Exhibition dates: 16th May – 13th October 2024

Curator: Tabitha Barber

Attributed to Levina Teerlinc (Flemish, 1510-1576)

Portrait of a Lady holding a Monkey

1560s

Watercolour and bodycolour heightened with gold and silver

Image: 46 × 46 mm

Frame, circular: 62 × 62 mm

Victor Reynolds and Richard Chadwick

There have been some mixed reviews of this exhibition – “tremendous show… an archaeological dig into the nation’s cultural past” (Jonathan Jones in The Guardian); “niggardly photography section… Only rarely do women’s art and women’s history spark together in this show… For even the best of the artists here are occasionally represented by the least of their works, quite apart from the mystifying omissions.” (Laura Cumming in The Guardian).

Indeed, Laura Cumming poses an interesting question: “Here is a dilemma straight away: which should take precedence, the painting or the fact? Should the show present art on its own terms, or as instance, evidence, expression of social history? It is an extremely complex remit…”

Having not been to London to see the exhibition I can only make generalised comment, but in my opinion the presentation should be a combination of both – art and social history – recognising that one does not exist, emerge, without the other. Art does not live in a bubble isolated from society and society itself is influenced by new ideas, new concepts of art. It’s not the chicken and the egg, it’s the scramble to make sense of living in this world using art as an expression, a (real, surreal, revolutionary, dream, abstract etc…) vision of the world that surrounds us.

Just from compiling this posting I have been enlightened as to the lives of many artists that I had never heard of before. I have admired their work and learnt about their lives and the conditions under which they worked. The exhibition has brought into my consciousness (and the consciousness of others) artists that I would have never have known about. It tells their stories in however fragmented a way … but at least it tells them. And that is a very good thing.

My particular favourites in the posting are three portraits where the sitter stares directly at you: Joan Carlile’s perceptive Portrait of a Lady Wearing an Oyster Satin Dress (1650s, below) so captivating of gaze, so incisive in its simplicity; Maria Cosway’s beautifully rendered Self Portrait (Nd, below) such a luminous and engaging presence; and Gwen John’s powerful Self-Portrait (1902, below) vibrant of colour, full of self-assurance. Wonderful evocations of humanity.

Scottish artist Dame Ethel Walker observes,

“There is no such thing as a woman artist. There are only two kinds of artist – bad and good.”

And that is what his exhibition gives you the obligation to do: to educate yourself, to make yourself a little more informed, to use your brain, eyes, and heart …and make up your own mind about the merit of the work.

I for one are very grateful for that opportunity.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. I have added relevant text from the large print guide and other bibliographic information from accredited sources to illuminate the works presented.

Many thankx to the Tate for allowing me to publish the art work and photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing at right, Lucy Kemp-Welch’s Colt Hunting in the New Forest 1897

Spanning 400 years, this exhibition follows women on their journeys to becoming professional artists. From Tudor times to the First World War, artists such as Mary Beale, Angelica Kauffman, Elizabeth Butler and Laura Knight paved a new artistic path for generations of women. They challenged what it meant to be a working woman of the time by going against society’s expectations – having commercial careers as artists and taking part in public exhibitions.

Including over 150 works, the show dismantles stereotypes surrounding women artists in history, who were often thought of as amateurs. Determined to succeed and refusing to be boxed in, they daringly painted what were usually thought to be subjects for male artists: history pieces, battle scenes and the nude.

The exhibition sheds light on how these artists championed equal access to art training and academy membership, breaking boundaries and overcoming many obstacles to establish what it meant to be a woman in the art world.

Text from the Tate Britain website

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura) c. 1638-1639 (below)

Artemisia Gentileschi (Italian, 1593-1653)

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura)

c. 1638-1639

Oil on canvas

98.6 x 75.2cm (support, canvas/panel/stretcher external)

Royal Collection Trust

© His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Artemisia Gentileschi (Italian, 1593-1653)

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura)

c. 1638-1639

Oil on canvas

98.6 x 75.2cm (support, canvas/panel/stretcher external)

Royal Collection Trust

© His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Gentileschi claimed that ‘all the … Princes’ displayed her self-portrait in their galleries. In addition to this work, Charles I owned another self-portrait, which is now lost. Here, Gentileschi uses her own image to portray the allegorical figure of Pittura (also the Italian feminine noun for painting), who she depicts in a working apron before an easel absorbed in the act of creation.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

As a self-portrait the painting is particularly sophisticated and accomplished. The position in which Artemisia has portrayed herself would have been extremely difficult for the artist to capture, yet the work is economically painted, with very few pentiments. In order to view her own image she may have arranged two mirrors on either side of herself, facing each other. Depicting herself in the act of painting in this challenging pose, the angle and position of her head would have been the hardest to accurately render, requiring skilful visualisation.

Text from the Royal Collection Trust website

Installation view of the exhibition ‘Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920’ at Tate Britain showing Artemisia Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders c. 1638-1640 (below)

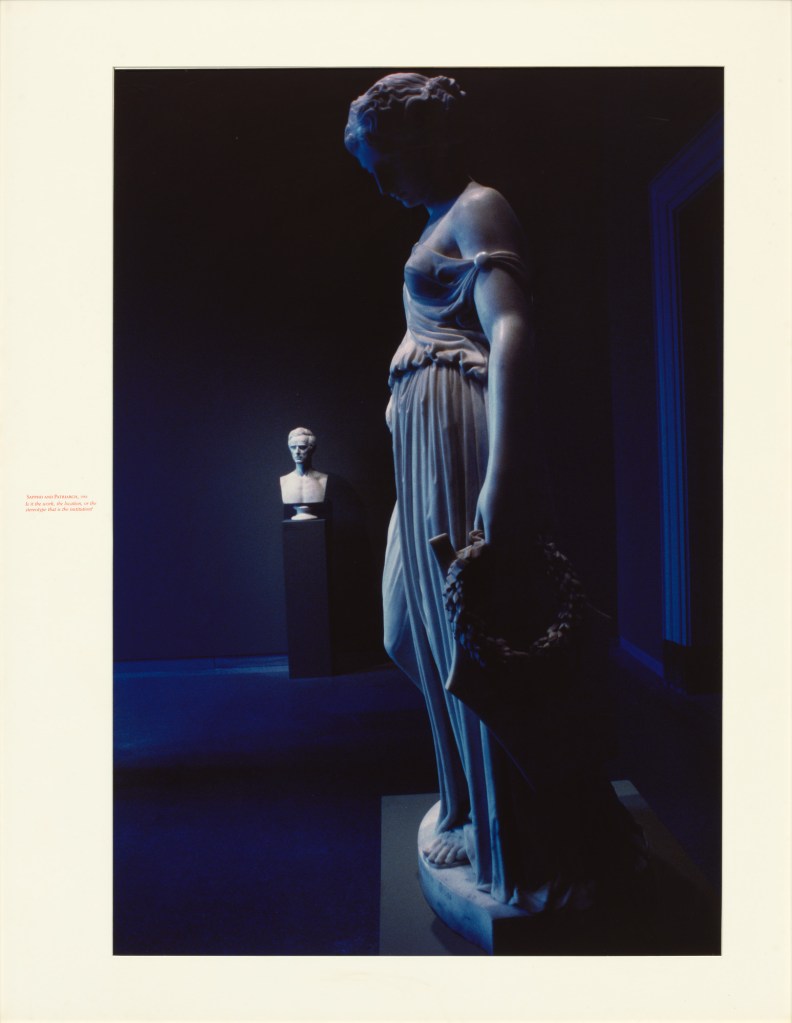

Artemisia Gentileschi (Italian, 1593-1653)

Susanna and the Elders

c. 1638-1640

Oil on canvas

189.0 x 143.2cm (support, canvas/panel/stretcher external)

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Artemisia Gentileschi (Italian, 1593-1653)

Susanna and the Elders

c. 1638-1640

Oil on canvas

189.0 x 143.2cm (support, canvas/panel/stretcher external)

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Likely commissioned by Queen Henrietta Maria, this work was displayed in her Withdrawing Chamber in Whitehall Palace. The subject is an Old Testament narrative on virtue and faith. Susanna, bathing in privacy, is spied on by two elders who attempt to sexually assault her. When she resists them, the men accuse her of adultery. Susanna is arrested and about to be put to death until the men are questioned, and her innocence is revealed. Here, Gentileschi depicts Susanna as vulnerable and fearful, shielding her nakedness. She returned to the subject throughout her career.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

This spring, Tate Britain will present Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920. This ambitious group show will chart women’s road to being recognised as professional artists, a 400-year journey which paved the way for future generations and established what it meant to be a woman in the British art world. The exhibition covers the period in which women were visibly working as professional artists, but went against societal expectations to do so.

Featuring over 100 artists, the exhibition will celebrate well-known names such as Artemisia Gentileschi, Angelica Kauffman, Julia Margaret Cameron and Gwen John, alongside many others who are only now being rediscovered. Their careers were as varied as the works they produced: some prevailed over genres deemed suitable for women like watercolour landscapes and domestic scenes. Others dared to take on subjects dominated by men like battle scenes and the nude, or campaigned for equal access to training and membership of professional institutions. Tate Britain will showcase over 200 works, including oil painting, watercolour, pastel, sculpture, photography and ‘needlepainting’ to tell the story of these trailblazing artists.

Now You See Us will begin at the Tudor court with Levina Teerlinc, many of whose miniatures will be brought together for the first time in four decades, and Esther Inglis, whose manuscripts contain Britain’s earliest known self-portraits by a woman artist. The exhibition will then look to the 17th century. Focus will be given to one of art history’s most celebrated women artists, Artemisia Gentileschi, who created major works in London at the court of Charles I, including the recently rediscovered Susanna and the Elders 1638-40, on loan from the Royal Collection for the very first time. The exhibition will also look to women such as Mary Beale, Joan Carlile and Maria Verelst who broke new ground as professional portrait painters in oil.

In the 18th century, women artists took part in Britain’s first public art exhibitions, including overlooked figures such as Katherine Read and Mary Black; the sculptor Anne Seymour Damer; and Margaret Sarah Carpenter, a leading figure in her day but little heard of now. The show will look at Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser, the only women included among the Founder Members of the Royal Academy of Arts; it took 160 years for membership to be granted to another woman. Women artists of this era are often dismissed as amateurs pursuing ‘feminine’ occupations like watercolour and flower painting, but many worked in these genres professionally: needlewoman Mary Linwood, whose gallery was a major tourist attraction; miniaturist Sarah Biffin, who painted with her mouth, having been born without arms and legs; and Augusta Withers, a botanical illustrator employed by the Horticultural Society.

The Victorian period saw a vast expansion in public exhibition venues. Now You See Us will showcase major works by critically appraised artists of this period, including Elizabeth Butler (née Thompson)‘s monumental The Roll Call 1874 (Butler’s work prompted critic John Ruskin to retract his statement that “no women could paint”), and nudes by Henrietta Rae and Annie Swynnerton, which sparked both debate and celebration. The exhibition will also look at women’s connection to activism, including Florence Claxton‘s satirical ‘Woman’s Work’: A Medley 1861 which will be on public display for the first time since it was painted; and an exploration of the life of Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, an early member of the Society of Female Artists who is credited with the campaign for women to be admitted to the Royal Academy Schools. On show will be the student work of women finally admitted to art schools, as well as their petitions for equal access to life drawing classes.

