Exhibition dates: 8th October – 28th November 2010

Exhibiting artists: Charles Anderson, George Armfield, Melanie Boreham, Bureau of Inverse Technology, Aleks Danko, Tacita Dean, Sue Ford, Garry Hill, Larry Jenkins, Peter Kennedy, Anastasia Klose, Arthur Lindsay, Dora Meeson, Anna Molska, TV Moore, Tony Oursler, Neil Pardington, Giulio Paolini, Mark Richards, David Rosetzky, Anri Sala, James Shaw, Louise Short, William Strutt, Darren Sylvester, Fiona Tan, Bill Viola, Annika von Hausswolff, Mark Wallinger, Lynette Wallworth, Gillian Wearing.

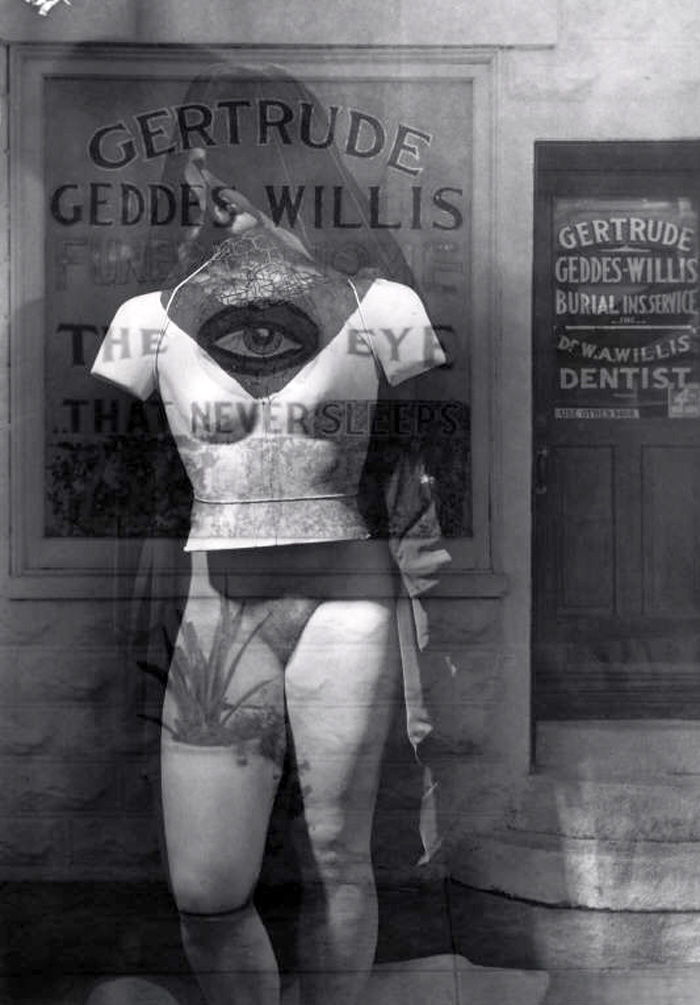

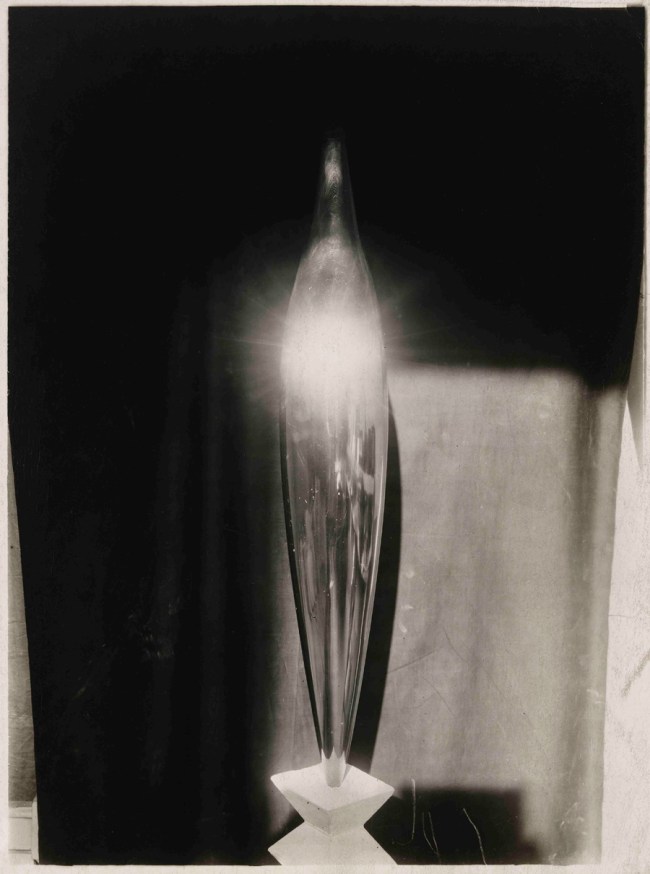

Fiona Tan (Indonesia, b. 1966)

Tilt

2002

DVD

Courtesy of the artist, Frith Street Gallery London

“… this immersive exhibition swallows us into a kind of spiritual and philosophical lifecycle. As we weave our way through a maze-like series of darkened rooms, we encounter life’s early years, a youth filled with mischief, wonderment, possibilities and choices, and a more reflective experience of mid and later life, preceding the eventual end.”

Dan Rule in The Age

I never usually review group exhibitions but this is an exception to the rule. I have seen this exhibition three times and every time it has grown on me, every time I have found new things to explore, to contemplate, to enjoy. It is a fabulous exhibition, sometimes uplifting, sometimes deeply moving but never less than engaging – challenging our perception of life. The exhibition proceeds chronologically from birth to death. I comment on a few of my favourite works below but the whole is really the sum of the parts: go, see and take your time to inhale these works – the effort is well rewarded. The space becomes like a dark, fetishistic sauna with it’s nooks and crannies of videos and artwork. Make sure you investigate them all!

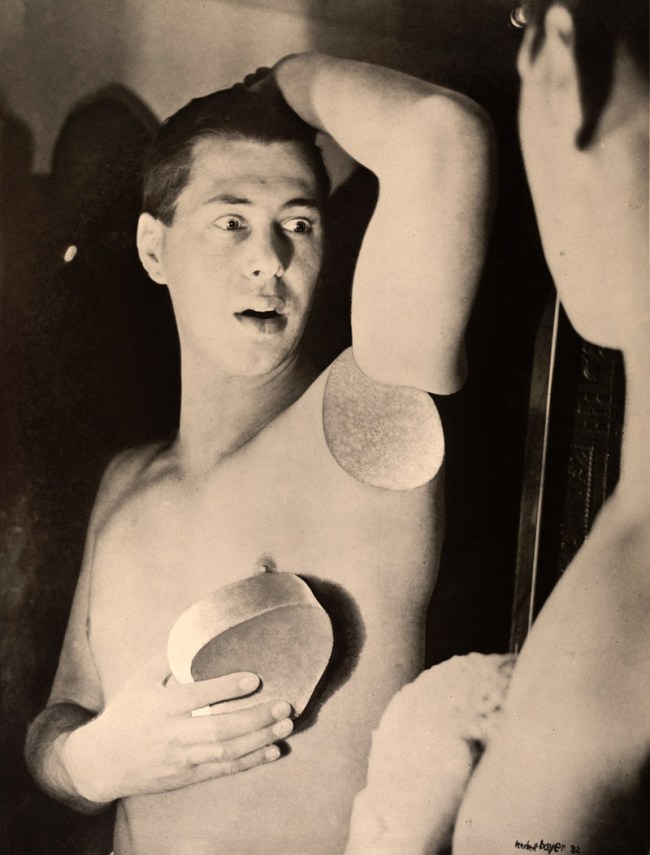

There is only one photograph by Gillian Wearing from her Album series of self portraits, Self Portrait at Three Years Old (2004, see photograph below) but what a knockout it is. An oval photograph in a bright yellow frame the photograph looks like a perfectly normal studio photograph of a toddler until you examine the eyes: wearing silicon prosthetics, Wearing confronts “the viewer with her adult gaze through the eyeholes of the toddler’s mask, Wearing plays on the rift between interior and exterior and raises a multitude of provocative questions about identity, memory, and the veracity of the photographic medium.”1

Tilt (2002, see photograph above) is a mesmeric video by Fiona Tan of a toddler strapped into a harness suspended from a cluster of white helium-filled balloons in a room with wooden floorboards. The gurgling toddler floats gently into the air before descending to the ground, the little feet scrabbling for traction before gently ascending again – the whole process is wonderful, the instance of the feet touching the ground magical, the delight of the toddler at the whole process palpable. Dan Rule sees the video as “enlivening and troubling, joyous and worrisome” and he is correct in this observation, in so far as it is the viewer that worries about what is happening to the baby, not, seemingly, the baby itself. It is our anxiety on the toddlers behalf, trying to imagine being that baby floating up into the air looking down at the floor, the imagined alienness of that experience for a baby, that drives our fear; but we need not worry for babies are held above the heads of fathers and mothers every day of the year. Fear is the adult response to the joy of innocence.

