Exhibition dates: 24th January – 21st April, 2025

Curators: Dr. Anna Hanreich and Dr. Astrid Mahler

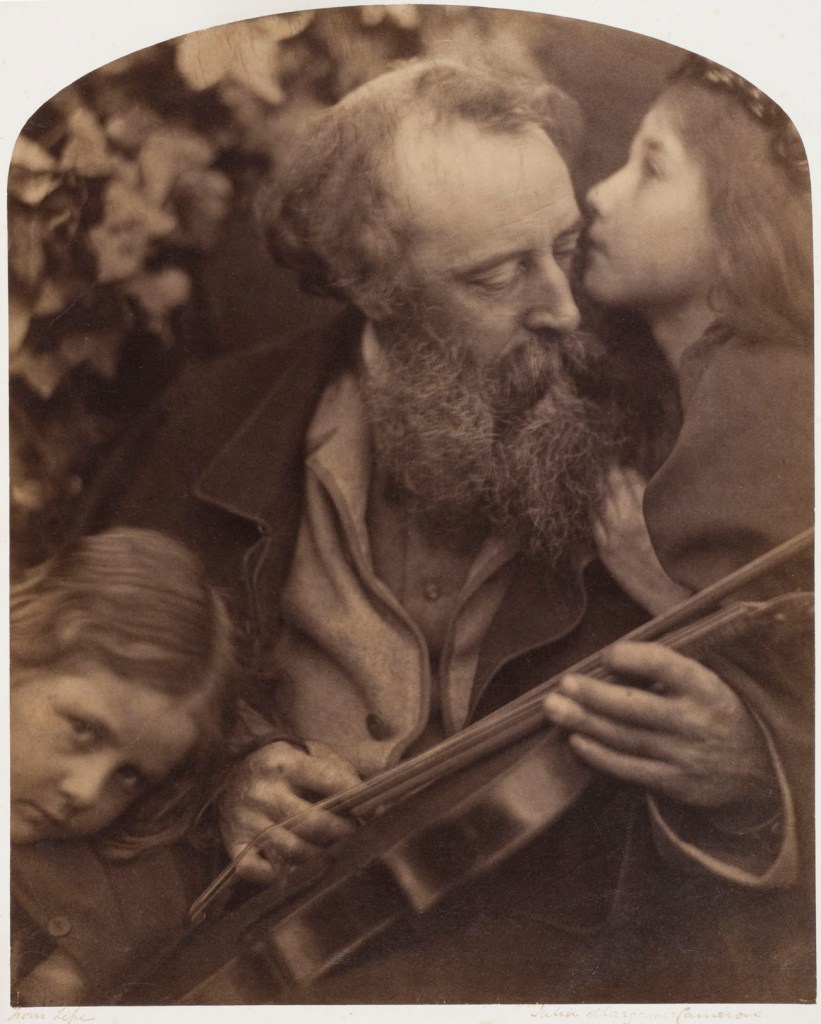

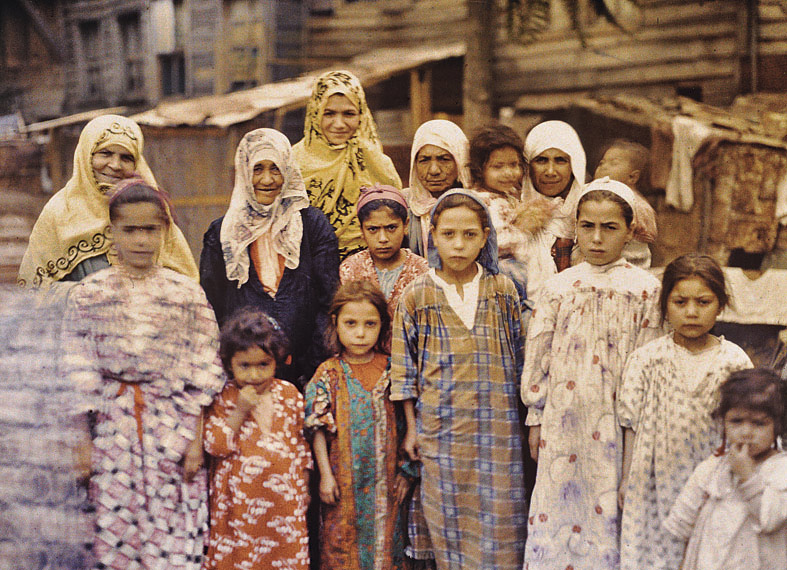

Auguste and Louis Lumière (French, 1862-1954) (French, 1864-1948)

Bangles

1893-1900

ALL Chroma

8.4 x 17.8cm

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna – Permanent loan by Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt

What a wonderful exhibition.

It’s so exciting to see the history and development of colour photography pre the ubiquitous, American artists William Eggleston and Stephen Shore, much as I like both artists.

I would have liked to have seen some early autochromes from Albert Kahn and The Archives of the Planet; some photographs by Bernard F. Eilers whom I greatly admire; and some early colour photographs by Paul Outerbridge Jr.

In my eyes, that would have made the exhibition even better!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Albertina Modern for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Gracious thankx also to Karin Svadlenak-Gomez for allowing me to use her wonderful photographs of the exhibition in the posting, noted below each image. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna showing in the bottom image, Léon Vidal’s photograph Oriental Onyx Saucier, 16th century, from Le Tresor artistique de la France, c. 1876-1878 (below)

Léon Vidal (French, 1833-1906)

Oriental Onyx Sardonyx Cup (16th century)

1876

Photomechanical proof (photochromy using the Léon Vidal process) mounted on cardboard

H. 20.8 ; L. 26.2 cm.

Don Fondation Kodak-Pathé, 1983

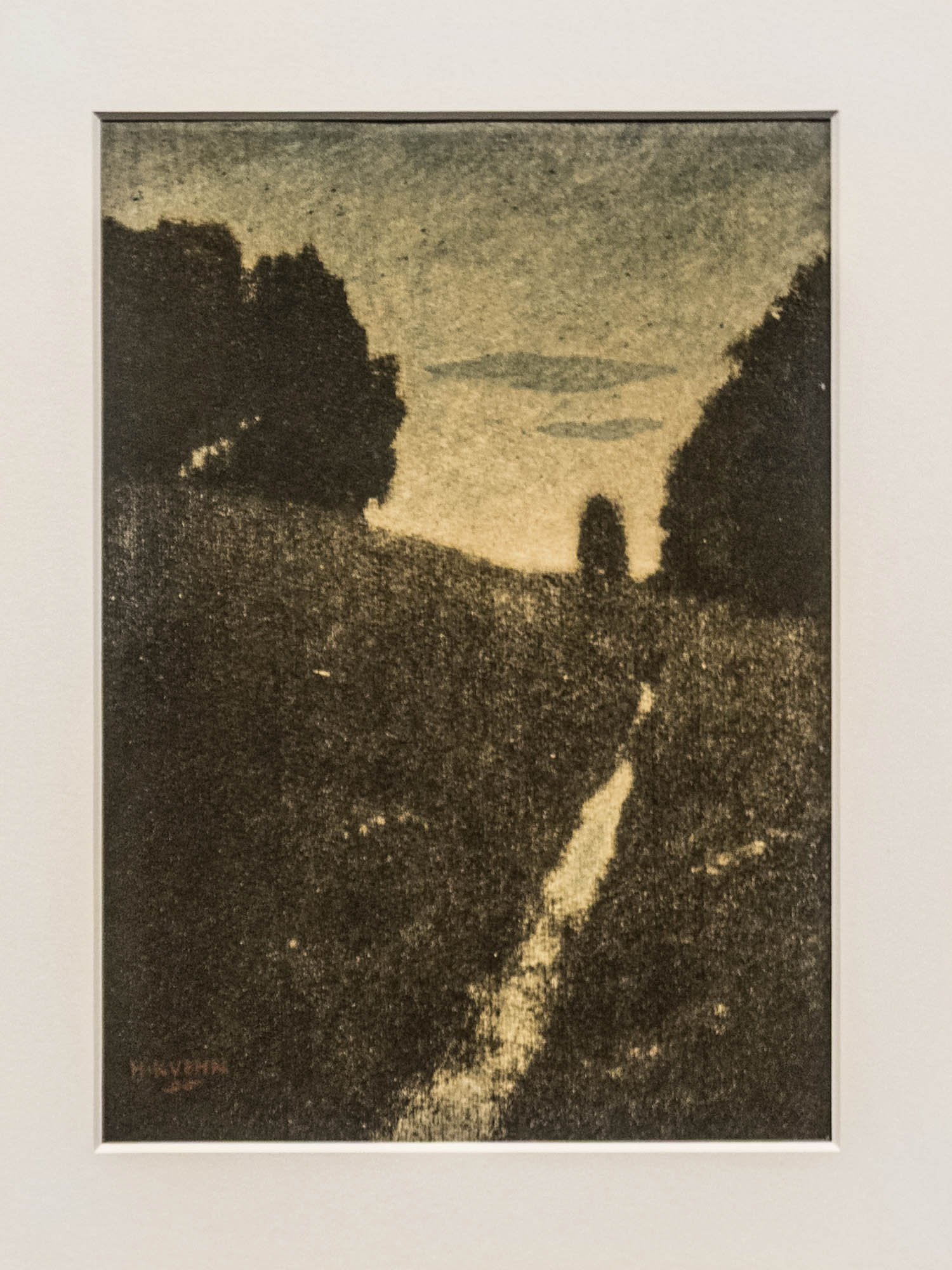

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna showing at left, Heinrich Kühn’s Twilight 1896 (below); and at right, Heinrich Bachmann’s Winter Landscape 1903

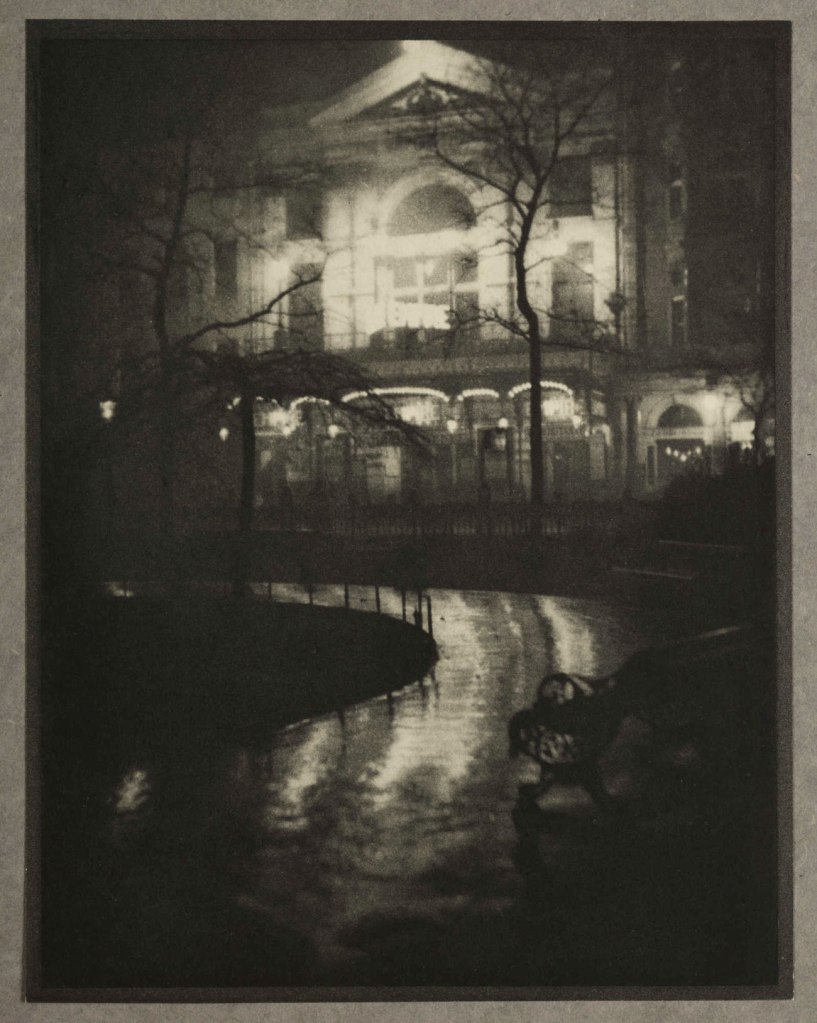

Heinrich Kühn (Austrian-German, 1866-1944)

Twilight

1896

Two-tone gum print

Photo: Karin Svadlenak-Gomez

The Pictorialist Aesthetic: Photography as Art

One of my personal highlights from True Colours was the section dedicated to pictorialist photography. Emerging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pictorialism sought to elevate photography to the level of fine art, favouring soft focus, painterly compositions, and atmospheric effects. In fact the Albertina modern had a whole exhibition on Pictorialism in 2023, which was a great joy to me.

