Exhibition dates: 21st October 2011 – 15th April 2012

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Captain Lawrence Oates and Siberian ponies on board ‘Terra Nova’

1910

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Continuing my fascination with all things Antarctic, here are more photographs from the Scott and Shackleton expeditions. The photograph Captain Lawrence Oates and Siberian ponies on board ‘Terra Nova’ by Herbert Ponting (1910, above) is simply breathtaking.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to The Royal Collection for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

This exhibition of remarkable Antarctic photography by George Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley marks the 100th anniversary of Captain Scott’s ill-fated journey to the South Pole. Ponting’s dramatic images record Scott’s Terra Nova expedition of 1910-1912, which led to the tragic death of five of the team on their return from the South Pole. Hurley’s extraordinary icescapes were taken during Ernest Shackleton’s polar expedition on Endurance in 1914-1917, which ended with the heroic sea journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia. Both collections of photographs were presented to King George V and are today part of the Royal Photograph Collection.

Union Jack taken by Scott to the South Pole

1911-1912

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

This Union Jack was given to Scott by the recently widowed Queen Alexandra on 25 June 1910 for him to plant at the South Pole. The flag was recovered with Scott’s body and returned to the queen by his wife, Kathleen, on 12 July 1913.

The photographs of Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley may be stencilled into the collective memory after nearly a century of over-exposure. But it’s not often you get to see them away from the printed page, and they certainly bring out fresh depths and new perspectives…

It turns out to be highly instructive seeing Hurley and Ponting hung in neighbouring rooms. I’ve always taken Ponting to be somehow the lesser snapper. Hurley had the greatest photostory ever captured land in his lap when Shackleton’s ship the Endurance was trapped in ice floes and held fast for months before pressure ridges eventually crushed it like a dry autumn leaf. Like a good journalist Hurley recorded these traumas and more while also taking the chance to experiment with the strange light and baroque shapes supplied by his surroundings.

Ponting’s story was different. Four or so years earlier, and on the other side of the Antarctic land mass, he didn’t stray far from the expedition base, and indeed was left on the Terra Nova while Scott’s polar party were still out on the ice, trudging balefully towards immortality. There’s something about Ponting’s floridly unmodern moustache which sets him apart from the clean-shaven younger men in either expedition, as if he never quite left the studio behind.

But the photographs are astonishing… The story here is the unequal battle between man and ice, the castellations and ramparts of bergs dwarfing explorers with dogs and sledges placed at their foot to give a sense of scale. Ponting also has a beautiful eye for filigree detail, never more than in one picture of long spindly icicles echoing the adjacent rigging of the Terra Nova.

One of the revelations is that the originals play up the drama of Ponting’s work much more than Hurley’s, which are printed at half the size. For all the astonishing pictures – a field of ice flowers, the masts of the Endurance all but shrouded by Brobdingnagian ice clumps – the final impact of Hurley’s collection lies in the fact that they exist at all… That is partly why Ponting trumps Hurley in this show. His pictures of Scott’s men have never felt more immediate.

Rees, Jasper. Review of “The Heart of the Great Alone: Scott, Shackleton and Antarctic Photography, Queen’s Gallery” on the Arts Desk website. Thursday, 27 October 2011 [Online] Cited 06/04/2012

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

The Terra Nova icebound in the pack

13 Dec 1910

Carbon print

73.5 x 58.2cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Photograph of the Terra Nova in sail, passing through ice and snow. Scott’s ship is seen here held up by the ice pack, with a curiously shaped ‘ice bollard’ in the foreground. The Terra Nova was launched in 1884 as a whaling ship. She had sailed to both the Arctic and Antarctic before serving as Scott’s ship in 1910. She survived until 1943 when she was damaged by ice and sank off the coast of Greenland.

British Antarctic Expedition

Scott and his men reached Antarctica on board the Terra Nova on 31 December 1910. The expedition had several aims that were scientific in nature, but the principal goal for Scott was to lead the first team to the South Pole.

