Exhibition dates: 14th May – 27th July 2014

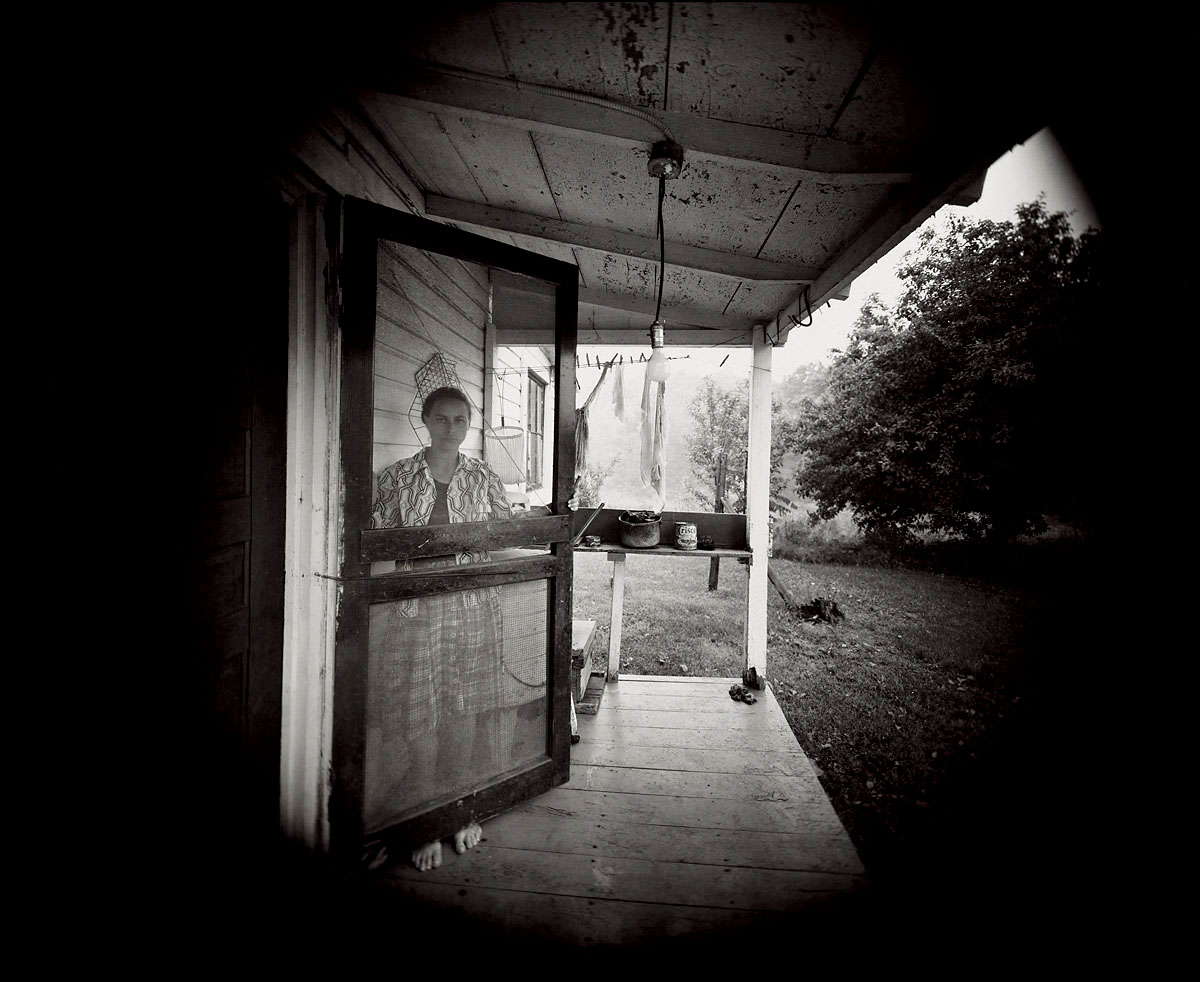

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Nancy, Danville (Virginia)

1969

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, cortesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin is a superlative photographic artist. His images possess a unique sensuality that no other artist, save Frederick Sommer, dare approach.

