Exhibition dates: 13th June, 2025 – 4th January, 2026

Curator: Maria L. Kelly, High Museum of Art assistant curator of photography

Aaron Siskind (American, 1903-1991)

Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation #37

1953

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Adair and Joe B. Massey in honour of Gus Kayafas

Aaron Siskind was recognised for the ways he rendered his surroundings into often stark shapes and forms, which reflected his fascination with contemporary trends in abstract art. He was an influential teacher at Chicago’s Institute of Design, which was founded by László Moholy-Nagy as the New Bauhaus. This image of a person flying or falling comes from a series Siskind made of the contorted bodies of divers plunging into Lake Michigan. He masterfully created its disorienting effect through tight focus on the floating figure without contextual elements.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

While contemporarily AI-powered technologies are revolutionising the way we interact with and consume media, enabling us to “to process and analyse vast amounts of data quickly, making it easier to find and access the information we need” in the 1920s and 1930s there was also a revolution in the way artists (and their use of the camera) viewed and felt the world – one not based on information, image quality or duplicity in the veracity of the image but one based on the word, perspective – be that point of view, context, close ups, surreality, fragmentation, scale, concept, construction, colour, aesthetics, identity, gender, or radical experimentation.

In this departure from traditional photographic methods, “New Vision photographers foregrounded experimental techniques, including photograms, photomontages and compositions that favoured extreme angles and unusual viewpoints, and these extended to movements such as surrealism and constructivism.” (Press release)

To me, this New Vision is about experiencing different perspectives – experiencing, sensing, feeling and seeing the world in a new light. After the disasters and machine-ations, the destruction of a conservative way of life before the First World War, here was a way to grasp hold of (and picture) the speed of a new world order, the dreams of physiological analysis, the diversity of new identities, and the fluidity of rapidly evolving technological and social cultures.

While today this (r)evolution continues at an ever expanding pace with the consumption of huge amounts of information and images, I believe it may be advantageous to rest for a while on certain experiences and images … so that we let the daggers drop from our eyes, to ‘not make images’ in our minds eye but just to be present in the viewing of a photograph, so that we appreciate and understand every aspect of the great life spirit of this wondrous earth.

Then and now, new vision.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the High Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The New Vision movement of the 1920s and 1930s offered a revolutionary approach to seeing the world. It represented a rebellion against traditional photographic methods and an embrace of avant-garde experimentation and innovative techniques. László Moholy-Nagy, an artist and influential teacher at the Bauhaus in Germany, named this period of expansion the “New Vision.” Today, the term encompasses photographic developments that took place between the two World Wars in Europe, America, and beyond. New Vision photographers foregrounded inventive techniques, including photograms, photomontages, and light studies, and made photographs that favoured extreme angles and unusual viewpoints. These approaches – which also extended to more defined movements like Surrealism – spoke to a desire to find and see different perspectives in the wake of World War I.

Uniting more than one hundred works from the High’s photography collection, the exhibition traces the movement’s impact, from its origins in the 1920s to today, and demonstrates its long-standing effect on subsequent generations.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

Photography’s New Vision: Experiments in Seeing

Named by the influential German artist and teacher László Moholy-Nagy, the “New Vision” comprised an expansive variety of photographic exploration that took place in Europe, America, and beyond in the 1920s and 1930s. The movement was characterised by its departure from traditional photographic methods. New Vision photographers foregrounded experimental techniques, including photograms, photomontages, and light studies, and made photographs that favoured extreme angles and unusual viewpoints.

This exhibition, uniting more than one hundred works from the High’s robust photography collection, will trace the impact of the New Vision movement from its origins in the 1920s to today. Photographs from that era by Ilse Bing, Alexander Rodchenko, Imogen Cunningham, and Moholy-Nagy will be complemented by a multitude of works by modern and contemporary artists such as Barbara Kasten, Jerry Uelsmann, Hiroshi Sugimoto, and Abelardo Morell to demonstrate the long-standing impact of the movement on subsequent generations.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

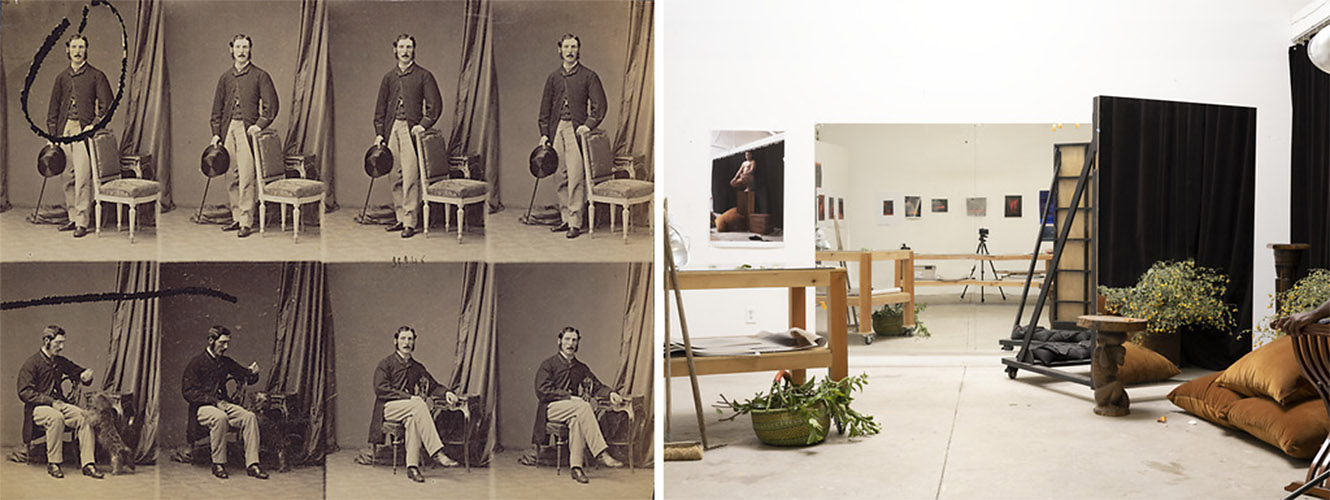

Installation views of the exhibition Photography’s New Vision: Experiments in Seeing at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, June 2025 – January 2026

Photos: Mike Jensen

The High Museum of Art presents “Photography’s New Vision: Experiments in Seeing” (June 13, 2025 – Jan. 4, 2026), an exhibition uniting more than 100 works from the High’s robust photography collection to trace the impact of the New Vision movement from its origins in the 1920s to today. Works include century-old photographs exemplifying themes from the movement and modern and contemporary images that emphasise the relevance of current artistic and social practices as a response to the technological and cultural changes that occurred in the early 20th century.

“This exhibition provides an opportunity to illuminate photographers’ creativity and innovative practices, all inspired by the progression of the medium in the 1920s and 30s,” said High Museum of Art Director Rand Suffolk. “Many of the works are rarely on view, so it will be an exciting experience for visitors to see them and learn about photographers’ abilities as they reflect reality while experimenting with technique and perspective.” Named by the influential German artist and teacher László Moholy-Nagy, the “New Vision” comprised an expansive variety of photographic exploration that took place in Europe, America and beyond in the 1920s and 1930s. The movement was characterised by its departure from traditional photographic methods. New Vision photographers foregrounded experimental techniques, including photograms, photomontages and compositions that favoured extreme angles and unusual viewpoints, and these extended to movements such as surrealism and constructivism.

