Exhibition dates: 30th September 2012 – 31st December 2012

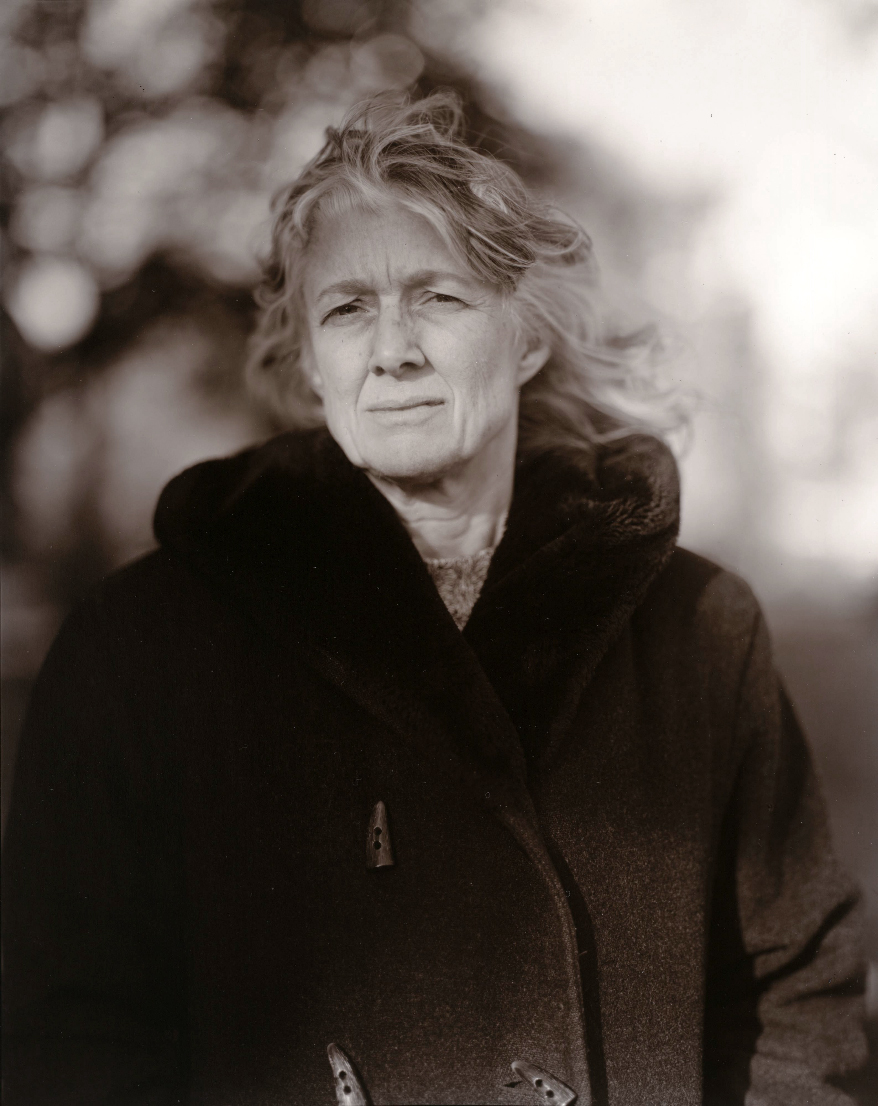

Figure 5. Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith, Danville, Virginia

1971

Gelatin silver print

20.2 x 25.2cm (7 15/16 x 9 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Patrons’ Permanent Fund

© Emmet and Edith Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

~ Alfred Stieglitz / Georgia O’Keeffe

~ Paul Strand / Rebecca Strand

~ Emmet Gowin / Edith Gowin

~ Harry Callahan / Eleanor and Barbara Callahan

~ Robert Mapplethorpe / Patti Smith

~ Nicholas Nixon / The Brown Sisters

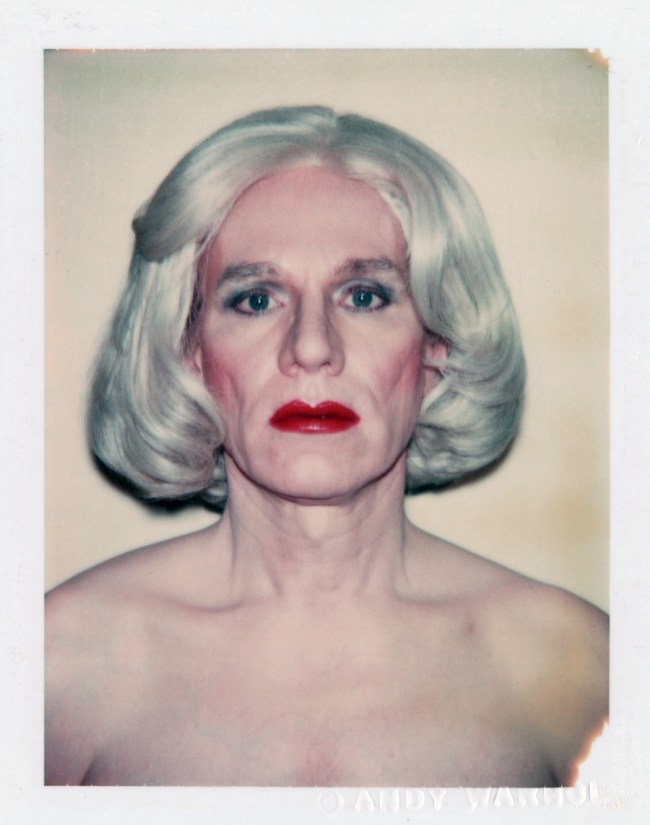

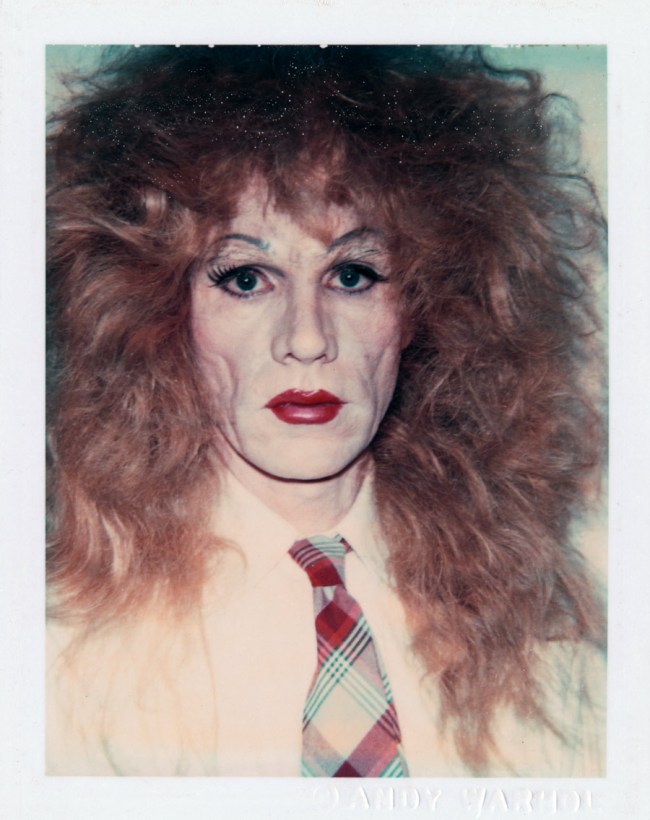

~ Andy Warhol / Serial Photography / Photo Booth Portraits

~ Mario Testino / Kate Moss

~ Baron Adolf de Meyer / Baroness Olga de Meyer

~ Edward Weston / Charis Weston

~ Lee Friedlander / Maria Friedlander

~ Paul Caponigro / The woods of Connecticut

~ Bernd and Hilla Becher / grids

~ Gerhard Richter / Overpainted Photographs

~ Masahisa Fukase / wife and family

~ Seiichi Furuya / Christine Furuya-Gößler

~ Sally Mann / children and husband

~ William Wegman / dogs

Australia?

Nobody that I can think of except Sue Ford.

Notice how all the artists are men except two: Sally Mann and Hilla Becher.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Introduction

Alfred Stieglitz, one of the most influential photographers of the twentieth century, argued that “to demand the [single] portrait… be a complete portrait of any person is as futile as to demand that a motion picture be condensed into a single still.” Stieglitz’s conviction that a person’s character could not be adequately conveyed in one image is consistent with a modern understanding of identity as constantly changing. For Stieglitz, who frequently made numerous portraits of the same sitters – including

striking photographs of his wife, the painter Georgia O’Keeffe – using the camera in a serial manner allowed him to transcend the limits of a single image.

Drawn primarily from the National Gallery of Art’s collection, the

Serial Portrait exhibition features twenty artists who photographed the same subjects – primarily friends, family, or themselves – multiple times over the course of days, months, or years. This brochure presents a selection of works by seven of these artists. Like Stieglitz’s extended portrait of O’Keeffe, Emmet Gowin’s ongoing photographic study of his wife, Edith, explores her character and reveals the bonds of love and affection between the couple. Milton Rogovin’s photographs of working-class residents of Buffalo, New York, record shifts in the appearance and situation of individuals in the context of their community over several decades.

A number of photographers in the exhibition have made serial self-portraits that investigate the malleability of personal identity. Photographing themselves as shadows, blurs, or partial reflections, Lee Friedlander and Francesca Woodman have made disorienting images that hint at the instability of self-representation. Ann Hamilton has employed unusual props and materials to transform herself into a series of hybrid objects. Finally, work by Nikki S. Lee takes the idea of mutable identity to its logical conclusion as the artist photographs herself masquerading as members of different social and ethnic groups.

