Exhibition dates: 8th April – 23rd July, 2023

Curator: Karen Haas, Lane Senior Curator of Photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Participating artists: Ansel Adams, 1902-1984; Matthew Brandt, b. 1982; Lois Conner, b. 1951; Binh Danh, b. 1977; Mitch Epstein, b. 1952; Lucas Foglia, b. 1983; Sharon Harper, b. 1966; Frank Jay Haynes, 1853-1921; CJ Heyliger, b. 1984; John K. Hillers, 1843-1925; Mark Klett, b. 1952; Chris McCaw, b. 1971; Laura McPhee, b. 1958; Arno Rafael Minkkinen, b. 1945; Richard Misrach, b. 1949; Abelardo Morell, b. 1948; Eadweard Muybridge, 1830-1904; Catherine Opie, b. 1961; Trevor Paglen, b. 1974; Meghann Riepenhoff, b. 1979; Mark Ruwedel, b. 1954; Victoria Sambunaris, b. 1964; Bryan Schutmaat, b. 1983; David Benjamin Sherry, b. 1981; John Payson Soule, 1827-1904; Stephen Tourlentes, b. 1959; Adam Clark Vroman, 1856-1916; Carleton E. Watkins, 1829-1916; Will Wilson, b. 1969; Byron Wolfe, b. 1967.

Please note: This posting may contain the names or images of people who are now deceased. Some Indigenous communities may be distressed by seeing the name or image of a community member who has passed away.

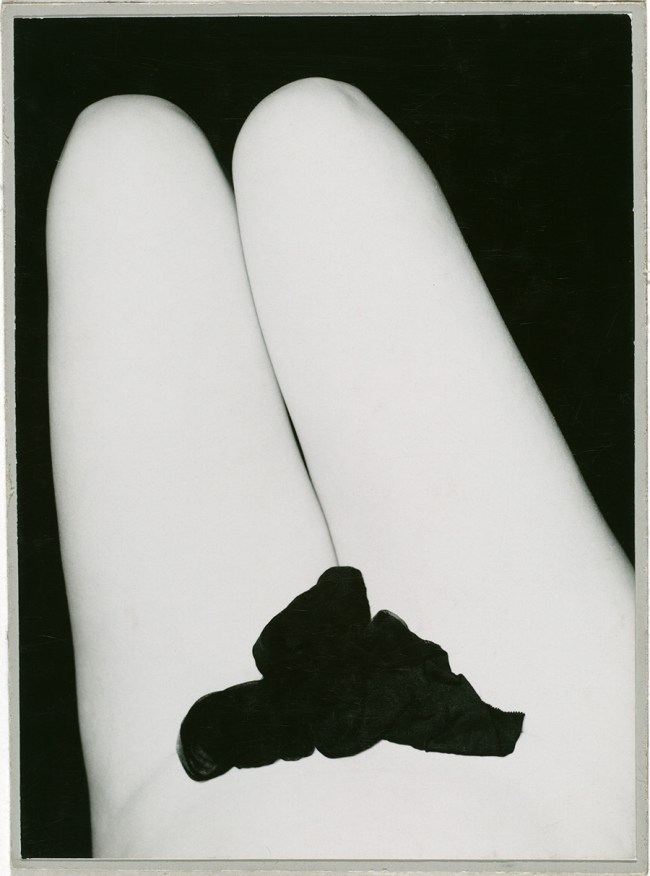

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Salt Flats Near Wendover, Utah

1953

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams made this remarkably abstract image of ancient salt beds during the first year of his national parks project. Barely visible in the distance is a delicate string of telephone poles and wires, a slightly jarring intervention into an otherwise empty space. Adams’ inclusion of the poles might be explained in part by the fact that Wendover was the meeting point for the first telephone line between New York and San Francisco. This achievement was celebrated at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition – a fair that the young Adams attended nearly every day, after his father gave him a season pass with instructions to visit daily, in place of formal schooling.

Exhibition label text

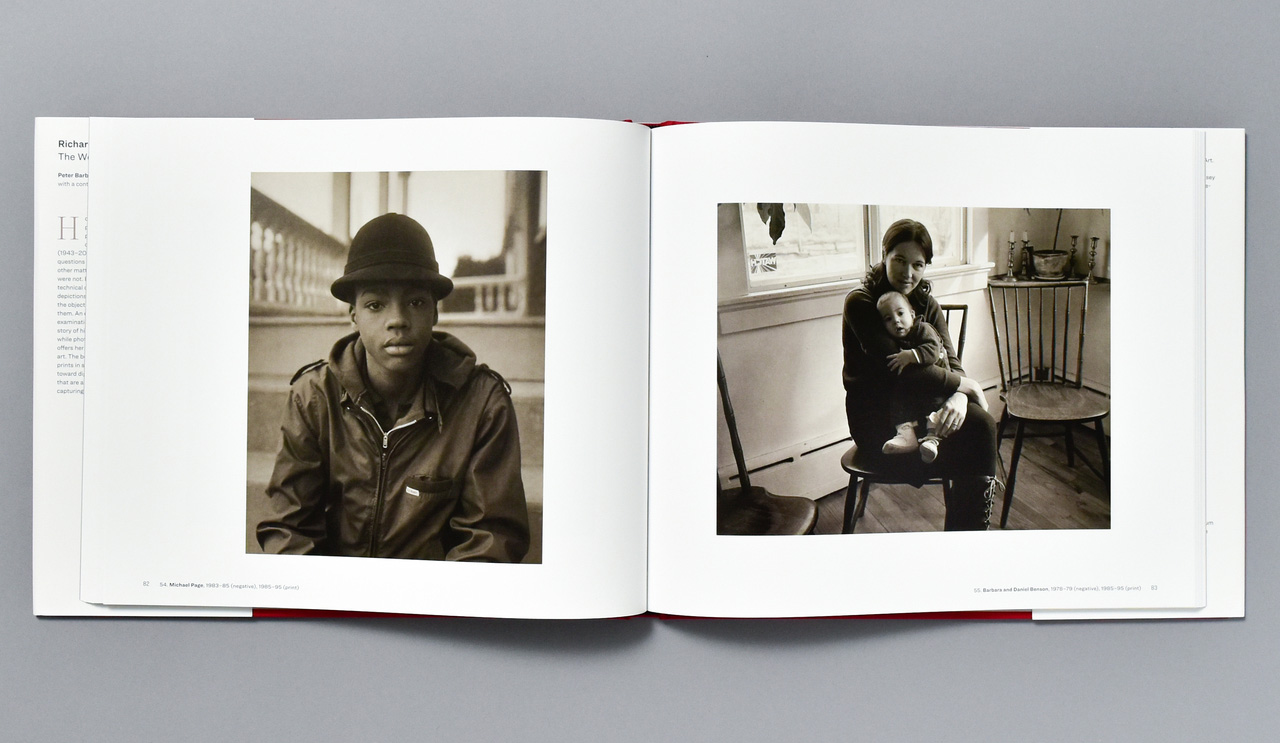

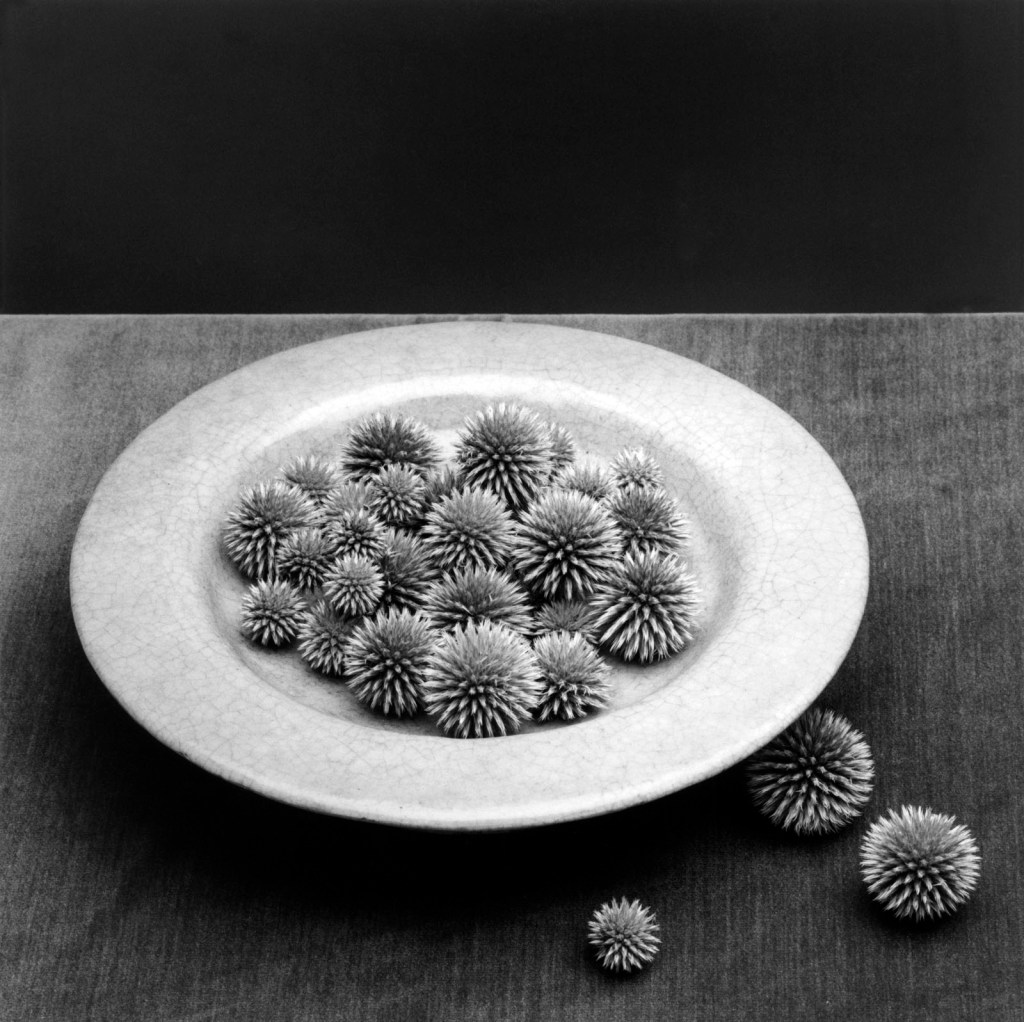

Man and imagination

Most could not fail to know the superb landscape work of Ansel Adams, that master of the large format camera used to produce stunning black and white silver gelatin photographs of great formal beauty and technical prowess, the rich detail and tonal range of his landscape photographs used “in service of what he called the “spiritual-emotional” aspects of parks and wilderness, conveying their restorative power to as wide an audience as possible.” His photographs are so well known that they became icons and he a legend in his own lifetime. But all is not as effortless in his beautiful modernist photographs as they seem.

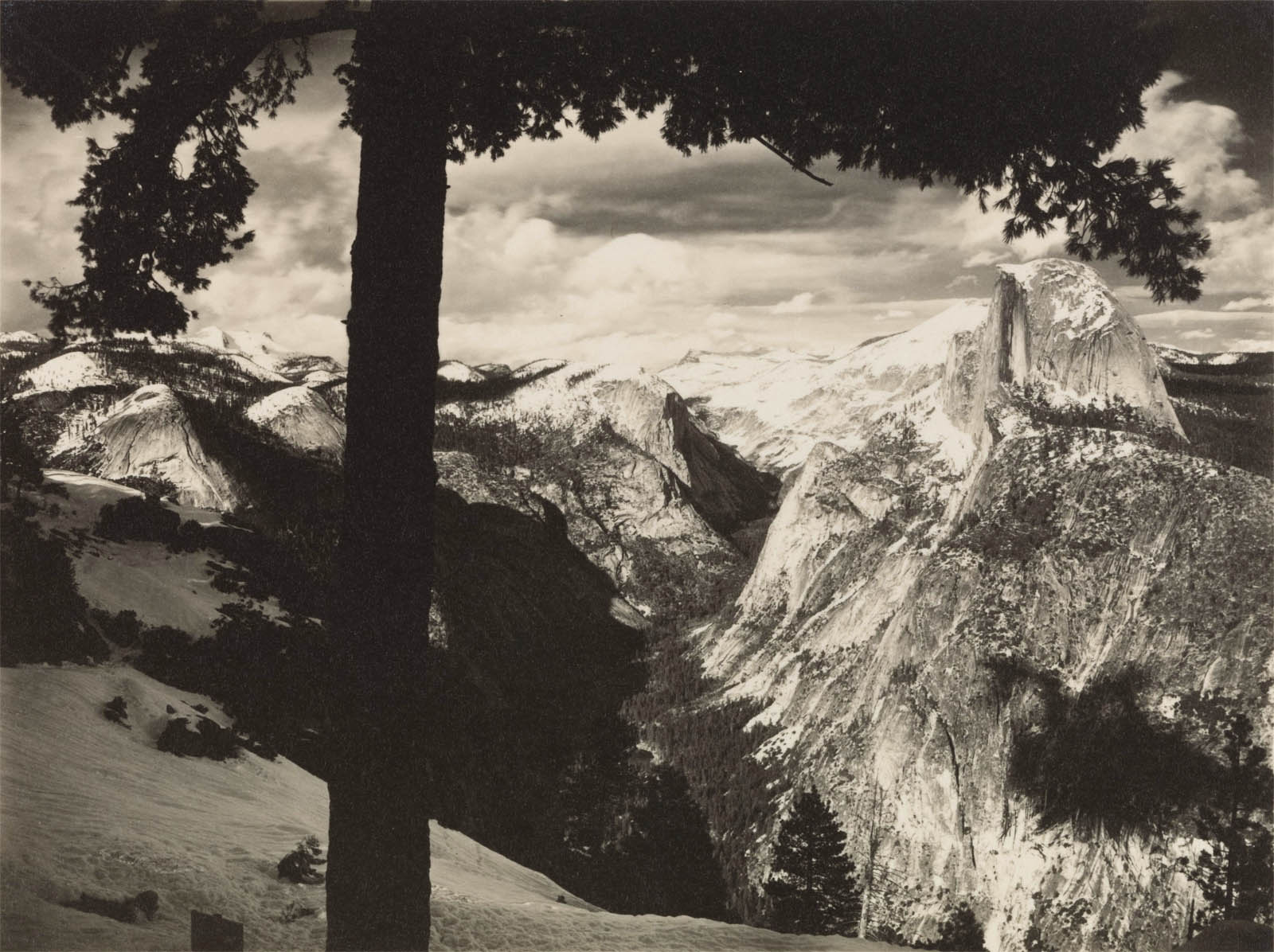

Early landscape photographs from his 1927 portfolio Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras (below) show Adams’ indebtedness to pictorialist and modernist photography. Indeed these elemental and muscular photographs show a dramatic use of dark and light hues in the near / far construction of the picture frame, the warm toned prints adding to their chthonic, almost underground and dystopian nature. Dark and brooding, dystopian and abstract. Those dark tones have a warmth that is contradictory – a lack of light: yet warmth! So there is a fiction at their heart… and that is why their dark brooding never seems a threat for they were based on a dream-world that couldn’t exist. What a difference to the later straight-ahead aesthetic of the artist and Group f64 (“a group founded by Adams of seven 20th-century San Francisco Bay Area photographers who shared a common photographic style characterised by sharply focused and carefully framed images seen through a particularly Western viewpoint.” ~ Wikipedia).

Other mutations and obfuscations are hidden from view “in order” that the artist achieve his desired transcendence of the American landscape. Adams cropped out attendant carparks and people viewing the scene even as other artists such as Seema Weatherwax incorporated them into their work (in the 1940s) as “indelible reminders of a Yosemite modernised for tourism – reminders that Adams typically left out of his artistic work.” Adams even manipulated the negative where necessary, for example removing a road that inconveniently ran through the centre of a canyon that destroyed his imaginative (and Western) vision of the pristine Sierra Nevada. So much for his “absolute realism” and honest simplicity in service of a maximum emotional statement.

Adam’s photographs of Indigenous Americans are also pictures seen from a particularly Western viewpoint, that of the fetishistic valorisation of Indigenous culture. “In the 1920s, writers and artists including D. H. Lawrence, Mabel Dodge Luhan, John Sloan, and Marsden Hartley projected an “authenticity” onto Pueblo visual culture, which justified their appropriation of its subject matter and form to create a native modernist aesthetic. Many photographers did the same, including Ansel Adams and Wright Morris…”1

When Adams first visited the American Southwest in 1927 to publish a book about Taos Pueblo “that aimed to communicate the threat tourism in the region posed to the artistic and religious traditions of Indigenous people [he] made images for the book only after receiving permission from the Taos Pueblo council, to whom he paid a fee and gifted a copy of the finished publication. He also photographed some Indian cultural observances that had become popular attractions among tourists. Adams’s own images of Native dancers have a complex legacy: although he was one of the non-Native onlookers, he carefully framed his views to leave out evidence of the gathered crowds.” (Exhibition wall text) As Joseph Aguilar (San Ildefonso Pueblo) notes in a further exhibition label text, “At the time, Pueblo people and other Native Americans in the Southwest were trying to navigate the outsiders who were interested in their culture. Some of them did not quite understand the circumstances surrounding the curiosity, while others did understand the extractive nature, and they had to weigh that in terms of their other needs. I get questions from members of my community about why they did not chase the archaeologists and photographers out, and I often respond it is because of the uneven power relations between Indigenous and non-Native people at the time.” This influx of artists and photographers did lead to the racist exoticisation and flattening of Indigenous identity performed by the photograph. What is heartening to see in this exhibition is that the curators have placed Adams’ Indigenous American portraits and landscapes in both a historical and contemporary setting, proffering alternative points of view from within the communities being photographed.

