Exhibition dates: 15th February – 12th May, 2024

Curator: Drew Sawyer

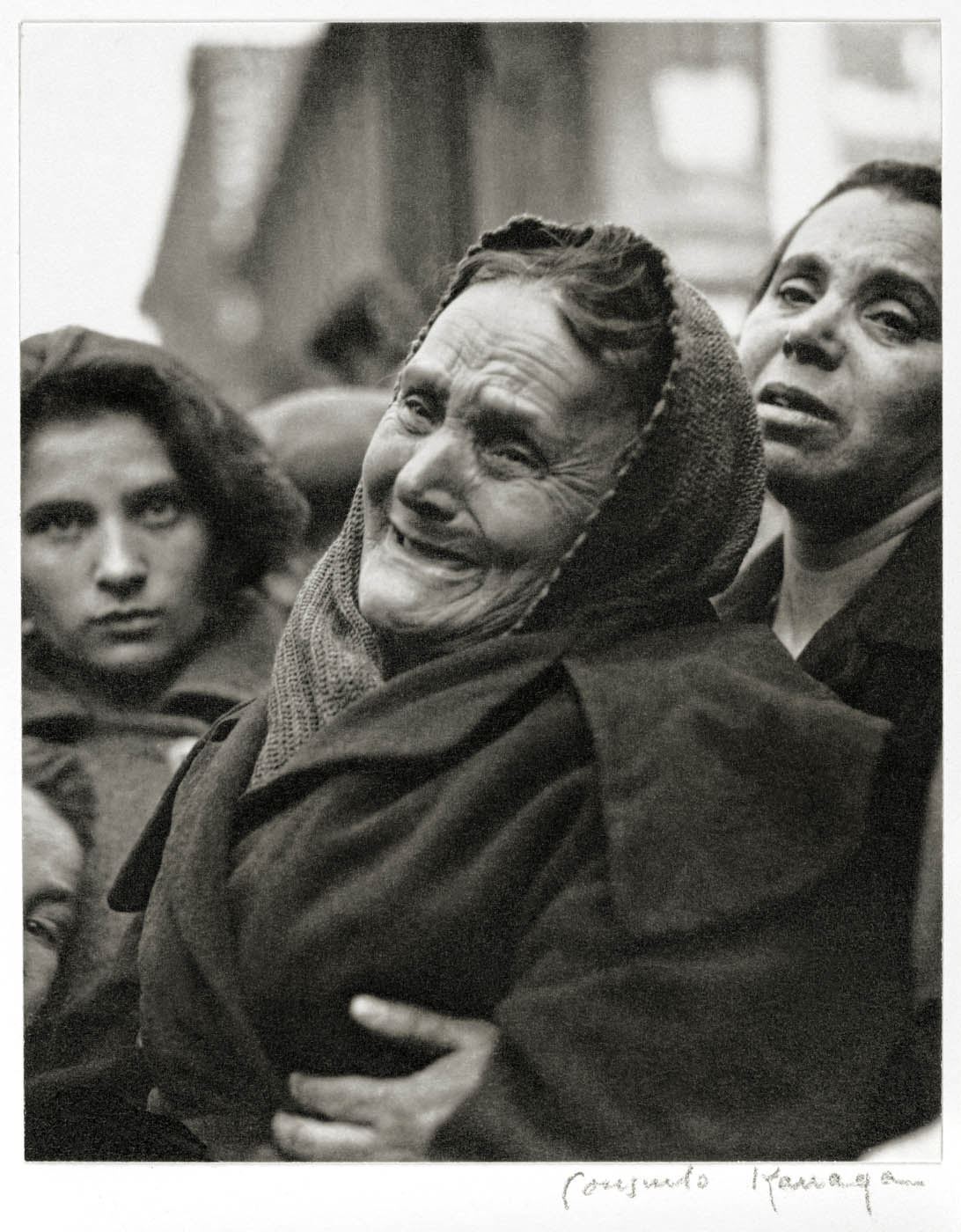

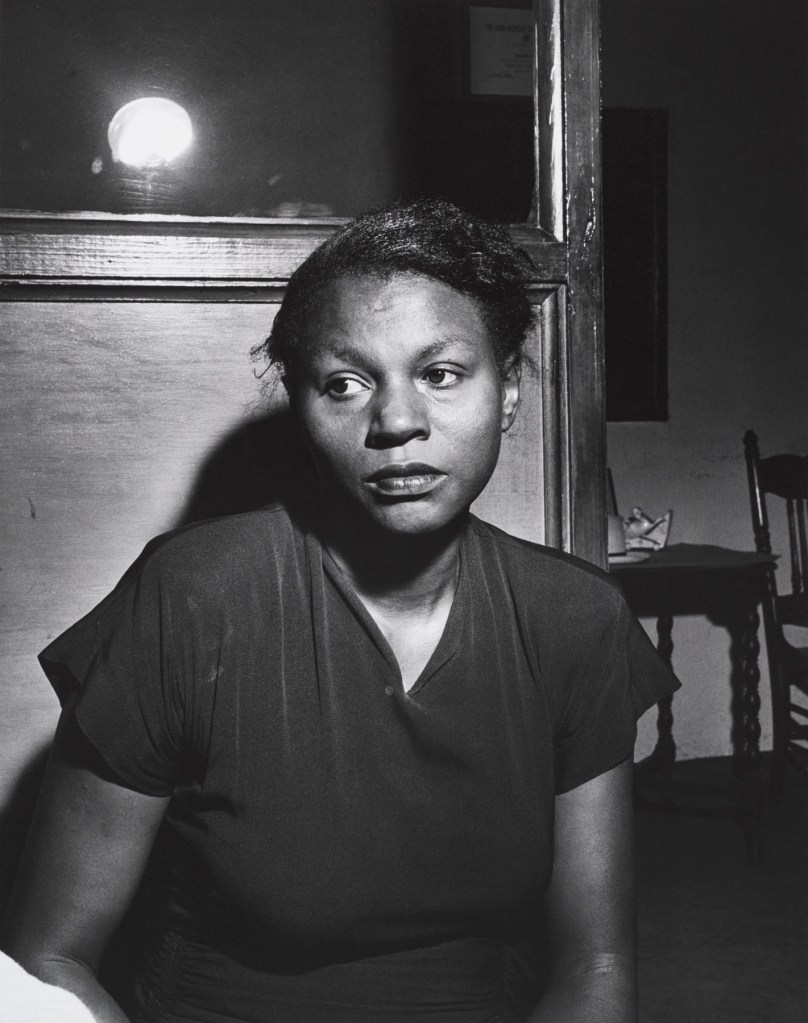

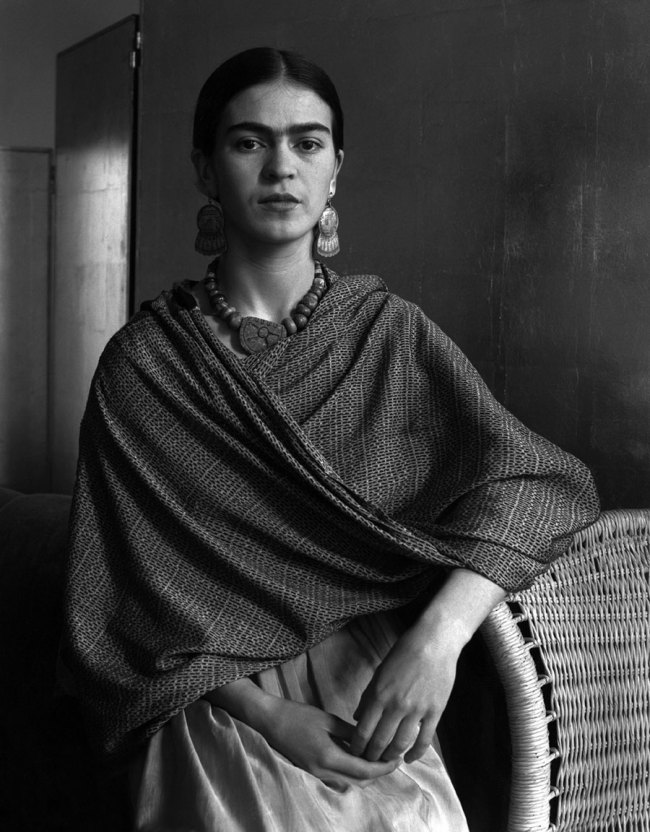

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Self-portrait

Nd

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

What have you got to say?

We must acknowledge the importance of the Consuelo Kanaga, a strong, compassionate human being, an under recognised photographer. What a trailblazer for future female and male photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Imogen Cunningham, Berenice Abbott and Milton Rogovin.

Kanaga is a story teller. Her photographs are strongly modernist, realist compositions. The portraits are direct and revealing, no external flourishes necessary in capturing the essence of the person; her landscapes, dark and brooding atmospheric iterations of land and spirit.

Consuelo Kanaga:

~ one of the pioneers of modern American photography

~ one of the first women photojournalists on staff at a newspaper (1918)

~ a great supporter and a confidant for Imogen Cunningham, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Dorothea Lange, Alma Lavenson, Tina Modotti, and Eiko Yamazawa, among many others

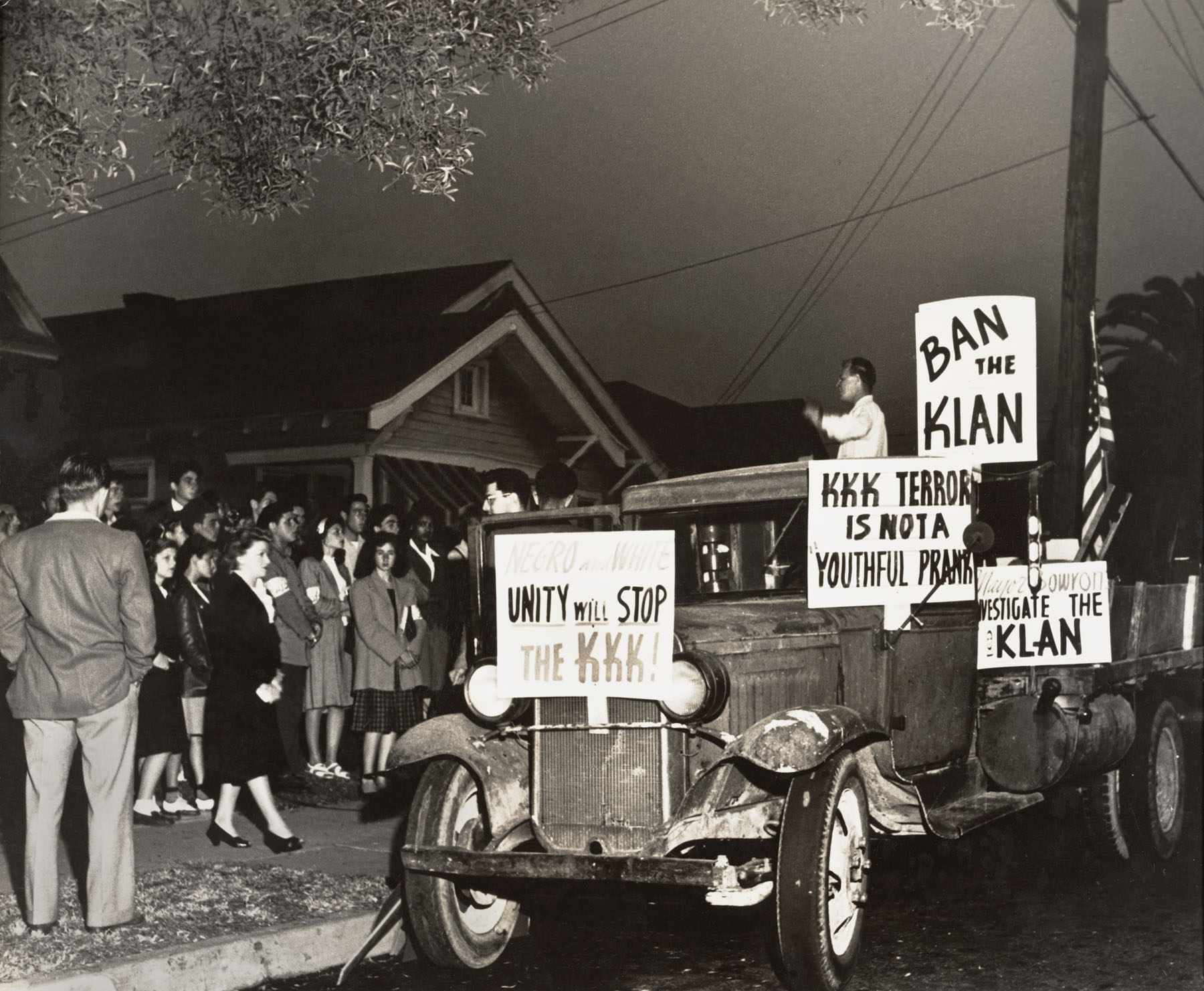

~ passionate about social justice … social marginalisation, poverty, racial harassment, inequality… especially in relation to the African-American population in the United States.

~ maintained a close relationship with avant-garde circles, in San Francisco with the f.64 Group and in New York with the Photo League

~ focused on marginal day to day and political motifs, including workers, African Americans, objects, and buildings that were often in a state of disrepair

