Exhibition dates: 21st March – 12th July 2009

Roy de Maistre (Australian, 1894-1968)

Colour Composition derived from three bars of music in the Key of Green

1935

Oil and pencil on composition board

Private Collection

Despite some interesting highlight pieces this is a patchy, thin, incoherent exhibition assembled by the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney now showing at Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne. Featuring a hotchpotch of work ranging across fields such as drawing, architecture, photography, painting, film, graphic design, craft, advertising, Australiana and aboriginal works the exhibition attempts to tell the untold story of Modernism in Australia to little effect. Within the exhibition there is no attempt to define exactly what ‘Modernism’ is and therefore an investigation into Modernism in Australia is all the more confusing for the visitor as there seems to be no stable basis on which to build that investigation. Perhaps reading the catalogue would give a greater overview of the development of Modernism in Australia but for the average visitor to the exhibition there seems to be no holistic rationale for the inclusion of elements within the exhibition which, much like Modernism itself, seems eclectically gathered from all walks of life with little regard for narrative structure.

With work spanning five decades from 1917-1967 we are presented with, variously, Robert Klippel’s kitsch Boomerang table from 1955, Robin Boyd’s ‘House of Tomorrow’ from 1949, Wolfgang Sievers ‘new objective’ photographs, Berlei’s scientific system for calculating beauty in woman in use till the 1960s, swimsuits from the 1920s-1940s, Featherston chairs from the Australian pavilion at the 1967 Expo, a recreation of Australian architect Harry Seidler’s office (the most interesting part of this being the books he had in his office library: Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van de Rohe and Concerning Town Planning by Le Corbusier) and the wind tunnel test model of the Sydney Opera House in wood from 1960. Etcetera, etcetera, etcetera …

Highlight pieces include the above mentioned test model of the Sydney Opera House which is stunning in its scale and woodenness, in it’s simplicity of shape and form. Other highlight pieces are the colour music compositions of Roy de Maistre which were the tour de force of the show for me, true revelations in their rhythmic synchronic Moebius-like construction with layered planes of colour swirling in purples, greens and yellows. The large vintage photographic print of Sunbaker (1934) by Max Dupain was also a revelation with it’s earthy brown tones, the blending of the atmospheric out of focus foreground with the clouds behind, the architectural nature of the outline of the body almost like the outline of Uluru, the darkness of the head with the sensuality of the head and shoulders framed against the largeness of the hand resting on the sand. Lastly the two paintings and one rug by French artist Sonia Delaunay are a knockout. It says something about an exhibition when the best work in the show are two paintings by a French artist seemingly plucked at random to show external influences on Australian artists and designers.

While the exhibition does attempt to portray the breadth of the development of Modernism in Australia ultimately it falls well short in this endeavour. The most striking example of this shortcoming is the true star of the exhibition – the building that is Heide II itself. Commissioned by John and Sunday Reed and designed by the Victorian architect David McGlashan of the architectural firm McGlashan and Eversit in 1963 the building epitomises everything that is good about architectural Modernism and it’s form overshadows the exhibition itself. In this building we have beautiful spaces and volumes, an amazing staircase down into the lower area, suspended decking overlooking gardens, the blending of inside and outside areas, large expanses of glass to view the landscape, nooks and studies for privacy and the simplicity and eloquence of form that is Modernist design. With money one can indulge in the best of elitist Modernism. With position, position, position one can side steep the alienation of the city and the spread of surburbia where the dream of Australians owning a home of their own still continues in the vast, tasteless expanses of McMansion estates.

Robert Nelson in his review of this exhibition sees the car as creating the suburbs and Modernism as the emptying of the city after 6pm, the lessening of community and the devaluing of space he insists that there is little difference between a Californian bungalow in the suburbs and a utopian geometric neo-Corbusian box by Harry Seidler because they were equally shackled to motor transport.1 This is to miss the point.

Although Modernism in its basic form influenced most walks of life in Australia from swimsuit design to milk bars, from cinema to naturism, from bodies to advertising the most effective expressions of Modernism are architectural (as evidenced by Heide II) and were only open to those with money, power and position. Although Le Corbusier’s concept of public housing was a space ‘for the people’ the most interesting of his houses were the private commissions for wealthy clients. And so it proves here. One can imagine the parties on the deck at Heide II in the 1960s with men in their tuxedo and bow ties and woman in their gowns, or the relaxation of the Reed’s sitting in front of their fire in the submerged lounge. For the ordinary working class person Modernism brought a sense of alienation from the aspirational things one cannot buy in the world, an alienation that continues to this day; for the privileged few Modernism offered the exclusivity of elitism (or is it the elitism of exclusivity!) and an aspirational alienation of a different kind – that of the separation from the masses.