An extractive, imaginative and emotional Western “nature” then, is at the heart of Adam’s work and his “marketing the view” – whether that be national parks, empty bays before the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, or Native Americans. While he was a tireless champion of photography as a legitimate form of fine art and an unremitting activist for conservation and wilderness preservation, Adams’ photographs are a creation of a myth of his own of a pristine wilderness which had never co-existed with man. To our benefit, Adams had his ideals and he let them manifest themselves in his imagination.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Yechen Zhao. “Photographic Fluency (Its Pleasures and Pains): Kyo Koike and Chao-Chen Yang,” in Josie R. Johnson. Reality Makes Them Dream: American Photography, 1929-1941. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, 2023, p. 55.

Many thankx to the de Young museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Only pictures that look as if they had been made easily can convincingly suggest that beauty is commonplace.”

Robert Adams. Beauty in Photography. New York: Aperture, 1996, p. 28.

A self-described “California photographer,” Ansel Adams had his first museum exhibition at the de Young in 1932. In a San Francisco homecoming, more than 100 of his most iconic works are on view in Ansel Adams in Our Time alongside those of 23 contemporary artists who share his deep concern for the environment, Catherine Opie, Richard Misrach, Trevor Paglen, and Binh Danh among them. An unremitting activist for conservation and wilderness preservation in the spirit of his 19th-century predecessors, Adams is today beloved for his lush gelatin silver prints of the national parks. Organised by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in partnership with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Ansel Adams in Our Time is enhanced at the de Young by the addition of works from the Museums’ permanent collection and new interpretive framing that explores Adams’ close connection to the Bay Area and the state of California more broadly.

Installation views of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco

Images courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Photos: Gary Sexton

Ansel Adams in Our Time brings iconic artist home to San Francisco

Beloved for his lush gelatin silver photographs of the national parks, Ansel Adams is a giant of 20th-century photography whose images have become icons of the American wilderness. Opening April 8 at the de Young, Ansel Adams in Our Time brings more than 100 works from this self-described “California photographer” to the site of his very first museum exhibition in 1932, placing him in dialogue with 23 contemporary artists who are engaging anew with the landscapes and environmental issues that inspired Adams. The exhibition is organised by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in partnership with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and enhanced at the de Young by the addition of works from the permanent collection and new interpretive framing exploring Adams’ close connection to his hometown of San Francisco.

“Ansel Adams’ photography is renowned for its formal beauty and technical prowess, but his work is equally one of advocacy,” remarked Thomas P. Campbell, Director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. “Adams was a tireless conservationist and wilderness preservationist who fully understood the power of images to sway public opinion. Ansel Adams in Our Time is exceptional in underscoring his brilliant legacy and the critical role that his works and others’ before him have played in safeguarding our national parks and other public lands.”

Instrumental to Adams’ development as a photographer was Yosemite, one of the oldest national parks in the country, which he visited regularly from the age of 14 with his Eastman Kodak Brownie camera in tow. Ansel Adams in Our Time examines the critical role that photography has played in the history of the national parks, with Adams following in the footsteps of predecessors such as Carleton Watkins, whose efforts first secured Yosemite as protected land. A longtime member of the Sierra Club, Adams would go on to perfect the rich detail and tonal range of his landscapes in service of what he called the “spiritual-emotional” aspects of parks and wilderness, conveying their restorative power to as wide an audience as possible. Presenting President Gerald Ford with a print of Yosemite: Clearing Winter Storm (c. 1937) in 1975, Adams urged, “Now, Mr. President, every time you look at this picture, I want you to remember your obligation to the national parks.”

At the de Young, the exhibition delves further into the artist’s Bay Area connections with new interpretive framing and works from the Fine Arts Museums’ permanent collection. Adams became a truly modernist photographer in San Francisco in the 1920s and 1930s, experimenting with the large-format camera that would yield the maximum depth of field and razor-sharp detail that are today considered his signature. He was a tireless champion of photography as a legitimate form of fine art. From his pristine Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras (1927), a landmark work in 20th-century photography, to images of oil derricks, ghost towns, drought conditions, and the sand dunes of Death Valley, Ansel Adams in Our Time spans the scope of the artist’s nearly seven-decade career and efforts to establish both environmental stewardship as a pillar of civic life and the photographic medium as a widely accepted art form.

The works of 23 contemporary artists, including Catherine Opie, Abelardo Morell, Binh Danh, Trevor Paglen, Mitch Epstein, and Victoria Sambunaris, among others, provide a new lens for Adams, drawing on his legacy of art as environmental activism to confront issues such as drought and fire, mining and energy, economic booms and busts, protected places and urban sprawl. The exhibition’s five thematic sections – Capturing the View, Marketing the View, San Francisco: Becoming a Modernist, Adams in the American Southwest, and Picturing the National Parks – open up new conversations around Adams’s work, looking both forward and backward in time to present a richer picture of the relationship between photography, art, environmentalism, and conceptions of landscape.

“Ansel Adams had close ties to San Francisco, and the California landscape, and the de Young museum was among the first institutions to celebrate his work when he was a rising artist,” noted Lauren Palmor, Associate Curator of American Art, who organised Ansel Adams in Our Time at the Fine Arts Museums. “His reverence for our region’s natural beauty drew him to photograph the natural diversity that can be found throughout the Bay Area over the course of his lifetime. Adams was also a tireless advocate for the environment, and the Bay Area shares that spirit as a global center of innovation in conservation and wilderness preservation today.”

Exhibition organisation

Ansel Adams in Our Time was organised by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in partnership with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. The exhibition was curated by Karen Haas, Lane Senior Curator of Photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Presenting Sponsor is the Clare C. and Jay D. McEvoy Endowment Fund. Lead Sponsors are The Lisa and Douglas Goldman Fund and the San Francisco Auxiliary of the Fine Arts Museums. Major Support is provided by the Byers Family and The Herbst Foundation, Inc. Significant Support is provided by The Ansel Adams Gallery. Generous Support is provided by David A. Wollenberg and Merrill Private Wealth Management.

About Ansel Adams

Ansel Easton Adams (1902-1984) made indelible images of the American landscape and successfully advocated for the environment and the preservation of natural resources. Adams was born in San Francisco in 1902, and he made his first trip to Yosemite when he was just 14 years old. Transfixed by the valley’s beauty, he took his first photographs of Yosemite’s waterfalls and rock formations. Adams went on to develop his photographic practice in parallel with his environmentalist outlook.

The de Young museum hosted several important early Adams exhibitions in the 1930s, celebrating the achievements of this local photographer whose star was rapidly rising nationally: Photographs by Ansel Easton Adams (1932); the landmark Group f.64 exhibition (1932-1933), which also featured the work of Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, Preston Holder, Consuelo Kanaga, Alma Lavenson, Sonya Noskowiak, Henry Swift, Willard Ames Van Dyke, Brett Weston, and Edward Weston; and Yosemite in Four Seasons: Photographs by Ansel Adams (1935).

Adams shaped the field for other practicing photographers on both coasts, and his impact is immeasurable. In addition to teaching, he authored a celebrated series of books on photographic techniques that distilled his expertise for generations of budding photographers. Parallel to his achievements in photography, Adams dedicated himself to environmental advocacy for over seven decades. In 1980, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, for his artistic and environmental efforts.

Press release from the de Young website

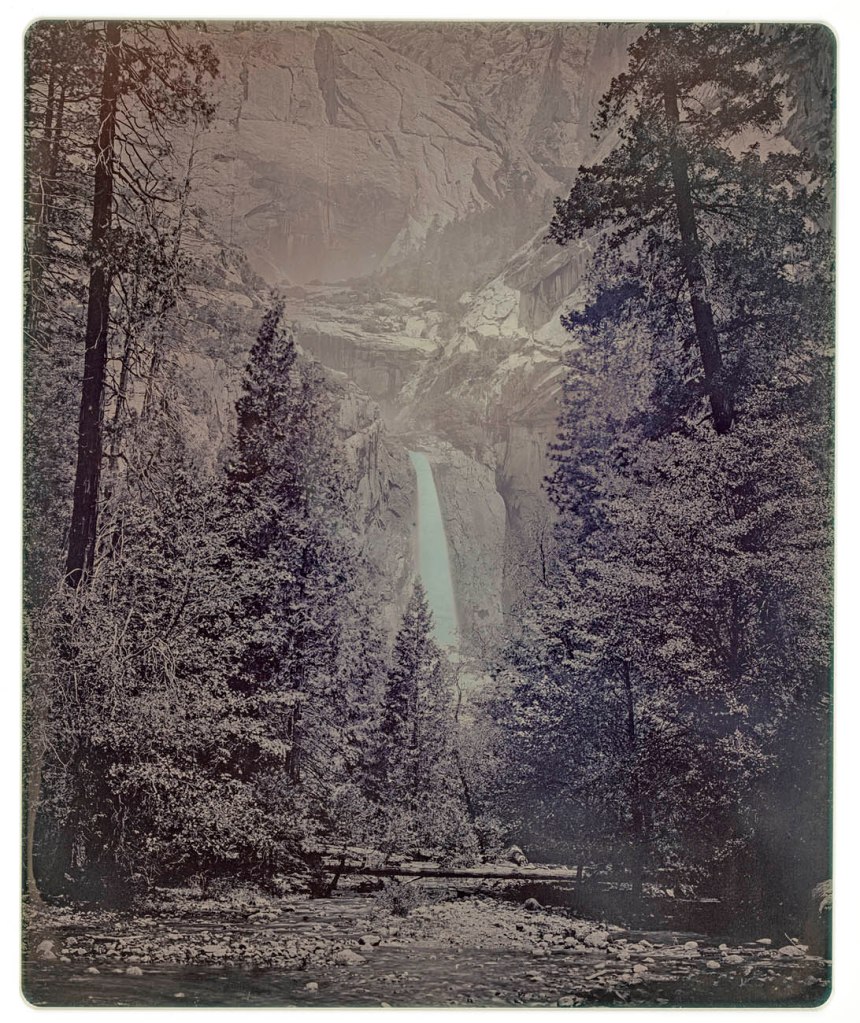

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Glacier Point, Yosemite National Park

c. 1923, printed 1927

From the portfolio Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, 1927

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

These photographs were issued together as a portfolio by San Francisco’s Grabhorn Press in 1927. Although photographic print portfolios would become common later in the century, Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras represents one of the first attempts to market photographs in this way. Looking back on this moment in his career, a time when he was struggling to make a living and gain recognition as an artist, Ansel Adams was embarrassed by the made-up term “Parmelian” in the title. His publisher thought it was necessary because photographs were not yet considered worthy of investment by fine art collectors. Later, Adams would use the same negative of Half Dome from this series to produce the larger version of Monolith – The Face of Half Dome [below] that appears at the start of this exhibition.

Exhibition label text

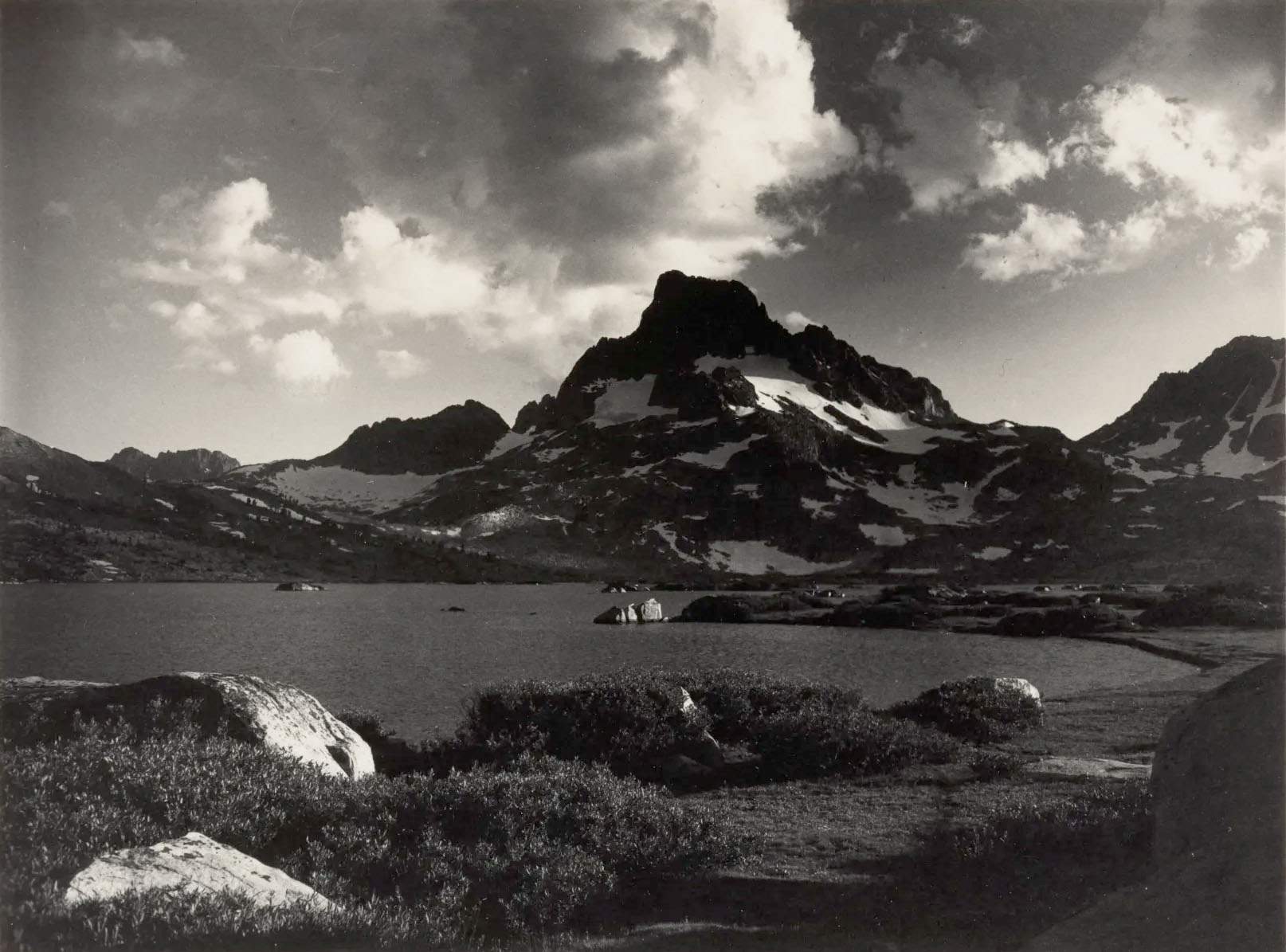

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Banner Peak – Thousand Island Lake, Sierra Nevada, California

c. 1923, printed 1927

From the portfolio Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, 1927

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Sierra Junipers

1927

From the portfolio Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, 1927

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Cloud and Mountain, Kings Canyon National Park, California

c. 1925, printed 1927

From the portfolio Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, 1927

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Monolith – The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park

1927, printed 1950-1960

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

This majestic view of Half Dome is one of Ansel Adams’ most important and groundbreaking early photographs. Shot on a hike in the spring of 1927, it represents his first conscious “visualisation” – an image fully anticipated before he tripped the shutter, and one that for Adams captured the emotional impact of the scene. He made this enlarged print years later, but the dramatic sky and the sharp contrast between the brilliant white snow and dark ridges in the granite were recorded in 1927 when Adams took the photograph, using a deep red filter and a long exposure (made possible by the windless conditions that day).

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Leaves on Pool, Sierra Nevada, California

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Spending time in the wilderness was a spiritual experience that Ansel Adams marvelled at his entire life. Describing one such transcendent moment, he wrote: “It was one of those mornings when the sunlight is burnished with a keen wind and long feathers of clouds move in a lofty sky. … I was suddenly arrested … by an exceedingly pointed awareness of the light. The moment I paused, the full impact of the mood was upon me; I saw more clearly than I have ever seen before or since the minute detail of the grasses, the clusters of sand shifting in the wind, the small flotsam of the forest, the motion of the high clouds streaming above the peaks.”

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Grass and Burned Stump, Sierra Nevada, California

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams made this photograph near Fish Camp, south of Yosemite National Park, in an area where forest fires raged some years earlier. In his close-up view, he juxtaposes the tender shoots of new grass and the charred surface of a burned stump. This is an example of what Adams liked to call the “microscopic revelation of the lens,” which he saw as the ideal of his “straight,” sharp-focus approach to photography.

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Mount Williamson from Manzanar, Sierra Nevada, California

1944

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

On a visit to Manzanar, a Japanese internment camp, in 1944, Ansel Adams drove to the field of boulders that extends to the base of Mount Williamson. “There was a glorious storm going on in the mountains,” he wrote. “I set up my camera on the rooftop platform of my car, [which] enabled me to get a good view over the boulders to the base of the range.” The resulting photograph captures a storm passing over the distant mountain range – an awe-inspiring image that confounds all sense of scale and perspective.

