Exhibition dates: 4th March – 25th May, 2020

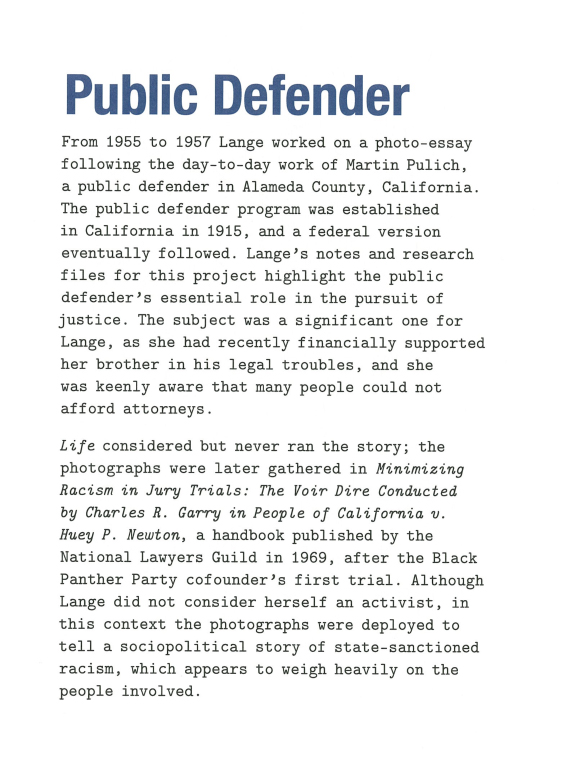

Curators: Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, Curator of British Art 1850-1915, and Stephen Calloway with Alice Insley, Assistant Curator, Historic British Art

#MuseumFromHome

![Frederick Evans (British, 1853-1943) 'Aubrey Beardsley [with hands]' 1893 from the exhibition 'Aubrey Beardsley' at Tate Britain, London, March - May, 2020 Frederick Evans (British, 1853-1943) 'Aubrey Beardsley [with hands]' 1893 from the exhibition 'Aubrey Beardsley' at Tate Britain, London, March - May, 2020](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/frederick-evans-portrait-of-aubrey-beardsley.jpg?w=736)

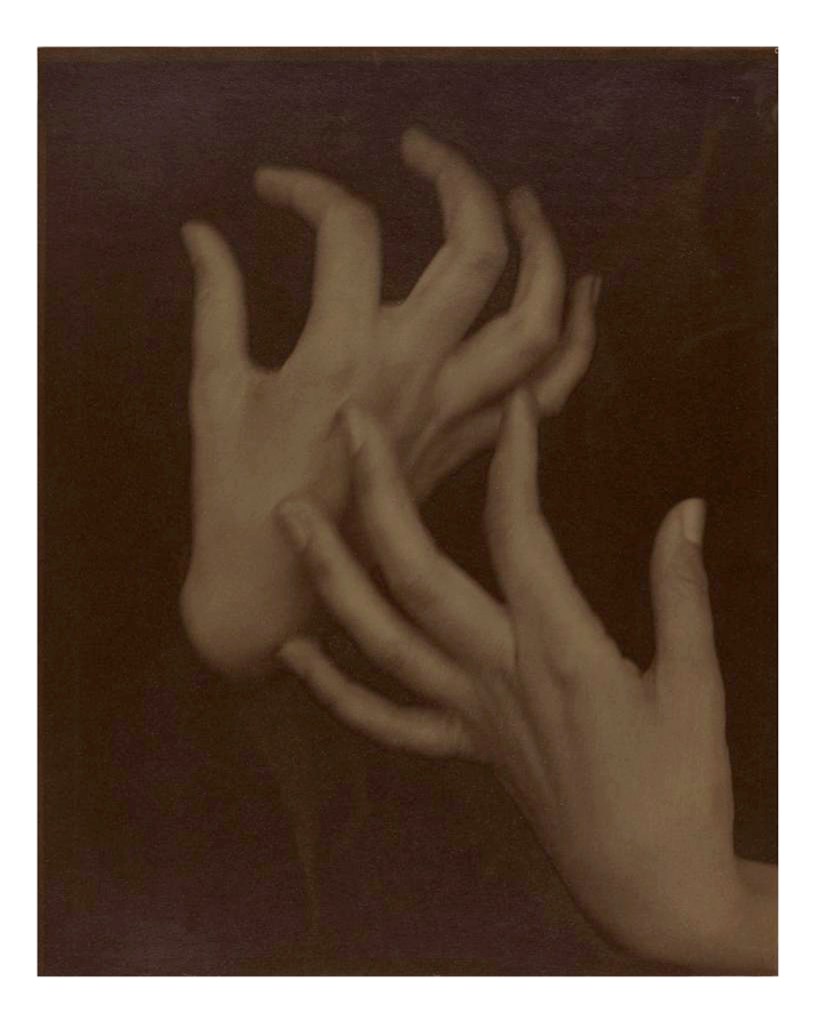

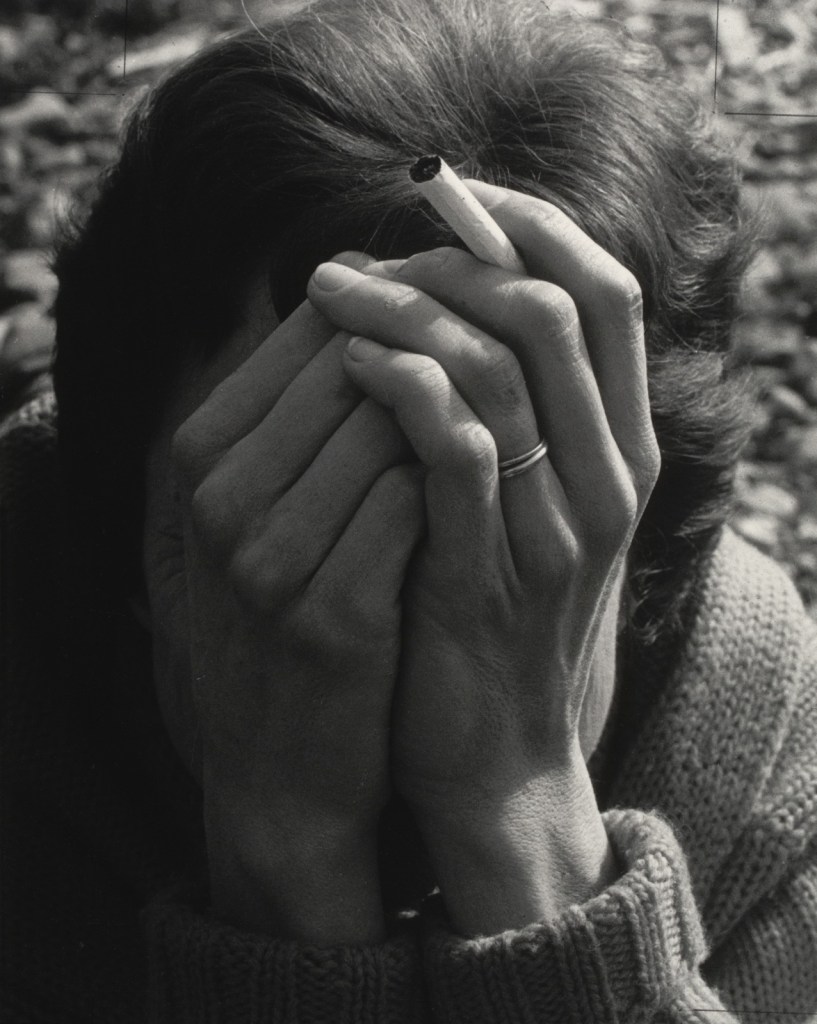

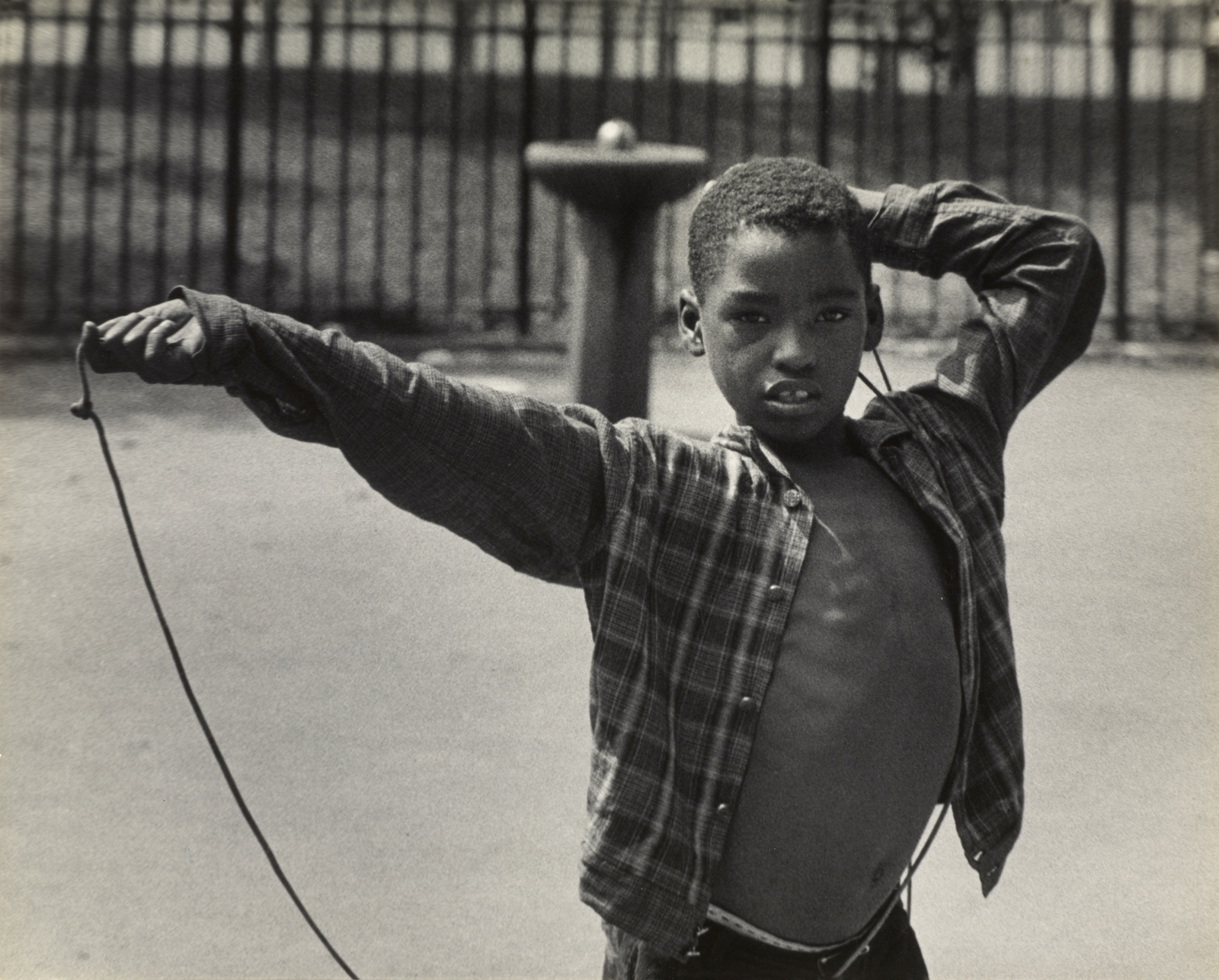

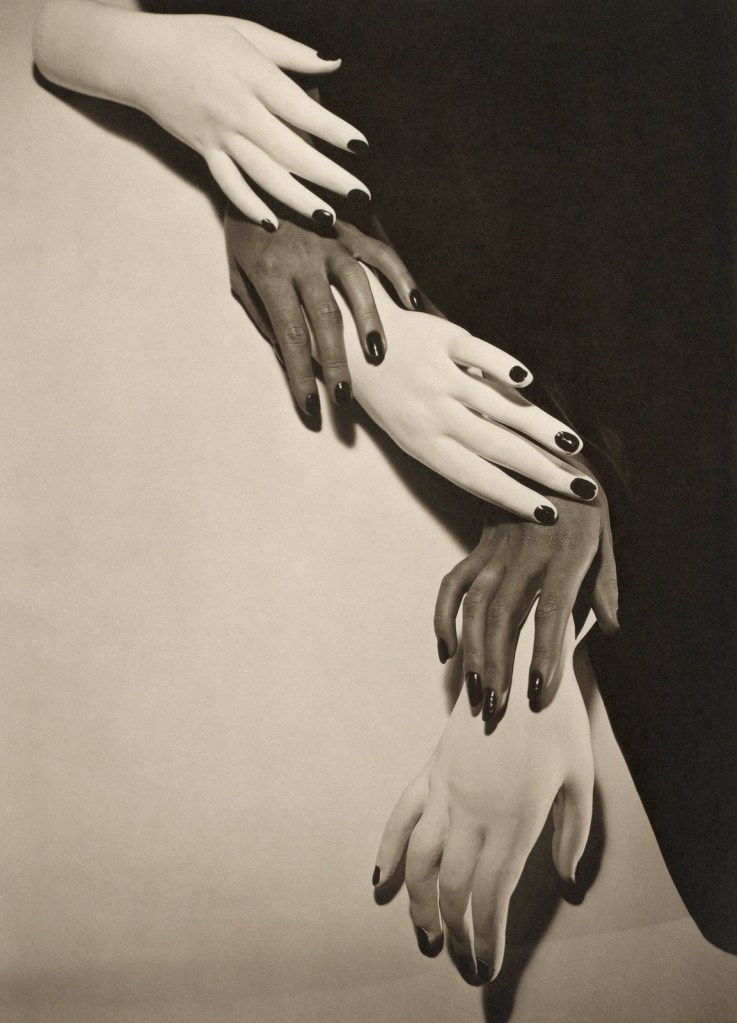

Frederick Evans (British, 1853-1943)

Aubrey Beardsley [with hands]

1893

Platinum print and photogravure, mounted on opposing pages of a paper folio

Wilson Centre for Photography

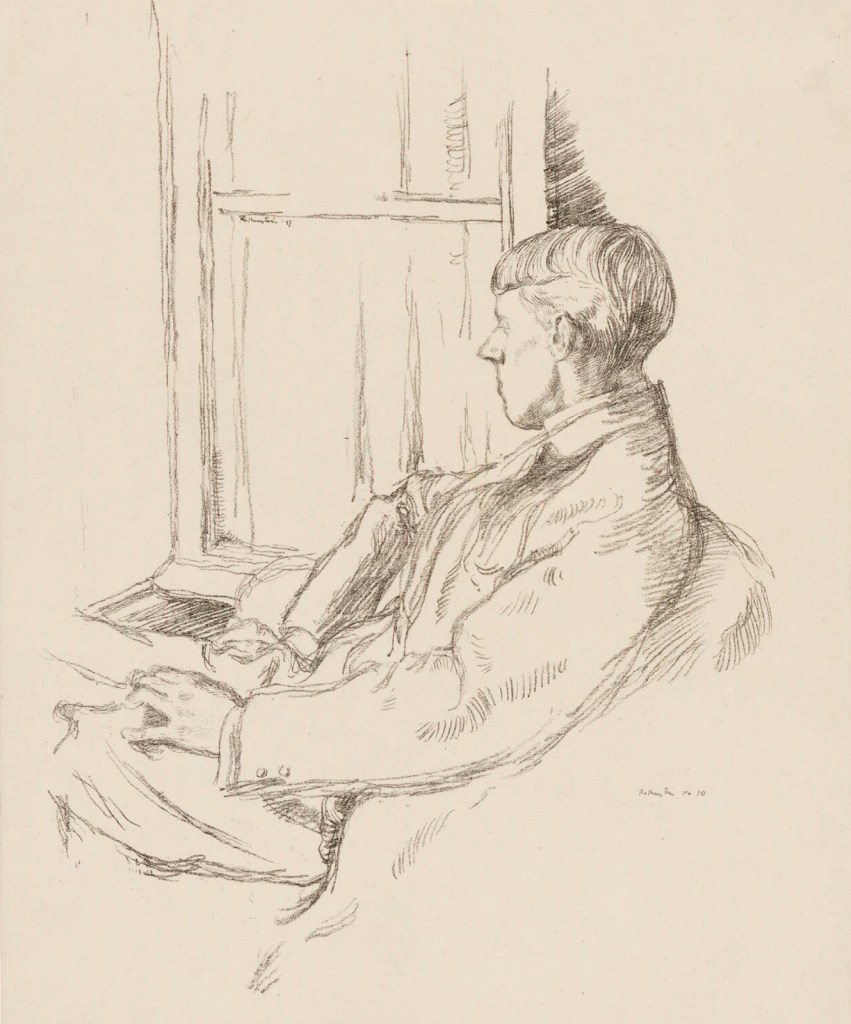

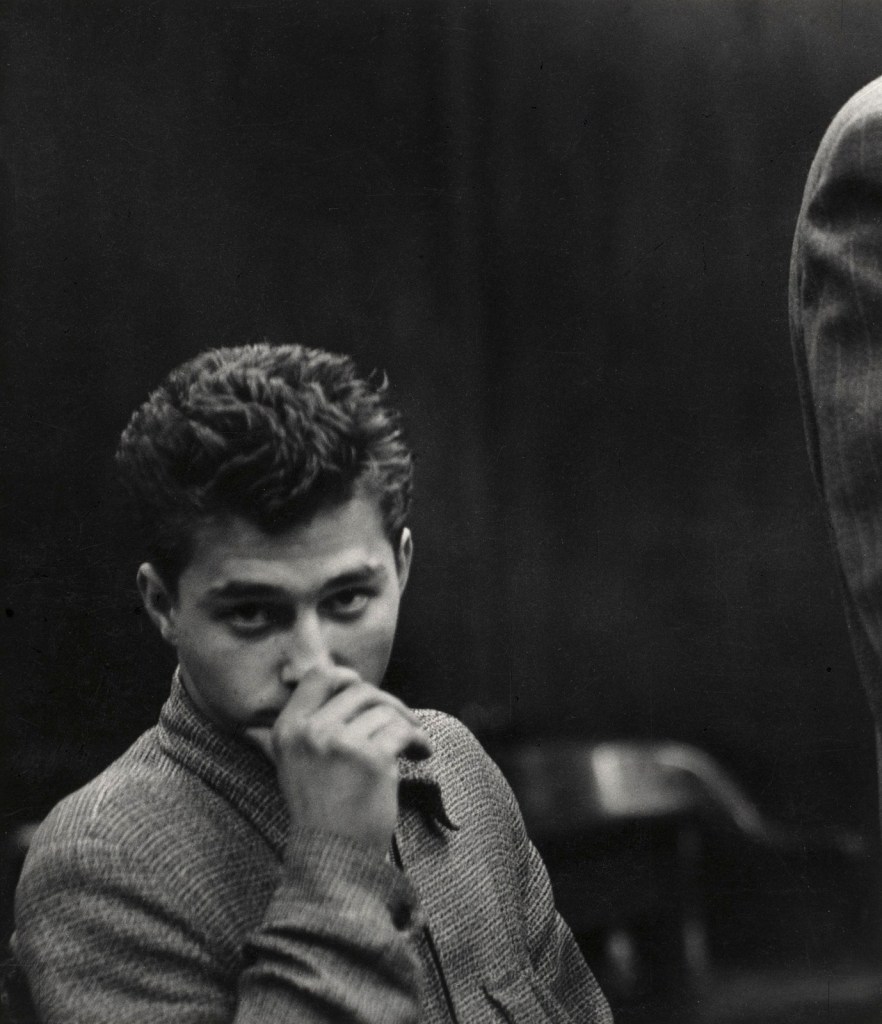

While working as a clerk, Beardsley spent his lunchtimes browsing in Frederick Evans’ nearby second-hand bookshop. This had an important impact on his developing artistic and literary tastes. Beardsley became close friends with Evans, who was also a talented amateur photographer. The image on the left has become known as the ‘gargoyle portrait’ because Beardsley’s pose echoes the famous carved figure on Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. This portrait was used in early editions of Beardsley’s work and has become the defining image of the artist.

There he is

There he is, all aquiline nose, patrician air; thin wrists and hands that infinity strengthens,

Mannerist hands, hands like the buttresses of some great cathedral, supporting that noble face.

There he is, this genius of invention, this suave sophisticate, this pervader of decadent beauty,

this grotesque who produced a thousand drawings in seven years, who lived a thousand lives in just seven years.

There he is, this son of Blake, this offspring of Lautrec and japonaiserie,

all primed in subtle sexualities, shocking, fame, subversion… strange.

There he is, love of yellow, flowering enormous genitalia, erotic illustrations of distorting scale, women ambiguity,

as bold as life, diseased as death, driving his body on while his mind accretes mythologies.

Now he stands, a fantastical visionary, existing as product of unchecked imagination.

An illusion, a fabrication of the mind; an unrealisable dream, a fancy,

his utopia a grotesque, chimerical beauty.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Tate Britain for allowing me to publish the media images in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Tate Britain’s major new exhibition celebrates the brief but astonishing career of Aubrey Beardsley. Although he died tragically young at the age of just 25, Beardsley’s strange, sinuous black-and-white images have continued to shock and delight for over a century. Bringing together 200 spectacular works, this is the largest display of his original drawings in over 50 years and the first exhibition of his work at Tate since 1923.

Beardsley (1872-1898) became one of the enfants terribles of fin-de-siècle London, best remembered for illustrating Oscar Wilde’s controversial play Salomé. His opulent imagery anticipated the elegance of Art Nouveau but also alighted on the subversive and erotic aspects of life and legend, shocking audiences with a bizarre sense of humour and fascination with the grotesque. Beardsley was prolific, producing hundreds of illustrations for books, periodicals and posters in a career spanning just under seven years. Line block printing enabled his distinct black-and-white works to be easily reproduced and widely circulated, winning notoriety and admirers around the world, but the original pen and ink drawings are rarely seen. Tate Britain exhibits a huge array of these drawings, revealing his unrivalled skill as a draughtsman in exquisite detail.