~ interested in worker’s rights and the worker movement

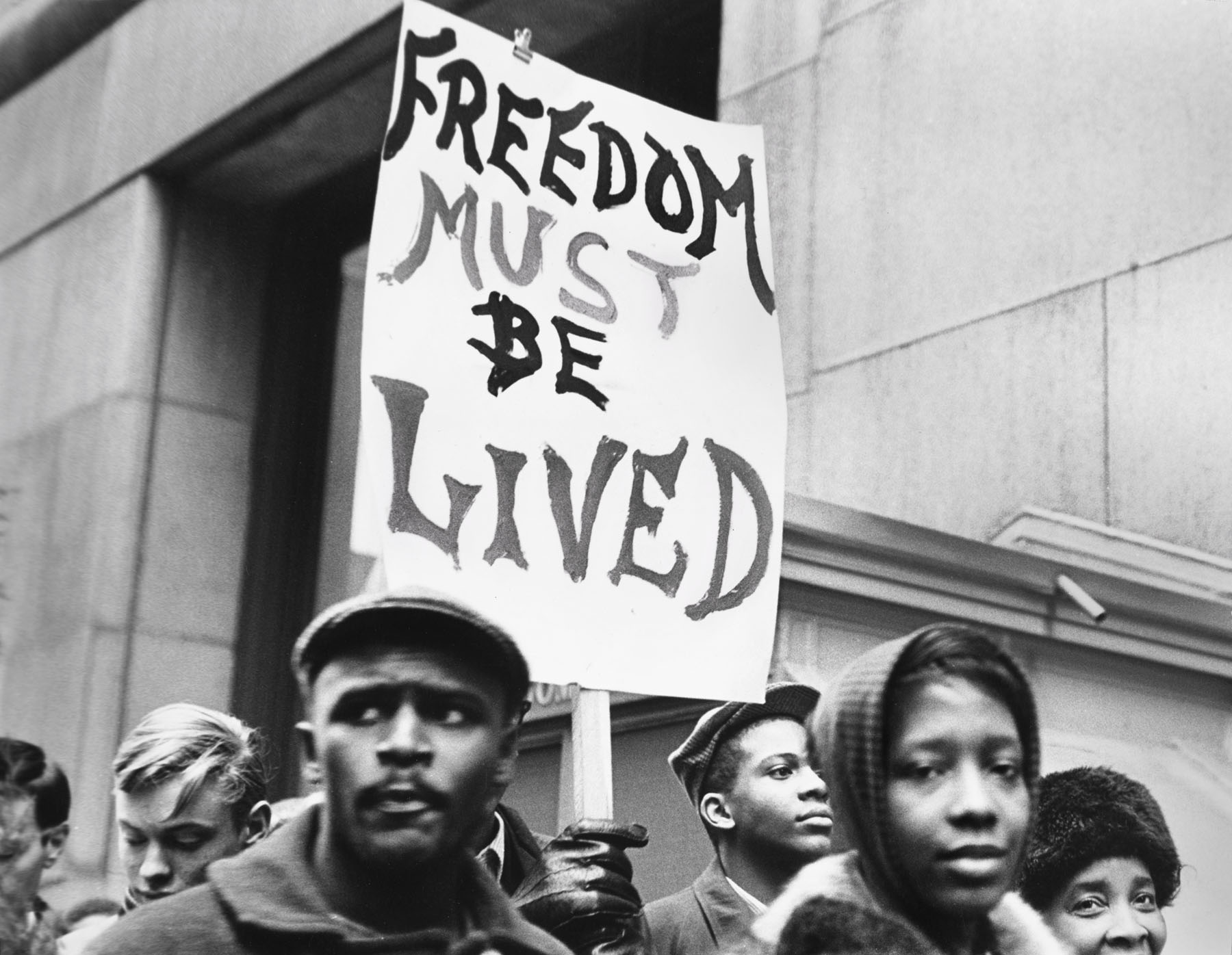

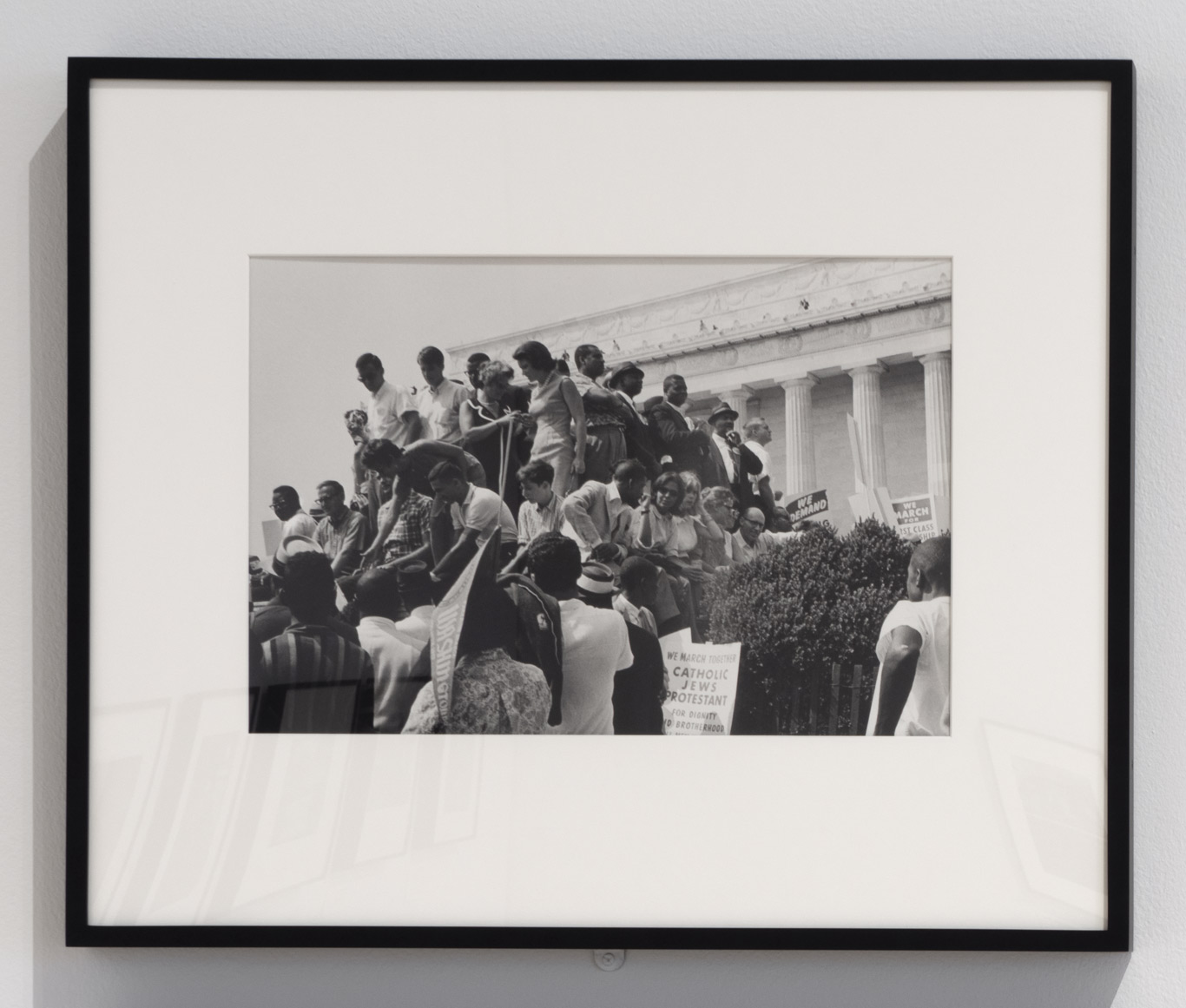

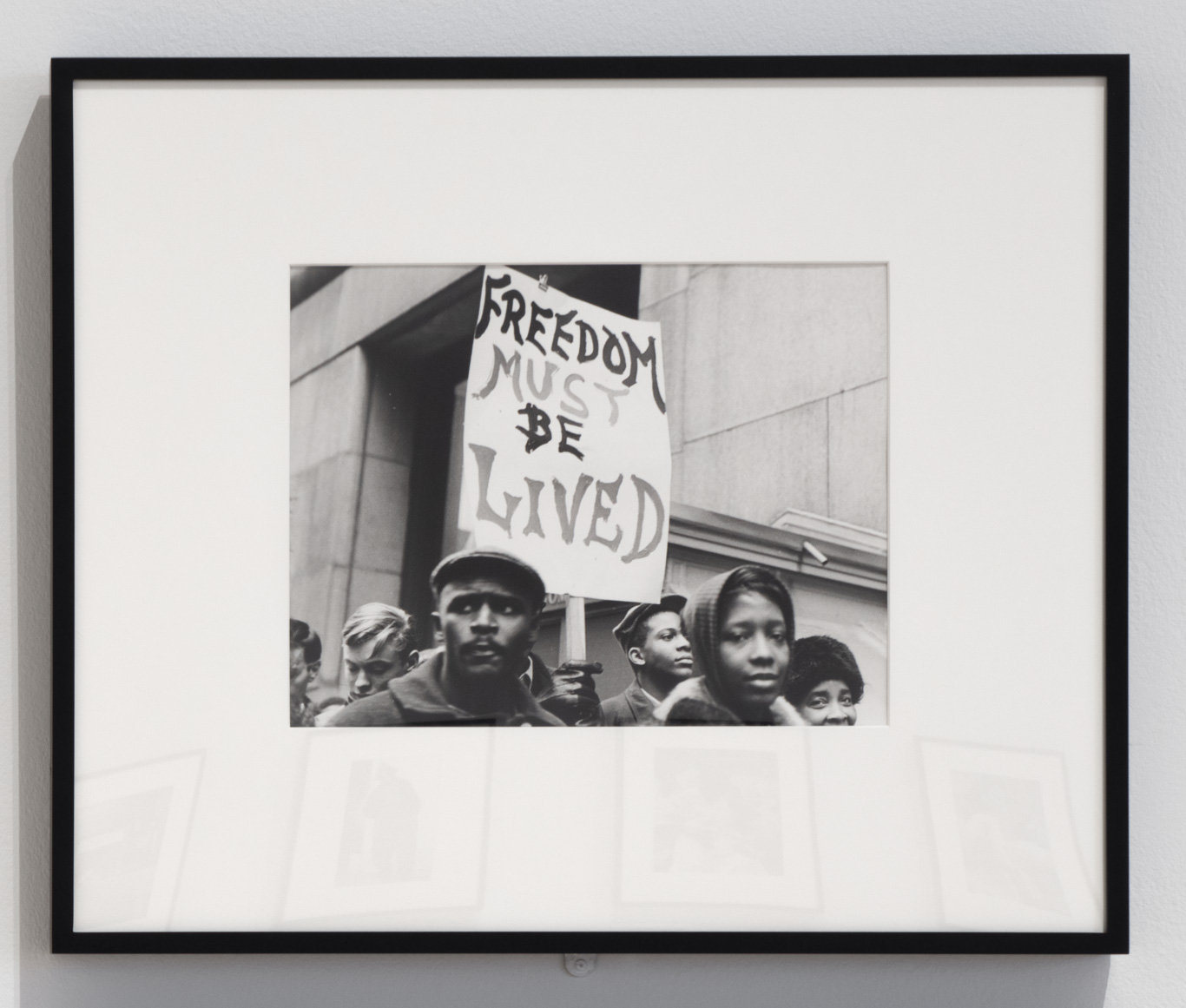

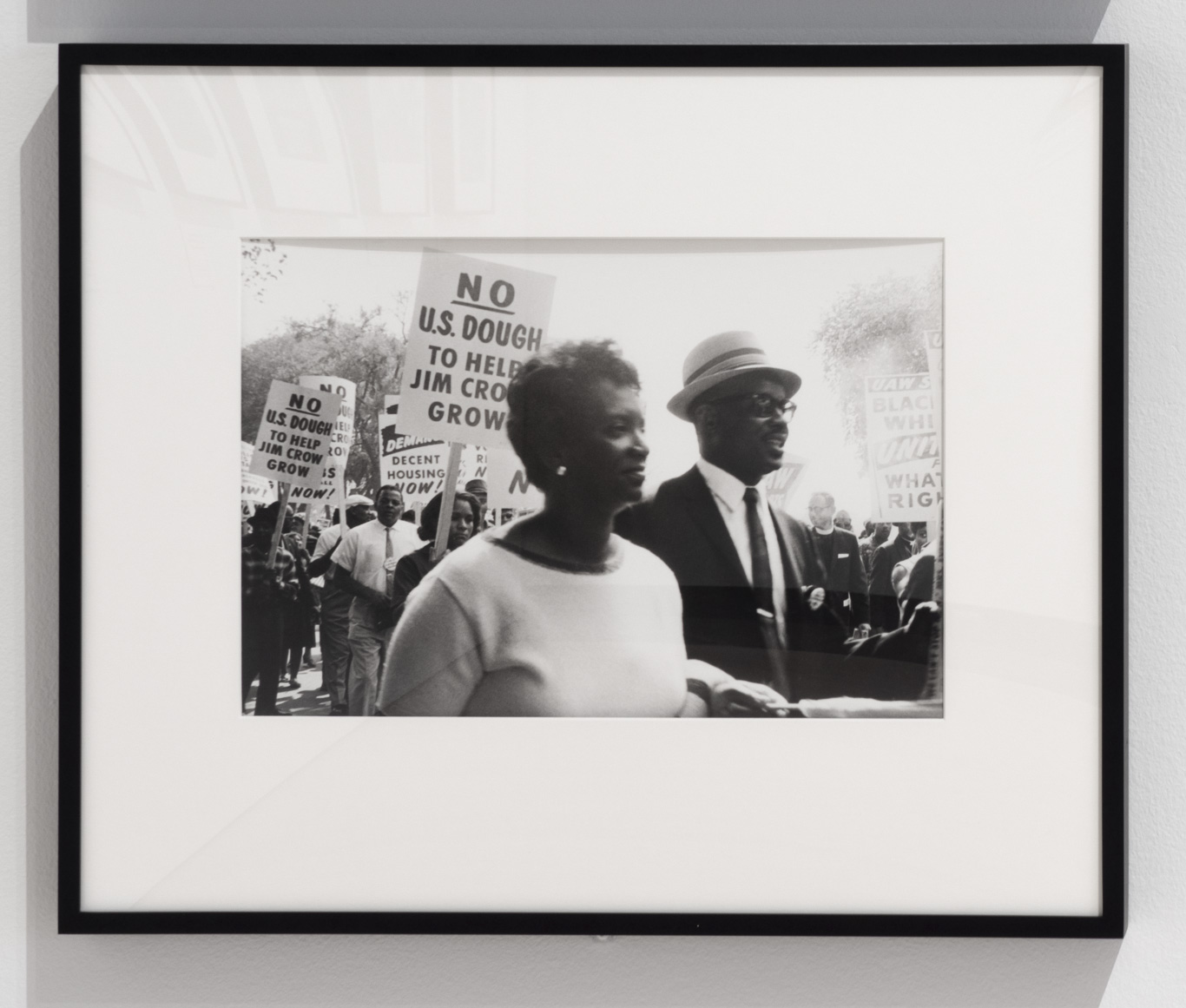

~ became very active in civil rights and took part in and photographed many demonstrations and marches in the 1960s

Whatever type of photograph Kanaga took (and there are many) her photographs are always perceptive = having or showing sensitive insight.

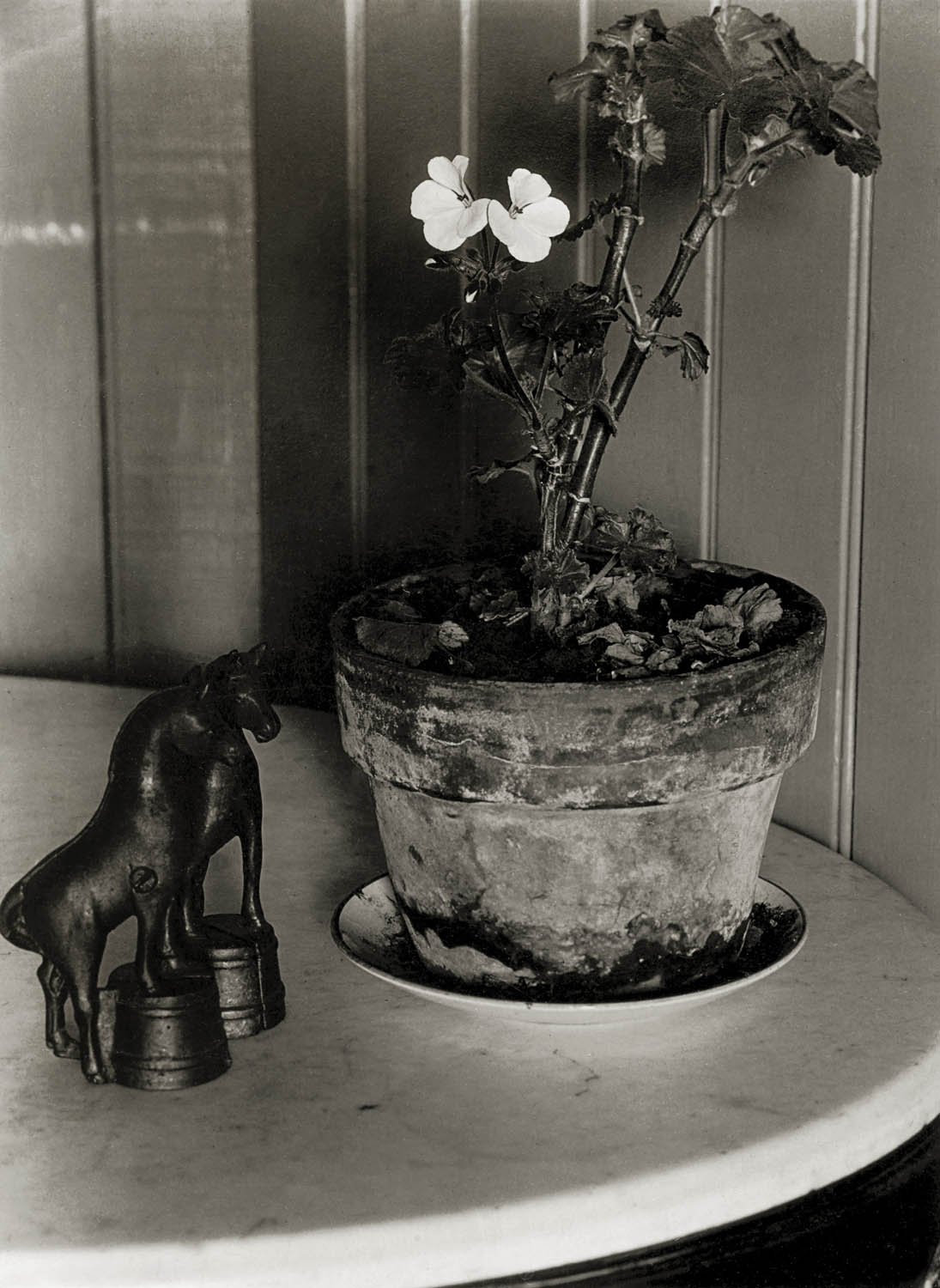

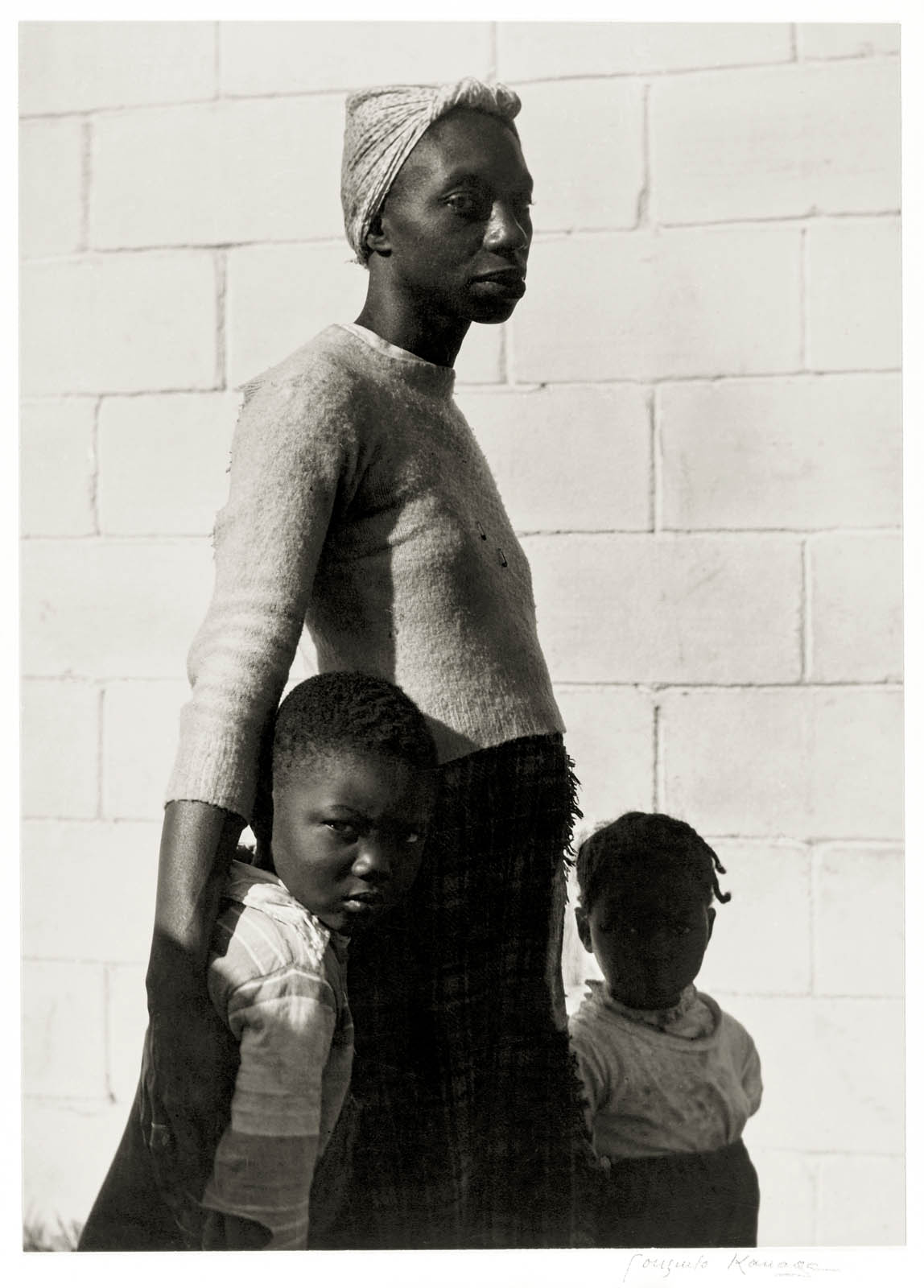

The sensitivity of Hands (1930, below); the tired eyes and clasped hands of the Widow Watson (1922-1924 below) contrasting with the mannerist hands of the boy staring off camera; the stoicism of the mother in Tree of Life (1950, below) with her children’s faces in deep shadow coupled with the subconscious symbology of the unyielding, white brick wall behind; and the dark mesa of Landscape Near Taos, New Mexico (Nd, below) hello Georgia O’Keeffe … all reflect Kanaga’s superb handling of shadow and light, of energy and spirit.

“Her body of work, though comparatively small, is consistently exceptional.”1

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Barbara Head Millstein. “A Pioneer of Realism,” in The New York Times October 9, 1993 on the New York Times website [Online] Cited 04/05/2024

Many thankx to the Fundación MAPFRE for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“One of America’s most transcendent yet, surprisingly, least-known photographers.”

Barbara Head Millstein and Sarah M. Lowe (1992). Consuelo Kanaga, An American Photographer. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 21-40.

“I could have done lots more, put in much more work and developed more pictures, but I had also a desire to say what I felt about life. Simple things like a little picture in the window or the corner of the studio or an old stove in the kitchen have always been fascinating to me. They are very much alive, these flowers and grasses with the dew on them. Stieglitz always said, “What have you got to say?” I think in a few small cases I’ve said a few things, expressed how I felt, trying to show the horror of poverty or the beauty of black people. I think that in photography what you’ve done is what you’ve had to say. In everything this has been the message of my life. A simple supper, being with someone you love, seeing a deer come around to eat or drink at the barn – I like things like that. If I could make one true, quiet photograph, I would much prefer it to having a lot of answers.”

Margaretta K. Mitchell (1979). Recollections: Ten Women of Photography. NY: Viking Press. pp. 158–160.