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Birds on Wire, Evening

1943, printed 1984

Gelatin silver print

This print from the Library of Congress

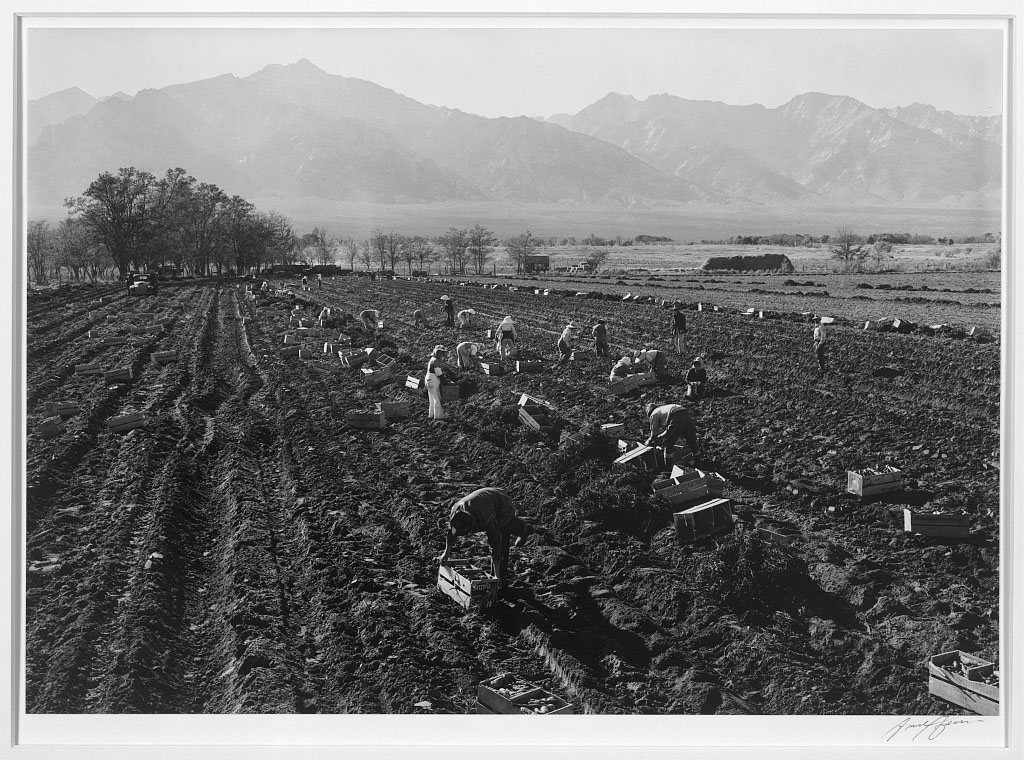

A few months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast (two-thirds of whom were American citizens) were quickly rounded up, separated from homes, possessions, and businesses, and quietly relocated to remote incarceration camps.

A total of 11,070 Japanese Americans were processed through Manzanar War Relocation Center in Inyo County, California. Ansel Adams was invited to photograph Manzanar by Ralph Merritt, a Sierra Club friend who had recently been appointed director of the isolated detention center. Although he was not allowed to photograph the center’s barbed wire or guns, Adams did see himself as a kind of conscientious objector for his work documenting the site and the people forced to live there.

Adams was personally moved by the treatment of Japanese Americans in World War II when an older Japanese man who worked for his family for many years was transferred to a detention center. When Adams first went to Manzanar in 1943, he was “profoundly affected” by photographing the camp and meeting its incarcerated inhabitants. He later presented his Manzanar images in an exhibition and book entitled Born Free and Equal. Manzanar means “apple orchard” in Spanish, but agriculture in the area had suffered since the diversion of water to Los Angeles began in 1913. Nonetheless, the internees were responsible for raising much of their own food in the fields near the camp.

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Potato Field, North Farm, Manzanar

1943, printed 1984

Gelatin silver print

This print from the Library of Congress

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake, Alaska

1948

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams shot this image of Mount McKinley in Denali National Park at 1:30 in the morning, just two hours after the setting of the midsummer sun. He described, “As the sun rose, the clouds lifted, and the mountain glowed an incredible shade of pink. Laid out in front of Mount McKinley, Wonder Lake was pearlescent against the dark embracing arms of the shoreline. I made what I visualised as an inevitable image. The scale of this great mountain is hard to believe – the camera and I were thirty miles from McKinley’s base.”

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Rails and Jet Trails, Roseville, California

c. 1953

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Marketing the view

In 1919, at the age of seventeen, Ansel Adams joined the Sierra Club. The organisation’s original focus on environmental preservation, and its initial failure to acknowledge Indigenous people and their homelands, helped lay the groundwork for the twentieth-century environmentalism he would come to represent. Adams participated in the club’s annual High Trips, serving as photographer and assistant manager from 1930 through 1936. He produced albums of photographs from these treks, inviting members to order contact prints or, for a higher fee, enlargements in “plain or soft-focus.” His ingenuity ultimately lad to his 1927 portfolio, Parmesan Prints of the High Sierras, on view in this gallery – one of the earliest experiments in custom printing, sequencing, and distributing fine photographs.

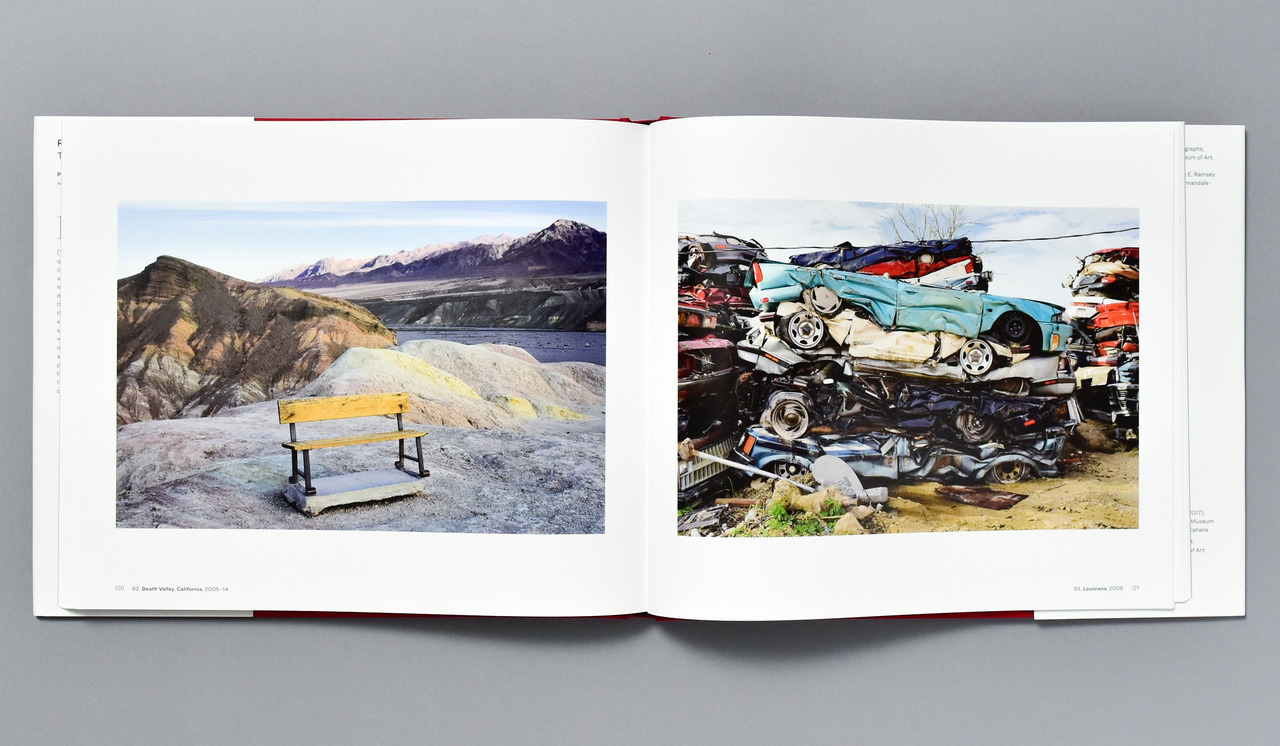

Adams was not the first to market view of the American West. In the nineteenth century, images of western landscapes were mass-produced and widely distributed, catering to a burgeoning tourist market. Today, contemporary artists are using photography to highlight the dynamic nature of landscapes and to document humans’ impact on the environment. Sometimes these works take the form of extended series or grids, as though invoking earlier methods of mass-distributing western views.

Exhibition wall text

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

The Golden Gate from Telegraph Hill, San Francisco

1868

Albumen silver print from wet-collodion-on-glass negative

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Museum purchase Prints and Drawings Art Trust Fund

Installation views of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco showing at centre Adams’ The Golden Gate Before the Bridge (1932, below)

Images courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Photos: Gary Sexton

San Francisco: Becoming a Modernist

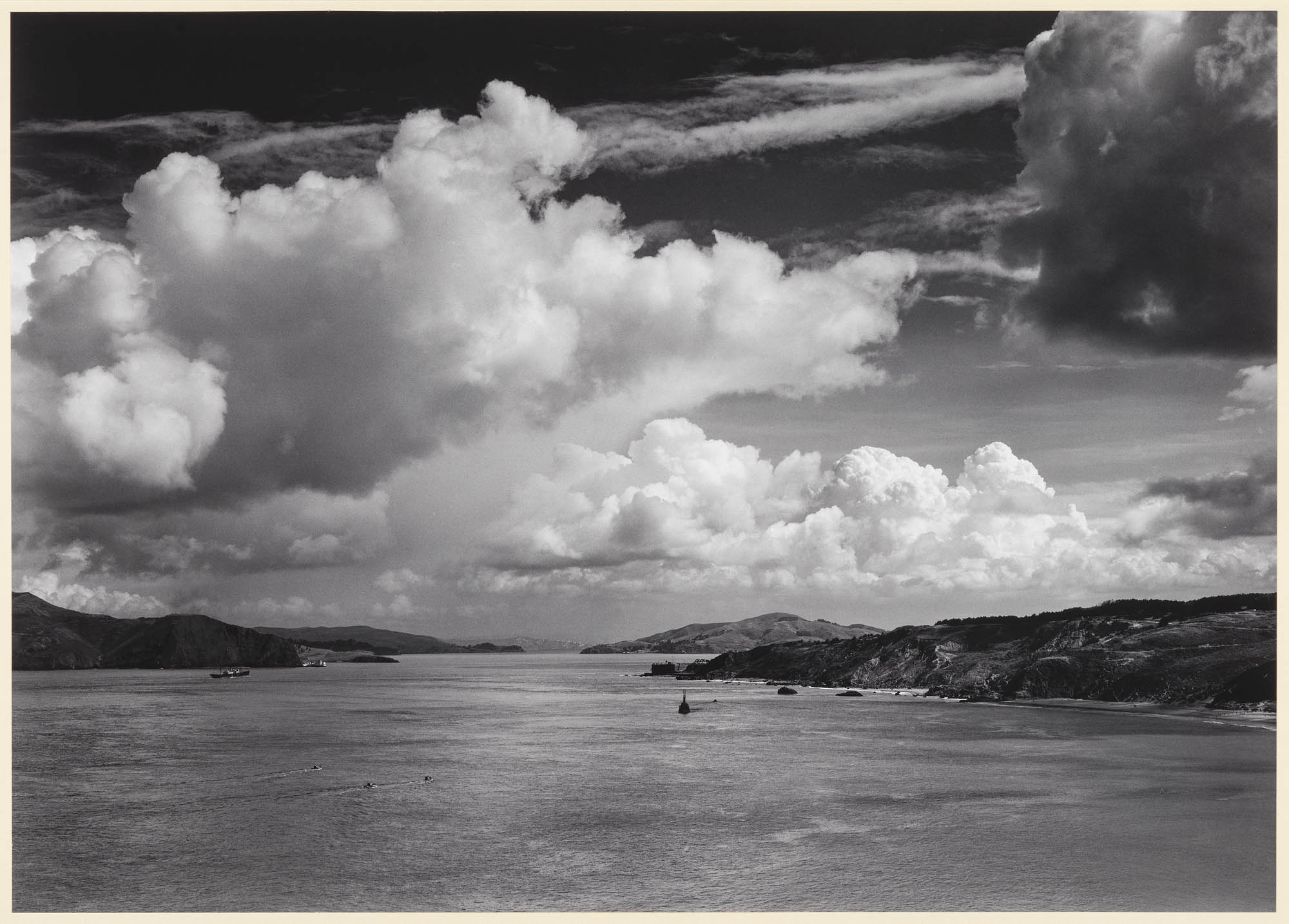

San Francisco is where Ansel Adams became a modernist photographer. He grew up in present-day Sea Cliff, where his family home overlooked the Presidio to the Marin Headlands beyond. These views made a lasting impact on his photographs – he later described constantly returning to the elements of nature that surrounded him in his childhood. Adams’ first exhibition, featuring photographs he took on Sierra Club hikes, was held at the club’s headquarters on Montgomery Street in 1928. Convinced that he could make a living as a photographer, he acquired a large-format camera and became an advocate of “straight” (unmanipulated) photography, leaving behind the soft-focus aesthetic of his earlier work. He experimented with abstraction and extreme close-ups, capturing texture and clarity of detail. He recorded cloud-filled skies and depicted landscapes as seemingly infinite spaces devoid of people. During the Great Depression, Adams began photographing a wider range of subjects, including the challenging reality of urban life in San Francisco and the region’s changing landscape. The latter included the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge (1937), which radically transformed the views of San Francisco Bay that had captivated Adams in his youth.

Golden Gate Bridge

Ansel Adams made this photograph [below] near his family home the year before construction began on the Golden Gate Bridge. He later recalled, “One beautiful storm-clearing morning, I looked out the window of our San Francisco home and saw magnificent clouds rolling from the north over the Golden Gate. I grabbed the 8-by-10 equipment and drove to the end of 32nd Avenue, at the edge of Sea Cliff. I dashed along the old Cliff house railroad bed for a short distance, then down to the crest of a promontory. From there grand view of the Golden Gate commanded me to set up the heavy tripod, attach the camera and lens, and focus on the wonderful evolving landscape of clouds.”

Exhibition wall text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

The Golden Gate Before the Bridge

1932

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Richard Misrach (American, b. 1949)

Golden Gate Bridge, 10.31.98, 5:18 pm

1998, printed 2016

Pigment prints

Courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

In 1997, Richard Misrach began what would become a three-year project photographing the Golden Gate Bridge from his porch in the Berkeley Hills. Placing his large-format 8-by-10-inch camera in the same position on each occasion, Misrach recorded hundreds of views of the distant span, at various times of day and in every season, set off against the constantly changing sky. The series was reissued in 2012 to mark the occasion of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the bridge’s landmark opening.

Exhibition label text

Richard Misrach (American, b. 1949)

Golden Gate Bridge, 12.19.99, 7:31 am

1999, printed 2020

Pigment prints

Courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

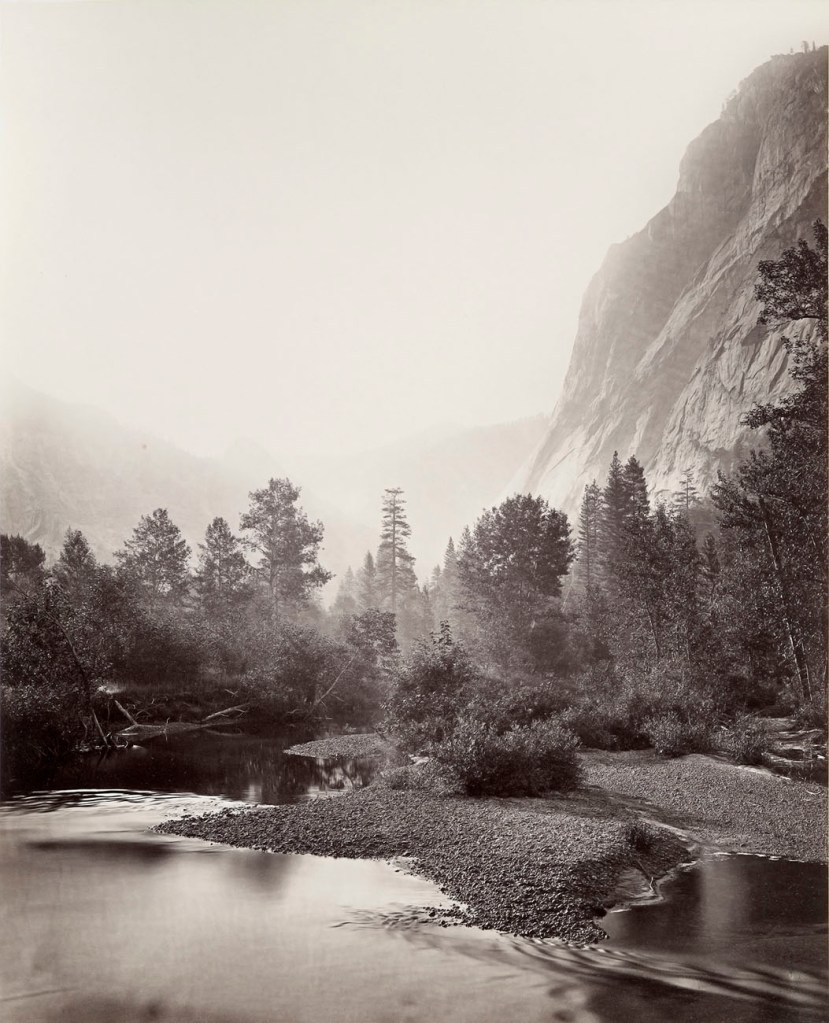

Picturing National Parks

Photography played a critical role in the establishment of the national parks. The dramatic views made by Carleton Watkins and other nineteenth-century photographers ultimately helped convince government officials to protect Yosemite and Yellowstone from private development. However, the formation of the national parks further dispossessed Indigenous people of their ancestral lands, overlooking their ongoing stewardship of the land and restricting their access to it.

