Exhibition dates: 3rd April – 14th July, 2025

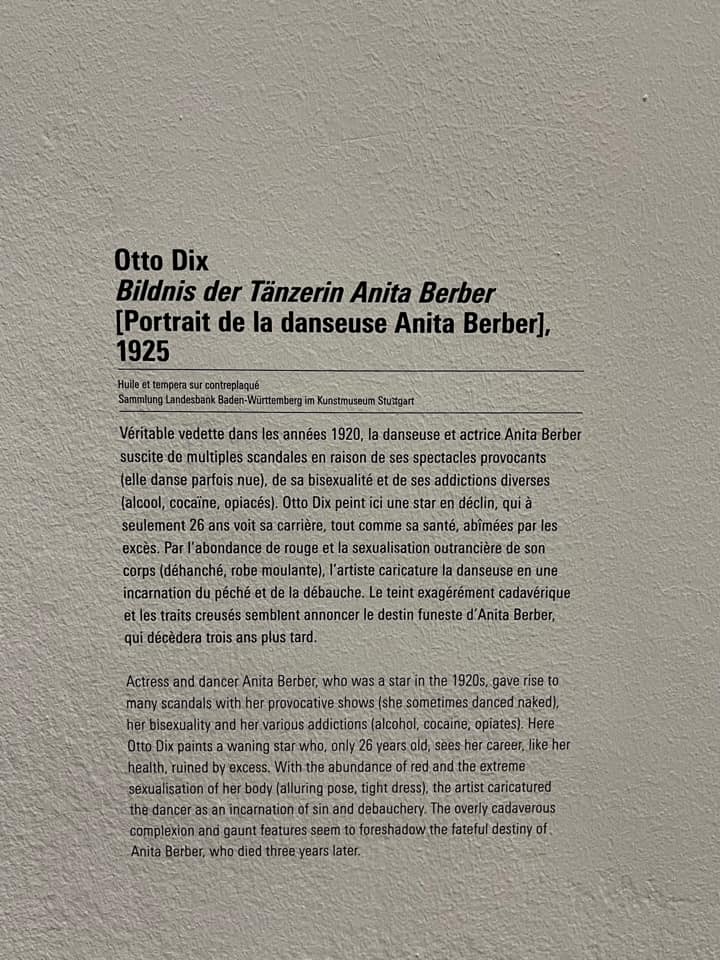

Curator: Susanne Pfeffer

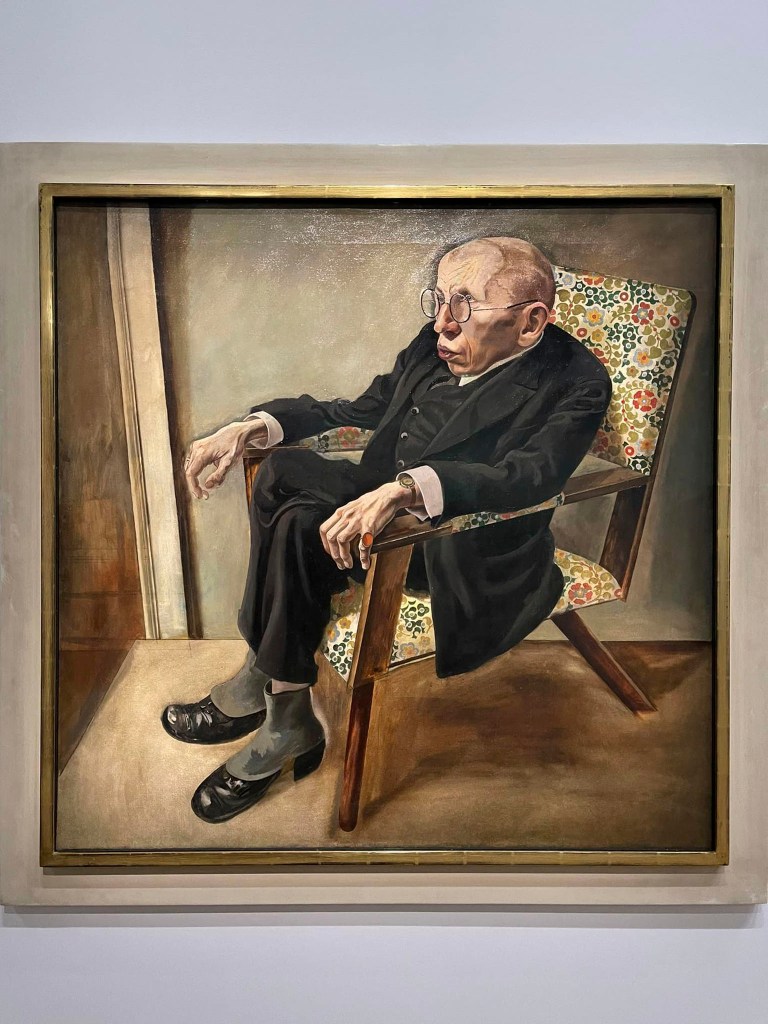

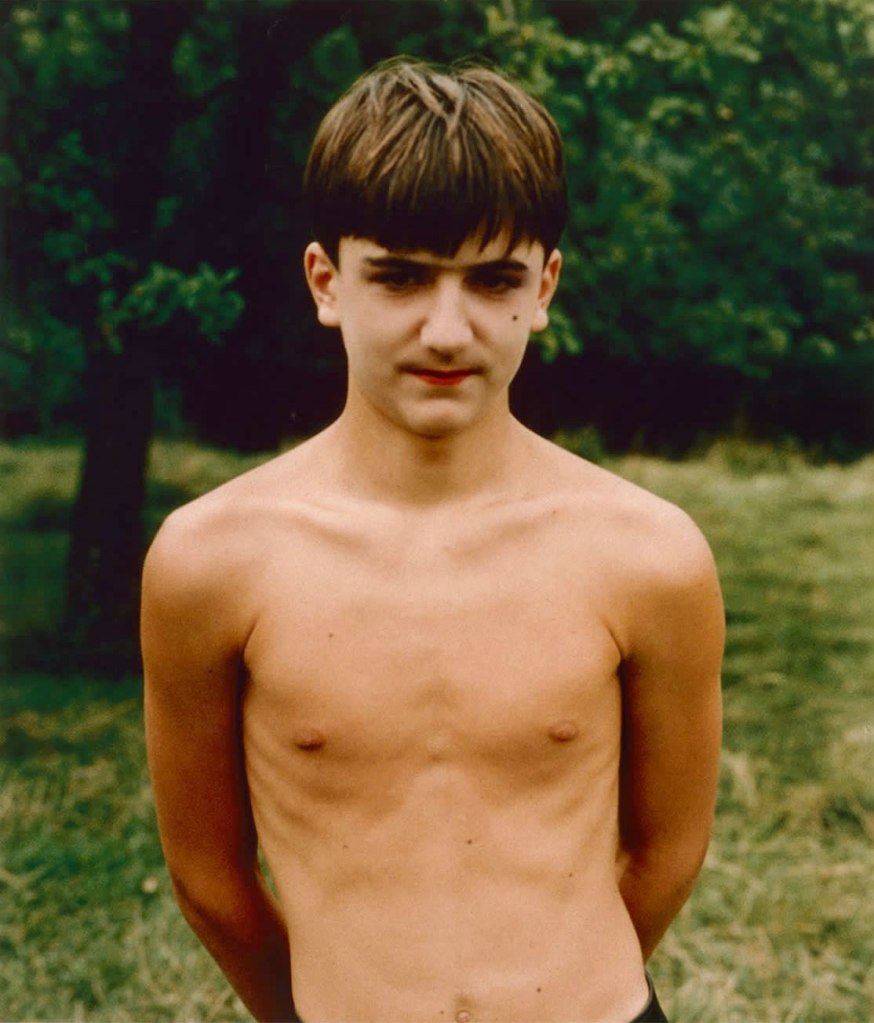

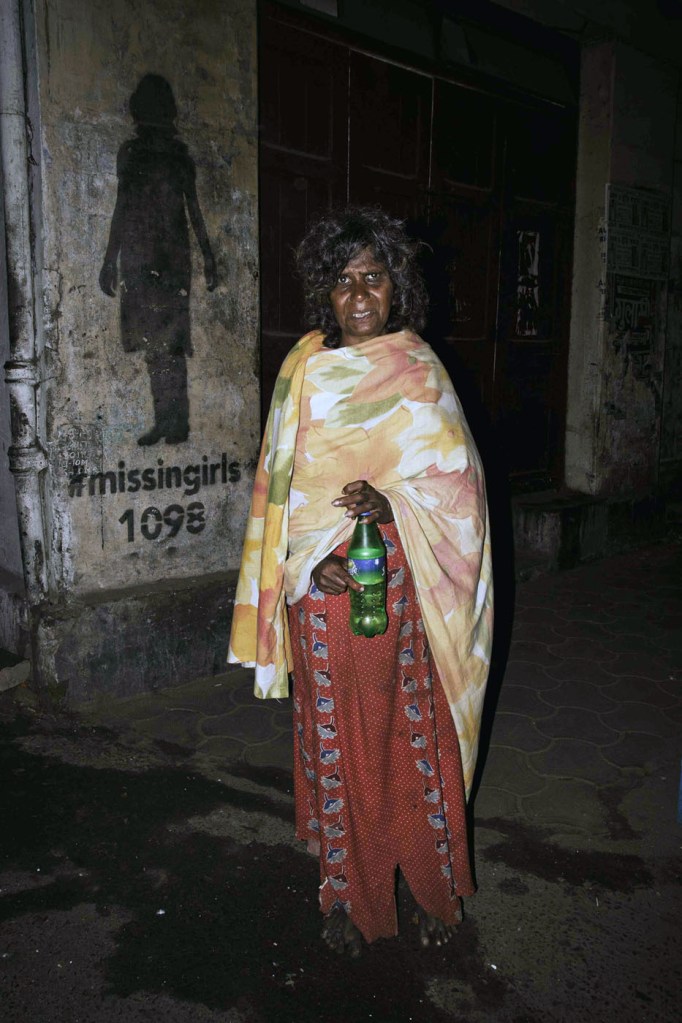

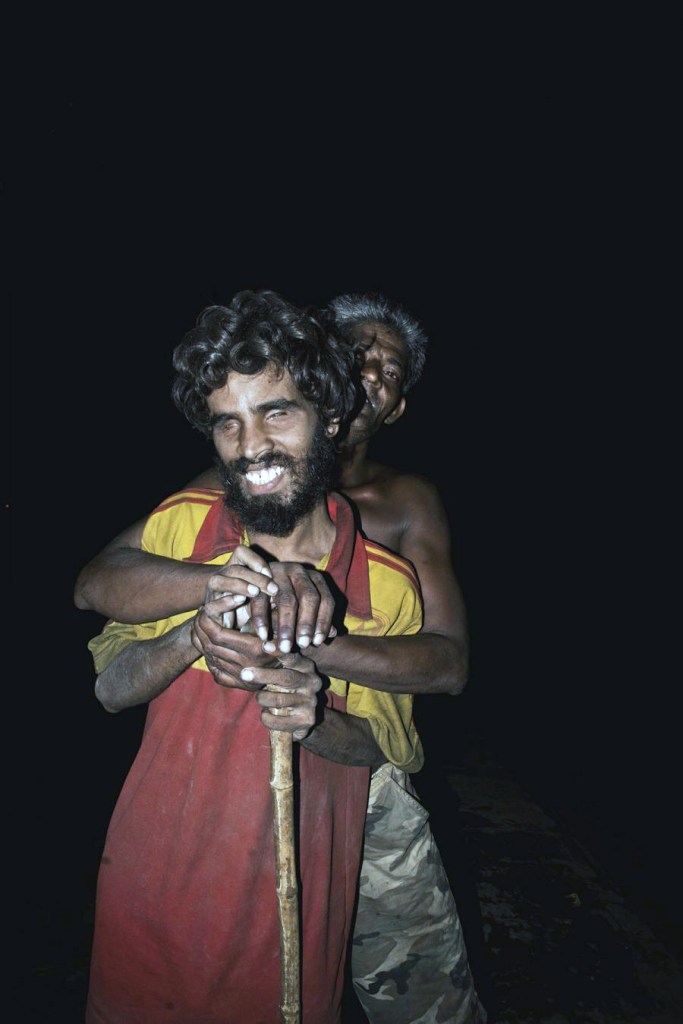

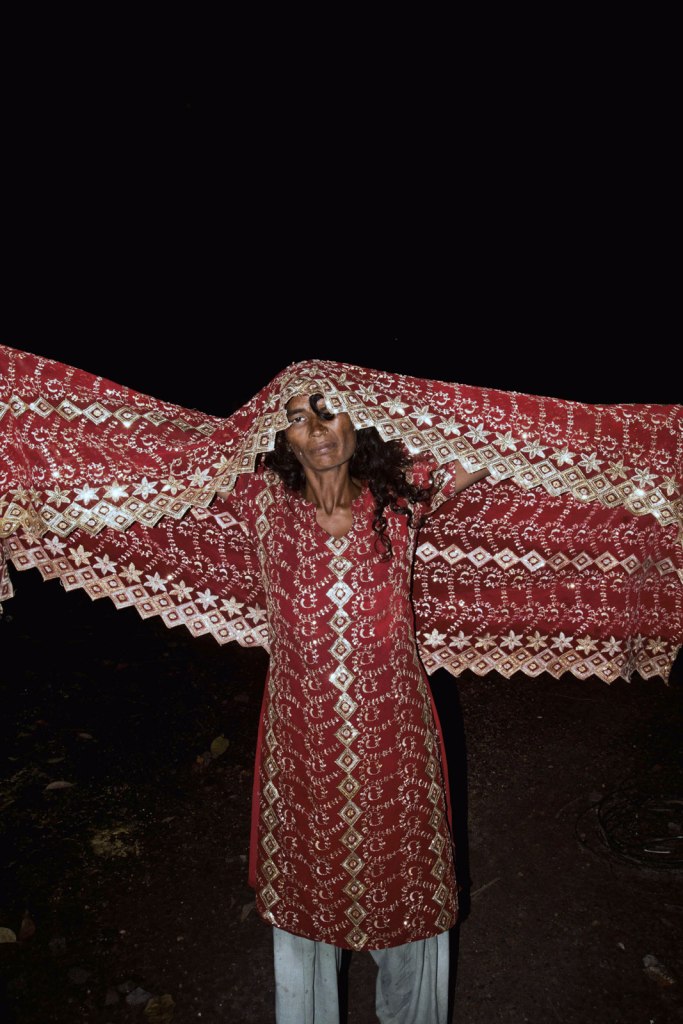

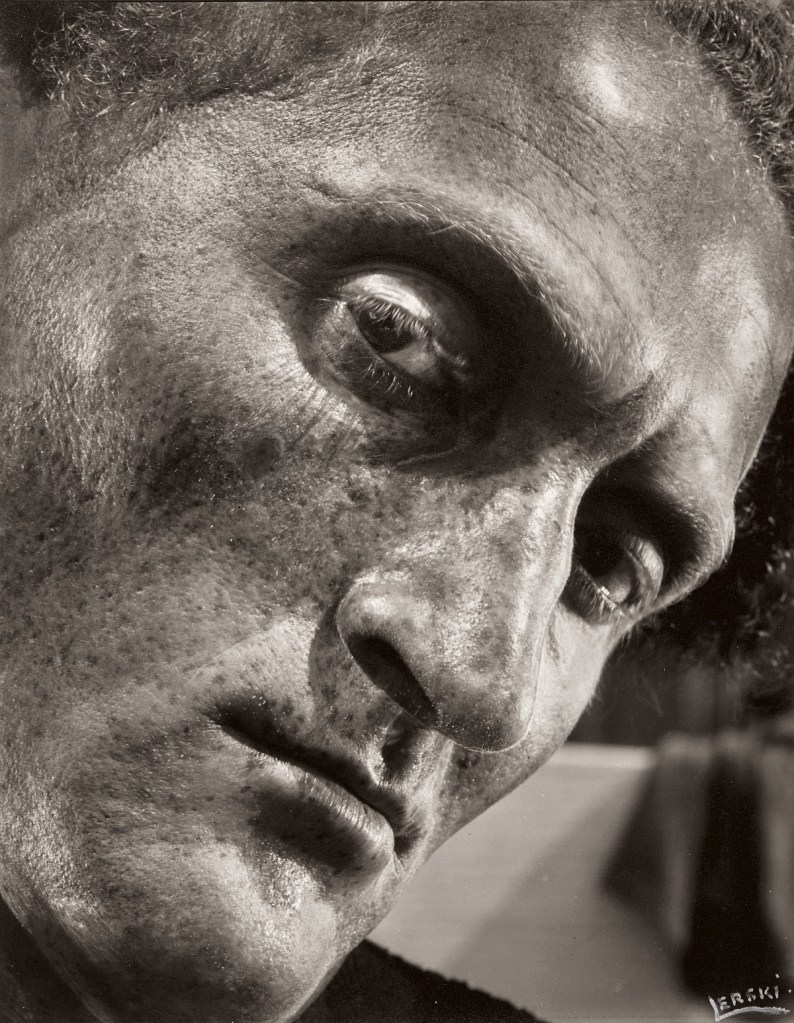

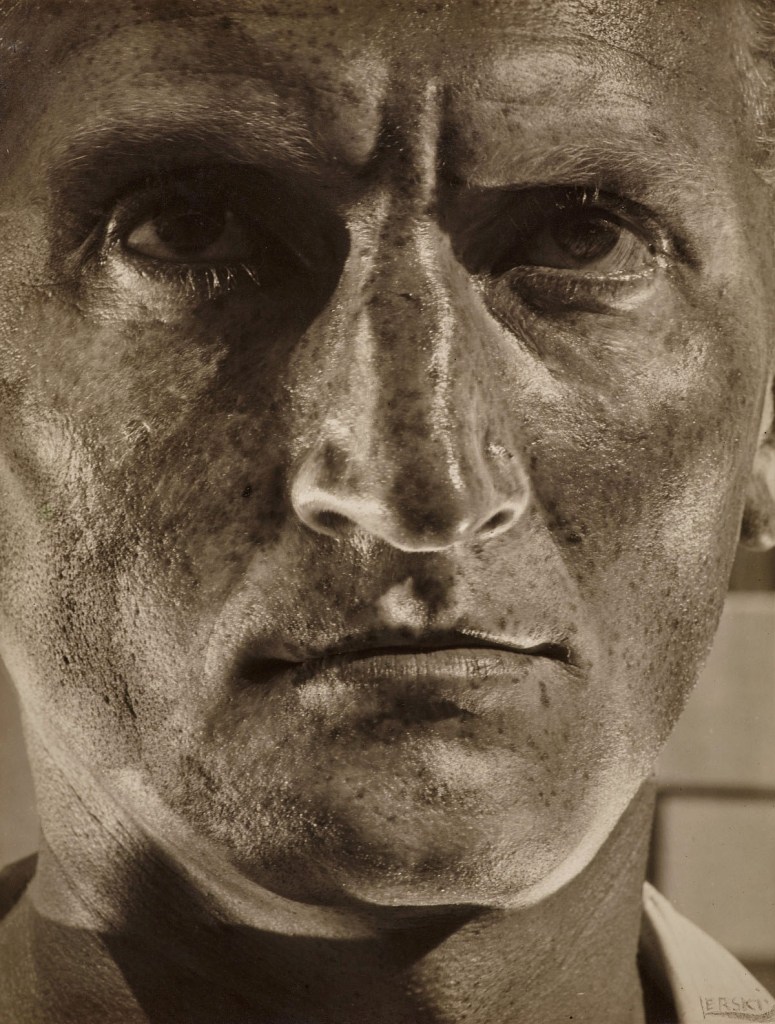

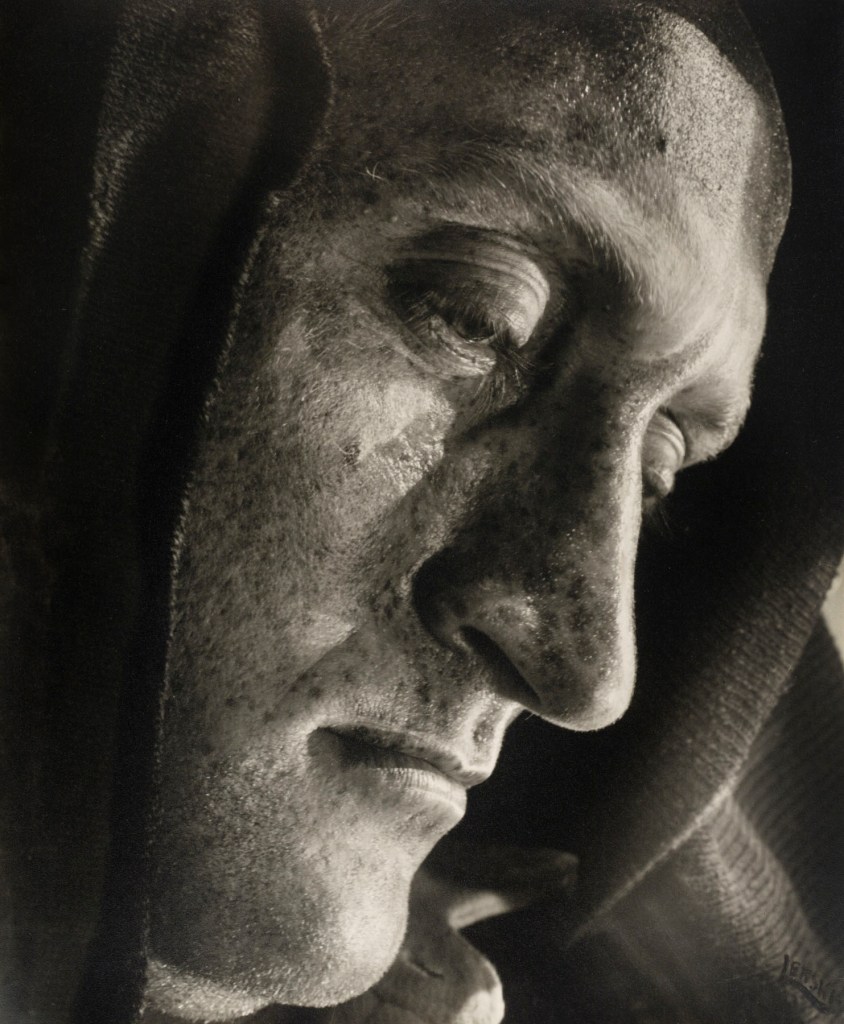

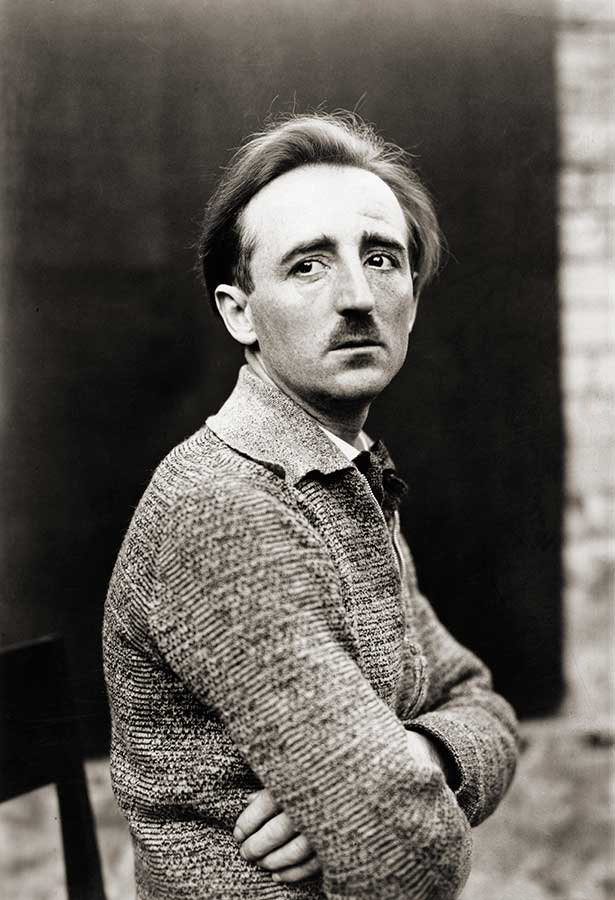

Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010)

Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969 [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969]

1969

Gelatin silver print, printed 2007

Kicken Berlin

© Heinrich Riebesehl, by SIAE 2025

Once more, with feeling

“Typology remains a highly challenging and complex notion. It operates in a paradoxical regime: on the one hand, this approach can lead to a systematic recording of people and objects based on extreme objectivity; on the other hand, typology corresponds to an individual and arbitrary choice, revealing itself as a disturbing and potentially subversive act.” (Press release)

Objective / subjective

Pattern / randomness

Isolation / extinction

Morphology / mutation

Specific / anonymous

Repetition / difference

Same / other

Structure / creativity

Orientation / disorientation

Universal / individual

Reality / imagination

Documentation / disruption

Omnipresent / unique

Exact / imprecise

Composed / emotional

Staged / snapshot

Concept / feeling

Formal / intuitive

Ritual / subversion

Collaboration / resistance

Et cetera, et cetera…

Inherent in one is the other.

Every photo within a Becher grid contains its own difference.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Fondazione Prada for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Let’s not beat around the bush. Despite protestations to the contrary (appeals to the objectivity of the image, eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion; the rigorous frontality of the individual images giving them the simplicity of diagrams, while their density of detail offers encyclopaedic richness) these are subjective images for all their objective desire. The paradox is the more a photographer strives for objectivity, the more ego drops away, the more the work becomes their own: subjective, beautiful, emotive.

Marcus Bunyan commenting on the exhibition Bernd and Hilla Becher: Mines and Mills – Industrial Landscapes at Fotomuseum Winterthur, Zurich, February, 2012

“What happens in the case of mutation? Consider the example of the genetic code. Mutation normally occurs when some random event (for example, a burst of radiation or a coding error) disrupts an existing pattern and something else is put in its place instead. Although mutation disrupts pattern, it also presupposes a morphological standard against which it can be measured and understood as mutation. We have seen that in electronic textuality, the possibility for mutation within the text are enhanced and heightened by long coding chains. We can now understand mutation in more fundamental terms. Mutation is critical because it names the bifurcation point at which the interplay between pattern and randomness causes the system to evolve in a new direction. It reveals the productive potential of randomness that is also recognized within information theory when uncertainty is seen as both antagonistic and intrinsic to information.

We are now in a position to understand mutation as a decisive event in the psycholinguistics of information. Mutation is the catastrophe in the pattern / randomness dialectic analogous to castration in the presence / absence dialectic. It marks a rupture of pattern so extreme that the expectation of continuous replication can in longer be sustained. But as with castration, this only appears to be a disruption located at a specific moment. The randomness to which mutation testifies is implicit in the very idea of pattern, for only against the background of nonpattern can pattern emerge. Randomness is the contrasting term that allows pattern to be understood as such.”

