Exhibition dates: 14th September, 2025 – 1st February, 2026

Curators: Stephanie D’Alessandro, Leonard A. Lauder Curator of Modern Art and Senior Research Coordinator in Modern and Contemporary Art at The Met, and Stephen C. Pinson, Curator in the Department of Photographs at The Met, with the assistance of Micayla Bransfield, Research Associate, Modern and Contemporary Art.

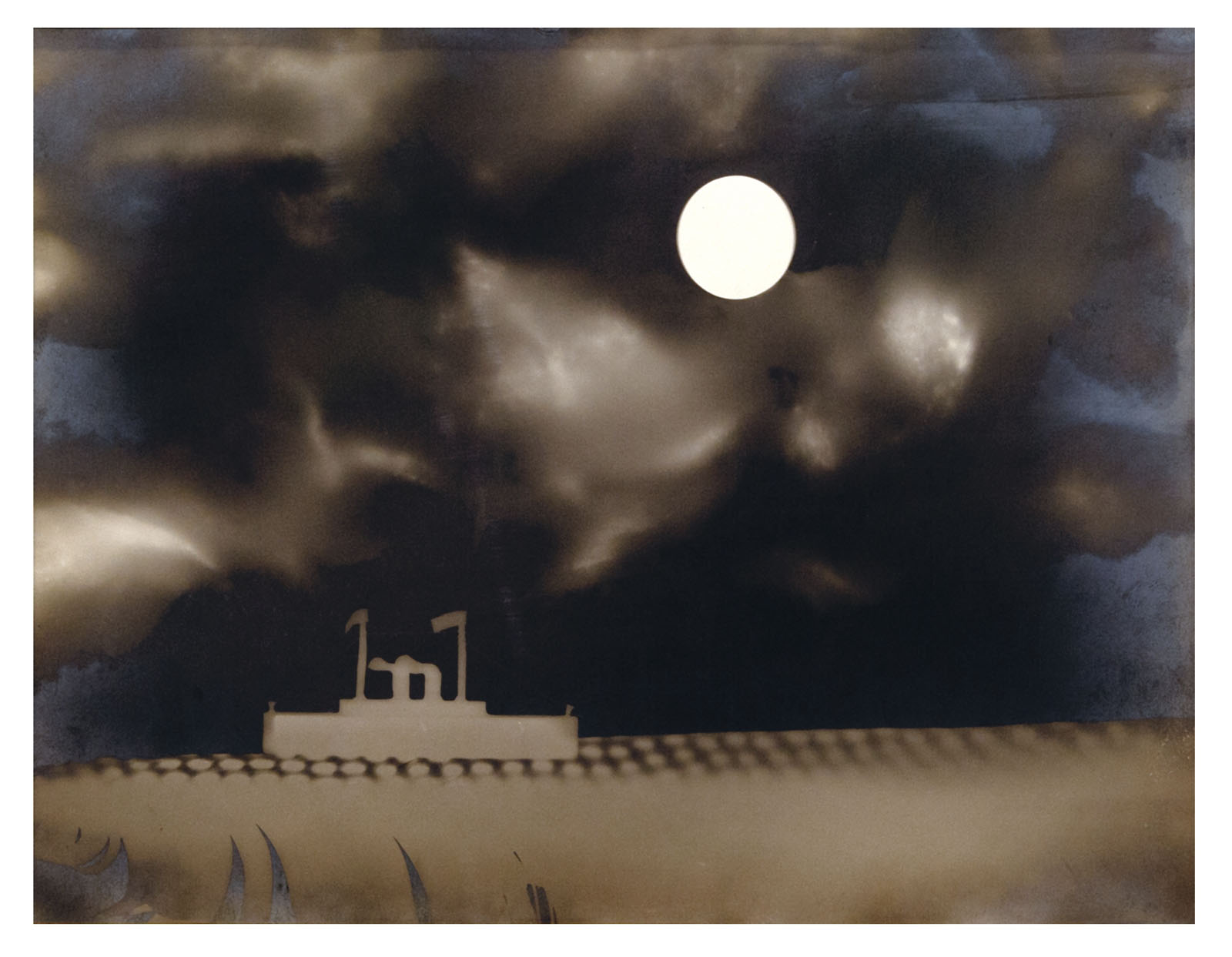

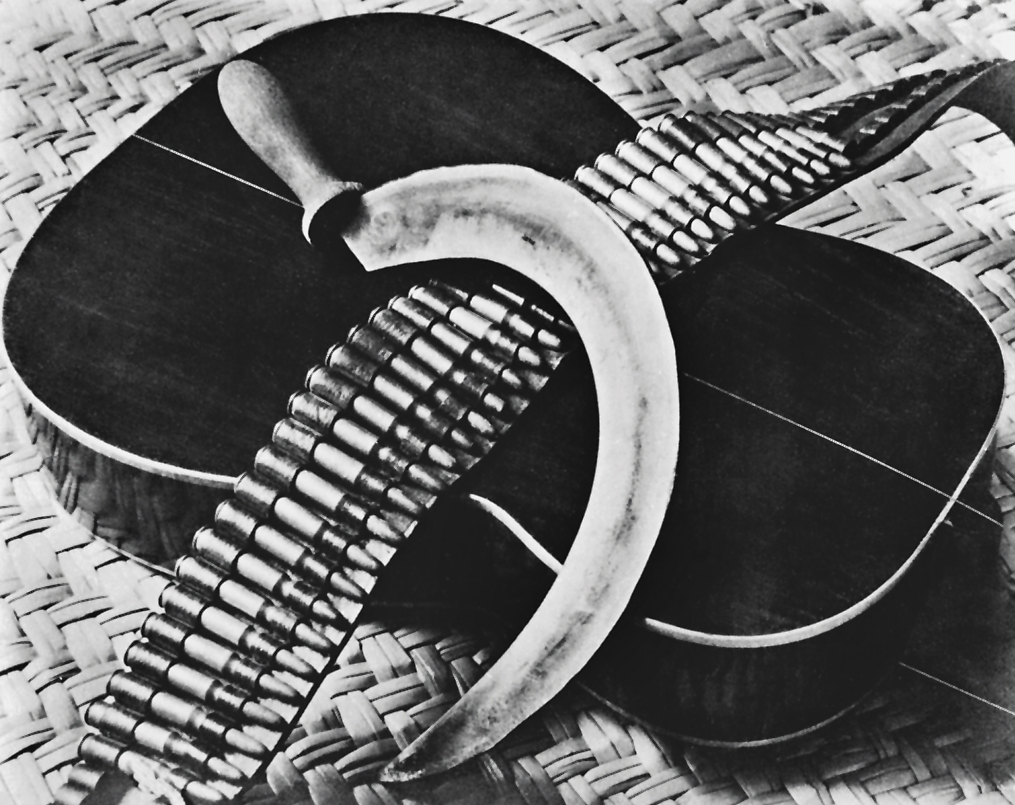

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Marine

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

8 3/4 × 11 9/16 in. (22.2 × 29.3cm)

Private collection; courtesy Galerie 1900-2000, Paris-New York

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

“Like the undisturbed ashes of an object consumed by flames these images are oxidized residues fixed by light and chemical elements of an experience, an adventure, not an experiment. They are the result of curiosity, inspiration, and these words do not pretend to convey any information.”

Man Ray1

The rayographs

Although not the inventor of the photogram, a photograph made without the use of a camera by placing objects directly onto sensitised photographic paper and then exposing the paper to light, Man Ray’s rayographs have become the most recognisable and famous form that photograms have taken. This is because of their inventiveness, their subliminal connection to the psyche, and the use of “objects from the real world to make ambiguous dreamscapes.”7

It is interesting that Man Ray called his images rayographs, for a graph implies a topographical mapping, a laying out of statistics, whereas Lucia Moholy and László Moholy-Nagy’s photograms imply in the title of their technique the transmission of some form of message, like a telegram. The paradox is that, as the quotation above states, Man Ray always insisted that his rayographs imparted no information at all; perhaps they are only dreams made (un)stable. Contrary to this the other two artists believed that, “photographic images – cameraless and other – should not deal with conventional sentiments or personal feelings but should be concerned with light and form,”8 quite the reverse of the title of their technique.

After his arrival in Paris Man Ray started experimenting in his darkroom and discovered the technique for his rayographs by accident. With the help of his friend the Surrealist poet Tristan Tzara, he published a portfolio of twelve Rayographs in 1922 called Les champs délicieux (The delicious fields). “This title is a reference to ‘Les champs magnétiques’, a collection of writings by André Breton and Philippe Soupault composed from purportedly random thought fragments recorded by the two authors.”9 The rayographs are visual representations of random thought fragments, “photographic equivalents for the Surrealist sensibility that glorified randomness and disjunction.”10

Man Ray, “denied the camera its simplest joy: the ability to capture everything, all the distant details, all the ephemeral lights and shadows of the world”11 but, paradoxically, the rayographs are the most ephemeral of creatures, only being able to be created once, the result not being known until after the photographic paper has been developed. In fact, for Man Ray to create his portfolio Les champs délicieux (The delicious fields), he had to rephotograph the rayographs in order to make multiple copies.12

Man Ray “insisted in nearly every interview that the rayograph was not a photogram in the traditional sense. He did something that a photogram didn’t; he introduced depth into the images,”13 which denied the images their photographic objectivity by depicting an internal landscape rather than an external one.14 What the rayographs do not deny, however, is the subjectivity of the artist, his skill at placing the objects on the photographic paper, expressed in their dream-like nature, both a subjective ephemerality (because they could only be produced once) and an ephemeral subjectivity (because they were expressions of Man Ray’s fantasies, and therefore had little substance).

Through an alchemical process the latent images emerge from the photographic paper, representations of Man Ray’s fantasies as embodied in the ‘presence’ of the objects themselves, in the surface of the paper. Perhaps these objects offer, in Heidegger’s terms, ‘a releasement towards things’,15 “a coexistence between a conscious and unconscious way of perceiving which sustains the mystery of the object confusing the distinction between real time and sensual time, between inside and outside, input and output becoming neither here nor there.”16

Finally, within their depth of field the rayographs can be seen as both dangerous and delicious, for somehow they are both beautiful and unsettling at one and the same time. As Surrealism revels in randomness and chance these images enact the titles of other Man Ray photographs: Danger-Dancer, Anxiety, Dust Raising, Distorted House. The rayographs revel in chance and risk; Man Ray brings his fantasies to the surface, an interior landscape represented externally that can be (re)produced only once – those dangerous delicious fields.

Extract from Marcus Bunyan. “The Delicious Fields: Exploring Man Ray’s ‘Rayographs’ in a Digital Future,” published in The University of Queensland Vanguard magazine ‘Man Ray: Life, Work & Themes’, 2004

Footnotes

1/ Man Ray quoted in Janus (trans. Murtha Baca). Man Ray: The Photographic Image. London: Gordon Fraser, 1980, p. 213

7/ Mark Greenberg (ed.,). In Focus: Man Ray: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1998, p. 38

8/ Naomi Rosenblum. A World History of Photography. New York: Abbeville Press, 1997, 394

9/ Greenberg, op. cit., p. 28

10/ Jed Perl (ed.,). Man Ray: Aperture Masters of Photography. New York: Aperture, 1997 pp. 11-12

11/ Perl, op. cit., pp. 5-6

12/ Greenberg, op. cit., p. 28

13/ Greenberg, op. cit., p. 112

14/ Greenberg, op. cit., p. 28

15/ “We stand at once within the realm of that which hides itself from us, and hides itself just in approaching us. That which shows itself and at the same time withdraws is the essential trait of what we call the mystery … Releasement towards things and openness to the mystery belong together. They grant us the possibility of dwelling in the world in a totally different way…”

Martin Heidegger. Discourse on Thinking. New York: Harper & Row, 1966, pp. 55-56 quoted in Mauro Baracco. “Completed Yet Unconcluded: The Poetic Resistance of Some Melbourne Architecture,” in Leon van Schaik (ed.,). Architectural Design Vol. 72. No. 2 (‘Poetics in Architecture’). London: John Wiley and Sons, 2002, 74, Footnote 6.

