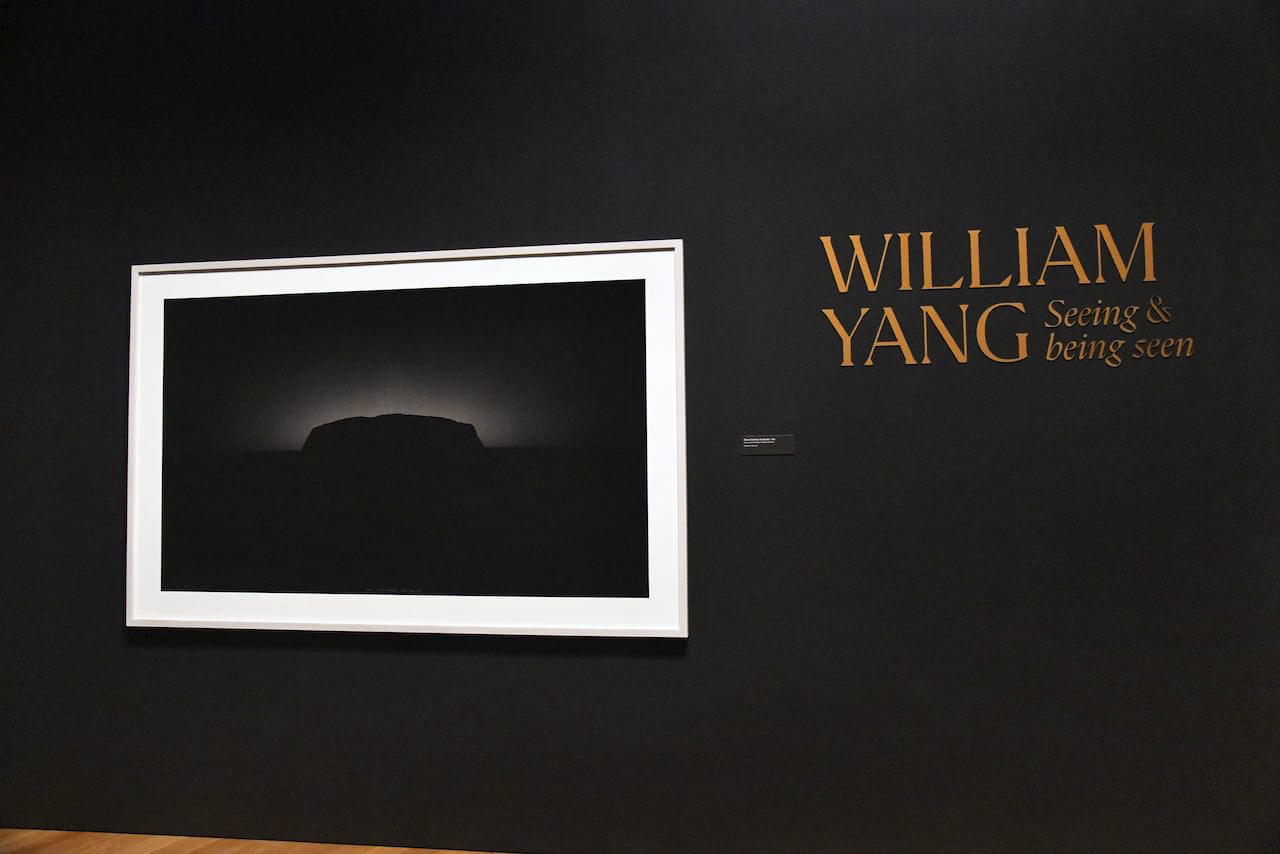

Exhibition dates: 8th May – 26th September, 2021

Curators: Sarah Hermanson Meister, Curator, with Dana Ostrander, Curatorial Assistant, Robert B. Menschel Department of Photography