“Experiments in Seeing” features nearly 100 photographers. It also demonstrates how the New Vision movement revolutionised the medium of photography in the early 20th century in response to the great societal, economic and technological shifts spurred by the upheaval of the two World Wars. Photographs from that era by Ilse Bing, Alexander Rodchenko, Imogen Cunningham and Moholy-Nagy have been complemented by a multitude of photographs by modern and contemporary artists such as Barbara Kasten, Jerry Uelsmann, Hiroshi Sugimoto and Abelardo Morell to demonstrate the long-standing impact of the movement on subsequent generations.

The first section of the exhibition delves into experimental techniques that foreground the light-sensitive aspects of photography, followed by works created through in-camera manipulations or additions to the surfaces of the prints. Subsequent sections explore inventive methods of capturing unexpected views of the world articulated with radical angles or detailed close-ups. Other works showcase surreal approaches to subjects such as humanlike forms and bodies, the use of mirrors and doubling, and everyday scenes heightened by uncanny moments or distorted through the interplay of light, shadow and water.

“Not only does the early 20th century and its art movements continue to be influential, but that time also echoes our current moment – one that feels similarly consequential and innovative with the development of new emerging technologies and methods of communicating,” said Maria L. Kelly, the High’s assistant curator of photography. “The movements and happenings of a century ago are akin to those of today and those shown in the exhibition. There remains a desire for alternative ways to see and approach the world through art, and particularly through photography.”

“Photography’s New Vision: Experiments in Seeing” is on view in the Lucinda W. Bunnen Galleries for Photography located on the Lower Level of the High’s Wieland Pavilion.

Press release from the High Museum of Art

“Light was considered the medium that permits photography. But for me it became the main subject: the protagonist of my photography.”

Ilse Bing, c. 1920s

Light Experimentation

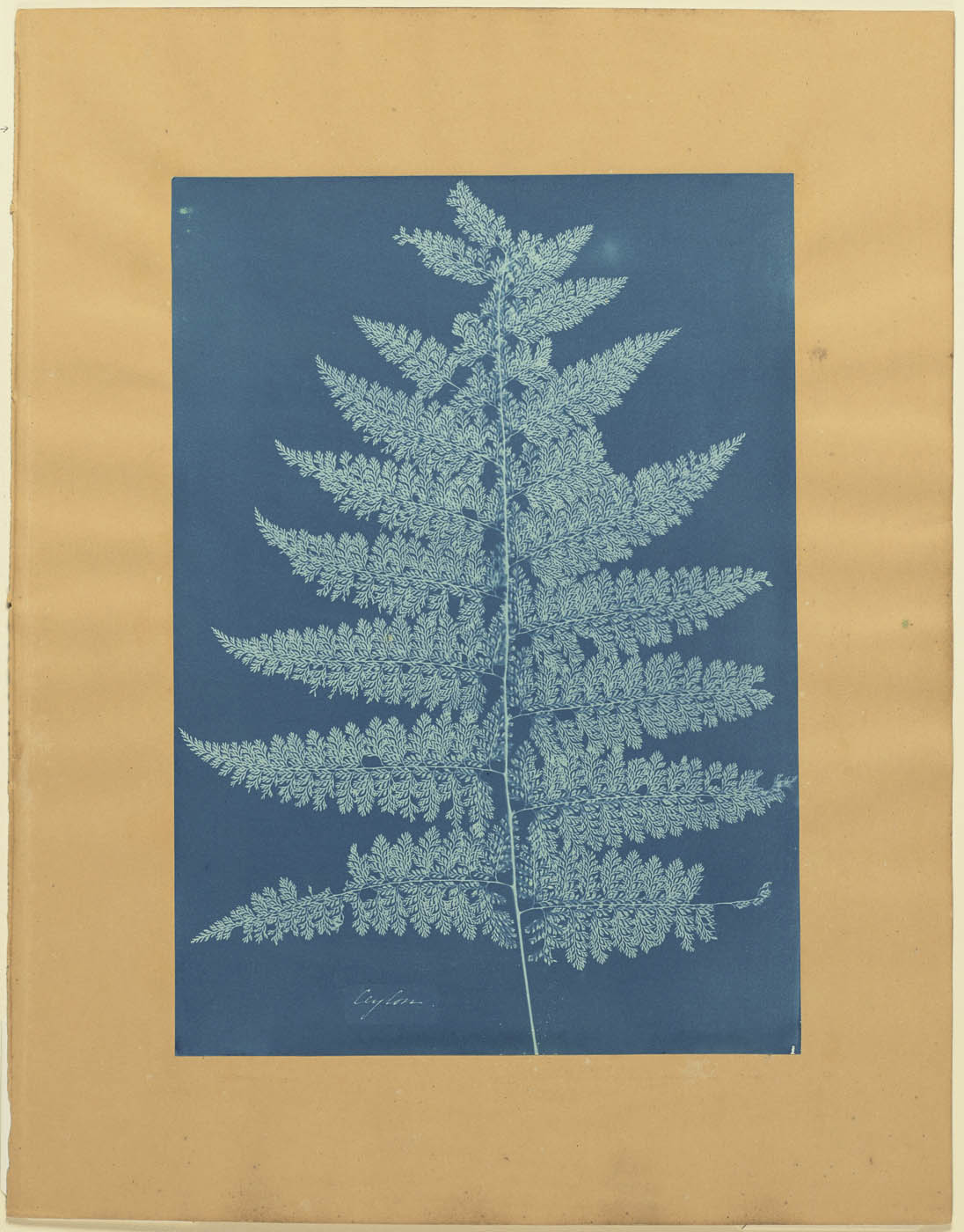

After the trauma of World War I, many artists felt compelled to reconsider conventional art making methods to better reflect and engage with the world. Some photographers turned their attention to the essential element of photography: light. Through innovative visual investigations, cameraless photographs were produced, viewes of the world altered, and scientific discoveries made.

Experimentations with illumination and light-sensitive paper in the darkroom gave rise to photograms, enabling artists to pursue abstraction and to wield light as a sculptural element. The process of solarisation – reversing tones in a print using a flash of light during developing – provided an unconventional view of a subject. Early attempts to capture traces of light on film led to scientific innovations such as using strove lights to freeze movement, depicting magnetic fields, and tracing electrical currents on light sensitive paper.

These processes aim to reveal the invisible, with the elements of change as a constant companion. While artists can insert some control over the elements, the process ultimately shapes the final image. Many artworks in this section exist as unique prints, challenging the assumption of the reproducibility of photography, and emphasising the singularity of the creative moment.

Wall text from the exhibition

Francis Bruguière (American, 1879-1945)

