Exhibition dates: 16th October 2012 – 20th January 2013

Please note: This posting contains photographs of nudity. If you do not like please do not look

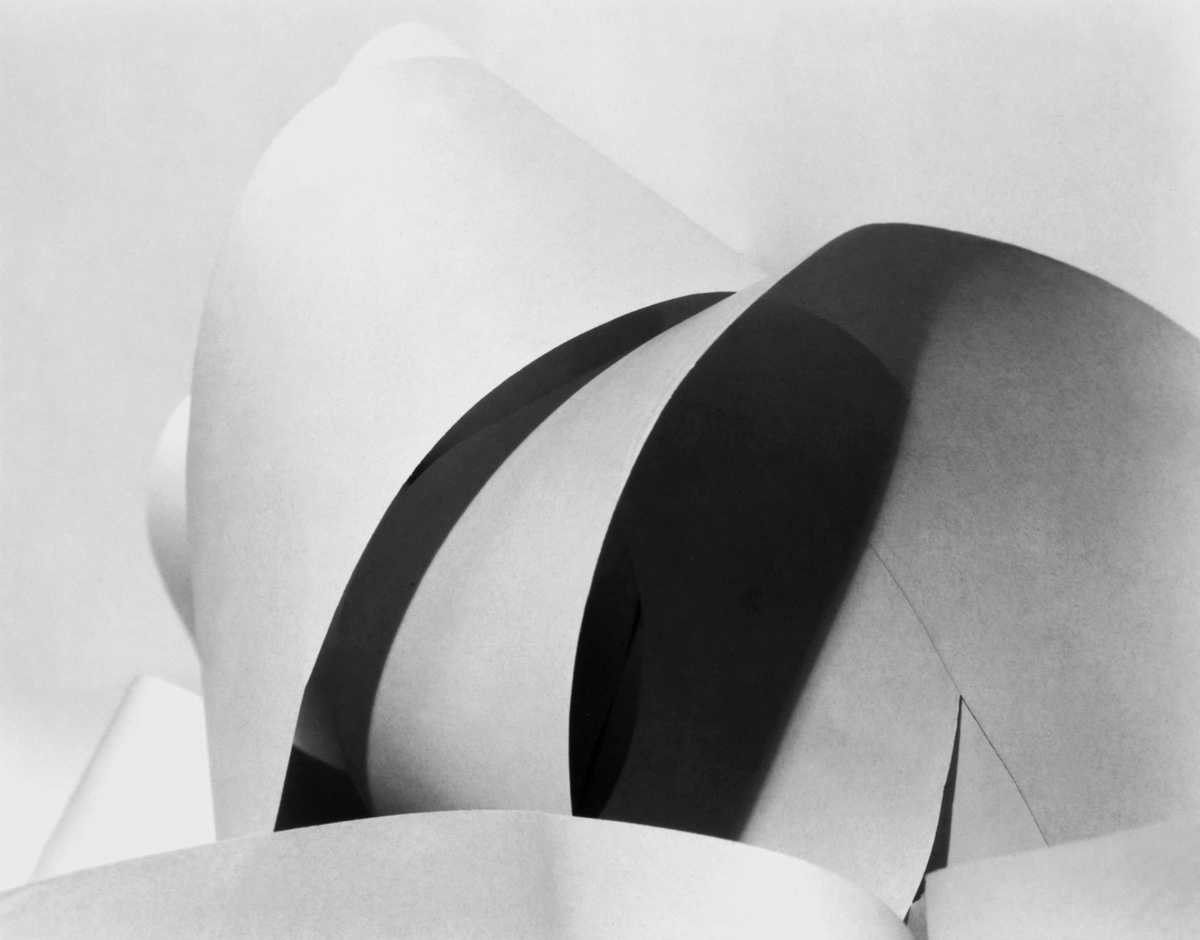

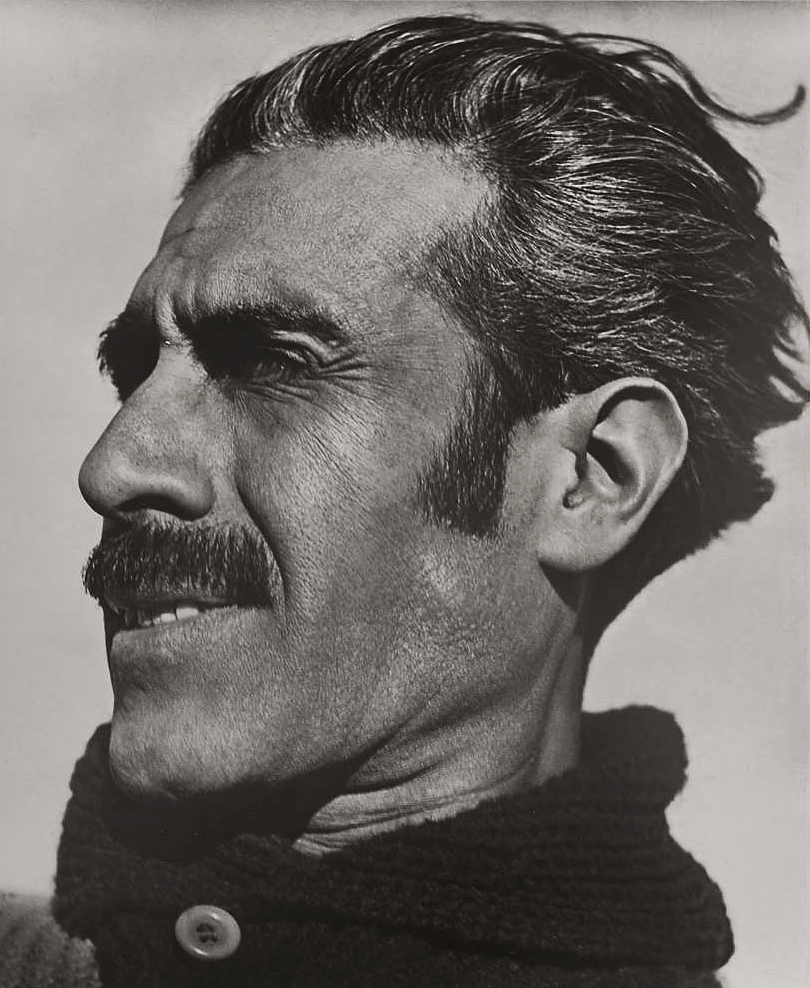

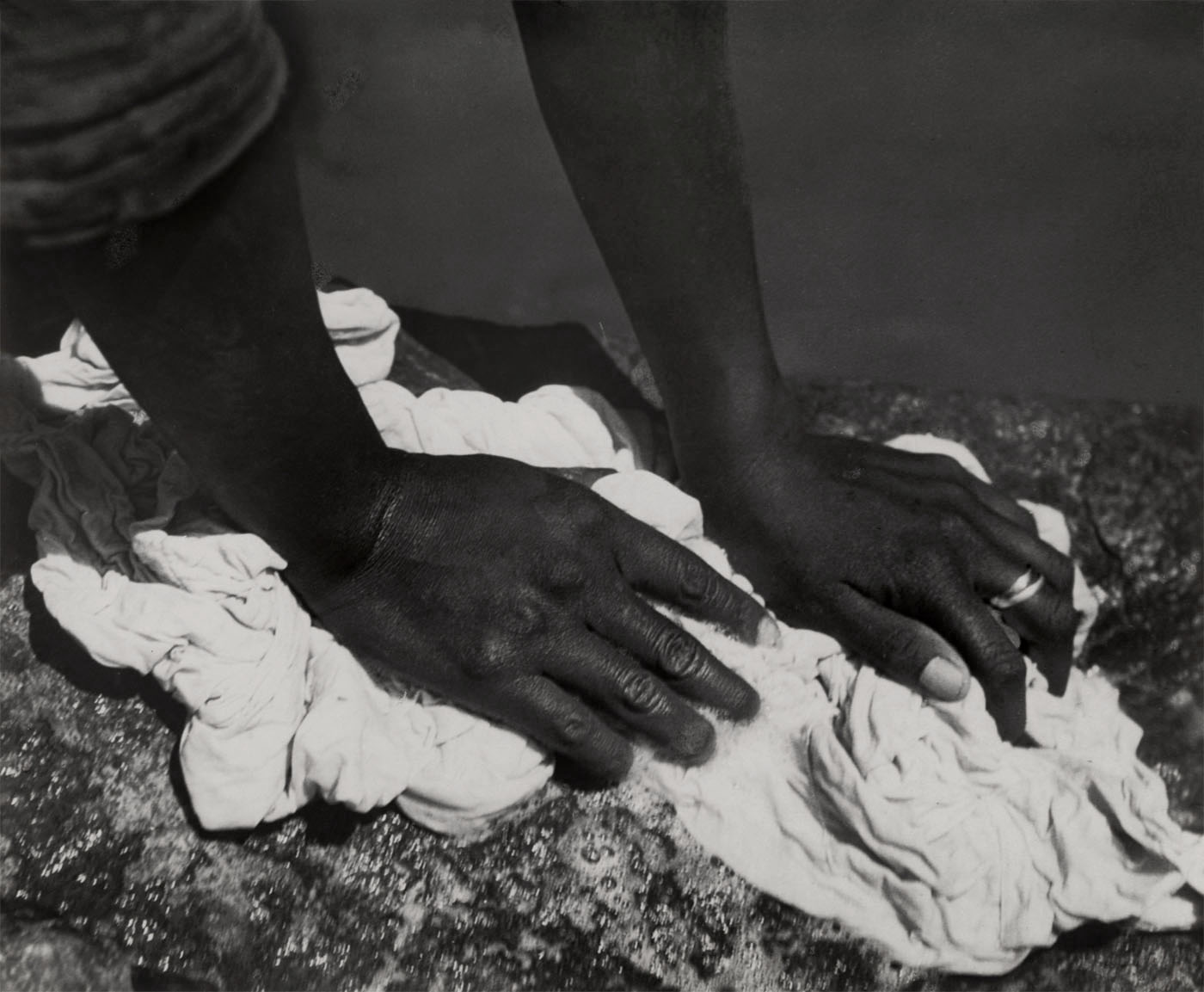

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Waves of paper (Ondas de papel / Vagues de papier)