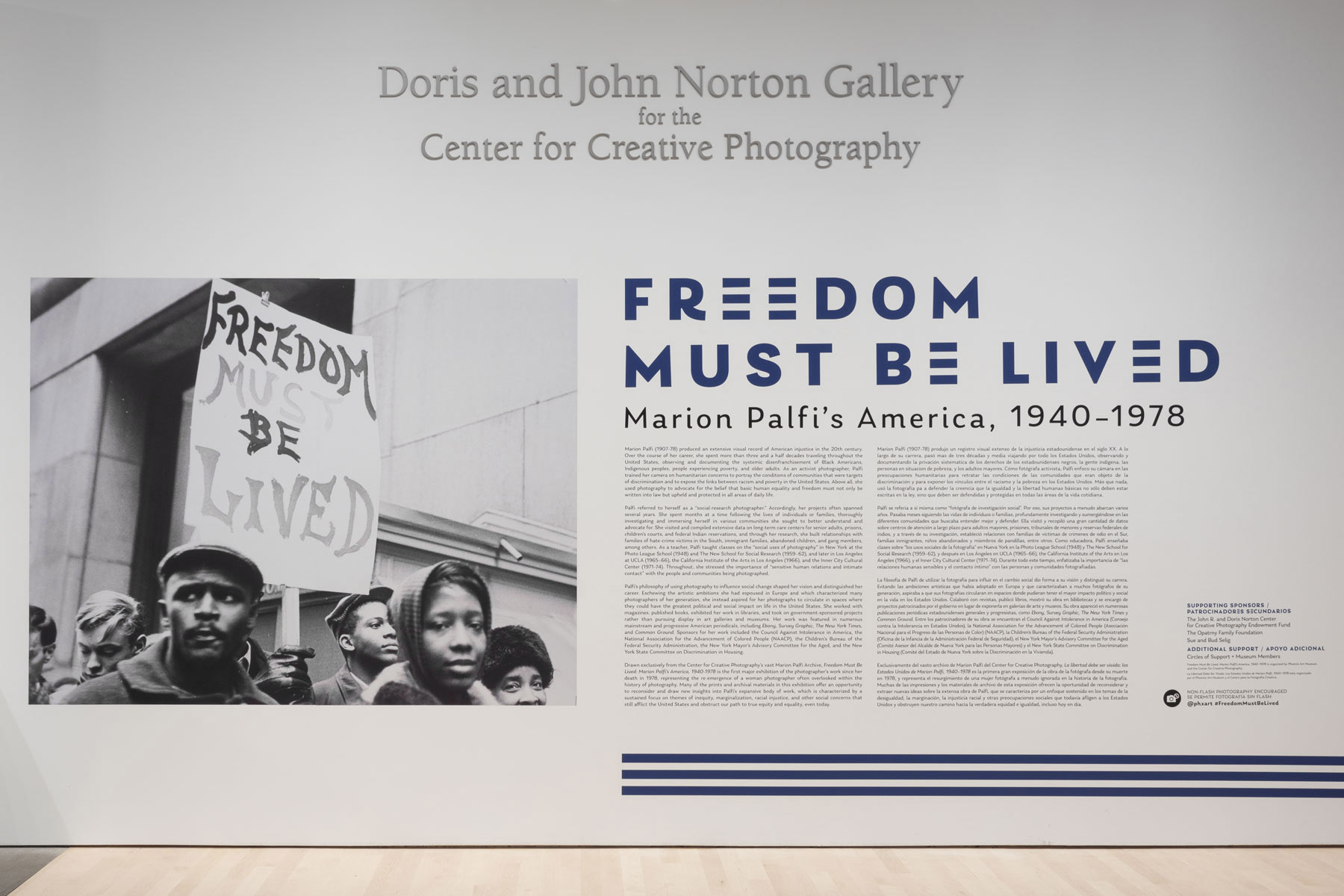

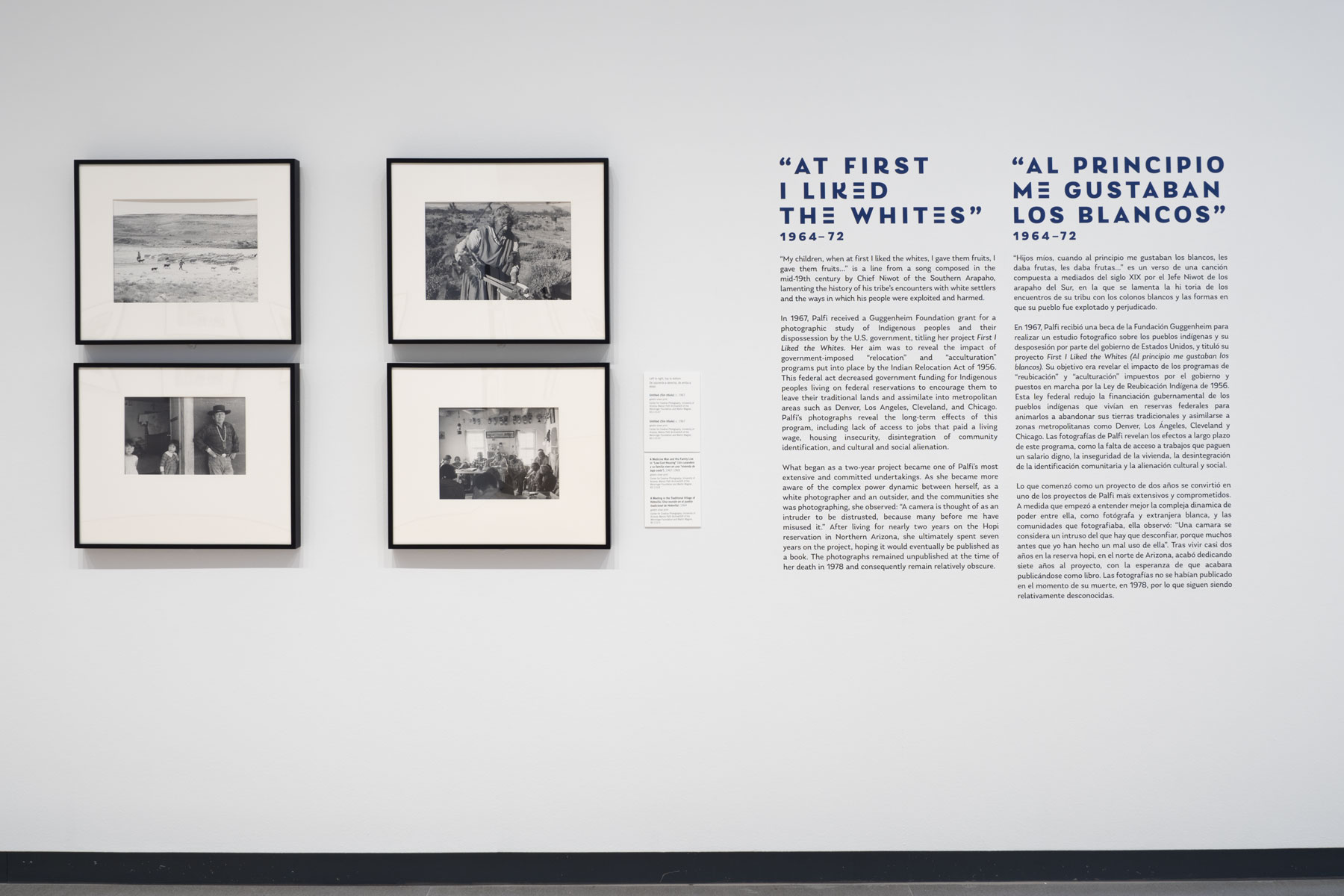

Consuelo Kanaga: Catch the Spirit is the first exhibition in Europe to present a comprehensive retrospective of the entire career of the American Consuelo Kanaga (Astoria, Oregon, 1894 – Yorktown Heights, New York, 1978). The exhibition covers six decades of her professional dedication to photography.

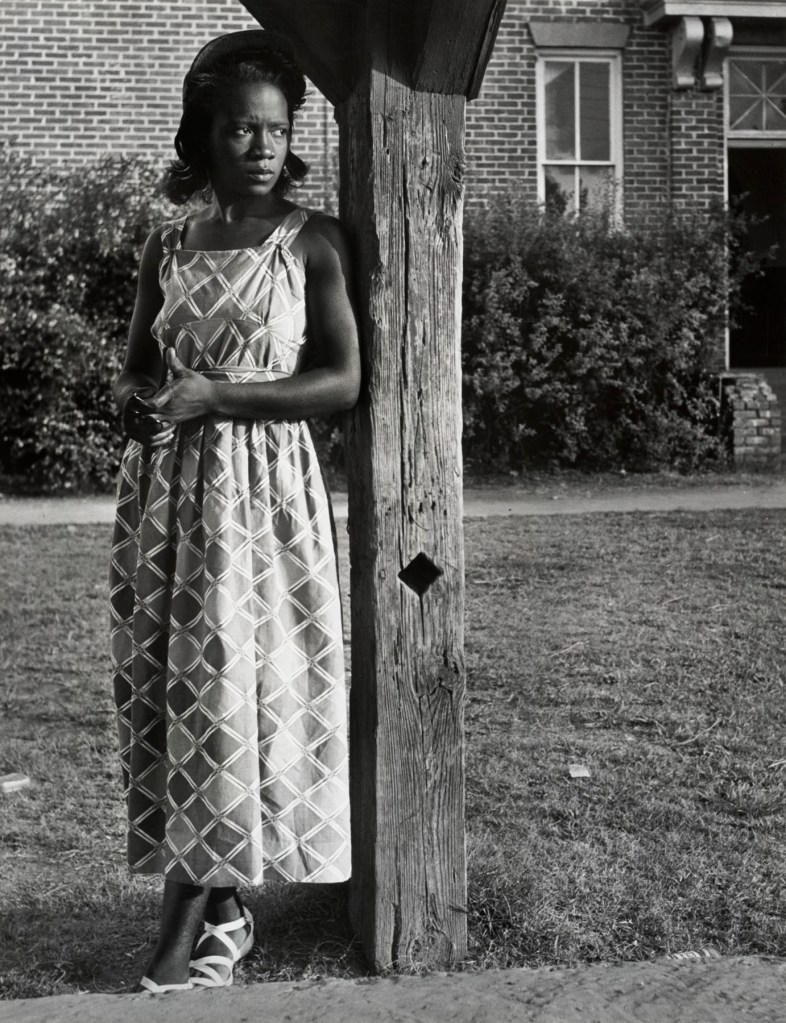

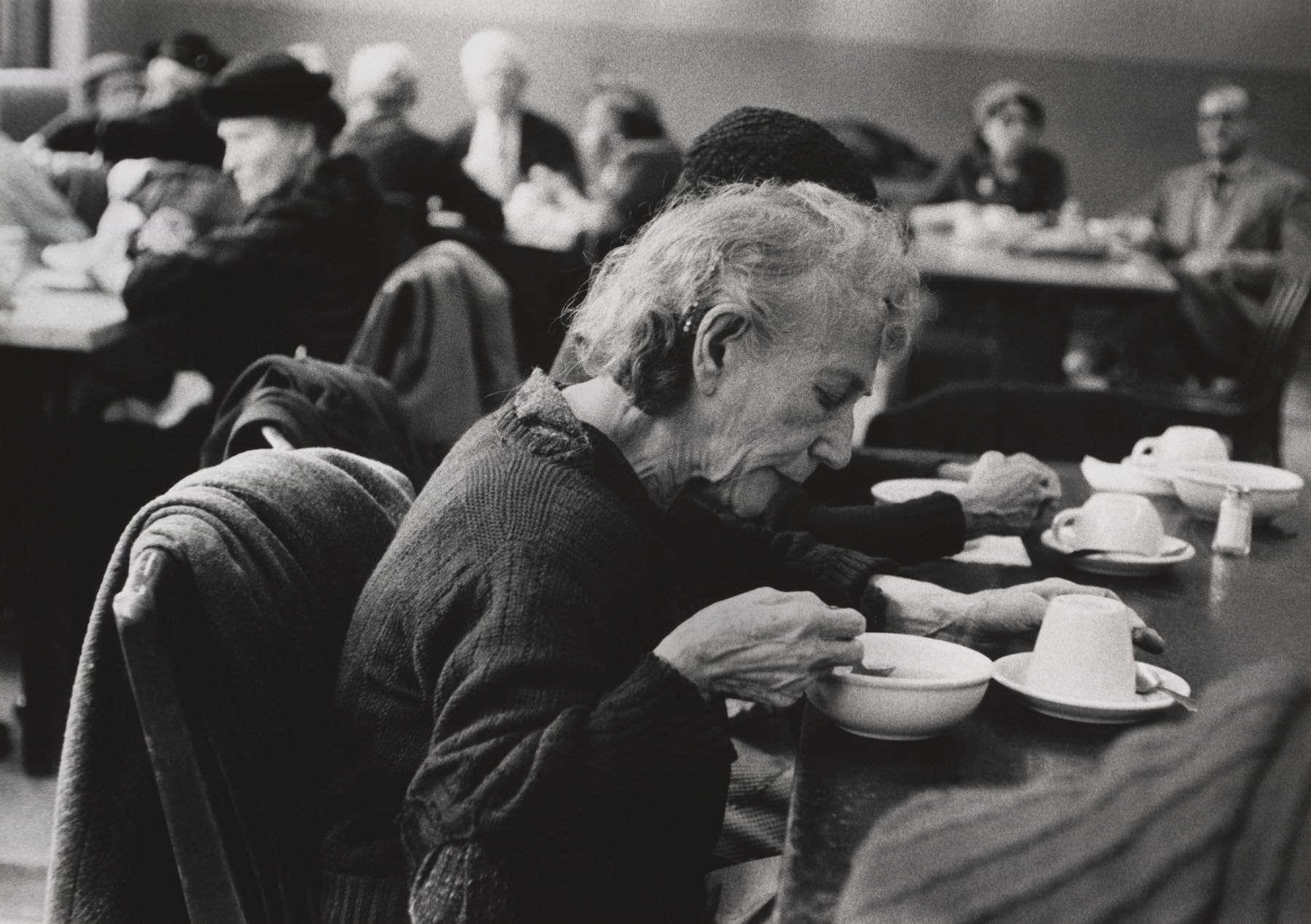

Passionate about social justice, Kanaga was more interested in people and their problems than in photography: social marginalisation, poverty, racial harassment, inequality…, especially in relation to the African-American population in the United States.

Consuelo Kanaga was one of the few women who became a professional photojournalist, and as early as the 1910s in the United States. She was also one of the few who maintained a close relationship with avant-garde circles, both in San Francisco and in New York, and whose friendship and professional support opened the way for important women photographers such as Imogen Cunningham and Dorothea Lange, among others.

Despite the fame she achieved during her lifetime, her work is still surprisingly little known. This exhibition aims to make a conclusive contribution to the recognition that Kanaga’s work undoubtedly deserves.

Exhibition organised by the Brooklyn Museum in New York in collaboration with Fundación MAPFRE and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE website

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Fire, New York

1922

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

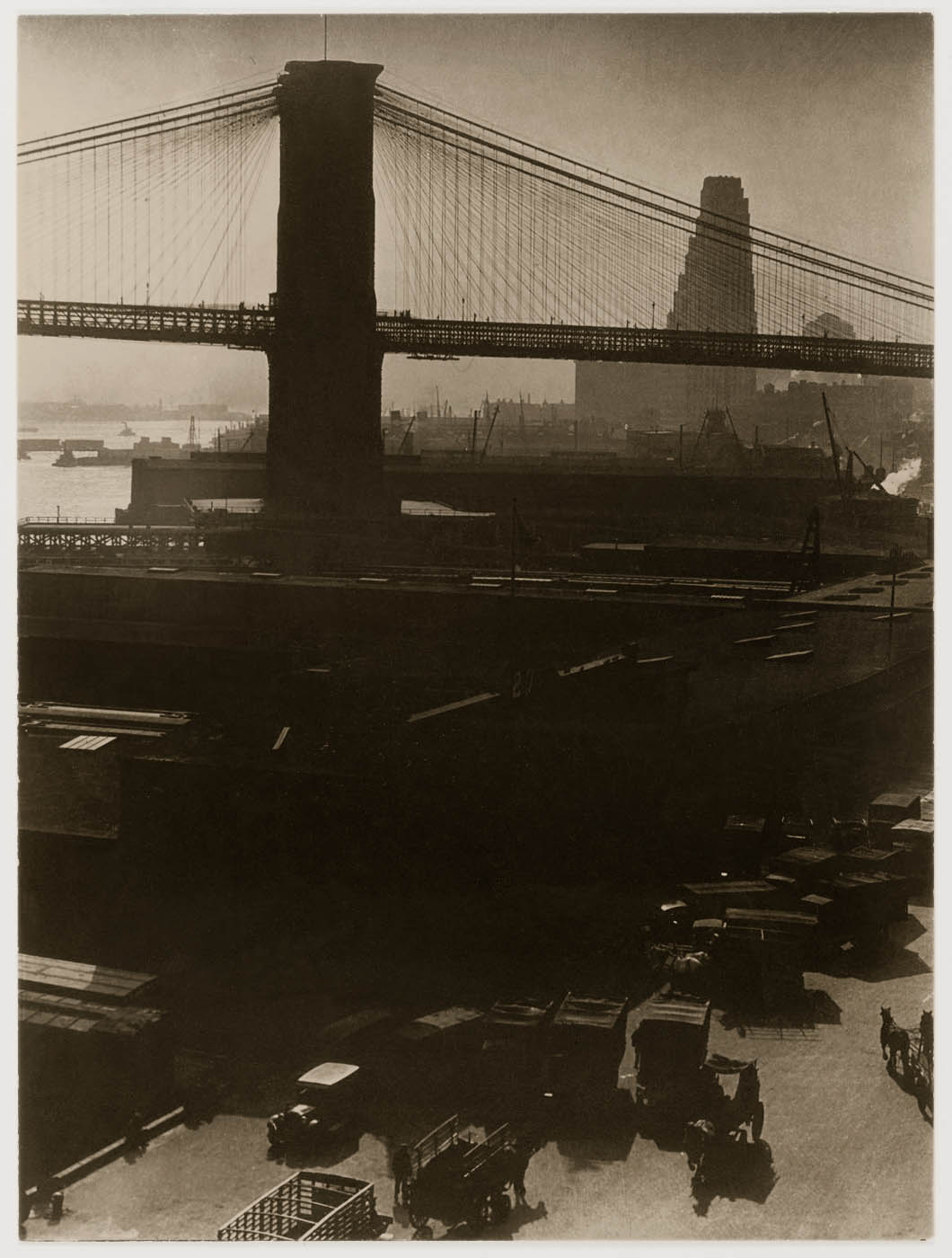

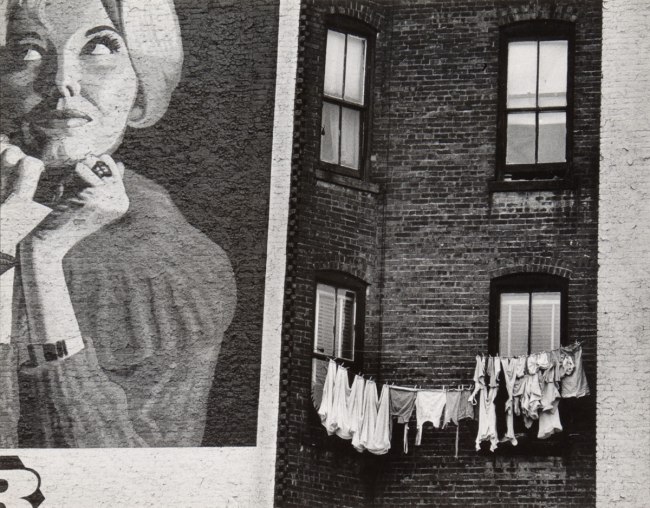

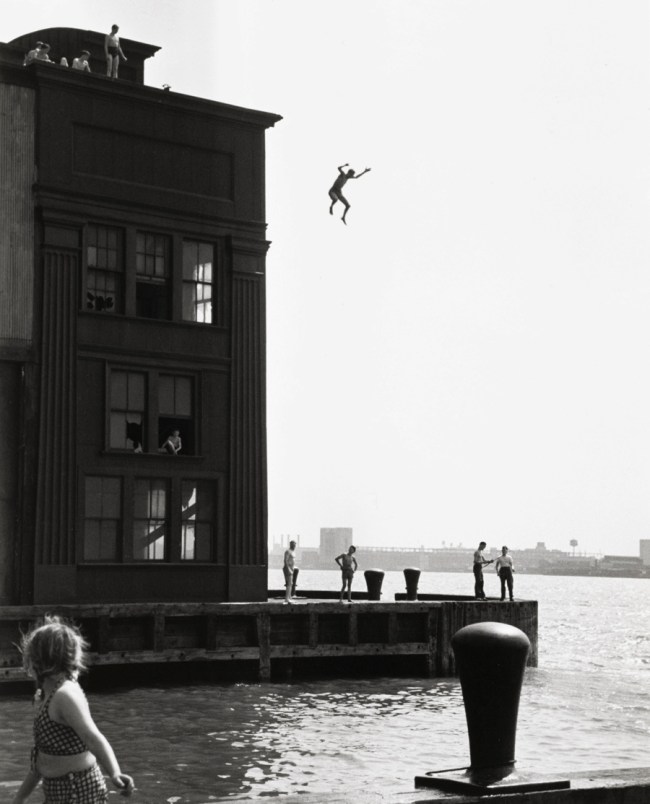

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Untitled (Downtown New York)