The Light That Never Was on Land or Sea

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Georgia-Pacific Corporation

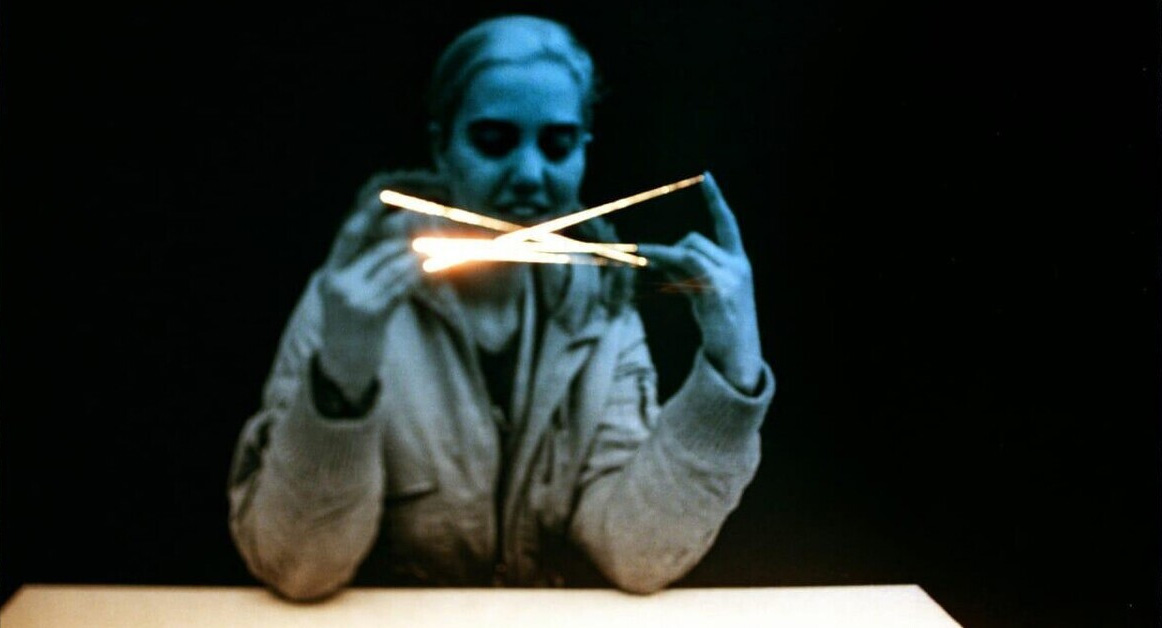

Nathan Lerner (American, 1913-1977)

Light Drawing #8 (Smoke)

1938-1939

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Hilary Leff and Elliot Groffman

![Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998) 'Untitled [Seated Woman with Necklace, Solarized]' 1943 Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998) 'Untitled [Seated Woman with Necklace, Solarized]' 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ilse-bing-seated-woman-with-necklace.jpg?w=734)

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Untitled [Seated Woman with Necklace, Solarized]

1943

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of the Estate of Ilse Bing Wolff

Harry Callahan (American, 1912-1999)

Camera Movement on Flashlight, Chicago

c. 1949

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the H. B. and Doris Massey Charitable Trust, Dr. Robert L. and Lucinda W. Bunnen, Collections Council Acquisition Fund, Jackson Fine Art, Powell, Goldstein, Frazer and Murphy, Jane and Clay Jackson, Beverly and John Baker, Roni and Sid Funk, Gloria and Paul Sternberg, and Jeffery L. Wigbels

© 2018 The Estate of Harry Callahan

Abelardo Morell (American born Cuba, b. 1948)

Still Life with Wine Glass: Photogram on 20″ x 24″ Film

2006

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of Photography

© Abelardo Morell

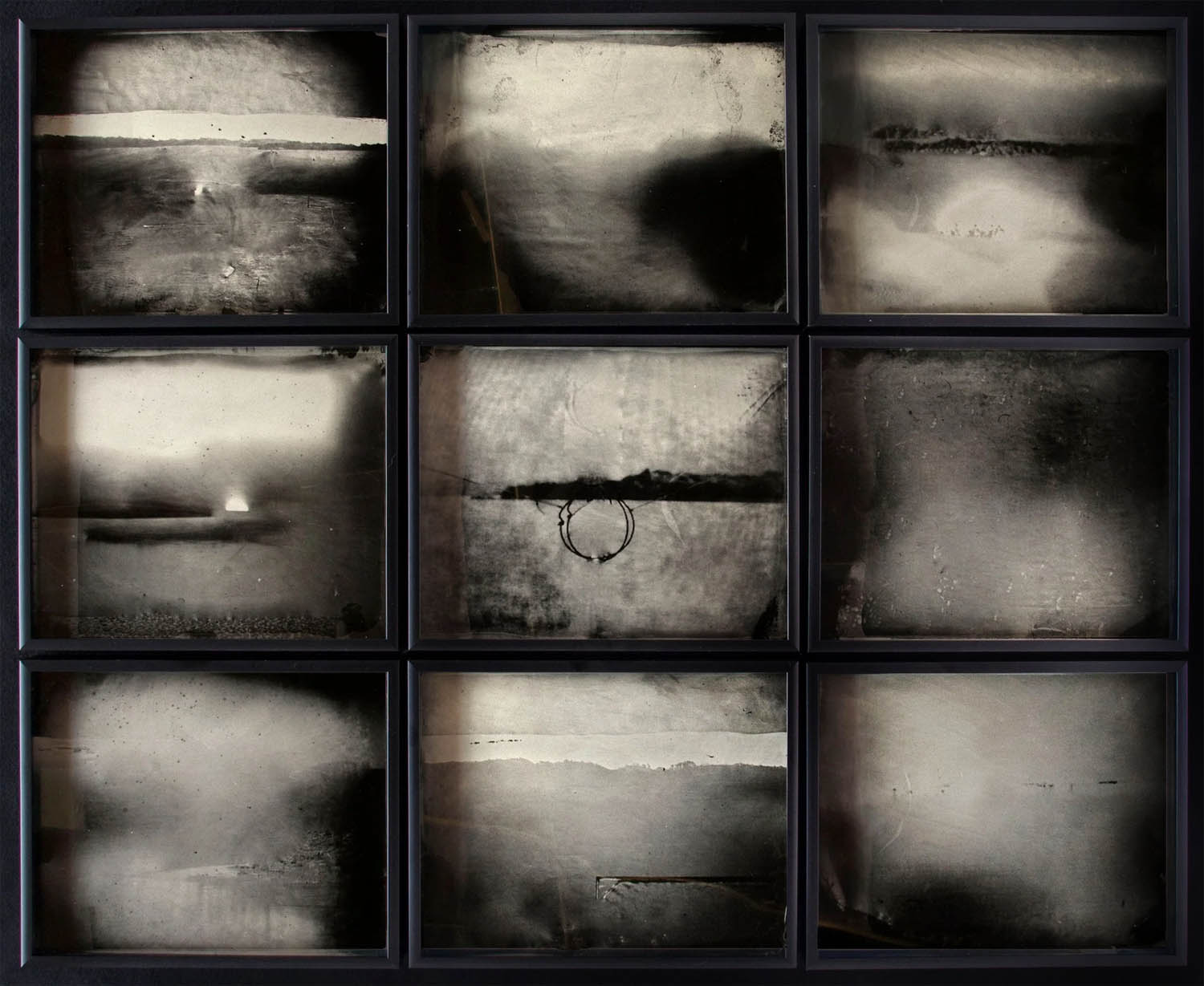

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Lightning Fields 182

2009

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase through funds provided by patrons of Collectors Evening 2012

© Hiroshi Sugimoto

Inspired by William Henry Fox Talbot, an inventor of photography who was fascinated with electromagnetic conduction, Hiroshi Sugimoto began applying charges of electricity directly to unexposed photographic film. After months of honing his technique in the darkroom, he managed to achieve remarkable results with a handheld wand charged by a generator. His Lightning Fields photographs are made without a camera or lens. Here, the abstract visual trace of an electric charge measuring over 400,000 volts sweeps across the composition, reading like the textures of a human hand, the upward tentacles of a fern, or the stark branches of a tree.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

Hans-Christian Schink (German, b. 1961)

2/26/2010, 7:54 am – 8:54 am, S36° 49.622′ E 175° 47.340′

2010

From the series 1h

© Hans-Christian Schink

Abelardo Morell (American born Cuba, b. 1948)

Camera Obscura: View of Philadelphia from Loews Hotel Room #3013 with Upside Down Bed, April 14th, 2014

2014

Pigmented inkjet print

High Museum of Art Atlanta, gift of Dr. Roger Hartl

© Abelardo Morell

V. Elizabeth Turk (American, b. 1945)

Calaeno

2018

Van Dyke print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection

© Elizabeth Turk

V. Elizabeth Turk is an Atlanta-based photographer whose work explores the connections between the human body and the natural world. To make this print, Turk used an analog process from the 1800s that involves coating a large sheet of paper with light-sensitive chemicals. She then arranged her model on top of the sheet and exposed it to light, creating a ghostly silhouette, before repeating the exposure with plants. The resulting photogram is a unique image in which botanical forms intersect with the body, alluding to bones, veins, and skin and suggesting a visceral bond between humans and the environment.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

“The limits of photography are incalculable; everything is so recent that even the mere act of searching may lead to creative results. […] The illiterate of the future will be the person ignorant of the use of the camera as well as of the pen.”