c. 1928

Vintage silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

What a dazzling, sensual (sur)realist Manuel Álvarez Bravo was, one of my favourite photographers of all time. What an eye, what an artist! The beauty of some of his images simply takes my breath away – such as The daughter of the dancers (La hija de los danzantes / La Fille des danseurs) (1933, below). Álvarez Bravo was one of a triumvirate of photographers that greatly influenced me when I started to study photography, along with Eugene Atget and Minor White. I feel a special affinity to him as we share the same initials.

The posting also includes two colour photographs, the first I have ever seen of Manuel Álvarez Bravo. Unfortunately the quality of some of the media photographs was again incredibly poor and I had to spend an inordinate amount of time repairing damage to the scans in order to bring them to you in this posting. Enjoy.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. Please see my posting Photography in Mexico: Selected Works from the Collections of SFMOMA and Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser for a discussion of Manuel Álvarez Bravo and contemporary Mexican photography.

Many thankx to the Jeu de Paume, Paris for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo au Jeu de Paume

Developed over eight decades, the photographic work of Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexico City, 1902-2002) constitutes an essential milestone in 20th-century Mexican culture. Both strange and fascinating, his photography has often been perceived as the imaginary product of an exotic country, or as an eccentric drift of the surrealist avant-garde.

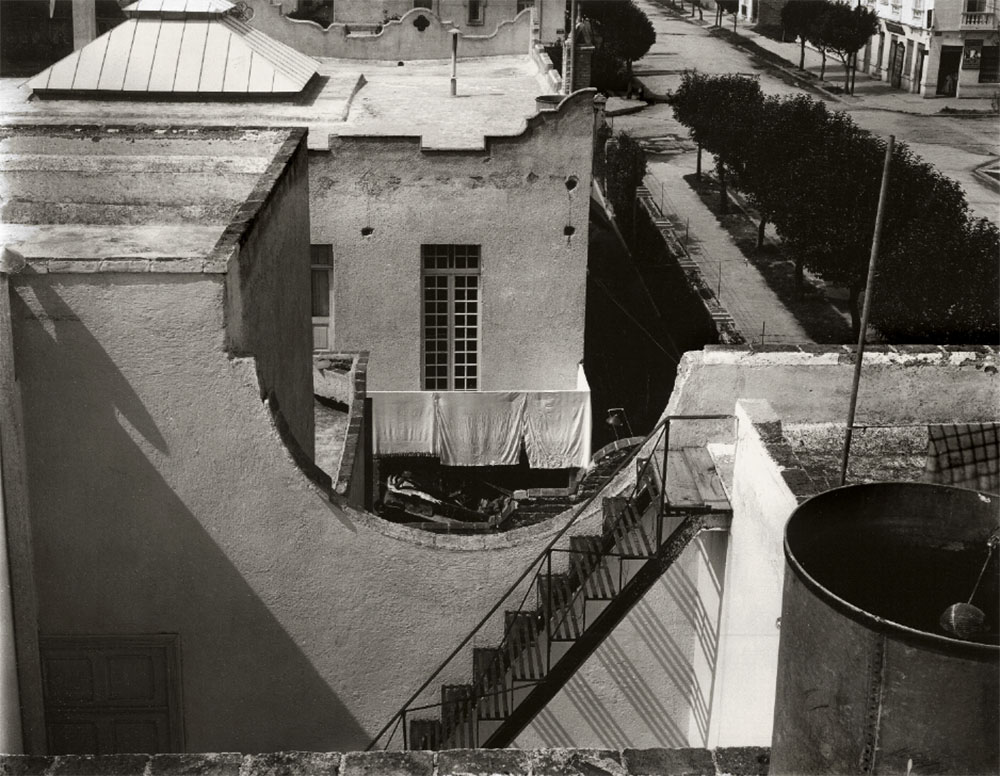

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Colchón / Mattress

1927

Gelatin silver print

Collection Familia González Rendón

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

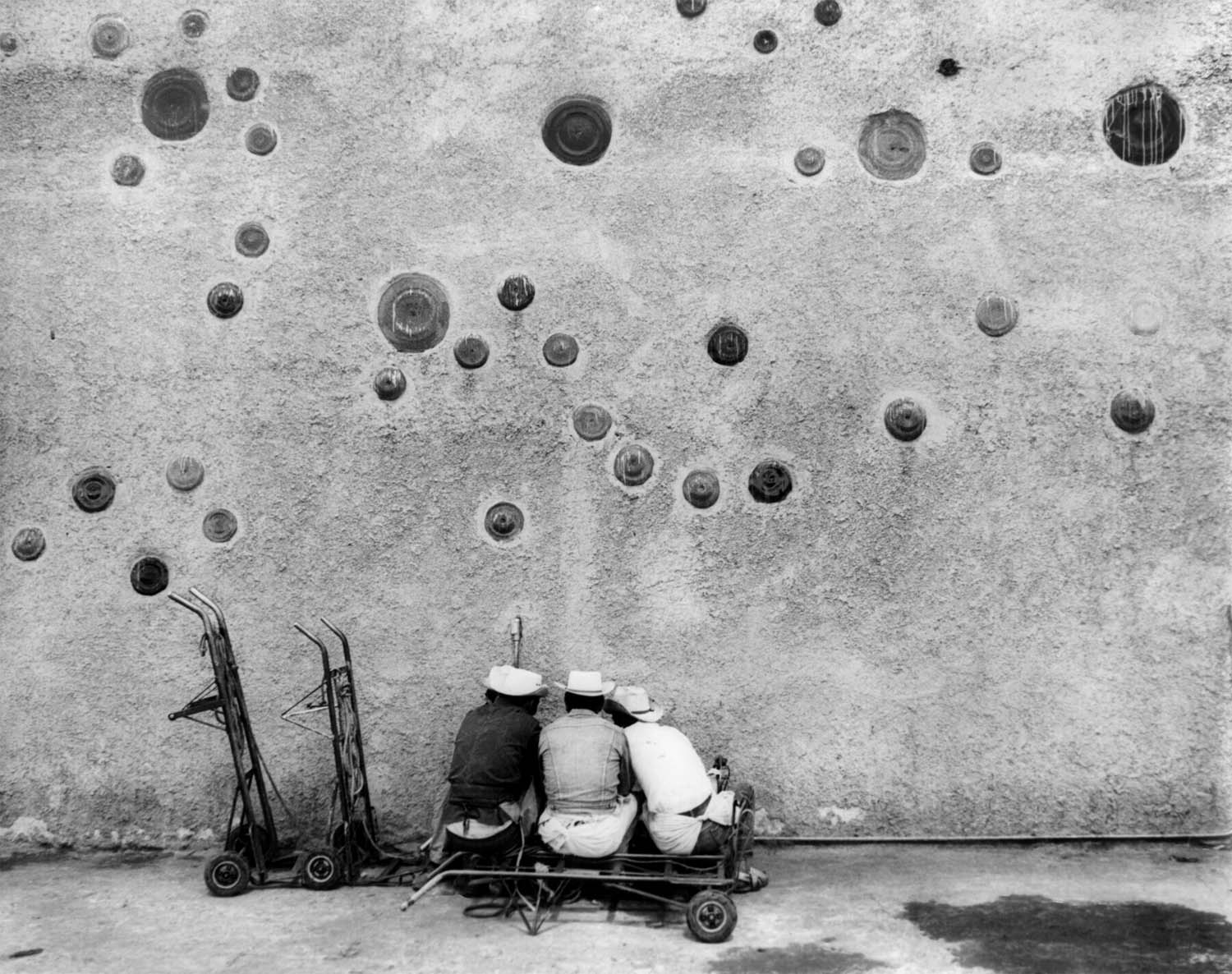

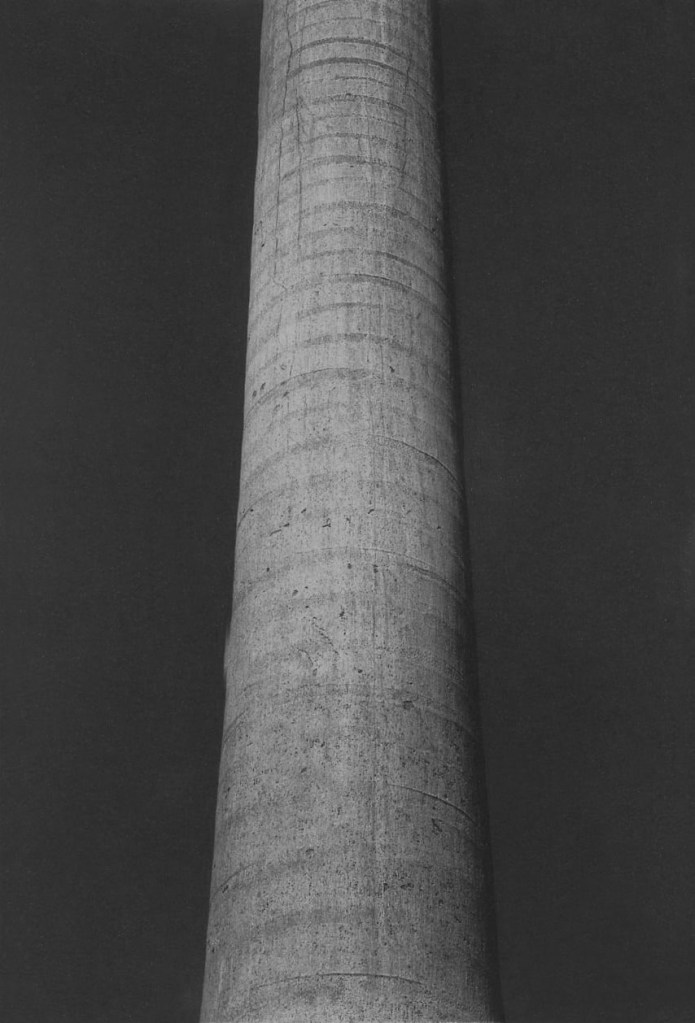

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Concrete triptych 2 / La Tolteca (Tri’ptico cemento-2 / La Tolteca. Triptyque béton-2 / La Tolteca)

1929

Vintage gelatin silver print

Collection Familia González Rendón

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Bicycle Heaven (Bicicleta al cielo / Bicyclette au ciel)

1931

Modern silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

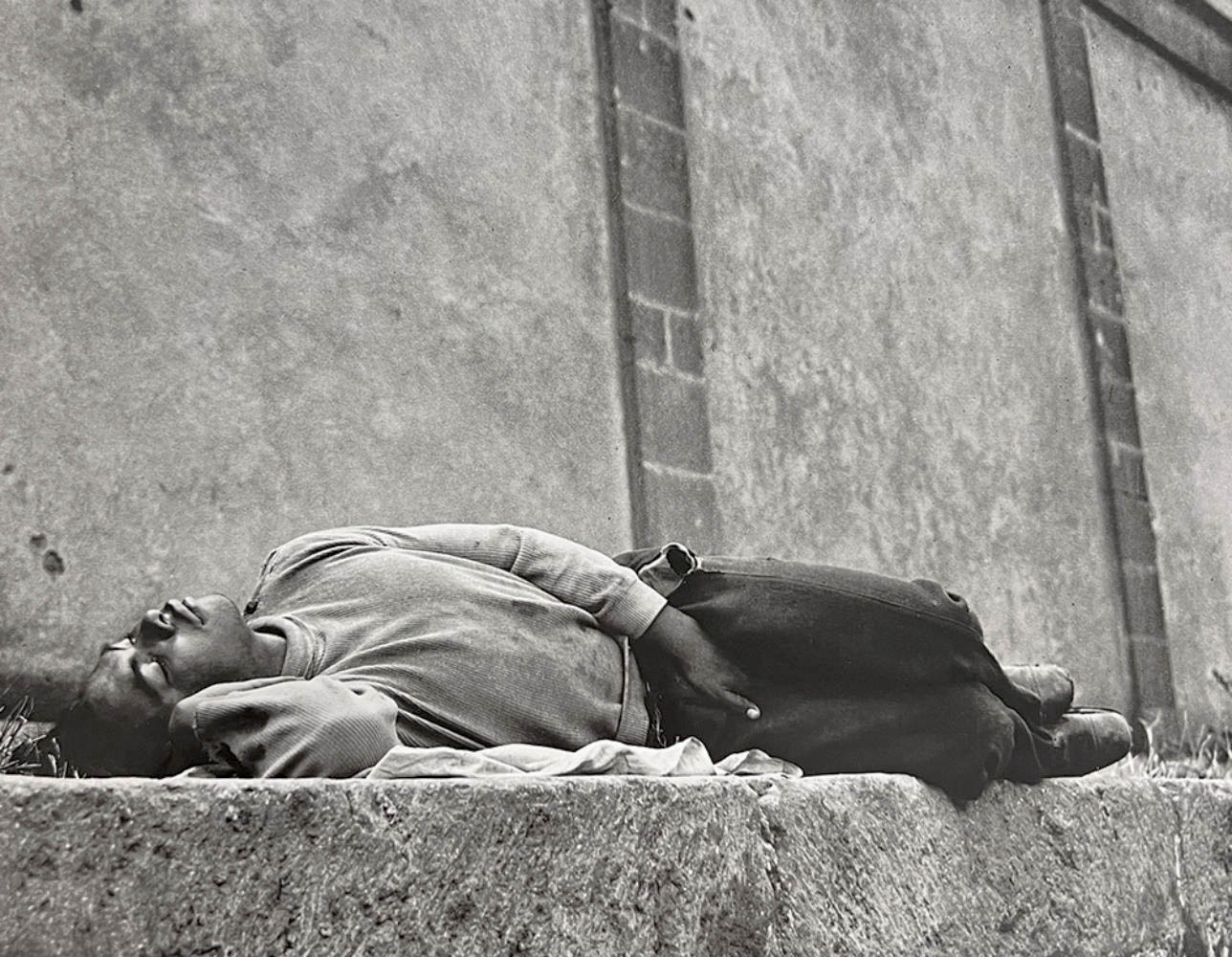

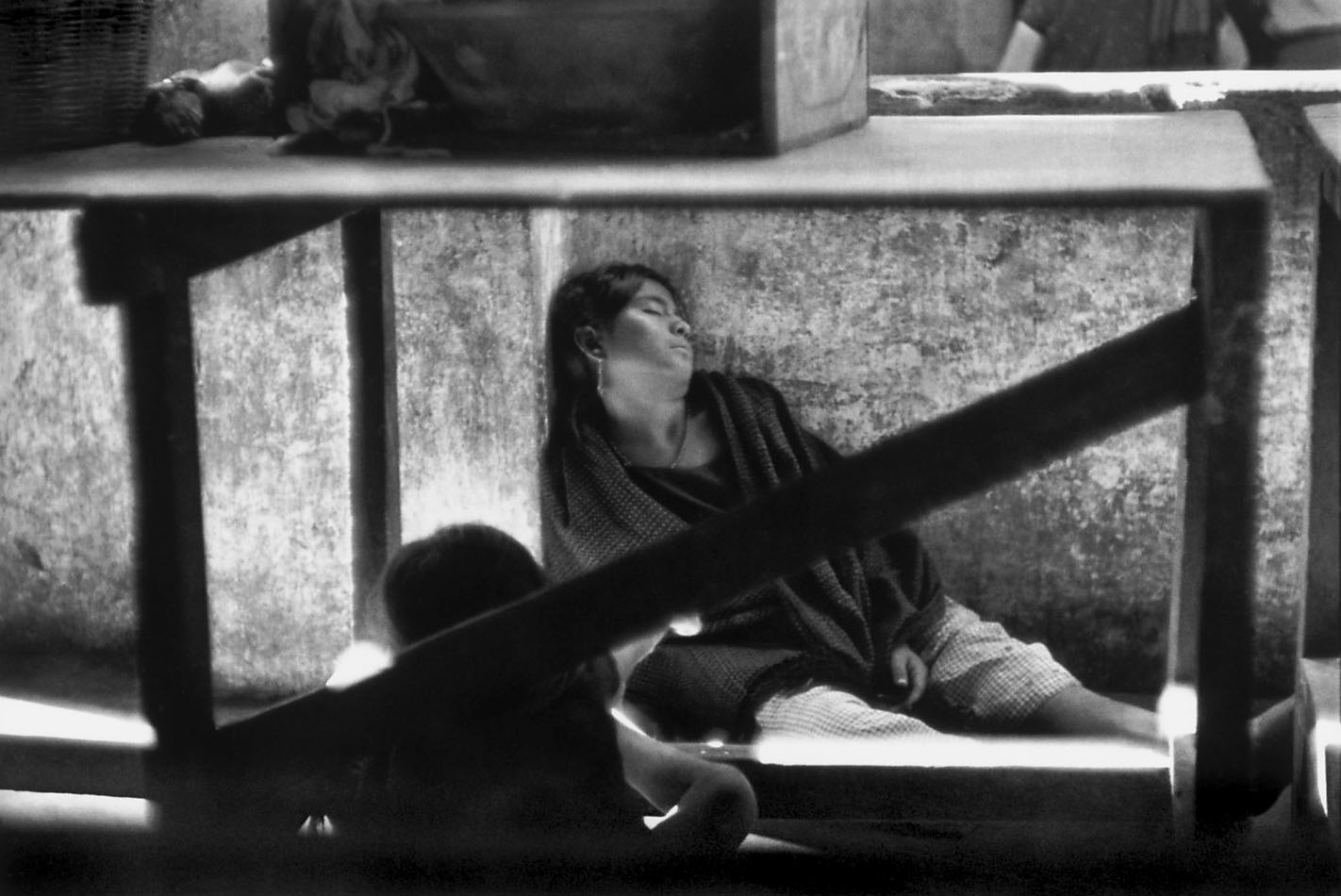

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

El Soñador (The dreamer)