Text from the NGA website

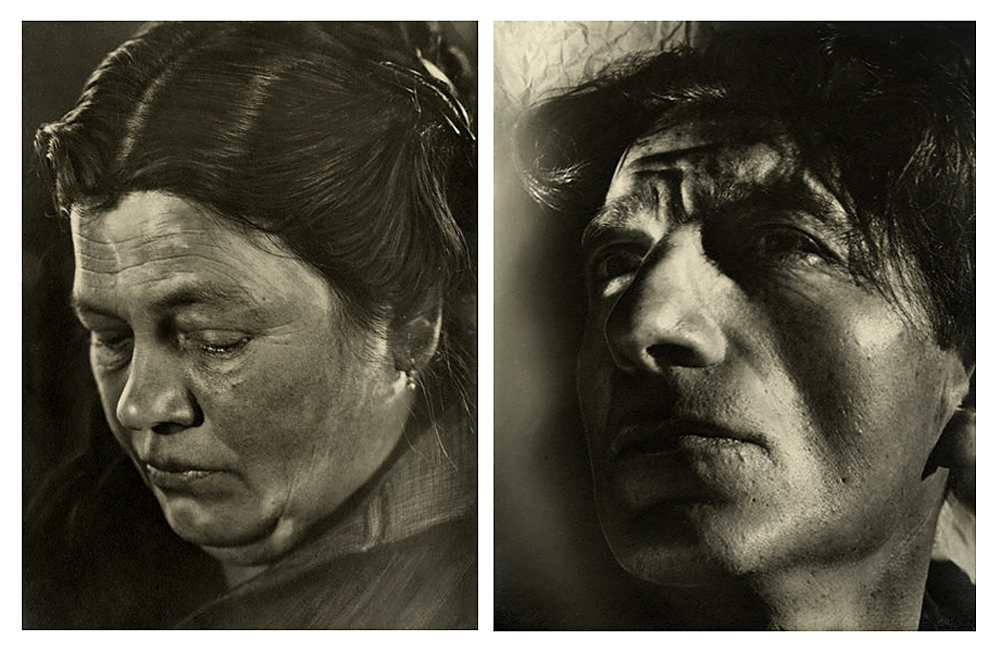

Figure 4. Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith, Danville, Virginia

1963

Gelatin silver print, printed 1980s

19.7 x 12.7cm (7 3/4 x 5 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Charina Endowment Fund

© Emmet and Edith Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin

Emmet Gowin (born 1941) met Edith Morris in 1961 in their hometown of Danville, Virginia, just as he had decided to abandon business school to study art. Several years later at the Rhode Island School of Design, his teacher Harry Callahan, who made numerous photographs of his wife, Eleanor, encouraged Gowin to photograph the subject he knew most intimately – his family and in particular Edith, whom he married in 1964.

The Gowins’ artistic and marital collaboration has endured for half a century, yielding an extraordinary series of quiet, attentive portraits. In some photographs, such as Edith, Danville, Virginia, 1963 (fig. 4, above), Edith appears contemplative, even reserved. The somber beauty of this work stems in part from Gowin’s use of a tripod-mounted, large-format camera, which requires a lengthy exposure but produces photographs with exquisite details, such as the delicate shadow of a twig that falls across Edith’s face. To make the dramatic circular shadow that surrounds her in Edith, Danville, Virginia, 1971 (fig. 5, above), Gowin attached a lens meant for a 4 × 5 camera to a large 8 × 10 camera. This focus draws our attention to her figure, but the screen door simultaneously frames and obscures her form, resulting in a play between presence and elusiveness. While Gowin’s photographs are born of a deep intimacy, they refuse to lay bare his wife’s soul or expose the couple’s private passions.

The same delicate balance between revelation and reserve marks a group of portraits made during the couple’s travels in Central and South America. Edith and Moth Flight, 2002 (fig. 6, below), made at night using a ten-second exposure, combines Gowin’s enchantment with natural beauty and his interest in the nuances of his wife’s gestures and moods. Placing a pulsing ultraviolet light behind Edith’s head, Gowin recorded the luminous traces left by moths as they danced around her blurred face, transforming her into a ghostly and even otherworldly presence, visible yet just out of our reach.

Text from the NGA website

Figure 6. Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith and Moth Flight

2002

Digital ink jet print

19 x 19cm (7 1/2 x 7 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Charina Endowment Fund

© Emmet and Edith Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

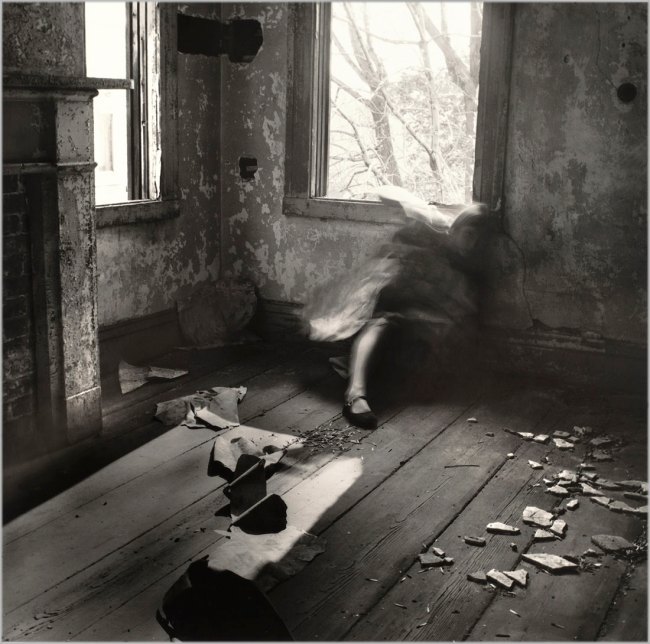

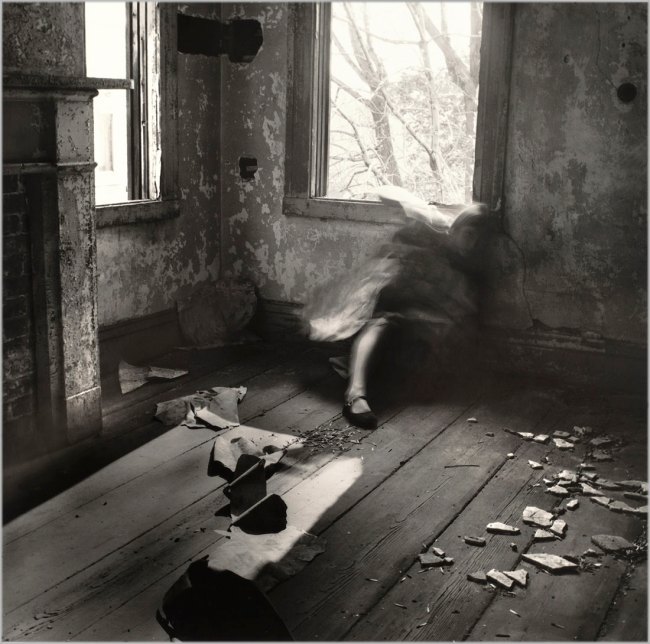

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

House #3, Providence, Rhode Island

1976

Gelatin silver print

16.1 x 16.3cm (6 5/16 x 6 7/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of the Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Francesca Woodman

Francesca Woodman (1958-1981) began making photographs at age thirteen, and by the time she entered the Rhode Island School of Design in 1975, she was already a skilled photographer. Using herself as the subject of nearly all her work, Woodman put her body in the service of exploring such themes as feminine identity, sexuality, mythology, and the relationship of the body to its surroundings. Conjuring visions of a complex inner world, Woodman’s photographs are powerful for their ability to suggest psychic turmoil within images of serene, ethereal beauty.

Woodman’s interest in the emotional affect of space can be seen in House #3, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 (fig. 14, above). Using an abandoned house as a makeshift studio, Woodman often photographed herself merging with her surroundings, including doors, walls, and windows, dissolving physical or psychic boundaries. She also frequently moved during long exposures or allowed the camera to record only part of her body in order to obscure her figure. By invoking a ghostly presence, Woodman’s photographs often present her as someone who refuses to commit to a solid image of herself.

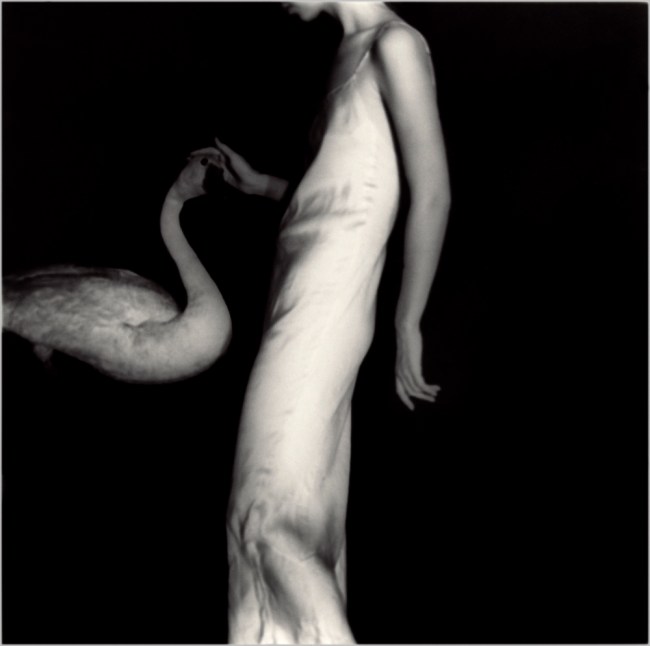

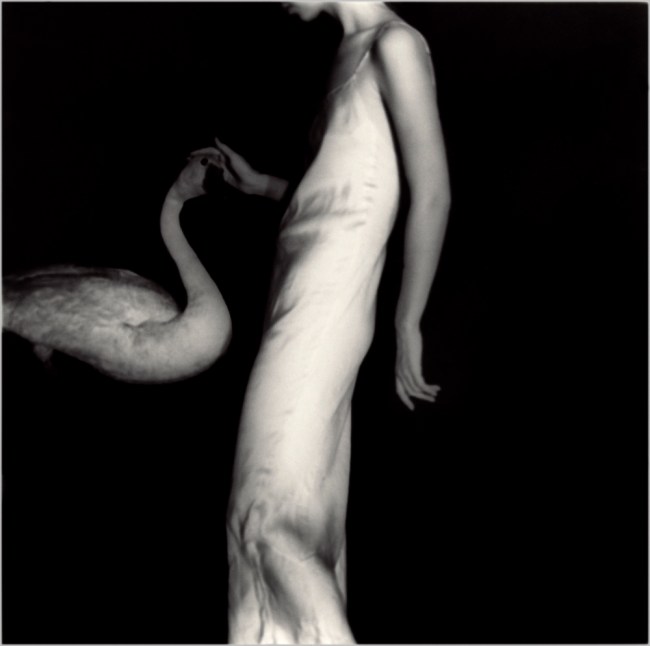

Woodman’s lush and intimate photographs thus offer a tantalising glimpse of a mysterious, private world. Yet they are more than romantic expressions of a young woman’s subjective experience. Notes in Woodman’s diary suggest, for instance, that Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-1978 (fig. 15, below), alludes to the Greek mythological story of Leda, who was seduced by the god Zeus in the form of a swan.

Toward the end of her brief but prolific career (Woodman committed suicide when she was twenty-two) the artist began working on a much larger scale, using her body more as a structural element. Caryatid, New York, 1980 (fig. 16, below), made as part of a monumental photo-installation called Temple Project, draws both its title and inspiration from the columns carved in the shape of women that were used in ancient Greek and Roman architecture. Although Woodman displays her figure in a more expansive and direct manner than in her earlier work, the gesture that obscures her face and leaves her partial and unknowable is typical for the artist, who always preferred suggestion over declaration.