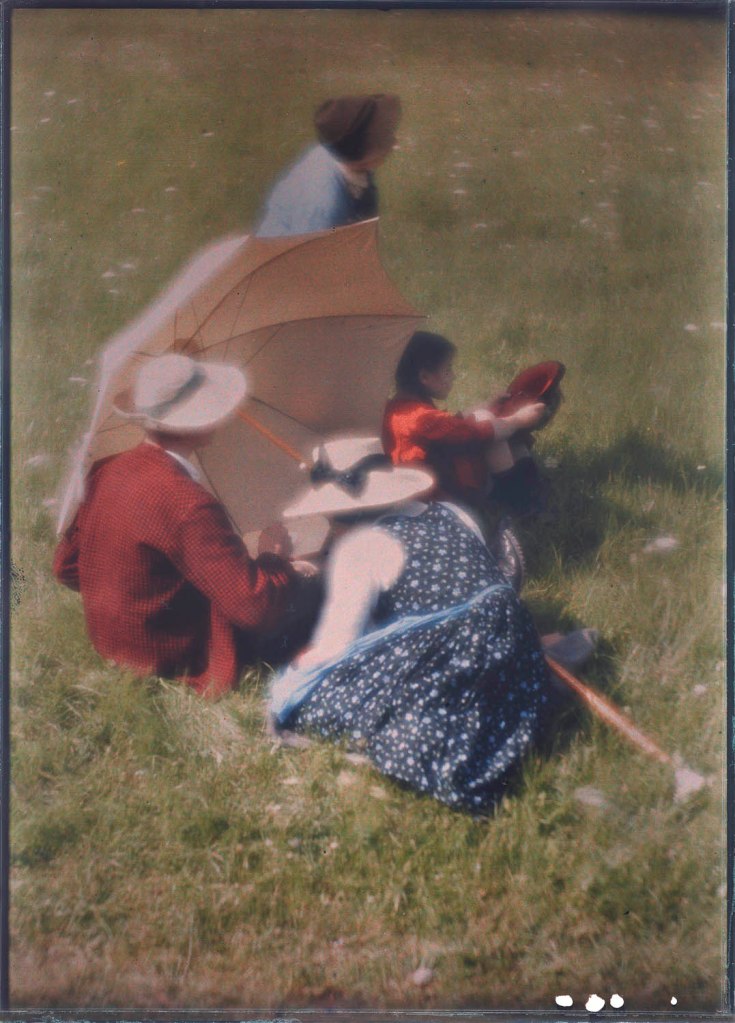

Heinrich Kühn’s Twilight (1896, above), produced through the autochrome process, was a standout for me, its subtle gradations of light and shadow creating an almost dreamlike serenity. Kühn was also one of the pioneers of the autochrome process, the first commercially successful colour photography method introduced by the Lumière brothers in 1907. Autochromes used a fine layer of dyed potato starch grains to filter light, creating rich and softly textured images. Kühn masterfully employed this process to enhance the painterly, impressionistic quality of his photographs, further bridging the gap between photography and fine art. Seeing these images up close, I was reminded of how photographers of the past fought for their medium to be recognised as more than mere documentation – it was, and remains, an art form in its own right.

Karin Svadlenak-Gomez. “Photography in Full Spectrum,” on the ViennaCultgram website 13th March 2025 [Online] Cited 25/03/2024

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna

Photo: Karin Svadlenak-Gomez

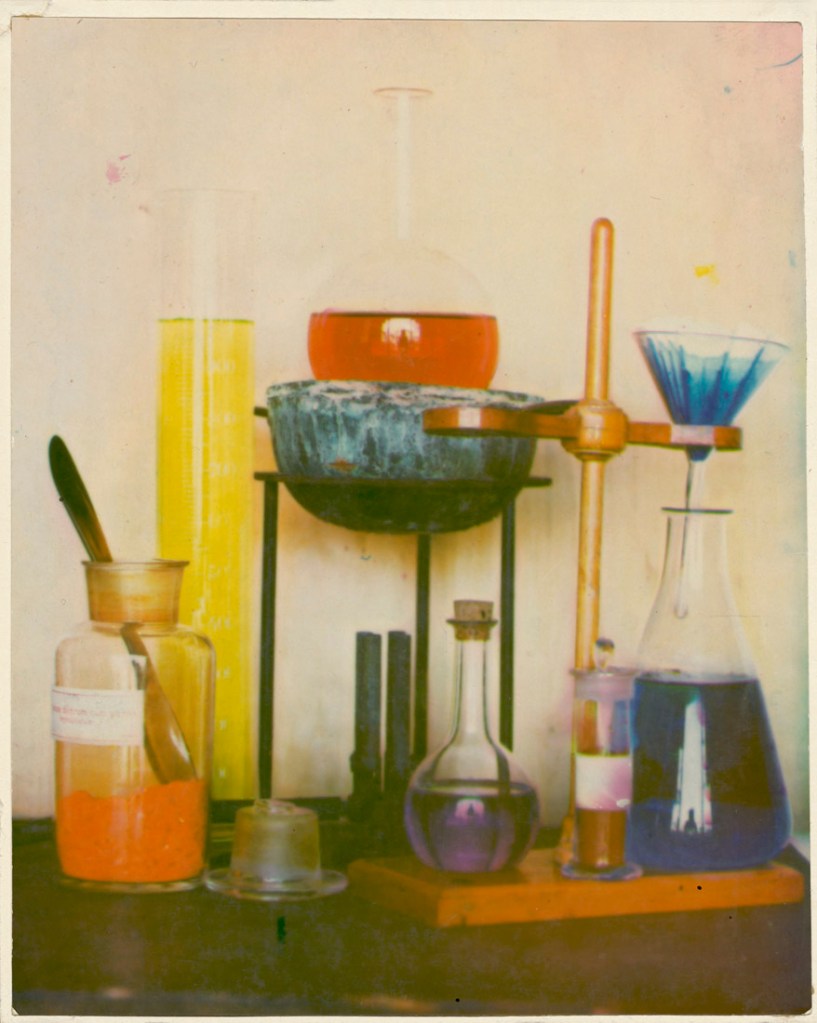

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna showing Anonymous. Laboratory Still Life 1906

Anonymous photographer

Laboratory Still Life

Around 1906

14.2 x 11.2 cm

Pinatype

The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Permanent Loan by Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt

© Photo: The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Ad. Braun et Cie. (Jean Adolphe Braun (French, 1812-1877))

Sample board of various pigment papers from Ad. Braun et Cie.

Around 1910

38.2 x 32.5cm

Pigment prints

The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Permanent loan by Höhere Graphische Bundes- Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt

© Photo: The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Ad. Braun et Cie. (Jean Adolphe Braun (French, 1812-1877))

Sample board of various pigment papers from Ad. Braun et Cie. (details)

Around 1910

38.2 x 32.5cm

Pigment prints

The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Permanent loan by Höhere Graphische Bundes- Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt

© Photo: The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna showing two photographs by Atelier D’Ora with at right, Maria Delvard as Tambour 1913

The aesthetics of fine art photography had their greatest impact on studio photograph. In the early twentieth century, such progressive studios as Atelier d’Ora (later called Atelier d’Ora Benda) adopted the reformed portrait style and its elaborate techniques. The bromoil and broccoli transfer processes finally offered an alternative to gum prints, so that works in colour could be produced in a much less complicated and inexpensive way.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna showing Kurt Husnik’s three photographs Untitled 1950s

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna showing Kurt Husnik’s Untitled 1950s

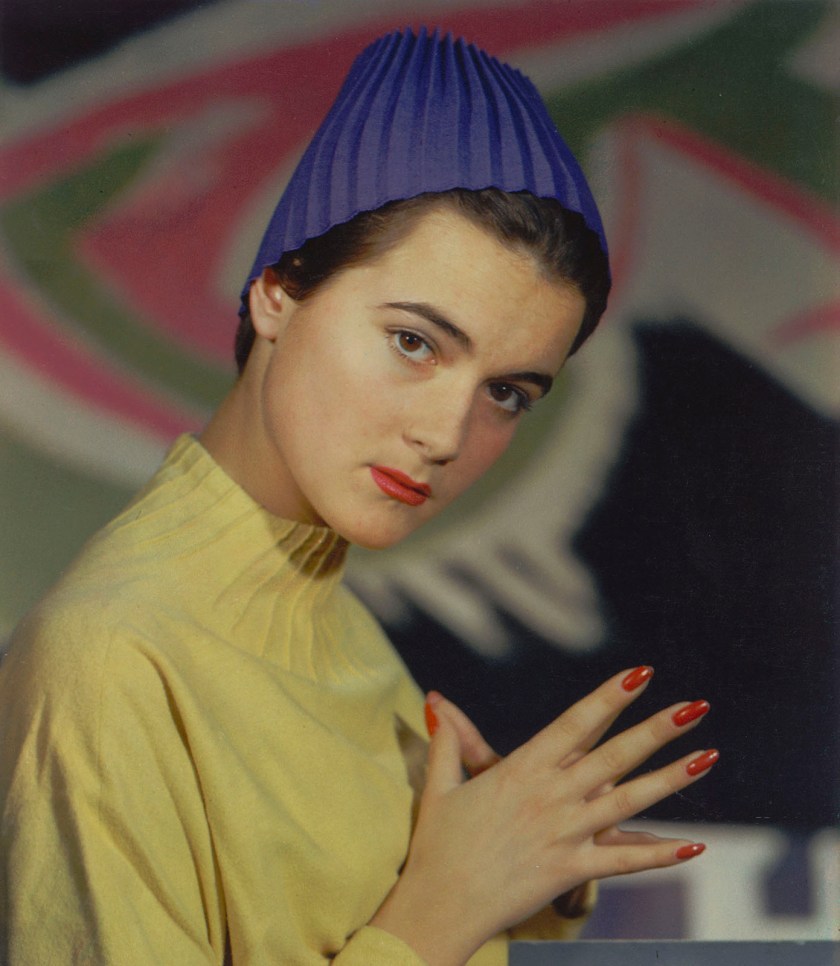

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna showing at left, Hans Madensky’s Fashion Portrait – Student of the Vienna-Hetzendorf School of Fashion 1952 (below)

Hans Madensky (Austrian, 1902-1978)

Fashion portrait – Student from the Vienna Hetzendorf Fashion School

1952

27 x 22.8cm

Kodak Dye Transfer Print

The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Permanent Loan by Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt

© Photo: The Albertina Museum, Vienna

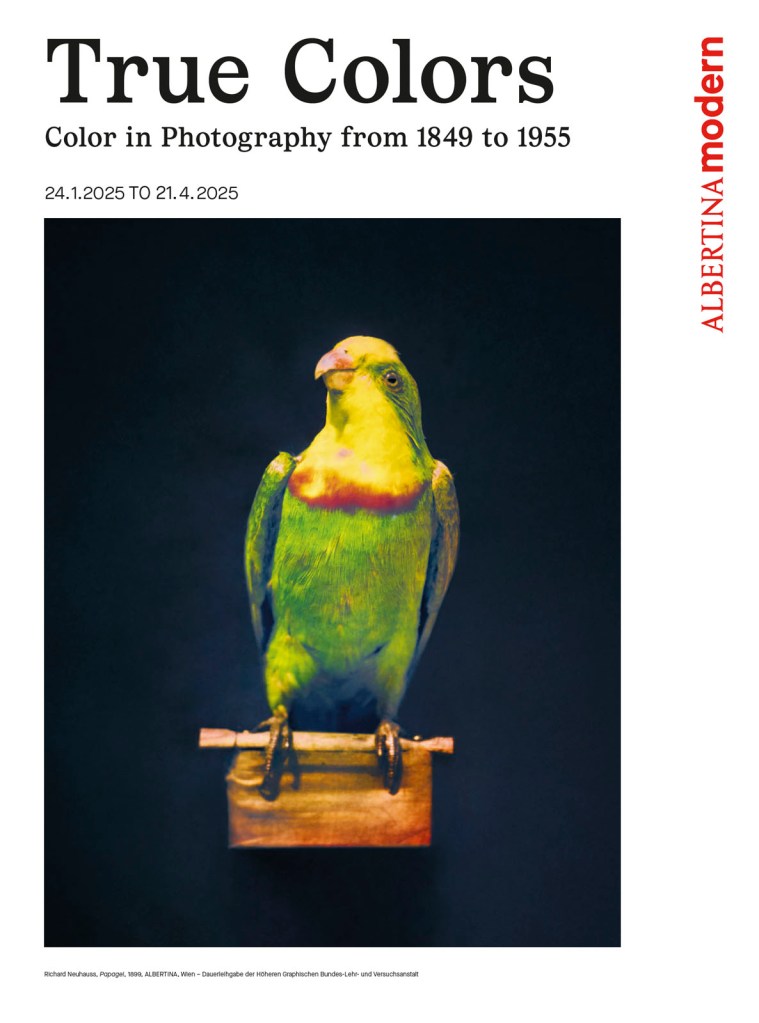

How did colour get into photography?