There are several photographs by Melbourne photographer Darren Sylvester in the exhibition and they are delightful in their wry take on adolescent life, girls eating KFC (If All We Have Is Each Other, Thats Ok), or pondering the loss of a first love – the pathos of a young man sitting in a traditionally furnished suburban house, reading a letter (in which presumably his first girlfriend has dumped him), surrounded by the detritus of an unfinished Subway meal (see photograph below).

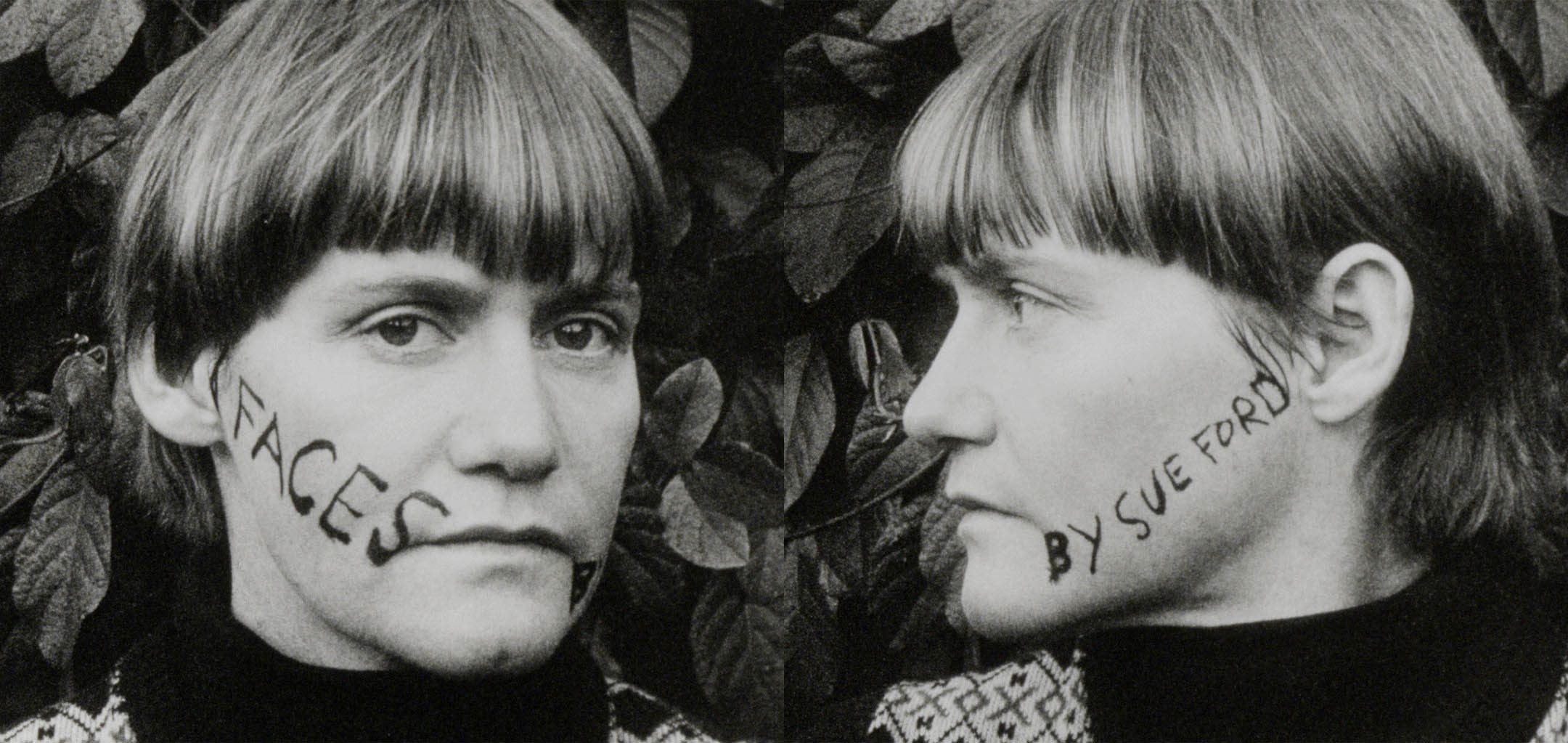

An interesting work by Sue and Ben Ford, Faces (1976-1996, see photograph below) is a video that shows closely cropped faces and the differences in facial features twenty years later. The self consciousness of people when put in front of a camera is most notable, their uncomfortable looks as the camera examines them, surveys them in minute detail. The embarrassed smile, the uncertainty. It is fascinating to see the changes after twenty years.

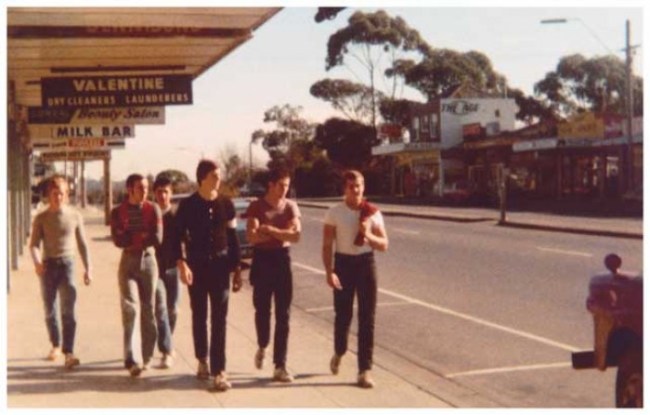

A wonderful series 70s coloured photographs of “Sharps” by Larry Jenkins that shine a spotlight on this little recognised Melbourne youth sub-culture. These are gritty, funny, in your face photographs of young men bonding together in a tribal group wearing their tight t-shirts, ‘Conte’ stripped wool jumpers (I have a red and black one in my collection) and rat tail hair:

“Larry was the leader of the notorious street gang the “BLACKBURN SOUTH SHARPS” from 1972-1977 when the Sharpie sub-culture was at its peak and the working class suburbs of Melbourne were a tough and violent place to grow up. These photographs represent a period from 1975-1976 in Australian sub-cultural history and are one of the few photographic records of that time. Larry began taking photos at the age of 16 using a pocket camera, when he started working as an apprentice motor mechanic and spent his weekly wage developing his shots… He captured fleeting moments, candid shots and directed his teenage mates through elaborate poses set against the immediate Australian suburban backdrops.”2

Immediate and raw these photographs have an intense power for the viewer.

