Exhibition dates: 3rd April – 26th August 2012

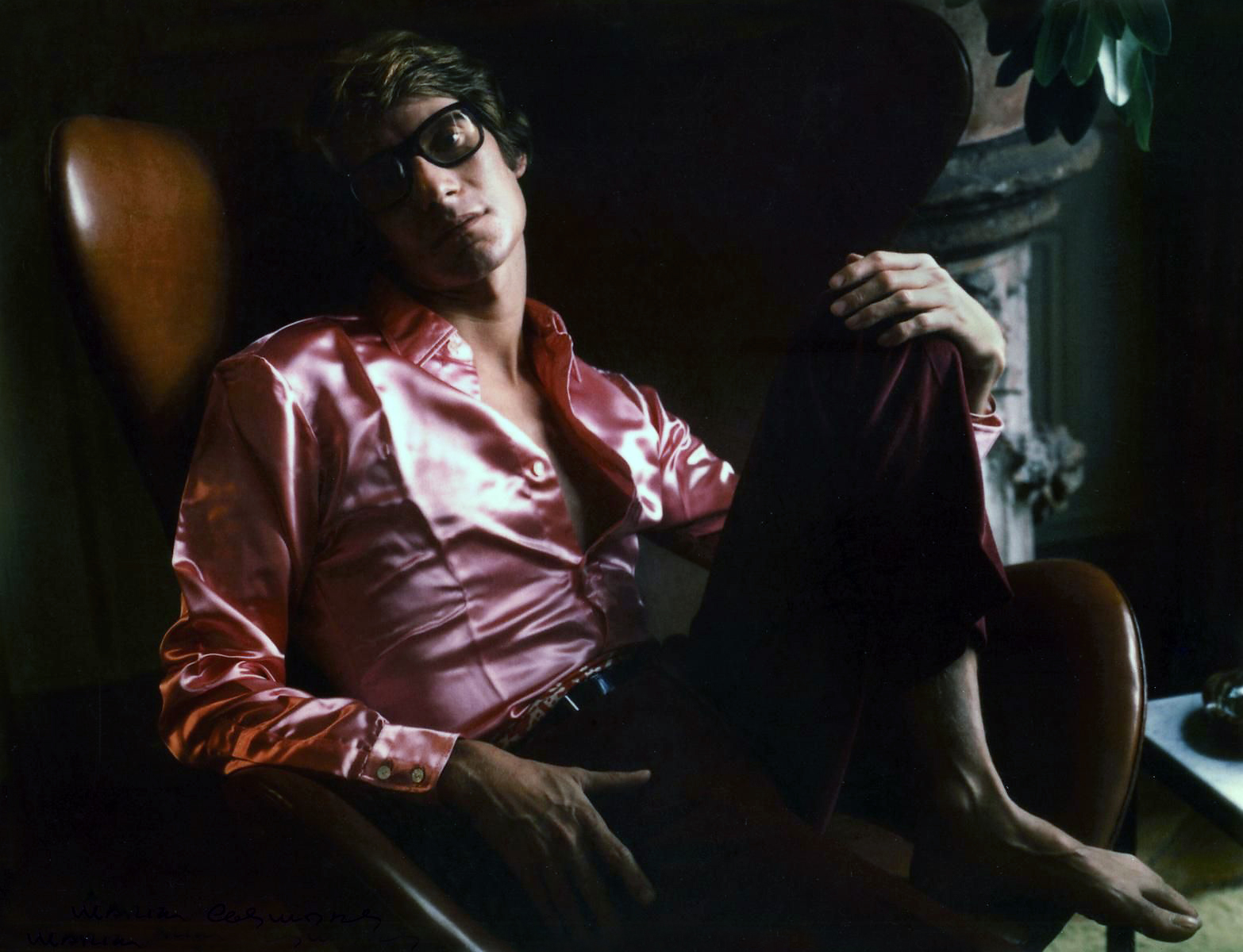

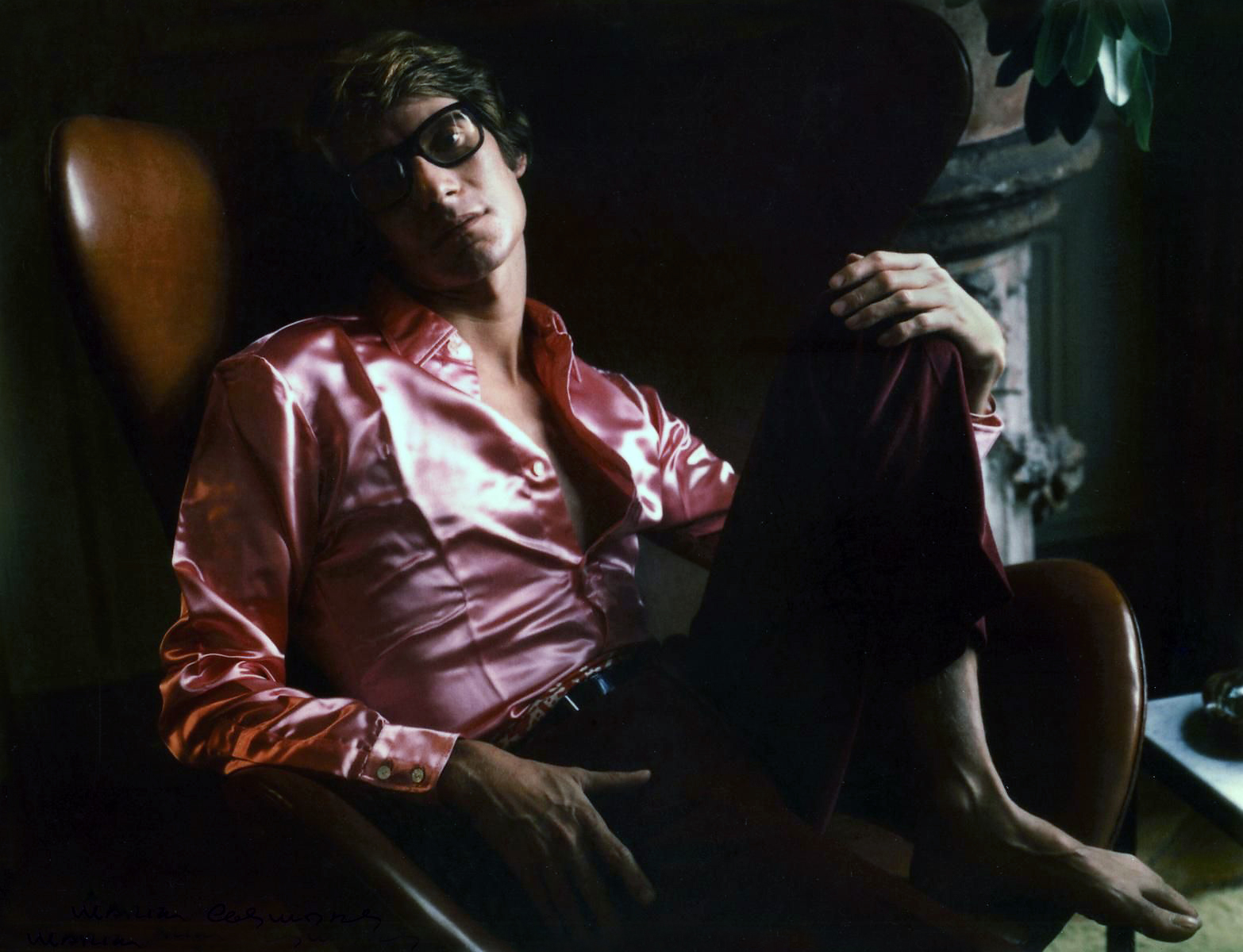

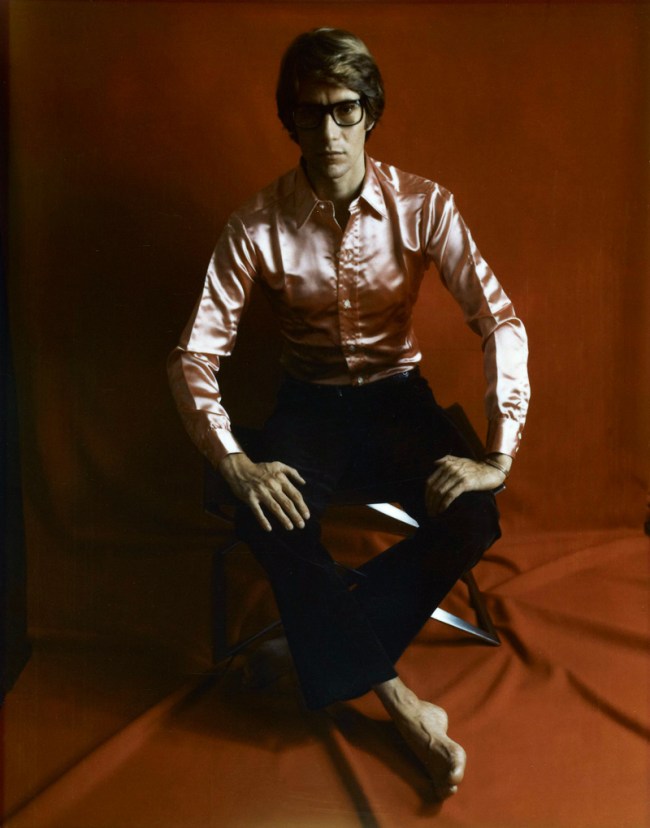

Marie Cosindas (American, 1925-2017)

Yves Saint Laurent, Paris

1968

Dye colour diffusion [Polaroid ®] print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Marie Cosindas

On the Nature of Photography

“To get from the tangible to the intangible (which mature artists in any medium claim as part of their task) a paradox of some kind has frequently been helpful. For the photographer to free himself of the tyranny of the visual facts upon which he is utterly dependent, a paradox is the only possible tool. And the talisman paradox for unique photography is to work “the mirror with a memory” as if it were a mirage, and the camera is a metamorphosing machine, and the photograph as if it were a metaphor… Once freed of the tyranny of surfaces and textures, substance and form [the photographer] can use the same to pursue poetic truth.”

Minor White quoted in Beaumont Hewhall (ed.,). The History of Photography. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1982, p. 281

“Carol Jerrems and I taught at the same secondary school in the 1970’s. In a classroom that was unused at that time, I remember having my portrait taken by her. She held her Pentax to her eye. Carols’ portraits all seemed to have been made where the posing of her subjects was balanced by an incisive naturalness (for want of a better description). As a challenge to myself I tried to look “natural”, but kept in my consciousness that I was having my portrait taken. Minutes passed and neither she nor her camera moved at all.

Then the idea slipped from my mind for just a moment, and I was straightaway bought back by the sound of the shutter. What had changed in my face? – probably nothing, or 1 mm of muscle movement. Had she seen it through the shutter? Or something else – I don’t know.”