The exhibition True Colors – Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 answers this question with outstanding works from the Albertina Museum’s photo collection.

The desire for colour in photography has dominated the world of photography from the very beginning. True Colors traces the development of colour photography, from the first experimental techniques in the 19th century to generally applicable analog colour photography.

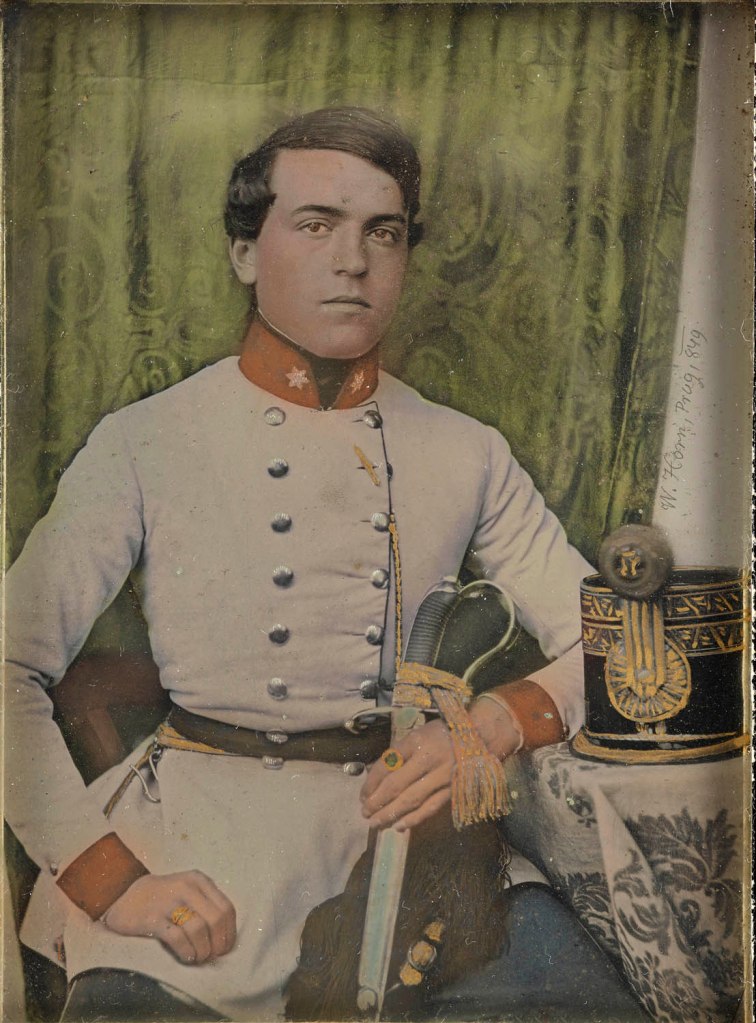

Even in the early days of photography, daguerreotypes and salt paper prints were colored by hand to create colorful images. Monochrome pigment papers, which enjoyed great popularity until the 1890s, also contributed to the broad chromatic diversity of 19th century photographs.

The first successful color process, which was reserved for an exclusive circle, was introduced in 1891. The brilliant images in the so-called interference colour process are based on the physical principle of standing waves, which also allows us to see coloured reflections in soap bubbles. The unique pieces from the Albertina Museum’s Collection represent a unique focal point.

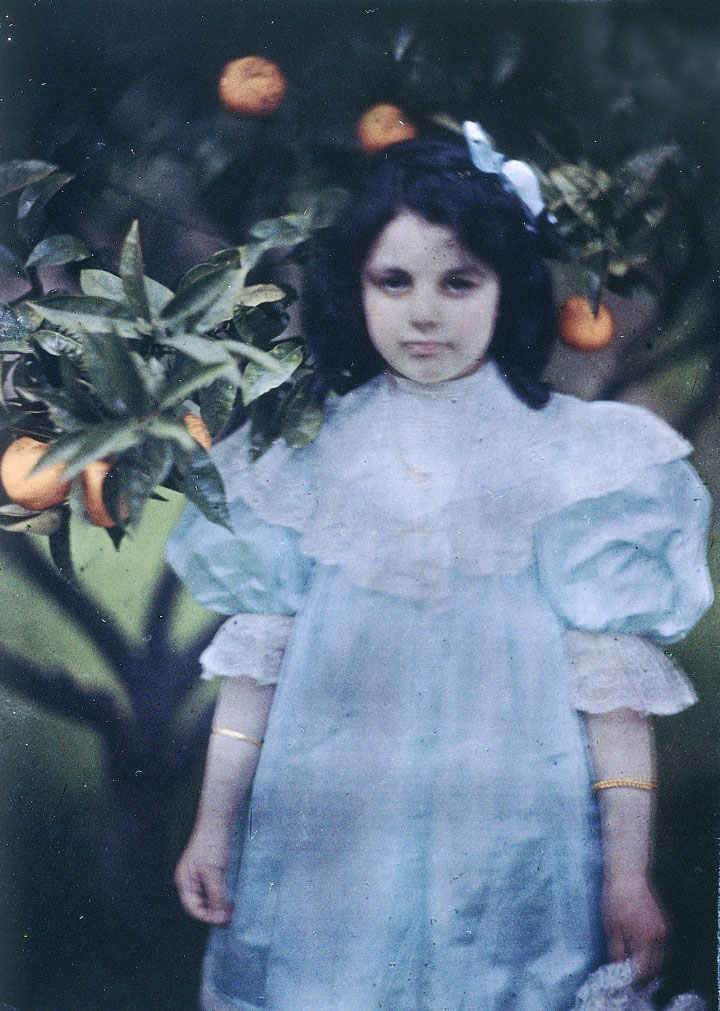

The autochrome process, which was introduced in 1907, brought about a major change in image culture. It was also practicable for amateurs and helped its inventors, the Lumière brothers, to achieve great commercial success. However, it was mainly used as a glass slide for projection. At the same time, around 1900, fine art printing processes were developed that used color pigments to produce multicolored image solutions. They fulfilled the artistic aspirations of the Pictorialists and were commonplace in large photo studios until the 1930s. For a long time, the challenge was to obtain colored prints on paper. This was also achieved at the beginning of the 20th century with the use of various three-color processes, which were assembled in several steps.