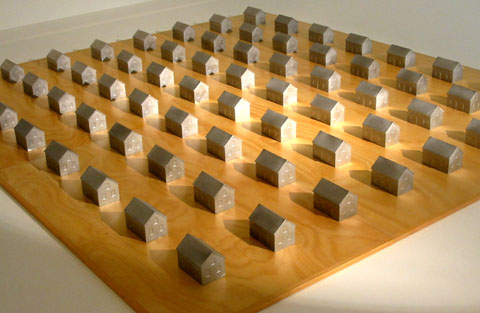

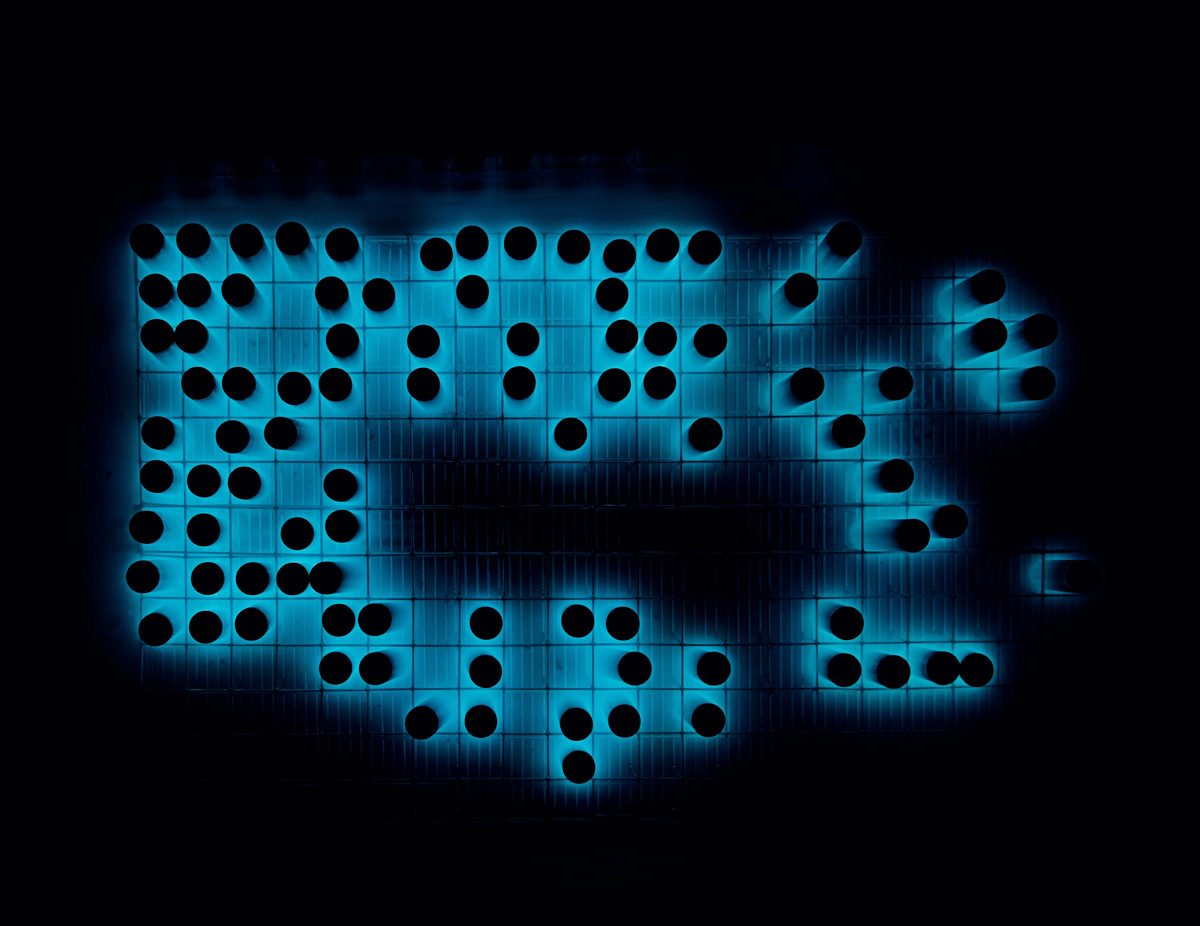

A personal favourite of the exhibition is Alex Danko’s installation Day In, Day Out (1991, see photograph below). Such as simple idea but so effective: a group of identical silver houses sits on the floor of the gallery and through a rotating wheel placed in front of a light on a stand, the sun rises and sets over and over again. The identical nature of the houses reminds us that we all go through the same process in life: we get up, we work (or not), we go to bed. The sun rises, the sun sets, everyday, on life. Simple, beautiful, eloquent.

Another favourite is Louise Short’s series of found colour slides of family members displayed on one of those old Kodak carrousel slide projectors. This is a mesmeric, nostalgic display of the everyday lives of family caught on film. I just couldn’t stop watching, waiting for the next slide to see what image it brought (the sound of the changing slides!), studying every nuance of environment and people, colour and space: recognition of my childhood, growing up with just such images.

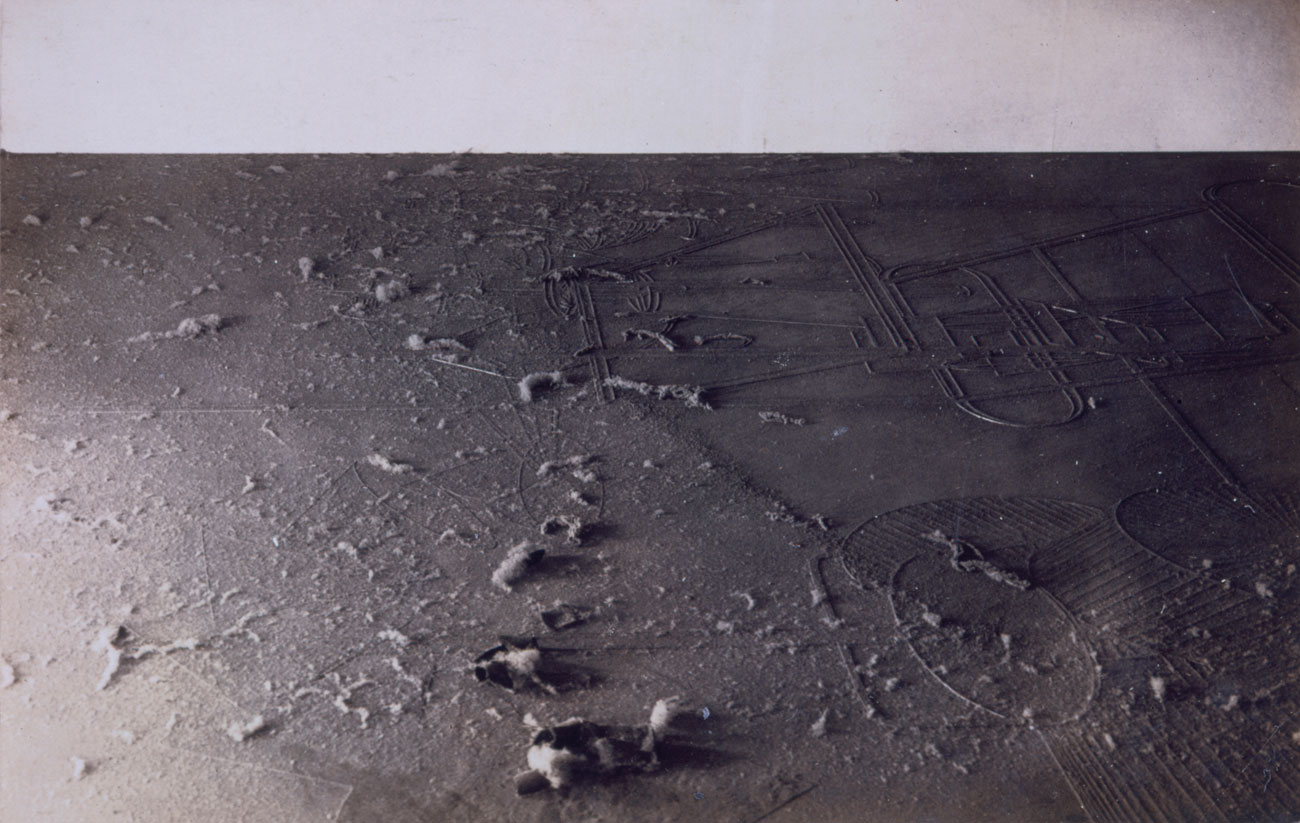

Anri Sala’s video Time After Time (2003, see photograph below) is one of the most poignant works in the exhibition, almost heartbreaking to watch. A horse stands on the edge of a motorway in the near darkness, raising one of it’s feet. It is only when the lights of a passing car illuminate the animal that the viewer sees the protruding rib cage and you suddenly realise how sick the horse must be, how near death.

The film Presentation Sisters (2005, see photographs below) by English artist Tacita Dean, “shows the daily routines and rituals of the last remaining members of a small ecclesiastical community as they contemplate their journey in the spiritual after-life.” Great cinematography, lush film colours, use of shadow and space – but it is the everyday duties of the sisters, a small order of nuns in Cork, Ireland that gets you in. It is the mundanity of washing, ironing, folding, cooking and the procedures of human beings, their duties if you like – to self and each other – that become valuable. Almost like a religious ritual these acts are recognised by Dean as unique and far from the everyday. We are blessed in this life that we live.