His own family was an early significant subject matter, one to which only he had ready access. “I was wondering about in the world looking for an interesting place to be, when I realised that where I was was already interesting.”1 I feel that the photographs of his family are his strongest work for they image an intimate story, and Gowin is nothing if not a magnificent storyteller. Look at the beauty of images such as Nancy, Danville (Virginia) (1969, above) or Ruth, Danville (Virginia) (1968, below) and understand what awareness it takes – first to visualise, then capture on the negative, then print these almost mystical moments of time.

As Gowin observed in his senior thesis, which was predicated upon the necessary co-ingredients of art and spirituality, “Art is the presence of something mysterious that transports you to a place where life takes on a clearness that it ordinarily lacks, a transparency, a vividness, a completeness.”2 He complemented this understanding of art and spirituality with an interest in science. He was in harmony with the physicists and the scientists, finding them to be the most poetic people of the age.3 Inspired by Sommer, Gowin perfected his printing technique through a respect for the medium, respect for the materials and conviction as to what the materials were capable of doing.4

“Sommer freely shared with Gowin his knowledge of photographic equipment, materials, chemicals and printing techniques and Gowin often repeats Sommer’s admonition to him: “Don’t let anyone talk you out of physical splendour.” Over the years Gowin developed methods of printing born from patient experimentation and a love of craft. His background in painting and drawing taught him that there are many solution to making a finished work of art… which he often builds to achieve the most satisfying integration of elements: “The mystery of a beautiful photograph really is revealed when nothing is obscured. We recognise that nothing has been withheld from us, so that we must complete its meaning. We are returned, it seems directly, to the sense and smell of its origin… A complete print is simply a fixed set of relationships, which accommodates its parts as well as our feelings. Clusters of stars in the sky are formed by us into constellations. Perhaps I feel that this constellation has enough stars, and doesn’t need any more. This grouping is complete. It feels right. Feeling, alone, tells us when a print is complete.””5

His later more universal work, such as the landscapes and aerial photographs, are no less emphatic than the earlier personal work but they are a second string to the main bow. The initial impetus of this work can be seen in the book Emmet Gowin Photographs as a development from still life photographs such as Geography Pages, 1974 (p. 62). This second theme took Gowin longer to develop but his photographs are no less powerful for it. His photographs of Petra possess the most amazing serenity of any taken at this famous site; his photographs of Mount St Helens after the volcanic eruption and the aerial photographs of nuclear sites and aeration ponds are among the strongest aerial photographs that I have ever seen. Gowin’s experimentation with the development of the negative, using different times and developers; his experimentation with the development of the print, sometimes using multiple developers and monotones or strong / subtle split toning (as can be seen in the photographs below) is outstanding. His poetic ability rouses the senses and is munificent but for me these photographs do not possess the “personality” or significance of his earlier family photographs. But only just, and we are talking fractions here!

“These photographs of the tracings of human beings reveal mankind not as a nurturer but as a blind and godlike power. Even his latest aerial agricultural landscapes made on route to nuclear sites have a magnificent indifference to human scale. For Gowin, confrontation of man’s part in the creation of ecological problems would seem to require the most transcendental point of view, and as his subjects have become more difficult and frightening, he has created his lushest and most seductive prints.”6

Gowin is an artist centred in a space of sensibility. An understanding of the interrelationships between people and the earth is evidenced through aware and clearly seen images. Gowin digs down into the essence of the earth in order to understand our habituation of it. How we fail to change the course we are on even as we recognise what it is that we are doing to the world. When the stimulus is constantly repeated there is a reduction of psychological or behavioural response and this is what Gowin pokes a big stick at. As he observes,

“We are products of nature. We are nature’s consciousness and awareness, the custodians of this planet… We begin as the intimate person that clings to our mother’s breast, and our conception of the world is that interrelationship. Out safety depends on that mother. And now I’m beginning to see that there’s a mother larger than the human mother and it’s the earth; if we don’t take care of that we will have lost everything.”7

I was luck enough to meet Emmet Gowin when he visited Australia in 1995. He had an exhibition in the small gallery in Building 2 in Bowens Lane at RMIT University, presented a public lecture and held a workshop with about 20 students. I remember I was bowled over by his intensity and star power and I admit, I asked a stupid question. The impetuousness of youth with stars in their eyes certainly got the better of me. Now when I look at the work again I am still in awe of the works sincerity, spirituality, sensuality and respect for subject matter. No matter what he is photographing.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Gowin, Emmet quoted in Chahroudi, Martha. “Introduction,” in Emmet Gowin Photographs. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1990, p. 10.