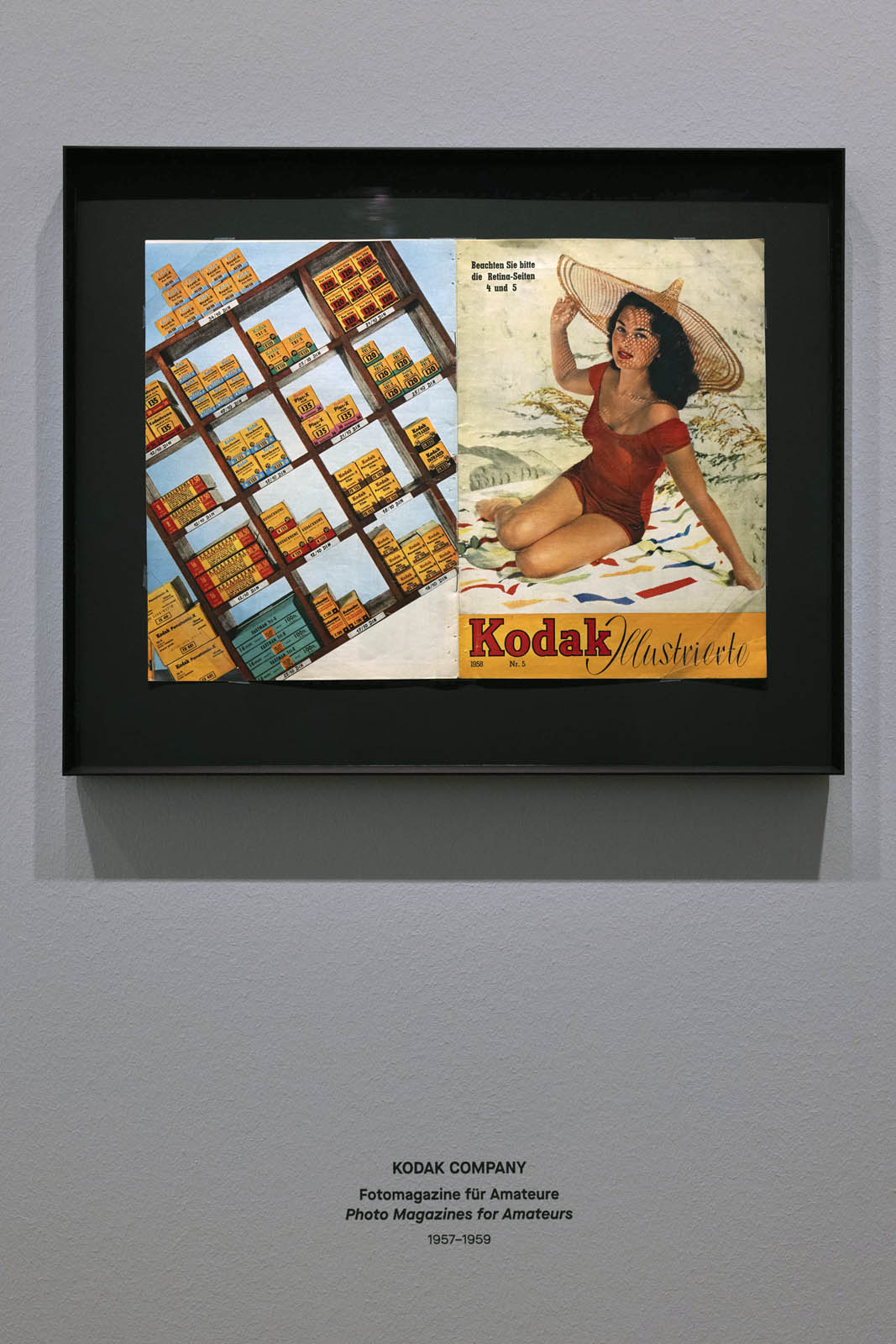

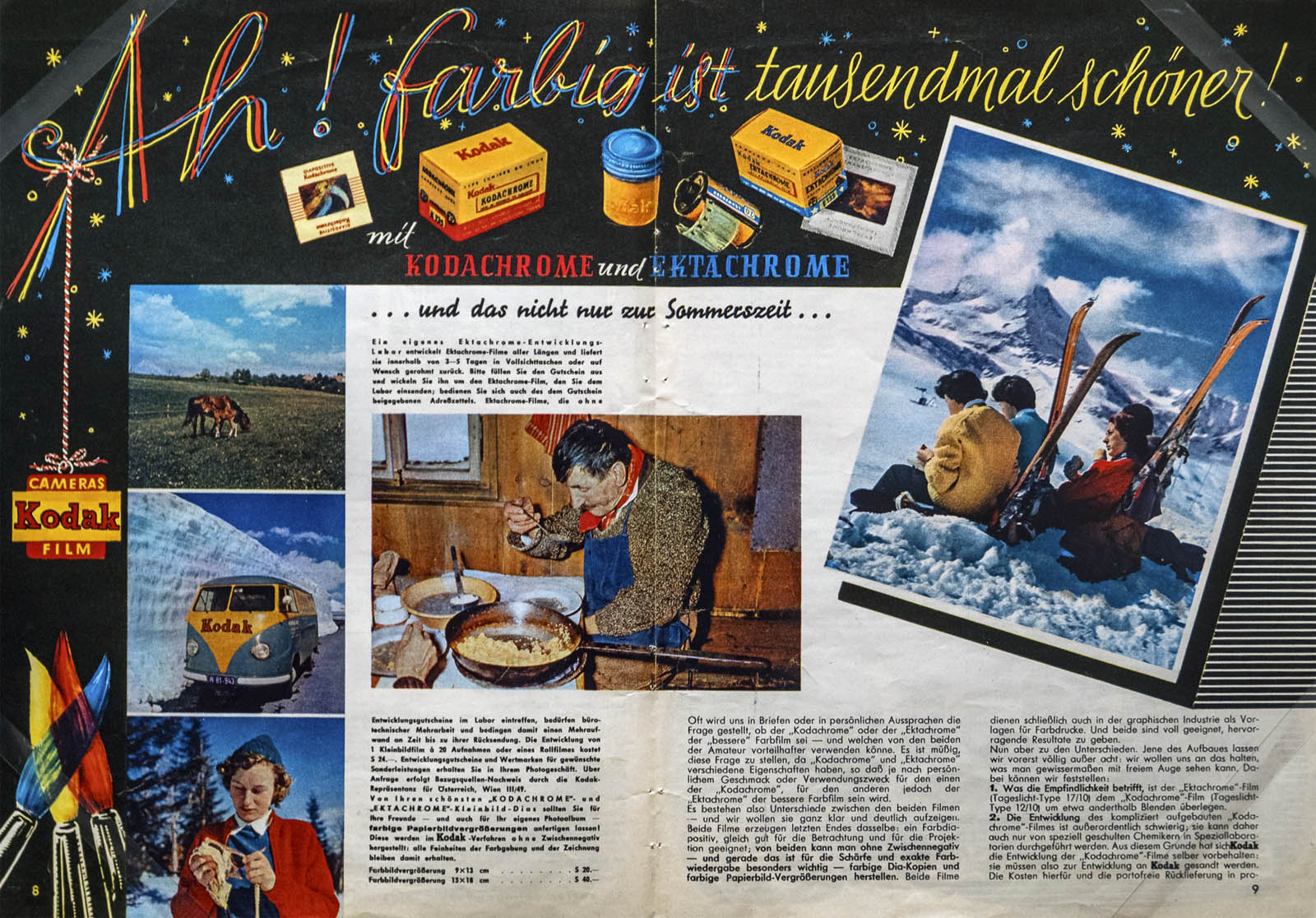

Kodak finally achieved the breakthrough to easy-to-use and therefore mass-market colour photography in 1936 with the first 35mm colour slide films. These products revolutionised the use of colour photography in the following decades, which form the conclusion of this Albertina Museum exhibition.

True Colors provides an insight into the rich holdings of the Albertina Museum’s photography collection, the historical part of which is based on the collection of the Höhere Graphische Bundes- Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt (GLV). The exhibition demonstrates the great public interest, the constant development and the various fields of application of historical photography in colour. True Colors also explores the impact of popular colour processes on the visual culture of the early 20th century.

The exhibition is on view from 24 January until 21 April 2025 at the Albertina Modern

Wilhelm Horn (Czech, 1809-1891)

Portrait of a Young Officer

1849

11 x 8.3cm

Daguerreotype, coloured

The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Permanent loan by Höhere Graphische Bundes- Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt

© Photo: The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern

Photo: Karin Svadlenak-Gomez

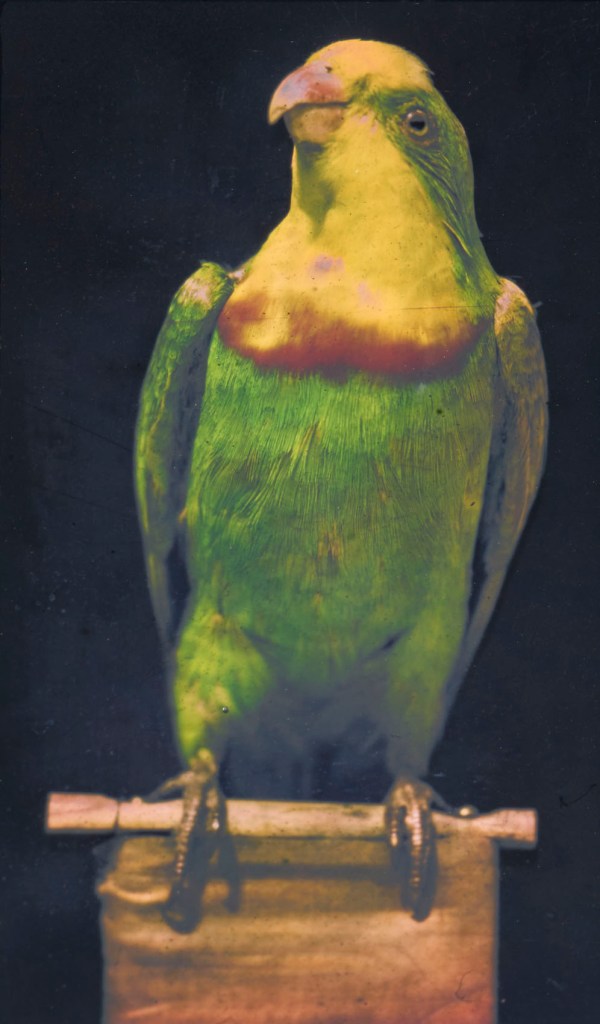

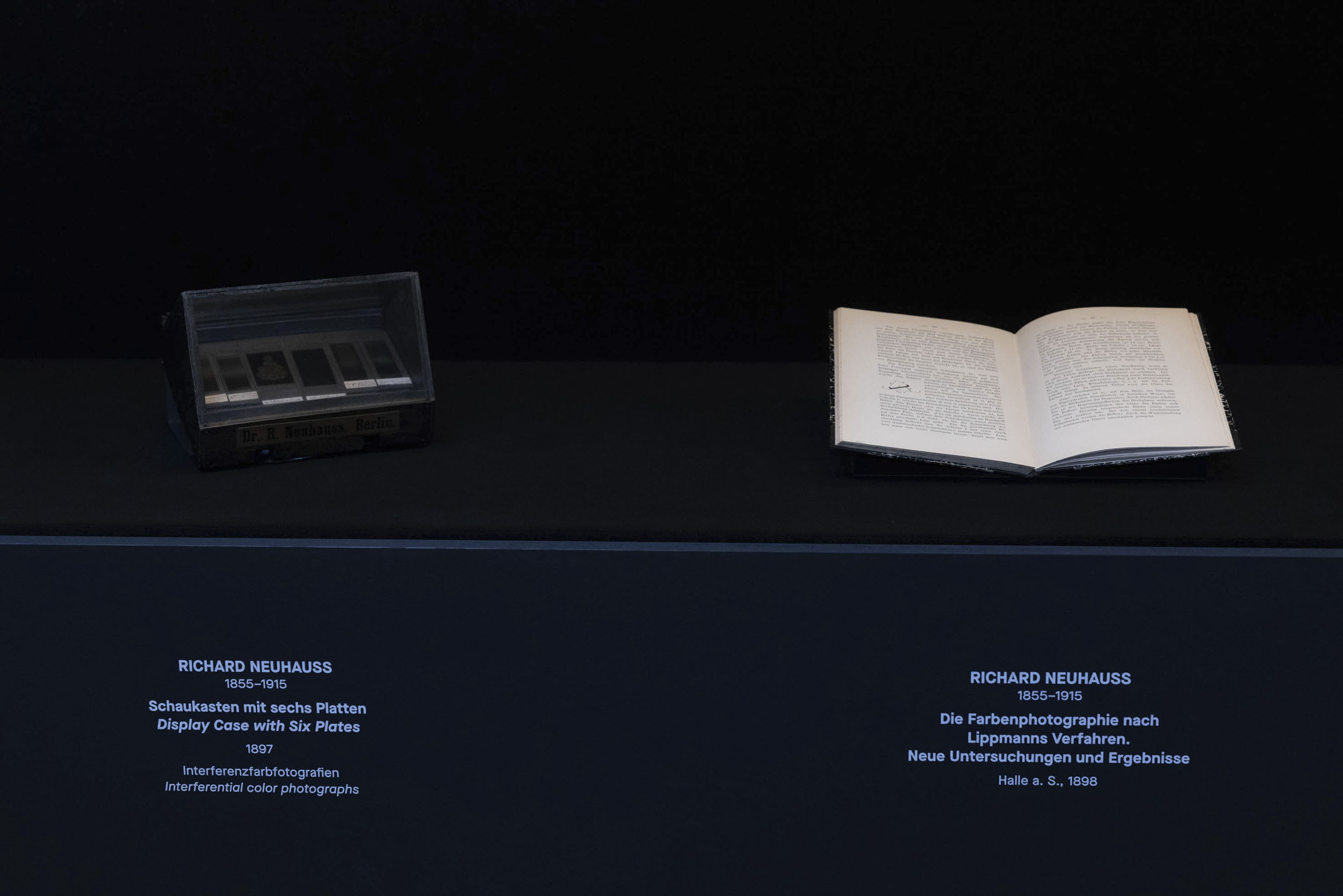

Richard Neuhauss (German, 1855-1915)

Parrot

1899

8.3 x 6.4cm

Colour photography

The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Permanent Loan by Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt

© Photo: The Albertina Museum, Vienna

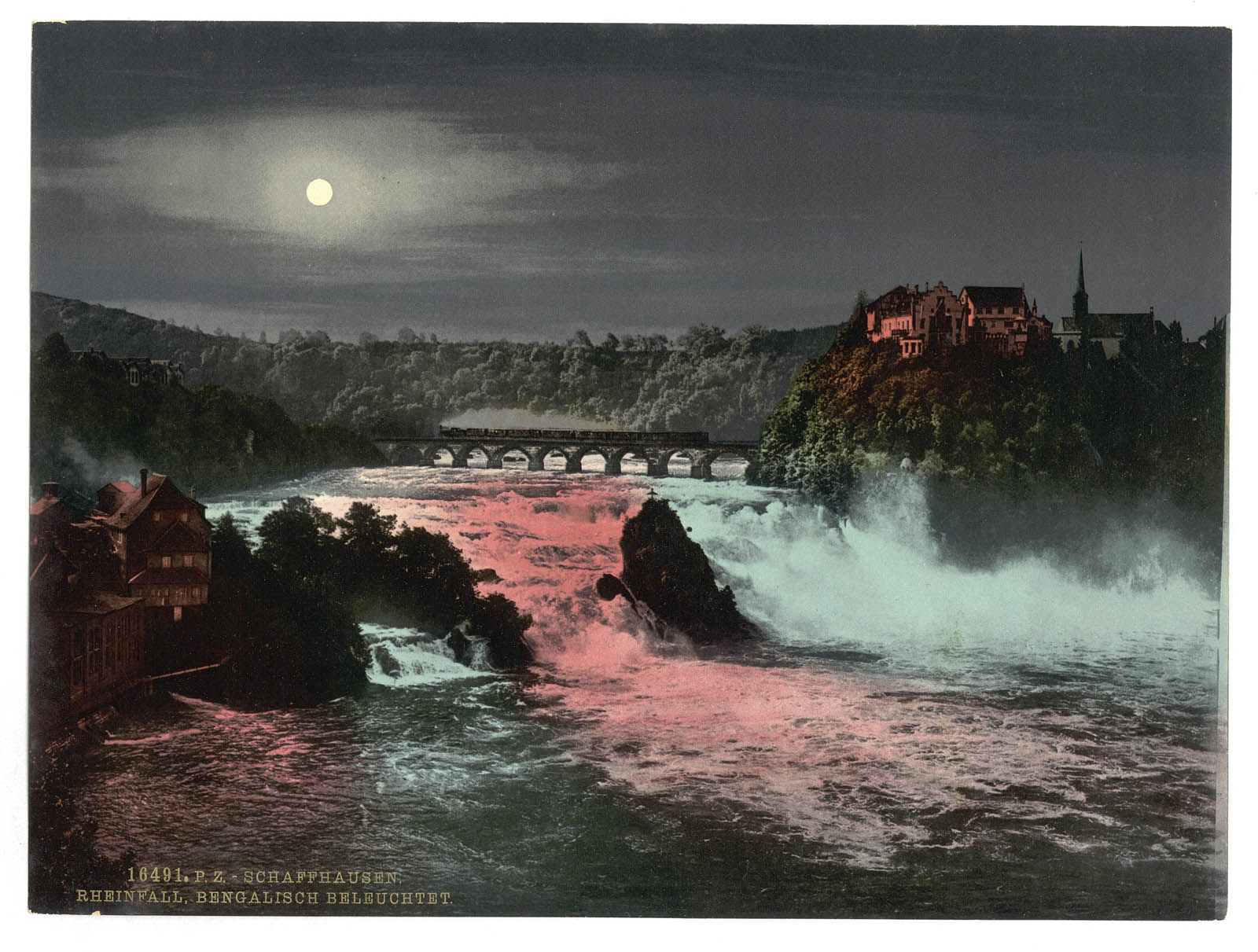

Photochrom Print Collection (photographer)

The Falls of the Rhine, by Bengal Light, Schaffhausen, Switzerland

Between 1890 and 1900

Print no. “16491”.; Forms part of: Views of Switzerland in the Photochrom print collection.; Title from the Detroit Publishing Co., Catalogue J-foreign section, Detroit, Mich.: Detroit Publishing Company, 1905.