László Moholy-Nagy 1928

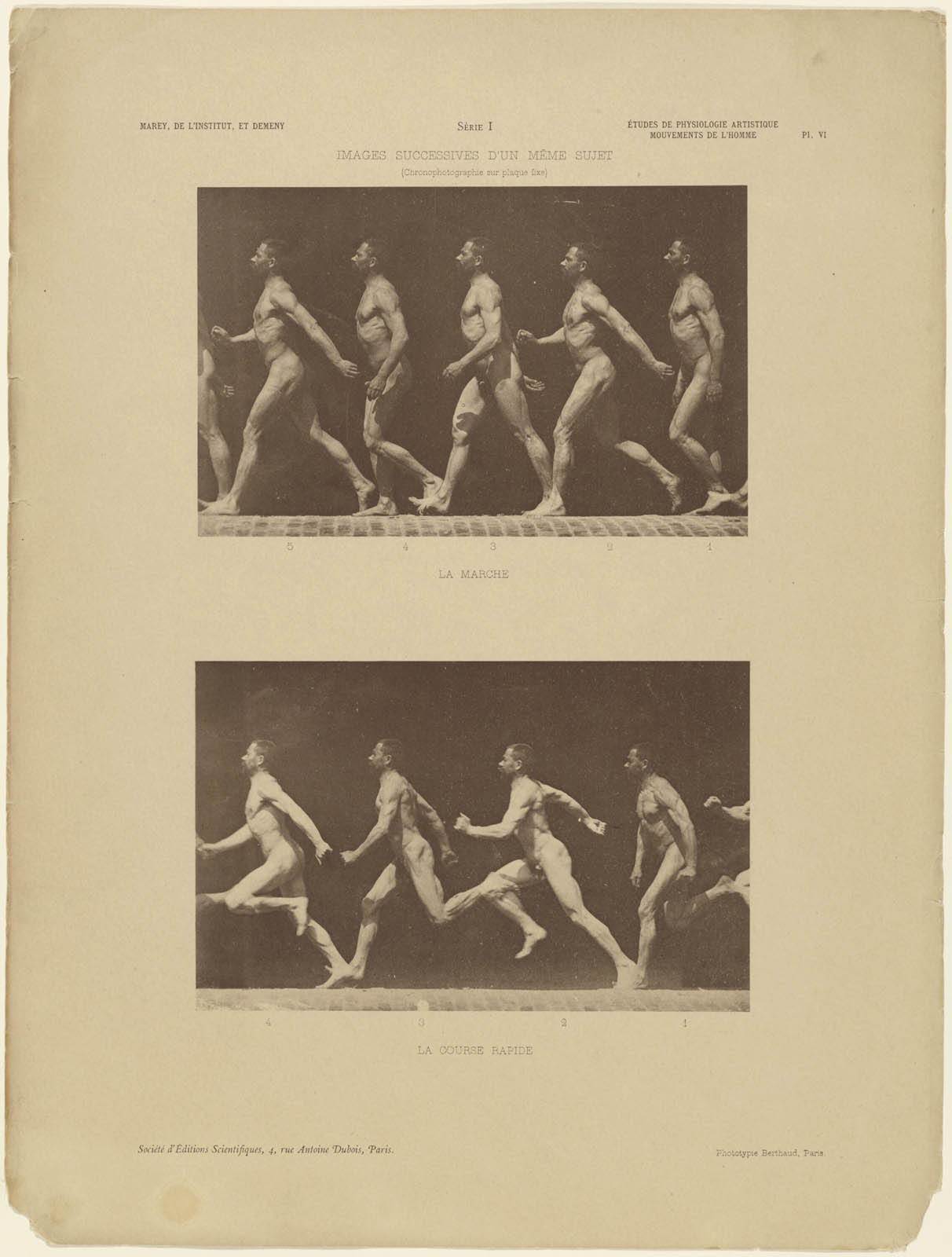

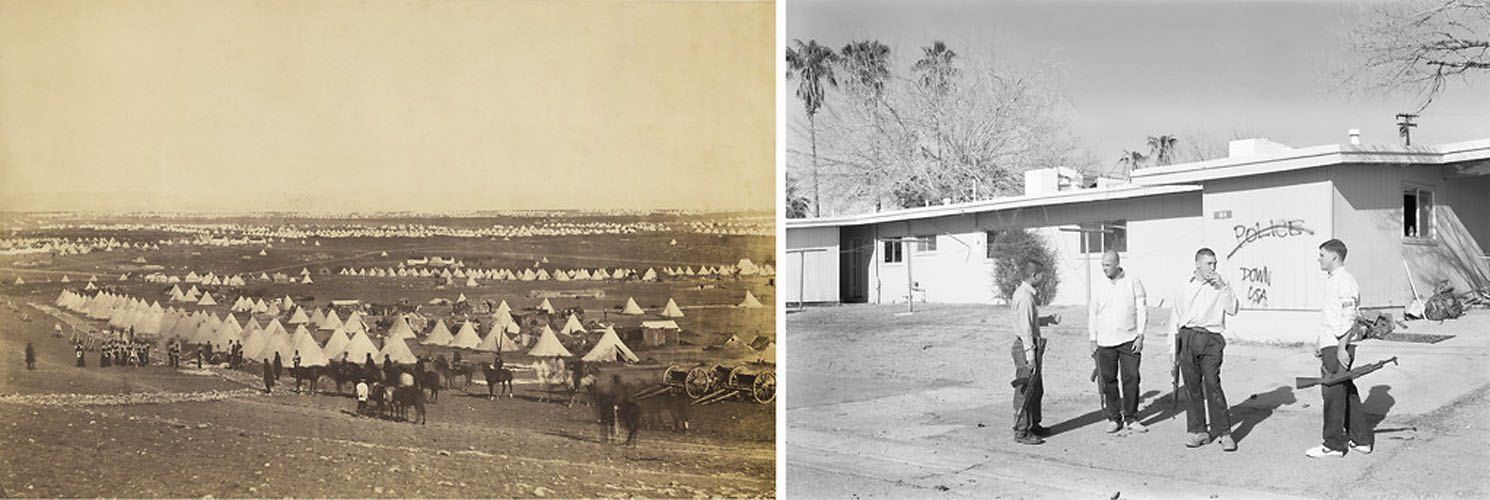

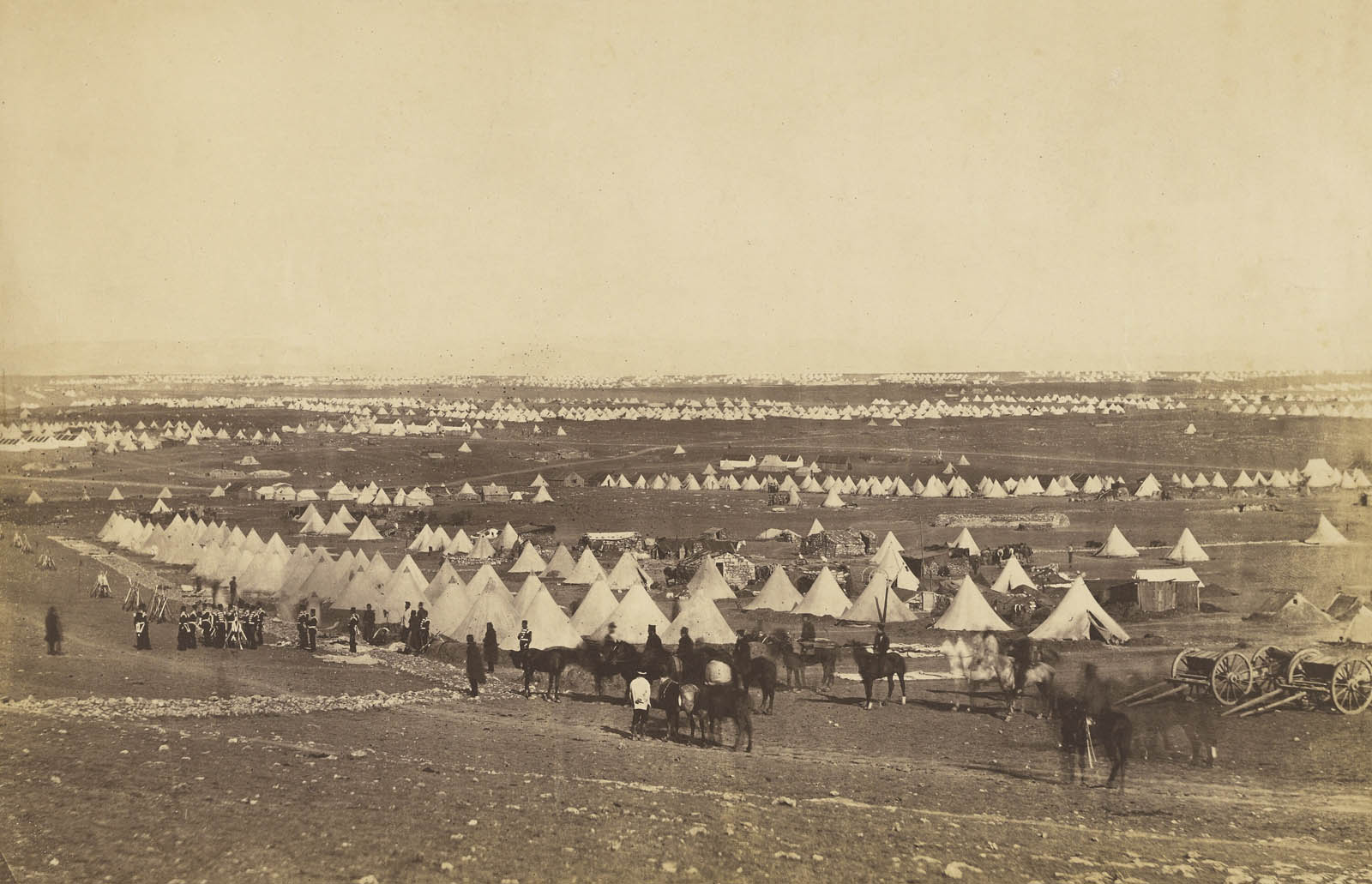

Radical Viewpoints

From photography’s inception in 1839, camera technology involved cumbersome equipment and time-consuming development processes until the advent of lightweight cameras in the 1920s. Photographers were then able to work more nimbly, transforming photography into a medium capable of capturing fleeting moments, unusual viewpoints, and multiple perspectives. The exploration of unexpected angles became a hallmark of New Vision photography. Sharp diagonals, extreme vantage points, and shortened perspectives opened novel pathways of perceiving otherwise commonplace environments.

Alexander Rodchenko, a pioneer in this method, championed the camera’s ability to reveal, stating, “in order to teach man to see from all viewpoints, it is necessary to photograph […] from completely unexpected viewpoints and in unexpected positions […] We don’t see what we are looking at. We don’t see marvellous perspectives.” This approach aimed to provide a fuller impression of subjects, prompting viewers to seek and appreciate what might otherwise be overlooked.

Though these early photographs may not appear groundbreaking today, their makers’ carefully considered methods transferred how photography is used. This is evident in photographers’ creative interpretations of their surroundings over the past century.

Wall text from the exhibition

Alexander Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1956)

Sbor na demonstratsia (Gathering for a Demonstration)

1928

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Joseph and Yolandra Alexander, Moscow/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

© Estate of Alexander Rodchenko/RAO, Moscow/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Alexander Rodchenko was a key figure in the movements of New Vision and Constructivism – abstract and functional art that reflected an industrial society. Advocating “to achieve a revolution in our visual thought,” he explored various methods, such as photographing from unexpected angles, to capture dynamic views and expose new realities. With a new, lightweight 35 mm camera, he often photographed from his apartment balcony to create dramatic scenes of the street below. The perspective in this photograph flattens the building’s stories into one visual field, giving the image a theatrical quality as an onlooker peers over the railing.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

The Bridge

1929

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Arnold H. Crane