Hayles, Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999, pp. 30-33

Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010)

Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969 [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969]

1969

Gelatin silver print, printed 2007

Kicken Berlin

© Heinrich Riebesehl, by SIAE 2025

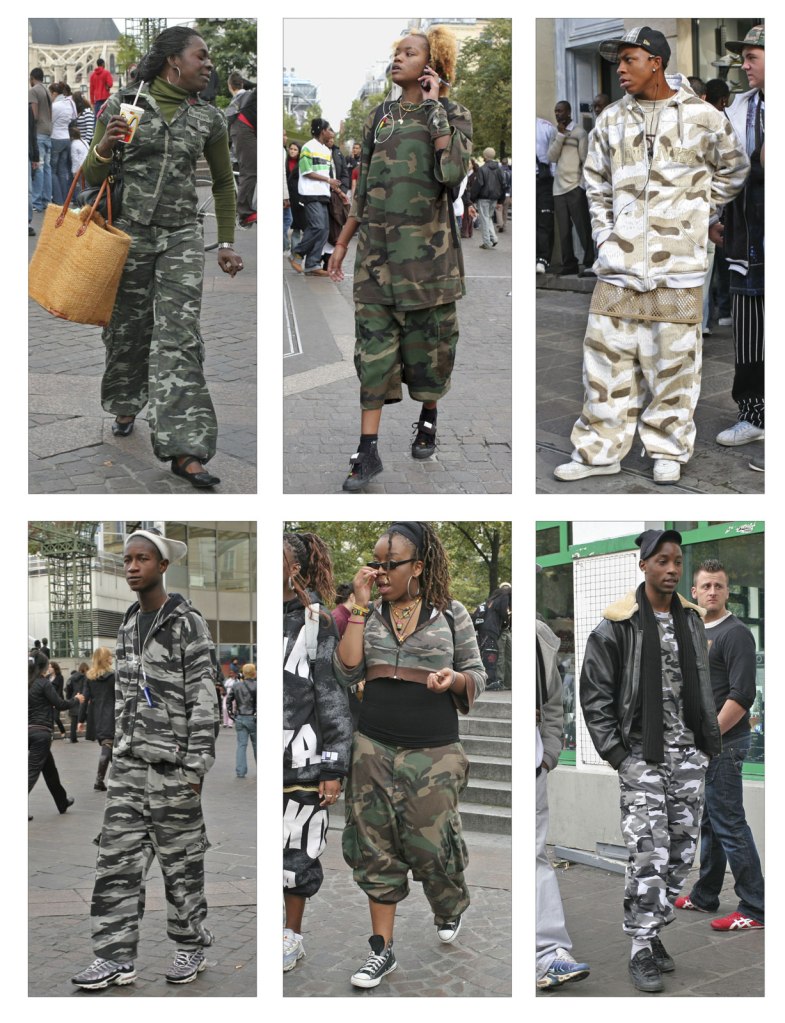

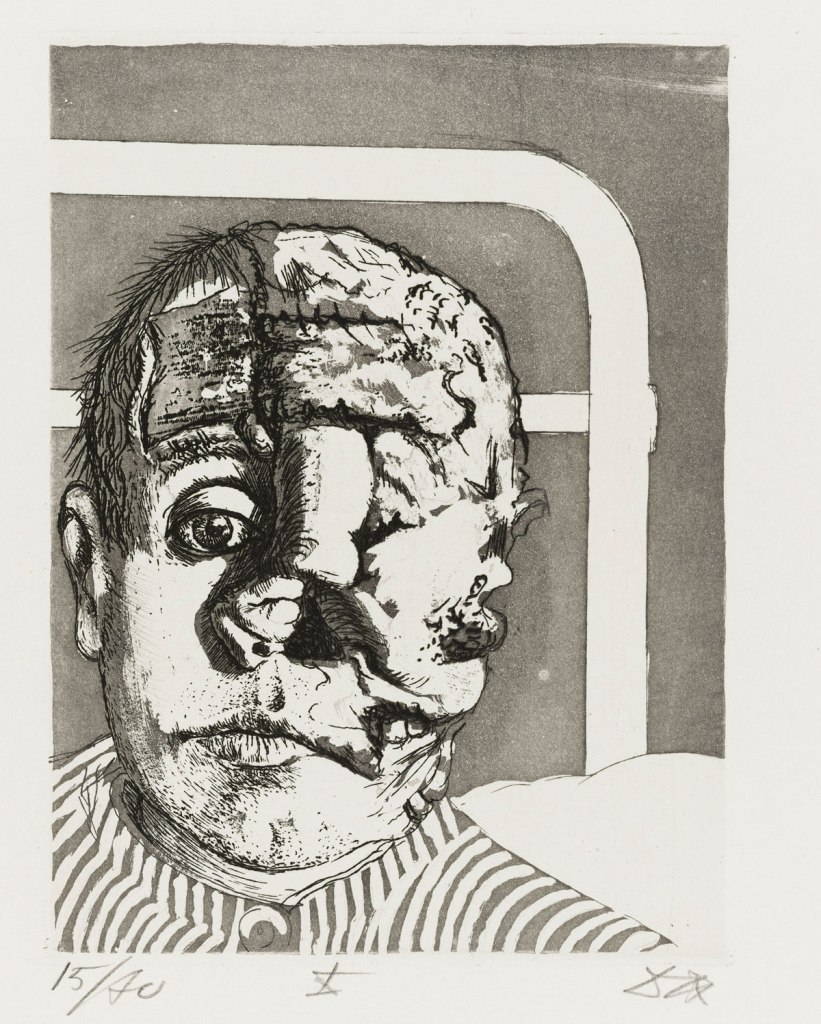

In the series Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969 (People in the elevator, 20.11.1969) shot in 1969, Heinrich Riebesehl conceptualised his interest in the photographic portrait. The portraits of the workers of the Hannoversche Presse (a daily newspaper in Hanover) – taken inside an elevator with a remotely operated small-format camera – are dated and numbered in sequential order: Riebesehl dispensed with a title or a more detailed description of the subjects portrayed. By omitting distinctive elements from the images, such as the profession or age of the subjects, he made the situation the key factor in the shots. In fact, the images are studies of the behaviors of people in that particular space, their body languages and gazes. Riebesehl knew that environment very well, because he had worked for a long time as a photojournalist, before turning to conceptual art photography.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

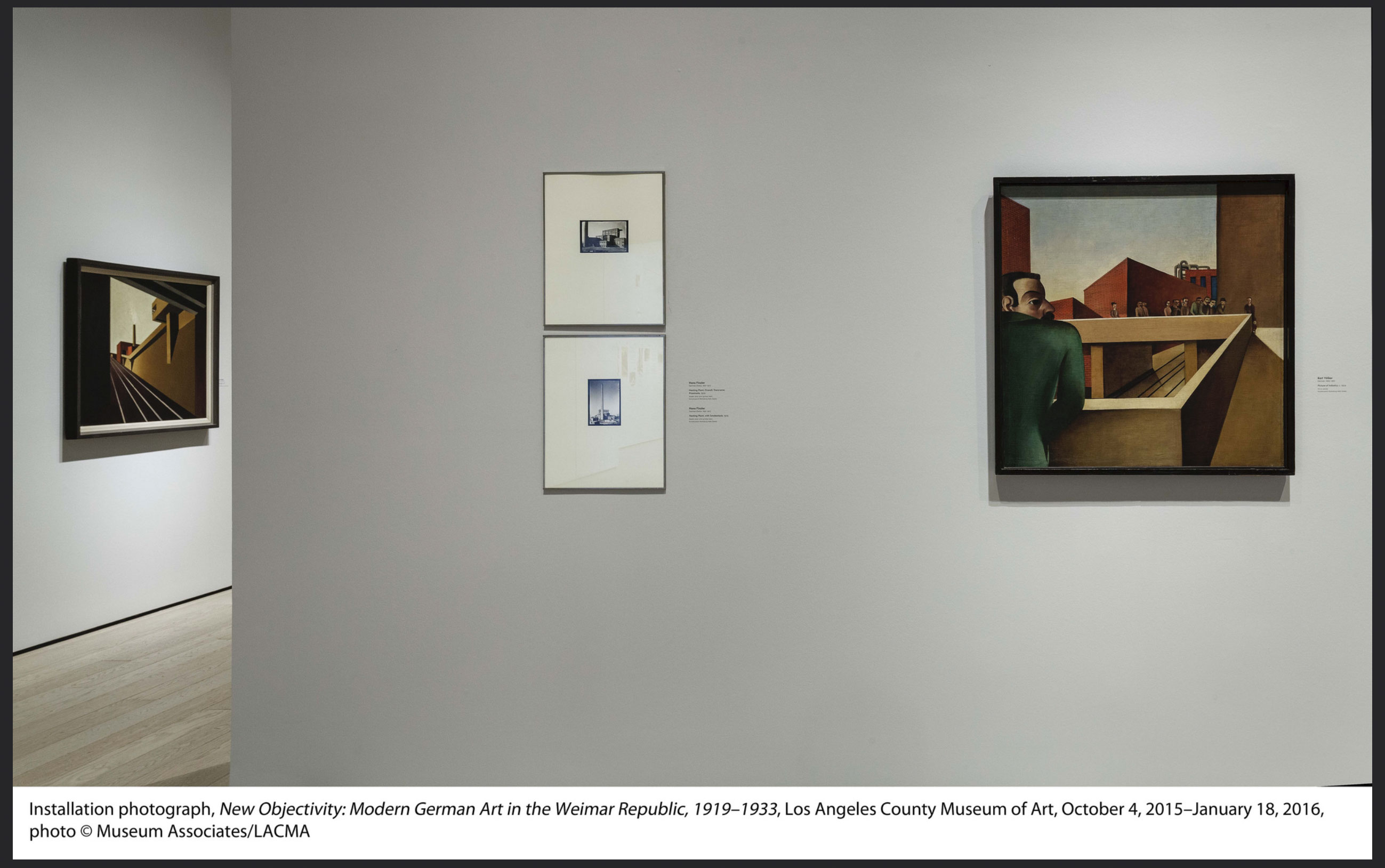

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing at left Bernd and Hiller Becher’s Hochöfen (Blast furnaces) 1970-1989; and at right, Candida Höfer’s Bibliotheque Nationale de France XXIII 1997

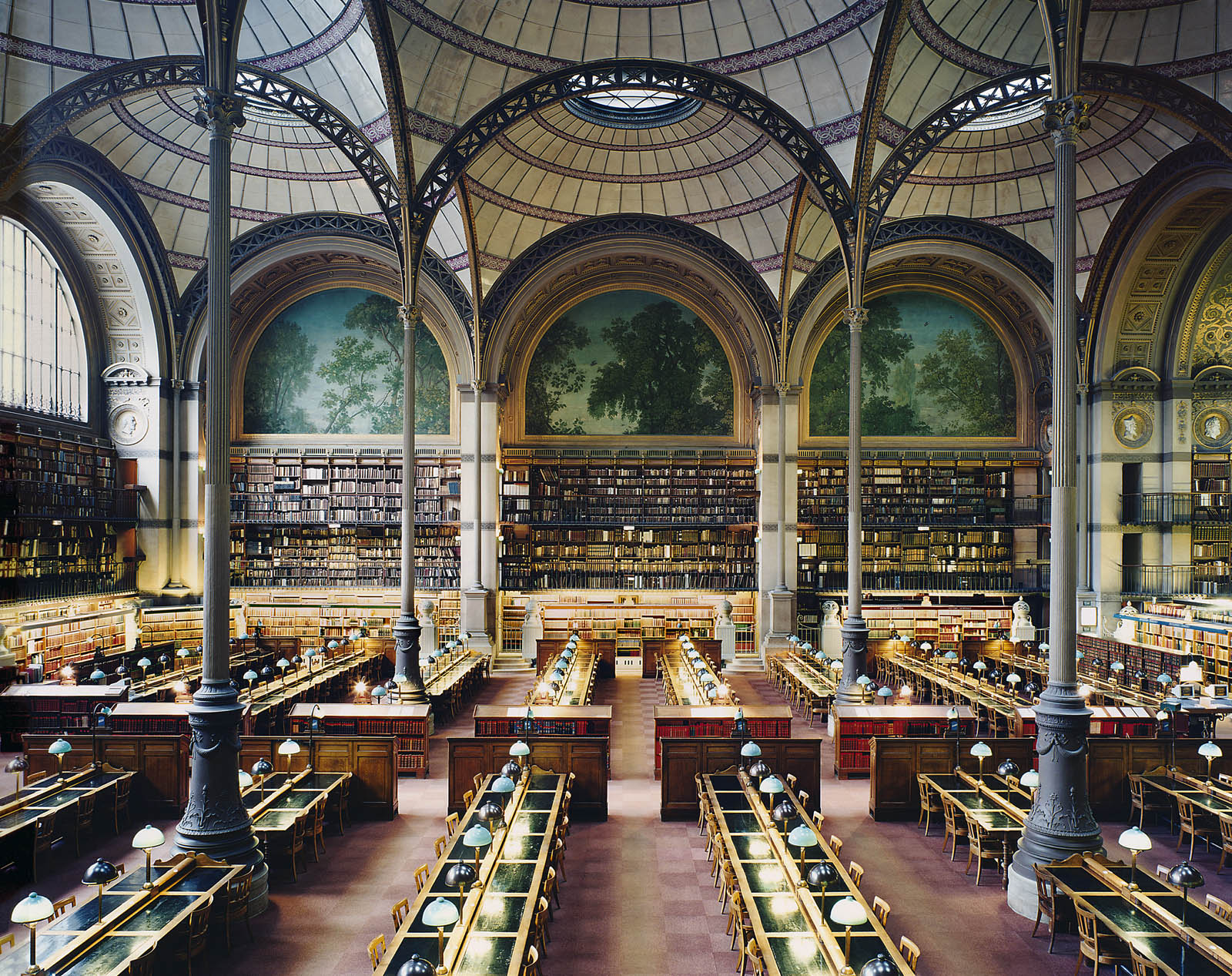

Candida Höfer (German, b. 1944)

Bibliotheque Nationale de France XXIII

1997

Inkjet print

© Candida Höfer, Cologne

In the photographs of libraries in London, Paris, and New York, which at first glance appear to be technically scientific records, Candida Höfer manages to capture something that is not visible: ingenuity. The libraries’ rooms have high ceilings, and the rows of seats are neatly arranged. In their impressiveness, they reflect the architecture of the 19th-century conception of knowledge and science, typical of the dominant nations of the time because of their commercial and colonial power. The objective nature of the deserted spaces, precisely in how they seem to be neutral to the individual needs of the students, suggests something in the image that could hardly be less objective: the possibility for intellectual exchange that these spaces promise and deliver in Höfer’s photographs.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Candida Höfer (German, b. 1944)

Zoologischer Garten Washington DC IV

1992

Inkjet print

© Candida Höfer, by SIAE 2025/VG BildKunst, Bonn 2025

In Candida Höfer’s photographs shot in zoos, the animals document a specific form of loneliness in modern times. In these images, the lines of development of two disciplines collide. Not only in the photographs, but also in reality, they function independently of each other: modern architecture and behavioural research. Modern architecture has become established in zoological gardens but has never considered the animal and its needs. Based on the knowledge gained from behavioural research, by choosing to portray iconic large mammals such as giraffes, lions, and polar bears, Höfer has represented the dilemma of a world in which entire species are threatened with extinction and in which zoos see themselves as a kind of ‘Noah’s Ark.’

