Exhibition dates: 26th February – 11th June 2012

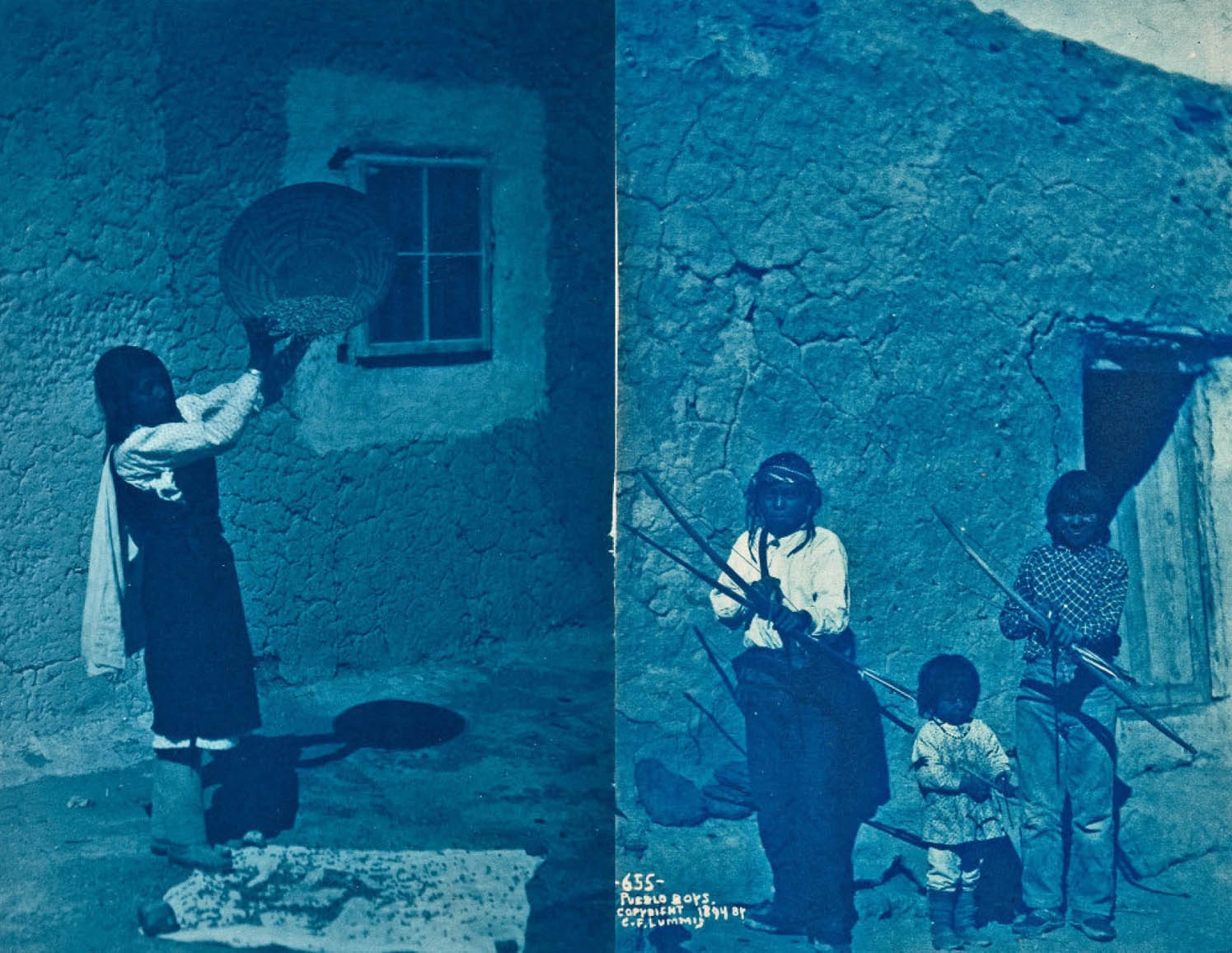

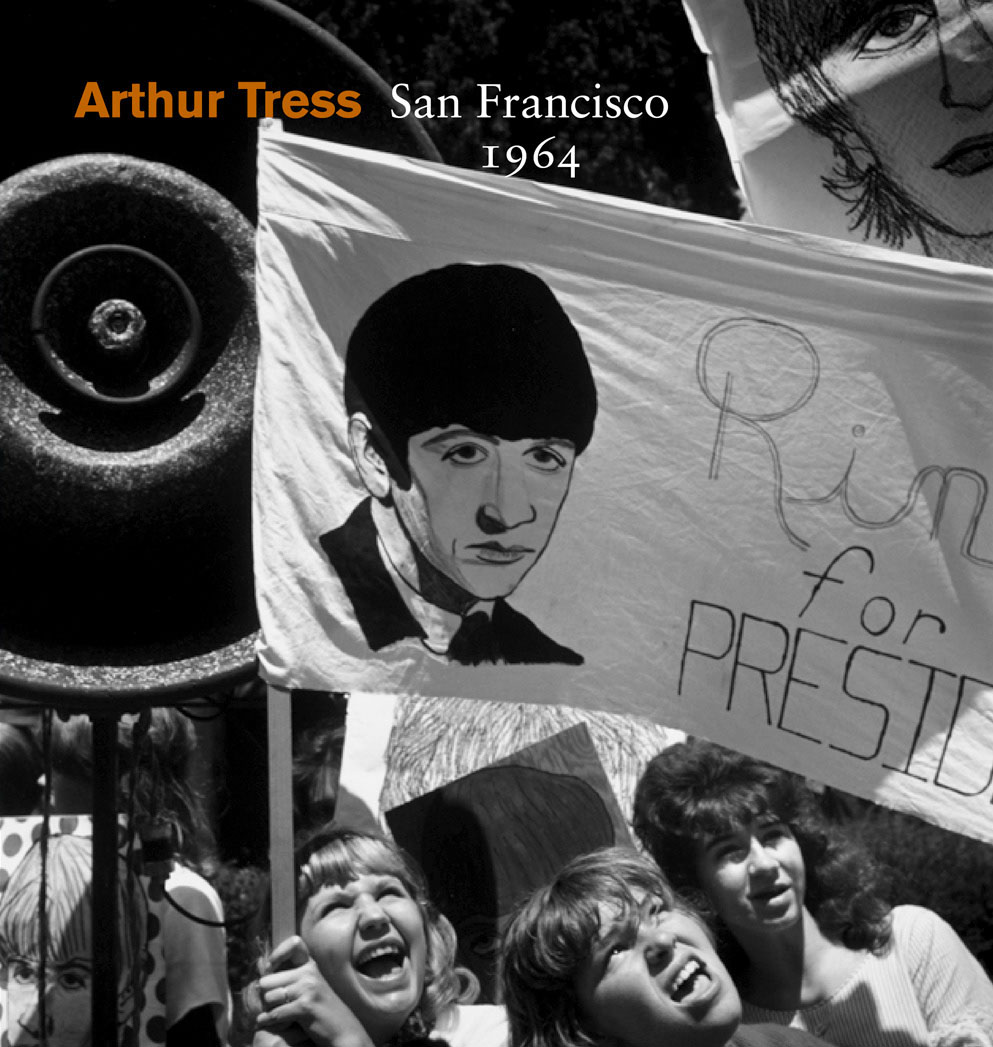

Installation view of the exhibition Cindy Sherman at MoMA, New York showing at left and centre, Cindy Sherman society portraits (2008)

Ceaselessly inventive, the bodies (literally) of work of Cindy Sherman are a wonder to behold. From film stills to head shots, from history portrait to society portraits, Sherman constantly reinvents herself, her variations of identity exploring “the complexity of representation in a world saturated with images,” her iterations into the construction of femininity and masculinity constantly “provocative, disparaging, empathetic, and mysterious.”