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A central figure among twentieth-century American photographers, Walker Evans created works in his early career that sample from the New Vision aesthetic, which he may have encountered while abroad in Paris in 1926. His photographs of New York City, made after he returned to the United States, feature dramatically angled or cropped scenes of architecture and city life. Evans made numerous photographic studies of the Brooklyn Bridge from both below and on the bridge, portraying it less as a recognisable landmark and more as a hulking expanse whose form fills each tight frame.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian 1895-1946)

Stage Set for Madame Butterfly

1931

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Georgia-Pacific Corporation

Moholy-Nagy, a leader of the New Vision, had an expansive artistic practice that included painting, photography, sculpture, film, and more. As a teacher at the Bauhaus, which connected art and industry, he believed in technology’s potential to advance art and society. In 1929, he became set designer at the Kroll Opera House and created avant-garde sets with translucent and perforated materials, often making light itself a sculptural element. Lucia Moholy, a photographer, writer, teacher, and Moholy-Nagy’s first wife, was commissioned as Kroll’s stage photographer. In this image, which either artist may have made, the sharp angle shot from above complicates the set of Madame Butterfly, emphasising intersecting, moving elements and heightening areas of light and shadow.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

Lucas Foglia (American, b. 1983)

Esme Swimming, Parkroyal on Pickering, Singapore

2014

Pigmented inkjet print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Irene Zhou

© Lucas Foglia

Close Ups

Similar to the practice of using unusual angles to offer unexpected perspectives, some photographers began capturing highly detailed, close-up views of objects. This approach affords a study of texture, pattern, and structure that may otherwise go unnoticed by the human eye. By eliminating surroundings that could offer a narrative, the physicality of the object becomes the primary focus, allowing it to transcend beyond its everyday existence.

Practitioners of straight photography in the United States and the concurrent New Objectivity movement in Germany shared a core desire to unearth a balance of the familiar and the foreign within intricate images of forms. While Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston perfected carefully composed studies of plants and other natural matter, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Alexander Rodchenko, and Ralph Steiner explored scientific and industrial objects. Such images celebrated the technological advancements of the time and revealed how mechanical structures often mimic those found in nature, suggesting a shared framework, and a shared beauty, between humanmade and natural. The emphasis on detail and abstraction invites viewers to reconsider their perceptions of both the ordinary and the extraordinary in the world around them.