Text from the NGA website

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island

1975-1978

Gelatin silver print

10.5 x 10.5cm (4 1/8 x 4 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of the Collectors

Committee and R. K. Mellon Family Foundation

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

Caryatid, New York

1980

National Gallery of Art, Washington

William and Sarah Walton Fund and Gift of the Collectors Committee

Figure 17. Ann Hamilton (American, b. 1956)

body object series #13, toothpick suit/chair

1984

Gelatin silver print, printed 1993

11 x 11cm (4 5/16 x 4 5/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Ann Hamilton

An artist known for multimedia environments, performances, and videos, Ann Hamilton (born 1956) made the first photographs in the body object series in 1984 with objects left over from an installation she had presented as an MFA student at Yale. Later images from the series were based on subsequent performances and installations, documenting both the objects used and the actions performed with them. Hamilton appears in each photograph with objects attached to or touching her body, her face only rarely visible. The results are striking, unsettling, and often witty.

Despite emerging from Hamilton’s installation and performance practice, the photographs in the series stand on their own as works of art. Paying close attention to the material qualities of familiar objects, Hamilton models creative new uses for them, changing their function and meaning. In body object series #13, toothpick suit/chair, 1984 (fig. 17, above), for example, thousands of toothpicks transform Hamilton’s clothes into a porcupine-like hide while a chair becomes a burdensome instrument of torture. The image elicits visceral emotions – alienation, hostility, fear – though it does so with a dose of absurdist humour.

As self-representations, the photographs in the body object series depart radically from any traditional notion of portraiture. Instead of insisting on Hamilton’s uniqueness as an individual, these images present her body almost as an object on a par with other objects. Some of the photographs are linked directly to her biography: Hamilton had studied textile design before getting her MFA, and the toothpick suit refers to her love of fabrics. In other photographs she makes abstract concepts more graspable through the senses. Sound is given tactile and visual form as tissue paper in body object series #14, megaphone, 1986 (fig. 18, below), while in body object series #15, honey hat, 1989 (fig. 19, below), Hamilton wrings her hands in honey to suggest the idea of washing one’s hands of guilt. Based on an installation in which the artist embedded money – 750,000 pennies – in a layer of honey, this image also gives new meaning to the phrase “sticky fingers” and highlights the connections between language, images, and objects that Hamilton explores in both her photographs and installations.

Text from the NGA website

Figure 18. Ann Hamilton (American, b. 1956)

body object series #14, megaphone

1986

Gelatin silver print, printed 1993

11 x 11cm (4 5/16 x 4 5/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

Figure 19. Ann Hamilton (American, b. 1956)

body object series #15, honey hat

1989

Gelatin silver print, printed 1993

11 x 11cm (4 5/16 x 4 5/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

The National Gallery of Art explores how the practice of making multiple portraits of the same subjects produced some of the most revealing and provocative photographs of our time in The Serial Portrait: Photography and Identity in the Last One Hundred Years, on view in the West Building’s Ground Floor photography galleries from September 30 through December 31, 2012. Arranged both chronologically and thematically, the exhibition features 153 works by 20 artists who photographed the same subjects – friends, family, and themselves – numerous times over days, months, or years to create compelling portrait studies that investigate the many facets of personal and social identity.

“The Gallery’s photography collection essentially began with the donation of Alfred Stieglitz’s ‘key set,’ so it is fitting that this exhibition opens with portraits by Stieglitz, who understood that a person’s character was best captured through a series of photographs taken over time,” said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. “Although the exhibition is drawn largely from the Gallery’s significant collection of photographs, we are grateful to the lenders who have allowed us to present more fully the serial form of portraiture that Stieglitz championed.”

Since the introduction of photography in 1839, portraiture has been one of the most widely practiced forms of the medium. Starting in the early 20th century, however, some photographers began to question whether one image alone could adequately capture the complexity of an individual. As Alfred Stieglitz, the era’s leading champion of American fine art photography, argued: “to demand the [single] portrait that will be a complete portrait of any person is as futile as to demand that a motion picture will be condensed into a single still.”

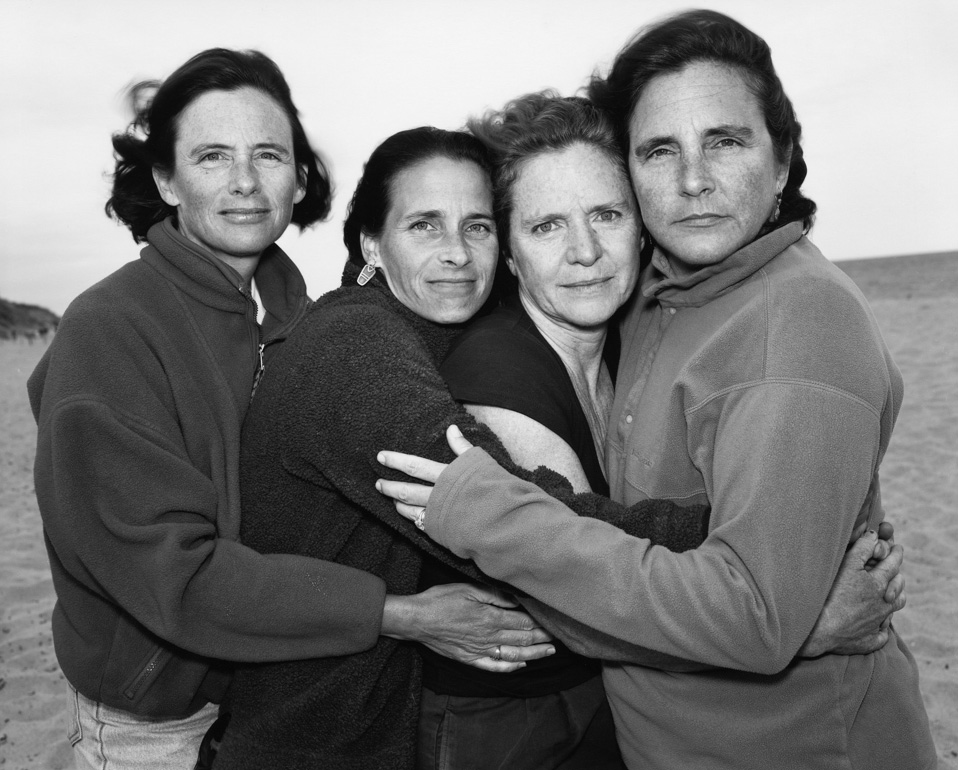

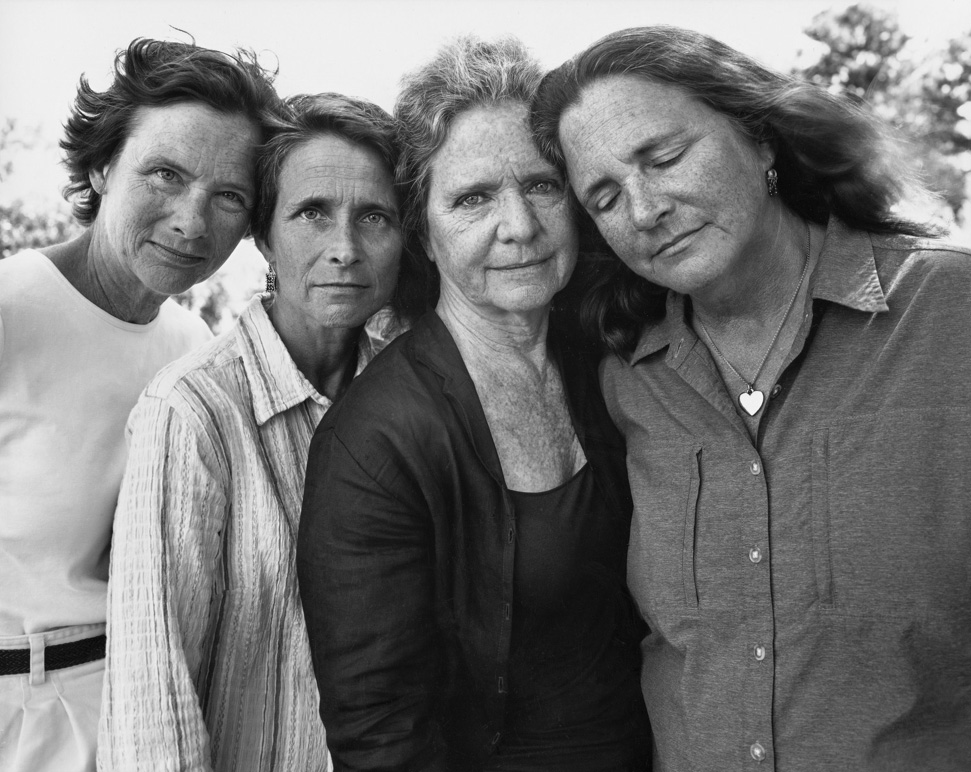

Along with Stieglitz, some of the 20th century’s most prominent photographers – Paul Strand, Harry Callahan, and Emmet Gowin – used the camera serially to transcend the limits of a single image. Each of these photographers made numerous studies of their lovers that sought to redefine the expressive possibilities of portraiture while probing the affective bonds of love and desire. By employing the camera’s capacity to record fluctuating states of being and mark the passage of time, other photographers such as Nicholas Nixon and Milton Rogovin have documented individuals – in families or communities – over four decades. Capturing subtle and dramatic shifts in appearance, demeanour, and situation, these series are poignant and elegiac memorials that remind us of our own mortality.

Other photographers have made serial self-portraits that explore the malleability of personal identity and the possibility of reinvention afforded by the camera. By photographing themselves as shadows, blurs, or partial reflections, Ilse Bing, Lee Friedlander, and Francesca Woodman have created inventive but elusive images that hint at the instability of self-representation. Conceptual artists of the 1970s and 1980s such as Vito Acconci, Blythe Bohnen, and Ann Hamilton have explicitly combined performance and self-portraiture to stage continual self-transformations. The exhibition concludes with work from the last 15 years by artists such as Nikki S. Lee and Gillian Wearing, who take the performance of self to its limits by adopting masquerades to delve into the ways identity is inferred from external appearance.

