Exhibition dates: 28th November 28 – 15th December 2012

Installation photograph of Ikea by Janina Green at Edmund Pearce Gallery, Melbourne

“It is necessary to revisit what Walter Benjamin said of the work of art in the age of its mechanical reproducibility. What is lost in the work that is serially reproduced, is its aura, its singular quality of the here and now, its aesthetic form (it had already lost its ritual form, in its aesthetic quality), and, according to Benjamin, it takes on, in its ineluctable destiny of reproduction, a political form. What is lost is the original, which only a history itself nostalgic and retrospective can reconstitute as “authentic.” The most advanced, the most modern form of this development, which Benjamin described in cinema, photography, and contemporary mass media, is one in which the original no longer even exists, since things are conceived from the beginning as a function of their unlimited reproduction.”

Jean Baudrillard. ‘Simulacra and Simulation’. 1981 (English translation 1994)

“To apprehend myself as seen is, in fact, to apprehend myself as seen in the world and from the standpoint of the world. The look does not carve me out in the universe; it comes to search for me at the heart of my situation and grasps me only in irresolvable relations with instruments. If I am seen as seated, I must be seen as “seated-on-a-chair,” … But suddenly the alienation of myself, which is the act of being-looked-at, involves the alienation of the world which I organise. I am seated on this chair with the result that I do not see it at all, that it is impossible for me to see it …”

Jean-Paul Satre. ‘Being and Nothingness’ (trans. Hazel Barnes). London: Methuen, 1966, p. 263

“It must be possible to concede and affirm an array of “materialities” that pertain to the body, that which is signified by the domains of biology, anatomy, physiology, hormonal and chemical composition, illness, age, weight, metabolism, life and death. None of this can be denied. But the undeniability of these “materialities” in no way implies what it means to affirm them, indeed, what interpretive matrices condition, enable and limit that necessary affirmation. That each of those categories [BODY AND MATERIALITY] have a history and a historicity, that each of them is constituted through the boundary lines that distinguish them and, hence, by what they exclude, that relations of discourse and power produce hierarchies and overlappings among them and challenge those boundaries, implies that these are both persistent and contested regions.”

Judith Butler. ‘Bodies That Matter’. New York: Routledge, 1993, pp. 66-67

Fable = invent (an incident, person, or story)

Simulacrum = pretends to be a faithful copy, but it is a copy with no original

Performativity = power of discourse, politicisation of abjection, ritual of being

Body / identity / desire = imperfection, fluidity, domesticity, transgression, transcendence

Intimate, conceptually robust and aesthetically sensitive.

The association of the images was emotionally overwhelming.

An absolute gem. One of the highlights of the year.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Edmund Pearce Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Janina Green (Australian born Germany, b. 1944)

Waterfall

1990

Silver gelatin print on Kentmere Parchment paper, tinted with coffee and photo dyes

58 x 48cm

Vintage print

Janina Green (Australian born Germany, b. 1944)

Pink vase

1990 reprinted 2012

Silver gelatin print on fibre based paper, hand tinted with pink photo dye

85 x 70cm

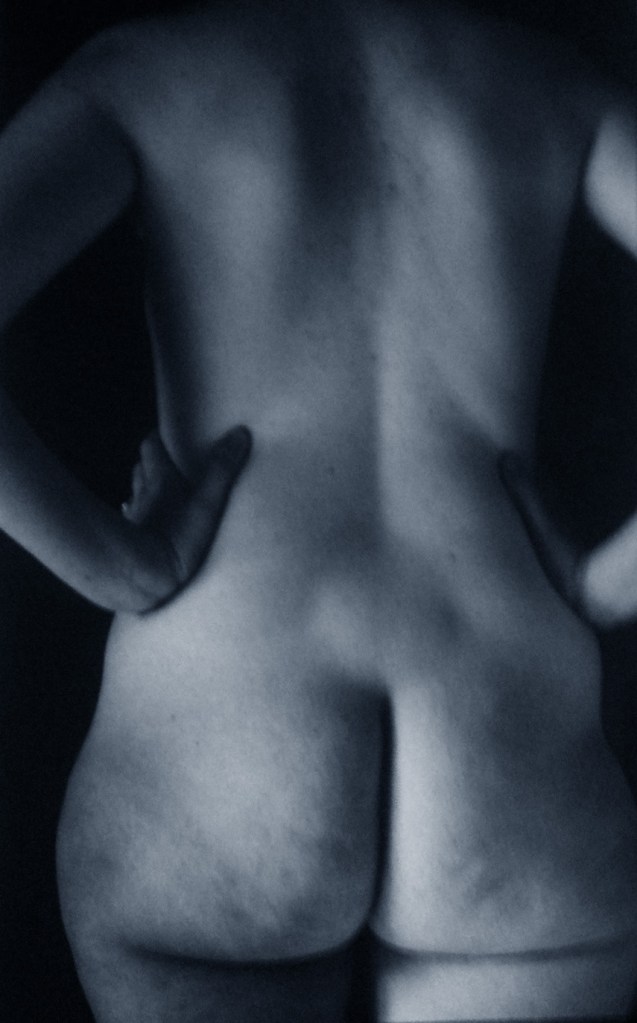

Janina Green (Australian born Germany, b. 1944)

Blue vase

1990 reprinted 2012

Silver gelatin print on fibre based paper, hand tinted with blue photo dye

85 x 70cm

Janina Green (Australian born Germany, b. 1944)

Nude

1986

Silver gelatin print on fibre based paper, hand tinted with blue photo dye

60 x 45cm

Vintage print

My photographs are always about the past.