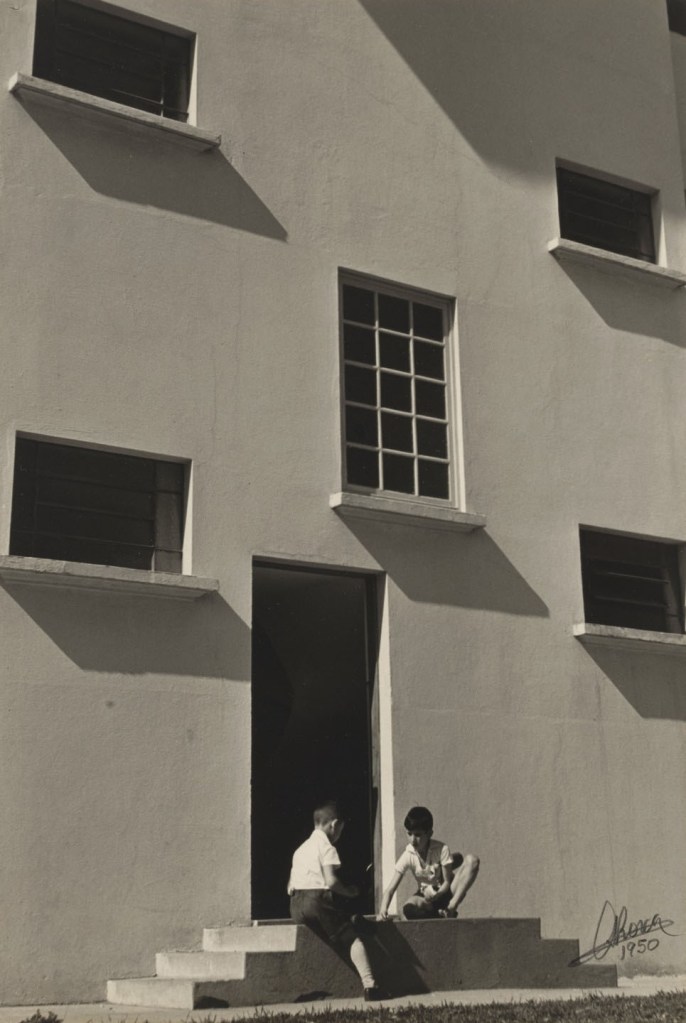

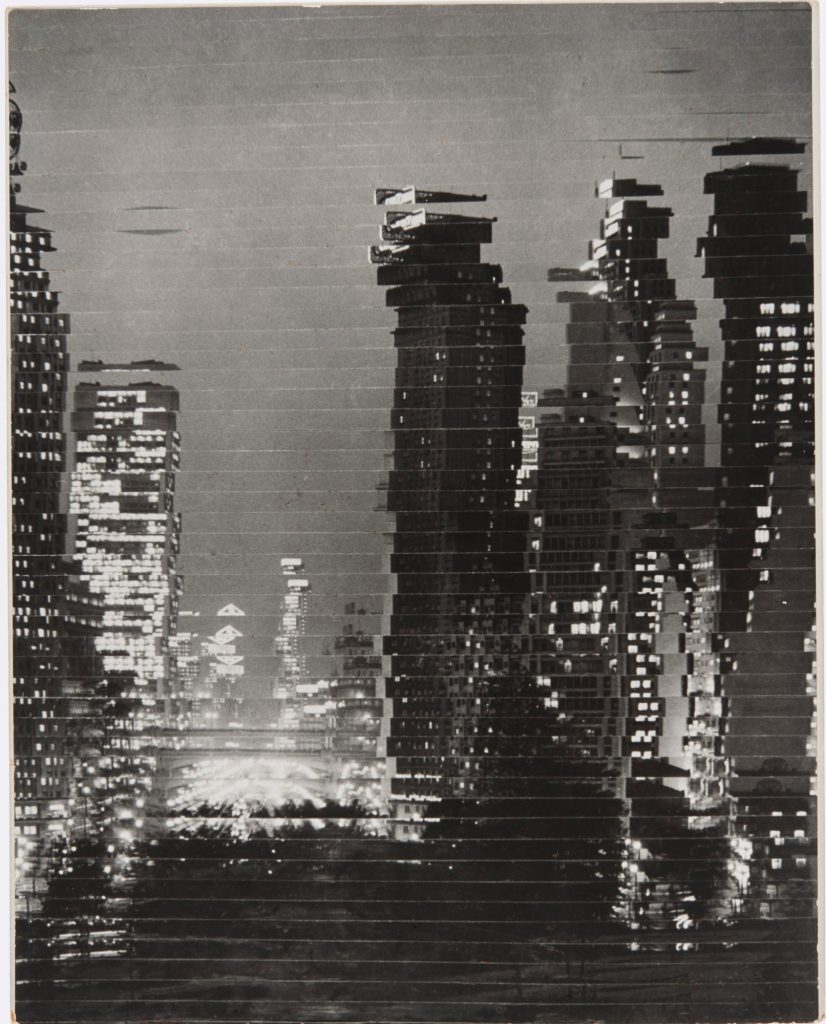

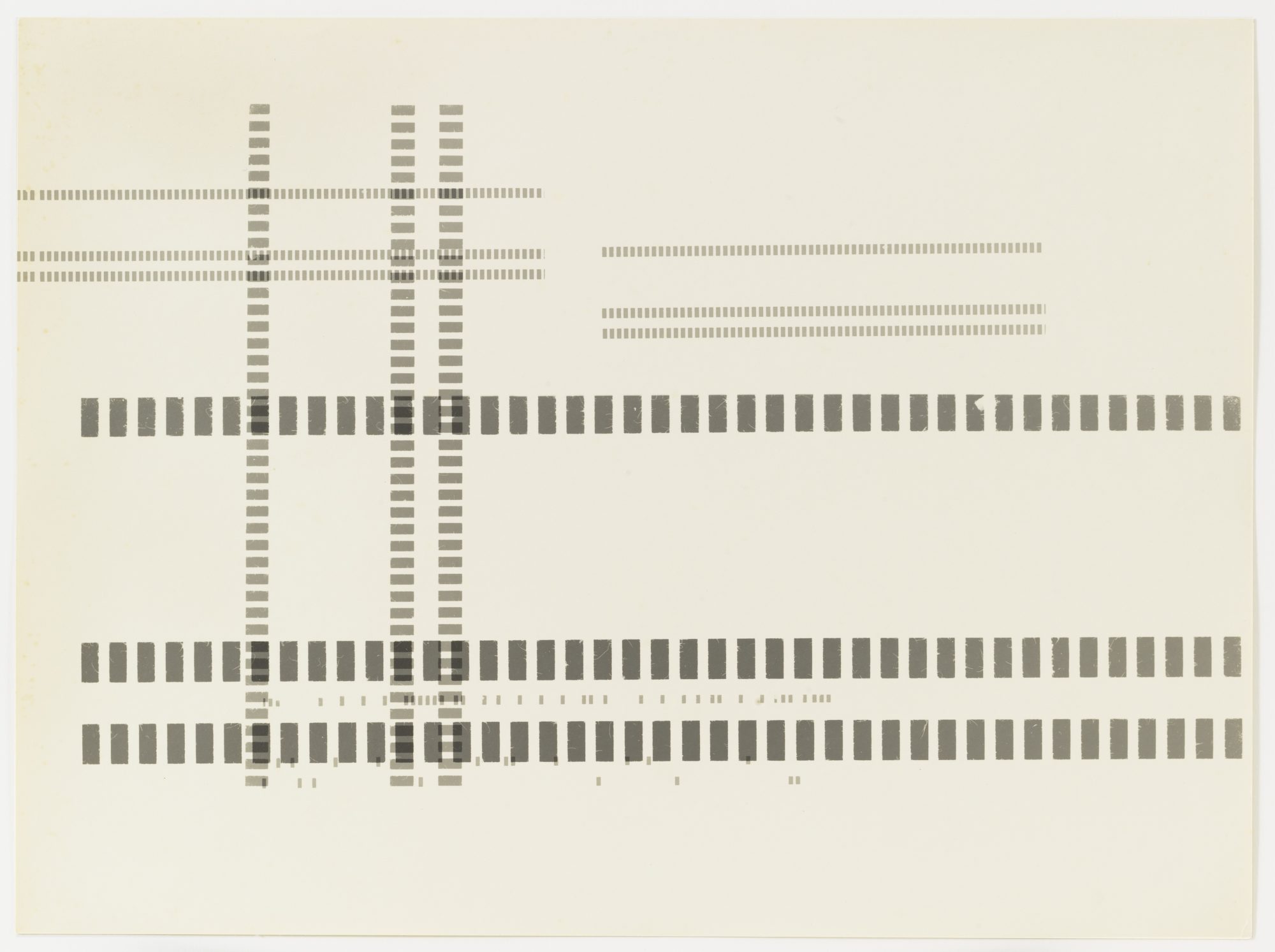

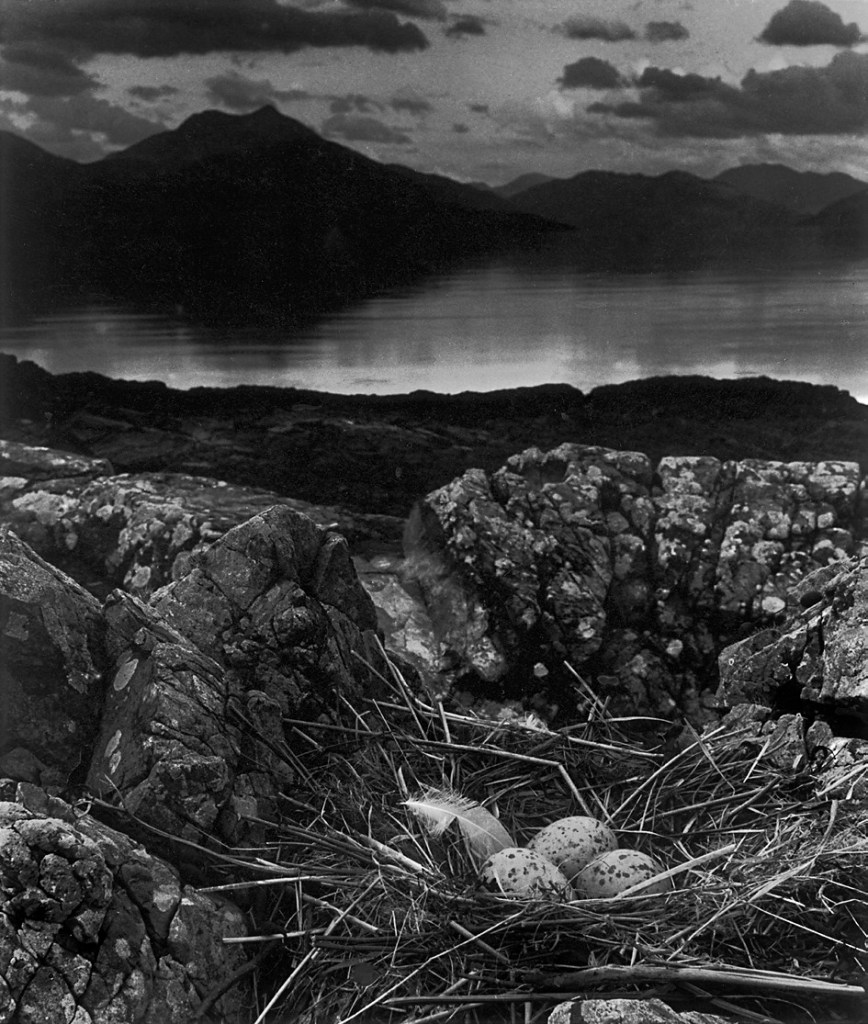

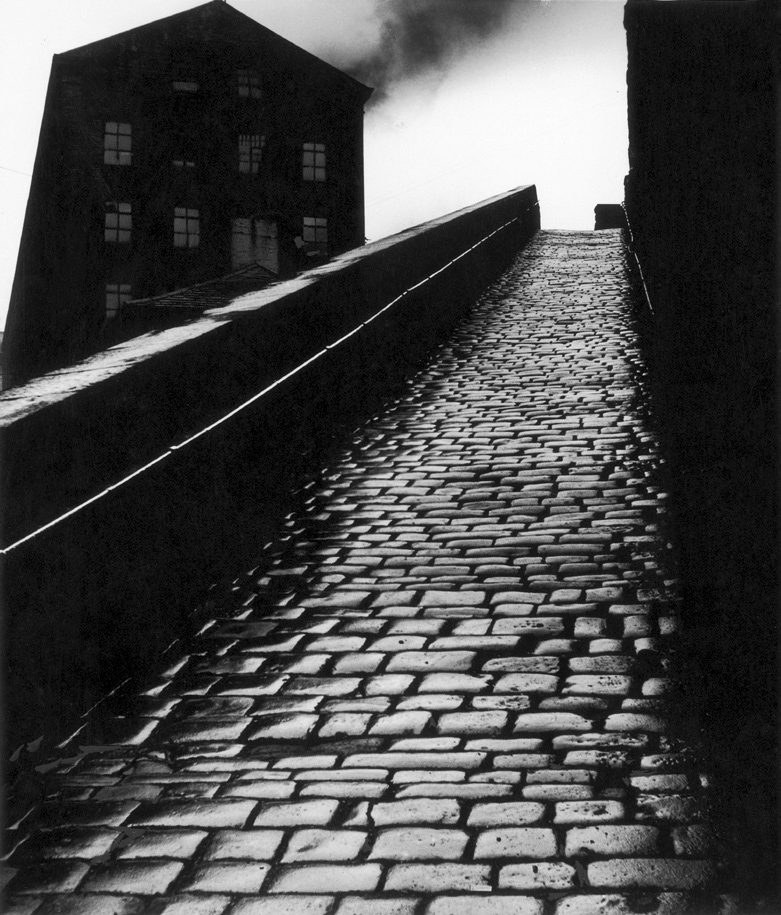

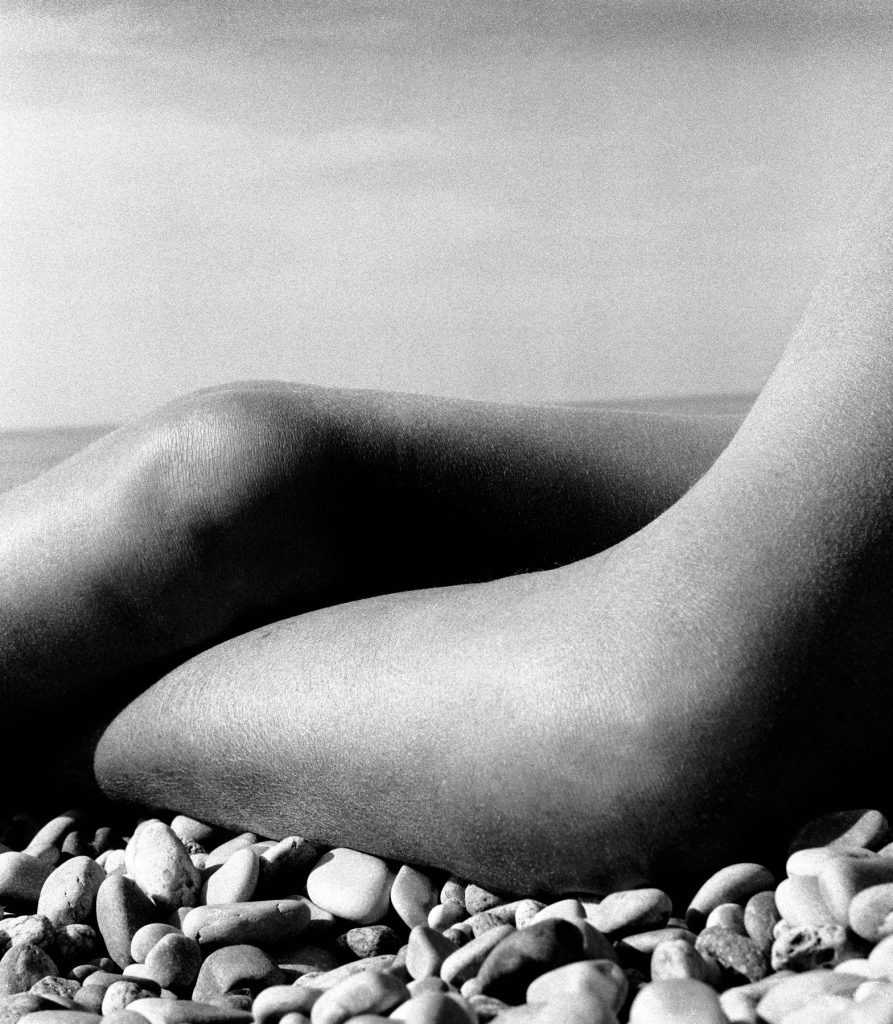

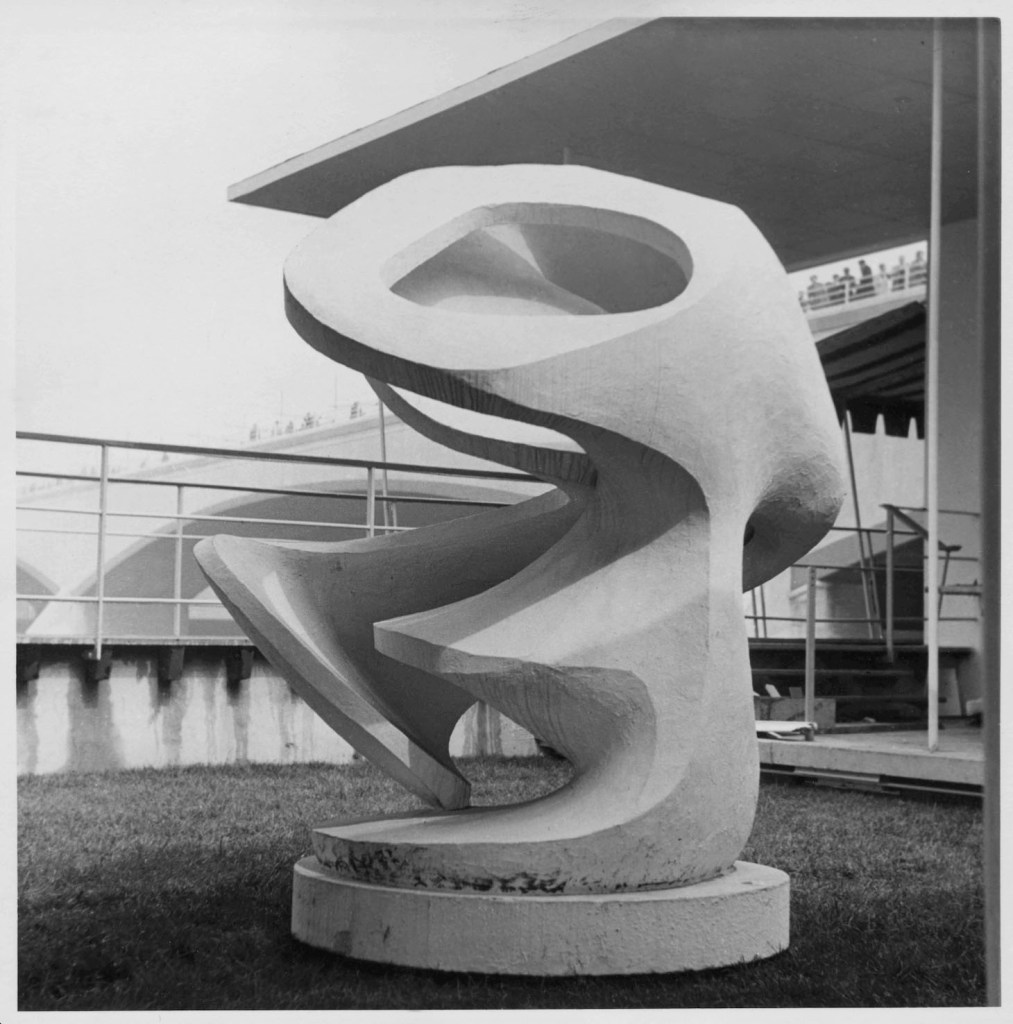

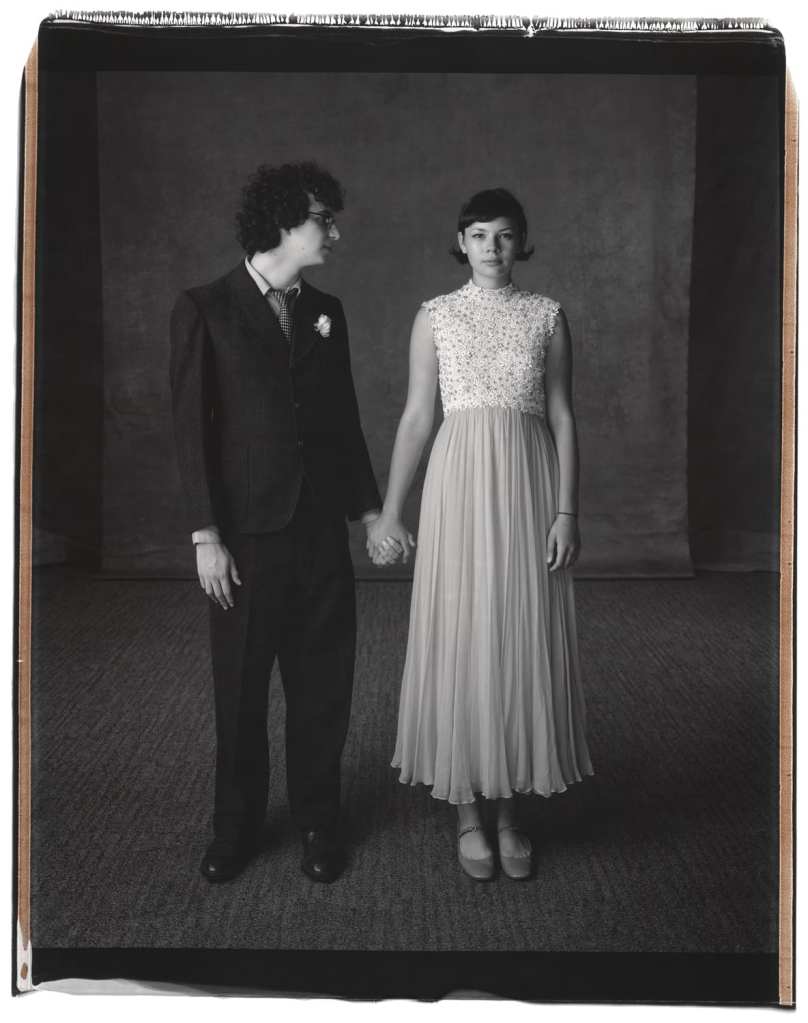

José Yalenti (Brazilian, 1895-1967)

Angles (Angulos)

1951

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Courtesy Fernanda Feitosa and Heitor Martins

While we can’t travel around the world physically, it’s fantastic to virtually discover these hidden gems of photographic history – this time “men and women who joined São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB) [who] bonded over their passion for photography: the club was instrumental to their individual artistic development and their esteemed reputation across a dynamic international circuit of amateur photo salons.”

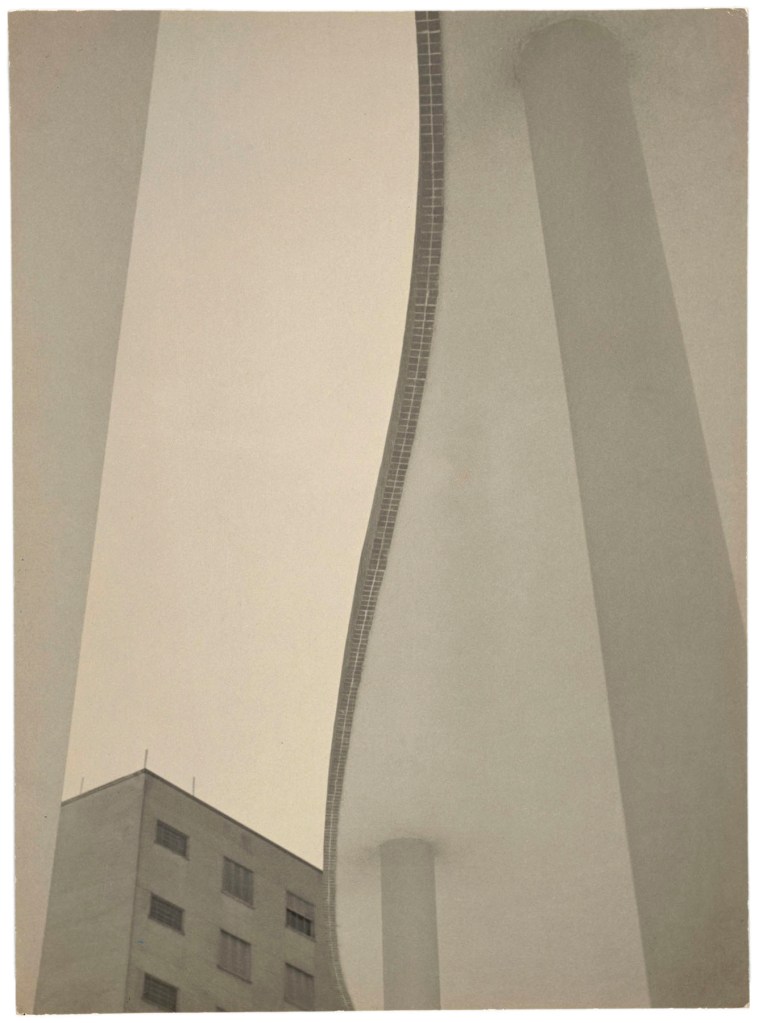

My favourite photograph in the posting is Marcel Giró’s Light and Power, for its modernist, abstract form and beauty, for the light, and for its intonation… staves of music, birds on the wire.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to MoMA for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

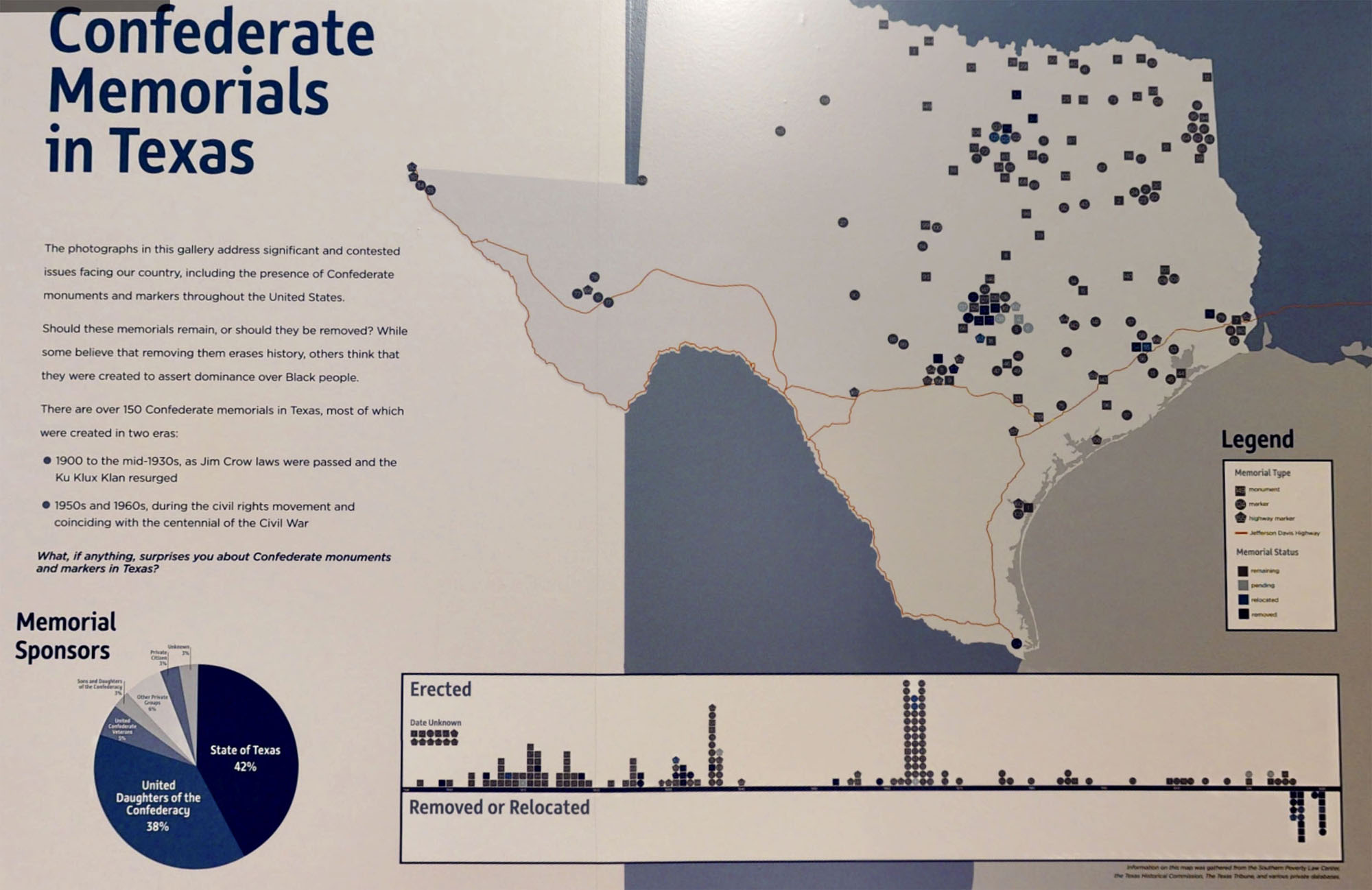

The Museum of Modern Art announces Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964, the first museum exhibition of Brazilian modernist photography outside of Brazil. On view May 8 – September 26, 2021, the exhibition will focus on the unforgettable creative achievements of São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante, a group of amateur photographers widely heralded in Brazil, but essentially unknown to European and North American audiences. Fotoclubismo is comprised of over 60 photographs drawn generously from MoMA’s collection; together, they bring forward the extraordinary range of achievements of this group, provide valuable insight into the way photographic aesthetics were framed in the 1950s, and afford opportunities to reflect on the significance of amateur status today.

The exhibition is divided into thematic categories: Simplicity, Gertrudes Altschul, Abstractions from Nature, Texture and Shape, Geraldo de Barros, Experimental Processes, Daily Life, and Solitude.

Read a short essay about Geraldo de Barros at the MoMa Post website

Read a short essay about Gertrudes Altschul at the MoMA Post website

Read a short essay about the Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB) at the MoMA Post website

The exhibition not only showcases the groundbreaking experimental and aesthetic sensibilities of FCCB, but it also invites the viewer to question the status of the amateur photographer.

Meister has positioned Fotoclubismo within the history of contemporary photography. Along with their stylistic merits, FCCB’s photos allow the viewer to reflect on the ways race, gender, and status affect how photography is consumed by the public.

“I’m particularly excited not only because I know that the work is going to resonate with audiences,” she [curator Sarah Meister] said, “but because it’s this wonderful opportunity to think, ‘what else can we do as curators or as museums to reflect and recuperate other elements of our history that have been overlooked and neglected?'” she told Deutsche Welle, Germany’s international broadcaster.