The exhibition will end in the early 20th century with women’s suffrage and the First World War. Women artists like Gwen John, Vanessa Bell and Helen Saunders played an important role in the emergence of modernism, abstraction and vorticism, but others, such as Anna Airy, who also worked as a war artist, continued to excel in conventional traditions. The final artists in the show, Laura Knight and Ethel Walker, offer powerful examples of ambitious, independent, confident professionals who achieved critical acclaim and – finally – membership of the Royal Academy.

Press release from Tate Britain

Joan Carlile (English, 1606-1679)

The Carlile Family with Sir Justinian Isham in Richmond Park

1650s

Oil on canvas

Lamport Hall

CC BY-NC-ND

Joan Carlile (English, 1600-1679)

Portrait of a Lady Wearing an Oyster Satin Dress

1650s

Oil on canvas

30.8 x 25.5cm

National Portrait Gallery, London

Government Art Collection

Purchased from Philip Mould Ltd, 2018

Joan Carlile or Carlell or Carliell (c. 1606-1679), was an English portrait painter. She was one of the first British women known to practise painting professionally. Before Carlile, known professional female painters working in Britain were born elsewhere in Europe, principally the Low Countries.

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing at left, Joan Carlile’s Portrait of an Unknown Lady known as Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart and Duchess of Lauderdale 1650s (below); and at right, Portrait of an Unknown Lady 1650-1655 (below)

Joan Carlile (English, 1606-1679)

Portrait of an Unknown Lady (installation view)

1650-1655

Oil on canvas

Support: 1107 × 900 mm

Frame: 1205 × 1012 × 73 mm

Photo: Tate

Joan Carlile (English, 1606-1679)

Portrait of an Unknown Lady known as Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart and Duchess of Lauderdale

1650s

Oil on canvas

The Bute Collection at Mount Stuart

Here, Carlile uses the same white satin dress seen in a nearby painting. The pose, with the sitter elegantly gathering a handful of fabric, is taken from works by Charles I’s portrait painter, Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641). The sitter is sometimes identified as Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart and Duchess of Lauderdale. She was Carlile’s near neighbour in Petersham, at Ham House. The broken columns in the background are often used to symbolise loss.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Joan Carlile (English, 1606-1679)

Portrait of an Unknown Lady

1650-1655

Oil on canvas

Support: 1107 × 900 mm

Frame: 1205 × 1012 × 73 mm

Photo: Tate

Portraits by Joan Carlile are rare and this is one of only approximately ten that can be identified. Of these, two are in public collections (Ham House, Surrey, and National Portrait Gallery, London), while others are held in historic house collections and family trusts in the United Kingdom, for example Lamport Hall, Burghley House and Berkeley Castle. Carlile seems to have specialised in small-scale full length portraits of figures, usually female, set in large landscape or garden settings. The composition employed here, in which the figure holds the skirt of her dress with one hand and shawl with another, was most likely a template arrangement. It appears in two other portraits, one showing the figure facing the same way as here, the other in reverse, but with both figures wearing the same white satin dress. This repeated composition adds weight to the proposition that Carlile was a professional artist. The wife of Lodowick Carlile (or Carlell), a minor poet and dramatist who also held the office of Gentleman of the Bows to Charles I, Joan Carlile lived with her husband in Petersham, a suburb of London. However, in 1653 their neighbour, Brian Duppa, recorded that ‘the Mistress of the Family intends for London, where she meanes to make use of her skill to som more Advantage then hitherto she hath don’ (quoted in Toynbee and Isham 1954, p.275). In 1654 Carlile is recorded as living in London’s Covent Garden, then the heart of the artistic community (see Burnett 2004/2010, accessed 2 October 2015).

Text from the Tate website

Joan Carlile challenged societal expectations by becoming one of Britain’s first professional women artists in the 1600s, earning her living as an oil painter. Initially employed in King Charles I’s household, Carlile liked to paint in her spare time. With the outbreak of the Civil War, she began painting to support herself.

Carlile moved to Covent Garden in the 1650s – then the centre of the art world – and set up a successful commercial portrait business. Her template of carefully posed figures in silk gowns against landscape backgrounds, seen here in Portrait of an Unknown Lady (1650-5), proved extremely popular. Admired as a professional artist in her lifetime, only a small number of her portraits still exist, some which have never been seen in public.

Text from the Tate website

In her Portrait of an Unknown Lady (1650-1655) the astonishing nacreous lustre of the sitter’s white silk gown, shown full length, shines against the foil of the dull brown foliage behind her. At this point, the Civil War had ended but the restoration of the monarchy was still in the future, and Carlile’s painting, with its overt celebration of luxury and leisure (the spotless pale fabric speaks of both) seems provocative.

It is possible that Carlile taught Anne Killigrew (1660-1685), an accomplished painter and poet whose family encouraged her creative pursuits, although it’s not clear if she ever painted professionally. Only a handful of Killigrew’s works survive today, including Venus Attired by the Three Graces, which reveals her interest in mythological scenes.

Although she died of smallpox aged just 25, Killigrew stands alongside Beale and Carlile as one of Britain’s first female artists.

Alicia Foster. “Blazing a trail: Britain’s first women artists deserve to be better known,” on the Art UK website 13 May 2024 [Online] Cited 03/09/2024

Anne Killigrew (English, 1660-1685)

Venus Attired by the Three Graces

c. 1680

Oil on canvas

Support: 1120 × 950 mm

Frame: 1282 × 1102 × 63 mm

Falmouth Art Gallery

Purchased with the assistance of the Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund, Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund, the Beecroft Bequest, Falmouth Decorative and Fine Arts Society, the Estate of Barry Hughes in memory of Grace and Thomas Hughes and generous donations from local supporters

Public domain

Anne Killigrew has been described as the most celebrated female English prodigy of the Seventeeth Century. A poet and artist of great beauty and repute, Killigrew died of smallpox at the age of just 25. Anne’s exceptional qualities as an artist and a poet were highly praised in her short lifetime. The poet John Dryden dedicated a poem to her in which he refers directly to this picture: ‘Where nymphs of brightest form appear, and shaggy satyrs standing near’ (from ‘To the Pious Memory of the Accomplished Young Lady Mrs Anne Killigrew Excellent In The Two Sister-Arts of Poesy And Painting: An Ode’). Anne Killigrew worked at the Royal Court of King James II as Lady-in-Waiting to the Queen. Anne’s grandfather, Sir William Killigrew, was the Governor of Pendennis Castle, and his son, Dr Henry Killigrew moved to London to work as chaplain to King Charles I. He later became master of the Savoy Hospital.

Text from the Falmouth Art Gallery website

Mary Beale (English, 1633-1699)

Sketch of the Artist’s Son, Bartholomew Beale, Facing Left

c. 1660

Oil on paper

Support: 325 × 245 mm

Frame: 421 × 340 × 32 mm

Tate

Purchased 2010

Photo: Tate

In the late 1650s and early 1660s Beale and her family were living on Hind Court, off Fleet Street in London. She painted privately and had a painting room in her home. Her husband had a civil service position as Deputy Clerk of the Patents. Portrait sittings of family and friends were often social occasions, with conversation and dinner afterwards. It is in this period that Beale produced small oil sketches on paper of family members, particularly her two young sons. Whether they relate to larger oil on canvas portraits is unclear.

This oil sketch of a young boy, shown in three-quarter profile, is of Mary Beale’s eldest son Bartholomew, baptised in 1656. His appearance, both in age and costume, is very similar to that in Mary Beale’s Self-portrait with her family (Geffrye Museum, London), painted c. 1659-60, before the birth of her youngest son Charles. It relates closely to another sketch of Bartholomew in oil on paper painted at the same time, Sketch of the Artist’s Son, Bartholomew Beale, in Profile c. 1660 (Tate T13245). Whether these sketches are connected to the production of the Geffrye Museum portrait, or were simply executed at around the same time, is not known. They are painted in oil on paper, which seems to have been a feature of Beale’s working method in the early 1660s but is not known in her later career, when she made preparatory sketches in chalk on paper or in oil on canvas (see, for example, Portrait of a Young Girl c. 1679-81, Tate T06612). When this sketch was made, the Beale family was living in Hind Court, off Fleet Street in London, where Mary Beale’s husband, Charles, was employed as Deputy Clerk of the Patents Office. It is difficult to determine whether Beale had much of a commercial portrait practice at this date, but documents certainly record the production of portraits of family and friends. In her ‘painting room’, Beale had ‘pencills [sic.], brushes, goose & swan fitches’, as well as ‘quantities of primed paper to paint on’ (George Vertue, transcription of Charles Beale’s 1661 notebook, now lost, quoted in Barber 1999, p. 16).

Text from the Tate website

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing Mary Beale’s Anne Sotheby 1676-1677

Mary Beale (English, 1633-1699)

Anne Sotheby

1676-1677

Oil on canvas

Tate

Purchased with funds provided by the Nicholas Themans Trust 2024

Beale’s husband kept a daily record of her activities in the studio. Two of his over 30 notebooks and a few partial transcripts are still known. They record Beale’s sitters, her painting stages, her painting materials and her prices. For her commissioned works, she borrowed poses from the portraits of the court artist Peter Lely (1618-1680). Anne Sotheby’s pose is taken from his portrait of Lady Essex Finch. Beale charged £10 for paintings of this size. Her sons acted as studio assistants; her youngest, Charles, was paid to paint the drapery in this portrait.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Mary Beale (née Cradock) (1633-1699) was an English portrait painter. She was part of a small band of female professional artists working in London. Beale became the main financial provider for her family through her professional work – a career she maintained from 1670/71 to the 1690s. Beale was also a writer, whose prose Discourse on Friendship of 1666 presents a scholarly, uniquely female take on the subject. Her 1663 manuscript Observations, on the materials and techniques employed “in her painting of Apricots”, though not printed, is the earliest known instructional text in English written by a female painter. Praised first as a “virtuous” practitioner in “Oyl Colours” by Sir William Sanderson in his 1658 book Graphice: Or The use of the Pen and Pensil; In the Excellent Art of PAINTING, Beale’s work was later commended by court painter Sir Peter Lely and, soon after her death, by the author of “An Essay towards an English-School”, his account of the most noteworthy artists of her generation.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Mary Beale (English, 1633-1699)

Mary Beale

c. 1666

Oil on canvas

109.2 x 87.6cm

National Portrait Gallery, London

Purchased, 1912

CC BY-NC-ND

Beale is shown holding an unframed canvas on which are sketch portraits of her two sons, Bartholomew (1656-1709) and Charles (1660-1714?)