Although Ansel Adams claimed he never intentionally made a creative photograph that related directly to an environmental issue, he was aware of an image’s power to sway opinions on conservation. Adams’ photographs of King’s River Canyon [below] helped the Sierra Club successfully campaign to establish the site as a national park. Over the following years, Adams photographed national parks from Alaska to Texas, Hawaii to Maine, creating images that conveyed the transformative power of the parks to a wide audience.

Many contemporary artists working in the national parks acknowledge, as Adams did, the efforts of the photographers who came before them. But the complicated legacies – and uncertain futures – of these protected lands have led some photographers to take more personal and political approaches to the work they are making in these places.

Exhibition wall text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Lake near Muir Pass, Kings Canyon National Park, California

1933

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams made this photograph while on a Sierra Club outing in Kings River Canyon. Three years later, he represented the club at a congressional hearing in Washington, DC. Armed with photographs like this one, he argued successfully for the transfer of Kings River Canyon from the Forest Service to the National Park Service. When it became a national park in 1940, the director of the Park Service wrote to Adams, saying, “I realise that a silent but most effective voice in the campaign was your book Sierra Nevada – John Muir Trail. As long as that book is in existence, it will go on justifying the park.”

Exhibition label text

Installation view of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco showing at left, Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park (about 1937, below); at centre, Rain, Yosemite Valley, California (c. 1940, below); and at right, Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite National Park (1960, below)

Images courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Photos: Gary Sexton

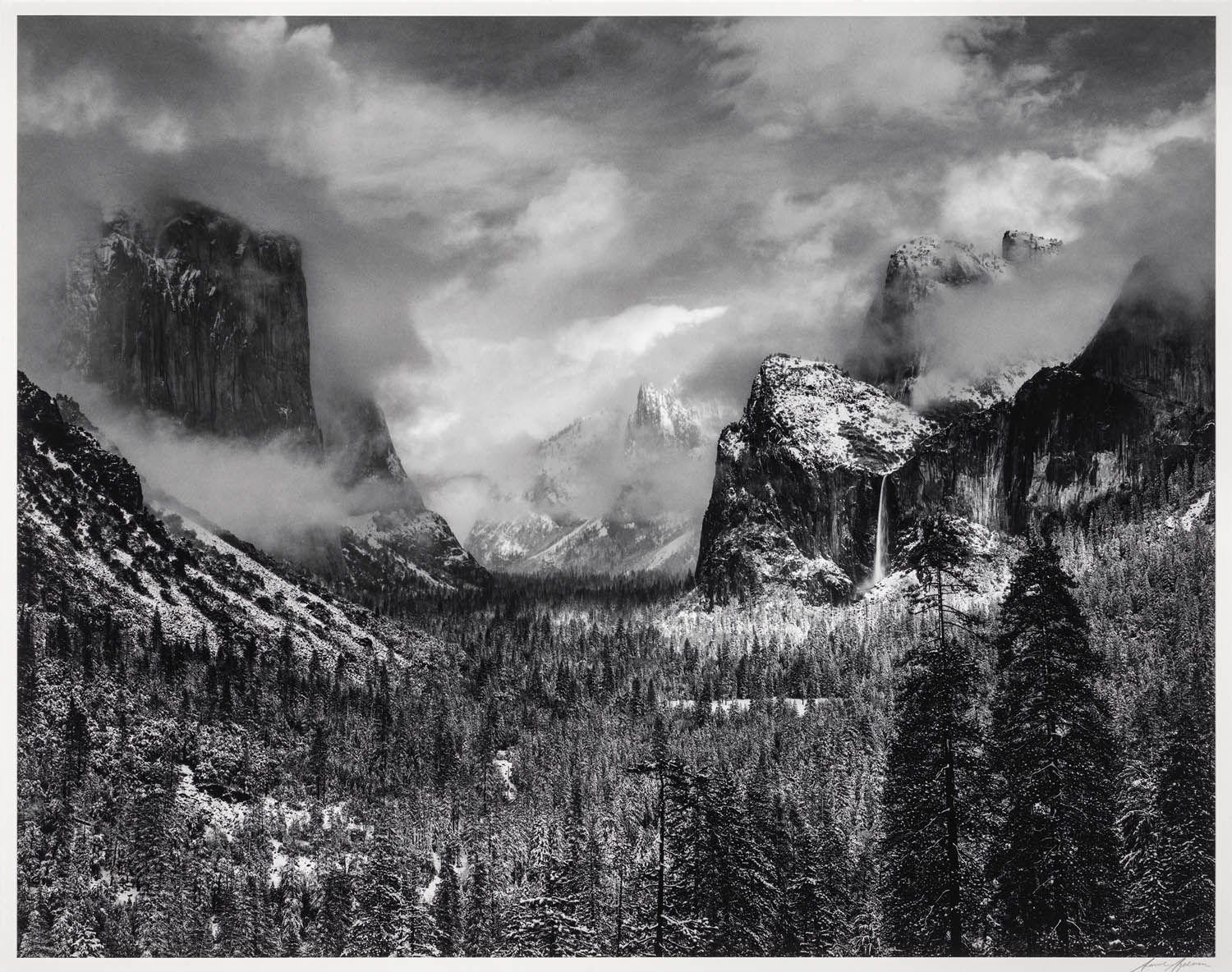

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park

About 1937

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams described photographs like Monolith and Clearing Winter Storm as his “Mona Lisas”: images so popular with the public that they were printed countless times over the course of his long career. He took this remarkable photograph from Yosemite’s Inspiration Point soon after a sudden rainstorm turned to snow and then, just as swiftly, began to clear. It records an expansive valley view that Adams had attempted on several previous occasions but never been successful in rendering in such shimmering detail. Trained as a pianist, Ansel Adams often compared the photographic negative to a musical score and described each print from a particular negative as an individual performance of that score.

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Rain, Yosemite Valley, California

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Like Clearing Winter Storm [above], this photograph features what the nineteenth-century photographer Carleton E. Watkins described as “the best general view” of Yosemite Valley, with the massive granite outcropping of El Capitan on the left and the silvery stream of Bridalveil Fall visible on the right. Yet here Yosemite’s famous features are shrouded in mist, and the pine tree in the foreground, its needles glistening with rain, stands in place of the distant peaks.

Exhibition label text

Installation view of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco showing at left, Abelardo Morell’s Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of Mount Moran and the Snake River from Oxbow Bend, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (2011, below); and at centre Adams’ The Tetons and Snake River, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (1942, below)

Images courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Photos: Gary Sexton

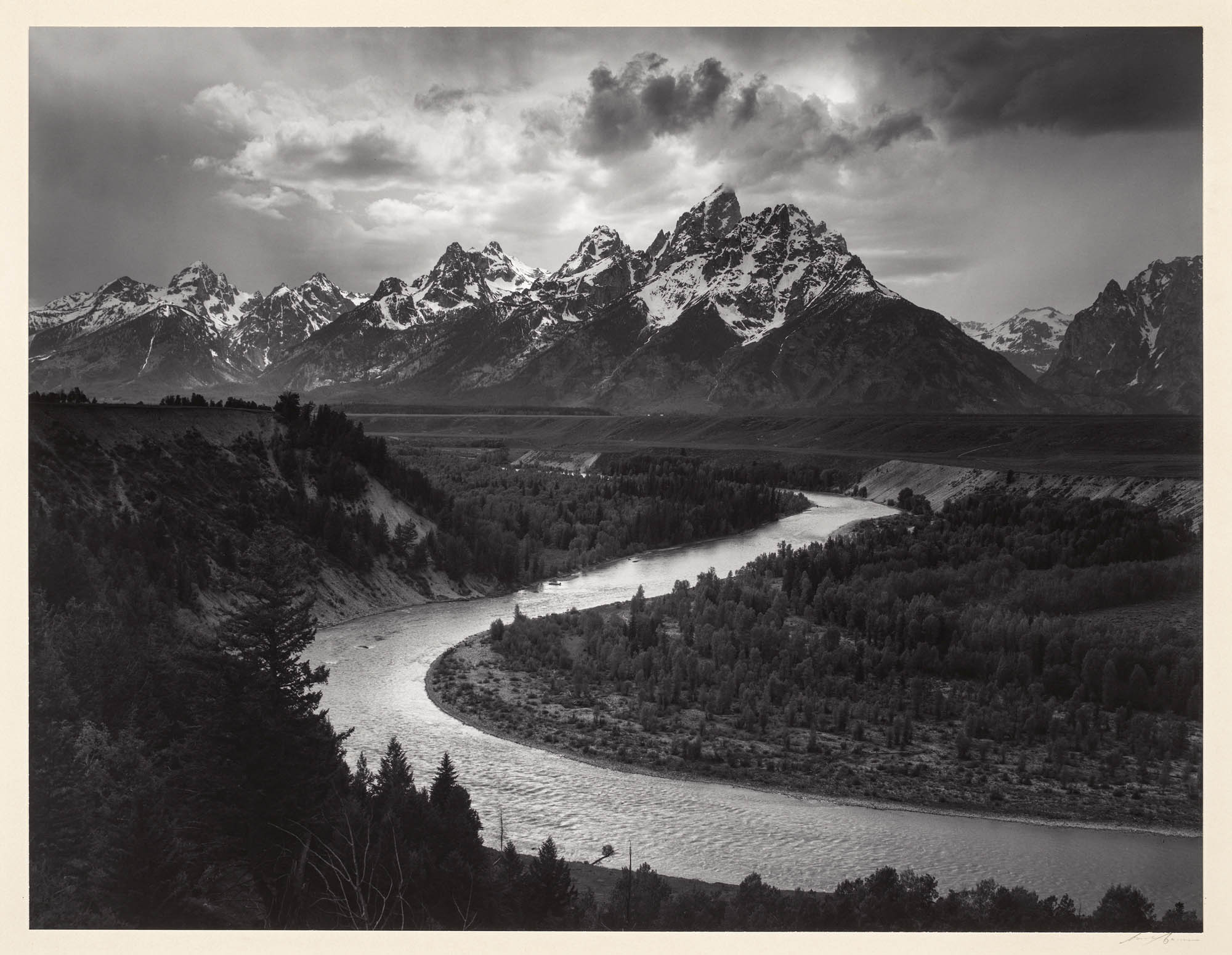

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

The Tetons and Snake River, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming

1942

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

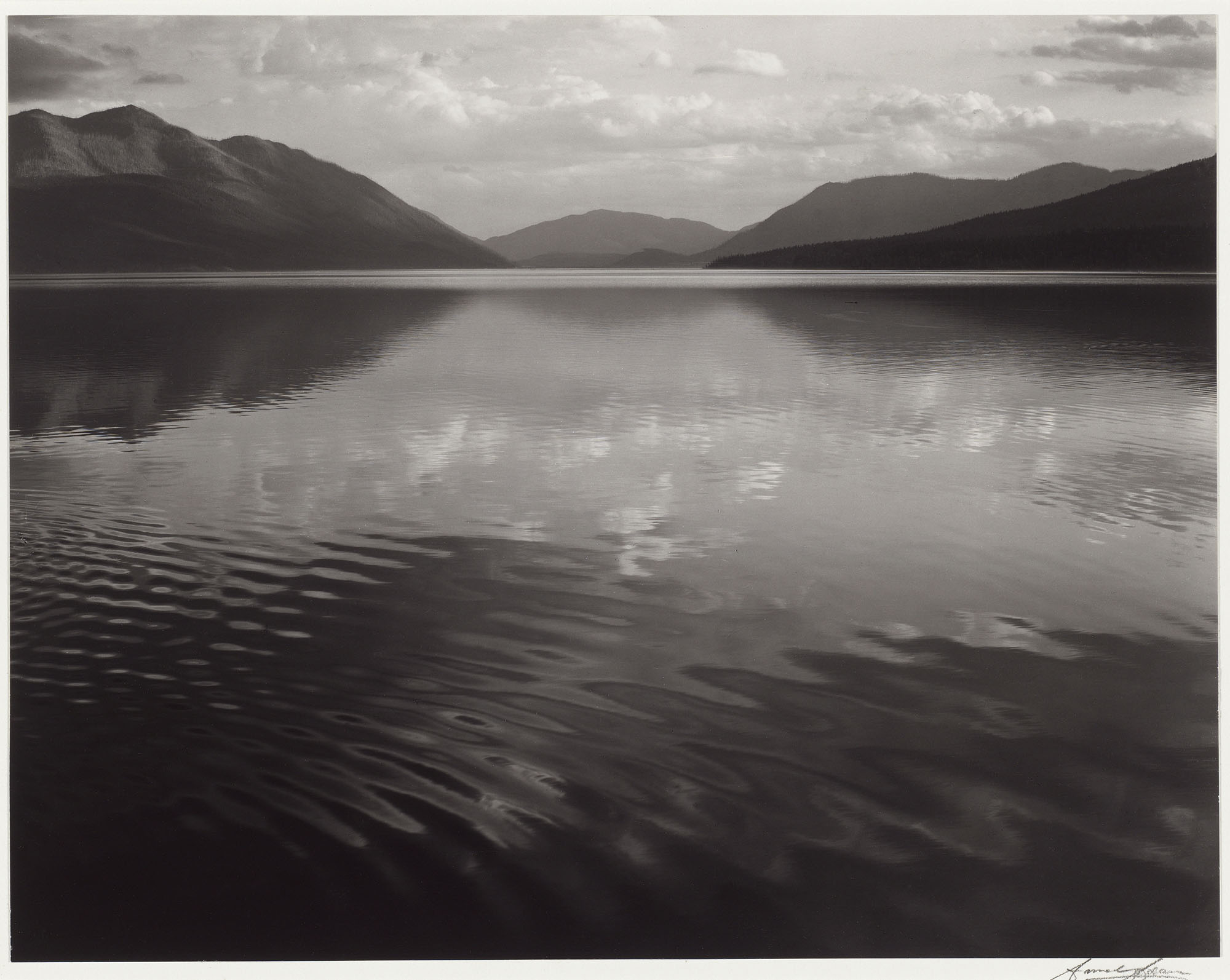

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Lake McDonald, Evening, Glacier National Park, Montana

1942

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Old Faithful Geyser, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

1942

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams began writing how-to books on photography in the mid-1930s, but he is best known for his series of technical books, including Camera and Lens, The Negative, The Print, and Natural Light Photography. In one of his later books, he uses an image of a Yellowstone geyser as an example of a particularly challenging subject that defies light-meter readings and tests a photographer’s ability to “visualise” in advance something so inherently fleeting and unpredictable. “It is difficult to conceive of a substance more impressively brilliant than the spurting plumes of white waters in sunlight against a deep blue sky,” he wrote.

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Grass and Reflections, Lyell Fork of the Merced River, Yosemite National Park

About 1943

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Lyell Fork was one of Ansel Adams’ favourite locations from his earliest years as a photographer in Yosemite. It was a place he also loved introducing to others—he took Georgia O’Keeffe and photography collector David McAlpin there when they hiked into the backcountry in 1938. Reflected in the placid water are several distant peaks, the most prominent of which was named Mount Ansel Adams after the photographer’s death in 1984.