Following his earlier polar experience on the Discovery expedition of 1901-1904, Scott realised the importance of good photographic images for fund-raising and publicising the achievements of the expedition. Scott employed the photographer Herbert Ponting to accompany him. This was the first time a professional photographer had been included in an Antarctic expedition.

Ponting had previously worked in the United States and Asia. He had a great deal of experience, and during his time in Antarctica, he produced around 2,000 glass plate negatives as well as making films. Ponting also taught photography to Scott and other members of the team so that they could record their assault on the Pole.

In March 1912 Ponting left the Antarctic, according to previously-laid plans. After his return to Britain, Ponting exhibited his work and lectured widely about Scott, thus ensuring that his photographs became inextricably linked with Scott and the heroic age of Antarctic exploration.

Text from the Royal Collection Trust website

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

The Castle Berg with dog Sledge

17 Sep 1911

Carbon print

53.2 x 75.0cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

This iceberg, which resembles a medieval castle, was greatly admired by members of the expedition. Ponting returned several times during 1911 to photograph it, including once in June, the middle of the Antarctic winter, when he set up flashlights to make an image. At its highest point the berg is around 100 feet high (30.5 m).

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

The ramparts of Mount Erebus

1911

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Mount Erebus, an active volcano on Ross Island which last erupted in 2008, was first climbed in 1908 by members of Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition. Ponting has contrasted the overwhelming size of the natural world against the tiny human figure pulling a sledge, in the lower left corner of the photograph.

It is a story of heroism and bravery, and ultimately of tragedy, that has mesmerised generations. One hundred years on from their epic voyages to the very limits of the Earth, and of man’s endurance, the legends of Scott and Shackleton live on.

To mark the centenary of Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s expedition to the South Pole, the Royal Collection brings together, for the first time, a collection of the photographs presented to King George V by the official photographers from Scott’s Terra Nova expedition of 1910-1913 and Shackleton’s expedition on Endurance in 1914-1916, and unique artefacts, such as the flag given to Scott by Queen Alexandra (widow of King Edward VII) and taken to the Pole.

The exhibition documents the dramatic landscapes and harsh conditions the men experienced, through the work of expedition photographers Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley. These sets of photographs are among the finest examples of the artists’ work in existence – and the men who took them play a vital part in the explorers’ stories. Highlights from Scott’s voyage include Ponting’s The ramparts of Mount Erebus, which presents the vast scale of the icescape, and the ethereal The freezing of the sea. Among the most arresting images from Hurley’s work on Shackleton’s expedition are those of the ship Endurance listing in the frozen depths and then crushed between floes.

The photographs also give insights into the men themselves. For instance, at the start of the journey Scott appears confident and relaxed, with his goggles off for the camera. In contrast, a photograph taken at the Pole shows him and his team devastated and unsmiling, knowing they had been beaten. The exhibition also records the lighter moments of expedition life, essential for teams cut off from the outside world for years at a time. On Shackleton’s expedition, a derby for the dogs was organised – with bets laid in cigarettes and chocolate. A menu for Midwinter’s Day, on 22 June 1911, shown in the accompanying exhibition publication, includes roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, ‘caviare Antarctic’ and crystallised fruits.

Antarctic adventurer David Hempleman Adams has been closely involved in the exhibition and has written an introduction to the catalogue. First given the taste for adventure by The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award scheme, he was inspired, like generations of school children, by the tales of discovery. As a South Pole veteran, the first Briton to reach the Pole solo and unsupported, he is still in awe of Scott and Shackleton’s achievements – and will return with his daughter this year to mark the centenary. David Hempleman Adams said: “We have a big psychological advantage today: We know it is possible to reach the South Pole. Nowadays you can go on Google Earth and see what’s there. Back then, it was just a big white piece of paper. Scott and Shackleton had no TVs, radios or satellite phones – they were cut off from the outside world – and in terms of equipment, the tents, skis and sledges, today, we carry about one tenth of what they carried, over the same mileage. What they achieved, with what they had, is really magnificent. This is the 100th anniversary and the legend has stood the test of time. Even in this modern world, there’s still just as much interest.”