Photomechanical print, photochrom, colour

Arthur von Hübl (Austrian, 1853-1932)

Exotic Butterflies

1908-1914

6.3 x 6.9cm

Autochrome

The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Permanent Loan by Höhere Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt

© Photo: The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Heinrich Kühn (Austrian-German, 1866-1944)

The Parasol

1912

18 x 13cm

Autochrome

The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© Photo: The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Philippe Pottier (French, 1905-1991)

Evening Gown by Madame Grès

1950/1954

22.2 x 16.5cm

Kodak Dye Transfer Print

The Albertina Museum, Vienna – Permanent Loan by Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt

© Photo: The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Exhibition Texts

Introduction

True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955

Today, colour photography is omnipresent, but the knowledge about its complex genesis is not very familiar. This exhibition highlights the multifaceted developments that were initiated starting in the mid-nineteenth century to bring colour into photography. Thanks to the extensive photographic collection of the Imperial-Royal Institution of Graphic Education and Research, the Albertina possesses unique holdings of important examples from this exciting chapter of photographic history.

As early as the middle of the nineteenth century, individual scientists managed to create unique photographs in color, which, however, were not intended for everyday use. Therefore, it was common from the early days to employ colouration or toned photographic papers. In 1891, Gabriel Lippmann achieved a crucial success in direct color photography by formulating the interferential colour process, which produced brilliantly vivid images. The Lumière brothers finally accomplished the first revolution in color photography: in 1907, they brought industrially manufactured autochromes to market. It was now for the first time that photographers and amateurs could access a practicable process for the production of colour glass slides. Thanks to more elaborate three-colour processes and Pictorialist fine art printing, which were developed around the same time, it was also possible to produce photographs in colour on paper.

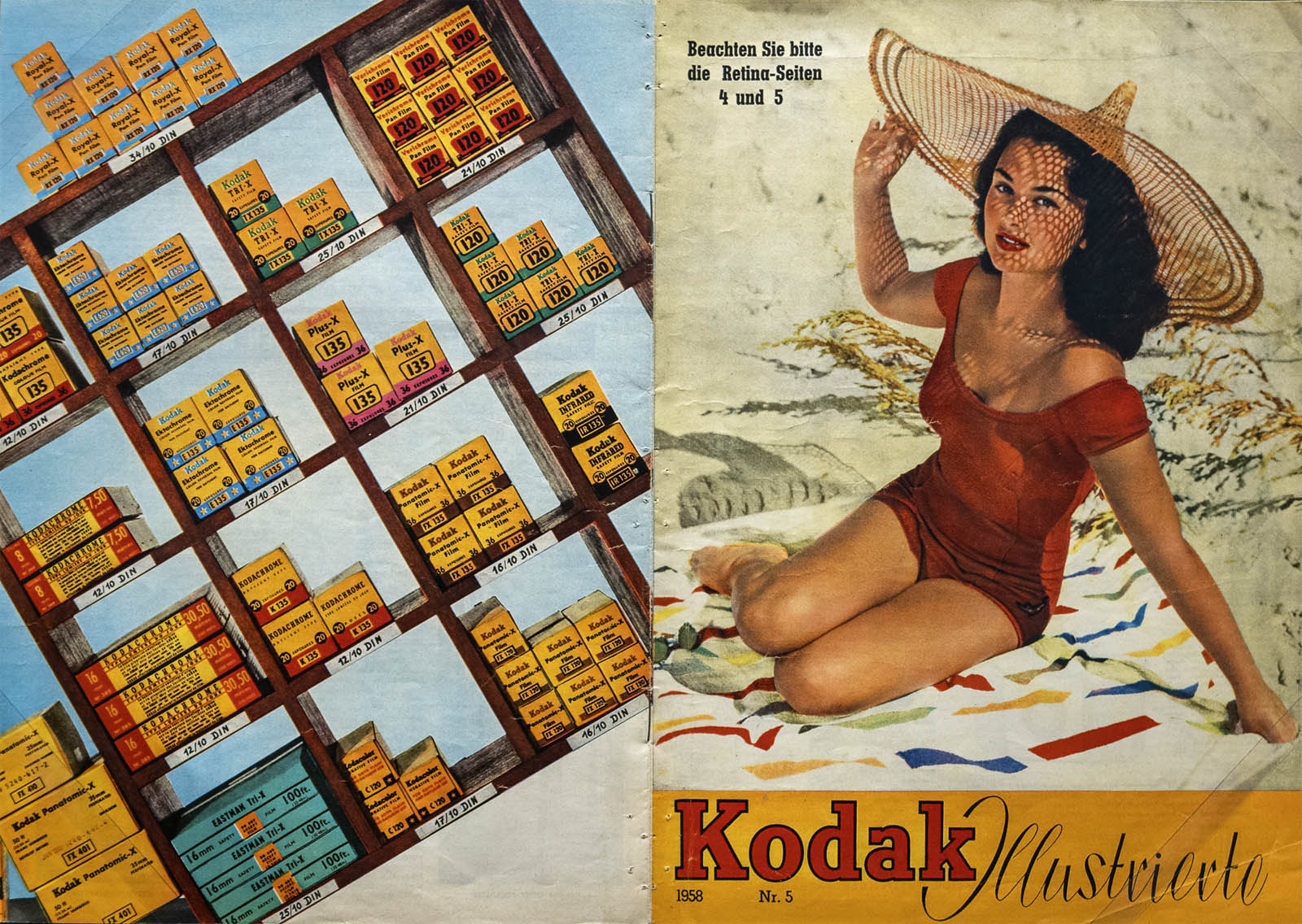

The desire for colour in photography, which had been evident since it had existed, continued to prevail in the twentieth century. A decisive breakthrough was achieved by the Kodak Company in the mid-1930s, when it produced the first 35 mm photographic color slide film. Starting out from the USA, more practical materials for analog color photography, which had been developed gradually, also established themselves in Europe after World War II. It was now impossible to stop the triumph of modern colour photography.

All objects on display here come from the holdings of the Albertina or are on permanent loan from the collection of the Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt [Higher Federal Institution of Graphic Education and Research].

Chromatic Diversity

Before it was possible to produce color photographs, photographers made use of a number of methods to bring color into their images. Even in the early days, daguerreotypes and salted paper prints were coloured by hand. While daguerreotypes were usually colored only partially, salted paper prints were sometimes heavily painted over. The so-called pigment papers, which enjoyed great popularity from the 1850s onward, enabled monochrome prints in various colours. Industrial manufacturers offered a wide range of nuances that could be variably used depending on the motif. Another way of lending prints uniform colour effects were toning baths. It was thus variable methods that were employed to produce photographs displaying a rich chromatic diversity.

A vital contribution to photography in colour was the introduction of the so called orthochromatic negative plates. In 1873, Hermann Wilhelm Vogel discovered the sensitisation of the photographic emulsion, so that the plates truthfully rendered the brightness values of blue, orange, yellow, and green. Earlier, the grey values of the blue areas had appeared overly bright, while the other colours had often seemed too dark. With the development of so-called panchromatic negative material it became possible from 1902 on to accurately record the entire visible spectral range according to tonal values. This progress was crucial for colour photography, as an incorrect recording of the tonal values during a shot could result in a distorted colour impression in the final product.

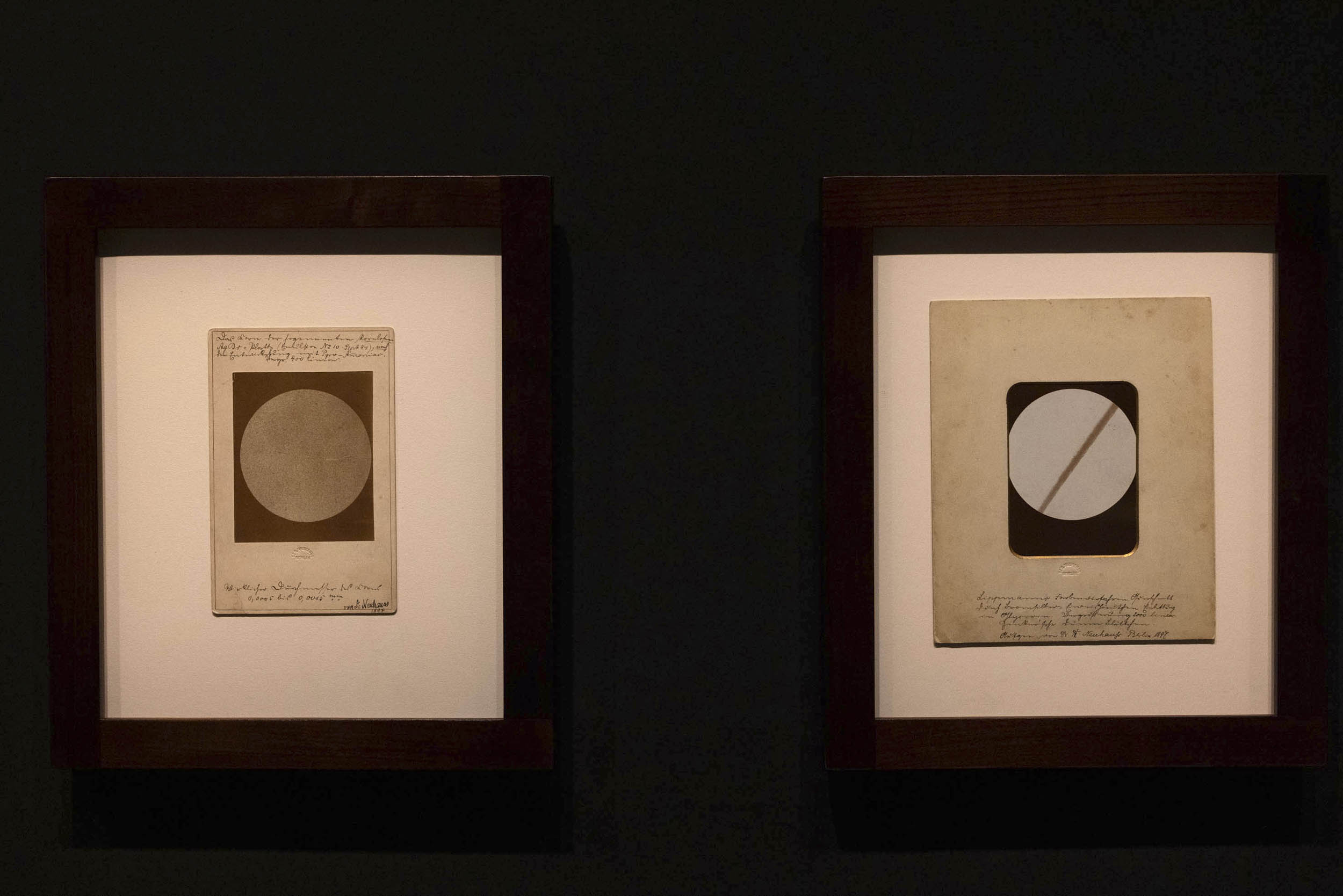

A Solitaire – the Interferential Colour Process

The interferential colour process, with which Gabriel Lippmann went public in Paris in 1891, is considered a first milestone in direct color photography. The method ensured permanently stable, brilliantly vivid colour images. It is based on the interference of light waves caused during exposure by the reflections of incident light rays off a reflective layer of mercury behind the negative. In the photographic emulsion, the finest layers are created alongside the standing waves, in which accumulations of silver are deposited. The spacing between the

layers corresponds to the wavelength of the recorded colour, so that when the image is viewed at the correct angle, the individual parts reflect their original colour. Standing waves are the phenomenon that also causes the colour effects on soap bubbles.