16/ Marcus Bunyan. Spaces That Matter: Awareness and Entropia in the Imaging of Place (2002) [Online] Cited 07/07/2004.

Many thankx to The Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

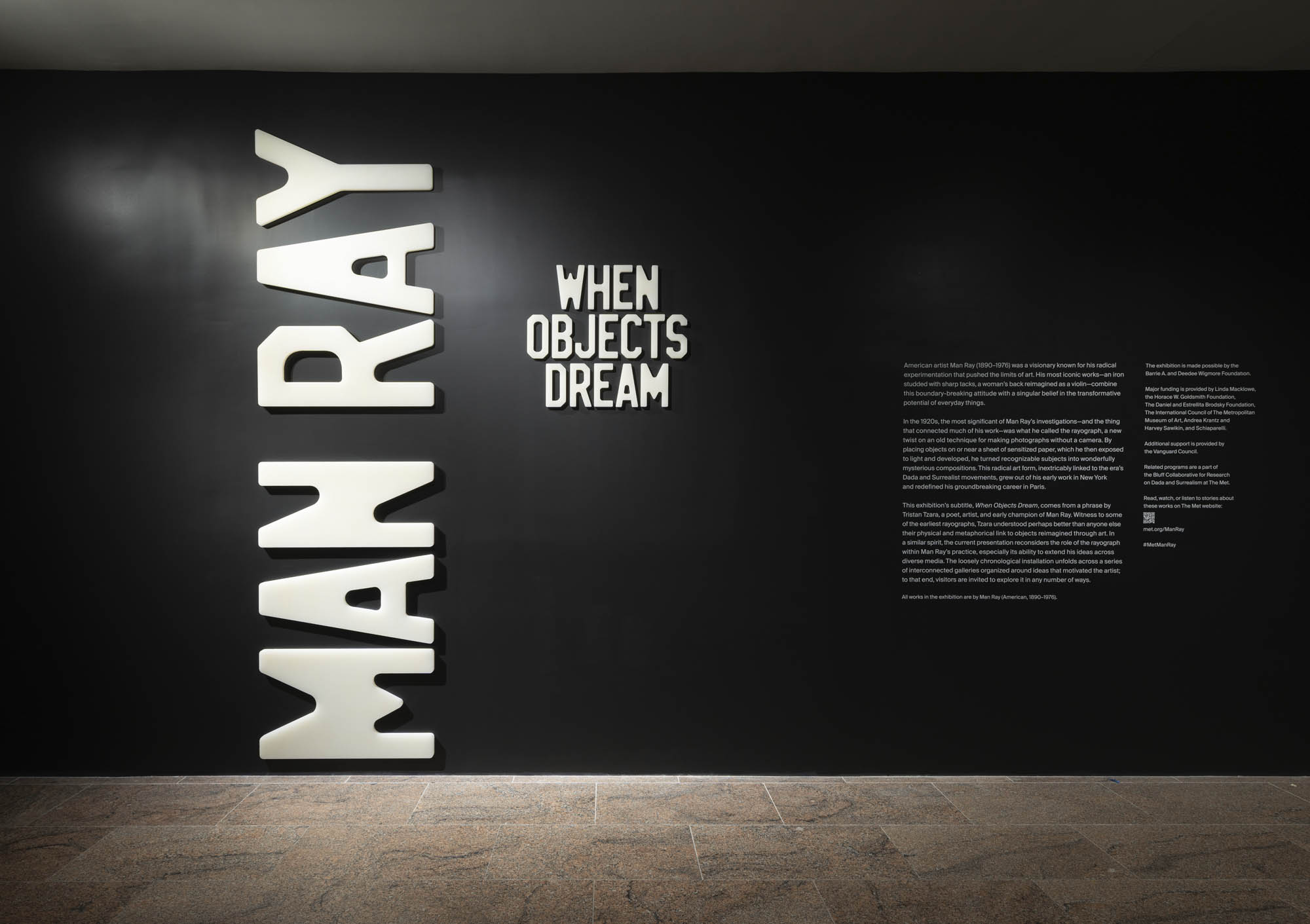

“Stepping into the exhibition Man Ray: When Objects Dream at The Metropolitan Museum of Art feels like entering the bellows of an old camera. Through a rectangular frame cut into the entry, the darkened walls unfold, accordion-like, to reveal a visual feast of the artist’s work, as Man Ray’s earliest film, “Retour à la raison (Return to Reason)” (1923), flickers across the screen opposite. Although the exhibition brings together approximately 160 works from an impressive array of lenders, it reveals itself gradually, taking the viewer through several turns before one can grasp its sheer enormity. When Objects Dream proves, thrillingly, that anyone left feeling jaded from the many, many recent exhibitions surrounding Surrealism’s centennial in 2024 can still see the movement’s key photographer with a fresh set of eyes.”

Julia Curl. “Man Ray Was So Much More Than a Photographer,” on the Hyperallergic website September 16, 2025 [Online] Cited 05/12/2025

“Objects to touch, to eat, to crunch, to apply to the eye, to the skin, to press, to lick, to break, to grind, objects to lie, to flee from, to honor, things cold or hot, feminine or masculine, objects of day or night which absorb through your pores the greater part of our life. … These are the projections surprised in transparence, by the light of tenderness, of objects that dream and talk in their sleep.”

.

Tristan Tzara, “When Objects Dream,” 1934

“One sheet of paper got into the developing tray – a sheet unexposed that had been mixed with those already exposed under the negatives. … Regretting the waste of paper, I mechanically placed a small glass funnel, the graduate, and the thermometer in the tray on the wetted paper. I turned on the light; before my eyes an image began to form, not quite a simple silhouette of the objects as in a straight photograph, but distorted and refracted by the glass more or less in contact with the paper and standing out against a black background. … I remembered when I was a boy, placing fern leaves in a printing frame with proof paper, exposing it to sunlight, and obtaining a white negative of the leaves. This was the same idea, but with an added three-dimensional quality and tone graduation. I made a few more prints … taking whatever came to hand; my hotel-room key, a handkerchief, some pencils, a brush, a candle, a piece of twine … excitedly, enjoying myself immensely. In the morning I examined the results. … They looked startlingly new and mysterious.”

Man Ray

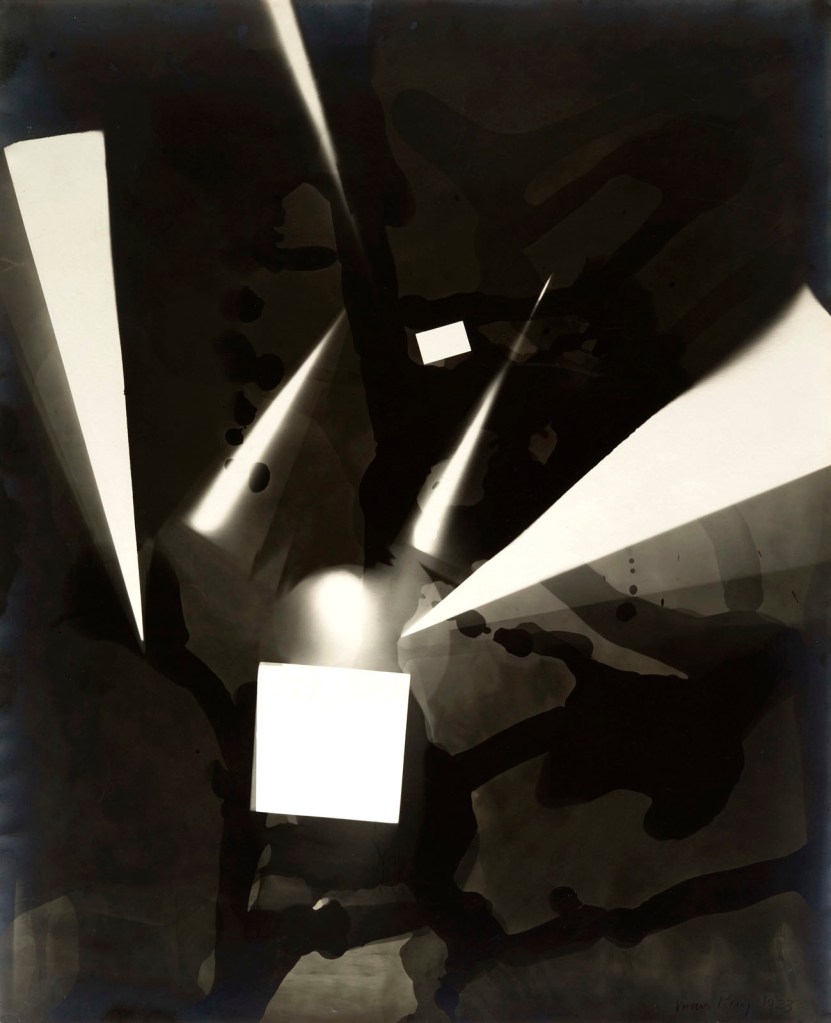

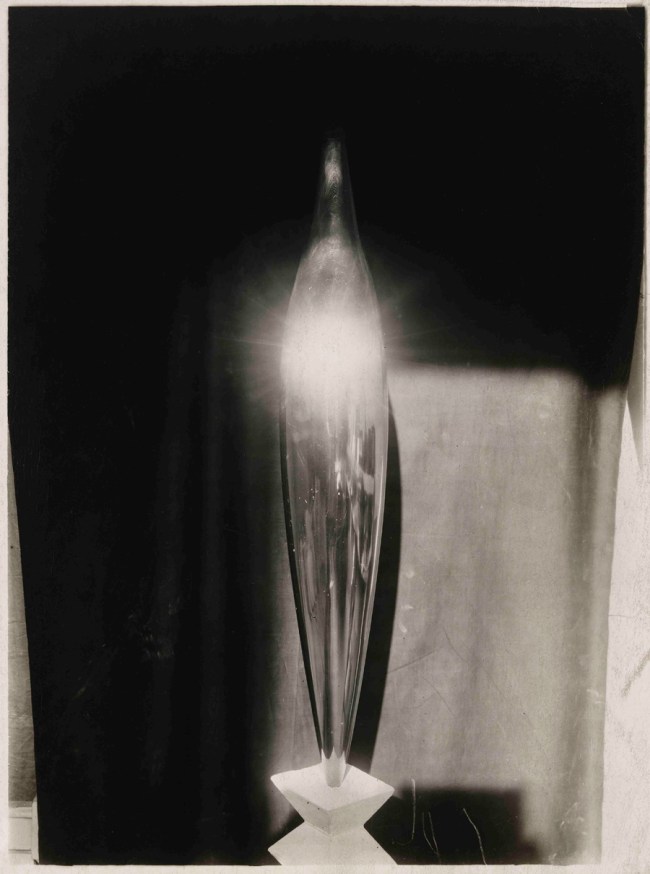

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Rayograph

1922

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 × 7 in. (24.1 × 17.8cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Photo by Ben Blackwell