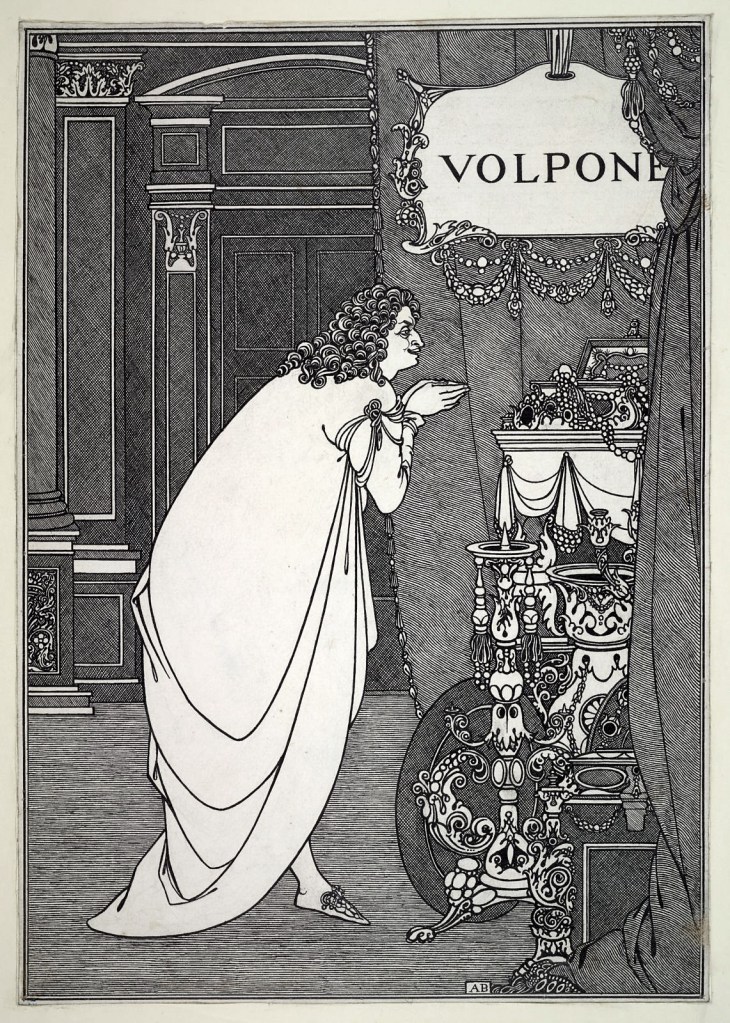

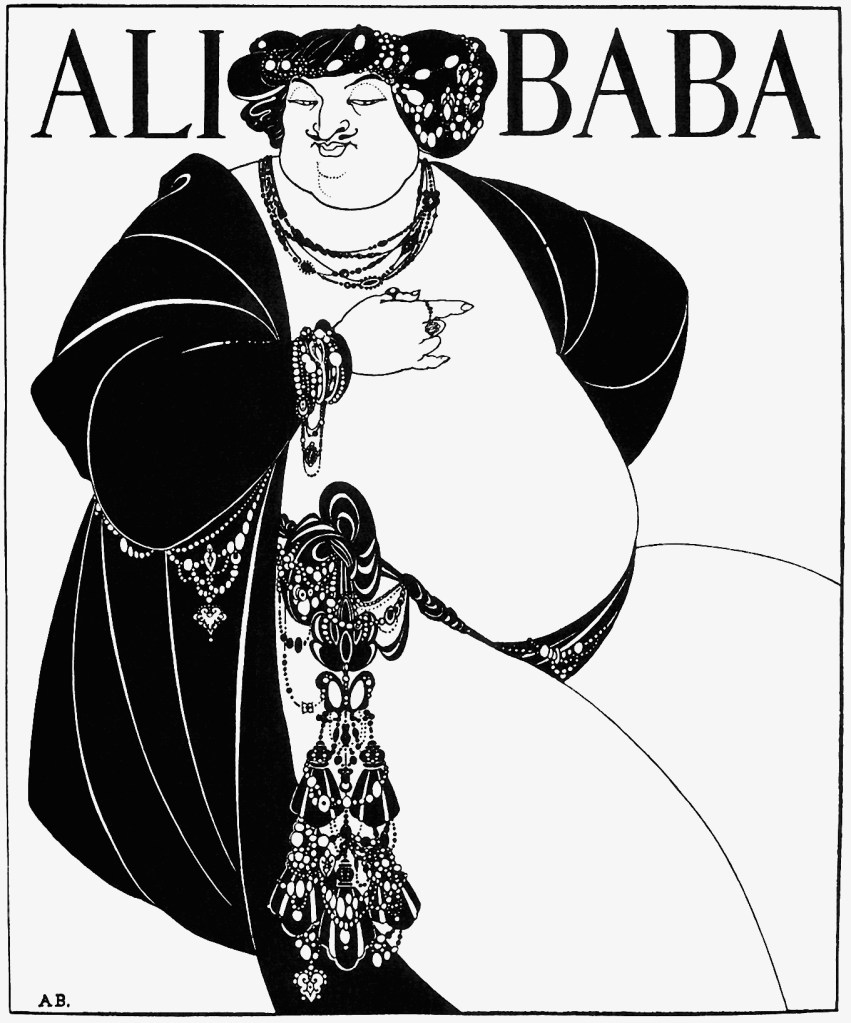

The exhibition highlights each of the key commissions that defined Beardsley’s career as an illustrator, notably Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur 1893-1894, Wilde’s Salomé 1893 and Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock 1896, of which five of the original drawings are shown together for the first time. As art director of the daring literary quarterly The Yellow Book, the artist also created seminal graphic works that came to define the decadence of the era and scandalised public opinion. Bound editions and plates are displayed alongside subsequent works from The Savoy and illustrations for Volpone 1898 and Lysistrata 1896, in which Beardsley further explored his fascination with eroticism and the absurd.

Beardsley’s imagination was fuelled by diverse cultural influences, from ancient Greek vases and Japanese woodblock prints, to illicit French literature and the Rococo. He also responded to his contemporaries such as Gustave Moreau, Edward Burne-Jones and Toulouse Lautrec, whose works are shown at Tate Britain to provide context for Beardsley’s individual mode of expression. A room in the exhibition is dedicated to portraits of Beardsley and the artist’s wider circle, presenting him at the heart of the arts scene in London in the 1890’s despite the frequent confinement of his rapidly declining health. As notorious for his complex persona as he was for his work, the artist had a preoccupation with his own image, relayed throughout the exhibition by striking self-portraits and depictions by the likes of Walter Sickert and Jacques-Emile Blanche.

Additional highlights include a selection of Beardsley’s bold poster designs and his only oil painting. Charles Bryant and Alla Nazimova’s remarkable 1923 film Salomé is also screened in a gallery adjacent to Beardsley’s illustrations, showcasing the costume and set designs they inspired. The exhibition closes with an overview of Beardsley’s legacy from Art Nouveau to the present day, including Picasso’s Portrait of Marie Derval 1901 and Klaus Voormann’s iconic artwork for the cover of Revolver 1966 by the Beatles.

Aubrey Beardsley is organised by Tate Britain in collaboration with the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, with the generous support of the V&A, private lenders and other public institutions. It is curated by Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, Curator of British Art 1850-1915, and Stephen Calloway with Alice Insley, Assistant Curator, Historic British Art.

Press release from the Tate Britain website

Aubrey Beardsley at Tate Britain – Exhibition Tour | Tate

Join Tate curators Caroline Corbeau-Parsons and Alice Insley as they discuss the iconic illustrator’s short and scandalous career.

Before his untimely death aged twenty-five, Beardsley produced over a thousand illustrations. He drew everything from legendary tales featuring dragons and knights, to explicit scenes of sex and debauchery. His fearless attitude to art continues to inspire creatives more than a century after his death.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Withered Spring

1891

Graphite, ink and gouache on paper

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection

The framing of the main image by ornamental panels and lettering shows the influence of aesthetic movement illustrators, as well as that of Burne-Jones. The inscription on the gate behind the figure is partly obscured. In full it would read ‘Ars Longa Vita Brevis’ (‘art is long-lasting, life is short’). As Beardsley was diagnosed with tuberculosis aged seven, this Latin saying must have had personal resonance.

Introduction

Few artists have stamped their personality so indelibly on their era as Aubrey Beardsley. He died in 1898 at the age of just 25 but had already become one of the most discussed and celebrated artists in Europe. His extraordinary black-and-white drawings were instantly recognisable. Then, as now, he seemed the quintessential figure of 1890s decadence.

At the end of the 19th century, a period that had seen vast social and technological changes, many began to fear that civilisation had reached its peak and was doomed to crumble. ‘Decadent’ artists and writers retreated into the imagination. Severing the link between art and nature, they created a new sensibility based upon self-indulgence, refinement and often a love of the bizarre. No other artist captured the danger and the beauty, the cynicism and brilliance of the age as Beardsley did with pen and ink.

Beardsley was diagnosed with tuberculosis at the age of seven. The disease was then incurable, so he knew from childhood that his life would be a brief one. This led him to work at a hectic pace. One contemporary described his determination ‘to fill his few working years with the immediate echo of a great notoriety’. Moving rapidly from style to style, he created well over a thousand illustrations and designs in just five years. Beardsley was catapulted to fame in 1893 by an article about his work in The Studio magazine. He went on to illustrate Oscar Wilde’s play Salome and become art editor of The Yellow Book, a periodical that came to define the era.

Beardsley’s illustrations displayed remarkable skill and versatility, but few people ever saw his actual drawings. He always drew for publication and his work was seen primarily in books and magazines. He was one of the first artists whose fame came through the easy dissemination of images, his reputation growing day by day as his sensational designs appeared.

This exhibition offers a rare chance to see many of Beardsley’s original drawings. It also sets Beardsley in his social and artistic context. Works by other artists punctuate the exhibition, showing how he absorbed diverse artistic influences but always retained his own style.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Incipit Vita Nova

1892

Graphite, ink and gouache on paper

Linda Gertner Zatlin

The title of this drawing refers to Dante Alighieri’s 1294 text La Vita Nuova and translates as ‘New Life Begins’. Some have seen the foetus as a potent symbol for Beardsley. Its significance is unclear beyond linking sexuality, life and death, all key themes in Beardsley’s work. It also reflects his fascination with shocking imagery and the grotesque, the term used traditionally to describe deliberate distortions and exaggerations of forms to create an effect of fantasy or strangeness. He once said, ‘if I am not grotesque I am nothing’.

Beginnings

Beardsley’s artistic career spanned just under seven years, between 1891 and 1898. When he was 18 he met the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, an artist he deeply admired. Having seen Beardsley’s portfolio, Burne-Jones responded: ‘I seldom or never advise anyone to take up art as a profession, but in your case I can do nothing else.’ On his recommendation, for a short time Beardsley attended classes at Westminster School of Art.

Beardsley longed for fame and recognition. This went hand in hand with an intensely cultivated self-image and pose as a dandy-aesthete. This important aspect of his identity is illuminated through self-portraits and portraits by his contemporaries throughout the exhibition.

Witty, tall, ‘spotlessly clean & well-groomed’, Beardsley was soon noted for his dandyism. A delight in refinement and artificiality in both dress and manner, dandyism was integral to the decadent creed. Some contemporaries related the artist’s extreme thinness and fragile physical appearance to ideas of morbidity also associated with decadence.

While Beardsley rejected the label of decadence, his work explores many aspects of it, such as a fascination with the ‘anti-natural’ and the bizarre, with sexual freedom and gender fluidity. What present-day society refers to as LGBTQIA+ identities were only just beginning to be formulated and articulated during his lifetime. Beardsley was attracted to women, but he was a pioneer in representing what we might now call queer desires and identities. Though fascinated by all aspects of sexuality, it seems likely that his explorations of these interests were primarily through literature and art.

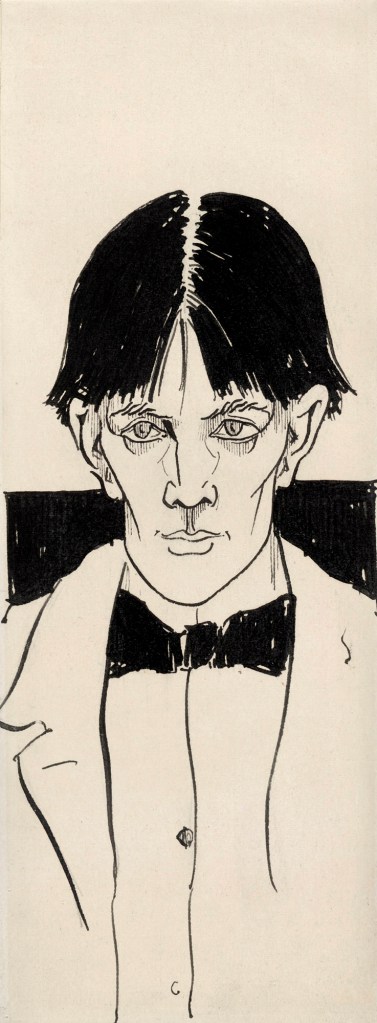

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Self-portrait

1892

Ink on paper

British Museum

Presented by Robert Ross in 1906

Apart from a few childish sketches, this is Beardsley’s first recorded self-portrait, made at the age of about 19. His newly adopted centre-parted fringe, fashionable high collar and large bow tie show that he had already formed a distinctive self-image. A few months earlier, he had described himself as having ‘a vile constitution, a sallow face and sunken eyes’.

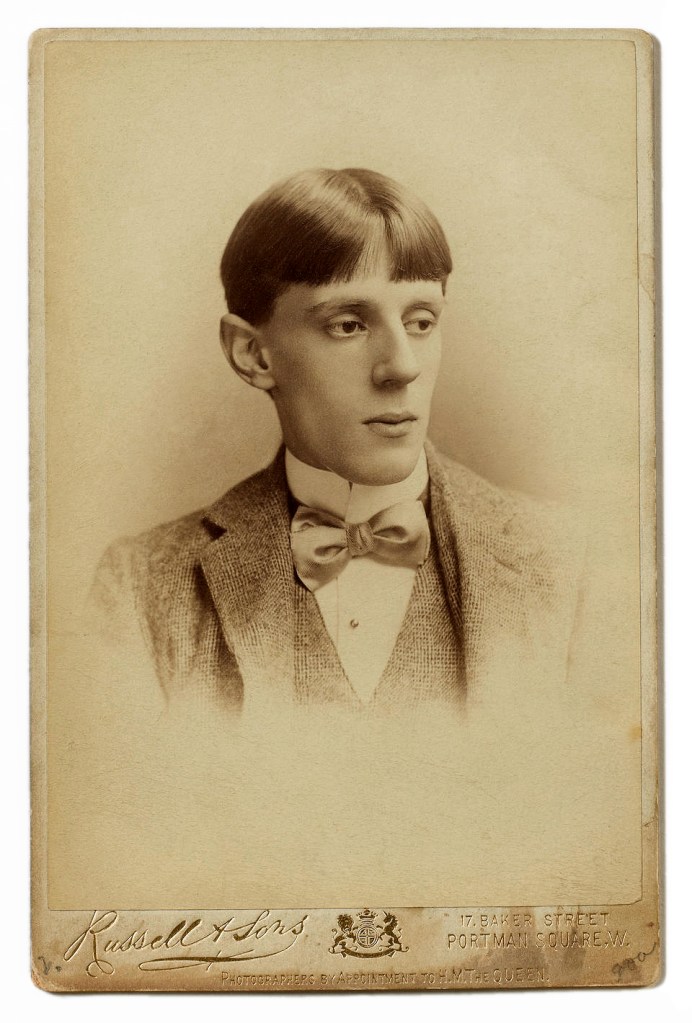

Russell & Sons (Photographers)

Portrait of Aubrey Beardsley

c. 1893?

Cartes de visite / cabinet card

Albumen print

Please note: This photograph is not in the exhibition

Edward Coley Burne-Jones (British, 1833-1898)

The Finding of Medusa; The Death of Medusa (The Birth of Pegasus and Chrysaor); Perseus Pursued by the Gorgons

1875-1876

Gouache, paint and ink on paper

Tate. Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1919

Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

This design forms part of Burne-Jones’s ambitious scheme for a series of large wall decorations on the theme of Perseus. Although the work was never completed as he intended, Burne-Jones still proudly displayed ten full-scale preparatory drawings for the panels in his garden studio. They must have made a strong impression on Beardsley when he visited Burne-Jones in August 1891.

Edward Coley Burne-Jones (British, 1833-1898)

The Finding of Medusa

1875-1876

Gouache, paint and ink on paper

Tate. Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1919

Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Edward Coley Burne-Jones (British, 1833-1898)

The Death of Medusa (The Birth of Pegasus and Chrysaor)

1875-1876

Gouache, paint and ink on paper

Tate. Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1919

Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Edward Coley Burne-Jones (British, 1833-1898)

Perseus Pursued by the Gorgons

1875-1876

Gouache, paint and ink on paper

Tate. Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1919

Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Perseus eventually discovers Medusa with her sisters, the Gorgons. Unlike her they are all immortal. Using Athena’s mirror to defend himself, Perseus beheads Medusa, at which point the winged horse Pegasus and the warrior Chrysaor spring from her decapitated body. When the Gorgons attempt to punish Perseus for killing their sister, he evades them by using the helmet given to him by the sea nymphs, thus becoming invisible.

Gallery label, June 1993

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Litany of Mary Magdalen

1891

Graphite on cream wove paper laid down on board

227 × 169 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago, The Charles Deering Collection

Public domain

The Italian painter Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506) was a key reference for both Burne-Jones and Beardsley. At Burne-Jones’s suggestion, Beardsley particularly studied the early engravings after Mantegna’s designs. Throughout his life Beardsley kept a set of reproductions of these prints pinned to his wall. In this subject of his own invention, he freely borrows details of costume, pose and gesture from figures in various of Mantegna’s works, particularly The Entombment (c. 1465-1470).

Andrea Mantegna (Italian, c. 1431-1506)

The Entombment of Christ

c. 1465-1475

Engraving and drypoint; second state of two

11 7/16 × 16 3/8 in. (29 × 41.6cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1937

Public domain

Please note: This engraving is not in the exhibition

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Tannhäuser

1891

Ink, wash and gouache on paper

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection

Public domain

Beardsley was an avid opera-goer. He attended several performances of Wagner’s works at this time, including Tannhäuser at Covent Garden in April or May 1891. He would return to Wagnerian subjects many times in his art and writings. The story of Tannhäuser was a particular favourite. He later made it the subject of his own erotic novella The Story of Venus and Tannhäuser. Here he shows the knight in pilgrim’s robes, among trees that appear like prison bars, trying to find his way back to the goddess’s enchanted realm, the Venusberg.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Die Götterdämmerung

1892

Ink, wash and gouache on paper

Aubrey Beardsley Collection, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University

Beardsley took this subject from Wagner’s opera, the title of which translates as ‘The Twilight of the Gods’. It has been suggested that the frieze-like composition depicts three different moments of the story. According to this interpretation, the scene to the right refers to the prologue, showing the Fates, with the bearded Wotan holding his magic spear. He also appears seated at the centre of the composition with Siegfried standing by him to tell his story to a group of hunters. Finally, Wotan may be represented again seated, in profile, wearing his Wanderer’s hat.

Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods), is the last in Richard Wagner’s cycle of four music dramas titled Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung, or The Ring for short). It received its premiere at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus on 17 August 1876, as part of the first complete performance of the Ring.

“Die Götterdämmerung,” notes Emma Sutton in Aubrey Beardsley and British Wagnerism in the 1890s (2002), “Beardsley’s only drawing of the concluding part of the Ring cycle, was probably prompted by the first performance for a decade of the Ring in London in June and July 1892. It is extremely likely that he attended a performance of the drama; he certainly attended Siegfried, and produced drawings on Siegfried and Götterdämmerung, and of the principle singers, in this year.

No interpretation of the drawing has, to my knowledge, ever been offered, perhaps because its stylistics might suggest that it is an incomplete or experimental, Impressionistic work. The drawing is, however, an intricate and highly knowledgeable representation of Wagner’s work, demonstrating Beardsley’s comprehensive knowledge of Die Götterdämmerung (and, indeed, of the whole cycle) from the very start of the decade. Beardsley presents the gods shrouded in long drapes in a bleak forest setting; with their elongated limbs and enveloping robes they appear androgynous figures, listless and melancholy, entrapped by the sharp bare stems that rise from the border and ground around them.

Despite the undulating lines of the landscape, Die Gotterdammerung is a scene of desolate stasis, bleakly portraying Wagner’s Twilight of the Gods. A compression of several scenes from Wagner’s drama, the drawing is, I would suggest, an extraordinarily innovative and ambitious attempt to evoke concisely the narrative events and cumulative tone of the entire drama.”

~ Emma Sutton, Aubrey Beardsley and British Wagnerism in the 1890s (2002)

Anonymous. “Aubrey Beardsley’s “Die Götterdämmerung”,” on the Graphic Arts Collection, Princeton website [Online] Cited 02/03/2020

Le Morte Darthur

In early 1892, Beardsley received his first major commission. His friend, the photographer and bookseller Frederick H. Evans, introduced him to J.M. Dent. The energetic and enterprising publisher was looking for an illustrator for Le Morte Darthur, Sir Thomas Malory’s 15th-century version of the legends of King Arthur. Dent planned a substantial edition in the style of William Morris’s Kelmscott Press books. Between autumn 1892 and June 1894 Beardsley produced 353 drawings, including full and double-page illustrations, elaborate border designs and numerous small-scale ornamental chapter headings. He received £250 over the course of this commission. This freed him to leave his hated job as a clerk and focus on art-making.

Beardsley gradually grew weary of this colossal undertaking and went off-brief. Subversive details started to appear in his drawings. He also introduced incongruous characters such as mermaids and satyrs, goat-legged hybrid creatures from classical mythology.

His illustrations were reproduced using the relatively new and economical line block printing process in which drawings are transferred onto printing plates photographically. Beardsley was at first disappointed with the printing of his drawings, but he quickly adapted his style to suit the line block process. Uniquely, this could reproduce both the finest of lines and large, flat areas of black.

The works in this room demonstrate the development of Beardsley’s art over two years, and how he combined many different sources to create his own visual language.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Achieving of the Sangreal

1892

Ink and wash on paper

Private collection

This is the sample drawing that secured Beardsley the Morte Darthur commission. Dent declared it ‘a masterpiece’, and it was used as the frontispiece for Volume II. It seems to refer to the crucial episode of the book, in Chapter XIV, where Sir Percival kneels to make a prayer to Jesus in the presence of Sir Ector, and the Sangreal (popularly called the Holy Grail) appears to him, ‘borne by a maiden’.