As the photographs show, animals played an important part in the expeditions. There are portraits of the ponies and of individual sledge dogs. In his diaries, Scott describes the relationship he struck up with the bad tempered husky Vida: “He became a bad wreck with his poor coat… and… I used to massage him; at first the operation was mistrusted and only continued to the accompaniment of much growling, but later he evidently grew to like the warming effect and sidled up to me whenever I came out of the hut… He is a strange beast – I imagine so unused to kindness that it took him time to appreciate it.”

Ponting also photographed wildlife, including seals, gulls and penguins. Scott writes of the moment Ponting tried to photograph killer whales and how the creatures crashed through the ice to catch him. Scott, watching but unable to help, observes, “It was possible to see their tawny head markings, their small glistening eyes, and their terrible array of teeth – by far the largest and most terrifying in the world.”

The inspirational qualities of the explorers were recognised by King George V. In his book, The Great White South, Ponting records what the Monarch said to him when he went to Buckingham Palace to show his Antarctic film: “His Majesty King George expressed to me the hope that it might be possible for every British boy to see the pictures – as the story of the Scott Expedition could not be known too widely among the youth of the nation, for it would help to promote the spirit of adventure that had made the Empire.”

Royal interest in polar exploration began with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, who followed the fortunes of the early adventurers, such as Sir John Franklin and William Bradford, and it continues to this day. The Duke of Edinburgh, who has written a foreword to the exhibition catalogue, has been the patron of many of David Hempleman Adams’s expeditions and has himself crossed the Antarctic Circle. HRH The Princess Royal is Patron of the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust.

Press release from The Royal Collection website

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Grotto in an iceberg

5 January 1911

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Photograph of the Terra Nova seen from inside a grotto that was formed by an iceberg as it turned over, carrying a large floe which froze onto it. Both Ponting and Scott were struck by the colours of the ice inside this ice grotto; they were a rich mix of blues, purples and greens. Ponting thought that this photograph, framing the Terra Nova, was one of his best.

Both Captain Scott and Herbert Ponting – the photographer accompanying him on the Terra Nova expedition – wrote about the intense colours that they encountered in the landscape of Antarctica. In this series of three short talks by Royal Collection curator Sophie Gordon, we examine how Ponting attempted to capture these magical blues, greens and oranges in his photographs beginning here with the blues of this grotto within an iceberg, taken in January, 1911.

Royal Collection: ‘A Lovely Symphony of Blue and Green’ – Grotto in an Iceberg

Both Captain Scott and Herbert Ponting – the photographer accompanying him on the Terra Nova expedition – wrote about the intense colours that they encountered in the landscape of Antarctica. In this series of three short talks by Royal Collection curator Sophie Gordon, we examine how Ponting attempted to capture these magical blues, greens and oranges in his photographs beginning here with the blues of this grotto within an iceberg, taken in January, 1911.

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

The Freezing of the Sea

1911, printed 1913-1914

Carbon print, tinted

74.6 x 58.1cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Photograph of a thin film of new ice covering the sea with ice blocks in the foreground. The Barne Glacier can be seen in the distance. This view, looking from Cape Evans towards Cape Barne on Ross Island, shows the moment when the sea began to freeze. The men would have realised that they could no longer leave Antarctica. Once winter began, no ships would be able to reach them to bring in supplies or to take anyone out.

Royal Collection: ‘A Lovely Symphony of Blue and Green’ – The Freezing of the Sea

In the second of these three short talks, Royal Collection curator Sophie Gordon, briefly considers this atmospheric photograph which captured the moment the sea began to freeze, cutting the men off in Antarctica for the winter.