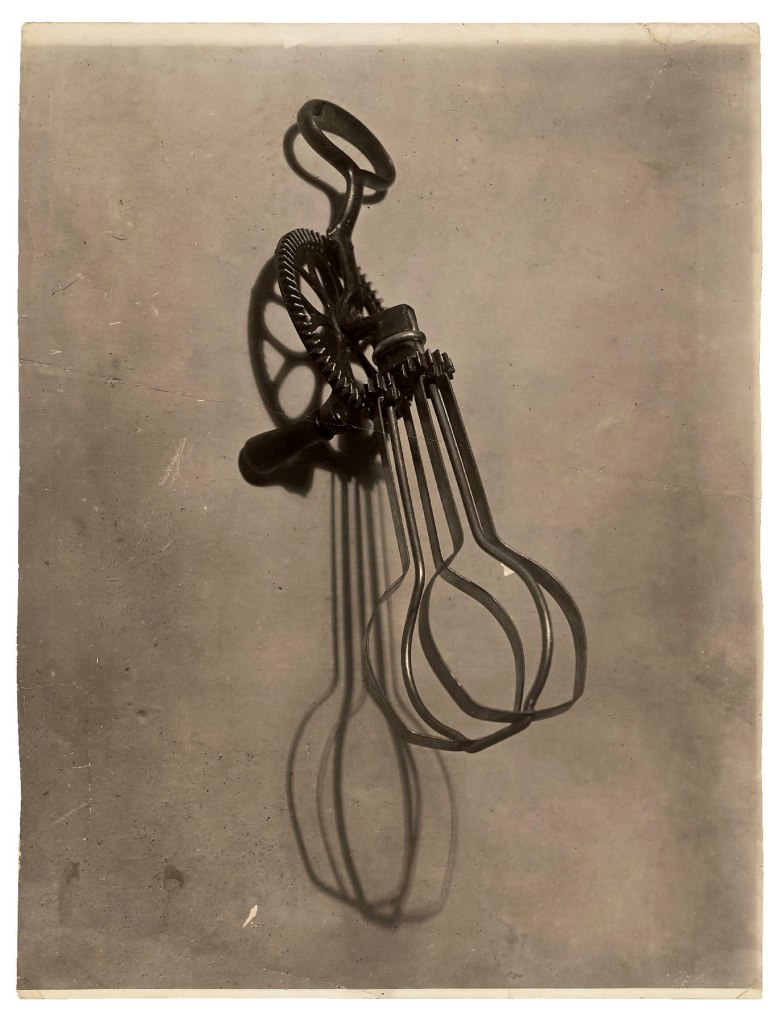

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Rayograph

1922

Gelatin silver print

9 3/8 × 7 in. (23.8 × 17.8cm)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Rayograph

1922

Gelatin silver print

9 3/8 x 7 in. (23.8 x 17.8cm)

Private collection

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Rayograph

1923

Gelatin silver print

11 1/2 × 9 5/16 in. (29.2 × 23.7cm)

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Gift of the Estate of Katherine S. Dreier

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Photo: Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Collection Société Anonyme

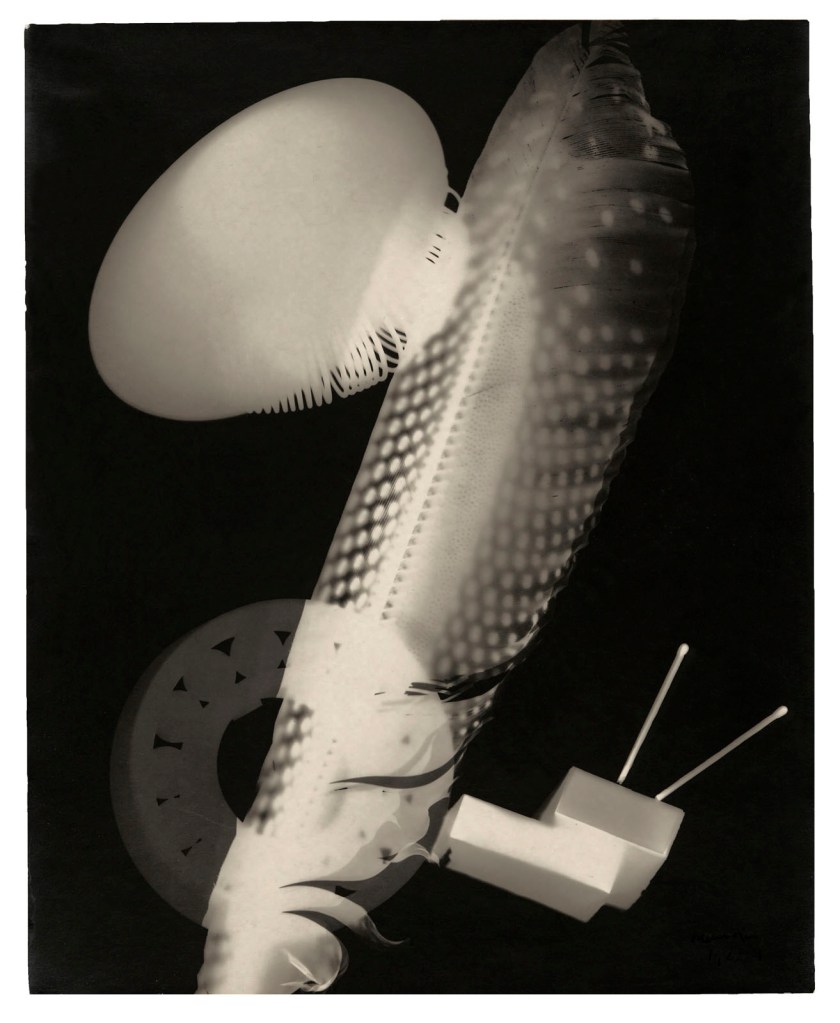

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Rayograph

1923-1928

Gelatin silver print

19 5/16 x 15 11/16 in. (49 x 39.8cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Mark Morosse

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Rayograph

1925

Gelatin silver print

19 15/16 × 15 13/16 in. (50.6 × 40.2cm)

MAH Musée d’art et d’histoire, City of Geneva. Purchase, 1968

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Photo © Musée d’art et d’histoire, Ville de Genève, photo by André Longchamp

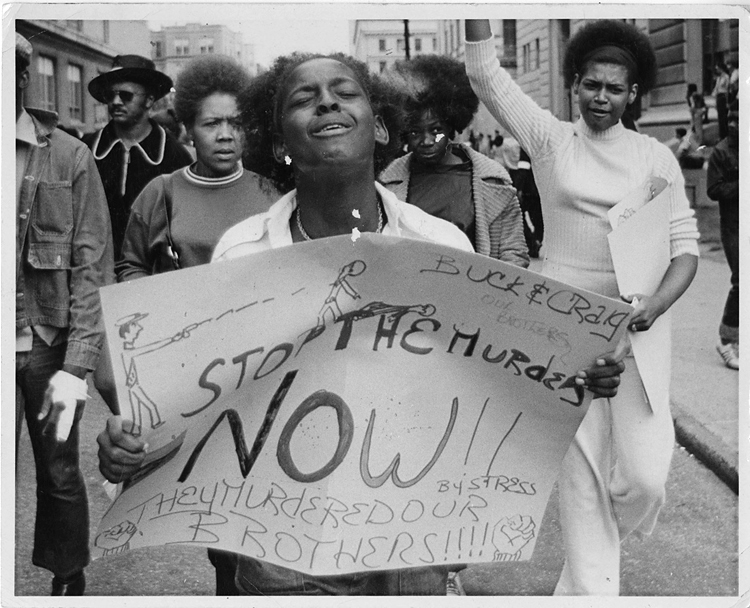

American artist Man Ray (1890-1976) was a visionary known for his radical experiments that pushed the limits of photography, painting, sculpture, and film. In the winter of 1921, he pioneered the rayograph, a new twist on a technique used to make photographs without a camera. By placing objects on or near a sheet of light-sensitive paper, which he exposed to light and developed, Man Ray turned recognisable subjects into wonderfully mysterious compositions. Introduced in the period between Dada and Surrealism, the rayographs’ transformative, magical qualities led the poet Tristan Tzara to describe them as capturing the moments “when objects dream.”

The exhibition will be the first to situate this signature accomplishment in relation to Man Ray’s larger body of work of the 1910s and 1920s. Drawing from the collections of The Met and more than 50 U.S. and international lenders, the exhibition will feature approximately 60 rayographs and 100 paintings, objects, prints, drawings, films, and photographs – including some of the artist’s most iconic works – to highlight the central role of the rayograph in Man Ray’s boundary-breaking practice.

“Before my eyes an image began to form, not quite a simple silhouette of the objects as in a straight photograph, but distorted and refracted … In the morning I examined the results, pinning a couple of the rayographs – as I decided to call them – on the wall. They looked startlingly new and mysterious.” ~ Man Ray

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Installation views of the exhibition Man Ray: When Objects Dream at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 2025 – February 2026

![Man Ray (American, 1890-1976) 'Torse (Retour à la raison)' (Torso [Return to Reason]) 1923, printed c. 1935 Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

'Torse (Retour à la raison)' (Torso [Return to Reason]) 1923, printed c. 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/man-ray-retour-c3a0-la-raison-web.jpg)

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Torse (Retour à la raison) (Torso [Return to Reason])

1923, printed c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

8 1/4 × 6 3/8 in. (21 × 16.2cm)

Private collection

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

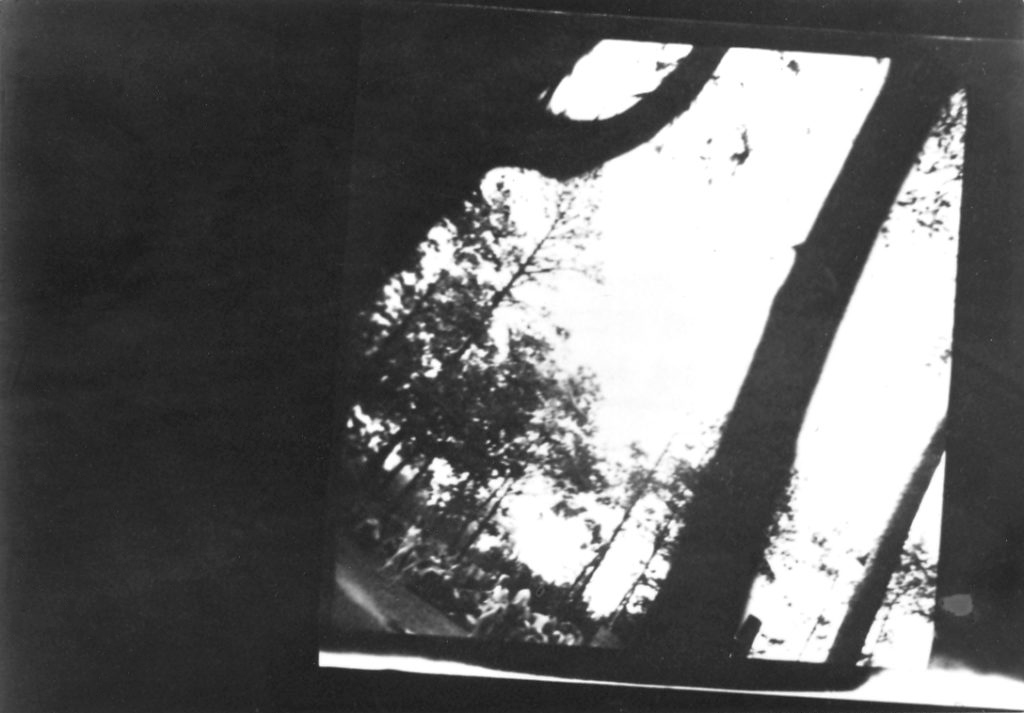

In the 1923 silent short of the same title, Man Ray filmed barely discernible scenes of Paris at night along with his own enigmatic photograms and conglomerations of spiraling or gyrating objects. The resulting sequence of near-total abstractions seems devoid of sense or purpose. The “return to reason” in the film comes finally in the form of a woman’s torso – modelled by cabaret personality Kiki de Montparnasse – turning to and fro beside a rain-covered windowpane. Man Ray reproduced the seductive finale, as well as other moments from the film, as photographs, singly and in strips. A still from Man Ray’s film, this particular photograph appeared on its own in the first issue of the key avant-garde journal La Révolution surréaliste, in 1924.

