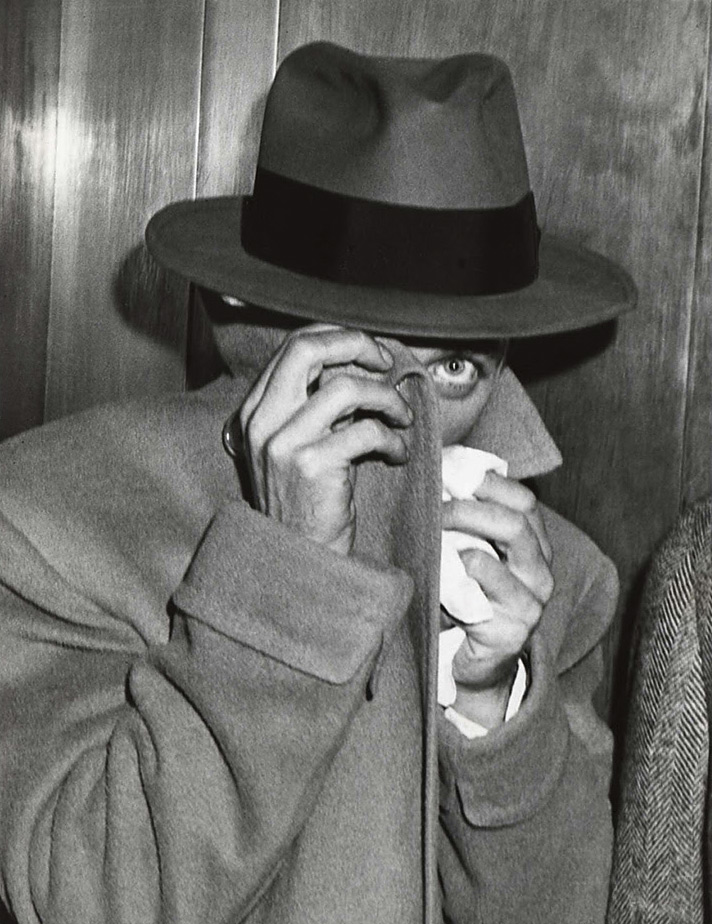

Camille Dolard (French, 1810-1884)

Self-portrait as ailing man

c. 1843-1845

Daguerreotype

Plate (whole): 8 1/2 × 6 1/2 inches (21.59 × 16.51cm)

Mat: 10 3/8 × 8 3/8 inches (26.37 × 21.29cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

French painter Camille Dolard briefly embraced photography in the 1840s as an innovative creative tool. This daguerreotype, and the one in the next case, are from a group of three theatrical self-portraits created by Dolard in his studio. Here, the artist performs for the camera, posing with props and costumes as a patient in the care of his attentive wife. In the other plate, he uses a similarly theatrical approach, depicting himself smoking a hookah (a water pipe used to smoke tobacco) while lounging on a patterned rug.

Text from the Nelson-Atkins Museum website

Jean-Pierre Thierry (French, 1810-1870)

Two ladies reading a letter

c. 1845

Daguerreotype

Plate (quarter): 4 1/4 × 3 1/4 inches (10.8 × 8.26 cm)

Mat: 6 1/16 × 5 1/8 inches (15.39 × 13.03 cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Philibert Perraud (French, 1815 – after 1863)

Deux femmes se recueillent sur la tombe d’une etre cher … (Two women at the grave of a loved one)

c. 1845

Daguerreotype

Plate (quarter): 4 1/4 × 3 1/4 inches (10.8 × 8.26cm)

Mount: 5 1/8 × 4 1/8 inches (13.02 × 10.48cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Unknown photographer

Actor in Costume

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

Plate (three-quarter): 6 × 4 1/2 inches (15.24 × 11.43 cm)

Case (open): 8 1/8 × 13 1/4 × 3/8 inches (20.64 × 33.66 × 0.95 cm)

Case (closed): 8 1/8 × 6 5/8 × 5/8 inches (20.64 × 16.83 × 1.59 cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Though the pose and expression in this photograph are stiff, the extensive hand-colouring enlivens the portrait, drawing attention to the fine details in the actor’s costume. Sitting for a daguerreotype portrait in the 1850s required patience and a certain degree of stamina. Photographic exposure times – which varied according to plate sensitivity and studio lighting – typically ranged from three to 30 seconds. Studio props, such as chairs and head braces, were used to help sitters remain as motionless as possible for the duration of the exposure.