Press release from the National Gallery of Art website

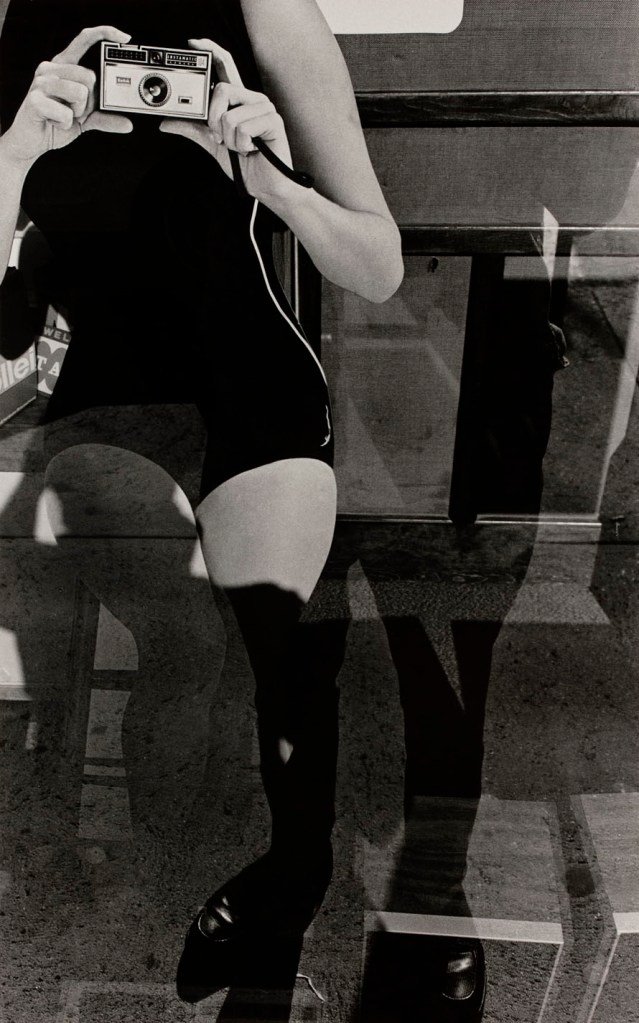

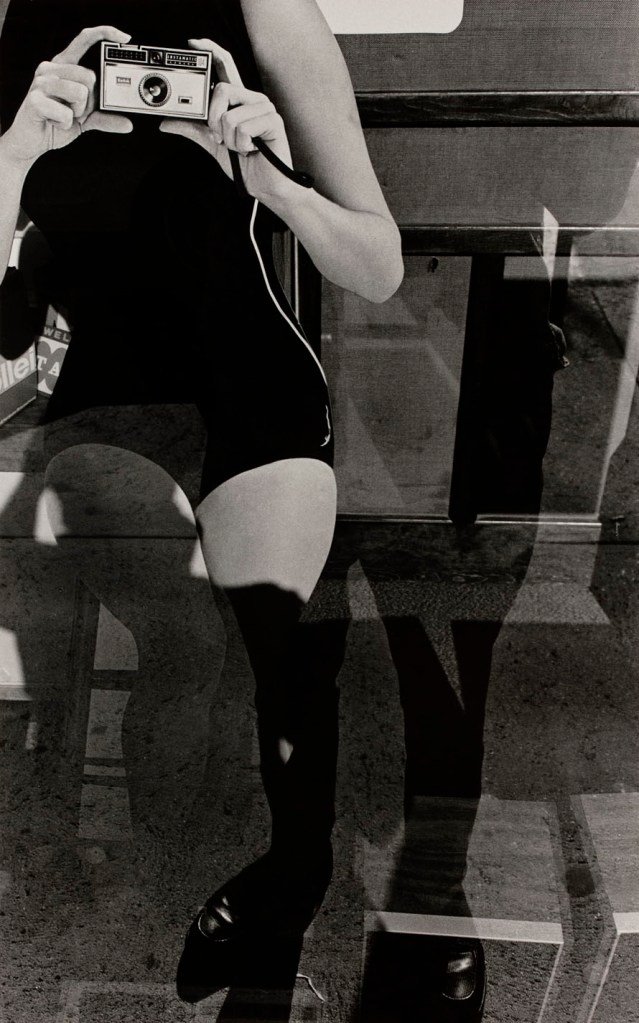

Figure 11. Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

Westport, Connecticut

1968

Gelatin silver print

19.8 x 12.3cm (7 13/16 x 4 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Trellis Fund

© Lee Friedlander, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

Lee Friedlander

In the 1960s Lee Friedlander (born 1934) sought, by his own account, to create images of “the American social landscape and its conditions.” Other photographers in his New York circle, including Diane Arbus and Garry Winogrand, also explored the chaotic beauty and contradictions of modern life. Friedlander, however, was the only member of this group to turn repeatedly to self-portraiture in order to understand the world around him. He stalked city streets with camera in hand, recording not only the haphazard incidents of daily life but also his own presence, often as a shadow or a reflection.

In the shop window of Westport, Connecticut, 1968 (fig. 11, above), for example, a reflection of Friedlander’s legs appears to merge with the shapely limbs of a woman in a bathing suit who points a camera at the viewer. The woman is an illusion, a cutout advertisement – but she is also a stand-in for the camera-wielding Friedlander, whose torso and head also appear faintly, as a shadow cast against her legs.

By letting the reflection in a window obscure what is inside, or allowing his shadow to intrude into the frame, Friedlander violates many of the rules of “good” photography. Works such as New York City, 1966 (fig. 12, below) testify to Friedlander’s ability to transform such “mistakes” into witty, ironic juxtapositions. In this case, the startling intrusion of Friedlander’s shadow onto the back of a fellow pedestrian is visually confusing, simultaneously threatening and humorous, as Friedlander’s spiky hair merges with the woman’s fur collar. A sly commentary on the predatory nature of such street photography, the looming shadow that engulfs the subject is also an effect of Friedlander’s equipment, a 35mm Leica with a wide-angle lens. In order to fill the picture frame with his chosen subject, Friedlander had to make the picture at close range, resulting in the inclusion of his own shadow.