2/ Ibid., p. 9.

3/ Ibid., p. 11.

4/ Ibid., p. 11.

5/ Gowin quoted in Kelly, Jain (ed.,). Darkroom 2. New York, 1978, p. 43 quoted in Chahroudi, Martha. “Introduction,” in Emmet Gowin Photographs. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1990, p. 11.

6/ Chahroudi, Op. cit., p. 15.

7/ Ibid., p. 15.

Only two of the images are from the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson – the rest I sourced from the internet. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“For me, pictures provide a means of holding, intensely, a moment of communication between one human and another.”

“There is a profound silence that whines in the ear, a breathless quiet, as if the light or something unheard was breathing. I hold my breath to make certain it’s not me. It must be the earth itself breathing.

Emmet Gowin

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith and Ruth, Danville (Virginia)

1966

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, cortesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Barry, Dwayne and Turkeys, Danville, Virginia

1970

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, cortesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin, the catalog accompanying a retrospective now touring in Spain, is a great introduction to the artist’s works and a great keepsake for a fan. The writings by Keith Davis, Carlos Gollonet and Gowin himself identify the photographer’s humanist and spiritual roots and detail his journey from 1960’s-era people pictures focused on his wife, Edith and family in Danville, VA, to aerial photographs of ravaged landscapes, like the nuclear test grounds in Nevada, and his most recent project archiving tropical, nocturnal-moths.

While his disparate bodies of work may look like geologic shifts in subject matter, Gowin talks in the book about the spiritual quest he’s on, and his realisation that humankind inhabits the land, and that the land is a vital part of who we are. To my eye, what holds all the works together is Gowin’s never-ceasing focus on non-conventional beauty. His way of photographing both people and the wasted landscapes plays up the dark sublime. These are not traditional pretty pictures, but they are exquisitely beautiful. All Gowin photos smoulder with emotion and feel like they were snapped with a breath held, bated with desire.

Roberta Fallon. “Emmett Gowin – From family of man to mariposas nocturnas at Swarthmore’s List Gallery,” on The Artblog website, March 22, 2012 [Online] Cited 05/07/2014

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith, Noël, Danville (Virginia)

1971

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith, Danville (Virginia)

1971

Gelatin silver print

7 3/4 x 9 7/8″ (19.7 x 25.1cm)

Gift of Judith Joy Ross

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith, Danville (Virginia)

1970

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith, Newtown (Pennsylvania)

1974

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, cortesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Ruth, Danville (Virginia)

1968

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, cortesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith, Chincoteague Island (Virginia)

1967

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

From May 14th to July 27th 2014, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson will hold an exhibition of the American photographer Emmet Gowin. This important retrospective is showing 130 prints of one of the most original and influential photographer of these last forty years. This exhibition shows on two floors his entire career: his most famous series from the end of the sixties, the moths’ flights and the aerial photographs. The exhibition organised by Fundación MAPFRE in collaboration with Fondation HCB is accompanied by a catalogue published by Xavier Barral edition.

Born in Danville (Virginia) in 1941, Emmet Gowin grows up in Chincoteague Island, in a religious family. His father, a Methodist minister gives him a righteous discipline and a strict education, while his mother, musician, was a gentle, nurturing presence. During his spare time, Emmet encounters the surrounding landscape and begins drawing.

He completes his high school education and enrols in a local business school in 1951 and works at the same time at the design department of Sears, the multinational department store chain. In 1961, Gowin enters in the Commercial Art Department at Richmond Professional Institute, where he studies drawing, painting, graphic design, and history of Art. After a few months, he realises that photography is the best mean of expression and gives him the possibility to seize the Fate and the Unexpected.

Gowin’s early photographic influences came in the form of books and catalogues such as Images à la Sauvette by Henri Cartier-Bresson, History of Photography by Beaumont Newhall or Walker Evans’s American Photographs. Emmet Gowin acquires his first Leica 35mm in 1962 and after two years spent observing the Masters of photography, he finally feels ready to affirm his own photographic style. In 1963, he goes for the first time in New York and meets Robert Franck who encouraged him.