Text from the Art Institute of Chicago website

Le retour à la raison (Return to Reason), Man Ray, 1923

Emak-Bakia (1926) – directed by Man Ray

Emak-Bakia (Basque for Leave me alone) is a 1926 film directed by Man Ray. Subtitled as a cinépoéme, it features many techniques Man Ray used in his still photography (for which he is better known), including rayographs, double exposure, soft focus and ambiguous features.

Emak-Bakia shows elements of fluid mechanical motion in parts, rotating artifacts showing his ideas of everyday objects being extended and rendered useless. Kiki of Montparnasse (Alice Prin) is shown driving a car in a scene through a town. Towards the middle of the film Jacques Rigaut appears dressed in female clothing and make-up. Later in the film a caption appears: “La raison de cette extravagance” (the reason for this extravagance). The film then cuts to a car arriving and a passenger leaving with briefcase entering a building, opening the case revealing men’s shirt collars which he proceeds to tear in half. The collars are then used as a focus for the film, rotating through double exposures.

The film features sculptures by Pablo Picasso, and some of Man Ray’s mathematical objects both still and animated using a stop motion technique.

Originally a silent film, recent copies have been dubbed using music taken from Man Ray’s personal record collection of the time. The musical reconstruction was by Jacques Guillot.

When the film was first exhibited, a man in the audience stood up to complain it was giving him a headache and hurting his eyes. Another man told him to shut up, and they both started to fight. The theatre turned into a frenzy, the fighting ended up out in the street, and the police were called in to stop the riot.

Emak bakia can also mean “give peace” (“emak” is the imperative form of the verb “eman”, which means “give”) in Basque.

Text from the YouTube website

L’étoile de mer, Man Ray, 1928

The film was based on Robert Desnon’s surrealist poem L’Étoile de mer.

The Met Presents First Major Exhibition on Man Ray’s Radical Reinvention of Art through the rayograph

Featuring 160 rayographs, paintings, objects, prints, drawings, films, and photographs, Man Ray: When Objects Dream highlights the principal place of the rayograph – a type of cameraless photograph – within the context of many of the artist’s most important works

This exhibition includes thirty-five works by Man Ray which are part of the major promised gift of nearly 200 works of Dada and Surrealist art from Trustee John Pritkzer

Man Ray: When Objects Dream at The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the first major exhibition to examine the radical experimentation of American artist Man Ray (1890-1976) through one of his most significant bodies of work, the rayograph. Man Ray coined the term rayograph to name his version of the 19th-century technique of making photographs without a camera. He created them by placing objects on or near a sheet of light-sensitive paper, which he then exposed to light and developed. These photograms – as they are also called – appear as reversed silhouettes, or negative versions, of their subjects. They often feature recognisable items that become wonderfully mysterious in the artist’s hands. Their transformative nature led the Dada poet Tristan Tzara to describe rayographs as capturing the moments “when objects dream.” While Man Ray acknowledged the photographic origins of his new works, he did not think of them as strictly bound by medium. Taking Man Ray’s lead, this presentation is the first – more than a century since he introduced the rayograph – to situate this signature accomplishment in relation to his larger artistic output. The exhibition is on view September 14, 2025, through February 1, 2026.

“As one of the most fascinating and multi-faceted artists in the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, Man Ray challenged traditional narratives of modernism through his daring experimentation with diverse artistic mediums,” said Max Hollein, The Met’s Marina Kellen French Director and Chief Executive Officer. “Anchored by Man Ray’s innovative and mesmerising rayographs along with new research and discoveries, this exhibition invites visitors to explore his ground-breaking manipulation of objects, light, and media, which profoundly reframed his artistic practice and impacted countless other artists. We’re so thrilled to include thirty-five works by Man Ray in this exhibition as part of John’s incredible promised gift.”

Drawing from the collections of The Met and more than 50 U.S. and international lenders, the presentation includes more than 60 rayographs, many of which were featured in important publications and exhibitions at the time of their making, and 100 paintings, objects, prints, drawings, collages, films, and photographs to highlight the central role of the rayograph in Man Ray’s boundary-breaking practice. The exhibition marks a collaboration with the recently closed Lens Media Lab, Yale University, under the direction of Paul Messier, and with photography conservators and curators at various lending institutions, to study more than fifty rayographs.

In the winter of 1921, while working late in his Paris darkroom, Man Ray inadvertently produced a photogram by placing some of his glass equipment on top of an unexposed sheet of photographic paper he found among the prints in his developing tray. As he wrote in his 1963 autobiography, “Before my eyes an image began to form, not quite a simple silhouette of the objects as in a straight photograph, but distorted and refracted … In the morning I examined the results, pinning a couple of the rayographs – as I decided to call them – on the wall. They looked startlingly new and mysterious.” This supposed accident, now the stuff of legend, has obscured the fact that rayographs might be seen as the culmination of Man Ray’s work up to 1921 as well as the frame through which he would redefine his work thereafter. They harnessed his interests in working between dimensions, media, and artistic traditions, fittingly at the moment between Dada and Surrealism, which writer Louis Aragon once called the mouvement flou (flou means “hazy, blurry, or out of focus” in French).

Unfolding in a series of spaces that intersect with a central, dramatic presentation of rayographs, the exhibition illuminates their connections with Man Ray’s work in other media, including assemblage, painting, photography, and film. In approaching the rayograph in this expansive way, the exhibition also offers a reappraisal of the most productive and creatively significant period of his long career, beginning in New York around 1915 with his ambitious paintings and concluding in Paris in 1929 with his fine-tuning of the solarization process with Lee Miller. A critical factor across the exhibition is the central role of objects for Man Ray’s career, both in the creation of many of the rayographs and in his work more generally.

At its core, Man Ray: When Objects Dream focuses new attention on some of the artist’s most recognised, but little-studied, works, most particularly the rayograph. The exhibition opens with Champs délicieux (Delicious Fields) (1922), a portfolio of 12 rayographs which marks the first time Man Ray presented his photograms to the public. Critics hailed them for putting photography on the same plane as original pictorial works. The presentation concludes with the working copy of Champs délicieux, which the artist canceled and dedicated to his friend, Dada artist Tristan Tzara, in 1959.

Between these two works, twelve thematic sections of the exhibition explore such concepts as the silhouette, the dream, the body, the object, and the game, which are inspired by Man Ray’s experimentation with the rayograph. Other groupings will focus on specific media and techniques, and the artist’s studio, as well as watershed moments in the artist’s production, such as the years of 1923 and 1929, when Man Ray unexpectedly returned to painting. Three of his newly restored films, Retour à la raison (Return to Reason) (1923), Emak Bakia (1926), and L’étoile de mer (The Starfish) (1928), will be screened within the exhibition.

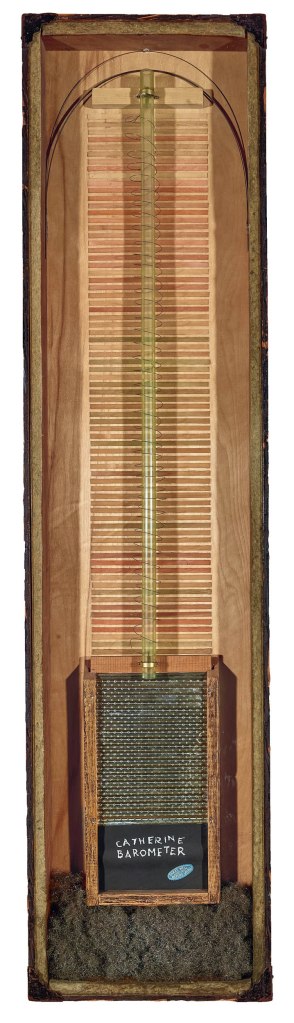

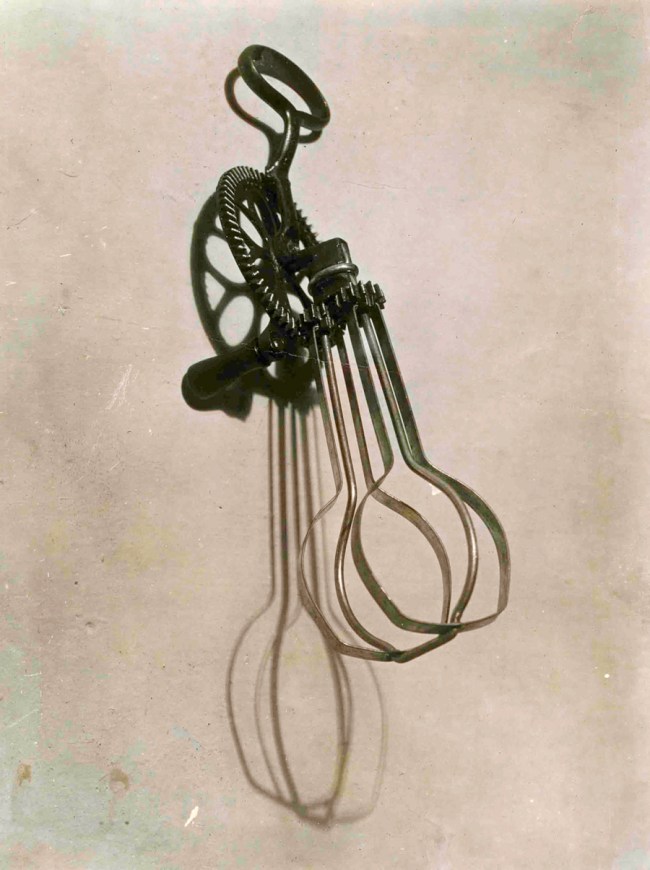

Highlights include such iconic objects like Man Ray’s iron studded with tacks, known as Cadeau (Gift) (1921), and his metronome, Object to be Destroyed (1923), that keeps time with the swinging eye of his companion, the photographer Lee Miller. Celebrated photographs, including his landmark Le violon d’Ingres (1924), in which the torso of the artist and performer Kiki de Montparnasse (Alice Prin) is depicted as a musical instrument, are also featured. The exhibition brings together some of his boldest but most refined experimental works – compositions like Aerograph (1919), a painting made with an airbrush and pigment sprayed through and around items from his studio. For Man Ray, objects could function as metaphors for the body, as demonstrated in works such as Catherine Barometer (1920) and L’homme (Man). Rarely seen paintings in the exhibition, including Paysage suédois (Swedish Landscape) (1926) record the artist’s great experimentation, working paint without a brush and in an almost sculptural way, building up and scraping down the surface that reflects his experiments in the darkroom.