Australian artist Ian Lobb on being photographed by the late Carol Jerrems

There is always something that you can’t quite put your finger on in an outstanding portrait, some ineffable other that takes the portrait into another space entirely. I still haven’t worked it out but my thoughts are this: forget about the pose of the person. It would seem to me to be both a self conscious awareness by the sitter of the camera and yet at the same time a knowing transcendence of the visibility of the camera itself. In great portrait photography it is almost as though the conversation between the photographer and the person being photographed elides the camera entirely. Minor White, in his three great mantras, the Three Canons, observes:

Be still with yourself

Until the object of your attention

Affirms your presence

Let the Subject generate its own Composition

When the image mirrors the man

And the man mirrors the subject

Something might take over

Freed from the tyranny of the visual facts something else emerges.

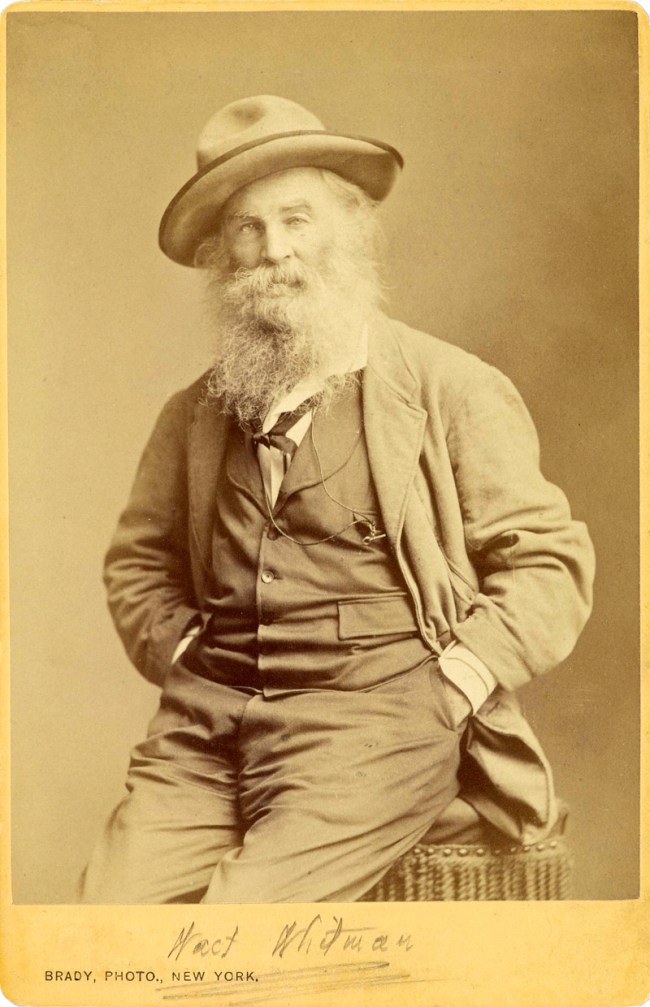

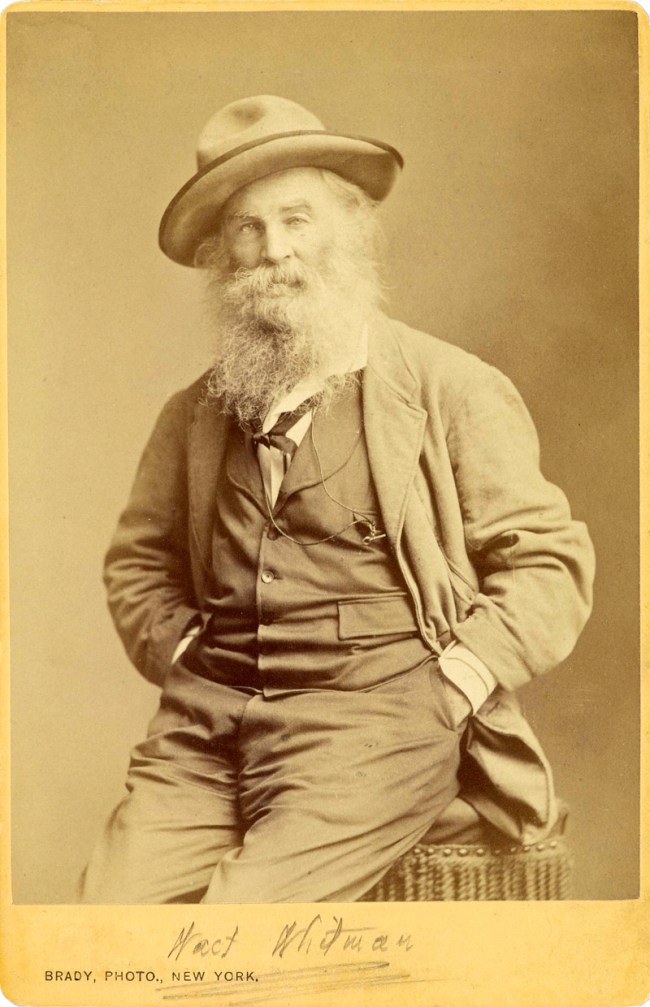

Celebrities know only too well how to “work” the camera but the most profound portraits, even of celebrities, are in those moments when the photographer sees something else in the person being photographed, some unrecognised other that emerges from the shadows – a look, a twist of the head, the poignancy of the mouth, the vibrancy of the dancer Josephine Baker, the sturdiness of the gaze of Walt Whitman with hands in pockets, the presence of the hands (no, not the gaze!) of Picasso. I remember taking a black and white portrait of my partner Paul holding a wooden finial like a baby among some trees, a most beautiful, revealing photograph. He couldn’t bear to look at it, for it stripped him naked before the lens and showed a side of himself that he had never seen before: vulnerable, youthful, beautiful.

Why do great portrait photographers make so many great portraits? Why can’t this skill be shared or taught? Why can’t Herb Ritts (for example) make a portrait that goes beyond a caricature? Why is it that what can be taught is so banal that it has no value?

In photography, maybe we edit out what is expected and then it seems that photography does something that goes beyond language; it goes beyond function that can be described as a part of speech, metonym or metaphor. When this something else takes over I think it is truly “unrecognised” in the best portraits (and landscape / urban photographs) – and it is fantastic and wonderful.

This is my understanding, then, of perception and vision (when spirit takes over) – [which is] the ability to see this certain something in the mind (previsualisation) before seeing it through the viewfinder and to then be able to reveal it in the physicality of the print. It is a liminal moment in time and space.

I believe this is the reality of photography itself in its absolute essential form – and here I am deliberately forgetting about post-photography, post-modernism, modernism, pictorialism, ism, ism – getting down to why I really like photography:

the BEYOND visualisation of a world, the transcendence of time and space that leads, in great photographs, to a recognition of the discontinuous nature of life but in the end, to its ultimate persistence.

This is as close as I have got so far…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

August 2012

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photograph for a larger version of the image.

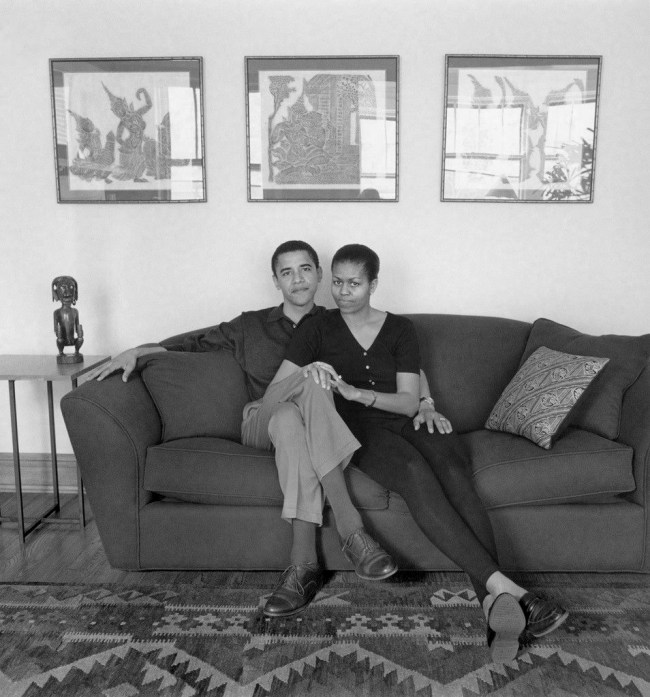

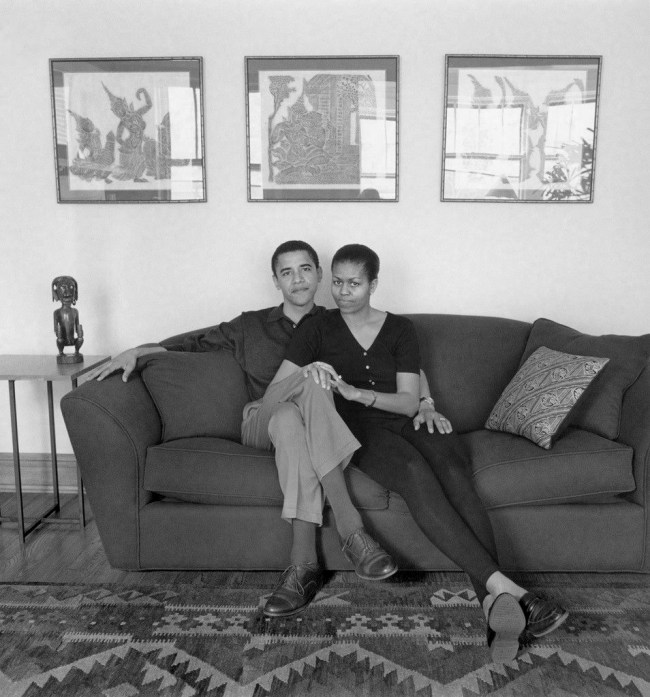

Mariana Cook (American, b. 1955)