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Cirrus clouds over the Barne Glacier

April 1911

Carbon print on dyed paper

43.4 x 58.8cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Royal Collection: ‘A Lovely Symphony of Blue and Green’ – Cirrus Clouds over the Barne Glacier

In this, the third in her series of talks, Royal Collection curator Sophie Gordon examines how Ponting captured the dramatic reds and oranges and the beauty of the natural landscape that he experienced during his time in the Antarctic.

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

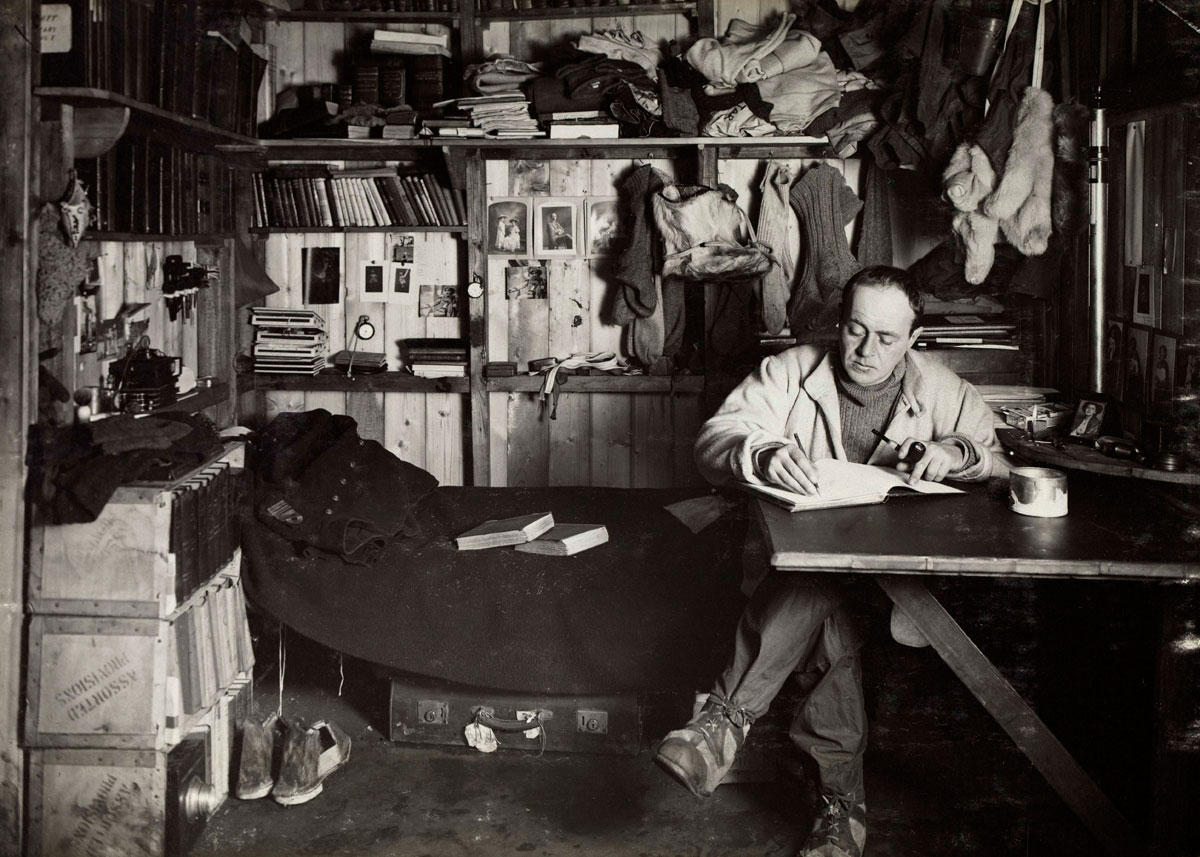

Scott writing in his area of the expedition hut, Scott’s cubicle

7 October 1911

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Captain Robert F. Scott, sitting at a table in his quarters, writing in his diary, during the British Antarctic Expedition.