Text from the Nelson-Atkins Museum website

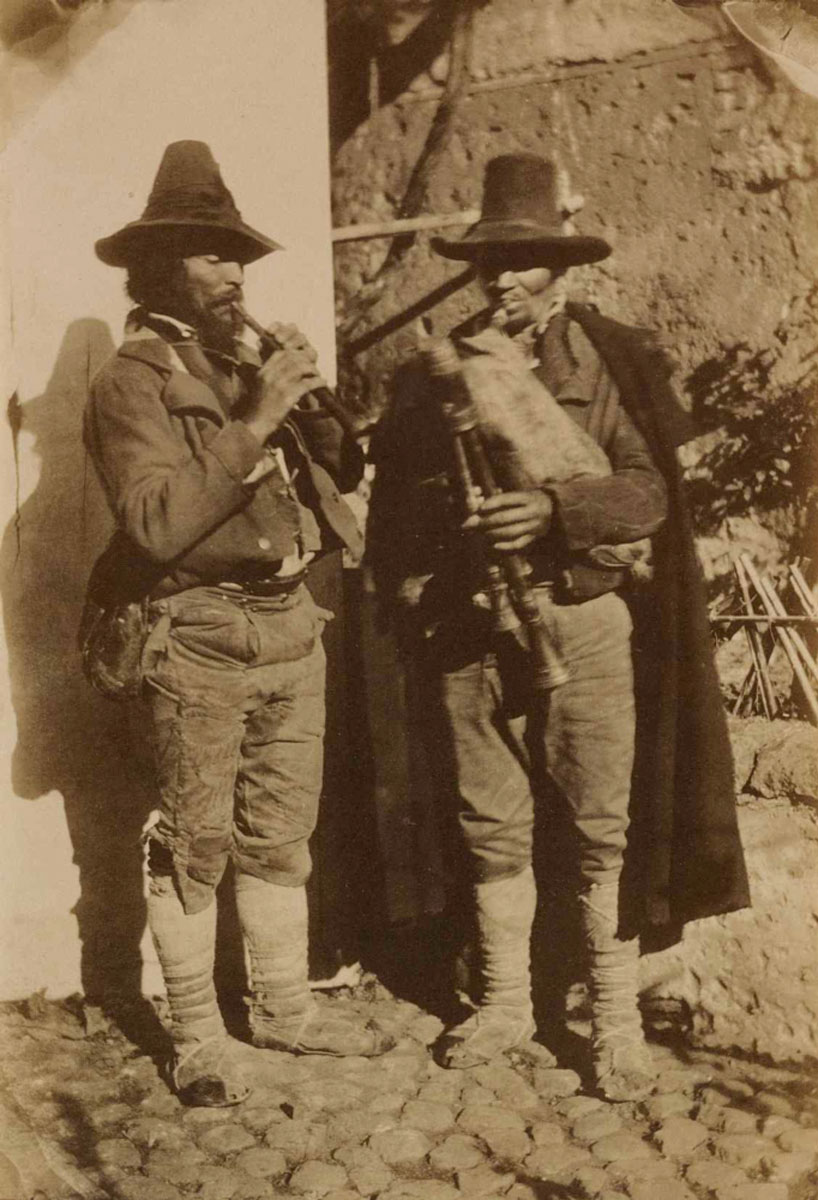

Giacomo Caneva (Italian, 1813-1865)

Two Pifferari

c. 1850s

Salt print

Image: 8 3/8 × 5 11/16 inches (21.27 × 14.45cm)

Sheet: 11 3/16 × 5 11/16 inches (28.42 × 14.45cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Nothing summed up picturesque modern Italy as well as the Pifferari; described by Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) in 1832: ‘These are strolling musicians who, towards Christmas, come down from the mountains in groups of four or five, armed with bagpipes and ‘pifferi’ (a sort of oboe), to play in homage before statues of the Madonna. They are generally dressed in large brown woollen coats and the pointed hats that brigands sport, and their whole appearance is instinct with a kind of mystic savagery that is most striking’. He admits that close to the music is ‘overpoweringly loud, but at a certain distance the effect of this strange ensemble of instruments is haunting and few are unmoved by it’.

Text from the Royal Collection Trust website

José Maria Blanco (Spanish, active c. 1850)

Man with mandolin

1851

Daguerreotype

Plate (quarter): 4 × 3 1/4 inches (10.16 × 8.26cm)

Mat: 5 5/8 × 4 7/8 inches (14.29 × 12.38cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866)

Portrait of Edouard Brindeau

1853

Salt print

6 1/4 × 4 5/8 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

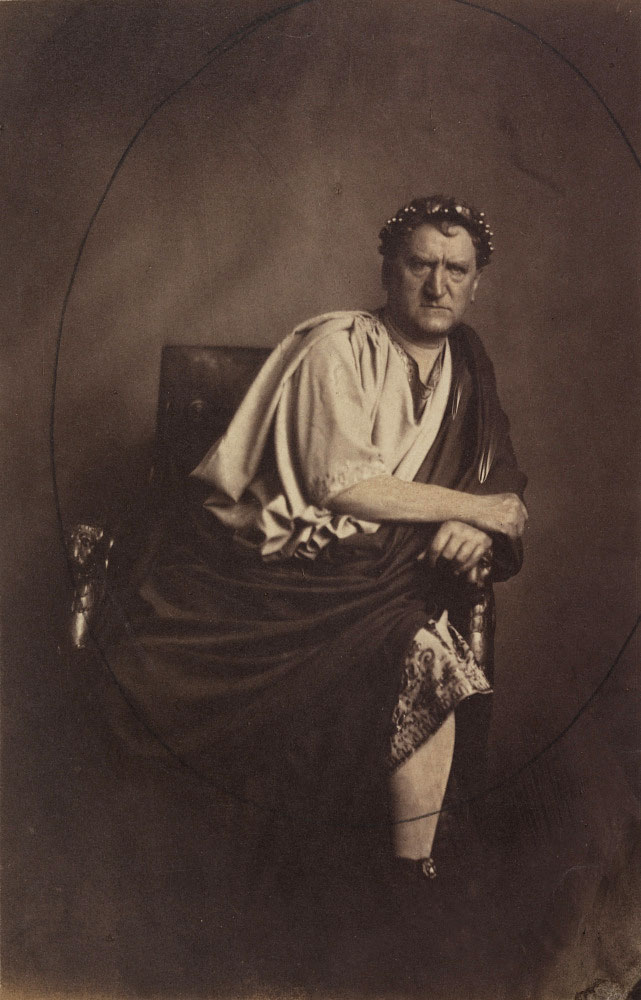

Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866)

Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Provost, in the role of the emperor Claude in the play Valeria

1853

Portraits of Actors from the Comédie Française

Salt print

Image and sheet: 6 7/16 × 4 1/8 inches (16.35 × 10.48cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

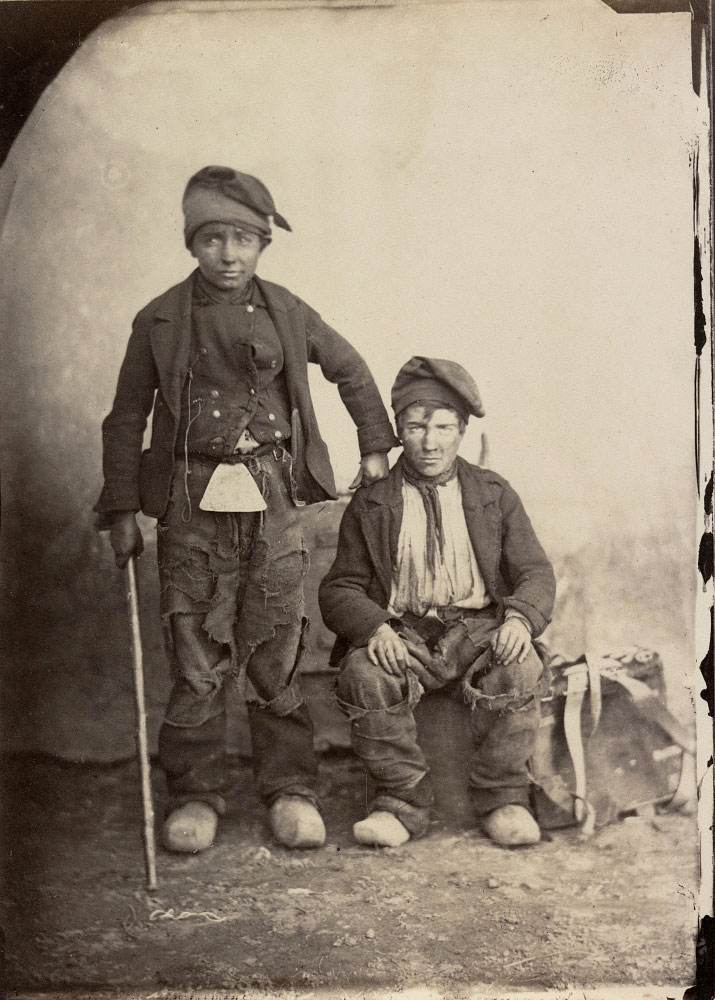

Charles Nègre (French, 1820-1880)

Two Small Savoyards

c. 1853

Albumen print

Image and sheet: 7 × 5 3/16 inches (17.78 × 13.12cm)

Mount: 17 × 15 inches (43.18 × 38.1cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Charles Nègre refers to the threadbare young men in this photograph as “Savoyards” (originating from the Savoy region of France). Impoverished, migrant Savoyards have appeared in European art since the 1700s, and Nègre’s title could be shorthand for a certain type of person seen in the streets of Paris, regardless of the two boys’ actual place of origin. A painter and a photographer, Nègre practiced the two mediums side-by-side. Like other artists of his time, he ascribed nobility to the poor, seeking to convey their “truth, warmth, and life.”

Text from the Nelson-Atkins Museum website

![Alban-Adrien Tournachon (French , 1825-1903) and Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Pierrot Yawning' 1854 from the exhibition 'Still Performing: Costume, Gesture, and Expression in 19th Century European Photography' at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City Alban-Adrien Tournachon (French , 1825-1903) and Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Pierrot Yawning' 1854 from the exhibition 'Still Performing: Costume, Gesture, and Expression in 19th Century European Photography' at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/tournachon-and-nadar-pierrot-yawning.jpg?w=857)

Alban-Adrien Tournachon (French , 1825-1903) and Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910)