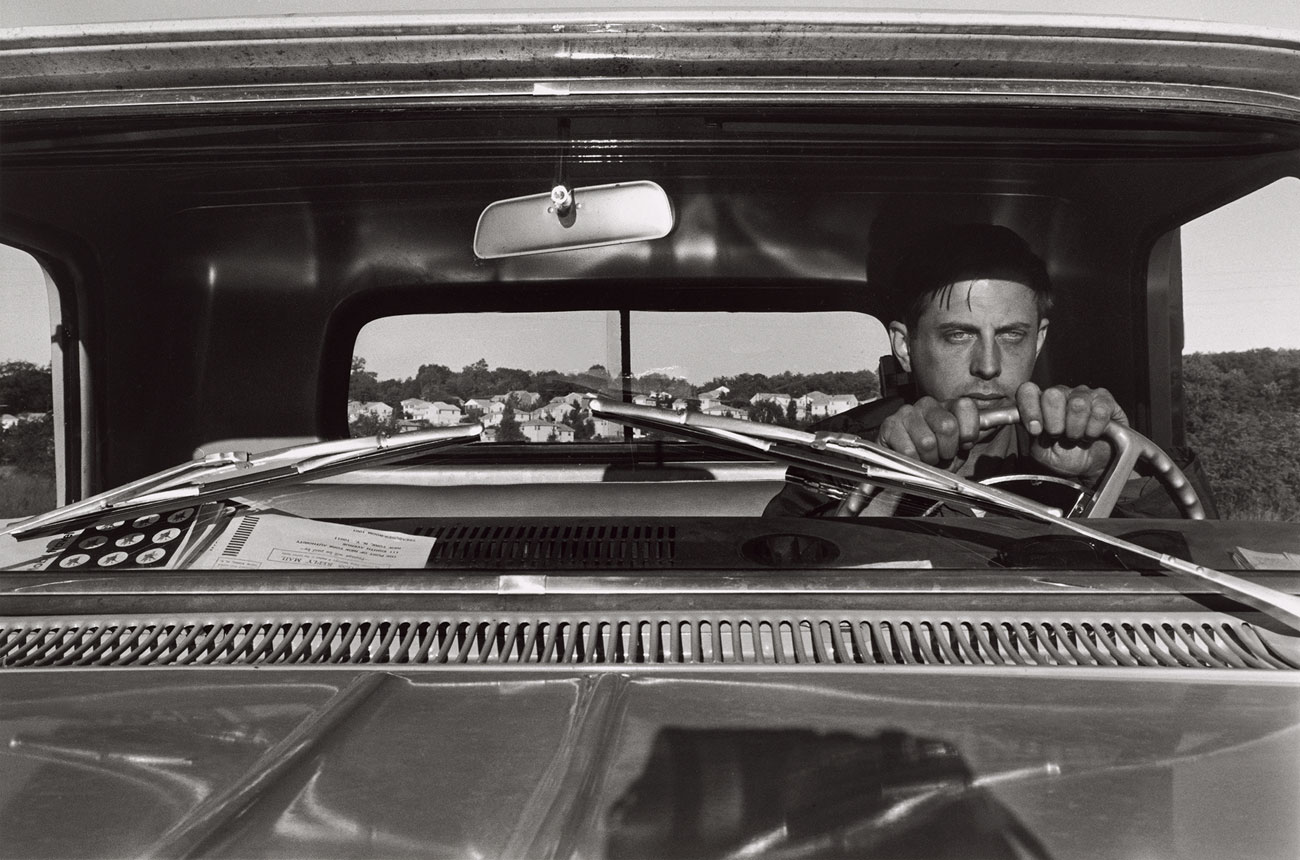

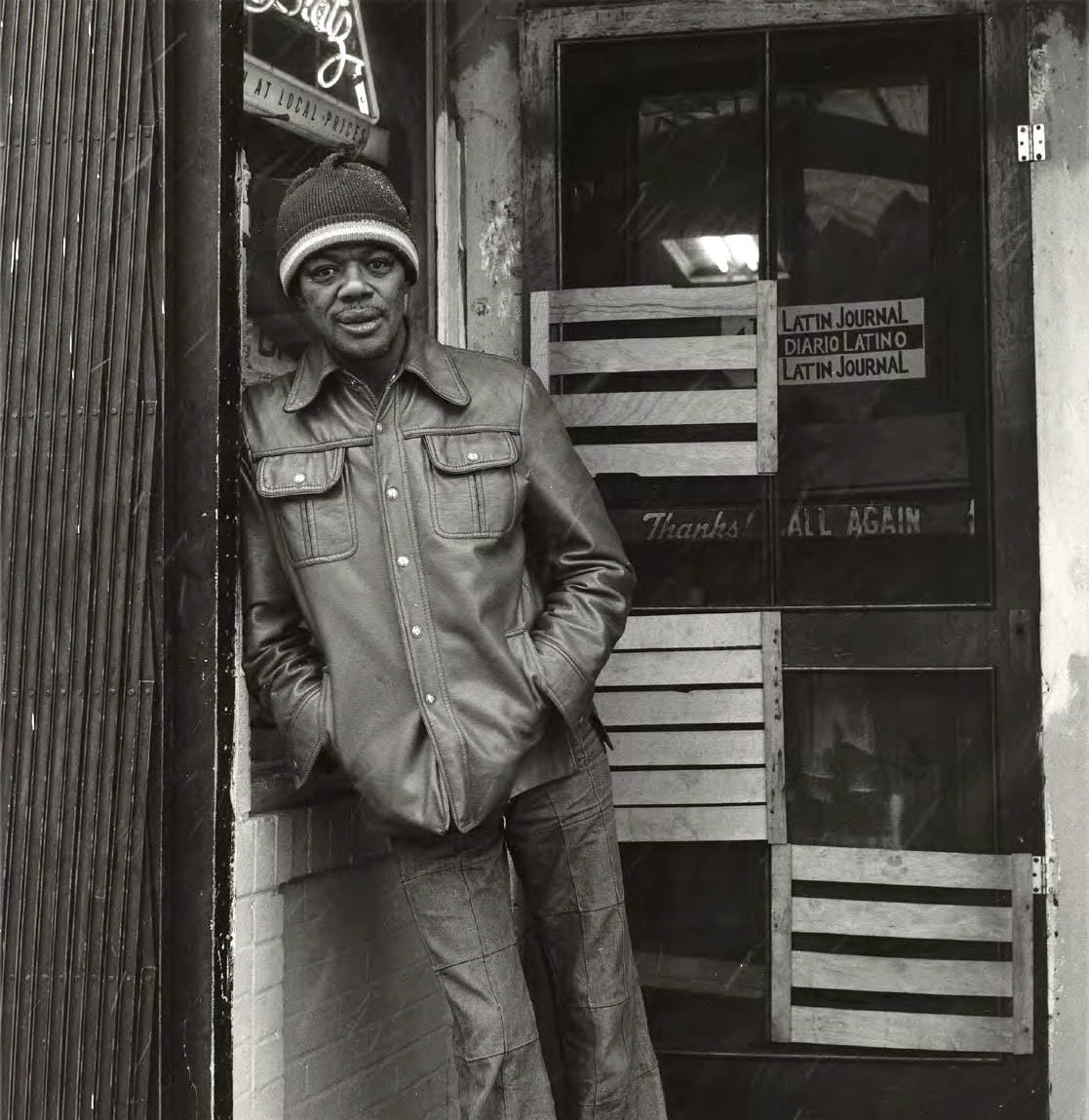

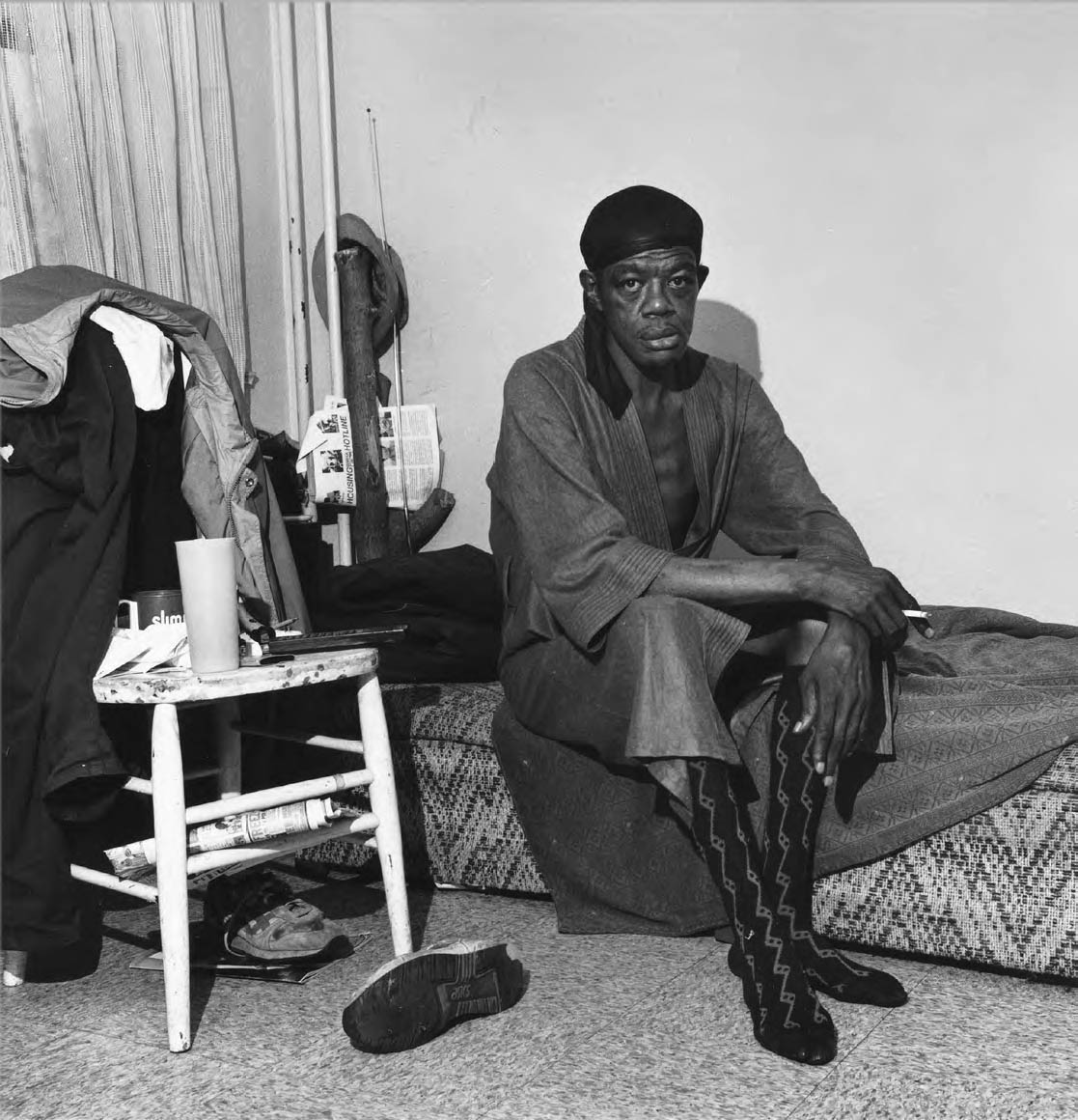

The first Gowin’s portfolios realised in 1965, is technically simple in approach. While the subjects vary considerably, all are drawn from everyday life: kids playing outdoors, Edith’s family, adults in the streets or squares, cars and early pictures of Edith. They get married in 1964. Edith Morris and Emmet Gowin are born in the same city but they grew up in totally different families. Edith’s one, was more exuberant and emotionally close than Emmet’s. As we can discover in the first floor of the exhibition, Edith and her family are the heart of the photograph’s creative universe. As mentioned by Carlos Gollonet, curator of the exhibition, Gowin’s work, seen cumulatively, is a portrait of the artist.