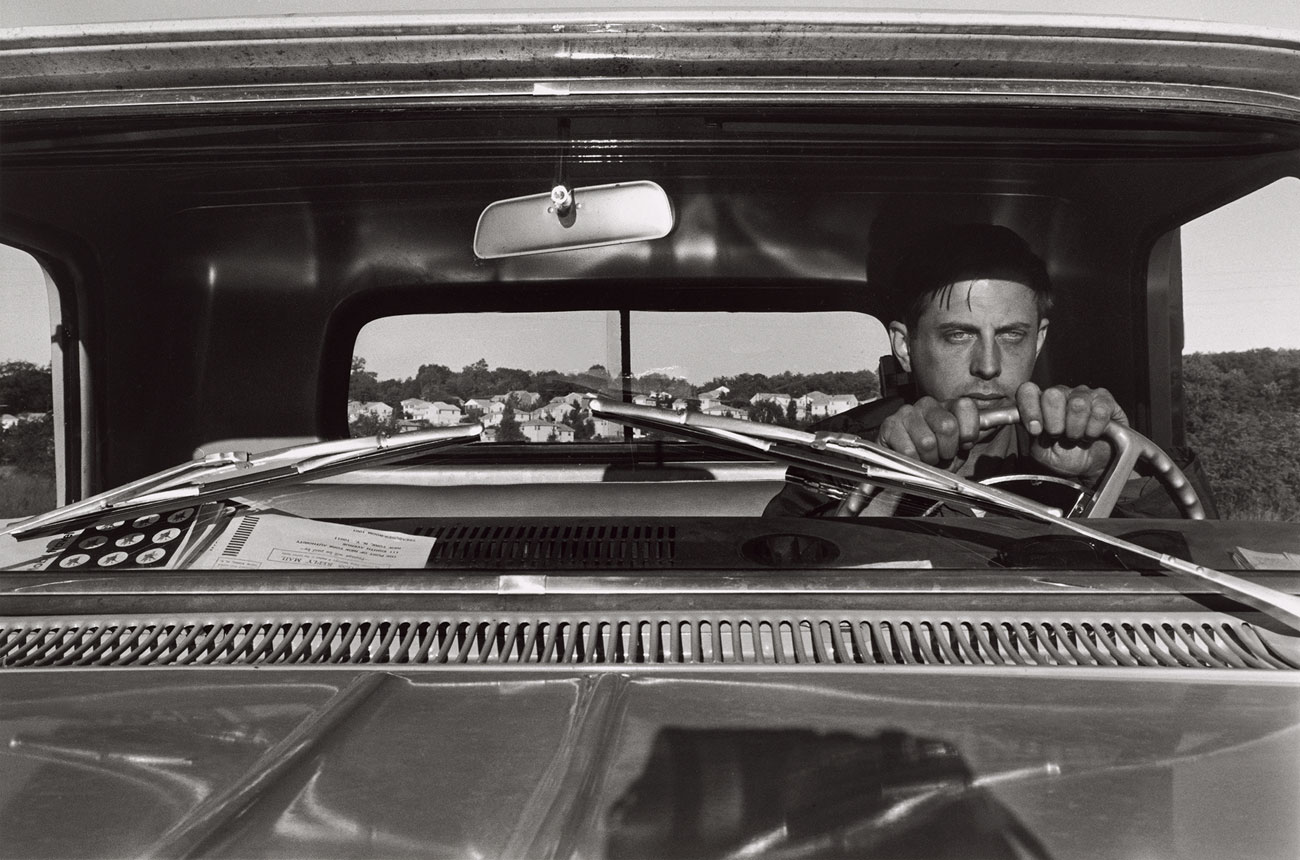

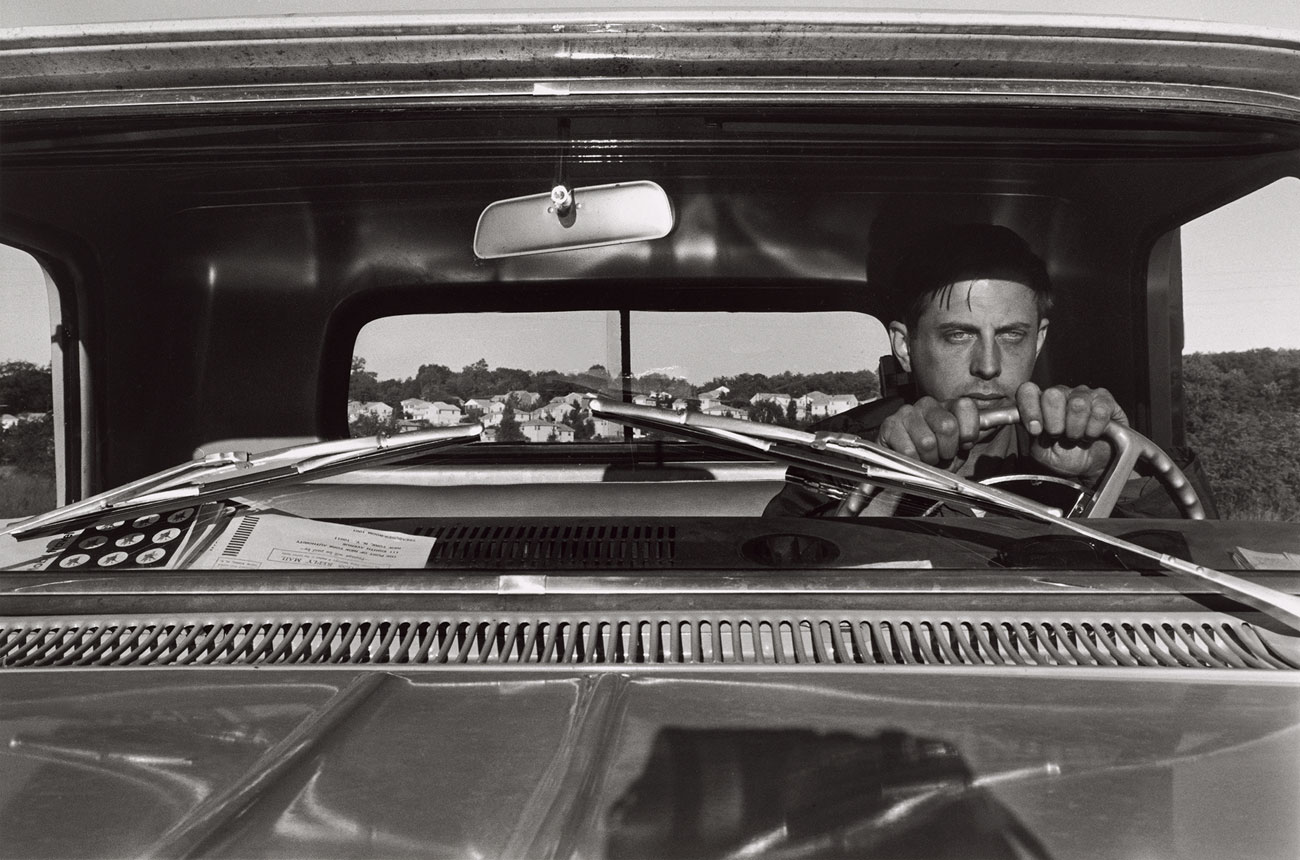

Even in self-portraits in which Friedlander makes himself fully visible to the camera, the artist often makes humorously self-deprecating deadpan images, appearing, for example, as a disheveled driver on a manic mission in Haverstraw, New York, 1966 (fig. 13, below). Edgy but unpretentious, brimming with pictorial detail, Friedlander’s self-portraits are visual puzzles that explore the place of the self in the chaos of contemporary urban life.

Text from the NGA website

Figure 12. Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

New York City

1966

Gelatin silver print

21.7 x 32.7cm (8 9/16 x 12 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Trellis Fund

© Lee Friedlander, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

Figure 13. Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

Haverstraw, New York

1966

Gelatin silver print

21.7 x 32.7cm (8 9/16 x 12 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Trellis Fund

© Lee Friedlander, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery

Ilse Bing (German, 1899-1998)

Self-Portrait with Leica

1931

Gelatin silver print, printed c. 1988

26.7 x 29.7cm (10 1/2 x 11 11/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of Ilse Bing Wolff

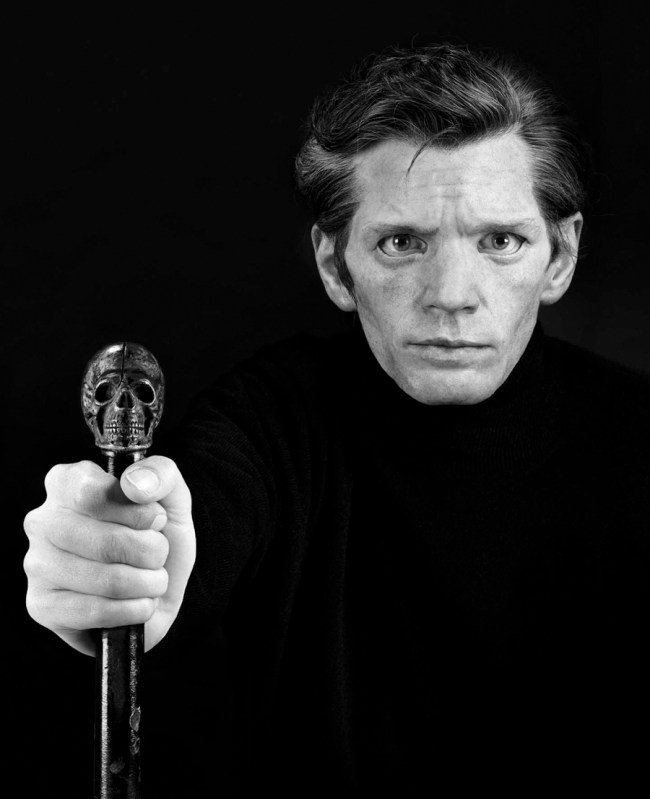

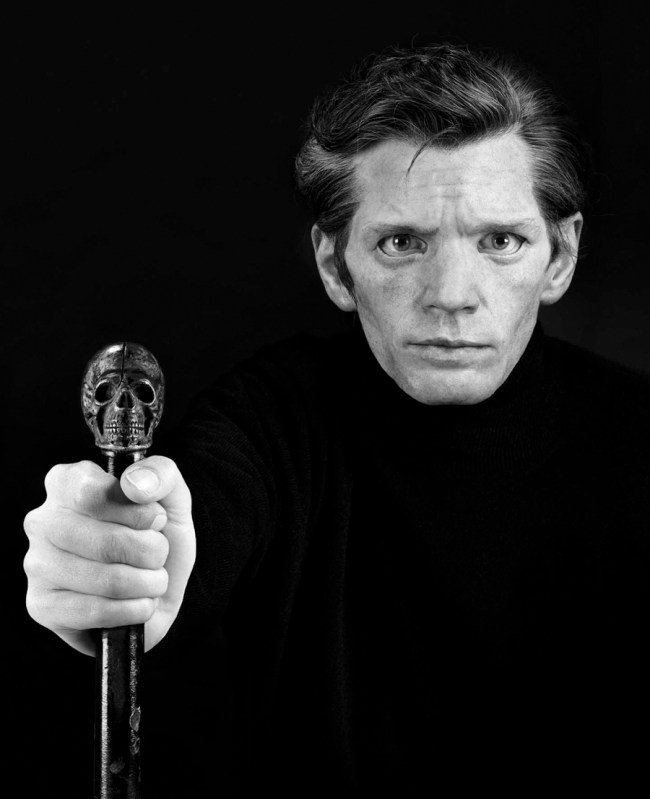

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

Me as Mapplethorpe

2009

Gelatin silver print (based upon Robert Mapplethorpe work: Self Portrait, 1988. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation)

149.86 x 121.92cm (59 x 48 in.)

Private Collection

Courtesy the artist; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York; Maureen Paley, London, Regen Projects, Los Angeles

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976)

Rebecca

1922

Platinum print

24.4 x 19.4cm (9 5/8 x 7 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Southwestern Bell Corporation Paul Strand Collection

© Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976)

Rebecca, New Mexico

1932

Platinum print

14.9 x 11.8cm (5 7/8 x 4 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Southwestern Bell Corporation Paul Strand Collection

© Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive

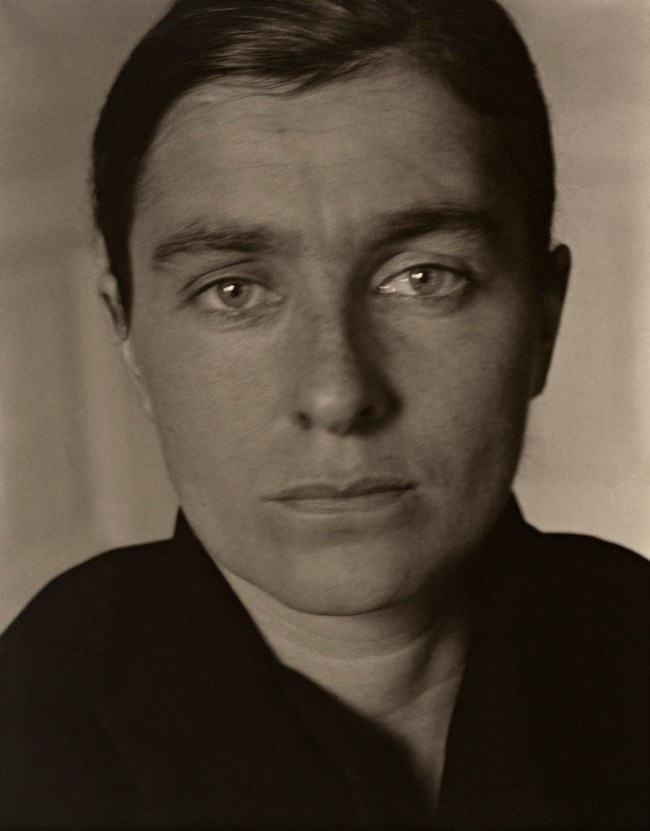

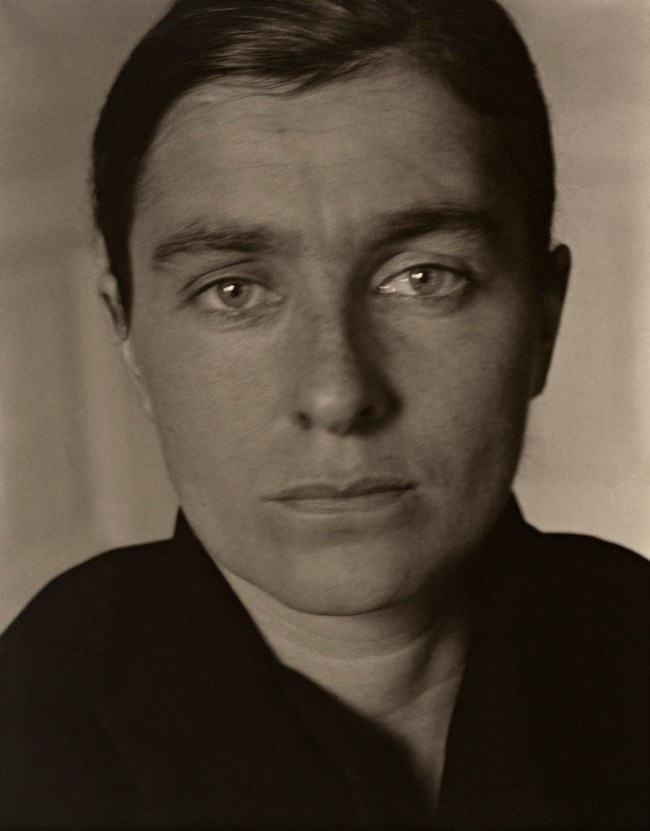

Figure 1. Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe

probably 1918

Platinum print

18.4 x 23.1cm (7 1/4 x 9 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) was already an accomplished photographer, publisher, and champion of modern art when he the first encountered the work of Georgia O’Keeffe in 1916. He made his first photographs of her in 1917 and sent them to her with the note, “I think I could do thousands

of things of you – a life work to express you.” Over the next two decades Stieglitz made more than three hundred photographs of O’Keeffe, whom he married in 1924, creating what he called a “composite portrait.” This extraordinary body of work charts the couple’s relationship and

expresses Stieglitz’s conviction that portraiture should function as a kind of “photographic diary.”