Exhibition label text

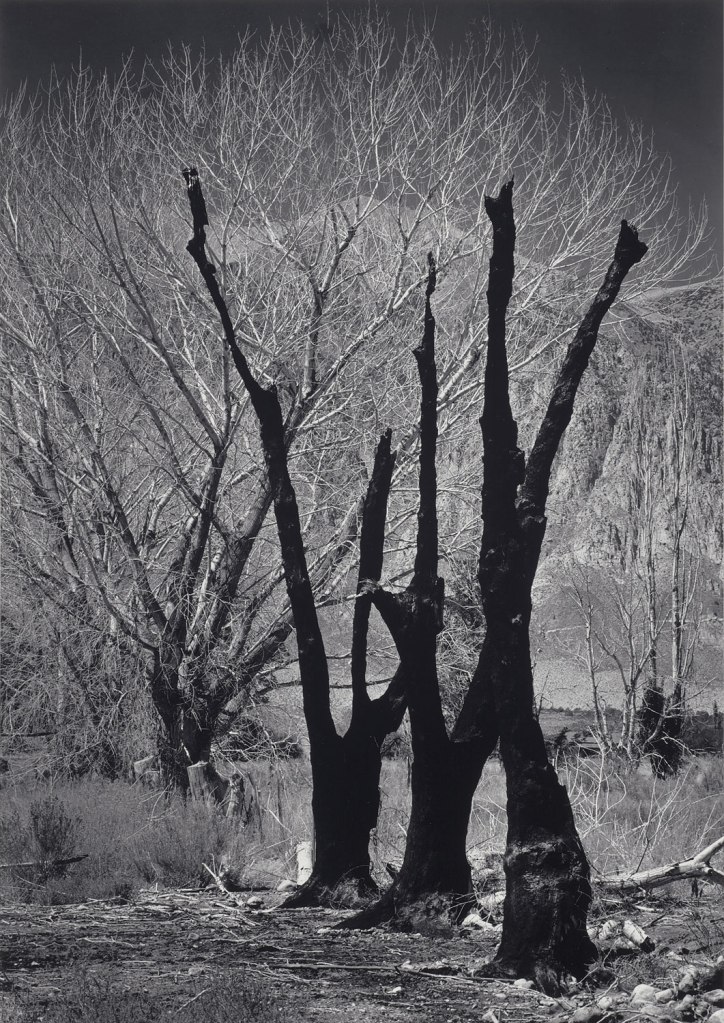

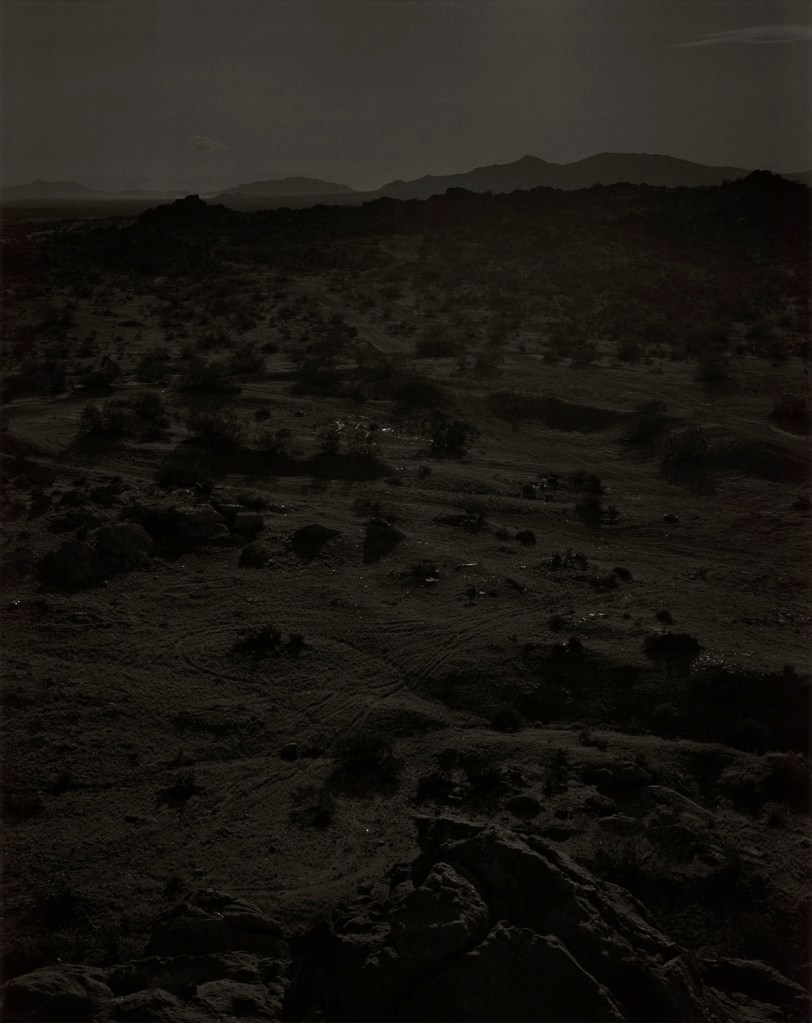

The Other Side of the Mountain

Ansel Adams made his reputation mainly through images of beautiful, seemingly unspoiled nature. Less well known are the images he produced in California’s Death Valley and Owens Valley [below], southeast of Yosemite. Yet he was drawn to these more forbidding landscapes multiple times – occasionally lured by a book or magazine project but often of his own volition.

Here, on the dry side of the Sierra Nevada, Adams and his work took a dramatic detour. The photographer Edward Weston introduced Adams to Death Valley, where he photographed sand dunes, salt flats, and sandstone canyons. Owens Valley was once farmland, but its residents struggled after their water supply was diverted to the growing city of Los Angeles. In 1943, Adams first traveled to nearby Manzanar, where he photographed Japanese Americans forcibly relocated to internment camps shortly after the US entered World War II. The resulting series explores the tension between the area’s open spaces and the physical restrictions imposed upon internees.

Contemporary photographers continue to find compelling subjects in these remote places. Their images explore the raw beauty of the terrain and the sometimes unsettling ways it is used today – including as the site of maximum-security prisons and clandestine military projects carried out under wide skies.

Exhibition wall text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Burned Trees, Owens Valley, California

Negative date: about 1936

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Installation view of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco showing at left, Salt Flats Near Wendover, Utah (1953, above); at second left, Self‑Portrait, Monument Valley, Utah (1958, below); at second left Trees Near Washburn Point, Illiloutte Ridge, Yosemite Valley (c. 1945, below); and at bottom right, Burned Trees, Owens Valley, California (1936, above)

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Photo: Gary Sexton

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Self‑Portrait, Monument Valley, Utah

1958

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

This unusual self-portrait depicts Ansel Adams, light meter in hand, standing next to his large-format camera and tripod. He made this image of his shadow falling across a fissured rock face while in Monument Valley to shoot a Colorama for display in New York’s Grand Central Station. Sponsored by Eastman Kodak, Coloramas were panoramic, backlit transparencies, almost eighteen feet high and sixty feet long, whose sweeping scale and luminous colour were the antithesis of this intimate image that Adams shot while waiting for the weather to cooperate.

Exhibition label text

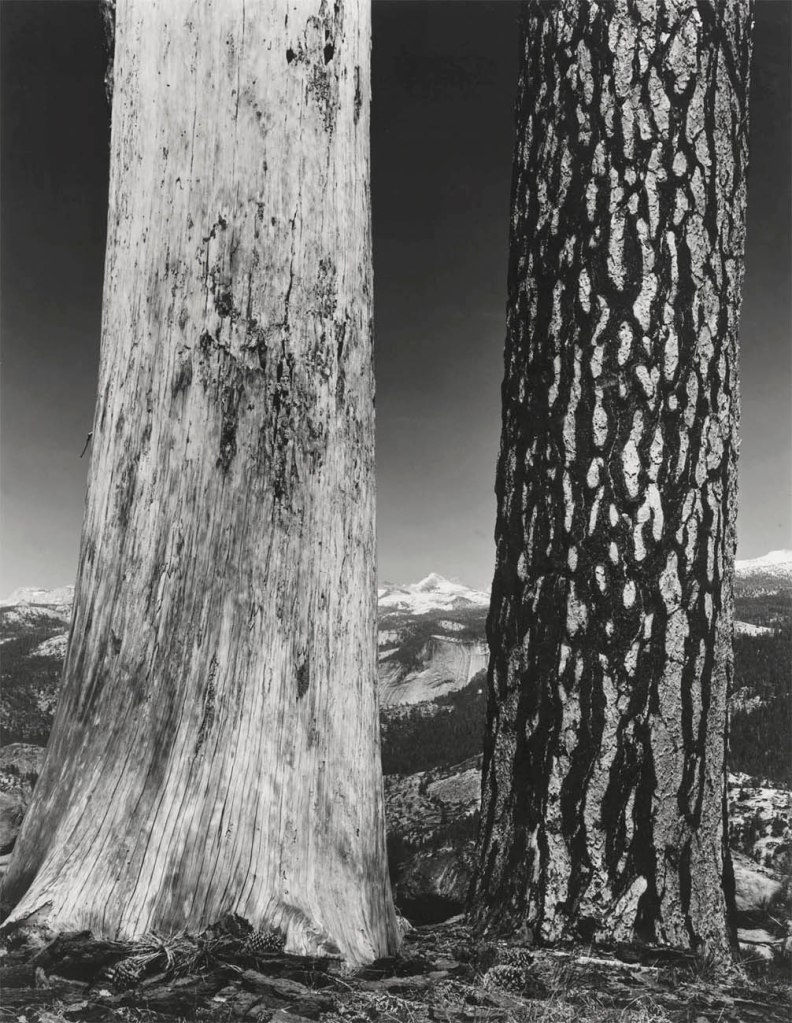

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Trees, Illilouette Ridge, Yosemite National Park

c. 1945

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

This stunning double portrait records a pair of massive tree trunks following a fire. The Illilouette Ridge is an area of Yosemite National Park that lies between Glacier Point and the valley floor. In recent decades, the Illilouette Creek basin has been the focus of an environmental study to measure the potential benefit of managing fires with minimal suppression and fewer controlled burns on the overall health and diversity of forests.

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Marin Hills from Lincoln Park, San Francisco

Negative date: 1952

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

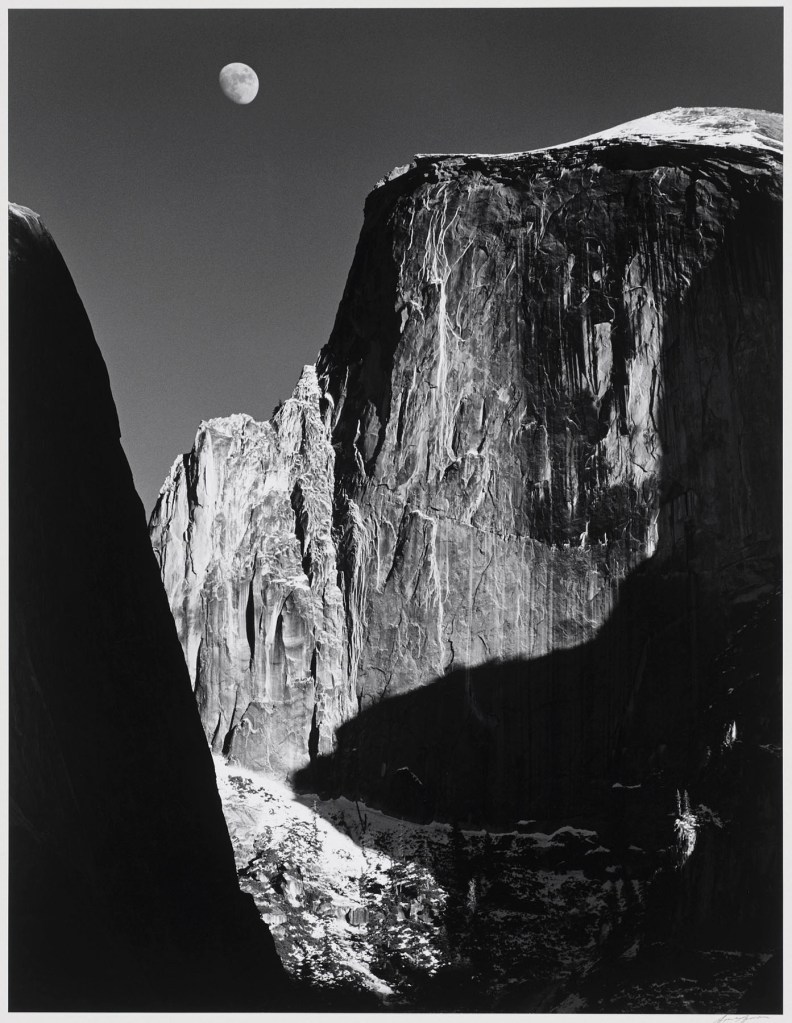

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite National Park

1960

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams made this spectacular image of two of his favourite subjects – Half Dome and the moon – on an autumn afternoon in 1960. He witnessed a brilliant gibbous moon rising to the left fo the vertical rock face and, using a long lens and orange filter, carefully framed what would become one of his most popular late works. “As soon as I saw the moon coming up by Half Dome, I had visualised the image,” Adams wrote.

Exhibition label text

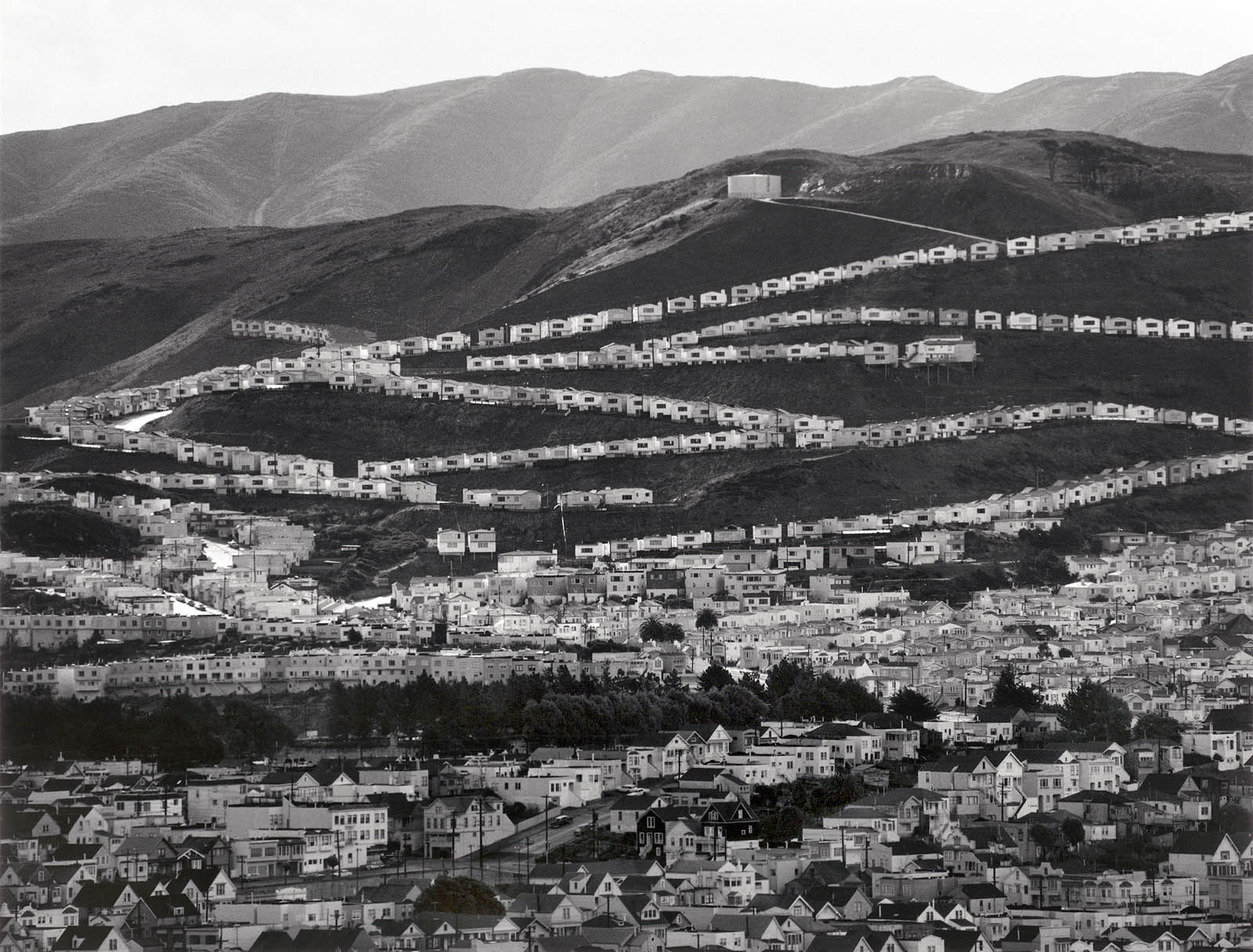

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Housing Development, San Bruno Mountains, San Francisco

About 1966

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

In the 1950s and 1960s, Ansel Adams often recorded urban subjects like this view looking toward San Bruno Mountain, just south of San Francisco. Here Adams documents one of the many tract housing developments built during this period, as it snakes across the steep hillsides surrounding the rapidly growing city.

Exhibition label text

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Mount Starr King and Glacier Point, Yosemite, No. 69

1865-1866

Mammoth albumen print from wet collodion negative

Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow Fund

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Carleton E. Watkins took this photograph from the floor of Yosemite Valley while working for the California State Geological Survey in the mid-1860s. It is a more intimate and less sweeping view than the photograph Watkins self-described as the “best general view of Yosemite” (below), which presents the most recognisable features of the landscape.

Mount Starr King, the distant peak at centre, was named for Thomas Starr King, the Unitarian minister from Boston whose life and ministry were powerfully influenced by his experiences in the Yosemite wilderness. Ansel Adams later shared his “disregard for the naming of things and [his skepticism] of those non-professionals who go through the wilderness classifying and labelling everything in sight.”

Exhibition label text

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Yosemite from the Best General View No. 2

1866

Installation view of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco showing at left, Adams’ The Golden Gate Before the Bridge (1932, above); and at second right, Eadweard J. Muybridge’s Valley of the Yosemite from Union Point, No. 33 (1872, below)

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Photo: Gary Sexton

Eadweard J. Muybridge (American, 1830-1904)

Valley of the Yosemite from Union Point, No. 33

1872

Albumen print

Gift of Charles T. and Alma A. Isaacs

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Eadweard Muybridge first came to Yosemite in the 1860s. Capitalising on the growing popularity of wilderness landscape subjects, he stayed for six months, making large-format albumen prints and stereo views. Hoping to compete with Carleton E. Watkins’s earlier grand vistas, he returned in 1872 with a mammoth-plate camera. Often, Muybridge shot his atmospheric images from unusual perspectives, with sharp contrasts between foreground and background, light and shadow. This is evident in this photograph taken from Union Point, which provided a closer view of the valley and a greater sense of three-dimensional space than the better-known Glacier Point above.

Exhibition label text

Frank Jay Haynes (American, 1853–1921)

Grand Canyon of Yellowstone and Falls

About 1887

Albumen print

Sophie M. Friedman Fund

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Frank Jay Haynes was one of the second generation of photographers to be employed by the railroads and government surveys in the American West in the late nineteenth century. In 1884, he was named official photographer and concessionaire of Yellowstone to serve the growing numbers of tourists coming to visit the first national park. Yellowstone is situated on top of a massive subterranean volcano, which produces its active hot springs and towering geysers, such as Old Faithful. For his photograph of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River, Haynes used a mammoth-plate camera to produce a large glass negative, from which he made this highly detailed contact print.