Mary Beale (English, 1633-1699)

Self Portrait

c. 1675

Oil on sacking

89 x 73cm

West Suffolk Heritage Service

Purchased

CC BY-NC-ND

The early English portrait painter Mary Beale (1622/1623-1699) had a father who was an amateur artist, miniature painter and a collector of paintings (her family owned work by Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck) and her husband, Charles, was also an amateur painter and ran her studio in London’s fashionable Pall Mall.

Unusually, in her case, her talent was matched by her spouse’s high regard of it, and she was allowed to supersede him and establish a professional career. She took on female apprentices, though no records of their subsequent careers survive.

Alicia Foster. “Blazing a trail: Britain’s first women artists deserve to be better known,” on the Art UK website 13 May 2024 [Online] Cited 03/09/2024

Exhibition guide

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 celebrates over 100 women who forged public careers as artists. The exhibition begins with the earliest recorded women artists working in Britain. It ends with women’s place in society fundamentally changed by the First World War and the first women gaining the right to vote. Across these 400 years, women were a constant presence in the art world. Now You See Us explores these artists’ careers and asks why so many have been erased from mainstream art histories.

Organised chronologically, the exhibition follows women who practised art as a livelihood rather than an accomplishment. The chosen works were often exhibited at public exhibitions, where these artists sold their art and made their reputations. Most of the women featured belonged to a social class that gave them the time and opportunity to develop their talents. Many were the daughters, sisters or wives of artists. Yet even these women were regarded differently. Now You See Us charts their fight to be accepted as professional artists on equal terms with men.

Many of the exhibited works reflect prejudiced notions of the most appropriate art forms and subjects for women. Others challenge the commonly held belief that women were best suited to ‘imitation’, proving they have always been capable of creative invention. From painting epic battle scenes to campaigning for access to art academies, these women defied society’s limited expectations of them and forged their own paths. Yet so many of their careers have been forgotten and artworks lost. Drawing on the artists’ own writings, art criticism, and new and established research, this exhibition attempts to restore these women to their rightful place in art history. Now You See Us aims to ensure these artists are not only seen but remembered.

Women at the Tudor Courts

There are significant gaps in our knowledge of women’s artistic lives in the sixteenth century. As is the case for many artists in this exhibition, their lives are poorly documented and often hidden behind those of their husbands and fathers. The problems this presents are evident in this room.

Susanna Horenbout (1503-1554) and Levina Teerlinc (c. 1510s-1576) are among the earliest women in Britain to be named as artists. Their reputations are clearly recorded. In 1521, Horenbout’s skill was admired by the German painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), and in 1567, both artists were praised by the Italian historian Lodovico Guicciardini (1521-1589). Yet no works by Horenbout have been identified, and those attributed to Teerlinc are not certain.

Horenbout and Teerlinc were both daughters of Flemish manuscript illuminators and were likely trained in their family workshops. Both arrived in England to work at the court of Henry VIII. But as women, they were not employed as artists. While Horenbout’s brother Lucas Horenbout (1490-1544) was Henry VIII’s painter, she served Anne of Cleves as one of her Gentlewomen of the Privy Chamber. Teerlinc served Elizabeth I likewise. This does not mean that they did not paint – at court, their artistic talents would have been a distinguishing skill – but, as is a common feature of this exhibition, written histories have failed to record their activities.

Working in a different context – as a scribe and calligrapher – the works of Esther Inglis (1571-1624) can be identified. Inglis authored more than 60 manuscript books and included her name and self-portrait in many. Raised in Scotland, she may have learnt the art of calligraphy from her mother, Marie Presot (active 1569-1574).

Artemisia Gentileschi

Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi arrived in London in c. 1638-9 by invitation of Charles I. Like other European rulers, Charles I employed artists of international reputation to signal the cultural sophistication of his court. Gentileschi had prestigious patrons across Europe, including the Grand Duke of Tuscany and Philip IV of Spain. She was the first woman to be a member of the Academy of the Arts of Drawing in Florence, and in Rome, her house had been ‘full of cardinals and princes’. Gentileschi’s fame as an artist was augmented by her status as a woman.

In London, Gentileschi worked for Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria. Records suggest she produced seven works for the royal collection. These included self-portraits and large history paintings, with subject matter drawn from classical history, mythology, and the Bible. Only the two displayed here are still known. Gentileschi often placed women at the centre of her works, depicting narratives that celebrate their strength and virtue. Susanna and the Elders is an example of the kind of work for which Gentileschi was celebrated.

Gentileschi achieved in her lifetime what many women who came after her had to fight to attain: she was a professional artist who ran her own studio, was a member of an art academy, worked from life models and was ranked as a serious artist alongside men. Despite this, Gentileschi’s status has fluctuated over time, and the artist has faded in and out of art history.

Early accounts of Gentileschi’s work focus on her personal life as much as her painting. Like many of the women artists who came after her, the details of her biography continue to dictate interpretations of her work.

The First Professionals

In 1658, historian William Sanderson (c. 1586-1676) published Graphice. The use of the pen and pensil. Or, The most excellent art of painting. The publication lists contemporary artists practising in England. He includes four women working in oil paint: ‘Mrs Carlile’ (Joan Carlile), ‘Mrs Beale’ (Mary Beale), ‘Mrs Brooman’ (probably Sarah Broman) and ‘Mrs Weimes’ (Anne Wemyss). Carlile and Beale are believed to be two of the earliest British women to have worked as professional artists. Very little is known about Broman or Wemyss beyond snatches of information in archives.

This short list highlights how unusual it was for British women to pursue art as a profession in the seventeenth century. Women had little agency over their own lives and were subject first to their fathers and then their husbands. Limited to the domestic sphere, they were not expected to conduct public lives. Many women painted privately with no thought of turning it into a career. While young men began as apprentices or assistants in the studios of professionals, this route was not open to most women.

In the seventeenth century women writers, poets, playwrights and artists began to give voice to those questioning their secondary status and petitioning for women’s rights. They argued that it was lack of education, not ‘weak minds’ that limited their opportunities. This fight for equality and access to education runs throughout the exhibition.

The First Exhibitors

The first public art exhibition in Britain took place in London in 1760, and art shows soon became an important part of the city’s social calendar. Founded in 1768, the Royal Academy quickly emerged as a driving force in cultural life, with its Summer Exhibition attracting tens of thousands of visitors every year. Other venues, including the Society of Artists and the British Institution also hosted exhibitions.

Women artists played an active part in this competitive world. An estimated 900 women exhibited their work between 1760 and 1830. Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser were both founding members of the Royal Academy (although, as women, they weren’t awarded full membership and were excluded from the Academy’s council meetings and governance). Despite this precedent, it would take more than 150 years for the next woman to be elected to membership.

Kauffman is one of the few women artists of the eighteenth century whose profile has been sustained. Many others made names for themselves, but their careers are not well documented. Even Moser is less well known, perhaps because she painted flowers while Kauffman pursued the ‘high genre’ of history painting, depicting historical, mythological and biblical narratives.

Art critics of the time often criticised women for their ‘weak’ figurative work, yet they were denied access to life-drawing classes. Women artists also had to battle social expectations. Publishing a private or studio address in an exhibition catalogue was a signal of commercial practice, but painting for money was considered improper. Women artists of higher social rank were listed as ‘honorary’ exhibitors; some exhibited simply as ‘a Lady’, and after marriage, many switched their status from ‘commercial’ to ‘amateur’.

‘Just What Ladies Do For Amusement’

In 1770, the Royal Academy banned ‘Needle-work, artificial Flowers, cut Paper, Shell-work, or any such baubles’ from its exhibitions. They also banned works that were copies. Other categories of art that the Academy considered ‘lower’, such as miniature painting, pastel and watercolour were also treated dismissively. Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), the Academy’s President, said that working in pastel was unworthy of real artists and was ‘just what ladies do when they paint for their own amusement’.

These ‘lower arts’ were ones that women practised the most. Small in scale and considered less technically challenging than oil painting, they demanded less equipment and could be pursued at home. They were taught to middle and upper-class girls and were the realm of women who pursued art as amateur accomplishment.

Despite this, these art forms offered opportunities for women to earn a living. Many turned miniature painting, needlework and pastel into lucrative professional careers, supplementing their income through tutoring. Their patrons were often women, and some boasted large, fashionable clienteles and even galleries which became tourist attractions.

Founded in 1754, the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (the Society of Arts) offered cash prizes and medals in many categories, including the ‘polite arts’. Awards were given for patterns for embroidery, copies of prints, drawings of statues and of ‘beasts, birds, fruit or flowers’, as well as landscapes. Some prizes were specifically intended for young women. The Society was a stepping stone to a career and many of the artists in this exhibition won medals. Yet most of the women recorded as submitting work for competition can no longer be identified beyond their names.

Flowers

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, painting flowers was considered a suitably delicate pursuit for women. Imitating nature (rather than demonstrating creative or imaginative flair) was thought to be an appropriate outlet for women’s artistic skills. Flowers were also at the heart of respectable hobbies like embroidery, botany and gardening. In the 1850s, the women’s periodical the Ladies’ Treasury called flower painting ‘a ladylike and truly feminine accomplishment’. When Mary Moser exhibited Cymon and Iphigenia (based on a poem by John Dryden, 1631-1700) at the Royal Academy in 1789, a reviewer urged her to stick to flowers. She painted flowers ‘transcendently’, he noted, and should do ‘nothing else’.

Many women were employed as professional illustrators, recording plant species for horticulturists and botanical publishers. Some conducted hybrid careers, working as illustrators and drawing tutors while exhibiting flower paintings for a wider market. In the Victorian era, critics applauded several women artists as leaders of the genre. Yet the idea that flower painting, especially in watercolour, was an exclusively amateur pastime has damaged the legacies of many accomplished artists who successfully worked within this genre.

Victorian Spectacle

Grand exhibitions were a defining part of the Victorian art world. The Royal Academy, the leading art institution since 1768, was still Britain’s most prestigious exhibition venue, but was later criticised for its traditional conservatism. New venues, such as London’s Grosvenor Gallery, which opened in 1877, became rival spaces, and exhibitions in Liverpool and Manchester offered fresh opportunities for exhibiting artists. The Victorian era was also the age of World Fairs. Major exhibitions were held in London and Paris, and in 1893, the World’s Exposition in Chicago was visited by over 25 million people.

This room explores the successes of women artists on this public stage. Many of the works on display were shown in these exhibitions. They won international medals, praise from art critics and public recognition. Yet women tackling ‘male’ subjects, such as battle scenes, caused surprise. Opinion was also divided on women painting the nude: some thought it immoral, others brave.

Exhibitions gave women a public platform to build substantial reputations, and some became popular names. Despite this, membership of the Royal Academy, which was a mark of professional recognition, remained out of reach. As a result, women had no automatic exhibiting rights and were reliant on committees of men selecting their works for exhibition. Without institutional support, they had to navigate the commercial art market on their own.

Women artists’ campaigns for access to the Academy joined calls for greater equality in society. From the 1850s, women petitioned for equal rights to education and work, as well as women’s suffrage. These causes are reflected in the works in this room.