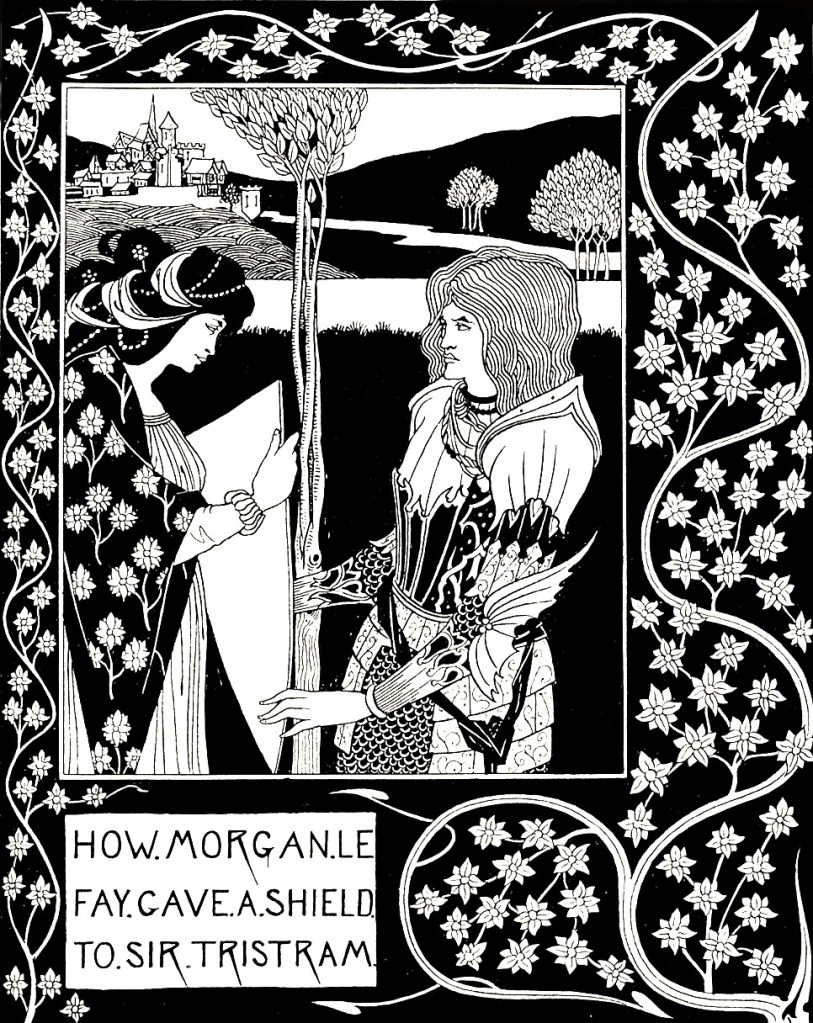

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

How Morgan Le Fay Gave a Shield to Sir Tristram

1893

Ink on paper

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

(Illustration from: Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte d’Arthur. London: Dent, 1894)

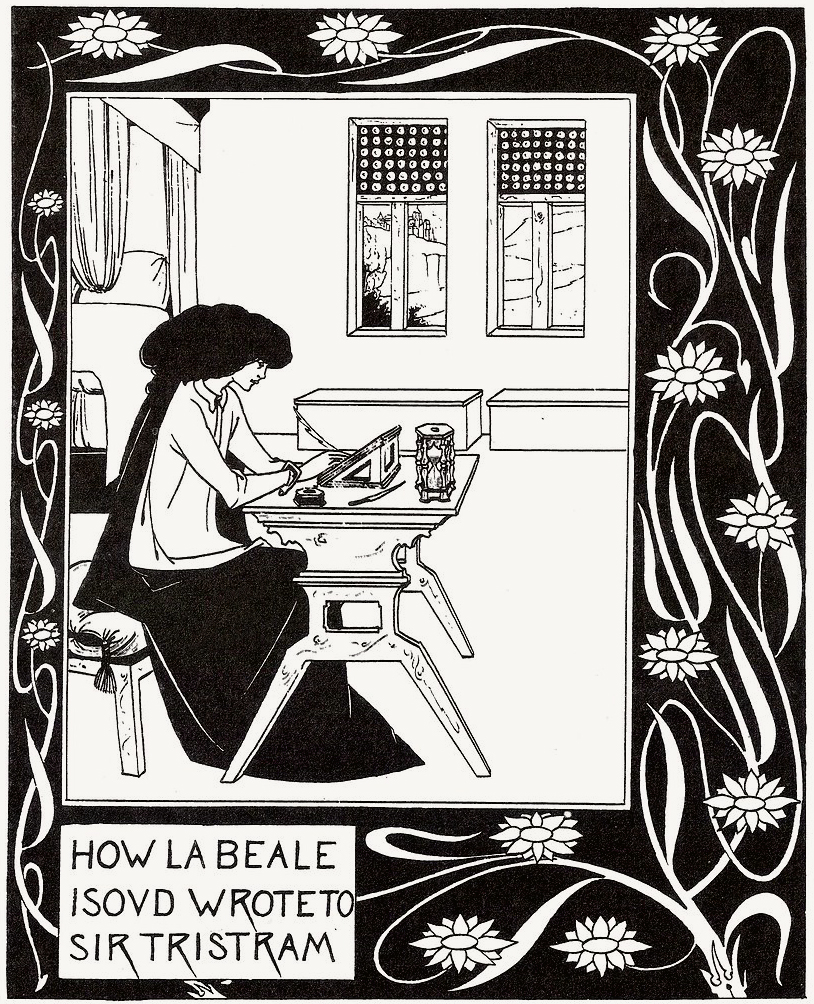

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

How la Beale Isoud Wrote to Sir Tristram

c. 1893

Ink over graphite on paper

Alessandra and Simon Wilson

This drawing brings to mind the comment by the art historian John Rothenstein that ‘the greatest among Beardsley’s gifts was his power of assimilating every influence and yet retaining, nay developing, his own peculiar individuality’.

Isoud (Isolde) here resembles the Pre-Raphaelite figure Jane Morris. The German Renaissance form of her desk is borrowed from Albrecht Dürer’s engraving St Jerome in his Study (1513-1514). The simple, flattened construction of the space reflects Beardsley’s interest in Japanese prints. These contrast with the flowing lines of the sunflower border, a typical aesthetic motif.

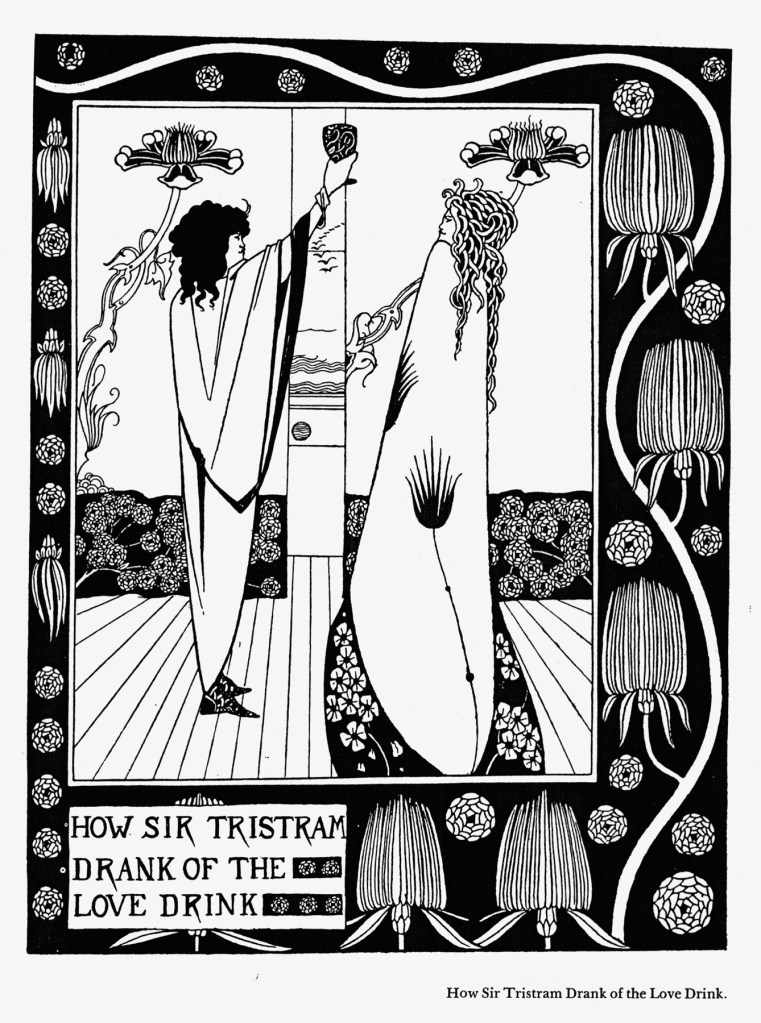

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

How Sir Tristram Drank of the Love Drink

1893

Ink on paper

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Scofield Thayer

This is one of Beardsley’s boldest and most rhythmic drawings. Tristram’s outstretched arm follows the movement of the hybrid flower. The flat outline of Isolde’s recoiling body parallels that of Tristram’s cloak, all against the strong vertical and horizontal lines formed by the curtains with their stylised rose border. Isolde’s long cape, seen from the back, is a forerunner of Beardsley’s famous Peacock Skirt in his Salome illustrations (on display later in this exhibition).

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

How La Beale Isoud Nursed Sir Tristram

1893

Ink over graphite on paper

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Scofield Thayer

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

How King Arthur saw the Questing Beast, and thereof had great marvel

1893

Ink and wash on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

Together with Siegfried Act II (shown nearby), this drawing reflects the height of Beardsley’s fine ‘hair-line manner’. The drawing has great variety of treatment, showing that Beardsley’s style evolved while working on the commission. To alleviate boredom, he took great liberties with Malory’s text. He introduced mythological characters with little to do with the Arthurian legend, such as Pan, here. There are also discreet additions, including a treble clef top right, and even a phallus on the far left of the bank.

Something suggestive of Japan

The European craze for Japanese visual culture had begun in the 1860s after trade links were re-established. Beardsley grew up surrounded by western interpretations of Japanese art. In the summer of 1891, together with his sister Mabel, he visited the London mansion of the shipping magnate Frederick Leyland. There he saw the ‘Peacock Room’ created 15 years earlier by the expatriate North American artist James McNeill Whistler. Decorated with borrowed and reworked Japanese motifs, this masterpiece of the aesthetic movement had become one of the most celebrated interiors in London. Mesmerised by his visit, Beardsley began to introduce such details into his own drawings.

Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e) were also an important influence. Beardsley adopted their graphic conventions. His new style included areas of flat pattern contrasted with precisely drawn figures against abstracted or empty backgrounds. Like several artists at this time, he also favoured the distinctive, tall and narrow format of traditional Japanese kakemono scrolls.

In a letter to a friend, Beardsley bragged, ‘I struck for myself an entirely new method of drawing and composition, something suggestive of Japan… The subjects were quite mad and a little indecent.’

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-98)

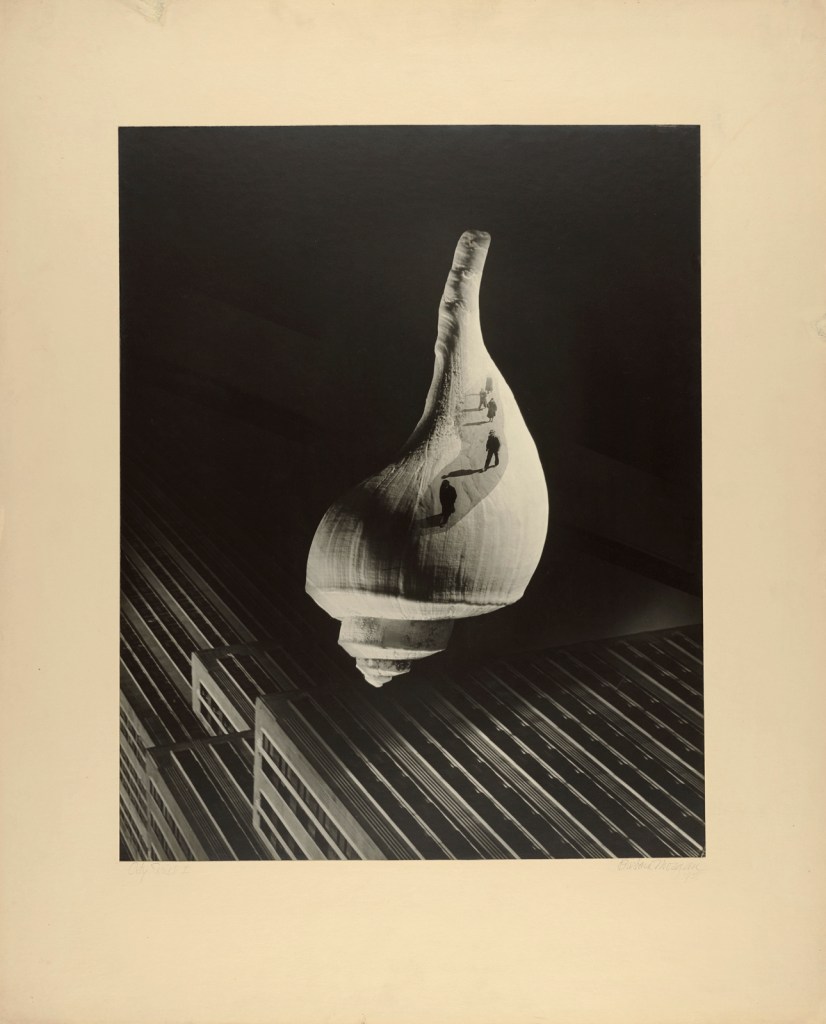

Design for a Frontispiece to Virgilius the Sorcerer

c. 1893

Ink over graphite on paper laid down on board

The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Robert Allerton

Following the glowing article in The Studio, many publishers approached Beardsley with commissions for illustrations and book covers. David Nutt, an old established publishing firm, generally specialised in early texts and folklore. Although made for Nutt’s ‘medieval legends’ series, Beardsley’s design is, somewhat incongruously, in the style of a Japanese print.

A New Illustrator

Beardsley first came to public notice in April 1893. He was the subject of the lead article, ‘A New Illustrator’, in the first issue of the new art magazine The Studio. In it, the graphic art expert Joseph Pennell praised Beardsley’s work as ‘quite as remarkable in its execution as in its invention: a very rare combination.’

Pennell welcomed Beardsley’s use of ‘mechanical reproduction for the publication of his drawings’. The article highlighted how photographic line block printing showed the true quality of an artist’s line.

The reproductions in The Studio article included both medieval and Pre-Raphaelite style illustrations for the forthcoming Le Morte Darthur and examples of Beardsley’s work inspired by Japanese woodblock prints. This displayed his versatility and led to further commissions for books and popular journals, such as the Pall Mall Magazine. J.M. Dent, the publisher of Le Morte Darthur, rightly worried Beardsley would get bored of that long-term project. To keep him interested, he invited him to create hundreds of tiny ‘grotesque’ illustrations for the Bon-Mots series, three miniature books of witty sayings. In this context, the term grotesque relates to distortion or exaggeration of form to create an effect of fantasy or strangeness. For Beardsley the idea was central to his way of seeing the world. Summing up his own art, he later said, ‘I am nothing if I am not grotesque.’

Grotesque

In art history, the grotesque – which originally referred to the decoration of grottoes – has come to denote a strand of Renaissance art composed of deliberately weird elements, often including imaginary hybrid forms. These often combine parts of human heads and bodies, animals and plants. Mermaids, satyrs, fauns and other mythical figures frequently appear in Beardsley’s art. But he also added foetuses, often with adult bodies, and other distorted figures to his grotesque repertoire. The resulting imagery is playful, irreverent and fantastical, but also has dark undertones. The grotesque lies at the heart of Beardsley’s art. He explained: ‘I see everything in a grotesque way. When I go to the theatre, for example, things shape themselves before my eyes just as a I draw them… They all seem weird and strange to me. Things have always impressed me in this way.’

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Kiss of Judas

1893

Ink on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

This drawing illustrates a short story by ‘X.L’ (the North American writer of horror fiction Julian Osgood Field). The macabre tale tells of a legend of the descendants of Judas, the disciple who betrayed Jesus in the Christian New Testament. It is written with the arch tone of much 1890s fiction:

‘They say that the children of Judas, lineal descendants of the arch traitor, are prowling about the world, seeking to do harm, and that they will kill you with a kiss.’ ‘Oh, how delightful!’ murmured the Dowager Duchess.

Smaller figures appear in many of Beardsley’s works, such as the nude in The Kiss of Judas. Some viewers have read these as representations of people with dwarfism. In most cases we do not know if this was Beardsley’s intention. He never strived for realism in his work. He played with scale, exaggerating and distorting lines and shapes, including in self-portraits. But the cultural stereotyping of people with dwarfism was prevalent in Beardsley’s lifetime. In the late 19th and early 20th century, they were predominantly seen as sources of entertainment in ‘freak shows’ and carnivals. These offensive attitudes almost certainly influenced Beardsley’s imagery to some extent.

Salomé

In 1892, Beardsley made a drawing in response to Salomé, Oscar Wilde’s play, originally written in French and based on the biblical story. Salomé falls in love with Iokanaan (John the Baptist). When he rejects her, she demands his head from her step-father, Herod Antipas, as a reward for performing the dance of the seven veils. Beardsley depicts her about to kiss Iokanaan’s severed head. Wilde admired the drawing and he and his publisher, John Lane, chose Beardsley to illustrate the English translation of the play. The illustrations weave together themes of sensuality and death, and explore a wide range of sexual desires. The play’s publication created a sensation, just as Beardsley and Wilde had hoped.

Beardsley delighted in hiding provocative elements in his drawings. Lane recalled, ‘one had, so to speak, to place his drawings under a microscope, and look at them upside down’. Nervously, he censored ‘problematic’ details in Beardsley’s title page and the illustration Enter Herodias and rejected two designs altogether from the first edition. Even so, Lane missed many erotic details and, surprisingly, also allowed publication of Beardsley’s teasing drawings that include caricatures of Wilde.

Beardsley produced 18 designs in total, of which only 10 appeared in the first printing of the play. The impressions exhibited here come from the portfolio which Lane issued in 1907, almost a decade after Beardsley’s death. This was the first edition to contain all the original designs and an additional one, Salome on Settle.

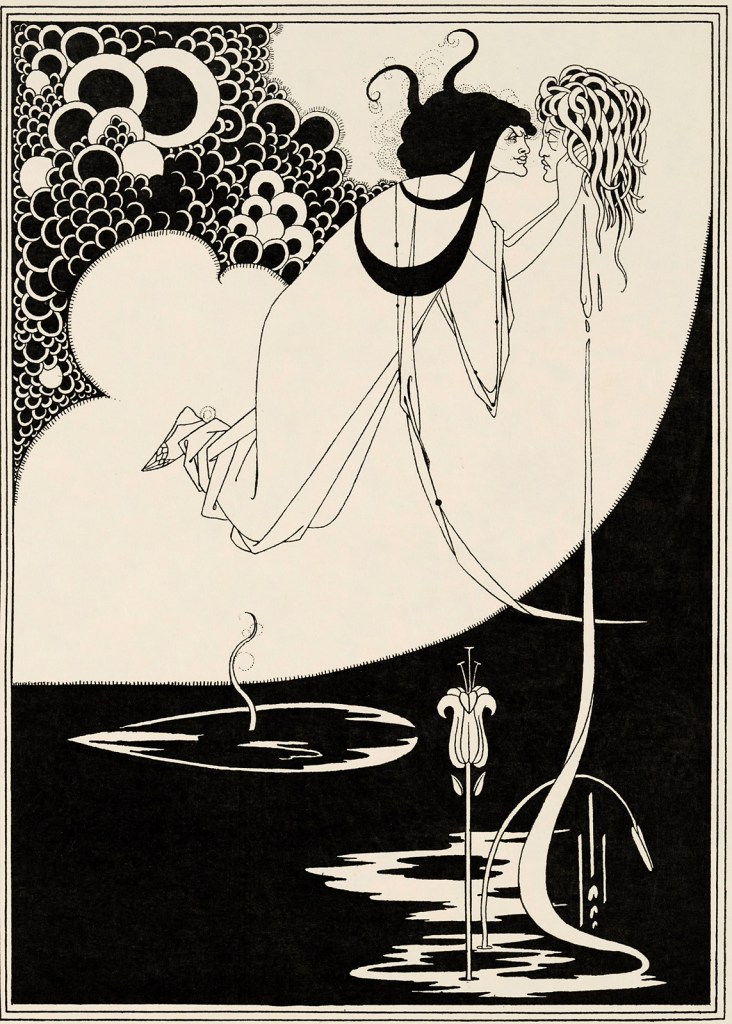

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Climax

1893

Line block print on paper

Stephen Calloway

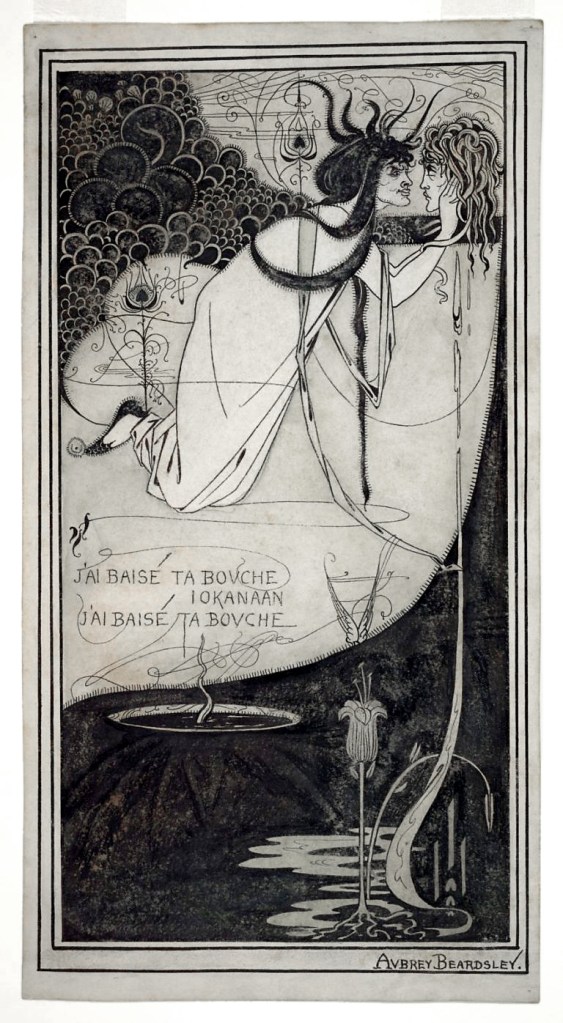

The flowing, sinuous lines in this design demonstrate how much art nouveau is indebted to Beardsley. He abandoned the Japanese kakemono format and hairline style of his original version of the image J’ai baisé ta bouche, Iokanaan (also in this room). By simplifying the lines of the design, he creates a more powerful focus on the moment when Salome can finally kiss Jokanaan’s lips – now that he has been beheaded. The stream of blood forms an elegant ribbon, while the lily rising from the pool that the fluid creates symbolises his chastity.