1922-1924

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

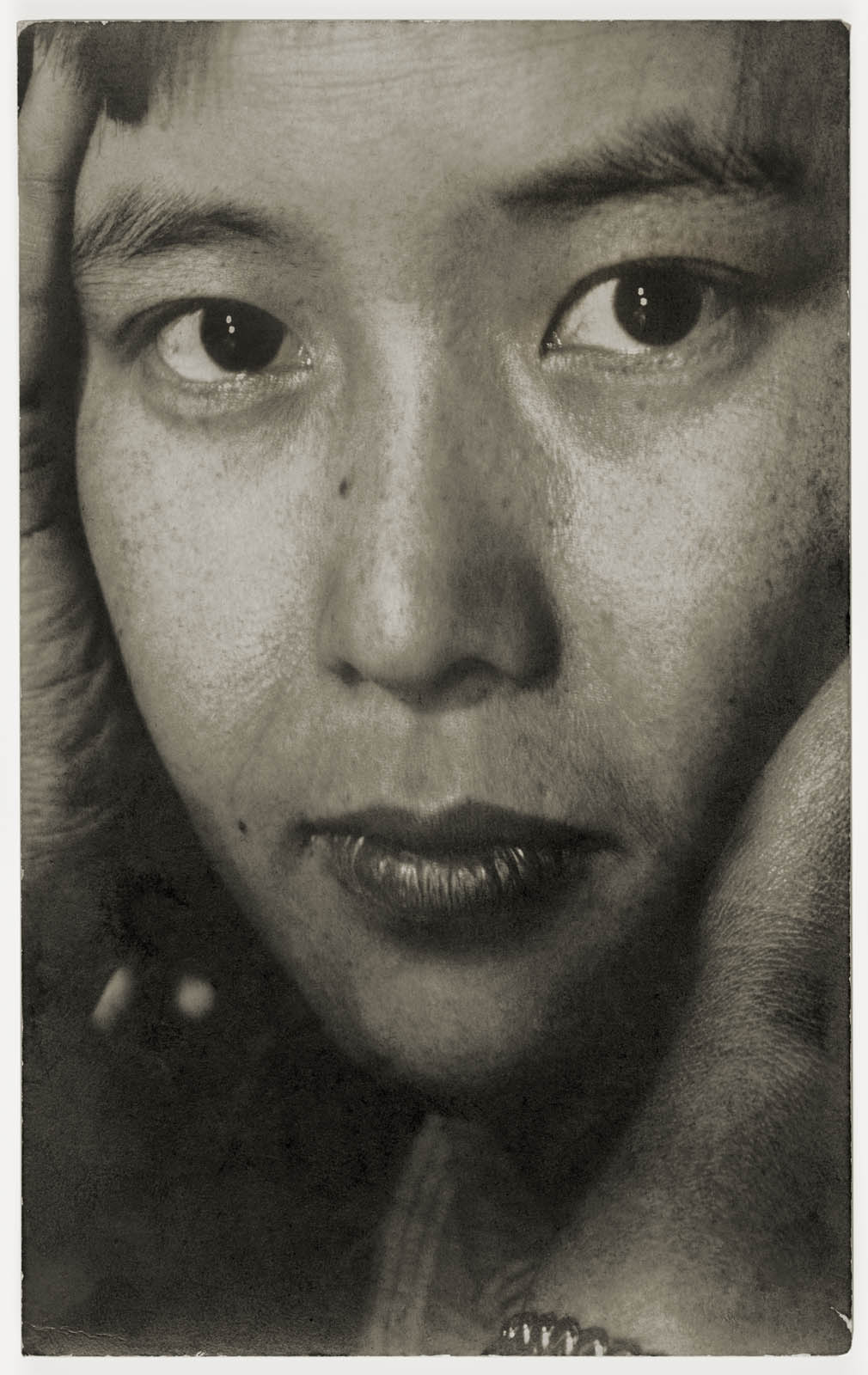

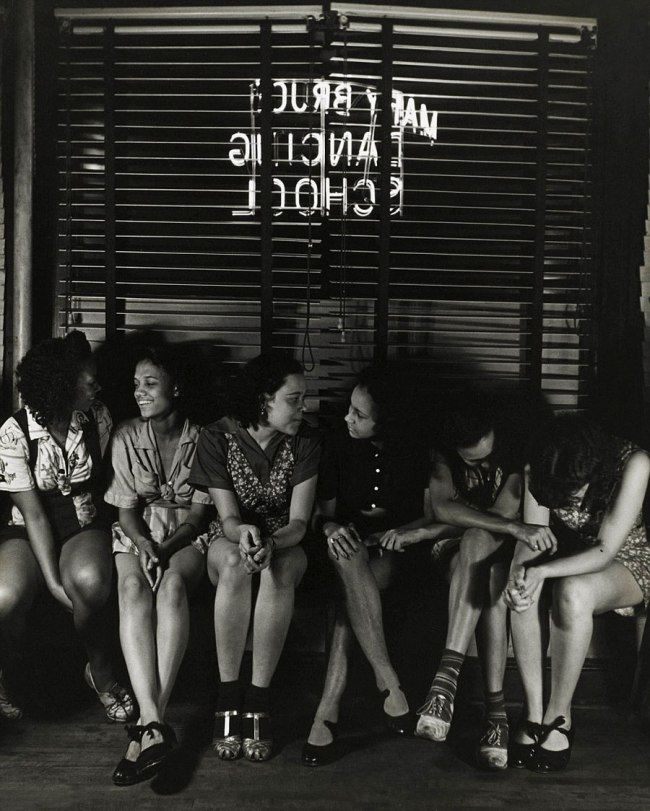

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Untitled

1920s

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

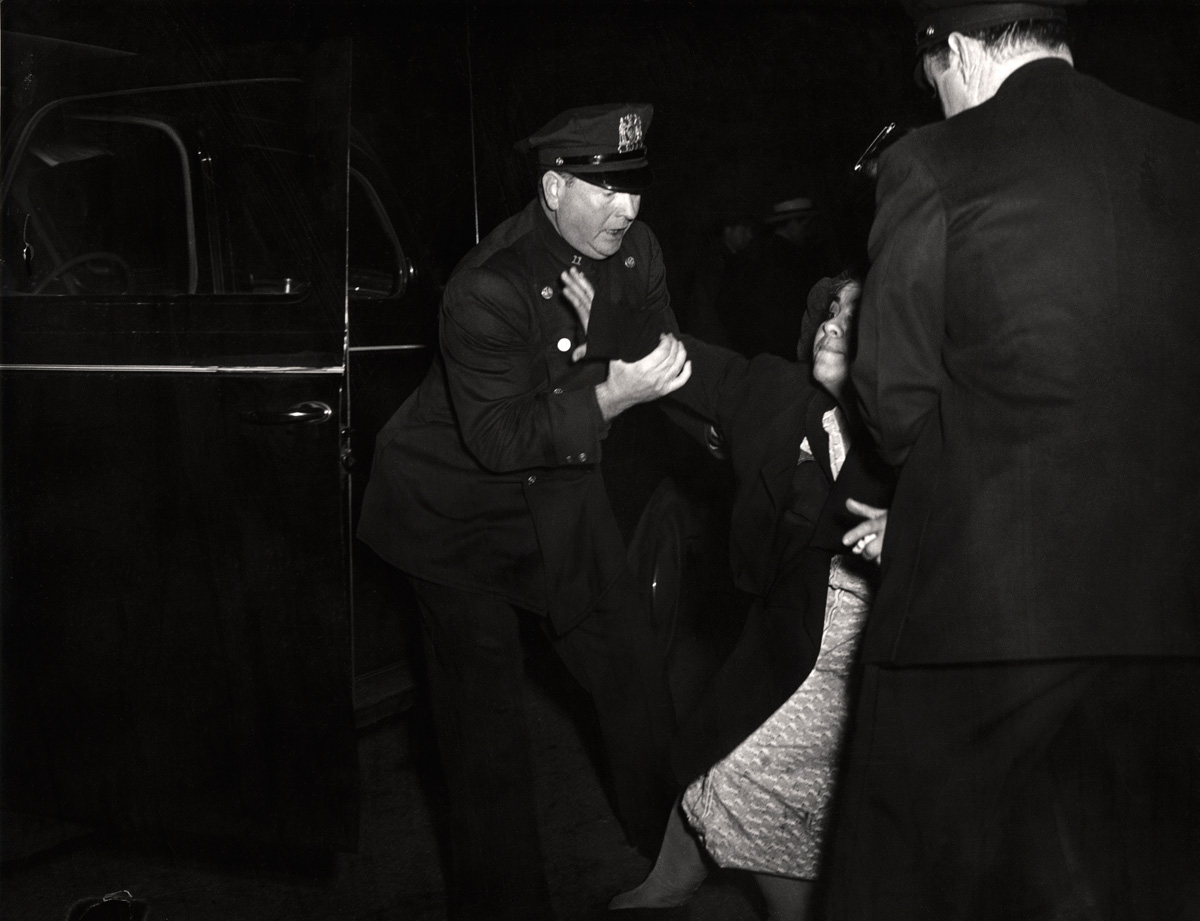

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Untitled

c. 1925

Toned gelatin silver print with graphite

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Louise Dahl-Wolfe

c. 1928

Gelatin silver print, printed 2023

4 × 5 in. (10.2 × 12.7cm)

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Louise Emma Augusta Dahl-Wolfe (November 19, 1895 – December 11, 1989) was an American photographer. She is known primarily for her work for Harper’s Bazaar, in association with fashion editor Diana Vreeland. At Harper’s Bazaar she pioneered a new standard in colour photography. …

Among the celebrated fashion photographers of the 20th century, Louise Dahl-Wolfe was an innovator and influencer who significantly contributed to the fashion world. She was most widely known for her work with Harper’s Bazaar. Dahl-Wolfe was considered a pioneer of the ‘female gaze’ in the fashion industry and credited for creating a new image of strong, independent American women during World War II.

From 1943, Dahl-Wolfe introduced the “New American Look” to fashion photography, which Vicki Goldberg describes as “all clean hair, glowing skin and a figure both lithe and strong”. Dahl-Wolfe was known for taking photographs outdoors, with natural light in distant locations from South America to Africa in what became known as “environmental” fashion photography. The outdoor settings helped to evoke “a mood of freedom and optimism” associated with women’s liberation. Her photographs brought a new naturalism to fashion photography which had previously been dominated by a stiff and haughty “European” or “Germanic” studio style. Dahl-Wolfe described it as “that heavy, heavy look, with everybody looking very clumsy”. Her methodology in using natural sunlight and shooting outdoors became the industry standard even now.

Her models appear to pose candidly, almost as if Dahl-Wolfe had just walked in on them. In fact the poses are highly, constructed with an “almost abstract formal perfection” which she credited partly to the influence of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Dahl-Wolfe innovatively used colour in photography and mainly concerned with the qualities of natural lighting, composition, and balance. Compared to other photographers at the time who were using red undertones, Dahl-Wolfe opted for cooler hues and also corrected her own proofs, with one example of her pulling proofs repeatedly to change a sofa’s colour from green to a dark magenta.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

House Plant

1930

Bromide print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

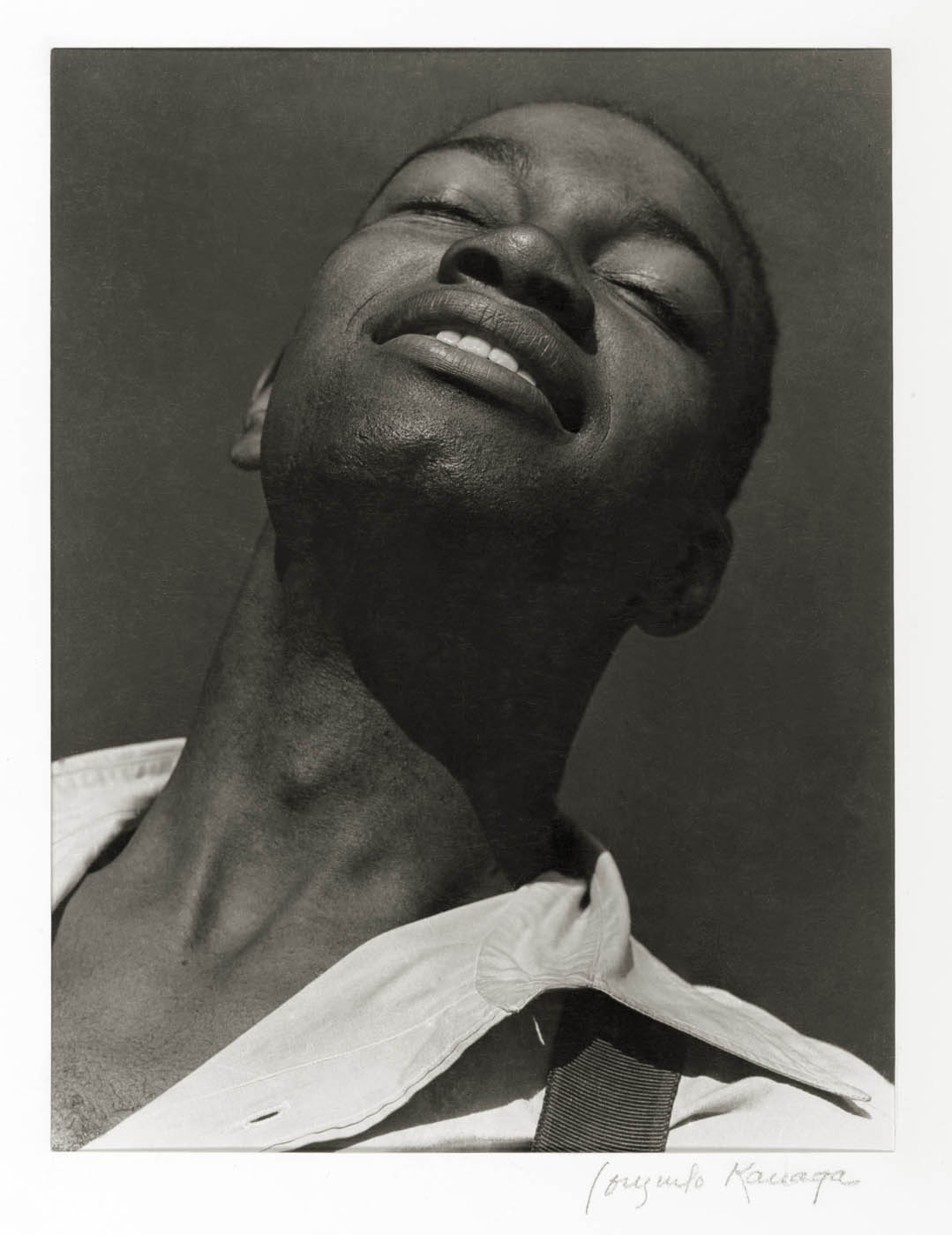

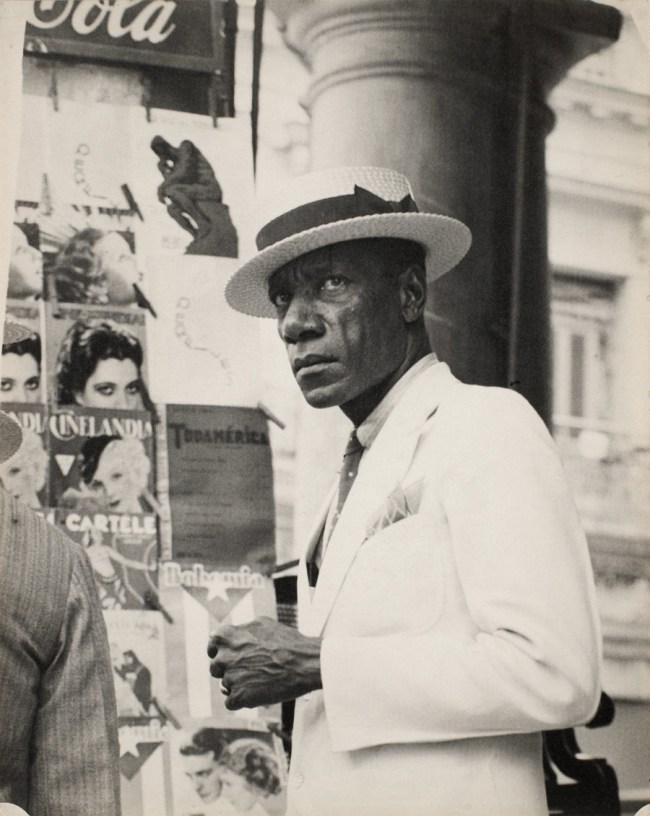

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Kenneth Spencer

1933

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Kenneth Spencer (25 April 1913 – 25 February 1964), was an American operatic singer and actor. Spencer starred in a few Broadway musicals and musical films in the United States during the 1940s. Frustrated with the racial prejudice he experienced in the United States as a black man, Spencer moved to West Germany in 1950 where he had a successful singing career. He also appeared in a number of German films. His career was cut short when he died in the crash of Eastern Air Lines Flight 304.

Text from the Wikipedia website

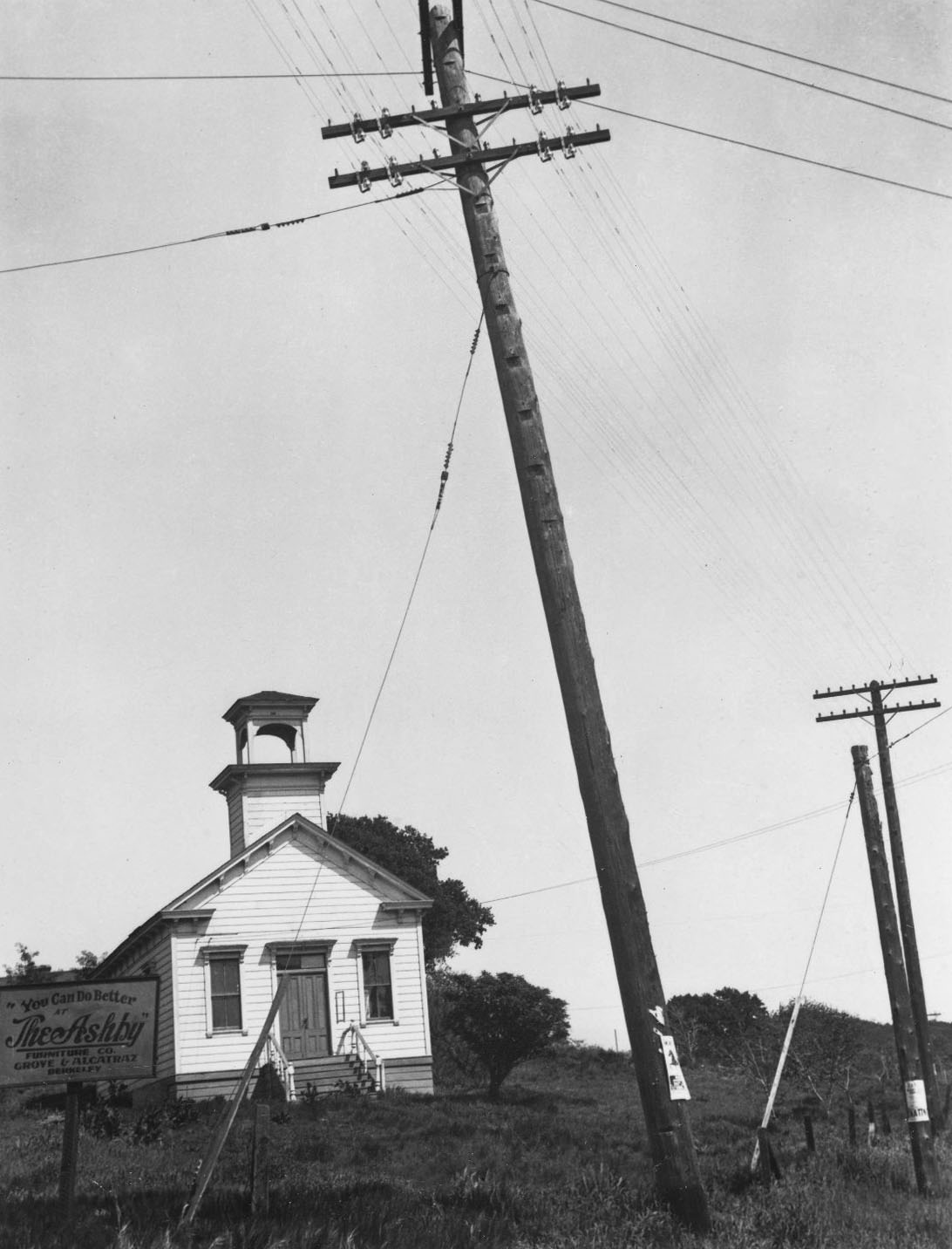

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Clapboard Schoolhouse

1930s

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

A Pioneer of Realism

Consuelo Kanaga (1894-1978) was one of America’s most important photographers. Yet largely because she disdained wealth, fame and self-promotion, her transcendent images have never received the acclaim they deserve. The photographs on this page appear in the first major retrospective of her work, “Consuelo Kanaga: An American Photographer,” which will open Friday at the Brooklyn Museum.

Born in Astoria, Ore., Kanaga was hired in 1915 as a reporter at The San Francisco Chronicle but quickly became more interested in the work of the paper’s photographers. She took a job in the darkroom and was eventually named a staff photographer.

Inspired by the images in Alfred Stieglitz’s magazine, Camera Work, she left the newspaper and moved to New York in 1922. She soon became closely associated with such photographers as Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange and Louise Dahl. In 1932, Miss Kanaga was represented in the landmark “f.64” exhibition in San Francisco, the first major photography show that stressed realism over romanticism.