Meka Boyle. “MoMA is the First Museum Outside of Brazil to Put the Spotlight on Brazilian Modernist Photography,” on the Art Dealer Street website May 28 2021 [Online] Cited 26/08/2021

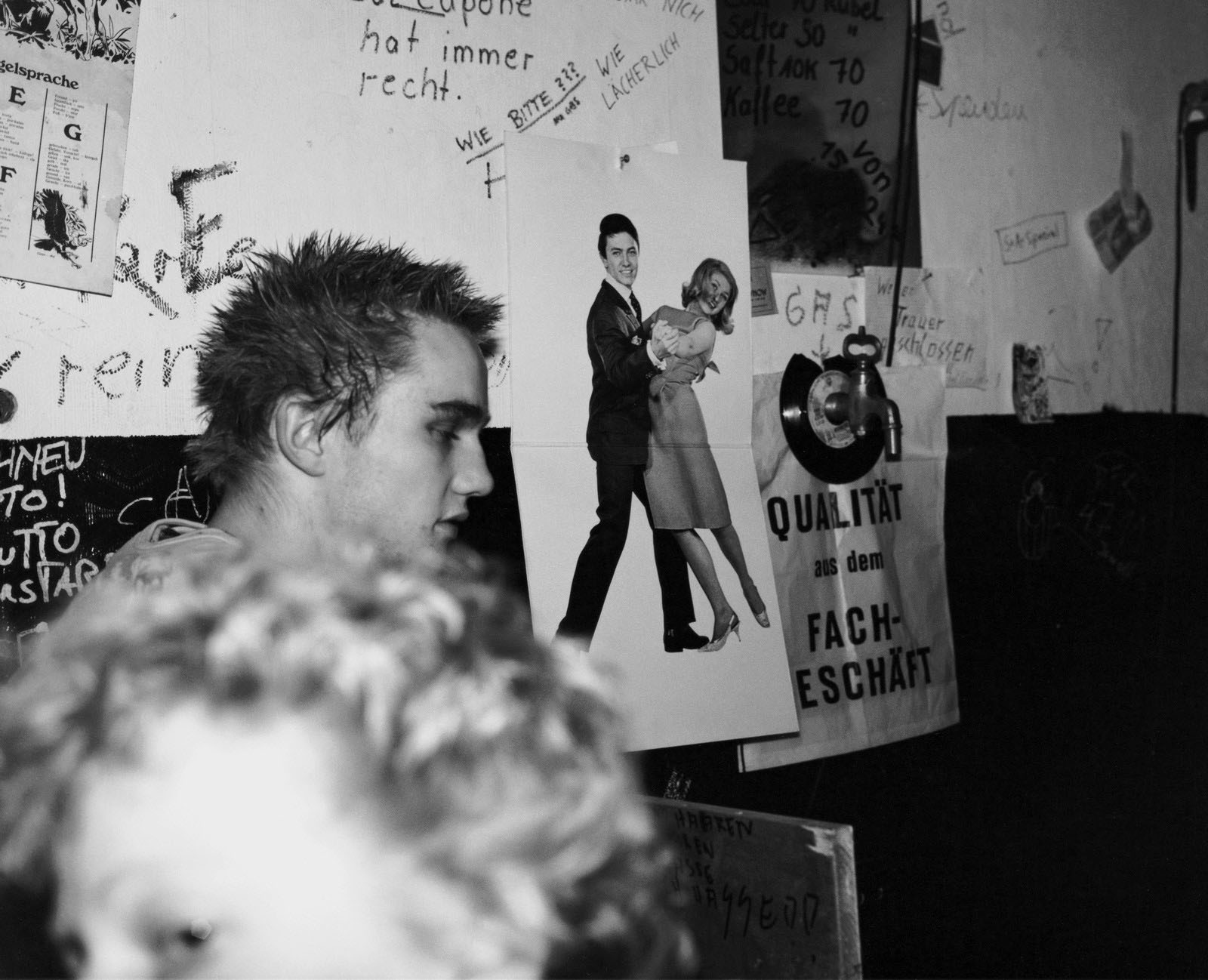

Installation view of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

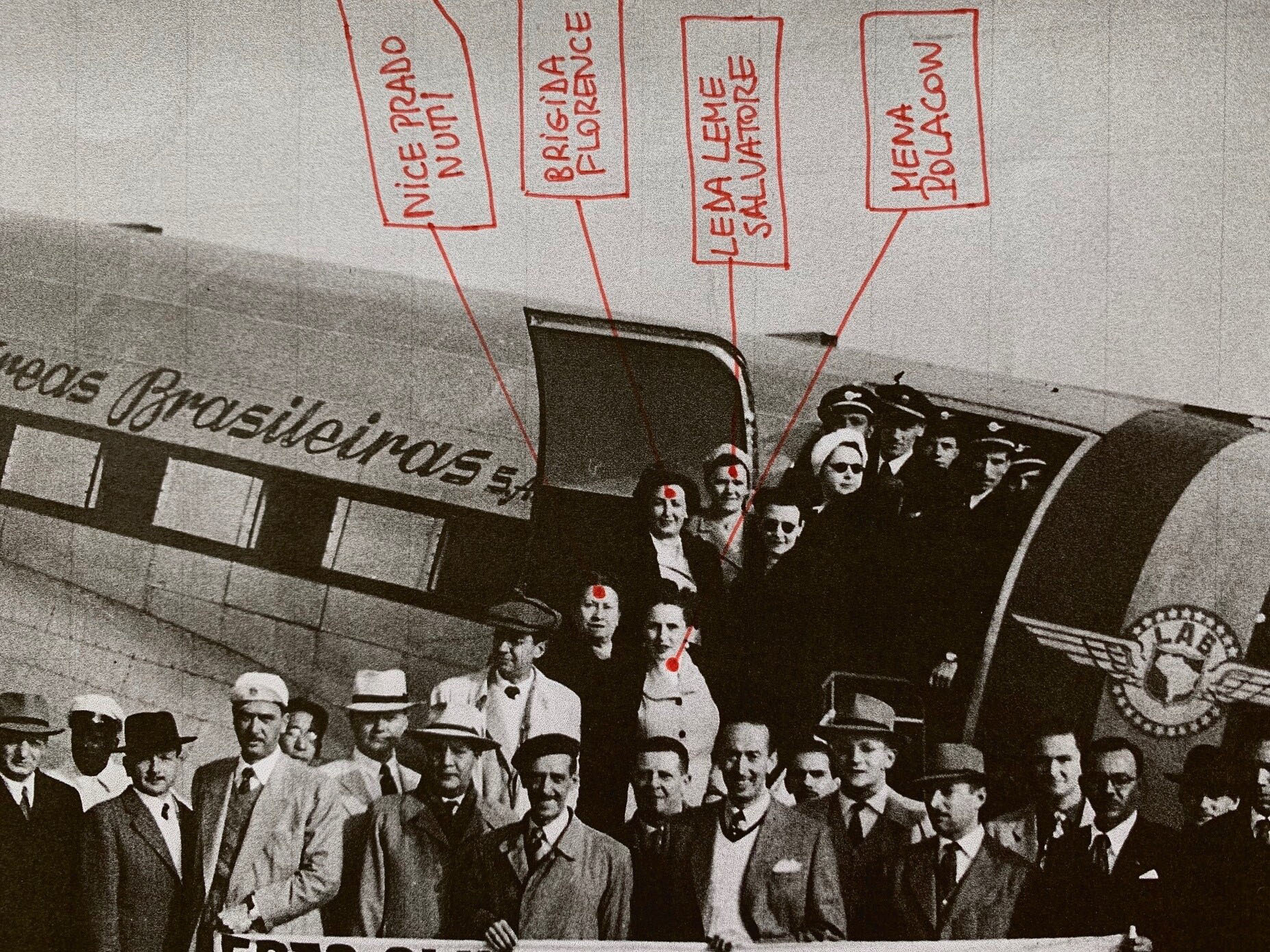

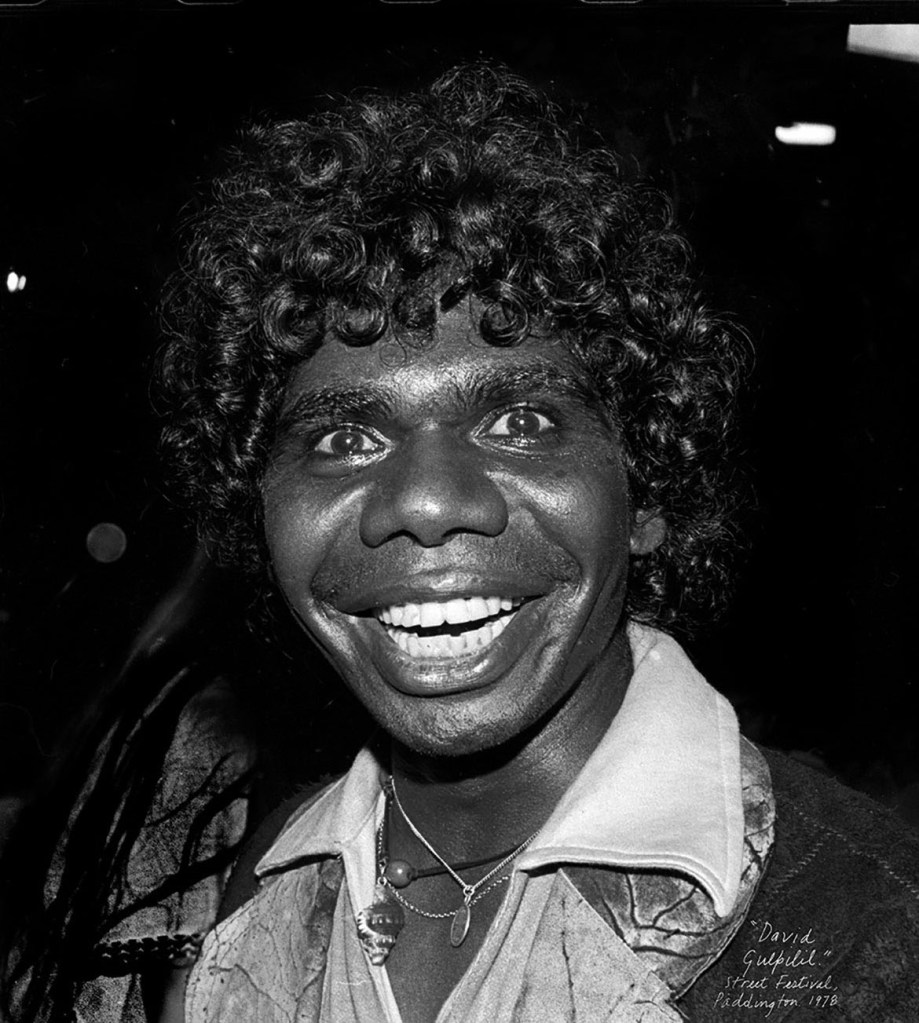

FCCB members on an excursion to Paquetá Island to visit the Sociedade Fluminense de Fotografia. Boletim foto-cine 17 (September 1947): 3. Image and annotations courtesy Rubens Fernandes Junior

FCCB members on an excursion to Paquetá Island to visit the Sociedade Fluminense de Fotografia, with some of the women photographers singled out. Boletim foto-cine 17 (September 1947): 3. Image and annotations courtesy Rubens Fernandes Junior

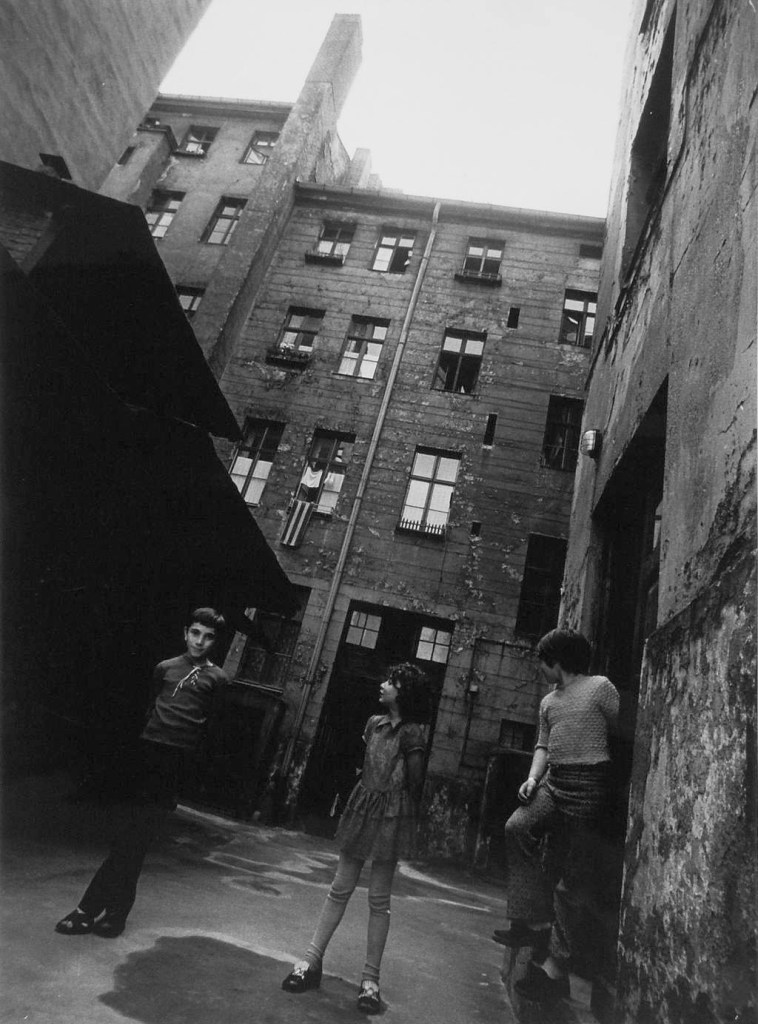

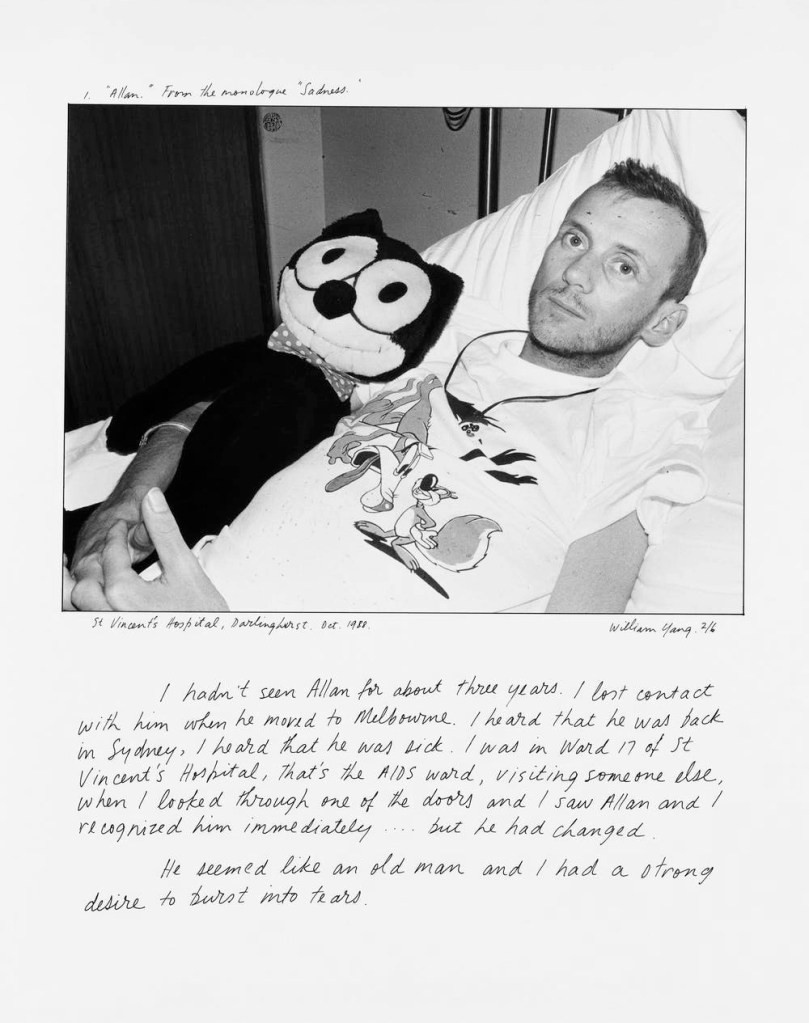

The men and women who joined São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB) bonded over their passion for photography: the club was instrumental to their individual artistic development and their esteemed reputation across a dynamic international circuit of amateur photo salons. The works on view in Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 highlight the achievements of more than 20 club members with unforgettable prints that traveled extensively along these networks. These are not intimate snapshots of family gatherings intended for the album page (a slightly different twist on the photographic amateur) but works of ambition and originality that had and continue to have a commanding presence on the walls of salons and museums. FCCB members’ success owes much to their distinctive blend of camaraderie and competition, nurtured in part by their frequent excursions.

Beginning in 1946 the FCCB published a small (often monthly or bimonthly) magazine, the Boletim foto-cine, which was given free to members and sold in local photo shops. Its modest scale belied its scope and seriousness: it won special awards for editorial content in the Photographic Society of America’s International Competition in 1949 and 1951. (It should be noted the Boletim was published exclusively in Portuguese, so perhaps the PSA was influenced by the fact that its own members and their writing – in translation – appeared frequently.)

The Boletim played a central role in advertising a social environment that drew people to the club, and also encouraged the competitive atmosphere within it. For many years, the Boletim published each new member’s name, birthday notices, wedding announcements, and snapshots from excursions, openings, and holiday celebrations at the club headquarters (Santa’s annual visit was a recurring feature). These personal touches served as a counter-balance to the equally prominent presence of club rankings: charts and accounts of prizes won and accolades received both domestically and around the world. One might conclude the social niceties were instrumental in fostering an environment in which critical feedback was possible, which in turn contributed to the club’s capacity for creative innovation.

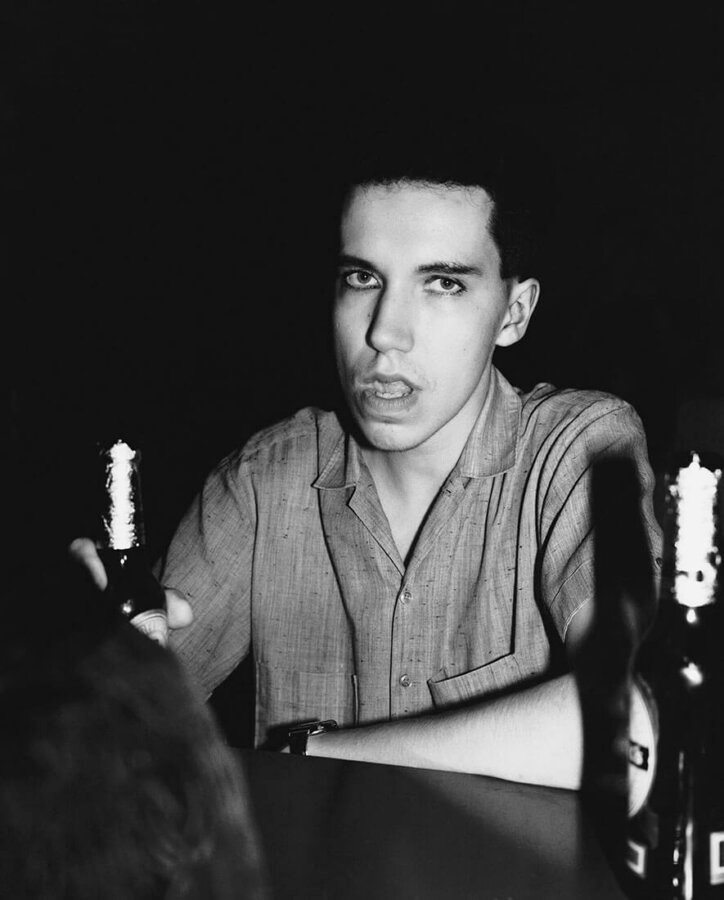

Geraldo de Barros is arguably the best known member of the FCCB. He earned a living at the Banco do Brasil, but his creative spirit was not squelched by his day job. His satirical cartoons are peppered throughout the Boletim. This one betrays the anxiety of those whose work is being judged: three diminutive members, one waving a white flag, are menaced by others wielding a gun, a bomb, and a knife. He experimented with collage, montage, multiple exposures, and other interventions in his photographs, he was a founding member of the Grupo Ruptura, an inventive association of painters, and he later pursued a successful career in furniture design. The Museum of Art of São Paulo held a one-person exhibition of his photo-based work in January 1951, which was so confounding to his fellow FCCB members (some photos were rendered as sculptures on pedestals; all played fearlessly with conventions of representation) that this major accomplishment went unmentioned in the Boletim. Despite occasional moments of misunderstanding, de Barros was a principal force in the presentation of work by FCCB members in the second São Paulo Bienal in 1953-1954, by which time even the club’s leadership had embraced the spirit of innovation de Barros had championed for years.