Go to Heide for the glorious gardens, the wonders of Heide II but don’t go to this exhibition expecting grand insights into the basis of Australian Modernism for that story, as Robert Nelson rightly notes, remains as yet untold.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

.

Many thankx to Heide Museum of Modern Art for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

An excellent review of the exhibition by Jill Julius Matthews, “Modern times: The untold story of modernism in Australia,” (reCollections Volume 4 number 1) can be found on the Journal of the National Museum of Australia website [Online] Cited 20/02/2019

1/ “Emanating from Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum, Modern Times “explores how modernism transformed Australian culture from 1917 to 1967.” But something is missing. The overwhelming modern development in these 50 years was the proliferation of automotive transport, which redefined the layout and function of Australian cities.The cars created the suburbs; and as the individual bungalow drew out the vast dormitories of Sydney and Melbourne, the city centre was spiritually drained, dedicated to bureaucratic and commercial premises.The story at Heide emphasises the gradual triumph of the tall buildings of the CBD. It doesn’t really reflect how these abstract monuments didn’t contain a soul after 6pm.Although the project makes such a big deal of being interdisciplinary, the social history doesn’t have a robust geographical basis. And because of this, the exhibition and book fail to handle the new alienation that modernism brings: the evacuation of the city and the insularity of suburban people in bungalows with little street life and roads increasingly deemed unsafe for children.

What does it really matter if a house looks like a Californian bungalow or a utopian geometric neo-Corbusian box by Harry Seidler? In social terms, they’re structurally the same, equally retracting from a sense of community and equally shackled to motor transport. In this sense, the styles are immaterial, except that one of them gives you a feeling of intimacy while the other has a bit more light and is easily wiped with a sponge.

At the end of the chosen period, the folly of the dominant suburban pattern came to be understood in its dire ecological consequences. Alas, it was too late. The modernist devaluation of space had already occurred, and our whole society had been reorganised around petrol.”

Robert Nelson. The Age. Wednesday 6th May, 2009

Roy de Maistre (Australian, 1894-1968)

Arrested Movement from a Trio

1934

Oil and pencil on composition board

72.3 × 98.8cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Roy de Maistre (Australian, 1894-1968)

Rhythmic composition in yellow green minor

1919

Oil on paperboard

85.3 x 115.3cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales

© Caroline de Mestre Walker

In late 1918, Roy de Maistre collaborated with fellow artist Roland Wakelin in exploring the relationship between art and music. Their experiments produced Australia’s first abstract paintings, characterised by high-key colour, large areas of flat paint and simplified forms. The works received critical acclaim, but modernist developments were largely derided by the conservative establishment.

This painting exemplifies de Maistre’s theory of colour harmonisation based on analogies between colours of the spectrum and notes of the musical scale. It is also aligned with de Maistre’s search for spiritual meaning through abstraction, akin to other artists such as Kandinsky who were interested in the ideas of the theosophy and anthroposophy movements, spiritualism and the occult.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website

Roy de Maistre (Australian, 1894-1968)

Colour chart

c. 1919

30.5 x 40.5cm

Oil on cardboard

Gift of the executors of the artist’s estate 1968

Art Gallery of New South Wales

© Caroline de Mestre Walker

Sonia Delaunay (Ukraine, b. 1885 moved Paris 1905-1979)

Rhythm

1938

Oil on canvas

Wolfgang Sievers (Australian born Germany, 1913-2007)

“House of Tomorrow” exhibition at Exhibition Building, Melbourne

1949

Gelatin silver print

National Library of Australia

Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski (Australian born Poland, 1922-1994)