Wall text from the exhibition

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976)

Agave Americanus

1929

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

© The Imogen Cunningham Trust

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976)

Agave Design I

c. 1920

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Georgia-Pacific Corporation

© The Imogen Cunningham Trust

Edward Weston (American 1886-1958)

Palma Cuernavaca II

1925

Palladium print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection to mark the retirement of Gudmund Vigtel

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Ralph Steiner (American, 1899-1986)

Electrical Switches

1929

Gelatin silver print

8 x 10 5/16 inches

Purchase with funds from Georgia-Pacific Corporation

Harry Callahan (American, 1912-1999)

Weed Against Sky, Detroit

1948

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of the Callahan and Hollinger Families

© 2018 The Estate of Harry Callahan

Eugenia de Olazabal (Mexican, b. 1936)

Espinas

c. 1985

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of the artist

“Surrealism lies at the heart of the photographic enterprise: in the very creation of a duplicate world, of a reality in the second degree, narrower but more dramatic than the one perceived by natural vision.”

Susan Sontag, 1973

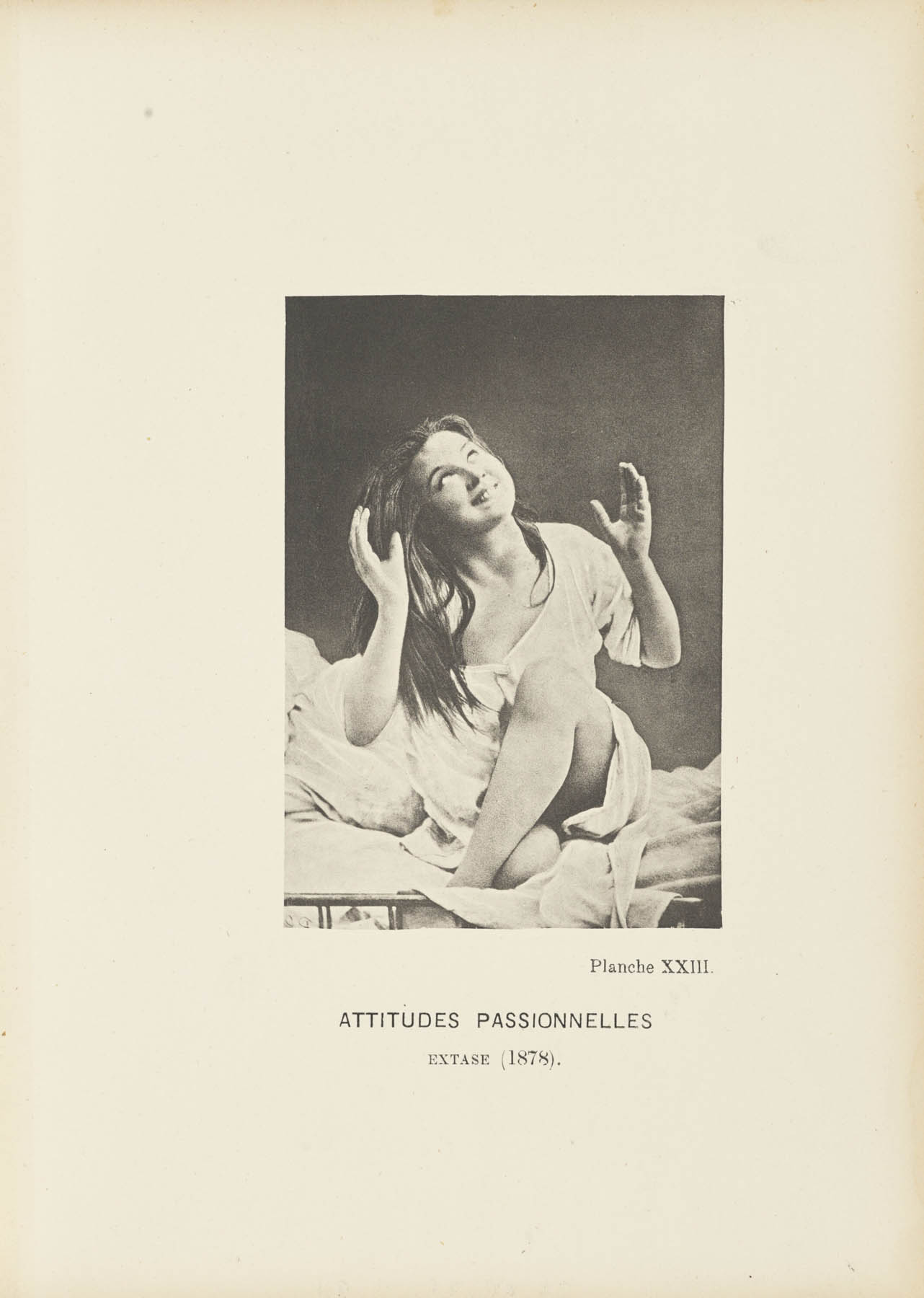

Surreality

Surrealism emerged as an artistic movement in reaction to the horrors of World War I. The often disconcerting imagery and literature of the movement reflected a world that felt disorienting and chaotic and captured how the very foundations of reason and humanity were tested and questioned through the realities of war. In his Surrealist Manifesto (1924), French writer Andre Breton advocates for a rejection of rational ways of approaching the world in four of dreams and imagination as pathways to new creative expressions.

Photography played an important role in the Surrealist movement. Artists valued how the medium could capture spontaneous moments that reveal the unexpected, be manipulated to stage scenes, or be altered with darkroom processes. They harness photography in a multitude of ways to create dreamlike and unconscious associations with reality. In these galleries, artists explore uncanny moments and create links to the human psyche by focusing on humanlike forms and fragmented body parts, mirrored and doubled views, and the impact of light and shadows in space.

Wall text from the exhibition

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Men’s Fashions (Avenue des Gobelins)

1925, printed 1956

Gelatin silver print

Purchase

Eugène Atget was the great chronicler of Paris at the turn of the century. His vast photographic archive captures a city on the precipice of modernisation. Though his photographs of empty city streets were documentary in nature, the Surrealists admired their dreamlike quality and claimed Atget as one of their own despite his protestations. They believed any photograph could shed its original context and intent when viewed with a surrealist sensibility. Atget’s photograph of mannequins peering out of a shop window appealed to the movement by embodying the uncanny valley, where the human likeness of a nonhuman entity evokes both affinity and discomfort in viewers.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

Florence Henri (Swiss born United States, 1893-1982)

Composition

1932, printed 1972

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Dr. Joe B. Massey in honor of Maria L. Kelly

Florence Henri is well known for her manipulations of light and form that create complex, surrealist scenes. She used angled mirrors to frame, obscure, and replicate portions of scenes to dissolve a sense of perspective and space, as seen in this still life comprising mirrors, pears, and an image of the sea. After only one semester studying under László Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus in 1927, Henri shifted her focus from painting to photography and began using various experimental techniques such as photomontage, multiple exposures, photograms, and negative printing.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

Barbara Kasten (American, b. 1936)

Construct NYC

1984

Dye destruction print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection

© Barbara Kasten

Barbara Kasten’s art is as much about the process of setting up innovative still life scenes as it is about the photographs she makes of them. Her Constructs series focuses on large-scale complex assemblages that she builds in her studio using a wide variety of materials, including painted wood, plaster, mirrors, screens, and fibers. Her work is not digitally altered; instead, she complicates the scene using mirrors and light, much in the tradition of Florence Henri, whose photograph is also on view in the exhibition.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