Man Ray: When Objects Dream is curated by Stephanie D’Alessandro, Leonard A. Lauder Curator of Modern Art and Senior Research Coordinator in Modern and Contemporary Art at The Met, and Stephen C. Pinson, Curator in the Department of Photographs at The Met, with the assistance of Micayla Bransfield, Research Associate, Modern and Contemporary Art.

Press release from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

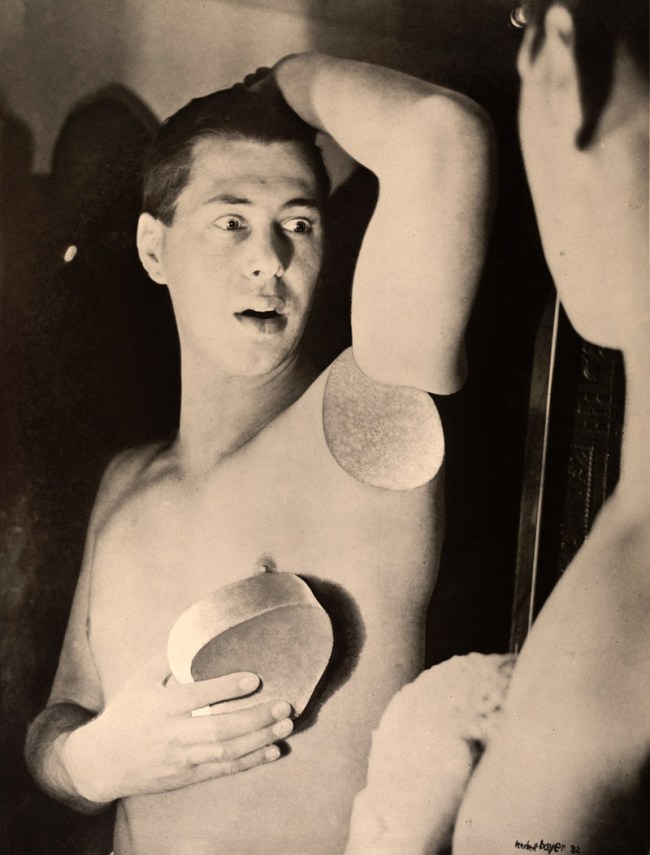

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

La Femme (Woman)

c. 1918-1920

Gelatin silver print

43.7 x 33.5cm (17 3/16 x 13 3/16in.)

Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

© 2016 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

L’homme (Man)

1918-1920

Gelatin silver print

19 × 14 1/2 in. (48.3 × 36.8cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Photo credit: Courtesy of The Bluff Collection, photo by Ben Blackwell

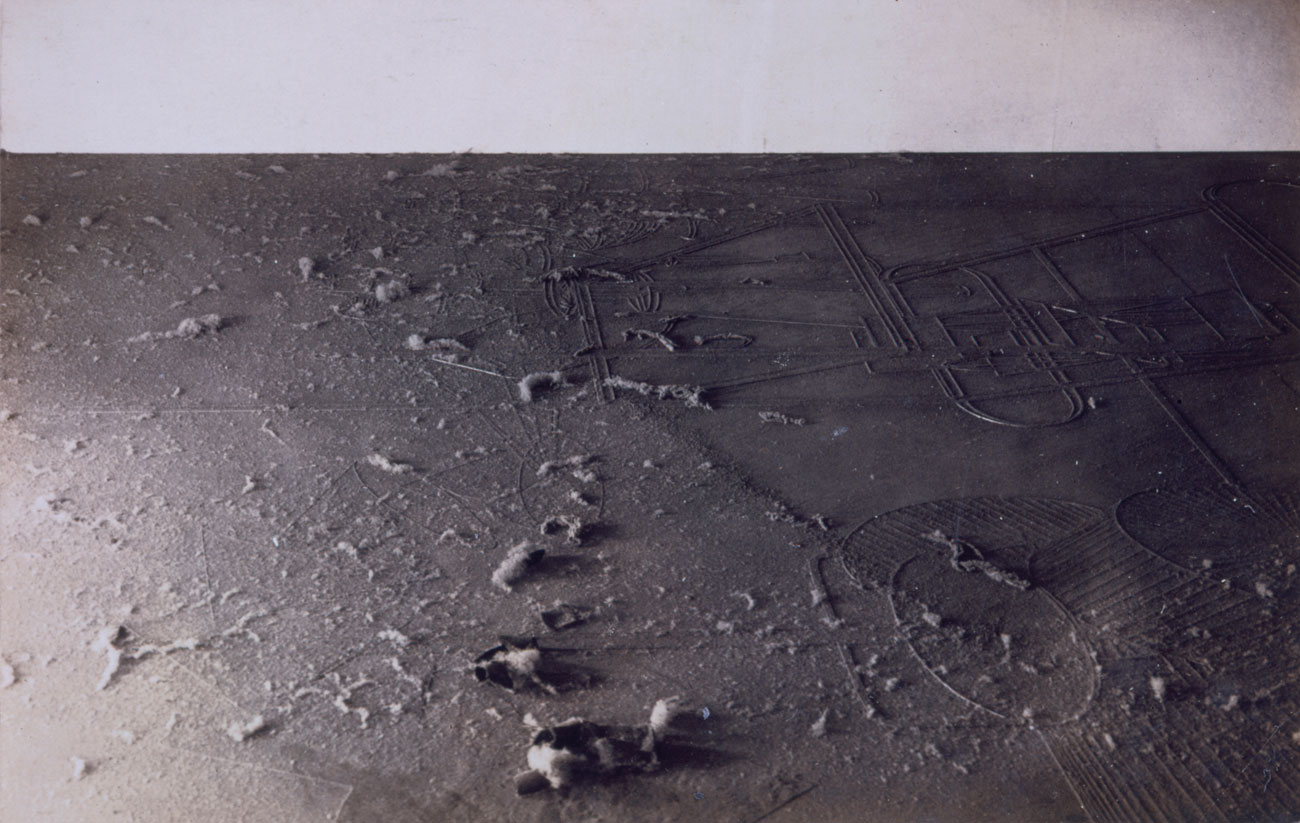

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Élevage de poussière (Dust Breeding)

1920

Gelatin silver print

2 13/16 × 4 5/16 in. (7.1 × 11 cm)

Private collection

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

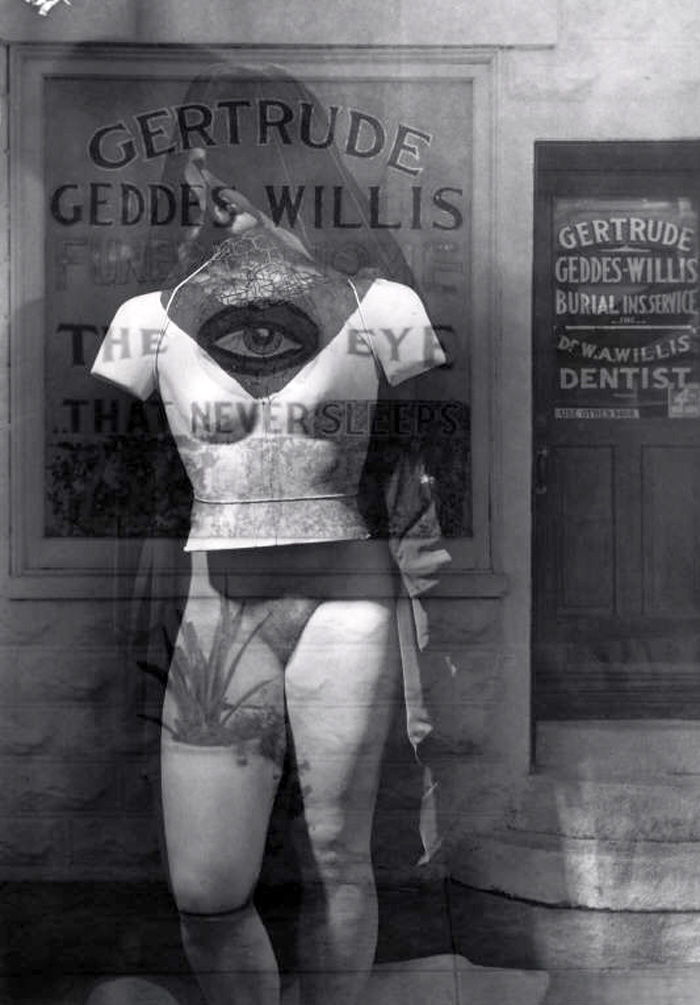

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Marchesa Luisa Casati

1922

Gelatin silver print

8 1/2 × 6 9/16 in. (21.6 × 16.7 cm)

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Carl Van Vechten

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Installation view of the exhibition Man Ray: When Objects Dream at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 2025 – February 2026 showing at centre, Man Ray’s photograph Le violon d’Ingres 1924 (below)

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Le violon d’Ingres

1924

Gelatin silver print

19 1/8 × 14 3/4 in. (48.5 × 37.5cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Photo by Ian Reeves

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Self-Portrait in 31 bis rue Campagne-Première Studio

1925

Gelatin silver print

6 1/8 × 4 1/2 in. (15.6 × 11.4cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Photo by Ian Reeves

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Noire et blanche

1926

Gelatin silver print

8 1/16 x 11 11/16 in. (20.5 x 29.7cm)

Private collection

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Primat de la matière sur la pensée (Primacy of Matter over Thought)

1929

Gelatin silver print

10 1/2 x 14 7/8 in. (26.7 x 37.8cm)

Private collection, San Francisco

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976)

Lee Miller

1929

Gelatin silver print

10 1/2 × 8 1/8 in. (26.7 × 20.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of James Thrall Soby

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Self-Portrait with Camera

1930

Gelatin silver print

4 3/4 x 3 1/2 in. (12.1 x 8.9cm)

The Jewish Museum, New York

Purchase: Photography Acquisitions Committee Fund, Horace W. Goldsmith Fund, and Gift of Judith and Jack Stern

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

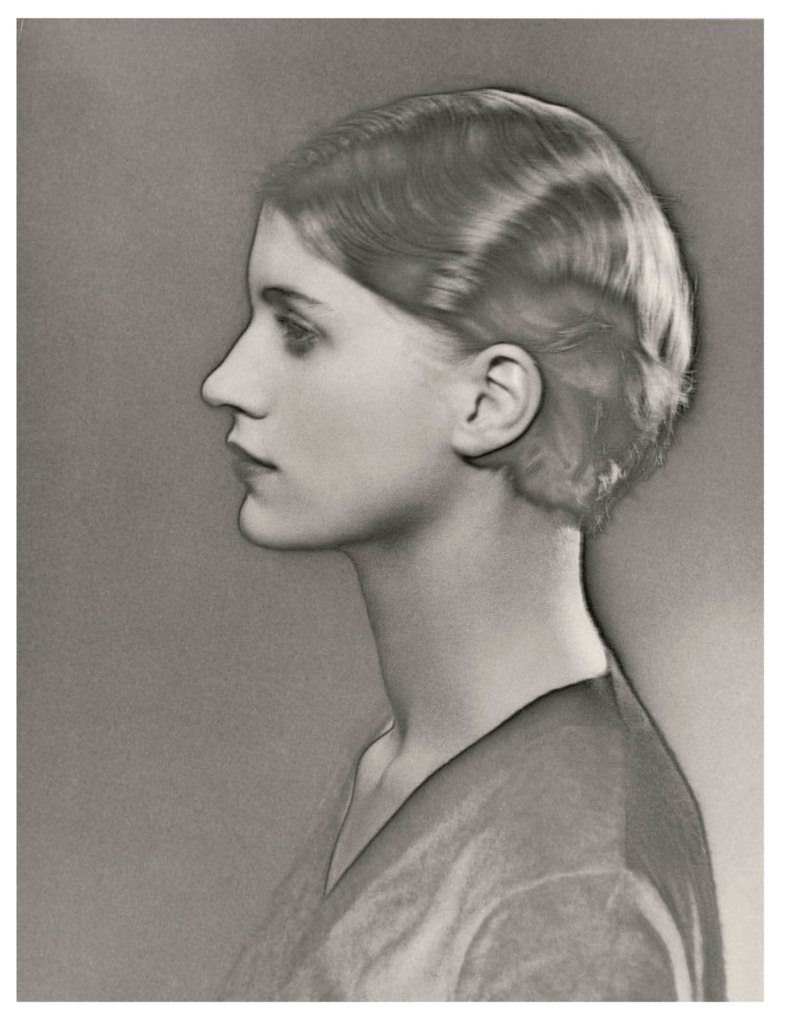

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Mary Gill

1930

Gelatin silver print

11 1/2 x 8 1/2 in. (29.2 x 21.6cm)