Where to next? Her recent series of digitally altered landscapes and portraits (Cindy Sherman at Metro Pictures, New York, April – June 2012) seem less resolved than her earlier work, becoming almost a pastiche of themselves. Despite their massive size they seem to lack resolution, the great female impersonator of our time relying for effect on Self as feminine earth (m)Other, tricked up in dubious, quasi-ethnic regalia. Sherman is almost sacrosanct with regard to criticism but it’s about time someone said it: these images are pretty awful.

After so many simulacra, so many layerings and expositions of identity isn’t it about time Sherman got back to basics and ditched these grandiose notions of identity sublime. The sublimation (an unconscious defence mechanism by which consciously unacceptable instinctual drives are expressed in personally and socially acceptable channels) of her/Self, her actual body, the energy of her (non) presence is finally starting to wear thin. Will the real Cindy Sherman (if ever there is such a thing) please stand up and tell us: what do you really stand for, where as a human being, is your spirit really at?

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to MoMA for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

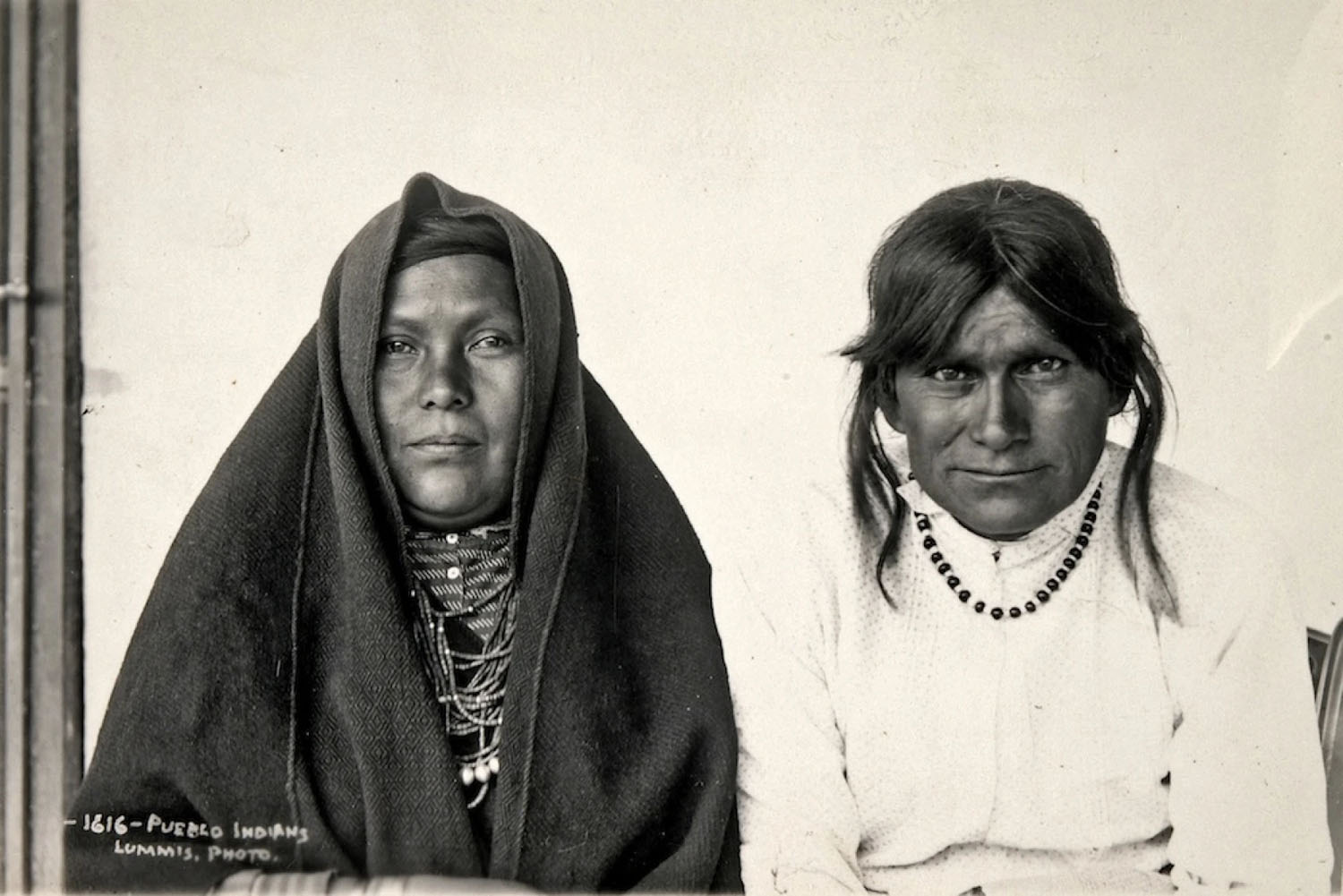

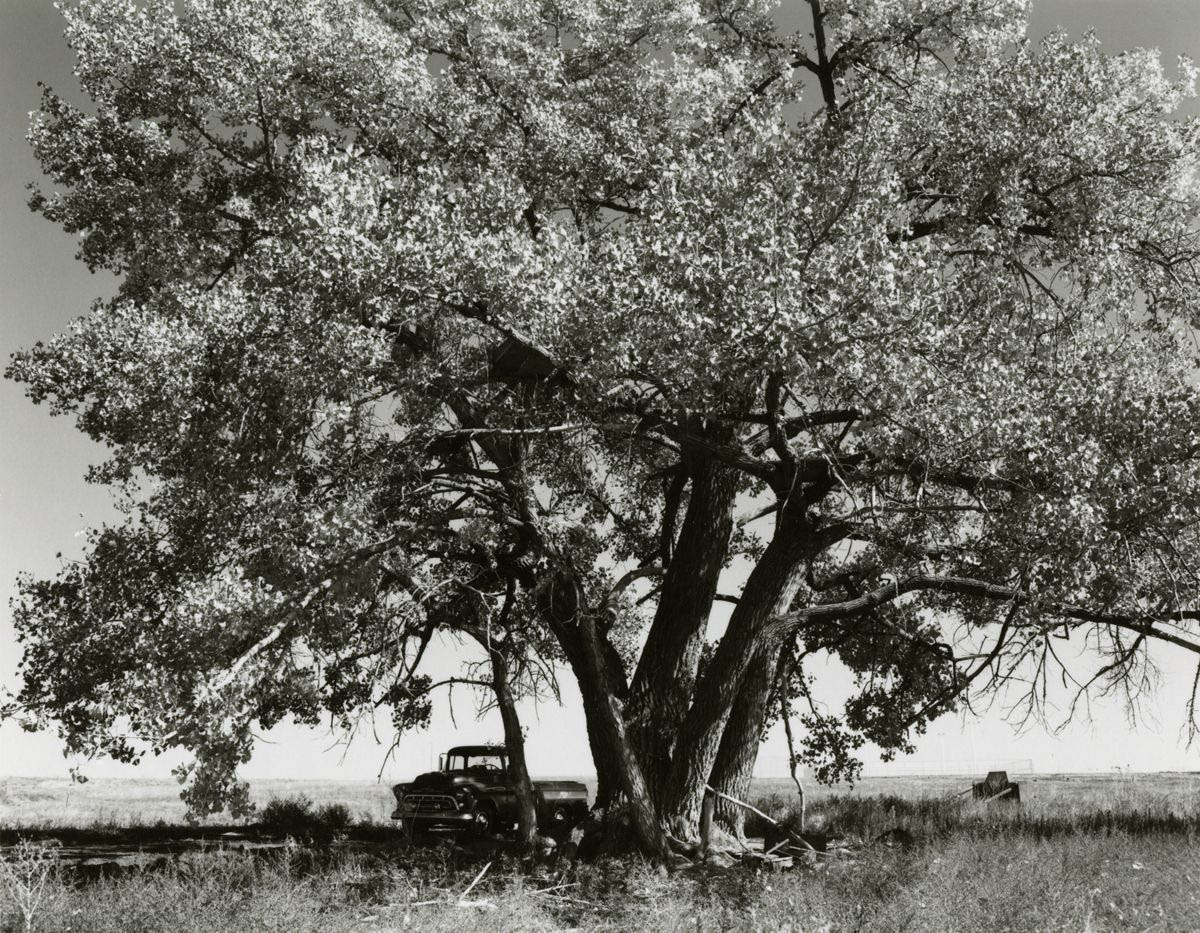

Installation view of the exhibition Cindy Sherman at MoMA, New York showing Cindy Sherman history portraits (1988-1990)