Pierrot Yawning

1854

Salt print

11 1/4 × 8 1/2 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

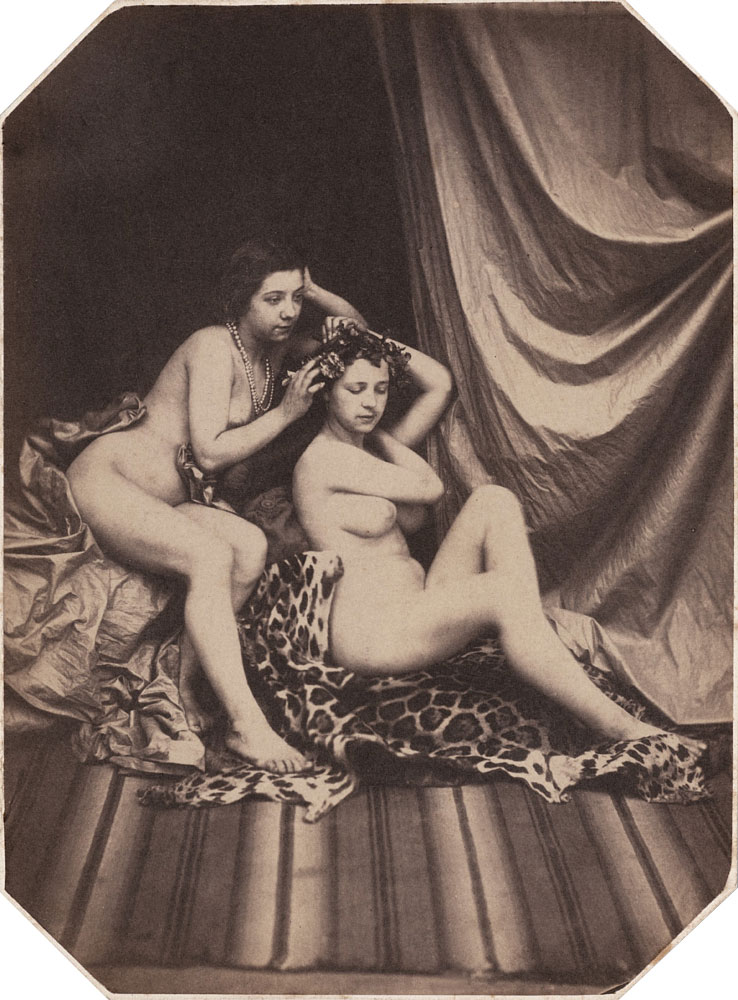

Auguste Belloc (French, 1805 -1873)

Une étude de nu de deux femmes

c. 1855

Salt print

Image and sheet: 8 5/16 × 6 1/8 inches (21.11 × 15.56cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

A masterful printer, Auguste Belloc created nudes that surpassed the typical erotic fare found in Parisian markets. In this scene, Belloc strategically positions the models and surrounding drapery to make the photograph appear more artistic than pornographic. Though nude paintings, drawings, and sculptures were immensely common, at this time photography was treated far more harshly by censors. In October 1860, the French government seized some 5,000 of Belloc’s photographs, declaring them obscene, and by 1868 he had abandoned his photographic studio.

Text from the Nelson-Atkins Museum website

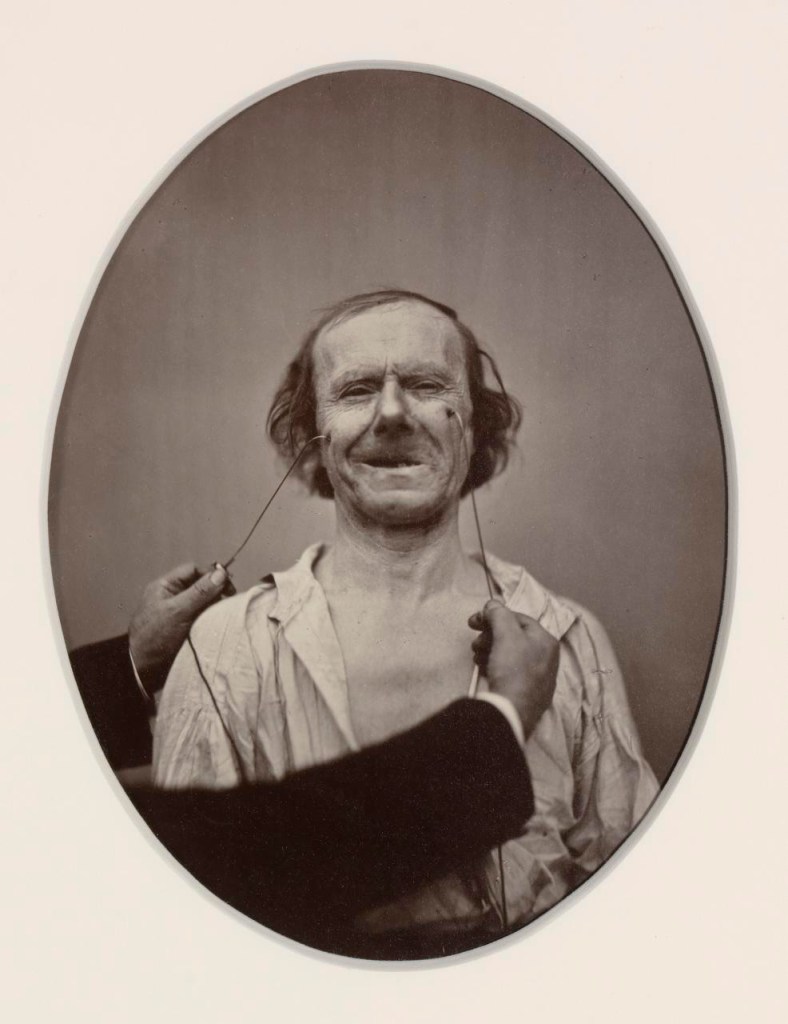

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne (French, 1806-1875) and Alban-Adrien Tournachon (French, 1825-1903)

The Muscles of Weeping and Whimpering

About 1855-1857

Albumen print

9 1/16 × 6 15/16 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Facial expressions and their corresponding emotions have been studied by artists for centuries. In the 1850s, Dr. Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne used photography to document the facial expressions produced by localised electric shock. Working in partnership with photographer Adrien Alban Tournachon, Duchenne felt these photographs truthfully recorded his experiments and that “none shall doubt the facts presented here.” Praising photography for its accurate rendering of the subject’s deep wrinkles, he wrote, “the distribution of light is in perfect harmony with the passions represented by these expressive lines. Thus, the face depicting the dark, concentric passions – aggression, wickedness, suffering, pain, dread, torture mixed with fear – gain an uncommon amount of energy.”