Exhibition label text

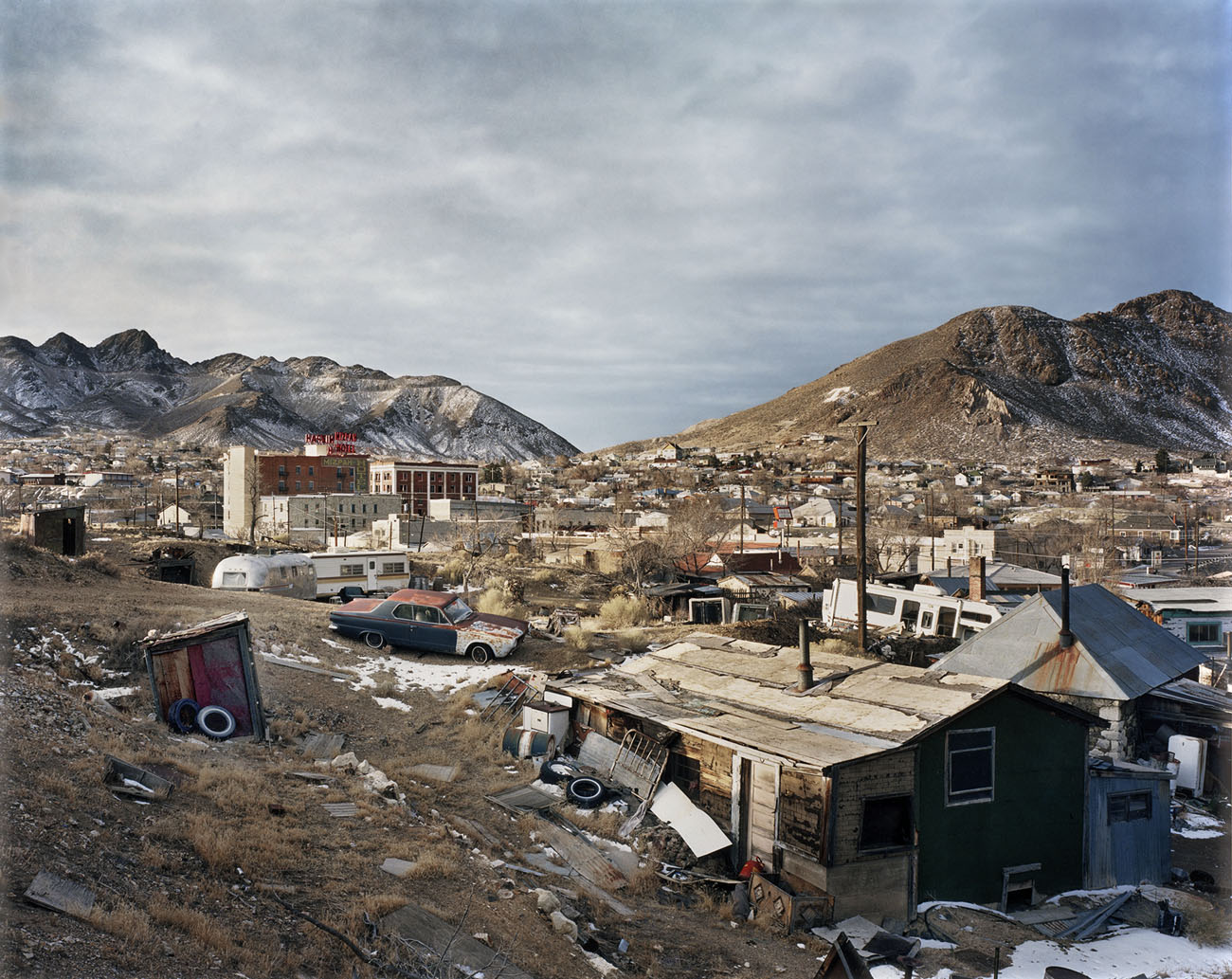

Bryan Schutmaat (American, b. 1983)

Tonopah, NV

Nd

Inkjet print

Gift of Jessie H. Wilkinson – Jessie H. Wilkinson Fund

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Bryan Schutmaat

These Nevada landscapes are from Grays the Mountain Sends, a series that depicts the landscapes, structures, and residents of former mining towns. Bryan Schutmaat seeks out these far-flung mountain communities, now mostly abandoned due to the loss of their mineral wealth.

Not unlike Ansel Adams’ fleeting view of Hernandez, New Mexico, first seen in his rearview mirror, Schutmaat’s vision is that of an extended road trip. And like Adams, he is drawn to the methodical way that his large-format camera forces him to work. He waits patiently for the changing light to activate a scene. For Schutmaat, each town’s deserted structures and lonely inhabitants stand as last “relics of hope” and proof of the tragic demise of the American dream. The fragile, hardscrabble beauty of these modern-day ghost towns is also a powerful reminder of the region’s uncertain future and its long history of economic booms and busts.

Exhibition label text

Installation view of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco showing at foreground left and right, works by Mark C. Klett (below)

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Photo: Gary Sexton

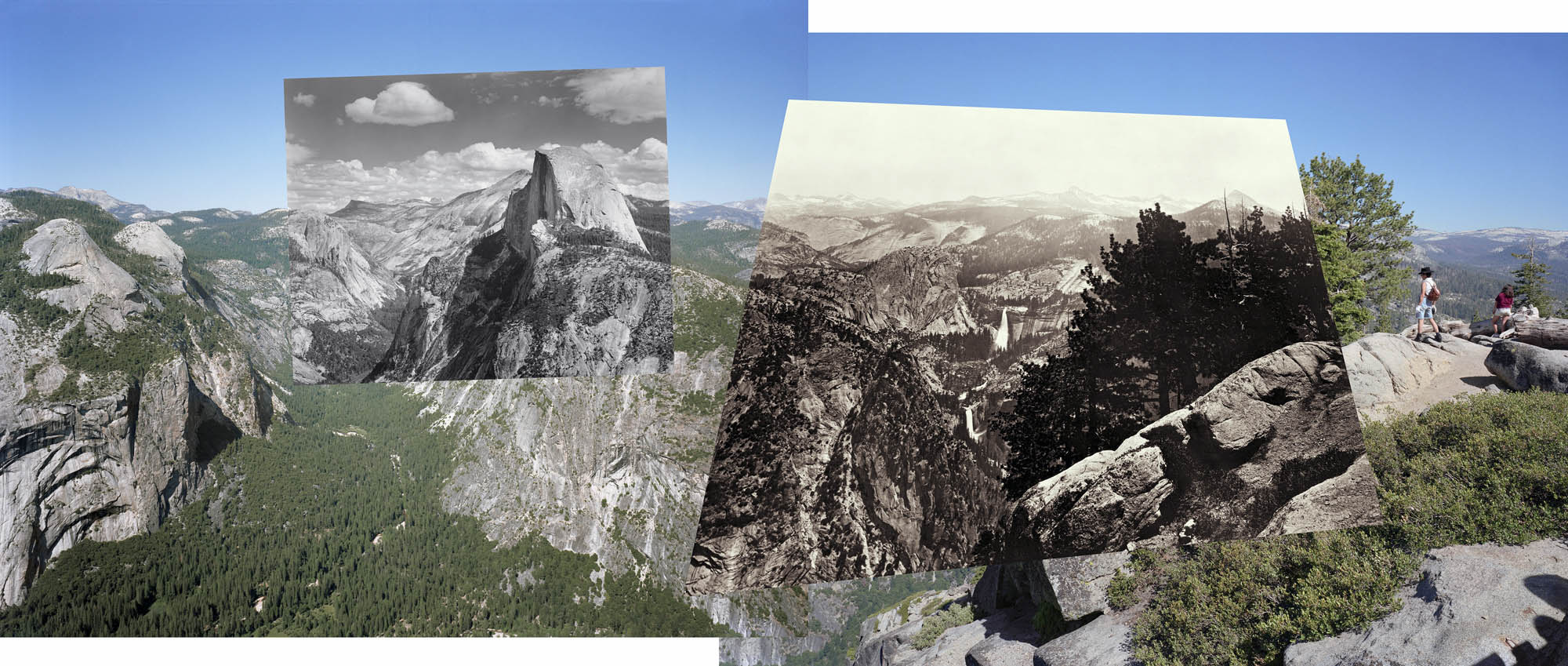

Mark C. Klett (American, b. 1952) and Byron Wolfe (American, b. 1967)

View from the handrail at Glacier Point overlook, connecting views from Ansel Adams to Carleton Watkins

2003

Archival pigment print

© Mark Klett & Byron Wolfe

Courtesy Etherton Gallery

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“[Ansel Adams’] depopulated scenes suggest that the landscape does best without our presence, and that wilderness is an entity defined by our absence. However, anyone who has visited the site of one of Adams’ photographs knows that the romance of his landscapes is often best experienced in the photographs themselves. The reality of place is quite different. … The natural beauty of the land is still there to be seen, but you will not see it alone.” ~ Mark Klett

Mark Klett has photographed and rephotographed the western American landscape for more than thirty years. With his longtime collaborator, Byron Wolfe, Klett carefully studies prints by Carleton E. Watkins and other nineteenth-century wilderness photographers, as well as twentieth-century modernists like Ansel Adams. By studying the shadows, they determine the time of year and time of day that an image was made. Once on-site, Klett photographs the view with Polaroid film, and Wolfe measures that image against the original photograph, repeating the process until they locate exactly where the earlier photographer stood. By visually collapsing time and space in this composite panorama of Yosemite Valley, Klett and Wolfe document changes to the landscape over more than a century.

Exhibition label text

The Changing Landscape

In his own time, Ansel Adams was aware of the environmental concerns facing California and the nation. Although Adams continued to make symphonic and pristine wilderness landscapes, as his career progressed, he began to create images that showed a more nuanced vision – images that decidedly break with widely held ideas about his work. He photographed urban sprawl, freeways, graffiti, oil drilling, ghost towns, rural cemeteries, mining towns, and the sometimes-dispossessed inhabitants of those places, as well as less romantic views of nature, such as the aftermath of forest fires.

Appreciated for their imagery and formal qualities, Adams’ photo-graphs also carry a message of advocacy. Photographers working in the American West today confront a changed, and changing, landscape. Human activity – urbanisation, logging, mining, ranching, irrigated farming – and global warming continue to alter the terrain. Works by contemporary artists bear witness to these changes and their impacts, countering notions that our natural resources are limitless. Placed in conversation with Adams’ photographs, these images aid our understanding of his singular contribution to the ways we envision the landscape and the urgency with which we must protect it.

Exhibition wall text

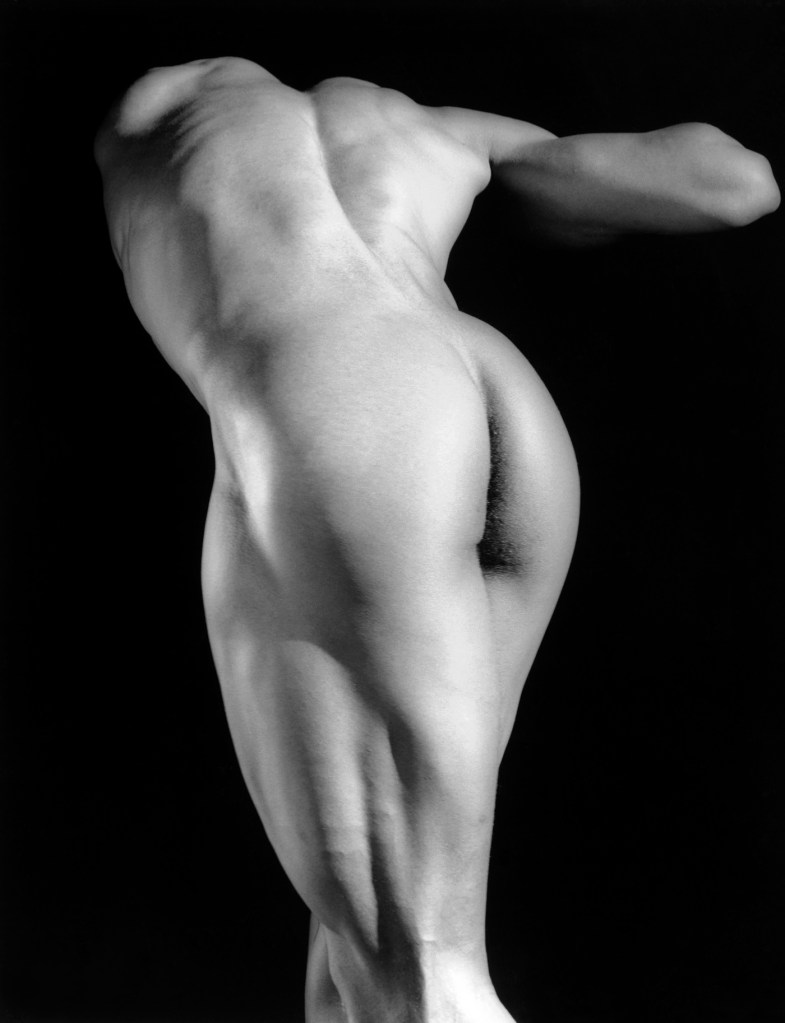

Arno Rafael Minkkinen (American born Finland, b. 1945)

Homage to Watkins, Yosemite

2007

Inkjet print

Sophie M. Friedman Fund

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Arno Rafael Minkkinen

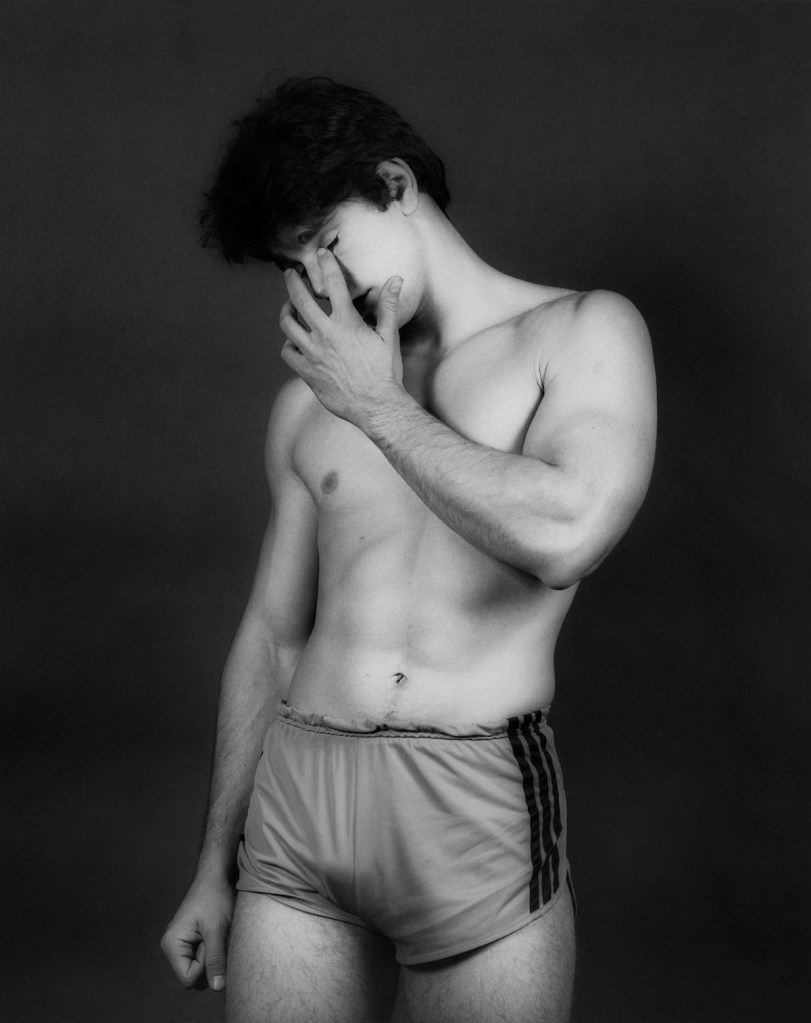

Several of the contemporary photographers in this exhibition call into question the archetypal images of empty wilderness spaces that have long held a central place in the popular imagination. Arno Rafael Minkkinen activates pristine, unpopulated landscapes by introducing his own naked body into them, without relying on digital manipulation. Here, the artist’s seemingly headless torso and the gentle curve of his outstretched arms perfectly echo the bowl-shaped Yosemite Valley as seen from Inspiration Point.

Exhibition label text

Installation view of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco showing at left in the light panel, Laura McPhee’s Early Spring (Peeling Bark in Rain) (2008, below); and at second right, Mitch Epstein’s Altamont Pass Wind Farm, California (2007, below)

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Photo: Gary Sexton

Mitch Epstein (American, b. 1952)

Altamont Pass Wind Farm, California

2007

Chromogenic print

Courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Reproduced with permission

Mitch Epstein’s American Power series investigates energy in its many forms by exploring how we create and consume it, as well as its impact on our daily lives. Often employing a bird’s-eye view and printed on a very large scale, Epstein’s photographs – like these showing oil drilling, wind turbines, desert irrigation, and suburban sprawl – call into question the very definition of power and point to our shared accountability for the abuse of our natural resources. In a world in which we are constantly inundated with photographs, these densely detailed views are also meant to slow down our “reading” of the images and remind us that each may be interpreted in a variety of ways.

“[The] American Power [series] is an active response to the American dream gone haywire. My project focuses on the United States not only because I am American, but because the US has exported its model of unrestricted growth around the world in the form of mass consumerism, corporatism, and sprawl.