Barack and Michelle Obama, Chicago

May 26, 1996

Selenium-toned gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

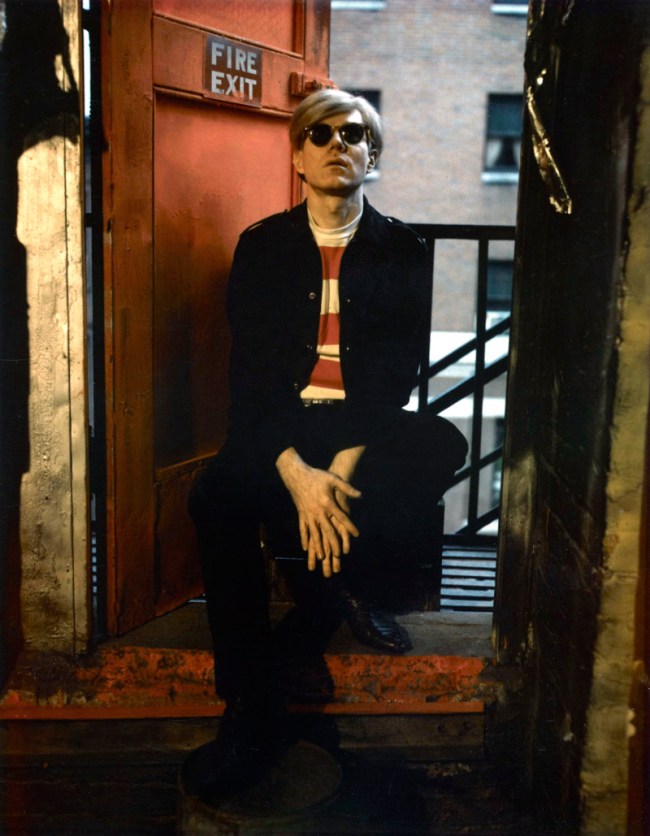

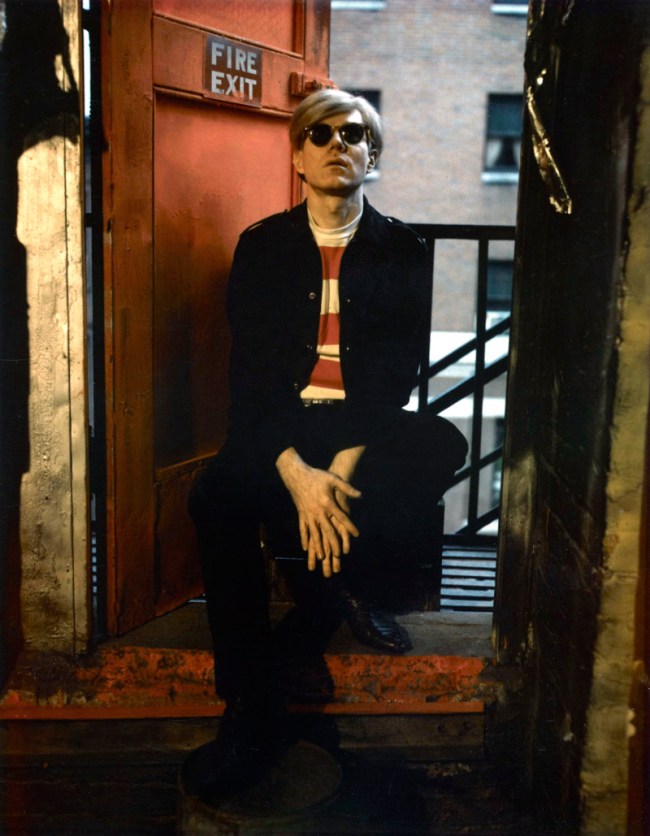

Marie Cosindas (American, 1925-2017)

Andy Warhol

1966

Dye colour diffusion [Polaroid ®] print

11.4 x 8.9cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Marie Cosindas

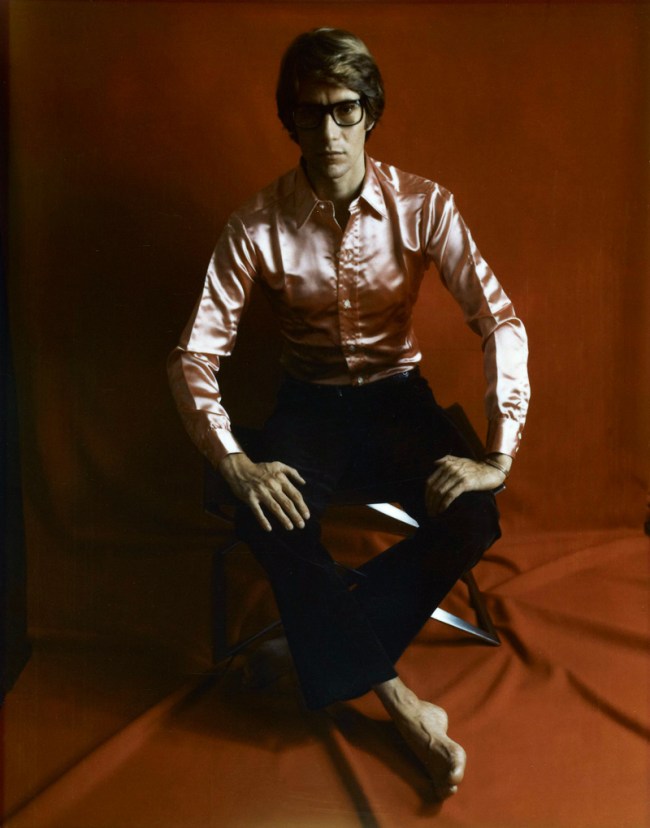

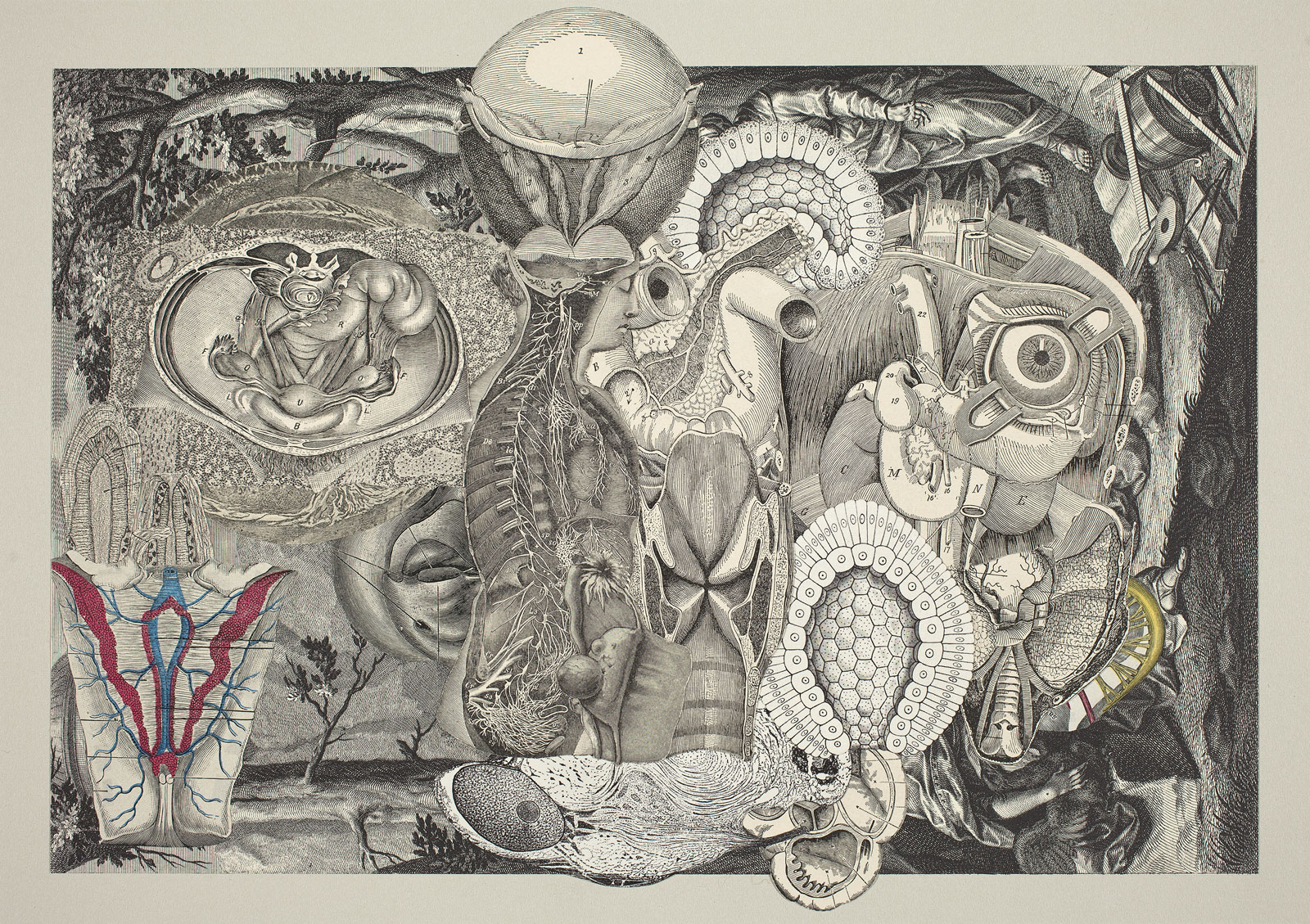

Marie Cosindas (American, 1925-2017)

Yves St Laurent

1968

Dye colour diffusion [Polaroid ®] print

11.4 x 8.9cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Marie Cosindas

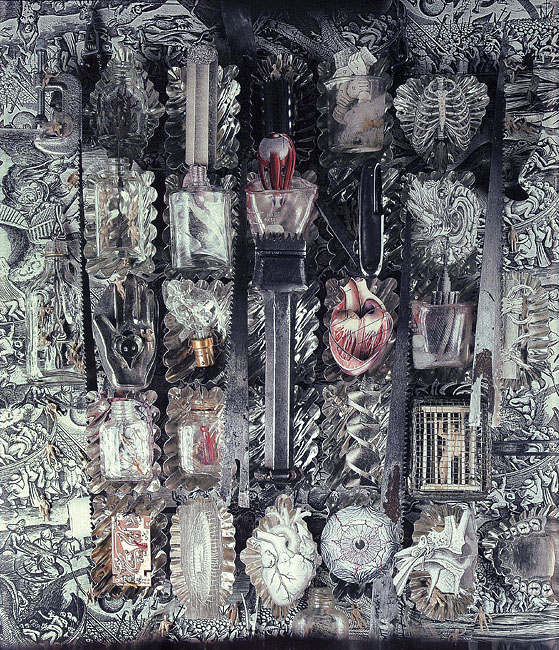

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Grace Jones

1984

Polaroid Polacolor print

9.5 x 7.3cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© 2011 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