1931

Silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

“When will we have sleeping logicians, sleeping philosophers? I would like to sleep, in order to surrender myself to the dreamers….,” wrote André Breton in the first Surrealist manifesto of 1924. Alvarez Bravo, a compatriot of Breton and the Surrealists in Mexico City during the 1920s and ’30s (although he was not an official member of the movement), made photographs that consistently seem to conjure Breton’s wish. His deep appreciation for the folklore and popular history of his native country-in which common objects were often imbued with a mystical symbolism of life and death and daily situations could easily assume political significance-produced moving images that seem to bask in sensuality while maintaining a connection to the intellectual process of metaphor. In this photograph, these seemingly paradoxical elements are solidly in evidence. Alvarez Bravo wrote of it: “There at number 20 Calle de Guatemala, I saw many things that marked me forever. I walked a lot through the adjoining streets; I especially liked to watch the customs porters in Santiago Tlatelolco station, who after work would fall asleep exhausted on the sidewalk. I felt great compassion for them. … I am happy to have lived in those streets. There everything was food for my camera, everything had an inherent social content; in life everything has social content.” His ability to render in this image Mexican life’s visceral confluence of pleasure, exhaustion, vulnerability, and reverie at the intersection of everyday life and the world of dreams is exceptional.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Muchacha viendo pájaros (Girl watching birds)

1931

Silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

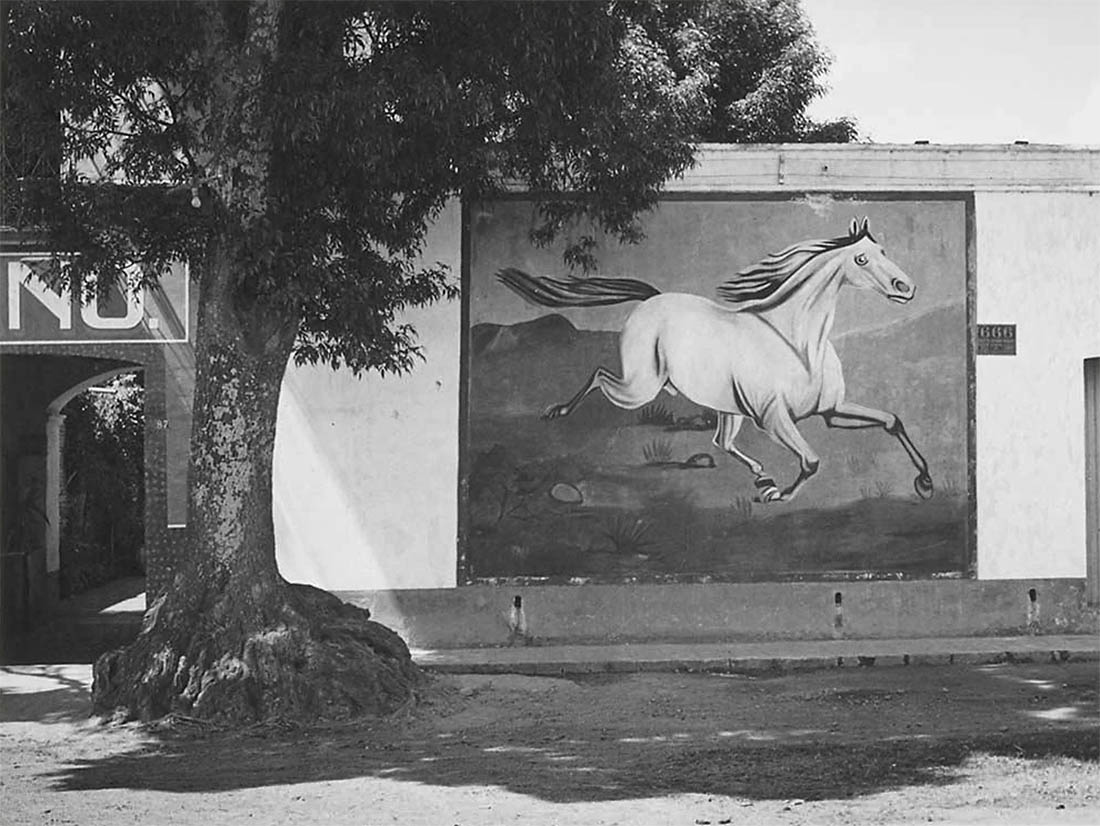

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Paisaje Y Galope (Landscape and Gallop)

1932

Gelatin silver print

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Striking Worker, Assassinated (Obrero en huelga, asesinado / Ouvrier en grève, assassiné)