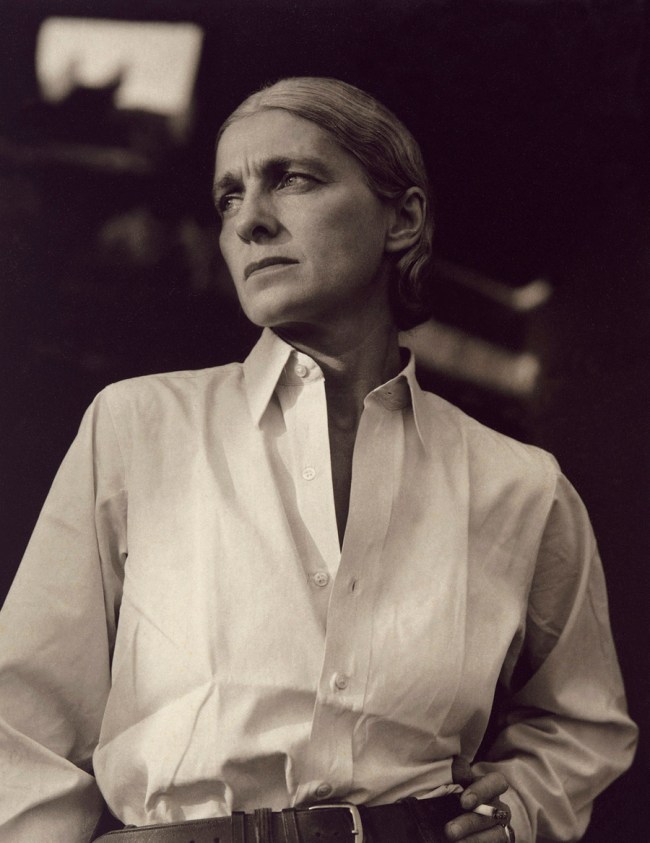

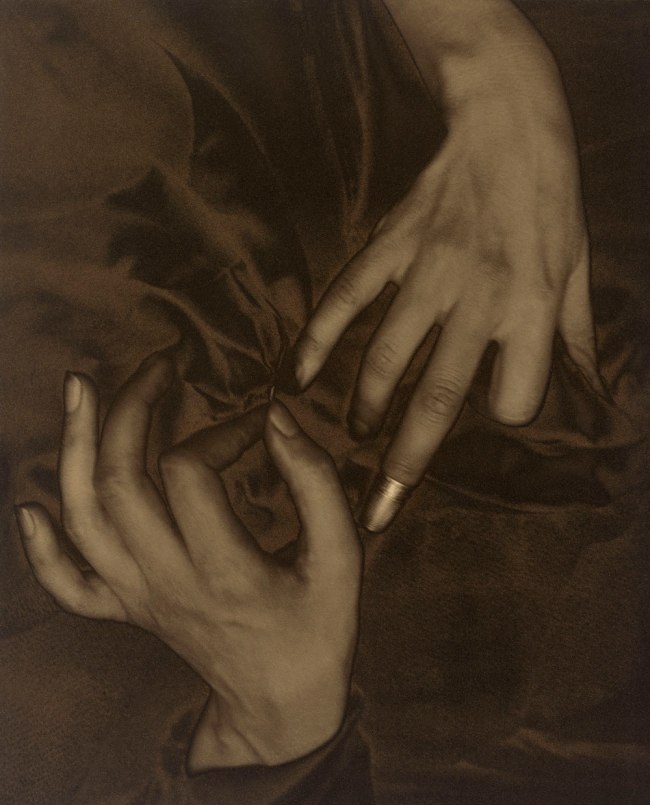

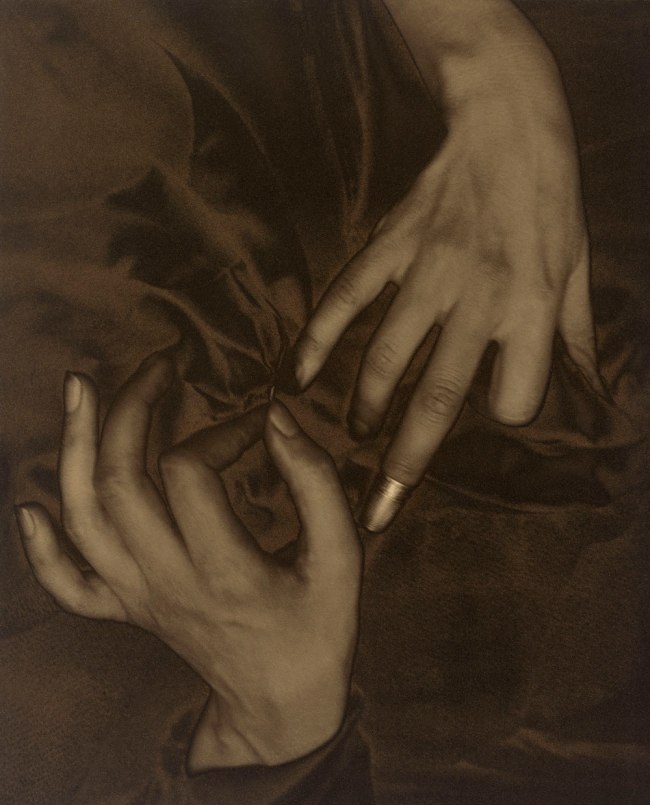

Many of the photographs Stieglitz made of O’Keeffe in the early years of their relationship, including Georgia O’Keeffe, c. 1918 (fig. 1, above), are palpably erotic, reflecting the intense passion they shared. Revealing herself to the lens with a bewitching vulnerability, O’Keeffe exudes a tenderness and seductiveness that belie the strain of holding the pose during the long exposures required by Stieglitz’s large-format camera. Often, his photographs express both his desire and admiration for O’Keeffe, at times verging on idealisation of the person he called “Nature’s child – a Woman.” Yet his portraits also look beyond her face to find eloquence in all

parts of her body, as in the print Georgia O’Keeffe – Hands and Thimble (fig. 2, below), where her hands display an almost tactile physicality. Here, Stieglitz used a printing technique that resulted in tonal reversal, causing deep shadows to print as bronze tones and creating the dark outlines that dramatise O’Keeffe’s graceful fingers and emphasise the metallic gleam of the thimble.

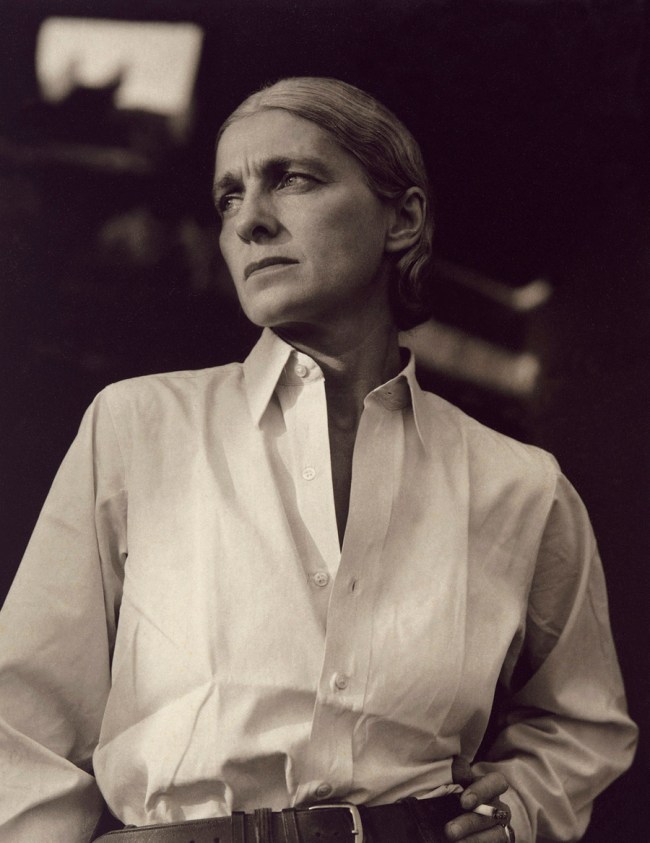

After Stieglitz exhibited more than forty portraits of O’Keeffe, including some provocative nudes, in 1921, the painter was dismayed to find that her own art began to be interpreted in a sexualised way, and she rarely posed unclothed after 1923. O’Keeffe’s desire to control her image, along with the increasingly attenuated nature of their relationship after 1929, when

she began spending several months a year working in New Mexico while he stayed in New York, further strained their partnership. In Georgia O’Keeffe, 1930 (fig. 3, below), the artist stands before one of the paintings she had made in New Mexico. Gazing steadily at the camera, she appears as a monumental force at one with her art, confident yet untouchable.