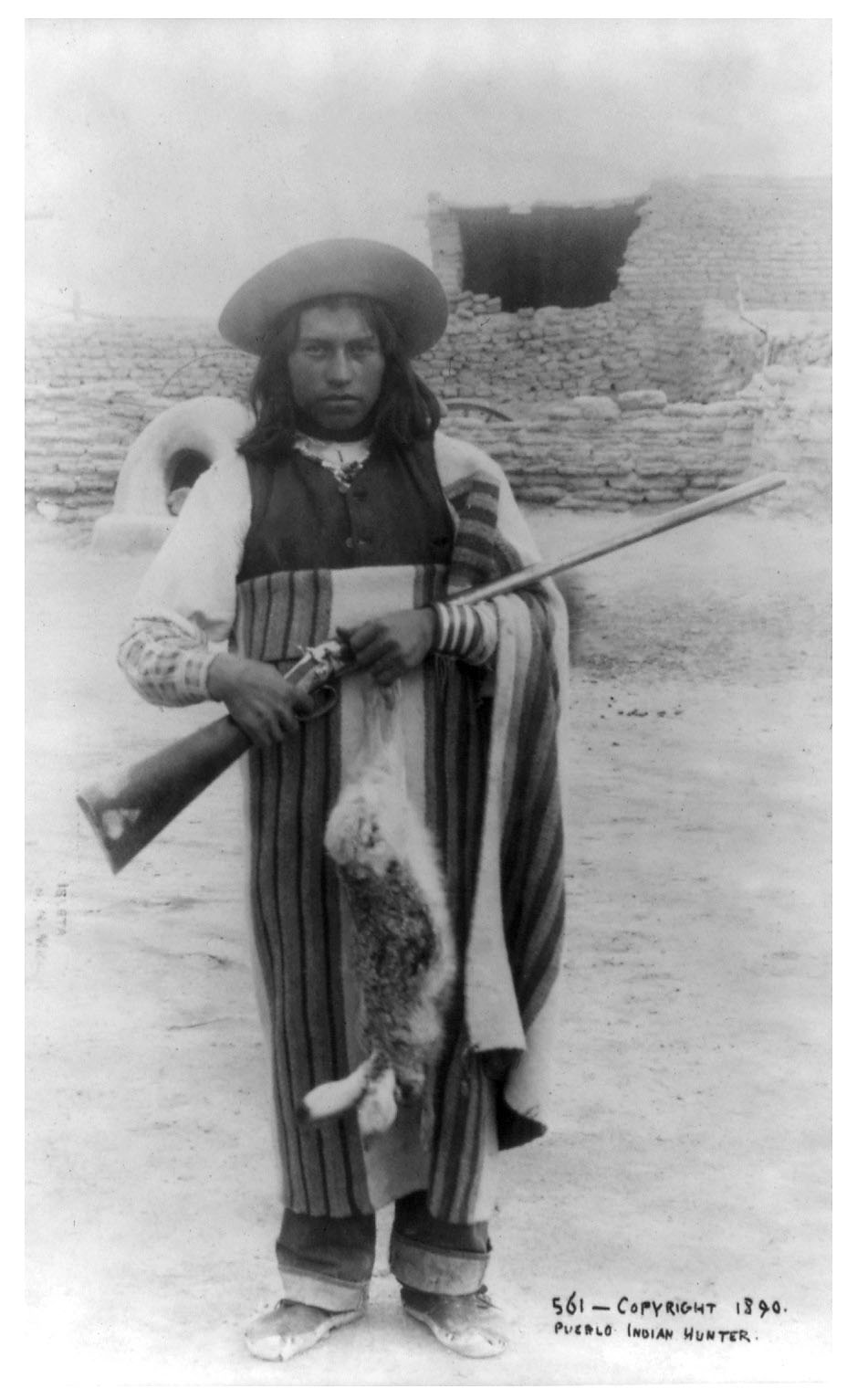

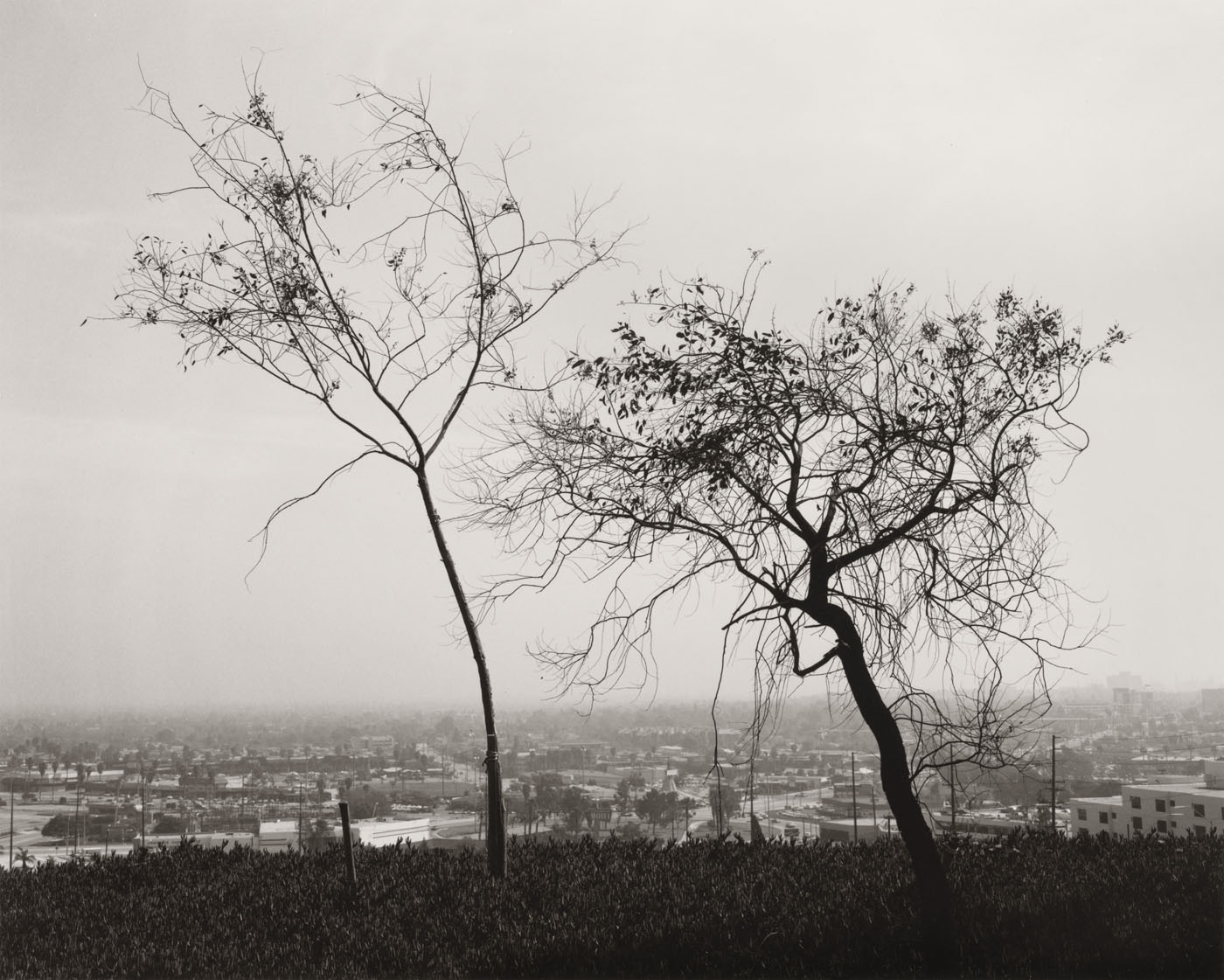

Installation view of the exhibition Cindy Sherman at MoMA, New York showing Cindy Sherman headshots (2000-2002)

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled Film Still #21

1978

Gelatin silver print

7 1/2 x 9 1/2″ (19.1 x 24.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Horace W. Goldsmith Fund through Robert B. Menschel

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled Film Still #6

1977

Gelatin silver print

9 7/16 x 6 1/2″ (24 x 16.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder in memory of Eugene M. Schwartz

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled Film Still #56

1980

Gelatin silver print

6 3/8 x 9 7/16″ (16.2 x 24cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder in memory of Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd