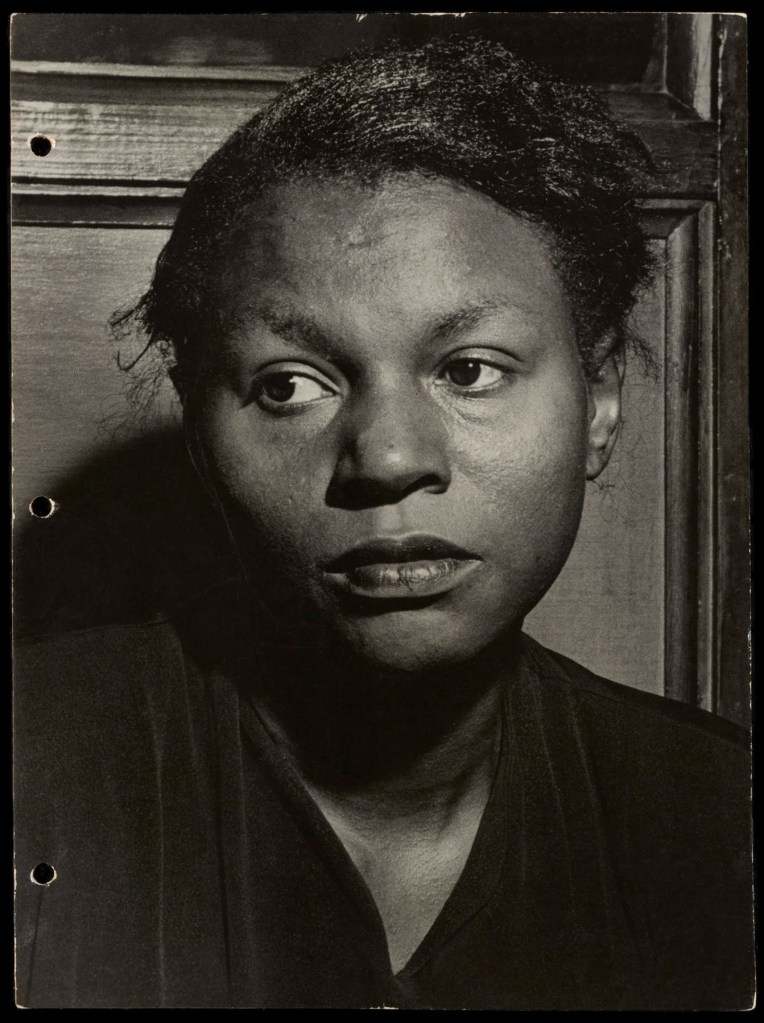

Her talent was rooted in an almost mystical belief that photography was a sacred trust — she felt obligated to capture the true essence of her subject. Her drive to fulfill this trust helped Kanaga, who was white, to understand the lives of blacks and to produce some of the most moving works ever done in African-American portraiture. She was equally talented in still-life and landscape photography, and her feeling for urban architecture was stimulated by her involvement with the socially committed New York Photo League during the 1930’s.

She continued to work into her 70’s, despite suffering from emphysema and cancer, which were probably caused by the chemicals used in creating her prints. Her body of work, though comparatively small, is consistently exceptional. Consuelo Kanaga died virtually unknown in 1978, but her talent endures.

Barbara Head Millstein. “A Pioneer of Realism,” in The New York Times October 9, 1993 on the New York Times website [Online] Cited 04/05/2024

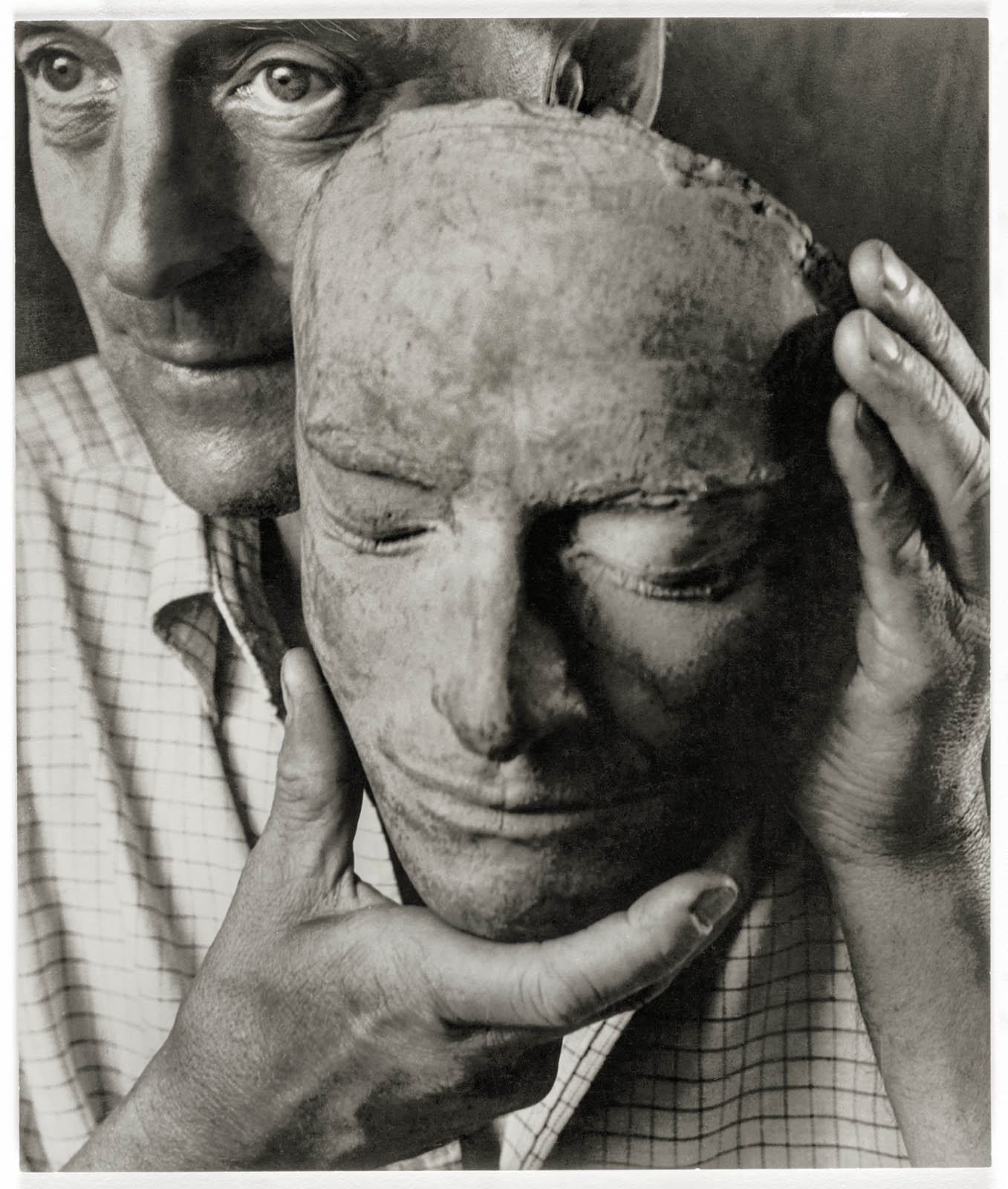

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Sargent Johnson

1934

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Sargent Claude Johnson (November 7, 1888 – October 10, 1967) was one of the first African-American artists working in California to achieve a national reputation. He was known for Abstract Figurative and Early Modern styles. He was a painter, potter, ceramicist, printmaker, graphic artist, sculptor, and carver. He worked with a variety of media, including ceramics, clay, oil, stone, terra-cotta, watercolour, and wood.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Untitled

1930s

Toned gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

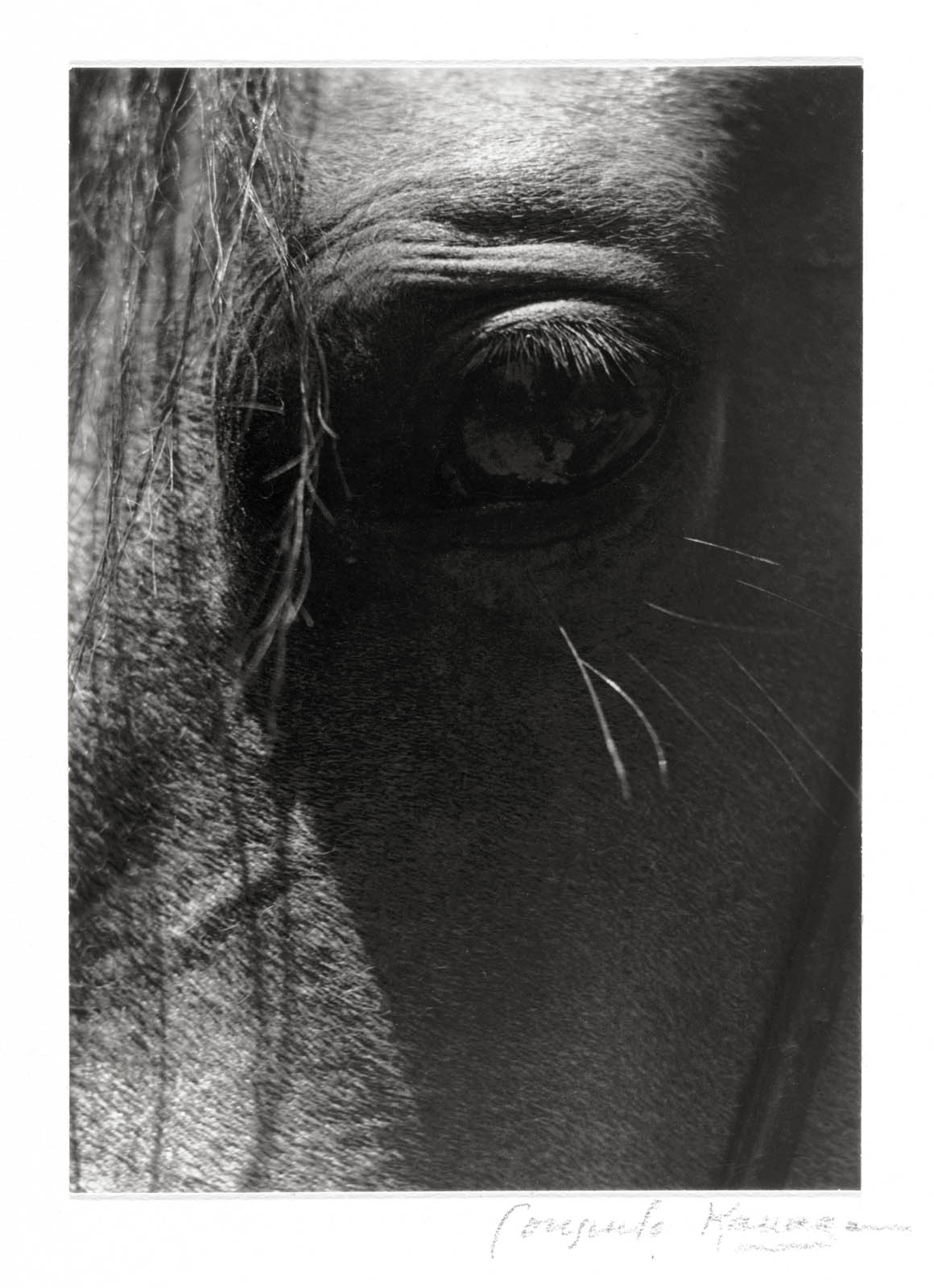

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Horse’s Eye

1930s

Gelatin silver print

4 × 3 1/2 in. (10.2 × 8.9cm)

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

The Bowery

1935

Toned gelatin silver print

22 13/16 × 16 13/16 × 1 1/2 in. (57.9 × 42.7 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

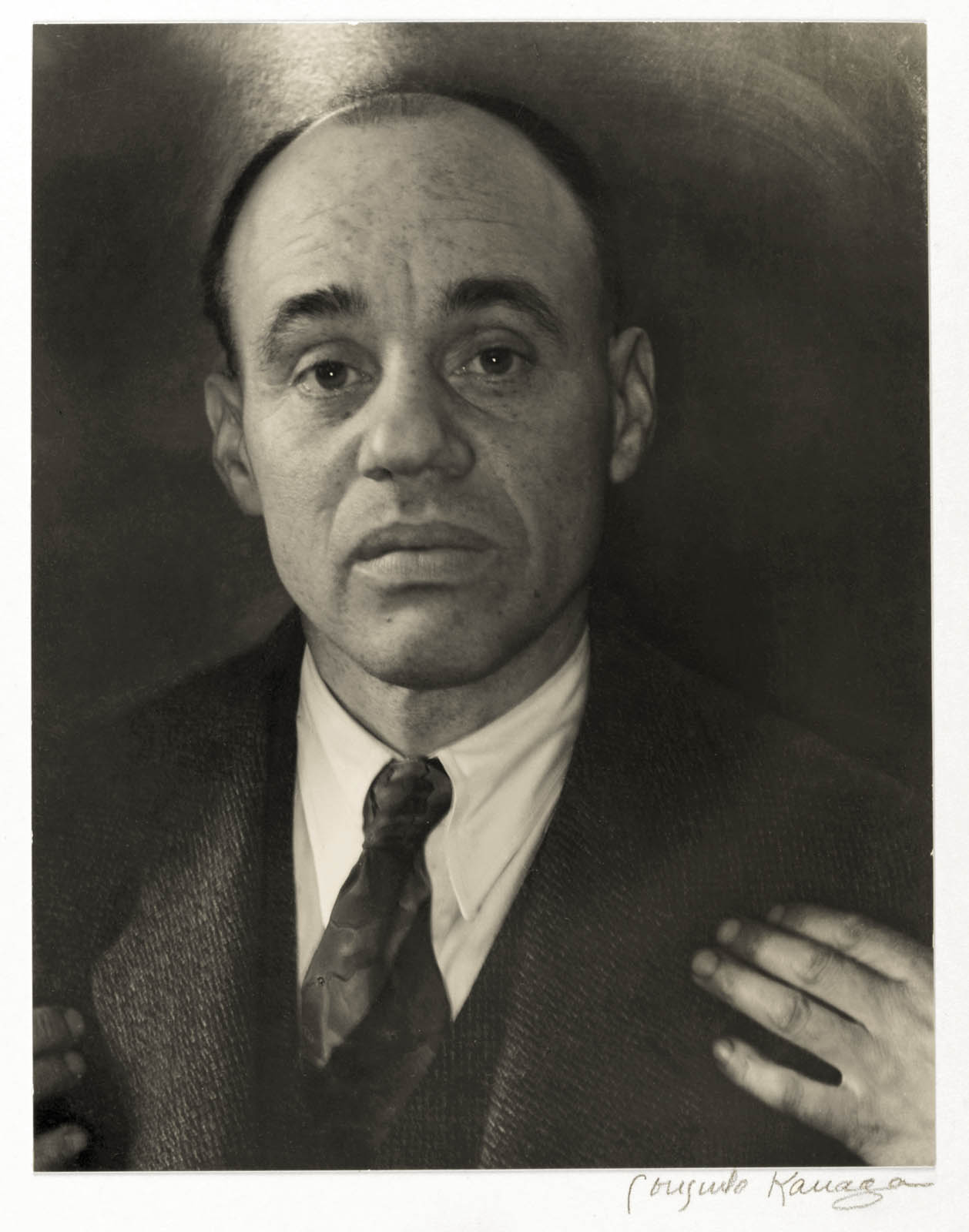

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Angelo Herndon

1936

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Angelo Braxton Herndon (May 6, 1913 – December 9, 1997) was an African-American labor organiser arrested and convicted of insurrection after attempting to organise black and white industrial workers in 1932 in Atlanta, Georgia. The prosecution case rested heavily on Herndon’s possession of “communist literature”, which police found in his hotel room.

Herndon was defended by the International Labor Defense, the legal arm of the Communist Party of America, which hired two young local attorneys, Benjamin J. Davis Jr. and John H. Geer, and provided guidance. Davis later became prominent in leftist circles. Over a five-year period, Herndon’s case twice reached the United States Supreme Court, which ruled that Georgia’s insurrection law was unconstitutional, as it violated First Amendment rights of free speech and assembly. Herndon became nationally prominent because of his case, and Southern justice was under review. By the end of the 1940s he left the Communist Party, moved to the Midwest, and lived there quietly.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Untitled

1936

Gelatin silver print, printed 2023

4 × 5 in. (10.2 × 12.7cm)

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Two Women, Harlem

c. 1938

Toned gelatin silver print

22 13/16 × 16 13/16 × 1 1/2 in. (57.9 × 42.7 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

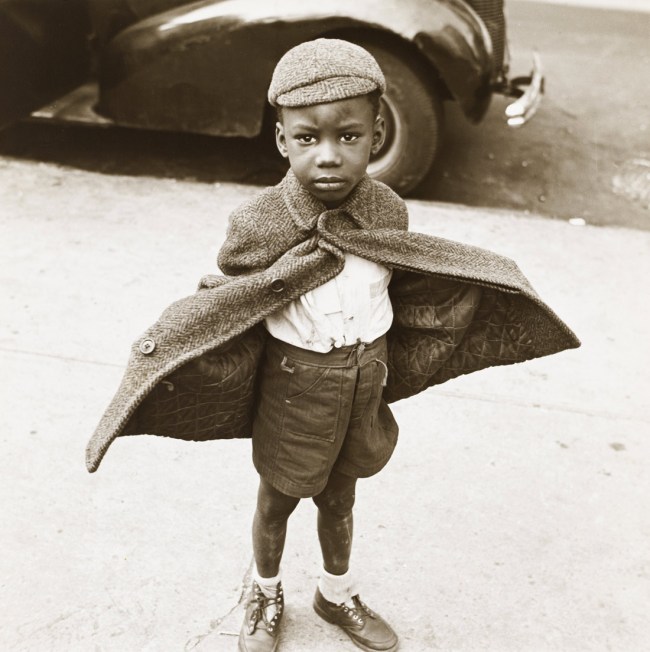

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Untitled (New York)

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

For the first time in Spain and Europe, Consuelo Kanaga. Catch the Spirit features the work of this North American photographer spanning her entire career. Kanaga (1894-1978) is considered today a key figure in the history of contemporary photography, both for her contribution toward the recognition of women in this field and for the intensity with which her images confront the spectator with the great social issues of our time, particularly the conditions of African Americans in the United States.

The exhibition

Consuelo Kanaga. Catch the Spirit features six decades of work by this key figure in the history of modern Photography. With this new project, Fundación MAPFRE renews its commitment to promote the work of women photographers. On this occasion, despite having garnered much notoriety in life, the artist’s work is today surprisingly little known. This exhibition aims to contribute conclusively toward the recognition that Kanaga’s oeuvre undoubtedly deserves.

Consuelo Kanaga (Astoria, Oregon, 1894 – Yorktown Heights, New York, 1978) was truly passionate about social justice. She was most interested in people and issues such as marginalisation, poverty, racial harassment, and inequality, particularly in relation to African Americans in the United States. These were some of the fundamental matters she addressed through her work. Likewise, she also defended the formal and poetic possibilities of photography as an art form.

An unconventional figure, Kanaga was able to become a professional photojournalist in the United States as early as the 1910s. She was also one of the few women involved in the avant-garde circles both in San Francisco with the f.64 Group and in New York with the Photo League, whose friendship and professional support paved the way for other important women photographers. However, gender inequalities and social conventions limited her ability to dedicate herself completely to her artistic work. Kanaga worked full time jobs during many years and was only able to practice her art on weekends. She repeatedly put her career on hold for her partners; these are but a few reasons why her work is not more recognised today.