Text from the NGA website

Figure 2. Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe – Hands and Thimble

1919

Palladium print

24 x 19.4cm (9 7/16 x 7 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Figure 3. Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe

1930

Gelatin silver print

23.9 x 19.1cm (9 7/16 x 7 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters

1975

Gelatin silver print

20.2 x 25.2cm (7 15/16 x 9 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Patrons’ Permanent Fund

© Nicholas Nixon, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco and Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

The Brown Sisters

1978

Gelatin silver print

Promised gift of James and Margie Krebs

© Nicholas Nixon, courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

For more images from this series please see my posting Nicholas Nixon: Family Album

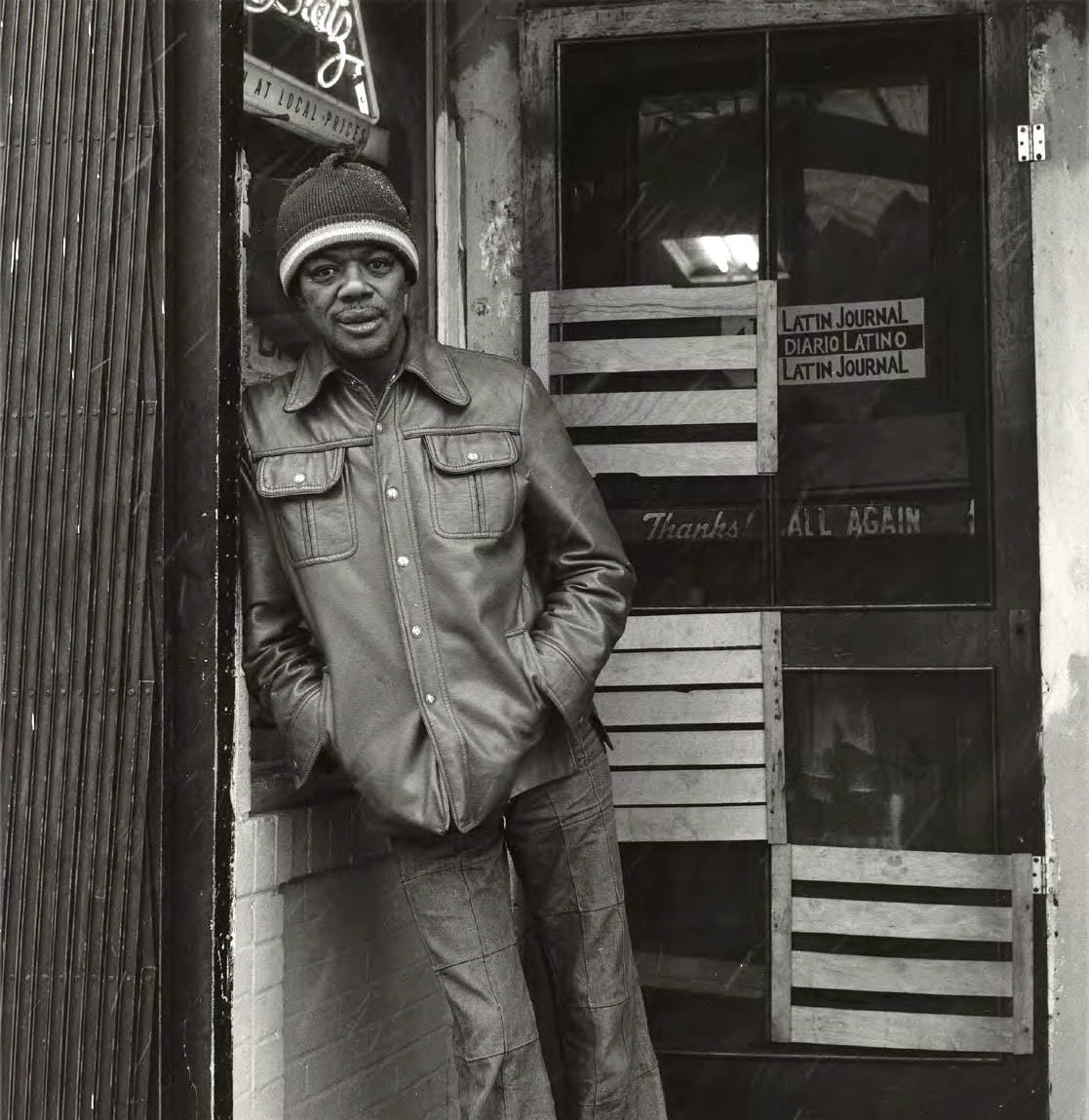

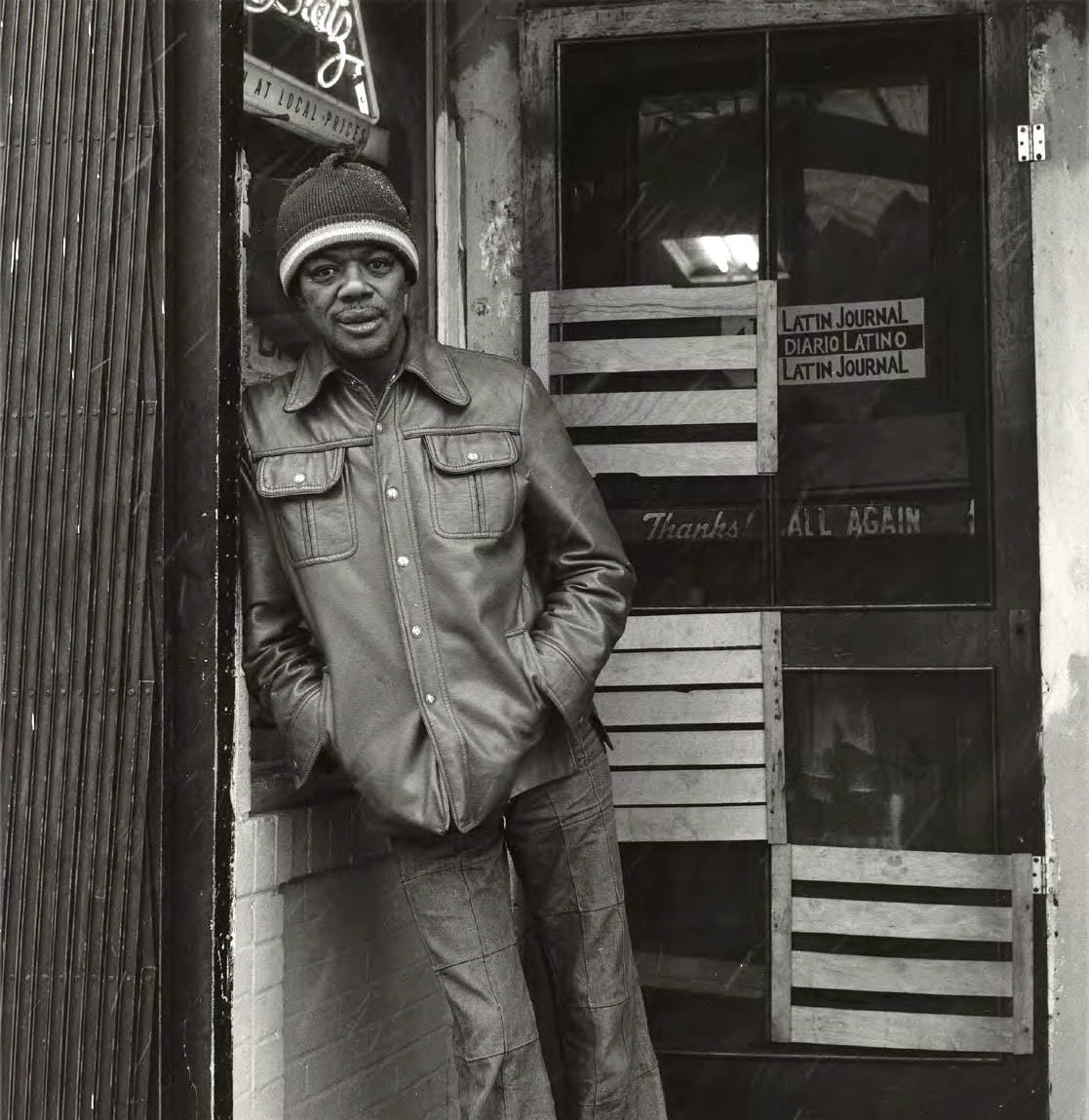

Figure 7. Milton Rogovin (American, 1909-2011)

Samuel P. “Pee Wee” West (Lower West Side series)

1974

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of Dr. J. Patrick and Patricia A. Kennedy

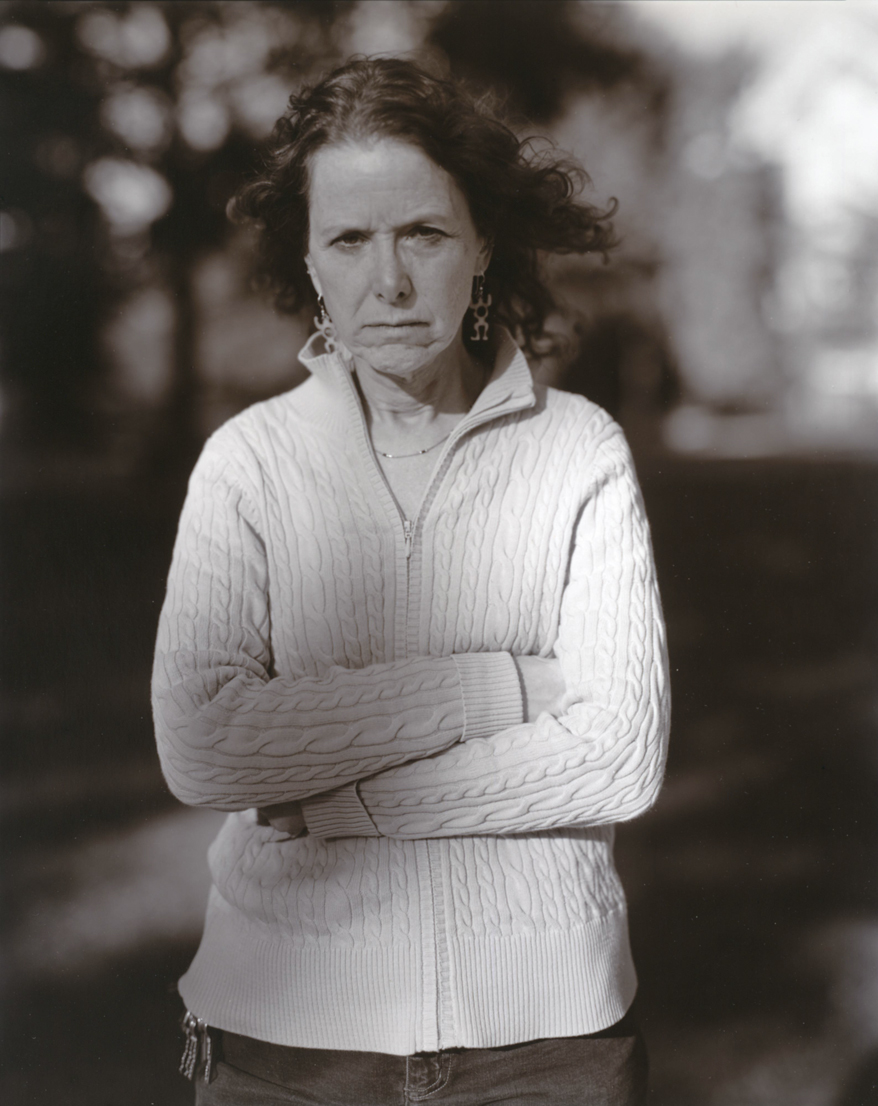

Milton Rogovin

Milton Rogovin (1909-2011) belongs to a rich photographic tradition of documenting the social and personal histories of people who would otherwise be forgotten. He did so serially, returning over many years to encapsulate not just single moments but entire lifetimes. Rogovin started his career as an optometrist in Buffalo, New York. In 1957, after he refused to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities about his association with the Communist Party, the local paper labeled him the “Top Red in Buffalo.” His optometry practice folded as a result, leaving his family of five to survive on the salary of his wife, Anne. With free time suddenly available, Rogovin turned to photography with a strong sense of purpose. “My voice was essentially silenced,” he recalled, “so I decided to speak out through photographs.”