Gallery 2

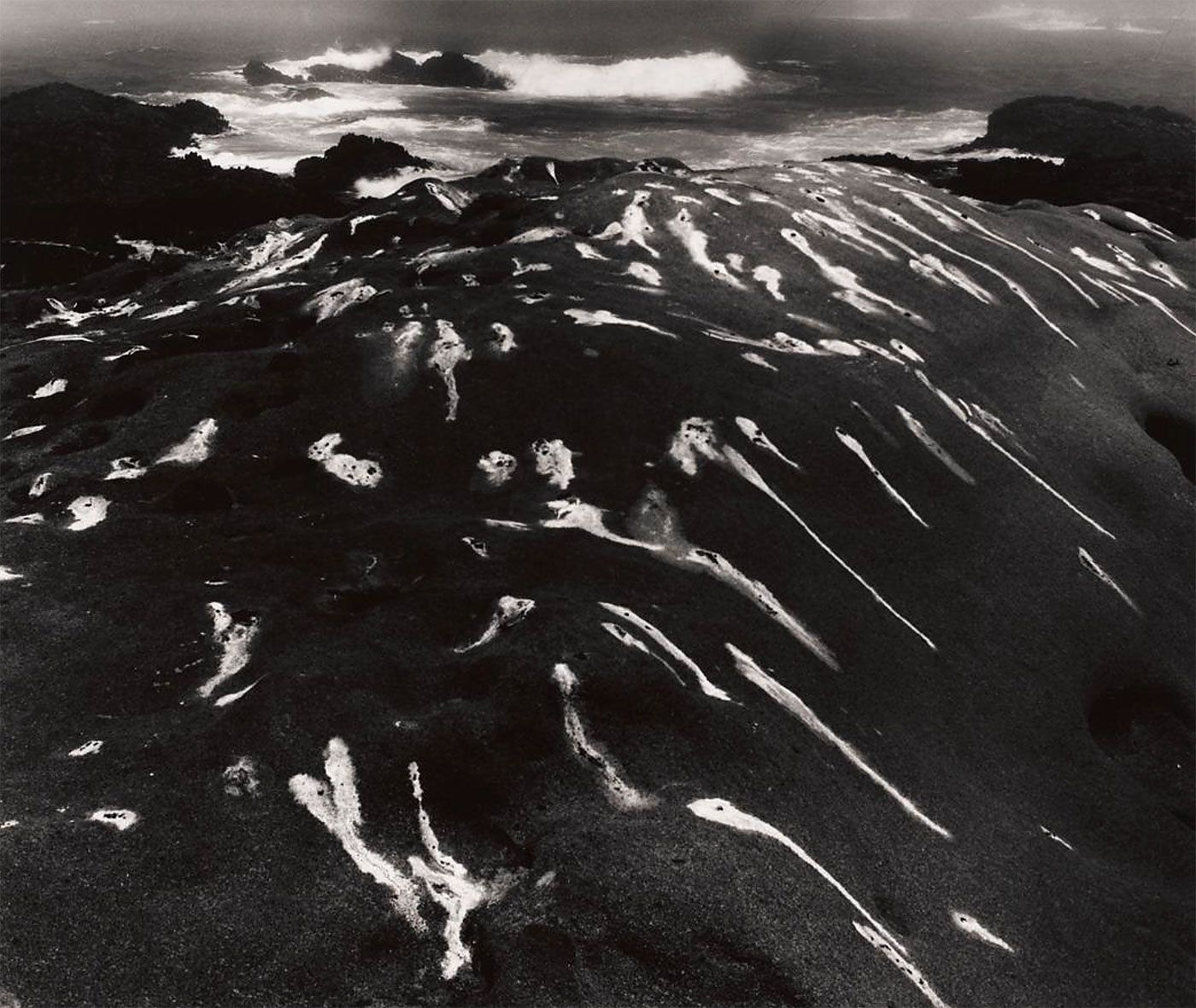

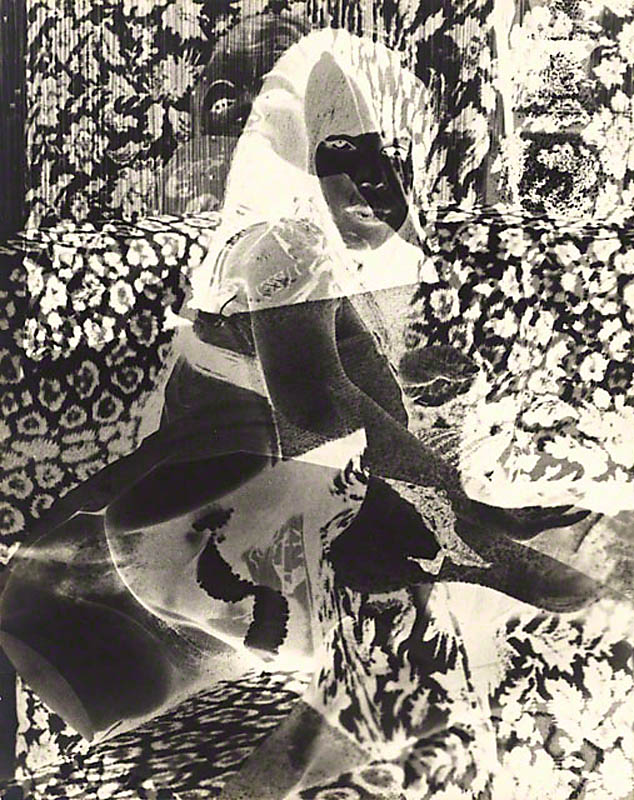

In fall 1977, Sherman began making pictures that would eventually become her groundbreaking Untitled Film Stills. Over three years, the series (presented here in its entirety) grew to comprise a total of seventy black-and-white photographs. Taken as a whole, the Untitled Film Stills – resembling publicity pictures made on movie sets – read like an encyclopaedic roster of stereotypical female roles inspired by 1950s and 1960s Hollywood, film noir, B movies, and European art-house films. But while the characters and scenarios may seem familiar, Sherman’s Stills are entirely fictitious; they represent clichés (career girl, bombshell, girl on the run, vamp, housewife, and so on) that are deeply embedded in the cultural imagination. While the pictures can be appreciated individually, much of their significance comes in the endless variation of identities from one photograph to the next. As a group they explore the complexity of representation in a world saturated with images, and refer to the cultural filter of images (moving and still) through which we see the world.

Wall text from the exhibition

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #137

1984

Chromogenic colour print

70 1/2 x 47 3/4″ (179.1 x 121.3cm)

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Purchased with the Alice Newton Osborn Fund, 1985

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #458

2007-08

Chromogenic colour print

6′ 5 3/8″ x 58 1/4″ (196.5 x 148cm)

Glenstone

Gallery 3

Fashion – a daily form of masquerade that communicates culture, gender, and class – has been a constant source of inspiration for Sherman and a leading ingredient in the creation of her work. Throughout her career the artist has completed a number of commissions for fashion designers and magazines, and this gallery gathers many of these works. Sherman’s fashion pictures challenge the industry’s conventions of beauty and grace. Her first such commission, made in 1983, parodies typical fashion photography. Rather than projecting glamour, sex, or wealth, the pictures feature characters that are far from desirable – whether goofy, hysterical, angry, or slightly mad. Later commissions resulted in more extreme images of characters with bloodshot eyes, bruises, and scars. These exaggerated figures reached ostentatious heights in a 2007-08 commission, in which fashion victims – including