1934

Vintage silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

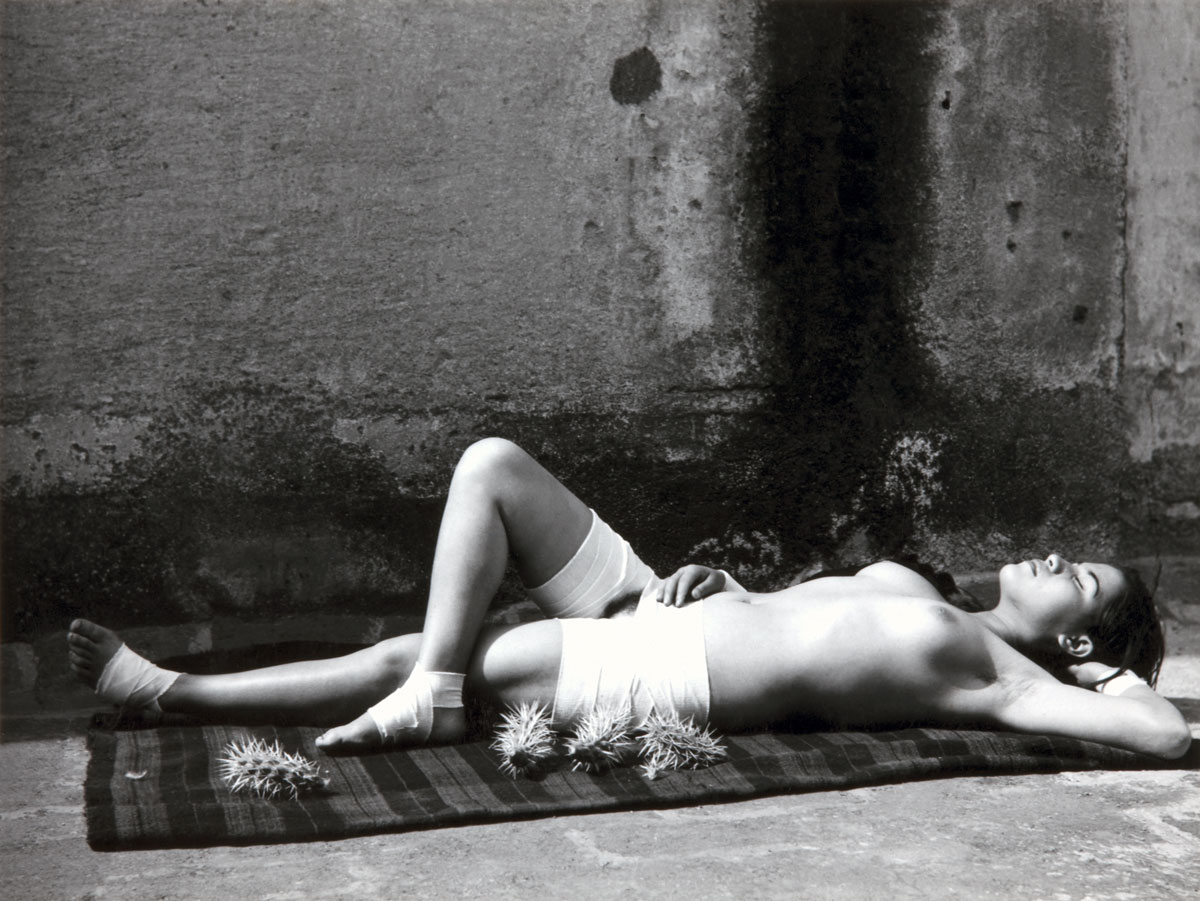

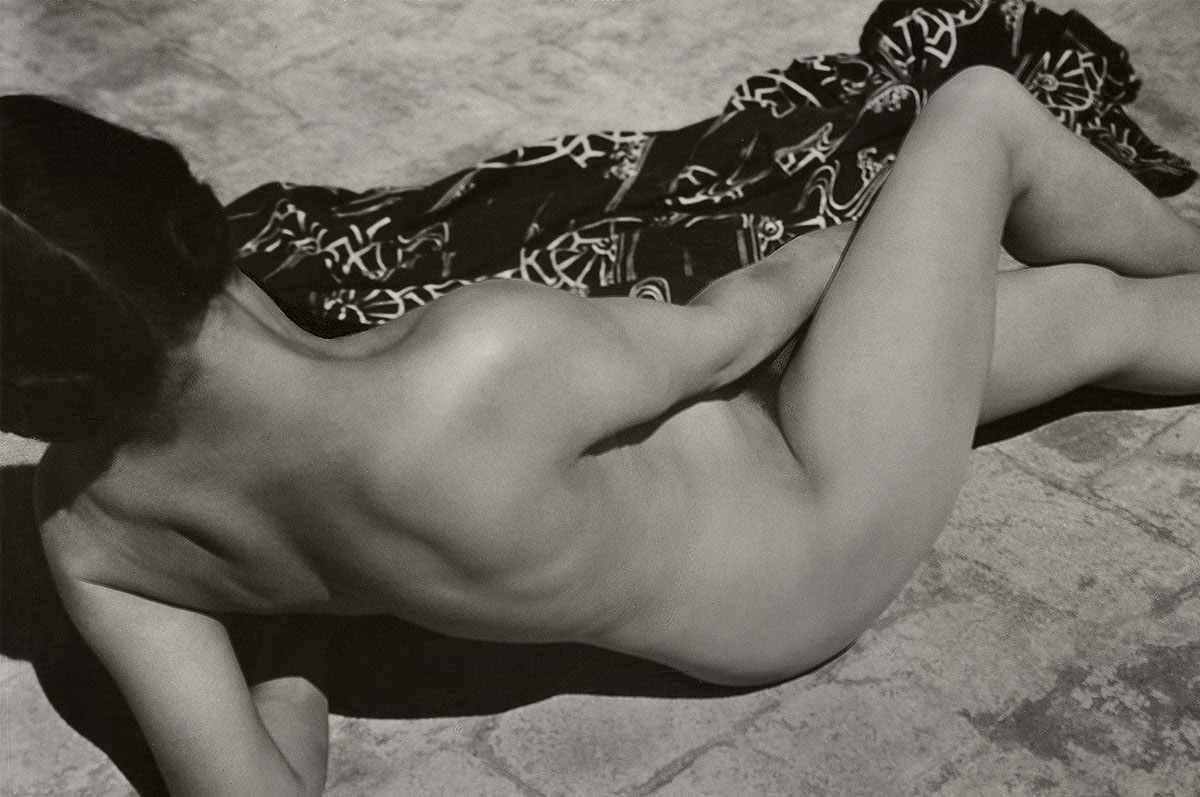

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

The Good Reputation Sleeping (La buena fama durmiendo / La Bonne Renommée endormie)

1938

Vintage silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

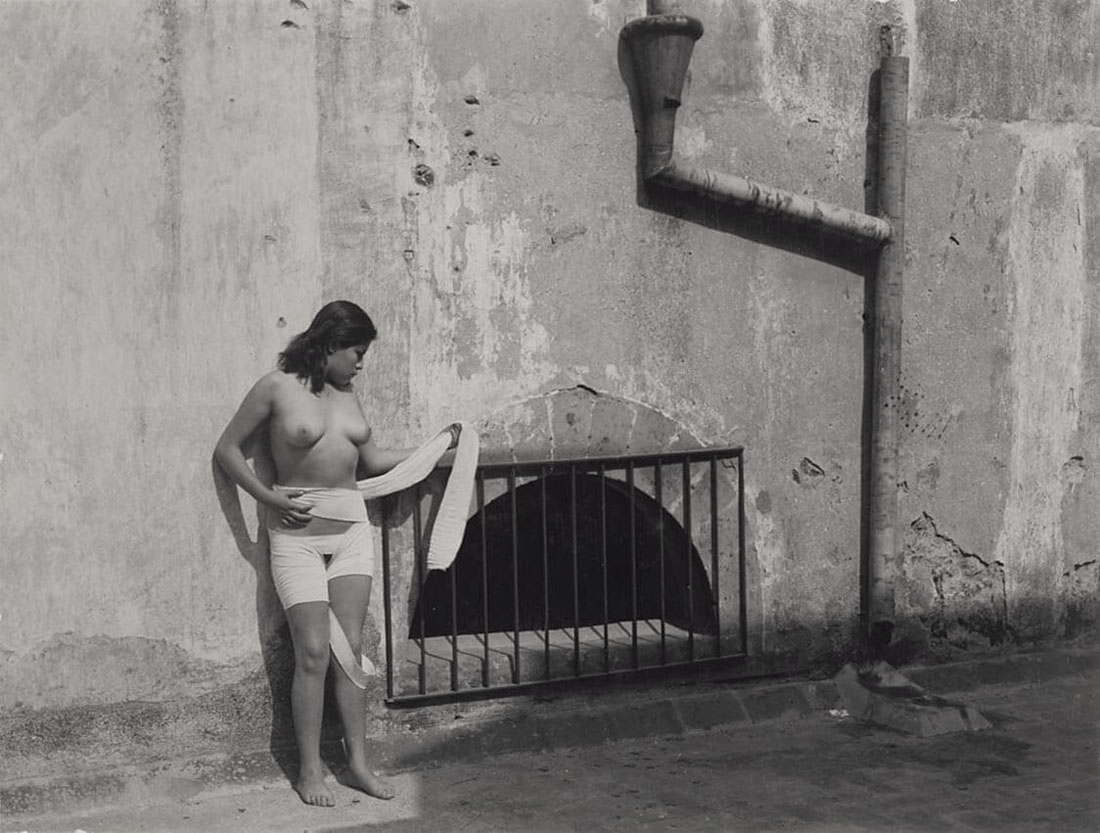

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

La desvendada #2 (The Unbandaged #2)

1939

Silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Que Chiquito es el Mundo (How Small is the World)

1942

Silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

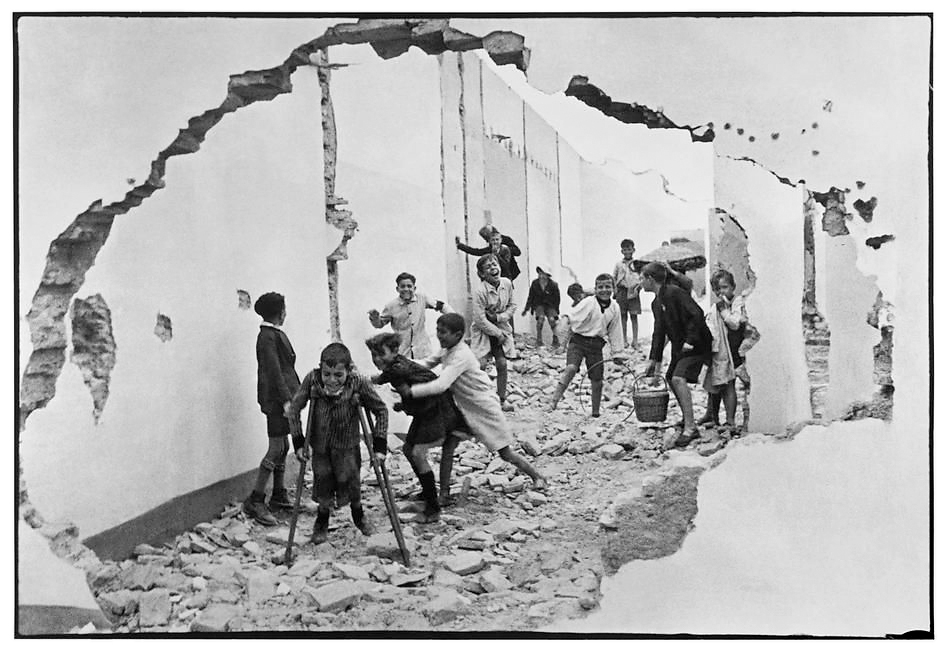

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Algo alegre

1942

Silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Boy in a triangle (Running Boy)