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

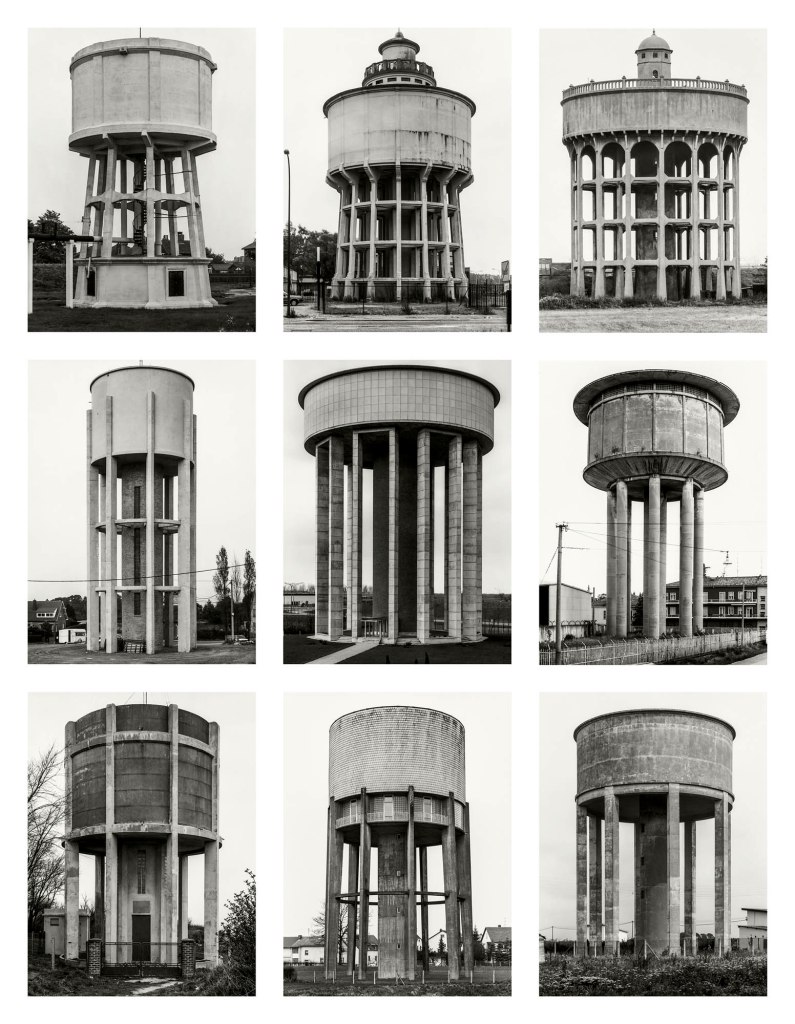

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing Bernd and Hilla Becher’s Wassertürme (Water towers) 1966-1986

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Wassertürme (Water towers)

1966-1986

Leeds, GB, 1966

Hasselt, B, 1985

Newton le Willows, GB, 1966

Beaufays/Liège, B, 1979

Kwaadmechelen, B, 1971

Padova, I, 1986

Outreau/Boulogne, F, 1973

Primasens, Saarland, D, 1980

Mesnil-Val, F, 1972

9 gelatin silver prints

© Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy of Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne, 2025

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing the work of Thomas Struth

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing the work of Thomas Struth with at left, Musée du Louvre IV Paris, 1989

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

Musée du Louvre IV

Paris, 1989

Colour photograph on C-print

© Thomas Struth / Courtesy ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe

In his practice, Thomas Struth demonstrates meticulous attention to the architectural environment, as well as to people and objects. In his large-format colour series Museum Photographs (1989-1992), Struth captures anonymous individuals and crowds gazing at artworks in museums. A significant example is Louvre 4, Paris 1989, in which the artist photographs from behind a group of viewers standing in front of Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819). Often made with a large-format camera, his images reflect what Struth calls “exact vision”: the framing must not conceal anything or suggest secret content, thus resulting in an enigmatic outcome.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

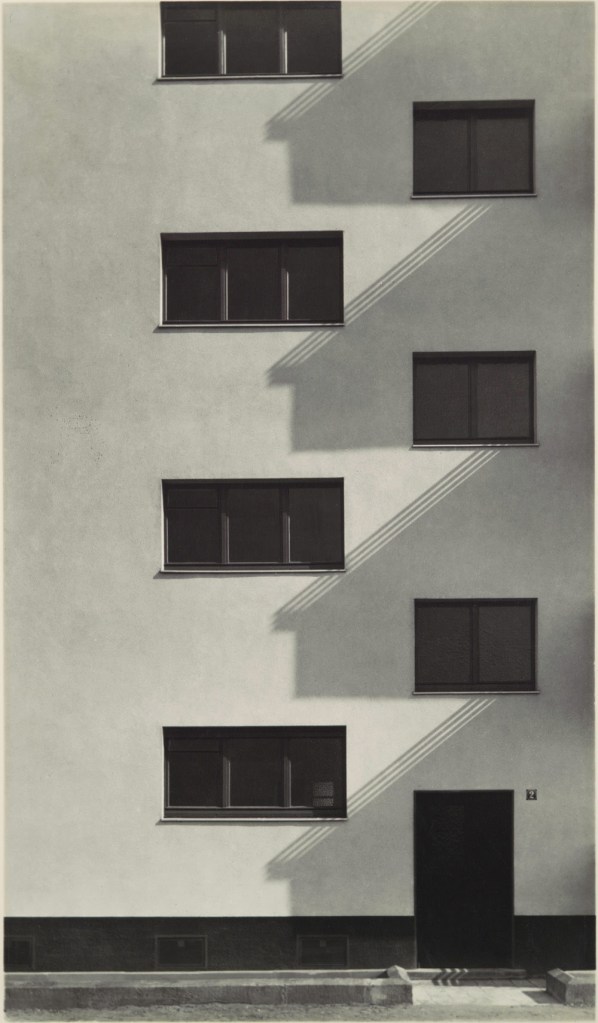

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing Andreas Gursky’s Paris, Montparnasse 1993

Andreas Gursky’s large-format work, Paris, Montparnasse (1993) has become an iconic example of his work. It depicts the Maine-Montparnasse II block of flats, located on Rue Commandant-Mouchotte in Paris and built between 1959 and 1964 on a design by French architect Jean Dubuisson. This is one of the first images that Gursky created using digital post-production. In real life, the building does not look the way it appears in the image: using a digital editing process, Gursky transformed the façade into a game of differences and repetitions by processing the windows. In fact, by reiterating forms that are always identical, he produced a seemingly infinite number of them, with colour variations that are activated by a calculated dynamic.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing Andreas Gursky’s 99 Cent 1999

In 99 Cent (1999), Andreas Gursky photographed supermarket shelves using the same formal scheme used in Paris, Montparnasse (1993). The shelves crammed with everyday products such as detergents represent the inexhaustible flow of goods in the global system of production and distribution. Gursky’s work conveys a feeling of disorientation generated by the excessive stimuli and details typical of a shelf in a hypermarket.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Andreas Gursky (German, b. 1955)

99 Cent

1999 (remastered 2009)

Inkjet print

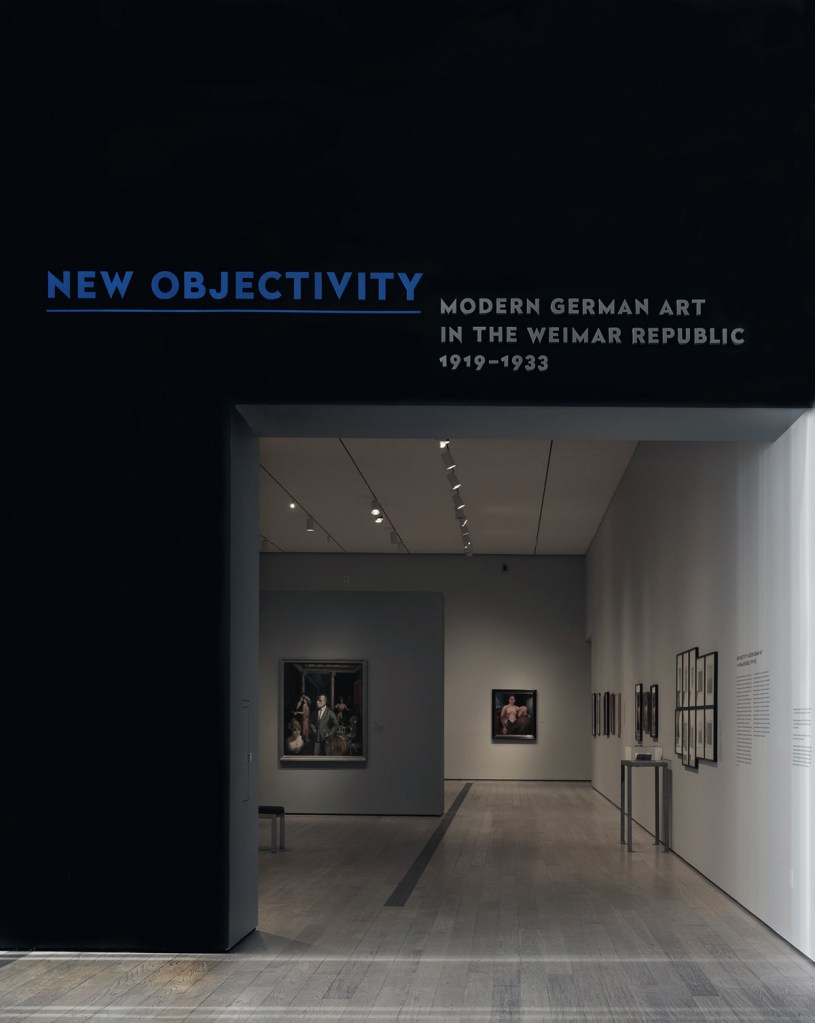

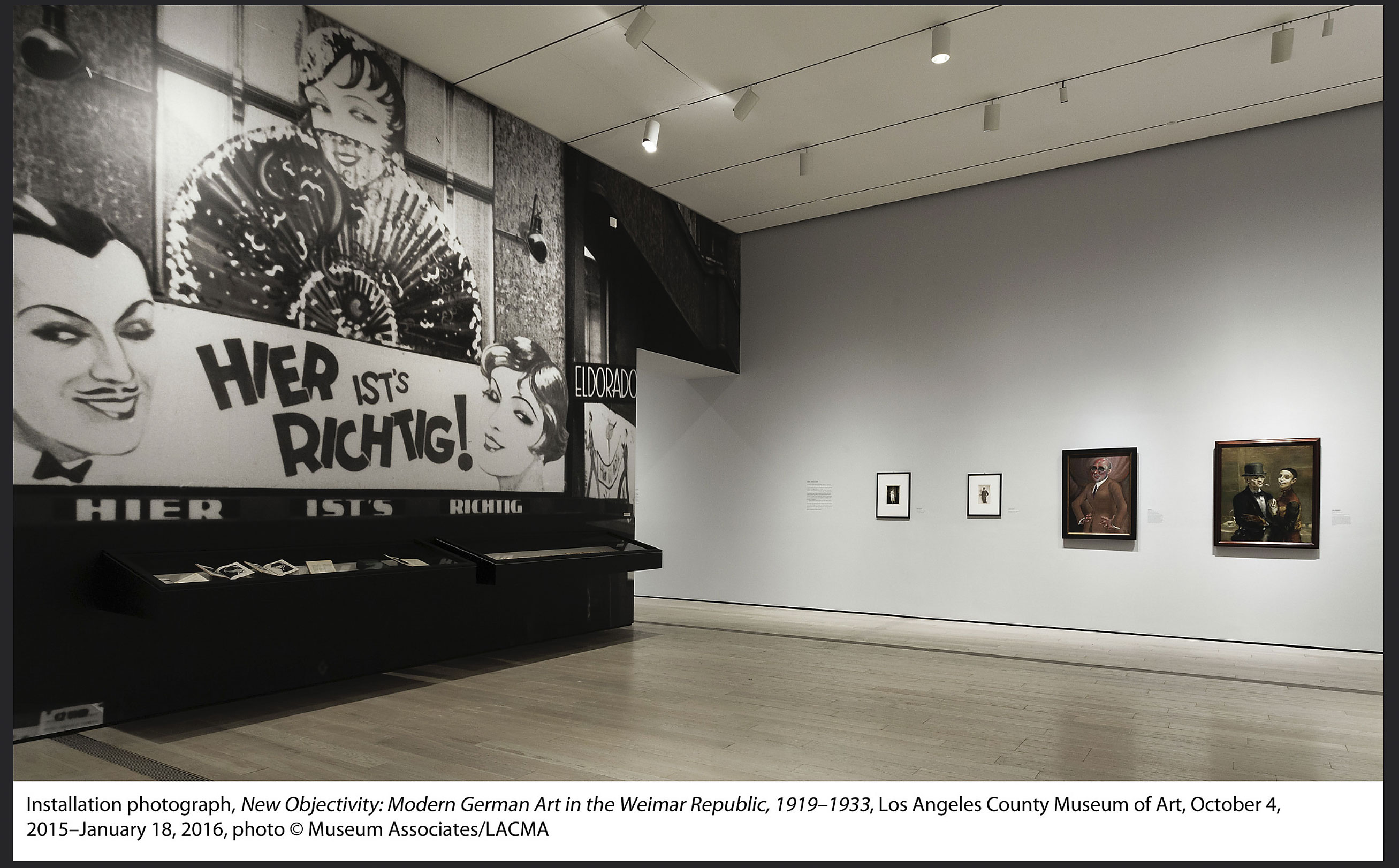

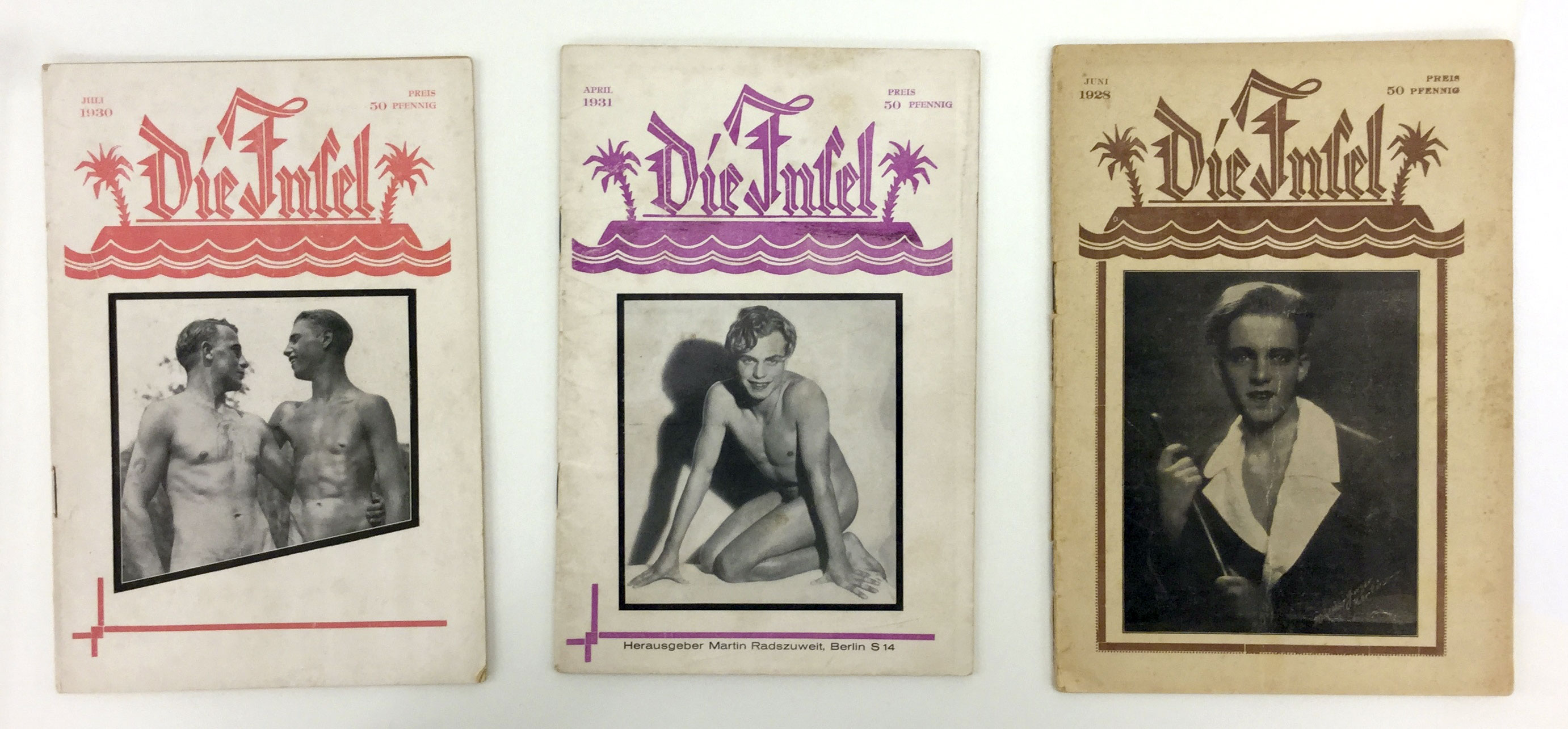

“Typologien” is an extensive study dedicated to 20th-century German photography. The exhibition, hosted within Podium, the central building of the Milan headquarters, is curated by Susanne Pfeffer, art historian and director of the MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST, Frankfurt.

The project attempts to apply the principle of “typology,” which originated in 17th- and 18th-century botany to categorise and study plants, and appeared in photography in the early 1900s, affirming itself in Germany throughout the 20th century. Paradoxically, the given formal principle allows for unexpected convergences of German artists spanning different generations and the manifestation of their individual approaches.

The exhibition path will follow a typological rather than a chronological order, bringing together more than 600 photographic works by 25 established and lesser-known artists essential for recounting a century of German photography, including Bernd and Hilla Becher, Sibylle Bergemann, Karl Blossfeldt, Ursula Böhmer, Christian Borchert, Margit Emmrich, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Isa Genzken, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Lotte Jacobi, Jochen Lempert, Simone Nieweg, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, Heinrich Riebesehl, Thomas Ruff, August Sander, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, Thomas Struth, Wolfgang Tillmans, Rosemarie Trockel, Umbo (Otto Umbehr), and Marianne Wex. A system of suspended walls will create geometric partitions in the exhibition space, forming unexpected connections between artistic practices that differ from each other, but are united by a common principle or intention of classification.

As stated by Susanne Pfeffer, “Only through juxtaposition and direct comparison is it possible to find out what is individual and what is universal, what is normative or real. Differences are evidence of the abundance of nature and the imagination of humans: the fern, the cow, the human being, the ear; the bus stop, the water tower, the stereo system, the museum. The typological comparison allows differences and similarities to emerge and the specifics to be grasped. Unknown or previously unperceived things about nature, the animal, or the object, about place and time become visible and recognisable.”

In photography, employing typologies means affirming an equivalence between images and the absence of hierarchies in terms of represented subjects, motifs, genres, and sources. Despite this, typology remains a highly challenging and complex notion. It operates in a paradoxical regime: on the one hand, this approach can lead to a systematic recording of people and objects based on extreme objectivity; on the other hand, typology corresponds to an individual and arbitrary choice, revealing itself as a disturbing and potentially subversive act.

The hypothesis that photography plays a key role not only in fixing distinctive phenomena but also in organising and classifying a plurality of visible manifestations remains a vital force in today’s artistic efforts to navigate the complexity of our social and cultural realities. With the spread of digital imagery and practices, the concept of typology continues to be questioned and re-defined by contemporary photographers and artists.

As underlined by Susanne Pfeffer, “The unique, the individual, seems to have been absorbed into a global mass, the universality of things is omnipresent. The Internet allows typologies to be created in a matter of seconds. And yet this is precisely when it seems important – to artists – to take a closer look.” As further explained by Pfeffer, “When the present seems to have abandoned the future, we need to observe the past more closely. When everything seems to be shouting at you and becoming increasingly brutal, it is important to take a quiet pause and use the silence to see and think clearly. When differences are not seen as something other, but turned into something that divides us, it is crucial to notice what we have in common. Typologies allow us to identify remarkable similarities and subtle differences.”

Text from the Fondazione Prada website

Typologien | Fondazione Prada Milano

An extensive study dedicated to 20th-century German photography. “Typologien” attempts to apply the principle of “typology,” which originated in 17th- and 18th-century botany to categorise and study plants, and appeared in photography in the early 1900s, affirming itself in Germany throughout the 20th century.

The exhibition, hosted within Podium, the central building of the Milan headquarters, is curated by Susanne Pfeffer, art historian and director of the MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST, Frankfurt.