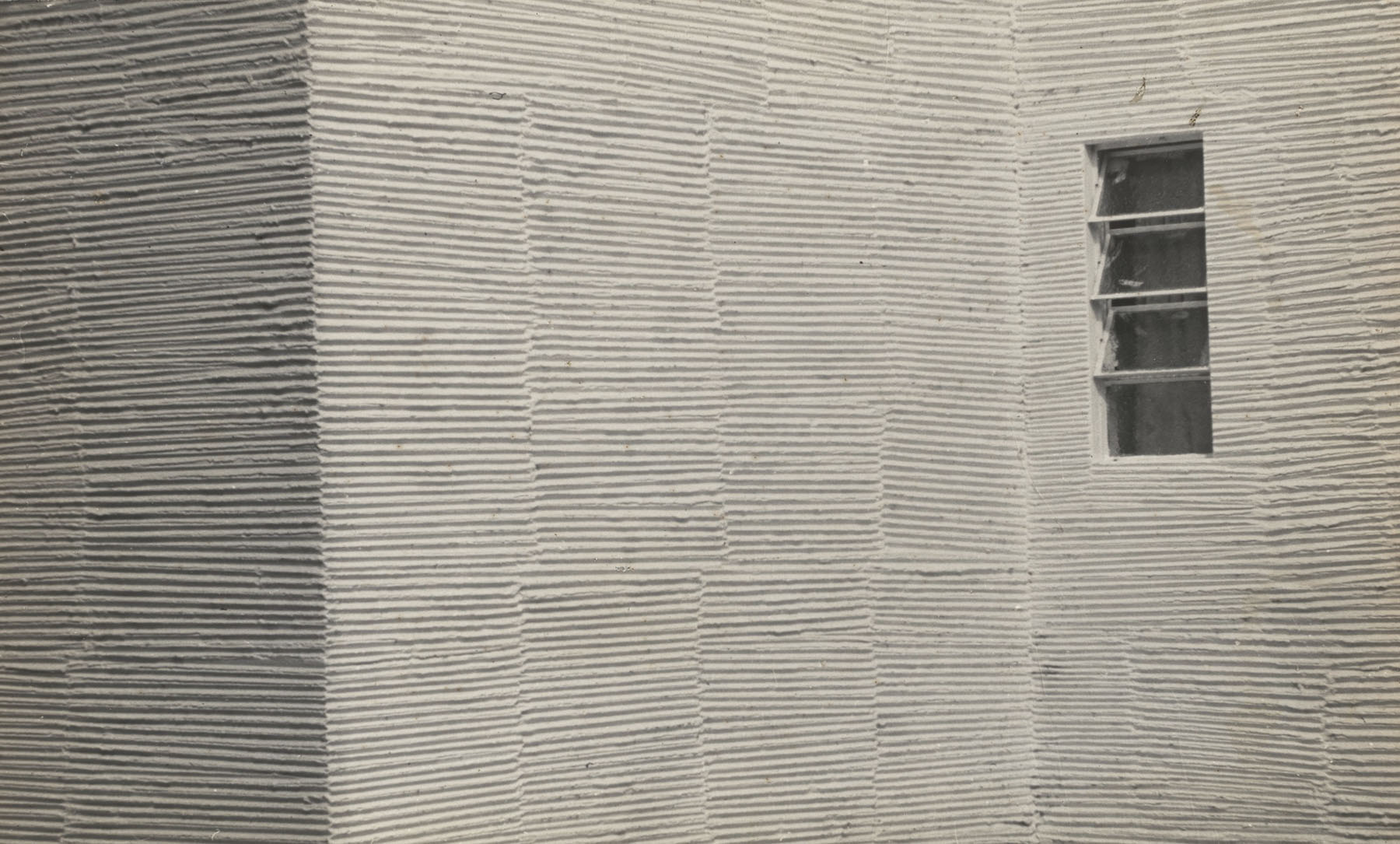

The excursions were not merely social outings: they were opportunities to learn alongside fellow members in the field, and to attempt to capture the “best” view of a particular subject. In one view of this distinctive building, German Lorca has accentuated the contrast between the corrugated roof and the adjacent shadows; in another, José Yalenti chose to frame the angular structure against the undulating form of a nearby building; in a third (noted in the Boletim as having been submitted to the club’s internal contest), Euclides Machado offered a study of texture, tone, and form. Although the club used “scorecards” to judge the relative strengths of images such as these, many of the attributes being judged were grouped within the category “factor psicológico” (psychological factors), which are surely more challenging to rank objectively. Then and now, it can be useful to acknowledge the ways in which something as invisible and inescapable as taste influences our judgment of a work of art.

Extract from Sarah Meister. “The Ambition and Originality of Fotoclubismo’s Amateur Photographers,” on the MoMA magazine website May 7, 2021 [Online] Cited 25/08/2021.

Installation views of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing in the bottom image the sections Daily Life and German Lorca with third right bottom, German Lorca’s Every Day Scenes (1949, below); at second right, German Lorca’s Rascality (Malandragem) (1949, below) and at right, Lorca’s Apartments (Apartamentos) (1950-1951, below)

Photos: Jonathan Muzikar

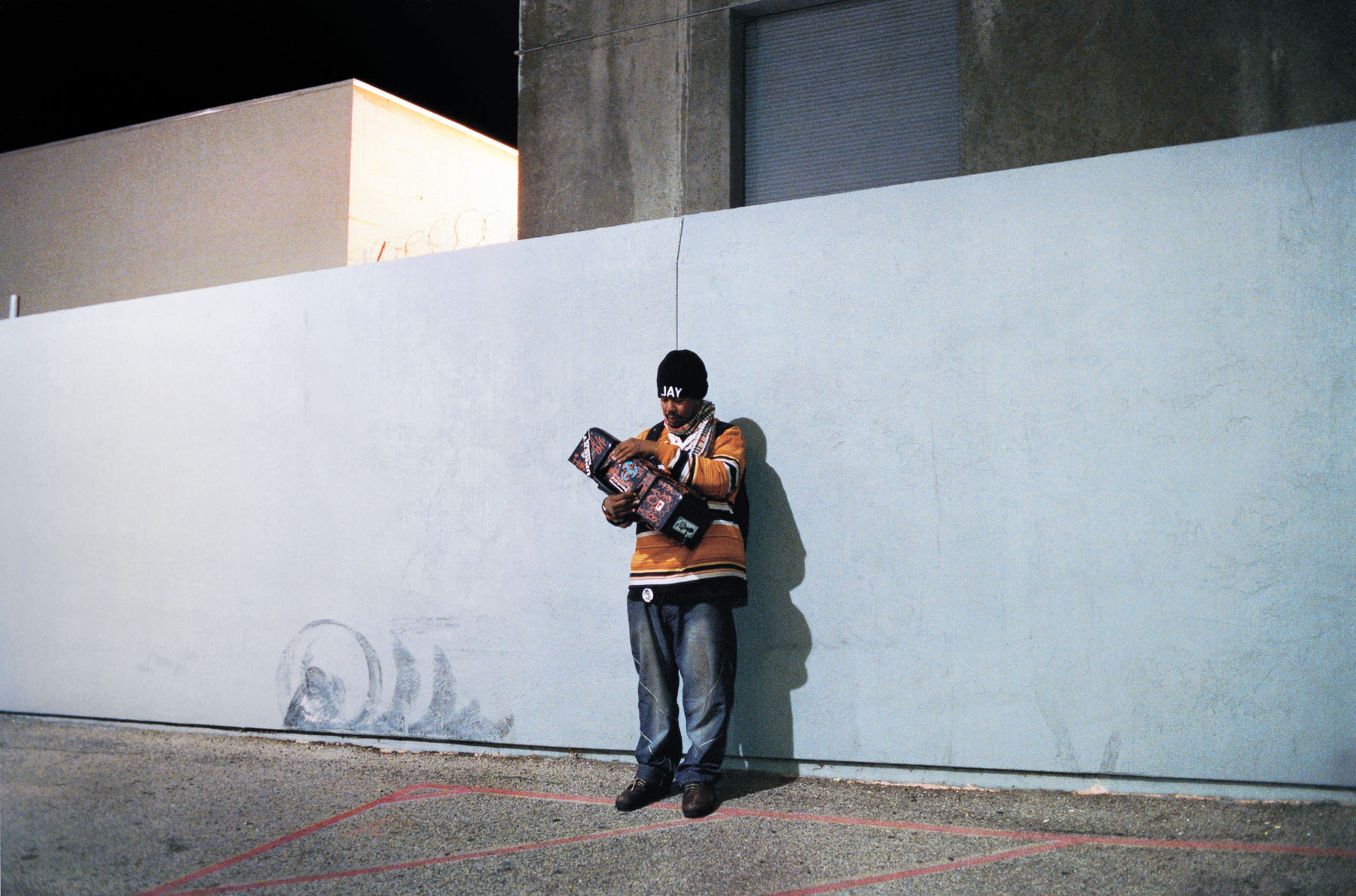

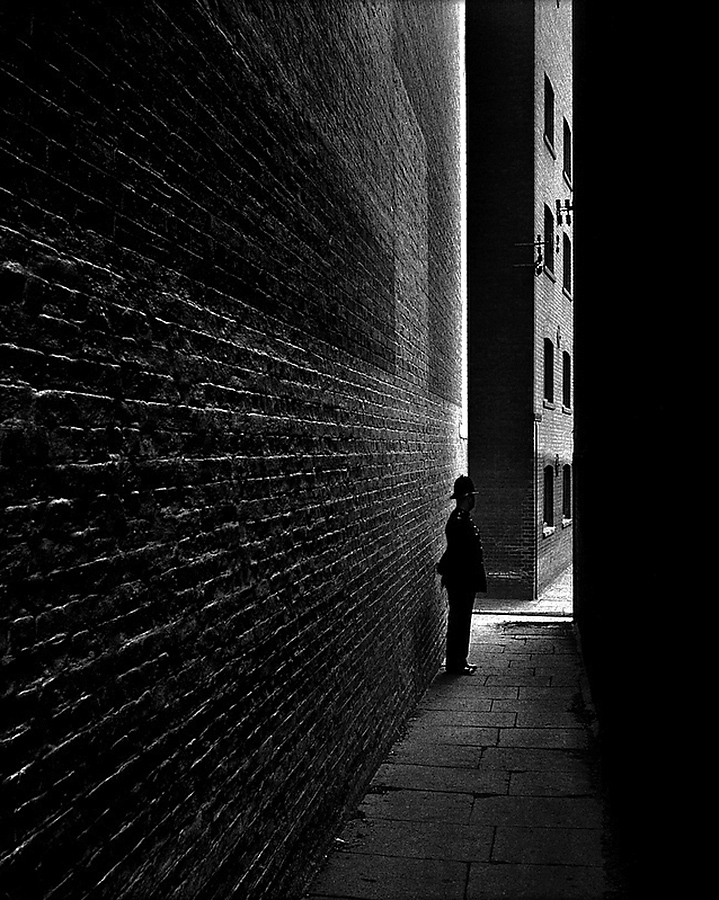

German Lorca (Brazilian, 1922-2021)

Everyday Scenes (Cenas quotidianas)

1949

Gelatin silver print

11 × 15″ (27.9 × 38.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Committee on Photography Fund

© 2021 German Lorca

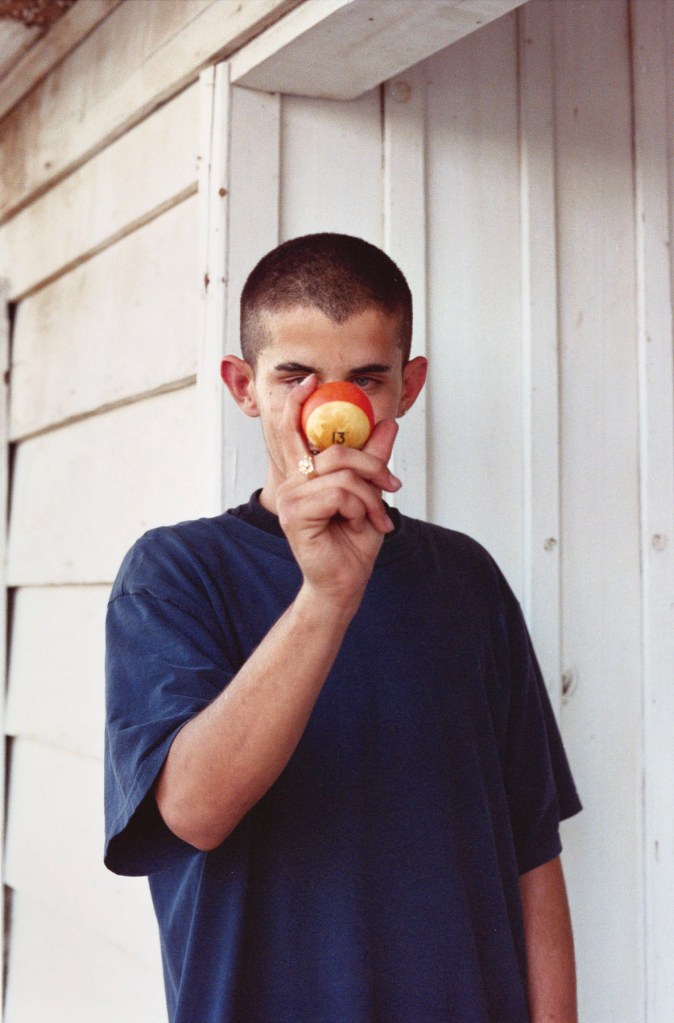

German Lorca (Brazilian, 1922-2021)

Rascality (Malandragem)

1949

Gelatin silver print

10 3/4 × 12 3/4″ (27.3 × 32.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Richard O. Rieger

© 2021 German Lorca

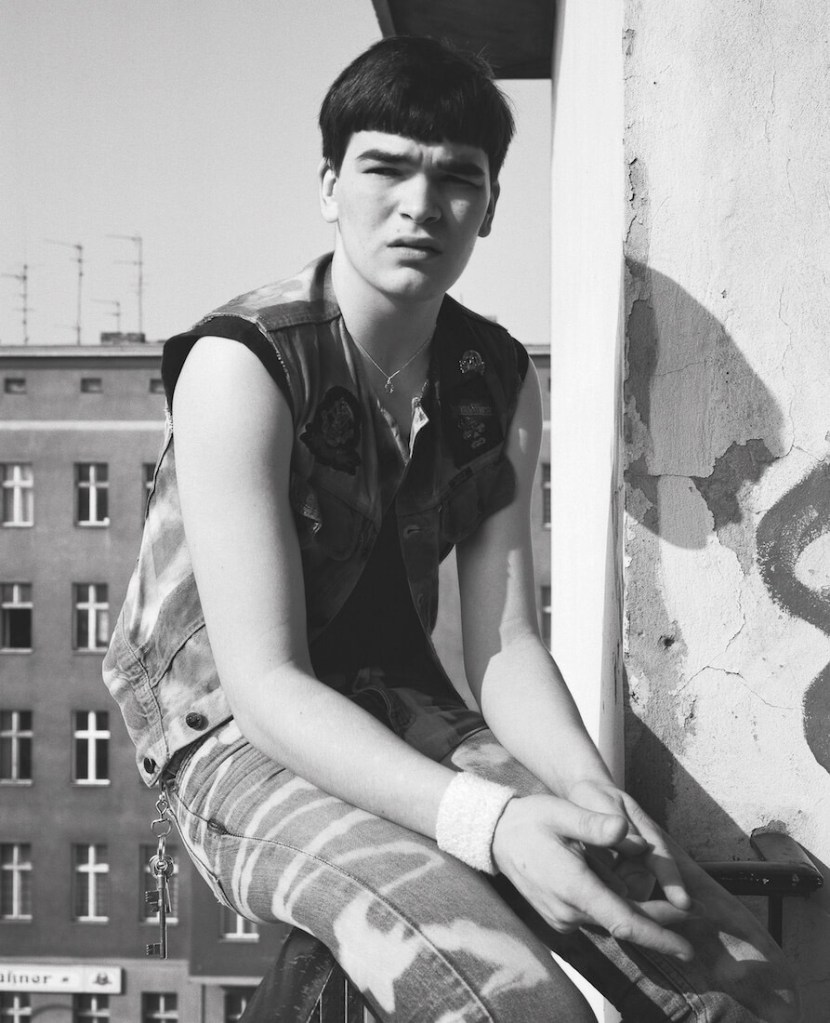

German Lorca (Brazilian, 1922-2021)

Apartments (Apartamentos)

1950-1951

Gelatin silver print

15 1/16 × 10 1/8″ (38.3 × 25.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Ernesto Poma through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund

© 2021 German Lorca

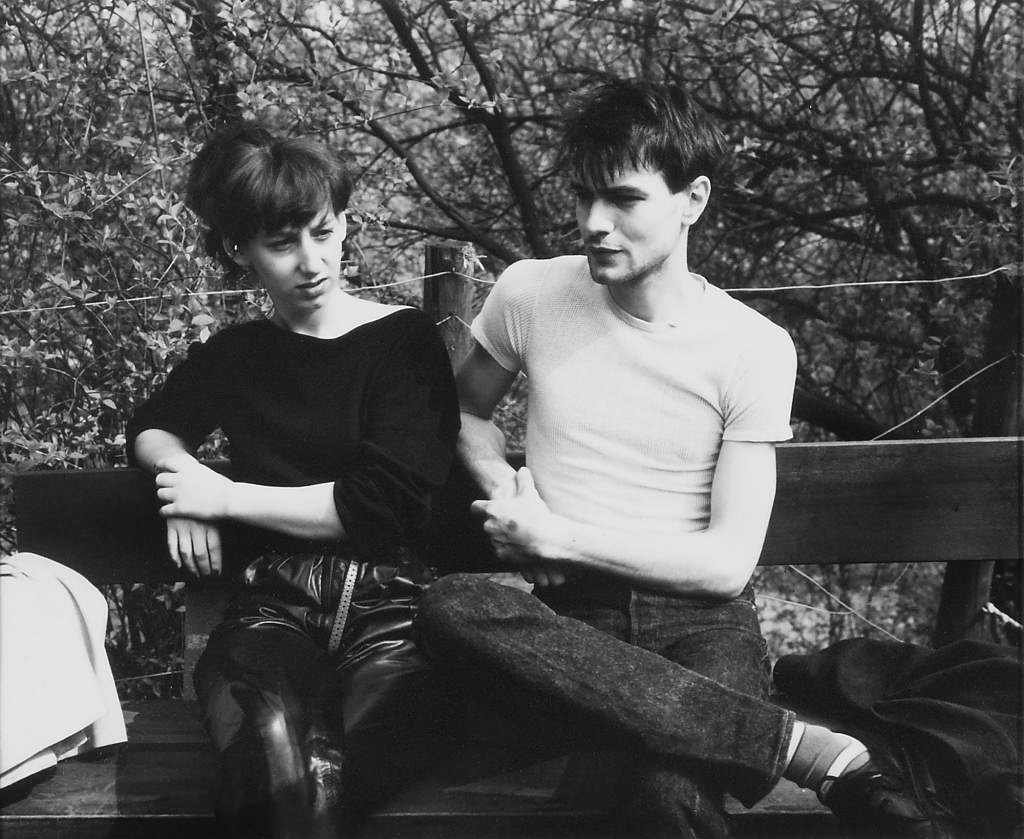

German Lorca (Brazilian, 1922-2021)