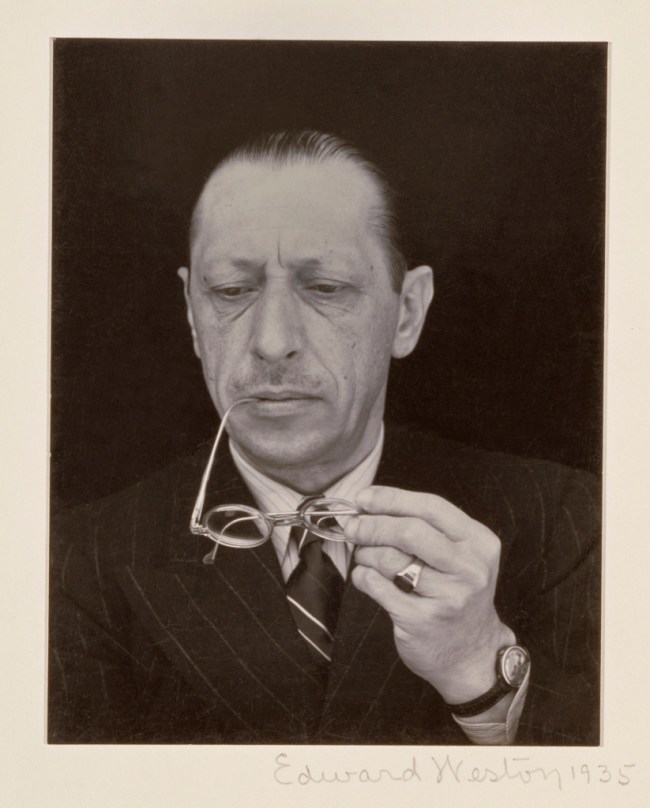

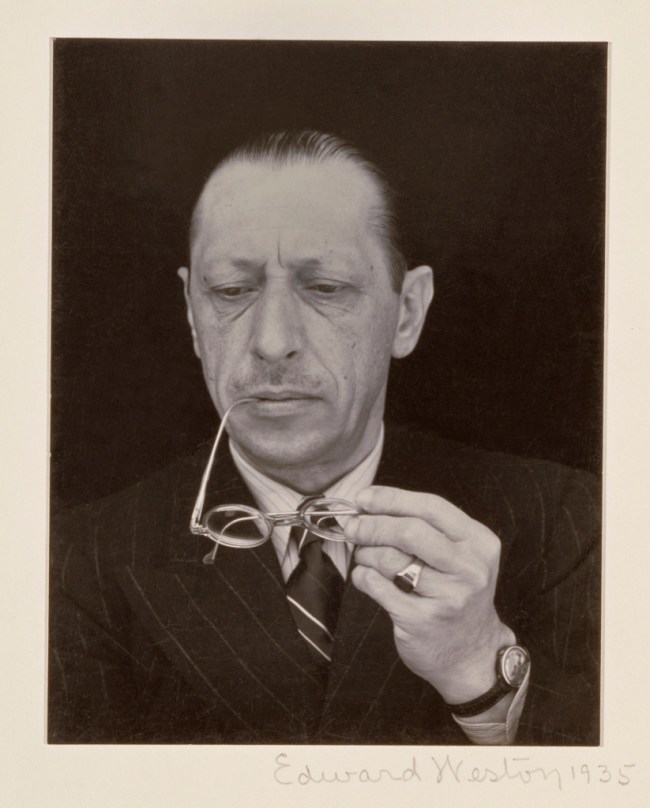

Edward Weston (American, 1889-1958)

Igor Stravinsky

1935

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

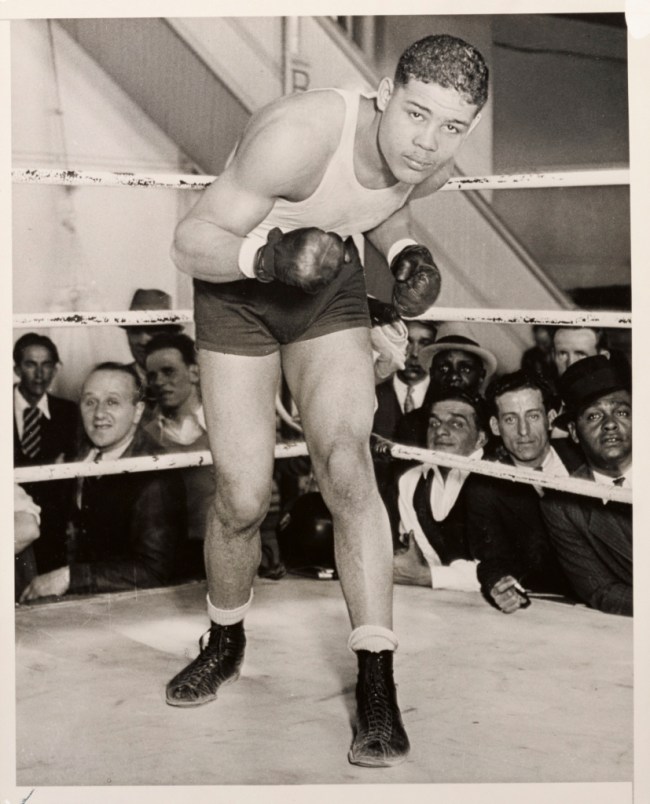

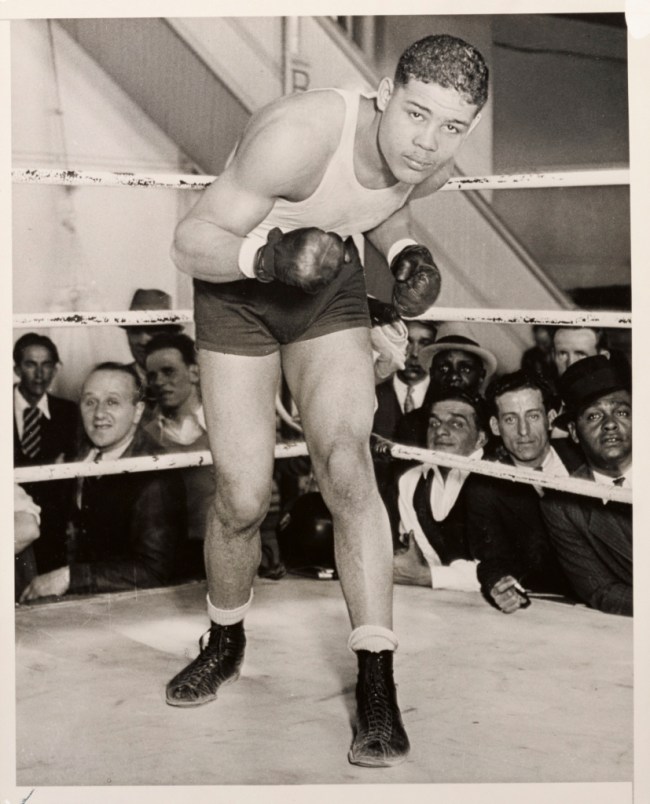

Coy Watson Jr. (American, 1912-2009)

Joe Louis – “The Brown Bomber”, Los Angeles, February 1935

1935

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Edward Steichen (American, 1879-1973)

Gloria Swanson

1924

Gelatin silver print

27.8 x 21.6cm (10 15/16 x 8 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Permission Joanna T. Steichen

Portraits of Renown surveys some of the visual strategies used by photographers to picture famous individuals from the 1840s to the year 2000. “This exhibition offers a brief visual history of famous people in photographs, drawn entirely from the Museum’s rich holdings in this genre,” says Paul Martineau, curator of the exhibition and associate curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum. “It also provides a broad historical context for the work in the concurrent exhibition Herb Ritts: L.A. Style, which includes a selection of Ritts’s best celebrity portraits.”

Photography’s remarkable propensity to shape identities has made it the leading vehicle for representing the famous. Soon after photography was invented in the 1830s, it was used to capture the likenesses and accomplishments of great men and women, gradually supplanting other forms of commemoration. In the twentieth century, the proliferation of photography and the transformative power of fame have helped to accelerate the desire for photographs of celebrities in magazines, newspapers, advertisements, and on the Internet. The exhibition is arranged chronologically to help make visible some of the overarching technical and stylistic developments in photography from the first decade of its invention to the end of the twentieth century.