The Climax

The Climax is an 1893 illustration by Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898), a leading artist of the Decadent (1880-1900) and Aesthetic movements. It depicts a scene from Oscar Wilde’s play Salome, in which the femme fatale Salome has just kissed the severed head of John the Baptist, which she grasps in her hands. Elements of eroticism, symbolism, and Orientalism are present in the piece. This illustration is one of sixteen Wilde commissioned Beardsley to create for the publication of the play. The series is considered to be Beardsley’s most celebrated work, created at the age of 21. …

First published in 1894, The Climax consists of strong, precise lines, decorative motifs characteristic of the developing Art Nouveau style, and the use of only black ink. Beardsley’s style was influenced by Japanese woodcuts also known as Ukiyo-e, which comes through in the flatness of imagery, compositional arrangement, and the stylistic motifs. Elements of eroticism are also apparent.

The main focus of this illustration, Salome, floats in midair and in her hands she holds the head of John the Baptist just after she kissed it, depicting the final words said by Salome in the play “J’ai baisé ta bouche Iokanaan, j’ai baisé ta bouche” (“I have kissed your mouth, Jokannan, I have kissed your mouth”). Her hair billows in snake-like tendrils above her as she stares powerfully into the eyes of John the Baptist. His severed head drips blood that nourishes the phallic lily. The flower also symbolises purity. Composing the background behind these two figures is a white quarter section of the moon and a stylised depiction of peacock feathers, a signature motif in Beardsley’s illustrations, made of concentric circles.

Beardsley satirised Victorian values regarding sex, that at the time highly valued respectability, and men’s fear of female superiority, as the women’s movement made gains in economic rights and occupational and educational opportunities by the 1880s. Salome’s power over men can be seen in the way that Beardsley presents her as a monster-like figure, reminiscent of Medusa.

Reaction

Beardsley said of his drawing that rather than using thicker lines for the foreground than those for the background, he felt that the lines should be the same width. Morgan Meis of The New Yorker states that “his influence on the look of Art Nouveau, and then on early modernism, is hard to overstate. His thick black lines fused the graphical ideas of the past with the techniques and subject matter of a new age just on the horizon.” He was an inspiration to Japanese illustrators, graphic designers, and printmakers of the early 20th century Taishō period.

The Climax is described as among his finest works by Ian Fletcher and established him as one of the “Decadence”. It was not appreciated, though, by mainstream art critics of the time, who found the Salome drawings repulsive and unintelligible. Art historian Kenneth Clark said that it “aroused more horror and indignation than any graphic work hitherto produced in England.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

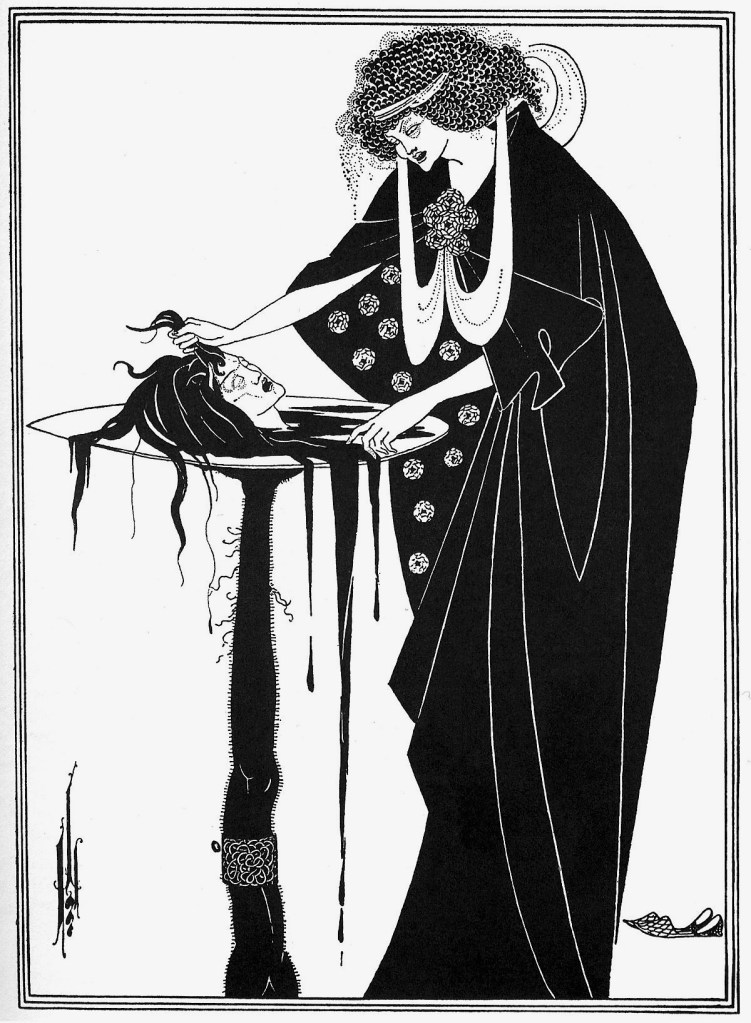

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Dancer’s Reward

1893

Line block print on paper

Stephen Calloway

Salome is contemplating her prize. Gaping, she tilts Jokanaan’s severed and bleeding head towards her. Once again, their expressions mirror each other. The elongated arm of the executioner holds up the platter on which the head rests. This drawing resonates with European symbolist art, in which the contemplation of a severed head is a recurring image.

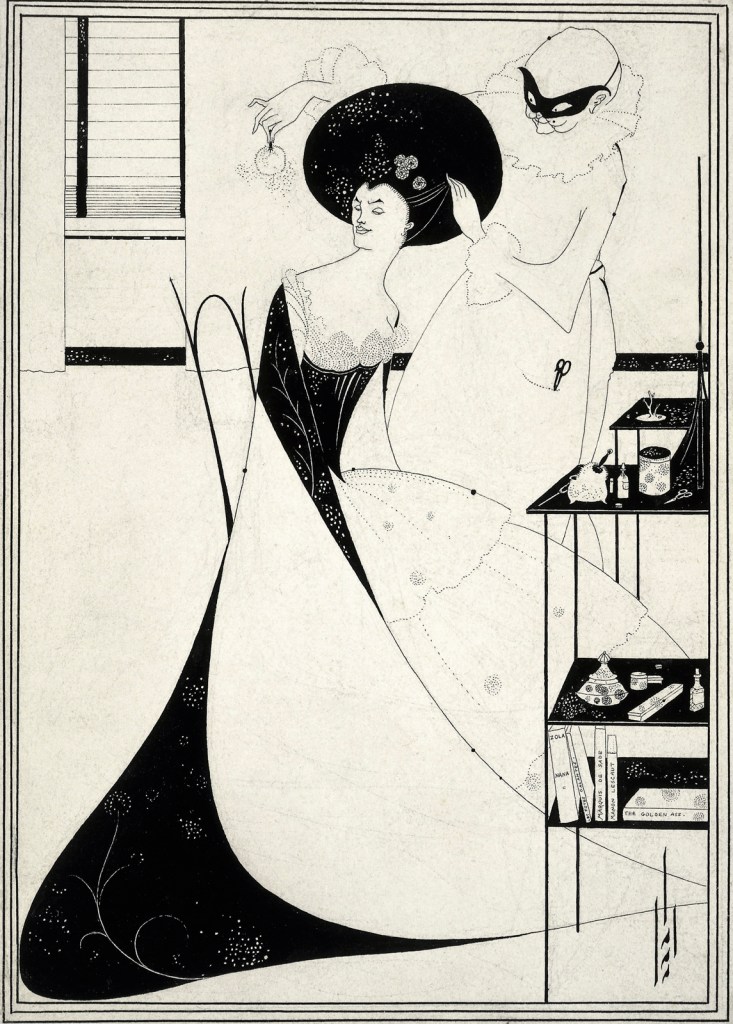

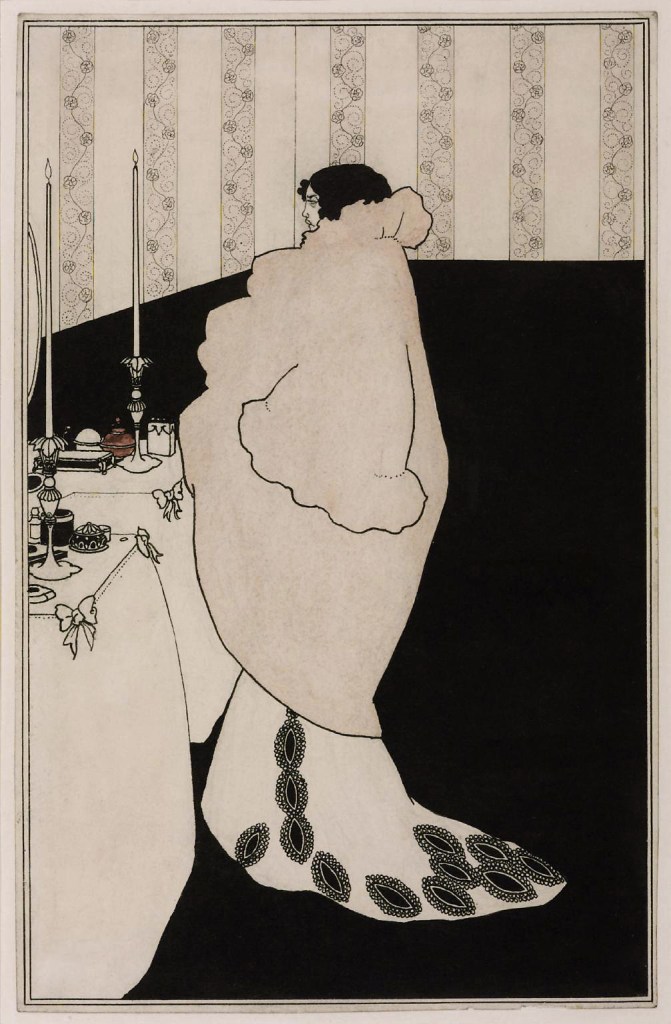

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Toilette of Salome (second version)

1893

Line block print on paper

Stephen Calloway

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

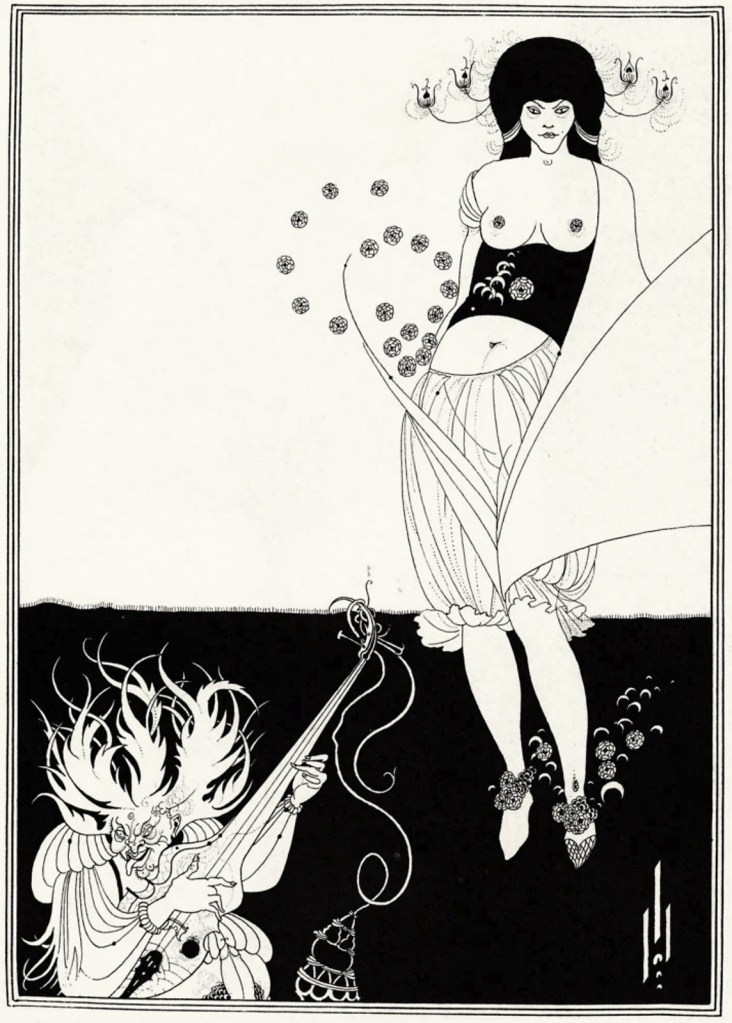

The Stomach Dance

1893

Line block print on paper

Stephen Calloway

Salome is shown performing her celebrated dance to the sounds produced by an impish musician. Wilde wrote appreciatively to Beardsley after Salome was published: ‘For Aubrey: for the only artist who, besides myself, knows what the dance of the seven veils is, and can see that invisible dance.’

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Eyes of Herod

1893

Line block print on paper

Stephen Calloway

This illustrates the passage before Salome’s famous dance in exchange for the head of Jokanaan. Talking about Herod, Salome remarks pensively: ‘Why does the Tetrarch look at me all the while with his mole’s eyes under his shaking eyelids? It is strange that the husband of my mother looks at me like that. I know not what it means. Of a truth I know it too well.’

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

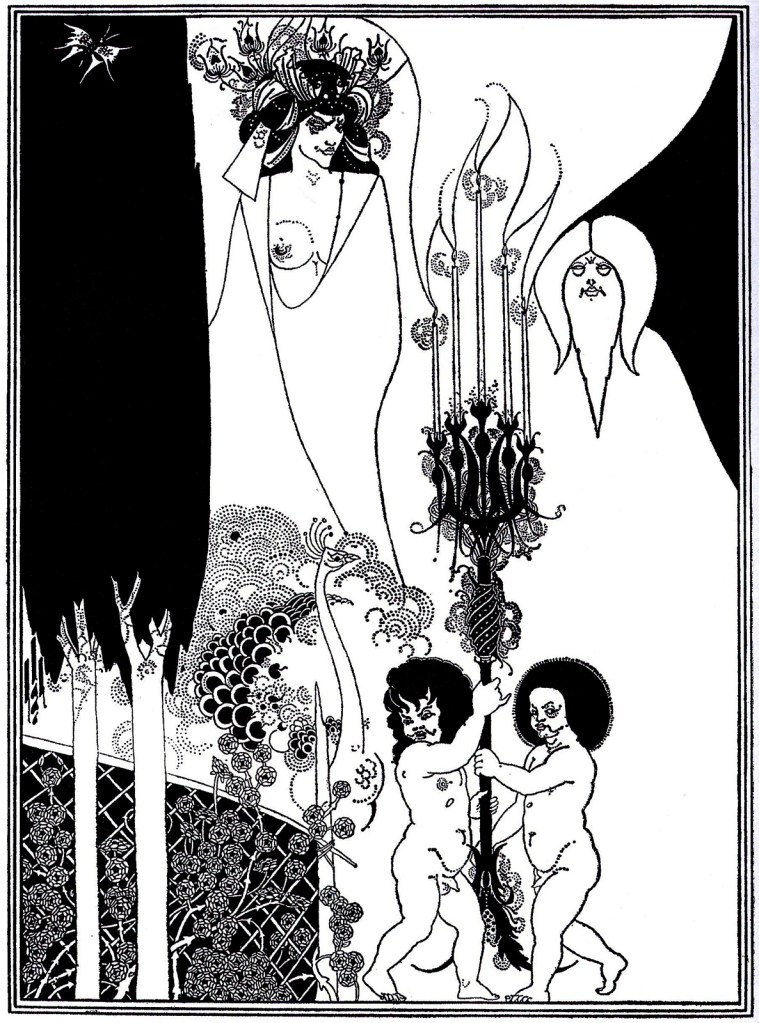

Enter Herodias

1893 (published 1907)

Stephen Calloway

Enter Herodias is named after a stage direction in Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé. Wilde originally wrote the play in French, and he chose Beardsley to illustrate the English translation of the play. Beardsley drew erotic and satirical images, some of which were entirely unrelated to the plot of play.

Enter Herodias shows the moment when Salome’s mother enters the stage. To the bottom right there is a caricature of Oscar Wilde holding a copy of Salome and gesturing up at his own play. It also includes two nude figures. Herodias’s breasts are exposed but she is covered by the large cloak. John Lane, who was Beardsley’s publisher, demanded that Beardsley cover the page on the right’s genitalia with a fig-leaf. But he failed to spot the penis-shaped candles the artist had drawn in the foreground, and the erection of the figure to the left.

Beardsley’s obsession with the erotic played upon Victorian taboos. Beardsley was often deliberately trying to be provocative. Many people at the time thought that Beardsley’s obsession with erotic art came from the fact that he was young and ‘consumptive’. Today we call ‘consumption’ Tuberculosis (or TB). A strange, but frequent 19th century perception of TB was that it went hand in hand with an obsession about sex.

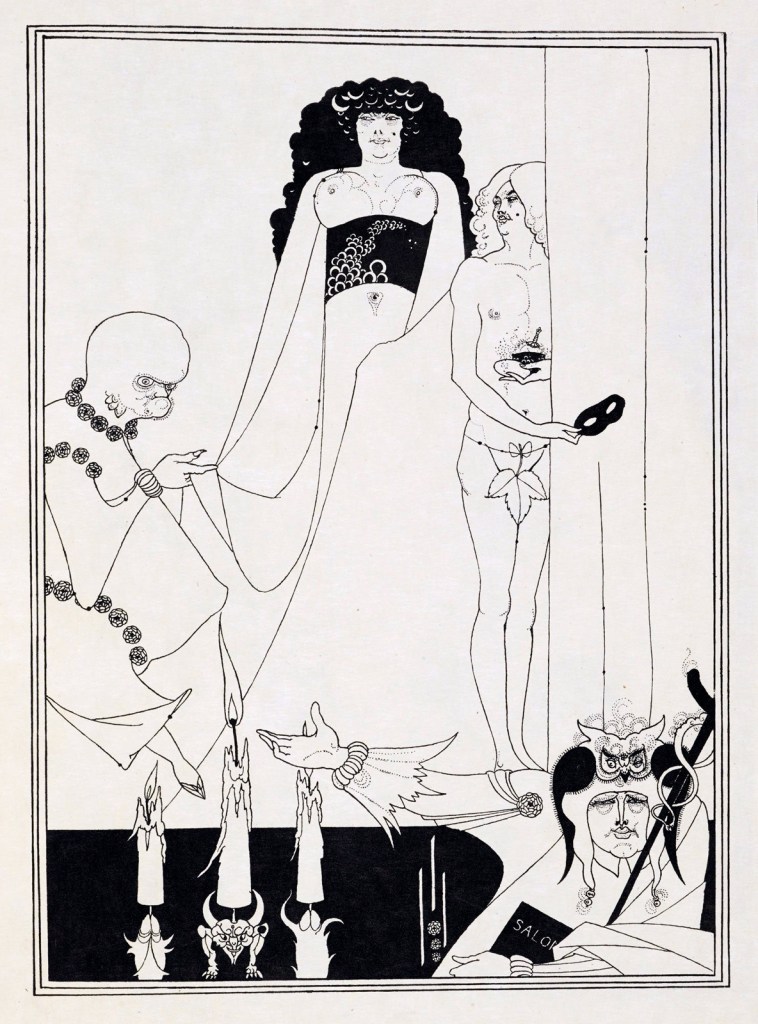

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

John and Salome

1893

Line block print on paper

Stephen Calloway

This depicts a scene of powerful tension between Jokanaan (left) and Salome (right). By the use of mirrored poses and interlocking folds of drapery – like an image of yin and yang – he expresses the characters’ conflicted feelings of attraction and rejection. John Lane refused the design, either because of the partial nudity of Salome, or possibly because of the androgynous appearance of the Baptist who could here be Salome’s twin.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Black Cape