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Scott’s birthday dinner

June 1911

Toned silver bromide print

43.6 x 61cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Photograph of the Officer’s table for Captain Scott’s birthday dinner with a variety of food and drink laid out on the table. The men are celebrating Scott’s 43rd birthday – his last – on 6 June 1911. He sits at the head of the table, and is surrounded by the officers and senior members of the team. The only man looking at the camera is the Norwegian naval officer Tryggve Gran (1889-1980). The atmosphere is both festive and patriotic.

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Vida

1911

Toned silver bromide print

38.0 x 27.5cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Photograph of Vida. One of Scott’s favourite dogs, Vida suffered from a bad coat and would creep up to Scott for attention. Scott noted in his diary that initially the dog would growl at him but eventually his suspicion grew less: ‘He is a strange beast – I imagine so unused to kindness that it took him time to appreciate it’.

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

The winter journey to Cape Crozier

June 1911

Silver bromide print

43.7 x 61cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Henry Bowers (1883-1912), Edward Wilson (1872-1912) and Apsley Cherry-Garrard (1886-1959) are shown shortly before departing for Cape Crozier in search of Emperor penguin eggs. Between 27 June and 1 August, the trio endured extreme weather conditions and winter darkness as they crossed Ross Island and then returned, having collected three eggs. Cherry-Garrard famously described it as ‘the worst journey in the world’.

Royal Collection: ‘The weirdest bird’s-nesting expedition that has ever been’ – Part Two

In the second in this series of talks, Royal Collection curator Emma Stuart takes us on a journey with three intrepid explorers as they faced the hostile conditions of the Antarctic to recover an Emperor Penguin’s egg.

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Captain Scott

February 1911

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

This photograph of Scott, with Mount Erebus in the background, was taken at the start of the expedition. He is wearing fur gloves with an attached cord, leather boots, gaiters and thick socks.

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

The Shore Party

Jan 1911

Silver bromide print

43.6 x 61.9cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Photograph of the Shore party. On the back row are (from left to right): T. Griffith Taylor; Apsley Cherry-Garrard; Bernard Day; Edward Nelson; Edward Evans; Lawrence Oates; Edward Atkinson; Robert Falcon Scott; Charles Wright; Patrick Keohane; Tryggve Gran; William Lashly; Frederick Hooper; Robert Forde; Anton Omelchenko; Dimitri Gerov. On the front row are (from left to right): Henry Bowers; Cecil Meares; Frank Debenham; Edward Wilson; George Simpson; Edgar Evans and Tom Crean. This group is the Shore Party – the men who remained in Antarctica throughout the winter of 1911, preparing for Scott’s final departure for the Pole. They pose in front of the expedition hut at Cape Evans. The only people not visible are Clissold, the cook, and Ponting, the photographer. Scott is at the centre of the group and all the men look relaxed. This was taken at the very beginning of the expedition, when they would have been optimistic and excited about the future.

Henry Bowers (British, 1883-1912)

Forestalled. Amundsen’s tent at the South Pole

18 Jan 1912

Silver bromide print

27.5 x 38cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Photograph of Scott’s party at Amundsen’s tent at the South Pole. (from left to right are): Robert Falcon Scott (1868-1912); Lawrence Oates (1880-1912); Edward Wilson (1872-1912) and Edgar Evans (1876-1912). This photograph shows the dejection of the team as they explore the tent left by Roald Amundsen, who reached the South Pole on 14 December 1911, thirty-five days before Scott. There is a Norwegian flag at the top of the tent; inside, Scott found a letter recording their achievement, left by Amundsen in case he did not return safely.

Henry Bowers (British, 1883-1912)

Scott and the Polar Party at the South Pole

17 January 1912

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914-1916

Shackleton set out in October 1914 on the Endurance with the intention of making the first crossing of the Antarctic continent via the South Pole. While he and his men planned to reach Antarctica through the Weddell Sea, another party aboard the Aurora sailed to the other side of the continent to lay food depots for the expected party.