steely fashion editors, PR mavens, assistant buyers, and wannabe fashionistas – wear clothing designed by Balenciaga and ham it up for the camera. Sherman’s interest in the construction of femininity and the mass circulation of images informs much of her work; the projects that take fashion as their subject illustrate the artist’s fascination with fashion images but also her critique of what they represent.

Wall text from the exhibition

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #424

2004

Chromogenic colour print

53 3/4 x 54 3/4″ (136.5 x 139.1cm)

Holzer Family Collection

Gallery 5

Sherman, who photographs alone in her studio, has used a variety of techniques to suggest different locations and imaginary (sometimes impossible) spaces, extending the narrative possibilities of her images. In her first foray into colour, in 1980, the artist photographed herself in front of rear-screen projections of various cityscapes and landscapes, evoking films from the 1950s and 1960s that used similar techniques to create the illusion of a change in location. In later series, such as the head shots (2000-2002), clowns (2003-04), and society portraits (2008), the artist used digital tools to create a variety of environments. The garish fluorescent colours in a clown picture contribute to the disturbing quality of the portrait, while a fairy tale forest provides a dreamy backdrop for a well-to-do lady.

Wall text from the exhibition

The Museum of Modern Art presents the exhibition Cindy Sherman, a retrospective tracing the groundbreaking artist’s career from the mid-1970s to the present, from February 26 to June 11, 2012. The exhibition brings together 171 key photographs from the artist’s significant series – including the complete Untitled Film Stills (1977-80), the critically acclaimed centerfolds (1981), and the celebrated history portraits (1988-90) – plus examples from all of her most important bodies of work, ranging from her fashion photography of the early 1980s to the breakthrough sex pictures of 1992 to her 2003-04 clowns and monumental society portraits from 2008. In addition, the exhibition features the American premiere of her 2010 photographic mural. An exhibition of films drawn from MoMA’s collection selected by Sherman will also be presented in the Museum’s theatres in April. Cindy Sherman is organised by Eva Respini, Associate Curator, with Lucy Gallun, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art.