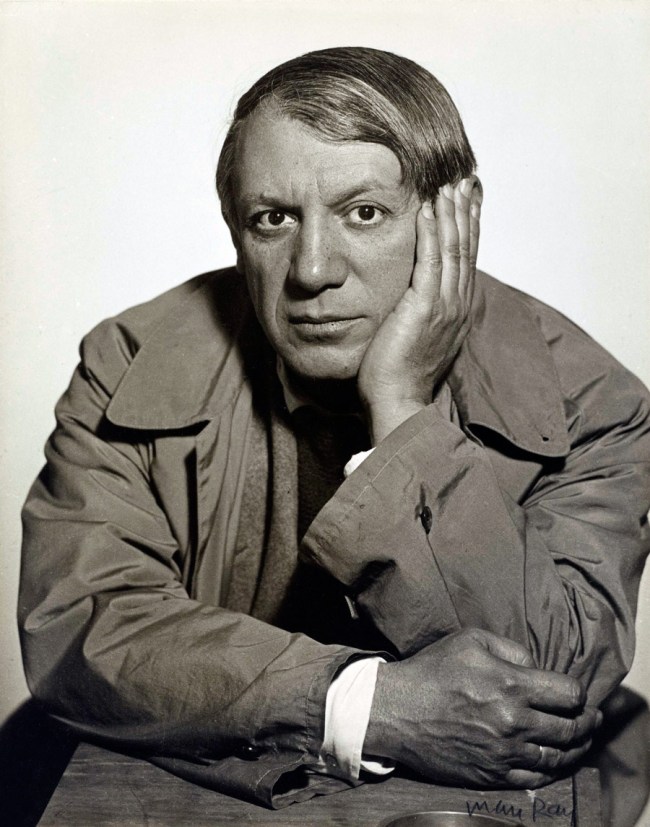

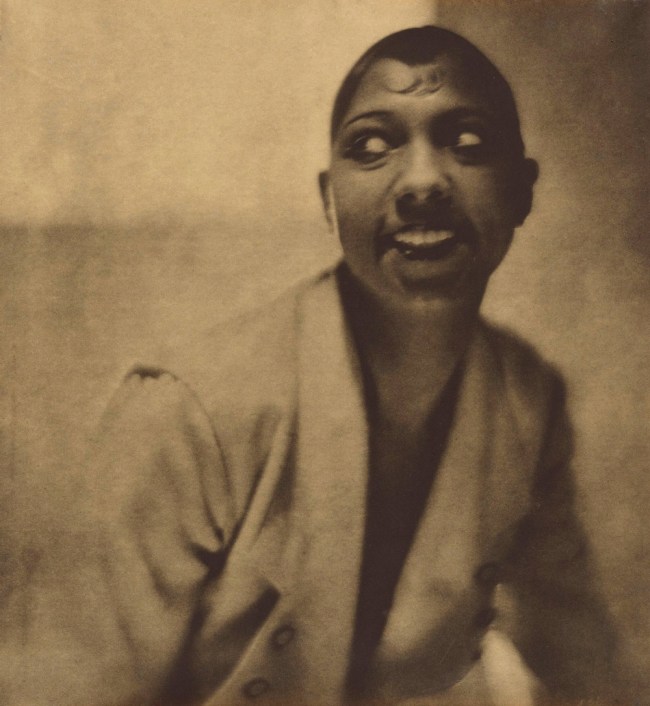

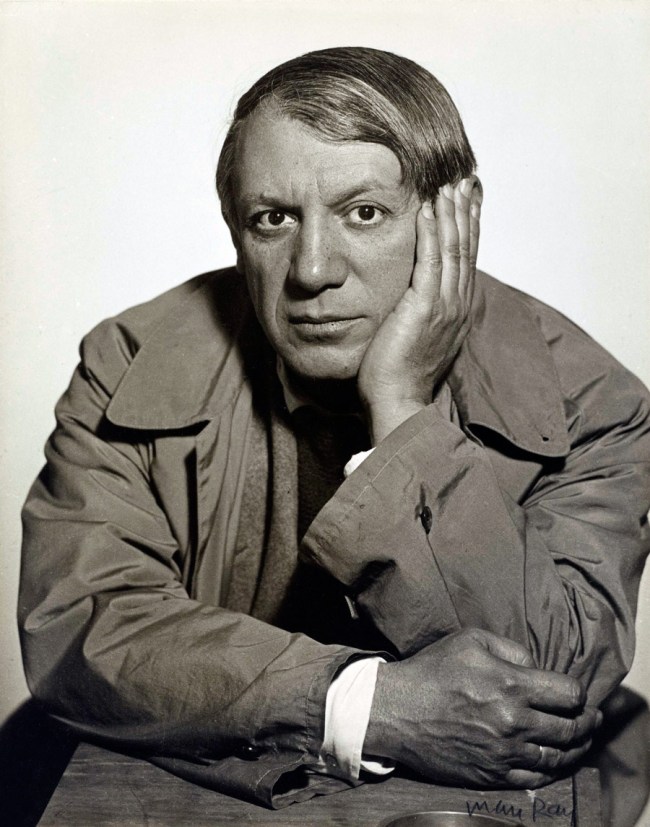

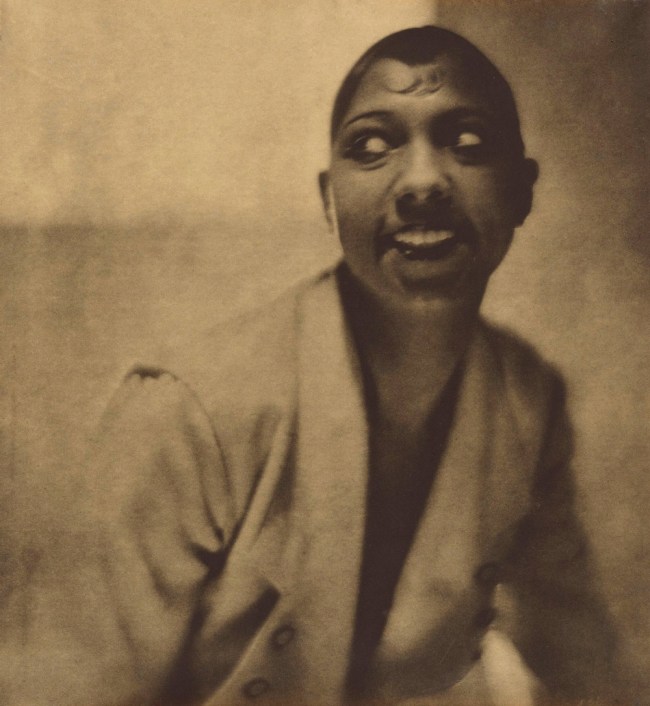

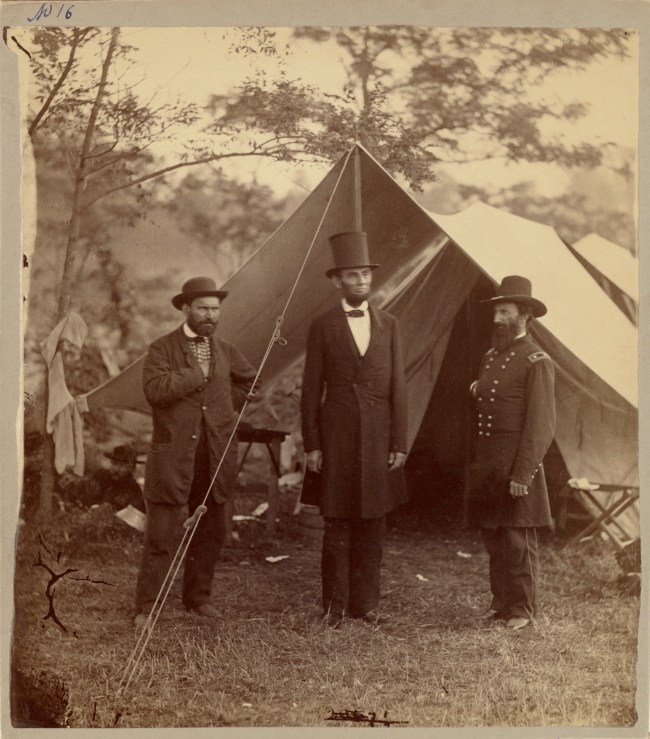

A wide range of historical figures are portrayed in Portraits of Renown. A photograph by Alexander Gardner of President Lincoln documents his visit to the battlefield of Antietam during the Civil War. Captured by Nadar, a portrait of Alexander Dumas, best known for his novels The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers, shows the author with an energetic expression, illustrating the lively personality that made his writing so popular. Baron Adolf De Meyer’s portrait of Josephine Baker, an American performer who became an international sensation at the Folies Bergère in Paris, showcases her comedic charm, a trait that proved central to her popularity as a performer. An iconic portrait of the silent screen actress, Gloria Swanson, created by Edward Steichen for Vanity Fair reveals both the intensity of its sitter and the skill of the artist. A picture of Pablo Picasso by his friend Man Ray portrays the master of Cubism with a penetrating gaze.

Yves St. Laurent, Andy Warhol, and Grace Jones are among the contemporary figures included in the exhibition. Fashion designer Yves St. Laurent was photographed by Marie Cosindas using instant color film by Polaroid. The photograph, made the year his first boutique in New York opened, graced the walls of the store for ten years. A Cosindas portrait of Andy Warhol shows the artist wearing dark sunglasses, which partially conceal his face. Warhol, who was fascinated by celebrity, delighted in posing public personalities like Grace Jones for his camera.

Press release from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Pablo Picasso

1934

Gelatin silver print

25.2 x 20cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Man Ray Trust ARS-ADAGP

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

James Joyce

1928

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Baron Adolf De Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

Portrait of Josephine Baker

1925

Collotype print

39.1 x 39.7cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In 1925 Josephine Baker, an American dancer from Saint Louis, Missouri, made her debut on the Paris stage in La Revue nègre (The Black Review) at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, wearing nothing more than a skirt of feathers and performing her danse sauvage (savage dance). She was an immediate sensation in Jazz-Age France, which celebrated her perceived exoticism, quite the opposite of the reception she had received dancing in American choruses. American expatriate novelist Ernest Hemingway called Baker “the most sensational woman anybody ever saw – or ever will.”

Baron Adolf de Meyer, a society and fashion photographer, took this playful portrait in the year of Baker’s debut. Given the highly sexual nature of her stage persona, this portrait is charming and almost innocent; Baker’s personality is suggested by her face rather than her famous body.

Text from the J. Paul Getty website

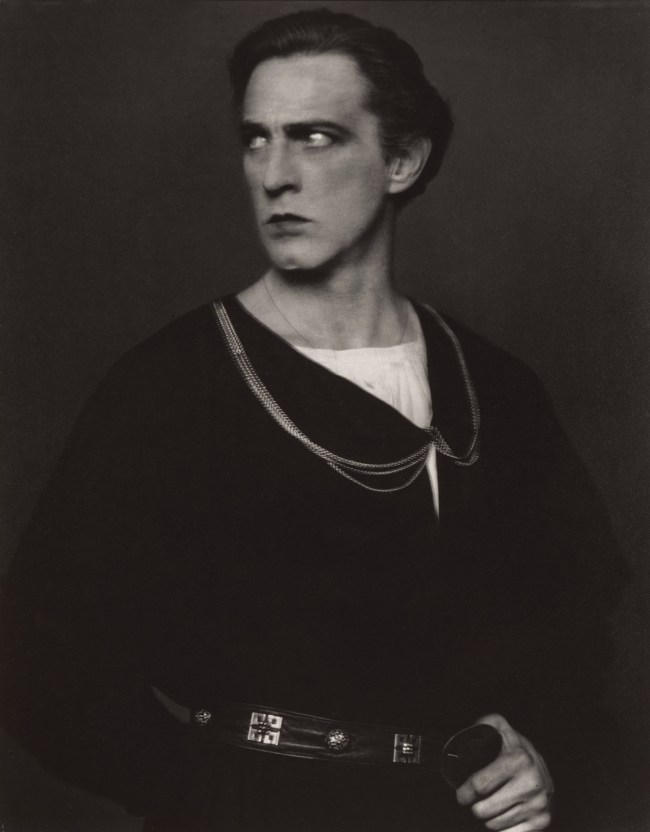

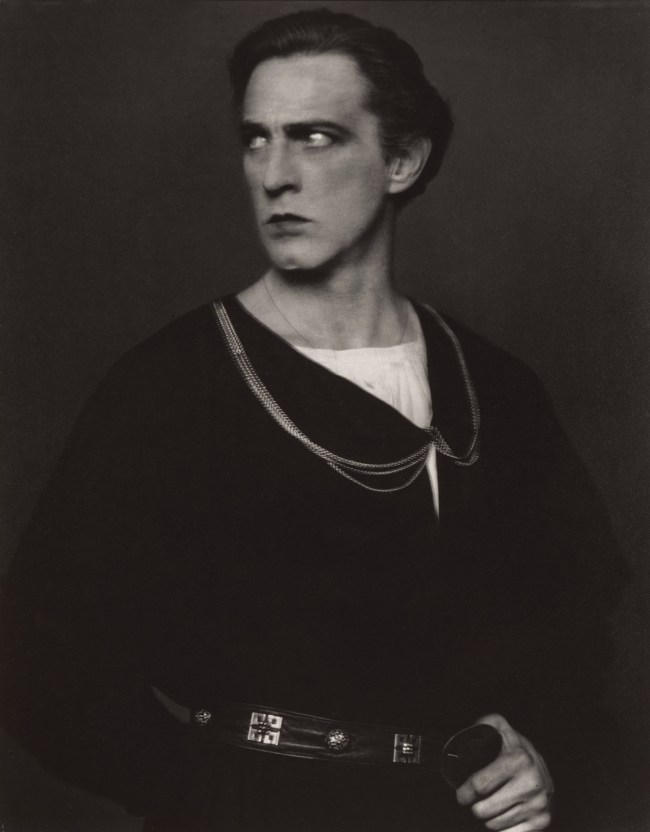

Edward Steichen (American, 1879-1973)

John Barrymore as Hamlet

1922

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1964-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe: A Portrait

1918

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Arnold Genthe (American born Germany, 1869-1942)

Anna Pavlowa

about 1915

Gelatin silver print

33.5 × 25.2cm (13 3/16 × 9 15/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The Russian ballerina Anna Pavlowa (or Pavlova) so greatly admired Arnold Genthe’s work that she made the unusual decision to visit his studio, rather than have him come to her rehearsals. The resulting portrait of the prolific dancer, leaping in mid-air, is the only photograph to capture Pavlowa in free movement. Genthe regarded this print as one of the best dance photographs he ever made.