1893

Line block print on paper

Stephen Calloway

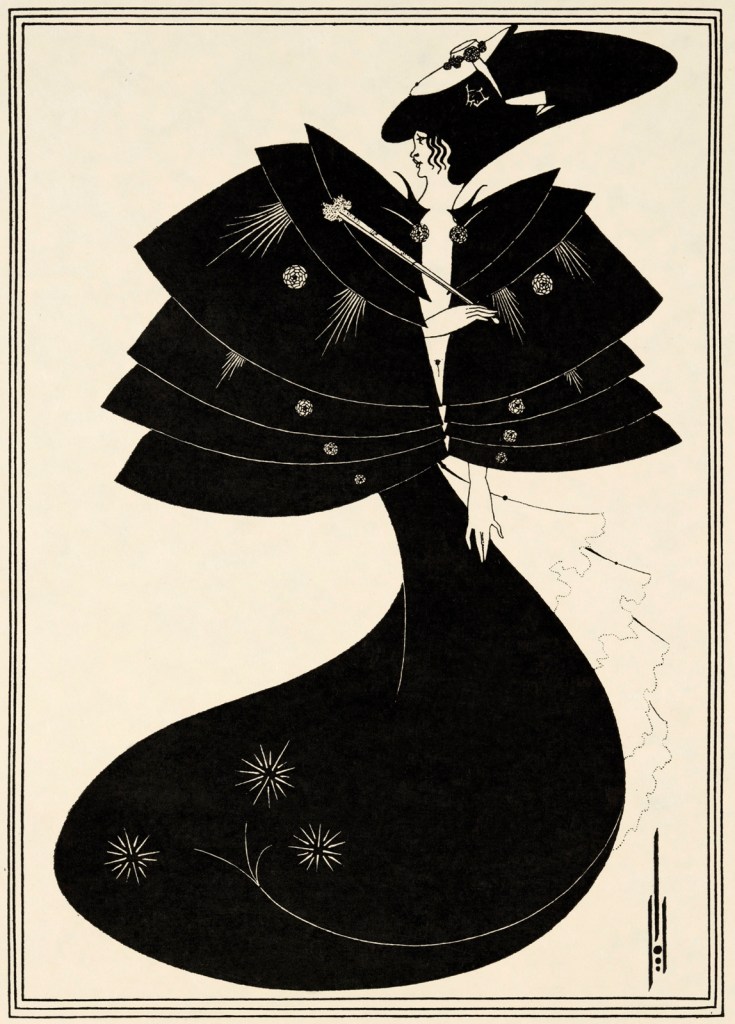

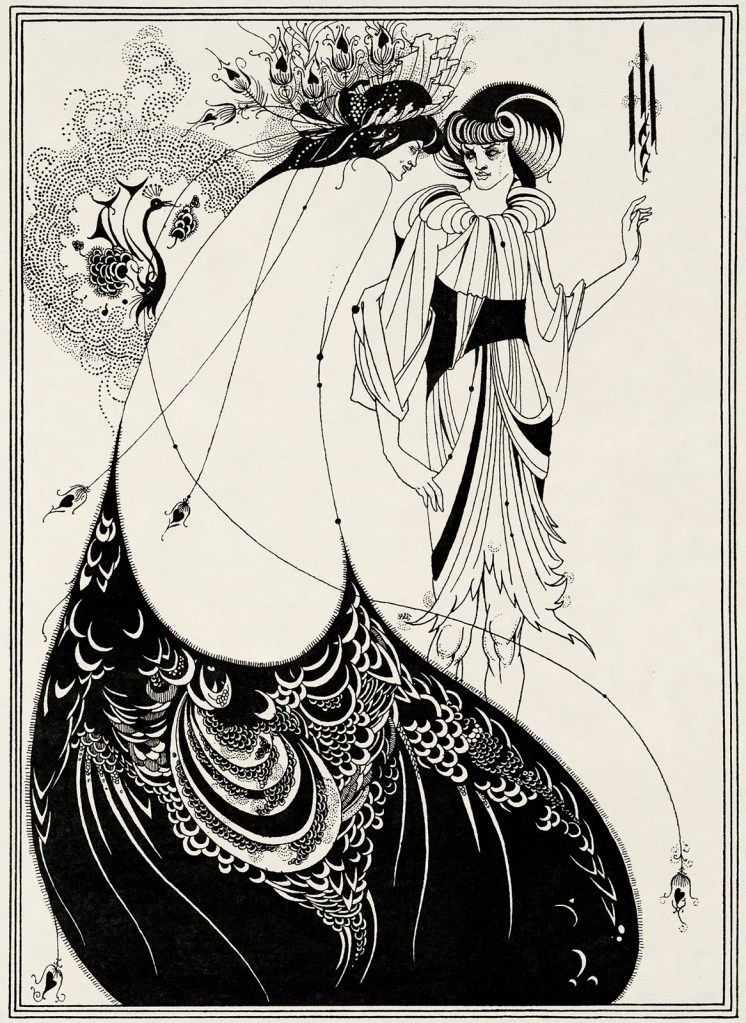

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Peacock Skirt

1893

Line block print on paper

Stephen Calloway

This is one of Beardsley’s most famous and acclaimed designs. It conflates two scenes from the play. In one, the page of Herodias warns the young Syrian about looking too much at Salome. In the other, Herod promises 50 of his white peacocks in exchange for Salome’s dance and imagines them forming a ‘great white cloud’ around her. The scene was abstracted by Beardsley in a flamboyant demonstration of his calligraphic skills.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

J’ai baisé ta bouche Iokanaan

1892-3

Ink and wash on paper

Aubrey Beardsley Collection, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University

This is Beardsley’s first interpretation of Oscar Wilde’s play, before it was translated into English. It was reproduced in the first issue of The Studio, and it is characteristic of Beardsley’s intricate hairline style. It may well have been a bid to illustrate the play. If it was, it paid off, as Wilde did ask John Lane to commission Beardsley. The artist applied some green watercolour to the drawing after it was published.

Gustave Moreau (French, 1826-1898)

The Apparition (detail)

1874-1876

Watercolour on paper

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, gift of Charles Ayem

This watercolour made a strong impression on Oscar Wilde at the 1876 Paris Salon exhibition. It represents the bloody vision of John the Baptist’s head appearing while Salomé dances for Herod. It featured in Joris-Karl Huysmans’s 1884 novel À Rebours (Against Nature). In it, the reclusive hero contemplates this watercolour. Wilde could quote at length from this ‘bible’ of decadence. Both the novel and The Apparition played a part in the creation of Wilde’s own Salomé.

Alla Nazimova (1879-1945)

Charles Bryant (1879-1948)

Salomé

1923

Film, 35 mm, black and white

Running time: 1hr 12mins

Sets and costumes by Natacha Rambova, after Aubrey Beardsley

This 1923 silent “Salome” is probably the best filmed version of the scandalous Oscar Wilde one-act play. It’s basically a photographed avant-garde theatre production performed on a single set based on Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for the published play.

Alla Nazimova’s Salomé

This 1923 silent film is an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s play. The imaginative set and costumes by Natacha Rambova are directly inspired by Beardsley’s drawings, and credited as such. The project was conceived and led by Alla Nazimova, a famous Hollywood actor during the silent movie era. She was drawn to Salome and financed its screen adaptation herself. Nazimova had relationships with women and her film reflects themes of same-sex desire present in Beardsley’s drawings. Charles Bryant, with whom she pretended to be married, was credited as the director, as women did not have equal status in Hollywood.

This film perpetuates some demeaning stereotypes that were current during Beardsley’s lifetime and beyond. This is reflected particularly in the portrayal of the musicians with dwarfism. At that time people with restricted growth were widely associated with servitude and treated as a source of spectacle.

Posters

When Beardsley first travelled to Paris in 1892, he was enthralled by the many posters that adorned the city. The French posters showed the possibilities of this new mass-produced outdoor format and the potential of large-scale colour reproduction. Beardsley was quick to embrace this. Understanding that posters would be viewed in passing, often at a distance, his designs experimented with bold, simplified forms and solid blocks of colour. For Beardsley, advertising was central to modern life and an opportunity to integrate art into everyday experience. As he put it, ‘Beauty has laid siege to the city’.

In the autumn of 1894, the first ever English exhibition of posters opened in London. Pictorial posters were enjoying a boom in Britain and were beginning to be recognised as an art form. The exhibition featured work by celebrated French artists such as Jules Chéret and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, known as the ‘fathers’ of the modern poster. Significantly, it also included several works by Beardsley. Not only did this place Beardsley’s posters on a par with the art that had inspired him, it also attested to his importance in the development of British poster design.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, 1864-1901)

Divan Japonais

1892

Colour lithograph on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

In Paris, Beardsley would have encountered Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters, including this one, on hoardings across the city. It advertises the popular cabaret nightspot, the Divan Japonais, and depicts two stars of Parisian nightlife, the singer Yvette Guilbert and the dancer Jane Avril. Beardsley was inspired as much by Toulouse-Lautrec’s vivid portrayal of modern life as his striking style, typified by dramatic blocks of colour, silhouettes and bold outlines. The admiration was mutual: Toulouse-Lautrec also expressed the wish to buy a copy of Salome.

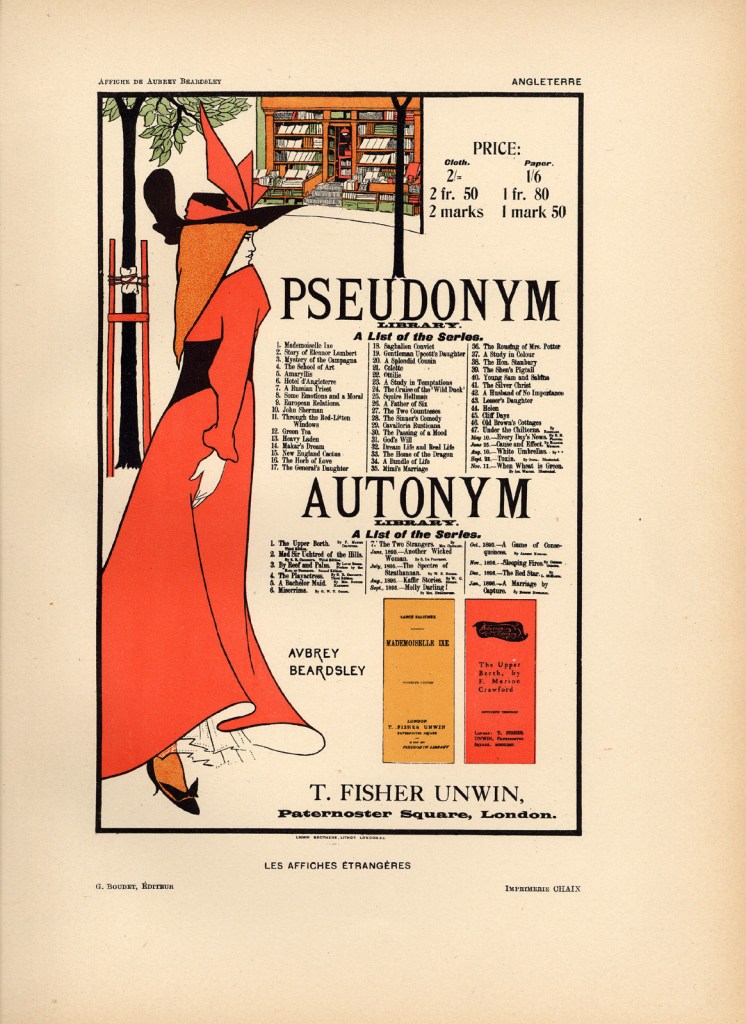

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Pseudonym and Autonym Libraries

1894

Colour lithograph on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

This poster shares its title with the series of novels and short story collections it promotes. The name was inspired by the publisher, T. Fisher Unwin’s, recognition that women often wrote under a pseudonym, whereas men used their actual name (autonym). The woman pictured here appears confident as she rushes towards the bookshop, implying that knowledge brings freedom.

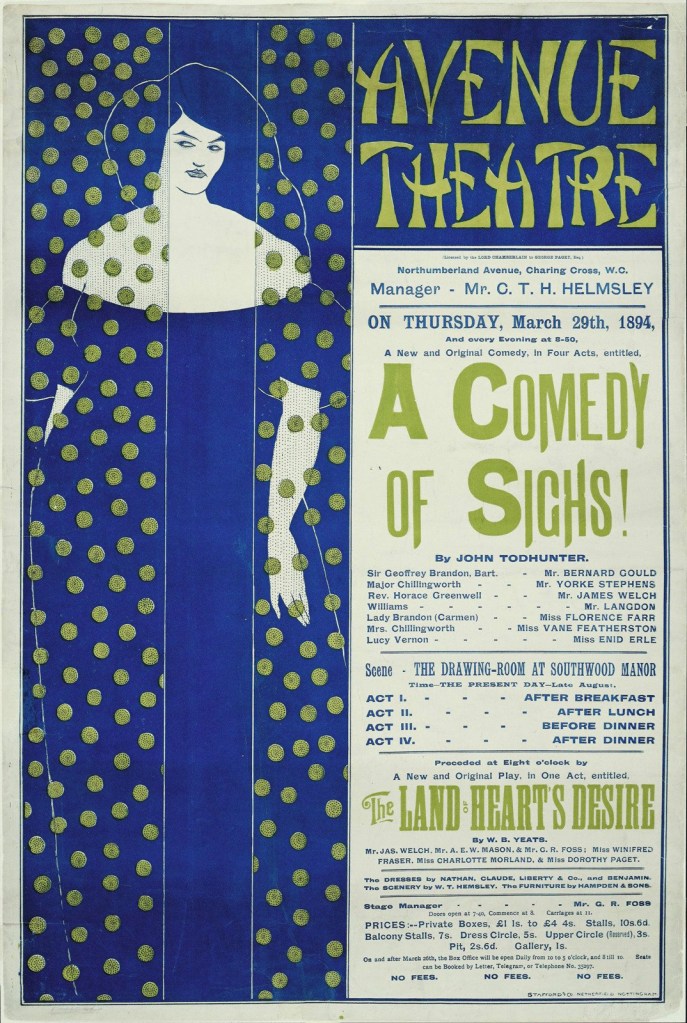

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Isolde

Printed 1899

Colour lithograph and line block print on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

Turning again to Wagner for inspiration, Beardsley depicts the tragic heroine, Isolde, on the brink of drinking the fateful love potion. She stands against a stage curtain, bright red in the original design and equally bold in the orange used for this first printing. Beardsley asserted, ‘I have no great care for colour, but [in posters] colour is essential’. This design was published as a colour lithograph supplement in The Studio in October 1895.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

A Comedy of Sighs

1894

Colour lithograph on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

This was Beardsley’s first poster design. It appeared on walls and hoardings around London shortly after the publication of Salome and introduced his art to an even wider audience. The poster stole the limelight from the performances of the two short plays it advertised. Critics were outraged by the woman’s ‘ugliness’ and the indecency of her plunging neckline. Punch magazine even punned, ‘Let’s “Ave-a-nue” Poster!’

Beardsley’s Circle

This room introduces the key figures in Beardsley’s life. The glowing article in The Studio and his success with Le Morte Darthur had brought him into the public eye at the age of 20. Following this, a sequence of fortuitous meetings with leading cultural figures of the day led him to the heart of avant-garde literary and artistic circles in 1890s London. Witty, talented and well-read, he was rapidly taken up by a group of young artists and writers who identified as aesthetes, acutely sensitive to art and beauty. These included the portrait painter William Rothenstein; Max Beerbohm, the essayist and caricaturist; and the art critic and dealer Robert Ross, the friend and former lover of Oscar Wilde. Beardsley’s fame grew with the publication of his illustrations to Wilde’s Salome in 1894 and his involvement in the fashionable magazine The Yellow Book, a period addressed in the following room. At this point his group of friends began to expand rapidly. But with the fall of Wilde early in 1895, Beardsley moved first to Dieppe, and thereafter spent little time in England.

In his last years his circle included fellow contributors to The Savoy magazine: the poets W.B. Yeats and Arthur Symons and the painter Charles Conder. The wealthy French-Russian poet and writer Marc-André Raffalovich became an important supporter and patron. His most significant friend in this period was Leonard Smithers, his endearing but unscrupulous publisher.

His mother and sister Mabel were constants throughout his brief life. They were with him when he died at Menton on the French Riviera in 1898.

This room nods at Beardsley’s orange and black decoration scheme in the Pimlico house that he and Mabel owned briefly in 1894. ‘Orangé’ was famously described as the chief decadent colour by Joris-Karl Huysmans in his 1884 novel À rebours (Against Nature), which may have informed Beardsley’s choice.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Professor Fred Brown

1892

Graphite and ink on paper

Tate. Presented by Mrs Helen Thorp 1927

In 1891 Beardsley enrolled at the Westminster School of Art on the advice of Edward Burne-Jones. For just a few months he attended evening classes given by the school’s principal, the painter Fred Brown. Brown was a pillar of the avant-garde exhibiting society, the New English Art Club. Beardsley added the society’s initials to Brown’s name in the title of this drawing.

Jacques-Émile Blanche (French, 1861-1942)

Charles Conder

1904

Oil paint on canvas

Tate, Presented by Georges A. Mevil-Blanche 1947

Conder specialised in painting fans and small pictures on silk depicting romanticised figures in 18th-century costume. He and Beardsley became close during the planning of The Savoy magazine in the summer of 1895 when many of their circle were gathered in Dieppe.

Jacques-Emile Blanche lived near Dieppe and was a friend of Degas, Manet and Renoir. However, he also made frequent visits to England, where he painted and exhibited and was well known in artistic and society circles. This is a portrait of the British painter Charles Conder (1868-1909), who was greatly interested in contemporary French art. Conder befriended Toulouse-Lautrec who helped him obtain an exhibition in Paris. Blanche first met Conder in Paris, but they became friends in 1895 when they both spent the summer in Dieppe. This portrait, which captures his flamboyant character, was painted in Conder’s house in London.

Gallery label, August 2004

Jacques-Émile Blanche (French, 1861-1942)

Aubrey Beardsley

1895

Oil paint on canvas

National Portrait Gallery, London

The society painter Blanche welcomed many of the English artists and writers who visited Dieppe to his nearby family home. This portrait, painted during the summer of 1895, shows the extent to which Beardsley had adopted the dress and cultivated the manner of Parisian dandies such as Comte Robert de Montesquiou.

Walter Richard Sickert (British, 1860-1942)

Aubrey Beardsley

1894

Tempera on canvas

Tate, Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund 1932

Sickert observed Beardsley in Hampstead churchyard following a ceremony for the unveiling of a bust commemorating the Romantic poet John Keats (1795-1821). Though angular and painfully thin, he was elegantly dressed as always. Keats had died young from tuberculosis. The parallel between the poet and the artist cannot have been lost on those friends, like Sickert, who knew of Beardsley’s condition.

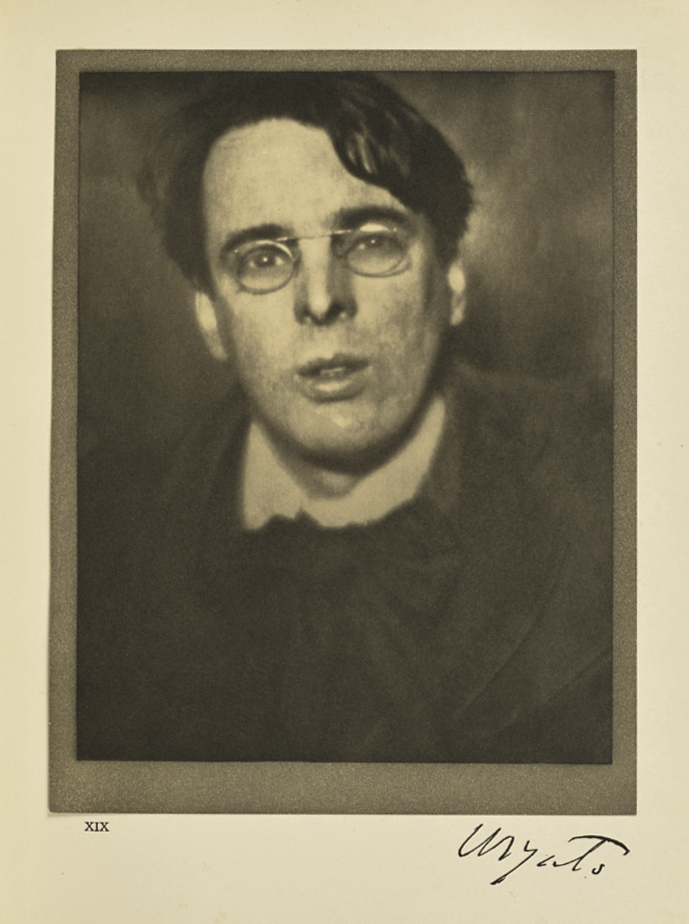

Alvin Langdon Coburn (English born America, 1882-1966)

W.B. Yeats

1908

Photo-etching on paper

National Portrait Gallery, London

Yeats was a leading figure of the Irish poetic and nationalist movement, the ‘Celtic Twilight’. He was also central as an activist in London literary circles. The idea of the poets, writers and artists of the 1890s as sensitive, decadent and doomed owes much to Yeats’s myth-making in his later memoirs. In these he painted a compelling picture of ‘The Tragic Generation’.

William Rothenstein (British, 1872-1945)

Robbie Ross

1895-1930

Oil on canvas

13 1/8 in. x 10 in. (333 mm x 254 mm)

Accepted in lieu of tax by H.M. Government and allocated to the Gallery, 2005

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The writer and art critic Robert Ross was a pivotal figure in the aesthetic and decadent culture of 1890s London. He was Oscar Wilde’s first male lover and later became his literary executor, working tirelessly to safeguard his works and re-establish his reputation. Ross also used his connections and influence to promote and protect many friends, including Beardsley and his family. His 1909 book on Beardsley was one of the first serious studies and remains a valuable source of insights.

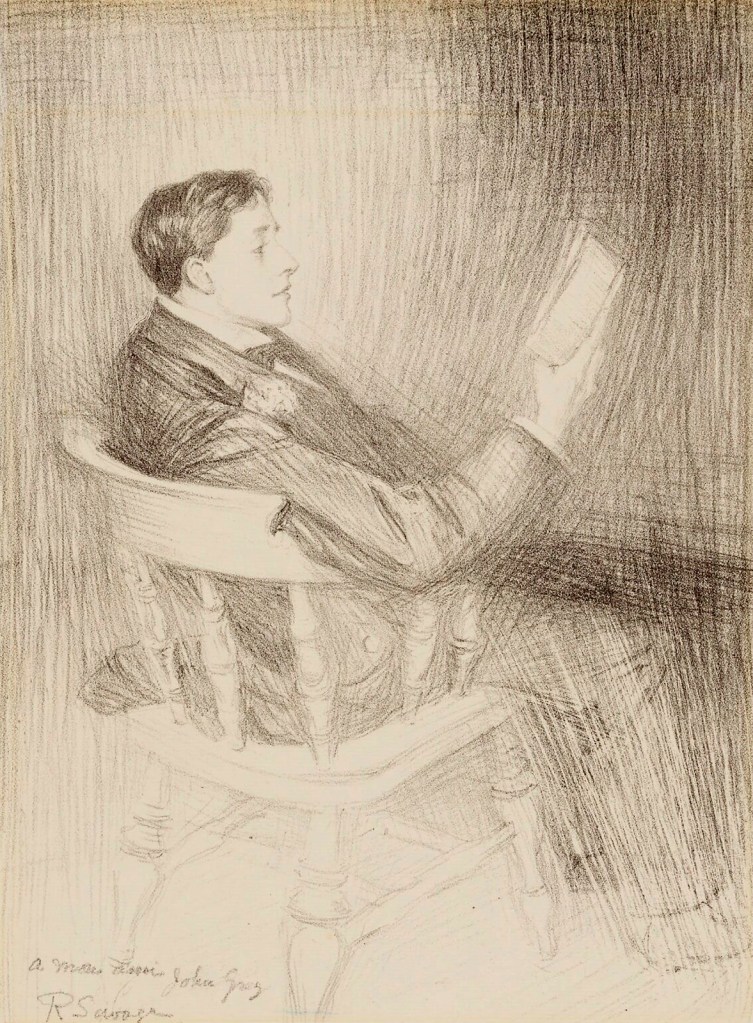

Reginald Savage (British, 1886-1932)

John Gray

c. 1896-1897

Lithograph on paper

National Portrait Gallery, London

As a young poet John Gray was initially a protégé of Oscar Wilde. He later moved away from the decadents and converted to Catholicism. He was ordained in 1901 and served for many years as the priest at St Peter’s Morningside, Edinburgh. The church was built by his lifelong companion Marc-André Raffalovich, a wealthy writer who provided Beardsley’s principal financial support in his last years.