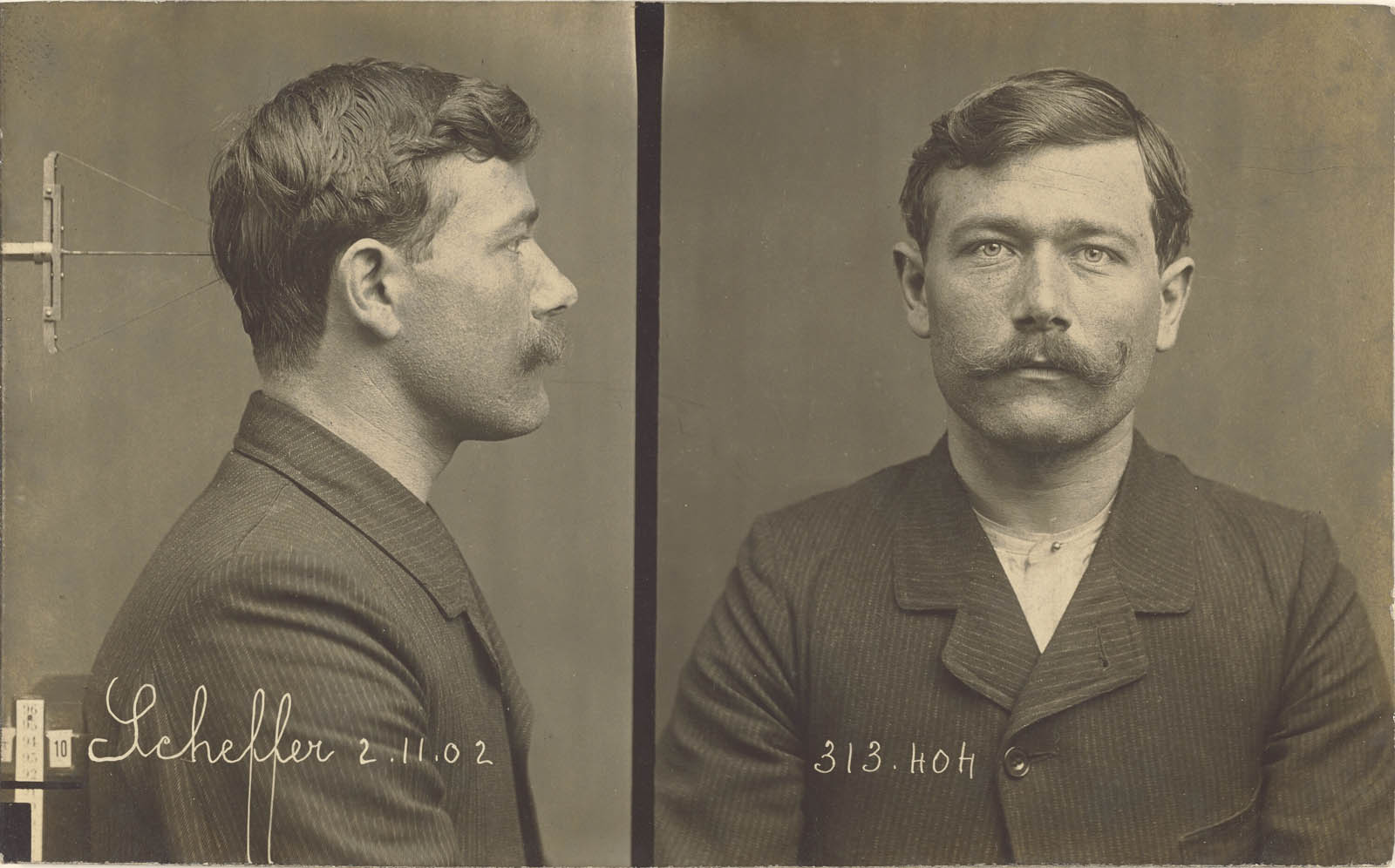

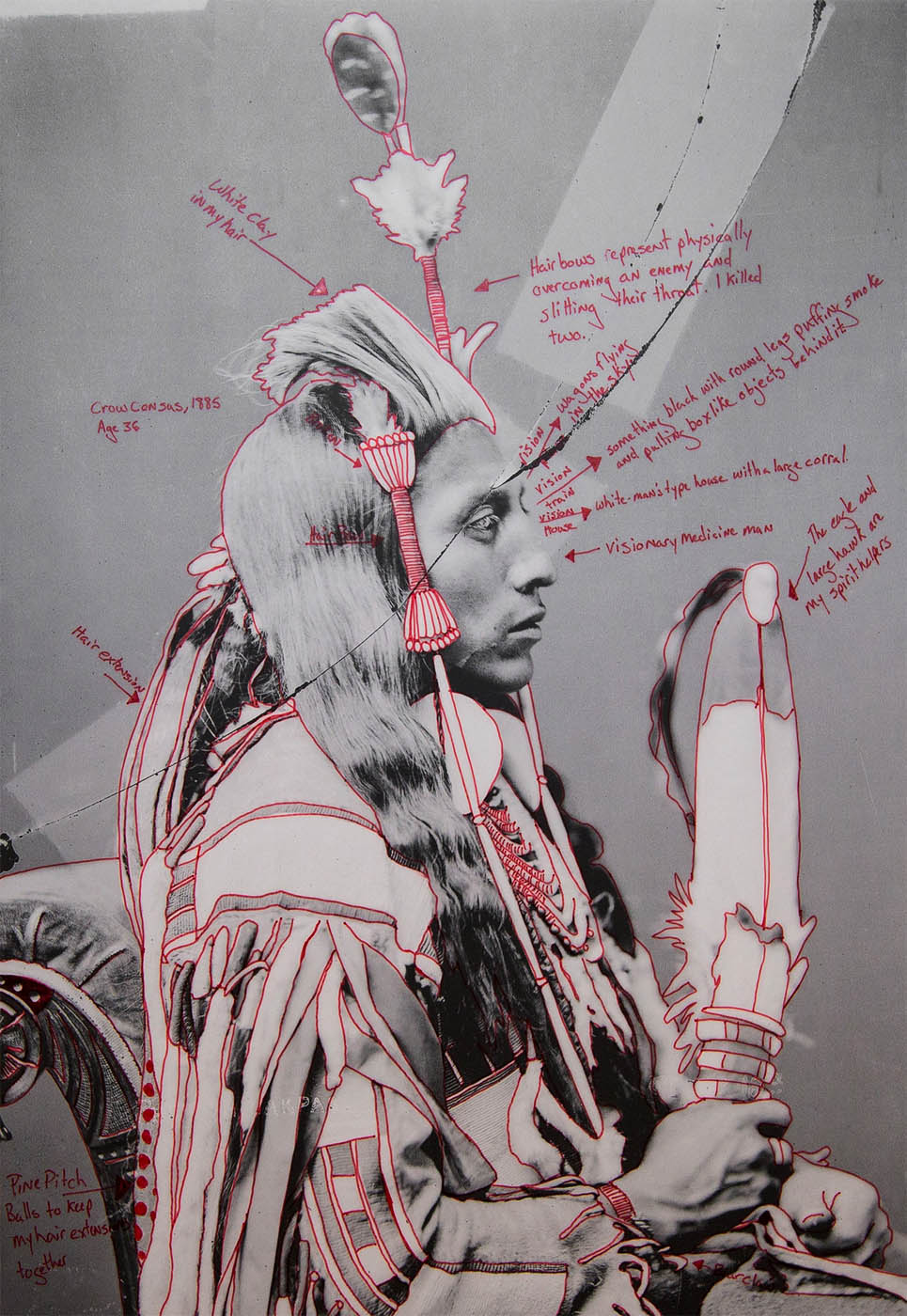

Manipulations

This final section features photographers from the New Vision period to the present day who experiment with physically manipulating photographs. Through approaches such as double exposure, photomontage, surface alteration, and multilayering, they challenge and expand our perceptions of reality. The artworks in this section prioritise the creative process through labour, intention, intervention, and theatricality.