Text from the J. Paul Getty website

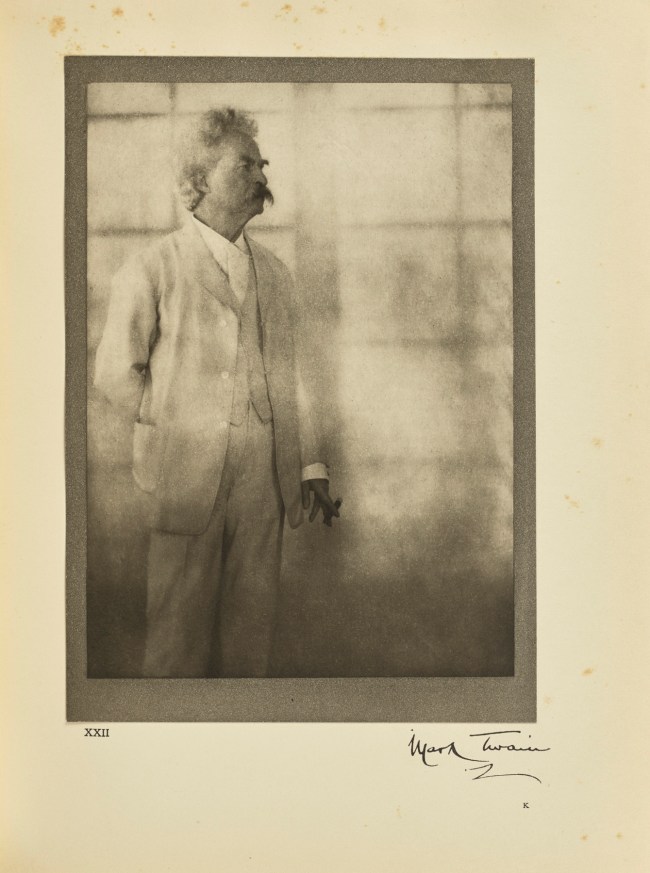

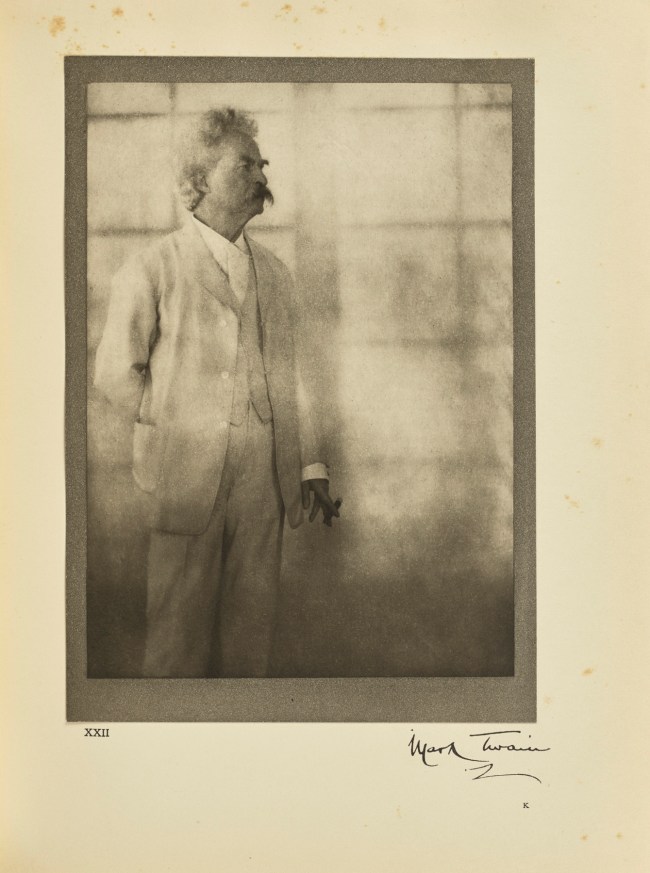

Alvin Langdon Coburn (British born United States, 1882-1966)

Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens)

Negative December 21, 1908; print 1913

Photogravure

20.6 × 14.8cm (8 1/8 × 5 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930 Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/stieglitz-self-portrait-1907.jpg?w=650&h=872)

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

[Self-Portrait]

Negative 1907; print 1930

Gelatin silver print

24.8 × 18.4cm (9 3/4 × 7 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Edward Steichen (American, 1879-1973)

Rodin – Le Penseur (The Thinker)

1902

Gelatin-carbon print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/sears-julia-ward-howe.jpg?w=650&h=825)

Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935)

[Julia Ward Howe]

about 1890

Platinum print

23.5 × 18.6cm (9 1/4 × 7 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Julia Ward Howe (May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American poet and author, known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and the original 1870 pacifist Mother’s Day Proclamation. She was also an advocate for abolitionism and a social activist, particularly for women’s suffrage.

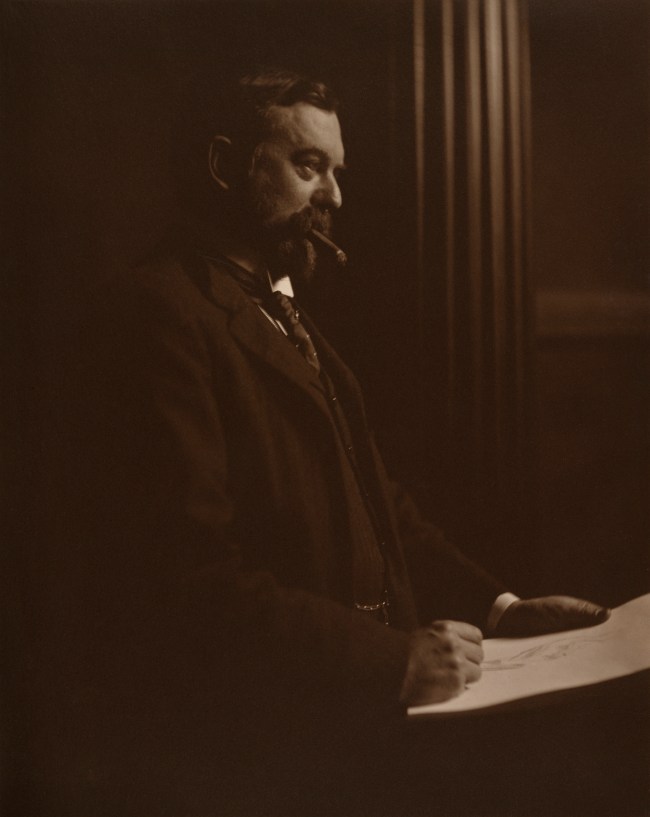

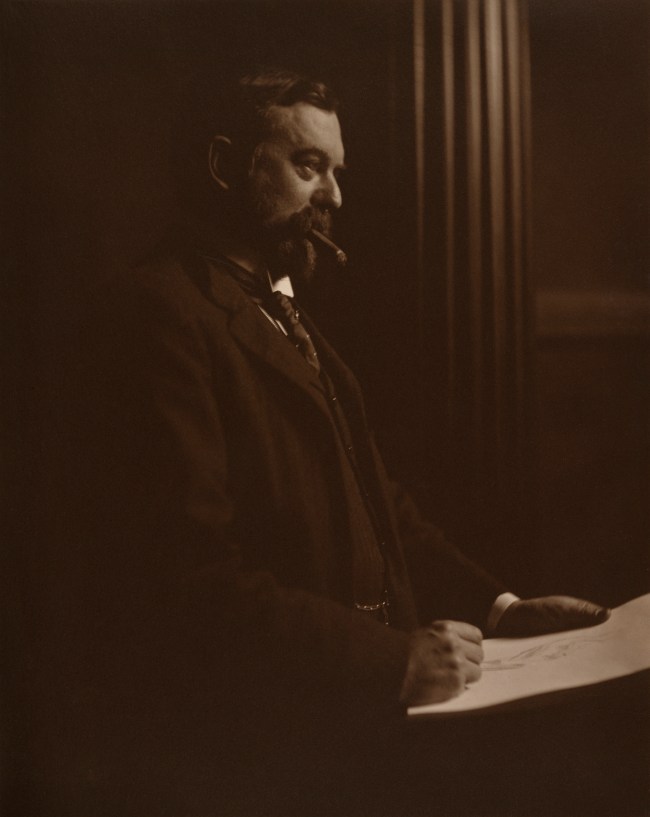

Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935)

John Singer Sargent

about 1890

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Although John Singer Sargent was the most famous American portrait painter of his time, he apparently did not like to be photographed. The few photographs that exist show him at work, as he is here, sketching and puffing on a cigar. His friend Sarah Choate Sears, herself a painter of some note, drew many of her sitters for photographs from the same aristocratic milieu as Sargent did for his paintings.

Text from the J. Paul Getty website

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar-sarah-bernhardt.jpg?w=650&h=994)

Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) (French, 1820-1910)

[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou’s “Theodora”]

Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889

Albumen silver print

14.6 × 10.5 cm (5 3/4 × 4 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

J. Wood (American, active New York, New York 1870s-1880s)

L.P. Federmeyer

1879

Albumen silver print

14.8 × 10 cm (5 13/16 × 3 15/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Ellen Terry at Age Sixteen

Negative 1864; print about 1875

Carbon print

24.1cm (9 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

This image of Ellen Terry (1847-1928) is one of the few known photographs of a female celebrity by Julia Margaret Cameron. Terry, the popular child actress of the British stage, was sixteen years old when Cameron made this image. This photograph was most likely taken just after she married the eccentric painter, George Frederick Watts (1817-1904), who was thirty years her senior. They spent their honeymoon in the village of Freshwater on the Isle of Wight where Cameron resided.

Cameron’s portrait echoes Watt’s study of Terry titled Choosing (1864, National Portrait Gallery, London). As in the painting, Terry is shown in profile with her eyes closed, an ethereal beauty in a melancholic dream state. In this guise, Terry embodies the Pre-Raphaelite ideal of womanhood rather than appearing as the wild boisterous teenager she was known to be. The round (“tondo”) format of this photograph was popular among Pre-Raphaelite artists.

Cameron titled another print of this image Sadness (see 84.XZ.186.52), which may suggest the realisation of a mismatched marriage. Terry’s anxiety is plainly evident – she leans against an interior wall and tugs nervously at her necklace. The lighting is notably subdued, leaving her face shadowed in doubt. In The Story of My Life (1909), Terry recalls how demanding Watts was, calling upon her to sit for hours as a model and giving her strict orders not to speak in front of distinguished guests in his studio.

This particular version was printed eleven years after Cameron first made the portrait. In order to distribute this image commercially, the Autotype Company of London rephotographed the original negative after the damage had been repaired. The company then made new prints using the durable, non-fading carbon print process. Thus, this version is in reverse compared to Sadness. Terry’s enduring popularity is displayed by the numerous photographs taken of her over the years. Along with the two portraits by Cameron, the Getty owns three more of Terry by other photographers.

Adapted from Julian Cox. Julia Margaret Cameron, In Focus: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1996), 12. ©1996 The J. Paul Getty Museum; with additions by Carolyn Peter, J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs, 2019.

![Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863 Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/fredricks-mlle-pepita.jpg?w=650&h=1046)

Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894)

[Mlle Pepita]

1863

Albumen silver print

9 × 5.4cm (3 9/16 × 2 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

![André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864 André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/disdecc81ri-rosa-bonheur.jpg?w=650&h=1062)

André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889)

[Rosa Bonheur]

1861-1864

Albumen silver print

8.4 × 5.2cm (3 5/16 × 2 1/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Rosa Bonheur, born Marie-Rosalie Bonheur (16 March 1822 – 25 May 1899), was a French artist, mostly a painter of animals (animalière) but also a sculptor, in a realist style. Her best-known paintings are Ploughing in the Nivernais, first exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1848, and now at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, and The Horse Fair (in French: Le marché aux chevaux), which was exhibited at the Salon of 1853 (finished in 1855) and is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City. Bonheur was widely considered to be the most famous female painter of the nineteenth century.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Mathew B. Brady (American, about 1823-1896)

Walt Whitman

about 1870

Albumen silver print

14.6 x 10.3cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Mathew B. Brady (American, about 1823-1896)

Robert E. Lee

1865

Albumen silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

![John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900 John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/parsons-portrait-of-jane-morris.jpg?w=650&h=779)

John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909)

[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]

Negative July 1865; print after 1900

Gelatin silver print

22.9 × 19.2cm (9 × 7 9/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=650&h=854)

Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) (French, 1820-1910)

George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin)

about 1865

Albumen silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dudevant, née Dupin, took the pseudonym George Sand in 1832. She was a successful Romantic novelist and a close friend of Nadar, and during the 1860s he photographed her frequently. Her writing was celebrated for its frequent depiction of working-class or peasant heroes. She was also a woman as renowned for her romantic liaisons as her writing; here she allowed Nadar to photograph her, devoid of coquettish charms but nevertheless a commanding presence.

This portrait is a riot of textural surfaces. The sumptuous satin of Sand’s gown and silken texture of her hair have a rich tactile presence. Her shimmering skirt melts into the velvet-draped support on which she leans, creating a visual triangle with the careful centre part of her wavy hair. The portrait details the exquisite laces, beads, and buttons of her gown, but her face, the apex of the triangle, is out of focus. Sand was apparently unable to remain perfectly still throughout the exposure, and the slight blurring of her facial features erases the unforgiving details that the years had drawn upon her.

Text from the J. Paul Getty website

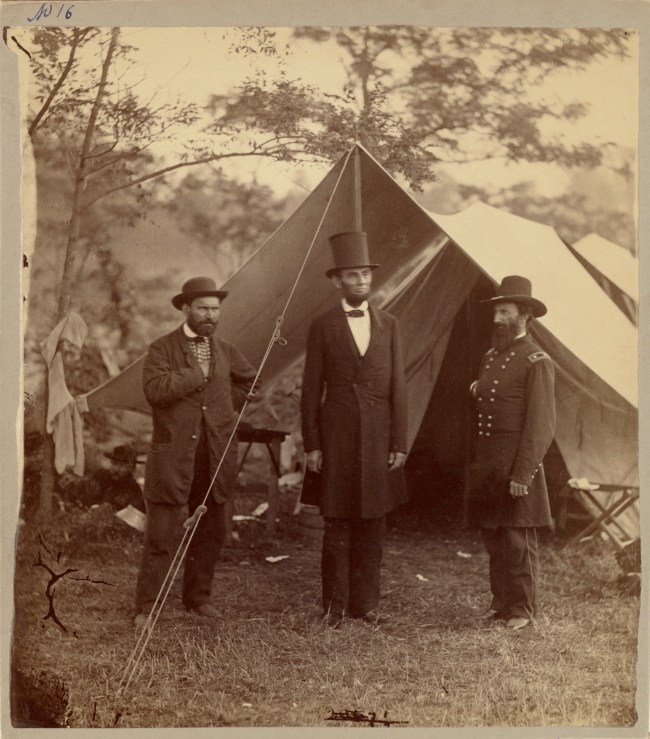

Alexander Gardner (American born Scotland, 1821-1882)

President Lincoln, United States Headquarters, Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, October 4, 1862

1862

Albumen silver print

21.9 x 19.7cm (8 5/8 x 7 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

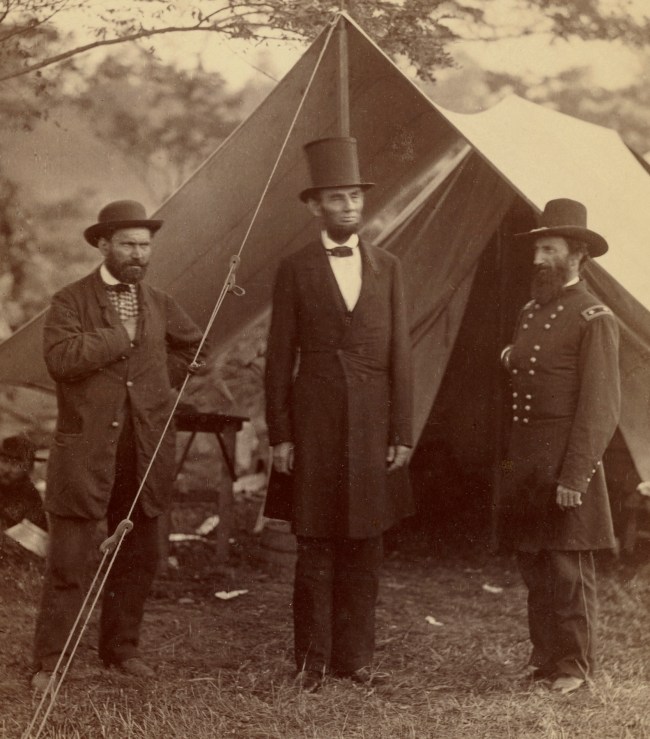

Twenty-six thousand soldiers were killed or wounded in the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, after which Confederate General Robert E. Lee was forced to retreat to Virginia. Just two weeks after the victory, President and Commander-in-Chief Abraham Lincoln conferred with General McClernand and Allan Pinkerton, Chief of the nascent Secret Service, who had organised espionage missions behind Confederate lines.

Lincoln stands tall, front and centre in his stovepipe hat, his erect and commanding posture emphasised by the tent pole that seems to be an extension of his spine. The other men stand slightly apart in deference to their leader, in postures of allegiance with their hands covering their hearts. The reclining figure of the man at left and the shirt hanging from the tree are a reminder that, although this is a formally posed picture, Lincoln’s presence did not halt the camp’s activity, and no attempts were made to isolate him from the ordinary circumstances surrounding the continuing military conflict.

Text from the J. Paul Getty website

Alexander Gardner (American born Scotland, 1821-1882)

President Lincoln, United States Headquarters, Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, October 4, 1862 (detail)

1862

Albumen silver print

21.9 x 19.7cm (8 5/8 x 7 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

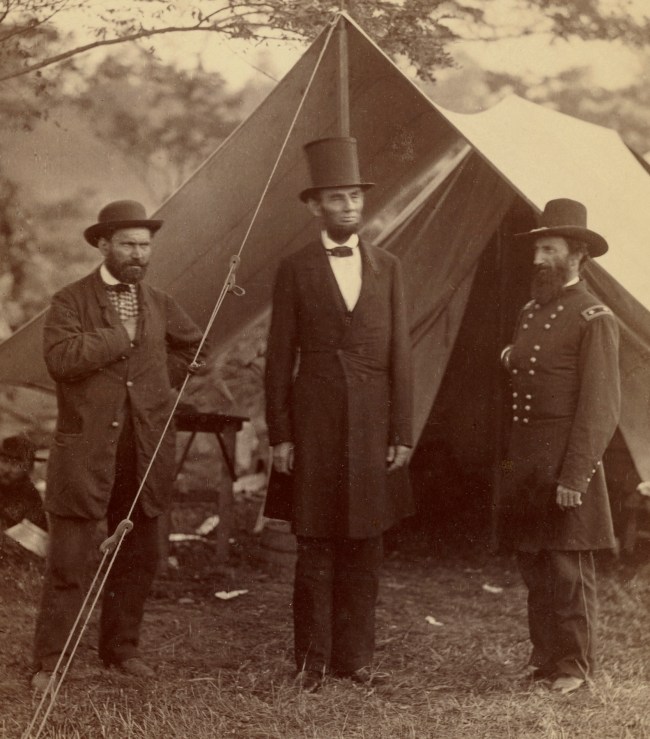

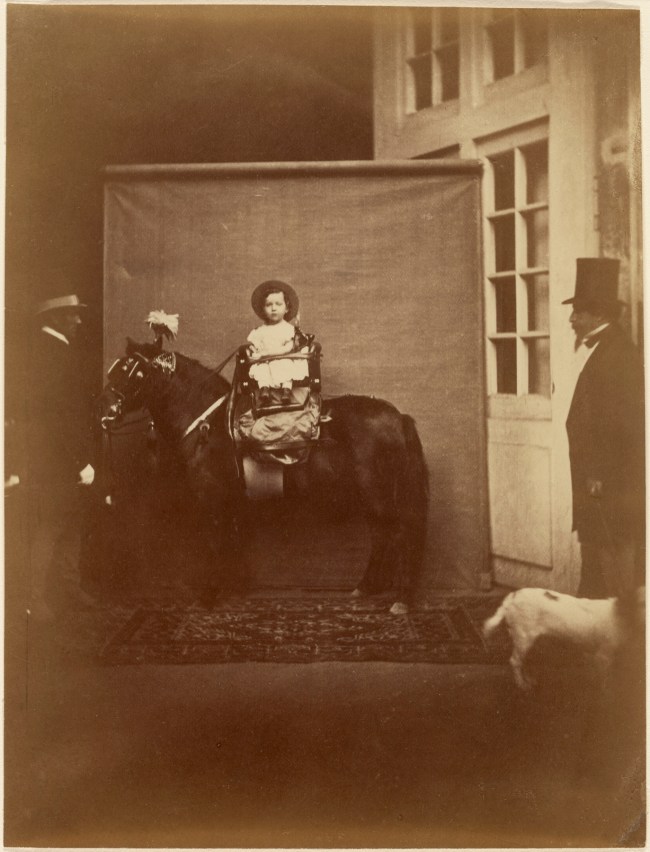

Pierre Louis Pierson (French, 1822-1913)

Napoleon III and the Prince Imperial

about 1859

Albumen silver print from a wet collodion glass negative

21 × 16cm (8 1/4 × 6 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The Prince Imperial, son of Napoleon III, sits strapped securely into a seat on his horse’s back, a model subject for the camera. An attendant at the left steadies the horse so that the little prince remains picture-perfect in the centre of the backdrop erected for the photograph. The horse stands upon a rug that serves as a formalising element, making the scene appear more regal. The Emperor Napoleon III himself stands off to the right in perfect profile, supervising the scene with his dog and forming a framing mirror-image of the horse and attendant on the other side.

Pierre-Louis Pierson placed his camera far enough back from the Prince to capture the entire scene and all the players, but this was not the version sold as a popular carte-de-visite. The carte-de-visite image was cropped so that only the Prince upon his horse was visible.