Cindy Sherman is widely considered to be one of the most important and influential artists of our time and her work is the unchallenged cornerstone of post-modern photography. Masquerading as a myriad of characters in front of her own camera, Sherman creates invented personas and tableaus that examine the construction of identity, the nature of representation, and the artifice of photography. Her works speak to an increasingly image-saturated world, drawing on the unlimited supply of visual material provided by movies, television, magazines, the Internet, and art history.

Ms. Respini says, “To create her photographs, Sherman works unassisted in her studio and assumes multiple roles as photographer, model, art director, make-up artist, hairdresser, and stylist. Whether portraying a career girl or a blond bombshell, a fashion victim or a clown, a French aristocrat or a society lady of a certain age, for over 35 years this relentlessly adventurous artist has created an eloquent and provocative body of work that resonates deeply with our visual culture.”

The American premiere of Sherman’s recent photographic mural (2010) will be installed outside the galleries on the sixth floor. The mural represents the artist’s first foray into transforming space through site-specific fictive environments. In the mural Sherman transforms her face via digital means, exaggerating her features through Photoshop by elongating her nose, narrowing her eyes, or creating smaller lips. The characters, who sport an odd mix of costumes and are taken from daily life, are elevated to larger-than-life status and tower over the viewer. Set against a decorative toile backdrop, her characters seem like protagonists from their own carnivalesque worlds, where fantasy and reality merge. The emphasis on new work presents an opportunity for reassessment in light of the latest developments in Sherman’s oeuvre.

Entering the galleries, the exhibition strays from a chronological narrative typical of retrospectives, and groups photographs thematically to create new and surprising juxtapositions and to suggest common threads across several series. A gallery devoted to her work made for the fashion industry brings together commissions from 1983 to 2011. Sherman’s interest in the construction of femininity and mass circulation of images informs much of the work that takes fashion as its subject, illustrating not only a fascination with fashion images but also a critical stance against what they represent. A gallery exploring themes of the grotesque focuses on bodies of work from the mid-1980s through the mid-1990s, including disasters (1986-89) and sex pictures (1992). Sherman’s investigation of macabre narratives followed a trajectory of the physical disintegration of the body, and features prosthetic parts as a stand-in for the human body. A gallery devoted to Sherman’s exploration of myth, carnival, and fairy tales pairs works from her 2003 clowns with her 1985 fairy tales series. These theatrical pictures revel in their own artificiality, with menacing characters and fantastical narratives.

Galleries devoted to single bodies of work are interspersed among the thematic rooms. Sherman’s seminal series the Untitled Film Stills, comprising 70 black-and-white photographs made between 1977 and 1980, are presented in their entirety (the complete series is in MoMA’s collection). Made to look like publicity pictures taken on movie sets, the Untitled Film Stills read like an encyclopaedic roster of female roles inspired by 1950s and 1960s Hollywood, film noir, B movies, and European art-house films. While the characters and scenarios may seem familiar, Sherman’s Stills are entirely fictitious. Her characters represent deeply embedded clichés (career girl, bombshell, girl on the run, housewife, and so on) and rely on the persistence of recognisable manufactured stereotypes that loom large in the cultural imagination.

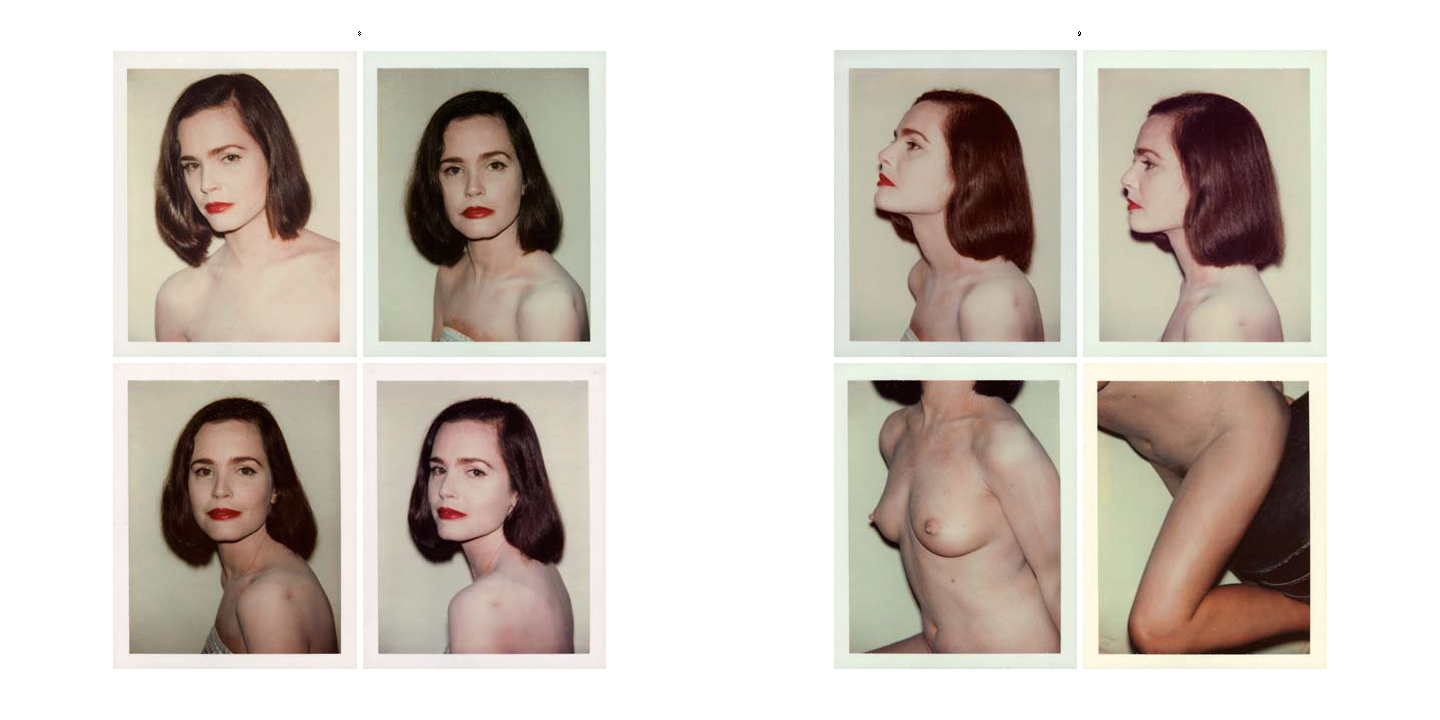

Other series presented in depth include Sherman’s 1981 series of 12-colour photographs known as the centerfolds. Originally commissioned by Artforum magazine, these send-ups of men’s erotic magazine centerfolds depict characters in a variety of emotional states, ranging from terrified to heartbroken to melancholic. With this series, Sherman plays into the male conditioning of looking at photographs of exposed women, but she turns this on its head by taking on the roles of both (assumed) male photographer and female pinup. The history portraits investigate the relationships between painter and model, and are featured in depth in the exhibition. These theatrical portraits borrow from a number of art historical periods, from Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, and Neoclassical. This free-association sampling creates an illusion of familiarity, but not with any one specific era or style (just as the Untitled Film Stills evoke generic types, not particular films). The subjects (for the first time, many are men) include aristocrats, Madonna and child, clergymen, women of leisure, and milkmaids, who pose with props, elaborate costumes, and obvious prostheses.