White Roofs (Telhados brancos)

1951

Gelatin silver print

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Courtesy Fernanda Feitosa and Heitor Martins

© 2021 German Lorca

Installation view of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the work of German Lorca with at fourth from right, Congonhas Airport (1961, below); at third from right Open Window (1951); at second from right, Eating an Apple (1953); and at right, Solarized Portrait (c. 1953)

Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

German Lorca (Brazilian, 1922-2021)

Congonhas Airport, São Paulo

1961

Gelatin silver print

10 1/2 × 15″ (26.7 × 38.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of the artist

© 2021 German Lorca

Installation view of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing Geraldo de Barros’ photographs – at top left, Untitled (1948-1950, below); at bottom left, Abstraction (1949, below); at second left, Geraldo de Barros’ Self-Portrait (Autorretrato) (c. 1949, below); and at fourth left, Fotoforma (c. 1949)

Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

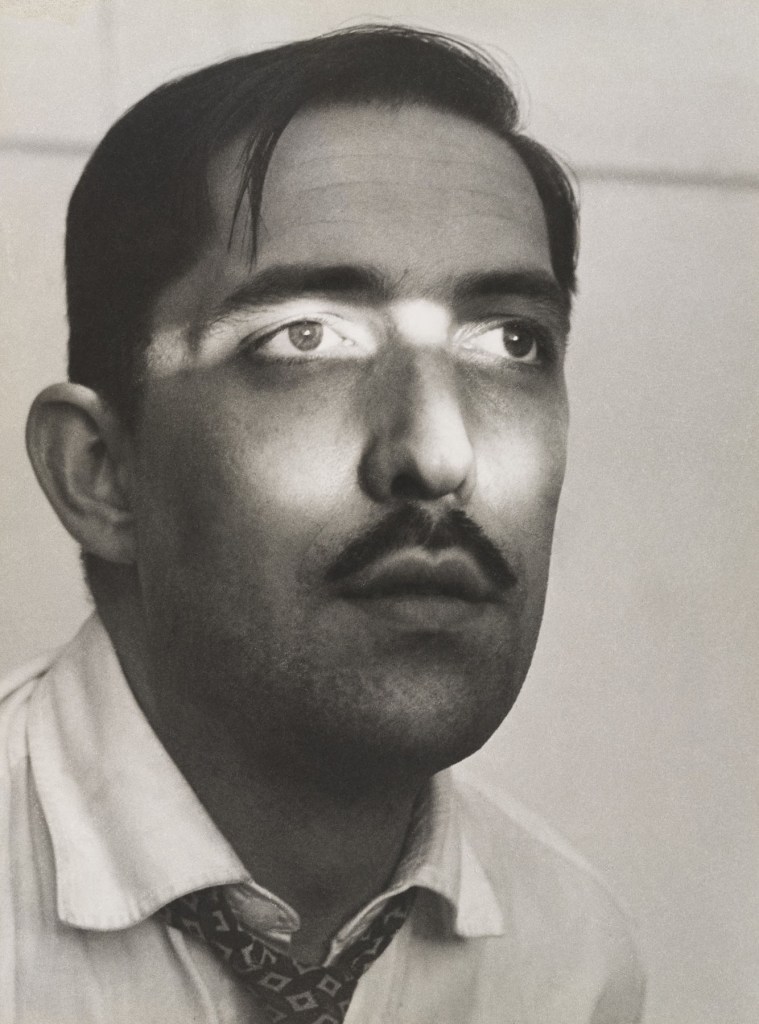

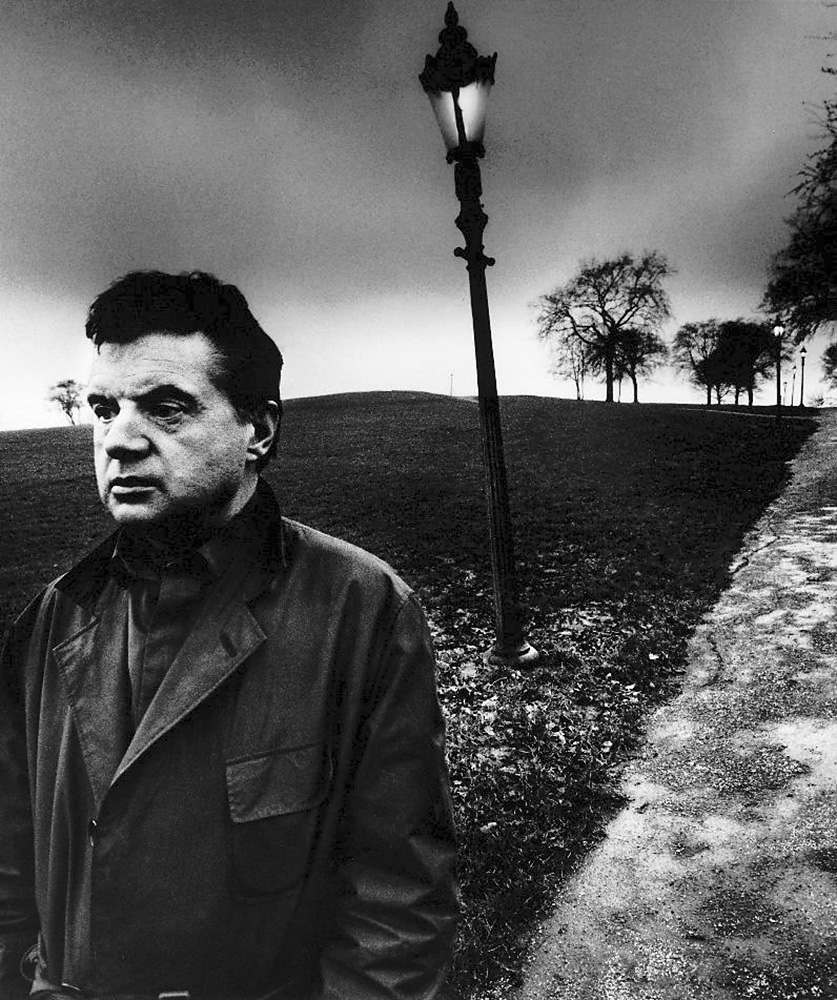

Geraldo de Barros (Brazilian, 1923-1998)

Untitled

1948-1950

Gelatin silver print

9 × 14 15/16″ (22.8 × 37.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Latin American and Caribbean Fund through gift of Agnes Gund

© 2021 Luciana Brito Galeria

Geraldo de Barros (Brazilian, 1923-1998)

Abstraction (Abstração)

1949

Gelatin silver print

10 3/4 × 14 3/4″ (27.3 × 37.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Latin American and Caribbean Fund

© 2021 Luciana Brito Galeria

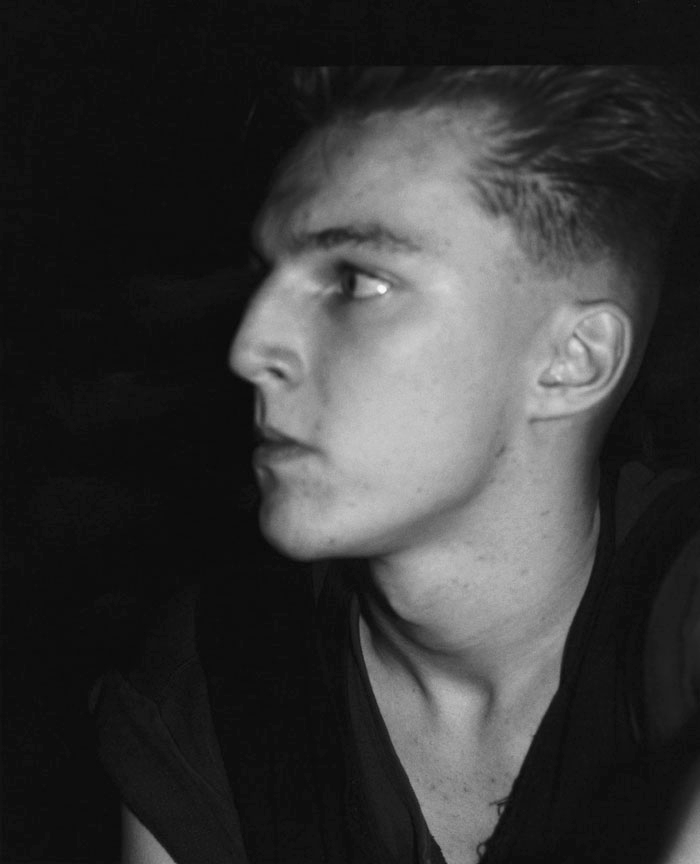

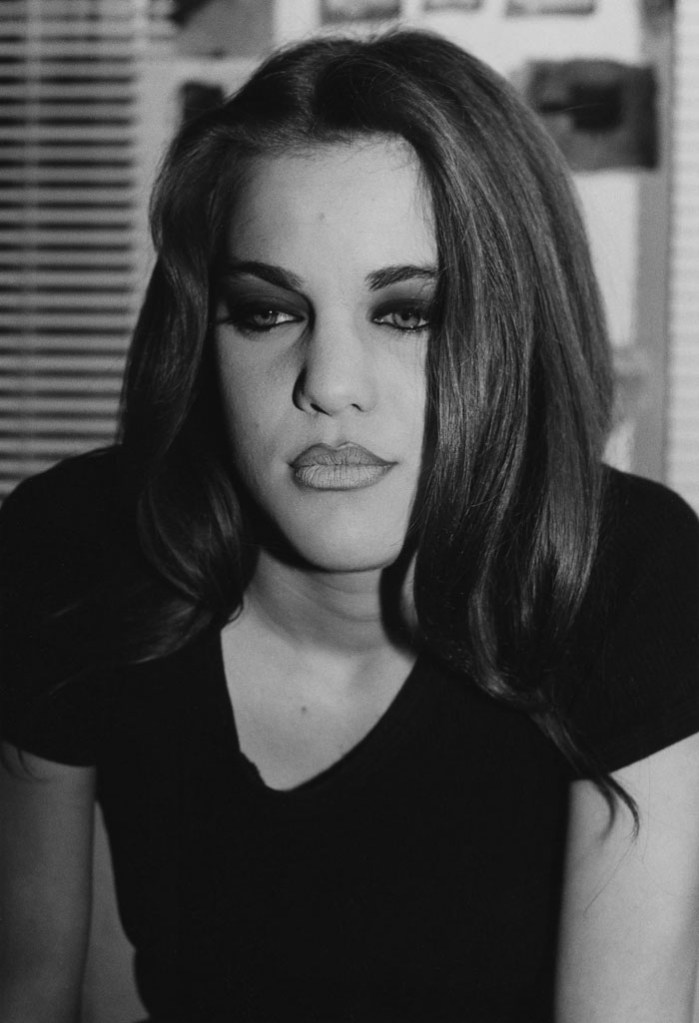

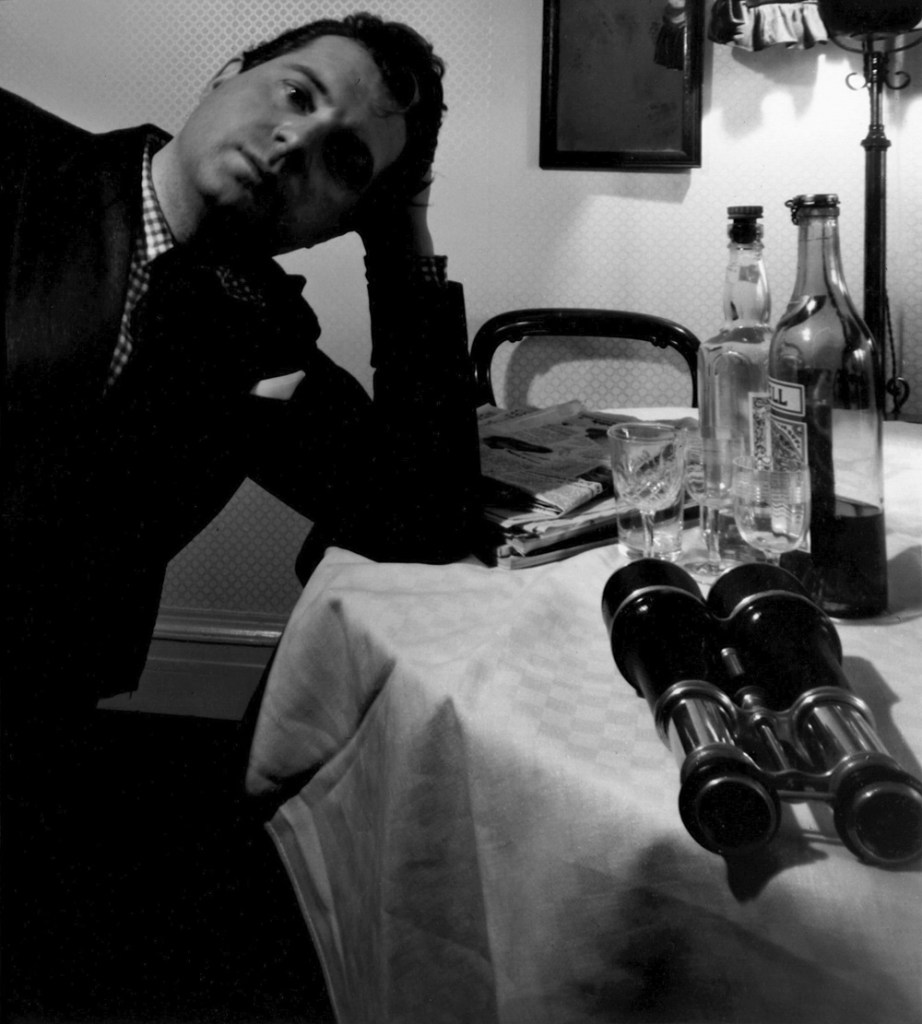

Geraldo de Barros (Brazilian, 1923-1998)

Self-Portrait (Autorretrato)

c. 1949

Gelatin silver print

15 7/16 × 11 1/2″ (39.2 × 29.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Christie Calder Salomon Fund

© 2021 Luciana Brito Galeria

Geraldo de Barros (Brazilian, 1923-1998)

Fotoforma

1952-1953

Gelatin silver print

11 13/16 × 15 1/8 in. (30 × 38.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of John and Lisa Pritzker

© 2020 Arquivo Geraldo de Barros. Courtesy Luciana Brito Galeria

Geraldo de Barros (Brazilian, 1923-1998)

Fotoforma

c. 1949

Gelatin silver print

14 13/16 × 10 11/16″ (37.7 × 27.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Latin American and Caribbean Fund

© 2021 Luciana Brito Galeria

Geraldo de Barros (Brazilian, 1923-1998)

Geraldo de Barros (February 27, 1923 – April 17, 1998) was a Brazilian painter and photographer who also worked in engraving, graphic arts, and industrial design. He was a leader of the concrete art movement in Brazil, co-founding Grupo Ruptura and was known for his trailblazing work in experimental abstract photography and modernism. According to The Guardian, De Barros was “one of the most influential Brazilian artists of the 20th century.” De Barros is best known for his Fotoformas (1946-1952), a series of photographs that used multiple exposures, rotated images, and abstracted forms to capture a phenomenological experience of Brazil’s exponential urbanisation in the mid-twentieth century.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Installation views of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the section Abstractions from Nature showing at middle top, Thomaz Farkas’s Rushing Water Number 2 (c. 1945, below); beneath that his Rushing Water Number 1 (c. 1945); at bottom left of the group Dulce Carneiro’s Oneiric (Onírica) (c. 1958); and at centre right, three sand photographs by José Yalenti (see below)