Text from the J. Paul Getty website

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar_alexander_dumas.jpg?w=650&h=803)

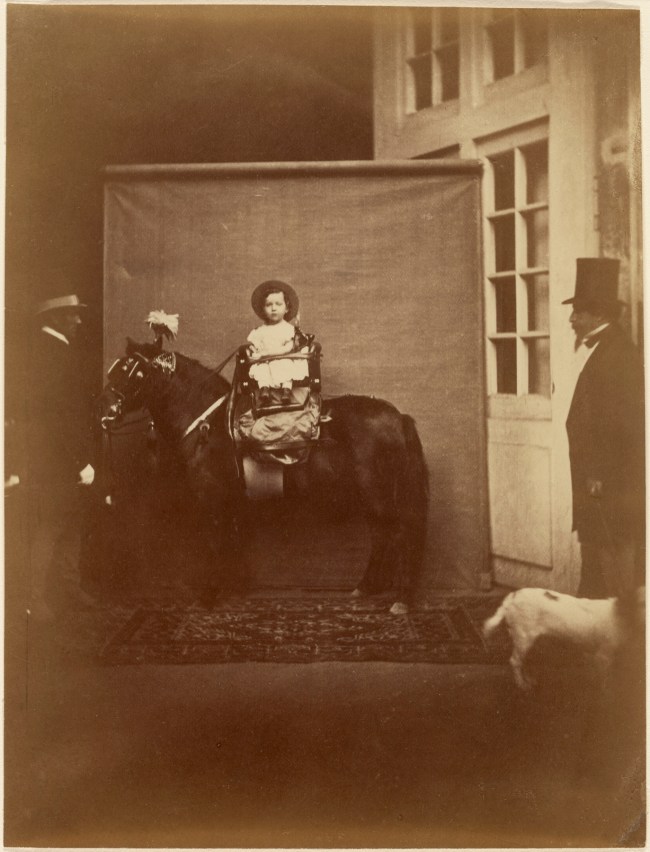

Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) (French, 1820-1910)

Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas

1855

Salted paper print

Image (rounded corners): 23.5 x 18.7cm (9 1/4 x 7 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

The writer Alexander Dumas was Nadar’s boyhood idol. Nadar’s father had published Dumas’s first novel and play, and a portrait of Dumas hung in young Nadar’s room. The son of a French revolutionary general and a black mother, Dumas arrived in Paris from the provinces in 1823, poor and barely educated. Working as a clerk, he educated himself in French history and began to write. In 1829 he met with his first success; with credits including The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, published in 1844 and 1845, respectively, his fame and popularity were assured.

Nadar was the first photographer to use photography to enhance the sitter’s reputation. Given Dumas’s popularity, this mounted edition print, signed and dedicated by him, was likely intended for sale.

Dumas is represented as a lively, vibrant man. The self-restraint of his crossed hands, resting on a chair that disappears into the shadows, seems like an attempt to contain an undercurrent of boundless energy that threatened to ruin the necessary stillness of the pose and appears to have found an outlet through Dumas’s hair. Around the time of this sitting, the prolific Dumas and Nadar were planning to collaborate on a theatrical spectacle, which was ultimately never staged.

Text from the J. Paul Getty website

Unknown maker (American)

Portrait of Edgar Allan Poe

1849

Daguerreotype

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

“A noticeable man clad in black, the fashion of the times, close-buttoned, erect, forward looking, something separate in his bearing … a beautifully poetic face.” ~ Basil L. Gildersleeve to Mary E. Phillips, 1915 (his childhood recollection of Poe)

Many of Edgar Allan Poe’s contemporaries described him as he appears in this portrait: a darkly handsome and intelligent man who possessed an unorthodox personality. Despite being acknowledged as one of America’s greatest writers of poetry and short stories, Poe’s life remains shrouded in mystery, with conflicting accounts about poverty, alcoholism, drug use, and the circumstances of his death in 1849. Like his life, Poe’s poems and short stories are infused with a sense of tragedy and mystery. Among his best-known works are: The Raven, Annabel Lee, and The Fall of the House of Usher.

This daguerreotype was made several months before Poe’s death at age 40. After his wife died two years earlier in 1847, Poe turned to two women for support and companionship. He met Annie Richmond at a poetry lecture that he gave when visiting Lowell, Massachusetts. Although she was married, they developed a deep, mutual affection. Richmond is thought to have arranged and paid for this portrait sitting. Poe is so forcibly portrayed that historians have described his appearance as disheveled, brooding, exhausted, haunted, and melancholic.

For reasons that are not entirely clear, relatively few daguerreotypes of notable poets, novelists, or painters have survived from the 1840s, and some of the best we have are by unknown makers. The art of the daguerreotype was one in which the sitter’s face usually took priority over the maker’s name, and many daguerreotypists failed to sign their works. This is the case with the Getty’s portrait of Poe.

Adapted from getty.edu, Interpretive Content Department, 2009; and Weston Naef, The J. Paul Getty Museum Handbook of the Photographs Collection (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1995), 35. © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum.

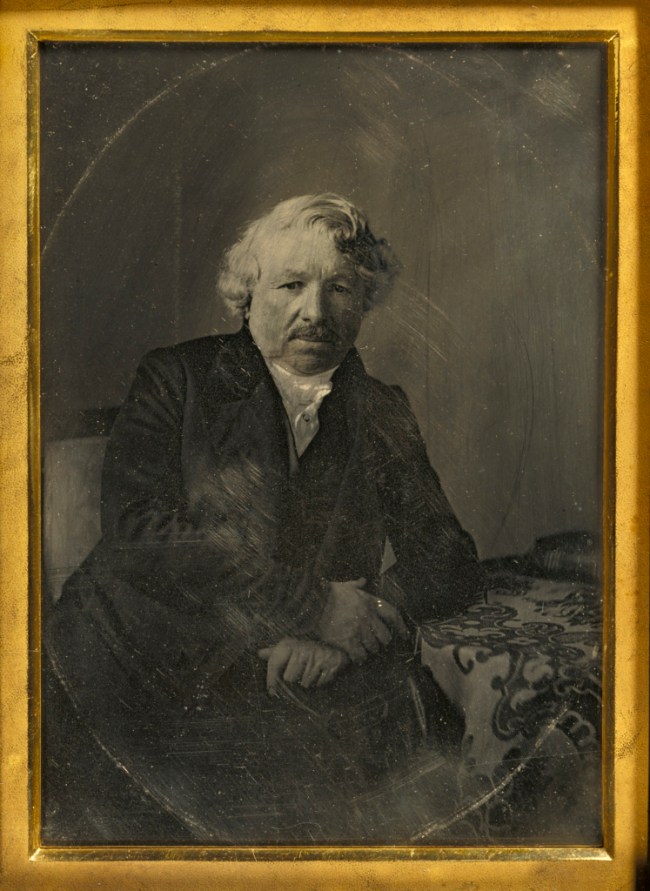

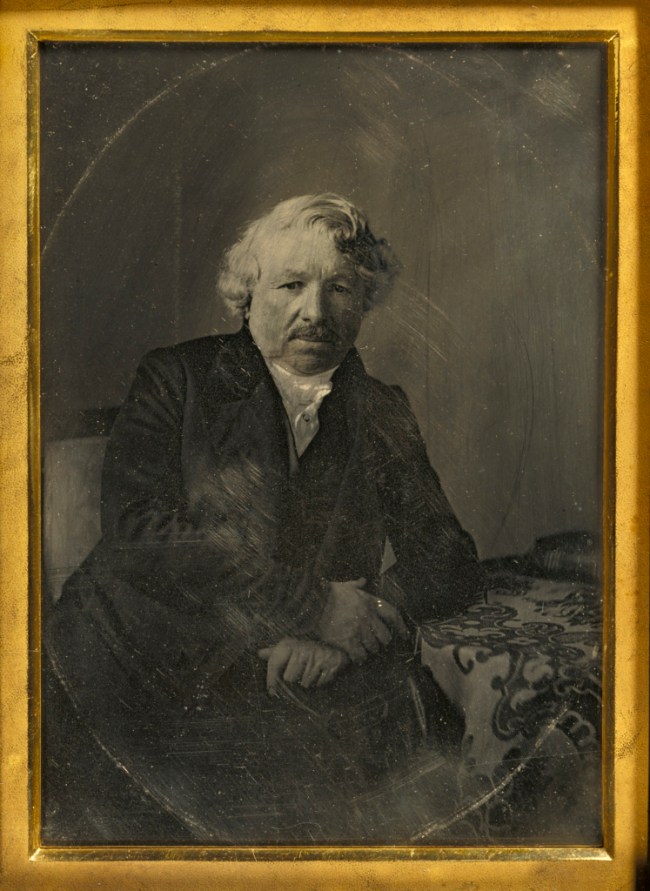

Charles Richard Meade (American, 1826-1858)

Portrait of Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre

1848

Daguerreotype, hand-coloured

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

By New Year’s Day of 1840 – little more than one year after William Henry Fox Talbot had first displayed his photogenic drawings in London and just four to five months after the first daguerreotypes had been exhibited in Paris at the Palais d’Orsay in conjunction with a series of public demonstrations of the process – Daguerre’s instruction manual had been translated into at least four languages and printed in at least twenty-one editions. In this way, his well-kept secret formula and list of materials quickly spread to the Americas and to provincial locations all over Europe. Photography became a gold rush-like phenomenon, with as much fiction attached to it as fact.

Nowhere was the daguerreotype more enthusiastically accepted than in the United States. Charles R. Meade was the proprietor of a prominent New York photographic portrait studio. He made a pilgrimage to France in 1848 to meet the founder of his profession and while there became one of the very few people to use the daguerreotype process to photograph the inventor himself.

A daguerreotype was (and is) created by coating a highly polished silver plated sheet of copper with light sensitive chemicals such as chloride of iodine. The plate is then exposed to light in the back of a camera obscura. When first removed from the camera, the image is not immediately visible. The plate must be exposed to mercury vapours to “bring out” the image. The image is then “fixed” (or “made permanent on the plate”) by washing it in a bath of hyposulfite of soda. Finally it is washed in distilled water. Each daguerreotype is a unique image; multiple prints cannot be made from the metal plate.

Adapted from Weston Naef, The J. Paul Getty Museum Handbook of the Photographs Collection (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1995), 33, © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum; with additions by Carolyn Peter, J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs, 2019.

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

The J. Paul Getty Museum website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930 Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/stieglitz-self-portrait-1907.jpg?w=650&h=872)

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/sears-julia-ward-howe.jpg?w=650&h=825)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar-sarah-bernhardt.jpg?w=650&h=994)

![Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863 Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/fredricks-mlle-pepita.jpg?w=650&h=1046)

![André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864 André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/disdecc81ri-rosa-bonheur.jpg?w=650&h=1062)

![John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900 John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/parsons-portrait-of-jane-morris.jpg?w=650&h=779)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=650&h=854)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar_alexander_dumas.jpg?w=650&h=803)

You must be logged in to post a comment.