1950

Silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Bicicletas en Domingo

1966

Vintage silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

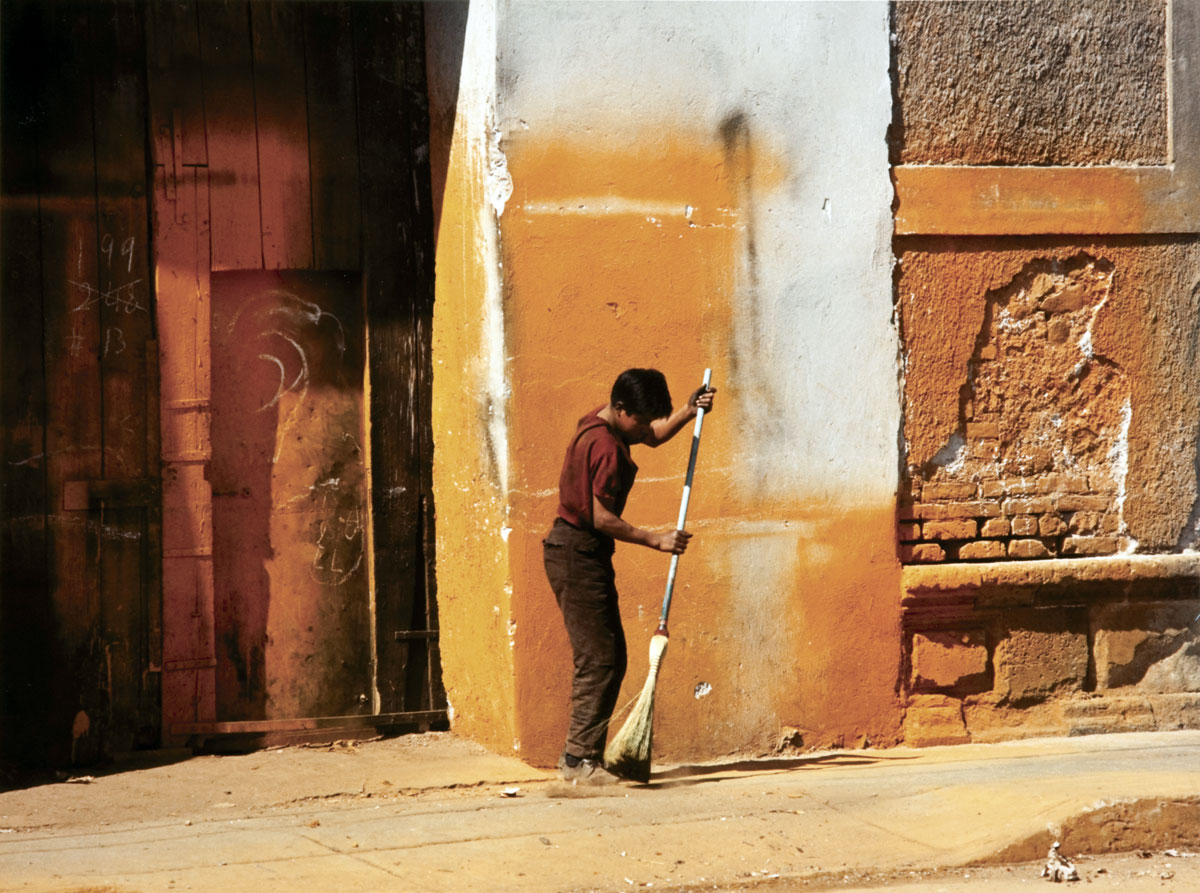

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

The Colour (El color / La Couleur)

1966

Vintage chromogenic print

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

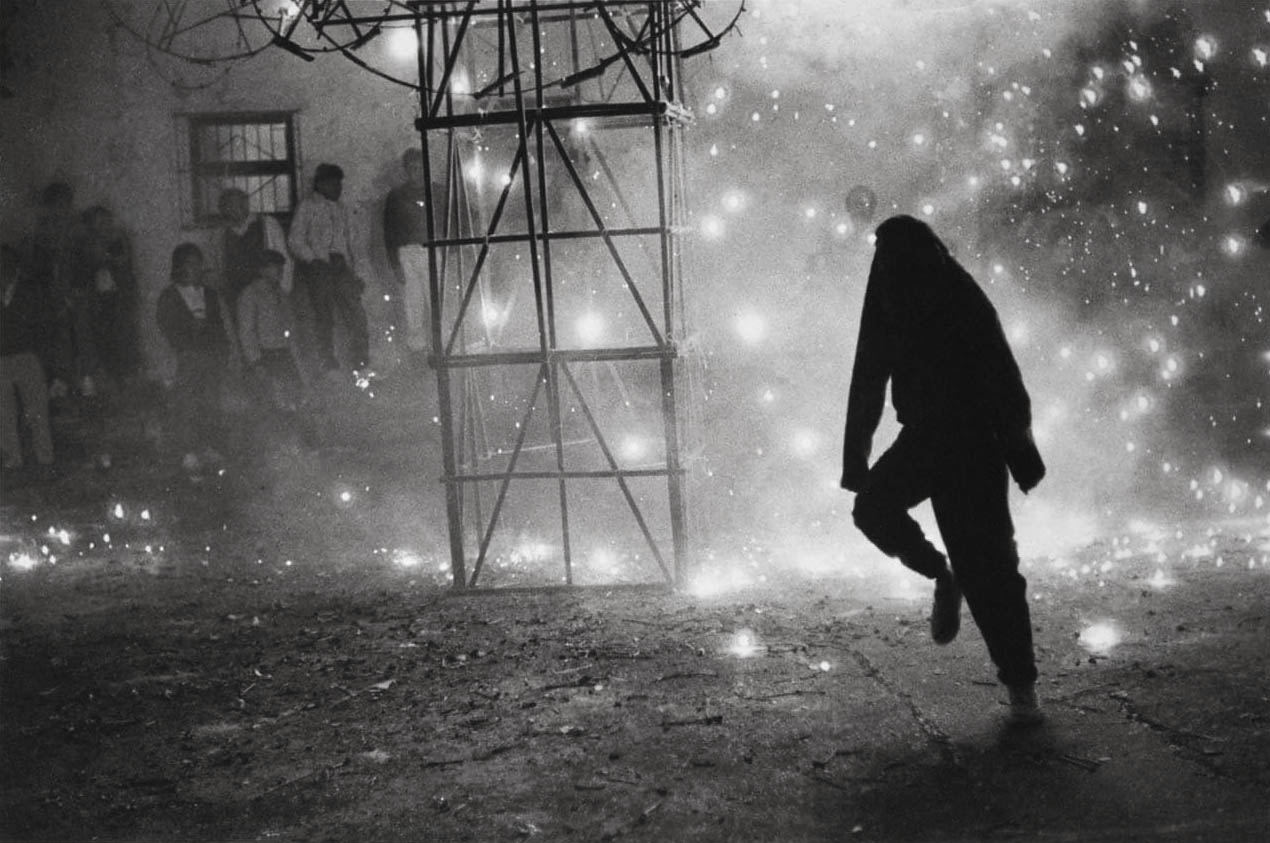

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Castillo en el Barrio del Niño (Fireworks for the Child Jesus)

1970

Silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

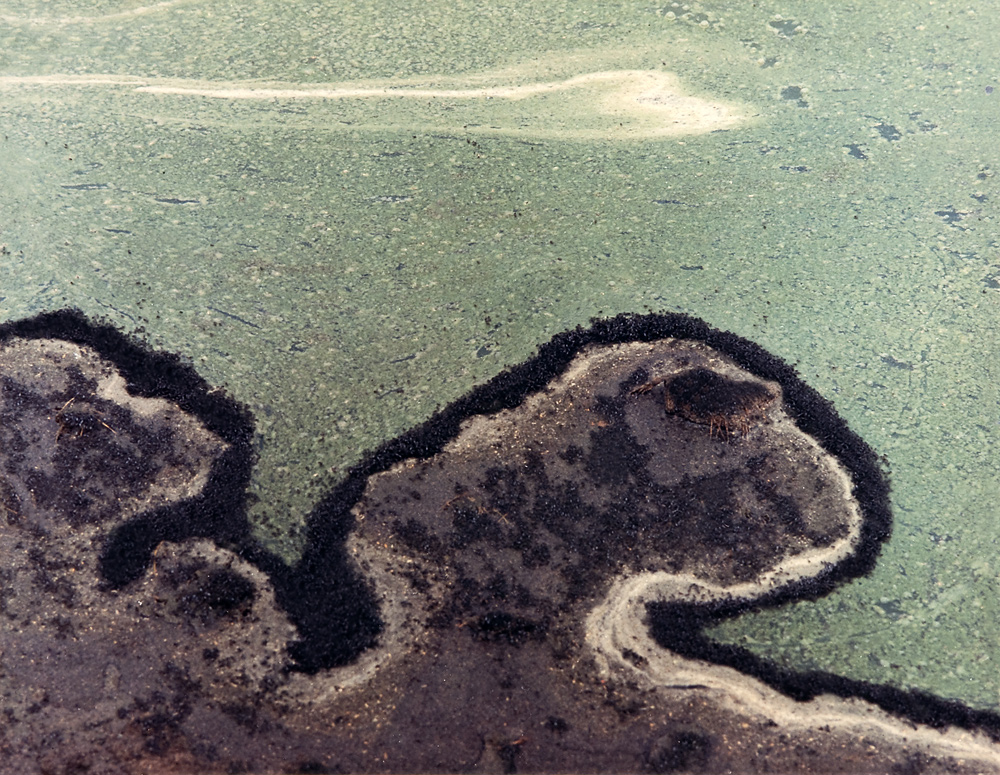

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Current, Texcoco (Corriente, Texcoco / Courant, Texcoco)

1974-1975

Vintage chromogenic print

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Getting away from the stereotypes about exotic Surrealism and the folkloric vision of Mexican culture, this exhibition of work by Manuel Álvarez Bravo at Jeu de Paume offers a boldly contemporary view of this Mexican photographer.

The photographic work done by Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexico City, 1902-2002) over his eight decades of activity represent an essential contribution to Mexican culture in the 20th century. His strange and fascinating images have often been seen as the product of an exotic imagination or an eccentric version of the Surrealist avant-garde. This exhibition will go beyond such readings. While not denying the links with Surrealism and the clichés relating to Mexican culture, the selection of 150 photographs is designed to bring out a specific set of iconographic themes running through Álvarez Bravo’s practice: reflections and trompe-l’œil effects in the big city; prone bodies reduced to simple masses; volumes of fabric affording glimpses of bodies; minimalist, geometrically harmonious settings; ambiguous objects, etc.