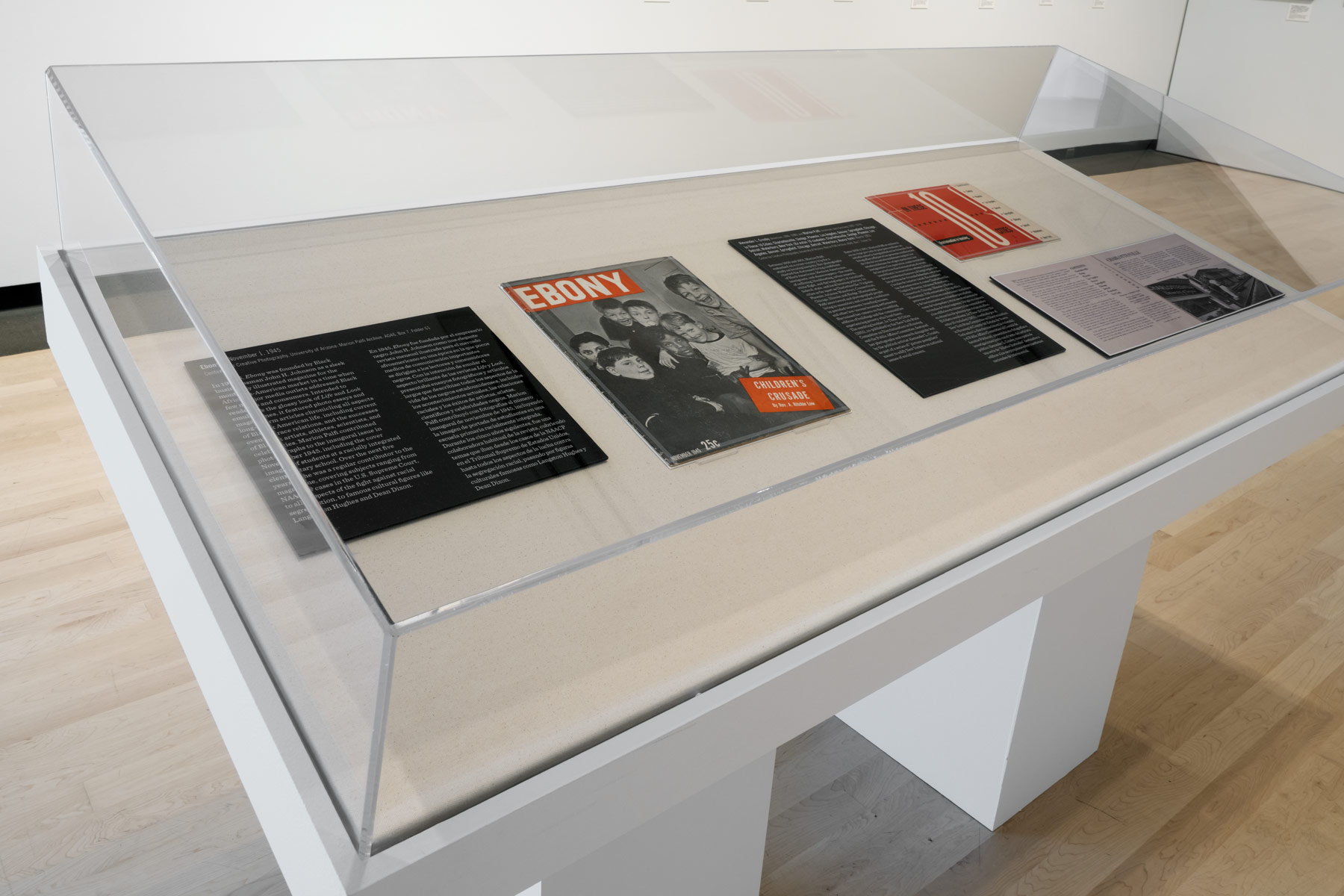

Organised around the Brooklyn Museum’s collection – the institution that has preserved the artist’s archive – the exhibition features nearly 180 photographs and a wide range of documentary material; contextualising Consuelo Kanaga’s work while focusing on some of her most iconic images and her portrayal of African American life in the 1930s through her photography.

Exhibition organised by the Brooklyn Museum in New York in collaboration with Fundación MAPFRE and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Curated by Drew Sawyer, former Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Curator of Photography, Brooklyn Museum.

Keys

New Negro Movement: From the late 19th century, magazines and novels published by black men and women began to emerge as a response to the prevailing racism in cities such as San Francisco, Washington, and New York. This literary explosion was the precedent of what became known as the New Negro Movement, which developed in Harlem, New York, between 1920 and 1930; a movement that also lent its name to the most comprehensive anthology dedicated to said cultural renaissance, written by Alain Locke and considered at the time as “the fundaments of the black canon”. Not only did black artists flourish during this time, white artists were also encouraged to join this movement in defence of the freedom, rights, and equality of African Americans through culture.

Kanaga Photojournalist: In 1915, when she was only 21 years old, Consuelo Kanaga began to write for the San Francisco Chronicle, where she learned photography in order to illustrate her assignments: “For my articles requiring photographs, I went with the photographer to help make the pictures more interesting,” she later recalled. “The editor liked the results and encouraged me to learn photography, ‘from scratch’.” In 1918 she began to work as a photographer for the newspaper and was also hired by the Daily News the following year. Kanaga was undoubtedly one of the first women photojournalists on staff at a newspaper; as her friend Dorothea Lange remarked: “she was the first newspaper photographer I’d ever met. She was a person way ahead of her time.”

Kanaga and Women Photographers: Kanaga’s career was interwoven with a solid and broad circle of women photographers who she cultivated special relationships with over the course of five decades. She was a great supporter and a confidant for Imogen Cunningham, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Dorothea Lange, Alma Lavenson, Tina Modotti, and Eiko Yamazawa, among many others, who she advised and shared her company and connections in the art world with. These women inspired her and likewise she was an inspiration for them. Despite the fact her accomplishments were as relevant as those of her colleagues, her oeuvre received much less attention. Kanaga spent little time self-promoting since she was always more interested in cultivating the affective bonds with the people closest to her.

Biography

Consuelo Delesseps Kanaga was born on May 15th, 1894, in Astoria, Oregon. The daughter of a lawyer who was interested in agriculture and of the writer Mathilda Carolina Hartwing, she helped her parents with tasks related to editing from a very young age, eventually leading her to study journalism. In 1915 she began writing for the San Francisco Chronicle. Three years later, she became staff photographer. Kanaga met Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, and Dorothea Lange at the California Camera Club and became interested in artistic photography thanks to Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work. Between 1927 and 1928 she travelled through Europe and northern Africa. Throughout her adult life, she lived both in San Francisco and New York, was married three times, and established her first portrait studio in San Francisco in 1932. She also participated in the f.64 Group and her images were exhibited for the first time at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco in 1932. Kanaga participated in West Coast liberal politics. After returning from New York in 1935, she became associated with the Photo League in 1938. Edward Steichen defended her photography and included her work in the renowned exhibition The Family of Man in 1955. In 1974 Kanaga held a solo exhibition at the Lerner-Heller gallery in New York and in 1976 she produced a small yet relevant retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum. In 1977 she exhibited her work at Wave Hill in Riverdale, New York. She passed away at her Yorktown Heights (New York) home in 1978. One year later, Kanaga’s work was included in the exhibition Recollections: Ten Women of Photography at the ICP and was the subject of a retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1992, where most of her work is currently preserved.

Press release from the Fundación MAPFRE

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

After Years of Hard Work (Tennessee)

1948

Toned gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

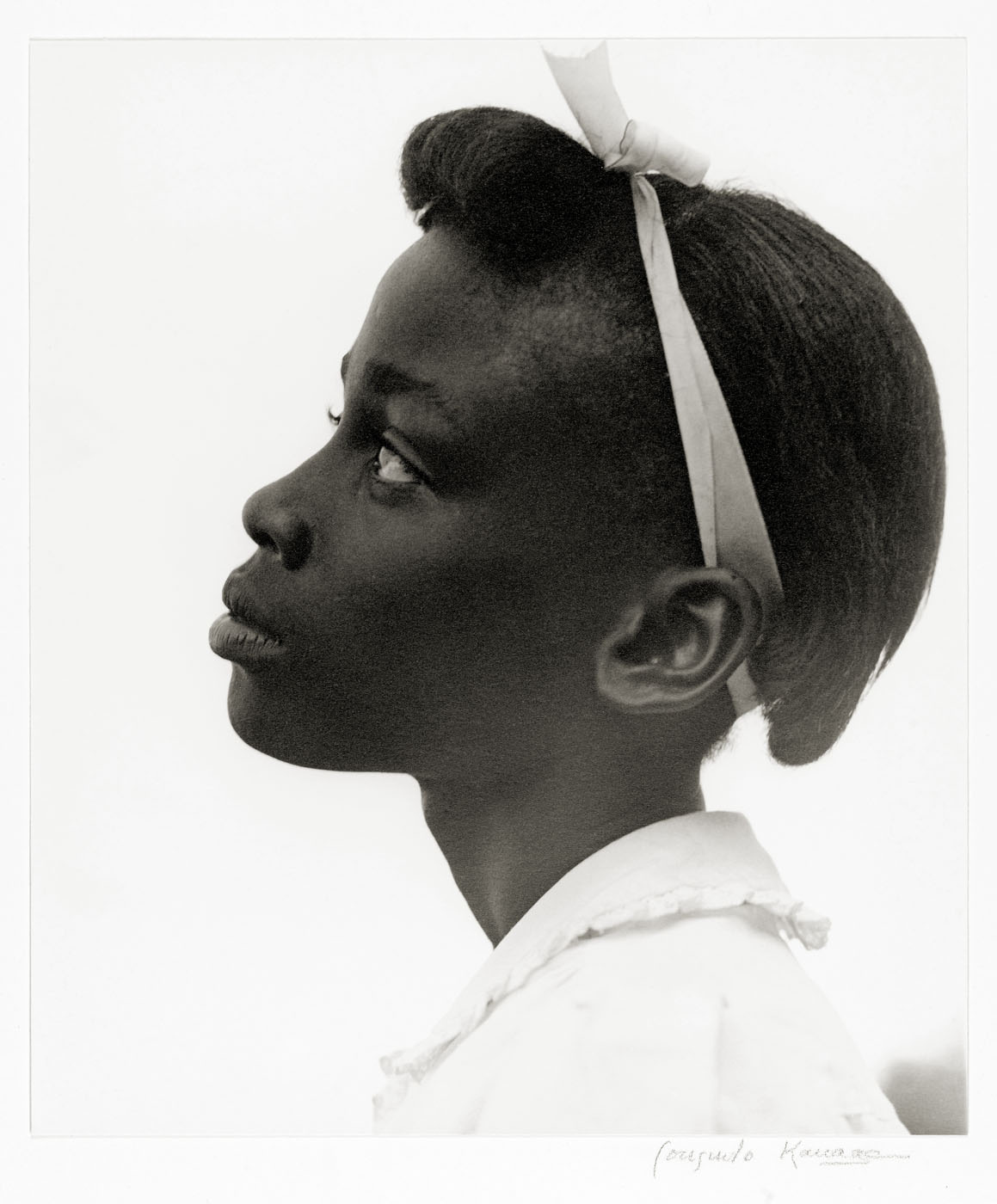

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Young Girl in Profile

1948

Toned gelatin silver print

22 13/16 × 16 13/16 × 1 1/2 in. (57.9 × 42.7 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Tennessee

1950

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

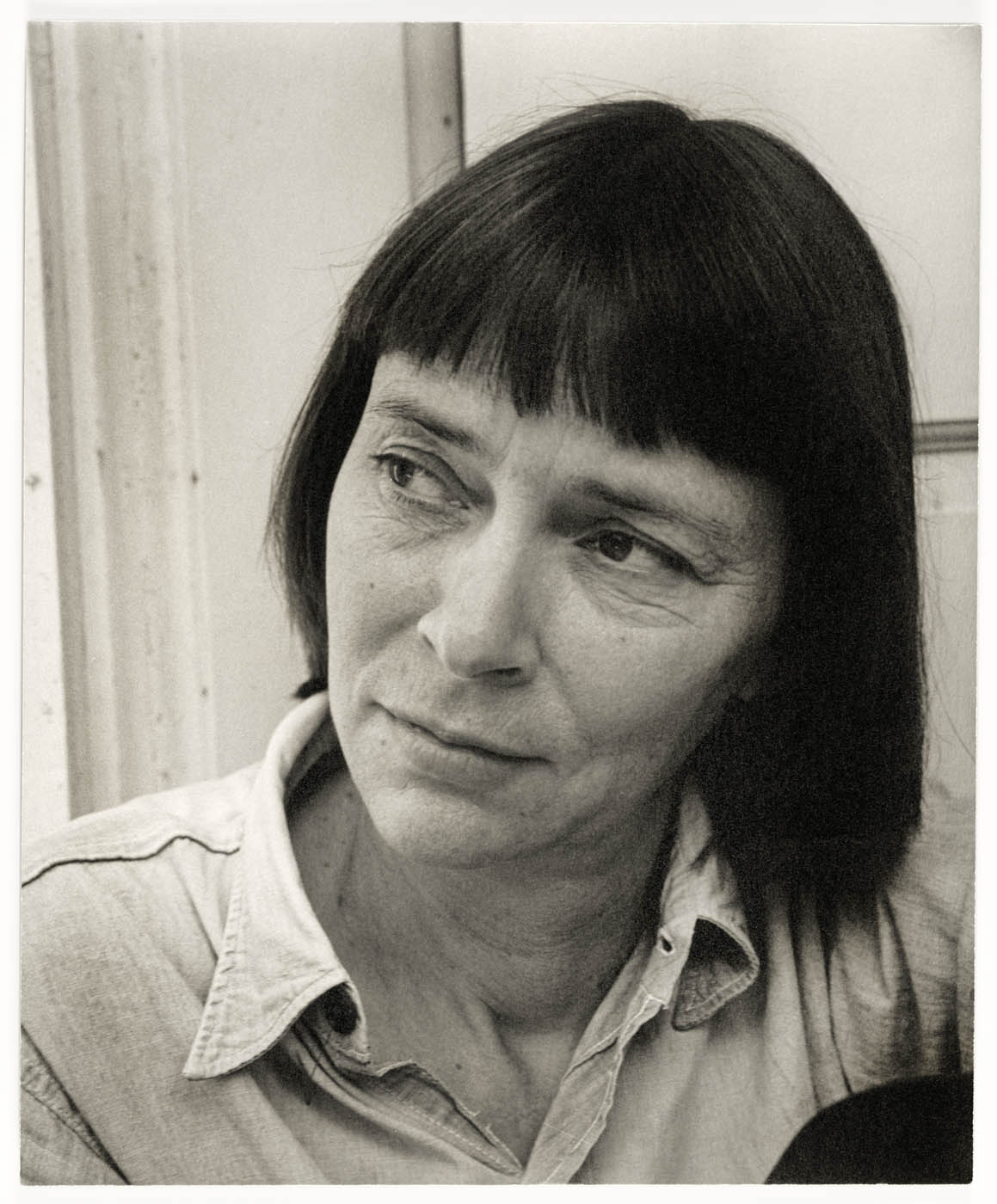

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Barbara Deming

c. 1964

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Barbara Deming (1917-1984) was one of the most dearly loved civil rights and feminist activists of her time. Born in New York City in 1917 and educated there at the Friends Meeting House Quaker School, she later studied literature and drama at Bennington College and earned a master’s degree in drama from Case Western Reserve University in 1941.

Deming began her career as a poet, professional writer, and film critic, and turned to political writing and human rights activism in the middle of her life. …

In the 1960s Deming joined demonstrations against Polaris submarines, took part in the 1962 San Francisco-to-Moscow walk for peace, and attended the International Peace Brigade in Europe. Protesting nuclear-weapons testing at the Atomic Energy Commission led to her first experience with being jailed for civil disobedience, this time at the Women’s House of Detention in New York City.

Acting on her belief that the struggles for racial equality and for peace were one effort, Deming marched in the bi-racial Nashville-to-DC walk for peace alongside SNCC members. In 1963 she joined black activists protesting segregation in Alabama and Georgia as well as attended the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings. In 1964 she participated in the 2800-mile Quebec-Guantanamo walk for peace and freedom, a racially integrated protest over US actions in Cuba. During this march, she was arrested and jailed in Albany, Georgia, an experience she describes in her book Prison Notes.

Deming participated in political actions whenever and wherever individual rights and human dignity were being threatened. In 1965-1967 Deming traveled to North and South Vietnam to protest the war. In the 1970s she demonstrated for gay rights and feminist causes. In 1983 she was arrested on the march through Seneca Falls, organised by the Women’s Peace Encampment to protest the deployment of cruise missiles in Europe. Despite failing health, she was once again jailed.

Anonymous. “Barbara Deming,” on the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund website Nd [Online] Cited 03/04/2024

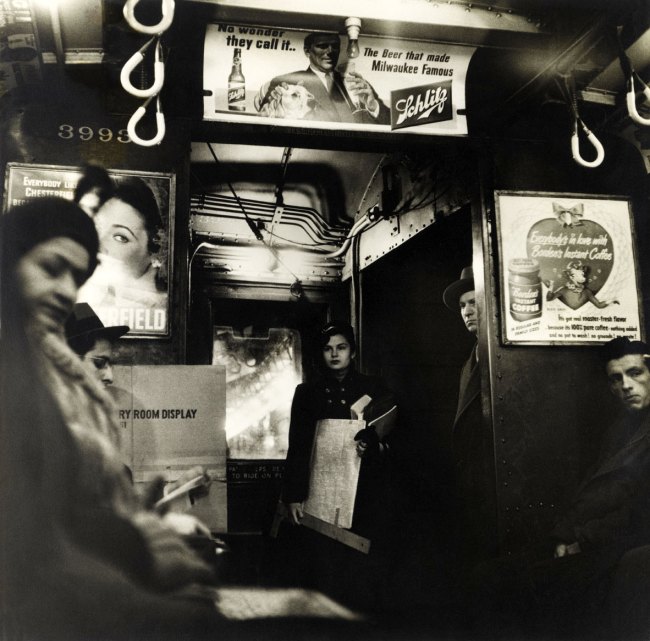

Photojournalism and the City

After having opted for journalism, influenced perhaps by her parents, Kanaga began to write for the San Francisco Chronicle in 1915, where she learned to produce photographs for her articles encouraged by the newspaper editor. In 1918 she became staff photographer, and the following year was hired by the Daily News, another San Francisco newspaper.

Between 1920 and 1950 she worked for newspapers and magazines in Denver and New York, capturing scenes of urban life and images of economic and racial inequality; as in The Widow Watson (1922-1924 below), which was taken while she was working for the newspaper New York American and depicts a woman suffering from tuberculosis next to her son.

Photojournalism led Kanaga to become aware of photography’s potential as an art form. Around 1918 she joined the California Camera Club in San Francisco. Not only did she gain access to a dark room and photographic equipment, but also books and magazines on the medium. The publication Camera Work by Alfred Stieglitz and the works of New York and San Francisco photographers, such as Arnold Genthe, who portrayed street scenes and urban architecture in their images, influenced her greatly.

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

The Widow Watson

1922-1924

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Portrait Gallery

Kanaga began to produce portraits for additional income as a complement to her journalistic work, initially in San Francisco and later in New York. She opened her first studio in the early 1920s and was able to support herself and her partners financially for the rest of her life by taking photographs of wealthy clients and friends who were part of the avant-garde movements in San Francisco and New York. Thus, the portrait became the main focus of Kanaga’s creative production. It is also important to note that while most of her work as a photojournalist was lost, her portraits remain well represented among the negatives and prints that have been preserved.

Influenced by Stieglitz, in her portraits Kanaga experimented with poses, cropping, lighting, and printing in order to highlight the expressive capabilities of her images. Aside from flash, she used dark room techniques such as over-and underexposure, manipulating exposure times in specific parts of a photographic print to accentuate the contrast between light and shade, which generated a theatrical effect. The artist also frequently toned her prints with metals such as gold, adding pencil or graphite to highlight certain features.

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Portrait of a Woman

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm)

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

North Americans Abroad

One of the fundamental experiences in Kanaga’s formative development was her time in Europe and northern Africa between 1927 and 1928, made possible through the financial support of the patron Albert M. Bender. Kanaga spent close to a year travelling through France, Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Tunisia, taking photographs and visiting museums, monuments, and churches. The artist also sought opportunities to learn modern photographic techniques. In Kairouan (Tunisia) she came into contact with a community of ex-pat artists and produced three photo albums portraying the city and its people, consolidating her interest in portraiture.