Text from the Nelson-Atkins Museum website

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne (French, 1806-1875) and Alban-Adrien Tournachon (French, 1825-1903)

The Muscle of Pain

c. 1854-1857

Figure 27, plate 63 from The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression

Albumen print

Image and sheet: 9 1/16 × 6 5/8 inches (23.01 × 16.84cm)

Mount: 16 1/16 × 10 13/16 inches (40.79 × 27.51cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

In this uncanny double portrait, the physiologist Dr. Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne holds a mechanical device to the face of a 52-year-old, Italian-born woman believed to have been institutionalised in a Parisian asylum. Duchenne asserted that localised electric shock could force facial muscles to “contract to speak the language of the emotions and the sentiments.” “Armed with electrodes,” he wrote, “one would be able, like nature herself, to paint the expressive lines of the emotions of the soul on the face of man.”

Text from the Nelson-Atkins Museum website

Roger Fenton (English, 1819-1869)

Self-portrait as a Zouave

1855

Salt print:

Image and sheet: 7 13/16 × 6 7/16 inches (19.84 × 16.35cm)

Mount: 22 1/8 × 16 1/8 inches (56.2 × 40.96cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Cocking a rifle and smoking a pipe, with alcohol by his side, Roger Fenton poses for his camera with bravado. Wearing the distinctive baggy uniform of a Zouave (skilled infantry soldiers from the French army in Algeria), Fenton fashions himself as a hardened, glowering soldier, though he never fought in any war. Fenton did, however, photograph the Crimean War (1853-1856) from a great distance. The war brought together an alliance of soldiers from England, Croatia, Algeria, Turkey, Egypt, and France whom Fenton encountered while photographing the conflict.

Text from the Nelson-Atkins Museum website

Marcel Gustave Laverdet (French, 1816-1886)

Masks from the album Selection of Ancient Terra Cotta from the Collection of M. Le Vicomte H. de Janzé

1857

Photolithograph

8 15/16 × 14 9/16 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Charles Nègre (French, 1820-1880)