Watercolour

Watercolour was considered one of the ‘polite arts’ best suited to women. However, there were few opportunities to practice professionally. The principal watercolour societies – the Old (founded in 1804) and the rival New (founded in 1807 and reconstituted in 1831) – restricted the membership of women. Membership of the Old was limited to six women (in practice, usually four), while the New admitted around ten.

In both societies, women were confined to the category of ‘Lady Members’ until the end of the nineteenth century. They had no say in governance and were denied access to the financial premiums awarded to full members. Since the annual exhibitions of both societies were closed to non-members, most women had limited opportunities to exhibit their work.

Against these odds, many women water colourists achieved significant commercial and critical success. They enjoyed solo shows and developed commercial relationships with dealers, taking control of their careers.

In 1857, a group of women founded the Society of Female Artists (later, the Society of Lady Artists in c. 1869, then the Society of Women Artists in 1899) to promote the work of women artists in Britain.

Photography

The announcement of photography in 1839 marked a major shift in the art world. In its first decades, photography was a laborious practice that required an understanding of chemistry and optics, as well as expensive equipment. It needed more money, specialist instruction and time than most other art forms. For women who had access to these privileges, the medium provided new opportunities.

From its foundation in 1853, the Photographic Society of London welcomed women members. However, they rarely attended meetings, which were scheduled in the evenings when women required a chaperone to leave the house. The atmosphere of the meetings was described as a ‘men’s club’ and it wasn’t until 1898 that the Society belatedly banned smoking ‘in respect of ladies’ attendance’. Meetings often included papers on new techniques and equipment, providing significant benefits to those who were able to join.

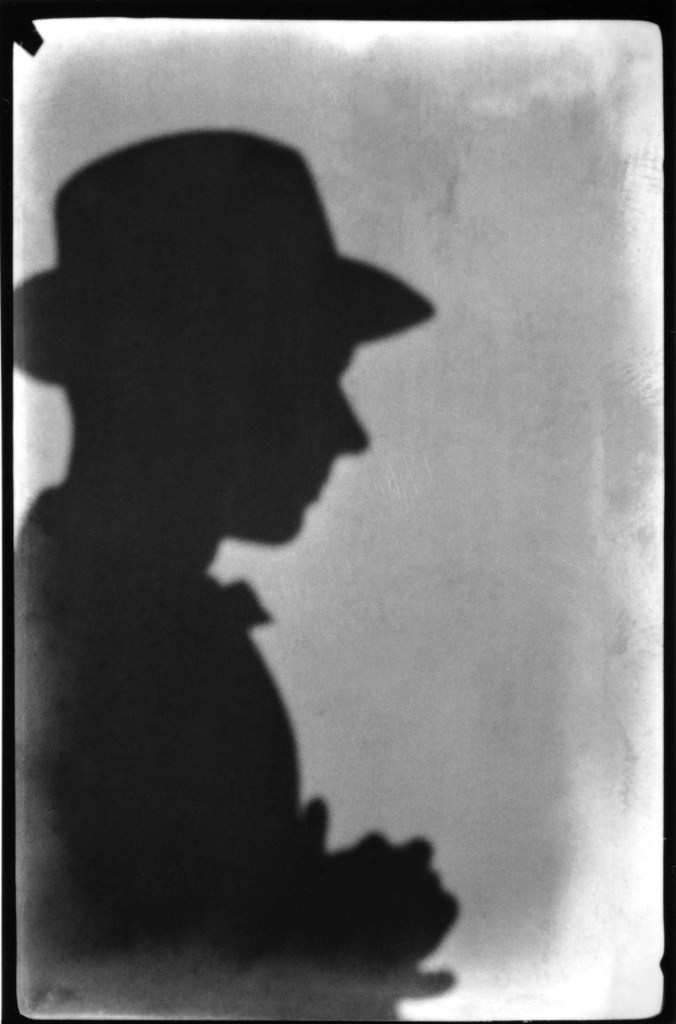

Women participated in London’s first public photographic exhibitions at the Royal Society of Arts in 1852-3 and at the Photographic Society in 1854. The Amateur Photographic Association, established in 1861, also welcomed women from its outset. In the 1890s and early 1900s, London’s Photographic Salon became a key venue. Founded by the Linked Ring Brotherhood, who promoted photography as a fine art, Salon exhibitors included women from across Europe and the US. A photograph of British photographer Carine Cadby in silhouette, examining one of her glass plate negatives, featured on the cover of the 1896 Salon catalogue. Despite this, women were not elected as members of the Linked Ring until 1900. By 1909, they numbered just 8 among 63 men.

Art School

Women were excluded from enrolment at the Royal Academy Schools, Britain’s principal art academy, until 1860. Laura Herford (1831-1870) was the first woman admitted. She had submitted her work for consideration using only her initials and was assumed to be a man. Once women gained entry, they were determined to achieve equal access to training.

Women were barred from the Academy’s life-drawing classes until 1893. Their exclusion from this vital component of art education was justified on many grounds. Chiefly, it was to ‘protect’ women’s supposed modesty, but also because they were considered amateurs who lacked the intellectual capacity to practice art at the highest level. Women students marshalled critical support for their cause and submitted petitions. Life drawing was considered essential to the training of men pursuing careers as artists. Why, they argued, was it not also essential for women?

The Female School of Art, founded in 1842, provided another route into art education. Like several regional schools, such as that in Manchester, it encouraged women into vocational careers in design. Women also had access to private academies, including Sass’s and Leigh’s (later Heatherleys) in London, which prepared students for admission to the Royal Academy Schools. And some women artists, such as Louise Jopling, established their own art school.

In 1871, the founding of the Slade School of Fine Art at University College London signalled a fundamental change of attitudes. From the outset, the Slade offered women an education on equal terms with men. Studying from life models was a central focus of teaching and by the turn of the century, women students outnumbered men by three to one. Access to life drawing had been regarded as the last barrier to equal opportunity. Now they could study from life, some critics argued it was up to women to prove they could be successful artists.

Being Modern

The first two decades of the twentieth century saw rapid change for women, with their rights, roles and opportunities evolving at an unprecedented pace. The First World War signalled a decisive change for women’s place in society and in 1918, after decades of campaigning, some women finally gained the right to vote.

At the same time, the art world was also changing. New art groups and exhibiting societies rejected tradition and promoted modernist aesthetics. Instead of figurative realism, they privileged form, colour and experimentation. Many saw modernism as an opportunity for greater artistic freedom. However, despite growing liberalism in art and society, women artists still faced challenges. The New English Art Club became a rival exhibiting venue to the Royal Academy but was slow to admit women. The Camden Town Group labelled itself ‘progressive’ but openly excluded women.

While modernism is often presented as the dominant movement of the early twentieth century, it doesn’t account for all artistic production of the period. Membership of the Royal Academy, an exhibiting venue many now regarded as too traditional, remained a symbolic goal for many women. When Annie Swynnerton was elected an Associate Member in 1922, Laura Knight said she had broken down the ‘barriers of prejudice’. In 1936, Knight was elected a Royal Academician, becoming the first woman to achieve full membership since the eighteenth century.

The artworks in the final room of the exhibition explore this complex period. Their variety reveals women forging their own paths and pursuing professional careers with purpose and confidence. While many chose not to challenge traditional artistic values, they pushed the boundaries of what was expected of them, paving the way for generations of women artists who came after them.

Text from the Tate exhibition guide

Mary Delany (English, 1700-1788)

Rubus Odoratus

1772-1782

The British Museum

Bequeathed by Augusta Hall, Baroness Llanover in 1897

Delany was not a professional artist. However, she pursued art with a seriousness of purpose, working in a range of artistic and decorative mediums. She was in her early seventies when she turned to botanical collage, which stemmed from the Dutch art known as knipkunst or schaarkunst. Over the course of a decade, Delany created nearly one thousand botanically accurate collages of plants made from intricately cut pieces of coloured paper. In this collage, Delany shows a flowering raspberry, which was introduced to Britain from North America in 1770.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Mary Knowles (English, 1733-1807)

Needlework Picture

1779

Silk (textile), wool, giltwood, glass (material) embroidered, dyeing

89.2 x 84.5cm (frame, external)

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Mary Morris Knowles, born of a Quaker family in Rugeley, Staffordshire, was celebrated as much for her intellect, religious conviction and unusual powers of conversation as for her skill with the needle. A friend of the poetess Anna Seward (‘The Swan of Lichfield’) and of Dr Johnson, she is now regarded as an important early protagonist of the feminist viewpoint in English cultural life. Her support for the abolition of slavery, her investigation into mystical science and her knowledge of garden design, in addition to her accomplishment as a needlewoman, suggest the breadth of her interests. In 1771 she was introduced by her fellow Quaker Benjamin West to Queen Charlotte, who remained on terms of friendship with her over the next thirty years and whose interest in female accomplishments, notably needlework, was well known. Mrs Knowles’s visits to Buckingham House included an occasion in 1778 on which she presented her 5-year-old son George to the King and Queen.

Following the first visit in 1771, the Queen commissioned Mrs Knowles to make a copy of Zoffany’s portrait of George III in needlework or ‘needle painting’ as it was also known. This technique ‘so highly finished, that it has all the softness and Effect of painting’ was achieved with a combination of irregular satin-stitch and long-and-short stitch, worked on hand-woven tammy in an arbitrary pattern and at speed, using fine wool dyed in a wide range of colours under her own supervision. Eight years later Mrs Knowles embroidered the self portrait showing her at work on the Zoffany which, like the earlier piece, she signed with initials and dated. This appears always to have been in the Royal Collection and was presumably also commissioned by Queen Charlotte.

Text from the Royal Collection Trust website

Mary Black (English, c. 1737-1814)

Messenger Monsey (1693-1788)

1764

Oil on canvas

127 x 101.6cm

Gift from Frederick Walford, 1877

Royal College of Physicians, London

CC BY-NC-ND

This portrait of the physician Messenger Monsey (1694-1788) is Black’s only known oil painting. Black likely hoped it was a step towards establishing herself as a professional artist, but the issue of payment caused friction. Black hope to charge her client £25, half the amount charged by leading portraitist Joshua Reynolds, but after Monsey’s complaint offered to drop it to a quarter. Monsey considered Black’s expectation of a fee improper. He claimed it would damage her reputation if word got out, and even referred to her as a ‘slut’ in a letter to his cousin.

Wall text from the exhibition

Little is known of the father-and-daughter artists Thomas and Mary Black. Thomas was mainly employed painting draperies for more successful painters, and Mary usually painted copies of old masters. In a letter from Monsey to Mary Black, the doctor wrote: ‘I was bedevilled to let you make your first attempt upon my gracefull person… drawn like a Hog in armour’.

Text from the Art UK website

Black was clearly unfazed by awkward sitters. She built a flourishing artistic practice, painting and teaching the aristocracy, earning enough to live independently (she never married) and keep servants and a horse and carriage at her London home. She died there in old age just as the nineteenth century began.