The Yellow Book

In 1894, Beardsley became art editor of The Yellow Book, a magazine that would become the most iconic publication of the decade. Its distinctive appearance immediately set the tone. Yellow was fashionable, urban, ironic and risqué, recalling the yellow wrappers of popular French erotic novels. The first volume was an instant and controversial success. Notably, it put art and literature on an equal footing. But it was Beardsley’s drawings that stole the show and gave the magazine its avant-garde reputation. Their bold style and daring modernity received praise and scorn in equal measure. With each new volume, his notoriety increased. To many the publication embodied the decadent spirit, and, as one critic observed, ‘to most, Aubrey Beardsley is The Yellow Book.‘

However, Beardsley’s meteoric success was short-lived. In 1895, Oscar Wilde was put on trial for sexual relationships with men and prosecuted for ‘gross indecency’. As the scandal tore through London, the backlash turned towards the notorious magazine and its audacious art editor. In the public mind, Beardsley was already connected to Wilde through his Salome illustrations. When Wilde was seen at his arrest carrying a yellow book (in fact a French novel, not The Yellow Book), the link between the author and the artist was damning. Outraged crowds broke the windows of the publishing house. John Lane, the publisher, succumbed to pressure and sacked Beardsley.

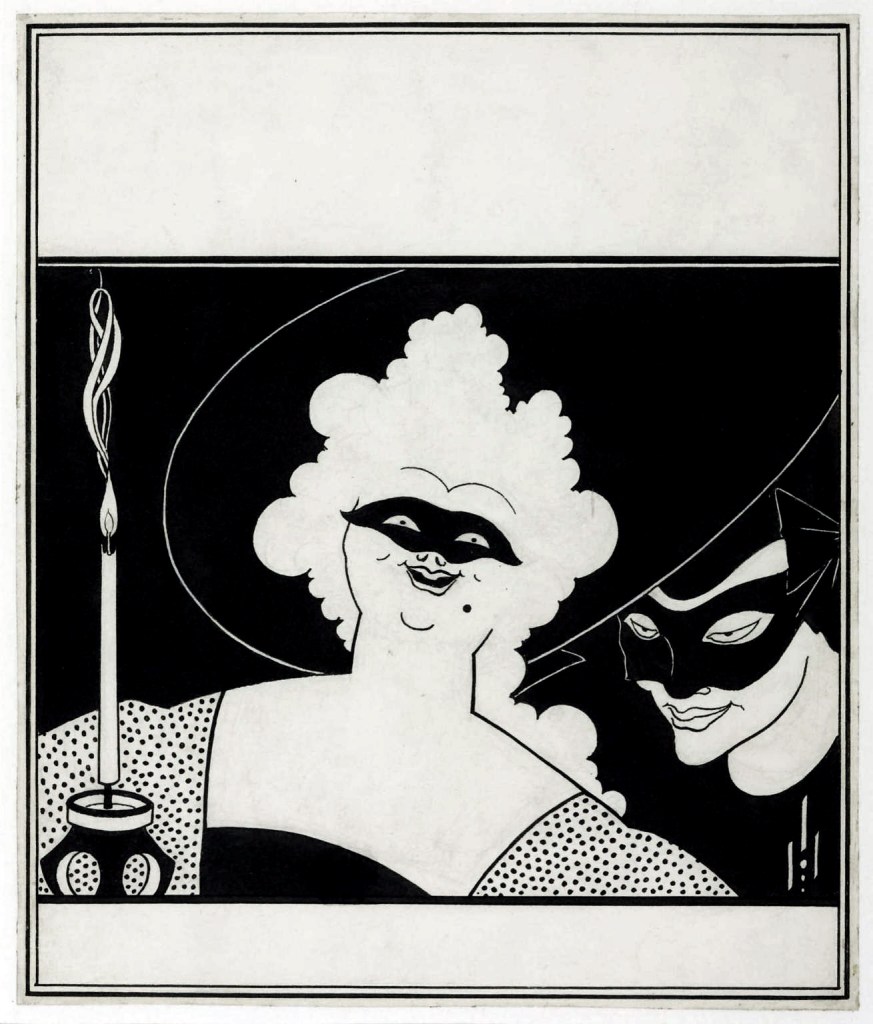

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Cover Design for The Yellow Book Vol.I

1894

Ink on paper

Tate. Bequeathed by John Lane 1926

Beardsley instantly set the tone for the magazine with this design for the first volume. His highly stylised manner, dramatically setting pure white against flat black, was completely new. The subject, two masked revellers abandoning themselves to hedonism, was also bold. The overt sensuality of the laughing woman was particularly shocking for the time. Oscar Wilde described her as ‘a terrible naked harlot’.

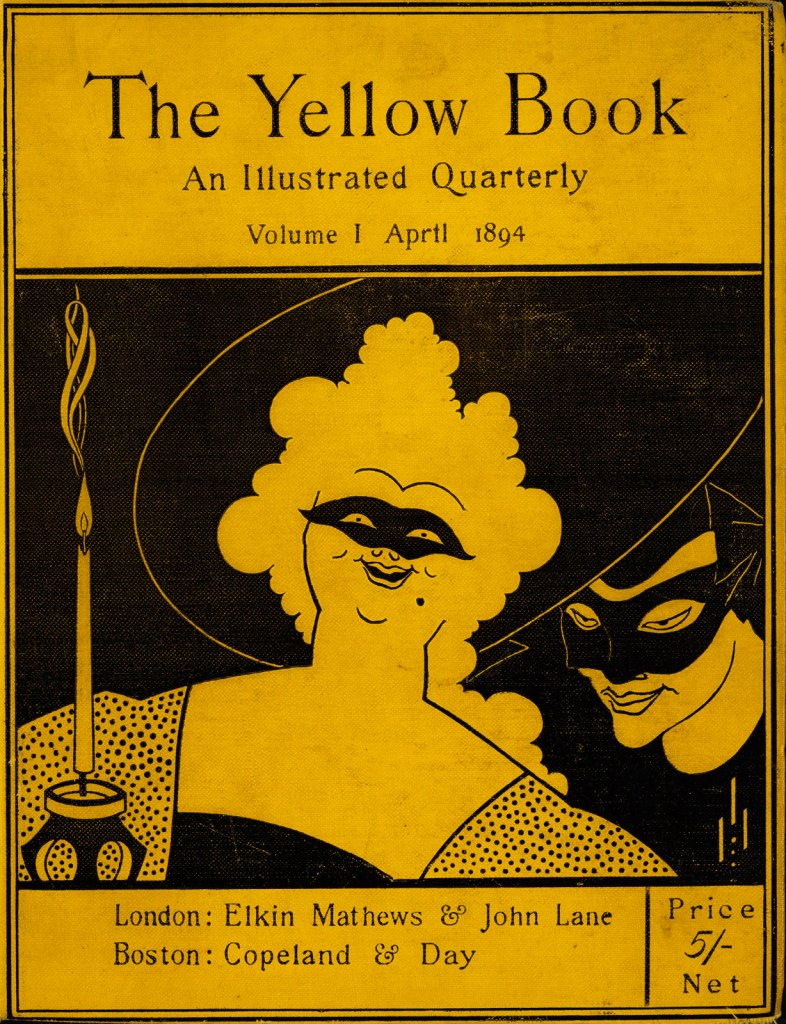

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Edited by Aubrey Beardsley 1872-1898 (art) and Henry Harland 1861-1905 (literature)

The Yellow Book, Volume I

1894

Elkin Mathews & John Lane, London April 1894

Stephen Calloway

In 1894 Aubrey Beardsley became the first Art Editor for The Yellow Book, a new literary periodical. There were hostile reactions to The Yellow Book from the wider press, who were alarmed by the shocking and ‘immoral’ illustrations and writing. The Westminster Gazette even commented that the publication should be made illegal. Things only got worse for Beardsley and The Yellow Book in 1895. The trial and conviction of Oscar Wilde for ‘gross indecency’ with men became linked to the publication. The press mistakenly reported seeing Wilde leaving the Cadogan Hotel with a copy of The Yellow Book under his arm. In fact, he was carrying a French erotic novel, which often had yellow covers.

Beardsley, who had collaborated with Wilde on Salome and whose art was strongly linked with The Yellow Book, was caught up in the scandal. He was dismissed as editor for The Yellow Book. Having lost his regular source of income, he was forced to sell his house and he temporarily moved to France.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Slippers of Cinderella

1894

Ink and watercolour on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press

This is one of the rare drawings in which Beardsley used colour. It was first printed in black and white as he added the watercolour later. When it was published in the second volume of The Yellow Book, it was accompanied by a caption, probably written by the artist himself. This outlined a darker version of the Cinderella story, in which she is poisoned by powdered glass from her own slippers.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

La Dame aux Camélias

1894

Ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by Colonel James Lister Melvill at the request of his brother, Harry Edward Melvill 1931

Beardsley was fascinated with the depiction of women at their dressing-tables. Here, the woman gazing into the mirror is the tragic heroine of the novel La Dame aux Camélias (1848), by French writer Alexandre Dumas. Beardsley may have identified with her because she, like him, had tuberculosis. He added washes of watercolour to the drawing between 1894 and 1897, after it had been published in The Yellow Book.

The title refers to the novel by Alexandre Dumas fils, published in 1852, which tells the tragic story of a courtesan who sacrificed herself for her lover. The picture is part of a group of drawings of a woman at her dressing table and was originally published simply as Girl at Her Toilet. It is not clear whether Beardsley intended it from the outset to be a portrait of Madeleine Gautier, but it appears to relate to an earlier drawing of 1890, which is inscribed with the title of Dumas’s novel and bears some resemblance to this work in the silhouetted figure and treatment of the draperies. Beardsley may have identified with Madeleine Gautier, since, like her, he suffered from tuberculosis and would eventually also die of the disease.

The leitmotif of a woman admiring herself in a mirror recalls the paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), which Beardsley would have known. He may also have had in mind the work of Edgar Degas (1834-1917), who devoted much of his later career to pictures of woman at their toilet. Like many of Beardsley’s drawings of this period the picture is highly stylised. A solid black mass envelops the lower half of the room and seems about to consume the figure. Her arms have disappeared altogether, and her face is barely revealed above the extravagant collar of her frilly overcoat. The influence of Japanese woodcuts, which Beardsley collected, is apparent in the broad flat areas of colour and the use of silhouette. The most carefully realised passages in the drawing are the objects on the dressing table and the floral pattern of the wallpaper, which depicts either roses or camellias. The woman’s profile reveals dark shadows under the narrowed eyes and a turned down mouth, giving the impression of either illness or dissipation. However, in general, realism and individuality are suppressed in favour of surface pattern and overall design.

The drawing was first published in the journal St Paul’s on 2 April 1894, and at the time it was one of Beardsley’s most popular works. Six months later it was illustrated with the present title in Volume Three of The Yellow Book, an avant-garde journal of which Beardsley was art editor. Between 1894 and 1897 Beardsley added watercolour washes of pinkish-purple to the drawing, reducing the clarity of the image.

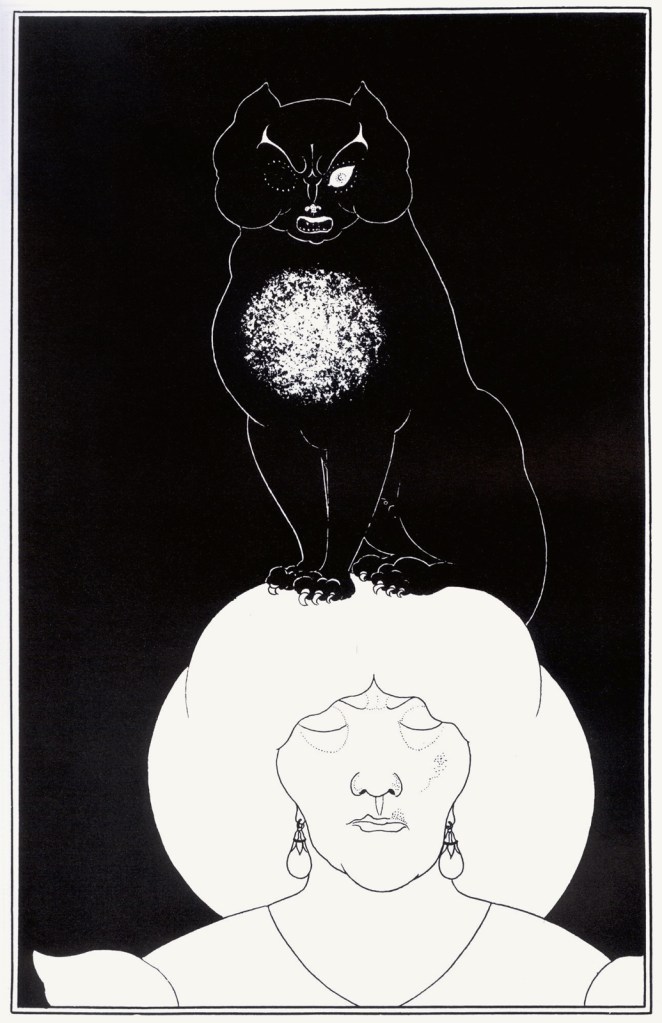

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Black Cat

1894-1895

Line block print on paper

Stephen Calloway

Commissioned by a North American publisher, Beardsley made four designs for the macabre tales of Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849). This illustrates Poe’s story of a man who tries to cover up the murder of his wife by concealing her body in the wall. He is betrayed by the shrieks of his black cat, mistakenly enclosed in the wall as well. The fearsome cat appears out of the darkness, its form outlined in white and starkly contrasting with the white of the dead woman’s face.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Frontispiece to Chopin’s Third Ballade

1895

Ink and wash on paper

Tate. Presented by the Patrons of British Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1999

Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

The Polish composer Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) was one of Beardsley’s musical heroes. Beardsley emphasises his delicately pointed fingers here. This relates to Chopin’s reputation as a powerful and subtle pianist. Beardsley’s setting is not historically accurate. Instead it is reminiscent of 1870s aesthetic movement interiors. The position of the figure and the curtain recall Whistler’s celebrated portrait of his mother, copied by Beardsley in the letter nearby.

Private collection, Maas Gallery

The Third Ballade was one of the greatest compositions by the Polish pianist and composer Frédéric Chopin who died in 1849 at the age of thirty nine. While an initial viewing might suggest a simple equestrian portrait, there is an implicit subtext of female domination in the woman’s mastery of the horse. Her determined expression, and the disparity between the horse and rider, reinforce this. Although never published in his lifetime, this design was used to illustrate Beardsley’s obituary in The Studio in 1898.

Gallery label, August 2004

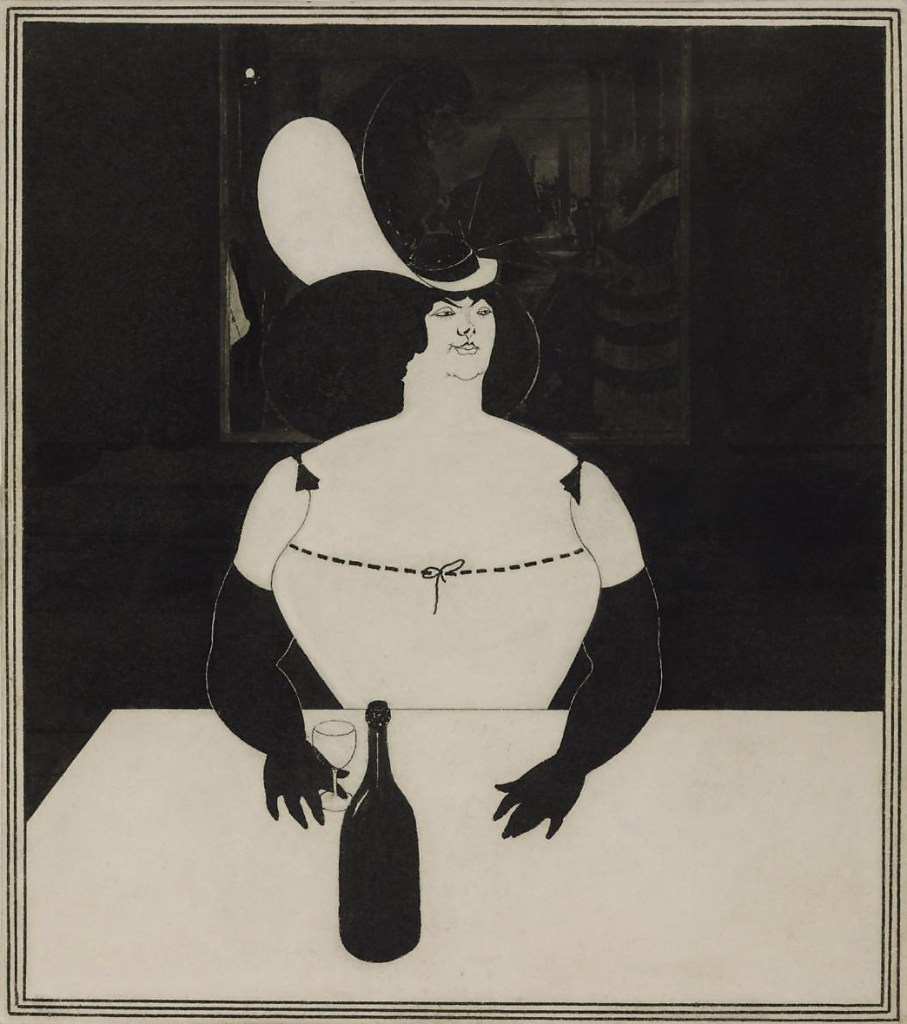

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Fat Woman

1894

Ink on paper

Tate. Presented by Colonel James Lister Melvill at the request of his brother, Harry Edward Melvill 1931

John Lane refused to publish this drawing in The Yellow Book. The most likely reason is because it is an unflattering caricature of the artist Beatrice Whistler, James McNeill Whistler’s wife. Seated in the Café Royal, she is depicted as a domineering member of the demi-monde. Beardsley’s alternative title for the drawing – A Study in Major Lines – emphasises its artistic qualities but also jibes at Whistler’s musical titles.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

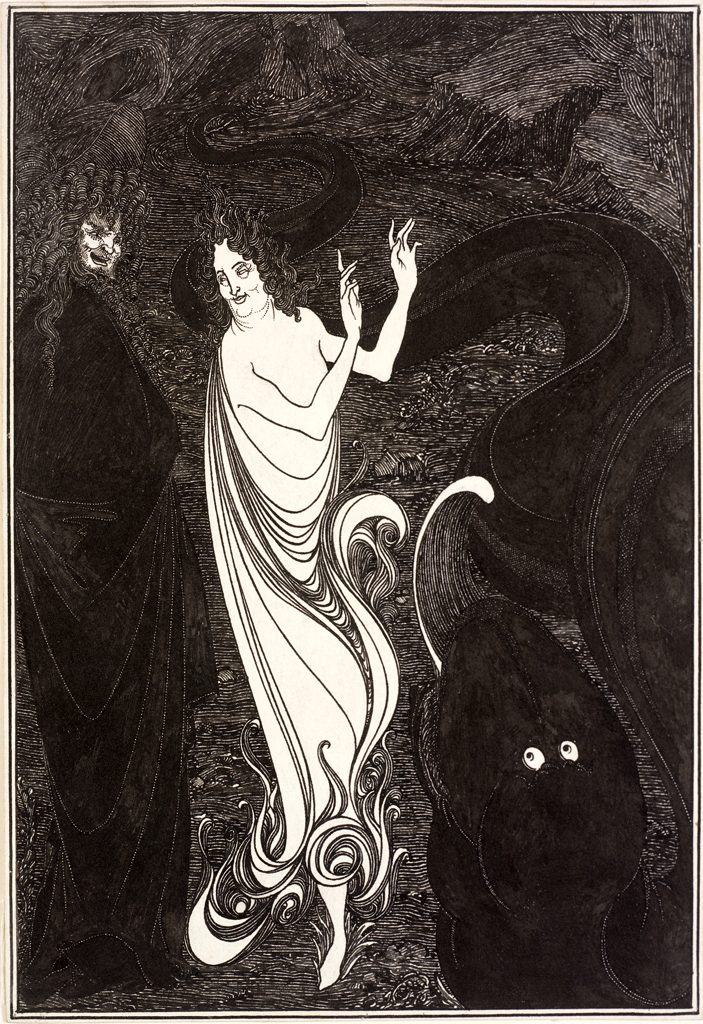

Title page to The Story of Venus and Tannhäuser

1895

Line block and letterpress print on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

This design was planned as the frontispiece for Beardsley’s own novel. The story was an erotic and humorous version of the Tannhäuser legend, in which the poet discovers the home of Venus and becomes one of her worshippers. Beardsley had ambitions to be a writer and he continued to obsess over the ultimately unfinished novel until his death. He admitted early on that it progressed ‘tortoise fashion but admirably’. Initially Lane agreed to publish the novel, but in the aftermath of Wilde’s trial he did not dare.