Photos: Jonathan Muzikar

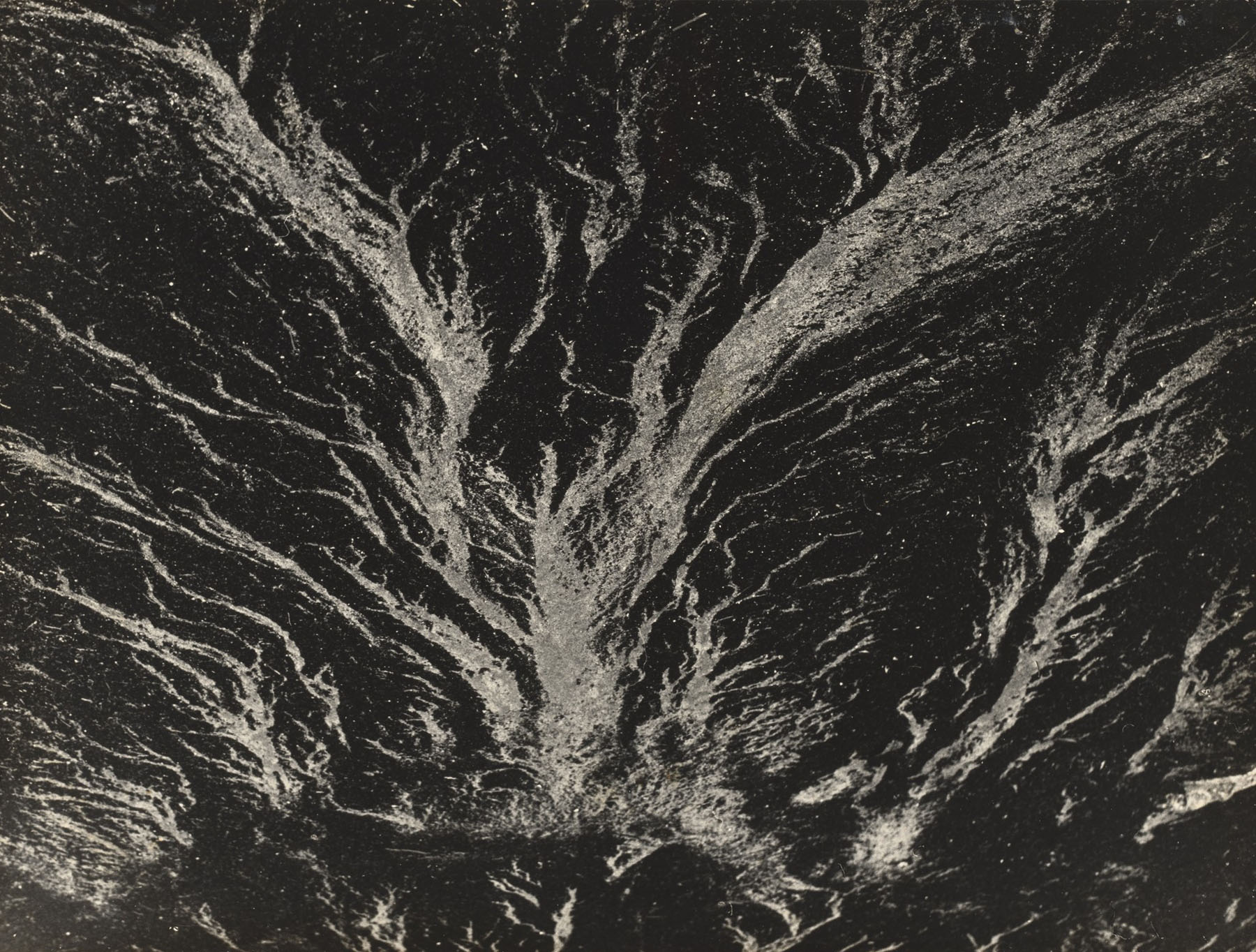

Abstractions from Nature

Thomaz Farkas (Brazilian, born Hungary. 1924-2011)

Rushing Water Number 2

c. 1945

Gelatin silver print

11 7/8 × 15 3/4″ (30.2 × 40cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of the artist

© 2021 Thomaz Farkas Estate

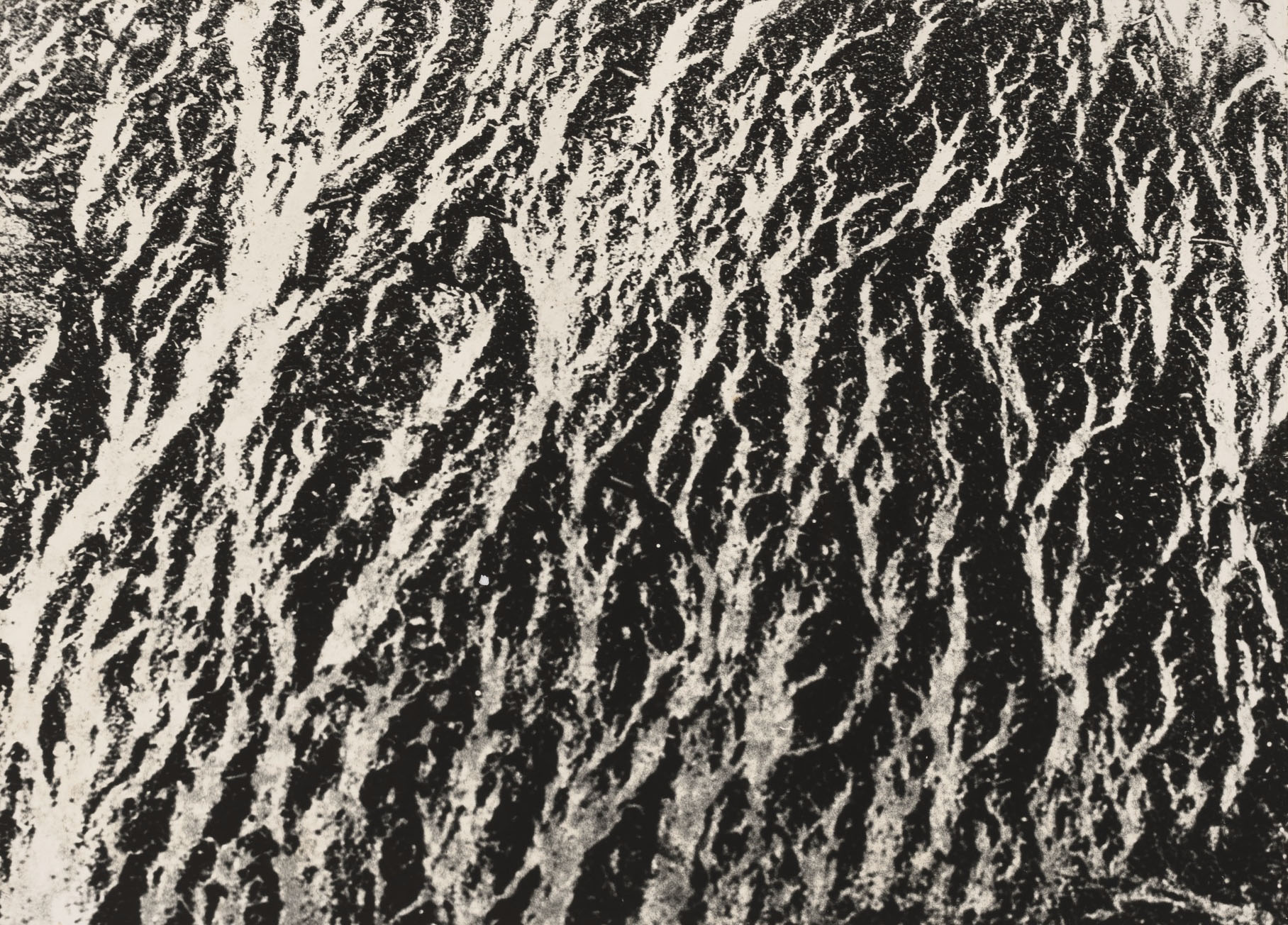

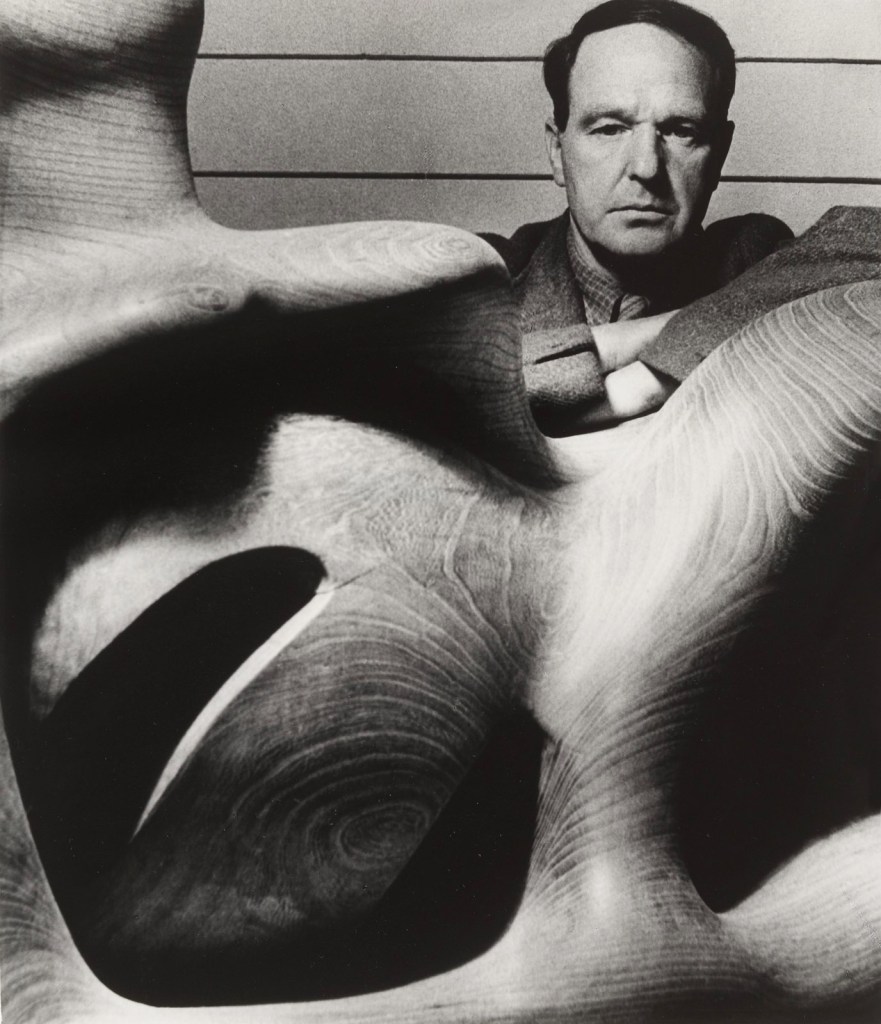

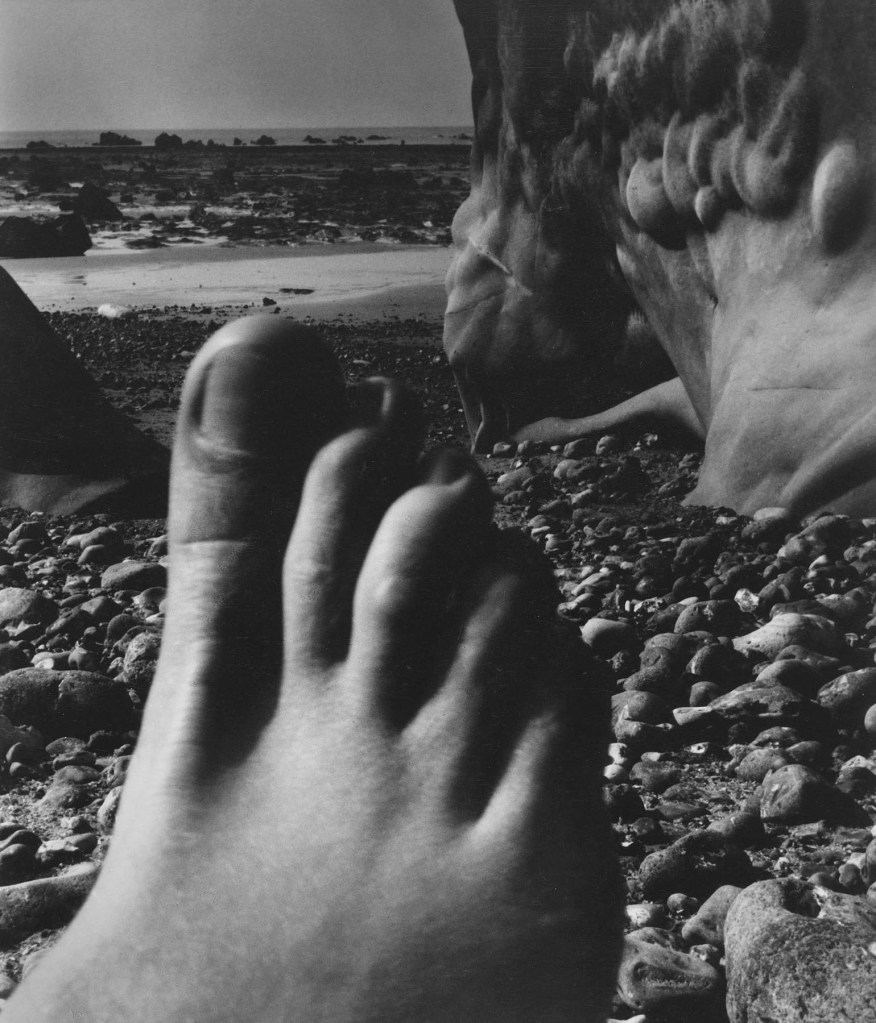

José Yalenti (Brazilian, 1895-1967)

Sand (Areia)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

11 7/8 × 15 3/4″ (30.1 × 40cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Committee on Photography Fund

© 2021 José Yalenti

José Yalenti (Brazilian, 1895-1967)

Sand (Areia)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

11 1/8 × 15 3/8″ (28.3 × 39cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Committee on Photography Fund

© 2021 José Yalenti

José Yalenti (Brazilian, 1895-1967)

Sand (Areia)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

15 3/4 × 11 7/8″ (40 × 30.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund

© 2021 José Yalenti

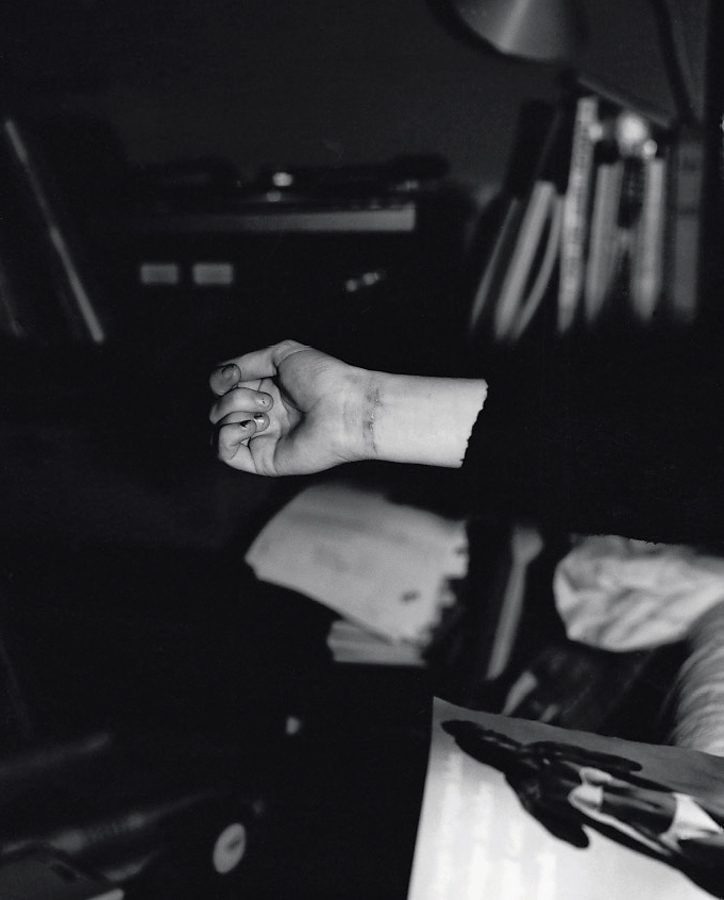

Installation views of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Daily Life, German Lorca and Solitude with in the bottom image at bottom right, Ademar Manarini’s Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo] (c. 1951, below)

Photos: Jonathan Muzikar

Ademar Manarini (Brazilian, 1920-1989)

Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]

c. 1951

Gelatin silver print

11 11/16 × 14 9/16″ (29.7 × 37cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Richard O. Rieger

© 2021 Estate of Ademar Manarini

Installation view of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing Marcel Giró’s photograph Light and Power (c. 1950, below)

Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

Marcel Giró (Spanish, 1912-2011)

Light and Power (Luz e Força)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

13 1/16 × 20 3/16″ (33.1 × 51.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Richard O. Rieger

© 2021 Estate of Marcel Giró

Installation view of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Texture and Shape and Geraldo de Barros, with at third from left top, Maria Helena Valente da Cruz’s The Broken Glass (O vidro partido) (c. 1952, below); at fourth from left top, Palmira Puig-Giró’s Untitled (c. 1960, below); at bottom left Marcel Giró’s Texture 2 (c. 1950, below); and at bottom centre, his Composition (Composição) (c. 1953)

Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

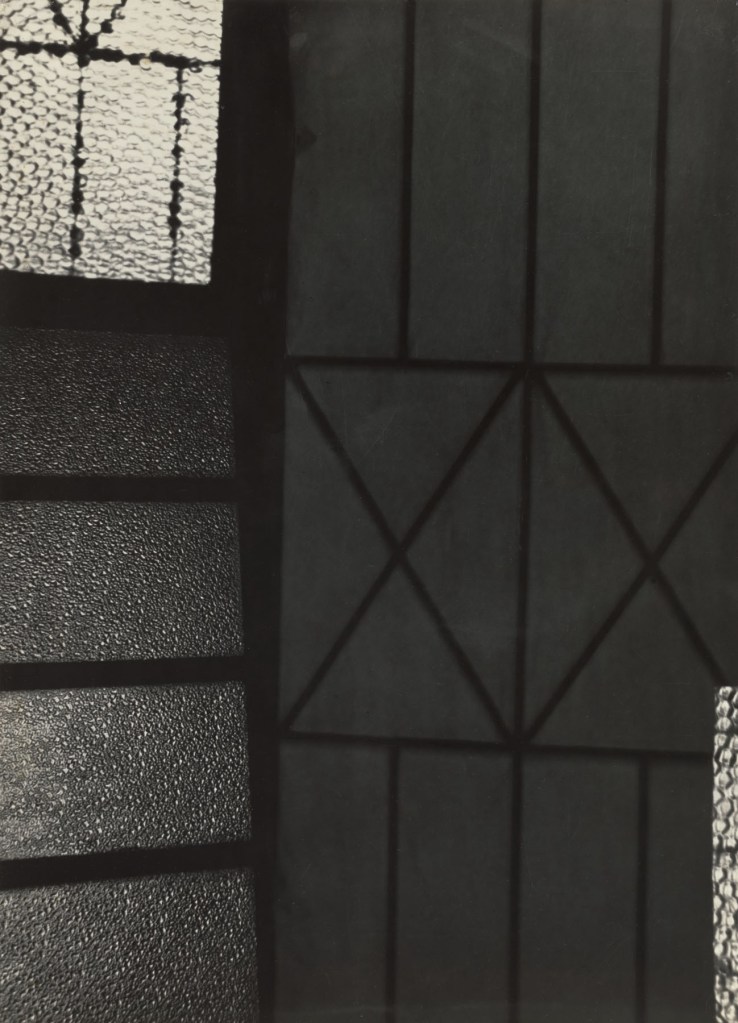

Texture and Shape

Maria Helena Valente da Cruz (Portuguese, b. 1927)

The Broken Glass (O vidro partido)

c. 1952

Gelatin silver print

11 7/8 × 11 1/2 in. (30.2 × 29.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Donna Redel