The process, which had its pitfalls, was enthusiastically received by specialists. The Lumière brothers, who as producers of photographic plates were highly interested in colour photography, collaborated with Lippmann to improve emulsions. The Berlin-based scientist Richard Neuhauss also dealt intensively with this method, based on the research conducted by the Viennese photochemist Eduard Valenta. Due to its chromatic purity, the spectrum offered itself as an ideal motif for images. Neuhauss’s plates fascinate us not only because of their luminous colours, but mainly for their wide range of motifs, which was facilitated by the reduction of exposure times.

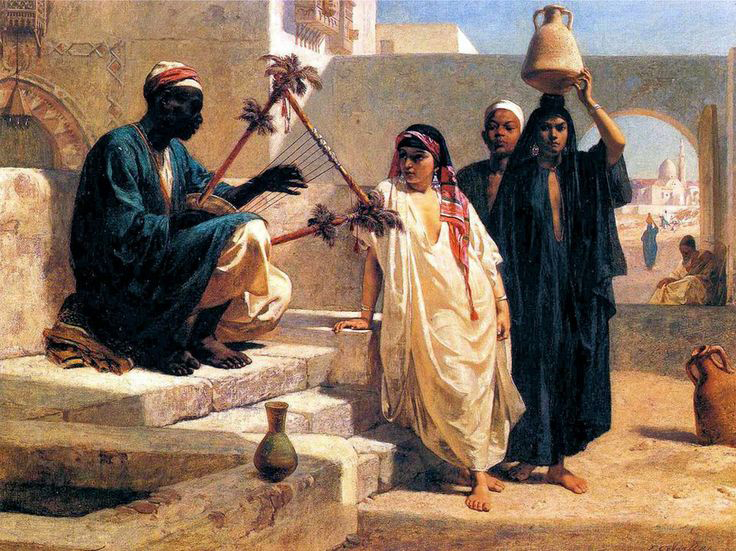

Photomechanical Color Printing Processes

Since the development of chromolithography in 1837, color reproductions had been increasingly used for luxury volumes. In combination with photography, the printing plates could either be exposed directly, or the photographic images were transferred to the plates by means of transfer printing. This and related procedures led to an increase of elaborately produced publications of scholarly character. For the work Le Trésor artistique de la France, which contained high-quality colour reproductions of art objects held by the Louvre, the French photographer Léon Vidal developed a complex process referred to as photochromie. Photographic prints constituted the base layer onto which he printed several tinted lithographic plates. Through the additional use of metallic colours or papers and a layer of varnish, Vidal achieved three-dimensional effects.

Another important step was the introduction of the collotype process, which, from 1868 onward, allowed printing black-and-white photographs in halftones. Institutions like the Imperial-Royal Austrian Trade Museum in Vienna published such luxurious scholarly publications as the illustrated volume Orientalische Teppiche [Oriental Rugs], which appeared in 1892. For this work, black-and-white collotypes and the chromolithographic plates were partly each executed across the entire surface and partly combined with each other in order to document the knotting technique and the colouration of the objects equally accurately. A colour sample based on the original rug was first painted on the collotype and then transferred by lithography. Up to thirteen individually tinted printing plates were employed in the process. Both publications stand out for the effort to imitate the object character in the coloured reproduction.

Commercial Successes – the Autochrome and Other Color Screen Processes

In 1893, in search of a viable color process, the industrialists Auguste and Louis Lumière developed the ALL Chroma, a transparency made up of three coloured layers. Since its production and use involved a high input of costs and time, the method did not prevail, despite the vivid colors it produced. Following further research, the Lumière brothers eventually achieved a breakthrough with the autochrome in 1907, which was to revolutionise colour photography for the first time. The autochrome is also a positive transparency, yet based on the principle of additive color synthesis. A glass plate functioning as carrier material is covered with a photosensitive layer on one side. A mixture of red, green, and blue starch granules is applied on top of it, forming an irregular pattern. The image is created after exposure and negative and positive development, as the granules fuse together to form coloured areas when viewed in transmitted light. Its vibrant colors and uncomplicated handling earned the inventors of this method great commercial success. The autochrome was no longer exclusively accessible to specialists. The process was not only employed for scientific images, but also and mainly in amateur photography.

In addition to the autochrome, there were numerous products relying on the principle of additive color synthesis, such as the Joly process, which had already been developed in England ten years earlier and which was based on a grid of vertical lines. By 1910, further colour screen processes had made it onto the market, such as Omnicolore or the Agfacolor plate. But the autochrome remained the most widely used colour process until the early 1930s because of its unsurpassed chromatic brilliance.

Colour by “Indirect” Means – Three-Colour Processes

Three-colour photographic printing methods on paper are based on the principle of subtractive colour mixing. The processes, their implementation differing in detail, followed a multistep procedure. At first, three subsequent black-and-white shots were taken behind red, green, and blue filters. The so called colour separation negatives were then inverted into positives. From the three positives, three matrices – in the complementary colours cyan,

magenta, and yellow – were then produced. The colour image was finally composed of these three colours.

For the pinatype, three matrices were transferred onto a sheet of prepared paper. What mattered for an accomplished picture was not only proper colour adjustment, but also an absolutely precise alignment of the images. The still life of various laboratory utensils demonstrates the individual steps leading to a colourful picture. The so-called interpositives provide the basis for the coloured matrices, which, printed one upon the other, provide the final version of the picture. Apart from still lifes, photographers also employed this technique, which was developed to market maturity by Ernst König in 1905, for portraits. In these photographs, they showcased their creative skills in handling colour.

Pictorialist Endeavors – Fine Art Printing Processes

Artistic photography around 1900 was propagated by wealthy amateurs who wished to elevate photography to the level of fine art. Their ambition was to be able to manipulate the photographic print by hand, as the mechanical aspect of photography was criticised as being inartistic. The gum bichromate print, a so-called fine art printing process, allowed them to control the work as much as possible. A mixture of pigments, gum arabic, and photosensitive salts was applied to coarse paper and then exposed. After washing out the unexposed areas, the image became visible. For multicolor works, this process could be repeated as often as desired, each time using a different pigment. This advancement of the gum bichromate printing technique toward multicolour printing was first implemented by members of the Camera Club in Vienna, an association of amateur photographers. The possibility of creating such colourful images that could be used as decorative works of art on the wall and sometimes reach large dimensions, was particularly enthusiastically received in German-speaking countries.

Paths to Modern Colour Photography

The consequential breakthrough to mass-market color photography was achieved in the mid-1930s, when the companies Eastman Kodak (USA) and, shortly thereafter, Agfa (Germany) put so-called modern multilayer films with dye couplers on the market. By 1936, the first 35mm colour slide films and, by 1942, the first colour films and corresponding photographic papers for the negative-positive process were available, the latter of which revolutionised colour photography a second time. Yet the outbreak of World War II initially delayed the spread of these innovations in Europe. But from the 1950s onward, the triumph of modern analog colour photography could not longer be stopped.

However, contemporary high-quality copying and printing processes were still extremely expensive and complicated. The Duxochrome and dye-transfer processes, for example, were valued not only for the brilliance and stability of their colours, but also because they could be manipulated during the production process. But due to the high cost of production, they were mainly used for commercial purposes. Product and fashion photography accommodated the needs of advertising and the press. In Vienna, the photographers Arthur Benda and Hans Madensky were very successful in these fields.

Text from the Albertina Museum

Installation views of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern

Photos: Karin Svadlenak-Gomez

Ernst König (German, 1869-1924)

Still-life with flowers

1905

Pinatype

Photo: Karin Svadlenak-Gomez

Atelier D’Ora (est. 1907)

Mrs. Oergan

1924

Bromoil transfer print

Photo: Karin Svadlenak-Gomez

Installation view of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna showing Kodak Company. Photo Magazines for Amateurs 1957-1959

Installation views of the exhibition True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern, Vienna