The Barthesian slogan, “this has been,” is for me, “I was there.” This series of images of a vase from Ikea consists of silver gelatin prints tinted in different coloured photographic dyes; photographs of a simple mass produced vase – its form the familiar vessel which so dominates Art History. “Ikea” for me is symbolic of the useful homely object and of the ideal home. The vase from Ikea no longer exists. The picture of that vase stands in for the vase that once existed. The photograph can be seen now – at this moment. It will continue to exist in the future. Its representation crosses time barriers.

My photographs are always documentations of a private performance.

Every photograph records what is in front of the camera, but my interest is in the occasion and the complex conditions of the making of the photograph – first the negative then the print. Each photograph ends up being a documentation of my state of mind during this intensely private moment as well as something for other people to look at. Because of changing conditions, every one of these prints from that same negative is different. For me each analogue print is an unsteady thing. They are now relics from another era, as is the vase.

As a counterpoint to the repetition of the vase prints, I have selected four vintage works from my archive.

Artists statement by Janina Green

Janina is represented by M.33

Janina Green (Australian born Germany, b. 1944)

Orange vase

1990 reprinted 2012

Silver gelatin print on fibre based paper, hand tinted with orange photo dye

85 x 70cm

Janina Green (Australian born Germany, b. 1944)

Green vase

1990 reprinted 2012

Silver gelatin print on fibre based paper, hand tinted with green photo dye

85 x 70cm

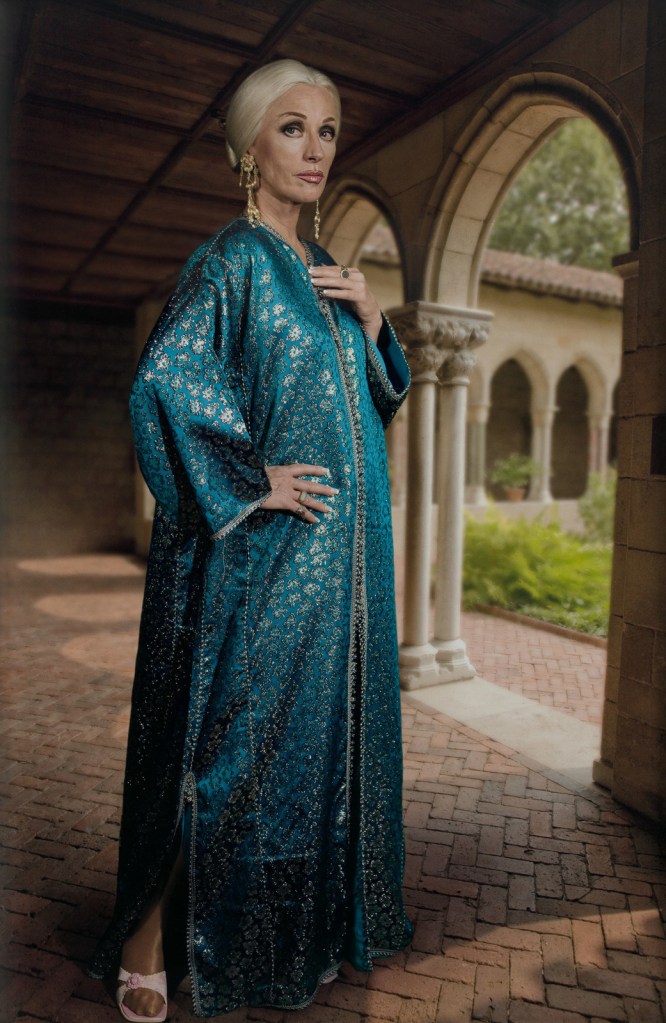

Janina Green (Australian born Germany, b. 1944)

Interior

1992

C Type print

38 x 30cm

Vintage print / edition of 5

Janina Green (Australian born Germany, b. 1944)

Telephone

1986 reprinted 2010

Silver gelatin print on fibre based paper, tinted with coffee

58 x 48cm

Janina Green (Australian born Germany, b. 1944)

Yellow vase

1990 reprinted 2012

Silver gelatin print on fibre based paper, hand tinted with yellow photo dye

85 x 70cm

Edmund Pearce Gallery

This gallery is now closed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.