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing the work of Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg (German, b. 1938)

Transit Sites-Armenia-Erevan-Ararat

2001

Gelatin silver print on Forte paper

© Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg was visiting convents and monasteries in Armenia when she happened to come across one of these unique bus stops, partly futuristic and partly surreal. From 1997 to 2011, she portrayed numerous bus stops, often in very remote locations. In a country that was experiencing a dramatic transition, from being part of the Soviet Union to its new status as an independent republic, these bus stops look like the remnants of a utopian socialism, which in Schulz-Dornburg’s images are kept alive mainly by women and children. The photographer said she was so impressed by the dignity of those women waiting at the bus stop, who even in the most extreme poverty looked as though they were on their way to the Opera, that she asked their permission to photograph them. What emerged was a document of a quiet life that manages with dignity to deal with even the harshest adversity.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Installation view of the exhibition ‘Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany’ at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing at left, flower photographs by Thomas Struth; and at right, Andreas Gursky’s Untitled XVIII 2015 (below)

Andreas Gursky (German, b. 1955)

Untitled XVIII

2015

Inkjet print

Atelier Andreas Gursky

Unlike works such as Paris, Montparnasse (1993), in the Untitled series he produced between 2015 and 2016, Andreas Gursky depicted rows of tulips without providing a title or location for the pictures. Viewed from a distance, the photographs are reminiscent of Abstract Expressionist paintings, but even looking at them at close range, the lushly blooming flowers are undiscernible. Living in Düsseldorf, close to the Dutch border, Gursky is familiar with the intensively cultivated Dutch tulip crops, where no unwanted insect or worm would possibly be allowed to spoil the bulbs. The sterility of industrial flower production, far from being harmless and healthy, is captured by Gursky in images that, in turn, are neither reassuring nor pleasant.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing the flower photographs of Thomas Struth with at left, Small Closed Sunflower, No. 18, Winterthur 1992 (below); and at third left, Single Red Lily – No. 51, Düsseldorf (Botanischer Garten) 1993 (below)

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

Small Closed Sunflower, No. 18, Winterthur

1992

Colour photograph on C-print

© Thomas Struth / Courtesy ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

Single Red Lily – No. 51, Düsseldorf (Botanischer Garten)

1993

C-print

Viehof Collection

© Thomas Struth / Courtesy Viehof Collection, Mönchengladbach

A student of the artist Gerhard Richter and later of the photographer Bernd Becher at the Art Düsseldorf Academy from 1973 to 1980, Thomas Struth habitually works in thematic cycles centered around museums, flowers, and portraits of families and passers-by. The “exact vision” – the intention underpinning Struth’s photography – can be seen in both the portraits of two cornflowers shoot in Düsseldorf and the image of a red lily in the city’s Botanical Garden. Struth notes down the name or address of the site where he took the photograph, as in the case of the flower of a hollyhock portrayed in Düsseldorf’s Nordpark. This is to evoke the poetry of the place and provide an exact account of the plants’ origin, preserving the authenticity of the shots without digitally altering them.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing the work of Hiller Becher

![Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015) 'Eichenblatt [Oak Leaf]' 1965 Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015) 'Eichenblatt [Oak Leaf]' 1965](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/8-typologien_hilla-becher_sm.jpg?w=772)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Eichenblatt [Oak Leaf]

1965

Gelatin silver print

© Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne, 2025

In terms of the objectivity of the approach, Hilla Becher’s 1965 photographic studies of an oak leaf, a cypress branch, and a ginkgo leaf are in keeping with the series on types of industrial buildings that she made with her husband Bernd Becher. Thematically, however, these studies represent a sort of return to the studies of branches and shoots made years earlier by Karl Blossfeldt. Unlike Blossfeldt’s images, the leaves, particularly the poplar leaves, are not uniformly lit. The shadowy areas cannot be clearly seen with the naked eye even on close and objective observation. One could say that nature has penetrated the technique, disappearing.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing the work of Karl Blossfeldt

![Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932) 'Adiantum pedatum, haarfarn, junge, noch eingerollte Wedel' [Maidenhair fern, young, still curled fronds] Nd Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932) 'Adiantum pedatum, haarfarn, junge, noch eingerollte Wedel' [Maidenhair fern, young, still curled fronds] Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/5-typologien_karl-blossfeldt_sm.jpg?w=814)

Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932)

Adiantum pedatum, haarfarn, junge, noch eingerollte Wedel [Maidenhair fern, young, still curled fronds]

Nd

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy Berlin University of Arts, Archive – Karl Blossfeldt Collection in cooperation with Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne

The young, still curling fronds of an ‘Unspecified fern’ are a kind of introduction to the themes that Karl Blossfeldt explored, and his working methods. Faced with a seemingly infinite variety of natural forms, the photographer tried to find an order by using tools borrowed from scientific botany. Blossfeldt collected plant samples tirelessly in and around Berlin, dried them, and enlarged those details not visible to the naked eye. However, the photographer was seeking something different from the aims of botanical research. This is already revealed by the title of the first volume, a publication of his photographs of plants – Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Plants, 1928). Right from the title, he explicitly refers to the model he used for the book’s conception: Ernst Haeckel’s Kunstformen in der Natur (Art Forms in Nature), published in 1924 and now a classic. Therefore, Blossfeldt sought archetypal formal models in nature, such as the fronds of the fern.

In his search for a primal form of nature that could then be shaped into art according to the natural model – as in the case of the curled fronds of

the fern – Karl Blossfeldt applied the systematic method specific to botany with a kind of exterior mimicry. He moved from the frond of an unidentified fern, in other words, not yet classified according to an order, to a fern that could at least be identified within a botanical classification. The frond of the order Polypodiales certainly has typological similarities to all the fronds photographed by Blossfeldt, but it remains a case apart in that it cannot be classified in any of the orders in which the other ferns are classified. However, this level of identification is a relevant indication: these very diverse plants in fact number about 9000 known species, and probably many more yet to be identified. Moreover, identifying their species is often only possible for a few specialists, and is even more difficult given the variety of forms that ferns take during their development.

The curled fronds of some ferns from the Osmundaceae family, royal ferns, with their botanical classification, confirm one of the fundamental intentions of Karl Blossfeldt’s studies: only by carefully analyzing the structure of a plant can one fully understand its natural form. He developed his approach opposite to that of the Jugendstil, the artistic movement – a variation of French Art Nouveau and Italian Liberty – that stylized plant forms and conceived of them primarily as ornamental elements. Blossfeldt was not interested in criticism or rejection of the ornamental, but in a radical reconfiguration of it. This could only be achieved by thoroughly studying natural forms.

Three still-curled fronds of a specimen of bracken fern – scientific name Hypolepidaceae – on the one hand, appear denaturalised, because Karl Blossfeldt focused his lens on the detail, leaving out the natural context. But on the other hand, they reveal a scrupulous observation of the plant world. By nature, in fact, fronds develop according to a strict formal principle – no natural form is purely random – and yet they eventually differ from one another. The fronds of ferns could appear as decalcomanias, given that in Blossfeldt’s representation they take on an almost mechanical quality for the observer. The emphasis on differences in resemblance, which Blossfeldt achieved more or less consciously by repeating the leaf motif in differently shaped ferns, can be considered one of the main aesthetic innovations of his photography.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing the work of Marianne Wex with at left, Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures 1977-2018 (below); and at right, Arm and Leg Positions, Lying on the Ground 1977/2018

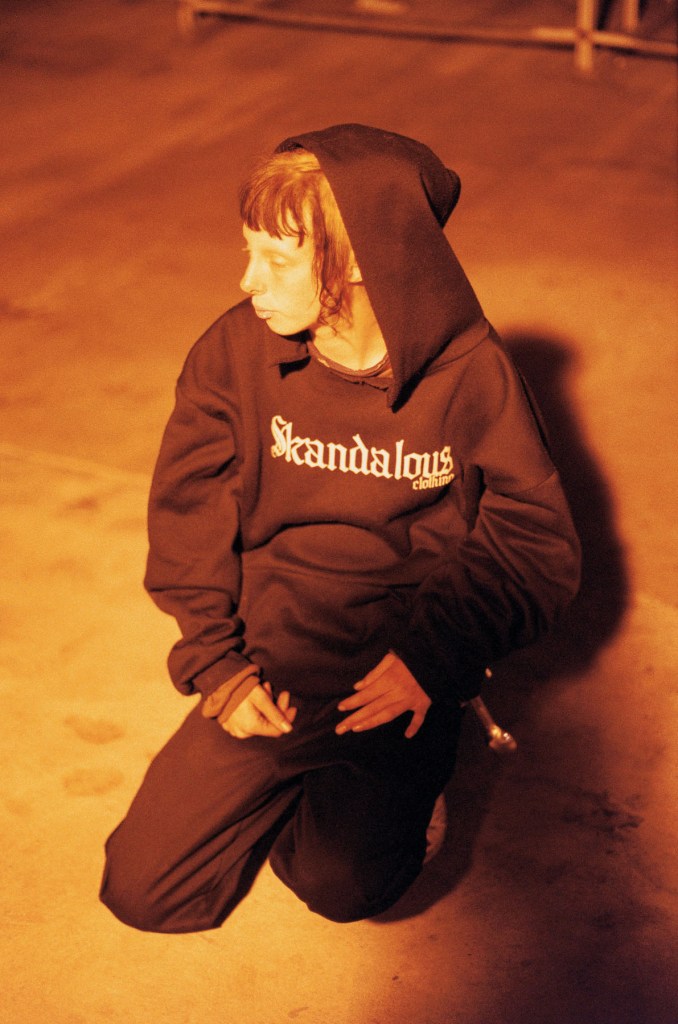

With the photographic project Let’s Take Back our Space, which resulted in a book published in 1979 with the subtitle “‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures,” Marianne Wex produced one of the seminal works in 1970s feminist art studies. Starting with a scrupulous observation of the body influenced by the method of structuralism, a scientific approach that studies a whole by breaking it down into elements and units, Wex took hundreds of photographs arranged in specific thematic sections devoted, for example, to specific leg and arm positions. Wex succeeded in showing how apparently natural body postures are actually the result of centuries of social and cultural structures, not a ‘natural’ or genetic predisposition. Her photographs capture movements, postures, and gestures, documenting habits of the body that have been taught and passed down for generations, shaping the behaviour of men and women according to patriarchal expectations.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Marianne Wex (German, 1937-2020)

Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures

1977-2018

Inkjet print

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing photographs from Wolfgang Tillmans’ series Concorde 1997

In 1997, Wolfgang Tillmans photographed the Concorde, a supersonic passenger plane, in flight during landing and take-off. For him, the plane represented one of the last remaining inventions of the 1960s technological utopia. With its futuristic shape, supersonic speed, and the formidable roar it made during take-off and landing, the plane fascinated generations of technology enthusiasts. Today, the Concorde is a thing of the past and, together with the Titanic, epitomises more of a technological shock than a promise in the history of technology. These photographs reveal one of the aspects that Tillmans wants to highlight: they are symbols of “a super-modern anachronism” that ultimately left nothing behind but air pollution and environmental destruction.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Concorde L449-21

1997

Inkjet print

Courtesy of Galerie Buchholz

Fondazione Prada presents Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany, an extensive study dedicated to 20-century German photography, at its Milan venue from 3 April to 14 July 2025. The exhibition, hosted within Podium, the central building of the Milan headquarters, is curated by Susanne Pfeffer, art historian and director of the MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST, Frankfurt.

The exhibition attempts to apply the principle of “typology,” which originated in 17th- and 18th-century botany to categorise and study plants, and appeared in photography in the early 1900s, affirming itself in Germany throughout the 20th century. Paradoxically, the given formal principle allows for unexpected convergences of German artists spanning different generations and the manifestation of their individual approaches.

The exhibition path follows a typological rather than a chronological order, bringing together more than 600 photographic works by 25 artists essential for recounting over a century of German photography. The exhibition features photographs by Bernd and Hilla Becher, Sibylle Bergemann, Karl Blossfeldt, Ursula Böhmer, Christian Borchert, Margit Emmrich, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Isa Genzken, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Lotte Jacobi, Jochen Lempert, Simone Nieweg, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, Heinrich Riebesehl, Thomas Ruff, August Sander, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, Thomas Struth, Wolfgang Tillmans, Rosemarie Trockel, Umbo (Otto Umbehr), and Marianne Wex. The project forms unexpected connections between artistic practices that differ from each other but are united by a common principle or intention of classification.

As stated by Susanne Pfeffer, “Only through juxtaposition and direct comparison is it possible to find out what is individual and what is universal, what is normative or real. Differences are evidence of the abundance of nature and the imagination of humans: the fern, the cow, the human being, the ear; the bus stop, the water tower, the stereo system, the museum. The typological comparison allows differences and similarities to emerge and the specifics to be grasped. Unknown or previously unperceived things about nature, the animal, or the object, about place and time become visible and recognizable.”

In photography, employing typologies means affirming an equivalence between images and the absence of hierarchies in terms of represented subjects, motifs, genres, and sources.

Despite this, typology remains a highly challenging and complex notion. It operates in a paradoxical regime: on the one hand, this approach can lead to a systematic recording of people and objects based on extreme objectivity; on the other hand, typology corresponds to an individual and arbitrary choice, revealing itself as a disturbing and potentially subversive act.

The hypothesis that photography plays a key role not only in fixing distinctive phenomena but also in organizing and classifying a plurality of visible manifestations remains a vital force in today’s artistic efforts to navigate the complexity of our social and cultural realities. With the spread of digital imagery and practices, the concept of typology continues to be questioned and re-defined by contemporary photographers and artists.

As underlined by Susanne Pfeffer, “The unique, the individual, seems to have been absorbed into a global mass, the universality of things is omnipresent. The Internet allows typologies to be created in a matter of seconds. In this very precise moment – it seems even more important to follow the artists’ gaze and look closely.” As further explained by Pfeffer, “When the present seems to have abandoned the future, we need to look closer at the past. When everything seems to be shouting at you and becoming increasingly brutal, it is important to take a quiet pause and use the silence to see and think clearly. When differences are no longer perceived seen as something other but are transformed into elements of division, we have to recognize what we have in common. Typologies allow us to identify undeniable similarities and subtle differences.”

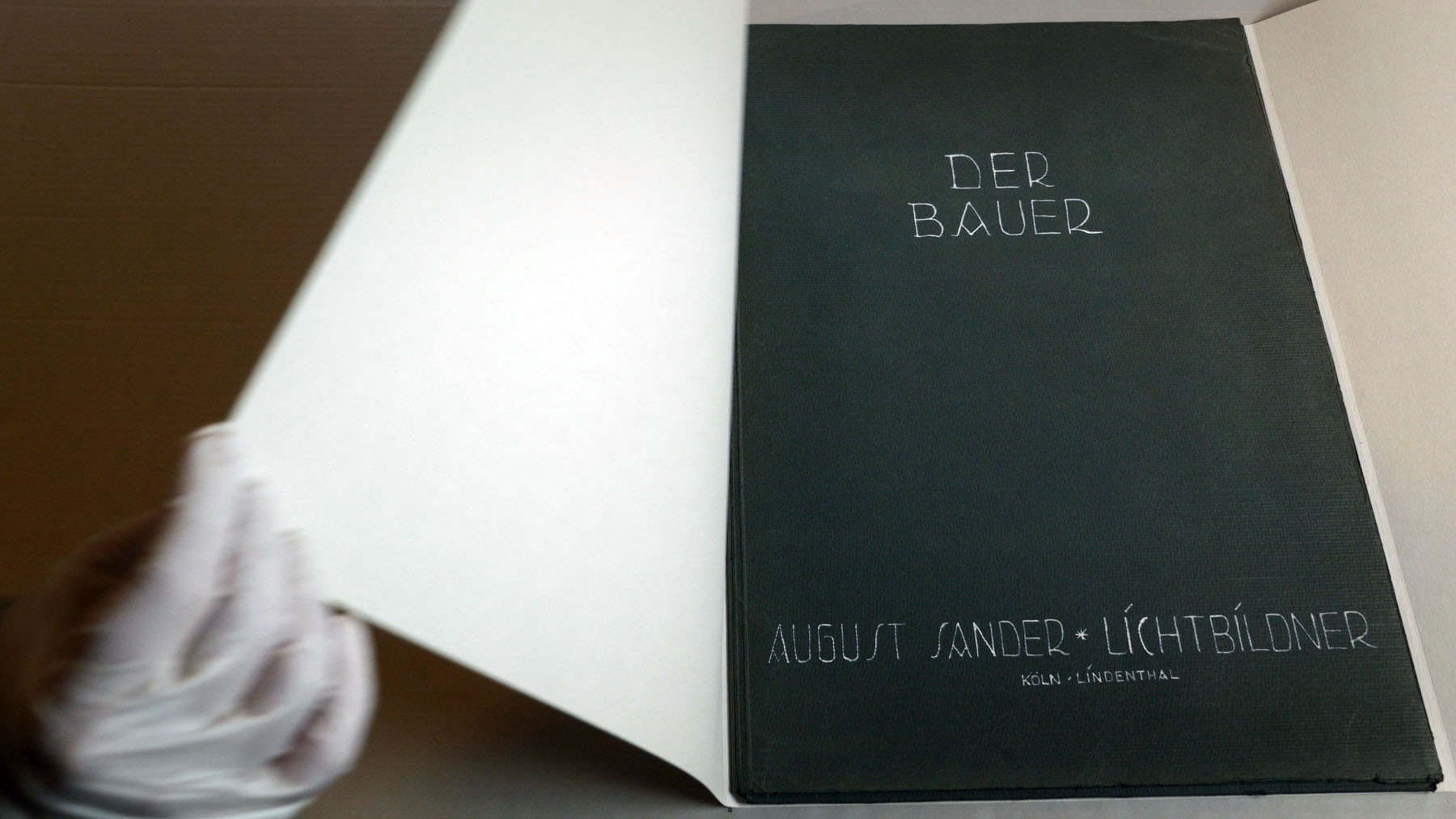

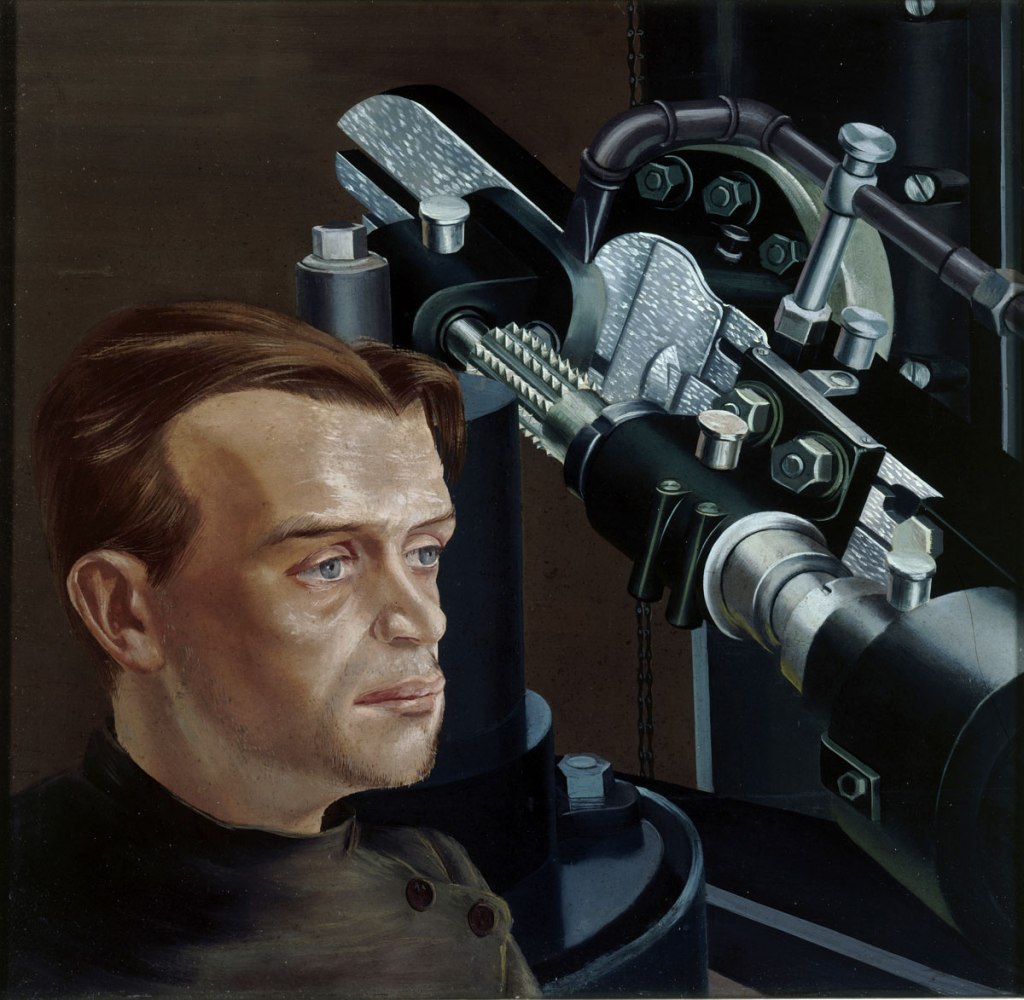

In the early 20th century, Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932) was one of the first artists to transfer the classification system used in botanical studies to photography. His vast and detailed plant atlas represented a foundational moment for German Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). This artistic and photographic movement emerged in the 1920s during the Weimar Republic and promoted the importance of categories and distinctions and the remarkable ability of photography as a medium to explore the very idea of typology.