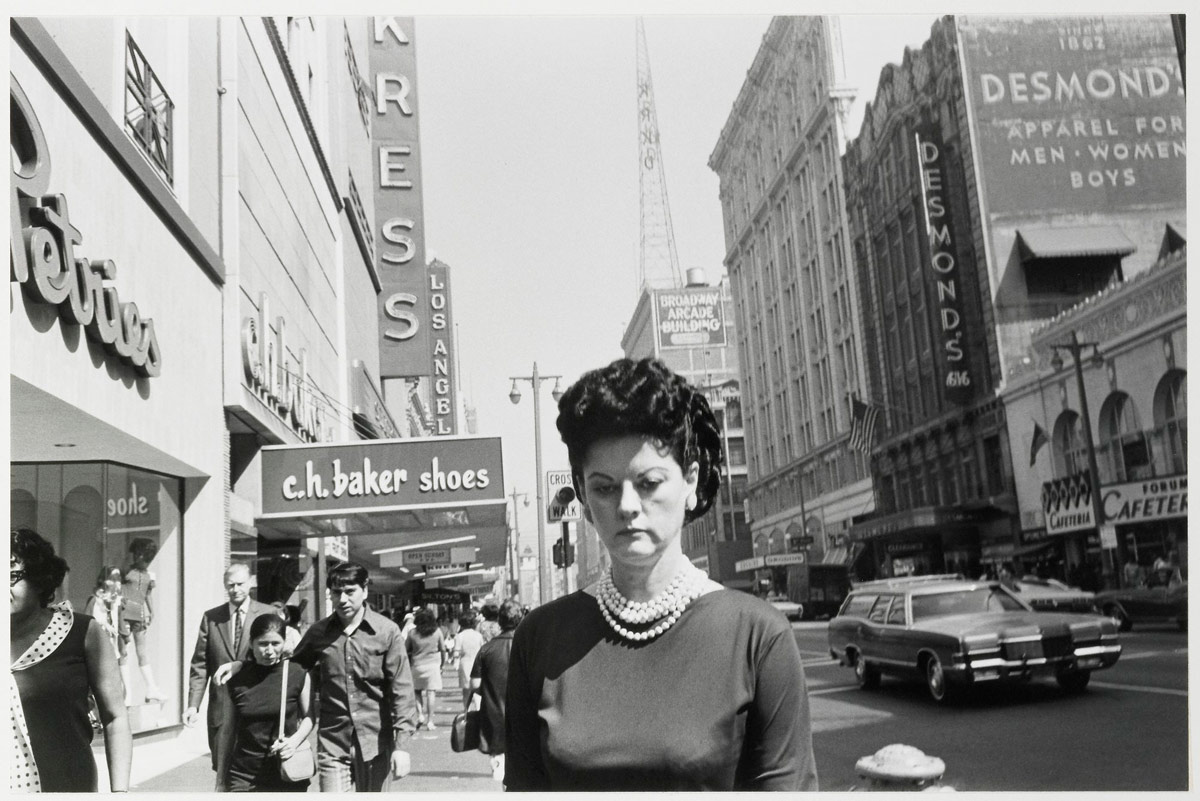

Sherman has explored the experience of ageing in a youth- and status-obsessed society with several bodies of work made since 2000. For her headshots from 2000-2002 (sometimes called Hollywood / Hamptons), the artist conceived a cast of characters of would-be or has-been actors (in reality secretaries, housewives, or gardeners) posing for head shots to get an acting job. With this series, Sherman underscores the transformative qualities of makeup, hair, expression, and pose, and the recognition of certain stereotypes as powerful transmitters of cultural clichés. Her monumental 2008 society portraits feature women “of a certain age” from the top echelons of society who struggle with today’s impossible standards of beauty. The psychological weight of these pictures comes through in the unrelenting honesty of the description of ageing and the small details that belie the attempt to project a certain appearance. In the infinite possibilities of the mutability of identity, these pictures stand out for their ability to be at once provocative, disparaging, empathetic, and mysterious.

Press release from the MoMA website

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #193

1989

Chromogenic colour print

48 7/8 x 41 15/16″ (124.1 x 106.5cm)

The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #213

1989

Chromogenic colour print

41 1/2 x 33″ (105.4 x 83.8cm)

Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #216

1989

Chromogenic colour print

7′ 3 1/8″ x 56 1/8″ (221.3 x 142.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Werner and Elaine Dannheisser

Gallery 7

Sherman’s history portraits (1988-90) investigate modes of representation in art history and the relationship between painter and model. These classically composed portraits borrow from a number of art-historical periods – Renaissance, baroque, rococo, Neoclassical – and make allusions to paintings by Raphael, Caravaggio, Fragonard, and Ingres (who, like all the Old Masters, were men). This free-association sampling creates a sense of familiarity, but not of any one specific era or style. The subjects (for the first time for Sherman, many are men) include aristocrats, Madonnas with child, clergymen, women of leisure, and milk-maids, who pose with props, costumes, and obvious prostheses. Theatrical and artificial – full of large noses, bulging bellies, squirting breasts, warts, and unibrows – the history portraits are poised between humorous parody and grotesque caricature.

A handful of Sherman’s portraits were inspired by actual paintings. Untitled #224 was made after Caravaggio’s Sick Bacchus (c. 1593), which is commonly believed to be a self-portrait of the artist as the Roman god of wine. In Sherman’s reinterpretation, the numerous layers of representation – a female artist impersonating a male artist impersonating a pagan divinity – create a sense of remove, pastiche, and criticality. Even where Sherman’s pictures offer a gleam of art-historical recognition, she has inserted her own interpretation of the canonised paintings, creating contemporary artefacts of a bygone era.