The exhibition thus takes a fresh look at the work, without reducing it to a set of emblematic images and the stereotyped interpretations that go with them. This approach brings out little-known aspects of his art that turn out to be remarkably topical and immediate. Images become symbols, words turn into images, objects act as signs and reflections become objects: these recurring phenomena are like visual syllables repeated all through his œuvre, from the late 1920s to the early 1980s. They give his images a structure and intentional quality that goes well beyond the fortuitous encounter with the raw magical realism of the Mexican scene. Indeed, Álvarez Bravo’s work constitutes an autonomous and coherent poetic discourse in its own right, one that he patiently built up over the years. For it is indeed time that bestows unity on the imaginary fabric of Álvarez Bravo’s photographs. Behind these disturbing and poetic images, which are like hieroglyphs, there is a cinematic intention which explains their formal quality and also their sequential nature. Arguably, Álvarez Bravo’s photographs could be viewed as images from a film. The exhibition explores this hypothesis by juxtaposing some of his most famous pictures with short experimental films made in the 1960s, taken from the family archives. The show also features some late, highly cinematic images, and a selection of colour prints and Polaroids. By revealing the photographer’s experiments, this presentation shows how the poetic quality of Álvarez Bravo’s images is grounded in a constant concern with modernity and language. Subject to semantic ambiguity, but underpinned by a strong visual syntax, his photography is a unique synthesis of Mexican localism and the modernist project, and shows how modernism was a multifaceted phenomenon, constructed around a plurality of visions, poetics and cultural backgrounds, and not built on one central practice.

Press release from the Jue de Paume website

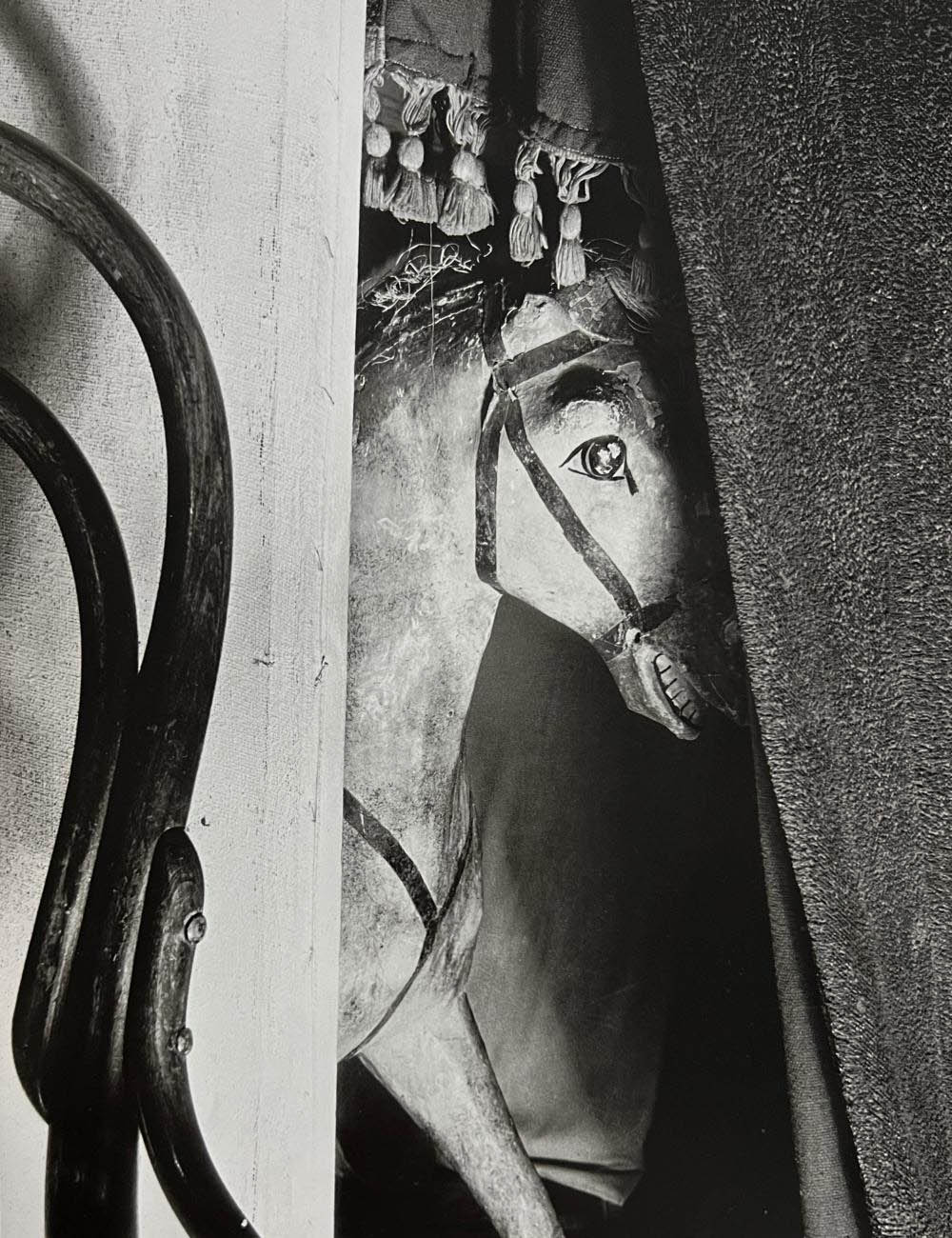

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Caballo de madera (Wooden horse)

c. 1928

Vintage platinum palladium photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Covered Mannequin (Maniquí tapado / Mannequin couvert)

1931

Vintage platinum palladium photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Optic Parable (Parábola óptica)