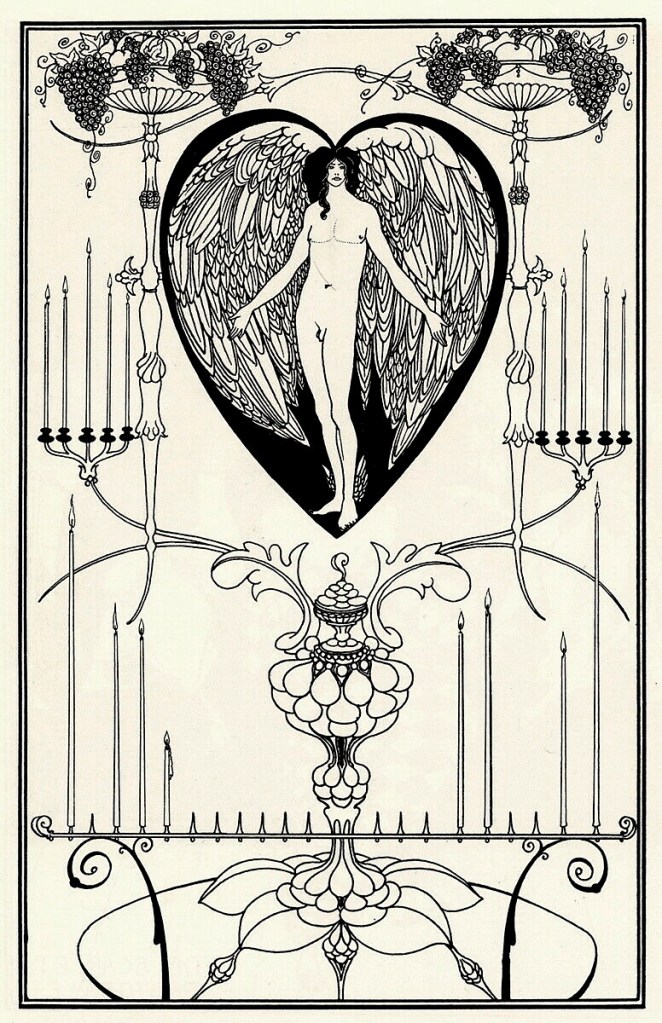

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Mirror of Love

1895

Ink over traces of graphite on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

Beardsley first met Marc-André Raffalovich, a poet and writer, in April 1895. It was not long afterwards that he drew this frontispiece for his collection of poems, The Thread and the Path. The figure in the mirror expresses the theme of the first poem: the quest towards a new ideal that transcended traditional definitions of gender and sexuality. However, the publisher, David Nutt, was shocked by the figure which he believed had both female and male attributes and refused to print it.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

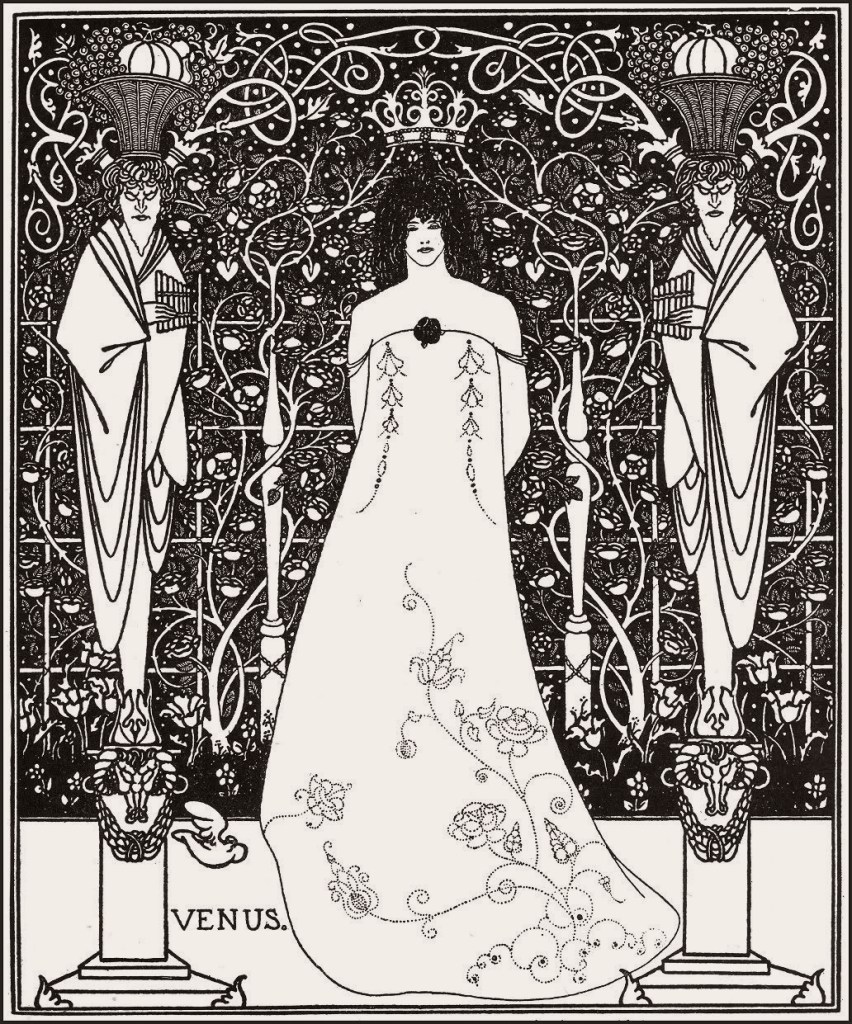

Venus between Terminal Gods

1895

Ink on paper

Trustees of the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery (The Higgins Bedford)

This drawing was also intended as an illustration for Beardsley’s unrealised novel for John Lane. It depicts Venus framed by two statues of male gods in the form of herms. Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), then President of the Royal Academy, was interested in the rising generation of artists and often commissioned drawings from them. Beardsley recorded that Leighton was encouraging about his work and greatly admired this design.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Caprice

Verso: Masked Woman with a White Mouse

c. 1894

Oil paint on canvas

Tate. Purchased 1923

This is Beardsley’s only known oil painting. Unusually, it is double-sided. He began it in Walter Sickert’s studio, under his guidance. The subject on the front, Caprice, was painted first and relates closely to The Comedy Ballet of Marionettes I, displayed nearby. It shows a young woman being led through a doorway by an unfinished figure in a fanciful 18th-century costume. In the late-17th and 18th centuries, servants in European noble households included people of colour who were often enslaved and people with dwarfism. They were considered as ‘trophies’, demonstrating the power and status of those they served. Servants with dwarfism were often treated as ‘pets’, expected to amuse and entertain.

This is the only known oil painting by the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley and was painted in the studio of Walter Sickert. It comprises two pictures on one canvas. Caprice, in which a woman is invited through a doorway by a dwarf, and on the back, Woman with a White Mouse. Both are ambiguous scenes that appear to represent carnival. Caprice derives from the drawing Comedy Ballet of Marionettes I which appeared in The Yellow Book in 1894. Like Beardsley’s drawings, Caprice simplifies shape and colour to strengthen the effect.

Gallery label, February 2016

This is the only known oil painting by Beardsley and, unusually, it comprises two pictures on the one canvas. The first painting to be completed appears to have been A Caprice, a fanciful yet sinister work, depicting a woman in a black dress with green trimmings and a black dwarf in a red costume. On the other side, painted between the stretchers, is an almost surreal image of a masked woman with a white mouse. Both works are unfinished, and should be regarded as experimental

A Caprice appears to derive from the drawing Comedy Ballet of Marionettes I, one of a series of three which appeared in the avant-garde journal, The Yellow Book, in July 1894. In both drawing and painting the woman is being invited by the sinister dwarf to pass through a doorway. The sexual connotations of this gesture are made more overt in the drawing, where the phallic form of the door is emphasised. Beardsley was constantly challenging the conventional view of male-female relations and in the second drawing in the series the woman approaches a door symbolising the female sexual organs.

The symbolism of Woman with a White Mouse also appears to be sexual, and Wilson refers to Freud’s theory that in dreams such things as mice become a substitute for the penis. Nevertheless, although Reade, too, describes the symbolism in this picture as ‘Freudian’, he also points out that Freud’s work was unknown in England in 1894.

Aware of the dramatic potential of black and shadowed areas, Beardsley contrasts areas of dark and light to great effect in both works. He also employs his favourite complementaries, red and green, to provide a stronger colour note in A Caprice. Stylistically he may have been influenced in these paintings by the early work of William Rothenstein (1872-1945), with whom he shared a studio, and whose pictures are inhabited by similarly bold and gloomy saturated forms. He may also have had in mind the work of the Venetian artist Pietro Longhi (1702-1783).

The title A Caprice was invented by the Beardsley scholar R.A. Walker who was the picture’s first owner. The name invites associations with the work of the fin-de-siècle poet Théodore Wratislaw (1871-1933), who published a selection of poems entitled Caprices in 1893.

Frances Fowle

December 2000

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Masked Woman with a White Mouse

c. 1894

Oil paint on canvas

Tate. Purchased 1923

Masked Woman with a White Mouse was painted second. Beardsley seems to have preferred this side and hung it on the wall in the house he bought in Pimlico.

The Savoy

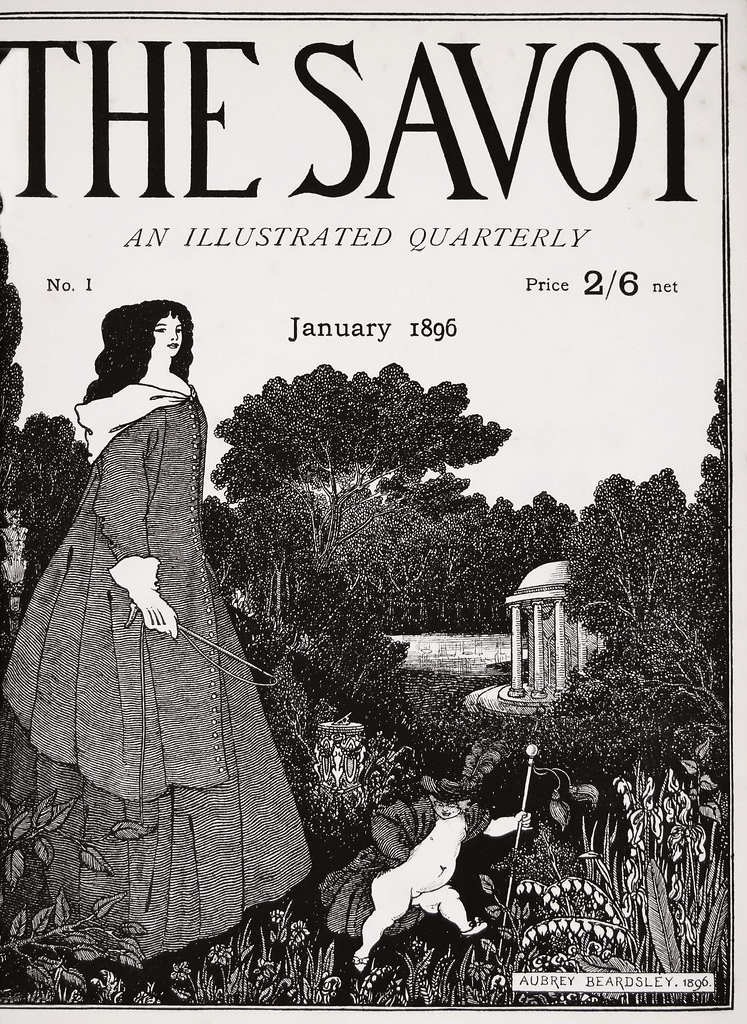

Dismissed from The Yellow Book, Beardsley faced the loss of his income and a newly hostile atmosphere in London. Despite his international fame, his financial situation was precarious, and he was forced to sell his house. Beardsley left England for Dieppe, the favourite French seaside resort of English writers and artists. There he encountered Leonard Smithers, an enterprising publisher (and occasional pornographer). Smithers proposed starting a new magazine to rival The Yellow Book.

With Beardsley as art editor and the poet Arthur Symons in charge of literature, The Savoy was launched in 1896, at first as a quarterly. After two issues, Smithers – perhaps unwisely – decided to publish monthly. The consequent strain on his resources meant The Savoy folded after just a year. However, over just eight numbers it became one of the most significant and most beautifully produced ‘little magazines’ of the period.

The Savoy was published in Britain, but social and artistic conservatism were on the rise there following Wilde’s trial. Smithers was the only publisher who would print work by Wilde or Beardsley at this time. Some booksellers, like W.H. Smith, refused to display works by Beardsley in their windows. W.B. Yeats famously declared that The Savoy had valiantly waged ‘warfare on the British public at a time when we had all against us’.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Savoy, Number 1

1896

Edited by Aubrey Beardsley 1872-1898 (art) and Arthur Symons 1865-1945 (literature)

Leonard Smithers, London, January 1896

Stephen Calloway

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Third Tableau of Das Rheingold

c. 1896

Ink on paper

Lent by Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Museum Appropriation Fund

This drawing, like a play-within-a-play, illustrates an episode in Under the Hill in which the Abbé is ‘ravished with the wit and beauty’ of a performance of Wagner’s opera Das Rheingold.

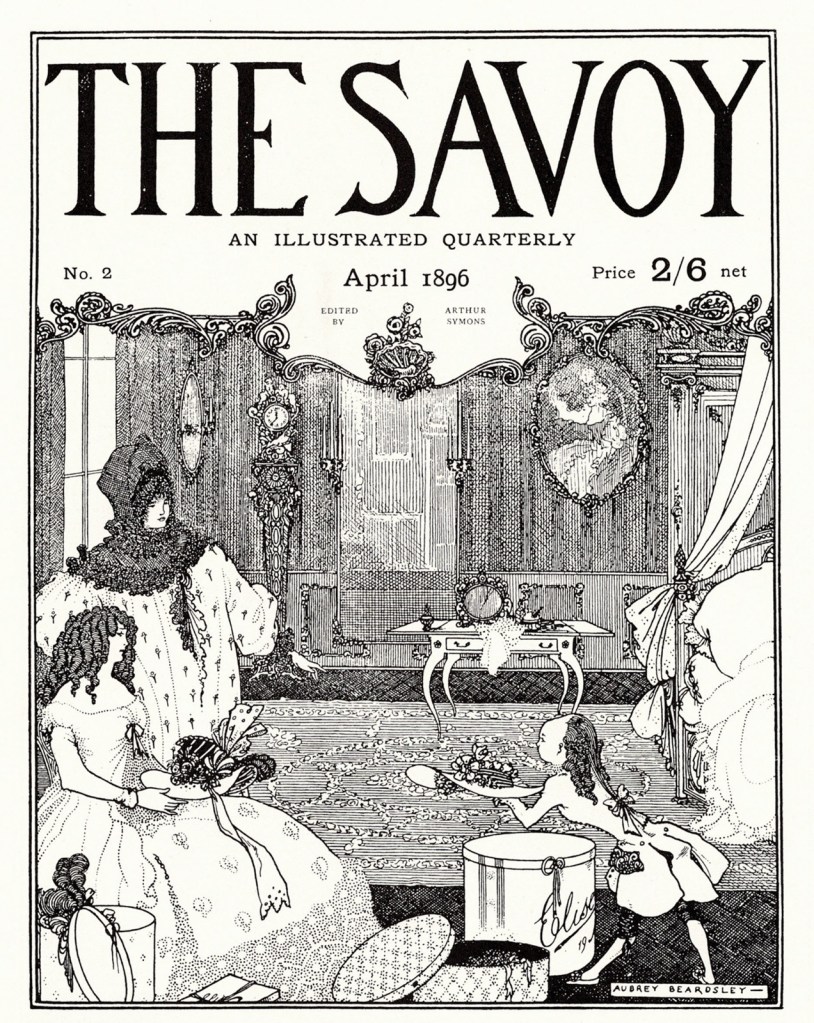

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Savoy, Number 2

1896

Edited by Aubrey Beardsley 1872-1898 (art) and Arthur Symons 1865-1945 (literature)

Leonard Smithers, London, April 1896

Stephen Calloway

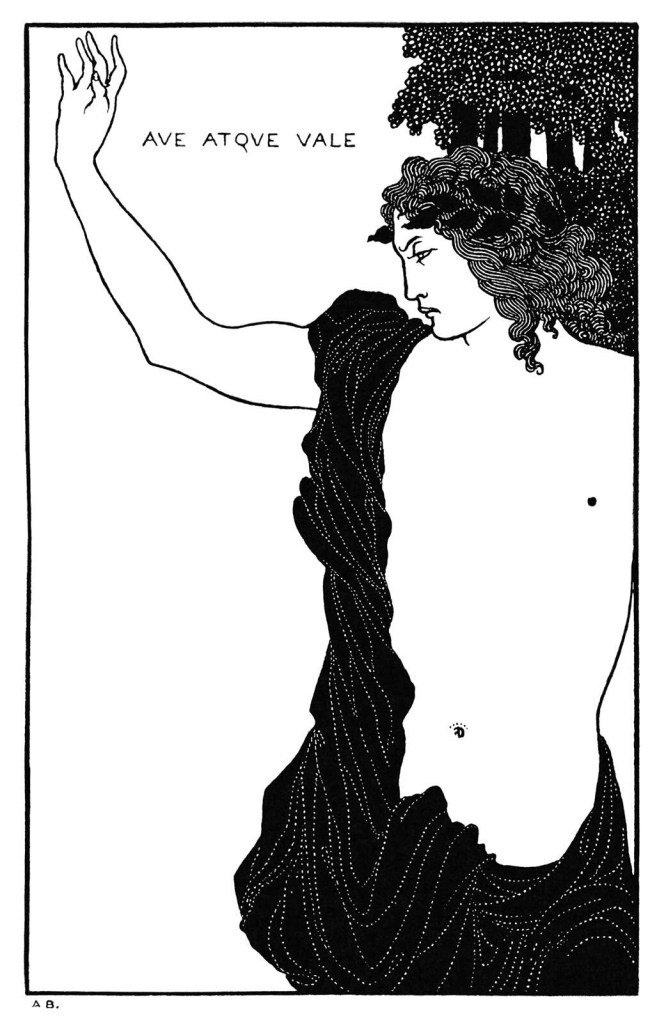

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Ave Atque Vale

1896

Ink on paper

Private collection

This drawing accompanies Beardsley’s translation of the Hail and Farewell poem (Carmen CI) by Catullus (c. 84 – c. 54 BCE). In it, the Roman poet addresses his dead brother. Beardsley’s spare and beautiful composition captures the moving spirit of the poem. It attracted considerable praise when it appeared in the seventh number of The Savoy. Max Beerbohm wrote that ‘Catullus could not have craved a more finely emotional picture for his elegy’.

The Rape of Lock

Beardsley was a great admirer of the poet Alexander Pope (1688-1744). Oscar Wilde had ridiculed his poetic taste, claiming ‘there are two ways of disliking poetry; one way is to dislike it, the other is to like Pope’.

Yet in 1896 Beardsley embarked on the illustration of his mock-epic poem, The Rape of the Lock (1712). In Pope’s title, the word ‘rape’ is used in its original sense of theft or abduction, rather than referring to sexual assault. The poem makes fun of a real incident during which Lord Petre (renamed ‘the Baron’) cut off a lock of the hair of Arabella Fermor (‘Belinda’ in the poem) without her permission, causing a feud between their families.

Inspired by the linear intricacies of French 18th-century copper-plate engravings, which he admired and collected, Beardsley developed a new, highly decorative style. The title page amusingly credits him as having ’embroidered’ the illustrations.

This is the first time that so many of the original drawings for the book have been exhibited together.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Dream

1896

Ink over graphite on paper

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Beardsley drew this as the frontispiece for Pope’s poem. It illustrates Ariel, Belinda’s guardian sylph (a spirit of the air), by her bed, while she is still dreaming. Beardsley used his new ‘stippled manner’ or use of dots, to render the intricate patterns on the bed curtains.

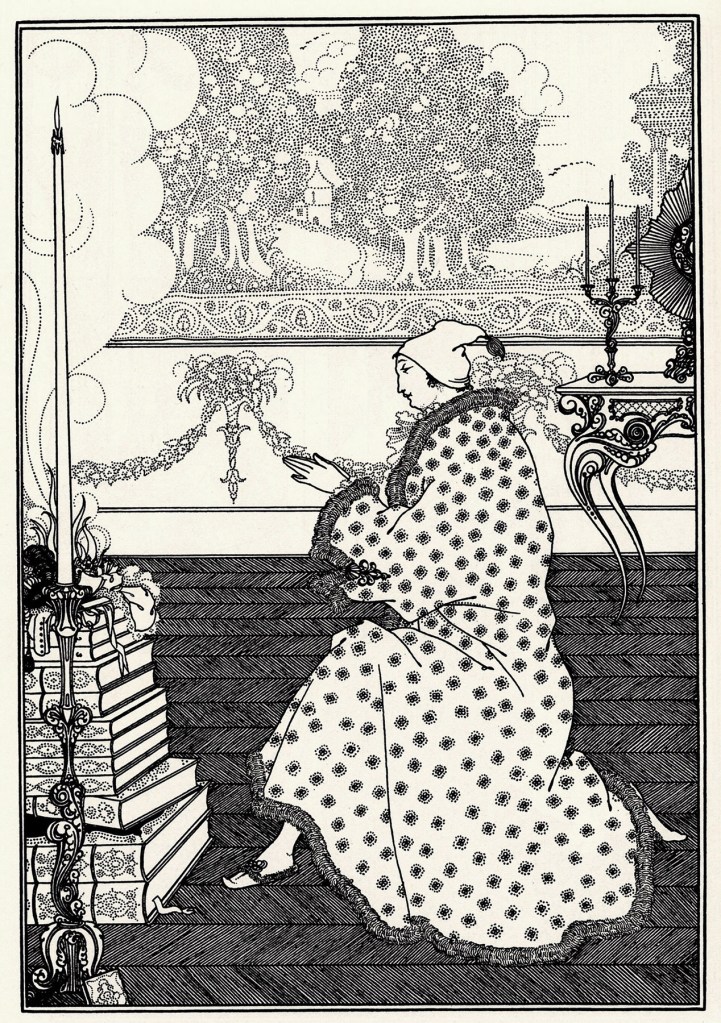

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Baron’s Prayer

1896

Ink and graphite on paper

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Scofield Thayer

The Baron is depicted kneeling at an altar made from a pile of books of love stories. He prays to the God of Love for help to obtain the prize of a lock of Belinda’s hair.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Rape of the Lock

1896

Ink over graphite on paper

Private collection

The drawing illustrates the fateful moment when the Baron approaches to cut a lock of Belinda’s hair. She is unaware, her back turned to him. The fancifully dressed pageboy in the foreground (who may be a person with dwarfism) seems to reference a similar character in The Toilette scene in the Marriage A-la-mode series by William Hogarth (1697-1764). This adds an 18th-century connection to the work. He is the only figure to engage with the viewer, as if to point knowingly to the Baron’s mischief.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Cave of Spleen

1896

Ink on paper

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. William Sturgis Bigelow Collection

Belinda, sitting to the right, across the drawing, has sought refuge in the Cave of Spleen. Umbriel, a gnome, is addressing her. Beardsley interpreted the author’s fantastical description of the cave and creatures within. This unleashed his delight in grotesque forms:

Unnumbered throngs on every side are seen

of bodies changed to various forms by Spleen.