Alicia Foster. “Blazing a trail: Britain’s first women artists deserve to be better known,” on the Art UK website 13 May 2024 [Online] Cited 03/09/2024

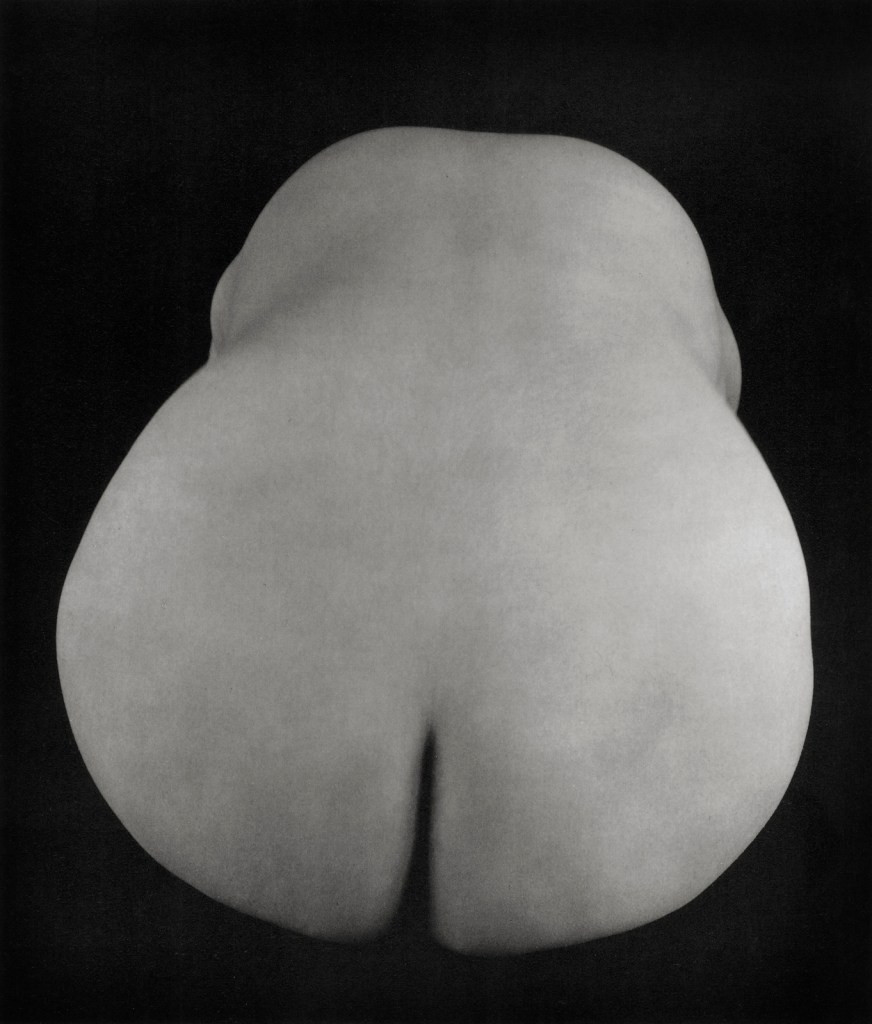

Mary Moser RA (English, 1744-1819)

Standing Female Nude

Nd

Black and white chalk on grey-green paper

49 x W 30.2cm

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

As women were excluded from life drawing classes, many took their own steps to improve their anatomical knowledge. They sketched from casts and statues and copied from other artists’ drawings and anatomy books. These rare works show that some artists found ways around these restrictions, although little is known about how Moser and Stone accessed life models.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Mary Moser RA (English, 1744-1819)

Flowers in a vase, which stands on a ledge

1765

Watercolour and bodycolour on paper

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

From the same series as the work nearby, this watercolour represents Sagittarius. The vase is filled with a cascade of late flowering plants: asters, chrysanthemums and rare pale nerines, captured in the cold light of winter. In addition to her professional profile as a Royal Academician, Moser acted as a royal tutor. She was part of Queen Charlotte’s circle and taught the princesses botany, embroidery and flower painting. She worked alongside other artists, including Meen and Delany, whose work is also displayed in this room.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Admired for her striking paintings of flowers, Mary Moser was recognised for her talent from a very young age. She trained with her father, an acclaimed artist and goldsmith, winning her first medal for flower drawing at 14. At just 24, she became one of only two female founders of the Royal Academy, alongside Angelica Kauffman.

Moser painted portraits and historical scenes, but her skilled floral still life works, like Flowers in a vase, which stands on a ledge (1765), were praised by critics. Though still life was traditionally seen as a ‘lesser subject’, her floral works were so widely appreciated she received royal commissions, including one from Queen Charlotte. Despite recognition and the exhibition of many paintings, few of Moser’s works survive today.

Text from the Tate website

Mary Moser RA (English, 1744-1819)

Vase of Flowers

Between 1758 and 1819

Oil on canvas

72.1 x W 53.6cm

The Fitzwilliam Museum

Gift from Major the Hon. Henry Rogers Broughton, 1966

The exquisite attention to detail in her painting, with its beads of dew and butterflies on the wing, was perhaps nurtured by seeing her father’s work; as a goldsmith and medallion maker, this was also his talent. But the gorgeous sensuality – seen also in her approach to the nude figure – was entirely her own. She married, aged 53, but also had an affair with the estranged husband of another artist: Maria Hadfield Cosway (1759-1839).

Alicia Foster. “Blazing a trail: Britain’s first women artists deserve to be better known,” on the Art UK website 13 May 2024 [Online] Cited 03/09/2024

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing Angelica Kauffman’s Colouring 1778-1780 (below)

Angelica Kauffman RA (Swiss, 1741-1807)

Colouring

1778-1780

Oil on canvas

1260 x 1485 x 25 mm

© Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo: John Hammond

This painting is part of a set of the four [titled ‘Elements of Art’] commissioned from Kauffman by the Royal Academy to decorate the ceiling of the Royal Academy’s new Council Room in Somerset House which opened in 1780. …

Kauffman represented each of her four Elements of Art as women. Female personifications of abstract concepts and values were commonplace in European art but depicting all four as women was unusual. Design (or Disegno), in particular, was known as ‘the father of all the arts’ and was traditionally depicted as a man, often in contrast to Colour or Painting personified as a woman (see Baumgartel). In Design and Colouring, the women are physically engaged in the act of creating whereas in Composition and Invention they are shown in contemplation. In Invention the figure looks to the sky for inspiration and in Composition she is deep in thought with her head resting on her hand in the traditional gesture of melancholy or reverie.

Text from the Royal Academy website

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing at centre, Maria Cosway’s Georgiana as Cynthia from Spenser’s ‘Faerie Queene’ 1781-1782 (below); and at right, Cosway’s A Persian Lady Worshipping the Rising Sun 1784 (below)

Maria Cosway (Italian-English 1760-1838)

Georgiana as Cynthia from Spenser’s ‘Faerie Queene’

1781-1782

Oil on canvas

Chatsworth House

Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees / Bridgeman Images

Public domain

Maria Cosway (Italian-English 1760-1838)

A Persian Lady Worshipping the Rising Sun

1784

Oil on canvas

61 x 73.7cm

Sir John Soane’s Museum

Gift from the artist, 1822

By courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

CC BY-NC-ND

As well as portraits, Cosway exhibited history paintings. This work was shown at the Royal Academy in 1784. Although only a few of Cosway’s history pictures can be located now, paintings such as this one were well known through reproductions made by leading engravers and print publishers. Cosway’s success was hindered by her husband, who did not like her to paint professionally. She reflected later that had he permitted it, she would have ‘made a better painter, but left to myself by degrees, instead of improving, I lost what I brought from Italy of my early studies.’

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Maria Cosway (Italian-English 1760-1838)

Bouquet of Flowers

1780

Watercolour on paper

The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)

Bequeathed by Sir Robert Clermont Witt, 1952

CC BY-NC-ND

Maria Cosway (Italian-English 1760-1838)

The Judgement of Korah, Dathan and Abiram

c. 1801

Pen, ink and oil on canvas

37.5 x 29.2cm

Yale Center for British Art

Paul Mellon Collection

CC BY-NC-ND

Maria Cosway (1759-1838) (after)

Self Portrait

Nd

Oil on canvas

61 x W 50.8cm

Temple Newsam House, Leeds Museums and Galleries

Bequeathed by Sam Wilson, 1925

CC BY-NC-ND

Sarah Biffin (English, 1784-1850)

Self-portrait

c. 1821

Watercolour and bodycolour on ivory

Private collection

Biffin, whose baptism record notes that she was born ‘without arms or legs’, taught herself to sew, write and paint using her mouth and shoulder. She wrote that, as a child, ‘I was continually practising every invention; till at length I could, with my mouth – thread a needle – tie a knot – do fancy work – cut out and make my own dresses’.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing at left, Clara Maria Pope’s Peony 1822 (below); and at right, Pope’s Peony 1821 (below)

Clara Maria Pope (British, 1767-1831)

Peony

1822

Bodycolour on card

The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

Courtesy the Natural History Museum

Clara Maria Pope (British, 1767-1831)

Peony

1821

Bodycolour on card

The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

Courtesy the Natural History Museum

Pope appears in museum records under many names: Clara Leigh, Clara Wheatley (her first husband was the artist Francis Wheatley, 1747-1801), Clara Maria Pope (she married actor Alexander Pope in 1807) and Mrs Alexander Pope. Her changes of name have obscured her career as an artist. She exhibited watercolour landscapes and portraits, miniatures and genre works, but above all, Pope was an artist of flowers. She worked for the leading botanical publisher Samuel Curtis (1779-1860). The scientifically accurate peonies depicted here are 2 of 11 designs. They may have been intended as plates for a work that was never published.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