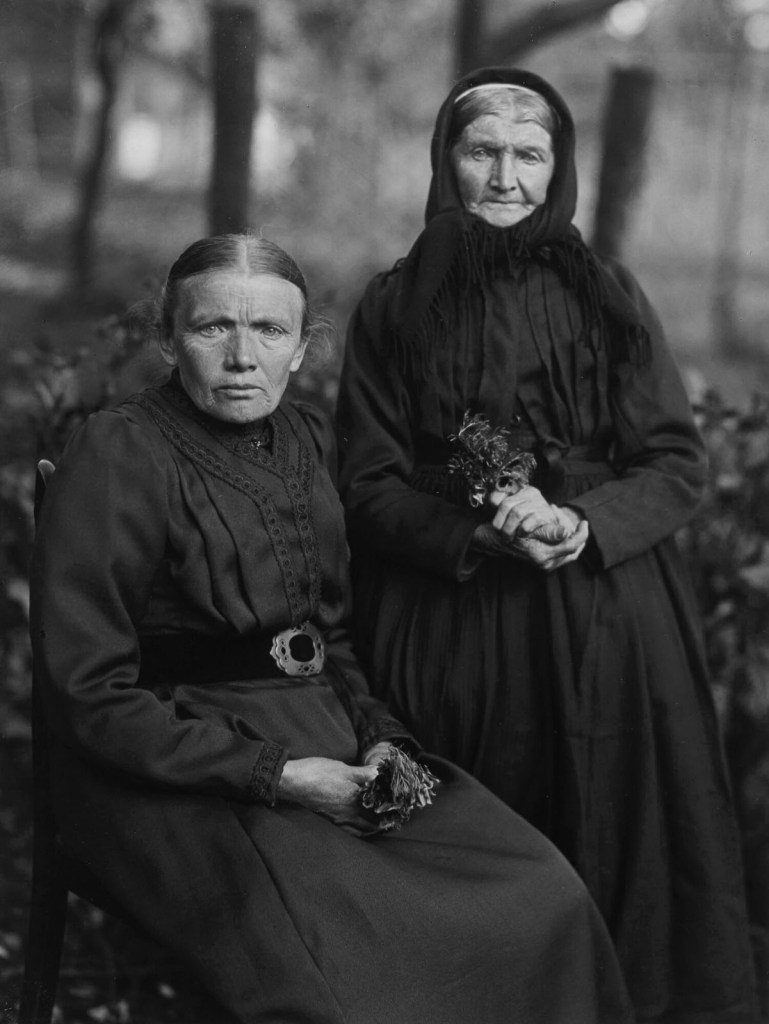

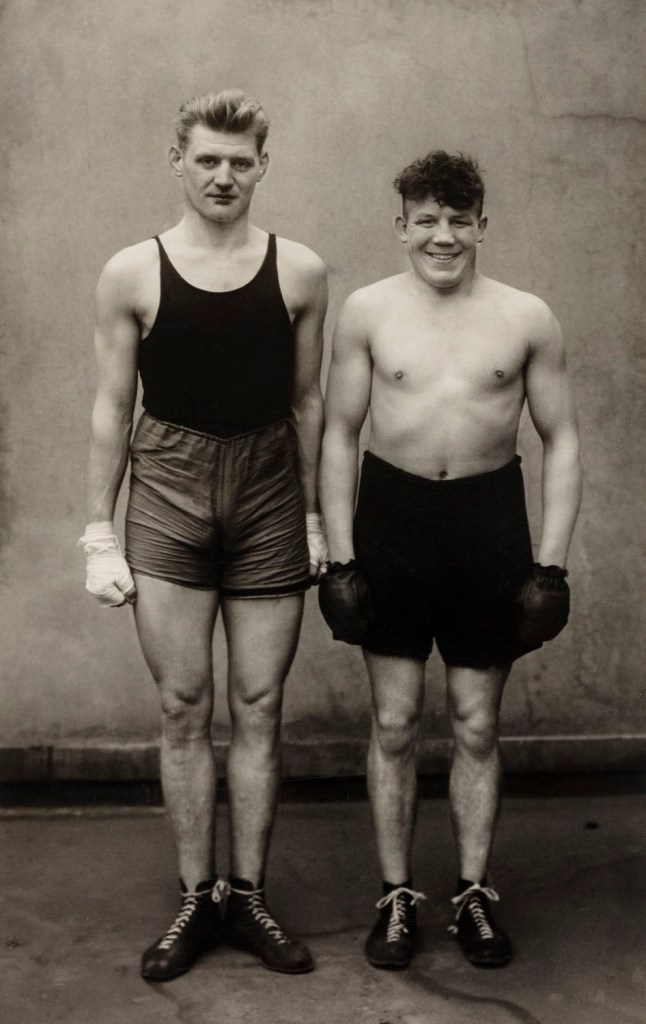

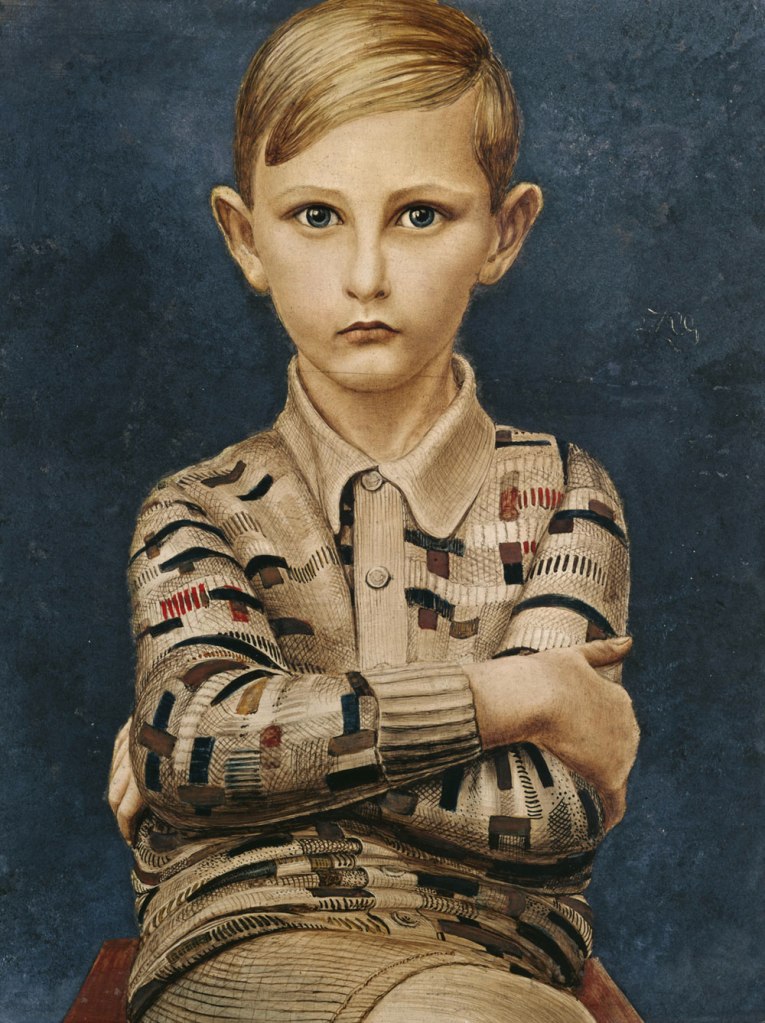

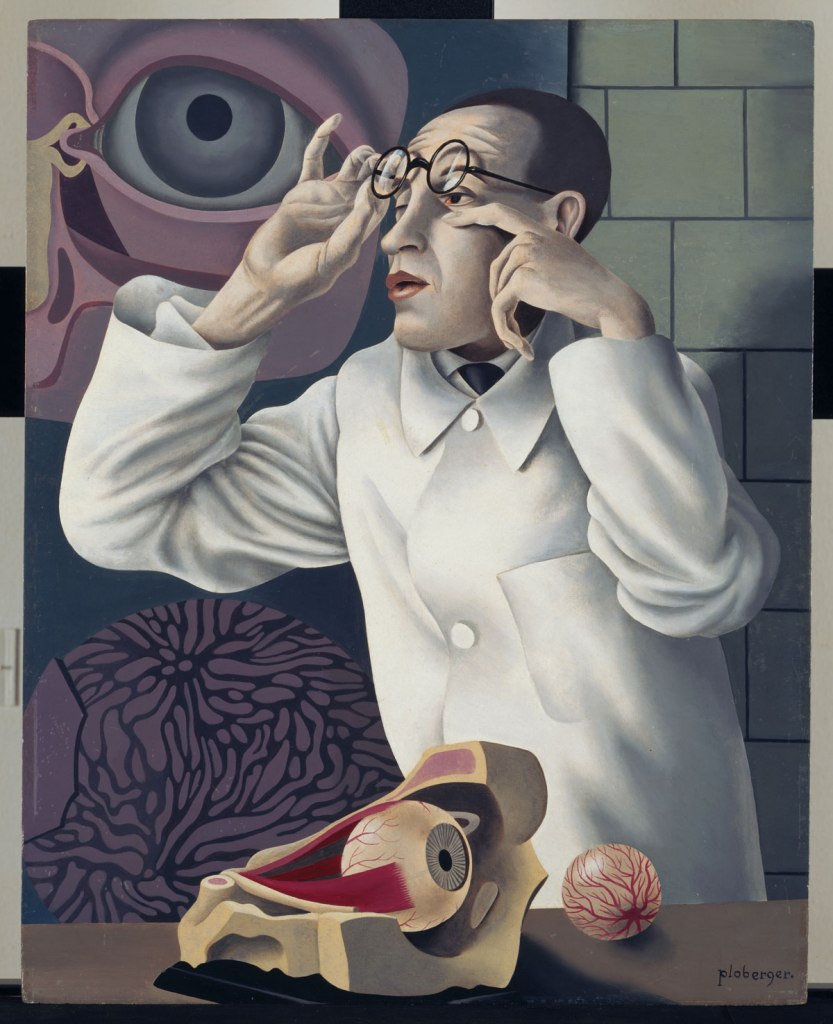

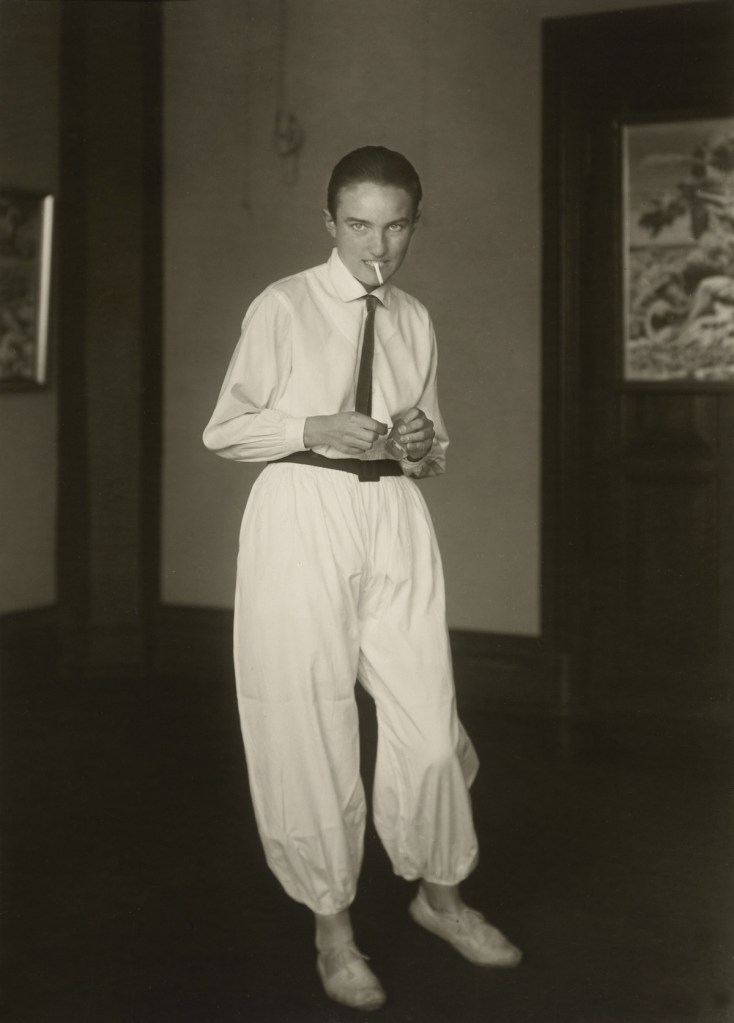

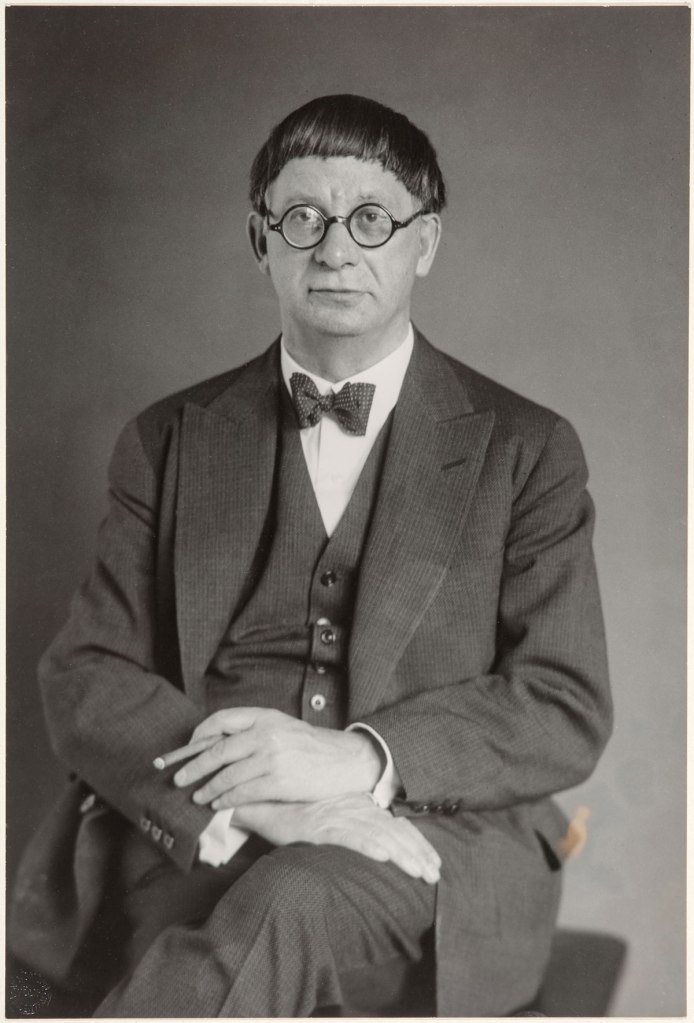

Another pioneering figure was August Sander (1876-1964), who published his photo book Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time) in 1929, at the time excerpted from his landmark project Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th Century). Described by Walter Benjamin as a “training atlas” of physiognomic perception, Antlitz der Zeit was an ambitious attempt to portray the diversity and the structure of German society using class, gender, age, occupation, and social background as distinct categories of a rigid and neutral classification system.

Both Karl Blossfeldt’s and August Sander’s typologies were fundamental for Bernd Becher (1931-2007) and Hilla Becher (1934-2015) when, at the end of the fifties, they began an enormous and lifelong documentation and preservation project of industrial architecture. In 1971, they described the “industrial constructions” as “objects, not motifs”. They stated that “the information we want to provide is only created through the sequence, through the juxtaposition of similar or different objects with the same function”. Their black-and-white monuments, or “anonymous sculptures”, isolated against a monochromatic sky, centered, framed in the same format and arranged in a block, became an essential reference for American and European Post-Minimalist and Conceptual artists. They also represented a rich heritage for younger generations of German artists and photographers, such as Andreas Gursky (b. 1955), Candida Höfer (b. 1944), Simone Nieweg (b. 1962), Thomas Ruff (b. 1958) and Thomas Struth (b. 1954), who studied at the Academy in Düsseldorf in the class led by Bernd and Hilla Becher from 1976.

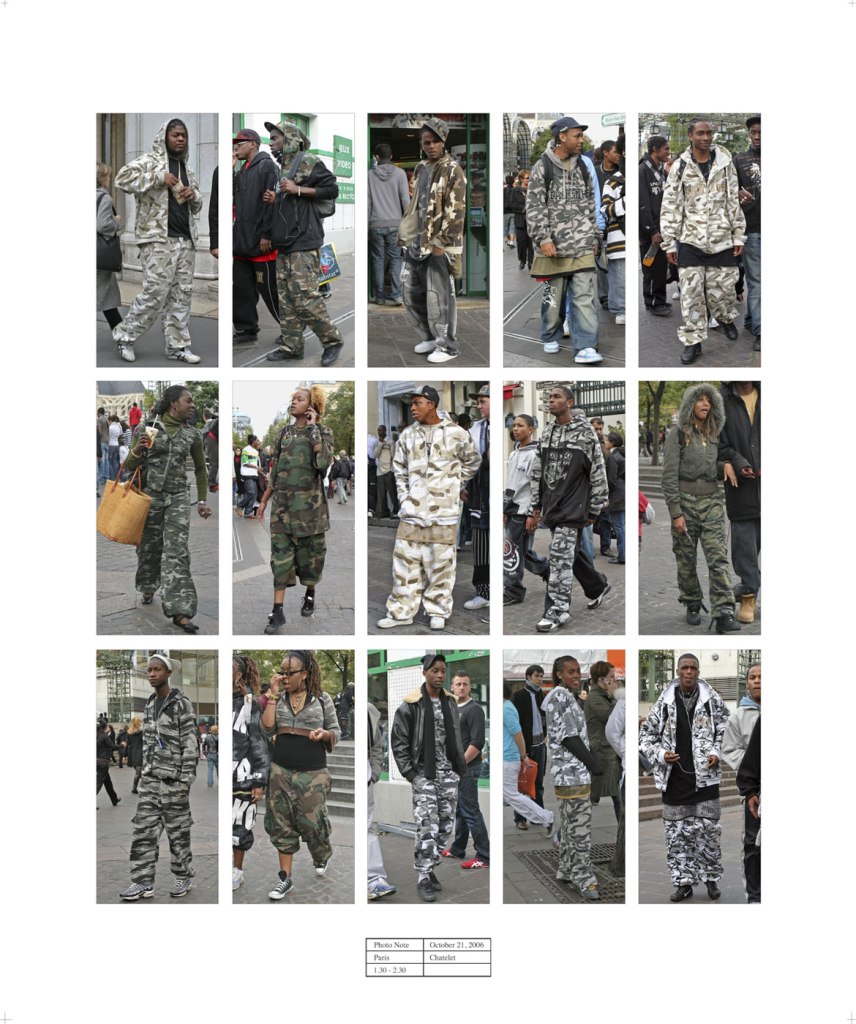

Hans-Peter Feldmann (1941-2023), internationally recognised for his fundamental contribution to conceptual art, traced a complementary trajectory in German photography. In his works, he documented everyday objects and historical events and combined deadpan humor with a systematic approach to accumulating, cataloguing, and rearranging elements of contemporary visual culture. In his series, he invented personal yet very political typologies and adopted a deliberate snapshot approach with a commercial aesthetic. For his work Alle Kleider einer Frau (All the Clothes of a Woman, 1975), he took 35mm-format photographs of underwear, hosiery, T-shirts, dresses, trousers, skirts, socks, and shoes, all hanging on hangers on the wall or laid on dark fabric. With his project Die Toten 1967-1993 (The Dead 1967-1993, 1996-1998), he paid homage to individuals murdered in the context of the political and terroristic movements in Post-War Germany. As pointed out by Susanne Pfeffer, “With his typologies, he emphasised the equal value of all photographs, their image sources and motifs, and underscored the de-hierarchisation inherent in every typology.”

In his apparently random collection of found, personal or pornographic images, press clippings, and historical photos of Nazi concentration camps, the Red Army Faction and German reunification, a “private album” named Atlas (1962 – present), Gerhard Richter (b. 1932) seemed to deny or challenge the very idea of typology. Instead, he took the principle of equivalence between images and their trivialization process to the limits, creating a jarring contrast and an acute awareness of a repressed collective memory.

In the seventies and eighties, in a dialectic relationship with the artistic lessons of the Bechers, Gursky, Höfer, Ruff, and Struth progressively abandoned the radicalism and black- and-white purism of their professors. They explored the colorful dominance of banality in their series of individual or family portraits, monumental and detailed city views, and spectacular documentation of cultural or tourist sites, generating a plethora of contemporary and conflicting typologies.