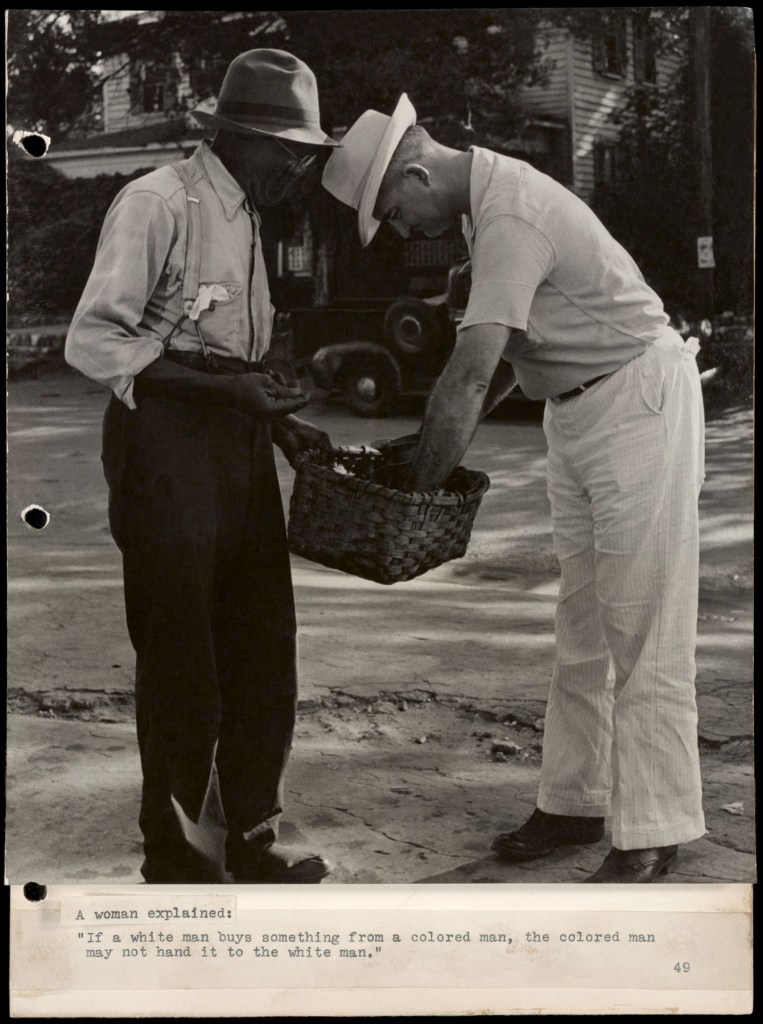

Consuelo Kanaga began to express her opinions on racism in the United States during these trips. A subject she would explore in more depth through photography during the 1930s. “I am sick of seeing colored men and women abused by stupid white people.”

Photography and the American Scene

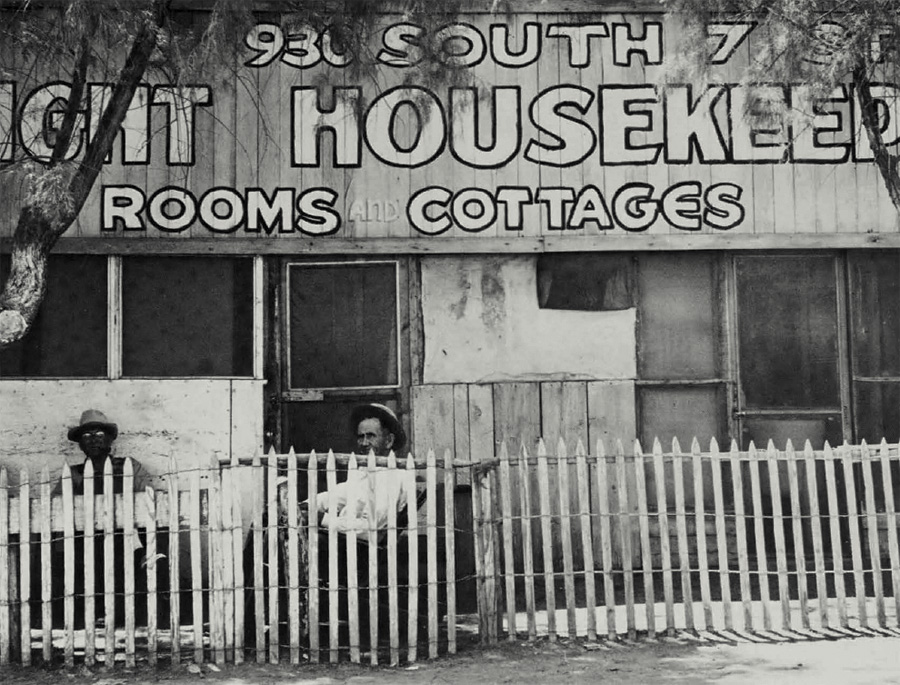

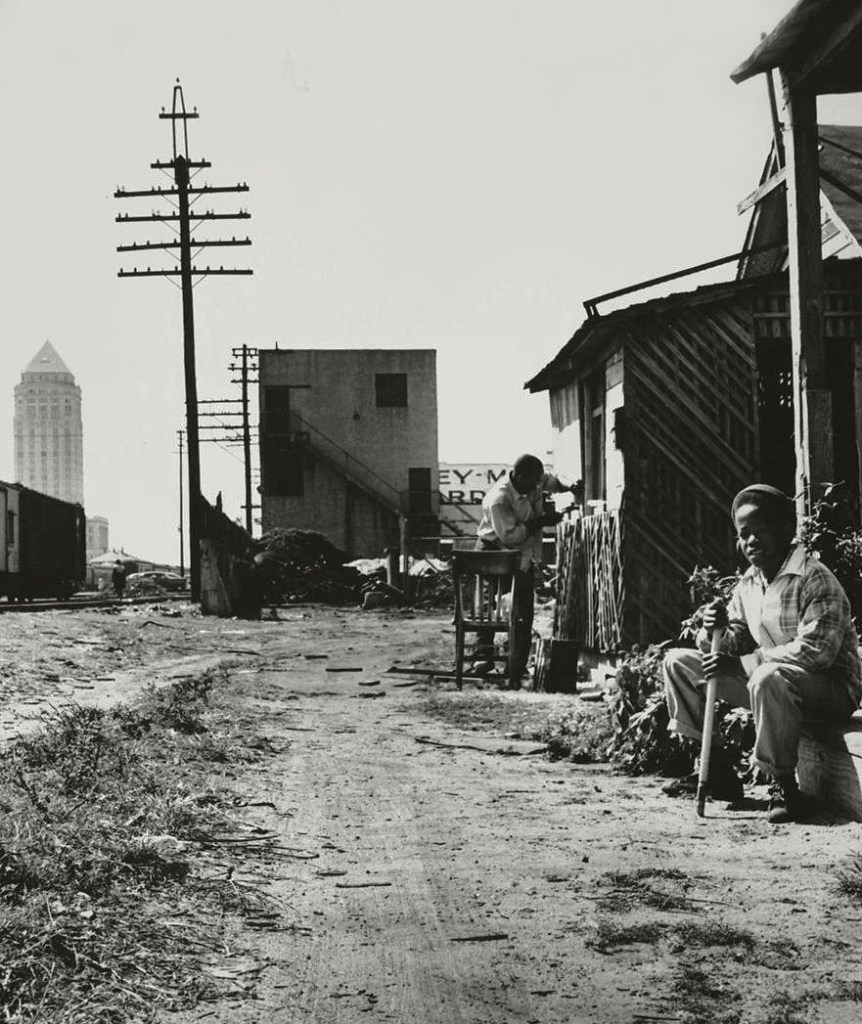

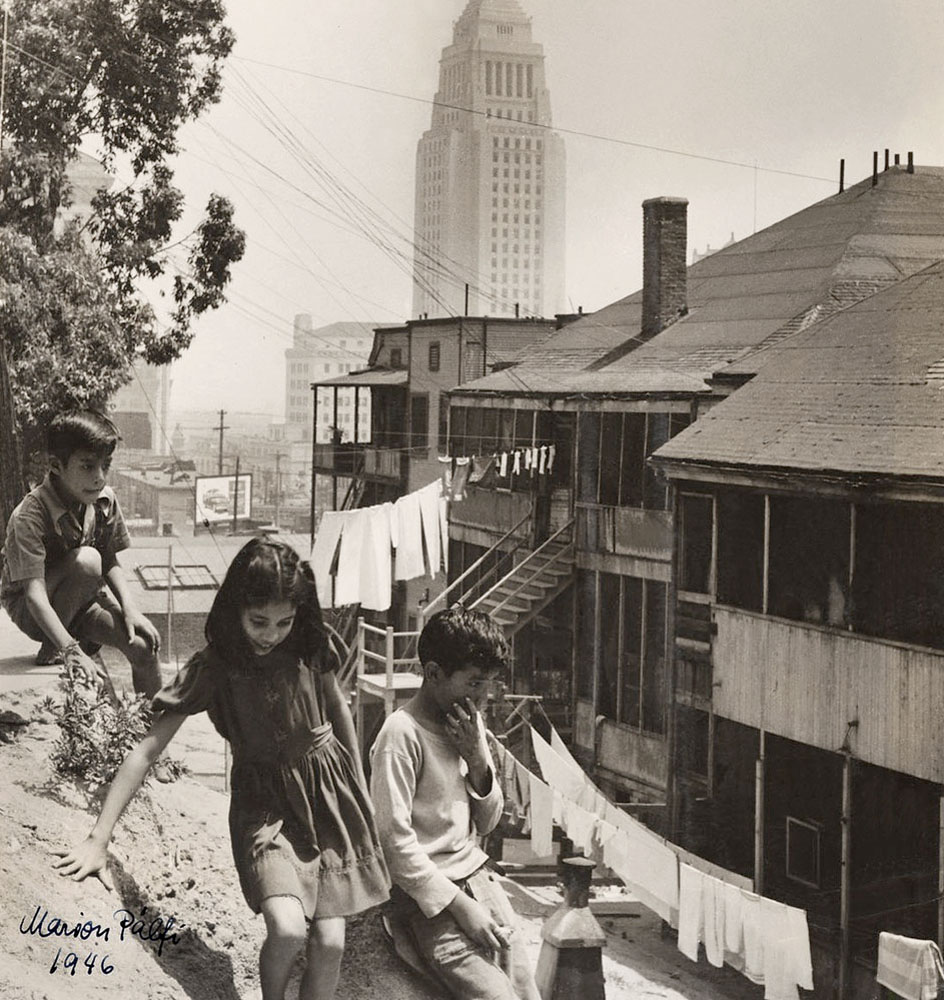

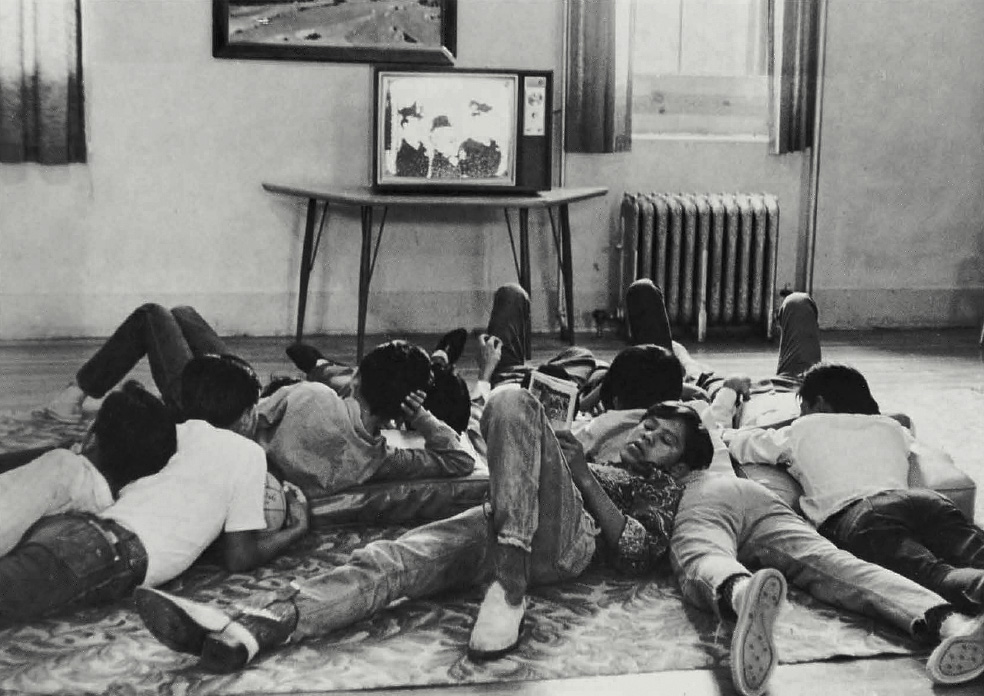

Beyond portraiture, Kanaga practiced numerous genres and styles throughout her career. Like other North American artists, she was attracted to what she encountered in the “American Scene”; naturalist and descriptive representations of national and regional heritage and everyday life. Kanaga mostly focused on marginal day to day and political motifs, including workers, African Americans, objects, and buildings that were often in a state of disrepair.

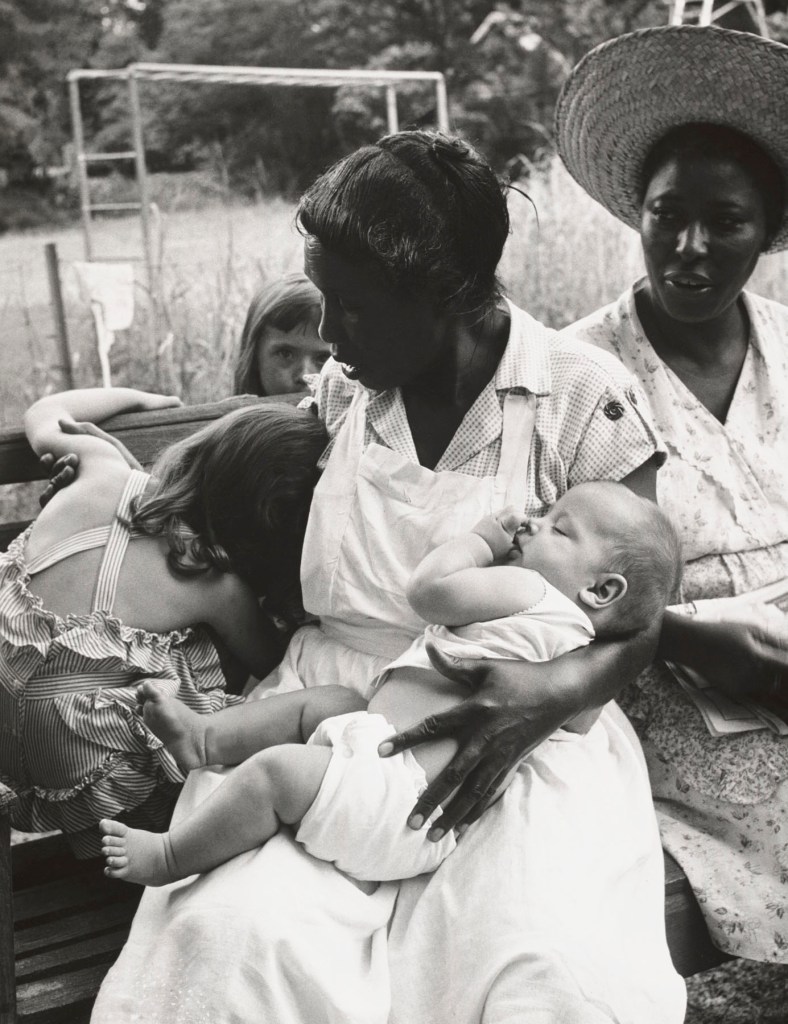

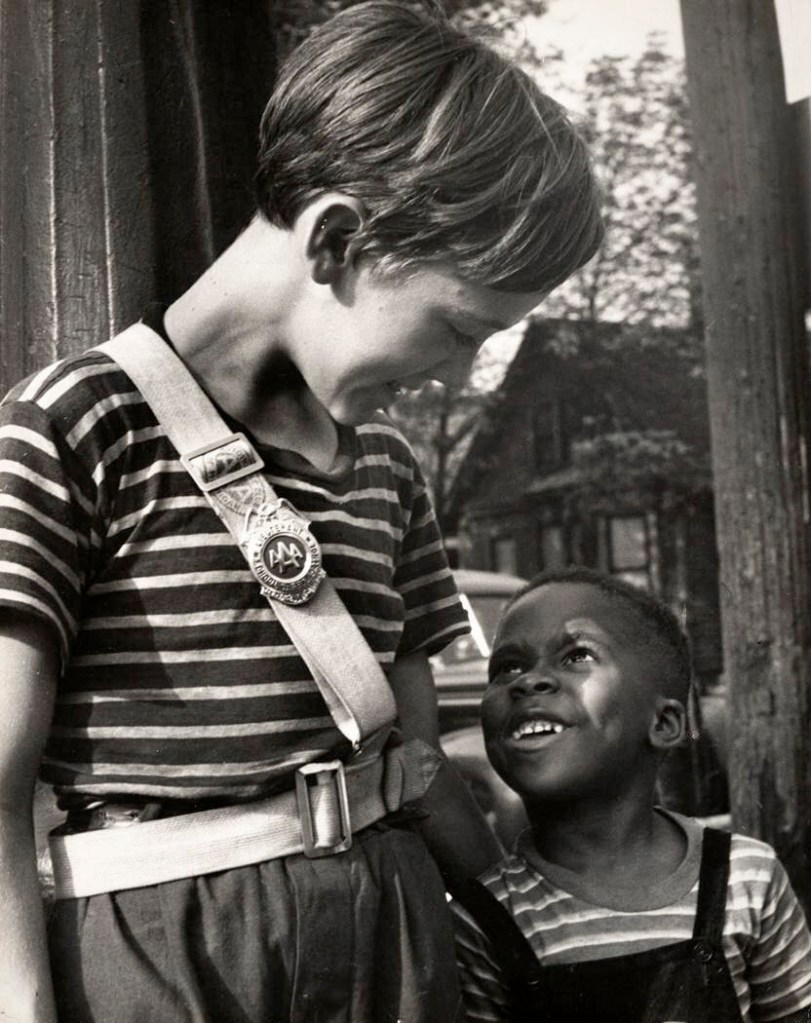

Her first portraits of African Americans were aligned with the New Negro Movement that arose in the 1920s and 30s. Black intellectuals and artists tried to redefine and celebrate African American identities through cultural self-expression, economic independence, and progressive policies. Likewise, they advocated for the creation of inspiring images of their community and of negritude at a time when lynchings and racial terror were some of the most pressing legal and ethical issues. Within this context, Kanaga’s photographs can be considered a true statement of intent: Hands (1930 below) is the first preserved photograph that captures her anti-racist ideals. She also portrayed the singer Kenneth Spencer, the poet Langston Hughes, and the painter and ceramist Sargent Johnson, among others.

Along with her interest in African American communities, Kanaga became interested in worker’s rights and the worker movement that emerged in the Soviet Union and Germany during the 1920s. After moving to New York in 1935, she took photographs for leftist publications and became involved with the Photo League. At a time marked by the will to promote solidarity among workers beyond race and gender, Kanaga focused on the experiences of African Americans and Workers in particular.

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Hands

1930

Gelatin silver print

23 1/16 × 29 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (58.6 × 73.8 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Portraits of Artists

Throughout the 1930s and 40s, Kanaga produced portraits of artists, writers, actors, and musicians. She met many of them thanks to her relationship with several photography clubs and collectives, as well as during her trips through the United States and Europe. Her images include portraits of the photographers Alfred Stieglitz and W. Eugene Smith, the painters Milton Avery and Mark Rothko, and of designers such as Wharton Esherick.

Conversely, Kanaga’s career was especially linked to a solid and broad circle of women photographers whose relationships she cultivated throughout her time as an artist. She was a great supporter and confidant for a series of photographers who often photographed each other, such as Berenice Abbott, Imogen Cunningham, Louse Dahl-Wolfe, Dorothea Lange, Alma Lavenson, Tina Modotti, and Eiko Yamazawa.