Nymphex

1966

Gelatin silver photograph from electronic image

50.6 x 60.8cm

Gift of Dr George Berger 1978

Art Gallery of New South Wales

@ Estate of Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski

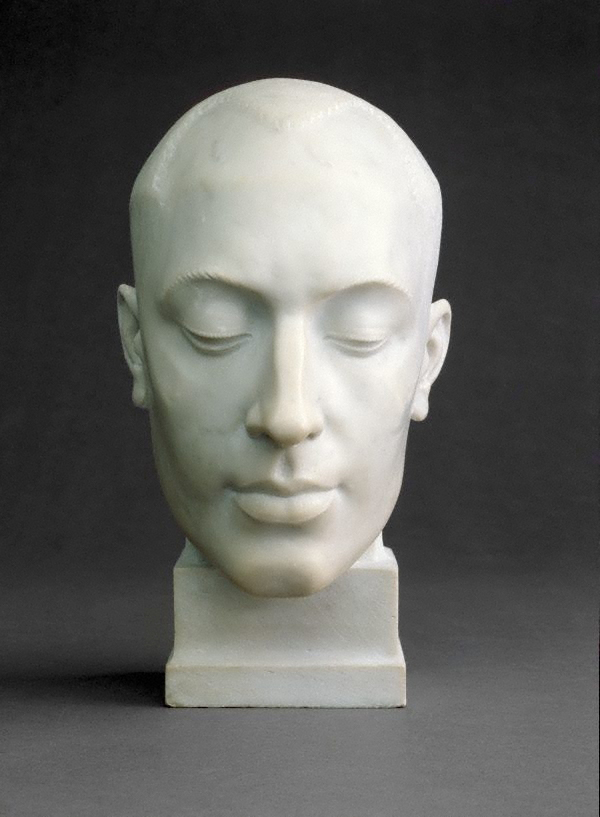

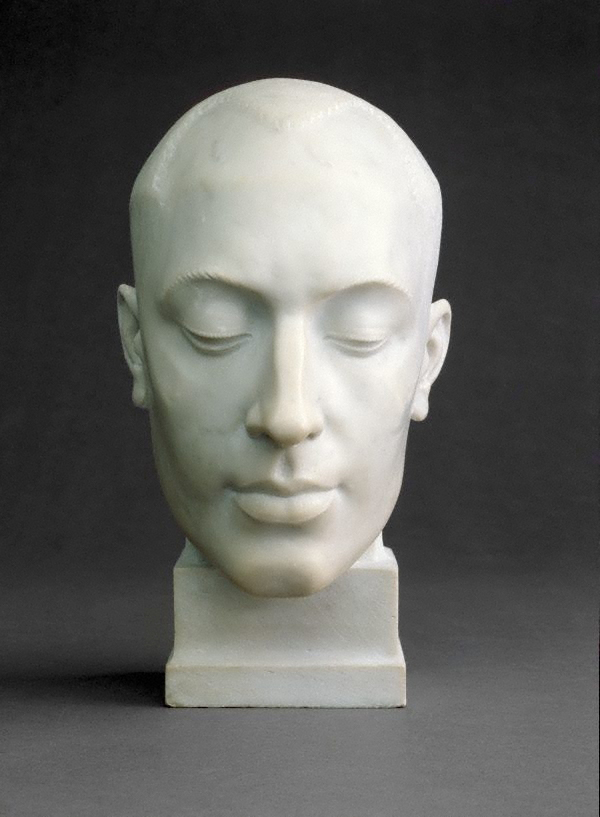

Rayner Hoff (Australian born United Kingdom, 1894-1937)

Decorative portrait – Len Lye

1925

Marble

30.5 x 22.5 x 16.5cm

Purchased 1938

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Sunbaker

1934 printed 1937

Gelatin silver print

Grace Cossington Smith (Australia, 1892-1984)

Rushing

c. 1922

Oil on canvas on paperboard

65.6 x 91.3cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales

© Estate of Grace Cossington Smith

Cossington Smith captures the drama of a crowd in Rushing, which depicts commuters clamouring down to the ferries of Circular Quay to get home after work. The flying scarf and fallen hat emphasise the speed at which the travellers are moving and the peril and claustrophobia of a, mostly faceless, city crowd. The steep gangplank and diagonal composition accentuates the dynamism of the painting.

A brilliant colourist, Cossington Smith’s work of the early 1920s adopts a darker palette than the vivid colours she is usually associated with. Inspired by a visit to Sydney in 1920 by the tonalist painter and teacher Max Meldrum, her paintings became studies in tone, rather than colour, a practice she had abandoned by 1925.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website

Robert Klippel (Australian, 1920-2001)

Boomerang coffee table

1955

The Powerhouse Museum travelling exhibition Modern times: the untold story of modernism in Australia explores how modernism transformed Australian culture from 1917 to 1967, a period of great social, economic, political and technological change. From the ideals of abstraction and functionalism to the romance of high-rise cities, new leisure activities and the healthy body, modernism encapsulated the possibilities of the twentieth century. This exhibition is the first interdisciplinary survey of the impact of modernism in Australia, spanning art, design, architecture, advertising, photography, film and fashion.