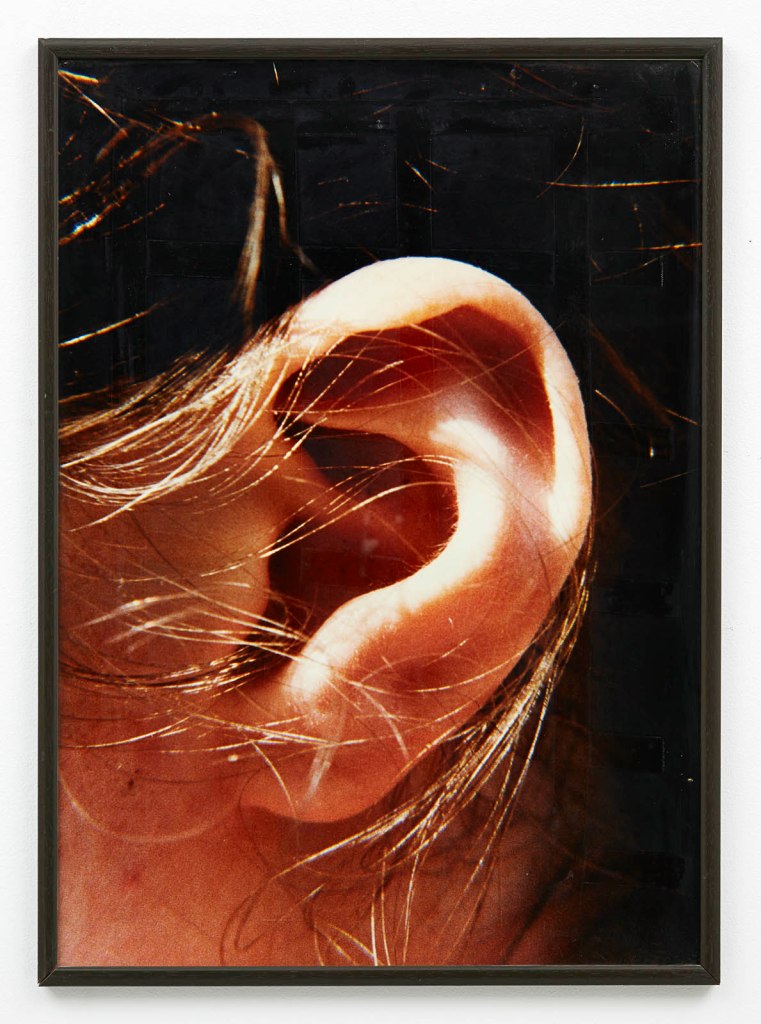

In the late seventies and early eighties, multimedia artist Isa Genzken (b. 1948) engaged in a direct dialogue with the photographic medium. In 1979, she created a series entitled Hi-Fi that featured advertisements of avant-garde Japanese stereo equipment, organising them in an imaginary commercial catalog. The second series entitled Ohr (Ear) (1980) depicted, in large-scale colour close-ups, the ears of random women Genzken photographed on the streets of New York City. She transferred the traditional portrait genre to physiognomic detail and ironically investigating the absolute singularity and infinite individual differentiation the photographic portrait can record.

An illustrated book, published by Fondazione Prada and designed by Zak Group, accompanies the exhibition “Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany”. It includes an introduction by Miuccia Prada, President and Director of Fondazione Prada, a text by the exhibition curator Susanne Pfeffer and three essays by renowned international art historians and curators Benjamin Buchloh, Tom Holert, and Renée Mussai.

Press release from Fondazione Prada

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing the work of August Sander

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Sekretärin beim Westdeutschen Rundfunk in Köln' [Secretary at West German Radio in Cologne] 1931-1950s August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Sekretärin beim Westdeutschen Rundfunk in Köln' [Secretary at West German Radio in Cologne] 1931-1950s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/6-typologien_august-sander_siae_sm.jpg?w=779)

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Sekretärin beim Westdeutschen Rundfunk in Köln [Secretary at West German Radio in Cologne]

1931-1950s

Gelatin silver print

Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archive, Cologne; SIAE, Roma, 2025

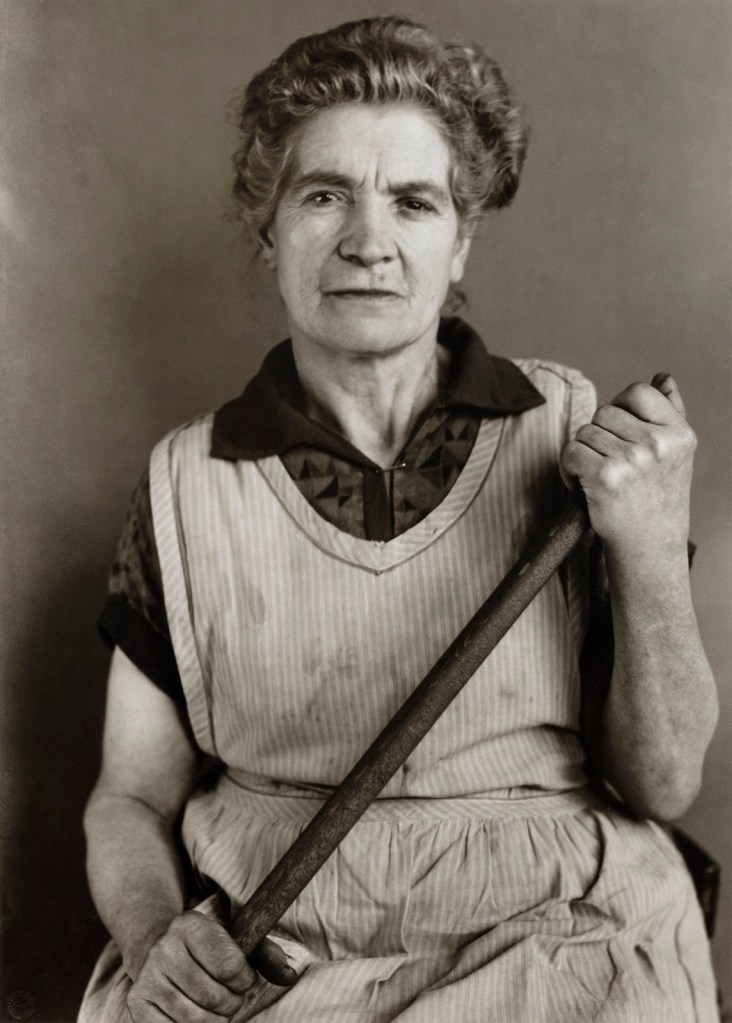

The series that August Sander dedicated to women is perhaps where the idea of categorising an archetype or social type shows the cracks most visibly. Whether it is an architect’s companion, an industrialist’s wife, or a high society lady, in Sander’s images the individuality of the female subject, in dress and posture, always prevails over type. And even when the subjects display characteristics that could be traced back to their class, origin, or occupation – such as the secretary who smokes – all the women depicted, from the sculptor to the photographer or the gym teacher, express ‘their own’ individuality. This is most evident when comparing the portraits of women with those of civil servants, whose gazes already show a serial uniformity associated with their positions.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

![Erich Sander for August Sander's studio. 'Politischer Häftling' [Political Prisoner] 1941-1944 (print date late 1940s) Erich Sander for August Sander's studio. 'Politischer Häftling' [Political Prisoner] 1941-1944 (print date late 1940s)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/7-typologien_august-sander_siae_sm.jpg?w=829)

Erich Sander for August Sander’s studio

Politischer Häftling [Political Prisoner]

1941-1944 (print date late 1940s)

Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts, 44a Politische Gefangene. [44a Political prisoners]

Gelatin silver print

Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne – August Sander Archive, Cologne; SIAE, Roma, 2025

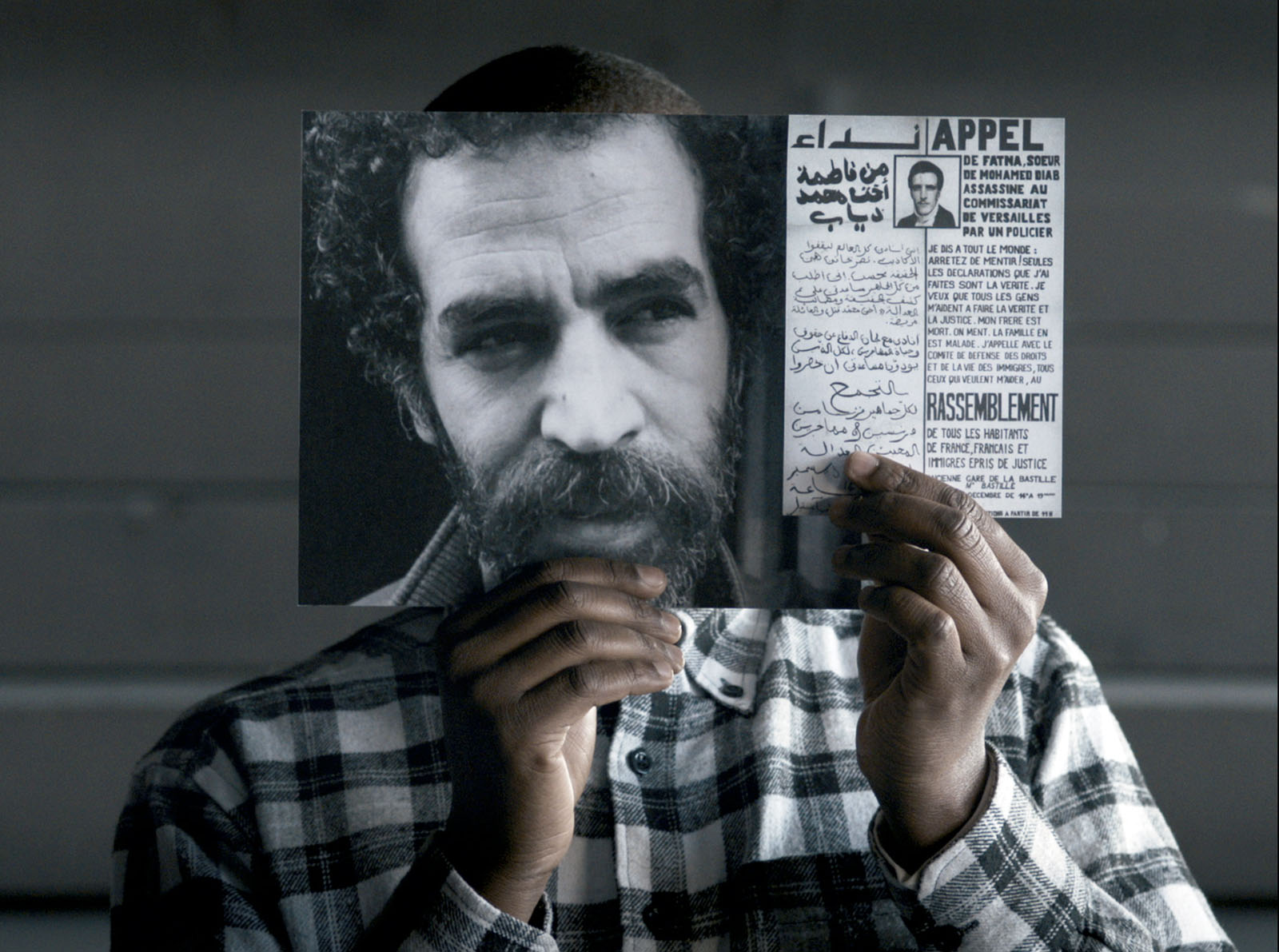

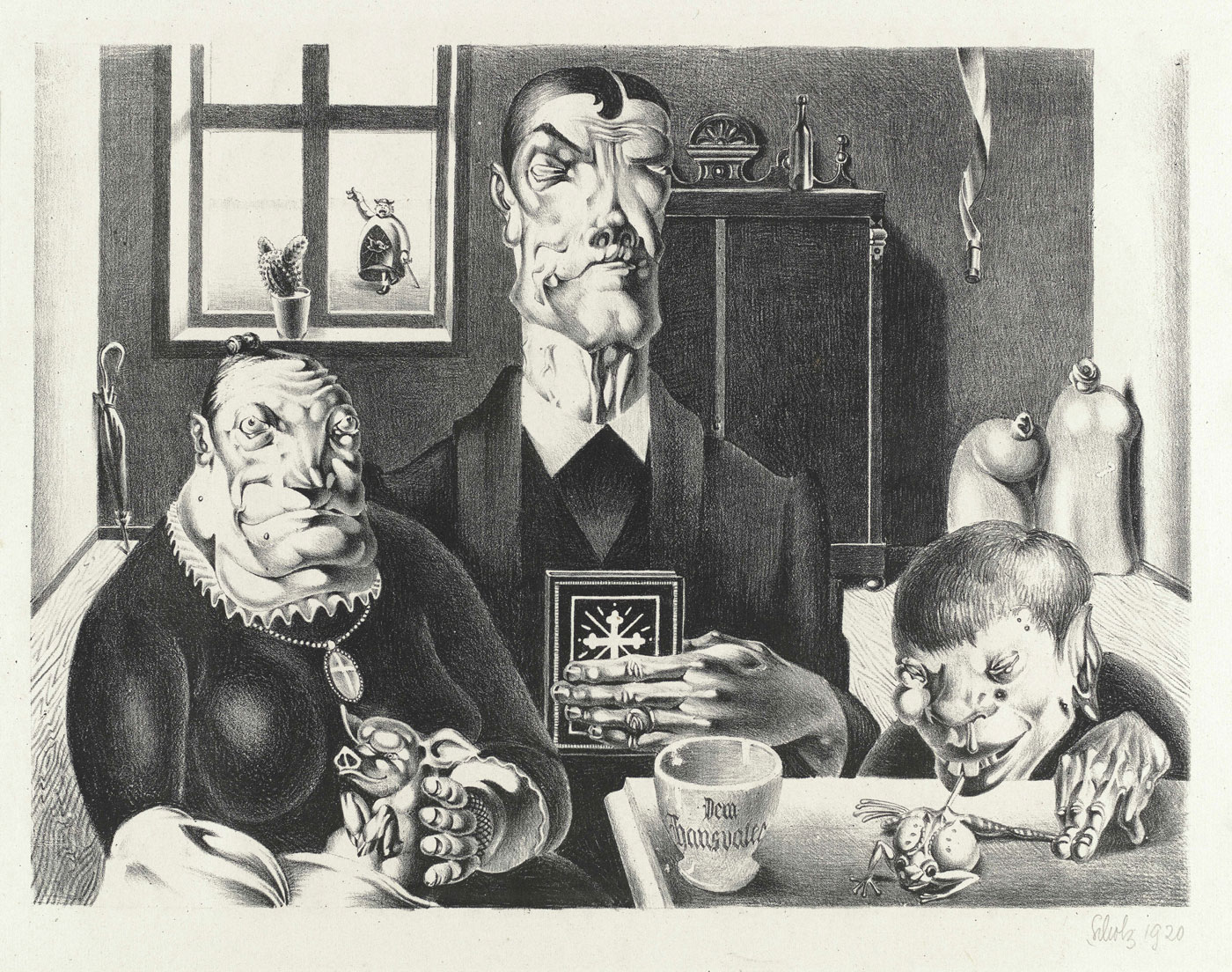

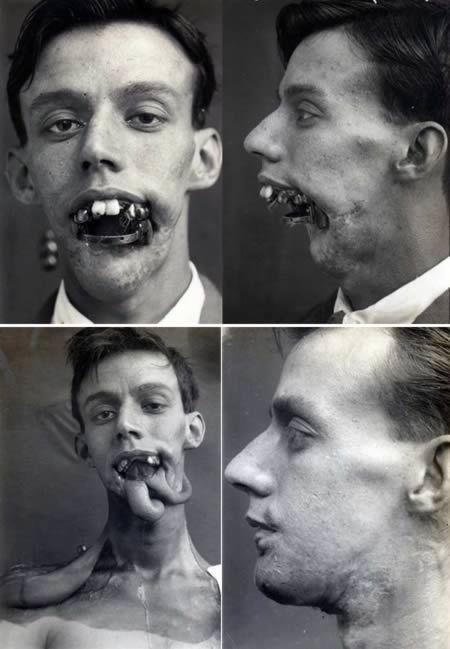

In 1935, Erich Sander, August Sander’s son, was sensationally put on trial and sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment for subversive activities. He served most of his sentence in Siegburg Prison, where he worked as the prison’s photographer. Determined to continue his resistance activities even in prison, he did not limit himself to taking ‘official’ photographs. He convinced his fellow prisoners to show him the scars of torture and have their portraits taken. Those photographs seemed to him to be in line with his father’s work. He had learned his trade from his father and worked with him before his imprisonment. He stayed in close contact with his parents during his ten years of imprisonment, and through them, managed to get many of those images out of the prison, leaving a valuable record of Nazi atrocities. Due to a misdiagnosis and lack of medical treatment during his imprisonment, Erich Sander died in 1944, six months before the end of his sentence.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing photographs by Thomas Struth with at left, The Richter Family 1, Cologne 2002; and at right, The Consolandi Family, Milan 1996

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

The Richter Family 1, Cologne (installation view)

2002

C-print

Courtesy of the artist

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

The Richter Family 1, Cologne

2002

C-print

Courtesy of the artist

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

The Consolandi Family, Milan (installation view)

1996

C-print

Courtesy of the artist

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing Thomas Ruff portraits

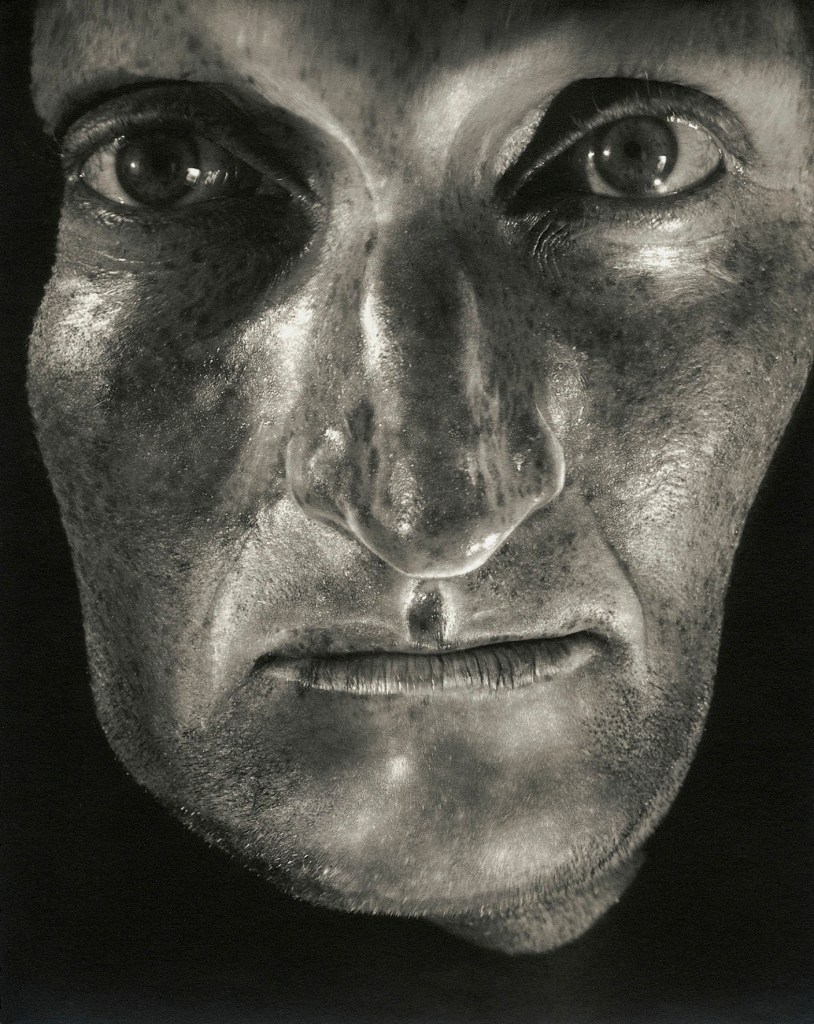

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Porträt (Pia Stadtbäumer)