The intention was that only six men would complete the crossing; the photographer Frank Hurley was to be one of the team. Hurley had been to the Antarctic before, as part of the Australasian Expedition of 1911-1914. He was intrepid in his search for dramatic images. The role of photographer was important not just to document the achievements of the expedition, but also to create a source of income. The rights to publish the images would be sold for a great deal of money after the return to Britain.

The expedition ran into difficulties almost immediately. By mid-January 1915, Endurance became trapped in ice and had to become a floating scientific station. The men waited out the harsh Antarctic winter in the hope that their situation would improve.

Text from the Royal Collection Trust website

Frank Hurley (Australian, 1885-1962)

Entering the pack ice. Weddell Sea, lat. 57° 59′ S. long. 22° 39′ W

9 Dec 1914

Silver bromide print

15.3 x 20.5cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Photograph of six members of Shackleton’s crew standing on the deck of Endurance. This was the men’s first view of the pack ice through which they had to navigate in order to reach the coast of Antarctica. The Endurance met the ice far further north than they had hoped. The whalers on South Georgia had warned them of the poor ice conditions before they set out. This was a warning of things to come.

Frank Hurley (Australian, 1885-1962)

Under the bow of the Endurance

Self-portrait with cinematograph next to the Endurance

1915

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Hurley poses with his cinematograph, which was used to shoot moving film footage. The footage was later turned into a film released after his return under the name of In the Grip of the Polar Pack Ice.

Frank Hurley (Australian, 1885-1962)

The Endurance in the garb of winter

June 1915

Silver bromide print

20.2 x 15.2cm

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Endurance sits benignly at rest in the midst of the ice field. A recent blizzard has coated the hummocks in a layer of snow, softening the contours. All looks peaceful, but within a few months these same hummocks will have crushed the ship.

Photograph of the bow and part of the left side of Endurance, lit by flashlight in the darkness of the night. This is probably Hurley’s best-known photograph, which he took with flashlights at -38 °F/-39 °C. It was later used on the front cover of Shackleton’s account of the expedition, South. Hurley described the scene in his autobiography: Never did the ship look quite so beautiful as when the bright moonlight etched her in inky silhouette, or transformed her into a vessel from fairy-land.

Frank Hurley (Australian, 1885-1962)

The night watchman spins a yarn

1915

Gelatin silver print

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

After Endurance became a winter station in February 1915, Shackleton abandoned the usual system of watches. The single nightwatchman had little to do, apart from tending the dogs and observing ice movements. It was private leisure time, to read, or do some washing, but often became a social occasion as shown here, as the men gather companionably round the fire.

Frank Hurley (Australian, 1885-1962)

The bi-weekly ablutions of the ‘Ritz’

The Scientists washing down the “Ritz” (living quarters in the hold)

James Wordie, Alfred Cheetham and Alexander Macklin, washing down the ‘Ritz’ living quarters in the hold of the Endurance

1915

Gelatin silver print

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Following the onset of winter and the transformation of Endurance into a scientific station, the main cargo hold was emptied and turned into a communal living space for the men, nicknamed the ‘Ritz’. The traditional Antarctic Christmas on Midwinter’s Day (22 June) saw the ‘Ritz’ transformed for a cabaret, featuring satirical speeches, songs, poems and even a drag act. From left to right are Wordie (1889-1962), Cheetham (1867-1918) and Macklin (1889-1967).

Herbert Ponting (British, 1870-1935)

Sir Ernest Shackleton arrives at Elephant Island to take off marooned men

30 August 1916

Presented to King George V, 1914

© 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

This photograph was actually taken at the time of the ‘James Caird’s’ departure on 24 April. Hurley has altered it to represent the moment of rescue, with the arrival of Shackleton on the ‘Yelcho’. The actual rescue was not photographed.

The Royal Collection

The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace

London SW1A 1AA

Opening hours:

Thursday – Monday 10.00 – 17.30

You must be logged in to post a comment.