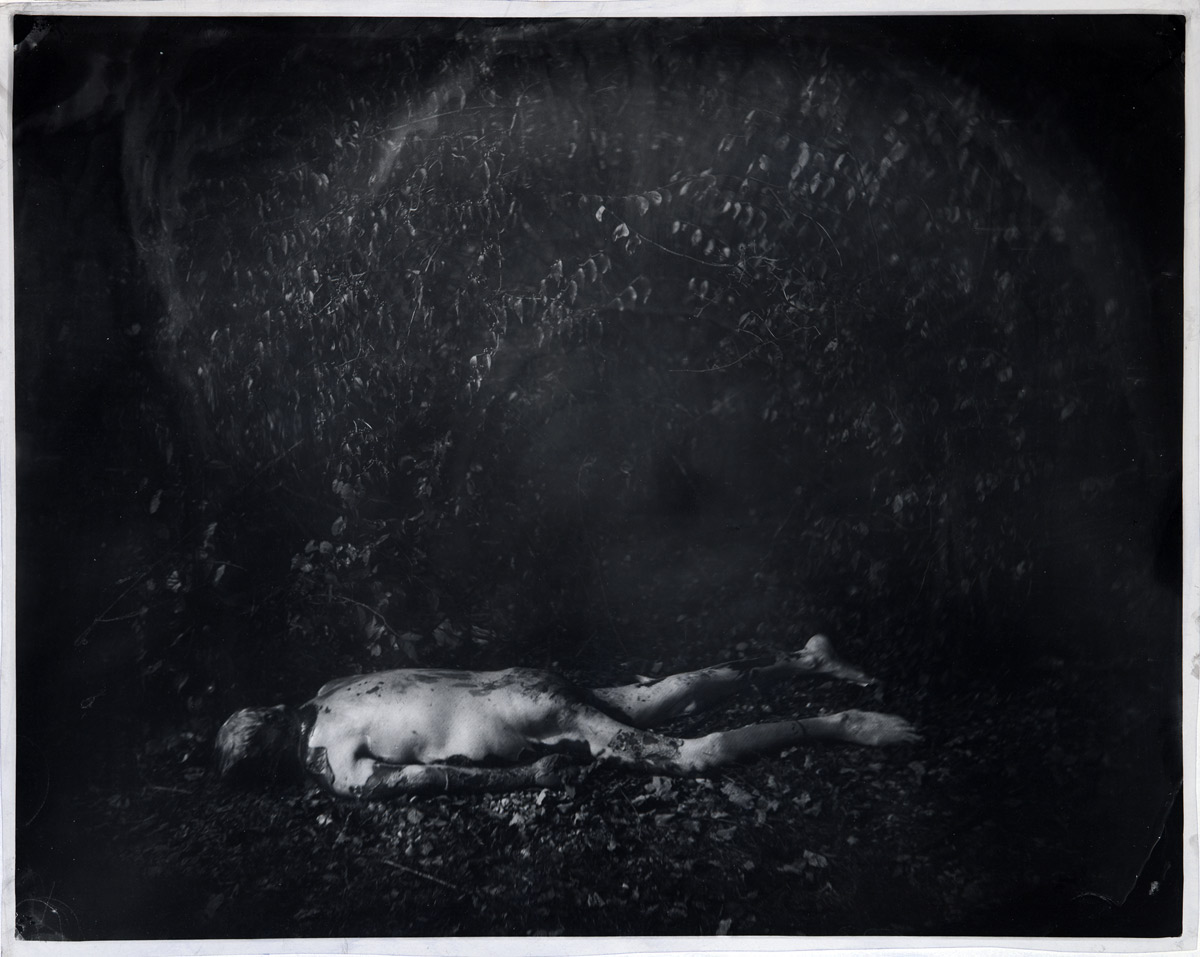

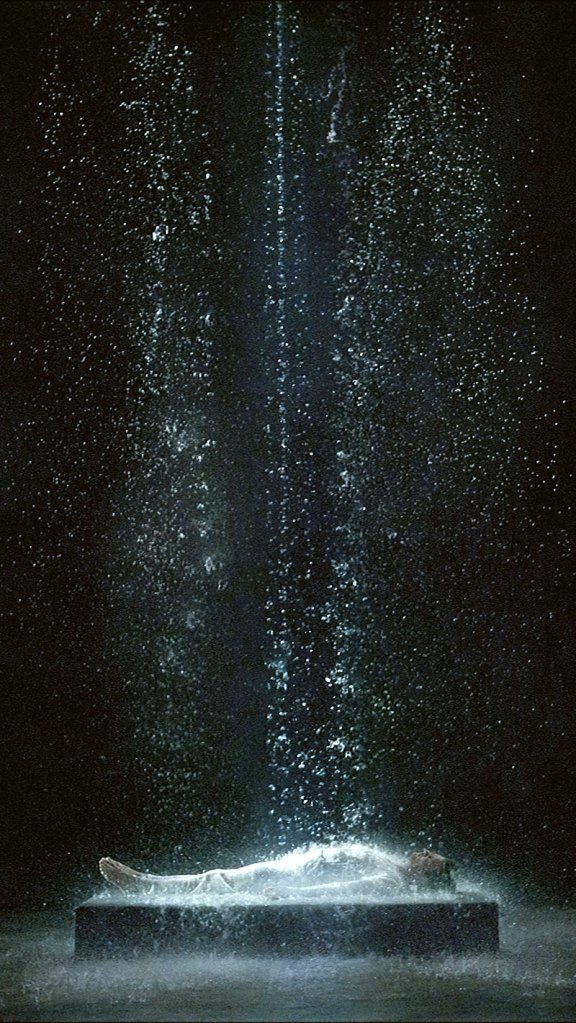

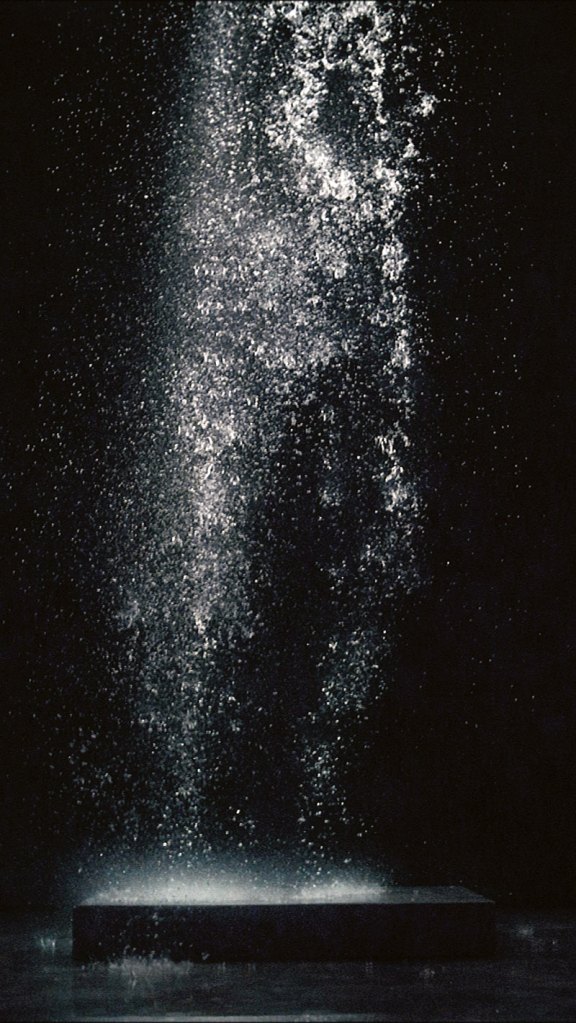

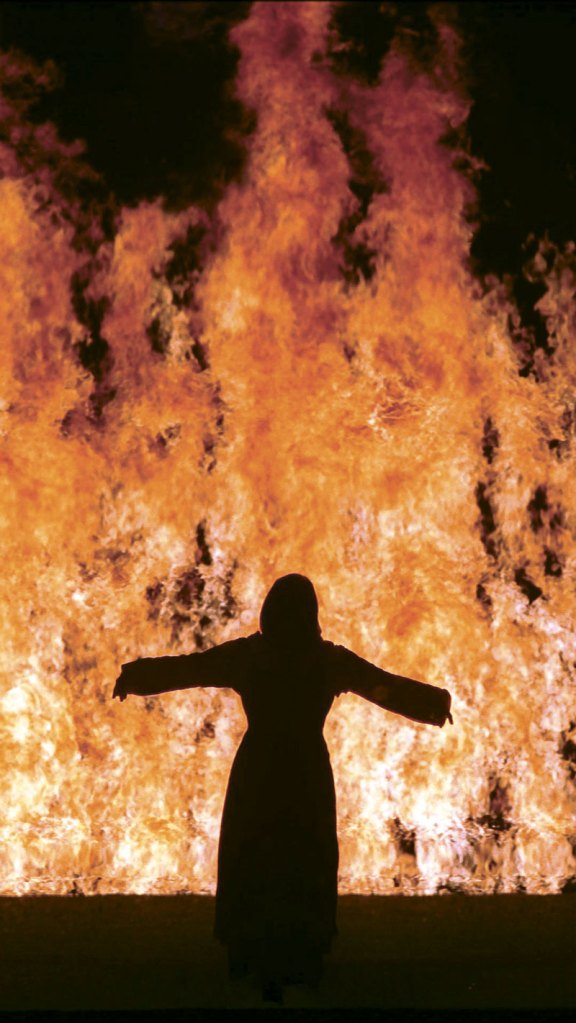

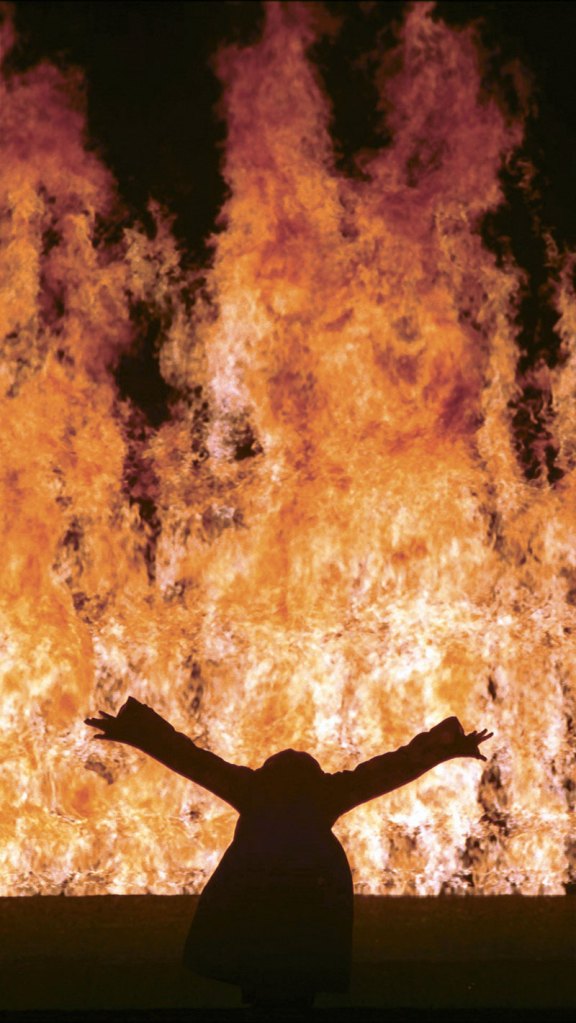

Finally two works by Bill Viola: Unspoken (Silver & Gold) 2001 and The Passing (1991, see photographs below). Both are incredibly moving works about the angst of life, the passage of time, of death and rebirth. For me the picture of Viola’s elderly mother in a hospital bed, the sound of her rasping, laboured breath, the use of water in unexpected ways and the beauty of cars travelling at night across a road on a desert plain, their headlights in the distance seeming like atomic fireflies, energised spirits of life force, was utterly beguiling and moving. What sadness with joy in life to see these two works.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Mann, Ted. “Self-Portrait at Three Years Old,” on the Guggenheim Collection website [Online] Cited 12/11/2010 no longer available online

2/ Anon. “History,” on the Blackburn South Sharps website [Online] Cited 12/11/2010 no longer available online

Many thankx to the Melbourne International Arts Festival and the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of some of the images.

Gillian Wearing (English, b. 1963)

Self-Portrait at Three Years Old

2004

Digital C-type print

© Gillian Wearing