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Robert M. Sedgwick II Fund

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Untitled (Glass Tears)

c. 1930-1933, printed 1935 or later

Gelatin silver print

8 7/8 x 11 1/4 in. (22.5 x 28.6cm)

Private collection

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray: When Objects Dream

American artist Man Ray (1890-1976) was a visionary known for his radical experimentation that pushed the limits of art. His most iconic works – an iron studded with sharp tacks, a woman’s back reimagined as a violin – combine this boundary-breaking attitude with a singular belief in the transformative potential of everyday things.

In the 1920s, the most significant of Man Ray’s investigations – and the thing that connected much of his work – was what he called the rayograph, a new twist on an old technique for making photographs without a camera. By placing objects on or near a sheet of sensitised paper, which he then exposed to light and developed, he turned recognisable subjects into wonderfully mysterious compositions. This radical art form, inextricably linked to the era’s Dada and Surrealist movements, grew out of his early work in New York and redefined his groundbreaking career in Paris.

Introduction

This exhibition’s subtitle, When Objects Dream, comes from a phrase by Tristan Tzara, a poet, artist, and early champion of Man Ray. Witness to some of the earliest rayographs, Tzara understood perhaps better than anyone else their physical and metaphorical link to objects reimagined through art. In a similar spirit, the current presentation reconsiders the role of the rayograph within Man Ray’s practice, especially its ability to extend his ideas across diverse media. The loosely chronological installation unfolds across a series of interconnected galleries organized around ideas that motivated the artist; to that end, visitors are invited to explore it in any number of ways.

All works in the exhibition are by Man Ray (American, 1890-1976).

Champs délicieux

In April 1922, readers of a French literary journal discovered a curious announcement for an album titled Champs délicieux (Delicious Fields). Its twelve “original photographs” by Man Ray feature objects from his studio – tongs, a comb, string, a hotel room key – composed in groupings. The images are ordered without clear logic or narrative. Instead, as advertised, they mark a “state of mind,” the artist’s free play, alone at night and without work obligations, in his studio darkroom.

Man Ray introduced Champs délicieux in the period between two revolutionary movements that arose in the wake of World War I: Dada and Surrealism. Both challenged conventional art and society by upending traditional subjects, techniques, and expectations. Inspired in part by a collection of unconsciously driven, automatic writings by poets André Breton and Philippe Soupault, Man Ray sought to render everyday objects unfamiliar. As early subscriptions attest, the album found an enthusiastic audience who appreciated the language of the rayograph and its ability to open up a new visual world.

A New Art

Before Man Ray first picked up a camera in 1915, he was focused on painting. He set out to stake his claim in the exhilarating avant-garde scene, his interest fueled by cutting-edge exhibitions at Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery, 291, and thrilling examples of Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism, and Futurism at the modern art presentation known as The Armory Show in 1913. Unexpectedly, photography offered Man Ray a path forward. Noting the way a camera lens could compress and flatten space, he determined to endow art with a similar “concentration of life” while simultaneously freeing it from the burden of illusionism. “The creative force and the expressiveness of painting,” he wrote at the time, “reside materially in the colour and texture of pigment, in the possibilities of form invention and organisation, and in the flat plane on which these elements are brought to play.” He made paintings using palette knives and other tools instead of brushes and employed patterns, cutouts, and collage to create a self-proclaimed “new art of two dimensions.”

Objects At Hand

NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR GOODS LEFT OVER THIRTY DAYS. So reads a sign in a photo, displayed nearby, of Man Ray’s West Eighth Street studio in New York. It was one of several items the artist discovered in the trash heap at his apartment building and brought up to his top-floor space. He considered retooling the sign to read LEFT OVER GOODS NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR THIRTY DAYS but decided it was perfect as is. This act – of elevating junk to art – is a familiar one in histories of the avant-garde, especially for the Dada movement. Art did not have to be painted or modelled or made with traditional materials and tools; it could be found in the everyday world and appreciated for the idea that it introduced, not for its beauty.

As Man Ray developed his “new art,” he came to see the latent potential of all the objects within his studio. This spurred further investigations that likewise tested the limits of two and three dimensions and blurred the boundaries between media. At the same time, he continued to explore how the camera could be used not only to document his work but to open new perspectives onto ordinary objects and their creative possibilities.

Clichés-verre

While the rayograph is often described as Man Ray’s first experiment with cameraless photography, that moment occurred years earlier. Around 1917 he explored several photographically based techniques, including the cliché-verre, or “glass-plate” print. A nineteenth-century reproductive process that incorporates both photography and printmaking, a cliché-verre is traditionally made by covering a plate of glass with a darkened medium and drawing into it to produce clear lines. When set onto sensitised paper and exposed to a light source, the plate transmits the scratched away areas as dark lines. Man Ray chose to incise directly into the emulsion of an exposed photographic plate, which he then subjected to light again with paper below it to make a contact print.

Photography

Man Ray first picked up a camera in 1915, to document his art. Through this experience, he discovered that the works acquired new qualities when reproduced in black and white. He made photographic portraits, too, which in Paris would become a dependable source of income. Revelling in the camera’s transformative optical abilities, Man Ray soon used it as a tool to facilitate his self-appointed role as a “marvellous explorer of those aspects that our retinas will never record.” He sought to reveal the creative potential of objects in his studio and in 1918 began a series of photographs using specifically arranged everyday items.

Aerographs

Still grappling with how to paint without a brush, Man Ray found inspiration at his day job working for an advertising agency, where he was introduced to an airbrush. He later brought the equipment back to his attic studio and began to experiment. Using an air compressor, the artist directed pigment through stencils and around masked areas and objects, which he rested on the composition board and repositioned as he worked. “It was thrilling,” he would later recount, “to paint a picture, hardly touching the surface – a purely cerebral act.” These works, which he termed “aerographs” were made, in effect, before they hit the paper. Objects were carved, shaped, and modeled in the air. Voids register as substance, and what we see on the paper is residue fused to the surface. “I tried above all,” Man Ray explained, “to create three-dimensional paintings on two-dimensional surfaces.”

Flou

Man Ray introduced his rayographs during a transitional period between the Dada and Surrealism movements that the French writer Louis Aragon called the mouvement flou – flou translating to “blurry” or “out of focus.” The term also suits these works, which viewers initially deemed curious and captivating but difficult to pin down. Rayographs, as cameraless photographs, exist in an indistinct place between photography and painting, the mechanical and the handmade, documentation and dream.

During the 1920s Man Ray also explored blurriness in his camera images. Even as technical improvements facilitated increased focus and detail, and the preference for sharp photographs grew, he generally pursued a flattering, soft-focus technique in his growing business of portrait commissions. At other times, he sought more radical effects, which the director Claude Heymann described as “strange, troubling blurs” produced “through distortions, prolonged poses or special focusing techniques.” The anomalies in the resulting photographs are visible signs of the effort and time Man Ray spent to realise the images – even if he later called them unplanned or accidental.

A New Field of Gravity

In his preface introducing the album Champs délicieux (Delicious Fields), Tristan Tzara remarked that rayographs “present to space an image that exceeds it, and the air, with its clenched fists and superior intelligence, seizes it and holds it next to its heart.” Indeed, objects in Man Ray’s images beckon us in but keep us thrillingly at the edge – or put another way, they test our senses of proximity and location. His experiments in New York expanded the bounds of the photograph, object, painting, and installation, and he developed a novel relationship between object and viewer. These works demonstrate in their construction what the French writer Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes would identify in the artist’s rayographs as a “new field of gravity.”

The rayograph

The term rayograph designates Man Ray’s version of a technique for making photographs without a camera: by setting objects on or near sensitised paper and exposing it to light. In his autobiography, the artist described happening upon the process by chance, late one night, while developing prints in his makeshift darkroom. For subjects, he looked no further than the things in his studio. When exposed to a directed flash of light, they appear as reversed silhouettes – but in Man Ray’s hands they also gained new life. The nature of the image depended on the items’ translucency, reflectivity, density, placement, and distance from the sheet, as well as the source and location of the illumination and the number of exposures. Surfaces could cast unexpected reflections or eclipse elements in darkness. Forms might multiply or transform. Sometimes Man Ray’s objects and the space between them acquired an insistent, compressed volume that registered on the paper. The resulting works present what writer Pierre Migennes described as a “metamorphosis of the most vulgar utensils.” Everyday things became wonderfully unfamiliar as Man Ray wielded light in the darkroom like a brush in paint.

As he prepared to launch his rayographs in Champs délicieux, Man Ray also considered how to disseminate them for reproduction in magazines. On November 1, 1922, he wrote to Harold Loeb, editor of Broom: “Each print is an original, no plate or duplicate exists, as the process is manipulated directly on the paper, like a drawing. If you could assure me that the … originals would be safely handled and returned, I shall gladly send them on [to Berlin]. If, however, you cannot guarantee their safe return, I can re-photograph them … which, while not having the intensity and contrast of the originals, would nevertheless reproduce well.” Loeb offered to transport them personally and published these four in Broom the following March.

Man Ray transformed and energised ordinary objects in his rayographs by tapping their powers of translucency or reflectance. Bodies and their proxies, however, remain stubbornly recognisable. Hands reach out, hold things, and interact with objects; heads turn to kiss and drink, even if the action might be staged. The artist’s rayographs tie the body to a kind of specificity that his objects do not experience; this might explain why there are fewer of these works with bodies than without. As Tristan Tzara explained in his appreciation of the rayographs in 1934, Man Ray approached objects in a manner that allowed them to be free “to dream.”