Self-portrait

About 1855-1860

Salt print

7 5/8 × 5 7/16 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

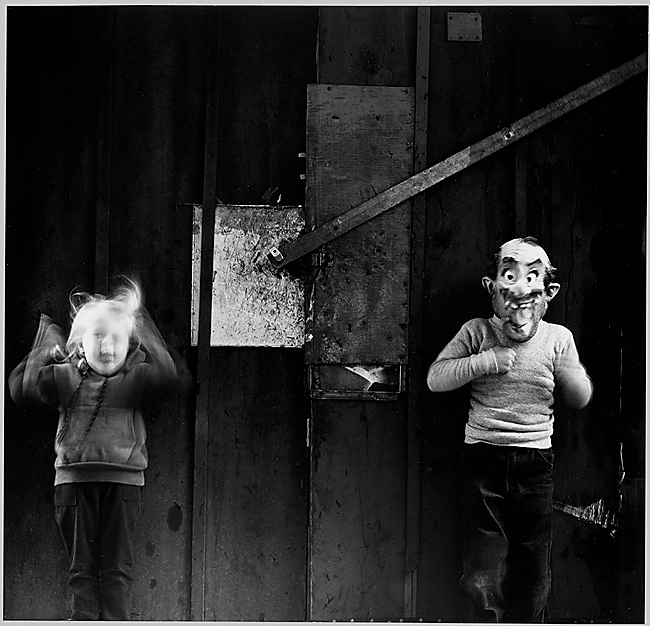

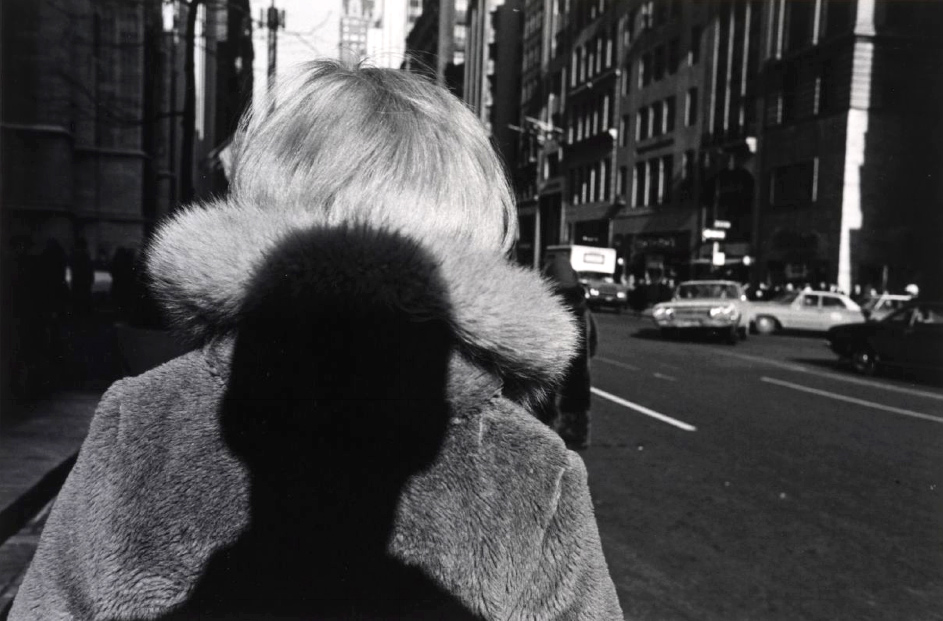

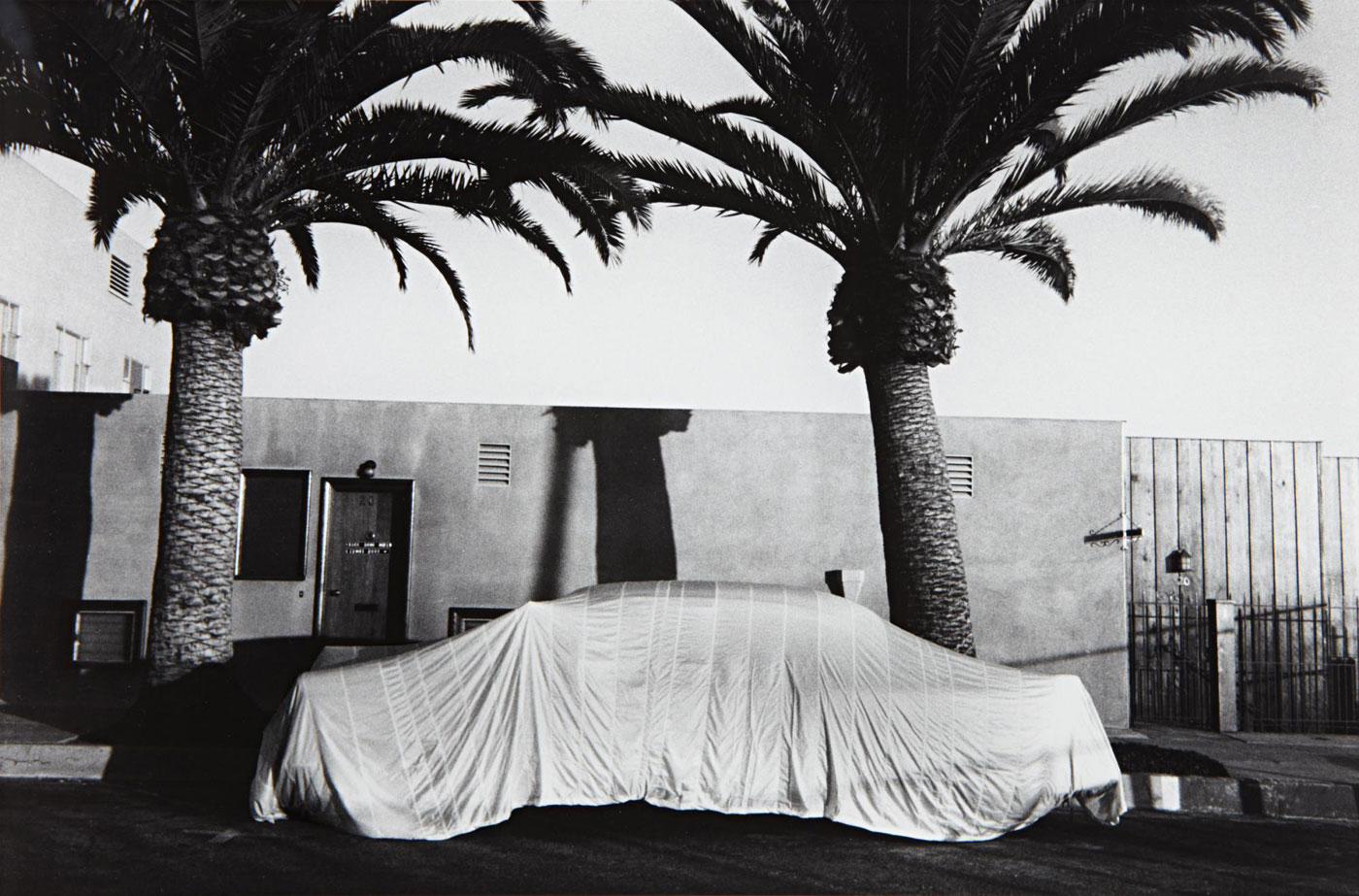

Early photography is ripe with creative fictions. Actors, children, aristocrats, models, artists, psychiatric patients, maids, and all manner of the working class posed in front of cameras and were transformed into figures from history, literature, the Bible, or into an idealised version of themselves. Still Performing: Costume, Gesture, and Expression in 19th Century European Photography, which opens at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City Aug. 24, celebrates the unique and compelling ways 19th century European photographers used the medium to explore and document performance, transforming the photographer’s studio into a theatrical stage. The exhibition runs through Jan. 12, 2025.

“The subjects in this exhibition were highly influenced by popular entertainment – live theatre, tableaux vivant, and dioramas – as well as tastes and trends in painting, drawing, and sculpture,” said Julián Zugazagoitia, Director & CEO of the Nelson-Atkins. “These works were made in a time of anxiety about photography’s relationships to the fine arts and reflect a close intermingling between the worlds of the ‘high’ and the ‘low’.”

Visiting a photographer’s studio in Europe in the mid to late 1800s was like going behind the scenes of a theatrical production. Props, backdrops, costumes, curtains, and controlled lighting converted otherwise ordinary portrait sessions into staged productions. Whether working in their homes or commercial studios, photographers cast themselves, friends, actors, models, and strangers in their photographs, transforming them into all types of characters, from young pickpockets to ancient Greek gods.