Photos: Karin Svadlenak-Gomez

True Colors: Color in Photography from 1849 to 1955 at Albertina Modern poster

The Albertina Museum

Albertinaplatz 1

1010 Vienna

Phone: +43 (0)1 534 83 0

Daily 10am – 6pm

Except Wednesday and Friday 10am – 9pm

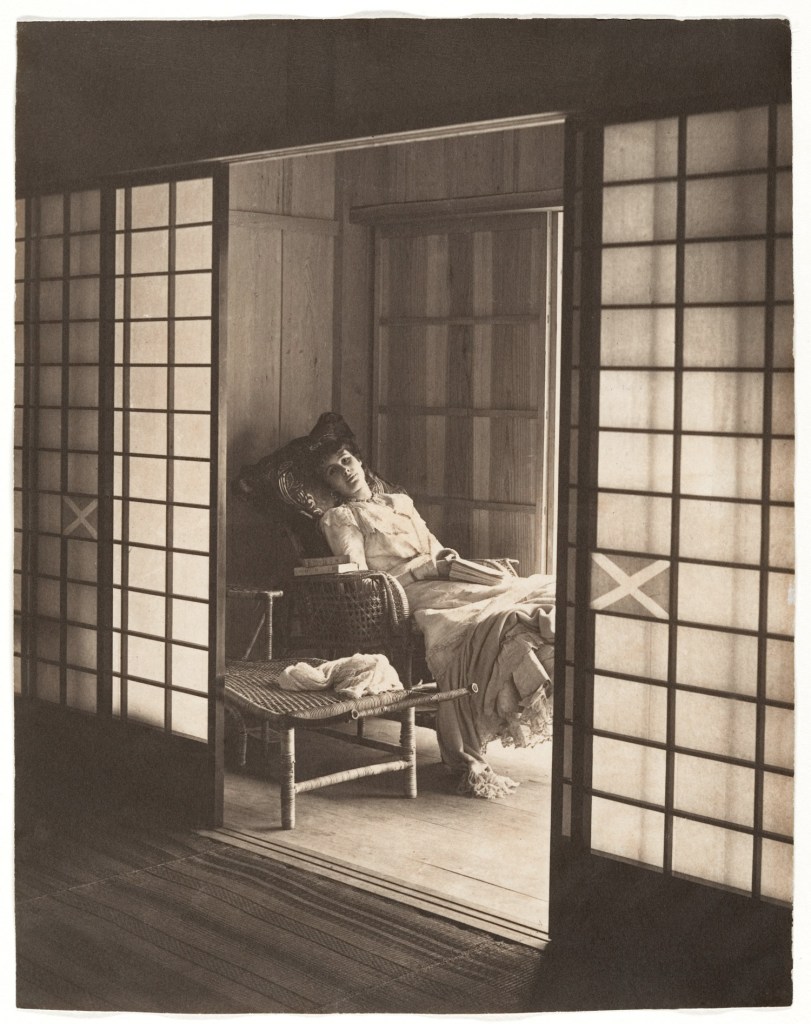

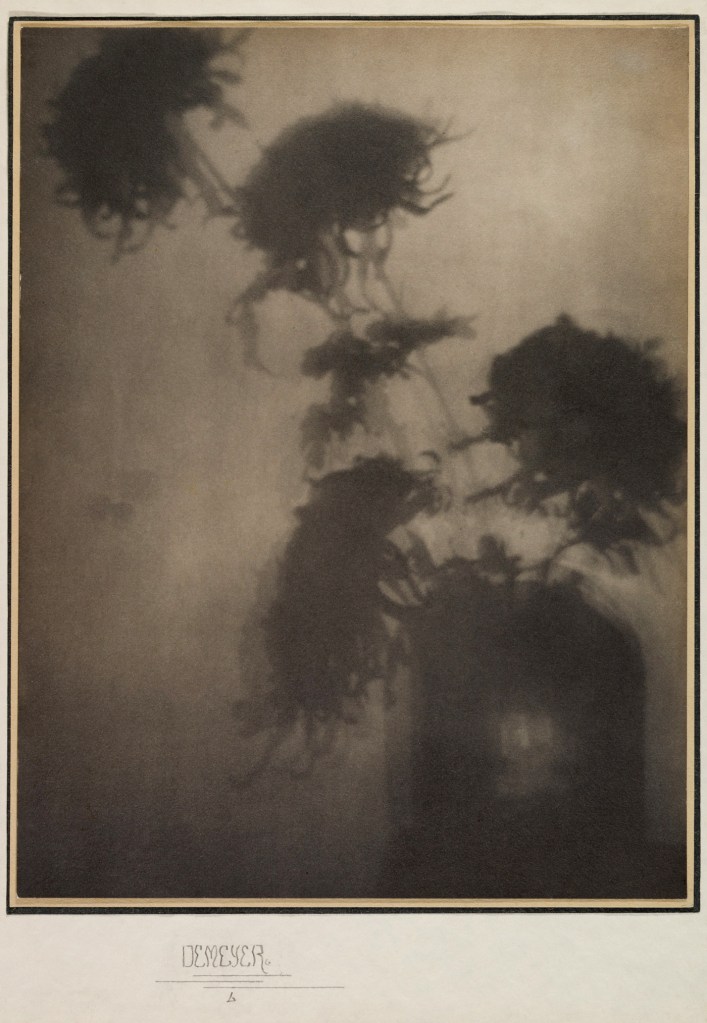

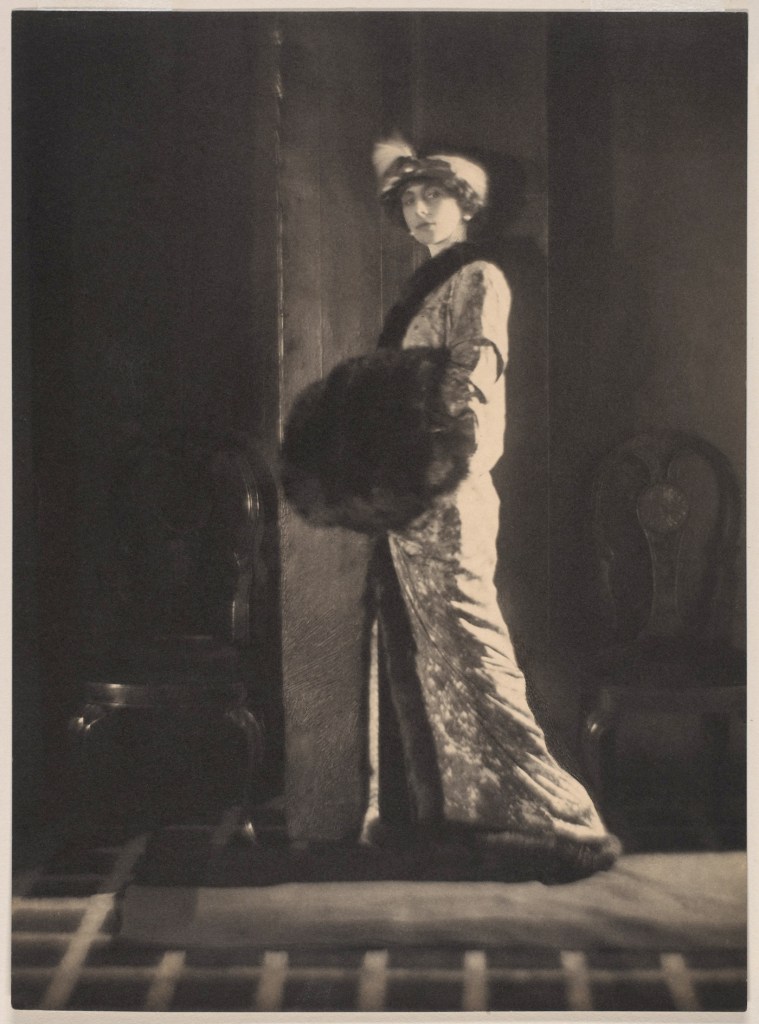

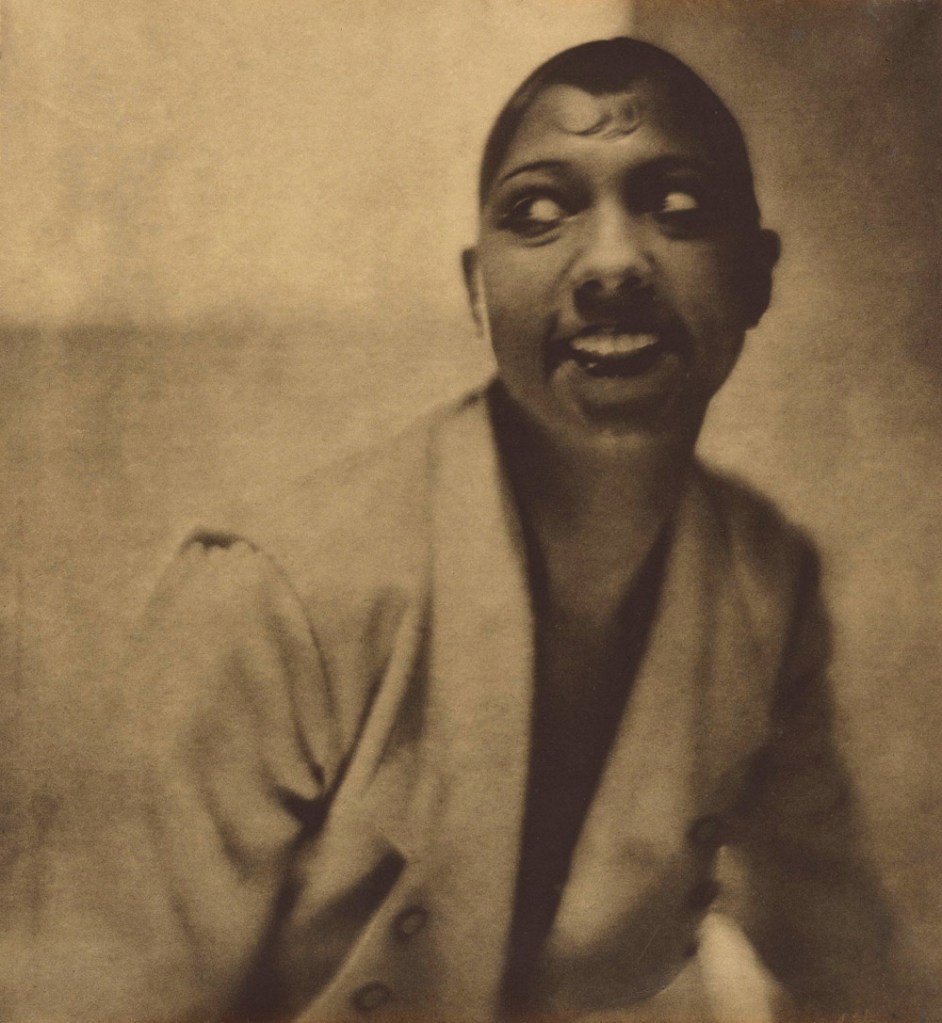

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Nude Models Posing for a Painting Class]' 1890s from the exhibition 'Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dec 2017 - March 2018 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Nude Models Posing for a Painting Class]' 1890s from the exhibition 'Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dec 2017 - March 2018](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-nude-models-posing-for-a-painting-class-web.jpg)

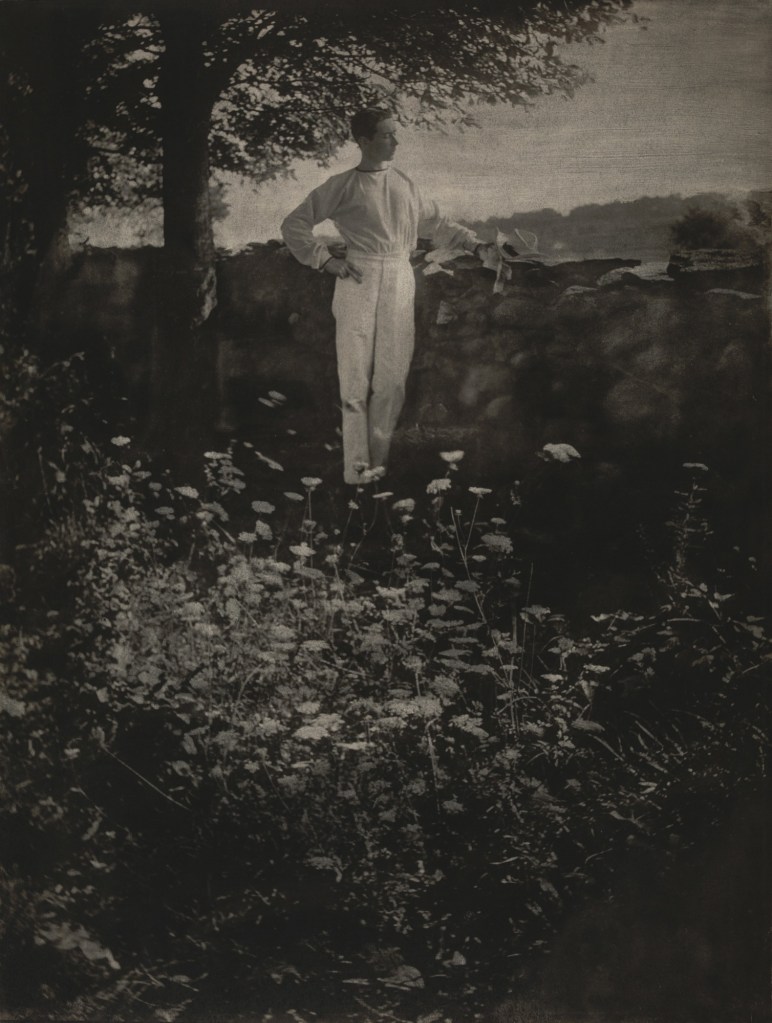

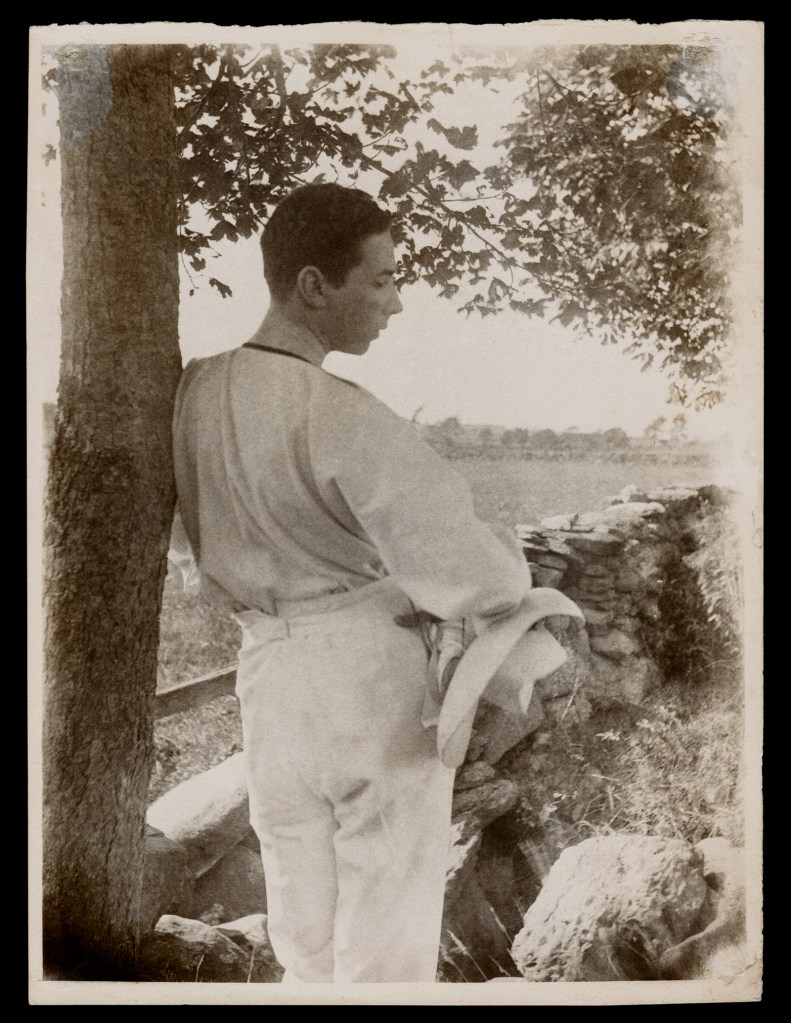

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Adolf de Meyer Photographing Olga in a Garden]' 1890s Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Adolf de Meyer Photographing Olga in a Garden]' 1890s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-photographing-olga-in-a-garden-web.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-self-portrait-in-india-web.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 (detail Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-self-portrait-in-india-detail.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Amida Buddah, Japan]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Amida Buddah, Japan]' 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-amida-buddah-web.jpg?w=775)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan]' 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-view-through-the-window-of-a-garden-web.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Lady Ottoline Morrell]' c. 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Lady Ottoline Morrell]' c. 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-lady-ottoline-morrell-web.jpg?w=764)