Wall text from the exhibition

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #359

2000

Chromogenic color print

30 x 20″ (76.2 x 50.8cm)

Collection Metro Pictures, New York

Gallery 8

After almost a decade of staging still lifes with dolls and props, in her 2000-2002 head-shots series Sherman returned to a more intimate scale and to using herself as a model. The format recalls ID pictures, head shots, or vanity portraits made in garden-variety portrait studios by professional photographers. First exhibited in Beverly Hills, the series explores the cycle of desire and failed ambition that permeates Hollywood. Sherman conceived a cast of would-be or has-been female actors posing for head shots in order to get acting jobs; later, for an exhibition in New York, she added East Coast types. Whichever part of the country they’re from, we’ve seen these women before – on reality television, in soap operas, or at a PTA meeting. With these pictures, Sherman underscores the transformative qualities of makeup, hair, expression, and pose, and the power of stereotypes as transmitters of cultural clichés. She projects well-drawn personas: the enormous pouting lips of the woman in Untitled #360 suggest a yearning for youth, while the glittery makeup and purple iridescent dress worn by the character in Untitled #400 indicate an aspiration to reach a certain social status. In her role as both sitter and photographer, Sherman has disrupted the usual power dynamic between model and photographer and created new avenues through which to explore the very apparatus of portrait photography itself.

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #465

2008

Chromogenic colour print

63 3/4 x 57 1/4″ (161.9 x 145.4cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase, with funds from the Painting and Sculpture Committee and the Photography Committee, 2009

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #466

2008

Chromogenic colour print

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #474

2008

Chromogenic colour print

7′ 7″ x 60 1/4″ (231.1 x 153cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of an anonymous donor, Michael Lynne, Charles Heilbronn, and the Carol and David Appel Family Fund

Gallery 10

Set against opulent backdrops and presented in ornate frames, the characters in Sherman’s 2008 society portraits seem at once tragic and vulgar. The figures are not based on specific women, but the artist has made them look entirely familiar in their struggle with the impossible standards of beauty that prevail in a youth – and status – obsessed culture. At this large scale, it is easy to decipher the characters’ vulnerability behind the makeup, clothes, and jewellery. The psychological weight of these pictures comes through the unrelenting honesty of their description of ageing, the tell-tale signs of cosmetic alteration, and the small details that belie the characters’ attempts to project a polished and elegant appearance. Upon careful viewing, they reveal a dark reality lurking beneath the glossy surface of perfection. As with much of her work, in her society portraits Sherman has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to channel the zeitgeist. These well-heeled divas presaged the financial collapse of 2008, the end of an era of opulence – the size of the photographs alone seems a commentary on an age of excess. Among the numerous iterations of contemporary identity, these pictures stand out as at once provocative, disparaging, empathetic, and mysterious.

Wall text from the exhibition

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954)

Untitled #475

2008

Chromogenic colour print

7′ 2 3/8″ x 71 1/2″ (219.4 x 181.6cm)

The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica

Gallery 11

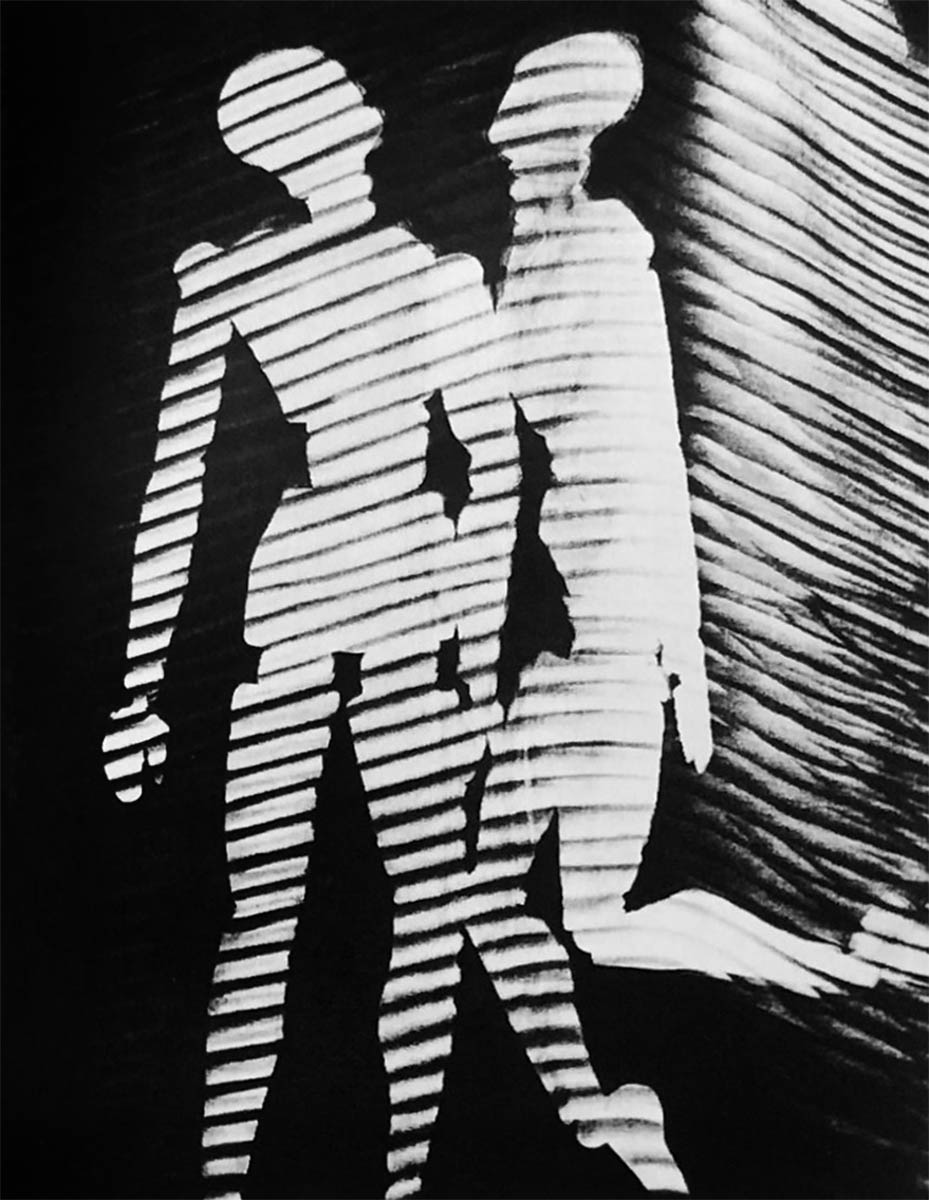

Because the majority of Sherman’s pictures feature the artist as model, they showcase a single character. In the 1970s Sherman experimented with cutouts of multiple figures, in her whimsical 1975 stop-motion animated short film Doll Clothes and her rarely seen 1976 collages, which were achieved through a labor-intensive process of cutting and pasting multiple photographs. When Sherman began working digitally in the early 2000s, she was able to more easily incorporate multiple figures in one frame, allowing for a variety of new narrative possibilities. Where the early works chart the movements and gestures of a single character through space, the multiple figures in recent works interact with one another to create tableaus.

Wall text from the exhibition

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

You must be logged in to post a comment.