Rogovin’s candid, powerfully direct pictures gave voice to those who traditionally had none: immigrants, minorities, and working-class people. Even though he traveled around the world making photographs of workers, his best-known work was made closer to home. In 1972 he began photographing residents of Buffalo’s Lower West Side, the city’s poorest

and most ethnically diverse neighbourhood. With his bulky twin-lens Rolleiflex camera, the photographer was sometimes suspected of working for the police or the FBI. Over time, however, Rogovin gained the trust of his sitters by visiting regularly and by giving them prints of their portraits. Dignified and occasionally tender, these photographs depict the circumstances of each subject with sober honesty.

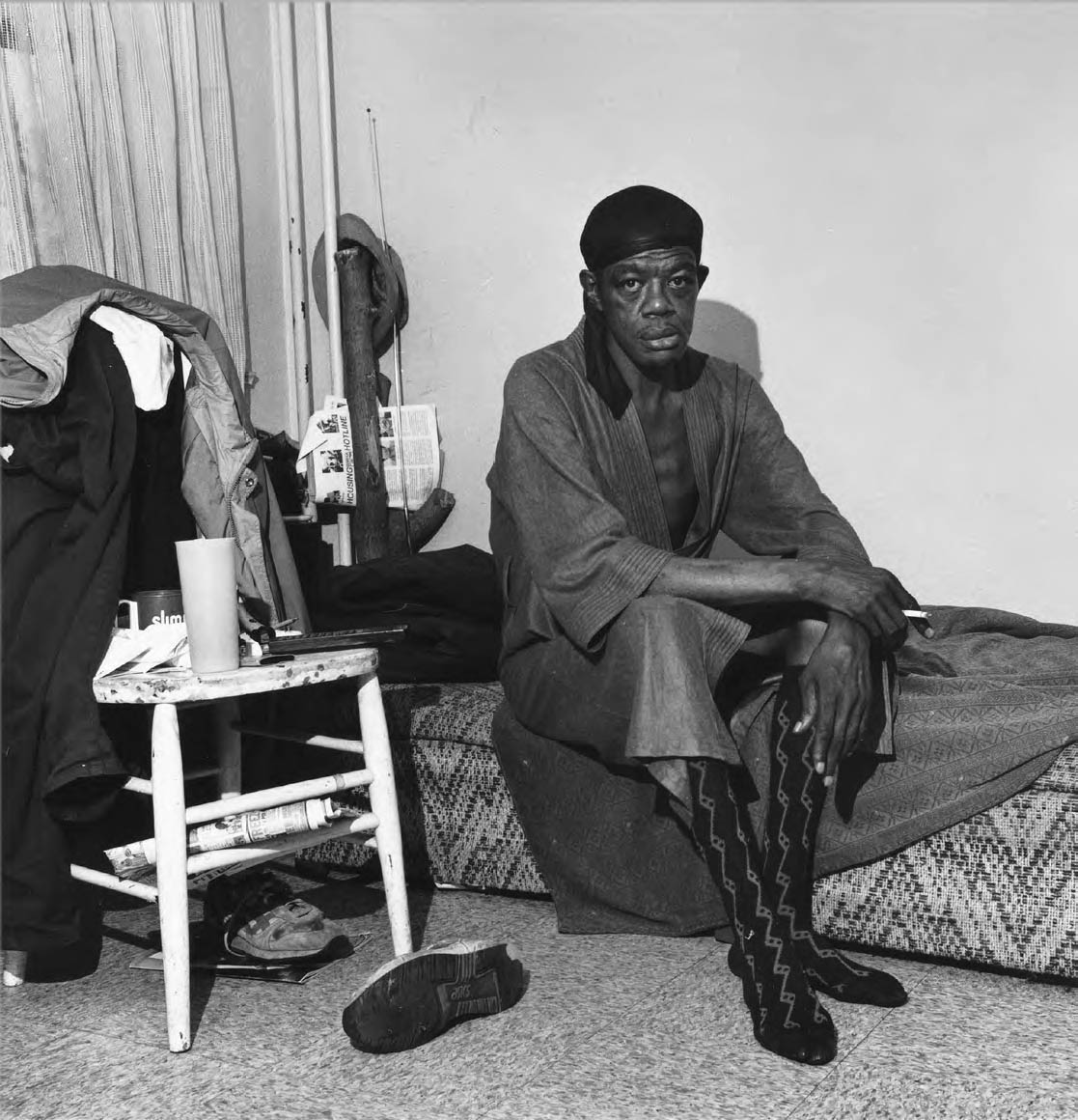

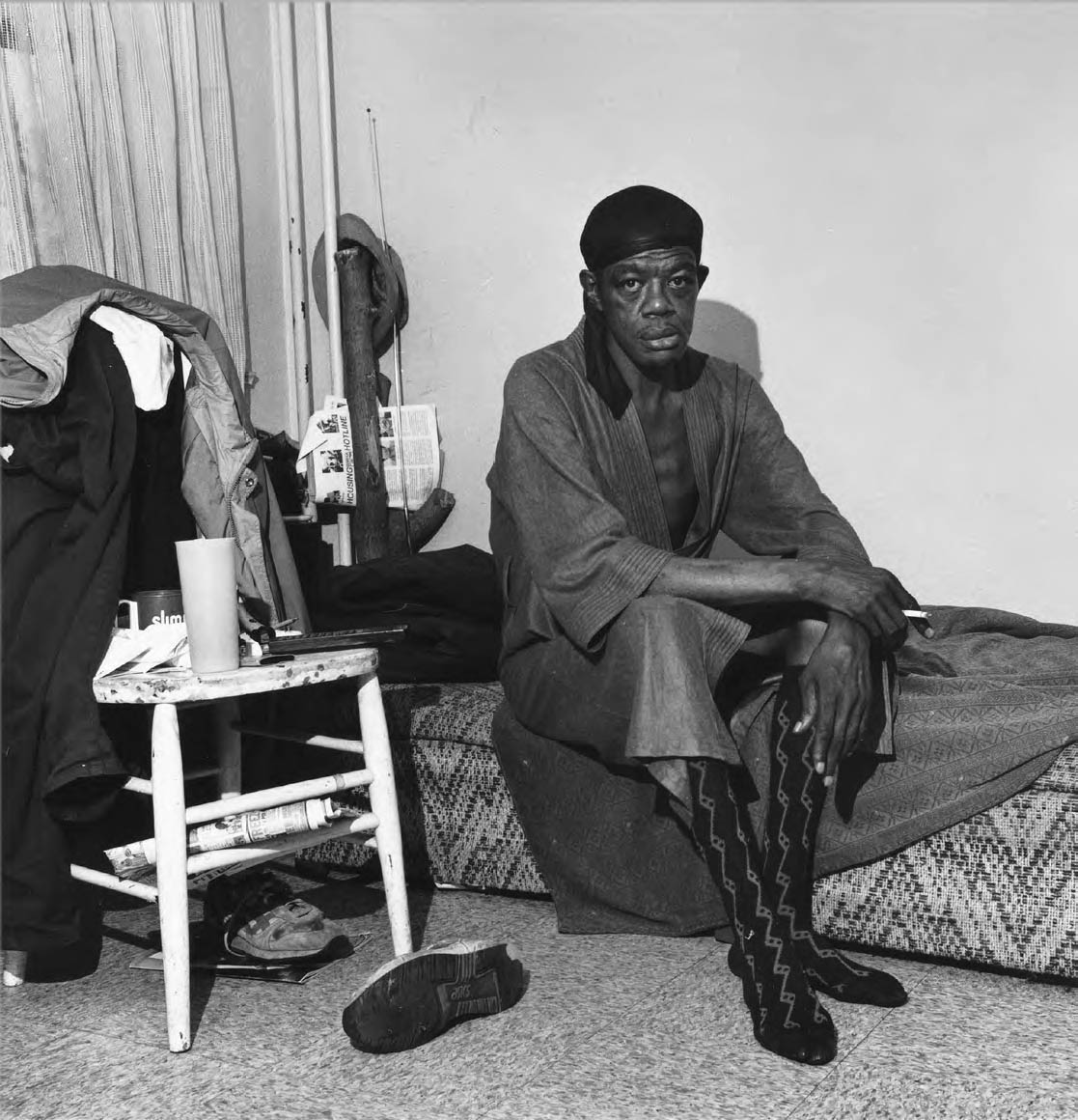

Several times over the next three decades, Rogovin sought out and re-photographed many of his original subjects, capturing the changes wrought by time and circumstance. The series Samuel P. “Pee Wee” West (figs. 7-10) registers changes in the sitter’s situation over the course of twenty-eight years, from 1974 to 2002. In 2003 the oral historian Dave Isay, working

alongside Rogovin, interviewed West, who related the story of his decades of heavy drinking. Reflecting on a photograph Rogovin had made of him in 1985 (fig. 8), West said, “That… picture actually changed my life”; it prompted him to stop drinking for six months before relapsing. A later brush with death led to permanent recovery and the founding of a program to help local youth reject drugs and alcohol. In this and other serial portraits, Rogovin honoured the everyday lives of his subjects, offering a powerful visual legacy of a community he respected and loved.

Text from the NGA website

Figure 8. Milton Rogovin (American, 1909-2011)

Samuel P. “Pee Wee” West (Lower West Side series)

1985

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gft of Dr. J. Patrick and Patricia A. Kennedy

Figure 9. Milton Rogovin (American, 1909-2011)

Samuel P. “Pee Wee” West (Lower West Side series)

1992

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gft of Dr. J. Patrick and Patricia A. Kennedy

Figure 10. Milton Rogovin (American, 1909-2011)

Samuel P. “Pee Wee” West (Lower West Side series)

2002

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of Dr. J. Patrick and Patricia A. Kennedy

National Gallery of Art

National Mall between 3rd and 7th Streets

Constitution Avenue NW, Washington

Opening hours:

Daily 11.00am – 4.00pm

National Gallery of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) [Farmer, Westerwald (Bauer, Westerwald)] 1910 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) [Farmer, Westerwald (Bauer, Westerwald)] 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/sander-farmer.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.