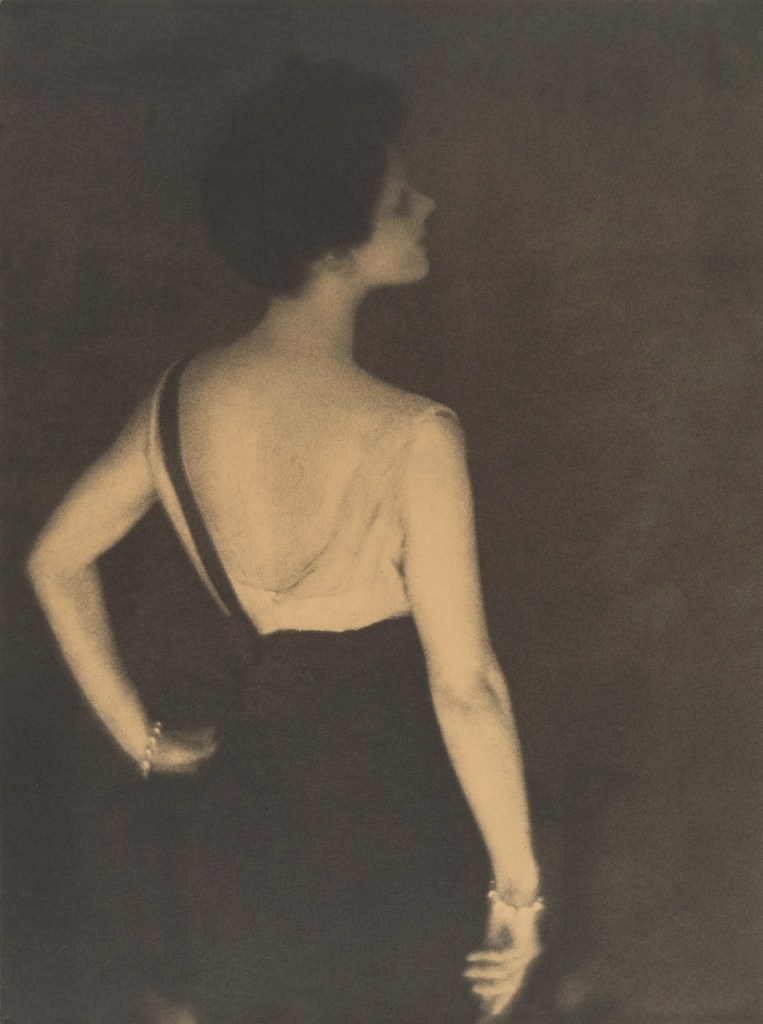

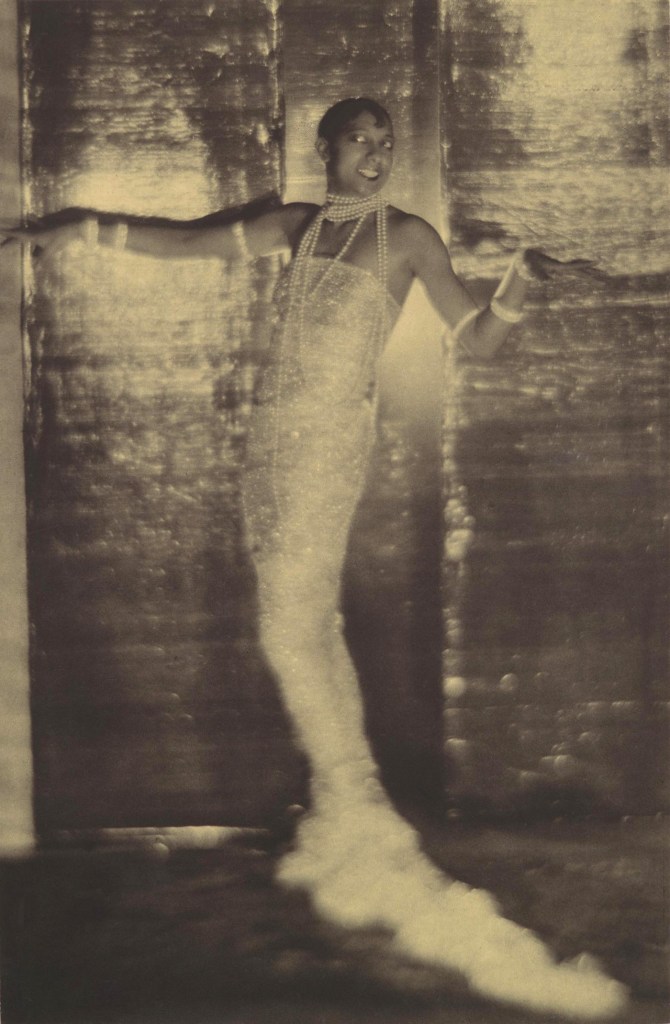

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-dance-study-web.jpg)

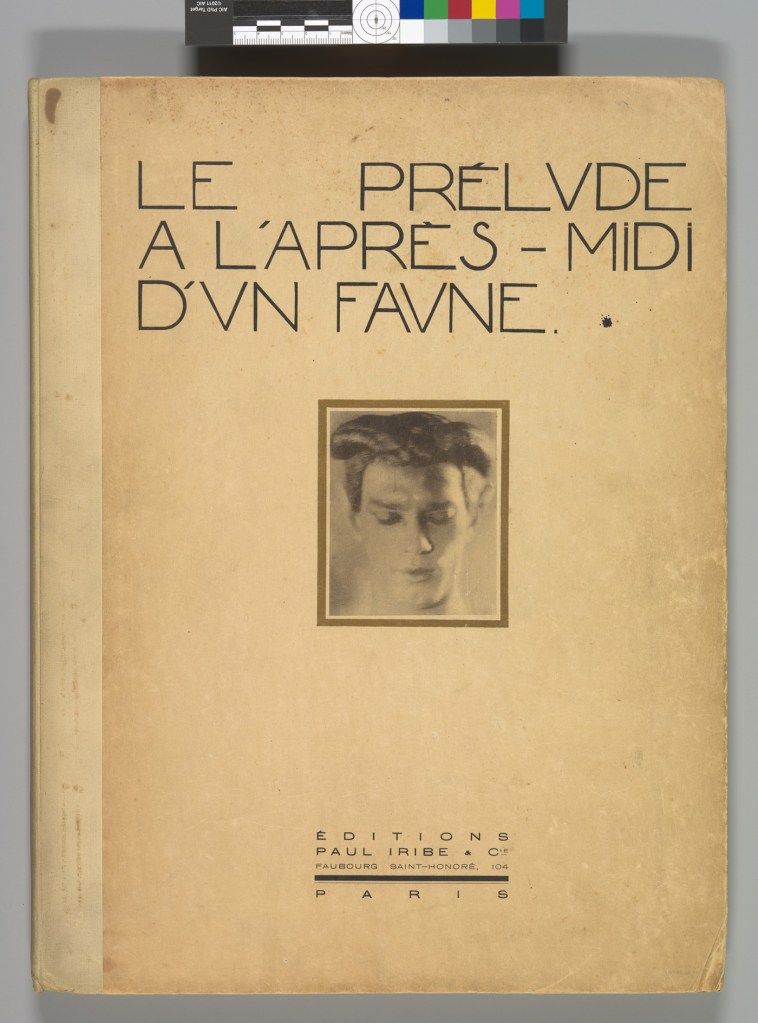

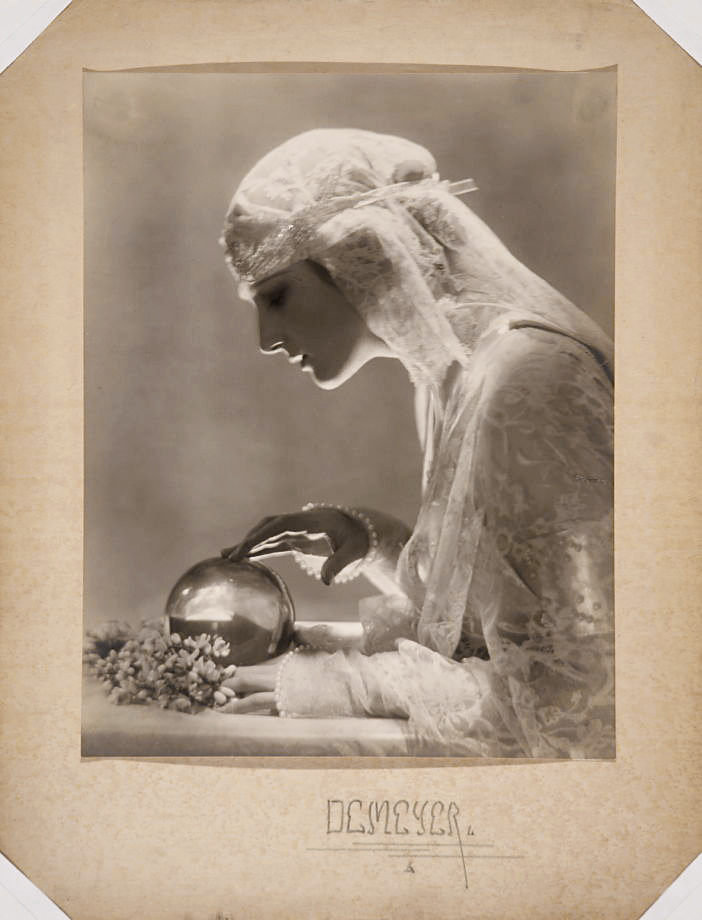

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-portrait-of-vaslav-nijinski-1912-web.jpg?w=785)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1914 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1914](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-nijinsky-plate-from-le-prelude-acc80-laprecc80s-midi-dun-faune-web.jpg?w=637)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Image from "Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un faune"]' 1914 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Image from "Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un faune"]' 1914](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-image-from-prelude-web.jpg)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Study for Vogue [Jan 1-1918, Betty Lee, Vogue, page 41]' 1918-1921 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Study for Vogue [Jan 1-1918, Betty Lee, Vogue, page 41]' 1918-1921](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-study-for-vogue-web.jpg?w=803)

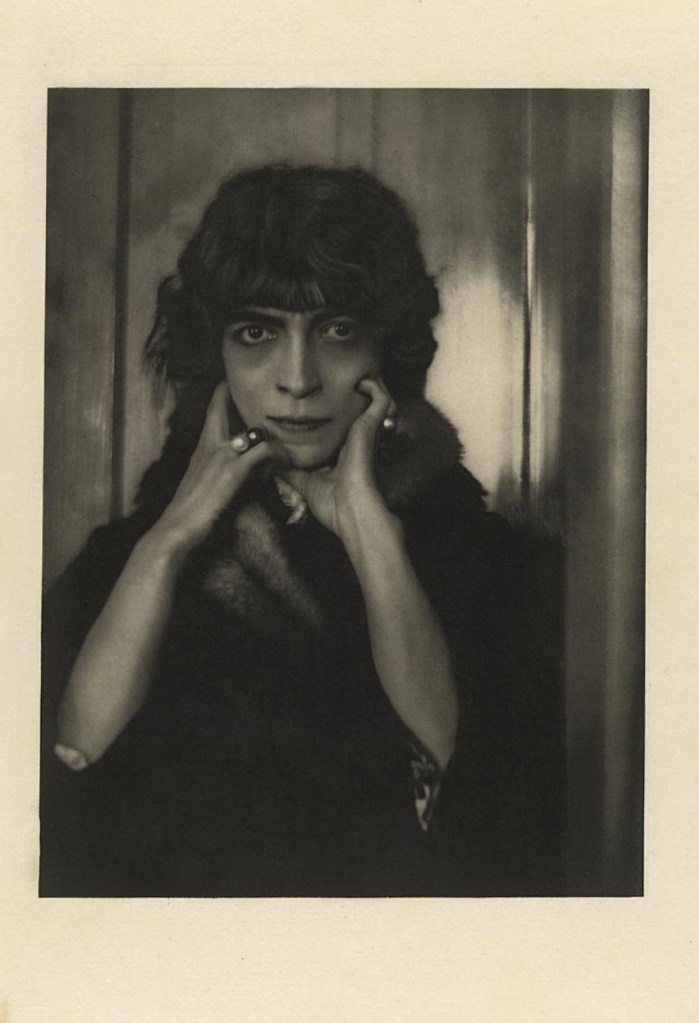

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Etienne de Beaumont [Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956)]' c. 1923 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Etienne de Beaumont [Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956)]' c. 1923](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-etienne-de-beaumont-web.jpg?w=808)

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) 'A Mexican [Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868-1946 Los Angeles, California)]' 1905 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) 'A Mexican [Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868-1946 Los Angeles, California)]' 1905](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/sears-adolf-de-meyer-web.jpg?w=808)

You must be logged in to post a comment.