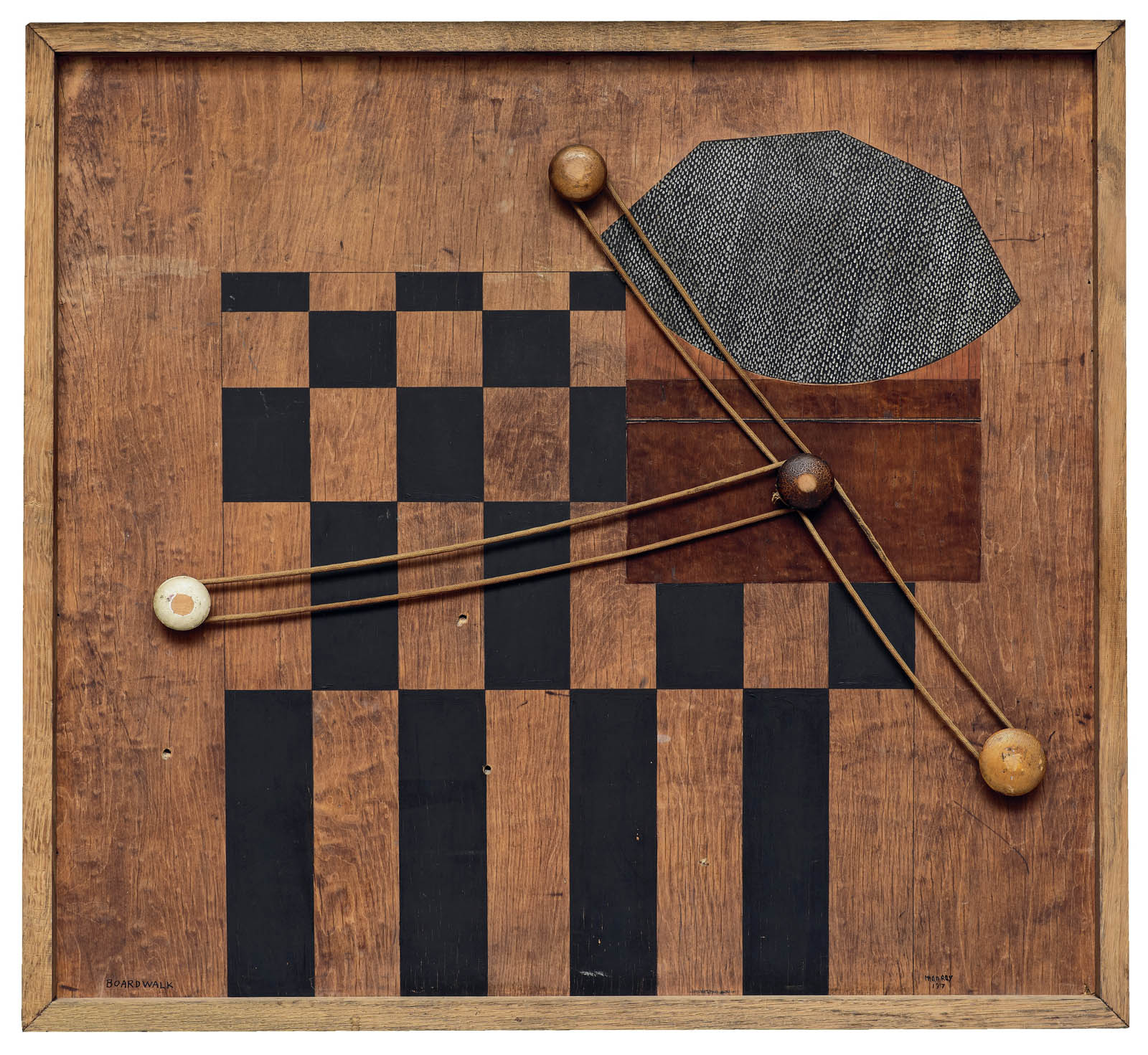

Dangerous Games

Reactions to Man Ray’s cameraless photographs consistently identified them with the realm of play. The first to comment on the rayograph was French poet Jean Cocteau, who wrote in an open letter, “You, my dear Man Ray, will nourish our minds with those dangerous games it craves.” He was soon joined by Tristan Tzara, who likened the rayograph to a “game of chess with the sun.”

Man Ray had a strong sense of the game as a strategy for producing art. For him, play was a state of readiness to engage. This comes through in the provocative humour of his objects and collages and in the invitation to chance embedded in the rayograph process – the “discovery” of which, he recounted, entailed real amusement. Marcel Duchamp once playfully defined his friend as synonymous with the joy of the game: “MAN RAY, n.m. synon. de joie, jouer, jouir” (joy, to play, to enjoy).

Chemical Paintings

In April 1922, the same month that the Champs délicieux album was announced, Man Ray proudly reported to friends and patrons that he had freed himself “from the sticky medium of paint.” His rayographs claimed a rebellious position aimed at the traditional hierarchy of fine art – and particularly its apex, painting. Critics asserted they had equal status, and New York’s Little Review even called them “chemical paintings.”

Just a year later, however, while his rayograph production remained steady, Man Ray quietly returned to painting. The works here show how his practice had changed. Abstract and relatively small, they were made on commercially available boards, wood, sandpaper, or metal supports. With their overlapping pictorial elements and dramatic contrasts of luminosity and shadow, angled and geometric forms, the compositions emulate aspects of rayographs. Each is a thorough exploration of depth on a flat surface and a bid to make paint reflect its own material reality.

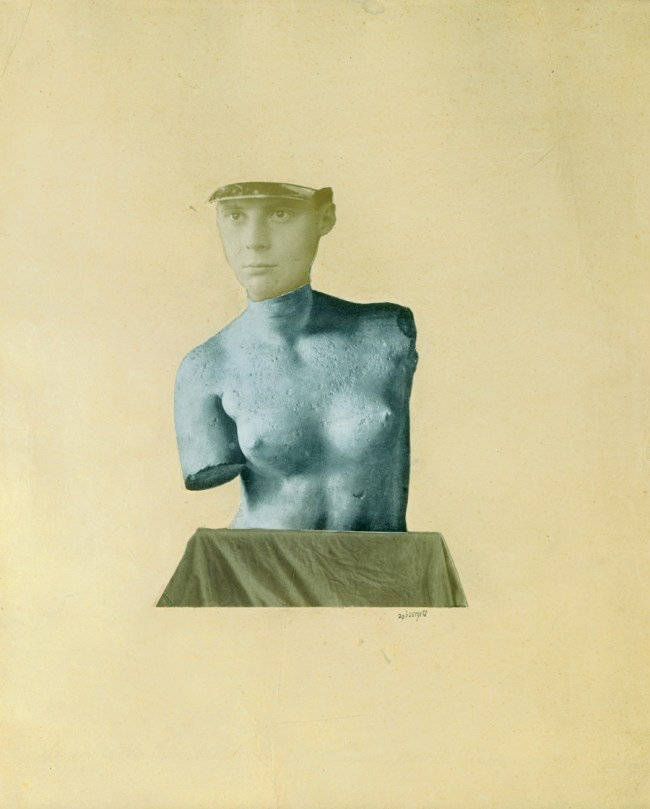

Objects and Bodies

Man Ray’s experience of making rayographs informed his consideration of the human body, which he handled, at times, like an object, devoid of personhood and open for manipulation. Writing about the artist’s portraits and rayographs, André Breton noted that Man Ray considered the bodies of women in his work no different from the objects at hand in his darkroom:

The very elegant, very beautiful women who expose their tresses night and day to the fierce lights in Man Ray’s studios are certainly not aware that they are taking part in any kind of demonstration. How astonished they would be if I told them that they are participating for exactly the same reasons as a quartz gun, a bunch of keys, hoar-frost or fern!

For Man Ray, a body could function as a kind of concentrated equivalence, like the essence represented by an object. This attitude is visible in some of the most iconic works of his career, in which his presentation of female models such as the artist and performer Kiki de Montparnasse (Alice Prin) also involved darkroom manipulation. While his approach to men’s bodies was notably less sexualised, they too were posed and set up like the objects in his rayographs.

Darkroom Manoeuvres

Like other pictures of Kiki de Montparnasse in this gallery, Le violon d’Ingres involved multiple darkroom campaigns. For the version published in Littérature, Man Ray worked on a print to sharpen the contours and smooth the forms; he added f-shaped sound holes directly onto it with dark ink.

The version here, larger than the first, is the result of further experimentation. Man Ray covered the entire print with a mask from which he hand cut two f-shaped forms. He then made a second exposure, which turned the exposed spaces black. Instead of ink shapes that disrupt the surface, these marks read as deep, dark space compressed within the flat surface of the photograph. Man Ray described this version as “a combination of a photo and a rayograph.” As such, the f-holes are eerily – seamlessly – part of the woman’s body. She appears as a kind of dreamlike human-instrument hybrid, a whole object to be visually taken in and possessed.

Dreams

Even before the Surrealist manifesto of 1924 claimed the fertile ground of the unconscious, many poets and artists in Man Ray’s circle focused on dreams. The same group, two years earlier, had followed André Breton’s experiments with hypnosis and trance states. They practiced séances and so‑called sleeping fits, writing down or drawing what came to them in order to reveal hidden desires. The poet Louis Aragon wrote of these slumberous escapades: “Dreams, dreams, dreams, the domain of dreams expands with every step.”

Apart from photographing the sleep sessions, Man Ray remained an independent supporter of the group, explaining, “It has never been my object to record my dreams, just the determination to realise them.” Even so, Aragon included him in his multipage inventory of dreamers, with a nod to the rayographs: “Man Ray … dreams in his own way with knife rests and salt cellars: he gives meaning to light, which now knows how to speak.” The artist found great support among the Surrealist circle in Paris, whose members acquired his work and included him in exhibitions and publications.

Dream Objects

Man Ray’s dreamlike rayographs have counterparts in the new kinds of hybrid objects he began to make at the same time. These mysterious works seize upon unexpected transformations: a fragile soap bubble rendered solid; the taut strings on a musical instrument’s neck turned loose and sensuous; or a budding plant metamorphosed into a pudgy hand.

The strange bundle wrapped with string has long been associated with the power of objects to stir the unconscious. In 1920 Man Ray assembled, photographed, and deconstructed the original object. The Untitled photograph appeared in the first issue of La revolution surréaliste, in 1924, with the text “Surrealism opens the door of the dream to all those for whom night is miserly.” Over the next decade, the image came to embody another phrase popular among the Paris Surrealist group, by the poet Isidore Ducasse: “as beautiful … as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table.”