“We need to now export a revised model of growth, a revised American dream. I included pictures in American Power of renewable energy – wind, biotech, solar – to show that a healthier, more economical, and compassionate way of life is possible. American Power bears witness to the cost of growth; it asks viewers to consider the landscape they have created – and take responsibility for it.” ~ Mitch Epstein

Exhibition label text

Laura McPhee (American, b. 1958)

Early Spring (Peeling Bark in Rain)

2008

Inkjet print (diptych)

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Courtesy of the artist

© Laura McPhee

Working with a large-format camera, Laura McPhee records the impact of human activity on the land, especially in Idaho, a state she loves and visits regularly. These photographs from her Guardians of Solitude series were made in the aftermath of a massive forest fire. Caused by human error, it devastated thousands of acres of woodland before it was finally extinguished. McPhee returned to the area three years later to find that it had burst into bloom. In the renewal of the charred landscape, she found a powerful metaphor for human resilience in the face of terrible personal loss.

Exhibition label text

Installation view of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco showing the work of Abelardo Morell including at left centre, Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of the Yosemite Valley from Tunnel View (2012, below); at centre, Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of Old Faithful Geyser, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming (2011, below); and at right his Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of Mount Moran and the Snake River from Oxbow Bend, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (2011, below)

Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Photo: Gary Sexton

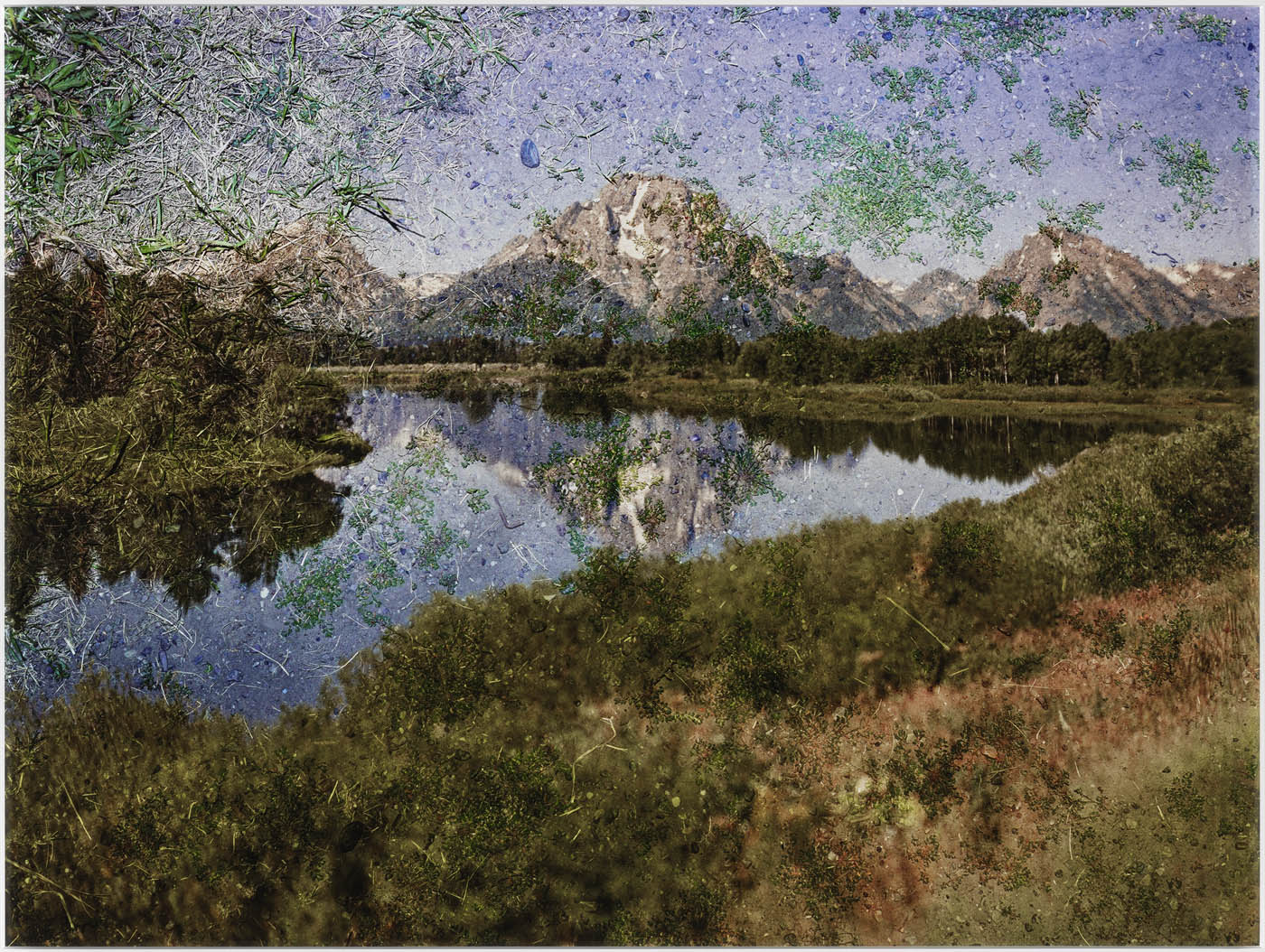

Abelardo Morell (American born Cuba, b. 1948)

Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of Old Faithful Geyser, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

2011

Inkjet print

Gift of the artist in memory of Robert Andrew McElaney

© Abelardo Morell/Courtesy Bonni Benrubi Gallery, NYC

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Early in his career, Abelardo Morell began experimenting with the camera obscura (from the Latin for “dark room”), a setup that allowed him to photograph the view outside, projected through a small hole (or lens) and inverted on the opposite wall of an interior. More recently, Morell has adapted this technology, using a tent fitted with a periscope and angled mirror, with a digital camera pointed downward to capture the sweeping landscapes reflected on the ground. This process of combining the distant view with the grass, pebbles, pine needles, sand – even pavement – underfoot, allows Morell to turn the terrain into his “canvas” and transform familiar scenes into otherworldly, impressionistic images.

Exhibition label text

Abelardo Morell (American born Cuba, b. 1948)

Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of Mount Moran and the Snake River from Oxbow Bend, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming

2011

Inkjet print

Gift of the artist in memory of Robert Andrew McElaney

© Abelardo Morell/Courtesy Bonni Benrubi Gallery, NYC

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Like several of the contemporary artists in this gallery, Abelardo Morell is a foreign-born photographer for whom US national parks hold special meaning. While growing up in Cuba, he fell in love with the popular Hollywood Westerns playing at the local cinema. Once he immigrated to the United States, he was eager to discover the region for himself. Here he takes in the sweeping grandeur of snowcapped Mount Moran and the Snake River from a vantage point similar to the one employed by Ansel Adams seventy years earlier for his photograph of Grand Tetons National Park (on view nearby).

Exhibition label text

Abelardo Morell (American born Cuba, b. 1948)

Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of the Yosemite Valley from Tunnel View

2012

Inkjet print

Gift of the artist in memory of Robert Andrew McElaney

© Abelardo Morell/Courtesy Bonni Benrubi Gallery, NYC

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Abelardo Morell made this photograph along the Rio Grande River, which runs for more than one hundred miles through Big Bend National Park in southwest Texas, forming the border between the United States and Mexico. The tranquility of the scene belies the fact that this is contested space, sometimes violently so. Morell’s tent camera optically inverts the river’s northern and southern banks, and the mysteriously floating compass further compounds the sense of dislocation or disorientation.

Exhibition label text

John K. Hillers (American born Germany, 1843-1925)

Zuni Pueblo, Looking Southeast

c. 1879

Albumen print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Images such as this one, created in the 1870s and 1880s as ethnographic data for the US government, often ended up in popular magazines, perpetuating problematic stereotypes of Indigenous people. Beginning in 1871, John K. “Jack” Hillers worked on John Wesley Powell’s survey expeditions for such data. He continued to work under Powell’s leadership at the US Bureau of Ethnology for nearly thirty years. Hired by Powell to photograph Indigenous people living in agrarian communities in New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, Hillers made his most extensive photographic record at Zuni Pueblo in the high plateau region of New Mexico. The photograph is taken at the middle place, or Halona I:diwanna in Zuni/A:shiwi.

Exhibition label text

Adam Clark Vroman (American, 1856-1916)

An Isleta Water Carrier (Nine of Spades)

c. 1894

Chara, Cacique at Pueblo (Jack of Clubs)

c. 1894

Playing cards with halftone prints

Lazarus and Melzer (Los Angeles), publishers

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Lewis A. Shepard, 2006

An amateur archaeologist and committed preservationist, Adam Clark Vroman owned a bookstore in Pasadena, California, that also sold photography supplies. In the mid-1890s, he made the first of many photographic trips to Navajo, Pueblo, and Hopi communities in Arizona and New Mexico. Like Edward S. Curtis and other Anglo-American photographers, he approached Indigenous subjects with concern for what he saw as their threatened lifeways. Nevertheless, when he produced this set of playing cards in 1900, his sitters, each representing a different Southwestern tribe, were reduced to elaborately costumed “types” and often were not identified by name, relegating Indigenous people to a novelty. For instance, in one example shown here, a group of young Walpi women is simply captioned “Bashful,” illustrating the limits of Vroman’s ability to respectfully record the identities of his sitters.

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Dance Group, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico

1929

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

“This photo of Cloud Dance (Po-Who-Geh-Owingeh) was taken at a time when there was an influx of tourists, archaeologists, anthropologists, artists, and photographers who were intrigued by Pueblo people. At the time, Pueblo people and other Native Americans in the Southwest were trying to navigate the outsiders who were interested in their culture. Some of them did not quite understand the circumstances surrounding the curiosity, while others did understand the extractive nature, and they had to weigh that in terms of their other needs. I get questions from members of my community about why they did not chase the archaeologists and photographers out, and I often respond it is because of the uneven power relations between Indigenous and non-Native people at the time.” ~ Joseph Aguilar (San Ildefonso Pueblo)

Exhibition label text

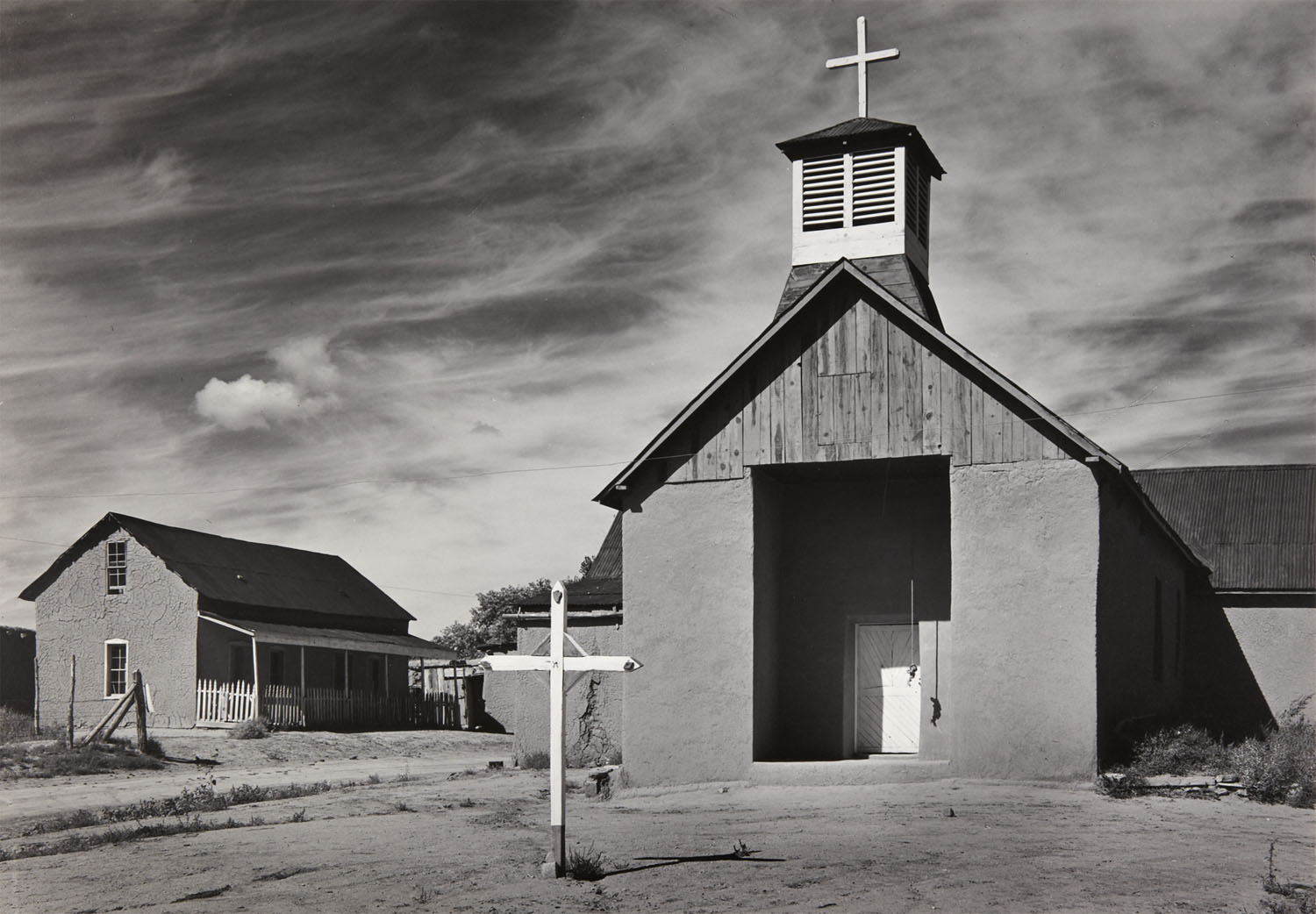

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

White Cross and Church, Coyote, New Mexico

1937

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

In 1937 Ansel Adams spent several weeks traveling in the Southwestern states with painter Georgia O’Keeffe and friends. Adams and O’Keeffe shared an interest in the region’s expansive skies and distinctive mesas, as well as the mix of Indigenous and Spanish cultures. The group first spent two weeks at Ghost Ranch, O’Keeffe’s home in the Chama River Valley of New Mexico. Adams made this picture in a nearby town, perhaps drawn by the way the foreground cross echoes a smaller one on the church steeple. Their road trip took them through Pueblo and Navajo lands in New Mexico and Hopi lands in Arizona; Monument Valley, Canyon de Chelly, and the Grand Canyon in Arizona; and Mesa Verde in Colorado.

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

White House Ruin, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona

1941

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

When a Sierra Club friend gave him a copy of the Wheeler geographical survey album (1871-1874), Ansel Adams had the opportunity to study Timothy H. O’Sullivan’s photographic technique, as well as his subject matter. In 1941, as Adams set out to work in Canyon de Chelly as part of his national parks project, he decided to try to rephotograph O’Sullivan’s view of an Ancestral Pueblo site. Adams used a green filter to replicate the dramatic striations in the canyon walls that are so pronounced in the early print, as otherwise they would not appear in a “straight” print from his modern negative. Of the power of works like this one, Adams said, “O’Sullivan had that extra dimension of feeling. You sense it, you see it.”

Exhibition label text

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American born Ireland, 1840-1882)

Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle

1873

Albumen silver print

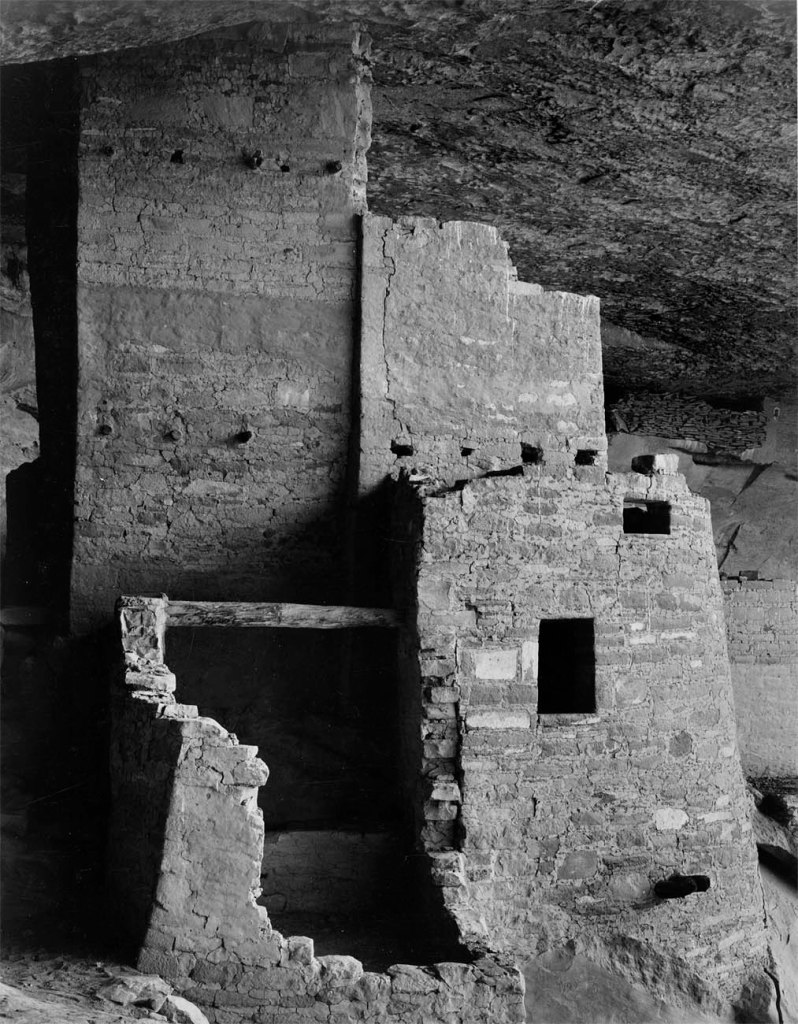

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

1941

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

John K. Hillers (American b. Germany, 1843-1925)

Hedipa, Diné (Navajo) Woman

c. 1879

Albumen print

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gift of Jessie H. Wilkinson – Jessie H. Wilkinson Fund

Between 1879 and 1881, Hillers extensively documented the pueblo at Zuni, photographing not only its people and distinctive multi-storied adobe architecture, but also its relationship to the surrounding land. He made panoramic views of the pueblo and recorded cultural observances including ceremonial dance and individual artisans at work.