“To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt” Susan Sontag wrote. Gillian Wearing registers this, and revisits herself at the age of 3 through the uncanny process of entering her own body. This performance of self, created by the artist putting on a full body prosthetic mask of herself as she was professionally photographed as a child, and peering out at the viewer with her 40-something eyes is a weird sarcophagi of identity. Is Gillian still 3? Is the adult inside the one she has become, or the one who was always there? Is identity pre-determined? Perhaps she would prefer to go back there, and yet this portrait is tinged with a kind of sadness. The eyes betray too much that has passed in the adult life, not yet known by the small child.

Extract from Juliana Engberg About Mortality catalogue

Darren Sylvester (Australian, b. 1974)

Your First Love Is Your Last Love

2005

© Darren Sylvester

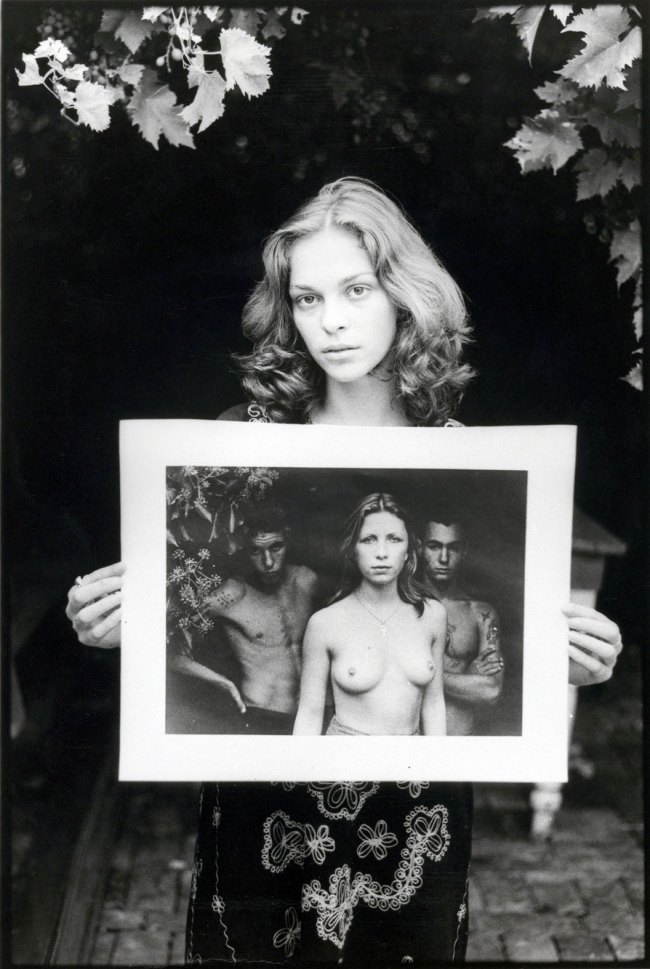

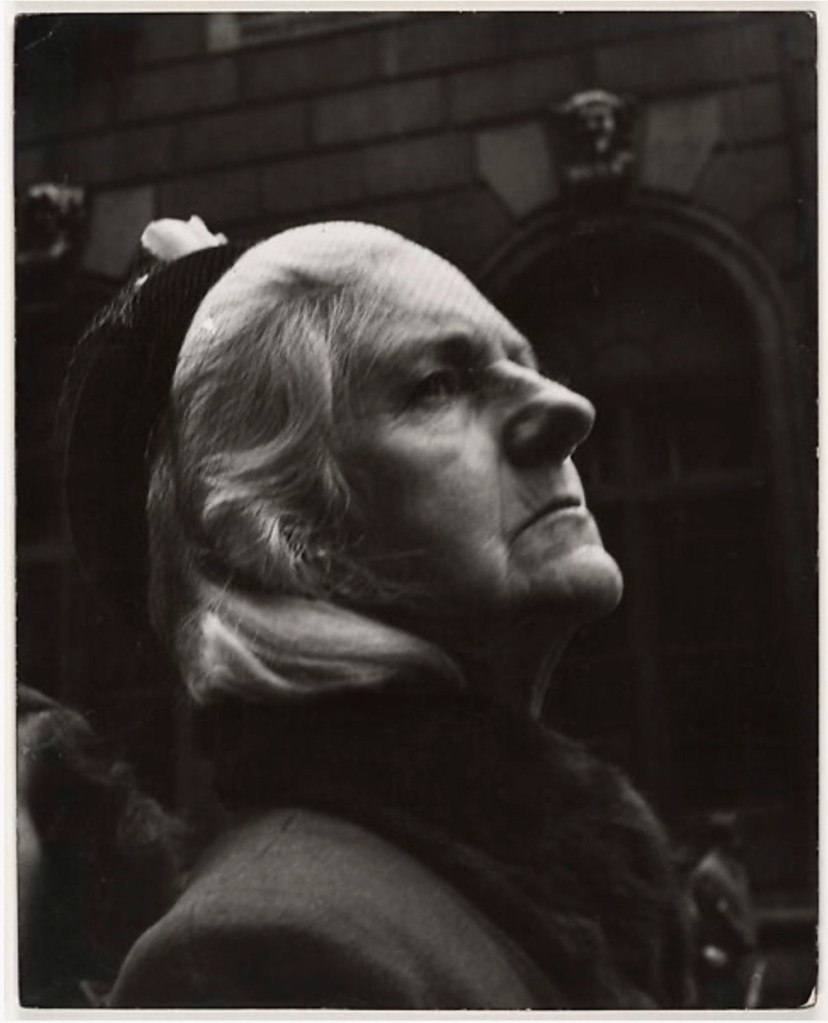

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009) and Ben Ford

Faces (still)

1976-1996

Detail

of 15 min b/w

reversal silent film

16mm, shot on b/w

reversal film

Photographer, Sue Ford, in her iconic work Faces uses the camera as a kind of mirror to register the changes that occur as we grow older. Without the sometimes pompous commentary of the filmic anthropological voice-over which narrates an imposed, meta-story, Ford allowed her straightforward, black and white, close-up images to suggest the accumulation of experience and the evolution of identity silently. In this version of the work, a video projection which brings old and newer faces together in a rolling sequence, we are able to register the passage of time in a number of ways. The face becomes a terrain of time travelled.