“Objects to touch, to eat, to crunch, to apply to the eye, to the skin, to press, to lick, to break, to grind, objects to lie, to flee from, to honor, things cold or hot, feminine or masculine, objects of day or night which absorb through your pores the greater part of our life. … These are the projections surprised in transparence, by the light of tenderness, of objects that dream and talk in their sleep.” (Tristan Tzara, “When Objects Dream,” 1934)

Returns

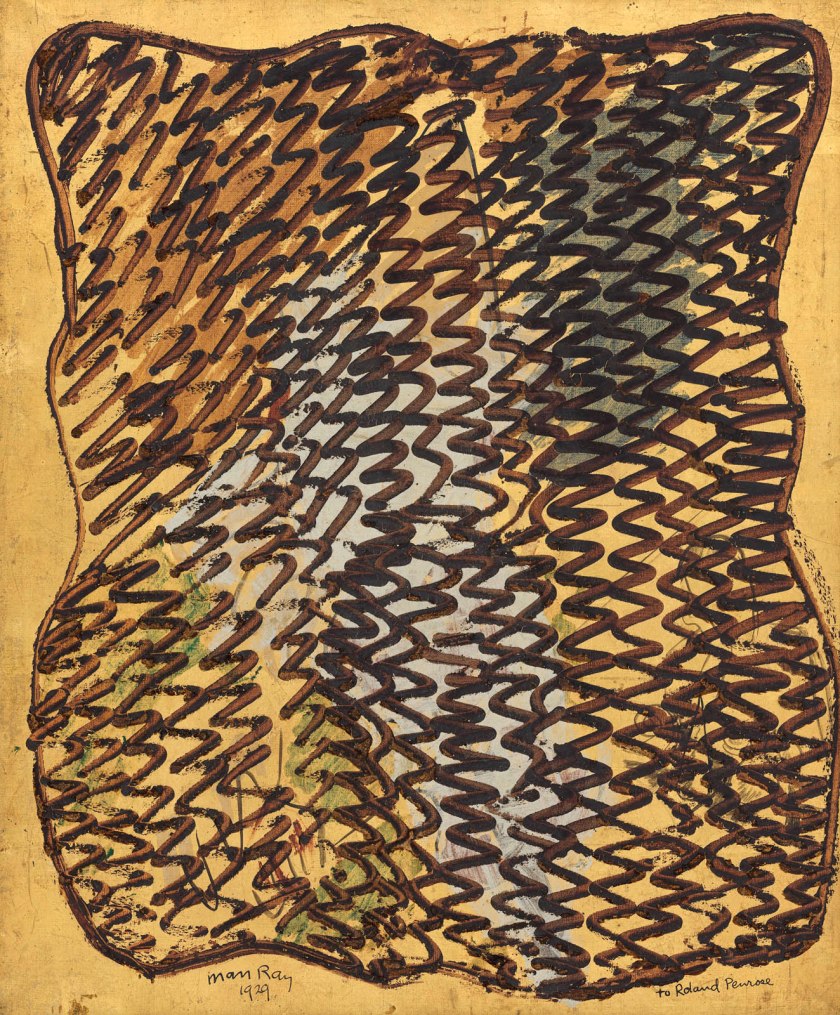

In 1929 Man Ray found himself “longing to touch paint again.” By the fall, he had taken a second Paris studio, near the Luxembourg Gardens, where he painted in the mornings before returning home to oversee photographic portraits and magazine work. In his new compositions, he let paint drip across a canvas from a poured line and squeezed pigment directly from the tube onto a support in a loose, calligraphic manner. Trading on narratives of chance and automatism, he later called these paintings “unpremeditated.”

Another return accompanied the arrival in Paris of Lee Miller, who became Man Ray’s apprentice in photography and then his personal and professional partner. As a result, he again embraced the camera as his primary tool of photographic experimentation, after years of making rayographs without one. Together, Miller and Man Ray discovered a creative synergy that led to their joint development of the solarization process. The same year signalled the near culmination of Man Ray’s exploration of the rayograph: by some accounts, he made one hundred in 1922, but just one in 1929.

Solarization

Together with Lee Miller, Man Ray developed a darkroom technique that complemented his return to painting. Like the rayograph, solarization was not entirely new, and both he and Miller claimed that it similarly resulted from an accident. The process involves exposing a negative a second time during development, which causes a reversal of the expected tonalities. Honed by Miller and Man Ray and applied to their portraits and nudes beginning in fall 1929, the process often endowed subjects with subtly glowing black contours that Miller called “halos.” This feature became so well-known – largely through reproductions of the solarized portrait of Miller shown nearby – that a 1932 article called it both “the beacon and despair of experimenters.” Like the drips and skeins in Man Ray’s 1929 paintings, these lines create a friction between the subject and surface of the image – a noted departure from the artist’s earlier approach to the flat plane.

Revisiting Champs délicieux

Man Ray completed his Champs délicieux project nearly forty years after its debut. A handwritten inscription to Tristan Tzara in the final copy (number 41, displayed here) refers to the sparks set off by their initial exploration of the rayograph; he added an almost identical inscription in his 1922 working copy. This suggests a Dada game between the two artists: the announcement laid out the rules and the inscriptions signified its end.

As promised in the 1922 first announcement of the album, the last copy features the canceled proofs (a practice meant to show that no further prints can be made from the originals). A canceled print edition is not unusual. In this case, however, a purposeful ambiguity was in play from the beginning of the project – when it was presented as an album of “original photographs” copied from unique rayographs – to the end. Only the negatives used to produce the album were canceled, meaning that the primary rayographs might still exist. Ever the prankster, Man Ray ensured that the game continues.

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Legend

1916

Oil on canvas

52 × 36 in. (132.1 × 91.4 cm)

Collection of Deborah and Edward Shein

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Photo by Stephen Petegorsky

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Boardwalk

1917

Oil, wood handles, and yarn on wood

26 9/16 × 29 × 15/16 in. (67.4 × 73.6 × 2.4cm)

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, acquired 1973 with Lotto Funds

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

By Itself I

1918

Wood, iron, and cork

17 1/4 × 7 11/16 × 7 5/16 in. (43.8 × 19.5 × 18.6cm)

LWL–Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Münster, Germany

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

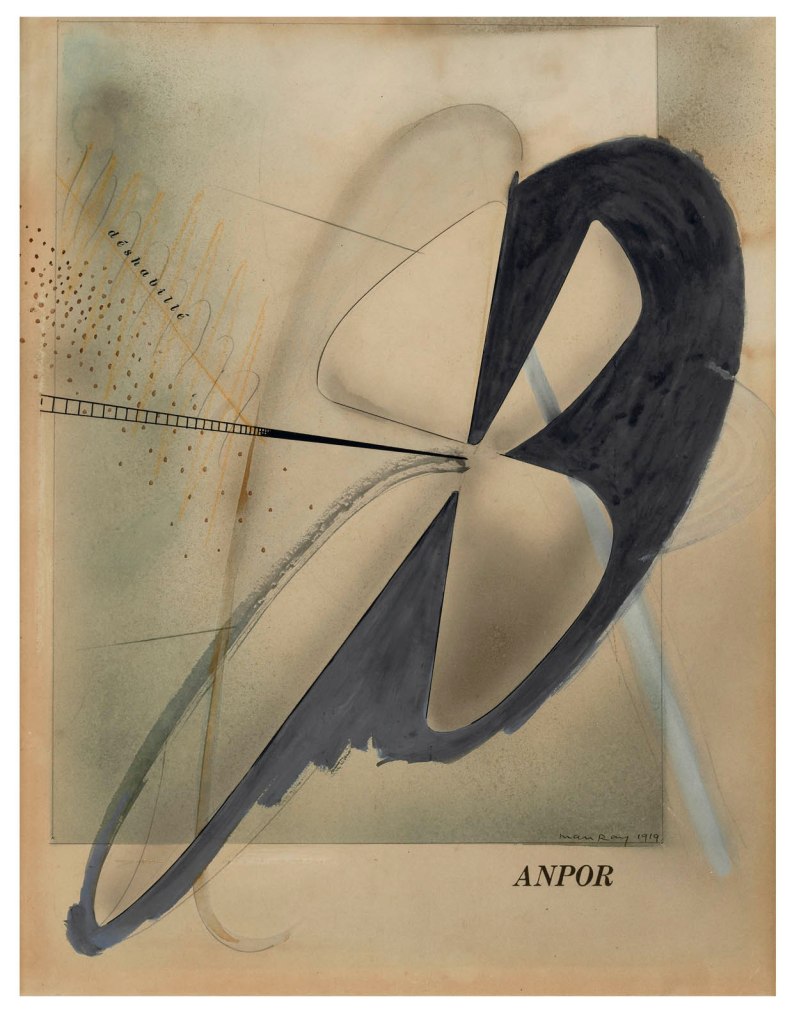

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

ANPOR

1919

Gouache, ink, and colored pencils on paper

15 1/2 × 11 1/2 in. (39.4 × 29.2cm)

Collection of Gale and Ira Drukier

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Bruce Schwarz

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Aerograph

1919

Gouache on paperboard

26 3/8 x 19 11/16 in. (67 x 50cm)

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Graphische Sammlung, acquired 1987

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Catherine Barometer

1920

Glass, metal, felt, washboard, tube, wire, wood, steel wool, gouache on paper, and paper stamp

48 1/8 × 12 × 2 1/8 in. (122.2 × 30.5 × 5.4cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker

Photo courtesy of The Bluff Collection, photo by Ian Reeves

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Cadeau (Gift) (installation view)

1921 reconstructed 1970

Iron with brass tacks and wooden base

Overall: 19.0 x 14.9 x 14.9cm; iron & base: 17.9 x 14.9 x 14.9cm; glass cover: 19.0cm (h.)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan

An example of this art work, not the actual one in the exhibition

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Paysage suédois (Swedish Landscape)

1926

Oil on canvas

18 × 25 1/2 in. (45.7 × 64.8 cm)

The Mayor Gallery, London

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Photo courtesy of The Mayor Gallery, London

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Torso

1929

Oil and gouache on gold foil paper on canvas

18 1/16 × 14 15/16 in. (45.9 × 38 cm)

The Penrose Collection

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Mark Morosse

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Thursday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Closed Wednesday

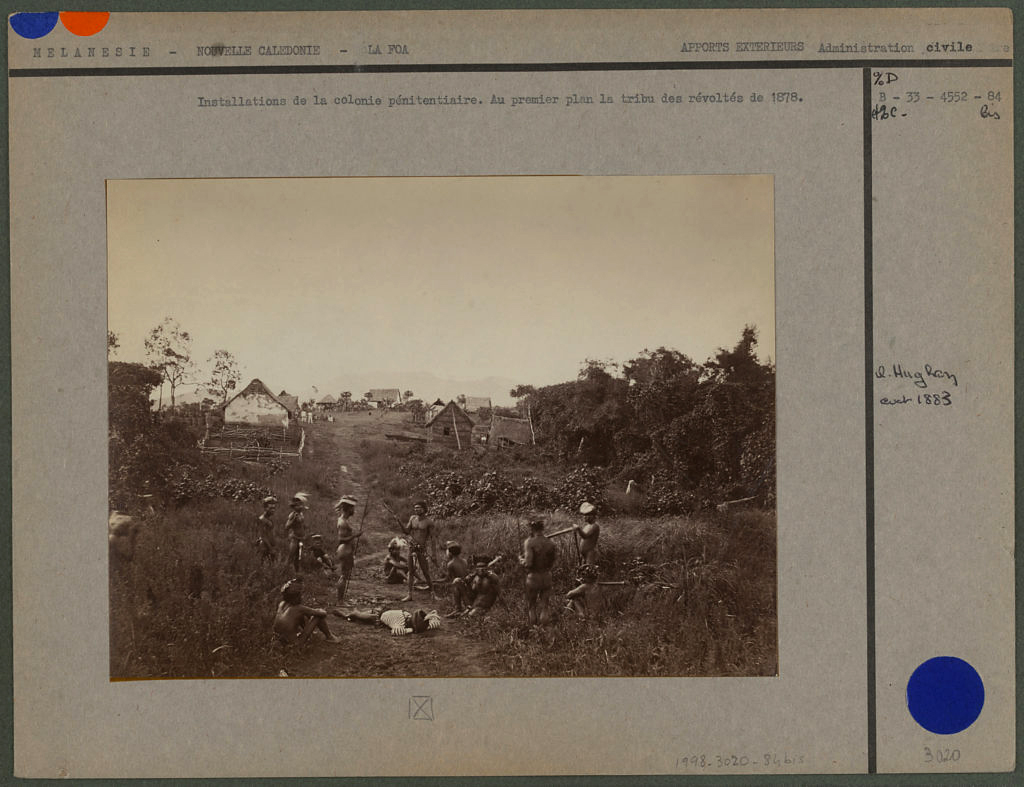

You must be logged in to post a comment.