The Paiutes of Utah gave John K. Hillers a name that meant “Myself in the Water,” a reference to his ability to record their likenesses using the wet-plate collodion process to produce glass negatives. Here, Hillers has photographed a Diné (Navajo) man and woman in front of boldly patterned blankets, which he used to create a backdrop for his outdoor portrait “studio.”

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Indian Mortar Holes, Big Meadow, Yosemite National Park

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

The Ahwahnechee (Miwok) of Yosemite prepared food and sharpened tools using semi-spherical holes ground into bedrock as mortars and smooth stones as grinding tools (or pestles). Acorns of the black oak trees were a diet staple once abundant in the region. Settler colonialism, logging in the nineteenth century, and modern-day fire suppression have led to the growth of mainly conifers in their place.

Exhibition label text

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984)

Freeway Interchange, Los Angeles

1967

Gelatin silver print

The Lane Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams made this aerial view of the famously tangled freeways of Los Angeles while photographing for Fiat Lux (1967), a publication commissioned by the University of California to celebrate its centennial. Intended to serve as a visual document of the entire University of California system, the project saw Adams travel to the nine UC campuses, along with the system’s various research stations, observatories, natural reserves, and agricultural extensions. The most extensive of all his commercial projects, Fiat Lux took Adams three years to complete and resulted in several thousand negatives.

Exhibition label text

Lois Conner (American, b. 1951)

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona

1988

Platinum print

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Otis Norcross Fund

Inspired by the stories told to her by her Cree maternal grandmother, Lois Conner regularly traveled throughout the Navajo Nation and Four Corners region with an old-fashioned banquet camera to document Indigenous people and their land. The elongated format and subtle tonal range of the platinum prints that resulted from these trips seem ideally suited to capturing subjects like the expansive desert landscape of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and the vertiginous rock face of Canyon de Chelly.

“The extended sweep of the panorama allows me to draw on multiple levels, much as cinema does, and to take something of the immediate present, and layer that with something from a few centuries before. The large-format camera can draw the particular in minute detail. Like adjectives in a sentence, they allow the viewer to look closer, engaging them in the little world contained by the frame.” ~ Lois Conner

Exhibition label text

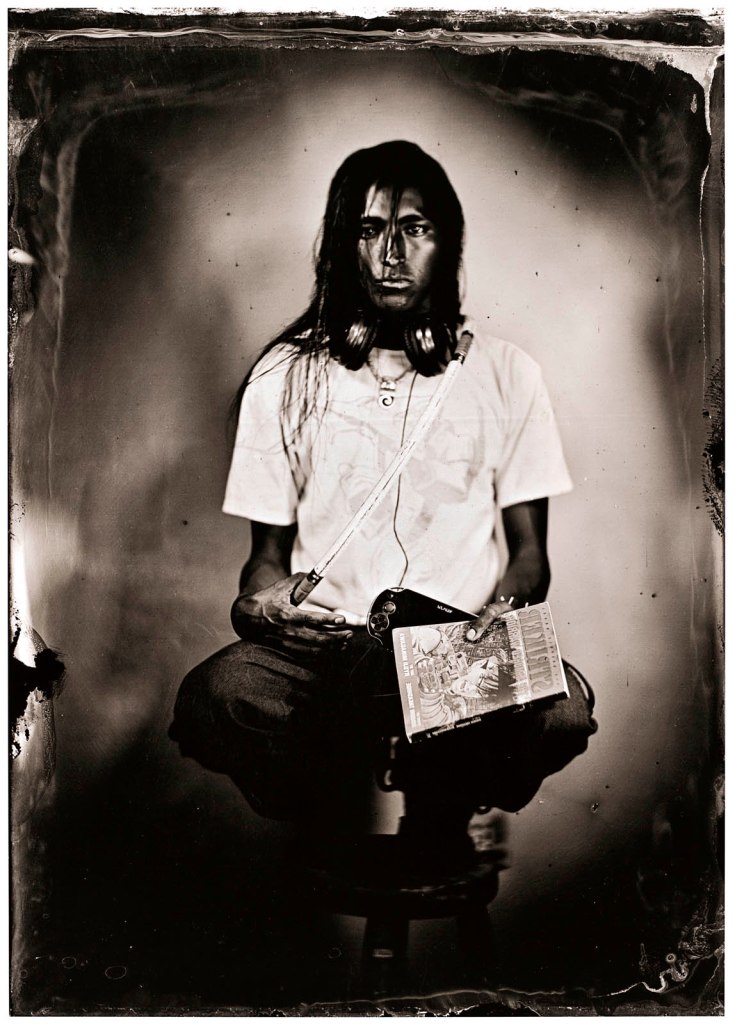

Will Wilson (Native American, Navajo (Diné), b. 1969)

Nakotah LaRance

2012

Inkjet print

The Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Will Wilson

This portrait of six-time world-champion hoop dancer Nakotah LaRance (1989-2020) is from an ongoing series that Will Wilson calls the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX). Using a large-format camera and the wet-plate collodion process – the first photographic process used to image Native Americans – Wilson produces a portrait; he then gives his sitter the original tintype, while he retains a digital copy. Wilson is aware of the long history of inaccurate and romanticised representations of Indigenous people in the United States. His goal is to negotiate a more collaborative relationship between photographer and sitter in order to return personal agency to his subjects, like this young Hopi man with his traditional dance hoop and contemporary headphones, game console, and Japanese manga.

Exhibition label text

Nakotah Lomasohu Raymond LaRance (August 23, 1989 – July 12, 2020) was a Native American hoop dancer and actor. He was a citizen of the Hopi Tribe of Arizona. …

At four years old, LaRance began dancing as a fancy dancer and competed in the youth division of the World Championship Hoop Dance Contest in Phoenix, Arizona. He performed on the Tonight Show with Jay Leno in 2004. LaRance won three championships in the youth division and three in the teenage division of the World Championship Hoop Dance competition.

In 2009, LaRance joined the Cirque du Soleil troupe as a principal dancer. He worked as a traveling performer with the troupe for over three years. In 2015, he danced at the opening of the Pan American Games in Toronto with Cirque du Soleil. He won the title of World Champion at the Hoop Dance Contest three times, as part of the adult division in 2015, 2016 and 2018. LaRance taught hoop dancing to students at the Lightning Boy Foundation in New Mexico.

LaRance died at age 30 on July 12, 2020, after a fall from climbing a bridge in Rio Arriba County, New Mexico.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Installation view of the exhibition Ansel Adams in Our Time at the de Young museum, San Francisco showing at left in the light panel, Will Wilson’s Nakotah LaRance (2012, above); and at centre Will Wilson’s How the West is One (2014, below)

Adams in the American Southwest

Ansel Adams first visited the American Southwest in 1927. While there he collaborated with author Mary Austin on an illustrated book about Taos Pueblo that aimed to communicate the threat tourism in the region posed to the artistic and religious traditions of Indigenous people. Adams made images for the book only after receiving permission from the Taos Pueblo council, to whom he paid a fee and gifted a copy of the finished publication. He also photographed some Indian cultural observances that had become popular attractions among tourists. Adams’s own images of Native dancers have a complex legacy: although he was one of the non-Native onlookers, he carefully framed his views to leave out evidence of the gathered crowds.

In Diné photographer Will Wilson’s ongoing series Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange, the artist responds to and confronts historical depictions of Native Americans by white artists. He focuses in particular on those who traveled west in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to document the Indigenous people they viewed as a “vanishing race” due to US government-sanctioned genocide and settler colonialism.

Exhibition wall text

Will Wilson (Native American, Navajo (Diné), b. 1969)

How the West is One

2014

Inkjet print

The Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Will Wilson

Born in San Francisco, Diné photographer Will Wilson spent his childhood in the Navajo Nation. Today he lives and works in Santa Fe. Made from his original tintypes, Wilson’s double self-portrait shows him in profile, facing off against himself: on one side wearing an elaborate silver and turquoise necklace, and on the other dressed in a cowboy hat and work gloves. The title riffs on the 1962 John Ford movie How the West Was Won, an epic Western of the type that helped turn stereotypical cowboys and Indians into potent symbols for the American public. Wilson’s dual portrait illustrates the disparate ways that he – as a Native American artist – might be portrayed and perceived by others, whereas in his case, the reality lies somewhere between the two.

Exhibition label text

CJ Heyliger (American, b. 1984)

Broken Glass

2015

Inkjet print

William E. Nickerson Fund

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Reproduced with permission

CJ Heyliger makes his desert landscapes in many different places, resulting in images that reveal the sites’ alien beauty and hallucinatory detail. His approach to mapping the terrain on film reduces it to the medium’s most basic elements – simply light and time. Here, he magically transforms a trail of broken glass into a constellation of stars in a night sky, and in North, East, South, West, his multiple exposures of a spiky yucca create a wildly spinning whirligig.

“My current work brings me to places that, for one reason or another, have become geographical outcasts,” says Heyliger. “These scraps of land are often hidden in plain view and are rife with artefacts and submerged histories of their own. Photography allows me to gather these shards of cultural debris and weave them into a new narrative constructed of diverse environments with varying relationships to reality.”

Exhibition label text

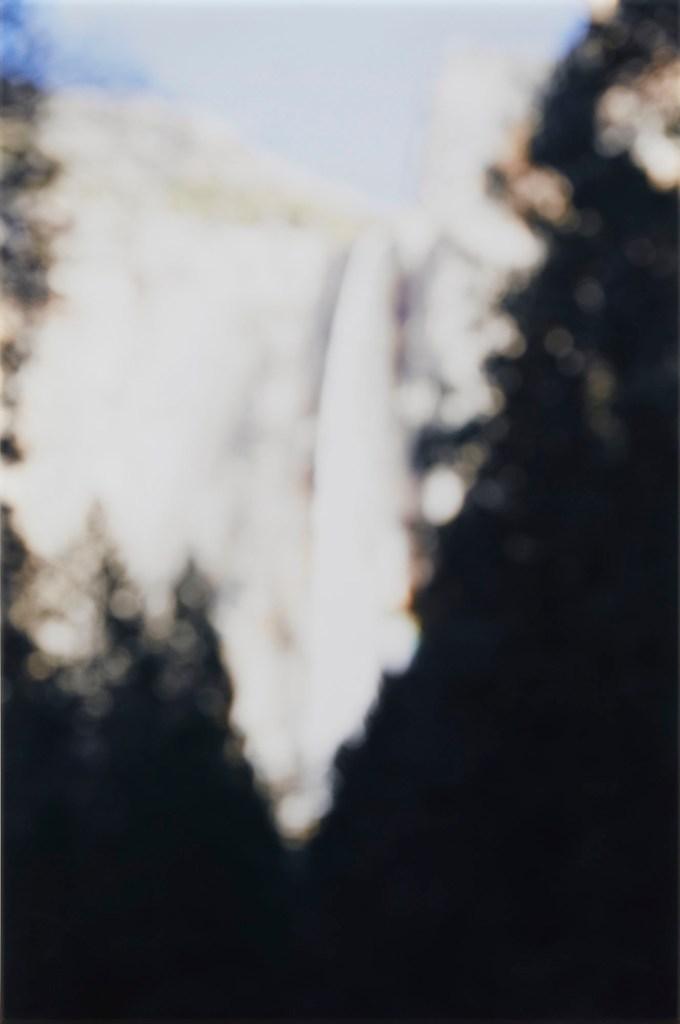

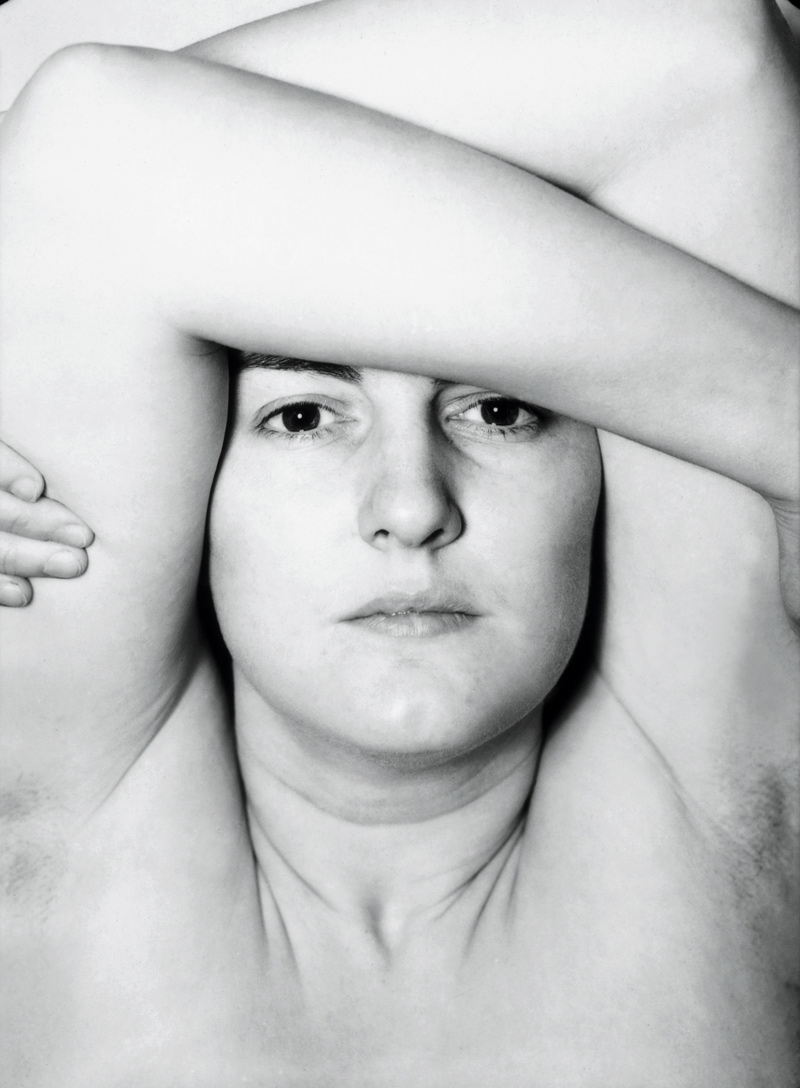

Catherine Opie (American, b. 1961)

Untitled #1 (Yosemite Valley)

2015

Pigment print

Stephen D. and Susan W. Paine Acquisition Fund for 20th century and Contemporary Art

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Catherine Opie. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

Based in Southern California, Catherine Opie is best known for her unflinching portraits – of herself and of members of the lesbian leather community to which she belongs. In 2015, she was commissioned to create a large-scale piece spanning the multi-story atrium of a new federal courthouse in Los Angeles, which inspired her to tackle a very different California subject: Yosemite National Park.

The opportunity to produce such a major work motivated Opie to take on the iconic views of the park’s natural wonders, examine her relationship with these Western landscapes, and try to “de-cliché” them. Her luminous colour images of Yosemite are often soft-focused yet still recognisable, thanks to the popularisation of such views by earlier photographers like Carleton E. Watkins and Ansel Adams. Depicting Yosemite through a feminist lens, Opie seeks to assert her equal rights to such wilderness subjects, previously considered the domain of photographers who are white men.

Exhibition label text

Lucas Foglia (American, b. 1983)

Beach Restoration after El Niño Waves

2016

Inkjet print

Courtesy of the Artist and Fredericks & Freiser, NY

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Lucas Foglia

Hurricane Sandy was a turning point for Lucas Foglia, who witnessed its disastrous impact on his family’s Long Island farm in 2012. Convinced that human behaviour and the changing weather patterns that produce such destructive storms are connected, he decided to document the many ways in which human beings use science and technology to respond to climate change. Now living in California, Foglia photographed workers and machines performing the extremely demanding and futile task of shoring up the Pacific coastline in the face of El Niño wind and waves. His sharply angled viewpoint from the highway above consciously echoes the abstract composition of Ansel Adams’ Surf Sequence of 1940.

Exhibition label text

Binh Danh (Vietnamese-American, b. 1977)

Lower Yosemite Fall, August 16, 2016

2016

Daguerreotype

Mary S. and Edward J. Holmes Fund

Copyright by Binh Danh

Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Binh Danh and his family immigrated to California after the Vietnam War. For much of his early life, he felt little personal connection to this country’s national parks, several of which were located near his home. That sentiment changed once Danh reached adulthood, took up photography, and discovered a new found pride while documenting these wilderness areas using a mobile darkroom and the daguerreotype process developed in France by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in 1839.

Made with a highly polished metal plate, the daguerreotype has a mirror-like surface that allows Danh to capture in stunning detail the same views that he admires in the photographs of Carleton E. Watkins and Ansel Adams. But it also makes it possible for him to create landscapes that reflect his own likeness back to him, literally situating him within those very American spaces.

Exhibition label text

de Young

Golden Gate Park

50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive

San Francisco, CA 94118

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 9.30am – 5.15pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.