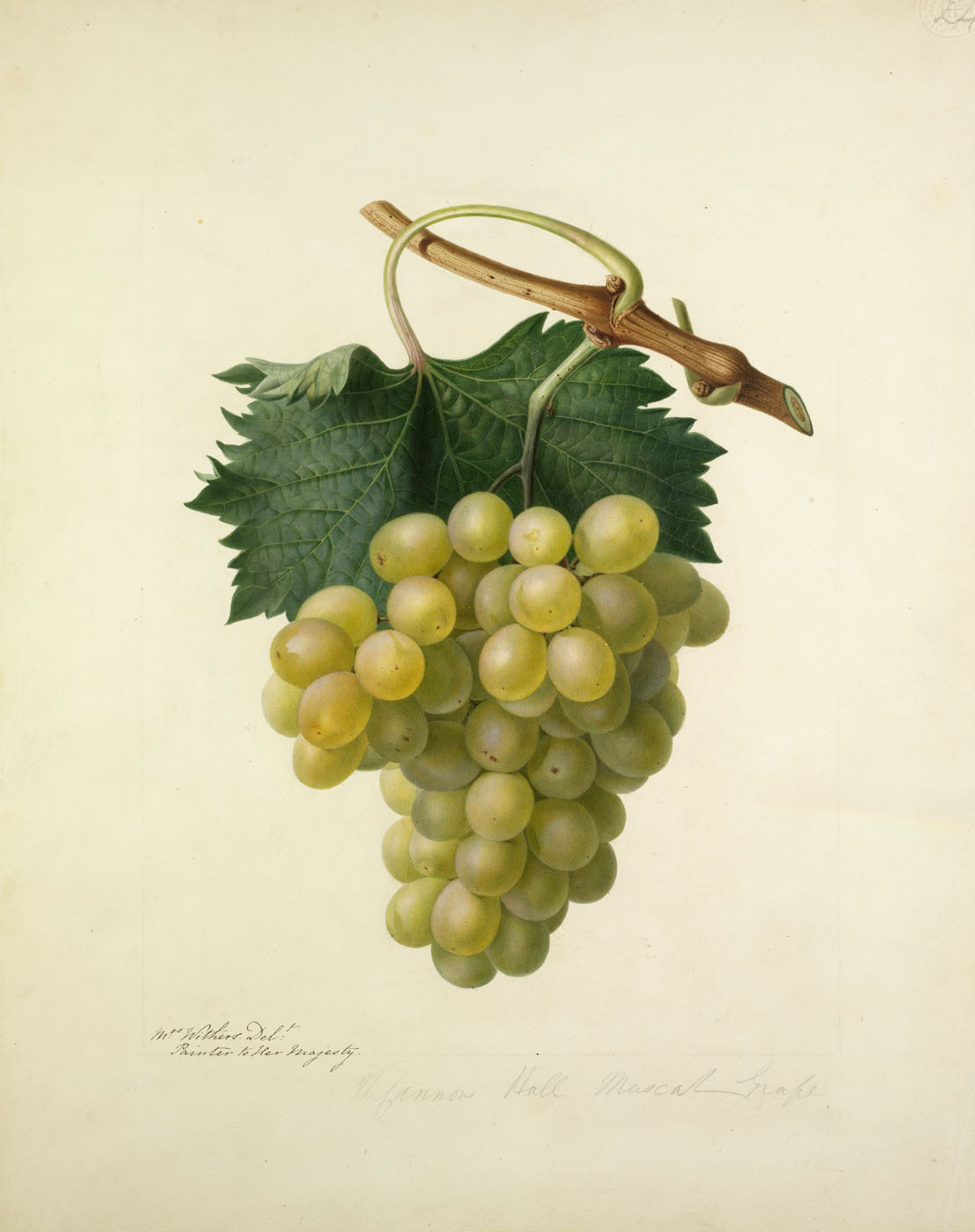

Augusta Innes Withers (English, 1792-1877)

The Canon Hall Muscat Grape

c. 1825

Watercolour on paper

444 × 352 mm

RHS Lindley Collections

Courtesy the Royal Horticultural Society, Lindley Library

Withers was employed by the Horticultural Society to make official ‘portraits’ of varieties of fruit growing in their orchards. The quality of Withers’s work meant her high fees were not questioned. Here, she paints sunlight glowing through grapes and the translucency of the skin of gooseberries in great detail. Withers drew and handcoloured engraved illustrations in the Horticultural Society’s Transactions and made illustrations of fruit for John Lindley’s Pomological Magazine in 1828 (Lindley was Secretary of the Society). Withers was also regarded as one of the best teachers of botanical illustration.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing at left, Rebecca Solomon’s Sherry, Sir?

c. 1858-1862 (below); and at right, Solomon’s A Young Teacher 1861 (below)

Rebecca Solomon (English, 1832-1886)

Sherry, Sir?

c. 1858-1862

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Solomon often painted scenes of domestic life and interiors, which were considered more suitable subjects for women artists than history painting. Solomon’s domestic scenes include subtle commentary on social hierarchies. Sherry, Sir? depicts a maid with a silver tray. It reprises a well-known painting of the same title, painted by William Powell Frith (1819-1909) in 1851, but unlike Frith’s painting, Solomon draws attention to domestic labour and the hierarchies of a middle-class home. Solomon was the sister of artists Abraham Solomon (1823-1862) and Simeon Solomon (1840-1905).

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Rebecca Solomon (London 26 September 1832 – 20 November 1886 London) was a 19th-century English Pre-Raphaelite draftsman, illustrator, engraver, and painter of social injustices. She is the second of three children who all became artists, in a prominent Jewish family. …

Solomon’s artistic style was typical of popular 19th-century painting at the time and falls under the category of genre painting. She used her visual images to critique ethnic, gender and class prejudice in Victorian England. When Solomon started painting genre scenes, her work demonstrated an observant eye for class, ethnic and gender discrimination. Solomon’s paintings reflect a combination of interest in the theatre and commitment to social consciousness that is not exist in other artist’s painting in the nineteenth century.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Solomon painted in a more equivocal manner… She [the subject of the painting] is equally attractive and demure, but, by being painted from the side and against the background of a middle-class interior, the viewer is invited to reflect on her social status.

This is framed in a genre painting and by no means a piece with pretensions to social realism, but Solomon seems to be underlining the definite restrictions on this young woman’s position in society.

The pictures hanging behind her may contribute to that interpretation of the artist. They are not yet identified, but it seems that on the left we are shown an allegorical subject later than Gainsborough or Reynolds, depicting a young peasant boy or young peasant girl holding a dog in a landscape. On the right, a more specific engraving of a genre painting from Solomon’s own time showing what appears to be an itinerant family of street vendors. By placing his servant girl between these two paintings, Solomon seems to be asking us to compare.

José Luis Jiménez García. “La otra versión de la ‘Sherry Girl’,” on the Diario de Jerez website 07 June 2023 [Online] Cited 28/08/2024 Translated from the Spanish by Google Translate

Rebecca Solomon (English, 1832-1886)

A Young Teacher

1861

Oil on canvas

61 by 51cm

Tate and the Museum of the Home

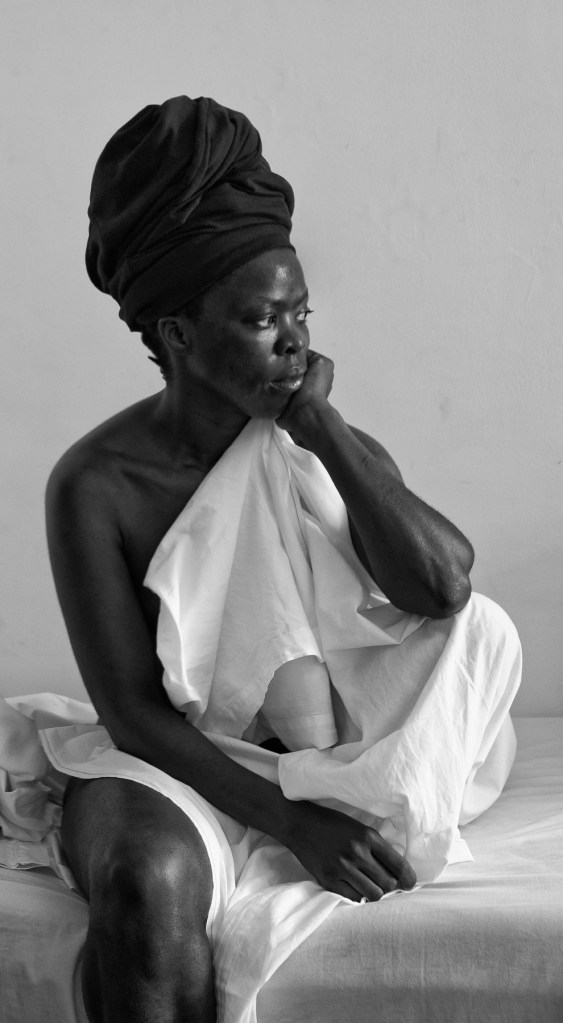

Rebecca Solomon’s painting is a complex reflection on gender, race, religion and education in mid-nineteenth century London. As with many of her works, it considers women who worked in better-off households as professional carers. In A Young Teacher, Solomon modifies a traditional domestic scene between mother and child, with the surrounding books stressing the theme of learning. The woman at the centre of the image was modelled by Jamaican-born Fanny Eaton, who became a prominent muse for many Victorian artists and featured in some of the most iconic paintings of the Pre-Raphaelite period. …

Believed to be the first Jewish woman to become a professional artist in England, Rebecca Solomon’s work shone a light on inequality and prejudice at a time when these subjects were far from mainstream. She was active in social reform movements, including as part of a group of 38 artists who petitioned the Royal Academy of Arts to open its schools to women.

Text from the Tate website

Emily Osborn (English, 1828-1925)

Nameless and Friendless.

“The rich man’s wealth is his strong city: the destruction of the poor is their poverty” (Proverbs: 10:15)

1857

Oil on canvas

Support: 825 × 1038 mm

Frame: 1042 × 1258 × 75 mm

Tate

Purchased with assistance from Tate Members, the Millwood Legacy and a private donor 2009

Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED

Osborn exhibited widely and was supported by wealthy patrons. She was also part of the ‘rights of woman’ debate, campaigning for more public roles for women. Nameless and Friendless, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1857, dramatises the difficulties faced by women artists. Osborn shows a young woman offering a painting to a sceptical dealer. With no reputation (‘Nameless’) and no connections (‘Friendless’), she has little chance of a sale. Behind her, two leering men emphasise the impression of her isolation and vulnerability.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing Emily Mary Osborn’s Barbara Bodichon (1827-1891) Nd (below)

Emily Mary Osborn (1828-1925)

Barbara Bodichon (1827-1891) (installation view)

Nd

Oil on canvas

120 x 97cm

Girton College, University of Cambridge

Martha Darley Mutrie (British, 1824-1885)

Wild Flowers at the Corner of a Cornfield

1855-1860

Oil on canvas

Support: 821 × 632 mm

Frame: 958 × 781 × 65 mm

Photo: Tate (Seraphina Neville)

Martha Darley Mutrie is considered one of the leading painters of flowers active in Britain in the nineteenth century. She was born in Ardwick, near Manchester. She trained together with her sister, the painter Annie Feray Mutrie (1826-1893), under George Wallis (1811-1891) at the Manchester School of Design from 1844 to 1846, and also undertook private lessons with him. The sisters began exhibiting at the Royal Manchester Institution from 1845 and at the Royal Academy, London, showing there consistently from the early 1850s. Their work was regularly well received by the critics. Mutrie and her sister moved to London in 1854, where they painted flowers in interior settings, carefully arranged, and also outdoors in mock natural settings.

Despite the prominence of women artists painting still lifes and flowers, the men practitioners of the genre, such as George Lance (1802-1864) and William Henry ‘Birds Nest’ Hunt (1790-1864), received greater critical and institutional attention. Martha and Annie Mutrie achieved success that was otherwise rare for women working as artists at the time.

The art critic John Ruskin admired both artists’ work and wrote about one of Annie’s pictures in his review of the 1855 Royal Academy exhibition. In his review Ruskin suggested that she abandon artificial compositions and paint instead ‘some banks of flowers in wild country, just as they grow’ (John Ruskin, Notes on Some of the Principal Pictures Exhibited at the Royal Academy, London, 1855). This painting might be seen as a response to Ruskin’s insight and the advances in science that in the 1850s brought a new focus to the study of nature, with arguments over beauty and truth.