Modern times is presented at Heide across all four of the Museum’s gallery spaces. It unfolds in thematic sections highlighting key stories about international exchange, the modern body, modernist ‘primitivism’, the city, modern pools, and the Space Age. Comprising over 300 objects and artworks, it showcases works by major artists including Sidney Nolan, Margaret Preston, Albert Tucker, Grace Cossington Smith, Max Dupain, Wolfgang Sievers, and Clement Meadmore, key architects Robin Boyd, Roy Grounds and Harry Seidler, and designers Fred Ward and Grant and Mary Featherston. An installation, Cannibal Tours, by Madrid-based Australian artist Narelle Jubelin is a contemporary adjunct to the exhibition.

Inspired by the futurist visions of various European avant-gardes, modernist ideas were often controversial and shaped by many competing positions. Modern times reveals how these ideas were circulated and took hold in Australia, via émigrés, expatriates, exhibitions, films and publications. Australian contact with significant international modernist sources, such as the Bauhaus school in Germany, occurred through figures such as influential artist and teacher Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, who taught Bauhaus principles at Geelong Grammar, and renowned architect Harry Seidler, who played a central role in shaping the modern city in Australia. Hirschfeld-Mack’s extraordinary film Colour Light Play of 1923 is shown for the first time in Australia, and Seidler’s 1948 studio, designed on his arrival from New York, has been re-created for the exhibition.

While modernism was international in character, an ‘Australian modernism’ was first championed in the 1920s by artist Margaret Preston, whose promotion of Aboriginal forms and motifs was important to the understanding of their artistic value. Preston’s designs, Len Lye’s stunning animation Tusalava (1929), Robert Klippel’s boomerang table (c. 1955) and other works show the development of a vernacular modernism.

Other highlights of Modern times include works from the visionary experiment in colour theory by Roy de Maistre and Roland Wakelin in 1919, a model of Robin Boyd’s innovative House of Tomorrow (1949), the iconic Featherston wing sound chairs from the Australian pavilion at the 1967 Montreal Expo, and a large wooden model for Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House.

Text from the Heide Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 06/06/2009 no longer available online

Athlete and movie-star Annette Kellerman’s Modern Kellerman Bathing Suit for Women which became commercially available by the mid-1920s. The one-piece bathing suit became Kellermans trademark

Gift of Dennis Wolanski Library, Sydney Opera House, 2000

Photo: Powerhouse Museum

On hot summer days cool off with Tooth’s KB Lager

About 1940

Advertising poster

Colour and process lithograph, artist name “Parker” in image lower right

100.4 x 75.4cm

Sydney Living Museums

Grant Featherston (Australian, 1922-1995) and Mary Featherston (Australian, b. London 1943, migrated to Australia 1952)

Expo mark II sound chair

1967

Aristoc Industries

Polystyrene, polyurethane foam, Dunlopillo foam rubber, Pirelli webbing, fibreglass, hardwood, sound equipment, upholstery fabric

Powerhouse Collection

The Expo Mark II sound chair, adapted for the Australian domestic market after Expo 67 in Montreal.

A cloth-covered high back winged chair with a circular base. The chair has a circular orange cloth covered cushion in the base and an integral full-width headrest. Two 125mm diameter inserts are pressed into the top of the back of the chair where speakers are fitted inside it. There is a cylindrical knob on the side of the chair.

National Archives of Australia

A modernist vision of Australia: Grant and Mary Featherston’s wing sound chairs were a feature of the Australian Pavilion, designed by architect James Maccormick with exhibits selected by Robin Boyd, at Expo 67 in Montreal, 1967

1967

In 1967 Australia participated in the International and Universal Exposition held in Montreal, Canada. Australia’s Expo ’67 theme was the ‘Spirit of Adventure’. In the 30,000 square feet glass-walled Australian Pavilion, developed by the Australian Government and designed by Robin Boyd, exhibits explored Australian science, arts, people and development. The pavilion was designed as a ‘haven’ of ‘space and tranquillity’ floating above an Australian bushland setting. Inside, 240 innovative sound chairs offered ‘foot-weary Expo visitors’ the chance to hear the voices of famous Australians describing the exhibits, in French as well as English. The Great Barrier Reef was re-created in a lagoon beneath the pavilion while wallabies and kangaroos could be viewed in a sunken enclosure.