© 2020 Estate of Maria Helena Valente da Cruz

Palmira Puig-Giró (Spanish, 1912-197)

Untitled

c. 1960

Gelatin silver print

15 3/8 × 11 1/16 in. (39.1 × 28.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Agnes Rindge Claflin Fund

© 2020 Estate of Palmira Puig-Giró

Marcel Giró (Spanish, 1912-2011)

Texture 2 (Textura 2)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

12 1/8 × 15 3/4″ (30.8 × 40cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Committee on Photography Fund

© 2021 Estate of Marcel Giró

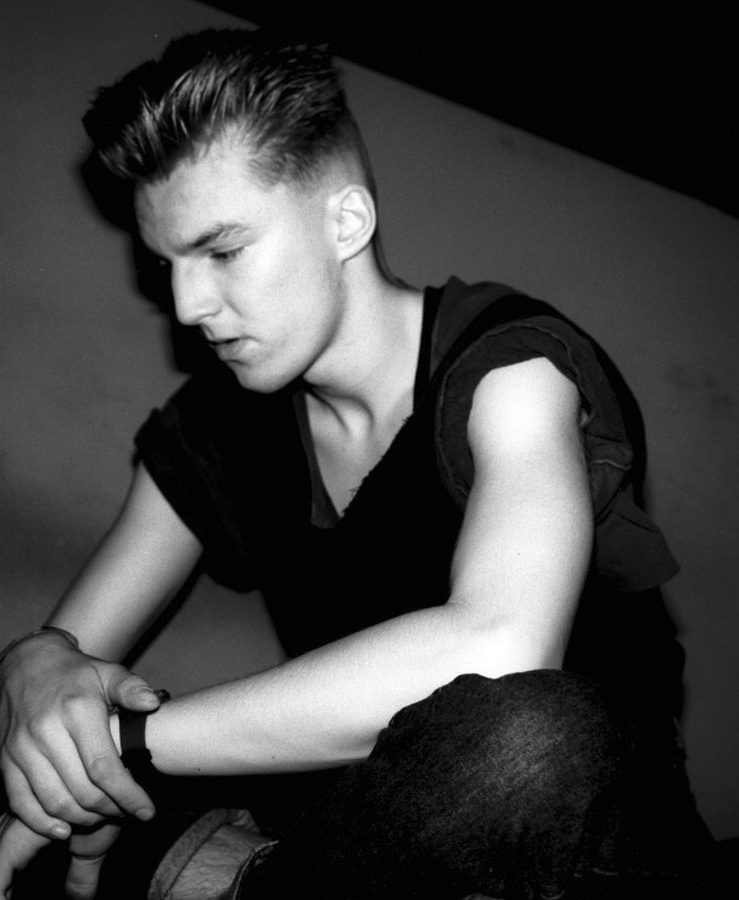

Installation views of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Simplicity and Gertrude Altschul, with at top left, Thomaz Farkas’ Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro] (c. 1945, below); and at right, Gertrudes Altschul’s Lines and Tones (Linhas e Tons) (c. 1953, below)

Photos: Jonathan Muzikar

![Thomaz Farkas (Brazilian, born Hungary. 1924-2011) 'Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro]' c. 1945 Thomaz Farkas (Brazilian, born Hungary. 1924-2011) 'Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro]' c. 1945](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/farkas.jpg?w=934)

Thomaz Farkas (Brazilian, born Hungary. 1924-2011)

Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro]

c. 1945

Gelatin silver print

12 13/16 × 11 3/4 in. (32.6 × 29.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of the artist

Gertrude Altschul

Gertrudes Altschul (Brazilian born Germany, 1904-1962)

Lines and Tones (Linhas e Tons)

c. 1953

Gelatin silver print

14 7/8 x 11″ (37.8 x 27.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Amie Rath Nuttall

Gertrudes Altschul was born in Germany in 1904 and, like many Jews in the 1930s, she was forced to leave the country under the threat of Nazism rise. Thus, in 1939, together with her husband Leon Altschul, she went into exile in Brazil and settled in the city of São Paulo, at the end of that year. She and her husband ran a business selling handmade decorative flowers for hats in São Paulo, Brazil.

See more Gertrudes Altschul photographs on the Isabel Amado Fotografia website.

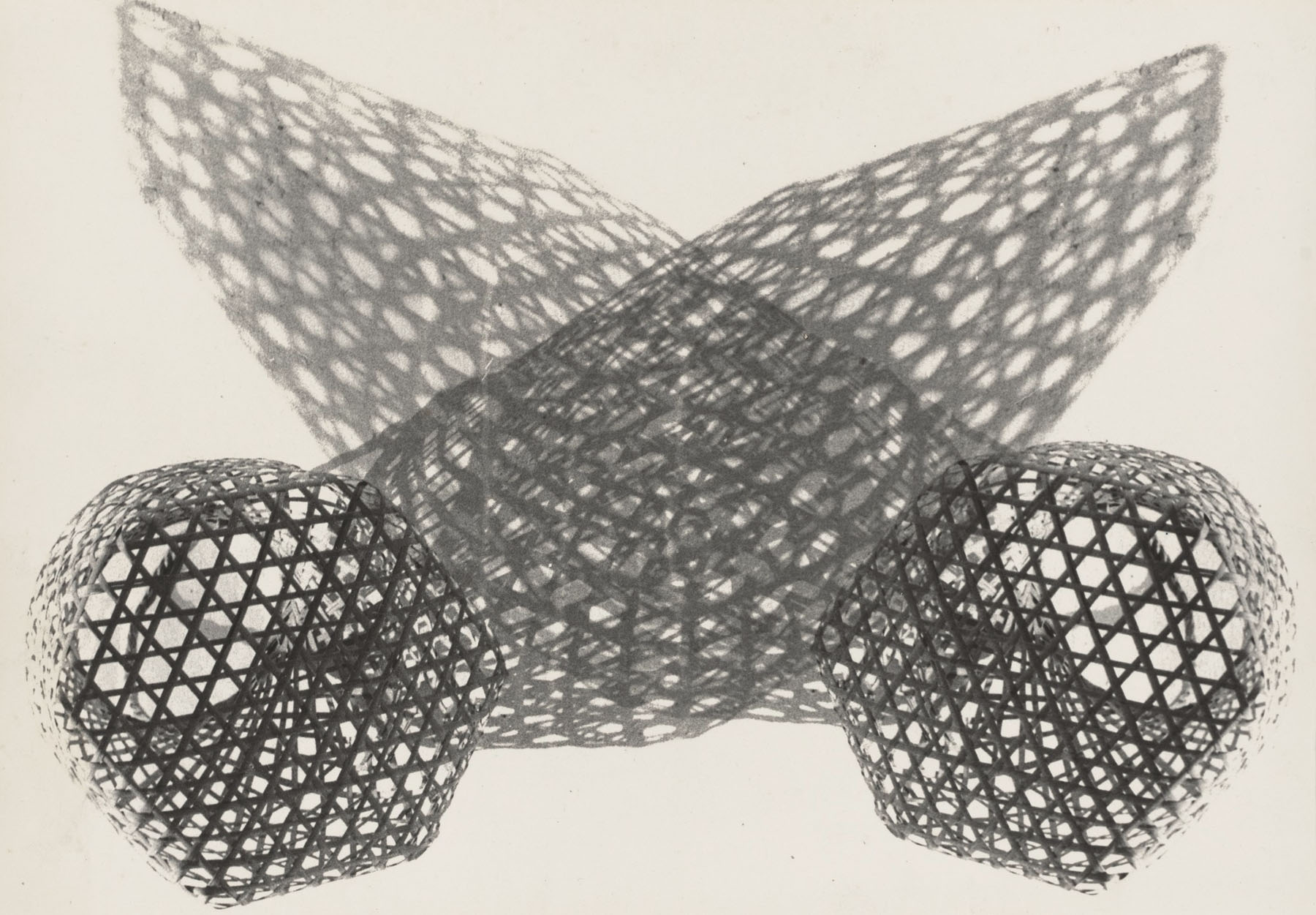

A little over a year after joining the Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB), an amateur camera club in São Paulo, Gertrude Altschul had already secured a spot for her work on the cover of its monthly bulletin. By September of 1953, her photograph Linhas e Tons (Lines and Tones) [above] was circulated to hundreds of fellow practitioners throughout Brazil. Lines and Tones reveals the urbanisation and precipitous vertical growth taking place in downtown São Paulo at midcentury; Altschul’s simple title strips away local context and persuades us to experience the image through its soaring curves and lines. This ability to reduce complex objects to their most elemental and visually striking forms would become a hallmark of her work.1

By the time Altschul joined the FCCB, the organisation had already been in operation for 13 years. During that time it succeeded in nurturing a passion for photography across a wide network of Paulistas (São Paulo residents), many of whom were recent European emigrés working as lawyers, doctors, accountants, or entrepreneurs. Altschul’s background was no different: after fleeing Nazi persecution in Germany, she settled in Brazil in 1939. With her husband, she ran a business making handmade decorative flowers for women’s hats and blouses. Her interest in botanical motifs found its way into her photographic work, resulting in dozens of lush vegetal prints.

Though Altschul belonged to a small contingent of women artists within the FCCB, her experimental ambitions rivaled those of her male peers. She photographed a diverse range of subjects, from urban landscapes to natural forms to still lifes. The resulting prints were routinely reproduced in the club’s monthly bulletin, mailed out for consideration by salons, and chosen for display in exhibitions. Between 1956 and 1962, Altschul was encouraged to submit Filigrana (Filigree) to no fewer than 18 different national and international salons, receiving an impressive eight acceptances.2 Despite its worldwide circulation, this photograph portrayed a thoroughly Brazilian subject: a papaya leaf, delicately transcribed into lattice-like veins.

Altschul fell ill in the late 1950s and, starting in 1957, her participation in the club waned. Following her death in 1962, the FCCB bulletin featured Filigree alongside her obituary, where it was praised as one of the first successful works of her brief but distinguished career.3

Dana Ostrander, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, 2020

1/ The supporting research for this biography was provided by Abigail Lapin Dardashti, former Museum Research Consortium Fellow. For more, see Abigail Lapin Dardashti, “Gertrudes Altschul and Modernist Photography at the Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante,” on Medium, MoMA: Features and perspectives on art and culture, The Museum of Modern Art, June 7, 2017.

2/ Paula Kupfer, “Gertrudes Altschul: An Adopted Brazilian Photographer in São Paulo,” on post: notes on art in a global context, The Museum of Modern Art, May 2, 2018

3/ Ibid.

In Black and White: Photography, Race, and the Modern Impulse in Brazil at Midcentury

Live stream of the keynote panel from In Black and White: Photography, Race, and the Modern Impulse in Brazil at Midcentury (May 2, 2017, The Museum of Modern Art).

Join us for a conversation on Brazilian modernist photography, its relationship to race, and its place within a dynamic international network of images and ideas, moderated by Edward Sullivan, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.

Guest speakers: Helouise Costa, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Universidade de São Paulo Roberto Conduru, Rio de Janeiro State University Heloísa Espada, Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo Sarah Hermanson Meister, The Museum of Modern Art

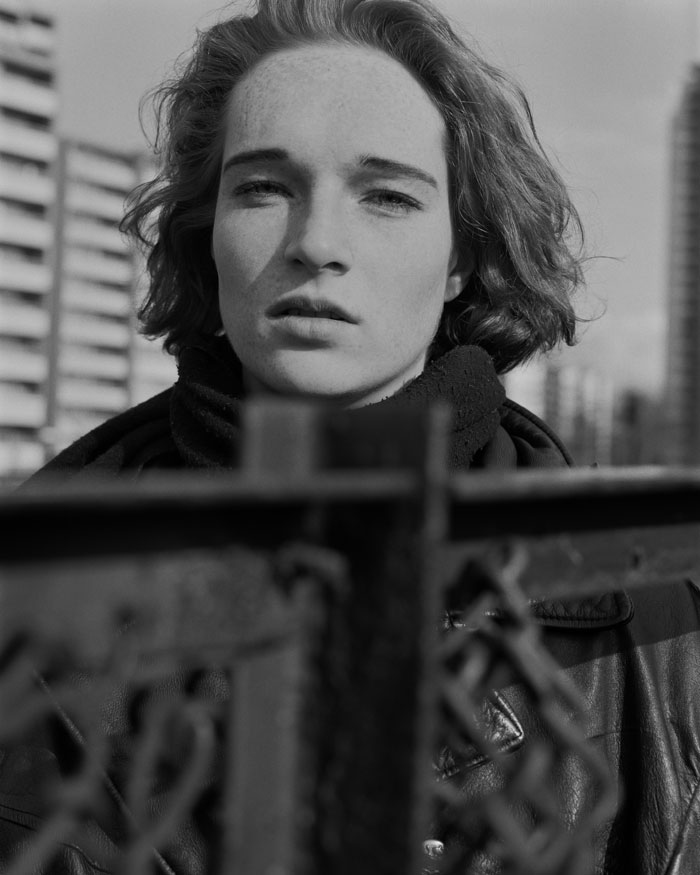

Installation view of the exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the section Gertrude Altschul with at centre left Untitled (c. 1955, below); at centre right, Untitled (c. 1955, below); at fourth right her Filigree, (Filigrana) (1953, below); and at top right, Untitled (c. 1955, below)

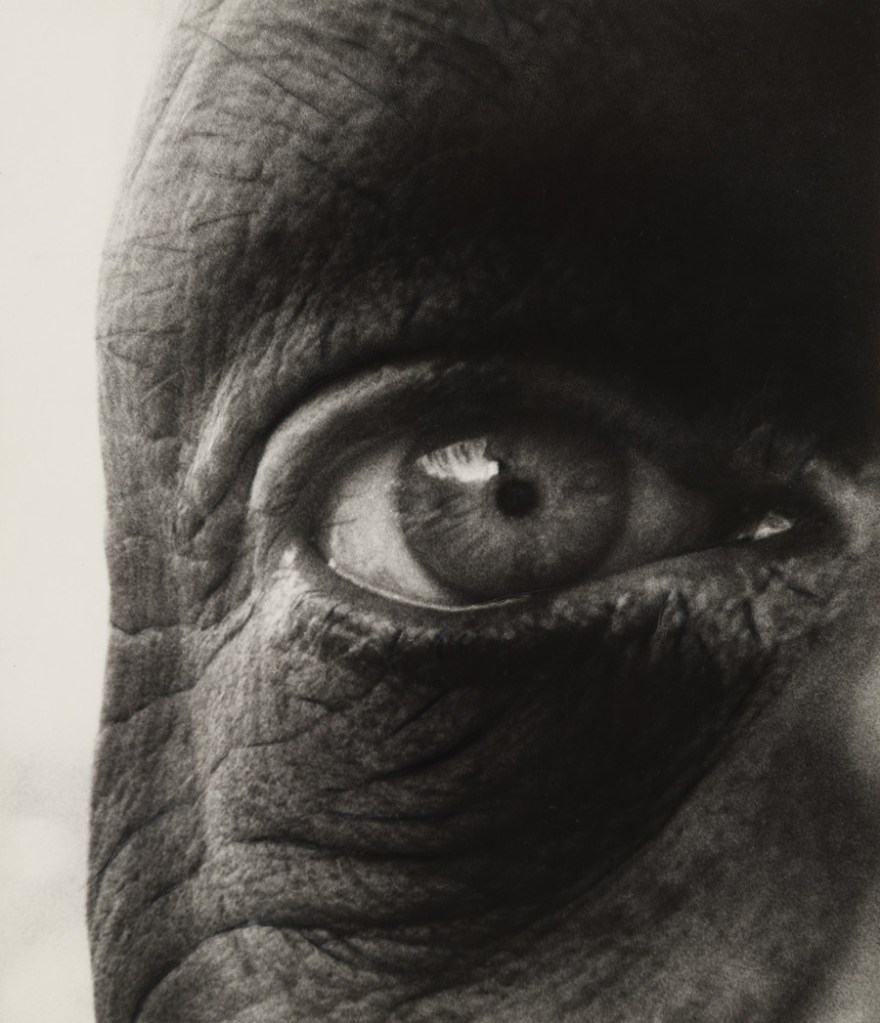

Gertrudes Altschul (Brazilian born Germany, 1904-1962)

Untitled

c. 1955

Gelatin silver print

10 13/16 × 15 1/4″ (27.5 × 38.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of David Dechman and Michel Mercure

© 2021 Estate of Gertrudes Altschul

Like almost every member of Sáo Paulo’s famed Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB), Altschul was an amateur, meaning she pursued photographic activity without any professional affiliation or ambition. She began attending workshops with the FCCB in the late 1940s and became a member in 1952. There are no written records of her creative intent, leaving only the visual evidence of her achievement: experimentations with process and form, and inventive compositions discovered within everyday life. These large-scale prints were made for the active circuit of contemporary salons and exhibitions that traveled throughout Brazil and internationally in this period.

Gallery label from Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction, April 19 – August 13, 2017.

Gertrudes Altschul (Brazilian born Germany, 1904-1962)

Untitled

c. 1955

Gelatin silver print

15 1/16 × 11 1/2″ (38.3 × 29.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

John Szarkowski Fund

© 2021 Estate of Gertrudes Altschul

Gertrudes Altschul (Brazilian born Germany, 1904-1962)

Filigree, (Filigrana)

1953

Gelatin silver print

13 5/8 × 11 5/8″ (34.6 × 29.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Amie Rath Nuttall

© 2021 Estate of Gertrudes Altschul

Gertrudes Altschul (Brazilian born Germany, 1904-1962)

Untitled

c. 1955

Gelatin silver print

11 13/16 × 15 1/2″ (30 × 39.4 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

John Szarkowski Fund

© 2021 Estate of Gertrudes Altschul

Fotoclubismo explores the unforgettable creative achievements of São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB), a group of amateur photographers whose ambitious and innovative works embodied the abundant originality of postwar Brazilian culture. Although their work was heralded around the world in the 1950s, it subsequently faded from view. This is the first museum exhibition to present this fascinating moment in photography’s history to audiences outside of Brazil.