Extract from Juliana Engberg About Mortality catalogue

Faces

Sue Ford’s experimental film “Faces” consists of portraits of the artist and her friends and acquaintances. Ford filmed each subject for roughly 25 seconds, using a wind-up Bolex camera that frames their faces in close-up. Variously self-conscious, serious, amused and distracted, the camera captures every small gesture, expression and flicker of emotion on the person’s face. The result is an examination of portraiture and the performance of identity, demonstrating the artist’s interest in using the camera to capture reality, time and change.

Text from the Youtube website

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009) and Ben Ford

Faces (still)

1976-1996

Detail

of 15 min b/w

reversal silent film

16mm, shot on b/w

reversal film

Continuing on from the Time series, in 1976 Ford created the experimental film Faces, in which she filmed portraits of herself, friends and acquaintances. Using a Bolex spring-wound clockwork camera where the film ran through the camera for approximately 25 seconds, Ford directed her subjects to behave as they liked for the duration of the portrait. The camera frames the subject’s face in close-up, steadfastly focusing on them; Memory Holloway described of the work, “While there is no acting, character is revealed by the comfort or uneasiness of the subject. Some laugh, others look romantically pensive, others blow clouds of smoke at the lens as a cover-up”[6]. By bringing an element of time into the creation of a portrait, the film both reveals a moment in that person’s subjective experience and experiments with the plasticity of time, extending and concentrating the 25-second span into a focused moment.

Julia Murphy. “The films of Sue Ford – now part of the ACMI Collection,” on the ACMI website Nd [ONline] Cited 11/03/2025

6/ Memory Holloway, ‘Reel Women: Narrative as a Feminist Alternative’, Art and Text, 1981