Text from the Tate website

Florence Claxton (British, 1838-1920)

‘Woman’s Work’: A Medley

1861

Oil on canvas

Martin Beisly Fine Art, London

In the 1850s, Claxton became part of the UK’s first organised movement for women’s rights. Woman’s Work satirises women’s opportunities for professional employment. At its centre a group of women fawn at the feet of a man seated below a statue of the Golden Calf – a false idol. Confined by

a surrounding wall, doors to professions such as medicine are shut to the women. Only the artist Rosa Bonheur has managed to scale the wall’s heights. The painting was exhibited at London’s National Institution for Fine Arts in 1861 and received mixed reviews. Some praised its comic strength but others described it as ‘vulgar’.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

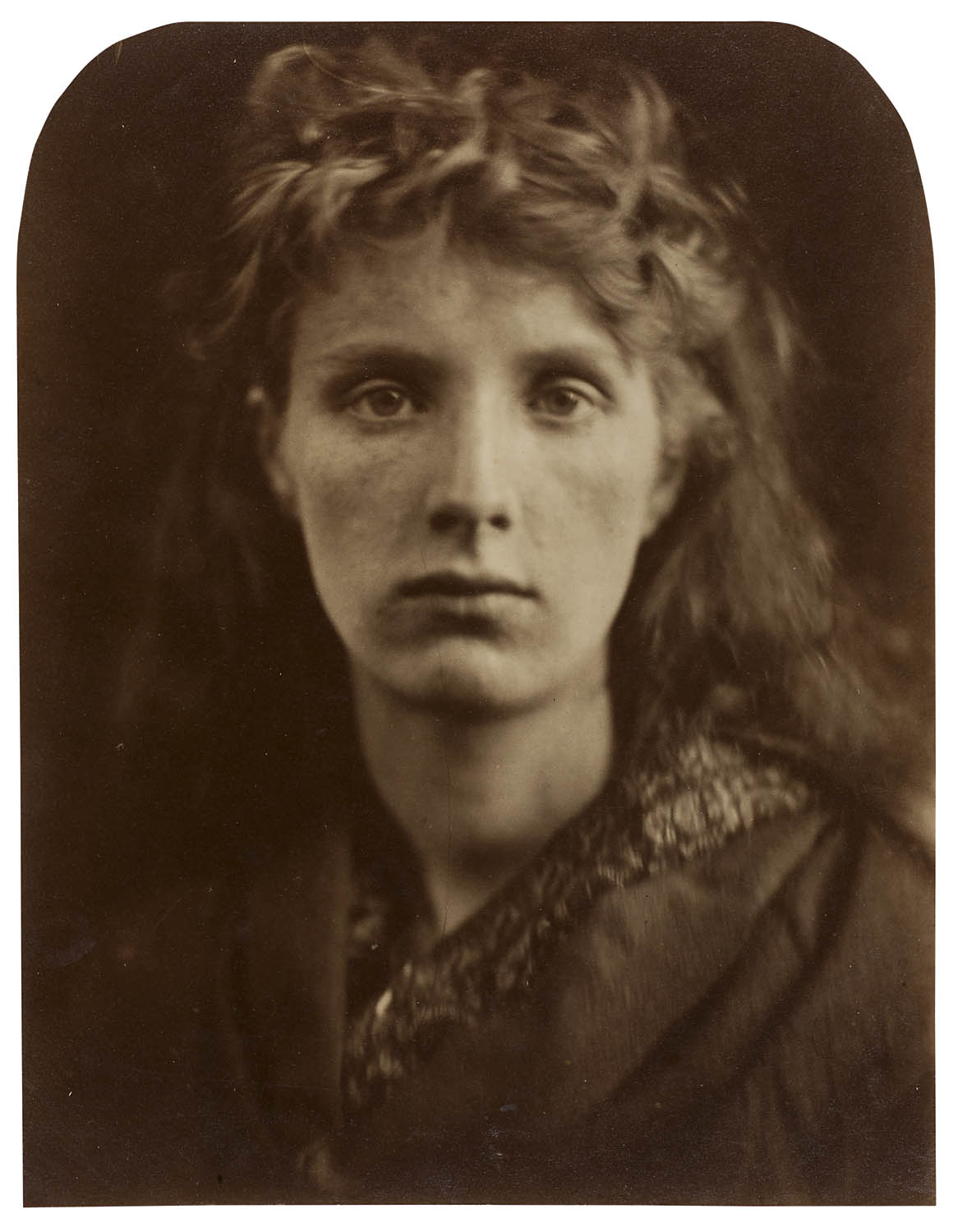

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Mountain Nymph, Sweet Liberty

1865

Albumen print

Wilson Centre of Photography

Annie Keene (1842/3-1901) was an artist’s model at the Royal Academy Schools. Cameron showed Keene’s portrait at the 1866 Hampshire and Isle of Wight Loan Exhibition, and it was for sale at her 1868 exhibition at London’s German Gallery. In this photograph, Cameron’s shallow depth-of-field gives a bold effect. Her friend, the scientist and photographic innovator John Herschel (1792-1871), praised the portrait as ‘a most astonishing piece of high relief – She is absolutely alive and thrusting out her head from the paper into the air’.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Elizabeth Butler (British, 1846-1933)

The Roll Call

1874

Oil on canvas

93.3 x 183.5cm (support, canvas/panel/stretcher external)

Royal Collection Trust

© Royal Collection Trust / His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Butler specialised in battle paintings, challenging society’s expectations of women artists. The exhibition of The Roll Call at the Royal Academy in 1874 was one of the greatest art sensations of the nineteenth century. It was praised by Academicians and hung ‘on the line’ (the most prestigious, eye-level position). The painting proved so popular with the public that a policeman had to be stationed nearby to protect the adjacent paintings. Queen Victoria summoned the work to Buckingham Palace for a private viewing, and the copyright sold for the enormous sum of £1,200.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

The Roll Call captured the imagination of the country when exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1874, turning the artist into a national celebrity. So popular was the painting that a policeman had to be stationed before it to hold back the crowds and it went on to tour the country in triumph. The painting’s focus on the endurance and bravery of ordinary soldiers without reference to the commanders of the army accorded with the mood of the times and the increasing awareness of the need for social and military reforms.

Though the public had been exposed to other images of the Crimean War, primarily prints, photographs and newspaper illustrations, never before had the plight of ordinary soldiers been portrayed with such realism. Butler researched her subject by studying A. W. Kinglake’s seminal history of the Crimean War, as well as by consulting veterans of the Crimea, several of whom served as models for the painting. She also painstakingly sought out uniforms and equipment from the Crimean period in order to be correct in the smallest military details. The sombre mood and simple yet dramatic composition Butler achieved in The Roll Call vividly epitomised the grimness not only of the Crimean War but of all wars.

Text from the Royal Collection Trust website

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing at left, Louise Jopling’s Through the Looking-Glass 1875 (below); and at right, Jopling’s A Modern Cinderella 1875 (below)

Louise Jopling (English, 1843-1933)

Through the Looking-Glass

1875

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 539 × 437 mm

Tate

Purchased with funds provided by the Nicholas Themans Trust and Tate Patrons 2024

Photo: Tate (Sonal Bakrania)

This is a self-portrait Jopling made while pregnant with her son, Lindsay, in 1875.

Jopling was one of the most successful and best-known women artists of the late nineteenth century. She exhibited regularly and, from the 1880s, ran her own art school for women. Jopling hosted receptions and established connections with many artists and art dealers. She carefully planned the exhibition of her work by choosing venues appropriate to each painting’s scale and ambition. Jopling sent this self-portrait to the Society of Lady Artists in 1875. In the same year, A Modern Cinderella, hanging nearby, was shown at the Royal Academy. Both works were purchased by the dealer Agnew: this work for £26, but Cinderella for £262.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Tabitha Barber, curator of the exhibition, said: “What’s happened to Jopling’s legacy is the story of what’s happened to most women artists … They have been regarded, studied and judged differently.”

Jopling, who in 1901 became one of the first women admitted to the Royal Society of British Artists, was a celebrated artist in her day, Barber said. Her patrons included the de Rothschild family, and the Grosvenor Gallery founders Sir Coutts and Lady Lindsay. “At a time when women weren’t allowed to be members of the Royal Academy, her works were exhibited there almost every year and spoken about in the press. She was reviewed by male art critics, and reviewed well.”

Jopling’s paintings were also commercially successful, selling for some of the highest prices that British female artists could command – albeit far less than their male contemporaries.

“She is among a handful of female artists who were society figures and household names – and it just seems so astonishing that they’re so little known now,” said Barber.

Donna Ferguson. “Tate Britain acquires first painting by pioneering English female artist overlooked for a century,” on The Guardian website 12 May 2024 [Online] Cited 02/09/2024

Louise Jopling (English, 1843-1933)

A Modern Cinderella

1875

Oil on canvas

Support: 910 × 700 mm

Private collection

Louise Jopling (English, 1843-1933)

A Modern Cinderella

1875

Oil on canvas

Support: 910 × 700 mm

Private collection

A Modern Cinderella shows a model removing her fine clothes at the end of a painting session. A glimpse of Jopling’s easel can be seen in the mirror’s reflection. In 1875, Jopling exhibited this work at the Royal Academy. There, the model’s naked shoulder was cause for criticism. Although one reviewer thought it was ‘quite harmless’, a picture dealer’s wife reportedly said that ‘she could never hang such a thing in her house’. Jopling also showed the painting at the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris, where she had also trained.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

If this is, indeed, a self-portrait, Jopling has painted herself as somewhere in the liminal space between the social groups she simultaneously belonged to and was excluded from. Despite Jopling’s notoriety and prominence among high-class Pre-Raphaelite artist circles, she experienced a high degree of discrimination. In 1883, she was commissioned to paint a portrait for 150 guineas but lost her employment in favour of Sir John Everett Millais, who requested 1000 guineas for the same project (Clement). In the traditional circles of high society, Jopling was looked down upon for pursuing a career in the fine arts, which was inherently a masculine task. The woman in the image is either taking the dress off or putting it on, but either way, has turned her back to her easel, which could be interpreted as forfeiting a part of her true identity to fit either end of the accepted spectrum of femininity. The underclothing she portrays herself in fit the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic style of dress, which fit natural waists and emphasised a woman’s beauty through medieval and Greek-inspired silhouettes (Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Shire Publications, 2016). The inclusion of this white aesthetic dress, as well as the scandalous drop of the strap is a signal of societal rebellion against traditional beauty norms. The woman in the image could also be read as shedding the skin of the two dresses before her to reveal her true, natural, artistic self below.