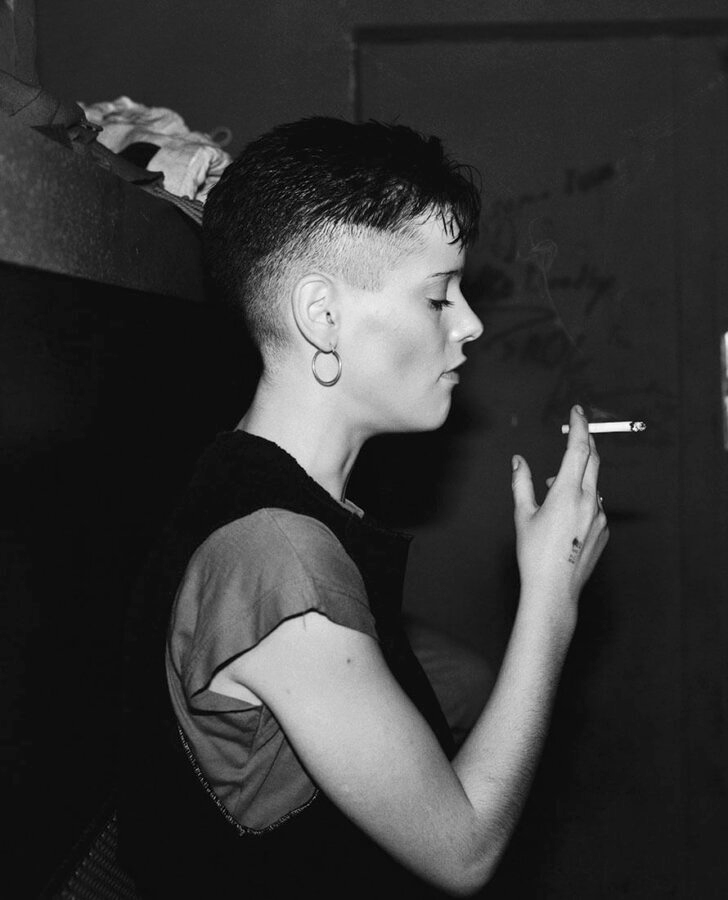

Photography was a hobby for most FCCB members: on weekdays, group members – many of whom were women – went to their jobs as businessmen, accountants, journalists, engineers, biologists, and bankers. On weekends, they often traveled to photograph together. They were nonetheless quite serious about their artistic ambition, not unlike millions of people on Instagram today. Their pictures assumed many forms – from inventive experiments to distillations from everyday life – and their attentiveness to abstraction evolved in dialogue with leading critical thinkers and peers in design, painting, and film.

More than 60 photographs, drawn almost exclusively from MoMA’s collection, demonstrate the group’s extraordinary range. Their absence from international histories of the medium provide a valuable opportunity to reflect on the biases that led to these exclusions, and invite us to reflect on the status of the amateur today. Organised by Sarah Hermanson Meister, Curator, with Dana Ostrander, Curatorial Assistant, Robert B. Menschel Department of Photography.

Introduction

The members of São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB), established in 1939, were doctors and lawyers, civil servants and businessmen, accountants and students. Though they pursued photography as a hobby, their work attests to the seriousness and skill with which they approached the medium. Their innovations were advanced by camaraderie as well as a competitive spirit: submissions to monthly internal contests were judged publicly, with points awarded accordingly. This installation is structured in constellations based on the themes of these contests, punctuated by focused presentations of the work of three key figures.

Bandeirante alludes to a colonial-era group of explorers and fortune hunters based in the São Paulo region, whom the FCCB celebrated for their pioneering spirit, overlooking their role in the enslavement of Indigenous people and the expansion of territory under Portuguese control. Though its identity was thus firmly anchored in the local, the club was an integral part of a dynamic international network of amateurs: the FCCB was widely heralded and its members’ work awarded prizes in salons on six continents. The club’s position in the Global South, and a bias against the amateur and its association with pictorial clichés, begin to explain its absence from international histories of the medium.

The dates that bracket this exhibition correspond to artistic and political realities in Brazil: the FCCB first published its monthly magazine (the Boletim foto-cine) in 1946, the year a new constitution restored democracy following a repressive regime. On the other end, 1964 marked the beginning of a brutal dictatorship, which contributed to the closing of an extraordinarily fertile chapter for photography in Brazil – one that has been, until now, largely overlooked beyond the country’s borders.

Text from the MoMA website

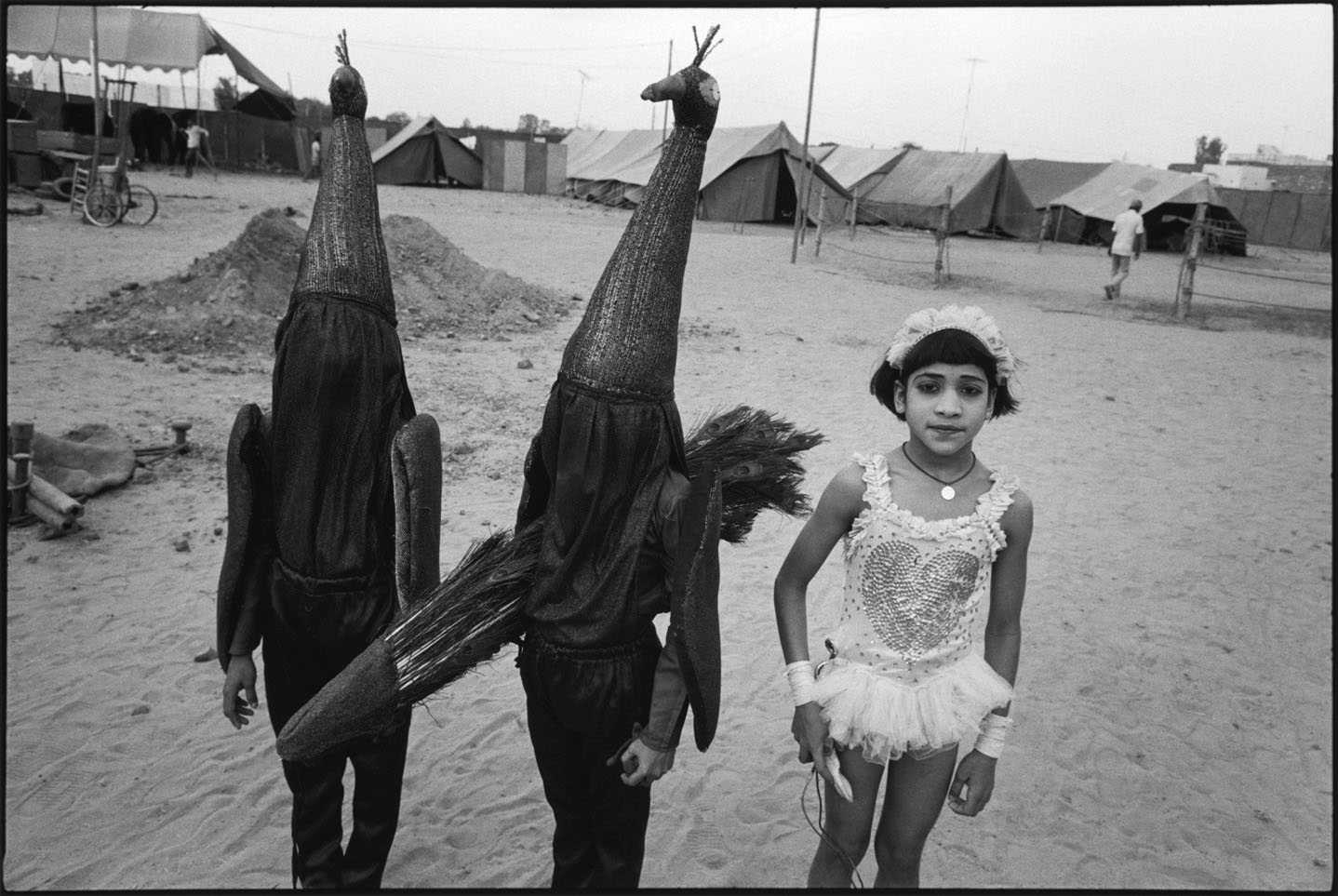

Julio Agostinelli (Brazilian, b. 1919)

Circus (Circense)

1951

Gelatin silver print

11 7/16 × 15″ (29 × 38.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of Richard O. Rieger

© 2020 Estate of Julio Agostinelli

The Museum of Modern Art opened Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964, the first museum exhibition of Brazilian modernist photography outside of Brazil. On view May 8 – September 26, 2021, the exhibition focuses on the unforgettable creative achievements of São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante, a group of amateur photographers widely heralded in Brazil, but essentially unknown to European and North American audiences. Fotoclubismo is comprised of over 60 photographs drawn generously from MoMA’s collection; together, they bring forward the extraordinary range of achievements of this group, provide valuable insight into the way photographic aesthetics were framed in the 1950s, and afford opportunities to reflect on the significance of amateur status today. The exhibition is organised by Sarah Meister, Curator, with Dana Ostrander, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography.

The vast majority of Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante members were amateurs, meaning they pursued photographic activity without any professional motive or affiliation. The club’s longtime president, Eduardo Salvatore, earned his living as a lawyer, and the list of professions on the membership cards includes businessmen, accountants, journalists, engineers, biologists, and bankers. While photography was an activity pursued outside their day jobs, FCCB members were nonetheless quite serious about their artistic ambition, as evidenced by the striking innovation of their photographs. Works such as Geraldo de Barros’s Fotoforma, São Paulo (1952-1953), Thomaz Farkas’s Ministry of Education and Health, Rio (c. 1945), or Gertrudes Altschul’s Filigree (Filigrana) (c. 1952), for example, represent a few of their radical experimentations with process and form and underscore the discovery of imaginative compositions within everyday life. FCCB members responded to the abundant originality of contemporary Brazilian architects, and their attentiveness to the fertility of abstraction as a creative strategy emerged alongside peers in design, painting, and literature. Considering these works together provides a compelling context through which to explore the complex status of the amateur, evolving biases of taste or judgment, and local dynamics of race and gender.

Beyond creating photographs, a critical aspect of the club’s activity was their monthly Concursos Internos (internal contests) and Seminarios, in which photographs were submitted for peer review and discussed in public and private forums.

As with most amateur photo clubs around the world, the FCCB fostered a collegial environment that tolerated a wide range of artistic approaches. Yet it was also a competitive one, where critical judgment and artistic ambition were central to the club’s identity (and contributed to the enduring quality of the work). The annual salon they hosted and Boletim, a monthly magazine published by the FCCB, both demonstrate the breadth of activity pursued under the aegis of the club and highlighted the club’s achievements to the international circuit of salons in which they participated, including Otto Steinert and his fellow “Subjective” photographers in Germany, the Groupe des XV in Paris, La Ventana in Mexico City, and the Carpeta de los Diez in Buenos Aires.

Fotoclubismo has been installed along two intertwined, complementary threads within the galleries: monographic and thematic. Of the display’s three sections, each is anchored by a focused monographic presentation of an individual member: Geraldo De Barros, German Lorca, and Gertrudes Altschul. These sections begin and end with thematic groupings that suggest the breadth of the photographic community active in São Paulo at that time and offer additional context for the individual achievements. Each theme is derived from the monthly Concursos Internos held at the FCCB, which prompted members to respond to a certain theme, often awarding the winner with full-page reproductions and cover features. Two paintings from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros gift and a generous selection of the FCCB’s monthly Boletim, recently acquired by the Museum Library, will expand the context for the photographs on view.

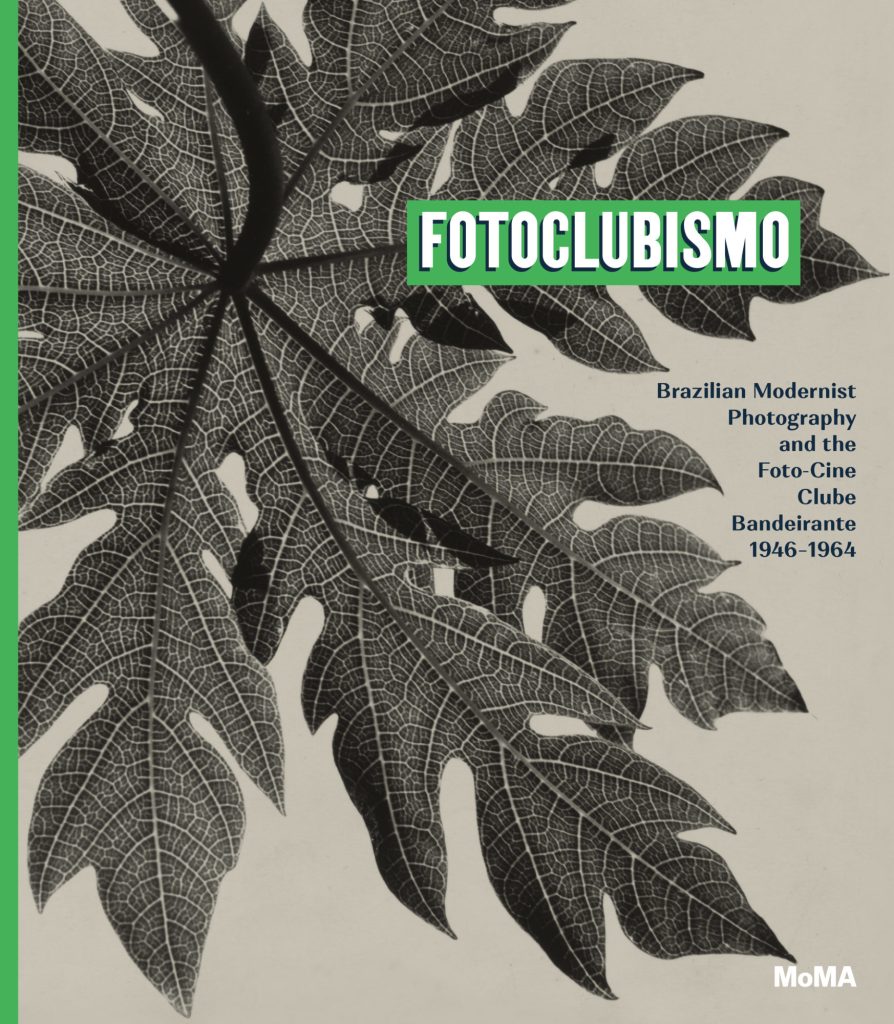

The exhibition is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue with 140 plates from the Museum Collection and a number of important public and private collections in São Paulo, presenting Brazilian modernist photography to an international audience for the first time. The book situates these achievements within the broader contemporary art scene in Brazil as well as within a dynamic network of photographers around the world, and offering fresh insight into the status of the amateur in the postwar era.

Press release from the MoMA website

José Medeiros (Brazilian, 1921-1990)

Pedra da Gávea, Morro Dois Irmãos and the Beaches Ipanema and Leblon, Rio de Janeiro

1952

Gelatin silver photograph

Courtesy Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

André Carneiro (Brazilian, 1922-2014)

Rails (Trilhos)

1951

Gelatin silver print

11 5/8 × 15 9/16 in. (29.6 × 39.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of José Olympio da Veiga Pereira through the Latin American and Caribbean Fund

© 2020 Estate of André Carneiro

Aldo Augusto de Souza Lima (Brazilian, 1920-1971)

Vertigo (Vertigem)

1949

Gelatin silver print

11 × 14 3/4 in. (28 × 37.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Acquired through the generosity of James and Ysabella Gara in honor of Donald H. Elliott

© 2020 Estate of Aldo Augusto de Souza Lima

Roberto Yoshida

Skyscrapers (Arranha-céus)

1959

Gelatin silver print

14 9/16 × 11 9/16 in. (37 × 29.3cm)

Collection Fernanda Feitosa and Heitor Martins

© 2020 Estate of Roberto Yoshida

Reproduction of the photographic collection by Hélio Martins

Boletim was pivotal for showcasing FCCB’s progress and attracting new members. The club held monthly photo competitions and listed the winners in each issue. The magazine fostered a healthy competition between members and provided an incentive to capture the “best view.”

Each issue there were internal competitions where photos were judged by visual qualities as well as psychological factors. Editors would list the winners’ names along with birthday announcements, weddings, and group photos. Recording the names of the members served as a way for FCCB to seal their place in history lest the world forgot.

And for a while, the world did forget.

It wasn’t until years after the club closed their doors that Helouise Costa, professor at University of São Paulo and curator of Museum of Contemporary Art, discovered FCCB in the eighties after applying for a grant at University of São Paulo meant to encourage academics to explore Brazilian photography.

Soon into her research, Costa came across works by members of FCCB and quickly realised that the group was the most influential photo collective in its time in both scope and skill.

Costa studied the club’s magazine and reached out to all the names listed in the pages. What she discovered was an entirely forgotten archive of some of the most influential mid century Brazilian photography. Costa was the first person to look at many of these prints in decades: many former members had been sitting on these negatives since the 50’s.

This discovery catapulted FCCB into national fame, although it wasn’t until another twenty plus years before the club’s legacy started to make a buzz internationally.

Meka Boyle. “MoMA is the First Museum Outside of Brazil to Put the Spotlight on Brazilian Modernist Photography,” on the Art Dealer Street website May 28 2021 [Online] Cited 26/08/2021

Cover of the exhibition catalogue Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography and the Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante, 1946-1964, published by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2021.

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Daily Life, German Lorca and Solitude with bottom right, Ademar Manarini's 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' (c. 1951) Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Daily Life, German Lorca and Solitude with bottom right, Ademar Manarini's 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' (c. 1951)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/fotoclubismo-installation-i.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Daily Life, German Lorca and Solitude with bottom right, Ademar Manarini's 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' (c. 1951) Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Daily Life, German Lorca and Solitude with bottom right, Ademar Manarini's 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' (c. 1951)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/fotoclubismo-installation-k.jpg)

![Ademar Manarini (Brazilian, 1920-1989) 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' c. 1951 Ademar Manarini (Brazilian, 1920-1989) 'Untitled [Várzea do Carmo housing complex, São Paulo]' c. 1951](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/manarini-housing-complex.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Simplicity and Gertrude Altschul, with at top left, Thomaz Farkas' 'Ministry of Education' (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro] (c. 1945); and at right, Gertrudes Altschul's 'Lines and Tones' (Linhas e Tons) (c. 1953) Installation view of the exhibition 'Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-1964' at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York showing the sections Simplicity and Gertrude Altschul, with at top left, Thomaz Farkas' 'Ministry of Education' (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro] (c. 1945); and at right, Gertrudes Altschul's 'Lines and Tones' (Linhas e Tons) (c. 1953)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/fotoclubismo-installation-t.jpg)

![Underwood & Underwood (American, founded 1881, dissolved 1940s) '[Women's Campaign Train for Hughes]' 1916 from the exhibition 'In Focus: Protest' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, June - Oct, 2021 Underwood & Underwood (American, founded 1881, dissolved 1940s) '[Women's Campaign Train for Hughes]' 1916 from the exhibition 'In Focus: Protest' at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, June - Oct, 2021](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/underwood-underwood-womens-campaign-train-for-hughes.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.