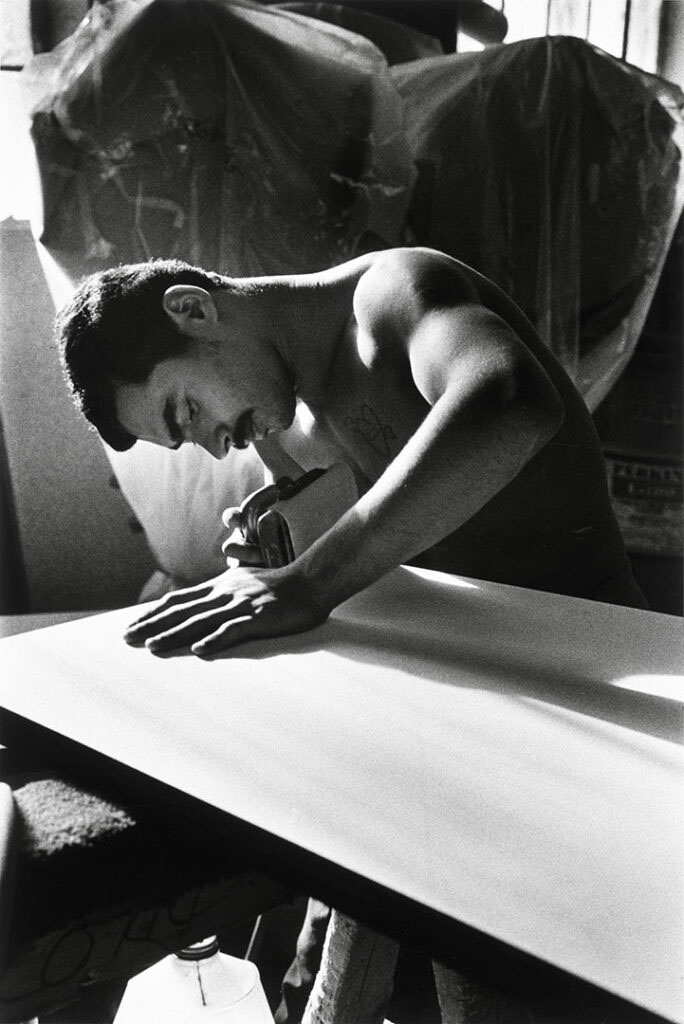

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

Wharton Esherick

1940

Bromide print

20 1/16 × 15 1/16 × 1 1/2 in. (51 × 38.3 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Wharton Esherick (July 15, 1887 – May 6, 1970) was an American sculptor who worked primarily in wood, especially applying the principles of sculpture to common utilitarian objects. Consequently, he is best known for his sculptural furniture and furnishings. Esherick was recognised in his lifetime by his peers as the “dean of American craftsmen” for his leadership in developing nontraditional designs and for encouraging and inspiring artists and artisans by example. Esherick’s influence is evident in the work of contemporary artisans, particularly in the Studio Craft Movement. His home and studio in Malvern, Pennsylvania, are part of the Wharton Esherick Museum, which has been listed as a National Historic Landmark since 1993.

Text from the Wikipedia website

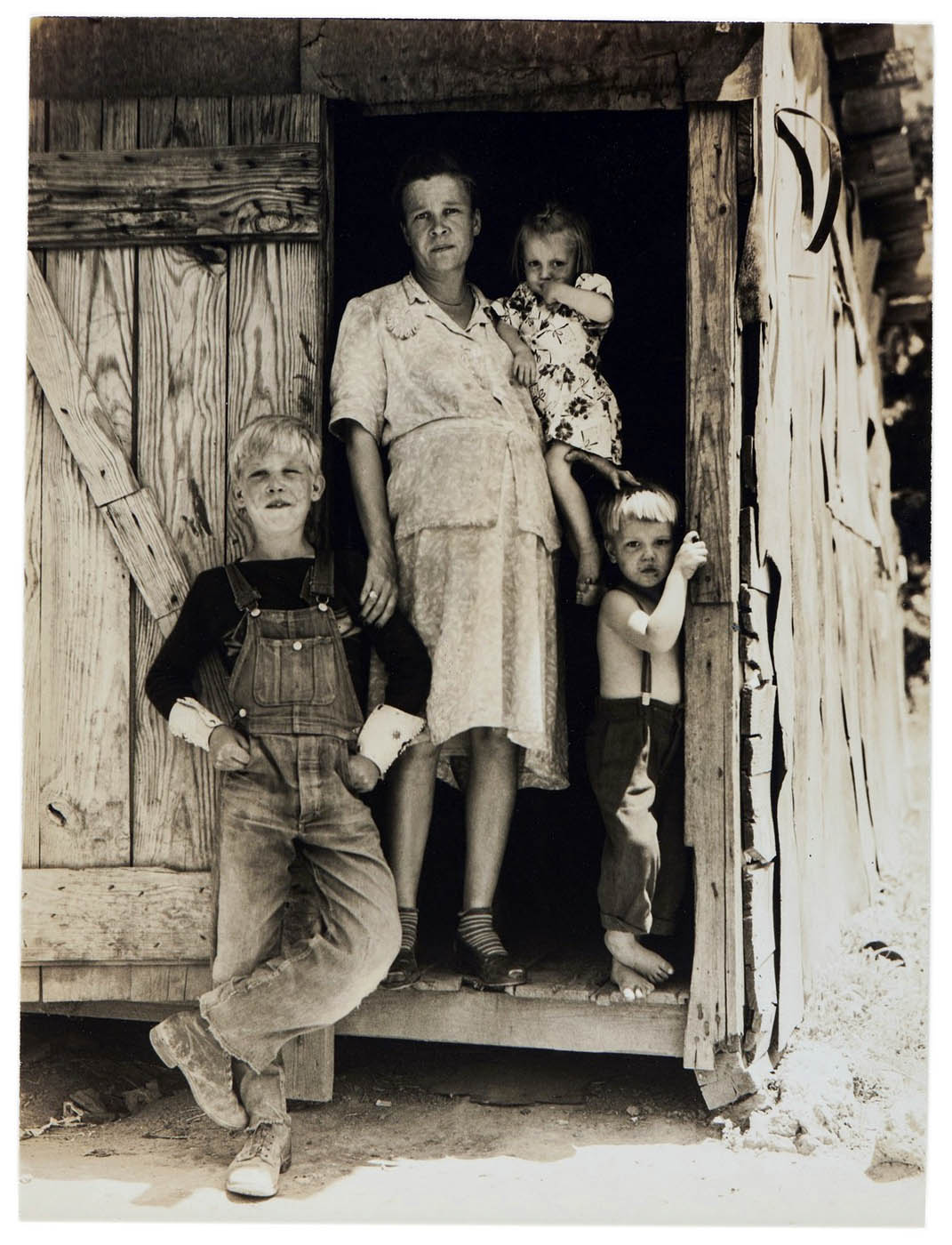

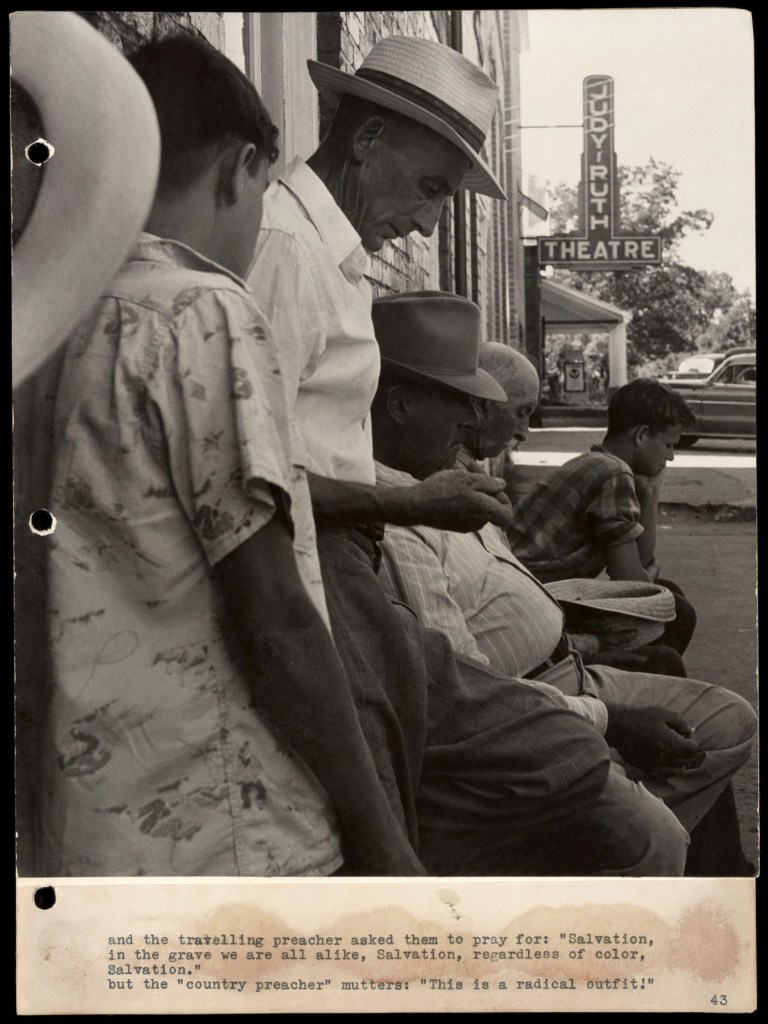

Trips to the Southern United States

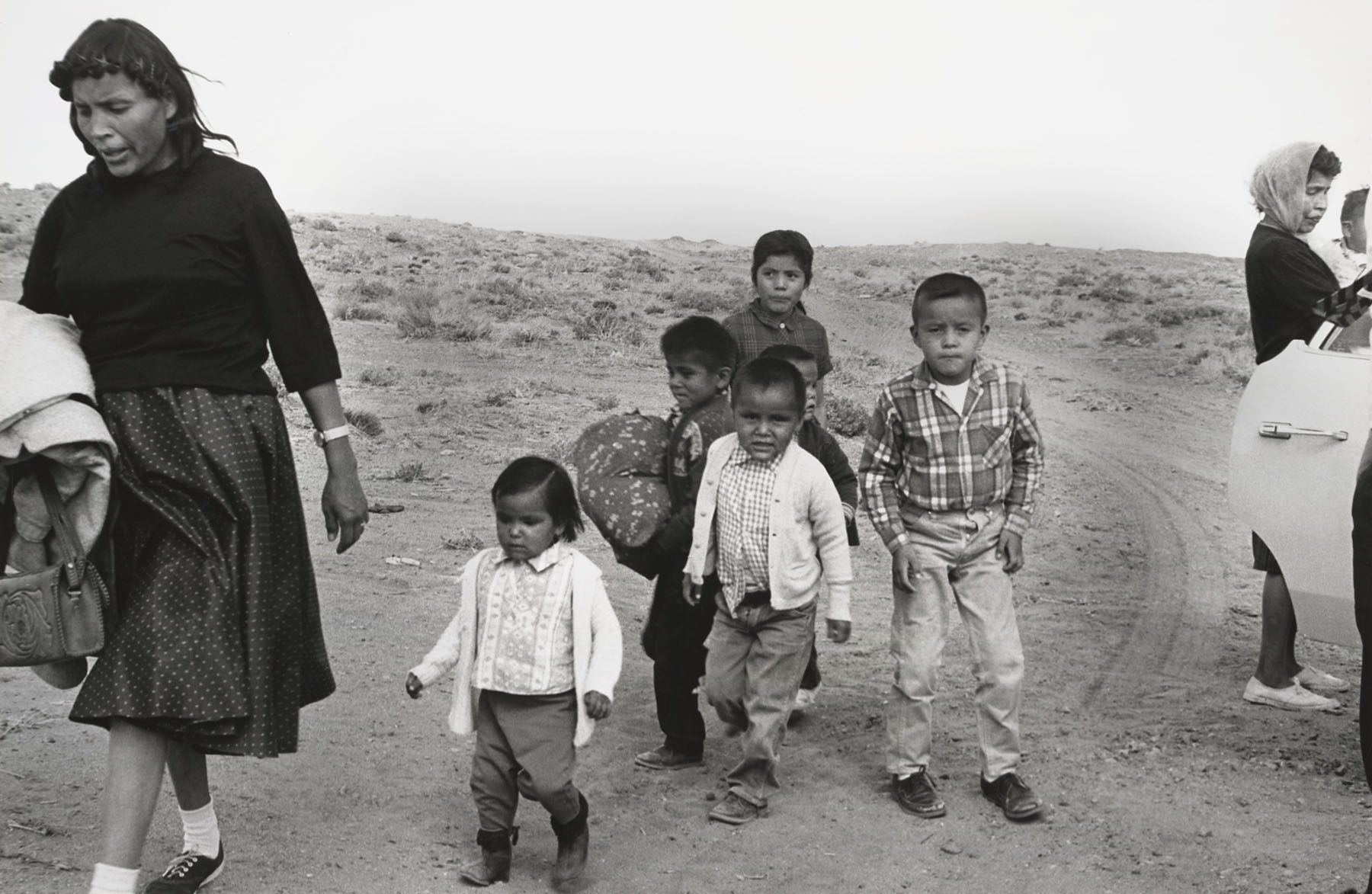

Between the late 1940s and early 60s, Kanaga went on numerous trips through the southern United States where she continued to photograph black children and workers. While in Florida, she produced a series of photographs dedicated to black families and farmhands working in recovered swamp lands known as mucklands. During those trips, she took one of her most renowned photographs titled She is a Tree of Life (1950 below), which depicts a stoic mother with her son and daughter on either side. In 1950 she also photographed self-taught black artist William Edmondson next to his carved stone sculptures.

In 1964, amidst the struggle for freedom of Black Americans in the United States, the activist and writer Barbara Deming invited Kanaga to photograph the Quebec-Washington-Guantanamo Walk for Peace in protest of United States actions against Cuba. During the march, Deming and other activists were arrested for demanding that all demonstrators be allowed to walk together on a “white only” sidewalk. The book Prison Notes, published by Deming in 1966, includes photographs by Kanaga.

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

She is a Tree of Life

1950

Gelatin silver print

22 13/16 × 16 13/16 × 1 1/2 in. (57.9 × 42.7 × 3.8cm) framed

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Studies of Nature

In 1940 Kanaga and her husband, the painter Wallace Putnam, purchased a house outside the city, in Yorktown Heights, seventy kilometres north of Manhattan. They moved there permanently in 1950. Meanwhile, Kanaga continued taking photographs for household magazines in order to support herself and her husband financially. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why, after having her work exhibited in important exhibitions during the 1940s, Kanaga’s artistic output decreased during the following two decades. Nevertheless, she photographed the natural environment surrounding her house and in 1948 one of the pictures she took of the pond in their back yard was included in the exhibition In and Out of Focus: A Survey of Today’s Photography, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Catalogue

The catalogue that accompanies this exhibition has been published in English, Spanish, and Catalan by Fundación MAPFRE and the Brooklyn Museum. It features an essay by the show’s curator Drew Sawyer and texts by Shalon Parker, Ellen Macfarlane, and Shana Lopes. The publication includes a complete overview of the artist’s life and work.

Press release from the Fundación MAPFRE

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

[Untitled] (Landscape Near Taos, New Mexico)

Nd

Gelatin silver print

4 3/4 x 7 3/4 in. (12.1 x 19.7cm)

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

[Untitled] (Landscape with Farmhouse)

Nd

Gelatin silver print

3 5/8 x 4 3/4 in. (9.2 x 12.1cm)

Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wallace B. Putnam from the Estate of Consuelo Kanaga

© Brooklyn Museum

Photo: Brooklyn Museum

KBr Photography Center

Avenida Litoral, 30 – 08005 Barcelona

Phone: +34 93 272 31 80

(Attention only during the opening hours of the exhibition hall)

Opening hours:

Mondays (except holidays): Closed

Tuesday to Sundays (and holidays): 11am – 8pm

![Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978) '[Untitled] (Landscape Near Taos, New Mexico)' Nd Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978) '[Untitled] (Landscape Near Taos, New Mexico)' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kanaga-landscape-untitled-near-taos-new-mexico.jpg?w=840&h=506)

![Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978) '[Untitled] (Landscape with Farmhouse)' Nd Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978) '[Untitled] (Landscape with Farmhouse)' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kanaga-untitled-landscape-with-farmhouse.jpg?w=840&h=655)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Boulevard de Clichy, Paris' [Boulevard de Clichy, París] 1951 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Boulevard de Clichy, Paris' [Boulevard de Clichy, París] 1951 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/03.-id40_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aubervilliers, France' [Aubervilliers, Francia] 1947 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aubervilliers, France' [Aubervilliers, Francia] 1947 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/02.-id37_p.jpg?w=801)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Concentric Circles, Construction Site, New York' [Círculos concéntricos, obra, Nueva York] 1952 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Concentric Circles, Construction Site, New York' [Círculos concéntricos, obra, Nueva York] 1952 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/11.-id737_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Manhole, Times Square, New York' [Tapa de alcantarilla, Times Square, Nueva York] 1954 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Manhole, Times Square, New York' [Tapa de alcantarilla, Times Square, Nueva York] 1954 from the exhibition 'Louis Stettner' at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Room (Madrid), June - August, 2023](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/08.-id68_p-b.jpg?w=689)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, New York' [Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, Nueva York] 1954 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, New York' [Brooklyn Promenade, Brooklyn, Nueva York] 1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/09.-id1_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Nancy Listening to Jazz, Greenwich Village, New York' [Nancy escuchando jazz, Greenwich Village, Nueva York] 1958 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Nancy Listening to Jazz, Greenwich Village, New York' [Nancy escuchando jazz, Greenwich Village, Nueva York] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/10.-id4211_p.jpg?w=744)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman Holding Newspaper, New York' [Mujer sujetando un periódico, Nueva York] 1946 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman Holding Newspaper, New York' [Mujer sujetando un periódico, Nueva York] 1946](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/01.-id1732_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Train Station Near Málaga, Spain' [Estación de tren cerca de Málaga, España] 1951 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Train Station Near Málaga, Spain' [Estación de tren cerca de Málaga, España] 1951](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/05.-id74_p.jpg?w=675)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Tony, "Pepe and Tony, Spanish Fishermen", Ibiza, Spain' [Tony, "Pepe y Tony, pescadores españoles", Ibiza, España] 1956 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Tony, "Pepe and Tony, Spanish Fishermen", Ibiza, Spain' [Tony, "Pepe y Tony, pescadores españoles", Ibiza, España] 1956](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/04.-id4569_p.jpg?w=669)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Commuters, Evening Train, Penn Station, New York' [Volviendo del trabajo en el tren de la tarde, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Commuters, Evening Train, Penn Station, New York' [Volviendo del trabajo en el tren de la tarde, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/06.-id179_p.jpg?w=684)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman with White Glove, Penn Station, New York' [Mujer con guante blanco, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Woman with White Glove, Penn Station, New York' [Mujer con guante blanco, Penn Station, Nueva York] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/07.-id461_p.jpg?w=683)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aluminum Foundry, Soviet Union' [Fundición de aluminio, Unión Soviética] 1975 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Aluminum Foundry, Soviet Union' [Fundición de aluminio, Unión Soviética] 1975](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/13.-id648_p.jpg?w=686)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Assembly Line Worker, Long Island City, New York' [Trabajadora en cadena de montaje, Nueva York] 1972-1974 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Assembly Line Worker, Long Island City, New York' [Trabajadora en cadena de montaje, Nueva York] 1972-1974](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/12.-id96_p-1.jpg?w=691)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Demonstrators on March in Support of United Farm Workers, New York' [Manifestantes en una marcha de apoyo a la Unión de Campesinos, Nueva York] 1975-1976 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Demonstrators on March in Support of United Farm Workers, New York' [Manifestantes en una marcha de apoyo a la Unión de Campesinos, Nueva York] 1975-1976](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/14.-id1307_p.jpg?w=685)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Self-Portrait, Santiago, Chile' [Autorretrato, Santiago de Chile] 2000-2001 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Self-Portrait, Santiago, Chile' [Autorretrato, Santiago de Chile] 2000-2001](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/16.-id1627_p.jpg)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Women from Texas, Fifth Avenue, New York' [Mujeres de Texas, Fifth Avenue, Nueva York] 1975 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Women from Texas, Fifth Avenue, New York' [Mujeres de Texas, Fifth Avenue, Nueva York] 1975](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/15.-id145_p.jpg?w=694)

![Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris' [Jardin du Luxembourg, París] 1997 Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016) 'Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris' [Jardin du Luxembourg, París] 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/17.-id2978_p.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York]' January 16, 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York]' January 16, 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/3-weegee_anthony-esposito-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/17-weegee_19982_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/6-weegee_19969_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/15-weegee_19961_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/16-weegee_19972_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled ["Ruth Snyder Murder" wax display, Eden Musée, Coney Island, New York]' c. 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled ["Ruth Snyder Murder" wax display, Eden Musée, Coney Island, New York]' c. 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/5-weegee_7221_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Hats in a pool room, Mulberry Street, New York]' c. 1943 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Hats in a pool room, Mulberry Street, New York]' c. 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/14-weegee_15595_1993-web.jpg)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Body of Dominick Didato, Elizabeth Street, New York]' August 7, 1936 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Body of Dominick Didato, Elizabeth Street, New York]' August 7, 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/8-weegee_2070_1993-web.jpg?w=650)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and lodge member looking at blanket-covered body of woman trampled to death in excursion-ship stampede, New York]' August 18, 1941 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and lodge member looking at blanket-covered body of woman trampled to death in excursion-ship stampede, New York]' August 18, 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/11-weegee_1016_1993-web.jpg?w=650)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and assistant removing body of Reception Hospital ambulance driver Morris Linker from East River, New York]' August 24, 1943 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Police officer and assistant removing body of Reception Hospital ambulance driver Morris Linker from East River, New York]' August 24, 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/9-weegee_133_1982-web.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.