Here living teapots stand, one arm held out,

One bent; the handle this, and that the spout…

Men prove with child, a powerful fancy works,

And maids, turned bottles, cry aloud for corks.

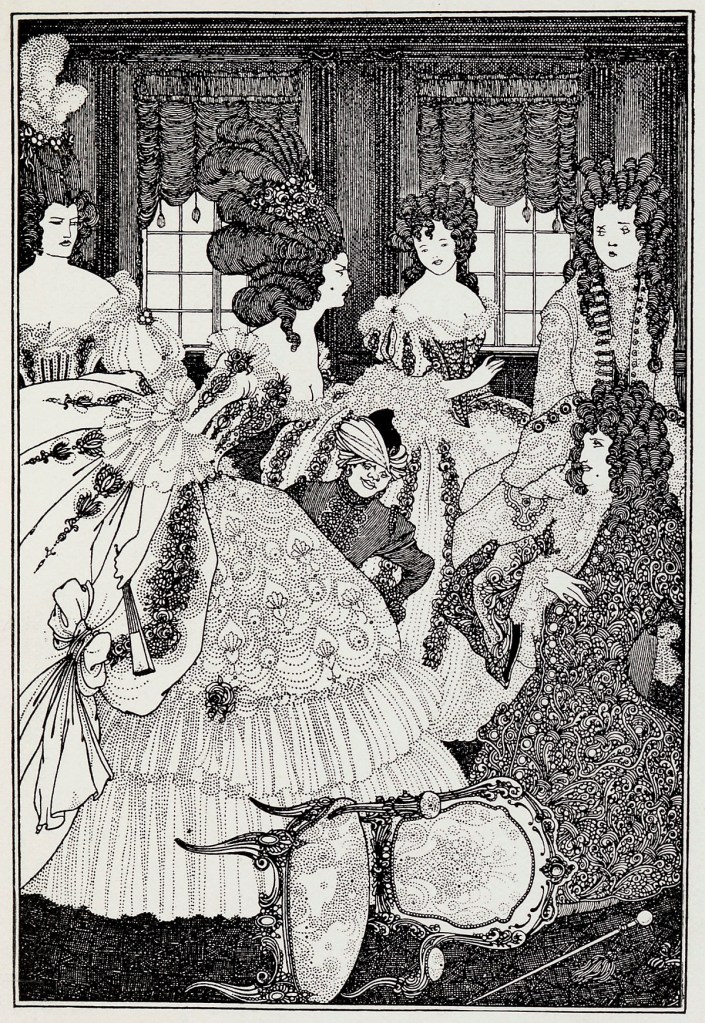

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Battle of the Beaux and the Belles

c. 1896

Ink on paper

The Henry Barber Trust, the Barber Institute of Fine Art, The University of Birmingham

Belinda, furious at the theft of the lock of her hair, faces her attacker the baron. Beardsley chose to depict the moment in the poem just before she throws a pinch of snuff in his face and overpowers him. This drawing was praised for its dramatic action. Beardsley’s virtuosity as a draughtsman is seen in the close-laid lines of his Rape of the Lock illustrations which were particularly admired by his contemporaries. Many thought this series of designs his best work.

Mademoiselle de Maupin

Beardsley worked on illustrating Théophile Gautier’s novel Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835) for Leonard Smithers between February and October 1897. The hero of the story, D’Albert, searches for the ‘perfect’ woman. Instead he becomes overwhelmingly drawn to a young man. The object of his desire is eventually revealed to be Madelaine de Maupin, a woman who does not conform to gender expectations of the day, particularly through dress, and is attracted to both men and women. The plot reflects on an ideal unification of male and female attributes, a widely discussed idea in literary and artistic circles in 19th-century Europe.

In his preface, Gautier promoted ‘art for art’s sake’. This would become the doctrine of the aesthetic movement, which developed in the late 19th century to promote beauty over meaning or morality in art. D’Albert and de Maupin’s sexual encounter is described in terms of aesthetic perfection. However, de Maupin leaves D’Albert immediately afterwards.

Beardsley used watercolour in his drawings to create a new softer decorative style. His friend Robert Ross suggested that this technique was ‘less demanding’ at a time when his health was in rapid decline. But Beardsley later reverted to a more detailed approach, showing that he was simply exploring new modes of expression.

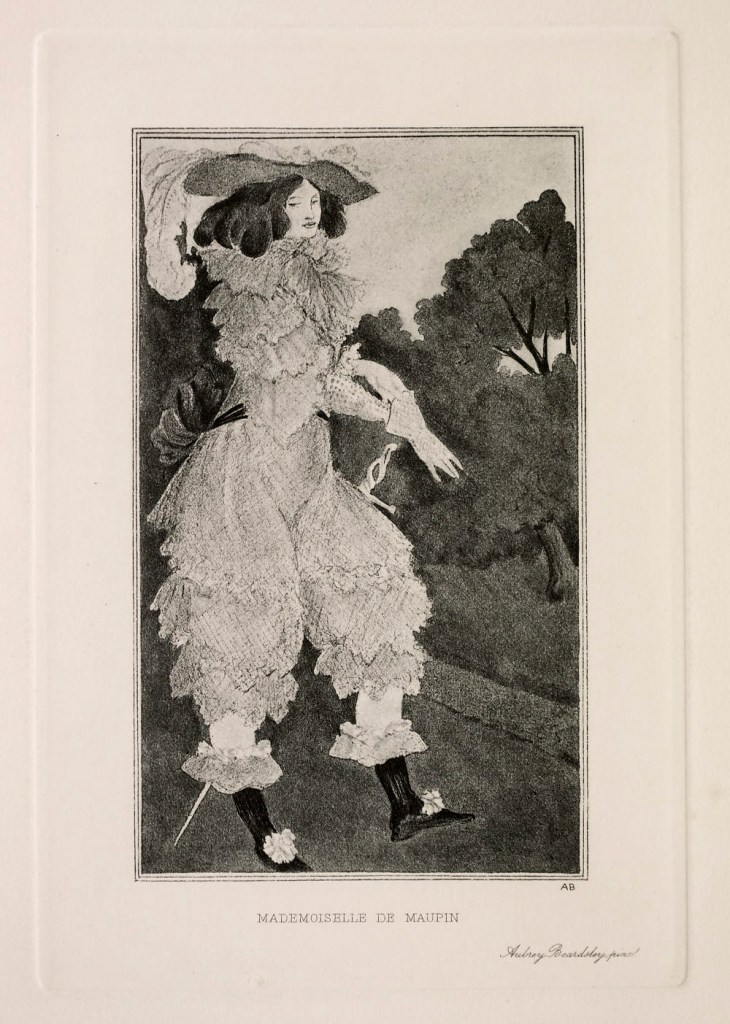

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Mademoiselle de Maupin

1898

Photo-etching on paper

Stephen Calloway

This is Beardsley’s frontispiece for Mademoiselle de Maupin. It shows the heroine dressed in her preferred outfit, men’s clothes as imagined by Beardsley. This is the first illustration of just six that Beardsley completed for Smithers’s planned edition of Gautier’s novel. He had optimistically intended to draw 32 but was too unwell to fulfil this ambition.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

The Lady with the Rose

1897

Ink, wash and graphite on paper

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Scofield Thayer

D’Albert does not find Madelaine de Maupin straight away. He first embarks on an affair with a woman he calls Rosette, the subject of this illustration. Beardsley developed different ‘types’ of women in his work, defined by particular features. Here, Rosette, sultry with large, heavy-lidded eyes, conforms to Beardsley’s late ‘type’. The striped walls of the room recall the style of interior decoration that Beardsley had favoured in his own house at 114 Cambridge Street, Pimlico.

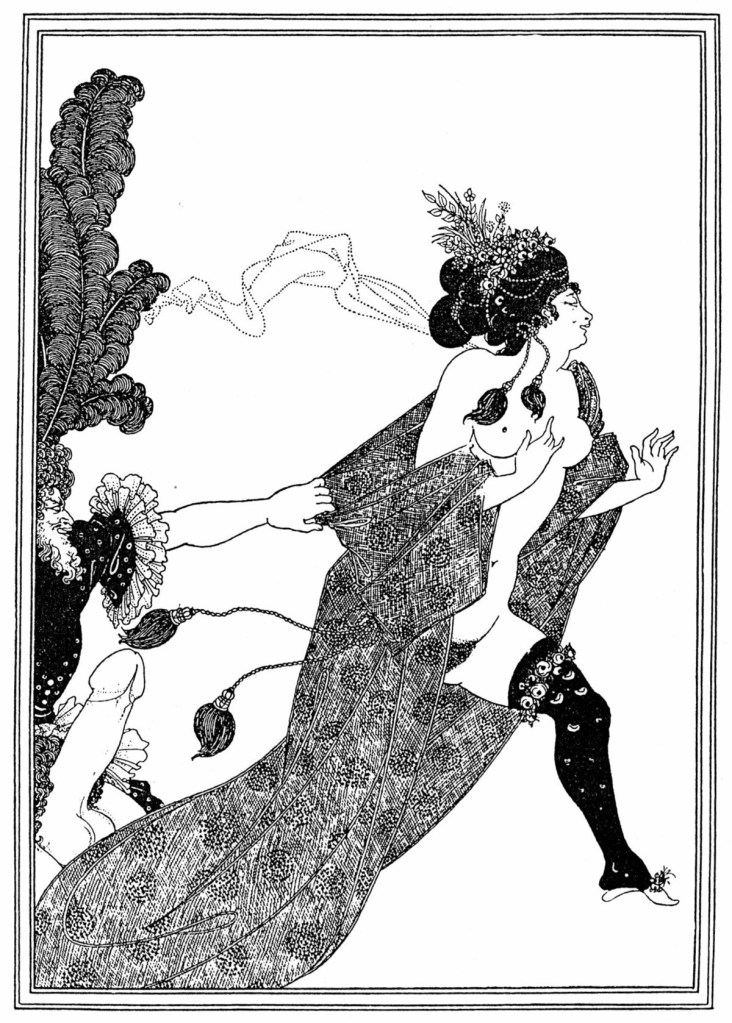

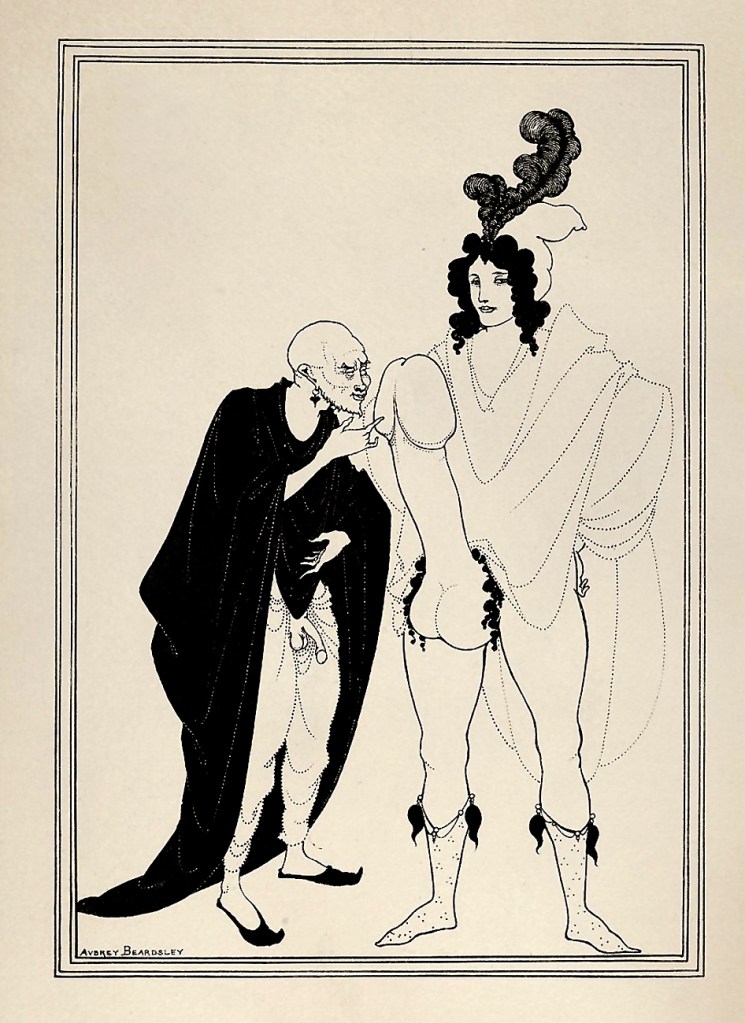

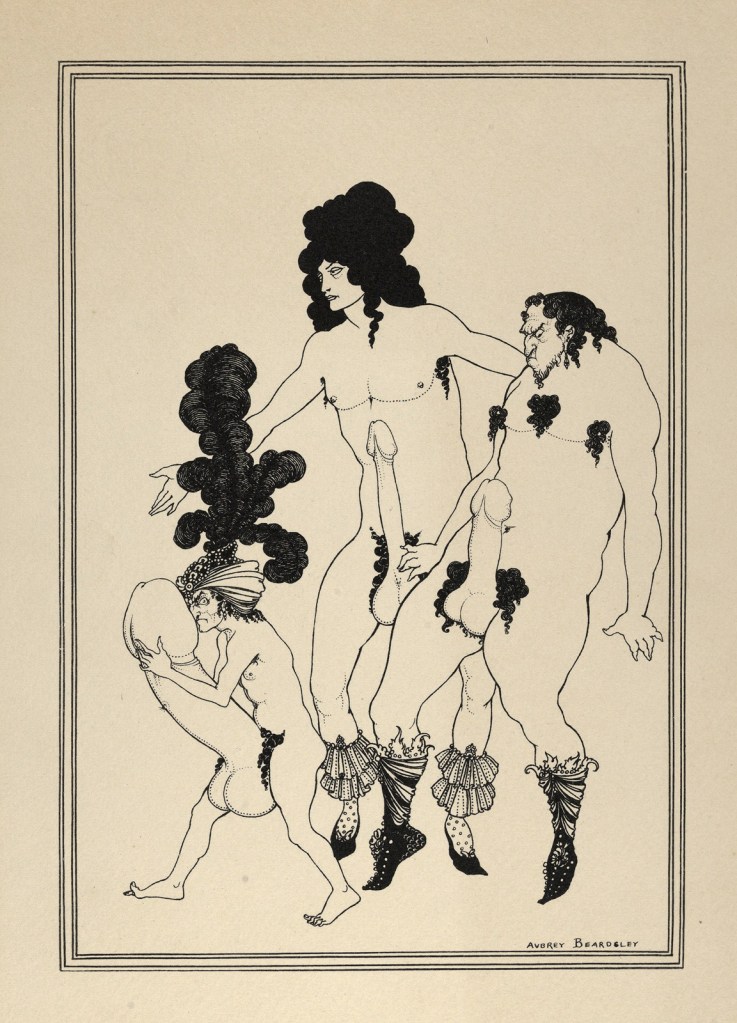

Curiosa

While recuperating in the south of England during the summer of 1896, Beardsley began his two most explicit series of drawings yet. These were both inspired by classical sources. The first was a set of eight designs for the Ancient Greek comedy, Lysistrata, by Aristophanes. In this famous satirical play, Athenian and Spartan women bring an end to conflict by refusing to have sex with their warring menfolk until there is peace between their two cities. Beardsley’s other, equally outrageous set of drawings was made for Juvenal’s Sixth Satire, a misogynistic attack on the morals and sexual habits of the women of Ancient Rome.

These subjects chimed with Beardsley’s own irreverent humour and fascination with all aspects of sexuality – and, perhaps, his own sexual frustrations. Smithers, who prided himself that he would ‘publish what all the others are afraid to touch’, no doubt encouraged him. Matching the exuberant eroticism of the texts, Beardsley adopted a starkly linear style for these drawings. This bold new direction was inspired by his knowledge of Ancient Greek vase painting and Japanese erotic prints.

Very few of Beardsley’s contemporaries would have known of these drawings. Their ‘indecency’ meant they could not be published and advertised in the usual way. Instead they were only made available by Smithers to a select group of like-minded collectors through private subscription. Even so, Beardsley seems to have had second thoughts, perhaps prompted by his growing Catholic faith. On his deathbed, he wrote to Smithers imploring him to destroy all his ‘obscene drawings’, a request that Smithers ignored.

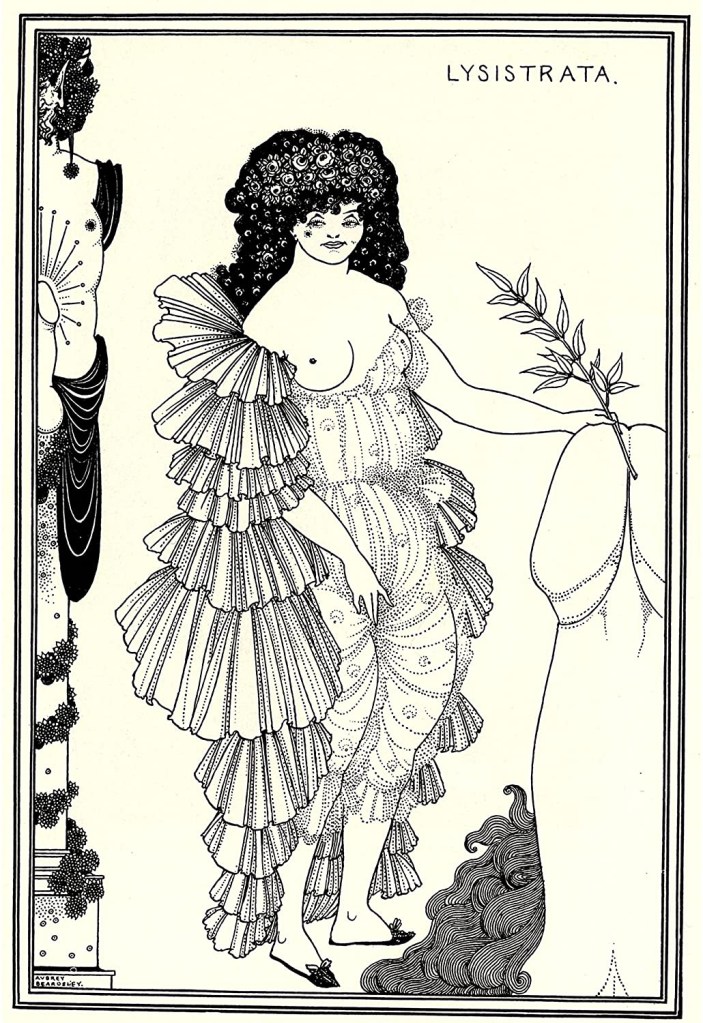

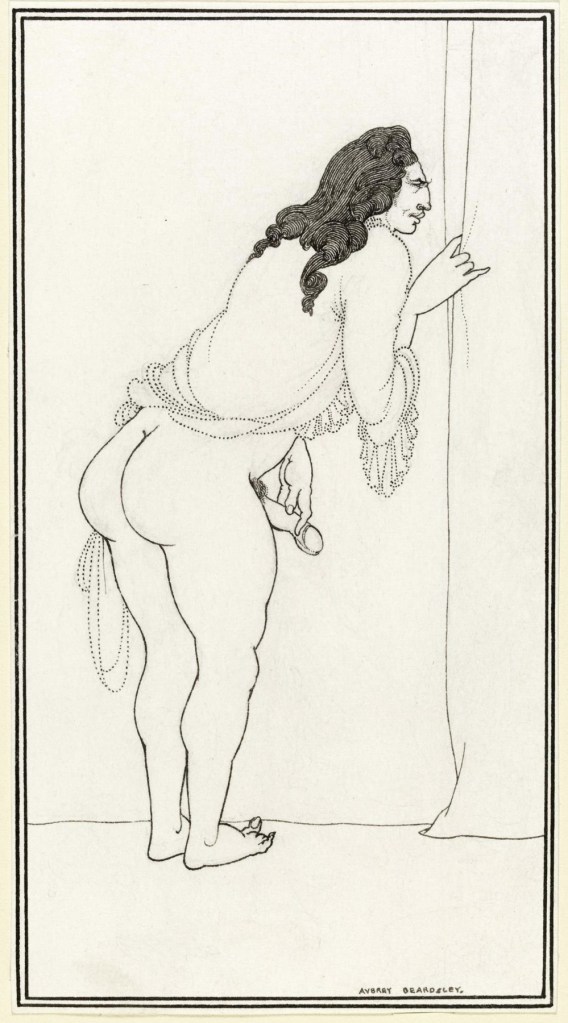

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Lysistrata Shielding her Coynte

1896

Ink over graphite on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum

Beardsley made this as the frontispiece image for the book. It introduces the key themes of the play. Lysistrata, the women’s leader, turns her back on a statue of an aroused male deity, usually a symbol of fertility and virility. With one hand she seems to bar sexual relations or, perhaps, pleasure herself. With the other she holds an olive branch and delicately touches the top of an enormous phallus. The implication is that peace will bring an end to war and male sexual frustration. Her knowing smile reveals her control. Her sexual empowerment disrupts traditional Victorian views of male power and of female ignorance about sex.

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872-1898)

Two Athenian Women in Distress

1896