Emily Goldstein. “‘A modern Cinderella, 1875. Oil on Canvas’ by Louise Jopling,” on the COVE Studio website 23/10/2020 [Online] Cited 02/09/2024

Marianne Stokes (Austrian, 1855-1927)

The Passing Train

1890

Oil on canvas

Support: 600 × 760 mm

Frame: 885 × 955 mm

Private collection

Marianne Stokes (née Preindlsberger; 1855-1927) was an Austrian painter. She settled in England after her marriage to Adrian Scott Stokes (1854-1935), the landscape painter, whom she had met in Pont-Aven. Stokes was considered one of the leading women artists in Victorian England.

Annie Louisa Swynnerton ARA (British, 1844-1933)

Mater Triumphalis

1892

Paris, musée d’Orsay

Donated by Edmund Davis, 1915

Swynnerton campaigned for women’s suffrage, access to professional training, and equal opportunities. She rebelled against the belief that ‘women could not paint’. Exhibited at the New Gallery in 1892, Mater Triumphalis was regarded as a bold work. It brought Swynnerton international recognition, winning a medal at the 1893 World Exposition in Chicago. Despite this, Swynnerton received mixed reviews from British critics. They were impressed by the artist’s skill and the painting’s ‘quivering life’ but found the ‘frank realism’ of the woman’s naked body disconcerting.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

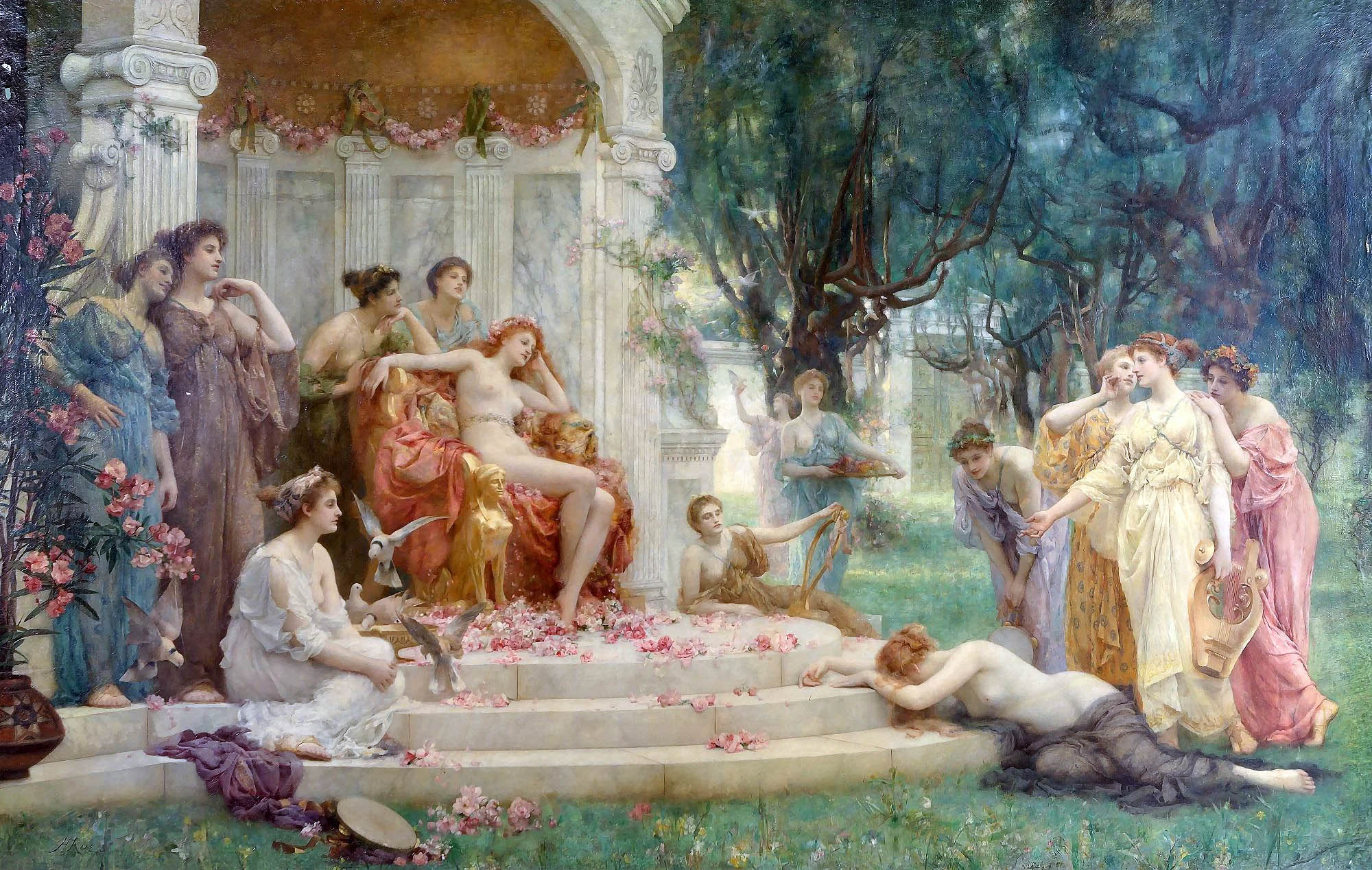

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing Henrietta Rae’s Psyche before the throne of Venus 1894 (below)

Henrietta Rae (British, 1859-1928)

Psyche before the throne of Venus

1894

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 1941 × 3058 × 31 mm

Frame: 2525 × 3826 × 270 mm

Lent from a private collection, courtesy of Martin Beisly Fine Art

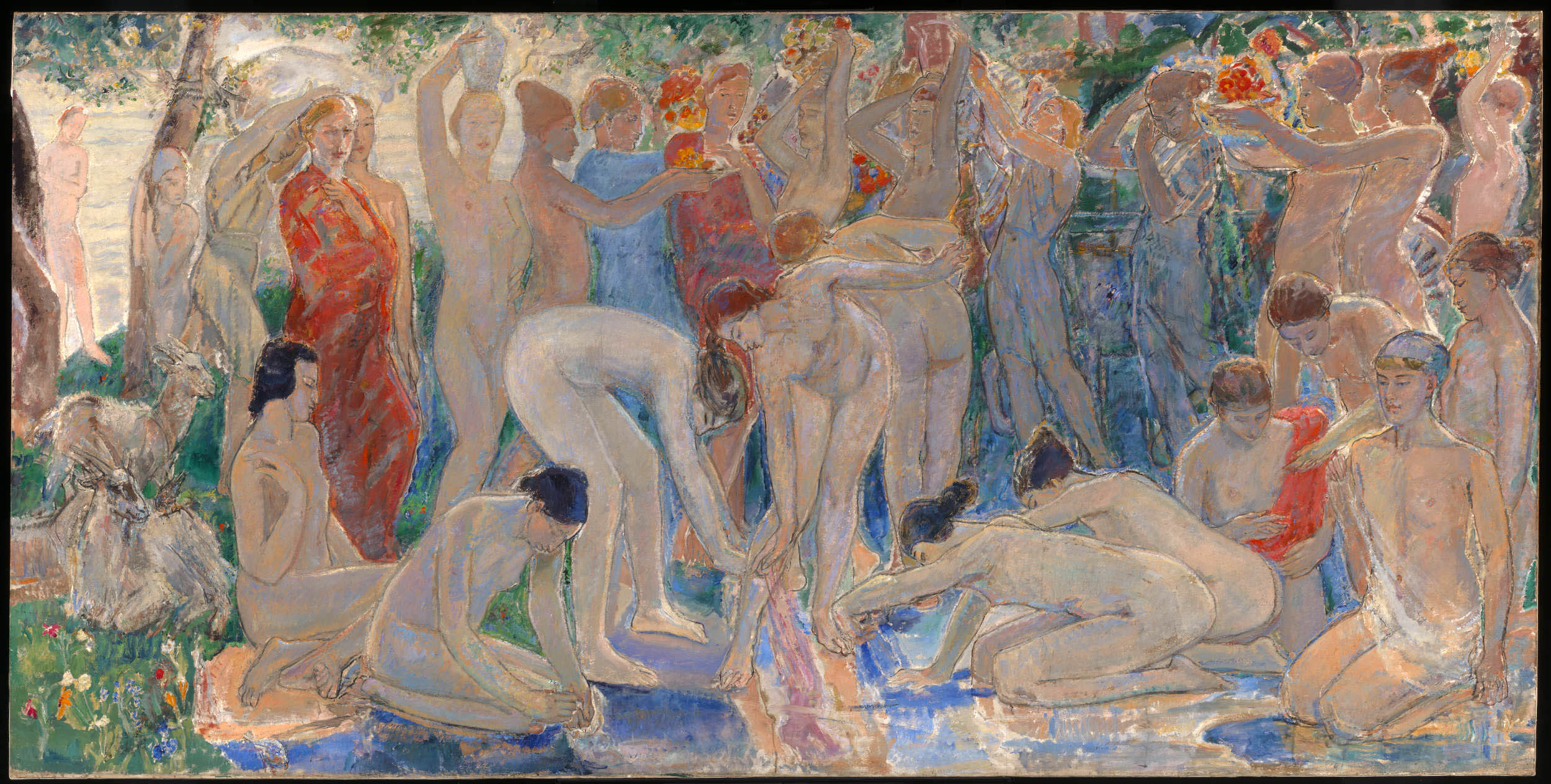

Rae was determined not to be pigeonholed as a ‘woman artist’. She painted classical nude compositions despite the belief that they were not a suitable subject for women artists. Against these odds, Psyche Before the Throne of Venus was a success at the 1894 Royal Academy Exhibition, and Rae received praise from critics as well as members of the Academy. The periodical The Englishwoman’s Review described the painting as ‘the most ambitious and successful woman’s work yet exhibited – one which could not have been executed a few years ago, when we had not the opportunity of studying from the life’.

Text from the exhibition large print guide

Installation view of the exhibition Now You See Us Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 at Tate Britain showing Lucy Kemp-Welch’s Colt Hunting in the New Forest 1897

One of the most important pieces of art ever inspired by the New Forest was a painting by Lucy Kemp-Welch (1869-1958), entitled ‘Colt Hunting in the New Forest’. This painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1897, when she was only 26 years old. It was an impressive canvas measuring 1537 x 3060 mm (approximately 5ft x 10ft) and was described as depicting ‘a wide glade in the forest, along which race a number of colts unwilling to relinquish their liberty and to fall into the hands of the four mounted lads who try to catch them’.[1] Lucy Kemp-Welch was born in Bournemouth, in 1869, and spent much of her time wandering in the New Forest, where she ‘personally studied the wild ponies in this pleasant part of England’.[2] Her love of horses and wild ponies remained with her all her life. In order to capture the energy and excitement of the pony drifts for ‘Colt Hunting’ she actually had the full-sized canvas transported to the Forest, where she sketched from life, as the commoners galloped their ponies past her. When the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy it caused a sensation and was promptly purchased for £525.00.[3] The buyers were trustees of the Chantrey Bequest, who administered a large sum of money left in the will of Sir F. L. Chantrey to obtain works of art by British artists, in order to create a national collection. It was only the third time, since its creation in 1875, that the Chantrey Bequest had purchased artwork by a woman. Lucy Kemp-Welch became a celebrity overnight.[4]