“These portraits are so fascinating, and I think our guests are going to be amazed at the rich creative complexity found in European photography’s first 50 years,” said Marijana Rayl, Assistant Curator, Photography.

Deliberately made, not casually taken, these staged photographs are often the result of collaborative efforts between photographer and sitter, such as with a series of portraits of Virginia Oldoini, the Countess of Castiglione. A prodigious narcissist, or perhaps just ahead of her time, the countess collaborated with the photographer Pierre-Louis Pierson to produce hundreds of portraits, directing every aspect of the picture-making process. Included in Still Performing is a very rare, hand-coloured portrait of the countess.

The resulting photographs are an outstanding array of complex and compelling fictions showcasing the medium’s early creative potential.

Press release from the Nelson-Atkins Museum

Oscar Gustav Rejlander (English born Sweden, 1813-1875)

Drawing Water from a Well (O.G. Rejlander and model)

c. 1858

Salt print

Image and sheet: 7 15/16 × 6 1/2 inches (20.16 × 16.51cm)

Mount: 14 1/16 × 11 5/16 inches (35.72 × 28.73cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Oscar Rejlander occasionally cast himself in staged photographs like this one, which was made to appear like a candid image of ordinary people going about their daily lives. Here he poses, turned away from the camera, as though he is helping a peasant woman retrieve water from a well. These kinds of genre scenes were immensely popular in the 1800s across painting, drawing, printmaking, and photography. Rejlander passionately advocated for photography to be treated as a fine art, believing that it must emulate painting.

Text from the Nelson-Atkins Museum website

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

Actress Rosa Csillag in the Role of Orpheus

1860

Albumen print

9 3/16 × 7 5/8 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Pierre-Louis Pierson (French, 1822-1913)

The Countess de Castiglione

1860s

Gelatin silver print (printed about 1930)

10 15/16 x 14 1/8 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Pierre-Louis Pierson (French, 1822-1913)

The Countess de Castiglione

1860s

Gelatin silver print (printed about 1930)

Image: 14 3/16 x 11 inches (36.04 x 27.94cm)

Sheet: 14 3/16 x 11 inches (36.04 x 27.94cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Pierre-Louis Pierson (French, 1822-1913)

Bal en Costume, Royaume de Belgique

c. 1860

Salt print

Image and sheet: 11 1/2 × 8 3/4 inches (29.21 × 22.23cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Lady Clementina Hawarden (English, born Scotland, 1822-1865)

Clementina Maude and Isabella Grace

c. 1863

Albumen print

Image and sheet: 9 13/16 × 9 11/16 inches (24.97 × 24.61cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Julia Margaret Cameron (English, born India, 1815-1879)

Sappho (Mary Hillier)

1865

Albumen print

Image and sheet: 12 15/16 × 10 1/8 inches (32.86 × 25.72cm)

Mount: 20 13/16 × 16 13/16 inches (52.86 × 42.7cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

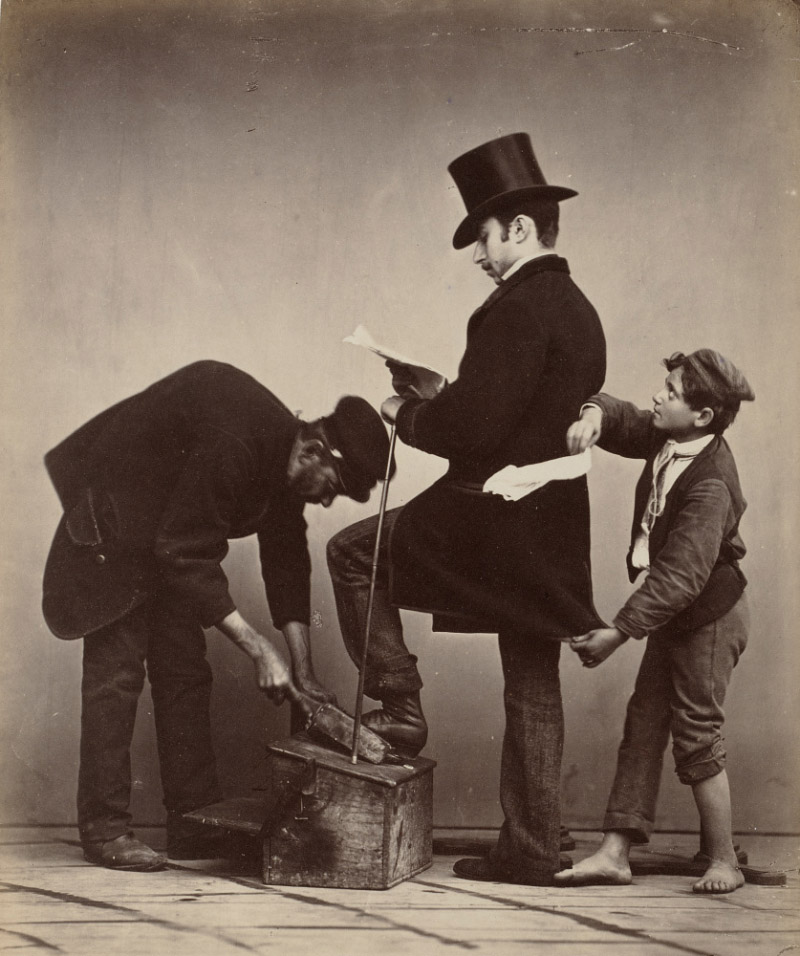

Giorgio Sommer (Italian born Germany, 1834-1914)