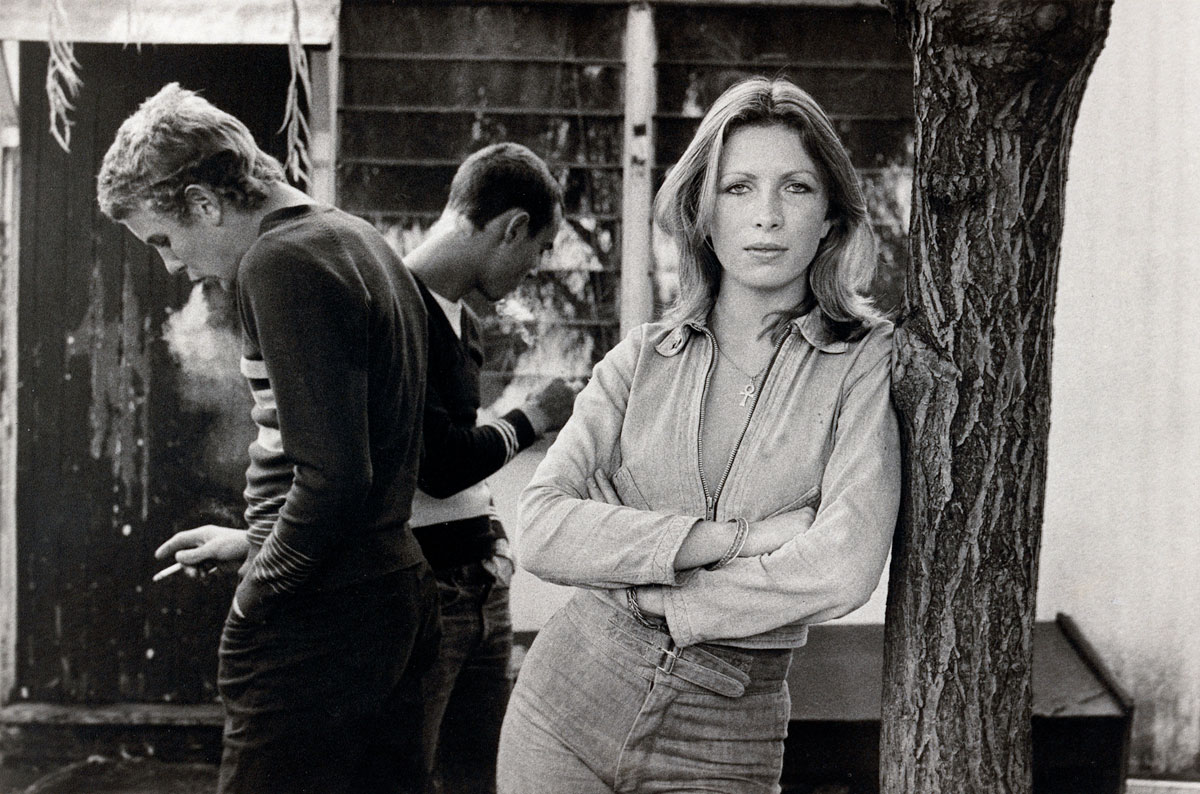

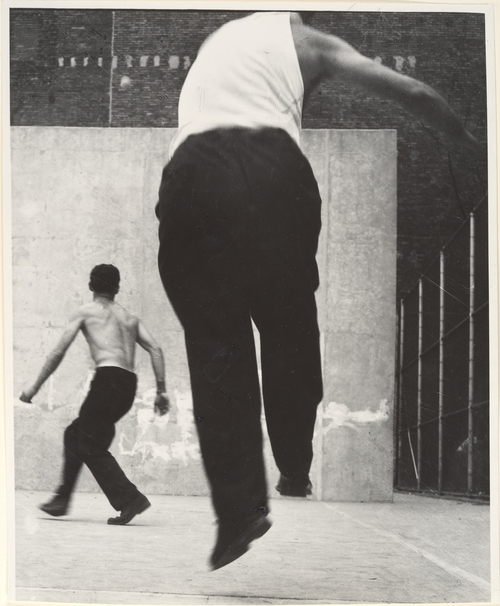

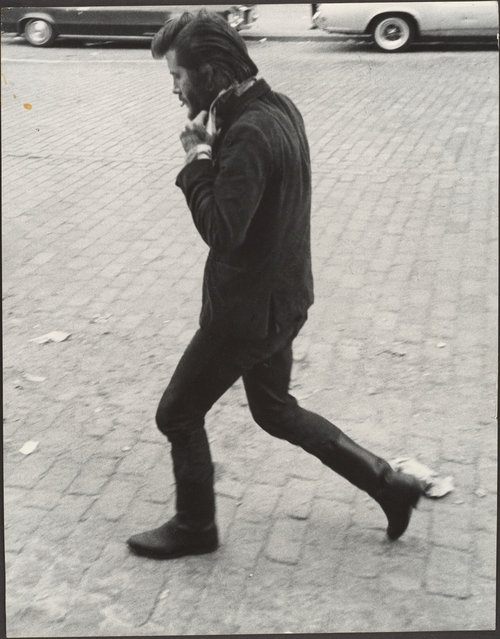

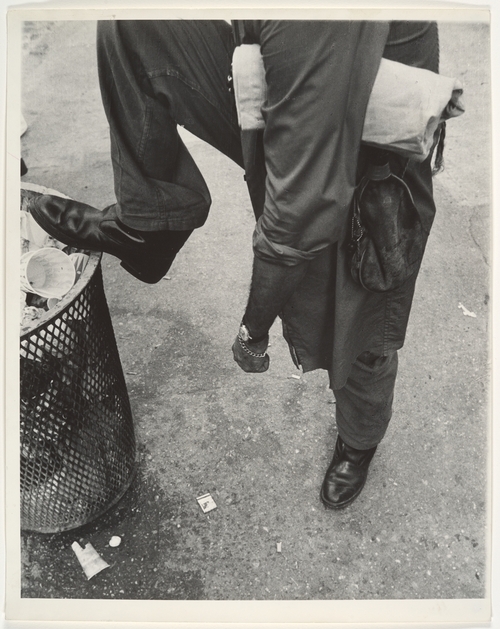

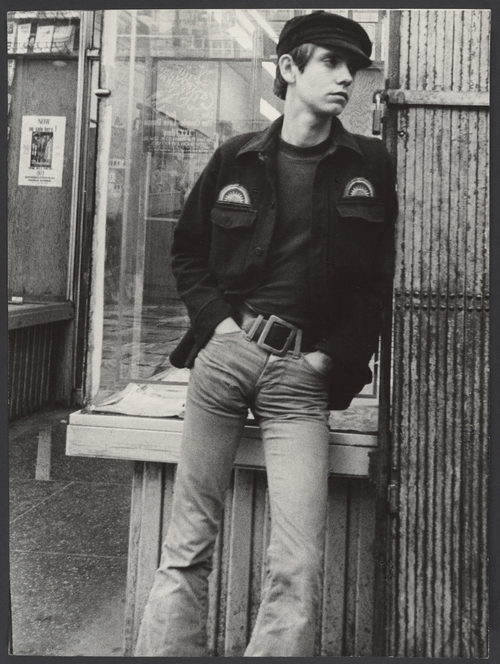

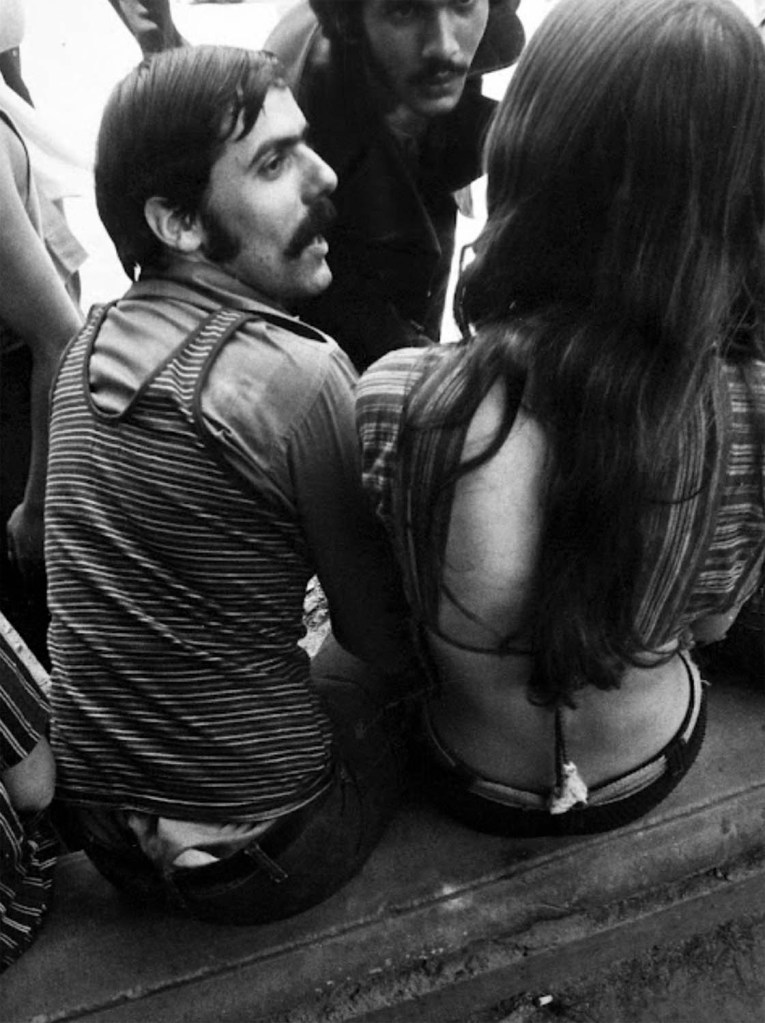

Larry Jenkins (Australian)

Chad, Jono and Mig, Twig, Beatie and Whitey walking down the street at Blackburn South shops

1975

© Larry Jenkins

The photographs of Larry Jenkins deliver an authentic tribalism. Taken with his instamatic camera, the photos of his sharpie friends, hanging out, posing, wrestling and testing out their manhood, are genuine documents of their time. Belonging to this group is an important and almost primate activity. Surviving the suburbs in the 70s was an ‘us and them’ kind of universe. These were the kinds of boys you crossed the street to avoid. Their collective power, while internally tumultuous as they each try to discover their own identities, nevertheless conveys externally a tight ball of testosterone. They are one, and if you are not them, you are nothing.

Extract from Juliana Engberg About Mortality catalogue

Alex Danko (Australian, b. 1950)

Day In, Day Out

1991

From the cradle to the grave… ACCA’s major exhibition Mortality takes us on life’s journey from the moment of lift off to the final send off, and all the bits in between. Curated by Juliana Engberg to reflect the Festival’s visual arts themes of spirituality, death and the afterlife, this transhistorical event includes metaphoric pictures and works by some of the world’s leading artists.

Exhibiting artists include:

Tacita Dean, an acclaimed British artist who works in film and drawing and has shown at Milan’s Fondazione Trussardi and at DIA Beacon, New York.

Anastasia Klose, one of Australia’s most exciting young video artists whose works also include performance and installation.

TV Moore, an Australian artist who completed his studies in Finland and the United States and who has shown extensively in Sydney, Melbourne and overseas.

Tony Oursler, a New York-based artist who works in a range of media and who has exhibited in the major institutions of New York, Paris, Cologne and Britain.

Giulio Paolini, an Italian born artist who has been a representative at both Documenta and the Venice Biennale.

David Rosetzky, a Melbourne-born artist who works predominantly in video and photographic formats and whose work has featured in numerous Australian exhibitions as well as New York, Milan and New Zealand galleries.

Louise Short, an emerging British artist who works predominately with found photographs and slides. Anri Sala, an Albanian-born artist who lives and works in Berlin. He has shown in the Berlin Biennale and the Hayward, London.

Fiona Tan, an Indonesian-born artist, who lives and works in Amsterdam. Tan works with photography and film and has shown in a number of major solo and group exhibitions, including representing the Netherlands at the 2009 Venice Biennale.

Bill Viola, one of the leaders in video and new media art who has shown widely internationally and in Australia.

Gillian Wearing, one of Britain’s most important contemporary artists and a Turner Prize winner who has exhibited extensively internationally.

Highlights of the exhibition include:

Albanian born artist Anri Sala’s acclaimed video work Time After Time, featuring a horse trapped on a Tirana motorway, repeatedly, heartbreakingly raising its hind-leg (see photograph below). Anri first came to acclaim in 1999 for his work in After the Wall, the Stockholm Modern Museum’s exhibition of art from post-communist Europe, and his work is characterised by an interest in seemingly unimportant details and slowness. Scenes are almost frozen into paintings.

Peter Kennedy’s Seven people who died the day I was born – April 18 1945, 1997-98 – a work from a series begun by the artist following the death of his father which connects individual lives with political and historical events. Kennedy’s birth in the last year of World War II and the seven people memorialised imply the multitude of others that died during this catastrophic event as well as the perpetual cycle of life.

A series of slides collected by British artist Louise Short, offering a beguiling insight into the everyday lives of everyday people accumulated as a life narrative.

Acclaimed British artist Tacita Dean’s Presentation Sisters, which shows the daily routines and rituals of the last remaining members of a small ecclesiastical community as they contemplate their journey in the spiritual after-life.

Three works from the Time series by influential Australian photographer Sue Ford, who passed away last year, will also be shown. The photographs capture the artist in various stages of her life.