Double exposures is the process of photographing multiple images with the same negative within the camera, resulting in layered images that often provide a frenetic, multifaceted view of a scene. In contrast to the in-camera process of double exposure, photomontage combines separate images in the darkroom to produce a final photograph that emphasises the image’s artifice and absurdity. Physically disrupting the surface of photographs with alterations such as adding unnatural colour, drawing connections, stitching into prints, or inscribing texts augments the visual experience and offers emotional and narrative depth. Finally, whether through ancient visual techniques like the camera obscure or new technologies like digital screens, these artists create enigmatic scenes by layering and physically transforming subject, composition, and image.

Wall text from the exhibition

Barbara Morgan (American, 1900-1992)

Protest

1940

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase

Charles Swedlund (American, b. 1935)

31 St. Beach

c. 1955

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Steven Nordman

© Charles Swedlund

Jerry Uelsmann (American, 1934-2022)

Untitled

1964

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from a friend of the Museum

Lucinda Bunnen (American, 1930-2022)

Untitled

1974

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Lawrence and Alfred Fox Foundation for the Ralph K. Uhry Collection

© Lucinda Bunnen

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Untitled

1989

From the Indomitable Spirit Portfolio

Gelatin silver print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Paul Mpagi Sepuya (American, b. 1982)

Studio (0X5A8180)

2021

Archival pigment print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family Foundation

© Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Noémie Goudal (French, b. 1984)

Phoenix V

2021

Dye coupler print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase through funds provided by patrons of Collectors Evening 2023

Noémie Goudal visualises “deep time” (geological history of the planet) and paleoclimatology (study of past climates) to challenge our perception of the world. Referring to the ancient continental split two billion years ago that formed South America and Africa, this image features the Phoenix atlantica, a palm tree that grows on both sides of the Atlantic. Goudal arranged strips of photographic prints of the palms made on one continent in front of the physical palms on the other and rephotographed the scene. The resulting image interweaves the two continents, creating a glitchy, kaleidoscopic view meant to unsettle our sense of stability and the constancy of the planet.

Text from the High Museum of Art website

Naima Green (American, b. 1992)

It Lingers Sweetly

2022

Pigmented inkjet print

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the LGBTQIA+ Photography Centennial Initiative

Naima Green’s practice centres connection and collaboration to cast a tender lens on her own queer community of colour. Her lyrical portraits take shape in intimate domestic spaces and airy outdoor environments that embody havens for the people in those spaces. Through double exposure and serial photographs, she provides what she calls “multiple entry points” into a moment in time, translating movements and emotions into a single image. She explains her interest in double exposure “as a means of capturing things that can’t be held in just one way … ,” allowing her to “play with loosening the narrative and letting go of some control.”

Text from the High Museum of Art website

The High Museum of Art

1280 Peachtree St NE

Atlanta, GA

30309

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Saturday 10am – 5pm

Sunday 12 – 5pm

Monday closed

![William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) '[A Stem of Delicate Leaves of an Umbrellifer]' probably 1843-1846 William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) '[A Stem of Delicate Leaves of an Umbrellifer]' probably 1843-1846](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/talbot-a-stem-of-delicate-leaves-of-an-umbrellifer.jpg)

![At left, Herbert Bell et al, '[Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers]' (2 page spread); and at right, Stephanie Syjuco (American born Philippines, b. 1974) 'Herbaria' 2021 (detail) At left, Herbert Bell et al, '[Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers]' (2 page spread); and at right, Stephanie Syjuco (American born Philippines, b. 1974) 'Herbaria' 2021 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bell-and-syjuco-herbaria.jpg)

![Herbert Bell (English, 1856-1946) Frederick Nutt Broderick (English, about 1854-1913) Gustave Hermans (Belgian, 1856-1934) Anthony Horner (English, 1853-1923) Michael Horner (English, 1843-1869) C. W. J. Johnson (American, 1833-1903) Léon & Lévy (French, active 1864-1913 or 1920) Léopold Louis Mercier (French, b. 1866) Neurdein Frères (French, founded 1860s, dissolved 1918) Louis Parnard (French, 1840-1893) Alfred Pettitt (English, 1820-1880) Francis Godolphin Osborne Stuart (British born Scotland, 1843-1923) Unknown maker Valentine & Sons (Scottish, founded 1851, dissolved 1910) L. P. Vallée (Canadian, 1837-1905) York and Son J. Kühn (French, active Paris, France 1885 - early 20th century) '[Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers]' (2 page spread) Herbert Bell (English, 1856-1946) Frederick Nutt Broderick (English, about 1854-1913) Gustave Hermans (Belgian, 1856-1934) Anthony Horner (English, 1853-1923) Michael Horner (English, 1843-1869) C. W. J. Johnson (American, 1833-1903) Léon & Lévy (French, active 1864-1913 or 1920) Léopold Louis Mercier (French, b. 1866) Neurdein Frères (French, founded 1860s, dissolved 1918) Louis Parnard (French, 1840-1893) Alfred Pettitt (English, 1820-1880) Francis Godolphin Osborne Stuart (British born Scotland, 1843-1923) Unknown maker Valentine & Sons (Scottish, founded 1851, dissolved 1910) L. P. Vallée (Canadian, 1837-1905) York and Son J. Kühn (French, active Paris, France 1885 - early 20th century) '[Amateur World Tour Album, taken with early Kodak cameras, plus purchased travel photographs by various photographers]' (2 page spread)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/amateur-world-tour-album.jpg)

![At left, William H. Mumler (American, 1832-1884) 'Mrs. Swan' 1869-1878; and at right, Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992) 'Nak Bejjen' [Cow's Horn] 2017-2018 At left, William H. Mumler (American, 1832-1884) 'Mrs. Swan' 1869-1878; and at right, Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992) 'Nak Bejjen' [Cow's Horn] 2017-2018](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/mumler-mrs.-swan-and-saye-nak-bejjen.jpg)

![Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992) 'Nak Bejjen' [Cow's Horn] 2017-2018 Khadija Saye (Gambian-British, b. 1992) 'Nak Bejjen' [Cow's Horn] 2017-2018](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/saye-nak-bejjen.jpg)

![At left, Unknown maker (American) '[Seated Woman with "Spirit" of a Young Man]' about 1865-1875; and at right, Lieko Shiga (Japanese, b. 1980) 'Talking with Me' 2005 From the series 'Lilly' At left, Unknown maker (American) '[Seated Woman with "Spirit" of a Young Man]' about 1865-1875; and at right, Lieko Shiga (Japanese, b. 1980) 'Talking with Me' 2005 From the series 'Lilly'](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/seated-woman-and-shiga-talking-with-me.jpg)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Seated Woman with "Spirit" of a Young Man]' about 1865-1875 Unknown maker (American) '[Seated Woman with "Spirit" of a Young Man]' about 1865-1875](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/seated-woman-with-spirit.jpg)

![A.J. Russell (American, 1830-1902) 'Embankment No. 3 West of Granite Cannon [Wyoming]' April 1868 A.J. Russell (American, 1830-1902) 'Embankment No. 3 West of Granite Cannon [Wyoming]' April 1868](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/russell-embankment-no.-3-west-of-granite-cannon.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.