1988

C-print laminated on acrylic glass

MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST, Frankfurt

© Thomas Ruff, by SIAE 2025 Photo by Axel Schneider, Frankfurt am Main

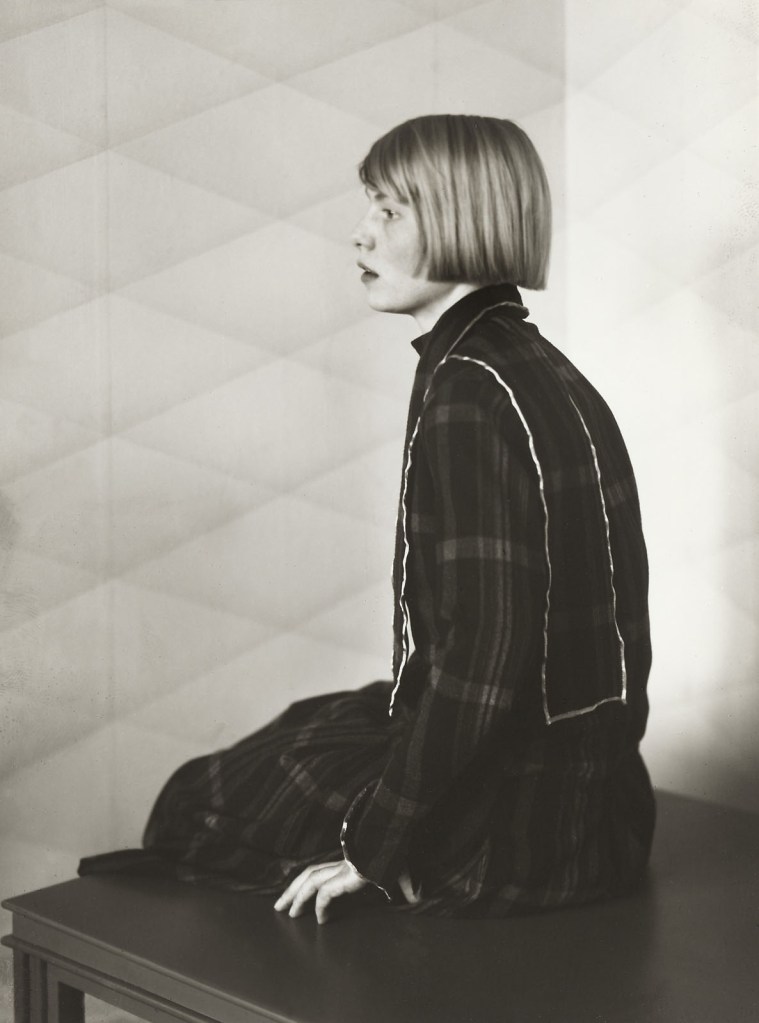

Between 1977 and 1985, Thomas Ruff studied with Bernd Becher at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf, where he himself has been teaching photography since 2000. During the 1980s, he photographed people from his circle of acquaintances in a series of identically framed shots. With the subjects portrayed in a half-length pose against a neutral background, the images are striking for their unusually large size. Every detail, every pore, and every imperfection in the skin is visible in the faces of the subjects, whose names Ruff also provides. The strictness of the composition, the uniform lighting, and the impassive gaze of the people portrayed give the images an objective and neutral atmosphere. What formally appears detached and unemotional immediately raises questions about the subject portrayed: who is this person? What does he or she do in life? With this series, Ruff challenges the conventions of the traditional portrait, encouraging the viewer to question not only the identity of the subject, but also the role of the photographer and the meaning of the portrait itself.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Porträt (Simone Buch)

1988

C-print laminated on acrylic glass

MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST, Frankfurt

© Thomas Ruff, by SIAE 2025 Photo by Axel Schneider, Frankfurt am Main

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing at left, Jochen Lempert’s The Skins of Alca Impennis 1992-2022; and at right, Thomas Ruff’s Portrait of Pia Stadtbäumer and Portrait of Simone Buch both 1988

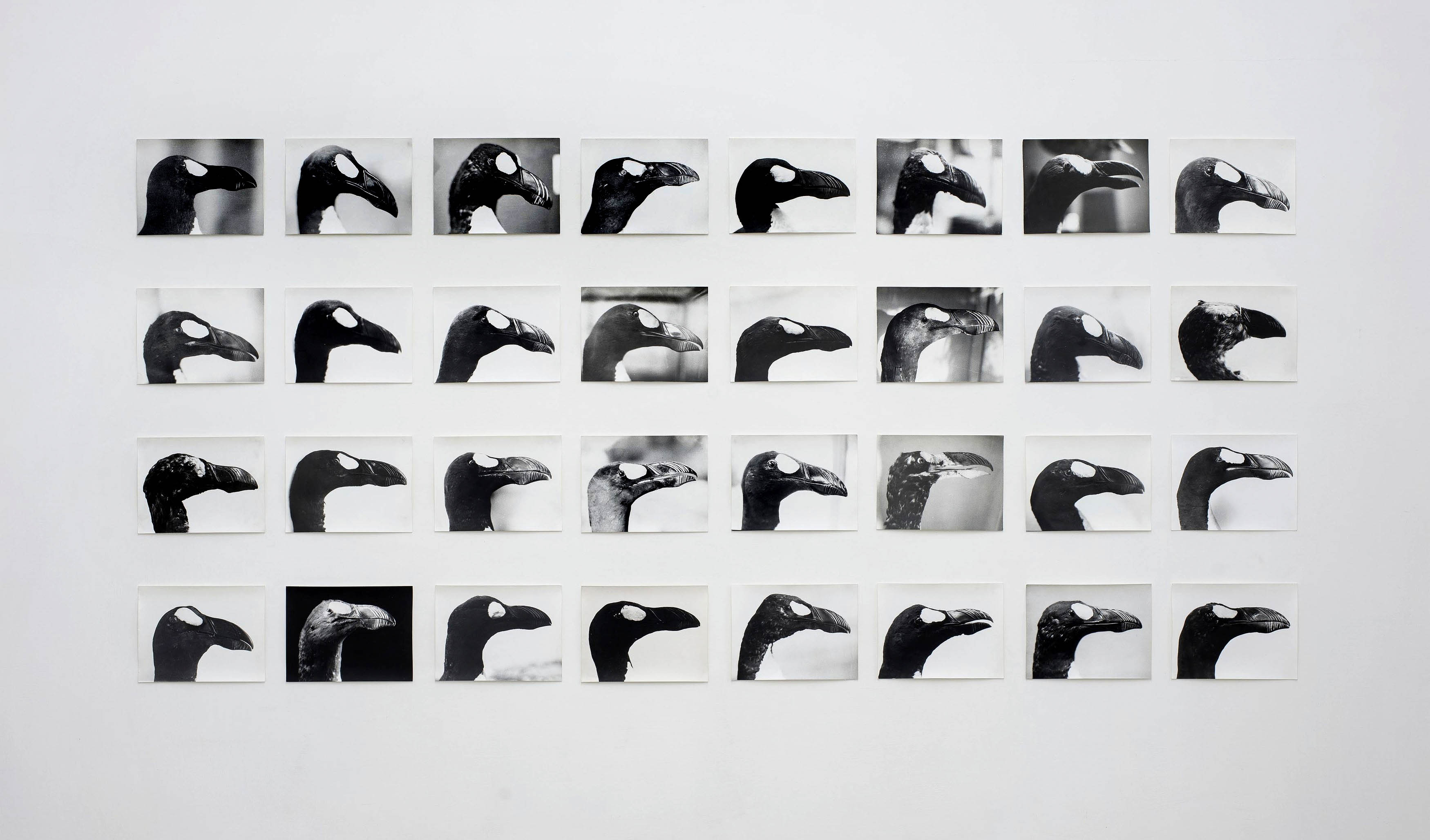

Jochen Lempert (German, b. 1958)

The Skins of Alca Impennis (detail)

1992-2022

Gelatin silver prints on Bartya paper

54 parts

Courtesy of Jochen Lempert, BQ, Berlin, and ProjecteSD, Barcelona

The fifty-four profiles of the Alca impennis (the great auk), a large flightless bird that became extinct after its last sighting in 1852, are part of a project that took Jochen Lempert more than a decade to complete. Using the same methods, Lempert photographed the profiles of many of the seventy-eight specimens of the Alca impennis preserved in natural history collections. Having become increasingly rare due to hunting, the Alca impennis was increasingly coveted by collectors, so the skins of this species fetched very high prices. The presence of such a large number of stuffed specimens in collections was therefore one of the causes of this species’ extinction.

Lempert’s portraits also hint at a more significant phenomenon. Very marked individual variations can be found in the appearance of individual specimens of a species, testifying to the great degree of differentiation within the species. Therefore, the concept of species, or its depiction in a scientific classification book, provides something akin to an ‘ideal type,’ rather than a true representation of the actual variety found in real life.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

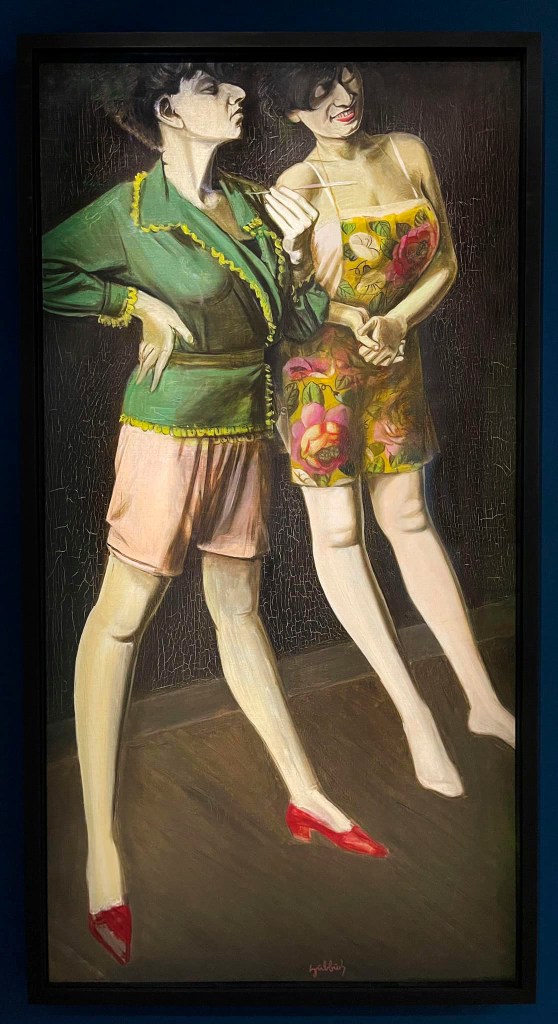

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing the work of Rosemarie Trockel, Elena I & II, 1993/2025, Maculata I & II, 1993/2025, Mela I & II, 1993/2025

The portraits of the dogs Mela, Elena, and Maculata grew out of Rosemarie Trockel’s interest in animals and the relationship between animals and humans, a subject she has been working with for a long time. From the drawings of monkeys, which represent a kind of monument to the profound melancholy of primates kept in captivity by humans, to A House for Pigs and People / Ein Haus føur Schweine und Menschen created with Carsten Höller for documenta X in 1997, Trockel’s exploration of the relationship between humans and animals involves various forms of expression and themes. However, in this case, the double portraits of the three dogs, photographed frontally and in profile, indicate a further correlation. If “every animal is an artist,” as Trockel has stated, these portraits seem to call these roles into question: who directs and who stages who? Does the artist portray the dogs or do the dogs direct the artist?

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Installation view of the exhibition Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany at Fondazione Prada, Milan showing at left, the work of Ursula Böhmer and her series All Ladies – Cows in Europe, 1998-2011; and at right, the work of Isa Genzken and her series Ohr, 1980

![Ursula Böhmer (German, b. 1965) 'Highland Grampians / Scotland [All Ladies – Cows in Europe]' 2011 Ursula Böhmer (German, b. 1965) 'Highland Grampians / Scotland [All Ladies – Cows in Europe]' 2011](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/21-typologien_ursula-bohmer_sm.jpg?w=840)

Ursula Böhmer (German, b. 1965)

Highland Grampians / Scotland

2011

From the series All Ladies – Cows in Europe, 1998-2011

Gelatin silver print on Baryta paper

© Ursula Böhmer

Getting a cow to stand still in a frontal pose and look towards the camera, as Ursula Böhmer managed to do with a Highlander in the Grampian Mountains, is certainly not an easy task, but one that requires patience and trust, one of the prerequisites for this project. Between 1998 and 2011, Böhmer visited 25 European countries to photograph specimens of cattle breeds in the places where their breeding history began. These breeds, many of them at risk of extinction, had to be portrayed in their own environments in order to illustrate how these environments had influenced their appearance. What emerged was a series of images of docile animals portrayed in often harsh landscapes, which at the same time document the ongoing conditioning by the environment on the forms of life also in breeding conditions.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Isa Genzken (German, b. 1948)

Ohr

1980

Colour C-print in artist’s frame

Galerie Buchholz Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz

© Isa Genzken, by SIAE 2025

In 1980, Isa Genzken took a series of close-ups of the ears of women she encountered on the streets of New York. The typical portraiture approach used in the photographs exalts and enhances the characteristics of the represented subject, on the one hand, but at the same time, with the anonymity of the immortalized figure, creates a contrast. In the course of the evolution of the human species, the ear has lost its value in terms of expressive power. While in many animal species ears still play an important role in expressing emotions, in the human being they are stiffly positioned at the sides of the head and no longer react to emotional states along with the facial muscles. Georg Simmel, a sociologist of the senses, sees the ear as merely a passive appendage in the human appearance. For Simmel, the ear is the selfish organ par excellence, which simply takes without giving. Genzken contradicts this verdict, because the ears she photographs, with all the ornaments attached, eloquently express individual differences.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

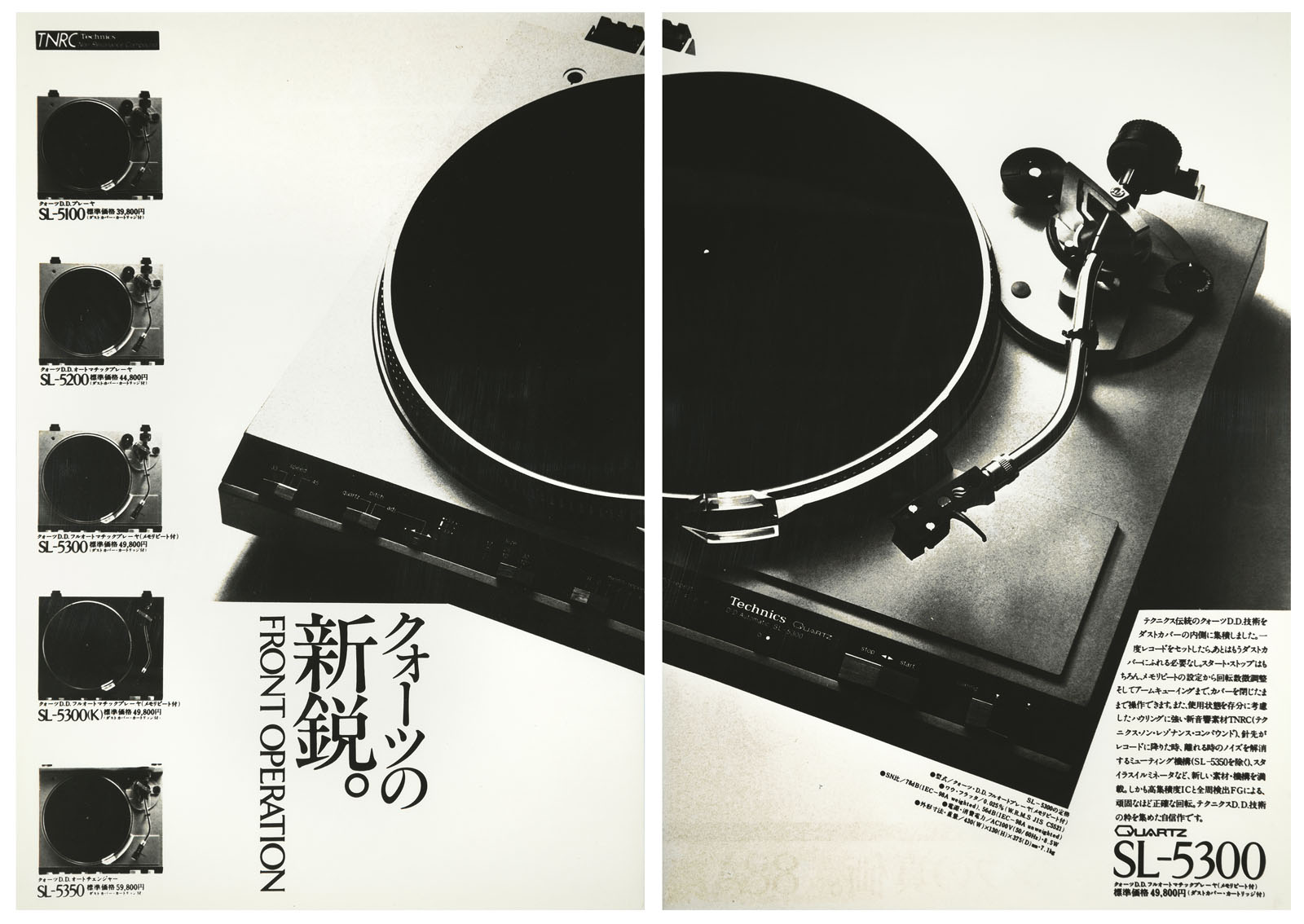

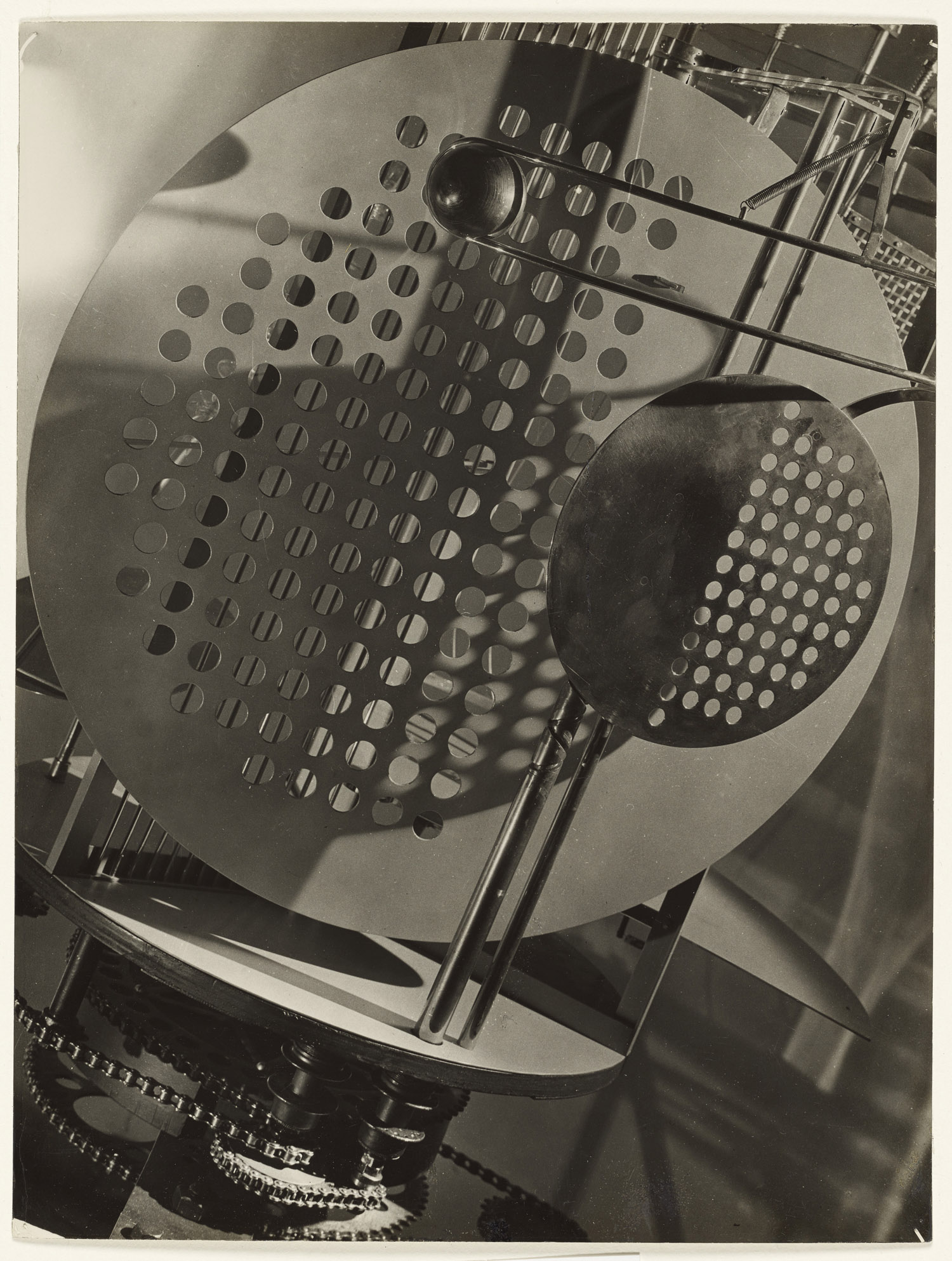

Isa Genzken (German, b. 1948)

Front Operation

1979

B/w photograph

Generali Foundation Collection – Permanent Loan to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Generali Foundation / Isa Genzken, by SIAE 2025