Text from the ACCA website

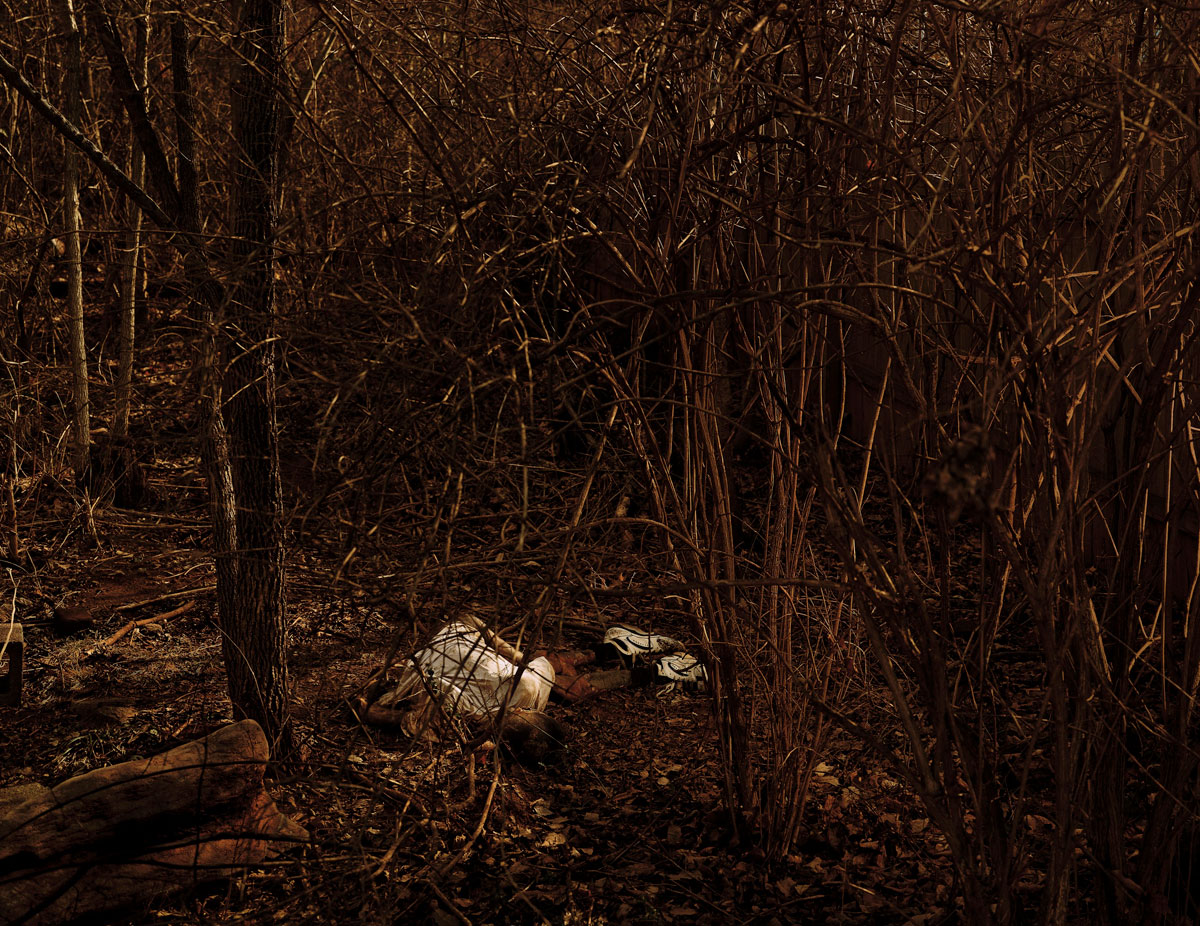

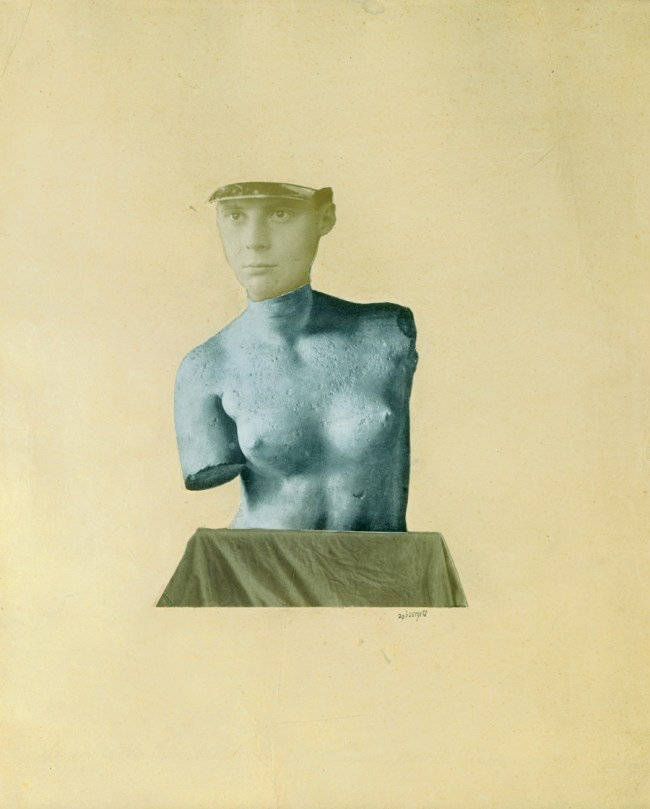

Annika von Hausswolff (Swedish, b. 1967)

Hey Buster! What Do You Know About Desire?

1995

Colour photograph

Courtesy of the artist and Moderna Museet

Anri Sala (Albanian, b. 1974)

Time After Time (still)

2003

Video, 5 minutes 22 seconds

Sometimes we stagger into dangerous territory. In life, some of us find ourselves on the wrong side of the track. Anri Sala’s Time After Time provides a metaphor for the unfortunate ones who have lost their way or who are marginalised or discarded. A horse has manoeuvred itself, or worse, been abandoned on the wrong side of the highway divider and is now trapped in an endless and shuddering encounter with heavy traffic. The horse visibly flinches and as viewers we are helpless to do anything to assist. It is past its prime and appears malnourished, injured and unwanted. Sala’s horse is symbolic of the scapegoat… the one sent away, or outcast in order for social cohesion to seem reinforced by its exclusion.

Extract from Juliana Engberg About Mortality catalogue

David Rosetzky (Australian, b. 1970)

Nothing like this (still)

DVD

2007

Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

David Rosetzky’s two videos Weekender and Nothing Like This, hyper-construct the languor of these rites of passage for introspective types. One video uses the faded colours of the 1970s Levi’s, Lee’s and Wrangler’s where-do-you-go-to-my-lovely era, through a smudgy David Hamilton Bilitis-like lens. In the other, with a postmodern crispness, Rosetzky establishes scenarios of inner intensity in which the participants narrate their disaffections and doubts. As compared to Ford’s messy, shabby and experimental aesthetic, everything in Rosetzky’s plot is sanitary. This is the synthetic age.

Rosetzky’s videos reference films like The Big Chill which pushes a group together to explore identity. In the instance of Rosetzky’s works however, action is limited and the conventional narrative eliminated in order to zero in on the heightened meditations. Devices such as mirrors refer to a kind of twenty-something narcissism; the beach is presented as a dynamic character of identity flux; time is compressed and delivered in mediated bites.

Things happen on beaches. In Australian culture, as elsewhere they are places of fun, but also menace. When I was a child, the news of the disappearance of children and adults at beaches inflicted a fear into the cultural psyche; children’s freedom was forever altered after the Beaumont Children case.

Extract from Juliana Engberg About Mortality catalogue

David Rosetzky (Australian, b. 1970)

Nothing like this (still)

DVD

2007

Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

Tacita Dean (British, b. 1965)

Presentation Sisters (still)

2005

16 mm film

courtesy of the artist, Frith Street Gallery London

Some people find solace in religion. And in this exhibition Tacita Dean’s superb film The Presentation Sisters offers a quiet reflection space. Dean emphasises the aspects of quiet devotion, internal contemplation and external dedication that define the Sisters’ spiritual and earthly existence.

In the same way Vermeer suggested spiritualism through domesticity and by using the uplift of light through windows, Dean enlists the ethereal light that travels through the lives and rooms of this small order of nuns who go about their routines and mundane tasks. Dean’s film studies light as a part of metaphysical and theological transformation. However, Dean’s film is also about a kind of Newtonian light: scientific and alchemical.

Her interest in the transformations that occur when light passes through celluloid, and when light passes through glass is a study of the beautiful refractions discovered by scientific observation and written into philosophical enquiries by writers such as Goethe and Burke. As always with Dean’s work, there are layers of encounter in the seemingly simple.

Extract from Juliana Engberg About Mortality catalogue

Tacita Dean (British, b. 1965)

Presentation Sisters (still)

2005

16 mm film

Courtesy of the artist, Frith Street Gallery London

Bill Viola (American, 1951-2024)

The Passing (still)

1991

In memory of Wynne Lee Viola

Videotape, black-and-white, mono sound

54 minutes

© Bill Viola

Bill Viola (American, 1951-2024)

The Passing (still)

1991

In memory of Wynne Lee Viola

Videotape, black-and-white, mono sound

54 minutes

© Bill Viola

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA)

111 Sturt Street

Southbank, Victoria 3006

Australia

Opening hours:

Tue – Fri 10am – 5pm

Sat – Sun 11am – 5pm

Mon Closed

Open all public holidays except Christmas Day and Good Friday

![Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Head of Man with Hat and Cigar]' c. 1960 from the exhibition 'Hipsters, Hustlers, and Handball Players: Leon Levinstein's New York Photographs, 1950-1980' at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, June - October, 2010 Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Head of Man with Hat and Cigar]' c. 1960 from the exhibition 'Hipsters, Hustlers, and Handball Players: Leon Levinstein's New York Photographs, 1950-1980' at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, June - October, 2010](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/leon-levinstein-head-of-man-with-hat-and-cigar.jpg)

![Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Beach Scene: Woman Wearing Paper Bag Hat, Coney Island, New York]' 1950s Leon Levinstein (American, 1910-1988) 'Untitled [Beach Scene: Woman Wearing Paper Bag Hat, Coney Island, New York]' 1950s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/leon-levinstein-beach-scene.jpg?w=809)

You must be logged in to post a comment.