In 1965, they move to Providence, and Emmet begins his studies with Harry Callahan at Rhode Island School of Design. He begins to consistently use a 4 x 5 inch view camera from this time on. This bigger negative produced prints with beautiful transparent details and correspondingly finer and smoother tonal scale.

Just before his first son’s birth, Elijah, in 1967, Emmet and Edith moved to Ohio, where he begins teaching at the Dayton Art Institute. This marks the start of a teaching career that spans more than four decades. He concentrates his work on Edith and let us going through his private life and proposes a very personal artistic vision of this work: I do not feel that I can make picture impersonally, but that I am affected by and involved with the situations which lead to, or beyond, the making of the pictures. In these years, he met Ralph Eugene Meatyard and Frederik Sommer, who would become his close friend and mentor.

At the end of the 1960’s, Gowin begins making circular images of Edith, her family, and their own household, both indoors and out. The Gowin’s second son, Isaac, born in 1974, was the subject – both before and after birth – of many of these circular 8×10 inch photographs, which give the impression of looking through a keyhole. At the beginning of the 1970’s, the exhibitions at the Light Gallery and MoMA mark a significant step toward his American success. In 1973, he’s appointed Lecturer at Princeton University. He is later appointed Full Professor, a position he will hold until his retirement in 2009. He inspired a new generation of photographers such as Fazal Sheikh, David Maisel or Andrew Moore.