The Pickpocket

About 1865

Albumen print

9 3/8 × 7 5/8 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

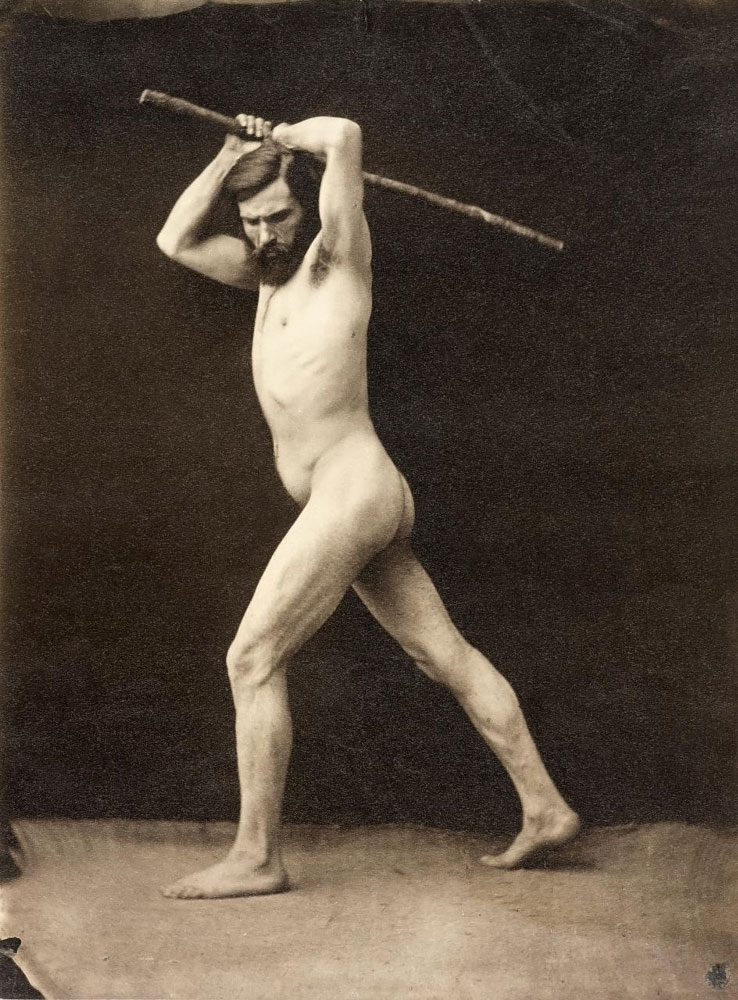

Gaudenzio Marconi (French born Switzerland, 1842-1885)

Male nude for artist

c. 1870

Albumen print

Image and sheet: 8 5/8 × 6 3/8 inches (21.91 × 16.19cm)

Mount: 12 9/16 × 9 3/4 inches (31.91 × 24.77cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Julia Margaret Cameron (English born India, 1815-1879)

Sir Galahad and the Pale Nun

1874

Albumen print

13 7/16 × 10 1/2 inches

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Giraudon’s Artist (French, active c. 1875)

Woman with bundle of twigs

c. 1875-1880

Albumen print

Image and sheet: 6 5/8 × 4 11/16 inches (16.83 × 11.91cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

Pierre-Louis Pierson (French, 1822-1913)

Portrait of the Countess of Castiglione from Série des Roses

1895

Albumen cabinet card

Image and sheet: 5 15/16 × 3 15/16 inches (15.06 × 9.98cm)

Mount: 6 3/8 × 4 1/4 inches (16.21 × 10.8cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Gift of the Hall Family Foundation

The Countess of Castiglione became reclusive with age, rumored to only leave her home at night, hidden behind veils. Social chroniclers of the time claimed that she removed all mirrors from her home to avoid her appearance; however, this portrait seems to contradict her alleged displeasure. Taken toward the end of her life, the countess admires her reflection in the mirror, donning a youthful blond wig elaborately decorated with roses.

Text from the Nelson-Atkins Museum website

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

4525 Oak Street

Kansas City, MO 64111

Opening hours:

Thursday – Monday 10am – 5pm

Closed Tuesdays and Wednesdays

![Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009) [Kids in a Box, on the Street, New York City] c. 1942 Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009) [Kids in a Box, on the Street, New York City] c. 1942](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/kids-levitt-web.jpg)

![Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009) [Kids on the Street Playing Hide and Seek, New York City] c. 1942 Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009) [Kids on the Street Playing Hide and Seek, New York City] c. 1942](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/levitt-hide.jpg)

![Attributed to Juliette Alexandre-Bisson (French, 1861-1956) [Birth of Ectoplasm During Séance with the Medium Eva C.] 1919-1920 Attributed to Juliette Alexandre-Bisson (French, 1861-1956) [Birth of Ectoplasm During Séance with the Medium Eva C.] 1919-1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/birth-of-ectoplasm-web.jpg)

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930 Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/stieglitz-self-portrait-1907.jpg)

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/sears-julia-ward-howe.jpg?w=650)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar-sarah-bernhardt.jpg)

![Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863 Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/fredricks-mlle-pepita.jpg)

![André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864 André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/disdecc81ri-rosa-bonheur.jpg)

![John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900 John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/parsons-portrait-of-jane-morris.jpg?w=650)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar_alexander_dumas.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.