1931

Silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

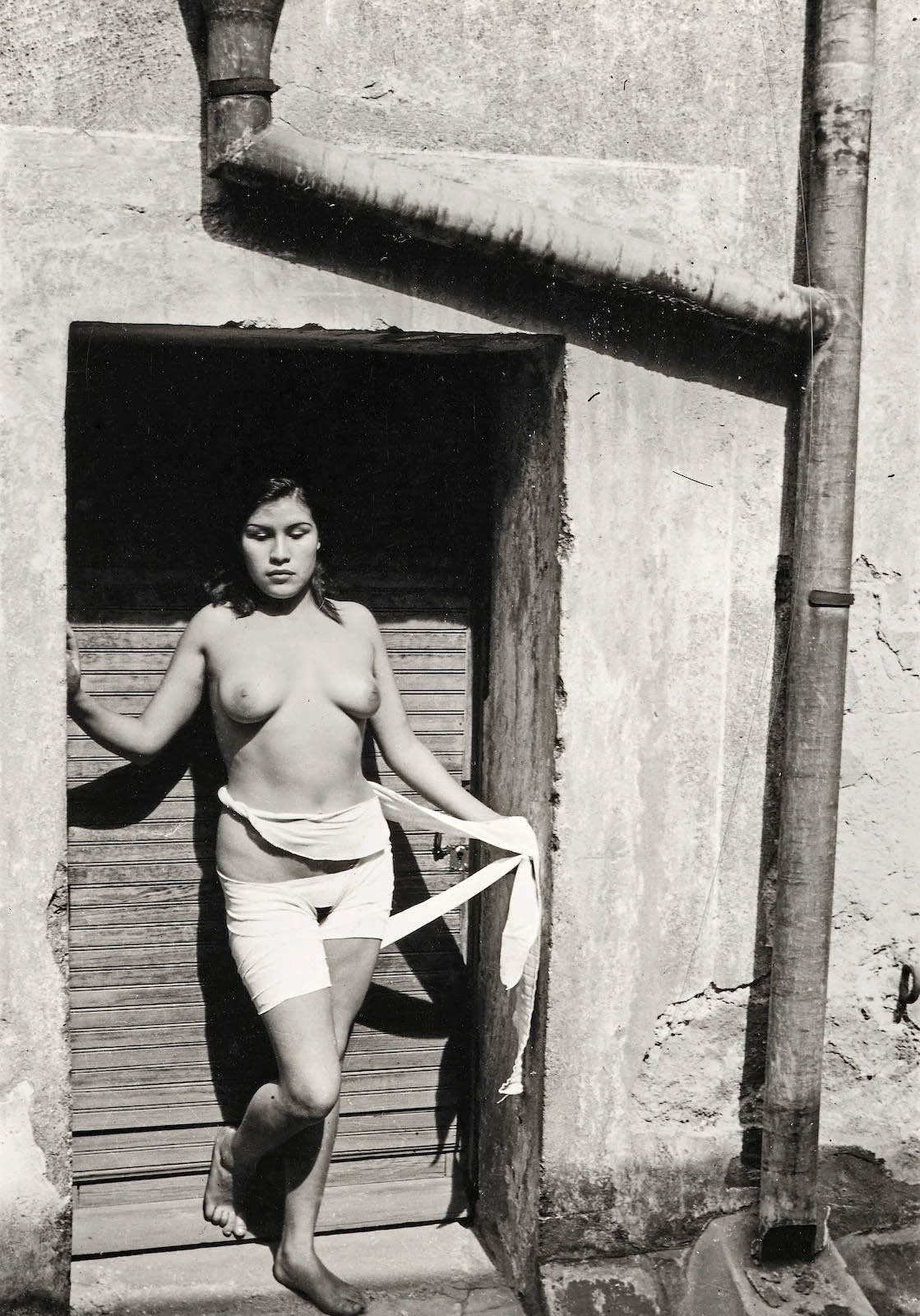

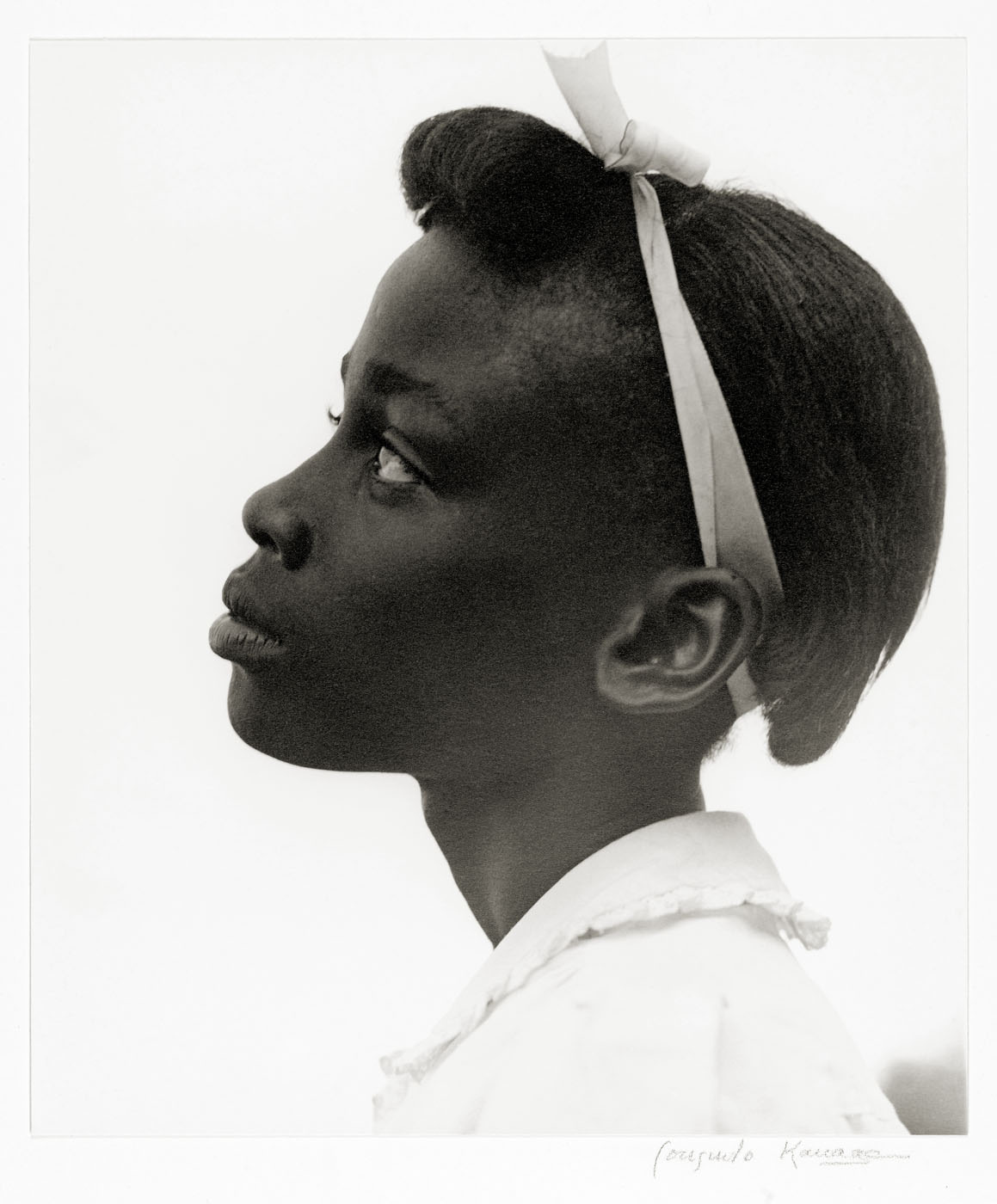

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

The Daughter of the Dancers (La hija de los danzantes)

1933

Gelatin silver print

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

The daughter of the dancers (La hija de los danzantes / La Fille des danseurs)

1933

Vintage platinum / palladium photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Cuando la buena fama despierta (when good reputation awakens)

1938

Gelatin silver print

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Hair on Patterned Floor (Mechón / Mèche)

1940

Modern silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Alvarez Bravo’s photograph of a long lock of wavy hair lying on a geometrically patterned floor juxtaposes texture and materials, dreams and taboos, and invokes questions about the drama taking place outside the photograph. Was this hair placed on the floor intentionally, or did it fall accidentally? The natural presumption is that the hair belonged to a woman, but could it have belonged to a man? Stripped of a luxurious mane, so symbolic of power and passion, is its one-time “owner” now weak and indifferent? This complex image has led one writer to assert that “in theme and form, the photograph is divided between the hint of seduction and that of punishment.”

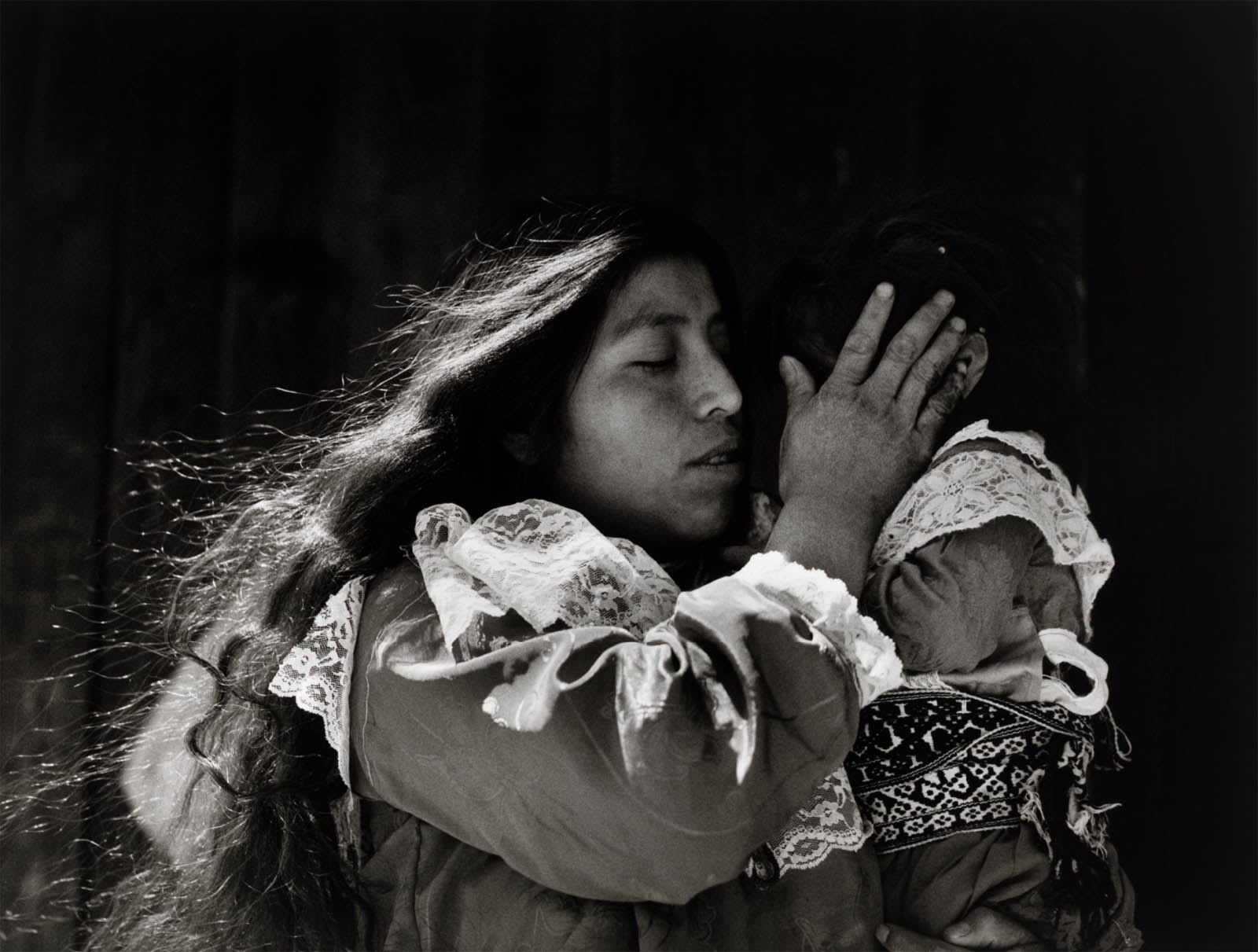

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Ways to Sleep (De las maneras de dormir / Des manières de dormir)

c. 1940

Modern silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Unpleasant portrait (Retrato desagradable / Portrait désagréable)

1945

Vintage silver gelatin photograph

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

El umbral / The Threshold

1947

Gelatin silver print

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Tentaciones en casa de Antonio (The Temptation of Antonio)

1970

Gelatin silver print

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

El trapo negro, Coyoacán, Ciudad de México

1986

Gelatin silver print

Collection Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

© Colette Urbajtel / Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo, s.c.

Jeu de Paume

1, Place de la Concorde

75008 Paris

métro Concorde

Phone: 01 47 03 12 50

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 12 – 8pm

Saturday – Sunday 11am – 7pm

Closed on Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.