From 1973, Gowin goes back to sources, nature and landscape and introduces the idea of Working Landscapes in which the contributions of many generations, overtime, shape the use and care of the land. He travels in Europe, Ireland and Italy, where he discovered the ancient Etruscan city of Matera. His first monograph, Emmet Gowin: photographs, is published in 1976. In 1982, the Queen Noor of Jordan, one of Gowin’s students at Princeton, invites him to photograph the archeological site of Petra. Some of these photos are exhibited on the second floor of the foundation. Later, he continues making views of nature and traveled overseas, reverting to a traditional rectangular format. His interest in gardens and the historical balance between nature and human culture stimulates a dedication to a larger landscape, recorded first from the ground and then from the air. He photographs the incredible destruction of the Mount St. Helens volcano, Washington, and spent years recording the inhabited – and often scarred – face of the American West. Gowin is not an environmental activist. Nonetheless, once he comes to know and experience these landscapes his acute moral and intellectual sense is also conveyed in his images. He wants to show the conflict that exists in our relationship with nature. “It is not a call for an action … It’s a call for reflection, meditation and consideration to be on a more intimate basis with the world.”

Over the past few years, Gowin has constantly photographed nocturnal moths. His scientific interest has led him to catalog thousands of species working alongside with biologists in tropical jungles. By chance, he traveled with a cutout silhouette of Edith in his wallet or luggage and produced a series of photographs in which Edith is once again the principal subject, in this case through her silhouette. They recall the instrument known as the physionotrace, a forerunner of the earliest photographs which was used to male silhouette reproducing the images of loved ones. Those images, printed on handmade paper with the silver image gold toned confirm that Emmet Gowin is one of the finest photographers of any period.

Press release from the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson website

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Old Handford City Site and the Columbia River, Handford Nuclear Reservation, near Richland (Washington)

1986

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

The aerial photos, taken while flying over bomb test sites and waste water catchment basins and other scenes of industrial/military destruction are almost abstract to the eye. They are also very beautiful. Getting nose to nose with these works and reading the title card, however, allows the slowly-dawning realisation that you are looking at a full blown horror. This suite of works dates from 1980 when Gowin took to the air to view the aftermath of the Mt. St. Helens volcanic eruption in Washington state and was taken with the way things not visible from “human” space below revealed themselves from above. In 1986 he started exploring man-made industrial inroads into the land from the air, flying over Hanford Reservation, for one, where nuclear reactors and chemical separation plants made scars on the land like nothing nature had done. These are truly devastating pictures, and what makes them more so is the thought that this is the tip of the iceberg and that many other sites on earth bear the scars of man-made intrusion.

Roberta Fallon. “Emmett Gowin – From family of man to mariposas nocturnas at Swarthmore’s List Gallery,” on The Artblog website, March 22, 2012 [Online] Cited 05/07/2014

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Aeration Pond, Toxic Water Treatment Facility, Pine Bluff, AK (Arkansas)

1989

Toned gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Golf Course under Construction (Arizona)

1993

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Aerial view: Mt. St. Helens rim, crater and lava dome

1982

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Every Time less than the pulsation of the artery

Is equal in its period & value to Six Thousand Years.

For in this Period the Poet’s Work is Done, and all the Great

Events of Time start forth & are conceiv’d in such a Period

Within an Moment, a Pulsation of the Artery. …

For every Space larger than a red Globule of Man’s blood,

Is visionary, and is created by the Hammer of Los:

And every Space smaller than a red Globule of Man’s blood opens

Into Eternity of which this vegetable Earth is but a shadow…

William Blake. From “Milton”

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

The Khazneh from the Sîq, Petra (Jordan)

1985

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith, Newtown (Pennsylvania)

1994

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith, Danville (Virginia)

1963

Gelatin silver print

© Emmet Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Emmet Gowin (American, b. 1941)

Edith and Moth Flight

2002

Digital ink jet print

19 x 19cm (7 1/2 x 7 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Charina Endowment Fund

© Emmet and Edith Gowin, Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

79 rue des Archives

75003 Paris

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 11am – 7pm

Closed on Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.