Text from the National Museum of Australia website [Online] Cited 20/02/2019

James Birrell (Australian, 1928-2019)

View of the elevated restaurant, Centenary Pool, Brisbane

Nd

Powerhouse Museum

“A major exhibition opening for Sydney Design 08 in August, Modern times looks closely at the transformation of modern city life. The advent of cars, freeways, skyscrapers and new entertainment such as cinemas, milk bars, swimming pools, cafes and pubs are all legacies of modernism as revealed through the exhibition. The exhibition spans five decades from 1917 to 1967 – a tumultuous period marked by global wars, economic depression, a technological revolution and major social changes – out of which a modern cosmopolitan culture was shaped.

“The modernist movement was inspired by various European avant-gardes that projected visions of a better future, shaped by many competing positions. It was through émigrés, expatriates, exhibitions and publications that modernism become known in Australia,” Ann Stephen said. Encompassing art, design and architecture, Modern times focuses on seven themes: 1. the human body, image and health; 2. international influences and exchanges; 3. Indigenous art and modernism; 4. Interdisciplinary projects with retailers; 5. city landscapes and urban life; 6. public pools and milk bars; and 7. the space age.

Several great modern public pools were designed in Australia initially as part of an international swimming boom in the 1930s and boosted by the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. These will be shown on a large, immersive, panoramic audio visual screen celebrating the most Australian of past-times, being poolside. The earliest 1920s swimming costumes by silent film star Annette Kellerman, several decades of Australian icon ‘Speedo’ cossies and an early bikini will also be on display.

The much-loved corner milk bar from the 1930s will also be recreated in the exhibition for visitors to enter, complete with lolly jars, milkshakes and a juke box.

Other story highlights in the exhibition include Robin Boyd’s ‘House of Tomorrow’ that featured at the 1949 Modern Home Exhibition in Melbourne; and Boyd’s memorable Australian pavilion at the 1967 Montreal Expo that showcased Australian design including the iconic Featherston wing sound chairs and hostess uniforms designed by Zara Holt, wife of then prime minister Harold Holt.

Modernism also inspired new forms of public art and design like the abstract fountains by Tom Bass on Sydney’s former P&O building and Robert Woodward’s El Alamein Memorial Fountain, a popular tourist site in Sydney’s Kings Cross. Modernism shaped an exultant explosion of experiment as part of the Space Age informing such spectacular architectural feats as Roy Grounds’ dome for the Australian Academy of Science in Canberra and Jørn Utzon’s internationally-acclaimed Sydney Opera House, both featured in the exhibition.”

Text by Ruzan Haruriunyan, “Modern Times: Untold Story Of Modernism In Australia,” on the Huliq News website [Online] Cited 20/02/2019

Hedie II photographs by Rory Hyde. More photos of Heide are on his Flickr photoset

Heide II – commissioned by John and Sunday Reed 1963, designed 1964, constructed 1964-1967

Designed by Melbourne architect David McGlashan of McGlashan Everist, it was intended as “a gallery to be lived in” and served as the Reeds’ residence between 1967 and 1980. The building is considered one of the best examples of modernist architecture in Victoria and awarded the Royal Institute of Architects (Victorian Chapter) Bronze Medal – the highest award for residential architecture in the State – in 1968. It is currently used to display works from the Heide Collection and on occasion projects by contemporary artists.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Australia Square: a keyhole to the future [Australia Square Tower]

1968

Gelatin silver print

49.9 × 39.2cm

Courtesy of Max Dupain and Associates

Jeff Carter (Australian, 1928-2010)

At the Pasha Nightclub, Cooma

c. 1957-1959

Gelatin silver print

Modern Times: The Untold Story of Modernism in Australia, edited by Ann Stephen, Philip Goad and Andrew McNamara, Powerhouse Publishing, 2008 (paperback).

Heide Museum of Modern Art

7 Templestowe Road,

Bulleen, Victoria 3105

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday

Public holidays

10am – 5pm

Heide Museum of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.