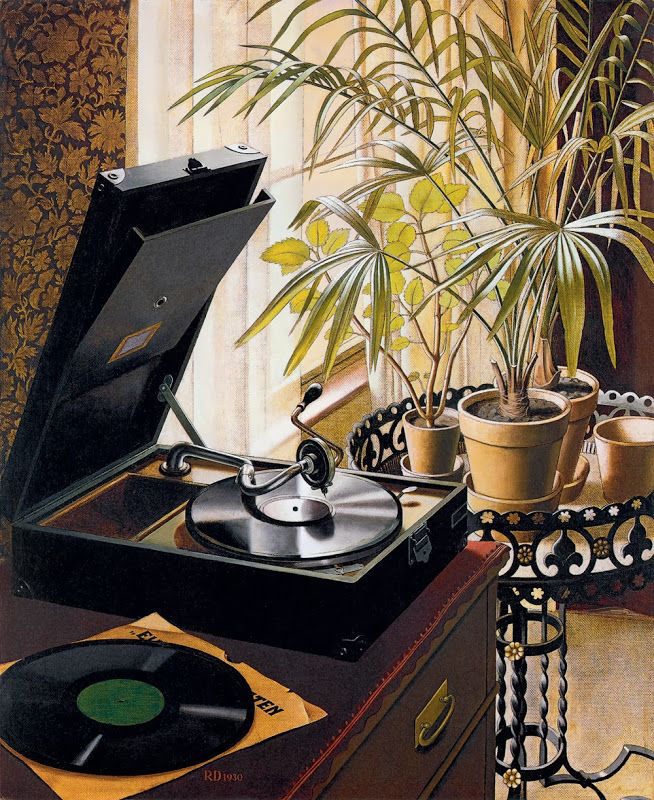

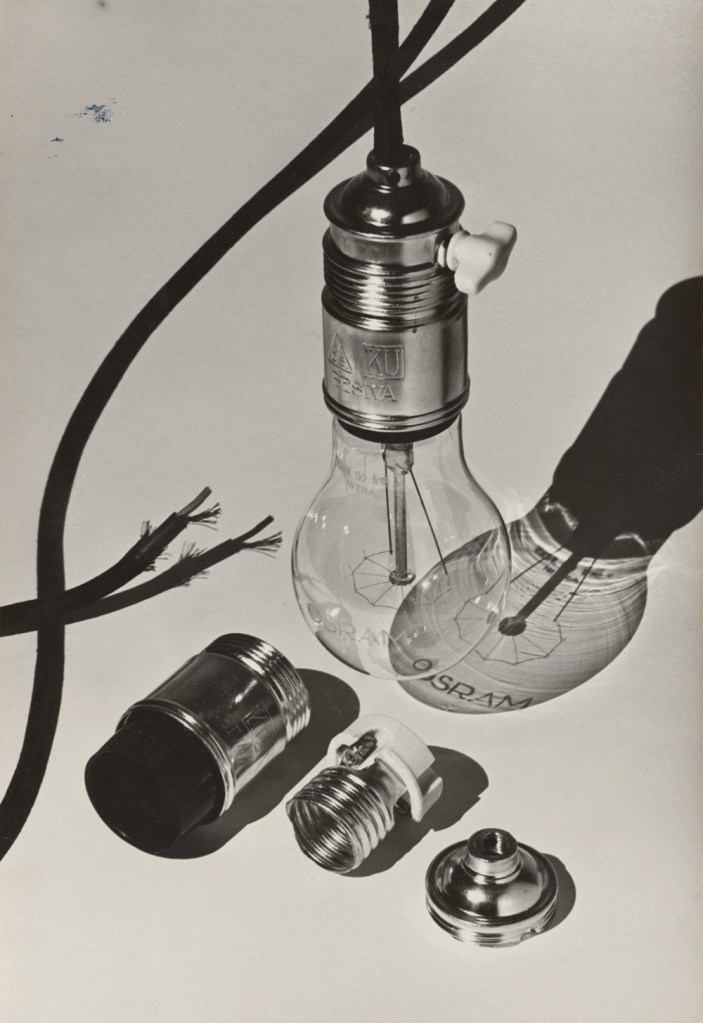

In her first institutional exhibition, presented at the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld in 1979, alongside sculptures and drawings, Isa Genzken exhibited a photography series dedicated to the latest and most expensive Hi-Fi systems. She created it by cutting out ads for turntables and amplifiers from international magazines and then photographing them. As she told photographer Wolfgang Tillmans in an interview, those advertisements showcased some of the most advanced technology of the time, highlighting cutting-edge design. Genzken also stated that a sculpture should be at least as modern as those devices. Her photography series dedicated to Hi-Fi systems can therefore be interpreted as a conceptual and aesthetic investigation of whether or not her sculptures and works could be compared to the everyday beauty of a stereo system.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

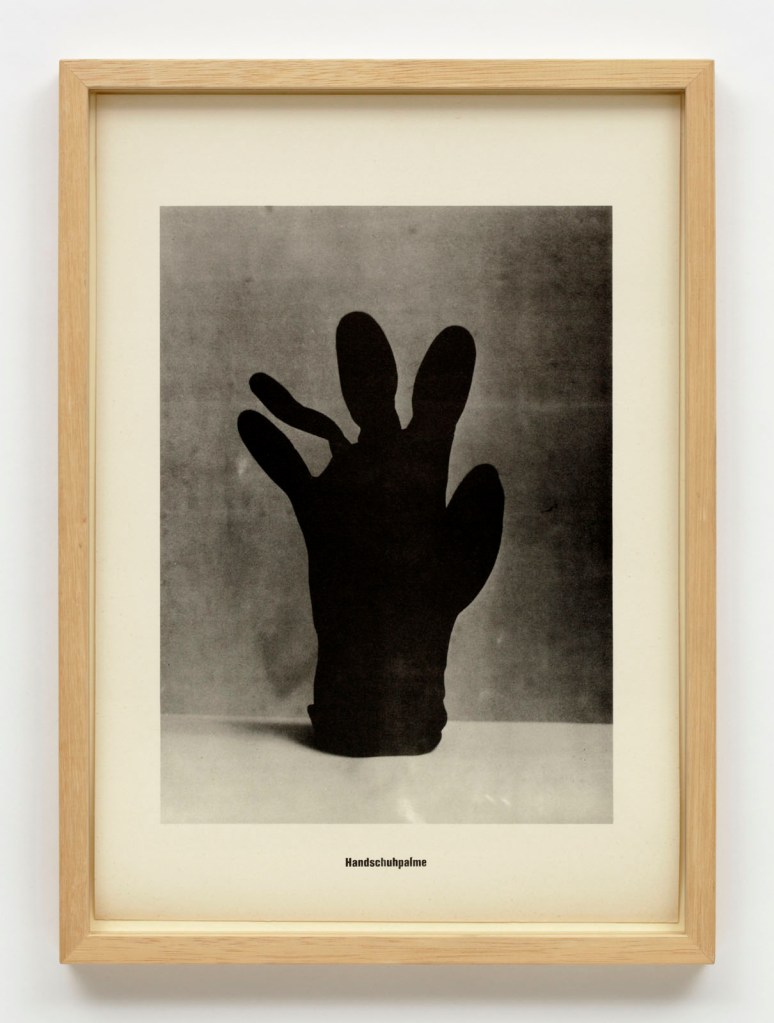

Sigmar Polke (German, 1941-2010)

Handschuhpalme (Glove palm tree)

1966

From the series … Höhere Wesen Befehlen, 1968 (… Higher beings Command, 1968)

13 stampe offset su carta artistica / 13 offset prints on art paper

MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST, Frankfurt am Main

Lotte Jacobi (American born Poland, 1896-1990)

Folkwang-Auriga-Verlag, Orch 152. Neottia nidus avis. Vogel-Nestwurz, einzelne Blüte [Bird’s-nest orchid, single flower]

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Berlinische Galerie – Museum of Modern Art, Photography and Architecture

© Lotte Jacobi

Lotte Jacobi, known for her portraits of intellectuals including Martin Buber and W.E.B du Bois, artists such as Marc Chagall, and poets including Robert Frost and Vladimir Mayakovsky, created a series of plant portraits in 1930. Apart from the individual flowers of the Orchis latifolia, the broad-leaved helleborine or orchid, and Neottia nidus avis, the bird’s nest, she photographed an orchid in its entirety. The names of the plants, which Jacobi, like Karl Blossfeldt, makes explicit in the titles of the photographs, are an integral part of the unique poetics of the subjects. With her plant portraits, Jacobi followed in the tradition of the 1920s workers’ movement’s vision of nature. In fact, Jacobi was a member of the Vereinigung der Arbeiterfotografen Deutschlands (Union of German Labor Photographers), an organisation of photographers who documented the social life and struggles of the German working class.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

People on the Street, Düsseldorf 1974-78

1974-1978

Gelatin silver print

Atelier Thomas Struth, Berlin

© Thomas Struth

In his photography, Thomas Struth has always been interested in the streets, squares, and houses of cities that consciously or unconsciously shape our experience, as well as that of the passers-by who walk through them. The study People on the Street, Düsseldorf 1974-78 explores the movements and figures of individuals passing in front of the camera lens. The subjects are never shot at close range. While some facial features are blurred in movement, others are clearly visible. Even if they are differentiated by their jackets, coats, or bags, all the subjects have a directional gait in common. No one is simply ‘here’: they all have an intention, which each person pursues in their own way.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

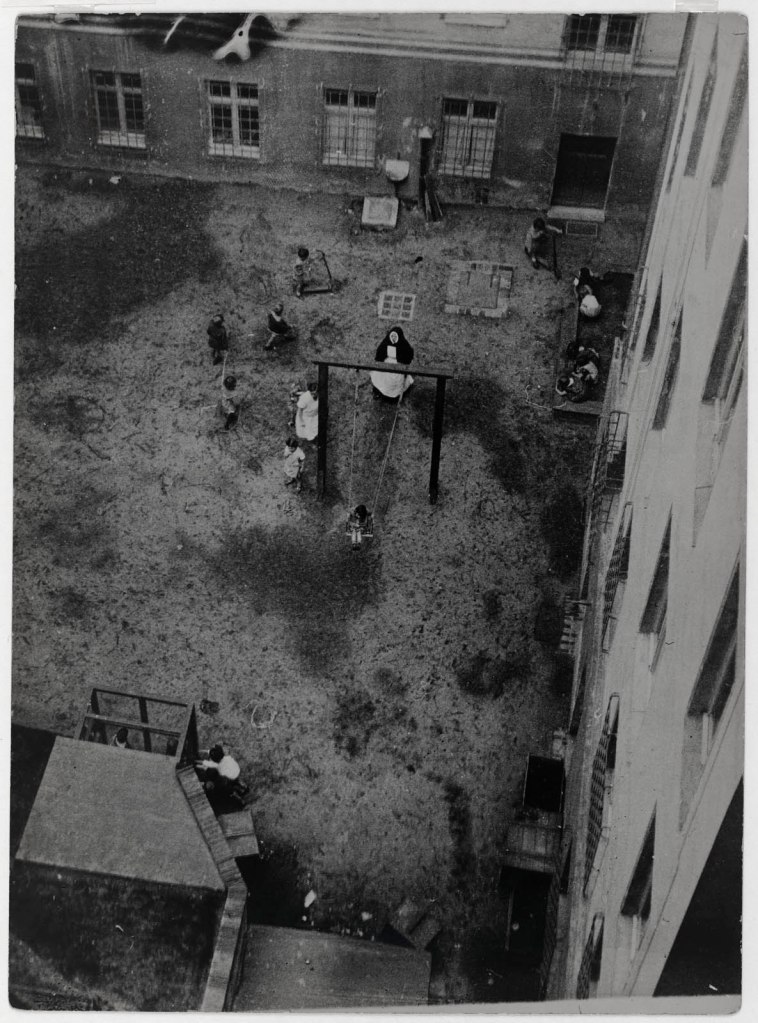

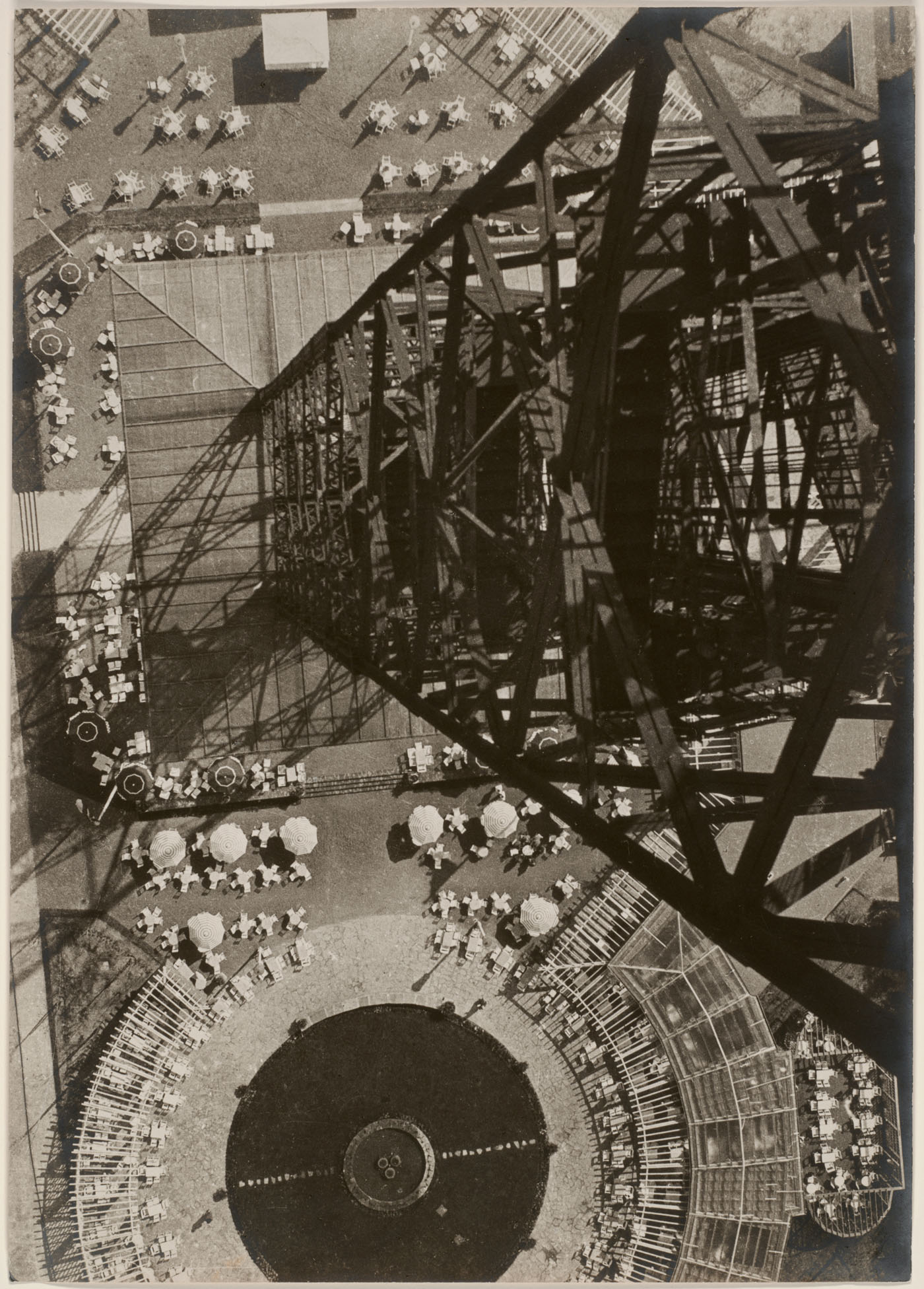

Umbo (Otto Umbehr) (German, 1902-1980)

Untitled (Kindergarten)

1928

Gelatin silver print

Berlinische Galerie – Museum of Modern Art, Photography and Architecture, Berlin

Permanent loan from the Federal Republic of Germany represented by the Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media

Umbo – born Otto Umbehr – found his expressive tool in the camera in 1926. In the early 1920s he studied at the Bauhaus with the intention of becoming a painter, until Walter Gropius, the director of the Institute, expelled him from the school for improper conduct. He then found in photography the medium that allowed him to work with his distinctive play of light and shadow. Photographs such as Unheimliche Straße (Eerie Street, 1928), Am Strand (auch Strandleben) (On the beach [also beach life], 1930) and Ohne Titel (Kindergarten) (Untitled [Kindergarten], 1930) epitomize his artistic innovations. There is nothing random in these images: everything has been composed. Umbo’s photographs are the opposite of snapshots or shots that capture the emotion of a moment; they express a formal intent without overpowering reality. Therefore, with all their poetry, they retain an abstract component. What clearly surfaces in this primacy of composition is his connection to the Bauhaus philosophy, which emphasised design and structure over emotion or spontaneity.

Exhibition text from the Fondazione Prada by Cord Riechelmann

Fondazione Prada Milan

Largo Isarco 2, within the Podium spaces

20139 MILAN

Phone: +39 02 5666 2611

Opening hours:

Mon-Sun, 10am – 7pm

![Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010) 'Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969' [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969] 1969 from the exhibition 'Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany' at Fondazione Prada, Milan, April - July, 2025 Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010) 'Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969' [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969] 1969 from the exhibition 'Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany' at Fondazione Prada, Milan, April - July, 2025](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/2-typologien_heinrich-riebesehl_siae_sm.jpg)

![Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010) 'Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969' [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969] 1969 Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010) 'Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969' [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969] 1969](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/1-typologien_heinrich-riebesehl_siae_sm.jpg)

![Lotte Jacobi (American born Poland, 1896-1990) 'Folkwang-Auriga-Verlag, Orch 152. Neottia nidus avis. Vogel-Nestwurz, einzelne Blüte' [Bird's-nest orchid, single flower] c. 1930 Lotte Jacobi (American born Poland, 1896-1990) 'Folkwang-Auriga-Verlag, Orch 152. Neottia nidus avis. Vogel-Nestwurz, einzelne Blüte' [Bird's-nest orchid, single flower] c. 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/4-typologien_lotte-jacobi_sm.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) '[Unemployed Man in Winter Coat, Hat in Hand]' 1920 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) '[Unemployed Man in Winter Coat, Hat in Hand]' 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/unemployed-man-in-winter-coat-hat-in-hand-1920-august-sander1.jpg?w=677)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter [Heinrich Hoerle]' 1928-1932 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter [Heinrich Hoerle]' 1928-1932](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/sander-maler-web.jpg?w=819)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Proletarian Intellectuals' [Else Schuler, Tristan Rémy, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Gerd Arntz] c. 1925 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Proletarian Intellectuals' [Else Schuler, Tristan Rémy, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Gerd Arntz] c. 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/august-sander-proletarian-intellectuals.jpg?w=809)

![George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959) 'Construction (Untitled)' (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel]) 1920 (installation view) George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959) 'Construction (Untitled)' (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel]) 1920 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/germany-installation-g.jpg?w=744)

![George Grosz. 'Construction (Untitled) (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel])' 1920 George Grosz. 'Construction (Untitled) (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel])' 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/grosz-construction.jpg?w=768)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928 Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-bugeleisen-fur-schuhfabrikation.jpg?w=761)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964). 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-30 (center) and 'Untitled [Remagen Bridge on the Rhine]' c. 1930 (right) August Sander (German, 1876-1964). 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-30 (center) and 'Untitled [Remagen Bridge on the Rhine]' c. 1930 (right)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-landscape-a.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-landscape-b1.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-landscape-b.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Das Siebengebirge: Blick vom Rolandsbogen' [The Siebengebirge: view from the Rolandsbogen] 1929-1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/sander-the-siebengebirge.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Remagen Bridge on the Rhine]' c. 1930 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Remagen Bridge on the Rhine]' c. 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-landscape-c.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s (left) and 'Professor Ludwig Behn' 1920s (right) August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s (left) and 'Professor Ludwig Behn' 1920s (right)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-installation-a.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-avant-garde-a.jpg?w=768)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Untitled [Bohemians: avant-garde of Cologne]' 1920s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-avant-garde.jpg?w=768)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter's Wife [Helene Abelen]' 1926 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter's Wife [Helene Abelen]' 1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sander-painters-wife.jpg?w=749)

![Gert Wollheim (German, 1894-1974) 'Untitled (Couple)' (Ohne Titel [Paar]), 1926 Gert Wollheim (German, 1894-1974) 'Untitled (Couple)' (Ohne Titel [Paar]), 1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/wollheim-untitled.jpg?w=757)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Stadtwald [Urban Forest]' c. 1938 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Stadtwald [Urban Forest]' c. 1938](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/sander-stadtwald-web.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Handlanger [Odd-job man]' 1928 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Handlanger [Odd-job man]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/sander-handlanger-web.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'The Architect [Hans Poelzig]' 1929 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'The Architect [Hans Poelzig]' 1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/sander-der-architekt-web.jpg)

![Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958) 'Portrait (T. Ruff)' [Selfportrait] 1987 Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958) 'Portrait (T. Ruff)' [Selfportrait] 1987](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ruff-self-portrait-web.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Der erdgebundene Mensch' [The Earthbound Human] 1910 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Der erdgebundene Mensch' [The Earthbound Human] 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/sander-der-erdgebundene-mensch-web.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Bauernpaar – Zucht und Harmonie' [Peasant Couple – Breeding and Harmony] 1912 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Bauernpaar – Zucht und Harmonie' [Peasant Couple – Breeding and Harmony] 1912](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/sander-bauernpaar-web.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter [Heinrich Hoerle]' 1928 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter [Heinrich Hoerle]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/sander-maler-web.jpg)

![Karl Grill (German active Donaueschingen, Germany 1920s) 'Untitled [Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet]' c. 1926-1927 Karl Grill (German active Donaueschingen, Germany 1920s) 'Untitled [Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet]' c. 1926-1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/grill-spiral-costume-from-the-triadic-ballet.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.